- Entertainment

10 years later, there’s still nothing like Journey’s multiplayer

Journey turns 10 today.

By Jay Peters , a news editor who writes about technology, video games, and virtual worlds. He’s submitted several accepted emoji proposals to the Unicode Consortium.

Share this story

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23307103/IMG_1885.jpeg)

I’ll never forget the first time I played Journey .

Throughout the game, real-life players can join you on your quest toward a mountain on the horizon. Players can fade in and out of your adventure — maybe they want to go faster than you, maybe they just quit — but in the latter half of my game, I had found somebody who stuck with me. Journey has no voice or text chat and no names identifying other players you meet. The only way we could communicate was through our movements, sticking close together to refill each other’s energy, and singsong chirps. Despite those limitations, we built a rapport.

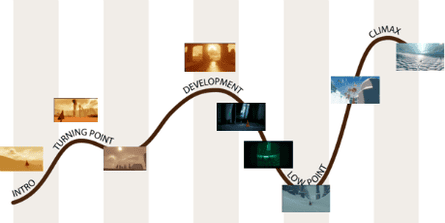

Near the end of Journey , you have to scale the mountain, and as you approach the peak, you get caught in a storm. Much of the game is filled with sunlight, flight, and joyful music, but the mountain is gray, winds buffet your character, and the music is, at times, uncomfortable. Even though the level was draining, I was happy that I had my companion, and we huddled together as we marched toward the peak.

Eventually, the music fades out, and you can only hear your footsteps trudging ever more slowly through the elements. Then, as the game grew silent, my friend collapsed into the snow. I actually cried out in dismay. Then my character fell over, too, and the screen faded to white.

In many video games, you die a lot. That was the only time a virtual death has made me feel like I had actually lost a friend.

Fortunately, that’s not actually the end. In a cutscene, I was revived soon after I fell, and then, in an exuberant celebration of color and music that’s perhaps my favorite video game “level” of all time, soared toward the top of the mountain — with my once-fallen friend flying alongside me.

Journey turns 10 years old today, March 13th, and I still haven’t experienced anything like that moment. To mark the anniversary and learn more about the game’s bond-forging multiplayer, I spoke with Jenova Chen, president and creative director of Journey developer thatgamecompany. While it may feel like the game is effortlessly pairing you with companions as you go along, based on what he told me, it wasn’t quite that simple.

The goal for Journey was to “innovate how it feels between people on the internet,” Chen said. “Can we invent the right environment, the right feedback, to bring out something that we’re more proud of? And to have an online game where people feel friendly and compassionate towards each other?” He elaborated further later in our conversation. “We want to see two people going through the journey together, [like when] in our life, we meet someone special, and we travel with them, and eventually, we might depart from each other.”

“Human beings, unfortunately, are giant babies”

While it was a profound ideal, “the reality is: human beings, unfortunately, are giant babies in the virtual world,” Chen said. “No matter how old you are, even if you’re in your 70s, if we move you from Earth and into a virtual space, [that person] would become a giant baby. A baby doesn’t know what is a good moral value versus what is a bad moral value. The baby only knows: if I’m in a new environment, I’m going to try to push the buttons and see what kind of feedback I can get, and babies are great at looking for maximum feedback.”

To encourage compassion, the team tested a lot of ideas. They tried a system inspired by Gears of War that let you help out an incapacitated friend but found that even in playtests among the developers, the player would rather not help the other person out. “That way, they create a lot of anxiety in the other player and make the other player more angry. And they actually get more gratification out of the feedback,” Chen said.

They also tested a mechanic where one person could push the other high up, and then that person would pull the first. “But once we gave this physics simulation to the players, they chose to push each other off the wall and see them fall from the cliff and die, waiting to be helped,” Chen said.

During those tests, people would say, “I would rather play this game alone. Why do you force me to play with this other person? I hate them,” according to Chen. That’s because “killing is much bigger feedback than just helping the other person to get on a ledge,” Chen said.

“At the time, I was like, ‘Is humanity at its core just dark?’”

The challenges of making those mechanics work affected Chen. “At the time, I was like, ‘Is humanity at its core just dark?’” he said. But a child psychologist helped Chen see things in terms of the way babies view feedback. “If you don’t want babies to do something terrible, give them zero feedback,” he recalled learning from her. “Don’t give them negative feedback because they will misinterpret that as positive feedback.”

That led to a change that would have a huge effect on the game: when you got close to someone, you’d recharge their energy. (In the final game, you use your energy to fly.) “And so that makes people feel like ‘Oh, I love to stay near someone because I don’t have to run to find the energy,’” he said. “So they end up sticking together, and they travel together, and they form a companionship. That was just one simple change. From assholes who want to kill each other and dancing around their corpse, creating hatred, to ‘hey, they’re all lovey-dovey, they’re helping each other, and they couldn’t leave each other.’”

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23307114/IMG_1886.jpeg)

The team also had to experiment to land on the musical chirps that players can use to communicate with each other. They tried a “thumbs up and thumbs down idea” where you could push the thumbstick up to show a green ping and push it down to show a red ping. But in testing, the majority of pings were red as players spammed them to bug their partner to do what they wanted, which created feelings of stress.

“Eventually, we realized it’s better just to keep it neutral,” Chen said. “And then we let the frequency and the amplitude [of the ping] be interpreted by the other player. But we noticed that when we don’t add context, people usually interpret the other person’s intention positively. I think that’s deep down our human nature.”

The chirp is like a musical instrument

Even though the chirp is intended to be neutral, it’s not a static noise. It’s almost like a musical instrument, and its sound evolves throughout the game, Journey composer Austin Wintory told me. “At the very beginning of the game, it’s very bird-like, and there’s flute and little bits of cello,” he said. But over the course of the game, you’ll hear more of a human voice within that sound. “So by the time you’re in the clouds and the very big finale, especially if you do one of the big charged up [pings], you can really hear there’s a human voice in there.” (The human voice used in the pings is Lisbeth Scott, who sings Journey’s end credits.)

The humanity in the design of Journey , from the human voice in the chirps to the multiplayer design that encourages cooperation, is so much of what makes the game memorable for me. As I climbed the mountain with my companion the first time I played the game, I realize now that while I may have been huddled close to my friend to try and share my energy, deep down, I just wanted to do everything I could to help them get up that mountain — and I knew they were doing the same for me.

Ahead of talking to Chen and Wintory, I replayed Journey for the first time since it came out. Despite how much I love the game, I’ve always worried another run would change how I feel about it. I was so fearful of how it might contort my memories that I was actively procrastinating on playing it.

To my surprise, the experience was just as powerful. Ten years on, there are still people playing Journey , and I met four other companions who were part of my adventure. I even made a new friend who stuck by my side through the snowy climb to the mountain’s summit — and through the joyful flight to the peak.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23307148/IMG_1890.jpeg)

Journey is available on PS3, PS4, PS5, PC, and iOS. Composer Austin Wintory has also just released a re-orchestration of the Journey soundtrack performed by the London Symphony Orchestra titled “Traveler — A Journey Symphony.” I’ve listened to it and thought it was very good.

Inside Microsoft’s mission to take down the MacBook Air

Sonos is teasing its ‘most requested product ever’ on tuesday, the new, faster surface pro is microsoft’s all-purpose ai pc, recall is microsoft’s key to unlocking the future of pcs, microsoft surface event: the 6 biggest announcements.

More from Entertainment

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23925998/acastro_STK054_03.jpg)

The Nintendo Switch 2 will now reportedly arrive in 2025 instead of 2024

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19336098/cwelch_191031_3763_0002.jpg)

The best Presidents Day deals you can already get

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25289972/vudu.jpg)

Vudu’s name is changing to ‘Fandango at Home’

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25289727/107711533.jpg)

Tommy Tallarico’s never-actually-featured-on-MTV-Cribs house is for sale

Cookie banner

We use cookies and other tracking technologies to improve your browsing experience on our site, show personalized content and targeted ads, analyze site traffic, and understand where our audiences come from. To learn more or opt-out, read our Cookie Policy . Please also read our Privacy Notice and Terms of Use , which became effective December 20, 2019.

