Types of migration

Return Migration

Recent trends, data sources, further reading.

There are two main forms of return migration: voluntary return and forced return . Data on forced return are usually collected by national and international statistical offices, border protection and immigration law enforcement agencies. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) collects data on assisted voluntary return and reintegration programmes that it implements worldwide.

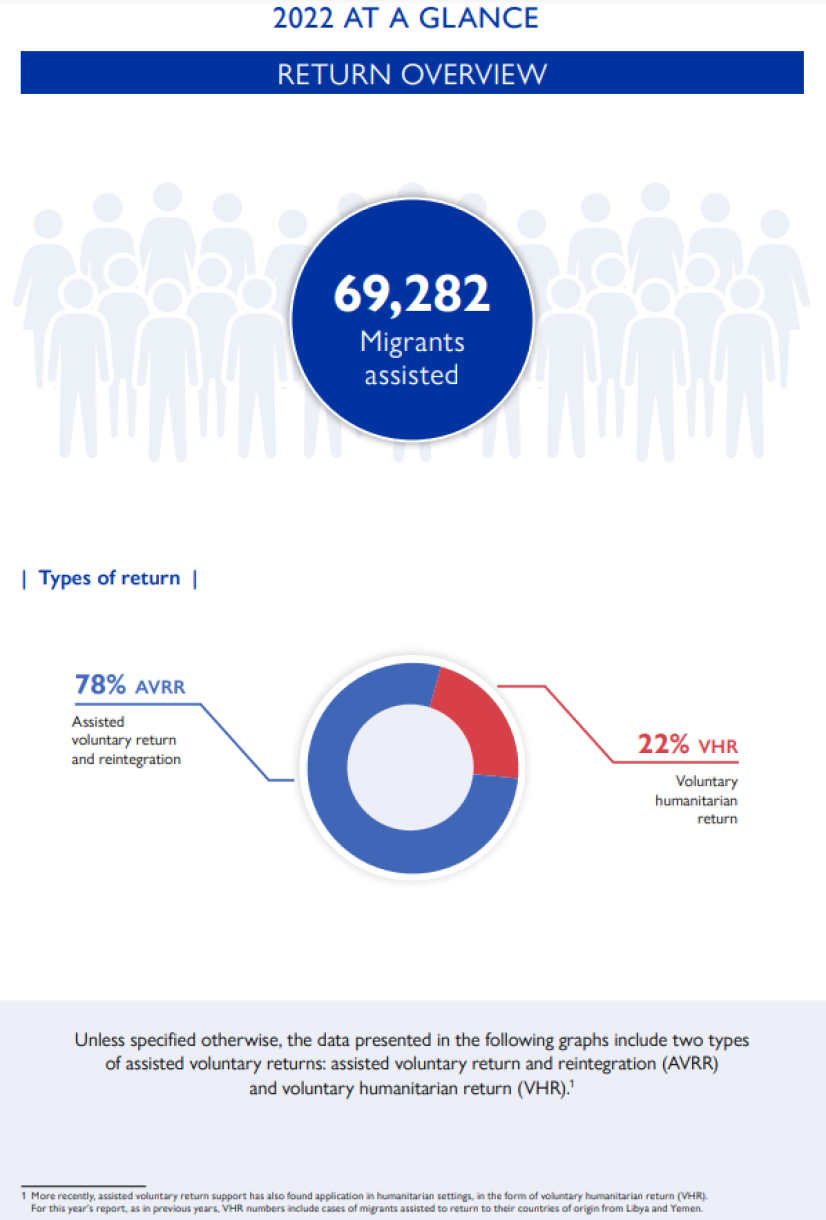

IOM Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration and Voluntary Humanitarian Return in 2022

There is no universally accepted definition of return migration.

Return is “in a general sense, the act or process of going back or being taken back to the point of departure. This could be within the territorial boundaries of a country, as in the case of returning internally displaced persons (IDPs) and demobilized combatants; or between a country of destination or transit and a country of origin, as in the case of migrant workers, refugees or asylum seekers” ( IOM Glossary on Migration, 2019 ).

Two main types of return migration are defined as follows: 1. Voluntary return - is “the assisted or independent return to the country of origin, transit or another country based on the voluntary decision of the returnee” ( IOM Glossary on Migration, 2019 ).

Voluntary returns can be either spontaneous or assisted:

- Spontaneous return is “the voluntary, independent return of a migrant or a group of migrants to their country of origin, usually without the support of States or other international or national assistance” ( IOM Glossary on Migration, 2019 ).

- Assisted voluntary return and reintegration (AVRR) is the "administrative, logistical or financial support, including reintegration assistance, to migrants unable or unwilling to remain in the host country or country of transit and who decide to return to their country of origin" ( IOM Glossary on Migration, 2019 ).

- Voluntary humanitarian return (VHR) is the application of assisted voluntary return and reintegration principles in humanitarian settings and “often represents a life-saving measure for migrants who are stranded or in detention” ( IOM, 2023 ).

2. Forced return - “a migratory movement which, although the drivers can be diverse, involves force, compulsion, or coercion.” ( IOM Glossary on Migration, 2019 ).

While millions of migrants return to their country of origin every year, not all returns are necessarily recorded. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic posed considerable challenges to return migration because of lockdowns, travel restrictions, limited consular services, and other containment measures, and had a decelerating effect on return activities. In 2021, many countries lifted travel restrictions and different types of migration, including return migration, resumed but not to pre-pandemic levels. In 2022, returns reached pre-pandemic levels once more ( IOM, 2023 ).

The number of beneficiaries of IOM’s Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration (AVRR) in 2022 increased by 24 per cent (from 43,428 in 2021 to 54,001 in 2022) ( IOM, 2023) . The number of beneficiaries of voluntary humanitarian return increased by 139 per cent, from 6,367 in 2021 to 15,281 in 2022 ( ibid. ).

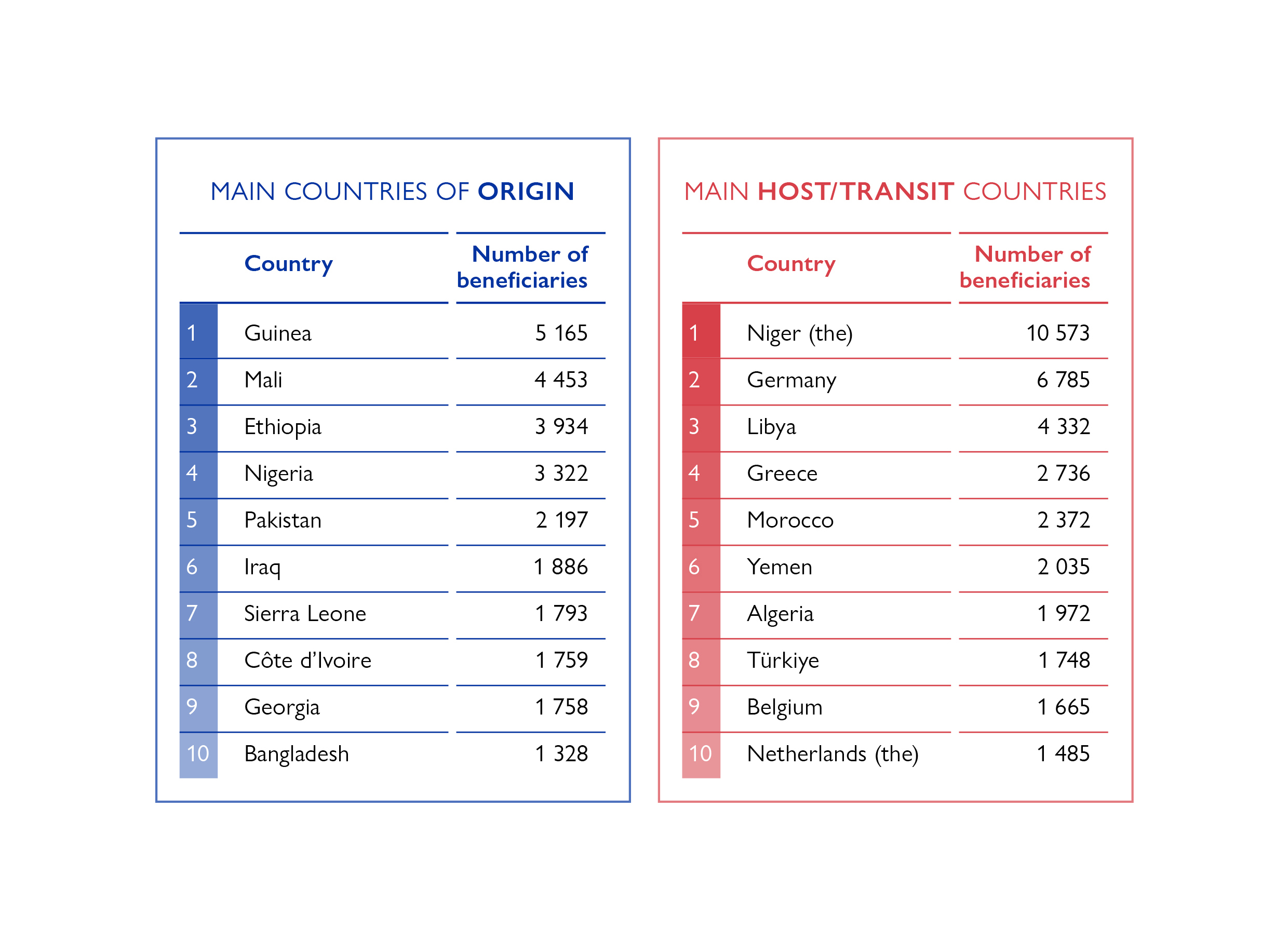

The top 5 host/transit countries for both AVRR and VHR in 2022 were: Niger (15,097), Libya (11,200), Germany (7,874), Yemen (4,080), and Greece (3,065) ( ibid. ).

