Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

Battle of Tours: Its Significance and Historical Implications

Celeste Neill

01 oct 2018.

On 10 October 732 Frankish General Charles Martel crushed an invading Muslim army at Tours in France , decisively halting the Islamic advance into Europe.

The Islamic advance

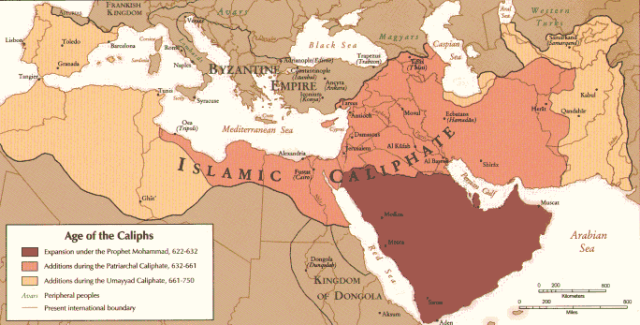

After the death of the Prophet Muhammed in 632 AD the speed of the spread of Islam was extraordinary, and by 711 Islamic armies were poised to invade Spain from North Africa. Defeating the Visigothic kingdom of Spain was a prelude to increasing raids into Gaul, or modern France, and in 725 Islamic armies reached as far north as the Vosgues mountains near the modern border with Germany .

Opposing them was the Merovingian Frankish kingdom , perhaps the foremost power in western Europe. However given the seemingly unstoppable nature of the Islamic advance into the lands of the old Roman Empire further Christian defeats seemed almost inevitable.

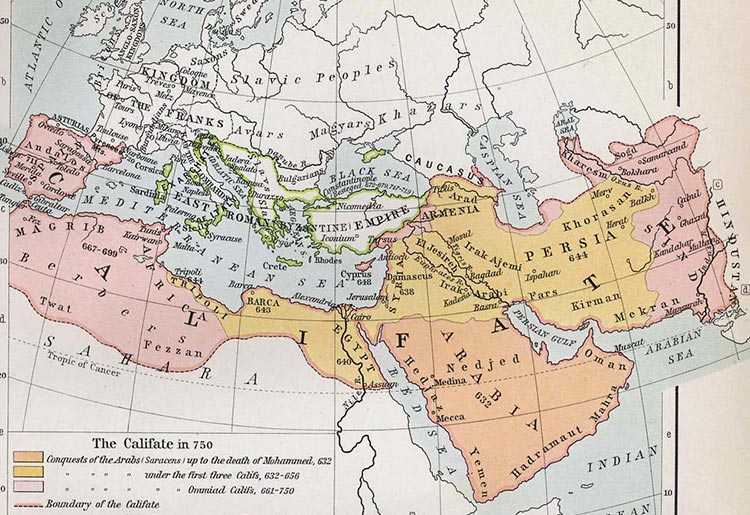

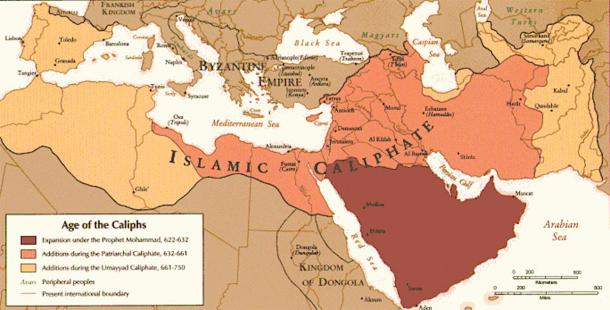

Map of the Umayyad Caliphate in 750 AD. Image credit: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In 731 Abd al-Rahman, a Muslim warlord north of the Pyrenees who answered to his distant Sultan in Damascus, received reinforcements from North Africa. The Muslims were preparing for a major campaign into Gaul.

The campaign commenced with an invasion of the southern kingdom of Aquitaine, and after defeating the Aquitanians in battle Abd al-Rahman’s army burned their capital of Bordeaux in June 732. The defeated Aquitanian ruler Eudes fled north to the Frankish kingdom with the remnants of his forces in order to plead for help from a fellow Christian, but old enemy: Charles Martel .

Martel’s name meant “the hammer” and he had already many successful campaigns in the name of his lord Thierry IV, mainly against other Christians such as the unfortunate Eudes, who he met somewhere near Paris . Following this meeting Martel ordered a ban , or general summons, as he prepared the Franks for war.

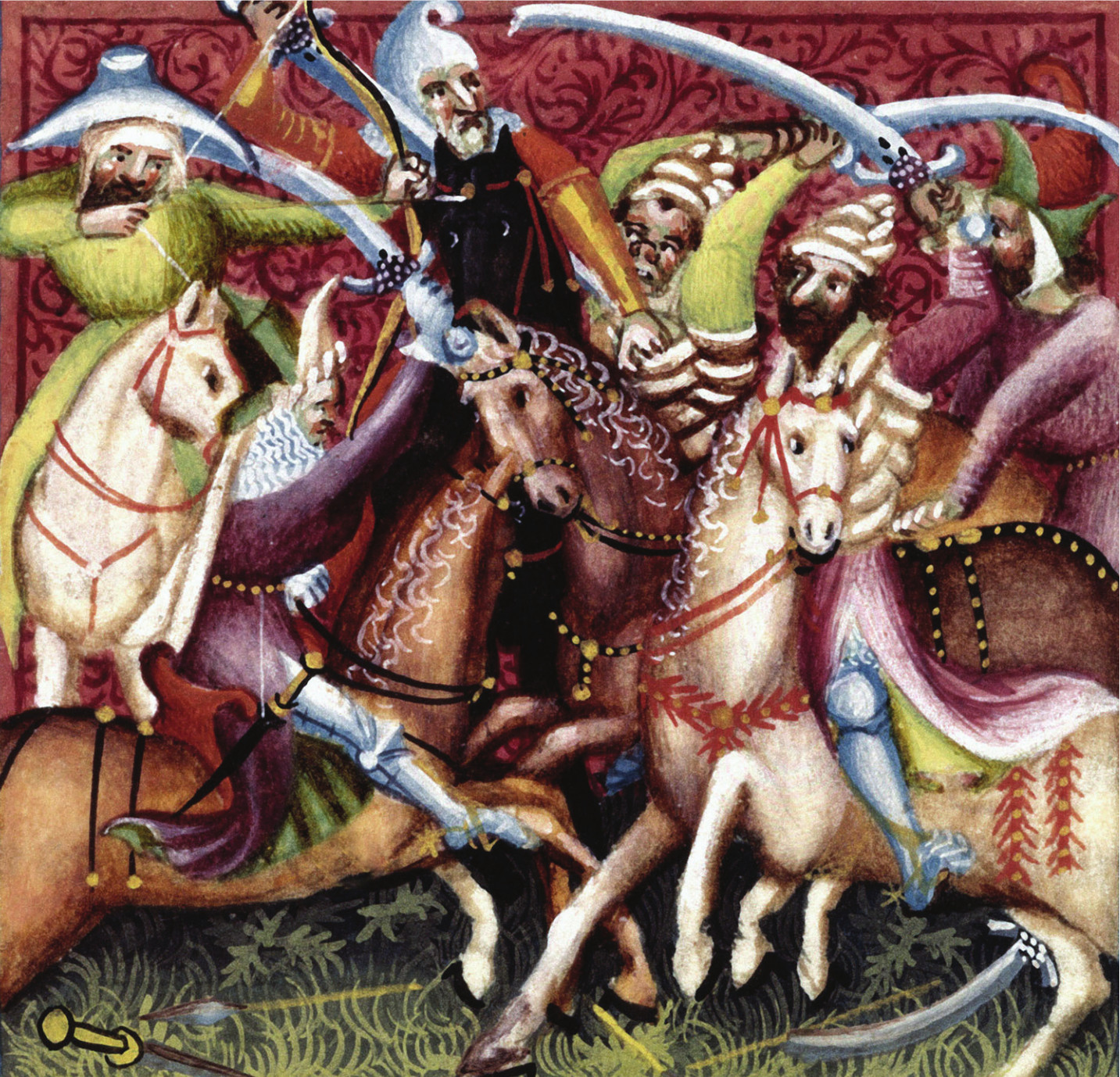

14th century depiction of Charles Martel (middle). Image credit: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Battle of Tours

Once his army had gathered, he marched to the fortified city of Tours, on the border with Aquitaine, to await the Muslim advance. After three months of pillaging Aquitaine, al-Rahman obliged.

His army outnumbered that of Martel but the Frank had a solid core of experienced armoured heavy infantry who he could rely upon to withstand a Muslim cavalry charge.

With both armies unwilling to enter the bloody business of a Medieval battle but the Muslims desperate to pillage the rich cathedral outside the walls of Tours, an uneasy standoff prevailed for seven days before the battle finally began. With winter coming al-Rahman knew that he had to attack.

The battle began with thundering cavalry charges from Rahman’s army but, unusually for a Medieval battle, Martel’s excellent infantry weathered the onslaught and retained their formation. Meanwhile, Prince Eudes’ Aquitanian cavalry used superior local knowledge to outflank the Muslim armies and attack their camp from the rear.

Christian sources then claim that this caused many Muslim soldiers to panic and attempt to flee to save their loot from the campaign. This trickle became a full retreat, and the sources of both sides confirm that al-Rahman died fighting bravely whilst trying to rally his men in the fortified camp.

The battle then ceased for the night, but with much of the Muslim army still at large Martel was cautious about a possible feigned retreat to lure him out into being smashed by the Islamic cavalry. However, searching the hastily abandoned camp and surrounding area revealed that the Muslims had fled south with their loot. The Franks had won.

