Running for My Life: One Lost Boy's Journey from the Killing Fields of Sudan to the Olympic Games

Lopez lomong , mark tabb.

240 pages, Hardcover

First published July 1, 2012

About the author

Lopez Lomong

Ratings & reviews.

What do you think? Rate this book Write a Review

Friends & Following

Community reviews.

Join the discussion

Can't find what you're looking for.

A long walk home | the story of a 'lost boy'

Text Widget

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- Manage subscriptions

To print the story please do so via the link in the story toolbar.

Lost Boys of Sudan and their Journey

I chose this topic because I had read a book about them, and I was extremely interested. I had wondered how they had escaped, and what they were escaping in the first place. After researching them, I wanted to know what journey they took and how they survived a seemingly impossible migration. Their story is amazing, and I am hoping that you think so too! This is why I am interested in this topic.

On which journey did the Lost Boys embark and how did they survive?

Many lost boys later on went to college and got good jobs.

Overview of The Lost Boys

The Lost Boys were boys who were caught during a civil war in Sudan. Southern Sudan was rebelling, and the Sudanese government was attacking villages in the South. Most of the women, parents, and girls were killed while their villages were being burnt, but the boys between ages 4 and 15, who were out taking care of cattle and whatnot, had ran away into bushes and hid. About 20000 boys in Southern Sudan were forced to flee in 1987. They walked over 1000 miles, half of them dying, before they reached Ethiopia. They died from wild animals, disease, hunger, thirst, or even exhaustion. However, only 4 years had passed until a civil war in Ethiopia had started, and forced the Lost Boys to flee for their lives once again. In 1991, the boys traveled south to Kenya, in Kakuma Refugee Camp. Later, the United Nations Refugee Agency helped move 2000 people from Kenya to the U.S.A. Most of them were adults, so instead of being placed in foster care like they usually would be, they were placed in apartment complexes with many of them living in the same room. To get good jobs to keep them going, they had to finish college. To finish college, they had to finish high school. To finish high school, they must start high school. So they did all this, and many of them actually lead good lives. Unfortunately, after hearing about a peace treaty signed in Sudan in 2005, many of them traveled back to their homeland to see their families again; but when they arrived, Sudan had split into South Sudan, where another war started in Juba in 2013, where they had to flee again.

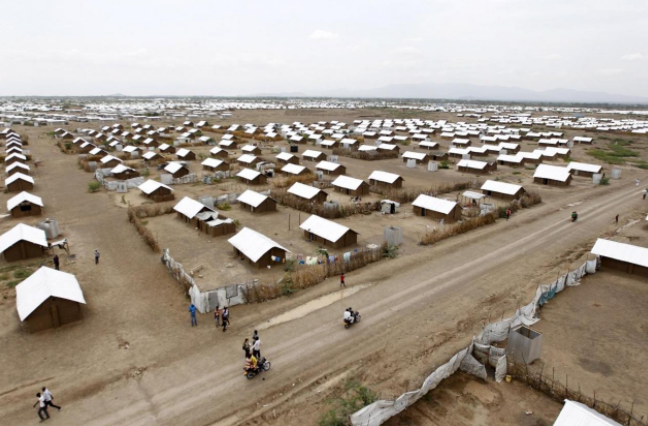

This is an image of Kakuma Refugee Camp, in Kenya. Many Lost Boys went there on their journey to safety.

The Journey they took

Most Lost Boys embarked on a treacherous journey across Sudan to Ethiopia, then to Kenya, less than half of them surviving. Many were eaten by wild animals, died from sickness, were killed by exhaustion, thirst, hunger, or heat, or were simply incapable of completing the journey. In Ethiopia, many had believed that they were finally at safety, but eventually a war broke out there and military soldiers shot them as they tried to cross the river to get away. The soldiers did not want any more immigrants to take care of, so they tried to shoot them to make the rest go away. However, as many were crossing the river, the crocodiles were attracted and many died either from gunshots or crocs. Those who did survive continued on a journey of hundreds of miles to Kenya, where they finally reached safety there.

Did you know?

The name "Lost Boys" actually came from Peter Pan's friends in the movie.

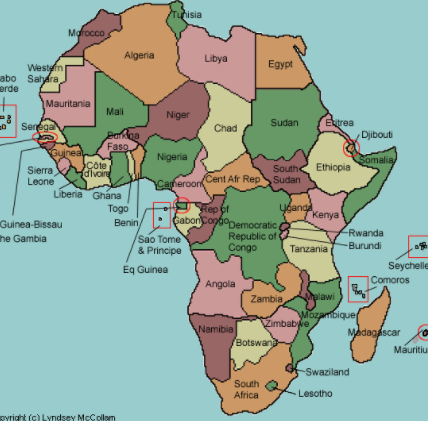

What countries and in which order did the Lost Boys pass through?

- Sudan, Ethiopia, Djiboudi

- Sudan, Kenya, Somalia

- Ethiopia, Sudan, Kenya

- Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya

- Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya

- Kenya, Somalia, Djiboudi

- Kenya, Eritrea, Sudan

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lost Boys of the Sudan , www.lostboyschicago.com/LostBoys.htm.

The Lost Boys of the Sudan , www.unicef.org/sowc96/closboys.htm.

“The Lost Boys of Sudan.” International Rescue Committee (IRC) , 3 Oct. 2014, www.rescue.org/article/lost-boys-sudan.

Mikva, Keren. “10 Things You Didn't Know About The Lost Boys Of Sudan.” AFKInsider , AFKInsider, 8 Apr. 2014, afkinsider.com/50117/10-things-didnt-know-lost-boys-sudan/2/.

The Lost Boys.gif by lamnater1225 from Wikia

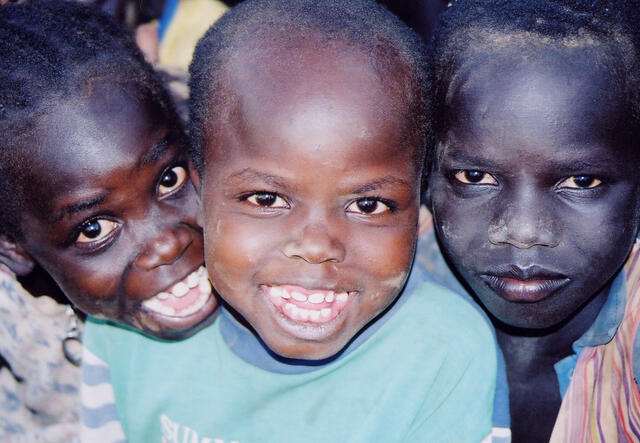

Young Refugees in Kakuma camp by Deborah DeWinter from rescue.org, IRC

Africa by and from lizardpoint.com

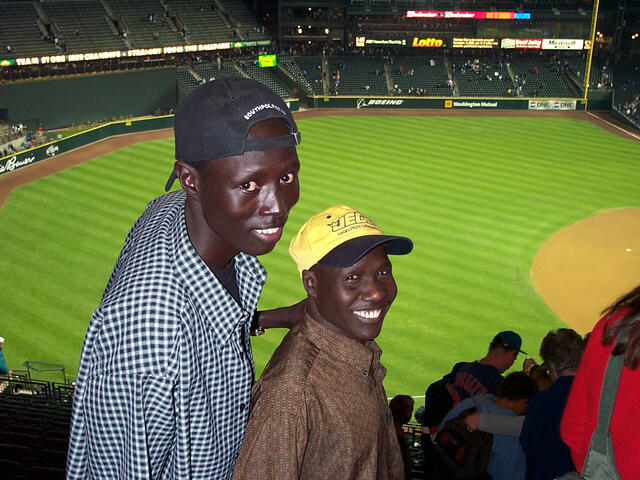

"Many of the Lost Boys went on to earn college degrees and become U.S. citizens." by and from rescue.org, IRC

