Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Transcendent Thrill of Watching the Tour de France

By Bill McKibben

I live in the mountains of the Northeast, and normally the last thing I want in the spacious days of summer is something to watch on TV. But this year we’ve had one flooding rain after another, and when the skies have cleared they really haven’t––the plume of smoke from Canada’s wildfires has hovered day after day, and many mornings, like this one, the roadside sign that usually offers up warnings about construction ahead has instead flashed this grim warning: “Air Quality Alert/Limit Outdoor Activity.” So I’ve been grateful for the daily distraction from climate dread provided by the Tour de France, arguably the world’s biggest annual sporting spectacle.

And in this case I come to praise not mainly the noble rivals Jonas Vingegaard and Tadej Pogačar (more on them later) but the broadcast crew assembled by Peacock, the NBC streaming service, to cover the contest’s twenty-one days of racing. Since each broadcast lasts five or six hours (the daily stages are hundreds of kilometres long, and even at the astonishing pace of these cyclists it takes a while), that’s more than a hundred hours of coverage in a month—maybe equivalent to an N.F.L. season’s worth of broadcasting time. And yet it is a steady pleasure.

The coverage begins each morning in a Connecticut studio where a trio—Paul Burmeister, Sam Bewley, and Brent Bookwalter—stand quite formally behind a lectern, wearing suits, ties, and pocket squares. (I have no idea why—perhaps a contract with some haberdasher.) Burmeister is a TV guy—his smooth patter has graced everything from Notre Dame football to ski jumping. But his two partners are bike guys—Bewley, a former Olympic bronze medallist for New Zealand, and Bookwalter, a Michigan native and a veteran of the Grand Tour, in Europe. They begin by forecasting the day ahead, which is a more complicated task than you might think.

The Tour de France is famous for the yellow jersey that its over-all leader wears—when the race finally ends up on the Champs-Élysées, on Sunday, the Danish cyclist Vingegaard will almost certainly wear the maillot jaune for having made the 3,405-kilometre trip in the shortest elapsed time. But his duel with the Slovene Pogačar has been only part of the story. The race also features the polka-dot jersey, awarded to the man who wins the most summit climbs in the mountains of the Alps and Pyrenees, and the green jersey, which goes to the fastest of the sprinters. On “flat stages,” which avoid the mountains, those sprinters usually wind up in a chaotic dash to the line; on mountainous stages, the sprinters gather far behind the main peloton, willing their bodies slowly up the hills to meet the daily time cutoff and stay in the race. Meanwhile, each day’s stage is a race of its own, with glory to whoever manages to win; each rider, in turn, is a member of an eight-man team, and they can and do work together, breaking the headwinds for their stars. All in all, there’s plenty to talk about.

And the talk, after half an hour of studio preliminaries, moves to France, and the persons of Phil Liggett and Bob Roll, as natural a TV pair as I’ve ever seen. Liggett, an Englishman who will turn eighty shortly after this Tour concludes, has covered the Tour for more than fifty years, which is very nearly half of its hundred and ten renditions. Roll is merely in his sixties, and declares his youth by pre-riding many of the hill climbs on the morning of the stage, the better to describe the pain the racers are about to endure. He is, I think, the actual heart of the coverage. Liggett talks more, chattering happily away with many useful references to the long history of the race. But sometimes he gets a name or a team or a time wrong. (He occasionally conflates young riders with their fathers or even grandfathers, who raced before them.) Roll, like the patient wife of an endearingly addled older husband, offers a gentle correction, but mostly he provides strategic insight that comes from his own long career in the saddle; he has an almost preternatural instinct for the glorious moment each day when one of the leaders will launch a superhuman uphill “attack” to open a gap on his rivals.

When that happens, the other key member of the team—another former pro cyclist, Christian Vande Velde—is often on hand to commentate. He spends each race day on the back of a motorcycle, watching the action up close and chatting through car windows with the directors of the various teams who will share bits of strategy. This sounds like an easy enough job, until you remember that, much of the time, he’s whipping downhill at sixty miles per hour or more, following the racers through the harrowing descents. (In the Tour de Suisse, a warmup race for this year’s Tour, one rider died after a high-speed crash.) Oh, and then there’s also Steve Porino, a dead ringer in look and affect for the late Fred Willard in his role as the broadcaster in “Best in Show”; Porino ranges ahead of the riders, looking for people along the road to interview, often managing to find the stars’ parents, whom he coaxes from their camper vans to offer anecdotes about the athletic precociousness of their sons as small boys.

Even with all these voices, there’s a lot of air to fill, and so Roll often serves as tour guide: the broadcast feed, provided to TV channels around the world by the Tour organizers, features many long helicopter shots, and when nothing much is happening in the race the camera tends to linger on châteaux and churches, and so there’s an ongoing impromptu lesson in medieval history. All in all, a low-key way to pass the day, a gentle frame for the eventual injections of high drama.

And, oh, that drama! This year’s two stars are so evenly matched that two weeks into the race only ten seconds separated them. (Vingegaard finally surged ahead on Tuesday’s time trial.) Many of the stages end with massive ascents into the lunar landscape of high and treeless mountains, and sooner or later one of the two tries to shake the other with a massive acceleration; the tension hinges on whether his foe will be able to match the pace or will watch his rival disappear up the mountain. The commentators are fully up to the task of capturing the nobility of these painful assaults, coming after hours of fast pedalling. (Oh, how one hopes these two are not doping.) That catharsis—it often lasts just seconds—is the centerpiece of these long broadcasts, and a daily reminder of why sports are, in some way, a serious part of our lives: there are few other venues for such public displays of courage and resolve, and the resulting joy or despair.

That’s a point, perhaps, that’s less obvious now than it once was. The Times announced earlier this month that it was disbanding its sports department. It will now send its readers to a subscription service that it recently acquired, the Athletic. I read it, and it occasionally offers long and engaging features in the lineage of Sports Illustrated . But mainly it provides acres of words about the main team sports in the U.S., often to do with contracts and statistics. It is sports as business—the comments sections are filled with disgruntled fans moaning about the general managers of their local teams. (One suspects that its most devoted readers are the ever-growing ranks of sports gamblers.) Transcendence is rare, unless you find it in a spreadsheet.

Endurance sports such as the Tour de France, which traditionally receive little coverage in the U.S., are perhaps a more reliable vehicle for that transcendence, and Peacock deserves credit for covering them—Liggett and Roll have also worked the Grand Tours of Spain and Italy, and the network also offers up coverage of swimming and track and field. Doubtless this has something to do with NBC owning the rights to the Olympics; we are always on the Road to Someplace (at the moment Paris, next summer). And my plaudits have limits: the network recently stopped covering Nordic skiing, which means that the winter TV sports scene features very little long-distance agony.

Still, the Tour de France redeems much else. There’s no escaping reality entirely—the weather has been heating up in Europe as the Tour proceeds, and this is easy to see as the racers warm up in ice-filled vests. But, when the race finishes, the commentators help viewers wind down their heart rates with another half hour of commentary—Roll is even able to translate from most of the European languages that the racers use to offer their post-race clichés. England was wise enough to award Liggett an M.B.E. (Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire), some years ago; we have no such way to honor our broadcasters save devoting a few hours each day to listening and appreciating. ♦

An earlier version of this article misstated the location of NBC Sports’ studios.

New Yorker Favorites

Why facts don’t change our minds .

How an Ivy League school turned against a student .

What was it about Frank Sinatra that no one else could touch ?

The secret formula for resilience .

A young Kennedy, in Kushnerland, turned whistle-blower .

The biggest potential water disaster in the United States.

Fiction by Jhumpa Lahiri: “ Gogol .”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Hanif Abdurraqib

By Nasser Rabah

By Gerald Marzorati

By Benjamin Wallace-Wells

The New York Times

Times insider | following the tour de france, times insider, following the tour de france.

Ian Austen , who writes about Canada for The Times from his base in Ottawa, has also covered the Tour de France for us on and off since 1992. Mr. Austen is a Masters Racing cyclist and rides in road races as well as cyclocross races. We asked him to tell us about the logistics of following the Tour and how it has evolved over the years.

What is a typical race day like for you?

