- Card Database

An Oral History of the First Pro Tour

In early 1996, Magic: The Gathering was just under three years old, but Organized Play was just taking its first wobbly steps. There had been a couple of World Championships, a US Nationals, and scattered local tournaments offering collections of the Power Nine and complete sets of Legends as prizes. Homelands had just come out, and there was this new format called Type 2 that was scuffling along behind a format in which you could Fork an Ancestral Recall , eat all your Moxen, and then Berserk your gigantic Atog .

Still, we were having fun even if nobody knew quite where it was all going—until an ad appeared in the pages of The Duelist for something called "The Magic: The Gathering Black Lotus Pro Tour." It was billed as a professional tournament with bigger cash prizes than anyone had ever seen for playing a game.

That event took place 20 years ago this February, and it had a profound effect on what we thought of as tournament Magic . Today, Wizards of the Coast gives away millions of dollars every year to an elite cadre of the game's best players through Grand Prix, Pro Tours, and the Pro Players Club, but back then, a tournament with a $12,000 first prize was unprecedented. I interviewed a handful of people who were at that event in an attempt to capture the oral history of the tournament.

Joining me to share their memories from that event are:

- Richard Garfield, the inventor of Magic: The Gathering .

- Skaff Elias, one of the original Magic playtesters and the first Magic Brand Manager. He pushed the idea of Magic as an intellectual sport.

- Mark Rosewater, the current Magic Head Designer, who has discussed his role at the Pro Tour on two podcasts. Those can be found here and here .

- Elaine Chase, the current Senior Director of Global Brand Strategy and Marketing for Magic: The Gathering . Before her long journey at Wizards, she was a competitor at the event.

- Charlie Catino, who, along with Skaff, was one of the first people to playtest Magic . In his role as an R&D Director, he has been responsible for Duel Masters for the past fifteen years.

- Jon Finkel is a Pro Tour Hall of Famer who has been playing at the highest level throughout the 20 years of the Pro Tour.

- Graham Tatomer, a Santa Barbara winemaker who won the Junior Division of that first Pro Tour.

- Michael Loconto, a Worchester social worker who defeated Bertrand Lestree in the finals of the first Pro Tour to become the very first Magic: The Gathering Pro Tour Champion.

Before the Black Lotus Pro Tour

Skaff : I came to be involved with Magic sheerly through pure luck. Richard Garfield was a fellow grad student in the math department at Penn. He had us all play games with him, and one of the games was this little thing he was working on for Wizards called "Magic." I think I was the third person to play it. And basically I have been playing it ever since.

Graham : It just turned out that Santa Barbara was kind of a hot spot for the game right when it came out. For Limited Edition (Alpha) and Limited Edition (Beta) we got an unusually high amount of players and actual cards. I was really drawn in by the fact that you got to make your own deck and that there were a lot of different avenues to take. There was this competitive factor to it that I liked as well. I was fifteen or sixteen years old when I got involved—around the release of Unlimited Edition . I was at the tail end of high school, where it felt like I didn't have that much to actually do. There was plenty of time to build decks and play against each other in local tournaments.

Elaine : Before the first Pro Tour, I was pretty active in the New York competitive scene. Gray Matter Conventions ran $1,000 tournaments at the time, and I played in those. I played in all sorts of communities in New York City, New Jersey, Upstate New York.... Magic at that time was a huge part of my life, and I would spend multiple days a week at multiple locations playing the game.

Charlie : I was one of the original playtesters for Richard Garfield's game. I basically played Magic before anyone else played Magic . I had a lot of experience and obviously, like all the players later on, when I first got into Magic I immediately realized what an awesome game it was and how much fun I had playing it. I just loved it so much and I dove incredibly deeply into it.

Michael : A lot of us played at SMK Collectibles in Hudson, Massachusetts. I remember buying Antiquities booster packs; that was the set that was out when we started to play. I'm sure everybody has a story about running to the store and hoping that there would be packs there. Unfortunately it wasn't Unlimited . We used to run a lot of tournaments for the store. Jim Lemire and I would be the judges. At the time, other than New York, the place to be was Hudson, Massachusetts.

Mark : I got hired by Wizards of the Coast in October 1995. I learned shortly afterwards from Skaff Elias that he was starting up a Pro Tour. Because I had been working freelance for Wizards, I wasn't allowed to play in tournaments. I told Skaff that I wanted to be involved, and he made me the liaison to R&D.

Jon : I was living in England when Magic came out. I was either fifteen or sixteen years old and I went to this local game store called Fun and Games. I walked in there and people were playing Dungeons & Dragons and other games, but the very first day people were playing Magic and it looked interesting. I asked about it and was pretty much instantly hooked. I moved back to the United States in New Jersey during the summer of '95 and started going to game stores and playing in some local tournaments. I thought I was pretty good—like every brash seventeen-year-old does—but I probably didn't play enough lands.

Richard : Obviously Magic was super-successful, but it was still in this turbulent non-stabilized state. I very much believed in this idea that if you took a game seriously that would help all levels of the game. The example that was used was that of basketball. The existence of the NBA didn't make it so that everybody's games are all super serious and exclude people who didn't participate in the NBA.

Balance | Art by Mark Poole

The Birth of the Pro Tour

Skaff : I was in R&D and at some point they needed a Brand Manager for the product, so I became the Brand and Business Manager for Magic —not too long before the Pro Tour. Part of the brand and marketing plan we came up with was to turn Magic into an intellectual sport. We felt that was really important for the long-term health of Magic .

Richard : When Ice Age came out, there were early posts analyzing the set, and they said there were only two good cards in the set. This is an unbelievably bad result for someone who's been working on the set for years and years. You look at that you just think, "This is ridiculous," with putting all this time, and in the end there were two cards that are of interest to people because they wanted to play with all these old, powerful cards. If we were in the business of selling cards to people, we were going to run out of cards sooner than we wanted. But if we were in the business of selling environments, we could make a new environment whenever we want. That's basically where the game was before the Pro Tour came around.

Mark : Skaff and I worked really closely together trying to get the event off the ground. Remember, in the early days there was nothing to model after. It was like the Wild West. Every tournament was run radically different.

Skaff : Golf and tennis were the two key examples for us that we were following. We talked to a lot of people at various sports marketing agencies and we decided that the best course of action was to start holding high-dollar tournaments and create stars out of the top people by having significant payouts. I understand the first Pro Tour wasn't necessarily that, but it was the first step towards that.

Mark : We wanted to name the Pro Tour, and one of the first things we came up with was "The Black Lotus Pro Tour." We sent out postcards announcing it, and we later learned that the lotus had connotations in some foreign markets that were not good. It is symbolic of drug trafficking in Asia, for example. We were just calling it the Magic: The Gathering Pro Tour internally, and eventually that stuck.

Richard : The main thing was that there were a lot of design issues. As far as designing the way the tournament would work at the time—payouts, what would happen if people took too long playing, and so on—that was hard work, but it was minor compared to politically getting the company on board with it. Because if it [didn't] have the support of the company and a unified vision coming from them, then it wasn't going to work.

I remember a board meeting in those days with people talking about how to get in touch with what the players wanted. I suggested we could hire the players, and most of the people at the board meeting laughed. It just showed such a huge lack of respect for the people buying the product. All this political stuff had to be overcome. For me, this was the [most pressing] of the difficulties we faced.

The Phone Lines Are Open

Mark : We invited everybody that we could think of who were good players, including using rankings for the first time ever. We invited the top 25 or top 50 or whatever. Then we needed to fill out the rest of the tournament and we had no other means to do it. So the way you got into the first Pro Tour was by calling in.

Graham : I don't even think there were qualifiers for it. Whoever called first just got in. It filled up in a couple hours if I remember correctly. It was the same for the Juniors Division, but it just never filled up. Sam Beavers was actually the guy my parents called to ask, "Hey, if we fly our son out to New York, does he have a chance to win this thing?" He told them I definitely had a chance and they said, "Let's do it." After that first Pro Tour it was never like that again—you actually had to qualify for things, there was no sign-up sheet.

Skaff : We weren't really that connected to the players at the time, because everything was so casual. For the first Pro Tour, it was really difficult to jump-start everything. That was the hardest part. We basically had no contact information for the vast majority of good players. We knew we had limited slots and it was a call-in. We used as much information as we could, but in the end we had to have a call-in.

Elaine : It was first come, first serve, and at the time I had really well-trained fingers because that's how you got concert tickets—by calling into Ticketmaster. There was a lot of redialing on the phone when you got a busy signal. I would just hit redial...redial...redial. I actually got through, and my fiancé—now husband—also wanted to play. I asked if I could sign us both up and they said I had to hang up and dial again. Fortunately I got us both in. It was in New York City, I was in New York; there was no way I was gonna miss it. I was really excited to participate.

