Call our 24 hours, seven days a week helpline at 800.272.3900

- Professionals

- Younger/Early-Onset Alzheimer's

- Is Alzheimer's Genetic?

- Women and Alzheimer's

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease

- Dementia with Lewy Bodies

- Down Syndrome & Alzheimer's

- Frontotemporal Dementia

- Huntington's Disease

- Mixed Dementia

- Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus

- Posterior Cortical Atrophy

- Parkinson's Disease Dementia

- Vascular Dementia

- Korsakoff Syndrome

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

- Know the 10 Signs

- Difference Between Alzheimer's & Dementia

- 10 Steps to Approach Memory Concerns in Others

- Medical Tests for Diagnosing Alzheimer's

- Why Get Checked?

- Visiting Your Doctor

- Life After Diagnosis

- Stages of Alzheimer's

- Earlier Diagnosis

- Part the Cloud

- Research Momentum

- Our Commitment to Research

- TrialMatch: Find a Clinical Trial

- What Are Clinical Trials?

- How Clinical Trials Work

- When Clinical Trials End

- Why Participate?

- Talk to Your Doctor

- Clinical Trials: Myths vs. Facts

- Can Alzheimer's Disease Be Prevented?

- Brain Donation

- Navigating Treatment Options

- Lecanemab Approved for Treatment of Early Alzheimer's Disease

- Aducanumab Discontinued as Alzheimer's Treatment

- Medicare Treatment Coverage

- Donanemab for Treatment of Early Alzheimer's Disease — News Pending FDA Review

- Questions for Your Doctor

- Medications for Memory, Cognition and Dementia-Related Behaviors

- Treatments for Behavior

- Treatments for Sleep Changes

- Alternative Treatments

- Facts and Figures

- Assessing Symptoms and Seeking Help

- Now is the Best Time to Talk about Alzheimer's Together

- Get Educated

- Just Diagnosed

- Sharing Your Diagnosis

- Changes in Relationships

- If You Live Alone

- Treatments and Research

- Legal Planning

- Financial Planning

- Building a Care Team

- End-of-Life Planning

- Programs and Support

- Overcoming Stigma

- Younger-Onset Alzheimer's

- Taking Care of Yourself

- Reducing Stress

- Tips for Daily Life

- Helping Family and Friends

- Leaving Your Legacy

- Live Well Online Resources

- Make a Difference

- Daily Care Plan

- Communication and Alzheimer's

- Food and Eating

- Art and Music

- Incontinence

- Dressing and Grooming

- Dental Care

- Working With the Doctor

- Medication Safety

- Accepting the Diagnosis

- Early-Stage Caregiving

- Middle-Stage Caregiving

- Late-Stage Caregiving

- Aggression and Anger

- Anxiety and Agitation

- Hallucinations

- Memory Loss and Confusion

- Sleep Issues and Sundowning

- Suspicions and Delusions

- In-Home Care

- Adult Day Centers

- Long-Term Care

- Respite Care

- Hospice Care

- Choosing Care Providers

- Finding a Memory Care-Certified Nursing Home or Assisted Living Community

- Changing Care Providers

- Working with Care Providers

- Creating Your Care Team

- Long-Distance Caregiving

- Community Resource Finder

- Be a Healthy Caregiver

- Caregiver Stress

- Caregiver Stress Check

- Caregiver Depression

- Changes to Your Relationship

- Grief and Loss as Alzheimer's Progresses

- Home Safety

- Dementia and Driving

- Technology 101

- Preparing for Emergencies

- Managing Money Online Program

- Planning for Care Costs

- Paying for Care

- Health Care Appeals for People with Alzheimer's and Other Dementias

- Social Security Disability

- Medicare Part D Benefits

- Tax Deductions and Credits

- Planning Ahead for Legal Matters

- Legal Documents

- ALZ Talks Virtual Events

- ALZNavigator™

- Veterans and Dementia

- The Knight Family Dementia Care Coordination Initiative

- Online Tools

- Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and Alzheimer's

- Native Americans and Alzheimer's

- Black Americans and Alzheimer's

- Hispanic Americans and Alzheimer's

- LGBTQ+ Community Resources for Dementia

- Educational Programs and Dementia Care Resources

- Brain Facts

- 50 Activities

- For Parents and Teachers

- Resolving Family Conflicts

- Holiday Gift Guide for Caregivers and People Living with Dementia

- Trajectory Report

- Resource Lists

- Search Databases

- Publications

- Favorite Links

- 10 Healthy Habits for Your Brain

- Stay Physically Active

- Adopt a Healthy Diet

- Stay Mentally and Socially Active

- Online Community

- Support Groups

Find Your Local Chapter

- Any Given Moment

- New IDEAS Study

- RFI Amyloid PET Depletion Following Treatment

- Bruce T. Lamb, Ph.D., Chair

- Christopher van Dyck, M.D.

- Cynthia Lemere, Ph.D.

- David Knopman, M.D.

- Lee A. Jennings, M.D. MSHS

- Karen Bell, M.D.

- Lea Grinberg, M.D., Ph.D.

- Malú Tansey, Ph.D.

- Mary Sano, Ph.D.

- Oscar Lopez, M.D.

- Suzanne Craft, Ph.D.

- About Our Grants

- Andrew Kiselica, Ph.D., ABPP-CN

- Arjun Masurkar, M.D., Ph.D.

- Benjamin Combs, Ph.D.

- Charles DeCarli, M.D.

- Damian Holsinger, Ph.D.

- David Soleimani-Meigooni, Ph.D.

- Donna M. Wilcock, Ph.D.

- Elizabeth Head, M.A, Ph.D.

- Fan Fan, M.D.

- Fayron Epps, Ph.D., R.N.

- Ganesh Babulal, Ph.D., OTD

- Hui Zheng, Ph.D.

- Jason D. Flatt, Ph.D., MPH

- Jennifer Manly, Ph.D.

- Joanna Jankowsky, Ph.D.

- Luis Medina, Ph.D.

- Marcello D’Amelio, Ph.D.

- Marcia N. Gordon, Ph.D.

- Margaret Pericak-Vance, Ph.D.

- María Llorens-Martín, Ph.D.

- Nancy Hodgson, Ph.D.

- Shana D. Stites, Psy.D., M.A., M.S.

- Walter Swardfager, Ph.D.

- ALZ WW-FNFP Grant

- Capacity Building in International Dementia Research Program

- ISTAART IGPCC

- Alzheimer’s Disease Strategic Fund: Endolysosomal Activity in Alzheimer’s (E2A) Grant Program

- Imaging Research in Alzheimer’s and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Zenith Fellow Awards

- National Academy of Neuropsychology & Alzheimer’s Association Funding Opportunity

- Part the Cloud-Gates Partnership Grant Program: Bioenergetics and Inflammation

- Pilot Awards for Global Brain Health Leaders (Invitation Only)

- Robert W. Katzman, M.D., Clinical Research Training Scholarship

- Funded Studies

- How to Apply

- Portfolio Summaries

- Supporting Research in Health Disparities, Policy and Ethics in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia Research (HPE-ADRD)

- Diagnostic Criteria & Guidelines

- Annual Conference: AAIC

- Professional Society: ISTAART

- Alzheimer's & Dementia

- Alzheimer's & Dementia: DADM

- Alzheimer's & Dementia: TRCI

- International Network to Study SARS-CoV-2 Impact on Behavior and Cognition

- Alzheimer’s Association Business Consortium (AABC)

- Global Biomarker Standardization Consortium (GBSC)

- Global Alzheimer’s Association Interactive Network

- International Alzheimer's Disease Research Portfolio

- Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Private Partner Scientific Board (ADNI-PPSB)

