- COVID-19 COVERAGE

- CALL FOR SUBMISSIONS

- PRE-PRODUCTION

- POST-PRODUCTION

- BEHIND THE SCENES

- SG FILM RESOURCES

- 100 SECONDS ON THE RED SOFA

- SEE WHAT SEE?!

- @HELLOMRCAMERA

- PRODUCTION DIARIES

- RYAN’S STREAMING TIPS

- Digital Cinema Package (DCP) Creation Services

- PROJECT CONSULTANCY & EVENT MANAGEMENT

- LIVESTREAM SOLUTIONS

- SINEMA SHOWOFF!

- SINEMA FIRESIDE CHATS

- ADVERTISE WITH US

- THE INCITING INCIDENT: COMEDY

- THE INCITING INCIDENT: ROMANCE

- THE INCITING INCIDENT: DRAMA

- THE INCITING INCIDENT: HORROR

- THE INCITING INCIDENT: LIGHTNING ROUND #01

- PATRICK’S BEST OF ASIAN CINEMA

- STEFAN SAYS SO

- SINEMA OLD SCHOOL

Psychosinematics: A Psychological Breakdown of the Magic of ‘Spirited Away’ 9 min read

Psychosinematics is a series where we look into films and characters with a psychological perspective. In this installment, we look into Chihiro’s mind and journey as the hero.

There’s something about Hayao Miyazaki’s films that makes it so comforting and relatable despite their fantastical quality. Spirited Away is one of Studio Ghibli’s most beloved films, often enjoyed with a child-like wonder. But just as Spirited Away taps into our innocent sentiments, so too it explores deeper themes hidden in plain sight. In fact, Spirited Away is a trove of psychological insights. The relatability of these psychological experiences that Miyazaki draws on not only explains our affinity for his films, but also imparts a few comforting lessons.

Spirited Away tells the story of Chihiro, who is on a mission to save her parents after they are turned into pigs. Chihiro ends up working for Yubaba, an evil witch and the proprietor of the Aburaya bathhouse. Yubaba’s employees are bound to work in the bathhouse until they’re able to remember their real names. The bathhouse accommodates a throng of spirits ( kami) , both good and evil, based on the Japanese Shinto folklore.

Like many of Miyazaki’s films, a major theme in Spirited Away is a child’s symbolic journey into the world of adulthood. If we take a psychological view, the film can be read as a manifestation of Chihiro’s unconscious as she navigates the cold and frantic world of adulthood.