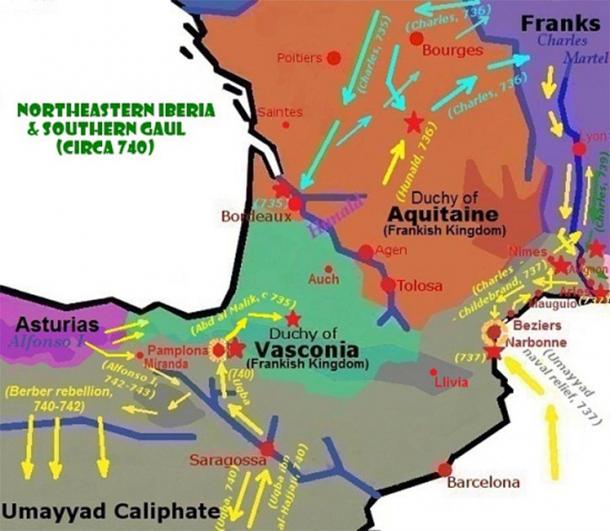

Despite the deaths of al-Rahman and an estimated 25,000 others at Tours, this war was not over. A second equally dangerous raid into Gaul in 735 took four years to repulse, and the reconquest of Christian territories beyond the Pyrenees would not begin until the reign of Martel’s celebrated grandson Charlemagne.

Martel would later found the famous Carolingian dynasty in Frankia, which would one day extend to most of western Europe and spread Christianity into the east.

Tours was a hugely important moment in the history of Europe, for though the battle of itself was perhaps not as seismic as some have claimed, it stemmed the tide of Islamic advance and showed the European heirs of Rome that these foreign invaders could be defeated.

You May Also Like

Mac and Cheese in 1736? The Stories of Kensington Palace’s Servants

The Peasants’ Revolt: Rise of the Rebels

10 Myths About Winston Churchill

Medusa: What Was a Gorgon?

10 Facts About the Battle of Shrewsbury

5 of Our Top Podcasts About the Norman Conquest of 1066

How Did 3 People Seemingly Escape From Alcatraz?

5 of Our Top Documentaries About the Norman Conquest of 1066

1848: The Year of Revolutions

What Prompted the Boston Tea Party?

15 Quotes by Nelson Mandela

The History of Advent

Charles Martel and the Battle of Tours and Poitiers

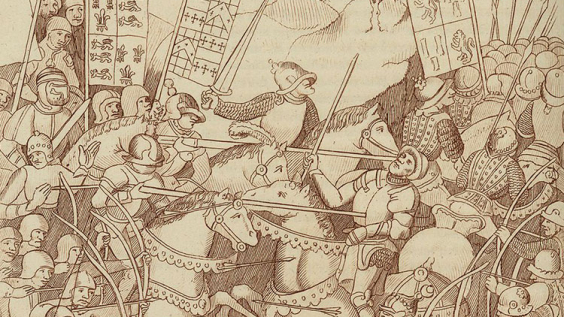

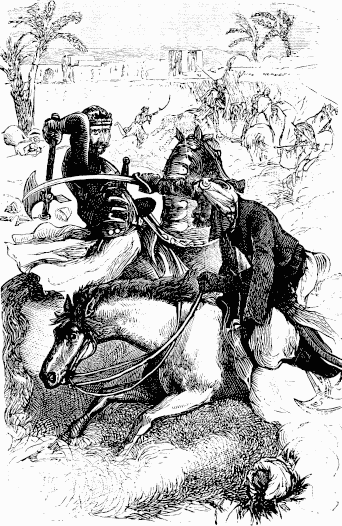

The battle of Tour and Poitiers, painting by Carl von Steuben, 1837.

On October 25, 732 AD, the Battle of Tours and Poitiers between the united Frankish and Burgundian forces under Austrasian Mayor of the Palace Charles Martel , against an army of the Umayyad Caliphate led by Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi , Governor-General of al-Andalus, ended the Islamic expansion era in Europe. It is argued among historians that Charles Martel’s victory was one of the most important events in European or even world history.

The Fate of Western Civilization at Stake

Again, probably the Fate of Western Civilization was at stake. You might remember our post about the legendary battle in the Catalaunian Plains , where Attila the Hun was defeated by a Western Roman army, preventing the Huns from conquering Europe and thus, changing our entire history. [ 6 ] Likewise, the rise of the Islam had become a threat when Islamic armies conquered Northern Africa spreading the new religion westward and finally traversed the Strait of Gibraltar led by Tariq ibn-Ziyad , entering European soil in southern Spain. The Umayyad Caliphate was the second of the four major Islamic caliphates established after the death of Muhammad and for 21 years they continued their conquest of the Visigothic Christian Kingdoms of the Iberian peninsula from 711 AD on until they reached the Frankish territories of Gaul, today’s southern France. According to one unidentified Arab chronicler, “ That army went through all places like a desolating storm “sacking and capturing the city of Bordeaux, and then defeating the army of Duke Odo of Aquitaine at the Battle of the River Garonne — where the western chroniclers state, ‘God alone knows the number of the slain’— and Duke Odo fled to Charles Martel, seeking help.”

The Frankish Realm under Charles Martel

The Frankish realm under Charles Martel was the foremost military power of Western Europe. Charles was the illegitimate son of Pepin, the powerful mayor of the palace of Austrasia and effective ruler of the Frankish kingdom. During most of his tenure in office as commander-in-chief of the Franks, the kingdom consisted of what is the north and the east of France, most of Western Germany, and the Low Countries (Luxembourg, Belgium and the Netherlands). The Frankish realm had begun to progress towards becoming the first real imperial power in Western Europe since the fall of Rome .[ 8 ] Meanwhile the Umayyad army utterly devastated southern Gaul. Their own histories saying they “ faithful pierced through the mountains, trampled over rough and level ground, plundered far into the country of the Franks, and smote all with the sword, insomuch that when Eudo (Duke Udo of Aquitaine) came to battle with them at the River Garonne, he fled .”

Charles Martel (718-748) from “ Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum ” (1553)

The Umayyad Advance in Europe

The Umayyad advance force was proceeding north towards the River Loire having outpaced their supply train and a large part of their army. Essentially, having easily destroyed all resistance in that part of Gaul, the invading army had split off into several raiding parties, while the main body advanced more slowly. The invading force went on to devastate southern Gaul with a possible motive to plunder the riches of the Abbey of Saint Martin of Tours, the most prestigious and holiest shrine in Western Europe at the time. Upon hearing this, Austrasia’s Mayor of the Palace, Charles Martel, collected his army and marched south, avoiding the old Roman roads and hoping to take the Umayyad forces by surprise. Because he intended to use a phalanx formation of heavy infantry, it was essential for him to choose the battlefield. His plan — to find a high wooded plain, form his men and force the Umayyad army to come to him — depended on the element of surprise.

The invading Muslims rushed forward, relying on the slashing tactics and overwhelming number of horsemen that had brought them victories in the past. However, the Frank army of foot soldiers armed only with swords, shields, axes, javelins, and daggers, was very well trained. Despite the effectiveness of the Umayyad army in previous battles, the terrain caused them a disadvantage. Their strength lay within their cavalry, armed with large swords and lances. But along with their baggage mules, they were limited in their mobility. The Frank army displayed great ardency and held its ground against a mounted attack. Actually, the length of the decisive battle near the city of Tours is undetermined. While Arab sources claim that it was two days, Christian sources hold that the fighting lasted for even seven days. In the end, the battle was decided when the Franks captured and killed the Umayyad leader Abd-er Rahman, which caused the muslim army to withdraw peacefully overnight, never to return again.

History is always written by the Winning Party

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Medieval Sourcebook: Arabs, Franks, and the Battle of Tours, 732: Three Accounts

- [2] The Battle of Tour

- [3] The Battle of Tours Revisited at De Re Militari

- [4] The Battle of Tours at History of Islam

- [5] Poke’s edition of Creasy’s 15 Most Important Battles Ever Fought According to Edward Shepherd Creasy Chapter VII. The Battle Of Tours, A.D. 732.

- [6] The Fate of Western Civilization at Stake on the Catalaunian Plains , SciHi Blog

- [7] Edward Gibbon and the Science of History , SciHi Blog

- [8] The End of the Roman Empire , SciHi Blog

- [9] Charlemagne and the Birth of Europe , SciHi Blog

- [10] Charles Martel at Wikidata

- [11] Paul Freedman, 19. The Early Middle Ages, 284–1000: Charlemagne , The Early Middle Ages, 284–1000 (HIST 210), YaleCourses @ youtube

- [12] Henny, Carlisle. “Charles “the Hammer” Martel King of the Franks” . genealogieonline .

- [13] Arabs, Franks, and the Battle of Tours, 732: Three Accounts from the Internet Medieval Sourcebook

- [14] Eggenberger, David, ed. (1985). “Acroinum (Moslem-Byzantine Wars), 739 & Tours (Moslem Invasion of France), 732” . An Encyclopedia of Battles: Accounts of Over 1,560 Battles from 1479 B.C. to the Present . Courier (Dover Publications). pp. 3, 441–442

- [15] Timeline of 8th Century Rulers in Europe via DBpedia and Wikidata

Harald Sack

Related posts, henry the navigator and the age of discoveries, henry iv and his walk to canossa, austerlitz – the battle of the three emperors, the battle of lützen and the death of the swedish king gustavus adolphus, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Further Projects

- February (28)

- January (30)

- December (30)

- November (29)

- October (31)

- September (30)

- August (30)

- January (31)

- December (31)

- November (30)

- August (31)

- February (29)

- February (19)

- January (18)

- October (29)

- September (29)

- February (5)

- January (5)

- December (14)

- November (9)

- October (13)

- September (6)

- August (13)

- December (3)

- November (5)

- October (1)

- September (3)

- November (2)

- September (2)

- Entries RSS

- Comments RSS

- WordPress.org

Legal Notice

- Privacy Statement

Biography of Charles Martel, Frankish Military Leader and Ruler

adoc-photos / Corbis Historical / Getty Images

- Key Figures

- Battles & Wars

- Arms & Weapons

- Naval Battles & Warships

- Aerial Battles & Aircraft

- French Revolution

- Vietnam War

- World War I

- World War II

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/khickman-5b6c7044c9e77c005075339c.jpg)

- M.A., History, University of Delaware

- M.S., Information and Library Science, Drexel University

- B.A., History and Political Science, Pennsylvania State University

Charles Martel (August 23, 686 CE–October 22, 741 CE) was the leader of the Frankish army and, effectively, the ruler of the Frankish kingdom, or Francia (present-day Germany and France). He is known for winning the Battle of Tours in 732 CE and turning back the Muslim invasions of Europe. He is the grandfather of Charlemagne, the first Holy Roman Emperor.

