- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Health Care

Why an er visit can cost so much — even for those with health insurance.

Terry Gross

Vox reporter Sarah Kliff spent over a year reading thousands of ER bills and investigating the reasons behind the costs, including hidden fees, overpriced supplies and out-of-network doctors.

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

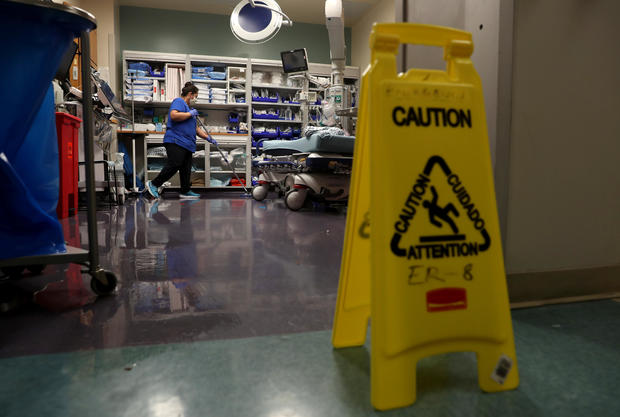

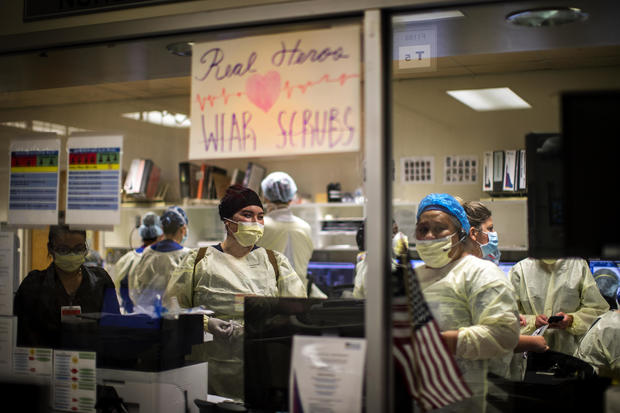

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. You wouldn't believe what some emergency rooms charge, or maybe you would because you've gotten bills. For example, one hospital charged $76 for Bacitracin antibacterial ointment. One woman who fell and cut her ear and was given an ice pack but no other treatment was billed $5,751. My guest, Sarah Kliff, is a health policy journalist at vox.com who spent over a year investigating why ER bills are so high even with health insurance and why the charges vary so widely from one hospital to the next.

Through crowdsourcing, she collected over a thousand ER bills from around the country. She interviewed many of the patients and the people behind the billing. She's reported her findings in a series of articles on Vox. She's also spent years reporting on the battle over health insurance policy. We'll get some updates on the state of Obamacare a little later in the interview.

Sarah Kliff, welcome back to FRESH AIR. Why did you want to do an investigation into emergency room billing?

SARAH KLIFF: You know, I wanted to do this because the emergency room is such a common place where Americans interact with the health care system. There are about 140 million ER visits each year. It's a place where you can't really shop for health care. You can't make a lot of decisions about where you want to go. So I think that is big-picture what got me interested.

Small picture was actually a bill that someone sent me almost three years ago now, where they took their daughter to the emergency room. A Band-Aid was put on the daughter's finger, and they left. And they got a $629 bill. And they said - you know, they - the parents sent this to me, saying, how could a Band-Aid cost $629? And I said, I don't know, but I'm going to find out. And that kind of opened up the door to this, you know, multi-year project I've been working on right now. It started with trying to figure out why a Band-Aid would cost $629.

GROSS: OK. So let's get to that $629 for treatment that was basically a Band-Aid placed on a finger. You investigated that bill.

KLIFF: Yes.

GROSS: Why'd it cost so much?

KLIFF: So what cost so much was really the facility fee. So this is a charge I hadn't heard about before as a health care reporter. This is a charge that hospitals make for just keeping their doors open, keeping the lights on, the cost of running an emergency room 24/7. So if you look at that particular patient's bill, the Band-Aid - you know, I hesitate to say only - but the Band-Aid only cost $7, which, as anyone who's bought Band-Aids knows, is quite expensive for a single Band-Aid.

But the other $622 of that bill were the hospital's facility fees for just walking in the door and seeking service. And these fees are not made public. They vary wildly from one hospital to another. And usually patients only find out what the facility fee of their hospital is when they receive the bill afterwards, like that patient, you know, that sent me this particular bill.

GROSS: And does the facility fee vary from facility to facility?

KLIFF: It does significantly. You know, I've seen some that are in the low hundreds. I've seen some that are in the high thousands. And it's impossible to know what facility fee you're going to be charged until you actually get the billing documents from your hospital. And if you try and call up a hospital and ask what the facility fee is, usually you won't get very far.

So it's this fee that, from all the ER bills I've read, is usually the biggest line item on the bill. But it's also one that is very, very difficult to get good information about until you've already been charged.

GROSS: So you're paying the facility fee to basically share in the cost of running the emergency room.

KLIFF: Yes, that's how hospital executives would describe the fee.

GROSS: But you don't know that when you're going to the emergency room.

KLIFF: You don't, no. And you don't know how much it'll be. You don't know how it's being split up between different patients. You don't know any of that.

GROSS: So is this also why one bill had $60 for the treatment of ibuprofen and another $238 for the treatment of eyedrops?

KLIFF: Yeah. And, you know, this is something I see all the time reading emergency bills - I've read about 1,500 of them at this point - is that things you could buy in a drugstore often cost significantly more in the emergency room. And the people I talked to who run hospitals will say this is because they have to be open all the time. They have to have so many supplies ready.

But I think one of the things that I find pretty frustrating is, you know, patients aren't usually told, we can give you an ibuprofen here, or you can pick some up at the drugstore if you leave, and the cost will be a fraction of what we would charge you here. That information often isn't conveyed to patients who are well enough, you know, to go to a drugstore on their own. But it's just huge variation for these simple items.

One place I see this a lot is pregnancy tests. If you're a woman who's of childbearing age, you go to the emergency room, they will often want to check if you're pregnant. I've seen pregnancy tests that cost a few dollars in emergency room. The most expensive one I saw was over $400. I believe that was at a hospital in Texas. It's just widespread variation for, you know, some pretty simple pieces of medical equipment.

GROSS: I want to get back to the $60 ibuprofen. Is that - does that include the facility fee? Or is that just for the ibuprofen, and the facility fee is separate?

KLIFF: That's just for the ibuprofen. The facility fee is totally separate.

GROSS: So how do they justify that?

KLIFF: They say they have to stock, like, a wide array of medicine, so they have to have everything on hand from ibuprofen, from, you know, expensive rabies treatments - I've talked to a lot of people who've been to the emergency room for exposure to bats and raccoons - and that they need to have all these things in stock. And, you know, one of the things you pay for at the emergency room is the ability to get any medication at any hour of the day right when you need it. I don't necessarily buy that explanation, to be clear. That's what I've heard from hospital executives.

I think it's pretty telling that ibuprofen has a very, very different price depending on which emergency room you go to. The fact that there's so much widespread price variation suggests to me that it's not just the cost of doing business driving it, that there's also business decisions being made behind ibuprofen that are driving the prices different hospitals are setting.

GROSS: Now, of course, trips to the emergency room aren't always as simple as getting a Band-Aid or ibuprofen or some eyedrops. I want you to describe the case of a young man who was hit by a pole on a city bus in San Francisco.

