- Skip to main content

- Skip to header right navigation

- Skip to site footer

tech news, reviews & how to's

This article may contain affiliate links.

3 Popular Time Travel Theory Concepts Explained

Time travel theory. It's one of the most popular themes in fiction. But every plotline falls into one of these three Time Travel Theories.

Time travel is one of the most popular themes in cinema . Although most time travel movies are in the sci-fi genre, every genre, even comedy, horror, and drama, have tackled complicated storylines involving time travel theory. Chances are, you’ve seen at least a few of the movies listed below:

- But what about...

The Possibility Of Time Travel

Time travel theory.

- Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989)

- The Time Machine (2002)

- Timeline (2003)

- Time Cop (2004)

- Back to the Future (1985)

- 12 Monkeys (1995)

- Terminator Series (1984)

- Star Trek (2009)

- Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004)

- Freejack (1992)

- Looper (2012)

But one thing you might not have realized, even if you’ve seen hundreds of time travel-related films, is that there are only 3 different theories of time travel. That’s it. Every time travel movie or book that you’ve ever enjoyed falls into one of these time travel theories.

Fixed Timeline: Time Travel Theory

Want to change the future on Earth by modifying the past or present? Don’t even bother according to this time travel theory. In a fixed timeline, there’s a single history that is unchangeable. Whatever you are attempting to change by time-traveling is what created the problems in the present that you’re trying to fix ( 12 Monkeys ). Or you’re just wasting your time because the events you are trying to prevent will happen anyway ( Donnie Darko ).

Dynamic Timeline: Time Travel Theory

History is fragile and even the smallest changes can have a huge impact. After traveling back in time, your actions may impact your own timeline. The result is a paradox. Your changes to the past might result in you never being born, like in Back to the Future (1985), or never traveling in time in the first place. In The Time Machine (2002), Hartdegen goes back in time to save his sweetheart Emma but can’t. Doing so would have resulted in his never developing the time machine that he used to try and save her.

One common way to explore this paradox theory is by killing your own grandfather. The grandfather paradox is when a time traveler attempts to kill their grandfather before the grandfather meets their grandmother. This prevents the time travel’s parents from being born and thus the time traveler himself from being born. But if the time traveler was never born, then the traveler would never have traveled back in time, therefore erasing his or her actions involving the death of their grandfather.

Multiverse: Time Travel Theory

Travel all over time and do whatever you want. It doesn’t matter because there are multiple universes and your actions only create new timelines. This is a common theory used by the science fiction TV series, Doctor Who . Using the multiverse theory of time travel, it’s assumed that there are multiple coexisting alternate timelines.

Therefore, when the traveler goes back in time, they end up in a new timeline where historical events can differ from the timeline they came from, but their original timeline does not cease to exist. This means the grandfather paradox can be avoided. Even if the time traveler’s grandparent is killed at a young age in the new timeline, he/she still survived to have children in the original timeline, so there is still a causal explanation for the traveler’s existence.

Time travel may actually create a new timeline that diverges from the original timeline at the moment the time traveler appears in the past, or the traveler may arrive in an already existing parallel universe. There’s just one problem… you can’t go back ( The One , 2002).

But what about…

Some may argue that people who are “trapped” in time are time travelers as well. This happens in countless time travel movies including Robin Williams ‘ character in the 1995 film Jumanji who gets trapped inside a board game. The list of “people who are cryogenically frozen and then successfully thawed out in the future” is even longer and includes Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me (1999), Planet of the Apes (1968) and so on.

Although these characters are “moving” through time, they are doing so by pausing and then rejoining the current timeline. The lack of a time machine device disqualifies them from technically being “time travelers” and included in this list of theories on time travel.

So will time travel ever be possible? All we know for sure is that the experts don’t agree. According to the Albert Einstein theory of relativity, time is relative, not constant and the bending of spacetime could be possible. But according to Stephen Hawking , time travel is not possible. The Stephen Hawking time travel theory suggests that the absence of present-day time travelers from the future is an argument against the existence of time travel — a variant of the Fermi paradox (aka where the hell is everybody?). But it’s fun to think about.

NERD NOTE: What happens to time in a black hole? We don’t know for sure, but according to both Stephen Hawking and Albert Einstein’s theory, time near a black hole slows down. This is because a black hole’s gravitational pull is so strong that even light can’t escape. Since gravity also affects light, time would also slow down.

If you could successfully travel into the future, or back in time, what would you do? Warn people about natural disasters? Buy a winning lottery ticket ? Try to prevent your own death? What do you think about these time travel theory ideas or the time travel movies that we included in this article? Please tell us in the comments below.

Related Articles:

- Beautiful Nature Time-Lapse Videos That Will Brighten Your Day

- Productivity Tips to Help You Focus, Save Time, And Stay Motivated

- Famous People Who Are Members Of The Sleepless Elite

- Should Scientists Clone The Woolly Mammoth?

Frank Wilson is a retired teacher with over 30 years of combined experience in the education, small business technology, and real estate business. He now blogs as a hobby and spends most days tinkering with old computers. Wilson is passionate about tech, enjoys fishing, and loves drinking beer.

You'll also enjoy these posts

MOST POPULAR posts

7 Pictures Of Naked People Captured By Google’s Cameras

Top 200 Nielsen DMA Rankings (2024) – Full List

How To Change The Default LG TV Home Screen To Live TV

MORE LIKE THIS

35 Famous Caddyshack Quotes That’ll Make You Laugh

The 28 Most Memorable Quotes From The Godfather Trilogy

Is Your Hatch Restore Already Registered? Here’s How To Fix It And Unregister A Hatch Restore.

check out these trending posts

5 Funny Resurrection Jokes To Share On Easter Sunday

Dating Acronyms: The Ultimate List Of Useful Dating Abbreviations

How To Erase iPod Tutorial — The Super Fix for Most iPod Problems

5 Compelling Reasons To Turn Your House Into A Smart Home

30 Dirty Irish Pick Up Lines That Will Probably Get You Slapped

20 Funny Irish Toasts That Are Easy To Memorize

10 Naked Sunbathers Busted By Google Earth

The 6 Best USB Data Blockers To Prevent Hackers From Juice Jacking Your Phone

Reader Interactions

Mar 24, 2015 at 11:24 PM

are there really only 3 theories? i feel like there are more but i cant think of any besides the movies listed here. hummmmmmmmm

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

The Different Types Of Time Travel And How They Work

Have you ever watched a movie or read a book where the characters travel through time? Maybe they go back to prevent a tragedy or forward to see what the world will look like in the future. Time travel is a fascinating concept that has captured our imaginations for centuries. But have you ever wondered about the different types of time travel and how they work?

Let's take the example of Marty McFly from Back to the Future. In this classic film, Marty travels back in time and accidentally changes his parents' meeting, leading to him potentially being erased from existence. This type of time travel is known as a fixed timeline or predestination paradox, where events that occur in the past are predetermined and cannot be changed. However, there are other types of time travel that allow for altering events in history or exploring alternate timelines altogether. Join us as we dive into the different types of time travel and how they work!

Fixed Timeline or Predestination Paradox

Dynamic timeline or multiverse theory, definition and explanation, examples in popular culture, theoretical implications, wormholes and black holes, the philosophy of time travel, the nature of time, the ethics and consequences of time travel, the role of free will and determinism, frequently asked questions, is it possible to travel through time without creating a paradox, what are the ethical implications of time travel, can time travel be used to alter history, how would time travel affect the concept of free will, are there any real-life experiments or technologies that could potentially enable time travel.

