Patient journey 101: Definition, benefits, and strategies

Last updated

22 August 2023

Reviewed by

Melissa Udekwu, BSN., RN., LNC

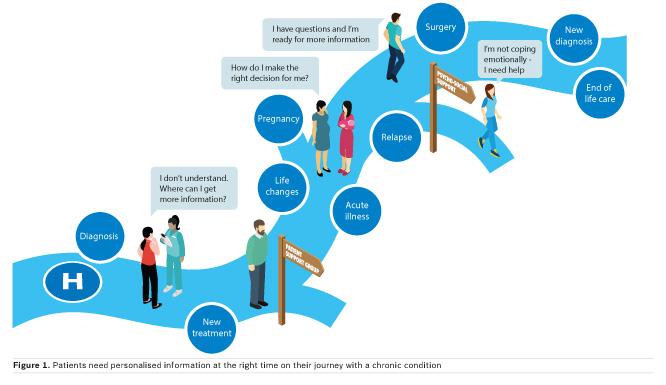

Today’s patients are highly informed and empowered. They know they have choices in their healthcare, which can put healthcare providers under a lot of pressure to provide solutions and meet their patients’ expectations.

Just like any customer, patients embark on a journey that begins before they ever contact the provider. This makes understanding the journey and where improvements can be made extremely important. Mapping the patient journey can help practitioners provide better care, retain a solid customer base, and ultimately identify ways to improve patient health.

- What is the patient journey?

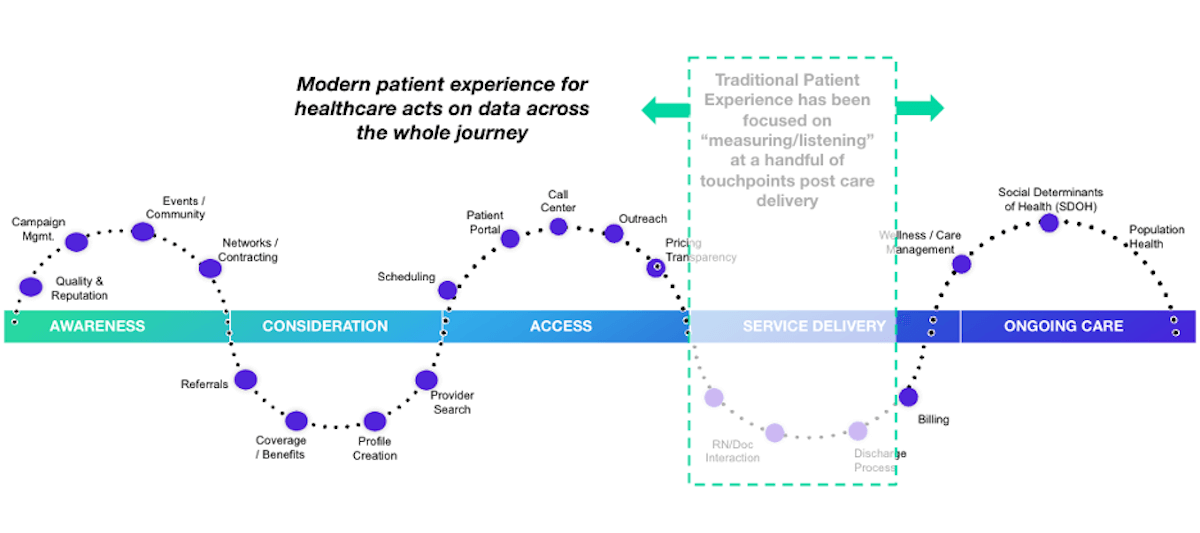

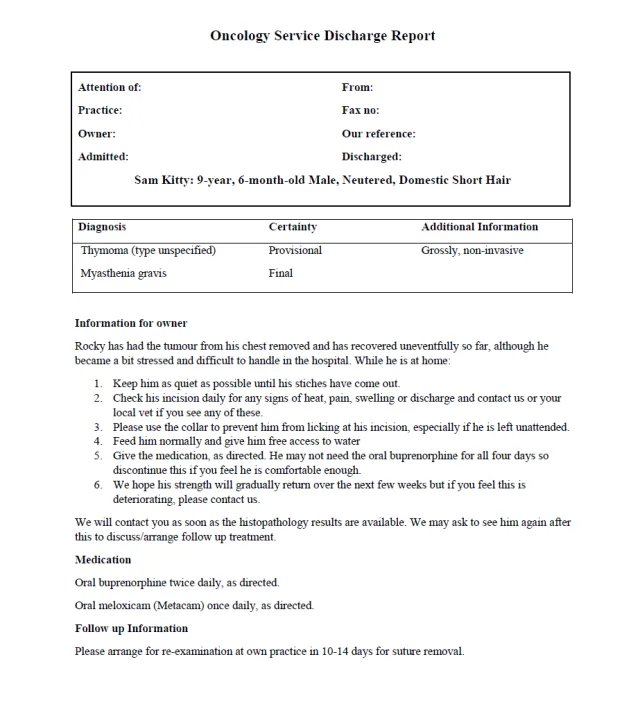

The patient journey is best described as the sequence of experiences a patient has from admission to discharge. This includes all the touchpoints between the patient and provider from beginning to end.

The patient journey continues through consultation, where they meet the potential caregiver. That portion of the journey includes interactions with a doctor and support staff, how long they wait to be seen, and the steps taken for diagnosis and treatment.

The patient’s post-care journey includes follow-ups from the healthcare provider, post-treatment care, and billing. For example, if the patient has questions about post-surgery care or how to read their invoice, how quickly their questions are answered and their problems resolved will impact their satisfaction.

Mapping the patient journey helps healthcare providers improve patient satisfaction at every step of the way. By collecting data at each stage and conducting an in-depth analysis, providers can identify patient concerns and make the necessary improvements to meet their patient satisfaction goals.

What is another name for the patient journey?

The term “patient funnel” describes the journey patients take from first learning about a healthcare provider or healthcare product to actually making an appointment or purchase. This “funnel” can be applied to any type of business, describing the stages a customer goes through to obtain a service.

- Understanding the stages of the patient journey

Each stage of the patient journey is essential to a positive patient experience . Gathering and analyzing data can alert healthcare providers to potential issues throughout the journey.

Data collection at each of the following stages will give healthcare providers the information they need to make the necessary improvements:

1. Awareness

Awareness is where the patient journey begins. This is when they first research symptoms and identify the need to see a medical professional.

They may consider at-home remedies and get advice from friends, social media, or websites. Once they identify the need for a healthcare provider, they continue their research via review sites, advertising campaigns, and seeking referrals from friends and family.

Determining the way patients become aware they need healthcare and the sources they use for research is important. The data collected at this stage could suggest your organization has an insufficient social media presence, inadequate advertising, or a website in need of an update.

To remedy these shortcomings, you might consider adding informational blogs to your website, performing a social media analysis, or closely monitoring customer reviews.

This stage in the patient journey is where the patient schedules services with the healthcare provider.

This engagement is essential for acquiring new patients and retaining current patients. Patients will contact you in several ways to schedule an appointment or get information. Most will call on the first attempt to schedule an appointment.

This is a crucial touchpoint in the journey. A new patient may become frustrated and move on if they find it difficult to access your services or are placed on hold for a long period or transferred numerous times.

Patient engagement occurs in other ways, such as your online patient portal, text messages, and emails. Your patients may interact differently, so it’s important to gather data that represents their preferred means of communication. Work to make the improvements required to correct access issues and ensure efficient communication.

The care stage can include everything from your patient’s interaction with the front desk to how long they have to wait in the examination room to see a doctor.

Check-in, check-out, admissions, discharge, billing, and of course, the actual visit with the healthcare provider are other touchpoints in the care stage.

There are a couple of ways to gather and analyze this data. Most organizations choose to analyze it holistically, even if it’s collected separately. For example, you might gather data about the patient’s interaction with the front desk, the clinical visit, and the discharge process, but you may want to analyze the care segment as a whole.

4. Treatment

Treatment may be administered in the office. For example, a patient diagnosed with hypertension may have medication prescribed. That medication is the treatment. Gathering information at this stage is critical to see how your patient views the healthcare provider’s follow-up or responses to inquiries.

In most cases, treatment extends beyond the initial clinical visit. For example, a patient might require additional tests to get a diagnosis. Providing the next steps to a patient in a timely manner and letting them know the test results is crucial to patient satisfaction .

5. Long term

A satisfied patient results in a long-term relationship and referrals to friends and family. Most of the data collected at this stage will be positive since the patient is continuing to use your services.

Gathering data after the treatment stage allows you to expand on the qualities that keep patients returning for your services in the long term.

- Benefits of patient journey mapping

The patient benefits from their healthcare provider understanding their journey and taking steps to improve it. Healthcare providers also reap several benefits, including the following:

1. Efficient patient care

When they understand the patient journey, healthcare providers can provide care more efficiently and spend less time and money on unnecessary, unwanted communications.

2. Proactive patient care

Proactive patient care is aimed at preventing rather than treating disease. For example, women who are over a certain age should have an annual mammogram, smokers may be tested for lung disease, and elderly women may need a bone density study. These preventative measures can help keep disease at bay, improve health outcomes, and build trust with patients.