KLIFF: Yeah. So this patient, his name is Justin. He was a community college student in northern California, was walking down a sidewalk in downtown San Francisco one day. And there was a pole hanging off the back of the bus that wasn't where it's supposed to be. It essentially flew off the back of the bus, hit him in the face and knocked him unconscious.

And the next thing he knows, he's waking up at Zuckerberg San Francisco General, which is the only Level I trauma center in the city. He ends up needing a CT scan to check out some brain injuries. He needs some stitches. And then he's discharged. He ends up with a bill for $27,000.

But, you know, as I began figuring out through my reporting, San Francisco General does not contract with private insurance, and they end up pursuing him for the vast majority of that bill. He has $27,000 outstanding. And somewhat ironically, San Francisco General, it is the city hospital. It is run by the city of San Francisco. So this student is hit by a city bus, taken by an ambulance to the city hospital and ends up with a $27,000 bill as a result.

GROSS: So did he have insurance?

KLIFF: He did. He had insurance through his dad.

GROSS: So why doesn't Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital contract with private insurers?

KLIFF: So what they have told me when I've talked to some spokespeople there is that they are a safety net hospital, and that is, you know, definitely true. They generally serve a lower-income, often indigent population in San Francisco that would have trouble getting admitted and seeking care at other hospitals in the city. So they have told me that their focus is on serving those patients and that therefore, you know, they're not going to contract with private insurance companies.

The thing I found a little bit confusing about that, though, is there are lots of public hospitals, say, that, you know, also serve low-income populations. And some of them for their inpatient units, you know, for their scheduled surgeries, they're not going to contract with private insurance because they want to make sure beds are available for the publicly insured folks and people on Medicaid and Medicare.

But when it comes to the emergency room, you know, every other public hospital I was in touch with would contract with private insurers there because people don't decide if they're going to end up in the emergency room. So, you know, that's the justification they offered, that it is a hospital meant to serve those with public insurance. But it is not something you see public hospitals typically doing.

GROSS: Isn't - I think legislation was proposed in California to change that. Did that pass?

KLIFF: It's still pending in the California State Assembly. And the hospital has also promised to reform its billing practices, although we haven't seen what exactly their new plan is yet.

GROSS: So the position that Justin was in is that, like, he's unconscious. He's not asking to be taken anyplace. (Laughter) But he's unconscious. He's taken to the emergency room and ends up getting this $27,000 bill. I mean, that just seems so unfair, especially since he has insurance.

KLIFF: Yeah.

GROSS: Like, it's supposed to cover him for things like that (laughter).

KLIFF: Yeah. You know, there's one other patient who kind of makes this point really well who was also seen at San Francisco General. Her name is Nelly. And she fell off a climbing wall and, somewhat amazingly, you know, turns out she had a concussion. But one of the first things she does is she calls her insurance's nursing hotline to ask, should I go to the ER?

And they say yes. And she says, can I go to Zuckerberg San Francisco General? It's the closest. They say, no, don't go there. It's not in network. Go to another hospital. She gets to the other hospital, but the other hospital won't see her because she's a trauma patient. She fell from a really high height. And San Francisco General is the only trauma center in San Francisco. So she tries to go to an in-network hospital. She's then ambulance-transferred to Zuckerberg San Francisco General, and she ends up with another bill over $20,000 that the hospital was pursuing from her until I started asking questions from it, and the hospital ultimately dropped the bill.

But I think it's just such a frustrating situation for someone like Justin, for someone like Nellie (ph). They're either shopping for this good unconscious, they're really trying to do the right thing, and the health care system is just so stacked against the patient. It's so stacked for the hospital to be able to bill the prices that they want to bill.

GROSS: So apparently, the moral of the story is if you want to challenge your emergency room bill, you should get Sarah Kliff to write about you. (Laughter).

KLIFF: It's - (laughter). That's what some people have said. But there's only one of me, and there's about 2,000 bills in our database. And, you know, we have had over $100,000 in bills reversed as a result of our series. But I don't think it's a great way to run a health care system where we just, you know, the people who get their bills reversed are those who are lucky enough to have a reporter write a story about them.

GROSS: Yes. Agreed. Let me reintroduce you. If you're just joining us, my guest is Sarah Kliff. She's a senior policy correspondent at Vox, where she focuses on health policy. She also hosts the Vox podcast, "The Impact," about how policy actually affects people.

So we're going to take a short break, and then we'll talk more about emergency billing. And then later, we'll talk about what's left of Obamacare, and what the president and Congress and candidates are saying about health care, after this break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF ALEXANDRE DESPLAT'S "SPY MEETING")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. And if you're just joining us, my guest is Sarah Kliff. We're talking about emergency room billing and why it's so unpredictable and often so incredibly high. She's a senior policy correspondent at Vox, where she focuses on health policy. She also hosts the Vox podcast, "The Impact," about how policy affects people.

So we were talking about the hidden facility fee, which most people don't know exists, and is responsible for a large chunk of a lot of emergency room bills. There's also, like, a trauma unit fee. It's a similar hidden fee in hospitals that have trauma centers in their emergency rooms. So explain the trauma fee and how that kicks in.

KLIFF: Yeah. This is something I also had never heard of till I started reading a lot of emergency room bills, and this is the fee that trauma centers charge for essentially assembling a trauma team to meet you when you're coming in and those folks out in the field, maybe the EMTs, for example, have determined that you meet certain trauma criteria.

So I've talked to people who have been charged trauma fees who were in serious car accidents. One case was a baby who fell from more than 3 feet, and that's considered to trigger a trauma activation. So this is essentially the price for having a robust trauma team - a surgeon, an anesthesiologist, nurses - all at the ready to receive you when you get to the hospital.

And again, these fees can be pretty hefty. San Francisco General, which, I've done the most reporting on their billing, you know, they can charge up to $18,000 for their trauma activation services. I wrote about one family who was visiting San Francisco from Korea when their young son rolled out of the hotel bed. They were nervous. They didn't know the American health care system well. So they called 911, which sent an ambulance, brought him over to the hospital. Turns out, he was fine. They gave him a bottle of formula. He took a nap and went home.

And then a few months later, they get an $18,000 charge for the trauma team that assembled for when that baby came to the hospital. And these are another, you know, pretty significant fee that, again, you don't really know about. You have no idea that the trauma team is assembling to meet you when you're coming into the hospital. You just find out after the fact. And you also have no say in the decision to assemble trauma. That's really left up to the hospital, not the patient.

GROSS: So I'm going to have you compare two possibilities. You go to an emergency room, and the bill is very high. There's two people who have the same problem who go to the emergency room. One of them has a copay. One of them has a high deductible that they haven't paid off yet. How are they treated differently, in terms of what they're billed for the emergency room visit?

KLIFF: Well, the person with the deductible will likely be billed significantly more. You know, if they're just, let's say, at the start of the year, they are going to essentially have to bear the costs of that emergency room visit up until the point they hit their deductible and the insurance kicks in, whereas the person who has a co-payment, they're just going to have to pay that flat fee and, you know, probably not worry about paying more, but there's often surprise bills lurking in the corner that could affect both of those patients as well.

GROSS: Like what?

KLIFF: So one of the most common things we see is out-of-network doctors working at in-network emergency rooms. So you know, you have an emergency, you look up a hospital, you see their ER is in network, so you go there. It turns out that emergency room is staffed by doctors who aren't in your insurance. There's pretty compelling academic research that suggests 1 in 5 emergency room visits involves a surprise bill like that one.

GROSS: That seems so unfair. How are you to know - if you're choosing a hospital that's in network, how are you to know whether the doctor treating you is in network or not?