The Fixed Timeline, also known as the Predestination Paradox, asserts that events in the past cannot be changed no matter what actions are taken in the present or future. This theory is based on the idea of temporal mechanics, which suggests that time is a fixed and unchangeable entity. In other words, everything that has happened in the past has already been determined and cannot be altered.

However, this does not mean that there are no consequences to our actions. Even though we cannot change the past, our present and future actions can still have an impact on alternate timelines. These alternate timelines may exist alongside our own reality and could potentially lead to different outcomes depending on the choices we make. With this understanding of temporal mechanics and alternate timelines, let's explore another type of time travel: dynamic timeline or multiverse theory.

So, let's talk about the dynamic timeline or multiverse theory. This concept suggests that when someone travels back in time and changes something, they don't actually alter their own timeline but instead create a new universe where those changes have already occurred. In simpler terms, every decision creates a new branching reality where every possibility exists simultaneously. Some examples of this can be seen in popular culture such as Marvel's "What If" series or the movie "The Butterfly Effect." The theoretical implications of this theory are mind-boggling as it suggests that there could be an infinite number of parallel universes with different versions of ourselves living out different realities.

You'll quickly understand the ins and outs of time travel once you grasp how each method takes you on a unique journey through the labyrinth of time. One such method is the dynamic timeline or multiverse theory, which posits that every action taken in the past creates an alternate universe in which those actions had different outcomes. This means that if one were to go back in time and change something, they would not be altering their own history but creating an entirely new reality altogether.

To better understand this concept, consider these emotional responses:

- Fear: The idea that any action taken in the past could potentially lead to disastrous consequences can be overwhelming.

- Fascination: The thought of multiple realities existing simultaneously can spark curiosity and wonder about what other versions of ourselves may exist out there.

- Discomfort: The realization that our actions may not have as much impact on our own lives as we once believed can be unsettling.

Examples in popular culture further illustrate this concept, from Marvel's "What If?" series to Christopher Nolan's "Interstellar." These stories showcase how even small changes made in the past can create vastly different futures, each with their own set of consequences.

Now let's explore some popular culture references that have made time travel a fascinating concept. One of the most iconic examples is the Back to the Future trilogy, where Marty McFly uses a DeLorean time machine to travel between different eras and alter his family's history. This classic film series not only introduced us to the concept of time travel but also explored the idea of changing one's future by altering events in the past.

Another example is Doctor Who, a science fiction television series that has been on air since 1963. The show follows an alien known as The Doctor who travels through time and space in a spaceship called TARDIS. Through this character, we see how different actions can have significant consequences throughout time and how even small changes can lead to drastic outcomes. These pop culture references not only entertain us but also make us question our own understanding of time travel and its implications on our lives.

As we delve further into these examples, it becomes clear that they raise important theoretical implications about the nature of time itself.

As you explore the theoretical implications of time travel, your mind begins to unravel the mysteries of the universe and you feel as though you are floating through a vortex of endless possibilities. One of the most fascinating aspects is the concept of the butterfly effect, where even small actions in the past can have major consequences on future events. This means that if someone were to go back in time and change even one minor detail, it could drastically alter the course of history as we know it.

Another significant theory is The Grandfather Paradox, which poses an interesting dilemma: if someone were to travel back in time and kill their own grandfather before they had children, would they still exist? This paradox highlights one potential consequence of time travel – that any changes made in the past have potentially irreversible effects on future events. These theories are just some examples of how complex and thought-provoking time travel can be. With such profound implications at stake, it's no wonder this topic has captivated audiences for generations.

With so many theories surrounding time travel and its potential impacts on our world and existence, it's clear that there is much more to explore. In fact, some scientists believe that certain types of time loops may actually be possible based on current research into quantum mechanics. As we delve deeper into these topics, we can only hope to uncover more about ourselves and our place within this vast universe.

So, let's talk about time loops. A time loop is when a specific event or sequence of events repeats itself over and over again in a cyclical manner. This concept has been explored in various forms of popular culture such as the movie "Groundhog Day" and the TV show "Supernatural." Not only is it fascinating to think about the possibilities and consequences of being stuck in a time loop, but it also has some profound theoretical implications for our understanding of the nature of time itself.

You probably know by now how time travel actually operates and its various forms. One of these forms is the Time Loop, which occurs when a certain event or series of events repeats itself indefinitely. This means that every action taken by an individual in the loop has already happened before and will continue to happen again and again, creating an endless cycle.

Time Loops have theoretical implications in the sense that they challenge our understanding of causality and free will. If every action we take is predetermined and destined to repeat itself, then do we truly have control over our own lives? Additionally, Time Loops have scientific applications such as studying the effects of repeated actions on physical objects or even exploring alternate timelines.

- A Time Loop can be triggered by a specific event or decision.

- The loop can be broken by making a different choice or taking a different action.

- Time Loops often involve character development as individuals must learn from their past mistakes in order to break the cycle.

Examples in popular culture range from classic films like Groundhog Day to contemporary television shows like Russian Doll. In each instance, characters are forced to confront their own limitations and weaknesses while facing seemingly insurmountable odds. However, through perseverance and self-reflection, they are able to break out of their respective loops and find redemption.

Take a look at how popular culture has tackled the concept of Time Loops, from characters repeating the same day over and over again in Groundhog Day to a woman reliving her death in Russian Doll. Time travel is not just limited to cinema and television shows, but can also be found in video games and literature. In video games, time travel often takes the form of rewinding time or jumping between different points in history. The popular game series Assassin's Creed incorporates this mechanic by allowing players to explore historical events and even alter them through their actions.

In literature, time travel has been explored for centuries with classics like H.G. Wells' The Time Machine and more recently with Audrey Niffenegger's The Time Traveler's Wife. These stories often examine the consequences of changing past events or exploring different timelines. The concept of time travel allows authors to explore philosophical questions about fate, free will, and causality. It raises questions about whether our actions have predetermined outcomes or if we can truly change our future. These theoretical implications make time travel an endlessly fascinating concept to explore across all forms of media.

Exploring the theoretical implications of time travel can lead us to question our understanding of fate and free will, as we grapple with the possibility of altering past events and shaping our own future. The concept of time travel challenges our perception of cause and effect, as we consider the potential consequences of changing even a single event in history. This raises philosophical considerations about whether or not we have control over our destiny, or if our path is predetermined.

Furthermore, time travel forces us to confront ethical dilemmas that arise from manipulating historical events for personal gain. If we are able to change the past, what responsibility do we have to ensure that those changes do not harm others? As we continue to explore the different types of time travel and their possible consequences, it becomes clear that this topic raises complex questions about human nature and morality. With these considerations in mind, let us delve into the fascinating world of wormholes and black holes.

As you approach a black hole or wormhole, you'll feel the intense gravitational pull that could potentially allow you to travel across space and time. This is due to the effects of time dilation caused by extreme gravitational forces near these objects. Time dilation is a phenomenon in which time appears to move slower for an observer who is closer to a stronger gravitational field. This means that as you get closer to a black hole or wormhole, time will appear to slow down for you compared to someone who is far away from these objects.

This effect can be harnessed for interstellar travel and time travel technology, but it comes with significant risks and challenges. The immense gravity of these objects can easily destroy any spacecraft attempting to enter them, making it difficult for us to explore their potential benefits. Additionally, there are still many unknowns about how exactly we could use wormholes and black holes for time travel, leaving this possibility largely in the realm of science fiction at this point. With all of these uncertainties surrounding the practical applications of wormholes and black holes for time travel, it's important to consider the philosophical implications behind this concept as well.

