- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 05 August 2017

Promoting active travel to school: a systematic review (2010–2016)

- Bo Pang 1 ,

- Krzysztof Kubacki 1 &

- Sharyn Rundle-Thiele 1

BMC Public Health volume 17 , Article number: 638 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

8142 Accesses

71 Citations

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

Interventions aiming to promote active school travel (AST) are being implemented globally to reverse AST decline. This systematic literature provides an update of AST interventions assessing study quality and theory use to examine progress in the field.

A systematic review was conducted to identify and analyse AST interventions published between 2010 and 2016. Seven databases were searched and exclusion criteria were applied to identify 18 AST interventions. Interventions were assessed using the Active Living by Design (ALBD) Community Action (5P) Model and the Evaluation of Public Health Practice Projects (EPHPP). Methods used to evaluate the effectiveness of each intervention and their outcomes and extent of theory use were examined.

Seven out of 18 studies reported theory use. The analysis of the interventions using the ALBD Community Action Model showed that Preparation and Promotion were used much more frequently than Policy and Physical projects. The methodological quality 14 out of 18 included interventions were assessed as weak according to the EPHPP framework.

Noted improvements were an increase in use of objective measures. Lack of theory, weak methodological design and a lack of reliable and valid measurement were observed. Given that change is evident when theory is used and when policy changes are included extended use of the ALBD model and socio-ecological frameworks are recommended in future.

Peer Review reports

Active school travel (AST) remains an important source of physical activity for children [ 1 ]. AST has been shown to provide benefits such as reduction in children’s Body Mass Index that long-term leads to a reduction in obesity-related diseases [ 2 ], improvement in academic performance at school [ 3 ], and as part of a larger picture, reduction in car use benefitting the environment [ 4 ]. Compared with other forms of physical activity, AST has the additional advantage of being convenient and free of monetary costs [ 5 ]. However, there is evidence that AST has significantly declined over the past 30 years [ 6 , 7 ]. Studies investigating the reasons behind the decline in AST point towards increasing use of car transportation, change in social norms [ 8 ], and parental concerns about safety (e.g. abduction, traffic, crime, and strangers) [ 9 ] as key contributors to the decline, amongst other factors.

Behavioural change interventions have attempted to reverse the decline in AST. For example, a systematic review by Chillon and colleagues [ 10 ] identified 13 interventions reporting a trivial to strong positive impact on AST behaviour. However, opportunities for improvement in future studies were identified including measurement, methodology and use of theory in intervention design and/or evaluation. A review update to consider progress in the field is timely to extend understanding.

Systematic literature reviews offer two key benefits. Firstly, systematic literature reviews guarantee that a more reliable knowledge base can be developed without biases that can occur in narrative reviews [ 11 , 12 ]. Secondly, systematic literature reviews can inform policy makers and practitioners by reporting the effectiveness of interventions [ 12 ]. Therefore, the purpose of the current study is three-fold. First, we aim to conduct a systematic literature review and analysis of AST interventions published between 2010 and 2016. Second, we compare the results of our review with Chillon et al. [ 10 ] to assess whether significant differences in theory use, measurement and design are evident between time periods. Third, we assess the extent of theory use for AST interventions reporting theory.

Data source and search strategy

This study followed Chillon et al. [ 10 ] search terms and systematic literature review procedures (see procedures outlined in13,14) to identify peer-reviewed journal articles reporting AST interventions published between 2010 and 2016. Seven databases (EBSCO All databases, Emerald, ProQuest All databases, Ovid All databases, ScienceDirect, Taylor & Francis, and Web of Science) were searched using the following terms:

active transport* OR active travel*

intervention* OR Randomi?ed Controlled Trial OR evaluation OR trial OR campaign* OR program* OR study OR studies

child* OR adolescent* OR parent* OR youth OR student* OR pupil*

The symbols ‘*’ and ‘?’ are used as wildcards to include possible plurals and American/British spelling versions of the relevant terms respectively. The search terms were determined by multiple experiments using different combinations of terms in database searches to maximize the likelihood of retrieving the most relevant results. The seven databases used in this review were selected as they include marketing- and health-oriented publications and these were consistent with databases reported in previous systematic literature reviews [ 13 , 14 ]. An additional file summarises the search strategy [see Additional file 1 ]. The numbers of articles retrieved from each database are shown in Table 1 below:

Exclusion criteria

A total of 1553 records were identified in the search. All records were downloaded and imported into EndNote. After removal of all duplicated records ( n = 696), 857 unique records were then checked against the following exclusion criteria to remove unqualified records:

not peer-reviewed journal articles, ensuring that all included sources had been peer-reviewed. Other types of records such as magazines, conference proceedings, newspapers, and dissertations were excluded;

not in English;

not related to AST;

policy related articles;

review/conceptual articles;

articles containing only formative research;

medical trials;

articles published before 2010.

After application of the exclusion criteria 27 qualified records remained. In the following stage backward and forward searches were conducted including examination of all reference lists of the 27 articles and searching authors’ names and websites, and intervention names in Google Scholar. A further 13 articles providing additional information about already identified AST interventions and one additional new intervention were identified. The process produced a total of 40 peer-reviewed articles published between 2010 and 2016 reporting a total of 18 AST interventions. PRISMA guidelines [ 15 ] were followed to systemically analyse the articles and report our review.

Figure 1 demonstrates the search process, and a full list of 40 papers for each intervention can be found in the Appendix .

The systematic review process

Data analysis

The following data was extracted and analysed from the papers:

Intervention strategy. In line with the method employed in Chillon et al.’s review [ 10 ], the Active Living by Design (ALBD) Community Action (5P) Model was adopted to analyse the strategies used in the interventions. This framework consists of five components: 1) Preparation, which includes “developing and maintaining a multidisciplinary community partnership, collecting relevant assessment data to inform program planning, providing relevant training, and pursuing financial and in-kind resources to build capacity” [ 16 ] (p. 315); 2) Promotion, which refers to engaging the target audience with dedicated messages and materials; 3) Program, which refers to ongoing organised activities that aim to engage individuals; 4) Policy, which refers to rules or standards that are set to regulate behaviours; and 5) Physical projects, which refer to environmental changes that are made to remove barriers to physical activity. Additionally, reported theory use was extracted and analysed as it has been linked to enhanced intervention outcomes [ 17 ], and theory use in AST interventions was previously found to be lacking [ 10 ]. The framework of assessing theory utilization was used in previous systematic reviews [ 18 , 19 ]. The framework consists of four levels, namely 1) Informed by theory, which means theory was identified but no or limited application of theoretical framework was used; 2) Applied theory, which means several components and measures were applied in the study; 3) Testing theory, which means more than half the theoretical constructs were explicitly measured and tested, or there exists theory comparison; 4) Building theory, which means revising or creating theory by measuring, testing, and analysing constructs.

Intervention design and delivery. The Evaluation of Public Health Practice Projects (EPHPP) [ 20 ] was adopted to assess the quality of the interventions and ensure consistency in reporting with earlier research [ 10 ]. EPHPP was developed to provide research evidence to support systematic intervention reviews by outlining step-by-step guidelines [ 21 ]. EPHPP has been used in a wide range of content areas, such as chronic disease prevention [ 22 ], family health [ 23 ], and substance abuse prevention [ 24 ]. EPHPP assesses six aspects of interventions: selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, withdrawals and drop-outs, all of which is synthesised to calculate a global study rating. In EPHPP, each of the aspects are rated on a three-point scale, and the final global rating is based on the rating of the six aspects and identified as strong, moderate, or weak, based on the EPHPP guidelines [ 20 ].

Evaluation methods and outcomes. In contrast to the methods reported in Chillon et al. [ 10 ], who calculated the effect size for each intervention using Cohen’s d, in this study we only extracted the information about the methods used to evaluate the effectiveness of each intervention and their outcomes as reported in the papers. Although Cohen’s d could be an indicator of the effect size of the interventions, the identified heterogeneity of outcome measures among interventions makes the effect sizes incomparable with each other.

All data were extracted from the articles by two independent researchers and the final data were compared and verified to ensure accuracy. Discrepancies were minor and were resolved by discussion with a third researcher. In order to compare our results with Chillon et al.’s [ 10 ], we adopted the Fisher’s exact test to calculate the p value. Fisher’s exact test has been widely used to compare differences among small samples [ 13 ], and can offer more accurate results than the conventional Chi-Square method [ 25 ].

Intervention overview

Forty articles were identified in this review, covering 18 AST interventions. Full intervention details can be found in Table 2 .

