Our Organisation

Our Careers

Tourism Statistics

Industry Resources

Media Resources

Travel Trade Hub

News Stories

Newsletters

Industry Events

Business Events

Tourism statistics

- Share Share on Facebook Share on Twitter Share on WhatsApp Copy Link

Explore the research that Tourism Australia provides to consumers and industry.

- International statistics

- Domestic statistics

International performance

Aviation data

International tourism snapshot

International travel sentiment tracker

Domestic performance

Domestic travel sentiment tracker

Subscribe to our Industry newsletter

Discover more.

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience. Find out more .

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

Acknowledgement of Country

We acknowledge the Traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Owners of the land, sea and waters of the Australian continent, and recognise their custodianship of culture and Country for over 60,000 years.

*Disclaimer: The information on this website is presented in good faith and on the basis that Tourism Australia, nor their agents or employees, are liable (whether by reason of error, omission, negligence, lack of care or otherwise) to any person for any damage or loss whatsoever which has occurred or may occur in relation to that person taking or not taking (as the case may be) action in respect of any statement, information or advice given in this website. Tourism Australia wishes to advise people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent that this website may contain images of persons now deceased.

Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

Search life-sciences literature (43,947,359 articles, preprints and more)

- Free full text

- Citations & impact

- Similar Articles

COVID-19 impacts of inbound tourism on Australian economy.

Author information, affiliations.

Annals of Tourism Research , 26 Feb 2021 , 88: 103179 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103179 PMID: 36540369 PMCID: PMC9754951

Abstract

Free full text .

COVID-19 impacts of inbound tourism on Australian economy

Tien duc pham.

a Griffith Institute for Tourism, Griffith Business School, Griffith University, 170 Kessels Road, Nathan, QLD 4111, Australia

Larry Dwyer

b University of Technology, Sydney, Broadway, Sydney 2007, Australia

The pandemic COVID-19 has severely impacted upon the world economy, devastating the tourism industry globally. This paper estimates the short-run economic impacts of the inbound tourism industry on the Australian economy during the pandemic. The analysis covers effects both at the macroeconomic as well as at the industry and occupation level, from direct contribution (using tourism satellite accounts) to economy-wide effects (using the computable general equilibrium modelling technique). Findings show that the pandemic affects a range of industries and occupations that are beyond the tourism sector. The paper calls for strong support from the government on tourism as the recovery of tourism can deliver spillover benefits for other sectors and across the whole spectrum of occupations in the labour market.

- Introduction

Tourism has for some decades experienced rapid growth worldwide, serving as an important source of export income for many countries, accounting for around 10% of global GDP ( World Travel and Tourism Council, 2020 ). Tourism becomes the main driver of growth in many countries and regions. With a strong social interaction nature, the industry is prone to recession, terrorism, natural disasters and infectious diseases. The outbreak of the coronavirus disease in late 2019 (hereafter, COVID-19) has severely and rapidly impacted human life on a global scale with respiratory illness that has effected more than 67 million infected cases and more than one and half million of deaths at the time of writing, an unprecedented crisis. Governments across the globe have taken wartime-like actions to curtail the spread of the illness and deaths by imposing strong restrictions on travel, social gathering and social distancing regulations. The social distancing measures constrain both the demand and supply sides of tourism services, causing significant flow-on effects throughout affected countries ( OECD, 2020a , OECD, 2020b ) with large reductions in employment and losses to household income. Even if a vaccine is available soon, with demand side recovery aided by progressive lifting of travel and social distancing restrictions, tourism supply chains may take years to adjust to the new circumstances of the travel experience ( Gössling et al., 2020 ).

Among all other countries, the Australian tourism industry is inevitably a victim to the outbreak, losing billions of dollars each month that the disease persists. Australia's tourism industry associations have united in new demands for support measures. These organisations include the Tourism and Transport Forum, the Accommodation Association, Cruise Lines International Association, the Australian Federation of Travel Agents the Restaurant and Catering Australia and the Business Events Council of Australia. Facing similar situations in respect of business closures, plummeting sales, losing jobs and incomes, these associations have acknowledged their dependence on government support to soften the effects of the pandemic both for current and future business operations. In a joint statement to the Prime Minister, the association group argued the case for the tourism industry's bigger businesses to be front and centre of any new economic lifeline package describing them as providing the scaffolding for the tourism sector and for business events. Claiming that the tourism industry will be critical to the Australian economy as it manages through the current survival phase and later into the eventual economic recovery phase, the peak group stated that:

The tourism industry is losing almost A$ 9bn every month that the global pandemic continues and is forecasting job losses of well over 300,000 so we are calling on government to recognise the urgency of providing these employers with sector-specific financial assistance. We acknowledge all of the steps taken by the Federal and State and Territory Governments are entirely necessary to ensure the health and wellbeing of Australians, but we are now at a point where our industry and its people are in the fight for survival. ( Colston, 2020 )

Included in the statement was a list of ‘sensible reforms’ that will help to ensure that Australia's tourism industry can survive the current crisis and become a stronger and more resilient industry. These reforms include investment incentives, tax concessions, rent abatements, and utility payments relief.

Without prejudging the appropriateness or otherwise of the suggested reforms, it is clear that their efficacy can only be determined in a context where the economic impacts of COVID-19 on the Australian tourism industry have been estimated. Since the effects of the pandemic are still unfolding, it is extremely difficult to predict with an accuracy what the ultimate health and economic impacts will be and what reform measures are most efficient and effective. The effects of the pandemic encompass many different aspects, including the health costs, human suffering, consumer behaviour and losses of tourism demand. All of these are important aspects of changes, and each warrants separate research on its own merit. This paper, however, focuses on the economic aspect of the pandemic only.

This paper will undertake what we believe to be the first detailed assessment of the economic impacts of COVID-19 on the Australian international tourism industry. The model employed has been substantially developed to include explicitly eleven international markets and three domestic markets to allow for full interaction between tourism and non-tourism demands by both international and domestic consumers. This is the first time that the full tourism satellite account (TSA) framework is incorporated into the tourism computable general equilibrium (CGE) modelling in order to reflect tourism markets explicitly and to allow flexibility for implementing individual shocks. Impacts are explained from direct to flow-on effects explicitly and results capture employment effects by occupation. This comprehensive approach is rare in the literature. The full details of the extension, as discussed below, provide rich sectoral results that have not been captured in tourism modelling previously.

The paper will review previous studies specifically of epidemics/pandemics on tourism, followed by a brief account of the pre-COVID-19 conditions of the world and Australian tourism sector. The paper then presents the adopted modelling framework, measures of the direct and flow-on effects on the pandemic. The final section will discuss in broad terms some strategies to reduce the effects of COVID-19 on the Australian tourism industry currently and in the future.

- Review of previous studies

The literature of tourism economic impact analysis is very broad, a review can be found in Dwyer (2015) . This section will focus specifically on economic impact studies of pandemics of infectious diseases such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Avian flu, Foot and Mouth Disease and recently COVID-19. The modelling approaches encompass a wide range of techniques for different objectives, including tourism demand assessment using the econometric technique ( Kuo et al., 2008 ; Kuo et al., 2009 ; McAleer et al., 2010 ; Liu, Moss and Zhang, 2011 , and Page et al., 2012 ), the market evaluation approach assessing impacts on the consumption and production sides separately (Australian Bureau of Statistics or ABS hereafter, 2020 ; OECD, 2020a , OECD, 2020b ; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2020a ); macro-econometric modelling ( Jonung & Roeger, 2006 ; Keogh-Brown, Wren-Lewis, et al., 2010 ; Kohlscheen et al., 2020 ); the Input-Output multiplier approach ( Hai, Zhao, Wang and Hou, 2004 ), dynamic stochastic general equilibrium ( Yang et al., 2020 ), and the computable general equilibrium modelling ( Blake et al., 2003 ; Dwyer et al., 2006 ; Lee & McKibbin, 2004 ; Maliszewska et al., 2020 ; McKibbin & Fernando, 2020 ; McKibbin & Sidorenko, 2006 ; Keogh-Brown, Smith, et al., 2010 ; Park et al., 2020 ; PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2020 ; Smith et al., 2011 ; World Bank, 2014 : and Yang & Chen, 2009 ).