KLIFF: You know, you really - there isn't a great way to tell, to be honest. This is - you know, when I had to go to the emergency room over the summer, you know, this is something I worried about. You know, I was seeing a doctor who worked for the hospital, but they were sending off my ultrasound to be read by a radiologist who I was never going to meet. I couldn't ask them if they were in-network. I just kind of had to cross my fingers and hope for the best, and luckily, I didn't get a surprise bill.

But I've talked to multiple patients who, you know, tried to do their research, who thought they were in network, only to get a bill, often for thousands of dollars, after leaving the emergency room, from someone who, you know, never mentioned to them, hey, I'm not in your network like this hospital is.

GROSS: So the bill that you'd get would be for the difference between what you pay when somebody is - when a doctor's in network and what you pay when they're not in network?

KLIFF: Yeah, often it's just what that out-of-network doctor wants to charge. So a good example of this is a patient I wrote about in Texas named Scott (ph), who was attacked in downtown Austin, left on the street unconscious, some bystander called him an ambulance, and he woke up at a hospital. And one of the first things he does, because this is the United States, is he gets on his phone and tries to figure out which hospital he is at, and, you know, is that in his insurance network? And he finds out - good news - it is. And a surgeon comes by, tells him he's going to need emergency jaw surgery because of the attack that happened.

So he says, OK. You know, he's not really in a place to go anywhere. Gets the surgery. Goes home. A few weeks later, he gets an $8,000 bill from that oral surgeon, who the insurance companies paid a smaller amount. The oral surgeon didn't have a contract with the insurance and said, you know, I think my services are worth a lot more, so pursued the balance of the bill from Scott.

GROSS: I have to say, I mean, that does seem unfair to the patient because they haven't been informed. They can't make a choice about it if they don't know. And, like, $8,000 is a lot of money.

KLIFF: Yeah. And I think, you know, even more, let's say he did say he was out of network. It kind of puts the patient in an unfair situation, too. You know, one of the things we talk about a lot in health policy is, what if we had more transparency? What if we let patients know the prices? What if we let patients know who is in and out of network? And that - it would be a good step.

But, you know, I think with someone like Scott, sitting in a hospital with a broken jaw, there's not much you can do with that information. He doesn't have, you know, the ability to go home, like, research, like, make an appointment with a new surgeon. So, you know, it'd be great if he knew that the doctor was out of network. It'd be even better if he had some kind of protections against those type of bills.

GROSS: What kind of protection could there be?

KLIFF: So we're actually seeing a lot of action on this in Congress. There's some pretty strong bipartisan support for tackling this specific issue and essentially holding the patient harmless. When there is a situation like Scott's, for example, where there's this $8,000 bill, that's really a dispute between a health insurance company and a doctor, where the doctor says, I want more money, the insurer says, I want to pay you less money. And what Congress wants to do - what a few states have already done with their laws - is said, you can't go to the patient for that money. You, the hospital, and you, the health insurance company, you have to get down to a table and work things out together.

And some state laws will set certain amounts that are allowed to be charged, other ones will force the insurance company and the hospital into an arbitration process. But the general concept is to take the patient out of this billing situation because, like you said, Terry, they really aren't in a position to negotiate. They aren't in a position to shop. They shouldn't be the ones who are left holding the bag at the end of the day.

GROSS: My guest is Sarah Kliff. She covers health policy for Vox. After a break, we'll talk more about why ER bills can have some unpleasant surprises, and she'll give us an update on Obamacare. And Maureen Corrigan will review two books about forgotten stories from Hollywood. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF JESSICA WILLIAMS TRIO'S "KRISTEN")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Let's get back to my interview with journalist Sarah Kliff, who covers health policy and how it affects people for Vox. For the past year and a half, she's been writing about why emergency room visits can be so expensive and the pricing so secretive and mysterious, as well as inconsistent from one hospital to the next. She collected over 1,000 bills and tracked down stories behind the billing. She interviewed many of the patients and the people behind the billing to decipher why ER bills can have some surprise costs.

Here's another surprise that often awaits people who go to emergency rooms - some insurance plans only cover true emergencies, and whether it is a true emergency is sometimes determined after the diagnosis is made. So how are you supposed to know before the diagnosis whether you're going to be categorized as a true emergency or not? Like, if you go to the hospital, you don't know if you have a broken bone or not.

KLIFF: Right.

GROSS: Somebody needs to X-ray it and tell you.

KLIFF: Right. The whole point you go to the emergency room is to help them figure out what the emergency is and what treatment you need. This is a policy that the insurance company Anthem has been pioneering for a few years. It's been in Kentucky. It's been in Georgia - a few other states. And, you know, I wrote about one patient out in Kentucky named Brittany, who - she was having really severe abdominal pain. She called her mom who is a nurse, and the nurse said, that might be appendicitis. You've got to get to the emergency room. Turns out it wasn't appendicitis. It was an ovarian cyst. She got it treated elsewhere later down the line.

And Anthem, you know, sent her a letter saying, we're not going to cover that visit because it was not a true emergency. She appealed it. Her appeal was denied. This is another one where, once I started asking them about it, the bill suddenly disappeared. But - and it seems like as Anthem has gotten more attention for this policy - they haven't announced it publicly, but some pretty compelling data The New York Times got their hands on suggest they've backed off this policy.

But it's just, you know - there are so many traps you can fall into going into an emergency room. It just feels like you're walking into this minefield, and this is kind of one of those mines that's lurking in there.

GROSS: Hospital pricing and emergency room pricing seems to vary so much from hospital to hospital. Are there, like, national guidelines that help determine what a hospital or a hospital emergency room charges for services? I mean, who decides, and why is there such a variation?

KLIFF: So hospital executives get to decide, and I think that is why there is such variation. There aren't really guidelines that they're following. You know, one thing you could do as a hospital executive - you could look at what Medicare charges - those prices are public - and, you know, maybe use that as a benchmark. There are some databases. There's one called FAIR Health, for example, where you could look and see, you know, some information on what local prices typically are. But in terms of, you know, what you want to charge, that's kind of up to you as someone running a hospital.

One of the things that's really, really unique about the United States, compared to our peer countries, is that we don't regulate health care prices. Nearly every other country in the developed world - they see health care something as, you know, akin to a utility that everyone needs, like electricity or water. It's so important that the government is going to step in and regulate the prices. That doesn't happen in the United States. You know, if you're a hospital, you just choose your prices. And, you know, that is, I think, why you see so much variation and why you see some really high prices in American health care.

GROSS: So what advice do you have for people who actually need an emergency room and don't want to get hit with a shocking bill afterwards?

KLIFF: Yeah, this is, you know, one of those questions - it just makes me a little frustrated that - 'cause this is the most common question I get - right? - is, how do I - how do we - how do I prevent a surprise bill? And I find it kind of upsetting that, you know, it has to be on the patient because honestly, there really isn't a great way to do this. I've talked to so many patients who tried so hard to avoid a big medical bill and weren't able to.

You know, there's certain things, yes, you can do. You can look up the network status of your hospital. You can try and badger each doctor you see about whether they are in network. You can try to be a really proactive patient, but I think that's just such a huge burden on people who are in, like, really emergent situations. And some people don't have that opportunity, you know, like Justin Zanders, the guy we were talking about earlier who was taken to a hospital while he was unconscious. I cannot think of anything he could've done to avoid that bill. It just was not possible.

GROSS: So your advice is, good luck.