By choosing I Accept , you consent to our use of cookies and other tracking technologies.

Filed under:

- Video Games

Ten Years Ago, ‘Journey’ Made a Convincing Case That Video Games Could Be Art

Creative director Jenova Chen conceived ‘Journey’ as an act of rebellion against commercial games. The decidedly emotional titles it inspired forgo violence and point scoring for matters closer to the heart.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/70607909/journey.0.jpeg)

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Ten Years Ago, ‘Journey’ Made a Convincing Case That Video Games Could Be Art

To borrow internet parlance for a moment, Journey is a video game designed to hit you right in the feels. You play as an androgynous character dressed in a sweeping red robe, dwarfed by stark landscapes of sand and snow. Pushing the PlayStation controller’s left analog stick, you move forward, slowly at first, and then, later in the game, with exuberant speed, as if you’re surfing. Most of the time you’re alone, but if you’re lucky, you’ll come across another figure, its silhouette fluttering in the distance. You might travel together for a few minutes and then part ways, or perhaps you’ll reach the end of the game in one another’s company. Regardless, this time will feel almost miraculous—a chance encounter at the very edge of the world.

The game’s setting gleams with flecks of Gustav Klimt gold while a single towering mountain dominates the horizon. The game is called Journey for a reason, and its deliberately allegorical story curves toward tragedy, as if this is the fate awaiting us all. Unlike most games, you die only once. Rather than a cheap metaphor for failure, it’s something heavier—a crescendo, an act of self-annihilation.

Now, it’s widely accepted that games can move us in ways similar to novels, movies, or music, but in March 2012, when Journey came out on PS3, this simply wasn’t the case. Sure, there were the works of Fumito Ueda, Ico and Shadow of the Colossus —stark, artful games of the aughts from Japan that tugged more on the heartstrings than the itchy trigger finger. So too had the rise of independent games from 2008 onward given birth to a slew of newly personal titles such as Braid . Journey , however, felt different—a video game with levels, an avatar, and enemies, but that, mechanically, eschewed almost all else to focus entirely on movement. The game had cutscenes, but these were reserved for establishing shots of glinting sand rather than moments of genuine dramatic thrust. What Journey achieved—which few, if any, video games had before—was giving you a lump in your throat while you actually interacted with it. This was a big deal.

In this way, Journey helped crystallize the idea that video games could and should be more. In 2007 and 2010, respectively, Bioshock and Red Dead Redemption , games with knotty philosophical questions at their violent cores, had pushed the blockbuster shooter and open-world adventure into newly grown-up territory. But these were also time-consuming experiences that asked you to sink tens of hours into them to get to their narrative payoffs. Journey , by comparison, could be finished in 90 minutes, the length of a film. Certain kids, myself included, grew up convinced of video games’ artistic merit but lacked a work to express this conviction succinctly. Journey was the perfect title to convert churlish nonbelievers—our parents, for example.

I wasn’t the only one who felt this way. Gregorios Kythreotis, the lead designer of 2021 indie breakout hit Sable , remembers it like this, too. Kythreotis, who was 19 in 2012, had just started studying architecture, a discipline perfectly suited to the thoroughly spatial medium of 3D games. He was struck by Journey ’s confidence: It was the rare minimalist game whose carefully chosen elements had been executed exactingly. The “biggest thing” he recalls, though, was the fact that he felt he could show it to people who didn’t play video games. “They would play it and often be wowed,” he says over Zoom. “It was a lot friendlier and [more] accessible in this regard.”

Alx Preston, the creator of critically acclaimed 2016 action game Hyper Light Drifter and the recent open-world adventure Solar Ash , tells me over a video call that it was Journey ’s singular style that caught his attention. “There weren’t a ton of games out there that had this type of look,” he explains. “This type of vibe, these types of color palettes, that wasn’t focused on violence or goofy, silly cartoony things. It was carving out its own niche.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23303895/1_1437471569.1.png)

Clayton Purdom, who was then writing at Kill Screen , one of the era’s hip new video game publications, echoes this point. (Disclosure: I wrote for Kill Screen while Purdom was editorial creative director.) “I remember interviewing someone who talked about it as a ‘dinner party game,’” he tells me over a video call. “I’m never gonna have a dinner party where we all sit around and play Journey , but it makes sense. The game’s this really digestible, concrete, audiovisual narrative experience that’s fundamentally interactive.” In 2013, a month before the game’s release, Kill Screen ran the headline : “Is Journey creator Jenova Chen the videogame world’s Terrence Malick?” The comparison doesn’t really land beyond a shared fondness for stirring panoramic landscapes, but the question speaks to a time when many were attempting to frame video games as worthy of serious cultural discussion—as if you’d talk about them with your friends in the same breath as the latest Sundance hit.

Chen, the creative director of Journey , was held up as the poster boy of this movement, and so he was first in line for criticism. In 2010, film critic Roger Ebert wrote a gamer-baiting piece titled “ Video games can never be art .” At the behest of a reader, Ebert was encouraged to check out a TED talk by Kellee Santiago, a cofounder of the studio behind Journey , thatgamecompany. Santiago made an argument to the contrary, referencing, among other games, the studio’s previous title, Flower , in which you play as the wind carrying an assembly of petals. Flower was heralded as a game changer when it was released in 2009, an emotional, nonviolent title that even a novice could play by virtue of its simple controls. (The player tilts the PlayStation 3 controller to change the wind’s direction.) In 2013, it was added to the Smithsonian’s permanent collection and described as “an important moment in the development of interactivity and art.” Ebert, however, took a different view, batting the game away with a typically terse one-liner in which he compared its aesthetic sensibility, not entirely unfairly, to that of a “greeting card.”

When I speak to Chen over Zoom, he doesn’t mention Ebert by name but references the wider discourse. It was a “sense of rebellion” that drove him to make Journey , the idea that games should appeal to an audience beyond the young men who were interested in fist-pumping shooters like Call of Duty . (These games “weren’t actually mainstream,” he says, “they just had billboards on the street.”) Linked to this was the perception of video games in his home country of China as “virtual drugs” that caused people to drop out of college and neglect their relationships.

During the early years of his pursuit of a computer science degree at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Chen snuck into art classes. A few years later, he studied digital art and design as part of a cross-university collaboration with Donghua University. At the time, he and a friend would make video games in their college dorms, Chen art directing and his friend programming. There was little information on video game software available in China, so Chen’s partner learned about game-making from books sent over by a cousin in the U.S. Still, even while Chen was making games as a hobby, he didn’t consider it a viable career path. He intended to become an animation director like those at Pixar. “I felt like that was an industry respected by society,” he says. “I could tell my parents that I wanted to be an artist in this field and they couldn’t say it wasn’t honorable.”

Art as a career was an ongoing point of contention between Chen and his parents. He was born in Shanghai in 1981, five years after the end of the cultural revolution that sought to purge China of its pre-communist art and culture. Despite being an avid drawer, he characterizes his childhood as one devoid of art. Of these early years, he remembers that the sky was always gray except when it had just rained. The dust from the construction sites of the rapidly expanding city would lift and he’d be able to “smell the soil in the air”—for a brief time, “the sky was blue.” In an effort to steer Chen toward “respectable” employment in the modernizing country, his parents enrolled him in a coding class at the age of 10. “In China there was no plan from the government to take care of the elderly. Your kid was your retirement insurance,” he says. Despite initial misgivings about the coding classes, Chen quickly came to look forward to them thanks to the video games his classmates played before lessons.

