ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Sustainable development for film-induced tourism: from the perspective of value perception.

- 1 School of Business and Trade, Nanchang Institute of Science & Technology, Nanchang, China

- 2 Media Art Research Center, Jiangxi Institute of Fashion Technology, Nanchang, China

- 3 Guangdong University of Finance and Economics, Guangzhou, China

- 4 Department of Art Integration, Daejin University, Pocheon, South Korea

- 5 School of Business, Foshan University, Foshan, China

- 6 College of Management, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China

- 7 School of Economics and Management, East China Jiaotong University, Nanchang, China

The tourism economy has become a new driving force for economic growth, and film-induced tourism in particular has been widely proven to promote economic and cultural development. Few studies focus on analyzing the inherent characteristics of the economic and cultural effects of film-induced tourism, and the research on the dynamic mechanism of the sustainable development of film-induced tourism is relatively limited. Therefore, from the perspective of the integration of culture and industry, the research explores the dynamic mechanism of sustainable development between film-induced culture and film-induced industry through a questionnaire survey of 1,054 tourism management personnel, combined with quantitative empirical methods. The conclusion shows that the degree of integration of culture and tourism is an important mediating role that affects the dynamic mechanism of sustainable development of film-induced tourism, and the development of film-induced tourism depends on the integration of culture and industry. Constructing a diversified industrial integration model according to local conditions and determining the development path of resource, technology, market, product integration, and administrative management can become the general trend of the future development of film-induced tourism.

Introduction

As an emerging industry, cultural tourism can make up for the economic difficulties caused by the weak growth of the primary and secondary industries, and replace it as a new driving force for economic growth ( Liu et al., 2021b ). As recognized by both the academic community and industry, cultural tourism products greatly impact tourism destination development; souvenir, local cuisines, and films/television programs can promote tourism destinations ( Liu et al., 2021a , b ). Among them, film/television is the most influential form of art in today’s society. Film and television can help potential tourists to have some sensory and emotional cognitions through empathy and vicarious feeling to the tourist destinations mentioned in the films ( Kim and Kim, 2018 ; Pérez García et al., 2021 ), thereby generating tourism motivation and ultimately promoting tourism behaviors. Film and television, without exception, have integrated commerciality and artistry since birth, and form a unique form of culture ( Riley et al., 1998 ).

Hence, these significant economic effects have been widely investigated by researchers from different perspectives, such as promotion of local brands ( Liu et al., 2021a ), and changes in aesthetic information dissemination ( Kim et al., 2019 ). With in-depth studies, researchers have identified the profound connotation of the rapid development of film-induced tourism: the extension of the immersive tourism ( Marafa et al., 2020 ), the endowment of modern fashion labels for tourism destinations ( Teng and Chen, 2020 ), and multi-dimensional integrations of modern media technology and traditional entertainment industry.

Culture is the soul of tourism, and tourism is an important carrier of culture. Although the experience of film/television is different from tourism—the former is provided to people by means of image transmission, and the latter is realized by the way of people moving—but the essence is both cultural experience ( Syafrini et al., 2020 ; Senbeto and Hon, 2021 ). The connotation and the applied research of film-induced tourism reveal the complexity and diversity of the integrations of modern media and traditional entertainment.

The traditional glimmering style sightseeing tour is just a shallow taste, and often cannot make tourists get a deep enjoyment. Film-induced tourism is different, mature film-induced tourism products can bring tourists wholehearted relaxation and enjoyment, and make tourists’ self-worth better reflect. To clarify the inherent characteristics of film-induced tourism, the interactive observation of both the film and television subject and the tourism subject provides a feasible solution. Film/television programs are the expression and substantiveness of culture ( Yi et al., 2020 ). Tourism as an economic carrier is the pattern and standardization of the industry ( Yen and Croy, 2016 ). The development of film-induced tourism relies on the mutual integration of culture and industry.

With the evolution of the world, sustainable development is leading the way in every industry including tourism. The early understanding of sustainable development in the academic community refers to meeting the needs of the current generation without damaging the needs of future generations’ development ( Jabareen, 2008 ; Yi et al., 2021a ). Based on this concept, the United Nations has formulated 17 sustainable development goals, proposed new standards for the prosperity and development of the earth, and standardized the assessment methods and indicators for sustainable development ( Böhringer and Jochem, 2007 ; Hacking and Guthrie, 2008 ; Singh et al., 2009 ). Since then, the concept of sustainable development has been fully implemented and has gradually become a well-known concept from the perspectives of the environment, economy, and society ( Adedoyin et al., 2021 ; Diep et al., 2021 ; Zhou et al., 2021 ). Currently, these three dimensions are identified as the motivations and mechanisms of sustainable development ( Steffen et al., 2015 ; Svensson and Wagner, 2015 ). Specifically, challenges in sustainable development are vital issues for exploring social and economic development. Economic benefits are the main dynamics of continuous action ( Hoogendoorn et al., 2015 ), with social effects as the main motivation of practice ( Williams and Schaefer, 2013 ), and environmental effects as the basic assurances of all activities ( Halme and Korpela, 2014 ). Hence, sustainable development research help explore the path of the industry development. The dynamic mechanism of sustainable development builds the foundation for the long-term influence of the culture and provides the way for continuous development and expansion of industrial effects ( Waheed et al., 2020 ). At present, to the best of our knowledge, very few studies have investigated the dynamic mechanism of the sustainable development for film-induced tourism. The existing studies which include the sustainable development dynamic mechanism can be divided into three aspects:

(1) The macro sustainable development concept of film-induced tourism ( Wen et al., 2018 ); (2) The sustainable development concept in the exploration of film-induced tourism ( Gong and Tung, 2017 ; Teng, 2021 ); (3) The micro sustainable development concept of film-induced tourism ( Suni and Komppula, 2012 ). Afterward, most of the studies believe that the dynamic mechanism of sustainable development is affected by its resource development, innovation mode, or artistic attractions. However, these have not yet conducted a quantitative study of the endogenous interactions between culture and industry. Accordingly, we try to fill the research gap; we study the relationship between culture and industry in film-induced tourism through structural equation modeling to promote the sustainable development dynamics brought about the integration of culture and industry.

Literature Review

Film-induced culture and tourism industry.

Film-induced culture plays a vital role in the global advertisement system. It is an effective approach for the advertisement of regional values and soft power, and it is a good pathway for cultural output and value proposition ( Yi et al., 2020 ). With the advance of economic development, consumers have broken the restrictions of basic needs spending ( Sun et al., 2017 , 2021 ; Du et al., 2020 ), and the needs for higher-level cultural consumption are becoming increasingly important ( Wang et al., 2020a , b ; Li et al., 2021 ). Film-induced culture is by no means limited to entertainment culture, and film-induced products are by no means limited to spiritual and cultural consumer goods ( Chen, 2018 ). Film/television is also a mass media. Film-induced culture has an unprecedented impact on people’s ways of thinking, social cognition, behavioral habits, and values, showing unique cultural tension and becoming an important structure of people’s spiritual life ( Misra, 2000 ; Janssen et al., 2008 ). Otherwise, as a fast-growing important new tourism trend, film-induced tourism creates connections between characters, places, stories, and tourists, and is inspired to immerse themselves in films to relive film-generated and film-driven emotions ( Riley et al., 1998 ). Essentially, both film and tourism provide an opportunity to relive or experience, see and learn novelties through entertainment and fun ( Teng, 2021 ). Film-induced tourism increases the overall economic effect of tourism industry and establishes the bonds of film and tourism industry. It provides not only pleasure and satisfaction for film-induced tourists, but also adequate and novel learning experience. The latest research trends are moving toward merging or collaborating two fields that already have similar goals.

The integration of film-induced culture spreads information through film-induced programs to “maximize” the effect of tourism cultural brands ( Huang and Liu, 2018 ). The fundamental reason is that the penetration of film-induced culture has driven the transformation and upgrading of tourism consumption ( Michael et al., 2020 ), which in turn makes film-induced culture a resource for tourism development, amplifies the effect of cultural integration in the process of transformation, and further enhances the influence of the tourism industry ( Marafa et al., 2020 ). The establishment of film-induced cities and film-induced bases creates the advantages of film-induced culture agglomeration, and the innovative path of developing film-induced cultural resources oriented by the tourism industry is becoming more and more popular ( Ringle, 2018 ). Cultural resources are further optimized and reorganized, and film-induced culture will gain a series of new integrated development in the promotion of tourism industry model ( Xin and Mossig, 2017 ). On the one hand, the film-induced bases can be used for film/television production, and on the other hand, it is an important place for tourism activities, which truly reflects the integration from products, markets, enterprises, and industries in film-induced tourism industry ( Stuckey, 2021 ). Accordingly, some researchers believe that the establishment of Hollywood Studios in 1963 marked the official beginning of film-induced tourism. Hence, film-induced culture can promote the tourism industry to shape brand culture, integrate useful resources, guide consumer trends, and induce convergence effect for rapid development and innovation ( Wu and Lai, 2021 ). Hence, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a: The development of film-induced culture is positively related to the growth of the tourism industry.

H1b: The cultural development in film-induced tourism is positively correlated to the degree of cultural and tourism integration.

H1c: The development of the tourism industry is positively correlated to the degree of culture and tourism integration.

Culture and Tourism Integration and Sustainable Development

The integration of culture and tourism is not only the objective need for the mutual prosperity of culture and tourism, but also the inevitable trend of the development. The elements compete, cooperate and co-evolve with each other, so that an emerging industry can be formed, and it has experienced “grinding-integration-harmony” of the dynamic development process ( Jovicic, 2016 ; Wang and Yi, 2020 ). Culture and tourism have a certain basis for mutual benefit and cooperation: for tourism, the integration of cultural-related content helps to acquire extensive knowledge, distant experience, and strong care; for culture, it is conducive to the protection and inheritance of cultural resources, image building, and propagation ( Loulanski and Loulanski, 2011 ; Jørgensen and McKercher, 2019 ). The integration of culture and tourism is an intimate contact between “poems and dreams,” which better meets people’s diverse needs for a beautiful life ( He et al., 2021 ). However, sustainable development refers to comprehensive and sustainable advancements in ecological, social, and economic aspects. The cognition that based on these three goals can be used to explore the dynamic mechanism for sustainable development of film-induced tourism.

