- Free general admission

Flinders circumnavigates Australia

1801–03: Matthew Flinders circumnavigates the continent that he names ‘Australia’

Bronze statue of Matthew Flinders' cat, Trim. Flinders described Trim as, 'The sporting, affectionate and useful companion of my voyages during four years', as he circumnavigated Australia. National Museum of Australia

British explorer Matthew Flinders was the first person to circumnavigate Australia. Flinders charted much previously unknown coastline, and the maps he produced were the first to accurately depict Australia as we now know it.

Flinders proved Australia was a single continent. By using the name ‘Australia’ in his maps and writings, he helped the word enter common usage.

Flinders in Voyage to Terra Australis , 1814:

Had I permitted myself any innovation upon the original term Terra Australis, it would have been to convert it into Australia; as being more agreeable to the ear, and as an assimilation to the names of the other great portions of the earth.

Flinders’ early career

Inspired by reading Robinson Crusoe , Matthew Flinders (1774–1814) joined the Navy as a midshipman in 1789 at the age of 15. He served on William Bligh’s second (and successful) voyage to Tahiti. It was here that Flinders honed the navigation skills that mark him as one of Britain’s most accomplished explorers.

In 1795 Flinders sailed to Sydney from where he made two short expeditions with the naval surgeon George Bass. The men, both in their early twenties, explored Botany Bay and the Georges River, and later Lake Illawarra. The boats they used for each of the expeditions were no more than three metres long.

Flinders also spent time on Norfolk Island and was sent to Cape Town to bring back livestock.

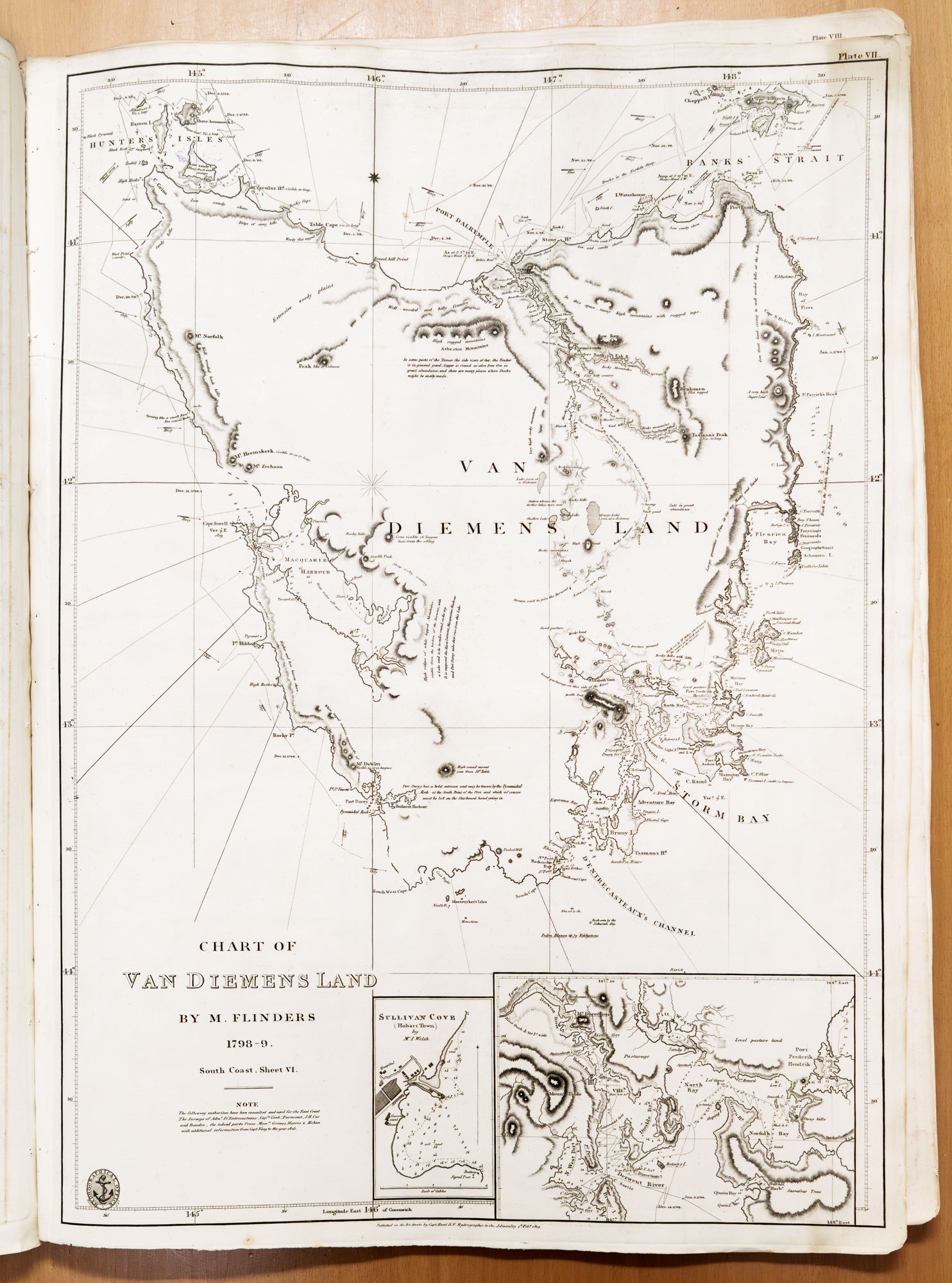

Van Diemen’s Land and Bass Strait

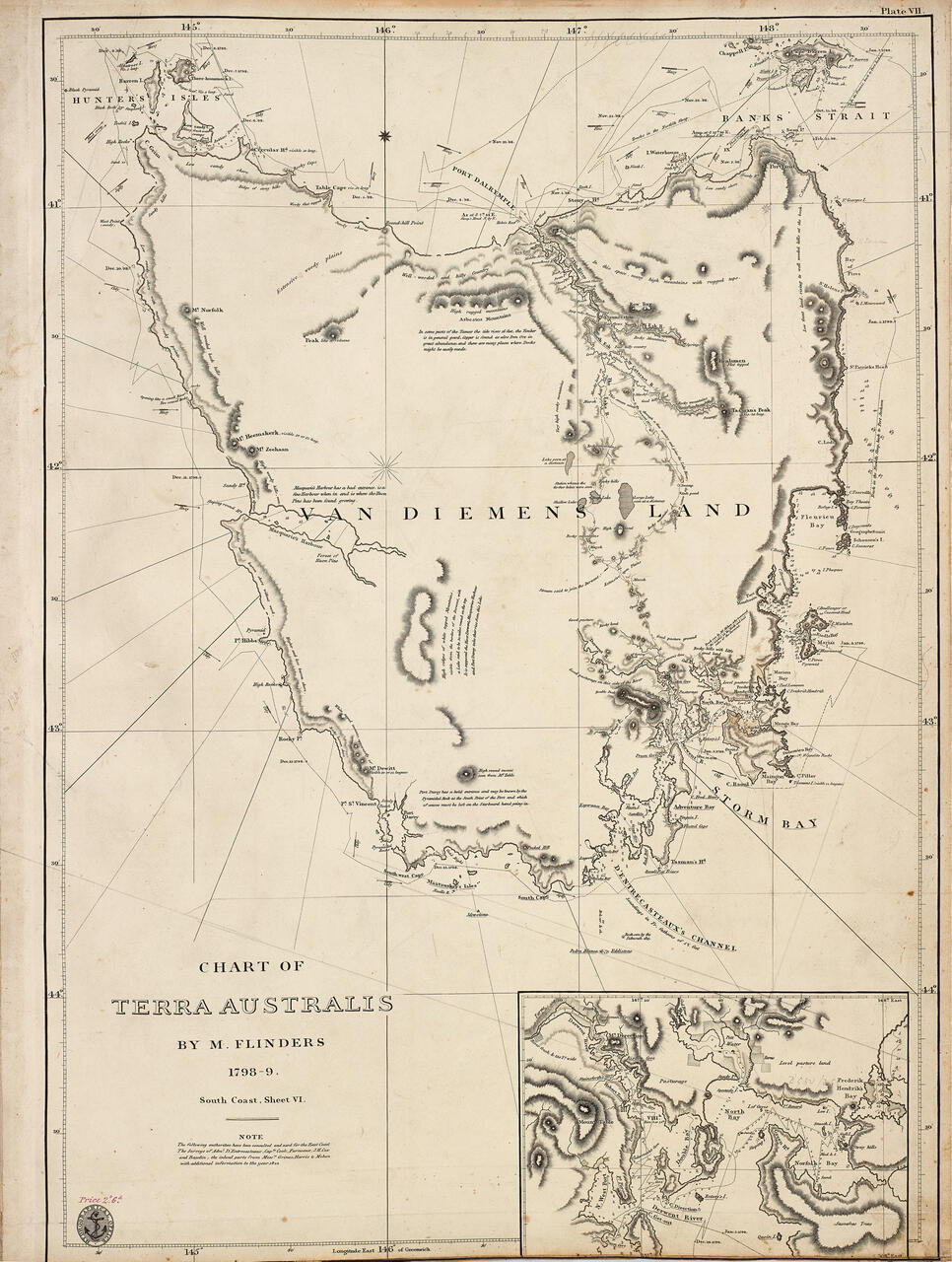

In 1798 Governor John Hunter gave Flinders, now a lieutenant, command of the sloop Norfolk and in this he and Bass circumnavigated Van Diemen’s Land, proving it to be an island. Flinders named the strait between the mainland and Van Diemen’s Land after his friend.

After exploring part of the Queensland coast, Flinders returned to England in 1800. The following year he published the findings of his expeditions, Observations on the Coasts of Van Diemen’s Land, on Bass’s Strait and its Islands, and on Part of the Coasts of New South Wales.

Circumnavigation of Australia

Flinders’ book won him some acclaim and he was able to persuade Sir Joseph Banks to support his proposal to explore the entire Australian coast.

Banks, who had great influence with the British Admiralty, backed Flinders because he was concerned that the French had designs on Australia. Banks knew that the explorer Nicolas Baudin was embarking on an expedition to explore the continent for Napoleon Bonaparte.

