Journey to the West | Full Story, Summary & Moral Lessons

- February 19, 2024

“Journey to the West” stands as one of the pinnacles of Chinese literature, a riveting blend of mythology, folklore, humor, and spirituality .

Authored by Wu Cheng’en in the 16th century during the Ming dynasty, this epic novel has transcended its cultural origins to become a global literary treasure!

The narrative follows the perilous journey of the Buddhist monk Xuanzang, historically known, as he travels to India to obtain sacred Buddhist scriptures. Accompanied by his three disciples— Sun Wukong , Zhu Bajie, and Sha Wujing—each with their own unique abilities, their quest is filled with divine interventions, battles with demons, and moral lessons.

Many of which we will be getting to know today!

Table of Contents

Historical Context

The “Journey to the West” is deeply entwined with the real-life travels of Xuanzang (602-664 CE), whose pilgrimage to India and back took 17 years, a journey undertaken to obtain authentic Buddhist scriptures.

Wu Cheng’en’s fictionalized account, however, does more than narrate a religious quest; it weaves a rich story of Chinese myths, Taoist and Buddhist philosophy, and satirical commentary on the social issues of his time, making it a multifaceted work of art.

If you’re interested in watching the Journey to the West, I highly recommend the 1986 series as it’s often lauded as being not only the most accurate but also you can really feel the love and respect given to the adaptation.

Key Characters

Tang Sanzang

Tang Sanzang, also known as Tripitaka , stands at the heart of “Journey to the West” as its protagonist. His mission to retrieve sacred Mahayana Buddhist scriptures from India serves as the narrative’s driving force. Tang Sanzang embodies virtues such as humility, compassion, and unwavering dedication to his spiritual quest.

His portrayal as the epitome of piety and moral integrity offers a rich canvas against which his interactions with disciples and various challenges unfold.

Tang Sanzang’s personality is a blend of devout faith and moral steadfastness. He is the moral compass for his disciples, guiding them not only towards their external goal but also on their internal journeys of growth and enlightenment .

Despite his virtues, Tang Sanzang is not portrayed as infallible. His naivety and strict adherence to religious doctrines sometimes lead him into trouble, requiring rescue by his more worldly and powerful disciples. This aspect of his character highlights the novel’s exploration of the balance between innocence and wisdom, as well as the necessity of worldly knowledge in achieving spiritual goals.

Throughout the novel, Tang Sanzang undergoes significant development. His journey is not only a physical one across dangerous terrains but also a spiritual odyssey that tests and refines his character. He learns to balance his strict moral codes with the practicalities of the world, growing in understanding and compassion towards his disciples and the beings they encounter.

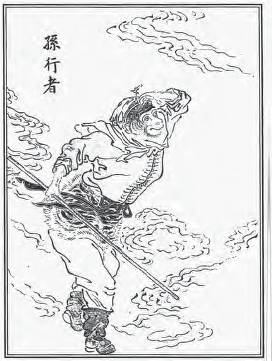

Sun Wukong , famously known as the Monkey King , is one of the most beloved characters in “Journey to the West.”

His origins are as magical as his personality; born from a stone egg on the Mountain of Flowers and Fruit, Sun Wukong acquires supernatural powers through Taoist practices.

His abilities include shape-shifting, immense strength, and the ability to travel vast distances in a single somersault. Despite his powers, Sun Wukong’s early journey is marked by rebellion and pride, leading him to challenge the heavens themselves.

His initial defiance against the celestial order and subsequent punishment—being imprisoned under a mountain by the Buddha—sets the stage for his redemption arc.

His release by Tang Sanzang and commitment to protect the monk on the journey to India is a turning point, marking his transition from a rebellious figure to a devoted disciple. This journey serves as a path of self-discovery and spiritual maturation for Sun Wukong, as he confronts challenges that test his ingenuity, patience, and fidelity.

The Monkey King’s personality is multifaceted; he is cunning and playful, yet capable of profound wisdom and bravery. His loyalty to Tang Sanzang is unwavering, and he becomes the monk’s most powerful protector, using his abilities to overcome demons and obstacles that the pilgrimage encounters. Sun Wukong’s transformation from a mischievous troublemaker to a protector embodies the novel’s themes of redemption and the possibility of spiritual growth regardless of one’s past.

In terms of symbolic significance, Sun Wukong represents the untamed mind and the potential for enlightenment within all beings. His journey from arrogance to enlightenment mirrors the Buddhist path, emphasizing the importance of humility, learning, and devotion.

Through Sun Wukong, “Journey to the West” explores the idea that even the most unruly spirits can achieve enlightenment through perseverance, guidance, and self-reflection.

Zhu Bajie, often referred to as Pigsy , is known for his complex and somewhat contradictory character traits. Originally a marshal in the celestial army, Zhu Bajie was banished to the mortal realm as a punishment for his indiscretions in heaven, particularly with the Moon Goddess, Chang’e .

Transformed into a pig-human hybrid, his appearance reflects his base nature and penchant for indulgence, especially in food and women. Despite these flaws, Zhu Bajie becomes one of Tang Sanzang’s disciples, joining the quest to retrieve the Buddhist scriptures from India.

Zhu Bajie’s personality is marked by a mix of bravery and cowardice, loyalty and self-interest, wisdom and folly. He often provides comic relief in the story through his antics and bumbling mistakes, yet his character also displays moments of insight and bravery.

His earthly desires and tendencies towards laziness often put him at odds with his more disciplined and spiritually focused companions, particularly Sun Wukong, with whom he shares a rivalry.

While he deeply respects Tang Sanzang and is committed to the pilgrimage, his weaknesses often lead to complications and challenges for the group. However, these shortcomings make his moments of courage and sacrifice all the more significant, highlighting the theme of redemption and the possibility of moral and spiritual growth regardless of one’s past actions or nature.

Zhu Bajie’s character serves as a reflection on human nature, embodying the struggles between base desires and higher aspirations, between selfishness and altruism. His journey alongside Tang Sanzang is as much about his own redemption and transformation as it is about the physical pilgrimage to India.

Sha Wujing, or Sandy , is the third disciple who joins Tang Sanzang. Once a celestial general, Sha Wujing was banished to the mortal world as punishment for a transgression in heaven, where he was transformed into a river ogre.

His frightening appearance belies a kind heart and a steadfast, loyal nature. Recognizing his past mistakes, Sha Wujing seeks redemption through service to Tang Sanzang on the perilous journey to the West.

Characteristically, Sha Wujing is the embodiment of stoicism and reliability. Compared to the more flamboyant Sun Wukong and the often comically flawed Zhu Bajie, Sha Wujing’s demeanor is subdued and earnest.

He is less prone to the antics and disputes that sometimes ensnare his fellow disciples, showcasing a level of maturity and wisdom that stabilizes the group. His role is often that of the peacemaker, bridging gaps between his more temperamental companions and ensuring the pilgrimage remains focused on its spiritual goals.

Armed with a magic staff that he uses to combat demons and other threats, he is a formidable fighter in his own right. His knowledge of aquatic environments also proves invaluable, as many of the journey’s challenges take place near or in water.

The Journey to the West

The Origins

In the lush, mystical expanse of the Mountain of Flowers and Fruit, a stone egg, nurtured by the elements and the heavens, gave birth to Sun Wukong, the Monkey King. This miraculous birth marked the beginning of an extraordinary being destined to leave an indelible mark on the realms of gods and mortals alike. Possessing incredible strength, agility, and a keen intellect from birth, Sun Wukong quickly established himself as the king of the monkeys, securing their loyalty through his bravery and wisdom.

Driven by an insatiable curiosity and the fear of death, Sun Wukong embarked on a quest for immortality. His journey led him to the tutelage of a Taoist sage, from whom he learned the secrets of magical arts, shape-shifting, and the way of immortality. These newfound powers, coupled with his natural cunning and prowess, made Sun Wukong a being of unmatched ability.

However, with great power came a great desire for recognition and respect. Sun Wukong’s ambitions soon turned him against the celestial order. Seeking to claim his place among the gods and immortals, he caused havoc in the heavens, challenging the authority of the Jade Emperor himself. His antics and defiance led to a celestial war between his monkey army and the heavenly forces.

