A Brief History of the Age of Exploration

The age of exploration brought about discoveries and advances

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

- Key Figures & Milestones

- Physical Geography

- Political Geography

- Country Information

- Urban Geography

The Birth of the Age of Exploration

The discovery of the new world, opening the americas, the end of the era, contributions to science, long-term impact.

- M.A., Geography, California State University - East Bay

- B.A., English and Geography, California State University - Sacramento

The era known as the Age of Exploration, sometimes called the Age of Discovery, officially began in the early 15th century and lasted through the 17th century. The period is characterized as a time when Europeans began exploring the world by sea in search of new trading routes, wealth, and knowledge. The impact of the Age of Exploration would permanently alter the world and transform geography into the modern science it is today.

Impact of the Age of Exploration

- Explorers learned more about areas such as Africa and the Americas and brought that knowledge back to Europe.

- Massive wealth accrued to European colonizers due to trade in goods, spices, and precious metals.

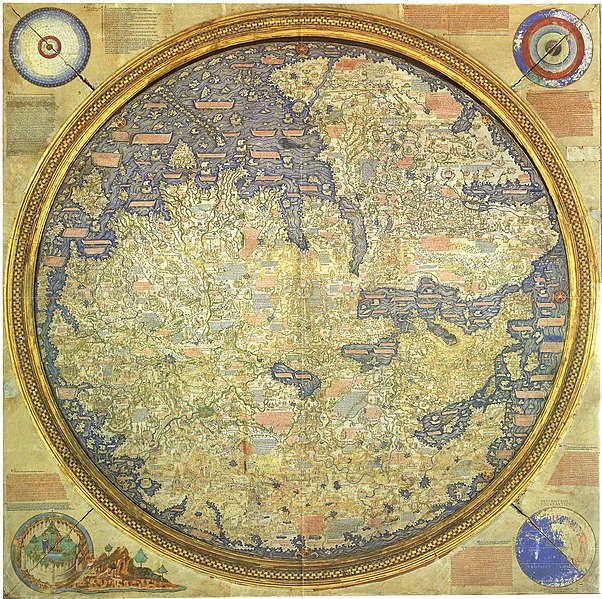

- Methods of navigation and mapping improved, switching from traditional portolan charts to the world's first nautical maps.

- New food, plants, and animals were exchanged between the colonies and Europe.

- Indigenous people were decimated by Europeans, from a combined impact of disease, overwork, and massacres.

- The workforce needed to support the massive plantations in the New World, led to the trade of enslaved people , which lasted for 300 years and had an enormous impact on Africa.

- The impact persists to this day , with many of the world's former colonies still considered the "developing" world, while colonizers are the First World countries, holding a majority of the world's wealth and annual income.

Many nations were looking for goods such as silver and gold, but one of the biggest reasons for exploration was the desire to find a new route for the spice and silk trades.

When the Ottoman Empire took control of Constantinople in 1453, it blocked European access to the area, severely limiting trade. In addition, it also blocked access to North Africa and the Red Sea, two very important trade routes to the Far East.

The first of the journeys associated with the Age of Discovery were conducted by the Portuguese. Although the Portuguese, Spanish, Italians, and others had been plying the Mediterranean for generations, most sailors kept well within sight of land or traveled known routes between ports. Prince Henry the Navigator changed that, encouraging explorers to sail beyond the mapped routes and discover new trade routes to West Africa.

Portuguese explorers discovered the Madeira Islands in 1419 and the Azores in 1427. Over the coming decades, they would push farther south along the African coast, reaching the coast of present-day Senegal by the 1440s and the Cape of Good Hope by 1490. Less than a decade later, in 1498, Vasco da Gama would follow this route all the way to India.

While the Portuguese were opening new sea routes along Africa, the Spanish also dreamed of finding new trade routes to the Far East. Christopher Columbus , an Italian working for the Spanish monarchy, made his first journey in 1492. Instead of reaching India, Columbus found the island of San Salvador in what is known today as the Bahamas. He also explored the island of Hispaniola, home of modern-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Columbus would lead three more voyages to the Caribbean, exploring parts of Cuba and the Central American coast. The Portuguese also reached the New World when explorer Pedro Alvares Cabral explored Brazil, setting off a conflict between Spain and Portugal over the newly claimed lands. As a result, the Treaty of Tordesillas officially divided the world in half in 1494.

Columbus' journeys opened the door for the Spanish conquest of the Americas. During the next century, men such as Hernan Cortes and Francisco Pizarro would decimate the Aztecs of Mexico, the Incas of Peru, and other indigenous peoples of the Americas. By the end of the Age of Exploration, Spain would rule from the Southwestern United States to the southernmost reaches of Chile and Argentina.

Great Britain and France also began seeking new trade routes and lands across the ocean. In 1497, John Cabot, an Italian explorer working for the English, reached what is believed to be the coast of Newfoundland. A number of French and English explorers followed, including Giovanni da Verrazano, who discovered the entrance to the Hudson River in 1524, and Henry Hudson, who mapped the island of Manhattan first in 1609.

Over the next decades, the French, Dutch, and British would all vie for dominance. England established the first permanent colony in North America at Jamestown, Va., in 1607. Samuel du Champlain founded Quebec City in 1608, and Holland established a trading outpost in present-day New York City in 1624.

Other important voyages of exploration during this era included Ferdinand Magellan's attempted circumnavigation of the globe, the search for a trade route to Asia through the Northwest Passage , and Captain James Cook's voyages that allowed him to map various areas and travel as far as Alaska.

The Age of Exploration ended in the early 17th century after technological advancements and increased knowledge of the world allowed Europeans to travel easily across the globe by sea. The creation of permanent settlements and colonies created a network of communication and trade, therefore ending the need to search for new routes.

It is important to note that exploration did not cease entirely at this time. Eastern Australia was not officially claimed for Britain by Capt. James Cook until 1770, while much of the Arctic and Antarctic were not explored until the 20th century. Much of Africa also was unexplored by Westerners until the late 19th century and early 20th century.

The Age of Exploration had a significant impact on geography. By traveling to different regions around the globe, explorers were able to learn more about areas such as Africa and the Americas and bring that knowledge back to Europe.

Methods of navigation and mapping improved as a result of the travels of people such as Prince Henry the Navigator. Prior to his expeditions, navigators had used traditional portolan charts, which were based on coastlines and ports of call, keeping sailors close to shore.

The Spanish and Portuguese explorers who journeyed into the unknown created the world's first nautical maps, delineating not just the geography of the lands they found but also the seaward routes and ocean currents that led them there. As technology advanced and known territory expanded, maps and mapmaking became more and more sophisticated.

These explorations also introduced a whole new world of flora and fauna to Europeans. Corn, now a staple of much of the world's diet, was unknown to Westerners until the time of the Spanish conquest, as were sweet potatoes and peanuts. Likewise, Europeans had never seen turkeys, llamas, or squirrels before setting foot in the Americas.

The Age of Exploration served as a stepping stone for geographic knowledge. It allowed more people to see and study various areas around the world, which increased geographic study, giving us the basis for much of the knowledge we have today.

The effects of colonization still persist as well, with many of the world's former colonies still considered the "developing" world and the colonizers the First World countries, holding a majority of the world's wealth and receiving a majority of its annual income.

- Profile of Prince Henry the Navigator

- A Timeline of North American Exploration: 1492–1585

- The History of Cartography

- Biography of Ferdinand Magellan, Explorer Circumnavigated the Earth

- The Portuguese Empire

- Explorers and Discoverers

- The Truth About Christopher Columbus

- The European Overseas Empires

- European Exploration of Africa

- Biography and Legacy of Ferdinand Magellan

- Biography of Christopher Columbus, Italian Explorer

- Amerigo Vespucci, Explorer and Navigator

- Biography of Juan Sebastián Elcano, Magellan's Replacement

- Amerigo Vespucci, Italian Explorer and Cartographer

- The Second Voyage of Christopher Columbus

- What Is Imperialism? Definition and Historical Perspective

Ch. 20 The Age of Enlightenment

The age of discovery, 19.2: the age of discovery, 19.2.1: europe’s early trade links.

