Dark Tourism… Wat is dat?

Bij het begrip dark tourism denk je misschien aan iets dat thuishoort in de diepe krochten van de nacht en aan illegale zaken. dan heb je het mis. want bijna iedereen heeft zich weleens ‘schuldig’ gemaakt aan dark tourism, terwijl het meestal best onschuldig is. dark tourism vind je op meer dan 800 plaatsen in 108 verschillende landen….

“Veel mensen hebben een negatieve associatie bij Dark Tourism, dat komt voornamelijk door het woord ‘dark’. Maar het is een begrip dat een aantal soorten toerisme bij elkaar brengt. Volgens de definitie gaat het om toerisme naar plekken die te maken hebben met de dood, lijden en schijnbare macabere, zoals begraafplaatsen en slagvelden, maar ook attracties als The Amsterdam Dungeon”, zegt Karel Werdler (senior lecturer aan Hogeschool Inholland Tourism Management en betrokken bij het Institute of Dark Tourism Research (IDTR) van Central Lancashire University). Dark Tourism kan je verdelen in drie categorieën: van heel donker – zoals Auschwitz – tot heel licht waarbij de nadruk ligt op entertainment, zoals het Torture Museum Amsterdam. Daar tussenin zitten de slagvelden uit de Eerste Wereldoorlog, maar ook Waterloo en begraafplaatsen. Werdler: “De schakering van licht naar donker is mede afhankelijk van hoelang een gebeurtenis is geleden. De Tweede Wereldoorlog is bijvoorbeeld voor de kinderen van nu lang geleden, zij kunnen hier moeilijk aan relateren. Maar deze oorlog zal voor iemand die er familieleden door heeft verloren van een heel andere betekenis zijn. Voor die kinderen is de Tweede Wereldoorlog dan ook minder duister, maar voor de ander inktzwart. Auschwitz zal voor mensen met een Joodse achtergrond van andere betekenis zijn dan voor iemand met een geheel andere cultuur. In welke categorie Dark Tourism valt, heeft vaak te maken met persoonlijke culture achtergrond.

De dood als hoofdthema De interesse in Dark Tourism werd lang geleden bij Werdler aangewakkerd, toen hij als reisleider in Europa en daarbuiten aan het werk was en weleens het verzoek kreeg om een begraafplaats te gaan bezoeken. “Die vraag vond ik in het begin maar vreemd. Vakantie is voor mij zon, zee en leuke dingen doen en daar hoort het bezoeken van een begraafplaats niet bij. Maar juist die tegenstelling integreerde me.” Hij besloot het te onderzoeken en is nu opdrachtgever vanuit het Institute of Dark Tourism Research in Lancashire en heeft het boek ‘Dark Tourism, de dood achterna’ geschreven. “Ik ben vervolgens naar de begraafplaats in Wenen geweest en dat vond ik cultuurhistorisch erg interessant. Ik zag de graven van verschillende beroemdheden; van Falko tot Beethoven en nog veel meer. In Azië heb ik een paar plekken gegidst waar de dood het hoofdthema was. Dat vond ik vanuit cultureel antropologische belangstelling enigszins begrijpelijk, maar ook wel weer gek. Ben je in India en dan wil je het cremeren van Hindoestanen in Varanasi zien. Ik vind vooral de motieven interessant.” Als ander voorbeeld noemt Werdler de rondreizen in Indonesië waarbij vaak de doden- en grafcultuur van Sulawesi centraal staan. Toeristen worden tijdens een uitvaart hartelijk ontvangen, krijgen wat te eten en kunnen mee dansen. “Stel je eens voor dat een groep Japanners zich aansluit tijdens een begrafenis in Nederland. Dat vinden we maar raar. Ik vind vooral de combinatie van vakantie en omgaan met de dood interessant. Ik denk overigens dat dit voor veel mensen een trigger is, want de dood is het laatste onbekende.”

Graf van beroemdheden De uitvaartbranche en musea spelen steeds vaker in op het fenomeen Dark Tourism, maar dat zal de reissector niet zo snel doen. “Voor reisbedrijven zal het niet gemakkelijk zijn om reizen te verkopen die met de dood in verband gebracht kunnen worden. Er zijn wel een aantal touroperators die reizen organiseren naar slagvelden, het zogenaamde Battlefield Tourism dat in Engeland en Amerika erg populair is. Er zijn ook touroperators die pelgrimsreizen en historische militaire reizen organiseren. Maar dan heb je het in Nederland wel gehad. Dat wil niet zeggen dat er geen geld mee te verdienen valt, maar in Nederland is de markt relatief klein en ook nog niet zo bekend. Ik weet ook niet of de markt groter kan worden. Ik vind het overigens terecht dat touroperators terughoudend zijn in Dark Tourism, want als het bestaande aanbod wordt uitgebreid met dood en verdoemenis dan kan dat een negatieve uitwerking hebben. In Amerika is er overigens wel een touroperator die zich uitsluitend met Dark Tourism bezighoudt, Holocaust Tourism. Ik vind dat een zeer onsmakelijke titel. En in Engeland bestaat een bedrijf waarmee je tegen forse betaling naar conflictgebieden kan. Dan loop je zwaarbeveiligd door Syrië of Somalië. Ik vind dat geen gezond toerisme, maar aan de andere kant is het wel interessant om te zien wat de beweegredenen van zo’n iemand zijn. Daar wordt veel onderzoek naar gedaan.” Om het wat dichterbij huis te houden, wordt er ook onderzoek gedaan naar waarom mensen begraafplaatsen in andere landen bezoeken. Volgens Werdler kan dat variëren van heel erg geïnteresseerd zijn in de cultuur en dan met name hoe een land omgaat met hun overledenen. “Een begraafplaats in Nederland is zo anders dan die in Italië. In Nederland is de dood ook veel minder aanwezig dan bijvoorbeeld in Mexico, Spanje en Italië. Daar is het uitbundiger en dichtbij. Anderzijds zijn mensen geïnteresseerd in begraafplaatsen, omdat er beroemdheden begraven liggen of uit kunsthistorisch oogpunt. Maar sommigen gaan ook omdat de begraafplaats de rustigste plek van een stad is.”

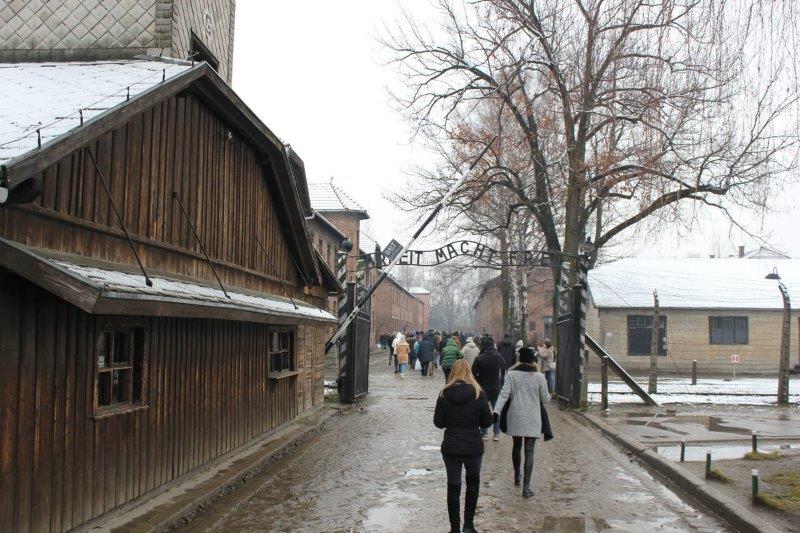

Indruk Auschwitz heeft de meeste indruk achtergelaten op Werdler. Het concentratiekamp nabij Krakau in Polen wordt jaarlijks door ruim één miljoen mensen bezocht. “Ik was er eind jaren ’70 en toen was het nog niet de ‘attractie’ die het nu is. Ik vond het erg aangrijpend en wil er geen tweede keer meer naartoe. Ik vind het wel goed dat ik het een keer heb gezien, maar vond het naar genoeg om te zien. Auschwitz is een voorbeeld van Dark Tourism waar je de geschiedenis echt kan voelen. Het is daar echt gebeurd en dat trekt mensen aan. Door deze plekken te bezoeken, zien mensen het als iets dat echt gebeurd is en niet meer als een verhaaltje uit een boek. Een andere indrukwekkend Dark Tourism is de begraafplaats Staglieno in Genua, een prachtige beeldenverzameling. Alle stijlen uit de negentiende eeuw zie je er.” Maar bij sommige facetten van Dark Tourism trekt Werdler zijn wenkbrauwen op, zoals de Killing Fields in Cambodja. “Ik vind het vreemd dat dit is ontwikkeld tot een toeristische attractie. Wellicht heeft de film Killing Fields ermee te maken, die was er namelijk eerder dan de Killing Fields als attractie. Het Genocidecentrum in Kigila, Rwanda vind ik erg aangrijpend om te zien. Buiten Kigali zijn er nog een aantal plaatsen waar de gevolgen van de genocide nog beter zichtbaar zijn en dus harder binnenkomen. Maar Varanasi in India vind ik toch wel het meest fascinerend, hoe mensen in een totaal andere cultuur met de dood omgaan, vooral omdat daar toeristen doorheen lopen. Hoe meer je van Dark Tourism weet, des te meer plekken je uit fascinatie wil zien.”

Ethiek Een crematie van een wildvreemde in India van dichtbij zien, de witte rozen bij de namen van de slachtoffers van 9/11 aanschouwen en de gaskamer in Auschwitz binnenlopen, hoe ethisch verantwoord is het allemaal? “Dat is een vraagstuk waar Dark Tourism steeds vaker tegenaan loopt. Wat ga je wel of niet laten zien? Hoe pak je het dan in? Wat is het verhaal dat je wil vertellen? Met name in Auschwitz komen veel vloggers en snapchatters, die ter plekke foto’s of video’s van zichzelf aan hun volgers laten zien. De ethiek gaat steeds vaker een rol spelen.”

Bucketlist Ondanks dat hij al veel van Dark Tourism wereldwijd heeft gezien, wil Werdler ooit nog een keer naar Tsjernobyl dat zich als toeristische attractie heeft ontpopt. “Ik zou weleens willen zien hoe dat allemaal in zijn werk gaat, ik hoorde namelijk dat je er een zendertje meekrijgt om de radioactiviteit te meten. Hoe is het georganiseerd, wat is het verdienmodel en is het allemaal wel ethisch verantwoord? Ik weet namelijk ook dat er allerlei souvenirs te koop zijn. Als wetenschapper en toeristisch professional kijk je er toch met andere ogen naar. Als ik een keer in buurt ben, ga ik het wel bezoeken. Maar ik heb geen donkere bucketlist. Integendeel zelfs.”

Dark Tourism, de dood achterna In al die jaren onderzoek doen naar Dark Tourism, verzamelde Karel Werdler genoeg materiaal om een boek mee te vullen. Dat heeft hij dan ook gedaan. Dark Tourism, de dood achterna is geen reisgids en ook geen wetenschappelijke verhandeling, maar hiermee wil Werdler inspiratie geven om deze bijzondere plekken te bezoeken, of om daar onderzoek naar te doen. “De dood is geen attractie, maar wel universeel en vaak vreemd of beangstigend, en zoals zal blijken maar al te vaak het object van onze toeristische fascinatie.”

Foto: B en Bryant/Shutterstock.com en Karel Werdler.

Deel dit artikel

Sharon Evers

Beluister de travelnext podcast, meest gelezen afgelopen 7 dagen.

Na regen komt zonneschijn!