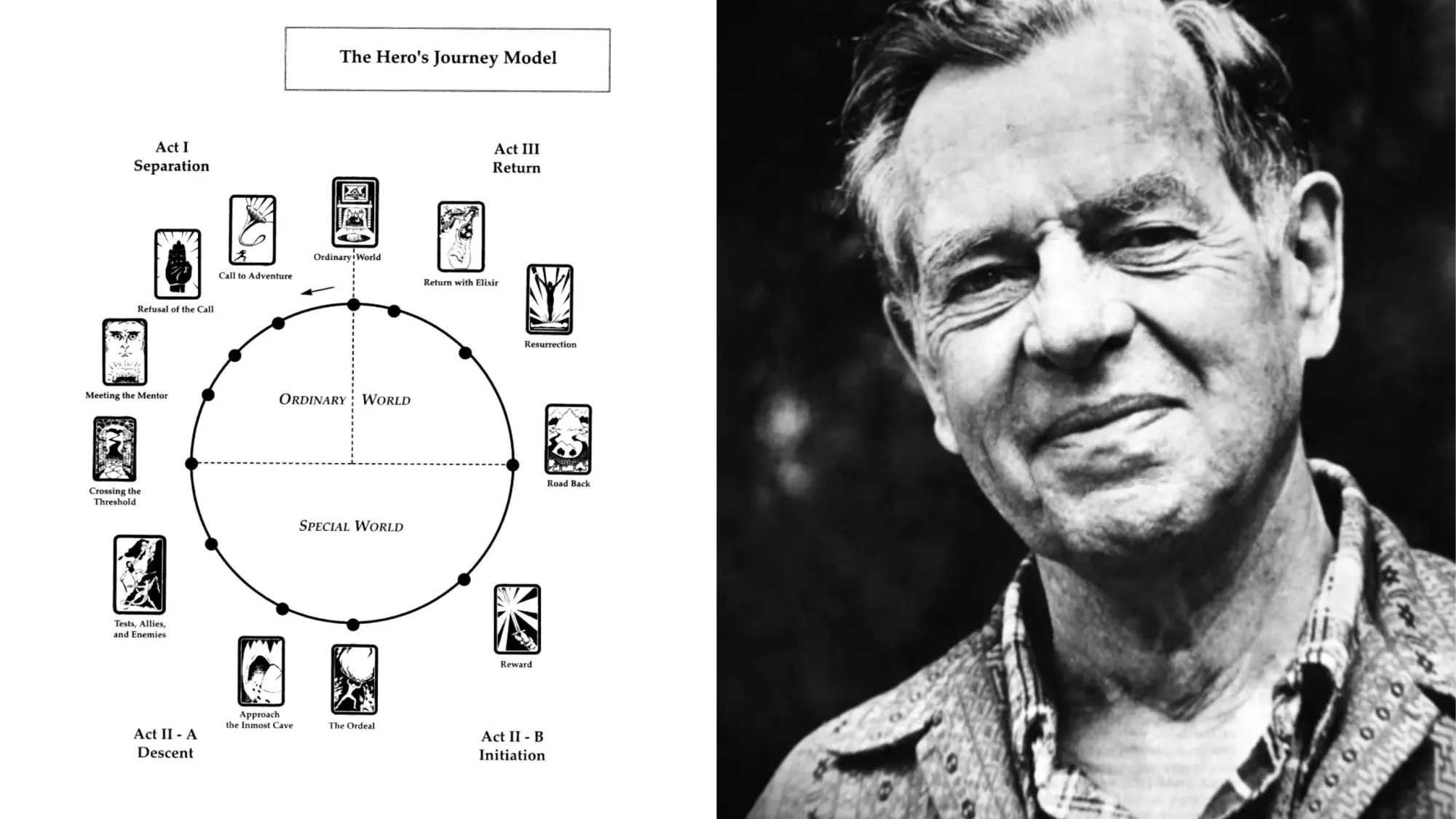

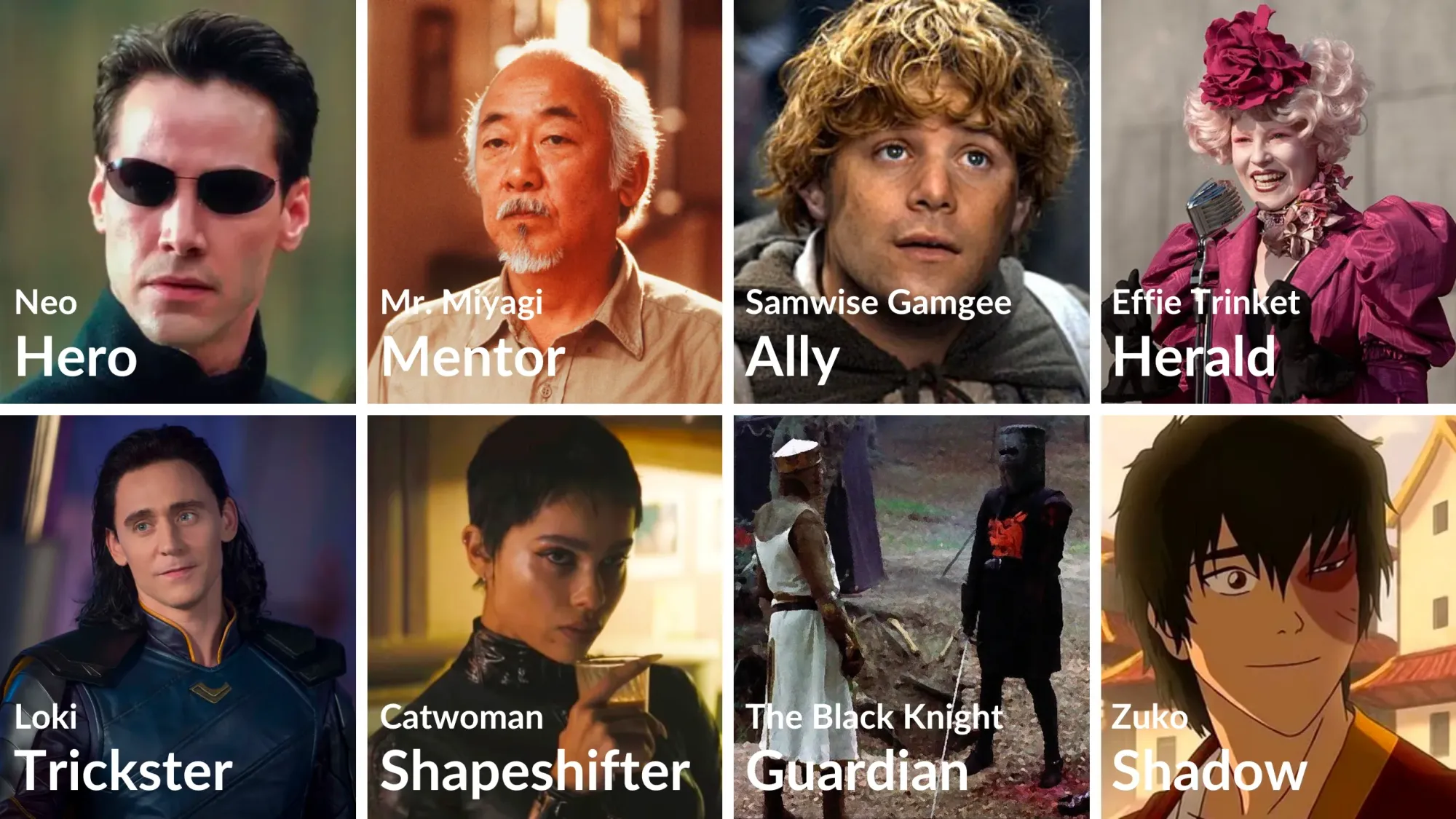

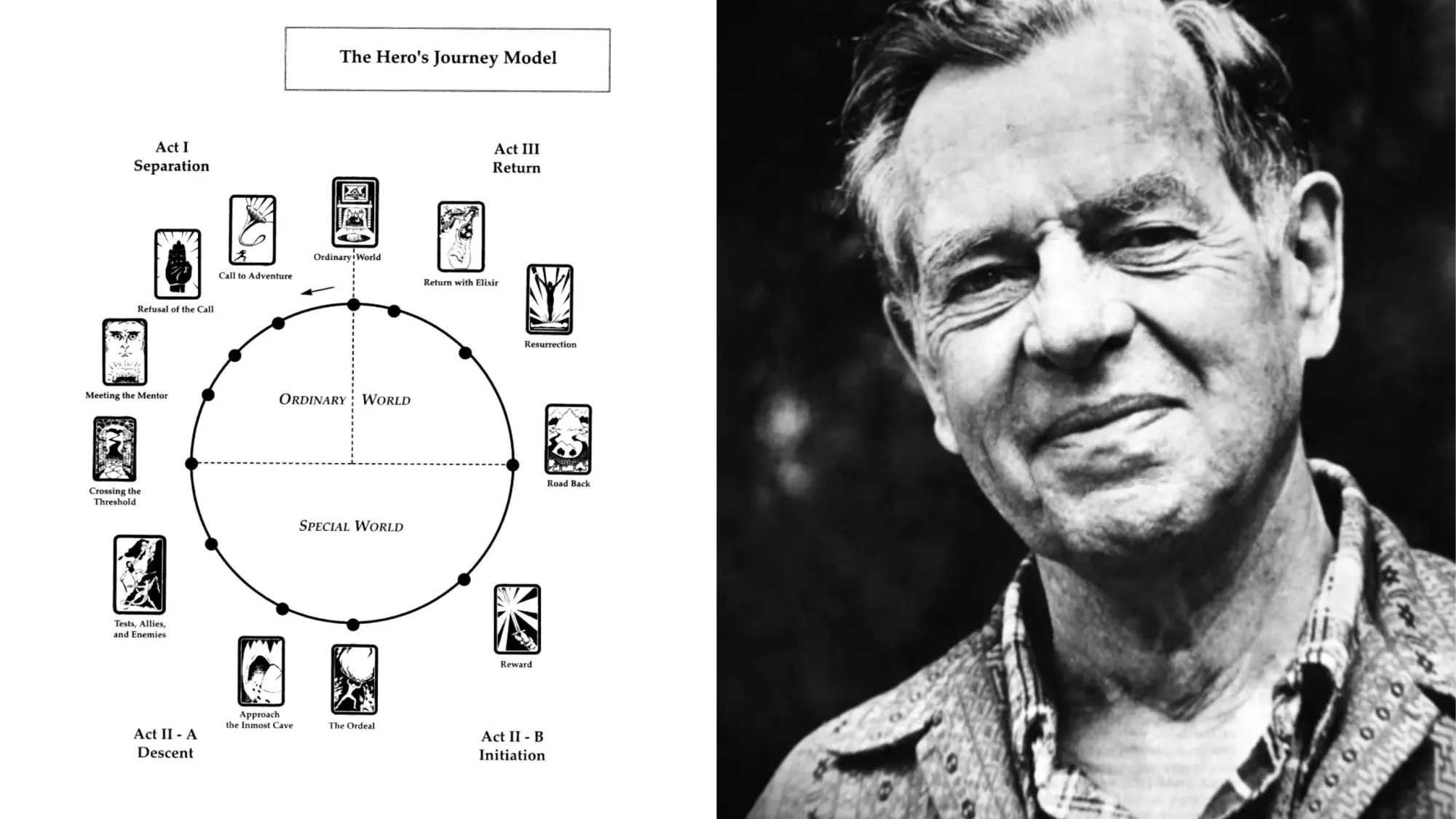

The unconscious mind is basically the part of the mind that contains underlying feelings, thoughts and urges that influence conscious behaviour and emotions. Psychologist C.G. Jung determined the idea of archetypes. They’re symbolic images and thoughts that represent our psychology, manifested in dreams, literature or art.

Spirited Away is rich in these archetypes and symbolism, reflecting Chihiro’s growth and the subconscious workings of her psyche. Let’s take a look at some of the psychological revelations in the film.

(Spoilers for Spirited Away!)

The Divine Child Archetype

According to Jung, the child hero archetype represents one’s journey to deal with growing up. The divine child archetype is a child with extraordinary potential and is often the protagonist in myths and legends.

In Spirited Away, Chihiro is the divine child. As she crosses the threshold into the spiritual realm, Chihiro is suddenly thrust into the adult world. Yubaba’s bathhouse is the symbol for this, with the hustle and bustle of the workers reminiscent of our own society. Chihiro struggles to figure her way around the bathhouse and the spirits, and to keep up with what’s needed of her.

The divine child is often described as “smaller than small yet bigger than big”. What this means is that as a child, Chihiro is inexperienced and naive. Yet the divine child possesses a potential that sets her apart as the hero.

Chihiro fits this archetype perfectly. The other spirits working in the bathhouse are harsh towards her because she’s human, receiving little kindness from others except for Haku, Yubaba’s apprentice, and Lin, a worker in the batthouse. She’s given difficult tasks, yet she puts on a strong face, because the only way she can save her parents is to follow Yubaba’s wishes.

When the stink spirit (Okusare) enters the bathhouse, Yubaba throws the responsibility to take care of him to Chihiro, while everyone else just stands around to watch her. Eager to please Yubaba, Chihiro tackles this hurdle head on in spite of her inexperience, to the surprise of everyone.

But she is still just a child. We often see Chihiro holding her tears in or crying her secret as she attempts to manage her responsibilities and her feelings.

When Chihiro suddenly bursts into tears while she eats, Jung would consider this as her unconscious emotions rising to the surface. She’s been too busy to meet everyone’s expectations of her that she hasn’t had the chance to even feel sad or process her emotions.

This is particularly moving, as Miyazaki exposes a universal human weakness that everyone can relate to at some point.

Subconsciously, these feelings that come with growing up are manifested in different ways. For Chihiro, they’re reflected through Yubaba’s bathhouse.

The Spirit Archetype

Now let’s look at an obvious element of Chihiro’s journey. Jung describes the spirit archetype as both helpful and evil energies that prompt the hero towards her purpose. The spirit archetype represents the contradictions and complexities of Chihiro’s psyche, which promote achieving “higher consciousness”.

The spirit archetype is usually involved in psychic transformations of the hero. It’s interesting to note that Yubaba is reminiscent of other mythical spirits. When Yubaba turns into her half-bird form, she looks like a harpy. Harpies in greek mythology are fearsome half-bird, half-human hybrids, who steal food and people.

Yubaba steals Chihiro’s name and calls her Sen, stripping Chihiro of her identity. This is similar to the psychological idea of diminution of personality, which means that one’s personality undergoes a drastic change. But this eventually ends with a transformation, kind of like a rebirth.

By the time she recovers her real name and is set free, Chihiro is now victorious. She has grown from a fearful child to the hero of her own psyche.

Yubaba is also similar to Baba Yaga, an evil witch in Slavic mythology. This evil witch is often sinister, but is sometimes seen as a benefactor to the hero’s cause. Like Jung’s description of the spirit archetype, she forces the hero to face the issue. Yubaba triggers Chihiro’s growth into adulthood by throwing challenges at the child hero.

While Yubaba is the embodiment of an evil spirit, Haku is the nurturing soul that supports the hero throughout her mission. Miyazaki alludes to Shinto folklore, where the dragon kami represents protection and loyalty.

A Hero’s Triumph

Chihiro overcomes her “mere human status” that everyone initially disregards her for, and not only succeeds in her mission to save her parents, but also becomes everyone’s saviour. Symbolically, Chihiro has overcome her unconscious emotions and fears, and has attained a higher consciousness that sets her apart from everyone else.

The world of Spirited Away is essentially a look into Chihiro’s psyche, as she evolves into her independence and the difficulties that come with growing up.

In the beginning, she feared entering the cave and crossing into the world of the kami. But by the end, she looks at that world longingly.

A comparison of the ending scene of the film to the opening reveals her growth from a child to a hero. Watching Chihiro’s journey gives us an insight into our own. And with this psychological view, it’s comforting to know that the challenges thrown our way is something everyone must contend with in our own ways.

“The hero’s main feat is to overcome the monster of darkness: it is the long-hoped-for and expected triumph of consciousness over the unconscious.” C.G. Jung

The beauty of Spirited Away is in its universality despite the fantastical atmosphere. Like Chihiro, we have all experienced some kind of subconscious transformation accompanied by challenges. Miyazaki’s film shows us the necessity of leaving our childhood behind, but also reminds us that the child hero will always live within us.

Spirited Away is now (finally) available for streaming on Netflix .

– Psychosinematics: An Introspection of ‘Baahubali’s’ Queen Sivagami

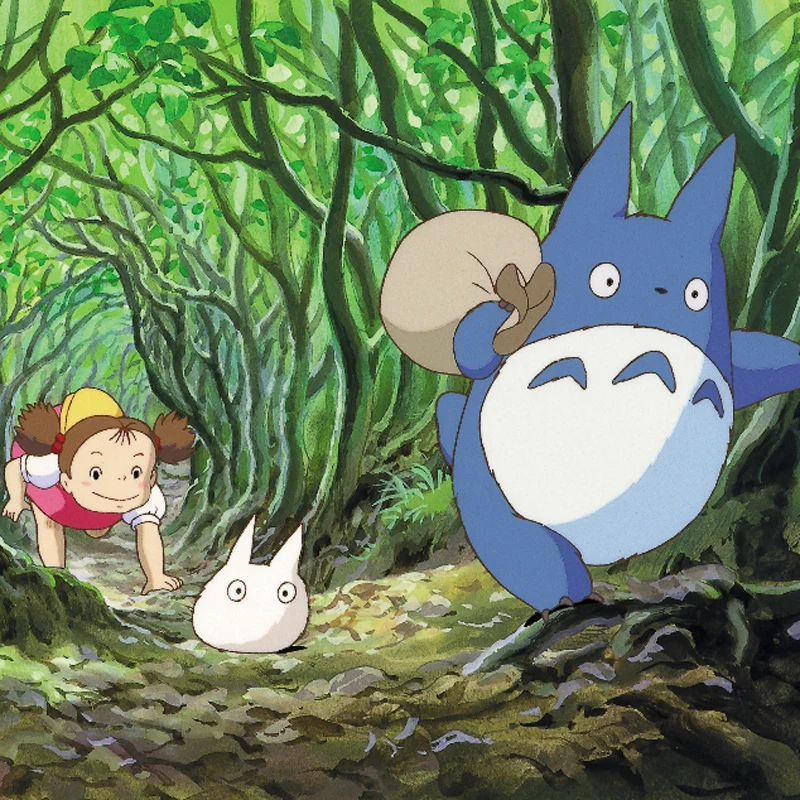

– A Masterclass in Animation Storytelling, MY NEIGHBOR TOTORO となりのトトロ Continues to Beguile Audiences 30 Years On

Share this:

Judith Ramirez

Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, great movies, chaz's journal, contributors, chihiro's journey: analyzing "spirited away".

