The Mayflower Voyage

It is hard for us in this present age to imagine what it would be like not to know certain things – not know how wide the oceans were; – not to know how far Virginia was from Plymouth, England; – or from Plymouth, Massachusetts, for that matter; not to know, even, how far a ship would sail in a day or a week, and not to have any maps or charts of a good degree of accuracy for any country or any ocean on earth. All of this lack of knowledge was the situation 1620.

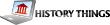

Now, of course, there was much sea-faring in 1620. Ships plied the English Channel, sailed up and down the coast of France and Spain and swarmed all over the Mediterranean. But this was mainly coastal, short voyage work. In any trip the length of time out sight of land was minimal. This is not to say that there were not trans-ocean voyages in the period. The gold trade between Spain and Mexico had flourished for years. The cost in lives and ships and cargo had been and continued to be terrific. The many recent treasure finds from sunken Spanish galleons in waters near Florida bear vivid witness to the awful costs of these many passages. These costs in men, ships and cargo were due in great degree to the ignorance of the crews and skippers and navigators. In those days the practitioners of the sea-faring art had no ability to determine accurately, on a day to day basis, their ship’s position or what dangers lurked.

So much for the state of the art in 1620. What do we find as to how many of these meager skills were possessed by Captain Jones and his crew aboard the Mayflower?

We know that Captain Jones was a part owner of the ship and had been Captain for several years. He had just returned from Spain, hauling a cargo of wine. He had traded at least once across the North Sea to Norway from Newcastle. He was probably as well suited to, and trained for, an Atlantic crossing as the average sea captain of the day. To understand just what is involved in making a crossing, whether back then or today, it is necessary to get a bit technical and describe some of the essentials of navigation and passage making in any age.

When out of sight of land, the navigator depends on several aids to keep his ship on course and to position her daily on the surface of the ocean. Then, as now, the first aid is the compass. With it he can shape his course steadily toward his destination. All of us know something about a compass, and how its north-seeking needle points to magnetic north. The discovery and use of the magnetic properties of ferrous compounds goes way, way back in time. One of the first references to a mariner’s compass is found in the writings of one Alexander Neckam, born in A.D. 1157. We are sure its use antedated this date by years and perhaps centuries.

The next aid is the traverse board . This is a kind of abacus and memo pad. A circle at the top of the board is divided by radii into the thirty-two points of the compass. Each of these radii has eight holes, evenly spaced out from the center, into which pegs can be fitted. The bottom of the board is divided by eight horizontal lines and these lines also have holes evenly spaced across their length for pegs. Then, as now, a steering watch was four hours long, divided into eight 30 minute glasses of time. At the turning of each glass (every thirty minutes), the quartermaster put a peg in the proper radius hole to represent the average course steered during the period and the proper glass number of the watch period.

This sounds quite impressive, but the results were far from anything but rough guesses. They were at least better than no guess at all. So, with compass, traverse board and log-ship, the 1620 navigator kept his accompt book of daily positions – his dead reckoning positions. Even today, with much better compass, perfect timing devices, and excellent speedometers, the position of a ship at sea by dead reckoning may be off by a substantial mileage each day.

This leads us to the next aid the navigator must have. He must have a way of figuring his position from day to day by means independent of course or speed. The aid he uses to do this is an altitude measuring device with which he can determine the altitude of some heavenly body and, with suitable calculations, find from this measurement his location at sea. In 1620 the aids used were either an astrolabe or a Davis backstaff .

This is where Celestial Navigation comes into the picture. Celestial Navigation, in all its mathematical and astronomical theory, is rather complicated but its basic principal is simplicity itself. Poets have referred to the heavenly bodies – the sun, moon, stars and planets – as the “Lighthouses of the Sky” This poetic fancy happens to be strict, practical fact. Consider for a moment. We are on the revolving earth. It revolves from west to east, and this motion makes it appear to us that the sun and all other bodies rise in the East and set in the West. Imagine, if you will, a string running from the center of the earth to the center of a heavenly body. This string would cut the surface of the earth at a certain point at a certain time. This point is called the “GP” of the body. “GP” stands for “geographical position.” It keeps changing from moment to moment as the earth turns. Today the GP’s of fifty-seven navigational stars, four planets, the moon and the sun are listed in a Government publication issued annually and called the Nautical Almanac. This book lists these positions in terms of degrees North or South of the equator, and degrees West of an arbitrary line running through Greenwich, England. They are listed for every second of time of the year.

In 1620 no such handy volume existed. Tables of the “Declination of the Sun” for every day of the year were available, however. Declination is merely the astronomer’s name for latitude and refers to the latitude on the earth’s surface of the GP of the body. Now, remember a heavenly body moves westward in the sky rapidly, about 15 degrees an hour, but it moves slowly north or south. So a daily table of the sun’s declination is useful.

Let’s review a bit now. The aids available to Captain Jones in 1620 were the compass , the traverse board , the log ship and, of course, the second glass and hourglass. With these he did the best he could to keep his accompt book , or Log of daily dead reckoning position – his “DR.” He used his Davis backstaff or astrolabe to measure the altitude of the sun. Today he would use a sextant. This beautifully accurate instrument in the hands of a skilled observer is capable of measuring altitude angles to one six-hundredth of a degree. Captain Jones with his instrument would do well to get within a degree – some six hundred times less accurate – on board the heaving and pitching Mayflower !

To do his best to keep from building up high cumulative errors in his dead reckoning accompt , Captain Jones practiced celestial navigation each day at high noon. High noon merely means that the sun is due north or due south of you, and is going from “rising” to “setting.” At this moment we say it is on your meridian – not A.M. or P.M. Captain Jones’s celestial navigation consisted of measuring the sun’s altitude at his best estimate of its highest point for the day.

This high point occurs at high noon (by a sun dial or compass). To make this measurement, the backstaff was probably used because it was a bit simpler on shipboard than an astrolabe. From the altitude of the sun, so obtained, and the declination for the day from the tables, Captain Jones could get his latitude by a simple calculation. We might mention here that Captain Allan Villiers carried a replica of a Davis backstaff on the voyage of Mayflower II and reported it quite useless for any meaningful accuracy. Even allowing Jones much greater accuracy than Villiers, due to more practice, it is doubtful if the latitudes obtained were much better than the DR figures which themselves were pretty awful by present day standards.

Now note that this bit of celestial observation only checked latitude. No attempt to obtain positions East or West of your departure was possible by celestial observations at that time. It would be more than a hundred years later before longitude could be found at sea.

We have mentioned the sun only as a method to obtain latitude. For centuries navigators had known that the altitude of the Pole Star, Polaris, roughly equaled the latitude of the observer. At the time of the Mayflower voyage, it is likely that Captain Jones felt he could get better results from observations of the sun. Of course, he might have observed either from time to time.

There is a whole set of circumstances in seventeenth century sailing which must not be overlooked. We must remember the life aboard a ship at those times– the almost unbelievable discomfort, the monotony, week after week after week, the cold, the wet, the poor food coupled with hard physical labor. This terrible environment made it practically impossible to exercise the careful judgment and carry out the accurate calculations which, then as now, are absolutely essential in the practice of navigation. There is no wonder that whole fleets of ships were sunk and wrecked on unfamiliar shores, and that a seaman’s life was hard and short in those far off times.

The Mayflower made history by carrying the Pilgrims to the New World. But never forget – SHE WAS ONE OF THE LUCKY ONES!

