NOTIFICATIONS

Food’s journey through the digestive system.

- + Create new collection

A look at the time it takes for food to pass through the gut from mouth to anus. In a healthy adult, transit time is about 24–72 hours.

Read the article The human digestive system for further information.

Before eating: Sights, sounds and smells of food

Digestive activity begins with the sights, sounds and smells of food. Just looking at or smelling appetising food can result in the brain sending signals to the salivary glands to make the mouth water and to the stomach to secrete gastric juice.

Chewing: Ingestion 1

Chewing mechanically mixes food with saliva from the salivary glands. Amylase in saliva chemically digests starch in the food. The mixing process is lubricated by mucin , a slippery protein in saliva. Each mouthful takes approximately 30–60 seconds.

Swallowing: Ingestion 2

The food is formed into a small ball called a bolus, which is pushed to the back of the mouth by the tongue. Involuntary muscle contractions in the pharynx then push the bolus down towards the oesophagus. This swallowing reflex takes about 1–3 seconds.

Peristalsis: Ingestion 3

In the oesophagus, the bolus is moved along by rhythmic contractions of the muscles present in its walls. For a medium-sized bolus, it takes about 5–8 seconds to reach the stomach.

Time to empty: Stomach

Food is mixed with gastric juice. Strong muscular contractions in the stomach wall reduce the food to chyme – a thick milky material. The pyloric sphincter at the lower end of the stomach slowly releases chyme into the duodenum. Emptying the stomach takes 2–6 hours.

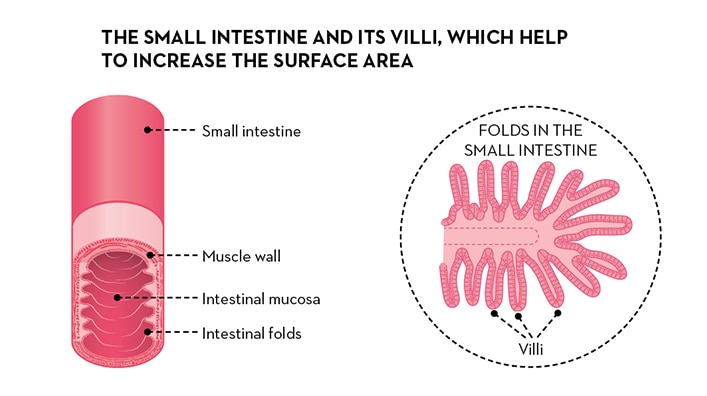

Time to empty: Small intestine

It takes 3–5 hours from entry to the duodenum to exit from the ileum. The small intestine’s structure of folds, villi and microvilli increases the absorptive surface area and allows maximum exposure to enzymes and complete absorption of the end products of digestion.

Digestion: Duodenum

Small amounts of chyme are ejected approximately every 20 seconds from the stomach into the duodenum. The chyme is mixed with secretions from the pancreas and gall bladder. These fluids contain bicarbonate, enzymes and bile salts essential to the digestion process.

Absorption: Jejunum

Peristaltic waves of muscular contraction mix and move the chyme down the duodenum and into the jejunum. It has a huge surface area created by finger-like structures called villi. These assist with the absorption of the end products of digestion into the bloodstream.

Absorption: Ileum

By the time chyme has reached the ileum, most of the digestion processes involving carbohydrate, protein and fats have occurred. Its main function is to absorb the end products of digestion and release hormones that regulate feelings of fullness.

Elapsed time: Ileocaecal valve

Undigested remains of food are passed through a one-way muscular valve into the first part of the large intestine known as the caecum – a small pouch that acts as a temporary storage site. By the time food remains have reached this point, about 5–12 hours have elapsed.

Colon time: Large intestine

The large intestine is 1.5–1.8m in length and is divided into the caecum, colon and rectum. The colon is further divided into 4 parts – ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon and sigmoid colon. Watch this video to find out more about the function of the large intestine .

Fermentation: Colon

Slower peristaltic movements push undigested food remains along the colon, which mix freely with the resident bacterial population. The bacteria ferment some of the food remains, producing short-chain fatty acids as well other important chemicals such as vitamin K.

Mass shift: Sigmoid colon

The liquid from the small intestine changes into a semi-solid form known as a stool. The sigmoid colon temporarily stores the stool until a mass movement empties it into the rectum. Residence time in the colon ranges from 4–72 hours, with a normal average of 36 hours.

Egestion: Rectum

The rectum’s external opening, the anus, is controlled by a set of muscles. When filled by a mass movement from the sigmoid colon, the rectum is stretched and produces the desire to defecate. If inhibited, the urge to defecate subsides but returns several hours later.

Watch this animated video: Digestion of food as a follow up to this article.

See our newsletters here .

Would you like to take a short survey?

This survey will open in a new tab and you can fill it out after your visit to the site.

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Digestion: How long does it take?

How long does it take to digest food — from the time you eat it to the time you excrete it?

Digestion time varies among individuals and between men and women. After you eat, it takes about six to eight hours for food to pass through your stomach and small intestine. Food then enters your large intestine (colon) for further digestion, absorption of water and, finally, elimination of undigested food. It takes about 36 hours for food to move through the entire colon. All in all, the whole process — from the time you swallow food to the time it leaves your body as feces — takes about two to five days, depending on the individual.

Elizabeth Rajan, M.D.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Goldman L, et al., eds. Disorders of gastrointestinal motility. In: Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Elsevier; 2020. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Nov. 11, 2019.

- Normal function. International Foundation for Gastrointestinal Disorders. https://aboutconstipation.org/normal-function.html. Accessed Nov. 11, 2019.

- Naish J, et al., eds. The alimentary system. In: Medical Sciences. 3rd ed. 2019. Elsevier; 2019. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Nov. 6, 2019.

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Your Digestive System and How It Works

The digestive system does important work for the body. Food isn't in a form the body can readily use, so it's the digestive system that has to break it down into parts. Through digestion, the body gets the nutrients it needs from foods and eliminates anything it doesn't need.

This is a really basic overview of the digestive system, but obviously, there's a whole lot more that goes into it that makes it all work. And, unfortunately, this also means that things can go wrong pretty easily.

Note: For the purposes of this article, we are discussing a healthy digestive tract that hasn't been altered by surgery, such as colectomy , gallbladder removal , or resection .

The Length of the Digestive System

The digestive system can vary in length from person to person but can be from about 25 to 28 feet long, with some being as long as about 30 feet in some people.

The esophagus is about 9 to 10 inches in length, the small intestine is about 23 feet long, and the large intestine is about 5 feet long, on average.

How Long It Takes for Food to Digest

The time it takes for food to digest can vary a bit from person to person, and between males and females. Studies have shown that the entire process takes about an average of 50 hours for healthy people, but can vary between 24 and 72 hours, based on a number of factors.

After chewing food and swallowing it, it passes through the stomach and small intestine over a period of 4 to 7 hours. The time passing through the large intestine is much longer, averaging about 40 hours. For men, the average time to digest food is shorter overall than it is for women.

Having a digestive condition that affects transit time (the time it takes for food to pass through the digestive system) can shorten or extend the time.

Why Digestion Is Important

We eat because we need nourishment but our food isn't something our bodies can easily assimilate into our cells. It is digestion that takes our breakfast and breaks it down. Once it's broken down into parts, it can be used by the body. This is done through a chemical process and it actually begins in the mouth with saliva.

Once the components of food are released they can be used by our body's cells to release energy, make red blood cells, build bone, and do all the other things that are needed to keep the body going. Without the digestive process, the body isn't going to be able to sustain itself.

From the Mouth to the Anus

The digestive system is one long tube that runs from your mouth to your anus. There are valves and twists and turns along the way, but eventually, the food that goes into your mouth comes out of your anus.

The hollow space inside the small and large intestines that food moves through is called the lumen . Food is actually pushed through the lumen throughout the digestive system by special muscles, and that process is called peristalsis.

When you chew food and swallow, these are the structures in your body that the food goes through during its journey down to the anus:

- Mouth: Food breakdown begins with chewing and the mixing of food with saliva. Once the food is chewed sufficiently, we voluntarily swallow it. After that, the digestive process is involuntary.

- Esophagus : Once the food is swallowed, it travels down the esophagus and through a valve called the lower esophageal sphincter to the stomach.