In July 2012, Roger wrote about viewing “ Spirited Away ” for a third time and how he was then “ struck by a quality between generosity and love. ” It was during that viewing he “ began to focus on the elements in the picture that didn’t need to be there. ” Recently, I was re-reading that essay as I was watching the Blu-ray of "Spirited Away" three times (Japanese, English dub and back to Japanese) back-to-back-to-back.

Suddenly, I was struck by the visual cues Hayao Miyazaki presents in the beginning of the film that set up the character of Chihiro before she becomes Sen. I called it my A-ha moment.

Chihiro has been characterized as whiny, but I think if you understand her situation and contrast her intuitiveness with her parents' obliviousness, she seems less so. In the real world before she becomes Sen, there is no doubt she is a bit sullen. Not unlike Riley in Pixar's " Inside Out ," she's unhappy with being forced to move away from her friends. Her friends have given her a nice bouquet. If there are five stages of loss and grief (denial/isolation, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance), then Chihiro is at the end of denial, and her comment about how unfortunate it is to get her first bouquet as a farewell gift indicates she is entering anger.

When her father, Akio, takes the rural street that leads them to what looks like an old unused amusement park, Chihiro picks up cues that her parents do not. She's troubled and a bit frightened by the moss-covered stone statues. Something about them makes her anxious. In this respect, she is not unlike Lucy Pevensie from "The Chronicles of Narnia." Narnia is closed off from children when they reach a certain age in the real world (until death returns Lucy, Edmund, Peter, Digory and Polly). Lucy is the most intuitive of the four Pevensies although she too has a moment of envy that signals she won't be able to return. Chihiro at ten is still more child than adult and thus more intuitive than her parents.

If we consider that Chihiro senses something is wrong, then her pleading with her parents not to enter the tunnel seem less whiny. She becomes Cassandra, a prophet whose warnings go unheeded. Out on the other side, there is a grass meadow and more stone statues. Chihiro's anxiety over the statues isn't the last bit of foreshadowing that Miyazaki provides visually.

In the following scenes, Miyazaki exploits the visual nature of the Japanese language. Japanese is not like English. Instead of an alphabet, it uses two syllabary systems and Chinese characters. The syllabary systems, hiragana and katakana, originated from Chinese characters, but are used to represent syllables. Hiragana is used for post-positionals and parts of words not fully expressed by Chinese characters (such as inflections for verbs and adjectives). Katakana is used for foreign words and onomatopoeia. Chinese characters often symbolize concrete things. Japanese poetry is filled with wordplay and the following scenes are filled with visual cues and words that can have double meanings.

On the first building we see an incomplete phrase. Alone the character 正 would be read "sho" or "sei" and means right, righteous, justice and genuine, but 正 also suggests 正しい, meaning correct, right, honest and truthful. There's more signs on the shops in the main road. At first casual glance as we go by, it does seem like they are all part of advertising for restaurants, but on closer examination, that proves not to be true.

When we get to the main street we see the characters 市場 for market (ichiba) and the word 自由 (jiyuu) for freedom. Then there are some disquieting Chinese characters. The mother says that all the places are restaurants. When you see 天 float by you might think 天ぷら (for tempura), but actually the characters are: 天祖 (tensoo) for the ancestral goddess of the sun, Amaterasu. In one frame we see only 天狗 (tengu), with "ten" above and "gu" below. The character 狗 means dog, but can be used for dog meat (狗肉)which is not commonly eaten in Japan (and could suggest the homophone 苦肉 or "kuniku," which literally means bitter meat meaning a countermeasure that requires personal sacrifice. The character usually used for dog is 犬. Tengu, however, or heavenly dog, a legendary creature or supernatural being (yookai) that can be either harbingers of war or protective spirits of the mountains and forests.

Floating at the corner of one building is 骨 which means bone and it could be a restaurant term as in the creamy broth: 豚骨 (tonkotsu) which is literally pig bone. Yet bone or "hone" is used in idiomatic phrases such as hone-nashi meaning to lack moral backbone.

Some of the Chinese characters are just a little off, enough to make you think. Most obviously is the one syllabary and one Chinese character that are written backwards when we look above at the arch. The characters are 飢と食と会 which seem to substitute for 飢える (ueru, to starve), 食べる(taberu, to eat) and 会う(au, to meet). The と signifies "and." It should read eat ( 食べる), drink (飲む) and meet (会う) or something like that, but the last two symbols are backwards on either side. Looking at these, perhaps Chihiro senses something is wrong.

Further, right before the father Akio turns down a small alleyway, he is framed by the characters for heaven on the left side of the screen and on the right side for devil. Soon after, what he sees is, especially in Japan, a supernaturally large buffet. While he assures Chihiro that he can pay for the feast and we remember he did have that foreign car, a Japanese person might be quickly calculating in their minds the exorbitant cost.

Chihiro briefly leaves her parents and above her head flashes a sign that reminds us both of family, pigs and death. The character 冢 (tsuka) means hill or mound. Yet this is not the preferred character which would be 塚 (also read tsuka). The small cross represents ground or earth. Without that radical, 冢 is only one stroke different than the word for house 家 (uchi) which is the same one used for the Chinese character combination that means family 家族 (kazoku). The significance here is that pig (豚 or buta) under a roof represents house/home 家. That quick flash of this character gives the suggestion of pig and family. Yet it is also like bone (骨 or hone) associated with death as in grave (冢穴).

This character 冢 (tsuka) seems to foreshadow the transformation of her parents into pigs and her journey to figure out how to save her parents from death. The more she sees of this amusement park, the more frightened she becomes. There's an expensive public bathhouse at the end of the pathway and all the lamps seems to be associated with it, but where are the people? Where are the vacationers, the retired old people and the middle-aged women on retreat? Where are the vendors, pushing you to buy anything and everything because everyone must return home with presents (omiyage) for their neighbors, co-workers and relatives. Anyone who has been on the trail to great temples or been on a hot springs tour will know that for such a grand feast and for such a splendid public bathhouse, these scenes are much too quiet.

Chihiro runs back, perhaps to warn her parents only to find her parents have been transformed into hogs.

The movie is called "Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi" (千と千尋の神隠し). Sen means a thousand, but the pronunciation of the character can change to "chi" as it does in the name Chihiro. The "hiro" in Chihiro means to ask questions. Kamikakushi means spirited away with kami meaning spirit or god and kakushi meaning hidden. So perhaps we can translate the title as "Sen and the Mysterious Disappearance of Chihiro."

"Spirited Away" was released in in July 2001. Most Studio Ghibli movies were released in July, and in Japan, I feel this is especially significant in the case of "Spirited Away" and " When Marnie Was There " because it is the Obon season, a time when Japanese believe the spirits of their ancestors walk the earth and return to their furusato (hometown). That time period (mid-July to August) is, much like New Year's week, a hard time to get things done in Japan due to the various celebrations and the people who leave on vacation. We do learn later in the movie that the character on the first building, 正, is part of a combination 正月 which we translate to mean New Year.

Although Roger didn't read or speak Japanese, he saw the rich detail. This is one of those movies worthy of a frame-by-frame analysis. For the people who read Japanese, some of what I have written above may have been intuitively realized. There are other things I still wonder about such as the prominence of the Japanese syllables of “me” and “yu” throughout. I’ve read one theory that put together into “yume” it means “dream.” I’d enjoy hearing other people’s thoughts, theories and feelings about “Spirited Away.”

Jana Monji, made in San Diego, California, lost in Japan several times, has written about theater and movies for the LA Weekly , LA Times , and currently, Examiner.com and the Pasadena Weekly . Her short fiction has been published in the Asian American Literary Review .

Latest blog posts

Cannes 2024: The Weirdo Films of Cannes

Cannes 2024: The Substance, Visiting Hours

Jack Flack Always Escapes: Dabney Coleman (1932-2024)

Cannes 2024 Video #3: Megalopolis, Kinds of Kindness, Oh Canada, Bird, Wild Diamond

Latest reviews.

The Garfield Movie

Horizon: An American Saga - Chapter 1

Robert daniels.

Back to Black

Peyton robinson.

The Strangers: Chapter 1

Brian tallerico.

The Big Cigar

Ghibli Wiki

Warning: the wiki content may contain spoilers!

- Português do Brasil

Spirited Away

- View history

The story is about the adventures of a young ten-year-old girl named Chihiro as she wanders into the world of the gods and spirits. She is forced to work at a bathhouse following her parents being turned into pigs by the evil witch Yubaba .

The film was made to please the ten-year-old daughter of Hayao Miyazaki's personal friend, director Seiji Okuda . Okuda's daughter even became the model for the film's protagonist, Chihiro. During the film's planning phase, Miyazaki gathered the daughters of Ghibli's staff in a mountain hut in Shinano Province to hold a training seminar. His experience led him to wanting to make a film for them, since he had never made a movie for girls at the age of 10.

The film earned a massive ¥31,680 billion in Japan, a record only beaten by Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba – The Movie: Mugen Train in 2020. [1] It received multiple international awards, including the Golden Bear Award at the 52nd Berlin International Film Festival and the second Oscar ever awarded for Best Animated Feature, the first anime film to win an Academy Award, and the only winner of that award to win among five nominees. Due to his efforts in promoting the film in North America, John Lasseter , one of the founding fathers of Pixar , became the executive producer of the English dub.

It won first place in the Studio Ghibli general poll held in 2016, and was re-screened in five movie theaters around Japan for seven days from September 10 to 16, 2016. It was adapted as a stage play by John Caird , starring Kanna Hashimoto and Mone Kamishiraishi , and debuted in February 2022 in Tokyo, Japan and premiered in April 2023 in the United States. [2]

The film is available for streaming on Max, and purchasable on most digital storefronts.

- 1.1 One Summer's Day

- 1.2 Nightfall

- 1.3 The Contract

- 1.4 Life at the Bathhouse

- 1.5 Sen's Courage

- 1.6 The Return

- 2 Characters

- 3 Director's Message

- 4.2 Child Labor

- 4.3 A World of No-Faces

- 4.4 Haku the Pretty Boy

- 4.5 Yubaba and Zeniba

- 4.6 Power of Words

- 4.7 Other Motifs

- 5.1.1 Inspired by Japan

- 5.1.2 Hostess Bars

- 5.2.2 Delay

- 5.2.3 Announcement

- 5.3 Dubbing

- 6 Sound Mixing

- 7.1 Home Media

- 7.2 Television

- 8 Version Differences

- 9 Reception

- 10 Awards and Achievements

- 11 Soundtracks

- 12.1 Additional Voices

- 14.1 Home Video

- 14.2 Publishing

- 15 References

- 16 External Links

- 17 Navigation

One Summer's Day [ ]

"What's this old building? It looks like an entrance." "Honey, get back in the car we're going to be late. Chihiro!" "Oh for God's sake... This Building's not old, it's fake. This stone is made of plaster. The wind's pulling us in. " "What is it?" "Come on, Let's go in, I want to see what's on the other side." "I'm not going! It's gives me the creeps!" "Don't be such a scaredy cat, Chihiro. Let's just take a look." —Chihiro's parents venture into the tunnel

Chihiro unsure about following her parents.