– November 1980 – VoL 46 No. 4

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

The Mayflower

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 27, 2023 | Original: March 4, 2010

In September 1620, a merchant ship called the Mayflower set sail from Plymouth, a port on the southern coast of England. Normally, the Mayflower’s cargo was wine and dry goods, but on this trip the ship carried passengers: 102 of them, all hoping to start a new life on the other side of the Atlantic. Nearly 40 of these passengers were Protestant Separatists—they called themselves “Saints”—who hoped to establish a new church in the so-called New World. Today, we often refer to the colonists who crossed the Atlantic on the Mayflower as “Pilgrims.”

Pilgrims Before the Mayflower

In 1608, a congregation of disgruntled English Protestants from the village of Scrooby, Nottinghamshire, left England and moved to Leyden, a town in Holland. These “Separatists” did not want to pledge allegiance to the Church of England , which they believed was nearly as corrupt and idolatrous as the Catholic Church it had replaced, any longer. (They were not the same as the Puritans, who had many of the same objections to the English church but wanted to reform it from within.) The Separatists hoped that in Holland, they would be free to worship as they liked

Did you know? The Separatists who founded the Plymouth Colony referred to themselves as “Saints,” not “Pilgrims.” The use of the word “Pilgrim” to describe this group did not become common until the colony’s bicentennial.

In fact, the Separatists, or “Saints,” as they called themselves, did find religious freedom in Holland, but they also found a secular life that was more difficult to navigate than they’d anticipated. For one thing, Dutch craft guilds excluded the migrants, so they were relegated to menial, low-paying jobs.

Even worse was Holland’s easygoing, cosmopolitan atmosphere, which proved alarmingly seductive to some of the Saints’ children. (These young people were “drawn away,” Separatist leader William Bradford wrote, “by evill [sic] example into extravagance and dangerous courses.”) For the strict, devout Separatists, this was the last straw. They decided to move again, this time to a place without government interference or worldly distraction: the “New World” across the Atlantic Ocean.

The Mayflower Journey

First, the Separatists returned to London to get organized. A prominent merchant agreed to advance the money for their journey. The Virginia Company gave them permission to establish a settlement, or “plantation,” on the East Coast between 38 and 41 degrees north latitude (roughly between the Chesapeake Bay and the mouth of the Hudson River). And the King of England gave them permission to leave the Church of England, “provided they carried themselves peaceably.”

In August 1620, a group of about 40 Saints joined a much larger group of (comparatively) secular colonists—“Strangers,” to the Saints—and set sail from Southampton, England on two merchant ships: the Mayflower and the Speedwell. The Speedwell began to leak almost immediately, however, and the ships headed back to port in Plymouth. The travelers squeezed themselves and their belongings onto the Mayflower, a cargo ship about 80 feet long and 24 feet wide and capable of carrying 180 tons of cargo. The Mayflower set sail once again under the direction of Captain Christopher Jones.

Because of the delay caused by the leaky Speedwell, the Mayflower had to cross the Atlantic at the height of storm season. As a result, the journey was horribly unpleasant. Many of the passengers were so seasick they could scarcely get up, and the waves were so rough that one “Stranger” was swept overboard. (It was “the just hand of God upon him,” Bradford wrote later, for the young sailor had been “a proud and very profane yonge man.”)

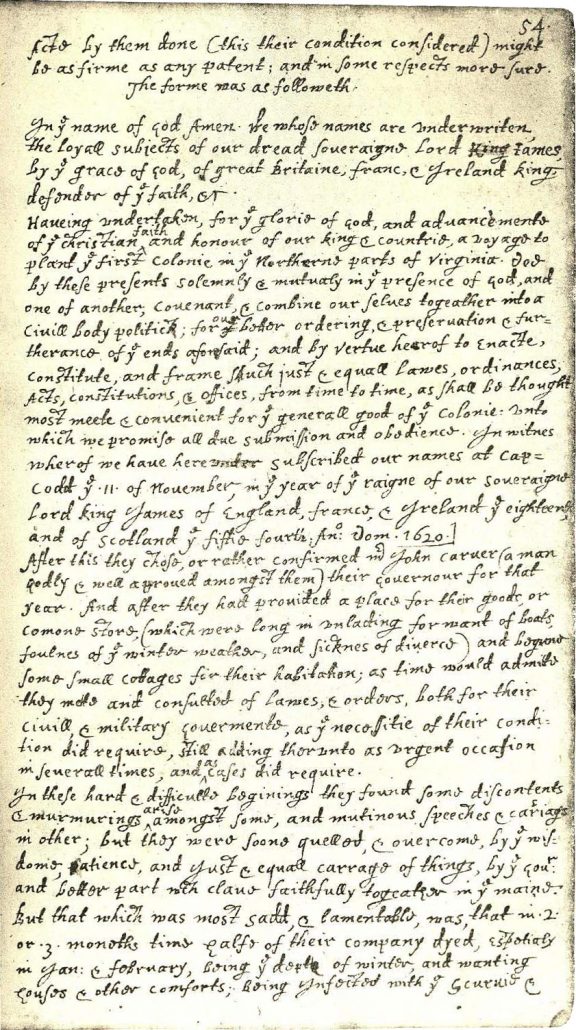

The Mayflower Compact

After sixty-six days, or roughly two miserable months at sea, the ship finally reached the New World. There, the Mayflower’s passengers found an abandoned Indian village and not much else. They also found that they were in the wrong place: Cape Cod was located at 42 degrees north latitude, well north of the Virginia Company’s territory. Technically, the Mayflower colonists had no right to be there at all.

In order to establish themselves as a legitimate colony (“Plymouth,” named after the English port from which they had departed) under these dubious circumstances, 41 of the Saints and Strangers drafted and signed a document they called the Mayflower Compact . This Compact promised to create a “civil Body Politick” governed by elected officials and “just and equal laws.” It also swore allegiance to the English king. It was the first document to establish self-government in the New World and this early attempt at democracy set the stage for future colonists seeking independence from the British .

The First Thanksgiving

The colonists spent the first winter living onboard the Mayflower. Only 53 passengers and half the crew survived. Women were particularly hard hit; of the 19 women who had boarded the Mayflower, only five survived the cold New England winter, confined to the ship where disease and cold were rampant. The Mayflower sailed back to England in April 1621, and once the group moved ashore, the colonists faced even more challenges.

During their first winter in America, more than half of the Plymouth colonists died from malnutrition, disease and exposure to the harsh New England weather. In fact, without the help of the area’s native people, it is likely that none of the colonists would have survived. An English-speaking Abenaki named Samoset helped the colonists form an alliance with the local Wampanoags, who taught them how to hunt local animals, gather shellfish and grow corn, beans and squash.

At the end of the next summer, the Plymouth colonists celebrated their first successful harvest with a three-day festival of thanksgiving. We still commemorate this feast and remember it as the first Thanksgiving , though it did not occur on the fourth Thursday in November like it does today, but sometime between late September and mid November 1621. The colonists were outnumbered two to one by their guests . Attendee Edward Winslow noted there were “many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men.”

Plymouth Colony

Eventually, the Plymouth colonists were absorbed into the Puritan Massachusetts Bay Colony. Still, the Mayflower Saints and their descendants remained convinced that they alone had been specially chosen by God to act as a beacon for Christians around the world. “As one small candle may light a thousand,” Bradford wrote, “so the light here kindled hath shone to many, yea in some sort to our whole nation.”

Today, visitors wishing to see Plymouth Colony as it appeared during the time of the Mayflower can witness reenactments of the first Thanksgiving and more at Plymouth Plantation.

Mayflower Descendants

There are an estimated 10 million living Americans and 35 million people around the world who are descended from the original passengers on the Mayflower like Myles Standish, John Alden and William Bradford. include Humphrey Bogart, Julia Child, Norman Rockwell, and presidents John Adams , James Garfield and Zachary Taylor .