3. Value-based patient care

Patients don’t want to feel they are being charged unfairly for their healthcare. Focusing on the individual patient promotes satisfaction and yields positive outcomes.

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has issued recent guidelines for participants that help offset the costs of high-quality care through a reward system.

4. Retention and referrals

Patients who are happy with their journey will keep returning for healthcare, and happy patients equal voluntary referrals. Many providers offer rewards to incentify referrals.

- How to get started with patient journey mapping

Follow the steps below to start the patient journey mapping process:

Establish your patient personas

Journey mapping is a great way to identify your patient’s characteristics so that their experience can be further enhanced.

Some of the following determinations can help you pinpoint your patient’s persona and establish protocols to provide a better service:

How do your patients prefer to communicate? Are they more comfortable with phone calls, texts, or other methods?

How are most patients finding your services? Are they being referred by friends or family members, or are they seeing advertisements?

Would the patient prefer in-person communication or telecommunication?

What are the patient’s expectations of care?

This data can be complex and widespread, but it can give you the information you need to more effectively and efficiently communicate with your patients.

Understand the entire patient lifecycle

Each patient is unique. Understanding the patient lifecycle can avoid confusion and miscommunication.

To positively engage the patient, you’ll need to gather data not only about communication methods but where they are in the patient journey, their health issue, and their familiarity with the healthcare provider’s procedures and treatment options.

Understand the moments of truth

With a few exceptions, most people seek healthcare services when they are ill or have a healthcare issue. These situations can cause patients to feel stressed and anxious. It’s these moments of interaction where compassion, knowledge, and understanding can provide relief and reassurance.

When patients see their healthcare provider, they are looking for solutions to problems. It’s the provider’s opportunity to identify these moments of truth and capitalize on them.

Get the data you need

Healthcare providers can collect vast amounts of data from patients, but the data collected rarely goes far enough in analyzing and determining solutions.

Your patients have high expectations regarding personalized treatment based on data. They want personalized, easy access to medical information and records, responsive treatments and follow-up, and communication in their preferred format.

You need more than clinical data to give patients what they want. You also need personal data that sets each patient apart and ensures a tailored experience.

For example, it might be challenging for parents of small children to contact the clinic and schedule appointments at certain times of the day. As a healthcare provider, you’ll need to be aware of the best times to contact this individual and offer simple methods for scheduling appointments.

Another example is patients with physical disabilities. You can take steps to improve their access to and experience at the healthcare facility.

Encourage referrals and loyalty

Although engagement on social media and online forums is becoming more and more common, the best way for new patients to find you is through referrals. Referrals stem from satisfactory experiences and trust.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 27 June 2023

Last updated: 22 July 2023

Last updated: 11 September 2023

Last updated: 10 October 2023

Last updated: 16 November 2023

Last updated: 28 September 2023

Last updated: 12 October 2023

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 3 July 2023

Last updated: 27 January 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 04 December 2019

“Patient Journeys”: improving care by patient involvement

- Matt Bolz-Johnson 1 ,

- Jelena Meek 2 &

- Nicoline Hoogerbrugge 2

European Journal of Human Genetics volume 28 , pages 141–143 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

24k Accesses

18 Citations

25 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cancer genetics

- Cancer screening

- Cancer therapy

- Health policy

“I will not be ashamed to say ‘ I don’t know’ , nor will I fail to call in my colleagues…”. For centuries this quotation from the Hippocratic oath, has been taken by medical doctors. But what if there are no other healthcare professionals to call in, and the person with the most experience of the disease is sitting right in front of you: ‘ your patient ’.

This scenario is uncomfortably common for patients living with a rare disease when seeking out health care. They are fraught by many hurdles along their health care pathway. From diagnosis to treatment and follow-up, their healthcare pathway is defined by a fog of uncertainties, lack of effective treatments and a multitude of dead-ends. This is the prevailing situation for many because for rare diseases expertise is limited and knowledge is scarce. Currently different initiatives to involve patients in developing clinical guidelines have been taken [ 1 ], however there is no common method that successfully integrates their experience and needs of living with a rare disease into development of healthcare services.

Even though listening to the expertise of a single patient is valuable and important, this will not resolve the uncertainties most rare disease patients are currently facing. To improve care for rare diseases we must draw on all the available knowledge, both from professional experts and patients, in order to improve care for every single patient in the world.

Patient experience and satisfaction have been demonstrated to be the single most important aspect in assessing the quality of healthcare [ 2 ], and has even been shown to be a predictor of survival rates [ 3 ]. Studies have evidenced that patient involvement in the design, evaluation and designation of healthcare services, improves the relevance and quality of the services, as well as improves their ability to meet patient needs [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Essentially, to be able to involve patients, the hurdles in communication and initial preconceptions between medical doctors and their patients need to be resolved [ 7 ].

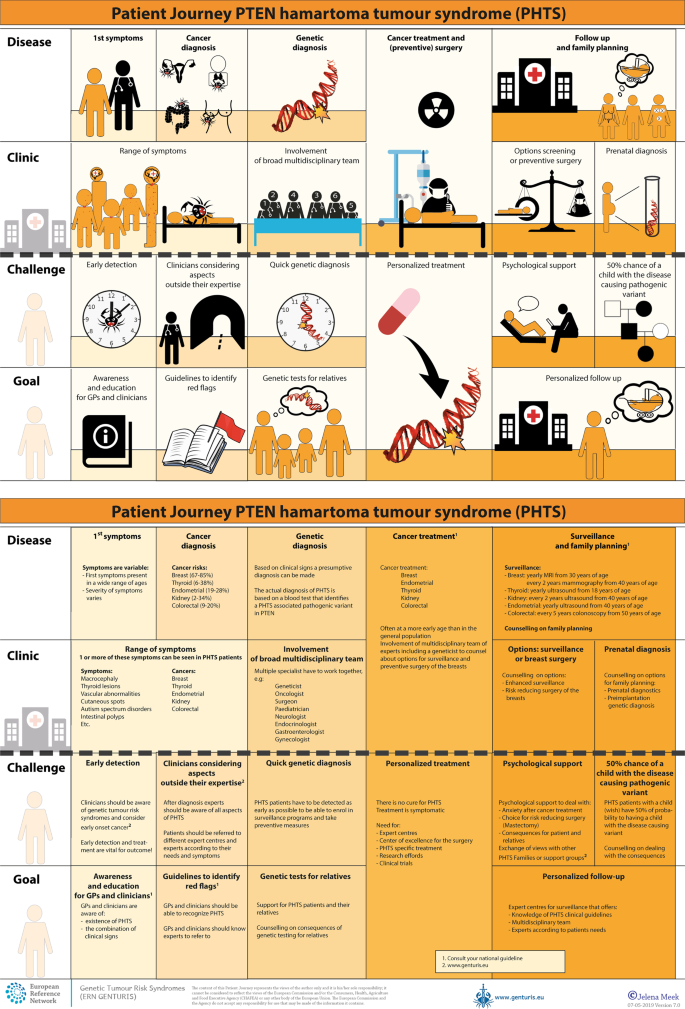

To tackle the current hurdles in complex or rare diseases, European Reference Networks (ERN) have been implemented since March 2017. The goal of these networks is to connect experts across Europe, harnessing their collective experience and expertise, facilitating the knowledge to travel instead of the patient. ERN GENTURIS is the Network leading on genetic tumour risk syndromes (genturis), which are inherited disorders which strongly predispose to the development of tumours [ 8 ]. They share similar challenges: delay in diagnosis, lack of cancer prevention for patients and healthy relatives, and therapeutic. To overcome the hurdles every patient faces, ERN GENTURIS ( www.genturis.eu ) has developed an innovative visual approach for patient input into the Network, to share their expertise and experience: “Patient Journeys” (Fig. 1 ).

Example of a Patient Journey: PTEN Hamartoma Tumour Syndrome (also called Cowden Syndrome), including legend page ( www.genturis.eu )

The “Patient Journey” seeks to identify the needs that are common for all ‘ genturis syndromes ’, and those that are specific to individual syndromes. To achieve this, patient representatives completed a mapping exercise of the needs of each rare inherited syndrome they represent, across the different stages of the Patient Journey. The “Patient Journey” connects professional expert guidelines—with foreseen medical interventions, screening, treatment—with patient needs –both medical and psychological. Each “Patient Journey” is divided in several stages that are considered inherent to the specific disease. Each stage in the journey is referenced under three levels: clinical presentation, challenges and needs identified by patients, and their goal to improve care. The final Patient Journey is reviewed by both patients and professional experts. By visualizing this in a comprehensive manner, patients and their caregivers are able to discuss the individual needs of the patient, while keeping in mind the expertise of both professional and patient leads. Together they seek to achieve the same goal: improving care for every patient with a genetic tumour risk syndrome.