Chihiro Ogino , a disaffected child, is annoyed about having to move to a new town. She is traveling with her parents in their 1996 Audi A4 Quattro to their new home. While driving to their new house, Chihiro's father attempts to follow a shortcut; they subsequently lose their way and come across a mysterious red gate and a tunnel which exits to a clock tower and leads to what appears to be an abandoned theme park , lined with seemingly empty restaurants. Finding a restaurant fully-stocked with unattended food, both parents eat the food they find there and, as a result, transform into pigs.

Nightfall [ ]

"It's just a dream. Wake up, wake up. Wake up! Please wake up. It's just a dream, a stupid dream. Go away, disappear. Disappear. I'm fading away! This has to be a dream." "Don't be afraid. I'm a friend." "No, no, no!" —Chihiro's starts to disappear

Chihiro starts to fade away as nightfall begins.

Chihiro's distress at losing her parents is compounded by the discoveries that the world around her has changed and that her body seems to be disappearing. A mysterious boy named Haku appears, comforts Chihiro, and gives her a red berry to eat, which makes her solid again. He smuggles her into a large bathhouse owned and operated by the evil witch Yubaba , where thousands of spirits come to refresh themselves. Haku tells Chihiro that the only way she can remain in the spirit-world long enough to rescue her parents is by gaining employment in Yubaba's bathhouse. When Chihiro asks Haku how he seems to know her so well, Haku replies that he has known Chihiro since she was very small.

The Contract [ ]

"Why on earth should I hire you? Anyone can see you're a lazy, spoiled, stupid crybaby. What job would I possibly have for someone like you? You're wasting your time. I've got all the bums I need. Or maybe I'll give you the nastiest job I've got... and work you night and day... until you breathe your very last breath!" —Yubaba considers hiring Chihiro

Haku helps Chihiro survive the night at the bathhouse.

At first, she tries to get work with Kamajī , who works at the boiler room , but is rejected. Kamajī instead hands Chihiro off to the worker, Lin , to take her to Yubaba. In Yubaba's penthouse suite , Chihiro repeatedly asks for a job, overriding the monstrous witch's refusals. Yubaba ultimately consents, on condition that Chihiro give up her name. Yubaba literally takes possession of Chihiro's real name (荻野 千尋 , Ogino Chihiro) by grasping the kanji characters from Chihiro's signed contract, leaving Chihiro with one part of one character of her original two-character name, in isolation pronounced "Sen" (千). Taking a person's name gives Yubaba power to keep its owner in her service permanently; it is revealed that Haku is also in Yubaba's service, and remains so because she has taken part of his full name.

Life at the Bathhouse [ ]

"It's a Stink Spirit - Yes, and a large one, too." "It's headed straight for the bridge! Please turn back. Please go!" "The baths are closed for the night. Please withdraw, please!" "Stinky!" "That's odd. Stink Spirits feel different." "Well, now that it's here, better go greet it! All we can do is get rid of it fast." —The Bathhouse staff encounter the Stink Spirit

Chihiro helps free a river spirit from his sludgy form.

While at work, Sen gives admittance to a wraithlike spirit called No-Face , who returns the favor by helping her obtain water needed to bathe a "stink sigil " whom no one else will help. After bathing, the stink spirit is revealed to be a powerful River Spirit who rewards Sen with a strong emetic dumpling.

Subsequently, Sen sees Haku in the form of a white dragon, and later on helps save him from attacking Shikigami . Searching for the injured Haku, Sen encounters Yubaba's big infant son, Boh at her apartment . Sen finds Haku, who was attacked by Zeniba , Yubaba's twin sister, because Haku had stolen her sigil. When Boh distracts Zeniba, she transforms Boh into a mouse, and Yu-Bird into a hummingbird. Zeniba tells Sen that Haku has stolen a magic gold seal from her, and warns Sen that it carries a deadly curse. Haku then rips up the remaining Shikigami, causing Zeniba to disappear. After Haku dives to the boiler room with Sen and Boh on his back, she feeds him part of the dumpling. Doing this, Sen causes Haku to spit out the stolen sigil, which he had swallowed. He also chokes up a black slug which Sen squishes, yet Haku remains unconscious. Hoping to lift Zeniba's curse and save Haku from a coma, Sen decides to set out to return the sigil to Zeniba.

No-Face develops an obsession for Chihiro, even propositioning her with gold.

Meanwhile, No-Face has become intoxicated with the greedy atmosphere of the bathhouse and swells into a huge monster, giving illusory gold to the bathhouse workers in exchange for food. When the workers do not comply with his demands, he eats several of them; this causes a panic and the entire bathhouse is thrown into pandemonium. Sen manages to solve the problem by feeding No-Face the remaining emetic, making him regurgitate several million tons of black poison and the bathhouse workers, then leads him out of the bathhouse. No-Face reverts to his former size and demure personality, and along with Sen and Boh, takes the sea railway and travel by train to Zeniba's faraway cottage at Swamp Bottom . At Zeniba's home, Sen gives the sigil back to Zeniba, apologizing for having squished the black slug. An amused Zeniba reveals that the slug had been one of Yubaba's means of controlling Haku, and that the curse put on the seal has already been broken by Sen's friendship.

Sen's Courage [ ]

"Who are you?" "Yubaba's older twin sister. Now hand over the dragon." "What are you going to do? He needs help." "That dragon's a thief. He works for my sister. He stole a valuable seal from my house." "Haku would never do that. He's too kind. All dragons are kind." "Kind and stupid... and eager to learn my sister's magical ways. This boy will do anything that greedy woman wants. Now step aside." —Chihiro meets Zeniba

Chihiro learning Haku's "real" name.

In the bathhouse, Yubaba discovers Boh's absence and is enraged. Haku, now revived and restored to his human form, offers Boh's safe return in exchange for Sen and her parents to be freed and restored to normal. Yubaba accepts, but promises to set Sen one final task. Along with Boh and Yu-Bird, Haku and Sen fly back to the bathhouse, leaving No-Face to live with Zeniba as her assistant. En route to the bathhouse, Chihiro remembers a previously suggested meeting with Haku: some time ago, she had fallen into a river and was rescued by the river's spirit. She then realizes that the spirit of this river, called Kohaku River, and her friend Haku are one and the same, and thus revealing Haku's real name, Nigihayami Kohakunushi , which literally translates to "God of the Swift Amber River." At this realization, Haku's dragon form is molted away, and he is completely freed from Yubaba's control.

The Return [ ]

"Go back the way you came. But don't look back until you're out of the tunnel." "But what about you?" "I'll tell Yubaba I'm quitting my apprenticeship. I'm fine now. I have my name back. Now I can go home too." "Will we meet again somewhere?" "I'm sure of it." "Promise?" "Promise." "Now go, and don't look back." —Haku says farewell to Chihiro

The bathhouse staff cheers as Chihiro breaks her contract from Yubaba .

Yubaba and a large crowd have gathered to witness Chihiro's final task: to pick out her cursed parents from a group of pigs. Chihiro correctly states that none of the pigs displayed by Yubaba are her parents, and thus wins back both her parents' humanity and her own freedom from the bathhouse. Afterward, Haku takes Chihiro to rejoin her restored parents. He bids her farewell and promises that he will come see her again. As Chihiro and her parents return to their world, her parents lose all memory of their visit to the spirit world. The family then gets back in their car and resume their journey to their new home. Miyazaki himself has stated that Chihiro also forgets her adventure in the spirit world, but it is hard to tell in the dub version whether or not she did because of extra lines of dialogue added at the end. These extra lines are from Chihiro's dad and herself; her dad worries about her having to live somewhere else and go to a different school, but Chihiro replies that she thinks she can handle it. In the sub version, she just silently thinks about her adventure.

Characters [ ]

Director's message [ ].

"This film is akin to an adventure story, but without the agitation of weapons or superpowers. And even if I speak of adventures, the subject is not the confrontation between good and evil, but rather the story of a little girl who, thrown into a world where brave people and characters mingle dishonest, will discipline themselves, learn friendship and dedication, and will use all resources to survive. She gets out of the situation, she dodges, and returns for a time to her daily life. At the same time, the world is not destroyed, and this is not due to the extermination of evil, but to the fact that Chihiro possesses this life force. Today the world has become ambiguous. The main subject of this film is to portray in a clear way this world which seems to be consumed, and this borrowing, despite this ambiguity, the form of a fantasy. In a world where they are guarded, protected, kept at a distance, children allow their frail arms and legs to hypertrophy. Chihiro's slender arms and legs, the angry expression on her face, typical of someone who doesn't easily have fun, reflects that. But in truth, when she finds herself confronted with a situation of crisis, where relations are blocked, one realizes that her strength of adaptation and her perseverance rebound, and that she commits her life to deploying a faculty of judgment. and a capacity to act decisively. Under the circumstances faced by Chihiro, most men would panic or refuse to believe it, but these men would end up being devoured. We can say that in fact, Chihiro's talent is to find the strength not to be devoured. In no way did she become the heroine because she would be a pretty little girl with an exceptional heart. On this point, it is one of the merits of this film, and it is also why I intended it for the little girls of ten years. Speech is a force. In the world where Chihiro got lost, the act of uttering a word constitutes an act of decisive weight. At the baths run by Yubâba, if Chihiro pronounces the words: "I don't want," "I want to go home," the witch immediately throws her outside; all that remains is to wander with nowhere to go and disappear, or be turned into a hen and lay eggs until eaten. Conversely, when Chihiro says: "I will work here," witch she is, Yubâba cannot ignore it. Today, the word has an unlimited lightness, you can say anything, it is received like a bubble and only restores a reflection of reality. Yet the fact that speaking is a force is still true today. A word is only vain, without force, because it is emptied of its meaning. The act of stealing the name is not that of transforming it into a nickname, it is an approach which aims to totally dominate his opponent. Sen is scared to find that she has forgotten her own name, Chihiro. In addition, every time she goes to visit her parents at the pigsty, she gradually becomes indifferent to the fate of these changed into pigs. In the world of Yubâba, one must continually live in fear of being devoured. In this difficult environment, Chihiro comes alive. Usually frowning, his face will radiate a charming expression for the finale of the film. However, the nature of the world is in no way modified. This film possesses or appeals to a persuasive force according to which the word represents an own will, an energy. There, the fact of having realized a fantasy taking place in Japan has a meaning. Even though this is a fairy tale, I didn't want to do a western fairy tale, with many loopholes. This film may seem to be in imitation of a different world, but rather I wanted to think about a direct line with the tales of the past like Suzume no Oyado (The house of the hawk) or Nezumi no Goten (The Palace of Mice). The fact of giving the world where Yubâba lives a Western side suggests something that we have already seen somewhere without being able to distinguish between the dream and the real, and at the same time, it is a melting pot. many images from traditional Japanese ideas. The whole range of folklore - stories, traditions, events, ideas, from religious rites to magic - as abundant and unique as it is, is simply ignored. Kachi-kachi Yama (The mountain that cracks) or Momotarô have certainly lost their persuasive force. However, I also have to say that just to load a cute world, like there is in folklore, with traditional elements, would really be limited imagination. Children, surrounded by high-tech, superficial products, are increasingly losing their roots. We have a very abundant tradition, a tradition that we have the duty to pass on to them. I think you have to introduce traditional ideas into a modern narrative, like you embed a piece in a vivid mosaic. The world of cinema will thus have a new persuasive force. At the same time, I realize once again that we Japanese are islanders. In an age without borders, men who do not own places will be looked down upon. A place is a past, it's a story. I think that the men who have no history and the people who have forgotten their past will disappear like mayflies, or will be turned into hens to lay eggs while waiting to be eaten. I think I made this film with the real wish that it would reach an audience of ten-year-old girls." —Hayao Miyazaki on the film's official website