- Stomach: In digestion, the stomach is where the rubber meets the road. There are digestive juices that help break down the food and the muscles in the stomach mix the food up. After the stomach has done its job, there's another valve, called the pyloric valve, that allows food to move from the stomach and into the first part of the small intestine, which is called the duodenum.

- Small intestine: Once food reaches the small intestine , it's mixed with even more digestive juices from the pancreas and the liver to break it down. The peristalsis in the muscles is still at work, moving everything through. The small intestine is where most of the nutrients are extracted from food. The intestinal walls absorb vitamins and minerals. Anything that the body can't use or can't break down is moved through the entirety of the small intestine, through the ileocecal valve, and on to its next adventure in the large intestine.

- Large intestine: The large intestine doesn't do much digesting, but it is where a lot of liquid is absorbed from the waste material. Undigested materials are moved through, which can take a day or more, and then into the last part of the colon, which is the rectum. When there is stool in the rectum, it precipitates an urge to defecate, and finally, the waste materials are expelled out through the anus as a bowel movement.

A Word From Verywell

The digestive system affects so much of the rest of the body because all body systems need nourishment to function. Diseases and conditions of the digestive tract can have far-reaching implications for the rest of the body if nutrients aren't being absorbed properly. The digestive system is complex, and while there are some variations, for most people with healthy digestive systems, food takes about 50 hours to pass all the way through.

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Short Bowel Syndrome . Reviewed July 2015.

Lee YY, Erdogan A, Rao SSC. How to assess regional and whole gut transit time with wireless motility capsule . J Neurogastroenterol Motil . 2014 Apr;20(2):265-270. doi:10.5056/jnm.2014.20.2.265

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Your digestive system and how it works . Reviewed December 2017.

By Amber J. Tresca Tresca is a freelance writer and speaker who covers digestive conditions, including IBD. She was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis at age 16.

Advertisement

How long it takes to digest food, from beginning to end.

Ashley Jordan Ferira, Ph.D., RDN is Vice President of Scientific Affairs at mindbodygreen. She received her bachelor's degree in Biological Basis of Behavior from the University of Pennsylvania and Ph.D. in Foods and Nutrition from the University of Georgia.

Everybody digests food. But what happens from when food enters your mouth to when it exits your body may not be top of mind for most of us. How long does it take for food to digest? And why are some foods more difficult to digest than others?

From your first bite to the trip to the bathroom, we got to the bottom of everything you need to know (and likely more) about the inner workings of your digestive system.

How long does food take to digest?

Once food enters your mouth, it can take between two to six hours to hit your small intestine in a process known as gastric emptying. From there, the food will be digested for between two to six hours before going to your large intestine. This is where the food spends the longest amount of time, as it can take anywhere from 10 to 59 hours to pass, explains nutritionist Mackenzie Burgess, RDN .

"In addition to the macronutrient composition and diversity of your diet and supplements (think prebiotic fibers and targeted probiotics ), there is also individual variety from person to person when it comes to GI motility and speed,"* mindbodygreen's Vice President of Scientific Affairs Ashley Jordan Ferira, Ph.D., RDN , explains.

How long it takes to digest different foods

What you eat also affects how quickly the digestion process happens. Here's what to know about how quickly different macronutrients travel through the body:

Simple carbohydrates

When you've eaten foods like simple carbohydrates (think sugar or white bread), your body can digest them much more quickly, which is why they do not satiate you as well as more nutrient-dense foods that keep your digestive system busy for longer. "In fact digestion of simple or fast carbs starts straight away in your mouth, whereas fiber and other macronutrients remain intact," Ferira explains.

Proteins and fats

Fats and proteins move through your body at a slower rate, increasing the amount of time you feel full. "This is because proteins and fats are complex compounds that require more steps to be broken down," notes Burgess. "Fats, in particular, take longer to digest because they don't dissolve in water, which means an additional substance, bile, is needed for their digestion," she adds.

"The fiber content 1 of a food impacts how quickly it's digested," explains Burgess. "Foods higher in soluble fiber form a gel-like substance in the stomach, which slows down the digestive process. In contrast, foods high in insoluble fiber speed up the digestive process because they quickly pass unabsorbed into the large intestine, where they add bulk to stool." Both types of fiber are important to consume regularly, explains Ferira.

How digestion works

You may be surprised to learn that digestion actually begins before you even take your first bite of food. This is called the cephalic phase of digestion and is kicked off by the mere sight or smell (or even thought or taste) of food as your body prepares to eat.

Here's a peek at the role that different parts of the body play in the digestion process:

- Mouth : Once you've taken your first bite of food, the saliva in your mouth both moistens and helps digest food. As Ferira explains, "Along with chewing, your mouth is where digestion, or the breakdown of food into smaller bits, begins. In fact, your mouth (aka oral cavity) features its own unique set of microbes known as the oral microbiome."

- Esophagus : From our mouth, the food, beverages, and supplements we consume journey down the pharynx and esophagus to the stomach, where they are broken down further.

- Stomach : There are unique acidic compounds and protein- and fat-digesting enzymes in the stomach. "Muscular contractions in the stomach also contribute to the digestive process," adds Ferira.

- Small intestine : Your meal, or "bolus of digested food known as chyme," Ferira explains, will then move into the small intestine via the pyloric sphincter, where digestive enzymes (many of which are secreted by the pancreas) and bile from the gallbladder break it into even smaller pieces. These pieces are absorbed from the gut into the bloodstream to be utilized by the entire body. "A unique array of probiotic species reside in the small intestine, also interacting with our dietary inputs," Ferira says. You can expect food to travel through the muscle-lined small intestine for one to five hours depending on what you've eaten.

- Large intestine : Immediately following the small intestine is the large intestine (aka colon), where the gut musculature gradually moves along any remaining digested and undigested compounds. Another unique habitat of gut flora microbiota reside in the large intestine (given that we nourish our body with microbe-friendly foods and supplements ). Another important act is achieved in the colon: bulk. While significant amounts of water are absorbed from the gut into the bloodstream in the small intestine, "the final water absorption activity occurs in the colon, to functionally solidify the remaining indigestible components of our diet, creating stool," Ferira explains.

- Rectum : Finally, food reaches the end of the colon. Fiber assists in bulking up the stool that will then exit your body (via the rectum and finally, anus) at the end of your digestive tract.

Factors that affect digestion speed

Many factors can affect the speed of digestion outside of the foods you're putting into your body, from physical activity to stress. Some of these include:

- Your stress levels

- The types of foods you eat

- How much you eat

- How quickly you eat

- The health of your gut microbiome

- Your exercise routine

- Your thyroid function

- Medications you take

- Your hydration levels

- Your metabolic health

How to improve your digestion

There are plenty of ways to help keep your digestion ticking along smoothly. Here are a few strategies to start with:

Eat plenty of fruits and vegetables

A diet rich in fruits and vegetables will allow digestion to flow more smoothly as these ingredients are naturally rich in fiber . "Fruits and vegetables contain both soluble and insoluble fibers that are important for maintaining a healthy gut," explains Burgess. "Soluble fiber feeds gut bacteria, which then produce substances that can support a healthy gut microbiome 2 ."

Ferira agrees, adding that, "consuming prebiotic fiber regularly directly fuels postbiotic abundance via fermentation processes in the gut. Not to mention the health benefits the wide array of phytonutrients in fruits and vegetables also deliver."

Prioritize omega-3s

Incredibly healthy omega-3 fatty acids (like EPA, DHA, and ALA) are another functional nutrient that can help move food through the body more efficiently. "Omega-3s have been found 3 to help maintain the proper balance of good bacteria in your gut and support the integrity of your gut wall," adds Burgess.

What's more, they are "antioxidant and anti-inflammatory powerhouse fats, especially the marine-derived EPA and DHA varieties ," Ferira explains.

Regular movement and physical activity are great for a number of areas of the body, and digestion just so happens to be one of them. This is because exercise can promote motility in the gut, effectively cutting down on the time it takes for food to move through the body. " Studies show that exercise may improve gut health in many ways," says Burgess.

