What is film tourism and why does it matter?

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

Film tourism is big- what is it, what impact does it have, and where are the best locations for it? Read on to find out…

What is film tourism?

How do movies affect tourism, positive impacts of film tourism, negative impacts of film tourism, james bond film tourism, game of thrones film tourism, indiana jones film tourism, lord of the rings film tourism, the beach film tourism, gladiator film tourism, harry potter studios, atlas film studios, universal studios, pinewood studios, film tourism- further reading.

Film tourism has been defined by the Scottish Tourist Board as being the business of attracting visitors through the portrayal of the place or a place’s storylines in film, video and television. People have seen a location in a movie and thought, I want to go there. This might be because they thought the destination was particularly beautiful, or because they *really* enjoyed the film and want to experience more of it in some way. It extends to TV shows, too, but film tourism is the name given to this phenomenon.

Movies affect tourism by offering another reason for a person to visit a particular location. Someone may have had no interest in visiting New Zealand, for example – until they saw Lord of the Rings and found out it was filmed there, and there are specific locations you can visit as a fan. Likewise, many people are drawn to Vis Island in Croatia because Mama Mia was filmed there .

Another way films affect tourism is by offering more avenues for income to be created. For example, gift shops and paid-for photo spots are becoming common in areas linked to particular films. Some companies are also offering specific guided tours of filming spots across certain cities.

Is this impact positive? In many ways, film tourism does have positive impacts. It works in both directions, too. Some people may be visiting a location anyway, then find out it is a filming location for a particular movie thanks to promotional material, the tours on offer and so on. This could then encourage them to watch the film when they may not have otherwise done so! Things like props, posters and signposting all impact the film industry in this way.

Of course, the biggest positive impact is for the location itself and the surrounding area(s). People are visiting destinations they may not have otherwise been interested in – and this means they are spending money. Whether that be with tour companies, local businesses, hotels and so on, money is flowing in. From this comes better jobs, a better standard of living and a sense of pride in the area.

By promoting themselves as a film location, areas are able to create a positive and fun image. The film is free publicity for them – and it is something that can continue to have an impact as more and more people watch the movie(s) over time. We’re talking years, especially if the film is particularly successful or becomes a cult classic.

It also encourages governments and citizens to work to protect the location, especially environmentally but also in terms of infrastructure. This is not only good for the visiting tourists , of course, but for the locals too!

Are there any negative impacts of film tourism? As with anything, there are negatives which can be explored alongside the many positive impacts. Firstly, destinations may not be prepared for a sudden influx of tourists if this shift happens very quickly. Destinations need time to ensure their roads are able to take a higher number of vehicles, and to make sure there are enough hotel rooms or other places to stay. Tour companies may feel under pressure to create tours, too.

There will likely be more traffic. This means roads could be congested, which is never good for the people who live there. More people also means less privacy, a frustration for many people who live in tourist-y areas. With film tourism, new destinations pop up all the time; this means you may have been living somewhere for decades without it being a popular visitor area and then one day, it suddenly is.

More vehicular traffic is, of course, an environmental impact of tourism . Air quality will decline and emissions will go up – all of this is a huge negative impact in terms of climate change. Extra footfall, more litter, and generally just a disrespect for nature can all have negative impacts on an area.

There is also the copyright issue to take into consideration. Some film franchises and studios will not allow areas to promote themselves with ties to the film or series itself; this means the location is seeing a higher number of visitors without being able to profit in their own (and usually the most beneficial) way.

Popular film-induced tourism destinations

There are so many locations which are popular with movie fans. You can see some major ones below!

James Bond fans flock to Thailand in order to visit Khao Phing Kan. This island featured in the 1974 movie The Man With The Golden Gun. Tour operators were quick to rebrand the island as ‘James Bond Island’ and almost overnight, Thailand became a popular destination for fans of 007.

There are two main locations visited by Game of Thrones fans looking to get a glimpse at where the series was filmed. The first is Northern Ireland , home to 25 filming locations such as Inch Abbey, Ballintoy Harbour and many more – you can do organised tours, or take yourself around for a few days and see how many you can tick off. There are self-guided driving routes available online and you’ll come across plenty of photo ops along the way… The second destination popular with GoT fans is Dubrovnik in beautiful Croatia ; again, organised tours are available or you can DIY it. From the setting of King’s Landing Harbour to Blackwater Bay, there are so many GoT filming locations here.

One film franchise with epic scenery has to be Indiana Jones. There are many places you can go to if you want to get in with Indy – the first of which is Cambodia. Head to the stunning Ta Prohm Temple, located at the Angkor Archaeological Park in Angkor Wat. This is where Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom was filmed! As a bonus, it also features in Lara Croft’s Tomb Raider. The more you know! Visit as part of an organised tour to see it up close.

Petra in Jordan is another fantastic location for Indiana Jones fans. It featured in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade – and Indy definitely put the location on the map for many people.

New Zealand is heaven for Lord of the Rings fans. This epic book-turned-film trilogy was filmed here, with its lush greenery and endless mountains providing the perfect backdrop for bringing Middle Earth to life. You can visit the film set itself, now a permanent tourist attraction in Matamata, and you can see Mount Ngauruhoe (which masquerades as Mount Doom) too! Wellington, Canterbury and other areas are also used as filming locations for these epic movies, as well as for The Hobbit film trilogy.

The Beach, a Danny Boyle film from 2000, is set in Thailand. Maya Bay on Ko Phi Phi Leh is an absolute paradise – but it has been subject to too much tourism over the years and has only just re-opened to tourists. This is a clear negative impact of tourism, as discussed above. There are now rules and restrictions for visitors, meaning it will hopefully remain open to tourists for years to come in its natural – and beautiful – state.

If you thought Russell Crowe’s famous 2000 movie Gladiator was filmed in Rome , you’d be wrong. Film tourists hoping to experience a bit of this particular magic need to head to Morocco, Tunisia and Malta. Starting with Morocco, Gladiator fans can visit a city built into the side of a hill: Aït Benhaddou, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the location used for ‘Zucchabar’. Malta, a historic military base, has many forts – and Fort Ricasoli played host to the cast of Gladiator for 19 weeks. Last but not least, Tunisia is also on the list of filming locations for the movie: specifically the El Jem amphitheatre.

Popular film studios for tourists

As well as larger areas such as towns or cities, or historic locations or pretty beaches, film tourism extends to studios. Many film studios are open to visitors for a fee, and you can easily visit and see props, sets and more!

The ‘Warner Bros. Studio Tour London’ is located in Watford, Hertfordshire – not far from London itself. This epic visitor centre is home to thousands of individual props from the film series, full-size set locations, a gift shop selling everything a Potter fan could want, and so much more. You can visit yourself, or book a guided tour which usually includes transport from London. Experience the magic of the Great Hall, ride in a ‘flying car’ and try a glass of delicious Butterbeer. It really is an experience you’ll never forget, whether you’re interested in how films are actually made or if you’re just a huge HP fan!

Cinema Studio Atlas, located in Ouarzazate in Morocco, is popular with film fans. This 30,000 sq metre film studio in the desert is open to visitors when there’s no filming on that day; if you want an authentic film studio experience, this is where you need to go! The Mummy (1999), Star Wars: A New Hope (1977), Black Hawk Down (2001) and many more have all been filmed here. It hasn’t necessarily been transformed into a tourist experience but if you want to see a real film set with original sets, this is where to go.

Now more famous as a theme park, California -based Universal Studios is in fact a fully working film studio. Here you can visit 13 city blocks across four acres of historic studio lot. It is actually the largest set construction project in studio history! The tour runs for around an hour, and gives you a real behind-the-scenes insight into Hollywood movie production.

Pinewood is another super-famous film studio. Located around 18 miles outside of London, it is not generally open to the public meaning it is less of a film tourism location. However, you *can* visit it as part of a TV audience or pre-arranged group visit.

If you enjoyed reading this article, I am sure that you will love these too!

- What is nature tourism and why is it so popular?

- What is disaster tourism and is it ethical?

- What is pro-poor tourism and why is it so great?

- Cultural tourism explained: What, why and where

- What is adventure tourism and why is it so big?

Liked this article? Click to share!

The French Journal of Media Studies

Accueil Numéros 9.1. Interviews Local Aspects and Impacts of Film...

Local Aspects and Impacts of Film-induced Tourism

Texte intégral.

- 1 Stefan Roesch, The Experiences of Film Location Tourists (Bristol: Channel View Publications, 2009) (...)

2 Visit California homepage. https://www.visitcalifornia.com/road-trips/movie-locations-tour/ <accessed on January 12, 2022>.

- 3 “Back to Bridgerton – 11 filming locations from the hit show,” Visit Britain. https://www.visitbrit (...)

- 4 “Game of Thrones,” Discover Northern Ireland. https://discovernorthernireland.com/things-to-do/tv-a (...)

- 5 “Film Tourism,” Tourism New Zealand . https://www.tourismnewzealand.com/markets-insights/sectors/fil (...)

1 In The Experiences of Film Location Tourists , Stefan Roesch mentioned that “film tourism is a specific pattern of tourism that drives visitors to see screened places during or after the production of a feature film or a television production.” 1 This trend has now definitely been taken up by different national and local tourism industries: California, home to many Hollywood studios, has of course its own specific internet page dedicated to film/TV tourism, 2 and VisitBritain , which had notably highlighted many Harry Potter -themed destinations, now focusses on Back to Bridgerton-11 filming Locations From the Hit Show . 3 Discover Northern Ireland has been surfing on the worldwide success of Game of Thrones 4 while New Zealand, which welcomed the famed shooting of The Lord of the Rings trilogy, devotes one section to film tourism on Tourism New Zealand . 5

6 See for example https://www.wbstudiotour.co.uk or https://www.gameofthronesstudiotour.com <accessed on January 12, 2022>.

- 7 « Suivez les traces du Da Vinci Code au cœur de paris », City Breaker . https://city-breaker.com/da- (...)

- 8 Different modifications were then added. CNC, Crédit d’impôt international, https://www.cnc.fr/prof (...)

- 9 Variety Staff, “France, Capital of Film, Provides 30% Rebate to Foreign Producers,” Variety.com . ht (...)