The European Economic Area (EEA) and the United Kingdom (UK)

During the pandemic, Frontex, the European Union Border and Coast Guard Agency, reported that travel restrictions and a decline in consular services had a decelerating effect on return migration ( Frontex, 2021 ).

Around 291,000 irregular migrants were given a “return decision” by European Union (EU) Member States in 2020 but only 61,951people were effectively returned (either forcibly or voluntarily) ( Frontex, 2021 ). In 2022, 24,850 people returned with Frontex’s support ( Frontex, 202 3 ).

In 2021, 9,508 people left the UK via enforced or voluntary return, the lowest annual level since 2012 ( Walsh, 2022 ). There were 2,800 enforced returns in 2021, 18 per cent fewer than in the previous year – due to changes in the immigration systems, such as a reduced use of detention ( ibid. ; Walsh, 2020). Voluntary returns have decreased since their peak in 2012, although provisional data for 2021 shows an increase from 2020 ( Walsh, 2022 ).

A total of 19,550 migrants were assisted to return from the EEA in 2022, which accounted for 28 per cent of the total global caseload ( IOM, 2023 ). Most of the beneficiaries were assisted to return from Germany (7,874, or 40% of the total number of beneficiaries assisted from the EEA). Next top countries were Greece (3,065), Belgium (2,078), the Netherlands (1,473), and Austria (1,323) ( ibid. ).

South-Eastern Europe, Eastern Europe and Central Asia (SEEECA)

Historically, the region had mostly countries of origin, but the movements have recently become more diverse, and it has countries of origin, transit as well as destination. In 2022, a total of 4,030 migrants were assisted to return from the SEEECA region ( ibid. ). Countries in the region, especially the Western Balkans, have increasingly become transit countries for migrants and refugees from the Middle East and Asia on their way to Western Europe. Also, intraregional migration remains key in the region even though most outflows are towards the European Union ( IOM, 2023 ).

Central America, North America and the Caribbean

The U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) reported 72,177 removals in fiscal year 2022 ( ICE, 2023 ).

In 2022, there were 1,580 cases of AVRR from Central and North America and the Caribbean, or more than double the cases in 2021 (742) and quadruple that of 2020 (359) ( IOM, 2023 ; 2022 ). 31 percent of the cases were children. Mexico continues to be the top country from which the majority of migrants (62% or 987) in the region were returned ( ibid. ). The next top host countries were Guatemala (243), Honduras (122), Belize (66) and Panama (63) ( ibid. ).

South America

In 2022, a total of 82 migrants returned from South America; 56 per cent were female and 44 per cent were male, but 34 per cent of the cases were children ( ibid. ). In contrast, 2,610 migrants were returned to South America, 85 per cent from the EEA ( ibid. )

Asia and the Pacific

In 2022, a total of 522 migrants were assisted to return from Asia and the Pacific region, 30 per cent fewer than the previous year (753) ( IOM, 2023) . As in 2018-2021, the majority of return flows from the region in 2021 were intraregional ( ibid. ). The top 5 host countries in the region were: Australia (174), Viet Nam (151), Indonesia (69),Thailand (41) and Malaysia (28) ( ibid. ).

The Middle East and North Africa

In 2022, a total of 22,551 migrants (7,270 migrants assisted under AVRR and 15,281 migrants assisted under VHR) were returned from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region ( IOM, 2023 ). 76 per cent of the cases were male and the rest were female ( ibid. ). The top 5 host countries in the regions were: Sudan (2,539), Iraq (1,907), Morocco (640), Algeria (627) and Tunisia (232) ( ibid. ).

West and Central Africa

In 2022, 18,551 returns from the West and Central Africa (WCA) region accounted for 27 per cent of the global AVRR caseload ( ibid. ). The Niger alone accounted for approximately 81 per cent (15,097) of all migrants assisted to return from the region ( ibid. ). The host countries with the second and third highest numbers of migrants assisted were Chad (1,338) and Mali (1,602) ( ibid. ). The majority of international migrants in WCA were intraregional, which confirms the trend of increasing numbers of returns taking place from transit countries. In 2022, the three main countries of origin within the region were Mali, with 6,624 returns, Guinea (6,468) and Nigeria (5,712) ( ibid. ).

East and Horn of Africa

In East and Horn of Africa, a total of 1,703 migrants were assisted to return from the region in 2022, 18 per cent fewer than in 2021 and 2 per cent of the total caseload ( ibid. ). The majority of the beneficiaries (74%) assisted to return were male. The majority of those assisted were also from Djibouti, representing around 56 per cent of the total regional caseload, or 953 cases. The second biggest host country in the region was the United Republic of Tanzania, with approximately 30 per cent of AVRRs from the region or 518 cases ( ibid. ).

Southern Africa

In 2022, a total of 713 migrants were assisted to return from Southern Africa; of these, 93 percent were male and the rest were female ( ibid. ). The top five host countries in this region from which migrants were assisted to return from were Malawi (506), Zimbabwe (55), South Africa (39), Mozambique (32)and Zambia (27) ( ibid. ).

As the largest global provider of Assisted Voluntary Return (AVR) and Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration (AVRR) programmes, IOM collects voluntary return data on a regular basis. IOM data include the number of participants, host and origin country, as well as sex, age and migration status in the host country prior to return. Since 2010, IOM has published key data on the AVRR website . IOM data also include information on assisted migrants by specific vulnerability (unaccompanied migrant children, migrants with health-related needs and victims of trafficking).

Data on returned or “repatriated” refugees – i.e. refugees who have returned to their country of origin spontaneously or in an organized manner (sometimes with help of IOM’s AVRR programmes)– are collected respectively by IOM and UNHCR .

Data on the outflows of the foreign population from selected OECD countries are collected by OECD’S Continuous Reporting System on International Migration (SOPEMI) and published in the annual International Migration Outlook report.

The EU-IOM Knowledge Management Hub has developed a Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) package for return and reintegration programmes, with the aim of harmonising M&E across global return and reintegration programmes.

Since 2014, Eurostat has provided the following data for EU Member States on return migration of people who are third-country nationals:

- Third country nationals ordered to leave - annual data (rounded);

- Third country nationals returned following an order to leave - annual data (rounded);

- Third-country nationals who have left the territory by type of return and citizenship;

- Third-country nationals who have left the territory by type of assistance received and citizenship.

Data on forced and voluntary return from EU Member States and the three Schengen Associated Countries (Iceland, Norway and Switzerland) are also published in the Frontex Risk Analysis Report s.

The Return Migration and Development Platform from the European University Institute promotes exchange and knowledge-sharing about return migrants’ realities and the contexts of their experiences.

United States

Data on the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency’s “enforcement and removal operations” (ERO), including forced returns , are summarized in its annual reports .

Central and South America

Data on return migration from and to Central and South (and Northern) American countries was collected by OECD’s Continuous Reporting System on International Migration in the Americas (SICREMI) and published in the International Migration in the Americas reports until 2017.

The Australian Government Department of Immigration and Border Protection publishes annual data on forced and voluntary return from Australia.

Afghanistan

IOM reports on undocumented returnees from Iran and Pakistan to Afghanistan here .

Some countries and/or organizations have collected data to monitor return migration and the outcomes of return programmes, for example:

- Four EU Member States – Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic and Norway – have collected data on post-return, monitoring returnees to identify longer-term outcomes.

- Switzerland: IOM tracked outcomes for returnees from Switzerland to Nigeria whom it assisted in 2015, at roughly 9 months post-return.

- In the UK in 2013, the charity Refugee Action compiled a small study of the post-return experiences of their beneficiaries.

A few research studies have assessed the sustainability of return and reintegration programmes. For example, Koser and Kuschminder (2015) developed a Return and Reintegration Index which was tested on 156 returnees in eight countries of origin. Strand et al. (2016) measured sustainable return based on the perception of returnees from Norway to Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Iraq and Kosovo 1 , and ICMPD (2015) conducted a study to evaluate the sustainability of AVR programmes from Austria to Kosovo. 1

Data strengths and limitations

Data on forced return and on voluntary return are scattered across different data sources and are often incomplete or only partially publicly available - For example, several countries that implement AVRR programmes (either under IOM or government auspices) are not reported on in the Eurostat database (e.g. Germany, The Netherlands, and the UK). In addition, voluntary departures are usually not tracked. In order to improve this, the EU is implementing the Integrated Return Management Application (IRMA), a secure web-platform for integrating all EU return activities.