Aerial View of Kakuma by Thomas Mukoya from Reuters.com

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

'Lost Boys' of Sudan Tell Their Story

Thousands of children were orphaned and displaced by the Sudanese civil war in the 1980s. Many children survived a gruesome 1,000-mile walk to get to the closest refugee camp. John Majok, one of the children from that journey, talks about survival and the power of love.

CHERYL CORLEY, host:

From time to time, we like to tell you about the movers and shakers who don't always make it to the front page. And today, we are joined by John Majok, a man whose story is both heartbreaking and inspirational. Majok is one of the Lost Boys of Sudan, the young boys who walk thousands of miles, fighting starvation and wild animals as they fled the violence of their country during civil war.

Majok sought refuge in Kenya, ultimately moving to Tucson, Arizona. And he's been in the United States for six years. He recently returned to the Kenyan camp that was his home. And he joins us today in the studio.

John, thanks for coming in.

Mr. JOHN MAJOK (Lost Boys of Sudan): Thank you very much for having me.

CORLEY: Well, you were only - were you 6 or 7 years old when the war erupted and your story began?

Mr. MAJOK: I was about seven.

CORLEY: You were seven. Tell us a little bit about that, what you remember from that time.

Mr. MAJOK: Well, I remember how I walked a thousand miles with other children of my age to unknown destination. Of course, we were chased by the then enemy who was fighting against Sudanese. And so, we just walked, went into hiding place, (unintelligible), and then we walk that distance to a (unintelligible). So I remember how I was so adjusted walking day and night nonstop, because the journey was so long, and we spent some day maybe taking rest, then we would have perished like others who did not make it because they were thirst on the way, hunger, wild animals, and so we were just walking day and night until we reached, where we eventually arrived, which was Ethiopia in 1987.

CORLEY: So Ethiopia, first?

Mr. MAJOK: Ethiopia first.

CORLEY: Mm-hmm. How many members of your family survived? I understand there are still some…

Mr. MAJOK: Yeah, my mother and my sister, they are the only surviving members. And I was having a huge family of 11 members, where I had eight siblings.

CORLEY: You actually went back to the Kakuma refugee camp in northwest Kenya. Tell us about that trip, and who did you see there?

Mr. MAJOK: It was a joyous moment for me to reunite with my family after six years of separation. And also, the highlight of my visit was that I got married to my beautiful wife whom I promised - we made our promises before I came here that this was going to be our plan, and we kept our promises.

CORLEY: When did you make that promise?

Mr. MAJOK: In 2001, when I left the refugee camp. She was still young, but I trusted her that she would keep my promise and trusted me that I will keep her promise, too. So that was the highlight of my journey. Eighty days in Kenya with a joyous family reunion, and also bringing in a new family member.

CORLEY: Well, congratulations.

Mr. MAJOK: Thank you.

CORLEY: So tell me a little bit about this, though. You were here in the United States. Your fiancee, who you had promised that you were going to marry, was still in the refugee camp?

Mr. MAJOK: Yes.

CORLEY: And so how did you date?

Mr. MAJOK: Well, it's sort of funny, because we had been dating each other over the phone.

CORLEY: Over the telephone. Okay.

Mr. MAJOK: The telephone. It's a long-distant telephone. I buy cards and talk to her, and she talk to me. So we're going out over the phone rather than just physically dating each other. But again, the words were very effective on each of us, and eventually they materialized into a reunion. So here we are.

CORLEY: Here you are. She is here as well? Or…

Mr. MAJOK: Not at all. That was the heartbreaking part of…

CORLEY: Yes.

Mr. MAJOK: …you know, getting married, then I - all of a sudden I had to leave, and so I am now separated again. I hope we eventually will unite again.

CORLEY: Because you have to go through the whole visa process.

Mr. MAJOK: Exactly. And that's my priority - my first priority now just to make sure I go through all those immigration procedures, which take a while.

CORLEY: Well, we are talking to John Majok, who recently returned to Kenya and the refugee camp that housed him after fleeing his war-torn home in Sudan. As he just mentioned, he got married while he was there and saw his mother and his sister - a joyous occasion as he say.

Let's talk a little bit about what's been happening since you came to the United States six years ago. You did make it, but was it difficult to make friends, or how was that for you?

Mr. MAJOK: When we came as political refugee when we're - when I resettled here, we were put in group of two or three or four or five people - Sudanese who know each other in the same apartment. And then eventually, each one of us start finding job and so you find yourself working, you know, totally different environment. But, you know, we are willing to learn and just be able to put yourself in the society you can just learn.

And so - but when I was in the college years, this was just difficult to go around with - especially the young people around here. I mean, everyone has a friend or a boyfriend or a girlfriend, whatever. But in terms of making friend, generally, the society has been, I would say, on my side, has been receptive and very hospitable - especially in Tucson, Arizona, where I settled.

CORLEY: Well, were you - as you mentioned, you first were in Tucson, Arizona, went to school there in college and persuaded a degree in the school of public administration and policy at the University of Arizona. Tell me why you chose public administration.

Mr. MAJOK: I - specifically, just to familiarize myself with this society a little bit, and you can find more of that in public administration. But the number one is that I have the skills and saw the value that I see I can apply in that field. But for me its a prerequisite of going to law school, which would be my long-term goal.

CORLEY: You want to be a lawyer?

Mr. MAJOK: That's it.

(Soundbite of laughter)

CORLEY: Okay. You're only 26 years old now.

Mr. MAJOK: Yes, I am.

CORLEY: And you've been through so much. What do you think kept you strong?

Mr. MAJOK: Number one, my faith in God. I have never lost hope in God that I believe, and I think that what is strengthened me and kept me going. Number two are my values - my family value. Even though I was very young by the time I left, in (unintelligible) a society, you know, a child as soon as she or he learns how to speak, is told the story and the family tradition.

And those values, especially my dad, who inspired me to be determined and goal oriented, I still remember his words. And those words kept me going. So the principle by which I live - determination, devotion, diligence and discipline. And these four Ds, plus my belief in God, telling me achieve what I want to achieve.

CORLEY: John, tell me a little bit about what you're doing now, and what you wish for yourself and hope for your people and hope people will learn from your story.