As pandemics affect economies on both supply and demand sides simultaneously ( Boissay & Rungcharoenkitkul, 2020 ), most economy-wide studies employ the CGE technique to reveal the impacts of pandemics at the industry as well as the macro aggregate level for both world and national economies under the influence of changes in prices and resource re-allocation. The initial direct effects of a pandemic reduce labour supply due to losses of workers through sickness and mortality. Further impacts are prompted by fear . Prophylactic absenteeism of workers is due to fear of being infected by asymptomatic co-workers, thus effecting an additional loss to the productive workforce. Government's public health policy imposes restriction on social distancing, social gathering, school closure, international border closure for fear of the virus spread ( World Bank, 2014 , p. 6); The combined effect of prophylactic absenteeism and school closure is the essential driving force of economic costs of a pandemic ( Keogh-Brown, Wren-Lewis, et al., 2010 ). Both health effect and fear factor cut labour supply significantly. Impact studies at the early stage of pandemics often have to base on assumptions of clinical attack rates and case fatality ratio in order to work out the reduction of labour supply (e.g. Keogh-Brown, Wren-Lewis, et al., 2010 ; McKibbin and Fernando, 2020 ; PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2020 ), which alters the relative prices of capital and labour and subsequently depresses rates of return significantly in the medium to long term, thus drives down investment ( Jordà et al., 2020 ). With border closure, regions and countries are locked down, production is shut down, leading to losses of household consumption. It appears that the literature focuses on reduced productive workforce mainly from the supply side, which might not cover employment losses due to production cut prompted by reduced demand for goods and services. Fiscal expansion is urgently recommended to governments to prop the economy through both supply and demand ( IMF, 2020 ). Previous studies all share a common modelling approach that incorporates shocks such as (i) reduced labour supply, (ii) reduced household consumption, (ii) changed production technology, (iv) increased government expenditure (higher budget deficit), and (v) increased risk premium or loss of capital productivity (e.g. McKibbin & Fernando, 2020 ; PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2020 ).

With all of the above shocks, past studies aim to project the position of the economy accounting for the overall economic impacts of the pandemics on the economy. The adverse impacts range from −0.1 to −6% for global GDP ( Boissay et al., 2020 ). Comparing across countries, previous studies indicate that developing countries tend to suffer more than developed countries ( Burns et al. 2006 ). For COVID-19, statistics from the IMF (2020) show the reverse, where impacts on developed countries (−8%) are much worse than the world average (−4.9%).

Given the importance of the tourism industry in the Australian economy, the industry is particularly vulnerable to an infectious pandemic. The question then arises as to the extent to which the tourism industry, alone, has impacted on the rest of the Australian economy. Answer to such question has valuable policy implications for the tourism industry during the recovery and is the motivation of this paper.

As the downturn of the domestic sector has not been completely settled, different states have applied different border closure schedules between themselves, this is not all that clear for a robust impact assessment. On the other hand, the international border closure is consistent, and the international tourism segment plays a crucial role in attracting foreign exchange to the Australian economy, an economic impact assessment of the pandemic on the international tourism market will provide valuable inputs for policy makers.

- Tourism before and after outbreak of COVID-19

The effect on tourism worldwide

Forecasts of the United Nations World Tourism Organization (2011) , hereafter UNWTO, projected international tourist arrivals to increase by 43 million annually on average to reach 1.8 billion by 2030, equivalent to 3.3% per year during 2010–2030. In 2019, 1.5 billion of international tourist arrivals were recorded globally, representing a 4% growth on the previous year. The report contained optimistic prospects for 2020, confirming tourism, in the UNWTO view, as a ‘leading’, ‘resilient’ and ‘reliable’ economic sector ( UNWTO, 2020a ).

The spread of COVID-19 worldwide has up-ended all tourism forecasts globally for all inbound, outbound and domestic travel. Acknowledging this, UNWTO issued a series of reports from January to May 2020, outlining in broad terms the impact of the pandemic on the global tourism industry. A key message of these reports is that the spread of COVID-19 represents an unparalleled, rapidly evolving pandemic with a substantial challenge to estimation of its impacts on tourism. Preliminary estimates are that international tourism could drop back to levels of 2012–2014. In its May Report (UNWTO, 7/5/2020), the UNWTO estimated international tourist arrivals could decline between 850 and 1.1 billion international tourists equivalent to between 60% to 80% loss of arrivals in 2020. This would translate into a loss of US 910 b i l l i o n t o U S 1.2 trillion in international tourism receipts (exports) and 100 to 120 million direct tourism jobs at risk. Similarly, the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) estimated that the COVID-19 pandemic could result in a loss of 75.2 million jobs worldwide in the travel and tourism industry in 2020 alone. The WTTC (2020) also warned that it could take up to 10 months or longer for the industry to recover, an estimate that now seems to be unduly optimistic. These estimates must be interpreted with caution. The pandemic could result in a 70% or greater decline in the international tourism economy in 2020, depending on its duration and the speed with which travel and tourism rebounds ( OECD, 2020a , OECD, 2020b ). As more data emerges regarding destination management strategies, estimates of the short- and longer-term losses to world tourism will become more accurate.

The Australian international tourism industry

Tourism has been one of Australia's fastest growing industries for some decades. Fig. 1 visualises the historical development of international arrivals in Australia over time. While the path has fluctuated over the whole period of nearly three decades, all the dips in arrivals prior to 2016 were due major shocks that cut arrival growth rates below the long-term average (5.2%). Since then, however, the overall growth of international arrivals to Australia has weakened but not due to any apparent shocks. Arrival growth rates have gradually dwindled down for the last four years and submerged below the long-term average in the last two years. In the absence of COVID-19, international tourism to Australia was forecast to grow in annual visitation from 9.4 million visitors to 14.6 million between 2018 and 19 and 2028–29 ( TRA, 2020 ).

Annual arrival growth in Australia (ABS, Cat no. 3401.0).

Over time, the origin country shares comprising Australia's inbound tourism markets have shifted; in favour of some markets (e.g. China) with stronger growth than the others. Collectively the top ten origins in Table 1 delivered 71.4% of the inbound visitation numbers to Australia and 70% of the revenue. While China and New Zealand contribute the most in terms of visitor arrivals, China by far has the largest revenue share among all countries.

Profiles of international markets in Australia in 2018/19.

The spread of COVID-19 has been described as an ‘economic wrecking ball’ for the Australian tourism sector. While the domestic tourism market can begin the early recovery as social gathering is relaxed, restrictions on international travel may be expected to continue for much longer, constraining the international tourism market severely.

High levels of uncertainty attend estimates of reductions in tourism numbers and the associated reductions in expenditure, given the ongoing development of the pandemic. The modelling estimates the likely outcome of the losses of international visitors as the international border closure is approaching the end 2020, making it a complete year of international isolation.

- Modelling the economic impact of COVID-19

The aim of this paper is to quantify the economic effects of the pandemic on the international tourism market and subsequently on all other industries of the Australian economy. In the present study, we employ the computable general equilibrium (CGE) modelling technique, enabling us to ‘drill down’ to assess effects on different industries and to determine ‘inter-industry effects’.

As the CGE modelling technique has been described widely in the literature ( Burfisher, 2017 ; Cardenete et al., 2012 ; Dixon et al., 1982 ; Dwyer, 2015 ) we herein provide a brief summary only. A typical CGE model encompasses both supply (industries) and demand (all users) of an economy embedded entirely in an input-output (IO) database. An industry's cost structure includes wages, rental to capital and all other intermediate inputs. On the demand side, industry outputs are purchased by final users such as household consumption, investment, government consumption and exports. Decisions regarding both supply and demand are modelled following the microeconomic optimisation theory using a constant elasticity of substitution (CES) functional form. This allows goods and services to be sourced from a cheaper source among all available supplies, for example domestic versus imported sources. For a given market price of the output, producers will minimise their production costs by selecting cheapest inputs; and, the household sector will select a bundle of goods and services to maximise their ‘satisfaction’ (or precisely, utility in the micro-economic theory) subject to their income constraint.

Algebraically, a CGE model can be presented as:

where X 1 is a set of n endogenous variables determined by the n differentiable equations F(.) while X 2 is another set of m variables determined exogenously. Examples of endogenous variables are household income, household consumption and industry output while import prices, consumer taste, input mix in industry production and expenditure pattern of visitors are common exogenous variables.