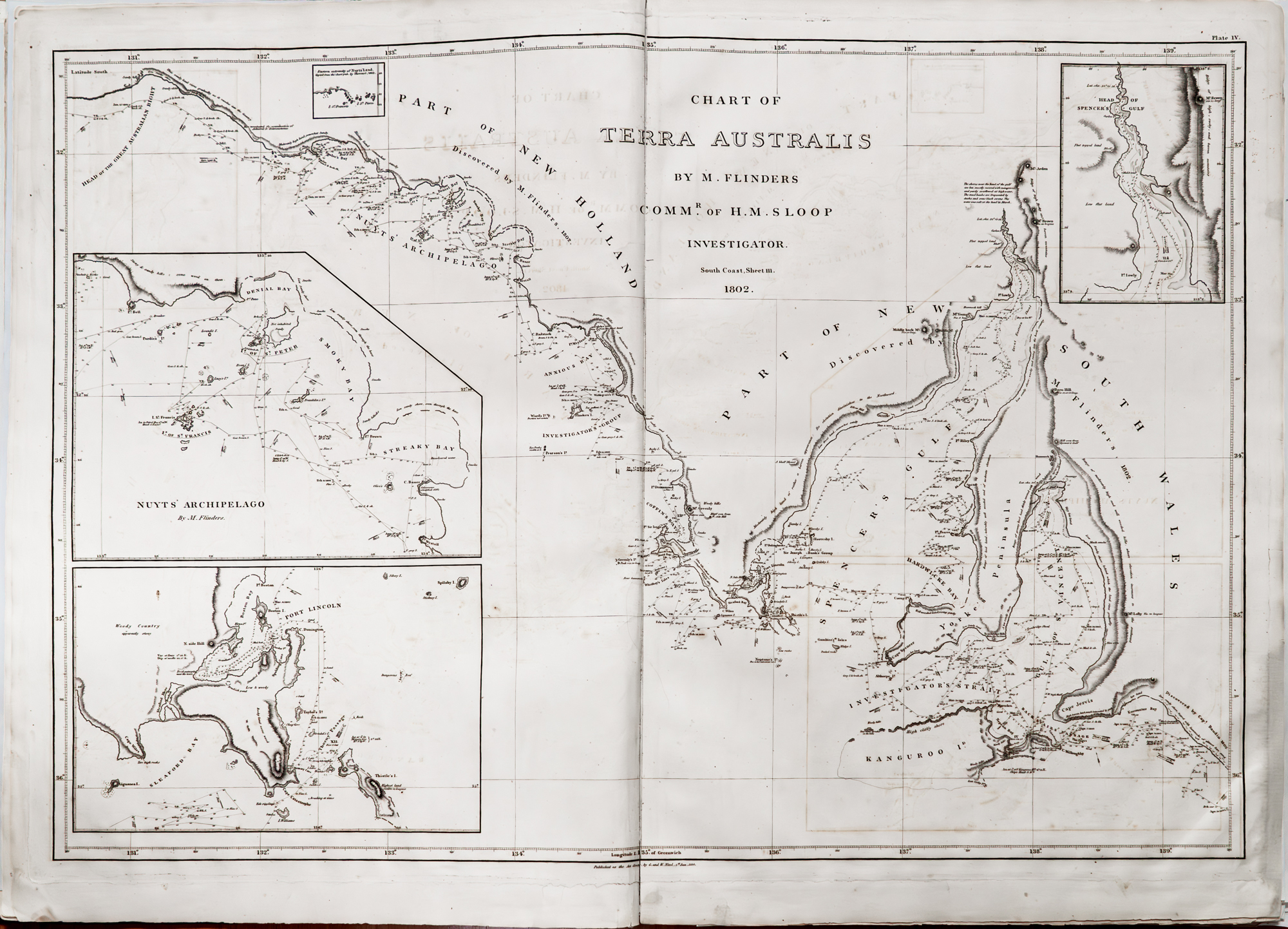

The Admiralty approved and financed the Flinders expedition. Promoted to commander, Flinders was given command of HMS Investigator in February 1801 and ordered to start his expedition by charting ‘the Unknown Coast’, namely the eastern part of the Great Australian Bight.

One of the purposes of the expedition was to establish whether New Holland (western Australia) and New South Wales (eastern Australia) were parts of the same continent.

The Investigator ’s stream anchor, recovered after 170 years on the seabed in the Recherche Archipelago, Western Australia. National Museum of Australia

Investigator

The Investigator was a collier, like James Cook’s vessels. She was eight metres wide and 33 long.

Her flat bottom made her suitable for exploration work, as she could navigate shallow waters and would remain upright if she ran aground.

Flinders arranged improvements for the Investigator , ensuring that more of her hull was copper-coated and that she was provided with additional boats.

Three months before sailing for Australia, Flinders married Ann Chappell whom he had hoped to take with him.

However, permission was refused and Ann stayed in England. Though the voyage was expected to take four years, the couple were not to see one another for nine.

Flinders sailed from England on 18 July 1801 and less than six months later arrived at Point Leeuwin – Australia’s south-western tip.

He headed east and arrived in Fowler Bay in South Australia on 28 January 1802. He then explored Kangaroo Island, the Spencer Gulf and Gulf St Vincent.

In April 1802 Flinders came across Baudin in what he named Encounter Bay where the Murray River empties into the Great Australian Bight.

Baudin was dismayed to find that Flinders had already mapped the nearby coastline. However, the meeting was cordial and Flinders told Baudin about food and water available on Kangaroo Island.

Flinders then set sail for Sydney, which he reached on 9 May 1802. Soon after, he again met Baudin, who had been forced to find refuge in the English colony because his crew were so debilitated by scurvy.

Flinders overhauled the Investigator and let his crew recuperate before heading north on 22 July 1802.

Portrait of Matthew Flinders, RN, 1774–1814 , Toussaint Antoine De Chazal De Chamerel, 1806–07, Mauritius, oil on canvas 65 x 50 cm. Gift of David Roche in memory of his father, JDK Roche, and the South Australian Government 2000, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Encounters with Aboriginal men

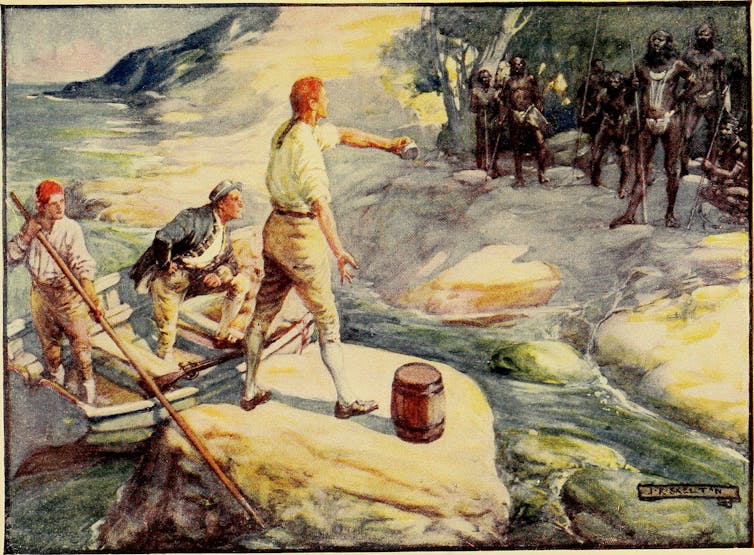

Two Aboriginal men named Bungaree and Nanbaree accompanied him. Bungaree had the delicate task of negotiating with local tribes whenever Flinders wanted to go ashore.

Though Bungaree did not speak the languages of those he encountered, he did at least know many of the required cultural protocols and would have been of great value to the expedition.

Flinders carefully mapped the southern Queensland coast then passed through the Torres Strait into the Gulf of Carpentaria.

There it became clear that the half-rotten and badly leaking Investigator would not be able to make the return journey to England.

Reluctantly, Flinders decided to return to Sydney, continuing anti-clockwise around Australia. To do this quickly and safely meant he was unable to chart much of the western coast with the same rigour.

Maps for much of the west coast had been created by the Dutch in the 17th century.

Flinders arrived in the colony on 9 June 1803, nearly a year after leaving Port Jackson. Scurvy and dysentery had plagued the crew, and several had died of these and other causes.

But the journey had been a remarkable feat of navigation. It meant that Flinders, his crew and their two Aboriginal passengers were the first people to circumnavigate the entire continent.

Under arrest in Mauritius

In August 1803, keen to complete his surveying work of the Torres Strait in particular, Flinders set sail as a passenger on HMS Porpoise .

Unfortunately, the ship struck a reef off Queensland. Before the ship sank, everyone on board found refuge on a nearby island. Flinders navigated one of the ship’s boats 1127 kilometres back to Sydney where he arranged the rescue of the 94 other survivors.

The Governor of New South Wales, Philip Gidley King, complied with Admiralty orders by helping Flinders in every possible way. However, in his haste to return to England, Flinders accepted command of the schooner Cumberland , a very small vessel that proved barely seaworthy.

This forced him to seek help at Mauritius, which was then ruled by the French. Flinders arrived there on 17 December 1803, unaware that seven months earlier England and France had once again gone to war.

The French governor, General Charles de Caen, had earlier fought against the British. He and Flinders clashed and the relationship worsened due to Flinders’ tactless handling of the governor at their first meeting.

Flinders had a French passport, but it had been issued for the Investigator . Baudin had earlier written to de Caen suggesting he extend hospitality towards the English and Flinders in particular because of their friendly meeting at Encounter Bay and the help rendered him at Sydney.

However, De Caen ignored these requests and put Flinders under arrest. He held Flinders on Mauritius for six years, disregarding orders from Paris to set him free.

This might have been motivated in part by personal animosity but de Caen was concerned that Flinders was a spy, or that he would at least reveal to the British how poorly defended Mauritius was.

But Flinders had the freedom of the island and he put the time to good use, forming close friendships and working on his journals and papers.

It was only when the British fleet blockaded the island that de Caen released Flinders, in June 1810.

Final years

In October 1810 Flinders finally returned home to England and his wife, with whom he subsequently had a daughter.

While Flinders languished on Mauritius, the account of Baudin’s voyage had been published by the expedition’s zoologist, François Péron. Baudin himself had died on Mauritius shortly before Flinders had arrived there. Baudin’s expedition was an impressive achievement and certainly more scientifically fruitful than that of Flinders.

However, Péron assigned French names to features first named by Flinders to whom he gave no credit of discovery at all.

Now promoted to post captain, Flinders spent four years setting the record straight in his magnum opus, A Voyage to Terra Australis . But his health was failing, having developed a bladder condition that was probably the result of gonorrhoea he contracted in Tahiti 20 years before.

Flinders died at the age of 40 on 18 July 1814 – the day after his book was published. A copy was placed in his hands but he was already unconscious. He died without seeing it.