All interventions were conducted in developed countries – including the United States ( N = 6) [ 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ], Europe ( N = 6) (1 in Netherlands [ 32 ], 1 in Belgium [ 33 ], 1 in Norway [ 34 ], 1 in Sweden [ 35 ], 1 in Denmark [ 36 ], and 1 in the UK [ 37 ]), Australia ( N = 2) [ 7 , 38 ], New Zealand ( N = 2) [ 39 , 40 ], Canada ( N = 1) [ 41 ], and both the UK and Canada ( N = 1) [ 42 ]. All of the interventions targeted children. The aims of each intervention varied: 13 interventions aimed to promote AST only [ 7 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 40 , 41 , 42 ], and five interventions had multiple aims [ 32 , 34 , 35 , 38 , 39 ], including promoting healthy eating and physical activity, in which AST only served as one of the physical activity aims. Only three out of 18 interventions conducted pilot tests [ 31 , 37 , 41 ]. The intervention lengths varied from 4 weeks to 5 years, and the sample sizes varied from 58 to 57,096.

Intervention strategy and theory use

Chillon et al. [ 10 ] noted “the studies generally failed to describe their theoretical frameworks” (p. 8), however they did not report whether each of the studies reported or adopted theories. In our review, seven out of 18 interventions reported using theory. The most commonly used theory was Social Cognitive Theory reported ( n = 5) [ 29 , 30 , 34 , 39 , 42 ], followed by the Social Ecological Framework reported ( n = 2) [ 34 , 35 ] and the Theory of Planned Behaviour ( n = 2) [ 37 , 39 ]. Two interventions [ 34 , 39 ] reported using more than one theory. In terms of theory utilization level, there are two studies [ 29 , 39 ] informed by theory and two studies [ 35 , 42 ] which applied theory. For example, in the “Beat the Street” [ 42 ] intervention, the researchers introduced competition to win points if children walk to school, underpinning social cognitive theory and learning theory. Three studies [ 30 , 34 , 37 ] tested theory. For example, in the “Traveling Green” [ 37 ] intervention, the factors of the Theory of Planned Behaviour were measured and tested to explain active commuting. None of the studies built theory.

All interventions were analysed using the ALBD Community Action Model (see Table 3 ). Three interventions included all five strategies from the Community Action Model [ 36 , 40 , 41 ]. Five interventions included four strategies, three of which did not implement policy [ 7 , 27 , 29 ], and two did not implement physical projects [ 35 , 38 ]. Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare the strategies used in the Chillon et al. review [ 10 ] and our review and none of the 5Ps were significantly different.

Quality assessment

The quality assessment of identified interventions was next conducted using the EPHPP tool Footnote 1 (see Table 4 ). Two researchers independently assessed all relevant articles and only minor discrepancies were identified and later resolved by discussion with the third researcher. Fourteen studies were assessed as weak in the global rating. None were assessed as strong. Comparing with the results reported in Chillon et al. [ 10 ], in which all 14 included studies were assessed as weak, a minor improvement was observed with four studies in the current review evaluated as moderate [ 29 , 31 , 38 , 39 ].

None of the studies reported representative sampling methods, which resulted in weak scores in category A - selection bias. In terms of study design, three studies reported using randomised control trial design [ 30 , 32 , 34 ] and were therefore assessed as strong; 13 studies were assessed as moderate, with nine cohort analytic (two groups pre + post) [ 26 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ], three cohort (one group pre + post) [ 7 , 41 , 42 ], and one interrupted time series design [ 33 ]. It is noteworthy that study [ 33 ] self-identified as quasi-experiment with pre- and post-tests, measuring effects during the intervention, therefore the study was classified as interrupted time series. Two studies were rated as weak, including one longitudinal study [ 40 ]. Although one study [ 27 ] self-identified as quasi-experimental design, no evaluation was reported and therefore the study was assessed as weak. In terms of confounders, six studies reported confounders and no major differences were found between groups, which resulted in a strong rating. The rest of the studies did not report accounting for confounders or had only one group in the design and were therefore assessed as weak.

None of the studies reported to be double blinded. Four studies were assessed as weak as neither assessors nor participants were blinded [ 7 , 33 , 35 , 42 ]. The rest of the studies were rated as moderate with either one-directional blinding or no relevant information reported. In terms of data collection methods, ten studies provided evidence of both reliability and validity and thus were assessed as strong [ 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 40 , 41 ]. Four were assessed as moderate with either reliability or validity being reported [ 27 , 33 , 38 , 39 ], and five were assessed as weak as they did not report reliability or validity [ 7 , 26 , 36 , 42 ]. Regarding the drop-out rate, seven studies were assessed as strong with more than 80% of participants completing the studies [ 7 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 35 , 36 ]. The remaining studies were assessed as moderate ( n = 4) [ 28 , 31 , 38 , 39 ] or weak ( n = 7) [ 26 , 27 , 34 , 37 , 40 , 41 , 42 ] due to either low completion rates or not providing enough withdrawal information.

Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare the EPHPP components between the Chillon et al. [ 10 ] review and our review.

Table 5 shows that apart from Data Collection Methods ( p = 0.011) none of the EPHPP components, including the global rating were significantly different.

Post-intervention evaluation and outcomes

A wide range of evaluation methods were reported in the 18 interventions identified in this review. They can be categorised into two main groups: self-reported and objective behavioural measures. Self-reported measures were identified in 14 interventions, and the most common methods included surveys ( n = 12) [ 7 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 40 , 41 , 42 ], interviews ( n = 2) [ 35 , 38 ], and diaries ( n = 1) [ 39 ]. Objective behavioural measures were identified in 12 interventions, and the most common methods included accelerometers, pedometer, and geographic information system (GIS) equipment ( n = 5) [ 27 , 31 , 34 , 37 , 39 ], BMI monitoring ( n = 5) [ 30 , 32 , 34 , 36 , 38 ], and observations ( n = 3) [ 26 , 28 , 30 ]. Eight studies combined self-reported and objective behavioural measures such as surveys and observations to triangulate and verify intervention effectiveness [ 27 , 28 , 30 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 42 ]. A comparison with Chillon et al. [ 10 ] indicates an increase in more objective assessment measures in recent years: in Chillon et al. [ 10 ], all studies used self-reported measurements and only three studies triangulated data including the addition of objective measurements.

All reported evaluation outcomes are summarised in Table 6 . Among 18 interventions, six interventions reported some positive effects on AST [ 26 , 27 , 29 , 38 , 40 , 42 ], two mixed effects on AST [ 7 , 41 ], and five reported no effect [ 32 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 39 ]. Five interventions did not measure AST behaviour [ 28 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 34 ] reporting other aims. Positive attitude change was reported in four interventions [ 30 , 33 , 34 , 41 ]; positive change in BMI was reported in two [ 32 , 38 ], positive policy change in two [ 33 , 35 ], knowledge and long-term infrastructure improvement were each reported in three interventions [ 7 , 29 , 41 ], and finally positive healthy eating and general physical activity changes were reported in one intervention each [ 30 , 32 ].

The purpose of this review was three-fold. First, we aimed to provide a contemporary review of AST interventions (2010-2016). Second, we aimed to compare the results of our review with Chillon et al. [ 10 ] to track progress in the field. Our review indicated that several issues identified by Chillon et al. [ 10 ] continue today and that theory use is limited in AST interventions. Third, we assessed theory utilization in AST interventions. We will focus our discussion on three key aspects, namely theoretical, methodological, and empirical.

Theoretical aspects

Previous research indicated that theory use in intervention design was associated with enhanced intervention outcomes [ 17 ], yet the extent of theory utilization had not been examined previously. In our review seven out of 18 studies reported theory use. Detailed examination identified that two were informed by theory, two applied theories, and three tested theories with examples highlighted in the results section. At the optimal level, theory should provide guidance on the constructs that become the strategic focus of a campaign. Moreover, the theory framework should be used to evaluate the intervention pre and post permitting comparisons of key theoretical constructs focussed upon to be made [ 43 ]. The importance of theory adoption and implementation in intervention design is advocated by many researchers [ 44 , 45 , 46 ]. Consistent with previous studies our results show that theory testing and building remains limited in AST. For example, Painter et al. [ 47 ], identified that 69.1% of health behaviour research used theory to inform a study, in 17.9% theories were applied, in 3.6% theories were tested, and only 9.4% of studies involved building/creating theory.