WTTC presenteert nieuwe rapporten over mogelijkheden en risico’s van AI

Riksja Travel gaat klantreis verder personaliseren en automatiseren

Uitbreiding samenwerking Travelport en Tourism Malaysia na succesvolle datagestuurde campagne

Airbus Tech Hub van start in Nederland

Inschrijven nieuwsbrief, gerelateerde berichten.

TRAVELNEXT is hét leading kennisplatform voor de gehele reisbranche, met een focus op de laatste updates en ontwikkelingen binnen de (online) reismarkt. Onderwerpen die worden behandeld zijn onder meer Technologie, Duurzaamheid, AI, Marketing, E-commerce en HR.

Categorieën

- Duurzaamheid

- Privacy en Cookiebeleid

- Volg ons op

- Copyright © TravelNext.nl, All rights reserved.

- Mind & body

Series & films

- Straf Verhaal

- Wedstrijden

- Kortingscodes

- Deel dit artikel:

Maakte jij ook een kiekje aan de Berlijnse Muur of bracht je misschien zelfs een bezoekje aan Tsjernobyl?

Dark tourism: wat is het en hoe komt het dat we er zo door geobsedeerd zijn?

Van het bijwonen van een exorcisme over het bezoeken van een bezeten bos tot feesten op een voodoofestival: journalist David Farrier maakt er in de Netflixdocumentaire ‘Dark Tourist’ een sport van om de meest macabere plekjes op aarde van zijn bucketlist af te vinken. Totaal geschift of een wel heel aparte vorm van toerisme? Dark tourism is hoe dan ook aan opmars bezig.

Dark tourism krijgt dankzij series als ‘Chernobyl’, ‘Reizen Waes’ en ‘Dark Tourist’ een heel andere, veel menselijkere dimensie. Maar wat is duister toerisme eigenlijk? Waneer ben je zelf een dark tourist ? En is het wel ethisch verantwoord ? Wij zochten naar een antwoord op jouw meest prangende vragen over donker toerisme.

Wat is dark tourism nu precies?

Duister toerisme ofte thanatoerisme wordt vaak geassocieerd met de dood, een ramp of een tragedie . Elke vorm van reizen naar een plek waar in het verleden iets gruwelijks gebeurde wordt beschouwd als duister toerisme. De reisvorm won doorheen de jaren aan populariteit en is nog steeds aan een serieuze opmars bezig. Interessant om te weten, is dat er verschillende gradaties van duister toerisme bestaan. Sommige toeristen vinden het interessant om foto’s te nemen aan de Berlijnse Muur – ja, ook dat is duister toerisme, maar wel in een lichte vorm – anderen houden ervan om in een attractie als London Dungeon op een ludieke manier op stang gejaagd te worden en nog anderen gaan dan weer op zoek naar de real deal.

Waarom zijn we zo geïnteresseerd in dark tourism ?

Feit is dat onze geschiedenislessen niet meteen de meest romantische lessen waren en onze geschiedenis vooral getekend wordt door gruwelijke gebeurtenissen. Het opzoeken van dergelijke duistere gebieden of gedenkplaatsen stelt ons in staat om na te denken over het verleden. Dark tourism leunt in de meeste gevallen dus sterk aan tegen educatief toerisme . En hoewel donker toerisme misschien geen prettige vrijetijdsbesteding is, genieten veel mensen van het educatieve aspect dat ermee gepaard gaat, althans zo blijkt uit een studie van de Taiwan Hospitality and Tourism University.

Paradoxaal genoeg lijkt het er zelfs op dat we ons beter voelen nadat we zo’n plek bezocht hebben, net omdat we zo zelf met eigen ogen kunnen zien, en dankzij een goede gids misschien zelfs kunnen ervaren, hoe het er vroeger aan toeging. Het feit dat we op die plaatsen ons medeleven betuigen, zou ons volgens de studie helpen om het verleden los te laten en beter na te denken over de huidige maatschappij.

Ben jij een dark tourist ?

Bezocht je ooit een oorlogsmuseum, een gedenkteken of een concentratiekamp? Of denk je erover na om dat te doen? Dan val ook jij in principe onder de categorie duistere toerist. Elk jaar bezoeken bijna een miljoen mensen de Berlijnse Muur: het is de topbestemming bij een bezoek aan de stad Berlijn, maar veel mensen staan er allang niet meer bij stil met welke gruweldaden de muur geassocieerd wordt. Dat neemt echter niet weg dat je geen dark tourist bent.

Is het ethisch correct?

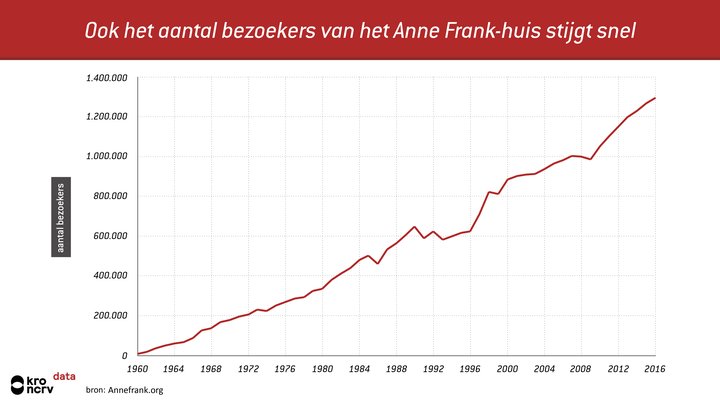

De recente toestroom van Instagramfoto’s die gemaakt worden in Auschwitz en Tsjernobyl zorgen voor een toestroom aan verontwaardigde reacties . De manier waarop sommige influencers op dergelijke sites poseren is problematisch, net zoals het ook allesbehalve oké is om je er verkeerd of respectloos te gedragen. Op welke plaatsen het al dan niet ethisch verantwoord is, is sterk afhankelijk van de lokale cultuur, de aard van de ramp en de impact ervan op onze geschiedenis. Sommige gedenkplaatsen móét je bezocht hebben, andere plekken sla je uit respect beter gewoon over. Wat op zo’n plek nooit ofte nimmer door de beugel kan?

- Mensen die het emotioneel moeilijk hebben fotograferen en/of lastig vallen.

- Lachen met de gebeurtenissen die er plaatsvonden.

- Ongepaste opmerkingen of lichaamsbewegingen maken.

- Respectloze kleding dragen.

- Luid praten over niet-gerelateerde problemen

In onderstaande Ted Talk legt professor Dorina-Maria Buda uit waarom duister toerisme van groot belang is en hoe we op een respectvolle én leerzame manier de sites kunnen bezoeken.

Wat zijn populaire duistere plaatsen?

Tsjernobyl, de Berlijnse Muur, Auschwitz, Hiroshima, National September 11 Memorial & Museum , Robbeneiland, Oradour-sur-Glane, Pompeii, ...

- 5 redenen om ook buiten het skiseizoen een reisje naar Les Trois Vallées te boeken

- ADD TO BUCKETLIST: Terme di Saturnia, hét paradijs op aarde voor waterratten

- ADD TO BUCKETLIST: 7 Kroatische eilanden waar je nog nooit eerder van hoorde

Fout opgemerkt of meer nieuws? Meld het hier

Partner Content

Reisgelukjes – reisblog

Reisgeluk voor 2 ♥️ eerlijker ♥️ voor een fijn budget

Dark tourism: meest verschrikkelijke bezienswaardigheden van de wereld

Dark tourism wordt een nieuwe trend genoemd. Bij dark tourism bezoek je de meest verschrikkelijke bezienswaardigheden van de wereld. Je gaat dan dus niet naar een bestemming omdat deze zo mooi is, maar vanwege de donkere en verschrikkelijke geschiedenis die samenhangt met een plek. Deze trend staat ook ter discussie, want hoe ethisch is het dat je als toerist deze plekken bezoekt? Vooral als je ook nog een vrolijke selfie op deze morbide plek maakt. In mijn blog ga ik in waarom het bezoeken van deze vreemde attracties je een repectvoller mens maken, wat je vooral niet moet doen en deel ik de meest verschrikkelijke bezienswaardigheden met je die ik heb bezocht.

Inhoud van dit blog

Waarom het bezoeken van de verschrikkelijkste bezienswaardigheden van de wereld volgens mij geen slechte trend is

Het hangt natuurlijk af van je intenties, maar ik denk dat de meeste toeristen niet aan dark tourism doen voor de mooie selfies. De meesten doen dit om zicht bewust te zijn van de volledige geschiedenis van een land, die meestal helaas nogal wat rafelige randjes kent. En dat is één van de redenen om deze verschrikkelijke bezienswaardigheden van de wereld te bezoeken.

We must never forget Wordt veel gezegd over de Holocaust

In Europa hebben veel van deze lugubere bezienswaardigheden hun oorsprong in de Eerste en Tweede Wereldoorlog. Iets wat we nooit mogen vergeten, al is het maar omdat dit nooit meer mag gebeuren. En nu kun je praten en lezen over de gruwelijkheden uit deze oorlog. Of je kunt Auschwitz bezoeken en dat nooit meer van je netvlies krijgen. Bijvoorbeeld door de rollen stof gemaakt van mensenhaar te zien. Dan weet je één ding zeker: we mogen dit nooit vergeten.

Het bezoeken van de meest verschrikkelijke bezienswaardigheden ter wereld maakt je een dankbaar mens

En al klinkt het niet als een reisgelukje, ik denk dat het bezoeken van deze plekken je een completer mens maakt. Vooral omdat we het hier in Nederland over het algemeen best goed hebben. Dit soort lugubere bezienswaardigheden bezoeken doet je inzien dat je best dankbaar mag zijn voor je huidige leven. En dat we ook eigenlijk ons leven mogen verdedigen tegen al die mensen die onze huidige vrijheden willen inperken. Mocht je op vakantie nou alleen maar dit soort gruwelijke plekken willen bezoeken, no judgement, is het misschien wel tijd om er eens met iemand over te praten.

Soms bezoek ik de meest verschrikkelijke bezienswaardigheden omdat bepaalde nieuwsgebeurtenissen grote indruk op mij hebben gemaakt. Eén van de eerste dingen die ik mij herinner is de kernramp bij Tsjernobyl. Ook vind ik dit wetenschappelijk interessant, dus zou ik dit gebied ooit graag willen bezoeken zodra het weer kan.

Soms kom ik ook per ongeluk op gruwelijke plekken terecht. Zo gingen we in 2006 vanaf de Kroatische kust een dagtrip maken naar de mooie meren van Plitvice. Niet wetende dat we onderweg nog kapotgeschoten huizen en huizen met kogelgaten zouden tegenkomen vanuit de Balkanoorlog. Dan komt zo’n oorlog in ene erg dichtbij.

Wat je volgens mij vooral niet moet doen als dark tourist op een van de verschrikkelijke plekken van de wereld

Volgens mij moet je als dark tourist altijd respectvol zijn op de plek waar je bent. Vaak hebben veel mensen op deze plek het leven gelaten, of worden zij op deze plek herinnert. Hoe zou jij het vinden als je opa of oma hier zou zijn omgekomen. Ga dus geen lachende selfies maken, of als model poseren en ga de foto’s al helemaal niet met grappige teksten op je social media zetten. Ga ook niet ter plekke luidruchtig zijn of de grapjurk uithangen. Gedraag je rustig en luister naar de verhalen die slachtoffers en gidsen je vertellen.

De ene verschrikkelijke bezienswaardigheid van de wereld is minder dark dan de ander

Oké, er gezegd zijn er plekken op de wereld die ik vooral heb bezocht om even lekker te griezelen die wel bekend staan als dark tourismplek. Is dat slecht? Zo hebben de catacomben van Parijs geen gruwelijke geschiedenis, maar ontstonden die toen de begraafplaatsen overvol raakten. Een macabere plek, maar daar houdt het ook mee op. Al kun je jezelf afvragen hoe respectvol het is dat we nu met duizenden bezoekers per dag tussen honderden jaren oude de skeletten lopen, ook al zijn ze niet vermoord voor dit doel. Deze bestemming wordt wel als dark tourism gezien.