Fast Facts: Charles Martel

- Known For : Ruler of the Frankish kingdom, known for winning the Battle of Tours and turning back the Muslim invasions of Europe

- Also Known As : Carolus Martellus, Karl Martell, "Martel" (or "the Hammer")

- Born : August 23, 686 CE

- Parents : Pippin the Middle and Alpaida

- Died : October 22, 741 CE

- Spouse(s) : Rotrude of Treves, Swanhild; mistress, Ruodhaid

- Children : Hiltrud, Carloman, Landrade, Auda, Pippin the Younger, Grifo, Bernard, Hieronymus, Remigius, and Ian

Charles Martel (August 23, 686–October 22, 741) was the son of Pippin the Middle and his second wife, Alpaida. Pippin was the mayor of the palace to the King of the Franks and essentially ruled Francia (France and Germany today) in his place. Shortly before Pippin's death in 714, his first wife, Plectrude, convinced him to disinherit his other children in favor of his 8-year-old grandson Theudoald. This move angered the Frankish nobility and, following Pippin's death, Plectrude tried to prevent Charles from becoming a rallying point for their discontent and imprisoned the 28-year-old in Cologne.

Rise to Power and Reign

By the end of 715, Charles had escaped from captivity and found support among the Austrasians who comprised one of the Frankish kingdoms. Over the next three years, Charles conducted a civil war against King Chilperic and the Mayor of the Palace of Neustria, Ragenfrid. Charles suffered a setback at Cologne (716) before winning key victories at Ambleve (716) and Vincy (717).

After taking time to secure his borders, Charles won a decisive victory at Soissons over Chilperic and the Duke of Aquitaine, Odo the Great, in 718. Triumphant, Charles was able to gain recognition for his titles as mayor of the palace and duke and prince of the Franks.

Over the next five years, he consolidated power as well as conquered Bavaria and Alemmania before defeating the Saxons . With the Frankish lands secured, Charles next began to prepare for an anticipated attack from the Muslim Umayyads to the south.

Charles married Rotrude of Treves with whom he had five children before her death in 724. These were Hiltrud, Carloman, Landrade, Auda, and Pippin the Younger. Following Rotrude's death, Charles married Swanhild, with whom he had a son Grifo.

In addition to his two wives, Charles had an ongoing affair with his mistress Ruodhaid. Their relationship produced four children, Bernard, Hieronymus, Remigius, and Ian.

Facing the Umayyads

In 721, the Muslim Umayyads first came north and were defeated by Odo at the Battle of Toulouse. Having assessed the situation in Iberia and the Umayyad attack on Aquitaine, Charles came to believe that a professional army, rather than raw conscripts, was needed to defend the realm from invasion.

To raise the money necessary to build and train an army that could withstand the Muslim horsemen, Charles began seizing Church lands, earning the ire of the religious community. In 732, the Umayyads moved north again, led by Emir Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi. Commanding approximately 80,000 men, he plundered Aquitaine.

As Abdul Rahman sacked Aquitaine, Odo fled north to seek aid from Charles. This was granted in exchange for Odo recognizing Charles as his overlord. Mobilizing his army, Charles moved to intercept the Umayyads.

Battle of Tours

In order to avoid detection and allow Charles to select the battlefield, the approximately 30,000 Frankish troops moved over secondary roads toward the town of Tours. For the battle, Charles selected a high, wooded plain which would force the Umayyad cavalry to charge uphill. Forming a large square, his men surprised Abdul Rahman, forcing the Umayyad emir to pause for a week to consider his options.

On the seventh day, after gathering all of his forces, Abdul Rahman attacked with his Berber and Arab cavalry. In one of the few instances where medieval infantry stood up to cavalry, Charles' troops defeated repeated Umayyad attacks .

As the battle raged, the Umayyads finally broke through the Frankish lines and attempted to kill Charles. He was promptly surrounded by his personal guard, who repulsed the attack. As this was occurring, scouts that Charles had sent out earlier were infiltrating the Umayyad camp and freeing prisoners.

Believing that the plunder of the campaign was being stolen, a large part of the Umayyad army broke off the battle and raced to protect their camp. While attempting to stop the apparent retreat, Abdul Rahman was surrounded and killed by Frankish troops.

Briefly pursued by the Franks, the Umayyad withdrawal turned into a full retreat. Charles reformed his troops expecting another attack, but to his surprise, it never came as the Umayyads continued their retreat all the way to Iberia. Charles' victory at the Battle of Tours was later credited for saving Western Europe from the Muslim invasions and was a turning point in European history.

Expanding the Empire

After spending the next three years securing his eastern borders in Bavaria and Alemannia, Charles moved south to fend off an Umayyad naval invasion in Provence. In 736, he led his forces in reclaiming Montfrin, Avignon, Arles, and Aix-en-Provence. These campaigns marked the first time he integrated heavy cavalry with stirrups into his formations.

Though he won a string of victories, Charles elected not to attack Narbonne due to the strength of its defenses and the casualties that would be incurred during any assault. As the campaigning concluded, King Theuderic IV died. Though he had the power to appoint a new King of the Franks, Charles did not do so and left the throne vacant rather than claim it for himself.

From 737 until his death in 741, Charles focused on the administration of his realm and expanding his influence. This included subduing Burgundy in 739. These years also saw Charles lay the groundwork for his heirs' succession following his death.

Charles Martel died on October 22, 741. His lands were divided between his sons Carloman and Pippin III. The latter would father the next great Carolingian leader, Charlemagne . Charles' remains were interred at the Basilica of St. Denis near Paris.

Charles Martel reunited and ruled the entire Frankish realm. His victory at Tours is credited with turning back the Muslim invasion of Europe, a major turning point in European history. Martel was the grandfather of Charlemagne, who became the first Roman Emperor since the fall of the Roman Empire.

- Fouracre, Paul. The Age of Charles Martel. Routledge, 2000.

- Johnson, Diana M. Pepin's Bastard: The Story of Charles Martel. Superior Book Publishing Co., 1999

- Mckitterick, Rosamond. Charlemagne: The Formation of a European Identity. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Muslim Invasions of Western Europe: The 732 Battle of Tours

- The Rulers of France: From 840 to Present

- Charlemagne Picture Gallery

- Charlemagne: King of the Franks and Lombards

- What Was the Umayyad Caliphate?

- Key Events in French History

- Timeline of Charlemagne's Life and Reign

- Charles "the Bald" II, Western Emperor

- Charlemagne: Battle of Roncevaux Pass

- What Made Charlemagne so Great?

- Great Northern War: Battle of Narva

- Biography of Judith of France

- The Troubled Succession of Charles V: Spain 1516-1522

- Brunhilde: Queen of Austrasia

- Saint Clotilde: Frankish Queen and Saint

The Battle of Tours - A Decisive Fight for Europe’s Future

- Read Later

The early medieval world of our ancestors was built upon struggles and decisive battles. The emerging nations united the broken tribes, expanded their borders, conquered their enemies, and often enough - fended off invaders. But rare are the battles that really left a long lasting impact that echoed through the generations that followed.

Rare are such conflicts that changed the history of the world with their importance and decided the future of us all for centuries to come. And one of those rare, world-changing battles is the Battle of Tours - fought in 732 AD between the Christian Frankish forces and the invading Muslim Umayyad Caliphate.

This fierce and destructive conflict, that shaped the future of Europe and echoed through time, was a great gamble, fought against all odds. But it remains as one of the biggest lessons of Europe’s past, and today we are going in detail about that fated day in 732.

A triumphant Charles Martel (mounted) faces Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi (right) at the Battle of Tours. Source: Bender235 / Public Domain .

The Prelude to the Battle of Tours

Around the very beginning of the 8 th century, in the year 700 AD, the Muslim Umayyad Caliphate was rapidly spreading its empire around the world. It was the second of the four great caliphates that emerged after the death of Muhammad and was one of the largest empires of the world at the time.

After conquering the lands of North Africa, they saw mainland Europe as the next prey for their conquests. From the shores of North Africa, they had a clear passage - in the form of the Gibraltar Strait. This would allow their forces to cross over onto the Iberian Peninsula , from which they would spread further inland.

At the time, Iberia was under the control of the Visigothic Kingdom, a centralized state under the rule of King Roderic. Nonetheless, the Umayyads crossed the strait in the year 711 AD, under the leadership of one Tariq ibn Ziyad, and soon after clashed with the Visigothic army in the Battle of Guadalete, in the same year, in the very south of Iberia.

The "Age of the Caliphs", shows the Umayyad dominance stretched from the Middle East to the Iberian Peninsula, including the port of Narbonne, c. 720. (McZusatz / Public Domain )

At the time of the Umayyad invasion, King Roderic was far in the north, attempting to fight a Basque rebellion. This unfortunately placed him in a bad situation, as he was forced to a long march south, to face this much bigger enemy. In the end, the Visigoths were defeated in the face of the overwhelming Muslim cavalry.

In the battle, King Roderic and most of the nobles of his kingdom lost their lives, which allowed the Umayyads to effectively conquer Iberia, step by step. This they managed in just a little under seven years. And once Iberia was theirs, Frankish Gaul was just a step away.