Mr. MAJOK: What I hope for my people, first, is that the situation that my people are in now has to change. Southern Sudan need stability and development because the civil war, which took 20 years and left two million people dead, has formally ended by the - with a comprehensive peace agreement. So this is a time where people our need, you know, the implementation, that peace, and further is development.

In the other part of the country, they need protection in place like Darfur. Those people need protection. They are being killed. We people who learn from my story is that no humanity should go through such horrible situation I've been in and other Sudanese who have been through the same tragedies.

And so we want to do whatever is necessary to avoid the situation that expelled people from their countries, because to be a refugee is to suffer, but to live in a refugee camp is far more worse, and I've been through those things.

So I want people just to keep themselves from bringing anything that cause harm to any other human being, but then put the principle of life as the number one in everything we do, because what we do affect other people somewhere.

CORLEY: All right. Well, thank you so much for joining us.

Mr. MAJOK: Thank you for having me.

CORLEY: John Majok is one of the thousands of boys who was displaced by the Sudanese civil war. He is now a man who is working with a non-profit who is hoping to rebuild the southern Sudan. And he joined us here in our studio.

Copyright © 2007 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Share this on:

Sudan's 'lost boys' reunited with the past.

- Sudanese "Lost Boys" were relocated around the world during the country's civil war

- The Lost Boys Reunited Project has created a digital archive of some 13,000 refugee records

- Most of the files include a photo - the only childhood picture many of the Lost Boys have

- The project is working on getting the records to Lost Boys in Sudan

(CNN) -- The wall of Ajak Dau Akech's Tempe, Arizona bedroom is decorated with a basketball poster and pictures of his native Sudan.

On a small, cluttered desk, next to his Arizona State University diploma, sits one of his most prized possessions -- a framed document, with a small photo of a young boy in the upper right corner.

It is the only photo 29-year-old Akech has ever seen of himself as a child. "You could see the frightfulness of his eyes; like that kid is not happy. You could see there's no smile," he said looking at the small black and white photo.

Akech is a "Lost Boy" of Sudan, one of the thousands of orphaned and displaced children who fled Sudan's civil war and trekked thousands of kilometers through Ethiopia to find refuge in Kenya, before being resettled around the world.

For the first time, Akech and other Lost Boys have access to never-before-seen documents about their war-torn childhood.

The Lost Boys Reunited Project , based in Phoenix, Arizona, has created a digital archive of some 13,000 refugee records. The documents come from interviews that field workers with Save the Children conducted with the Lost Boys at refugee centers in Ethiopia in the late 1980s.

It has taken years to track down and scan all the papers. But last November, the Lost Boys were finally able to order their personal records from the website.

"When I found out (about) the record, I was kind of nervous and so excited about what I was going to find out," Akech said.

Most of the files include a photo -- the only childhood picture many of the Lost Boys have -- plus notes on their health, family members left behind, travel companions and the names of people who did not survive the journey.

For Akech, it was a lot to take in. "I was surprised about what the writer wrote down about who I was," he said.

"In one of the pages, they wrote down that I was sick, and then I was admitted twice in the hospital. And then one of the guys wrote it down that I was crying, back when they took my picture, which I'm like, 'did I really cry?'" he continued.

As Akech leafs through the pages, he hesitates at the section where he named two of his uncles, who are no longer alive.

"I saw their names in the paper, so I had tears when I saw them," he said. "I don't know where it came from, but it's just because I lost a lot of relatives."

"But I hold on to it," he continued. "And I was just happy that I could see what I wrote in that paper a long time ago."

Word about the records spread fast in Phoenix, where about 600 Lost Boys currently live.

In its first month, the Lost Boys Reunited website, which was launched by the AZ Lost Boys Center , got nearly 4,000 hits from more than 30 countries.

The center is currently working on getting the records to Lost Boys in Sudan who do not have internet access or valid mailing addresses.

Project managers hope the documents will help reunite families and friends, and help others heal from their losses. They are especially eager to reach those who have lost loved ones.

Some Lost Boys have asked to access records for friends who died along the way, explained Ann Wheat, founder of the AZ Lost Boys Center.

"When they make trips back to their villages in Sudan, they'd be able to return those records to parents who lost their children so long ago," she said.

Kuol Awan, the center's executive director, was one of the first to receive his own records last November. Even today, as he looks over them in his office, he said it's still hard for him to read what he calls the "dark parts" of his document.

"I have two people on the top of my list who are not here anymore," said Awan, referring to the page where he listed the members of his family.

"My dad died in '95 in the displaced camp in Sudan, and then my brother got killed in '91, in the war. So that part is not good," he continued.

Awan said he looks back, in order to move forward. For some of the Lost Boys who live in denial, he said, going through the records can be cathartic.

"This document puts the cap on the history of the Lost Boys for me, that I went through what I went through," Awan said.

Now, he has a piece of his past to share with others. "This is the highlight of my document," he said, with a wide grin on his face, pointing to the picture of himself as a child.

"I kind of know a lot about my childhood, but I don't have any picture to kind of tie it into it," he said. "All the time I carry it with me and show it to people."

For the Lost Boys who lost their childhoods to war, the documents will play various roles in healing and reconstructing stories. But for Ajak Akech, the records have become an inspiration.

"The thing that made me proud was my education," he said. "In the paper, they wrote I was in first grade. Some people didn't have that."

Akech holds a degree in economics from Arizona State University, and is now looking for a job in his field. He said having the records is important, just to be able to compare the child in the photo with the man he is today.

"I would not say I'm so successful, but I am," he said, staring at the picture from his childhood.

"It was just a dead, dead body out there. So ... one time, I wake up, and I'm like, how could this happen to this child at this age, leaving (his) parents? And look at it, see the eyes of that person," said Akech. "You could see the difference of the person of today."

Most Popular

Fine art from an iphone the best instagram photos from 2014, after ivf shock, mom gives birth to two sets of identical twins, inside north korea: water park, sacred birth site and some minders, 10 top destinations to visit in 2015, what really scares terrorists.

The Lost Boys of Sudan

Over 30 years ago, Sudan’s civil war uprooted 20,000 Sudanese children. They were known as the Lost Boys.

In 1987, civil war drove an estimated 20,000 young boys from their families and villages in southern Sudan. Most just six or seven years old, they fled to Ethiopia to escape death or induction into the northern army. They walked more than a thousand miles, half of them dying before reaching Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya. The survivors of this tragic exodus became known as the Lost Boys of Sudan.

In 2001, close to four thousand Lost Boys came to the United States seeking peace, freedom and education. The International Rescue Committee helped hundreds of them to start new lives in cities across the country.

War and flight

The outbreak of civil war in Sudan in 1983 brought with it circumstances that would permanently alter the lives of thousands of Sudanese boys and young men. As forces of the government of northern Sudan resumed its campaign against the Sudanese People's Liberation Army (SPLA), the southern-based rebel group began inducting boys into the movement.