Mark : I remember I had friends, such as Mark Chalice, who desperately wanted to get in and they couldn't get through. They would call me and I just told them to keep trying, keep trying.

Michael : I remember all my friends trying to get in. I remember that I got through once and then the person on the other end hung up on me. And then it was busy...busy...busy. And then somehow—God bless—I got through on the phone lines. The rest is history I guess. Literally. It's amazing that that's how they did the first one.

Apocalypse Chime | Art by Mark Poole

A New Standard for Deck Construction

While it was still pretty common for tournaments to be held using what would now be considered Vintage as the default format, the format for that first Pro Tour was a modified version of Standard—or, as it was known at the time, Type 2. For this tournament, players build their decks including at least five cards from each set that was legal in the format: Fourth Edition , Chronicles , Ice Age , Fallen Empires , and Homelands .

Mark : The whole point of the Pro Tour is that it's a marketing vehicle. We want to be aspirational, but we were also trying to get them to focus on what the latest sets were going to be. Obviously right now Pro Tours are named after the new set that's just come out. Our problem was that the latest set to come out right before that first Pro Tour was Homelands ....

Elaine : I can't even remember what all the sets were except that Homelands was one of them. It was the biggest pain ever. I mean, which Homelands cards were I going to force in? Do you actually build a deck with the Homelands cards in it, or do you just try and stick them in the sideboard? It was one of the things that made Autumn Willow stand out for that tournament. I built White Weenie and I put Aysen Highway in the sideboard. That was my big tech. If I played against another White Weenie player, I could drop it and swing for the kill. I guess I was trying to make "Plainswalkers" a thing before I even worked here.

Skaff : The idea at the time was that we wanted people to have to rethink deck construction. We wanted deck construction and what teams/individuals would be thinking about to be a little bit off the normal. It was pretty close to Type 2, so we wanted to promote Type 2 with this added skill twist to it.

Jon : I don't think Alliances was out yet, because as soon as I saw Thawing Glaciers I thought it was the best card ever and I definitely would've played that. I remember that Homelands and Fallen Empires were the really hard ones there. Fallen Empires had Hymn to Tourach , Order of the Ebon Hand , and Order of Leitbur . I ended up playing a blue-white Millstone deck, but I played Serra Angel s, Blinking Spirit s, and two Order of Leitbur s. Homelands had Serrated Arrows and then the terrible tri-lands.

Charlie : We really wanted to encourage diversity and make sure that all sets were represented. We wanted the environment to be interesting and a little different. We wanted to make sure no sets felt bad to the players.

Michael : I remember trying to get Homelands cards in there—that was a hard one. Looking back now, I can see why people rip my deck. People don't know what it was like back then. They just know 60 cards, but back then it was different. I knew a kid who played 100-card decks competitively. Hallowed Ground was one of the cards I wasn't sold on; it was just in there because it needed to be.

Mark : Anyone who's ever heard me talk about this knows that [ Homelands ] is the weakest set—on every level—that we've ever made. It was not a particularly strong set-design-wise, was not a very powerful set development-wise. It was just a very kind of "eh" set. But that was the set that was out and we needed to focus on it. We wanted people to play with Homelands cards, but how do we make that happen other than maybe a Serrated Arrows here or there? We came up with a format that made you play with five cards from every set that was legal in Type 2.

Upstairs/Downstairs

In the early days of the Pro Tour, the field was broken up into two divisions: Seniors and Juniors. The Junior Division was held on an entirely different floor of the building that housed that first tournament. While the Seniors were cutting to a Top 16, the Juniors cut to a Top 8. Also all the prize money for Juniors was paid out in the form of college scholarships.

Skaff : I know this sounds almost quaint now, but at the time it was very controversial to put money on tournaments. You could put all sorts of other prizes, but you very rarely saw straight cash payouts. We wanted to not get on the bad side of parents, and it felt like that could happen if we put cash on the Juniors. So the prizes for the Juniors at the first Pro Tour weren't cash, they were scholarships. For the whole Junior tour they were managed as scholarships. There was a bit of marketing there, and we wanted the right emphasis for kids. We wanted to encourage kids to go to college.

Graham : I almost didn't go to college, because I already knew I wanted to work in the wine industry and I had a fair amount of experience. It was because I had that $12,000 scholarship—which essentially paid for all my tuition and books—that I was able to go to community college in Santa Barbara and then UCSB. It's pretty incredible that it worked out that way. It was really awesome.

Richard : Wow, that's cool!

Skaff : Honestly that makes me feel so good. That is exactly what we wanted to happen. We were all nerds growing up and we felt bad that people with hand-eye coordination and muscles could get scholarships. There are just not the amount of academic scholarships that there are for sports. We really wanted people to be able to take their hobby—which is essentially what you do with baseball or basketball—and have that equivalent for intellectual sports. We wanted more respect for intellectual pursuits.

Merchant Scroll | Art by Liz Danforth

Getting Ready

Graham : It's not hard to see in general what the most powerful cards are. It's unusual that something totally out of the blue comes along, but I guess the deck I brought—Necropotence—was pretty out of the blue. The way that came about was there was this one guy—I don't know his name, we just called him Frenchy—and Joel Unger had this unbelievable respect for him as a deck builder. He was the first person messing around with Necropotence . I got the deck from Joel, who had just gotten it from Frenchy and was testing it at our local tournaments.

Michael : At the time, Necro decks were just not a thing around here. We weren't really prepared for that situation that much—thank God I ducked a couple of those. After the first tour, the Necro deck just busted out all over the place.

Jon : I just played a lot of Magic . There were a couple of stores I went to, especially Hero's Outpost in North Plainfield, which was the most local store. I went to Outer Realms in Linden, which was the store where the best people played. People like Eric Phillipps, David Bachman, Andy Longo, and Aaron Kline—who did well at that first Pro Tour—all went there.

Elaine : [My husband] Kierin was my playtesting partner, and for the most part it was just the two of us building a bunch of different decks and playing them against each other, just like we would for any of the Gray Matter events we went to. There wasn't this huge playtesting regimen like there is now; it was just "Hey there's a tournament with wonky deck restrictions, let's see what we can build."

Skaff : That first Pro Tour was insane. You don't want to just put an event on and then have no one hear about it. It was really supposed to drive excitement through the whole Magic community. You don't even do it to begin with unless you have that strategy in place so that you can leverage the value. Then if you are going to have press there, you want to make it look good. We had real budget constraints, but we wanted a good site. We wanted it to be in NY because that was the center of the Magic community. Without much money, we made it look really good. For a little random game company just coming it out, we made it look astounding. Maybe it is rose-colored glasses, but it was really impressive.

Jon : That first Pro Tour was very much a media event with very high production values. Now the Pro Tour is really designed to be viewed online, but then we had this huge gala event. That site was beautiful, although it couldn't hold very many people.

Skaff : When a player went there, we wanted them to feel like it was a respectable event. We wanted them to say "Hey! This is kind of cool. This is real." Because those players go out and tell their friends about it. That was the seed of the original Magic Pro Tour community. We wanted them to feel some confidence that we would be around.

Elaine : The funny thing about the first Pro Tour is that I didn't even think there would be a second one. They had done a big Ice Age Prerelease and the Homelands event in New York called "The Gathering 1," and there was no The Gathering 2. They were just all these different types of events that were doing all these different things. At the time, my take on it was that it was the new marketing flavor of the month and that they were going to keep trying things and move on and do something else.

Charlie : It's hard to put people in the mindset where we were back then. We had a lot of passion for Magic , we had a lot of great ideas for Magic , we just didn't have much experience. We were trying to learn from all these things that happened and trying to improve, but when you do something for the first time you're gonna try a lot of stuff that nowadays maybe you wouldn't do. The important thing is to learn from it. A lot of the early starts for the judge programs and forming tournament environments came from all the decisions that went into that tournament.

Skaff : Even things like registration don't sound hard, but if you don't think about it you are going to screw it up. The registration, how everything is calculated, scheduling the number of rounds and the tournament structure. We studied every tournament format known to man. Before, when it was casual, it really didn't matter—but now that there was money on it, people were going to game the system at every opportunity. We had to think about how we would manipulate this, how we would screw the system over so that we could win money by figuring out loopholes in the system. All of the tournaments that were run after that were completely different than they were before it.