The only thing that divided the Umayyads from their prey - the Frankish Kingdom - were the Pyrenees Mountains . This was a fitting natural barrier - but it was in no way untraversable. In time, the Umayyads began crossing over and making incursions into the very south of Gaul. By 720 they conquered the southern province of Septimania.

In the following year, they focused on the large city to the immediate west, Toulouse, which they besieged. This siege was brought to an end by the prominent Frankish Duke Odo - who managed to overwhelm the Umayyad forces outside Toulouse and defeat them. Nonetheless, large numbers of Umayyads kept crossing over the Pyrenees and laying waste to the southern provinces of Gaul.

The Duchy of Aquitaine laid in the south and faced the brunt of this invasion. Its largest towns, Bordeaux and Toulouse were ravaged, and in no time the invaders reached even the Duchy of Burgundy to its north.

But it wasn’t until 732 that the Umayyad Caliphate truly amassed its forces with proper conquering intentions and adequate strength. The man that was at the head of this force was Abdul Rahman al Ghafiqi, the then-Governor General of Muslim Iberia. He led his forces across the Pyrenees once again and plundered the land and all the cities he came across.

- Unique Iberian Male DNA was Practically Wiped Out by Immigrant Farmers 4500 Years Ago [New Study]

- Raiders of Hispania: Unravelling the Secrets of the Suebi

- Was the First Islamic Siege of Constantinople (674 – 678 AD) a Historical Misnomer?

Abdul Rahman al Ghafiqi led his troops over the Pyrenees Mountains toward the Battle of Tours. (Jean-Christophe BENOIST / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

The Umayyads greatly coveted riches, and their main activity during this conquest was plunder. After completely ransacking Bordeaux once again, the Umayyad forces faced Duke Odo once more. Odo led his army in an attempt to stop the invasion as he did a few years before.

But this time, he was terribly outnumbered and outmaneuvered, and his forces were crushed. Realizing the gravity of the situation, and that his own lands of Aquitaine were overrun, Odo fled to the north seeking assistance from the de-facto ruler of the Frankish Kingdom - Charles Martel.

Before the Umayyad invasion Odo and Charles were enemies. Charles sought to expand his lordship over Aquitaine and Odo saw the Franks as invaders. But with this new and much greater threat, Odo had no choice but to seek help from the Franks. Charles Martel agreed to join up with him, but the “price” was Odo’s acceptance of Frankish overlordship. Odo agreed.

The Hammer Enters the Fray

Charles Martel was a seasoned ruler and a battle hardened veteran. His troops were equally experienced having been in constant clashes along the eastern borders of their kingdom, fighting neighboring tribes.

Charles also understood how important the situation was and began gathering his levies from all over the north. And he would show his shrewdness as a battle commander, when he carefully understood the intentions of his enemy.

Meanwhile, the Umayyad forces moved slowly across the Frankish lands, their forces spread into war parties that ravaged the countryside and amassed an enormous amount of plunder. This “greedy” focus on war booty would greatly influence their future undoing. They had to take their time, as they greatly depended on the crop season for their food source.

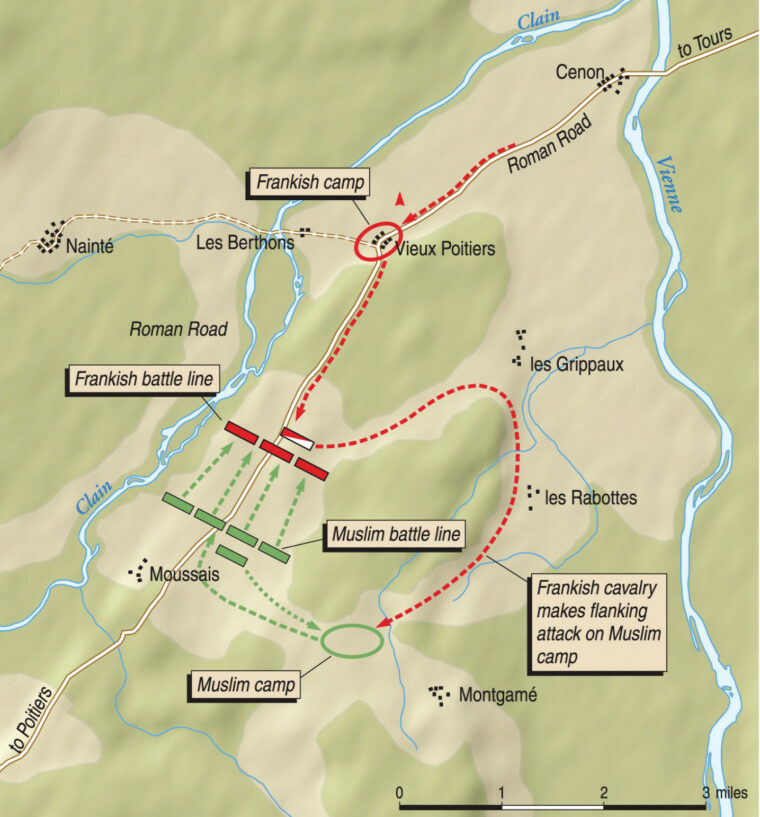

But their destination was clear to Charles Martel. It was the rich city of Tours - prominent and wealthy, filled with abbeys of great importance. Thus, Charles placed his Frankish forces directly on the path of the coming Umayyads. He situated his army roughly in between the city of Tours and the ravaged town of Poitiers further south.

The Franks were placed close to the confluence of rivers Clain and Vienne, on a slightly elevated and forested hill. Charles Martel deliberately and shrewdly chose this position. First of all - he was outnumbered and knew it.

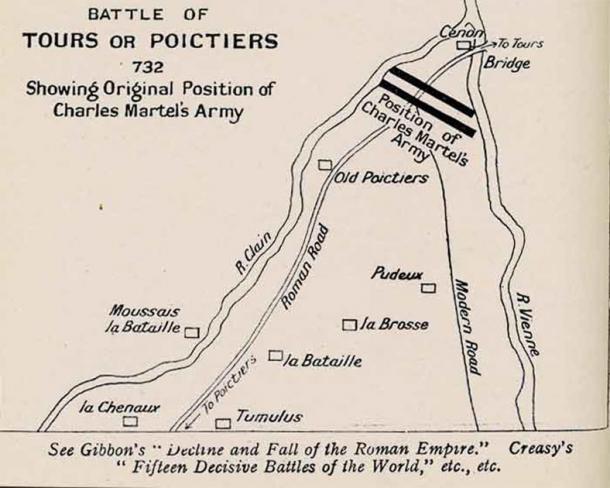

Map of the Battle of Tours with the position of Charles Martel's army. (Evzen M / Public Domain )

Thus he chose the cover of the forest to displace his troops and hide his number in hope to not reveal his disadvantage. Secondly - he chose a place where the Umayyads would have to enter into battle, as the only crossing over the rivers was behind the Frankish forces. Thirdly - the forest protected his troops - mainly the second lines - from the full brunt of a cavalry charge, and somewhat protected his sides from flanking attacks.

When the Umayyads approached the assembled Christian army, their leader Abdul Rahman al Ghafiqi - also a seasoned commander - knew that Charles Martel took the upper hand, by choosing his preferred place of battle. Even so, al Ghafiqi trusted in his strength and deployed for battle.

One thing he must have noticed is the difference in the troops - Umayyads relied heavily on cavalry, while the Franks were mostly footmen. But he failed to take several things into account.

The Muslim cavalry was lightly armored - they preferred to adorn themselves with chainmail and not much else in terms of armor. Riches and trinkets were much more to their liking.

They also rode willful Arabic horses, which were difficult to break in, and thus not the truly perfect cavalry mounts. Some historians also mention that this cavalry was in large part armed with spears - which were unseasoned and would break on first impact.

The Muslim cavalry rode willful Arabic horses during the Battle of Tours. (Trzęsacz / Public Domain )

On the other hand, the Frankish infantry was thoroughly seasoned. Most of the army were veterans, with only a small part of fresh recruits reserved in the second lines. They were well armored for the time, and well-armed as well. They stood packed in tight lines and ready for a cavalry charge.

But the battle did not begin immediately. The opposing forces “tested the waters”, with sporadic small skirmishes going on for seven days.

This was in truth a deliberate stalling from al Ghafiqi, who waited for his whole army to assemble fully. In the end, with the Umayyads fearing the approaching winter, they commenced battle on the seventh day - on the 10th of October 732 AD.

The Umayyad Wave That Broke On the Frankish Rock

The Umayyad commander, al Ghafiqi, heavily relied on his cavalry, even though he didn’t possess much knowledge about the assembled enemy. He sent waves of cavalry charges in an attempt to break the Frankish lines - but this did not happen. The seasoned Franks were tightly packed - shoulder to shoulder - and withstood all assaults.

The rare combination of slight elevation, good arms and armor, and tree cover allowed them to hold their ground - when it was almost impossible for infantry to hold against cavalry in medieval times. Even when some small parts of the line faltered and broke under the cavalry, the fresh second lines were quick to react - sealing the gap.

Frankish knight fighting against an Umayyad horseman. (Helix84 / Public Domain )

As the battle went on in that way, Duke Odo commenced a crucial flanking operation that greatly tipped the scales in Frankish favor. He gathered a cavalry force and flanked wide - reaching the distant Muslim encampment - i.e. their rear. This was where the Umayyad tents were and all of their abundant plunder.

Odo managed to inflict great losses here, retrieve the precious plunder, free around 200 captive Franks, and draw the eye of the enemy. But what happened next was more than he hoped for. Upon realizing that their camp and their plunder were under attack, many Umayyad units from the central battlefield rushed back in a frenzy to save their loot.

This was an unprecedented situation, one that al Ghafiqi never expected. His attempts at rallying his troops were in vain, and Charles Martel - who knew exactly what he was doing - seized this opportunity.