2 Films and TV series also generate their own dedicated tourism activities, whether it be on their official sites 6 or through private companies’ like City Breaker’s still active Da Vinci Code -themed tour. 7 France is a rather late comer to the full panoply of film-induced tourism as the law facilitating hosting foreign runaway productions on its territory was only voted in 2009. 8 Since then Dunkirk (Christopher Nolan, 2017), Fantastic Beast s: The Crimes of Grindelwald (David Yates, 2018), Inception (Christopher Nolan, 2010), M:I – Impossible - Fallout (Christopher McQuarrie, 2018), Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows (Guy Ritchie, 2011), Thor (Keneth Branagh, 2011), Wonder Woman (Patty Jenkins, 2017) and the TV series Merlin (Shine and BBC Wales, 2008-2012) were among the big-budget productions that have benefited from the enticing French tax rebate. 9

- 10 For more on this, see for example the works of Sue Beeton, Kerry Seagrave Daniel Steinhart and Jane (...)

- 11 Busby, G. and Klug, J. , “Movie-induced Tourism: The Challenge of Measurement and Other Issues , ” Jou (...)

3 As studied by several academics 10 across a variety of disciplines (for example film studies, economics, geography, adaptation studies, etc.), national legislature’s passage of such tax rebates is expected to reap benefits during and after the shooting of films and TV series on their territories. Film/TV-induced tourism is one of the expected benefits, which has been catalogued into nine different forms, according to Busby and Klug: 11

Table 1: Forms and Characteristics of Movie Tourism

12 Roesch, The Experiences of Film Location Tourists , 14.

4 This section presents some of these forms through three interviews with “involved tourism stakeholders” 12 taking about different local aspects and impacts of film-induced tourism.

- 13 Simon Hudson and J.R. Brent Ritchie, “ Promoting Destinations via Film Tourism: An Empirical Identif (...)

- 14 CNC, “L’impact des tournages sur le tourisme,” and “Cinéma et tourisme font bon ménage à Dunkerque, (...)

- 15 Sarah Kelley, “Tourism, Cinema and TV Series Conference,” Transatlantica 2, (2018). https://journal (...)

- 16 The film sheds light on Operation Dynamo during which the allied troops were evacuated from the Fre (...)

5 The interview “ Dunkerque and Dunkirk, ” which can be said to embody the first four forms of Busby and Klug’s classification, highlights the now widespread example of the impact of the “placement of destinations in movies and its influence on tourism” 13 through the case of Dunkirk (Christopher Nolan, 2017), a film that benefited from the French tax rebate and led to a case study by the CNC. 14 In this interview derived from the 2018 day-conference on Tourism, Film and TV Series , 15 Jean-Yves Frémont, town councilor in employment, economic development and tourism, and Sabine l’Hermet, director of Dunkerque tourist office, detail how the locally-shot American blockbuster 16 points to the link between the film industry and the role of tourism in local and regional development, notably for the French Hauts-de-France territory and the city where those historical events took place.

17 Busby and Klug, “Movie-induced Tourism: The Challenge of Measurement and Other Issues,” 318 .

6 In the “Bayeux and the Game of Thrones ® tapestry” interview, which can be related to the fourth and fifth forms defined by Busby and Klug, 17 Fanny Garbe, head of advertising and communication at the French Bayeux Museum, and Séverine Lecart, consumer marketing manager at Tourism Ireland, explain how Bayeux came to benefit from the television series’ Bayeux-inspired tapestry. The now famous Game of Thrones ® television series has no physical links to Bayeux nor its surrounding area. But its subsequent Bayeux-inspired tapestry came to be exhibited in Bayeux as its layout visually echoes its ‘ancestor’s’ depiction of the conquest of England in 1066 by the Duke of Normandy. Commissioned by HBO and Tourism Ireland, the Game of Thrones® tapestry has thus a narrative and visual link to Bayeux and is another example of the impact film/TV-induced tourism can have on regional economic development.

- 18 The festival presents itself as “the biggest European event entirely dedicated to television series (...)

7 Finally, film/TV-induced tourism can also be linked to festivals, which can be related to the third and ninth forms described in Busby and Klug’s classification . Derived from the exchange also held at the 2018 day-conference on Tourism, Film and TV Series , the interview with Karina Hocquette, education, and audience-development manager for the Séries Mania festival, underlines the festival’s impact on the French Hauts-de-France territory. The city of Lille in Northern France has in fact been hosting Séries Mania 18 since 2018 with different Séries Mania-labelled events and performances linked to the best international television series. It has subsequently led to a Series-Mania impact on the tourism industry for the Hauts-de-France region.

1 Stefan Roesch, The Experiences of Film Location Tourists (Bristol: Channel View Publications, 2009), 6.

3 “Back to Bridgerton – 11 filming locations from the hit show,” Visit Britain. https://www.visitbritain.com/gb/en/bridgerton-11-filming-locations-hit-show <accessed on January 12, 2022>.

4 “Game of Thrones,” Discover Northern Ireland. https://discovernorthernireland.com/things-to-do/tv-and-film/game-of-thrones <accessed on November 23, 2021>.

5 “Film Tourism,” Tourism New Zealand . https://www.tourismnewzealand.com/markets-insights/sectors/film-tourism/ <accessed on January 12,2022>.

7 « Suivez les traces du Da Vinci Code au cœur de paris », City Breaker . https://city-breaker.com/da-vinci-code-paris/ <accessed on January 12, 2022>.

8 Different modifications were then added. CNC, Crédit d’impôt international, https://www.cnc.fr/professionnels/aides-et-financements/multi-sectoriel/production/credit-dimpot-international_778354 <accessed on November 29, 2021> and “Aperçu du système français de crédits d’impôts pour la production cinématographique et audiovisuelle, http://enter-law.com/french-tax-credit-for-film-and-tv-production/?lang=fr <accessed on November 30, 2021>.

9 Variety Staff, “France, Capital of Film, Provides 30% Rebate to Foreign Producers,” Variety.com . https://variety.com/2018/artisans/production/france-production-incentives-2-1202666453/ <accessed on January 11, 2022>.

10 For more on this, see for example the works of Sue Beeton, Kerry Seagrave Daniel Steinhart and Janet Wasko.

11 Busby, G. and Klug, J. , “Movie-induced Tourism: The Challenge of Measurement and Other Issues , ” Journal of Vacation Marketing 7, no. 4 (October 2001): 318 .

13 Simon Hudson and J.R. Brent Ritchie, “ Promoting Destinations via Film Tourism: An Empirical Identification of Supporting Marketing Initiatives, ” Journal of Travel Research 44, (May 2006): 387-396. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237807231_Promoting_Destinations_via_Film_Tourism_An_Empirical_Identification_of_Supporting_Marketing_Initiatives <accessed on April 24, 2021>.

14 CNC, “L’impact des tournages sur le tourisme,” and “Cinéma et tourisme font bon ménage à Dunkerque,” CNC , https://www.cnc.fr/cinema/etudes-et-rapports/etudes-prospectives/limpact-des-tournages-sur-le-tourisme_227677 and https://www.cnc.fr/cinema/actualites/cinema-et-tourisme-font-bon-menage-a-dunkerque_44888 <both accessed on January 11, 2022>.

15 Sarah Kelley, “Tourism, Cinema and TV Series Conference,” Transatlantica 2, (2018). https://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/13571 <accessed on June 30, 2021>.

16 The film sheds light on Operation Dynamo during which the allied troops were evacuated from the French city of Dunkerque in 1940.

18 The festival presents itself as “the biggest European event entirely dedicated to television series in Europe,” Series Mania . https://seriesmania.com <accessed on June 9, 2021>.

Pour citer cet article

Référence électronique.

Nathalie Dupont , « Local Aspects and Impacts of Film-induced Tourism » , InMedia [En ligne], 9.1. | 2021, mis en ligne le 15 janvier 2022 , consulté le 02 mai 2024 . URL : http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/3027 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/inmedia.3027

Nathalie Dupont

Nathalie Dupont is Associate professor of American studies at the University du Littoral Côte d'Opale (ULCO). Her research focuses on the contemporary films produced by American studios, and what those films tell us about American society. It also focuses on the links between Hollywood and American Christians. She has published several articles on those subjects, as well as Between Hollywood and Godlywood: the Case of Walden Media (Peter Lang, London, 2015). She is a co-founder of CinEcoSA ( https://www.cinecosa.com ) and co-organizer of several of its conferences.

Articles du même auteur

- Introduction [Texte intégral] Paru dans InMedia , 9.1. | 2021

- Bayeux and the Game of Thrones ® tapestry [Texte intégral] An interview with Fanny Garbe, head of advertising and communication at Bayeux Museum, and Séverine Lecart, consumer marketing manager at Tourism Ireland Paru dans InMedia , 9.1. | 2021

- Marketing Films to the American Conservative Christians: The Case of The Chronicles of Narnia [Texte intégral] Paru dans InMedia , 3 | 2013

- Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices [Texte intégral] Paru dans InMedia , 3 | 2013

Droits d’auteur

Le texte seul est utilisable sous licence CC BY-NC 4.0 . Les autres éléments (illustrations, fichiers annexes importés) sont « Tous droits réservés », sauf mention contraire.

- Index de mots-clés

Numéros en texte intégral

- 9.1. | 2021 Film and TV-induced Tourism: Some Contemporary Aspects and Perspectives

- 8.2. | 2020 What do Pictures Do? (In)visibilizing the Subaltern

- 8.1. | 2020 Ubiquitous Visuality

- 7.2. | 2019 Documentary and Entertainment

- 7.1. | 2018 Visualizing Consumer Culture

- 6 | 2017 Fields of Dreams and Messages

- 5 | 2014 Media and Diversity

- 4 | 2013 Exploring War Memories in American Documentaries

- 3 | 2013 Cinema and Marketing

- 2 | 2012 Performing/Representing Male Bonds

- 1 | 2012 Global Film and Television Industries Today

Tous les numéros

Appels à contribution.

- Appels en cours

- Appels clos

- Editor's Statement

- Editorial Board

- Contents and Submission Guidelines

- International Scientific Board

- International Correspondents

Informations

- Politiques de publication

Suivez-nous

Lettres d’information

- La Lettre d’OpenEdition

Affiliations/partenaires

ISSN électronique 2259-4728

Voir la notice dans le catalogue OpenEdition

Plan du site – Flux de syndication

Politique de confidentialité – Gestion des cookies – Signaler un problème

Nous adhérons à OpenEdition Journals – Édité avec Lodel – Accès réservé

Vous allez être redirigé vers OpenEdition Search

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Sustainable development for film-induced tourism: from the perspective of value perception.