HISTORY Vault: America the Story of Us

America The Story of Us is an epic 12-hour television event that tells the extraordinary story of how America was invented.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

MayflowerHistory.com

Voyage of the mayflower.

The Mayflower was hired in London, and sailed from London to Southampton in July 1620 to begin loading food and supplies for the voyage--much of which was purchased at Southampton. The Pilgrims were mostly still living in the city of Leiden, in the Netherlands. They hired a ship called the Speedwell to take them from Delfshaven, the Netherlands, to Southampton, England, to meet up with the Mayflower . The two ships planned to sail together to Northern Virginia. The Speedwell departed Delfthaven on July 22, and arrived at Southampton, where they found the Mayflower waiting for them. The Speedwell had been leaking on her voyage from the Netherlands to England, though, so they spent the next week patching her up.

On August 5, the two ships finally set sail for America. But the Speedwell began leaking again, so they pulled into the town of Dartmouth for repairs, arriving there about August 12. The Speedwell was patched up again, and the two ships again set sail for America about August 21. After the two ships had sailed about 300 miles out to sea, the Speedwell again began to leak. Frustrated with the enormous amount of time lost, and their inability to fix the Speedwell so that it could be sea-worthy, they returned to Plymouth, England, and made the decision to leave the Speedwell behind. The Mayflower would go to America alone. The cargo on the Speedwell was transferred over to the Mayflower ; some of the passengers were so tired and disappointed with all the problems that they quit and went home. Others crammed themselves onto the already very crowded Mayflower .

Finally, on September 6, the Mayflower departed from Plymouth, England, and headed for America. By the time the Pilgrims had left England, they had already been living onboard the ships for nearly a month and a half. The voyage itself across the Atlantic Ocean took 66 days, from their departure on September 6, until Cape Cod was sighted on 9 November 1620. The first half of the voyage went fairly smoothly, the only major problem was sea-sickness. But by October, they began encountering a number of Atlantic storms that made the voyage treacherous. Several times, the wind was so strong they had to just drift where the weather took them, it was not safe to use the ship's sails. The Pilgrims intended to land in Northern Virginia, which at the time included the region as far north as the Hudson River in the modern State of New York. The Hudson River, in fact, was their originally intended destination. They had received good reports on this region while in the Netherlands. All things considered, the Mayflower was almost right on target, missing the Hudson River by just a few degrees.

As the Mayflower approached land, the crew spotted Cape Cod just as the sun rose on November 9. The Pilgrims decided to head south, to the mouth of the Hudson River in New York, where they intended to make their plantation. However, as the Mayflower headed south, it encountered some very rough seas, and nearly shipwrecked. The Pilgrims then decided, rather than risk another attempt to go south, they would just stay and explore Cape Cod. They turned back north, rounded the tip, and anchored in what is now Provincetown Harbor. The Pilgrims would spend the next month and a half exploring Cape Cod, trying to decide where they would build their plantation. On December 25, 1620, they had finally decided upon Plymouth, and began construction of their first buildings.

The Mayflower attempted to depart England on three occasions, once from Southampton on 5 August 1620; once from Darthmouth on 21 August 1620; and finally from Plymouth, England, on 6 September 1620.

The Mayflower departed Plymouth, England, on 6 September 1620 and arrived at Cape Cod on 9 November 1620, after a 66 day voyage.

After sighting Cape Cod, the Mayflower heads south hoping to reach the mouth of the Hudson River in modern-day New York (then a part of Northern Virginia), but were forced back to Provincetown Harbor in Cape Cod after encountering treacherous seas.

- American History

- European History

- World History

The Mayflower’s Voyage and Arrival in Massachusetts

On September 16, 1620, 102 English passengers set sail on the Mayflower as it made its way from Plymouth and arrived in Cape Cod in November of the same year. Protestant Separatists who wanted to establish a church in the New World made up a large portion of the passengers. All of them though, just wanted to create a new life in a new place. Today, the Mayflower is one of the most iconic stories of the founding of America, and the passengers on the ship are now what we call Pilgrims.

During mid-July of 1620, sixty-five passengers aboard the Mayflower left from where it was docked in Rotherhithe. The Mayflower made its way from the Thames River and into the English Channel. From there, it reached Southampton Water and anchored there for a week. After seven days, the Mayflower joined a group of Leiden church members aboard the Speedwell that had come from Holland. Two weeks later, the Mayflower and the Speedwell set sail on about August 5, 1620. The Speedwell quickly had to go into repairs in Dartmouth after it sprang a leak. When repairs were done, the ships set sail again, but the Speedwell sprang yet another leak not long after, It was early September by this point, and the Speedwell was abandoned. Eleven of its passengers boarded the Mayflower, while the rest stayed in London.

source: historyextra.com

By the time the Mayflower set sail once more on September 6, 1620 from Plymouth, there were 102 passengers and about 25-30 crew members with the exact numbers unknown, making for about 130 people in all. It is said that Plymouth was the Mayflower’s final stop before reaching Massachusetts, but it may have stopped at Newlyn, Cornwall for fresh water because the water was leading to disease. It is unknown if this happened or not, but there is a good chance it did.

It was a miserable voyage. Large waves constantly rocking the boat, food shortages, a fractures main support beam, and many other things led to the misery of the passengers. By the time the Mayflower had finally been able to leave England, storm season out on the Atlantic had already began. Many even became seasick because of it. A young sailor had even been swept overboard by the huge waves. Over the course of the sixty-six day journey, only two passengers died. A woman named Elizabeth Hopkins also gave birth to a baby boy named Oceanus during the journey.

Land, Cape Cod to be exact, was first spotted on November 9, 1620. The plan was to sail to Virginia because they had received permission to begin colonizing the area, but the stormy seas forced them to have to anchor the ship in Cape Cod. The Mayflower Compact was drafted and signed by the new colonists so they could settle and anchor the ship there.

Captain Christopher Jones sent out an exploring expedition to find a place for them to settle on November 27th. Jones, ten sailors, and twenty-four passengers all went on the expedition. No one was expecting the harsh winter weather they got when they set foot on land. It was much harsher than the winters they experienced back in England. In fact, about half of the people aboard the Mayflower would die that first winter mainly due to the cold. All they found though, was snow covered land and an abandoned Native American village. The men looted what they could find that once belonged to the Natives before settling in a place they called Plymouth.

source: history.com

The Mayflower’s passengers stayed aboard the ship until the following spring. That winter, Peregrine White, son of Susanna and William White, was born on the ship, becoming the first European child to be born in New England. Only fifty-three of the original 102 passengers lived through the first winter due to disease such as scurvy, pneumonia, and tuberculosis and the cold. Men began building huts on shore when spring came. The passengers left the ship to move into their new home in Plymouth on March 21, 1621. The small village was protected by six iron cannons in fear of Native Americans attacking them.

On April 5, 1621, Christopher Jones and his remaining crew members left Plymouth and set sail for England, and just over a month later, arrived at its destination.

In Plymouth, John Carver became the small colony’s first governor, and William Bradford took on the role not long after in 1621. There were only forty-seven remaining settlers, and only a few had the strength to look over the rest. Eventually, most of them were able to recover. Houses had thatched roofs (which were later replaced by plank because it caught on fire too easily), dirt floors, and a chimney. They were built mainly of wood, and each family had their own field plot for growing food.

Today we celebrate Thanksgiving in America on the last Thursday of every November. This started when the Pilgrims in Plymouth held a feast in the fall of 1621 with the Pokanoket tribe.