As the Umayyad forces dissipated to retrieve the loot, he swung his forces from left, right, and center, and engaged in both pursuit and encirclement. The remaining body of the Umayyads was surrounded and suffered immense casualties.

The chief of these was al Ghafiqi himself - who fell in battle while attempting to rally his troops. Meanwhile, Duke Odo swung north again and cut off the fleeing Umayyads, inflicting great losses. In effect, the Umayyad forces fled.

- The Heroic Story of Roland: A Valiant Knight With an Unbreakable Sword

- Cataphracts: Armored Warriors and their Horses of War

- The Mighty Magyars, a Medieval Menace to the Holy Roman Empire

Charles Martel gathered his cavalry at Battle of Tours and attacked the Umayyad encampment. (Levan Ramishvili / Public Domain )

Now, Charles Martel expected a second day of battles and remained in his position, treating the wounded and re-organizing. But another day never came. The Umayyads, with their commander dead, could not successfully organize another attack or choose a fitting leader. They had suffered great losses as well.

Charles Martel feared an ambush and would not descend from the hill at any cost. Eventually, he sent out extensive reconnaissance parties to survey the Umayyad forces - but only to learn that there were none. They had gathered all the remaining plunder they could and fled during the night - extremely hastily. They had returned to Iberia.

Charles Martel won a crushing and glorious victory that cemented his reputation of a noble and capable leader. He was praised all across Europe as the savior of the Christendom and the “Hammer that Broke the Muslims”. Thus he earned his nickname - Martel - meaning Charles the Hammer.

He subsequently expanded his rule over Aquitaine and successfully isolated the invaders to the southern region of Septimania, where they remained for another 27 years and were completely unable to break through. Charles’ wealth, influence, power, and ability led to the emergence of the Carolingian dynasty , which would rise and last for centuries to follow.

Charles Martel's military campaigns in Aquitaine, Septimania, and Provence after the Battle of Tour-Poitiers (734–742). (Iñaki LLM / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Changing the Future of the World

The Europe of the early 18 th century desperately needed a capable and strong commander that would stop the Muslim Umayyad invaders dead in their tracks. And that commander was Charles Martel. He stood up to ravaging flood of conquerors and using his superior tactics, shrewdness, and reputation, he managed to win a crushing battle - against all odds. Like a beacon that kept burning throughout a storm, his Frankish warriors defied their enemy in battle. And it is this battle that changed the course of European history, and with that - the history of the World.

Top image: Medieval soldier at war. Credit: Andrey Kiselev / Adobe Stock

By Aleksa Vučković

Creasy, E. 2016. The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World . Enhanced Media.

Neiberg, M. 2003. Warfare in World History . Taylor & Francis.

Scott, J. 2011. Battle of Tours - A New Look at an Old Enemy . eBookIt.

I am a published author of over ten historical fiction novels, and I specialize in Slavic linguistics. Always pursuing my passions for writing, history and literature, I strive to deliver a thrilling and captivating read that touches upon history's most... Read More

Related Articles on Ancient-Origins

- Terms of Use

War News | Military History | Military News

Ad 732, battle of tours: charles martel the ‘hammer’ holds the line of battle.

Few Empires emerged as quickly as that of the Muslim Caliphates. Bursting out from what is now Saudi Arabia in the mid-7 th century, the Islamic Caliphate expanded outward in all directions.

Early on they won a crushing victory over the long established Byzantine Empire at the Battle of Yarmouk and swept westward across northern Africa. Eventually, they would cross the Strait of Gibraltar, defeat the Visigoths and seize Spain.

The Muslim conquests were not inherently about religion, especially seeing as the conquerors allowed freedom of religion in conquered territories, but their presence and culture was a direct threat to Western Christianity.

Similar to how the Vikings targeted churches for loot, so did the conquering Muslims. Furthermore, over time many of the people conquered by the Muslims adopted their religion.

The Muslims in Spain began threatening modern day France, by the early 8 th century.

Spain had been under the rule of the Visigoths, the descendants of the men who sacked Rome, but they were unable to put up much of a fight and the Islamic Caliphate had no setbacks until they met Odo of Aquitaine. He won a victory at the Battle of Toulouse that temporarily halted the previously unstoppable force, and is sometimes held up as being equally important as the later battle of Tours.

Though Toulouse was a setback for the Muslim conquest of France, they would still conduct raids for the next decade. While the Muslims focused on raids, Charles Martel focused on building an army to unify and strengthen the Frankish people.

Odo of Aquitaine had recently suffered defeats and pleaded to Charles for help against the invading Muslims. Charles agreed to the stipulation that Odo submit to Frankish authority. A Frankish power was growing steadily stronger under Charles, and the Caliphate had no real idea of what they would find when they decided to venture north with a stronger army.

The Franks and The Muslims under the Umayyad Caliphate would meet in northeastern France in October of 732. Charles Martel, commander of the Franks, who were largely infantry based, and likely equal in number to the Muslim army, would fight General Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi, who commanded the Umayyad army that had a large amount of cavalry.

Charles’ force was well trained and fought with the equipment and close order style that echoed the hoplite formations of the ancient Greeks. He occupied an elevated position and used the trees and rough terrain in front of his infantry to protect them from cavalry charges.

The first several days resulted in several skirmishes with no clear winner. Charles had adopted a defensive position while Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi was quite frankly (pun intended) surprised by the presence of such a large force.

Reinforcements arrived for the Muslims, but Charles had arguably better reinforcements. Many of his veterans, who had personally fought under him came in huge numbers. These professional fighting men would have been amongst the best and most experienced in all Europe. Their arrival meant that the main battle was at hand after a week of skirmishing.

The Muslims had a tried and true method of wearing down the enemy with light cavalry peppering and repeated heavy cavalry charges. With no real reason to try something different, ‘Abd-al-Raḥmân’s cavalry crashed into the Frankish formations who stood firm like “A Bulwark of Ice” according to later Muslim accounts. Frankish troops withstood the attacks and lashed out hard whenever the experienced troops saw an opportunity.

Deep into the fighting (perhaps into a second day according to some sources) The cavalry broke into a Frankish formation and towards Charles. His guard, and perhaps Charles himself, entered the fray. Several Frankish scouts were sent at the same time to raid the enemy camp, causing havoc and freeing prisoners.

The Muslims feared for the safety of their booty, obtained during the campaign and many rushed back to the camp. This was seen as a full retreat by many other members of the Muslim army and an actual full retreat soon followed. ‘Abd-al-Raḥmân valiantly attempted to rally his troops but was killed in the fighting as the victorious Franks swarmed upon their retreating foes.

The degree to which the Muslims were defeated can be inferred by the following events. The survivors retreated to their camp where they fled in the middle of the night, carrying mostly their prized loot. The next morning, Charles was deeply concerned that his enemies were setting up an ambush, trying to get him to march downhill to more open fields.

After extensive scouting, it was discovered that the enemy had fled. This would point to the battle surely being a great victory, but not a crushing one as Charles still had to fear a possible ambush. Also, most casualties in battle come after one side starts to retreat, but in this case, it was a victorious infantry army chasing down a largely cavalry based army, so there were likely plenty of Muslim survivors.

Estimates are that the Muslims lost around 8-10,000 compared to roughly 1,000 for the Franks. Though not a crushing victory it was a definite turning point for the push of Islam into Europe. The battle was unequivocally lost, and a great general was lost by the Ummayids.

They had become overextended and would eventually be forced to withdraw back into Spain. Charles was granted the nickname of Charles “the Hammer” for crushing his enemies and both he and Odo, who had won the first great victory and served at Tours, would be considered heroes of Christianity.

Charles would go on to establish the Frankish kingdom, and his family line would produce such greats as Charlemagne.

Please enter at least 3 characters

Photo Credit: With a Christian cross prominently displayed at left, Charles Martel’s Frankish forces beat back Muslim invaders at Tours in Charles Steuben’s 19th-century painting.

Charles The Hammer At Tours

An army of fast-moving Muslim raiders collided with a phalanx of Frankish heavy infantry under Charles “the Hammer” Martel at Tours in ad 732. It would be the highwater mark of the Islamic tide in Europe.

This article appears in: December 2010

By William E. Welsh

In the late spring of ad 732, an 80,000-man-strong Muslim army spilled northward through gaps in the western Pyrenees onto the verdant, gently rolling landscape of Gascony. The invaders crossed the 3,800-foot Roncesvalles Pass, shedding extra layers of clothing they had worn as they passed through the snow-covered mountains. As they descended, the air became pleasantly warm in the Duchy of Aquitaine and they were greeted by heavy rains in sharp contrast to the desert air with which they were more familiar.

The supremely confident warriors were looking to slake their thirst for riches by looting the Christian abbeys, churches, and towns in the area. Although by rights one-fifth of the spoils belonged to the Umayyad caliph in Damascus, each man in the ranks was also assured some portion of the plunder. The invading army, led by Abd er-Rahman, governor of al-Andalus, the Muslim-controlled territory on the Iberian Peninsula, reflected the sheer breadth of appeal of the Prophet Muhammad and his teachings. Within its ranks were Arab professional soldiers, Persian warriors, Turkish adventurers, and Berber tribesman. The mounted invaders, armed with lances and shields, wore chain mail beneath loose-fitting, brightly colored robes. They protected their heads with egg-shaped helmets, while the poorer Berbers, toting spears and swords but lacking armor, wore turbans and drab robes.

Abd er-Rahman and his army intended to subjugate and punish Aquitaine’s ruler, Prince Eudes, who had resisted the steady encroachments into Aquitaine by the governor and his Muslim minions for the past several years. The vacuum left by the dissolution of the Western Roman Empire had set the stage for the dramatic spread of Islam by armed conquest across the shores of North Africa in the 7th century. Muslim warriors of the Umayyad caliphate of Damascus, the second of four Islamic caliphates established after Muhammad’s death, reached the shores of the Atlantic in ad 710. Seeking more plunder for the caliph (and for themselves), the invaders cast their eyes on the Iberian Peninsula to the north.