Chris Bell, a designer on Journey who joined thatgamecompany halfway through the game’s production, says Chen possesses the complete package of skills needed to make video games. “He’s an artist, a programmer, and an engineer,” Bell tells me over a call. Having excelled in programming, Chen rekindled his childhood artistic impulse as a teenager when Shanghai began to open its door to international artists in the 1990s. On the way back from school, he’d stop off at the art galleries in People’s Square. “I would check literally every single show,” says Chen, who savored these “windows to the outside.” When it came to contemporary art, the teenager would ask a central, probing question: “Why does it deserve to be on the wall?”

Fast-forward to 2009. Chen, who had moved to the States six years earlier to study interactive media at the University of Southern California, was wrapping up production of Flower , the second of three thatgamecompany games published by Sony. (The first was a life simulator called Flow .) He was vibing off how people were responding to the game, particularly the finale of its movielike three-act structure, and he was ready to take the lessons learned at USC to the next level. But Zynga had just exploded onto the scene with its interpretation of social gaming, the hit Facebook game FarmVille . Chen remembers watching the company’s CFO give a talk at an industry conference. Having proclaimed the future of gaming as social, the CFO urged indie developers to quit their passion projects and join the company. “Everybody was pissed,” he recalls. “I felt their anger, too. I was like, ‘Who are you? How can you say that you define social games?’” For Chen, social meant an emotional connection between people, not just “trading vegetables with someone on FarmVille .”

This became the seed from which the rest of Journey grew. Chen wanted to show the world a game in which you truly emotionally engaged and connected to another person. It was another “act of rebellion,” against both Zynga’s transactional idea of connection and traditional multiplayer games filled with “foul-mouthed, teabagging” kids. When Matt Nava, the art director on Journey , interviewed to join thatgamecompany in 2008, the first question Chen asked was how he’d approach the social world of Journey : What would it look like, where would it take place, what would happen? Nava, “sweating bullets,” replied, “When you see another player in the game, through the visuals and the setting, you should immediately want to go to them. You want them to be the respite in the environment.”

Nava’s art, both elegantly minimalist and capable of summoning a deep, mythical history, is central to the success of Journey . In the same interview with Chen, Nava suggested brightly colored characters inhabiting a barren desert setting. This would become the game’s defining image. These creatures are humanoid but not identifiably human; they have bright eyes but no other facial features. The world they inhabit is filled with ruinous temples, tombstones, and sand that glints and glitters as if its very surface is dancing. When your character moves over these particles, their pointed legs deform it as if the grains have a physical presence, not just a flat, lifeless texture. Your character’s scarf, flapping in the wind like a ribbon, has a tangible quality, too, another component that tricks you into thinking this is less a computer program than an actual place of elemental forces.

You’re also swept along by Austin Wintory’s rousing soundtrack, which (in lieu of any text or dialogue) functions much like a narrator. “The music is very much a guide for the player,” says Wintory, who admits he felt a huge amount of pressure as a result of the soundtrack’s prominence in the experience. The composer was keen to avoid dictating emotions to players; rather, he wanted to create a musical environment in which they could bring their own “emotional projection into the equation.” Wintory refers to a feeling of “camaraderie” between himself and Nava; the pair would “riff a lot,” almost as if they were in a “feedback loop” with one another.

Nava, whose father is also an artist (the creator of a series of grand tapestries that hang in a cathedral in downtown Los Angeles), says he was obsessed with creating an “iconic” art style . He did so while working within the technical limitations of the PlayStation 3 and, more importantly, what he and the small team could physically produce in the allotted schedule. In the late aughts, out-of-the-box game-making software such as Unity and Unreal (now industry standards) weren’t yet widely used, so thatgamecompany had to build their own set of custom tools. In the early phase of development, Nava and graphics programmer John Edwards went back and forth constantly about what was and wasn’t possible. Ultimately, it was a case of “if you don’t need it, you don’t make it,” so they homed in on the fundamentals of the world: characters, architecture, sand, and fabric.

Despite a strong central idea and a mass of raw talent at thatgamecompany, the production of Journey was challenging. Executive producer Robin Hunicke, speaking five months after the game’s release at Game Developers Conference Europe, referred to a nearly catastrophic level of miscommunication within the team. Bell, who was hired initially as a producer and who later transitioned to a game designer role, took it upon himself to act as a mediator. Some relationships became so fraught that Hunicke described them as breaking down into “personal grudges.” At one stage, Nava arrived at work to find there was already a full-blown argument happening. He quit on the spot, only for Santiago to chase him down the sidewalk and coax him back into the building.

As time wore on, one deadline with Sony passed, and then another. The company’s finances were in such dire straits that Chen and the founding members of thatgamecompany all dropped to half salaries for the final six months of development. Nava says the team fell into the same trap as so many creators who believe that “in order to make great art, it was worth the suffering.”

During a period of acute creative drift, an exasperated Nava took it upon himself to design a level, much to Chen’s annoyance (as lead artist, this was categorically not Nava’s remit). From his perspective, there were a handful of mechanics but nothing was really sticking, so he focused instead on creating a series of “atmospheres” that the player would progress through. Nava thought back to specific “moments” he had in mind when he was painting the concept art, and then fed them back into the levels. The most famous of these sees you hurtling through a stone tunnel while a sumptuous orange sun sets to your right. “Thinking about it as moments was the real trick,” says Nava. “That’s what people remember the game for.”

The gambit paid off. When it was released on March 13, 2012, Journey received rave reviews from outlets such as The Guardian (“the best video game I have ever played”), Eurogamer (“a “sand-blown chunk of spiritual eye candy”), and IGN (“one of gaming’s most beautiful, most touching achievements”). Nava is right to point to the “moments,” which Kythreotis remembers as “a really special aesthetic experience,” as key to its creative success. But the multiplayer is integral, too—arguably an overlooked aspect of the game that to this day breathes an improvisatory life into it. Humans behave differently from AI characters; they move erratically and compulsively, both too slowly and too quickly, and this discord, which takes place against the game’s pristinely melancholic world, is vital to its balance.

Still, the production took its toll on the team. Bell and Nava both exited soon after, citing difficulties relating to the company culture. As Nava explains, they weren’t the only ones: “I don’t think many people fully understand what happened,” he says, “but [thatgamecompany] shut down basically. Everyone left.”

The studio was later revived for the production of 2019 iOS title Sky: Children of the Light , another multiplayer exploration game albeit set amid billowing clouds. In 2017, Bell returned as a designer, noting a broadly positive change in work culture. Chen was now decidedly in charge, whereas before there had been wrangling over decisions between him and his thatgamecompany cofounders. With a bucketload of VC funding rather than a Sony publishing deal, the company had more time and money to explore different ideas. Since then, thatgamecompany has continued to grow. A few days after my conversation with Chen, his company announced a $160 million investment deal alongside the recruitment of Pixar cofounder Ed Catmull, who will serve as principal adviser on creative culture and strategic growth. I suspect a younger Chen would be pleased at this development: a titan of Hollywood animation joining his artistically committed video game studio.

How should one assess Journey ’s influence? It’s not Grand Theft Auto III , a blockbuster behemoth that inspired a deluge of imitators (mostly hyper-violent open-world crime games such as Saints Row ). If you look at the following decade of games, few bear the explicit influence of thatgamecompany’s flagship title. Oceanic explorer ABZÛ and open-world puzzler The Pathless are exceptions, but these were both made by Giant Squid, the studio Nava cofounded in 2013 following his departure from thatgamecompany. Importantly, Journey showed Nava both what games could be and how not to make them, a lesson he carried into his new studio, one built on making “artistic games” in a culture that is “sustainable and happy.”