The Patient Journeys encourage experts to look into national guidelines. In addition, they identify a great need for evidence-based European guidelines, facilitating equal care to all rare patients. ERN GENTURIS has already developed Patient Journeys for the following rare diseases ( www.genturis.eu ):

PTEN hamartoma tumour syndrome (PHTS) (Fig. 1 )

Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC)

Lynch syndrome

Neurofibromatosis Type 1

Neurofibromatosis Type 2

Schwannomatosis

A “Patient Journey” is a personal testimony that reflects the needs of patients in two key reference documents—an accessible visual overview, supported by a detailed information matrix. The journey shows in a comprehensive way the goals that are recognized by both patients and clinical experts. Therefore, it can be used by both these parties to explain the clinical pathway: professional experts can explain to newly identified patients how the clinical pathway generally looks like, whereas their patients can identify their specific needs within these pathways. Moreover, the Patient Journeys could serve as a guide for patients who may want to write, in collaboration with local clinicians, diaries of their journeys. Subsequently, these clinical diaries can be discussed with the clinician and patient representatives. Professionals coming across medical obstacles during the patient journey can contact professional experts in the ERN GENTURIS, while patients can contact the expert patient representatives from this ERN ( www.genturis.eu ). Finally, the “Patient Journeys” will be valuable in sharing knowledge with the clinical community as a whole.

Our aim is that medical doctors confronted with rare diseases, by using Patient Journeys, can also rely on the knowledge of the much broader community of expert professionals and expert patients.

Armstrong MJ, Mullins CD, Gronseth GS, Gagliardi AR. Recommendations for patient engagement in guideline development panels: a qualitative focus group study of guideline-naive patients. PloS ONE 2017;12:e0174329.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gupta D, Rodeghier M, Lis CG. Patient satisfaction with service quality as a predictor of survival outcomes in breast cancer. Supportive Care Cancer Off J Multinatl Assoc Supportive Care Cancer. 2014;22:129–34.

Google Scholar

Gupta D, Lis CG, Rodeghier M. Can patient experience with service quality predict survival in colorectal cancer? J Healthc Qual Off Publ Natl Assoc Healthc Qual. 2013;35:37–43.

Sharma AE, Knox M, Mleczko VL, Olayiwola JN. The impact of patient advisors on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:693.

Fonhus MS, Dalsbo TK, Johansen M, Fretheim A, Skirbekk H, Flottorp SA. Patient-mediated interventions to improve professional practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;9:Cd012472.

PubMed Google Scholar

Cornman DH, White CM. AHRQ methods for effective health care. Discerning the perception and impact of patients involved in evidence-based practice center key informant interviews. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2017.

Chalmers JD, Timothy A, Polverino E, Almagro M, Ruddy T, Powell P, et al. Patient participation in ERS guidelines and research projects: the EMBARC experience. Breathe (Sheff, Engl). 2017;13:194–207.

Article Google Scholar

Vos JR, Giepmans L, Rohl C, Geverink N, Hoogerbrugge N. Boosting care and knowledge about hereditary cancer: european reference network on genetic tumour risk syndromes. Fam Cancer 2019;18:281–4.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work is generated within the European Reference Network on Genetic Tumour Risk Syndromes – FPA No. 739547. The authors thank all ERN GENTURIS Members and patient representatives for their work on the Patient Journeys (see www.genturis.eu ).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

SquareRootThinking and EURORDIS – Rare Diseases Europe, Paris, France

Matt Bolz-Johnson

Human Genetics, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Jelena Meek & Nicoline Hoogerbrugge

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nicoline Hoogerbrugge .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bolz-Johnson, M., Meek, J. & Hoogerbrugge, N. “Patient Journeys”: improving care by patient involvement. Eur J Hum Genet 28 , 141–143 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0555-6

Download citation

Received : 07 August 2019

Revised : 04 October 2019

Accepted : 01 November 2019

Published : 04 December 2019

Issue Date : February 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0555-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Care trajectories of surgically treated patients with a prolactinoma: why did they opt for surgery.

- Victoria R. van Trigt

- Ingrid M. Zandbergen

- Nienke R. Biermasz

Pituitary (2023)

Designing rare disease care pathways in the Republic of Ireland: a co-operative model

- E. P. Treacy

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2022)

Rare disease education in Europe and beyond: time to act

- Birute Tumiene

- Harm Peters

- Gareth Baynam

Development of a patient journey map for people living with cervical dystonia

- Monika Benson

- Alberto Albanese

- Holm Graessner

Der klinische Versorgungspfad zur multiprofessionellen Versorgung seltener Erkrankungen in der Pädiatrie – Ergebnisse aus dem Projekt TRANSLATE-NAMSE

- Daniela Choukair

- Min Ae Lee-Kirsch

- Peter Burgard

Monatsschrift Kinderheilkunde (2022)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Patient Perspectives

- Methods Corner

- ESC Content Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Instructions for reviewers

- Submission Site

- Why publish with EJCN?

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Read & Publish

- About European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing

- About ACNAP

- About European Society of Cardiology

- ESC Publications

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- War in Ukraine

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, why patient journey mapping, how is patient journey mapping conducted, use of technology in patient journey mapping, future implications for patient journey mapping, conclusions, patient journey mapping: emerging methods for understanding and improving patient experiences of health systems and services.

Lemma N Bulto and Ellen Davies Shared first authorship.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Lemma N Bulto, Ellen Davies, Janet Kelly, Jeroen M Hendriks, Patient journey mapping: emerging methods for understanding and improving patient experiences of health systems and services, European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing , 2024;, zvae012, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvae012

- Permissions Icon Permissions

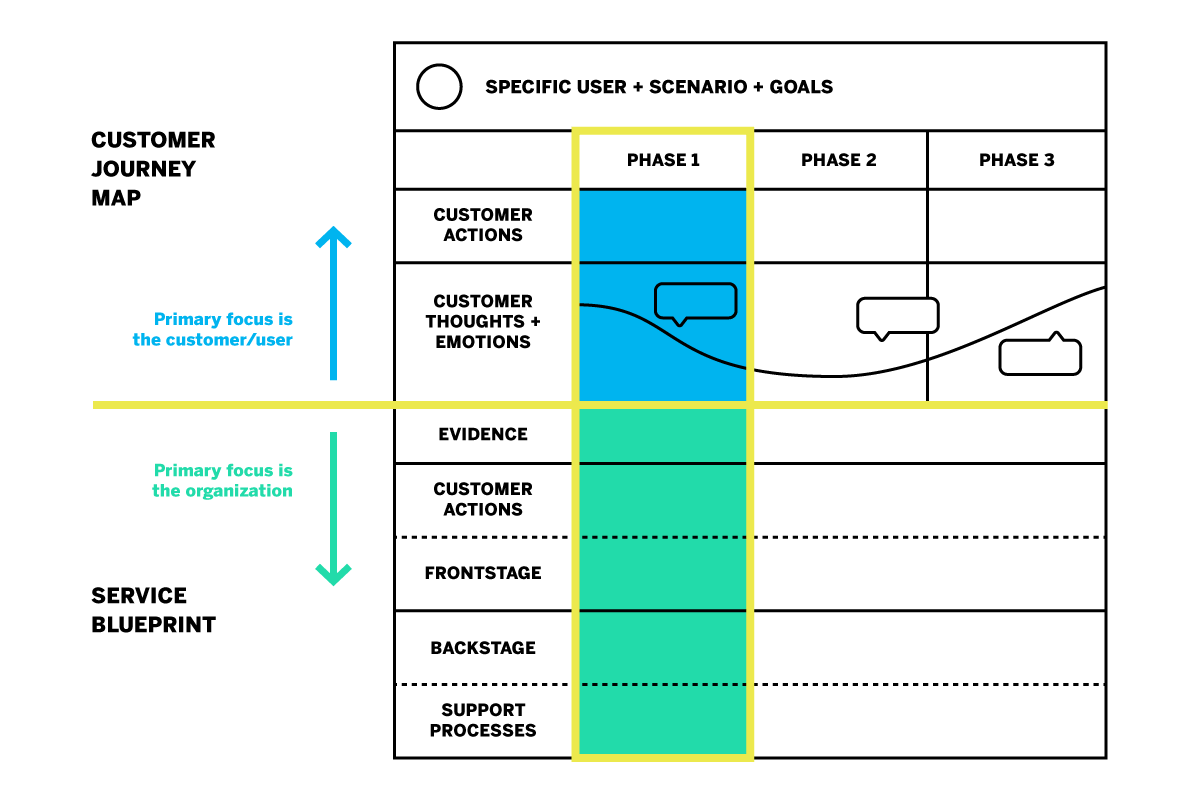

Patient journey mapping is an emerging field of research that uses various methods to map and report evidence relating to patient experiences and interactions with healthcare providers, services, and systems. This research often involves the development of visual, narrative, and descriptive maps or tables, which describe patient journeys and transitions into, through, and out of health services. This methods corner paper presents an overview of how patient journey mapping has been conducted within the health sector, providing cardiovascular examples. It introduces six key steps for conducting patient journey mapping and describes the opportunities and benefits of using patient journey mapping and future implications of using this approach.

Acquire an understanding of patient journey mapping and the methods and steps employed.

Examine practical and clinical examples in which patient journey mapping has been adopted in cardiac care to explore the perspectives and experiences of patients, family members, and healthcare professionals.