A prelude to the Age of Discovery was a series of European land expeditions across Eurasia in the late Middle Ages. These expeditions were undertaken by a number of explorers, including Marco Polo, who left behind a detailed and inspiring record of his travels across Asia.

Learning Objective

Understand the exploration of Eurasia in the Middle Ages by Marco Polo, and why it was a prelude to the advent of the Age of Discovery in the 15th Century

- European medieval knowledge about Asia beyond the reach of Byzantine Empire was sourced in partial reports, often obscured by legends.

- In 1154, Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi created what would be known as the Tabula Rogeriana—a description of the world and world map. It contains maps showing the Eurasian continent in its entirety, but only the northern part of the African continent. It remained the most accurate world map for the next three centuries.

- Indian Ocean trade routes were sailed by Arab traders. Between 1405 and 1421, the Yongle Emperor of Ming China sponsored a series of long range tributary missions. The fleets visited Arabia, East Africa, India, Maritime Southeast Asia, and Thailand.

- A series of European expeditions crossing Eurasia by land in the late Middle Ages marked a prelude to the Age of Discovery. Although the Mongols had threatened Europe with pillage and destruction, Mongol states also unified much of Eurasia and, from 1206 on, the Pax Mongolica allowed safe trade routes and communication lines stretching from the Middle East to China.

- Christian embassies were sent as far as Karakorum during the Mongol invasions of Syria. The first of these travelers was Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, who journeyed to Mongolia and back from 1241 to 1247. Others traveled to various regions of Asia between 13th and the third quarter of the 15th centuries; these travelers included Russian Yaroslav of Vladimir and his sons Alexander Nevsky and Andrey II of Vladimir, French André de Longjumeau and Flemish William of Rubruck, Moroccan Ibn Battuta, and Italian Niccolò de’ Conti.

- Marco Polo, a Venetian merchant, dictated an account of journeys throughout Asia from 1271 to 1295. Although he was not the first European to reach China, he was the first to leave a detailed chronicle of his experience. The book inspired Christopher Columbus and many other travelers in the following Age of Discovery.

European medieval knowledge about Asia beyond the reach of Byzantine Empire was sourced in partial reports, often obscured by legends, dating back from the time of the conquests of Alexander the Great and his successors. In 1154, Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi created what would be known as the Tabula Rogeriana at the court of King Roger II of Sicily. The book, written in Arabic, is a description of the world and world map. It is divided into seven climate zones and contains maps showing the Eurasian continent in its entirety, but only the northern part of the African continent. It remained the most accurate world map for the next three centuries, but it also demonstrated that Africa was only partially known to either Christians, Genoese and Venetians, or the Arab seamen, and its southern extent was unknown. Knowledge about the Atlantic African coast was fragmented, and derived mainly from old Greek and Roman maps based on Carthaginian knowledge, including the time of Roman exploration of Mauritania. The Red Sea was barely known and only trade links with the Maritime republics, the Republic of Venice especially, fostered collection of accurate maritime knowledge.

Indian Ocean trade routes were sailed by Arab traders. Between 1405 and 1421, the Yongle Emperor of Ming China sponsored a series of long-range tributary missions. The fleets visited Arabia, East Africa, India, Maritime Southeast Asia, and Thailand. But the journeys, reported by Ma Huan, a Muslim voyager and translator, were halted abruptly after the emperor’s death, and were not followed up, as the Chinese Ming Dynasty retreated in the haijin, a policy of isolationism, having limited maritime trade.

Prelude to the Age of Discovery

A series of European expeditions crossing Eurasia by land in the late Middle Ages marked a prelude to the Age of Discovery. Although the Mongols had threatened Europe with pillage and destruction, Mongol states also unified much of Eurasia and, from 1206 on, the Pax Mongolica allowed safe trade routes and communication lines stretching from the Middle East to China. A series of Europeans took advantage of these in order to explore eastward. Most were Italians, as trade between Europe and the Middle East was controlled mainly by the Maritime republics.

Christian embassies were sent as far as Karakorum during the Mongol invasions of Syria, from which they gained a greater understanding of the world. The first of these travelers was Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, who journeyed to Mongolia and back from 1241 to 1247. About the same time, Russian prince Yaroslav of Vladimir, and subsequently his sons, Alexander Nevsky and Andrey II of Vladimir, traveled to the Mongolian capital. Though having strong political implications, their journeys left no detailed accounts. Other travelers followed, like French André de Longjumeau and Flemish William of Rubruck, who reached China through Central Asia. From 1325 to 1354, a Moroccan scholar from Tangier, Ibn Battuta, journeyed through North Africa, the Sahara desert, West Africa, Southern Europe, Eastern Europe, the Horn of Africa, the Middle East and Asia, having reached China. In 1439, Niccolò de’ Conti published an account of his travels as a Muslim merchant to India and Southeast Asia and, later in 1466-1472, Russian merchant Afanasy Nikitin of Tver travelled to India.

Marco Polo, a Venetian merchant, dictated an account of journeys throughout Asia from 1271 to 1295. His travels are recorded in Book of the Marvels of the World , (also known as The Travels of Marco Polo , c. 1300),a book which did much to introduce Europeans to Central Asia and China. Marco Polo was not the first European to reach China, but he was the first to leave a detailed chronicle of his experience. The book inspired Christopher Columbus and many other travelers.

The Travels of Marco Polo Marco Polo traveling, miniature from the book The Travels of Marco Polo (Il milione), originally published during Polo’s lifetime (c. 1254-January 8, 1324), but frequently reprinted and translated.

The geographical exploration of the late Middle Ages eventually led to what today is known as the Age of Discovery: a loosely defined European historical period, from the 15th century to the 18th century, that witnessed extensive overseas exploration emerge as a powerful factor in European culture and globalization. Many lands previously unknown to Europeans were discovered during this period, though most were already inhabited, and, from the perspective of non-Europeans, the period was not one of discovery, but one of invasion and the arrival of settlers from a previously unknown continent. Global exploration started with the successful Portuguese travels to the Atlantic archipelagos of Madeira and the Azores, the coast of Africa, and the sea route to India in 1498; and, on behalf of the Crown of Castile (Spain), the trans-Atlantic Voyages of Christopher Columbus between 1492 and 1502, as well as the first circumnavigation of the globe in 1519-1522. These discoveries led to numerous naval expeditions across the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific oceans, and land expeditions in the Americas, Asia, Africa, and Australia that continued into the late 19th century, and ended with the exploration of the polar regions in the 20th century.

Attributions

- “Age of Discovery.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Age_of_Discovery . Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0 .

- “Tabula Rogeriana.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tabula_Rogeriana . Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0 .

- “Pax Mongolica.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pax_Mongolica . Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0 .

- “Maritime Republics.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maritime_republics . Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0 .

- “Marco Polo.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marco_Polo . Wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0 .

- “Marco Polo traveling.” http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marco_Polo_traveling.JPG . Wikimedia Public domain .

- Boundless World History. Authored by : Boundless. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-worldhistory/ . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Privacy Policy

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Europe and the age of exploration.