Take probiotics

If your digestion needs a boost of daily support, adding a targeted gut health supplement like mbg's probiotic+ can be a smart strategy to help ease bloat, promote regularity, and even aid in making the digestion process that much smoother.*

Eat slowly and mindfully

Eating at your computer isn't doing your digestion any favors! Stress has been known to cause you to feel full more quickly, leading to stomach discomfort and even queasiness from slowed digestion.

For this reason, it's important to eat slowly and savor your food so it can move smoothly through your gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

The takeaway

Seeing as digestion is a natural process that everybody completes, it can be useful to understand the ins and outs of what gets things move more smoothly. To aid digestion, focusing on eating a nutrient-dense diet with plenty of fiber. Taking an effective targeted probiotic can also help to move things along, bulk up stool, and support your overall health.*

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128051306000033

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23541470/

- https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/18/12/2645

Enjoy some of our favorite clips from classes

What Is Meditation?

Mindfulness/Spirituality | Light Watkins

Box Breathing

Mindfulness/Spirituality | Gwen Dittmar

What Breathwork Can Address

The 8 limbs of yoga - what is asana.

Yoga | Caley Alyssa

Two Standing Postures to Open Up Tight Hips

How plants can optimize athletic performance.

Nutrition | Rich Roll

What to Eat Before a Workout

How ayurveda helps us navigate modern life.

Nutrition | Sahara Rose

Messages About Love & Relationships

Love & Relationships | Esther Perel

Love Languages

This Decadent Dark Chocolate Granola Is High In Fiber & Low In Sugar

Jess Damuck

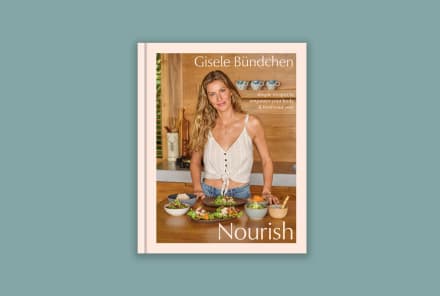

Here’s What Gisele Bündchen’s Daily Routine Looks Like (Smoothie Recipe Included)

Devon Barrow

Gisele's Pesto Chicken Lettuce Wraps Make The Perfect High-Protein Lunch

Gisele Bündchen

These Chocolate Walnut Bars Are A Sweet Treat That Won't Spike Your Blood Sugar

Tamara Green & Sarah Grossman

These Ice Cream Cookies Pack 41 Grams Of Protein For The Perfect Snack

Molly Knudsen, M.S., RDN

5 Cooking Oils To Avoid, Plus 8 Healthier Options To Reach For

Stephanie Eckelkamp

These 10-Minute Protein Pancakes Will Start Your Morning On The Right Foot

Valerie Bertinelli

Need A Make-Ahead Breakfast? Try These Anti-Inflammatory Smoothie Bombs

Carleigh Bodrug

I Grew Up Eating Macrobiotic—Try My Mom's Go-To Grain Bowl

Remy Morimoto Park

Popular Stories

Food’s transit time through body is a key factor in digestive health

The time it takes for ingested food to travel through the human gut – also called transit time – affects the amount of harmful degradation products produced along the way. This means that transit time is a key factor in a healthy digestive system. This is the finding of a study from the National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark, which has been published in the renowned journal Nature Microbiology.

Food has to travel through eight meters of intestine from the time it enters the mouth of an adult person until it comes out the other end. Recent research has focused mainly on the influence of the bacterial composition of the gut on the health of people’s digestive system.

Taking this a step further, Postdoc Henrik Munch Roager from the National Food Institute has studied how food’s transit time through the colon affects gut bacteria’s role in the activity and health of the digestive system by measuring the products of bacterial activity, which end up in urine.

The effect of food’s transit time

Intestinal bacteria prefer to digest dietary carbohydrates, but when these are depleted, the bacteria start to break down other nutrients such as proteins. Researchers have previously observed correlations between some of the bacterial protein degradation products that are produced in the colon and the development of various diseases including colorectal cancer, chronic renal disease and autism.

“In short, our study shows that the longer food takes to pass through the colon, the more harmful bacterial degradation products are produced. Conversely, when the transit time is shorter, we find a higher amount of the substances that are produced when the colon renews its inner surface, which may be a sign of a healthier intestinal wall,” Henrik’s supervisor and professor at the National Food Institute, Tine Rask Licht, explains.

It is commonly thought that a very diverse bacterial population in the gut is most healthy, however both the study from the National Food Institute and other brand news studies show that bacterial richness in stool is also often associated with a long transit time.

”We believe that a rich bacterial composition in the gut is not necessarily synonymous with a healthy digestive system, if it is an indication that food takes a long time to travel through the colon,” Tine Rask Licht says.

Better understanding of constipation as a risk factor

The study shows that transit time is a key factor in the activity of the intestinal bacteria and this emphasizes the importance of preventing constipation, which may have an impact on health. This is highly relevant in Denmark where up to as much as 20% of the population suffers from constipation from time to time.

The National Food Institute’s findings can help researchers better understand diseases where constipation is considered a risk factor, such as colorectal cancer and Parkinson’s disease as well as afflictions where constipation often occurs such as ADHD and autism.

Influencing food’s transit time

Tine Rask Licht emphasizes that people’s dietary habits can influence transit time:

”You can help food pass through the colon by eating a diet rich in fibre and drinking plenty of water. It may also be worth trying to limit the intake of for example meat, which slows down the transit time and provides the gut bacteria with lots of protein to digest. Physical activity can also reduce the time it takes for food to travel through the colon.”

- Gastrointestinal Problems

- Colon Cancer

- Agriculture and Food

- Food and Agriculture

- Gastrointestinal tract

- Healthy diet

- Cystic fibrosis

- Food groups

- Organic food

Story Source:

Materials provided by Technical University of Denmark (DTU) . Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference :

- Henrik M. Roager, Lea B. S. Hansen, Martin I. Bahl, Henrik L. Frandsen, Vera Carvalho, Rikke J. Gøbel, Marlene D. Dalgaard, Damian R. Plichta, Morten H. Sparholt, Henrik Vestergaard, Torben Hansen, Thomas Sicheritz-Pontén, H. Bjørn Nielsen, Oluf Pedersen, Lotte Lauritzen, Mette Kristensen, Ramneek Gupta, Tine R. Licht. Colonic transit time is related to bacterial metabolism and mucosal turnover in the gut . Nature Microbiology , 2016; 1: 16093 DOI: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.93

Cite This Page :

Explore More

- Asthma: Disease May Be Stoppable

- Stellar Collisions and Zombie-Like Survivors

- Tiny Robot Swarms Inspired by Herd Mentality

- How the Brain Regulates Emotions

- Evolution in Action? Nitrogen-Fixing Organelles

- Plastic-Free Vegan Leather That Dyes Itself

- Early Mesozoic Animals: High Growth Rates

- Virus to Save Amphibians from Deadly Fungus?

- 100 Kilometers of Quantum-Encrypted Transfer

- Intelligent Liquid

Trending Topics

Strange & offbeat.

Practical information

- Opening hours & Entrance fees

- Eat & Drink

- Getting here

Experience from home

- Virtual exhibitions

- E-collection

Exhibitions and activities

- Exhibitions

- Self-guided & Guided tours

- Workshops & Activities

April - September:

10:00 to 18:00

October - March:

10:00 to 17:00

Adults: CHF 15.00 Reduced rate: CHF 12.00 Children 6-15: CHF 6.00

Quai Perdonnet 25 1800 Vevey Switzerland

Our content

- Themes & stories

- Teaching resources

- Fact Sheets

- Potionarium

Our courses

Surprise me.

- Our mission

- Our history

- The Foundation

- Our partners

Think. Learn. Interact.

Create an account in seconds and discover the amazing Alimentarium experience !

A food journey through the body

The journey continues into the intestines, starting with the small intestine. Can you imagine that your small intestine is around 5 meters long? And that its total surface area amounts to approximately 200 m2, roughly equivalent to the size of a tennis court, due to folds and other projections (villi)? This 400-fold increase in surface area is important when it comes to ensuring that nutrients from our food can be absorbed in sufficient quantities.