The turmoil caused by Sun Wukong could not go unpunished. Despite his might, he was eventually captured by the combined efforts of the Buddha and the celestial army. To curb his rebellious spirit, Buddha imprisoned Sun Wukong under the Five Elements Mountain, sealing him with a magical spell for five hundred years. This punishment was not just a consequence of his actions but also a pivotal moment of transformation. Under the mountain, Sun Wukong was forced to reflect on his deeds and the consequences of his unchecked ambition.

This period of imprisonment was a crucible, tempering Sun Wukong’s fiery spirit with a newfound understanding of responsibility and the importance of humility. It was here, in the shadow of his actions and under the weight of the mountain, that the foundation was laid for his redemption and eventual role as a protector on the journey to the West.

The Calling of Tang Sanzang

In the empire of the Tang Dynasty, under the watchful eyes of celestial beings, the birth of Tang Sanzang was foretold with a prophecy. He was destined to be no ordinary monk, but one whose journey would mark a pivotal moment in the spiritual fabric of the world. From an early age, Tang Sanzang displayed an uncommon devotion to his Buddhist faith, his heart set on understanding the deepest truths of existence and alleviating the suffering of all beings. His life was filled with piety, scholarship, and an unwavering commitment to the path of enlightenment, setting him apart as a vessel for divine purpose.

The turning point in Tang Sanzang’s life came through a divine revelation, where the Bodhisattva Guanyin presented him with a mission of paramount importance. He was to travel to the Western regions of India to retrieve sacred Buddhist scriptures not yet available in China . These texts held the key to deepening the spiritual understanding and salvation for countless souls in his homeland. This was not just a journey across lands; it was a pilgrimage that would test the limits of his faith, endurance, and spirit.

The gravity of this mission was clear; the scriptures were vital for the propagation of Buddhism in China, promising a new era of spiritual insight and enlightenment. However, the path to the West was fraught with perils beyond imagination—demons, treacherous landscapes, and trials that would challenge the very essence of his being. It was a journey that no one could undertake alone and survive, let alone succeed.

Recognizing the monumental challenges that lay ahead, the Bodhisattva Guanyin promised Tang Sanzang divine assistance in the form of disciples who would protect and guide him through the dangers. These disciples, each with their own paths to redemption and enlightenment, were destined to be united with Tang Sanzang, forming an unlikely fellowship bound by a shared mission.

Thus began Tang Sanzang’s journey, a quest that was not only his own but one that carried the hopes and spiritual aspirations of the entire Buddhist community. With the divine mandate bestowed upon him, Tang Sanzang set forth, stepping into the annals of legend.

Assembling the Disciples

As Tang Sanzang began his perilous journey to the West, the first to join him was none other than Sun Wukong, the Monkey King. Freed from his five-century imprisonment under the Five Elements Mountain by Tang Sanzang himself, Sun Wukong was bound to him by a vow. This vow, forged in the fires of redemption (and the head-tightening band), was Sun Wukong’s promise to protect Tang Sanzang throughout the journey. The release symbolized not only Sun Wukong’s second chance but also the formation of an unbreakable bond between the disciple and his master. With his unparalleled martial prowess and magical abilities, Sun Wukong was a formidable protector, one whose loyalty and dedication to Tang Sanzang’s mission were beyond question.

The next to join this celestial mission was Zhu Bajie, once a marshal in the heavens, now living as a half-human, half-pig being as punishment for his lascivious behavior in the celestial realm. Encountered by Tang Sanzang and Sun Wukong, Zhu Bajie was persuaded to join the pilgrimage, seeking redemption for his past misdeeds.

Sha Wujing, the third disciple, was once a celestial general who, due to a grave mistake, was banished to a river, taking the form of a fearsome water ogre. His encounter with Tang Sanzang and the promise of redemption through service transformed Sha Wujing from a feared monster into a loyal disciple.

Together, these three disciples, each with their unique strengths, weaknesses, and backgrounds, formed the core of Tang Sanzang’s entourage. Their assembly was no mere coincidence but a divinely orchestrated gathering of souls seeking redemption, enlightenment, and the fulfillment of a sacred mission.

Trials and Tribulations

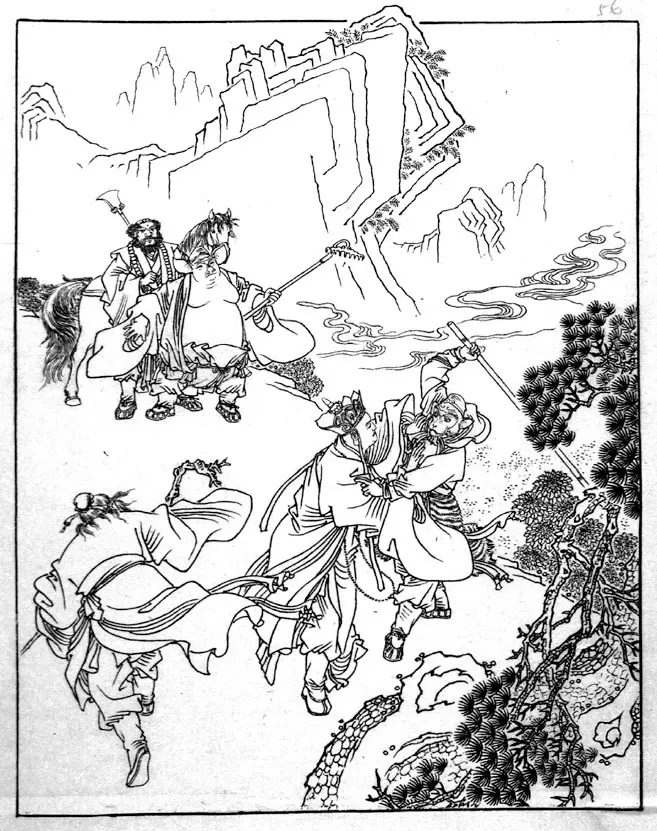

As Tang Sanzang and his newly assembled disciples embarked on their journey to the West, they were soon met with a series of trials that tested their resolve, unity, and individual capabilities. These challenges served not only as obstacles to be overcome but also as crucibles for character development and bonding among the pilgrims.

One of the first major trials they faced was the Black Wind Mountain, where a fierce demon known for capturing and eating travelers threatened their mission. It was here that Sun Wukong’s prowess and quick thinking were first put to the test, showcasing his ability to protect Tang Sanzang against seemingly insurmountable odds.

Another significant challenge came in the form of the White Bone Demon, a creature capable of changing its form to deceive and capture Tang Sanzang. This trial tested not only the physical strength of the disciples but also their wisdom and ability to see through deception.

These early trials also brought to the forefront the dynamics and interactions among the disciples. Sun Wukong’s impulsive nature and readiness to use force were often at odds with Tang Sanzang’s more compassionate and pacifistic approach, leading to tensions within the group. Zhu Bajie and Sha Wujing, each with their distinct personalities and strengths, found themselves navigating the complex dynamics between their desire for redemption and the often chaotic leadership of Sun Wukong.

The Final Challenges

As Tang Sanzang and his disciples neared the end of their epic quest to retrieve the sacred scriptures from the West, they encountered the Fiery Mountain, a vast barrier of flames that seemed insurmountable. This natural obstacle was a metaphor for the burning trials of the spirit, a test of their resolve and unity. To pass, they needed the fan of the Princess Iron Fan, a task that proved to be as much about diplomacy and wisdom as it was about strength and courage. The quest for the fan was marked by deception and challenges that tested their patience and ingenuity, especially for Sun Wukong, whose confrontations with the Princess pushed him to find non-violent solutions.

Following this, the pilgrims faced the ordeal of the Tenfold Maze, a bewildering labyrinth that tested their mental endurance and faith. The Maze, crafted by powerful magic, represented the inner confusions and doubts that can lead one astray from the path of enlightenment. Each turn and dead end forced the disciples to rely not just on Sun Wukong’s strength or Zhu Bajie’s might, but on Tang Sanzang’s unwavering faith and Sha Wujing’s quiet determination. It was their unity and collective wisdom that eventually led them through the maze, symbolizing the triumph of shared purpose over individual despair.

Perhaps the most significant trial came in the form of a spiritual challenge directly from the Buddha. Before granting them the scriptures, Buddha tasked Tang Sanzang and his disciples with a final test of their virtues and understanding of the Buddhist teachings. This trial was not about battling demons or overcoming physical barriers but confronting their inner selves and the essence of their journey. Each disciple, including Tang Sanzang, faced manifestations of their past errors, fears, and desires, challenging them to apply the lessons of compassion, humility, and perseverance they had learned on their journey.