Hey, let's talk about the philosophy of time travel! It's a fascinating subject that raises some big questions about the nature of time itself. We'll explore the ethics and consequences of time travel, as well as the role of free will and determinism in shaping our understanding of this complex topic. So buckle up and get ready for a mind-bending ride through the twists and turns of temporal theory!

Time is a mysterious force that we can never truly control, but as the saying goes, 'time heals all wounds.' The subjective experience of time is something that varies greatly based on our individual perceptions. Some days seem to drag on forever while others fly by in the blink of an eye. Theories of time perception suggest that our brains may alter our sense of time based on external stimuli or internal emotions.

One sub-list suggests that external stimuli like music or movies can make us feel as though time is passing faster or slower than it actually is. Another sub-list proposes that internal emotions such as fear or excitement can also distort our sense of time, making moments seem longer or shorter than they really are. Lastly, some theories suggest that our brain's internal clock may be responsible for how we perceive the passage of time. Understanding these various theories about the nature of time helps us appreciate just how complex and mysterious this concept truly is.

As we delve into the ethics and consequences of time travel, we must consider how actions in one moment can ripple throughout history and change everything that comes after.

You're about to explore the dark and unpredictable consequences of messing with the fabric of reality, and it's going to make your heart race with both fear and excitement. Time travel is an exciting concept, but it comes with a serious set of ethical implications that cannot be ignored. Imagine traveling back in time to prevent a tragedy from happening, only to realize that by doing so, you've inadvertently caused another one. This is known as the butterfly effect - the idea that even the smallest change in the past can have significant repercussions in the present.

The ethical implications of time travel are not limited to accidental outcomes like this either. What if someone were to go back in time and kill Hitler before he rose to power? Would they be justified in doing so? Or would they be altering history in such a way that it ultimately leads to a worse outcome? These are difficult questions without easy answers, and they highlight just how complex time travel can be. With so much at stake, it's no wonder that people are both fascinated by and afraid of this concept.

As we delve deeper into this topic, we will explore another crucial aspect of time travel: its relationship with free will and determinism.

Now, imagine you could go back in time and change a decision you regret; would the outcome still be predetermined or does your free will play a role in altering it? This question brings up the long-standing philosophical debate of determinism vs free will. Determinism is the belief that all events are predetermined and inevitable, while free will asserts that humans have the ability to make choices independent of external factors. Time travel adds another layer to this already complex issue as altering past events can create paradoxes and affect causality.

To understand the role of free will and determinism in time travel, we must first consider the paradoxes that arise when attempting to change past events. The grandfather paradox is one such example where traveling back in time and killing your own grandfather before he has children would mean you were never born, making it impossible for you to travel back in time to commit the act. This paradox highlights how changing past events can lead to contradictions and inconsistencies. Additionally, if we assume that all events are predetermined, then any attempt at altering them through time travel would ultimately fail because those events were always meant to occur. However, if we believe in free will, then it's possible that our actions could alter future outcomes despite their predetermined nature. Ultimately, whether determinism or free will reigns supreme depends on your personal beliefs about fate and choice.

As much as we would love to travel through time without causing any paradoxes, it seems like a tricky business. The idea of alternate timelines comes into play when considering the possibility of avoiding the Grandfather paradox, where traveling back in time and altering something could prevent your own existence. However, even with alternate timelines, there is still the risk of creating new paradoxes and complications that could have unforeseen consequences. While it's fun to imagine the possibilities of time travel, it's important to consider the potential ramifications and embrace the present moment.

When it comes to time travel, there are a lot of ethical considerations to take into account. For starters, what impact will our actions have on the course of history? Will we be altering the past in ways that could negatively affect the future? Additionally, how will our presence in different cultures and time periods impact those around us? It's important to approach time travel with sensitivity and respect for the people and places we encounter. Furthermore, we must consider the cultural impact of introducing modern ideas and technologies into ancient societies. While time travel may seem like an exciting adventure, it's crucial to think about the potential consequences of our actions before jumping headfirst into such an endeavor.

Alternate realities and butterfly effects are two concepts that come to mind when considering the possibility of altering history through time travel. The very idea of changing something in the past can lead to a sense of excitement and curiosity, but it also raises many ethical questions. What if altering one event leads to unintended consequences in the future? Would we be willing to take responsibility for those outcomes? It's easy to get lost in the allure of changing history, but we must remember that every action has a reaction, and even the smallest alteration could have drastic effects on our present-day reality. As intriguing as the idea may be, we must approach it with caution and consider all possible outcomes before making any decisions about altering history.

The philosophical debate surrounding time travel centers on the question of whether or not it would affect the concept of free will. Some argue that if time travel were possible, our past actions would be predetermined and therefore we wouldn't truly have agency over our choices. However, others believe that even with knowledge of the future, individuals would still have the ability to make their own decisions. While there is no scientific evidence to support either side of this argument, it remains a fascinating topic for discussion and speculation.

When it comes to time travel, there are several theories and experiments that have been explored by physicists. Two of the most popular ones are Quantum Entanglement and Wormhole Theories. Quantum Entanglement suggests that two particles can be connected in a way that their states remain correlated, regardless of distance or time. This means that manipulating one particle could potentially affect its entangled counterpart, even if it's light-years away in space or years into the future or past. Wormhole Theories propose the existence of shortcuts through space-time via hypothetical tunnels called wormholes. If these tunnels could be utilized for travel, they could potentially allow us to move through time as well. While these theories have yet to be proven experimentally, the potential for them to enable time travel is certainly exciting and worth continued exploration.

So there you have it - the different types of time travel and how they work. From fixed timelines to dynamic ones, from time loops to wormholes and black holes, each theory offers a unique perspective on the possibility of traveling through time.

But no matter which theory you subscribe to, one thing is certain: time travel remains a fascinating topic that captures our imaginations and challenges our understanding of the universe. As the philosopher Heraclitus once said, "no man ever steps in the same river twice," reminding us that time is constantly moving forward and changing. Whether we will ever be able to manipulate it for our own purposes remains to be seen, but one thing is for sure - we'll keep dreaming about it as long as we live.