In the next few years, an estimated 20,000 Sudanese children fled their homeland in search of safety in what turned out to be a treacherous 1,000-mile journey to Ethiopia .

Wandering in and out of war zones, these "Lost Boys" spent the next four years in dire conditions. Thousands of boys lost their lives to hunger, dehydration, and exhaustion. Some were attacked and killed by wild animals; others drowned crossing rivers and many were caught in the crossfire of fighting forces.

Kakuma refugee camp

In 1991, war in Ethiopia sent the young refugees fleeing again and approximately a year later they began trickling into northern Kenya . Some 10,000 boys, between the ages of eight and 18, eventually made it to the Kakuma refugee camp—a sprawling, parched settlement of mud huts where they would live for the next eight years under the care of refugee relief organizations like the IRC.

The IRC began working in Kakuma in 1992 to assist the Lost Boys and other refugees fleeing the fighting in Sudan. Its programs expanded over time to include all of the camp’s health services: treating refugees who arrived malnourished or sick, offering rehabilitation programs for those who were disabled, and working to prevent outbreaks of disease.

Older boys took part in IRC education programs, and received support to learn trades and start small businesses to earn money to supplement relief rations. The IRC also helped these young entrepreneurs start savings accounts and access small loans to invest in their futures .

“The IRC’s health, sanitation, community services and education programs touched, in one way or another, the lives of all the Lost Boys who were in Kakuma and who were eventually resettled in the U.S.A.,” recalled Jason Phillips, who managed IRC programs in the camp from 2000 to 2001. “We accompanied and supported them throughout a large part of their journey.”

A refuge in the United States

As the war in Sudan continued to rage, the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) determined that repatriation and family reunification was no longer an option for the Lost Boys. UNHCR recommended approximately 3,600 of them for resettlement in the United States and the U.S. State Department concurred.

The Kakuma youth began arriving in the U.S. in small groups in the fall of 2000. Over the next year the IRC helped hundreds resettle in and around Atlanta , Boston, Dallas , Phoenix , Salt Lake City , San Diego , Seattle and Tucson .

They have been like family to each other for so long now, so it's best for them to continue to live as a family unit here.

Because many of the newly arrived Lost Boys were over 18 and considered adults, they were not placed into foster care. "We place the older boys together in apartments to try to maintain the kind of support network that they developed throughout their difficult journey and while living in the Kakuma camp," said Jon Merrill, who was then director of the IRC's resettlement program in Tucson. "They have been like family to each other for so long now, so it's best for them to continue to live as a family unit here."

Quest for education

Most of the older boys who came to the United States were eager to capitalize on opportunities for higher education, but found that their idea of becoming full time students was not a realistic goal. Since most were over 18 and living on their own they needed to support themselves. And even though the majority attended school within Kakuma camp and had completed or were well on their way to completing high school, they did not necessarily qualify for entry into U.S. colleges. For these young men, IRC staff members stressed the importance of finding a job soon after arrival, and continuing their educational pursuits part-time.

The IRC helped the Lost Boys find jobs with local employers and connected them with volunteer mentors for help studying for exams to enable them to receive a General Equivalency Diploma (GED), and in turn, apply for college.

Adjusting to life in America

The Lost Boys faced enormous challenges in adjusting to American culture and modern society. IRC case workers worked closely with the boys in orienting them to their new communities, making sure that they were as comfortable as possible, and offering guidance on such issues as personal safety, social customs, public transportation, shopping, cooking, nutrition and hygiene.

Volunteers , many of whom became aware of the immense needs of this group through media coverage, also played a significant role in this area. They served as an essential link to the greater community, helping to generate additional employment opportunities, as well as increase donations and awareness.

Volunteers at the IRC's Boston office (now closed) took part in a mentoring program for newly arrived Kakuma youth, providing support and guidance, and organizing recreational activities to bring the young men together.

Many of the Lost Boys resettled by the IRC also took part in IRC programs aimed at helping them cope with their traumatic past and easing their transition into such a different culture. The IRC's Phoenix resettlement office, for example, worked with clinical psychologists to provide specialized counseling services.

What happened to the Lost Boys of Sudan?

Over the next decade the Lost Boys built new lives for themselves in their adopted country. Many of them went on to earn college degrees and attain U.S. citizenship , while wondering whether they would someday have the opportunity to return to their homeland and reunite with the families they left behind.

Then, in 2005, news came that gave them hope: A peace agreement had been signed between North and South. The civil war, which had claimed more than two million lives, was over.

The tenuous peace held, and in 2011 southern Sudan held a referendum in which its people almost unanimously decided to secede from Sudan and form a new nation.

I don’t want to see another generation of children go through what I’ve gone through and what other children of my generation went through.

Some of the Lost Boys were among the many thousands of South Sudanese refugees who streamed home during these optimistic years. They were eager to use their education to help build the world’s newest independent country. One of them, Abraham Awolich, told The New York Times: “I don’t want to see another generation of children go through what I’ve gone through and what other children of my generation went through.”

Returning home to violence

In December 2013, political tensions between factions loyal to President Salva Kiir and opposition leader Riek Machar erupted into fighting in South Sudan's capital, Juba. Since then thousands of people have been killed and more than a million forced to flee their homes.

The fighting put an end to three years of peace and a shaky stability following South Sudan’s declaration of independence from Sudan. Now South Sudan is facing a humanitarian catastrophe and an upsurge of violence between ethnic groups. Many of the Lost Boys who fled civil war three decades ago have returned home only to find a new war.

Explore related topics:

- IRC History

Related news & features

- Where We Work

- How To Help

- Code of Conduct

- Ethics Hotline

- 87% Program services

- 8% Management and general

- 5% Fundraising

Get the latest news about the IRC's innovative programs, compelling stories about our clients and how you can make a difference. Subscribe

- U.S./Global

- Phone Opt Out

- Respecting Your Privacy

- Terms and Conditions

- Fraud Prevention

Watch CBS News

The Lost Boys of Sudan: 12 years later

April 2, 2013 / 5:53 PM EDT / CBS News

The following script is from "The Lost Boys" which aired on March 31, 2013. Bob Simon is the correspondent. Draggan Mihailovich, producer.

Twelve years ago, 60 Minutes aired a story about Lost Boys from Sudan who fought off unspeakable dangers and then flew off to the United States. It all began in the 1980s, during Sudan's civil war in which more than two million people died. The boys' parents were killed; their sisters often sold into slavery. Many of the boys died too. But the survivors, thousands of them, started walking across East Africa. Alone.

How to help the Lost Boys of the Sudan

Five years later they walked into a refugee camp in Kenya. That's where we first met them, when many were hoping to go to the United States. Well 3,000 did, as part of the largest resettlement of its kind in American history. We followed the boys for more than a decade and couldn't resist revisiting them, to see how they're doing. But first, we'll take you back to northern Kenya, to the Kakuma Refugee Camp. Springtime 2001.

Nothing drew a crowd like the list. Once a week, the Lost Boys saw their destiny on a bulletin board. The staples of life. On this day, 90 learned they'd be going to America. .