Salvator Mundi

Albrecht Dürer

The Celestial Map- Northern Hemisphere

Astronomical table clock

Astronomicum Caesareum

Michael Ostendorfer

Mirror clock

Movement attributed to Master CR

Portable diptych sundial

Hans Tröschel the Elder

Celestial globe with clockwork

Gerhard Emmoser

The Celestial Globe-Southern Hemisphere

James Voorhies Department of European Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2002

Artistic Encounters between Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas The great period of discovery from the latter half of the fifteenth through the sixteenth century is generally referred to as the Age of Exploration. It is exemplified by the Genoese navigator, Christopher Columbus (1451–1506), who undertook a voyage to the New World under the auspices of the Spanish monarchs, Isabella I of Castile (r. 1474–1504) and Ferdinand II of Aragon (r. 1479–1516). The Museum’s jerkin ( 26.196 ) and helmet ( 32.132 ) beautifully represent the type of clothing worn by the people of Spain during this period. The age is also recognized for the first English voyage around the world by Sir Francis Drake (ca. 1540–1596), who claimed the San Francisco Bay for Queen Elizabeth ; Vasco da Gama’s (ca. 1460–1524) voyage to India , making the Portuguese the first Europeans to sail to that country and leading to the exploration of the west coast of Africa; Bartolomeu Dias’ (ca. 1450–1500) discovery of the Cape of Good Hope; and Ferdinand Magellan’s (1480–1521) determined voyage to find a route through the Americas to the east, which ultimately led to discovery of the passage known today as the Strait of Magellan.

To learn more about the impact on the arts of contact between Europeans, Africans, and Indians, see The Portuguese in Africa, 1415–1600 , Afro-Portuguese Ivories , African Christianity in Kongo , African Christianity in Ethiopia , The Art of the Mughals before 1600 , and the Visual Culture of the Atlantic World .

Scientific Advancements and the Arts in Europe In addition to the discovery and colonization of far off lands, these years were filled with major advances in cartography and navigational instruments, as well as in the study of anatomy and optics. The visual arts responded to scientific and technological developments with new ideas about the representation of man and his place in the world. For example, the formulation of the laws governing linear perspective by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) in the early fifteenth century, along with theories about idealized proportions of the human form, influenced artists such as Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519). Masters of illusionistic technique, Leonardo and Dürer created powerfully realistic images of corporeal forms by delicately rendering tendons, skin tissues, muscles, and bones, all of which demonstrate expertly refined anatomical understanding. Dürer’s unfinished Salvator Mundi ( 32.100.64 ), begun about 1505, provides a unique opportunity to see the artist’s underdrawing and, in the beautifully rendered sphere of the earth in Christ’s left hand, metaphorically suggests the connection of sacred art and the realms of science and geography.

Although the Museum does not have objects from this period specifically made for navigational purposes, its collection of superb instruments and clocks reflects the advancements in technology and interest in astronomy of the time, for instance Petrus Apianus’ Astronomicum Caesareum ( 25.17 ). This extraordinary Renaissance book contains equatoria supplied with paper volvelles, or rotating dials, that can be used for calculating positions of the planets on any given date as seen from a given terrestrial location. The celestial globe with clockwork ( 17.190.636 ) is another magnificent example of an aid for predicting astronomical events, in this case the location of stars as seen from a given place on earth at a given time and date. The globe also illustrates the sun’s apparent movement through the constellations of the zodiac.

Portable devices were also made for determining the time in a specific latitude. During the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, the combination of compass and sundial became an aid for travelers. The ivory diptych sundial was a specialty of manufacturers in Nuremberg. The Museum’s example ( 03.21.38 ) features a multiplicity of functions that include giving the time in several systems of counting daylight hours, converting hours read by moonlight into sundial hours, predicting the nights that would be illuminated by the moon, and determining the dates of the movable feasts. It also has a small opening for inserting a weather vane in order to determine the direction of the wind, a feature useful for navigators. However, its primary use would have been meteorological.

Voorhies, James. “Europe and the Age of Exploration.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/expl/hd_expl.htm (October 2002)

Further Reading

Levenson, Jay A., ed. Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration . Exhibition catalogue. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1991.

Vezzosi, Alessandro. Leonardo da Vinci: The Mind of the Renaissance . New York: Abrams, 1997.

Additional Essays by James Voorhies

- Voorhies, James. “ Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) and the Spanish Enlightenment .” (October 2003)

- Voorhies, James. “ Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ School of Paris .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Art of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries in Naples .” (October 2003)

- Voorhies, James. “ Elizabethan England .” (October 2002)

- Voorhies, James. “ Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and His Circle .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Fontainebleau .” (October 2002)

- Voorhies, James. “ Post-Impressionism .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Domestic Art in Renaissance Italy .” (October 2002)

- Voorhies, James. “ Surrealism .” (October 2004)

Related Essays

- Collecting for the Kunstkammer

- East and West: Chinese Export Porcelain

- European Exploration of the Pacific, 1600–1800

- The Portuguese in Africa, 1415–1600

- Trade Relations among European and African Nations

- Abraham and David Roentgen

- African Christianity in Ethiopia

- African Influences in Modern Art

- Anatomy in the Renaissance

- Arts of the Mission Schools in Mexico

- Astronomy and Astrology in the Medieval Islamic World

- Birds of the Andes

- Dualism in Andean Art

- European Clocks in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries

- Gold of the Indies

- The Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburgs, 1400–1600

- Islamic Art and Culture: The Venetian Perspective

- Ivory and Boxwood Carvings, 1450–1800

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)

- The Manila Galleon Trade (1565–1815)

- Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art

- Polychrome Sculpture in Spanish America

- The Solomon Islands

- Talavera de Puebla

- Venice and the Islamic World: Commercial Exchange, Diplomacy, and Religious Difference

- Visual Culture of the Atlantic World

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1400–1600 A.D.

- Florence and Central Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Venice and Northern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- 15th Century A.D.

- 16th Century A.D.

- Architecture

- Astronomy / Astrology

- Cartography

- Central America

- Central Europe

- Colonial American Art

- Colonial Latin American Art

- European Decorative Arts

- Great Britain and Ireland

- Guinea Coast

- Iberian Peninsula

- Mesoamerican Art

- North America

- Printmaking

- Renaissance Art

- Scientific Instrument

- South America

- Southeast Asia

- Western Africa

- Western North Africa (The Maghrib)

Artist or Maker

- Apianus, Petrus

- Bos, Cornelis

- Dürer, Albrecht

- Emmoser, Gerhard

- Gevers, Johann Valentin

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Ostendorfer, Michael

- Troschel, Hans, the Elder

- Zündt, Matthias

Online Features

- 82nd & Fifth: “Celestial” by Clare Vincent

- MetCollects: “ Ceremonial ewer “

Brewminate: A Bold Blend of News and Ideas

Causes and Impacts of the European Age of Exploration

Share this:.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

A time when Europe was swept up in the Renaissance and the Reformation, other major changes were taking place in the world.

Introduction

With today’s global positioning satellites, Internet maps, cell phones, and superfast travel, it is hard to imagine exactly how it might have felt to embark on a voyage across an unknown ocean. What lay across the ocean? In the early 1400s in Europe, few people knew. How long would it take to get there? That depended on the wind, the weather, and the distance. Days would have run together, with no sounds but the voices of the captain and the crew, the creaking of the sails, the blowing wind, and the splash of waves against the ship’s hull.

Would you be willing to undertake such a voyage? Only those most adventurous, most daring, and most confident in their abilities to sail in any weather, manage any crew, and meet any circumstance dared do so. They sailed west from England, Spain, and Portugal to North America. They sailed south from Portugal and Spain to South America, to lands where the Incas lived. They traveled to Africa, past the kingdoms of Ghana, Mali, and Songhai. The crew of one Portuguese expedition even sailed completely around the world.

European explorers changed the world in many dramatic ways. Because of them, cultures divided by 3,000 miles or more of water began interacting. European countries claimed large parts of the world. As nations competed for territory, Europe had an enormous impact on people living in distant lands.

The Americas, in turn, made important contributions to Europe and the rest of the world. For example, from the Americas came crops such as corn and potatoes, which grew well in Europe. By increasing Europe’s food supply, these crops helped create population growth.

Another great change during the early modern age was the Scientific Revolution. Between 1500 and 1700, scientists used observation and experiments to make dramatic discoveries. For example, Isaac Newton formulated the laws of gravity. The Scientific Revolution also led to the invention of new tools, such as the microscope and the thermometer.

Advances in science helped pave the way for a period called the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment began in the late 1600s. Enlightenment thinkers used observation and reason to try to solve problems in society. Their work led to new ideas about government, human nature, and human rights.