We propose three recommendations for future AST intervention implementation and reporting. Firstly, future studies should use theory to inform intervention development, execution and evaluation, and detail theory use to facilitate its full comparative assessment across multiple interventions. For example, Schuster et al. [ 48 ] used the Theory of Planned Behaviour to gain insights to inform an AST intervention. Results of the study indicated that four variables were found to be highly important in distinguishing carers segments, namely distance to school, current walk to/from school behaviour, subjective norms and intentions to increase their child’s walk to school behaviour. Given that theory can increase the effectiveness of interventions [ 19 , 47 ] extended application of theory in AST interventions is recommended. Research studies have been undertaken to systematically implement, assess, and report theory utilization in health promotion interventions, such as the UK MRC guidelines [ 49 , 50 ] and the four-step Theoretical Domains Framework [ 43 ], and these are recommended to guide future AST intervention design.

Secondly, the theories used in the interventions identified in our review, such as social ecological theory, social cognitive theory and the Theory of Planned Behaviour, have been considered traditionally as behaviour explanation theories [ 51 ]. However, as the ultimate purpose of AST interventions is to change behaviours, predictive theories and model testing should be deployed in future to develop theories focussed on behavioural change. Among all three studies in our review that tested theory [ 30 , 34 , 37 ], theoretical examination depended on cross-sectional regressions limiting understanding to explanation rather than causal understanding. AST interventions should embed predictive theory testing involving longitudinal design across multiple time points to simultaneously explore potential behavioural change determinants. This also requires researchers to focus on utilising more causal/predictive methods rather than variance-based explanation methods in future study design, which is consistent with calls to advance theory to examine behaviour change [ 52 ].

Social ecological theory, social cognitive theory and the Theory of Planned Behaviour were most frequently reported and this provides a rich avenue for future research. Lu et al. [ 53 ] notes that social ecological theory lacks sufficient specificity suggesting additional testing is needed [ 53 ] to establish reliable and valid measures. Individual focussed theories such as Theory of Planned Behaviour and social cognitive theory are limited overlooking structural factors (e.g. policy) which limits understanding of how behavioural change can be facilitated [ 54 ]. Therefore, we recommended that theories that were specifically developed in the AST context, such as the McMillan model [ 55 ] and the Ecological and Cognitive Active Commuting (ECAC) model [ 56 ], should be empirically explored in future AST interventions. For example, the ECAC model specifies three levels of determinants, namely policy, neighbourhood, and individual; that are correlated with AST, covering environmental, social, and psychological aspects providing a wider system view. The McMillan model has been shown to be effective among the general population [ 57 ] and young adolescents [ 58 ], whereas the ECAC model needs to be empirically tested.

Methodological aspects

The EPHPP framework was used in this review to assess methodological quality. Fourteen out of 18 studies were assessed as weak. Notably, selection biases, lack of double blinding, and not controlling for confounders were key issues identified in both the current and earlier review [ 10 ]. While selection biases arise from practical considerations [ 28 , 41 ] such as recruiting schools to participate in AST, making it difficult for researchers to control in all circumstances, the current study points to the need for large scale funding permitting optimal study design to be achieved. Issues such as controlling for confounders, on the other hand, can be implemented in most AST interventions. Use of statistical methods, such as case-matching sampling [ 59 ], MANCOVA [ 60 ], and multi-level modelling [ 61 ], are recommended for future AST interventions.

Due to the complexity and diversity of intervention aims, evaluation methods and outcome reporting, we were unable to make direct comparisons of effectiveness between reviews. Standardised outcome measures would permit comparisons and meta-analysis to deliver more detailed understanding in the future. In addition, we recommend that objective measurement methods should be carried out in future intervention design – especially given declining monetary cost of equipment (e.g. smart phones and wearable technology that can automatically capture data) [ 62 , 63 , 64 ]. Governments or other funding bodies need to call for more rigour in methodological design and measurement in future.

Empirical aspects

In line with the results reported in Chillon et al. [ 10 ], the current review confirmed the heterogeneity of included studies in terms of their length, sample size, and objectives (see Table 2 for details). However, analysis of the interventions indicated that significant room for improvement remains in terms of broader application of intervention activities. The analysis of the interventions using the ALBD Community Action Model showed that Preparation and Promotion were used much more frequently than Policy and Physical projects. Policy implementation and infrastructure improvements remained limited despite documented positive effects [ 27 , 29 ] indicating policy use may be a necessary condition for effectiveness [ 53 , 65 , 66 ]. Consistent with the theoretical utilization in AST, Physical programs seem to be effective in promoting AST (see for examples [ 29 , 31 ]). Our findings are consistent with Lu et al. [ 53 ]. In their systematic review, Lu et al. [ 53 ] found that social ecological theory is widely adopted and can explain factors preventing children’s walking to school. We recommend that intervention designers should incorporate more school and local policies and infrastructural improvement such as crime prevention and traffic control in order to reduce the perceived risk of AST among parents, observed in many previous reviews [ 67 , 68 ]. Moreover, habit was not identified as a behavioural determinant in any of included studies although transport habit is an important factor in AST [ 69 ]. Future intervention designs should consider facilitating long-term support to convert occasional AST behaviour to a habitual behaviour.

Many of the studies embedded compulsory educational workshops and informational sessions into curriculum (e.g., [ 32 , 39 , 40 ]). Evidence shows that curricular-based interventions results in low attendance and are less effective, which may explain drop-out rates observed for studies employing educational workshops and informational sessions [ 70 ]. Therefore, we recommend that instead of educating schools, parents, and children using traditional curricular-based strategies, approaches with more audience engagement be adopted. For example, gamification has been drawing increased attention from intervention designers in recent years, and programs such as GOKA [ 71 ] and ONESELF [ 72 ] have been shown to achieve substantial audience engagement while delivering outcome effects. Future research should test gamification within AST interventions to extend understanding.

Limitations

This review has several important limitations, many of which represent opportunities for future research. The search parameters used in the current review limit the studies identified. For example, grey literature and studies not in the English literature were not included in this review. Further, all of the 18 interventions were carried out in developed countries, yet physical inactivity among children is a significant challenge in many developing countries [ 73 ] suggesting there is an opportunity to extend AST intervention testing geographically.

A range of outcome measures and methods (self-report and non-self-report) were used to assess AST interventions including attitudes, policy, physical activity, active school travel, BMI, knowledge and infrastructure. The diversity of outcome measures prevents meta-analysis from being undertaken. Different evaluation methods limit potential comparisons between interventions. Further, given physical activity self-report data varies when compared to objective measures (non-self-report) despite high correlations with objective forms such as pedometers and diaries [ 74 ], biases must be acknowledged [ 75 ]. Moving forward, a unified and consistent approach in reporting AST intervention outcomes is needed to enable meta-analysis to be undertaken in future. Standardisation of outcome reporting would permit effect sizes to be calculated enabling comparison between interventions. Future research is recommended to determine whether there is a relationship between EPHPP quality levels and effect size – an understanding that would inform AST practice.

Meanwhile, the analysis presented in this paper is also limited to the information reported in sources identified in the search process. Employment of a standard reporting framework for AST intervention reporting warrants future research attention ensuring that quality assessments take practicalities into account. For example, full blinding procedures such as those advocated in EPHPP may not be feasible in local government and State funded interventions thereby making this assessment component redundant. Such endeavours may assist to standardise reporting and in turn enhance quality assessment exercises informing future intervention development.

This review has provided a detailed analysis of AST interventions published in peer-reviewed journals between 2010 and 2016. Following systematic literature review procedures’ 18 AST interventions were identified and subsequently analysed. The main findings of our study are:

Theory utilization in AST interventions published between 2010 and 2016 is limited. Where theory is used, interventions informed by theory and interventions that apply theory are much more common than theory testing and building.

Considering the ALBD Community Action Model, Preparation and Promotion were reportedly used much more frequently than Policy and Physical projects. Given that change is evident where policy changes are made extended use of the ALBD model is recommended (Preparation, Promotion, Program, Policy and Physical projects).

Using the EPHPP framework, 14 out of 18 interventions were weak, largely due to selection biases, lack of double blinding, and not controlling for confounders.

Finally, an increase in more objective assessment measures in AST interventions published between 2011 and 2016 was observed, in comparison to the rates reported in Chillon et al. [ 10 ].

Issues such as weak methodological design and lack of reliable and valid measurements continue to persist in reported AST interventions, all of which indicate opportunities for further improvements in terms of intervention effectiveness and evaluation.