There is a large data gap on post-return data mainly due to the lack of definitions and established indicators for measuring “reintegration”. However, in January 2016, the EMN released guidelines for the monitoring and evaluation of AVR(R) programmes that provide a list of questions and indicators to be included in post-return monitoring activities.

In 2017, the DFID-funded MEASURE Project (Mediterranean Sustainable Reintegration), a pilot project that fosters the sustainability of reintegration support in the framework of Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration in the Mediterranean, led to the development of a set of 15 field-tested indicators and a scoring system to measurement of reintegration outcomes and improving understanding of returnees’ progress towards sustainability. These indicators are based on a revised definition of sustainable reintegration in the context of return ( IOM, 2017 ), and therefore relate to the three economic, social and psychosocial dimensions of reintegration. The scoring system allows comparison of trends in returnees’ reintegration across country contexts and over time.

1 References to Kosovo shall be understood to be in the context of United Nations Security Council resolution 1244 (1999).

Explore our new directory of initiatives at the forefront of using data innovation to improve data on migration.

Migration flows data capture the number of migrants entering and leaving (inflow and outflow) a country over the course of a specific period, such as one year ( UN SD, 2017 ). Data on migration flows...

Diasporas, sometimes referred to as expatriates or transnational communities, play an important role in leveraging migration’s benefits for development. Measuring issues relating to diaspora groups is...

Through a large footprint of offices worldwide, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) collects and reports on original data from a number of sources in its own programmes and operations...

- UN Network on Migration

Partnerships

- Where we work

Work with us

Get involved.

- Data and Research

- 2030 Agenda

About migration

Nearly 50,000 Migrants Assisted to Voluntarily Return Home: 2021 Return and Reintegration Key Highlights

As part of community reintegration, IOM partnered with a local NGO to rehabilitate a multi-purpose community center in Khartoum, Sudan and aims to support host communities and returnees in the area. Photo: IOM/Muse Mohammed

Geneva – Nearly 50,000 migrants were assisted to voluntarily return to their countries of origin with more than 113,000 reintegration activities supported globally in 2021, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) 2021 Return and Reintegration Key Highlights .

Last year saw an increase of global mobility. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of returns is still short of pre-pandemic movements. In 2021, IOM assisted 49,795 migrants to return to their countries of origin, which represents an increase of 18 per cent compared to 2020. Among them, 6,367 migrants were assisted to return under IOM’s Voluntary Humanitarian Return (VHR) programme, a type of return assistance applied in humanitarian settings.

Just like in the previous year, the European Economic Area was the main host region in 2021 with 16,993 migrants assisted to voluntarily return to their countries of origin. Likewise, the Niger remained the main host country with a total of 10,573 migrants assisted to return, highlighting the continued trend of increasing returns from transit countries in other host regions outside of the European Economic Area.

“This publication highlights IOM’s ability to meet an increasing demand by migrants for safe and dignified returns as well as to support their reintegration into the countries of origin following the lifting of many travel restrictions imposed during the pandemic,“ said Yitna Getachew, Head of IOM’s Protection Division.

Reintegration is a key aspect of assisted voluntary return programmes to provide opportunities to returnees and promote sustainable development in their countries of origin. In 2021, IOM offices in 121 countries worldwide supported 113,331 reintegration activities at the individual, community, and structural levels. Overall, the top three countries, including both host and countries of origin, that provided reintegration support in 2021 were Germany (15%), Nigeria (12%) and Guinea (8%). The support consisted mainly of social assistance, economic assistance, and reintegration counselling.

“The publication offers rich insights into global trends in terms of return and reintegration assistance provided by IOM in accordance with its rights-based approach and protection framework. IOM is assisting migrants who are seeking to return to their countries of origin in full respect of their human rights and is contributing to their sustainable reintegration,” Getachew added.

In 2021, IOM released its Policy on the Full Spectrum of Return, Readmission and Reintegration , which guides the Organization’s work and engagement with partners on return migration through a holistic, rights-based, and sustainable development-oriented approach that facilitates return, readmission, and sustainable reintegration. It focuses on the well-being of individual returnees and the protection of their rights throughout the entire return, readmission, and reintegration process, placing individuals at the centre of all efforts and empowering those making an informed decision to participate in assisted voluntary return programmes.

The main host countries of migrants assisted by IOM to voluntarily return to their countries of origin are presented in the list below.

The report which highlights the Organization’s Return and Reintegration programmes includes trends, figures, and initiatives to assist migrants in their safe and dignified return and sustainable reintegration.

The 2021 Return and Reintegration Key Highlights report is available in full here .

For more information, please contact:

Kennedy Omondi Okoth, [email protected]

Claudette Walls, [email protected]

Silvan Lange Nesat, [email protected]

RELATED NEWS

Iom welcomes, pledges support to new eu pact on migration and asylum , venezuelan migrants drive usd 529.1m boost to colombia’s economy: iom study, 24 migrants dead in new shipwreck off djibouti coast; second deadly incident in two weeks, iom unveils “wearin’ it together” at the european parliament.

Migration updates

Subscribe to IOM newsletter to receive the latest news and stories about migration.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Special Issues

- Editor's Choice

- Submission Site

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- About Journal of Refugee Studies

- Editorial Board

- Early-Career Researcher Prize

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Books for Review

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, methodology, conditions of return, experience of the first visit, impact of return, after the visit, back home refugees' experiences of their first visit back to their country of origin.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

HELEN MUGGERIDGE, GIORGIA DONÁ, Back Home? Refugees' Experiences of their First Visit back to their Country of Origin, Journal of Refugee Studies , Volume 19, Issue 4, December 2006, Pages 415–432, https://doi.org/10.1093/refuge/fel020

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This paper argues that the first visit ‘back home’ is important for refugees because it acts as a catalyst for renewed engagements with host country and country of origin. The study shows that conditions in both countries impact on decision-making and ultimately that integration and return can coexist. The first re-connection with ‘home’ is described as a memorable event in and of itself. Marked by an awareness of the passing of time, it provides both an end to waiting and worrying and a measure of one's progress (or lack of) in life, thus enabling participants to move on. Establishment of safety nets in both host and home countries as a condition for permanent return distinguishes the predicament of these refugees from that of other migrants. As the meeting between imagination and reality, the first visit contributes to the re-examination of the refugee cycle, the myth of return and the meaning of home in a context where return encompasses one discrete experience, the visit, and subsequent events. Overall, the paper provides a link between the literature on return as imagined while in exile and accounts of the reality of post-return.

MS received September 2003; revised MS received January 2006

The notion that refugees ‘would return home if conditions changed’ ( Krulfield and Macdonald 1998 : 125) has evolved from a basic equation of return = homecoming to a more sophisticated debate.

‘Repatriation’ is the term often used by UN agencies and policy makers to refer to the physical act of returning to the country of origin. The term ‘return’ is usually adopted by researchers and refugees to describe individual and socio-cultural experiences. This study will use the two interchangeably to refer to a general psychological or physical desire or act of voluntarily going home.

Research on return could be viewed as encompassing two main trends: imagining return and the reality of post-return. From exile, return is envisaged through concepts like the meaning of home and belonging ( McMichael 2002 ; Said 2000 ) and the prominent notion of the myth of return ( Al-Rasheed 1994 ; Israel 2000 ; Zetter 1999 ). The reality of post-return draws attention to challenges similar to those researched in contexts of post-conflict reconciliation and re-integration ( Arowolo 2000 ; Doná 1995 ; Essed et al . 2004 ; Kumar 1996 ; Long and Oxfeld 2004 ). Increased appreciation of the complexity of return has led researchers to overcome this distinction. The gap between pre- and post-return is bridged by studies that focus on the impact of exile on return ( Farwell 2001 ; Rousseau et al . 2001 ), return linked to transnational practices ( Al Ali and Koser 2002 ; Moran-Taylor and Menjívar 2005 ; Sorensen 2003 ; Van Hear 2003 ; Werbner 1999 ), return as one period of serial migration ( Ossman 2004 ) and the experience of a visit home ( Barnes 2001 ; Israel 2000 ) as ‘provisional return’ ( Oxfeld and Long 2004 : 9).

Aligning itself with recent trends that recognize the complexity of return beyond it being permanent and final, the present study explores the first visit home after a period of exile, examining individual decision-making strategies leading to decisions to return ‘home’ for a visit for the first time, the experience, and the impact the first visit may have on future decisions in relation to ‘back home’ and ‘host homes’. By isolating the first visit as the topic of the research, it is suggested that this can be considered a discrete element of the literature on return and that, independent of the eventual outcome, its analysis is valuable for a broader understanding of the meeting of imagination and reality.

Therefore, if the 1990s were named the decade of repatriation, the 2000s can be said to be about factors beyond permanent return, about the connection between imagination and reality, and about flexible relations between home and host countries. Consequently, this study examines return in fluid terms as it encompasses one event, a first visit home, and subsequent relationships with home and host countries following a first visit, whether this is a decision to return permanently or not.

Part of the information presented in this paper is based on research conducted by the first author for her MA in Refugee Studies at the University of East London (2001). An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 8 th IASFM Conference ‘Forced Migration and Global Processes’ in Thailand in 2003.