Capela dos Ossos in het Portugese Evora is ook een macabere plek waar de botten en schedels van zo’n 5000 monniken zijn verwerkt, al vond men hier het een grote eer om er een plek te krijgen. Zowel de catacomben als de kapel drukken je ook weer even met je neus op de feiten: het leven is vergankelijk. In Evora luidt de inscriptie niet voor niets dat deze botten op de jouwe wachten.

Met de meest verschrikkelijke bezienswaardigheden van de wereld bedoel ik dus de meest gruwelijke. Niet de toeristenfuiken die prachtig zijn, maar helaas te druk geworden.

De meest verschrikkelijke bezienswaardigheden van de wereld waar ik dark tourist ben geweest

Ik heb al op verschillende plekken ter wereld de Dark tourist uitgehangen. Soms bedoeld en soms onbedoeld. Op sommige plekken om een beter gevoel te krijgen bij historische gruweldaden uit het verleden. Maar soms ook om gewoon te griezelen bij het macabere. Ja, ook daar heb ik mij soms schuldig aan gemaakt.

1. De landingsstranden van D-day zijn een verschrikkelijke bezienswaardigheid

Eén van de eerste plekken die ik bezocht, als dark tourist avant la lettre, waren als tiener de landingsstranden van D-Day in het Franse Normandië. Eigenlijk ook als onderdeel van mijn opvoeding. Wanneer je deze plek bezoekt kun je niet anders dan respect krijgen voor die buitenlandse soldaten die de vrijheid van Europa hebben bevochten. Vooral pont du hoc maakte indruk op mij met de meer dan manshoge kraters. Maar bovenop de krijtrotsen naar beneden kijkend kun je niet anders dan bedenken hoe soldaten hier kanonnenvoer waren.

Eigenlijk vind ik dat iedereen de landingsstranden van D-Day in ieder geval1 keer zou moeten bezoeken in zijn/haar leven. En ik hoop zeker Tom nog een keertje mee te nemen hier mee naartoe.

2. De meest verschrikkelijke bezienswaardigheid ter wereld die ik ooit heb bezocht: Auschwitz

Terugdenkend aan Auschwitz lopen de rillingen nog steeds over mijn rug. Natuurlijk bezochten we deze plek op een donkere en koude decemberdag, wat ook al niet helpt, omdat je zo extra veel gevoel krijgt bij alle ontberingen die de gevangenen moesten ondergaan. Wat ook niet hielp was dat er bij aankomst alleen nog plek was in de Duitstalige tourgroep, waardoor we de hele rondleiding rondliepen met een Duits vlaggetje op onze jassen.

We begonnen bij Auschwitz I, waar het startte als gevangenenwerkkamp. Hier werden we door de poort met Arbeit macht Frei naar de verschillende stenen barakken geleid. Waaronder de plek waar alle spullen verzameld werden: kamers vol koffers, schoenen en kleding, want alles werd hergebruikt. Het toppunt van efficiency van de nazi’s waren voor mij de rollen stof gemaakt van mensenhaar. Daarna gingen we verder naar Auschwitz II – Birkenau. Het eigenlijke vernietigingskamp. Na een korte introductie in één van de weinige houten barakken mag je hier in je eentje langs het spoor dwalen om je fantasie de vrije loop te laten gaan. En ja, daar wordt je extreem treurig van.

Dit was voor ons een stop bij Auschwitz onderweg naar Krakau . Maar die avond in Krakau waren we er nog stil van. We aten bij een heel goed restaurant, maar daar konden wij niet meer van genieten.

3. Berlijn Hohenschönhausen – voormalige Stasi gevangenis

Een andere plek die hoog bovenaan mijn lijstje staat van meest lugubere plekken waar ik ooit ben geweest is Hohenschönhausen in Berlijn . In deze voormalige Stasi-gevangenis krijg je rondleidingen van voormalig gevangenen, en ook dat ging mij niet in de koude kleren zitten. De Stasi was namelijk geoefend in verschillende martelpraktijken. Zo was er een uitgebreid systeem waardoor je nooit medegevangenen tegenkwam en je helemaal werd geïsoleerd in de hoop dat je dan brak en je gevangenisbewaarders in vertrouwen ging nemen. Donkere opsluiting, waarbij je cel vol met water liep was ook een optie.

Ten midden van alle kerstmarkten die we Berlijn bezochten was dit wel een bezienswaardigheid die je de andere kant van Berlijn laat zien en die je nederig maakt. Vooral als je gids verteld dat hij ook opgesloten is geweest en dat ze nog steeds bedreigd worden door voormalige wachten van de gevangenis!

Nu is Berlijn sowieso een hotspot voor dark tourism. Je vind hier een aantal van de meest verschrikkelijke bezienswaardigheden ter wereld. Zo bezochten we ook het indrukwekkende en enorme holocaust-monument en probeerden we een stuk langs de voormalige Berlijnse muur te fietsen. Ook bezochten we het Topographie des Terrors op het terrein van voormalige SS- hoofdkwartieren, dat onder andere over de misdaden tegen de menselijkheid van de nazi’s gaat.

In het Estse Tallinn bezochten we een oude KGB-gevangenis , wat ook een gruwelijke bezienswaardigheid is. Die je laat zien dat deze gruwelijkheden zo dichtbij en nog maar zo kort geleden waren.

Boek een hotel in Berlijn via de eerlijke boekingssite Moonback

4. Kamp Westerbork is ook een verschrikkelijke bezienswaardigheid

Na Auschwitz vonden we dat we onszelf niet alleen de meest verschrikkelijke bezienswaardigheid van de wereld moesten confronteren, maar dat we die van Nederland ook moesten bezoeken: Kamp Westerbork . Hier begonnen veel Nederlandse Joden, en andere slachtoffers met hun reis naar één van de vernietigingskampen in het buitenland. Je krijgt hier een verschrikkelijk beeld van de hoeveelheid mensen die dit is overkomen. De afgebogen treinrails en het huis van de kampcommandant verstild onder de kas complementeren deze nare ervaring. Zowel heen- als terug is het een flink stuk lopen naar de parkeerplaats en kun je alles even van je af lopen.

Sowieso hebben eigenlijk alle dark tourism-spots in Nederland te maken met de Tweede Wereldoorlog en de verschrikkingen van de nazi’s. Wat denk je van het Anne Frank-Huis en kamp Amersfoort? En ik wil zeker eens mijn respect betuigen op de Waalsdorpervlakte.

5. De Actun Tunichil Muknal grot in Belize

Eén van de meest bizarre bezienswaardigheden ter wereld waar ik ooit ben geweest, is de Actun Tunichil Muknal grot in Belize . De manier waarop je bij deze grot komt is al erg avontuurlijk: al wadend door een rivier in een grot. De Maya’s hebben in dit grottenstelsel ruim 1000 jaar geofferd, ook mensen. Je ziet hier dus ook skeletten liggen van mensen. In totaal zijn er 14 skeletten gevonden, tot nu toe. Maar hoe vrijwillig die mensen zich hebben laten offeren, dat is de vraag. Wellicht onder invloed van drugs, of was het hun geloof waardoor ze zich aanboden? Maar mensenoffers zien, vrijwillig of niet, is vrij macaber. Dus zit de ATM-grot voor mij toch in mijn top 5 van meest verschrikkelijke bezienswaardigheden van de wereld.

Nu ben ik benieuwd: welke verschrikkelijke bezienswaardigheden van de wereld heb jij bezocht en welke staat nog op je netvlies gebrand?

Over auteur

Ik ben Maaike van het reisblog Reisgelukjes. Ik schrijf over de leukste reizen voor 2, adultproof, voor een fijne prijs en liefst met een duurzamer karakter.

Je kunt je voorstellen dat het onderhouden van een reisblog veel tijd en geld kost. Daarom zijn sommige van de links op deze website gesponsord. Als je via deze links iets besteld of boekt, dan kost het jou niets extra's, maar krijg ik een kleine bijdrage. Wat mij weer helpt om deze website zo interessant mogelijk te houden.

Vind je een blog leuk? Laat dan vooral een reactie achter! Ook dat helpt mij om deze website zo actueel mogelijk te houden.

Dit vind je misschien ook leuk...

Leuk Aken: fijne kerstmarkt en meer in deze Duitse stad

8x Wintersportgebied voor als je meer wilt zien

De leukste kerstmarkten van Europa volgens reisbloggers

Populaire berichten.

Wandelroute uitstippelen Castricum: langs 4 restaurants in de Kennemerduinen

Vakantie Waddeneiland Schiermonnikoog: een groot natuurgebied van Oost naar West

How to: Een oud campertje pimpen in 10 stappen

Fietsroute Castricum plannen: een unieke culinaire tocht

De tofste adresjes voor een vakantie in Castricum volgens locals

Campings voor tweedehands campers: boek snel 1 van deze hippe plekjes

Oh zat! Vooral veel WW2 musea, Auschwitz was wel het meest verschrikkelijke, maar ook die in Jeruzalem bijvoorbeeld. Misselijkmakend. En de ruimtes ter grootte van een voetbalveld gevuld met botten in Napels, ook vreselijk.

Ja, wat een naargeestige plekken zijn dat he! Wat waren dat voor ruimtes in Napels? Als ik er zo naar kijk was Pompeii ook naar met die gipsafdrukken in de vorm van de mensen die de holtes hadden achtergelaten in de lava…

Het dorp Oradour-sur-Glane net boven Limoges in Frankrijk. Misschien ook eerst boeken lezen erover. Er is een grote camperplaats in het nieuwe dorp.

Oh, wat een verschrikkelijk verhaal zeg!

Geef een reactie Reactie annuleren

Het e-mailadres wordt niet gepubliceerd. Vereiste velden zijn gemarkeerd met *

Mijn naam, e-mail en site bewaren in deze browser voor de volgende keer wanneer ik een reactie plaats.

Ontvang maximaal 1 keer per maand de nieuwste artikelen en reistips

Je aanmelding voor de nieuwsbrief is gelukt! Ik zal je niet spammen, beloofd!

Er is een error opgetreden, probeer het opnieuw.

- WO2 Onderzoek uitgelicht

- Herdenken & vieren

- Leven met oorlog

- Bronmateriaal

- Over deze portal

- Juridische informatie

Dark tourism nader verklaard

door Frank van der Elst (redactie WO2 Onderzoek uitgelicht) – leesduur 7 minuten

Wanneer het over oorlogstoerisme gaat, is de term dark tourism nooit ver weg. Maar wat betekent deze term nu eigenlijk? En op wat voor manieren wordt hij toegepast? WO2 Onderzoek uitgelicht vroeg het dé expert op dit terrein in Nederland: Karel Werdler, docent toerisme aan de Hogeschool Inholland in Diemen en daarnaast verbonden aan het Institute of Dark Tourism Research (iDTR) in Lancashire, Engeland. Samen met student Lisanne Antenbrink licht hij het begrip dark tourism toe. “Een complex en tegelijk razend interessant vakgebied.”