Plimoth Plantation. Source: wikipedia.org

After the reaming Pilgrims had settled and made a home in Plymouth, other Europeans decided to leave their countries and settle in America as well. Plymouth is still standing and lived in today with tourist attractions from when Plymouth was only a settlement. There is one reaming home called the Jabez Howland house where Mayflower passengers lived. Also, there is a recreation of the first settlement in Plymouth called the Plimoth Plantation, the famous Plymouth rock, a replica of the Mayflower, and other historical tourist attractions.

The UK National Charity for History

Password Sign In

Become a Member | Register for free

The 1620 Mayflower voyage and the English settlement of North America

Historian article

- Add to My HA Add to folder Default Folder [New Folder] Add

On the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the Pilgrims in New England on the Mayflower , Martyn Whittock explores the reasons for migration to the New World in 1620 and later, and the significance of those migrants, both at the time and their impact on the evolution of the USA today.

In November 1620, a battered sailing ship wearily worked its way up the coast of what is today Massachusetts. Called the Mayflower , there was little about the ship and its passengers that indicated it might ever have a place in future history, myth and legend. In fact, everything pointed towards hardship, perhaps disaster. As those on the ship looked out on the shoreline of Cape Cod their anxieties must have mounted. Not only had the voyage from a very distant England been long and hard, but this was not where they intended to be...

This resource is FREE for Historian HA Members .

Non HA Members can get instant access for £2.49

Add to Basket Join the HA

The Mayflower, 1620-2020: tracing voyages of discovery in Plymouth’s past

Today, Plymouth is home to the largest naval base in western Europe, but it boasts a much longer maritime history. For centuries it served as a gateway to new worlds, launching ambitious expeditions towards distant horizons – voyages that brought prosperity to Britain, but which frequently signalled exploitation rather than exploration to the indigenous communities that they encountered. Francis Drake, Walter Raleigh, James Cook, and Charles Darwin all set sail from its port, and the city was the birthplace of another intrepid, if ill-fated adventurer: the polar explorer Robert Falcon Scott.

This year marks the 400th anniversary of another famous journey that set out from Plymouth docks: the sailing of the Mayflower in 1620, which carried the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ across the Atlantic to found a colony in the New World – a settlement that they named ‘Plymouth Plantation’. This milestone is being marked by an exhibition, Mayflower 400: Legend and Legacy, at The Box, a new museum recently opened in Plymouth to tell the city’s story (see ‘further information’ box on p.55). What can we learn of the Plymouth that the Mayflower passengers knew?

A nuanced history

The Box’s permanent galleries house a host of artefacts reflecting the lives and interests of post-medieval Plymothians. These objects paint a picture, by the late 1500s, of a diverse mariner community with an eager appetite for new styles – they were early adopters of smoking tobacco, and gladly imported foreign fashions such as Venetian glass beads. In the 17th century, this was undeniably a seafaring town, with more than 600 sailors in residence, and with commercial contacts stretching all over the world. Plymouth’s Port Books document local, British, and international ships coming and going, as well as the cargoes they carried: Newfoundland cod and Irish beef, French wine and Dutch beer, Spanish wool and Italian glass.

The city was also a key player in the early slave trade: Francis Drake may be celebrated for his circumnavigation of the globe aboard the Golden Hind, which departed Plymouth in 1577, but a decade earlier he had made one of the first English slaving voyages to Africa, in a fleet led by his cousin John Hawkins. Such journeys laid the foundations for a European trade that Britain came to dominate by the 1700s. In The Box’s galleries, this heritage is openly acknowledged: artefacts associated with Drake’s life stand opposite a case containing iron neck- and handcuffs – stark reminders of the real people who were forced to wear them, and of the dignity that they were denied. Yet post-medieval Plymouth was also a popular destination for refugees fleeing religious persecution on the Continent – French Protestant Huguenots in the 1600s, while a century later northern European Jews established the oldest Ashkenazi synagogue still active in the English-speaking world.

It was religion that motivated many of the Mayflower passengers to travel, too. A significant portion of the founders of Plymouth Colony were ‘Separatists’ – dissenters who were dissatisfied with the progress of the English Reformation, and believed that the Church of England was still not sufficiently Protestant. Instead, they wanted the freedom to form independent congregations with like-minded individuals – something that was seen as a dangerous challenge to the authority of the state. Bloody religious conflicts between Protestants and Catholics had flared during the reigns of Mary I and Elizabeth I, and the 1605 Gunpowder Plot showed that England under James I was no less volatile. Differences of faith were determinedly (and often violently) suppressed by the anxious authorities, and in 1608 the Separatists left England to settle in the Dutch city of Leiden, where they hoped to be able to worship as they wished. In these more-tolerant surroundings they built a comfortable life for themselves – many found work in the clothing trade, as tailors, weavers, shoemakers, and hatters, while others operated the Pilgrim Press, smuggling books that were banned in England back across the Channel. This sense of safety lasted for a decade, but when the Thirty Years War between Catholics and Protestants began in 1618, it was time to move on, and, by 1620, the community had resolved to emigrate to America.

Colonisation was no small step – it was a costly and dangerous venture, spending weeks at sea to create a new life from nothing in an unknown land. But the Separatists were determined, securing permission from the Virginia Company (see box on p.54) to establish a new settlement on the Hudson River, and investment from the Company of Merchant Adventurers in London to finance the journey. They would not be travelling alone – the London merchants had also recruited hired hands, servants, and farmers to help establish the fledgling colony, and in 1620 the Leiden community set sail in the Speedwell to meet their new neighbours, and the Mayflower, at Southampton.

The Speedwell was not a new ship – she was a veteran of fighting the Spanish Armada in 1588 – and soon proved to be barely seaworthy, decried by Robert Cushman, one of the expedition’s purchasing agents, as ‘open and leaky as a sieve’. Shortly after departing Southampton, the voyagers had to put in at Dartmouth so that the Speedwell could be repaired, and the journey was delayed again when further leaks forced the ships to turn back once more, this time to Plymouth. Enough was enough: it was clear that the vessel would never survive the transatlantic crossing. Some of the Speedwell’s passengers chose to abandon their journey altogether, while others came aboard the Mayflower. It was this (now rather overcrowded) ship that set out alone for America.

Seeking the settlers

Given the historical significance of the Mayflower voyage, it seems surprising that it is not mentioned in any of Plymouth’s port records of the time – nor are there any known contemporary images of the ship. This lack of official interest was down to financial concerns – cargoes of objects meant money for the city, but ships laden with emigrants did not, and so there was no desire to log the ship’s arrival or departure in the Port Books. We also have very few depictions of 17th-century Plymouth itself, though one map helps to evoke the sights that the Mayflower passengers would have seen: it shows the old castle or ‘barbican’, and, beneath that, what are probably the steps that had been built in 1584 to allow people to enter boats and reach large ships moored in the Cattewater (a stretch of open water where the mouth of the Plym meets Plymouth Sound). Today the location of these steps is marked by a stone portico that was built in 1934, and it is thought that they may have been used by the would-be colonists as they took their last steps on English soil.

How did the passengers feel as they boarded the Mayflower? Excited, surely, and relieved to be finally under way – but it would be surprising if they did not also feel a degree of trepidation. Sea voyages were treacherous, and even departing from the confines of Plymouth harbour was fraught with danger. Plymouth Sound hides a vast maritime graveyard scattered with shipwrecks, victims of the submerged rocks that claimed hundreds of vessels over the centuries – the earliest-known such loss dates from 1362. Artefacts from two wrecks are displayed in The Box’s ‘Port of Plymouth’ gallery, one of them an anonymous early 16th-century vessel now known as the ‘Cattewater Wreck’. Found during dredging operations in 1973, it was the first ship to be safeguarded under the Protection of Wrecks Act, which had been passed the same year.