The Age of Exploration, the Scientific Revolution, and the Enlightenment helped to shape the world we live in today.

The Causes of European Exploration

Why did European exploration begin to flourish in the 1400s? Two main reasons stand out. First, Europeans of this time had several motives for exploring the world. Second, advances in knowledge and technology helped to make the Age of Exploration possible.

Motives for Exploration

For early explorers, one of the main motives for exploration was the desire to find new trade routes to Asia. By the 1400s, merchants and Crusaders had brought many goods to Europe from Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Demand for these goods increased the desire for trade.

Europeans were especially interested in spices from Asia. They had learned to use spices to help preserve food during winter and to cover up the taste of food that was no longer fresh.

Trade with the East, however, was difficult and very expensive. Muslims and Italians controlled the flow of goods. Muslim traders carried goods to the east coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Italian merchants then brought the goods into Europe. Problems arose when Muslim rulers sometimes closed the trade routes from Asia to Europe. Also, the goods went through many hands, and each trading party raised the price.

European monarchs and merchants wanted to break the hold that Muslims and Italians had on trade. One way to do so was to find a sea route to Asia. Portuguese sailors looked for a route that went around Africa. Christopher Columbus tried to reach Asia by sailing west across the Atlantic.

Other motives also came into play. Many people were excited by the opportunity for new knowledge. Explorers saw the chance to earn fame and glory, as well as wealth. As new lands were discovered, nations wanted to claim the lands’ riches for themselves.

A final motive for exploration was the desire to spread Christianity beyond Europe. Both Protestant and Catholic nations were eager to make new converts. Missionaries of both faiths followed the paths blazed by explorers.

Advances in Knowledge and Technology

The Age of Exploration began during the Renaissance. The Renaissance was a time of new learning. A number of advances during that time made it easier for explorers to venture into the unknown.

One key advance was in cartography, the art and science of mapmaking. In the early 1400s, an Italian scholar translated an ancient book called Guide to Geography from Greek into Latin. The book was written by the thinker Ptolemy (TOL-eh-mee) in the 2nd century C.E. Printed copies of the book inspired new interest in cartography. European mapmakers used Ptolemy’s work as a basis for drawing more accurate maps.

Discoveries by explorers gave mapmakers new information with which to work. The result was a dramatic change in Europeans’ view of the world. By the 1500s, Europeans made globes, showing Earth as a sphere. In 1507, a German cartographer made the first map that clearly showed North and South America as separate from Asia.

In turn, better maps made navigation easier. The most important Renaissance geographer, Gerardus Mercator (mer-KAY-tur), created maps using improved lines of longitude and latitude. Mercator’s mapmaking technique was a great help to navigators.

An improved ship design also helped explorers. By the 1400s, Portuguese and Spanish shipbuilders were making a new type of ship called a caravel. These ships were small, fast, and easy to maneuver. Their special bottoms made it easier for explorers to travel along coastlines where the water was not deep. Caravels also used lateen sails, a triangular style adapted from Muslim ships. These sails could be positioned to take advantage of the wind no matter which way it blew.

Along with better ships, new navigational tools helped sailors travel more safely on the open seas. By the end of the 1400s, the compass was much improved. Sailors used compasses to find their bearing, or direction of travel. The astrolabe helped sailors determine their distance north or south from the equator.

Finally, improved weapons gave Europeans a huge advantage over the people they met in their explorations. Sailors could fire their cannons at targets near the shore without leaving their ships. On land, the weapons of native peoples often were no match for European guns, armor, and horses.

Portugal Begins the Age of Exploration

The Age of Exploration began in Portugal. This small country is located on the Iberian Peninsula. Its rulers sent explorers first to nearby Africa and then around the world.

Key Portuguese Explorers

The major figure in early Portuguese exploration was Prince Henry, the son of King John I of Portugal. Nicknamed “the Navigator,” Prince Henry was not an explorer himself. Instead, he encouraged exploration and planned and directed many important expeditions.

Beginning in about 1418, Henry sent explorers to sea almost every year. He also started a school of navigation where sailors and mapmakers could learn their trades. His cartographers made new maps based on the information ship captains brought back.

Henry’s early expeditions focused on the west coast of Africa. He wanted to continue the Crusades against the Muslims, find gold, and take part in Asian trade.

Gradually, Portuguese explorers made their way farther and farther south. In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias became the first European to sail around the southern tip of Africa.

In July 1497, Vasco da Gama set sail with four ships to chart a sea route to India. Da Gama’s ships rounded Africa’s southern tip and then sailed up the east coast of the continent. With the help of a sailor who knew the route to India from there, they were able to across the Indian Ocean.

Da Gama arrived in the port of Calicut, India, in May 1498. There he obtained a load of cinnamon and pepper. On the return trip to Portugal, da Gama lost half of his ships. Still, the valuable cargo he brought back paid for the voyage many times over. His trip made the Portuguese even more eager to trade directly with Indian merchants.

In 1500, Pedro Cabral (kah-BRAHL) set sail for India with a fleet of 13 ships. Cabral first sailed southwest to avoid areas where there are no winds to fill sails. But he sailed so far west that he reached the east coast of present-day Brazil. After claiming this land for Portugal, he sailed back to the east and rounded Africa. Arriving in Calicut, he established a trading post and signed trade treaties. He returned to Portugal in June 1501.

The Impact of Portuguese Exploration

Portugal’s explorers changed Europeans’ understanding of the world in several ways. They explored the coasts of Africa and brought back gold and enslaved Africans. They also found a sea route to India. From India, explorers brought back spices, such as cinnamon and pepper, and other goods, such as porcelain, incense, jewels, and silk.

After Cabral’s voyage, the Portuguese took control of the eastern sea routes to Asia. They seized the seaport of Goa (GOH-uh) in India and built forts there. They attacked towns on the east coast of Africa. They also set their sights on the Moluccas, or Spice Islands, in what is now Indonesia. In 1511, they attacked the main port of the islands and killed the Muslim defenders. The captain of this expedition explained what was at stake. If Portugal could take the spice trade away from Muslim traders, he wrote, then Cairo and Makkah “will be ruined.” As for Italian merchants, “Venice will receive no spices unless her merchants go to buy them in Portugal.”

Portugal’s control of the Indian Ocean broke the hold Muslims and Italians had on Asian trade. With the increased competition, prices of Asian goods—such as spices and fabrics—dropped, and more people in Europe could afford to buy them.

During the 1500s, Portugal also began to establish colonies in Brazil. The native people of Brazil suffered greatly as a result. The Portuguese forced them to work on sugar plantations, or large farms. They also tried to get them to give up their religion and convert to Christianity. Missionaries sometimes tried to protect them from abuse, but countless numbers of native peoples died from overwork and from European diseases. Others fled into the interior of Brazil.

The colonization of Brazil also had a negative impact on Africa. As the native population of Brazil decreased, the Portuguese needed more laborers. Starting in the mid–1500s, they turned to Africa. Over the next 300 years, ships brought millions of enslaved West Africans to Brazil.

Later Spanish Exploration and Conquest

After Columbus’s voyages, Spain was eager to claim even more lands in the New World. To explore and conquer “New Spain,” the Spanish turned to adventurers called conquistadors , or conquerors. The conquistadors were allowed to establish settlements and seize the wealth of natives. In return, the Spanish government claimed some of the treasures they found.

Key Explorers

In 1519, Spanish explorer Hernán Cortés (er–NAHN koor–TEZ), with and a band of fellow conquistadors, set out to explore present-day Mexico. Native people in Mexico told Cortés about the Aztecs. The Aztecs had built a large and wealthy empire in Mexico.

With the help of a native woman named Malinche (mah–LIN–chay), Cortés and his men reached the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlán (tay–nawh–tee–TLAHN). The Aztec ruler, Moctezuma II, welcomed the Spanish with great honors. Determined to break the power of the Aztecs, Cortés took Moctezuma hostage.