Quality and safety guidelines in healthcare services are increasingly encouraging and mandating engagement of patients, clients, and consumers in partnerships. 1 The aim of many of these partnerships is to consider how health services can be improved, in relation to accessibility, service delivery, discharge, and referral. 2 , 3 Patient journey mapping is a research approach increasingly being adopted to explore these experiences in healthcare. 3

a patient-oriented project that has been undertaken to better understand barriers, facilitators, experiences, interactions with services and/or outcomes for individuals and/or their carers, and family members as they enter, navigate, experience and exit one or more services in a health system by documenting elements of the journey to produce a visual or descriptive map. 3

It is an emerging field with a clear patient-centred focus, as opposed to studies that track patient flow, demand, and movement. As a general principle, patient journey mapping projects will provide evidence of patient perspectives and highlight experiences through the patient and consumer lens.

Patient journey mapping can provide significant insights that enable responsive and context-specific strategies for improving patient healthcare experiences and outcomes to be designed and implemented. 3–6 These improvements can occur at the individual patient, model of care, and/or health system level. As with other emerging methodologies, questions have been raised regarding exactly how patient journey mapping projects can best be designed, conducted, and reported. 3

In this methods paper, we provide an overview of patient journey mapping as an emergent field of research, including reasons that mapping patient journeys might be considered, methods that can be adopted, the principles that can guide patient journey mapping data collection and analysis, and considerations for reporting findings and recognizing the implications of findings. We summarize and draw on five cardiovascular patient journey mapping projects, as examples.

One of the most appealing elements of the patient journey mapping field of research is its focus on illuminating the lived experiences of patients and/or their family members, and the health professionals caring for them, methodically and purposefully. Patient journey mapping has an ability to provide detailed information about patient experiences, gaps in health services, and barriers and facilitators for access to health services. This information can be used independently, or alongside information from larger data sets, to adapt and improve models of care relevant to the population that is being investigated. 3

To date, the most frequent reason for adopting this approach is to inform health service redesign and improvement. 3 , 7 , 8 Other reasons have included: (i) to develop a deeper understanding of a person’s entire journey through health systems; 3 (ii) to identify delays in diagnosis or treatment (often described as bottlenecks); 9 (iii) to identify gaps in care and unmet needs; (iv) to evaluate continuity of care across health services and regions; 10 (v) to understand and evaluate the comprehensiveness of care; 11 (vi) to understand how people are navigating health systems and services; and (vii) to compare patient experiences with practice guidelines and standards of care.

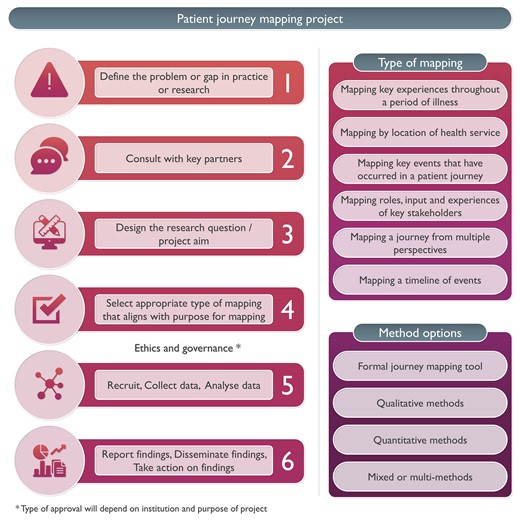

Patient journey mapping approaches frequently use six broad steps that help facilitate the preparation and execution of research projects. These are outlined in the Central illustration . We acknowledge that not all patient journey mapping approaches will follow the order outlined in the Central illustration , but all steps need to be considered at some point throughout each project to ensure that research is undertaken rigorously, appropriately, and in alignment with best practice research principles.

Steps for conducing patient journey mapping.

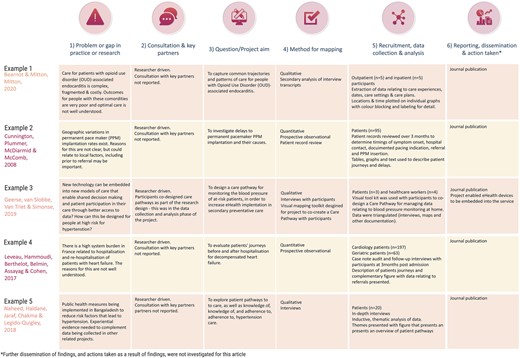

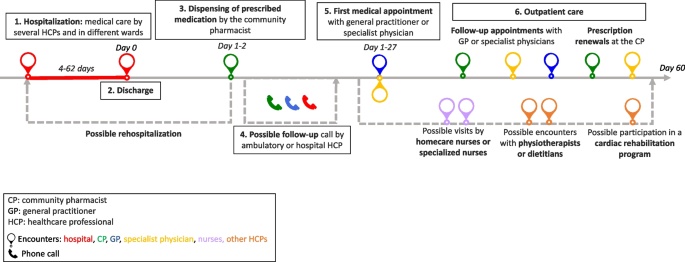

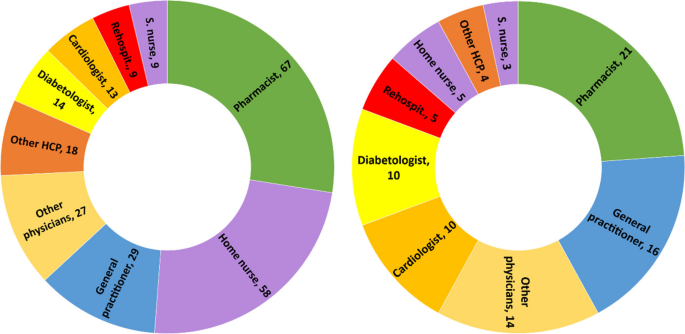

Five cardiovascular patient journey mapping research examples have been included in Figure 1 , 12–16 to provide specific context and illustrate these six steps. For each of these examples, the problem or gap in practice or research, consultation processes, research question or aim, type of mapping, methods, and reporting of findings have been extracted. Each of these steps is then discussed, using these cardiovascular examples.

Examples of patient journey mapping projects.

Define the problem or gap in practice or research

Developing an understanding of a problem or gap in practice is essential for facilitating the design and development of quality research projects. In the examples outlined in Figure 1 , it is evident that clinical variation or system gaps have been explored using patient journey mapping. In the first two examples, populations known to have health vulnerabilities were explored—in Example 1, this related to comorbid substance use and physical illness, 13 and in Example 2, this related to geographical location. 13 Broader systems and societal gaps were explored in Examples 4 and 5, respectively, 15 , 16 and in Example 3, a new technologically driven solution for an existing model of care was tested for its ability to improve patient outcomes relating to hypertension. 14

Consultation, engagement, and partnership

Ideally, consultation with heathcare providers and/or patients would occur when the problem or gap in practice or research is being defined. This is a key principle of co-designed research. 17 Numerous existing frameworks for supporting patient involvement in research have been designed and were recently documented and explored in a systematic review by Greenhalgh et al . 18 While none of the five example studies included this step in the initial phase of the project, it is increasingly being undertaken in patient partnership projects internationally (e.g. in renal care). 17 If not in the project conceptualization phase, consultation may occur during the data collection or analysis phase, as demonstrated in Example 3, where a care pathway was co-created with participants. 14 We refer readers to Greenhalgh’s systematic review as a starting point for considering suitable frameworks for engaging participants in consultation, partnership, and co-design of patient journey mapping projects. 18

Design the research question/project aim

Conducting patient journey mapping research requires a thoughtful and systematic approach to adequately capture the complexity of the healthcare experience. First, the research objectives and questions should be clearly defined. Aspects of the patient journey that will be explored need to be identified. Then, a robust approach must be developed, taking into account whether qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods are more appropriate for the objectives of the study.

For example, in the cardiac examples in Figure 1 , the broad aims included mapping existing pathways through health services where there were known problems 12 , 13 , 15 , 16 and documenting the co-creation of a new care pathway using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods. 14

In traditional studies, questions that might be addressed in the area of patient movement in health systems include data collected through the health systems databases, such as ‘What is the length of stay for x population’, or ‘What is the door to balloon time in this hospital?’ In contrast, patient mapping journey studies will approach asking questions about experiences that require data from patients and their family members, e.g. ‘What is the impact on you of your length of stay?’, ‘What was your experience in being assessed and undergoing treatment for your chest pain?’, ‘What was your experience supporting this patient during their cardiac admission and discharge?’

Select appropriate type of mapping

The methods chosen for mapping need to align with the identified purpose for mapping and the aim or question that was designed in Step 3. A range of research methods have been used in patient journey mapping projects involving various qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods techniques and tools. 4 Some approaches use traditional forms of data collection, such as short-form and long-form patient interviews, focus groups, and direct patient observations. 18 , 19 Other approaches use patient journey mapping tools, designed and used with specific cultural groups, such as First Nations peoples using artwork, paintings, sand trays, and photovoice. 17 , 20 In the cardiovascular examples presented in Figure 1 , both qualitative and quantitative methods have been used, with interviews, patient record reviews, and observational techniques adopted to map patient journeys.