- Research Roundtable

- About WW-ADNI

- North American ADNI

- European ADNI

- Australia ADNI

- Taiwan ADNI

- Argentina ADNI

- WW-ADNI Meetings

- Submit Study

- RFI Inclusive Language Guide

- Scientific Conferences

- AUC for Amyloid and Tau PET Imaging

- Make a Donation

- Walk to End Alzheimer's

- The Longest Day

- RivALZ to End ALZ

- Ride to End ALZ

- Tribute Pages

- Gift Options to Meet Your Goals

- Founders Society

- Fred Bernhardt

- Anjanette Kichline

- Lori A. Jacobson

- Pam and Bill Russell

- Gina Adelman

- Franz and Christa Boetsch

- Adrienne Edelstein

- For Professional Advisors

- Free Planning Guides

- Contact the Planned Giving Staff

- Workplace Giving

- Do Good to End ALZ

- Donate a Vehicle

- Donate Stock

- Donate Cryptocurrency

- Donate Gold & Sterling Silver

- Donor-Advised Funds

- Use of Funds

- Giving Societies

- Why We Advocate

- Ambassador Program

- About the Alzheimer’s Impact Movement

- Research Funding

- Improving Care

- Support for People Living With Dementia

- Public Policy Victories

- Planned Giving

- Community Educator

- Community Representative

- Support Group Facilitator or Mentor

- Faith Outreach Representative

- Early Stage Social Engagement Leaders

- Data Entry Volunteer

- Tech Support Volunteer

- Other Local Opportunities

- Visit the Program Volunteer Community to Learn More

- Become a Corporate Partner

- A Family Affair

- A Message from Elizabeth

- The Belin Family

- The Eliashar Family

- The Fremont Family

- The Freund Family

- Jeff and Randi Gillman

- Harold Matzner

- The Mendelson Family

- Patty and Arthur Newman

- The Ozer Family

- Salon Series

- No Shave November

- Other Philanthropic Activities

- Still Alice

- The Judy Fund E-blast Archive

- The Judy Fund in the News

- The Judy Fund Newsletter Archives

- Sigma Kappa Foundation

- Alpha Delta Kappa

- Parrot Heads in Paradise

- Tau Kappa Epsilon (TKE)

- Sigma Alpha Mu

- Alois Society Member Levels and Benefits

- Alois Society Member Resources

- Zenith Society

- Founder's Society

- Joel Berman

- JR and Emily Paterakis

- Legal Industry Leadership Council

- Accounting Industry Leadership Council

Find Local Resources

Let us connect you to professionals and support options near you. Please select an option below:

Use Current Location Use Map Selector

Search Alzheimer’s Association

Sundowning is increased confusion that people living with Alzheimer's and dementia may experience from dusk through night. Also called "sundowner's syndrome," it is not a disease but a set of symptoms or dementia-related behaviors that may include difficulty sleeping, anxiety, agitation, hallucinations, pacing and disorientation. Although the exact cause is unknown, sundowning may occur due to disease progression and changes in the brain.

Factors that may contribute to trouble sleeping and sundowning

Tips that may help manage sleep issues and sundowning, if the person is awake and upset.

- Mental and physical exhaustion from a full day of activities.

- Navigating a new or confusing environment.

- A mixed-up "internal body clock." The person living with Alzheimer's may feel tired during the day and awake at night.

- Low lighting can increase shadows, which may cause the person to become confused by what they see. They may experience hallucinations and become more agitated.

- Noticing stress or frustration in those around them may cause the person living with dementia to become stressed as well.

- Dreaming while sleeping can cause disorientation, including confusion about what's a dream and what's real.

- Less need for sleep, which is common among older adults.

Share your experiences and find support

Join ALZConnected®, a free online community designed for people living with dementia and those who care for them. Post questions about dementia-related issues, offer support, and create public and private groups around specific topics.

- Encourage the person living with dementia to get plenty of rest.

- Schedule activities such as doctor appointments, trips and bathing in the morning or early afternoon hours when the person living with dementia is more alert.

- Encourage a regular routine of waking up, eating meals and going to bed.

- When possible, spend time outside in the sunlight during the day.

- Make notes about what happens before sundowning events and try to identify triggers.

- Reduce stimulation during the evening hours. For example, avoid watching TV, doing chores or listening to loud music. These distractions may add to the person’s confusion.

- Offer a larger meal at lunch and keep the evening meal lighter.

- Keep the home well lit in the evening to help reduce the person’s confusion.

- Try to identify activities that are soothing to the person, such as listening to calming music, looking at photographs or watching a favorite movie.

- Take a walk with the person to help reduce their restlessness.

- Talk to the person's doctor about the best times of day for taking medication.

- Try to limit daytime naps if the person has trouble sleeping at night.

- Reduce or avoid alcohol, caffeine and nicotine, which can all affect the ability to sleep.

- If these suggestions do not help, discuss the situation with the person's doctor.

Talk to a doctor about sleep issues

Discuss sleep problems with a doctor to help identify causes and possible solutions. Physical ailments, such as urinary tract infections or incontinence problems, restless leg syndrome or sleep apnea, can cause or worsen sleep problems. For sleep issues primarily due to Alzheimer's disease, most experts encourage the use of non-drug measures rather than medication. In some cases when non-drug approaches fail, medication may be prescribed for agitation during the late afternoon and evening hours. Work with the doctor to learn the risks and benefits of medication before making a decision.

- Approach them in a calm manner.

- Find out if there is something they need.

- Gently remind them of the time.

- Avoid arguing.

- Offer reassurance that everything is all right.

- Don't use physical restraint. Allow the person to pace back and forth, as needed, with supervision.

Other pages in Stages and Behaviors

- Care Options

- Caregiver Health

- Financial and Legal Planning for Caregivers

Related Pages

Connect with our free, online caregiver community..

Join ALZConnected

Our blog is a place to continue the conversation about Alzheimer's.

Read the Blog

The Alzheimer’s Association is in your community.

Keep up with alzheimer’s news and events.

- Alzheimer's & Dementia

- Asthma & Allergies

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Breast Cancer

- Cardiovascular Health

- Environment & Sustainability

- Exercise & Fitness

- Headache & Migraine

- Health Equity

- HIV & AIDS

- Human Biology

- Men's Health

- Mental Health

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

- Parkinson's Disease

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Sexual Health

- Ulcerative Colitis

- Women's Health

- Nutrition & Fitness

- Vitamins & Supplements

- At-Home Testing

- Men’s Health

- Women’s Health

- Latest News

- Medical Myths

- Honest Nutrition

- Through My Eyes

- New Normal Health

- 2023 in medicine

- Why exercise is key to living a long and healthy life

- What do we know about the gut microbiome in IBD?

- My podcast changed me

- Can 'biological race' explain disparities in health?

- Why Parkinson's research is zooming in on the gut

- Health Hubs

- Find a Doctor

- BMI Calculators and Charts

- Blood Pressure Chart: Ranges and Guide

- Breast Cancer: Self-Examination Guide

- Sleep Calculator

- RA Myths vs Facts

- Type 2 Diabetes: Managing Blood Sugar

- Ankylosing Spondylitis Pain: Fact or Fiction

- Our Editorial Process

- Content Integrity

- Conscious Language

- Health Conditions

- Health Products

What to know about dementia wandering

Some people with dementia may wander away from their homes or caregivers if they experience confusion about where they are.

Dementia refers to symptoms affecting memory, communication, and cognition that result from underlying conditions and brain disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

This article explores who is at risk of wandering with dementia, the stage at which this behavior may occur, and the causes of wandering. It also looks at ways to reduce the risk of wandering and steps to take when wandering occurs.

Information for caregivers

As a person’s condition progresses, they may need help reading or understanding information regarding their circumstances. This article contains details that may help caregivers identify and monitor symptom progression, side effects of drugs, or other factors relating to the person’s condition.

Who is at risk of wandering?

A 2021 article relates wandering to “aimless locomotion behavior” and states that it is common.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association , all people living with Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia are at risk of wandering. This is because Alzheimer’s disease causes people to lose the ability to recognize familiar settings and people.

Wandering can be dangerous, and the risks it poses can prove stressful for caregivers and loved ones.

Signs of increased risk

A person may be at risk of wandering if they begin:

- returning later than usual from a regular walk or drive

- forgetting directions to familiar places inside and outside the house

- talking about fulfilling former obligations, such as going to work after retiring

- trying to go home even when at home

- becoming restless and pacing

- making repetitive movements

- asking the whereabouts of deceased friends and family

- appearing lost in new environments

- becoming nervous in busy places

Read more about other behavioral changes associated with dementia .

When does wandering occur?

The Alzheimer’s Association suggests 60% of people with dementia will experience wandering at least once. Some may do it repeatedly.

It notes that wandering can occur at any stage of dementia, but the risk may increase as symptoms progress.

It may be best for family or caregivers to speak with a doctor if they notice signs that a person may be at risk of wandering or if the behavior occurs.

People can seek support from organizations such as the Alzheimer’s Association. It organizes support groups that offer a safe place for caregivers and loved ones of people with dementia to meet and share their experiences.

Find out more about the stages of dementia .

Why might people with dementia wander?