The confrontation with their inner demons was a profound moment for the pilgrims, especially for Sun Wukong, whose journey from rebel to protector had been fraught with pride and anger. For Zhu Bajie, it was a moment to transcend his baser instincts and desires, while Sha Wujing confronted the solitude and obscurity of his existence with newfound peace. For Tang Sanzang, it was the ultimate test of his faith and his commitment to his mission, proving his worthiness to receive the sacred texts.

Arrival in the West

After overcoming the final, daunting challenges set before them, Tang Sanzang and his disciples reached their sacred destination in the West. It was here, in the presence of the Buddha, that they were finally granted the sacred scriptures.

The attainment of the sacred scriptures was an achievement of monumental significance. For Tang Sanzang, it represented the fulfillment of a divine mission entrusted to him, affirming his unwavering faith and dedication. The scriptures themselves were not just texts but beacons of wisdom, destined to enlighten countless generations to come. Their acquisition symbolized the bridging of divine knowledge from the West to the East, promising an era of spiritual awakening and understanding for Tang Sanzang’s homeland.

For the disciples, the journey to the West and the acquisition of the scriptures were transformative. Sun Wukong, once a rebellious figure driven by pride and the desire for immortality, emerged as a being of enlightenment, his actions tempered by wisdom and compassion. The journey refined his character, turning his immense power and cunning into instruments of protection and service to a cause greater than himself.

Upon their return to the Tang Empire, the pilgrims were received with reverence. The sacred scriptures were translated and spread, seeding the growth of Buddhism and its teachings throughout the land. The disciples, each awarded divine recognition for their service, achieved a form of enlightenment that transcended their former selves ( Both Sun Wukong and Tang Sanzang were turned into Buddhas .)

Summary of the Journey to the West

“Journey to the West” is a chronicling of the pilgrimage of the Buddhist monk Tang Sanzang and his quest to retrieve sacred scriptures from India. Alongside him are his three disciples: Sun Wukong, the Monkey King, with his unparalleled martial prowess and magical abilities; Zhu Bajie, the gluttonous and lecherous pig demon with a heart of gold; and Sha Wujing, the steadfast and reliable river demon. Each disciple, once celestial beings now seeking redemption for past transgressions, brings unique strengths and weaknesses to the journey, creating a dynamic and sometimes volatile mix of personalities.

The narrative begins with the birth and rise of Sun Wukong, who, after acquiring magical powers and challenging the heavens, is imprisoned under a mountain by the Buddha for his arrogance. Meanwhile, Tang Sanzang, chosen by the Bodhisattva Guanyin , embarks on a mission to the West to obtain Buddhist sutras that will enlighten the East. Along the way, he liberates and recruits Sun Wukong, Zhu Bajie, and Sha Wujing, who vow to protect him in exchange for their spiritual redemption.

Their journey is fraught with peril, encountering a series of demons and monsters intent on capturing Tang Sanzang for their own gain. Each challenge tests the group’s resolve, faith, and unity, with Sun Wukong’s quick wit and might often saving the day. Despite their differences and the difficulties they face, the pilgrims learn valuable lessons in compassion, patience, humility, and perseverance. These trials serve not only as physical obstacles but as spiritual tests, refining each disciple’s character and strengthening their bonds.

The pilgrimage is marked by significant trials, from battling the fiery Red Boy and outsmarting the cunning Spider Demons to navigating the treacherous Flaming Mountain and the illusion-filled Tenfold Maze. Each ordeal brings them closer together, teaching them the importance of teamwork, sacrifice, and the pursuit of enlightenment.

Upon reaching the West and passing the final tests set by the Buddha, Tang Sanzang and his disciples are granted the scriptures. Their return to the Tang Empire is triumphant, with each disciple achieving enlightenment and recognition for their service. The sacred texts they bring back promise a new era of spiritual awakening for their homeland.

- Loyalty and Devotion: The loyalty of Sun Wukong, Zhu Bajie, and Sha Wujing to Tang Sanzang is a central theme that underscores the importance of fidelity in the face of adversity. Their unwavering commitment to protect their master and ensure the successful retrieval of the sacred scriptures speaks to the value of loyalty in achieving a higher spiritual purpose.

- Perseverance through Trials: The pilgrims’ journey is fraught with challenges that test their resolve, faith, and endurance. Each trial, whether it be a confrontation with demons or overcoming natural obstacles, symbolizes the inner struggles individuals face on their path to enlightenment.

- The Quest for Enlightenment: At its heart, “Journey to the West” is a spiritual odyssey that mirrors the Buddhist path to enlightenment. The journey to retrieve the scriptures symbolizes the pursuit of wisdom and understanding, essential for liberation from suffering and the cycle of rebirth. The transformations of the characters, especially the disciples, reflect the individual’s journey toward enlightenment, marked by self-discovery, repentance, and spiritual growth.

- The Battle between Good and Evil: The frequent encounters with demons and the celestial trials faced by Tang Sanzang and his disciples embody the eternal struggle between good and evil. This theme is not only external, in the battles with literal demons, but also internal, representing the moral and spiritual conflicts within each character.

- Characters as Symbolic Archetypes: The main characters of “Journey to the West” are rich in symbolic significance. Sun Wukong, with his rebellious nature and transformative journey, symbolizes the untamed mind and the potential for enlightenment through discipline and self-cultivation. Zhu Bajie represents human desires and flaws, highlighting the struggles and potential for redemption despite one’s imperfections. Sha Wujing embodies steadfastness and humility, qualities essential for spiritual progress.

- Events as Metaphors for Spiritual Lessons: Many of the events and trials encountered by the pilgrims are metaphors for spiritual lessons. For example, the crossing of the Flaming Mountain can be seen as a metaphor for overcoming the burning passions and attachments that hinder spiritual growth. The encounters with various demons can represent the overcoming of personal obstacles on the path to enlightenment.

- The Journey Itself: The journey to the West is symbolic of the Buddhist path towards enlightenment. It is fraught with difficulties and distractions, much like the spiritual journey of an individual.

Moral Lessons

- Redemption and the Potential for Change : The characters of “Journey to the West,” especially the disciples of Tang Sanzang, embody the theme of redemption and the belief in the potential for change. Sun Wukong, Zhu Bajie, and Sha Wujing, each banished for their transgressions, find in their journey an opportunity for transformation. Their willingness to protect Tang Sanzang and endure hardships for the sake of obtaining the sacred scriptures illustrates the possibility of redemption, regardless of past misdeeds. This reflects the Buddhist concept of karma and the idea that positive actions can counteract negative past actions, leading to spiritual growth and liberation.

- Virtue and Moral Integrity : Throughout the novel, Tang Sanzang serves as a moral compass, embodying virtue and moral integrity. His compassion, patience, and unwavering commitment to non-violence, even in the face of danger, highlight the importance of upholding one’s principles. Tang Sanzang’s interactions with demons, often opting for understanding and conversion rather than conflict, reinforce the novel’s message that compassion and wisdom are more powerful than force.

- The Pursuit of Knowledge and Enlightenment : “Journey to the West” places great emphasis on the pursuit of knowledge and enlightenment, both as a personal quest and for the benefit of others. The journey to obtain the Buddhist scriptures symbolizes the quest for spiritual knowledge and truth. This quest is not portrayed as easy or straightforward but rather as a path filled with obstacles that require perseverance, sacrifice, and moral fortitude to overcome.

- Humility and Self-Cultivation : Finally, “Journey to the West” teaches the importance of humility and self-cultivation. The characters, particularly Sun Wukong, learn to temper their pride and recognize their limitations. This humility, coupled with a commitment to self-improvement and spiritual cultivation, is portrayed as essential for growth and enlightenment. The novel thus conveys the moral lesson that true strength and wisdom come from understanding oneself, acknowledging one’s flaws, and striving for self-betterment.

SHARE THIS POST

Read this next.

15 Incredible Things to Do in Dhaka | Ultimate Travel Guide

Secrets of Giza | The Pyramids, Astronomy & Other Fun Facts

13 Spheres of the Fruit of Life Symbolism | Sacred Geometry

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Hi, I’m Brandon

A conscious globe-trotter and an avid dreamer, I created this blog to inspire you to walk the Earth.

Through tales of travel, cultural appreciation, and spiritual insights, let’s dive into the Human Experience.