It is noteworthy that six interventions have multiple published papers. As the EPHPP was designed to assess studies rather than interventions [ 20 ], and in order to minimise the discrepancies between papers reporting different components of interventions, only one paper reporting information relevant to the EPHPP framework was selected for each intervention. Excluded papers did not provide any information that would affect the EPHPP rating of the study. The papers used in the EPHPP assessment are marked in the Appendix .

Abbreviations

Active Living by Design

Active School Travel

Body mass index

Ecological and Cognitive Active Commuting

Effective Public Health Practice Project

Health eating

- Physical activity

Faulkner GE, Buliung RN, Flora PK, Fusco C. Active school transport, physical activity levels and body weight of children and youth: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2009;48(1):3–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Dollman J, Lewis NR. Active transport to school as part of a broader habit of walking and cycling among south Australian youth. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2007;19(4):436.

Dwyer T, Sallis JF, Blizzard L, Lazarus R, Dean K. Relation of academic performance to physical activity and fitness in children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2001;13(3):225–37.

Article Google Scholar

Moodie M, Haby MM, Swinburn B, Carter R. Assessing cost-effectiveness in obesity: active transport program for primary school children—TravelSMART schools curriculum program. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8(4):503–15.

Rosenberg DE, Sallis JF, Conway TL, Cain KL, McKenzie TL. Active transportation to school over 2 years in relation to weight status and physical activity. Obesity. 2006;14(10):1771–6.

Mammen G, Stone MR, Faulkner G, Ramanathan S, Buliung R, O’Brien C, Kennedy J. Active school travel: an evaluation of the Canadian school travel planning intervention. Prev Med. 2014;60:55–9.

Crawford S, Garrard J. A combined impact-process evaluation of a program promoting active transport to school: understanding the factors that shaped program effectiveness. J Environ Public Health. 2013. Article ID 816961. 14 pages.

Newman P, Kenworthy J. Sustainability and cities: overcoming automobile dependence. Washington DC: Island Press; 1999.

DiGuiseppi C, Roberts I, Li L, Allen D. Determinants of car travel on daily journeys to school: cross sectional survey of primary school children. BMJ. 1998;316(7142):1426–8.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chillón P, Evenson KR, Vaughn A, Ward DS. A systematic review of interventions for promoting active transportation to school. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(1):1.

Tranfield D, Denyer D, Smart P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br J Manag. 2003;14(3):207–22.

Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide. Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2008.

Carins JE, Rundle-Thiele SR. Eating for the better: a social marketing review (2000–2012). Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(7):1628–39.

Kubacki K, Rundle-Thiele S, Pang B, Buyucek N. Minimizing alcohol harm: a systematic social marketing review (2000–2014). J Bus Res. 2015;68(10):2214–22.

PRISMA Statement. http://www.prisma-statement.org/ . Accessed 14 Dec 2016.

Bors P, Dessauer M, Bell R, Wilkerson R, Lee J, Strunk SL. The active living by design national program: community initiatives and lessons learned. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):S313–21.

Thackeray R, Neiger BL. Establishing a relationship between behavior change theory and social marketing: implications for health education. J Health Educ. 2000;31(6):331–5.

Webb T, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S. Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(1):e4.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:399–418.

Effective Public Health Practice Project: Quality assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. http://www.ephpp.ca/tools.html . Accessed 14 Dec 2016.

Thomas B, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2004;1(3):176–84.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ganann R, Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Ciliska D, Peirson L. Community-based interventions for enhancing access to or consumption of fruit and vegetables among five to 18-year olds: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):1.

Peirson L, Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Morrison K, Warren R, Ali MU, Raina P. Treatment of overweight and obesity in children and youth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ open. 2015;3(1):E35–46.

Bryden A, Roberts B, McKee M, Petticrew M. A systematic review of the influence on alcohol use of community level availability and marketing of alcohol. Health Place. 2012;18(2):349–57.

Larntz K. Small-sample comparisons of exact levels for chi-squared goodness-of-fit statistics. J Am Stat Assoc. 1978;73(362):253–63.

Bungum TJ, Clark S, Aguilar B. The effect of an active transport to school intervention at a suburban elementary school. Am J Health Educ. 2014;45(4):205–9.

McDonald NC, Yang Y, Abbott SM, Bullock AN. Impact of the safe routes to school program on walking and biking: Eugene, Oregon study. Transp Policy. 2013;29:243–8.

Heinrich KM, Dierenfield L, Alexander DA, Prose M, Peterson AC. Hawai ‘i's opportunity for active living advancement (HO ‘ĀLA): addressing childhood obesity through safe routes to school. Hawaii Med J. 2011;70(7 suppl 1):21.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hoelscher D, Ory M, Dowdy D, Miao J, Atteberry H, Nichols D, Evans A, Menendez T, Lee C, Wang S. Effects of funding allocation for safe routes to school programs on active commuting to school and related behavioral, knowledge, and psychosocial outcomes results from the Texas childhood obesity prevention policy evaluation (T-COPPE) study. Environ Behav. 2016;48(1):210–29.

Mendoza JA, Watson K, Baranowski T, Nicklas TA, Uscanga DK, Hanfling MJ. The walking school bus and children's physical activity: a pilot cluster randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3):e537–44.

Sayers SP, LeMaster JW, Thomas IM, Petroski GF, Ge B. A walking school bus program: impact on physical activity in elementary school children in Columbia, Missouri American. J Prev Med. 2012;43(5):S384–9.

van Nassau F, Singh AS, van Mechelen W, Paulussen TG, Brug J, Chinapaw MJ. Exploring facilitating factors and barriers to the nationwide dissemination of a Dutch school-based obesity prevention program “DOiT”: a study protocol. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1.

Vanwolleghem G, D’Haese S, Van Dyck D, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Cardon G. Feasibility and effectiveness of drop-off spots to promote walking to school. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(1):1.

Lien N, Bjelland M, Bergh IH, Grydeland M, Anderssen SA, Ommundsen Y, Andersen LF, Henriksen HB, Randby J, Klepp K-I. Design of a 20-month comprehensive, multicomponent school-based randomised trial to promote healthy weight development among 11-13 year olds: the HEalth in adolescents study. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38(5 suppl):38–51.

Elinder LS, Heinemans N, Hagberg J, Quetel A-K, Hagströmer M. A participatory and capacity-building approach to healthy eating and physical activity–SCIP-school: a 2-year controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9(1):1.

Østergaard L, Støckel JT, Andersen LB. Effectiveness and implementation of interventions to increase commuter cycling to school: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1.

McMinn D, Rowe DA, Murtagh S, Nelson NM. The effect of a school-based active commuting intervention on children's commuting physical activity and daily physical activity. Prev Med. 2012;54(5):316–8.

Mathews LB, Moodie MM, Simmons AM, Swinburn BA. The process evaluation of It's your move!, an Australian adolescent community-based obesity prevention project. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):1.

Duncan S, McPhee JC, Schluter PJ, Zinn C, Smith R, Schofield G. Efficacy of a compulsory homework programme for increasing physical activity and healthy eating in children: the healthy homework pilot study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(1):1.

Hinckson EA, Garrett N, Duncan S. Active commuting to school in New Zealand children (2004-2008): a quantitative analysis. Prev Med. 2011;52(5):332–6.

Buliung R, Faulkner G, Beesley T, Kennedy J. School travel planning: mobilizing school and community resources to encourage active school transportation. J Sch Health. 2011;81(11):704–12.

Hunter RF, de Silva D, Reynolds V, Bird W, Fox KR. International inter-school competition to encourage children to walk to school: a mixed methods feasibility study. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):1.

French SD, Green SE, O’Connor DA, McKenzie JE, Francis JJ, Michie S, Buchbinder R, Schattner P, Spike N, Grimshaw JM. Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):1.

Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):361–6.

Baker EA, Brennan Ramirez LK, Claus JM, Land G. Translating and disseminating research- and practice-based criteria to support evidence-based intervention planning. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(2):124–30.

Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(4):295–309.

Painter JE, Borba CP, Hynes M, Mays D, Glanz K. The use of theory in health behavior research from 2000 to 2005: a systematic review. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(3):358–62.

Schuster L, Kubacki K, Rundle-Thiele S. A theoretical approach to segmenting children’s walking behaviour. Young Consumers. 2015;16(2):159–71.

Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, Kinmonth AL. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. Br Med J. 2000;321(7262):694.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Medical Research Council (Great Britain). Health services and public Health Research Board. A framework for development and evaluation of RCTs for complex interventions to improve health: Medical Research Council; 2000.