Cortés now controlled the Aztec capital. In 1520, he left the city of Tenochtitlán to battle a rival Spanish force. While he was away, a group of conquistadors attacked the Aztecs in the middle of a religious celebration. In response, the Aztecs rose up against the Spanish. The soldiers had to fight their way out of the city. Many of them were killed during the escape.

The following year, Cortés mounted a siege of the city, aided by thousands of native allies who resented Aztec rule. The Aztecs ran out of food and water, yet they fought desperately. After several months, the Spanish captured the Aztec leader, and Aztec resistance collapsed. The city was in ruins. The mighty Aztec Empire was no more.

Four factors contributed to the defeat of the Aztec Empire. First, Aztec legend had predicted the arrival of a white-skinned god. When Cortés appeared, the Aztecs welcomed him because they thought he might be this god, Quetzalcoatl. Second, Cortés was able to make allies of the Aztecs’ enemies. Third, their horses, armor, and superior weapons gave the Spanish an advantage in battle. Fourth, the Spanish carried diseases that caused deadly epidemics among the Aztecs.

Aztec riches inspired Spanish conquistadors to continue their search for gold. In the 1520s, Francisco Pizarro received permission from Spain to conquer the Inca Empire in South America. The Incas ruled an empire that extended throughout most of the Andes Mountains. By the time Pizarro arrived, however, a civil war had weakened that empire.

In April 1532, the Incan emperor, Atahualpa (ah–tuh–WAHL–puh), greeted the Spanish as guests. Following Cortés’s example, Pizarro launched a surprise attack and kidnapped the emperor. Although the Incas paid a roomful of gold and silver in ransom, the Spanish killed Atahualpa. Without their leader, the Inca Empire quickly fell apart.

The Impact of Later Spanish Exploration and Conquest

The explorations and conquests of the conquistadors transformed Spain. The Spanish rapidly expanded foreign trade and overseas colonization. For a time, wealth from the Americas made Spain one of the world’s richest and most powerful countries.

Besides gold and silver, ships from the Americas brought corn and potatoes to Spain. These crops grew well in Europe. The increased food supply helped spur a population boom. Conquistadors also introduced Europeans to new luxury items, such as chocolate.

In the long run, however, gold and silver from the Americas hurt Spain’s economy. Inflation, or an increase in the supply of money, led to a loss of its value. It now cost people a great deal more to buy goods with the devalued money. Additionally, monarchs and the wealthy spent their riches on luxuries, instead of building Spain’s industries.

The Spanish conquests had a major impact on the New World. The Spanish introduced new animals to the Americas, such as horses, cattle, sheep, and pigs. But they destroyed two advanced civilizations. The Aztecs and Incas lost much of their culture along with their wealth. Many became laborers for the Spanish. Millions died from disease. In Mexico, for example, there were about twenty-five million native people in 1519. By 1605, this number had dwindled to one million.

Other European Explorations

Spain and Portugal dominated the early years of exploration. But rulers in rival nations wanted their own share of trade and new lands in the Americas. Soon England, France, and the Netherlands all sent expeditions to North America.

Key Explorers

Explorers often sailed for any country that would pay for their voyages. The Italian sailor John Cabot made England’s first voyage of discovery. Cabot believed he could reach the Indies by sailing northwest across the Atlantic. In 1497, he landed in what is now Canada. Believing he had reached the northeast coast of Asia, he claimed the region for England.

Another Italian, Giovanni da Verrazano, sailed under the French flag. In 1524, Verrazano explored the Atlantic coast from present-day North Carolina to Canada. His voyage gave France its first claims in the Americas. Unfortunately, on a later trip to the West Indies, he was killed by native people.

Sailing on behalf of the Netherlands, English explorer Henry Hudson journeyed to North America in 1609. Hudson wanted to find a northwest passage through North America to the Pacific Ocean. Such a water route would allow ships to sail from Europe to Asia without entering waters controlled by Spain.

Hudson did not find a northwest passage, but he did explore what is now called the Hudson River in present-day New York State. His explorations were the basis of the Dutch claim to the area. Dutch settlers established the colony of New Amsterdam on Manhattan in 1625.

In 1610, Hudson tried again, this time under the flag of his native England. Searching farther north, he sailed into a large bay in Canada that is now called Hudson Bay. He spent three months looking for an outlet to the Pacific, but there was none.

After a hard winter in the icy bay, some of Hudson’s crew rebelled. They set him, his son, and seven loyal followers adrift in a small boat. Hudson and the other castaways were never seen again. Hudson’s voyage, however, laid the basis for later English claims in Canada.

The Impact of European Exploration of North America

Unlike the conquistadors in the south, northern explorers did not find gold and other treasure. As a result, there was less interest, at first, in starting colonies in that region.

Canada’s shores did offer rich resources of cod and other fish. Within a few years of Cabot’s trip, fishing boats regularly visited the region. Europeans were also interested in trading with Native Americans for whale oil and otter, beaver, and fox furs. By the early 1600s, Europeans had set up a number of trading posts in North America.

English exploration also contributed to a war between England and Spain. As English ships roamed the seas, some captains, nicknamed “sea dogs,” began raiding Spanish ports and ships to take their gold. Between 1577 and 1580, sea dog Francis Drake sailed around the world. He also claimed part of what is now California for England, ignoring Spain’s claims to the area.

The English raids added to other tensions between England and Spain. In 1588, King Philip II of Spain sent an armada, or fleet of ships, to invade England. With 130 heavily armed vessels and about thirty thousand men, the Spanish Armada seemed an unbeatable force. But the smaller English fleet was fast and well armed. Their guns had a longer range, so they could attack from a safe distance. After several battles, a number of the armada’s ships had been sunk or driven ashore. The rest turned around but faced terrible storms on the way home. Fewer than half of the ships made it back to Spain.

The defeat of the Spanish Armada marked the start of a shift in power in Europe. By 1630, Spain no longer dominated the continent. With Spain’s decline, other countries—particularly England and the Netherlands—took a more active role in trade and colonization around the world.

Bartolomé de Las Casas: From Conquistador to Protector of the Indians

Bartolomé de las Casas experienced a remarkable change of heart during his lifetime. At first, he participated in Spain’s conquest and settlement of the Americas. Later in life, he criticized and condemned it. For more than fifty years, he fought for the rights of the defeated and enslaved peoples of Latin America. How did this conquistador become known as “the Protector of the Indians?”

Bartolomé de las Casas (bahr–taw–law–MEY day las KAH-sahs) ran through the streets of Seville, Spain, on March 31, 1493. He was just nine years old and on his way to see Christopher Columbus, who had just returned from his first voyage to the Americas. Bartolomé wanted to see him and the “Indians,” as they were called, as they paraded to the church.

Bartolomé’s father and uncles were looking forward to seeing Columbus, as well. Like many other people in Europe during the late 1400s, they saw the Americas as a place of opportunity. They signed up to join Columbus on his second voyage. Two years after that, Bartolomé followed in his father’s footsteps and voyaged to the Americas himself. He sailed to the island of Hispaniola, the present-day nations of Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Las Casas as Conquistador and Priest

One historian wrote that when Las Casas first arrived in the Americas, he was “not much better than the rest of the gentlemen-adventurers who rushed to the New World, bent on speedily acquiring fortunes.” He supported the Spanish conquest of the Americas and was a loyal servant of Spain’s king and queen, Ferdinand and Isabella. Once in Hispaniola, Las Casas helped to manage his father’s farms and businesses. Enslaved Indians worked in the family’s fields and mines.

Spanish conquistadors wanted to gain wealth and glory in the Americas. They had another goal, as well—to convert Indians to Christianity. Las Casas shared this goal. So, the young conquistador went back to Europe to become a priest. He returned to Hispaniola sometime in 1509 or 1510. There he began to teach and baptize the Indians. At the same time, he continued to manage Indian slaves.

On a Path to Change

History often seems to be made up of moments when someone has a change of heart. The path that he or she has been traveling takes a dramatic turn. It often appears to others that this change is sudden. In reality, a series of events usually causes a person to make the decision to change. One such event happened to Las Casas in 1511.