KLIFF: Short of that, I mean, good luck. You know, I'm actually in the middle of reporting a story right now about people who have successfully negotiated down their bills. And, you know, you can certainly - if you do end up with a surprise bill, you can call up the hospital, see if there's a discount. Sometimes there will be. Sometimes there won't. You can call again. Customer service representatives - different ones - often offer you different discounts, I've learned from interviewing patients. You can ask for a prompt pay discount if you pay right away.

You can - you know, one health attorney who negotiates these a lot on behalf of patients - he says one of his favorite tactics is to choose the amount you want to pay; send a check with that amount; and in the note, write, paid in full; and hope they don't come after you after that. I have no idea if that works or not, but he says it works for his patients. But it's a mixed bag. And at the end of the day, the hospital has all the power. You can ask for discounts. You can ask nicely. You can ask angrily. It's up to the hospital if they want to grant you that or not.

GROSS: So what is the status of Obamacare now? You know, Republicans promised to repeal and replace. That didn't work out. So have Republicans given up on repeal and replace?

KLIFF: For the time, it seems pretty clear that repeal and replace is dead on arrival, especially with Democrats taking control of the House this year. Those proposals aren't being talked about as much. They're not really going anywhere. The one big thing we did see Republicans succeed at is repealing Obamacare's individual mandate, the requirement that all of us carry health insurance. That happened as part of the big tax package that passed at the end of 2017.

So we've seen, you know, President Trump, for example, essentially declare victory, declare that repealing the individual mandate is repealing Obamacare, so we're good on that goal. But, you know, generally, Obamacare is still standing. There are millions of people getting their coverage through the Affordable Care Act still today.

GROSS: So now that there's no individual mandate, conservative attorney generals are challenging Obamacare - the Affordable Care Act - and saying it's no longer constitutional after Congress's repeal of the individual mandate. Could you explain that?

KLIFF: Yeah, so this is a challenge that's come up through the courts in the past few months. Obamacare is constantly being challenged in court. It's been through multiple Supreme Court suits. This one - you know, it's a multiple-part argument, so I'll try my best to walk through it.

KLIFF: So essentially, it starts with the fact that the individual mandate - they weren't quite able to repeal it for boring technical reasons. But what they were able to do is change the fee for not having health insurance from $700 to $0. So it - in all practical terms, it feels like repealing it because there is no fee for not carrying health insurance. The individual mandate was upheld as a tax when the Supreme Court said, yes, this is constitutional. The government has a right to tax people. Now that there is no fee associated with not carrying health insurance, the conservative attorneys general who are bringing this case argue that it's not a tax anymore, and therefore, it is not constitutional. That whole defense that John Roberts wrote in 2012 is moot. So that's the first part of it.

They go even further and say the individual mandate is so core to the Affordable Care Act, it is not severable. And if you, the courts, rule the individual mandate unconstitutional, then you need to rule all of Obamacare unconstitutional. And the first judge who heard this case - he is a, you know, judge in a district court in Texas. He agreed with them. He agreed that - first step - that the individual mandate is no longer constitutional. And second step, that means that the entirety of Obamacare has to fall. This is now being appealed up to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals.

And I will say there are a lot of critics of this case. There are a lot of people who were parties to previous Supreme Court challenges to Obamacare who think this is a bad legal argument and that it will not succeed. But it is already, you know, gone through the district court level. It's moving up to the appellate court level. It is something that is in the mix that could become a threat to the Affordable Care Act.

GROSS: Well, if it goes to the Supreme Court, it would be very interesting to see what Justice Roberts says since he voted for the ACA, saying that the individual mandate was a tax.

KLIFF: Yeah. You know, and I think where some legal scholars would see it shaking out is that the - someone like John Roberts, he might agree, OK, yeah, the individual mandate is unconstitutional, but would not make the leap to the second half of this, that the rest of the law has to fall.

I think one of the most compelling arguments against this case is that Congress knew what they were doing when they repealed the individual mandate. You know, they had the opportunity to repeal Obamacare. They didn't. They'd specifically took aim at this one specific part. So it feels like it might be a bit of a reach to argue that what Congress really meant to do was repeal all these other parts of the Affordable Care Act. But, you know, the Supreme Court is changing. We have a new justice. You know, we have a lot in the mix. So it's always an open question of how a decision like this could go.

GROSS: So correct me if I'm wrong here - the Department of Justice has sided with the conservative attorneys general who are challenging Obamacare, saying it's no longer constitutional, and I think that the Justice Department is also asking the judge to strike down the ACA's mandatory coverage of pre-existing conditions.

KLIFF: Yeah, that's right. So it's a kind of unusual situation. Usually, it's the Justice Department that is going to defend a federal law in court. But, you know, given the Trump administration's opposition to the Affordable Care Act, they have decided to side with the conservative attorneys general. They have a slightly different argument. They don't think all of Obamacare should fall if the mandate falls, but they do think some big parts, like you mentioned, the protections for pre-existing conditions, should be ruled unconstitutional if the mandate falls.

So this has led to a bit of an unusual situation where you've had this coalition of Democratic attorneys general step in and take over the case, basically saying that the federal government is going - is not going to defend the Affordable Care Act. We are going to defend the Affordable Care Act. So you have this coalition of Democratic attorneys general, led by the attorney general of California, stepping in and, you know, offering a defense as this case works its way up through the court system.

GROSS: Let's take a short break here, and then we'll talk some more. If you're just joining us, my guest is Sarah Kliff. She's senior policy correspondent at Vox, where she focuses on health policy. And she hosts the Vox podcast "The Impact," about how policy actually affects people. We'll be right back. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF THE WEE TRIO'S "LOLA")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. And if you're just joining us, my guest is Sarah Kliff, senior policy correspondent at Vox, where she focuses on health policy.

Do you think health insurance is shaping up to be a big issue in the 2020 campaign?

KLIFF: I do, and I think it's going to be a big issue both in the primary, where you're already seeing candidates get pressed on, should we still have private health insurance, and giving pretty different answers to that question.

And then I think one of the things you're also going to see is whoever is the Democratic nominee is probably going to run on Obamacare. They are going to point at the fact that President Trump tried to repeal the Affordable Care Act. That's pretty different than, you know, the 2012 election, where Democrats were pretty scared to run on Obamacare. It still wasn't popular. The benefits hadn't rolled out. In this past midterm and now again in the 2020 election, it seems pretty clear that Democrats are pretty excited to point out that Republicans wanted to repeal Obamacare. So I think it really will come up.

GROSS: What are some of the biggest falsehoods you've heard from politicians about health insurance costs or health insurance policy?

KLIFF: You know, one of the ones that's come up a lot is actually around the role of private health insurance. So I've - I don't know if it counts as a falsehood, but I think it's a bit of a misunderstanding of how health insurance often works is, you know, when I talk to single-payer supporters, most of them want to eliminate private insurance completely. They just don't think there is a role for it in the health care system.

And one of the things I think that's actually pretty interesting, when you look at any other country - you look at Canada, you look at the U.K., you look at France, which all have national health care systems - all of them have a private health insurance market, too. There are always some kind of gap in the system that the public insurance can't cover, where the government step - where the private industry steps in and offers coverage. In Canada, for example, their public health plan doesn't cover prescription drugs, so two-thirds of Canadians take out a private plan, often through their employer, like us, to cover prescription drugs, to cover their eyeglasses, to cover their dental. So I think that's a confusion I see a lot in the "Medicare for All" debate coming up right now.