In the dimension of sustainable ecological development, with the advent of the scientific revolution and the industrial revolution, the world is entering a new era. The utilization of resources is not limited to the development of physical resources but is more prone to the rational use of new resources, such as talented person, technology, intelligence, and data ( Waheed et al., 2020 ; Zhang et al., 2020 ; Li et al., 2021 ), cultural resources, such as historical culture, red culture, and folk culture, are integrated with tourism resources, such as landscape pastoral, to develop complementary advantages. The maximization of resource utilization has become the key to the sustainable development of the film-induced tourism society, and culture has become a regulator of various innovation factors, which promotes the scientific management of technological and industrial resources ( Delai and Takahashi, 2011 ; Liu et al., 2021b ). When transforming and utilizing film-induced cultural resources, do not trample or destroy the ecological environment for tourism development, and comprehensively optimize the tourism environment and tourism routes. Environmentalism and related laws and regulations have begun to pay attention to tourists’ needs ( Li et al., 2020 ). Hence, the further integration of culture and tourism can reflect the transformation of the overall ecological commitment ( Zhou et al., 2021 ), and the resulting human–environment relationship has become a new aspect of sustainable development.

In the dimension of sustainable social development, on the one hand, the improvement of cultural quality of the whole society is a prerequisite for the organic integration of culture and tourism ( Tien et al., 2021 ), with harmonious coexistence becoming the core aspect of economic and cultural development of the new era, tourists and other stakeholders of the film-induced tourism industry begins to focus on human capital development, social recognition, job creation, and health and safety-related issues ( Choi and Ng, 2011 ). With the deepening of research, researchers found that the above-mentioned problems are ideologically attributed to culture and are the society’s force for inducing the sustainable development of industries ( Cai and Zhou, 2014 ). The extension and connotation of tourism need the guidance of tourism culture. Cultural display or visitable production expands the scope of displayable culture, from material to non-material, to the integration of non-material and material, and then to the contemporary creative cultural display, which makes culture continuously “commoditized” ( Silberberg, 1995 ; Marques and Pinho, 2021 ). At present, many scholars have reached a consensus that the integration of culture and industry can promote the construction of the social community ( Jakhar, 2017 ; Yi et al., 2021b ) and promote the relevant members of the society to change their misconduct, thereby strengthening the sustainable development of the film and television industry and the tourism industry.

In the dimension of sustainable economic development, scholars generally agree that economic factors, which refer to the renewable and non-renewable resources invested in the production process, are composed of factors, such as cost, profit, and business development ( Mamede and Gomes, 2014 ; Wagner, 2015 ). Given the direct impact of economic effect on tourist activities is significant, most researchers directly view economic factors as the main driving force for the sustainable development of film-induced tourism, owing to the direct influence of economic effects on tourists’ tourism activities ( Horbach et al., 2013 ; Hojnik and Ruzzier, 2016 ). As been defined by researchers, sustainable economic development involves the exploration and innovation of business models, creating market opportunities, the processes of resolving unsustainable environmental and social problems ( Schaltegger et al., 2016 ). When film-induced culture is continuously produced into cultural tourism products, the commercial interests of tourism sales promote the industrialization and gradually form a complete industrial chain-cultural tourism industry. In the studies of film-induced tourism, many researchers view film-induced culture as a resource for creating new business models and market opportunities and regard the integration of film-induced culture with the tourism industry as a solution for unsustainable development problems. In summary, in film-induced tourism, in both the ecological, social, and economic dimensions, the integration of culture and industry will influence the path of sustainable development. Hence, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a: The degree of integration between film-induced culture and the tourism industry is positively related to the sustainable development of the ecology (human–environment integration).

H2b: The degree of integration between film-induced culture and tourism industry is positively correlated to the sustainable development of the society (harmonious coexistence).

H2c: The degree of integration between film-induced culture and the tourism industry is positively related to the sustainable development of the economy.

Above all, we proposed the following effect hypothesis:

H3a: Film-induced tourism culture has a significant impact on sustainable development through integration degree;

H3b: Film-induced tourism industry has a significant impact on sustainable development through integration degree.

Methodology

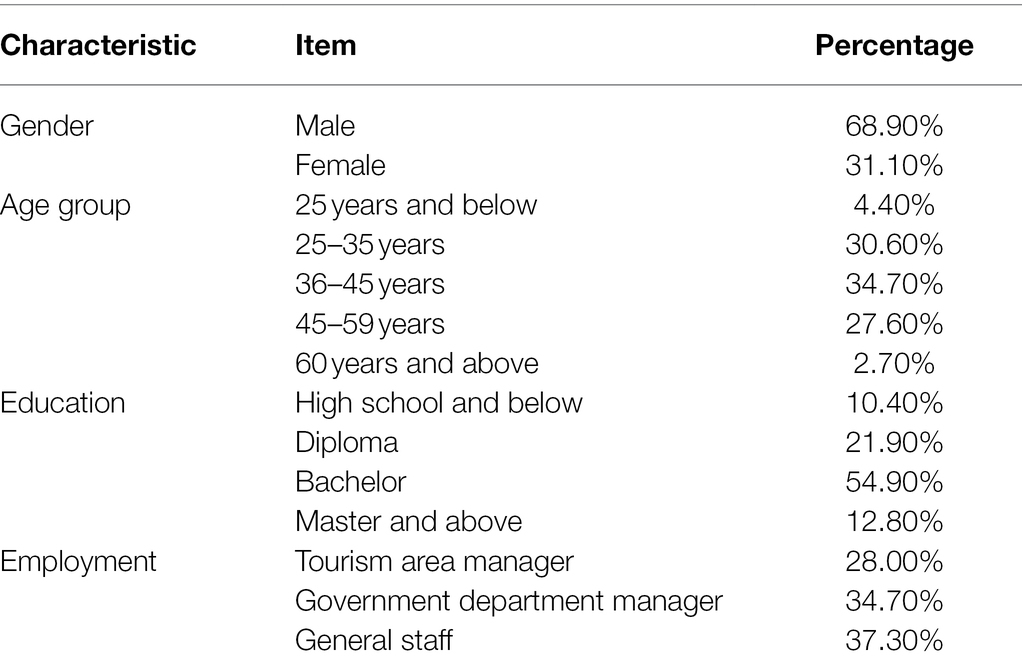

To get a better and professional understanding of the dynamic mechanism of the culture and industry associated with film-induced tourism, the research subjects are limited to the management staff of the film-induced tourism industry. A total of 1,200 questionnaires were distributed, and 1,054 valid questionnaires were collected, with a recovery rate of 87.8%. The collected questionnaires were randomly divided into two equal sets (527 questionnaires in each set): one dataset is used for exploratory factor analysis and the other is used for confirmatory factor analysis. The demographic characteristics of the sample population are shown in Table 1 . From Table 1 we can see, most of the responders are males (accounting for 68.9%), in the age groups of 25–35 and 36–45 (the total number of the two age groups accounting for 65.3%) and have a bachelor’s degree (accounting for 54.9%). 28% of the responders are tourism area managers; 34.7% of the responders are government department managers; and 37.3% of the responders are general staff. And the demographic characteristics of the responders generally follow the demographic distribution of the entire population in the area, indicating a good representativeness of the data and makes it an effective data source.

Table 1 . Sample basic information.

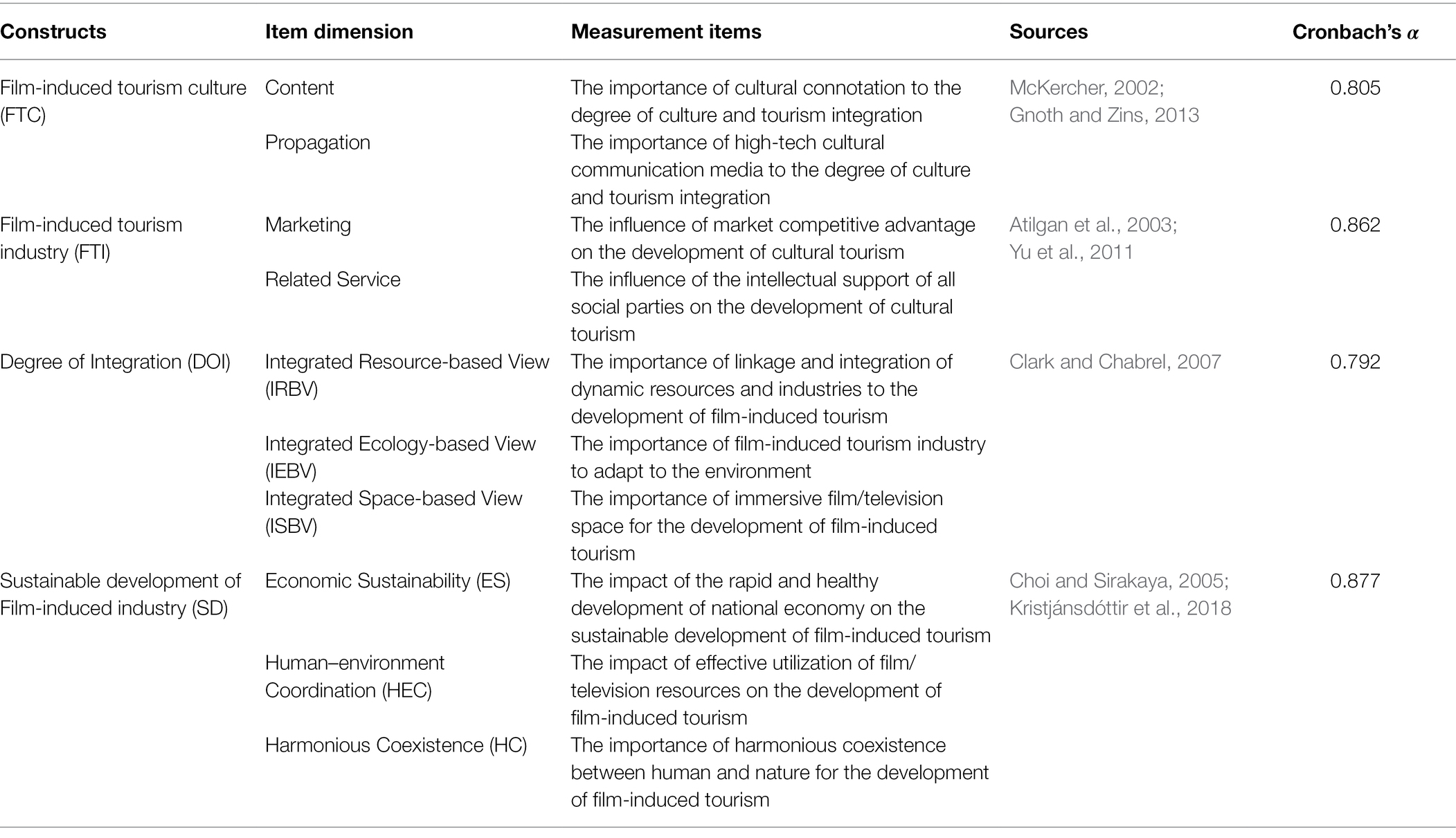

We draw on the mature scales used in previous studies for reference, and the initial scale was formed after corresponding modifications according to research topic. Then, two scholars who have been engaged in film-induced tourism and sustainable development were invited for analysis and discussion, and the scale was modified and improved. We use 5-level Likert scale to measure all variables, with 1 indicating “very unimportant” and 5 indicating “very important.” The specific measurement items and reliability are shown in the appendix. In addition, SPSS 26.0 was used for validity test, and KMO was 0.906 (>0.8). The results show that the scale has good reliability and validity, indicating that there is internal consistency among the variables ( Table 2 ).