Typically, the equation system in F(.) reflects:

- • Demands for goods and services by industries, investment, household, government and exports (product markets);

- • Market clearing equations for each industry (total output equals total sales);

- • Demands for labour, capital, and land by industry (factor markets), reflecting explicitly resource constraints in CGE models;

- • Production costs by industry (supply); and,

- • Pricing system with all components of production costs, import costs, net commodity taxes, and margins to provide relative price movements.

The tourism CGE model in this study is adapted from The Enormous Regional Model, hereafter TERM, ( Horridge et al., 2005 ). The model was developed by the Centre of Policy Studies using all available published and unpublished data and information compiled by the ABS. The model database is regularly updated to the latest data by the modelling team at the Centre. The platform of the model has been applied across many countries and widely used by economists in both government departments and academia; it is a well-tested model and a sound basis for the modelling undertaken. Use of this model allows us to focus on the development of the tourism module specifically. The database was expanded to include eleven international markets and three domestic markets (day trip, intra-state and inter-state overnight trips) to allow for full interaction between (1) tourism and non-tourism demand for the same commodity in the final demand and (2) among individual markets in response to shocks.

The rationale for such development is due to the fact that within each commodity, apart from the amount consumed by tourists, there is also another proportion of non-tourism consumption. This non-tourism consumption exists in both household consumption final demand (related to domestic tourists) and exports demand (related to international tourists). Without an explicit separation of tourism and non-tourism components in the final demands, shocks imposed on the model to reflect changes in tourism demand will effectively have no impacts on the non-tourism demand component. This would be an undesirable approach as the shock can have a different impact on the non-tourism component, and is complicated under the influence of income and macro effects. For example, if the shock is an increase in demand for “food, alcohol and other beverages” products by international visitors, it will (i) increase the domestic production costs of these products and at the same time (ii) it will make the exchange rate appreciate. Both changes will have an adverse impact on exports of the non-tourism component of these commodities. If not separated, the adverse impacts will be overlooked. The separation of tourism and non-tourism components is sparsely captured in the literature.

On the second aspect, given the different speeds of virus spread across countries, changes in international visitor numbers of all markets were also different. It is important to capture the actual decline in visitor number from each market so that changes in each market can be reflected accurately, as each market has a specific expenditure pattern. For this reason, the international tourism segment was further disaggregated down into eleven markets: the top ten and the rest of the world. Similarly, the domestic tourism segment was modelled with three different expenditure patterns of day trip, intra-state overnight and inter-state overnight markets. Tourism expenditure data for each market was carefully developed using the tourism satellite account (TSA) framework to provide a comprehensive coverage of goods and services consumed by visitors. Following the CGE modelling framework that explicitly incorporated TSA data for the tourism sector ( Pham et al., 2010 ; Pham & Dwyer, 2013 ), the stylised TSA data for each market was embedded into the model database. In comparison, the model development in this study is far more comprehensive, offering more advanced features for policy applications, as earlier models only cover domestic and international tourism at the aggregate level.

The type of model developed in this paper provides rich sectoral results that have not been captured in tourism modelling previously. Although the model can be used for both international and domestic shocks, the on-and-off imposition of the social distancing and social gathering due to the resurgence of the virus makes impact analysis on the domestic segment very difficult. As such, this paper focuses mainly on the international markets.

The structure of the comprehensive tourism model is presented in Fig. 2 . Each individual international tourism market is represented by the etour and domestic tourism markets ( day trip and domestic overnight markets) are represented by dtour in the figure. The model was run using GEMPACK ( Horridge et al., 2018 ). The original database of the model is large. The full dimensions of the database are not always needed in simulations and can make the interpretation of results more complicated unnecessarily. Thus, we focussed on only 75 commodities and 8 regions. The practice of using an aggregated database is very common among all TERM users. This does not compromise the coverage of the model in our analysis. The set of 75 commodities selected for this paper is appropriate for the Australian tourism industry.

Model structure of the tourism CGE model.

The version of the TERM model database was in 2012/13. The database was then updated to the latest year (2018/19) in this study. At the macro level, the update targets aggregate household consumption, government consumption, investment and exports, published by the Australia Bureau of Statistics (2020). The update also targets some important commodities for exports selected for the micro level. Exports of mining commodities are obtained from the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (2020) while export data for agricultural commodities are obtained from the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (2020) . All individual tourism markets were updated to 2018/19 levels using the latest tourism expenditure data from Tourism Research Australia, or TRA hereafter ( TRA, 2020 ) to calibrate the latest expenditure patterns of all markets. The method allows us to estimate the impacts on the economy from lost inbound visitor numbers compared to the benchmark year 2018/19. The shock is a decrease in the demand of international tourism. Therefore, the original expenditure patterns of the international visitors are crucial in order to reflect accurately the loss in economic activity in 2020. The pandemic may potentially change visitor expenditure patterns once the international border closure is lifted and visitors start travelling again. Such longer-term changes are important in the impact analysis of the recovery, but are beyond the scope of this study. As this study examines the losses compared to what we had before COVID-19, the pattern of 2018/19 is most suitable and will provide accurate estimates.

- Direct impacts of COVID-19 from the international tourism market

The impacts of COVID-19 from the international tourism market are measured through two stages. In the first stage, the tourism satellite account (TSA) approach is used to measure the economic impacts on industries providing goods and services directly to visitors. The second stage measures how far the direct impacts can permeate through the inter-industry linkages to generate further effects on other industries in the whole economy using the tourism CGE model.

Estimating the shocks

The base year of the model database is in 2018/19. However, as the time frame of the pandemic is currently spreading over the calendar year 2020, covering two financial years of 2019/20 and 2020/21, for convenience, the impacts are estimated for the calendar year 2020 on the basis of expenditure patterns and industry structure for 2018/19.

Table 2 presents the historical data of visitor arrivals to Australia in 2018/19 and period between January to September of 2020 by inbound market. Arrivals from overseas started to decline significantly in February. The numbers of arrivals from all markets effectively ended in April ( ABS, 2020 ). All inbound markets experienced significant declines compared to the same period the year previously. Losses of visitor arrivals are calculated for individual markets. For example, over the first nine months of 2020 there were only 206,690 visitors from China, or just 14% of the 2018/19 base. This implies a loss of 86% of Chinese visitors for nearly the whole 2020. All individual markets are estimated to experience a major downturn for 2020, losing at least 73% of their visitors. The percentage declines are displayed as (negative) shocks in the right-hand column of Table 2 .

Effects of COVID-19 on estimated losses of visitor arrivals.

Direct impacts

Tourism revenue is assumed to change proportional to the change in visitor number for individual markets estimated in Table 2 . Taking China for example, 86% less inbound tourists means 86% less inbound tourism expenditure, equivalent to A$10,062 million as presented in Table 3 . Tourism expenditure is measured at purchasers' prices that include values of goods and services produced by domestic industries as well as imports from overseas, net taxes payable to the government and margins to bring goods and services to visitors. To measure the direct impacts, expenditure measured at purchasers' prices is decomposed so that only values contributed by domestic industries providing goods and services directly to visitors are reflected ( Pham et al., 2009 ).

Direct impacts of COVID-19 from the international tourism market in Australia.

Based on TRA's unpublished TSA data ( TRA, 2020 ) on tourism revenue and tourism contribution of each market to the Australian economy in terms of gross value-added, gross domestic product and numbers employed in tourism, the COVID-19 direct impacts of those international markets are calculated on the pro-rata basis of the revenue losses for those international markets for 2020. The total loss is estimated to be more than A 31.8 b i l l i o n , e q u a l t o 81.2 A14.5 billion of lost tourism gross domestic product (TGDP). Total loss of direct tourism employment from these international tourism markets is estimated as 152,000 employed persons, which adds 1.15 percentage points of unemployment to the current unemployment at the national level. Relatively, the direct impacts are greater in terms of lost tourism employment (1.2%) than reduced tourism GDP (0.75%), as tourism is a labour-intensive industry.

The estimated effects above were calculated using a strong assumption that Australia will not open up the international border until 2021 at the earliest, as the number of active cases and daily new cases are still increasing across many countries, reducing the likelihood of resurgence without a vaccine. The loss of tourism revenue from China is estimated to be the largest loss to Australia compared to other markets. The loss from the China market alone contributes a dominant share of 26% of the total loss in Australia's international tourism revenue in 2018/19. Such impact is significant and warrants a separate study of the effects of market dependency and strategies to overcome this.