I think the other thing I see a lot of confusion around - and we've talked about this a little bit with emergency room billing - is the role of transparency in health care. I see a lot of, you know, if we just made the prices public, like, that is what we need to do to fix the system, and I think that really misses the fact that, even if the prices were public, health care is so different from everything else we shop for. It might be - I think it is the only thing we purchase when we are unconscious.

GROSS: (Laughter).

KLIFF: And when you're unconscious, you're not really going to be great at price shopping. So I see that as, you know, a halfway solution that I often hear talked about here in Washington that would be great but is not going to suddenly result in, you know, prices dropping because they've been exposed in a spotlight.

GROSS: Is there a country that you think has a good health care model that we could borrow?

KLIFF: Oh, yeah. I've been thinking about this a lot lately actually. So I've gotten very interested in the Australia health care system, which is a little far away. But I think they're a really interesting model because they have a public system, everyone's enrolled in it, but they also really aggressively try and get people to buy a private plan, too, and that private plan will get you sometimes faster access to doctors, maybe a private room at a hospital.

It's really hard for me to see the U.S. creating a health care system, similar to Canada's actually, where you can't buy private insurance, where if you're rich or you're poor, everyone waits in the exact same queue, you can't jump to the front of the line. Because I think wealthier Americans have gotten so used to having really good access to health care that they would be very upset with a system like that.

I think Australia is a kind of interesting hybrid between, you know, where we're at in the U.S. right now and what Canada is like, where it says, yes, we're going to create a public system for everybody, but we're also going to have these private plans that compete against the public system. So I've become increasingly, you know, interested in how Australia's system works. And they have - about 47 percent of Australians are buying a private plan to cover the same benefits that the public plan does.

GROSS: So it's not supplemental. It's instead of.

KLIFF: Right. So it's very different from Canada. So in Canada, you can buy complementary insurance, you know, to cover the benefits the public plan doesn't but the government expressly outlaws supplemental insurance. You know, like, what people buy here to cover the gaps in Medicare, that is not allowed. You cannot buy your way to the front of the line in Canada.

One of my favorite sayings about the Canadian health care system is from a doctor in a book I read about Canadian health care is they said, you know, we're fine waiting in lines for health care in Canada as long as the rich people and the poor people have to wait in the exact same line. Their system is all about equality. And I just don't know that we're at a place as a country where we value the same sort of equality in our health care system.

GROSS: Is there any developed country around the world that has a system similar to ours with all these competing insurance companies and, you know, some government plans and, like, a thousand different bureaucracies that doctors have to deal with and that patients have to deal with?

KLIFF: Absolutely not. There's nothing like it. I mean, our system is so unique. I'd say the closest but it's not even close are a few countries that have national health care systems, but they do it through tightly regulated private health insurance plans. So if you look at, like, Netherlands or Israel, there isn't a government-run plan. Instead, in both countries, you actually have four tightly regulated health insurance plans that compete against each other for the citizens' business. I guess that's the closest, but that is so different from what we have here right now. There's really nothing like it in any developed country.

GROSS: Sarah Kliff, thank you so much for talking with us.

KLIFF: Well, thank you for having me.

GROSS: Sarah Kliff covers health policy for Vox, where you'll find her series about emergency room bills. After we take a short break, Maureen Corrigan will review two books about forgotten stories from Hollywood. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF GEORGE FENTON AND PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA'S "MISS SHEPHERD'S WALTZ")

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

How much does an ER visit cost?

$1,500 – $3,000 average cost without insurance (non-life-threatening condition), $0 – $500 average cost with insurance (after meeting deductible).

Average ER visit cost

An ER visit costs $1,500 to $3,000 on average without insurance, with most people spending about $2,100 for an urgent, non-life-threatening health issue. The cost of an emergency room visit depends on the severity of the condition and the tests, treatments, and medications needed to treat it.

Cost data is from research and project costs reported by BetterCare members.

Emergency room visit cost with insurance

The cost of an ER visit for an insured patient varies according to the insurance plan and the nature and severity of their condition. Some plans cover a percentage of the total cost once you meet your deductible, while others charge an average co-pay of $50 to $500 .

The No Surprises Act , effective January 1, 2022, protects insured individuals from unreasonably high medical bills for emergency services received from out-of-network providers at in-network facilities. The act also established a dispute resolution process for both insured and uninsured or self-pay individuals.

Cost of an ER visit without insurance

An ER visit costs $1,500 to $3,000 on average without insurance for non-life-threatening conditions. Costs can reach $20,000+ for critical conditions requiring extensive testing or emergency surgery. Essentially, the more severe your condition or issue, the more you are likely to pay for the ER visit.

Factors that impact ER visit costs

Many factors affect the cost of an ER visit, including:

Facility type – Freestanding emergency departments often cost 50% more than hospital-based emergency rooms.

Time of day – An ER visit at night typically costs more than the same type of visit during the day.

Level of care – The more severe your condition is, the more time and expertise it takes to diagnose and treat, and the higher the total ER visit cost.

Ambulance ride – An ambulance ride costs $500 to $1,300 on average, depending on whether you need basic or advanced life support during transport.

Medications – Oral medications, injections, or IVs needed during your stay all add the total cost of your ER visit.

Medical equipment & supplies – Any other supplies used to diagnose and treat you—such as a cast for a broken bone or bandages and sutures to close an open wound—increase the cost.

Testing – Each medical test is typically a separate charge. Tests may include urine tests, blood tests, X-rays, or other more advanced imaging tests.

Insurance coverage:

Out-of-pocket costs may be higher for those with high-deductible insurance plans.

While ER visit costs are generally higher for the uninsured, many hospitals offer discounts for self-pay patients.

ER facility fee by level

An ER facility fee ranges from $200 to $4,000 , depending on the severity level of your symptoms and condition. The facility fee is the cost to walk in the door and be evaluated by a physician. Other services you may need, such as lab tests, imaging, and surgical procedures, are charged separately.

To understand your ER bill: Emergency rooms rank severity levels 1 through 5, with Level 1 being the most severe or urgent. However, most of the billing codes for emergency room visits are reversed, with level 1 being the least severe.

Common conditions and procedures

The table below shows the average ER visit cost for common ailments. Prices vary greatly depending on how much testing and expertise is required to accurately diagnose and treat you.

Emergency room vs. urgent care

An ER visit costs $1,500 to $3,000 , while the average urgent care visit costs $150 to $250 without insurance. Urgent care facilities can treat most non-life-threatening conditions and typically have less wait time than the ER. For more detail, check out our guide comparing the cost of an emergency room vs. urgent care .

Other alternatives to the ER for less serious health issues include primary care, telemedicine, and free clinics. Check with the National Association of Free and Charitable Clinics to find a free clinic near you.

FAQs about ER visit costs

Why are er visits so expensive.

ER visits are expensive because emergency rooms run on a 24-hour schedule and require a large and wide range of staff, including front desk personnel, maintenance, nurses, doctors, and surgeons. ERs also run and maintain a lot of expensive equipment and need a constant supply of medications and medical supplies.

While ER visits can be expensive, ER bills are negotiable. If you receive an unexpectedly large ER bill, ask for a discount and question the coding.

Does insurance cover ER visits?

Insurance typically covers some or all of an ER visit, though you may need to meet a deductible first, depending on the plan. The Affordable Care Act requires insurance providers to cover ER visits for "emergency medical conditions" without prior authorization and regardless of whether they are in or out-of-network.

An "emergency medical condition" is considered something so severe that a reasonable person would seek help right away to avoid serious harm.

When should you go to the ER?