Researchers still do not know the exact cause of wandering with dementia, but they link it to the severity of cognitive impairment, including issues with:

- recent and remote memory

- time and place orientation

- the ability to react appropriately to a given conversation subject

They note that people with Lewy body dementia are more likely than those with vascular dementia to wander.

People with dementia who are receiving antipsychotic treatment , have comorbid conditions, or display behaviors such as arguing and threatening may also be more likely to wander. These conditions include depression and psychosis .

Potential causes

According to researchers, wandering behavior may have a neurophysical explanation that relates to the following:

- visuospatial dysfunction , which affects a person’s spatial awareness or ability to judge distances

- visuoconstructional impairment , which reduces the ability to accurately copy or draw objects, recognize shapes and patterns, and complete visual puzzles

- reduced topographical memory , which affects a person’s ability to locate where they are

They suggest it may also be an attempt to fulfill physiological or psychological needs, such as a response to stress, trauma, or loneliness.

Alternatively, it may be due to unfamiliarity with the environment, changes to medications or schedules, or a severe decline in cognitive function.

The United Kingdom’s Alzheimer’s Society provides further potential reasons for wandering, such as:

- memory loss

- confusion about the time at which the person usually performs activities

- pain or distress

- anxiety or agitatation

- a lack of physical activity

- continuing a previous habit

- searching for someone in the past

- feeling lost

How to reduce the risk of wandering

Caregivers or family members may be able to reduce the risk of wandering. However, they may not be able to guarantee that a person living with dementia will not wander.

The following strategies may help:

- providing opportunities for structured and engaging activities throughout the day

- identifying the time of the day when a person is likely to wander, such as the “ sundowner’s period ” as night approaches, and planning activities during this time

- ensuring the person’s needs for food, drink, and use of the bathroom are met

- involving the person in daily activities, such as folding laundry or preparing dinner

- providing reassurance when the person is lost, anxious, or disoriented

- using a GPS device if it is safe for the person to go out walking or driving

- avoiding busy places that may be stressful, such as shopping malls

- assessing the person’s reactions and feelings toward new environments

In the early stages

The Alzheimer’s Association suggests individuals with early stage dementia may benefit from engaging in the following with family or caregivers:

- deciding on a set time each day to check in with each other

- reviewing schedules and appointments together

- identifying companions who can support the person when others are not available

- considering transportation to avoid wandering

Learn more about early stage dementia .

Preparing the home

The National Institute of Aging suggests the following may help prevent a person with dementia from wandering away from home:

- keeping doors locked

- using loosely fitting doorknob covers

- removable gates

- installing devices on windows to limit how much they can open

- installing bells, alarms, or pressure-sensitive mats when the door opens

- securing outside areas with fencing and a locked gate

- keeping keys, shoes, suitcases, and other items that may trigger the instinct to leave out of sight

Safety measures

If the risk of wandering increases, the following safety measures may help :

- placing deadbolts on the door, out of sight, but only locking them when someone is in the house with the person

- camouflaging doors with the same colors as the walls

- supervising the person when they are in new or changed surroundings or a car

- creating a threshold in front of the door with paint or tape to create a visual barrier

- using night lights and safety gates

- monitoring noise levels to reduce excessive stimulation

- creating safe spaces to explore inside or outside the house

- labeling rooms with signs to explain their purpose

Alzheimer’s Association support groups may provide additional support and resources for caregivers of a person with dementia.

Read more about caring for someone with dementia .

Planning ahead

Families and caregivers may also benefit from having a plan in place in case of an emergency. This may involve:

- enrolling the person living with dementia in a wandering response service

- asking neighbors or other people to call if they see a person wandering

- keeping recent photos of the person to give to police in case of emergency

- getting to know the person’s neighborhood well and identifying potential hazards

- creating a list of places the person may wander to

The National Institute of Aging suggests it may also help to:

- make sure the person carries identification or wears a medical bracelet to let people know about their dementia

- sew labels on the person’s clothing to aid identification

- keep an item of the person’s worn, unwashed clothing in a plastic bag to aid in finding them with the use of dogs, if necessary

People can reach out to support groups and various organizations for additional advice.

Find out more about dementia support groups .

Taking action when wandering occurs

If a person with dementia wanders away from home, people can act immediately by taking the following steps :

- Start search efforts immediately and consider looking in the direction that relates to the missing person’s dominant writing hand first.

- Search the surrounding area and places where a person has wandered in the past, if applicable.

- Check local landscapes, such as ponds, tree lines, or fence lines.

- Call 911 if they do not find the person within 15 minutes and inform any other relevant local authorities.

People at any stage of dementia are at risk of wandering. Family and caregivers can look for signs a person may be at risk of wandering, such as forgetting directions, asking about deceased family members, or making repetitive movements.

Protecting a person from wandering may involve keeping the home as secure as possible and storing items that may trigger the instinct to leave the house out of sight.

Family or caregivers can also implement plans that allow them to act immediately in an emergency. For example, they may enroll the person in a wandering response service and create a list of places they may wander to. People should call 911 if they do not find a person with dementia who has wandered away from home within 15 minutes.

Last medically reviewed on December 14, 2023

- Alzheimer's / Dementia

How we reviewed this article:

- Agrawal AK, et al. (2021). Approach to management of wandering in dementia: Ethical and legal issue. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8543604/

- How can dementia change a person's perception? (2022). https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/symptoms-and-diagnosis/how-dementia-changes-perception

- Lim TS, et al. (2010). Topographical disorientation in mild cognitive impairment: A voxel-based morphometry study. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3024525/

- Simons R. (2023). Exploring visuoconstructional impairment in dementia syndromes? https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/exploring-visuoconstructional-impairment-in-dementia-syndromes-125676.html

- Support groups. (n.d.). https://www.alz.org/alzwa/helping_you/support_groups

- Wandering and Alzheimer's disease. (2017). https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/wandering-and-alzheimers-disease

- Wandering and dementia. (n.d.). https://alzheimer.ca/bc/en/help-support/programs-services/dementia-resources-bc/wandering-disorientation-resources/wandering-dementia

- Wandering and getting lost: Who’s at risk and how to be prepared. (2023). https://www.alz.org/media/documents/alzheimers-dementia-wandering-behavior-ts.pdf

- Wandering. (n.d.). https://www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/stages-behaviors/wandering

- Why a person with dementia might be walking about. (2021). https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/symptoms-and-diagnosis/why-person-with-dementia-might-be-walking-about

Share this article

Latest news

- Poor diet increases cancer risk: Scientists uncover missing link

- Newly identified genetic variant may protect against Alzheimer’s

- How high blood pressure can raise the risk of uterine fibroids

- Heart disease: How the DASH diet can help lower the risk after breast cancer treatment

- Exercise may help reverse aging by reducing fat buildup in tissues

Related Coverage

Some forms of dementia, such as Alzheimer's disease and Lewy body dementia, may have a genetic component. Single genes may cause the condition in some…

Treatment for dementia agitation may include medications and creating a supportive, comforting environment.

It can be difficult to know how to talk with someone with dementia. Learn more about different communication techniques and how to get started.

Researchers from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) have developed a smartphone app featuring cognitive tests that accurately detect…

People’s brains have been getting larger over the past 100 years, and scientists think this increased brain reserve could — potentially — reduce the…

Diseases & Diagnoses

Issue Index

- Case Reports

Cover Focus | June 2022

Wandering & Sundowning in Dementia

Preventive and acute management of some of the most challenging aspects of dementia is possible..

Taylor Thomas, BA; and Aaron Ritter, MD

Alzheimer disease (AD) and related dementias are complex disorders that affect multiple brain systems, resulting in a wide range of cognitive and behavioral manifestations. The behavioral symptoms often have clinical analogs in idiopathic psychiatric disorders and are frequently referred to as neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) of dementia. Many therapeutic strategies for NPS are borrowed from treatment of idiopathic psychiatric disorders. For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) commonly used to treat major depressive disorder may also be prescribed for depressive symptoms in AD. This strategy has been deemed the “therapeutic metaphor” and has shown varying degrees of success in clinical trials. 1

Clinicians face significant challenges, however, when there is no suitable metaphor to guide treatment for behaviors that emerge solely in dementia. This is particularly problematic for 2 of the most burdensome behavioral manifestations of dementia—sundowning (the worsening of symptoms in the late afternoon and early evening) and wandering. Despite being among the most impactful behaviors in dementia, there is very little research evidence to guide therapeutic approaches. This review provides a brief update of the current literature regarding wandering and sundowning in dementia. Using evidence-based approaches from the research literature, where available, and best practices adopted from our own clinical practice when little evidence exists, we outline a practical treatment algorithm that can be used in the clinic when facing either of these common and problematic behaviors.