At the time, the Visigoths controlled the Iberian Peninsula, having settled there in the 5th Century. They were ruled by King Roderic, whose sovereignty was disputed by rival factions in Septimania, a former province of Rome just northeast of the Pyrenees. Taking advantage of the discord, the Umayyad governor of North Africa, Musa ibn Nusair, assembled an invasion army bound for Iberia. Lacking their own transport, the Muslims found a willing Byzantine official who bore a grudge against Roderic. Because of the lack of transport and the attendant difficulties of supporting an amphibious invasion, Damascus granted permission for only a small expedition consisting of 400 men. The subsequent success of the expedition, including the sack of Algeciras, and the knowledge that Roderic was tied down in a protracted conflict with Basque tribesmen in northern Iberia, fed the Muslim thirst for even larger riches.

The following year Musa entrusted a second invasion, this time comprising 7,000 Berbers and Arabs, whom the Europeans called Saracens, to Berber leader Tarik ibn Ziyad. Roderic perished fighting the Muslim invaders, and Musa crossed to Iberia to administer the conquered areas. By 712, the Muslims had subjugated most of the population of Iberia, with the exception of the Asturias and the Basques. Driven by their unquenchable thirst for plunder, the Umayyads began raiding north of the Pyrenees into the sprawling Duchy of Aquitaine. To the northeast lay Septimania, the last bastion of the Visigoths. At the time, Aquitaine was nominally ruled by the Merovingian Franks.

Duke Eudes, the ruler of Aquitaine, had taken advantage of civil strife in the Frankish kingdom following the death of the Frankish leader, Pepin of Herstal, to expand his control of the borders of Aquitaine and bestow upon himself the title of prince, a self-anointing act that did not sit well with the Franks. Pepin had ruled the Frankish kingdom from 679 until his death in 714. Before dying, Pepin had designated his young grandson, Theobald, as his heir. Fearing that Pepin’s illegitimate son, Charles, would seize power, Pepin’s wife had Charles imprisoned. He escaped and fought a series of battles over the next several years, during which time he consolidated his power and crushed his opponents in the tripartite Frankish kingdom of Austrasia, Neustrasia, and Burgundy, while also reasserting his control over key dependencies such as Aquitaine. By 723, Charles was firmly in control of the Frankish kingdom and serving as mayor of the palace, as his father had done before him. He spent the next year fighting the Saxons and Bavarians on Austrasia’s eastern flank.

The Umayyads began launching large-scale raids north of the Pyrenees in 717, and two years later they captured the port of Narbonne in Septimania, transforming it into an Islamic city. The successful capture of Narbonne led to even greater schemes of conquest. In 721, the al-Andalus governor at the time, al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani, led a large force bent on conquering all or part of Aquitaine by marching on the key city of Toulouse. The confident Muslims brought with them a long train of siege weapons and a large number of camp followers. After crossing the eastern Pyrenees in the springtime, the invaders laid siege to Toulouse. Meanwhile, Eudes set about gathering a relief force composed of Gascons, Basques, and Visigoths.

Eudes attacked the Muslim forces around Toulouse on June 9, scattering and overrunning them as they sought to withdraw. It was a decisive victory, one that greatly enhanced his prestige. The Muslims, however, were by no means through with their military efforts in the region. Four years later they closed their grip on Septimania by capturing the fortresses of Carcassonne and Nimes and driving the Visigoths from their last holdings. These would serve as bases for far-ranging Muslim raids into Burgundy.

Eudes, who found himself in the unenviable position of being sandwiched between the Muslims in al-Andalus and the resurgent Frankish kingdom under Charles, entered into an alliance in 729 with Munusa, the rebel governor of Cerdagne, a district in the eastern Pyrenees, to augment his army in future conflicts. To parry the growing strength of the Franks, Eudes also began meddling in Frankish political affairs.

As part of an ongoing attempt to subjugate the lands bordering the Pyrenees, Abd er-Rahman invaded Cerdagne and forcibly removed Munusa as a threat. Believing it was imperative to punish Eudes for daring to resist Muslim encroachments, er-Rahman began assembling an army in the western Pyrenees at Pamplona to remove Eudes as a threat once and for all. Professional soldiers flooded into the encampment from throughout al-Andalus and from North Africa, giving er-Rahman a sizable army. At the same time, Charles shifted his attention from the Frankish kingdom’s eastern frontier to its western one, launching two punitive raids in 731 on northern Aquitaine and ultimately sacking Bourges.

Keenly aware of the fate that had befallen al-Samh before the gates of Toulouse, er-Rahman purposely chose not to follow the same invasion path through the eastern Pyrenees. Instead, the high Roncesvalles Pass offered the Muslims a more direct route to Bordeaux, which Eudes was bound to defend. When they reached level ground, the Muslims divided into two columns. The main column, led by er-Rahman, took an inland route, stopping north of Aire to burn the abbey of Saint-Sever-de-Rustan. Meanwhile, a smaller column took a coastal route of march, stopping to pillage Bayonne and Dax before resuming its march toward Bordeaux. As the two columns advanced, they met no resistance. Vastly outnumbered, the small garrisons in Gascony had fled north to the Garonne River, where they planned to join Eudes’s main army to defend Bordeaux.

Eudes was presented with two choices for doing battle with the Muslims, both of which favored the invaders. If he fell back on Bordeaux, he risked being trapped on the Medoc peninsula and defeated outside the city walls. Yet if he gave battle in the open countryside in the Garonne valley, his army was likely to be overwhelmed by er-Rahman’s much larger force. Eudes opted for the latter choice, and in early June he suffered a decisive defeat along the banks of the Garonne. The remnants of his army retreated northward to the Dordogne River, a tributary of the Garonne, leaving Bordeaux uncovered. The Muslims immediately plundered Bordeaux, extracting from the city a large treasure of booty that included countless gold objects richly decorated with gems and pearls. They left the town in smoldering ruins when they departed in late June.

While Eudes raised new forces from northern Aquitaine for another clash with the Muslims, er-Rahman rode east along the southern bank of the Garonne until he reached the town of Agen, midway between Bordeaux and Toulouse. There, he crossed the wide river, defeated the town’s small garrison, and added still more plunder to his growing baggage train. Meanwhile, smaller raiding parties gathered additional booty from nearby towns and churches.

The Muslim leader turned his army back west to do battle once again with Eudes. His scouts found Eudes’s army in a defensive position on the north side of the Dordogne, defending a bridge on the Roman road to Saintes. After receiving this information, er-Rahman sent one wing of his army on a wide flanking march upstream of the Franks, which brought his horsemen in on their flank. A major battle occurred at the junction of the Garonne and Dordogne Rivers, and Eudes once again was soundly defeated. No longer able to offer substantial resistance to the advancing Muslims, Eudes rode north with his retainers into the heart of the Frankish kingdom to petition Charles for aid in defending Aquitaine.

News of the Muslim victories in Aquitaine reached Charles while he was in the midst of a campaign against the Bavarians along the Danube River. With Muslim forces operating deep in Aquitaine and Burgundy, Charles rode first to Reims and then on to Paris. In a no doubt uncomfortable meeting with Eudes, he agreed to help—provided that Eudes pledge his allegiance to Charles and agree to maintain Aquitaine as a Frankish dependence rather than an independent principality. After the meeting, Charles issued a summons calling upon all able-bodied men throughout the kingdom to defend the realm. The army assembled at Paris and marched to Orleans and Tours to protect wealthy church properties that were likely targets of marauding Muslims. Charles dispatched advance forces to guard the Basilica of St. Martin, which lay outside the city’s protective walls.

Tours itself was in no immediate danger. The Muslims spent the next three months encamped in central Aquitaine. During that time, they plundered the surrounding cities of Saintes, Perigueux, and Angouleme. In a systematic manner, er-Rahman’s troops stole treasure and artifacts from church properties and dismantled and burned fortifications to remove any local resistance to their authority. Once they had secured all the treasure they believed was to be had in central Aquitaine, the invaders broke camp at Saintes and marched northward via the Roman road toward Poitiers.

Poitiers, a key crossroads in northern Aquitaine on the Clain River, was situated about 60 miles south of the Neustrian border. The second largest town in Aquitaine after Toulouse, Poitiers was surrounded by an inner wall built during Roman times and an outer wall constructed by the Visigoths. Scattered around the city and its outskirts were a number of important religious structures, including the abbey and church of Saint Hilaire and the funerary basilica of Saint-Radegonde. Saint Hilaire, which lay beyond the protection of the outer wall south of the city, was adorned with gold mosaic and undoubtedly would be a prime target for the treasure-seeking Muslim raiders.

A network of tributaries of the Loire River was located east of Poitiers. Among these tributaries, which had their headwaters on the northwestern slope of the Massif Central, were the Vienne, Cher, and Indre Rivers. On their way to join the Loire, the tributaries flowed through a landscape that consisted primarily of upland pastures and valleys and ridges blanketed by thick forests.

As expected, the Muslims attacked the lightly defended Saint Hilaire in mid-September and carried off its religious treasures. At that point, er-Rahman decided to forego a siege of the walled city in favor of sacking Saint-Martin, outside Tours. The Muslims had learned from locals that Saint-Martin contained even greater wealth, and despite the risk inherent in invading another dominion of the Frankish kingdom, they continued north in late September marching past the fortifications of Poitiers. While the largest column led by er-Rahman marched along the Roman road, smaller columns advanced toward the Loire River on less direct routes to the left and right of the main column.

As they marched north along the Roman Road with the Clain River, a tributary of the Vienne, to their left, the Muslims passed by the ruins of a Roman settlement at Vieux-Poitiers that included an amphitheater with a tower that afforded a bird’s-eye view of the surrounding farmland. When er-Rahman reached the village of Cenon on the Vienne River, he paused for a time before crossing. Scouts were sent up and down the river and across to the north bank to make sure Frankish forces were not in the vicinity. After it was determined that a safe passage could be made, the main body of the Muslim army crossed to the north bank.