RECENT ARTICLES

10 Fantastic Things to Do in Lalitpur, Nepal | Travel Guide

The Seven Subtle Bodies | A Deep Dive

15 Incredible Things to Do in Kathmandu | A Travel Guide

Popular articles.

8 Fun Ways to Practice Wu Wei | The Art of Effortless Action

What is Sacred Geometry? Learn from 12 Examples

15 Exciting Things to Do in Colombo, Sri Lanka

Why is Pali Important? | Learn the Origin, History & Secrets

Subscribe for the latest blog drops, photography tips, and curious insights about the world.

© 2023 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

- Destinations

- Privacy Policy

Want to get in touch? Feel free to fill in the form below or drop me an e-mail at [email protected]

"Journey to the West" Summary

By Wu Cheng'en

classics | 2346 pages | Published in NaN

First published in 1952, The Journey to the West, volume I, comprises the first twenty-five chapters of Anthony C. Yu's four-volume translation of Hsi-yu Chi, one of the most beloved classics of Chinese literature. The fantastic tale recounts the sixteen-year pilgrimage of the monk Hsüan-tsang (596-664), one of China's most illustrious religious heroes, who journeyed to India with four animal disciples in quest of Buddhist scriptures. For nearly a thousand years, his exploits were celebrated and embellished in various accounts, culminating in the hundred-chapter Journey to the West, which combines religious allegory with romance, fantasy, humor, and satire.

Estimated read time: 4 min read

One Sentence Summary

A Buddhist monk and his companions embark on a pilgrimage to obtain sacred scriptures, encountering supernatural beings and obstacles along the way.

Table of Contents

Introduction, brief synopsis, main events, main characters, themes and insights, reader's takeaway.

"Journey to the West" is a classic Chinese novel written by Wu Cheng'en during the Ming Dynasty. It is one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature and is based on the real-life pilgrimage of the Buddhist monk Xuanzang to India in the 7th century. The novel is a blend of fantasy, adventure, and spiritual enlightenment, and has been widely adapted in various forms of media, including TV series, films, and video games.

Plot Overview

The novel follows the adventures of the monk Xuanzang as he travels to India in search of Buddhist scriptures. Along the way, he is accompanied by three disciples: Sun Wukong, the Monkey King; Zhu Bajie, the Pig Demon; and Sha Wujing, the Friar Sand. Together, they encounter numerous challenges and adversaries, including demons, monsters, and gods, as they journey across different lands and overcome various obstacles.

The story is set in ancient China and India, with the journey taking the characters through diverse landscapes, from bustling cities to treacherous mountains and mystical realms. The novel is rich in mythical elements, featuring a wide array of supernatural beings and magical creatures that inhabit the fantastical world the characters traverse.

The Buddhist monk and protagonist of the story, Xuanzang is on a mission to retrieve sacred Buddhist scriptures from India.

Also known as the Monkey King, Sun Wukong possesses incredible strength, magical abilities, and a mischievous nature. He is fiercely loyal to Xuanzang.

Zhu Bajie, or Pigsy, is a former celestial marshal who was banished to the mortal realm and transformed into a half-human, half-pig creature. He is known for his gluttony and laziness.

Sha Wujing, also called Friar Sand, is a former celestial general who was exiled to the mortal realm and turned into a river ogre. He is the most obedient and humble of Xuanzang's disciples.

The Quest for Enlightenment

The novel explores the theme of spiritual enlightenment, as Xuanzang and his disciples face numerous trials and tribulations on their journey to obtain the Buddhist scriptures. Each character undergoes personal growth and transformation, learning valuable lessons along the way.

Loyalty and Friendship

The bond between Xuanzang and his disciples, particularly Sun Wukong, exemplifies the enduring values of loyalty and friendship. Despite their differences and conflicts, the characters remain steadfast in their commitment to each other.

Overcoming Adversity

As the travelers encounter various challenges, including powerful adversaries and natural obstacles, the novel emphasizes the importance of resilience, determination, and resourcefulness in overcoming adversity.

"Journey to the West" offers readers a captivating blend of mythical adventure, moral lessons, and profound insights into the human experience. The novel's enduring appeal lies in its timeless themes, colorful characters, and the epic scale of the journey, which continues to resonate with audiences across generations.

"Journey to the West" is a literary masterpiece that has left an indelible mark on Chinese culture and literature. Its enduring popularity and cultural significance make it a must-read for anyone interested in classic literature, mythology, and spiritual quests. Through its vivid storytelling and rich symbolism, the novel continues to inspire and entertain readers around the world.

Journey to the West FAQ

What is the genre of 'journey to the west'.

Journey to the West is a classic Chinese novel that falls into the genres of mythology, fantasy, and adventure.

Who is the author of 'Journey to the West'?

The author of 'Journey to the West' is Wu Cheng'en, a Chinese novelist and poet.

What is the main storyline of 'Journey to the West'?

The novel follows the adventures of the monk Xuanzang and his disciples, including the Monkey King, as they journey to India to obtain Buddhist scriptures.

Is 'Journey to the West' based on a true story?

While the novel is based on the historical journey of the Buddhist monk Xuanzang, it incorporates elements of mythology and fantasy, so it is not a strictly true story.

What are the major themes in 'Journey to the West'?

Some major themes in 'Journey to the West' include the journey of self-discovery, the pursuit of knowledge and enlightenment, and the importance of friendship and loyalty.

Books like Journey to the West

By James Joyce

One Hundred Years of Solitude

By Gabriel García Márquez

Don Quixote

By Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra

The Great Gatsby

By F. Scott Fitzgerald

Journey to the West: Volume I

85 pages • 2 hours read

The Journey to the West: Volume I

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more. For select classroom titles, we also provide Teaching Guides with discussion and quiz questions to prompt student engagement.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Chapters 1-5

Chapters 6-10

Chapters 11-15

Chapters 16-20

Chapters 21-25

Character Analysis

Symbols & Motifs

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Chapters 21-25 Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Chapter 21 summary.

Pilgrim fights the wind demon for many rounds. He uses his favorite transformative trick: He plucks out hairs, blows on them, and commands them to change; they each change into doppelgängers of himself. To counter this, the demon summons a hurricane that takes control of all the little monkeys and flings them around. There is only one who can subdue the demon: a bodhisattva named Lingji of Sumeru. Lingji defeats the demon, who reverts to its true form: a brown marten. Pilgrim is about to vanquish the brown marten when Lingji stops him and explains that Tathāgata must see the little rodent. The creature had stolen pure oil and fled because he feared he would get in trouble, and then turned into a demon. Pilgrim and Eight Rules can then rescue Tripitaka.

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,700+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,850+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Chapter 22 Summary

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By these authors

Monkey: A Folk Novel of China

Wu Cheng'en, Transl. Arthur Waley

Featured Collections

Chinese Studies

View Collection

Good & Evil

Order & Chaos

Pride & Shame

Screen Rant

Summer house: are west wilson & ciara miller still together.

Your changes have been saved

Email Is sent

Please verify your email address.

You’ve reached your account maximum for followed topics.

20 Best Reality TV Shows Right Now

Lpbw’s matt roloff reveals where he stands with ex-wife amy, why the golden bachelor gerry turner should have picked leslie fhima.

- West Wilson and Ciara Miller's relationship blossomed on Summer House, with on-camera chemistry and a slow-paced courtship.

- Their wholesome dynamic stands out among the drama of unhappy housemates in Summer House season 8.

- While signs suggest they are together, Ciara's recent revelation has sparked speculation about the status of their relationship.

West Wilson and Ciara Miller's showmance blossomed during Summer House season 8, but did the couple stay together after cameras stopped rolling? West and Ciara's relationship has taken place almost entirely on camera. Like many young New Yorkers, Ciara, West, and several of their friends rent a weekend house together in the Hamptons every summer. The pair met on camera during the first official weekend of the summer; they hit it off instantly and had immediate chemistry. They spent the rest of the summer being adorable as their relationship transitioned from friendship to something more.

The wholesome start to their courtship was a lovely contrast to the relationship dramas of some of their housemates during Summer House season 8. Married couple Kyle Cooke and Amanda Batula fought all season long, while Lindsay Hubbard and Carl Radke broke off their engagement right before their wedding. Among all the unhappy couples, Ciara and West are like a beacon of happiness in a vast abyss of heartache .

Reality TV is more popular than ever. With so many to choose from, here are some of the best reality TV shows to stream or watch right now.