Mark : When Magic first came out, Richard Garfield's vision for the game was one of discovery. Richard didn't want information put out, he wanted people to discover Magic cards in the wild. So for the first year or year and a half, people were super secretive about what was in a deck. I covered Worlds in 1995 and I wasn't allowed to list the decks. I did play-by-play, and I showed what was in their hands, but we didn't tell you their whole decks. At this tournament not only were we going to tell you, but we were going to print [commemorative copies of] the decks so you could buy them—you could play them. That was a very different approach from how we handled Magic in the past.

Richard : By the time we were doing the Pro Tour, I had completely given up on that idea already. I think it [lasted] a year maybe where it was a real part of the game, and I took immense satisfaction when lists would come out in magazines or online that were incomplete or incorrect because people had to do all the research on their own. My memory is, which again could be fuzzy, that after about a year it was clear that the idea of people discovering things in that way was impossible and they wanted to get the answer. I had given up on [my previous vision].

In the beginning, the way I imagined Magic being played was with people buying one deck, having some fun, and then maybe buying another deck. Then maybe mixing and matching them. I didn't anticipate people buying more than four or five decks. If everyone in your group only bought four to five, there was going to be this process of exploration. That play group of eight people wouldn't even see all the cards, they're not even gonna all be there. It was pretty clear, pretty early, that this is not how it was going to go down. And I embraced that reality.

Jon : It wasn't the way it is now where everybody knows everything all the time.

Skaff : We had these sports marketing people from the beginning telling us we were crazy if we didn't make it all single-elimination, but we were confident that we wanted Swiss for two reasons. One, it is more skill-testing. It gives people more play. You don't want to drive six hours in that snowstorm and lose in the first round. So we knew we wanted Swiss, but you have this strong pressure of wanting single-elimination. Single-elimination is very easy for people to understand. It is crystal clear and every game is exciting and nail-biting. We wanted a combo of those two...so we just did it. We are sort of proud of that format. It has become the standard for Magic stuff, but you see it in other places too now.

Necropotence | Art by Mark Tedin

A Snow-Covered Island

Perhaps running a tent-pole marketing event in the middle of the winter in New York City was not the best idea.

Mark : Skaff had it in his mind that it had to be in New York City. He also really wanted the Pro Tour to start in February, but he never seemed to piece together that it snows in February in New York City.

Jon : It was the blizzard of '96—how could you forget the blizzard of '96? I probably drove in—at the time I lived really close to the Holland Tunnel. My car was this old Mitsubishi Mirage hatchback that was definitely not optimized for winter driving. I'd drive the car to PTQs and $1,000 tournaments all over the place, and there must have been a 20% chance that I got into an accident, but somehow I always came out on the right side of it. I min-crashed with it.

Elaine : There had already been two huge blizzards, including the blizzard that dumped two feet of snow in New York. Then the Pro Tour happens and there's this third blizzard with another ten-plus inches. We nearly didn't make it to the city, our car was slipping and sliding all over the place. Once we got there, all of Manhattan was closed. Try to picture Manhattan with no cars, with nobody going anywhere; it was the most insane thing ever.

Richard : I used to attend the MIT puzzle hunt, and it was always held on Martin Luther King Jr. Day—or as we who did the hunt used to call it, the coldest day of the year. This idea of having a large group of people get together in terrible weather and play games indoors was something I had lived through several times, and I thought maybe in some ways that was how it ought to be.

Michael : Oh my God, the weather! I remember being scared, I can tell you that. Jim Allen and I, we rented a van or something; he was driving and I was up front with him. Everyone else was either sleeping or passed out and I remember try to get one of my other friends to stay awake. I said, "I don't want to die."

Graham : I am from Southern California and New York was covered in snow. I had never been to New York City. I was just so wowed by the city, seeing everything so tall and covered in snow. I was just going with the flow, you know? I don't remember anything out of the ordinary other than it being very cold.

Charlie : The reason I remember that is because I didn't bring a winter coat. I wasn't thinking along those lines. I remember walking back one of those nights from the tournament site to the hotel with Skaff Elias, who also didn't bring a winter coat, and never wearing anything other than shorts. The snow is coming down like crazy and we were there without jackets, wearing tennis shoes.

Skaff : And I was out there on the roof of the Puck Building in my shorts, trying to fix stuff, with baling wire trying to hang signs and banners. It was obviously a disaster. We had talked about it before and asked "What if this happens?" but we were pretty adamant that it had to be in NY for a number of reasons. Number one was that it was a lot easier for international travel, and we wanted to make sure we had people from other countries there. The Magic community there was so strong and so many people could drive to it. It was by far the best city for the first Pro Tour.

Michael : Jim Allen was driving crazy. It was like a bat out of hell. It looked like the Millennium Falcon with the lights in the snow going by the windshield, and I was legit scared we were going to go off the road or something. My friend Jim would just maniacally laugh. I couldn't tell if he was really insane or just teasing me. To this day I don't know.

Mark : I grew up in the Snow Belt, where you really needed a foot and a half of snow for a real shot at a snow day. When I shot the video, I tried to do an introduction outside the building. It was so windy, with so much snow, that we did eight takes on it before we gave up. It was so snowy that we delayed the start of Day One. It was supposed to start at like 9 or 10 a.m. and we delayed until the afternoon.

Skaff : You never know...once your boss gives you approval to do stuff, you gotta do it because the rug could be yanked out from under you at the next turn. We didn't really have options. We knew that the weather could be a factor and we kept altering things—how late registration was, when the rounds would start. We did everything we could to bend things to accommodate people. It was nerve-wracking but—and maybe it was false optimism—I never thought things would be ruined. I am from the Northeast. I have driven stupidly in snowstorms a lot, so I thought, "Get there, suck it up, put some scrapes on the side of your car. That's what guard rails are for."

In the Eye of the Storm

Elaine : There was this party the night before for the people who were able to make it. There were people passing around pseudo-fancy appetizers, but everyone was starving because nobody could get anything to eat. They actually ordered a bunch of pizzas for us, which was really awesome. The pizzas would come out and people would just devour them.

Michael : The first night we got there...we were partying pretty hard. I'll never forget this, though: Richard Garfield, who at the time was kind of a big deal, was there and I had never met him. We were all practicing in the hallways of the hotel and I'd had a few too many drinks. I went up to him and I said, "Hey Richard! I'm Michael Loconto and I'm gonna see you Sunday when I win this thing!"

And then after it was all said and done and I'm standing there with him, he was shaking his head saying, "I can't believe you actually won." We used to have a really good time when we played.

Mark : We wanted to make sure that it was a spectacle. The night before, there was a party where we had food and drinks for the players. We even had to make sure all the players actually came; I had to get on the phone with the players and make sure they knew that this was going to be a big deal for Magic .

Elaine : Later that night, we went back to the hotel and we were watching Letterman. It was hilarious because nobody could get in or out of the city and Letterman taped in front of a live audience. He has the camera guy turn around to show the audience and there were like five people in the audience for Letterman. Then they went to check out the standby line and there were like twelve people on the standby line. He lets them all in and they don't even fill up the first row. Kierin and I just looked at each other and said "Holy crap! We should've gone to Letterman!"

Stormbind | Art by NéNé Thomas & Phillip Mosness

Pairings Are Up

Graham : There were a lot of little kids there. It felt like maybe there were fifteen of us that were actually competing in the tournament. It was just unfair that a twelve-year-old had to play a seventeen-year-old, you know? The fact that I had a Necropotence deck and I was given that playing field? My entire match would be done in ten or twelve minutes.

I do remember judges laughing when I played Demonic Consultation for the first time. I was like "Okay, laugh all you want." They certainly weren't laughing at the end. I remember an incredible number of fast matches. I remember losing to this guy who played Karma [in his main deck]. That was my only loss. I had to have a judge question if that was seriously in his [main] deck and the judge said it was.

Charlie : Not only was I the head judge for the Juniors, I was also the tournament organizer. I had note cards and I had pencils with erasers. I knew ahead of time how to do pairings — I played chess tournaments and I knew how a tournament should be run. I just got the note cards out, put all the 1-0s in a pile, put all the 0-1s in a pile, and paired them for Round 2. I kept track of all the results on the notecards. I took the pile of notecards back to my hotel room after dinner and spent quite a bit of time calculating—by hand—all the players' tiebreakers. I used that to determine the order that everybody finished in. Obviously I had to double-check that because it was an important thing. Not only did I calculate the tiebreakers, but I double-checked all my math. I had to calculate this for all 120-something competitors.

Elaine : I do remember that there was a big delay at the beginning of Round 1 because they were scouring the room and looking under tables and things to make sure there weren't any cheating implements. You could only go into the room with your deck and tournament materials—you couldn't bring anything else in with you. They had an enforced coat and backpack check that they didn't tell anybody they were going to have, and they were charging people money for it. At the time, we were poor Magic players and nobody wanted to pay the couple bucks to have them check our stuff. We complained loudly enough until they said we didn't have to pay...although I'm not sure if they just made that a special case for us or if they did it for everybody.