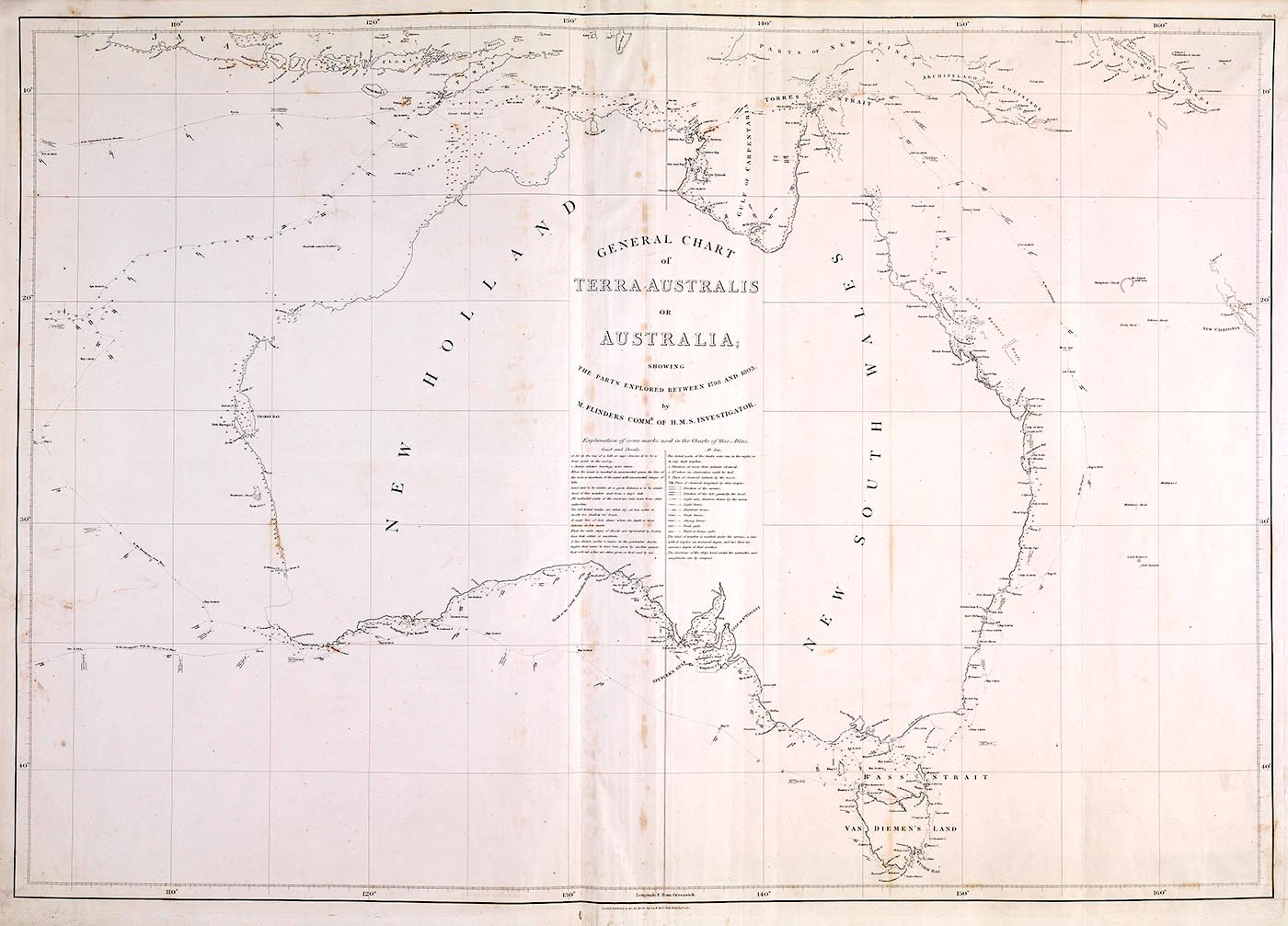

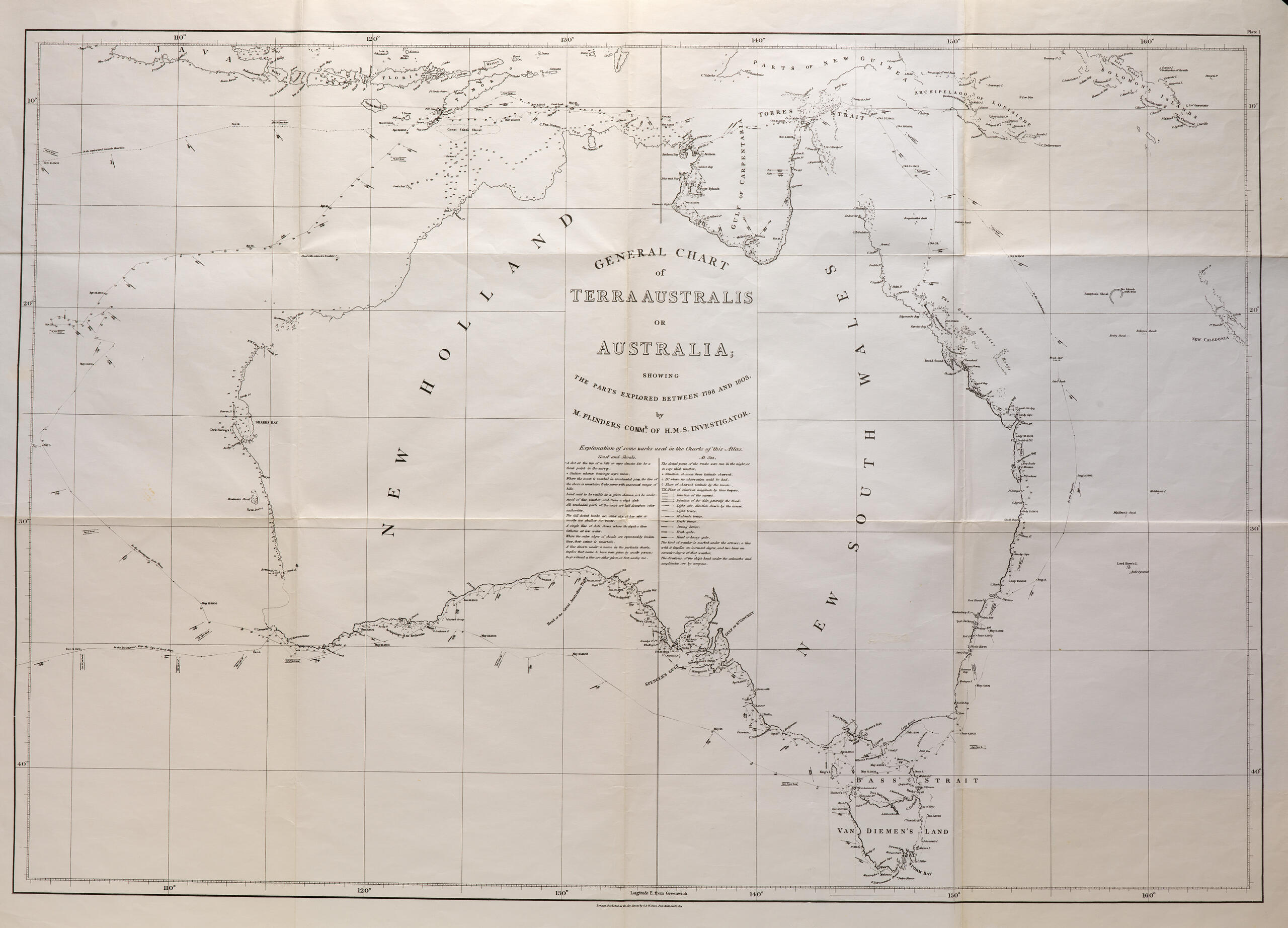

General chart of Terra Australis or Australia by Matthew Flinders. This is the first map of Australia depicting it as a single continent. Flinders marked the coastline he charted himself with heavier lines. The map also shows his route. Tooley Collection, National Library of Australia T 1494

Mapping the continent

Flinders wrote to Sir Joseph Banks from Mauritius in 1804 enclosing his map of Australia. This map, and subsequent versions, were the first to present an accurate depiction of the continent.

Much of Australia’s coast had already been mapped, but Flinders came close to completing the picture. With great care and accuracy, he filled in enormous gaps, such as Bass Strait and the eastern part of the Great Australian Bight, and improved existing charts of Queensland and the Gulf of Carpentaria.

Most importantly he was able to show that Australia was a single continent.

He did this all in a ship that was barely seaworthy for much of the voyage, while enduring, along with his crew, a variety of privations and diseases over extended periods.

Naming the continent

Because the expedition proved that New South Wales in the east and New Holland in the west were the two halves of one landmass it was clear to Flinders that the continent needed a new name.

He labelled the map A chart of Terra Australis or Australia – Terra Australis meaning ‘southern land’, which was in common usage to describe the large southern landmass that was thought to ‘balance’ the great landmasses of the northern hemisphere.

The name ‘Australia’ had appeared in print before, again to describe the legendary southern landmass. The earliest printing of the name appears on a world map in a German astronomical treatise published in 1545.

The name appeared in English works 80 years later and was used occasionally after that, mostly in books. It is not clear whether Flinders knew of the word, or whether he coined it himself.

Banks did not support using ‘Australia’ and prevailed on Flinders to retain the Latin term, which he did in the title of his book. However, Flinders added the footnote quoted above, in which he indicates the term he preferred.

In 1817 Governor Macquarie received a copy of A Voyage to Terra Australis and used the term ‘Australia’ in his correspondence from then on. Britain formally named the continent Australia in 1824 and by the end of that decade it was in common usage.

- exploration

- australian history

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

You may also like

Encounter 1802–2002, State Library of South Australia

General chart of Terra Australis, National Library of Australia

Matthew Flinders, Australian Dictionary of Biography

Science in the colony in our Exploration and Endeavour exhibition

Mapping our World: Terra Incognita to Australia , National Library of Australia, Canberra 2013.

Tim Flannery (ed), Terra Australis: Matthew Flinders’ Great Adventures in the Circumnavigation of Australia , Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2000.

Geoffrey C Ingleton, Matthew Flinders, Navigator and Chartmaker , Genesis Publications, Guildford, UK, 1986.

The National Museum of Australia acknowledges First Australians and recognises their continuous connection to Country, community and culture.

This website contains names, images and voices of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

- Buy Tickets

- Join & Give

Matthew Flinders

- Updated 11/06/21

- Read time 3 minutes

- Share this page:

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Linkedin

- Share via Email

- Print this page

On this page... Toggle Table of Contents Nav

Readers note: This is an excerpt from the Trailblazers: Australia’s 50 Greatest Explorers exhibition, developed in 2015. This content was written as a brief biography on why this person was included in the exhibition.

Matthew Flinders was one of our greatest seafaring explorers, charting much of Australia’s coastline despite a series of trials and wild adventures. An outstanding sailor, surveyor, navigator and scientist, he was a considerate and self-sacrificing leader who looked after all under his command.

Born in England on 16 March 1774, Flinders developed a longing for adventures at sea, partly through reading Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe . He entered the navy at 15 years of age, served under William Bligh on a voyage to Tahiti in 1791 and fought against the French in the naval battle of the Glorious First of June 1794.

In 1795 Flinders sailed to Australia, where he carried out vital coastal survey work. In 1798 he and George Bass circumnavigated Tasmania (then known as Van Diemen’s Land), proving it was separate from mainland Australia.

Portrait of Captain Matthew Flinders, RN,1774-1814 Creator: Toussaint Antoine DE CHAZAL DE CHAMEREL Date created: 1806-07 Location: Mauritius Physical Dimensions: w50 x h64.5 cm Type: Painting Rights: Gift of David Roche in memory of his father, J.D.K. Roche, and the South Australian Government 2000, Medium: oil on canva

Flinders returned to England briefly, where he was promoted to commander of the 334-tonne HMS Investigator , with instructions to explore the southern coastline of Australia. He reached Cape Leeuwin, southern Western Australia, late in 1801 and set about mapping Australia’s ‘Unknown Coast’. His precise, detailed maps are the result of his methodical practice of personally taking all bearings and returning each day to where the previous day’s work had ended.

The Investigator was resupplied and refitted in Sydney in May 1802, before Flinders began his circumnavigation of the continent, accompanied by an Aboriginal translator, Bungaree. But the vessel was leaking badly as it reached the Gulf of Carpentaria. Flinders abandoned the charting work, but continued the circumnavigation to Sydney, limping back into port in June 1803.