ELR has since been replaced by humanitarian protection and discretionary leave.

Participants were 8 women and 7 men, ranging in age from 27 to 50 years. They arrived in the United Kingdom from Turkey (3), Iran (3), Bosnia (2), Kosovo/a (2), Chile (1), Kenya (1), Uganda (1), Ethiopia (1) and Croatia (1). Prior to the visit, they had been in exile for a number of years, ranging from 4 to 27: 4–7 years (5), 8–11 years (2), 12–15 years (5), 16–19 years (2), and 24–27 years (1). The non-probability ‘snowballing’ selection method was used, as the study did not aim to obtain a representative sample but rather to highlight the variety of their experiences. Multiple interviews were carried out; at first, semi-structured interviews were conducted, which produced somewhat stifled responses. Therefore, questions were abandoned and replaced by open-ended interviews that began with the ‘grand tour’ question, ‘Tell me about your first visit back to your country’. Follow-up interviews and informal conversations with participants also took place on subsequent occasions. The advantage of this method was that a large amount of often-sensitive data could be gained; a disadvantage was that capacity for comparison of data was reduced.

Home is generally assumed to be the country of origin except where ‘home’ is defined differently by participants. See the Discussion for a theoretical analysis of the concept.

Participants' reasons to return for a first visit were many and interlinked, and some decisions were taken with a degree of compulsion. Most respondents cited at least one of the following factors as the reason for making a first visit home: conditions of safety for the individual in the home country, having secured immigration status in the UK, death of a parent, homesickness, and missing friends and family.

Conditions in the Home Country

Since the reasons for claiming asylum entailed very grave dangers, safety upon return for a first visit was of paramount concern to participants and was incorporated into the decision to visit. Official declarations of safety and personal perceptions differed, and even after assurances from trusted sources were received, anxiety about crossing borders often persisted.

Respondents returned after there was a change of government or of political circumstances. José fled Chile in the 1970s and returned for the first visit 17 years later ‘when the dictatorship had ended’, but he only felt it was safe to return two years after the formal change in government. For some respondents, the decision to return was predicated on advice and information from family in the home country. Mohsen left Iran and did not return for 15 years, one of the main reasons being his fear of being conscripted. Due to changing conditions in the home country, he was eventually advised by family that he could return with a very low risk of being conscripted. Joy returned to Kenya when her family had given assurances that the disturbances had stopped.

If assurances contributed to the decision to visit, the perception of safety in the home country continued to be an uncertainty until tested personally. Some took precautions. Rana is a Turkish political exile who returned for a first visit after 17 years. She felt it was ‘her turn’ to go back. Her husband and daughter had already gone for a visit and her best friend had moved back and holidayed in the UK, keeping her updated as to the situation in Turkey. At the airport, she ensured that she was met ‘just in case’. She travelled to her country on a British passport with a visa for Turkey. She spoke English to the immigration officials and stated that, as her surname is unusual and foreign-sounding in her home country, she experienced fewer problems than anticipated.

Mahin and Jusuf came to the UK from Iran as a young married student couple in the late 1970s and were unable to return due to their leftist sympathies which were antithetical to the 1979 revolution that brought an Islamic regime to power. They decided to return to visit after an amnesty to political exiles was granted by the government, albeit cautiously for fear of remaining on a ‘black list’ of government opponents. Both British nationals at the time of the visit, they made the journey separately in order that, ‘if anything happened’, the wife could ‘do something’ from the UK. Often the experience of the flight was dominated by anxieties. Mahin visited Iran after 15 years' exile in the UK. She travelled with her sister as she states that she could not cope alone. During the flight, she took so many tranquillizers she was ‘drugged up to her eyebrows’. She took her last tranquillizer when the pilot announced that ‘We will be in Iran in 10 minutes time’.

The gate-keeping role of immigration officials, endowed with the power to interrogate, arrest, reject or detain (and the possible torture that may entail) is feared and despised. Successfully passing through immigration without officials ‘pressing the button’ to call colleagues to advise them of one's presence on ‘the list’ was described as a relief and a joy. If anxiety about immigration controls in countries of asylum is to be expected, there is an assumption that immigration controls in the country of origin would not entail similar preoccupations; but for these respondents, fear at immigration control was a feature of trying to get in to their own countries. Even though in possession of reassurances and often a secure legal status in the UK, most still worried about crossing the border. If security in the home country is of paramount importance, equally significant in deciding to return for a visit are conditions in the host country.

Conditions in the Host Country

The interviews document refugee decision-making strategies that involve risk assessment. Almost all respondents (12) said that they waited to be naturalized as British citizens before returning; one risked losing refugee status by returning and another travelled to a neighbouring country for the same fear of re-availment, that is, forgoing refugee status by accepting the protection of the country of origin upon return.

Nimet left Turkey in 1990 and her temporary immigration status in the UK did not permit her to visit her country as she would not be re-admitted to the UK. Whilst she was waiting to be granted Indefinite Leave to Remain her mother died. This came as very sudden news since her family had not informed her of her mother's illness because they knew that she could not travel and did not wish to cause her anxiety. She was unable to return for the funeral as this would have jeopardized her Leave to Remain. Nimet described how, prior to her mother's death, she had developed ‘some mechanism’ to cope with the thought of not visiting her home country for seven years. As soon as her mother died, she started to want to go back, as she was worried that the same fate would meet her father, and as soon as she was granted status, she returned.

Maja, whose family lived in Serbia, is of mixed Serb and Croat ethnicity. Having a temporary status in the UK, after six years, she met her family in a hotel in Hungary and then travelled to Croatia, which she described as returning home. From there she could see the small border post to Serbia—one man in a hut. Given the burden of the prohibition to return, she found that this ‘naïve’ scene at the border of her country did not compare to the heaviness of possible loss of refugee status if she did cross into Serbia. Her mother advised against jeopardizing her status and she reluctantly did not return, instead suffering the torment of being able to see her home whilst being unable to visit.

Conversely, Haki, an Albanian Kosovar, was granted refugee status after seven years, with the usual prohibition on return to country of origin. He was so ‘homesick and desperate to go’ that he decided to risk his refugee status by visiting his family. He took a flight to the neighbouring country, Macedonia, and crossed the border illegally. He bribed border guards and travelled via the cigarette-smuggling route, information about which he had obtained from friends in the UK. He stated ‘Technically, I didn't go to Kosova’. The fact that his immigration status was at risk had a profound influence on his first visit home. It caused anxiety to him during the visit and to his British wife in the UK who expressed her disapproval during the interview. He was worried about ‘getting caught’ throughout the visit and being denied entry to the UK on return.

While improvements in conditions in the home country were generally described as decisive factors about return, the individual cases of this section expose an additional complexity of events: the decision to return cannot be divorced from status in the host country. The participants in this study were more likely to return once they had been granted refugee status or indefinite leave to remain. Refugees' risk-assessment as part of their decision-making strategies meant that the majority of those interviewed waited until their status allowed them to return without risking jeopardizing their legal position in the host country and putting themselves in a precarious position where they may be forced to seek asylum again. Those respondents who did risk status in the UK reveal the desperation to re-connect with home for the first time after flight. Emphasis on refugees as political exiles can overshadow the fact that refugees are individuals for whom exile means missing out on ordinary family life and significant events back home.

The experience of the first visit brings together the imagination and the ‘reality’ of home. The initial visit is the first contact between the imaginings of years in exile and the present. Emotions on arrival were strong. After the anxiety of crossing immigration controls, euphoria exemplified by phrases such as breaking a pair of ‘unbreakable’ spectacles; ‘shaking with excitement’ and ‘crying without noise’ prevailed amongst all respondents, even those for whom the visit as a whole produced mixed feelings. Expressions such as ‘overwhelming’, ‘enjoyed every minute’, ‘no negative impressions whatsoever’ were used by some to describe the visit but when the reason for return was the loss of a family member, the focus of the visit became inevitably sad.

For some, the encounter with reality still carried an element of imagination as they described the visit as ‘unreal’, ‘surreal’, ‘like a dream’ and ‘like a film’. Respondents were aware that political, economic and social changes had taken place during their absence, but first hand experience of these changes was felt with some surprise. Upon arrival, many respondents remarked on the visible changes in their countries such as dangerous road traffic, noise, dirt and crowded cities, many now populated by rural people of whom some respondents seemed to disapprove. Some were shocked at visible evidence of economic and political devastation as a result of upheaval. Participants also commented about the difficulties they experienced re-adjusting related to changes in political regimes, languages and currency.

Passing of time was acknowledged as widening the gap between imagination and reality and became a strong feature of all first visits. Some respondents pinpointed indicators of time passing. Mahin, who had left home prior to the Islamic Revolution in Iran and returned afterwards, joked that she left her country like this (pointing to her Western clothes) and return meant that she had to be ‘all wrapped up’ (in hijab). Mohsen experienced dreams over his fifteen years in exile from Iran in which he saw faces of friends and relatives at the age at which he had left the country. Upon return, he was unable to recognize some. Some part of return is inevitably nostalgic and about returning to memories of youth. Respondents described walking in the alleyways and visiting old schools and bars that held particular good memories to get a ‘feel’ for the place.