Wandering Frequency, Consequences & Causes

Wandering is a complex behavioral phenomenon that is frequent in dementia. Approximately 20% of community-dwelling individuals with dementia and 60% of those living in institutionalized settings are reported to wander .2 Most definitions of wandering incorporate a variety of dementia-related locomotion activities, including elopement (ie, attempts to escape), repetitive pacing, and becoming lost. 3 More recently, the term “critical wandering” or “missing incidents” have been used to draw distinctions between elopement and pacing vs wandering and becoming lost. 4 Critical wandering episodes have a high mortality rate of 20%, placing this symptom among the most dangerous behavioral manifestations of dementia. 5

The risk of wandering increases with severity of cognitive impairment, with the highest rate in those with Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) scores of 13 or less. 6 Individuals who frequently wander (ie, multiple times per week) almost always have at least moderate dementia. Few studies have compared wandering rates among people with different types of dementia. 7 Experience from our clinical practice suggests that wandering is most common in AD—where spatial disorientation and amnesia are common clinical features—but can also occur in moderate to advanced stages of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and Lewy body dementia (LBD). The presence of comorbid NPS (eg, severe depression, sleep disorders, and psychosis) may increase the likelihood of wandering. 8

Causes of wandering are not well understood. Some hypothesize wandering emerges from disconnection among brain regions responsible for visuospatial, motor, and memory functions. A positron-emission tomography (PET) study of 342 individuals with AD, 80 of whom were considered wanderers, found a distinct pattern of hypometabolism in the cingulum and supplementary motor areas among wanderers. Correlations between specific brain regions and the type of wandering (eg, pacing, lapping, or random) were also seen. 9

A relatively larger body of research informs psychosocial perspectives on wandering with 3 scenarios identified in which wandering behaviors commonly emerge, including 1) escape from an unfamiliar setting; 2) desire for social interaction; and 3) exercise behavior triggered by restlessness or lack of activity. Other factors that increase wandering behavior include lifelong low ability to tolerate stress, an individual’s belief that they are still employed at a job, and a repeated desire to search for people (eg, dead family members) or places (eg, a home where they no longer reside). 10

Managing Wandering

There is little empiric evidence to inform treatment approaches to wandering in dementia. Nonpharmaceutical interventions that promote “safe walking” instead of aimless wandering are preferred initial approaches. Several “low tech” options with low associated costs and negligible side effects have some evidence for use, including exercise programs, aromatherapy, placing murals and other paintings in front of exit doors, or hiding door handles. 11 More recently, the explosion of discrete and affordable wearable devices that have global positioning system (GPS) tracking ability have significantly expanded the number of “high-tech” options available to address elopement. These include GPS tagging, bed and door alarms, and surveillance systems. Few have been tested in prospective, placebo-controlled studies, however, making it hard to make firm conclusions regarding efficacy. 12 The ethical implications of using these technologies—including potential infringements on privacy, dignity, and autonomy of individuals—are seldom considered in clinical trials or clinical practice. 13

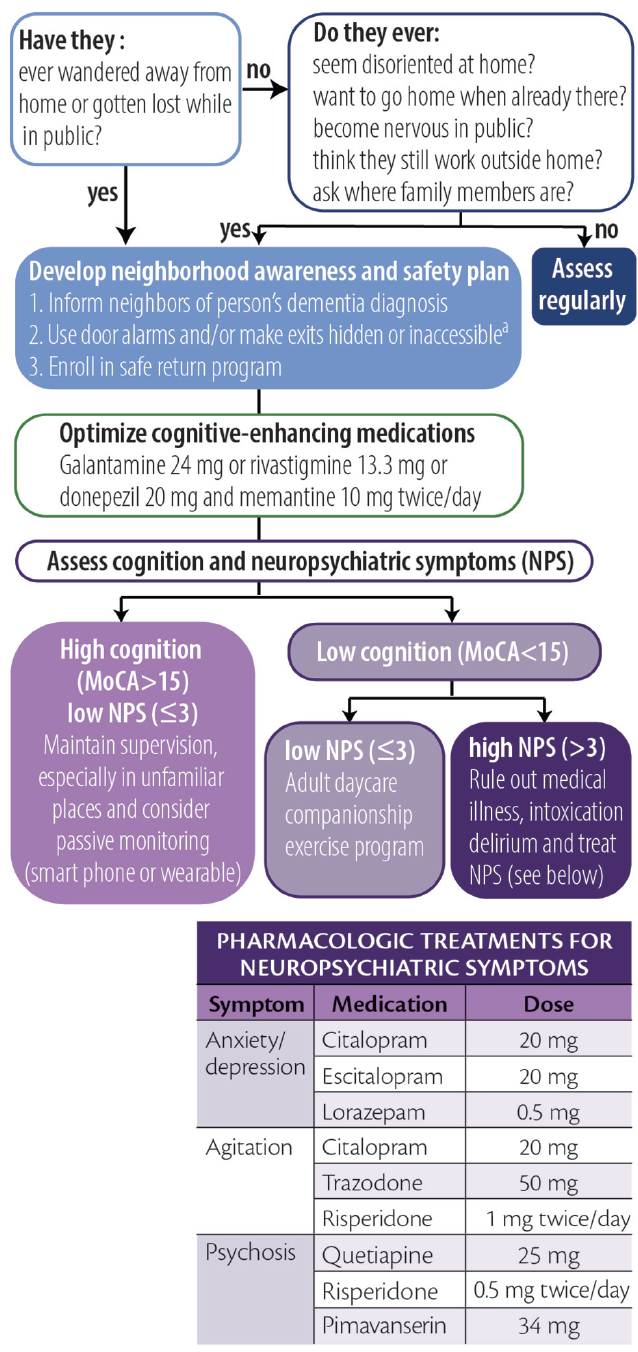

Considering the high prevalence and often deadly consequences associated with wandering, we offer a practical, algorithmic approach to wandering in dementia (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Algorithmic approach to wandering. Abbreviation: MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment. a Persons with dementia should never be left alone behind locked doors.

Click to view larger

Screening for Wandering

To screen for wandering behavior, we ask the following 2 questions of or about all persons with dementia:

1. Have they ever wandered away from their home?

2. Have they ever gotten lost while in public?

If either of these are responded to affirmatively, we make recommendations and stratify risk as described below. If both questions are responded to with “no,” we ask if they:

1. ever seem disoriented at home or in familiar places?

2. ever report a desire to go home even while at home?

3. become excessively nervous while in public?

4. talk about needing to fulfill prior work obligations?

5. ask about the whereabouts of past family or friends?

An affirmative answer to any of these 5 questions may indicate an increased risk for wandering. For those who wander or are at high risk for wandering we provide basic education, recommend increased diligence, and maximize behavioral strategies to improve orientation (eg, display a written calendar and/or a large digital clock with time and date and optimize use of cognitive-enhancing agents when appropriate).

Creating a Wandering Safety Plan

Once a wandering event has occurred, we recommend families develop a neighborhood awareness and safety plan. The Alzheimer’s Association’s website has excellent resources devoted toward developing this plan ( https://www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/stages-behaviors/wandering ). At a minimum, the safety plan should include notifying neighbors that the person has dementia, keeping a list of places they are likely to wander to, and having a recent photo readily available for emergency medical and other services. We also educate families about the initial steps to take if wandering occurs, including immediately searching areas favoring the direction of the dominant hand, focusing the search within 1.5 miles of the home, and calling 9-1-1 no more than 15 minutes after a person with dementia has been determined to be missing. Additional recommendations include obtaining medical identification jewelry, installing door alarms, and making locks inaccessible (ie, hiding them or placing them out of reach). Families should be encouraged to enroll in a safe return program (eg, MedicAlert, Project Lifesaver, or Silver Alert) if one is available in their area. It is important to note that people with dementia should never be locked by themselves inside a home.

Managing Risk by Stratified Wandering Type

Cluster analyses show people who wander can largely be grouped into 1 of 3 different types based on cognitive and behavioral characteristics. 14 These groupings are useful for tailoring interventions and can be identified for an individual with combined cognitive test scores and behavioral symptom profiles. We use the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) 15 and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Questionnaire (NPI-Q) 16 because they are relatively quick to administer while providing important information and can be simultaneously administered to caregivers (NPI-Q) and patients (MoCA). These assessments can be used to stratify patients as follows.