In a wider sense, Journey helped engender what we’d now call a vibe shift. Put simply, if video games mostly traded in the various emotions related to killing shit, point scoring, or problem solving, Journey was part of a new wave that broadened their dramatic texture. Purdom threads a line between Journey and small-scale interactive works such as Florence , If Found … , and, most recently, puzzle game Unpacking , each of which tells decidedly personal stories. “I think, in some ways, it did help break ground on the whole ‘games are emotional’ angle,” he says. Some titles arguably leaned into sentimentality too hard—2016’s Unravel , for example, an almost unbearably cute platformer starring a yarn of wool. Despite a slew of games Purdom refers to as “feelings porn,” Journey also led to experiences that were, for lack of a better word, more “honest.”

Purdom, however, is rightly wary of ascribing too much importance to Journey . It came out the same year as Gone Home , a first-person exploration game that centers on a queer relationship, and 13 months after Dear Esther , a macabre, William Burroughs–inspired adventure set on a blustery Scottish island. Each was influential in its own way, but the legacy of these games resides more in how they collectively pushed a different emotional, intellectual, and aesthetic agenda to the mainstream. ( Kentucky Route Zero , Cart Life , and Papers, Please are a few of my favorites from the time.) Still, these were all games you had to play on your PC with a keyboard and mouse. Journey , published by Sony for the PS3, “helped kick open the door in a more popular way,” says Purdom. “You could throw that game on and play it on the couch.”

Journey immediately became the fastest-selling game on the PlayStation Network at a time when most titles were still bought in brick-and-mortar stores. For Nick Suttner, who was working as a senior product evaluator in Sony’s third party department, the game was “perfect ammunition.” He and a small team were responsible for getting games onto the PlayStation Store in an era when resources for such titles were highly contested. “We had to fight for everything,” he tells me over Zoom. “Indies just weren’t part of the ecosystem.” The success of Journey fed into what Suttner calls a “holistic push” at Sony, which had also included a three-year, $20 million publishing fund for indie games that was announced in 2011. A year after Journey ’s release, explosive blockbusters Killzone: Shadow Fall , Destiny , and Watch Dogs dominated the PlayStation 4’s glitzy announcement, but amid all the gunfire was The Witness , a serene, first-person puzzle game. It felt like part of a sea change in priorities at Sony that Journey was partly responsible for.

However, Sony’s support for indies wouldn’t last. A few years later, when it became clear that the PlayStation 4 was trouncing the Xbox One, the company’s focus shifted back to blockbuster game development. Sony poured resources into the next generation of megahits, such as The Last of Us Part II , Marvel’s Spider-Man , and Ghost of Tsushima . Along the way, Sony’s Santa Monica Studio, which was both the developer of the God of War series and an incubator and publisher for indie developers, had a game canceled. This meant layoffs on the development side and a deprioritizing of the publishing division that had launched Journey a few years earlier.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23303900/1_1437471570.3.png)

On December 1, 2016, the indie-oriented publisher Annapurna Interactive announced its formation, led by Nathan Gary, the creative director of Sony Santa Monica’s indie development efforts. Chen, who has been variously described as a “scout” and “spiritual adviser” to the company, refers to himself as “more of a cofounder.” Having sourced investment for Journey ’s follow-up, Sky: Children of the Light , Chen was perfectly placed to introduce Gary to potential funders. After securing a deal with Annapurna, itself a film production company behind a string of auterist hits including The Master , Zero Dark Thirty , and Her , attention turned toward signing games. If there was a guiding principle, says Chen, it’s that he and Gary were looking for game makers who were ready to put an aspect of their personal life into the game. Chen describes this as an “innately artistic” approach; the creators are “honest,” saying something that is “truthful to their own lives.” Crucially, these works are more likely to resonate because, as Chen sees it, “our lives are all intertwined.” In other words, we see ourselves in these games.

Chen says Annapurna was also looking for emotional tones underrepresented in games. He mentions 2017’s What Remains of Edith Finch , a game he characterizes by its “dark humor,” and one that his former colleague Bell took a lead role in designing. Maquette , released in 2021, fits the bill, too, a decidedly Hollywood-feeling romantic drama wrapped around a mind-bending puzzle mechanic. In fact, almost the entirety of Annapurna Interactive’s roster is a reflection of the central thesis that has steered Chen’s career, namely that gaming must look beyond the 15-to-35 male demographic if it’s ever going to evolve, let alone be taken seriously.

When I ask Chen about Journey ’s influence on the wider gaming landscape, he doesn’t mention specific titles or trends, but pulls focus back onto the work itself with, to my surprise, an extended music metaphor. “If you want an orchestra to move people, then every instrument has to perform the same piece of music. Every element contributes to the storytelling,” he says. “And what we learned is that the interactivity is the soloist. It’s the lead of the orchestra in gaming. A lot of games in the past have told emotional stories— Final Fantasy , for example—but they relied on traditional media. I love it, but the moving part, the part where you cry, is when you watch the cutscenes. At that moment, what really touched you is cinema, not games.”

In a way, it’s surprising how few blockbuster games have internalized this lesson. The recently released Horizon Forbidden West is a good example. When I play that game, it moves me, but mostly because of the sense of awe I feel at its shimmering, windy world . It’s the same for Ghost of Tsushima and the Uncharted games. That’s not to deny the validity of these experiences, but their moments of personal drama are delivered without the player’s input. Journey , in its own very specific way, figured out how to make drama interactive. Purdom refers to Signs of the Sojourner , an indie card game about friendships and conversation, as a “next step” in this regard. “It’s a mechanically complex game entirely in service of inspiring these kinds of emotional experiences,” he says. “It’s like, ‘Wow, I’m feeling regret because I hurt a friend’s feelings thanks to the way these cards played out.” My own mind is drawn to Hideo Kojima’s postapocalyptic hiking simulator, Death Stranding , and the grueling slogs my character endured through snowy mountains. These interactive journeys mirrored the protagonist’s emotional arc, and each landed with greater heft as a result.

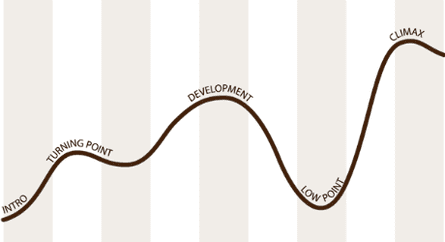

This is the magic of Journey . At the start, you move tentatively but curiously. In the mid-game, you’re cascading down dunes at extreme speed. And during the very lowest moments, you’re barely making a step at a time. Then, when you have nothing left to give, you stop moving entirely, however hard you push forward on the controller. “What Journey did really well,” says Chen, “was to make interactivity the climax—the memorable moment.”

Lewis Gordon is a writer and journalist living in Glasgow who contributes to outlets including The Verge , Wired , and Vulture .

The 2004 Video Game Draft

‘knuckles’ and ‘stellar blade’ reactions, ‘fallout’ season 1 reactions.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

A Journey to Make Video Games Into Art

By Laura Parker

The critic Roger Ebert once drew a crucial distinction between video games and art: he said that the ultimate objective of a video game—unlike that of a book, film, or poem—is to achieve a high score, vaporize falling blocks, or save the princess. Art, he argued, cannot be won.

But Journey, which was released last spring, is not like other games. You play a faceless, cloaked figure who glides through a vast desert towards a mountain on the horizon. Along the way, you may encounter a second player, with an identical avatar, who is plucked from the Internet through an online matchmaking system. Both players remain anonymous—there are no usernames or other identifying details—and communication is limited to varying combinations of the same, one-note chirp. No words ever appear onscreen during gameplay. The idea of the two-hour game is to make a pair of players connect, despite those limitations, and help each other move forward. Along the way, they solve puzzles and explore the remnants of a forgotten civilization.

This kind of purity of form is at odds with most contemporary games. As the gaming industry has increasingly come to resemble Hollywood in its pursuit of guaranteed blockbuster franchises, the titles that dominate the sales charts—the shooters and the sports games—are designed to trigger the kind of escapism that rarely invites contemplation or self-reflection. Few games are willing to stray from familiar territory, and even fewer do so successfully. By delighting critics and smashing sales records, Journey, a weird game from an unconventional game-development studio, joins the small pantheon of titles to have done both with ease.