You should go to the ER for any serious, potentially life-threatening symptoms, including:

Trouble breathing

Serious head injury

Sudden severe pain

Severe burn

Severe allergic reaction

Major broken bones

Uncontrollable bleeding

Suddenly feeling weak or unable to move, speak, or walk

Sudden change in vision

Sudden confusion

Fever that does not resolve with over-the-counter medicine

Tips to reduce your ER bill

An ER visit can cost thousands of dollars, even if you have insurance. Here are some guidelines to ensure you are not overpaying:

Determine if you truly need an emergency room. If your health issue is not life threatening, consider going to an urgent care facility instead as the cost for the same care can be much less.

Go to a hospital-based ER. Freestanding ER centers typically cost much more than a hospital-based emergency room.

Call ahead to confirm payment options and the current wait time.

Ask about costs up front. If you are uninsured, consider asking the following questions to prevent you from surprises on your future bill:

Do you have discounted pricing for patients without insurance?

Will it cost less if I pay with cash?

What will the fee be for my specific issue?

Do you think I will need additional tests, and what will they cost?

How much do you charge for X-rays?

If I need medication, how much will it cost?

We use our proprietary database of project costs, personally contact industry experts to compile up-to-date pricing and insights, and conduct in-depth research to ensure accuracy in all our guides.

In this article

- Introduction

What is the average cost of an emergency room visit?

Will your health insurance cover the emergency room cost, when should you go to the emergency room, determining the average emergency room cost.

Emergency room (ER) visits are not something anyone plans for, but they are an inevitable fact of life. Whether you're suffering from a serious illness or have been in an accident, there are situations where you need emergency care. While these visits are vital for your health and well-being, they can also come with a hefty price tag if you're uninsured or the reason for your visit isn't covered. That's why it's essential to understand the average price of emergency room visits. You might be surprised how much they can vary depending on your insurance plan and what condition you're there to treat, but there are ways to protect yourself from high medical bills. Check out our guide below to learn what you can expect with regard to the emergency room cost when you are in a life-threatening situation.

According to most sources, the average cost of an emergency room visit in the United States is around $2,200, but this number can vary depending on a variety of factors, including the severity of the condition, where you live, and what type of insurance plan you have. For example, if you have health insurance through the Affordable Care Act (ACA), your out-of-pocket expenses will be capped. But, even with insurance, you may still end up paying several hundred dollars or more for an ER visit.

The ACA sets a number of limits on the out-of-pocket costs that individuals can be charged for healthcare services, including emergency room visits. However, this does not mean that you will have no cost for these services; it is likely that you may still need to pay copays, coinsurance, or deductibles in addition to what your insurance covers. Additionally, insurers are only required to provide coverage up until a patient's condition becomes stable—any other treatment costs could be on the consumer themselves if they choose an out-of-network provider or hospital.

To reduce the emergency room cost of a visit, you need to understand what kinds of conditions require this level of care. If you can avoid going to the ER for minor issues such as a cold or fever, you may be able to prevent a costly medical bill altogether. Furthermore, if you don’t have health insurance, many hospitals offer payment options like charity care and financial assistance programs to help people manage their medical bills.

It's a common worry for many people—what happens if you suddenly need to go to the emergency room? Will your health insurance cover the cost? Since 2010, the ACA requires insurance companies to cover the care you receive in the ER if you have an emergency medical condition. One of the key provisions of the ACA is that it requires insurance companies to cover emergency medical care for those that have an emergency medical condition regardless. This provision ensures individuals who experience sudden and unexpected medical emergencies will receive the care they need without worrying about the high cost of emergency room visits.

The ACA defines an emergency medical condition as a medical condition that manifests itself in such a way that a reasonable person would believe that the absence or the delay of emergency medical care could result in some type of serious harm or even death. It's crucial to note that the ACA does not require insurance companies to cover non-emergency care in the ER. If you go to the ER for a non-emergency condition such as a headache, flu, or minor injuries, your insurance company may not cover the cost of your visit. Take advantage of resources like our learning center at HealthInsurance.com to educate yourself on your plan.

Knowing when to go to the emergency room can be challenging for many individuals, particularly if your goal is to avoid paying a high emergency room cost for a visit that your insurance company deems unnecessary. While some medical emergencies are obvious, others may not be so clear-cut. In general, the emergency room is for medical emergencies that require immediate attention. Conditions that pose an imminent threat to the patient's life or health should be treated as emergencies. Some situations that warrant a visit to the nearest emergency room include:

- Difficulty Breathing

- Severe Abdominal Pain

- Head Injury

- Loss of Consciousness

- Allergic Reaction

- Heart Attack or Stroke Symptoms

Not all conditions require a trip to the ER and you do have some other options to consider when you're experiencing a medical issue. For non-life-threatening conditions, a visit to a primary care physician or urgent care center may be more appropriate. Patients with minor injuries, minor illnesses, or conditions that can wait until the next day or two should consider seeking non-emergency care. As a general rule, if you're in doubt or cannot handle the situation at home, seek emergency care or call 911. It is always better to be safe than sorry when it comes to your health.

The cost of an emergency room visit can vary greatly, depending on the hospital you go to, the level of treatment you require, and your insurance coverage. Knowledge of ER costs can help you make informed decisions when choosing an insurance plan . Some plans may have higher premiums but lower out-of-pocket expenses , while others may have lower premiums and higher costs when you need to use them. By researching the emergency room cost of visits, you'll be able to find a health insurance plan that fits your needs and budget. When you're ready to start learning about your options so you can get the insurance coverage you need, you can visit HealthInsurance.com to compare plans.

What to read next More on Short Term Medical →

Browse by category

Medicare Insurance

Information About Medicare By State

Browse Medicare Advantage Plans by State

Browse Medicare Drug Plans by State

Member Resources

Short Term Medical Insurance

Choice Advantage

Browse Short Term Medical Insurance Plans by State

ACA Insurance

Limited Fixed Indemnity Plans

Legion Limited Medical

Browse Limited Benefit Medical Insurance Plans by State

Accident Insurance

Browse Accident Insurance Plans by State

Dental Insurance

Delta Dental

United Concordia

Browse Dental Insurance Plans by State

Telemedicine Insurance

Florida Quotes

Georgia Quotes

North Carolina Quotes

Texas Quotes

Learning Center

Frequently Asked Questions

Prescription Drug Directory

Policy Holders Information

California Privacy Notice

Do Not Sell My Info

Interpreter Services

Notice of Nondiscrimination

Licensing for AgileCore

Licensing for Medicare

Quotes by State

© 2021-2024 HealthInsurance.com, LLC

Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions

GENERAL DISCLAIMERS Healthinsurance.com is a commercial site designed for the solicitation of insurance from selected health insurance carriers and HealthInsurance.com , LLC is a licensed insurance agency. It is not a government agency. It is also not an insurer, or a medical provider. HealthInsurance.com , LLC is a licensed representative of Medicare Advantage (HMO, PPO, PFFS, and PDP) organizations that have a Medicare contract. Enrollment depends on the plan’s contract renewal. We do not offer every plan available in your area. Currently we represent nine carrier plan organizations nationally. Please contact Medicare.gov , 1-800-MEDICARE, or your local State Health Insurance Program (SHIP) to get information on all of your options. Alternatively, you may be referred, via a link, to a selected partner website, which is independently owned and operated and may have different privacy and terms of use policies from us. If you provide your contact information to us, an insurance agent/producer or insurance company may contact you. If you do not speak English, language assistance service, free of charge, is available to you; contact the toll-free number listed above. This site is not maintained by or affiliated with the federal government's Health Insurance Marketplace website or any state government health insurance marketplace. The plans we represent do not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, or sex. To learn more about a plan's nondiscrimination policy, please Learn more about a plan’s nondiscrimination policy here . Not all plans offer all of these benefits. Benefits may vary by carrier and location. Limitations and exclusions may apply. Multi-Plan_HIC_Web_M

We've detected unusual activity from your computer network

To continue, please click the box below to let us know you're not a robot.