In a recent scoping review investigating patient journey mapping across all health care settings and specialities, six types of patient journey mapping were identified. 3 These included (i) mapping key experiences throughout a period of illness; (ii) mapping by location of health service; (iii) mapping by events that occurred throughout a period of illness; (iv) mapping roles, input, and experiences of key stakeholders throughout patient journeys; (v) mapping a journey from multiple perspectives; and (vi) mapping a timeline of events. 3 Combinations or variations of these may be used in cardiovascular settings in the future, depending on the research question, and the reasons mapping is being undertaken.

Recruit, collect data, and analyse data

The majority of health-focused patient journey mapping projects published to date have recruited <50 participants. 3 Projects with fewer participants tend to be qualitative in nature. In the cardiovascular examples provided in Figure 1 , participant numbers range from 7 14 to 260. 15 The 3 studies with <20 participants were qualitative, 12 , 14 , 16 and the 2 with 95 and 260 participants, respectively, were quantitative. 13 , 15 As seen in these and wider patient journey mapping examples, 3 participants may include patients, relatives, carers, healthcare professionals, or other stakeholders, as required, to meet the study objectives. These different participant perspectives may be analysed within each participant group and/or across the wider cohort to provide insights into experiences, and the contextual factors that shape these experiences.

The approach chosen for data collection and analysis will vary and depends on the research question. What differentiates data analysis in patient journey mapping studies from other qualitative or quantitative studies is the focus on describing, defining, or exploring the journey from a patient’s, rather than a health service, perspective. Dimensions that may, therefore, be highlighted in the analysis include timing of service access, duration of delays to service access, physical location of services relative to a patient’s home, comparison of care received vs. benchmarked care, placing focus on the patient perspective.

The mapping of individual patient journeys may take place during data collection with the use of mapping templates (tables, diagrams, and figures) and/or later in the analysis phase with the use of inductive or deductive analysis, mapping tables, or frameworks. These have been characterized and visually represented in a recent scoping review. 3 Representations of patient journeys can also be constructed through a secondary analysis of previously collected data. In these instances, qualitative data (i.e. interviews and focus group transcripts) have been re-analysed to understand whether a patient journey narrative can be extracted and reported. Undertaking these projects triggers a new research cycle involving the six steps outlined in the Central illustration . The difference in these instances is that the data are already collected for Step 5.

Report findings, disseminate findings, and take action on findings

A standardized, formal reporting guideline for patient journey mapping research does not currently exist. As argued in Davies et al ., 3 a dedicated reporting guide for patient journey mapping would be ill-advised, given the diversity of approaches and methods that have been adopted in this field. Our recommendation is for projects to be reported in accordance with formal guidelines that best align with the research methods that have been adopted. For example, COREQ may be used for patient journey mapping where qualitative methods have been used. 20 STROBE may be used for patient journey mapping where quantitative methods have been used. 21 Whichever methods have been adopted, reporting of projects should be transparent, rigorous, and contain enough detail to the extent that the principles of transparency, trustworthiness, and reproducibility are upheld. 3

Dissemination of research findings needs to include the research, healthcare, and broader communities. Dissemination methods may include academic publications, conference presentations, and communication with relevant stakeholders including healthcare professionals, policymakers, and patient advocacy groups. Based on the findings and identified insights, stakeholders can collaboratively design and implement interventions, programmes, or improvements in healthcare delivery that overcome the identified challenges directly and address and improve the overall patient experience. This cyclical process can hopefully produce research that not only informs but also leads to tangible improvements in healthcare practice and policy.

Patient journey mapping is typically a hands-on process, relying on surveys, interviews, and observational research. The technology that supports this research has, to date, included word processing software, and data analysis packages, such as NVivo, SPSS, and Stata. With the advent of more sophisticated technological tools, such as electronic health records, data analytics programmes, and patient tracking systems, healthcare providers and researchers can potentially use this technology to complement and enhance patient journey mapping research. 19 , 20 , 22 There are existing examples where technology has been harnessed in patient journey. Lee et al . used patient journey mapping to verify disease treatment data from the perspective of the patient, and then the authors developed a mobile prototype that organizes and visualizes personal health information according to the patient-centred journey map. They used a visualization approach for analysing medical information in personal health management and examined the medical information representation of seven mobile health apps that were used by patients and individuals. The apps provide easy access to patient health information; they primarily import data from the hospital database, without the need for patients to create their own medical records and information. 23

In another example, Wauben et al. 19 used radio frequency identification technology (a wireless system that is able to track a patient journey), as a component of their patient journey mapping project, to track surgical day care patients to increase patient flow, reduce wait times, and improve patient and staff satisfaction.

Patient journey mapping has emerged as a valuable research methodology in healthcare, providing a comprehensive and patient-centric approach to understanding the entire spectrum of a patient’s experience within the healthcare system. Future implications of this methodology are promising, particularly for transforming and redesigning healthcare delivery and improving patient outcomes. The impact may be most profound in the following key areas:

Personalized, patient-centred care : The methodology allows healthcare providers to gain deep insights into individual patient experiences. This information can be leveraged to deliver personalized, patient-centric care, based on the needs, values, and preferences of each patient, and aligned with guideline recommendations, healthcare professionals can tailor interventions and treatment plans to optimize patient and clinical outcomes.

Enhanced communication, collaboration, and co-design : Mapping patient interactions with health professionals and journeys within and across health services enables specific gaps in communication and collaboration to be highlighted and potentially informs responsive strategies for improvement. Ideally, these strategies would be co-designed with patients and health professionals, leading to improved care co-ordination and healthcare experience and outcomes.

Patient engagement and empowerment : When patients are invited to share their health journey experiences, and see visual or written representations of their journeys, they may come to understand their own health situation more deeply. Potentially, this may lead to increased health literacy, renewed adherence to treatment plans, and/or self-management of chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease. Given these benefits, we recommend that patients be provided with the findings of research and quality improvement projects with which they are involved, to close the loop, and to ensure that the findings are appropriately disseminated.

Patient journey mapping is an emerging field of research. Methods used in patient journey mapping projects have varied quite significantly; however, there are common research processes that can be followed to produce high-quality, insightful, and valuable research outputs. Insights gained from patient journey mapping can facilitate the identification of areas for enhancement within healthcare systems and inform the design of patient-centric solutions that prioritize the quality of care and patient outcomes, and patient satisfaction. Using patient journey mapping research can enable healthcare providers to forge stronger patient–provider relationships and co-design improved health service quality, patient experiences, and outcomes.

None declared.

Farmer J , Bigby C , Davis H , Carlisle K , Kenny A , Huysmans R , et al. The state of health services partnering with consumers: evidence from an online survey of Australian health services . BMC Health Serv Res 2018 ; 18 : 628 .

Google Scholar

Kelly J , Dwyer J , Mackean T , O’Donnell K , Willis E . Coproducing Aboriginal patient journey mapping tools for improved quality and coordination of care . Aust J Prim Health 2017 ; 23 : 536 – 542 .

Davies EL , Bulto LN , Walsh A , Pollock D , Langton VM , Laing RE , et al. Reporting and conducting patient journey mapping research in healthcare: a scoping review . J Adv Nurs 2023 ; 79 : 83 – 100 .

Ly S , Runacres F , Poon P . Journey mapping as a novel approach to healthcare: a qualitative mixed methods study in palliative care . BMC Health Serv Res 2021 ; 21 : 915 .

Arias M , Rojas E , Aguirre S , Cornejo F , Munoz-Gama J , Sepúlveda M , et al. Mapping the patient’s journey in healthcare through process mining . Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020 ; 17 : 6586 .

Natale V , Pruette C , Gerohristodoulos K , Scheimann A , Allen L , Kim JM , et al. Journey mapping to improve patient-family experience and teamwork: applying a systems thinking tool to a pediatric ambulatory clinic . Qual Manag Health Care 2023 ; 32 : 61 – 64 .

Cherif E , Martin-Verdier E , Rochette C . Investigating the healthcare pathway through patients’ experience and profiles: implications for breast cancer healthcare providers . BMC Health Serv Res 2020 ; 20 : 735 .

Gilburt H , Drummond C , Sinclair J . Navigating the alcohol treatment pathway: a qualitative study from the service users’ perspective . Alcohol Alcohol 2015 ; 50 : 444 – 450 .

Gichuhi S , Kabiru J , M’Bongo Zindamoyen A , Rono H , Ollando E , Wachira J , et al. Delay along the care-seeking journey of patients with ocular surface squamous neoplasia in Kenya . BMC Health Serv Res 2017 ; 17 : 485 .

Borycki EM , Kushniruk AW , Wagner E , Kletke R . Patient journey mapping: integrating digital technologies into the journey . Knowl Manag E-Learn 2020 ; 12 : 521 – 535 .

Barton E , Freeman T , Baum F , Javanparast S , Lawless A . The feasibility and potential use of case-tracked client journeys in primary healthcare: a pilot study . BMJ Open 2019 ; 9 : e024419 .

Bearnot B , Mitton JA . “You’re always jumping through hoops”: journey mapping the care experiences of individuals with opioid use disorder-associated endocarditis . J Addict Med 2020 ; 14 : 494 – 501 .

Cunnington MS , Plummer CJ , McDiarmid AK , McComb JM . The patient journey from symptom onset to pacemaker implantation . QJM 2008 ; 101 : 955 – 960 .

Geerse C , van Slobbe C , van Triet E , Simonse L . Design of a care pathway for preventive blood pressure monitoring: qualitative study . JMIR Cardio 2019 ; 3 : e13048 .

