2-FOR-1 GA TICKETS WITH OUTSIDE+

Don’t miss Thundercat, Fleet Foxes, and more at the Outside Festival.

GET TICKETS

BEST WEEK EVER

Try out unlimited access with 7 days of Outside+ for free.

Start Your Free Trial

Remembering Armstrong’s First Tour Victory

Before the seven Tour victories and the yellow bracelets. Before Sheryl Crow, the bestselling books, and the doping allegations. Before the comeback, there was a comeback. Ten years ago this month, Lance Armstrong was a little-known cancer survivor who showed up at the Tour de France. And no one had any idea what would happen next.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! >","name":"in-content-cta","type":"link"}}'>Download the app .

It almost never happened. Though he was a world-champion cyclist at 21, by 1998 Lance Armstrong was a 26-year-old cancer survivor who'd never finished better than 36th at the Tour de France and was struggling to reenter professional cycling. The big teams didn't want him, and he wasn't sure he wanted the sport. His first race back was the five-day Ruta del Sol, a February warmup for the long season ahead. He finished an encouraging 14th. But just two weeks later, while contesting the much more difficult ParisNice, he rolled to a stop in the middle of a cold, windy second stage and got off his bike. Even he doubted he would ever get back on.

Here, Armstrong's coaches, teammates, and closest friends recall their efforts to coax him back, the mental and psychological transformations that followed, and a miraculous Tour de France that ended ten years ago this month with a new American hero.

Too Much, Too Soon MARCHAPRIL 2008 PAUL SHERWEN (cycling commentator and former pro cyclist): I remember Lance's result in Ruta del Sol. To me, that was already a great success. But Ruta del Sol is a startup race. ParisNice is the first vicious race of the season.

LANCE ARMSTRONG: I just didn't feel like being there, so I pulled over and said, “That's it.” It was an instinctual reaction, totally irrational.

BART KNAGGS (Armstrong's longtime friend and fellow racer from their junior days, now a partner in Armstrong's management firm): He had big expectations, and all of a sudden he was just one more guy getting pissed on in the rain, with grit in his teeth. He's saying, “Look, I don't need this. Maybe I'll go to school, maybe I'll get a job.” We started talking to people about things he could dobe a real-estate guy, a financial guy. But at the same time, we sort of came to a consensus: You know what? This is what he was born to do. Let's rekindle that passion.

CHRIS CARMICHAEL (Armstrong's longtime coach): I really remember one discussion. I said, “Look, you say you've proven enough to the cancer community because you got back to professional cycling and proved you were competitive. Dude, you pulled over and quit, and that's what everyone's going to remember.” He didn't like that.

I flew back home, and he called me and said, “All right, we'll do one more race,” the U.S. Pro. But he was like “Look, I gotta get out of Austin. I've just been playing golf and drinking beer. If I'm gonna do this, I gotta go flat out.”

So we started talking about Boone, North Carolina. Cool hippie town with a college. Really good atmosphere and some great climbing. Then he needed a training partner, and I remember saying, “Hey, what about [American Tour de France veteran] Bob Roll? He'd be perfect.” He's funnier than hell, and he was still racing on mountain bikes at the time. And Bob has a good way of getting a guy thinking about stuff in an introspective way, without being forceful.

PHIL LIGGETT (longtime cycling journalist and commentator): Bob and Chris were trying to straighten his mind out more than his body, because he took a real hammering in ParisNice. So they went up to Boone in April and they raced on the hard roads, seven hours a day in atrocious weather.

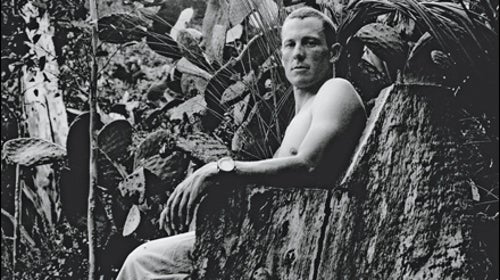

ARMSTRONG: It was just Chris, Bob, and me in a cabin, training long hours and eating at home. It was a monk's lifestyle that we ended up adopting for ten years after that. The weather was really, really bad, but we nutted up and we rode every day. I proved to myself that I loved what I was doing.

CARMICHAEL: The last day was 120 miles, and the guys were going to finish on Beech Mountain, a hard climb. Then I was going to load the bikes and drive the 30 miles back to the cabin. As soon as we hit the climb, Lance dropped Bob. I was following him, and he kept getting out of his saddle and really hammering. It's not even raining now; it's snowing. I just want to get through the thing, but he's attacking. There's nobody there, just a cow on the side of the road and me. I remember pulling up and rolling down the window, laying on the horn and yelling at him, pounding on the side of the car, saying “Yeah, come on!” like he was racing.

I don't know why.

We got to the top, and I remember exactly what he said to this day. It was “Give me my rain jacket. I'm riding back.”

This was a Thursday, and there was a race in Atlanta on Sunday. By the time we got back to the cabin, he was like “I gotta do that race.” I remember him arguing with the team manager because they didn't have race wheels for him. It really pissed Lance off. I was doing backflips, because he's better when he's pissed off. There it was. Game on.

Back on the Bike APRIL 1998JUNE 1999 That spring, Armstrong didn't just reenter the race world; he tore through it. He finished fourth in the U.S. Pro, then won three smaller stage races in quick succession. He skipped the '98 Tour de France but entered September's three-week Vuelta a España, finishing fourth overall, just six seconds off the podium. He followed that up with fourth place at the world championships in both the time trial and the road race. “From July to August to September, who was riding better?” Knaggs says. “I don't think there was anybody.” After the season, Armstrong and his associates had their first serious discussions about the Tour de France, a race where he'd never before been a threat. It came together when they recruited recently retired racer Johan Bruyneel to manage the team. Bruyneel instituted a Tour-first mentality and, with Armstrong, diligently previewed every stage of the race. Their revolutionary approach would eventually serve as the model for all serious Tour contenders.

JIM OCHOWICZ (Armstrong's longtime mentor, former Olympic cyclist and coach, and founder of the 7-Eleven pro cycling team): Lance had gotten really beat up by the chemo and now he was starting to transfer back into someone who looked like a bike racer, but different than when he left the sport. A bit smaller, and his legs looked leaner.

SHERWEN: Oh, bloody hell. Fourth in the Vuelta, then fourth in the time trial and fourth in the road race at the worlds. The Vuelta, you could say, “It's not the Tour, not the Giro.” But then to back it up and do that at the world championships, that's icing on the cake. If you have a good end of the season, you usually have a very good following season. So we thought Lance could be a contender at the Tour, like top five.

CARMICHAEL: And remember, this is still a very young rider. He was only 26.

ARMSTRONG: I didn't even think about what the Vuelta meant with regard to the Tour until Johan and I hooked up and he said, “Dude, you can win it.”

JOHAN BRUYNEEL (former pro cyclist and team director for all seven of Armstrong's Tour wins): This was all new for me, because I was still in the mind of a rider. So I said, If I could decide on my own calendar to prepare for the Tour, without any other obligations, what would it be? By obligations I mean having to prove myself or having to satisfy sponsors who want us to race in this country or that country. So I took a blank sheet of paper and worked backwards from the Tour to make my dream calendar. We were lucky to have an American sponsor [the U.S. Postal Service] who wasn't really interested in any other races. It was all about the Tour. I think it wasa good thing that we were a little naive, because it was not a logical choice.

GEORGE HINCAPIE (Armstrong's longtime teammate): Johan got things a lot more organized. We didn't really have a Tour team, so to speak. It was just some American guysthat year we had seven Americans and two foreigners. But we tried to get the guys we had as good as possible, show them the mountain stages, work on their time trial, and just get everybody psyched.

CARMICHAEL: It was really different this time. I'd like to consider it a scientific approach, but a lot of it comes down to compliance. Before, Lance would commit for a few weeks at a time, but then he'd lose his focus. Now he gave a greater commitment. He realized he had a second chance.

BRUYNEEL: We spent a lot of time previewing the stages of the Tour. That was something that had never been done. Some people see a few crucial stages, but never as thoroughly as we did.

BILL STAPLETON (Armstrong's agent): I wasn't attuned to how committed he was until I went over there in early May. He was very focused on what I thought we could get him, in terms of bonuses, for winning. I remember walking away from that meeting thinking, This guy really thinks he's gonna win the Tour de France.