Why did this happen?

Please make sure your browser supports JavaScript and cookies and that you are not blocking them from loading. For more information you can review our Terms of Service and Cookie Policy .

For inquiries related to this message please contact our support team and provide the reference ID below.

Thanks for visiting! GoodRx is not available outside of the United States. If you are trying to access this site from the United States and believe you have received this message in error, please reach out to [email protected] and let us know.

How Much Does an ER Visit Cost? Free Local Cost Calculator

It’s true that you can’t plan for a medical emergency, but that doesn’t mean you have to be surprised when it’s time to pay your hospital bill. In 2021, the U.S. government enacted price transparency rules for hospitals in order to demystify health care costs. That means it should be easier to get answers to questions like how much an ER visit costs.

While the question seems pretty straightforward, the answer is more complicated. Your cost will vary based on factors such as if you’re insured, whether you’ve met your deductible, the type of plan you have, and what your plan covers.

There is a lot to consider. This guide will take you through specific scenarios and answer questions about insurance plans, deductibles, co-payments, and discuss scenarios such as how much it costs if you go to the ER when it isn’t an emergency.

You’ll learn a few industry secrets too. Did you know that if you don’t have insurance you might see a higher bill? According to the Wall Street Journal , it’s common for hospitals to charge uninsured and self-pay patients higher rates than insured patients for the same services. So, where can you go if you can’t afford to go to the ER?

Keep reading for all this plus real-life examples and cost-saving tips.

How Much Does an ER Visit Cost Without Insurance?

Everything is more expensive in the ER. According to UnitedHealth, a trip to the emergency department can cost 12 times more than a typical doctor’s office visit. The average ER visit is $2,200, and doesn’t include procedures or medications.

If you want to get a better idea of what an ER visit will cost in your area, check out our medical price comparison tool that analyzes data from thousands of hospitals.

Compare Procedure Costs Near You

Other out-of-pocket expenses you may incur include bills from third parties. A growing number of emergency departments in the United States have become business entities separate from the hospital. So, third-party providers may bill you too, like:

- EMS services, like an ambulance or helicopter

- ER physicians

- Attending physician

- Consulting physicians

- Advanced practice nurses (CRNA, NP)

- Physician assistants (PA)

- Physical therapists (PT)

And if your insurance company fails to pay, you may have to pay these expenses out-of-pocket.

How Much Does an ER Visit Cost With Insurance?

The easiest way to estimate out-of-pocket expenses for an ER visit (or any other health care service) is to read your insurance policy. You’ll want to look for information around these terms:

- Deductible: The amount you have to pay out-of-pocket before your insurance kicks in .

- Copay: A set fee you pay upfront before a covered medical service or procedure.

- Coinsurance: The percentage you pay for a service or a procedure once you’ve met the deductible.

- Out-of-pocket maximum: The most you will pay for covered services in a rolling year. Once met, your insurance company will pay 100% of covered expenses for the rest of the year.

Closely related to out-of-pocket expenses like deductibles and co-insurance are premiums. A premium is the monthly fee you (or your sponsor) pay to the insurance company for coverage. If you pay a higher premium, you’ll have a lower deductible and fewer out-of-pocket costs whenever you use your insurance to pay for services such as a visit to the ER. The opposite is also true — high deductible health plans (HDHP) offer lower monthly payments but much higher deductibles.

Sample ER Visit Cost

Using a few examples from plans available on the Marketplace on Healthcare.gov (current as of November 2021), here’s how this might play out in real life:

Rob is a young, healthy, single guy. He knows he needs health insurance but he feels reasonably sure that the only time he’d ever use it is in case of an emergency. Here’s the plan he chooses:

Plan: Blue Cross/Blue Shield Bronze Monthly premium: $394 Deductible: $7,000 Out-of-pocket maximum: $7,000 ER coverage: 100% after meeting the deductible

Rob does the math and considers the worst case scenario. If he does go to the ER, he’ll pay full price if he hasn’t yet met his deductible. But since both his deductible and his maximum out-of-pocket are the same, $7,000 is the most he’ll have to pay before his insurance kicks in at 100%.

Now imagine that Rob gets married and is about to start a family. He might need a different insurance plan to account for more hospital bills, doctors appointments, and inevitable emergency room visits.

Since Rob knows he’ll be using his insurance more often, he picks a plan with a lower deductible that covers more things.

Plan: Bright HealthCare Gold Monthly premium: $643 Deductible: $0 Out-of-pocket maximum: $6,500 ER coverage: $500 Vision: $0 Generic prescription: $0 Primary care: $0 Specialist: $40

This time Rob goes with a zero deductible plan with a higher monthly premium. It’s more out-of-pocket each month, but since his plan covers doctor’s visits, prescription drugs, and vision, he feels more prepared as his lifestyle shifts into family mode.

If he has to go to the ER for any reason, all he’ll pay is $500 and his insurance pays the rest. And worse case scenario, the most he’ll pay out-of-pocket in a year is $6,500.

How Much Does an ER Visit Cost if You Have Medicare?

Medicare Part A only covers an emergency room visit if you’re admitted to the hospital. Medicare Part B covers 100% of most ER costs for most injuries, or if you become suddenly ill. Unlike private insurance and insurance purchased on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace, Medicare rarely covers ER visits that happen while you’re outside of the United States.

To learn more, read: How to Use the Healthcare Marketplace to Buy Insurance

How Much Does an ER Visit Cost for Non-Emergencies?

When you have a sick child but lack insurance, haven’t met your deductible, or if you’re between paychecks, just knowing you can go to the ER without being hassled for money feels like such a relief. ER staff won’t demand payment upfront, and they usually don’t ask about insurance or assess your ability to pay until after discharge.

There are other reasons, too. You might be tempted to go to the ER for situations that are less than emergent because emergency departments provide easy access to health services 24/7, including holidays and the odd hours when your primary care physician isn’t available. If you’re one of the 61 million Americans who are uninsured or underinsured , you might go to the ER because you don’t know where else to go.

What you may not understand is the cost of an ER visit without insurance can total thousands of dollars. Consumers with ER bills that get sent to collections face some of the most aggressive debt collection practices of any industry. Collection accounts and charge-offs could affect your credit score for the better part of a decade.

Did you know that charges begin racking up as soon as you give the clerk your name and Social Security number? There are tons of horror stories out there about people receiving medical bills after waiting, some for many hours, and leaving without treatment.

4 ER Alternatives Ranked by Level of Care

First and foremost, if you’re experiencing a medical emergency, call 911 or go to the closest emergency room. Do not rely on this or any other website for advice or communication.

If you’re not sure whether your condition warrants immediate, high-level emergency care, you can always call your local ER and ask to speak to their triage nurse. They can quickly assess how urgent the situation is.

If you are looking for a lower-cost alternative to the ER, this list provides a few options. Each option is ranked by their ability to provide you with a certain level of care from emergent care to the lowest level, which is similar to the routine care you would receive at a doctor’s office.