Plotnikoff RC, Costigan SA, Karunamuni N, Lubans DR. Social cognitive theories used to explain physical activity behavior in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2013;56(5):245–53.

Rhodes RE, Nigg CR. Advancing physical activity theory: a review and future directions. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2011;39(3):113–9.

Lu W, McKyer ELJ, Lee C, Goodson P, Ory MG, Wang S. Perceived barriers to children’s active commuting to school: a systematic review of empirical, methodological and theoretical evidence. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(1):1.

Sniehotta FF. Towards a theory of intentional behaviour change: plans, planning, and self-regulation. Br J Health Psychol. 2009;14(2):261–73.

McMillan TE. The relative influence of urban form on a child’s travel mode to school. Transp Res A Policy Pract. 2007;41(1):69–79.

Sirard JR, Slater ME. Walking and bicycling to school: a review. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2008;2(5):372–96.

Blamey AAM, MacMillan F, Fitzsimons CF, Shaw R, Mutrie N. Using programme theory to strengthen research protocol and intervention design within an RCT of a walking intervention. Evaluation. 2013;19(1):5–23.

Kaplan S, Nielsen TAS, Prato CG. Walking, cycling and the urban form: a Heckman selection model of active travel mode and distance by young adolescents. Transp Res Part D: Transp Environ. 2016;44:55–65.

Kirwan M, Duncan MJ, Vandelanotte C, Mummery WK. Using smartphone technology to monitor physical activity in the 10,000 steps program: a matched case–control trial. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(2):e55.

KAM G, Tomasone JR, Latimer-Cheung AE, Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, Bassett-Gunter RL, Wolfe DL. Developing physical activity interventions for adults with spinal cord injury. Part 1: a comparison of social cognitions across actors, intenders, and nonintenders. Rehabil Psychol. 2013;58(3):299.

Crespo NC, Elder JP, Ayala GX, Slymen DJ, Campbell NR, Sallis JF, McKenzie TL, Baquero B, Arredondo EM. Results of a multi-level intervention to prevent and control childhood obesity among Latino children: the Aventuras Para Niños study. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43(1):84–100.

Lobelo F, Kelli HM, Tejedor SC, Pratt M, McConnell MV, Martin SS, Welk GJ. The wild wild west: a framework to integrate mHealth software applications and Wearables to support physical activity assessment, counseling and interventions for cardiovascular disease risk reduction. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;58(6):584–94.

Hickey AM, Freedson PS. Utility of consumer physical activity trackers as an intervention tool in cardiovascular disease prevention and treatment. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;58(6):613–9.

Wang JB, Cataldo JK, Ayala GX, Natarajan L, Cadmus-Bertram LA, White MM, Madanat H, Nichols JF, Pierce JP. Mobile and wearable device features that matter in promoting physical activity. J Mob Technol Med. 2016;5(2):2–11.

Boarnet MG, Anderson CL, Day K, McMillan T, Alfonzo M. Evaluation of the California safe routes to school legislation: urban form changes and children’s active transportation to school. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(2):134–40.

Fusco C, Moola F, Faulkner G, Buliung R, Richichi V. Toward an understanding of children’s perceptions of their transport geographies:(non) active school travel and visual representations of the built environment. J Transp Geogr. 2012;20(1):62–70.

Davison KK, Lawson CT. Do attributes in the physical environment influence children's physical activity? A review of the literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3(1):1.

Carver A, Timperio A, Crawford D. Playing it safe: the influence of neighbourhood safety on children's physical activity—a review. Health Place. 2008;14(2):217–27.

Murtagh S, Rowe DA, Elliott MA, McMinn D, Nelson NM. Predicting active school travel: the role of planned behavior and habit strength. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9(1):65–73.

Jago R, Baranowski T. Non-curricular approaches for increasing physical activity in youth: a review. Prev Med. 2004;39(1):157–63.

Rundle-Thiele S, Schuster L, Dietrich T, Russell-Bennett R, Drennan J, Leo C, Connor JP. Maintaining or changing a drinking behavior? GOKA's short-term outcomes. J Bus Res. 2015;68(10):2155–63.

Allam A, Kostova Z, Nakamoto K, Schulz PJ. The effect of social support features and gamification on a web-based intervention for rheumatoid arthritis patients: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(1):e14.

Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev. 2012;70(1):3–21.

Sallis JF, Strikmiller PK, Harsha DW, Feldman HA, Ehlinger S, Stone EJ, Williston J, Woods S. Validation of interviewer-and self- administered physical activity checklists for fifth grade students. Age (mean, SD). 1996;10(0):53.

Google Scholar

Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior: the reasoned action approach. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2011.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

No fund was received to conduct the study.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its Additional file 1 ].

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Marketing and Social Marketing @ Griffith, Griffith University, 117 Kessels Road, Nathan, QLD, 4111, Australia

Bo Pang, Krzysztof Kubacki & Sharyn Rundle-Thiele

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors were involved in research design. BP and KK led the literature search strategy, extracted data elements, and compiled the studies. Data analysis was undertaken by BP and KK, and reviewed by SRT. BP developed the first draft of the manuscript. All authors worked on subsequent versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Bo Pang .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:.

Active Transport to School Database Search. (DOC 66 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Pang, B., Kubacki, K. & Rundle-Thiele, S. Promoting active travel to school: a systematic review (2010–2016). BMC Public Health 17 , 638 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4648-2

Download citation

Received : 21 February 2017

Accepted : 28 July 2017

Published : 05 August 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4648-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Active school travel

- Interventions

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Skip to content

- Skip to navigation

- Your account Your account

bristol.gov.uk

- For residents

- Streets and travel

- Bristol's Clean Air Zone

- Get free active travel support

We can help you reduce your car journeys with free cycling trials, eScooter credit and bus taster tickets.

The council has funding to help people travel more sustainably.

We can all help reduce air pollution and improve air quality in Bristol by walking, cycling and using public transport for more journeys.

Walking and cycling also helps us keep fit and stay healthy. We're exposed to less pollution than when travelling in a vehicle. We also save money on the cost of travelling.

Help with sustainable travel

Our free offers include:

- one month bike and e-bike trials

- adult cycle training to build your confidence

- taster bus tickets

- taster train tickets

- car club credit

Register for free support

Register for free active travel support

Once you've registered your interest, our travel advisors will contact you to talk through the options.

Contact information

Clean air zone.