V oordat Werdler als docent aan de slag ging, was hij jarenlang werkzaam voor verschillende touroperators, onder meer als reisleider. In die hoedanigheid bezocht hij de meest uiteenlopende plekken op de wereld. Ook plekken die niet op ieders to-do-lijstje voor de vakantie zullen staan: begraafplaatsen, gevangenissen, martelkamers, voormalige kampen, executieplaatsen. “Het waren vaak de reizigers zelf die mij vroegen hen hiernaartoe te brengen”, aldus Werdler. “Zo is mijn interesse voor deze vorm van toerisme ontstaan. Ik heb zelf ooit één keer een bezoek aan Auschwitz gebracht, lang geleden. Ik wil daar nooit meer naartoe. Een verschrikkelijke plek. Maar er zijn dus heel veel mensen die tijdens hun vakantie wel dit soort plekken bezoeken. Ik wil weten wat hen beweegt.”

De aantrekkingskracht van dit soort locaties komt volgens Werdler mede voort uit het feit dat we in een tijd leven waarin we heel ver zijn gevorderd op technologisch gebied, we van alles weten, van alles begrijpen en van alles kunnen aantonen, behalve wat er na de dood is en wat er dan met ons gebeurt. “Het laatste grote mysterie”, noemt hij het. “En ook dat willen we ontrafelen.” De toename van rondleidingen op begraafplaatsen ziet Werdler dan ook als een treffend voorbeeld van hoe we tegenwoordig met de dood omgaan. “We zoeken het steeds meer op.”

Containerbegrip

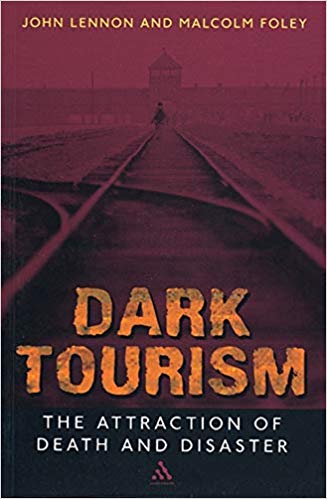

De term dark tourism werd in 1996 voor het eerst geïntroduceerd, in een wetenschappelijk artikel geschreven door onderzoekers John Lennon en Malcolm Foley. Enkele jaren later verscheen van hun hand het boek Dark Tourism. The Attraction of Death and Disaster .

Omslag van het boek Dark Tourism van John Lennon en Malcolm Foley.

De definitie die Werdler hanteert voor dark tourism is bedacht door Philip Stone, directeur van het iDTR en co-auteur van het boek The Darker Side of Travel: The Theory and Practice of Dark Tourism uit 2009. Werdler: “ Dark tourism is het reizen naar locaties die in verband kunnen worden gebracht met de dood, het lijden en het schijnbaar macabere.” Dat hierbij een groot onderling verschil bestaat tussen de diverse locaties is evident. “Er zijn pikzwarte plekken, denk aan de voormalige vernietigingskampen in Oost-Polen of de killing fields in Cambodja. Hier is het verleden nog relatief dichtbij en is de dood, het lijden, alom aanwezig. Maar er zijn natuurlijk ook beduidend lichtere plekken als The Amsterdam Dungeon, waar amusement een grote rol speelt en het vooral om griezelen gaat”, aldus Werdler. “Musea vallen hier tussenin. Afhankelijk van de collectie die ze tonen en de vorm waarin ze dat doen, zijn ze lichter of donkerder te noemen. Het maakt daarnaast een groot verschil of je een museum bezoekt op de historische plek zelf of een museum dat een historisch verhaal vertelt, maar losstaat van de feitelijke plek waar dat verhaal zich heeft afgespeeld. De authentieke plek brengt altijd een extra lading met zich mee.”

Het eerste wat je ziet als je het Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh bezoekt: een galg die het Pol Pot-regime gebruikte om tegenstanders te vermoorden. Foto: Marcin Konsek op Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Ondanks de grote onderlinge verschillen vallen al deze locaties onder het containerbegrip dark tourism , een begrip dat onvermijdelijk associaties oproept met ramptoerisme of verheerlijking van geweld. Niet iedereen is dan ook even gelukkig met deze term. “Ik adviseer mijn studenten om in hun contact met musea en herinneringscentra, bijvoorbeeld in het kader van een onderzoeksopdracht, voorzichtig te zijn met het gebruik van de term dark tourism . Het kan afschrikken en dat begrijp ik best. Het Anne Frank Huis valt onder de definitie van dark tourism , maar zelf zien ze dat absoluut niet zo. Het wordt dan erg moeilijk om ze te overtuigen van je goede bedoelingen. Ik ben daarom nog op zoek naar een passende Nederlandse vertaling.”

Een plek waar het toerisme rond een zwarte bladzijde uit de geschiedenis een industrie op zichzelf is geworden, is Ieper en omgeving. Mensen van over de hele wereld bezoeken daar de talloze loopgraven, musea en begraafplaatsen die herinneren aan de Eerste Wereldoorlog. Battlefield tourism wordt het wel genoemd.

Vlakbij Ieper valt een reconstructie van een Duitse loopgraaf te bezoeken. Foto: Sandra Fauconnier op Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 4.0)

Ook de herdenking onder de Menenpoort in Ieper – waar al decennialang iedere avond om klokslag 20.00 uur de Last Post wordt geblazen – trekt vele belangstellenden; merendeels toeristen die, naast het bezoeken van de historische plekken, ook het bijwonen van deze herdenking op hun ‘verlanglijstje’ hebben staan. Is dit ook (een vorm van) dark tourism ? “Dat zou je zo kunnen noemen, ja. Een groot deel van de mensen die daar staan, herdenkt inderdaad niet, maar is toeschouwer van de herdenking. Ze willen het een keer meegemaakt hebben. Op basis van de definitie van Philip Stone kun je dat als een uiting van dark tourism beschouwen. Maar voor je zoiets stelt, moet je toch echt eerst de persoonlijke motieven van al die mensen kennen. Waarom staan zij daar? Dat maakt dit vakgebied zowel complex als razend interessant. Er zijn zo veel invalshoeken mogelijk. Waarom wordt iets aangeboden? Voor wie wordt dat gedaan? En wat beweegt iemand om aan een bepaalde activiteit deel te nemen of een bepaalde historische plek te bezoeken?”

Die laatste vraag, naar de motivatie van mensen om plekken die in verband staan met de dood te willen zien, vindt Werdler de meest interessante. Ook voor Lisanne Antenbrink, een van Werdlers studenten, was interesse in die motivatievraag het startpunt voor haar afstudeeronderzoek naar bezoekers van herinneringscentra in Nederland en België. “Nadat ik beelden zag van jongeren in Auschwitz die ogenschijnlijk vrolijk selfies stonden te maken in het kamp, raakte ik geïnteresseerd in de motieven van mensen om dergelijke plekken te bezoeken en hoe dat hun gedrag ter plaatse beïnvloedt.” Antenbrink zag grote verschillen in hoe mensen zich tijdens hun bezoeken aan verschillende kampen in Nederland en België gedroegen. Waar het voor ouderen over het algemeen vanzelfsprekend is dat dit zwarte plekken zijn en dat daar een zekere ingetogenheid en stilte bij past, ligt dat voor jonge bezoekers anders. De afstand in tijd heeft invloed op die vanzelfsprekendheid en dat zie je terug in de manier waarop jongeren zich op die plekken gedragen. Werdler: “Dit is een ontwikkeling waar Tweede Wereldoorlog-locaties de komende jaren meer en meer mee te maken gaan krijgen. Hoe verder de oorlog in het verleden ligt, hoe minder zwart deze plekken door het publiek zullen worden ervaren.”

Antenbrink constateerde bij schoolgroepen dat een goede voorbereiding in de klas van grote invloed is op hoe scholieren zich gedragen tijdens een bezoek. “Jongeren die van tevoren actief met het onderwerp bezig waren geweest en wisten wat voor soort plek ze gingen bezoeken, gedroegen zich over het algemeen rustiger en stelden zich geïnteresseerder op dan scholieren met weinig voorkennis en nauwelijks voorbereiding.” Het is dit soort kennis dat musea en herinneringscentra kan helpen in hun omgang met schoolbezoeken of bij het opstellen van gedragsregels. Veel van de studenten die bij Karel Werdler zijn afgestudeerd, komen dan ook terecht in adviserende of publieksgerichte functies bij musea, touroperators of gemeenten.

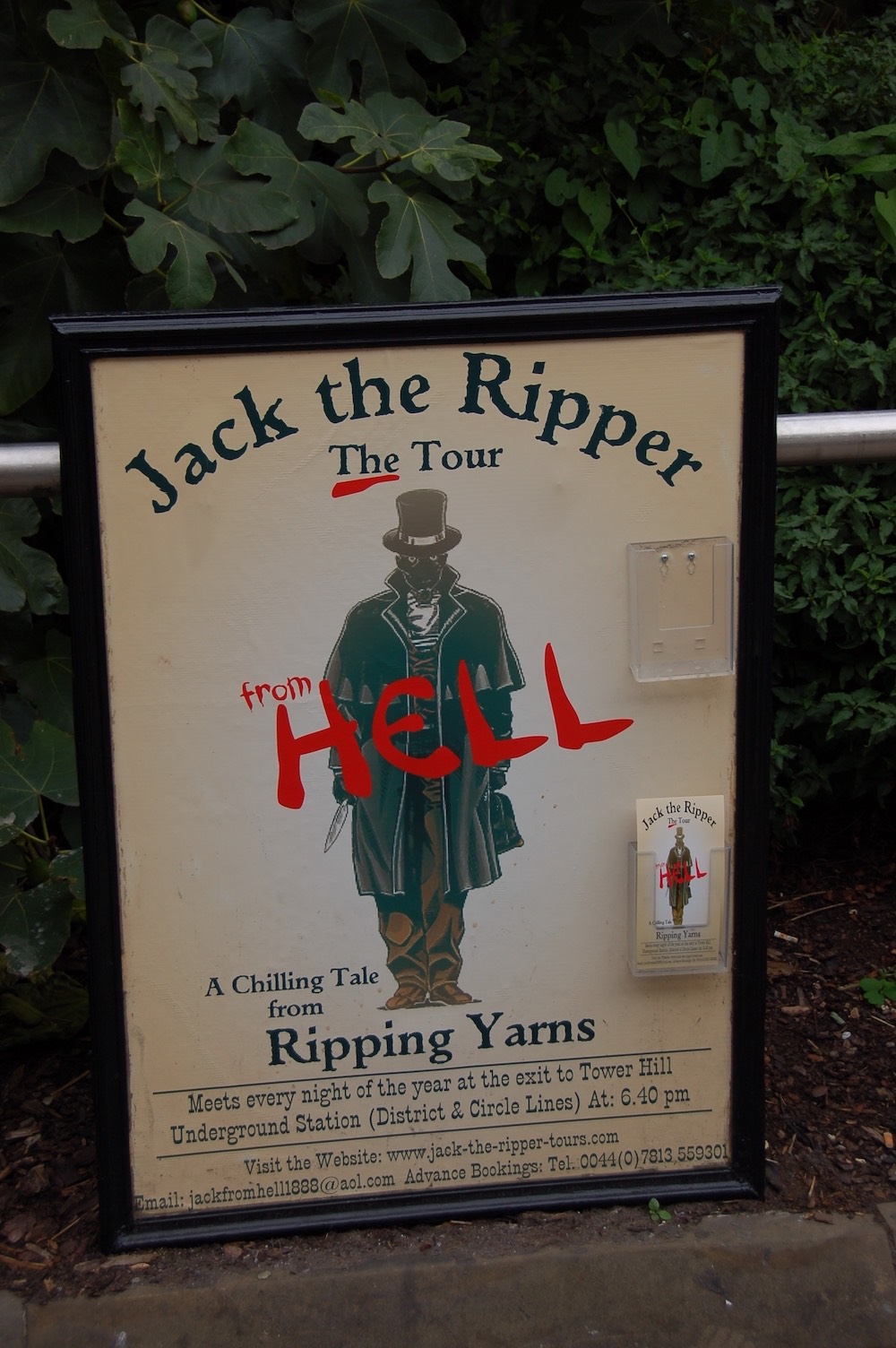

Griezelgeschiedenissen als vermaak: Jack the Ripper-tours in Londen zijn een groot succes. Foto: Ralf Roletschek op Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND)

Hoewel dark tourism een veelvoorkomend verschijnsel is, ontmoet Werdler maar weinig mensen die er openlijk voor uitkomen een dark tourist te zijn. “In al die jaren dat ik mij met dit onderwerp bezighoud, heb ik slechts twee mensen gesproken die onomwonden toegaven dark tourist te zijn en me vertelden het bezoeken van plekken die in verband staan met de dood oprecht leuk en spannend te vinden. Eén van hen nam deel aan een Jack the Ripper-tour in Londen, ging daarna naar de vernietigingskampen van de Tweede Wereldoorlog om vervolgens via een stop in Rwanda door te reizen naar de killing fields in Cambodja. Toen ik dat hoorde, stond ik wel even verbaasd te kijken.” Voor de meeste mensen gelden echter andere drijfveren. Een algemene interesse in geschiedenis bijvoorbeeld, of een meer gerichte belangstelling voor de Tweede Wereldoorlog. Die laatste interesse kan dan weer toegespitst zijn op wapentuig, veldslagen, de Jodenvervolging, het verzet of andere specifieke thema’s. “Ook hier kun je op basis van de definitie van Stone stellen dat dit allemaal dark tourism betreft”, aldus Werdler. “Maar een battlefield tourist zal zichzelf vaker niet dan wel als dark beschouwen. Het is sterk afhankelijk van de motieven van de bezoeker.”