Crash JULY 3, 1999 Armstrong finished several notoriously brutal spring races in 1999including ParisNiceand took a heartbreaking second in April's Amstel Gold one-day classic. He also suffered several accidents, one of which sidelined him for two weeks. Then, heading into the Tour, his dedication to previewing stages nearly derailed his comeback.

HINCAPIE: We were doing the prologue course a couple hours before the start, trying to memorize the corners, and Lance wanted to see if he could do the last hill in the big chainring. We were coming down this straight, and he was looking down at his gearing. I was behind him, and a T-Mobile car pulled out right in front of him. I yelled “Lance!” He looked up at the last minute and swerved. He still hit the mirror and went down, but not as hard as he would have. It's kinda funnyhis whole Tour history could have been over right at that moment.

First Taste of Yellow JULY 3 A prologue is a short time trial at the beginning of a stage race, used primarily to put someone in the leader's jersey for the first real stage. Armstrong covered the 4.2-mile course in 8:02 and beat second-place Alex Zülle, of Switzerlandmost people's pick to win the Tourby seven seconds, an eternity in such a short event.

BRUYNEEL: It was confirmation of the fact that he was in top shape. And there was of course a huge morale boostthat first yellow jersey.

ARMSTRONG: You never expect to be in that position. I thought on a good day I would be top ten, top five maybe. It was surreal.

KNAGGS: It was nine in the morning in Austin. I bet I talked to Stapleton and Carmichael for two hours each that day. I didn't get out of my boxer shorts until like two in the afternoon. I mean, holy shit, he just won the prologue in the Tour de France! He's got the jersey. Guys spend years chasing the jersey. Not chumpsgood guys.

STAPLETON: We'd been in talks with Bristol-Myers Squibb since late 1997they made the chemotherapy drugbut the deal had never gotten done. When Lance won the prologue, I remember picking up the phone, and it was this guy who I'd probably talked to 100 times. He said, “I'm embarrassed to be making this call right now, but we're ready to do this.” Full-page ad in USA Today, New York Times, Wall Street Journal: “This miracle brought to you by Bristol-Myers Squibb.”

A Tactical Coup JULY 5 Stage 2 took the riders over the Passage du Gois, a cobbled path off France's west coast that's rideable only at low tide. Slippery, narrow, and with water on both sides, it was a section where passing would be nearly impossible. Armstrong's team fought to keep him at the front of the field as they entered the stretch. Though he surrendered the yellow jersey that day, he finished several minutes ahead of most challengers for the overall, including Zülle and Spaniard Fernando Escartin, another favorite, who were caught behind a series of crashes.

BRUYNEEL: I was mostly worried about having the jersey and having to control the race. With all due respect, it was not a strong team. We had three or four strong riders and three or four others who were there because we had to have nine riders.

HINCAPIE: When the shit is hitting the fan and there are guys trying to get by on a road the size of a bike path, I'm there, 99.9 percent of the time. That's one of the reasons Lance always wanted me therebecause he knew I could get him through those situations. We entered [the Passage] in third or fourth wheel and came out with only ten or so other guys who didn't get caught behind the crashes. Some guys lost the Tour that day.

ARMSTRONG: The images from the helicopter are amazing. It was just carnage behind. There are dudes basically in the sea.

KNAGGS: Go back to '99 and take out the Passage du Goisit's a totally different race.

Reclaiming Yellow JULY 11 The first real test for the overall contenders was the Stage 8 individual time trial in the town of Metz. At 35 miles, it would bring the strongest racers to the front before the Tour hit the mountains. The riders started at two-minute intervals, and Armstrong caught the three who'd started immediately before him, including the world time-trial champion, Colombian Abraham Olano. He ended the day back in yellow.

HINCAPIE: Yeah, he crushed that time trial. He passed Olano! He caught me, and I'd started four minutes ahead of him.

OCHOWICZ: He was showing themthem being the other sport directors and ridershow to do it for the first time, and they were watching. The first day I got to the raceoh, man, all those directors who I tried to talk into signing Lance the year before were kicking themselves.

SHERWEN: His win at Metz confirmed that the prologue was a solid ride, but it didn't confirm that he would get out of the mountains. His weakest times in the Vuelta had been in the climbing stages.

BRUYNEEL: What I saw from Lance on a few of our training rides impressed me so much, because I know how fast it goes in the mountains. I remember saying to the mechanic in the car, Julien, “If that's the way he's going to ride in July, then we've got the winner of the Tour.”

KNAGGS: They didn't think Lance was going to go up hills. But he knew. He'd been doing all this work in the mountains, and he was just waiting for the first day.

Sestrière JULY 13 Stage 9 marked the first day in the mountains, with a route that included the monstrous Col du Galibier and finished with a harsh climb to the Italian ski resort of Sestrière. It was here, most observers still believed, that Armstrong would finally crack.

LIGGETT: He blew everyone on the road away: Zülle, Escartin. He tacks onto the climbers partway into the day, and then he jumps every one of them and rides alone to the finish. And all of those guys were already very far behind him in the overall. He could have ridden to the top alongside them and still had a huge lead. But he goes and hammers all shades of shit out of them. The look on Zülle's face: “Where the hell am I? This guy is a robot.” The same with Escartin, a great climber. Lance just rode him away.

ARMSTRONG: My nature was always, and probably still is, to attack, to be aggressive and open up the race. Not always the smartest thing to do; there have been times when I've paid for that. But I felt like I was having a good day, and you might as well give yourself a cushion for future days.

THOM WEISEL (financier who backed the U.S. Postal Team and gave Armstrong his first pro contract after cancer): I was in the main car with Johan, right behind Lance, and we were just going nuts. We were hysterical. Lance is yelling in his earpiece, “How do you like them apples?” It was the best moment I ever had at any Tour.

SHERWEN: Once someone dominates a time trial like that and dominates a mountaintop finish, everybody starts to go, Uh-oh, we made a mistake here.

The Team July 14 Though Armstrong now held a lead of more than six minutes, the Tour was not yet halfway over. With several more mountain stages to come, his teammates would have to ride better than anyone thought they could to defend the yellow jersey all the way to Paris.

HINCAPIE: It was up to us. Once the others saw that Lance was riding so well, they thought that their only chance was that he had a weak team, so they'd try and attack us. Nobody was confident in the team. We were criticized from all over the place. They all said, “They're just a bunch of Americans, they've never been there before. How are they going to protect the lead?”

SHERWEN: When you have absolutely no responsibility to yourself, you can push yourself harder. These guys all rode above themselves…because they felt that the man they were defending was invincible.

LIGGETT: [Teammate] Frankie Andreu was always a strongman; Tyler Hamilton was good in those days. Two of their riders never got to the finish: Jonathan Vaughters and the Danish rider Peter Meinert Neilsen. Christian Vande Velde was not a big player at that time, because he was too young. But George Hincapie will die for the master. He's such a fantastic guy.

WEISEL: Kevin Livingston was a big key. Hamilton was a talented climber, but Kevin was definitely the main guy that was able to stay with Lance in the mountains.

ARMSTRONG: All those guys were damn good bike riders. It's just that nobody had heard of them yet. We were the Bad News Bears. We didn't even have a team bus back then, just a camper. We were kind of crammed in there. But we didn't know any better. And the pressuresometimes the best way to cut it is to burp and fart and laugh. We tried to keep it light.

Hero and Villain JULY 1523 After Sestrière, the French press, still bitter over a doping scandal that had derailed the Tour a year earlier, began openly suggesting that Armstrong's performances were too good to be true. Simultaneously, the American public was starting to learn his name.

OCHOWICZ: I don't know if the French ever really understood what Lance went through with cancer, the dramatic change, physiologically and mentally. I think Americans are more open about it. I can't think of five people I know in Europe who have had cancer. They never talk about it.

CRAIG NICHOLS (Armstrong's oncologist at the Indiana University Medical Center and board member of the Lance Armstrong Foundation): I started receiving lots of phone calls, particularly from the French. Part of that, I think, speaks to the cancer stigma. To see him come back strong seemed paradoxical, and they kept asking what I had done. Jokingly, I said, “Well, we put in a third lung.” I don't think it translated well. There was just silence on the end of the line.

CARMICHAEL: It got pretty nastypeople accusing him of using drugs, saying the cancer was fake. Crazy stuff. Hostile.