fill in our Clean Air Zone contact form

call 0117 903 6385

- Bristol's Clean Air Zone charges and vehicle checker

- Pay the Bristol Clean Air Zone daily charge

- View a map of Bristol's Clean Air Zone

- Clean Air Zone and road diversions

- Clean Air Zone Exemptions

- Clean Air Zone traffic signs

- Pay a Clean Air Zone Penalty Charge Notice

- Appeal a Clean Air Zone Penalty Charge Notice

- Apply for a Clean Air Zone charge refund

- Apply for Clean Air Zone financial support

- What a Clean Air Zone is, why we need one

- Clean Air Zone charges and Penalty Charge Notices revenue

Active School Travel

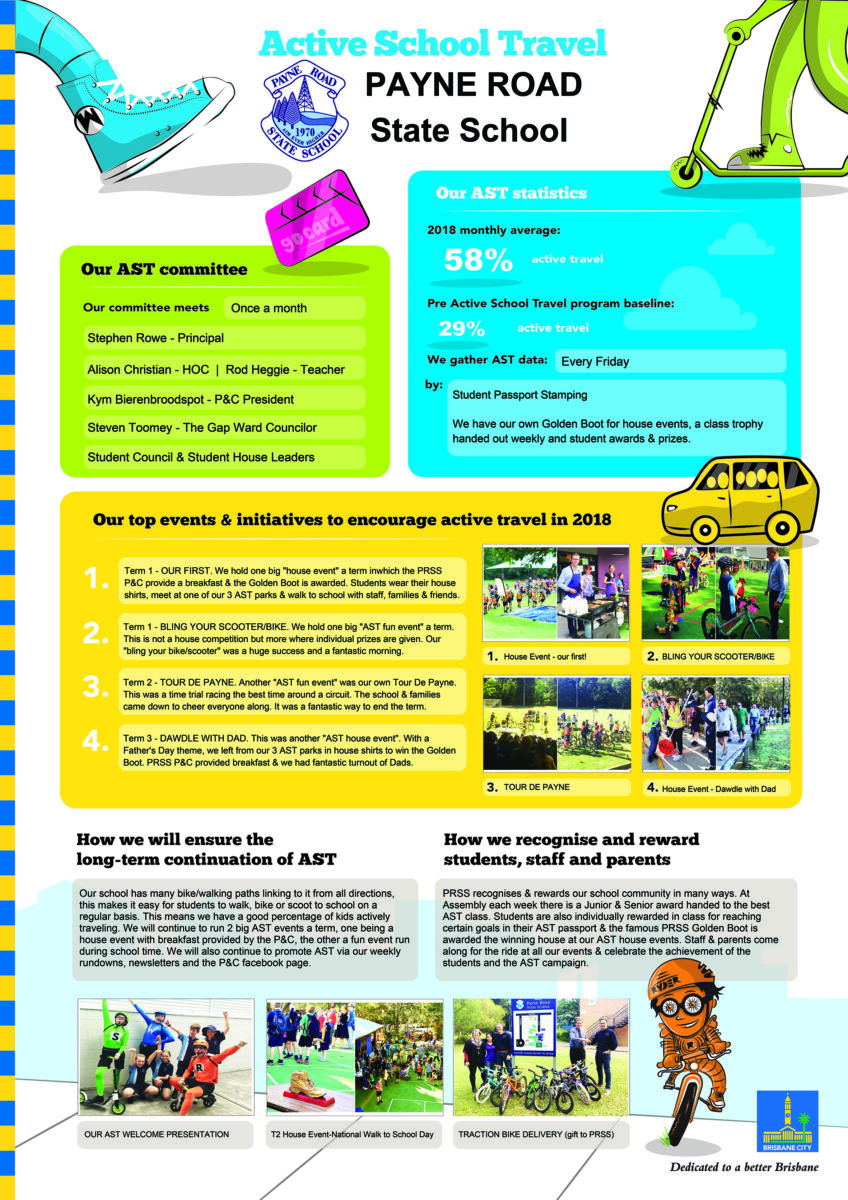

The Active School Travel (AST) program is a BCC initiative and offers Brisbane primary schools free resources, tools and incentives to enable students, parents, carers and teachers to leave the car at home and actively travel to school. It’s all about creating healthier, more active students and families, increasing road safety awareness, safer streets and continuing to tackle traffic congestion. The award-winning three-year program promotes road safety and sustainable and healthy travel options such as walking, cycling, scootering, carpooling and public transport.

Back in 2013 PRSS was an AST school enjoying the resources on offer but the program was only for 1 year. 2013 saw our students enjoying AST assembly performances, taking bike and scooter skills classes and enjoying Friday as the active day to travel to school with class awards.

Below is a photo of the BCC Active School Travel team at Assembly in 2013 and after that, the same performance 8 years on in 2020.

Over the last 3 years PRSS has taken part in the AST program, we are currently in our last year. We have had years of fun with walks, rides, event days, dress-ups, breakfasts, performances, award nights, skill classes and more. Below is a rundown of our last 3 years.

If you are interested in knowing more about AST this year please contact Kym B at [email protected]

YEAR 1 – 2018

AST assembly performance AST meetings every month in the first year Scooter Skills Training to lower grades Bike Skills Training to upper grades Awards night

- Term 1 WALK Our AST LAUNCH Walk to School from Parks & P&C Brekky (Pancakes)

- Term 1 FUN EVENT Bling Your Bike/Scooter Parade before School

- Term 2 WALK Walk Safely to School Day from Parks & P&C Brekky (Toasties)

- Term 2 FUN EVENT Tour De Payne During the last day of term

- Term 3 WALK Dawdle with Dad from Parks & P&C Brekky (Toasties)

- Term 3 FUN EVENT Scooter Challenge before School

- Term 4 WALK Walk to School in Red from Parks (coincides with Day for Daniel & P&C Brekky (Toasties)

- Term 4 FUN EVENT No event as the term was too busy.

2018 Awards night Poster

YEAR 2 – 2019

AST meetings once a term (Missed T3) Scooter Skills Training to lower grades Bike Skills Training to upper grades Awards night

- Term 1 WALK No event, start of term was too busy

- Term 1 FUN EVENT Bling Your Helmet Parade before School

- Term 2 FUN EVENT Tour De Payne During the last day of term – CANCELLED DUE TO RAIN

- Term 3 FUN EVENT Silly Socks and Funny Feet Walk from Parks and Parade before school

- Term 3 FUN EVENT (3 events in term 3) Tour De Payne During the last day of term (Principal Stephen Rowe’s Last day)

- Term 4 WALK Walk to School in Red from Parks (coincides with Day for Daniel) & P&C Brekky (Toasties)

- Term 4 FUN EVENT No event as the term is too busy.

2019 Awards Night Poster

YEAR 3 – 2020

AST assembly performance AST meetings once a term

- Term 1 WALK Clean Up Australia Walk from Parks – council van – P&C Brekky (Toasties) – AST Certificate given to those that participated

- Term 1 FUN EVENT Ride to school day – No event, house points – AST Certificate given to winning house participants

- Term 1 FUN EVENT Bling your bike/Scooter in Easter Style – CANCELLED DUE TO COVID

- Term 2 WALK Walk Safely to School Day (wacky COVID walk to school or around your neighbourhood if home schooling) – No event, house points – AST Certificate given to those that participated.

- Term 2 WALK 2 Red Nose Day Walk to replace Tour De Payne – No meeting at park – event at school for house points – AST Certificate given to those that participated.

- Term 2 FUN EVENT Tour De Payne – CANCELLED DUE TO COVID

Term 3 & 4 to continue………

- Principal's Message

- The Kid in the Crest

- School Prayer

- School Song

- School Expectations

- House Teams

- School Theme 2024

- Acknowledgment of Country

- Our Facilities

- Defence School Mentor Program

- Policies & Procedures

- School Routine

- School History

- 70 Years Reunion Photo Gallery

- Mandatory School Report

- Complaints Management

- Visit Our Lady of Dolours

- Enrolment Application

- Make an enquiry

- School Fees

- Booklists 2024

- School Uniform

- Mary Mackillop Fund

- 2024 Annual Improvement Plan

- Religious Education

- How We Learn

- ACER Testing

- RE in the classroom

- Reading in Year 1

- Mathematics

- Make and Meld

- Challenging Tasks

- Curriculum V9

- Maths at Our House

- Maths Incursion

- Fine Writing

- Prep Technology

- Mathematics Work

- Year 2 Roving Reporters

- Prep & Materials

- Year 2 Research & Writing

- Year 1 Mathematics

- Little Code Makers

- School Calendar

- School-Theme

- Acts of Kindness

- Library Week

- First Week 2024

- Parents & Friends

- School Board

- Defence School Mentor program

Active Travel

- Volunteer Training

- Outside School Hours Care

- School Facilities Hire

- Community Access

- Student Protection

Active-Travel //

- Active Travel Currently selected

Update April 12, 2024

Information for u.s. citizens in the middle east.

- Travel Advisories |

- Contact Us |

- MyTravelGov |

Find U.S. Embassies & Consulates

Travel.state.gov, congressional liaison, special issuance agency, u.s. passports, international travel, intercountry adoption, international parental child abduction, records and authentications, popular links, travel advisories, mytravelgov, stay connected, legal resources, legal information, info for u.s. law enforcement, replace or certify documents, tourism & visit.

Study & Exchange

Other Visa Categories

U.S. Visa: Reciprocity and Civil Documents by Country

Share this page:

Visitor Visa

Visa Waiver Program

Travel Without a Visa

Citizens of Canada and Bermuda

Border Crossing Card

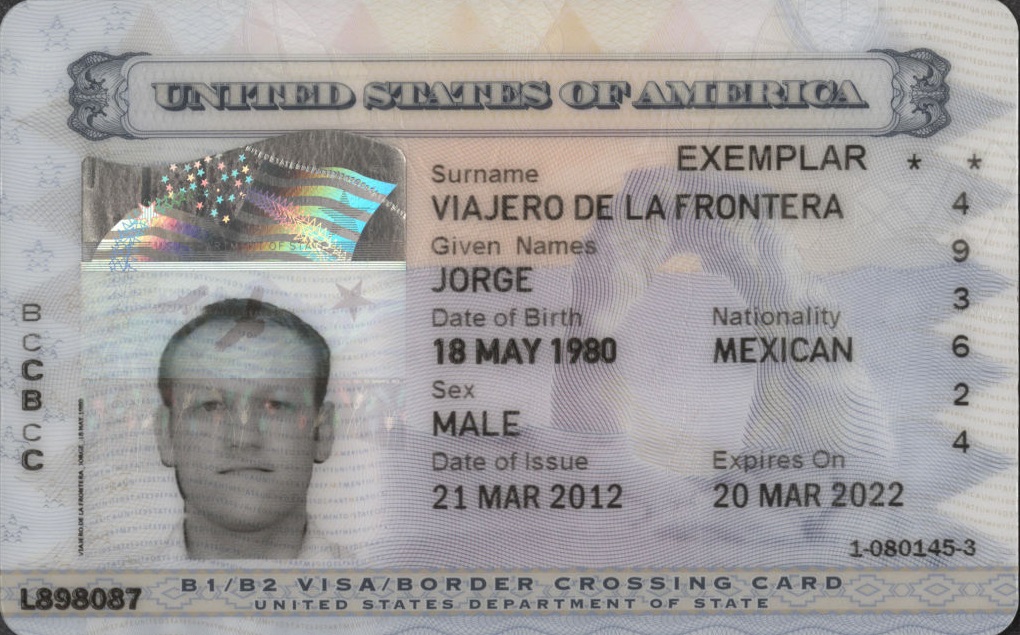

For citizens of mexico.

