- The Contents

- The Making of

- Where Are They Now

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Q & A with Ed Stone

golden record

Where are they now.

- frequently asked questions

- Q&A with Ed Stone

The Golden Record

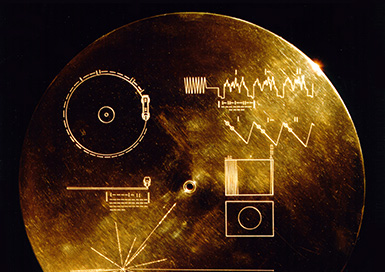

Pioneers 10 and 11, which preceded Voyager, both carried small metal plaques identifying their time and place of origin for the benefit of any other spacefarers that might find them in the distant future. With this example before them, NASA placed a more ambitious message aboard Voyager 1 and 2, a kind of time capsule, intended to communicate a story of our world to extraterrestrials. The Voyager message is carried by a phonograph record, a 12-inch gold-plated copper disk containing sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth.

Here’s What Humanity Wanted Aliens to Know About Us in 1977

I t was nearly 30 years ago—Jan. 24, 1986, nearly a decade after it had been launched—that the Voyager 2 spacecraft made its closest pass to Uranus and, as TIME phrased it, “taught scientists more about Uranus than they had learned in the entire 205 years since it was discovered.”

But the sophisticated equipment that sent information back to NASA wasn’t the only important thing on board the spacecraft. The Voyager 2, like the Voyager 1, carried with it a record, plated in gold, on which had been encoded sounds and images meant to “portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth,” according to NASA . The message from Earth was curated by a committee led by Carl Sagan and contained 115 images of “scenes from Earth.”

It was estimated in 1977, when the Voyagers launched, that it would take 40,000 years for them to reach a star system where there might be a being capable of deciphering the record. But, should that ever happen, what exactly could those photos say about humanity? Here’s a hint, from a few of the pictures on the golden record, and our best guesses at how hypothetical aliens might interpret them:

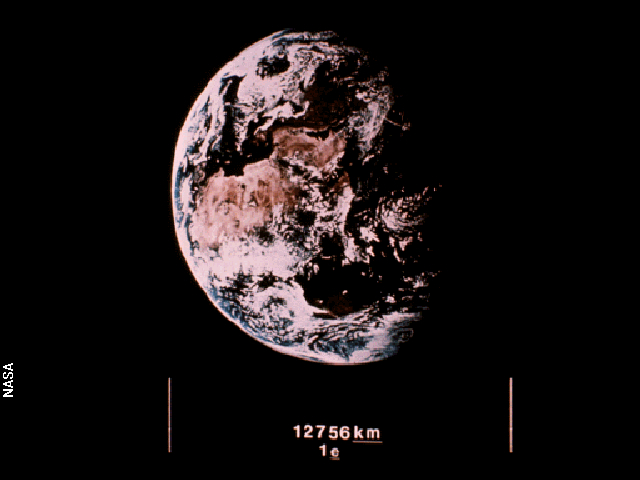

Cute young Earthlings and an image of their planet, or maybe giant Earthlings and a smaller planet under their control:

A fully grown earthling, or maybe a demonstration of the kinds of weapons available on earth:.

An Earth city building at sunset, or maybe the spacecraft with which a large number of Earthlings will come find you:

Earth traffic jam, or maybe why Earthlings will be fleeing to move to your home planet:

Earth scientist at work, or maybe an Earthling with goggles that can see you right now:

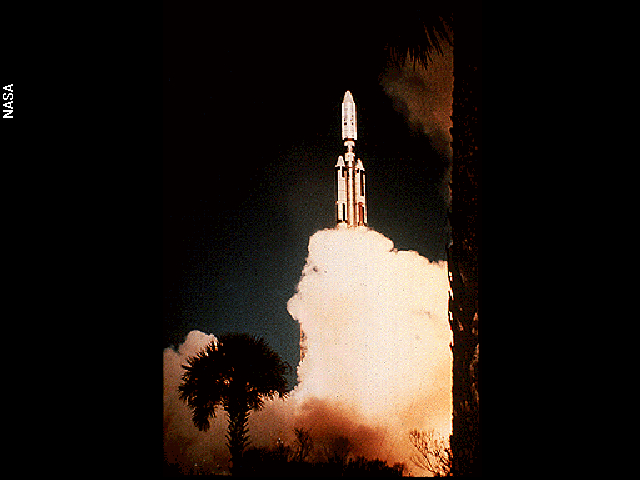

How this thing got to you, or maybe a missile:

An image of early Earth spaceflight, or a being we abandoned in space:

Celestial bodies near the Earth, Jupiter, Mercury and Mars, or maybe the places we’ve already conquered:

Where to find us, or maybe where to stay away from:

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Why We're Spending So Much Money Now

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- Breaker Sunny Choi Is Heading to Paris

- Why TV Can’t Stop Making Silly Shows About Lady Journalists

- The Case for Wearing Shoes in the House

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How the Voyager Golden Record Was Made

By Timothy Ferris

We inhabit a small planet orbiting a medium-sized star about two-thirds of the way out from the center of the Milky Way galaxy—around where Track 2 on an LP record might begin. In cosmic terms, we are tiny: were the galaxy the size of a typical LP, the sun and all its planets would fit inside an atom’s width. Yet there is something in us so expansive that, four decades ago, we made a time capsule full of music and photographs from Earth and flung it out into the universe. Indeed, we made two of them.