Flinders hoped to return to England on the HMS Porpoise to procure another vessel to finish his surveying work, but the Porpoise struck a reef and sank. Flinders expertly sailed her cutter 1130 kilometres back to Sydney, arranged for the rescue of his wrecked shipmates, then sailed for England in another leaky boat, the Cumberland . He pulled into Mauritius for repairs, where the French governor arrested him as a spy and detained him for six years.

Many memorials to Matthew Flinders are found throughout South Australia, New South Wales and Victoria, and coastal features include Flinders Bay (SA) and the Flinders Group of islands in far north Queensland. A small iron rod placed near a ship’s compass is named Flinders bar, as he found it counteracted the vertical magnetism of a vessel.

Subscribe to our eNewsletter

Keep up to date on events, special offers and scientific discoveries with our What's On eNewsletter. Receive the latest news on school holiday programs and much more!

The Australian Museum respects and acknowledges the Gadigal people as the First Peoples and Traditional Custodians of the land and waterways on which the Museum stands.

Image credit: gadigal yilimung (shield) made by Uncle Charles Chicka Madden

A Voyage to Terra Australis 1814, by Matthew Flinders

This rare edition, published as two volumes of journals and two volumes of charts in 1814, is one of the outstanding treasures of the RGSSA. Flinders was the first to circumnavigate Australia and chart its entire coastline.

The following is taken from the title page of A Voyage to Terra Australis;

"A voyage to Terra Australis; undertaken for the purpose of completing the discovery of that vast country, and prosecuted in the years 1801, 1802, and 1803 in His Majesty's ship the Investigator, and subsequently in the armed vessel Porpoise and Cumberland, schooner. With an account of the shipwreck of the Porpoise, arrival of the Cumberland at Mauritius, and imprisonment of the commander during six years and a half in that island .

By Matthew Flinders (1774-1814), commander of the Investigator. Printed by W. Bulmer & Co. and published by G. & W. Nicol, London, 1814."

The RGSSA copy's title page bears the intriguing hand-written inscription "To Captain Sir John Franklin, R.N., Governor of Van Diemen's Land from his attached friend Robert Brown".

When Flinders returned to England from his travels in 1810 he spent his time completing his journals and charts for publication, including re-calculating his astronomical observations. Together with Sir Joseph Banks and John Barrow from the Admiralty, he was appointed to supervise the publication of A Voyage to Terra Australis. Aaron Arrowsmith was the cartographer who prepared the charts for publication and George Nicol the publisher. The first copies of A Voyage to Terra Australis were delivered by Nicol to Matthew Flinders on 18th July 1814, the day before he died.

RGSSA catalogue and location

(rgs) 919.4042 F 622 c

(rgs) 919.4042 F 622 d (Atlas)

More about Matthew Flinders and his voyages

Matthew Flinders made many voyages in his naval career - some of the most notable being;

The voyage (August 1791 - August 1793) around the world, as a seventeen year old, under Captain Bligh to Tahiti (Bligh's second breadfruit voyage) including charting through the Torres Strait.

The voyage (October 1798 - January 1799) around Van Diemen's Land, now Tasmania, proving that it was an island and not connected to the mainland.

The voyage (July 1801 - June 1803) in Investigator circumnavigating the continent of Australia and charting the coastline. The Investigator was in such poor condition that Flinders had to cut short his journey and he wondered if it would make it back home to Port Jackson (Sydney). Maps prepared by Flinders on this voyage are so accurate they were used as authoritative sea charts until around 1947.

The final voyage with Flinders in command was in the small 29 ton schooner Cumberland with a crew of only ten, the plan being they would sail this back to England. Flinders was none too pleased at being offered such an inadequate ship but had no alternative but to accept. They sailed from Sydney Cove on 21st Septmber1803 and headed north to Wreck Reef where the Rolla and the Francis picked up the survivors of the wreck of the Porpoise . Flinders continued sailing north before reaching the Torres Strait where he was able to do some charting in spite of the fact that the Cumberland was leaking badly and one of the pumps was inoperable. He then put into Kupang in the hope of getting repairs made but this proved impossible. He decided to sail on heading for Cape Town but the ship was in such bad condition that he could not continue on that course and turned west and put into Mauritius unaware that France and Britain were at war. As result he was held captive for six and a half years and did not get back to England until 1810.

Flinders was a superb captain, seaman and navigator and saved many lives by insisting on good hygiene and a healthy diet for his crew. His feats of seamanship in small open boats are legendary. This included in Tom Thunb with George Bass along the south-east coast on New South Wales and in Hope which he sailed 1,100km in order to secure the rescue of survivors from the wrecks of the Porpoise and Cato .

A timeline of Flinders' Voyages

The Ships & Voyages of Matthew Flinders

Alert - Matthew Flinders joined the Royal Navy on the muster of Alert on 23rd October 1789 although he never sailed on her.

Scipio - transferred to Scipio in May1790 and then to Bellerophon as a midshipman

Providence - 2nd August 1791 to 7th August 1793 - Flinders' first major voyage - sailed with William Bligh on his second breadfruit voyage as a mid shipman.

Bellerophon - fighting the French from November 1793 to June 1794 as aide- de -camp to Admiral William Pasely.

Reliance - voyage to Port Jackson under Captain John Hunter as masters mate - sailed February 1795 arrived Port Jackson September 1795.

Tom Thumb - an 8 foot skiff- with George Bass and 14 year old William Martin -sailed from Port Jackson 29th October 1795 to Botany Bay and explored the Georges River- arrived back early November to Port Jackson.

Reliance - voyage to supply Norfolk Island -sailed from Port Jackson 21st January 1796 with Matthew and Samuel Flinders.

Tom Thumb I I - a 12 foot sailing boat with the same crew - departed Port Jackson 24th March 1796 and sailed as far south as present Woolongong and Lake Illawara. Arrived back at Port Jackson 1st April 1796.

Reliance - sailed from Norfolk Island with Supply and Britannia 25th October 1796 to Cape Town to pick up livestock to supply the settlement at Port Jackson. Reliance and Flinders arrived back 26th June 1797.

Francis - voyage under Capt. William Reed to rescue survivors of the wreck of the Sydney Cove. Left Port Jackson 1st February 1798 and returned 9th March 1798. Flinders was on board as surveyor and map - maker.

Norfolk - the epic voyage in the 25-ton, 35-foot sloop that proved Van Diemen's Land an island and having named Bass Strait. Lieutenant Matthew Flinders and George Bass left Port Jackson 7th October 1798 arriving back 11th January 1799.

Norfolk - Flinders was given eight weeks to sail north along the coast of New South Wales and carry out further charting. He left 8th July 1799 and returned 20th August having got as far as the Glasshouse Mountains and Morten Bay.

Reliance - two short voyages to supply Norfolk Island - completed December 1799.

Reliance - voyage back to England under Captain Henry Waterhouse sailing from Port Jackson 3rd March 1800. Arrived Plymouth 26th August 1800. It was five years since Flinders had been back in England.

Investigator - the historic voyage that included the first circumnavigation of Terra Australis. With Sir Joseph Banks' backing Flinders was commissioned to make the voyage in the Investigator . He was promoted to commander and they set sail on 18 July 1801, sighting Cape Leeuwin on 7th December. They reached Port Jackson on 8th May 1802 having "encountered " Captain Nicholas Baudin in Le Geographe off the coast of what is now South Australia on 8th April 1802. (On board also was Matthew's cousin Midshipman John Franklin later Sir John Franklin).

Investigator - sailed north from Port Jackson 22nd July 1802 to complete the circumnavigation. Reached Thursday Island 2nd November and then sailed around the coast of the Gulf of Carpentaria proving that it did not bisect the continent as some had suggested. The Investigator was in poor condition and many of the crew were sick so they put into Kupang for repairs and supplies. Flinders was concerned that the ship might not get them home and decided their only hope was to sail for Port Jackson as quickly as possible. This they did only stopping for water and food and not charting or collecting specimens along the way .The Investigator arrived back at Port Jackson on 9th June 1803.

Porpoise - Flinders was to return to England as a passenger on the P orpoise and sailed on 10 August 1803 from Port Jackson under the command of Capt. Robert Fowler. Sailing with them were the Cato and Bridgewater. On the night of 17th August Porpoise and Cato struck a reef and were wrecked. Fortunately ninety -four members of the crew were rescued and were able to set up camp on a nearby sand cay.

Flinders then took one of the cutters which had been saved and with thirteen crew members sailed and rowed the nearly 1,100km back to Port Jackson departing 26 August and arriving at 8th September 1803. "Wreck Reef " was named by Flinders and is located off the coast of Townsville.

Cumberland - Governor Gidley King organised a rescue party consisting of Rolla , Francis and Cumberland to sail up the coast to Wreck Reef and rescue the remaining crewmen. As part of this rescue effort Flinders was offered the Cumberland for the return journey back to England. He was none too pleased to be offered such a small ship (29 tons and a crew of only ten plus a captain) for the long journey back to England but accepted thinking it would be the quickest way for him to get home.

Setting sail from Port Jackson on 21st September they arrived at Wreck Reef on 7th October and left shortly thereafter on 11th October having rescued the surviving crewmen and salvaged Flinders maps and journals.

Flinders then sailed north up the east coast and into the Torres Strait where he was able to do some charting. He then put in to Kupang arriving on 10th November. He only stayed four days before resuming his voyage his destination being Cape Town. However the poor condition of the Cumberland and the weather made him decide to put in at Ile de France (Mauritius) on 12th December 1803 where he was detained for six and a half years by the French.

Harriet, Otter and Olympia - Flinders was finally given his release by the French on 28th March 1810. The Harriet was a ship of truce (a cartel) which was to take him back to England via India and they sailed on 13th June1810 from Port Louis. He then transferred to the Otter which sailed directly to Cape Town. After a wait of some weeks Flinders boarded Olympia on 28th August 1810, which took him on to England where he landed 2nd October 1810 and received a belated promotion to post captain.

Matthew Flinders did not go to sea again and died in London 19th July 1814.

Notes prepared by Hugh Orr

© The Royal Geographical Society of South Australia

Celebrating the cartographer who circumnavigated Australia.

To mark the 250 th birthday of matthew flinders, the australian national maritime museum is publishing this short exclusive extract from peter fitzsimons’ forthcoming book on the great navigator. , below, fitzsimons’ writes about flinders and his attitude to indigenous australians. .