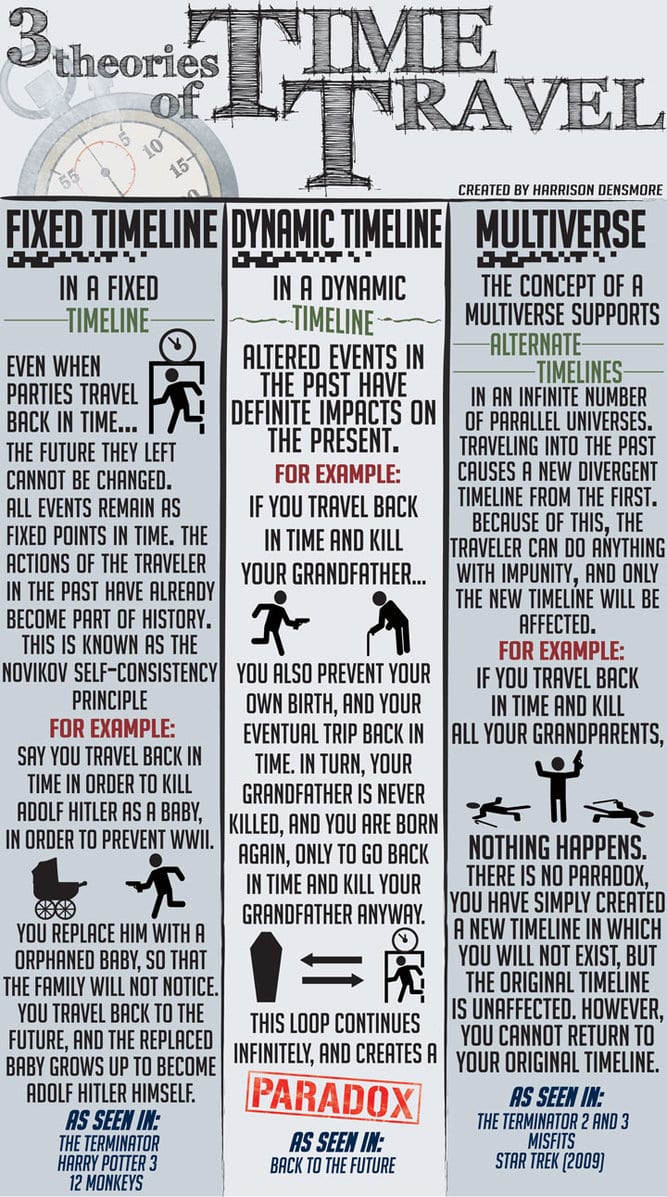

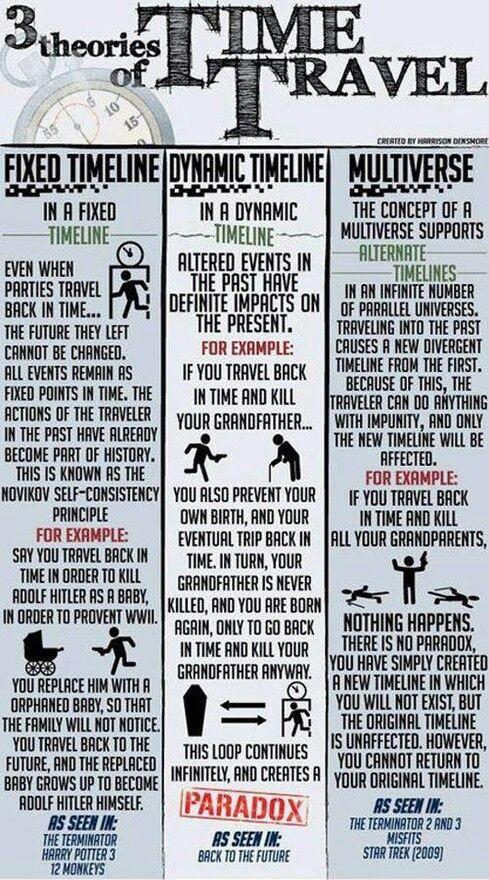

The Three Major Theories of Time Travel

Above we have a rather interesting (and thankfully rather short) infographic from Harrison Desnmore about pretty much all the kinds of time travels you see in movies. Did you time traveling actions make history the way it’s always been? Did they screw up time and reality itself? Or did you create an entirely new universe based on your f-ing around in the past?

The middle one is what’s known as a “plot hole” in most instances, but the other two could fall under that category too if you expand on them enough. I’m of the firm belief that all time travel movies ultimately never make sense once you start trying to extrapolate them to their logical conclusion. Still, this is all enough to make your brain hurt for a while.

Not pictured: Primer, which is it’s own category that can’t even be explained by human words.

I think I'm a part of the first generation of journalists to skip print media entirely, and I've learned a lot these last few years at Forbes. My work has appeared on TVOvermind, IGN, and most importantly, a segment on The Colbert Report at one point.

Similar Posts

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: The Ecstasy of Gold by Ennio Morricone Meets Metal

The history of the iconic theme song for The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly has its beginnings in the old Spaghetti styled Western movies. The movie is just as iconic, and starred Clint Eastwood,…

This Week In Movie Trailers!

This past weekend I went, I saw and I loved Gone Girl. It was absolutely one heck of a thrill to watch and it truly kept me guessing the entire time. I was constantly coming…

Some Rather Excellent Artist-Made Godzilla Posters

Somehow, Godzilla has managed to become one of the most anticipated movies of 2014 through a series of fantastic trailers alone. The film has inspired a bunch of artists to come up with their own…

The Dark Knight Rages

httpv://youtu.be/G753IcaaIwQ What happens when Batman plays video games? He rages, of course, and in the video above, Robin suffers the brunt of his wrath. From the amount of “Robin getting the crap beaten out of…

IMDB’s Bottom 10: The Starfighters

Perhaps it’s because I hate myself, but more likely it’s because I love movies. Even bad movies. Especially bad movies, come to think of it. Call it noble, call it stupid, but I have decided…

Five Lesser Known but Incredible Lines from Die Hard

I had the pleasure of seeing Die Hard on the big screen a couple of weeks ago. There’s this special theater in Brooklyn that shows 80s movies on weekends and needless to say it was…

10 Comments

I have always been a fan of the multiverse concept. It has always made the most sense to me.

All time travel talk is incomplete unless Dr. Who is taken into account.

Dynamic Lazy Timeline Time travelers from the future affected by present events will be altered in the easiest way possible for the universe. If you go back in time and kill your grandfather, you will cease to exist from that moment forward. The new timeline will see that you never existed to travel back in time, but it will see that you arrived before the murder and the actions leading up to that point.

As seen in Looper. This style greatly reminds me of lightning. It takes the path of least resistance.

My understanding is that Primer follows Multiverse. The infograph Paul pointed to for Primer explained that as you left a timeline, that timeline no longer had you in it. When you witness yourself going into a box, they were leaving for the next timeline while you gained the opportunity to take their place in this timeline.

Primer infograph: https://unrealitymag.com/index.php/2011/09/30/at-last-a-definitive-timeline-for-primer/

Misfits also have fixed timeline, different timetraveling abilities work differently so it really depends on the timetravele.

One of the things that I found weird about this year’s MIB3 is(spoilers) That Will Smith travels to the past from an altered time to correct it. He prevents another character’s death at the hands of a time traveler, restoring the timeline.

But he also travels back a few minutes within the past to more effectively defeat his enemy after being wounded. But when he travels back, he doesn’t find himself standing there, planning to travel in time. If he went back a few minute to a timeline which exists because of his own actions, shouldn’t he bump into his past, time traveled self?

But I’m thinking way too much about this, aren’t I?

Something time travel movies don’t take into account – you don’t travel just back in time, but also move distance.

The earth is moving around the sun, and the earth is also rotating (Not exactly 24 hours for one rotation).

Doctor Who can do it because the TARDIS travels in time and space.

Physic nerd alert!

I’ve always considered the fixed timeline as the only possible structure for time in the universe. Consider that you travel to the future. From that perspective our present is in the past and a matter of record. Our actions in the present do not result in constantly changing newspaper headlines to the future based time traveler any more than our newspaper heading are not in flux from events happening (in a simultaneous) yesterday.

Other multiverse versions of our universe may or may not exist, but they must surely exist separately from our own even if the split point hasn’t occurred yet, because if a universe is created for every difference that occurs then what’s the cut off point? Human decisions? The change in the charge of an electron? Do these new time lines then split? and split again? It would be less a split and more of an exponential explosion. Where would the energy come from for that?