The time capsules, really a pair of phonograph records, were launched aboard the twin Voyager space probes in August and September of 1977. The craft spent thirteen years reconnoitering the sun’s outer planets, beaming back valuable data and images of incomparable beauty . In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first human-made object to leave the solar system, sailing through the doldrums where the stream of charged particles from our sun stalls against those of interstellar space. Today, the probes are so distant that their radio signals, travelling at the speed of light, take more than fifteen hours to reach Earth. They arrive with a strength of under a millionth of a billionth of a watt, so weak that the three dish antennas of the Deep Space Network’s interplanetary tracking system (in California, Spain, and Australia) had to be enlarged to stay in touch with them.

If you perched on Voyager 1 now—which would be possible, if uncomfortable; the spidery craft is about the size and mass of a subcompact car—you’d have no sense of motion. The brightest star in sight would be our sun, a glowing point of light below Orion’s foot, with Earth a dim blue dot lost in its glare. Remain patiently onboard for millions of years, and you’d notice that the positions of a few relatively nearby stars were slowly changing, but that would be about it. You’d find, in short, that you were not so much flying to the stars as swimming among them.

The Voyagers’ scientific mission will end when their plutonium-238 thermoelectric power generators fail, around the year 2030. After that, the two craft will drift endlessly among the stars of our galaxy—unless someone or something encounters them someday. With this prospect in mind, each was fitted with a copy of what has come to be called the Golden Record. Etched in copper, plated with gold, and sealed in aluminum cases, the records are expected to remain intelligible for more than a billion years, making them the longest-lasting objects ever crafted by human hands. We don’t know enough about extraterrestrial life, if it even exists, to state with any confidence whether the records will ever be found. They were a gift, proffered without hope of return.

I became friends with Carl Sagan, the astronomer who oversaw the creation of the Golden Record, in 1972. He’d sometimes stop by my place in New York, a high-ceilinged West Side apartment perched up amid Norway maples like a tree house, and we’d listen to records. Lots of great music was being released in those days, and there was something fascinating about LP technology itself. A diamond danced along the undulations of a groove, vibrating an attached crystal, which generated a flow of electricity that was amplified and sent to the speakers. At no point in this process was it possible to say with assurance just how much information the record contained or how accurately a given stereo had translated it. The open-endedness of the medium seemed akin to the process of scientific exploration: there was always more to learn.

In the winter of 1976, Carl was visiting with me and my fiancée at the time, Ann Druyan, and asked whether we’d help him create a plaque or something of the sort for Voyager. We immediately agreed. Soon, he and one of his colleagues at Cornell, Frank Drake, had decided on a record. By the time NASA approved the idea, we had less than six months to put it together, so we had to move fast. Ann began gathering material for a sonic description of Earth’s history. Linda Salzman Sagan, Carl’s wife at the time, went to work recording samples of human voices speaking in many different languages. The space artist Jon Lomberg rounded up photographs, a method having been found to encode them into the record’s grooves. I produced the record, which meant overseeing the technical side of things. We all worked on selecting the music.

I sought to recruit John Lennon, of the Beatles, for the project, but tax considerations obliged him to leave the country. Lennon did help us, though, in two ways. First, he recommended that we use his engineer, Jimmy Iovine, who brought energy and expertise to the studio. (Jimmy later became famous as a rock and hip-hop producer and record-company executive.) Second, Lennon’s trick of etching little messages into the blank spaces between the takeout grooves at the ends of his records inspired me to do the same on Voyager. I wrote a dedication: “To the makers of music—all worlds, all times.”

To our surprise, those nine words created a problem at NASA . An agency compliance officer, charged with making sure each of the probes’ sixty-five thousand parts were up to spec, reported that while everything else checked out—the records’ size, weight, composition, and magnetic properties—there was nothing in the blueprints about an inscription. The records were rejected, and NASA prepared to substitute blank discs in their place. Only after Carl appealed to the NASA administrator, arguing that the inscription would be the sole example of human handwriting aboard, did we get a waiver permitting the records to fly.

In those days, we had to obtain physical copies of every recording we hoped to listen to or include. This wasn’t such a challenge for, say, mainstream American music, but we aimed to cast a wide net, incorporating selections from places as disparate as Australia, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, China, Congo, Japan, the Navajo Nation, Peru, and the Solomon Islands. Ann found an LP containing the Indian raga “Jaat Kahan Ho” in a carton under a card table in the back of an appliance store. At one point, the folklorist Alan Lomax pulled a Russian recording, said to be the sole copy of “Chakrulo” in North America, from a stack of lacquer demos and sailed it across the room to me like a Frisbee. We’d comb through all this music individually, then meet and go over our nominees in long discussions stretching into the night. It was exhausting, involving, utterly delightful work.

“Bhairavi: Jaat Kahan Ho,” by Kesarbai Kerkar

In selecting Western classical music, we sacrificed a measure of diversity to include three compositions by J. S. Bach and two by Ludwig van Beethoven. To understand why we did this, imagine that the record were being studied by extraterrestrials who lacked what we would call hearing, or whose hearing operated in a different frequency range than ours, or who hadn’t any musical tradition at all. Even they could learn from the music by applying mathematics, which really does seem to be the universal language that music is sometimes said to be. They’d look for symmetries—repetitions, inversions, mirror images, and other self-similarities—within or between compositions. We sought to facilitate the process by proffering Bach, whose works are full of symmetry, and Beethoven, who championed Bach’s music and borrowed from it.