These losses did not stop even with the construction of Plymouth Sound’s first lighthouse in 1699 – the other wreck featured in the museum is the Danish trader Die Frau Metta Catharina von Flensburg, which sank in 1786 while sailing from Russia to Italy with a cargo of hemp and reindeer hides. The Mayflower passengers had no such comforting beacon to offer them hope, however, and thanks to the leaky Speedwell delaying their progress, they were now to cross the Atlantic in late September and October, a time of dangerous storms. Indeed, records of the voyage attest that one passenger, John Howland, was swept overboard during just such a squall – fortunately, he was rescued. Even without the storms, though, the colonists would not have had a comfortable passage across the Atlantic, crammed for 66 days into a cargo ship designed to carry far fewer than the c.102 people who made the crossing – as well as animals including dogs, chickens, and pigs. The Mayflower was not a large ship, and below decks it would have been dark, airless, and uncomfortably cramped – anyone over 5ft (1.52m) tall would have been unable to stand upright.

What do we know of the passengers themselves? Although the voyagers are often popularly known as the ‘Pilgrim Fathers’, only around a third were travelling for religious reasons, and they also counted 18 women among their number (three of whom were pregnant), as well as at least 30 children. They came from 15 different counties in England, and ranged in age from infants to 64-year-old James Chilton, originally of Kent. These details and more are preserved thanks to one of the colony’s leaders, William Bradford, who composed ‘Of Plimouth Plantation [sic]’, an account of the colony’s early years, between 1630 and 1651. From this, we learn of William Mullins, an enterprising shoemaker from Dorking, who was accompanied not only by his wife and two of their four children, but also around 250 shoes and 13 pairs of boots. Edward Winslow was a printer from Droitwich, who had worked for the Pilgrim Press in Leiden, while Samuel Fuller, the colony’s doctor, travelled with an indentured servant, ‘a youth’ called William Butten. William was the only passenger to die during the journey, succumbing to sickness three days before they sighted land.

While many of the passengers were family groups, others had taken the difficult decision to leave their wives and children in Leiden, hoping that they would follow later. In some cases, this hope was fulfilled – for example, Francis Cooke, a Norwich woolcomber, whose wife and four children travelled to the colony on a subsequent voyage – but other journeys had less happy ends. Digory Priest’s wife and two children stayed in Leiden when he sailed in 1620 – sadly, when they came to be reunited with him in 1623, he had already died. Bradford’s account also documents some of the more eventful episodes during the voyage: we learn that 14- and 16-year-old John and Francis Billington, Lincolnshire boys who were travelling with their parents, caused an explosion onboard ship after meddling with their father’s musket. But more joyful news comes with mention of the Hopkins family: Elizabeth Hopkins gave birth during the voyage and, rather fittingly, her son was given the name Oceanus.

Indigenous encounters

The Mayflower colonists had been given permission to settle on the Hudson River, but they were blown off course, landing instead at the tip of Cape Cod. It was there that 41 of the male passengers signed the Mayflower Compact, an agreement committing them to caring for the interests of the colony, but they were on shaky legal ground, with no official authorisation to settle. Eventually, the Virginia Company issued the Second Peirce Patent to sanction a colony further south than had been agreed – this manuscript granted each settler 100 acres of land, as well as ‘all such liberties, privileges, profits, and commodities’ that they could get from the land and rivers, but no reference is made to the desires of the indigenous people living there already.

As they set out in a small boat to find a suitable place to build their new home, the Mayflower colonists were travelling through lands belonging to the Wampanoag people, who had lived in the area for c.12,000 years. In the summer, indigenous communities lived in houses called ‘wetus’ on the coast, where they harvested seafood; in the autumn, they moved inland to hunt and farm corn, squash, and beans. Women were in charge of managing agricultural activities, and farmland was passed down the female line.

At the outset of the 1600s there were around 70 Wampanoag villages, but early encounters with Europeans brought devastating diseases to which they had no resistance, and between 1616 and 1619 it is estimated that as much as 70%-90% of their population died. Initially, the new arrivals of 1620 did little to endear themselves to their indigenous neighbours; as they searched for a place to settle, the colonists stole stocks of corn stored for the winter, disturbed burial mounds, and plundered pots, bowls, baskets, and food from wetus that they stumbled across.

Eventually, the colonists discovered a spot with good resources of food and fresh water. The Wampanoag knew it as Patuxet, but the settlers renamed it ‘Plymouth’. The first house-frame was raised on Christmas Day, but progress was slow and the community’s first winter proved brutal. Despite some happy events, including the birth of the plantation’s first baby, Peregrine White (‘Peregrine’ means a traveller or pilgrim), by the end of the first year over half the original colonists had died. Given the settlers’ initial lack of consideration for the indigenous population, it may seem surprising that the Wampanoag people proved the colony’s salvation, teaching its inhabitants how to farm the land and survive in their new environment – though it could be that, with their dramatically reduced numbers meaning that they were now outnumbered by threatening neighbours, they were glad of the cooperation.

While Thanksgiving legends present a rather oversimplified (and romanticised) story, relations were initially good, with the two communities sharing harvests and trading goods. Excavations at the site of Plymouth Colony show that the settlers had ceramics that they had brought from the West Country, but that they were also using pots and plates with Wampanoag designs. Sadly, the concord was not to last.

Colonial expansion encroached ever-deeper into indigenous territories, and competition for resources created further ill-feeling. Escalating tensions sparked into flashes of violence such as the 1623 Wessagusset massacre and the 1636 Pequot War, and after William Bradford died in 1657, and the Wampanoag chief Massasoit died in 1660, the personal bonds that had helped to maintain a fragile peace were broken. Hostilities culminated in King Philip’s War of 1675, a conflict with devastating consequences for both communities. Plymouth Colony lost an estimated eight per cent of its male population, while Massasoit’s successor, Metacomet, was killed and many surviving indigenous people were enslaved and forcibly transported to the Caribbean.

Although their political sovereignty was destroyed, however, the Wampanoag people have endured to the present day – while Plymouth Colony has not. From 1685, the English Crown began to restructure its colonies, revoking some charters and combining territories, and after 72 years of existence, Plymouth was dissolved. By contrast, the Wampanoag’s distinctive culture has been passed down the generations, and is honoured in The Box’s exhibition. The displays were created in partnership with the Wampanoag Advisory Committee, who helped to source objects reflecting their culture; these artefacts span 5,000 years and represent both pre-contact activities and items documenting interactions with colonists. The displays also feature a new commission by Wampanoag artist Nosapocket/Ramona Peters: a ceramic cooking pot created in traditional style specifically for the exhibition, illustrating how creativity and innovative approaches to this 400-year-old story still endure.

Earlier colonies

The Mayflower was not the first ship to carry settlers from Plymouth to the New World. In 1584, Walter Raleigh founded a colony at Roanoke, in North Carolina, but by 1590 it had vanished in circumstances that remain mysterious today. More attempts followed: in 1606 James I approved the creation of the London Company of Virginia and the Plymouth Company of Virginia to explore America and create colonies. The following year saw the establishment of Jamestown, but by 1610 most of the 500 settlers had died, and the rest were reduced to cannibalism in a desperate existence called ‘the Starving Time’. Famously, their fortunes were revived with the help of Pocahontas and the Powhatan people (see CA 330). Interestingly, one of the Mayflower passengers had been present at Jamestown: Stephen Hopkins, the father of little Oceanus. Evidently a fortunate man, he had also survived being shipwrecked off Bermuda in 1609.