Laveau F , Hammoudi N , Berthelot E , Belmin J , Assayag P , Cohen A , et al. Patient journey in decompensated heart failure: an analysis in departments of cardiology and geriatrics in the Greater Paris University Hospitals . Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2017 ; 110 : 42 – 50 .

Naheed A , Haldane V , Jafar TH , Chakma N , Legido-Quigley H . Patient pathways and perceptions of treatment, management, and control Bangladesh: a qualitative study . Patient Prefer Adherence 2018 ; 12 : 1437 – 1449 .

Bateman S , Arnold-Chamney M , Jesudason S , Lester R , McDonald S , O’Donnell K , et al. Real ways of working together: co-creating meaningful Aboriginal community consultations to advance kidney care . Aust N Z J Public Health 2022 ; 46 : 614 – 621 .

Greenhalgh T , Hinton L , Finlay T , Macfarlane A , Fahy N , Clyde B , et al. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: systematic review and co-design pilot . Health Expect 2019 ; 22 : 785 – 801 .

Wauben LSGL , Guédon ACP , de Korne DF , van den Dobbelsteen JJ . Tracking surgical day care patients using RFID technology . BMJ Innov 2015 ; 1 : 59 – 66 .

Tong A , Sainsbury P , Craig J . Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups . Int J Qual Health Care 2007 ; 19 : 349 – 357 .

von Elm E , Altman DG , Egger M , Pocock SJ , Gøtzsche PC , Vandenbroucke JP , et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies . Lancet 2007 ; 370 (9596): 1453 – 1457 .

Wilson A , Mackean T , Withall L , Willis EM , Pearson O , Hayes C , et al. Protocols for an Aboriginal-led, multi-methods study of the role of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers, practitioners and Liaison officers in quality acute health care . J Aust Indigenous HealthInfoNet 2022 ; 3 : 1 – 15 .

Lee B , Lee J , Cho Y , Shin Y , Oh C , Park H , et al. Visualisation of information using patient journey maps for a mobile health application . Appl Sci 2023 ; 13 : 6067 .

Author notes

Email alerts, citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1873-1953

- Print ISSN 1474-5151

- Copyright © 2024 European Society of Cardiology

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Process mapping the...

Process mapping the patient journey: an introduction

- Related content

- Peer review

- Timothy M Trebble , consultant gastroenterologist 1 ,

- Navjyot Hansi , CMT 2 1 ,

- Theresa Hydes , CMT 1 1 ,

- Melissa A Smith , specialist registrar 2 ,

- Marc Baker , senior faculty member 3

- 1 Department of Gastroenterology, Portsmouth Hospitals Trust, Portsmouth PO6 3LY

- 2 Department of Gastroenterology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London

- 3 Lean Enterprise Academy, Ross-on-Wye, Hertfordshire

- Correspondence to: T M Trebble tim.trebble{at}porthosp.nhs.uk

- Accepted 15 July 2010

Process mapping enables the reconfiguring of the patient journey from the patient’s perspective in order to improve quality of care and release resources. This paper provides a practical framework for using this versatile and simple technique in hospital.

Healthcare process mapping is a new and important form of clinical audit that examines how we manage the patient journey, using the patient’s perspective to identify problems and suggest improvements. 1 2 We outline the steps involved in mapping the patient’s journey, as we believe that a basic understanding of this versatile and simple technique, and when and how to use it, is valuable to clinicians who are developing clinical services.

What information does process mapping provide and what is it used for?

Process mapping allows us to “see” and understand the patient’s experience 3 by separating the management of a specific condition or treatment into a series of consecutive events or steps (activities, interventions, or staff interactions, for example). The sequence of these steps between two points (from admission to the accident and emergency department to discharge from the ward) can be viewed as a patient pathway or process of care. 4

Improving the patient pathway involves the coordination of multidisciplinary practice, aiming to maximise clinical efficacy and efficiency by eliminating ineffective and unnecessary care. 5 The data provided by process mapping can be used to redesign the patient pathway 4 6 to improve the quality or efficiency of clinical management and to alter the focus of care towards activities most valued by the patient.

Process mapping has shown clinical benefit across a variety of specialties, multidisciplinary teams, and healthcare systems. 7 8 9 The NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement proposes a range of practical benefits using this approach (box 1). 6

Box 1 Benefits of process mapping 6

A starting point for an improvement project specific for your own place of work

Creating a culture of ownership, responsibility and accountability for your team

Illustrates a patient pathway or process, understanding it from a patient’s perspective

An aid to plan changes more effectively

Collecting ideas, often from staff who understand the system but who rarely contribute to change

An interactive event that engages staff

An end product (a process map) that is easy to understand and highly visual

Several management systems are available to support process mapping and pathway redesign. 10 11 A common technique, derived originally from the Japanese car maker Toyota, is known as lean thinking transformation. 3 12 This considers each step in a patient pathway in terms of the relative contribution towards the patient’s outcome, taken from the patient’s perspective: it improves the patient’s health, wellbeing, and experience (value adding) or it does not (non-value or “waste”) (box 2). 14 15 16

Box 2 The eight types of waste in health care 13

Defects —Drug prescription errors; incomplete surgical equipment

Overproduction —Inappropriate scheduling

Transportation —Distance between related departments

Waiting —By patients or staff

Inventory —Excess stores, that expire

Motion —Poor ergonomics

Overprocessing —A sledgehammer to crack a nut

Human potential —Not making the most of staff skills

Process mapping can be used to identify and characterise value and non-value steps in the patient pathway (also known as value stream mapping). Using lean thinking transformation to redesign the pathway aims to enhance the contribution of value steps and remove non-value steps. 17 In most processes, non-value steps account for nine times more effort than steps that add value. 18

Reviewing the patient journey is always beneficial, and therefore a process mapping exercise can be undertaken at any time. However, common indications include a need to improve patients’ satisfaction or quality or financial aspects of a particular clinical service.

How to organise a process mapping exercise

Process mapping requires a planned approach, as even apparently straightforward patient journeys can be complex, with many interdependent steps. 4 A process mapping exercise should be an enjoyable and creative experience for staff. In common with other audit techniques, it must avoid being confrontational or judgmental or used to “name, shame, and blame.” 8 19

Preparation and planning

A good first step is to form a team of four or five key staff, ideally including a member with previous experience of lean thinking transformation. The group should decide on a plan for the project and its scope; this can be visualised by using a flow diagram (fig 1 ⇓ ). Producing a rough initial draft of the patient journey can be useful for providing an overview of the exercise.

Fig 1 Steps involved in a process mapping exercise

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

The medical literature or questionnaire studies of patients’ expectations and outcomes should be reviewed to identify value adding steps involved in the management of the clinical condition or intervention from the patient’s perspective. 1 3

Data collection

Data collection should include information on each step under routine clinical circumstances in the usual clinical environment. Information is needed on waiting episodes and bottlenecks (any step within the patient pathway that slows the overall rate of a patient’s progress, normally through reduced capacity or availability 20 ). Using estimates of minimum and maximum time for each step reduces the influence of day to day variations that may skew the data. Limiting the number of steps (to below 60) aids subsequent analysis.

The techniques used for data collection (table 1 ⇓ ) each have advantages and disadvantages; a combination of approaches can be applied, contributing different qualitative or quantitative information. The commonly used technique of walking the patient journey includes interviews with patients and staff and direct observation of the patient journey and clinical environment. It allows the investigator to “see” the patient journey at first hand. Involving junior (or student) doctors or nurses as interviewers may increase the openness of opinions from staff, and time needed for data collection can be reduced by allotting members of the team to investigate different stages in the patient’s journey.

Data collection in process mapping

- View inline

Mapping the information

The process map should comprehensively represent the patient journey. It is common practice to draw the map by hand onto paper (often several metres long), either directly or on repositionable notes (fig 2 ⇓ ).

Fig 2 Section of a current state map of the endoscopy patient journey

Information relating to the steps or representing movement of information (request forms, results, etc) can be added. It is useful to obtain any missing information at this stage, either from staff within the meeting or by revisiting the clinical environment.

Analysing the data and problem solving

The map can be analysed by using a series of simple questions (box 3). The additional information can be added to the process map for visual representation. This can be helped by producing a workflow diagram—a map of the clinical environment, including information on patient, staff, and information movement (fig 3 ⇓ ). 18

Box 3 How to analyse a process map 6

How many steps are involved?

How many staff-staff interactions (handoffs)?

What is the time for each step and between each step?

What is the total time between start and finish (lead time)?

When does a patient join a queue, and is it a regular occurrence?

How many non-value steps are there?

What do patients complain about?

What are the problems for staff?

Fig 3 Workflow diagram of current state endoscopy pathway

Redesigning the patient journey

Lean thinking transformation involves redesigning the patient journey. 21 22 This will eliminate, combine and simplify non-value steps, 23 limit the impact of rate limiting steps (such as bottlenecks), and emphasise the value adding steps, making the process more patient-centred. 6 It is often useful to trial the new pathway and review its effect on patient management and satisfaction before attempting more sustained implementation.