Table 2 . Measurement items and reliability.

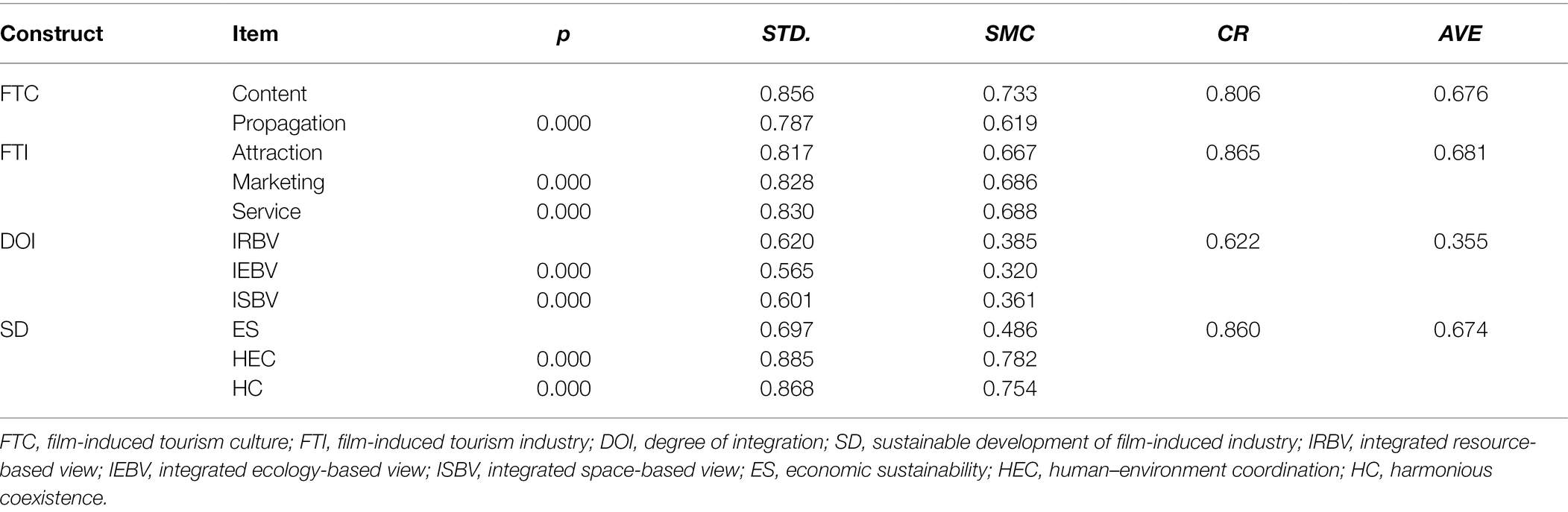

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) showed ( Table 3 ) that P<0.01, and the Composite Reliability of all variables was 0.622–0.865, so that the polymerization validity and the convergence validity is good. AVE was in a reasonable range. Therefore, the results of CFA all meet the standard, and all dimensions have good convergence validity.

Table 3 . Confirmatory factor analysis.

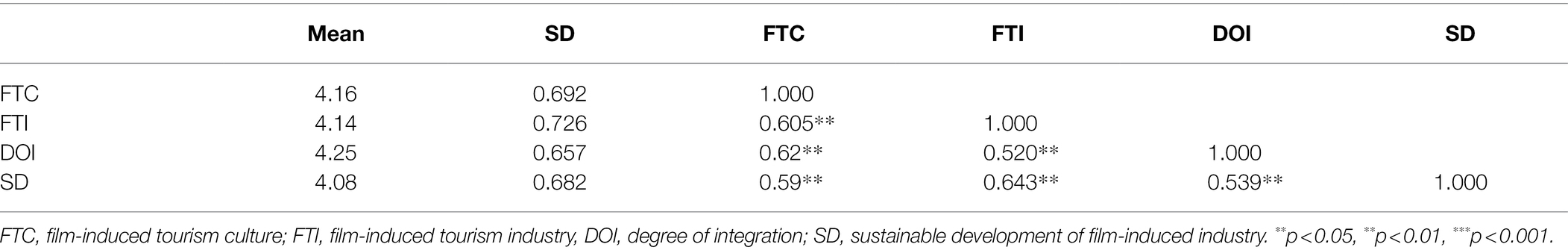

Correlation Analysis

Through the correlation coefficient test, it can be seen that the values below the diagonal are, respectively, the correlation coefficients between potential variables ( Table 4 ). Each potential variable has different connotations in theory, and each variable has relatively high correlation and good discriminant validity.

Table 4 . Correlation analysis.

Goodness of Fit of the Structural Model

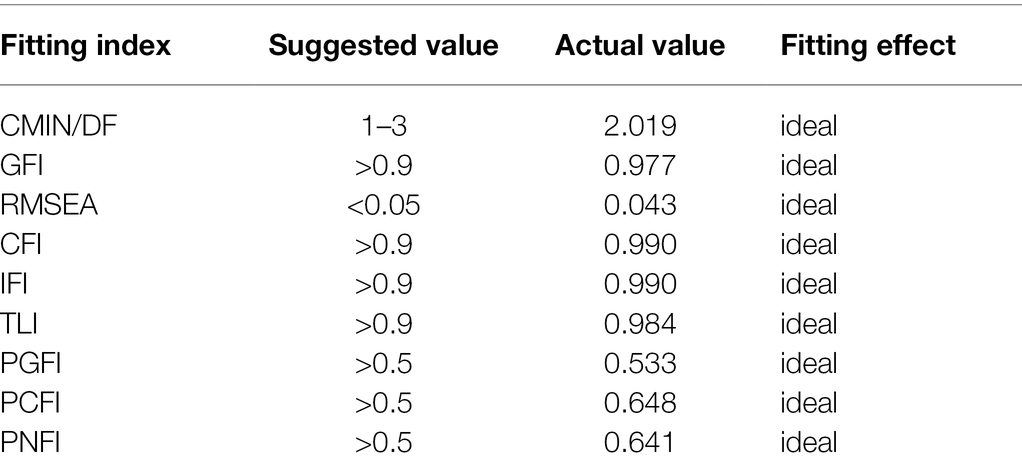

Based on the previous research results, the path relationship diagram between potential variables and observed variables has been built, the goodness of fit of the model to be verified have been tested from AMOS 26.0. The main fitting indicators all meet the ideal standard, that is, the model fitting effect is ideal.

