The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

Voyager’s Nonstop Around-the-World Adventure

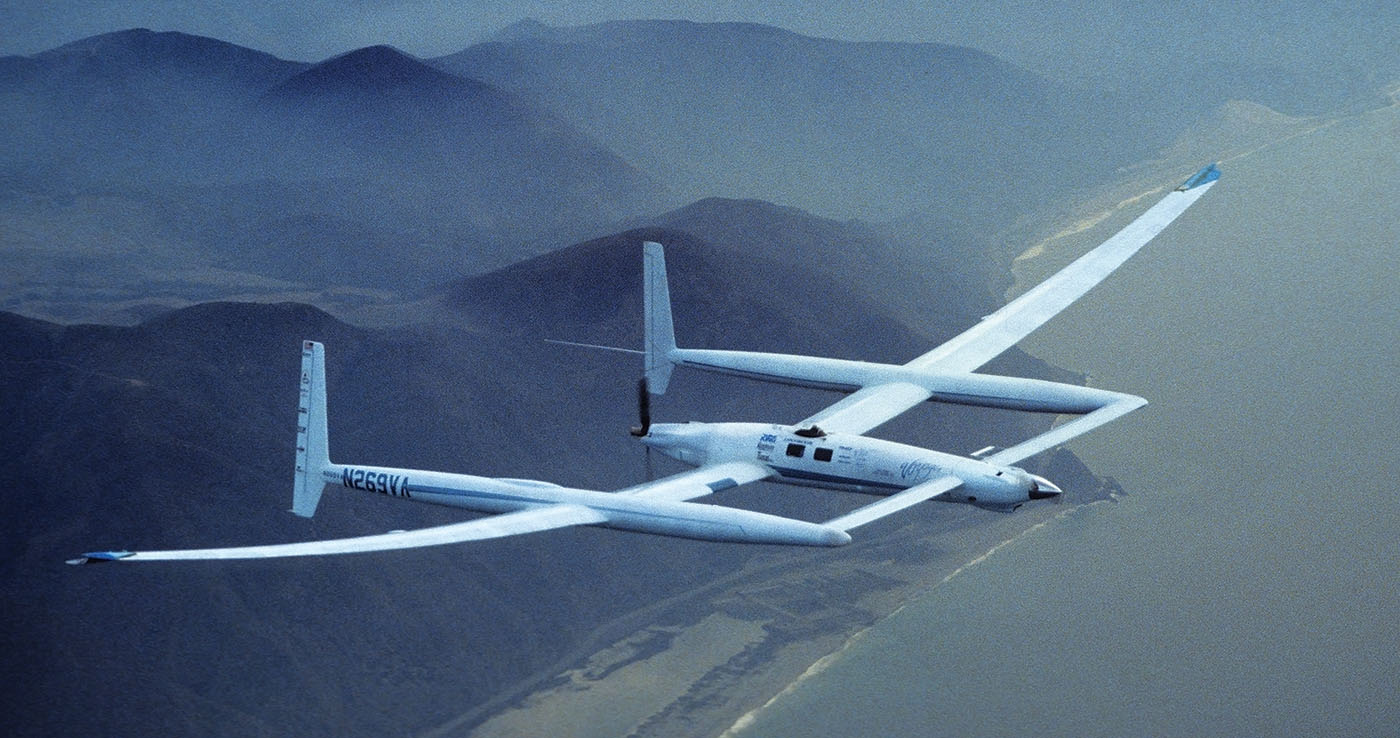

When Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager landed at California’s Edwards Air Force Base in the Rutan Voyager on December 23, 1986, they completed a historic flight that tested the limits of aircraft design and human endurance. The pair had left Edwards on December 14, having spent nine days and three minutes in the air during their nonstop, unrefueled flight around the world—the first of its kind. Along the way they nearly came to grief several times, as they grappled with exhaustion, mechanical problems, severe weather and even political considerations.

Dick’s brother Burt had first sketched Voyager’s design on a paper napkin at a Mojave, Calif., restaurant in 1981. Such an airplane—essentially a flying fuel tank—had been thought impossible.

The challenges Burt Rutan faced were daunting. He had to balance the necessary fuel capacity with the need for increased lift to overcome the fuel weight and higher induced drag. That required additional wing area, which in turn increased drag, compelling Rutan to use a high-aspect-ratio wing—long span and narrow chord—and enormously complicating the structural design.

The wing he needed could not be built without the aid of carbon composites, which boasted a strength-to-weight ratio seven times greater than that of steel. At the time Voyager was the largest composite aircraft ever to fly.

Construction of Voyager in the Rutan hangar at Mojave took two years of day and night work by a team of dedicated volunteers. Over the next three years, the airplane made 67 test flights, revealing serious operational issues. During a three-day flight, Dick and Jeana found the interior noise level generated by the tandem-mounted, push-pull engines almost unendurable, threatening permanent hearing loss, so the team added active-noise-suppression headsets. On another flight the electric propeller pitch-control motor on the front engine shorted out. Before it could be shut down, the engine shook off its mounts and the propeller departed. The only thing that saved Voyager and its crew was a flexible strap holding the engine to the fuselage.

Heading to Oshkosh, Wisc., in 1984 for the Experimental Aircraft Association fly-in, Voyager encountered a rainstorm that reduced lift from its wide canard to the point where the airplane kept losing altitude no matter what Dick tried. “I had a horrible feeling in the pit of my stomach,” he said, “as the airplane was coming down, and I couldn’t stop it.” Voyager emerged from the storm and regained lift just in time to avoid the terrain ahead. To fix the problem, team members installed tiny vortex generators on the canard that smoothed the airflow. Solving these and other issues occupied the next two years.

Preparations for the around-the-world flight involved numerous additional tasks, such as securing the many overflight clearances required, studying regional weather patterns and setting up global communications relays. The support team included recognized experts in such fields as meteorology, communications, instrumentation and control engineering.

Burt Rutan’s design was precisely tailored to the mission, but Dick and Jeana learned that with a high fuel load Voyager was barely flyable. The long-span, unusually flexible wings went from a pronounced droop at the start of takeoff to a hawk-like upward curve as they generated lift. The transition from takeoff to climb had to be flown with knife-edge accuracy to avoid dangerous wing oscillations. Designer and pilots knew Voyager was fundamentally unsafe. “This thing flies like a turkey vulture,” Dick said.

In order to save weight, the airplane’s fuel system—16 individual tanks and two pumps (one per side) transferring fuel into a single central tank feeding both the forward and rear engines—was not equipped with automatic valves or individual fuel pumps. Hence keeping Voyager within center-of-gravity limits was a continuous burden, mostly on Jeana, who kept a meticulous fuel transfer record.

To reach its maximum range, Voyager had to maintain a best lift-over-drag attitude, with a specific constant angle of attack for each speed. Burt’s carefully planned vertical profile specified the speed for each successive stage as fuel weight diminished. On a flight lasting over a week, that task required an autopilot.

On the morning of December 14, Voyager was loaded with 7,011.5 pounds of fuel, 15 percent more than on its heaviest previous flight. The aircraft’s gross takeoff weight was 9,694.5 pounds, supported by an airframe that weighed just 939 pounds. The landing gear was designed to handle that one-time load on takeoff, which would be made from Edwards’ 15,000-foot runway.

Team members pumped air into the gear struts to provide a bit more clearance for Voyager’s drooping wings, then added more fuel to the forward tanks. Those actions slightly twisted the wings forward and down, inadvertently setting the stage for a potential disaster. In anticipation of the extra weight, the tires were inflated to a pressure of 3,200 psi, almost twice the rated maximum.

The halfway point on the runway, at 7,500 feet, was the agreed abort point in the event Voyager hadn’t reached the required 83 knots to begin rotation. As Voyager lumbered down the runway just after 8 a.m., it was still four knots short when it reached that point. Over the radio, Burt yelled, “Dick, pull the stick back, dammit!” But knowing he didn’t have adequate speed for liftoff and refusing to abort, Dick left the throttles wide open, staking their lives on that crucial decision. “The airplane was accelerating smoothly,” he later said, “and the end of the runway was still a mile and a half ahead.”

Dick was unaware that the extra fuel weight had caused the wingtips to scrape the runway, and that the outboard wing sections were now generating negative lift. Voyager was at the 11,000-foot point when it reached 83 knots, but still Dick didn’t rotate; a premature attempt at liftoff might fracture the wings between the inner sections generating lift and the outer sections still under downward pressure from negative lift. He held the airplane on the runway until Jeana called “87 knots,” and only then began to ease back on the stick as the assembled crowd screamed “Pull up, pull up!” Voyager finally lifted off 14,200 feet down the runway, a mere 800 feet from the end. “One hundred knots,” Jeana called out, as Voyager reached 100 feet altitude. “We needed the extra lift from ground effect—within our 110-foot wingspan—which I used to boost our airspeed to the climb target,” Dick explained.