The small intestine is divided into three sections: the duodenum, the jejunum and the ileum. On leaving our stomach, the chyme first enters the duodenum, where the small intestine is connected to the pancreas and the gallbladder, organs that are important for the digestive process in the intestines. The pancreas produces enzymes that are released into the small intestine and supports the breakdown of proteins, fats and carbohydrates. In addition to this, via the bicarbonate contained in the pancreatic juice neutralises the acidic chyme as it leaves the stomach. The gallbladder stores the bile fluid that is produced in the liver and enters the small intestine through the bile duct. The most important components of the bile fluid are the bile acids that are important for fat digestion. The chyme is thus combined with and digested by the digestive juices of the pancreas, bile fluid and the enzymes produced in the intestine. The large majority of nutrients, i.e. protein, fat and carbohydrates and vitamins, minerals and trace elements, are broken down into smaller components in the small intestine and transported to the body through the intestinal wall . The final section of the gastrointestinal tract is the large intestine (colon), which is approximately 1.50 meters long and ends at the rectum. The large intestine contains the intestinal flora - i.e. your large intestine is occupied by approximately 10 billion intestinal bacteria for every millilitre of colonic fluid . The role of the intestinal flora is to ferment fibers.

In comparison with the small intestine, not so much takes place in here in terms of digestion. The primary function of the large intestine is to remove water from the remaining chyme and thereby make it more concentrated, producing the faeces that are excreted through the anus. The length of time that the faeces remain in the anal canal depends on the amount of fibre in your diet – if you eat a high-fibre diet, the transport time is faster. By way of comparison, the chyme transit time in the large intestine is 2 – 3 days with a diet that is low in fibre, or 1 – 2 days with a high-fibre diet . The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) recommends daily consumption of 25g of fibre .

Biesalski, H-K; Grimm, P: Taschenatlas Ernährung. Thieme Verlag Stuttgart, 2011

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA; Hrsg.:): Scientific Opinion on Dietary Values for carbohydrates and dietary fibre. EFSA Journal 8, 3 (2010) 1462; http://www.efsa.europa.eu

Can’t find information on the site about your health concern or issue?

- Infographics

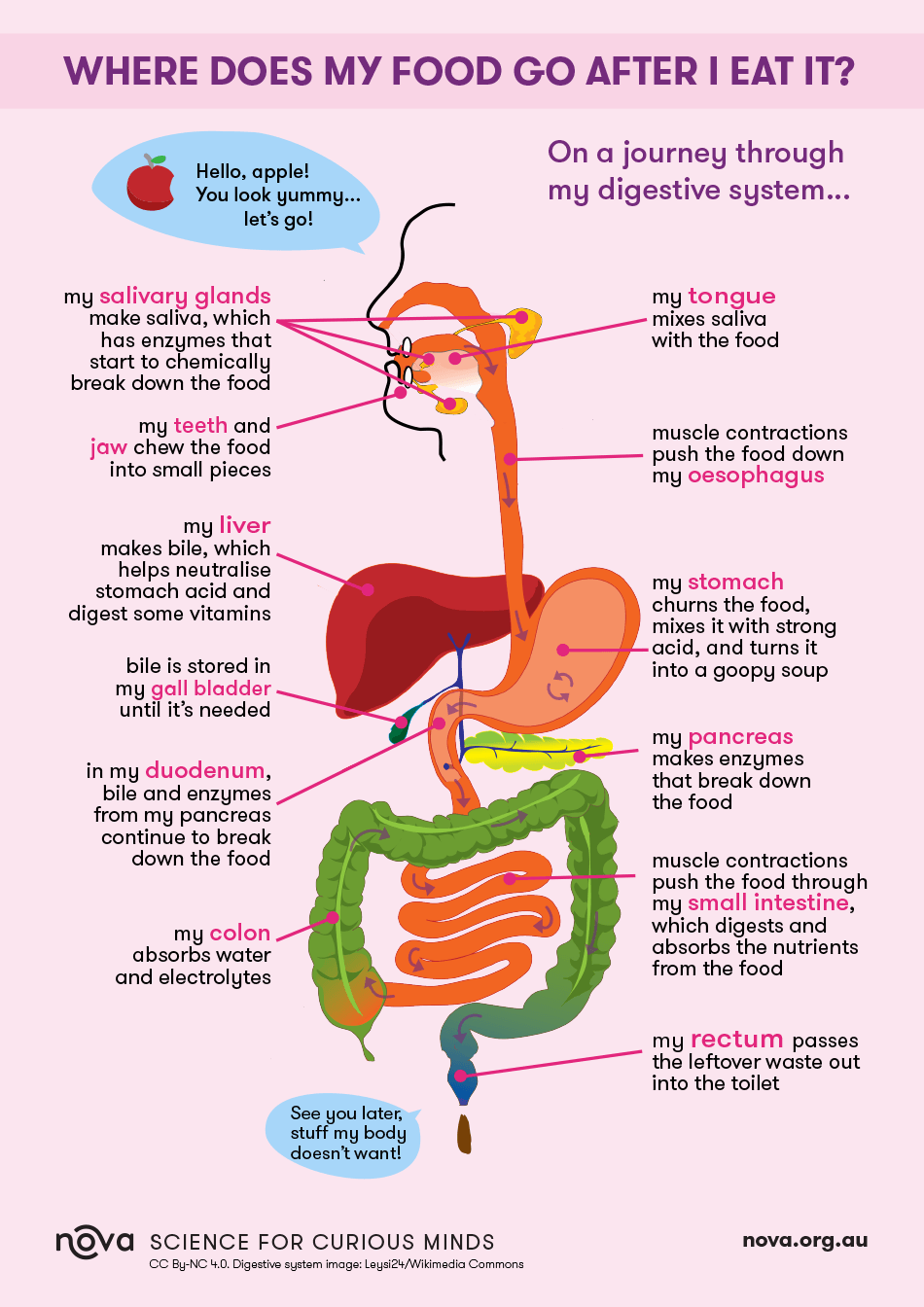

Where does my food go after I eat it?

Here’s what happens to your food as it travels through your body.

This infographic in text arrow

Where does my food go after I eat it? On a journey through my digestive system...

Hello, apple! You look yummy… let’s go!

- My salivary glands make saliva, which has enzymes that start to chemically break down the food

- My teeth and jaw chew the food into small pieces

- My tongue mixes saliva with the food

- Muscle contractions push the food down my oesophagus

- My stomach churns the food, mixes it with strong acid, and turns it into a goopy soup

- My liver makes bile, which helps neutralise stomach acid and digest some vitamins

- Bile is stored in my gall bladder until it’s needed

- In my duodenum, bile and enzymes from my pancreas continue to break down the food

- My pancreas makes enzymes that break down the food

- Muscle contractions push the food through my small intestine, which digests and absorbs the nutrients from the food

- My colon absorbs water and electrolytes

- My rectum passes the leftover waste out into the toilet

See you later, stuff my body doesn’t want!

More food, cleaner food—gene technology and plants

Feeding a hot, hungry world, the ins and outs of our digestive system.

How Far Does Your Food Travel to Get to Your Plate?

On the Hawaiian island of Maui is a sugar museum. It is next door to a sugar processing plant, and surrounded by acres of sugarcane growing. The museum tells the story of the history of sugarcane production on the island, and it is a fascinating testament to the power of one crop to shape the cultural makeup of a place.

The sugarcane growing on those fields is processed in the plant across the street, but only to the “raw sugar” stage. It is then shipped to the C & H Sugar Refinery in Contra Costa County, not far from San Francisco. C & H stands for “California and Hawai’i.” Here, it is refined into the white sugar that is such a ubiquitous part of our American diet.

But that’s not the end of its journey: the sugar is then shipped cross-country to New York, where it is packaged into little individual paper packages of sugar to go on tabletops, which are then distributed all across the country—including Hawai’i.

So if you drive a mile away from that sugarcane field and sit in a café, the sugar packets on your table have traveled about 10,000 miles: to California, to New York, and back again to Hawai’i, instead of the one mile you have between the field and the café.

How Far Does an Apple Travel?

Long-distrance travel is not the exception, but rather the rule, in our current food system. Shipping foodstuffs long distances for processing and packaging, importing,and exporting foods that don’t need to be imported or exported—these are standard practices in the food industry.

In 1996, it was reported that Britain imported more than 114,000 metric tons of milk. Was this because British dairy farmers did not produce enough milk for the nation’s consumers? No, since the UK exported almost the same amount of milk that year, 119,000 tons. Does this make sense?