Hypothesis Testing

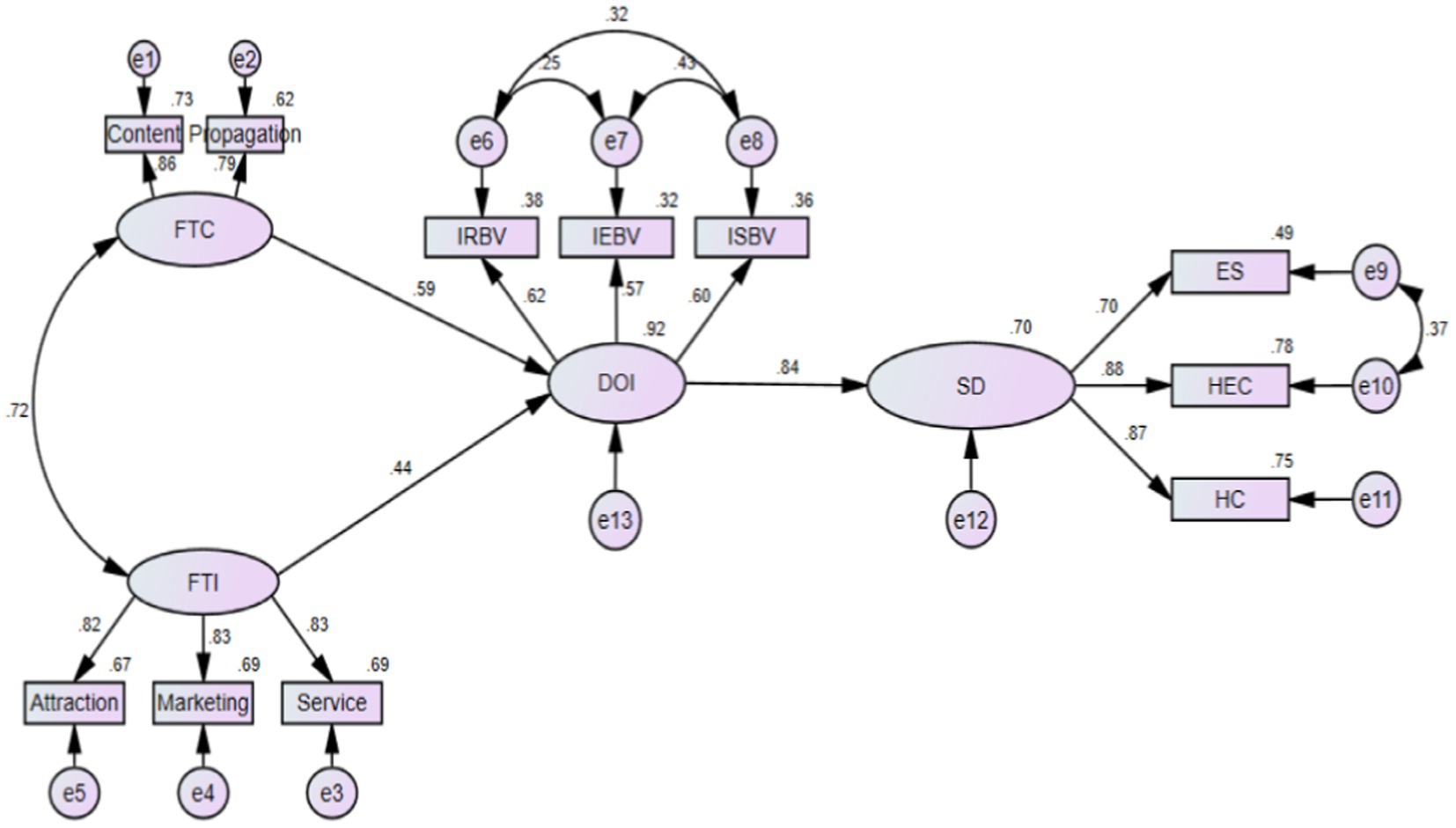

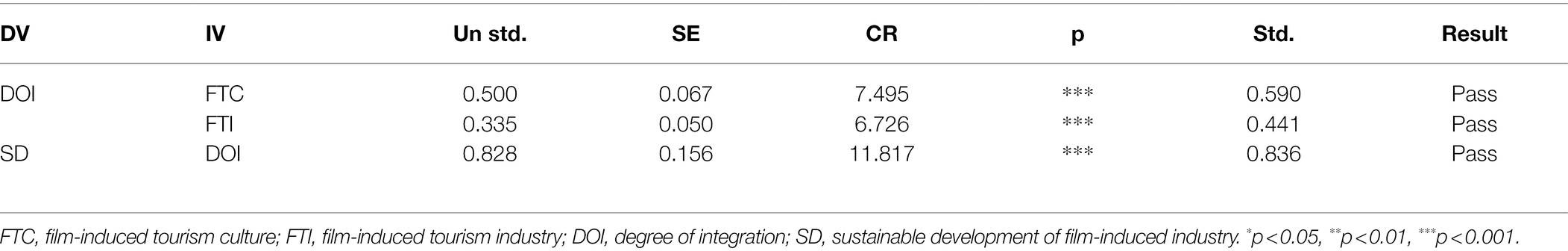

In order to further test the hypothesis proposed above, we run a structural equation model with mediation (see Figure 1 ). The results are shown in Table 5 . There is a correlation between film-induced culture and film-induced industry ( r = 0.720). Film-induced culture has a significant impact on the degree of integration ( r = 0.590, C R = 7.495, p < 0.01); The film-induced tourism industry has a significant impact on the degree of integration ( r = 0.441, C R = 6.326, p < 0.01), then hypothesis 1a, 1b, 1c are supported. The degree of integration has a significant positive impact on film-induced tourism ( r = 0.836, C R = 11.817, p < 0.01), so hypothesis 2a, 2B, and 2C are also supported.

Figure 1 . Structural equation model. FTC, film-induced tourism culture; FTI: film-induced tourism industry; DOI, degree of integration; SD, sustainable development of film-induced industry; IRBV, integrated resource-based view; IEBV, integrated ecology-based view; ISBV, integrated space-based view; ES, economic sustainability; HEC, human–environment coordination; HC, harmonious coexistence.

Table 5 . Goodness of fit of the structural model.

Empirical Testing of Mediating Effects

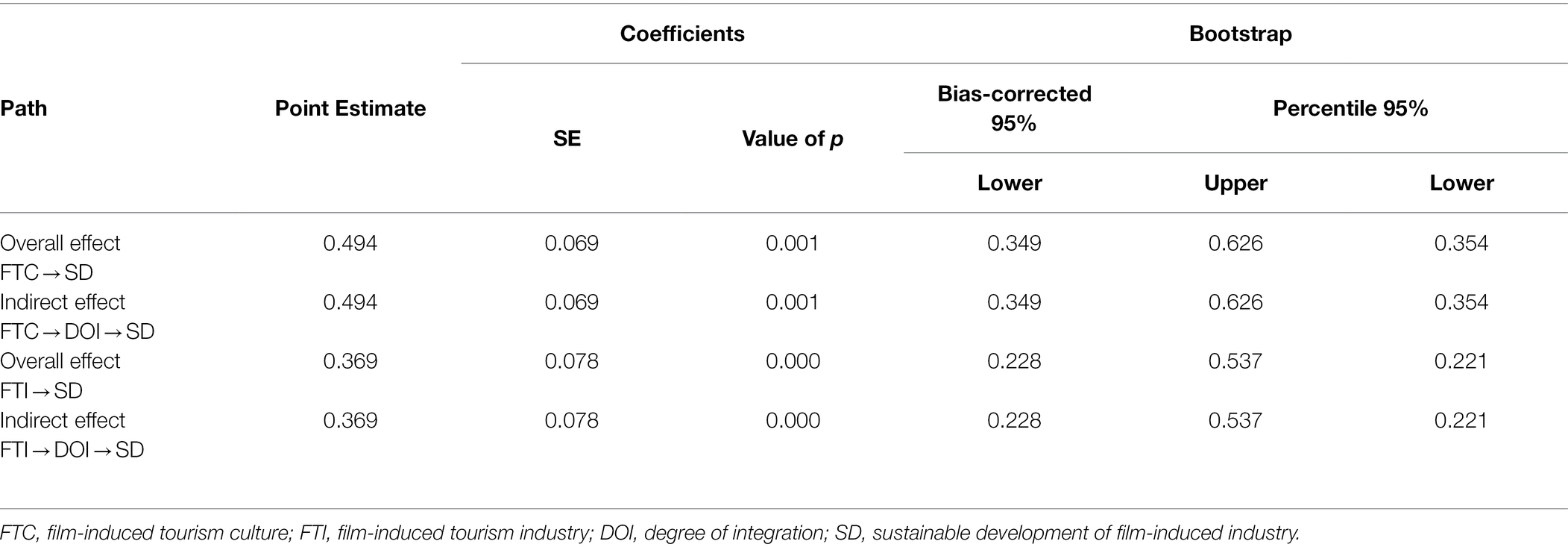

In order to test the reliability of the path hypothesis, we further use Bootstrapping to calculate the mediating effect of culture and tourism integration. Bootstrapping test performs 3,000 samplings and selects a 95% confidence interval, then the final test results are shown in Table 6 , so both hypothesis H3a and H3b are assumed to hold ( Table 7 ).

Table 6 . Hypothesis testing.

Table 7 . Empirical testing of mediating effects.

Given previous scholars’ studies on film-induced tourism ( Ringle, 2018 ; Marafa et al., 2020 ), we assume that cultural tourism will significantly affect the dynamic mechanism of sustainable development. More specifically, we believe that the organic integration of film-induced culture and tourism industry will have a significant impact on economic, social, and ecological sustainable development, which are the three dimensions of sustainable development. The results generally support our hypothesis that we view culture and tourism as a systematic whole rather than separate them and that culture and tourism integration is not simply “culture + tourism” or “tourism + culture.” We also confirm that the degree of integration of film-induced culture and tourism industry plays an important mediate role in the sustainable development of film-induced tourism. Although culture and tourism seem to be combined with each other in contemporary society, they have not developed the sustainable development dynamics of products and services innovation, nor developed a systematic operation mechanism. Consequently, the integration of culture and tourism is not to mechanically copy the two independent elements, but the key lies in the functional replacement and format innovation, complementary advantages, and the optimal combination of industrial elements.

Managerial Implications

As culture and tourism are two huge and complex systems, both have relatively mature management operation mechanism, working path, industrial rules, and industry norms, while they are currently characterized by high growth and rapid development ( Richards, 2018 ; McKercher, 2020 ). Therefore, in constructing the path of the integration of culture and tourism to promote sustainable development, the resource characteristics, functional differences, and technological advantages of film-induced culture and tourism industry should be fully considered in theory, and their similarity and relevance should be taken into account. In practice, we should not only make full use of the location conditions, resource endowments, and social and economic systems of film-induced culture and tourism destinations, but constantly identify the intersection points of products, industries, and enterprises according to the changes in market demand, and construct diversified industrial integration modes according to local conditions to determine develop directions in the integration of resources, technology, market and products, and administrative management.

From the perspective of tourism industry, support the development of organization forms that meet the needs of film-induced tourism development. The integration of industry should finally be reflected in the integration of organizations. Although the fundamental dynamics for the development of film-induced tourism is the development of market demand ( Connell, 2005 ), it needs enterprises to be discovered and satisfied to find business opportunities. We suggest relevant departments relax film-induced tourism business licensing, strengthen information services, support enterprises to explore new business areas, support various cooperation, and even merger and acquisitions. From the perspective of film-induced culture, enrich the cultural connotation of film-induced tourism. Film-induced tourism should not be equated with general implanted advertising or simply build film-induced bases, but should dig deeply into the cultural connotation of film-induced tourism, closely focus on the core theme of film/television works, and deeply develop “post-film products” related to tourism derivative industry, and then systematically integrate them to form a cross-industry and compound film-induced tourism industry chain ( Young and Young, 2008 ; Fan and Yu, 2021 ). In order to promote sustainable development, we further suppose that we should strengthen the research on film-induced tourism and explore the development mode and regulations of film-induced tourism.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study provides some enlightenments on the theoretical exploration and practical management of film-induced tourism. Inevitably, there are several limitations, which can be addressed in future studies. First, the verification of the hypotheses is through the empirical analysis of collected questionnaires, lacking the support of actual cases. This can be improved by case analysis in follow-up studies. Second, the degree of integration between culture and industry is measured and defined by their characteristics in this study. However, the integration may also be affected by their underlying relationship. Their spatial production characteristics are also valuable for further investigation. In summary, in this research, the dynamic mechanism for sustainable development of film-induced tourism has been investigated, and conclusions have been drawn. This topic, however, still requires in-depth follow-up investigations from the research community.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by School of Economics and Management, East China Jiaotong University, Nanchang, China. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