And after Plymouth? Dutch colonists founded Fort Amsterdam, later New York, in 1624. Boston was established in 1630 (this expedition is depicted in a stained glass window in St Botolph’s Church in Boston, Lincolnshire), and over the next decade more than 20,000 Europeans settled in New England. Today, over 30 million people claim a connection with the Mayflower passengers alone.

Latest from Current Archaeology

A villa unveiled: Uncovering luxury living and ‘ritual activity’ in Roman Oxfordshire

Ringing the changes: Investigating an enigmatic monument at Aspull

Horse power: Tracing the trade and travels of elite animals in late medieval and Tudor London

Museum news

Current Archaeology’s May Listings: exhibitions, events, and heritage from home

A wonder of the world: Wandering along London’s post-medieval waterfront

Amesbury History Centre

Excavating around Salisbury Plain

A conflict reimagined: Creating a digital model of the Roman assault on Burnswark Hill

Sherds CA 411

Discover more from the past.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Mayflower II

Top choice in South Shore

If Plymouth Rock tells us little about the Pilgrims, Mayflower II speaks volumes. Climb aboard this replica of the small ship in which the Pilgrims made the fateful voyage, where 102 people lived together for 66 days as the ship passed through stormy North Atlantic waters. Actors in period costume are on board, recounting harrowing tales from the journey.

The ship is back in Plymouth after a thorough restoration in preparation for the 2020 quadricentennial of the Pilgrims' landing.

State Pier, Water St

Get In Touch

https://www.plimoth.org/what-see-do/mayflower-ii

Lonely Planet's must-see attractions

Plimoth Plantation

Three miles south of Plymouth center, Plimoth Plantation authentically re-creates the Pilgrims’ settlement in its primary exhibit, entitled 1627 English…

Pilgrim Hall Museum

Claiming to be the oldest continually operating public museum in the country, Pilgrim Hall Museum was founded in 1824. Its exhibits are not reproductions…

Provincetown Art Association & Museum

25.73 MILES

Founded in 1914 to celebrate the town’s thriving art community, this vibrant museum showcases the works of hundreds of artists who have found their…

Pilgrim Monument & Provincetown Museum

25.19 MILES

Climb to the top of the country's tallest all-granite structure (253ft) for a sweeping view of town, the beaches and the spine of the Lower Cape. The…

Heritage Museums & Gardens

16.58 MILES

Fun for kids and adults alike, the 100-acre Heritage Museums & Gardens sports a superb vintage automobile collection in a Shaker-style round barn, an…

Captains' Mile

27.81 MILES

Nearly 50 historic sea captains' homes are lined up along MA 6A (the Old King's Hwy) in Yarmouth Port, on a 1.5-mile stretch known as the Captains' Mile…

John F Kennedy Hyannis Museum

28.82 MILES

Hyannis has been the summer home of the Kennedy clan for generations. Back in the day, JFK spent the warmer months here – times that are beautifully…

Georges Island

28.32 MILES

Georges Island is one of the transportation hubs for the Boston Harbor Islands. It is also the site of Fort Warren, a 19th-century fort and Civil War…

Nearby South Shore attractions

1 . Plymouth Rock

Thousands of visitors come each year to look at this weathered granite ball and consider what it was like for the Pilgrims who stepped ashore on a foreign…

2 . Mayflower Society Museum

The offices of the General Society of Mayflower Descendants are housed in the magnificent 1754 house of Edward Winslow, the great-grandson of Plymouth…

3 . 1749 Spooner House

On pretty North St, this 18th-century house was the home of the Spooner family for more than two centuries. Nowadays, the two-story house still contains…

4 . 1809 Hedge House

You can't miss this grand, Federal edifice overlooking Plymouth Harbor. Originally built on Court St for a sea captain, it became the home of merchant…

5 . Pilgrim Hall Museum

6 . 1667 Jabez Howland House

This is the only house in Plymouth that was home to a known Mayflower passenger. John Howland lived here with his wife, Elizabeth Tilley, and their son…

7 . Richard Sparrow House

Plymouth's oldest house was built by one of the original Pilgrim settlers in 1640. Today, there is a small art gallery in the more recent addition, while…

8 . Plimoth Grist Mill

In 1636, local leaders constructed a gristmill on Town Brook so that the growing community could grind corn and produce cornmeal. Today, the replica mill…

SIGN IN YOUR ACCOUNT TO HAVE ACCESS TO DIFFERENT FEATURES

Forgot your details.

- Account Details

- Member’s Resources

- Rider’s Resources for Volunteers/Instructors

- MY CART No products in cart.

- Sponsors & Partners

- Membership Information

- Contact Information

- Marty Brown Memorial

- Basic Firearms Safety

- Rifle Programs

- Pistol Programs

- Other Shooting Programs

- Rifle 125 (Basic Rifle)

- Rifle 223 (Carbine)

- Rifle 262 (Field Rifle)

- Pistol 100 (Basic Pistol)

- Pistol 145 (Intro to Defensive Pistol)

- Pistol 209 (Defensive Pistol)

- American History

- Civic Engagement

- Event Notification Signup

- Rimfire Friendly Events

- Filter by Ladies Only

- First Steps Pistol

- First Steps Rifle

- Rifle 308 (Precision Rifle/Adv Field Rifle)

- Battle Road Biathlon

- Whittemore Weekend

- Marksman Match

- Hunter Education

- Virtual Event

- A&A Optics Range (Liberty, IN)

- Atlanta Conservation Club (Atlanta, IN)

- Camp Atterbury Joint Maneuver Training Center (Edinburgh, IN)

- Gray Property (Zionsville, IN)

- Lost Creek Conservation Club (Seelyville, IN)

- Red Brush Rifle Range (Newburgh, IN)

- Dark Planet (Campton, KY)

- Thompson Farm (Willisburg, KY)

- Samuel Whittemore Memorial Range (Three Forks, MT)

- Erie County Conservation League (Milan, OH)

- Meeker Sportsmen Center (Marion, OH)

- Middletown Sportsman’s Club (Middletown, OH)

- Oak Harbor Conservation Club (Oak Harbor, OH)

- Tusco Rifle Club (Dennison, OH)

- Wolf Creek Sportman’s Club (Curtice, OH)

- Lower Providence Rod & Gun Club (Audubon, PA)

- Laramie Rifle Range (Laramie, WY)

- Al “Meadow” Field

- Becki Gibson

- Bradley “Slim” Settle

- Bruce “Gopher” Williams

- Frank “LPRGC” Tait

- John “Hop” Hopkins

- Kevin “Unbridled Liberty” Fitz-Gerald

- Matt “SmileDocHill” Hill

- Nigel Downton

- Richard “Sleepy” Jamharian

- Steve “Corvette” Branam

- “TJ” Kackowski

- Photo/Video Gallery

- Recent News

- Newsletter Signup

- Memberships

- Basic Pistol

- Basic Rifle

- Defensive Pistol

- Field Rifle

- Sporting Shotgun

- Safety & Range Gear

- Sponsorships

On This Day: 401 Years Ago, The Mayflower Landed

401 years ago today, November 21st, 102 passengers and 30 crew on the Mayflower landed at Plymouth Rock near modern day Cape Cod, Massachusetts after 10 weeks at sea.

The passengers on the Mayflower were separatists from the Church of England who had fled to The Netherlands to escape what they viewed as religious persecution in England. In 1559, the Act of Uniformity required all Englishmen to attend official Church of England services or suffer a fine. Those who opposed being forced to attend Church of England services as well as other aspects of Church of England doctrine and administration were referred to as Brownists or Puritans . The Brownists and Puritans distinguished themselves from other religious “separatists” in that they believed they should be allowed to worship outside of the Church of England.