Work Motif [ ]

While the film featured a climactic flying scene with Haku and Chihiro , Miyazaki was more enamored by the train scenes, but feared adding too many would recall Kenji Miyazawa's Night on the Galactic Railroad .

Upon completion of the film, Hayao Miyazaki held a press conference at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. He was asked that towards the end of the film, audiences finally saw a flying scene, with Chihiro and Haku flying again. Miyazaki responded, "I never thought about whether we should include scenes of Haku or Chihiro flying or not. But on my own, I did think about having Chihiro ride on a train. And since I spent so much time telling people we should do this, I was really happy when she finally did get on board. We were collecting sounds of train audible through the shadows of trees, or shots of the trains running, but from my experience that usually just results in train scenes and nothing more. So in that sense I thought it really was wonderful to have Chihiro actually ride the train, even better than flying through the air."

"I actually wanted to include a few more train scenes, but we were ultimately unable to do because of the structure of the film. Since I had spent a lot of time talking about the train idea, it got to the point where those around me were asking if there wasn't some way we could include the other scenes. I planned to tell them that, if we could include them, this could wind up being like Kenji Miyazawa's Night on the Galactic Railroad. Unfortunately we couldn't include the scenes. It's the sort of things that happens in making films, and it can't be helped.

Child Labor [ ]

Miyazaki recalled seeing an NHK documentary of child labor in Peru, and said that it is still ever present in other parts of the world, and was also part of Japanese history.

When asked why the film centered around Chihiro having to work, Miyazaki explained, "I got the idea from a documentary I saw on the NHK TV channel, about child labor in Peru. I thought that, if I were to make a film for the sake of all the children on earth, it would have to be something that any child could understand, no matter what sort of life they were living. I really didn't want to make a film that only Japanese kids would understand. And besides, the idea that children don't have to work is really very new. My grandfather, for example, went off to work as an apprentice at the age of eight, and as a result he never learned how to read. That's the way things were in Japan until recently. The only reason kids don't have to work today is because Japan experienced a period of high economic growth after the war. In reality, most children in the world still have to work. I'm not saying that's good or bad, just that we need to remember it. In truth, people are social animals, so it's not good for us to live without some sort of connection to society. We have to work.

A World of No-Faces [ ]

For Miyazaki, No-Face represented people's unknowable intent.

When asked what is No-Face's purpose, Miyazaki responded, "There are No-Faces all around us. Because there's only a paper-thin difference between evil spirits and gods. And on top of that, this film is set in Aburaya, a bathhouse. So once you open the doors, all sorts of things come in." When asked to explain if Miyazaki were referring to the youth of today, he explained, "I didn't make the film with that in mind. No-Face is just a name and a mask, and other than that we don't really know what he's thinking or what he wants to do. We just named him No-Face because his expression almost never changes; that's all. But I do think there are people like him everywhere, people who want to glom on to someone but have no sense of self.

Haku the Pretty Boy [ ]

When describing why he made Haku a bishōnen or 'pretty boy character', Miyazaki responded that he originally had no intention to, "But if you've got a girl, you've got a boy; if there's a boy, there's a girl. That's what makes our world. And since our heroine's a tad ugly, I thought without a fair and handsome boy, it would be too boring." When asked to elaborate on whether it was intentional in depicting Chihiro as ugly, "No, but I really don't think she's your typical beautiful girl. I didn't draw her thinking that at all. I wanted to depict a girl who would make viewers worry about what she would become in the future. And while I was drawing her, I thought that she would probably become cool. Because they can change so suddenly. Take people's faces; I think that people create the faces they wear. So I didn't want to draw Chihiro with your stand cute-girl face. And I was right in making that decision."

Yubaba and Zeniba [ ]

Character designer Masashi Ando initially wanted Yubaba's twin to be an older, taller sister.

Miyazaki described Yubaba as the "everyman" type, and were "symbols of modern working people". As for his decision in creating the twin sister Zeniba , "Ultimately , when we were getting down to the wire in the latter half of the production, Masashi Ando , the animation director, begged me not to add new characters. So I created a twin for Yubaba. Of course, in retrospect, it could have been taller, older sister and not just a twin. But either way, it's still really like two faces of the same person. When we're at work like Yubaba, yelling and making a mess and getting people to work, but when we go home we try to be good citizens. This schism is the painful part of being human." Some people who live a calm life like Zeniba at home may treat their subordinates as strict bosses like Zeniba while facing stress at work.

"Taking Yubaba as a single character, we spent ten times more time connected to her, observing her, and thinking about how to depict her, than we did actually drawing storyboards for her-so much so that I don't even remember how far we developed her in the storyboards." [3]

Miyazaki further elaborated on Zeniba's true nature, "We skipped all explanations (on the fact) that Yubaba and Zeniba are really the same person. I'm that way too. I'm completely a different person when I'm at Ghibli, when I'm at home, and when I'm out and about in the community. In fact, I live in amost schizoid fashion. I was worried about how children would accept this aspect of the movie, but they seem to have accepted it with no problem at all, so I've been greatly relieved." [4]

Power of Words [ ]

Some suggest that the film is an allegory on the progression from childhood to maturity, and the risk of losing one's nature in the process. The theme of a character being lost inside a (fictional/different) world if they forget their real name is a common folk theme. True names having magic power are a staple of folks tales such as Rumplestilskin or Earthsea . Similarly, Chihiro and Haku stay under Yubaba's control forever if they forget their real names and consequently their real identities.

The contract between Yubaba and Chihiro represented an old tradition in Japan where you had no right to refuse someone who really wanted to work.

When Miyazaki was interviewed by journalist Tetsuya Chikushi on January 11, 2002, Chikushi noted shocking it was when Chihiro was told "if you say 'No!', you'll be turned into a chicken and have to go on laying eggs until you're eaten,", stating how that was cosmic retribution.

Miyazaki explained, "Recently my friends and I use the word asamashii [despicable or disgraceful] a lot. It's a word that's fallen out of favor these days, but it seems perfectly suited to describe the current Japan. It originally refereed to things that should have been more embarrassing and shameful of all."

Chikishi responded, "There's a problem with language in Spirited Away, isn't there? Some of the key words for the young heroine are simple, such as when she declares repeatedly, "I'll keep working here". I watching this, thinking that you were trying to tell us how much power words have."

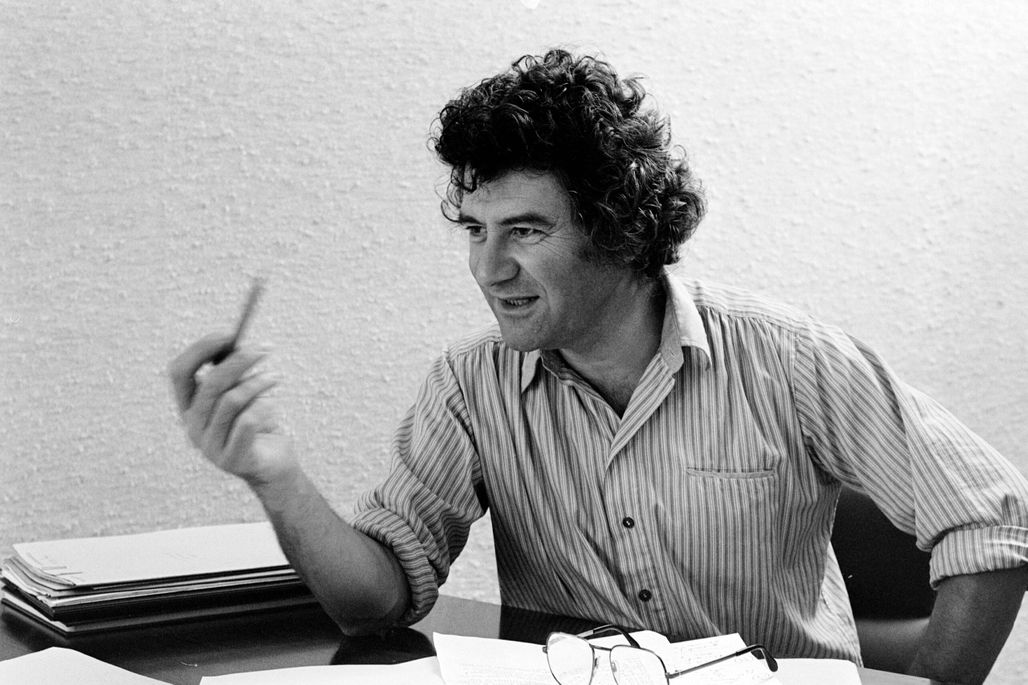

Hayao Miyazaki and Rumi Hiiragi , the actress who played Chihiro Ogino , photographed at the Edo Tokyo Open Air Park on March 26, 2001.

Miyazaki then said, "Actually, we thought about having Yubaba use an actual labor contract of some sort there, but since no one would get it even if we included an explanation, we just left it with her saying, "we're using a boring old oath." But there is a labor agreement in effect in her world because she has to give work to those who want it. Because that's the kind of society Japan originally was; people had to give work to those who wanted it. To want to work is to want to live. To live in a specific place. We skipped all the explanations. The same with the fact that Yubaba and Zeniba are really the same person. I'm that way too. I'm completely a different person when I'm at Ghibli, when I'm at home, and when I'm out and about in the community. In fact, I live in most schizoid fashion. I was worried children would accept this aspect of the movie, but they seem to have accepted it with no problem at all, so I've been greatly relieved." [5]

Other Motifs [ ]

The main character is a very modern Japanese ten-year-old who's being forced to grow up and adapt when faced with more traditional Japanese culture and manners. Miyazaki himself has said that there is an element of nostalgia for an older Japan in this film and several of his others.