Thatgamecompany, the independent studio responsible for creating Journey, is a fourteen-person firm that operates out of a small, one-room office in suburban Santa Monica, California.

TGC’s creative director, Jenova Chen, sits by the front door, next to a shelf packed with a growing collection of industry trophies and awards. Now thirty-one, Chen co-founded TGC with Kellee Santiago during his final year at the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts, in 2006. Since Santiago’s departure, in 2012, Chen has become the company’s leader, ideas man, and public face. He believes that TGC is “the Pixar of games”: “Right now, most games feel like summer blockbuster films, all explosions and crappy dialogue,” Chen said. “A big part of the games industry still hasn’t figured out how to give players something new. That’s what I want to do.”

The concept of the auteur is relatively new to gaming. Only a small group of developers have earned the title, people like Shigeru Miyamoto , Hideo Kojima, and Warren Spector. Chen considers himself a commercial artist, whose role is as much to create “real art”—the kind that Ebert referred to—as it is to produce marketable entertainment. He wears suits to work instead of the jeans-and-T-shirt uniform adopted by most game developers. And he describes himself as a perfectionist; he redesigned TGC’s 2009 title, Flower, twelve times before being convinced it was ready for release. Even his name is overly designed: he adopted “Jenova” from the antagonist of one of his favorite video games, Final Fantasy VII, while he was in high school. (His real name, “Xinghan,” means “Milky Way” in Chinese.)

In the industry press, TGC’s games are often described as “experimental.” The studio’s past three titles, released on the PlayStation Network as part of an exclusive three-game deal with Sony Computer Entertainment America, featured no dialogue or conventional protagonists. Flow, released in 2007, requires players to guide a microorganism through a series of underwater two-dimensional plains; in Flower, the player guides a single flower petal across different environments. Journey, released in spring of 2012, was TGC’s first online game. Following its release, it became the fastest-selling PlayStation Store title in both North America and Europe. (Sony did not reveal how many copies the game sold, saying only that it broke sales records.)

In the first week of sales, TGC received over three hundred emails and letters from gamers expressing awe at Journey’s ability to rouse their altruistic spirit. Meanwhile, critics pointed to Journey as evidence of a cultural shift in gaming—the start of a new era of thought-provoking, meaningful experiences that stretch the boundaries of the medium. This year, Journey was nominated for almost every recognizable game-of-the-year award, eclipsing games with many times its budget. Overnight, TGC became the gaming industry’s new heroes.

But in a keynote speech shortly after Journey had won Game of the Year at the 2013 DICE Summit, Chen announced that the studio had run out of money while developing the game.

TGC had begun work on Journey in 2009. Sony’s strict budget for the title determined many of the firm’s design decisions: Chen originally intended for the game to be set in a forest but switched the backdrop to a desert because there was “less stuff to draw.” The fully animated human protagonist was reduced to a pair of matchstick legs. The game’s striking visual aesthetic was the fortunate result of limitations.

At the end of 2011, a few months before Journey’s deadline, TGC asked Sony for an extension. It was the third in as many years—the development cycle had been unusually long, and Chen didn’t want to submit the game until it had “achieved its intended emotional impact.” He had spent twelve months reading sociology books. Knowing he couldn’t anticipate players’ reactions, he reasoned that they might be more willing to invest emotionally in the game if they were forced to play anonymously. (This runs contrary to current conventional wisdom about how online speech becomes more civil if you attach people’s real names to their actions.) “Right now, when you think about online players, you just think of jerks that couldn’t be happier than when they see you suffer,” Chen said. “I wanted a game where players could connect to someone, someone they could trust but who they knew nothing about.”

Sony gave the studio more time but no additional money. Chen used the last of TGC’s savings to finish Journey; it submitted the game to Sony in January, 2012. A week later, the company shut down. Most of the employees left for new jobs; the rest were quietly let go. Chen, his lead engineer, and his lead designer held on to await the verdict on the game that had bankrupted them.

Chen waited long enough to be convinced the game would succeed before flying to San Francisco to meet with Benchmark Capital, a Silicon Valley venture capital firm whose list of investments includes Twitter, Instagram, and Yelp. Mitch Lasky, the Benchmark general partner who agreed to meet with Chen, was already impressed by Journey. After Chen finished his pitch and left the room, one of the partners who sat in on the meeting told Lasky, “Don’t let him leave the parking lot without a handshake.”

A week later, Benchmark signed off on a five-and-a-half-million-dollar investment. “I’m a venture capitalist, not a patron of the arts,” Lasky explained to me. “He’s an outlier, and in our business, it’s the outliers who can produce the biggest returns. Journey may be the video-game industry’s ‘Toy Story’ moment.”

A week before our interview, Chen stopped at the Electronic Entertainment Expo in downtown Los Angeles, to see if anyone had one-upped him on his next idea. “I was proud to see that no one is doing what we’re doing, but also worried because I know why,” he said. “It’s risky.” Earlier this year, an ex-TGC employee promised that the company’s next game would “change the industry.”

Chen called it “the bastard child” of all his past games and a continuation of TGC’s past themes of connection, nostalgia, and self-reflection. He aims to give people who play it a memory as vivid and emotionally gratifying as their most cherished childhood moments; he compared it to watching “E.T.” for the first time.

In the as-yet-untitled new game, which, according to Chen, is at least another two years away, people can play alone or with others. It will again feature non-verbal communication, although the studio hasn’t yet planned how players will interact. Chen just wants to enable people to play side-by-side in the same room: “A lot of people asked us why Journey didn’t let them play with friends or family, and obviously we had a reason—because that would have defeated the purpose of the game. But for a game to be truly be accessible, to both children and adults and to men and women, it has to allow people to play with the ones they love.”

And, unlike before, the game will be released on multiple platforms. Chen, at first, said the game would “obviously” not be made for devices that don’t make sense, like BlackBerries. But then he added, “Well, why not?”

After talking about the game, but swearing me to secrecy about some of its details, Chen showed me a letter he received earlier this year from a fifteen-year-old girl whose father had passed away from cancer a few months ago. The girl describes spending hours playing and re-playing Journey with her dad in the last weeks of his life, and how it was their last activity as father and daughter. “Every artist wants his or her work to connect with someone,” Chen said. “I think that’s why people make art.”

Illustration: Thatgamecompany.

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Louisa Thomas

By Jay Caspian Kang

By Susan B. Glasser

By Richard Brody

10 Years On: 8 Things You Didn't Know About Journey

Journey is a beloved indie title to this day, and here are just a few things you might not have known about its making.

Journey is certainly one of the most famous indie games that's ever been made, and easily one of the most successful. Its legacy still manages to draw in new fans to this day, and said fans are still awed by its environments, its soundtrack, and how it manages to tell a story with zero dialogue.

Related: Best Games To Play On iPad

However, even ten years after its release , there are still new things left to discover about Journey. It may be easy to assume things were plain sailing for developers thatgamecompany, but game development can often be a strange and stressful process, even for games that are deliberately simple to play.

8 It Was Created By No More Than 18 People

Over the three-year development period, thatgamecompany went from just seven employees to a maximum of 18 . The team had also been given only a year by Sony to complete it, but thatgamecompany knew there was no way they'd be able to finish Journey in such a short amount of time with so few people.

Related: The Best Games Made By Just One Person

Looking back, it seems pretty outlandish to have expected a fully completed game in just one year from only seven people, indie or otherwise.

7 The Traveller Actually Dies During The Finale

When the protagonist (known as the traveller) collapses in the snow near the summit, you may think that you've simply fallen unconscious, and the other travellers are using their energy to help you reawaken and reach the mountain's summit.

However, according to the game's lead director , Jenova Chen, the traveller does die at that point. The finale is more of a spiritual journey because the physical one has now come to an end. It's still a happier scene, but this knowledge makes the overall ending feel sadder .