In 1607 or 1608, many of the Puritans moved to Leiden in The Netherlands where they would be allowed religious freedom. The move was mostly successful as some in the group found work at Leiden University while others found work in the trades. However, both language and a substantially more liberal culture were a barrier that many found difficult to overcome. Some of the group exhausted their finances and were forced to return to England while it became increasing difficult to convince other Puritans in England to come to The Netherlands due to the expense and lack of meaningful work. The liberal Dutch culture was also proving to be a strong enticement for Puritan youth to leave the group. By 1617, the group started work on plans to leave The Netherlands for the New World.

The voyage to the New World was an audacious and dangerous undertaking. Jamestown Virginia , founded in 1607, saw 440 of the original 500 settlers die of starvation during the first six months of winter. The Puritans were also undoubtedly aware of reports of near constant threat of attacks by indigenous peoples in the New World. Despite this, the Puritans wrote:

We verily believe and trust the Lord is with us and that He will graciously prosper our endeavors according to the simplicity of our hearts therein.

Not all of the Puritans in The Netherlands were able to make the trip as many could not settle their affairs in time or had insufficient finances to afford the trip. It was decided that the first voyage to the New World be primarily undertaken by the younger and stronger members. The remainder agreed to follow if and when it became possible.

The trip to the New World was to be undertaken using two ships: the smaller Speedwell along with the Mayflower . The Speedwell would first carry Puritans from Leiden to England where they would be joined by additional passengers and supplies to depart on the Mayflower with Speedwell accompanying them. Unfortunately, the Speedwell suffered leaks on three separate departure attempts each of which required both ships to return to England for repairs to the Speedwell .

After the third leak, the Puritans sold the Speedwell and consolidated all their passengers and cargo onto to the, now overloaded, Mayflower . While the Puritans initial departure was in mid July 1620, the delays caused by the leaks to the Speedwell had forced a dangerously late final departure of September 16, 1620. The delay had also caused a depletion of the Puritans’ supplies:

We lie here waiting for as fair a wind as can blow… Our victuals will be half eaten up, I think, before we go from the coast of England; and, if our voyage last long, we shall not have a month’s victuals when we come in the country.

The ocean voyage proved pleasant for the first half of the journey. However, the weather changed and the Mayflower was lashed by vicious northeasterly winds and heavy seas forcing her crew to drop sails continue under bare masts lest her sails be ripped to shreds.

On November 19, 1620, land was sighted near present day Cape Cod, far north of the intended destination in Virginia. The Mayflower attempted to sail south but was thwarted by strong winter weather and forced to return to Cape Cod.

Before setting anchor in Provincetown Harbor, the Puritans drew up the Mayflower Compact designed to provide a framework for governance of their little group in the New World.

While the original version of the Mayflower Compact is lost to history, one of the Puritans, William Bradford, would copy it to his journal, Of Plymouth Plantation . The Mayflower Compact required of it’s male signatories:

- loyalty to King James

- the power to enact “laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions and offices…” for the good of the colony, and to abide by those laws

- to remain as one society and work together to further it

- to live in accordance with the Christian faith

The full text of the Mayflower Compact is as follows:

In the name of God, Amen. We, whose names are underwritten, the Loyal Subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord King James, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, King, defender of the Faith, etc.: Having undertaken, for the Glory of God, and advancements of the Christian faith, and the honor of our King and Country, a voyage to plant the first colony in the Northern parts of Virginia; do by these presents, solemnly and mutually, in the presence of God, and one another; covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil body politic; for our better ordering, and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions, and offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the colony; unto which we promise all due submission and obedience. In witness whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names at Cape Cod the 11th of November, in the year of the reign of our Sovereign Lord King James, of England, France, and Ireland, the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth, 1620.

As such, the Mayflower Compact is the first form of self-rule in the New World.

The Puritans explored the area around Provincetown Harbor and eventually settled on a site for construction of shelters. On December 26th, a site was chosen and construction commenced with the first structure completed by January 19th, 1621.

This structure immediately became a hospital for the sick. By the end of February, 31 had died. By March, only 47 of the original 102 Puritan passengers on the Mayflower were still alive. Half of the crew had also perished.

In October 1621, the surviving 53 passengers and crew of the Mayflower were joined by the Wampanoag chief Massosoit and 90 of his men to celebrate a harvest feast which has became known as “The First Thanksgiving”.

We now refer to the group of Puritans who voyaged on the Mayflower to the New World as the “Pilgrims”. The Plymouth Colony survived until 1691.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Mayflower400 partner destinations:

The Mayflower Voyage

For the passengers and crew who boarded the Mayflower some four centuries ago, the odds were firmly stacked against them as they looked to cross the Atlantic to start a new life .

By the time the group set sail from Plymouth on 16 September 1620, many of them had experienced religious persecution; trouble with the law (including time in prison for some); betrayal from those they trusted; numerous stops in ports around the country, and the eventual demise of the Mayflower’s sister ship, the Speedwell.

Little did they know, their hardships would only get worse during a voyage which saw emergency repairs, disease, death and even the birth of a new child.

Below you can read stories about the Mayflower’s historic journey, and how the colonists finally reached North America after 66 gruelling days at sea.

The Mayflower Story

The Mayflower set sail on 16 September 1620 from Plymouth, UK, to start its long voyage to America.

But its history and story start long before that in the villages, towns and cities of England.

Mayflower – The journey to 16 September

The Mayflower eventually set sail from Plymouth, UK, on 16 September 1620 to start what would prove to be a treacherous transatlantic voyage to America.

This is the fascinating story of how the colonists made the trip possible, and the events that led to them gathering on the water’s edge in Devon some 400 years ago.

How the Mayflower prepared for its historic transatlantic voyage

As with any long trip, preparation is key - and the colonists had spent many months leading up to their departure gathering provisions and supplies that would last them during their voyage and beyond.

One can only image how cramped and crowded conditions would have been on the Mayflower with more than 100 passengers on board and provisions to match.

66 days at sea: What life was like on board the Mayflower

The odds were firmly stacked against the passengers and crew who boarded the Mayflower some four centuries ago in a bid to start a new life across the Atlantic.

Little did the group know, their hardships would only get worse during a voyage which saw emergency repairs, disease, death and even the birth of a new child.

The Mayflower Compact

With America almost close enough to touch, the battered and broken Mayflower passengers knew their journey was far from over, for they had no right to settle on the land upon which they had unintentionally arrived.

The Pilgrims anchored in what is now Provincetown Harbour, Massachusetts, and decided to draw up an agreement that would give them some attempt at legal standing.

Millions owe their lives to Mayflower passenger who fell overboard

As if the colonists' perilous transatlantic crossing wasn't harrowing enough, imagine how frightened John Howland must have been when he fell overboard as a storm of epic proportions battered the Mayflower?

Howland was thrown overboard during nightmare sea conditions but managed to grab hold of a trailing rope, giving the Mayflower crew just enough time to rescue him with a boat-hook.

The Boy Who Fell From The Mayflower

The Boy Who Fell From The Mayflower (Or John Howland’s Good Fortune) is a beautifully illustrated children’s book that tells the imagined story of a real-life passenger aboard the pioneering ship.

John Howland was a teenager in 1620 when he sailed to America as an indentured servant. His story and the Mayflower’s dramatic voyage from Plymouth is vividly brought to life by writer and illustrator P.J. Lynch.

What happened after the Mayflower landed in America?