[Voices: Boston. I'm going to Flororida...Flororida]

Every Sunday, a plane arrived at the camp to take the boys from nowhere to somewhere, from Kakuma to JFK and beyond. Not all of the Lost Boys got to go. Joseph Taban Rufino had walked to the board so many times, he tried not to get excited.

Bob Simon: What's new?

Joseph Taban Rufino: Something new. I've seen my name on the board.

Bob Simon: Your name is on the board. Where are you going?

Joseph Taban Rufino: That's Kansas City.

Bob Simon: Do you know where it is?

Joseph Taban Rufino: I don't know...

Abraham Yel Nhial was taking this walk for the 25th time. He was an ordained minister of Sudan's Episcopal Church at Kakuma. He looked at the board as if it were a holy scroll.

Abraham Yel Nhial: I'm going to Chicago...Is it interesting?

Bob Simon: Oh, it's very interesting.

Abraham Yel Nhial: Thank you for that.

They were known as the Lost Boys because they were between five and 11 when their Christian villages in southern Sudan were attacked by Islamist forces from the north. When they saw their villages burning, they started running. Streams of boys became rivers. Hundreds became thousands until an exodus of biblical proportions was underway. They walked for three months across Sudan, barefoot. Twelve thousand found refuge in Ethiopia. But after four years, they were chased out at gunpoint, chased to the Gilo River where the waters did not part. For Joseph Taban, that day will never go away.

Joseph Taban Rufino: We saw so many people who were just floating on the river.

Bob Simon: Dead bodies.

Joseph Taban Rufino: Dead bodies, yeah, who are floating on the river...

Many were shot. Many drowned. Many were eaten by crocodiles. Zachariah Magok was there.

Zachariah Magok: One thousand to 2,000 who died in that river.

Bob Simon: One or 2,000 died in that river?

Zachariah Magok: Yes.

It wasn't much better on the other side. They walked across deserts, over mountains. They had no food or water. Paul Deng was seven when he started the walk.

Paul Deng: You have to urinate so that you drink your own urine.

Bob Simon: Did you ever do it yourself?

Paul Deng: Yeah. I didn't want to die. Other people didn't want to die.

In the spring of 1992, after walking more than a thousand miles, the boys made it over the border into Kenya, to a desolate place called Kakuma. For the UN, it was an emergency of vast proportions, these emaciated children. For the boys, it was the safest they'd been in five years.

Joseph became a medical assistant at the camp clinic.

Abraham found a job, preaching the gospel in a church built of mud. The Lost Boys couldn't go home to Sudan and Kenya didn't want them. Then, in the year 2000, the State Department decided they deserved a break and invited them to come live in the United States.

Sasha Chanoff: What we want to do is give you a correct understanding of what life will be like in America.

Before they took off for their new lives in the new world, Sasha Chanoff, a teacher from Boston, gave them a crash course: America 101.

To learn about what Sasha Chanoff is doing now to help refugees in Africa, click here

[Sasha Chanoff: Does anybody know who the president in the U.S. is now?

Voice: George Bush W...]

Things they could not imagine, like winter.

[Sasha Chanoff: This is a little what winter in America feels like (begins ice demonstration).

Voice: It's very cold!

Voice: Will you die because of that coolness?

Sasha Chanoff: No, you will not die because of the coolness.]

He had three days to prepare them for a leap of a thousand years.

Sasha Chanoff: Many of them have never been exposed to lights or to a fork and a knife. Or seeing a TV. It's a group that's lost in time.

They had four days to pack their luggage. They took little, left less behind.

Abraham was taking a book he'd been carrying for 10 years.

Bob Simon: You still have the bible that you carried from Ethiopia here?

Abraham Yel Nhial: Yes. It's my life. I have been called a lost boy. But I'm not lost from God. I'm lost from my parents.

As in any farewell, the lost boys were saying, "See you soon," but they knew better. Kakuma was losing its doctor and its priest.

The boys had never been on a plane before. They'd never even been on a bus.

Five planes in two days. First initiation rite: airplane food. And then changing planes in Brussels -- getting their feet on the ground in the Western world.

Next stop for Joseph Taban and his brothers: Kansas City.

Abraham the preacher man was supposed to go to Chicago but at the last minute that was changed to Atlanta. Volunteers introduced them to their new apartments, to American mysteries like a sink or a stove...

[Volunteer: Don't touch because it burns. It's hot] .

...a vacuum cleaner or a can, let alone a can opener.

[Voice: Wonderful machine.]

Within a few weeks, Joseph had his first job in a sweltering fabric factory when he got home from work at 11 at night, he stayed up studying for that medical career he'd always dreamed of.

You won't be surprised to learn that Abraham found his salvation in church. All Saints, one of the largest Episcopal churches in Atlanta. A month after his arrival, he was invited to be a guest deacon.

[Abraham Yel Nhial: Hallelujah, Hallelujah...]

[Parishioner: You were terrific Abraham, you were so good.]

A big problem was the sheer size of America and everything in it. Home Depot was a long way from home.

[Abraham Yel Nhial: This store is too big.

Clerk: Oh, I know it is.

Abraham Yel Nhial: This is confusing. ]

Confusing? Try to imagine what a fountain looks like to a man who walked a thousand miles through a desert. Sasha Chanoff, who taught the boys back in Kenya, said it was not easy for them to distinguish between what was real and what was pure fantasy in America.

Sasha Chanoff: They're hearing that people have gone to the moon. If you're telling me people have gone to the moon, then they're seeing on TV that a horse can talk. Why is a horse talking so different from someone going to the moon? It's hard for people to distinguish what is reality and what is not. Some boy saw a street sign that said, "Dead end." And they thought, well, if I go down there, am I going to die?

Then came 9/11, just a few months after the boys got here. They thought they had left that kind of thing far behind, forever.

Abraham Yel Nhial: And it seem that war is following us. Wherever we go, war came after us.

[Joseph Taban Rufino:: Let's pray.]

As it did once again. The boys weren't surprised by it, not the way Americans were. For them, Islam and terrorism went together. Always had. Their reaction was immediate. Help the victims. In Atlanta, they offered to donate blood for the survivors in New York. But they were turned away.

Abraham Yel Nhial: So, what we did, we did collect some money, two dollars, five dollars. Because we have nothing. And we give about four hundred...

Bob Simon: Four hundred dollars?

Abraham Yel Nhial: Yes. And that's amazing.

Bob Simon: It really is.

Abraham Yel Nhial: Yes. A community with nothing. People just come from Africa.

But they weren't coming any more. After 9/11 the flights scheduled to bring over more lost boys were stopped. And the boys already here were having a tough time of it. That dreaded American winter was now upon them. They'd been warned, but it still came as a shock.

[Joseph Taban Rufino: Look, look, look!]

Winter gave them fun times, as well, though -- ice capades.

[Joseph laughing hysterically]

What Americans call a learning experience. And, Christmas, their first.

Bob Simon: In America, we call him Santa Claus.

Dominic Leek: Oh, yeah, I've heard of him.