Miyazaki also included a theme advocating the prevention of greed: those swallowed by No-Face were attempting to receive the gold he made. Similarly, in a monomyth format, Yubaba's rich accommodations and interest in gold dominate the "road of trials" portions of the film, while Zeniba's rustic home and grandmotherly demeanor arguably mark Chihiro's gain of the "boon" in her quest. Also, Chihiro's parents' grotesque transformation after consuming too much food not meant for them is another representation of human greed, and may also be a reference to The Odyssey .

Environmental awareness is a theme explored by Roger Ebert. The most obvious examples of this are the river spirit's dramatic and beautiful transformation once he has been freed from the material dumped in him by humans, and Haku's discovery that the reason he cannot go home is that the River Kohaku, whose spirit he was, had been filled in by apartment buildings. This environmental awareness is present in several of Miyazaki's works, such as Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Princess Mononoke .

Behind the Scenes [ ]

Development [ ].

"I think certain motifs appear over and over in our deep psyches. Even Krabat isn't something that the author suddenly thought up, because it's based on folktale that's been handed down from the Middle Ages. So when making Spirited Away, there were many things I wanted to include but couldn't. When working on it, I frankly felt like I was lifting the lid on areas of my brain that I wasn't supposed to expose. But creating fantasy is all about lifting the lid of your brain, flaunting things that you don't normally expose. IT's about treating the world we discover there as though it's a reality, to the point where the real world itself sometimes seems to lack reality. AT some point, this other world takes on a greater reality than that of our own ordinary lives. In just talking about this subject now, we lose a type of reality, because all the focus is on the other world" —Hayao Miyazaki [6]

Seiji Okuda (center) and his then 10-year-old daughter helped give Miyazaki a starting point to work on the film.

Following the grueling production of Princess Mononoke Miyazaki considered retiring once again to focus on his personal projects, such as opening the Ghibli Museum . He did not think he would be able to embark once again on such a long and tiring experience. However, the vacuum left by the death in 1998 of his designated successor Yoshifumi Kondō pushes him to roll up his sleeves once again. His stance changed upon meeting the daughter of his friend Seiji Okuda , on whom the main protagonist of Spirited Away is based. Chihiro's father, Akio Ogino , was based on the real-life father of the girl Chihiro is based on. Miyazaki said Okuda is similar to Akio in that he had a habit of getting lost while driving and ate too quickly. Chihiro's mother, Yuko Ogino , is based on a friend of Miyazaki's; an idiosyncratic hand-gesture of Miyazaki's friend is copied when Yūko is eating in Spirited Away . Chihiro's best friend's name is Rumi (the one who gave her the flowers in the opening), which is the name of Chihiro's voice actor.

Marvelous Village Veiled in Mist by Sachiko Kashiwaba proved to be a major inspiration for Miyazaki.

As with his other film projects, the initial idea germinated several years before becoming the film we know. Prior to the production of Princess Mononoke , Miyazaki had considered adapting the children's book, Kiri no Mukô no Fushigi na Machi (霧のむこうのふしぎな町), also known as Rin and the Chimney Painter or Marvelous Village Veiled in Mist , a 1975 novel by Sachiko Kashiwaba about a young student forced to repaint the chimney of a bathhouse left behind. A member of the Studio Ghibli team loved this book when he was about ten, and read it many times.

Like Japan's most famous children's writer, Kenji Miyazawa (another source of inspiration for Miyazaki), Kashiwaba is from Iwate. The story goes that during the summer holidays six year old Rina is sent on her own to stay in the village in the countryside where her father had stayed as a child. Where Rina gets off the train, the village people are only half convinced that her destination, the valley of mist, exists, but following their uncertain directions, she sets off, and helped by her umbrella, which gets blown away so that she has to chase after it, she finds herself in a strange one street village.

The house where she will be staying belongs to a tiny old lady, who seems perpetually angry and delights in putting people on the wrong foot.

"What are you dawdling for? If there's one thing I hate, it's dawdlers," the voice she had heard earlier sounded angry. Rina inched fearfully into the room. By the window there was a big flowery sofa, and on that sofa, like a black fleck, a little old woman was sitting. The old woman did not look at Rina. As if she knew who it was without looking, she went on eating her biscuit and drinking tea. Rina, not knowing what to do, stared at the old woman who was ignoring her. Finally, the old woman broke the silence, "Six years old and you still don't know how to greet a person." "Uesugi Rina," Rina said, bowing, "Thank you for your kindness in having me." "Who said anything about kindness? Anyone who stays in her house must work while they're there," she tells Rina. [7]

Miyazaki likened the bathhouse to how Studio Ghibli is run, and made comparisons to its producer Toshio Suzuki .

So Rina helps in the house or is sent to the different shops that make up the village. But this is no punishment, as they are all fascinating places run by different magicians. As she works Rina becomes more self confident and finds her true character. Miyazaki didn't understand why he found this story so interesting and, intrigued, he wrote a project proposal around it, but it was also rejected.

Another source of inspiration for Spirited Away was, by its director's own admission, Studio Ghibli itself. Thus the intense activity that reigns in the bathhouses evokes that of the studio. The character of Yubaba , who governs the establishment, would correspond to the producer Toshio Suzuki , while the very overwhelmed Kamajī with multiple arms would be like Miyazaki. Chihiro , she has to work hard if she does not want to disappear, which is equivalent to being sent back to the studio.

Inspired by Japan [ ]

"As we say in Japan, 'The customer is always god.' That's just a bit of a pun, but I think it's true." —Hayao Miyazaki

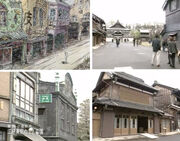

Yubaba's opulent apartment floor was inspired by places like Romkumeikan (Top) and Meguro Gajoen (Bottom).

In an interview on the film's Roman Album dated September 10, 2001, Miyazaki refers to the strange world Chihiro wanders into as Japan itself. "Until recently, the dormitories for female workers of textile companies or wards in long-term care facilities all looked like the employee rooms in the bathhouse where Chihiro lives. That's what Japan was like until just a while ago. I felt a real sense of nostalgia when depicting them. We've forgotten what the buildings, streets, and lifestyles were just like a little while back." Meanwhile, regarding Yubaba's Western-style home, "That's supposed to be something like Romkumeikan or Meguro Gajoen . I think that for us Japanese, what seems really deluxe is to have something that is a mishmash of a traditional-style palace, a grand Western-style (or quasi-Western style) mansion, and something like the Palace of the Dragon King, and then to live in it, Western style. The Aburaya bathhouse, I should say, is really like one of today's leisure land theme parks, but it's something that could have also existed in the Muromachi and Edo periods. So we're ultimately depicting is the real Japan."

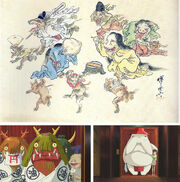

Unlike the designs of gods seen in ancient scroll paintings like Hyakki yagyozu , Spirited Away's gods are more modest in design.

As for the depiction of the spirits, Miyazaki mentions how Japanese gods are quite modest in design. "Tenjin has been turned into a god for those who pray for success in their school exams, and I'm sure it's tough for him because he doesn't even understand English. [laughs]" Other traditional Japanese gods have been lumped in with Buddhism and made into wooden idols of worship, but that wasn't what they originally were. What Miyazaki is trying to say is that Japanese spirits "originally never had a form. And if people give them form without being careful, they start looking like yokai . But even that's vague since all the yokai in the famous scroll painting Hyakki yagyozu were all given forms after the fact. So in principle, I didn't want to depict my Japanese spirits to be based on any existing images. But one exception is the masks at Kasuga Taisha shrine. When I saw photos of them, they were too fascinating not to use as reference. When I gave form to the spirits, I didn't want them to look like deities. So if you ask my why I depicted the spirits the way I did in the film, it's because I think Japanese gods are probably quite exhausted. So it made sense to me that they would want to come to a bathhouse and stay two nights and three days. Sort of like the Shimotsuki festival.

Hostess Bars [ ]

Finally, another starting point for Spirited Away is an anecdote told by Suzuki to Miyazaki. The latter spoke of hostess bars, where the latter are often shy, forced to learn to communicate with men. They pay to be able to express themselves as well. This image has remained etched in Miyazaki's mind and exploited it in his film: Chihiro is forced to learn to express himself when she is serving in the baths, while No-Face fails to express himself. and uses violence and money to be able to do so. All these elements combined led to the creation of the final proposal of the film.

Production [ ]

Many of the film's locations were inspired by the Edo-Tokyo Open Air Architectural Museum.

Production of the film began at the end of 1999 and ended in June 2001. As usual, Hayao Miyazaki realized that the film would last more than three hours, if he had made it according to his original proposal. Much of the original script was cut to expedite the film's length. Due to relatively tight production deadlines (one and a half years instead of three for Princess Mononoke ), Spirited Away is the studio's first film not to have been entirely made in Japan. The development of part of the scenes was therefore entrusted to the Korean studio DR Digital, which had already worked on animated films as prestigious as Metropolis or Jin-Roh .

【FOCUS新聞】TVBS專訪宮崎駿 72歲不老頑童

A 2013 interview with Hayao Miyazaki and TVBS, a Taiwanese news agency. Here he denies that the backgrounds in Spirited Away were inspired by the shops at Jiufen in Taiwan.

Hayao Miyazaki sought authenticity in the representation of the bathhouse, admitting to having been inspired by the buildings at the Edo-Tokyo Open Air Architectural Museum , which was near the studio where he liked to walk. Its park indeed offers a reconstruction of the Japanese capital, between the 17th and the beginning of the 20th century. For Miyazaki, to represent this place is to plunge the Japanese viewer into a certain nostalgia. Ghibli staff conducted location scouting at this park on March 17, 2000. The public bathhouse Kodakara-yu was Miyazaki's favorite exhibit, and many of its details were used as reference when designing the bathhouse in the film. The main building at Dōgo Onsen in Matsuyama was also referenced, following a past Ghibli company trip. The interiors of Meguro Gajoen and the ceilings of Nijō Castle was used as reference. Kamajī's workplace was based on the Takei Sansho-do (stationery store) at the Edo-Tokyo Museum. Meanwhile, the film's bathhouse's girl's dormitories was based on the Japanese garment factories from the 1950s. The National Sanatorium Tama Zenshōen's multi-tenant room also served as inspiration.