- 1 School of Business and Trade, Nanchang Institute of Science & Technology, Nanchang, China

- 2 Media Art Research Center, Jiangxi Institute of Fashion Technology, Nanchang, China

- 3 Guangdong University of Finance and Economics, Guangzhou, China

- 4 Department of Art Integration, Daejin University, Pocheon, South Korea

- 5 School of Business, Foshan University, Foshan, China

- 6 College of Management, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China

- 7 School of Economics and Management, East China Jiaotong University, Nanchang, China

The tourism economy has become a new driving force for economic growth, and film-induced tourism in particular has been widely proven to promote economic and cultural development. Few studies focus on analyzing the inherent characteristics of the economic and cultural effects of film-induced tourism, and the research on the dynamic mechanism of the sustainable development of film-induced tourism is relatively limited. Therefore, from the perspective of the integration of culture and industry, the research explores the dynamic mechanism of sustainable development between film-induced culture and film-induced industry through a questionnaire survey of 1,054 tourism management personnel, combined with quantitative empirical methods. The conclusion shows that the degree of integration of culture and tourism is an important mediating role that affects the dynamic mechanism of sustainable development of film-induced tourism, and the development of film-induced tourism depends on the integration of culture and industry. Constructing a diversified industrial integration model according to local conditions and determining the development path of resource, technology, market, product integration, and administrative management can become the general trend of the future development of film-induced tourism.

Introduction

As an emerging industry, cultural tourism can make up for the economic difficulties caused by the weak growth of the primary and secondary industries, and replace it as a new driving force for economic growth ( Liu et al., 2021b ). As recognized by both the academic community and industry, cultural tourism products greatly impact tourism destination development; souvenir, local cuisines, and films/television programs can promote tourism destinations ( Liu et al., 2021a , b ). Among them, film/television is the most influential form of art in today’s society. Film and television can help potential tourists to have some sensory and emotional cognitions through empathy and vicarious feeling to the tourist destinations mentioned in the films ( Kim and Kim, 2018 ; Pérez García et al., 2021 ), thereby generating tourism motivation and ultimately promoting tourism behaviors. Film and television, without exception, have integrated commerciality and artistry since birth, and form a unique form of culture ( Riley et al., 1998 ).

Hence, these significant economic effects have been widely investigated by researchers from different perspectives, such as promotion of local brands ( Liu et al., 2021a ), and changes in aesthetic information dissemination ( Kim et al., 2019 ). With in-depth studies, researchers have identified the profound connotation of the rapid development of film-induced tourism: the extension of the immersive tourism ( Marafa et al., 2020 ), the endowment of modern fashion labels for tourism destinations ( Teng and Chen, 2020 ), and multi-dimensional integrations of modern media technology and traditional entertainment industry.

Culture is the soul of tourism, and tourism is an important carrier of culture. Although the experience of film/television is different from tourism—the former is provided to people by means of image transmission, and the latter is realized by the way of people moving—but the essence is both cultural experience ( Syafrini et al., 2020 ; Senbeto and Hon, 2021 ). The connotation and the applied research of film-induced tourism reveal the complexity and diversity of the integrations of modern media and traditional entertainment.

The traditional glimmering style sightseeing tour is just a shallow taste, and often cannot make tourists get a deep enjoyment. Film-induced tourism is different, mature film-induced tourism products can bring tourists wholehearted relaxation and enjoyment, and make tourists’ self-worth better reflect. To clarify the inherent characteristics of film-induced tourism, the interactive observation of both the film and television subject and the tourism subject provides a feasible solution. Film/television programs are the expression and substantiveness of culture ( Yi et al., 2020 ). Tourism as an economic carrier is the pattern and standardization of the industry ( Yen and Croy, 2016 ). The development of film-induced tourism relies on the mutual integration of culture and industry.

With the evolution of the world, sustainable development is leading the way in every industry including tourism. The early understanding of sustainable development in the academic community refers to meeting the needs of the current generation without damaging the needs of future generations’ development ( Jabareen, 2008 ; Yi et al., 2021a ). Based on this concept, the United Nations has formulated 17 sustainable development goals, proposed new standards for the prosperity and development of the earth, and standardized the assessment methods and indicators for sustainable development ( Böhringer and Jochem, 2007 ; Hacking and Guthrie, 2008 ; Singh et al., 2009 ). Since then, the concept of sustainable development has been fully implemented and has gradually become a well-known concept from the perspectives of the environment, economy, and society ( Adedoyin et al., 2021 ; Diep et al., 2021 ; Zhou et al., 2021 ). Currently, these three dimensions are identified as the motivations and mechanisms of sustainable development ( Steffen et al., 2015 ; Svensson and Wagner, 2015 ). Specifically, challenges in sustainable development are vital issues for exploring social and economic development. Economic benefits are the main dynamics of continuous action ( Hoogendoorn et al., 2015 ), with social effects as the main motivation of practice ( Williams and Schaefer, 2013 ), and environmental effects as the basic assurances of all activities ( Halme and Korpela, 2014 ). Hence, sustainable development research help explore the path of the industry development. The dynamic mechanism of sustainable development builds the foundation for the long-term influence of the culture and provides the way for continuous development and expansion of industrial effects ( Waheed et al., 2020 ). At present, to the best of our knowledge, very few studies have investigated the dynamic mechanism of the sustainable development for film-induced tourism. The existing studies which include the sustainable development dynamic mechanism can be divided into three aspects:

(1) The macro sustainable development concept of film-induced tourism ( Wen et al., 2018 ); (2) The sustainable development concept in the exploration of film-induced tourism ( Gong and Tung, 2017 ; Teng, 2021 ); (3) The micro sustainable development concept of film-induced tourism ( Suni and Komppula, 2012 ). Afterward, most of the studies believe that the dynamic mechanism of sustainable development is affected by its resource development, innovation mode, or artistic attractions. However, these have not yet conducted a quantitative study of the endogenous interactions between culture and industry. Accordingly, we try to fill the research gap; we study the relationship between culture and industry in film-induced tourism through structural equation modeling to promote the sustainable development dynamics brought about the integration of culture and industry.

Literature Review

Film-induced culture and tourism industry.

Film-induced culture plays a vital role in the global advertisement system. It is an effective approach for the advertisement of regional values and soft power, and it is a good pathway for cultural output and value proposition ( Yi et al., 2020 ). With the advance of economic development, consumers have broken the restrictions of basic needs spending ( Sun et al., 2017 , 2021 ; Du et al., 2020 ), and the needs for higher-level cultural consumption are becoming increasingly important ( Wang et al., 2020a , b ; Li et al., 2021 ). Film-induced culture is by no means limited to entertainment culture, and film-induced products are by no means limited to spiritual and cultural consumer goods ( Chen, 2018 ). Film/television is also a mass media. Film-induced culture has an unprecedented impact on people’s ways of thinking, social cognition, behavioral habits, and values, showing unique cultural tension and becoming an important structure of people’s spiritual life ( Misra, 2000 ; Janssen et al., 2008 ). Otherwise, as a fast-growing important new tourism trend, film-induced tourism creates connections between characters, places, stories, and tourists, and is inspired to immerse themselves in films to relive film-generated and film-driven emotions ( Riley et al., 1998 ). Essentially, both film and tourism provide an opportunity to relive or experience, see and learn novelties through entertainment and fun ( Teng, 2021 ). Film-induced tourism increases the overall economic effect of tourism industry and establishes the bonds of film and tourism industry. It provides not only pleasure and satisfaction for film-induced tourists, but also adequate and novel learning experience. The latest research trends are moving toward merging or collaborating two fields that already have similar goals.

The integration of film-induced culture spreads information through film-induced programs to “maximize” the effect of tourism cultural brands ( Huang and Liu, 2018 ). The fundamental reason is that the penetration of film-induced culture has driven the transformation and upgrading of tourism consumption ( Michael et al., 2020 ), which in turn makes film-induced culture a resource for tourism development, amplifies the effect of cultural integration in the process of transformation, and further enhances the influence of the tourism industry ( Marafa et al., 2020 ). The establishment of film-induced cities and film-induced bases creates the advantages of film-induced culture agglomeration, and the innovative path of developing film-induced cultural resources oriented by the tourism industry is becoming more and more popular ( Ringle, 2018 ). Cultural resources are further optimized and reorganized, and film-induced culture will gain a series of new integrated development in the promotion of tourism industry model ( Xin and Mossig, 2017 ). On the one hand, the film-induced bases can be used for film/television production, and on the other hand, it is an important place for tourism activities, which truly reflects the integration from products, markets, enterprises, and industries in film-induced tourism industry ( Stuckey, 2021 ). Accordingly, some researchers believe that the establishment of Hollywood Studios in 1963 marked the official beginning of film-induced tourism. Hence, film-induced culture can promote the tourism industry to shape brand culture, integrate useful resources, guide consumer trends, and induce convergence effect for rapid development and innovation ( Wu and Lai, 2021 ). Hence, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a: The development of film-induced culture is positively related to the growth of the tourism industry.

H1b: The cultural development in film-induced tourism is positively correlated to the degree of cultural and tourism integration.

H1c: The development of the tourism industry is positively correlated to the degree of culture and tourism integration.

Culture and Tourism Integration and Sustainable Development

The integration of culture and tourism is not only the objective need for the mutual prosperity of culture and tourism, but also the inevitable trend of the development. The elements compete, cooperate and co-evolve with each other, so that an emerging industry can be formed, and it has experienced “grinding-integration-harmony” of the dynamic development process ( Jovicic, 2016 ; Wang and Yi, 2020 ). Culture and tourism have a certain basis for mutual benefit and cooperation: for tourism, the integration of cultural-related content helps to acquire extensive knowledge, distant experience, and strong care; for culture, it is conducive to the protection and inheritance of cultural resources, image building, and propagation ( Loulanski and Loulanski, 2011 ; Jørgensen and McKercher, 2019 ). The integration of culture and tourism is an intimate contact between “poems and dreams,” which better meets people’s diverse needs for a beautiful life ( He et al., 2021 ). However, sustainable development refers to comprehensive and sustainable advancements in ecological, social, and economic aspects. The cognition that based on these three goals can be used to explore the dynamic mechanism for sustainable development of film-induced tourism.