Of the total 152,000 estimated job losses presented in Table 3 , we extended the standard TSA framework to disaggregate the employment impacts by tourism-related industries and by occupation. The TSA base data of 2018/19 for employment was first further disaggregated into individual markets by tourism-related industry to give the distribution of tourism impacts by sector ( Fig. 3 ).

Distribution of direct impacts on employment by sector (per cent).

The definition of tourism by the ABS includes education where visitors attend short courses, workshops or students who spend less than twelve months on their visits to Australia. While most countries have a very small proportion of education in their total tourism expenditure, education accounts for nearly 35% of total tourism expenditure in Australia for visitors from China, taking up slightly more than 50% of the total tourism expenditure on education in Australia ( TRA, 2019a, unpublished data ). This explains the significant impact of 30% on employment accounted for from education in Fig. 3 . Restaurants and bars, retails and hotels are the three sectors that account largely for the total loss of employment, as expected, 53%.

The results show that the employment effects of COVID-19 extend across many tourism relevant industries, with education the most badly affected, followed by restaurants and bars, retail trading and hotels. The results reinforce the fact that, given its links with other industries, a downturn in tourism will adversely affect many other sectors. An implication of this is that rescue strategies directed at tourism can deliver spillover benefits for other sectors along tourism's value chain where the links with tourism may not be immediately evident ( Song, 2012 ).

The industries listed in Fig. 3 , are then mapped back to the ANZSIC industries. Given the occupation structure by the ANZSIC industry provided by the ABS (2020, Cat. 6291.0) , the employment impacts of the international tourism markets are then translated into occupations as seen in Fig. 4 .

Distribution of direct impacts on employment by occupation (per cent).

Among all occupations affected by the international tourism market, nearly 57% are among the low-skilled and basic-skilled groups. Managers, professionals and technicians and trades account for 43% in total job losses. Relatively, the direct impacts have more effect on the low-income groups of workers. The results also indicate that a downturn in tourism has adverse effects on employment in many occupations that may not be obviously thought of as ‘tourism related’. In addition to sales and service workers, conventional thinking of tourism workforce, the COVID-19 crisis affects employment among professionals, managers and technicians. This reflects the widespread effects that tourism has on employment along its value chain ( Song, 2012 ).

- Economy-wide impacts of the international tourism market

The magnitude of the COVID-19 impact can potentially render long-term changes in expenditure patterns, behaviours among industries and consumers that require careful attention in modelling tasks. For example, the losses of employment so far have triggered a lower propensity to consume for all households. Using the (high) value of the old parameter for propensity to consume to estimate sales revenue during and post-COVID19 will likely overestimate the industry sales revenue, as consumers are not prepared to spend as much as previously. This is a challenge for Treasury Departments world-wide in their preparation for upcoming budgets. In contrast, estimates of industry output losses from COVID-19 will be underestimated when imposing a lower value of the new parameter for the propensity to consume in the model. The losses must be based on the income level, and subsequently the associated behavioural parameters, before the crisis event. Depending on the objectives of analysis, either a projection or an impact assessment, a certain set of parameters, ex-post or ex-ante respectively, would be required specifically. It is not necessarily that all economic analyses must now adopt new parameters. This really depends on what effects we are trying to capture.

As the literature reveals, pandemics induce a wide range of changes to the economy including an unplanned large fiscal expansion from the government, changes in household consumption and the associated expenditure pattern, new relationship among industries and changes in labour supply. These are important factors in projecting where the economy is on its trajectory going through the pandemic or predicting tax revenue for government budget purposes.

This paper has a different objective. It focuses solely on the costs of losing the inbound segment to provide insights into the path that the Australian Government can assist the industry in its fight for survival . Therefore, the modelling scenarios are conducted in a ceteris paribus condition so that impacts from the losses of the inbound segment are clearly isolated from impacts of all of the aforementioned factors. Results in this paper are strictly due to the international border closure, and subsequently the losses of international arrivals.

This explains the rationale in our approach not to modify model parameters nor to include the fiscal expansion of billions of dollars that the Australian Government has injected into the economy. If such fiscal expansion policy or parameters were to be incorporated, results would be distorted, thus would not, and cannot, be interpreted as the impacts of the losses of the inbound tourism markets on the Australian economy due to COVID-19.

Macro results

The direct impacts of reduced inbound tourism will have further effects on other industries in the rest of the economy through the inter-industry linkages that generates larger impacts on the economy. The tourism CGE model was applied to estimate the flow-on economic impacts of COVID-19 in 2020. Given the comparative nature of the model, results are not traced explicitly on any time path. We adopt a standard short-run scenario, usually within a year. The short-run results are of particular relevance as they will help the Australian Government to understand the likely immediate impacts on the economy through losses to tourism so that relevant policies can be put in place to support the industry. In the short run, nominal wages are assumed to be fixed while changes in demand for labour lead to fluctuations of employment numbers. For the capital market, capital stocks are normally fixed in the short run as buildings and equipment take time to build up, while the rates of return will vary in response changes in demand for capital. Investment, however, is assumed to respond to the prevailing conditions in the economy. If the income from capital is growing faster than the costs of investment, this will entice more investment. The benefits of having more capital stocks will materialise beyond the short-run timeframe. In contrast, when the costs of investment are growing faster than the income from capital, this implies a decline in the rates of return, thus discouraging investment. This could lead to reduction of capital stocks and affect the supply side of industries in the longer run. Although the Australian Government has applied a fiscal stimulus package to the economy, the stimulus is not incorporated in the analysis as doing so will dilute the impacts of the travel restrictions on visitor flows to the country. Government consumption is held constant in this paper. Finally, the exchange rate is set exogenously as a numeraire in this study.

Although the direct impacts ( Table 3 ) were estimated for each market individually, the economy-wide impacts are measured for the international tourism market as a whole. The losses of international visitor arrivals in the percentage form in Table 2 were imposed onto the model simultaneously to generate the overall simulations of impacts.

The reduced tourism demand will have adverse impacts on the tourism industry, and as a result, the tourism industry will release its resources to the rest of the economy. This, in effect, can reduce the cost pressures on production and can help to increase exports of other industries. However, given the current condition that almost all of countries are focusing on fighting the pandemic for the rest of 2020, it is likely that the released resources might not be utilised to the full extent, particularly when the tension between the Chinese Government (Australia's major trading partner) and the Australian Government has escalated due to the call for an enquiry into the origin of COVID-19. Potentially, the reduced production costs could be used for trade diversion strategy so that the Australian exports can reach markets other than China. This could help Australia's traditional exporting industries such as coal, mining and basic metal products. Thus, this study examines the loss of international tourism demand in both scenarios, with and without export increases from other industries.

Table 4 shows the macro results in percentage change form and values measured at 2018/19 prices. Columns 1 and 3 are results of the scenario with ‘increased exports’ from the traditional exporting sectors, while columns 2 and 4 are results of the ‘without increased exports’ scenario. We begin our explanation of results with the most stringent scenario in columns 2 and 4, assuming ‘no exports’. In the absence of the responses of the traditional export sectors, the travel restrictions associated with the international tourism sector are estimated to result in a decline of 6.84% of total exports or a total loss of A$31.802 billion, purely from the international tourism sector as previously indicated in Table 3 . This reduction in tourism revenue will directly lower demand for goods and services of tourism, thus reducing employment and income for those working in tourism-related industries such as hotels, restaurants, travel agencies and retail trade. The income losses of tourism employees will further result in lower demands for output of other industries, and lower returns on investment, driving down investment by nearly 3.38% (or A$15.2 billion).

The COVID-19 impacts of the international market on the Australian economy.

The overall reduction in demand from the domestic economy reduces demands for imports by 3.28% (A$14.487 billion). The reduction in imports could also be influenced by the fact that domestic products are relatively cheaper than those from overseas, domestic consumers shift toward domestically produced goods and services. Cheaper products from the domestic economy are reflected by the decline of 2.76% in the consumer price index (CPI) from the demand side, or 2.63% of GDP deflator from the supply side.