Roman Catholics in Hispaniola witnessed horrible acts of cruelty and injustice against the native peoples of the West Indies at the hands of the Spanish conquistadors. One of the priests there, Father Antonio de Montesinos, spoke out against the harsh treatment of the Indians in a sermon delivered to a Spanish congregation in Hispaniola in 1511. De Montesinos said:

You are in mortal sin . . . for the cruelty and tyranny you use in dealing with these innocent people . . . by what right or justice do you keep these Indians in such a cruel and horrible servitude? . . . Why do you keep them so oppressed? . . . Are not these people also human beings?

One historian called this sermon “the first cry for justice in America” on behalf of the Indians. Las Casas recorded the sermon in one of his books, History of the Indies . No one is sure if he was present at the sermon or heard about it later. But one thing seems certain; even though he must have seen some of the same injustices described by de Montesinos, Las Casas continued to support the Spanish conquest and the goals of conquering new lands, earning wealth, and converting Indians to Christianity.

However, in 1513, something happened that changed Las Casas’s life. He took part in the conquest of Cuba. As a reward, he received more Indian slaves and an encomienda , or land grant. But he also witnessed a massacre. The Spanish killed thousands of innocent Indians, including women and children, who had welcomed the Spanish into their town. In his book The Devastation of the Indies: A Brief Account , he wrote, “I saw here cruelty on a scale no living being has ever seen or expects to see.”

A Turning Point

The Cuban massacre in 1513 and other scenes of violence against Indians Las Casas witnessed finally pushed him to a turning point. He could no longer believe that the Spanish conquest was right. Before, he had thought that only some individuals acted cruelly and inhumanely. Now he saw that the whole Spanish system of conquest brought only death and suffering to the people of the West Indies.

On August 15, 1514, when he was about thirty years old, Las Casas gave a startling sermon. He asked his congregation to free their enslaved Indians. He also said that they had to return or pay for everything they had taken away from the Indians. He refused to forgive the colonists’ sins in confession if they used Indians as forced labor. Then he announced that he would give up his ownership of Indians and the business he had inherited from his father.

Protector of the Indians

For the rest of his life, Las Casas fought for the rights of the Indians in the Americas. He traveled back and forth to Europe working on their behalf. He talked with popes and kings, debated enemies, and wrote letters and books on the subject.

Las Casas influenced both a pope and a king. In 1537, Pope Paul III wrote that Indians were free human beings, not slaves, and that anyone who enslaved them could be thrown out of the Catholic Church. In 1542, Holy Roman emperor Charles V, who ruled Spain, issued the New Laws, banning slavery in Spanish America.

In 1550 and 1551, Las Casas also took part in a famous debate against Juan Ginés Sepúlveda in Spain. Sepúlveda tried to prove that Indians were “natural slaves.” Many Spanish, especially those hungry for wealth and glory, shared this belief. Las Casas passionately argued against Sepúlveda with the same message he would deliver over and over throughout his life. Las Casas argued that:

• Indians, like all human beings, have rights to life and liberty. • The Spanish stole Indian land through bloody and unjust wars. • There is no such thing as a good encomienda. • Indians have the right to make war against the Spanish.

Las Casas died in 1566. The voices and the deeds of the conquistadors slowly eroded the memory of his words. But in other European countries, people began to read The Devastation of the Indies: A Brief Account . As time passed, more of Las Casas’s works were published. In the centuries to follow, fighters for justice took up his name as a symbol for their own struggles for human rights.

The Legacy of Las Casas

Today, historians remember Las Casas as the first person to actively oppose the oppression of Indians and to call for an end to Indian slavery. Later, in the 19th century, Las Casas inspired both Father Hidalgo, the father of Mexican independence, and Simón Bolívar, the liberator of South America.

In the 1960s, Mexican American César Chávez learned about injustice at an early age. His family worked as migrants, moving from place to place to pick crops. With barely an eighth-grade education, Chávez organized workers, formed a union, and won better pay and better working and living conditions. Speaking for the powerless, he rallied people to his side with his cry, “Sí, Se Puede!” (“Yes, We Can!”) Just as the name “Chávez” will always be connected to the struggles of the farm workers, the name “Las Casas” will forever be connected to any fight for human rights and dignity for the native people of the Americas.

The Impact of Exploration on Europe

The voyages of explorers had a dramatic impact on European commerce and economies. As a result of exploration, more goods, raw materials, and precious metals entered Europe. Mapmakers carefully charted trade routes and the locations of newly discovered lands. By the 1700s, European ships traveled trade routes that spanned the globe. New centers of commerce developed in the port cities of the Netherlands and England.

Exploration and trade contributed to the growth of capitalism. This economic system is based on investing money for profit. Merchants gained great wealth by trading and selling goods from around the world. Many of them used their profits to finance still more voyages and to start trading companies. Other people began investing money in these companies and shared in the profits. Soon, this type of shared ownership was applied to other kinds of businesses.

Another aspect of the capitalist economy concerned the way people exchanged goods and services. Money became more important as precious metals flowed into Europe. Instead of having a fixed price, items were sold for prices that were set by the open market. This meant that the price of an item depended on how much of the item was available and how many people wanted to buy it. Sellers could charge high prices for scarce items that many people wanted. If the supply of an item was large and few people wanted it, sellers lowered the price. This kind of system, based on supply and demand, is called a market economy.

Labor, too, was given a money value. Increasingly, people began working for hire instead of directly providing for their own needs. Merchants hired people to work from their own cottages, turning raw materials from overseas into finished products. This growing cottage industry was especially important in the manufacture of textiles. Often, entire families worked at home, spinning wool into thread or weaving thread into cloth. Cottage industry was a step toward the system of factories operated by capitalists in later centuries.

A final result of exploration was a new economic policy called mercantilism. European rulers believed that building up wealth was the best way to increase a nation’s power. For this reason, they tried to reduce the products they bought from other countries and to increase the items they sold.

Having colonies was a key part of this policy. Nations looked to their colonies to supply raw materials for their industries at home. These industries turned the raw materials into finished goods that they could sell back to their colonies, as well as to other countries. To protect this valuable trade with their colonies, rulers often forbade colonists from trading with other nations.

Originally published by Flores World History , free and open access, republished for educational, non-commercial purposes.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 1

Motivation for european conquest of the new world.

- Origins of European exploration in the Americas

- Christopher Columbus

- Consequences of Columbus's voyage on the Tainos and Europe

- Christopher Columbus and motivations for European conquest

- The Columbian Exchange

- Environmental and health effects of European contact with the New World

- Lesson summary: The Columbian Exchange

- The impact of contact on the New World

- The Columbian Exchange, Spanish exploration, and conquest

- Historians generally recognize three motives for European exploration and colonization in the New World: God, gold, and glory.

- Religious motivations can be traced all the way back to the Crusades, the series of religious wars between the 11th and 15th centuries during which European Christians sought to claim Jerusalem as an exclusively Christian space.

- Europeans also searched for optimal trade routes to lucrative Asian markets and hoped to gain global recognition for their country.

The Crusades: increased religious intolerance and forceful religious conversion

The lure of gold: finding new routes to trade eastern goods, a thirst for glory: european competition for global dominance, what do you think.

- David Kennedy and Lizabeth Cohen, The American Pageant: A History of the American People , 15th (AP) ed. (Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning, 2013)

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Schoolshistory.org.uk

History resources, stories and news. Author: Dan Moorhouse

Voyages of Discovery – Elizabethan Explorers

Voyages of discovery.

The Elizabethan period was one in which the major European powers were engaged in many voyages of discovery. The discovery of the Americas had opened up new lands to explore. There was a desire to find faster, more economical, routes to the far east. Explorers became famous and their work has had a lasting legacy.