In the dimension of sustainable ecological development, with the advent of the scientific revolution and the industrial revolution, the world is entering a new era. The utilization of resources is not limited to the development of physical resources but is more prone to the rational use of new resources, such as talented person, technology, intelligence, and data ( Waheed et al., 2020 ; Zhang et al., 2020 ; Li et al., 2021 ), cultural resources, such as historical culture, red culture, and folk culture, are integrated with tourism resources, such as landscape pastoral, to develop complementary advantages. The maximization of resource utilization has become the key to the sustainable development of the film-induced tourism society, and culture has become a regulator of various innovation factors, which promotes the scientific management of technological and industrial resources ( Delai and Takahashi, 2011 ; Liu et al., 2021b ). When transforming and utilizing film-induced cultural resources, do not trample or destroy the ecological environment for tourism development, and comprehensively optimize the tourism environment and tourism routes. Environmentalism and related laws and regulations have begun to pay attention to tourists’ needs ( Li et al., 2020 ). Hence, the further integration of culture and tourism can reflect the transformation of the overall ecological commitment ( Zhou et al., 2021 ), and the resulting human–environment relationship has become a new aspect of sustainable development.

In the dimension of sustainable social development, on the one hand, the improvement of cultural quality of the whole society is a prerequisite for the organic integration of culture and tourism ( Tien et al., 2021 ), with harmonious coexistence becoming the core aspect of economic and cultural development of the new era, tourists and other stakeholders of the film-induced tourism industry begins to focus on human capital development, social recognition, job creation, and health and safety-related issues ( Choi and Ng, 2011 ). With the deepening of research, researchers found that the above-mentioned problems are ideologically attributed to culture and are the society’s force for inducing the sustainable development of industries ( Cai and Zhou, 2014 ). The extension and connotation of tourism need the guidance of tourism culture. Cultural display or visitable production expands the scope of displayable culture, from material to non-material, to the integration of non-material and material, and then to the contemporary creative cultural display, which makes culture continuously “commoditized” ( Silberberg, 1995 ; Marques and Pinho, 2021 ). At present, many scholars have reached a consensus that the integration of culture and industry can promote the construction of the social community ( Jakhar, 2017 ; Yi et al., 2021b ) and promote the relevant members of the society to change their misconduct, thereby strengthening the sustainable development of the film and television industry and the tourism industry.

In the dimension of sustainable economic development, scholars generally agree that economic factors, which refer to the renewable and non-renewable resources invested in the production process, are composed of factors, such as cost, profit, and business development ( Mamede and Gomes, 2014 ; Wagner, 2015 ). Given the direct impact of economic effect on tourist activities is significant, most researchers directly view economic factors as the main driving force for the sustainable development of film-induced tourism, owing to the direct influence of economic effects on tourists’ tourism activities ( Horbach et al., 2013 ; Hojnik and Ruzzier, 2016 ). As been defined by researchers, sustainable economic development involves the exploration and innovation of business models, creating market opportunities, the processes of resolving unsustainable environmental and social problems ( Schaltegger et al., 2016 ). When film-induced culture is continuously produced into cultural tourism products, the commercial interests of tourism sales promote the industrialization and gradually form a complete industrial chain-cultural tourism industry. In the studies of film-induced tourism, many researchers view film-induced culture as a resource for creating new business models and market opportunities and regard the integration of film-induced culture with the tourism industry as a solution for unsustainable development problems. In summary, in film-induced tourism, in both the ecological, social, and economic dimensions, the integration of culture and industry will influence the path of sustainable development. Hence, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a: The degree of integration between film-induced culture and the tourism industry is positively related to the sustainable development of the ecology (human–environment integration).

H2b: The degree of integration between film-induced culture and tourism industry is positively correlated to the sustainable development of the society (harmonious coexistence).

H2c: The degree of integration between film-induced culture and the tourism industry is positively related to the sustainable development of the economy.

Above all, we proposed the following effect hypothesis:

H3a: Film-induced tourism culture has a significant impact on sustainable development through integration degree;

H3b: Film-induced tourism industry has a significant impact on sustainable development through integration degree.

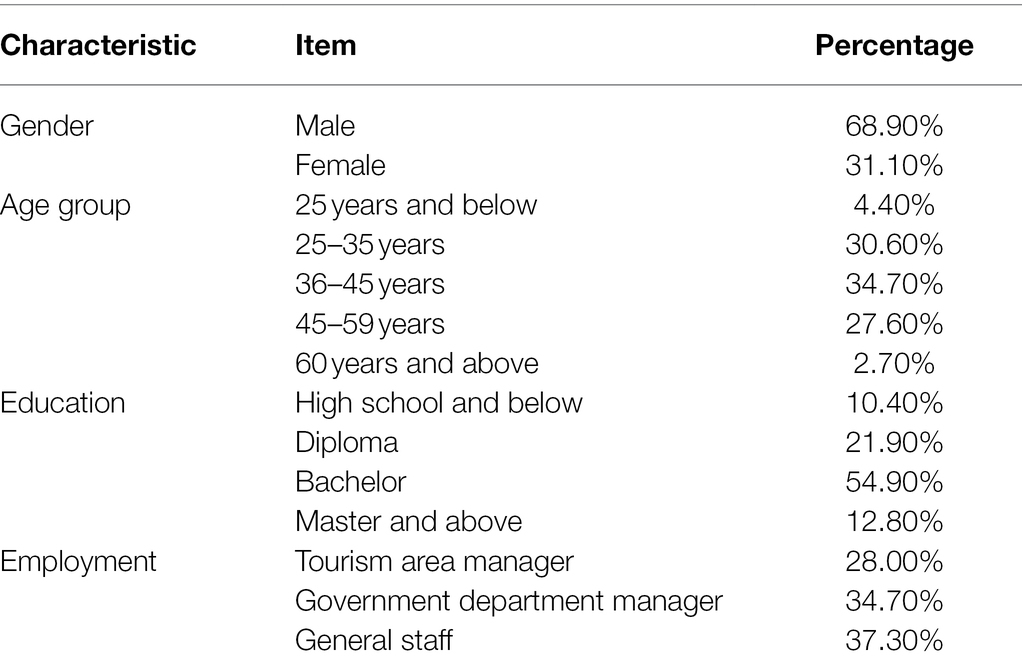

Methodology

To get a better and professional understanding of the dynamic mechanism of the culture and industry associated with film-induced tourism, the research subjects are limited to the management staff of the film-induced tourism industry. A total of 1,200 questionnaires were distributed, and 1,054 valid questionnaires were collected, with a recovery rate of 87.8%. The collected questionnaires were randomly divided into two equal sets (527 questionnaires in each set): one dataset is used for exploratory factor analysis and the other is used for confirmatory factor analysis. The demographic characteristics of the sample population are shown in Table 1 . From Table 1 we can see, most of the responders are males (accounting for 68.9%), in the age groups of 25–35 and 36–45 (the total number of the two age groups accounting for 65.3%) and have a bachelor’s degree (accounting for 54.9%). 28% of the responders are tourism area managers; 34.7% of the responders are government department managers; and 37.3% of the responders are general staff. And the demographic characteristics of the responders generally follow the demographic distribution of the entire population in the area, indicating a good representativeness of the data and makes it an effective data source.

Table 1 . Sample basic information.

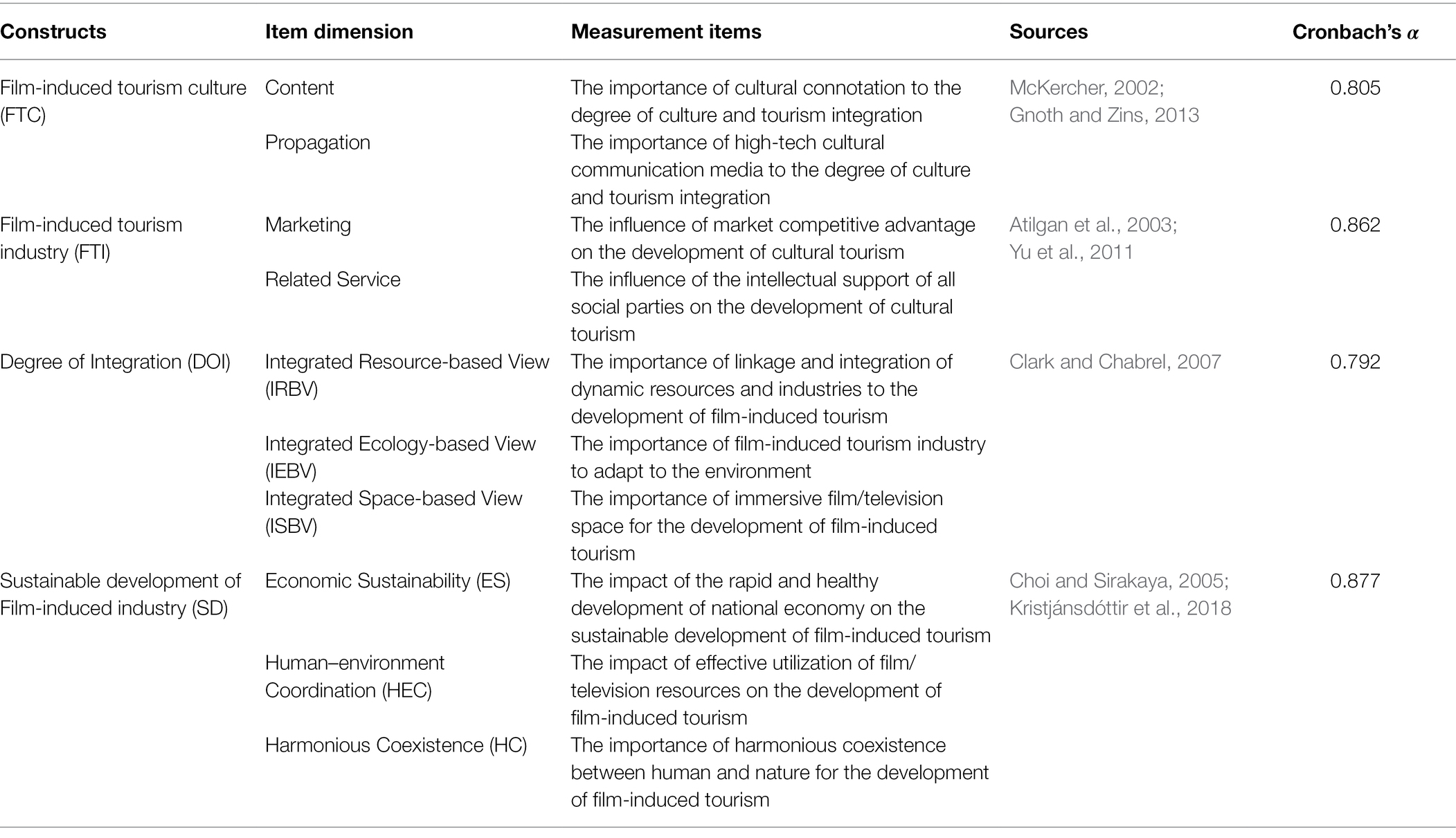

We draw on the mature scales used in previous studies for reference, and the initial scale was formed after corresponding modifications according to research topic. Then, two scholars who have been engaged in film-induced tourism and sustainable development were invited for analysis and discussion, and the scale was modified and improved. We use 5-level Likert scale to measure all variables, with 1 indicating “very unimportant” and 5 indicating “very important.” The specific measurement items and reliability are shown in the appendix. In addition, SPSS 26.0 was used for validity test, and KMO was 0.906 (>0.8). The results show that the scale has good reliability and validity, indicating that there is internal consistency among the variables ( Table 2 ).