Group 1: High Cognitive Function, Low Behavioral Disturbances. Individuals who score greater than 15 on the MoCA and have 3 or fewer behavioral symptoms wander infrequently (<1 time/month) and often only in unfamiliar settings. Because wandering is usually triggered by unexpected stressors, the main goal for these individuals is to provide adequate supervision in unfamiliar settings. Those in this group may also still carry a mobile phone with several high-tech options (eg, GPS systems or “find my phone” apps) that may be beneficial.

Group 2: Low Cognitive Function, Low Behavioral Disturbances. Persons with lower cognitive test scores (eg, ≤10 on the MoCA) and fewer than 3 NPS may wander because of boredom or a lack of physical or cognitive stimulation. For this group, we recommend a companion caregiver or adult daycare program to engage the patient in enjoyable activities and incorporate supervised walks or exercise programs during the day. Individuals in this group may benefit from the creation of an outdoor area that may be explored safely.

Group 3: Low Cognitive Function, High Behavioral Disturbances. People in this group require the most proactive approaches because they are likely to be the most frequent wanderers and may be at highest risk for dangerous outcomes. Wandering in this group may be driven by delusions, particularly the persecutory type. 8 We recommend, as a first step, determining whether other factors such as pain, delirium, or intoxication may be contributing to the person’s NPS. If no additional etiologies can be clearly identified, comorbid NPS should be addressed with best clinical practices, borrowing heavily from psychiatry with the “therapeutic metaphor” (See Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Dementia in this issue). Many in this group may require institutionalization or constant supervision from hired caregivers to prevent harm. Nonpharmacologic strategies recommended for this group include taping a 2-foot black threshold in front of each door to serve as a visual barrier, installing cameras and warning alarms for outward facing doors, and installing safety gates around the house.

Sundowning Frequency, Consequences & Causes

Sundowning is the term used to describe the emergence or intensification of NPS occurring in the early evening. This phenomenon, thought to be unique to people with dementia, has long been recognized by researchers and caregivers as being among the most challenging elements of dementia care. 17 Although most frequently seen in AD, sundowning has also frequently been observed in other forms of dementia. Sundowning is among the most common behavioral manifestations of dementia, with rates in institutionalized settings exceeding 80%. 18 The risk of sundowning increases in moderate and severe dementia and because of its close association with sunlight, is more common in the autumn and winter seasons. 19

The impact of sundowning on persons with dementia is immense. Sundowning is among the most common reasons for institutionalization and is associated with faster rates of cognitive decline and increased risk for wandering. 17 Sundowning also increases care partner stress, which, in turn, may increase risk for agitation in patients. 18

The causes of sundowning are likely multifactorial. Sundowning is commonly linked to alterations in circadian rhythms. 19 Autopsy studies of people who had AD show a disproportionate loss of neurons in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which regulates the release of melatonin in response to light. 20 Other research links sundowning to reductions in cholinergic neurotransmission, 21 and at least 1 study showed increased levels of cortisol, which may suggest alterations of the entire hypothalamic-pituitary axis. 21 Sleep disruption, inadequate sunlight exposure, and disrupted routines increase the likelihood of sundowning. 17 Medications with anticholinergic properties and sedatives may also exacerbate sundowning.

Management of Sundowning

The Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold (PLST) model provides a framework for understanding and managing sundowning. 22 In this model, sundowning occurs because diurnal alterations in circadian rhythms temporally correlate with increases in pain, hunger, or fatigue that occur later in the day. Disruptions in emotional regulation emerge when a person’s ability to tolerate such stressors is exceeded.

As with wandering, there is little empiric evidence to guide pharmacologic management of sundowning. Melatonin has been studied in several open-label studies and case series with varying levels of success. 23 Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine reduce agitated behaviors, but have not been studied for management of sundowning. 24 Nonpharmacologic interventions (eg, eliminating daytime naps, increasing sunlight exposure, aerobic exercise, and playing music) can reduce sundowning, 17 but it is difficult to make firm conclusions about the efficacy of these measures because most have not been evaluated in prospective, placebo-controlled studies.

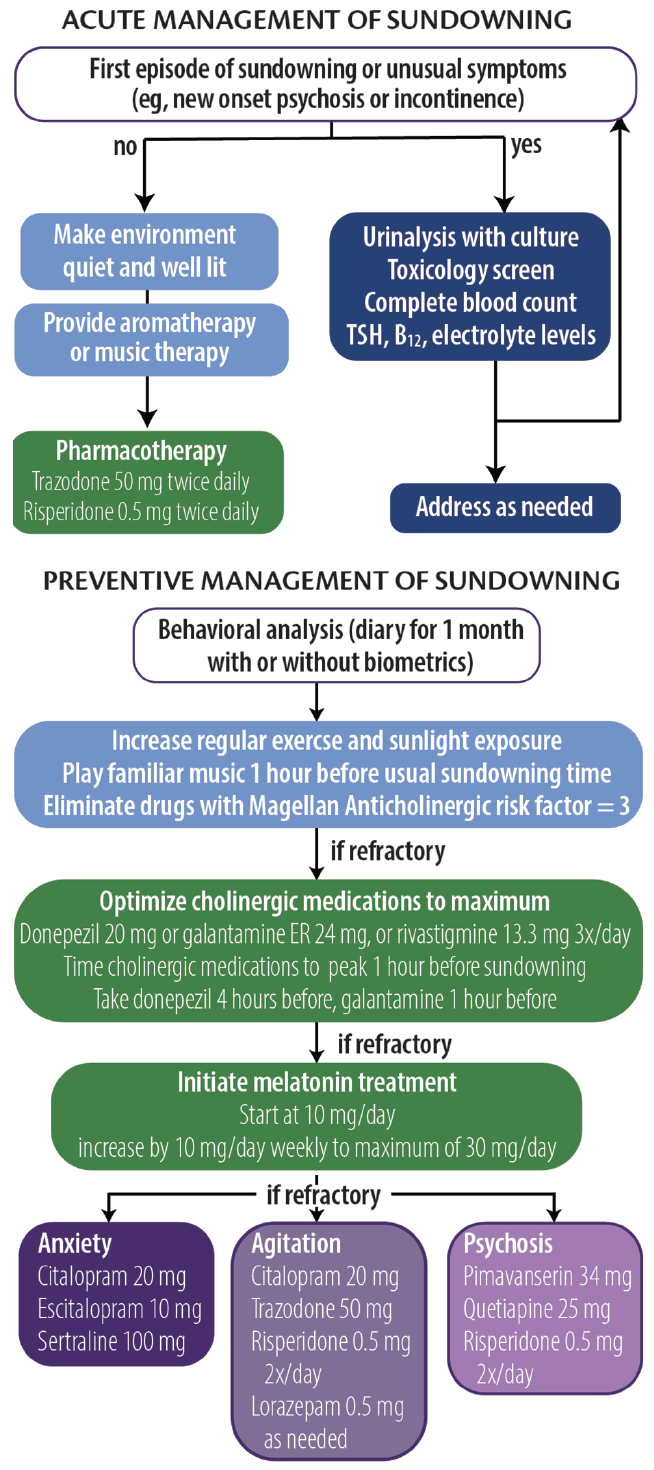

Analogous to headache management, approaches to sundowning can be broadly categorized as acute or preventive (Figure 2). Although preventive approaches may be more effective, caregivers may be able to reduce NPS associated with sundowning when it occurs.

Figure 2. Acute and preventative approaches to sundowning. Abbreviation: TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Acute Management

The PLST model can be used to identify any and all triggers that may contribute to sundowning episodes. For a first or unusual episode, it is recommended that a targeted medical and laboratory evaluation including urine culture, complete blood count, drug toxicology, and levels of electrolytes, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and vitamin B 12 be obtained. During an episode, whenever possible, a quiet, well-lit environment should be provided. Aromatherapy and familiar music at a medium volume may also help reduce anxiety and agitation. For persons at risk of hurting themselves or others, a low-dose psychotropic medication (eg, trazodone 50 mg repeated 1 hour later followed by risperidone 0.5 mg) may be necessary.

Preventive Management

In our clinical experience, prevention strategies may reduce the severity and frequency of sundowning. The first step is to conduct a behavioral analysis of the sundowning behavior. We recommend a daily journal be maintained for at least 1 month to document the types of behavior (eg, agitation, anxiety, psychosis, and disorientation) that occur, time of onset, and any extenuating circumstances that may have contributed to episodes of sundowning. Care partners can also provide information regarding medication administration and sleeping behavior to inform the analysis. The health care professional should analyze the journal, looking for patterns and correlations with other factors (eg, shift changes at care homes or changes to daily routines). The journal can be supported by biometric data from wearable technologies that provide objective measures of physical activity and sleep, which can be helpful in tailoring both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches.