The Border Crossing Card (BCC) is both a BCC and a B1/B2 visitor’s visa. A BCC (also referred to as a DSP-150) is issued as a laminated card, which has enhanced graphics and technology, similar to the size of a credit card. It is valid for travel until the expiration date on the front of the card, usually ten years after issuance.

Border Crossing Card Validity

- The new card is valid for ten years after issuance, except in the cases of some children (see Border Crossing Card Fees ).

- “Laser visas” issued prior to October 1, 2008 are still valid for travel until the expiration date on the front of the card.

Qualifying for a Border Crossing Card

- B1/B2 visa/Border Crossing Cards are only issued to applicants who are citizens of and resident in Mexico.

- Applicants must meet the eligibility standards for B1/B2 visas.

- They must demonstrate that they have ties to Mexico that would compel them to return after a temporary stay in the United States.

Applying for a Border Crossing Card

BCC applicants must make an application using the normal procedures set by consular sections in Mexico. Refer to the websites of the U.S. Embassy and Consulates in Mexico for details.

Required Documentation

All applicants for a B1/B2 visa/Border Crossing Card must have a valid Mexican passport at the time of application.

Border Crossing Card Fees

For current fees for Department of State services, select Fees .

Mexican children under 15 years of age pay a reduced fee for a Border Crossing Card. The child must have at least one parent who holds a valid BCC or is applying for a BCC. BCC's issued for the reduced fee expire on the child’s 15 th birthday. If the full fee is paid, the child receives a BCC valid for the full ten years.

References - U.S. Laws

Section 104 of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA) serves as the legal basis for the issuance of Border Crossing Cards.

More Information

A-Z Index Latest News What is a U.S. Visa? Diversity Visa Program Visa Waiver Program Fraud Warning Find a U.S. Embassy or Consulate Straight Facts on U.S. Visas

External Link

You are about to leave travel.state.gov for an external website that is not maintained by the U.S. Department of State.

Links to external websites are provided as a convenience and should not be construed as an endorsement by the U.S. Department of State of the views or products contained therein. If you wish to remain on travel.state.gov, click the "cancel" message.

You are about to visit:

Border Crossing Card BCC – Information and Requirements

All you need to know about border crossing card (bcc).

The United States is one of the most visited countries in the world. Millions of people visit the United States every year for tourism, business, and other purposes. Most of the foreign tourists come from Mexico and Canada. The US immigration authorities have established a streamlined entry process through permits and cards to make it convenient for the residents of Mexico to visit the country.

This article will provide a brief introduction to Border Crossing Card (BCC) and how it helps Mexican citizens enter the United States without going through a stressful and lengthy process:

What is a Border Crossing Card (BCC)?

The US Department of State introduced the Border Crossing Card (BCC) in 1988. It is an identity document as well as a B1/B2 visa that entitles Mexican citizens to enter the United States. The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 provide the legal basis for the issuance of BCC.

Previously known as the “laser visa”, a Border Crossing Card also serves as a DSP-150. A BCC comes in the form of a laminated card designed with advanced technology and graphics. When first issued in the year 1988, Border Crossing Cards were designed with basic technology. However, the latest version of a BCC is technologically sophisticated.

Being a Mexican, when you’re granted with a Border Crossing Card, you can visit the United States for tourism or business purposes for three days (72 hours). It’s prohibited to travel to the US for work on a BCC.

How Far Can I Travel Within the U.S. on a BCC?

There are some limitations in terms of how far someone can travel within the United States on a Border Crossing Card. You can travel up to 25 miles beyond the border into Texas and California. However, in New Mexico, you can go as far as 55 miles from the border and 75 miles into Arizona. If you wish to travel farther or stay longer, you can request an I-94 from the Custom and Border Protection Officer. I-94s are now issued electronically at air and sea ports.

Does a BCC Entitle You to Stay in the US for 10 Years?

A BCC card usually remains valid for ten years. It’s important to understand that the ten-year validity is the time period during which you can cross the border; it doesn’t mean you can stay in the United States for 10 years on a BCC. As mentioned earlier, a BCC allows you to stay in the US for three days. If you live in the country beyond the allowed time period, it will lead to serious consequences.

What Does a Border Crossing Card Look Like?

Take a look at the following image which is the front of the updated version of a BCC:

Source: wikipedia.org

How to Qualify For a Border Crossing Card?

The process involves fairly strict eligibility criteria when it comes to qualifying for a BCC . If you want a Border Crossing Card, you should meet the following requirements:

- You must be a Mexican citizen residing in Mexico

- You have to convince the authorities that you will return to your home country within the allowed time period and that there is no intention to stay in the US beyond the allowed time.

- You must meet all the requirements for B1/B2 visas: sufficient funds to cover the stay, documents to prove that you don’t have a criminal record, etc.

Applying for a Border Crossing Card (BCC)

You need to apply using the standard procedures set by consular sections in Mexico. The process to obtain a BCC is somehow similar to that of a B1 or B2 visa . You need to gather all the relevant and required documents. The standard fee for a BCC is $185.

Mexican citizens under the age of 15 have to pay $15 if their guardian or parents are also applying for a BCC. At the time of your interview with the consular, you have to produce all the necessary documents along with the fee receipt.

Typically, a BCC remains valid for 10 years. For children under the age of 15, a BCC either expires after ten years or when the children turn 15. You can find the expiration date of your BCC on the front of your card.

If you’re planning to visit the United States, it’s advisable to seek guidance to avoid unnecessary stress and red tape. Contact us for more information!

- (888) 777-9102

- Learning Center

- How It Works

- All Packages & Pricing

- I-90 Application to Replace Permanent Resident Card

- I-129F Petition for Alien Fiancé

- I-130 Petition for Alien Relative

- I-131 Application for Travel Document

- I-485 Adjustment of Status Application

- I-751 Remove Conditions on Residence

- I-765 Application for Employment Authorization

- I-821D DACA Application Package

- I-864 Affidavit of Support

- N-400 Application for Naturalization

- N-565 Application to Replace Citizenship Document

- Citizenship Through Naturalization

- Citizenship Through Parents

- Apply For Citizenship (N-400)

- Apply for Certificate of Citizenship (N-600)

- Replace Citizenship Document (N-565)

- Apply for a Green Card

- Green Card Renewal

- Green Card Replacement

- Renew or Replace Green Card (I-90)

- Remove Conditions on Green Card (I-751)

- Green Card through Adjustment of Status

- Adjustment of Status Application (I-485)

- Affidavit of Support (I-864)

- Employment Authorization (I-765)

- Advance Parole Application (I-131)

- Adjustment of Status Fee

- Family-Based Immigration Explained

- Search the Learning Center

- Request Support

- Find an Immigration Attorney

- General Immigration Questions

Border Crossing Card Explained

Home » Border Crossing Card Explained

July 25, 2021

A border crossing card (BCC) is a U.S. immigration identification card which serves as a B-1/B-2 visa for Mexican citizens. The U.S. Department of State (DOS) issues a border crossing card to Mexican citizens to enter the United States for temporary purposes. The BCC is generally valid for a period of 10 years, except in the cases of some children.

The BCC has a photo and machine-readable biometric information. The card even has a built-in RFID chip and Integrated Contactless Circuit. The format makes it easy for immigration officials at the border to scan and admit visitors at a port of entry. In that past, it was known as a “laser visa.” Immigration officials may also refer to the card its internal name, Form DSP-150.