KY contributed to the empirical work, the analysis of the results, and the writing of the first draft. JinZ and JiaZ supported the total work of the KY. YZ and CX contributed to overall quality and supervision the part of literature organization and empirical work. RT contributed to developing research hypotheses and revised the overall manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This project was supported by the General Project of the National Social Science Fund of China: Tracking Research on the Development of Western Urban Politics (20BZZ055), General project of Humanities and Social Sciences General Research Program of the Ministry of Education: Research on the Generation Mechanism and Resolution Path of “Fragmentation Phenomenon” of Urban Social Governance (19YJA810002), Social Science Planning General Project in Jiangxi Province (No. 21XW06), Jiangxi Province Culture and Art Science Planning General Project (No. YG2021087), and Jiangxi Province Colleges Humanities and Social Science Project (No. GL20214).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Adedoyin, F. F., Nathaniel, S., and Adeleye, N. (2021). An investigation into the anthropogenic nexus among consumption of energy, tourism, and economic growth: do economic policy uncertainties matter? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 2835–2847. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-10638-x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Atilgan, E., Akinci, S., and Aksoy, S. (2003). Mapping service quality in the tourism industry. Manag. Serv. Qual. 13, 412–422. doi: 10.1108/09604520310495877

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Böhringer, C., and Jochem, P. E. (2007). Measuring the immeasurable—A survey of sustainability indices. Ecol. Econ. 63, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2007.03.008

Cai, W. G., and Zhou, X. L. (2014). On the drivers of eco-innovation: empirical evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 79, 239–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.05.035

Chen, C. Y. (2018). Influence of celebrity involvement on place attachment: Role of destination image in film tourism. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 23, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2017.1394888

Choi, S., and Ng, A. (2011). Environmental and economic dimensions of sustainability and price effects on consumer responses. J. Bus. Ethics 104, 269–282. doi: 10.1007/s10551-011-0908-8

Choi, H. S. C., and Sirakaya, E. (2005). Measuring residents’ attitude toward sustainable tourism: development of sustainable tourism attitude scale. J. Travel Res. 43, 380–394. doi: 10.1177/0047287505274651

Clark, G., and Chabrel, M. (2007). Measuring integrated rural tourism. Tour. Geograp. 9, 371–386. doi: 10.1080/14616680701647550

Connell, J. (2005). Toddlers, tourism and Tobermory: destination marketing issues and television-induced tourism. Tour. Manag. 26, 763–776. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2004.04.010

Delai, I., and Takahashi, S. (2011). Sustainability measurement system: a reference model proposal. Soc. Res. J. 7, 438–471. doi: 10.1108/17471111111154563

Diep, L., Martins, F. P., Campos, L. C., Hofmann, P., Tomei, J., Lakhanpaul, M., et al. (2021). Linkages between sanitation and the sustainable development goals: A case study of Brazil. Sustain. Dev. 29, 339–352. doi: 10.1002/sd.2149

Du, Y., Li, J., Pan, B., and Zhang, Y. (2020). Lost in Thailand: A case study on the impact of a film on tourist behavior. J. Vacat. Mark. 26, 365–377. doi: 10.1177/1356766719886902

Fan, Z., and Yu, X. (2021). The regional rootedness of China’s film industry: cluster development and attempts at cross-location integration. J. Chin. Film Stu. 1, 463–486. doi: 10.1515/jcfs-2021-0027

Gnoth, J., and Zins, A. H. (2013). Developing a tourism cultural contact scale. J. Bus. Res. 66, 738–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.09.012

Gong, T., and Tung, V. W. S. (2017). The impact of tourism mini-movies on destination image: The influence of travel motivation and advertising disclosure. J. Travel Tour. Market. 34, 416–428. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2016.1182458

Hacking, T., and Guthrie, P. (2008). A framework for clarifying the meaning of triple bottom-line, integrated, and sustainability assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 28, 73–89. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2007.03.002

Halme, M., and Korpela, M. (2014). Responsible innovation toward sustainable development in small and medium-sized enterprises: A resource perspective. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 23, 547–566. doi: 10.1002/bse.1801

He, K., Wu, H., Wu, J., Lu, Q., and Meng, J. (2021). The research of Libo County integrated development of cultural and tourism in the new era. Tour. Manage. Technol. Eco. 4, 1–8.

Google Scholar

Hojnik, J., and Ruzzier, M. (2016). What drives eco-innovation? A review of an emerging literature. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 19, 31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2015.09.006

Hoogendoorn, B., Guerra, D., and Van der Zwan, P. (2015). What drives environmental practices of SMEs? Small Bus. Econ. 44, 759–781. doi: 10.1007/s11187-014-9618-9

Horbach, J., Oltra, V., and Belin, J. (2013). Determinants and specificities of eco-innovations compared to other innovations—an econometric analysis for the French and German industry based on the community innovation survey. Ind. Innov. 20, 523–543. doi: 10.1080/13662716.2013.833375

Huang, C. E., and Liu, C. H. (2018). The creative experience and its impact on brand image and travel benefits: The moderating role of culture learning. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 28, 144–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2018.08.009

Jabareen, Y. (2008). A new conceptual framework for sustainable development. Environ. Dev. Sustain 10, 179–192. doi: 10.1007/s10668-006-9058-z

Jakhar, S. K. (2017). Stakeholder engagement and environmental practice adoption: The mediating role of process management practices. Sustain. Dev. 25, 92–110. doi: 10.1002/sd.1644

Janssen, S., Kuipers, G., and Verboord, M. (2008). Cultural globalization and arts journalism: The international orientation of arts and culture coverage in Dutch, French, German, and US newspapers, 1955 to 2005. Am. Sociol. Rev. 73, 719–740. doi: 10.1177/000312240807300502

Jørgensen, M. T., and McKercher, B. (2019). Sustainability and integration–the principal challenges to tourism and tourism research. J. Travel Tour. Market. 36, 905–916. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2019.1657054

Jovicic, D. (2016). Cultural tourism in the context of relations between mass and alternative tourism. Curr. Issue Tour. 19, 605–612. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2014.932759

Kim, S., and Kim, S. (2018). Perceived values of TV drama, audience involvement, and behavioral intention in film tourism. J. Travel Tour. Market. 35, 259–272. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2016.1245172

Kim, S., Kim, S., and King, B. (2019). Nostalgia film tourism and its potential for destination development. J. Travel Tour. Market. 36, 236–252. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2018.1527272

Kristjánsdóttir, K. R., Ólafsdóttir, R., and Ragnarsdóttir, K. V. (2018). Reviewing integrated sustainability indicators for tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 26, 583–599. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2017.1364741

Li, F., Katsumata, S., Lee, C. H., Ye, Q., Dahana, W. D., Tu, R., et al. (2020). Autoencoder-enabled potential buyer identification and purchase intention model of vacation homes. IEEE Access 8, 212383–212395. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3037920

Li, X., Wirawan, D., Ye, Q., Peng, L., and Zhou, J. (2021). How does shopping duration evolve and influence buying behavior? The role of marketing and shopping environment. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 62:102607. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102607

Liu, A., Fan, D. X., and Qiu, R. T. (2021a). Does culture affect tourism demand? A global perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 45, 192–214. doi: 10.1177/1096348020934849

Liu, B., Wang, Y., Katsumata, S., Li, Y., Gao, W., and Li, X. (2021b). National Culture and culinary exploration: Japan evidence of Heterogenous moderating roles of social facilitation. Front. Psychol. 12:784005. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.784005

Loulanski, T., and Loulanski, V. (2011). The sustainable integration of cultural heritage and tourism: A meta-study. J. Sustain. Tour. 19, 837–862. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2011.553286

Mamede, P., and Gomes, C. F. (2014). Corporate sustainability measurement in service organizations: A case study from Portugal. Environ. Qual. Manag. 23, 49–73. doi: 10.1002/tqem.21370

Marafa, L. M., Chan, C. S., and Li, K. (2020). Market potential and obstacles for film-induced tourism development in Yunnan Province in China. J. China Tour. Res. 18, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/19388160.2020.1819498

Marques, J., and Pinho, M. (2021). Collaborative research to enhance a business tourism destination: A case study from Porto. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leisure Events 13, 172–187. doi: 10.1080/19407963.2020.1756307

McKercher, B. (2002). Towards a classification of cultural tourists. Int. J. Tour. Res. 4, 29–38. doi: 10.1002/jtr.346

McKercher, B. (2020). Cultural tourism market: a perspective paper. Tour. Rev. 75, 126–129. doi: 10.1108/TR-03-2019-0096

Michael, N., Balasubramanian, S., Michael, I., and Fotiadis, S. (2020). Underlying motivating factors for movie-induced tourism among Emiratis and Indian expatriates in the United Arab Emirates. Tour. Hosp. Res. 20, 435–449. doi: 10.1177/1467358420914355

Misra, J. (2000). Integrating" the real world" into introduction to sociology: making sociological concepts real. Teach. Sociol. 28, 346–363. doi: 10.2307/1318584

Pérez García, Á., Sacaluga Rodríguez, I., and Moreno Melgarejo, A. (2021). The development of the competency of “cultural awareness and expressions” using movie-induced tourism as a didactic resource. Educ. Sci. 11:315. doi: 10.3390/educsci11070315

Richards, G. (2018). Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 36, 12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.03.005

Riley, R., Baker, D., and Van Doren, C. S. (1998). Movie induced tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 25, 919–935. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00045-0

Ringle, C. (2018). In print and On screen: film columns, criticism, and culture in early Hollywood-Richard Abel. Enterp. Soc. 19, 216–225. doi: 10.1017/eso.2017.51

Schaltegger, S., Hansen, E. G., and Lüdeke-Freund, F. (2016). Business models for sustainability: origins, present research, and future avenues. Organ. Environ. 29, 3–10. doi: 10.1177/1086026615599806

Senbeto, D. L., and Hon, A. H. (2021). Shaping organizational culture in response to tourism seasonality: A qualitative approach. J. Vacat. Mark. 27, 466–478. doi: 10.1177/13567667211006759

Silberberg, T. (1995). Cultural tourism and business opportunities for museums and heritage sites. Tour. Manag. 16, 361–365. doi: 10.1016/0261-5177(95)00039-Q

Singh, R. K., Murty, H. R., Gupta, S. K., and Dikshit, A. K. (2009). An overview of sustainability assessment methodologies. Ecol. Indic. 9, 189–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2008.05.011

Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S. E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E. M., et al. (2015). Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 347:1259855. doi: 10.1126/science.1259855

Stuckey, A. (2021). Special effects and spectacle: integration of CGI in contemporary Chinese film. J. Chin. Film Stu. 1, 49–64. doi: 10.1515/jcfs-2021-0005

Sun, G., Han, X., Wang, H., Li, J., and Wang, W. (2021). The influence of face loss on impulse buying: An experimental study. Front. Psychol. 12:700664. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.700664

Sun, G., Wang, W., Cheng, Z., Li, J., and Chen, J. (2017). The intermediate linkage between materialism and luxury consumption: evidence from the emerging market of China. Soc. Indic. Res. 132, 475–487. doi: 10.1007/s11205-016-1273-x

Suni, J., and Komppula, R. (2012). SF-Film village as a movie tourism destination—a case study of movie tourist push motivations. J. Travel Tour. Market. 29, 460–471. doi: 10.1080/10548408.2012.691397

Svensson, G., and Wagner, B. (2015). Implementing and managing economic, social and environmental efforts of business sustainability: Propositions for measurement and structural models. Manage. Environ. Q. Int. J. 26, 195–213. doi: 10.1108/MEQ-09-2013-0099

Syafrini, D., Fadhil Nurdin, M., Sugandi, Y. S., and Miko, A. (2020). The impact of multiethnic cultural tourism in an Indonesian former mining city. Tour. Recreat. Res. 45, 511–525. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2020.1757208

Teng, H. Y. (2021). Can film tourism experience enhance tourist behavioural intentions? The role of tourist engagement. Curr. Issue Tour. 24, 2588–2601. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2020.1852196

Teng, H. Y., and Chen, C. Y. (2020). Enhancing celebrity fan-destination relationship in film-induced tourism: The effect of authenticity. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 33:100605. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100605

Tien, N. H., Viet, P. Q., Duc, N. M., and Tam, V. T. (2021). Sustainability of tourism development in Vietnam's coastal provinces. World Rev. Ent. Manage. Sustainable Dev. 17, 579–598. doi: 10.1504/WREMSD.2021.117443

Wagner, B. (2015). Implementing and managing economic, social and environmental efforts of business sustainability. Manage. Environ. Q. Int. J. 26, 195–213. doi: 10.1108/MEQ-09-2013-0099

Waheed, A., Zhang, Q., Rashid, Y., Tahir, M. S., and Zafar, M. W. (2020). Impact of green manufacturing on consumer ecological behavior: Stakeholder engagement through green production and innovation. Sustain. Dev. 28, 1395–1403. doi: 10.1002/sd.2093

Wang, W., Chen, N., Li, J., and Sun, G. (2020a). SNS use leads to luxury brand consumption: Evidence from China. J. Consum. Mark. 38, 101–112. doi: 10.1108/JCM-09-2019-3398

Wang, W., Ma, T., Li, J., and Zhang, M. (2020b). The pauper wears prada? How debt stress promotes luxury consumption. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 56:102144. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102144

Wang, C., and Yi, K. (2020). Impact of spatial scale of ocean views architecture on tourist experience and empathy mediation based on “SEM-ANP” combined analysis. J. Coast. Res. 103, 1125–1129. doi: 10.2112/SI103-235.1

Wen, H., Josiam, B. M., Spears, D. L., and Yang, Y. (2018). Influence of movies and television on Chinese tourists perception toward international tourism destinations. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 28, 211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2018.09.006

Williams, S., and Schaefer, A. (2013). Small and medium-sized enterprises and sustainability: Managers' values and engagement with environmental and climate change issues. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 22, 173–186. doi: 10.1002/bse.1740

Wu, X., and Lai, I. K. W. (2021). The acceptance of augmented reality tour app for promoting film-induced tourism: the effect of celebrity involvement and personal innovativeness. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 12, 454–470. doi: 10.1108/JHTT-03-2020-0054

Xin, X. R., and Mossig, I. (2017). Co-evolution of institutions, culture and industrial organization in the film industry: The case of Shanghai in China. Eur. Plan. Stud. 25, 923–940. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2017.1300638

Yen, C. H., and Croy, W. G. (2016). Film tourism: celebrity involvement, celebrity worship and destination image. Curr. Issue Tour. 19, 1027–1044. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2013.816270

Yi, K., Li, Y., Peng, H., Wang, X., and Tu, R. (2021a). Empathic psychology: A code of risk prevention and control for behavior guidance in the multicultural context. Front. Psychol. 12:781710. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.781710

Yi, K., Wang, Q., Xu, J., and Liu, B. (2021b). Attribution model of travel intention to internet celebrity spots: A systematic exploration based on psychological perspective. Front. Psychol. 12:797482. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.797482

Yi, K., Zhang, D., Cheng, H., Mao, X., and Su, Q. (2020). SEM and K-means analysis of the perceived value factors and clustering features of marine film-induced tourists: A case study of tourists to Taipei. J. Coast. Res. 103, 1120–1124. doi: 10.2112/SI103-234.1

Young, A. F., and Young, R. (2008). Measuring the effects of film and television on tourism to screen locations: A theoretical and empirical perspective. J. Travel Touri. Market. 24, 195–212. doi: 10.1080/10548400802092742

Yu, C. P., Chancellor, H. C., and Cole, S. T. (2011). Measuring residents’ attitudes toward sustainable tourism: A reexamination of the sustainable tourism attitude scale. J. Travel Res. 50, 57–63. doi: 10.1177/0047287509353189

Zhang, L., Yi, K., and Zhang, D. (2020). The classification of environmental crisis in the perspective of risk communication: A case study of coastal risk in mainland China. J. Coast. Res. 104, 88–93. doi: 10.2112/JCR-SI104-016.1

Zhou, Z., Zheng, F., Lin, J., and Zhou, N. (2021). The interplay among green brand knowledge, expected eudaimonic well-being and environmental consciousness on green brand purchase intention. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 28, 630–639. doi: 10.1002/csr.2075

Keywords: film-induced tourism, tourism destination, sustainable development, dynamic mechanism, culture and industry integration

Citation: Yi K, Zhu J, Zeng Y, Xie C, Tu R and Zhu J (2022) Sustainable Development for Film-Induced Tourism: From the Perspective of Value Perception. Front. Psychol . 13:875084. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.875084

Received: 13 February 2022; Accepted: 13 May 2022; Published: 03 June 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Yi, Zhu, Zeng, Xie, Tu and Zhu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yanqin Zeng, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

This website requires Javascript for some parts to function properly. Your experience may vary.

How can the film‐induced tourism phenomenon be sustainably managed?

O'Connor, N. (2011). How can the film‐induced tourism phenomenon be sustainably managed?. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 3(2), 87-90.

Location, location, location: Film corporations' social responsibilities

Beeton, S. (2008). Location, location, location: Film corporations' social responsibilities. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 24(2-3), 107-114.

Partnerships and social responsibility: leveraging tourism and international film business

Beeton, S. (2008). Partnerships and social responsibility: leveraging tourism and international film business. In International business and tourism (pp. 270-286). Routledge.

Advancing social sustainability in film tourism

Buchmann, A. (2012). Advancing social sustainability in film tourism. Tourism review international, 16(2), 89-100.

‘What’s the story in Balamory?’: The impacts of a children’s TV programme on small tourism enterprises on the Isle of Mull, Scotland

Connell, J. (2005). ‘What’s the story in Balamory?’: The impacts of a children’s TV programme on small tourism enterprises on the Isle of Mull, Scotland. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 13(3), 228-255.

Film Tourism: Sustained Economic Contributions to Destinations

Croy, W. Glen. “Film Tourism: Sustained Economic Contributions to Destinations.” Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, vol. 3, no. 2, Apr. 2011, pp. 159–64.

Film Tourism Planning and Development—Questioning the Role of Stakeholders and Sustainability

Heitmann, Sine. “Film Tourism Planning and Development—Questioning the Role of Stakeholders and Sustainability.” Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, vol. 7, no. 1, Mar. 2010, pp. 31–46. Taylor & Francis Online,

Sustainable development for film-induced tourism: from the perspective of value perception

Kui, Y., Jing, Z., Yanqin, Z., Changqing, X., Rungting, T., & Jianfei, Z. (2022). Sustainable development for film-induced tourism: from the perspective of value perception, 13.

Sustainable Management of Popular Culture Tourism Destinations: A Critical Evaluation of the Twilight Saga Servicescapes

Lundberg, Christine, and Kristina N. Lindström. “Sustainable Management of Popular Culture Tourism Destinations: A Critical Evaluation of the Twilight Saga Servicescapes.” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 12, 5177, June 2020,

Creating a sustainable brand for Northern Ireland through film-induced tourism

O'Connor, N., & Bolan, P. (2008). Creating a sustainable brand for Northern Ireland through film-induced tourism .Tourism Culture & Communication, 8(3), 147-158.

Film tourism and ecotourism: mutually exclusive or compatible?

Sakellari, M. (2014). Film tourism and ecotourism: mutually exclusive or compatible?. International journal of culture, tourism and hospitality research.

Is Tourism Going Green? A Literature Review on Green Innovation for Sustainable Tourism

Satta, Giovanni, et al. “Is Tourism Going Green? A Literature Review on Green Innovation for Sustainable Tourism.” Tourism Analysis, vol. 24, no. 3, Cognizant, LLC, July 2019, pp. 265–80.

KPMG Personalisation

Transforming location into vacation - A report on film tourism

The report emphasises the need for India to leverage its abundant cinematic heritage to position itself as a leading film tourism destination.

- Share Share close

- Download Transforming location into vacation - A report on film tourism pdf Opens in a new window

- 1000 Save this article to my library

- Go to bottom of page

- Home ›

- Insights ›

The report emphasises the need for India to leverage its abundant cinematic heritage and diverse landscapes to position itself as a leading film-tourism destination, thereby contributing to its economic growth and cultural preservation. It highlights the current state of the film tourism industry and explores successful global and Indian case studies of film tourism, demonstrating the economic, cultural, and promotional benefits while addressing challenges such as over-commercialisation and ecological damage. It concludes with recommendations for India to unlock its film tourism potential and establish itself as a preferred destination for film tourism.