LIGGETT: He'd seen death in the face and he wasn't going back. And that's always his response when I ask him if he's taking drugs. “I've been on my deathbed, and I'm not going back there. The answer is no, and they can call that what they like.” He told me that years ago, to my face.

STAPLETON: It was pretty stunning at the time, going over there and seeing how the French press was reacting to this versus how the Americans were.

KNAGGS: People magazine was calling. The craziest stuff was going on.

HINCAPIE: I was getting messages from people I went to school with, people who didn't know what cycling was.

STAPLETON: Lance wasn't aware of what was happening in the U.S. He was in the Tour bubble. I get to France the night before the [Stage 19] Futuroscope time trial. Johan has everyone focused on the race, and in comes me, the agent from America, saying, “Hey, as soon as this is over, we've got to go to New York. Nike wants to do something, and we have this deal. It's in the papers, it's on TV. It's the biggest sports story of the year.” Lance was like “You're kidding.” He didn't believe me.

ARMSTRONG: I said, “Is it in USA Today, for example?” And Bill's like “Um…It's on the cover every day.”

The Final Blow JULY 24 On the morning of July 24, the only thing that stood between Armstrong and a victory lap during the ceremonial final stage into Paris was a 35-mile time trial. With a massive 6:15 lead over second-place Escartin, Armstrong would have been forgiven for taking it easy. Once again, he crushed the field.

STAPLETON: I was not from the cycling world, so I didn't care if he won the time trial. I remember saying, “Hey, man, how about taking it easy? Stay on two wheels.” He looked at me and he said, “I'm gonna fucking win.” “OK, I got it. I got it.” I've learned since that time trials are where the champions win. You don't put it in park; you win.

ARMSTRONG: The time trial is called “the race of truth.” I think the yellow jersey has a certain obligation to show himself there.

LIGGETT: If you can do that and you're wearing the yellow, of course you can just lay down the fact that you're the best cyclist in the Tour.

Winning JULY 25 On the triumphant final stage, Armstrong rode onto the Champs-Elysees to the cheers of a crowd that would never again be so small. From this point on, cycling, cancer, and Lance himself would not be the same.

OCHOWICZ: As far as Lance's family and friends, there were probably only 25 of us, at the most, waiting on the finish line, to see all the awards and do all the hugging and all that. No bodyguards; everybody just moved around.

WEISEL: We rented the top floor of the Musee d'Orsay for the victory party. There were probably 200 of us at most.

KNAGGS: We're sitting around after dinner, and all of a sudden Lance picks up his phone and leaves. He comes back and says, “That was cool. That was President Clinton.”

ARMSTRONG: It started hitting me then, all the stuff that Stapleton said.

OCHOWICZ: Once he got back home, he finally understood why we wanted him to be in the Tour back in the eighties and nineties. It creates a lot of heroes, and he had just become a Tour de France hero.

NICHOLS: About a year after Lance's diagnosis, when it was clear that he was going to be cured, I talked to Lance about his obligationas somebody who was curedto give back. I've had the same conversation with many other people who say, “Yeah, that's a good idea.” And they never do anything. But if Lance takes something on, he does it. It's actually been written about with different cancers, certainly with testes cancer: Over the last ten years there has been a noticeable migration to earlier-stage disease. That is, people are coming in earlier, which makes treatments easier and cure rates higher. And it's been dubbed the Lance Armstrong effect.

STAPLETON: The next week, we were going to New York to do Letterman and a bunch of stuff. Nike chartered a jet. We'd never been on a private plane. Lance picked up a bottle of red wine and looked at us.

ARMSTRONG: And I said, “Hey, boys, let's guess which race we're going to focus on next year.”

- Road Biking

- Snow Sports

Popular on Outside Online

Enjoy coverage of racing, history, food, culture, travel, and tech with access to unlimited digital content from Outside Network's iconic brands.

Healthy Living

- Clean Eating

- Vegetarian Times

- Yoga Journal

- Fly Fishing Film Tour

- National Park Trips

- Warren Miller

- Fastest Known Time

- Trail Runner

- Women's Running

- Bicycle Retailer & Industry News

- FinisherPix

- Outside Events Cycling Series

- Outside Shop

© 2024 Outside Interactive, Inc

Lance Armstrong's Greatest Tour de France Moments

1993: a glimpse into the future.

1999: Making a Statement

- Tour de France Home

1999: Sealing the Victory

2003: le train bleu, 2005: a historic end, .css-1t6om3g:before{width:1.75rem;height:1.75rem;margin:0 0.625rem -0.125rem 0;content:'';display:inline-block;-webkit-background-size:1.25rem;background-size:1.25rem;background-color:#f8d811;color:#000;background-repeat:no-repeat;-webkit-background-position:center;background-position:center;}.loaded .css-1t6om3g:before{background-image:url(/_assets/design-tokens/bicycling/static/images/chevron-design-element.c42d609.svg);} tour de france.

Challengers of the 2024 Giro d'Italia and TdF

2024 Tour de France May Start Using Drones

The 2024 Tour de France Can’t Miss Stages

Riders Weigh In on the Tour de France Routes

2024 Tour de France Femmes Can't-Miss Stages

How Much Money Do Top Tour de France Teams Make?

2024 Tour de France/ Tour de France Femmes Routes

How Much Did Tour de France Femmes Riders Earn?

5 Takeaways from the Tour de France Femmes

Who Won the 2023 Tour de France Femmes?

Results From the 2023 Tour de France Femmes

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : October 22

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Cyclist Lance Armstrong is stripped of his seven Tour de France titles

On October 22, 2012, Lance Armstrong is formally stripped of the seven Tour de France titles he won from 1999 to 2005 and banned for life from competitive cycling after being charged with systematically using illicit performance-enhancing drugs and blood transfusions as well as demanding that some of his Tour teammates dope in order to help him win races. It was a dramatic fall from grace for the onetime global cycling icon, who inspired millions of people after surviving cancer then going on to become one of the most dominant riders in the history of the grueling French race, which attracts the planet’s top cyclists.

Born in Texas in 1971, Armstrong became a professional cyclist in 1992 and by 1996 was the number-one ranked rider in the world. However, in October 1996 he was diagnosed with Stage 3 testicular cancer, which had spread to his lungs, brain and abdomen. After undergoing surgery and chemotherapy, Armstrong resumed training in early 1997 and in October of that year joined the U.S. Postal Service cycling team. Also in 1997, he established a cancer awareness foundation. The organization would famously raise millions of dollars through a sales campaign, launched in 2004, of yellow Livestrong wristbands.

In July 1999, to the amazement of the cycling world and less than three years after his cancer diagnosis, Armstrong won his first Tour de France. He was only the second American ever to triumph in the legendary, three-week race, established in 1903. (The first American to do so was Greg LeMond, who won in 1986, 1989 and 1990.) Armstrong went on to win the Tour again in 2000, 2001, 2002 and 2003. In 2004, he became the first person ever to claim six Tour titles, and on July 24, 2005, Armstrong won his seventh straight title and retired from pro cycling. He made a comeback to the sport in 2009, finishing third in that year’s Tour and 23rd in the 2010 Tour, before retiring for good in 2011 at age 39.

Throughout his career, Armstrong, like many other top cyclists of his era, was dogged by accusations of performance-boosting drug use, but he repeatedly and vigorously denied all allegations against him and claimed to have passed hundreds of drug tests. In June 2012, the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA), following a two-year investigation, charged the cycling superstar with engaging in doping violations from at least August 1998, and with participating in a conspiracy to cover up his misconduct. After losing a federal appeal to have the USADA charges against him dropped, Armstrong announced on August 23 that he would stop fighting them. However, calling the USADA probe an “unconstitutional witch hunt,” he continued to insist he hadn’t done anything wrong and said the reason for his decision to no longer challenge the allegations was the toll the investigation had taken on him, his family and his cancer foundation. The next day, USADA announced Armstrong had been banned for life from competitive cycling and disqualified of all competitive results from August 1, 1998, through the present.

On October 10, 2012, USADA released hundreds of pages of evidence—including sworn testimony from 11 of Armstrong’s former teammates, as well as emails, financial documents and lab test results—that the anti-doping agency said demonstrated Armstrong and the U.S. Postal Service team had been involved in the most sophisticated and successful doping program in the history of cycling. A week after the USADA report was made public, Armstrong stepped down as chairman of his cancer foundation and was dumped by a number of his sponsors, including Nike, Trek and Anheuser-Busch.On October 22, Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), the cycling’s world governing body, announced that it accepted the findings of the USADA investigation and officially was erasing Armstrong’s name from the Tour de France record books and upholding his lifetime ban from the sport. In a press conference that day, the UCI president stated: “Lance Armstrong has no place in cycling, and he deserves to be forgotten in cycling.”