Before the start of a stage is the most productive time to interview riders, when they’re not exhausted. They’re fresh and have something to say, so I generally try to be there an hour before they leave.

Then, depending on whom I’m traveling with, we will leave shortly before the riders do and drive the course. If you want to drive the course, you need a minimum of two journalists in the car. The number of people who actually do it these days has declined, and many take the alternate route that Tour organizers propose. But it’s very useful to drive the course. We had driven over and seen the potholes that eventually knocked Alberto Contador, the Spanish favorite to win, off his bike . Lunch along the way is often a dismal affair. Most of my lunches have been salads purchased from gas stations. Sometimes we stop well into the route and watch the riders go by, then we take the alternate routes to the press room at the finish line. Or we drive straight through to the end. In either case, we watch the last two hours or so on TV and wait for the riders to come in. Years ago, the Tour revived a motorcycle that takes one reporter a day on the route. But for a comprehensive view you have to rely on the tube.

There’s a series of news conferences afterward. Because the television rights are so important to the economics of the race, the riders queue up and speak to networks that have paid to broadcast the race first, then the those that haven’t, then the radio networks get them, and the print reporters (sometimes just me because there’s a video link to the press room) get them last. On good days, you can also nab riders just after they finish. If neither works out, I rely on texts, emails and the phone. Then it’s time to file and start driving to the next starting hotel, which we usually reach at about 9 p.m.

What are you looking for as you watch?

When we’re driving, we don’t know what will happen, so I’m looking for two things. I look for bits of color. For example, this Tour has been marked with bad weather, and in one story I included a detail about a handwritten sign I had seen on a house that said: “ Sorry 4 the weather. It’s not my fault .” I make notes about the steepness of a hill, really large or unruly crowds or problems with the pavement, and then I can remember those things when a rider is knocked down.

For our audience, I don’t go into all of the detail, but I do look for team strategies and who looks strong and who doesn’t, then at the news conference I’ll interview riders, team officials and watch the news conferences to try to flesh that out.

What are the logistical challenges of traveling to a different city every day?

Stages that finish on top of a mountain are the biggest logistical challenge. The roads are closed to the public on the way up, and when the riders finish, the police escort them and other race cars down while we are still filing. When we leave, we’re creeping down with hundreds of vehicles containing the finish line grandstands and other equipment as well as spectators. In rural France, the hotels and restaurants just stop serving at 9 p.m., so by the time we get to the next town, food options are limited.

It is a lot of driving. I think we have put on as many as 13,000 kilometers (about 8,000 miles) between driving to and from hotels to the starting lines and then along the route. But in my years covering the Tour, I’ve always made it to a hotel. I’m proud to say I’ve never slept in my car, as many have.

How is the access to riders?

The access is good, but not the same as North American sports and not as free as it was when the riders showed up in team cars rather than customized buses. If the riders get off their bus, you can stop them and chat with them in a way that’s not possible with other pro sports. It’s impressive, considering how hard they are working.

How has the Tour evolved in the years you’ve been covering it?

The Tour has escalated since 1992, when I first covered it. The Tour has become the focus of cycling in general, which I don’t think is very good for the sport. It used to be that the Italian and Spanish equivalents were up there, but right now this Tour is everything, especially in North America. The crowds are sometimes too big, and since it’s become so important the pressure on teams to do something at the Tour is immensely strong. It’s a bit like the Super Bowl and because of that everyone is often playing safe and it can be kind of boring at times.

This year hasn’t been like that; so it’s been good for me, and the story has been interesting every day.

What is different this year?

It’s not like the Miguel Indurain or Lance Armstrong eras, where you had one dominant rider. This year the race started out with two clear favorites, Alberto Contador and Chris Froome of Britain , now both have been knocked out. I can’t tell you how long you would have to go back to find one favorite knocked out, but to have two is off the scale.

Traditionally the first week of the Tour was flat, but Christian Prudhomme, the race director, wanted to make the Tour interesting from the start, so the first week’s route was much more challenging than it’s ever been. That, and then the freakish weather have made it more interesting.

Has there been one Tour low for you?

Our car got towed in Belgium this year. We left it in the press parking lot and in the morning it was gone, along with some other accredited cars. James Startt, of Bicycling Magazine, whom I traveled with for the first week of this Tour, had to take a 50 euro cab ride and pay a 90 euro towing fee to get our car back.

A high point?

I see all of these places for four minutes at a time, but it can be kind of marvelous. It’s work, but you get a view of France you would never get as a tourist. This is the centennial anniversary of World War I, and passing the battlefields is evocative and incredible. I had never seen the Verdun Memorial, and when the race went by there everyone was instructed to be silent . A caretaker there let me go up in the tower of the mausoleum to watch and seeing the race come through silently, from 150 feet up, was really exceptional.

What's Next

Saturday, March 30, 2024 9:50 am (Paris)

- Tour de France

Tour de France: The new wave of American cycling

Seven riders from the United States were on the starting line for this year's Tour, the most since 2014. The new generation has finally freed itself from the shadow of Lance Armstrong.

By Aude Lasjaunias

Time to 3 min.

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Messenger

- Share on Facebook

- Share by email

- Share on Linkedin

When he was a child, Quinn Simmons wasn't really into cycling. The American from Durango, in the mountains of Colorado, was a little "annoyed" to see his father spending so much time in front of the television watching the Tour de France. Young Quinn was more into skiing and mountaineering.

Five years later, however, the 21-year-old is sporting a smile – rarely masked despite the threat of Covid-19 – as he takes part in road cycling's premier event for the first time. "The final decision was made during the Tour de Suisse [which he finished on June 21, with the polka-dot jersey of best climber]. In my head I had prepared as if I was going, but you are always a little nervous until the last yes," the Trek-Segafredo rider said.

Simmons is the youngest rider in this year's Tour de France, and one of seven Americans who left from the starting line in Copenhagen on July 1 – a first since 2014. "I'm convinced that this number will continue to grow," said Kevin Vermaerke (DSM), who was forced to pull out on the 8 th stage, between Dole (Jura) and Lausanne (Switzerland), on July 9.

'Less support in the US'

"There have been several American waves in the Tour: in the 1980s with Greg LeMond, then in the early 2000s with Lance Armstrong. We're on the third," said French-American photojournalist James Startt, the author of Tour de France/Tour de Force. A Visual History of the World's Greatest Bicycle Race (2000), who has 33 Tours under his belt.

What is striking about this new wave is both its youth and the fact that is shared throughout the peloton. Apart from climbers Sepp Kuss (Jumbo-Visma), 27, and Joe Dombrowski (Astana-Qazaqstan), 31, the other five riders are 25 years old or younger. Most importantly, they all ride for different teams, whereas in the past, the American contingent rode for US-based teams such as 7-Eleven, Motorola or US Postal.

Brent Bookwalter, who spent much of his career with one of them (BMC Racing), sees this as a sign of changing attitudes. "As a young rider, as an American, riding for a French or Spanish team means immersing yourself in a different culture, and that used to seem very intimidating," said the Albuquerque, N.M., native and Tour consultant for Flo TV.

There is another, more prosaic explanation: "There is less support for road cycling in the United States: fewer races, fewer teams, less infrastructure," he said. This is due to the economic situation, but also the doping cases that had a strong impact on sponsor engagement and the public's enthusiasm.

The ambiguous legacy of Armstrong

In the mid-2000s, the United States could boast of having won the Tour de France 11 times: Greg LeMond (1986, 1989 and 1990), Lance Armstrong (1999-2005), and Floyd Landis (2006), which at the time was more than Italy and Spain. But Floyd Landis was disqualified after being tested with a testosterone level 11 times higher than normal. He was followed by Lance Armstrong in 2012.

Former road rider Ian Boswell grew up watching the "boss." In his eyes, Armstrong's legacy remains ambiguous: "Lance is the reason why we have invested so much in cycling in the United States," said the 30-year-old. "This guy from Texas who managed to dominate the most prestigious event in the world showed us that it was possible."

His fall left a void and his countrymen have long been stereotyped as "dirty" riders. But the biggest problem, he insists, was that a good part of his generation wanted to be general classification riders, "when they would have been better on more specific terrain." Like Tejay Van Garderen, a time trial specialist, but rarely consistent over a three-week race.