Key Contact

Best Practices in Hospitality and Tourism Marketing and Management pp 181–199 Cite as

Film Tourism and Its Impact on Residents Quality of Life: A Multi Logit Analysis

- Subhash Kizhakanveatil Bhaskaran Pillai 3 ,

- Kaustubh Kamat 4 ,

- Miriam Scaglione 5 ,

- Carmelita D’Mello 6 &

- Klaus Weiermair 7 , 8

- First Online: 31 July 2018

1094 Accesses

2 Citations

Part of the book series: Applying Quality of Life Research ((BEPR))

Past research has confirmed film tourism emerging as a major growth sector for research in tourism and a driver of tourism development for many destinations. To date, there has been relatively substantial literature on the subject, yet this paper tries to shed some light on the quality of life perception with respect to the International Film Festival of India (IFFI). Earlier research results have shown different impacts of film tourism on the quality of life of the local community, and the perceptions and attitudes of residents towards tourism, but no research has shown neither how nor how much these perceptions and attitudes change according to a change in the demographic profile of the local community. The empirical findings show that: age, income, education and marital status have a significant impact on residents’ attitude towards film tourism. Factor analysis resulted in 4 latent factors which drive residents’ perception about quality of life, viz., Community Pride, Personal Benefits, Negative Environmental effect and Negative Social effect. The results have shown that a variation in the demographic profile of the resident community determines a variation in the attitudes towards tourism impacts. In a time of mass movement of people, man power and immigration, changes in the demographic profile of residents are very likely and this research shows that it should be taken into consideration when managing tourism destinations and planning new tourism policies.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Andereck, K. L., & Vogt, C. A. (2000). The relationship between residents’ attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options. Journal of Travel Research, 39 (1), 27–36.

Article Google Scholar

Ap, J. (1992). Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 19 (4), 665–690.

Ap, J., & Crompton, J. L. (1993). Residents’ strategies in responding to tourism impacts. Journal of Travel Research, 17 (4), 610–616.

Google Scholar

Beeton, S. (2001). Smiling for the camera: The influence of film audiences on a budget tourism destination. Tourism, Culture and Communication, 3 , 15–25.

Beeton, S. (2004a). The more things change. A legacy of film-induced tourism. In W. Frost, W. G. Croy, & S. Beeton (Eds.), Proceedings of the international tourism and media conference (pp. 4–14). Melbourne: Australia, Tourism Research Unit, Monash University.

Beeton, S. (2004b). Rural tourism in Australia: Has the gaze altered? Tracking rural images though film and tourism promotion. International Journal of Tourism Research, 6 (3), 125–135.

Beeton, S. (2005). Film-induced tourism . Clevedon: Channel View Publications.

Book Google Scholar

Brayley, R., Var, T., & Sheldon, P. (1990). Perceived influence of tourism on social issues. Annals of Tourism Research, 17 (2), 284–289.

Busby, G., & Klug, J. (2001). Movie-induced tourism: The challenge of measurement and other issues. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 7 (4), 316–332.

Busby, G., Ergul, M., & Eng, J. (2013). Film tourism and the lead actor: An exploratory study of the influence on destination image and branding. Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 24 , 395–404.

Connell, J. (2005a). Toddlers, tourism and Tobermory: Destination marketing issues and TV-induced tourism. Tourism Management, 26 , 763–776.

Connell, J. (2005b). What’s the story in Balamory? The impacts of a children’s TV programme on small tourism enterprises on the Isle of Mull, Scotland. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 13 , 228–255.

Connell, J. (2012). Film tourism: Evolution, progress and prospects. Tourism Management, 33 (5), 1007–1029.

Couldry, N. (2005). On the actual street. In D. Crouch, R. Jackson, & F. Thompson (Eds.), The media and the tourist imagination. Converging cultures (pp. 60–75). London: Routledge.

Crompton, J. L., Lee, S., & Shuster, T. J. (2001). A guide for undertaking economic impact studies: The Springfest example. Journal of Travel Research, 40 (1), 79–87.

Croy, W. G. (2010). Planning for film tourism: Active destination image management. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 7 (1), 21–30.

Croy, W. G. (2011). Film tourism: Sustained economic contributions to destinations. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 3 (2), 159–164.

Croy, W. G., & Heitmann, S. (2011). Tourism and film. In P. Robinson, S. Heitmann, & P. Dieke (Eds.), Research themes in tourism (pp. 188–204). Wallingford: CABI.

Chapter Google Scholar

Croy, G., & Walker, R. D. (2003). Rural tourism and film e issues for strategic rural development. In D. Hall, L. Roberts, & M. Mitchell (Eds.), New directions in rural tourism (pp. 115–133). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Deprez, C. (2013). The film division of India, 1948–1964: The early days and the influence of the British documentary film tradition. Film History, 25 (3), 149–173.

DFF. (2015). International Film Festival of India. Directorate of Film Festivals. http://www.dff.nic.in/iffi.asp . Accessed 9 June 2015.

D’Mello, C., Chang, L., Kamat, K., Scaglione, M., Weiermair, K., & Subhash, K. B. (2015). An examination of factors influencing tourists attitude towards tourism in Goa. International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Systems, 8 (2), 1–11.

D’Mello, C., Fernandes, S., Zimmermann, F. M., Subhash, K. B., & Ganef, J. P. (2016a). Multi-stakeholder perceptions about sustainable tourism in Goa: A structural equation modeling. International Journal of Tourism and Travel, 9 (1–2), 21–39.

D’Mello, C., Chang, L., Subhash, K. B., Kamat, K., Zimmermann, F. M., & Weiermair, K. (2016b). Comparison of multi-stakeholder perception of tourism sustainability in Goa. International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Systems, 11 (2), 1–13.

Getz, D., & Page, S. J. (2016). Progress and prospects for event tourism research. Tourism Management, 52 , 593–631.

Giacopassi, D., & Stitt, B. G. (1994). Assessing the impact of casino gambling on crime in Mississippi. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 18 (1), 117–131.

Heitmann, S. (2010). Film tourism planning and development - questioning the role of stakeholders and sustainability. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 7 (1), 31–46.

Hudson, S., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (2006a). Promoting destinations via film tourism: An empirical identification of supporting marketing initiatives. Journal of Travel Research, 44 , 387–396.

Hudson, S., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (2006b). Film tourism and destination marketing: The case of Captain Corelli’s Mandolin. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 12 (3), 256–268.

Hudson, S., & Tung, V. W. T. (2010). “Lights, camera, action...!” Marketing film locations to Hollywood. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 28 (2), 188–205.

Hudson, S., Wang, Y., & Gil, S. M. (2010). The influence of a film on destination image and the desire to travel: A cross-cultural comparison. International Journal of Tourism Research, 13 , 177–190.

IFFI. (2015). International Film Festival of India. http://www.iffi.nic.in/aboutus.asp . Accessed 9 June 2015.

Jurowski, C. (1994). The interplay of elements affecting host communityresident attitudes toward tourism: A path analytic approach . Unpublished Ph.D.dissertation, Department of Hospitality and Tourism Management, VirginiaPolytechnic Institute and State University.

Jurowski, C., Uysal, M., & Williams, D. R. (1997). A theoretical analysis of host community resident reactions to tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 34 (2), 3–11.

Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39 , 31–36.

Kamat, K., Chen, R. F., D’Mello, C., Scaglione, M., Weiermair, K., & Subhash, K. B. (2016). The social, economic, and environmental impacts of Casino tourism on the residents of Goa. Latin American Tourismology Review [Revista Latino-Americana De Tourismologia], 2 (1), 44–54.

Kim, K., Uysal, M., & Sirgy, M. J. (2013). How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tourism Management, 36 , 527–540.

Kim, S. (sean), Kim, S. (San), & Oh, M. (2017). Film tourism town and its local community. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration . https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2016.1276005 . Accessed 9 June 2017.

Knowindia. (2015). Cinema in India: Film Division . http://knowindia.gov.in/knowindia/cinema.php . Accessed 9 June 2015.

Lankford, S. V., & Howard, D. (1994). Revising TIAS. Annals of Tourism Research, 21 (4), 829–831.

Lee, C. K., Kang, S. K., Long, P., & Reisinger, Y. (2010). Residents’ perceptions of casino impacts: A comparative study. Tourism Management, 31 (2), 189–201.

Li, S., Li, H., Song, H., Lundberg, C., & Shen, S. (2017). The economic impact of on-screen tourism: The case of The Lord of the Rings and the Hobbit. Tourism Management, 60 , 177–187.

Lin, Y. S., & Huang, J. Y. (2008). Analyzing the use of TV mini-series for Korea tourism marketing. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 24 (2–3), 223–227.

Lin, Y. S., Lin, P. L., & Huang, H. L. (2007). Study on correlation among tourists’ travel behavior, service quality, satisfaction and loyalty – Using Jian Hu Shan Theme Park as an example. Journal of Sport, Leisure and Hospitality Research, 2 (2), 67–83.

Mordue, T. (2001). Performing and directing resident/tourist cultures in heartbeat country. Tourist Studies, 1 , 233–252.

Mordue, T. (2009). Television, tourism and rural life. Journal of Travel Research, 47 (3), 332–345.

Mueller, C. (2006). Film festival tourism . http://www.filmfestivals.com/cgi-bin/shownews.pl . Accessed 15 Sept 2008.

Murphy, P. E., & Carmichael, B. A. (1991). Assessing the tourism benefits of an open access sports tournament: The 1989 B.C. winter games. Journal of Travel Research, 29 , 32–36.

O’Neill, K., Butts, S., & Busby, G. (2005). The corellification of Cephallonian tourism. Anatolia, 16 (2), 207–226.

Pizam, A., & Pokela, J. (1985). The perceived impacts of casino gambling on the community. Annals of Tourism Research, 12 (2), 147–165.

Riley, R., & van Doren, C. (1992). Movies as tourism promotion: A push factor in a pull location. Tourism Management, 13 , 267–274.

Riley, R., Baker, D., & van Doren, C. (1998). Movie-induced tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 25 , 919–935.

Rojek, C. (1995). Decentring leisure. Rethinking leisure theory . London: Sage.

Sine, H. (2010). Film tourism planning and developments – Questioning the role of stakeholders and sustainability. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 7 (1), 31–46.