After years of denials, Armstrong finally admitted publicly, in a televised interview with Oprah Winfrey that aired on January 17, 2013, he had doped for much of his cycling career, beginning in the mid-1990s through his final Tour de France victory in 2005. He admitted to using a performance-enhancing drug regimen that included testosterone, human growth hormone, the blood booster EPO and cortisone.

Also on This Day in History October | 22

This Day in History Video: What Happened on October 22

First parachute jump is made over paris, gay sergeant challenges the air force.

President Lyndon Johnson signs the Highway Beautification Act

Jfk’s address on cuban missile crisis shocks the nation, germans capture langemarck during first battle of ypres.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

South Vietnamese President Thieu turns down peace proposal

American forces suffer first casualties in vietnam, jean-paul sartre wins and declines nobel prize in literature, fbi agents kill fugitive “pretty boy” floyd, 173rd airborne trooper dives onto live grenade, saving comrades.

This story is over 5 years old.

So wait, who actually won all those tour de france titles.

ONE EMAIL. ONE STORY. EVERY WEEK. SIGN UP FOR THE VICE NEWSLETTER.

By signing up, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy & to receive electronic communications from Vice Media Group, which may include marketing promotions, advertisements and sponsored content.

WHERE ARE THEY NOW? The Lance Armstrong team that dominated the Tour de France

Disgraced former American cyclist Lance Armstrong on Thursday settled federal fraud charges against him for $5 million. The charges were related to his use of performance-enhancing drugs during his professional racing career.

It ended a protracted legal battle that involved former teammate Floyd Landis and the US government on behalf of the US Postal Service, Armstrong's Tour de France team sponsor from 1999 through 2005. Landis had filed the original lawsuit — which had sought $100 million — in 2010 and is eligible for up to 25% of the settlement.

The deal came as the two sides prepared for a trial that was scheduled to start May 7 in Washington, The Associated Press reported. Armstrong said he was happy to have "made peace with the Postal Service."

For a decade, Armstrong was not only one of the world's most dominant athletes but one of its most recognizable figures. Armstrong did what no one had ever done: He won the Tour de France seven times, and he did so consecutively from 1999 to 2005.

But that was all before the US Anti-Doping Agency found that his team had run " the most sophisticated, professionalized and successful doping program that sport has ever seen."

As we know now, Armstrong used a variety of performance-enhancing drugs, and all his wins in the greatest bicycle race were eventually stripped from him.

As recently as 2016 Armstrong still blasted USADA , calling it "one of the most ineffective and inefficient organizations in the world" and claiming its CEO, Travis Tygart, went after him only because he needed a case and a story.

Armstrong didn't act alone, and it was, darkly so, a team effort. A calculating tactician, Le Boss handpicked his teammates carefully, and together they were cycling's most successful team.

Several of the riders who served under Armstrong's tainted reign are still involved in the sport.

Here's a look at what he and his old teammates have been up to:

An indelible image from the era was that of the US Postal Service's "Blue Train" setting a blistering pace at the front of the peloton, one that no one could match, let alone beat.

Levi Leipheimer was an all-rounder who rode with Armstrong on a few different teams at the Tour. He later admitted doping during his career.

Source: USADA

He now lives in Santa Rosa, California, where he runs a mass-participation bike ride. He also does promotion videos and coaches cyclists.

Sources: levination , Levi's GranFondo

Kevin Livingston was a climber who rode on two of Armstrong's Tour-winning teams. A French Senate report accused Livingston of using EPO in the 1998 Tour.

Sources: VeloNews , USADA

Livingston now lives in Austin, Texas, where he runs a company that coaches cyclists. It's located in the basement of Mellow Johnny's Bike Shop, which is owned by Armstrong.

Source: PedalHard.com

Tyler Hamilton helped Armstrong win Tours by leading him through the Alps and Pyrenees. He later admitted doping during his career.

Hamilton now lives in Missoula, Montana. He works in real estate and helps run a company that coaches cyclists. He also gives talks. He wrote a tell-all best-seller, "The Secret Race."

Sources: TylerHamilton Training.com , " The Secret Race "

George Hincapie was Armstrong's most loyal and trusted teammate and the only person to ride on all seven of Armstrong's Tour-winning teams. He admitted doping during his career.

He now lives in Greenville, South Carolina, where he runs a cycling-apparel company and a mass-participation bike ride. He wrote a book, "The Loyal Lieutenant," about his career.

Sources: GeorgeHincapie.com, " The Loyal Lieutenant "

Floyd Landis was an all-rounder who helped Armstrong win Tours and won one himself. He, too, was stripped of his Tour title because of PEDs.

In 2016 Landis started a business that sells cannabis products.

Related: Ex-Tour de France winner to open cannabis business, plans to go back to the Tour this July

Frankie Andreu was a cocaptain of the US Postal team with Armstrong in 1998, 1999, and 2000. He was one of the first riders to admit he had doped to help Armstrong win the Tour.

Sources: USADA , The New York Times

Andreu lives in the Detroit area and works in domestic cycling as a commentator.

Sources: FrankieAndreu.com , Business Insider

Related: Andreu: Lance 'is out to wreck me'

Christian Vande Velde rode on the first two of Armstrong's Tour-winning teams. He later admitted doping during his career.

Vande Velde lives in Greenville, South Carolina, and works as a cycling commentator for NBC.

Sources: christianvdv.com , Comcast , Chicago Tribune

Tom Danielson was hailed as "the next Lance Armstrong," and though he didn't race the Tour with Armstrong, they were teammates for a few years. He admitted doping.

Sources: The New York Times , USADA

Danielson is currently provisionally suspended after testing positive for synthetic testosterone. He could face a lifetime ban from cycling, having previously admitted doping while riding with the Discovery Channel team. He lives in Boulder, Colorado, and has written a book on training for cycling. He owns a company that runs training camps for cyclists.

Sources: USADA , Cinch Cycling Camps , " Tom Danielson's Core Advantage "

Dave Zabriskie was a strong time-trial rider and a teammate of Armstrong for a few years. He later admitted doping during his career.

He now lives in Los Angeles, where he runs a company that makes chamois cream.

Source: DaveZabriskie.com

Jonathan Vaughters took the start with Armstrong's Tour-winning team in 1999, but he crashed out on stage two. He later admitted doping during his career.

He now manages a team that competes in the Tour de France. He is outspoken against doping.

Source: Slipstream Sports

Related: VAUGHTERS: It's time for cycling to grow up and take its place among top professional sports

Belgian Johan Bruyneel was Armstrong's team director during his seven Tour wins.

He now lives in Madrid and London. USADA handed him a 10-year ban from cycling for being "at the apex of a conspiracy to commit widespread doping."

Sources: Twitter , USADA

Armstrong made history by winning a record seven Tours de France but was later stripped of his titles because he used PEDs.

Armstrong now owns multimillion-dollar properties in Aspen, Colorado, and Austin, Texas. He settled federal fraud charges against him for $5 million on April 19, 2018, ending a protracted legal battle with former teammate Floyd Landis. Banned from cycling for life, Armstrong sought counseling after his doping confession. He launched a podcast in June 2016.

Sources: Business Insider , The Telegraph , The Forward Podcast With Lance Armstrong

- Main content

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Dark Turn in the Tale of a First Title

By Jeré Longman

- Oct. 10, 2012

Just before the 1999 Tour de France, a teammate pointed out that Lance Armstrong had a bruise on his upper arm caused by a syringe.

According to a doping investigation, Armstrong cursed and said, “That’s not good.”

A public weigh-in of the riders was to be attended by the news media. A team masseuse found some makeup, and Armstrong’s bruise, and the doping that investigators assert caused it, was ultimately concealed.

The 1999 Tour was supposed to be one of renewal after a doping scandal engulfed the 1998 race. Instead, Armstrong won his first of his seven Tours by using the prohibited blood-boosting agent EPO and the steroid hormone testosterone, according to a 200-page report released Wednesday by the United States Anti-Doping Agency.