Going forward, the ambitions are more subdued and varied. "I'll probably never be a general classification rider in a three-week race, but maybe after a few years on the road I can aim for the one-week races," said Simmons, for example.

'The image of the champion'

The results are starting to show. On July 7, 2021, Sepp Kuss crossed the finish line in Andorra la Vella solo, giving the United States its first Tour de France stage win since Tyler Farrar in Redon in 2011.

In the first week of the 2022 race, Neilson Powless (EF Education EasyPost) came within seconds of donning the yellow jersey. Not since Tejay Van Garderen in 2018 has an American been so close to the top of the overall standings, when Van Garderen was tied on time with Belgian teammate Greg Van Avermaet after the team time trial.

According to many followers, the Star-Spangled Banner of the United States is less visible on the roadside than during Armstrong's heyday. Throughout the country, "road cycling is still very much tied to the image of a champion," said James Startt. "I've seen it as a teammate of Tejay's, riding with him through the highs and lows of his career: the Americans loved him when he was doing well and booed him when he was doing poorly," said Brent Bookwalter. "This group, today, can share that burden. It's not as if any of them are being branded as 'the' new face of American cycling who is the focus of all hope." They will have time to find their strengths and build this new wave over time.

Aude Lasjaunias

Translation of an original article published in French on lemonde.fr ; the publisher may only be liable for the French version.

Lecture du Monde en cours sur un autre appareil.

Vous pouvez lire Le Monde sur un seul appareil à la fois

Ce message s’affichera sur l’autre appareil.

Parce qu’une autre personne (ou vous) est en train de lire Le Monde avec ce compte sur un autre appareil.

Vous ne pouvez lire Le Monde que sur un seul appareil à la fois (ordinateur, téléphone ou tablette).

Comment ne plus voir ce message ?

En cliquant sur « Continuer à lire ici » et en vous assurant que vous êtes la seule personne à consulter Le Monde avec ce compte.

Que se passera-t-il si vous continuez à lire ici ?

Ce message s’affichera sur l’autre appareil. Ce dernier restera connecté avec ce compte.

Y a-t-il d’autres limites ?

Non. Vous pouvez vous connecter avec votre compte sur autant d’appareils que vous le souhaitez, mais en les utilisant à des moments différents.

Vous ignorez qui est l’autre personne ?

Nous vous conseillons de modifier votre mot de passe .

Lecture restreinte

Votre abonnement n’autorise pas la lecture de cet article

Pour plus d’informations, merci de contacter notre service commercial.

Tour de France stage NYT Crossword

Tour de France stage Crossword Clue Nytimes The NYTimes Crossword is a classic crossword puzzle. Both the main and the mini crosswords are published daily and published all the solutions of those puzzles for you. Two or more clue answers mean that the clue has appeared multiple times throughout the years.

TOUR DE FRANCE STAGE Ny Times Crossword Clue Answer

This clue was last seen on NYTimes May 09, 2021 Puzzle . If you are done solving this clue take a look at the other clues found on today's puzzle in case you may need help with another. Before each clue, you have its number and orientation on the puzzle for easier navigation.

How to Watch the Tour De France 2022: Schedule, Streaming, More

Cycling's biggest event begins on friday, by nbc sports staff • published june 30, 2022 • updated on june 30, 2022 at 6:12 pm.

How to watch the Tour de France 2022: Schedule, streaming, more originally appeared on NBC Sports Chicago

The 2022 Tour de France starts Thursday with a 13km individual time trial in Copenhagen and ends on July 24 with its traditional finish on the Champs-Elysees in Paris.

Could we see a three-peat champion crowned this year? That could be the case as Slovenian Tadej Pogacar looks to make it three in row, having won the last two Tours.

Could this be the year we see a U.S. cyclist take the Tour de France crown? Sepp Kuss and Brandon McNulty are a few of the American hopefuls that are looking to bring back an eligible win at the event for the first time since Greg LeMond's back-to-back victories in 1989 and 1990.

Get Tri-state area news and weather forecasts to your inbox. Sign up for NBC New York newsletters.

Check out everything you need to know as the gears get cranking for all 176 riders (22 teams with eight riders per team) on this grueling and tough 21-stage event.

Where can you watch the Tour de France and what time does it start?

You can catch all 21 st ages on Peacock an d USA Network from July 1 through July 24. Full coverage begins with Stage 1 on Friday at 9:30 a.m. ET.

Minnesota baseball team keeping ‘Ozempig' mascot despite online backlash

No. 11 NC State advances to men's Elite Eight. What's the lowest seed to ever reach that round?

Action can also be streamed on the NBC Sports app.

Tour de France 2022 schedule

For those keeping track, the 2022 Tour de France is set to take place during a span of 24 days.

Cyclists will go through a daily contested stage and see a total of three rest days during the event. The first rest day lands on July 4 (between Stages 3 and 4), the second is set for July 11 (between Stages 9 and 10), and the final one comes on July 18 (between Stages 15 and 16).

This article tagged under:

Catch the latest in Opinion

Get opinion pieces, letters and editorials sent directly to your inbox weekly!

- Copy article link

Power Take: Tour de France must make crowd control a priority

- By Amy Moritz

- Jul 14, 2016

Tour de France officials need to do a better job of protecting its riders during the cycling's premier event. (Ian Austen/The New York Times)

The passion of the fans along the route of the Tour de France can be exhilarating. This year it can also be downright dangerous. It came to a head Thursday during Stage 12 on one of the most iconic climbs of the Tour – the Mont Ventoux.

Overnight, race organizers moved the finish line, making it 6 kilometers shorter because of high winds at the summit. But what the organizers failed to do was extend the barricades in the final kilometers of the race. The crowds were out of the control in the final kilometer, forcing a motorbike to stop in the road. Three cyclists, including the yellow jersey of Chris Froome, crashed.

Chaos ensued. It was the third time spectators got too close for comfort. Froome, you may recall, punched a spectator whose flag was about to get caught in his front wheel. On another day, a fan unplugged a generator causing the 1K banner to deflate and fold – right on top of rider Adam Yates. The energy of the fans and their proximity to the riders is part of the majesty of the cycling. But there’s a line. You can’t host a bike race if you can’t keep the crowd at bay.

Related to this story

- Notifications

Get up-to-the-minute news sent straight to your device.

News Alerts

Breaking news.

- >", "name": "top-nav-watch", "type": "link"}}' href="https://watch.outsideonline.com">Watch

- >", "name": "top-nav-learn", "type": "link"}}' href="https://learn.outsideonline.com">Learn

- >", "name": "top-nav-podcasts", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.outsideonline.com/podcast-directory/">Podcasts

- >", "name": "top-nav-maps", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.gaiagps.com">Maps

- >", "name": "top-nav-events", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.athletereg.com/events">Events

- >", "name": "top-nav-shop", "type": "link"}}' href="https://shop.outsideonline.com">Shop

- >", "name": "top-nav-buysell", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.pinkbike.com/buysell">BuySell

- >", "name": "top-nav-outside", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.outsideonline.com/outsideplus">Outside+

Become a Member

Get access to more than 30 brands, premium video, exclusive content, events, mapping, and more.

Already have an account? >", "name": "mega-signin", "type": "link"}}' class="u-color--red-dark u-font--xs u-text-transform--upper u-font-weight--bold">Sign In

Outside watch, outside learn.