In 2018 zond Netflix de eerste afleveringen van de nieuwe serie Dark Tourist uit. Foto: Netflix

Op Netflix is sinds 2018 een documentaireserie te zien met de titel Dark Tourist . Hierin bezoekt een journalist “ongelooflijk bizarre, en soms gevaarlijke, toeristische bestemmingen over de hele wereld”, zoals de makers het verwoorden. De serie biedt vooral sensatie en is niet direct interessant voor mensen die naar achterliggende motivaties of verbanden zoeken. Toch ziet Werdler hier een kans. “Het is onvermijdelijk dat mensen sociaal wenselijke antwoorden geven wanneer je ze vraagt naar hun motieven om bijvoorbeeld een voormalig kamp te bezoeken. De populariteit van zo’n Netflix-serie zou ertoe kunnen leiden dat meer mensen openlijk toegeven een fascinatie met de dood te hebben. Wellicht zijn er veel meer dark tourists dan we op dit moment aannemen. Als dat inderdaad het geval is, geeft dat het onderzoek een heel nieuwe dimensie.”

Over de geïnterviewden

Van Karel Werdler verscheen in 2015 het boek Dark tourism, de dood achterna (momenteel niet leverbaar). Na zijn pensionering over twee jaar gaat hij zich meer toeleggen op zijn werkzaamheden voor het iDTR. Ook werkt hij dan verder aan zijn proefschrift over dark tourism . Lisanne Antenbrink studeert onder begeleiding van Karel Werdler in het voorjaar van 2019 af aan de opleiding Tourism Management.

Foto bovenaan artikel

De slogan ‘Fear is a funny thing’ bij de ingang van The Amsterdam Dungeon laat zien: angst kun je op vele manieren beleven. Tobias Niepel op Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

Dark Tourist | Reizen naar meest bizarre & gevaarlijkste plekken ter wereld

Hey wereldreizigers, kennen jullie Dark Tourist al? Dark Tourist is een bizarre documentaireserie uit Nieuw-Zeeland over het fenomeen Dark Tourism, oftwel duister / donker toerisme. Dark Tourism is een snel groeiend fenomeen waarbij je naar plekken en ervaringen op zoek gaat die verre van ‘normaal’ zijn. Het Netflix programma gaat dus niet naar de mooiste stranden ter wereld, maar duikt juist in de duistere kant van het toerisme en gaat op zoek naar bizarre gebeurtenissen en de gevaarlijkste plekken ter wereld. Dark Tourist wordt gepresenteerd door journalist David Farrier . De serie heeft acht afleveringen en is een must-see voor elke wereldreiziger die op zoek is naar ervaringen buiten het boekje.

Bovenin deze pagina kun je alvast de officiële trailer bekijken. Ben je nieuwsgierig welke plekken en onderwerpen allemaal voorbij komen? Lees dan de korte samenvattingen per aflevering hieronder. Wie meteen erin wilt duiken: hier kun je meteen de serie op Netflix aanzetten!

Inhoudsopgave

Dark Tourist afleveringen

Aflevering 1 | latijns amerika.

David reist naar Medellín, waar hij de erfenis van Pablo Escobar onderzoekt. Hij toert later La Catedral met Escobar’s voormalige huurmoordenaar Popeye . Hij reist vervolgens naar Mexico-Stad, waar hij volgelingen van Santa Muerte ontmoet en getuige is van een exorcisme voordat hij een illegale grensovergang naar de VS ervaart.

Aflevering 2 | Japan

David onderneemt een spannende reis naar Tomioka, die werd geëvacueerd tijdens de nucleaire ramp in Fukushima, waar hij hogere stralingsniveaus ontdekt dan verwacht. Hij stopt dan bij een hotel dat uitsluitend bemand wordt door robots in het themapark Huis Ten Bosch voordat hij aankomt in Aokigahara; een zelfmoord-hotspot. Davids tijd in Japan wordt beëindigd op het verlaten eiland Hashima.

Aflevering 3 | Verenigde Staten

David sluit zich aan bij Dark Tourist Natalie in Milwaukee, waar ze meer te weten komen over Jeffrey Dahmer door een rondleiding te volgen langs de locaties van Dahmer’s moorden voordat ze zijn advocaat, Wendy Patrickus, ontmoeten. David bezoekt vervolgens Dallas, waar hij twee zeer verschillende tours maakt met betrekking tot de moord op JFK. Zijn tijd in Amerika loopt ten einde in New Orleans, waar hij tijd doorbrengt met enkele echte vampiers.

Aflevering 4 | Kazachstan & Baikonoer

In Kazachstan voegt David zich bij de Dark Tourist Andy en samen bezoeken ze de stad Kurchatov, waar ze meer te weten komen over de nabijgelegen testlocatie Semipalatinsk, de belangrijkste testlocatie voor de nucleaire wapens van de Sovjet-Unie. David reist vervolgens door Kazachstan naar Baikonoer, een gesloten stad en de thuisbasis van het Sovjetruimteprogramma.

Lees ook: Kazachstan is één van de 10 grootste landen ter wereld

Vliegend over de grens, bezoekt David de Turkmeense hoofdstad Ashgabat, waar hij de persoonlijkheidscultus rond president Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow ziet, voordat hij probeert, maar faalt, om de poorten van de hel te bezoeken. Na een korte reis naar het ziekenhuis hoopt David de openingsceremonie van de Asian Indoor and Martial Arts Games 2017 te zien.

Lees ook: Kazachstan naar stembus voor economische hervorming

Aflevering 5 | Europa

Net buiten Maidstone neemt David deel aan ’s werelds grootste re-enactment uit de Tweede Wereldoorlog. Na een schijngevecht te hebben overleefd, reist David door de breedte van Engeland naar Littledean, waar hij een controversieel museum bezoekt met een tentoonstelling gewijd aan Fred & Rose West en een lampenkap uit het nazi-tijdperk die zogenaamd gemaakt is van menselijke huid. Naar aanleiding van zijn museumreis krijgt David een telefoontje van Charles Bronson. Vervolgens reist hij door Europa naar Cyprus, waar hij probeert binnen te sluipen naar Famagusta, een ommuurde spookstad.

Lees ook: Wereldwijs | Wat zijn de veiligste en gevaarlijkste landen in Europa?

Aflevering 6 | Zuid-Oost Azië

Op een schietbaan in Phnom Penh, gesteund door het Cambodjaanse leger, krijgt David een reeks zware artillerie in handen en wordt hij geconfronteerd met een moreel dilemma. David reist naar Myanmar en bezoekt de gloednieuwe hoofdstad Naypyidaw, waarvan hij ontdekt dat het beduidend rustiger is dan de meeste hoofdsteden. Als hij naar Indonesië vliegt, ontmoet David een Toraja-man die al twee jaar ‘rust’ en deelneemt aan de Ma’nene-begrafenisrituelen.

Aflevering 7 | Afrika

In Ouidah, Benin, leert David meer over Voodoo, en ondergaat hij een voodoo-discipelritueel onder de god Thron. Daarna woonde hij een ceremonie bij die Kokou veel gewelddadiger was in Lake Nokoué met de tofinu die op het eiland Ganvié wonen. Reizend naar Johannesburg, onderzoekt hij de township Alexandra om te zien hoe gevaarlijk dergelijke townships zijn. Davids tijd in Zuid-Afrika loopt ten einde in Orania, waar hij een kleine groep Afrikaner-nationalisten ontmoet voordat hij verder naar het noorden trekt, naar Randfontein en de Suidlander-survivalisten ontmoet.

Lees ook: Wereldwijs | Wat zijn de veiligste en gevaarlijkste landen in Afrika?

Aflevering 8 | Terug in de Verenigde Staten

Terugkerend naar de Verenigde Staten , arriveert David in Los Angeles, waar hij deelneemt aan een tour langs de Manson Family-moorden en ontmoetingen met fans en vrienden van Manson. David vliegt door het land naar Kentucky, waar hij een replica op ware grootte van de ark van Noach bezoekt voordat hij een prepper in Virginia ontmoet. Bij zijn laatste stop bezoekt hij Tennessee, waar hij het engste horrorhuis ter wereld bezoekt, McKamey Manor.

Lees ook: Alle Nationale Parken in de Verenigde Staten van Amerika | Lijst

Rondleidingen “Dark Tourism” door FEG en Clio Muse

De European Federation of Tourist Guide Associations (FEG) organiseert en host in samenwerking met Clio Muse Tours 30 educatieve webinars over ‘Dark Tourism’ rondleidingen. Ondersteund door het door de EU gefinancierde project RePAST zijn deze webinars, die plaatsvinden van half januari tot eind maart 2021, gericht aan gecertificeerde toeristengidsen in Cyprus, Duitsland, Polen, Griekenland, Bosnië, Kosovo, Ierland en Spanje.

Als partner van RePAST heeft Clio Muse Tours acht digitale tours gemaakt, één voor elk van de landen die in het project zijn opgenomen. Deze rondleidingen kwamen tot leven na het ontwikkelen van een onderzoeksmethodologie, evaluatie van talrijke geschreven en mondelinge historische bronnen, tijdschriften, artikelen en boeken uit universiteitsbibliotheken en archieven, evenals overheidsrapporten en juridische documenten.

Als onderdeel van de levenslange training van de FEG zullen de Clio Muse-tours, samen met de belangrijkste resultaten van RePAST en ander educatief materiaal worden gebruikt tijdens de online webinars om professionals in cultureel toerisme kennis te laten maken met de etiquette van duistere toeristische tours.

Het doel is om gekwalificeerde toeristische gidsen te voorzien van de vaardigheden om zinvolle en impactvolle ervaringen op locatie van hoge kwaliteit te bieden. Met een toename van de populariteit van donker toerisme, geloven we dat deze webinars een waardevol hulpmiddel zullen worden bij de verdere ontwikkeling van gekwalificeerde toeristengidsen die in deze landen actief zijn en die hen zullen helpen ongeziene aspecten van het culturele erfgoed van deze landen onder de aandacht te brengen.