Skaff : Once the tournament started, I don't remember very much. I had been called up to the Juniors several times. Finkel was crying, and I had to take care of that.

Jon : Ten minutes after I won my first round, there were three cards sitting on our table. I had been Jester's Capped in Game 2 and our match went to three games. The judge asked me if they were my cards. I said they were, and I got a game loss for Game 3. I had won the match—those cards could've been there for any number of reasons. I threw what could charitably be called a tantrum. It definitely involved crying—I'm glad there was no video. That's actually how I met Skaff, I was demanding my money back and stuff. They calmed me down, but I still think that game loss was kinda [unfair].

Charlie : I remember being a little worried about making the rules call, but fortunately I was given Beth Moursand, who was really good at the rules. That helped a little bit for my concerns. I don't remember there being anything that extreme though.

Mark : There are so many things about how a Pro Tour is run that you take for granted now. For example, I'm the creator of Feature Matches—and that didn't even happen until the second Pro Tour. And there it was me putting up a list of tables with matches you might want to go see. It wasn't until the third Pro Tour that we created a special area where you could go as a spectator. For the first Pro Tour, spectators could just walk around and watch any match they wanted.

Elaine : I did horribly and lost very quickly. As soon as both Kierin and I were out of Top 16 contention, we went to get lunch. We went up to Brian David-Marshall and he told us to stay, because even if we weren't gonna make the cut, there were still going to be invites given out—I don't remember if it was Top 32 or Top 64—to the next tour in LA. And I remember saying specifically "Yeah right! Like they're going to do another one of these! Do you want us to bring you back anything?" So we dropped and of course I spent the next two years of my life trying to get back on the Pro Tour.

Jon : I won my next five rounds and then I was playing against Ross Sclafani; the winner was going to be in the Top 8. The tiebreaker was game win percentage and I suggested to Ross that we should say whoever wins won the match 2-0. He called the judge and the judge said we couldn't do that. Now, of course, you know that now—but then? You had no idea. I ended up losing, but I made the Top 8 anyway and lost in the quarters.

Demonic Consultation | Art by Rob Alexander

After a day of Swiss play and a laborious evening of tiebreaker calculations, the Top 16 for the Seniors and the Top 8 for the Juniors came back to play on Sunday. Bertrand Lestree and Michael Loconto were the last two Seniors playing at the end of their bracket, while Graham Tatomer faced off against Aaron Kline.

Graham : I played the final match against a White Weenie deck played by Aaron Kline. That was a really tough match, and I topdecked a couple times to save my [bacon]. I remember topdecking a Nevinyrral's Disk to win. That was gnarly.

They told us to play slow and explain everything. I was always a very fast Magic player. I felt like if I played too slow I might lose my natural instinct for the game. I remember at one point they announced that Aaron had won the match. We didn't really communicate when it happened. I was gonna kill him the next turn, but he had Karma out. I had a Zuran Orb and could sacrifice my lands to gain life. I looked at him and he said "Yeah I get it." I just swept up all my cards and so did he. They just thought he had won. I would have died to Karma if I didn't sacrifice any lands, but I could just sacrifice all my lands—it didn't matter—[and] I was about to kill him.

At any Pro Tour after that, you would've had to be very specific about what you were doing—about every step. Aaron was nice enough to say "Yes, you're totally not gonna die to Karma while you have the Zuran Orb out." I think about that moment a lot. I should've been more professional, but I was a kid. It was just this minute of confusion where all the people thought that he won. He would've won the tournament with that game, but we went the full five games.

Michael : My deck used Millstone s to run people out of cards. It was mainly defensive with lots of board wipes: Wrath of God , Swords to Plowshares (thank God for Swords), and Balance . You had Blinking Spirit s and Mishra's Factories to block all their stuff. I was just trying to make the games last as long as I could and hopefully run [my opponents] out of cards.

I remember at the end it was gonna be a best-of-seven match for the finals and the deck just took way too long. I don't think they ever expected that kind of thing. They brought me and Bertrand in after—I think I lost the first game and won the second game—and said it was super late and they didn't rent the venue for long enough. They needed to have a winner. They said we could just split the money and play one game for the title. That's how it went.

Graham : Oh my God! Is that what happened—they went from best-of-seven to best-of-three? Ours was nothing like that, we finished all five games! They even made a comment about it in the video. "These Juniors don't hold back, they're playing really fast." I think Aaron also had a tendency to be a really fast player. I think he was a regular White Weenie player and that's not like playing a control deck. I think that was the slowest that both Aaron and I each played those decks, but you could only go so slow with those. It's time to play Hypnotic Specter and get things done.

Charlie : I remember finishing our tournament and coming down and being asked to sub in for one of the judges because they needed a break—the final was just going so long. The other thing that I remember is a friend of mine and some other judges going to grab dinner. They went to a place kind of far away, someplace they had to wait a while. When they eventually came back, they had no idea that the match would still be going.

Mark : They both understood that this was the first Pro Tour and they both wanted to be the guy that won it. On top of that—people don't remember this—but Bertrand Lestree played in the World Championship and lost to Zak Dolan in the finals. On paper Bertrand was supposed to win that match, but Zak won that one. He did not want to become the guy who also lost in the finals of the first-ever Pro Tour. He was going to take his time. They were playing slow, slow decks to start with, and they just didn't want to make any mistakes. Originally we were gonna play best-of-seven, but then after five hours we decided it was gonna be best-of-three.

Michael : It was the final game and he had a Whirling Dervish that was just wrecking me. I'm not sure, but I think I made a mistake—maybe something with my Mishra—I had to topdeck a Swords to Plowshares and I had already used a few in that game. [Man], did I get lucky. I was holding one Plains in my hand—I had no lands. I just held that one Plains and laughed. I had to draw that Swords right there. He probably lost his mind after that.

We ended up becoming really good friends after that; he was a real character. He was like Shawn "Hammer" Regnier. He would always dig and say stuff and try to get inside your head, but after I won we really hit it off. We would always hang out after a Pro Tour. I remember asking him for his autograph. He wrote, "[Expletive deleted] Swords!" and then he signed it "Bertrand." I still have that. That, I'll never get rid of.

Swords to Plowshares | Art by Kaja Foglio

Summer Is Coming

Before that Pro Tour, the card Necropotence was not regarded as a tournament-viable card by the vast majority of the tournament goers.

Mark : Necropotence got a one-star rating in Inquest magazine. What was interesting about the tournament was Graham Tatomer obviously wins with the Necro deck and Leon Lindbeck makes the Top 8 with it—a really early version of the deck. It wasn't until that summer that that deck really took off.

Richard : I don't remember if we knew exactly how powerful that card was, but I knew it didn't surprise me. My design philosophy in those days was that if you didn't make a few banned cards, you weren't being aggressive enough. You had to be taking chances. My philosophy was give the players lots of interesting tools and let them play with those tools. My philosophy of discovery regarding the cards had gone by the wayside, but the discovery of combinations was very much a part of the game. Players are constantly finding new ways to combine cards in the game that we didn't anticipate.

Michael : I definitely dodged a few bullets that day in the pairings.

Graham : You were so powerful with that deck and you could really demoralize your opponent. I tried to use psychology as far as putting pressure on the opponent, and that deck really worked out for that—it forces people to makes mistakes or give up too early.

Closing Thoughts

Richard : The experience of going to events, where people were excited to meet me, have me sign cards, and play with me, was not new. I'd been doing that for a few years—but the tenor here was changing, because this was the first time that I felt like the players were starting to become really good and were taking the game really seriously. On the surface this was very much like all those previous meetings, but I felt like something had changed. Before the Pro Tour I could go in any card shop and beat most of the players with an all-commons deck. It was ridiculous. Then the Pro Tour came around and I couldn't walk into a card shop and beat everybody with an all-commons deck anymore.

Graham : It was incredible, obviously. My dad was with me and he was just thrilled. He's kind of a nerd himself. He would rather be the smartest one instead of the strongest one. For his son to win was kind of a big deal. Joel Unger was there, and it was great to have him there. It was incredible. They were also happy for me. When I got back to Santa Barbara, most of the people hadn't even heard yet. We weren't all that connected yet with texting and the internet. But everyone was thrilled when they found out that I won. It was pretty positive.

Skaff : The Pro Tour is probably the thing I am most proud of out of everything I have ever worked on. It is such a standard part of the game. I don't think people understand how important it is to the success of the game, because they have never lived in a world without it.