- >", "name": "mega-backpacker-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.backpacker.com/">Backpacker

- >", "name": "mega-climbing-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.climbing.com/">Climbing

- >", "name": "mega-flyfilmtour-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://flyfilmtour.com/">Fly Fishing Film Tour

- >", "name": "mega-gaiagps-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.gaiagps.com/">Gaia GPS

- >", "name": "mega-npt-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.nationalparktrips.com/">National Park Trips

- >", "name": "mega-outsideonline-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.outsideonline.com/">Outside

- >", "name": "mega-outsideio-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.outside.io/">Outside.io

- >", "name": "mega-outsidetv-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://watch.outsideonline.com">Outside Watch

- >", "name": "mega-ski-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.skimag.com/">Ski

- >", "name": "mega-warrenmiller-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://warrenmiller.com/">Warren Miller Entertainment

Healthy Living

- >", "name": "mega-ce-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.cleaneatingmag.com/">Clean Eating

- >", "name": "mega-oxy-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.oxygenmag.com/">Oxygen

- >", "name": "mega-vt-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.vegetariantimes.com/">Vegetarian Times

- >", "name": "mega-yj-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.yogajournal.com/">Yoga Journal

- >", "name": "mega-beta-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.betamtb.com/">Beta

- >", "name": "mega-pinkbike-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.pinkbike.com/">Pinkbike

- >", "name": "mega-roll-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.rollmassif.com/">Roll Massif

- >", "name": "mega-trailforks-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.trailforks.com/">Trailforks

- >", "name": "mega-trail-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://trailrunnermag.com/">Trail Runner

- >", "name": "mega-tri-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.triathlete.com/">Triathlete

- >", "name": "mega-vn-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://velo.outsideonline.com/">Velo

- >", "name": "mega-wr-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.womensrunning.com/">Women's Running

- >", "name": "mega-athletereg-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.athletereg.com/">athleteReg

- >", "name": "mega-bicycleretailer-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.bicycleretailer.com/">Bicycle Retailer & Industry News

- >", "name": "mega-cairn-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.getcairn.com/">Cairn

- >", "name": "mega-finisherpix-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.finisherpix.com/">FinisherPix

- >", "name": "mega-idea-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.ideafit.com/">Idea

- >", "name": "mega-nastar-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.nastar.com/">NASTAR

- >", "name": "mega-shop-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.outsideinc.com/outside-books/">Outside Books

- >", "name": "mega-veloswap-link", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.veloswap.com/">VeloSwap

- >", "name": "mega-backpacker-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.backpacker.com/">Backpacker

- >", "name": "mega-climbing-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.climbing.com/">Climbing

- >", "name": "mega-flyfilmtour-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://flyfilmtour.com/">Fly Fishing Film Tour

- >", "name": "mega-gaiagps-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.gaiagps.com/">Gaia GPS

- >", "name": "mega-npt-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.nationalparktrips.com/">National Park Trips

- >", "name": "mega-outsideonline-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.outsideonline.com/">Outside

- >", "name": "mega-outsidetv-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://watch.outsideonline.com">Watch

- >", "name": "mega-ski-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.skimag.com/">Ski

- >", "name": "mega-warrenmiller-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://warrenmiller.com/">Warren Miller Entertainment

- >", "name": "mega-ce-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.cleaneatingmag.com/">Clean Eating

- >", "name": "mega-oxy-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.oxygenmag.com/">Oxygen

- >", "name": "mega-vt-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.vegetariantimes.com/">Vegetarian Times

- >", "name": "mega-yj-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.yogajournal.com/">Yoga Journal

- >", "name": "mega-beta-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.betamtb.com/">Beta

- >", "name": "mega-roll-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.rollmassif.com/">Roll Massif

- >", "name": "mega-trail-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://trailrunnermag.com/">Trail Runner

- >", "name": "mega-tri-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.triathlete.com/">Triathlete

- >", "name": "mega-vn-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://velo.outsideonline.com/">Velo

- >", "name": "mega-wr-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.womensrunning.com/">Women's Running

- >", "name": "mega-athletereg-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.athletereg.com/">athleteReg

- >", "name": "mega-bicycleretailer-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.bicycleretailer.com/">Bicycle Retailer & Industry News

- >", "name": "mega-finisherpix-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.finisherpix.com/">FinisherPix

- >", "name": "mega-idea-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.ideafit.com/">Idea

- >", "name": "mega-nastar-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.nastar.com/">NASTAR

- >", "name": "mega-shop-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://shop.outsideonline.com/">Outside Shop

- >", "name": "mega-vp-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.velopress.com/">VeloPress

- >", "name": "mega-veloswap-link-accordion", "type": "link"}}' href="https://www.veloswap.com/">VeloSwap

2-FOR-1 GA TICKETS WITH OUTSIDE+

Don’t miss Thundercat, Fleet Foxes, and more at the Outside Festival.

GET TICKETS

OUTSIDE FESTIVAL JUNE 1-2

Don't miss Thundercat + Fleet Foxes, adventure films, experiences, and more!

The New Plan to Get More Americans into the Tour de France

A paltry few Americans race the Tour de France these days—despite the fact that junior bike racing is booming on this side of the Atlantic. A new plan aims to shift America’s Tour participation into high gear.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! >","name":"in-content-cta","type":"link"}}'>Download the app .

This story appeared in the June/July issue of Outside Magazine .

American cyclist Matteo Jorgenson can trace his participation in this year’s men’s Tour de France back to an email he sent in the winter of 2017. Jorgenson was 18 years old at the time, a top racer in the U.S. junior cycling ranks, the sport’s version of Little League baseball. He sought a career in cycling’s highest echelon, the WorldTour, but big-league teams showed little interest in him. So Jorgenson spent several months emailing squads in Europe’s development scene asking for a job.

“Every day I’d try to write three emails after my training rides, because I was trying really hard to market myself,” Jorgenson told me this spring as he was preparing for the Tour. “I was spending an hour on each.”

One finally generated a lead. After notching an impressive racing result in France with the U.S. national team, Jorgenson messaged a French squad that employs 19-to-22-year-old riders, a development category called espoir (French for “hope”) in cycling terminology. He received a reply in broken English, and a few days later Jorgenson met with the team’s director. Jorgenson spoke little French and the director spoke hardly any English, but they found ways to hash out a deal. The director offered Jorgenson a job for the following season. All he needed to do was learn French and then relocate from his home in Boise, Idaho, to a village in the Alps, to continue his career. Jorgenson didn’t hesitate. He said yes.

Now 24 and one of America’s top Tour de France riders, Jorgenson says the email and meeting changed his life. In France, he blossomed into a top racer in the espoir category and became fluent in French; after two seasons, he was hired by a Spanish WorldTour squad called Team Movistar. In 2022 he made his debut at the Tour de France. “I was completely driven for one goal, which was to get to the WorldTour, and I pursued just about every avenue I could,” Jorgenson says. “I honestly don’t know if everyone is cut out for that.”

Jorgenson’s tale illustrates the arcane professional pathway that many American cyclists follow to try and reach the Tour these days. A paltry few are strong enough to enter the WorldTour straight from the junior ranks. Those left behind either quit, burn out, or attempt to navigate a confusing network of European developmental leagues. It’s a career track that requires both persistence and luck—in addition to strong legs and lungs. It’s also a journey that explains why so few Americans ever reach the Tour de France.

The development path for Americans has gotten tougher in recent years, due to the rapid disappearance of America’s own professional road cycling circuit. But new investment from the sport’s national federation, USA Cycling, and from WorldTour teams, could make things easier for future generations.

Jorgenson says he tells aspiring American pros that the ascent to the Tour begins with a major life decision. “My general advice is to move to Europe and start racing as soon as you can,” he says. “It’s the only way you can show yourself in the races that matter and hopefully get picked up by a team.”

More Kids on Bikes, Fewer Americans at the Tour

Americans have always been the minority at the Tour de France, even during the eras of Greg LeMond and Lance Armstrong. The most to ever start the race is ten, which occurred twice: in 1986 (when there were a total of 209 total riders) and 2011 (when there were 198). Even when they were winning—and more than a few American victories were erased due to doping—U.S. riders were few and far between. American participation has actually waned since the eras of Lance and LeMond: just three raced it in 2019, 2020, and 2021, before a dramatic uptick in 2022 to seven (seven!) riders. In 2023, six riders started the race. (By contrast, France often serves up more than 40.) Women’s participation has been equally slim: six Americans (of 144 riders) raced the inaugural women’s Tour in 2022.

Oddly enough, America’s dismal Tour participation numbers come amid bike racing’s decade-long boom as a youth sport in U.S. schools. The National Interscholastic Cycling Association, founded in 2009, now has competitive leagues in 31 states, while Georgia and Colorado both support their own independent school leagues. According to NICA’s 2021 annual report, 26,945 kids either raced or attended a team practice that year. And much of this growth is due, at least in part, to the league’s focus on fun rather than developing star cyclists.

“Our program doesn’t have tryouts—if you can commit to the schedule and the rules, you’re on a team,” Austin McInerny, NICA’s former president, told me in 2019. “It doesn’t matter if you’re a superjock or new to cycling.”