Nowadays, it is not only tropical foodstuffs, such as sugar, coffee, chocolate, tea, and bananas, that are shipped long distances to come to our tables. It also fruits and vegetables that once grew locally, in household gardens and on small farms. An apple imported to California from New Zealand is often less expensive than an apple from the historic apple-growing county of Sebastopol, just an hour away from San Francisco. But is it really less expensive in the long run?

The True Cost of Food Miles

It is estimated that the meals in the United States travel about 1,500 miles to get from farm to plate. Why is this cause for concern? There are many reasons:

- This long-distance, large-scale transportation of food consumes large quantities of fossil fuels. It is estimated that we currently put almost 10 kcal of fossil fuel energy into our food system for every 1 kcal of energy we get as food.

- Transporting food over long distances also generates great quantities of carbon dioxide emissions. Some forms of transport are more polluting than others. Airfreight generates 50 times more CO2 than sea shipping. But sea shipping is slow, and in our increasing demand for fresh food, food is increasingly being shipped by faster—and more polluting—means.

- In order to transport food long distances, much of it is picked while still unripe and then gassed to “ripen” it after transport, or it is highly processed in factories using preservatives, irradiation, and other means to keep it stable for transport and sale. Scientists are experimenting with genetic modification to produce longer-lasting, less perishable produce.

Those of us who shop at farmers markets have begun to make the transition to supporting a local food system. At the Ferry Plaza Farmers Market in San Francisco, you are able to buy fruits, vegetables, meat, dairy products, eggs, honey, beans, and potatoes that are all grown within a couple of hundred miles of where you live.

An amazing array of foods can be grown here in California, with the Bay Area’s Mediterranean climate, the heat of the Central Valley, and the fog of the coast. We can eat locally and seasonally with very little sacrifice. Still, some crops simply aren’t appropriate for our climate. But we can begin to look at imported foods as things that supplement our local foods, rather than supplant them. We can make a coconut milk curry filled with local seasonal vegetables; we can put local cream into our imported coffee; we can dip local strawberries into melted, fair trade chocolate from cacao grown in the tropics.

Rebuilding a local food system doesn’t mean you never eat anything that has flown overseas, it just means that you start with what is fresh, local, and seasonal. Shopping at the farmers market, maintaining a home garden, or participating in a CSA are wonderful ways to support a local food system. At the same time we help build food security for future generations, feed ourselves and our families food that is delicious and nutritious, and support small-scale local farmers as they work each day to steward our land.

Food Mile Comparisons

A study called “Food, Fuel, and Freeways” put out by the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture in Iowa compiled data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to find out how far produce traveled to a Chicago “terminal market,” where brokers and wholesalers buy produce to sell to grocery stores and restaurants. We compared these figures to our Ferry Plaza Farmers Market to give you an idea of the difference.

Average Distances from Farm to Market

Terminal Market vs. Ferry Plaza Farmers Market

Apples: 1,555 miles vs. 77 miles

Tomatoes: 1,369 miles vs. 117 miles

Grapes: 2,143 miles vs. 134 miles

Beans: 766 miles vs. 101 miles

Peaches: 1,674 miles vs. 173 miles

Winter Squash: 781 miles vs. 98 miles

Greens: 889 miles vs. 99 miles

Lettuce: 2,055 miles vs. 102 miles

MSU Extension

How far did your food travel to get to you.

Becky <[email protected]> Henne, Michigan State University Extension - September 20, 2012

Choosing foods grown closer to home makes for more nutritious and better tasting foods, reducing air pollutants and helping the local economy.

As you sit down to your next meal, consider how many miles the food you are eating had to travel to arrive on your plate. Was it food grown locally or on some farm a continent or two away? According to a July 2003 study done by Michigan State University’s Center for Regional Food Systems , produce grown locally in Iowa traveled an average of 56 miles to market. While at the same time, conventionally-grown food traveled an average 1,494 miles to get to market. The study also reported that produce “traveled eight times (pumpkins) to 92 times (broccoli) farther than the local produce to reach the points of sale.”

According to the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), in 2007 the typical American meal had ingredients that on average originated from at least five foreign countries. Transporting this food to the U.S. requires several modes of transportation and the accompanying release of carbon emissions. Selecting food that has traveled a shorter distance reduces the demand for food that requires the long distance transportation air pollutants. In a study that the NRDC highlights in their November 2007 issue , when emissions from food grown locally was combined, it produced fewer carbon dioxide emissions than the import of one imported product.

Eating and purchasing food from the community supports your community by supporting the farms that grow the food and the businesses the farm in turn uses. The food less traveled is typically more nutritious and favored by many chefs for better taste. Chef Denene Vincent of Le Chat Gourmet attempts to source her food locally in order to find the best tasting ingredients.

The health tip for today is to decrease the miles your food travels and increase the distance your body travels.

This article was published by Michigan State University Extension . For more information, visit https://extension.msu.edu . To have a digest of information delivered straight to your email inbox, visit https://extension.msu.edu/newsletters . To contact an expert in your area, visit https://extension.msu.edu/experts , or call 888-MSUE4MI (888-678-3464).

Did you find this article useful?

Check out the Nutritional Sciences B.S. program!

Check out the Dietetics B.S. program!

new - method size: 3 - Random key: 0, method: tagSpecific - key: 0

You Might Also Be Interested In

AC3 Podcast episode 3

Published on June 30, 2021

What does this cover crop do for my farm?

Published on May 6, 2020

Innovative Online Tools for Conservation

Published on February 14, 2020

MSU Dairy Virtual Coffee Break: Fresh Research on Milk fever

Published on April 7, 2021

MI Community Minutes: Sustainability Efforts in Local Government with City of Holland's Dan Broersma

Published on January 24, 2022

MSU Dairy Virtual Coffee Break: Feed management 101

- community food systems

- food & health

- msu extension

- community food systems,

- food & health,

- msu extension,

Watch CBS News

How to travel around the Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse in Baltimore: A look at the traffic impact and alternate routes

By Rohan Mattu

Updated on: April 4, 2024 / 8:10 AM EDT / CBS Baltimore

BALTIMORE -- The collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore early on the morning of March 26 led to a major traffic impact for the region and cut off a major artery into and out of the port city.

Drivers are told to prepare for extra commuting time until further notice.

Alternate routes after Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse

Maryland transit authorities quickly put detours in place for those traveling through Dundalk or the Curtis Bay/Hawkins Point side of the bridge. The estimated 31,000 who travel the bridge every day will need to find a new route for the foreseeable future.

The outer loop I-695 closure shifted to exit 1/Quarantine Road (past the Curtis Creek Drawbridge) to allow for enhanced local traffic access.

The inner loop of I-695 remains closed at MD 157 (Peninsula Expressway). Additionally, the ramp from MD 157 to the inner loop of I-695 will be closed.

Alternate routes are I-95 (Fort McHenry Tunnel) or I-895 (Baltimore Harbor Tunnel) for north/south routes.

Commercial vehicles carrying materials that are prohibited in the tunnel crossings, including recreation vehicles carrying propane, should plan on using I-695 (Baltimore Beltway) between Essex and Glen Burnie. This will add significant driving time.

Where is the Francis Scott Key Bridge?

The Key Bridge crosses the Patapsco River, a key waterway that along with the Port of Baltimore serves as a hub for East Coast shipping.

The bridge is the outermost of three toll crossings of Baltimore's Harbor and the final link in Interstate 695, known in the region as the Baltimore Beltway, which links Baltimore and Washington, D.C.

The bridge was built after the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel reached capacity and experienced heavy congestion almost daily, according to the MDTA.

Tractor-trailer inspections

Tractor-trailers that now have clearance to use the tunnels will need to be checked for hazardous materials, which are not permitted in tunnels, and that could further hold up traffic.

The MDTA says vehicles carrying bottled propane gas over 10 pounds per container (maximum of 10 containers), bulk gasoline, explosives, significant amounts of radioactive materials, and other hazardous materials are prohibited from using the Fort McHenry Tunnel (I-95) or the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel (I-895).

Any vehicles transporting hazardous materials should use the western section of I-695 around the tunnels, officials said.