The net effect on output is estimated to result in a large reduction in demand for labour across all industries by 3.58%. While nominal wages are constant, real wages actually increase for those who are still employed, due to the reduction in the CPI. Nevertheless, the job losses dominate the effect of lower income for the household sector leading to lower household consumption in real terms by 0.9%, equivalent to A$9.6 billion, as seen in Table 4 .

Overall, reduced inbound tourism is estimated to shrink the Australian economy by 2.2%, equivalent to A$42.1 billion, compared to the base 2018/19. The downturn of the international tourism markets is estimated to cut 456,500 jobs across all industries, adding 3.45 percentage points of unemployment to the current level of unemployment.

In the event that the released resources (primarily labour) from the tourism-related industries can be utilised in the traditional exporting industries, the loss of international tourism revenue is offset by a modest increase of A 1.8 b i l l i o n i n t r a d i t i o n a l e x p o r t s d u e t o l o w e r p r o d u c t i o n c o s t s , r e s u l t i n g i n a t o t a l d e c l i n e o f e x p o r t s o f A 29.9 billion, or 6.4% reduction. The adverse impacts are softened slightly for all macro variables in columns 1 and 3 of Table 4 . Household consumption is estimated to reduce by A 8.8 b i l l i o n , i n v e s t m e n t b y A 13.5 billion and GDP by A$39.2 billion. The number of job losses is slightly smaller compared to the No Trade case, estimated to be approximately 423,500 jobs or 3.2 percentage points of unemployment nationally.

The exogenous setting of the exchange rate for the short-run closure restricts reallocation of resources across industries in the domestic economy to suit the current conditions of the pandemic. The magnitude of the offset can be larger within a longer-term setting that allows for greater labour mobility. Nevertheless, the results highlight an opportunity for Australia to broaden its trade portfolio in order to minimise risks by reducing dependency on just one or two main trading partners for its traditional exporting industries.

Sectoral results

Among all industries, as expected, tourism-related industries including accommodation, air, rail and road transport, and restaurants are primarily the hardest hit as seen in Table 5 . The output losses of accommodation and air and rail transport industries range between 12% to 17%. The impacts on employment are even greater, between 20% to 23%, since these industries are labour intensive. These results displayed in Table 5 reinforce the importance of tourism for the output of a large range of industries and demonstrate that the tourism effects of the pandemic extend across almost all industry sectors.

Impacts on industry output.

An important note for industries in Table 5 is that the result for construction masks its significant impact of the industry. Given its very larger output base, and labour intensiveness, the range of output losses in construction between 2.5 and 2.8% is significant for the economy. This output reduction is induced by the decline in investment as seen in Table 4 .

Occupations

Fig. 4 provides the distribution of the employment impacts by occupations using the ABS classification. The distribution was derived by applying the simulation results of labour demand by occupation on the actual level occupations for 2018/19 ( ABS, 2020, Cat 6291.0 ). The differences of employment impacts between the two scenarios on the proportion basis are marginal, thus Table 6 provides a representative composition of occupations for both scenarios (with and without trade). For comparison, Table 6 reproduces the composition/distribution of occupations from the direct impacts displayed in Fig. 4 and also includes the national profile of occupations for 2018/19 – the base year. While the pattern of the direct effect highlights the typical nature of employment in tourism with large shares of employment of service workers, sales workers and labourers, the distribution of employment effects in the economy-wide impacts tends to resemble broadly the structure of occupations across all industries in 2018/19. The impacts of COVID-19 are not only on the low-skilled groups, workers in the skilled labour groups (managers, professional and technicians and trades) are also affected. Since the skilled labour groups tend to have higher wage rates, the absolute income loss is relatively more for the skilled labour groups.

Distribution of the international tourism effects by occupation (negative per cent).

- Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic is still developing and its incidence varies greatly by destination. Policy responses are highly specific to country's economic and public health contexts. Despite the industry's proven resilient capability, the depth and breadth of the pandemic impacts on tourism and the wider economy imply that an early recovery is unlikely. This paper thus focuses on only the short-term impacts for 2020 on the Australian economy.

The results of our study for Australia are instructive. Not surprisingly, the pandemic affects tourism directly with a decline in output and employment not only in characteristic tourism industries such as accommodation, restaurants, and transportation, but also in a range of many other industries. The study highlights the significance of Australia's inbound tourism industry, which is estimated to result in an immediate decline of between A 39 − A 42 billion in GDP. The results show direct job losses of around 152,000 in tourism, extending to between 423,000 and 456,000 across many industries along the tourism value chain. As a labour-intensive industry, the impacts on the basis of percentage change of employment is estimated to be greater than the reduction in national GDP. This paper confirms the pattern of long-term declining investment and depressed rates of return, as observed from past pandemic studies ( Jordà et al., 2020 ). If this is not addressed adequately, the industry will lose its economy of scale during a slow recovery in tourism demand, lowered output with higher prices might be the outcome at the end, a long and steep road ahead for tourism businesses. To what extent JobSeeker and JobKeeper programs ( Australian Government, 2020 ) are required remains an important question for the Australian government.

Tourism industry stakeholders, public and private, should be aware of the fact that the tourism effects of COVID-19 extend beyond the direct impacts on a narrow set of (characteristic) industries related to tourism. Among industries, education is the industry that most suffers from the decline in inbound visitor expenditure. The study reveals that the tourism downturn has adverse effects on direct employment in many occupations that may not be obviously thought of as ‘tourism related’, including professionals, managers and technicians. These consequences reinforce the depth and complexity of tourism's value chain. It is important for the government to provide support evenly and equally across all groups of labour occupations in society, as the pandemic affects employment widely over a lengthy period.

While resources released from the tourism industry can be re-employed by other industries, it is unlikely that these resources can be taken up significantly by non-tourism industries in present conditions. But, potentially, the released resources could be used, to some extent, for trade diversion strategy supporting other exporting industries. The study explored differences in the results between ‘no trade’ and ‘with trade’ scenarios. Impacts generally are softened in the ‘with trade’ assumption compared to the alternative. The reduced losses experienced when trade remains open indicates the potential gains to the Australian economy of diversifying its export industries in a post COVID world.

As the pandemic unfolds, Australian governments, from state to national level, are taking aggressive and co-ordinated policy action to maintain employment levels and reduce business closures. The economy-wide stimulus package targets three areas: individuals and households, businesses, flow of credit ( Australian Government, 2020 ). Within the overall economic stimulus package, specific strategies have been directed at the tourism and hospitality industries to ensure business survival. These include reduced fees and charges for tourism businesses across several sectors; taxation relief for domestic airlines; and targeted measures to boost domestic tourism after the crisis. The crisis has revealed the need for sharing crucial and timely data and information, such as the extent and pattern of the impacts, among all tourism stakeholders to support informed decision making, and for national, regional and local destination managers to adopt an integrated governmental and all -industry approach so that their own response measures are consistent and complementary to achievement of accepted macroeconomic goals ( OECD, 2020a , OECD, 2020b ). The findings of this study concerning both the macroeconomic, sectoral and occupational effects of reduced inbound tourism to Australia can help to formulate specific policies to stimulate the industry. Further, industry interactive effects between tourism and other industries identified in this study indicate that policies directed at Australia's tourism recovery can deliver spillover benefits to other areas of economic activity. As tourism output increases, so too will the outputs of many connected industries.

Beyond the immediate industry focussed responses to stimulate the economy, it would be useful if the Australian policy makers can broaden up the current experiences in crisis management strategies to better prepare the country for future shocks of any types. Although productive activities need to bounce back to provide jobs and income for households, it is imperative to take this opportunity to develop inbuilt-sustainable growth for the industry because sustainability is a prerequisite condition for growth in the long run. The established mindset underpinning tourism planning, development and research is under criticism on the grounds that the ‘business as usual’ emphasis on economic growth and resource degradation is impossible to reconcile with sustainability of travel and tourism ( Bramwell & Lane, 2011 ). Ignoring this type of criticism, the majority of ‘priorities for tourism recovery’ and ‘global guidelines’ promulgated by the United Nations World Tourism Organization, 2020a , United Nations World Tourism Organization, 2020b , United Nations World Tourism Organization, 2020c are just ‘nods and tweaks’ to ‘business as usual’, with no real substance to progress sustainably in the post COVID world.