That said, some percentage of NICA racers desire a more competitive environment, and to meet the demand, junior club racing teams have popped up across the country. Boulder Junior Cycling, Swift Cycling, Twenty24, Hot Tubes, and others are the next step in the country’s development pipeline. Toby Stanton, who has operated Hot Tubes in Shirley, Massachusetts, since 1993, says NICA has had a dramatic impact on the young riders he recruits.

“The kids are so good now—they come in fitter and closer to their best than I’ve ever seen,” he says. “High school cycling is really good at bringing new athletes into competitive sports, and you can see who the good ones are.”

Long story short: More young Americans are racing bikes than at any moment in the sport’s history, and many have the talent to someday reach the WorldTour. But few of them ever reach the WorldTour, and fewer still get to the Tour de France. Somewhere along the American pipeline, the system breaks down. Sources I spoke to point to the espoir category as the missing link. In Europe, teams in this category act like a safety net for top riders who aren’t yet ready for the WorldTour when they leave the junior ranks. In the espoir category, these cyclists can race, train, and continue to develop.

In the U.S., espoir racers struggle to find opportunities to compete. American espoir team Aevolo Cycling, which is operated by retired pro Mike Creed, raced at pro events across the country upon its founding in 2016. With few racing opportunities in the U.S. today, the team must travel across the Atlantic a few times each year to compete. The constant travel is tough for Aevolo’s riders, all of whom are also pursuing college degrees. And since they aren’t racing in Europe day-in, day-out, the riders often struggle at the events.

“I wish we didn’t have to go to Europe as much,” Creed says. “The guys we get need a little more time to mature and aren’t the junior wunderkinds. If you’re not ready for racing in Europe, it can get depressing fast.”

Another U.S. espoir team, called Hagens Berman Axeon, often gets invited to bigger events in Europe. But in recent years the squad has started hiring more European riders than Americans. For 2023, just three of the squad’s 12 riders are from the U.S. Creed says the struggles of espoir teams and riders is an area where American cycling can improve, because right now, some talented athletes are falling through the cracks.

“What you don’t want is for guys to get lost in the shuffle,” Creed says. “I think you can look at Matteo [Jorgenson] and a few guys in his cohort and give them a lot of credit, because nothing has come easy for them.”

Pioneers in Europe

Jorgenson is hardly the first American to chase his Tour de France dreams by uprooting to Europe. In the seventies, cycling pioneers Mike Neel, George Mount, and Jonathan Boyer made the jump overseas; in 1981, Boyer became the first American to start the Tour. Others followed: 19-year-old Greg LeMond relocated to France in 1980; he would go on to win the Tour in 1986, 1989, and 1990.

Still others made the move but never reached the Tour. Cyclist and author Joe Parkin relocated to Belgium in 1985 at age 19, spent years navigating the Flemish development scene, and raced professionally but never made the Tour. He says plenty of Americans washed out in Europe’s hyper-competitive lower-tier races.

“Some of these guys went over there with this ‘I’m gonna win the Tour’ mentality and they’d just get so demoralized by how competitive it was,” Parkin told me. “I was an average shit kicker but I wouldn’t quit. I just found a way to keep going.”

Americans were plenty strong—at the 1984 Olympics, U.S. cyclists claimed nine medals—but they weren’t accustomed to the narrow European roads or breakneck speeds. On wide American roadways, the strongest cyclist can simply ride around everyone else and prevail. Winning a race in Europe, however, requires strategic acumen as well as knowledge of the route’s twists and turns, plus the attitude required to elbow your way to the front. “A lot of American guys were faster than me, but they never figured out how to master the flow of the races,” Parkin says.

In the eighties and nineties, American cycling’s governing body sent juniors to race in Europe’s lower leagues to learn this style of racing, a practice that continued for decades, and in 1999, USA Cycling established a permanent home for development riders in Izegem, a tiny town in West Flanders. It was run out of a hostel owned by retired Flemish cyclist Noël Dejonckheere, who served as the coach and team director.

In 2009, I spent a week living in the Izegem house while reporting a story for VeloNews , and I marveled at what I saw. More than a dozen rosy-cheeked American espoirs and juniors lived in the house—they trained on the same narrow cobblestone lanes used for pro races, and they competed almost every weekend. USA Cycling’s women’s national team was also at the house, learning the finer points of European road racing. A grant from WorldTour teams High Road and Slipstream Sports had just pumped tens of thousands of dollars into the program. There were new bikes and shiny team cars wrapped in star-spangled decals.

It sure looked good, but Dejonckheere said the American racers were still far behind their European counterparts in terms of bike handling, tactics, and positioning in the peloton—deficiencies that doomed them in races. “These are things that kids in Belgium learn when they are 14 or 15 years old,” he told me. “We try to narrow the gap, but even if you start Americans when they are 21 or 22, it is perhaps too late.”

A handful of the riders I met there eventually graduated to the WorldTour, but most returned to the U.S. to race in its thriving professional scene, which by then supported the Amgen Tour of California and the Tour of Missouri, among other pro races. A few later jumped to WorldTour teams after turning heads in the U.S. For these riders, racing abroad was prep school—and racing at home was a safety net.

Boom and Bust

A decade after my visit to Izegem, I headed to the Low Countries to follow up on America’s cycling-development program . A lot had changed in the interim. USA Cycling had moved on from Dejonckheere and relocated to a sports complex in Sittard, in the Netherlands. The sponsorship cash from the two WorldTour teams was long gone. As a result, the program was smaller, humbler. There were no espoirs —just six junior men and six junior women. Jorgenson had graduated two seasons prior.

But the American coaches worked just as hard to teach their students how to survive in European races.

“People think amazing pro riders just appear. They don’t—they all start as juniors,” the team coach at the time, Billy Innes, told me. “We still have to introduce riders to this style of racing, because there’s nothing like it back home.”

In the U.S., things were even more bleak. The domestic pro road scene had all but disappeared, with teams and events folding amid a rapid exodus of sponsors. In the spring of 2019, the Amgen Tour of California held its final edition—a death blow. The few teams that survived—Aevolo, Hagens Berman Axeon, Human Powered Health—all switched focus to compete overseas. The divestment was also starting to hit U.S. junior road-cycling races, which were also dropping off the calendar in droves.

Things would get worse before they improved. When COVID-19 struck, the federation halted its European development program and kept it shuttered for two seasons. After decades, the steady march of young Americans overseas had stopped.

In an email, USA Cycling’s new road-team manager, Tanner Putt, called the two-year stretch a “low point.” Yet the hiatus also offered time to rebuild, said Putt, who went through the organization’s development ranks more than a decade ago. And in 2022, USA Cycling returned to Europe with new riders and more cash.

The federation has carried that momentum into 2023, and at the moment, U.S. cycling development appears to be on the upswing. The new plan in American cycling seems to be to create more pathways to the WorldTour—and ultimately, the Tour de France—from the junior ranks. Last year, Hot Tubes rider Magnus Sheffield jumped from the juniors to British WorldTour squad Team Ineos Grenadiers, and his success prompted the pro team to begin a recruiting relationship with the U.S. junior team. In January, Hot Tubes star AJ August traveled to Mallorca, Spain, to train with the WorldTour squad.

Earlier this year, American WorldTour squad EF Education–EasyPost followed suit, creating a similar bond with an American junior program called Onto-Hincapie. In a release announcing the partnership, EF Education-EasyPost CEO Jonathan Vaugthers said his WorldTour team will use the relationship to scout North American junior riders—even if those riders aren’t able to race overseas.

“We’re going to be keeping a close eye on North American junior races,” Vaughters said in a release. “Prove yourself there, and EF Education-Onto could be your shot to learn what it takes to race as a pro and show what you can do against the best in the world.”

The EF Education and Ineos Grenadiers relationships represent two new inroads to the pro ranks that didn’t exist before.

“The WorldTour teams want them earlier than ever now, and that’s good and bad,” says Hot Tubes’ Stanton. “Some guys have the results and the physiological markers, but how are they off the bike and around the team? Some aren’t ready.”