Nicholas: The Time Machine (2002) shows the machine physically staying where it was as time rapidly moved past. Looper suggest that it’s machine is able to place a person in different locations, though they don’t show that the future is actively calculating where the destination is. I do agree that your point is highly valid.

Monstrinho: I’ve tried to figure out potential plots for a time movie where the time line is a matter of record in that people, even those from alternate times or those holding newspapers or the like from alternate times, but without some being able to at some point recognize changes a story has characters that have bouncing motivations and goals that likely leave the audience confused.

Timelines that lend themselves well to theory don’t always lend themselves to Hollywood.

Going with the fixed timeline direction with the multiverse splitting, perhaps all of the decisions that are ever made (where ever their split point is at) already exist in the first place, with all lines being identical at the beginning, then half of them become the left side of the first ‘split’ and the other half the right. No need for energy creation among these already existing parallels.

The problem with the Dynamic Timeline model is that it assumes time travel is possible and history can be changed, but it still insists that there’s only one timelike dimension.

While a single timelike dimension works fine for the Fixed Timeline model, the Dynamic Timeline model requires a minimum of *two* timelike dimensions. One of the timelike dimensions corresponds to how events play out within the timeline, and the other timelike dimension corresponds to the timeline being changed by time travelers. There’s also an implication that if time travel is possible in the first place, then it probably occurs naturally at the quantum level, not just when a living creature invents a time machine. Random quantum events could be changing history underneath us all the time.

“Not pictured: Primer, which is it’s own category that can’t even be explained by human words.” – Loved this line; because it is so true.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Infographic Category Education

Get infographics right to your inbox.

Sign up to receive the daily infographic in your email inbox each morning...

Inconceivable Paradoxes: 3 Theories of Time Travel

Time travel is one of those things that seems like it should be possible. After all, it’s been a plot device in countless works of fiction and pop culture . But serious physicists have never been able to come up with a way to do it. These theories explain why we’re not zipping around through time as much as we’d like to—and why you shouldn’t get your hopes up about ever going on a Star Trek-style adventure through history.

The Fixed Timeline

The Fixed Timeline is the theory of time travel where you can only travel to a point in your own future. It’s like time is like a train track and everything that happens has always happened and will always happen. The train cannot go backwards, it cannot go off the track and if you’re on the train you can only move forward with it. This means that if we were to travel back in time then our actions would already have been done before they could even happen in front of us again! This theory also suggests that there are parallel universes out there where every single event that ever happened or will ever happen has already happened somewhere else (and probably more than once).

The Dynamic Timeline

The Dynamic Timeline is a theory that says that the timeline is dynamic and can be changed. The theory is that the timeline is not fixed and can be changed by time travelers or other events in one’s life. This means that it’s possible for you to change your past, present and future if you travel back in time like in Back to the Future or 12 Monkeys.

The Multiverse

The multiverse theory , also known as the many-worlds interpretation (MWI), is a theory that states that our universe is just one of many universes. In this model, all possible alternative histories and futures actually exist; it’s just that we can’t see most of them. The MWI suggests that time travel is possible because we are constantly traveling through time—just in different directions than we normally experience in our everyday lives. The MWI has its roots in quantum mechanics, where it was first developed by Hugh Everett III during his PhD work at Princeton University. Basically, according to this theory you could go back in time if there were infinite universes: You’d simply hop across one of these other universes—and therefore a different timeline—when you tried to change something about your life or world line. It sounds confusing but it makes sense when explained more clearly:

Time travel is possible . You’ve probably heard of three different theories about time travel: the fixed timeline, dynamic timeline and multiverse. The first theory is that time travel isn’t possible. The second theory states that it is possible, but only in one direction (from future to past). The third says you can go back and forth between past and future in both directions. In the end, I think we’re going to have to accept that time travel is possible in some form. Whether it’s in the future or right now, the question isn’t whether there are people who can get around through time. It’s how they do it and why we haven’t seen them yet. They may have been there all along without us noticing—or maybe they’re still working on figuring out their own theories about what time really means in order for us humans (and our brains) to understand!

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Time Travel

Introduction, general overviews.

- David Lewis’s Analysis, Its Forerunners and Critics

- Gödel and the Ideality of Time

- Models and Issues from Relativity

- Models and Issues from Quantum Theory

- Causal Loops and Probability

- Time Travel in Many Worlds and the Autonomy Principle

- Travel in Dynamic Time and Multi-Dimensional Time

- General Metaphysical Issues

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Contemporary Metaphysics

- Foreknowledge

- Laws of Nature

- Persistence

- Philosophy of Cosmology

- Space and Time

- Time and Tense

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Alfred North Whitehead

- Feminist Aesthetics

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Time Travel by Alasdair Richmond LAST REVIEWED: 28 May 2019 LAST MODIFIED: 26 October 2015 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195396577-0295

Time travel is a philosophical growth industry, with many issues in metaphysics and elsewhere recently transformed by consideration of time travel possibilities. The debate has gradually shifted from focusing on time travel’s logical possibility (which possibility is now generally although not universally granted) to sundry topics including persistence, causation, personal identity, freedom, composition, and natural laws, to name but a few. Besides metaphysical discussions, some time travel works draw on the philosophies of science, spacetime, and computation. Some interesting forerunners notwithstanding, serious physical interest in time travel begins with Gödel’s 1949a demonstration that general relativity permits space-times that are riddled with closed timelike curves (“CTCs” henceforth). A key philosophical text on time travel is Lewis 1976 and its argument for the logical possibility of certain backward time travel journeys and even for the possibility of casual loops. Lewis concludes that time travel could occur in a possible world, albeit perhaps a strange world that would feature (or seem to feature) strange restrictions on actions. In Lewis’s analysis, a traveler can arrive in the past of the same history they come from provided that the traveler’s actions on arrival are consistent with the history that they come from. So other worlds or multiple temporal dimensions are not necessary to make time travel consistent. Granted, the physics, persistence conditions, agency, and epistemology of agents in such worlds might look weird indeed. Since Lewis, philosophical time travel questions include the following: given that a traveler into the past cannot create any paradoxical outcomes on arrival, what then would stay their hand? Are the constraints on a traveler’s actions admissible within our ordinary understanding of physical law or human agency? Is time travel compatible with dynamic time or even with the existence of time itself? Can backward time travel be physically possible within a single history? If a time traveler meets another stage of him- or herself, is the traveler in two places at once, and what theory of persistence can cope with this puzzling multiplication? Can time-travel spacetimes resolve otherwise intractable computational problems?

Despite several hundred philosophical and scientific articles, book chapters, and Internet resources devoted to philosophical problems posed by time travel, there is currently no full-length monograph or anthology on the subject. The best introduction to the topic in general so far is chapter 8 of Dainton (second edition 2010), Dainton 2010 being the best general philosophical resource available on time and space. The key work is Lewis 1976 , a defense of the logical possibility of backward time travel, from which a large number of subsequent treatments take their cue. A useful overview, albeit largely from a physical science perspective, is Nahin 1999 . Also largely physical in emphasis but comprehensive and thorough is Earman 1995 . Richmond 2003 surveys philosophical work on time travel to date. Arntzenius 2006 details the problems of free action and nomological constraint posed by backward time travel. Arntzenius and Maudlin 2005 is helpful on (especially) problems of physical law. Carroll 2008 is perhaps the best single online resource available on any aspect of time travel. Le Poidevin 2003 is a highly commendable introduction to the philosophy of time in general but especially good on problems of time travel. Bourne 2006 offers some useful arguments and clarifications centered on Gödel’s arguments about time travel and the relations between time travel and the status of times themselves. Earman and Wüthrich 2006 offers scientifically well informed but approachable and philosophically cogent discussions of what physics might, and might not, allow by way of time travel.