Who Are West Wilson & Ciara Miller?

The beauty & the nice guy.

Ciara is a 28-year-old former nurse who recently embarked on an already promising modeling career . Ciara made her television debut during Summer House season 6, and returned for season 7 and season 8. She also appeared on the Summer House spin-off series, Winter House , for two seasons, where she met and began a relationship with Southern Charm star Austen Kroll.

After Austen broke Ciara's heart, fans were hoping she'd finally meet a nice guy.

West, a 28-year-old sportswriter, is the quintessential nice guy , so fans were excited when he and Ciara hit it off. Ciara wanted to take the relationship slowly, and West respected her wishes every step of the way. The Summer House newcomer has supported Ciara's commitment to her budding modeling career throughout the season, even if her success would mean she wouldn't be around as much.

West & Ciara's Summer House Journey

Taking it nice & slow.

West and Ciara's chemistry was off the charts from the moment they met. At first, their relationship started in the kitchen of their shared Hamptons rental that they shared with mutual friends. The Summer House season 8 stars flirted as they cooked meals together. Things got more serious as the pair graduated from cooking together to cuddling in each other's beds . Later during the season, it was revealed Ciara and West were spending time together between weekends when they were back living their regular lives in New York City.

By the end of Summer House season 8, West was taking Ciara on dates and Ciara was jokingly referring to West as her boyfriend.

It hasn't been all smooth sailing. During Summer House season 8, episodes 12 and 13, Lindsay and Paige DeSorbo confronted West about him still talking to other women. West explained he has been respectful to Ciara but feels it wouldn't be wrong to stop talking to other women when Ciara still wants to continue to take things slow. Paige even threatened to " kill " West if he hurt Ciara .

Are West & Ciara Still Together?

Signs point to yes - and no.

Neither Ciara nor West have confirmed whether they're in a committed romantic relationship, but several signs point to yes. During an April appearance on Watch What Happens Live , Ciara confirmed to Andy Cohen that she had recently visited West's family in Missouri. “ His parents are amazing ,” Ciara said. “ His mom is so frickin smart and beautiful and his dad [is] hilarious, ” she added.

West appeared on the show a few weeks later and said his parents loved Ciara.

On the other hand, during a recent Page Six interview with Ciara and Paige posted on YouTube, Ciara made a revelation that led to speculation that she was no longer seeing West. Ciara claimed she had spent Valentine's Day with friends . It's possible this means she's no longer dating West, but it could also mean West was simply out of town for work. The status of Ciara and West's relationship will, hopefully, be explored in greater detail during the upcoming Summer House season 8 reunion.

Summer House airs Thursday at 9 p.m. EDT on Bravo and stream the next day on Peacock.

Sources: Page Six /YouTube

Summer House

*Availability in US

Not available

Beginning in 2017, Bravo’s Summer House centers on a group of friends who spend Memorial Day through Labor Day in a luxurious beach house. Their high-end lifestyle, mixed with drama-filled romances, made for a successful reality TV show that led to a spinoff called Winter House. Series regulars include Kyle Cooke, Lindsay Hubbard, and Carl Radke.

Lost in translation: Migrant kids struggle in segregated Chicago schools

Yennifer Ruiz walks her daughter Gabriela, 12, — both from Venezuela — to school most days in their South Shore neighborhood, as seen on April 10, 2024. (Colin Boyle / Block Club Chicago)

Sign up for Chalkbeat Chicago’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the latest education news.

This story was reported and published in collaboration with Block Club Chicago. Sign up for their newsletters here.

Leer en español.

Gabriela Aquino Ruiz relies on a translation app to learn, but some of her teachers talk so fast in English, the software can’t keep up.

The soft-spoken 12-year-old, who speaks only Spanish, loves to read, but her school — Isabelle C. O’Keeffe School on Chicago’s South Side — doesn’t have books in her native language, and she’s struggling to make friends, she said.

Gabriela misses her school in Venezuela, where she and her family emigrated from in October.

“I want to learn,” she said in Spanish through a translator. “I feel frustrated when I get home.”

Gabriela is one of nearly 9,000 migrant students enrolled in Chicago Public Schools as of April. Many of those students are leaving shelters and finding housing that provides them much needed stability.

Gabriela’s family moved from a shelter in Little Village to an apartment in South Shore, the top neighborhood where families have resettled in Chicago through a state program that helps cover their rent, according to data obtained by Chalkbeat and Block Club Chicago through a Freedom of Information Act request.

But the promise of housing comes with a cost: Families are moving to more affordable neighborhoods that also are some of the city’s most segregated. As a result, students are landing in schools with little to no bilingual staff or support, according to data obtained through open records requests and more than 50 interviews with families, teachers and experts.

That has resulted in some students falling further behind in their studies, custodians taking on translation roles, and school leaders struggling to comply with a state requirement that they provide bilingual education if student enrollment meets certain thresholds.

The surge of new students, many of whom fled political and economic turmoil in Central and South American countries, is exposing the cracks in a school system that has for years struggled to fully comply with state and federal laws around bilingual education.

Even before buses carrying migrants began arriving in waves from Texas in 2022, Chicago’s public schools failed to fully comply with multiple internal and state audits related to bilingual instruction, documents show.

CPS schools that already had bilingual programs have fallen short of a range of requirements, such as providing bilingual instruction in core subjects to all students who need it, having properly certified teachers, and teaching students about their native country and culture. Now, a crop of additional schools that have enrolled waves of migrant students need to bolster staff.

“We are very concerned about those language deserts in the city … where there are no English learner services,” said Karime Asaf, the chief of the district’s Office of Language and Cultural Education, which oversees instruction for English learners.

As of March, at least 72 K-12 schools across the district had vacancies for bilingual staff or teachers certified to teach English as a new language, at least a quarter of which are in the top 10 neighborhoods where asylum-seeking families are moving.

District officials said creating bilingual programs and complying with audits require finding properly certified teachers, which has been a nationwide challenge. They pointed to newer efforts, such as recruiting existing CPS students to become teachers, but added that CPS needs more funding.

“There is always a need for additional support and improvements in the process, and we are working to secure more funding from the state and federal governments to support all of our students,” said CPS spokesperson Sylvia Barragan.

Asked why the district and city are still struggling to provide support to migrant students, Mayor Brandon Johnson told Chalkbeat and Block Club that asylum-seeking families are settling in “neighborhoods that have been historically disinvested,” which puts “pressure on that system that is already weighted,” referring to neighborhood schools that he believes lack adequate resources.

As a former middle school teacher and Chicago Teachers Union organizer, Johnson has called for investing more money in neighborhood schools.

In response to the rapid arrival of migrant students over the past two years, CPS opened a “welcome center” at Roberto Clemente High School and is working with the city and shelter staff to help families with school enrollment, officials said. The district is also trying to attract more bilingual educators and is prioritizing extra support for schools that have traditionally not served English learners, officials said.

But teachers say the district’s efforts haven’t translated into more resources on the ground, and migrant kids are missing out on vital instruction. At Laura S. Ward Elementary School on the West Side, which has gained dozens of English learners, a kindergarten teacher and two custodians are translating for the whole building.

“They were dropped at our doorstep, and we’re supposed to keep it moving, accept these children, educate them and keep it moving,” said Dewanda Watt, first grade teacher at Ward, one of dozens of schools CPS identified as lacking enough staff for English learners.

“There should’ve been a plan. There was no plan from Chicago Public Schools.”

Migrant families resettle on South and West sides

Like many migrants, Gabriela and her family left Venezuela for Chicago in October to escape the country’s socioeconomic and political turmoil, said Gabriela’s mother, Yennifer Ruiz.

The family lived in the Englewood Police District station for a few months before moving into a shelter in Little Village, a historically Mexican neighborhood. Ruiz enrolled her son and daughter in schools with Spanish-speaking staff: Eli Whitney Elementary School and Richards Career Academy.

But when the family moved about 13 miles southeast to an apartment in South Shore, Ruiz decided to switch her daughter to O’Keeffe, a mostly Black, low-income school that lacks bilingual resources but was close to home.

Like the Ruizes, one in 10 families seeking asylum have landed in the South Shore area through a state resettlement program called the Asylum Seeker Emergency Rental Assistance Program , according to data obtained by Block Club and Chalkbeat.