Whilst general information on the country was known in exile, it was the details of what had happened on a local scale that bridged the gap between imagination and reality. Family and friends told stories of past events, as if to ‘fill them in on what happened’, but also because locals ‘needed to tell their story’. After this initial recounting, family and friends assisted and encouraged the visitor to move on and accept what had happened.

Respondents also realized a time-gap in their experiences in the way in which life had gone on for people back home. Many who had fled when their country was in chaos, were amazed upon return to see friends, family and local people ‘going about their daily lives as if nothing had happened’ and even that ‘they did not want to talk about the war all the time’. Some were surprised at how stayees accepted the status quo. Respondents quickly realized this, as they understood that those living there had time to deal with the upheaval naturally and out of necessity and that it was they who were ‘stuck’ in the time when it happened. For example, Gzim, a Kosovar Albanian, was shocked by the international military presence in Kosovo/a. During the first day of his first visit, he described being driven across a bridge, responsibility for which had been shared between three national forces. The Russian soldiers took out his baggage and he felt he must protect his younger brother. For his family, however, this was a normal daily occurrence and they told him to ‘calm down’. Gzim also realized change when he made a joke using the Serbian language and his family warned him that it was dangerous to do so in front of some local people given that anti-Serbian sentiment now ran high.

Relationships had changed over time as they were magnified in imaginations unmatched by the experience of the visit. Some male respondents were disappointed that relationships were ‘not what they used to be’. Haki described his visit to his uncle by saying that he had left his uncle's life and his uncle had left his life. ‘There is a huge gap to fill on both sides’. He went further and said ‘we pretend we love each other but we don't know each other’. The parody of being close to someone, having imagined them for years and built up a picture and then being worried about holding an everyday conversation with them was a concern.

The discrepancy between past and present was shown by uneasiness about ‘not knowing how to act and react’. Returnees displayed a high level of self-awareness and took a great deal of care in their actions towards others. They were uncomfortable and displayed fear both of resentment and awe of perceived wealth on the part of compatriots who wished to leave the home country and come to the UK. As a result, they ‘played down’ the impact of coming from a Western country and emphasized rather the disadvantages of life in the West such as the high cost of living in London. As returnees, they felt that their compatriots were not aware of ‘what they had’, that is, the quality of human relations rather than Western material goods. In contrast to stories told to Gzim by family and friends of how ‘your neighbours came to slaughter you’, he felt his stories of London weren't worth telling as ‘they were not brave enough’.

As well as not knowing how to act, respondents were even more concerned as to how others would react. Returning to visit is about managing human relations after time apart and differing experiences. Before the visit, some feared resentment and questioning due to absence in wartime, in particular those from relatively recent conflicts in Former Yugoslavia. Those who fled before a war felt anxious about being seen as a ‘traitor’. Many respondents were pleasantly surprised when they were, instead, welcomed and made to feel at home. For example, Senad from Bosnia worried that people would ask him ‘what were you doing during the war and why weren't you here?’ He was relieved when this did not occur. However, he said that this judgement was, in fact, ‘saved for later’.

To conclude, the first visit is the first connection, physical and ‘emotional’, to borrow from the respondents' language, with the country from where they escaped. The first visit was a meeting of past and present, of imaginations about the home country built up over years of exile and the reality of the present. There is a complexity of feelings exemplified by comments such as: ‘you are strangers and it is like nothing happened’ or ‘you are a stranger and yet you know exactly what is going on and understand the small talk and can read between the lines’. Whatever the experience, none of the respondents regretted the first visit.

The experience of returning home had an influence on returnees' lives, in that it provided an end to inner feelings of uncertainty and limbo. Some respondents had described the years in exile in terms of ‘limbo’. Rana stated about life in the UK: ‘everything I do here seems fake’, while Moses felt he was making no progress in the UK and his life was work, home and television whereas his contemporaries at home had families. The first visit home shifted these perceptions and altered some sort of equilibrium as refugees faced feelings about the past and their home country that may have been put on hold in an effort to control difficult feelings whilst in exile.

Irrespective of the decision taken after returning to the UK, the first visit meant that their minds were put at rest and made them ‘more settled in their head’. This was predominantly achieved through some form of reassurance. For instance, Gzim feared that his friends and relatives in Kosovo/a would never have been able to survive the war. During his first visit, he was relieved and reassured that they were living their normal lives. He returned to the UK feeling less worried for his family. Others were able to clarify their roots. Sanja found the first visit reassuring about her identity. Being a refugee in the UK had made her feel stateless. The impact of her first visit to Bosnia was the feeling that she was not stateless, she ‘did not just drop from the sky’ but that she had roots. She described the visit as ‘the end of one chapter’ which led to her realization of ‘having two lives’, before in Bosnia and now in exile.

Another impact of the first visit was the opportunity it afforded to examine aspects of life in exile such as progress in relationships, career and maturity of character. This provided confidence and a feeling of achievement in the face of adversity. Two female respondents who had arrived in the UK in their early twenties described how they had gained their independence, ‘managed to survive’ and had ‘grown up’ in the UK. ‘Starting from zero’, they had learnt English and begun paying bills for the first time. Defining the UK experience in terms of ‘formative years’ explained an attachment and belonging to the country of exile. For Senad, the first visit was useful as a measure of how much he had changed and succeeded. He described the latter as a ‘typical immigrant feeling’. He returned with a career as a manager ‘not in catering’, having bought property in the UK and achieved an MA. The first visit made this progress apparent to the refugees.

The visit also had impact on one's perception of ‘home’, transforming relationships with country of origin and exile. For Gzim the visit reconfirmed the idea of home as an inexplicable ‘gut feeling’ about memory and fitting in. Conversely, Jose's reassessment of home meant that his visit to Chile was experienced as being a ‘tourist with friends’, indicating the reversal of the idea of home from country of origin to country of exile. For five respondents, the first visit was seen as beneficial as it prompted the realization that they felt at ‘home’ in the UK. This often occurred when respondents were returning from the first visit as the plane was coming into land. Some said they ‘couldn't wait to get back’ to the UK. These feelings of the UK as home were for some tempered by a feeling that the UK would never truly be ‘home’, as home is defined as a place where you are born and grow up. Some respondents said they would ‘always feel like a foreigner’, and return to the UK after a first visit was, for one respondent, return to my ‘almost new life’. Thanks to the visit, Senad managed to integrate previously uncertain feelings about home. He said: ‘one of the beautiful things about the visit was the realization that I have two homes’ and he believes that Europe will be able to incorporate both his Bosnian and UK homes in the future.

One respondent who stood out as different was Asther, for whom the realization of the UK as ‘home’ was the outcome of the negative experience of her visit. The picture held in her imagination was shattered by the experience of the first visit, which involved a great deal of pain and disappointment. Asther explains that anticipation of her first visit invoked vivid memories of childhood, the moment of leaving the country and people left behind. She describes her life in exile in the UK as being ‘not living but survival’, waiting to return to live in Ethiopia and begin her ‘real life’ once more. She described how she had meticulously planned her return to Africa. For example, she did not buy an electric kettle in the UK as she thought she might not need it when she finally returned to live in her country. During her visit she felt extremely unsafe, unwelcome and was forced to accept that her dream of return would never be realized. This shattered her perception of ‘home’ and she was forced to view the UK as a permanent place of residence. The UK consequently became the sole option of a place to call home: Asther applied for naturalization after her first visit, as she realized that she did not wish ever to return to Ethiopia. While the visit painfully shattered her dream of return to her country of origin, she commented that it enabled her to move on and ‘begin’ life in the UK.

Whatever the outcome, and independently of whether the actual experience was painful or joyful, the first visit was seen by respondents as valuable, made them realize whether they had made progress or ‘wasted’ time in exile, or where their ideas of home had ended up. It further led to renewed engagements with ‘home’ and ‘host’ countries after the visit.

By closing a chapter, the first visit enabled individuals to go on with their lives, whether this entailed remaining in the UK or returning to settle in the country of origin. Those respondents who had no desire to return permanently cited reasons that ranged from viewing return as ‘like another exile’ to worries about securing employment as a member of an ethnic minority, to not fitting in or concerns about continued corruption. For some respondents there were certain things they never liked about their culture and they said that they did not ‘fit in’ even before they left. For example, Sanja stated that ‘Of course I cannot say that I am glad the war happened, but my life has worked out well for me’. She is a Bosnian married to a British doctor and they have now moved to the USA.

Some were considering return ‘sometime in the future’ because the desire to go home was ‘always in the back of the mind’ but a nostalgic view of home was tempered by a realistic assessment that they could not return due to family commitments in the UK or the ‘mentality’ at home. Others who said that they ‘did not want to grow old’ in the UK also acknowledged that they are currently enjoying successful careers and friends in the UK, suggesting that ideas about return are complex and diverse.