Wereldreizigers

Wereldreizigers.nl | Alles over verre reizen, wereldreizen, reisnieuws, reisfotografie, backpacken, reistips en meer.

You may also like

Reistrends 2024 | Goedkope en meest populaire bestemmingen

Top 10 | Wat zijn de beste backpack bestemmingen in Azië?

VANLIFE | How to: Camperbus kopen of ombouwen

Cursus dromen realiseren kun je leren! | Wereldreizigers korting t.w.v. € 25,-

Elke maand leuke reistips en extra voordelen ontvangen? En wist je dat we maandelijks een wereldkaart weggeven onder onze abonnees? Het enige wat je daarvoor hoeft te doen is hieronder je e-mailadres achter laten, je maakt dan elke maand opnieuw kans!

Wereldreis plannen

Wereldreis sparen

Wereldreis route

Wereldreis vaccinaties

Goedkope vliegtickets

Wereldreis inspiratie

Wereldreis bankzaken

Wereldreis en malaria

Waarom op wereldreis

Goedkoopste landen wereldreis

Continenten & werelddelen

Alle landen ter wereld

Grootste landen

Grootste eilanden

Gevaarlijkste landen Europa

Gevaarlijkste landen Afrika

Alle landen in Afrika

Vliegtijd landen in Azië

Verschil AM en PM

Wereld informatie

NATIONALE PARKEN

Nationale parken Amerika

Nationale parken Europa

Nationale parken Nieuw-Zeeland

Nationale parken Nepal

Nationale parken Vietnam

Nationale parken Thailand

Nationale parken Costa Rica

Nationale parken Zuid-Afrika

Nationale parken Mexico

Nationale parken Finland

Bucketlist plekken Zuid-Amerika

Bucketlist plekken Afrika

Bucketlist Tahiti Frans-Polynesië

Bucketlist zwembaden

Bucketlist Wildlife

Bucketlist Dubai

Bucketlist Australië

Bucketlist Walvissen

Bucketlist Zanzibar

Bucketlist Japan

Alle rechten voorbehouden | Copyright © 2024 Wereldreizigers.nl | Onderdeel van Orbital Media | Travel Marketing & PR .

- Vliegtickets

- Pakketreizen

- Scooterreis

- Overlanden (4×4)

- Stedentrips

- Digital Nomads

- Nationale Parken

- Camper bouwen

- Midden-Oosten

- Noord-Amerika

- Midden-Amerika

- Zuid-Amerika

- Kopieer link

- Film & serie Reviews

- NPO3 Exclusives

- Programma's

- Op NPO Start

- Afleveringen

- Alle zoekresultaten

- Videosnacken

6 dingen die je over Bali moet weten voordat je er aan een zwembad gaat liggen

Op welke plekken is ‘dark tourism’ groot geworden?

- Achtergrond

- 01 mei 2017

- 2 minuten leestijd

Jerry Vermanen

Ruim zeventig jaar na de Tweede Wereldoorlog wordt toerisme naar plekken zoals concentratie- en vernietigingskamp Auschwitz en het Anne Frank Huis steeds populairder. Dit zogeheten ‘dark tourism’ heeft een schaduwkant: toeristen die bijvoorbeeld veel te vrolijke foto’s maken op plekken waar duizenden mensen zijn overleden. Wij hebben een overzicht gemaakt van een aantal plekken waar dit duistere toerisme plaatsvindt.

9/11 Memorial Site, New York, USA

Op de plek waar op 11 september 2001 de Twin Towers werden neergehaald, staat sinds 2011 een grote herdenkingsplek met de namen van de bijna drieduizend slachtoffers. In 2016 trok deze herdenkingsplek zo’n zeven miljoen bezoekers. Daarmee is het waarschijnlijk de grootste ‘dark tourism’-locatie ter wereld. Bekijk hieronder de voor- en-na-foto’s van Ground Zero. Of beter gezegd, tijdens-en-na-foto’s van de aanslag en het monument zoals het nu staat.

Alcatraz, San Francisco, USA

Het voormalige gevangeniseiland Alcatraz wordt jaarlijks door ruim 1,5 miljoen toeristen bezocht. De gevangenis was geopend van 1932 tot en met 1963, en werd in 1972 voor het grote publiek geopend.

Pripyat, Chernobyl, Oekraïne

Het gebied rondom de kerncentrale in het Oekraïense Chernobyl werd in 1986 nog ontruimd, maar is tegenwoordig een trekpleister voor ramptoeristen. Jaarlijks mogen zo’n tienduizend toeristen het voormalige geëvacueerde gebied in om de verlaten flats, het leegstaande zwembad en de vervallen kermis te bekijken.

Foto: Jerry Vermanen

Auschwitz, Krakau, Polen

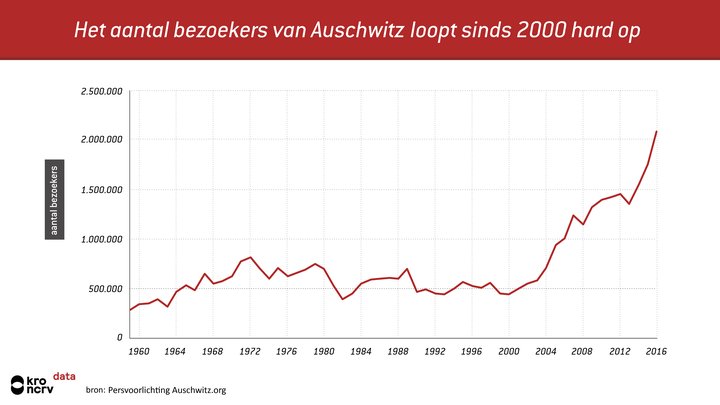

Sinds het zestigjarige jubileum is het aantal bezoekers in het voormalige concentratie- en vernietigingskamp Auschwitz nooit meer onder de miljoen personen gekomen.

Die enorme toestroom van toeristen levert ook problemen op. Een Duitse kunstenaar maakte daarom het project Yolocaust , waarin hij toeristen die ongepaste foto’s maken op de hak neemt.

Anne Frank Huis, Amsterdam, Nederland

Ook Nederland kent een eigen populair WWII-monument waar toeristen jaarlijks naar afreizen. Sinds het Anne Frank Huis in 1960 openbaar is gesteld voor het publiek, zijn de bezoekcijfers bijna jaarlijks gestegen.

In 2016 hebben liefst 1,3 miljoen bezoekers het Anne Frank Huis bezocht. Dat komt neer op ruim 3.500 mensen per dag. De aankomende twee jaar wordt het museum verbouwd om nog meer mensen te kunnen ontvangen.

- tweede wereldoorlog

- Big brother

Deze website maakt gebruik van cookies om de ervaring te optimaliseren. Lees meer .

- Onze diensten Ruimtelijke Economie Duurzaamheid Vastgoed Duurzame Bezoekerseconomie Achtfacettenmodel

- Over ons Over Areaal Advies Ons team Missie & visie Maatschappelijke Impact Vacatures & Traineeship

- Duurzame bezoekerseconomie

Tussen griezelen en gedragen: hoe gaan we om met dark tourism?

Een vorm van toerisme waar het allemaal draait om locaties die een verbinding houden met dood, tragedie, lijden of andere duistere gebeurtenissen uit het verleden: het fenomeen dark tourism wordt steeds populairder. Het speelt in op de nieuwsgierigheid van de mens en combineert geschiedenis met een ervaring die gezien kan worden als bijzonder en spannend. Nu is dark tourism niet een uniform concept; elke locatie is anders en dus ook de geschiedenis en ervaring kunnen erg divers zijn.

Het duistere van dit toerisme is als het ware op te delen in verschillende gradaties, ofwel tinten. De meeste mensen zullen bij deze vorm van toerisme al snel denken aan locaties als Auschwitz of Tsjernobyl, maar ook de toeristische commerciële martelmusea die in veel grote steden te vinden zijn of de ‘Jack the Ripper tour’ in Londen behoren tot het concept. Grote kans dus dat je wel eens deelgenoot van dark tourism bent geweest.

Dark tourism is een interessant fenomeen, zeker vanuit sociaal en cultureel oogpunt. Het kan echter wel tot negatieve gevolgen leiden. Net als bij andere vormen van toerisme kan ook dark tourism leiden tot overlast of milieuschade. Massale bezoekersaantallen kunnen leiden tot fysieke schade aan historische en culturele waardevolle plekken. Daarnaast heeft dark tourism ook vaker culturele erosie als gevolg. Door de toenemende komst van bezoekers kunnen lokale gemeenschappen en culturen hun tradities en gewoontes aanpassen om meer aan de verwachtingen van de bezoekers te voldoen. Wanneer dit in hogere mate gebeurt kan het leiden tot het verlies van de culturele authenticiteit of het verstoren van de inheemse manier van leven.

Tot slot is er voornamelijk kritiek op dark tourism wanneer het gaat over de ethische kant van het verhaal. Het gedrag dat sommige bezoekers vertonen wanneer zij deelnemen aan dark tourism wordt vaak met een afkeurende blik bekeken. Rondrennen, hard praten (of zelfs schreeuwen), dingen aanraken of ongegeneerd foto’s maken zijn allemaal voorbeelden van wat gezien wordt als ‘onethisch gedrag’. Natuurlijk verschilt de acceptatie van dit gedrag van locatie tot locatie. Zo zal niemand gek opkijken wanneer je selfies of gekke foto’s maakt in een martelmuseum, die daar zelfs ook gelegenheid toe bieden, maar zul je wel verwijtende blikken vangen wanneer je dit doet in het Anne Frank Huis. Zulk gedrag wordt dus voornamelijk bij de meest donkere tinten van dark tourism als negatief gezien. Daarentegen lijkt men zich wel steeds meer bewust te worden van dit fenomeen. Zo heeft een influencer, die een ‘sexy’ foto van haarzelf in Tsjernobyl op Instagram had gepost, zoveel kritiek over zich heen gekregen dat ze de foto heeft verwijderd en haar account op privé heeft gezet.

Daarnaast is het tegenwoordig eenvoudiger om je op het bezoek aan z0’n locatie voor te bereiden. Wanneer je googlet op dark tourism verschijnen er ook steeds vaker artikelen als ‘Hoe bezoek je dark-tourism-locaties op een ethische manier’. De opkomst van deze ‘ethical guides’ tonen aan dat men steeds meer gaat nadenken over zijn of haar invloed op de omgeving.

Hoewel dark tourism dus weldegelijk negatieve gevolgen kan hebben biedt het daarnaast ook positieve kanten. Net als andere vormen van toerisme kan een toename aan bezoekers gezien worden als een economische stimulans voor de omgeving. Door het groeiende aantal bezoekers wordt er meer werkgelegenheid gecreëerd en worden de lokale ondernemingen gestimuleerd. Dit draagt bij aan de economische groei van de omgeving, wat een verbetering van de levensstandaard van de lokale bevolking kan betekenen.

Maar deze unieke vorm van toerisme heeft nog meer positiefs te bieden. Voornamelijk wanneer het gaat om bewustwording, educatie en het behouden van het historisch erfgoed kan dark tourism een steentje bijdragen. Dark tourism zorgt voor bewustzijn bij de mensen die de locaties bezoeken. Het bezoeken van zulke plekken kan zorgen voor meer begrip en inzicht in de geschiedenis en de impact die deze heeft gehad op de omgeving en samenleving. Doordat bezoekers op de locatie zelf de gevolgen en geschiedenis kunnen zien en meemaken ontstaat er een grotere kans dat zij zich beter kunnen gaan inleven in de slachtoffers. Het bezoeken van een dark-tourism-locatie kan dus uitermate leerzaam zijn.