Hand coloured engraving of Captain Matthew Flinders RN

Joyce Gold, published 30 September 1814 by the Naval Chronicle Office

7 April, 1802, Kangaroo Head, the first Australians On his own voyage up the East Coast of New Holland, as he called it, Captain Cook found the elusiveness of the “Indians” very puzzling. Rarely more than flitting figures in the distance, they seemed to have no interest in any interactions at all, no matter how much they try to entice them. But perhaps, Captain Flinders wonders, his mighty forebear was trying too hard? For as they proceed, the protégé of Cook’s protégé, his humble self, develops an entirely different tactic to engage them. Take this day, when calls are heard, native voices, from bodies unseen, yelling to them from dense scrubland: “No attempt was made to follow them, for I had always found the natives of this country to avoid those who seemed anxious for communication; whereas, when left entirely alone, they would usually come down after having watched us for a few days.” [1] Eminently sensible, this observation leads Flinders to further musing and empathy on the Indigenous caution that seems beyond his time. After all, Flinders reasons, from that perspective, the response of the natives is exactly what we white people would do. “For what, in such case, would be the conduct of any people, ourselves for instance, were we living in a state of nature, frequently at war with our neighbours, and ignorant of the existence of any other nation? On the arrival of strangers so different in complexion and appearance to ourselves, having power to transplant themselves over, and even living upon, an element which to us was impossible, the first sensation would probably be terror, and the first movement flight. “We should watch these extraordinary people from our retreats in the woods and rocks, and if we found ourselves sought and pursued by them, should conclude their designs to be inimical; but if, on the contrary, we saw them quietly employed in occupations which had no reference to us, curiosity would get the better of fear, and after observing them more closely, we should ourselves risk a communication. Such seemed to have been the conduct of these Australians.” [2] “Australians?” It is the first time that the native population has been so called, and it has a certain ring to it. They are “Indians” no longer. Flinders is also sure to try and move beyond bartering and has simply left gifts for these unseen Australians: hatchets, ropes, cups and the like. Hopefully, goodwill might be purchased with these gifts, the better to benefit “succeeding visitors” [3] .

[1] Matthew Flinders, Voyage To Terra Australis Vol.1, G. and W. Nichol, London, 1814, p. 146 [2] Matthew Flinders, Voyage To Terra Australis Vol.1, G. and W. Nichol, London, 1814, pp. 146-147 [3] Matthew Flinders, Voyage To Terra Australis Vol.1, G. and W. Nichol, London, 1814, pp. 146-147

Charts of Matthew Flinders

Matthew Flinders was born on March 16 1774 in Donington, Lincolnshire, England.

With George Bass, he confirmed Tasmania, then named Van Diemen’s land, as an island and in 1802-03, he led the first inshore circumnavigation of Australia.

Flinders is also credited as the first to use Australia as the continent’s name. He died in London on July 19, 1814. He was 40 years old. Peter FitzSimons’ forthcoming book on Flinders will be published by Hachette.

Find out more about Peter's books

Footage by Craig Bender

More from the Museum

The Australian National Maritime Museum celebrates our nations's history and connection to the sea. We protect t he National Maritime collection, a rich and diverse range of over 160,000 historic artefacts.

Among these objects are fascinating treasures, such as a copy of Flinders' A Voyage to Terra Australis and an array of charts based on these important surveys of Australia's coatline.

Explore Matthew Flinders in the collection

00004101 - Chart of Van Diemens Land, 1798 - 1799. Matthew Flinders , engraved by L Welsh.

ANMM Collection

Heroes of Colonial Encounters, Helen S Tiernan, 2017

Explore this collection

ANMM Collection reproduced courtesy of Helen S Tiernan and licenced for use by the Museum. If you would like to use this image please contact the Museum at [email protected]

00055142 - Heroes of Colonial Encounters- Matthew Flinders, Helen S Tiernan, 2017.

ANMM Collection reproduced courtesy of Helen S Tiernan and licenced for use by the Museum. If you would like to use this image please contact the Museum at [email protected]

© Helen S Tiernan

00055144 - Heroes of Colonial Encounters- Bungaree, Helen S Tiernan, 2017.

While Matthew Flinders circumnavigated the Australian continent he was assisted by Bungaree, who acted as a type of diplomat with other First Nations people they encountered on the voyage. As a consequence Bungaree became the first known person born in the country to circumnavigate it.

Although Bungaree became well versed in the ways of the new inhabitants and took to wearing elements of European dress, he remained very much a Kuringgai man and a respected elder amongst his people. The last years of Bungaree's life were spent in Sydney on the land now known as The Domain. He died on Wednesday 24 November 1830 and was buried at Rose Bay.

Read more about Flinders and Bungaree

00001899 - Chart from A voyage to Terra Australia, volume 2. Matthew Flinders, published by G and W Nicol, 1814.

Voyages of Matthew Flinders

- 1 Understand

Captain Matthew Flinders (16 March 1774 – 19 July 1814) was an English navigator who led the first inshore navigation of inland Australia.

Understand [ edit ]

Captain Matthew Flinders was an English navigator, cartographer and officer of the Royal Navy who led the second circumnavigation of New Holland, that he would subsequently call "Australia", and identified it as a continent. Flinders made three voyages to the southern ocean between 1791 and 1810. In the second voyage, George Bass and Flinders confirmed that Van Diemen's Land was an island. In the third voyage, Flinders circumnavigated the Australian mainland; heading back to England in 1803, Flinders' vessel needed urgent repairs at Isle de France . Although Britain and France were at war, Flinders thought the scientific nature of his work would ensure safe passage, but a suspicious governor kept him under arrest for more than six years. Although he reached home in 1810, he did not live to see the success of his widely praised book and atlas, A Voyage to Terra Australis . The location of his grave was lost by the mid-19th century, but archaeologists excavating a former burial ground near London 's Euston railway station for the High Speed 2 (HS2) project, announced in January 2019 that his remains had been identified. Flinders' remains will be reinterred in the parish Church of St Mary and the Holy Rood in Donington , Lincolnshire, where he was baptised, on 13th July 2024. While largely forgotten in his home country England, he is a household name in Australia , where over 100 places and monuments have been named after him.

See [ edit ]

- -34.921146 138.600671 1 Matthew Flinders Memorial , North Terrace, Adelaide , South Australia . Flinders is seen as being particularly important in South Australia, where he is considered the main explorer of the state. His statue stands on an attractive, tree-lined boulevard in a South Australian colonial tradition.

- -34.072688 151.15439 4 Bass and Flinders Memorial , Cronulla , New South Wales ( south along the beachfront esplanade from South Cronulla Beach ). Bass and Flinders discovered the Port Hacking waterway around Cronulla. A memorial to them and explanation of their journey is on the headland near the entrance to Port Hacking. Nice views across the river and ocean from here.

- -25.2893 152.908 5 Matthew Flinders' Lookout , Urangan , Queensland . Commemorates Flinders' explorations of the Hervey Bay area. ( updated May 2020 )

See also [ edit ]

- Voyages of James Cook

- Voyages of George Vancouver

- Has custom banner

- Has mapframe

- Maps with non-default alignment

- Maps with non-default size

- Has map markers

- Usable topics

- Usable articles

- Age of Discovery

- Topic articles

- Pages with maps

Navigation menu

The limits of empathy: Matthew Flinders’ encounters with Indigenous Australians

Adjunct associate, Flinders University

Disclosure statement

Gillian Dooley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Flinders University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

The Investigator arrived off Cape Leeuwin, on the southwest tip of Western Australia, on 6 December 1801, captained by the 26-year-old Matthew Flinders . Feeling as though I know Flinders well through working on his personal writings over the past few years, I’ve become intrigued by his accounts of his dealings with the Indigenous people of Australia as the ship circumnavigated Australia. How might his habit of fair-mindedness have affected his behaviour?

Flinders left two accounts of his Investigator voyage. One was the official Voyage to Terra Australis (1814), written on his return to England seven years after the end of the voyage, during which time he was shipwrecked and then detained by the French on Mauritius. The other is a fair copy of his captain’s log, which has recently been published as Australia Circumnavigated .

Flinders and his crew first met some Noongar people on 14 December 1801. Before that, as Flinders reported in his Voyage to Terra Australis, they had not seen any of the “natives”, although “marks of the country being inhabited were found every where”. The people they met were “shy but not afraid”, Flinders wrote. Nine days later a group set off inland, and were met by a Noongar man:

He was very anxious that we should not go further; and acted with a good deal of resolution in first stopping one and then another of those who were foremost. He was not able to prevail; but we accommodated him so far as to make a circuit round the wood, where it seemed probable his family and female friends were placed. The old man followed us, hallooing frequently to give information of our movements; … at length, growing tired of people who persevered in keeping a bad road in opposition to his recommendation of a better, which, indeed, had nothing objectionable in it but that it led directly contrary to where our object lay, he fell behind and left us.

Encounters like this, where no shots were fired, were often characterised as “friendly”, but, as academic Tiffany Shellam has pointed out, there were undercurrents of fear and insecurity, and Flinders, despite his rather sardonic tone here, actually had no idea what was happening.

If there were undercurrents of violence and fear even in this “friendly” encounter, they surfaced with tragic results a year later when the Investigator reached Blue Mud Bay, the land of the Djalkiripuyngu people, part of the Yolngu-speaking territory in the Northern Territory.

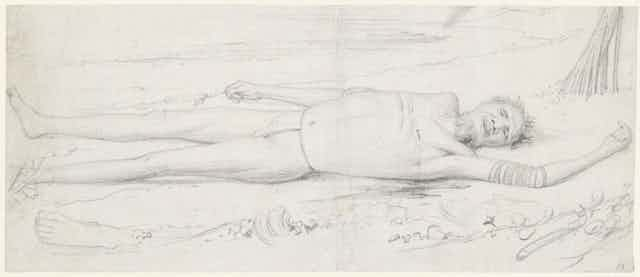

The Master’s Mate of the Investigator was speared while collecting wood with some of his crew mates, and in retaliation at least one Djalkiripuyngu man was killed.

Flinders was not in the landing party, and was angry with the Master for initiating a revenge attack, “forgetting the orders I had given him”. Though he didn’t understand the motives behind the spearing, Flinders knew the danger posed by his men’s aggressive behaviour.

However, he recorded no punishments for those involved, and, to add insult to injury, sent a boat ashore the next day to collect the dead body for his scientists to examine. He doesn’t mention returning the body later. Such disrespect seems like a flagrant breach of the behaviour Flinders expected of himself and those under his command. Did he think that the claims of science overrode respect for the dead?

The evidence of Flinders’ feelings of empathy with the Aboriginal people he encountered is, I concede, slight. In Australia Circumnavigated, he expressed mild though not insurmountable regret at the death of the man at Morgan’s Island.

He refers to Woga, a young man held hostage on the ship for a day in February 1803 as “the poor Indian”. So far this is more sympathy than empathy. The most direct expression of empathy is in Voyage to Terra Australis :

What … would be the conduct of any people, ourselves for instance, were we living in a state of nature, frequently at war with our neighbours, and ignorant of the existence of any other nation?

This, written ten years after the voyage, after many trials and disappointments, and after much time for contemplation during his detention by the French, might be a unique instance of Flinders’ imaginative identification with the Aboriginal people.

As for the way any feelings of empathy might have been expressed in his actions during the Investigator voyage, I just don’t think they entered the equation. As a matter of pure humanity he would prefer not to cause pain to other human beings, but in all his actions as captain of the Investigator his duty was to explore and map the Australian coast, to keep his ship’s company safe, and to smooth the way for future explorations.

In most cases, he deemed that humane treatment and forbearance was the best way to do this, but if a show of force, even firing with intent to wound, was needed “to convince them that we were not to be insulted”, he would not shrink from doing his duty as he saw it.