We also recommend increasing the amount of regular exercise and sunlight exposure, preferably in the early afternoon. Caregivers are advised to start playing soothing or familiar music approximately 1 hour before sundowning behavior typically starts. Any medication with Magellan Anticholinergic Risk Scale scores of 3 should be eliminated, which requires scrutiny of medication lists. 25 Optimization of cognitive-enhancing medication doses and timing administration such that mean peak plasma concentrations are reached 1 hour before a person’s typical time of sundowning behavior may be beneficial.

If problematic sundowning behavior still persists, we recommend melatonin supplementation at an initial dose of 10 mg taken at nighttime, followed by a weekly increase by 10 mg to a maximum dose of 30 mg. This regimen is instituted regardless of reported sleep quality. If symptoms persist, the next step is to target NPS based on the individual’s most recent NPI-Q profile. The mantra of “start low and go slow” should guide therapeutic interventions, waiting at least 2 weeks before altering doses. In general, antidepressants are preferred first steps unless safety concerns necessitate more proactive approaches.

1. Cummings J, Ritter A, Rothenberg K. Advances in management of neuropsychiatric syndromes in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Psychiatry Rep . 2019;21(8):79.

2. Cipriani G, Lucetti C, Nuti A, Danti S. Wandering and dementia. Psychogeriatrics . 2014;14(2):135-142.

3. Algase DL, Moore DH, Vandeweerd C, Gavin-Dreschnack DJ. Mapping the maze of terms and definitions in dementia-related wandering. Aging Ment Health . 2007;11(6):686-698.

4. Petonito G, Muschert GW, Carr DC, Kinney JM, Robbins EJ, Brown JS. Programs to locate missing and critically wandering elders: a critical review and a call for multiphasic evaluation. Gerontologist. 2013;53(1):17-25.

5. Rowe MA, Vandeveer SS, Greenblum CA, et al. Persons with dementia missing in the community: is it wandering or something unique? BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:28.

6. Hope T, Keene J, McShane RH, Fairburn CG, Gedling K, Jacoby R. Wandering in dementia: a longitudinal study. Int Psychogeriatr . 2001;13(2):137-147.

7. Ballard CG, Mohan RNC, Bannister C, Handy S, Patel A. Wandering in dementia sufferers. Int J Geriat Psychiatry . 1991;6:611-614.

8. Klein DA, Steinberg M, Galik E, et al. Wandering behaviour in community-residing persons with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry . 1999;14(4):272-279.

9. Yang Y, Kwak YT. FDG PET findings according to wandering patterns of patients with drug-naïve Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Neurocogn Disord . 2018;17(3):90-99.

10. Hope RA, Fairburn CG. The nature of wandering in dementia: a community-based study. Int J Geriat Psychiatry . 1990;5(4):239-245.

11. Neubauer NA, Azad-Khaneghah P, Miguel-Cruz A, Liu L. What do we know about strategies to manage dementia-related wandering? A scoping review. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2018;10:615-628.

12. Neubauer NA, Lapierre N, Ríos-Rincón A, Miguel-Cruz A, Rousseau J, Liu L. What do we know about technologies for dementia-related wandering? A scoping review: Examen de la portée: Que savons-nous à propos des technologies de gestion de l’errance liée à la démence? Can J Occup Ther. 2018;85(3):196-208.

13. O’Neill D. Should patients with dementia who wander be electronically tagged? No. BMJ. 2013;346:f3606.

14. Logsdon RG, Teri L, McCurry SM, Gibbons LE, Kukull WA, Larson EB. Wandering: a significant problem among community-residing individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53(5):P294-P299.

15. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment [published correction appears in J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(9):1991]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

16. Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci . 2000;12(2):233-239.

17. Canevelli M, Valletta M, Trebbastoni A, et al. Sundowning in dementia: clinical relevance, pathophysiological determinants, and therapeutic approaches. Front Med (Lausanne) . 2016;3:73.

18. Gallagher-Thompson D, Brooks JO 3rd, Bliwise D, Leader J, Yesavage JA. The relations among caregiver stress, “sundowning” symptoms, and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(8):807-810.

19. Madden KM, Feldman B. Weekly, seasonal, and geographic patterns in health contemplations about sundown syndrome: an ecological correlational study. JMIR Aging 2019;2(1):e13302. doi:10.2196/13302

20. Wang JL, Lim AS, Chiang WY, et al. Suprachiasmatic neuron numbers and rest-activity circadian rhythms in older humans. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(2):317-322.

21. Weinshenker D. Functional consequences of locus coeruleus degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res . 2008;5(3):342-345.

22. Smith M, Gerdner LA, Hall GR, Buckwalter KC. History, development, and future of the progressively lowered stress threshold: a conceptual model for dementia care. J Am Geriatr Soc . 2004;52(10):1755-1760.

23. Cohen-Mansfield J, Garfinkel D, Lipson S. Melatonin for treatment of sundowning in elderly persons with dementia - a preliminary study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr . 2000;31(1):65-76.

24. Gauthier S, Feldman H, Hecker J, et al. Efficacy of donepezil on behavioral symptoms in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(4):389-404.

25. Rudolph JL, Salow MJ, Angelini MC, McGlinchey RE. The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch Intern Med . 2008;168(5):508-513.

TT reports no disclosures AR's work on this paper was supported by NIGMS P20GM109025

Taylor Thomas, BA

University of Nevada-Las Vegas School of Medicine Las Vegas, NV

Aaron Ritter, MD

Clinical Assistant Professor of Neurology Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health Las Vegas, NV

Treating Dementias With Care Partners in Mind

Dylan Wint, MD

Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Dementia

Jeffrey L. Cummings, MD, ScD

This Month's Issue

Anne Møller Witt, MD; Louise Sloth Kodal, MD; and Tina Dysgaard, MedScD

Matthew C. Varon, MD; and Mazen M. Dimachkie, MD

Nicholas J. Silvestri, MD

Related Articles

Abdalmalik Bin Khunayfir, MD; and Brian Appleby, MD

Simon Ducharme, MD, MSc, FRCPC

Sign up to receive new issue alerts and news updates from Practical Neurology®.

Related News

- Português Br

- Journalist Pass

Alzheimer’s and dementia: Understand wandering and how to address it

Dana Sparks

Share this:

Wandering and becoming lost is common among people with Alzheimer's disease or other disorders causing dementia. This behavior can happen in the early stages of dementia — even if the person has never wandered in the past.

Understand wandering

If a person with dementia is returning from regular walks or drives later than usual or is forgetting how to get to familiar places, he or she may be wandering.

There are many reasons why a person who has dementia might wander, including:

- Stress or fear. The person with dementia might wander as a reaction to feeling nervous in a crowded area, such as a restaurant.

- Searching. He or she might get lost while searching for something or someone, such as past friends.

- Basic needs. He or she might be looking for a bathroom or food or want to go outdoors.

- Following past routines. He or she might try to go to work or buy groceries.

- Visual-spatial problems. He or she can get lost even in familiar places because dementia affects the parts of the brain important for visual guidance and navigation.

Also, the risk of wandering might be higher for men than women.

Prevent wandering

Wandering isn't necessarily harmful if it occurs in a safe and controlled environment. However, wandering can pose safety issues — especially in very hot and cold temperatures or if the person with dementia ends up in a secluded area.

To prevent unsafe wandering, identify the times of day that wandering might occur. Plan meaningful activities to keep the person with dementia better engaged. If the person is searching for a spouse or wants to "go home," avoid correcting him or her. Instead, consider ways to validate and explore the person's feelings. If the person feels abandoned or disoriented, provide reassurance that he or she is safe.

Also, make sure the person's basic needs are regularly met and consider avoiding busy or crowded places.

Take precautions

To keep your loved one safe:

- Provide supervision. Continuous supervision is ideal. Be sure that someone is home with the person at all times. Stay with the person when in a new or changed environment. Don't leave the person alone in a car.

- Install alarms and locks. Various devices can alert you that the person with dementia is on the move. You might place pressure-sensitive alarm mats at the door or at the person's bedside, put warning bells on doors, use childproof covers on doorknobs or install an alarm system that chimes when a door is opened. If the person tends to unlock doors, install sliding bolt locks out of his or her line of sight.