It has been claimed that Miyazaki was inspired by the shopkeepers at Jiufen, a town near Taipei in Taiwan. However, when Miyazaki was asked about this by Taiwanese media, he denied it.

Art director Yôji Takeshige (left), Noboru Yoshida and Kazuo Oga took inspiration from several real-life locations. Yoshida painted the fusuma painting of a giant demon seen here.

Art director Yoji Takeshige and assistant art director is Noboru Yoshida helped to refine Miyazaki's original e-konte and image boards. Takeshige ran the drawing department, and helped guide many of the new hires at the studio as production began to ramp up. Normally, background art production is done in three stages. A rough drawing of the background is laid out, and an art board is drawn over it to serve as a guideline before actual background painting begins. The head of this process specifies the color and texture in detail. For Spirited Away , Takeshige did not create the art setting as Miyazaki already created the background via his e-konte (storyboard). Art director and background artist Kazuo Oga , who previously worked on My Neighbor Totoro , worked on the opening backgrounds before Chihiro's family enters the theme park, and the natural landscapes towards the end of the film. Noboru Yoshida was in charge of the fusuma painting of a giant demon in the bathhouse.

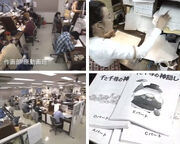

The grueling work at Studio Ghibli, and the storyboards for the film. Many employees reported working to exhaustion.

Likewise, for the character design of the characters, the director was inspired by those close to him. Chihiro is the faithful representation of the little girl who motivated him in making the film. Chihiro's father is the faithful portrait of the little girl's father, particularly in his voracious attitude. The mother of the heroine is the carbon copy of a regular Miyazaki collaborator within the studio. This was clearly his attempt at anchoring this fantastical work to contemporary Japan.

With regards to the animation of certain scenes, Miyazaki showed great concern for realism. He explained in detail the movement of Haku, in the form of a dragon, falling to the ground, akin to a lizard or a green snake wriggling on a wall and suddenly collapsing. He encouraged the animators to go to an eel restaurant to observe their movement. Likewise, when Miyazaki directs a scene where Chihiro gives Haku a dumpling to eat, he explains to the young designers that he wants a mouth similar to that of a dog. In order to respect the director's instructions, the animators went to a veterinarian to observe the behavior of a dog, its teeth, the way in which it is necessary to maintain its mouth. These few examples perfectly evoke Miyazaki's desire to achieve a certain realism of the staging, in a however fantastic setting.

For the first time, Miyazaki wouldn't be able to check and correct the work of the other animators himself because of a major problem with his eyesight. To help him, he therefore called on Masashi Ando , who has been working in the studio since its inception. He assisted the director, sometimes to the point of exhaustion, to maintain his exacting standards.

Miyazaki demonstrating to his staff how to depict scenes. One involved feeding Haku like a dog, so the staff visited a veterinarian.

100 shots out of the 1,400 that make up the film were produced by the 3D-CG section, directed by Mitsunori Kataama . These are scenes that proved far too complex to animate by hand, often including rapid movements of the 3D camera (such as the stone statue seen in the woods or the Chihiro race between the hedges of flowers) and the animation of the 'complex elements like water.

Several techniques were used. According to Kataama, “We added depth to the original 2D images by projecting the hand-drawn backgrounds onto 3D models. Then, we used Softimage 3D to calculate the light reflections and the lighting components that we then added to the sets. We have also implemented an original 2D texture shading process, making it possible to obtain the appropriate projection of the image of the scenery from different angles. Finally, we have developed a plug-in that makes it easier to change the field of view on a given plane."

Another significant challenge taken up by the 3D team at Studio Ghibli is the creation for the sea of a realistic and ever-changing surface. This required internal development of another 2D texture shading process, and the use of several shading and lighting tools to simulate reflections and refractions on the water surface.

Yasuyoshi Tokuma was an eccentric figure, who was close with Toshio Suzuki and owned Studio Ghibli until they became independent a few years after his passing.

On September 20, 2000, chairman of Tokuma Shoten and Studio Ghibli president Yasuyoshi Tokuma passed away. [8] A farewell ceremony was held at Grand Prince Hotel Takanawa on October 16th of that year.. Miyazaki presided over the association. According to Seiji Kano, in Miyazaki's speech, he mentioned that all the attendees in mourning looked like frogs, implying a relationship with the frog men in Spirited Away . [9] Tokuma died without having seen the final cut of the film, but he was posthumously credited as "Executive Producer".

At the same time, Spirited Away's production was facing serious delays. Several new animation directors were hired, although Toshio Suzuki was worried the film would not meet its deadline. New animators were given at least "one cut per person in a week" to complete. Only half of the animation cuts were made in-house at Ghibli, while the rest was outsourced. Veteran animator Kenichi Konishi was asked to find any available animator he could hire for support the production.

It soon became clear that outsourcing video and coloring to other domestic studios and talent would not be enough. Therefore, for the first time since the founding of Studio Ghibli, Suzuki decided to outsource to an overseas studios. Four people were sent from Ghibli to South Korea to oversee the operation. [10] Korea's DR DIGITAL was placed in charge of video and coloring, while JM Animation Co. was in charge of coloring. Their work was produced at a high standard, which satisfied the Suzuki et al.

Announcement [ ]

Due to Miyazaki's deteriorating eyesight, Masashi Ando stepped in to help check all the key drawings.

The announcement in December 1999 of Miyazaki's new film created a stir. The emotional charge of waiting for the new baby is further reinforced by the little information that the production deigns to let filter out, if we except the title, Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi (literally The strange disappearance of Sen and Chihiro), and a 40-minute documentary broadcast on May 4, 2000, on the NHK channel.

But things became clearer at the beginning of 2001. At the beginning of January, the magazine Animage presented the images of the teaser (short trailer), then screened in Japanese theaters. On January 26, the NTV channel broadcasts it exclusively on television. Soon follow a new trailer, the trailer and finally a clip illustrating the magnificent song of the end credits. But there is more to promoting the film than advertisements on television. Tôhô , the film's distributor in Japan, is carrying out a Disney-worthy marketing campaign and, with such media hype, observers expect a tidal wave.

Dubbing [ ]

Spirited Away Sound & Music 1of3.mov

Scenes from the NHK documentary of the cast dubbing at Studio 2 of Studio Ghibli.

For the dubbing, Hayao Miyazaki chose confirmed actors to embody the voice of his characters. The young actress Rumi Hiiragi , aged 13, known in Japan for a morning drama on the NHK channel, was hired while Miyu Irino was given the role of Haku . Their interpretation is marked by accuracy and moderation. Bunta Sugawara , with a 45-year acting career, lends his voice to Kamajī and Mari Natsuki , truly transcends her slim figure and her soft voice to embody an earthy and directive Yubaba . The most surprising thing is to discover that the enormous baby Boh is played by Ryûnosuke Kamiki , a little boy of 4 or 5 years old, considered a little genius in Japan.

Regarding the recording of these voices, Miyazaki has chosen this time, and for the first time, not to separate the recording room from the one where the sound engineer and the director are usually located. Miyazaki, but also Toshio Suzuki, are therefore in the same room as the actors. The goal of this novelty is to be able above all to be able to better direct the voice actors and to be able to better explain the intonations that Miyazaki are looking for a particular character. Miyazaki will even go so far as to mimic the dance and sing the ritornello of the manager of the baths to the actor Takehiko Ono.

Sound Mixing [ ]

「千と千尋の神隠し」公開直前スペシャル!

TV special of Spirited Away that aired before the film's release, featuring Rumi Hiiragi , the voice actress for Chihiro and Takashi Naitô, voice actor of Chihiro's father exploring the Edo-Tokyo Museum.

This is a first for studio Ghibli, Spirited Away benefits from the digital DLP format. Like Star Wars: Episode 1 - The Phantom Menace , the film is directly recorded on hard disk, without going through the reel stage. It also benefits from the EX 6.1 sound system, using six channels to give it its full sonic breadth.

The soundtrack is once again extremely polished and contributes beautifully to the viewer's immersion in the strange world of Aburaya. Sound engineer Shûji Inoue travels to Kusatsu to record the noise produced by the water from its famous hot springs. He will thus store up a multitude of sounds: brooms rubbing the floors of public baths, crockery colliding in a kitchen or in a reception room, the engine of Chihiro's father's car. Tôru Noguchi, who has been dealing with cartoon sound effects for 20 years, recreates other sounds in the studio, like those of the multitude of footsteps of the characters in the film. All of these sounds make Spirited Away very realistic, and once again,despite the fantastic context of the story.

Release [ ]

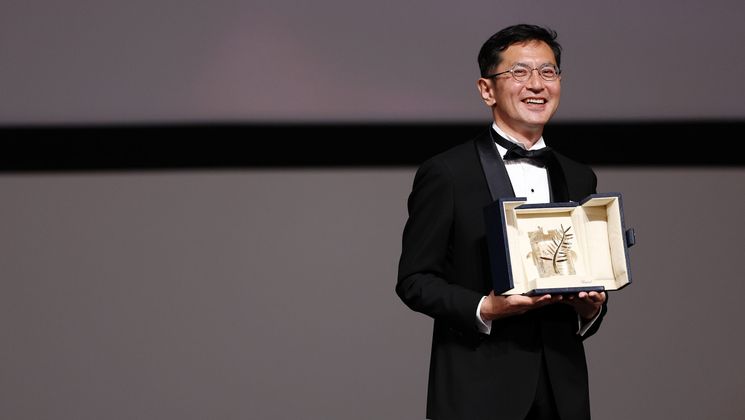

On February 17, 2002, Hayao Miyazaki's Spirited Away won the Golden Bear Award, the highest award at the 52nd Berlin International Film Festival. This is the first time in the world that an animated cartoon has won the award. Miyazaki flew to Germany for the ceremony, accompanied by Toshio Suzuki and Steve Alpert .

Spirited Away was released in Japan in July 2001, drawing an audience of around 23 million and revenues of ¥30 billion (approx. US$250 million), to become the highest-grossing film in Japanese history (surpassing the film Princess Mononoke for highest-grossing animated motion pictures). It was the first movie to have earned $200 million at the worldwide box office before opening in the United States. By 2002, a sixth of the Japanese population had seen it.

The film was dubbed into English by Walt Disney Pictures, under the supervision of Pixar's John Lasseter. It was subsequently released in the United States on September 20, 2002, and had made slightly over $10 million by September 2003.

Home Media [ ]

The film was released in North America by Disney's Buena Vista Distribution arm on DVD format on April 15, 2003, where the attention brought by the Oscar win made the title a strong seller. Spirited Away is often marketed, sold and associated with other Miyazaki movies such as Castle in the Sky , Kiki's Delivery Service , and Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind .

The North American English-dubbed version was released on DVD in the UK on March 29, 2004. In 2005 it was re released by Optimum Releasing with a more accurate subtitle track and additional bonus features.

After Miyazaki returned to Japan, he was greeted by the press. A conference was held where he said a few words regarding his experience.

The back of the Region 1 DVD from Disney and the Region 4 DVD from Madman states that the aspect ratio is the original ratio of 2.00:1. This is incorrect; the ratio is actually 1.85:1 but has been windowboxed to 2.00:1 to compensate for the overscan on most television sets. There is much dispute over the validity of this practice, as many displays are capable of showing the entire picture, and as a result the DVD picture has a noticeable border around it.

All Asian releases of the DVD (including Japan and Hong Kong) have a noticeably accentuated amount of red in their picture transfer. This is another case of compensating for home theatre displays, this time supposedly for LCD television which, it was claimed, had a diminished red color in its display. Releases in other DVD regions such as the US, Europe and Australia use a picture transfer where this "red tint" has been significantly reduced.

Television [ ]

Spirited Away received a stage adaptation, Spirited Away: Live on Stage , which premiered at the Tokyo’s Imperial Theater in February 28, 2022. Subsequent performances were held in Osaka, Fukuoka, Sapporo and Nagoya. The stage adaptation starred Kanna Hashimoto and Mone Kamishiraishi. It was written and directed by John Caird, an honorary associate director of the Royal Shakespeare Company and a big fan of Miyazaki’s work.

The U.S. television premiere of this film was on Turner Classic Movies in early 2006, closely followed by its premiere on Cartoon Network's "Fridays" on February 3, 2006. On March 18, Cartoon Network's Toonami began a "Month of Miyazaki" that featured four movies directed by Hayao Miyazaki, with Spirited Away being the first of four. Cartoon Network showed the movie three times more: once on Christmas 2006, for Toonami's "New Year's Eve Eve" on December 30, and on March 31, 2007. It was also shown again on Turner Classic Movies on June 3, 2007.

The first European television showing of the film (both the subtitled Japanese and dubbed English versions) was in the UK on December 29, 2004, on Sky Cinema 1, and it has since been repeated several times. The first UK terrestrial showing of this film (dubbed into English) was on BBC2 on December 30, 2006. The Japanese subtitled version was first shown on BBC4 on the 26th January 2008.

The Canadian television premiere of the film was on CBC Television on September 30, 2007. In order to fit the film into a two-hour time slot with commercials, extensive time cuts were made during this airing.

Australian television audiences premiered Spirited Away on March 24, on its SBS channel. The movie had been heavily marketed previously, and was featured in the Australian TV Guide; no edits were made during viewing.

Version Differences [ ]

Some changes were made to the film by John Lasseter and the other writers of the English dub.

Changes include:

- The insertion of a significant portion of background chatter.

- Adjusting the translated dialogue to match the visible mouth movements of the characters.

- The addition of dialogue explaining or emphasizing certain on-screen elements: for example, when Chihiro reaches a massive, red, steaming building, she comments, "It's a bathhouse." These insertions are mostly used to explain certain aspects of Japanese culture that are foreign in America and many other English-speaking countries.

- In the English dub, in order to escape from Boh, Chihiro convinces him that the bloodstain on her hands is, in fact, germs. In the original script, she simply tells the truth and refers to it as blood.

- One example: In the English dub, upon hearing Haku's request to return 'Sen' and her parents to the human world in exchange for Boh, Yubaba says that she will still give 'Sen' one final test. In the original film, she threatens to tear Haku to pieces unless Boh is returned, with the possibility that an extensive argument occurred offscreen before reaching the agreement.

- Another example: In the English dub, after Zeniba asks Chihiro what the gold seal is upon returning it to her, Chihiro answers "yes, it's the gold seal you were looking for". In the original film, Chihiro doesn't know, but she acknowledges that it is very valuable to Zeniba.

- New lyrics were improvised by John Ratzenberger for the English version of a song sung by Aogaeru, as well as his exclamation, "Now that's an esophagus!"

- During the cleansing of the Stink Spirit in the Japanese Version, Lin arrives on the scene and simply states that Kamajī is sending his best herbal water to the bath. In the English dub, Lin asks if Chihiro is all right and promises to not let her get hurt.

Miyazaki himself has stated that Chihiro, at the end of the film, does not remember what happened to her in the spirit world, but that her adventures were also not a dream. To show the audience that something did happen, he gave several hints, such as dust and leaves on the car. Chihiro's hairband, given to her by Zeniba, glittering by the sunlight was also one of the hints. The English dub adds a line "I think I can handle it," indicating that Chihiro has come away from her adventure as a better person.

Reception [ ]

Based on 146 reviews at Rotten Tomatoes, it ranks as the fifth-best animation film, having a 97% rating on the site. Source Reviewer Grade / Score Notes AnimeOnDVD Chris Beveridge Content: C Audio: A- Video: A+ Packaging: N/A Menus: B Extras: A+ DVD/Anime Movie Review THEM Anime Reviews Carlos Ross and Jacob Churosh 5 out of 5 Anime Review

Awards and Achievements [ ]

- Best Animated Feature Film; 75th Annual Academy Awards [11]

- Winner of Best Film; 2002 Japanese Academy Awards [12]

- Golden Bear (tied); 2002 Berlin International Film Festival [13]

- Best Animated Feature; 2002 New York Film Critics Circle Awards

- Special Commendation for Achievement in Animation; 2002 Boston Society of Film Critics Awards

- Best Animated Feature; 2002 Los Angeles Film Critics Awards

- Outstanding Achievement in an Animated Feature Production; 2002 Annie Awards

- Best Directing in an Animated Feature Production; 2002 Annie Awards

- Best Writing in an Animated Feature Production; 2002 Annie Awards

- Best Music in an Animated Feature Production; 2002 Annie Awards

- Best Animated Feature; 2002 Critics' Choice Awards

- Best Animated Feature; 2002 New York Film Critics Online Award

- Best Animated Feature; 2002 Florida Film Critics Circle

- Best Animated Feature; 2002 National Board of Review

- Best Original Score in the Category of Comedy or Musical; 78th Annual Glaubber Awards

- Motion Picture, Animated or Mixed Media; 7th Annual Golden Satellite Awards

- Audience Award for Best Narrative Feature; 45th San Francisco International Film Festival

- Special Mention from the Jury; 2002 Sitges Film Festival

- Best Asian Film; 2002 Hong Kong Film Awards

- Best Animated Film; 29th Annual Saturn Awards

- Best Film (tied); Cinekid 2002 International Children's Film Festival

- Best Animated Feature; Online Film Critic Society

- Best Animated Feature; Dallas-Fort Worth Critics

- Best Animated Film; Phoenix Film Critics Society

- Silver Scream Award; 19th Amsterdam Fantastic Film Festival

- Best Family/Animation Trailer; Fourth Annual Golden Trailer Awards

- Brilliant Dreams Award 2003; Bulgari

- Award Winner, Film; 2003 Christopher Awards

- Award Winner, Most Spiritually Literate Films of 2002 (You); Spirituality & Health Awards

- Best Movie for Grownups who Refuse to Grow Up, Best Movies for Grownups Awards; AARP The Magazine

Soundtracks [ ]

The closing song, Always with Me (いつも何度でも , Itsumo Nandodemo , literally, Always, No Matter How Many Times) was written and performed by Yumi Kimura , a composer and lyre-player from Osaka. The lyrics were written by Kimura's friend Wakako Kaku. The song was intended to be used for a different Miyazaki film which was never released, Rin the Chimney Painter (煙突描きのリン , Entotsu-kaki no Rin ).

The other 20 tracks on the original soundtrack were composed by Joe Hisaishi . His The River of That Day (あの日の川 , Ano hi no Kawa ) received the 56th Mainichi Film Competition Award for Best Music, the Tokyo International Anime Fair 2001 Best Music Award in the Theater Movie category, and the 16th Japan Gold Disk Award for Animation Album of the Year. Later, Hisaishi added lyrics to "Ano hi no Kawa" and named the new version The Name of Life (いのちの名前 , Inochi no Namae ) which was performed by Hirahara Ayaka.

Beside the original soundtrack, there is also an Image Album, which contains 10 tracks.

Additional Voices [ ]

- Original: Shigeru Wakita, Shirô Saitô , Michiko Yamamoto, Keiko Tsukamoto , Shinji Tokumaru , Kaori Yamagata , Yayoi Kazuki , Masahiro Asano , Kazutaka Hayashida, Ikuko Yamamoto, Mina Meguro, Tetsurô Ishibashi, Katsutomo Shîbara, Shinobu Katabuchi , Noriko Kitou , Naoto Kaji , Yoshitaka Sukegawa, Aki Tachikawa , Noriko Yamada , Katsuhisa Matsuo, Masayuki Kizu, Yôko Ôno , Sachie Azuma, Shigeyuki Satô, Mayumi Sako , Sonoko Soeda, Akiko Tomihira , Minako Masuda, Orika Ono, Rina Yamada, Miwa Takachi , Hiromi Takeuchi, Makiko Oku

- English: Mickie McGowan (Bath House Woman), Sherry Lynn , Mona Marshall , Candi Milo , Colleen O'Shaughnessey , Jennifer Darling , Phil Proctor (Frog-like Chef)

Credits [ ]

Related products [ ], home video [ ].

- Spirited Away VHS - Buena Vista Home Entertainment (July 19, 2002)

- Spirited Away DVD Buena Vista Home Entertainment (July 19, 2002)

- DVD (Director Hayao Miyazaki's Works) -Walt Disney Studios Japan Released on July 2, 2014

- Spirited Away Blu-ray Disc --Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment (July 16, 2014)

- Blu-ray Disc (Director Hayao Miyazaki) --Walt Disney Studios Japan Released on July 2, 2014

Publishing [ ]

- Chihiro and the Mysterious Town Chihiro and Chihiro's God Hidden <Thorough Strategy Guide> (July 20, 2001) ISBN 4-04-853383-5

- 40 eyes to read "Spirited Away" by Kine Shun Mook (August 15, 2001) ISBN 4-87-376574-9

- Eureka Poetry and Criticism August 2001 Special Issue General Feature Hayao Miyazaki The World of "Spirited Away" Fantasy Power (August 25, 2001) ISBN 4-79-170078-3

- Spirited Away (Tokuma Anime Picture Book) (August 31, 2001)

- Spirited Away-Film Comic (1) (September 1, 2001) ISBN 4-19-770082-2

- Spirited Away-Film Comic (2) (September 10, 2001) ISBN 4-19-770083-0