From Cenon, er-Rahman marched north to the village of Port-de-Piles, where he halted his forces on the south bank of the Creuse River, another tributary of the Vienne. In an effort to reconnoiter the road ahead, er-Rahman sent his vanguard across the Creuse. Meanwhile, the Muslim column operating east of the main body ran headlong into a group of Christian pilgrims bound for Rome. They promptly attacked and robbed the pilgrims, leaving a number of the unlucky travelers dead by the roadside.

Advancing cautiously northward in early October, the lead elements of the main Muslim body ran into Frankish positions guarding Tours. Bloody skirmishes foreshadowed a larger battle to come. In a clash with the Franks north of the Creuse River, the Muslim vanguard suffered a serious reverse and was forced to fall back. In another clash farther west, the Franks overran a Muslim encampment near the village of Loudun, forcing the invaders to fall back to a safer position.

In response to these setbacks, er-Rahman ordered his vanguard to fall back behind the Creuse. Still feeling exposed, he withdrew the main body of the Muslim army across the Vienne. In mid-October, the Muslims began constructing a fortified camp on high ground between the Vienne and Clain Rivers just north of marshland along a stream that emptied into the Clain. The military encampment, known as a khandaq, was protected on all sides by ditches and guarded around the clock. Just beyond the ditches were thick woods. A gap in the woods to the west led toward the Roman road, while a gap to the northeast led to two small villages in the Vienne River valley. As the Muslims fell back, Charles ordered his army to advance to the Vienne and halt opposite Cenon.

While the Muslims built their khandaq, the Franks crossed the Vienne and began a cautious advance southward along the Roman road. The Franks made camp at the Roman ruins located on the western side of the old road. They used the tower that was part of the Roman amphitheater as an observation post. For the better part of a week, the two armies warily observed each other, neither willing to launch an attack.

On Saturday, October 25, Charles ordered his troops to form a defensive line astride the Roman road just south of the ruins at Vieux-Poitiers on a narrow tract of cleared land. The position allowed Charles to anchor both flanks in dense woods. By securing his flanks, the Frankish commander ensured that the Muslim cavalry would not be able to ride around his army and fall on his main line from the rear.

The Frankish army, numbering about 30,000 men, was divided into four divisions. It consisted of Frankish infantry, both mounted and on foot, and a body of irregular cavalry composed of mounted bands of Bretons, Basques, and Gascons that was commanded by Eudes. Rather than pit his less-agile cavalry against the well-trained Muslim horsemen, Charles ordered the mounted infantry to dismount and take their place in one of three divisions that would form a formidable phalanx to await the Muslim attack. The soldiers in the main line of battle stood shoulder to shoulder in order to leave no gap through which their line might be breached. The fourth division, under Eudes, formed a rear guard that was stationed behind the main line and had orders to respond to any Muslim cavalry that might be clever enough to find a way around or through the front line.

Just after sunrise, the Muslim army marched west until it reached the Roman road. It then formed for battle just beyond the village of Moussais-le-Bataille. In keeping with Muslim tradition, the army was organized into five divisions consisting of a center, two wings, a vanguard, and rear guard. The rear guard did not march into battle, but stayed behind to protect the khandaq. Muslim tactics were to overwhelm their adversaries by moving swiftly across open ground, outflanking the enemy’s position, and disrupting the opposing forces so that the enemy could be ridden down and slaughtered in small groups.

The Franks fighting under Charles would use tactics that completely negated the Muslim advantage in numbers and speed. The Frankish tactics closely resembled those of the Romans. The Franks used heavy spears and short swords as their main weapons. On the whole, these weapons were heavier than those used by the mounted Muslim forces. The Franks were clad in chain-mail shirts or leather jerkins reinforced with metal scales. Their primary protection in battle was an impressive round, wooden shield covered in leather that was three feet in diameter. The concave shield, with an iron boss in the center, protected the soldiers from their necks to their thighs. It was used not only for protection against incoming projectiles or slashing swords, but also as an offensive weapon to drive back and batter the enemy in close-quarters combat. To protect their heads, the Frankish infantry wore conical hats angled to deflect blows to the head, whether delivered from an enemy on foot or on horseback.

The élan that the Frankish heavy infantry exhibited in battle was derived from the fact that they were free men serving to protect their homeland against marauding invaders. In preparation for the Muslim attack, the Franks presented an unbroken wall of shields. They rested their spears on the ground to impale any Muslim horsemen who might be foolish enough to charge them directly.

The battle began when the Muslims rode at the Franks and began hurling javelins or firing arrows into their ranks at close range. Some brave men rode close enough to slash at the Franks with their swords, a dangerous proposition considering that the Franks was armed with multiple weapons and well protected by their armor, shields, and helmets. The Muslims tried to inflict sufficient casualties to open a gap in the enemy line or, failing that, to entice the Franks to advance to the attack and then work their way inside their lines. At no time did the Muslims try to break the enemy phalanx. It was simply impossible for light cavalry to overrun a strong line of heavy infantry. “The Muslim horsemen dashed fierce and frequent forward against the battalions of the Franks, who resisted manfully, and many fell dead on either side,” wrote an anonymous Muslim chronicler.

The Franks exhibited discipline and control while under attack by a numerically superior foe. “The men of the north stood motionless as a wall,” wrote al-Andalusian chronicler Isidorus Pacensis. “They were like a belt of ice frozen together, and not to be dissolved, as they slew the Arab with sword. The Austrasians, vast of limb, and iron of hand, hewed bravely in the thick of the fight.” When the Muslims came close to their line, the Franks did their best to thrust their spears into the enemy horses and stab and slash at the riders with their swords. They also employed their shields to tear or puncture the enemy mounts. Large numbers of Muslim cavalry were unhorsed near the Frankish line and then either dispatched with swords or trampled as the Franks advanced a short distance to drive back the enemy. Incensed by the constant Muslim looting of their homeland, particularly their churches, the Franks did not take any prisoners.

For most of the day, the fight was an even one, but as the battle wore on into the afternoon the Muslims had yet to punch through the solid Frankish phalanx. As a result of hard fighting, Muslim casualties were particularly heavy. Nevertheless, Charles was concerned about the strength of his line in the agonizing hours that the sun arced slowly across the sky. Late in the day he made a bold decision to switch to the offensive. Taking advantage of the Aquitainians’ superior local knowledge of geography, he ordered Eudes to take his mounted division on a wide flanking march and fall on the enemy’s fortified camp.

Having completed their flank march, Eudes’s men advanced on the Muslim camp from the northeast just before sunset through a passage in the forested country east of the Vienne. The Muslim rear guard detected the enemy on its flank and fell back to protect the khandaq, the riders dismounting and filing into the surrounding ditches. Armed with spears and swords, the defenders were backed by archers with simple bows who fired on the Franks as they advanced.

Eudes’s attack on the Muslim khandaq essentially spelled the end of the main battle. When Muslim front-line forces learned that their camp was under full-scale attack, one squadron of cavalry after another peeled off and rode back toward the encampment. The Muslims were determined to protect the hard-fought treasures amassed during their raids on Aquitaine.

Some of Eudes’s men attacked the khandaq on foot, while others remained mounted in order to hurl their spears and javelins over the defensive barriers. In hand-to-hand combat in the ditches surrounding the encampment, the Franks gained the upper hand in a matter of minutes. As the resistance in front of him crumbled on his front, Charles brushed aside the remaining Muslims and marched his men in good order toward the enemy camp as darkness began to swallow up the last light of day on the bloody hilltop.

“Charles boldly drew up his battle line against them and the warriors rushed in against them,” wrote an observer, the Continuator of Fredegar. “With Christ’s help, he overturned their tents, and hastened to battle to grind them small in slaughter.” While directing the defense of the Muslim camp, er-Rahman was killed by a javelin thrown with expert marksmanship by one of the mounted Gascons or Bretons riding with Eudes.

Although Charles’s well-disciplined army killed large numbers of the Muslims, they failed to capture the fortified camp by nightfall. Satisfied with the day’s achievements, Charles ordered his men to quit the field and await the morning’s developments. Meanwhile, learning that er-Rahman had fallen, the Muslims prepared to withdraw southward under the cover of darkness. To hasten their escape, the Muslim survivors made the heartbreaking decision to abandon the baggage train containing their spoils of war. In a skilled move that reflected their military professionalism, the Muslims purposely left their tents standing to deceive the Franks.

On Sunday, the Franks formed up with the intent of resuming the battle. After sending forward several small groups to probe the Muslim defenses, Charles learned that the bulk of the Muslim army had fled during the night, leaving behind their prisoners and plunder so that neither would impede their flight. The rank and file of the Frankish army were spellbound by the treasure they found in the abandoned khandaq. They were anxious to divide the spoils and return to their homes and families with a portion of the recovered loot.

Charles, who was acutely in tune with the mood of his troops, was reluctant to order a pursuit of the Muslims with an unwilling body of men. Furthermore, he feared that the Franks might become strung out during the pursuit, allowing the Muslims to turn on their pursuers and maul them severely. Last but not least, Charles wanted the Muslims to remain a serious threat to the security of Aquitaine, forcing Eudes to focus his political and military efforts against the Muslims rather than the Franks.

Casualties for the battle are difficult to gauge. Muslim accounts state that the Franks lost 1,500 men, but those numbers seem light given that the battle lasted most of the day. In all probability, the Franks lost several thousand men. Muslim casualties were significantly greater than those of the Franks, with the Muslims losing an estimated 10,000 men in the day-long battle.