Bob Simon: He lives in the North Pole and rides reindeer.

Joseph Taban Rufino: You mean he lives in the North Pole? Is he from--how do I call these people?

Bob Simon: Eskimos.

Joseph Taban Rufino: Eskimos, yeah.

Bob Simon: Well, he's the guy who brings presents to all the children on Christmas.

Joseph Taban Rufino: OK, OK.

Bob Simon: He makes kids happy, that's the important thing.

Joseph Taban Rufino: Oh that's good.

Within a year, a Kansas City investment banker, Joey McLiney, took Joseph under his wing and put him in the saddle. McLiney offered up his brand new car for Joseph's first driving lesson.

[Joey McLiney: Here we go. Stop Joseph, stop. Brake, brake, brake. Brake! OK don't...Lamp post! Hit the brake, that's the brake, the big one.

Joseph Taban Rufino: Oh boy. I'm so sorry, what a mess.]

That was nearly 12 years ago.

In a moment, we'll give you a picture of the road the Lost Boys have been taking in America.

Before their arrival in America in 2001, the Lost Boys of Sudan knew very little about what would be a totally new world for them. For the U.S. government, it was quite a social experiment. America may be a country of immigrants, but it's not often that the State Department organizes an airlift of people who know virtually nothing about the modern world.

The Lost Boys were sent all over the place from Fargo, N.D., to Phoenix, Ariz. Joseph Taban Rufino landed in Kansas City. Abraham Yel Nhial was sent to Atlanta. We never forgot about them and their fellow Lost Boys and we felt good when it appeared they hadn't forgotten about us.

[Abraham Yel Nhial: Hey, Bob Simon! How're you doing? Long time no see.

Joseph Taban Rufino: How you doing buddy?]

We visited the Lost Boys from time to time over the last 12 years -- wanted to be there for the moments they never could have imagined.

On this day, Abraham was one of 92 people from 37 countries to get a new piece of paper.

[Woman: Congratulations, you are now a United States citizen.]

A Lost Boy who now belongs somewhere.

Bob Simon: Do you think of yourself as an American?

Abraham Yel Nhial: Yes. This, this home for me.

Abraham is so proud of his American passport he carries it with him wherever he goes.

Abraham Yel Nhial: The only papers we have are from America.

Bob Simon: Are you telling me that passport in that jacket pocket of yours is the first identity paper you've ever had?

Abraham Yel Nhial: This it.

Bob Simon: Before that you had no document at all?

Abraham Yel Nhial: No.

Joseph still hasn't gotten a passport. His driver's license was stolen from him in Kansas City. And that was just the beginning.

Bob Simon: You've had your car flooded.

Joseph Taban Rufino: Right.

Bob Simon: You've been stabbed.

Joseph Taban Rufino: Exactly.

Bob Simon: You've been hit by a car.

Joseph Taban Rufino: That's right.

Bob Simon: Your kitchen was set on fire.

Joseph Taban Rufino: Indeed.

Bob Simon: And you like it here.

Joseph Taban Rufino: You know, things, things happen.

There was more bad news at work. Joseph was laid off a few times from his job at a grain company, a victim of the tough economy. He's back at work now, and in his small, dimly lit apartment still studies medical books, even while his dream of going to med school is slipping away.

Bob Simon: Do you feel like you've been successful in America?

Joseph Taban Rufino: Not at all. My main aim was to go to the school in order to be what I've said, to be a doctor. But things fall apart.

Bob Simon: So unless you're a doctor, you will not feel that you are successful?

Joseph Taban Rufino: That's true.

Abraham did graduate from college.

Abraham Yel Nhial: It's been a long journey but God blessed me.

After many 4 a.m. bus rides to school, he got a degree in biblical studies from Atlanta Christian College.

Sasha Chanoff, who led those orientation classes back at Kakuma, now runs an organization called RefugePoint which champions refugees in Africa. He still stays in touch with the Lost Boys.

Sasha Chanoff: I would say this is one of the most successful resettlements in U.S. history.

Bob Simon: Wow.

Sasha Chanoff: Some of them are in law school. Some are in medical school. But of course when you have 4,000 guys or so who arrive, some don't do as well. Some struggle.

Some have had problems with drugs and alcohol. A few are in jail. But some Lost Boys who were orphaned by war, have been wounded fighting for the U.S. military in Iraq and Afghanistan. Daw Dekon made it out unscathed.

Bob Simon: So you were in Iraq?

Daw Dekon: Three times.

Bob Simon: Three times?

Daw Dekon: Yes.

He joined the Army after 9/11.

Daw Dekon: I'm a young man able to hold a gun or to go with other young men in this country who were born here, why not? That's my duty.

Bob Simon: So you joined the Army because you wanted to give something back to America?

Dominic Leek: (singing) Thank you America, I want to let the whole world know...

Dominic Leek, a friend of Joseph's in Kansas City, wrote a song he says represents the feelings of many Lost Boys.

Dominic Leek: When I came to this country, I was helped by the government of this country and the people of America. So, what I did was, I thank them for the opportunity they gave to me and my fellow lost boy.

[Abraham Yel Nhial: And we were forced into the river.]

Abraham feels he has a mission - to make sure people will not forget. He speaks at universities across the country. Here he was at Yale, explaining to students why he believes God kept the boys alive.

Abraham Yel Nhial: God kept us alive to be witness of what took place in

Sudan. That the only thing. It's not because we were more important than the others, than our mothers, our fathers and brothers who have dies (sic). But simple is so that we will be witness.

It happened a long time ago, so the Lost Boys don't have too much trouble talking about it, but at night time...

Bob Simon: Do you have a lot of nightmares?

Joseph Taban Rufino: Oh, indeed, a lot. During the young age where we were when I was there, we're not supposed to see the dead body, or bury the dead body. And we did that. And that's all come, like sometimes in form of dream.

For the Lost Boys, the most momentous news came in July of 2011. Their long-suffering homeland, South Sudan, was declared the world's newest nation.

Bob Simon: You saw the independent celebrations on your cell phone. How did it make you feel?

Joseph Taban Rufino: Oh, I was overwhelmed, going into tears.

Sasha Chanoff: They were an important factor that led to that independence.

Bob Simon: Hang on. They were an important factor that led to independence?

Sasha Chanoff:: I think so. They created a political environment in the U.S. where people were finally realizing what was happening in this remote genocide in Sudan that nobody had really heard of on a large scale before.

Not long ago, Sudanese flocked by the hundreds to a town called Aweil for a celebration. It wasn't Independence Day or anything like that. They came to a newly built brick cathedral to witness the installation of that preacher named Abraham as the first Episcopal bishop of his region in South Sudan.

A lost boy no more. It's Bishop Abraham now and who knows what's coming next.

Bob Simon: Maybe your next name will be Archbishop?

Abraham Yel Nhial: I don't know about that.

Abraham divides his time now between Africa and America. Not only is he an Anglican bishop, but a husband and a father.

Bob Simon: Oh, my heavens. This is your family?