Arntzenius, Frank. “Time Travel: Double Your Fun.” Philosophy Compass 6 (2006): 599–616.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1747-9991.2006.00045.x

Entertaining survey of the philosophical terrain around time travel that concentrates particularly on the constraints on action likely to be suffered by travelers in the past. An excellent introduction to the nomological contrivance problem and more. Available online for purchase or by subscription.

Arntzenius, Frank, and Tim Maudlin. “ Time Travel and Modern Physics .” In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Edited by Edward N. Zalta. 2005.

Notably acute survey of physical possibilities for time travel, including detailed arguments that backward time travel threatens to create correlations that conflict with standard quantum predictions.

Bourne, C. A Future for Presentism . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199212804.001.0001

Although primarily devoted to defending presentism, chapter 8 offers one of the best treatments of Gödel’s ideality argument around and pp. 132–134 offer some interesting sidelights on the possible compatability of time travel and presentism.

Carroll, John W. A Time Travel Website . 2008–.

Extremely thorough, engagingly-written, well-designed, and continually evolving online resource that offers helpful discussions, well-chosen readings, and helpful animations to boot.

Dainton, Barry. Time and Space . 2d ed. Durham, NC: Acumen, 2010.

Revised and expanded edition of Dainton’s classic 2001 introduction to the philosophy of space and time. Can be highly recommended but notable here for its extensive, essential treatments of time travel, relativity, and Gödel’s “ideality” argument.

Earman, John. “Recent Work on Time Travel.” In Time’s Arrows Today . Edited by Steven F. Savitt, 268–310. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511622861

Thorough discussion of the then-current state of play in the philosophical and physical literature on time travel. This is still a valuable resource.

Earman, John, and Christian Wüthrich. “ Time Machines .” In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Edited by Edward N. Zalta. 2006.

Comprehensive discussion of physical resources for time travel, among other intriguing suggestions, develops the view that physically realistic time machines might be uncontrollable even if they become a possiblility.

Le Poidevin, Robin. Travels in Four Dimensions: The Enigmas of Space and Time . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Engaging and clearly written introduction to the philosophy of space and time. Often offers problems and discussions that lend themselves to time travel interpretation. An excellent introductory and pedagogical resource.

Lewis, David. “ The Paradoxes of Time Travel .” American Philosophical Quarterly 13 (1976): 145–152.

The philosophical time travel work. Includes Lewis’s discrepancy definition of time travel: the most useful by far. Invokes the notion of compossibility to disambiguate “Grandfather paradox” arguments and argues that backward time travel and causal loops can occur in (nonbranching) possible worlds. Usefully distinguishes between replacement change and counterfactual change. (This is often cited and sometimes rebutted but never refuted.)

Nahin, Paul. Time Machines: Time Travel in Physics, Metaphysics and Science Fiction . 1st ed. New York: American Institute of Physics, 1999.

DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4757-3088-3

Engaging and comprehensive attempt at surveying all the scientific, philosophical, and fictional literature on time travel. Perhaps slightly more at ease with physics and fiction than with philosophy, but this is a detailed and thorough treatment.

Richmond, Alasdair. “Recent Work: Time Travel.” Philosophical Books 44 (2003): 297–309.

DOI: 10.1111/1468-0149.00308

Survey of the time travel debate from Lewis 1976 onward, sketching links with debates in persistence, philosophy of spacetime and temporal topology. Available online by subscription.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Philosophy »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- A Priori Knowledge

- Abduction and Explanatory Reasoning

- Abstract Objects

- Addams, Jane

- Adorno, Theodor

- Aesthetic Hedonism

- Aesthetics, Analytic Approaches to

- Aesthetics, Continental

- Aesthetics, Environmental

- Aesthetics, History of

- African Philosophy, Contemporary

- Alexander, Samuel

- Analytic/Synthetic Distinction

- Anarchism, Philosophical

- Animal Rights

- Anscombe, G. E. M.

- Anthropic Principle, The

- Anti-Natalism

- Applied Ethics

- Aquinas, Thomas

- Argument Mapping

- Art and Emotion

- Art and Knowledge

- Art and Morality

- Astell, Mary

- Aurelius, Marcus

- Austin, J. L.

- Bacon, Francis

- Bayesianism

- Bergson, Henri

- Berkeley, George

- Biology, Philosophy of

- Bolzano, Bernard

- Boredom, Philosophy of

- British Idealism

- Buber, Martin

- Buddhist Philosophy

- Burge, Tyler

- Business Ethics

- Camus, Albert

- Canterbury, Anselm of

- Carnap, Rudolf

- Cavendish, Margaret

- Chemistry, Philosophy of

- Childhood, Philosophy of

- Chinese Philosophy

- Cognitive Ability

- Cognitive Phenomenology

- Cognitive Science, Philosophy of

- Coherentism

- Communitarianism

- Computational Science

- Computer Science, Philosophy of

- Computer Simulations

- Comte, Auguste

- Conceptual Role Semantics

- Conditionals

- Confirmation

- Connectionism

- Consciousness

- Constructive Empiricism

- Contemporary Hylomorphism

- Contextualism

- Contrastivism

- Cook Wilson, John

- Cosmology, Philosophy of

- Critical Theory

- Culture and Cognition

- Daoism and Philosophy

- Davidson, Donald

- de Beauvoir, Simone

- de Montaigne, Michel

- Decision Theory

- Deleuze, Gilles

- Derrida, Jacques

- Descartes, René

- Descartes, René: Sensory Representations

- Descriptions

- Dewey, John

- Dialetheism

- Disagreement, Epistemology of

- Disjunctivism

- Dispositions

- Divine Command Theory

- Doing and Allowing

- du Châtelet, Emilie

- Dummett, Michael

- Dutch Book Arguments

- Early Modern Philosophy, 1600-1750

- Eastern Orthodox Philosophical Thought

- Education, Philosophy of

- Engineering, Philosophy and Ethics of

- Environmental Philosophy

- Epistemic Basing Relation

- Epistemic Defeat

- Epistemic Injustice

- Epistemic Justification

- Epistemic Philosophy of Logic

- Epistemology

- Epistemology and Active Externalism

- Epistemology, Bayesian

- Epistemology, Feminist

- Epistemology, Internalism and Externalism in

- Epistemology, Moral

- Epistemology of Education

- Ethical Consequentialism

- Ethical Deontology

- Ethical Intuitionism

- Eugenics and Philosophy

- Events, The Philosophy of

- Evidence-Based Medicine, Philosophy of

- Evidential Support Relation In Epistemology, The

- Evolutionary Debunking Arguments in Ethics

- Evolutionary Epistemology

- Experimental Philosophy

- Explanations of Religion

- Extended Mind Thesis, The

- Externalism and Internalism in the Philosophy of Mind

- Faith, Conceptions of

- Feminist Philosophy

- Feyerabend, Paul

- Fichte, Johann Gottlieb

- Fictionalism

- Fictionalism in the Philosophy of Mathematics

- Film, Philosophy of

- Foot, Philippa

- Forgiveness

- Formal Epistemology

- Foucault, Michel

- Frege, Gottlob

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg

- Geometry, Epistemology of

- God and Possible Worlds

- God, Arguments for the Existence of

- God, The Existence and Attributes of

- Grice, Paul

- Habermas, Jürgen

- Hart, H. L. A.