The limits of empathy are defined by duty – and Flinders’ duty was in the final analysis dictated by policy rather than feelings or morality.

Gillian Dooley will present a paper based on this research at the InASA Conference in Fremantle this week. With Danielle Clode, she is co-editing a book titled The First Wave: Exploring Early Coastal Contact History in Australia.

- Australian history

- Colonialism

- Indigenous Australia

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

Project Officer, Student Program Development

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Operations Manager

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

- MATTHEW FLINDERS

- Bring him home !

- Volunteering

- Announcements

- MFBHH Group

- Matthew's early life

- Early Naval career

- Charting Australia

- Return to England

- Final years and publication

- Rememberance and celebration

- Ann Flinders

- ann flinders grave

- to the memory of trim

- collections

- Captain flinders goes home - a poem

- Accommodation nearby

- 2020 MFBHH Calendars

- Local Businesses

- +44-01775820158

- [email protected]

- Project Gutenberg

- 73,321 free eBooks

- 2 by Matthew Flinders

A Voyage to Terra Australis — Volume 2 by Matthew Flinders

Read now or download (free!)

Similar books, about this ebook.

- Privacy policy

- About Project Gutenberg

- Terms of Use

- Contact Information

A Voyage to Terra Australis Vol 1

Matthew flinders.

PRODUCTION NOTES: Notes referred to in the book (*) are shown in square brackets ([ ]) at the end of the paragraph in which the note is indicated. References to the charts have been retained though the charts are not reproduced in the ebook. The original punctuation and spelling and the use of italics and capital letters to highlight words and phrases have, for the most part, been retained. I think they help maintain the "feel" of the book, which was published over 200 years ago. Flinders notes in the preface that "I heard it declared that a man who published a quarto volume without an index ought to be set in the pillory, and being unwilling to incur the full rigour of this sentence, a running title has been affixed to all the pages; on one side is expressed the country or coast, and on the opposite the particular part where the ship is at anchor or which is the immediate subject of examination; this, it is hoped, will answer the main purpose of an index, without swelling the volumes." This treatment is, of course, not possible, where there are no defined pages. However, Flinders' running titles are included at appropriate places where they seem relevant. These, together with the Notes which, in the book, appear in the margin, are represented as line headings with a blank line before and after them. Colin Choat

A VOYAGE TO TERRA AUSTRALIS UNDERTAKEN FOR THE PURPOSE OF COMPLETING THE DISCOVERY OF THAT VAST COUNTRY, AND PROSECUTED IN THE YEARS 1801, 1802 AND 1803, IN HIS MAJESTY'S SHIP THE INVESTIGATOR, AND SUBSEQUENTLY IN THE ARMED VESSEL PORPOISE AND CUMBERLAND SCHOONER. WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE SHIPWRECK OF THE PORPOISE, ARRIVAL OF THE CUMBERLAND AT MAURITIUS, AND IMPRISONMENT OF THE COMMANDER DURING SIX YEARS AND A HALF IN THAT ISLAND. BY MATTHEW FLINDERS COMMANDER OF THE INVESTIGATOR. IN 2 VOLUMES WITH AN ATLAS. VOLUME 1. LONDON: PRINTED BY W. BULMER AND CO. CLEVELAND ROW, AND PUBLISHED BY G. AND W. NICOL, BOOKSELLERS TO HIS MAJESTY, PALL-MALL. 1814

[facsimile edition, 1966].

TO The Right Hon. George John, Earl Spencer, The Right Hon. John, Earl of St Vincent, The Right Hon. Charles Philip Yorke, and The Right Hon. Robert Saunders, Viscount Melville, who, as First Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, successively honoured the Investigator's voyage with their patronage, This account of it is respectfully dedicated, by their Lordships' most obliged, and most obedient humble servant,

Matthew Flinders.

London, 20 May 1814.

This chart was published in 1814. It did NOT appear in A Voyage to Terra Australis. .

From the general tenour of the explanations here given, it will perhaps be inferred that the perfection of the Atlas has been the principal object of concern; in fact, having no pretension to authorship, the writing of the narrative, though by much the most troublesome part of my labour, was not that upon which any hope of reputation was founded; a polished style was therefore not attempted, but some pains have been taken to render it clearly intelligible. The first quire of my manuscript was submitted to the judgment of a few literary friends, and I hope to have profited by the corrections they had the kindness to make; but finding these to bear more upon redundancies than inaccuracy of expression, I determined to confide in the indulgence of the public, endeavour to improve as the work advanced, and give my friends no further trouble. Matter, rather than manner, was the object of my anxiety; and if the reader shall be satisfied with the selection and arrangement, and not think the information destitute of such interest as might be expected from the subject, the utmost of my hopes will be accomplished.

N.B. Throughout this narrative the variation has been allowed upon the bearings, and also in the direction of winds, tides, etc. ; the whole are therefore to be considered with reference to the true poles of the earth, unless it be otherwise particularly expressed; and perhaps in some few cases of the ship's head when variations are taken, where the expression by compass , or magnetic , may have been omitted.

A VOYAGE TO TERRA AUSTRALIS

TABLE OF CONTENTS. (For both volumes)

IN THE FIRST VOLUME.

INTRODUCTION.

PRIOR DISCOVERIES IN TERRA AUSTRALIS.

SECTION I. NORTH COAST.

Preliminary Remarks: Discoveries of the Duyfhen; of Torres; Carstens; Pool; Pietersen; Tasman; and of three Dutch vessels. Of Cook; M'Cluer; Bligh; Edwards; Bligh and Portlock; and Bampton and Alt. Conclusive Remarks.

SECTION II. WESTERN COASTS.

Preliminary Observations. Discoveries of Hartog: Edel: of the Ship Leeuwin: the Vianen: of Pelsert: Tasman: Dampier: Vlaming: Dampier. Conclusive Remarks.

SECTION III. SOUTH COAST.

Discovery of Nuyts. Examination of Vancouver: of D'Entrecasteaux. Conclusive Remarks.

SECTION IV. EAST COAST, WITH VAN DIEMEN'S LAND.

Preliminary Observations. Discoveries of Tasman; of Cook; Marion and Furneaux. Observations of Cook; Bligh; and Cox. Discovery of D'Entrecasteaux. Hayes.

TRANSACTIONS FROM THE BEGINNING OF THE VOYAGE TO THE DEPARTURE FROM PORT JACKSON.

CHAPTER II.

Chapter iii., chapter iv., chapter vi., chapter vii., chapter viii., chapter ix., chapter xi..

Account of the observations by which the Longitudes of places on the north coast of Terra Australis have been settled.

IN THE SECOND VOLUME.

TRANSACTIONS DURING THE CIRCUMNAVIGATION OF TERRA AUSTRALIS, FROM THE TIME OF LEAVING PORT JACKSON TO THE RETURN TO THAT PORT.

The Keppel Isles, and coast to Cape Manifold. A new port discovered and examined. Harvey's Isles. A new passage into Shoal-water Bay. View from Mount Westall. A boat lost. The upper parts of Shoal-water Bay examined. Some account of the country and inhabitants. General remarks on the bay. Astronomical and nautical observations.

Departure from Shoal-water Bay, and anchorage in Thirsty Sound. Magnetical observations. Boat excursion to the nearest Northumberland Islands. Remarks on Thirsty Sound. Observations at West Hill, Broad Sound. Anchorage near Upper Head. Expedition to the head of Broad Sound: another round Long Island. Remarks on Broad Sound, and the surrounding country. Advantages for a colony. Astronomical observations, and remarks on the high tides.

The Percy Isles: anchorage at No. 2. Boat excursions. Remarks on the Percy Isles; with nautical observations. Coral reefs: courses amongst them during eleven days search for a passage through, to sea. Description of a reef. Anchorage at an eastern Cumberland Isle. The Lady Nelson sent back to Port Jackson. Continuation of coral reefs; and courses amongst them during three other days. Cape Gloucester. An opening discovered, and the reefs quitted. General remarks on the Great Barrier; with some instruction relative to the opening.

Passage from the Barrier Reefs to Torres' Strait. Reefs named Eastern Fields. Pandora's Entrance to the Strait. Anchorage at Murray's Islands. Communication with the inhabitants. Half-way Island. Notions on the formation of coral islands in general. Prince of Wales's Islands, with remarks on them. Wallis' Isles. Entrance into the Gulph of Carpentaria. Review of the passage through Torres' Strait.

Examination of the coast on the east side of the Gulph of Carpentaria. Landing at Coen River. Head of the Gulph. Anchorage at Sweers' Island. Interview with Indians at Horse-shoe Island. Investigator's Road. The ship found to be in a state of decay. General remarks on the islands at the Head of the Gulph, and their inhabitants. Astronomical and nautical observations.

Departure from Sweers' Island. South side of C. Van Diemen examined. Anchorage at Bountiful Island: turtle and sharks there. Land of C. Van Diemen proved to be an island. Examination of the main coast to Cape Vanderlin. That cape found to be one of a group of islands. Examination of the islands; their soil, etc. Monument of the natives. Traces of former visitors to these parts. Astronomical and nautical observations.

Departure from Sir Edward Pellew's Group. Coast from thence westward. Cape Maria found to be an island. Limmen's Bight. Coast northward to Cape Barrow: landing on it. Circumnavigation of Groote Eylandt. Specimens of native art at Chasm Island. Anchorage in North-west Bay, Groote Eylandt; with remarks and nautical observations. Blue-mud Bay. Skirmish with the natives. Cape Shield. Mount Grindall. Coast to Caledon Bay. Occurrences in that bay, with remarks on the country and inhabitants. Astronomical and nautical observations.

Departure from Caledon Bay. Cape Arnhem. Melville Bay. Cape Wilberforce, and Bromby's Isles. The English Company's Islands: meeting there with vessels from Macassar. Arnhem Bay. The Weasel's Islands. Further examination of the North Coast postponed. Arrival at Coepang Bay, in Timor. Remarks and astronomical observations.

Departure from Timor. Search made for the Trial Rocks. Anchorage in Goose-Island Bay. Interment of the boatswain, and sickly state of the ship's company. Escape from the bay, and passage through Bass' Strait. Arrival at Port Jackson. Losses in men. Survey and condemnation of the ship. Plans for continuing the survey; but preparation finally made for returning to England. State of the colony at Port Jackson.

Advantages of this passage over that round New Guinea.

OCCURRENCES FROM THE TIME OF QUITTING PORT JACKSON IN 1803, TO ARRIVING IN ENGLAND IN 1810.

Departure from Port Jackson in the Porpoise, accompanied by the Bridgewater and Cato. The Cato's Bank. Shipwreck of the Porpoise and Cato in the night. The crews get on a sand bank; where they are left by the Bridgewater. Provisions saved. Regulations on the bank. Measures adopted for getting back to Port Jackson. Description of Wreck-Reef Bank. Remarks on the loss of M. de La Pérouse.

Departure from Wreck-Reef Bank in a boat. Boisterous weather. The Coast of New South Wales reached, and followed. Natives at Point Look-out. Landing near Smoky Cape; and again near Port Hunter. Arrival at Port Jackson on the thirteenth day. Return to Wreck Reef with a ship and two schooners. Arrangements at the Bank. Account of the reef, with nautical and other remarks.