Independently of decisions to return or remain, the first visit broke a barrier by closing one chapter and unlocking a process of engagement with subsequent events. For all except Asther, respondents made subsequent visits that contributed to a process of normalization of return. For some, the first visit acted as the catalyst for a decision to return permanently. For those taking return into serious consideration, it was not to an imagined ideal place. Having been home for a visit, negative aspects of home such as chaos, nepotism, disorganization, inefficiency and corruption had been thrown into the equation. Some spoke with resigned fondness of the chaos that characterized the home country and yet, at the same time, it was anticipated as the main difficulty on permanent return. In this way, home appeared to be viewed both nostalgically and with an element of realism. For example, Joy spoke of her inexplicable attachment to home and yet stated that she ‘didn't want to think too much’ about the corruption in Kenya where one was required to offer bribes ‘for every small thing’.

The main reasons for return were feelings about ‘home’, higher quality of social life and being with family. Increased financial capital and standard of living and the possibility of early retirement were given as reasons for return; in this way, buying property in the home country was not expressed as a nostalgic tie to the land but as an astute financial move.

One common element of the decision-making process was respondents incorporating a safety net both in the UK and the country of origin. This included maintaining a mortgage on a UK property, securing career breaks and retaining a British passport. As for the country of origin, it meant being as independent as possible by purchasing land and private property and by securing self-employment. Maintaining property in the UK meant that the refugees were more likely to return to the country of origin as they had increased financial security and an income from rent. In addition, for those with (British) children, it meant that they could provide a base should the child want to return. Such strategies may on the surface appear economic; however, they mask real attempts to avoid exposure to political fluctuations, vulnerability to persecution and being ‘back to square one’ and having to seek asylum.

For example, Mahin and Jusuf, from Iran, considered returning after approximately twenty years in exile as they wished to contribute to re-building the country at what they described as ‘an exciting time’. Even if unsuccessful upon return, they were determined to at least try to live in Iran. However, in light of their perception of the forecast political instability, they rented out rather than selling their house in the UK and Mahin obtained a career break. As of 2005, Mahin and Jusuf had been back in their country for a year; both in highly paid jobs of high status. Mahin has successfully managed to transfer her skills working for a civil society NGO in the UK back to her country and Jusuf went back to being an established artist.

Moses, from Uganda, said that he wanted to be a self-employed businessman after return as gaining private or government employment would be difficult due to nepotism since he comes from ‘a poor ethnic group that was favoured under British colonialism but is no longer’. It was also anticipated that by not being dependent on employment in the country of origin, potential contact and thus conflict with those not of one's choice could be minimized. In addition, it was pointed out that in Uganda, Iran and Bosnia, nepotism exists as far as jobs are concerned and an awareness of being less connected (often by choice, since those in power may be the very people from whom they fled persecution) and/or not a member of a favoured ethnic group meant that employment prospects may be few.

Conclusions can be drawn about the relationship of the first visit and subsequent considerations about country of exile and origin. Having a positive experience on the first visit does not translate into a decision to return permanently, and the majority of respondents had no immediate plans to return. For those not wishing to return, many do not live a life of anguish over the location of home and life between different cultures, but rather manage their relationship with different locations well. Irrespective of decisions to return, these participants are not motivated solely or principally by economic factors; even where they share similarities with ‘return migrants’, security issues as a result of political factors remain paramount. Indeed, the two are linked as returning participants plan economically to free themselves from dependency on political forces.

Various commentators on return have recommended concentration not simply on legal and political factors but also on social and economic ones ( Allen and Morsink 1994 ; Rogge 1994 ; Zarzosa 1998 ; Farwell 2001 ) and a recognition of the ‘importance of analysis of individual agency’ ( Pilkington and Flynn 1999 : 195). In line with an increased sophistication about understanding return, this study examined the complexity of individual agency, decision-making and refugees' negotiations with home and host countries.

The findings confirm the value of the first visit as a memorable event in and of itself, which no respondent regretted, independently of the emotions associated with it. Its main function is that of a catalyst: it put an end to waiting, to worry about family, and to wondering about ‘back home’; it created the setting for an assessment of progress (or lack of) in life and a verification of identity; most importantly, it enabled participants to move on, whatever this might mean for each of them. The first visit broke a barrier by closing one chapter and unlocking a process of engagement with subsequent events. Except one, all participants made subsequent visits that contributed to a process of normalization of return. In the context of an increasingly comprehensive understanding of return, the first visit occupies a unique place as the intersection of imagination and reality.

A Meeting of Imagination and Reality

The Visit as the End of a Chapter . Black and Koser (1999) argue that although return may bring an end to one cycle, it is often the beginning of a new cycle and that this post-return situation should be researched. Similarly, Hammond (1999) refutes the idea of the end of a cycle when challenging the ‘repatriation = homecoming’ model. A number of factors enter the ‘return and homecoming’ relationship in a non-circular way, and the first visit home is one of them. The findings of this study indicate that there is not one end to the refugee cycle but rather many different ‘endings’, and that the image of the cycle may not be the best metaphor to capture refugees' experience of return. One participant in this study alluded to an alternative image, that of a book, when describing the visit as the ‘end of a chapter’.

The meeting of imagination and reality achieved through the first visit brought something to an end, which does not necessarily mean regaining what one had before, implicit in the image of a cycle, but rather it entails the end to a condition of waiting. This is usually described as being in limbo. Eastmond (1997 : 12) for instance, likens exile to anthropological ideas of liminality, of being in ‘betwixt and between’. She describes how, forcibly removed from the native land but with a project to return, lives are put ‘on hold’ in exile. The past and the future become important points of reference: the future seems to extend directly from the past, with the present as a temporary anomaly, a suspended existence. Exiles' outwardly well-adjusted and materially secure lives are seen as masking the reality of their ‘existing, not living’ ( Eastmond 1997 : 144). For Muñoz (1981) , the rupture with the individual's past, society and country is likened to the clinical process of bereavement. Exiles live in a ‘ghost reality’, accepting neither dynamic change in the home country nor their own reality in exile.

Perhaps some of the cases presented in this paper could be said to be ‘existing, not living’ in the UK. The first visit created a setting that allowed participants to assess their place in life, which for some, though not all, was the realization that exile was like ‘not living’. Of more significance in keeping individual lives on hold were Home Office delays in recognizing status, an uncertainty that can be seen as ‘enforced’ limbo. In a different study, waiting for a decision on status was described as ‘like being in prison’ and unable to ‘get on with life’, leading to deterioration in health status and negatively affecting daily decision-making ( Muggeridge 1999 ).

Conversely to those who describe exile as being in limbo, Hammond (1999 : 233) argues that refugees do not inhabit a decultured liminal space, but rather are ‘people who maximize the social, cultural and economic opportunities available to them while in exile’. In this way, refugees are viewed as individuals whose identities evolve, which are ‘neither entirely like nor entirely unlike the identities and the world views that people held prior to fleeing from their country of origin.’ For a number of respondents, the visit contributed to an awareness of precisely such a progress. The fact that participants in this study fit both descriptions—being in limbo and identity evolution—calls for research into the conditions in which one or the other of these apparently contradictory experiences prevails.

Return: Myth or Ideal? In her analysis of the constituent elements of the myth of return, the former referring to ‘the realm of imagination and creativity’ and the latter referring to a ‘concrete movement, an actual physical displacement, a migration or more accurately a re-migration to a point fixed in space’, Al-Rasheed (1994 : 199–200) described in the abstract what this study considers the first visit concretely achieved, namely the meeting of imagination and reality.

Though frequently used, the myth of return has been criticized by a number of writers. Israel (2000) manifestly rejects it in favour of ‘ideologies’ of return, while Mouncer (2000 : 63) argues that concepts such as myth and nostalgia deny that refugees are social actors, capable of determining their future. He describes the Kurds' dream of return as not ‘a product of their nostalgic imaginations but of their determinations to show that, since they cannot return to the past, they can at least have a role in constructing the future.’ Zetter (1999 : 15) contributes to this discussion by suggesting a distinction between ‘belief’ and ‘hope’, as expressed in the myth of return. While both involve a process of abstraction, belief is about mythologizing the past and overshadowing the present while hope refers to using the past to come to terms with the present, understanding that new factors constantly intervene and modify that hope.

It could be said that the first visit acted as a transition from belief to hope, from mythologizing the past to coming to terms with the present. Current discussions on the myth of return, however, refer to an idea of permanent return. Together with Israel and Mouncer, who suggest that the myth of return should be replaced by concepts such as ideology, dream or action, here the term ‘ideal’ is suggested. Participants were aware of the existence of an ideal of permanent return and that it was exactly that: an ideal. They were fully aware of the fact that this ideal may be aspirational and could articulate the dilemma they were in. This did not prevent them from returning for short follow-up visits, or strengthening links that might in the future translate into permanent return.

The Passing of Time . Many ideas about return are about life events and, in particular, the passing of time. Wong (1991) outlines that underlying the experience of exile is a process of temporal dispossession, that exile entails the loss of life-time: persecution, flight and resettlement all take time. The first visit created an intellectual and emotional connection between imagination and reality, past and present. Return implies reconnecting not only with space but also with time. Participants in this study often described their experience of the visit by referring to changes over time, surprised at how spaces and people looked and astonished at how those who had stayed behind had dealt with the passage of time, despite previous knowledge of changes having taken place. These findings are similar to those reported by Israel (2000) and Barnes (2001) of South African war resisters and Vietnamese refugees respectively, who, returning for a visit, were surprised and at times shocked by the transformation of their home countries. In this study, respondents were initially surprised not only by external changes but also by their own reaction to them.