There’s other investment occurring in the development pipeline focused squarely on juniors. USA Cycling has invested additional resources into youth cycling with a new program called the Athlete Development Pathway. Putt says the framework is inspired by the one that died in 2020, but with some tweaks. USA Cycling wants to cast a net to find the best juniors from the NICA and club programs through a series of regional and local talent-identification camps—not just racing results. Teenagers who turn heads there will go to Europe to compete, just as before.

“While development work is more difficult due to the demise of so many great domestic road races, ultimately what creates international-caliber riders is race days in Europe—not the U.S.,” Putt says. “So our focus at the higher end of the pathway is to maximize race days in Europe.”

“My general advice is to move to Europe and start racing as soon as you can,” says Matteo Jorgenson, an American cyclist on the Movistar WorldTour squad. “It’s the only way you can show yourself in the races that matter and hopefully get picked up by a team.”

The focus on juniors makes sense, and it represents a big step toward funneling more American racers to the Europe, and then to the WorldTour, and eventually onto the Tour de France. USA Cycling wants to capitalize on the groundswell in scholastic leagues. But I worry that future espoir riders—young talents who are in Matteo Jorgenson’s position—will continue to fall through the cracks. Some cyclists require a few more years of development before they’re ready for the big leagues. And with few racing opportunities appearing for 19-to-22-year-old riders in the U.S., those who are almost good enough still face a tough road.

The federation isn’t ignoring espoirs —it will organize a national team for specific races like the UCI world championships. And Creed’s Aevolo program will enter some overseas races as well. Is it enough? We’ll have to wait and see. In women’s cycling, infrastructure is more robust: USA Cycling is funding a team based in France called Cynisca Cycling, which Putt called a “critical launchpad for getting American women to the WorldTour.”

“Structured support, exposure, and adequate resources will have a significant impact on the trajectory and length of their cycling careers,” he says. “USA Cycling has a responsibility and opportunity to step in and intercede in this space.”

He’s right, of course. But for how long? Cycling development generates no revenue, and a return on investment will take years to materialize—if ever. In my time reporting on the topic, I’ve seen funding for these programs soar, crash, return, and crash again. The American ascent to the Tour de France may indeed become easier in the coming years. But it’s a safe bet that, in the future, the trick to getting to the Tour will again become simple to define, if seemingly impossible to actually do: move to Europe and race your bike.

Outside articles editor Frederick Dreier was previously the editor in chief of VeloNews . He has reported on U.S. youth cycling development since 2005.

- Road Biking

- Tour de France

Popular on Outside Online

>", "path": "https://www.outsideonline.com/outdoor-gear/cars-trucks/two-oregon-pros-return-home-for-adventure-rally/", "listing_type": "recirc", "location": "list", "title": "two oregon pros return home for adventure rally"}}'> two oregon pros return home for adventure rally, >", "path": "https://www.outsideonline.com/outdoor-gear/cars-trucks/ready-for-adventure/", "listing_type": "recirc", "location": "list", "title": "ready for adventure"}}'> ready for adventure, >", "path": "https://www.outsideonline.com/health/wellness/4-reasons-to-plan-a-wellness-getaway-in-dallas/", "listing_type": "recirc", "location": "list", "title": "4 reasons to plan a wellness getaway in dallas"}}'> 4 reasons to plan a wellness getaway in dallas, >", "path": "https://www.outsideonline.com/outdoor-gear/water-sports-gear/4-ways-the-texas-gulf-coast-will-amaze-you/", "listing_type": "recirc", "location": "list", "title": "4 ways the texas gulf coast will amaze you"}}'> 4 ways the texas gulf coast will amaze you.

- Weird But True

- Sex & Relationships

- Viral Trends

- Human Interest

- Fashion & Beauty

- Food & Drink

- Health Care

- Men’s Health

- Women’s Health

- Mental Health

- Health & Wellness Products

- Personal Care Products

trending now in Lifestyle

Trump ordered $200 worth of burgers from Long Island drive-in for...

Conjoined twin Abby Hensel, of TLC's 'Abby & Brittany,' is...

My best friend demanded I pay $2.5K to attend their wedding, tip...

Women love men with 'dad bods' like Travis Kelce — and there's...

I was traumatized by my first cruise vacation after two...

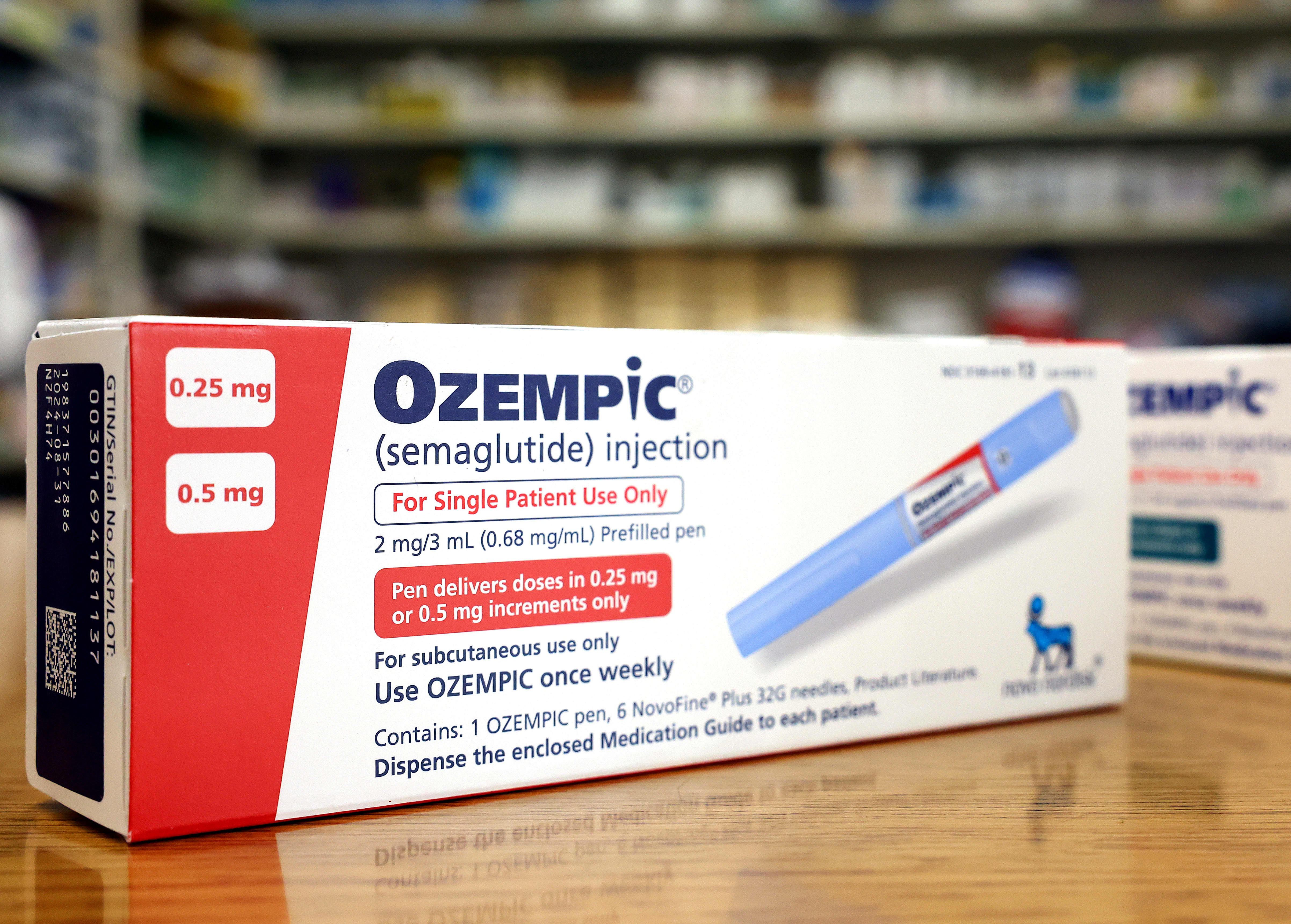

'Oatzempic challenge' helped dieters lose 40 pounds in 2 months,...

Content creator stunned to learn $15 Goodwill dress has...

Italy's got another leaning tower —and this one could actually...

Pregnant women are basically endurance athletes: study.

- View Author Archive

- Get author RSS feed

Thanks for contacting us. We've received your submission.