Worked example: How to undertake a process mapping exercise

South Coast NHS Trust, a large district general hospital, plans to improve patient access to local services by offering unsedated endoscopy in two peripheral units. A consultant gastroenterologist has been asked to lead a process mapping exercise of the current patient journey to develop a fast track, high quality patient pathway.

In the absence of local data, he reviews the published literature and identifies key factors to the patient experience that include levels of discomfort during the procedure, time to discuss the findings with the endoscopist, and time spent waiting. 24 25 26 27 He recruits a team: an experienced performance manager, a sister from the endoscopy department, and two junior doctors.

The team drafts a map of the current endoscopy journey, using repositionable notes on the wall. This allows team members to identify the start (admission to the unit) and completion (discharge) points and the locations thought to be involved in the patient journey.

They decide to use a “walk the journey” format, interviewing staff in their clinical environments and allowing direct observation of the patient’s management.

The junior doctors visit the endoscopy unit over two days, building up rapport with the staff to ensure that they feel comfortable with being observed and interviewed (on a semistructured but informal basis). On each day they start at the point of admission at the reception office and follow the patient journey to completion.

They observe the process from staff and patient’s perspectives, sitting in on the booking process and the endoscopy procedure. They identify the sequence of steps and assess each for its duration (minimum and maximum times) and the factors that influence this. For some of the steps, they use a digital watch and notepad to check and record times. They also note staff-patient and staff-staff interactions and their function, and the recording and movement of relevant information.

Details for each step are entered into a simple table (table 2 ⇓ ), with relevant notes and symbols for bottlenecks and patients’ waits.

Patient journey for non-sedated upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

When data collection is complete, the doctor organises a meeting with the team. The individual steps of the patient journey are mapped on a single long section of paper with coloured temporary markers (fig 2 ⇑ ); additional information is added in different colours. A workflow diagram is drawn to show the physical route of the patient journey (fig 3 ⇑ ).

The performance manager calculates that the total patient journey takes a minimum of 50 minutes to a maximum of 345 minutes. This variation mainly reflects waiting times before a number of bottleneck steps.

Only five steps (14 to 17 and 22, table 2 ⇑ ) are considered both to add value and needed on the day of the procedure (providing patient information and consent can be obtained before the patient attends the department). These represent from 13 to 47 minutes. At its least efficient, therefore, only 4% of the patient journey (13 of 345 minutes) is spent in activities that contribute directly towards the patient’s outcome.

The team redesigns the patient journey (fig 4 ⇓ ) to increase time spent on value adding aspects but reduce waiting times, bottlenecks, and travelling distances. For example, time for discussing the results of the procedure is increased but the location is moved from the end of the journey (a bottleneck) to shortly after the procedure in the anteroom, reducing the patient’s waiting time and staff’s travelling distances.

Fig 4 Workflow diagram of future state endoscopy pathway

Implementing changes and sustaining improvements

The endoscopy staff are consulted on the new patient pathway, which is then piloted. After successful review two months later, including a patient satisfaction questionnaire, the new patient pathway is formally adopted in the peripheral units.

Further reading

Practical applications.

NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement ( https://www.institute.nhs.uk )—comprehensive online resource providing practical guidance on process mapping and service improvement

Lean Enterprise Academy ( http://www.leanuk.org )—independent body dedicated to lean thinking in industry and healthcare, through training and academic discussion; its publication, Making Hospitals Work 23 is a practical guide to lean transformation in the hospital environment

Manufacturing Institute ( http://www.manufacturinginstitute.co.uk )—undertakes courses on process mapping and lean thinking transformation within health care and industrial practice

Theoretical basis

Bircheno J. The new lean toolbox . 4th ed. Buckingham: PICSIE Books, 2008

Mould G, Bowers J, Ghattas M. The evolution of the pathway and its role in improving patient care. Qual Saf Health Care 2010 [online publication 29 April]

Layton A, Moss F, Morgan G. Mapping out the patient’s journey: experiences of developing pathways of care. Qual Health Care 1998; 7 (suppl):S30-6

Graban M. Lean hospitals, improving quality, patient safety and employee satisfaction . New York: Taylor & Francis, 2009

Womack JP, Jones DT. Lean thinking . 2nd ed. London: Simon & Schuster, 2003

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;341:c4078

Contributors: TMT designed the protocol and drafted the manuscript; TMT, MB, JH, and TH collected and analysed the data; all authors critically reviewed and contributed towards revision and production of the manuscript. TMT is guarantor.

Competing interests: MB is a senior faculty member carrying out research for the Lean Enterprise Academy and undertakes paid consultancies both individually and from Lean Enterprise Academy, and training fees for providing lean thinking in healthcare.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- ↵ Kollberg B, Dahlgaard JJ, Brehmer P. Measuring lean initiatives in health care services: issues and findings. Int J Productivity Perform Manage 2007 ; 56 : 7 -24. OpenUrl CrossRef

- ↵ Bevan H, Lendon R. Improving performance by improving processes and systems. In: Walburg J, Bevan H, Wilderspin J, Lemmens K, eds. Performance management in health care. Abingdon: Routeledge, 2006:75-85.

- ↵ Kim CS, Spahlinger DA, Kin JM, Billi JE. Lean health care: what can hospitals learn from a world-class automaker? J Hosp Med 2006 ; 1 : 191 -9. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Layton A, Moss F, Morgan G. Mapping out the patient’s journey: experiences of developing pathways of care. Qual Health Care 1998 ; 7 (suppl): S30 -6. OpenUrl

- ↵ Peterson KM, Kane DP. Beyond disease management: population-based health management. Disease management. Chicago: American Hospital Publishing, 1996.

- ↵ NHS Modernisation Agency. Process mapping, analysis and redesign. London: Department of Health, 2005;1-40.

- ↵ Taylor AJ, Randall C. Process mapping: enhancing the implementation of the Liverpool care pathway. Int J Palliat Nurs 2007 ; 13 : 163 -7. OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Ben-Tovim DI, Dougherty ML, O’Connell TJ, McGrath KM. Patient journeys: the process of clinical redesign. Med J Aust 2008 ; 188 (suppl 6): S14 -7. OpenUrl PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ King DL, Ben-Tovim DI, Bassham J. Redesigning emergency department patient flows: application of lean thinking to health care. Emerg Med Australas 2006 ; 18 : 391 -7. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Mould G, Bowers J, Ghattas M. The evolution of the pathway and its role in improving patient care. Qual Saf Health Care 2010 ; published online 29 April.

- ↵ Rath F. Tools for developing a quality management program: proactive tools (process mapping, value stream mapping, fault tree analysis, and failure mode and effects analysis). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008 ; 71 (suppl): S187 -90. OpenUrl PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Womack JP, Jones DT. Lean thinking. 2nd ed. London: Simon & Schuster, 2003.

- ↵ Graban M. Value and waste. In: Lean hospitals. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2009;35-56.

- ↵ Westwood N, James-Moore M, Cooke M. Going lean in the NHS. London: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2007.

- ↵ Liker JK. The heart of the Toyota production system: eliminating waste. The Toyota way. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004;27-34.

- ↵ Womack JP, Jones DT. Introduction: Lean thinking versus Muda. In: Lean thinking. 2nd ed. London: Simon & Schuster, 2003:15-28.

- ↵ George ML, Rowlands D, Price M, Maxey J. Value stream mapping and process flow tools. Lean six sigma pocket toolbook. New York: McGraw Hill, 2005:33-54.

- ↵ Fillingham D. Can lean save lives. Leadership Health Serv 2007 ; 20 : 231 -41. OpenUrl CrossRef

- ↵ Benjamin A. Audit: how to do it in practice. BMJ 2008 ; 336 : 1241 -5. OpenUrl FREE Full Text

- ↵ Vissers J. Unit Logistics. In: Vissers J, Beech R, eds. Health operations management patient flow logistics in health care. Oxford: Routledge, 2005:51-69.

- ↵ Graban M. Overview of lean for hospital. Lean hospitals. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2009;19-33.

- ↵ Eaton M. The key lean concepts. Lean for practitioners. Penryn, Cornwall: Academy Press, 2008:13-28.

- ↵ Baker M, Taylor I, Mitchell A. Analysing the situation: learning to think differently. In: Making hospitals work. Ross-on-Wye: Lean Enterprise Academy, 2009:51-70.

- ↵ Ko HH, Zhang H, Telford JJ, Enns R. Factors influencing patient satisfaction when undergoing endoscopic procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 2009 ; 69 : 883 -91. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Del Rio AS, Baudet JS, Fernandez OA, Morales I, Socas MR. Evaluation of patient satisfaction in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007 ; 19 : 896 -900. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Seip B, Huppertz-Hauss G, Sauar J, Bretthauer M, Hoff G. Patients’ satisfaction: an important factor in quality control of gastroscopies. Scand J Gastroenterol 2008 ; 43 : 1004 -11. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Yanai H, Schushan-Eisen I, Neuman S, Novis B. Patient satisfaction with endoscopy measurement and assessment. Dig Dis 2008 ; 26 : 75 -9. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

Patient Journey Mapping: What it is and Why it Matters

How can healthcare organizations make every stage of the patient journey better?