While Armstrong has long protested his innocence, retroactive testing found EPO in six of Armstrong’s urine samples from the 1999 race, according to the report. In addition, the report said, five fellow riders on Armstrong’s 1999 United States Postal Service team — George Hincapie, Frankie Andreu, Tyler Hamilton, Jonathan Vaughters and Christian Vande Velde — provided affidavits testifying to firsthand knowledge that Armstrong violated antidoping rules, the report said.

The evidence that Armstrong used EPO in the 1999 race was overwhelming, the report said, adding, “No other conclusion is even plausible.”

The tale behind Armstrong’s first Tour triumph, an achievement that made him an instant celebrity, is laid out in the investigative report in almost novelistic fashion. It involves a man on a motorcycle who delivered drugs to Armstrong’s team, an Italian doctor who was famous for helping riders dope, a training regimen designed to avoid drug testing, and the active complicity of the team masseuse.

The 1999 racing season began, the report said, with an unlikely goal for Armstrong, a cancer survivor: to win the Tour de France. He would skip many of the buildup races to concentrate on his sport’s major event. And for fuel, the report said, he would rely on banned substances.

A new team director, Johan Bruyneel, and team doctor, Luis Garcia del Moral, were hired that year for the Postal Service team. Armstrong called the team the Bad News Bears. He wanted a new team, according to the affidavit by Vaughters, his teammate, because the outgoing doctor, Pedro Celaya, “had not been aggressive enough for Armstrong in providing banned products.”

Bruyneel and del Moral, on the other hand, had formerly been associated with a racing team widely known, the report said, for “its organized team doping.”

Cyclists who wanted to dope had two main advantages in 1999, the report noted. Cycling’s international governing body had no organized out-of-competition drug testing program — considered the only effective way to catch those using banned substances. The governing body also did not require riders to make their whereabouts known during training so that they could be screened.

Much of Armstrong’s pre-Tour training in 1999 was spent along remote mountain roads of the Alps and the Pyrenees. Two teammates — Hamilton and Kevin Livingston — assisted him with arduous climbing, the report said. A regular attendee at these training camps, the report said, was an Italian sports doctor named Michele Ferrari, who would later be accused by American doping officials of trafficking in banned substances.

Hamilton was first injected with EPO in 1999 by Ferrari during training at Sestriere, an Italian ski village that would be a mountaintop finish during the Tour, the report said. Andreu said in an affidavit that he received EPO injections at races that year from del Moral, the Postal Service team doctor.

Pepe Marti, the Postal Service team trainer, also provided EPO to riders in 1999, the report said. At a late dinner in Nice, France, Betsy Andreu, Frankie’s wife, said that Marti arrived to provide what she was told was EPO to Armstrong. The dinner was held late, she said, because Marti was traveling from Spain and considered it “safer to cross the border at night.”

Armstrong took a brown paper bag from Marti, held it up and, according to Andreu, called it “liquid gold.”

In May 1999, Emma O’Reilly, the team masseuse, made an 18-hour round-trip drive from Nice to Spain to deliver a bottle of pills to Armstrong that, according to the report, “she understood to be banned drugs.”

That same month, Hamilton was at Armstrong’s villa in Nice, and received a vial of EPO from Armstrong that had been stored in Armstrong’s refrigerator, the report said.

On June 10, 1999, less than a month before the Tour began, Armstrong’s hematocrit level — the percentage by volume of oxygen-carrying red blood cells in whole blood — hovered at 41 percent, below the allowable race limit of 50 percent, the report said.

When O’Reilly, the masseuse, asked Armstrong how he would optimize his performance, the report said that he responded, “What everybody does.” O’Reilly understood this to mean Armstrong would use EPO, the report said.

The Tour de France opened July 3, 1999, and ran through July 25. Armstrong won the prologue, but a few days later, he received notice of a positive test for a corticosteroid, a chemical that helps regulate inflammation, metabolism and electrolyte levels.

Because Armstrong did not have medical authorization to use corticosteroids, the report said, a story was fabricated to backdate a prescription for cortisone cream and claim that the medication had been prescribed to treat a saddle sore, the report said.

According to the report, Armstrong told O’Reilly, the masseuse, “Now, Emma, you know enough to bring me down.”

During the first two weeks of the Tour, Armstrong, Hamilton and Livingston used EPO every third or fourth day in their camper or hotel rooms, the report said. Armstrong, Hamilton and Livingston traveled in a newer, bigger camper during that Tour, while other Postal Service riders shoehorned into a smaller, older vehicle. Hamilton and Livingston also shared a hotel room so they could speak openly with Armstrong about doping, the report said.

The three riders would “inject quickly and then put the syringes in a bag or Coke can and Dr. del Moral would get the syringe out of the camper as quickly as possible,” the report said.

Because security was tight, the EPO was smuggled to the Postal Service team by a personal assistant and handyman for Armstrong, the report said. He was a motorcycle enthusiast who followed the Tour on his motorcycle, and the riders who knew his purpose gave him the nickname Motoman.

Armstrong also used testosterone, which builds muscle and aids recovery from exertion, during the 1999 Tour, the report said. He mixed it with olive oil in a concoction that was taken orally. After one stage, the report said, Armstrong squirted the “oil” in Hamilton’s mouth.

After relinquishing the yellow jersey, Armstrong reclaimed first place in a time trial, then rode to a dominant mountaintop finish in Sestriere, the Italian ski village. He was not then known as a great climber, and Christophe Bassons, a French rider, noted in a newspaper column that the peloton had been “shocked” by Armstrong’s ride up to Sestriere.

At the race’s end, however, Armstrong proclaimed his innocence. He won the Tour six more times.

Cycling Around the Globe

The cycling world can be intimidating. but with the right mind-set and gear you can make the most of human-powered transportation..

Are you new to urban biking? These tips will help you make sure you are ready to get on the saddle .

Whether you’re mountain biking down a forested path or hitting the local rail trail, you’ll need the right gear . Wirecutter has plenty of recommendations , from which bike to buy to the best bike locks .

Do you get nervous at the thought of cycling in the city? Here are some ways to get comfortable with traffic .

Learn how to store your bike properly and give it the maintenance it needs in the colder weather.

Not ready for mountain biking just yet? Try gravel biking instead . Here are five places in the United States to explore on two wheels.

- OlympicTalk ,

Trending Teams

Lance armstrong timeline: cancer, tour de france, doping admission.

- OlympicTalk

MONTAIGU, FRANCE - JULY 04: TOUR DE FRANCE 1999, 1.Etappe, MONTAIGU - CHALLANS; Lance ARMSTRONG/USA - GELBES TRIKOT - (Photo by Andreas Rentz/Bongarts/Getty Images)

Bongarts/Getty Images

A look at the rise and fall of Lance Armstrong , who beat testicular cancer to win a record seven Tour de France titles, then was found guilty of and admitted to doping for the majority of his career ...

Aug. 2, 1992: Armstrong, then a 20-year-old amateur cyclist who had left triathlon because it wasn’t an Olympic sport, makes his Olympic debut at the Barcelona Games. He finishes 14th in the road race as the top American, missing a late breakaway. “I don’t think it was one of my better days, unfortunately,” Armstrong said on NBC. “Last couple weeks, everything has been perfect, but today, I just didn’t have what it took.” A week later, Armstrong finished last of 111 riders in his pro debut.

Aug. 29, 1993: Wins the world championships road race, becoming the second U.S. man to win a senior road cycling world title after three-time Tour de France winner Greg LeMond . Armstrong prevails by 19 seconds over Spain’s Miguel Indurain , who won five straight Tours de France from 1991-95. “I’m not sure I’m cut out to be a Tour racer,” Armstrong said, according to the Chicago Tribune . “I love the Tour de France; it’s my favorite bike race, but I’m not fool enough to sit here and say I’m going to win it. For the time being, I’m a one-day rider.”

Aug. 3, 1996: After failing to finish three of his first four Tour de France appearances (and placing 36th in the other), is sixth in the Atlanta Olympic time trial. “This was a big goal and something that I wanted to do well in and wanted the American people to see success,” Armstrong said on NBC. “The legs just weren’t there to win or to medal. I have to move forward and look to the next thing.”