The scraped wingtips were damaged to the point where they were soon shed, leaving tattered foam and loose wires exposed at the ends. How close was the wingtip damage to the fuel tanks? Could a leak have been started? Could the exposed wires cause a short during a storm? Nobody knew, so Voyager simply flew westward. Early in the flight, the overburdened airplane burned fuel so fast that a pound of fuel yielded less than two miles of flight distance.

One hour into the flight, Voyager was 7,400 feet above the Pacific. The aircraft’s inherent instability would continue to pose a threat even after it was safe to turn on the autopilot. Dick had to be at the controls in case significant oscillations began that the autopilot couldn’t immediately correct. Although Jeana had a few hundred hours of flying experience, she hadn’t yet learned how to prevent those dangerous oscillations, which could break up the airplane while it was so fuel-heavy. Jeana looked out the cockpit window and exclaimed, “See the wings! They’re almost flapping.”

For the next three days, Dick stayed at the controls. His lack of adequate sleep set the stage for new dangers ahead. Jeana’s neck grew stiff as she lay on her side watching the instruments while Dick catnapped. “He needed the rest,” she said, “so I had to monitor what the airplane was doing, and reach around him to make any adjustments.”

After passing Hawaii, they entered the Intertropical Convergence Zone, with high-altitude westerly winds and low-altitude easterly winds. Voyager stayed at 7,500 feet, along the five-degree north parallel, an area of frequent storm activity. As they approached Guam, the weather guru at Mission Control in Mojave, Len Snellman, warned the crew about a large typhoon just to the southeast. Voyager was able to pick up some tailwind from the typhoon’s counterclockwise circulation by skirting it on the north side. That tailwind would provide an important gain in fuel savings.

From about mid-Pacific all the way to Africa, the crew and Mission Control became increasingly concerned about the rate of fuel consumption indicated by Jeana’s log. For reasons unknown, possibly leaks from the wingtip damage, there might not be enough fuel to complete the mission. They began to actively consider possible emergency landing sites. Dick remembered “a sinking feeling in my stomach; I wanted to cry. We were looking at failure.”

Overflying Sri Lanka, with its 10,000-foot runway, Dick felt so tired he could hardly resist the temptation to land. But his mother’s words, “If you can dream it, you can do it,” ran through his mind, and he knew Jeana wanted to fly on, so they did. Later, Jeana discovered a reverse flow of fuel from the feeder tank back to the selected fuel tank. Dick guessed the amount was insufficient to drain the feeder tank and stop the engine, but there was no way to know for sure.

Voyager approached the African coast well south of Somalia (for which they had no overflight clearance) on a moonless dark night. Jeana was at the controls while Dick slept in the rear compartment. Fuel was still a concern, so she ran the rear engine lean. Their radar revealed a storm ahead, just south of their course. Jeana awakened Dick, and as he got into the cockpit they were at the edge of the storm. They were through the turbulence in a few minutes, about to start across a continent with few airfields and a sky full of storm clouds.

Voyager was over western Kenya, on its planned course, heading for Lake Victoria and cumulus buildups, with mountainous terrain beyond. They were five hours late for an inflight rendezvous with Doug Shane, who had flown by airline to Kenya and rented a Beech Baron in order to observe Voyager up close to see if the wingtip damage had caused fuel leaks requiring a mission abort. Voyager already was climbing to avoid Mt. Kenya and other peaks ahead over 17,000 feet. Shane was nearing the Baron’s ceiling, with only a few minutes to approach Voyager and inspect for fuel leaks in the early morning light. “No ugly blue streaks,” he called. Relieved to know Voyager was not leaking fuel, they climbed to 20,500 feet to clear the mountains ahead.

this article first appeared in AVIATION HISTORY magazine

Dehydration and equally insidious hypoxia threatened their survival. Neither Dick nor Jeana had managed to drink enough fluid to replenish their losses flying so high. Nor were they breathing 100-percent oxygen, required for that altitude, because earlier Dick had dialed it back to conserve their supply. Dick could see Jeana’s reflection in the radar screen; she was curled up like a cat, sleeping soundly—too soundly. Dick called, “Jeana, wake up! Wake up!” while reaching back to shake her. “What, what?” she finally responded, then quickly fell back asleep. Soon after, Dick said, “Jeana, look at this,” shaking her awake again. “Look at the instrument panel! It’s bulging out; it may explode!” “It’s o.k., Dick,” she reassured him, “you’re just tired. I’ll take care of it.” As Voyager descended to 14,000 feet, Dick’s hallucinations stopped. Jeana squeezed past him and took the controls. Her head was pounding with a migraine headache. “My stomach was churning, I started vomiting into my little throw-up bag,” she said. “I just kept flying; Dick was in worse shape.”

Night overtook them as Jeana let Dick sleep longer than planned because of his extreme fatigue. After he was back at the controls, Dick realized they were very late for the course change to avoid Mt. Cameroon. “Why didn’t you wake me?” he yelled. “There’s a mountain out there and we almost ran into it.” “So, why didn’t you remind me of it?” Jeana replied.

Clearing Africa, the two fliers experienced an overwhelming sense of relief. Looking at Dick, “I saw big tears rolling down his cheeks,” Jeana remembered. “I reached over his shoulder and gave him a hug.”

On crossing the South Atlantic, things took a turn for the worse. As Voyager approached the coast of Brazil, Mission Control lacked weather satellite data and could not provide adequate guidance for the location. With bad weather ahead, Dick was forced to thread his way through an area of dense thunderstorms, in the dark. Their radar showed storm cells close ahead, at right, left and center. Turbulence tossed Voyager like a cork, and a cell swallowed the aircraft. One wing was forced high and the other low as the aircraft quickly went into a 90-degree bank. Voyager was about to go inverted. “Well babe, this is it, I think we’ve bought the farm this time,” Dick said. “Look at the attitude indicator. We ain’t gonna make it.” Jeana stayed quiet.

The cell ejected Voyager, but it was still far over on its side—an attitude out of a bad dream. Dick knew the only way to recover was to unload the G-force on the wings and regain airspeed, and only after that gently roll back level while ensuring airspeed didn’t build too rapidly to recover. “We never banked Voyager over 20 degrees before,” Dick noted. “I’d rather go back across Africa than tangle with one of these storms again.” Mission Control was soon getting better weather satellite coverage and helping the crew find the safest way through the remaining storm cells.

After the adrenaline wore off, Dick desperately needed rest. Jeana took over, dodging cumulus clouds for the next three hours. The airplane had by this time consumed most of its fuel and was lighter, so fuel economy increased, allowing them to shut down the forward engine. Over the Caribbean, north of Venezuela, Voyager’s fuel economy climbed to five miles per pound—30 miles per gallon. Nevertheless, the uncertain fuel situation prompted the crew to run the engine very lean. Mission Control warned of cumulus buildups over Panama, and suggested overflying Costa Rica instead.

Later, heading northwest off the Nicaraguan coast, Voyager aimed for home as dawn broke on the flight’s eighth day. Headwinds slowed its ground speed to 65 knots. Dick flew on as Jeana managed the fuel flow. Suddenly the right side fuel pump went into overspeed and failed. Dick had anticipated such a possibility and arranged a bypass of the feeder tank through the engine’s mechanical pump. Now he made the switch and fuel again flowed. But the sight tube had to be checked constantly, to detect the first bubbles of air in the line.

When the engine coughed a few times, changing tanks brought it back to life. Dick switched to a tank in the canard that he thought had plenty of fuel, but it didn’t and the engine stopped. Voyager had been running at 8,000 feet on the rear engine, to conserve fuel. Now they heard only the wind. Dick lowered the nose, hoping higher airspeed would restart the windmilling engine, to no avail. Without engine power, the mechanical pump couldn’t operate.

Voyager was now down to 5,000 feet. Mike Melvill in Mission Control suggested starting the front engine, but Dick feared that would block the rear engine, with its still windmilling prop, from restarting. They needed both engines to get home. The situation was critical; Voyager was rapidly losing altitude.

Dick and Jeana followed the cold-engine-start checklist. “Elbow flying now,” Dick said, needing both hands for the restart sequence. “Just take it easy, Dick,” Jeana said. “You’re doing fine.” Voyager, heavy on the right side due to the fuel imbalance, continued down. Dick used the avionics backup battery to avoid an instrument-killing current surge from the main battery. Still, the front engine would not start. At 3,500 feet Dick leveled out, allowing the fuel to flow, and the engine finally coughed to life.

Now they had to finish replacing the right-side pump to relieve the imbalance from Voyager’s fuel-heavy right wing. Dick installed the pump while Jeana got the many valves turned correctly. An anxious half-hour passed before enough fuel to get them home flowed slowly into the feeder tank.

Finally Voyager left the ocean behind, and at first light was over California’s San Gabriel Mountains. Chase planes flown by Melvill and Shane joined up while Dick and Jeana kept their focus on precision flying. Voyager appeared over Edwards at 7:32 a.m. Dick did a flyby at 400 feet and a few more with the chase planes. He wanted to do one more flyby, at just 50 feet, but Jeana chimed in, “Dick, time to land, we’re running low on fuel.” Thousands of people were waiting as they carefully landed, taxied to the parking area and shut down the engines that had taken them around the world. When the leftover fuel was drained, little more than 108 pounds (18 gallons) of the original 7,000-plus pounds remained.

Voyager’s world flight remains one of the greatest achievements in aviation history. For their feat, the Rutans, Yeager and the Voyager team were awarded the 1986 Collier Trophy.

Pierre Hartman is a former light-sport pilot who lives in Tehachapi, Calif., 20 miles from Mojave. Further reading: Voyager , by Jeana Yeager and Dick Rutan, with Phil Patton; and Voyager: The World Flight , by Jack Norris.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2019 issue of Aviation History.

Related stories

Portfolio: Images of War as Landscape

Whether they produced battlefield images of the dead or daguerreotype portraits of common soldiers, […]

Jerrie Mock: Record-Breaking American Female Pilot

In 1964 an Ohio woman took up the challenge that had led to Amelia Earhart’s disappearance.

This Frenchman Tried to Best the Wright Brothers on Their Home Turf

The Wrights won.

The Scandal that Led to Harry S. Truman Becoming President and Marilyn Monroe Getting Married

Did Curtiss-Wright deliberately sell defective engines to the U.S. Army during WWII?

Simple Flying

Rutan voyager: the first plane to circumnavigate the world without refueling or stopping.

The Rutan Voygaer holds the record for the longest flight in the world even today.

The Rutan Voyager Model 76 was the first plane to successfully circumnavigate the globe without making any stops at all. The thin airframe took five years to develop and set off on its journey on December 14th, 1986, landing a full nine days later on December 23rd. Here's a look at this record-breaking aircraft.

From a napkin to the skies

The Voyager was built by Burt Rutan, Dick Rutan, and Jeana Yaeger. Burt reportedly first sketched the design of the plane on a paper napkin in 1981 and started work not long after in Mojave, California under the banner of its aerospace company. Dick Rutan and Jeana Yaeger were the pilots of the historic flight.

To sustain flight over 216 hours, keeping the weight of the aircraft at a minimum was essential. To do this, Rutan used a combination of composite materials like kevlar and fiberglass to bring the airframe weight to just 426kgs. The engines alone weighed more than this at 594kgs, with two propellers running in the middle section on either end.

At first glance, the Voyager Model 76 is unlike any commercial aircraft design , having no clear tail or fuselage, instead seeing one long wing cutting across three fuselage sections and a parallel connector for the trio. Rutan's design was built to maximize lift to drag ratio, which would be crucial to keeping the plane in the skies for days.

The design process took over five years until the plane was ready to take to the skies in June 1986 for the first time.

Testing to takeoff

Burt Rutan's design proved to be a successful one, with the two pilots using the Model 76 to break the record for the longest flight in the world in testing in July 1986 alone. However, the trio hoped to take the voyager on a journey like no other, circumnavigating the globe without any refueling or technical stops.

After over 60 test flights, the Rutan Voyager set off for its nonstop global flight on December 14th, 1986 from Edwards Air Force Base. However, things did not go too smoothly from the beginning, with the tips of the wings hitting the runway surface and eventually ripping off in the initial stages of the flight. However, the pilots opted to continue given the plane still met its technical range even without the tips.

The pair of pilots flew heroically, avoiding closed airspace, storms, and other weather events to ensure the plane's performance was not hampered significantly. With little space in the cockpit, Dick Rutan and Jeana Yaeger were only able to switch over controls occasionally, with days passing at times.

Stay informed: Sign up for our daily and weekly aviation news digests.

After a fuel pump failure toward the end of the flight, the two pilots managed to complete the voyage successfully at 08:06 AM on 23rd December at Edwards AFB, with a recorded journey time of over 216 hours and circumnavigating the globe. 38 years later, this record remains in place, with no endurance flight even close to beating the Rutan Model 76 Voyager.

Site Navigation

Rutan voyager, object details, related content.

- Air & Spacecraft

- Aircraft Details

Rutan Model 76 Voyager Replica

More than a dozen innovative aircraft designs have sprung from the mind of Burt Rutan. After early work as a flight test engineer, then a designer for Bede Aircraft, Rutan formed his own company in the mid-1970s. He was a pioneer in the use of composite materials such as fiberglass and later formed Scaled Composites to produce prototypes for himself and the aerospace industry.

Rutan's Model 76 Voyager is an all-composite airframe made primarily from a 1/4-inch sandwich of paper honeycomb and graphite fiber, which was shaped and then cured in an oven. The front and rear propellers are powered by two difference engines. The front engine, an air-cooled Teledyne Continental O-240, provides extra power for take-off and during the initial flight stage while the plane was heavily loaded with fuel. The rear engine is a water-cooled Teledyne Continental IOL-200, which acts as the main source of power throughout the flight.

The Voyager accomplished the first nonstop, non-refueled flight around the world. Piloted by Dick Rutan (Burt's brother) and Jeana Yeager, the plane began its flight on December 14, 1986. On December 23, Nine days, 3 minutes, and 44 seconds later, it landed back at Edwards Air Force Base.

The original Rutan Voyager is displayed at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. The Museum of Flight's facsimile of the Model 76 Voyager is on loan to the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (Sea-Tac), where it can be seen on display in the main terminal.

sign up for our newsletter

This website may use cookies to store information on your computer. Some help improve user experience and others are essential to site function. By using this website, you consent to the placement of these cookies and accept our privacy policy.

The New York Times

The learning network | dec. 23, 1986 | voyager aircraft completes first nonstop around-the-world flight.

Dec. 23, 1986 | Voyager Aircraft Completes First Nonstop Around-the-World Flight

Historic Headlines

Learn about important events in history and their connections to today.

- Go to related On This Day page »

- Go to related post from our partner, findingDulcinea »

- See all Historic Headlines »

On Dec. 23, 1986, the experimental airplane Voyager, piloted by Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager, completed the first nonstop, around-the-world flight without refueling. It landed safely at Edwards Air Force Base in California.

The idea for the Voyager came about as Mr. Rutan, his brother Burt and Ms. Yeager ate lunch together one day in 1981; the three sketched the design for the plane on a napkin. The Rutans, Ms. Yeager and a team made mostly of volunteers built the Voyager over the next five years. The enterprise was funded entirely by private investors. The Voyager, made of a lightweight composite material containing primarily graphite, Kevlar and fiberglass, weighed just 939 pounds but could carry more than 7,000 pounds of fuel in its 17 fuel tanks.

The Voyager took off from Edwards Air Force Base on Dec. 14, 1986. Mr. Rutan and Ms. Yeager flew the plane in short shifts over the next 9 days 3 minutes and 44 seconds, covering about 25,000 miles. The pilots, as reported by The New York Times, rested in “a 7 1/2-by-2-foot compartment beside the even smaller cockpit … equipped with food, water, a five-foot rubber band for exercising, and rudimentary toilet facilities. The aviators’ diet consisted of bland food supplements like powdered milk shakes.”

Mr. Rutan and Ms. Yeager did encounter some trouble during the trip. As The Times reported: “Seven and a half hours before the landing, as the plane cruised at 8,500 feet on the power of the rear engine alone, Mr. Rutan radioed, ‘The engine has stopped.’ Over the next five minutes, the plane descended more than 3,000 feet as the ground crew tried to stay calm. Then a Voyager staff member, Mike Melville, blurted out, ‘Well, damn it, start the front engine!’ Mr. Rutan did, and the plane recovered.

The Voyager flight came 62 years after the first around-the-world flight, completed by two U.S. Army planes that made 57 stops during their 175-day journey. At a news conference held after the landing, Mr. Rutan said, “This was the last major event of atmospheric flight.”

Connect to Today:

Today, the Voyager is on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington.

Mr. Rutan said of the flight, “That we did it as private citizens says a lot about freedom in America.” What do you think this statement means? As grants and other sources of government financing dwindle, should engineers and scientists look to the Rutan Voyager as an example? Do you think private investors may be the solution to financing major science and technology breakthroughs in the future? Why or why not?

Learn more about what happened in history on Dec. 23 »

Learn more about Historic Headlines and our collaboration with findingDulcinea »

Comments are no longer being accepted.

What's Next

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : December 23

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Voyager completes global flight

After nine days and four minutes in the sky, the experimental aircraft Voyager lands at Edwards Air Force Base in California, completing the first nonstop flight around the globe on one load of fuel. Piloted by Americans Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager, Voyager was made mostly of plastic and stiffened paper and carried more than three times its weight in fuel when it took off from Edwards Air Force Base on December 14. By the time it returned, after flying 25,012 miles around the planet, it had just five gallons of fuel left in its remaining operational fuel tank.

Voyager was built by Burt Rutan of the Rutan Aircraft Company without government support and with minimal corporate sponsorship. Dick Rutan, Burt’s brother and a decorated Vietnam War pilot, joined the project early on, as did Dick’s friend Jeanna Yeager (no relation to aviator Chuck Yeager ). Voyager ‘s extremely light yet strong body was made of layers of carbon-fiber tape and paper impregnated with epoxy resin. Its wingspan was 111 feet, and it had its horizontal stabilizer wing on the plane’s nose rather than its rear–a trademark of many of Rutan’s aircraft designs. Essentially a flying fuel tank, every possible area was used for fuel storage and much modern aircraft technology was foregone in the effort to reduce weight.

When Voyager took off from Edwards Air Force at 8:02 a.m. PST on December 14, its wings were so heavy with fuel that their tips scraped along the ground and caused minor damage. The plane made it into the air, however, and headed west. On the second day, Voyager ran into severe turbulence caused by two tropical storms in the Pacific. Dick Rutan had been concerned about flying the aircraft at more than a 15-degree angle, but he soon found the plane could fly on its side at 90 degrees, which occurred when the wind tossed it back and forth.

Rutan and Yeager shared the controls, but Rutan, a more experienced pilot, did most of the flying owing to the long periods of turbulence encountered at various points in the journey. With weak stomachs, they ate only a fraction of the food brought along, and each lost about 10 pounds.

On December 23, when Voyager was flying north along the Baja California coast and just 450 miles short of its goal, the engine it was using went out, and the aircraft plunged from 8,500 to 5,000 feet before an alternate engine was started up.

Almost nine days to the minute after it lifted off, Voyager appeared over Edwards Air Force Base and circled as Yeager turned a primitive crank that lowered the landing gear. Then, to the cheers of 23,000 spectators, the plane landed safely with a few gallons of fuel to spare, completing the first nonstop circumnavigation of the earth by an aircraft that was not refueled in the air.

Voyager is on permanent display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Also on This Day in History December | 23

The journal "science" publishes first report on nuclear winter, madam c.j. walker is born, chaminade shocks no. 1 virginia in one of greatest upsets in sports history, pittsburgh steelers' franco harris scores on "immaculate reception" iconic nfl play.

This Day in History Video: What Happened on December 23

“balloon boy” parents sentenced in colorado.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Japanese war criminals hanged in Tokyo

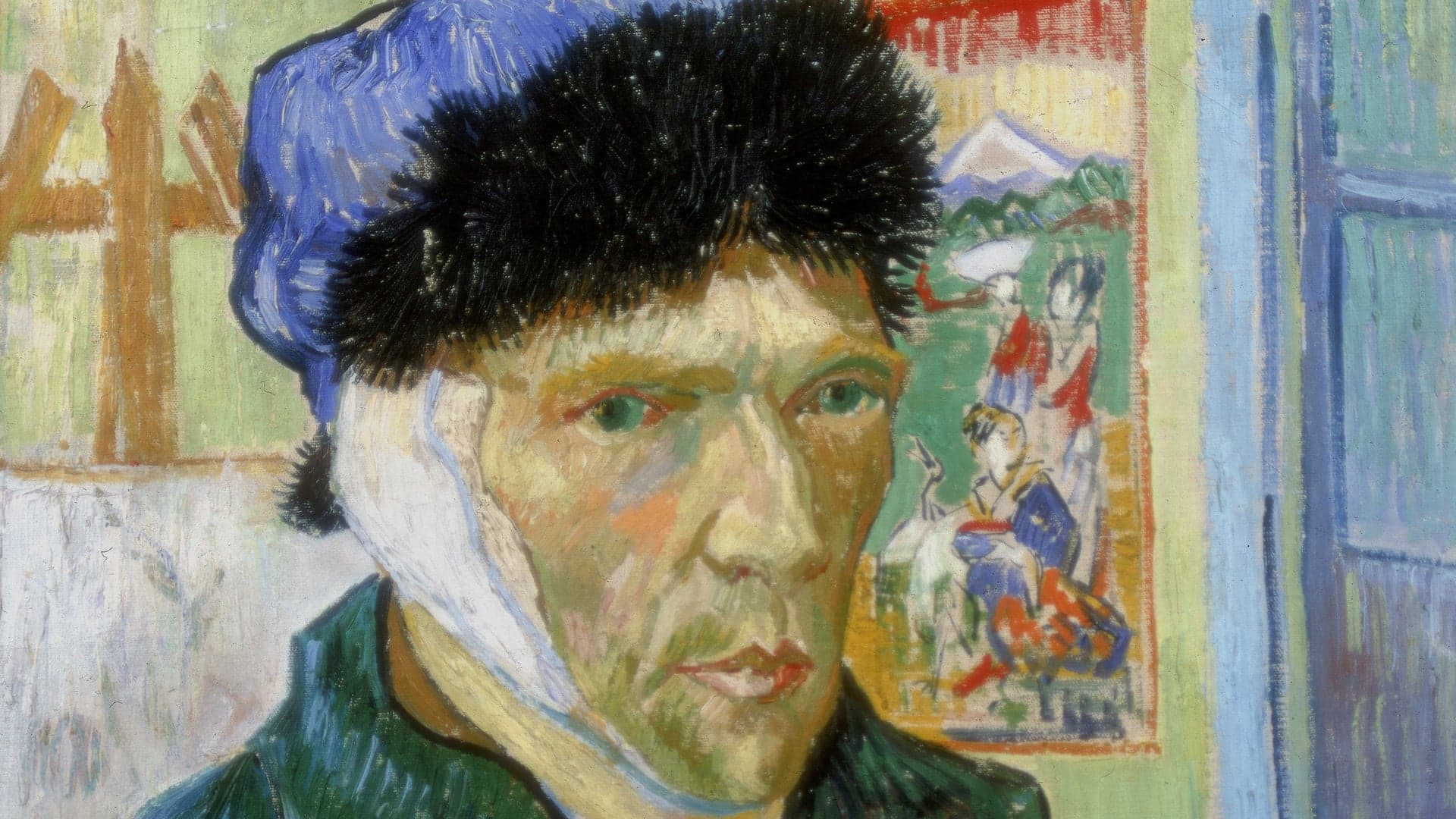

Construction of plymouth settlement begins, vincent van gogh chops off his ear, the execution of eddie slovik is authorized, chuck berry is arrested on mann act charges in st. louis, missouri, woody allen marries soon-yi previn, subway shooter bernhard goetz goes on the lam, crew of uss pueblo released by north korea, chemical contamination prompts evacuation of missouri town.

Naval Postgraduate School

Where Science Meets the Art of Warfare

Aviator Dick Rutan Tells of Record-Breaking Flight Aboard the Voyager

Amanda Stein | April 14, 2010

Renowned aviator and retired Air Force pilot Dick Rutan shares with NPS students, faculty and guests the story of his nearly 25,000-mile record-breaking, non-stop trip around the world aboard the Voyager, an aircraft designed for the feat by Rutan, his brother Burt and Jeana Yeager.

In early April, renowned aviator and retired Air Force Lt. Col. Richard Glenn “Dick” Rutan spoke to a packed audience in the MAE Auditorium at NPS about his time in the Armed Forces and his record-breaking flight around the world. Rutan made aviation history in 1986 when he flew the first non-stop flight around the world alongside Jeana Yeager aboard the Voyager, an airplane designed by his brother Burt Rutan, and built by Burt, Dick and Jeana.

On December 14, 1986, the Voyager took off from Edwards Air Force Base and returned to the same airport nine days, three minutes and 44 seconds later, without stopping to refuel. The team traveled 24,986 miles, breaking the distance record of 12,532 miles previously held by a B-52 Stratofortress bomber. The flight secured their place in aviation history, and earned the Voyager a spot in the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, where the record-setting aircraft is on permanent display.

With a passion for flying that was ignited as a child, Rutan spoke about his time in the Air Force during the Vietnam War, and the code of conduct that has stuck with him since his retirement from the service. “I still remember what it said: ‘I’m an American fighting man. And I serve in the force, which guards my country and my way of life. And I am willing to give my life in their defense.’” He added, “What a profound statement. What a huge meaning that is. That you are willing to give your life for the flag, for your liberty, and for what it means.” Rutan took his oath to heart and flew over 100 high-risk classified missions, and was even shot down over North Vietnam in 1968.

After 20 years of service, 325 missions, and being awarded the Silver Star, five Distinguished Flying Crosses, 16 Air Medals and a Purple Heart, Rutan retired from the Air Force in 1978 and joined his younger brother’s aircraft company, Rutan Aircraft Factory, in Mojave, Calif. With few safety regulations and restrictions for aviation in the early 80s, the barren high desert proved to be a great place to try new things and push the boundaries of design and performance.

It was there that Dick’s brother Burt had established himself as an innovative aircraft designer, and thrived on doing the seemingly impossible. “My brother, he is a visionary. He is a consummate designer, thinking, trying to do something different,” said Rutan. “One of his faults is that he won’t do anything that anyone else has done. Whether it’s better than what [someone else] did or not, it’s gotta be different.”

Aviator Dick Rutan shares the details of his non-stop un-refueled flight around the world. On April 2nd, Rutan spoke with NPS students, faculty and guests about the monumental task of designing and building a plane that could handle the trip.

It was no surprise then when Yeager and the Rutan brothers were out to lunch together one day in 1980 and Burt brought up the idea of building a plane that could fly non-stop around the world. A quick sketch on a napkin was the start of a six-year project that took over 50 volunteers and dozens of private donations to see to fruition.

Burt designed the plane, with a 110-ft. wingspan and 17 fuel tanks. “I laid up every single strand of carbon fiber on that airplane personally. I thought if this thing breaks or if there’s a mistake made in the structure, when the airplane is spinning in, there will be only one person to blame, and that will be myself,” said Rutan. “Besides that, we didn’t have any money to hire anybody.” Designed for maximum fuel efficiency, there were doubts about the structural integrity of an aircraft weighing only 939lbs (unloaded) and carrying 7,011lbs of fuel. After two years of construction, the Voyager began extensive test flights.

With every ounce of weight being accounted for, the team was forced to cut out any excess fuel or material that might weigh the plane down. “There was a big argument between my brother and I about the amount of fuel. I thought he was too conservative and I ordered 300 more pounds of fuel be put aboard the plane. It increased the risk in getting airborne, but I thought it was a greater risk to run out of fuel in Mexico and have to do the whole darn thing over again. I wanted the darn thing over with.”

After a mishap on a test run left the cabin filled with fuel fumes, Rutan landed safely and wondered if he would ever see the Voyager complete the trip around the world. “I landed, I got out of the airplane, and I thought: It’s gonna take us a year to fix this. I’ve got another year to live.” He said, “I really, honestly thought that I would die in this airplane. I didn’t think that there was any way it could fly ten days without a major malfunction of the airplane itself. We had no backups for anything. Everything had to be absolutely ultralight.”

The weight factor also forced the team to equip the plane with minimal safety gear, should they need to jump to safety. The plane held two small pouches with an inflatable navy life raft and parachutes that were barely adequate for a safe water landing. Flexible wings and rough handling also added to the stress of flying the Voyager. “The airplane was really a handful to fly,” said Rutan, “I hated flying it. In fact, I loathed flying it.”

After 68 test flights and 360 hours in the air, the weather team gave the go-ahead and the crew scrambled to get everything ready for takeoff. On December 14, 1986, the Voyager took off to circumnavigate the globe. With limited resources and a heightened sense of anxiety, Rutan and Yeager got little sleep in the cramped cabin space and the controls needed constant attention to correct it if the plane started to gallop. Set on a route largely determined by the weather, they maintained an average altitude of 11,000 ft, and kept a sharp eye for cumulus clouds that threatened to tear the wings off of their fragile plane.

“Every time the sun would come up, I was totally amazed that we were still flying. We’re little homebuilders. We’re not a government, space program, or some multi-billion dollar contract going on out there. We’re just a couple of homebuilders with this hokey little airplane,” said Rutan. “We had done it, and I absolutely could not believe it. It was actually successful.”

After nearly nine days in the air, Rutan prepared to touch down at Edwards Air Force Base for the successful end to what he long expected to be the final flight of his life. With only 18 gallons of fuel remaining, a few wing tips missing, a broken fuel pump and a dehydrated and exhausted crew, the Voyager had covered 24, 986 miles in 9 days. Upon completing the monumental flight, Rutan and Yeager were flooded with offers for interviews, endorsements and opportunities. Not expecting any attention, let alone attention of this magnitude, they were ill prepared for big corporations looking to take advantage of them and to monopolize on the Voyager story. Court battles ensued, but for Rutan, knowing that they had succeeded was enough of a reward.

“The airplane hangs in the National Air and Space Museum as a tribute to free spirit. If you can dream it, you can do it if you’ve got enough guts to try it. Anytime I feel sorry for myself, I walk into the museum and I look up at that airplane, and realize that we built it.” He said, “I built that son of a gun, and I flew it around the world. And that’s the only thing that matters. And that’s the only thing that those attorneys and those agents couldn’t steal from us. And that turned out to be the only thing that was worth a darn. And that’s the Voyager story.”

MEDIA CONTACT

Office of University Communications 1 University Circle Monterey, CA 93943 (831) 656-1068 https://nps.edu/office-of-university-communications [email protected]

AIR & SPACE MAGAZINE

The notorious flight of mathias rust.

Ronald Reagan was president, there was still a Soviet Union, and a 19-year-old pilot set out to change the world

Tom LeCompte

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/MatthiasRust.jpg)

ON A MILD SPRING DAY IN LATE MAY 1987, military analyst John Pike was at the U.S. embassy in Moscow on business when he looked out the window and saw a small airplane circling over Red Square. Gee, that’s peculiar , thought Pike. There’s no private aviation in the Soviet Union. Hell, there’s no private anything.

The aircraft belonged to West German teenager Mathias Rust—or, more accurately, to Rust’s flying club. In a daring attempt to ease cold war tensions, the 19-year-old amateur pilot had flown a single-engine Cessna nearly 550 miles from Helsinki to the center of Moscow—probably the most heavily defended city on the planet—and parked it at the base of St. Basil’s Cathedral, within spitting distance of Lenin’s tomb. Newspapers dubbed the pilot “the new Red Baron” and the “Don Quixote of the skies.” The stunt became one of the most talked-about aviation feats in history. But it was politics, not fame, that motivated Rust.

There is nothing in Rust’s neat two-bedroom apartment outside Berlin—no mementos, no photographs, no framed newspaper headlines—nothing at all to indicate that for a few short weeks 18 years ago he was the most famous pilot in the world. But the memory of the flight has stayed fresh. “It seems like it happened yesterday,” says Rust, now 36. “It’s alive in me.”

As a child in Hamburg, Rust had been preoccupied by two things: flying and nuclear Armageddon. Belligerence and distrust marked East-West relations of the time. U.S. President Ronald Reagan seemed to be on a personal crusade against the Soviet Union. Many Germans were on edge. “There was a real sense of fear,” Rust says, “because if there was a conflict, we all knew we would be the first to be hit.”

To many Europeans, Mikhail Gorbachev’s ascendancy to the Soviet leadership in 1985 offered a glimmer of hope. Glasnost , his policy of transparency in government, and perestroika , economic reforms at home, were radical departures from the policies of his predecessors. So when the U.S.-Soviet summit in Reykjavik, Iceland, in October 1986 ended without an arms reduction deal, Rust felt despair. He was particularly angered by Reagan’s reflexive mistrust of the Soviet Union, which Rust felt had blinded the president to the historic opportunity Gorbachev presented.

Rust decided he must do something—something big. He settled on the idea of building an “imaginary bridge” by flying to Moscow. If he could reach the Soviet capital, if he could “pass through the Iron Curtain without being intercepted, it would show that Gorbachev was serious about new relations with the West,” says Rust. “How would Reagan continue to say it was the ‘Empire of Evil’ if me, in a small aircraft, can go straight there and be unharmed?” Rust also prepared a 20-page manifesto he planned to deliver to Gorbachev on how to advance world peace.

Rust had taken his first flying lessons only a couple of years before his decision to fly to Moscow. A data processor at a mail-order trinket company, he spent all of his money (and some of his parents’) flying. But by the spring of 1987, he had barely 50 hours of licensed flight time, and had completed just a handful of cross-country trips.

“I thought my chances of actually getting to Moscow were about 50-50,” Rust says, noting that in 1983, the Soviets blew Korean Airlines flight 007 out of the sky after it strayed into Soviet airspace near the Kamchatka Peninsula; all 269 persons aboard were killed. “But I was convinced I was doing the right thing—I just had to dare to do it.”

To prepare himself for his mission, he planned a practice flight to Reykjavik, the site of the doomed arms talks. It would be “a long time flying over open water with very little navigation aids,” says Rust. “I figured if I succeeded, I would be able to cope with the pressure of flying to Moscow.”

Rust meticulously planned his route and signed out a 1980 Cessna Skyhawk 172 from his flying club for three weeks. The four-seat airplane was equipped with auxiliary fuel tanks that boosted the aircraft’s range by 175 nautical miles to 750 nautical miles—range he would need in order to safely reach Reykjavik, and later Moscow. The club didn’t ask him where he was going, and Rust didn’t say. He packed a small suitcase, a satchel with maps and flight planning supplies, a sleeping bag, 15 quarts of engine oil, and a life vest. As a final precaution, Rust packed a motorcycle crash helmet. The helmet was for his final leg to Moscow, “because I didn’t know what [the Soviets] would do, and if I was forced down it would give me extra protection [in case of a crash].”

On May 13, 1987, Rust took off from Uetersen Airfield, outside Hamburg, and flew for five hours across the Baltic and North seas before reaching the Shetland Islands. The next day he flew to Vagar, on Denmark’s Faröe Islands, in the middle of the north Atlantic. On May 15 he flew to Reykjavik.

Rust spent a week in the Icelandic capital. He visited Hofdi House, the white villa that was the site of the Reagan-Gorbachev summit. “It was locked,” Rust says, “but I felt I got in touch with the spirit of the place. I was so emotionally involved then and was so disappointed with the failure of the summit and my failure to get there the previous autumn. So it gave me motivation to continue.”

On May 22, Rust set out for Finland by way of Hofn, Iceland; the Shetlands; and Bergen, Norway. He landed at Malmi airport in Helsinki on May 25. Since leaving Hamburg, he had covered nearly 2,600 miles and had doubled his total flight time to more than 100 hours. He had proven to himself he had the flying skills he needed, but he still had doubts about his nerve. His resolve constantly wavered: Yes, it was something he had to do/No, it was crazy.

The night of May 27 was a restless one for Rust. In the morning he drove to the airport, fueled the Cessna, checked the weather, and filed a flight plan for Stockholm (“My alternate if I chickened out,” he says), a two-hour trip to the southwest.

At about 12:21 p.m., Rust took off. Controllers at Malmi had him turn west toward Stockholm, asking him to keep the airplane low to avoid traffic. Although the Cessna was equipped with a transponder, a device that transmits a response to radar interrogation and thus helps to identify an aircraft, Helsinki controllers didn’t assign him a setting, so he turned the device off—the controllers would track Rust’s airplane by the reflection of radar signals off its metal skin. Rust held course for about 20 minutes, at which point controllers radioed to say he was leaving their control area. Rust thanked them and said goodbye.

He continued toward Stockholm for several minutes; then, as he closed in on his first waypoint, near the Finnish town of Nummela, he chose. “All of a sudden, I just turned the airplane to the left [toward Moscow],” he says. “It wasn’t really even a decision…. I wasn’t nervous. I wasn’t excited. It was almost like the airplane was on autopilot. I just turned and headed straight across [the Gulf of Finland] to the border.”

At the Tampere air traffic control facility in Finland, controllers noticed Rust’s near-180-degree change of course. As the radar blip headed south and then east across the water, passing through restricted Finnish military airspace, controllers tried to contact him and failed. At about 1 p.m., Rust’s airplane disappeared from radar screens. Fifteen minutes later, a helicopter pilot radioed that he spotted an oil slick and some debris on the water near where Rust’s airplane was last detected. A search-and-rescue operation was activated—only to be called off when news of Rust’s landing reached Finland. (Years later Finnish aviation authorities investigated a series of incidents in which airliners mysteriously disappeared from Tampere radar screens while in the same area.)

Meanwhile, at a radar station in Skrunda, now in the independent state of Latvia, Soviet military personnel were also tracking Rust. All foreign aircraft flying into the Soviet Union were required to get a permit and to fly along designated corridors, and Rust’s was not an approved flight. As the unidentified aircraft neared the coastline at around 2:10 p.m. Moscow time (an hour ahead of Helsinki), three missile units were put on alert.

From Helsinki, Rust’s flight plan was simple: Turn to a heading of 117 degrees and hold course. As he crossed his first waypoint, the Sillamyae radio beacon near Kohtla-Jarve, on the coast of the now-independent state of Estonia, he climbed to 2,500 feet above sea level, a standard altitude for cross-country flight, which would keep him about 1,000 feet above the ground for the entire route. He trimmed the airplane out and flew straight and level. He also put on his crash helmet. “The whole time I was just sitting in the aircraft, focusing on the dials,” says Rust. “It felt like I wasn’t really doing it.”

Soviet controllers continued to monitor the unidentified airplane’s progress. Now that it was well inland, army units in the area were put on high alert and two fighter-interceptors at nearby Tapa air base were scrambled to investigate. Peering through a hole in the low clouds, one of the pilots reported seeing an airplane that looked similar to a Yak-12, a single-engine, high-wing Soviet sports airplane that from a distance looks very similar to a Cessna. The fighter pilot, or his commander on the ground, perhaps thinking the airplane must have had permission to be there, or didn’t pose any threat, decided the airplane did not require a closer inspection.

Not long after being seen by the Soviet fighter pilot, Rust descended in order to avoid some low clouds and icing. For a brief period, his blip disappeared from Soviet radar screens. Once the weather cleared, Rust climbed back to 2,500 feet, and an image of the unidentified airplane appeared on the radar screen in a new sector, one whose commander ordered two more fighter-interceptors to investigate.

Now nearly two hours into his flight, Rust says the sun was shining when he saw “a black shadow shooting in the sky and then disappear.” A few moments later, from out of a layer of clouds in front of him, an aircraft appeared. “It was coming at me very fast, and dead-on,” Rust recalls. “And it went whoosh !—right over me.

“I remember how my heart felt, beating very fast,” he continues. “This was exactly the moment when you start to ask yourself: Is this when they shoot you down ?”

From below and to the left, a Soviet MiG-23 fighter-interceptor pulled up beside him. With nearly three times the wingspan and more than 10 times the weight of Rust’s Cessna, the MiG seemed huge. Designed to fly at more than twice the speed of sound, the swing-wing fighter had to be put into full landing configuration—gear and flaps extended, wings swung outward—in order to slow it enough to fly alongside the Cessna. Its nose rode high as it hovered at the edge of a stall.

“I realized because they hadn’t shot me down yet that they wanted to check on what I was doing there,” Rust says. He kept watching the Soviet airplane, “but there was no sign, no signal from the pilot for me to follow him. Nothing.” Soviet investigators later told Rust that the MiG pilot attempted to reach Rust over the radio but there was no response. Only later did Rust realize that the Soviet fighter could only communicate over high-frequency military channels.

After the two pilots had eyed each other for a minute, the Soviet pilot retracted the jet’s gear and flaps. The MiG accelerated and peeled away, only to return and draw two long arcs around the Cessna at a distance of about a half-mile. Finally, it disappeared.

From both the registration number painted on the side of the airplane (D-ECJB) and the West German flag decal on its tail, the MiG-23 crew should have been able to tell that Rust’s aircraft was neither a Yak nor Soviet. Marshall Sergei Akhromeyev, chief of staff of all the Soviet armed forces, admitted in a 1990 interview cited in Don Oberdorfer’s book From the Cold War to the New Era that the fighter pilot’s commander either did not believe the pilot’s report or did not think it was significant, so the information was never passed up the chain of command.

At 3 p.m., with the weather improving, Rust entered a Soviet air force training zone where seven to 12 aircraft—all with performance characteristics and radar signatures similar to Rust’s—were being used in training exercises such as takeoffs and landings.

Rust’s altitude probably helped him appear harmless. Had he attempted to evade radar, as many later speculated he did, the Soviets likely would have taken more aggressive action to stop him, but even in that scenario, the Soviets’ options for dealing with him were fairly limited. Since the KAL 007 tragedy, strict orders were given that no hostile action be taken against civilian aircraft unless orders originated at the very highest levels of the Soviet military, and at that moment, Defense Minister Sergei Sokolov and other top military commanders were in East Berlin with Gorbachev for a meeting of Warsaw Pact states.

As a security procedure, Soviet radar has aircraft under its control regularly reset their transponder codes at prearranged times. If a pilot failed to make the switch, his airplane’s radar signature would look “friendly” one minute and “hostile” the next, after the ground had switched over. On the day of Rust’s flight, 3 p.m. was one of those times. As Rust proceeded, a commander looking over the shoulder of a radar operator—apparently thinking Rust’s radar return was that of a student pilot who had forgotten to make the transponder switch—ordered the officer to change the Cessna’s radar signature to “friendly.” “Otherwise we might shoot some of our own,” he explained.

By 4 p.m., Rust crossed radar sectors near Lake Seliger, a popular summer retreat near the town of Kushinovo, about 230 miles from Moscow. As the radar return for the Cessna popped up on a new set of radar screens, controllers once again took note of the unidentified aircraft. Once again a pair of fighter-interceptors was launched to investigate, but according to a Russian report on Rust’s flight, commanders considered it too dangerous for the airplanes to descend through the low cloud deck, so visual contact was never made. Rust was now a little more than two and a half hours away from his destination.

About 40 miles west of the city of Torzhok, another radar controller saw the signal for Rust’s airplane and assumed it was one of two helicopters that had been performing search-and-rescue operations nearby. On his radar screen, he flagged it as such, and once again Rust’s airplane was marked as a “friendly.”

Rust flew on, leaving the Leningrad military district and entering that of Moscow. In the handoff report, the Leningrad commander related to his Moscow counterpart that his controllers had been tracking a Soviet airplane flying without its transponder turned on. But the report said nothing about tracking an unidentified airplane from the Gulf of Finland, nothing about fighter-interceptors intercepting a West German aircraft, and nothing about an unidentified aircraft on a steady course to Moscow. As such, the report set off no alarms.

For Rust, the flight was going flawlessly. He had no problem identifying the landmarks he had chosen as waypoints, and he was confident that his goal was within reach. “I had a sense of peace,” he says. “Everything was calm and in order.” He passed the outermost belt of Moscow’s vaunted “Ring of Steel,” an elaborate network of anti-aircraft defenses that since the 1950s had been built up as a response to the threat of U.S. bombers. The rings of missile placements circled the city at distances of about 10, 25, and 45 nautical miles, but were not designed to fend off a single, slow-flying Cessna.

At just after 6 p.m., Rust reached the outskirts of Moscow. The city’s airspace was restricted, with all overflights—both military and civilian—prohibited. At about this time, Soviet investigators would later tell Rust, radar controllers realized something was terribly wrong, but it was too late for them to act.

As Rust made his way over the city, he removed his helmet and began to search for Red Square. Unlike many western cities, Moscow has no skyline of glittering office towers that Rust could see and head for. Unsure where to go, Rust headed from building to building. “As I maneuvered around, I sort of narrowed in on the core of the city,” he says. Then he saw it: the distinctive turreted wall surrounding the Kremlin. Turning toward it, Rust began to descend and look for a place to land.

“At first, I thought maybe I should land inside the Kremlin wall, but then I realized that although there was plenty of space, I wasn’t sure what the KGB might do with me,” he remembers. “If I landed inside the wall, only a few people would see me, and they could just take me away and deny the whole thing. But if I landed in the square, plenty of people would see me, and the KGB couldn’t just arrest me and lie about it. So it was for my own security that I dropped that idea.”

As he circled, Rust noticed that between the Kremlin wall and the Hotel Russia, a bridge with a road crossed the Moscow River and led into Red Square. The bridge was about six lanes wide and traffic was light. The only obstacles were wires strung over each end of the bridge and at its middle. Rust figured there was enough space to come in over the first set of wires, drop down, land, and then taxi under the other wires and into the square.

Rust came in steeply, with full flaps, his engine idling. As planned, he came in over the first set of wires, dropped down, and flared for landing. As he rolled out under the middle set of wires, Rust noticed an old Volga automobile in front of him. “I moved to the left to pass him,” Rust says, “and as I did I looked and saw this old man with this look on his face like he could not believe what he was seeing. I just hoped he wouldn’t panic and lose control of the car and hit me.”

Rust passed under the last set of wires and rolled onto the square. Slowing, he looked for a place to park. He wanted to pull the airplane into the middle of the square, in front of Lenin’s tomb. But surrounding St. Basil’s Cathedral was a small fence with a chain strung across it that blocked his way. Rust pulled up in front of the church.

He shut down the engine, then closed his eyes for a moment and sucked in a deep breath. “I remember this great feeling of relief, like I had gotten this big load off my back.” He looked at the Kremlin clock tower. It was 6:43 p.m., almost five and a half hours since he’d left Helsinki.

He got out of the Cessna. Expecting to be stormed by hordes of troops and KGB agents, Rust leaned against the aircraft and waited. The people in Red Square seemed nervous or stunned, not sure what was going on. Some thought Rust’s airplane might be Gorbachev’s private aircraft, or that it was all part of a movie production. But once the crowd realized that Rust and the Cessna were foreign—and that he’d just pulled off one of the most sensational exploits they had ever witnessed—they drew closer.

“A big crowd had formed around me,” Rust says. “People were smiling and coming up to shake my hand or ask for autographs. There was a young Russian guy who spoke English. He asked me where I came from. I told him I came from the West and wanted to talk to Gorbachev to deliver this peace message that would [help Gorbachev] convince everybody in the West that he had a new approach.”

The atmosphere was festive. One woman gave him a piece of bread as a sign of friendship. According to Rust, an army cadet told him that “he admired my initiative, but that I should have applied for a visa and made an appointment with Gorbachev—but he agreed that they most likely would not have let me.”

Rust did not notice that KGB agents were moving through the crowd, interviewing people and confiscating cameras and notebooks. More than an hour after the landing, two truckloads of armed soldiers arrived and roughly shoved the crowd away. They also put up barriers around the airplane.

Three men emerged from a black sedan and introduced themselves. The youngest, an interpreter, politely asked for Rust’s passport and whether he was carrying any weapons. They then asked to inspect the aircraft. After a few more questions, they asked Rust to get into the car. The mood, Rust says, was still very friendly, almost mirthful. The Cessna was hauled to Moscow’s Sheremetyevo International Airport and disassembled for inspection. Rust was taken to Lefortovo prison, a notorious complex the KGB used to hold political prisoners.

Given the level of planning put into the flight, as well as the number of obstacles that had apparently been overcome, the Soviets could not believe that this was the work of one man, much less an idealistic boy. Investigators believed Rust’s journey was part of a much larger plot. Take the date itself, May 28. It was Border Guards Day. Many speculated Rust chose that day thinking the border would be more lightly defended, or perhaps to maximize the embarrassment the flight would cause the military. “I didn’t know about it,” Rust says. “I said, ‘I’m a West German. How should I know about your holidays?’ It was just a lucky circumstance.” His interrogators also accused him of obtaining maps from the CIA or the German military, but when the Soviet consul general in Hamburg was able to obtain the same maps from a mail order company, as Rust had, the interrogators relented.

Rust’s investigators showed him photographs of the bridge he’d landed on. In the photos, many sets of wires stretched across the bridge, each about six feet apart. They asked Rust how he could possibly land with so many wires in his way. Perplexed himself, Rust explained that when he landed he could see only three sets of wires. Upon further investigation, the Soviets learned that the morning of the day Rust landed, a public works crew had removed most of the wires for maintenance; they were replaced the next day. “They said I must have been born with a shirt”—a Russian expression meaning born lucky.

One German periodical published a story saying Rust did the stunt on a bet. Another reported that he did it to impress a girl. Yet another said he did it in order to drop leaflets seeking to free nonagenarian Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s lieutenant, from jail. The Communist newspaper Pravda accused Rust of being a patsy in an international plot in which he was supposed to have been shot down and killed in order to provoke an international incident. However ridiculous the rumors were, the Soviets methodically looked into every allegation.

On June 23, 1987, the Soviets completed their investigation. Shortly afterward, prosecutors charged Rust with illegal entry, violation of flight laws, and “malicious hooliganism.” Rust pleaded guilty to all but the last charge. There was, he argued, nothing malicious in his intentions.

On September 4, after a three-day trial, a panel of three judges found Rust guilty of all charges and sentenced him to four years at Lefortovo. The prison, though starker and more restrictive than a labor camp, ensured Rust’s safety. He spent his time there quietly and was afforded special privileges: He was allowed to work in the garden and receive visits by his parents every two months.

On August 3, 1988, two months after Reagan and Gorbachev agreed to a treaty to eliminate intermediate-range nuclear weapons in Europe, the Supreme Soviet, in what Tass described as a “goodwill gesture,” ordered Rust released from prison.

According to William E. Odom, former director of the National Security Agency and author of The Collapse of the Soviet Military , Rust’s flight damaged the reputation of the vast Soviet military and enabled Gorbachev to remove the staunchest opponents to his reforms. Within days of Rust’s landing, the Soviet defense minister and the Soviet air defense chief were sacked. In a matter of weeks, hundreds of other officers were fired or replaced—from the country’s most revered war heroes to scores of lesser officers. It was the biggest turnover in the Soviet military command since Stalin’s bloody purges of the 1930s.

More important than the replacement of specific individuals, analyst John Pike says, was the change Rust’s flight precipitated in the public’s perception of the military. The myth of Soviet military superiority had been punctured, and with it the almost religious reverence the public had held for its armed forces.

For decades, Soviet citizens had been led to believe “the West was poised to destroy them…that if they let their guard down for an instant that they would be obliterated,” says Pike. It was this thinking that helped perpetuate the cold war. Rust’s flight proved otherwise: The Soviet Union could suffer a breach without being destroyed by external forces. Ultimately, of course, it would be internal forces that would do the job.

The flying club’s Cessna changed hands several times (in 1988, it was listed for sale in Trade-A-Plane ) before ending up with a Japanese developer who intended to make it an attraction at an amusement park. That project went bankrupt and the airplane disappeared.

Rust never piloted an airplane again. In fact, he spent many years trying to distance himself from his famous flight. In 2002 he founded a mediation service designed to “fight violence by providing proper redress,” for which he has spent a lot of time in the Middle East, mostly in Palestinian territories, but to help pay the bills Rust also works for a London-based investment firm.

Though frustrated that he never got to meet Gorbachev, he takes satisfaction in having had a small but important impact on relations between the superpowers. Four years after his “mission,” the forces that his flight helped to strengthen dissolved the Soviet Union, and the cold war ended.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Home • Biography

In 2004 Rutan made international headlines as the designer of SpaceShipOne , the world’s first privately-built manned spacecraft to reach space. Financed by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen , SpaceShipOne won the $10 million Ansari X-Prize , the competition created to spur the development of affordable space tourism.

“Manned space flight is not only for governments to do,” says Rutan. “We proved it can be done by a small company operating with limited resources and a few dozen dedicated employees. The next 25 years will be a wild ride; one that history will note was done for everyone’s benefit.”

Sir Richard Branson (L) and Burt Rutan pose for a photo in front of the SpaceShip2 resting under the Mothership WhiteKnight2 inside a hangar in Mojave,Ca. The SpaceShip2 will have its worldwide debut. Monday evening at the airport for dignitaries and future “astronauts”.

Inspired by the success of SpaceShipOne, Virgin Group founder Sir Richard Branson started Virgin Galactic and engaged SCALED Composites (the company Rutan founded in 1982) to develop and produce a line of commercial spaceships to fly the public ( SpaceShipTwo ). In 20 years, Rutan predicts, “space tourism will be a multibillion-dollar business.”

Aerospace engineer Burt Rutan, founder of Scaled Composites LLC, left, speaks with Paul Allen, co-founder of Microsoft Corp., during a news conference for the launch of Stratolaunch Systems Inc. in Seattle, Washington, U.S., on Tuesday, Dec. 13, 2011. Allen said Stratolaunch Systems Inc. will bring “airport-like operations” to space flights, including eventual human missions. The first flight is planned within five years. Photographer: Kevin P. Casey/Bloomberg via Getty Images

In 2012 Paul Allen announced Stratolaunch Systems with Rutan as a board member. SCALED Composites is now building what will be the world’s largest airplane to serve as the carrier ship for this revolutionary orbital space launch system.

Rutan designed the legendary Voyager , the first aircraft to circle the world non-stop, without refueling. He also developed the GM Ultralite , an all-composite 100 mpg show car for General Motors, and the Proteus “affordable U-2” aircraft. His Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer broke the Voyager’s record time, becoming the first non-stop, solo flight around the world.

The success of SCALED Composites owes itself to Rutan’s philosophy that the best ideas come from the collaborative efforts of small, closely-knit project teams and an environment unlimited by adversity to risk. According to Aviation Week, Rutan is “a capable manager who has been able to attract technicians, pilots and workers who revel in the entrepreneurial and creative spirit existing at SCALED Composites.”

Winner of the Presidential Citizen’s Medal, the Charles A. Lindbergh Award, two Collier Trophies and included on Time Magazine’s “100 most influential people in the world,” Rutan is the founder of SCALED Composites, the most aggressive aerospace research company in the world. Based in Mojave, CA, his company has developed and tested a variety of groundbreaking projects, from military aircraft to executive jets, showcasing some of the most innovative and energy-efficient designs ever flown ( Overview Video ).

Rutan retired on March 31, 2011 and now lives in North Idaho.

Rights Usage:

Terms of use:.

For print or commercial use please see permissions information .

- Get Involved

- Host an Event

Thank you. You have successfully signed up for our newsletter.

Error message, sorry, there was a problem. please ensure your details are valid and try again..

- Free Timed-Entry Passes Required

- Terms of Use

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Rutan Model 76 Voyager was the first aircraft to fly around the world without stopping or refueling. It was piloted by Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager.The flight took off from Edwards Air Force Base's 15,000 foot (4,600 m) runway in the Mojave Desert on December 14, 1986, and ended 9 days, 3 minutes and 44 seconds later on December 23, setting a flight endurance record.

Voyager departing the coast of California on Dec. 14, 1986, soon to leave behind Burt Rutan in the Duchess chase plane. As it turned out, you needed 17 tanks of fuel all in one vehicle from start to finish. Voyage r, the ultimate homebuilt, was the brainchild of unconventional designer Burt Rutan and two record-setting pilots, his brother Dick ...

In September of 2013, Dick Rutan recounted the Voyager's almost 25,000-mile circumnavigation of the globe to employees at NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center. "I got to really hate this ...

This object is not on display at the National Air and Space Museum. It is either on loan or in storage. Around the World in Nine Days On December 23, 1986, Voyager completed the first nonstop, non-refueled flight around the world. Pilots Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager completed the flight in nine days. 1984 United States of America CRAFT-Aircraft ...

On December 23, 1986, nine days, three minutes, and 44 seconds after taking off, Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager touched down at Edwards Air Force Base, CA, in the Rutan Voyager aircraft to finish the first flight around the world made without landing or refueling. Rutan's brother Burt had designed Voyager but it was the availability of carbon-fibers coated with epoxy allowing Burt to design an ...

When Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager landed at California's Edwards Air Force Base in the Rutan Voyager on December 23, 1986, they completed a historic flight that tested the limits of aircraft design and human endurance. The pair had left Edwards on December 14, having spent nine days and three minutes in the air during their nonstop, unrefueled ...

The Rutan Voyager Model 76 was the first plane to successfully circumnavigate the globe without making any stops at all. The thin airframe took five years to develop and set off on its journey on December 14th, 1986, landing a full nine days later on December 23rd. ... With little space in the cockpit, Dick Rutan and Jeana Yaeger were only able ...

Dick Rutan is a decorated Air Force fighter pilot and test pilot, and both he and Jeana Yeager set records in Rutan-designed aircraft. Construction began in the summer of 1982 at the Civilian Flight Test Center, Mojave Airport, California. The first flight was made on June 22, 1984. Voyager was designed for maximum fuel efficiency and therefore ...

DESCRIPTION: The Voyager earned its place in history after becoming the first airplane to make a non-stop flight around the world without refueling. The story of the Voyager began when famed aeronautical engineer Burt Rutan formed Scaled Composites and began constructing revolutionary home-built aircraft. His designs, like the VariEze, used ...

Rutan's Model 76 Voyager is an all-composite airframe made primarily from a 1/4-inch sandwich of paper honeycomb and graphite fiber, which was shaped and then cured in an oven. The front and rear propellers are powered by two difference engines. The front engine, an air-cooled Teledyne Continental O-240, provides extra power for take-off and ...

Twenty-five years ago, Burt Rutan's Voyager became the first aircraft to make an around-the-world flight without refueling. George C. Larson. January 2012. Voyager (here, ...

The idea for the Voyager came about as Mr. Rutan, his brother Burt and Ms. Yeager ate lunch together one day in 1981; the three sketched the design for the plane on a napkin. The Rutans, Ms. Yeager and a team made mostly of volunteers built the Voyager over the next five years.

A Rutan business jet, the eight-passenger, twin-turbofan Triumph was tested to 41,000 feet and 0.69 Mach in 1988, when Scaled Composites was still owned by Raytheon's Beech Aircraft division ...

One museum, two locations Visit us in Washington, DC and Chantilly, VA to explore hundreds of the world's most significant objects in aviation and space history. Free timed-entry passes are required for the Museum in DC. Visit National Air and Space Museum in DC Udvar-Hazy Center in VA Plan a field trip Plan a group visit At the museum and online Discover our exhibitions and participate in ...

The Rutan Voyager which was conceived in 1981 would in one flight become the first aircraft to fly nonstop around the world without refuelling, so breaking the records for the longest timed flight and the longest distance flight. Burt Rutan utilized his experience in the design of ultra-light home-build aircraft such as the VariViggen and the ...

On December 23, when Voyager was flying north along the Baja California coast and just 450 miles short of its goal, the engine it was using went out, and the aircraft plunged from 8,500 to 5,000 ...

Rutan made aviation history in 1986 when he flew the first non-stop flight around the world alongside Jeana Yeager aboard the Voyager, an airplane designed by his brother Burt Rutan, and built by Burt, Dick and Jeana. On December 14, 1986, the Voyager took off from Edwards Air Force Base and returned to the same airport nine days, three minutes ...

Rutan made aviation history in 1986 when he flew the first non-stop flight around the world alongside Jeana Yeager aboard the Voyager, an airplane designed by his brother Burt Rutan, and built by Burt, Dick and Jeana. On December 14, 1986, the Voyager took off from Edwards Air Force Base and returned to the same airport nine days, three minutes ...

The aircraft belonged to West German teenager Mathias Rust—or, more accurately, to Rust's flying club. In a daring attempt to ease cold war tensions, the 19-year-old amateur pilot had flown a ...

Rutan designed the legendary Voyager, the first aircraft to circle the world non-stop, without refueling. He also developed the GM Ultralite, an all-composite 100 mpg show car for General Motors, and the Proteus "affordable U-2" aircraft.

JetPhotos.com is the biggest database of aviation photographs with over 5 million screened photos online!

One museum, two locations Visit us in Washington, DC and Chantilly, VA to explore hundreds of the world's most significant objects in aviation and space history. Free timed-entry passes are required for the Museum in DC. Visit National Air and Space Museum in DC Udvar-Hazy Center in VA Plan a field trip Plan a group visit At the museum and online Discover our exhibitions and participate in ...

The Mikoyan MiG-31 (Russian: Микоян МиГ-31; NATO reporting name: Foxhound) is a supersonic interceptor aircraft developed for the Soviet Air Forces by the Mikoyan design bureau as a replacement for the earlier MiG-25 "Foxbat"; the MiG-31 is based on and shares design elements with the MiG-25.. The MiG-31 is the fastest operational combat aircraft in the world.