Run by the Illinois Housing Development Authority and the Illinois Department of Human Services in partnership with Catholic Charities, the rental assistance program covers three months of rent for people migrating from the southern border who are seeking asylum and arrived in the city’s shelters before Nov. 17, 2023. It is the city’s main strategy to get families into permanent housing once they leave shelters.

Data show nearly 60% of the roughly 5,000 families using the program to resettle in Chicago are finding housing in predominantly Black, low-income communities on the South and West sides — historically neglected neighborhoods with schools that don’t serve many English language learners and often don’t have staff certified to teach those students.

Through the state program, families can choose where to live, and “ultimately, low rental cost is what drives selection,” said Daisy Contreras, a spokesperson for the Illinois Department of Human Services.

State law requires schools to launch bilingual programs — instruction in English and a child’s native language — when they enroll 20 or more English learners who speak the same native language. Schools must also teach students about their native country’s history and culture.

But as families leave shelters and find housing in relatively cheap, segregated neighborhoods, they’re encountering segregated schools that suffer from years of declining enrollment and inadequate resources, much less fully-staffed bilingual programs.

This was the case for Nathaly Garcia when she recently moved out of a downtown shelter to a three-bedroom apartment in South Shore with rent covered by the state program. Her 11-year-old son, Santiago, had enrolled at Ogden International School in the Gold Coast and moving meant their commute time would triple.

But Garcia didn’t want to enroll her son in the school near the new apartment because she had heard bad things about it and felt the school’s reading and math test scores were not high enough, she said.

Even after families leave shelters, their children are legally entitled to stay in the school where they originally enrolled because the district’s guidelines classify those students as homeless, providing them with certain federal protections.

So Garcia and her son now take two buses an hour and a half each way to continue at Ogden. Garcia said no one told them they could apply for yellow bus service.

In Yennifer Ruiz’s case, no one explained that her daughter had a legal right to stay at Eli Whitney, the school the girl went to when they lived in the Little Village shelter, she said. In fact, when Ruiz showed Eli Whitney staff where she was moving, they said she would be “too far” outside of the attendance boundaries, she said.

District officials said they help families enroll in or transfer to other schools that are not in their neighborhood, but may have better resources, such as bilingual programs. Asaf said migrant families, like all Chicago families, can choose where to send their children to school.

“They’re individual, independent residents of the city,” Asaf said, adding that the district gets in touch with principals “the moment we hear school calls for support.”

O’Keeffe’s principal has requested help from the district, and Gabriela has recently started learning English through an after-school program, Ruiz said.

The school district spokesperson said O’Keeffe recently enrolled enough English learners to warrant a bilingual program, and the school has been approved to hire a part-time teacher to work with those students.

Still, Yennifer Ruiz is saving up so the family can move out of the neighborhood and closer to a school that better serves her daughter, she said.

‘We have to build a program from the bottom up’

Ward Elementary School is in West Humboldt Park, a neighborhood that has affordable housing and sees a high number of drug and gun crimes. Nearly all of the school’s students are Black and come from low-income families.

Data show nearly 140 families have resettled in the Humboldt Park area through the state program.

After years of declining enrollment, Ward’s numbers stabilized this school year as migrant families found apartments near the school, said Watt, the school’s first-grade teacher.

Watt now has nine new students from Venezuela and Ecuador. But like other adults at Ward, she doesn’t speak Spanish. The elementary school has dozens of English learners, but no bilingual teachers or bilingual program, according to Watt and preliminary enrollment data.

It’s an “overwhelming” predicament, Watt said. Before this year, Watt, a teacher for 25 years, had never taught non-English-speaking students.

A CPS audit of Ward last April found the school, which had about 20 English learners at the time, wasn’t providing required instruction to all kids learning English and lacked enough certified staff, according to documents obtained by Chalkbeat and Block Club.

Ward is one of 72 K-12 schools CPS identified with vacancies for staff certified to teach ESL or bilingual classes as of April, according to district data. That excludes the district’s Virtual Academy. An ESL certification doesn’t mean the teacher speaks another language — just that they’re certified to teach ESL classes.

Those schools have seen the number of English language learners increase by an average of more than 40% this school year, according to a Chalkbeat and Block Club analysis of preliminary enrollment data.

Earlier this year, Ward enrolled enough English language learners to warrant a bilingual program and is now working to establish one, according to a district spokesperson. The school was approved in October to hire a part-time teacher position to work with English learners and can hire for a full-time position next year now that the school has enrolled more than 50 English learners, a CPS spokesperson said.

Currently at Ward, Watt and other teachers rely on Spanish-speaking staff who don’t have bilingual credentials — the kindergarten teacher and two custodians — to help them communicate with migrant students and families seeking help with school applications.

For a while, the kindergarten teacher was getting pulled out of her classroom up to five times a day to translate, she said. The district gave teachers translation devices, but Ward teachers said they don’t always function properly and are not a substitute for speaking the language.

The kindergarten teacher, who did not want to be identified because she wasn’t authorized to speak to the press, said she’s torn between her teaching responsibilities and her unofficial job as school translator. Watt said some of her migrant students are progressing academically, but others are struggling to understand their classwork and learn English.

“Some [teachers] are in schools where the [bilingual] program is already up and running; they’re just continuing on. As opposed to us, where we have to build a program from the bottom up,” the kindergarten teacher said.

Asaf, the head of the district’s Office of Language and Cultural Education, said CPS has been opening teaching positions for schools that are enrolling many more English learners. She acknowledged that help may not come right away, and it takes time to build bilingual programs.

“It’s not always easy and it’s not always immediate and it’s not always fast,” Asaf said. “This is a big district, and we are constantly paying attention to the number of [English learners] we have.”

A history of failing bilingual students

This is not the first time Chicago has been under scrutiny for how it serves students learning English.

In 1980, a federal consent decree forced CPS to come up with a plan to desegregate schools and to ensure English language learners were receiving an adequate amount of support. The decree had to be updated twice, in part because the district was failing to provide enough staffing and materials for English learners.

Schools are responsible for screening their students to determine which of them are learning English as a new language. Those students are legally entitled to additional support, such as specialized English instruction.

In addition to state requirements for bilingual programs, schools with 19 or fewer English language learners must have a program known as Transitional Point of Instruction, which teaches students in English. It’s not clear how many CPS schools are now required to have bilingual programs but don’t have them yet.

Segregation can play a large role in whether schools have bilingual support for students.

Chicago’s immigrants have always settled in neighborhoods with people who share their ethnicity or native language, said Jim Lewis, senior research specialist for Great Cities Institute at the University of Illinois at Chicago, who has studied segregation.

But some of Chicago’s recent Latin American newcomers, such as Venezuelans, do not have enclaves, Lewis said. Also, many historically Latino neighborhoods have become unaffordable for families who don’t have a stable income, potentially driving today’s newcomers to segregated neighborhoods that have been long ignored.

To get an apartment under the state program, families have to find a landlord who will participate in the program or get matched with one through Catholic Charities. The only stipulation is rent must be affordable, said Catholic Charities spokeswoman Emily Dagostino.

Catholic Charities is not involved in the school enrollment process, Dagostino said.

District officials said CPS works with the city’s Department of Family and Support Services, shelters and principals to help families enroll in school, and Asaf, the head of the district’s Office of Language and Cultural Education, emphasized that families have options.

But the district’s practice of helping families enroll in schools outside their neighborhoods doesn’t “follow the spirit” of what CPS says it aims to provide: equal access to quality neighborhood schools, said Jesse Ruiz, former interim CPS CEO and Chicago Board of Education vice president.

Ruiz led the charge to audit all of the district’s bilingual and ESL programs in 2015 . That school year, 71% of schools audited were in serious violation of state requirements for bilingual education, the Chicago Reporter found at the time .

The issues have persisted.

During the 2021 school year — before buses from Texas began arriving — the Illinois State Board of Education put CPS on what’s called a “corrective action plan” after officials determined the district was out of compliance with bilingual education requirements, said Lindsay Record, a spokesperson for the board.

In a follow-up visit last year, the state found several improvements. But the district still failed to have bilingual programs at all schools that were supposed to have them, as well as enough certified teachers, according to corrective action plan documents.

Ruiz, also a former chairman of the Illinois State Board of Education, said he understands why under-resourced schools haven’t had bilingual programs if they didn’t historically serve English learners.

“But now they have these students, and that’s what the law says, that you have to provide bilingual education services to those students,” Ruiz said. “The district is going to have to provide those resources.”