- Heaven and Hell

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich: Aesthetics

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich: Metaphysics

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich: Philosophy of History

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich: Philosophy of Politics

- Heidegger, Martin: Early Works

- Hermeneutics

- Higher Education, Philosophy of

- History, Philosophy of

- Hobbes, Thomas

- Horkheimer, Max

- Human Rights

- Hume, David: Aesthetics

- Hume, David: Moral and Political Philosophy

- Husserl, Edmund

- Idealizations in Science

- Identity in Physics

- Imagination

- Imagination and Belief

- Immanuel Kant: Political and Legal Philosophy

- Impossible Worlds

- Incommensurability in Science

- Indian Philosophy

- Indispensability of Mathematics

- Inductive Reasoning

- Instruments in Science

- Intellectual Humility

- Intentionality, Collective

- James, William

- Japanese Philosophy

- Kant and the Laws of Nature

- Kant, Immanuel: Aesthetics and Teleology

- Kant, Immanuel: Ethics

- Kant, Immanuel: Theoretical Philosophy

- Kierkegaard, Søren

- Knowledge-first Epistemology

- Knowledge-How

- Kristeva, Julia

- Kuhn, Thomas S.

- Lacan, Jacques

- Lakatos, Imre

- Langer, Susanne

- Language of Thought

- Language, Philosophy of

- Latin American Philosophy

- Legal Epistemology

- Legal Philosophy

- Legal Positivism

- Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm

- Levinas, Emmanuel

- Lewis, C. I.

- Literature, Philosophy of

- Locke, John

- Locke, John: Identity, Persons, and Personal Identity

- Lottery and Preface Paradoxes, The

- Machiavelli, Niccolò

- Martin Heidegger: Later Works

- Martin Heidegger: Middle Works

- Material Constitution

- Mathematical Explanation

- Mathematical Pluralism

- Mathematical Structuralism

- Mathematics, Ontology of

- Mathematics, Philosophy of

- Mathematics, Visual Thinking in

- McDowell, John

- McTaggart, John

- Meaning of Life, The

- Mechanisms in Science

- Medically Assisted Dying

- Medicine, Contemporary Philosophy of

- Medieval Logic

- Medieval Philosophy

- Mental Causation

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice

- Meta-epistemological Skepticism

- Metaepistemology

- Metametaphysics

- Metaphilosophy

- Metaphysical Grounding

- Metaphysics, Contemporary

- Metaphysics, Feminist

- Midgley, Mary

- Mill, John Stuart

- Mind, Metaphysics of

- Modal Epistemology

- Models and Theories in Science

- Montesquieu

- Moore, G. E.

- Moral Contractualism

- Moral Naturalism and Nonnaturalism

- Moral Responsibility

- Multiculturalism

- Murdoch, Iris

- Music, Analytic Philosophy of

- Nationalism

- Natural Kinds

- Naturalism in the Philosophy of Mathematics

- Naïve Realism

- Neo-Confucianism

- Neuroscience, Philosophy of

- Nietzsche, Friedrich

- Nonexistent Objects

- Normative Ethics

- Normative Foundations, Philosophy of Law:

- Normativity and Social Explanation

- Objectivity

- Occasionalism

- Ontological Dependence

- Ontology of Art

- Ordinary Objects

- Other Minds

- Panpsychism

- Particularism in Ethics

- Pascal, Blaise

- Paternalism

- Peirce, Charles Sanders

- Perception, Cognition, Action

- Perception, The Problem of

- Perfectionism

- Personal Identity

- Phenomenal Concepts

- Phenomenal Conservatism

- Phenomenology

- Philosophy for Children

- Photography, Analytic Philosophy of

- Physicalism

- Physicalism and Metaphysical Naturalism

- Physics, Experiments in

- Political Epistemology

- Political Obligation

- Political Philosophy

- Popper, Karl

- Pornography and Objectification, Analytic Approaches to

- Practical Knowledge

- Practical Moral Skepticism

- Practical Reason

- Probabilistic Representations of Belief

- Probability, Interpretations of

- Problem of Divine Hiddenness, The

- Problem of Evil, The

- Propositions

- Psychology, Philosophy of

- Quine, W. V. O.

- Racist Jokes

- Rationalism

- Rationality

- Rawls, John: Moral and Political Philosophy

- Realism and Anti-Realism

- Realization

- Reasons in Epistemology

- Reductionism in Biology

- Reference, Theory of

- Reid, Thomas

- Reliabilism

- Religion, Philosophy of

- Religious Belief, Epistemology of

- Religious Experience

- Religious Pluralism

- Ricoeur, Paul

- Risk, Philosophy of

- Rorty, Richard

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques

- Rule-Following

- Russell, Bertrand

- Ryle, Gilbert

- Sartre, Jean-Paul

- Schopenhauer, Arthur

- Science and Religion

- Science, Theoretical Virtues in

- Scientific Explanation

- Scientific Progress

- Scientific Realism

- Scientific Representation

- Scientific Revolutions

- Scotus, Duns

- Self-Knowledge

- Sellars, Wilfrid

- Semantic Externalism

- Semantic Minimalism

- Senses, The

- Sensitivity Principle in Epistemology

- Shepherd, Mary

- Singular Thought

- Situated Cognition

- Situationism and Virtue Theory

- Skepticism, Contemporary

- Skepticism, History of

- Slurs, Pejoratives, and Hate Speech

- Smith, Adam: Moral and Political Philosophy

- Social Aspects of Scientific Knowledge

- Social Epistemology

- Social Identity

- Sounds and Auditory Perception

- Speech Acts

- Spinoza, Baruch

- Stebbing, Susan

- Strawson, P. F.

- Structural Realism

- Supererogation

- Supervenience

- Tarski, Alfred

- Technology, Philosophy of

- Testimony, Epistemology of

- Theoretical Terms in Science

- Thomas Aquinas' Philosophy of Religion

- Thought Experiments

- Time Travel

- Transcendental Arguments

- Truth and the Aim of Belief

- Truthmaking

- Turing Test

- Two-Dimensional Semantics

- Understanding

- Uniqueness and Permissiveness in Epistemology

- Utilitarianism

- Value of Knowledge

- Vienna Circle

- Virtue Epistemology

- Virtue Ethics

- Virtues, Epistemic

- Virtues, Intellectual

- Voluntarism, Doxastic

- Weakness of Will

- Weil, Simone

- William of Ockham

- Williams, Bernard

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig: Early Works

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig: Later Works

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig: Middle Works

- Wollstonecraft, Mary

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.194.105.172]

- 185.194.105.172

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

- Amazon Alexa

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Paradox-Free Time Travel Is Theoretically Possible, Researchers Say

Matthew S. Schwartz

A dog dressed as Marty McFly from Back to the Future attends the Tompkins Square Halloween Dog Parade in 2015. New research says time travel might be possible without the problems McFly encountered. Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

A dog dressed as Marty McFly from Back to the Future attends the Tompkins Square Halloween Dog Parade in 2015. New research says time travel might be possible without the problems McFly encountered.

"The past is obdurate," Stephen King wrote in his book about a man who goes back in time to prevent the Kennedy assassination. "It doesn't want to be changed."