Stitt, B. G., Nicholas, M., & Giacopassi, D. (2003). Does the presence of casinos increase crime? An examination of casino and control communities. Crime & Dilinquency, 49 , 253–283.

Subhash, K. B., & Chen, R. (2012). Geography of transnational terrorism: An Indian perspective. In S. Sharma, D. Das, R. Jain, & P. S. Sangwan (Eds.), India emerging: Opportunities and challenges (pp. 106–124). New Delhi: Pragun Publication.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (1989). Using multivariale statistics (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Harper & Row.

Tooke, N., & Baker, M. (1996). Seeing is believing: The effect of film on visitor numbers to screened locations. Tourism Management, 17 , 87–94.

Wiki. (2015a). History of Goa . https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Goa . Accessed 18 June 2015.

Wiki. (2015b). Timeline of Goan History . https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_Goan_history . Accessed 18 June 2015.

Zhang, X., Ryan, C., & Cave, J. (2016). Residents, their use of a tourist facility and contribution to tourist ambience: Narratives from a film tourism site in Beijing. Tourism Management, 52 , 416–429.

Download references

Acknowledgement

Authors acknowledge the constructive criticism received from two anonymous referees, which helped in bringing the paper in its present form. Authors also acknowledge the English proofreading and editing support by Simone Dimitriou, Assistant of Research, Institute of Tourism, University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland, Valais.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Commerce, Goa University, Goa, India

Subhash Kizhakanveatil Bhaskaran Pillai

Department of Business Administration, Goa Multi-Faculty College, Goa, India

Kaustubh Kamat

Institute of Tourism, University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland, HES-SO Valais, Sierre, Switzerland

Miriam Scaglione

Department of Commerce, St. Xavier’s College of Arts, Science & Commerce, Goa, India

Carmelita D’Mello

Schulich School of Business, York University Toronto, York, Canada

Klaus Weiermair

Department of Tourism and Service Management, Institute of Strategic Management, Marketing and Tourism, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Subhash Kizhakanveatil Bhaskaran Pillai .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Business, Finance and Tourism, University of Extremadura, Cáceres, Spain

Ana María Campón-Cerro , José Manuel Hernández-Mogollón & José Antonio Folgado-Fernández , &

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Pillai, S.B., Kamat, K., Scaglione, M., D’Mello, C., Weiermair, K. (2019). Film Tourism and Its Impact on Residents Quality of Life: A Multi Logit Analysis. In: Campón-Cerro, A.M., Hernández-Mogollón, J.M., Folgado-Fernández, J.A. (eds) Best Practices in Hospitality and Tourism Marketing and Management. Applying Quality of Life Research. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91692-7_9

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91692-7_9

Published : 31 July 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-91691-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-91692-7

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Sustainable Development for Film-Induced Tourism: From the Perspective of Value Perception

1 School of Business and Trade, Nanchang Institute of Science & Technology, Nanchang, China

2 Media Art Research Center, Jiangxi Institute of Fashion Technology, Nanchang, China

3 Guangdong University of Finance and Economics, Guangzhou, China

Yanqin Zeng

4 Department of Art Integration, Daejin University, Pocheon, South Korea

Changqing Xie

5 School of Business, Foshan University, Foshan, China

Rungting Tu

6 College of Management, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China

Jianfei Zhu

7 School of Economics and Management, East China Jiaotong University, Nanchang, China

Associated Data

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The tourism economy has become a new driving force for economic growth, and film-induced tourism in particular has been widely proven to promote economic and cultural development. Few studies focus on analyzing the inherent characteristics of the economic and cultural effects of film-induced tourism, and the research on the dynamic mechanism of the sustainable development of film-induced tourism is relatively limited. Therefore, from the perspective of the integration of culture and industry, the research explores the dynamic mechanism of sustainable development between film-induced culture and film-induced industry through a questionnaire survey of 1,054 tourism management personnel, combined with quantitative empirical methods. The conclusion shows that the degree of integration of culture and tourism is an important mediating role that affects the dynamic mechanism of sustainable development of film-induced tourism, and the development of film-induced tourism depends on the integration of culture and industry. Constructing a diversified industrial integration model according to local conditions and determining the development path of resource, technology, market, product integration, and administrative management can become the general trend of the future development of film-induced tourism.

Introduction

As an emerging industry, cultural tourism can make up for the economic difficulties caused by the weak growth of the primary and secondary industries, and replace it as a new driving force for economic growth ( Liu et al., 2021b ). As recognized by both the academic community and industry, cultural tourism products greatly impact tourism destination development; souvenir, local cuisines, and films/television programs can promote tourism destinations ( Liu et al., 2021a , b ). Among them, film/television is the most influential form of art in today’s society. Film and television can help potential tourists to have some sensory and emotional cognitions through empathy and vicarious feeling to the tourist destinations mentioned in the films ( Kim and Kim, 2018 ; Pérez García et al., 2021 ), thereby generating tourism motivation and ultimately promoting tourism behaviors. Film and television, without exception, have integrated commerciality and artistry since birth, and form a unique form of culture ( Riley et al., 1998 ).

Hence, these significant economic effects have been widely investigated by researchers from different perspectives, such as promotion of local brands ( Liu et al., 2021a ), and changes in aesthetic information dissemination ( Kim et al., 2019 ). With in-depth studies, researchers have identified the profound connotation of the rapid development of film-induced tourism: the extension of the immersive tourism ( Marafa et al., 2020 ), the endowment of modern fashion labels for tourism destinations ( Teng and Chen, 2020 ), and multi-dimensional integrations of modern media technology and traditional entertainment industry.

Culture is the soul of tourism, and tourism is an important carrier of culture. Although the experience of film/television is different from tourism—the former is provided to people by means of image transmission, and the latter is realized by the way of people moving—but the essence is both cultural experience ( Syafrini et al., 2020 ; Senbeto and Hon, 2021 ). The connotation and the applied research of film-induced tourism reveal the complexity and diversity of the integrations of modern media and traditional entertainment.

The traditional glimmering style sightseeing tour is just a shallow taste, and often cannot make tourists get a deep enjoyment. Film-induced tourism is different, mature film-induced tourism products can bring tourists wholehearted relaxation and enjoyment, and make tourists’ self-worth better reflect. To clarify the inherent characteristics of film-induced tourism, the interactive observation of both the film and television subject and the tourism subject provides a feasible solution. Film/television programs are the expression and substantiveness of culture ( Yi et al., 2020 ). Tourism as an economic carrier is the pattern and standardization of the industry ( Yen and Croy, 2016 ). The development of film-induced tourism relies on the mutual integration of culture and industry.

With the evolution of the world, sustainable development is leading the way in every industry including tourism. The early understanding of sustainable development in the academic community refers to meeting the needs of the current generation without damaging the needs of future generations’ development ( Jabareen, 2008 ; Yi et al., 2021a ). Based on this concept, the United Nations has formulated 17 sustainable development goals, proposed new standards for the prosperity and development of the earth, and standardized the assessment methods and indicators for sustainable development ( Böhringer and Jochem, 2007 ; Hacking and Guthrie, 2008 ; Singh et al., 2009 ). Since then, the concept of sustainable development has been fully implemented and has gradually become a well-known concept from the perspectives of the environment, economy, and society ( Adedoyin et al., 2021 ; Diep et al., 2021 ; Zhou et al., 2021 ). Currently, these three dimensions are identified as the motivations and mechanisms of sustainable development ( Steffen et al., 2015 ; Svensson and Wagner, 2015 ). Specifically, challenges in sustainable development are vital issues for exploring social and economic development. Economic benefits are the main dynamics of continuous action ( Hoogendoorn et al., 2015 ), with social effects as the main motivation of practice ( Williams and Schaefer, 2013 ), and environmental effects as the basic assurances of all activities ( Halme and Korpela, 2014 ). Hence, sustainable development research help explore the path of the industry development. The dynamic mechanism of sustainable development builds the foundation for the long-term influence of the culture and provides the way for continuous development and expansion of industrial effects ( Waheed et al., 2020 ). At present, to the best of our knowledge, very few studies have investigated the dynamic mechanism of the sustainable development for film-induced tourism. The existing studies which include the sustainable development dynamic mechanism can be divided into three aspects:

(1) The macro sustainable development concept of film-induced tourism ( Wen et al., 2018 ); (2) The sustainable development concept in the exploration of film-induced tourism ( Gong and Tung, 2017 ; Teng, 2021 ); (3) The micro sustainable development concept of film-induced tourism ( Suni and Komppula, 2012 ). Afterward, most of the studies believe that the dynamic mechanism of sustainable development is affected by its resource development, innovation mode, or artistic attractions. However, these have not yet conducted a quantitative study of the endogenous interactions between culture and industry. Accordingly, we try to fill the research gap; we study the relationship between culture and industry in film-induced tourism through structural equation modeling to promote the sustainable development dynamics brought about the integration of culture and industry.

Literature Review

Film-induced culture and tourism industry.

Film-induced culture plays a vital role in the global advertisement system. It is an effective approach for the advertisement of regional values and soft power, and it is a good pathway for cultural output and value proposition ( Yi et al., 2020 ). With the advance of economic development, consumers have broken the restrictions of basic needs spending ( Sun et al., 2017 , 2021 ; Du et al., 2020 ), and the needs for higher-level cultural consumption are becoming increasingly important ( Wang et al., 2020a , b ; Li et al., 2021 ). Film-induced culture is by no means limited to entertainment culture, and film-induced products are by no means limited to spiritual and cultural consumer goods ( Chen, 2018 ). Film/television is also a mass media. Film-induced culture has an unprecedented impact on people’s ways of thinking, social cognition, behavioral habits, and values, showing unique cultural tension and becoming an important structure of people’s spiritual life ( Misra, 2000 ; Janssen et al., 2008 ). Otherwise, as a fast-growing important new tourism trend, film-induced tourism creates connections between characters, places, stories, and tourists, and is inspired to immerse themselves in films to relive film-generated and film-driven emotions ( Riley et al., 1998 ). Essentially, both film and tourism provide an opportunity to relive or experience, see and learn novelties through entertainment and fun ( Teng, 2021 ). Film-induced tourism increases the overall economic effect of tourism industry and establishes the bonds of film and tourism industry. It provides not only pleasure and satisfaction for film-induced tourists, but also adequate and novel learning experience. The latest research trends are moving toward merging or collaborating two fields that already have similar goals.