Oct. 2, 1996: Diagnosed with testicular cancer. A day later, he undergoes surgery to have the malignant right testicle removed. Five days later, he begins chemotherapy. Six days later, Armstrong holds a press conference to announce it publicly, saying the cancer spread to his abdomen (and, later, his brain). He described it as “between moderate and advanced” and that his oncologist told him the cure rate was between 65 and 85 percent. “I will win,” Armstrong says. “I intend to beat this disease, and further, I intend to ride again as a professional cyclist.”

Oct. 27, 1996: Betsy Andreu later testifies that, on this date, Armstrong told a doctor at Indiana University Hospital that he had taken performance-enhancing drugs; EPO, testosterone, growth hormone, cortisone and steroids. Andreu said she and others were in a room to hear this. Her husband, Frankie Andreu , an Armstrong cycling teammate, confirmed her recollection to the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA). Armstrong, in admitting to doping in 2013, declined to address what became known as “the hospital room confession.”

January 1997: Establishes the Lance Armstrong Foundation, later called Livestrong, to support cancer awareness and research. Is later declared cancer-free.

Feb. 15, 1998: Returns to racing. Later in September, finishes fourth in his Grand Tour return at the Vuelta a Espana, one of the three Grand Tours after the Giro d’Italia and Tour de France.

1999 Tour de France: Achieves global fame by winning cycling’s most prestigious event in his first Tour de France start since his cancer diagnosis. Armstrong was not a pre-event favorite, but he won the opening 4.2-mile prologue to set the tone. He won all three time trials and, by the end, distanced second-place Alex Zulle by 7 minutes, 37 seconds in a Tour that lacked the previous two winners -- Jan Ullrich and Marco Pantani . Armstrong faced doping questions during the three-week Tour. An Armstrong urine sample revealed a small amount of a corticosteroid, after which Armstrong produced a prescription for a cream to treat saddle sores to justify it. “There’s no secrets here,” Armstrong said after Stage 14. “We have the oldest secret in the book: hard work.”

2000 Tour de France: With Ullrich and Pantani in the field, Armstrong crushed them on Stage 10, taking the yellow jersey by four minutes. He ends up winning the Tour by 6:02 over Ullrich, who over the years became the closest thing Armstrong had to a rival. In a Nike commercial that debuted in January that year , Armstrong again attacked his critics, saying, “Everybody wants to know what I’m on. What am I on? I’m on my bike, busting my ass six hours a day. What are you on?”

Sept. 30, 2000: Takes bronze in the Sydney Olympic time trial, behind Russian Viatcheslav Ekimov (a teammate on Armstrong’s Tour de France teams) and Ullrich. Armstrong would be stripped of the bronze medal 12 years later for doping. “I came to win the gold medal,” he said on NBC. “When you prepare for an event and you come and you do your best, and you don’t win, you have to say, I didn’t deserve to win.”

2001 Tour de France: Third straight Tour title. In Stage 10 on the iconic Alpe d’Huez, Armstrong gave what came to be known as “The Look,” turning back to stare in sunglasses at Ullrich, then accelerating away to win the stage by 1:59 over the German. “I decided to give a look, see how he was, then give a little surge and see what happened,” Armstrong said after the stage. Also that year, LeMond gives a famous quote to journalist David Walsh on Armstrong: “If it is true, it is the greatest comeback in the history of sport. If it is not, it is the greatest fraud.”

2002 Tour de France: Fourth title in a row -- by 7:17 over Joseba Beloki sans Ullirch and Pantani -- with few notable highlights. Maybe the most memorable, French fans yelling “Dope!” as he chased Richard Virenque (another disgraced doper) up the esteemed Mont Ventoux. Armstrong would be named Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year.

2003 Tour de France: By far the closest of the Tour wins -- by 1:01 over Ullrich -- with two very close calls. In Stage 9, Armstrong detoured through a field to avoid a crashing Beloki, who broke his right femur and never contended at a Grand Tour again. In Stage 15, Armstrong’s handlebars caught a spectator’s yellow bag . He crashed to the pavement, remounted and won the stage, upping his lead from 15 seconds to 1:07 over Ullrich.

2004 Tour de France: Record-breaking sixth Tour de France title. Jacques Anquetil , Eddy Merckx , Bernard Hinault and Indurain shared the record of five, and now share the record again after Armstrong’s titles were stripped. Earlier in 2004, the Livestrong yellow bracelet/wristband is introduced. Tens of millions would be sold. He skips the 2004 Athens Olympics, which began three weeks after the Tour ended.

April 18, 2005: Announces he will retire after the 2005 Tour de France. “My children are my biggest supporters, but at the same time, they are the ones who told me it’s time to come home,” Armstrong says. On the same day, former teammate and 2004 Olympic time trial champion Tyler Hamilton is banned two years for blood doping.

2005 Tour de France: Finishes career with seventh Tour de France title. Armstrong remains defiant until the end. In his victory speech atop a podium on the Champs-Elysees, he says with girlfriend Sheryl Crow looking on, “The last thing I’ll say, for the people that don’t believe in cycling, the cynics and the skeptics, I"m sorry for you. I’m sorry you can’t dream big. And I’m sorry you don’t believe in miracles.” A month later, French sports daily newspaper L’Equipe publishes a front-page article headlined, “Le Mensonge Armstrong” or “The Armstrong Lie.” It reports that six Armstrong doping samples at the 1999 Tour de France showed the presence of the banned EPO.

Sept. 9, 2008: Announces comeback, the reason being “to launch an international cancer strategy,” in a video on his foundation’s website . In his 2013 doping confession, Armstrong says he regrets the comeback. “We wouldn’t be sitting here if I didn’t come back,” he tells Oprah Winfrey on primetime TV.

2009 Tour de France: Finishes third, 5:24 behind rival Astana teammate and Spanish winner Alberto Contador . “I can’t complain,” Armstrong said on Versus after the penultimate stage finishing atop Mont Ventoux. “For an old fart, coming in here, getting on the podium with these young guys, not so bad.” USADA later reported that scientific data showed Armstrong used EPO or blood transfusions during that Tour, which Armstrong denied in 2013 when admitting to doping earlier in his career.

2010 Tour de France: Finishes 23rd in his last Tour de France. Armstrong races after former teammate Floyd Landis admits to doping and accuses Armstrong and other former teammates of doping during the Tour de France wins. “At some point, people have to tell their kids that Santa Claus isn’t real,” Landis says in a “Nightline” interview that aired the final weekend of the Tour.

Feb. 16, 2011: Announces retirement, citing tiredness (in multiple respects) at age 39. “I can’t say I have any regrets. It’s been an excellent ride. I really thought I was going to win another Tour,” Armstrong said, according to The Associated Press. “Then I lined up like everybody else and wound up third.”

Aug. 24, 2012: USADA announces Armstrong is banned for life , and all of his results dating to Aug. 1, 1998, annulled, including all seven Tour de France titles. Armstrong chose not to contest the charges, which were first sent to him in a June letter, though he did not publicly admit to cheating. USADA releases details of the investigation in October. The International Cycling Union chooses not to contest USADA’s ruling, formally stripping him of the Tour de France titles. “Lance Armstrong has no place in cycling,” UCI President Pat McQuaid says. In November, a defiant Armstrong tweets an image of him lying on a couch in a room with seven framed Tour de France yellow jerseys on the walls.

Jan. 17, 2013: Admits to doping during all of his Tour de France victories in the Oprah confession that airs on primetime TV. “I viewed this situation as one big lie that I repeated a lot of times,” Armstrong says in a pre-recorded interview. “It’s just this mythic, perfect story, and it wasn’t true.” Armstrong said he did not view it as cheating while he was taking PEDs because others did, too. On the same day, the International Olympic Committee strips Armstrong of his 2000 Olympic bronze medal.

MORE: Giro, Vuelta overlap in new cycling schedule

OlympicTalk is on Apple News . Favorite us!

Lance Armstrong

Who Is Lance Armstrong?

Lance Armstrong became a triathlete before turning to professional cycling. His career was halted by testicular cancer, but Armstrong returned to win a record seven consecutive Tour de France races beginning in 1999. Stripped of those titles in 2012 due to evidence of performance-enhancing drug use, Armstrong in 2013 admitted to doping throughout his cycling career, following years of denials.

Early Career

Born on September 18, 1971, in Plano, Texas, Armstrong was raised by his mother, Linda, in the suburbs of Dallas, Texas. Armstrong was athletic from an early age. He began running and swimming at 10 years old, and took up competitive cycling and triathlons at 13. At 16, Armstrong became a professional triathlete—he was the national sprint-course triathlon champion in 1989 and 1990.