COVID-19 will forever change the way we travel and may be expected to have a substantial impact on the implementation of each of the United Nation's Sustainable Development Goals in which tourism can play a major participative role ( UNWTO, 2017 ). There is insufficient space to explore this issue here; but suffice to say that the pathways to facilitate tourism's transition to the new sustainable future paradigm have been identified ( Dwyer, 2018 ) and have substantial relevance to construction and operation of the global tourism industry post COVID-19.

- Declaration of competing interest

I have no declaration of interest to make.

- Biographies

Tien Pham ( [email protected] ) is an A/Prof at Griffith University, with strong interests in CGE modelling, tourism satellite accounts and demand analysis.

Larry Dwyer is Visiting Research Professor. He has published widely across many areas of tourism research including economic impact analysis and TSA.

Jen-Je Su (PhD) is a Senior Lecturer at Griffith Business School, with research interests in forecast and economic demand modelling.

Tramy Ngo (PhD; Griffith University) is an experienced tourism market analyst.

Associate editor: Haiyan Song

- Australian Bureau of Statistics . Detailed labour force data collected on a quarterly basis; July: 2020. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-australia-detailed-quarterly/latest-release [ Google Scholar ]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2020a) 3401.0 - Overseas Arrivals and Departures, Australia, July https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/tourism-and-transport/overseas-arrivals-and-departures-australia/latest-release , November 2020.

- Australian Government . Australian Treasury; 2020. https://treasury.gov.au/coronavirus> accessed 8/04/2020. [ +accessed+8/04/2020+" target="pmc_ext" ref="reftype=other&article-id=8590504&issue-id=382147&journal-id=3821&FROM=Article%7CCitationRef&TO=Content%20Provider%7CLink%7CGoogle%20Scholar">Google Scholar ]

- Blake A., Sinclair M.T., Sugiyarto G. Quantifying the impact of foot and mouth disease on tourism and the UK economy. Tourism Economics. 2003; 9 (4):449–465. [ Google Scholar ]

- Boissay F., Patel N., Shin H.S. Trade Finance, and the COVID-19 Crisis. 2020. (June 19, 2020) [ Google Scholar ]

- Boissay F., Rungcharoenkitkul P. “Macroeconomic effects of Covid-19: An early review”, BIS Bulletin , no. 7. April. 2020; 2020 [ Google Scholar ]

- Bramwell B., Lane B. Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2011; 19 (4–5):411–421. [ Google Scholar ]

- Burfisher M. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- Burns A., Van der Mensbrugghe D., Timmer H. World Bank; Washington, DC: 2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cardenete M.A., Guerra A.I., Sancho F. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 2012. [ Google Scholar ]

- Colston P (2020) ‘Australia's tourism industry associations united in new demands for support measures’ conference and meetings world cmw-net, march 3.

- Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (2020) Agricultural Outlook- March 2020 https://www.agriculture.gov.au/abares/research-topics/agricultural-outlook/mar-2020

- Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (2020) Resources and Energy Quarterly – March 2020, https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/resources-and-energy-quarterly-march-2020

- Dixon P.B., Parmenter B.R., Sutton J., Vincent D.P. Contributions to economic analysis. Vol. 142. North-Holland Publishing Company; 1982. (pp. xviii + 372) [ Google Scholar ]

- Dwyer L. Computable general equilibrium Modelling: An important tool for tourism policy analysis. Tourism and Hospitality Management. 2015; 21 (2):111–126. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dwyer L. Saluting while the ship sinks: The necessity for tourism paradigm change. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2018; 26 (1):29–48. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dwyer L., Forsyth P., Spurr R. Effects of the SARS crisis on the economic contribution of tourism to Australia. Tourism Review International. 2006; 10 (1–2):47–55. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gössling S., Scott D., Hall C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2020:1–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hai W., Zhao Z., Wang J., Hou Z.G. The short-term impact of SARS on the Chinese economy. Asian Economic Papers. 2004; 3 (1):57–61. [ Google Scholar ]

- Horridge J.M., Jerie M., Mustakinov D., Schiffmann F. 2018. (GEMPACK software) [ Google Scholar ]

- Horridge M., Madden J., Wittwer G. The impact of the 2002–2003 drought on Australia. Journal of Policy Modeling. 2005; 27 (3):285–308. [ Google Scholar ]

- IMF (2020), World Economic Outlook Update: A Crisis Like No Other, An Uncertain Recovery, June 2020.

- Jonung L., Roeger W. 2006. (European Communities) [ Google Scholar ]

- Jordà, O, S Singh and A Taylor (2020), “Longer-run economic consequences of pandemics”, unpublished manuscript, March.

- Keogh-Brown M., Wren-Lewis S., Edmunds W.J., Beutels P., Smith R.D. The possible macroeconomic impact on the UK of an influenza pandemic. Health Economics. 2010; 19 :1345–1360. [ Abstract ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keogh-Brown M.R., Smith R.D., Edmunds J.W., Beutels P. The macroeconomic impact of pandemic influenza: estimates from models of the United Kingdom, France, Belgium and The Netherlands. The European Journal of Health Economics. 2010; 11 [ Abstract ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohlscheen, E. B. Mojon and D. Rees (2020), “The Macroeconomic Spillover Effects of the Pandemic on the Global Economy”, BIS Bulletin, no 4.

- Kuo H.I., Chang C.L., Huang B.W., Chen C.C., McAleer M. Estimating the impact of avian flu on international tourism demand using panel data. Tourism Economics. 2009; 15 (3):501–511. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuo H.I., Chen C.C., Tseng W.C., Ju L.F., Huang B.W. Assessing impacts of SARS and avian flu on international tourism demand to Asia. Tourism Management. 2008; 29 (5):917–928. [ Europe PMC free article ] [ Abstract ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee J.-W., McKibbin W. In: Learning from SARS: Preparing for the next outbreak. Knobler S., Mahmoud A., Lemon S., Mack A., Sivitz L., Oberholtzer K., editors. The National Academies Press; Washington DC: 2004. (0-309-09154-3) [ Abstract ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu J., Moss S.E., Zhang J. The life cycle of a pandemic crisis: SARS impact on air travel. J. Int. Bus. Res. 2011; 10 (2) [ Google Scholar ]

- Maliszewska M., Mattoo A., van der Mensbrugghe D. Policy Research Working Paper no. 9211. World Bank Group; 2020. April 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- McAleer M., Huang B., Kuo H., Chen C., Chang C. An econometric analysis of SARS and avian flu on international tourist arrivals to Asia. Environmental Modeling and Software. 2010; 25 (1):100–106. [ Europe PMC free article ] [ Abstract ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McKibbin W., Fernando R. CAMA Working Paper, no 19/2020. 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- McKibbin W., Sidorenko A. Lowy Institute Analysis; 2006. February. [ Google Scholar ]

- OECD (2020a), Tourism policy responses. Tacking coronavirus, contributing to a global effort (COVID-19), OECD Tourism Committee https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=124_124984-7uf8nm95se&Title=Covid-19:%20Tourism%20Policy%20Responses .

- OECD . 2020. (27 March) [ Google Scholar ]

- Page S., Song H., Wu D. Assessing the impacts of the global economic crisis and swine flu on inbound tourism demand in the United Kingdom. Journal of Travel Research. 2012; 51 (2):142–153. [ Google Scholar ]

- Park C., Villafuerte J., Abiad A., Narayanan B., Banzon E., Samson J., …Tayag M. ADB Briefs. 2020. no. 133, ISBN 978-92-9262-215-2; May 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pham T.D., Dwyer L. In: The handbook of tourism economics – Analysis, new applications and case studies, chapter 22. Tisdell, editor. World Scientific Publishing; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pham T.D., Dwyer L., Spurr R. Constructing a regional TSA: The case of Queensland. Tourism Analysis. 2009; 13 (5/6):445–460. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pham T.D., Simmons D., Spurr R. Climate change induced impacts on tourism destinations: The case of Australia Special Issue for Climate Change. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2010; 18 (3):449–473. [ Google Scholar ]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers (2020), The possible economic consequences of a novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, Australia matters.