I’m often asked whether we quarrelled over the selections. We didn’t, really; it was all quite civil. With a world full of music to choose from, there was little reason to protest if one wonderful track was replaced by another wonderful track. I recall championing Blind Willie Johnson’s “Dark Was the Night,” which, if memory serves, everyone liked from the outset. Ann stumped for Chuck Berry’s “ Johnny B. Goode ,” a somewhat harder sell, in that Carl, at first listening, called it “awful.” But Carl soon came around on that one, going so far as to politely remind Lomax, who derided Berry’s music as “adolescent,” that Earth is home to many adolescents. Rumors to the contrary, we did not strive to include the Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun,” only to be disappointed when we couldn’t clear the rights. It’s not the Beatles’ strongest work, and the witticism of the title, if charming in the short run, seemed unlikely to remain funny for a billion years.

“Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground,” by Blind Willie Johnson

Ann’s sequence of natural sounds was organized chronologically, as an audio history of our planet, and compressed logarithmically so that the human story wouldn’t be limited to a little beep at the end. We mixed it on a thirty-two-track analog tape recorder the size of a steamer trunk, a process so involved that Jimmy jokingly accused me of being “one of those guys who has to use every piece of equipment in the studio.” With computerized boards still in the offing, the sequence’s dozens of tracks had to be mixed manually. Four of us huddled over the board like battlefield surgeons, struggling to keep our arms from getting tangled as we rode the faders by hand and got it done on the fly.

The sequence begins with an audio realization of the “music of the spheres,” in which the constantly changing orbital velocities of Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, and Jupiter are translated into sound, using equations derived by the astronomer Johannes Kepler in the sixteenth century. We then hear the volcanoes, earthquakes, thunderstorms, and bubbling mud of the early Earth. Wind, rain, and surf announce the advent of oceans, followed by living creatures—crickets, frogs, birds, chimpanzees, wolves—and the footsteps, heartbeats, and laughter of early humans. Sounds of fire, speech, tools, and the calls of wild dogs mark important steps in our species’ advancement, and Morse code announces the dawn of modern communications. (The message being transmitted is Ad astra per aspera , “To the stars through hard work.”) A brief sequence on modes of transportation runs from ships to jet airplanes to the launch of a Saturn V rocket. The final sounds begin with a kiss, then a mother and child, then an EEG recording of (Ann’s) brainwaves, and, finally, a pulsar—a rapidly spinning neutron star giving off radio noise—in a tip of the hat to the pulsar map etched into the records’ protective cases.

“The Sounds of Earth”

Ann had obtained beautiful recordings of whale songs, made with trailing hydrophones by the biologist Roger Payne, which didn’t fit into our rather anthropocentric sounds sequence. We also had a collection of loquacious greetings from United Nations representatives, edited down and cross-faded to make them more listenable. Rather than pass up the whales, I mixed them in with the diplomats. I’ll leave it to the extraterrestrials to decide which species they prefer.

“United Nations Greetings/Whale Songs”

Those of us who were involved in making the Golden Record assumed that it would soon be commercially released, but that didn’t happen. Carl repeatedly tried to get labels interested in the project, only to run afoul of what he termed, in a letter to me dated September 6, 1990, “internecine warfare in the record industry.” As a result, nobody heard the thing properly for nearly four decades. (Much of what was heard, on Internet snippets and in a short-lived commercial CD release made in 1992 without my participation, came from a set of analog tape dubs that I’d distributed to our team as keepsakes.) Then, in 2016, a former student of mine, David Pescovitz, and one of his colleagues, Tim Daly, approached me about putting together a reissue. They secured funding on Kickstarter , raising more than a million dollars in less than a month, and by that December we were back in the studio, ready to press play on the master tape for the first time since 1977.

Pescovitz and Daly took the trouble to contact artists who were represented on the record and send them what amounted to letters of authenticity—something we never had time to accomplish with the original project. (We disbanded soon after I delivered the metal master to Los Angeles, making ours a proud example of a federal project that evaporated once its mission was accomplished.) They also identified and corrected errors and omissions in the information that was provided to us by recordists and record companies. Track 3, for instance, which was listed by Lomax as “Senegal Percussion,” turns out instead to have been recorded in Benin and titled “Cengunmé”; and Track 24, the Navajo night chant, now carries the performers’ names. Forty years after launch, the Golden Record is finally being made available here on Earth. Were Carl alive today—he died in 1996 at the age of sixty-two—I think he’d be delighted.

This essay was adapted from the liner notes for the new edition of the Voyager Golden Record, recently released as a vinyl boxed set by Ozma Records .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Anthony Lydgate

By Marie Howe

By Rivka Galchen

11 Pieces of Media on the Voyager Golden Record

By michele debczak | apr 11, 2021.

At this moment, two gold-plated copper records are hurtling through space, speeding beyond our solar system. The Voyager 1 and 2 probes launched in 1977 , and they’ve since traveled billions of miles from Earth. They are currently the loneliest human-made objects in the universe—and they may stay that way forever—but they were built to make a connection.

The purpose of NASA ’s Voyager mission is to illustrate life on Earth to any intelligent aliens that come across the spacecraft. The records on board contain media selected by a committee chaired by scientist Carl Sagan. If extraterrestrials can use the instructions engraved on the disc's cover to access its contents, they’ll be exposed to animal noises, classical music, and photographs of people from around the world. Here are some pieces of media that were chosen to represent our planet.

1. Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony

Ludwig van Beethoven is one of many classical artists representing the music of Earth on the Voyager record. In addition to his Fifth Symphony , the composer’s String Quartet No. 13, Opus 130, is also included on the track list.

2. Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode”

Though there are many musical compositions on the Voyager Golden Record , the inclusion of “Johnny B. Goode” stirred controversy. Critics claimed rock n’ roll was too adolescent for a project of such significance. Carl Sagan responded by saying, “There are a lot of adolescents on the planet.”