- Francis Scott Key Bridge

- Bridge Collapse

- Patapsco River

Rohan Mattu is a digital producer at CBS News Baltimore. Rohan graduated from Towson University in 2020 with a degree in journalism and previously wrote for WDVM-TV in Hagerstown. He maintains WJZ's website and social media, which includes breaking news in everything from politics to sports.

Featured Local Savings

More from cbs news.

In Baltimore, Biden announces more federal assistance after bridge collapse

Baltimore Ravens, Baltimore Orioles collectively donate $10 Million to Key Bridge Emergency Fund

Local organization set to host free job support days for displaced Port of Baltimore workers

Families of Key Bridge collapse victims will greet President Biden Friday

What we know about Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse

The Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore collapsed early Tuesday after being hit by a cargo ship, with large parts of the bridge falling into the Patapsco River.

At least eight people fell into the water, members of a construction crew working on the bridge at the time, officials said. Two were rescued, one uninjured and one in serious condition, and two bodies were recovered on Wednesday. The remaining four are presumed dead. The workers are believed to be the only victims in the disaster.

Here’s what we know so far.

Baltimore bridge collapse

How it happened: Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge collapsed after being hit by a cargo ship . The container ship lost power shortly before hitting the bridge, Maryland Gov. Wes Moore (D) said. Video shows the bridge collapse in under 40 seconds.

Victims: Divers have recovered the bodies of two construction workers , officials said. They were fathers, husbands and hard workers . A mayday call from the ship prompted first responders to shut down traffic on the four-lane bridge, saving lives.

Economic impact: The collapse of the bridge severed ocean links to the Port of Baltimore, which provides about 20,000 jobs to the area . See how the collapse will disrupt the supply of cars, coal and other goods .

Rebuilding: The bridge, built in the 1970s , will probably take years and cost hundreds of millions of dollars to rebuild , experts said.

- Baltimore bridge collapse: Crane arrives at crash site to aid cleanup March 29, 2024 Baltimore bridge collapse: Crane arrives at crash site to aid cleanup March 29, 2024

- Wes Moore envisioned economic revival. Then the Key Bridge collapsed. April 1, 2024 Wes Moore envisioned economic revival. Then the Key Bridge collapsed. April 1, 2024

- Officials studied Baltimore bridge risks but didn’t prepare for ship strike March 29, 2024 Officials studied Baltimore bridge risks but didn’t prepare for ship strike March 29, 2024

- Share full article

For more audio journalism and storytelling, download New York Times Audio , a new iOS app available for news subscribers.

Israel’s Deadly Airstrike on the World Central Kitchen

The story behind the pioneering aid group and how it mistakenly came under attack..

From “The New York Times,” I’m Michael Barbaro. This is “The Daily.”

The Israeli airstrike that killed seven aid workers delivering food in Gaza has touched off outrage and condemnations from across the world. Today, Kim Severson on the pioneering relief crew at the center of the story, and Adam Rasgon on what we’re learning about the deadly attack on the group’s workers. It’s Thursday, April 4.

Kim, can you tell us about the World Central Kitchen?

World Central Kitchen started as a little idea in Chef José Andrés’ head. He was in Haiti with some other folks, trying to do earthquake relief in 2010. And his idea at that point was to teach Haitians to cook and to use solar stoves and ways for people to feed themselves, because the infrastructure was gone.

And he was cooking with some Haitians in one of the camps, and they were showing him how to cook beans the Haitian way. You sort of smash them and make them a little creamy. And it occurred to him that there was something so comforting for those folks to eat food that was from their culture that tasted good to them. You know, if you’re having a really hard time, what makes you feel good is comfort food, right? And warm comfort food.

So that moment in the camp really was the seed of this idea. It planted this notion in José Andrés’ mind, and that notion eventually became World Central Kitchen.

And for those who don’t know, Kim, who exactly is Chef José Andrés?

José Andrés is a Spanish chef who cooked under some of the Spanish molecular gastronomy greats, came to America, really made his bones in Washington, DC, with some avant-garde food, but also started to expand and cook tapas, cook Mexican food. He’s got about 40 restaurants now.

Yeah. And he’s got a great Spanish restaurant in New York. He’s got restaurants in DC, restaurants in Miami.

Come with me to the kitchen. Don’t be shy.

He’s also become a big TV personality.

Chef, are you going to put the lobster in the pot with the potatoes?

We’re going to leave the potatoes in.

Leave the potatoes in!

He’s one of the most charismatic people I’ve ever been around in the food world.

He’s very much the touchstone of what people want their celebrity chefs to be.

So how does he go from being all those things you just described, to being on the ground, making local comfort food for Haitians? And how does this all go from an idea that that would be a good idea, to this much bigger, full-fledged humanitarian organization?

So he started to realize that giving people food in disaster zones was a thing that was really powerful. He helped feed people after Hurricane Sandy, and he realized that he could get local chefs who all wanted to help and somehow harness that power. But the idea really became set when he went to Houston in 2017 to help after Hurricane Harvey.

And that’s when he saw that getting local chefs to tap into their resources, borrowing kitchens, using ingredients that chefs might have had on hand or are spoiling in the fridge because the power is out and all these restaurants needed something to do with all this food before it rotted — harnessing all that and putting it together and giving people well-cooked, delicious — at least as delicious as it can be in a disaster zone — that’s when World Central Kitchen as we know it today sort of emerged as a fully formed concept.

The first pictures now coming in from Puerto Rico after taking a direct hit — Hurricane Maria slamming into the island. And as you heard, one official saying the island is destroyed.

Shortly after that, he flew to Puerto Rico, where Hurricane Maria had pretty much left the entire island without water and in darkness.

He flew in on one of the first commercial jets that went back in. He got a couple of his chef buddies whose kitchens were closed, and they just decided to start cooking. They were basically just serving pots of stew, chicken stew, in front of the restaurants.

The lines got longer. And of course, chefs are a really specific kind of creature. They really like to help their community. They’re really about feeding people.

So all the people who were chefs or cooks on the ground in Puerto Rico who could wanted to help. And you had all these chefs in the States who wanted to fly down and help if they could, too. So you had this constant flow of chefs coming in and out. That’s when I went down and followed him around for about a week.

And what did you see?

Well, one of the most striking things was his ability to get food to remote places in ways the Salvation Army couldn’t and other government agencies that were on the ground couldn’t. You know, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, FEMA, doesn’t deliver food. It contracts with people to deliver food.

So you have all these steps of bureaucracy you have to go through to get those contracts. And then, FEMA says you have to have a bottle of water and this and that in those boxes. There’s a lot of structure to be able to meet the rules and regulations of FEMA.

So José doesn’t really care about rules and regulations very much. So he just got his troops together and figured out where people needed food. He had this big paper map he’d carry around and lay out. And he had a Sharpie, and he’d circle villages where he’d heard people needed food or where a bridge was out.

And then he would dispatch people to get the food there. Now, how are you going to do that? He was staying in a hotel where some National Guard and military police were staying to go patrol areas to make sure they were safe. He would tuck his big aluminum pans of food into the back of those guys’ cars, and say, Could you stop and drop these off at this church?

During that time in Puerto Rico, he funded a lot of it off of his own credit cards or with cash. And then he’s on the phone with people like the president of Goya or his golf buddies who are well-connected, saying, hey, we need some money. Can you send some money for this? Can you send some money for that?

So he just developed this network, almost overnight. I mean, he is very much a general in the field. He wears this Orvis fishing vest, has cigars in one pocket, money in the other. And he just sets out to feed people.

And there were deliveries that were as simple as he and a couple of folks taking plastic bags with food and wading through a flooded parking lot to an apartment building where an older person had been stuck for a few days and couldn’t get out, to driving up to a community that had been cut off. There was a church that was trying to distribute food.

We drive through this little mountain road and get to this church. We start unloading the food, and the congregation is inside the church. José comes in, and the pastor thanks him so much. And the 20 people or so who are there gather around José, and they begin praying.

And he puts his head down. He’s a Catholic. He’s a man who prays. He puts his head down. He’s in the middle of these folks, and he starts to pray with them. And then, pulls out his map, circles another spot, and the group is off to the next place.

And when Russia invades Ukraine, he immediately decided it was time for World Central Kitchen to step into a war zone. You know, so many people needed to eat. So many Ukrainians were crossing the border into Poland.