Naast educatie kan dark tourism ook bijdragen aan het historisch en cultureel behoud van een locatie. Door de toename van bezoekers en hun interesse in de locatie en de geschiedenis worden er vaak middelen beschikbaar gesteld voor het behouden en restaureren van de locatie. Dit draagt bij aan het voortbestaan van waardevol cultureel erfgoed dat anders verwaarloosd zou kunnen worden. Daarbij kan het bezoek van toeristen de lokale gemeenschap ertoe stimuleren om het erfgoed beter te gaan onderhouden en meer waarderen.

Tot slot kan dark tourism een manier zijn om de getroffen gemeenschappen te herdenken en te helen. Bezoekers die verbonden zijn met de locatie, bijvoorbeeld doordat zij slachtoffer of familie van slachtoffers zijn, kunnen erkenning en steun voelen. De locatie kan voor deze mensen een platform bieden om hun verhalen te delen en in contact te komen met anderen. Door het verleden te herdenken, en hiervan te leren, kan een gemeenschap sterker worden en zo ook een gevoel van eenheid ontwikkelen.

Dark tourism heeft dus zowel historisch als educatief potentieel, maar het is essentieel om op een respectvolle manier met deze locaties om te blijven gaan. Met zorgvuldige inpassing en voldoende respect kan het een manier zijn om ook de duistere kant van de menselijke geschiedenis te begrijpen en belangrijke lessen uit het verleden te trekken.

Nadeshe Ferdinandus is sociaal-geograaf en schreef haar masterscriptie over Dark Tourism. Bij Areaal Advies houdt ze zich onder meer bezig met Duurzame Bezoekerseconomie.

- Dark Tourism

Deel dit bericht via

Ja, ik ontvang dit document graag (direct) in mijn e-mailbox.

17 Must-Visit Dark Tourism Destinations Around the World

Dark Tourism destinations were once the remit of a select group of travellers. However, after the launch of popular Netflix show Dark Tourist, these attractions have hit the mainstream.

If you’re interested in the morbid and the macabre, look no further. After making several visits to dark history sites myself, I’ve teamed up with other travellers to bring you this list of dark tourism destinations all around the world.

Read more: (opens in new tab)

- What is Dark Tourism?

- Are Bolivia’s Mine Tours Ethical?

- Chernobyl Exclusion Zone Photographic Guide

17 Must-Visit Dark Tourism Destinations

1. chernobyl exclusion zone – kyiv, ukraine.

The abandoned amusement park in Pripyat is one of dark tourism’s crowning images. The haunting stills of the fairground that never heard the laughs of children hang in modern consciousness, a symbol of tragic loss and a warning of the mistakes men can make.

In 1986, the nuclear reactor at the Chernobyl power plant exploded, causing the worst nuclear accident in the world’s history. The effects were huge; people were forced to evacuate their homes and the surrounding areas became a hotbed of radiation. It was predicted that never again in our lifetime, would Chernobyl be inhabited by anything living.

Surprisingly, the Chernobyl exclusion zone has recovered quicker than was ever predicted. Although there are still risks with spending long periods in the exclusion zone, wild animals have returned and are thriving. Despite its recovery, Chernobyl acts as a very sobering reminder of the damage humanity can do without intention.

2. Sucre Cemetery – Sucre, Bolivia

Sucre Cemetery is an unlikely attraction in Bolivia’s capital. Regularly appearing on tourist maps, it is a peaceful place which attracts visitors who come to see how the Bolivians handle death and all that comes after.

Also frequently visited by locals, this cemetery is a surprisingly popular spot for catching up with friends, studying and paying homage to the dearly departed.

Unlike other cemeteries I’d visited, these graves were arranged in a block system above ground. The vast majority of these were carefully maintained and were regularly stocked with gifts for departed loved ones. Small bottles of spirits were a common appearance, alongside slices of cake!

In Bolivia, death is accepted as an inevitability of life. While graveyards ultimately provide a space for burial, they hold a far more important symbolic role in Bolivian culture. Although death is traditionally seen as a dividing force, Sucre Cemetery demonstrates that death can continue to unite us all, long after somebody is gone.

3. The Poison Garden – Alnwick, England

Home to around 100 toxic and narcotic plants, the Poison Garden is undoubtedly one of the best things to do in Alnwick . This small but deadly garden is home to some of the world’s most dangerous plants and visitors are only allowed to enter on a guided tour.

Deadly nightshade, cannabis and coca (the plant from which cocaine is derived) are a few examples of the plants housed in the Poison Garden. Visitors are prohibited from touching any of the greenery and there have even been cases of people passing out after smelling the plants!

The tour guides at the Poison Garden are great at explaining the real-life application of the plants using case studies such as Harold Shipman (Doctor Death) and Graham Young (The Teacup Poisoner). The garden also runs tours for local school children, educating them about drug use.

4. Paneriai Massacre Site – Vilnius, Lithuania

Paneriai is one of Vilnius’ many neighbourhoods. However, it will be forever remembered as the Ponary massacre site. The Einsatzgruppen (Nazi death squads) rounded up groups of Jews from the Vilna Ghetto, took them to Paneriai, executed them and forced other Jewish prisoners to dig mass graves and bury them.

There are six burial sites within the complex, each the site of multiple mass executions. Because so many sets of bodies are stacked on each other, it is impossible to know the exact number of deaths. It is estimated to be around 100,000.

Those brought to Paneriai were burned to death in an attempt to destroy evidence. They were then shovelled into the pits, which today are marked by memorials. Like many of the massacre sites in the Baltics, Paneriai is a forested area. This makes walking around a surreal experience as it is quiet, peaceful and beautiful, a stark contrast to the memorials reminding you that thousands of people were slaughtered there.

Contributed by Cultura Obscura . Follow them on Facebook !

5. St. Nicholas’ Church – Hamburg, Germany

In July 1943, Hamburg was the target of an allied aerial World War Two bombing. The tall spire of St. Nicholas’ Church was used as an orientation marker and the building was almost completely destroyed. All that remained were some external walls, the crypt and most of the tower.

Today, St. Nicholas’ Church stands as a memorial to the victims of WWII. The memorial exhibits in the crypt provide many details of the events leading up to Operation Gomorrah , the air war over Europe. Beautiful sculptures sit inside, illustrating the futility of war and its disastrous consequences. A 51-bell carillon has been installed in the tower and sounds every Thursday at noon.

We visited the church on a walking tour of Hamburg and the experience still haunts me. The vast majority of people in Hamburg during Operation Gomorrah would have been perfectly ordinary citizens going about their daily lives – people just like me.

Contributed by Lesley of Freedom 56 Travel . Follow her on Twitter !

6. Comuna 13 – Medellin, Colombia

Medellin was once the most dangerous city in the world. When infamous drug lord Pablo Escobar controlled the city, crime was extremely high and the locals lived in fear. The neighbourhood of Comuna 13 had direct access to the main highway, making the exportation of drugs, weapons and other illegal goods extremely easy.

Drug cartels fought over control of the area and as a result, Comuna 13 was a very dangerous place. It was not uncommon to hear gunshots throughout the day and even to see dead bodies piled on the street. With that in mind, it might come as a surprise that Comuna 13 is now one of the most visited neighbourhoods in Medellin.

Over recent years, a tremendous amount of money has been invested in Comuna 13. A cable car system was installed to link it to the city centre. The resulting increase in tourism has sparked real change for the locals and the neighbourhood has become one of the country’s leading creative hubs.

Contributed by LivingOutLau . Follow him on Instagram !

7. Gulag Labour Camps – Karaganda, Kazakhstan

My trip to Kazakhstan left a deep impression on me. While I had heard about the so-called gulags, I did not know that most of them were in Kazakhstan. Stalin deported whole ethnic groups to the remotest corners of the country. This is how during WWII, the Volga Germans ended up in Karaganda .

Stalin wanted to develop the farms and coal mines in Karaganda and set up a network of labour camps to support these projects. Political prisoners and deportees provided the free labour that was necessary.

Even though not much of the labour camps remain, Karaganda is the perfect example of a dark tourist site. There is an excellent Gulag Museum in the former headquarters of the labour camp in Dolinka.

Also nearby, the Ecological Museum covers other dark parts of Soviet history. The museum has an exhibition on the nuclear tests done in Kazakhstan and the debris that falls from the sky from the space program in Baikonur.

Contributed by Ellis of Backpack Adventures. Follow her on Instagram !

8. The Eruption of Mount Vesuvius – Pompeii, Italy

Pompeii was a thriving coastal city in Italy that was completely destroyed in 79AD when the neighbouring Mount Vesuvius erupted and covered the city in ash. It is a prime example of what is termed disaster tourism, where tourists visit a location where an environmental disaster has occurred.

What makes the eruption of Mount Vesuvius more tragic was that the majority of people who died were slaves, who either had no means of escaping or were trapped. When archaeologists began excavating the site, they found several bodies. The ash preserved these bodies which allowed historians to create the human casts we see on site today.

Seeing these casts in crouching positions while covering their faces, gave me shivers. To get a greater understanding of the site and everything inside of it, I highly suggest finding a good tour guide. This photographic travel guide to Pompeii gives lots more tips for planning a visit.

Contributed by Natasha of And Then I Met Yoko. Follow Natasha on Instagram !

9. Mary King’s Close – Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Below the Royal Mile in Edinburgh hides an underground street paved with dark history. Mary King’s Close was alive with residents when the bubonic plague seized the country in 1645. The grievous epidemic turned the once-thriving close into a dreadful place, where its inhabitants suffered a slow and torturous death.

Mary King’s Close was sealed off and used as a foundation for the Royal Exchange in the late 1700s. Years passed and its terrible secrets were left trapped within its dark walls. In the 1990s, the close was rediscovered and opened to the public, allowing people to explore the subterranean streets that once festered with disease.

The mental image of the street once bustling with life left a lump in my throat – the locals had no idea how many would lose their lives to the Great Plague. Like Mary King’s Close, the entire city of Edinburgh is filled with dark and spooky places so be sure to check out Scotland’s capital if you’re a fan of the macabre.

Contributed by Wandering Crystal. Follow her on Instagram !

10. The Killing Fields and S-21 – Phnom Penh, Cambodia

During the Khmer Rouge genocide in Cambodia, execution, starvation and disease were allowed to flourish, killing an estimated three million people. Led by Pol Pot, the regime attempted to enforce brutal and inhumane policies to push Cambodia into being a classless society.

Phnom Penh and the surrounding area are home to S-21, a political prison used by the regime, and Choeung Ek, the largest of the Killing Fields. Over 12,000 prisoners were held at S-21 during the regime and with only seven known survivors, it’s a place known for unthinkable torture and suffering. The S-21 site now houses the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum where you can learn more about the Cambodian massacre.

Much like S-21, a tour of the Cambodian Killing Fields can be hard to digest. There is a memorial stupa filled with the skulls of victims and you can still see bone fragments and strips of clothing along the paths. It’s a horrifying place but important to visit to ensure history doesn’t repeat itself.

Contributed by Ben at Horizon Unknown . Follow him on Facebook !

11. Abandoned Ghost Palace – Bali, Indonesia

Located near the village of Bedugul lies an abandoned hotel. Legend has it that in the early 1990s, the hotel began to be constructed by Tommy Suharto, the youngest son of the former Indonesian President. Tommy was later convicted of ordering the assassination of a judge who previously found him guilty of corruption and he subsequently went to prison. The hotel was never completed.

Another theory is that the hotel is haunted by the landlocked souls of labourers who were worked to death during its construction. The hotel, originally named Hotel Pondok Indah Bedugul, isn’t open for visitors but if you hand the guard 10,000 IDR, he’ll let you in to explore. I recommend seeing it as soon as possible because rumours indicate that visitors will no longer be permitted entrance (even with a bribe) because of how dangerous it is.