3. A Mandarin Greeting and Invitation

The Voyager project recorded UN delegates from around the world saying greetings in 54 different languages. Most are straightforward, but the Mandarin message includes an invitation. Translated to English, it says: "Hope everyone's well. We are thinking about you all. Please come here to visit when you have time."

4. Humpback Whale Songs

The greetings section of the record features one language that doesn’t belong to humans. Interspersed between the spoken audio clips are the sounds of singing humpback whales . There’s a reason whales were included with the greetings rather than the other animal noises on the record—it was the committee’s way of acknowledging that humans aren’t the only intelligent life on Earth.

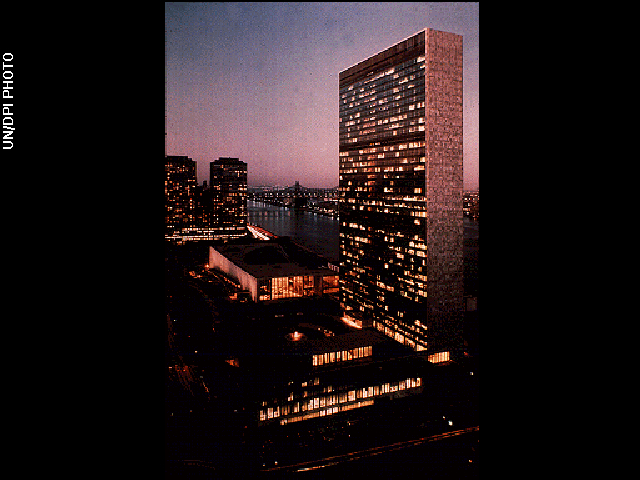

5. The UN Building

The Voyager committee chose the UN Building to represent modern urban architecture. The record includes two images of the New York City skyscraper, both taken at the same angle. One depicts the structure during the day and the other shows it at night .

6. A Traffic Jam

The Voyager record highlights many technological marvels from the time it was made, including a rocket and an airplane. The photo of a traffic jam in Thailand that was included may seem less impressive, but it accurately depicts how we use cars on our planet.

7. A Bulgarian Folk Song

The Voyager committee wanted the record's music to represent a wide range of eras and cultures. One track, titled "Izlel je Delyo Hagdutin," is a traditional folk song from Bulgaria . Sung by Valya Balkanska, it’s about a famous rebel leader from the country’s history. Folk music from Azerbaijan, Georgia, and the Navajo people also made it onto the compilation.

8. Ann Druyan’s Brainwaves

While working on the Voyager committee, Ann Druyan had the idea to record her brainwaves, turn them into audio, and copy them onto the record. She spent an hour hooked up to electrical impulse-measuring systems while thinking various thoughts, including what it’s like to fall in love. She and Sagan—her collaborator on the Voyager record project—had recently gotten engaged.

9. A Map of the Solar System

The Voyager mission is designed to travel far, but it will always hold evidence of where it came from. One of the images on the record shows a picture of our solar system with a map illustrating Earth’s location.

10. People Eating

Some human behaviors are tricky to capture in one image. To show the different ways people consume food and drink, the Voyager committee included a photo of someone licking ice cream, someone else biting into a sandwich, and a third person pouring water into their mouth.

11. A Morse Code Message

Another type of communication represented on the Voyager record is Morse code . The message translates to the Latin saying ad astra per aspera , or “to the stars through hard work.”

Advertisement

What Voyager's golden record tells ET about Earth

18 April 2009

Douglas Vakoch of the SETI Institute says any future messages sent to ET should reflect the human race as it really – warts and all . Click through this gallery to see what an alien civilisation might learn about earthlings from images on a golden record placed on each of the twin Voyager probes. Since launching in 1977, the spacecraft have travelled to the edge of the solar system.

Read more: “ Where am I? Voyager on the solar system’s frontier “

NASA's Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecraft, which launched in 1972 and 1973, carried this design , which was etched on a 15x23-cm gold-anodised aluminium plate. The plaque was intended to inform any extraterrestrials who might come upon it when and where the spacecraft launched (using 14 pulsars as a reference point). "There's also an image of a man and woman - perhaps the most cryptic for an extraterrestrial to understand," says Vakoch. "The response NASA got [to that image] was quite surprising to them. Some were concerned that NASA was sending pornography into space." (Illustration: NASA)

NASA placed a more ambitious message aboard the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft, which launched in 1977. Sounds and images intended to portray the diversity of life and cultures on Earth were encoded on a phonograph record made of gold-plated copper. A committee chaired by Carl Sagan assembled its contents: 115 images, a variety of natural sounds, music from different cultures and eras, and spoken greetings in 55 languages. Each record is encased in a protective aluminium jacket, together with a cartridge and a needle. Instructions, in symbolic language, explain the origin of the spacecraft and how to play the record. "The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilisations in interstellar space," said Sagan. "But the launching of this bottle into the cosmic ocean says something very hopeful about life on this planet." (Image: NASA)

"Like other messages that have been created for extraterrestrial audiences, the starting point of the Voyager recording was something we would expect extraterrestrials to have in common with us - and that's basic math and science," says Vakoch. (Illustration: Frank Drake)

This image defines basic units of mass, length and time. (Illustration: Frank Drake)

Included on the Voyager record are images of (clockwise from upper left) Mercury, Earth, Jupiter and Mars. (Image: NASA)

Overlaid on this satellite image of Egypt are some of the some of the most important gases in Earth's atmosphere and their concentrations. The chemical formulas used here also appear in other Voyager slides, where there are diagrams of various atoms. (Illustration: NASA)