Cranky pregnant moms, prepare for vindication.

Researchers studying the limits of human endurance have determined that the physical intensity of pregnancy is basically like running a 40-week marathon.

“Pregnancy is the most energetically expensive activity the human body can maintain for nine months,” Duke University evolutionary anthropology professor Herman Pontzer, who co-authored the study, tells The Post.

The report, published in June’s edition of Science Advances , analyzed elite athletes from some of the most demanding races in the world, such as Ironman, the Tour de France and the 3,000-mile Race Across the USA, in which runners complete six marathons a week for four months.

Researchers looked at basal metabolic rates, or how many calories you need in order to function when your body is at rest. The most anyone can sustain, according to the study, is burning calories at 2.5 times the person’s BMR, or about 4,000 calories a day for the average adult.

Pregnant women operate at 2.2 times their BMR — almost the maximum possible, every day, for some 270 days, researchers found. A rate much higher than that and pregnancy would be unsustainable, damaging to the body and potentially deadly.

“I don’t think any mother is surprised to learn how difficult pregnancy is!,” Pontzer says. “But I’ve had a few friends — including my wife — tell me it was good to see pregnancy recognized as extremely challenging.”

What is the limit to human #endurance ? Study of multi-day events suggests it's 2.5X a person's metabolic rate. Above that energy stores deplete limiting how many days one can continue @sciencemagazine : https://t.co/UqBCoka1wP Energy used during #pregnancy reaches this limit. pic.twitter.com/OBwImf1zZA — Scott Lear, PhD (@DrScottLear) June 8, 2019

Marathoners’ energy use peaks at around 15.6 times their BMR, but maintain the exceedingly high rate for only a short period of time, the study revealed. By contrast, Tour de France cyclists move at 4.9 times their resting rate during the 23-day race, and Antarctic trekkers who heave 500-pound sleds across the grueling, snow-covered terrain for 95 days go at 3.5 times their BMR.

“Pregnancy of course is very long compared to other sporting events, but pregnant and lactating women seem to be working close to the boundary for their duration,” study co-author John Speakman, professor of biology at the UK’s University of Aberdeen, tells The Post.

“The limit seems to be imposed by the speed at which the [digestive tract] can process the food that we eat,” he adds. “So simply piling more food in at the mouth — [such as] protein bars — isn’t going to speed that process up further down the gut.”

Humans simply cannot properly process enough calories to sustain an energy use higher than the 2.5 ceiling. More than that and our bodies would begin eating away at their own tissue.

“There’s just a limit to how many calories our guts can effectively absorb per day,” Pontzer says.

So, pregnant people of the world, next time you feel guilty about backsliding on prenatal yoga or sending your partner out for that gallon of ice cream, remember that having this baby will be the greatest race of your life — and you deserve a prize.

Share this article:

New York and Washington DC have been made for Tour de France Grand Départ on Pro Cycling Manager

A user of the game has made the 2024 route starting in the Big Apple before heading from Philadelphia to Washington DC then France

- Sign up to our newsletter Newsletter

One of the users of the popular cycling PC game, Pro Cycling Manager, has built the landscape of New York and Washington DC, to allow the cities to host the 2024 Tour de France Grand Départ in the game.

The computerised cities were demonstrated in a recent video by YouTuber Benji Naesen in his career with Italian team, EOLO-Kometa.

The race started with a 16.99km individual time trial around the city centre, taking in the likes of the Guggenheim Museum, Central Park West as well as some of the city's biggest skyscrapers.

The next stage was also around 187.1km NYC with an intermediate sprint just outside of Manhattan and a King of the Mountains point on Fort George Hill both coming in the second half of the stage.

>>> Mathieu van der Poel delays cyclocross season start again due to knee injury

After that it's yet another sprinters stage from Philadelphia, where it was indeed as sunny as the TV show suggests, to the capital city of Washington DC over 221.3km. And no, the race doesn't finish outside the White House sadly. There is an intermediate sprint in Baltimore, though.

Of course this route would be near impossible in real life, so why not live it in the world of PCM.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The full route is available to view on La Flamme Rouge where the original was designed back in 2015.

The joy of PCM is that users can easily make mods and create completely new routes with amazing details, making it look as realistic as possible.

Unfortunately, the riders faces as well as the fans aren't particularly realistic, but this game doesn't have the budget of a game like FIFA 22 or GTA for example.

The individual behind making this pack for PCM is also one of the people behind the well known page of La Flamme Rouge (LFR), Emmea90 told Cycling Weekly that he used a site called Track4Bikers when he started making these routes but now does it himself, thus creating LFR.

"Then you have the hard part. Because once you've got a good route design, you have to make it for PCM.

"From the editor you can export Garmin GPXs that the tool that PCM provides for designing stages can read. All you get on the tool is basically the GPX black line and if you have a stage editor version for developers, the Google maps as background

"Then you have to just use the editor provided by the game and draw the stage, that it's a long process, can be also from three to six hours per stage.

"These routes are usually released on the packs that are in the steam workshop of the games."

There is also a PCM World Cup at the end of the year online, where around 150 people come together to compete in races. There are also packs that allow you to race in the women's peloton as well as go back in time with some of the legendary riders and kits of the past.

The original layout for New York was made in 2013 by Le Guppetto user Leon40.

I should know how fun this game is seen as though, since mid-2016, I've roughly played a pretty ridiculous one and a half years on this game once hours played are calculated. Although, I would like to stress I do sometimes just leave it on as it also keeps the laptop awake.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Hi, I'm one of Cycling Weekly's content writers for the web team responsible for writing stories on racing, tech, updating evergreen pages as well as the weekly email newsletter. Proud Yorkshireman from the UK's answer to Flanders, Calderdale, go check out the cobbled climbs!

I started watching cycling back in 2010, before all the hype around London 2012 and Bradley Wiggins at the Tour de France. In fact, it was Alberto Contador and Andy Schleck's battle in the fog up the Tourmalet on stage 17 of the Tour de France.

It took me a few more years to get into the journalism side of things, but I had a good idea I wanted to get into cycling journalism by the end of year nine at school and started doing voluntary work soon after. This got me a chance to go to the London Six Days, Tour de Yorkshire and the Tour of Britain to name a few before eventually joining Eurosport's online team while I was at uni, where I studied journalism. Eurosport gave me the opportunity to work at the world championships in Harrogate back in the awful weather.

After various bar jobs, I managed to get my way into Cycling Weekly in late February of 2020 where I mostly write about racing and everything around that as it's what I specialise in but don't be surprised to see my name on other news stories.

When not writing stories for the site, I don't really switch off my cycling side as I watch every race that is televised as well as being a rider myself and a regular user of the game Pro Cycling Manager. Maybe too regular.

My bike is a well used Specialized Tarmac SL4 when out on my local roads back in West Yorkshire as well as in northern Hampshire with the hills and mountains being my preferred terrain.

American seals first cobbled Classic win after Visma-Lease a Bike lose Wout van Aert to injury after a big crash

By Tom Thewlis Published 27 March 24

'It's about budget,' says team boss Danny Stam

By Tom Davidson Published 27 March 24

Useful links

- Tour de France

- Giro d'Italia

- Vuelta a España

Buyer's Guides

- Best road bikes

- Best gravel bikes

- Best smart turbo trainers

- Best cycling computers

- Editor's Choice

- Bike Reviews

- Component Reviews

- Clothing Reviews

- Contact Future's experts

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookies policy

- Advertise with us

Cycling Weekly is part of Future plc, an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate site . © Future Publishing Limited Quay House, The Ambury, Bath BA1 1UA. All rights reserved. England and Wales company registration number 2008885.

2024 Could Be a Make-Or-Break Year for the Tour de France Femmes

I f there’s one depressing fact I’ve learned in nearly two decades of covering women’s cycling, it’s that, sadly, there’s rarely a moment to rest on one’s laurels in this sport—and that’s particularly true for race organizers, and team owners.

Just because a race does fantastically well one year in terms of unprecedented levels of viewership and media coverage or because a team is arguably the absolute best in the world doesn’t guarantee anything. It’s all easy come, easy go. That’s why I’m nervous about the Tour de France Femmes avec Zwift and why I believe that this year could be the most pivotal year for the race.