Mark : What the first Pro Tour really did was establish standards of how to run a tournament. The funny thing is that first tournament...we got a lot wrong. We learned a lot along the way, but it was a giant leap from what came before.

Jon : I think that if you look at the first Pro Tour and you hold up the Juniors against the Seniors and look at lifetime Pro Points, it has to be a blowout for the Juniors—an absolute blowout. Darwin was probably the best player who played in the Seniors. The Juniors had me, Steve O'Mahoney-Schwartz, Bob Maher, and Brian Kibler.

Elaine : For me, the Black Lotus Pro Tour really was a turning point in terms of the scale and scope that Magic had in the gaming universe—and in my universe.

Charlie : Twenty years ago, we were just formulating all of this: what a tournament should be like, what formats should be like, what's fun about Magic —all that kind of stuff. I definitely felt like we accomplished a lot. We learned so much from that very first event, it gave us so much to think about how we could make the next event better.

Michael : Years and years later, somebody came up to me and told me I was in a magazine again. They showed me and I was like "Wow." I showed my mom and she ended up calling out to Wizards asking them if they still had the cover painting [of me and Bertrand]. Wizards was super cool and they put it in a frame and sent it out to her. It is hanging next to the uncut sheet of my deck.

Mark : There are also some stories I could tell you that probably shouldn't be printed, so if you want to shut that recorder off—

Illustration by Cassie Murphy

The surprising history of the Magic Pro Tour

The pro tour has hardly changed since 1996, though circumstances have..

Internet Culture

Posted on Apr 5, 2016 Updated on May 27, 2021, 12:00 am CDT

The following is an excerpt from A Brief History of Magic Cards , a new book exploring the real-life, human history of Magic cards, currently being funded on Kickstarter . (Rewards include a print and tote of the fantasy map below above, drawn by Seattle artist Cassie Murphy .)

According to old-school Wizards of the Coast employee John Tynes, author of the magnificent Minotaur article (on the early history of Wizards—and that of its signature intellectual property, Magic cards), CEO Peter Adkison “had a vision for a new kind of company, a company that could change the corporate world forever.” He would do this by empowering nerds, elevating their hobbies from the basement to the convention center—where they would stand as equals next to the outside world’s idea of success. It was in this spirit that Wizards started the Magic Pro Tour (PT).

The Pro Tour was—and still is—a tournament where the best players fly in from all over the world to duel with recently released cards, crown a champion, and hand out cash prizes. Today the PT is an institution, with established roads to qualification, long-standing cliques, and modest stipends for frequent competitors. It has outlasted any competition of its kind, and is unlikely to ever change much. In the 90s, though, the PT was as limitless as Magic itself. It could have been anything.

The first Magic Pro Tour was held from Feb. 16-18, 1996, in New York City. There had never been anything like it. Entry was first-come, first-serve. Organization was shambolic but eventually effective. A snowstorm delayed the start of the event by four hours. The player who was supposed to win, did not.

It was a massive success. Hundreds of Quixotes attended, eager to tilt together. More importantly, thousands more watched, or read about it later: on the Internet, or in the same magazines that covered (and priced) the cards my allowance would only let me dream of buying.

On the day of PT New York, Magic finally ascended beyond Richard Garfield’s original vision. It loomed so wonderfully above the skyline of gaming, a paunchy giant on a lean nag, that it lived and would live through its sheer vitality. It stood for everything that was gentle, forlorn, pure, unselfish, and gallant. The parody had become a paragon. Adkison had, for a spell, brought his fantasy world into being.

Wizards capitalized on the PT’s success very well, by selling facsimiles of the top eight decks and releasing a video of the event. The Pro Tour has hardly changed since then, though circumstances have. Next to esports in the mid-2010s, the Pro Tour is small, with Dota ’s $10 million-plus prize pool dwarfing its purse of $250,000; but in 1996, the same sum made the PT both well-endowed and mind-blowingly cool. There was even a junior division, which would turn into the Junior Super Series—helping the degenerate scamps of the WotC flagship put themselves through college. After PT New York, Wizards put on PT Los Angeles, then PT Columbus, then the World Championships, in Seattle. The competitors were real characters. Thunderstruck, I watched them with admiration and envy.

The parody had become a paragon.

I cannot overstate the importance of the advent of the Pro Tour and its counterpart, Friday Night Magic (FNM). At FNM, lesser mages could spend an evening playing tournament Magic against similarly inexperienced players, in a relaxed atmosphere. Each FNM is like a mini-convention, selling swag and fostering community. Once the players got good enough, they could “level up” to more competitive tournaments, like Grand Prix (GPs—the closest thing Magic has to its own big conventions) and Pro Tour Qualifiers (PTQs). A victory in the latter earned a berth in the PT itself, which before poker and esports was the pinnacle of competitive gaming.

By connecting FNM with the PT “tournament of tournaments,” Wizards made it possible for Magic players to live out a fantasy of fantasies. When the PT was well-established, a few years later, Adkison declared Wizards had “created a lifestyle opportunity for a young generation of Magic players, fresh out of school, to be professionals.” The reality of professional Magic , a decade before esports, was a big part of Wizards’ marketing strategy: Thanks to the “new kid of company,” you could make a living playing a card game. Once again, Adkison had worked his Magic : The Pro Tour might not have “changed the corporate world forever,” but it changed gaming—and gaming culture—indelibly.

Today Magic competes with Dota , and a dozen other big games, for market share, power, and prestige. But the PT and FNM, and all the tournament types between them, still make Magic what it is: a fun way to spend time with people, in person. The draw of Magic cards in the era of Dota and League of Legends is the friends you make, in the tournament hall or around the kitchen table.

Wizards had started out as a handful of friends in Peter Adkison’s basement; after the success of the PT and the set Mirage , it climbed skyward, like a tech firm lifted by angels. Now most of its efforts would center around not promoting Magic , but on profiting off of it—by making more games of its kind.

From 1996 to 2000, Wizards went from 150 to 950 employees, hiring anyone who wanted a job. The company generated many clones: Netrunner , a cyberpunk-themed CCG; BattleTech , a CCG whose cards were walking battle-tanks (gum sold separately); Xena: Warrior Princess , which needs no explanation; and MLB Showdown , a callback to Garfield’s original vision of a card game that was both playable and collectible. At this time, Wizards also bought out TSR, the creators of Dungeons & Dragons . It was thought that the indiscriminate acquisition of licenses was the only way to keep the high of Magic ’s early days alive. But the Knights of the Kitchen Table—my friends and I—scorned the proliferation of ersatz Magic s, because we thought they threatened the game we loved.

Though the above games could not rival Magic in quality and popularity, we didn’t know how right we were. Wizards released Pokémon cards in 1998, and the Knights didn’t want to play Magic with me anymore.

With Magic , the Pro Tour, and WotC in general, Brave Sir Adkison had realized a fantasy, starting from scratch a fiefdom in accordance with his noblest instincts and dearest narratives. But making a new world would not be enough to change this one. Fantasy would yield to reality. In 1999, Wizards sold out, and the tragic- Magic cultural contradictions began to take form.

It took a lot of gold for Hasbro—the acquirers—to sway the gallant Sir Adkison: $325 million. Yet it was an offer the noble don couldn’t refuse, not with his faithful company of riders also set to cash out. So they did what any knight-errants would do—left the court to the courtiers, and rode off to their next adventure under the sun. Crowds at Origins, GenCon, BlizzCon, PAX, greeted Garfield and Adkison with cries of adulation, as they do to this very day. The founders’ fame has made them the people closest to living out Don Quixote’s dream, but it was fortune that freed them from “the corporate world.” In the Hasbro sale, Sir Adkison made some $80 million. Sir Richard Garfield got $100 million. Other founding members, like Lady Veep Lisa Stevens, also did OK.

Each Friday Night Magic is like a mini-convention, selling swag and fostering community.

Back at WotC headquarters, in Renton, a drab suburb at the foot of Seattle, the work of making Magic continued under a foreign flag. For the first 15 months, Hasbro seemed to be a benevolent despot—which is what most nerds, fans of sword and sorcery, crave. Pokémon swelled the royal coffers, and Magic tournament play made an appearance on ESPN2. Wizards operated its businesses with continuity and autonomy: the buyout agreement gave them great freedom, so long as the money kept flowing.

Then, in May 2000, Pokémon tanked. It was a chain reaction: The fewer people that played, the fewer people played. Not that many people, only 9 percent of collectors, had ever played Pokémon in the first place. By overvaluing collectors, Wizards had neglected game design and thwarted their chance at capitalizing on a huge franchise. But Magic ’s original business model, “combining the play of card games with the collectibility of baseball cards,” let it once again carry the day. (When MTGOX.com switched from the Magic: the Gathering Online eXchange to a Bitcoin exchange website, it signed its own death warrant. Cryptocurrency fans and beanie-baby collectors, take note!)