The Elizabethan period came as exploration of the seas and New World was emerging as one of great importance. For centuries Europe had traded with the far east, though through middle-men. The discovery of the Americas and then the first circumnavigation of the globe made exploration of economic importance. Now it was known that ships could travel around the globe, the race was on to find the fastest routes and discover new lands.

The Spanish and Portuguese empires were the first to colonise the New World of the Americas. Following this the Dutch, French and English sought to explore themselves. North America offered the Elizabethans several things. First, it was unsettled land. No Europeans had colonised it as yet. Elizabeth’s court granted Sir Walter Raleigh the rights to colonise. This attempt at a first North American Colony can be read here .

North America also offered hope. If it was possible to sail around the toe of South America, was the same true of the North? Could shipping make its way through river systems and emerge on the other side of the New World? If either of these were possible, it would speed up trade with Asia.

Searches for the Northern Passages

1497 John Cabot discovered Newfoundland

1553 Sir Henry Willoughby sets sail with 3 ships in search of a Northeast Passage. Only one ship survives, making contact with the Muscovite court of Ivan the Terrible having reached the port of Archangel.

1555 Richard Chancellor, who had sailed under Willoughby, returns to Russia and establishes the Muscovy Company.

1576 Sir Martin Frobisher sets sail in search of a Northwest passage. He fails to find one, landing instead in Greenland and Canada.

1585 John Davies uses Greenland as a stepping stone into the Northern seas. He fails to find a passage through but sails further north than any other Englishman had done previously.

At the same time as these men were sailing in search of a Northern Passage, people continued to seek out new lands. In 1577, Sir Francis Drake set sail. He was searching for new lands in the Southern Oceans. On his voyage he plundered gold from the Spanish. His voyage led him to becoming the first Englishman to circumnavigate the globe. He returned to England and fame in 1580.

North America

1583 Newfoundland was claimed for England by Gilbert.

Raleigh was commissioned to establish a colony in North America. This was attempted by Sir Humphrey Gilbert, on Raleigh’s behalf, at Roanoke Island . The first colony was started in 1585. This was abandoned the following year. In 1587 a further 117 colonists were sent to reestablish the colony. Among these settlers was Elizabeth Dare, who gave birth to the first English child born in the Americas. This colony vanished without trace though, an English ship visited in 1591 and found the site abandoned.

Colonisation of the Americas was delayed due to the Spanish Armada . It resumed following the English victory.

Africa and the Slave Trade

In 1562 John Hawkins began a trade that is now thought of as horrific and inhumane. Hawkins realised that he could profit from triangular trading. He bought or captured native Africans. Then he sailed to Spanish colonies and sold them as slaves. The Spanish needed workers, Hawkins could provide them. From the New World he could return to England with goods that would reach a high price. With the three stopping points this became known as triangular trade and continued until the abolition of slavery in the British Empire in 1807. The trade did cause some friction with the Spanish and was sometimes linked with the privateers.

Northern Europe

In 1598 the Baltic Sea became open to British shipping. Prior to this a monopoly on trade had existed with only the Hanseatic League able to trade there. With the league losing their monopoly, the ships of British merchats could enter the Baltic and trade.

Principles of Colonisation

Richard Hakluyt wrote several pieces on the principles of colonisation. These were presented to influential people such as Sir Walter Raleigh. His work spanned the reigns of Elizabeth and James I. It was his book, The Principal Navigations, Voyages and Discoveries of the English Nation (1589), that influenced the development of Virginia.

British History – Elizabethan Era – Tudors (KS2)

British Library – Exploration and Trade in Elizabethan England

BBC – Revision guide, explorers

Encyclopedia.com – Elizabethan explorers and colonisers

- 37476 Share on Facebook

- 2372 Share on Twitter

- 6823 Share on Pinterest

- 2959 Share on LinkedIn

- 5422 Share on Email

Subscribe to our Free Newsletter, Complete with Exclusive History Content

Thanks, I’m not interested

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.1: The Impact of "Discovery" - The Columbian Exchange

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 7878

- Catherine Locks, Sarah Mergel, Pamela Roseman, Tamara Spike & Marie Lasseter

- George State Universities via GALILEO Open Learning Materials

Most historians in the twenty-first century insist that the merits of Columbus and his experience must be measured in terms of fifteenth and sixteenth century standards and values, and not in terms of those of the twenty-first century. Columbus was a product of the crusading zeal of the Renaissance period, a religious man, whose accomplishments were remarkable. He sailed west and though he did not make it to the East Indies, he did encountered continents previously unknown to the Europeans. The subsequent crop and animal exchange revolutionized the lifestyle of Europeans, Asians, and Africans. Historians refer to this process as the “Columbian Exchange.” The Exchange introduced (or in the case of the horse, reintroduced) into the New World such previously unknown commodities as cattle, horses, sugar, tea, and coffee, while such products as tobacco, potatoes, chocolate, corn, and tomatoes made their way from the New World into the Old World. Not all exchanges were beneficial, of course; European diseases such as smallpox and influenza, to which the Native Americans had no resistance, were responsible for the significant depopulation of the New World.

Because of such crops as the potato, the sweet potato, and maize, however, Europeans and later the East Asians were able to vary their diets and participate in the technological revolution that would begin within 200 years of Columbus’s voyage.

The biological exchange following the voyages of Columbus was even more extensive than originally thought. Europeans discovered llamas, alpacas, iguana, flying squirrels, catfish, rattlesnakes, bison, cougars, armadillos, opossums, sloths, anacondas, electric eels, vampire bats, toucans, condors, and hummingbirds in the Americas. Europeans introduced goats and crops such as snap, kidney, and lima beans, barley, oats, wine grapes, melons, coffee, olives, bananas, and more to the New World.

From the New World to the Old: The Exchange of Crops

Corn (or maize) is a New World crop, which was unknown in the Old World before Columbus’s voyage in 1492. Following his four voyages, corn quickly became a staple crop in Europe. By 1630, the Spanish took over commercial production of corn, overshadowing the ancient use of maize for subsistence in Mesoamerica. Corn also became an important crop in China, whose population was the world’s largest in the early modern period. China lacked flat lands on which to grow crops, and corn was a hearty crop which grew in many locations that would otherwise be unable to be cultivated. Today corn is produced in most countries of the world and is the third-most planted field crop (after wheat and rice).

Both the white and the sweet potato were New World crops that were unknown in the Old World before Columbus. The white potato originated in South America in the Andes Mountains where the natives developed over 200 varieties and pioneered the freeze-dried potato, or chuño, which can be stored for up to four years. Incan units of time were based on how long it took for a potato to cook to various consistencies. Potatoes were even used to divine the truth and predict weather. It became a staple crop in Europe after Columbus and was brought to North America by the Scots-Irish immigrants in the 1700s. The white potato is also known as the “Irish” potato as it provided the basic food supply of the Irish in the early modern period. The potato is a good source of many nutrients. When the Irish potato famine hit in the nineteenth century, many Irish immigrated to the Americas.

The sweet potato became an important crop in Europe as well as Asia. Because China has little flat land for cultivation, long ago its people learned to terrace its mountainous areas in order to create more arable land. During the Ming (1398-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) Dynasties, China became the most populous nation on Earth. The sweet potato grew easily in many different climates and settings, and the Chinese learned to harvest it in the early modern period to supplement the rice supply and to compensate for the lack of flat lands on which to create rice paddies.

Tobacco was a New World crop, first discovered in 1492 on San Salvador when the Arawak gave Columbus and his men fruit and some pungent dried leaves. Columbus ate the fruit but threw away the leaves. Later, Rodrigo de Jerez witnessed natives in Cuba smoking tobacco in pipes for ceremonial purposes and as a symbol of good will.

By 1565, tobacco had spread throughout Europe. It became popular in England after it was introduced by Sir Walter Raleigh, explorer and national figure. By 1580, tobacco usage had spread from Spain to Turkey, and from there to Russia, France, England, and the rest of Asia. In 1614, the Spanish mandated that tobacco from the New World be sent to Seville, which became the world center for the production of cigars. In the same year, King James I of England created a royal monopoly on tobacco imports, though at the same time calling it “that noxious weed” and warning of its adverse effects.