Table 2 . Measurement items and reliability.

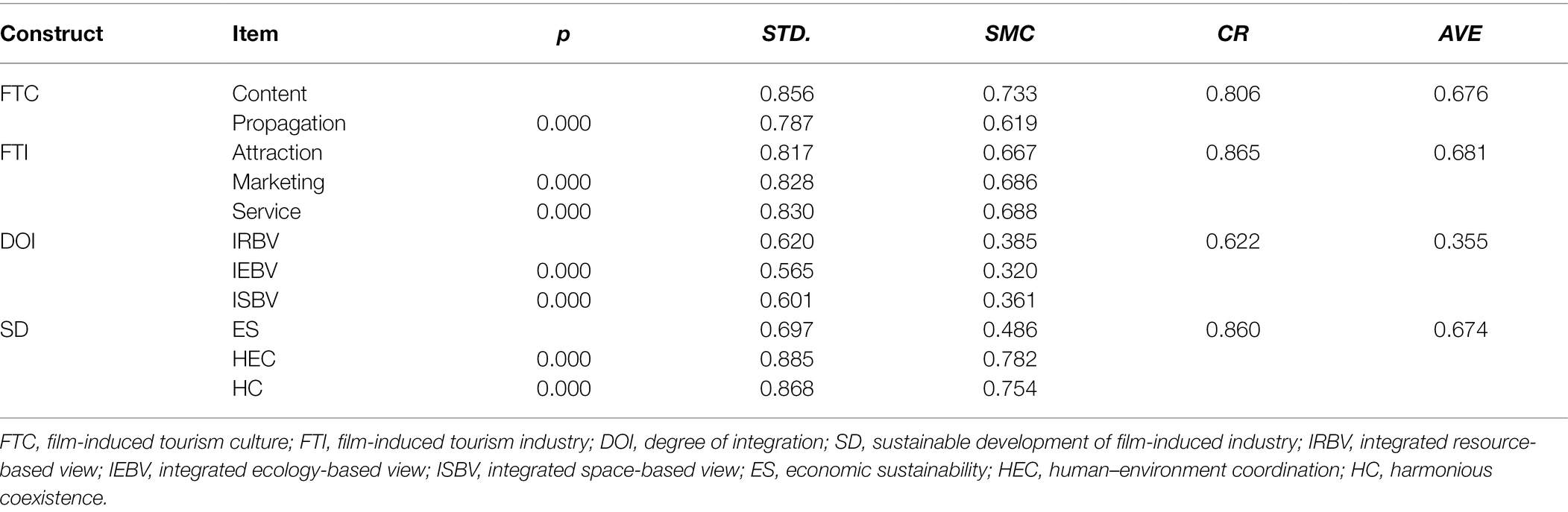

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) showed ( Table 3 ) that P<0.01, and the Composite Reliability of all variables was 0.622–0.865, so that the polymerization validity and the convergence validity is good. AVE was in a reasonable range. Therefore, the results of CFA all meet the standard, and all dimensions have good convergence validity.

Table 3 . Confirmatory factor analysis.

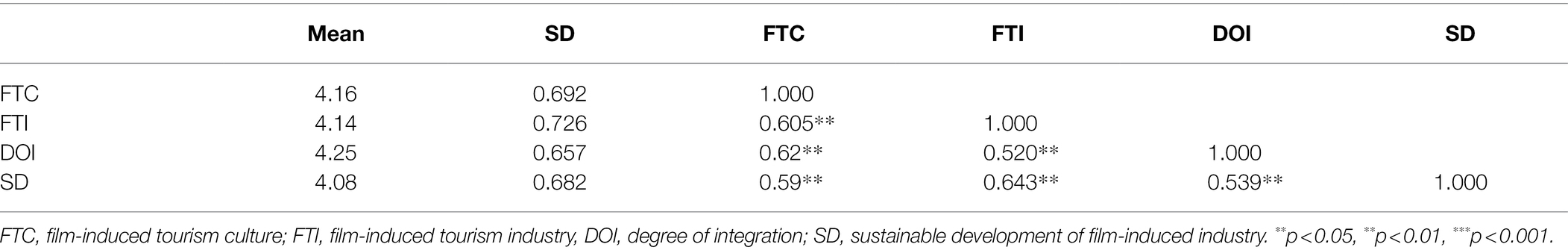

Correlation Analysis

Through the correlation coefficient test, it can be seen that the values below the diagonal are, respectively, the correlation coefficients between potential variables ( Table 4 ). Each potential variable has different connotations in theory, and each variable has relatively high correlation and good discriminant validity.

Table 4 . Correlation analysis.

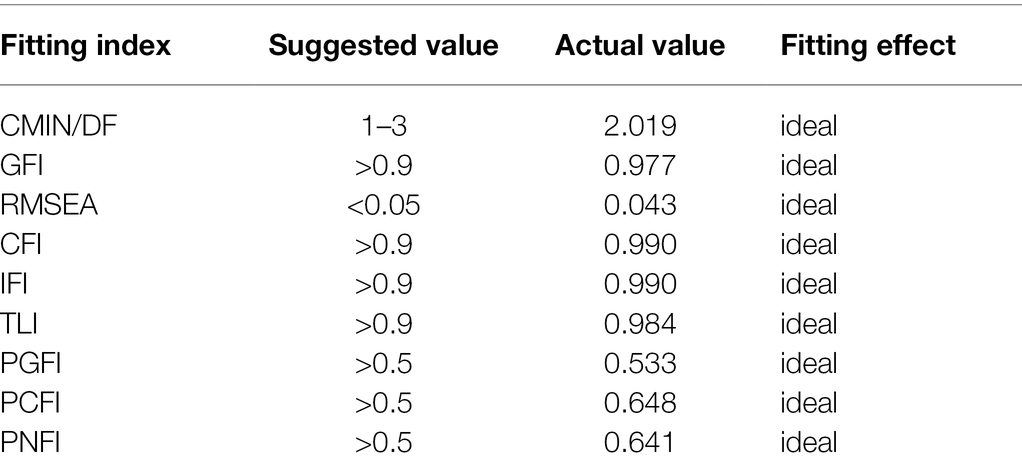

Goodness of Fit of the Structural Model

Based on the previous research results, the path relationship diagram between potential variables and observed variables has been built, the goodness of fit of the model to be verified have been tested from AMOS 26.0. The main fitting indicators all meet the ideal standard, that is, the model fitting effect is ideal.