This illustration of DNA (top left) shows how "the chemistry of Earth is tied into our genetic material", says Vakoch. Human reproduction is also the focus of multiple Voyager images, from the fertilisation of an egg by a sperm to a developing foetus to a silhouette of a man and a pregnant woman. "There's an emphasis on reproduction in the Voyager recording, but also considerable caution in depicting nude human beings," says Vakoch. "The image [of the man and woman] nicely portrays our ambivalence about sexuality." (Illustrations: Jon Lomberg)

This image illustrates "licking, eating and drinking" (Image: National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center)

There are some Voyager images that relate to health and the human body, including this X-ray of a hand, says Vakoch - "but nothing that explicitly says, 'Our bodies are frail.'" "The Voyager recordings intentionally minimise negative aspects of [human culture]," says Vakoch. "There was an intentional decision not to include a picture of a nuclear mushroom cloud [or] poverty and disease." But long-lived alien civilisations are the ones most likely to be around to intercept our messages. "If they're older, perhaps they're also much more advanced than we are," says Vakoch. "What would we have to say that would be of interest to them?" "I think the greatest thing we have to offer is to be honest about our current level of development, to highlight that we're not sure that we're even going to survive the next century . . . but that we have enough faith that we will continue to exist that we are making an effort to reach out to other civilisations." (Image: National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center)

This illustration of vertebrate evolution shows representatives of the major vertebrate groupings, including amphibians, birds and mammals. The image of the man and woman at top right is quite similar to the drawing that was on the Pioneer plaque , with one difference - in the Pioneer image of the early 1970s, the man is raising a hand in greeting, but in this image from a few years later, the woman is waving hello. "Just in the span of a few short years, we saw a responsiveness in NASA to [include] a more adequate representation of women by showing a woman not as passively standing next to a man but as being a member of a couple that was actively sending greetings to other worlds," says Vakoch. (Illustration: Jon Lomberg)

NASA really made an effort with Voyager to include images and sounds from around the world. "What's unique about the Voyager recording is there's really an emphasis on describing the breadth of human experience," says Vakoch. "Really it's the best portrayal of human diversity of any messages that have been sent out in space." Still, the diversity it displays is limited – there are no images representing homosexuality, for example. "I think any interstellar message is in part a reflection of its times," he says. "It may well be that if NASA sends out another image in the future, it may include a picture of two men or two women holding hands." (Images: United Nations)

Sign up to our weekly newsletter

Receive a weekly dose of discovery in your inbox! We'll also keep you up to date with New Scientist events and special offers.

More from New Scientist

Explore the latest news, articles and features

Physicists have worked out how to melt any material

Subscriber-only

Environment

Heatwaves now last much longer than they did in the 1980s, unprecedented gps jamming attack affects 1600 aircraft over europe, tooth loss linked to early signs of alzheimer’s disease, popular articles.

Trending New Scientist articles

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The Voyager Golden Record Finally Finds An Earthly Audience

Alexi Horowitz-Ghazi

The Voyager Golden Record remained mostly unavailable and unheard, until a Kickstarter campaign finally brought the sounds to human ears. Ozma Records/LADdesign hide caption

The Voyager Golden Record remained mostly unavailable and unheard, until a Kickstarter campaign finally brought the sounds to human ears.

The Golden Record is basically a 90-minute interstellar mixtape — a message of goodwill from the people of Earth to any extraterrestrial passersby who might stumble upon one of the two Voyager spaceships at some point over the next couple billion years.

But since it was made 40 years ago, the sounds etched into those golden grooves have gone mostly unheard, by alien audiences or those closer to home.

"The Voyager records are the farthest flung objects that humans have ever created," says Timothy Ferris, a veteran science and music journalist and the producer of the Golden Record. "And they're likely to be the longest lasting, at least in the 20th century."

In the late 1970s, Ferris was recruited by his friend, astronomer Carl Sagan, to join a team of scientists, artists and engineers to help create two engraved golden records to accompany NASA's Voyager mission — which would eventually send a pair of human spacecraft beyond the outer rings of the solar system for the first time in history.

Carl Sagan And Ann Druyan's Ultimate Mix Tape

Ferris was tasked with the technical aspects of getting the various media onto the physical LP, and with helping to select the music. In addition to greetings in dozens of languages and messages from leading statesmen, the records also contained a sonic history of planet Earth and photographs encoded into the record's grooves. But mostly, it was music.

"We were gathering a representation of the music of the entire earth," Ferris says. "That's an incredible wealth of great stuff."

Ferris and his colleagues worked together to sift through Earth's enormous discography to decide which pieces of sound would best represent our planet. They really only had two criteria: "One was: Let's cast a wide net. Let's try to get music from all over the planet," he says. "And secondly: Let's make a good record."

That meant late nights of listening sessions while "almost physically drowning in records," Ferris says.

The final selection, which was engraved in copper and plated in gold, included opera, rock 'n' roll, blues, classical music and field recordings selected by ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax .

When Voyager 1 and its identical sister craft Voyager 2 launched in 1977, each carried a gold record titled T he Sounds Of Earth that contained a selection of recordings of life and culture on Earth. The cover contains instructions for any extraterrestrial being wishing to play the record. NASA/Getty Images hide caption

When Voyager 1 and its identical sister craft Voyager 2 launched in 1977, each carried a gold record titled T he Sounds Of Earth that contained a selection of recordings of life and culture on Earth. The cover contains instructions for any extraterrestrial being wishing to play the record.

Ferris says that from the very start, many people on the production team expected and hoped for the record to be commercially released soon after the launch of Voyager.

"Carl Sagan tried to interest labels in releasing Voyager," Ferris says. "It never worked."