A study by FASIC (1981) discovered that although refugees had a high level of knowledge about the home country, since this knowledge had been impossible to verify through personal experience, the information was internalized in an idealized and intellectualized manner. Such a disjuncture explains why exiles can be surprised in the face of reality of which they are not ignorant. The report argues that integration of the emotional and intellectual level is an essential basis for the development of realistic understanding. The refugees interviewed in this study achieved such integration through their first visit, which became the catalyst for a different engagement with subsequent events, particularly relations with host and ‘home’ countries.

Integration and Return

All respondents referred to their country of origin as ‘home’ using the common phrase ‘back home’, but the complexity of what home means can be seen in one participant's use of the term to refer to a neighbouring country while for another a change in borders meant that home was now in a new foreign country. It is acknowledged that ‘home’ has multiple meanings ( Bascom 2005 ; Black 2002 ; Mallett 2004 ; McMichael 2002 ). Popular, shared ideals about home and homesickness equate home with the past. Return visits serve as ‘reality checks’ against the tendency to idealize the homeland and to think that society has remained unchanged and static ( Barnes 2001 : 408). Meanings of home may change as a result of a dictatorship or political regime and the initial visit home becomes the first opportunity to experience the outcome of a regime against which some had fought and eventually fled.

The first visit acted as a catalyst to revisit and, for some, reverse the nature and location of home, with the country of origin turning into a place where they felt like outsiders and the host country becoming home. However, feelings of ambivalent belonging surfaced, and some respondents distinguished between feeling at home in the UK and declaring the UK as home. This finding supports Brah's (1996 : 193) statement that ‘It is quite possible to feel at home in a place and, yet, the experience of social exclusion may inhibit public proclamations of the place as home’. For some, the visit contributed to a feeling of having two homes, and to being able to integrate the two, showing that socio-cultural change in conditions of forced migration is more complex and ambiguous than linear models of ‘refugee adaptation’ assume ( Eastmond 1997 : 10).

The visit did not translate into decisions to return permanently or stay in the host country, but it showed that integration and return can coexist. Acquisition of legal status and socio-economic self-sufficiency in the host country does not inhibit but can enable return, and certainly allows for considerations of permanent return, challenging assumptions that the two are contradictory ( Blitz et al . 2005 ). Encouraging go-and-see visits with no loss of status provides an opportunity for individuals to compare their imaginings with reality and to make informed choices about the future.

Return to the country of origin after a period of protracted exile represents a complex interplay of social, political, economic and emotional factors. Security issues were paramount and returning refugees employed risk-minimization strategies prior to and during the visit. The same principle applied to those planning to return permanently and for whom return was not a myth but rather a plan. One common element of the decision-making process of those respondents who were making plans to return permanently was incorporating a safety net both in the UK and country of origin. Such strategies that may on the surface appear economic, mask real attempts to avoid exposure to political fluctuations, vulnerability to persecution and being ‘back to square one’ and having to seek asylum. They are strategies that ensure long-term protection and enhance the chances that return can really be a ‘durable’ solution, distinguishing return of these forced migrants from that of other migrants and returnees.

The findings of this study show that the first visit was instrumental in enabling refugees to interact with both countries of birth and exile in new ways, including but not being limited to subsequent return. Together with remittances and political diasporic involvements, the first visit may be seen as an example of transnational practices and belonging ( Al-Ali and Koser 2002 ; Vertovec 1999 ).

By way of conclusion, this analysis of the first visit home showed that the visit can bring one ‘end’ to the refugee cycle and enable refugees to make informed choices for their future. As one respondent said: ‘when you are not settled inside, you cannot be settled anywhere’. For Vietnamese refugees in Australia ( Barnes 2001 ), returning to visit had profound impacts on their minds, with dreams about home disappearing after the visit and feelings of belonging to the host country consolidating. The first visit may go some way towards being ‘settled inside’ and consequently being better able to engage with subsequent events, whether they entail permanent return, naturalization or an acceptance of transnational identity.

AL-ALI, N. and KOSER, K. (eds) ( 2002 ) New Approaches to Migration? Transnational Communities and the Transformation of Home . London: Routledge.

ALLEN, T. and MORSINK, H. (eds) ( 1994 ) When Refugees Go Home . Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

AL-RASHEED, M. ( 1994 ) ‘The Myth of Return: Iraqi Arab and Assyrian Refugees in London’, Journal of Refugee Studies 7 (2/3): 199 –219.

AROWOLO, O. O. ( 2000 ) ‘Return Migration and the Problem of Reintegration’, International Migration 38 (5): 59 –82.

BARNES, D. ( 2001 ) ‘Resettled Refugees’ Attachment to their Original and Subsequent Homelands: Long-term Vietnamese Refugees in Australia', Journal of Refugee Studies 14 (4): 394 –411.

BASCOM, J. ( 2005 ) ‘The Long “Last Step”? Reintegration of Repatriates to Eritrea’, Journal of Refugee Studies 18 (2): 165 –180.

BLACK, R. ( 2002 ) ‘Conceptions of “Home” and the Political Geography of Refugee Repatriation: Between Assumption and Contested Reality in Bosnia-Herzegovina’, Applied Geography: An International Review 22 (2): 123 –138.

BLACK, R. and KOSER, K. ( 1999 ) The End of the Refugee Cycle? Refugee Repatriation and Reconstruction . Oxford: Berghahn Books.

BLITZ, B., SALES, R. and MARZANO, L. ( 2005 ) ‘Non-voluntary Return? The Politics of Return to Afghanistan’, Political Studies: Journal of the Political Studies Association UK 53 (1): 182 –200.

BRAH, A. ( 1996 ) Cartographies of Diaspora . London: Routledge.

CUNY, F. and STEIN, B. ( 1990 ) ‘Prospects for and Promotion of Spontaneous Repatriation’ in Loescher, G. and Monahan, L. (eds) Refugees and International Relations . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

DONÁ, G. ( 1995 ) ‘Report on Field Research with Guatemalan Returnees’, Refugee Participation Network 19 (May): 44.

EASTMOND, M. ( 1997 ) The Dilemmas of Exile: Chilean Refugees in the USA , Acta Universitatis Gothoburgenesis, Sweden.

EASTMOND, M. and ÖJENDAL, J. ( 1999 ) ‘Revisiting a “Repatriation Success”: The Case of Cambodians’ in Black, R. and Koser, K. (eds) The End of the Refugee Cycle? Refugee Repatriation and Reconstruction . Oxford: Berghahn Books.

ESSED, P., FRERKS, G. and SCHRIJVERS, J. (2004) Refugees and the Transformation of Societies: Agency, Policies, Ethics and Politics . Oxford: Berghahn Books.

FARWELL, N. ( 2001 ) ‘“Onward through Strength”: Coping and Psychological Support among Refugee Youth Returning to Eritrea from Sudan’, Journal of Refugee Studies 14 (1): 43 –69.

FASIC ( 1981 ) ‘A Socio-psychological Study of 25 Returning Families’ in World University Service (WUS) Paper, Mental Health and Exile . London: World University Service.

GHANEM, T. ( 2003 ) When Forced Migrants Return Home: The Psychosocial Difficulties Returnees Encounter in the Reintegration Process . Oxford: Refugee Studies Centre Working Paper 16.

HAMMOND, L. ( 1999 ) ‘Examining the Discourse of Repatriation: Towards a More Proactive Theory of Return Migration’, in Black, R. and Koser, K. (eds) The End of the Refugee Cycle? Refugee Repatriation and Reconstruction . Oxford: Berghahn Books.

ISRAEL, M. ( 2000 ) ‘South African War Resisters and the Ideologies of Return from Exile’, Journal of Refugee Studies 13 (1): 26 –42.

KRULFIELD, R. M. and MACDONALD, J. L. (eds) ( 1998 ) Power, Ethics and Human Rights: Anthropological Studies of Refugee Research and Action . Boulder, CO: Rowman and Littlefield.

KUMAR, K. ( 1996 ) Rebuilding Societies after Civil War: Critical Roles of International Assistance . Boulder, Co: Lynne Rienner.

LONG, L. D. and OXFELD, E. ( 2004 ) Coming Home! Refugees, Migrants and Those Who Stayed Behind . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

MALLETT, S. ( 2004 ) ‘Understanding Home: A Critical Review of the Literature’, Sociological Review 52 (1): 62 –89.

MAJODINA, Z. ( 1995 ) ‘Dealing with Difficulties of Return to South Africa: The Role of Social Support and Coping’, Journal of Refugee Studies 8 (2): 210 –227.

McMICHAEL, C. ( 2002 ) ‘Everywhere is Allah’s Place: Islam and the Everyday Life of Somali Women in Melbourne, Australia', Journal of Refugee Studies 15 (2): 171 –188.

MORAN-TAYLOR, M. and MENJlVAR, C. ( 2005 ) ‘Unpacking Longings to Return: Guatemalans and Salvadorans in Phoenix, Arizona’, International Migration 43 (4): 92 –121.