- Smith R.D., Keogh-Brown M.R., Barnett T. Estimating the economic impact of pandemic influenza: An application of the computable general equilibrium model to the UK. Social Science & Medicine. 2011; 73 (2):235. (1982) (0277e–9536) [ Europe PMC free article ] [ Abstract ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Song H. Routledge; NY: 2012. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tourism and Transport Forum (2020) Coronavirus set to hit Australian tourism industry much harder than SARS, Sydney, https://www.ttf.org.au/coronavirus-set-to-hit-australian-tourism-industry-much-harder-than-sars/

- Tourism Research Australia (2019a) Tourism Satellite Accounts 2029 , unpublished data, Canberra.

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (2011) Tourism towards 2030, Global Overview.

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (2020a) World Tourism Barometer Volume 18, Issue 1. January 2020, https://www.unwto.org/world-tourism-barometer-n18-january-2020

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (2020b), ‘ International tourism growth continues to outplace the global economy’ , 24/03/2020, available at: https://unwto.org/international-tourism-growth-continues-to-outpace-the-economy

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (2020c) Global Guidelines to Restart Tourism May 28 https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2020-05/UNWTO-Global-Guidelines-to-Restart-Tourism.pdf

- United Nations World Tourism Organization and United Nations Development Programme . UNWTO; Madrid: 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- World Bank . 2014. (October) [ Google Scholar ]

- World Travel and Tourism Council (2020) Global Economic Impact and Trends, June file:///C:/Users/105893/Downloads/Global_Economic_Impact_&_Trends_2020.pdf.

- Yang H.Y., Chen K.H. ‘A general equilibrium analysis of the economic impact of a tourism crisis: A case study of the SARS epidemic in Taiwan’ Journal of Policy Research in Tourism . Leisure and Events. 2009; 1 (1):37–60. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yang Y., Zhang H., Chen X. Coronavirus pandemic and tourism: Dynamic stochastic general equilibrium modeling of infectious disease outbreak. Annals of Tourism Research. 2020 10.1016/j.annals.2020.102913. [ Europe PMC free article ] [ Abstract ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Full text links

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103179

Citations & impact

Impact metrics, citations of article over time, smart citations by scite.ai smart citations by scite.ai include citation statements extracted from the full text of the citing article. the number of the statements may be higher than the number of citations provided by europepmc if one paper cites another multiple times or lower if scite has not yet processed some of the citing articles. explore citation contexts and check if this article has been supported or disputed. https://scite.ai/reports/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103179, article citations, predicting the impact of the covid-19 pandemic on globalization..

Zhang Y , Sun F , Huang Z , Song L , Jin S , Chen L

J Clean Prod , 409:137173, 21 Apr 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37101511 | PMCID: PMC10119637

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourist Travel Risk Perception and Travel Behaviour: A Case Study of Poland.

Jęczmyk A , Uglis J , Zawadka J , Pietrzak-Zawadka J , Wojcieszak-Zbierska MM , Kozera-Kowalska M

Int J Environ Res Public Health , 20(8):5545, 17 Apr 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 37107828 | PMCID: PMC10139158

Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on China's tourism economy and green finance efficiency.

Hu Z , Zhu S

Environ Sci Pollut Res Int , 30(17):49963-49979, 14 Feb 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 36787070 | PMCID: PMC9926458

Exploring the Coordination and Spatial-Temporal Characteristics of the Tourism-Economy-Environment Development in the Pearl River Delta Urban Agglomeration, China.

Pang X , Zhou Y , Zhu Y , Zhou C

Int J Environ Res Public Health , 20(3):1981, 21 Jan 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 36767348 | PMCID: PMC9915974

The Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis on Air Travel Demand: Some Evidence From China.

Wu X , Blake A

Sage Open , 13(1):21582440231152444, 30 Jan 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 36751691 | PMCID: PMC9895287

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Impact of Economic Policy Uncertainty and Pandemic Uncertainty on International Tourism: What do We Learn From COVID-19?

Zhao X , Meo MS , Ibrahim TO , Aziz N , Nathaniel SP

Eval Rev , 47(2):320-349, 18 Oct 2022

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 36255210 | PMCID: PMC9579821

The impacts of COVID-19 containment on the Australian economy and its agricultural and mining industries.

Dixon JM , Adams PD , Sheard N

Aust J Agric Resour Econ , 65(4):776-801, 01 Oct 2021

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 34899034 | PMCID: PMC8652510

The impact of crisis events and macroeconomic activity on Taiwan's international inbound tourism demand.

Tour Manag , 30(1):75-82, 10 Jul 2008

Cited by: 24 articles | PMID: 32287727 | PMCID: PMC7115617

The Post Pandemic Revitalization Plan for the Medical Tourism Sector in South Korea: A Brief Review.

Seo BR , Kim KL

Iran J Public Health , 50(9):1766-1772, 01 Sep 2021

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 34722371 | PMCID: PMC8542822

Assessing the Impacts of COVID-19 on the Industrial Sectors and Economy of China.

Tan L , Wu X , Guo J , Santibanez-Gonzalez EDR

Risk Anal , 42(1):21-39, 26 Aug 2021

Cited by: 10 articles | PMID: 34448216 | PMCID: PMC8662127

Europe PMC is part of the ELIXIR infrastructure

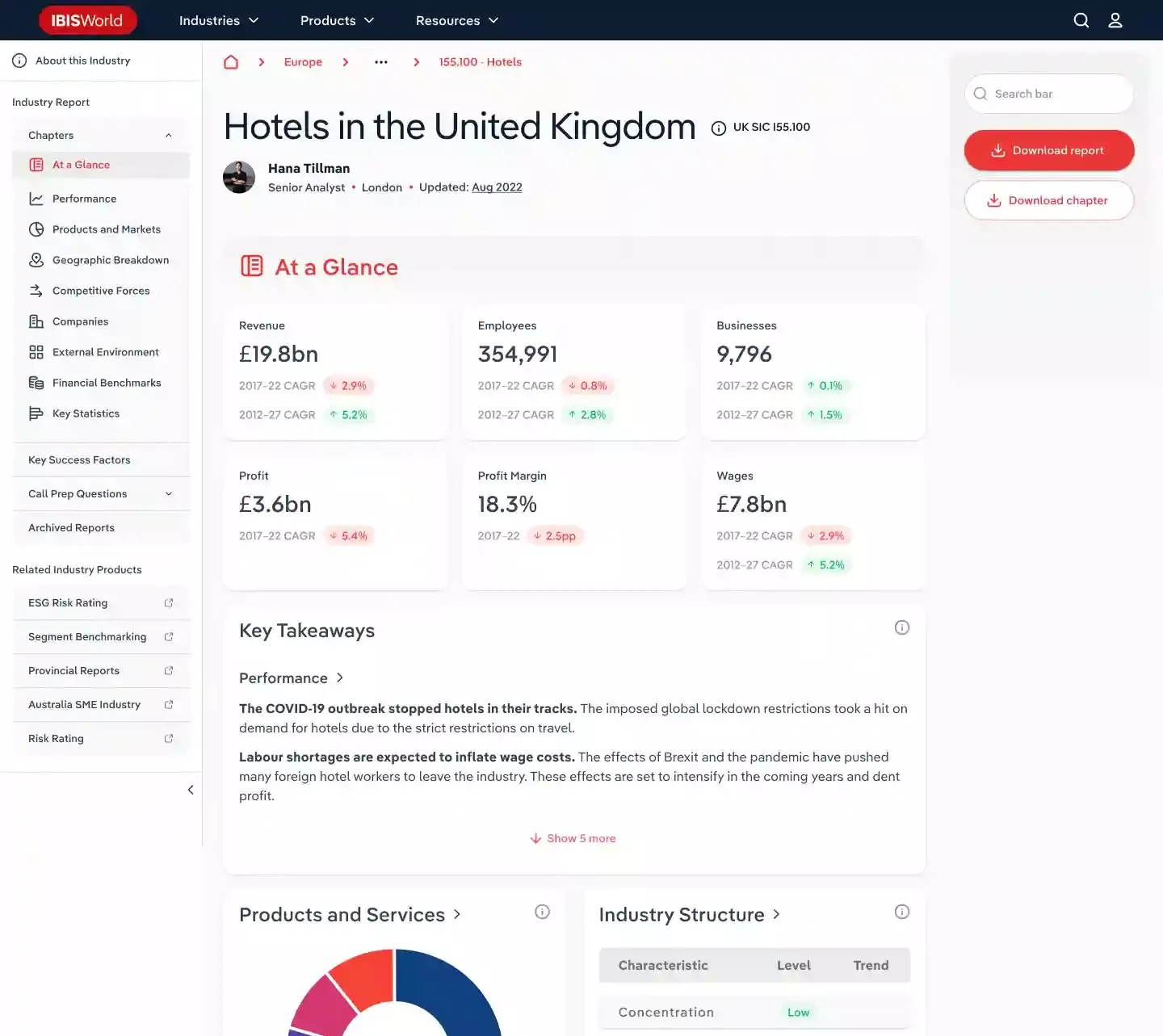

Tourism in Australia - Market Size, Industry Analysis, Trends and Forecasts (2024-2029)

Instant access to hundreds of data points and trends.