Abraham Yel Nhial: Yes.

He goes back to Africa whenever he can to visit his new family. He got married in Kenya, has four kids, He wants them to join him in Atlanta but red tape keeps getting in the way.

Abraham Yel Nhial: Well, I would love that to happen, Bob. I've been trying for them to come but they not came. Maybe one day somebody will, will surprise me, that you and your kids come to America.

Joseph hasn't gone back to Africa, has had no reason to. His whole family was dead, as far as he knew. Then, incredible news: his mother Perina was alive, had survived the war, had made it to a refugee camp in Uganda.

And there was another miracle: Skype. So, a few months ago, Joseph ironed his best suit and went over to his mentor's house. His mother had been driven three hours to the offices of IOM, the international resettlement agency in South Sudan. It was the first time mother and son were going to see each other since they were separated by war 25 years ago.

His mother had thought Joseph was dead, had held a funeral service for him. Even now, she had no idea what he'd been through. When Joseph tried to tell her, he just couldn't do it.

But there were light moments too, shared memories of Joseph's happy childhood in a country village before the war ended childhood and everything else. And, of course, his mother wanted to know why, after all these years, Joseph had not married a nice American girl. After almost an hour, their time was almost up. His mother asked Joseph what all mothers ask their sons: When will come see me? And Joseph answered the only possible answer: As soon as I can mom, as soon as I can.

More from CBS News

- Mision & Vision

- Board of Directors

- The World Today

- Groundbreaking New Surrogacy Research

- Comprehensive Report on the Risks of Assisted Reproductive Technology

- Egg “Donation”

- Sperm Donation

- Stem Cell Research

- Fetal Genetic Testing

- Human Cloning

- Therapy vs. Enhancement

- CRISPR Technology

- Transhumanism

- Stop Surrogacy Now

- About the Institute

- Meet Paul Ramsey

- Become a Fellow

- How to Apply

- Institute Alumni

- 2024 Ramsey Award Winner

- Ramsey Award Recipients

- Ramsey Award Dinner

- Award Committee

- Lost Boys: Searching for Manhood

- The Detransition Diaries

- Trans Mission

- #BigFertility

- Anonymous Father’s Day

- Eggsploitation

- Maggie’s Story

- Compassion & Choice DENIED

- Lines That Divide

- Venus Rising Podcast

Select Page

The Lost Boys: Searching for Manhood Is Now Out!

Posted by CBC-Network | Jan 16, 2024 | Detransition , Documentary , Film , Front Page , Transgenderism

Lost Boys: Searching for Manhood is live now on YouTube and Rumble . Through the stories of five detransitioned young men, who now accept their natural bodies, The Lost Boys explores themes that caused them to experience gender dysphoria, their feelings of inadequacy as men, and the journey that led them to believe they were “born in the wrong body”.

Praise for the new film is already rolling in. On Claire Fox’s shared this warm review from her Substack , “Wow, The Lost Boys is essential viewing and I want everyone to watch it now. It shines a light on why young boys may feel as though they are born in the wrong body – from mental-health issues such as OCD and extreme social anxiety through to the impact of the social fad for problematising masculinity, leading to shame about being male.”

Libby Emmons, writing at The Post Millenial , calls the film, “…a message to those who are pushing these ideas: the doctors, mental health professionals, teachers and activists who claim that taking drugs and undergoing surgeries to fix having been “born in the wrong body” is appropriate and “life saving.”

The mission of the CBCNetwork is always to gather diverse voices and educate the public on these important issues. In Lost Boys , you will hear this message in the voices of men who have experienced first hand every stage from dysphoria, to medical affirmation, to detransition.

Author Profile

Latest entries

Related Posts

This week in bioethics.

September 22, 2017

Top Ten Posts (#7) #TBT

November 13, 2014

The Gobbledygook Gender Word Salad Helps Destroy Young Lives

December 13, 2021

“Souls on Ice” and the Surrogate Women Who Would Be Their Mothers

August 20, 2015

Subscribe for News & Updates

Recent posts.

- The Rise of International Gestational Surrogacy in the U.S.

- Founder Jennifer Lahl’s Speech on Surrogacy to the Casablanca Declaration

- Gloria’s Surrogacy Story: Road to Recovery & Warning to Others

- Lost Boys Screening and Panel Discussion in London, May 29th

- Gloria’s Surrogacy Story: Pregnancy & Birth

- “The Lost Boys: Searching for Manhood” screened in Glasgow at an educational conference opposing indoctrination in schools

- Gloria’s Surrogacy Story: From Contract to Conception

- Thailand’s Colossal Mistake: Returning to Reproductive Tourism

- Gloria’s Surrogacy Story: Matchmaker, Make Me a Match

- The Battle to Keep Commercial Surrogacy Out of Michigan

- Motivational

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $13.95 $13.95 FREE delivery Thursday, May 2 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Buy used: $3.34

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

A Lost Boy: One Man's Journey From Childhood Abuse To Authentic Freedom Paperback – September 4, 2014

Purchase options and add-ons.

- Print length 190 pages

- Language English

- Publication date September 4, 2014

- Dimensions 5.5 x 0.48 x 8.5 inches

- ISBN-10 1490850066

- ISBN-13 978-1490850061

- See all details

Product details

- Publisher : WestBowPress (September 4, 2014)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 190 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1490850066

- ISBN-13 : 978-1490850061

- Item Weight : 8.6 ounces

- Dimensions : 5.5 x 0.48 x 8.5 inches

- #58,442 in Motivational Self-Help (Books)

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Lost Gustav Klimt painting sells for €30m at auction in Vienna

Unfinished Portrait of Fräulein Lieser resurfaced in private collection but questions remain about its journey and its subject

A painting by the Austrian artist Gustav Klimt that was considered lost for 100 years has sold for €30m (£26m) at an auction in Vienna.

Entitled Portrait of Fräulein Lieser, the unfinished picture was painted in the spring of 1917, when Klimt was one of the most celebrated portraitists in Europe , and a year before his death.

Until the Viennese auction house im Kinsky announced at a press conference in January that the portrait had been re-discovered in a private collection, only a black-and-white photograph of the painting was known.

The artwork’s sudden re-emergence, coupled with an intriguing backstory, built up considerable buzz around the painting.

In the run-up to Wednesday afternoon’s sale, about 15,000 visitors had taken the opportunity to see the work displayed at im Kinsky.

The sum the painting fetched was at the bottom of its €30m to €50m valuation, and some way off the £74m that another late-period Klimt portrait, Dame mit Fächer (Lady with a Fan), fetched in London last June – a record for any artwork ever sold at an auction in Europe.

Some key questions about the painting remain unanswered, including the identity of its subject and its provenance during the Nazi era.

A commissioned portrait, it is believed to depict one of the daughters of either Adolf or Justus Lieser, who were brothers from a wealthy family of Jewish industrialists. Some art historians have identified the sitter as Margarethe Constance Lieser, Adolf Lieser’s daughter.