There are refugees in several countries surrounding Ukraine. So a lot of the work that they did was feeding the refugees. They set up big operations around train stations, places where refugees were coming, and then they were able to get into cities.

One of their operations did get hit with some armaments early on. Nobody was hurt badly. But I think that was the first time that they realized this was an actually more dangerous situation than perhaps going in after there’s been an earthquake.

But the other thing that really made a difference here is, José Andrés and World Central Kitchen would broadcast on social media, live from the kitchens. In the beginning, he’d be holding up his phone and saying, we put out 3 million meals for the people of Puerto Rico, chefs for Puerto Rico. It was very infectious.

And now, one of the standard operating procedures for people who are in the World Central Kitchens is to hold up the phone like that — you can see the kitchen, busy in the back — and talk about how many meals they’ve served. They have these kind of wild meal counts, which one presumes are pretty accurate. But they’re like, we served 320,000 meals this morning to the people of Lviv.

I mean, that scale seems important to note. This is not the kind of work that feeds a few people and a few towns. When you’re talking about 300,000 meals in a morning, you’re talking about something that begins, it would seem, to rival the scope and the reach of the groups that we tend to think of as the most important in the disaster-relief world.

Absolutely. And the meals — there are lots and lots and lots of meals. But also, World Central Kitchen hires local cooks. They’ll hire food truck operators, who obviously have no work, and pay them to go out and deliver the meals. They’ll pay local cooks to come in and cook. That’s what they do with a lot of their donations, which is very different than other aid organizations. And this then helps the local economy. He’s trying to buy as much local food as he can. That keeps the economy going in the time of a disaster. So that’s a piece of his operation that is a little different than traditional aid operations.

So walk us up to October 7, when Hamas attacked Israel. What does Chef José Andrés and the World Kitchen do?

Well, he had had such impact in Ukraine. And I think the organization itself thought that they had the infrastructure to now take food into another war zone. Gaza, of course, was nothing like Ukraine. But World Central Kitchen shows up. They’re nimble. They start to connect with local chefs.

Right now, they have about 60 kitchens in the areas around Gaza, and they’ve hired about 400 Palestinians to help do that. But getting the food into Gaza became the difficulty.

How do you actually get the food into the Gaza Strip? Large amounts of food that require trucks? You’ve got to realize, getting food into Gaza right now requires going through Israeli checkpoints.

And that slows the operation down. You might get eight trucks a day in, and that is such a small amount of food. And this has been incredibly difficult for any aid operations.

So World Central Kitchen, playing on the experience that they had in a war zone and working with government entities and trying to coordinate permissions — they took that experience from Ukraine and were trying to apply it in the Gaza Strip. Now, they had worked for a long time with Israeli officials. They wanted to make sure that they could get their food in.

And they decided that the best way to do it would be to take food off of ships, get it in a warehouse, and then get that food into Gaza. It took a long time to pull those permissions through, but they were able to get the permissions they needed and set this system up, so they could move the food fairly quickly into North Gaza.

And once they get those permissions, how big a player do they become in Gaza?

World Central Kitchen became a kind of a fulcrum point for getting food aid in to Gaza in a way that a larger and more established humanitarian aid operations couldn’t, in part because they were small and nimble in their way. So the amount of food they were moving maybe wasn’t as large as some of the more established humanitarian aid organizations, but they had so much goodwill. They had so much logistical knowledge.

They were working with local Palestinians who knew the food systems and who understood how to get things in and out. So they were able to find a way to use a humanitarian corridor to have permissions from the Israeli government, to be able to move this food back and forth. And that’s always been the secret to World Central Kitchen — is incredibly nimble. So —

Just like in Puerto Rico, they seemed to win over just about everybody and do the seemingly impossible.

Right. And World Central Kitchen says they delivered 43 million meals to Gazans since the start of the war. And I don’t think there was any other group that could have pulled this off.

Hey, this is Zomi and Chef Olivier. We’re at the Deir al-Balah kitchen. And we’ve got the mise en place. Tell us a little bit about it, Chef.

And then, this caravan, this fairly efficient caravan of armored vehicles, labeled with World Central Kitchen logo on the roof, on the sides — the idea was they head on — this humanitarian quarter, they head on this road. The seven people who went all in vests — three of whom are security people from Great Britain — you have another World Central Kitchen employee who has handled operations in Asia, in Central America. She’s quite a veteran of the World Central Kitchen operation.

And you have a young man who someone told me was like the Michael Jordan of humanitarian aid, who hooked up with World Central Kitchen in Poland. He was a hospitality student and had just become an indispensable make-it-happen guy. And you have a Palestinian guy who’s 25, a driver.

So this is the team. They have all the clearances. They have the well-marked vehicles. It seemed like a very simple, surgical kind of operation. And of course, now, as we know, it was anything but that.

After the break, my colleague Adam Rasgon on what happened to the World Central Kitchen workers in that caravan. We’ll be right back.

So Adam, what ends up happening to this convoy that our colleague Kim Severson just described from World Central Kitchen?

So what we know is that members of the World Central Kitchen had been at a warehouse in Deir al-Balah in the Central Gaza Strip. They had just unloaded about 100 tons of food aid that had been brought via a maritime route to the coast of the Gaza Strip. When they departed the warehouse, they were in three cars.

Two of the cars were armored cars, and one was a soft-skinned car, according to the organization. When the cars reached the coastal road, known as Al Rashid Street, they started to make their way south.

And what do we know about how much the World Central Kitchen would have told the Israeli military about their plans to be on this road?

Yeah. So the World Central Kitchen said that its movements were coordinated. And in military speak or in technical speak, people often refer to this as deconfliction. So basically, this process is something that not only the World Central Kitchen but the UN, telecommunications companies going out to repair damaged telecommunications infrastructure, others would use, where they basically provide the Israeli military with information about the people who are traveling — their ID numbers, their names, the license plate numbers of the cars they’ll be traveling in.

They’ll sort of explain where their destination is. And the general process is that the Israelis will then come back to them and say, you’re approved to travel from this time, and you can take this specific route.

And do we know if that happened? If the IDF said, you’re approved, use this route on this night?

So we heard from the World Central Kitchen that they did receive this approval. And the military hasn’t come out and said that it wasn’t approved. So I think it’s fair to assume that their movements were coordinated and de-conflicted.

OK. So what happens as this seemingly pre-approved and coordinated convoy trip is making this leg of the journey?

They started to make their way south towards Rafah. And the three cars suddenly came under fire. The Israeli army unleashes powerful and devastating strikes on the three cars in the convoy, most likely from a drone. The strikes rip through the cars, killing everyone inside.

Shortly thereafter, ambulances from the Palestine Red Crescent are dispatched to the location. They retrieve the dead bodies.

They bring those bodies to a hospital. And at the hospital, the bodies are laid out, and journalists start to report to the world that indeed, five members of the World Central Kitchen staff have been killed. And the Palestine Red Crescent teams were continuing to search for other bodies and eventually brought back two more bodies to the hospital for a total of seven people killed in these airstrikes.

And when the sun comes up, what does it end up looking like — the scene of these struck trucks from this convoy?

So early in the morning when the sun comes up, a number of Palestinian journalists headed out to the coastal road and started taking pictures and videos. And I received a series of videos from one of the reporters that I was in touch with, essentially showing three cars, all heavily damaged. One had a World Central Kitchen logo on top of it, with a gaping hole in the middle of the roof.

A second car was completely charred. You could barely recognize the structure of the car. The inside of it had been completely charred, and the front smashed.

And do we know if the strike on this convoy was the only strike happening in this area? In other words, is it possible that this convoy was caught in some kind of a crossfire or in the middle of a firefight, or does it appear that this was quite narrow, and was the Israeli army targeting these specific vehicles, whether or not they realized who was in it?

We don’t have any other indication that there was another strike on that road around that time.

What that suggests, of course, is that this convoy was targeted. Now, whether Israeli officials knew who was in it, whether they were aid workers, seems like a yet-unresolved question. But it does feel very clear that the trucks in this convoy were deliberately struck.

Yes. I do think the trucks in this convoy were deliberately struck.

What is the reaction to these airstrikes on this convoy and to the death of these aid workers?

Well, one of the first reactions is from the World Central kitchen’s founder, José Andrés.

Chef José Andrés, who founded World Central Kitchen, calling them angels.

He said he was heartbroken and grieving.