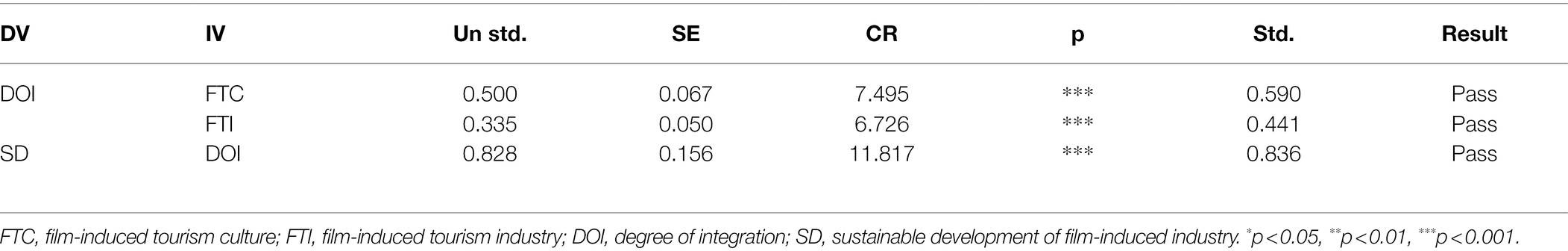

Hypothesis Testing

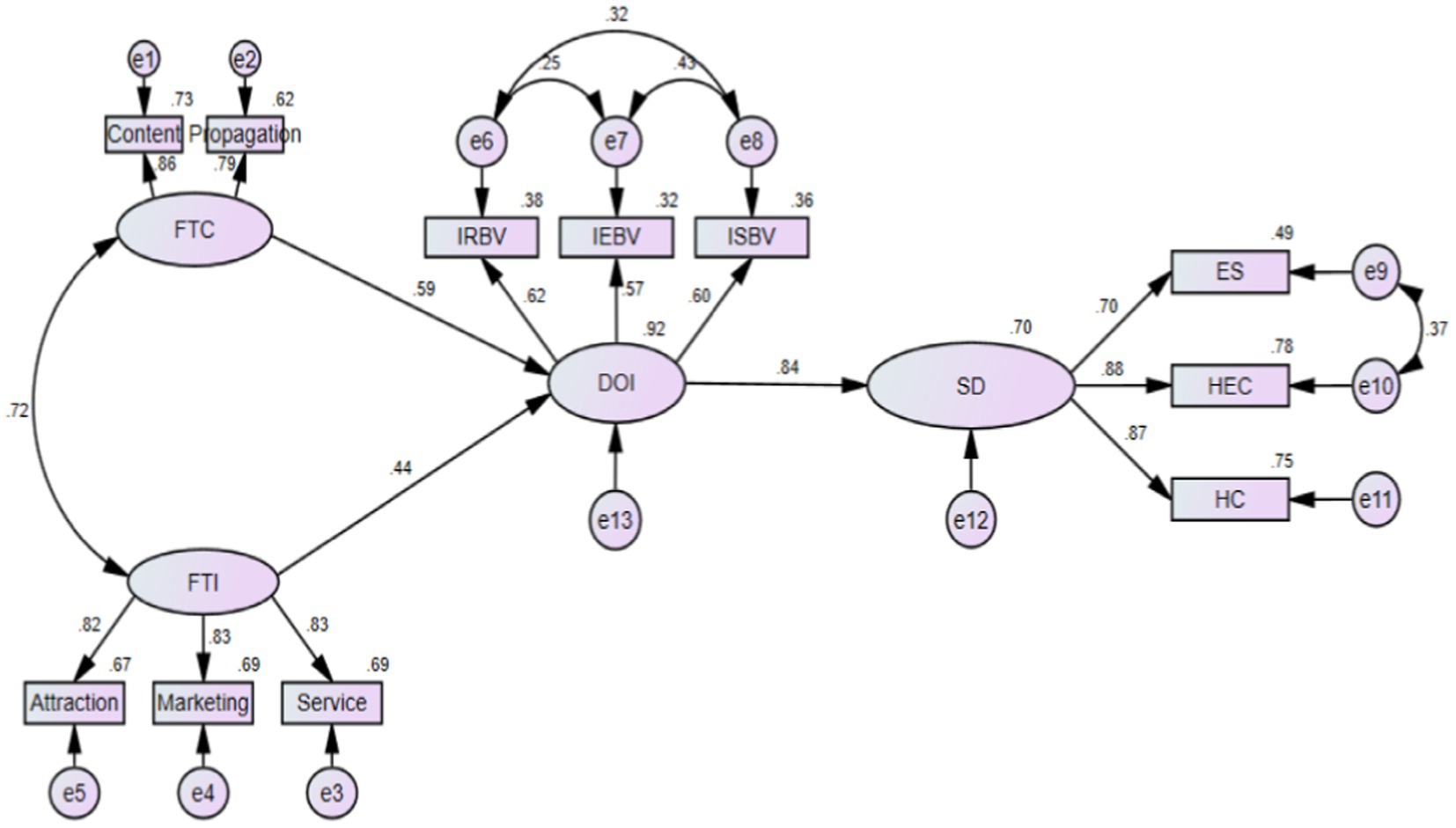

In order to further test the hypothesis proposed above, we run a structural equation model with mediation (see Figure 1 ). The results are shown in Table 5 . There is a correlation between film-induced culture and film-induced industry ( r = 0.720). Film-induced culture has a significant impact on the degree of integration ( r = 0.590, C R = 7.495, p < 0.01); The film-induced tourism industry has a significant impact on the degree of integration ( r = 0.441, C R = 6.326, p < 0.01), then hypothesis 1a, 1b, 1c are supported. The degree of integration has a significant positive impact on film-induced tourism ( r = 0.836, C R = 11.817, p < 0.01), so hypothesis 2a, 2B, and 2C are also supported.

Figure 1 . Structural equation model. FTC, film-induced tourism culture; FTI: film-induced tourism industry; DOI, degree of integration; SD, sustainable development of film-induced industry; IRBV, integrated resource-based view; IEBV, integrated ecology-based view; ISBV, integrated space-based view; ES, economic sustainability; HEC, human–environment coordination; HC, harmonious coexistence.

Table 5 . Goodness of fit of the structural model.

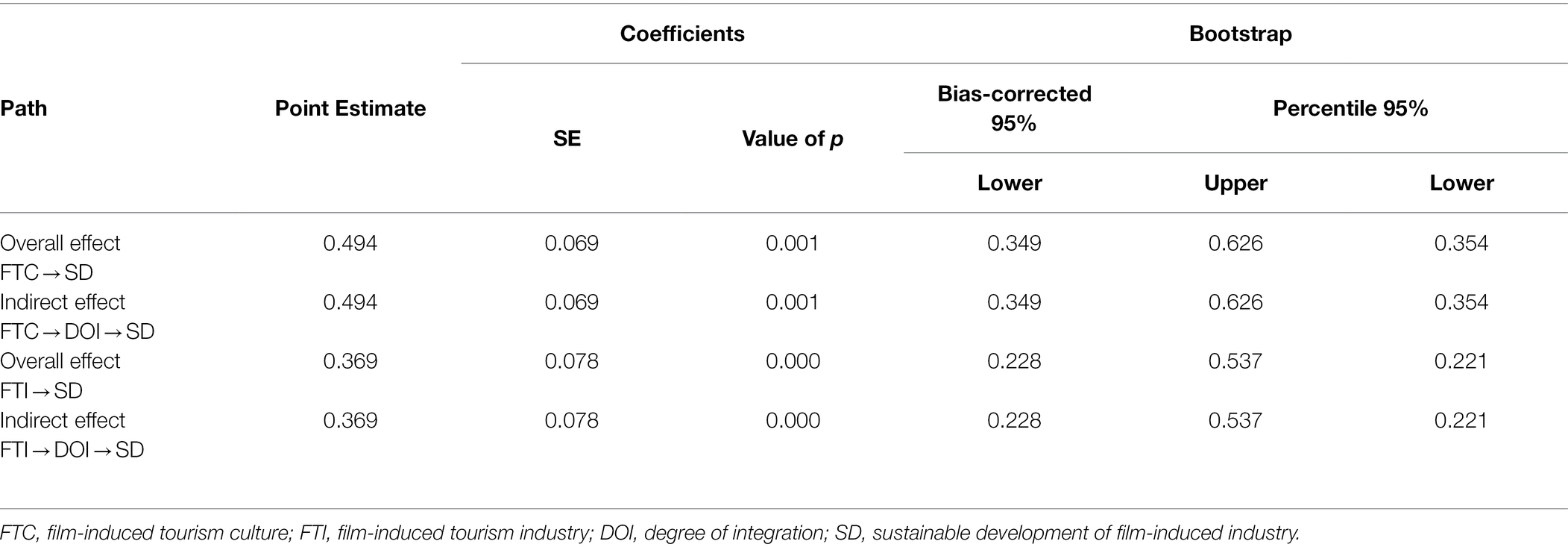

Empirical Testing of Mediating Effects

In order to test the reliability of the path hypothesis, we further use Bootstrapping to calculate the mediating effect of culture and tourism integration. Bootstrapping test performs 3,000 samplings and selects a 95% confidence interval, then the final test results are shown in Table 6 , so both hypothesis H3a and H3b are assumed to hold ( Table 7 ).

Table 6 . Hypothesis testing.

Table 7 . Empirical testing of mediating effects.

Given previous scholars’ studies on film-induced tourism ( Ringle, 2018 ; Marafa et al., 2020 ), we assume that cultural tourism will significantly affect the dynamic mechanism of sustainable development. More specifically, we believe that the organic integration of film-induced culture and tourism industry will have a significant impact on economic, social, and ecological sustainable development, which are the three dimensions of sustainable development. The results generally support our hypothesis that we view culture and tourism as a systematic whole rather than separate them and that culture and tourism integration is not simply “culture + tourism” or “tourism + culture.” We also confirm that the degree of integration of film-induced culture and tourism industry plays an important mediate role in the sustainable development of film-induced tourism. Although culture and tourism seem to be combined with each other in contemporary society, they have not developed the sustainable development dynamics of products and services innovation, nor developed a systematic operation mechanism. Consequently, the integration of culture and tourism is not to mechanically copy the two independent elements, but the key lies in the functional replacement and format innovation, complementary advantages, and the optimal combination of industrial elements.

Managerial Implications

As culture and tourism are two huge and complex systems, both have relatively mature management operation mechanism, working path, industrial rules, and industry norms, while they are currently characterized by high growth and rapid development ( Richards, 2018 ; McKercher, 2020 ). Therefore, in constructing the path of the integration of culture and tourism to promote sustainable development, the resource characteristics, functional differences, and technological advantages of film-induced culture and tourism industry should be fully considered in theory, and their similarity and relevance should be taken into account. In practice, we should not only make full use of the location conditions, resource endowments, and social and economic systems of film-induced culture and tourism destinations, but constantly identify the intersection points of products, industries, and enterprises according to the changes in market demand, and construct diversified industrial integration modes according to local conditions to determine develop directions in the integration of resources, technology, market and products, and administrative management.

From the perspective of tourism industry, support the development of organization forms that meet the needs of film-induced tourism development. The integration of industry should finally be reflected in the integration of organizations. Although the fundamental dynamics for the development of film-induced tourism is the development of market demand ( Connell, 2005 ), it needs enterprises to be discovered and satisfied to find business opportunities. We suggest relevant departments relax film-induced tourism business licensing, strengthen information services, support enterprises to explore new business areas, support various cooperation, and even merger and acquisitions. From the perspective of film-induced culture, enrich the cultural connotation of film-induced tourism. Film-induced tourism should not be equated with general implanted advertising or simply build film-induced bases, but should dig deeply into the cultural connotation of film-induced tourism, closely focus on the core theme of film/television works, and deeply develop “post-film products” related to tourism derivative industry, and then systematically integrate them to form a cross-industry and compound film-induced tourism industry chain ( Young and Young, 2008 ; Fan and Yu, 2021 ). In order to promote sustainable development, we further suppose that we should strengthen the research on film-induced tourism and explore the development mode and regulations of film-induced tourism.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study provides some enlightenments on the theoretical exploration and practical management of film-induced tourism. Inevitably, there are several limitations, which can be addressed in future studies. First, the verification of the hypotheses is through the empirical analysis of collected questionnaires, lacking the support of actual cases. This can be improved by case analysis in follow-up studies. Second, the degree of integration between culture and industry is measured and defined by their characteristics in this study. However, the integration may also be affected by their underlying relationship. Their spatial production characteristics are also valuable for further investigation. In summary, in this research, the dynamic mechanism for sustainable development of film-induced tourism has been investigated, and conclusions have been drawn. This topic, however, still requires in-depth follow-up investigations from the research community.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by School of Economics and Management, East China Jiaotong University, Nanchang, China. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

KY contributed to the empirical work, the analysis of the results, and the writing of the first draft. JinZ and JiaZ supported the total work of the KY. YZ and CX contributed to overall quality and supervision the part of literature organization and empirical work. RT contributed to developing research hypotheses and revised the overall manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This project was supported by the General Project of the National Social Science Fund of China: Tracking Research on the Development of Western Urban Politics (20BZZ055), General project of Humanities and Social Sciences General Research Program of the Ministry of Education: Research on the Generation Mechanism and Resolution Path of “Fragmentation Phenomenon” of Urban Social Governance (19YJA810002), Social Science Planning General Project in Jiangxi Province (No. 21XW06), Jiangxi Province Culture and Art Science Planning General Project (No. YG2021087), and Jiangxi Province Colleges Humanities and Social Science Project (No. GL20214).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Adedoyin, F. F., Nathaniel, S., and Adeleye, N. (2021). An investigation into the anthropogenic nexus among consumption of energy, tourism, and economic growth: do economic policy uncertainties matter? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 2835–2847. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-10638-x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Atilgan, E., Akinci, S., and Aksoy, S. (2003). Mapping service quality in the tourism industry. Manag. Serv. Qual. 13, 412–422. doi: 10.1108/09604520310495877