1. Charitable Hospitals

There are around 1,400 charity hospitals , clinics, and pharmacies dedicated to serving low-income families, including the uninsured. Most charitable, not-for-profit medical centers provide emergency room services, making it a good option if you’re uninsured and worried about accruing substantial medical debt.

ERs at charitable hospitals provide the same type of medical care for conditions like trauma, broken bones, and life-threatening issues like chest pain and difficulty breathing. The major difference is the price tag. Emergency room fees at a charity hospital are usually flexible and almost always based on your income.

2. Urgent Care Centers

Urgent care centers are free-standing facilities designed to treat patients with serious but not life-threatening conditions. Also called “doc in a box,” these ambulatory care centers are a good choice for treating stable but chronic health issues, fever, urinary tract infections, back pain, abdominal pain, and moderately high blood pressure, to name a few.

Urgent care clinics usually have a medical doctor on-site. Some clinics offer point-of-care diagnostic tests like ultrasound and X-rays, as well as basic lab work. The average cost for an urgent care visit is around $180, according to UnitedHealth.

3. Retail Health Clinics

You may have noticed small retail health clinics (RHC) popping up in national drugstore chains like CVS, Walgreens, and in big-box stores like Target and Walmart. The Little Clinic is an example of an RHC that offers walk-in health care services at 190 supermarkets across the United States.

RHCs help low-acuity patients with minor medical problems like sore throat, cough, flu-like symptoms, and other conditions normally treated in a doctor’s office. If you think you’ll need lab tests or other procedures, an RHC may not be the best choice. Data from UnitedHealth puts the average cost for an RHC visit at $100.

4. Telehealth Visits

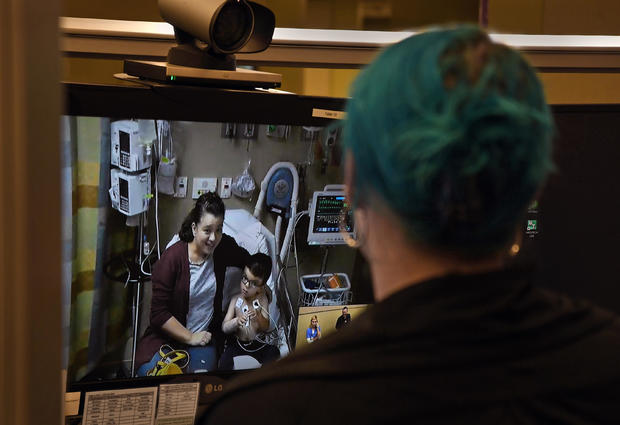

Telehealth, in some form, has been around for decades. Until recently, it was mostly used to provide access to care for patients living in the most remote or rural areas. Since 2020, telehealth visits over the phone, via chat, or through videoconferencing have become a legitimate and extremely cost-effective alternative to in-person office visits.

Telehealth is perfect for some types of mental health therapies, follow-up appointments, and triage. For self-pay, a telehealth visit only costs around $50, according to UnitedHealth.

Tips for Taking Control of Your Health Care

- Don’t procrastinate. Delaying the care you need for too long will end up costing you more in the end.

- Switch your focus from reactive care to proactive care. Figuring out how to pay for an ER visit is a lot harder (and costlier) than preventing an ER visit in the first place. Data show that preventive health care measures lead to fewer illnesses and better outcomes.

- Plan for the unknown. It’s inevitable that at some point in your life you’ll need health care. Start a savings account fund or better yet, enroll in a health savings account (HSA). If you’re employed (even part-time) you already qualify for an HSA. A contribution of just $9 a paycheck could add up to $468 tax-free dollars for you to spend on health care every year. Unlike the use-it-or-lose-it savings plans of the past, modern plans don’t expire. You can use HSA dollars to pay for out-of-pocket costs like copayments, deductibles, and for services that your health insurance may not cover, like dental and vision services.

- Advocate for yourself. There is nothing more empowering than taking charge of your health. Shop around for services and compare prices on procedures to make sure you’re getting the best prices possible.

- If you are uninsured or doing self-pay, negotiate your bill and ask for a cash discount.

Estimate the Cost of the ER Before You Need It

It’s stressful to think about money when you’re facing an emergency. Research the costs of your nearest ER before you actually need to go with Compare.com’s procedure cost comparison tool .

All you have to do is enter your ZIP code and you’ll immediately see out-of-pocket costs for ER visits at your local emergency rooms. It works for other medical services too, like MRIs, routine screenings, outpatient procedures, and more. Find the treatment you need at a price you can afford.

Disclaimer: Compare.com does not offer medical advice and is in no way a substitute for any medical advice received from health professionals. Compare.com is unable to offer any advice on any medical procedure you may need.

Nick Versaw leads Compare.com's editorial department, where he and his team specialize in crafting helpful, easy-to-understand content about car insurance and other related topics. With nearly a decade of experience writing and editing insurance and personal finance articles, his work has helped readers discover substantial savings on necessary expenses, including insurance, transportation, health care, and more.

As an award-winning writer, Nick has seen his work published in countless renowned publications, such as the Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, and U.S. News & World Report. He graduated with Latin honors from Virginia Commonwealth University, where he earned his Bachelor's Degree in Digital Journalism.

Compare Car Insurance Quotes

Get free car insurance quotes, recent articles.

Featured Clinical Reviews

- Screening for Atrial Fibrillation: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement JAMA Recommendation Statement January 25, 2022

- Evaluating the Patient With a Pulmonary Nodule: A Review JAMA Review January 18, 2022

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

The Costs of US Emergency Department Visits

The US population made 144.8 million emergency department (ED) visits in 2017, costing a total of $76.3 billion, estimated a recent statistical brief from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP).

That year, 13.3% of the US population incurred an expense for an ED visit, and more than half of hospital inpatient stays originated with an ED visit. More than half of 2017 ED costs for the entire US, $39.5 billion, were incurred in large metropolitan areas. Aggregate ED visit costs and share of ED visit volume were highest for hospitals in the South. (ED charges were converted to costs using HCUP Cost-to-Charge Ratios based on Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services hospital accounting reports.)

Read More About

Rubin R. The Costs of US Emergency Department Visits. JAMA. 2021;325(4):333. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.26936

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Watch CBS News

The most expensive states for ER visits, ranked

By Jessica Learish

December 4, 2020 / 3:56 PM EST / CBS News

Have you ever been in a hospital emergency room? Maybe you broke your leg or had a burst appendix. When medical emergencies strike, an ER visit could spell the difference between life and death.

But, like many things in the American health care system , the cost of this kind of life-saving hospital care varies widely based on where you live or which hospital you visit.

Hospital Pricing Specialists collected billing data from nearly 4,500 hospitals across the country to gauge the average price of a moderate-severity ER visit — the most common kind of visit — in each state. (Think acute pain of unknown origin, or a fever greater than 100.5 degrees Fahrenheit.)

The overall price tag is made up of emergency room charges, lab and radiology tests, pharmacy and supply costs, and other hospital fees. Each line item also includes charges that go toward paying the health care providers themselves.

In this gallery, the numbers are presented before any medical insurance is applied. Here are the 50 states (and Washington, D.C.) ranked by the pre-insurance cost of a moderate-severity ER visit.

51. Maryland

A moderate-severity ER visit in Maryland costs an average of $623 before insurance.

Maine hospitals charge an average of $952 for moderate-severity emergency room visits.

49. West Virginia

A visit to a West Virginia ER will run you $1,127 on average.

48. Montana

The average price of emergency hospital care in Montana is $1,138.

47. Louisiana