6 The Game Had A Very Strained Development Cycle

Whilst Journey may be the ideal chill-out game , the development process was anything but. On top of the constant worries about time pressures, reducing overtime, and trying to avoid tension between team members during stressful periods, Jenova Chen revealed at a DICE talk in 2013 that thatgamecompany also had to file for bankruptcy as development finally came to a close.

It was so bad that some of the developers went unpaid for a few months near the end. They even had to use their own money to fund the game.

5 One Playtester Experienced A Much Sadder Ending

According to Austin Wintory (the composer for Journey) , he brought in a friend to experience the game during development. When said friend exited the room, they remarked to Austin Wintory and Jenova Chen about how moved they were by the ending, without realizing there was still more of the game to play.

This is because the game had crashed after fading to white during the snowfield section. This actually caused Jenova and the other devlopers to change the finale to better reflect this moment.

4 The Game Had Two Prototypes

The first concept for Journey was a 2D game called "Roping," and it involved two players helping each other climb up some platforms via ropes. The second concept was called "Dragon," and it involved players trying to lead others away from a large monster.

Both of these concepts were scrapped because the team felt that they went against Journey's core point: it's a co-operative experience that can also be completed solo if the player wishes, and if they do meet someone, there won't be any ill feelings towards them.

3 It's Designed To Feel As Universal As Possible

Journey is designed in such a way that it can be approached by anyone, and this applies to every aspect of the game. For example, the traveller is purposefully blank so anyone can project themselves onto them, and the architecture is purposefully designed to belong in Journey's world, rather than act as a reflection of our own.

Related: Indie Games Made With Unity

This even extends to the multiplayer. You can be playing with anyone in the world and whilst you have no idea who they are, you both know why you're here.

2 The Hardcover Artbook Can Be Viewed In AR

A few months after Journey was released, an official artbook was released which compiled some unseen concept art along with art from fans who had enjoyed Journey. To make it a bit more special, thatgamecompany worked with AR company Daqri (now defunct).

This means that readers have the opportunity to look at 3D models of the artwork on phones or tablets. Unfortunately, it's much harder to get a copy of the book nowadays because it was never digitized, and resale copies of the book sell for astronomical prices.

1 The Soundtrack's Release Was Purposefully Delayed By A Few Weeks

Journey's OST is one of the best-selling in gaming. However, it wasn't actually released on the same day the game came out (as is often the norm for video game releases). Instead, Jenova Chen decided to release the OST about a month later.

This is because the soundtrack basically tells the entire story of Journey, and Jenova didn't want people who hadn't yet played the game to be spoiled by listening to the OST first . This strategy also boosted the sales of the OST when it finally did release.

Next: Modern But Minimal: Best Minimalist Games On Current Consoles

Journey Review

Just deserts?

If Journey is about God, then God has played an awful lot of video games. One of the most fascinating things about thatgamecompany's sand-blown chunk of spiritual eye candy isn't that it reinvents gaming, or extends the medium's reach: it's that it takes old ideas - sometimes very old ideas - and repackages them in clever, stylish, and unexpected ways.

That glowing mountain on the horizon is a case in point. It seems like a straight lift from the Old Testament at first, but in Journey it's also your ultimate objective. It's both goal and waypoint marker, far less artificial than the breadcrumb trails of Perfect Dark Zero or Fable 2, but no less effective when it comes to the simple, crucial things that a game has to do - like keeping its players oriented as they move through large, artfully empty environments.

Or check out the scarf that billows and flaps around your devout and pin-legged avatar as you lean into the wind. It's part of a distinctive moth-brown uniform that comes teasingly close to referencing religious garb as varied as the burqa or a Franciscan's habit, but it's also there to tell you how much magical energy you have left for jumping and floating. It's a piece of standard UI, essentially, yet it's stuck right into the game world, tracing pretty little spirals in the desert air as form and function merge.

The more you explore, the more natural it all seems. Checkpoints become mysterious stone altars that you kneel before while saving your progress. The in-game economy, such as it is, comes in the shape of shreds of cloth that spin and tumble in the wind. Your climbing frames are made from ancient temples, smashed and broken in the dust, their finials and ornaments always a hair's breadth away from conforming to Middle-eastern, European, or Asian architectural styles. Daringly uncluttered maps fence you in with invisible walls that take the form of brutal winds or cascading rivulets of falling sand.

Journey's a fairly short adventure - if you're bringing such worldly concerns to this delicate piece of whimsy, you'll probably want to know that an initial play-through will clock in at about an hour and a half - but it makes a lot of pleasantly familiar stops along the way. The storyline leaves much to your own interpretation: you wake, alone, in the desert, and must then head towards a glowing peak in the distance. Everything beyond that is what you make of it. Yet the game's mechanics waste no time at all explaining exactly what you should be doing from one moment to the next.

This part's a little bridge puzzle. This glowing thing is an end-of-level marker. Over here you'll get to slide downhill for a while like you're playing SSX - see if you can aim for the gates, eh?

Journey has room for physics challenges, stealth sections, and even some gentle levelling up as you collect tokens that allow you to hover in the air for longer periods of time. But it does all of this with an unusual economy of control - you're basically limited to move, jump, float and, um, sing - and with a kind of sparse, widescreen, biblical imagination that redesigns classic gaming elements to the point that you'll barely recognise them.

The main beats of the narrative borrow much from thatgamecompany's previous game, Flower, but in terms of straight-up visual storytelling - when it comes to introducing mechanics wordlessly and prodding you through levels so that you always end up in exactly the right place - Journey's creators now seem the equal of Valve or even Nintendo. Infrequent prompts tell you how to press a button to float or how to rotate the pad to turn the camera (this is annoying, incidentally, and a real design imposition - thankfully you can also use the right thumbstick) but most of the guidance takes place without you even realising it.

Your viewpoint might shift gently as you head towards a tumbledown ruin so that you can pick an easy path onto its roof, while pools of light and murky shadows in the distance do much to draw you from one short chapter to another. There's room to explore as you make your way past rusting machinery, ancient gantries and desert canyons sparkling with tiny pieces of quartz - just as there's room, in such a sombre experience, to muck about a little and surf down the sides of dunes leaving large trenches in your wake. As the name suggests, though, this isn't really a game about hanging around. It's about moving on and making progress - as steadily, in fact, as if you were Link riding on Epona.

If Journey's in love with games, it's also quietly enamoured of cinema, too. Each hill you crest frames your next objective as a dreamy Technicolor spectacle, while there are distinct traces of Spielberg in particular in the lighting, the pacing, and the willingness to let a swooping, arching soundtrack dictate the mood. All of that is great, of course - nobody makes inhuman forces as warmly comforting as Spielberg - but Journey's picked up some of the director's weaknesses, too. This is elegant, masterful stuff, but it can actually seem a touch too polished on occasion. It's put together with such obvious skill that it can feel calculating - and even a little hollow.

That's how I felt on my first play-through, at least. Journey initially seemed to be an attempt to manufacture a kind of non-denominational religious experience for players: to make them feel like a small yet crucial part of something vast, mysterious and powerful. It's very hard to construct free-floating reverence, though, even if you're working with such a potent tool as a video game. You can design your way towards it, but you'll end up relying on shorthand: cathedral buttresses, shafts of light, planes shifting ominously beneath skies latticed by falling stars.

On my first trip through Journey, I was amazed at the craft and the scene-setting, and appreciative of the way that the storyline left careful gaps so as to allow for a handful of different interpretations, but the whole thing came off like a complex magic trick that didn't quite work. I felt admiration more often than awe. I was appreciative, but unmoved.

It turns out that I was missing a crucial piece of the experience, however. On my second play-through, I found it.

Two thirds of the way through Journey, the going gets tough. This isn't a hard game by any standards, but it's very good at creating a sense of hardship as you reach the final act. I was trudging along, wind-swept and battered, and I knew that things were only going to get worse. Then the clouds parted, just for a second. I turned a corner and caught a quick glimpse of a moth-brown shadow, clambering along in the distance.