MOUNCER, B. ( 2000 ) ‘An Impossible Dream? Assessing the Notions of “Home” and “Return” in Two Kurdish Communities’, M.A. dissertation, University of East London, Unpublished.

MUGGERIDGE, H. ( 1999 ) ‘Consultation with Refugee Women’, unpublished report.

MUÑOZ, L. ( 1981 ) ‘Exile as Bereavement: Socio-psychological Manifestations of Chilean Exiles in Britain’ in World University Service (WUS) Paper, Mental Health and Exile . London: World University Service.

OSSMAN, S. ( 2004 ) ‘Studies in Serial Migration’, International Migration 42 (4): 111 –122.

OXFELD, E. and LONG, L. D. ( 2004 ) ‘Introduction: An Ethnography of Return’ in Long, L. D. and Oxfeld, E. (eds) Coming Home! Refugees, Migrants and Those Who Stayed Behind . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

PILKINGTON, H. and FLYNN, M. ( 1999 ) ‘From “Refugees” to “Repatriate”: Russian Repatriation Discourse in the Making’, in Black, R. and Koser, K. (eds) The End of the Refugee Cycle? Refugee Repatriation and Reconstruction . Oxford: Berghahn Books.

PRESTON, R. ( 1999 ) ‘Researching Repatriation and Reconstruction: Who is Researching What and Why?’ in Black, R. and Koser, K. (eds) The End of the Refugee Cycle? Refugee Repatriation and Reconstruction . Oxford: Berghahn Books.

ROGGE, J. R. ( 1994 ) ‘A not so Simple “Optimum” Solution’ in Allen, T. and Morsink, H. (eds) When Refugees Go Home . Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

ROUSSEAU, C., MORALES, M. and FOXEN, P. ( 2001 ) ‘Going Home: Giving Voice to Memory Strategies of Young Mayan Refugees who Returned to Guatemala as a Community’, Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 25 : 135 –168.

SAID, E. ( 2000 ) Reflections on Exile and other Literary Essays . London: Granta.

SORENSEN, N. N. ( 2003 ) ‘From Transationalism to the Emergence of a new Transnational Research Field’, Journal of Urban and Regional Research 27 (2): 465 –469.

VERTOVEC, S. ( 1999 ) ‘Conceiving and Researching Transnationalism’, Ethnic and Racial Studies 22 (2): 447 –462.

VAN HEAR, N. ( 2003 ) ‘From Durable Solutions to Transnational Relations: Home and Exile among Refugee Diaspora’, New Issues in Refugee Research 83 : Geneva: UNHCR

WERBNER, P. ( 1999 ) ‘Global Pathways: Working Class Cosmopolitans and the Creation of Transnational Ethnic Worlds’, Social Anthropology 7 (1): 17 –35.

WONG, D. ( 1991 ). ‘Asylum as a Relationship of Otherness: a Study of Asylum Holders in Nuremberg, Germany’, Journal of Refugee Studies 4 (2): 150 –163.

ZARZOSA, H. L. ( 1998 ) ‘Internal Exile, Exile and Return: a Gendered View’, Journal of Refugee Studies 11 (2): 189 –198.

ZETTER, R. ( 1999 ) ‘Reconceptualizing the Myth of Return: Continuity and Transition amongst the Greek-Cypriot Refugees of 1974’, Journal of Refugee Studies 12 (1): 1 –22.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1471-6925

- Print ISSN 0951-6328

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Toward a path to sustainable refugee return

Xavier devictor.

In public debates, return is often regarded as the most natural solution for refugees: they are “out of place” and return seems the most sensible way to restore the natural order of things. But is it that simple?

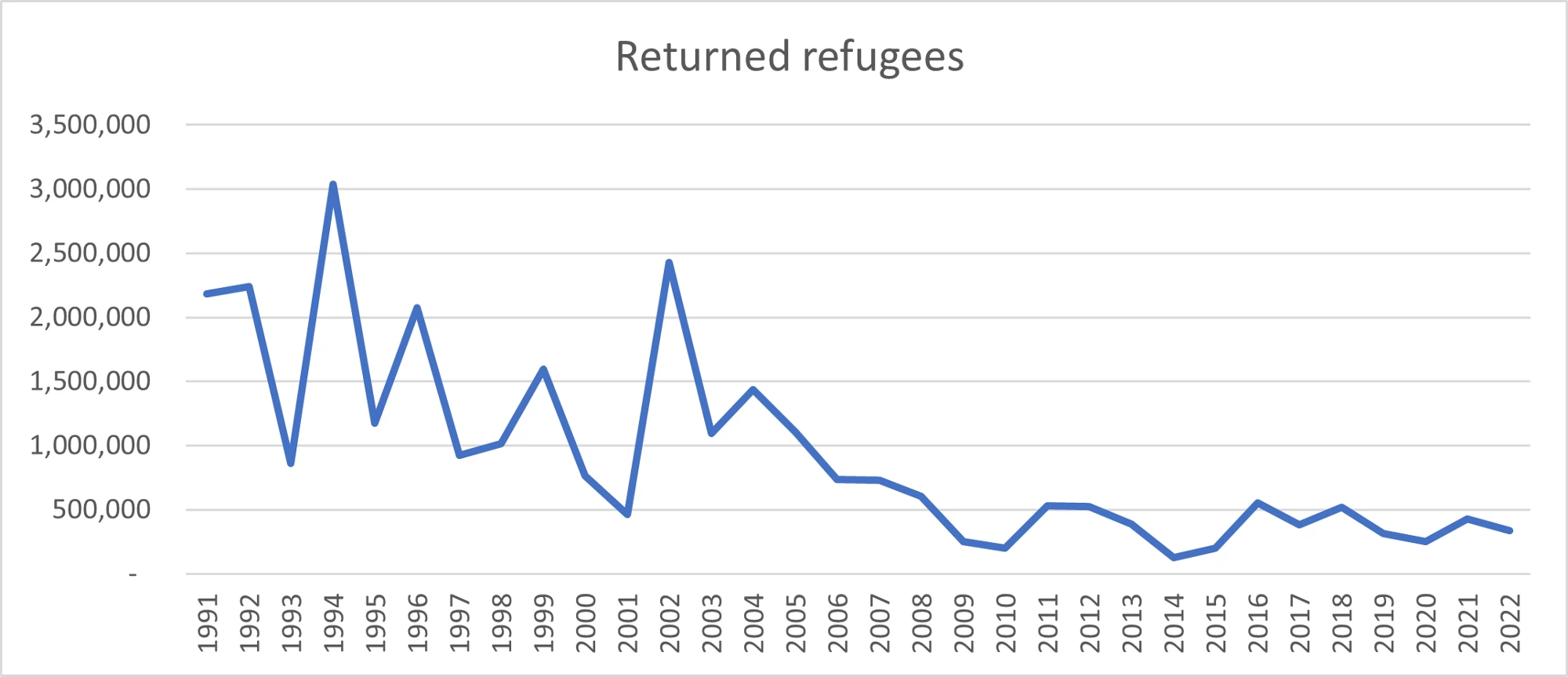

In every large-scale refugee situation, some return, others do not. From the end of the Cold War in 1991 to 2022 about 30 million refugees returned to their countries of origin, with the pace of returns slowing down over time (Figure 1). Four situations account for over two-thirds of these returns — Afghanistan following the withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1989 and the collapse of the Taliban regime in 2001; Rwanda immediately after the 1994 genocide and following the entry of Rwandan troops in Zaire; Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War; and Mozambique after peace was concluded in the early 1990s. Refugee returns tend to happen in peaks, typically about one to three years after the end of a conflict; past this period the pace of returns is much slower.

That refugees want to return is sometimes taken as a given, and their motivation for repatriating is assumed. Voluntary repatriation is often discussed in terms of a return “home” even a generation or more after the flight from conflict. And even when the descendants of the original refugees may never have seen their “homeland” or when the place of origin, affected by conflict and violence, has undergone wrenching social, economic, and political changes. In fact, voluntary repatriation is not a simple return to the preexisting order of things, but rather a new movement. It is not about reentering a condition that existed in the past, but rather about taking part in the emergence of a new social fabric and a new social contract in a post-conflict environment.

Return is hence a challenging process — and it is not always successful. Many returnees remain destitute or settle in unfamiliar parts of their country of origin, often as internally displaced persons (IDPs). Each wave of returns from Pakistan to Afghanistan has been followed by the expansion of informal settlements and slums around Kabul. Large numbers of failed returns can also add to destabilizing pressures in the country of origin when peace is fragile — of the 15 largest episodes of return since 1991, about one-third were followed by a new round of fighting within a couple of years — as repeatedly happened in South Sudan.

For hosting countries and their international partners, a new way of thinking is needed, one that focuses not only on refugee returns but also on the success of such returns. Indeed, failed returns create significant challenges for host countries. Many failing returnees go back to the country of asylum within a few years, creating renewed burdens for host communities. In fact, such back-and-forth cross-border movements, a succession of exiles and returns, are so common that the total number of returnees over time typically exceeds the peak number of refugees by about 30 percent . And when countries of origin are destabilized and experience renewed violence, new refugee outflows ensue.

What makes return successful?