Turns out, King might have been on to something.

Countless science fiction tales have explored the paradox of what would happen if you went back in time and did something in the past that endangered the future. Perhaps one of the most famous pop culture examples is in Back to the Future , when Marty McFly goes back in time and accidentally stops his parents from meeting, putting his own existence in jeopardy.

But maybe McFly wasn't in much danger after all. According a new paper from researchers at the University of Queensland, even if time travel were possible, the paradox couldn't actually exist.

Researchers ran the numbers and determined that even if you made a change in the past, the timeline would essentially self-correct, ensuring that whatever happened to send you back in time would still happen.

"Say you traveled in time in an attempt to stop COVID-19's patient zero from being exposed to the virus," University of Queensland scientist Fabio Costa told the university's news service .

"However, if you stopped that individual from becoming infected, that would eliminate the motivation for you to go back and stop the pandemic in the first place," said Costa, who co-authored the paper with honors undergraduate student Germain Tobar.

"This is a paradox — an inconsistency that often leads people to think that time travel cannot occur in our universe."

A variation is known as the "grandfather paradox" — in which a time traveler kills their own grandfather, in the process preventing the time traveler's birth.

The logical paradox has given researchers a headache, in part because according to Einstein's theory of general relativity, "closed timelike curves" are possible, theoretically allowing an observer to travel back in time and interact with their past self — potentially endangering their own existence.

But these researchers say that such a paradox wouldn't necessarily exist, because events would adjust themselves.

Take the coronavirus patient zero example. "You might try and stop patient zero from becoming infected, but in doing so, you would catch the virus and become patient zero, or someone else would," Tobar told the university's news service.

In other words, a time traveler could make changes, but the original outcome would still find a way to happen — maybe not the same way it happened in the first timeline but close enough so that the time traveler would still exist and would still be motivated to go back in time.

"No matter what you did, the salient events would just recalibrate around you," Tobar said.

The paper, "Reversible dynamics with closed time-like curves and freedom of choice," was published last week in the peer-reviewed journal Classical and Quantum Gravity . The findings seem consistent with another time travel study published this summer in the peer-reviewed journal Physical Review Letters. That study found that changes made in the past won't drastically alter the future.

Bestselling science fiction author Blake Crouch, who has written extensively about time travel, said the new study seems to support what certain time travel tropes have posited all along.

"The universe is deterministic and attempts to alter Past Event X are destined to be the forces which bring Past Event X into being," Crouch told NPR via email. "So the future can affect the past. Or maybe time is just an illusion. But I guess it's cool that the math checks out."

- grandfather paradox

- time travel

Can we time travel? A theoretical physicist provides some answers

Emeritus professor, Physics, Carleton University

Disclosure statement

Peter Watson received funding from NSERC. He is affiliated with Carleton University and a member of the Canadian Association of Physicists.

Carleton University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA.

Carleton University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

- Bahasa Indonesia

Time travel makes regular appearances in popular culture, with innumerable time travel storylines in movies, television and literature. But it is a surprisingly old idea: one can argue that the Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex , written by Sophocles over 2,500 years ago, is the first time travel story .

But is time travel in fact possible? Given the popularity of the concept, this is a legitimate question. As a theoretical physicist, I find that there are several possible answers to this question, not all of which are contradictory.

The simplest answer is that time travel cannot be possible because if it was, we would already be doing it. One can argue that it is forbidden by the laws of physics, like the second law of thermodynamics or relativity . There are also technical challenges: it might be possible but would involve vast amounts of energy.

There is also the matter of time-travel paradoxes; we can — hypothetically — resolve these if free will is an illusion, if many worlds exist or if the past can only be witnessed but not experienced. Perhaps time travel is impossible simply because time must flow in a linear manner and we have no control over it, or perhaps time is an illusion and time travel is irrelevant.

Laws of physics

Since Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity — which describes the nature of time, space and gravity — is our most profound theory of time, we would like to think that time travel is forbidden by relativity. Unfortunately, one of his colleagues from the Institute for Advanced Study, Kurt Gödel, invented a universe in which time travel was not just possible, but the past and future were inextricably tangled.

We can actually design time machines , but most of these (in principle) successful proposals require negative energy , or negative mass, which does not seem to exist in our universe. If you drop a tennis ball of negative mass, it will fall upwards. This argument is rather unsatisfactory, since it explains why we cannot time travel in practice only by involving another idea — that of negative energy or mass — that we do not really understand.

Mathematical physicist Frank Tipler conceptualized a time machine that does not involve negative mass, but requires more energy than exists in the universe .

Time travel also violates the second law of thermodynamics , which states that entropy or randomness must always increase. Time can only move in one direction — in other words, you cannot unscramble an egg. More specifically, by travelling into the past we are going from now (a high entropy state) into the past, which must have lower entropy.

This argument originated with the English cosmologist Arthur Eddington , and is at best incomplete. Perhaps it stops you travelling into the past, but it says nothing about time travel into the future. In practice, it is just as hard for me to travel to next Thursday as it is to travel to last Thursday.

Resolving paradoxes

There is no doubt that if we could time travel freely, we run into the paradoxes. The best known is the “ grandfather paradox ”: one could hypothetically use a time machine to travel to the past and murder their grandfather before their father’s conception, thereby eliminating the possibility of their own birth. Logically, you cannot both exist and not exist.

Read more: Time travel could be possible, but only with parallel timelines

Kurt Vonnegut’s anti-war novel Slaughterhouse-Five , published in 1969, describes how to evade the grandfather paradox. If free will simply does not exist, it is not possible to kill one’s grandfather in the past, since he was not killed in the past. The novel’s protagonist, Billy Pilgrim, can only travel to other points on his world line (the timeline he exists in), but not to any other point in space-time, so he could not even contemplate killing his grandfather.

The universe in Slaughterhouse-Five is consistent with everything we know. The second law of thermodynamics works perfectly well within it and there is no conflict with relativity. But it is inconsistent with some things we believe in, like free will — you can observe the past, like watching a movie, but you cannot interfere with the actions of people in it.

Could we allow for actual modifications of the past, so that we could go back and murder our grandfather — or Hitler ? There are several multiverse theories that suppose that there are many timelines for different universes. This is also an old idea: in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol , Ebeneezer Scrooge experiences two alternative timelines, one of which leads to a shameful death and the other to happiness.

Time is a river

Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote that:

“ Time is like a river made up of the events which happen , and a violent stream; for as soon as a thing has been seen, it is carried away, and another comes in its place, and this will be carried away too.”

We can imagine that time does flow past every point in the universe, like a river around a rock. But it is difficult to make the idea precise. A flow is a rate of change — the flow of a river is the amount of water that passes a specific length in a given time. Hence if time is a flow, it is at the rate of one second per second, which is not a very useful insight.

Theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking suggested that a “ chronology protection conjecture ” must exist, an as-yet-unknown physical principle that forbids time travel. Hawking’s concept originates from the idea that we cannot know what goes on inside a black hole, because we cannot get information out of it. But this argument is redundant: we cannot time travel because we cannot time travel!

Researchers are investigating a more fundamental theory, where time and space “emerge” from something else. This is referred to as quantum gravity , but unfortunately it does not exist yet.

So is time travel possible? Probably not, but we don’t know for sure!

- Time travel

- Stephen Hawking

- Albert Einstein

- Listen to this article

- Time travel paradox

- Arthur Eddington

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

Technical Skills Laboratory Officer

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis