Every product is independently selected by editors. Things you buy through our links may earn Vox Media a commission.

‘We Pinch Ourselves That We Get to Live Here’

Life inside louis kahn’s esherick house..

This story was originally published by Curbed before it joined New York Magazine. You can visit the Curbed archive at archive.curbed.com to read all stories published before October 2020.

The story of how Paul Savidge and Dan Macey became the owners of Louis Kahn’s Esherick House in Philadelphia started decades before the couple even met.

“I knew of the house as a young child because my parents were interested in modern architecture,” recalls Savidge. “I distinctly remember looking at the Esherick House while riding in the car, when I was 9 or 10 years old.”

When Savidge returned to the Chestnut Hill neighborhood as an adult in 2014, he had Macey by his side and the keys to the house in his hand.

“Sometimes, we forget it’s our house,” says Macey. “We’re amazed every morning when we wake up, and find the light different every time. We pinch ourselves that we get to live here.”

The Esherick House is one of a handful of homes in the Philadelphia region that Kahn designed during his prolific career. But of those nine homes , the Esherick House is arguably the most recognizable and iconic.

Kahn was a close friend of renowned sculptor Wharton Esherick, whose niece Margaret Esherick was in need of a house of her own, preferably one that could store all of her books. In 1959, Kahn agreed to design a boxy, two-story, one-bedroom house for the single woman, with her uncle taking the lead on the kitchen. Margaret was so eager to have her own place, she moved in before the home was even finished. Yet tragically, she died unexpectedly after living there for just six months.

Another family lived in the Esherick House for many years, until in 2008 it was put up for auction. Despite its claim to fame, the home languished on the market for years. A one-bedroom home is a tough sell, even with a pedigree. Over time, the asking price dropped little by little, with no bite.

Finally, half out of curiosity, Savidge and Macey decided to take a look.

“We went to see the house, walked out, looked at each other and said, ‘We can do this,’” recalls Savidge. “This would be really perfect for us, and we could be really good stewards of it — it could change our lives.”

It helped that, besides a few signs of wear and tear, the house was in remarkably sound shape. “It was in a very good state, for the most part,” says Macey. “The previous owners had taken care of it.”

But Macey, a professional food stylist, wasn’t sure he could work with the Esherick-designed kitchen. “It is a tough kitchen to use every day, just because of how beautiful it is,” he says. “The previous owners didn’t cook very much and went out to dinner a lot — take-out is a great form of preservation.”

So before they even closed on the house, Macey and Savidge sought help from the Philadelphia Historical Commission — the house is locally certified historic — and Bill Whitaker, a Kahn expert and curator and collections manager of the Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania School of Design. Almost immediately, they realized they’d need to find an architect willing to take on a Louis Kahn project.

“Finding an architect proved to be more difficult than we expected,” says Savidge. “We talked to close to 10, and some were hesitant to take on the project because of the responsibility of preserving Kahn’s design.”

Savidge and Macey ultimately found the right architect in Kevin Yoder of k YODER Design. The designer had experience in renovating modernist homes — he restored his own I. M. Pei-designed townhouse — and was willing to work with the couple and a large team of contractors, restoration experts, and the Historical Commission.

Yoder admits he took the project on with a mix of both excitement and apprehension. “My first thought was, ‘Do they know what house they’re buying? Do they understand the significance of the house and the kitchen?’ But it wasn’t too long into the conversation that I realized they had already done their homework and knew of its significance,” Yoder says. “They expressed their philosophy of stewardship to and conservation of the house, as well as a need to bring it up to date for their uses.”

The restoration’s biggest undertaking involved finding a way to preserve the Esherick kitchen while at the same time incorporating a second, 21st-century kitchen into the home. The most plausible fix, Macey and Savidge concluded, would be to turn the utility room into the new kitchen.

“We weren’t violating any of Kahn’s philosophies,” says Yoder. “So it was the perfect location to make that happen.”

It involved a lot of planning and engineering, though. Namely, the gas meter had to be moved from the inside of the house to the detached carport on the side of the property. Once that was taken care of, construction could begin on the new, galley-style kitchen.

Macey and Savidge wanted to ensure that the new didn’t detract from the old, so Yoder put a lot of consideration into the types and tones of wood used for the new kitchen. “We wanted to differentiate it from the Wharton Esherick kitchen and the Kahn cabinetry throughout the house, but not to the point that it felt discontinuous as you walked through,” says Yoder.

The kitchen cabinetry has a similar warm tone and features a continuous grain pattern to match the original wood finishes throughout the home. There are also no visible pulls or knobs, as Kahn’s cabinetry always used latches or finger holes instead. The soapstone counters are also in keeping with the materials used in the upstairs bathroom.

As for the original kitchen, the couple brought in experts from the Wharton Esherick Museum, who figured out which parts of the room were original and which were added over the years. When the more recent cabinetry was removed, they discovered that the original walls had never been painted.

“The entire house had been painted white inside,” says Macey. “But one of the walls inside the cabinets was not painted, which we learned was Kahn’s original intent. He didn’t like the white paint, and had instead wanted the natural plaster to be visible so that when the light hit it, it could read gray, pink, or purple.”

To restore the walls to their original state, Andrew Fearon of Materials Conservation created a special mixture of colors and faux-painted the rest of the kitchen to match the original plaster.

It’s a testament to the home’s previous owners — and Kahn’s work — that, for the most part, not much else needed to be restored or renovated. Says Yoder, “We basically got rid of years of wear and tear and left what we could in its original condition. We weren’t trying to make it look new. We were trying to bring it back in the best possible way.”

After the 17-month-long renovation, Savidge and Macey moved into the Esherick House. As the new stewards of a Kahn home, they have been ushered into a special community of homeowners — one where restoration advice and remodel stories are swapped.

In a way, the couple has also put themselves in the public eye. They’ll often see groups of people make their way down their leafy street and admire their house from the road.

“We understand that this house evokes a very emotional response from a lot of people — time and time again we meet people who have literally traveled from all over the world to Philadelphia just to see the house,” says Macey. “It’s one thing to see it in pictures, but to experience the light through the windows and have it embrace you and wrap its arms around you…you can only feel that by being there.”

Savidge says that even though they have lived in the home for three years, they are still discovering things about the house and its architect. “We learn all the time, and I hope that we never get to a point where we take it for granted,” he says. “We’re certainly not there now.”

Macey adds, “I think some people have called this the biggest littlest house in America and I certainly know why they say that. It’s a small space, yet it feels monumental.”

Interior Design by Louise Cohen Interiors.

- design hunting

Most Viewed Stories

- A Greenpoint Condo With a Private Outdoor Pool

- A Burlesque Family at Home

- Good Luck Trying to Resell This West Elm Coffee Table

- Mica Ertegun’s East 81st Townhouse Hits Market

- The City’s Boat-Breakers Get to Work

- A Robert Durst Refresher

Editor’s Picks

Most Popular

What is your email.

This email will be used to sign into all New York sites. By submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy and to receive email correspondence from us.

Sign In To Continue Reading

Create your free account.

Password must be at least 8 characters and contain:

- Lower case letters (a-z)

- Upper case letters (A-Z)

- Numbers (0-9)

- Special Characters (!@#$%^&*)

As part of your account, you’ll receive occasional updates and offers from New York , which you can opt out of anytime.

The Esherick House and its friendly owners

by Helena | May 25, 2017 | architecture

Louis Kahn was one of the most important architects of the 20th century in the United States . Not only was Philadelphia the city where he grew up, but also where he opened his architectural firm in 1935. Thus, in our trip to the city, we visited some of his work.

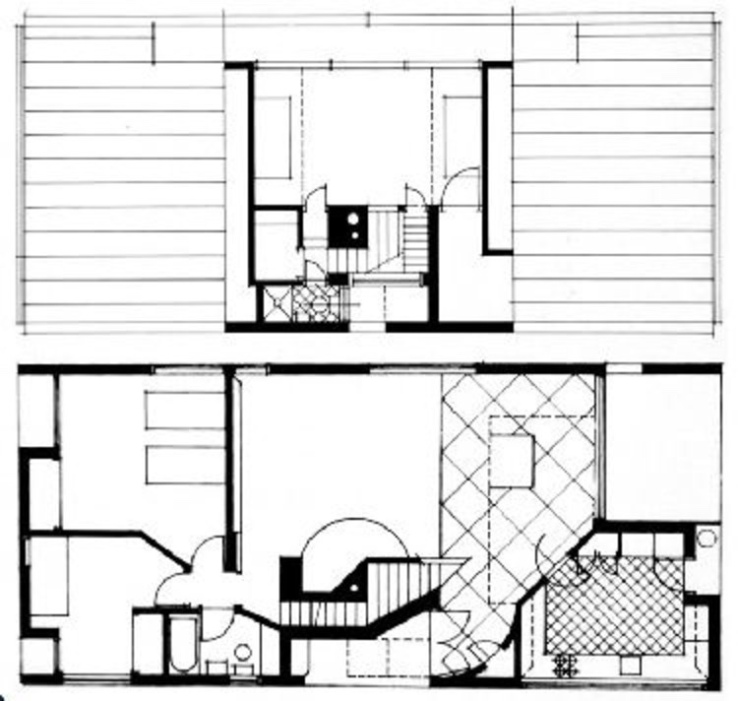

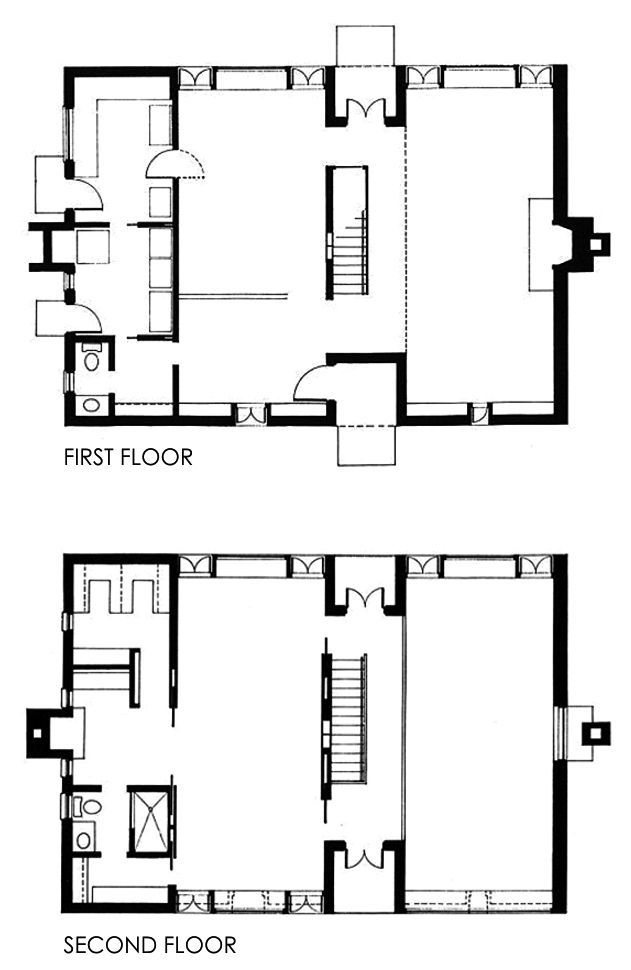

Here you have the Esherick House, commissioned by Margaret Esherick in 1959 and completed in 1961. It has a rectangular floor plan, only changed at the lateral facades by including two chimneys. The interior is organized in a very practical and usual way from Kahn’s architecture. He divided the house into served and servant spaces.

An unexpected surprise

The house is located in a residential neighborhood called Chestnut Hill, far away from the center of Philadelphia . Even though I knew that the house is private and the owners do not offer public tours, we went to see it from the exterior . Nevertheless, I was not even close to imagine what would happen later.

One of the friendly owners of the Esherick House walked out the door that you can see in the picture. When he saw that I was taking pictures of the facades, he invited me to visit the interior of the house . Even today, I cannot believe my luck. It was amazing visiting all the rooms and living spaces.

Visiting the Esherick House

The interior of the Esherick House is outstanding . Besides the exquisite taste of the owners for the furniture and decoration, all the details and finishes are superb. The floor plan -a perfect rectangle- is simple but fully functional. But what I liked the most was how the natural light came into all the rooms . Kahn designed an unusual configuration with windows and shutters to control exterior light and also provide natural ventilation.

The current owners assured me that it was a pleasure to live in the Esherick House . And with good reason, as this is one of the most studied of the nine built houses designed by Louis Kahn.

To conclude, I can only hope that some day the owners find this space and decide to invite me again. Only then could I bring you interior photographs of the Esherick House and post a whole Architectural Visit .

Relacionado

I had the exact same experience in 1976 as an architecture student attending the AIA convention. I have no idea if the same owner lives there, but my friends and I. were invited in and had the best experience of the trip, if not of my college career. I remember the framed photo the owner had of “Lou.” After, we walked around the corner to find the Vanna Venturi house, but we didn’t get invited inside.

Hi David! I bet it was a great experience! However, I don’t think they are the same owners. The current ones were young, and bought the house only some years ago. I’m happy to hear that the former owners were as nice as the new ones!

By the way, I also tried the same with the Vanna Venturi House, but with no luck either…

Thank you for your comment!

I went to the Esherick house as a student about 20 years ago. I grew up in the area so it was exciting to see something architecturally stimulating in a fairly conservative. I much preferred it to Venturi’s mothers house down the street. The connection between the two is evident and I believe that Venturi was a teaching assistant to Louis Kahn so it’s great to see this discourse between modernism and post modernism. We didn’t go into the Esherick house but I think we were invited into Mothers House and spoke with the owner. It’s been so long now that the details are a blur. But it was pre internet so would have been great to have a blog to replay the experience.

Wow! Thank you so much for your comment! I did not know that Venturi worked with Louis Kahn… But I totally agree that it is great to have both houses in the same area. Unfortunately I couldn’t visit the Vanna Venturi House, so I hope to be able to do it in the future! I would really like to see the interiors and how you can feel inside. I’m happy to bring back your memories of your student years! I hope to keep doing it 😉 Best.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Architectural Visits World Map

Helena Ariza | Architect, passionate about photography and traveling . My purpose is to take you on a journey to the best architectural works.

SUBSCRIBE AND DOWNLOAD

New york architecture guide 7+3.

- INSPIRATION

The Margaret Esherick House by Louis Kahn

Nestled at 204 Sunrise Lane in the Chestnut Hill neighborhood of Philadelphia , the Margaret Esherick House is a modernist house designed by American architect Louis Kahn. Completed in 1961, the house is a paradigm of Kahn’s prowess in integrating space, light, and function. Its significance has been recognized through numerous awards, including the Landmark Building Award in 1992 by the Philadelphia chapter of the American Institute of Architects. The house was further immortalized in 2023, gaining a listing on the National Register of Historic Places by the United States Department of the Interior.

The Esherick House Technical Information

- Architects 1 : Louis Kahn

- Location: Philadelphia , Pennsylvania, United States

- Topics: American Houses

- Area: 230 m 2 | 2500 ft 2

- Project Year: 1959-1961

- Photographs: © Doctor Casino, © Jeffrey Totaro, © Jon Reksten, © Arnout Fonck

A room is not a room without natural light. – Louis Kahn 2-3

The Esherick House Photographs

The Genesis and the Design Elements

Commissioned by Chestnut Hill bookstore owner Margaret Esherick, the house was not merely an architectural project but a family affair. Margaret’s uncle, Wharton Esherick, a nationally recognized craftsman and artist, was responsible for designing the home’s iconic kitchen. Comprised of wood and copper, the kitchen remains an exemplar of craftsmanship, marrying utility with aesthetics.

Kahn was a master of space and often divided his buildings into ‘served’ and ‘servant’ spaces. The Esherick house elegantly embodies this philosophy. The dwelling is organized into four alternating served and servant spaces, each extending the full width of the house from front to back. The most striking served space is the two-story living room, situated to the right of the front door.

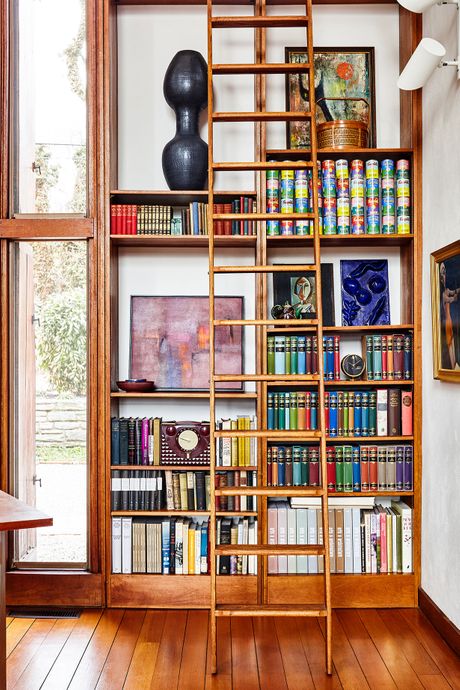

A built-in bookcase occupies its front wall, accentuating Margaret Esherick’s profession as a bookseller. In contrast, the adjacent servant space serves as a thin communication strip containing the house’s stairway, front and back doors, and balconies—all set in alcoves. The house offers a unique fluidity of space, providing an uninterrupted experience from the foyer and dining room on the ground floor to the bedroom on the upper floor.

What sets the Esherick House apart is its ingenious use of light and windows. Kahn’s design employs different window configurations on each side of the house. The front of the house features a T-shaped two-story window design providing both privacy and openness, complemented by shutters for ventilation. The rear of the house, facing a garden adjacent to a public park, has large single-pane windows arranged in pairs. These windows do not open but are accompanied by two-story stacks of shutters, which can be manipulated in various combinations, essentially blurring the boundaries between indoors and outdoors.

The Unbuilt Extension, Renovations, and Legacy

In 1962-1964, Kahn designed an extension for a prospective owner, Mrs. C. Parker. However, she never purchased the house, and the addition was never built. The unbuilt design aimed to blend seamlessly with the existing structure, proposing a significant extension to the left of the front door. The hypothetical enlargement captures the dynamism of the original concept, underlining its adaptability and potential for future growth.

In 2016, the house underwent a sensitive renovation spearheaded by K YODER Design . The renovation aimed to preserve the house’s essential character while enhancing its functionality. Modern appliances were added in an adjunctive kitchen space, and the insulating ability of the windows was improved—all without compromising the home’s visual and architectural integrity.

The Esherick House is more than an architectural masterpiece; it’s a testament to the relationships and shared ethos of the Esherick and Kahn families. Kahn’s friendship with Wharton Esherick was not an isolated connection; Margaret’s brother, Joseph Esherick, even took over Kahn’s schematic design for the Graduate Theological Union Library after Kahn’s death. Furthermore, the house shares the neighborhood with the Vanna Venturi House , another iconic structure designed by Robert Venturi . The Venturi and Kahn link further highlights the concentration of architectural greatness in this small part of Philadelphia.

Through its spatial innovations, unique window configurations, and deeply rooted family connections, the Esherick House continues to captivate architects, scholars, and lovers of design, serving as an enduring symbol of mid-century modern architecture at its finest.

The Esherick House Plans

The Esherick House Image Gallery

About Louis Kahn

Louis Kahn was a prominent American architect, born in 1901 in what is now Estonia, and later emigrated to the United States. Known for his monumental and iconic structures that often employed the use of natural light and raw materials, Kahn left an indelible mark on 20th-century architecture. He gained critical acclaim for several public buildings, including the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California ; the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas ; and the National Assembly Building in Dhaka, Bangladesh . A teacher at Yale University and the University of Pennsylvania, Kahn’s influence extended beyond his built work into architectural theory and education. He passed away in 1974, but his legacy lives on through his timeless designs and philosophic approach to architecture.

Notes & Additional Credits

- Engineer: Keast & Hood Co.

- The quote is not specifically about the Margaret Esherick House, but it encapsulates Kahn’s general philosophy on the importance of natural light in residential spaces, a principle evident in the design of the Esherick House itself.

- GA 76 – Louis I Kahn Esherick House and Fisher House by Yukio Futagawa

Share this:

Leave a reply cancel reply.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- * ArchEyes Topics Index

- Architects Index

- 2020’s

- 2010’s

- 2000’s

- 1990’s

- 1980’s

- 1970’s

- 1960’s

- 1950’s

- 1940’s

- 1930’s

- 1920’s

- American Architecture

- Austrian Architecture

- British Architecture

- Chinese Architecture

- Danish Architecture

- German Architecture

- Japanese Architecture

- Mexican Architecture

- Portuguese Architecture

- Spanish Architecture

- Swiss Architecture

- Auditoriums

- Cultural Centers

- Installations

- Headquarters

- Universities

- Restaurants

- Cementeries

- Monasteries

- City Planning

- Landscape Architecture

Email address:

Timeless Architecture

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- United States

AD Classics: Esherick House / Louis Kahn

- Written by Megan Sveiven

- Architects: Louis Kahn

- Photographs Photographs: Todd Eberle

Text description provided by the architects. An architect celebrated for his breathtaking studies of light and materiality in the creation of memorable architecture, Louis Kahn did not fail to maintain his rigor in the Esherick House of Philadelphia , Pennsylvania.

Admired for it's spatial and luminous qualities, this is the first residence of its kind to convey the grand ideas of Kahn-style architecture. The two story dwelling, which is one of only nine private houses designed by Kahn to come into realization, rests on a lively six acre garden.

Kahn's fusion of materials, natural Apitong wood with manmade beige concrete, is true to his geometrically simple style which allows more emphasis to be placed on lighting and environmental context. The very orthogonal, monolithic composition is punctured by an irregular pattern of windows, revealing the warm interior. As is common in many styles of architecture, the interior walls are primarily white to accentuate the richness of the wood.

Designing the residence for a book lover, Kahn's open floor plan allows natural light to penetrate every corner through the floor-to-ceiling windows. The living room features built-in bookshelves that stretch up to the ceiling of the double-height space. A staircase that is reminiscent of Japanese architecture overlooks this living room space.

Kahn breaks the boundaries of the box in only two instances, both of which are chimneys that symmetrically protrude from opposite ends of the dwelling. His seemingly simple floor plan can be further analyzed into four strips which house the service spaces, dining areas, circulation, and living room.

When experienced from the outside, the windows hint to the contents of the internal double height spaces. Their primary purpose is to allow the flow of light while permitting views to the beautiful surrounding landscape.

In 1992, the house was awarded the distinguished honor of a Landmark Building Award from the Philadelphia chapter of the American Institute of Architects in 1992. Photographer Todd Eberle was brought in by Richard Wright to capture the beauty of the dwelling, to be published in the auction catalogue. It was put up for sale in May of 2008, and sold for an estimated three-million dollars.

Project gallery

Materials and Tags

- Sustainability

世界上最受欢迎的建筑网站现已推出你的母语版本!

想浏览archdaily中国吗, you've started following your first account, did you know.

You'll now receive updates based on what you follow! Personalize your stream and start following your favorite authors, offices and users.

Check the latest Free Standing Lights

Check the latest Chandeliers

Wharton Esherick Museum

Top ways to experience nearby attractions

Most Recent: Reviews ordered by most recent publish date in descending order.

Detailed Reviews: Reviews ordered by recency and descriptiveness of user-identified themes such as wait time, length of visit, general tips, and location information.

Wharton Esherick Museum - All You Need to Know BEFORE You Go (2024)

- Thu - Sun 2:00 PM - 3:00 PM

- (2.07 mi) Embassy Suites by Hilton Philadelphia Valley Forge

- (2.60 mi) Desmond Hotel Malvern, a DoubleTree by Hilton

- (3.96 mi) Hilton Garden Inn Valley Forge/Oaks

- (3.10 mi) Avia Residences On Lincoln

- (2.68 mi) Homewood Suites by Hilton Philadelphia-Great Valley

- (4.64 mi) Founding Farmers King of Prussia

- (2.61 mi) Nook and Kranny Kafe

- (5.25 mi) Seasons 52

- (5.39 mi) The Capital Grille

- (3.69 mi) Iron Hill Brewery & Restaurant

- Random Project

- Collaborate

Esherick House

Introduction.

Did you find this article useful?

Really sorry to hear that...

Help us improve. How can we make this article better?

Subscribe Today!

Save up to 64% and get a free gift. Subscribe »

A Visit to the Wharton Esherick House

We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Blue door. The entry door to Esherick’s home hints at visual and tactile delights to come.

This summer I spent a couple of weeks driving around the East Coast delivering furniture, giving talks related to English Arts & Crafts Furniture and Making Things Work , and photographing kitchens for the book I’m writing for Lost Art Press. (There was also an event at Tools for Working Wood featuring a Hello Kitty pinata stuffed with chocolate half-melted by the end-of-July heat.)

Lots of people love road trips. I am not one of them. I mean, YES to solitary hours immersed in music played at high volume. But sitting still for so long while feeling like a video-game pawn as I try to avoid being pushed off the road by speeding semis? Not my idea of fun.

I must have spent about a week’s worth of grocery costs on tolls as I drove from our nation’s capital to Brooklyn by way of Philadelphia, then on to New Haven, Plymouth (Mass.), Upstate New York, and back to Philly. The nadir, for me as a driver, was negotiating rush-hour traffic in NYC. Along the way, I met some lovely people, many of them woodworkers, and visited a few friends, family members, and clients. In Hartford, I toured Harriet Beecher Stowe’s last home, along with Mark Twain’s gobsmackingly excessive Aesthetic Style manse. Through all of it, I looked forward to my final stop: the home of Wharton Esherick.

Fastened to the stone wall near the entry door is a row of hooks carved by Esherick, each honoring the craftsmen who helped create the place (including one of the woodland birds who serenaded them as they worked). This one represents Esherick himself, swinging a mallet.

I’ve wanted to visit Esherick’s home since I became aware of him about 17 years ago. For much of his life, Esherick (1883-1970), a pioneer in the American Studio Craft movement, lived and worked in this place that qualifies as a work of sculpture in its own right.

Instead of following his father’s advice to go into business, Esherick studied painting at the Philadelphia School of Industrial Arts and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Chafing at the formal instruction, he left without graduating. In 1913, recently married, he bought a dilapidated farm in the countryside near Paoli, 25 miles west of Philadelphia, where he put the barn to use as a studio and gallery. His paintings did not prove sufficiently popular to provide a livelihood, so starting in 1919 he taught art at the progressive community of Fairhope, Alabama . There he became friends with writer Sherwood Anderson, who was experimenting with carved woodblock prints as an artful form of illustration for books and magazines. Anderson gave Esherick a set of chisels, and Esherick went on to produce hundreds of prints .

Drop-leaf desk, 1927.

In the early 1920s, Esherick returned to Pennsylvania and borrowed money to buy the hillside above his farm to keep it from being despoiled by industry. Under greater financial pressure now due to the loan payments, he started making carved wooden painting frames and simple wooden furniture. Both sold more successfully than his paintings.

The shift from painting to designing in three dimensions proved pivotal to Esherick’s career. Commissions provided opportunities for creative expression through architecture in addition to furnishings. In 1940 his work formed part of an exhibit at the World’s Fair. Today Esherick is recognized as one of the twentieth century’s pre-eminent artist-craftsmen, and some of his pieces, such as the small spiral library ladders he made, have become icons of modern design.

Over the years, Esherick built a studio and house of wood and stone from his property, employing traditional construction techniques gleaned from historic local buildings. He continued adding to the buildings, especially the house, for the rest of his life.

In his sculpture and furniture design, Esherick eschewed rectilinearity in favor of twisting, taut, and arcing forms inspired by nature, availing himself of the abstract freedom championed by Fauvist and Cubist painters. The following images offer a few examples.

Esherick created a multi-story space inside his home in which sinuous forms appear to be growing organically. It put me in mind of an indoor arboretum.

In the upstairs sitting/sleeping room, a bookcase follows the curve of the wall. Above it (not visible here) is another curved shelf.

Esherick built extra-deep drawers into the base of his bed, which looks out to the forest.

Esherick’s iconic staircase has two branches–one going up to the sitting/sleeping loft, the other to the dining area, kitchen, and elevated deck.

Dining with a view. The dining room is just off the kitchen and leads out to a deck. The pendant light shade, along with others in the house, is also Esherick’s work.

The museum reception center and bookstore are housed in this fantastically engineered 1928 Expressionist garage.

In 1966, four years before he died, Esherick added a three-story silo housing a colorful kitchen.

Not surprisingly, this kitchen has few straight lines. Esherick fashioned a sink with a fitted cutting board that sits flush with the surrounding counter.

Esherick put lights inside desks and cabinets. This base cabinet in his kitchen has a wooden front with green-painted interior, sculpted shelves, and a light that turns on when you open the door.

The Esherick Museum exceeded my expectations as an expression of artistic skill, vision, and a life fully lived. This post merely skims the surface. If you have an opportunity to visit, do. You’ll leave bursting with inspiration.

Further information:

Wharton Esherick Museum

Wharton Esherick and the Birth of the American Modern Edited by Paul Eisenhauer and Lynne Farrington

Wharton Esherick: The Journey of a Creative Mind , by Mansfield Bascom

Artists’ Handmade Houses , by Michael Gotkin with photography by Don Freeman

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Brad Point Bits

Drill & Impact Driver

PSA Sandpaper Roll

- How to Videos

- Customer Service

- Advertise/Media Kit

- Affiliate Program

- Become a Contributor

- Active Interest Media

Start typing and press Enter to search

anonymous_architecture

Proud Owners, Nosy Visitors: On Touring the Vanna Venturi and Margaret Esherick houses

Better ask for forgiveness rather than permission . As an architect who mostly travels for the sake of experiencing architecture, I have tried to adhere to that motto whenever I encounter a space that I have not planned.

For instance, a few years ago my wife Claudia and I made a trip to Philadelphia and while there, we decided to visit the Vanna Venturi House and the neighboring Esherick House, both at Chestnut Hill East , a 45-minute train ride from Philly. The first was designed by Robert Venturi for his mother in 1962 , and the latter for Margaret Esherick by the great Louis I. Kahn in 1959 .

Both houses are privately owned and we had not contacted the owners prior to our visit. The idea was to take pictures of the exteriors and if lucky, try to persuade the owners for an interior peek.

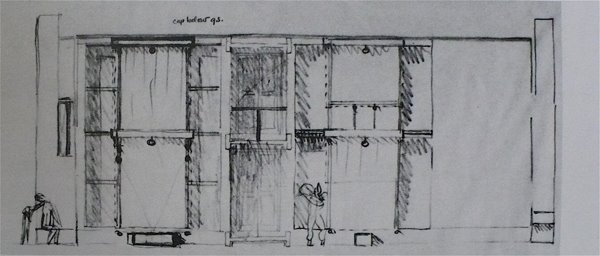

It was a chilly Sunday morning when we arrived. The Venturi House was first on our path. As we arrived the property, (and after jumping of excitement for how accessible the house was) I started sketching the iconic main elevation while Claudia was preparing herself to take some pictures.

Suddenly we devised a figure, who spotted us through the windows, that immediately rushed to the main door. We’re caught! was our first thought, knowing pretty well how many owners dislike such an invasion of privacy (especially on a Sunday morning). I mean, even if we had spent most of the train trip rehearsing how we would have explained our intentions, it was certainly to early for such shenanigans.

To our surprise, the owner greeted us by saying “you’re in luck! A few more minutes and I had already left the house!” And he kindly invited us in because he had a few minutes to spare and he recognized that we came from afar just to look at the house. Still in disbelief, we started apologizing for the intrusion.

He proceeded to let us know that he was a lawyer and that he had recently acquired the house and was well aware of its significance. While encouraging us to wander around he assured us that he enjoyed allowing to tour the house, more so if they were from out of town. He recounted the multiple times that Bob Venturi and Denise Scott-Brown brought visitors to tour the house.

After our tour, he pointed us towards the Esherick House and assured us that the owners also enjoyed visitors, but were much more careful since they had recently restored the entire wood flooring.

When we arrived at the Esherick it was still quite early and we did not feel as confident to push our luck so we sketched the house and took some pictures and left. A few weeks after posting our photos on social media, a friend from DC sent us an article about the house, and how much its current owners enjoyed having visitors touring the house. Needless to say, I felt disappointed for failing to adhere to the motto and not even trying to ring the door bell. I guess I’ll keep that in mind next time.

More about the houses

Designed by Robert Venturi for hi s mother, the Vanna Venturi House was built between 1962 and 1964. It was conceived during the period that Venturi was writing his seminal book Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture . Therefore, through the house, Venturi positioned himself against the stances of Modern Architecture. In contrast to the, less is more approach of Mies van der Rohe, at the Vanna House , Venturi preferred “… elements which [were] hybrid rather than “pure,” compromising rather than “clear,” distorted rather than “straightforward.”

Considered one of the first projects of Postmodernism — a movement in architecture when the ideas and ideals of Modernism were discarded and replaced with traditional (classical) elements and theories.

Notwithstanding, Venturi sought to push back against the purism of Modernism in praise for “complexity and contradiction” of hibridity in architecture which was more reflective of the times. Therefore, the classically arranged façade contrasted with the dynamism of the interior spaces.

Inside, an open living-dining area is located at the center, with a covered porch, kitchen space and the foyer on one side, and two bedrooms and a full bathroom on the other. The second floor, which account for one-third of the first level, there is a studio-bedroom, with its bathroom, walk-in closets and, a small balcony overlooking the backyard.

The fireplace has a dominant presence, not only at the main elevation, but also at the inside, where its central position. Seems to distort the main stairs. Indeed it seems that Venturi did not wanted to highlight the stairwell, which at first glance looks more like a sculpture, reducing its width as it abruptly ascends around the chimney.

The Esherick House was built between 1959 and 1962 for bookseller Margaret Esherick. The two-story one bedroom house is organized into what Kahn often referred as served spaces (primary areas like living rooms and bedrooms) and servant spaces (secondary areas like bathrooms, storages, corridors, and the like). Therefore, the Esherick House is divided into four main zones of served and servant spaces which run the full width of the house, from front to back.

On the ground floor, the two main served zones include on one side the foyer and dining room and on the other the living room. The double-height living room is the hierarchical space of the house. At the north wall there is a built-in bookcase and on the opposite side a window that spans the two floors.

Between the living room and the dining room, there is the thinnest of the servant zones. It contains the front and backyard entrances on the first floor; two small balconies above these entrances on the second; and the main stairs as well as a corridor overlooking the living room.

Parallel to the dining room, on the first floor, is the remaining servant zone that includes the kitchen*, originally the laundry room, recently converted into a secondary kitchen for daily use, and a half bath. On the second level, the main bathroom, laundry, and a walking closet are located.

On both ends of the longitudinal axis of the house, Kahn designed two sculptural fireplaces that articulate the — somewhat — blank walls.

* The renowned wood sculpture and cabinetmaker Wharton Esherick (uncle of Ms. Esherick) designed the original kitchen, used today only on special occasions.

Share this:

Published by jlorenzotorres

architect, urban designer, educator, draftsman View all posts by jlorenzotorres

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Visit Planning

- Plan Your Visit

- Event Calendar

- Current Exhibitions

- Family Activities

- Guidelines and Policies

Access Programs

- Accessibility

- Dementia Programs

- Verbal Description Tours

Explore Art and Artists

Collection highlights.

- Search Artworks

- New Acquisitions

- Search Artists

- Search Women Artists

Something Fun

- Which Artist Shares Your Birthday?

Exhibitions

- Upcoming Exhibitions

- Traveling Exhibitions

- Past Exhibitions

Art Conservation

- Lunder Conservation Center

Research Resources

- Research and Scholars Center

- Nam June Paik Archive Collection

- Photograph Study Collection

- National Art Inventories Databases

- Save Outdoor Sculpture!

- Researching Your Art

Publications

- American Art Journal

- Toward Equity in Publishing

- Catalogs and Books

- Scholarly Symposia

- Publication Prizes

Fellows and Interns

- Fellowship Programs

- List of Fellows and Scholars

- Internship Programs

Featured Resource

For Lifelong Learners

- Adult Learners

- Group Tour Request

Learn from Home

- Resources for Learning at Home

- Support the Museum

- Corporate Patrons

- Gift Planning

- Donating Artworks

- Join the Director's Circle

- Join SAAM Creatives

Become a member

About the Author

Fátima Olivieri A native of Puerto Rico, Fátima Olivieri is a designer/writer who has called Philadelphia home since early 2011. Prior to moving to the city, Fátima worked at an architecture firm in Charlottesville, VA and taught at the University of Virginia School Of Architecture, where she graduated with her Master of Architecture in 2010. She currently works at an architecture firm in Center City and has been guest critic at various architecture schools in the area.

One Comment:

Given that the National Trust was given Kahn’s Fisher House last year and turned around and sold it, it doesn’t seem they have much interest in owning any more modernist buildings at the moment.

It’s a shame, as the Esherick House seems almost too important to remain in private hands.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to access savingplaces.org.

National Trust for Historic Preservation: Return to home page

Site navigation, america's 11 most endangered historic places.

This annual list raises awareness about the threats facing some of the nation's greatest treasures.

Join The National Trust

Your support is critical to ensuring our success in protecting America's places that matter for future generations.

Take Action Today

Tell lawmakers and decision makers that our nation's historic places matter.

Save Places

- PastForward National Preservation Conference

- Preservation Leadership Forum

- Grant Programs

- National Preservation Awards

- National Trust Historic Sites

Explore this remarkable collection of historic sites online.

Places Near You

Discover historic places across the nation and close to home.

Preservation Magazine & More

Read stories of people saving places, as featured in our award-winning magazine and on our website.

Explore Places

- Distinctive Destinations

- Historic Hotels of America

- National Trust Tours

- Preservation Magazine

Saving America’s Historic Sites

Discover how these unique places connect Americans to their past—and to each other.

Telling the Full American Story

Explore the diverse pasts that weave our multicultural nation together.

Building Stronger Communities

Learn how historic preservation can unlock your community's potential.

Investing in Preservation’s Future

Take a look at all the ways we're growing the field to save places.

About Saving Places

- About the National Trust

- African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund

- Where Women Made History

- National Fund for Sacred Places

- Main Street America

- Historic Tax Credits

Support the National Trust Today

Make a vibrant future possible for our nation's most important places.

Leave A Legacy

Protect the past by remembering the National Trust in your will or estate plan.

Support Preservation As You Shop, Travel, and Play

Discover the easy ways you can incorporate preservation into your everyday life—and support a terrific cause as you go.

Support Us Today

- Gift Memberships

- Planned Giving

- Leadership Giving

- Monthly Giving

What Life is Like in Louis Kahn's Esherick House

- More: Modern Architecture

- By: Katherine Flynn

In early January, we rounded up the current status of each of the nine private homes designed by renowned Modern architect Louis Kahn, all located in the greater Philadelphia metro area. After seeing our post, the new owners of the Esherick House in Chestnut Hill reached out to us, hoping to share their story.

Paul Savidge, the head of policy at a pharmaceutical company, and his husband Dan Macey, a food stylist, purchased the house in February of 2014 after falling in love with it on a realtor’s tour. The house had been on the market for several years due to what Savidge calls “livability issues”—i.e. its small size and single bedroom, ideal for one person but not well-suited for any more than two.

Built between 1959 and 1962 for bookseller Margaret Esherick and featuring a kitchen designed by her uncle, the renowned wood sculptor and cabinetmaker Wharton Esherick, the house’s southeast-facing wall, comprised almost entirely of windows, lets in an abundance of light. It’s also only one of two of Kahn’s houses to have historic designation, and in 2016, Savidge and Macey won a Citation of Merit in the annual Docomomo Modernism in America Awards for their restoration efforts on the structure.

photo by: Paul Savidge

The southeast-facing back wall of the Esherick House floods the home with natural light.

I chatted with Savidge about the unique rewards and challenges of living in the house, and the couple's plans for its future.

Architecture students from the University of Pennsylvania listen to architectural historian William Whitaker speak in the Esherick House’s living room in fall 2014.

What initially drew the two of you to the house?

Well, we were aware that it was for sale for a significant period of time. We love great modern architecture and design and of course we’re familiar with Kahn, and in the fall of 2013 we decided to go see the house with a real estate agent we know. We had lived in Chestnut Hill once before, and we were probably more curious than serious. And then [we] were quite taken with it, and thought, “Why shouldn’t we be the stewards of this house and have the opportunity to promote its welfare and all the good things that go along with living in such a place?”

So, I think it was a number of things—based mostly in our love of good design. It’s thrilling to think that we’ve become associated with something like this, and we felt very strongly that we were going to be able to take really good care of it.

What has living in the house been like?

It’s been great for a number of reasons. We’ve been able to meet a whole society, a whole group of people that are new to us, people that are part of the architecture and design community—people like Bill Whitaker at the Kahn Archive at the University of Philadelphia. It’s been an education and it’s been thrilling to make the acquaintance of all these people, people who have interest in Kahn and the house.

We have a lot of visitors to the house, especially in nice weather. I think we’ve been very gracious to people who are interested in and have come to see the house. So that’s been great, just enjoying and sharing the house with other people.

The house is a very special place. It was very well maintained by its previous owners, the Gallaghers, who we bought the house from. I think one of the reasons why the house took so long to sell was because it had some livability issues, and we’re trying to address those now. Our idea is that the house is only going to survive and be viable as a private residence, so we needed to bring the house into the 21st century and let technology and modern advances in mechanics really give the house advantages in its sustainability. We’re not doing anything that injures the integrity of the house.

As I understand it, this is one of only two Kahn houses to have historic designation. What are the constraints on what you can and can’t do to the house?

The house has been on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places since 2009. That makes certain kinds of changes to the home, especially those to the exterior, subject to the review of the commission [the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places]. We just went to meet [with our architect] and talk about what we were thinking about, and subsequently got approval on all the work that we’re doing. The line between what is subject to their approval and what is not is not entirely clear—but, we’ve been very forthcoming because we didn’t want anyone to be surprised. We’ve also been the same way with the University of Pennsylvania and the head of the Kahn library there, Bill Whitaker, because he’s been a very good source of information to us.

Has living in the house posed any unique challenges?

Nothing that we didn’t foresee. The fact that you get a lot of attention from the public and people come by—we’re more delighted by it than anything else. In the summer, we can put the air conditioning on, but when it gets cold the house tends to be cold, so we’re installing a new heating system, for example, just to upgrade what was there.

I would say the major challenge we had was using the kitchen in the house. The kitchen, as you probably know, was designed by Wharton Esherick, who was the uncle of Margaret Esherick. It’s a very special kitchen, but sensitive. It wasn’t the kind of place where you felt comfortable really doing a lot of cooking because you didn’t want to disturb any of the woodwork and things like that. So, entertaining in the house was a challenge, and oftentimes if we had people over we would bring food into the house from external sources.

The street view of the Esherick House.

We’re in the midst of a preservation effort of the kitchen—we’ve brought in the people from the Wharton Esherick Museum [in Malvern, Pennsylvania] to help us. And then, the utility room that Kahn designed—all of the utilities of that room, the furnace, the heater, the gas meter, and some very ugly plumbing—we’re creating a modern kitchen in that space. Now the house will have a new kitchen next to the Wharton Esherick kitchen, which will be highly usable. That work is underway, and it’ll be finished sometime this spring.

Who are you working with on the kitchen redesign?

The architect and designer are really working with Dan and me and being drivers of the design and the changes. The architect’s name is Kevin Yoder, and he’s a Philadelphia architect. He has some experience working with important contemporary houses. The designer’s name is Louise Cohen. So together with the contractor, it’s been a very good team, and we continue to work with them. Obviously, the job isn’t finished.

What’s your absolute favorite thing about the house?

The house has amazing light. It’s a house where—and I think Kahn made a study of this house, the light at any time of the day the light in the house changes, but it’s a very soothing light—it’s a light that makes [the house] a wonderful place to read, a wonderful place to study. At the Fisher house , I think they made some more comments about that, but it’s true—it can be just a very glorious place to be, really in any type of weather, but on a sunny day it’s just striking. It’s a house with a lot of energy—it’s just a remarkable place to live.

Katherine Flynn is a former assistant editor at Preservation magazine. She enjoys coffee, record stores, and uncovering the stories behind historic places.

- X (Twitter)

Like this story? Then you’ll love our emails. Sign up today.

Sign up for email updates, sign up for email updates email address.

Related Stories

This May, our Preservation Month theme is “People Saving Places” to shine the spotlight on everyone doing the work of saving places—in big ways and small—and inspiring others to do the same!

Today Explained

Listen live.

Fresh Air opens the window on contemporary arts and issues with guests from worlds as diverse as literature and economics. Terry Gross hosts this multi-award-winning daily interview and features program.

- Urban Planning

- Architecture & Design

- Preservation

Restoration of Louis Kahn’s Esherick House honored

One of the world’s best known midcentury modern homes, designed by one of the 20th century’s greatest architects and a renowned sculptor, will be in the spotlight this week for a restoration that made it a comfortable, livable space for 21st century inhabitants.

The team involved in the restoration of the Margaret Esherick House in Chestnut Hill has been honored by the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia with a Preservation Achievement Award , celebrated at ceremonies hosted Wednesday. They will be honored as much for the way they protected the original integrity of the house as for the actual changes they made to the iconic structure.

“This was a really sensitive restoration of an important Louis Kahn house – one of only nine homes designed by Kahn,” explained Carolyn Boyce, outgoing executive director of the Preservation Alliance. “It’s widely regarded as one of his best works.”

“The jury was very impressed with the level of detail and care,” in the team’s approach to the project, Boyce said.

Paul Savidge and Dan Macey purchased the house in February 2014, after years on the market. Savidge and Macey found that the home, which was built in 1959-62, had been very well maintained by its previous owners. But it needed new utility systems, as many midcentury houses do after 50-plus years, and it needed a more practical kitchen.

The house had been built for the niece of the woodworking sculptor and furniture maker Wharton Esherick, who designed an exquisitely turned kitchen for Margaret.

“We wanted to figure out a way to protect the Esherick kitchen and have facilities to entertain and use on a daily basis,” Savidge said. “So the focus of the restoration was on finding a space for a new kitchen and reducing the wear and tear on the original kitchen.”

The 16-month project meant Savidge and Macey spent only occasional periods actually living in their new house. It also meant engaging a group of experts who could plan and execute a preservation effort that would respect the original, historic design.

“We had never lived in a place like this before. It was absolutely critical to us to maintain the dignity of the house as Kahn had designed it,” Savidge said.

To lead the restoration project, the owners chose architect Kevin Yoder, who had never worked on a Kahn building before. But he had worked on projects in homes designed by I.M. Pei, and lives in a Pei townhouse. He had also helped restore a house designed by Philadelphia midcentury architect Vincent Kling, and became familiar with the materials and details of modernist design and the excitement and inspiration of working with the designer’s original documents.

Yoder worked closely with Savidge and Macey, “who were extremely concerned with being good stewards for the architecture,” he said.

The initial phase of the Esherick House restoration – the investigation of how the work would be done – took at least as much time as the actual construction, Yoder said. “The strategy was the thing that was most important, and we took the appropriate time to do as much homework and research” as needed.

Developing the plan involved consultation with the Philadelphia Historical Commission, which had listed the house on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places in 2009. Yoder also turned to Bill Whitaker, curator of the Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania and an expert on Kahn who was able to provide Kahn’s drawings for the house.

“So we had a very good framework and background for knowing what was originally there and what was appropriate,” Yoder said.

The solution to making the midcentury house into a livable home was moving modernizations into hidden and secondary spaces. The creation of a supplemental kitchen in the utility room next to Esherick’s original copper and wood kitchen. That involved “discretely” relocating the utilities throughout the building and installing a functional kitchen in the room, Yoder explained. “The utility room was not of historic nature.”

The furnace was transplanted in a crawl space, which meant turning it on its side to fit into the 40-inch high space. “That was a major breakthrough,” Savidge recalled.

The water heater was replaced with a tankless water heater tucked into the crevice of the chimney. The washer/dryer was moved to a closet on the second floor.

The other challenge was the new kitchen cabinetry. The design team consulted with Whitaker and the experts at the Wharton Esherick Museum in Malvern. Careful consideration was given to the work of Esherick and Kahn and finding a way to make the new kitchen fit the context of the house.

“Our intent was to make it new. We decided to pick up the coloration of the original wood and have a simple clean design, distinctly different from the rest of the house,” Yoder said.

The overall project was a “combination of conservation and restoration,” he said. “Our goal in the design was to respect the original house and make it livable for the new owners. Adding a secondary kitchen allows them to preserve the original kitchen and minimize its use. At the same time, we’re didn’t change any historic elements of the house and maintained the living spaces” as Kahn had intended, Yoder said.

“We paid strict attention to the spatial rigor of the house as designed by Kahn. All our solutions and interventions were in support of that goal.”

In addition to k YODER Design , the Preservation Achievement Award recognizes Louise Cohen Interiors; Hansell Contractors, Inc.; Keast & Hood Structural Engineers; Materials Conservation Co.; University of Pennsylvania; Wharton Esherick Museum; The Marble Restoration Company; AV Environments; Lafont Studio; and Jeffrey Totaro Architectural Photographer. The award also names the owners, Savidge and Macey, who credit the “crackerjack team” involved in the project.

“All this was done with little impact on Kahn’s vision for the house,” Savidge said. “We didn’t do any damage; we just improved its livability.

“It’s a very terrific place to live, and still a great house.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

Brought to you by PlanPhilly

In-depth, original reporting on housing, transportation, and development.

You may also like

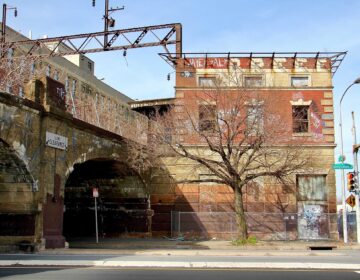

Developer files appeal to halt demolition of Reading Railroad station

A spokesperson for Arts & Crafts Holdings said Reading International needs to clean up the derelict Spring Garden Street station.

3 years ago

Former Mayor John Street criticizes Kenney’s record on preservation; backs new PAC

6 years ago

On Market East, an unusual fight in old battle pitting preservation against progress

About Alan Jaffe

Want a digest of WHYY’s programs, events & stories? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Together we can reach 100% of WHYY’s fiscal year goal

RESERVATIONS REQUIRED: BOOK YOUR TOUR HERE

Explore the studio, stay connected to the optimism and warmth of esherick’s studio through our online resources., dancing with esherick: eurythmy workshop and exhibition talk, april 27 @ 1:00 pm - 3:45 pm, exhibition talk: wharton esherick’s rhythmic art, april 27 @ 3:00 pm - 4:00 pm, spotlight talk: preserving esherick’s 1966 silo, april 30 @ 12:00 pm - 12:30 pm.

View Past Programs

Take a Virtual Tour

Enjoy a virtual visit to the museum no matter where you are. use the highlighted spaces at the bottom of the screen to move directly to your favorite spots in esherick’s studio., our e-newsletter brings you monthly news and special updates from the hilltop including programs, exhibitions, discoveries from our archives — and other esherick fun you won’t want to miss, join our mailing list:, ready for a new zoom background why not make your next video call from the studio.

Download Image

View Zoom instructions for uploading a background

Arts of Wharton Esherick

By Colin Fanning

The unconventional artistic trajectory and prolific work of prominent Philadelphia-area artist and craftsman Wharton Esherick (1877–1970) have been claimed for and by multiple movements in the history of twentieth-century American art, from early-twentieth-century Arts and Crafts to postwar studio craft. Working across a wide variety of media, including printmaking, sculpture, furniture, and theatrical design, Esherick also attained fame for the studio he built over several decades in Paoli, Pennsylvania, which became a draw for other creative figures from Greater Philadelphia and farther afield. Directly shaped by him over the course of decades, the building and its site became an extension of his integrative approach to the arts.

Born to a well-to-do West Philadelphia family, Esherick attended the Central Manual Training High School and trained in printmaking and commercial art at the Pennsylvania Museum School of the Industrial Arts (later University of the Arts). In 1908 he received a scholarship to study painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts , where he worked under some of the leading Pennsylvania Impressionist painters of the day. However, apparently dissatisfied with academic constraints, he left the academy before completing his studies and began working as a commercial artist and book illustrator while attempting to sell paintings. In 1913, he moved with his new wife Leticia (“Letty,” 1892–1975) to a small farm in Paoli that they called Sunekrest (pronounced “sunny crest”), drawn by an idealized notion of rural life that would allow him to develop as an artist. Although Esherick struggled to find an audience for his paintings, the wood frames he began carving for them drew praise, and from the early 1920s he increasingly worked as a sculptor in wood, as well as a printmaker and maker of functional objects. His prints and sculptural work in particular exhibited the smooth contours and semi-abstraction that characterized the growing modernist art movement in the United States.

In 1926, he began building a barnlike studio on his land, somewhat removed from the farmhouse he shared with Letty and their children Mary (1917–96), Ruth (1923–2015), and Peter (1926–2013). Esherick modeled his studio after the region’s historic barns, constructing thick stone walls with the help of a local stonemason and intentionally introducing curves to the architecture in a suggestion of timelessness. Esherick’s conscious evocation of vernacular barn architecture was influenced by Expressionist tradition and certainly by Greater Philadelphia’s rural Arts and Crafts art colonies (like nearby Rose Valley ), with their attempts to integrate the visual, applied, and performing arts into a utopian vision of “honest” labor and social cohesion.

Esherick had an even more direct connection to Rose Valley through his involvement in the Hedgerow Theater , established in 1923 in the colony’s former mill building after the Rose Valley Association and its workshops had disbanded in 1910. He designed and built furniture, stage sets, and interior fittings for the theater and made prints to promote performances. He even displayed his sculpture works there, using the theater as a kind of informal gallery. Esherick maintained close connections to the performing and literary arts throughout his career. He developed friendships with many of the authors, playwrights, dramaturges, and educators who worked with the Hedgerow Theater; those he met in New York City or during his family’s summer travels to dance camps; and the circle of Philadelphia’s Centaur Book Shop and Press, whose focus on small-edition fine book printing appeal to Esherick’s sense of workmanship. He would also occasionally host literary and theatrical guests at his home and studio, which acted as a kind of crossroads between art forms.

Although furniture would become his best-known work, it was initially a somewhat tangential endeavor for Esherick, who early on designed and built pieces as need arose or for special favors to friends. His early designs were heavily built and vaguely inspired by medieval forms, clearly expressing the joinery and carving techniques that went into their making. Some prominent furniture and interior commissions in the Philadelphia area, New York City, and elsewhere in the late 1920s and into the 1930s brought Esherick increasing attention as a designer. Many of his inventive asymmetric furniture forms—called “prismatic” or later even “Cubist” by commentators—showed an attention to the growing popularity of Art Deco , while his commitment to a high level of craftsmanship brought his functional work increasing acclaim. His growing success was all the more notable for the relative lack of a robust professional network for fine woodworking (academic programs, professional organizations, publications, and galleries) at the time.

Esherick’s largest commission in both physical and financial terms began in 1935 for the judge Curtis Bok (1897–1962; son of the Philadelphia publisher Edward Bok [1863–1930]) and took three years to complete. He provided stylistically inventive architectural elements and furniture for a suite of rooms including a library, a dining room, a music room, as well as a dramatic spiral staircase for the house’s entry hall. By the late 1930s, he was creating slender, organic furniture forms that became his signature in the latter part of his career, which lasted well into the postwar decades. A key vehicle of his success was the inclusion of some of this furniture—along with the dynamically cantilevered spiral stair he had added to his studio in 1930—in the “Pennsylvania Hill House” display at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, designed in collaboration with Philadelphia architect George Howe (1886–1955). Esherick also continued expanding the studio building, adding a kitchen and living quarters as he spent ever more time on his work, especially after separating from Letty in 1937.

After Esherick’s death in 1970, his children and heirs incorporated the nonprofit Wharton Esherick Museum , preserving the studio building and its contents almost entirely intact. Open to the public since 1972, Esherick’s former studio tells the story of his practice through the preservation and interpretation of his living and working environment. Individual works by Esherick have been acquired by public collections around the United States—as have some of the interiors from the Bok House, salvaged before its demolition in 1989—but the Wharton Esherick Museum’s establishment created an institution uniquely placed to conserve and study Esherick’s varied artistic career and its lasting impact on Greater Philadelphia’s cultures of making. While commentators and historians have described him variously as an inheritor of the Arts and Crafts tradition, a linchpin of interwar modernism, or a father of postwar studio craft, Esherick’s chief legacy lies in his ability to bridge these categories and their wide chronological span.

Colin Fanning is Curatorial Fellow in the Department of European Decorative Arts and Sculpture at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He holds an M.A. in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture from the Bard Graduate Center. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

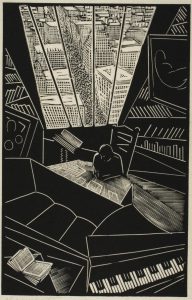

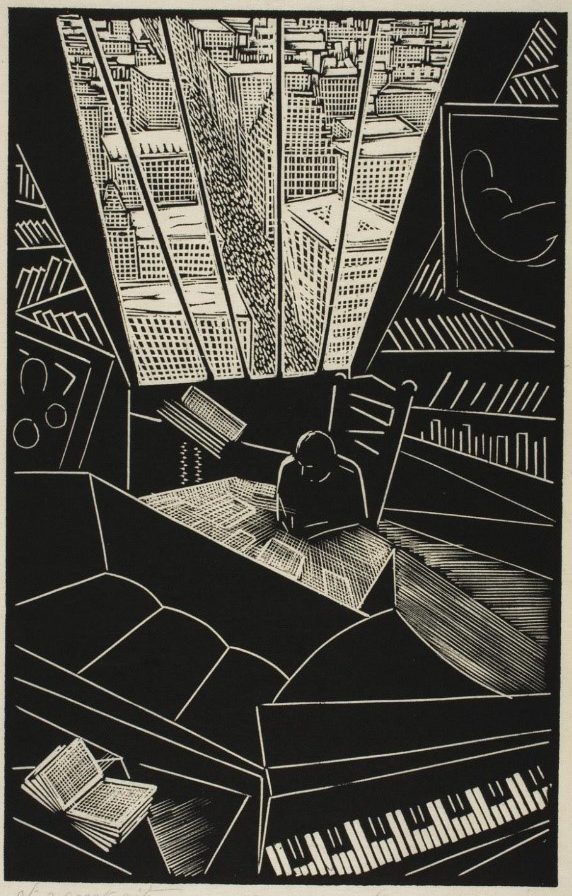

Of a Great City , 1927

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

One of Esherick’s early jobs after he left the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts was as a commercial artist, and the graphic arts—drawing, printmaking, and book illustration—would continue to play a prominent role in his artistic practice. Closely connected to the theater and literary communities of both Greater Philadelphia and New York City, he made a number of prints to promote theatrical performances or to be published as illustrations in books written by his friends and acquaintances (or, in one notable case, a small-batch edition of Walt Whitman’s Song of the Broad Axe, which Esherick deeply admired). This woodblock print, however, was more personal in nature, completed as a gift for the novelist and journalist Theodore Dreiser, whom Esherick had met in 1924 and often visited in New York City. This dynamic composition shows a fragmented, almost Cubist view of Dreiser’s apartment in midtown Manhattan. Despite Esherick’s penchant for rustic living on his Paoli homestead, he frequently traveled to and showed work in New York, moving with apparent ease between urban and rural settings.

“Of a Great City,” 1927. By Wharton Esherick (American, 1887–1970). Wood engraving. Sheet: 11 7/16 × 7 1/2 inches (29.1 × 19.1 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art, Purchased with the Lola Downin Peck Fund from the Carl and Laura Zigrosser Collection, 1979.

Abstract Head , 1927

Esherick worked at a range of scales in his sculpture, shaping wood into streamlined forms that meshed with wider trends in American art of the 1920s and 1930s. He completed a number of abstracted heads and busts like this work—some intended as specific portraits of other artists and authors he met and hosted at his rural home and studio—along with monumental figures in a similar streamlined style. Dance as an art form held significant appeal to Esherick, and a number of his sculptures and prints were more finished versions of sketches he made to study the fluidity of bodies in motion.

“Abstract Head,” 1927. By Wharton Esherick (American, 1877–1970). Rosewood. 10 1/2 × 5 1/2 inches (26.7 × 14 cm). © Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Gertrude W. Dennis, 1996.

Drop-Leaf Desk, 1927

Wharton Esherick Museum

Esherick’s early furniture forms expressed influence from the American Arts and Crafts movement—typically built in heavy, solid shapes that referenced medieval forms, with decoration carved into the surfaces. This drop-leaf desk from 1927 is in this vein, but the carving has echoes of his printmaking work from the same period and shows his gradual move towards more original kinds of woodworking. The desk’s overall shape is relatively simple, but the faces are expressively carved with an abstracted scene of a winter forest—roots and bark patterns on the lower doors, bare branches on the desk front, and two birds (identified anecdotally as turkey vultures) on the upper cabinet doors. Esherick referred to such illustration-like ornament as “literature” and, although he would later move away from carved surfaces towards more sculptural forms in his furniture, this alludes to his belief in the importance of integration among the arts rather than hierarchical division.

Red Oak Drop-Leaf Desk, 1927, by Wharton Esherick. Photograph by James Mario. Image courtesy of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

Fireplace and Doorway from the Bok House Library

Esherick’s largest commission was for Judge Curtis Bok, for whom he completed several architectural woodworking schemes and items of furniture between 1935 and 1938. This photograph shows the fireplace and doorway in the small library of the house (called the “book room” by the family). The forms seem to express an influence from the angular language of Cubism, but Esherick’s design also brings the material itself into sharp focus, emphasizing the visual qualities of the wood grain and the detailed joinery techniques used in its construction. Through the doorway was the music room, and this photograph provides a glimpse of Esherick’s “prismatic” furniture and wall and ceiling paneling, and hints at his clever schemes to disguise the audio system equipment: the painting over the fireplace could be raised to expose a speaker grille, also designed by Esherick. Before the Bok House was demolished in 1989, the library fireplace and doorway, as well the music room and its contents, were carefully disassembled for acquisition by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, preserving an important aspect of his dynamic experiments in architectural form during the 1930s.

Bok House fireplace and doorway, c. 1938. Photograph by Edward Quigley. Photograph courtesy of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

Esherick Studio Spiral Stair

Library of Congress

One of the most distinctive interior features of Esherick’s studio is this cantilevered spiral staircase, which he added in 1930. Made from ax-hewn red oak, the impressive structural engineering of the stair (each step is a solid piece of wood, attached with a mortise-and-tenon joint to an upright log) plays counterpoint to the unusual trapezoidal forms and the elegant twisted spiral of the central trunk. This staircase became one of the most iconic pieces of Esherick’s work when it was removed from the studio for display at the “Pennsylvania Hill House” exhibition at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. Designed by Philadelphia architect George Howe, the Hill House display also contained a set of chairs, a sofa, and a table by Esherick, gaining a massive amount of exposure for his innovative designs and fine workmanship. In this photograph, the short hanging stair at left dates from a later addition when Esherick added another second-floor room to his studio.