- Market estimates from

- Competitive analysis, industry segmentation, financial benchmarks

- Incorporates SWOT, Porter's Five Forces and risk management frameworks

- PDF report or online database with Word, Excel and PowerPoint export options

100% money back guarantee

Industry statistics and trends.

Access all data and statistics with purchase. View purchase options.

Tourism in Australia

Industry Revenue

Total value and annual change from . Includes 5-year outlook.

Access the 5-year outlook with purchase. View purchase options

Trends and Insights

Market size is projected to over the next five years.

Market share concentration for the Tourism industry in Australia is , which means the top four companies generate of industry revenue.

The average concentration in the sector in Australia is .

Products & Services Segmentation

Industry revenue broken down by key product and services lines.

Ready to keep reading?

Unlock the full report for instant access to 30+ charts and tables paired with detailed analysis..

Or contact us for multi-user and corporate license options

Table of Contents

About this industry, industry definition, what's included in this industry, industry code, related industries, domestic industries, competitors, complementors, international industries, performance, key takeaways, revenue highlights, employment highlights, business highlights, profit highlights, current performance.

What's driving current industry performance in the Tourism in Australia industry?

What's driving the Tourism in Australia industry outlook?

What influences volatility in the Tourism in Australia industry?

- Industry Volatility vs. Revenue Growth Matrix

What determines the industry life cycle stage in the Tourism in Australia industry?

- Industry Life Cycle Matrix

Products and Markets

Products and services.

- Products and Services Segmentation

How are the Tourism in Australia industry's products and services performing?

What are innovations in the Tourism in Australia industry's products and services?

Major Markets

- Major Market Segmentation

What influences demand in the Tourism in Australia industry?

International Trade

- Industry Concentration of Imports by Country

- Industry Concentration of Exports by Country

- Industry Trade Balance by Country

What are the import trends in the Tourism in Australia industry?

What are the export trends in the Tourism in Australia industry?

Geographic Breakdown

Business locations.

- Share of Total Industry Establishments by Region ( )

Data Tables

- Number of Establishments by Region ( )

- Share of Establishments vs. Population of Each Region

What regions are businesses in the Tourism in Australia industry located?

Competitive Forces

Concentration.

- Combined Market Share of the Four Largest Companies in This Industry ( )

- Share of Total Enterprises by Employment Size

What impacts market share in the Tourism in Australia industry?

Barriers to Entry

What challenges do potential entrants in the Tourism in Australia industry?

Substitutes

What are substitutes in the Tourism in Australia industry?

Buyer and Supplier Power

- Upstream Buyers and Downstream Suppliers in the Tourism in Australia industry

What power do buyers and suppliers have over the Tourism industry in Australia?

Market Share

Top companies by market share:

- Market share

- Profit Margin

Company Snapshots

Company details, summary, charts and analysis available for

Company Details

- Total revenue

- Total operating income

- Total employees

- Industry market share

Company Summary

- Description

- Brands and trading names

- Other industries

What's influencing the company's performance?

External Environment

External drivers.

What demographic and macroeconomic factors impact the Tourism in Australia industry?

Regulation and Policy

What regulations impact the Tourism in Australia industry?

What assistance is available to the Tourism in Australia industry?

Financial Benchmarks

Cost structure.

- Share of Economy vs. Investment Matrix

- Depreciation

What trends impact cost in the Tourism in Australia industry?

Financial Ratios

- 3-4 Industry Multiples (2018-2023)

- 15-20 Income Statement Line Items (2018-2023)

- 20-30 Balance Sheet Line Items (2018-2023)

- 7-10 Liquidity Ratios (2018-2023)

- 1-5 Coverage Ratios (2018-2023)

- 3-4 Leverage Ratios (2018-2023)

- 3-5 Operating Ratios (2018-2023)

- 5 Cash Flow and Debt Service Ratios (2018-2023)

- 1 Tax Structure Ratio (2018-2023)

Data tables

- IVA/Revenue ( )

- Imports/Demand ( )

- Exports/Revenue ( )

- Revenue per Employee ( )

- Wages/Revenue ( )

- Employees per Establishment ( )

- Average Wage ( )

Key Statistics

Industry data.

Including values and annual change:

- Revenue ( )

- Establishments ( )

- Enterprises ( )

- Employment ( )

- Exports ( )

- Imports ( )

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the market size of the tourism industry in australia.

The market size of the Tourism industry in Australia is measured at in .

How fast is the Tourism in Australia market projected to grow in the future?

Over the next five years, the Tourism in Australia market is expected to . See purchase options to view the full report and get access to IBISWorld's forecast for the Tourism in Australia from up to .

What factors are influencing the Tourism industry in Australia market trends?

Key drivers of the Tourism in Australia market include .

What are the main product lines for the Tourism in Australia market?

The Tourism in Australia market offers products and services including .

Which companies are the largest players in the Tourism industry in Australia?

Top companies in the Tourism industry in Australia, based on the revenue generated within the industry, includes .

How many people are employed in the Tourism industry in Australia?

The Tourism industry in Australia has employees in Australia in .

How concentrated is the Tourism market in Australia?

Market share concentration is for the Tourism industry in Australia, with the top four companies generating of market revenue in Australia in . The level of competition is overall, but is highest among smaller industry players.

Methodology

Where does ibisworld source its data.

IBISWorld is a world-leading provider of business information, with reports on 5,000+ industries in Australia, New Zealand, North America, Europe and China. Our expert industry analysts start with official, verified and publicly available sources of data to build an accurate picture of each industry.

Each industry report incorporates data and research from government databases, industry-specific sources, industry contacts, and IBISWorld's proprietary database of statistics and analysis to provide balanced, independent and accurate insights.

IBISWorld prides itself on being a trusted, independent source of data, with over 50 years of experience building and maintaining rich datasets and forecasting tools.

To learn more about specific data sources used by IBISWorld's analysts globally, including how industry data forecasts are produced, visit our Help Center.

Deeper industry insights drive better business outcomes. See for yourself with your report or membership purchase.

Discover how 30+ pages of industry data and analysis can give you the edge you need..

International tourism to Australia

Quarterly results from the International Visitor Survey, trends and forecasts of international visitor activity.

Main content

Tourism Research Australia produces quarterly results from the International Visitor Survey, as well as trends and forecasts of international visitor activity.

International tourism results

Annual and quarterly International Visitor Survey results providing statistics on international visitors in Australia.

International tourism trends

Time series data for international visitors to Australia.

International Visitor Survey methodology

The International Visitor Survey (IVS) measures the contribution of international tourism to Australia’s economy and provides input into modelling spend for its regions.

Footer content

- The Star ePaper

- Subscriptions

- Manage Profile

- Change Password

- Manage Logins

- Manage Subscription

- Transaction History

- Manage Billing Info

- Manage For You

- Manage Bookmarks

- Package & Pricing

Global tourism is on the up and up this year

- Asia & Oceania

Tuesday, 16 Apr 2024

Related News

Smart Asia en route for listing on ACE Market

Smart asia to issue 93.5mil shares, en route to ace market listing, asia stocks bounce as soaring dollar pauses.

Photo: Pixabay

Next month, Melbourne in the Australian state of Victoria will play host to the Australian Tourism Exchange (ATE24). It is said to be the biggest tourism event to be held in the country since the pandemic ended.

For those of us in the industry, the ATE24 – held from May 19 to 23 at the Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre – is also one of the largest business-to-business or B2B events in the world. It is hoped that the event will bring lots of benefits to Australia’s inbound tourism market, as well as act as a platform for the country to show off its tourism products to the world.

This will be the 44th edition of the ATE, organised by both Tourism Australia and Visit Victoria.