Soon after, Armstrong chose to focus on cycling, his strongest event as well as his favorite. During his senior year of high school, the U.S. Olympic development team invited him to train in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Armstrong left high school temporarily to do so, but later took private classes and received his high school diploma in 1989.

The following summer, he qualified for the 1990 junior world team and placed 11th in the World Championship Road Race, with the best time of any American since 1976. That same year, he became the U.S. national amateur champion and beat out many professional cyclists to win two major races, the First Union Grand Prix and the Thrift Drug Classic.

International Cycling Star

In 1991, Armstrong competed in his first Tour DuPont, a long and difficult 12-stage race, covering 1,085 miles over 11 days. Though he finished in the middle of the pack, his performance announced a promising newcomer to the world of international cycling. He went on to win a stage at Italy's Settimana Bergamasca race later that summer.

After finishing second in the U.S. Olympic time trials in 1992, Armstrong was favored to win the road race in Barcelona, Spain. With a surprisingly sluggish performance, however, he came in only 14th. Undeterred, Armstrong turned professional immediately after the Olympics, joining the Motorola cycling team for a respectable yearly salary. Though he came in dead last in his first professional event, the day-long San Sebastian Classic in Spain, he rebounded in two weeks and finished second in a World Cup race in Zurich, Switzerland.

Armstrong had a strong year in 1993, winning cycling's "Triple Crown"—the Thrift Drug Classic, the Kmart West Virginia Classic and the CoreStates Race (the U.S. Professional Championship). That same year, he came in second at the Tour DuPont. He started off well in his first-ever Tour de France, a 21-stage race that is widely considered cycling's most prestigious event. Though he won the eighth stage of the race, he later fell to 62nd place and eventually pulled out.

In August 1993, the 21-year-old Armstrong won his most important race yet: the World Road Race Championship in Oslo, Norway, a one-day event covering 161 miles. As the leader of the Motorola team, he overcame difficult conditions—pouring rain made the roads slick and caused him to crash twice during the race—to become the youngest person and only the second American ever to win that contest.

The following year, he was again the runner-up at the Tour DuPont. Frustrated by his near miss, he trained with a vengeance for the next year's event and went on to finish two minutes ahead of rival Viatcheslav Ekimov of Russia for the win. At the Tour DuPont in 1996, he set several event records, including the largest margin of victory (three minutes, 15 seconds) and the fastest average speed in a time trial (32.9 miles per hour).

Also in 1996, Armstrong rode again for the Olympic team in Atlanta, Georgia. Looking uncharacteristically fatigued, he finished sixth in the time trials and 12th in the road race. Earlier that summer, he had been unable to finish the Tour de France, as he was sick with bronchitis. Despite such setbacks, Armstrong was still riding high by the fall of 1996. Then the seventh-ranked cyclist in the world, he signed a lucrative contract with a new team, France's Team Cofidis.

Battling Testicular Cancer

In October 1996, however, came the shocking announcement that Armstrong had been diagnosed with testicular cancer. Well advanced, the tumors had spread to his abdomen, lungs and lymph nodes. After having a testicle removed, drastically modifying his eating habits and beginning aggressive chemotherapy, Armstrong was given a 65 to 85 percent chance of survival. When doctors found tumors on his brain, however, his odds of survival dropped to 50-50, and then to 40 percent. Fortunately, a subsequent surgery to remove his brain tumors was declared successful, and after more rounds of chemotherapy, Armstrong was declared cancer-free in February 1997.

Throughout his terrifying struggle with the disease, Armstrong continued to maintain that he was going to race competitively again. No one else seemed to believe in him, however, and Cofidis pulled the plug on his contract and $600,000 annual salary. As a free agent, he had a good deal of trouble finding a sponsor, finally signing on to a $200,000-per-year position with the United States Postal Service team.

Tour de France Dominance

At the 1998 Tour of Luxembourg, his first international race since returning from cancer, Armstrong showed he was up for the challenge by winning the opening stage. A little over a year later, he capped his comeback in grand style by becoming the second American, after Greg LeMond, to win the Tour de France. He repeated that feat in July 2000 and followed with a bronze medal at the Summer Olympic Games.

Armstrong bolstered his legacy as his generation's dominant rider by handily winning the Tour in 2001 and 2002. However, notching a fifth victory, tying the record held by Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx, Bernard Hinault and Miguel Indurain, proved his most difficult accomplishment. Stricken by illness before the start of the race, Armstrong fell at one point after snagging a spectator's bag, and barely avoided another crash by swerving across a field. He finished one minute and one second ahead of Germany's Jan Ullrich, the closest of his Tour triumphs.

Armstrong was back in top form to claim his record-breaking sixth Tour win in 2004. He won five individual stages, finishing a comfortable six minutes and 19 seconds ahead of Germany's Andreas Kloden. After capping his astounding run with a seventh consecutive Tour victory in 2005, he retired from racing.

Return to Competition

On September 9, 2008, Armstrong announced that he planned to return to competition and the Tour de France in 2009. A member of Team Astana, he placed third in the race, behind teammate Alberto Contador and Saxo Bank team member Andy Schleck.

After the race, Armstrong told reporters that he intended to compete again in 2010, with a new team endorsed by RadioShack. Slowed by multiple crashes, Armstrong finished 23rd overall in what would be his final Tour de France, and he announced he was retiring for good in February 2011.

Drug Controversy

Despite the inspiring narrative of Armstrong's triumph over cancer, not everyone was convinced it was valid. Irish sportswriter David Walsh, for one, became suspicious of Armstrong's behavior and sought to shed light on the rumors of drug use in the sport. In 2001, he wrote a story linking Armstrong to Italian doctor Michele Ferrari, who was being investigated for supplying performance enhancers to cyclists. Walsh later secured a confession from Armstrong's masseuse, Emma O'Reilly, and laid out his case against the American champion as co-writer of the 2004 book L.A. Confidential.

The plot thickened in 2010, when former U.S. Postal rider Floyd Landis, who had been stripped of his 2006 Tour de France win for drug use, admitted to doping and accused his celebrated teammate of doing the same. That prompted a federal investigation, and in June 2012 the U.S Anti-Doping Agency brought formal charges against Armstrong. The case heated up in July 2012, when some media outlets reported that five of Armstrong's former teammates, George Hincapie, Levi Leipheimer, David Zabriskie and Christian Vande Velde—all of whom participated in the 2012 Tour de France—were planning to testify against Armstrong.

The cycling champion vehemently denied using illegal drugs to boost his performance, and the 2012 USADA charges were no exception: He disparaged the new allegations, calling them "baseless." On August 23, 2012, Armstrong publicly announced that he was giving up his fight with the USADA's recent charges and that he had declined to enter arbitration with the agency because he was tired of dealing with the case, along with the stress the case created for his family.

"There comes a point in every man's life when he has to say, 'Enough is enough.' For me, that time is now," Armstrong said in an online statement around that time. "I have been dealing with claims that I cheated and had an unfair advantage in winning my seven Tours since 1999. The toll this has taken on my family and my work for our foundation and on me leads me to where I am today—finished with this nonsense."

Banned From Cycling

The following day, on August 24, 2012, the USADA announced that Armstrong would be stripped of his seven Tour titles—as well as other honors he received from 1999 to 2005—and banned from cycling for life. The agency concluded in its report that Armstrong had used banned performance-enhancing substances. On October 10, 2012, the USADA released its evidence against Armstrong, which included documents such as laboratory tests, emails and monetary payments. "The evidence shows beyond any doubt that the U.S. Postal Service Pro Cycling Team ran the most sophisticated, professionalized and successful doping program that the sport had ever seen," Travis Tygart, chief executive of the USADA, said in a statement.

The USADA evidence against Armstrong also contained testimony from 26 people. Several former members of Armstrong's cycling team were among those who claimed that Armstrong used performance-enhancing drugs and served as a type of a ringleader for the team's doping efforts. According to The New York Times , one teammate told the agency that "Lance called the shots on the team" and "what Lance said went."

Armstrong disputed the USADA's findings. His attorney, Tim Herman, called the USADA's case "a one-sided hatchet job" featuring "old, disproved, unreliable allegations based largely on axe-grinders, serial perjurers, coerced testimony, sweetheart deals and threat-induced stories," according to USA Today .