It was another player. Journey does this: it sneakily shoves someone into your game from time to time, and then gives you the option to travel along with them. There's no voice chat available, and there are no naff combo moves to pull off in concert, but you can sing to them - this is essentially Journey's musical spin on a multi-purpose interact button - and you can often get basic points across in a kind of heavy-handed mime.

It sounds like rudimentary co-op, but it feels like nothing else. You're together, but separated. You meet, but you're always kept at arm's length, and you have no say in who you'll encounter.

So now I was able to work through Journey's darkest, most troublesome section with a companion. We pushed through the wind together, each singing one note, and then having the other echo it back. We recharged each other's jump power - a trick that normally only those scraps of floating cloth can do - and I guided my fellow traveller through some of the nastiest parts of the game: past traps and sudden winds and severe drops, onwards and upwards, until the mountain towered directly above us.

It was a total transformation. Play Journey with a random - and chances are that you will - and all the convenient metaphors and artificiality melt away. The game's lunges at profundity disappear, and you're left to focus on the core of the experience: a pilgrimage, filled with incident, compacted into the space of a few glorious set-pieces.

Granted, thatgamecompany's done most of the work for you. The studio has poured the deserts, trashed the temples and filled the world with the floating presence of a nameless almighty. The truly brilliant move, though, was to leave a space at the very centre of the design that only a stranger can fill.

The master stroke, as in all great myths, lies not with God, but with the human element.

Read this next

- Journey, Skyrim and Spider-Man developers announce new studio Gardens

- Uncharted: The Nathan Drake Collection, Journey free on PS4 later this week

- Serene platformer Journey makes a surprise debut on iOS

Review | Songs of Conquest review - fantasy tactics that favours breadth over depth

Review | Indika review - a dark, surreal, and devilishly playful drama

Review | 1000xResist review - a deeply personal exploration of diaspora politics and psychology

Review | Animal Well review - this one gets deep

Review | Hades 2 early access review - polish and terrifying power from some of the best out there

Digital Foundry | MSI MPG 321URX review: the best QD-OLED monitor for US buyers

Review | Sand Land review - a fitting tribute to a wonderful author

Review | No Rest For the Wicked early access review - a shaky start, but there's potential

'Journey' Review

Your changes have been saved

Email Is sent

Please verify your email address.

You’ve reached your account maximum for followed topics.

10 Best PS3 RPG Side Quests

Steam giving away critically-acclaimed 2014 game for free, assassin’s creed shadows’ stealth system explained.

Game Rant's Jeff Schille reviews Journey

Journey is a confounding game to review. That is largely by design, and one could say the same about thatgamecompany's previous efforts, flOw and Flower . Although it is possessed of mechanics that evolve over the course of the experience, Journey isn't about its mechanics in the way that, say, Modern Warfare 3 is about shooting things.

Indeed, discovery defines the experience of playing Journey as much as anything can be said to. Discovery of the game's simple, minimalist mechanics, discovery of the hidden features and meanings of the game's world, and best of all, the discovery of other travellers on the same journey.

Truthfully, the less players know about Journey at the outset, the better. As such, this review will endeavor to be as spoiler-free as possible (although players determined to go in with a little extra knowledge may want to check out this list of Journey's trophies ). For readers who simply want to know whether or not the game earns a recommendation from this reviewer, it does. Frankly, I'd like everyone to play Journey . I am not, however, sure that everyone will appreciate it equally.

Journey opens on a hill in the desert, with a volcano-like peak visible in the distance that is the player's destination. Covering the distance between those two points makes up the entirety of the experience. In that sense, Journey can accurately be described as a game about traversal, though to do so would be reductive (for more details, check out Game Rant's E3 2011 Journey preview ).

Though it is not demanding mechanically --in fact, completing the short game is a cinch -- Journey is demanding of players' attention. Everything that happens in Journey happens in the game world and to the character -- there is no in-game map, no status bar, no arrow to point the way forward. Save for a few brief control prompts early on, there is no onscreen UI at all -- nothing to get in the way of Journey's gorgeous, singular visual presentation.

Though the game's landscapes are stylized and occasionally abstract (and sometimes resemble the legendary album covers drawn by Roger Dean), thatgamecompany did not use Journey's visual design as an excuse to present a flat, featureless world. Journey's often expansive environments shimmer and glitter in the heat of the sun, while sand is blown all around and reacts as players move through it (see for yourself in this Journey beta footage ), though desert is not the only terrain waiting to be crossed.

Journey is not merely pretty, it is often breathtakingly beautiful -- almost hypnotically so. Everything moves as if under water, slowly and with flowing grace. Journey's orchestral score, alternately somber and soaring, matches the game's measured pace.

At its best, the game envelops players with remarkable beauty and the wonder of discovery, creating a calm reverie that is wholly unique. That said, much rests on players giving themselves to that reverie. Players who, for whatever reason, are unmoved by Journey's visual splendor will likely be left wondering what all the fuss is about. There is little in Journey , mechanically, to compensate, and the game's intentionally obscure storytelling all but ensures that the short attention span crowd need not apply.

Still, Journey is wondrous. It is a game with a point of view. There is a pervading sense that the designers at thatgamecompany strove to deliver a very personal, very specific message to players through the game. Though opinion will likely vary on exactly what that message is, the presence of an authorial perspective palpably enriches the experience at hand.

Take, for instance, Journey's online multiplayer. Players who opt in will, sooner or later, encounter other travellers. There is absolutely no verbal or written communication between characters, no requirement that players collaborate, and no penalty for simply going ahead alone. Nonetheless, it is quietly fascinating to watch another random player working through the game, and it is telling that there are opportunities for players to behave benevolently. Despite the anonymity of the experience, travelling with a companion manages to make Journey's rewards that much richer.

There is a temptation to look at the whole of Journey as a rebuke to the violence and viscera-obsessed titles that regularly dominate sales charts (it's true that if there is a polar opposite to those games, Journey is it). As such, players who love nothing more than curb stomping a Locust head in Gears of War might not be expected to embrace Journey -- and that would be their loss.

However, there is a downcast, exclusionary cynicism in that evaluation that Journey simply does not abide -- cynicism is not a part of the game's worldview. Rather, Journey is an uplifting, ultimately joyous exploration of what games can accomplish and convey. It is a celebration of the medium and its myriad possibilities, and a gift of great and singular beauty to players -- all players. This Journey truly is its own reward, and comes highly recommended.

Journey is available now, exclusively for PlayStation 3.

Follow me on Twitter @ HakenGaken

Our Rating:

Deciphering the Journey

Posted in Features

Video Gamer is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Prices subject to change. Learn more

It doesn’t take much longer than an hour to reach the end of Journey, thatgamecompany’s recent indie jaunt across the desert. On the surface, it’s also a relatively lean game, stripped of all but the most basic interaction methods and never overtly thrusting a story in your face. In its seas of colour and its wordless narrative, it’s a fabulous exercise in minimalism. At least, that’s how it first appears.

In Journey, you walk, jump and play. You interact with the world by leaping or by singing at it, and you solve the game’s few puzzles via experimentation, learning the rules of this land as you exist within it. There are no dramatic characters intoning long, expository dialogue sequences, and you won’t find any diary entries bafflingly ripped out in chronological order. You uncover Journey’s mystery simply by experiencing it.

An hour isn’t long to unfurl the tale of an entire world, especially when much of that time is spent experimenting with its systems, sliding down sand dunes and singing to the co-op buddies who sometimes quietly drop into your game. And yet, Journey is infused with more character, more ideas and more meaning than any other recent release that springs to mind.

So: what does it all mean?