- Camouflage doors. Place removable curtains over doors. Cover doors with paint or wallpaper that matches the surrounding walls. Or place a scenic poster on the door or a sign that says "Stop" or "Do not enter."

- Keep keys out of sight. If the person with dementia is no longer driving, hide the car keys. Also, keep out of sight shoes, coats, hats and other items that might be associated with leaving home.

Ensure a safe return

Wanderers who get lost can be difficult to find because they often react unpredictably. For example, they might not call for help or respond to searchers' calls. Once found, wanderers might not remember their names or where they live.

If you are caring for someone who might wander, inform the local police, your neighbors and other close contacts. Compile a list of emergency phone numbers in case you can't find the person with dementia. Keep on hand a recent photo or video of the person, his or her medical information, and a list of places that he or she might wander to, such as previous homes or places of work.

Have the person carry an identification card or wear a medical bracelet, and place labels in the person's garments. Also, consider enrolling in the MedicAlert and Alzheimer's Association safe-return program. For a fee, participants receive an identification bracelet, necklace or clothing tags and access to 24-hour support in case of emergency. You also might have your loved one wear a GPS or other tracking device.

If the person with dementia wanders, search the immediate area for no more than 15 minutes and then contact local authorities and the safe-return program — if you've enrolled. The sooner you seek help, the sooner the person is likely to be found.

This article is written by Mayo Clinic Staff . Find more health and medical information on mayoclinic.org .

- Answers to common questions about whether vaccines are safe, effective and necessary Consumer Health: Treating and living with HIV and AIDS

Related Articles

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

Alzheimer's: managing sleep problems.

If you're caring for a loved one who has Alzheimer's, sleep disturbances can take a toll on both of you. Here's help promoting a good night's sleep.

Sleep problems and Alzheimer's disease often go hand in hand. Understand what contributes to sleep problems in people with Alzheimer's or other dementia — and what you can do to help.

Common sleep problems related to dementia

Many older adults have problems sleeping, but people with dementia often have an even harder time. Sleep disturbance may affect up to 25% of people with mild to moderate dementia and 50% of people with severe dementia. Sleep disturbances tend to get worse as dementia progresses in severity.

Possible sleep problems include excessive sleepiness during the day and insomnia with difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep. Frequent awakenings during the night and premature morning awakenings are also common.

People with dementia might also experience a phenomenon in the evening or during the night called sundowning. They might feel confused, agitated, anxious and aggressive. Night wandering in this state of mind can be unsafe.

Obstructive sleep apnea is also more common in people with Alzheimer's disease. This potentially serious sleep disorder causes breathing to repeatedly stop and start during sleep.

Factors that might contribute to sleep disturbances and sundowning include:

- Mental and physical exhaustion at the end of the day

- Changes in the body clock

- A need for less sleep, which is common among older adults

- Disorientation

- Reduced lighting and increased shadows, which can cause people with dementia to become confused and afraid

Supporting a good night's sleep

Sleep disturbances can take a toll on both you and the person with dementia. To promote better sleep:

- Treat underlying conditions. Sometimes conditions such as depression, sleep apnea or restless legs syndrome cause sleep problems.

- Establish a routine. Maintain regular times for eating, waking up and going to bed.

- Avoid stimulants. Alcohol, caffeine and nicotine can interfere with sleep. Limit use of these substances, especially at night. Also, avoid TV during periods of wakefulness at night.

- Encourage physical activity. Walks and other physical activities can help promote better sleep at night.

- Limit daytime sleep. Discourage afternoon napping.

- Set a peaceful mood in the evening. Help the person relax by reading out loud or playing soothing music. A comfortable bedroom temperature can help the person with dementia sleep well.

- Manage medications. Some antidepressant medications, such as bupropion and venlafaxine, can lead to insomnia. Cholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, can improve cognitive and behavioral symptoms in people with Alzheimer's but also can cause insomnia. If the person with dementia is taking these kinds of medications, talk to the doctor. Administering the medication no later than the evening meal often helps.

- Consider melatonin. Melatonin might help improve sleep and reduce sundowning in people with dementia.

- Provide proper light. Bright light therapy in the evening can lessen sleep-wake cycle disturbances in people with dementia. Adequate lighting at night also can reduce agitation that can happen when surroundings are dark. Regular daylight exposure might address day and night reversal problems.

When a loved one wakes during the night

If the person with dementia wakes during the night, stay calm — even though you might be exhausted yourself. Don't argue. Instead, ask what the person needs. Nighttime agitation might be caused by discomfort or pain. See if you can determine the source of the problem, such as constipation, a full bladder, or a room that's too hot or cold.

Gently remind him or her that it's night and time for sleep. If the person needs to pace, don't restrain him or her. Instead, allow it under your supervision.

Using sleep medications

If nondrug approaches aren't working, the doctor might recommend sleep-inducing medications.

But sleep-inducing medications increase the risk of falls and confusion in older people who are cognitively impaired. As a result, sedating sleep medications generally aren't recommended for this group.

If these medications are prescribed, the doctor will likely recommend attempting to discontinue use once a regular sleep pattern is established.

Remember that you need sleep, too

If you're not getting enough sleep, you might not have the patience and energy needed to take care of someone with dementia. The person might also sense your stress and become agitated.

If possible, have family members or friends alternate nights with you. Or talk with the doctor, a social worker or a representative from a local Alzheimer's association to find out what help is available in your area.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Sleeplessness and sundowning. Alzheimer's Association. https://www.alz.org/care/alzheimers-dementia-sleep-issues-sundowning.asp. Accessed Dec. 2, 2019.

- Treatments for sleep changes. Alzheimer's Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/treatments/for-sleep-changes. Accessed Dec. 2, 2019.

- 6 tips for managing sleep problems. National Institute on Aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/6-tips-managing-sleep-problems-alzheimers. Accessed Dec. 2, 2019.

- Kryger MH, et al., eds. Alzheimer disease and other dementias. In: Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 6th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2017. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Dec. 2, 2019.

Products and Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Alzheimer's Disease

- A Book: Day to Day: Living With Dementia

- Alzheimer's: New treatments

- Caregiver stress

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

- Alzheimer s Managing sleep problems

Make twice the impact

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

How to Stop Dementia Patients from Wandering

Understanding why dementia patients wander, step 1: describe what you are seeing, step 2: consider the time of day and frequency, step 3: contemplate the underlying causes, what is the best way to handle wandering patients, dementia-related wandering may evolve and end, recent questions, popular questions, related questions.

- Best of Senior Living

- Most Friendly

- Best Meals and Dining

- Best Activities

- How Our Service Works

- Testimonials

- Leadership Team

- News & PR

Dementia and Wandering: Causes, Prevention, and Tips You Should Know

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Treatment of sleep disorders in dementia

Sharon ooms.

a Department of Geriatric Medicine, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands

b Radboud Alzheimer Centre, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands

c Department of Neurology, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, Missouri

Introduction

Dementia is associated with sleep and circadian disturbances, worse than the expected gradual sleep quality with aging[ 1 ], which negatively affect patient quality of life and increase caregiver burden [ 2 ]. Disrupted sleep and circadian functions in dementia are attributed to neurodegeneration of brain regions and networks involved in these functions, such as the suprachiasmatic nucleus [ 3 , 4 ]; however, there are additional factors that contribute to the burden of sleep disturbances in dementia. Alzheimer's Disease (AD) is associated with a delay in circadian phase, unlike the typical advance in circadian phase with aging [ 5 ]. This delay likely contributes to sundowning—agitation and confusion in the evening—as well as to difficulty sleeping at night. Due to wandering and subsequent risk of injury, nighttime insomnia increases morbidity and mortality directly, and therefore is a common reason for institutionalization [ 6 ]. During the daytime, excessive sleepiness may contribute to worse cognitive function, unintentional naps that impact driving safety, and decreased ability to engage in social functions and therapies. Given the substantial negative impact of sleep and circadian problems in dementia patients, there is keen interest in identifying effective treatments, with the hope of reducing caregiver burden, improving patient quality of life, postponing institutionalization, and potentially slowing cognitive decline.