On a personal level, Pokémon ’s fall was great: Magic reasserted itself above a passing fad, and the Knights reconvened around the Square Table. At a corporate level, it was a catastrophe, the dot-com bubble bursting in miniature. Hasbro, which has always governed Wizards remotely (from Rhode Island) and has never really understood its fiefdom at the foot of Seattle, blamed Wizards for the losses. The overlords sold off electronic and movie rights by the franchiseful, fired 280 skilled artisans, and restructured the fief’s finances around five brands: Dungeons & Dragons , MLB Showdown , Pokémon , Harry Potter , and Magic .

Have you ever heard of Harry Potter TCG ? Me neither.

At the same time, some of the kingdom’s finest work moldered and decayed. A game called Legend of the Five Rings , reputed to be on Magic ’s level, was no longer supported: The brand wasn’t big enough. So Legend died off, a victim of Hasbro’s neglect, indifference, and failure of imagination. So much for benevolent despotism.

Hasbro was, in fact, cutting costs in all other divisions. The days of fanciful extravagances, like “ Magic camp,” where kids would gather around the University of Washington and the Wizards flagship store to binge on Magic for a week, were numbered. Wizards Retail, which operated the flagship and other outlets, was always a small and separate company, sometimes losing out on supply to larger card peddlers: the troubled relationship of Wizards with Wizards. I remember the smaller Wizards store, in Northgate Mall, shutting down, and thinking nothing of it—I was in the know; I went to Floyd’s shop now.

But the writing was on the wall. With the nosedive of Pokémon , Wizards’ prodigal childhood was over. The only things that would be spared would have to be profitable, in the narrowest sense. The first casualty was the flagship.

Have you ever heard of Harry Potter TCG ? Me neither.

Wizards was making little money from the flagship, and spending a lot. The things that made it a gamer’s dream— BattleTech sims; the big Minotaur statue; the extravagant waste of space downstairs that was a community center for gamers—made it a CEO’s nightmare. Even the for-profit stuff was ineptly executed or hopelessly dated: For example, half of the basement was ringed in horseshoes of computers, which you could rent at exorbitant rates. A friend’s dad once bought us a half-hour of StarCraft ; we got to play the beginning of a game. Home high-speed Internet was becoming popular—DSL was my 2000 Christmas present—and soon the horseshoe would serve no purpose.

The lighting in the whole basement, community center and computer lab, was abysmal; Wizards had spent five figures installing a light fixture around the computers, but had taken it down after employees had suffered eye injuries. It was like a joke about nerds in Plato’s cave, and Hasbro was, then as now, as humorless as Quixote himself.

In 2001, with Brave Sir Adkison long-gone into the sunset, Hasbro shuttered the flagship. John Tynes’ Salon article details the grisly process, including the death by hacking of the minotaur above the dungeon entrance, which will forever be a symbol of my lost childhood. Thoughts of the store still fill me with nostalgia. Though it had the fragility of any fiction, it did embody Peter Adkison’s fantasy of “making Wizards a new kind of company,” and its demise was the first time I thought the greatest game ever made was anything other than perfect.

Corporate culture soldiered on. The flagship was replaced by Tower Records and is currently an Urban Outfitters.

Featured Local Savings

The End of the Magic: The Gathering Pro Tour

The numbers, the significance, the history—it's all finally been scrambled.

By Jeff Cunningham | @WJC83 | Published 2/7/2023 | 21 min read

A scrub is a player who is handicapped by self-imposed rules that the game knows nothing about. A scrub does not play to win. The scrub would take great issue with this statement for he usually believes that he is playing to win, but he is bound up be an intricate construct of fictitious rules that prevents him from ever truly competing.

-David Sirlin, Playing to Win

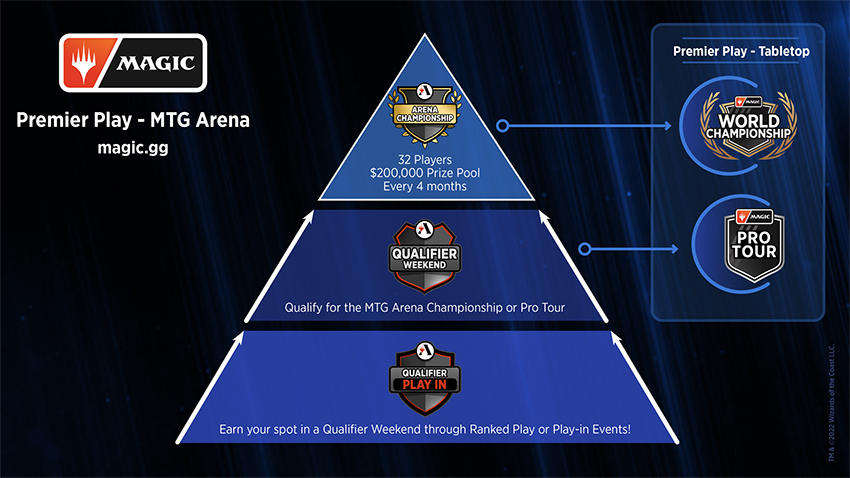

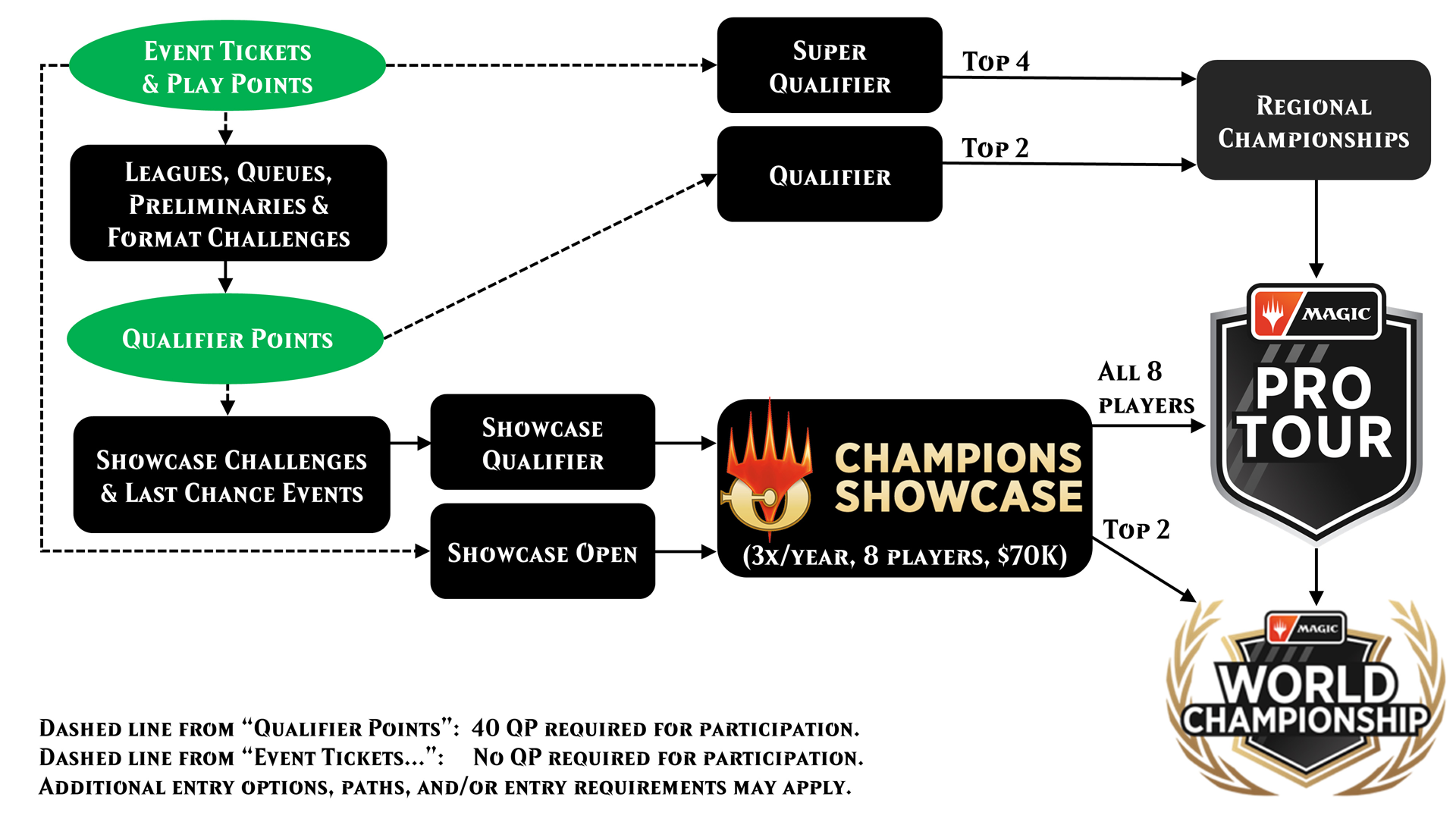

The final Magic: The Gathering Pro Tour took place in Richmond, Virginia on November 2019, almost 25 years after the first one was held in the middle of a blizzard in New York City in 1996. Technically, Pro Tours had already been rebranded as Mythic Championships, and technically they'll continue as Players Tours—but the original competitive structure that defined them has finally been sufficiently changed to represent the end of an era.