Most people applying for a nonimmigrant visa are temporary visitors coming to the United States for business or pleasure. The State Department issues B-1 visas to temporary visitors for business and short-term training. They issue B-2 visas to temporary visitors for pleasure. Generally, DOS will issue a combined B-1/B-2 visa either in the form of a Border Crossing Card (BCC/mica) or a foil affixed to their Mexican passport (BBBCV/Laser Visa).

BCC Privileges

The border crossing card is valid for an unlimited number of U.S. entries during the 10-year period. However, the cardholder may only stay in the U.S. for a period 30 days and travel only within a certain area (generally no more than 25 miles from the border).

If you want to stay longer or travel further into the United States, request a Form I-94 Arrival/Departure Record from the immigration officer at the time of entry. The I-94 will generally be valid up to six months. You’ll be able to travel throughout the United States.

However, just as with a standard issue B-1 or B-2 visa, the BCC does not provide you with employment authorization. In other words, you may not work in the United States.

RECOMMENDED: How to Find an Electronic I-94 Record

Requirements for the Border Crossing Card

To qualify for the BCC, you’ll need to meet some fundamental requirements including:

- Have a valid Mexican passport at the time of application;

- Be a citizen of and resident in Mexico;

- Meet the eligibility standards for B1/B2 visas; and

- Demonstrate that you have ties to Mexico that would compel you to return after a temporary stay in the United States.

Applying for a Border Crossing Card

Start by visiting the website for the U.S. embassy in Mexico City or one of the nine U.S. consulates closest to you. Generally, Mexican border crossing card applicants can apply at one of these locations. The website may have specific guidance for you.

Next, complete the online nonimmigrant visa application (DS-160) for a B-1/B-2 visa. During the application process, you’ll need to upload a passport-style photo. Be sure to review the State Department’s photograph requirements . Print a copy of your application. You’ll need it for your interview.

Currently, a border crossing card costs . It is the same fee as most nonimmigrant visas. ( Check DOS for the most current fee. )

Mexican children under 15 years of age pay a reduced fee for the card. The child must have at least one parent who holds a valid BCC or is applying for a BCC. BCC’s issued for the reduced fee expire on the child’s 15th birthday. If the full fee is paid, the child receives a BCC valid for the full ten years.

Mistakes on USCIS forms can cause costly delays or a denial.

Applying for a green card after a border crossing card entry.

It is possible to adjust status to permanent resident (green card holder) after entering with a border crossing card. However, an individual should not enter the U.S. with the intent to adjust status with the BCC.

In order to apply for a green card, a foreign national must be eligible. If the applicant has a valid family-based immigration relationship, he or she must also have a lawful entry. Entering with a valid border crossing card counts as a lawful entry. You’ll need to include evidence of your lawful entry when applying for a green card through adjustment of status. Although you technically entered legally with the card, it is hard to prove this without documentation that indicates the date and location. When entering the United States at a border crossing, Mexican visitors with a border crossing card may request a Form I-94 Arrival/Departure Record. The I-94 will evidence the exact date and location of the specific visitor. The I-94 is critical evidence of a lawful entry when filing the green card application.

Again, the B-1/B-2 visa is for the purposes of temporary visits. When entering the U.S., the card holder is reaffirming the intent to visitor temporarily and depart as required. Therefore, you should not enter the U.S. with immigrant intent. However, life circumstances can sometimes change intentions during the course of a trip. For example, if a Mexican national visited her U.S. citizen spouse in the United States with a B-1/B-2 visa, she couldn’t go with the intent to apply for a green card. But if COVID-19 hit during her visit and she decided to stay in the U.S. permanently with her husband, her intentions changed. This would likely be the basis to proceed with an application after the BCC entry.

RECOMMENDED: Can I come to the U.S. for the purpose of adjusting status?

Immigration Form Guides Form I-90 Form I-129F Form I-130 Form I-131 Form I-131A Form I-134 Form I-485 Form I-751 Form I-765 Form I-821D Form I-864 Form N-400 Form N-565 Form N-600

Sign Up to Receive Free Monthly Information for Your Immigration Journey

© Copyright 2013-2024, CitizenPath, LLC. All rights reserved. CitizenPath is a private company that provides self-directed immigration services at your direction. We are not affiliated with USCIS or any government agency. The information provided in this site is not legal advice, but general information on issues commonly encountered in immigration. CitizenPath is not a law firm and is not a substitute for an attorney or law firm. Your access to and use of this site is subject to additional Terms of Use .

Active School Travel

Get Involved

- Watch our informational webinar for an introduction to the program.

- Learn more about the pilot program.

- See the list of schools that participated in the 2021 and 2022 cohorts.

- Email us for more information about the pilot project.

The Active School Travel (AST) Pilot Program is a pilot initiative led by BC Healthy Communities Society (BCHC) and is funded by the B.C. Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure.

What is the goal of the Pilot Program?

The goal of the pilot is to support more students to walk, bike and scoot to and from school. The pilot will test adapted materials from existing evidence-based Active School Travel Programs in a small cohort of B.C. school communities from January to December 2022. With guidance and support, selected schools will implement plans and activities using a range of tools, resources and templates provided by BC Healthy Communities.

What are the benefits Active School Travel provides?

The Active School Travel (AST) Pilot Program aims to support B.C. students and families to be more active, more often for the school journey. Using active modes of travel such as walking and cycling allows students to spend more time outside while staying connected with family and peers in a way that ensures safe physical distancing. When school communities invest in developing sustainable projects and plans that encourage students to walk and cycle more often for at least part of their school journey, they also support lasting changes in physical, mental and social well-being for students, staff and families. More walking and cycling also means less traffic congestion around schools, resulting in improved air quality and safer traffic conditions, which supports the safety of students, families, staff and the surrounding community. For more information on the benefits of Active School Travel programs, including evidence-based best practice examples of strategies that lead to increases in active school travel outcomes, download this Active School Travel Fact Sheet from Ontario Active School Travel .

How do I get my school involved?

We are not currently accepting grant applications for Active School Travel grants.

If you have questions, you can watch the recording of our recent info session , review the Application Guide , or contact BC Healthy Communities for more information.

The Active School Travel Pilot Program is conducted in partnership with the Ministry of Transportation and is managed and delivered by BC Healthy Communities Society.

Schools who are selected for the cohort will receive:

- An online Community of Learning and Practice (CoLP)

- Support with data collection, monitoring, and evaluation

- Phone/digital-based coaching

- Sharing of evidence-based tools and resources

- Capacity building learning, training, planning sessions (workshops, meetings either in person or via other delivery mechanisms)

As participants of the pilot, schools will be required to:

- Agree to participate in the pilot for the entirety of the program term (until December 31, 2022)

- Complete a baseline survey about existing active school travel activities

- Use the materials that are being tested as part of the pilot to plan, implement and evaluate your Active School Travel project

- Apply a whole-school approach to program-related activities (i.e. funding cannot be used to support actions that affect only one classroom or grade level – all students must benefit at the school).

- Provide ongoing feedback about the program and materials to BC Healthy Communities

- Submit a (brief) final report that includes outcomes, learnings, and recommendations as a result of participation in the pilot

In order for a school to be eligible to apply to participate in the AST Pilot Program, they must meet the following criteria:

- Preference for inclusion in pilot will be given to schools located in rural, semi-rural, and suburban communities

- School must be located within a neighbourhood setting, with sufficient infrastructure in place to ensure active travel to/from school is feasible for the duration of the pilot.

- A ‘champion’ staff member at the school to lead the project planning;

- An existing school travel plan or program in place;

- A commitment from school partners and/or parents for an active school travel project

- Schools must be willing to promote the pilot to staff and students, and actively encourage participation in data collection and evaluation measures for the purposes of the pilot.

- Modeshift STARS

- Act TravelWise

- Corporate Premium Members

- Staff Delivery Team

- Executive Board Members

- Associate Members

- Honorary members

- Awards 2021

- Awards 2022

- Awards 2023

- TravelWise Week Awards

- TravelWise Week

- Team Modeshift Events Calendar

Supporting Sustainable Travel

Welcome to the UK’s leading sustainable travel organisation.

Modeshift is a membership organisation. Our mission is to share best practice in sustainable travel delivery.

Modeshift aims to secure increased levels of safe, active and sustainable travel in business, education and community settings. We do this by representing our members needs and supporting sustainable travel practitioners through a range of new and existing services.

Modeshift works with its members and partners in striving towards a world in which communities are free to make healthy and sustainable travel choices where active travel is seen as the norm