Contributed by Nat Wanderlust.

12. Auschwitz-Birkenau – Oświęcim, Poland

The “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” was the official code name for the murder of Jews during World War II. At least 1.3 million people were sent to Auschwitz by the Nazis and a shocking 1.1 million people were murdered by the SS, mainly in gas chambers.

Auschwitz-Birkenau is located on two different sites. Auschwitz I comprises brick buildings and the Death Block where people were gassed. Auschwitz II, known as Birkenau, was opened as they could not cope with the scale of death at Auschwitz I.

On arrival, you’ll see the famous train tracks where people were transported in and either sent to the gas chambers or given labour duty. Once the latter were emaciated, they were gassed and replaced with new prisoners.

I cried in horror seeing the piles of shoes, suitcases and false legs that once belonged to people. Human hair was used to make felt for socks given to the forces in submarines – 293 sacks of hair were found on liberation. Words cannot describe the emotions you’ll have upon seeing this symbol of this horrific dark chapter in our history.

Contributed by Vanessa from Wanders Miles, follow her on Instagram !

13. Day of the Dead – Oaxaca, Mexico

The Mexican Day of the Dead festival is a darkly uplifting event that occurs each year between October 31st and November 2nd. On these days, family and friends celebrate the lives of loved ones passed. It is widely believed that for three days each year, the veil between this world and the next is especially thin.

During the Day of the Dead festival, the spirits of the departed return to provide counsel to their living family members and friends. Much of the reunion is celebrated within the cemetery, where graves are cleaned and decorated for the occasion. On certain dates, families spend the whole night in the cemetery eating sugar skull sweets, drinking alcohol and playing music.

UNESCO recognises ‘Dia de Los Muertos’ as being ‘ Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity ’. Experiencing the Day of the Dead is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity; especially in Oaxaca where visiting graves is commonplace. Prepare for everything you have ever thought about death to be challenged.

Contributed by Castaway With Crystal. Follow her on Instagram!

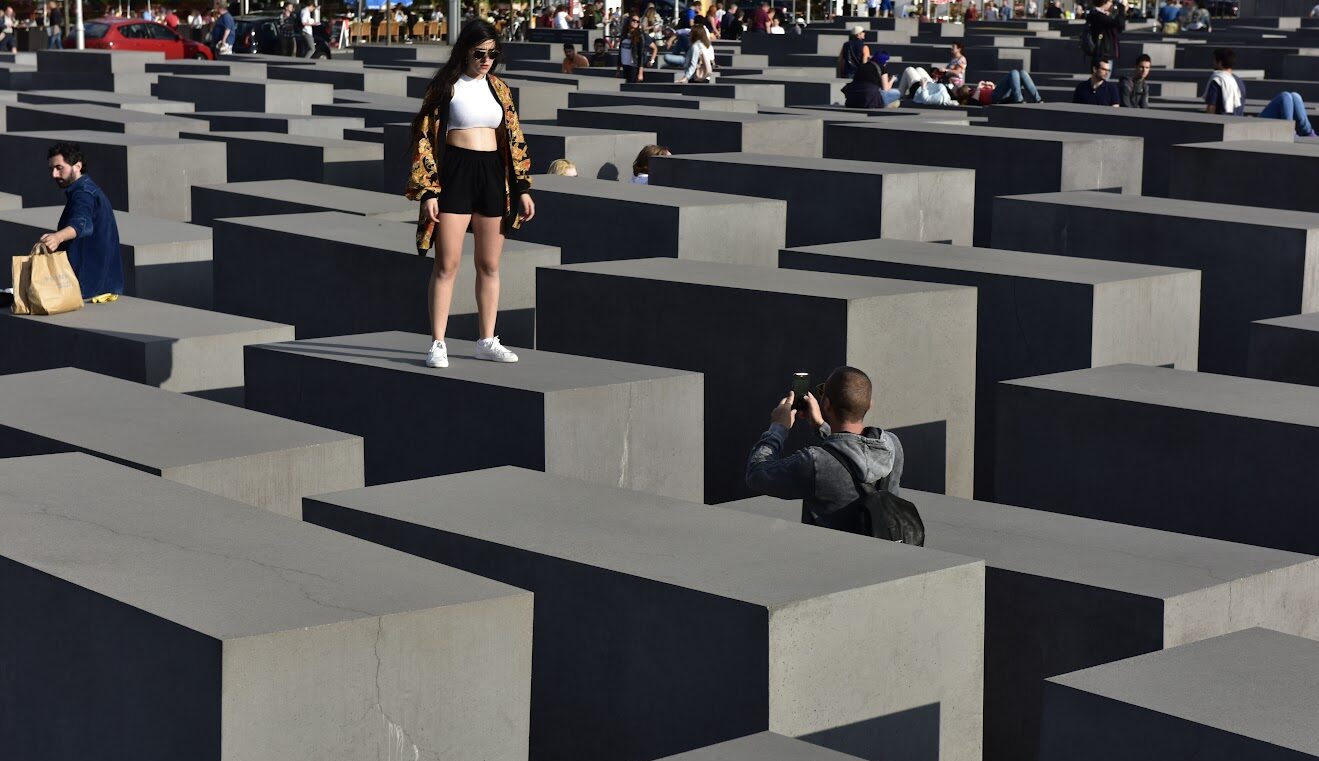

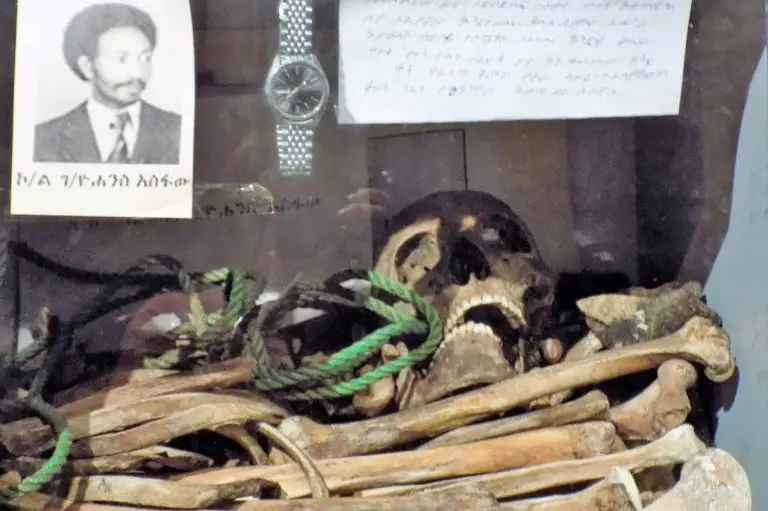

14. Red Terror Martyrs’ Museum – Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

The military junta who took power after Ethiopia’s Emperor Haile Selassie was ousted were known as the Derg. After prolonged internal wranglings, Mengistu, a soldier from the ranks, emerged as their leader and the dictator of Ethiopia.

Within a couple of years, the Derg had created terror among ordinary Ethiopians, tens of thousands of whom had been imprisoned without trial and tortured, or worse, executed. The term ‘Red Terror’ comes from Mengistu’s famous speech when he smashed a bottle of blood to illustrate the killings to come. His regime is estimated to be responsible for the deaths of between 1.2 and 2 million Ethiopians.

Today, the horrors of Mengistu’s regime are remembered in the Red Terror Martyrs’ Museum in Addis Ababa . Opened in 2010, this small museum teaches about the atrocities of the regime. Photos of victims cover the walls alongside displays of human remains recovered from mass graves. We came away from the Martyrs’ Museum appalled by man’s inhumanity to man.

Contributed by Andrea of Happy Days Travel Blog. Follow her on Facebook !

15. Constitution Hill – Johannesburg, South Africa

Constitution Hill is now a living museum which tells the story of South Africa’s journey to democracy. It’s hard to comprehend that people like Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi served time here in the 1960s and that the prison was still operational until 1982.

There are several sites that you can visit at Constitution Hill. The Old Fort is where white male prisoners were housed. Although the cells were overcrowded and unhygienic, the rooms are larger than those of the black prisoners. They were held in Block number 4. There was very little daylight and as I stepped inside, I was terrified that someone would shut the cell door behind me.

There’s also the Awaiting Trial Block. The block was demolished and the bricks were used to build South Africa’s new Constitutional Court. Thankfully this court serves to uphold the rights of all South Africans, regardless of colour, but the bricks are a poignant reminder of its troubled past.

Contributed by Fiona of Passport and Piano . Follow her on Facebook !

16. Shanghai Tunnels – Portland, USA

In a city known for the slogan ‘ Keep Portland Weird ,’ the Shanghai Tunnels fit right in. It’s believed that from 1850 until 1941, men in Portland, Oregon, were regularly kidnapped and sold to ship captains as labourers. During this period, there was a shortage of labour available for the city’s booming shipping industry and this created a black market.

To capture these men, underground tunnels originally built to move inventory between businesses were repurposed for illicit use. Trapdoors were even installed in some of the local bars so that drunk men would drop into the tunnel below.

Today, tours of these tunnels are offered daily by a non-profit organisation, Shanghai Tunnels/Portland Underground. All tour participants are advised to be prepared for spending an hour in a confined space. While the nature of the tour is sad and tragic, it’s an important part of Portland’s history.

Contributed by Wendy of Empty Nesters Hit the Road. Follow her on Facebook !

17. Brno Ossuary – Brno, Czech Republic

Of the attractions in Brno , several of them could be classed as dark tourism attractions. The one that moved me the most, though, was the ossuary underneath the St. James Church.

Surrounding this church, which is known as the ‘Kostnice u sv. Jakuba’ in Czech, was one of the main churchyard cemeteries in Brno. Eventually, as the city grew, there was no room left for new burials so a grave rotation system was adopted.

When a burial took place, the body was left in the grave for between 10 to 12 years. After that, the bones were taken out to make room for the next burial. The displaced remains were then relocated to the ossuary, where bones from thousands of graves were piled up.

It’s estimated that Brno Ossuary holds the bones of more than 50,000 people, which makes it the second-largest ossuary in Europe; only second to the Paris catacombs. The mortal remains laid to rest here include victims of the Swedish siege of Brno and the Thirty Years’ War, as well as many victims of plague and cholera epidemics.

Contributed by Wendy of The Nomadic Vegan. Follow her on Instagram !

Do you have any dark tourism examples to share? Let us know in the comments!

9 thoughts on “17 Must-Visit Dark Tourism Destinations Around the World”

Comuna 13 is spellt with only 1 -m-.

I wonder why choose the cemetery in Sucre, when so many others are more characteristic (eg. Père Lachaise in Paris) or even ‘livelier’ (eg. in Santiago de Chile).

Interesting & important topic though. I’m in the process of rewriting an article about the mines of Potosi. That is one dark tourism destination I strongly oppose, for one simple reason; people are still dying in there.

Thanks for the heads up Anthony! 🙂

I chose the cemetery in Sucre because it was a little bit off the beaten track – I like visiting the lesser known places as well as the more famous ones.

I can understand your point about the mines of Potosí and can see why you disagree with it. I must say though, from my own personal experience, I found my visit to be hugely enlightening. I was initially very torn about the idea of visiting an active mine but in the end, we chose a company run by an ex-miner who took us into the mine personally. In my opinion, our visit never felt voyeuristic at all and the miners seemed very grateful for the tourists visiting. A percentage of the tour cost went directly into the funding the healthcare of the miners when needed and also towards maintenance of the mine.

Such a great and informative post, Sheree! There were so many sites here that I was not even aware of – that is why sharing posts about dark tourist sites is so important! It really helps educate the world and helps us honour the past and the lives that were lost at some of these sites.