Peppers have been found in prehistoric remains in Peru, where the Incas established their empire. They were grown in Central and South America. Spanish explorers first carried pepper seeds to Spain in 1493, and the plants then spread throughout Europe. Peppers are now cultivated in the tropical regions of Asia and in the Americas near the equator.

Tomatoes originated in the coastal highlands of western South America and were later cultivated by the Maya in Mesoamerica. The Spanish took them to Europe, where at first the Europeans believed them to be poisonous because of the pungent odor of their leaves. The Physalis pubescens, or husk tomato, was called tomatl by the natives, whereas the early common tomato was the xitomatl. The Spaniards called both fruits tomatoes. The use of tomatoes in sauces became known as “Spanish” cuisine. American tomatoes gradually made their way into the cuisine of Portugal, North Africa, and Italy, as well as the Germanic and Slavic regions held by the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs. By the late seventeenth century, tomatoes were included in southern Italian dishes, where they were known as also poma d’oro. Raw and cooked tomatoes were eaten in the Caribbean, Philippines, and southeastern Asia.

The peanut plant probably originated in Brazil or Peru. Inca graves often contain jars filled with peanuts to provide food for the dead in the afterlife. When the Spanish arrived in the New World, peanuts were grown as far north as Mexico. The explorers took peanuts back to Spain, where they are still grown. From Spain, traders and explorers took peanuts to Africa and Asia. Africans believed the plant possessed a soul, and they brought peanuts to the southern part of North America when they were brought there as slaves. The word “goober” comes from the Congo name for peanuts, nguba.

The wonderful commodity we know as chocolate is a product of the cacao tree. This tree requires the warm, moist climate which is found only within fifteen or twenty degrees of the equator. The first written records of chocolate date to the sixteenth century, but this product of cacao trees was likely harvested as long as three or four thousand years ago. This product consists of pods containing a pulpy mass, inside of which are seeds. The cacao bean is a brown kernel inside the seed.

The Olmec used cacao beans as early as 400 BCE; later the Mayans, Aztecs, and Toltecs also cultivated the crop. Eventually, the Indians learned how to make a drink from grinding the beans into a paste, thinning it with water, and adding sweeteners such as honey. They called the drink xocolatl (pronounced shoco-latle). The Aztecs used cacao beans as currency, and in 1502, Columbus returned from one of his expeditions with a bag full of cacao beans as a sample of the coins being used in the New World. In 1519, Cortés observed the Aztec Emperor Montezuma and his court drinking chocolate. In 1606, Italians reached the West Indies and returned with the secret of this splendid potion. The drink became popular in Europe, and in 1657, the first chocolate house opened in London.

Exchange of Diseases

Although the origin of syphilis has been widely debated and its exact origin is unknown, Europeans like Bartolomé de las Casas, who visited the Americas in the early sixteenth century, wrote that the disease was well known among the natives there. Skeletal remains of Native Americans from this period and earlier suggest that here, in contrast to other regions of the world, the disease had a congenital form. Skeletons show “Hutchinson’s Teeth”, which are associated with the congenital form of the disease. They also show lesions on the skull and other parts of the skeleton, a feature associated with the late stages of the disease.

A second explanation which has received a good deal of support in the twenty-first century is that syphilis existed in the Old World prior to the voyages of Columbus, but that it was unrecognized until it became common and widely spread in the years following the discovery of the New World.

The eighteenth century writer Voltaire called syphilis the “first fruits the Spanish brought from the New World.” The disease was first described in Europe after Charles VIII of France marched his troops to Italy in 1494; when his men returned to France, they brought the disease with them and from there it spread to Germany, Switzerland, Greece, and other regions. When Vasco da Gama sailed around the tip of Africa in 1498, he carried the disease to India. In the 1500s, it reached China; in 1520 it reached Japan, where fifty percent of the population in Edo (modern Tokyo) was infected within one hundred years. Hernán Cortés contracted the disease in Haiti as he made his way to Mesoamerica. So widespread was the disease in the sixteenth century, it was called the “Great Pox” or, in a reflection of politics associated with the development of nation states, the disease was called the “French Pox,” the “Italian Pox,” or whatever name reflected the antagonisms of the time.

The Europeans brought smallpox, influenza, measles, and typhus to the New World, devastating the Native American population. Although Europeans had resistance to these diseases, the Native Americans did not. In Europe, measles was a minor irritant; in the New World, it killed countless natives. In the twenty-five years after Columbus landed on Hispaniola, the population there dropped from 5,000,000 to 500.

Some scholars estimate that between fifty to ninety percent of the Native American population died in the wake of the Spanish voyages. If these percentages are correct, they would represent an epidemic of monumental proportions to which there are no comparisons. For example, during the fourteenth century, the Black Death ravaged Europe, killing about fourteen million people, or between thirty to fifty percent of the population. By contrast, in Mexico alone, eight million people died from the diseases brought by the Spanish; there is really no accurate count as to how many other natives died in other regions of the Americas. The impact of smallpox on the native population continued for many centuries after Columbus. During the westward expansion of the United States, pioneers and the army often gave Native Americans blankets laced with smallpox germs in order to more quickly “civilize” the West.

Exchange of Animals

Fossil evidence shows that turkeys were in the Americas ten million years ago. Wild turkeys are originally native to North and Central America. Mesoamericans domesticated the turkey, and the Spanish took it to Europe. By 1524 the turkey reached England, and by 1558, it was popular at banquets in England and in other parts of Europe. Ironically, English settlers brought the domesticated turkey back to North America and interbred it with native wild turkeys. In 1579, the English explorer Martin Frobisher celebrated the first formal Thanksgiving in the Americas with a ceremony in Newfoundland to give thanks for surviving the long journey. The pilgrims who settled in Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1621 celebrated their first harvest in the New World by eating wild turkey.

Although the horse very likely originated in the Americas, it migrated to Asia over the Bering Strait land bridge and became extinct in the Americas after prehistoric times. The horse was completely unknown to the Native Americans prior to the Spanish conquest. In 1519, Hernán Cortés wrote: “Next to God, We Owe Our Victory to Our Horses.” Cortés had brought only sixteen horses, but because the Aztecs fought primarily on foot, the Spaniards had a decided advantage. After their victory over the Aztecs, the Spanish brought more horses. In 1519, Coronado had 150 horses when he went to North America, and de Soto had 237 horses in 1539. By 1547, Antonio de Mendoza, the first governor of New Spain (Mexico), owned over 1,500 horses. The Spanish forbade Native Americans to ride horses without permission.

Cattle were unknown in the Americas before the arrival of the Europeans. The Vikings brought European cattle to the Americas in 1000 CE. When their colony disappeared, so did their cattle. Columbus brought cattle to Hispaniola in 1493. In 1519, Cortés brought cattle to Central America. These cattle sported very long horns, hence the term “longhorns.” Spanish missionaries brought longhorns to Texas, New Mexico, and California; the breed also thrived in South America, especially near modern Brazil and Argentina. The Jamestown colony got its first cattle from England in 1611, and other European powers later brought cattle to their colonies. As the westward expansion began in the nineteenth century, the eastern cattle supplanted the longhorn, as they were better for meat and proved to be hardy in difficult weather. Today, there are few longhorns in North America.

Pigs were unknown in the Americas before Hernán do de Soto brought thirteen of these animals to the Florida mainland. Columbus brought red pigs to the Americas on his second voyage. They were also brought into the United States from the Guinea coast of Africa on early slave-trading vessels. Today, the state of Kansas alone produces enough pigs every year to feed ten million people.

Sheep were first introduced in the southwestern United States by Cortés in 1519 to supply wool for his soldiers. Navajo sheep are descended from the multi-colored sheep from the Spanish. During the westward expansion of the nineteenth century, there would be great conflict between cattle and sheep owners over grazing land.

From the Columbian Exchange to Transculturation