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Böhringer, C., and Jochem, P. E. (2007). Measuring the immeasurable—A survey of sustainability indices. Ecol. Econ. 63, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.03.008

Cai, W. G., and Zhou, X. L. (2014). On the drivers of eco-innovation: empirical evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 79, 239–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.05.035

Chen, C. Y. (2018). Influence of celebrity involvement on place attachment: Role of destination image in film tourism. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 23, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2017.1394888

Choi, S., and Ng, A. (2011). Environmental and economic dimensions of sustainability and price effects on consumer responses. J. Bus. Ethics 104, 269–282. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-0908-8

Choi, H. S. C., and Sirakaya, E. (2005). Measuring residents’ attitude toward sustainable tourism: development of sustainable tourism attitude scale. J. Travel Res. 43, 380–394. doi: 10.1177/0047287505274651

Clark, G., and Chabrel, M. (2007). Measuring integrated rural tourism. Tour. Geograp. 9, 371–386. doi: 10.1080/14616680701647550

Connell, J. (2005). Toddlers, tourism and Tobermory: destination marketing issues and television-induced tourism. Tour. Manag. 26, 763–776. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2004.04.010

Delai, I., and Takahashi, S. (2011). Sustainability measurement system: a reference model proposal. Soc. Res. J. 7, 438–471. doi: 10.1108/17471111111154563

Diep, L., Martins, F. P., Campos, L. C., Hofmann, P., Tomei, J., Lakhanpaul, M., et al. (2021). Linkages between sanitation and the sustainable development goals: A case study of Brazil. Sustain. Dev. 29, 339–352. doi: 10.1002/sd.2149

Du, Y., Li, J., Pan, B., and Zhang, Y. (2020). Lost in Thailand: A case study on the impact of a film on tourist behavior. J. Vacat. Mark. 26, 365–377. doi: 10.1177/1356766719886902

Fan, Z., and Yu, X. (2021). The regional rootedness of China’s film industry: cluster development and attempts at cross-location integration. J. Chin. Film Stu. 1, 463–486. doi: 10.1515/jcfs-2021-0027

Gnoth, J., and Zins, A. H. (2013). Developing a tourism cultural contact scale. J. Bus. Res. 66, 738–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.09.012

Gong, T., and Tung, V. W. S. (2017). The impact of tourism mini-movies on destination image: The influence of travel motivation and advertising disclosure. J. Travel Tour. Market. 34, 416–428. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2016.1182458

Hacking, T., and Guthrie, P. (2008). A framework for clarifying the meaning of triple bottom-line, integrated, and sustainability assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 28, 73–89. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2007.03.002

Halme, M., and Korpela, M. (2014). Responsible innovation toward sustainable development in small and medium-sized enterprises: A resource perspective. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 23, 547–566. doi: 10.1002/bse.1801

He, K., Wu, H., Wu, J., Lu, Q., and Meng, J. (2021). The research of Libo County integrated development of cultural and tourism in the new era. Tour. Manage. Technol. Eco. 4, 1–8.

Google Scholar

Hojnik, J., and Ruzzier, M. (2016). What drives eco-innovation? A review of an emerging literature. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 19, 31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2015.09.006

Hoogendoorn, B., Guerra, D., and Van der Zwan, P. (2015). What drives environmental practices of SMEs? Small Bus. Econ. 44, 759–781. doi: 10.1007/s11187-014-9618-9

Horbach, J., Oltra, V., and Belin, J. (2013). Determinants and specificities of eco-innovations compared to other innovations—an econometric analysis for the French and German industry based on the community innovation survey. Ind. Innov. 20, 523–543. doi: 10.1080/13662716.2013.833375

Huang, C. E., and Liu, C. H. (2018). The creative experience and its impact on brand image and travel benefits: The moderating role of culture learning. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 28, 144–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2018.08.009

Jabareen, Y. (2008). A new conceptual framework for sustainable development. Environ. Dev. Sustain 10, 179–192. doi: 10.1007/s10668-006-9058-z

Jakhar, S. K. (2017). Stakeholder engagement and environmental practice adoption: The mediating role of process management practices. Sustain. Dev. 25, 92–110. doi: 10.1002/sd.1644

Janssen, S., Kuipers, G., and Verboord, M. (2008). Cultural globalization and arts journalism: The international orientation of arts and culture coverage in Dutch, French, German, and US newspapers, 1955 to 2005. Am. Sociol. Rev. 73, 719–740. doi: 10.1177/000312240807300502

Jørgensen, M. T., and McKercher, B. (2019). Sustainability and integration–the principal challenges to tourism and tourism research. J. Travel Tour. Market. 36, 905–916. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2019.1657054

Jovicic, D. (2016). Cultural tourism in the context of relations between mass and alternative tourism. Curr. Issue Tour. 19, 605–612. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2014.932759

Kim, S., and Kim, S. (2018). Perceived values of TV drama, audience involvement, and behavioral intention in film tourism. J. Travel Tour. Market. 35, 259–272. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2016.1245172

Kim, S., Kim, S., and King, B. (2019). Nostalgia film tourism and its potential for destination development. J. Travel Tour. Market. 36, 236–252. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2018.1527272

Kristjánsdóttir, K. R., Ólafsdóttir, R., and Ragnarsdóttir, K. V. (2018). Reviewing integrated sustainability indicators for tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 26, 583–599. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2017.1364741

Li, F., Katsumata, S., Lee, C. H., Ye, Q., Dahana, W. D., Tu, R., et al. (2020). Autoencoder-enabled potential buyer identification and purchase intention model of vacation homes. IEEE Access 8, 212383–212395. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3037920

Li, X., Wirawan, D., Ye, Q., Peng, L., and Zhou, J. (2021). How does shopping duration evolve and influence buying behavior? The role of marketing and shopping environment. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 62:102607. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102607

Liu, A., Fan, D. X., and Qiu, R. T. (2021a). Does culture affect tourism demand? A global perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 45, 192–214. doi: 10.1177/1096348020934849

Liu, B., Wang, Y., Katsumata, S., Li, Y., Gao, W., and Li, X. (2021b). National Culture and culinary exploration: Japan evidence of Heterogenous moderating roles of social facilitation. Front. Psychol. 12:784005. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.784005

Loulanski, T., and Loulanski, V. (2011). The sustainable integration of cultural heritage and tourism: A meta-study. J. Sustain. Tour. 19, 837–862. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2011.553286

Mamede, P., and Gomes, C. F. (2014). Corporate sustainability measurement in service organizations: A case study from Portugal. Environ. Qual. Manag. 23, 49–73. doi: 10.1002/tqem.21370

Marafa, L. M., Chan, C. S., and Li, K. (2020). Market potential and obstacles for film-induced tourism development in Yunnan Province in China. J. China Tour. Res. 18, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/19388160.2020.1819498

Marques, J., and Pinho, M. (2021). Collaborative research to enhance a business tourism destination: A case study from Porto. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leisure Events 13, 172–187. doi: 10.1080/19407963.2020.1756307

McKercher, B. (2002). Towards a classification of cultural tourists. Int. J. Tour. Res. 4, 29–38. doi: 10.1002/jtr.346

McKercher, B. (2020). Cultural tourism market: a perspective paper. Tour. Rev. 75, 126–129. doi: 10.1108/TR-03-2019-0096

Michael, N., Balasubramanian, S., Michael, I., and Fotiadis, S. (2020). Underlying motivating factors for movie-induced tourism among Emiratis and Indian expatriates in the United Arab Emirates. Tour. Hosp. Res. 20, 435–449. doi: 10.1177/1467358420914355

Misra, J. (2000). Integrating" the real world" into introduction to sociology: making sociological concepts real. Teach. Sociol. 28, 346–363. doi: 10.2307/1318584

Pérez García, Á., Sacaluga Rodríguez, I., and Moreno Melgarejo, A. (2021). The development of the competency of “cultural awareness and expressions” using movie-induced tourism as a didactic resource. Educ. Sci. 11:315. doi: 10.3390/educsci11070315

Richards, G. (2018). Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 36, 12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.03.005

Riley, R., Baker, D., and Van Doren, C. S. (1998). Movie induced tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 25, 919–935. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00045-0

Ringle, C. (2018). In print and On screen: film columns, criticism, and culture in early Hollywood-Richard Abel. Enterp. Soc. 19, 216–225. doi: 10.1017/eso.2017.51

Schaltegger, S., Hansen, E. G., and Lüdeke-Freund, F. (2016). Business models for sustainability: origins, present research, and future avenues. Organ. Environ. 29, 3–10. doi: 10.1177/1086026615599806

Senbeto, D. L., and Hon, A. H. (2021). Shaping organizational culture in response to tourism seasonality: A qualitative approach. J. Vacat. Mark. 27, 466–478. doi: 10.1177/13567667211006759

Silberberg, T. (1995). Cultural tourism and business opportunities for museums and heritage sites. Tour. Manag. 16, 361–365. doi: 10.1016/0261-5177(95)00039-Q

Singh, R. K., Murty, H. R., Gupta, S. K., and Dikshit, A. K. (2009). An overview of sustainability assessment methodologies. Ecol. Indic. 9, 189–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2008.05.011

Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S. E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E. M., et al. (2015). Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 347:1259855. doi: 10.1126/science.1259855

Stuckey, A. (2021). Special effects and spectacle: integration of CGI in contemporary Chinese film. J. Chin. Film Stu. 1, 49–64. doi: 10.1515/jcfs-2021-0005

Sun, G., Han, X., Wang, H., Li, J., and Wang, W. (2021). The influence of face loss on impulse buying: An experimental study. Front. Psychol. 12:700664. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.700664

Sun, G., Wang, W., Cheng, Z., Li, J., and Chen, J. (2017). The intermediate linkage between materialism and luxury consumption: evidence from the emerging market of China. Soc. Indic. Res. 132, 475–487. doi: 10.1007/s11205-016-1273-x

Suni, J., and Komppula, R. (2012). SF-Film village as a movie tourism destination—a case study of movie tourist push motivations. J. Travel Tour. Market. 29, 460–471. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2012.691397

Svensson, G., and Wagner, B. (2015). Implementing and managing economic, social and environmental efforts of business sustainability: Propositions for measurement and structural models. Manage. Environ. Q. Int. J. 26, 195–213. doi: 10.1108/MEQ-09-2013-0099