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/faf1/journey_16.jpg)

There are lots of theories, of course. It’s that way by design. Journey’s like a silent movie without any captions, and one in which the action on-screen is always faintly abstract, otherworldly and expressive. Or perhaps it’s like a ballet, an aural and kinetic display of ideas, but one where you’re not familiar with the source material. You come away with a thousand possible answers, but nothing to confirm your suspicions. You just know it was a hell of a show.

I’ve heard quite a few of these theories now. They range from the sensible to the surreal, from religious to scientific. I even had a discussion with a friend recently who was absolutely certain that Journey is a game about the nine months between conception and birth: he thought the ducking and diving fabric creatures represented sperm cells, the occasional enemies were threats of miscarriage, and the mountain – with that gaping opening at its peak – was the game’s enormous vagina.

For what it’s worth, I don’t think Journey is a game about sperm and vaginas, but I do think it’s a game about life. In fact, I think it’s a game about quite a lot of things. I spent a couple of days after finishing Journey thinking about what it could all mean. Each time I came up with a theory, or heard someone else’s, it seemed eminently plausible but still didn’t quite seem to fit. That lightbulb moment, the one where it all clicks into place, stubbornly refused to arrive.

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/55b9/journey_13.jpg)

And then it did, and I settled on the theory I’ve stuck with. So here goes: Journey is a game about everything .

I do distinctly mean ‘everything’ rather than ‘anything’, too. While Journey was clearly intended to have its intricacies discussed and debated, I don’t view it as a story without a specific meaning. The reason none of those individual interpretations seemed quite right on their own is because they function as part of a much larger picture – a microcosm of an entire universe, its past, its present and its future.

The most obvious of Journey’s strands is the story of a civilisation, one that was built up from nothing but ultimately collapsed, leaving the starkly ruined landscape you see before you. This story is the one told in the abstractly animated cutscenes that bookend each chapter – the beautiful mural that scratches and paints itself as you watch, its symbols slowly growing into something more recognisable.

Why did this civilisation grow so huge, and why did it ultimately fail? These answers prove more elusive. We see what appears to be electricity flowing through a city’s veins, and it seems to be brought to its knees by explosive blasts. There are hints at scientific advancement, and of war, which would make perfect sense given the content explored in the rest of the game.

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/56dd/journey_18.jpg)

There are very obvious religious overtones. At times the symbolism is enormous, with spiritual apparitions, Middle Eastern architecture and, in the game’s closing moments, a joyous take on the rapture that sees you rise from your body, through the snow-filled clouds and into the beautiful blue skies above. After lingering on your dying moments for an uncomfortable length of time, Journey shakes things up, and the game turns out not to end with your death, but with your incredible reincarnation.

But while Journey is a game about religion, it’s also a game about science. One of its other major themes is evolution: it’s about species adapting to their environment, growing and changing, gaining new abilities as they fight for survival. This is the case with your own character – you begin the game without the ability to jump, and the distance you may do so develops over time, allowing you to rise to Journey’s challenges. By the end, you find yourself in a place where the conditions are radically different – a blizzard-filled mountainous region, instead of a baking desert – and natural selection ostensibly writes you out of the story.

There are other visual cues to evolution, too. It might sound strange, but it’s the fabric that’s key. It begins as floating particles whose only ability is to increase the length of your own scarf. By the end they’ve become enormous floating dragons that transport you around the world, or coral-like formations that boost you skywards, allowing you access to areas you’d otherwise be unable to reach.

Journey is a game that operates on a macro and micro level simultaneously. So, while it’s a game about evolution, it’s also a game about simply growing up. You don’t understand Journey’s world when you first arrive in it. You learn by experimenting, by playing, and with the gentle guidance of others whom you don’t always fully understand.

/https://oimg.videogamer.com/images/63f7/journey_6.jpg)

As you progress, you begin to understand them better. You meet more people. They all have slightly different ways of communicating – always through sound and movement, but in idiosyncratic styles – and you learn to recognise patterns. Meet someone late on in the game and you’ll likely find yourself communicating effortlessly, guiding new players around the world or being tempted towards hidden secrets by more experienced journeyers. You’ve learnt the communication systems of this world. It’s a game about language acquisition.

And it’s a game, perhaps most significantly, about the inevitability that life will follow its own path. Of course Journey’s society fell: it was inhabited by living, sentient beings, with all the flaws that come with such an existence. But along the way it birthed culture, and belief, and wonderful technology, the remnants of which you can see scattered around the retrospective showcase you experience as you jump, slide and glide your way through the game.

I might be wrong, naturally, but I hope I’m not – because I haven’t played many games that tackle such a range of huge topics with this majestic confidence. Come to think of it, I haven’t seen many films, or read many novels, for which I could say that either.

For something so starkly minimalist in its presentation, and a game without any dialogue, Journey is an extraordinary achievement: a game about life and death, and a tale that’s both personal and vast in its scope. It’s the story of existence, the enormous number of ways we interpret our lives, and the ways in which we react to those beliefs. Not bad for an hour-long game in which all you do is walk, jump and play.

Journey Wiki

Journey's 12th Anniversary Poster Winner! Congratulations Kbak! Join players around the world in celebration of Journey's 12th Anniversary fan event on March 13th!

- View history

Journey is an adventure game developed by ThatGameCompany and released by Sony Computer Entertainment in 2012 on PlayStation 3, as a Sony Exclusive title.

Due to its ongoing success, it got ported to several platforms:

- See Release dates

Since the very start, the game had a very strong community, people that fell in love with the game and playing it all over again. Over the years, they discovered many interesting things and are still playing it. Journey is a very special game, it's best enjoyed "blind", with no knowledge about it before playing it for the first time.

The Journey effect [ ]

"According to Chen (one of the founders of TGC), the company focuses on creating video games that provoke emotional responses from players." [1]

You will be thrown into a scary, yet, wonderful new world, with no idea who you are or what you're doing, besides one singular goal.

Even worse: there is no guidance, no helpful hints to bail you out: you have to find out everything by yourself and make your way through the what seems like an endless desert.

The stunning visuals (best enjoyed on a big screen, played with a controller) and the Grammy nominated soundtrack will do their part to cause a wide variety of emotions.

Beware: Journey is a beautiful game, but it often manages to cause emotions like despair, confusion, fear or sadness too. This is part of the experience.

Journey is all about empathy and respect. Upon meeting a figure like you, you are forced to make decisions. Sometimes, they want to go further or go on an endless exploration. If both are stubborn, they will part ways.

Just like finding a new friend in life, you might walk for a while, lose contact or stay friends until the very end. You will enjoy the time spent together and probably respect each others flaws.

Journey is also a game about sand, cloth, and various creatures you meet on the way.

The more you play Journey you will discover slight differences or see things, that seem new. It may be hard to describe, but here are some expressions from longterm fans of Journey :

- Does this look different now?

- This never happened before.

- It's so scary.

- I have never seen this.

- It is a hard game. (meaning not only gameplay, often the game causes emotions and not all are "nice", just like experiences in life)

- I want to learn more about this.

- Interactive zen video. So relaxing.

- Everytime something new.

- It's so funny.

Journeys success continues through the years, it received over 100 awards. Several "Game of the Year", many BAFTA awards, the soundtrack got nominated for a Grammy (Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media ) and so on.

Wikipedia link to awards: Journey (2012 video game), Reception .

Game support [ ]

This wiki does not provide technical support for Journey .

If you have any technical support questions or concerns, please contact platform support teams:

- PlayStation versions: Sony Computer Entertainment

- PC and iOS versions: [email protected]

As of mid-2021 it appears that technical support and updates have ceased from SCE and Annapurna Interactive

https://thatgamecompany.com/journey/

Trailer [ ]

Further reading [ ]

For further hints about approximate game length, bug warnings, settings etc. Read this Guide .

ThatGameCompany

- Homepage: https://thatgamecompany.com/journey/

- Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thatgamecompany

Annapurna Interactive

- Homepage http://annapurna.pictures/interactive/