However, im Kinsky has suggested the painting could also depict one of the two daughters of Justus Lieser and his wife, Henriette, a patron of modern art. An AI-based “ageing” of the portrait shows up apparent similarities to Helene Lieser, an economist who died in 1962, the auction house has claimed.

The identity of the sitter is crucial: after Klimt’s death in 1918 the painting ended up with the Lieser family, though which branch of the dynasty could rightfully claim ownership of the picture has been hard to establish. Art historians have struggled to piece together the painting’s journey between 1925 and 1961.

The auction house said the painting’s journey during the Nazi period was “unclear”.

It said: “What is known is that it was acquired by a legal predecessor of the consignor in the 1960s and went to the current owner through three successive inheritances.”

The identity of the last Austrian owners before Wednesday’s sale has not been made public.

- Gustav Klimt

Claudette Johnson’s art for Cotton Capital nominated for Turner prize

‘Not even a pipe dream’: John Akomfrah represents Britain at Venice Biennale

German art museum fires worker for hanging his own painting in gallery

‘Englishness is constantly revised’: Umbro exhibition shows evolution of football shirts

Marlborough Gallery: ‘blue chip’ art institution to close after nearly 80 years

Ron’s Place: Birkenhead flat of outsider art granted Grade II listing

‘Sport is never just sport’: Olympics exhibition in Paris reflects 20th century’s highs and lows

Piero della Francesca’s Augustinian altarpiece reassembled after 450 years

Liverpool museum appeals for information on subject of The Black Boy

Most viewed.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Please join me in my ongoing journey as a lost boy of Sudan. I have included several pages here, History of The Lost Boys and Agencies of Help. ... They have made a huge difference in my own life - and in the lives of my friends and fellow Lost Boys. Recent Posts. News Channel 9 Interview. November 21, 2016 December 22, 2016 by hollerscholar ...

There's an issue and the page could not be loaded. Reload page. 2M Followers, 1,112 Following, 267 Posts - See Instagram photos and videos from Vikas Gupta (@lostboyjourney)

Lopez Lomong chronicles his inspiring ascent from a barefoot lost boy of the Sudanese Civil War to a Nike sponsored athlete on the US Olympic Team. Though most of us fall somewhere between the catastrophic lows and dizzying highs of Lomong's incredible life, every reader will find in his story the human spark to pursue dreams that might seem ...

This is the inspiring story of one of the " Lost Boys" Lopez Lomong from South Sudan, who was abducted by brutal rebel soldiers at age six and miraculously escaped by running 3 days through the desert with the help of older boys to a Kenyan refugee camp. ... One Lost Boy's Journey from the Killing Fields of Sudan to the Olympic Games by Lopez ...

The story of a former Lost Boy of Sudan is really a journey, one that takes Lopez Lomong from his life as a 6-year-old boy in a refugee camp to a whole new world as a teen in the United States. How he gets to America is an amazing story, but even more amazing are the new wonders and possibilities of his new life here.

The true story in their own words of the 14-year journey of three Lost Boys who came to the United States in 2001 before 9/11. 2005: The Lost Boys of Sudan: An American Story of the Refugee Experience, by Mark Bixler, a nonfiction book about "Lost Boys" resettled in the United States. 2005: The Journey of the Lost Boys, by Joan Hecht.

In 1987, 26 thousand young children were forced to flee for their lives during a civil war that had broken out in 1983. I was among their number. Our long walk to the safety of Ethiopia a thousand miles a way took only three weeks but became the journey of a lifetime. This is my story; past, present, and future.

Most Lost Boys embarked on a treacherous journey across Sudan to Ethiopia, then to Kenya, less than half of them surviving. Many were eaten by wild animals, died from sickness, were killed by exhaustion, thirst, hunger, or heat, or were simply incapable of completing the journey. In Ethiopia, many had believed that they were finally at safety ...

Majok is one of the Lost Boys of Sudan, the young boys who walk thousands of miles, fighting starvation and wild animals as they fled the violence of their country during civil war. Majok sought ...

Lost boy journey :). 9,769 likes · 3 talking about this. video create and quotes

The lost boy journey - cinematic Video#lost #trending

Sudanese "Lost Boys" were relocated around the world during the country's civil war. The Lost Boys Reunited Project has created a digital archive of some 13,000 refugee records. Most of the files ...

In the next few years, an estimated 20,000 Sudanese children fled their homeland in search of safety in what turned out to be a treacherous 1,000-mile journey to Ethiopia. Wandering in and out of war zones, these "Lost Boys" spent the next four years in dire conditions. Thousands of boys lost their lives to hunger, dehydration, and exhaustion.

Running for My Life: One Lost Boy's Journey from the Killing Fields of Sudan to the Olympic Games. Paperback - August 2, 2016. Running for My Life is not a story about Africa or track-and-field athletics. It is about outrunning the devil and achieving the impossible; it is about faith, diligence, and the desire to give back.

The Lost Boys Foundation 100 Auburn Avenue Suite 200 Atlanta, GA 30303 Phone: 404-475-6035 Email: btgonline.org. Don Bosco Center The Lost Boys Contact: Meredith Hollingsworth 531 Garfield Kansas ...

How a 60 Minutes team fell for the Lost Boys of Sudan and became part of their new family in America

"The Journey of the Lost Boys is a very moving story. One that every young person should read." -- Bishop Nathaniel Garang South Sudan Diocese of Bor Fascinating! I could not put it down! -- Ray Storms Author and Lost Boy mentor Highly recommended! Joan Hecht was voted "2005 POW Author of the Year" and her book won 1st Place in Education.

Twelve years ago, 60 Minutes aired a story about Lost Boys from Sudan who fought off unspeakable dangers and then flew off to the United States. It all began in the 1980s, during Sudan's civil war ...

Through the stories of five detransitioned young men, who now accept their natural bodies, The Lost Boys explores themes that caused them to experience gender dysphoria, their feelings of inadequacy as men, and the journey that led them to believe they were "born in the wrong body". Praise for the new film is already rolling in. On Claire ...

Lost Boy: The True Story of One Man's Exile from a Polygamist Cult and His Brave Journey to Reclaim His Life [Jeffs, Brent W., Szalavitz, Maia] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. Lost Boy: The True Story of One Man's Exile from a Polygamist Cult and His Brave Journey to Reclaim His Life

The Journey of the Lost Boys (2005) is a non-fiction book by Joan Hecht about The Lost Boys of Sudan. "The Lost Boys" are a group of young children who became separated from their parents due to civil war in their homeland. With little food and water and no protection from wild animals and enemy soldiers that stalked them night and day, these ...

A Lost Boy chronicles Mike's relentless search and misguided pursuit of a false and elusive freedom, only to receive what he desperately longed for through the one true Savior he intentionally avoided. If you have experienced trauma, feelings of worthlessness, divorce, failure as a parent, addiction, or financial loss, this book will provide an ...

A painting by the Austrian artist Gustav Klimt that was considered lost for 100 years ... together the painting's journey between 1925 and 1961. ... on subject of The Black Boy. 21 Mar 2024 ...