Ferris says that's likely because the music rights were owned by several different record labels who were hesitant to share the bill. So — except for a limited CD-ROM release in the early 1990s — the record went largely unheard by the wider world.

David Pescovitz, an editor at technology news website Boing Boing and a research director at the nonprofit Institute for the Future, was seven years old when the Voyager spacecraft launched.

"When you're seven years old and you hear that a group of people created a phonograph record as a message for possible extraterrestrials and launched it on a grand tour of the solar system," says Pescovitz, "it sparks the imagination."

A couple years ago, Pescovitz and his friend Tim Daly, a record store manager at Amoeba Music in San Francisco, decided to collaborate on bringing the Golden Record to an earthbound audience.

Pescovitz approached his former graduate school professor — none other than Ferris, the Golden Record's original producer — about the project, and Ferris gave his blessing, with one important caveat.

Voyagers' Records Wait for Alien Ears

"You can't release a record without remastering it," says Ferris. "And you can't remaster without locating the master."

That turned out to be a taller order than expected. The original records were mastered in a CBS studio, which was later acquired by Sony — and the master tapes had descended into Sony's vaults.

Pescovitz enlisted the company's help in searching for the master tapes; in the meantime, he and Daly got to work acquiring the rights for the music and photographs that comprised the original. They also reached out to surviving musicians whose work had been featured on the record to update incomplete track information.

Finally, Pescovitz and Daly got word that one of Sony's archivists had found the master tapes.

Pescovitz remembers the moment he, Daly and Ferris traveled to Sony's Battery Studios in New York City to hear the tapes for the first time.

"They hit play, and the sounds of the Solomon Islands pan pipes and Bach and Chuck Berry and the blues washed over us," Pescovitz says. "It was a very moving and sublime experience."

Daly says that, in remastering the album, the team decided not to clean up the analog artifacts that had made their way onto the original master tapes, in order to preserve the record's authenticity down to its imperfections.

"We wanted it to be a true representation of what went up," Daly says.

Pescovitz and Daly teamed up with Lawrence Azerrad, a graphic designer who has made record packaging for the likes of Sting and Wilco , to design a luxuriant box set, complete with a coffee table book of photographs and, of course, tinted vinyl.

"I mean, if you do a golden record box set, you have to do it on gold vinyl," Daly says.

They put the project on Kickstarter and expected to sell it mostly to vinyl collectors, space nerds and audiophiles — but they underestimated the appeal.

"The internet was just on fire, talking about this thing," Daly says.

They blew past their initial funding goal in two days, eventually raising more than $1.3 million dollars, making it the most successful musical Kickstarter campaign ever. Among the initial 11,000 contributors were family members of NASA's original Voyager mission team.

An Alien View Of Earth

Last week, Ferris got his box set in the mail. He says that his friend, the late Carl Sagan, would be delighted by what they made.

"I think this record exceeds Carl's — not only his expectations, but probably his highest hopes for a release of the Voyager record," Ferris says. "I'm glad these folks were finally able to make it happen."

Pescovitz says he's just glad to have returned the Golden Record to the world that created it.

At a moment of political division and media oversaturation, Pescovitz and Daly say they hope that their Golden Record can offer a chance for people to slow down for a moment; to gather around the turntable and bask in the crackly sounds of what Sagan called the "pale blue dot" that we call home.

"As much as it was a gift from humanity to the cosmos, it was really a gift to humanity as well," Pescovitz says. "It's a reminder of what we can accomplish when we're at our best."

The Signal's Golden Record Explained: The True Story Of The Voyager's Vinyl & Message

- The Signal on Netflix includes the Voyager's golden record and its message to potential extraterrestrial beings.

- The end of the Signal briefly touches on the history of the Voyager probes and the effort to introduce Earth's culture to alien civilizations.

- Carl Sagan's son, Nick, voices the iconic "hello" message on the golden record, hoping for a future connection with extraterrestrial life.

The golden record aboard the Voyager, shown in Netflix's The Signal , includes a fascinating true story and meaning. In The Signal, Paula keeps hearing a message saying "hello," convincing herself that it was aliens trying to contact them and mimic their voices. However, the major twist at the end of The Signa l is that the aliens use the Voyager's golden record to send the "hello" message rather than mimicking the English language and inflection with their voices. Additionally, they send back the probe and message as a way to investigate the temperament of the human race before coming themselves.

While it might've seemed anticlimactic for the Voyager to land instead of an extraterrestrial ship, this narrative choice grounds The Signal in reality. Voyager 1 and 2 are real spacecrafts launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, in 1977. When creating the probes, scientists affixed a golden record to the outside of each probe in case extraterrestrials discovered the Voyagers. These elements make The Signal seem like a more plausible alien story than many alien invasion movies . Additionally, the narrative choice introduces viewers to a great piece of scientific history – the golden records – which the NASA Voyager website explains at length.

10 Great Sci-Fi Shows Like Netflix's The Signal

What’s on the voyager's golden records in real life.

When creating the phonographic records for the Voyager probes, a committee was formed to decide what exactly would be included. This committee was led by famous planetary astronomer Dr. Carl Sagan, who pushed the scientific community to search for extraterrestrial life. The idea behind the records was to introduce aliens to life and different cultures on Earth. To start with, the committee included 115 images in analog form from historical moments, landmarks, and science. This gives a visual understanding of the human race's development. However, the more famous parts of the golden record are the greetings, sounds, and music.

As shown in The Signal , the Golden Record includes salutations in different languages. While there were only a few played in the miniseries, 55 different languages were included on the record in real life . Due to time constraints, the team collected speakers from Cornell University's language departments and the nearby communities. Rather than giving the speakers a prompt, the scientists simply told speakers to say a brief greeting to potential aliens.