‘It was a long journey’

Maria, a Venezuelan migrant who came to Chicago last summer, moved from a downtown shelter this February to an apartment in South Shore through the state’s rental assistance program. Block Club and Chalkbeat are using a pseudonym for Maria out of concerns for her family’s safety.

After the move, the family struggled to enroll their 8-year-old daughter in school. The first school noted that it lacked bilingual staff, and they were turned away from a second school for living outside of attendance boundaries, Maria said.

Desperate for another option, Maria’s family sought help from the Welcome Center at Clemente High School , where a staffer directed them to Erie Elementary Charter School, a dual-language school in Humboldt Park 90 minutes away via public transit from their South Shore apartment.

The long commute to Erie wasn’t easy, but Maria said it was worth it because her daughter was learning more English and “engaging in conversations.” Her daughter left Erie recently when the family moved to the suburbs.

Many of Erie’s 49 newcomer students are coming from all over the city, said Carlos Perez, the school’s executive director.

Erie is better-equipped than other schools to serve native Spanish speakers learning English. As one of 43 dual-language schools in the city , Erie teaches English learners and native English speakers in Spanish and English. Eight of Erie’s teachers are from Latin American countries, Perez said.

“It was a long journey that a lot of them have gone through to get to us. This was their target: to bring their kids to a school in America ... There’s a weight and responsibility that comes with it,” Perez said.

Even with those resources, teachers face big challenges. Most migrant students come to Erie more than two grade levels behind, and some haven’t attended formal school for up to two years, Perez said. In 2022, Erie was out of compliance with bilingual and ESL program requirements, according to the school’s most recent CPS audit.

Multiple principals questioned whether the audits are effective. Perez said one teacher who they consider effective is not certified to teach English learners — one reason the school is out of compliance.

“Are we aiming for compliance, or are we aiming to get good people in front of students who can educate them?” Perez said. “Oftentimes, those are not interchangeable things.”

According to CPS, it has about 7,500 teachers who are certified to teach bilingual classes, ESL or both — a figure that has grown in recent years. Many teachers certified to teach those classes are in regular teaching positions, a spokesperson said.

District officials said they’ve tried to attract more bilingual teachers by subsidizing the cost of earning bilingual or ESL endorsements and extending early job offers to teachers who are completing their requirements. But it’s difficult to fill teaching positions midway through the year, said Ben Felton, the district’s chief talent officer.

Felton said “we simply don’t have the talent” for every school to have big bilingual programs “because historically there haven’t been as many bilingual students in these schools.”

One child is thriving, another is ‘just stuck’

While Yennifer Ruiz switched Gabriela’s school after moving to South Shore, she opted to keep her 16-year-old son, Gabriel, at Richards Career Academy, which has a bilingual program.

After just five months in Chicago, Ruiz said she has seen how those bilingual resources have helped Gabriel thrive — he is rapidly learning English and even joined the school’s baseball team — and how the lack of services has left Gabriela feeling lost at school.

Gabriela wishes she could go back to Eli Whitney, where she liked being able to communicate with her teachers and other kids, she said.

“I feel really bad because all the objective of moving here was to get quality of life,” Ruiz said in Spanish through a translator. “I know how my son is getting to his maximum potential, but she is just stuck.”

Interviews with Spanish- speakers were conducted with translation help from Yoha Salmeron Chaparro, an intern at the Center for Immigrant and Refugee Accompaniment at Loyola University, and Alex Hernandez, a reporter for Block Club Chicago.

Reema Amin is a reporter covering Chicago Public Schools. Contact Reema at [email protected] .

Mina Bloom is an investigative reporter for Block Club Chicago. Contact Mina at [email protected].

TCU Horned Frogs

West Virginia Mountaineers

Game information, scoring summary, thompson and hewett reveal vandy's winning formula, tears seals tennessee's survival with a three-run bomb vs. texas a&m, thompson sets stage for vandy win over ms state.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Disney Ad Sales Site

- Work for ESPN

- Corrections

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

The journey to the west: a platform for learning about china past and present.

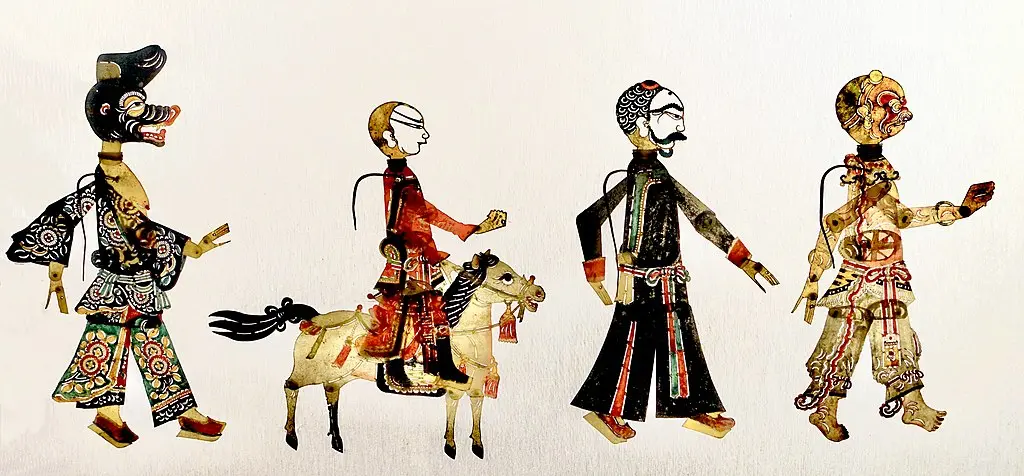

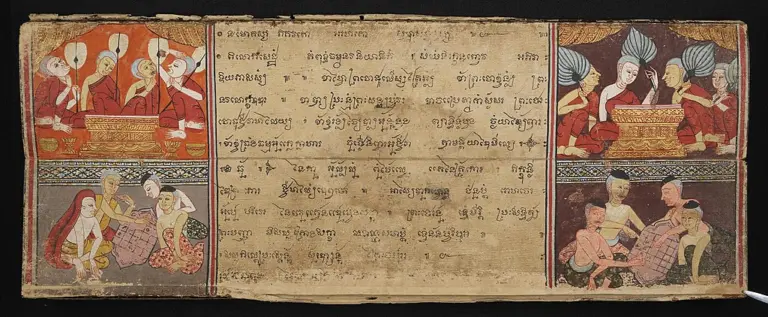

In US college students’ first course on China, the challenge for instructors is to pack the maximum amount of punch into the experience so that the course will inspire them to seek more opportunities to learn about China at and beyond the college level. One way to achieve this goal is to use a rich text with many applications to help students unpack the complexities of Chinese history, language, politics, economics, and thought. For this purpose, the sixteenth-century novel The Journey to the West, with its many incarnations, is ideal. 1 It features a rousing adventure story, which can be read as historical fiction, political satire, and religious allegory. The novel has been reproduced for many types of audiences in many different media, including children’s books, puppet shows, operas, comics, TV series, and movies; each version is different enough to allow instructors to discuss them in the context of important Chinese historical events and cultural elements. Because well-told stories help us make sense of the world, instructors can use this novel as a foundational element to facilitate students’ connections with and between the various elements of the course. In this article, we show how The Journey to the West and its multiple incarnations can be used to help students unpack the complexities of China as a subject and develop a critical awareness or appreciation for a culture different from their own. We first show how the story may be introduced in a way that sets students’ minds for embracing the immense complexity of humanity and Chinese culture. Then, we show how various elements and incarnations of the story can be used to facilitate discussions about some outstanding aspects of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Maoist China (1949–1976), and postreform Communist China.

A Glance at The Journey to the West

Developed into its full length in the sixteenth century, the 100-chapter novel The Journey to the West (The Journey hereafter) is believed to have its historical basis in the epic pilgrimage of the monk Xuanzang (c. 596–664) to India and has been a popular subject for storytellers since the late Tang dynasty. The fictionalized pilgrimage as depicted in the novel sees Xuanzang accompanied by four nonhuman disciples: Monkey, Pigsy, Sandy, and Dragon Horse. The four disciples have been expelled by the Daoist Celestial Court (i.e., Heaven) due to misbehaviors, but will beaccepted by the Bodhisattva Guanyin (AKA the Goddess of Mercy) into Buddhism on condition that they promise to assist Xuanzang’s pilgrimage.