After more than two months battling everything the Atlantic had to throw at them, the Mayflower passengers' horrific ordeal was far from over.

What lay ahead were many more months of trials and tribulations which would test their spirit and, ultimately, decimate their numbers as they lost family, friends and loved ones to disease and the elements.

The unbreakable bond of the original Mayflower passengers who survived their first winter in America

Shared pain is undoubtedly one of the most powerful factors in bringing people together.

So, it’s no surprise that those who reached America in November 1620 and survived the subsequent first harsh winter had shared an experience that no other European could possibly understand.

How the Mayflower passengers started to build a colony

The Mayflower passengers and crew reached the coast of America during a harsh winter which brought with it heavy snow.

Conditions made it incredibly difficult, but the group put together three exploring parties over the course of the month between the middle of November and the middle of December.

Who were the children of the Mayflower?

Little is known about the children who sailed on the Mayflower some 400 years ago, but it is thought that there were around 30 on board the ship when the group departed Plymouth.

Richard Pickering, Deputy Director of Plimoth Patuxet Living Museum, explores more about the children of the Mayflower.

Sign up for the latest Mayflower 400 news

You'll be the first to hear the latest Mayflower news, events, and more.

Forgotten Password?

Mayflower 400 Proudly Supported by our National Sponsors and Funding Partners

- Website Privacy Policy

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Mayflower, in American colonial history, the ship that carried the Pilgrims from England to Plymouth, Massachusetts, where they established the first permanent New England colony in 1620. Although no detailed description of the original vessel exists, marine archaeologists estimate that the square-rigged sailing ship weighed about 180 tons and ...

Mayflower was an English sailing ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After 10 weeks at sea, Mayflower, with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, reached what is today the United States, dropping anchor near the tip of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, on November 21 [O.S. November 11], 1620.

Navigation in 1620: The. Mayflower. Was One of the Lucky Ones. From Diamond Jubilee Edition 27. Robert A. Harper. Presented at a meeting of the Myles Standish Colony of the Florida Society, in Naples, Florida. W hen I first thought of discussing the art of navigation in 1620 and how Captain Christopher Jones of the Mayflower probably employed ...

The Mayflower set sail on 16th September 1620 from Plymouth, UK, to voyage to America. But its history and story start long before that. Its passengers were in search of a new life - some seeking religious freedom, others a fresh start in a different land. They would go on to be known as the Pilgrims and influence the future of the United ...

Pilgrims boarding the Mayflower for their voyage to America. The Pilgrim's arduous journey to the New World technically began on July 22, 1620, when a large group of colonists boarded a ship ...

The Mayflower was a merchant ship that carried 102 passengers, including nearly 40 Protestant Separatists, on a journey from England to the New World in 1620.

The Mayflower was hired in London, and sailed from London to Southampton in July 1620 to begin loading food and supplies for the voyage--much of which was purchased at Southampton.The Pilgrims were mostly still living in the city of Leiden, in the Netherlands. They hired a ship called the Speedwell to take them from Delfshaven, the Netherlands, to Southampton, England, to meet up with the ...

The trip was supposed to be made in two ships, the Mayflower and the Speedwell, but after the latter repeatedly sprung leaks in the early stage of the voyage, it was abandoned and some of its passengers taken aboard the Mayflower.The ship left Europe on 6 September and dropped anchor off the coast of North America on 11 November 1620 CE. After a harrowing winter during which 50% of the ...

The Mayflower is the name of the cargo ship that brought the Puritan separatists (known as pilgrims) to North America in 1620 CE. It was a type of sailing ship known as a carrack with three masts with square-rigged sails on the main and foremast, three decks (upper, gun, and cargo), and measured roughly 100 feet (27 m) long and 25 feet (7 m) wide. The pilgrim passengers, and those not ...

With a view to eventually building homes and harvesting crops, the Mayflower would have been stocked with axes, chisels, hammers, handsaws, hoes, nails, shovels, spades, and many other useful items. Of all the tools on board, though, only one turned out to be absolutely critical to the success of the Mayflower voyage.

Exploring the Mayflower trail. The Mayflower trail follows the journey of the Mayflower Pilgrims, the ship and their voyage through villages, towns and cities. Follow in the footsteps of the Mayflower Pilgrims. Visit the birthplace of Williams Bradford and Brewster and trace their journeys as they began to worship in secret and made attempts to ...

Transcript. The Mayflower sailed from England on September 6, 1620, heading for the New World. Though the Pilgrims' journey is an iconic one, not much is known about the ship that made it possible. Few records exist prior to its purchase by English merchant Christopher Jones in 1608. While historians can make assumptions based on similar ...

Well it's all down to a ship that left England on this day 400 years ago. On 16 September 1620, the ship called the Mayflower set sail from Plymouth - on board were more than 100 passengers all ...

THE VOYAGE OF THE MAYFLOWER (1620)1 The first permanent English settlement in North America was founded by merchants and entrepreneurs as a royally chartered company in 1607 in Jamestown (at a site now lost) in what today is Virginia. Thirteen years later, ardent religious believers seeking to separate

The Mayflower's Voyage and Arrival in Massachusetts. AO August 12, 2023. American History Articles 0 Comments 0. On September 16, 1620, 102 English passengers set sail on the Mayflower as it made its way from Plymouth and arrived in Cape Cod in November of the same year. Protestant Separatists who wanted to establish a church in the New World ...

On the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the Pilgrims in New England on the Mayflower, Martyn Whittock explores the reasons for migration to the New World in 1620 and later, and the significance of those migrants, both at the time and their impact on the evolution of the USA today. In November 1620, a battered sailing ship wearily worked its ...

Stories of the Mayflower. Mayflower 400 is a commemoration to remember the lives of the passengers who travelled on the Mayflower and the Native American people they encountered. There are countless stories connected to the pioneering transatlantic voyage and its passengers - the places from where they came, the people they were and the legacy they left.

This year marks the 400th anniversary of another famous journey that set out from Plymouth docks: the sailing of the Mayflower in 1620, which carried the 'Pilgrim Fathers' across the Atlantic to found a colony in the New World - a settlement that they named 'Plymouth Plantation'. This milestone is being marked by an exhibition ...

If Plymouth Rock tells us little about the Pilgrims, Mayflower II speaks volumes. Climb aboard this replica of the small ship in which the Pilgrims made the fateful voyage, where 102 people lived together for 66 days as the ship passed through stormy North Atlantic waters.

The Plymouth Colony survived until 1691. 401 years ago today, November 21st, 102 passengers and 30 crew on the Mayflower landed at Plymouth Rock near modern day Cape Cod, Massachusetts after 10 weeks at sea. The passengers on the Mayflower were separatists from the Church of England who had fled to The Netherlands to escape what they viewed as ...

Virtual Voyages. Mayflower 400 UK has been presenting three series of digital programmes in the build-up to the 400-year anniversary of the ship's historic voyage. One of those is Virtual Voyages which showcases the places woven into the Mayflower story. Watch our episodes below to discover hidden secrets and fascinating insights, told through ...

Answers for Mayflower traveler crossword clue, 7 letters. Search for crossword clues found in the Daily Celebrity, NY Times, Daily Mirror, Telegraph and major publications. Find clues for Mayflower traveler or most any crossword answer or clues for crossword answers.

The Mayflower Voyage. For the passengers and crew who boarded the Mayflower some four centuries ago, the odds were firmly stacked against them as they looked to cross the Atlantic to start a new life.. By the time the group set sail from Plymouth on 16 September 1620, many of them had experienced religious persecution; trouble with the law (including time in prison for some); betrayal from ...