Additionally, these greetings aren't the only sounds included on the records. The golden records aboard the Voyager probes also include a large variety of sounds recorded around Earth, such as elephants, trains, heartbeats, and laughter . These are meant to represent the different facets of our world that may be unfamiliar to extraterrestrials. It also could serve as a time capsule of sorts for generations, thousands of years in the future.

The Voyager's Golden Record Playlist Explained

While the Golden Record in The Signal only included some of the greetings, the real vinyl also includes a carefully curated playlist that lasts 90 minutes. The songs come from all over the world, integrating as many cultures as possible. Some pieces like those written by Bach and Beethoven are classical, while others represent nations like the Navajo Nation and Senegal. Any extraterrestrials encountering this record would be able to see the various styles of music the world has to offer.

Controversially, the record also included modern hits like "Johnny B. Goode" by Chuck Berry and Dark Was The Night by Blind Willie Johnson. These additions, while different from the rest, are important because they represent the Black American community's music that is often appropriated. However, they're played by the original artists, granting them the recognition they deserve.

Carl Sagan’s Son Recorded The “Hello” Voice Heard In The Signal

While the world has failed to come together in the way they hoped when making the Voyager's Golden Record, there is still time to change that

The voice heard throughout The Signal saying hello really appears on the Voyager's Golden Record. When Voyager 1 entered the interstellar, Eos interviewed Nick Sagan, Carl Sagan's son, who voiced the message . He recounted that his father sat him in front of a microphone at six years old and asked what he would want to say to theoretical aliens if they existed. His message, "Hello from the children of the planet Earth," has become iconic and known all around the world.

When reflecting on his experience, he said that he feels giddy and thrilled that his voice represents the English language on the object that's gone the furthest into the universe. However, Sagan doesn't necessarily think that his voice will ever be heard by extraterrestrials. While he acknowledges the lack of concrete evidence for the existence of aliens, he hopes that extraterrestrials will one day hear the Voyager's record, reach out to us, and discuss the history of their own civilization.

Nick Sagan's hope is reflective of The Signal 's overall message . While the world has failed to come together in the way they hoped when making the Voyager's Golden Record, there is still time to change that. Society can become a representation of the beauty and diversity on the Golden Record. Then, if aliens do come to see us, they can find a thriving world full of peace and joy instead of war and separation.

The Signal Cast & Character Guide

How the golden records were made in real life.

According to NASA, the creation of the Golden Record was a group project that required the most skilled people from various fields. In addition to the team that curated the contents of the record, the Pyral S.A. of Creteil France provided the blank records which were then sent to Boulder, Colorado. There, JVC Cutting Center created the masters, which then went to Gardena, California. There, the copper records were cut and plated. In total, eight to ten records were created. Two were placed on the Voyager probes. The others were sent to the following institutions and people according to a Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) expert (via Business Insider ):

- NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- Johnson Space Center

- Kennedy Space Center

- Glenn Research Center

- Langley Research Center

- Goddard Space Flight Center

- The Smithsonian's National Air & Space Museum

- The Library of Congress

- President Carter

- The United Nations

The Voyager's Golden Record Has A Bigger Mystery That The Signal Doesn't Tell You

While the main mystery of The Signal is who is saying "hello," there's a much bigger real-life mystery surrounding the Golden Records. Of the ten records on Earth, only eight are accounted for. According to the JPL expert, the copies sent to The President and Langley Research Center cannot be located . This raises questions as to where the Golden Records are. To make matters more complicated, the original materials are for sale, meaning identical replicas could soon be on the market. This real-life mystery could make for a great true crime Netflix documentary .

Source: NASA Voyager website , Eos , and Business Insider

The Signal (2024)

Cast Katharina Schuttler, Sheeba Chadda, Hadi Khanjanpour, Yuna Bennett, Florian David Fitz, Peri Baumeister

Release Date March 7, 2024

Genres Sci-Fi, Drama, Mystery

Streaming Service(s) Netflix

Writers Kim Zimmermann, Nadine Gottmann, Florian David Fitz, Sebastian Hilger

Directors Philipp Leinemann, Sebastian Hilger

Rating TV-MA

AIR & SPACE MAGAZINE

What would you have put on voyager’s golden record.

An author puts together his own “Earthling mixtape” in a new book.

Heather Goss

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ab/9e/ab9e36dc-dd53-4595-9b4f-a71fce87b00c/540486main_pia14113-43_946-710.jpg)

How one would describe life on Earth to aliens is one of the ultimate thought experiments. Carl Sagan headed up a committee to do just that in the mid-1970s, when NASA placed copies of the so-called Golden Record on Voyagers 1 and 2, now on their way out of the solar system. If extraterrestrials find it and and figure out how to play it, they’ll be greeted with a few hundred images and audio recordings of animals, nature, and people speaking in 55 languages, as well as music. This Earthling mixtape features Bach, Chuck Berry, more Bach, Mexican Mariachi music, a Pygmy girl’s initiation song, and some more Bach.

Representing all of human culture, of course, is an impossible task no matter how big the record. In his new book, The Voyager Record: A Transmission , Anthony Michael Morena takes an artful, stream-of-conscious look back at the record’s unavoidable limitations, considering the era in which it was created. And he wonders what he might have included had he been in Sagan’s shoes.

“Creating an updated tracklist for Voyager is always a risk,” writes Morena. “It’s presumptuous, it’s biased, it’s seductive and self-centered. It is also something that a lot of people have tried to do before. And yet it still feels necessary.” Below are some of his choices (we’ve put them in a list here, not in order).