But why am I worried about the Tour de France Femmes in year three? After all, viewership numbers have been high, enthusiasm hasn’t waned, and sports bars are full of fans screaming for Demi Vollering and Kasia Niewiadoma. And yet... There are a few important factors to consider.

Last year, Zwift’s Kate Verroneau told me that the second year of the TDFF was scary for her: The first year, you’re riding a wave of hype. In the second year, the race has to stand as a great race, not just a “first.” What about the third year?

“There’s no kind of resting on the fact that last year was really successful,” Veronneau said then. “I look at it and think, ‘Last year was pretty easy sell: It was the first women’s Tour de France in over 30 years. That was easy to get the media on board, easy to get sponsors on board. It was the first time that that huge of an audience watched women’s racing.”

Year two was hugely successful, but what about year three?

The sponsorship dynamics at play

First, there’s the simple fact that this is year three of Zwift’s four-year commitment to the Tour de France Femmes in partnership with ASO. That means if Zwift isn’t planning to continue its support or is going to cut back its sponsorship budget, this is the year the race needs to look for a new sponsor.

Leaving it entirely to next year, the final year in their contract, is foolhardy. So I have to imagine that there’s some buzz happening behind the scenes already. I haven’t heard any scuttlebutt about them giving up their title sponsorship position, to be clear, but considering Zwift just had a round of layoffs and a shuffle in their C-suite , who knows where they’re heading? Hopefully into another lengthy contract, but it’s unclear. My fingers are crossed.

Viewership challenges

Viewership this year will also be more important than ever. High viewership numbers mean a better chance of securing new or renewed sponsorship dollars, and TdFF viewership has been undeniably impressive. But this year is going to make that tricky. The men’s Tour de France and the Tour de France Femmes are separated this year by the Olympics. That means three weeks between the races, rather than the men’s race ending on the day the women’s race began.

In the past two years, it was easy to just continue tuning in if you’d been watching the men’s race. This year, viewers will have to actively seek it out starting August 12—the day after the Olympics finish. That is a lot of TV watching for cycling/sports fans to contend with. While serious fans will still tune in, those ‘medium’ fans may not.

The state of the cycling industry

Then, there’s the cycling industry landscape. Brands like Trek and Specialized are slashing budgets , and Shimano is reporting quarter after quarter of losses . To blithely assume that there’s a cycling company capable of taking Zwift’s place as title sponsor in the current landscape is a mistake.

I say all this not to be discouraging. It’s meant to be a rallying cry. What does this all mean for you, the person reading this?

I want to believe that this race will survive and thrive in the same way that Le Tour has for over a century. But I also know that it takes more than love to keep a race of this magnitude running. It takes cold, hard cash. It takes commitment from big businesses that often see women’s cycling as a line item that they can scrap when it’s time to tighten up their belts. It took decades to get back to a point where we have this race. It’s happened before, it’s been lost before. Let’s not let it happen again.

It’s time to get fired up and ensure that the Tour de France Femmes isn’t just a blip in the cycling history books. Mark your calendars, set a Google alert for the Tour de France Femmes, follow racers on social media, and plan watch parties—let’s make this the loudest Tour de France Femmes yet.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Tour De France

Lynn talks to reporter Samuel Abt about what's happening in this years Tour de France. Today, three-time winner Lance Armstrong pulled into the lead as the race hit the mountains. Samuel Abt covers the Tour de France for the International Herald Tribune and The New York Times .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The median time of the nearly 21,000 rides posted to Strava for the Col du Platzerwasel was 42 minutes. One of those riders was Christophe Schmitt, a 36-year-old newspaper journalist from Mulhouse ...

For Women's Cyclists, It's a Steep Climb to Tour Equality. 138. By Juliet Macur. Photographs by Monique Jaques. July 27, 2022. MEAUX, France — After winning Stage 2 of the Tour de France ...

Tour de France Route Steers Clear of Olympics, and Paris. The 2024 Summer Games have pushed the iconic bike race out of its traditional finish in Paris. The Tour will instead end in Nice, in the ...

July 21, 2022. Tadej Pogacar's last chance to position himself to win his third straight Tour de France arrived Thursday on the steep slopes of the Hautacam in the Pyrenees Mountains. Pogacar ...

July 22, 2022. The cyclists competing in this year's Tour de France will spend nearly a month on their bikes, earning only two days off during their sport's most famous marathon. When the race ...

By Victor Mather. June 30, 2022. The Tour de France is preparing to roll out of the starting gate again on Friday, with this year's race set to feature a dominant young champion, a climb up the ...

The Tour de France is famous for the yellow jersey that its over-all leader wears—when the race finally ends up on the Champs-Élysées, on Sunday, the Danish cyclist Vingegaard will almost ...

The Tour de France peloton, the amoeba-like mass of more than 100 cyclists who ride fast and hip-to-hip, had come to one of the ubiquitous roundabouts when Pinot and his team made a split-second ...

Survive and Conquer: A Soaked Mackey Overcomes Tourmalet. 7 hours after the end of the Étape. Today's ride: 105 soggy miles from Pau to Hautacam, along the route of next week's 10th stage of the Tour de France, up four climbs, two rated third-category in degree of difficulty and two rated "beyond category.".

Ian Austen, who writes about Canada for The Times from his base in Ottawa, has also covered the Tour de France for us on and off since 1992.Mr. Austen is a Masters Racing cyclist and rides in road races as well as cyclocross races. We asked him to tell us about the logistics of following the Tour and how it has evolved over the years.

In the mid-2000s, the United States could boast of having won the Tour de France 11 times: Greg LeMond (1986, 1989 and 1990), Lance Armstrong (1999-2005), and Floyd Landis (2006), which at the ...

Two or more clue answers mean that the clue has appeared multiple times throughout the years. TOUR DE FRANCE STAGE Ny Times Crossword Clue Answer. ETAPE. This clue was last seen on NYTimes May 09, 2021 Puzzle. If you are done solving this clue take a look at the other clues found on today's puzzle in case you may need help with another.

The New York Times Victor Mather Everyone expected this year's Tour de France to be a two-cyclist race between the defending champion, Jonas Vingegaard of Denmark, and the 2020 and 2021 winner ...

Published July 24, 2022. Jonas Vingegaard of Denmark won his first Tour de France title on Sunday after coming out on top in a thrilling three-week duel with defending champion Tadej Pogacar. The ...

Action can also be streamed on the NBC Sports app. Tour de France 2022 schedule. For those keeping track, the 2022 Tour de France is set to take place during a span of 24 days.

Tour de France officials need to do a better job of protecting its riders during the cycling's premier event. (Ian Austen/The New York Times) The passion of the fans along the route of the Tour de ...

On Thursday, streaming giant Netflix released Tour de France: Unchained, an eight-part cycling docuseries that takes viewers inside the 2022 Tour. I received advanced screeners for Unchained, and ...

With huge demand to see the baseball superstar play for the Dodgers, M.L.B. teamed up with a Japanese travel agency. Fans began plotting trips. By Scott Miller It has already been a sweet life for ...

The federation has carried that momentum into 2023, and at the moment, U.S. cycling development appears to be on the upswing. The new plan in American cycling seems to be to create more pathways ...

By contrast, Tour de France cyclists move at 4.9 times their resting rate during the 23-day race, and Antarctic trekkers who heave 500-pound sleds across the grueling, snow-covered terrain for 95 ...

Tour de France Noah speaks with Samuel Abt, who covers the Tour de France for the International Herald Tribune and the New York Times. He joins us by phone to talk about the last leg of the ...

One of the users of the popular cycling PC game, Pro Cycling Manager, has built the landscape of New York and Washington DC, to allow the cities to host the 2024 Tour de France Grand Départ in ...

The men's Tour de France and the Tour de France Femmes are separated this year by the Olympics. That means three weeks between the races, rather than the men's race ending on the day the women ...

Jonas Vingegaard blossomed from a talented rookie to a dominant leader in his own right over three weeks of epic racing to win his first Tour de France title on Sunday. The former fish factory ...

Tour De France Lynn talks to reporter Samuel Abt about what's happening in this years Tour de France. Today, three-time winner Lance Armstrong pulled into the lead as the race hit the mountains.