Shortly after the release of the USADA findings, the International Cycling Union (cycling's governing body) supported the USADA's decision and officially stripped Armstrong of his seven Tour de France victories. The union also banned Armstrong from the sport for life. ICU president Pat McQuaid said in a statement that "Lance Armstrong has no place in cycling."

Admission and Later Events

Of the interview, Winfrey said in a statement, "He did not come clean in the manner I expected. It was surprising to me. I would say that, for myself, my team, all of us in the room, we were mesmerized by some of his answers. I felt he was thorough. He was serious. He certainly prepared himself for this moment. I would say he met the moment. At the end of it, we both were pretty exhausted."

Around the same time that the interview was conducted, it was reported that the U.S. Department of Justice would join a lawsuit already in place against the cyclist, over his alleged fraud against the government. Armstrong's attempts to have the lawsuit dismissed were rejected, and in early 2017 the case was allowed to proceed to trial.

Fraud Settlement

In spring 2018, two weeks before his trial was scheduled to begin, Armstrong agreed to pay the U.S. Postal Service $5 million to settle their claims of being defrauded. According to his legal team, the settlement ended "all litigation against Armstrong related to his 2013 admission" of using performance-enhancing drugs.

"I am particularly glad to have made peace with the Postal Service," said Armstrong said in a statement. "While I believe that their lawsuit against me was without merit and unfair, I have since 2013 tried to take full responsibility for my mistakes, and make amends wherever possible. I rode my heart out for the Postal cycling team, and was always especially proud to wear the red, white and blue eagle on my chest when competing in the Tour de France."

Landis, the whistle-blower in the case, stood to receive $1.1 million of the amount paid to the government. Additionally, Armstrong agreed to shell out $1.65 million to cover his old teammate's legal expenses.

Movie and Documentaries

In 2015, the Armstrong biopic The Program , with Ben Foster portraying the fallen cyclist, premiered at the Toronto Film Festival. Armstrong had little to say about the film, other than criticizing its star for taking performance-enhancing drugs to prepare for the role.

Armstrong was far more receptive to the release of Icarus , a Netflix documentary in which amateur cyclist Bryan Fogel also pumps up on PEDs before uncovering a Russian state-sponsored system created to mask its athletes' use of such drugs. In late 2017, Armstrong tweeted: "After being asked roughly a 1000 times if I’ve seen @IcarusNetflix yet, I finally sat down to check it out. Holy hell. It’s hard to imagine that I could be blown away by much in that realm but I was. Incredible work @bryanfogel!"

It was subsequently announced that on January 6, 2018, the day after Academy Award voters could begin submitting their ballots, Armstrong would co-host a screening and reception for Icarus in New York.

The cyclist returned to the spotlight with the Marina Zenovich-directed documentary Lance , which premiered at the January 2020 Sundance Film Festival before airing on ESPN that May. Along with examining the formative influences that drove him to become such a ruthless competitor, the doc showcased Armstrong's attempts to adapt to public life in the years after he had fallen from his pedestal as one of the world's most admired athletes.

Charity, Personal Life and Children

Armstrong has lived in Austin, Texas, since 1990. In 1996, he founded the Lance Armstrong Foundation for Cancer, now called LiveStrong, and the Lance Armstrong Junior Race Series to help promote cycling and racing among America's youth. He is the author of two best-selling autobiographies, It's Not About the Bike: My Journey Back to Life (2000) and Every Second Counts (2003).

In 2006, Armstrong ran the New York City Marathon, raising $600,000 for his LiveStrong campaign. He stepped down from LiveStrong in October 2012 following the USADA report about his use of performance-enhancing drugs.

Armstrong married Kristin Richard, a public relations executive he met through his cancer foundation, in 1998. The couple had a son, Luke, in October 1999, using sperm frozen before Armstrong began chemotherapy. Twin daughters, Isabelle and Grace, were born in 2001. The couple filed for divorce in 2003. Afterward, he dated rocker Sheryl Crow , fashion designer Tory Burch and actresses Kate Hudson and Ashley Olsen .

In December 2008, Armstrong announced that his girlfriend, Anna Hansen, was pregnant with his child. The couple had been dating since July after meeting through Armstrong's charity work. The baby boy, Maxwell Edward, was born on June 4, 2009. A daughter, Olivia Marie, followed on October 18, 2010.

In July 2013, Armstrong made headlines again when it was reported that he would be competing in The Des Moines Register 's Annual Great Bicycle Ride Across Iowa, a statewide cycling race sponsored by the newspaper.

"I'm well aware my presence is not an easy topic, and so I encourage people if they want to give a high-five, great," Armstrong stated shortly after the news broke, according to the Daily Mail . "If you want to shoot me the bird, that's OK too. I'm a big boy, and so I made the bed, I get to sleep in it."

In 2015, Armstrong returned to the Tour de France course to ride in a leukemia charity event one day before the start of the race.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Lance Armstrong

- Birth Year: 1971

- Birth date: September 18, 1971

- Birth State: Texas

- Birth City: Plano

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Lance Armstrong is a cancer survivor and former professional cyclist who was stripped of his seven Tour de France wins due to evidence of performance-enhancing drug use.

- Astrological Sign: Virgo

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Lance Armstrong Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/athletes/lance-armstrong

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: April 23, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- There comes a point in every man's life when he has to say, 'Enough is enough.' For me, that time is now.

- My ruthless desire to win at all costs served me well on the bike but the level it went to, for whatever reason, is a flaw. That desire, that attitude, that arrogance.

- The biggest challenge of the rest of my life is to not slip up again and not lose sight of what I have to do. I had it but things got too big and too crazy.

- If you're trying to hide something, you wouldn't keep getting away with it for 10 years. Nobody is that clever.

- I know the truth. The truth isn't what was out there. The truth isn't what I said, and now it's gone—this story was so perfect for so long.

- There was more happiness in the process, in the build, in the preparation. The winning was almost phoned in.

- If you're asking me if I want to compete again, the answer is hell yes, I'm a competitor.

- I learned a lesson that day. No more gifts."[On giving Marco Pantani a stage win in the 2000 Tour de France]

- The Look was just one part of a great battle with the Telekom team all day.

- Nobody believed I was able to do that after the crash. But I was a desperate man, and I knew that was my last chance to win the Tour de France.

- I'm well aware my presence is not an easy topic, and so I encourage people if they want to give a high-five, great. If you want to shoot me the bird, that's OK too. I'm a big boy, and so I made the bed, I get to sleep in it.

- I am deeply flawed ... and I'm paying the price for it, and I think that's okay. I deserve this."[On being stripped of his seven Tour de France titles for doping as a pro cyclist.]

- Two things scare me: The first is getting hurt. But that's not nearly as scary as the second, which is losing.

- Pain is temporary. It may last a minute, or an hour, or a day, or a year, but eventually it will subside and something else will take its place. If I quit, however, it lasts forever.

Famous Athletes

The Final Four Is Personal for Caitlin Clark

Sha’Carri Richardson

Aaron Rodgers

Florence Joyner

Lionel Messi

10 Things You Might Not Know About Travis Kelce

Every Black Quarterback to Play in the Super Bowl

Patrick Mahomes

What Is Soccer Star Cristiano Ronaldo’s Net Worth?

Jackie Joyner-Kersee

Rubin Carter

Watch CBS News

Lance Armstrong On Tour De France: I'm Still The Record-Holder For Victories

June 28, 2013 / 12:31 PM EDT / CBS New York

PORTO VECCHIO, Corsica (CBSNewYork/AP) — The dirty past of the Tour de France came back on Friday to haunt the 100th edition of cycling's showcase race, with Lance Armstrong telling a newspaper he couldn't have won without doping.

Armstrong's comments to Le Monde were surprising on many levels, not least because of his long-antagonistic relationship with the respected French daily that first reported in 1999 that corticosteroids were found in the American's urine as he was riding to the first of his seven Tour wins. In response, Armstrong complained he was being persecuted by "vulture journalism, desperate journalism."

Now seemingly prepared to let bygones be bygones, Armstrong told Le Monde he still considers himself the record-holder for Tour victories, even though all seven of his titles were stripped from him last year for doping . He also said his life has been ruined by the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency investigation that exposed as lies his years of denials that he and his teammates doped. And Armstrong took another swipe at cycling's top administrators, darkly suggesting they could be brought down by other skeletons in the sport's closet.

The interview was the latest blast from cycling's doping-tainted recent history to rain on the 100th Tour.