Dementia subtypes and sleep disorders

Various etiologies of dementia are associated with different types of sleep and circadian disturbances. In AD, the most common cause of dementia, 44% of patients are affected with a sleep disorder[ 7 , 8 ], and the prevalence and severity of sleep disorders increase with dementia severity. Sleep disturbance occurs very early in AD; even the preclinical stage of AD prior to cognitive symptoms is associated with worse sleep quality and shorter sleep duration [ 9 , 10 ]. There is increasing evidence that there is a bi-directional relationship between AD pathology, especially amyloid-β plaque accumulation, and poor sleep[ 11 ]. Additional sleep disturbances in AD include daytime hypersomnia, delayed circadian phase, sundowning, and adverse effects of dementia medications such as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors [ 12 ]. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), a primary sleep disorder, is particularly common in AD[ 13 , 14 ].

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson's disease (PD) with dementia (PDD) are pathologically similar and can be grouped together as Lewy Body Disease (LBD). LBD has the highest prevalence of sleep and circadian disturbances of any dementia, affecting approximately 90% of patients [ 15 ]. Insomnia is the most common sleep disturbance in LBD, a combination of prolonged sleep latency, increased sleep fragmentation, nightmares, and early-morning awakenings [ 16 ]. Daytime hypersomnia, including “sleep attacks,” is also common (~50% prevalence) and contributes to worse quality of life and safety risks in LBD[ 17 , 18 ]. Hypersomnia may be related to loss of orexinergic neurons[ 19 ] However, there are no studies correlating orexin (hypocretin) levels with hypersomnia severity in LBD. Hallucinations, particularly visual hallucinations in the evening or night, may contribute to sleep problems in LBD. In terms of primary sleep disorders, REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), a parasomnia characterized by potentially violent or injurious dream enactment behavior, is common in LBD and is a supportive diagnostic criterion for DLB. In fact, the majority of patients with RBD in “idiopathic” form without dementia develop LBD eventually[ 20 ]. Another primary sleep disorder associated with PD is restless legs syndrome (RLS), with a prevalence of approximately 20%[ 21 ].

Vascular dementia (VD), the second leading cause of dementia, is commonly associated with OSA. In the acute post-stroke period, there is a high prevalence of central apneas, which typically resolve[ 22 ]. Otherwise, due to the wide range of vascular disease (localization in the brain, micro- versus macro-vascular disease, and co-occurrence with other neurodegenerative pathology), there are no other characteristic associations with specific sleep disorders or symptoms.

There is a similar prevalence of sleep disorders in frontotemporal dementia (FTD) as in AD, but they differ in their manifestation[ 23 ]. The activity rhythm in FTD is more fragmented, and there can be circadian advance or delay[ 24 ].

In addition to the sleep and circadian disturbances primarily associated with various dementias, there are additional factors that may worsen symptoms or complicate treatment. Co-morbidities that cause pain or discomfort, or psychiatric conditions such as depression[ 15 ], worsen nighttime insomnia. Medications for the underlying dementia as well as medications for co-morbid conditions ( e.g. β2 agonist inhalers for pulmonary disease, anti-hypertensive medications) may contribute to sleep disturbance. Sleep hygiene, which includes the regularity and timing of sleep, napping, bedtime ritual, daytime activity, light and nocturnal noise (especially in nursing homes [ 25 ]), may be poor in dementia and therefore exacerbate sleep-wake problems[ 8 ]. Due to the complex inter-relationships between dementia pathophysiology, dementia effect on sleep hygiene, co-morbid primary sleep disorders, medication effects, and other factors, a comprehensive approach is necessary for diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders in dementia. ( Table 1 )

Current existing evidence and expert guidelines on the evaluation and treatment of sleep disorders in dementia are summarized. The approach should proceed in the listed order, starting with “Clinical Assessments,” and proceeding downward only if symptoms persist. “Benefits” listed for sleep treatments include only RCT's and meta-analyses.

MMT = Multi-modality treatment

RCT = Randomized controlled trial

RLS = Restless legs syndrome

NBBRA = Non-benzodiazepine benzodiazepine receptor agonists

BLT = Bright light therapy

Assessment of sleep and circadian disturbances in dementia begins with a complete history. Since demented people may not recall symptoms accurately, collateral history from caregivers is essential. The clinical history should assess for symptoms of primary sleep disorders, such as snoring, hypersomnia, witnessed apneas, parasomnias, restless legs, and leg movements during sleep. The timing and regularity of nighttime sleep and daytime naps (intentional and inadvertent) are important to ascertain. In addition to these clinical features typically queried during a sleep evaluation, individuals with dementia should be specifically asked about sundowning, hallucinations, sleep attacks, injurious parasomnias, and nighttime wandering. If the cause of dementia is known, the history should query for sleep-wake problems characteristic of the underlying disease. For example, in someone with Parkinson's Disease, a detailed temporal relationship between dopaminergic medication dosing and RLS symptoms should be obtained. In all cases, the overall burden of sleep disturbances on both patient and caregiver should be taken into account.

Contributory factors should be assessed, including 1) depression and anxiety; 2) co-morbidities causing pain or discomfort; 3) co-morbidities that cause awakenings ( e.g. prostatic hypertrophy causing frequent nocturia); 4) medications including supplements and over-the-counter medications; 5) current and prior alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, and other substance use; 6) living and sleeping arrangements; 7) degree, frequency, and regularity of physical activity; 8) social and occupational activity; 9) timing and regularity of meals; 10) light and noise exposure during daytime and nighttime.

Scales typically used for sleep evaluation, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) [ 26 ] or Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [ 27 ] have not been validated specifically for use in dementia, and, caregivers may complete questionnaires for patients. Therefore, typical normal/abnormal cutoffs may not be applicable. However, these and other scales are still useful for following individual trends over time. Additionally, dementia-specific scales may be helpful. Examples include the Sleep Disturbance Inventory (SDI), which was developed to assess caregiver burden due to sleep disturbance in AD [ 28 ], and the Behavior Pathology In Alzheimer's Disease Rating Scale (BEHAVE-AD). In LBD, the Parkinson's Disease Sleep Scale and the SCOPA-sleep scale may be helpful[ 29 ].

Objective data about circadian activity patterns and overnight sleep are helpful for diagnosing sleep disorders and assessing response to treatment. Sleep logs alone may not be accurate in individuals with dementia. Actigraphy, using non-invasive wearable motion sensors, is helpful for assessing suspected circadian disorders. Furthermore, validated sleep-scoring algorithms are available to analyze actigraphy data, to calculate objective measurements of nocturnal sleep such as total sleep time and sleep efficiency. The standard practice committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) has recommended actigraphy and sleep logs to be routinely used to assess for irregular sleep wake rhythms in dementia[ 30 ].

If there are symptoms of a primary sleep disorder such as OSA, periodic limb movement disorder, or RBD, polysomnography (PSG) is the gold standard for diagnosis. If possible, a caregiver should stay in the sleep lab to assist with PSG, since a strange environment and numerous sensors may cause confusion. Ambulatory studies for OSA can be done in the patient's usual sleeping environment, however patients with dementia may have difficulty using the home recording devices. Additionally, ambulatory studies are less sensitive for mild OSA compared to PSG[ 31 ].

Approach to treatment

The treatment approach to sleep problems in dementia is similar to that in the general population, but with additional attention paid to avoid exacerbating cognitive dysfunction, reducing injury risk, and reducing caregiver burden. First, any underlying primary sleep disorders should be assessed for and treated. Second, any co-morbid mood and anxiety disorders should be addressed. Third, pain, nocturia, or other comorbid conditions that interfere with sleep should be addressed to the best extent possible, and medications that affect sleep (including those for the underlying dementing disease) should be adjusted to optimize sleep-wake functioning. For example, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors ( e.g. donepezil and rivastigmine) and MAO-B inhibitors ( e.g. selegiline) may cause insomnia, and dosing should be moved earlier in the daytime. Additionally, dopaminergic medications for Parkinsonism should be adjusted to minimize bothersome nighttime motor symptoms that may awaken the patient, as well as minimize sedating effects during the daytime (especially dopamine agonists). Management of a patient's co-morbid conditions and medications requires close co-ordination with the patient, the caregiver, and the patient's other physicians and other healthcare professionals, and is usually the most time-consuming aspect of care of demented patients with sleep disturbances. Lastly, if sleep-wake problems persist, non-pharmacological treatments are preferred, due to the risk of sedation, cognitive symptoms, falls, injuries, and medication interactions with pharmacological treatments. In recalcitrant cases, pharmacological treatments can also be added cautiously. Ideally, objective measurements such as actigraphy and subjective measurements of patient and caregiver symptoms should be obtained serially to follow response to treatment.

Treatment of primary sleep disorders