Syafrini, D., Fadhil Nurdin, M., Sugandi, Y. S., and Miko, A. (2020). The impact of multiethnic cultural tourism in an Indonesian former mining city. Tour. Recreat. Res. 45, 511–525. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2020.1757208

Teng, H. Y. (2021). Can film tourism experience enhance tourist behavioural intentions? The role of tourist engagement. Curr. Issue Tour. 24, 2588–2601. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2020.1852196

Teng, H. Y., and Chen, C. Y. (2020). Enhancing celebrity fan-destination relationship in film-induced tourism: The effect of authenticity. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 33:100605. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100605

Tien, N. H., Viet, P. Q., Duc, N. M., and Tam, V. T. (2021). Sustainability of tourism development in Vietnam's coastal provinces. World Rev. Ent. Manage. Sustainable Dev. 17, 579–598. doi: 10.1504/WREMSD.2021.117443

Wagner, B. (2015). Implementing and managing economic, social and environmental efforts of business sustainability. Manage. Environ. Q. Int. J. 26, 195–213. doi: 10.1108/MEQ-09-2013-0099

Waheed, A., Zhang, Q., Rashid, Y., Tahir, M. S., and Zafar, M. W. (2020). Impact of green manufacturing on consumer ecological behavior: Stakeholder engagement through green production and innovation. Sustain. Dev. 28, 1395–1403. doi: 10.1002/sd.2093

Wang, W., Chen, N., Li, J., and Sun, G. (2020a). SNS use leads to luxury brand consumption: Evidence from China. J. Consum. Mark. 38, 101–112. doi: 10.1108/JCM-09-2019-3398

Wang, W., Ma, T., Li, J., and Zhang, M. (2020b). The pauper wears prada? How debt stress promotes luxury consumption. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 56:102144. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102144

Wang, C., and Yi, K. (2020). Impact of spatial scale of ocean views architecture on tourist experience and empathy mediation based on “SEM-ANP” combined analysis. J. Coast. Res. 103, 1125–1129. doi: 10.2112/SI103-235.1

Wen, H., Josiam, B. M., Spears, D. L., and Yang, Y. (2018). Influence of movies and television on Chinese tourists perception toward international tourism destinations. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 28, 211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2018.09.006

Williams, S., and Schaefer, A. (2013). Small and medium-sized enterprises and sustainability: Managers' values and engagement with environmental and climate change issues. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 22, 173–186. doi: 10.1002/bse.1740

Wu, X., and Lai, I. K. W. (2021). The acceptance of augmented reality tour app for promoting film-induced tourism: the effect of celebrity involvement and personal innovativeness. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 12, 454–470. doi: 10.1108/JHTT-03-2020-0054

Xin, X. R., and Mossig, I. (2017). Co-evolution of institutions, culture and industrial organization in the film industry: The case of Shanghai in China. Eur. Plan. Stud. 25, 923–940. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2017.1300638

Yen, C. H., and Croy, W. G. (2016). Film tourism: celebrity involvement, celebrity worship and destination image. Curr. Issue Tour. 19, 1027–1044. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2013.816270

Yi, K., Li, Y., Peng, H., Wang, X., and Tu, R. (2021a). Empathic psychology: A code of risk prevention and control for behavior guidance in the multicultural context. Front. Psychol. 12:781710. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.781710

Yi, K., Wang, Q., Xu, J., and Liu, B. (2021b). Attribution model of travel intention to internet celebrity spots: A systematic exploration based on psychological perspective. Front. Psychol. 12:797482. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.797482

Yi, K., Zhang, D., Cheng, H., Mao, X., and Su, Q. (2020). SEM and K-means analysis of the perceived value factors and clustering features of marine film-induced tourists: A case study of tourists to Taipei. J. Coast. Res. 103, 1120–1124. doi: 10.2112/SI103-234.1

Young, A. F., and Young, R. (2008). Measuring the effects of film and television on tourism to screen locations: A theoretical and empirical perspective. J. Travel Touri. Market. 24, 195–212. doi: 10.1080/10548400802092742

Yu, C. P., Chancellor, H. C., and Cole, S. T. (2011). Measuring residents’ attitudes toward sustainable tourism: A reexamination of the sustainable tourism attitude scale. J. Travel Res. 50, 57–63. doi: 10.1177/0047287509353189

Zhang, L., Yi, K., and Zhang, D. (2020). The classification of environmental crisis in the perspective of risk communication: A case study of coastal risk in mainland China. J. Coast. Res. 104, 88–93. doi: 10.2112/JCR-SI104-016.1

Zhou, Z., Zheng, F., Lin, J., and Zhou, N. (2021). The interplay among green brand knowledge, expected eudaimonic well-being and environmental consciousness on green brand purchase intention. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 28, 630–639. doi: 10.1002/csr.2075

Keywords: film-induced tourism, tourism destination, sustainable development, dynamic mechanism, culture and industry integration

Citation: Yi K, Zhu J, Zeng Y, Xie C, Tu R and Zhu J (2022) Sustainable Development for Film-Induced Tourism: From the Perspective of Value Perception. Front. Psychol . 13:875084. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.875084

Received: 13 February 2022; Accepted: 13 May 2022; Published: 03 June 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Yi, Zhu, Zeng, Xie, Tu and Zhu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yanqin Zeng, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Exploring the Benefits of Film Tourism

Film tourism is a growing phenomenon worldwide, motivated by both the growth of the entertainment industry and the increase in international travel. By Leonie Berning.

Table of Contents

What is film tourism?

Film-induced tourism explores the effects that film and TV-productions have on the travel decisions made when potential tourists plan their upcoming holiday or visit to a destination.

Films, documentaries, TV-productions and commercials inspire people to experience the locations seen in the content screened, to explore new destinations. Film tourism is an excellent vehicle for destination marketing and also creates opportunities for product and community entrepreneur development such as location tours or film heritage museums to name but a few.

One of the best examples of film-induced niche tourism relates to ‘The Lord Of The Rings’ trilogy, filmed in New Zealand. Research studies revealed that at least 72% of the current and potential international tourists visiting New Zealand, had seen at least one of the trilogy films. Although this is no concrete evidence that their destination choice was as a result of the films, it was definitely a motivating component.

In a demonstration to of the power of film to raise the profile of New Zealand and reveal the influence a film has in destination choices for tourists, more than two-thirds of the tourists questioned agreed that they would visit the country as a result of the movie. (source: Film-Induced Tourism by Sue Beeton).

Film tourism and destination branding

Integrating film tourism with destination branding has an even bigger spin-off effect on tourism. “A decade after Jackson’s three-film adaptation of JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings emerged to critical and popular acclaim, the countdown to ‘The Hobbit’ – in its film form, also a trilogy – began shortly after in earnest”.

In earnest and in fact: Wellington mayor Celia Wade-Brown unveiled a giant clock, complete with an image of Martin Freeman as Bilbo Baggins, counting down the minutes to the 28 November premiere. The clock sits atop the Embassy Theatre, the handsome 1920s cinema that will host the screening. A bevvy of international stars, led, it’s safe to predict, by Freeman, will return to Wellington to walk the red carpet down Courtenay Place. The last time the 500m carpet was unrolled, for the world premiere of ‘The Return of the King’ in 2003, about 120,000 people came to watch the procession. Organisers expect a similar turnout this time. “It will be a real carnival atmosphere,” promises Wade-Brown.

According to Tourism New Zealand, an average of 47,000 visitors each year visit a film location. Following the release of the Lord of the Rings trilogy, six per cent of visitors (around 120,000 – 150,000 people) cite The Lord of the Rings as being one of the main reasons for visiting New Zealand. One per cent of visitors said that the Lord of the Rings was their main or only reason for visiting. This one per cent related to approximately NZ$32.8m in spend.

There is nothing subtle about efforts to piggyback. The national tourism slogan “100% Pure New Zealand” has become “100% Middle-earth” , while in the days leading up to the premiere Wellington will be ‘renamed’ as “Middle of Middle-earth”.

It is all a huge contrast from the ‘Lord of the Rings’ experience. Back then, tourist operators felt “ambushed” by fans of the films, says Melissa Heath, owner of Southern Lakes Sightseeing, which specialises in ‘Lord of the Rings’ location tours. “I don’t think anyone in New Zealand was ready for it.”

Britain has been a destination for over a hundred international film and television productions over the past decade. The filming of ‘Harry Potter’ and ‘Sherlock Holmes’ had a surge of tourists as a result. Films such as ‘Braveheart’ resulted in a 300% increase of tourism a year after its release in cinemas and the release of the film “Troy” resulted in a 72% increase for tourism in Turkey.

Film-induced tourism and destination branding are one of the fastest growing sectors in tourism currently. However, there are some key issues that need to be considered before promoting a location for film productions and tourism. Applying responsible tourism practices, creating a film-friendly environment in advance, through community participation and awareness campaigns, safety and security, service excellence and understanding the impact of destination branding to name but a few, especially in South Africa where film tourism is still a fairly unexplored concept.

Film tourism provides an abundance of community and product development opportunities if approached responsibly and applied correctly. It is a fast-paced industry, driven by creative passion, positive energy and tremendous enthusiasm, which I believe can be cross-pollinated into the tourism and services sector.

For more information email [email protected] or visit www.etc-africa.com

About the author: Leonie Berning is a member of the KwaZulu-Natal Film Commission Executive Board of Directors. With a collective seventeen years in human relations, eco-tourism, marketing and film industry experience, exploring and exposing the opportunities for film tourism and identifying film industry scarce skills and infrastructure needs, are her priorities. As a Consulting Manager and part of a project team for ETC-Africa, in partnership with Enterprise iLembe, uThungulu District Municipality and Umhlosinga Development Agency, Leonie successfully set up and managed the Zulu Coast Film Office project from 1 January 2011 – 30 March 2012.

Read more on this topic:

Using film festivals as a tourism marketing tool.

- 20 Niche Tourism Groups

- How to Become a Tourist Guide in South Africa

Tourism Tattler

Related articles.

How To Tap Into The Ecotourism Niche Market

Red tape tourism

Cruise tourism gets a boost as luxury ship sets sail for south africa.

Privacy Overview

- Help & FAQ

Film tourism stakeholders and impacts

- Department of Management

Research output : Chapter in Book/Report/Conference proceeding › Chapter (Book) › Research › peer-review

Access to Document

- 10.4324/9781315559018-34

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

T1 - Film tourism stakeholders and impacts

AU - Croy, W. Glen

AU - Kersten, Marieke

AU - Mélinon, Audrey

AU - Bowen, David