Passage in the Cumberland to Torres' Strait. Eastern Fields and Pandora's Entrance. New channels amongst the reefs. Anchorage at Half-way Island, and under the York Isles. Prince of Wales's Islands further examined. Booby Isle. Passage across the Gulph of Carpentaria. Anchorage at Wessel's Islands. Passage to Coepang Bay, in Timor; and to Mauritius, where the leakiness of the Cumberland makes it necessary to stop. Anchorage at the Baye du Cap, and departure for Port Louis.

Arrival at Port Louis (or North-West) in Mauritius. Interview with the French governor. Seizure of the Cumberland, with the charts and journals of the Investigator's voyage; and imprisonment of the commander and people. Letters to the governor, with his answer. Restitution of some books and charts. Friendly act of the English interpreter. Propositions made to the governor. Humane conduct of captain Bergeret. Reflections on a voyage of discovery. Removal to the Maison Despeaux or Garden Prison.

Prisoners in the Maison Despeaux or Garden Prison. Application to admiral Linois. Spy-glasses and swords taken. Some papers restored. Opinions upon the detention of the Cumberland. Letter of captain Baudin. An English squadron arrives off Mauritius: its consequences. Arrival of a French officer with despatches, and observations thereon. Passages in the Moniteur, with remarks. Mr. Aken liberated. Arrival of cartels from India. Applicatiou made by the marquis Wellesley. Different treatment of English and French prisoners. Prizes brought to Mauritius in sixteen months. Departure of all prisoners of war. Permission to quit the Garden Prison. Astronomical observations.

Parole given. Journey into the interior of Mauritius. The governor's country seat. Residence at the Refuge, in that Part of Williems Plains called Vacouas. Its situation and climate, with the mountains, rivers, cascades, and views near it. The Mare aux Vacouas and Grand Bassin. State of cultivation and produce of Vacouas; its black ebony, game, and wild fruits; and freedom from noxious insects.

Occupations at Vacouas. Hospitality of the inhabitants. Letters from England. Refusal to be sent to France repeated. Account of two hurricanes, of a subterraneous stream and circular pit. Habitation of La Pérouse. Letters to the French marine minister, National Institute, etc. Letters from Sir Edward Pellew. Caverns in the Plains of St. Piérre. Visit to Port Louis. Narrative transmitted to England. Letter to captain Bergeret on his departure for France.

Effects of repeated disappointment on the mind. Arrival of a cartel, and of letters from India. Letter of the French marine minister. Restitution of papers. Applications for liberty evasively answered. Attempted seizure of private letters. Memorial to the minister. Encroachments made at Paris on the Investigator's discoveries. Expected attack on Mauritius produces an abridgment of Liberty. Strict blockade. Arrival of another cartel from India. State of the public finances in Mauritius. French cartel sails for the Cape of Good Hope.

A prospect of liberty, which is officially confirmed. Occurrences during eleven weeks residence in the town of Port Louis and on board the Harriet cartel. Parole and certificates. Departure from Port Louis, and embarkation in the Otter. Eulogium on the inhabitants of Mauritius. Review of the conduct of general De Caen. Passage to the Cape of Good Hope, and after seven weeks stay, from thence to England. Conclusion.

Account of the observations by which the Longitudes of places on the east and north coasts of Terra Australis have been settled.

On the errors of the compass arising from attractions within the ship, and others from the magnetism of land; with precautions for obviating their effects in marine surveying.

General Remarks, geographical and systematical, on the Botany of Terra Australis. By ROBERT BROWN, F. R. S. Acad. Reg. Scient. Berolin. Corresp. NATURALIST TO THE VOYAGE.

A LIST OF THE PLATES, WITH DIRECTIONS TO THE BINDER.

View from the south side of King George's Sound.

Entrance of Port Lincoln, taken from behind Memory Cove.

View on the north side of Kangaroo Island.

View of Port Jackson, taken from the South Head.

View of Port Bowen, from behind the Watering Gully. View of Murray's Islands, with the natives offering to barter. View in Sir Edward Pellew's Group--Gulph of Carpentaria. View of Malay Road, from Pobassoo's Island. View of Wreck-Reef Bank, taken at low water.

VII. Particular chart of Van Diemen's Land. (Detail from Plate VII.)

XVIII. Thirteen views on the east and north coasts, and one of Samow Strait. (Detail from Plate XVIII.)

Ten plates of selected plants from different parts of Terra Australis. (Detail from Plate 10.)

[Errata have been corrected in this ebook]

[* "La carte que l'on a mise icy, tire sa première origine de celle que l'on a fait tailler de piéces rapportées, sur le pavé de la nouvelle Maison-de-Ville d'Amsterdam." Rélations de divers Voyages curieux. --Avis.]

[* Had I permitted myself any innovation upon the original term, it would have been to convert it into AUSTRALIA; as being more agreeable to the ear, and an assimilation to the names of the other great portions of the earth.]

[* Cook's third Voyage , Introduction. p. xv.]

[* Histoire générale des Voyages . Tome XVI. (à la Haye) p. 7-14.]

[** Histoire des Navigations aux Terres Australes . Tome I. p. 102-120.]

[* A more particular account of these charts, now in the British Museum , will be found in Captain Burney's " History of Discoveries in the South Sea ." Vol. I. p. 379-383. An opinion is there expressed concerning the early discoveries in these regions, which is entitled to respectful attention.]

[* See the letter of Torres, dated Manila, July 12, 1607, in Vol. II. Appendix, No I. to Burney's " History of Discoveries in the South Sea ;" from which interesting work this sketch of Torres' voyage is extracted.]

[* Hist. des Navigations aux Terres Aust. Tome 1. p. 432.]

[* In the old charts, a river Spult is marked, in the western part of Arnhem's Land; and it seems probable, that the land in its vicinity is here meant by THE SPULT.]

[* The Great Inlet or Cove, where the passage was to be sought, is the north-west part of Torres' Strait. It is evident, that a suspicion was entertained, in 1644, of such a strait; but that the Dutch were ignorant of its having been passed. The "high islands" are those which lie in latitude 10°, on the west side of the strait. Speult's River appears to be the opening betwixt the Prince of Wales' Islands and Cape York; through which captain Cook afterwards passed, and named it Endeavour's Strait. This Speult's River cannot, I conceive, be the same with what was before mentioned under the name of THE SPULT.]

[* Hist. des Nav. aux Terres Aust . Tome I. page 439.]

[* Hawkesworth's Voyages , Vol. III. page 211.]

[* Bligh's " Voyage to the South Seas in H. M. Ship Bounty ," page 218-221.]

[* Commonly written Otaheite ; but the 0 is either an article or a preposition, and forms no part of the name: Bougainville writes it Taïti.]

[** In Plates I. and XIII. Murray's Islands are laid down according to their situations afterwards ascertained in the Investigator; and the reefs, seen by the Pandora, are placed in their relative positions to those islands.]

[* See " A Voyage round the World in H. M. frigate Pandora ," by George Hamilton, Surgeon; page 123, et seq. ]

[* In Plate XIII. some small alterations are made in the longitudes given by captain Bligh's time keepers, to make them correspond with the corrected longitudes of the Investigator and Cumberland.]

[* The name for iron at Taheity, is eure-euree , or ooree , orj, according to Bougainville, aouri .]

[** See a Voyage to New Guinea , by Captain Thomas Forrest.]

[* This mountain, in latitude 10° 12' south, longitude 142° 13' east, was seen by captain Bligh from the Bounty's launch, and marked in his chart, ( Voyage, etc. p. 220.) It appears to be the same island indistinctly laid down by captain Cook, in latitude 10° 10', longitude 141° 14'; and is, also, one of those, to which the term Hoge Landt is applied in Thevenot's chart of 1663.]

[* It does not appear in the journal, when, or where this boy was set on shore; nor is any further mention made of him.]

[* It had probably been obtained from the crews of either the Providence or Assistant; which had anchored under Stephens' Island, nine months before.]

[** Mr. Bampton's description of this animal is briefly as follows. Size and shape, of the opossum. Colour, yellowish white with brown spots. End of the tail, deep red: prehensile. Eyes, reddish brown: red when irritated. No visible ears. Used its paws in feeding: five nails to each. Habit, dull and slothful: not savage. Food, maize, boiled rice, meat, leaves, or any thing offered. Odour, very strong at times, and disagreeable.]

[* Captain Hill and four of the seamen were murdered by the natives. Messieurs Shaw and Carter were severely wounded; but with Ascott, the remaining seaman, they got into the boat, cut the grapnel rope, and escaped. They were without provisions or compass; and it being impossible to reach the ships, which lay five leagues to windward, they bore away to the west, through the Strait; in the hope of reaching Timor. On the tenth day, they made land; which proved to be Timor-laoet . They there obtained some relief to their great distress; and went on to an island called by the natives, Sarrett ; where Mr. Carter died: Messieurs Shaw and Ascott sailed in a prow, for Banda, in the April following. See Collins' Account of the English Colony in New South Wales . Vol. I. page 464, 465.]

[* This latitude is from 4' to 6' more south than captain Bligh's positions; and the same difference occurs in all the observations, where a comparison can be made.]

[* Mr. Bampton's chart and journal are more at variance here than in the preceding parts of the Strait, and I have found it very difficult to adjust them; but have attempted it in Plate XIII.]

[* I am aware that the president de Brossed says, "This same year also (1628) CARPENTARIA was thus named by P. Carpenter, who discovered it when general in the service of the Dutch Company. He returned from India to Europe, in the month of June 1628, with five ships richly laden." ( Hist. des Nav. aux Terres Aust . Tome I. 433). But the president here seems to give either his own, or the Abbé' Prevost's conjectures, for matters of fact. We have seen, that the coast called Carpentaria was discovered long before 1628; and it is, besides, little probable, that Carpenter should have been making discoveries with five ships richly laden and homeward bound. This name of Carpentaria does not once appear in Tasman's Instructions, dated in 1644; but is found in Thevenot's chart of 1663.]

[* See Dalrymple's Collection concerning Papua , note, page 6.]

[* Thevenot says six miles , and does not explain what kind of miles they are; but it is most probable that he literally copies his original, and that they are Dutch miles of fifteen to a degree. Van Keulen, in speaking of Houtman's Abrolhos, says, page 19, "This shoal is, as we believe, 11 or 12 leagues ( 8 ä 9 mijlen) from the coast."]

[* For an account of the miseries and horrors which took place on the islands of the Abrolhos during the absence of Pelsert, the English reader is referred to Vol. I. p. 320 to 325 of Campbell's edition of Harris' Voyages ; but the nautical details there given are very incorrect.]

[* The French editor of the Voyage de Découvertes aux Terres Australes , published in 1807, Vol. I. p. 128, attributes the formation of the North-west Coast in the common charts to the expedition of the three Dutch vessels sent from Timor in 1705. But this is a mistake. It is the chart of Thevenot, his countryman, published forty-two years previously to that expedition, which has been mostly followed by succeeding geographers.]