Charles made a wise decision not to follow the retreating Muslims. The Muslim retreat was by no means the rout of a panicked army. Because of its professional nature, the army’s withdrawal was conducted in a cohesive fashion, with some elements retreating through Aquitaine and others through Burgundy to the safety of al-Andalus and Septimania. The main army turned west toward Burgundy, where it was assisted in its withdrawal by Muslim raiding parties operating deep in the Rhone Valley. Those elements operating west of the Muslim main army slipped across the Dordogne and Garonne Rivers to Gascony and then on to al-Andalus.

After the battle, Charles withdrew through Neustria with his army, but not before replacing the bishops of Tours and Poitiers, both of whom had shown questionable allegiance to him. Eudes, who still had a sizable command despite many months of hard campaigning, marched south, battling the Muslim raiders remaining in Aquitaine as he went.

The battle marked the highwater mark of the Islamic tide that had swept into Western Europe during the Middle Ages. By turning back the Muslims at Tours, the Franks broke the string of Muslim conquests that had spread like a terrible storm through the Iberian Peninsula and beyond. Charles was given the sobriquet Martel (the Hammer) by contemporary chroniclers for the way he had battered his enemies in battle. As the centuries passed, the saga of his defeat of the Muslims at Tours grew in importance until he was credited with nothing less than saving Western Christianity from Islamic subjugation. While there is some truth to the idea, the Muslim raids into Aquitaine and Burgundy were more of a nuisance than a true threat to Western Europe. Charles, for his part, considered rival nobles and hostile clergy in the Frankish dependencies far more of a threat to his rule than the Muslims.

Nevertheless, Charles’s victory at Tours had unanticipated benefits beyond stopping the Muslim advance at the Loire. The Franks enjoyed a significant boost in prestige throughout Europe, particularly in the eyes of the papacy, for having defeated the fearsome Muslims in a set-piece battle. That victory, in turn, laid the foundation for the establishment of the Holy Roman Empire two generations later by Charles’s grandson, Charlemagne. Either way, the Muslims’ halcyon days of raiding Western Europe at will were over.

Back to the issue this appears in

Join The Conversation

Leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share This Article

- via= " class="share-btn twitter">

Related Articles

Military History

Military Intelligence in the Roman Republic

“Give Them One Fire and I’ll Charge Them”

Slugfest at Kunersdorf

Was the 1917 Enfield a Good Rifle Compared to the Springfield?

From around the network.

Frederick the Great and the Battle of Leuthen: Triumph of Tactics

The Greek Trireme

Joseph Goebbels: Shaping Nazi War Propaganda

Book Reviews

Michael Livingston’s ‘Never Greater Slaughter’

Battle of Tours 732 Charles Martel

What was the battle of tours.

The Battle of Tours was fought in 732 between a sizable Moorish invading force and a Frankish army under Charles Martel.

Martel was able to check the Moorish advance by routing the Muslim army at the Battle of Tours in 732.

The battle is considered highly significant in that it was crucial in stemming the tide of Muslim advance into north-eastern Europe after the Moors had successfully taken over southern Iberia.

Moors in various costumes

Modern historians believe that had Martel not defeated the Moorish army at Tours, Christianity may have lost a vital sphere of influence in Western Europe.

The outcome of the battle was the routing of the Muslim army and a resounding victory for Charles Martel, earning him the title of being the “Savior of Christianity”.

Prelude to the Battle of Tours

Muslim forces were defeated at the 721 Battle of Toulouse in their advance into northern Iberia. Duke Odo of Aquitaine secure this victory but by 732, another sizable Muslim army arrived to invade northern Iberia.

Odo attempted to stem the tide but was defeated and fled. He then turned to the Franks who were conventionally considered rivals of Aquitaine.

Charles Martel, the Frankish military general, agreed to come to Odo’s help if Odo agreed to bend the knee to Frankish authority. Between the threats of a complete Muslim invasion and the condition of submitting to the Franks, Odo chose the latter.

Charles Martel *Frankish Military General

Battle Tactics Battle of Tours

The key advantage that the invading Moorish army had over the Franks was its highly mobile cavalry.

Martel, on the other hand, had thousands of veteran troops. While the Frankish had no cavalry advantage over Muslims, Martel managed a crucial advantage by setting up his army at the ridge of a hill.

The Battle of Tours was also known as the Battle of Poitiers

The phalanx-like formation of his infantry, surrounded by trees on both sides, ensured that any charge from the Muslim cavalry would have little advantage against the Frankish infantry.

Being able to choose the terrain and the condition of the battle played the most central role in ensuring the subsequent Frankish victory in the battle.

Frankish Troops

Battle of Tours Battle

The Muslim army was led by Abd er Rehman. He had been able to victories in many previous battles using the might of Muslim heavy cavalry. At the Battle of Tours , the importance of Rehman’s cavalry was greatly diminished.

The Muslim army was positioned at the foot of the hill while the Frankish stood in a defensive formation atop the ridge of the hill. After waiting for six days, Ab der Rehman made the tactical mistake of making his troops charge uphill.

This negated the cavalry advantage the Muslims had. The Franks, on the other hand, stood in highly organized formations and withstood one cavalry charge after another from the Muslims.

Although the Muslim army was able to pierce through the Frankish formations, they couldn’t penetrate deep enough and sustained heavy losses at the hands of the Frankish infantry.

After the battle which had lasted nearly a day, rumors spread that the Franks had attacked the Muslim camp.

A sizable portion of the Muslim army immediately broke off to reach the camp. Muslim general, Ab der Rehman, was consequently killed while trying to restore order in his army.

- Medieval Battles | Wars

- 10 Key Facts About the Battle of Hastings

- 10 Key Facts About the Hundred Years’ War

- 10 Medieval Battles That Shaped the Course of History

- A Brutal and Transformative Conflict: Exploring the Battles & Sieges of the Hundred Years’ War

- Battle for the Crown: Stephen and Matilda’s Epic Conflict

- Battle of Agincourt 1415

- Battle of Bannockburn 1314

- Battle of Bosworth Field 1485

- Battle of Bouvines 1214

- Battle of Castillon 1453

- Battle of Courtrai 1302 ‘Golden Spurs’

- Battle of Crécy 1346 – 100 Years War

- Battle of Edington took place in 878 AD

- Battle of Falkirk *1298

- Battle of Grunwald: An Epic Conflict That Shaped Medieval Europe

- Battle of Hastings *1066 *Norman Conquest

- Battle of Nicopolis *1396

- Battle of Poitiers 1356

- Battle of Shrewsbury 1403: History, Tactics and Key Players

- Famous Medieval Battles List

- Famous Naval Battles

- Famous Siege List – Medieval Period

- Hundred Years War 1337- 1453 *116 Years of Warfare!

- Medieval Battles Timeline

- Medieval Battles Wars and Sieges Questions & Answers

- Medieval War Tactics

- Medieval Warfare

- Pivotal Moments in History: 10 Fascinating Facts About the Battle of Hastings

- Relive the Epic Battles and Sieges of the Middle Ages

- The 10 Worst Medieval Battles

- The Battle of Crécy and the ‘Rain of Arrows’ 10 Fascinating Facts

- The Battle of Halidon Hill: Scotland’s Fateful Defeat

- The Battle of the Standard *Battle of Northallerton

- The Bloody Military Campaigns of Vlad the Impaler

- The Hundred Years’ War: Key Moments and Decisive Battles

- The Mongol Onslaught: The Battle of Legnica

- The Top 10 Events of the Hundred Years’ War: A Decade-by-Decade Account

- The Wars of the Roses 1455 – 1487 *37 Year War

- Top 10 Bloodiest Battles of the Medieval Period: Fierce Clashes and Heavy Casualties

- Top 10 Fascinating Facts about the Battle of Hastings

- Top 10 Most Historically Important Medieval Battles

- Top 10 Most Historically Important Medieval Wars

- Top 10 Most One-Sided Battles of the Medieval Period: Devastating Defeats

- What was the Burgundian War?

- What were the Social and Economic Impacts of Medieval Wars on the General Population?

Main Categories

- Medieval People

- Medieval Castles

- Medieval Weapons

- Medieval Armour | Shields

- Medieval Clothing

- Medieval Knights

- Medieval Music

- Medieval Torture

- Medieval Swords

- Medieval Food

- Medieval Life

- Medieval Times History

- Medieval Art

- Medieval Europe

- Medieval Kings

- The Crusades

- Medieval Architecture

- Medieval Period – 1000 years of Intriguing History!

- This Day In History

- History Classics

- HISTORY Podcasts

- HISTORY Vault

- Link HISTORY on facebook

- Link HISTORY on twitter

- Link HISTORY on youtube

- Link HISTORY on instagram

- Link HISTORY on tiktok

Charles Martel Repels the Moors

Charles Martel, commander of the Franks, repels the Moorish advance through France and becomes the savior of Christianity in Europe.

Need help with the site?

Create a profile to add this show to your list.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Battle of Tours was a significant military conflict that occurred in 732 near the city of Tours, in modern-day France. Charles Martel, the leader of the ...

Short animation covering details of one of the most important battles in European history. In 732 AD Charles Martel, Frankish Mayor of the Palace stopped Ara...

Support my work on Patreon:https://www.patreon.com/RealCrusadesHistoryGet my book about the Crusades:http://www.amazon.com/Why-Does-Heathen-Rage-Crusades/dp/...

Charles Martel. Battle of Tours, (October 732), victory won by Charles Martel, the de facto ruler of the Frankish kingdoms, over Muslim invaders from Spain. The battlefield cannot be exactly located, but it was fought somewhere between Tours and Poitiers, in what is now west-central France.

The Battle of Poitiers aka the Battle of Tours took place over roughly a week in early October of 732. The opposing sides consisted of a Frankish army led by Charles Martel (r. 718-741) against an invading Muslim army under the nominal sovereignty of the Umayyad Caliphate (c. 661-750) based in Damascus, Syria.. These two forces came together as Umayyad power sought expansion and plunder in ...