How was your last experience in a healthcare facility? Think about every step of that patient care journey - the phone calls, in person meetings, wait times, communication and all of the healthcare professional/ patient interactions. It’s a lot.

Healthcare organizations are working diligently to improve patient satisfaction and quality of care by asking, “How can we make the patient experience better?” But that’s no mean feat, trying to capture the multitude of challenges patients face when navigating a healthcare journey. That makes improving it even more difficult.

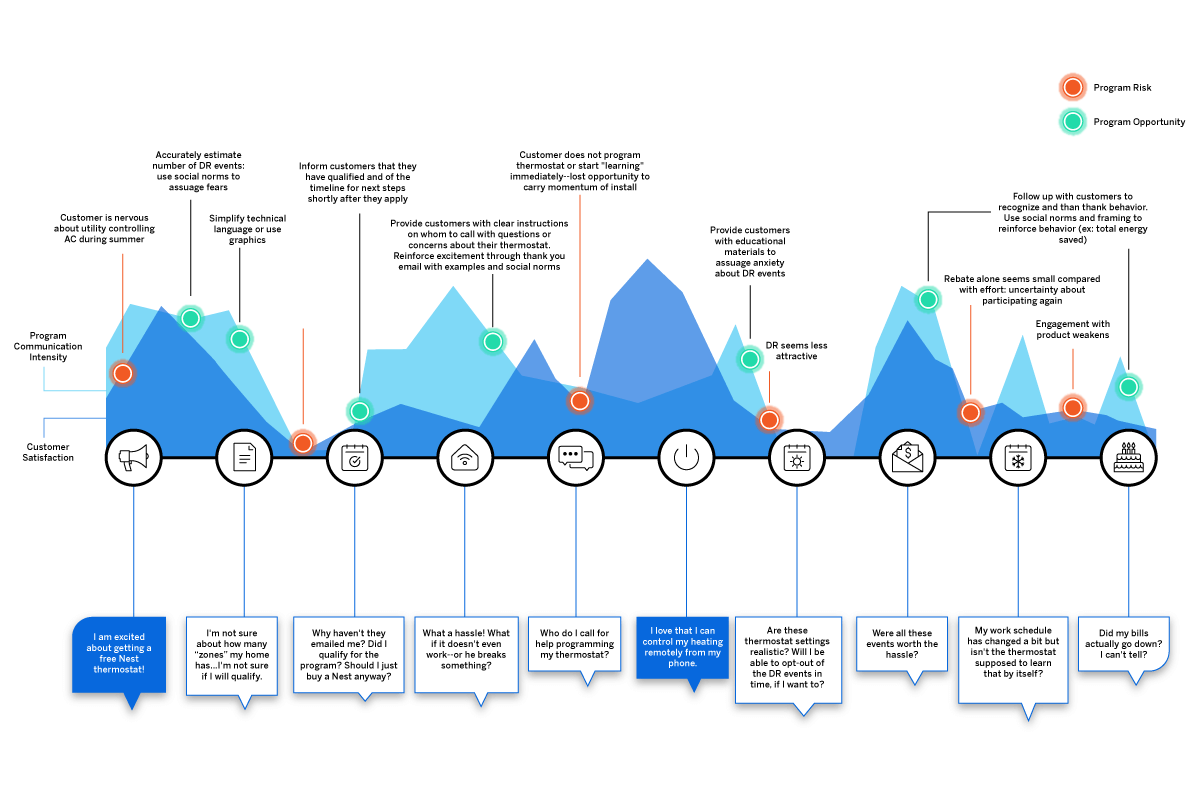

A first, fundamental step to improving patient experience is understanding what that experience looks like today. This is where patient journey mapping comes into play. You can use patient journey maps to understand the highs and lows, pain points and gaps to begin pinpointing which interventions will be most impactful. Then you can assess which changes you have the power to make.

As a result, you’ll be better able to manage your patient’s journey, improve care pathways and meet—and exceed—patient expectations, needs, and wants.

What is Patient Journey Mapping?

Patient journey mapping works to identify and understand the details of all patient touchpoints within a specific healthcare experience. It helps you visualize the process patients go through to receive care, complete a treatment plan, and/or reach a desired outcome. When done correctly, patient journey maps make it easier for you to identify pain points, discover opportunities and re-align treatment and care approaches across the entire healthcare system.

What makes up a patient’s journey?

A patient’s journey represents the entire sequence of events or touchpoints that a patient experiences within a given health system, with a specific provider, or within a specific facility. These touchpoints are either virtual or in-person. They range from the mundane to the nerve-wracking or life-changing. They comprise events from scheduling an appointment online to reviewing post-surgery instructions with a doctor.

It’s key for healthcare professionals and clinicians to recognize the patient journey extends well beyond the most obvious in-person interactions at a treatment facility. The patient journey happens before, during and after a healthcare service: pre-visit, during-visit, and post-visit. These include but are not limited to:

- Finding the right service or practitioner

- Scheduling an appointment

- Submitting a list of current medications

- Arriving at the medical facility

- Identifying where to check-in.

These experiences can instil a sense of reassurance or unease before a patient even receives care. In essence, they set the tone and expectations for the physical visit. A frustrating or confusing experience during the pre-visit stage will impact the emotional state of the patient and family for the rest of their interactions.

During-visit

- Checking in at the front desk

- Waiting in the lobby to be called

- Discussion with nurses before speaking to a doctor

- Family waiting for updates in the lobby during a procedure

- Care from doctor and staff.

There are an infinite number of touchpoints during the delivery of healthcare. Each one will have a different level of impact on the patient’s experience.

- Post-care instructions at hospital

- Hospital discharge process

- Completing a patient feedback survey

- Paying for the medical treatment

- Post-surgery calls or online messages from the nurse or doctor.

The patient experience after a hospital visit plays a vital role in either reinforcing a positive experience or mitigating a negative one. Actions such as post-appointment follow-ups extend the care relationship and may help the likelihood of the patient sticking to the treatment plan

All these individual touchpoints are crucial to understand. Altogether, these positive and negative experiences — no matter how big or small — comprise the patient journey.

Who are the stakeholders?

The healthcare ecosystem is complex, involving multiple stakeholders and a wide range of internal and external factors, including:

- People (patients, their families and caregivers, doctors, nurses, administration, parking attendants, volunteers)

- Technology and systems (online registration, parking tickets, surgery updates, mobile app, website, social media)

- Facilities (hospital campus navigation, parking availability, building accessibility).

Investigation of all players and systems involved is essential to seeing the multidimensional layers impacting the experience. To do this, patient journey maps should include the perspectives of patients, providers, and staff - and those perspectives must be of the same journey. Often, an interaction that occurs from one point of view will show only one reality. However, further investigation will show the many contributing factors across the care delivery process. This is only apparent by examining multiple perspectives.

Once you understand the entire journey, with pain points, you’ll be able to identify patterns across patient personas and different demographics, and any gaps within the healthcare process. You can then begin asking important questions like:

- Which moments are most painful?

- Why do they happen?

- What must we change in order to improve the experience?

- Who must we impact?

- Which do we have the power to change?

Benefits of patient journey mapping

Patient journey mapping provides the opportunity to turn the healthcare experience from a primarily reactive experience to a proactive one. By building out care journeys for your patients, you can close any gaps in provision and establish robust preventative routines that ultimately help your patients stay healthier for as long as possible. Engaging consumers and patients based on where they are and what they want, builds trust and confidence. That retains patients in your system and encourages them to make friends and family referrals.

But how does the process work?

- Streamline patient processes and workflows: upgrading the usability and functionality of online patient portals, websites and mobile apps can put more control in the patients’ hands, increasing patient flow and cutting operational expenses.

- Increase staff efficiency : enhancing internal online tools and creating automation within systems can assist hospital staff in implementing protocols and schedules and help them anticipate and solve problems more easily. It can help to align the expected service delivery with the actual one.

- Clear routes and direction across medical facilities: hospitals can be incredibly complicated to navigate - whether it’s using the right entrance, finding parking or making your way to the cafeteria for a snack. Improving signage, making visible pathways, and using landmarks to help orient users can help patients and families readily access the resources they need.

- Improve communication between patients and providers: exchanging patient information and coordinating care can be a challenge for providers and a frustration for patients. This misalignment can be due to silos within organizations, incompatible technology systems or many other factors. Working to bridge the appropriate organizational or technological gap can help alleviate stress and anxiety.

- Develop seamless and timely patient and family updates: waiting while a family member is in surgery or communicating with a doctor to secure care for a child is typically an extremely stressful process. Families wait anxiously for updates which can be infrequent and lacking detail. Implementing a seamless system for families to communicate directly and receive regular updates, through an app or text, can help ease these pain points.

- Better ‘in-between visit’ care and check-ins with patients and families: communication between patients, including families and caregivers and providers can feel ‘hit or miss.’ Patients may be scrambling to answer phone calls or missing phone calls only to find themselves unable to get hold of the provider when they call back. Alternatively, providers are challenged to communicate critical information to a wide range of patients. Establishing better communication systems can improve patient engagement, build the patient’s confidence in the care they receive, and ease the care provider’s job.

In short, we’re talking happier patients who experience better communication and levels of empathy at every stage of the patient journey.

What tools and methods are used for creating a patient journey map in healthcare?