Pro Tours were invitation-only tournaments of about 300-500 players which, after two or three days of Swiss matchplay, broke into a Top 8. They happened every few months, and while not always the absolute pinnacle of organized play, became the yardstick against which competitive aspirations and achievements were measured. The gold standard of induction criteria for Magic's Hall of Fame, for example, throughout a flurry of changes in other areas of organized play, remained number of Pro Tour Top 8s—with five meaning a player was a lock, and three or four meaning they were in the conversation. The Pro Tour's large difficult field, coupled with Magic's inherent variance, meant that making a Top 8 involved extremes of both skill and luck—it was Magic's longstanding competitive threshold that, once attained, could never be taken away.

Now, the upper tier of competitive play has been effectively divided between small tournaments—comprised of the ultra-elite and low-mobility Magic Pro League, the lesser Rivals League, and some hand-picked streamers and personalities—and larger tournaments—Players Tours—occurring simultaneously in multiple regions. The numbers, the significance, the history—it's all finally been scrambled.

The Pro Tour was crafted by Magic's first brand manager, Skaff Elias. At the time, Magic's inner circle was anxious about stabilizing the game's runaway success, fearing that it was following the trajectory of a passing fad rather than a perennial classic—more Beanie Babies than Monopoly.

The issue had been latent since the beginning. Richard Garfield has said that the epiphany that spawned Magic—and with it the entire trading card game genre—was that players didn't need to have the same game pieces . They could start with different distributions and trade amongst themselves to refine their lot. At the same time, however, as this visionary aspect of acquisition and trade was expanding gameplay beyond the box, and making Magic compulsively playable and buyable, it was beginning to threaten the longevity and profitability of the game itself.

The general problem, as Skaff saw it, was that with expansions being continuously released, players would eventually grow tired of endless acquisition. More immediately, a collector class had emerged that not only stockpiled the most powerful cards and drove up their prices, but dominated those players who wouldn't pay for them. And so the original game was turning into a largely monetary "meta-game," in danger of becoming known as a pay-to-win gimmick.

Skaff's solution was to establish an ongoing series of high-profile tournaments with big cash prizes at the top—an aspirational peak that would allow players to rationalize continuous spending. At the same time, the tournaments would limit the available card pool, reducing the influence someone's collection had on their ability to compete. In short, the function of the Pro Tour was to make gameplay central, limiting and regulating the investment needed to play to win.

In March 2019, I played in Pro Tour London. I'd played in 33 Pro Tours before, with one Top 8, but this was my first one in 12 years. The previous December, I'd made Top 4 at Grand Prix Vancouver to qualify .

I'd told myself then that I'd show up at my best for what was most likely my last ticket to the big game. It's not that I doubt my competitiveness, it's that, as an adult, investing in succeeding at the game doesn't make sense. Achieving consistent qualification requires dead-eyed determination in playing tournament after tournament where anything less than a top finish against similarly prepared players doesn't matter. After a decade of more-or-less casual involvement, I'd made my critical hit, and I wasn't expecting it to happen again.

Over the years, I'd helped other players prepare for the Pro Tour, often to good effect. I've developed tenets to help them evade common pitfalls—ways of tuning up their play, avoiding reactive decisions, and choosing a deck suited to their aptitudes. By the time I arrived, though, I'd fallen into old habits. I hadn't gotten a coach of my own, I hadn't improved my physical conditioning, and despite no shortage of games played my own deck selection process remained nitty, fussing over details with a similarly minded playgroup. I'd done things the same way I always had.

I was staying with Jason Adams, who'd won GP Vancouver. We'd tried to put in the time and think through Modern from every angle. But he also fell short, settling on a stock Dredge deck that seemed well-positioned but that he didn't know very well. We shared a compact room with twin beds in the Moxy hotel, designed according to a sort of millennial take on a rock star motif.

But when I think about PT London, I think about the eastern exterior of the ExCeL Convention center, located in an area known as the docklands. Overcast, drizzling, set against a man-made waterway, a few stragglers making their way inside, passing an already derelict Marvel Avengers promotional escape room as they go.

Inside, in contrast—crowded, a wide walkway, with conference rooms and upscale food vendors on each side. One entrance opening up to a Grand Prix, the next to the Pro Tour beside it. Industrial-strength HMIs blasting hard light onto concrete floors, the walls reverberating with gamers' screeches.

One of the things I like most about Magic tournaments is how they eclipse everything else. For two or three days, the competition takes over. Adventure. Escape. And winning could change your life.

The Pro Tour was invented by Skaff Elias to channel Magic's aspect of trade and acquisition—an addition necessary for the original game's survival. But Richard Garfield would have identified the Pro Tour itself as a sort of "meta-game"—one with special properties.

In a 1995 article for The Duelist , "Games Within Games," Garfield tells us that a metagame is a game composed of games: "When you play a number of games, not as ends unto themselves but as parts of a larger game , you are participating in a metagame."

The Pro Tour is a "metagame" not only as a series of competitions but insofar as that series provides the proving grounds for an especially fundamental metagame—the ladder system.

The ladder system visibly organizes players by rank. As such, it provides them with a quantifiable axis of success, since "even moving up a single rung of the ladder feels like a victory." Garfield observed that this metagame—which gives players a constant reflection of their own perceived value and progress—was especially compelling. He even made the bold claim that he could make any game popular so long as he could augment it with a ladder system, a claim well vindicated by the 21st century marketing development known as gamification.

The Pro Tour structured Magic's ladder system. Magic was no longer limited to one game against one opponent. The games became interconnected, serving as the bases for escalating levels of competition, played for stakes that determined one's rank.

When Odysseus entered Hades and found Achilles there, he tried to console him by remarking on his rule over the dead. Achilles responded that he'd rather be alive as the lowliest worker imaginable than a king in the shadow realm.

In terms of the Pro Tour, I'm alive again. Acquaintances I've known for 20 years, long since reduced to two-dimensional avatars, are once again rendered in 3D. Of course, for my part, the sensory overload and preoccupation with the task at hand has me reserving energy too much to engage in what, in other circumstances, could be interesting conversations.

Each day is broken into three rounds of drafting and five rounds of Constructed. The Limited format is War of the Spark—Magic's take on an MCU brawl—but as a prerelease, forcing players to learn the set in a short time. In order to keep my head fresh in the days leading up to the tournament, I streamlined my preparation. I'd figured out quickly that tempo-based blue/red stood above the archetypes and fit my style—I was somewhere between forcing it and really hoping I'd be able to draft it.

In the first draft I get a simple but solid version of the deck composed almost entirely of commons. In the first round, I'm paired against someone in my extended testing group. In the final game, I make an attack that telegraphs a marginal combat trick ( Samut's Sprint ) that, if I have it, will effectively end the game.

He blocks. I play the trick.

His face drops, and then twists into an expression of disgust.

"You play that? That card is terrible ."

Apparently the group had ranked cards in the Discord the night before and decided that this one was unplayable, biasing him towards the likelihood that I wouldn't have it.

I shrug, "it's fine."

"It's terrible !"

Almost immediately, though, he regains his composure. The lapse is relatable as grief. The viscerally felt response to a sudden plunge into a newly unfavorable reality. The retrospective impression of entire tournaments hinges on moments like this that seem as though they could've gone either way. In this case, the psychic disturbance can't linger too long—he was almost certainly losing anyway.

I win the next round but lose the finals. My opponent there has a slow controlling deck with a powerful card ( Command the Dreadhorde ) capable of reanimating our entire graveyards if the game goes long. I board in a conditional counterspell ( Crush Dissent ) that might be able to catch it by surprise. In the deciding game, though, I have an empty board, and when he hits six lands and plays something cheap, I decide to burn the Crush Dissent for the 2/2 that comes along with it. He plays the Command the Dreadhorde the following turn and I lose.