[* This expression indicates, that the before-mentioned places were not then included under the term NEW HOLLAND by Witsen: he wrote in 1705.]

[* The Abbé Prévost in his Hist. gen. des Voyages , Tome XVI. (à la Haye) p. 79-81, has given some account of Vlaming's voyage in French; but the observations on the coast between Shark's Bay and Willem's River are there wholly omitted.]

[* The account in Van Keulen is somewhat different. He says "we steered for the Land of Endragt: and on Dec. 28, got soundings in 63 fathoms, sandy bottom. The ensuing day we had 30 fathoms, and the coast was then in sight. The Island Rottenest, in 32° south latitude, was the land we steered for; and we had from 30 to 10 fathoms, in which last we anchored on a sandy bottom."]

[* This appears to be the first mention made of the black swan: the river was named Black-Swan River .]

[* It was near this place that captain Pelsert put the two Dutch conspirators on shore in 1629. Vlaming appears to have passed within Houtman's Abrolhos without seeing them.]

[* These two openings, which in the original are called rivers, were nothing more than the entrance into Shark's Bay. A small island, lying a little within the entrance, probably made it be taken for two openings.]

[* For the full account of Dampier's proceedings and observations, with views of the land, see his Voyages , Vol. III. page 81, et seq .]

[* Dampier could not have examined these rocks closely; for there can be little doubt that they were the ant hills described by Pelsert as being "so large., that they might have been taken for the houses of Indians."]

[* Hist. des Nav. aux Terres Australes . Tome I. page 429.]

[* For captain Vancouver's account of his proceedings and observations on the South Coast, see his Voyage round the World , Vol. I. page 28-57.]

[*When the Investigator sailed, the journal of M. Labillardière , naturalist in D'Entrecasteaux's expedition, was the sole account of the voyage made public: but M. DE ROSSEI one of the principal officers, has since published the voyage from the journals of the rear-admiral and it is from this last that what follows is extracted.]

[* It afterwards appeared, that lieutenant James Grant had discovered a part of it in 1800, in his way to Port Jackson with His Majesty's brig Lady Nelson.]

[* Complete Collection of Voyages and Travels, originally published by John Harris, D. D. and F. R. S. London, 1744. Vol. I. page 325.]

[* I am proud to take this opportunity of publicly expressing my obligations to the Right Hon. President of the Royal Society; and of thus adding my voice to the many who, in the pursuit of science, have found in him a friend and patron. Such he proved in the commencement of my voyage, and in the whole course of its duration; in the distresses which tyranny heaped upon those of accident; and after they were overcome. His extensive and valuable library has been laid open; and has furnished much that no time or expense, within my reach, could otherwise have procured.]

[* This and the following courses and distances run from one noon to another, do not always agree with the latitudes and longitudes; but the differences are not great: They probably arose from the distances being marked to the nearest Dutch mile on the log board; whereas the latitude and longitude are taken to minutes of a degree.]

[* In Vol. III. just published, of captain Burney's History of Discoveries in the South Sea , a copy is given of Tasman's charts, as they stand in the original.]

[* Hawkesworth's Voyages , Vol. III. page 77, et seq .]

[* According to captain Cook, the longitude should be 148° 10'.]

[* It is more probable, that these trees are able to resist the fire better than the others.]

[* Cook's Second Voyage , Vol. I. p. 109.]

[* See Cook's Third Voyage , Vol. I. p. 93-117.]

[* Observations, etc., made during a voyage in the brig Mercury ; by Lieut. G. Mortimer of the Marines. London, 1791.]

[* Voyage de D'Entrecasteaux, rédigé par M. de Rossel : À Paris 1808. Tome I. p. 48.]

Preliminary Information. Boat expeditions of Bass and Flinders. Clarke. Shortland. Discoveries of Bass to the southward of Port Jackson; of Flinders; and of Flinders and Bass. Examinations to the northward by Flinders. Conclusive Remarks.

[* A small cask, containing six or eight gallons.]

[* These islets seem to be what are marked as rocks under water in captain Cook's chart. In it, also, there are three islets laid down to the south of Red Point, which must be meant for the double islet lying directly off it, for there are no others. The cause of the point being named red , escaped our notice.]

[* This Dilba was one of the two Botany-Bay natives, who had been most strenuous for Tom Thumb to go up into the lagoon, which lies under the hill.]

[* Afterwards captain of the Junon . He was mortally wounded, whilst bravely defending his Majesty's frigate against a vastly superior force; and died at Guadaloupe .]

[* But the latitude observed appears to be 8' or 10' too little; and if so, the length of the beach would be something more than 150 miles. It is no matter of surprise if observations taken from an open boat, in a high sea, should differ ten miles from the truth; but I judge that Mr. Bass' quadrant must have received some injury during the night of the 31st, for a similar error appears to pervade all the future observations, even those taken under favourable circumstances.]

[* The true latitude of the east entrance into Western Port, is about 38° 33' south.]

[* I have continued to make use of the term Furneaux's Land conformably to Mr. Bass' journal; but the position of this land is so different from that supposed to have been seen by captain Furneaux, that it cannot be the same, as Mr. Bass was afterwards convinced. At our recommendation governor Hunter called it WILSON'S PROMONTORY, in compliment to my friend Thomas Wilson, Esq. of London.]

[* This appears to be from 10' to 15' too little: an error which probably arose from the same cause as others before noticed.]

[* Nothing more had been beard of these five men., so late as 1803.]

[* The true latitude of the mouth of Two-fold Bay is 37° 5', showing an error of 12' to the north, nearly similar to what has been specified in the observations near Wilson's Promontory.]

[* The bearings in the following account are corrected, as usual, for the variation; but I am sorry to say that the steering compasses of the schooner proved to be bad, and there was no azimuth compass on board.]

[* Hawkesworth, Vol. III. p. 80. Mr. Bass sailed close round the cape in his whale boat, but did not ace any island lying there.]

[* It was 147° 10'; but as I afterwards found that observations of the sun to the east gave 27' less, by this small five inch sextant, and those to the west 27' greater than the mean of both, that correction is here applied; but not any which might be required from errors in the solar or lunar tables.]

[* The longitude of the large group, as given by my time keepers in a future voyage, is 147° 17'.]

[* Cook's Second Voyage , Vol. I. page 114.]

[* Mr. Bass' Journal of observations upon the lands, etc. discovered or seen in this voyage, has been published by colonel Collins, in his Account of the English Colony in New South Wales , Vol. II. page 143 et seq. ; his observations will, therefore, be generally omitted in this account.]

[* The highest part of Mount Dromedary appears to lie in 36° 19' south, and long

[* Kent's large group is not, however, so barren and deserted as appearances bespoke. It has since been ascertained that, in the central parts of the larger islands, there are vallies in which trees of a fair growth make part of a tolerably vigorous vegetation, and where kangaroos of a small kind were rather numerous; some seals, also, were found upon the rocks, and fresh water was not difficult to be procured in certain seasons.]

[* The chart will show from later examinations, how far the river is navigable, and whence its different sources are derived.]

[* Nine thousand skins of the first quality, with several tons of oil, were procured by the Nautilus, and Furneaux's Islands have since been frequented by small vessels from Port Jackson upon the same errand. Unfortunately, this species of fishery is soon exhausted in any one place; or it would have been the means of raising up an useful body of seamen, and thus proved of advantage, both to the colony and to the mother country.]

[* The longitude of Low-Head, deduced from the Investigator's time keepers, combined with my surveys in the Francis and Norfolk, is 146° 47½ east; as the observations with the large sextant, No. 251, taken alone, would give it very nearly.] Port Dalrymple and the River Tamar * occupy the bottom of a valley betwixt two irregular chains of hills, which shoot off north-westward, from the great body of inland mountains. In some places, these hills stand wide apart, and the river then opens its banks to a considerable extent; in others, they nearly meet, and contract its bed to narrow limits. The Tamar has, indeed, more the appearance of a chain of lakes, than of a regularly-formed river; and such it probably was, until, by long undermining, assisted perhaps by some unusual weight of water, a communicating channel was formed, and a passage forced out to sea. From the shoals in Sea Reach, and more particularly from those at Green Island which turn the whole force of the tides, one is led to suppose, that the period when the passage to sea was forced has not been very remote. [* So named by the late lieut. colonel Paterson, who was sent from Port Jackson to settle a new colony there, in 1804. The sources of the river were then explored, and the new names applied which are given in the chart. The first town established was Yorktown at the head of the Western Arm, but this proving inconvenient as a sea port, it was proposed to be removed lower down, near Green Island. Launceston , which is intended to be the capital of the new colony, is fixed at the junction of the North and South Esks , up to which the Tamar is navigable for vessels of 150 tons. The tide reaches nine or ten miles up the North Esk, and the produce of the farms within that distance may be sent down the river by boats, but the South Esk descends from the mountains by a cataract, directly into the Tamar, and, consequently, is not accessible to navigation of any kind.]

[* In Mr. Horsburgh's Sailing Directions, etc. Part II., are given, upon my friend captain Kent's authority, notices of the beacons laid down, and directions respecting them; to which I add, from the information of lieut. Oxley, that a rock, on which H. M. ship Porpoise struck, lies W. ½ N. by compass, one cable's length from Point Roundabout . There is no more than four feet upon it at low water, but it way be safely passed on either side.]

[* In 1804, Mr. Charles Robbins, acting lieutenant of His Majesty's ship Buffalo, was sent from Port Jackson to examine this great bight; and from his sketch it is, that the unshaded coast and soundings written at right angles are laid down in the chart.]

[* Taking the stream to have been fifty yards deep by three hundred in width, and that it moved at the rate of thirty miles an hour, and allowing nine cubic yards of space to each bird, the number would amount to 151,500,000. The burrows required to lodge this quantity of birds would be 75,750,000; and allowing a square yard to each burrow, they would cover something more than 181 geographic square miles of ground.]

[* Future visitants to these islands have seen the Indians passing over in bodies, by swimming, similar to those whom Dampier saw on the north-west coast of New Holland. Why the natives of Port Dalrymple should not have had recourse to the same expedient, where the distance to be traversed is so much less, seems incomprehensible.]

[* This head opened round the Cape at E. 14° N.. magnetic, the sloop's head being E. by N.; and shut at W. 20° S., when the head was north. In the first case I allow 3½° east variation, and in the last, 8°; which makes them agree as nearly as can be expected from bearings taken under sail.]

[** Captain Furneaux says (in Cook's second Voyage , Vol. I. page 109), that on March 9, 1773, at noon, the South-west Cape bore north, four leagues ; and by referring to the Astronomical Observations , p. 193, I find that his latitude was 43° 45 2/3', which would place the Cape in 43° 33 2/3'; nevertheless the captain says it is in 43° 39', and it is so laid down in his chart. The observation by which captain Cook appears to have fixed the South-west Cape, is that of Jan. 24, 1777, at noon; when he says, "our latitude was 43° 47' south" ( Third Voyage , Vol. I. p. 93.) But the Astronomical Observations of that voyage show (p. 101), that the observed latitude on board the Resolution was 43° 42½'; which would make the Cape in 43° 32½' south. I consulted captain King's journal at the Admiralty, but found no observed latitude marked by him on that day.]