Music Stand

RISD Museum

One of Esherick’s few works to be produced in serially (in an edition of twenty-four), this music stand typifies the slender organic quality of his later furniture work—which, in some ways, recalls the fluid treatment of material in his early wood sculpture. The prototype of this form was made for a cellist friend, and includes the small but thoughtful detail of a lower shelf to hold a drink. By the time of the stand’s small-batch production, the postwar resurgence of interest in “studio craft” in the United States had taken hold, with many commentators placing Esherick in the simultaneous position as both a pioneer of the movement and one of its current driving forces.

Music Stand, 1962. Wharton Esherick (American, 1887–1970) Cherry wood. 43 3/4 × 19 inches (111.1 × 48.3 cm). Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, The Felicia Fund, 1988.002. Photography by Erik Gould, courtesy of the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence.

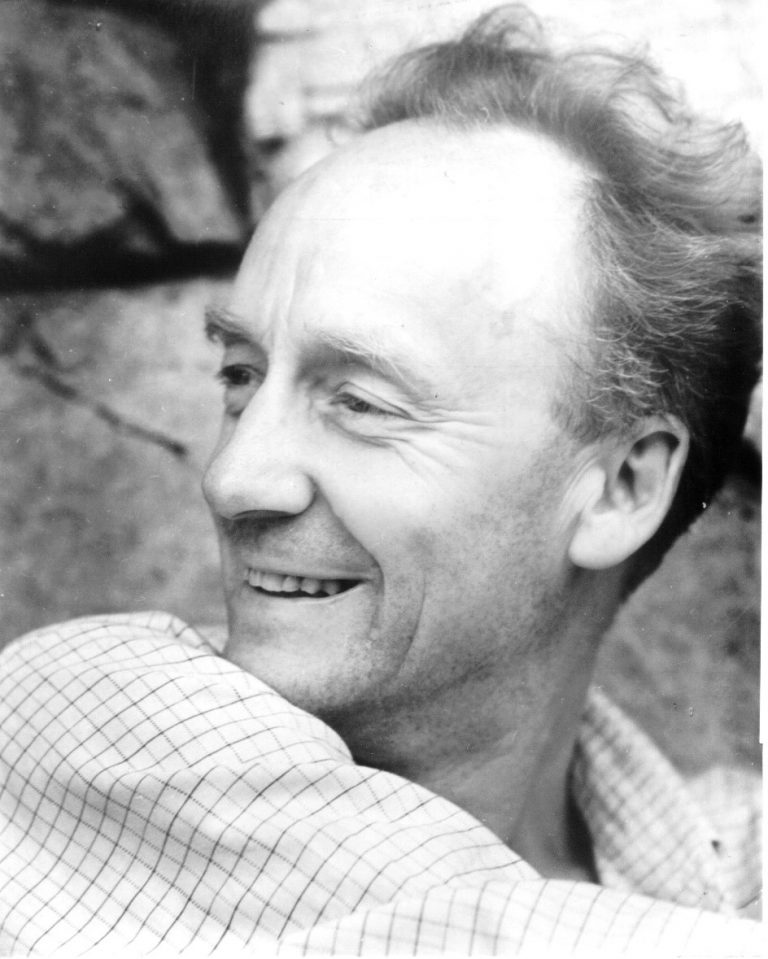

Wharton Esherick c. 1930

Born in West Philadelphia in 1877, trained in painting and printmaking at Philadelphia-area institutions, and by 1911 making a living as a commercial artist, Wharton Esherick was hailed as “the dean of American craftsmen.” His interest in woodworking developed from early efforts at making and carving his own frames for his Impressionist-style paintings he tried (mostly unsuccessfully) to sell. By the time this photograph was taken in about 1930, by Esherick’s friend, photojournalist Conseulo Kanaga, Esherick had completed some of the furniture and interior commissions that would propel him to renown for his designs and high level of craftsmanship. Indeed, Kanaga was introduced to Esherick by one of his clients from New York City, Marjorie Content, also a photographer.

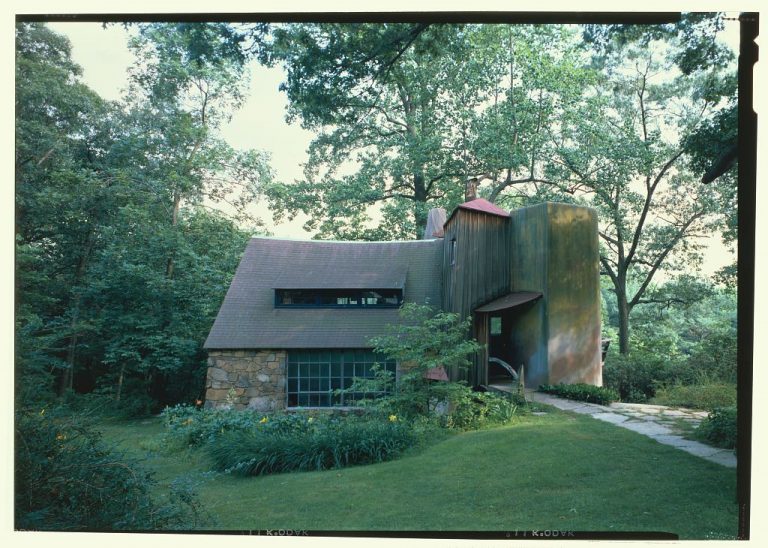

Wharton Esherick Paoli Studio

Esherick began building his studio in 1926 on the land in Paoli, Pennsylvania, he had bought with his wife, Letty. He sited it at a remove from the farmhouse he shared with Letty and their children, preferring to work in relative solitude. Esherick built the heavy, tapering stone walls with the help of local stonemason Bert Kulp and introduced an intentional “sag” to the roof. His aim was to mimic the regional architecture of old barns, and he used cast-off stone and recycled timbers to enhance the impression of age. Despite these romantic touches, the studio was also designed with a keen eye toward function, with large north-facing windows for ample light and wide double doors for the passage of large logs or finished sculptures. Over the decades, Esherick also built living quarters and a kitchen within the barn-like structure and spent an increasing majority of his time there, sometimes renting out the farmhouse for extra income. Despite its seeming isolation, though, the studio was a gathering place for his friends, colleagues, and collaborators. Its bucolic location made it a peaceful place, and Esherick’s careful crafting of the building’s exterior and interior gave it a sense of timelessness. The last major alteration can be clearly seen in this photograph: the tower, which Esherick called a “silo,” was built around 1966 and appears as an irregular oval in plan. Esherick mixed pigment into the tower’s stucco as it was applied, creating a kind of abstract fresco of autumn colors.

Related Topics

- Greater Philadelphia

- Philadelphia and the Nation

- Athens of America

Time Periods

- Twentieth Century after 1945

- Twentieth Century to 1945

- Chester County, Pennsylvania

- Arts and Crafts Movement

- Book Publishing and Publishers

- Furnituremaking

- Pennsylvania Impressionism

- Printmaking

- Painters and Painting

Related Reading

Bascom, Mansfield. Wharton Esherick: The Journey of a Creative Mind . New York: Abrams, 2010.

de Muzio, David. “Wharton Esherick’s Museum Room from the Curtis Bok House, Gulph Mills, Pennsylvania, 1935–1938.” Winterthur Portfolio 46, No. 2/3 (Summer/Autumn 2012): E58–E74.

Eisenhauer, Paul, ed. Wharton Esherick Studio and Collection . 3 rd edition. Atglen, Pa: Schiffer Publishing, 2010.

Eisenhauer, Paul, and Lynne Farrington, eds. Wharton Esherick and the Birth of the American Modern . Atglen, Pa: Schiffer Publishing, 2010.

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Wharton Esherick, Master of the Woodcut . Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1991.

Polsky, Richard. “Oral history interview with Mansfield Bascom and Ruth Esherick Bascom about Wharton Esherick,” July 13, 1990. Washington, D.C.: Archives of American Art.

Ramljak, Suzanne. Crafting a Legacy: Contemporary American Crafts in the Philadelphia Museum of Art . Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2002.

Renwick Gallery and Minnesota Museum of Art. Woodenworks; Furniture Objects by Five Contemporary Craftsmen: George Nakashima, Sam Maloof, Wharton Esherick, Arthur Espenet Carpenter, Wendell Castle . St. Paul: Minnesota Museum of Art, 1972.

Skinner, Tina. Esherick, Maloof, and Nakashima: Homes of the Master Wood Artisans . Atglen, Pa: Schiffer Publishing, 2009.

Woodmere Art Museum and Wharton Esherick Museum. Prints by Wharton Esherick . Philadelphia: Woodmere Art Museum, 1984.

Related Collections

- Metropolitan Museum of Art 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y.

- Museum of Arts and Design 2 Columbus Circle, New York, N.Y.

- Philadelphia Museum of Art 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia.

- Renwick Gallery Smithsonian Institution 1661 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington, D.C.

- Wharton Esherick Studio and Museum 1520 Horseshoe Trail, Malvern, Pa.

- Wolfsonian-FIU Museum 1001 Washington Avenue, Miami Beach, Fla.

Related Places

- Wharton Esherick Studio and Museum

- Wolfsonian-FIU Museum

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Woodblock prints from first steps of Wharton Esherick's career published again (WHYY, July 14, 2015)