According to combinatorial game theory, as related by Richard Garfield in the appendix to his Characteristics of Games , games can often be decomposed into "positions"—units understandable as games. Subjectively, a position is just a decision— this or that —against a background of information. The core challenge is one of decryption: selecting the details relevant to a consistent interpretation and then tracing back the actions implied to the decision at hand.

My Constructed deck is U/R Phoenix.

Magic: The Gathering TCG Deck - U/R Phoenix by Jeff Cunningham

'U/R Phoenix' - constructed deck list and prices for the Magic: The Gathering Trading Card Game from TCGplayer Infinite!

Created By: Jeff Cunningham

Event: Mythic Championship London 2019

Market Price: $310.31

Nonbasic lands are Mountains.

+2: Look at the top card of target player's library. You may put that card on the bottom of that player's library. 0: Draw three cards, then put two cards from your hand on top of your library in any order. −1: Return target creature to its owner's hand. −12: Exile all cards from target player's library, then that player shuffles their hand into their library.

Spirebluff Canal enters the battlefield tapped unless you control two or fewer other lands. {T}: Add {U} or {R}.

{T}, Pay 1 life, Sacrifice Scalding Tarn: Search your library for an Island or Mountain card, put it onto the battlefield, then shuffle.

({T}: Add {R}.)

Whenever you cast an instant or sorcery spell that has the same name as a card in your graveyard, you may put a quest counter on Pyromancer Ascension. Whenever you cast an instant or sorcery spell while Pyromancer Ascension has two or more quest counters on it, you may copy that spell. You may choose new targets for the copy.

Defender Thing in the Ice enters the battlefield with four ice counters on it. Whenever you cast an instant or sorcery spell, remove an ice counter from Thing in the Ice. Then if it has no ice counters on it, transform it. // When this creature transforms into Awoken Horror, return all non-Horror creatures to their owners' hands.

Flash When Snapcaster Mage enters the battlefield, target instant or sorcery card in your graveyard gains flashback until end of turn. The flashback cost is equal to its mana cost. (You may cast that card from your graveyard for its flashback cost. Then exile it.)

Flame Slash deals 4 damage to target creature.

Target player mills two cards. Draw a card.

Add two mana in any combination of colors. Draw a card.

Scry 1. Draw a card.

Delve (Each card you exile from your graveyard while casting this spell pays for {1}.) Put target nonland permanent on top of its owner's library.

Devoid (This card has no color.) Exile target nonbasic land. Search its controller's graveyard, hand, and library for any number of cards with the same name as that land and exile them. Then that player shuffles.

({B/P} can be paid with either {B} or 2 life.) Choose target card in a graveyard other than a basic land card. Search its owner's graveyard, hand, and library for any number of cards with the same name as that card and exile them. Then that player shuffles.

{T}, Pay 1 life, Sacrifice Polluted Delta: Search your library for an Island or Swamp card, put it onto the battlefield, then shuffle.

Draw a card. Scry 2.

Draw two cards, then discard two cards. Flashback {2}{R} (You may cast this card from your graveyard for its flashback cost. Then exile it.)

{R}, {T}, Exile two cards from your graveyard: Grim Lavamancer deals 2 damage to any target.

({T}: Add {U} or {R}.) As Steam Vents enters the battlefield, you may pay 2 life. If you don't, it enters the battlefield tapped.

Counter target noncreature spell unless its controller pays {2}.

Replicate {R} (When you cast this spell, copy it for each time you paid its replicate cost. You may choose new targets for the copies.) Destroy target artifact.

Counter target colorless spell.

Flying, haste At the beginning of combat on your turn, if you've cast three or more instant and sorcery spells this turn, return Arclight Phoenix from your graveyard to the battlefield.

{T}, Pay 1 life, Sacrifice Flooded Strand: Search your library for a Plains or Island card, put it onto the battlefield, then shuffle.

Lightning Bolt deals 3 damage to any target.

If an opponent had three or more cards put into their graveyard from anywhere this turn, you may pay {0} rather than pay this spell's mana cost. Exile target player's graveyard.

({T}: Add {U}.)

Flying Crackling Drake's power is equal to the total number of instant and sorcery cards you own in exile and in your graveyard. When Crackling Drake enters the battlefield, draw a card.

I've chosen it because it rarely gets manascrewed or flooded and it beats up on the variety of Tier 2 & 3 decks people tend to play in Modern. But, as I would have advised a newer Pro Tour player, this is PTQ-winner thinking—ie., failing to sufficiently factor that the PT is largely composed of a winner's metagame. Phoenix is only winning at about 50-55% against the expected Tier 1 of Humans and Tron. Not that this Modern offered too much room to move. Jason said I should've just played a tuned version of Tron, which I could do in my sleep.

U/R Phoenix is standardized to a remarkable degree, with about 54 maindeck cards—mostly cantrips—effectively set in stone, making the remaining choices especially significant. I'm playing three copies of a card I think is versatile and underrated— Set Adrift —and otherwise have a closely managed list. I spent most of the ride into the city debating between two of three cards for the last two sideboard slots.

In the fourth round, I'm playing against a Dredge player I know from online, and he's playing too slow, insufficiently trained to the physical interactions demanded by the deck. I should've called a judge sooner—a mistake I've made before—but instead rush my play to compensate. I probably would've lost anyway.

Jason ends up suffering from the same mechanical issues as my last opponent, losing out his remaining matches. Somewhere in between, he remarks at the surreal flow of the day. That he feels tired and dull, even during decisive moments. We'd attempted such precision in testing, afforded the upcoming event such significance, that we'd forgotten that peak mental acuity wasn't a given.

I'm able to stay focused for the time being. I win the next three rounds, despite tough opposition—Robin Dolar on his W/U Control, Ken Yukuhiro on Cheerios, and Antonio Del Moral Leon on Humans. In the last game of the day, against a Jund opponent who only speaks Chinese, I play a card draw spell at the end of his turn and then forget to draw one on my turn. A spectator—after audibly muttering to himself "this is the Pro Tour?"—calls a judge. My opponent argues the case that I shouldn't get the card—even snapping at the spectator for meddling—but the ruling follows protocol and I get the card and grind out the game.

Winning a series of matches always ends the day on a high note. I'm at 6-2 with plausible avenues to the Top 8. It's one thing to be a participant, it's another to be a competitor. I'm eager to join some members of the team for dinner, which turns out to be some distance away. I'm surprised by how similar it is to the dinners I remember from 15 years ago. I'm foggy. I get back late. And just as I'm starting to drift off to sleep at the Moxy, the fire alarm goes off.

We're not only playing in Richard's game, we're playing in Skaff's. We're experiencing the game implicit in all ranked competition—more specifically in this case, competition built around a game involving a considerable degree of variance. Skaff's "meta-game" is complex only because the outcome of its underlying game is determined by both luck and skill.

As Richard Garfield has frequently explained, variance, or luck, is not the opposite of skill. A variant of chess in which, at the end of any game, a die was rolled to modify the outcome, would involve just as much skill as the original game. Instead, as luck increases, only the returns to skill decrease—the better player wins less. They'll still recoup the value of their superiority—it'll just take more time.

Luck increases the uncertainty of a single game's outcome by varying the respective advantages dispensed to players over the course of the game. This turbulence obscures the causes of the game's outcome, preventing players from knowing entirely whether a win or a loss was a matter of luck or skill. This uncertainty shelters players' egos, allowing them to continue chasing the rank they feel they deserve. The function of luck, then, is to increase confusion and controversy—about the relative strength of players, about the best strategies, even about one's own skill level—in order to keep a game vital and contested.

One sign of a superior player is their ability to focus on decisions they can control. The game always offers up an excuse—a way to blame the loss on factors they can't control. And sometimes in sum they might have made a loss inevitable. But by not dwelling on them and instead scrutinizing their decisions the superior player accelerates their improvement. In other words, the winning strategy in the ladder metagame is to ignore luck.

So, if one understands this simple heuristic, wherein lies the challenge? How does the metagame of competition itself remain vital?

I make my way down to what could loosely be described as a continental breakfast—alive.

My draft Day 2 goes badly. I open one of the most powerful cards in the set, a blue/black rare ( Enter the God-Eternals ), and get passed a pack where the best card is a good blue/black uncommon ( Tyrant's Scorn ). Around fifth pick I'm given the choice between a solid red card ( Raging Kronch ) and a barely playable black card ( Vampire Opportunist ), and seal my fate by taking the black card. It's easy to become "pot-committed" in these scenarios because even as the first pack is drying up, you've cut off the person you're passing to, which justifies the hope the second pack will be good. And by the time the second pack runs dry, it's too late.