And adding the Israeli government needs to stop this indiscriminate killing.

And then, he accused Israel of using food as a weapon.

What I know is that we were targeted deliberately, nonstop, until everybody was dead in this convoy.

And he just seemed devastated and quite angry.

And so what is the reaction from not just World Central Kitchen, but from the rest of the world to this airstrike?

There’s, frankly, fury and outrage.

The White House says it is outraged by an Israeli airstrike that killed seven aid workers in Gaza, including one American.

President Biden, who has been becoming increasingly critical of Israel’s approach to this war — he came out and said that he was outraged and heartbroken.

Certainly sharper in tone than we have heard in the past. He says Israel has not done enough to protect aid workers trying to deliver desperately needed help to civilians. Incidents like yesterday’s simply should not happen. Israel also has not —

And we’re seeing similar outrage from foreign governments. The British Foreign Secretary David Cameron —

The dreadful events of the last two days are a moment when we should mourn the loss of these brave humanitarian workers.

— said that the airstrikes were completely unacceptable. And he called on Israel to explain how this happened and to make changes to ensure that aid workers could be safe.

So amid all this, what does Israel have to say about the attack — about how it happened, about why it happened?

The response from Israel this time was much different, compared to other controversial airstrikes on the Gaza Strip. Often, when we’re reporting on these issues, we’ll hear from the army that they’re investigating a given incident. It will take days, if not weeks, to receive updates on where that investigation stands.

There are instances where Israel does take responsibility for harming civilians, but it’s often rare. This time, the Prime Minister —

[NON-ENGLISH SPEECH]

— Benjamin Netanyahu comes out with a video message —

— saying that Israel had unintentionally harmed innocent civilians. And that was the first indication or public indication that Israel was going to take responsibility for what had happened.

The IDF works together closely with the World Central Kitchen and greatly appreciates the important work that they do.

We later heard from the military’s chief of staff. Herzi Halevi issued a video statement in English.

I want to be very clear the strike was not carried out with the intention of harming aid workers. It was a mistake that followed a misidentification.

And he said this mistake had come after a misidentification. He said it was in the middle of a war, in a very complex condition. But —

This incident was a grave mistake. We are sorry for the unintentional harm to the members of WCK.

He was clear that this shouldn’t have happened.

I want to talk about that statement, because it seems to suggest — that word, “misidentification”— that the Israeli army believed that somebody else was in this convoy, that it wasn’t a bunch of aid workers.

That’s possible, although it’s extremely vague and cryptic language that genuinely is difficult to understand. And it’s a question that us in the Jerusalem Bureau have been asking ourselves.

I’m curious if the Israeli government has said anything in all of its statements so far about whether it noticed these markings on these three cars in the convoy. Because that, I think, for so many people, stands out as making misidentification hard to understand. It seems like perhaps a random pickup truck could be misidentified as perhaps a vehicle being used by a Hamas militant. But a group of World Central Kitchen trucks with their name all over it, driving down a known aid corridor — that becomes harder to understand as misidentification.

Yeah, it’s an important question. And at this moment, we don’t know exactly what the Israeli reconnaissance drones could see, and whether or not they were able to see, in the darkness of the night, the markings of the World Central Kitchen on the cars. But what is clear is that when the cars were found in the morning, right there was the big emblazoned logo of the World Central Kitchen.

Mm-hmm. I’m curious how you think about the speed with which Israel came out and said it was in the wrong here. Because as you said, that’s not how Israel typically reacts to many of these situations. And that makes me think that it might have something to do with the nature of the aid group that was the target of these airstrikes — the World Central Kitchen — and its story.

I think it does have to do with this particular group. This is a group that’s led by a celebrity chef, very high-profile, who is gone around the world to conflict zones, disaster areas, to provide food aid. And I also think it has to do with the people who were killed, most of who were Western foreign aid workers. Frankly, I don’t think we would be having this conversation if a group of Palestinian aid workers had been killed.

Nor, perhaps, would we be having the reaction that we have had so far from the Israeli government.

I would agree with that.

Adam, at the end of the day, what is going to be the fallout from all of this for the people of Gaza? How do we think that this attack on World Central Kitchen is going to impact how food, medicine, aid is distributed there?

So the World Central Kitchen has said that it’s suspending its operations across Gaza. Because it essentially seems that they don’t feel they can safely operate there right now. And several ships that carried aid for the organization, which were sort of just on the coast — those ships ended up turning back to Cyprus, carrying more than 200 tons of aid.

So aid that was supposed to reach the people of Gaza is now leaving Gaza because of this attack.

Yes. And it’s also had a chilling effect. Another aid group, named INARA, has also suspended its operations in Gaza. And it seems that there is concern among humanitarians that other aid groups could follow.

So in a place where people are already suffering from severe hunger, poor sanitation, the spread of dangerous disease, this is only going to make the humanitarian situation, which is already dire, even worse.

Well, Adam, thank you very much. We appreciate it.

Thanks so much for having me.

We’ll be right back.

Here’s what else you need to know today. The magnitude-7.4 earthquake that struck Taiwan on Wednesday has killed nine people, injured more than 1,000, and touched off several landslides. It was Taiwan’s strongest quake in the past 25 years. But in a blessing for the island’s biggest cities, its epicenter was off the island’s east coast, relatively far from population centers like Taipei.

And the first patient to receive a kidney transplant from a genetically modified pig has fared so well that he was discharged from a Massachusetts hospital on Wednesday just two weeks after surgery. Two previous transplants from genetically modified pigs both failed. Doctors say the success of the latest surgery represents a major moment in medicine that, if replicated, could usher in a new era of organ transplantation.

Today’s episode was produced by Lynsea Garrison, Olivia Natt, and Carlos Prieto, with help from Asthaa Chaturvedi. It was edited by Marc Georges, with help from Paige Cowett, contains original music by Marion Lozano and Dan Powell, and was engineered by Chris Wood. Our theme music is by Jim Brunberg and Ben Landsverk of Wonderly.

That’s it for “The Daily.” I’m Michael Barbaro. See you tomorrow.

- April 5, 2024 • 29:11 An Engineering Experiment to Cool the Earth

- April 4, 2024 • 32:37 Israel’s Deadly Airstrike on the World Central Kitchen

- April 3, 2024 • 27:42 The Accidental Tax Cutter in Chief

- April 2, 2024 • 29:32 Kids Are Missing School at an Alarming Rate

- April 1, 2024 • 36:14 Ronna McDaniel, TV News and the Trump Problem

- March 29, 2024 • 48:42 Hamas Took Her, and Still Has Her Husband

- March 28, 2024 • 33:40 The Newest Tech Start-Up Billionaire? Donald Trump.

- March 27, 2024 • 28:06 Democrats’ Plan to Save the Republican House Speaker

- March 26, 2024 • 29:13 The United States vs. the iPhone

- March 25, 2024 • 25:59 A Terrorist Attack in Russia

- March 24, 2024 • 21:39 The Sunday Read: ‘My Goldendoodle Spent a Week at Some Luxury Dog ‘Hotels.’ I Tagged Along.’

- March 22, 2024 • 35:30 Chuck Schumer on His Campaign to Oust Israel’s Leader

Hosted by Michael Barbaro

Featuring Kim Severson and Adam Rasgon

Produced by Lynsea Garrison , Olivia Natt , Carlos Prieto and Asthaa Chaturvedi

Edited by Marc Georges and Paige Cowett

Original music by Dan Powell and Marion Lozano

Engineered by Chris Wood

Listen and follow The Daily Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music

The Israeli airstrike that killed seven workers delivering food in Gaza has touched off global outrage and condemnation.

Kim Severson, who covers food culture for The Times, discusses the World Central Kitchen, the aid group at the center of the story; and Adam Rasgon, who reports from Israel, explains what we know about the tragedy so far.

On today’s episode

Kim Severson , a food correspondent for The New York Times.

Adam Rasgon , an Israel correspondent for The New York Times.

Background reading

The relief convoy was hit just after workers had delivered tons of food .

José Andrés, the Spanish chef who founded World Central Kitchen, and his corps of cooks have become leaders in disaster aid .

There are a lot of ways to listen to The Daily. Here’s how.

We aim to make transcripts available the next workday after an episode’s publication. You can find them at the top of the page.