I still have to consider exactly what my revised Golden Record might sound like, but I know that I don’t listen to enough world music to make it fair. I don’t think I listen to enough music to make any decision about what represents planet Earth. I’d probably only choose the kind of stuff I like to listen to. Which is to say that I can admit to myself what all the Bach fans couldn’t admit to themselves. It’s hard not to be biased, especially when the music sounds so good. Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s “ The Message .” Definitely. Mongolian long song . A style of music where almost every syllable of the song is performed as a sustained note. Meaning it could take three minutes to sing just 10 words. A form of singing that originated as a way to communicate over vast, empty distances of grass. Maybe something from the Norwegian black metal community. Highlighting the distinctive style of power chord that Øystein “Euronymous” Aarseth invented in the 90s. When I listen to the songs from the Golden Record I do this type of revision, where I remove two of the Bach compositions from the playlist. I leave “ Gavotte en Rondeaux from the Partita No. 3 in E Major for Violin .” I take out the Beethoven, Stravinsky, and Mozart, too. Serapis Bey’s “ Paranauê .” Otherwise known as That Capoeira Song. Because if a martial arts dance music exists, I think the aliens should know about it. Tibetan throat singing . Seems kind of obvious. Maybe some of the music we’ve imagined aliens would enjoy: the Mos Eisley Cantina Band , traditional Klingon Opera , the Diva Plavalaguna .

If you’re in the Washington, D.C. area, you can attend a book reading with the author at Upshur Street Books this Sunday, April 17, 6 p.m.

If you could hit “record” on your own Golden Record, what would you include?

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Heather Goss | | READ MORE

Heather Goss is the Departments Editor at Air & Space .

Voyager Golden Record Album

The Voyager Golden Record.

- Astronomy Picture of the Day

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Golden Record. Pioneers 10 and 11, which preceded Voyager, both carried small metal plaques identifying their time and place of origin for the benefit of any other spacefarers that might find them in the distant future. With this example before them, NASA placed a more ambitious message aboard Voyager 1 and 2, a kind of time capsule ...

The Voyager Golden Records are two identical phonograph records which were included aboard the two Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977. The records contain sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth, and are intended for any intelligent extraterrestrial life form who may find them.

The "Golden Record" would be an upgrade to Pioneer's plaques. Mounted on Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, twin probes launched in 1977, the two copies of the record would serve as time capsules and ...

The Voyager Golden Record contains 116 images and a variety of sounds. The items for the record, which is carried on both the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft, were selected for NASA by a committee chaired by Carl Sagan of Cornell University.Included are natural sounds (including some made by animals), musical selections from different cultures and eras, spoken greetings in 59 languages ...

January 22, 2016 4:56 PM EST. I t was nearly 30 years ago—Jan. 24, 1986, nearly a decade after it had been launched—that the Voyager 2 spacecraft made its closest pass to Uranus and, as TIME ...

How the Voyager Golden Record Was Made. Forty years ago, we sent a message to extraterrestrials—a collection of sights and sounds of life on Earth. We inhabit a small planet orbiting a medium ...

Voyager 1 is currently the farthest human-made object from Earth. This humble piece of technology has now reached interstellar space. The message it carries is a bold message to the void of space ...

The Voyager Golden Records are two phonograph records that were included aboard both Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977. The records contain sounds and imag...

7. A Bulgarian Folk Song. The Voyager committee wanted the record's music to represent a wide range of eras and cultures. One track, titled "Izlel je Delyo Hagdutin," is a traditional folk song ...

What Voyager's golden record tells ET about Earth. 18 April 2009. Douglas Vakoch of the SETI Institute says any future messages sent to ET should reflect the human race as it really - warts and ...

The Voyager Golden Record shot into space in 1977 with a message from humanity to the cosmos - and decades later, it stands as a reminder that we are all con...

"The Voyager records are the farthest flung objects that humans have ever created," says Timothy Ferris, a veteran science and music journalist and the producer of the Golden Record.

The golden record aboard the Voyager, shown in Netflix's The Signal, includes a fascinating true story and meaning. In The Signal, Paula keeps hearing a message saying "hello," convincing herself ...

The Voyager Golden Record On board each Voyager spacecraft is a time capsule: a 12-inch, gold-plated copper disk carrying spoken greetings in 55 languages from Earth's peoples, along with 115 images and myriad sounds representing our home NASA/JPL. Most NASA images are in the public domain. Reuse of this image is governed by NASA's image use ...

A Voyager probe, with the Golden Record attached. NASA/Public Domain This kind of thing is a large part of why, just 40 years on, certain aspects of the record look ridiculous to Earthlings, too .

Voyager Golden Record. December 4, 2017. Credit. NASA/JPL-Caltech. Language. english. Each Voyager spacecraft carries a copy of the Golden Record, which has been featured in several works of science fiction. The record's protective cover, with instructions for playing its contents, is shown at left.

What Would a Modern "Golden Record" Include? Now that several decades have passed since the launch of Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 in 1977, we look back on that time with a hazy sense of history ...

Carl Sagan headed up a committee to do just that in the mid-1970s, when NASA placed copies of the so-called Golden Record on Voyagers 1 and 2, now on their way out of the solar system.

The Voyager Golden Record. Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech. Download Share. Tags . Astronomy Picture of the Day; Image Credit NASA/JPL-Caltech. Size 640x639px. Return to top. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration. NASA explores the unknown in air and space, innovates for the benefit of humanity, and inspires the world through discovery.

Related article See the new 'golden record' launching to an ocean world this year Meanwhile, Voyager 2 has traveled more than 12.6 billion miles (20.3 billion kilometers) from our planet.