The mischievous Monkey character and his dedicated master Xuanzang have the central roles in the novel, and the first thirteen chapters establish the backstories of how the two became destined for the journey. The exciting part of the tale begins in chapter 14, when Xuanzang releases Monkey from a mountain and together they embark on a journey filled with the humor of Monkey’s mischievous battles against bandits and demons, interspersed with moments of Buddhist enlightenment. Starting here, students get a taste of the original novel and are introduced to the two main characters. A useful in-class exercise is to brainstorm words to describe the two characters. Through this activity, students come to understand the complexity and contrast of the characters’ personalities and why this dynamic is so important not only for the success of the story, but also metaphorically for understanding the complex nature of Chinese culture and society. For example, how have the three distinct and often-contradictory teachings—Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism—been able to operate relatively harmoniously in the lived religious experience of everyday Chinese? An understanding of how each individual has contradictory tendencies and how a story needs such individuals to be successful will set students’ minds for embracing the complexity of the topics to be discussed in the course, such as the various adaptations of Monkey and The Journey, and how they relate to different aspects of China.

Learning about Traditional China through The Journey

Written in the late Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and based on a true event during the Tang dynasty (618–907), The Journey offers the opportunity to introduce two of the “golden eras” in Chinese history. With almost 4,000 years of written history, there is a lot of Chinese history to potentially cover, but for a course that seeks to introduce China studies through multiple disciplinary lenses, a focus on the Ming dynasty, alongside the more recent events of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, may suffice. The chapter on the Ming in Patricia Ebrey’s Cambridge Illustrated History of China offers a vivid depiction of Ming society. 2 After reading the chapter and watching episodes 2 and 3 from the 1986 TV series of The Journey , students can quickly map the hierarchical structure of the court of the Ming government onto that of the Celestial Court in The Journey . 3 Students can also connect Monkey’s eagerness to seek a position in the Celestial Court with the civil service examination in the Ming dynasty. 4 From these connections, students can get a sense of China’s hierarchical social structure and its traditional emphasis on self-improvement through education. These connections serve as foundations for students to understand the historical continuities and differences when discussing the political structure and educational system of contemporary China.

The history of the Ming dynasty is also important because it is one of the wealthiest eras in China’s history and has some interesting correlations with contemporary China, such as both being periods of international economic interactions. Employing The Journey as a fictional account of history offers a unique opportunity for the correspondences and differences between traditional and contemporary China to be highlighted and analyzed.

The syncretism of the three major teachings of traditional China, namely Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism, culminated when Ming General and statesman Wang Yangming’s (1472–1529) teaching of “learning of the mind” became popularized in the empire. Inspired by Chan (Japanese, Zen) Buddhist philosophy, Wang emphasized that a true understanding of the essence of morality can only be achieved through cultivating one’s own mind, which means persistent personal enactment of moral principles. The Journey depicts the lived religious experience of everyday Chinese. To help appreciate the interplay of belief systems, students can read Asian Studies Professor Joseph Adler’s Chinese Religious Traditions , accompanied by some application exercises to highlight the distinct reasoning patterns of the three major teachings. Such application exercises might include asking students to play the roles of hardcore Confucianists, Daoists, and Buddhists, who are requested to comment on such phenomena as family reverence, gender roles, death, humanity, and the vicissitudes of life.

At this point, students begin to realize that the journey actually represents the ongoing effort to end attachment to worldly things such as fame and money, which often make the mind susceptible to moral corruption. Students will also be able to identify the Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist elements as they read other selected chapters from the novel and view other adaptations of the story, such as the movie Conquering the Demons . 5 Conquering the Demons is a fun movie to watch, and it presents a lively and modern interpretation of The Journey as Buddhist allegory. 6

The three major teachings and their syncretism should be included in an introductory course in their own right, but they also frame the Chinese worldview and inform people’s daily practices across much of East and Southeast Asia. A solid understanding can provide a useful lens for appreciating the perspectives and practices prevalent across the region. Further, discussing the three teachings offers the opportunity to remind students of the limitation of English translations of Chinese concepts, which is an important issue involved in cross-cultural studies. For example, the Chinese word zongjiao (the clan’s teaching), a compound that first appeared in Chinese translations of Buddhist sutras referring to different schools of Buddhist thoughts, has often been equated as religion and applied to Confucianism and Daoism. 7 Reflecting on what they have learned about traditional Chinese thought, students may discuss whether the three teachings, especially Confucianism, count as “religions” in the English sense.

The fact that novels like The Journey proliferated during the Ming dynasty reveals the advanced printing technology and expanded readership during the period. 8 This opens up a variety of different inquiries. For example, what kinds of books got printed? How was copyright handled? Who read the books? What social changes came with the printing technology? Questions like these lead students to discussions about various aspects of social life in the Ming, such as the role of media, censorship, literacy, leisure, and women’s education and social status. These topics could and should be revisited and expanded throughout the course. The roles of technology and media also provide a useful lens for understanding contemporary China.

Learning about Maoist China through The Journey

Maoist China refers to the period from the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 to the launch of the Reform and Opening Up initiative in 1978. 9 The founding of the PRC was celebrated by much of the nation at the time as a great victory of the Chinese people over the oppression from imperialism, feudalism, and bureaucratic capitalism. Mao Zedong, the national leader of China from 1949 until 1976, was given the status of perfect hero or “the people’s great savior” by his cadres. 10 Of course history proved that despite some positive reforms, Mao was, along with Stalin and Hitler, one the twentieth century’s most evil tyrants. It was in such historical context that the mischievous Monkey was transformed into a proletarian revolutionary hero, as depicted in the cartoon movie Havoc in Heaven (AKA The Monkey King) and several of its immediate antecedents in popular art forms and in print. 11 To facilitate the discussion of the cartoon movie, background readings may include chapter 3 of Hongmei Sun’s book Transforming Monkey, which reviews the various adaptations of Monkey’s story up to the Mao years and discusses how the Monkey character was then transformed from trickster to hero.

From the 1963 cartoon movie’s depiction of the officials in the Celestial Court, students can see a prevalent Communist Chinese view of the backwardness of the alleged Chinese feudal system and the corruption of elites. By comparing the storyline of this cartoon with either the two episodes they have watched from the 1986 TV series, which also emphasize the story of Monkey’s uproar in Heaven, or chapters 3 to 7 in the novel, students will notice how the changes to the details of the cartoon make Monkey almost entirely an innocent victim of the Celestial Court. The cartoon’s ending with Monkey’s victory over the celestial troops without being subjugated by Buddha is also an interesting point for discussion. It symbolizes the victory of the proletarian revolutionaries, while ignoring religion.

Since media resources about Maoist China abound both online and in print, instructors can provide students with a list of events during this period, such as the Korean War (1950–1953), the Great Leap Forward (1958–1963), the China–USSR border dispute in the late 1960s, and the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). Students can do research outside class and then present in class their analyses of why and how the events happened and were related. As a starting point, students should watch the documentary titled China: A Century of Revolution 1949–1976 on YouTube or read Clayton Brown’s EAA article, one of the most succinct and useful introductions to the Great Leap Forward. 12 The research and discussions should get students ready for the economic reformto come, which has been the direct cause of the economic boom that lifted hundreds of millions of Chinese out of abject poverty and a series of side effects, including corruption, environmental issues, and intensifying social inequality.

Learning about Postreform Communist China through The Journey

The launch of the Reform and Opening Up initiative by Deng Xiaoping (1904–1997) in 1978 marked a new era for China. Through a series of dramatic economic reforms and opening China’s economy to the outside world by 1980, this initiative transformed China into, until a few years ago, the world’s fastest-growing industrializing country and now the world’s second-largest economy. The famous Taiwanese cartoonist Tsai Chih-Chung’s comic version Journey to the West, first published in 1987, is an amusing way to introduce how the story was adapted to mock the popular social practices and perspectives during the early days of the economic reform. 13 The inclusion of this text allows instructors to remind students why The Journey remains relevant to China and Chinese peoples, as the numerous twentieth- and twenty-first-century adaptations demonstrate. It also offers a lighthearted insight into the impact of the economic reform period. Students may also read the first two chapters of Chinese–American journalist Leslie Chang’s Factory Girls and chapters from major contemporary Chinese author Yu Hua’s book China in Ten Words for vivid depictions of Chinese society during the economic boom, and discuss where China might go next.