clock This article was published more than 2 years ago

China was a brutal communist menace. In 1972, Richard Nixon visited, anyway.

A stunned world watched as the u.s. president met dictator mao zedong, whose rule had killed millions of chinese..

Chinese dictator Mao Zedong woke up early and got a shave and a haircut for the first time in months. He put on a crisp new suit and new shoes specially made for the occasion. He sat down in an armchair in the study of his home, a porcelain spittoon on the floor nearby.

Not far away, President Richard M. Nixon rested in a guesthouse, making notes on a legal pad. He wore a dress shirt with cuff links. He had just arrived in Beijing for a visit that had shocked the world. He hoped to meet Mao but was not certain when, or if, the Chinese leader would see him.

Suddenly, the word came, as if from an emperor, aides remembered: Mao would see Nixon. Immediately.

It was Feb. 21, 1972, and as stunned observers looked on, the hard-line, anti-communist president was taken away in a black limousine to meet the ruthless champion of global revolution.

The meeting between the two arch foes, 50 years ago Monday, and Nixon’s week-long visit to “Red China,” were earthshaking, the historian Margaret MacMillan wrote in her 2006 book “Nixon in China.”

Back then, it was inconceivable that China would one day be hosting the international spectacle of the Winter Olympics.

Winston Lord, a young American diplomat who was on the trip and present for the meeting with Mao, wrote later: “I run out of adjectives in describing its drama.”

“If Mr. Nixon had revealed he was going to the moon he could not have flabbergasted his world audience more,” The Washington Post had said in an editorial. “It is very nearly mind blowing.”

All the top American journalists were there — newspaper reporters from The Post and New York Times, famous network anchormen including Walter Cronkite, who had brought along electrically heated socks to ward off the cold of northern China.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning author James A. Michener was there. Future TV news superstar Barbara Walters was one of only three women in the media group, according to MacMillan.

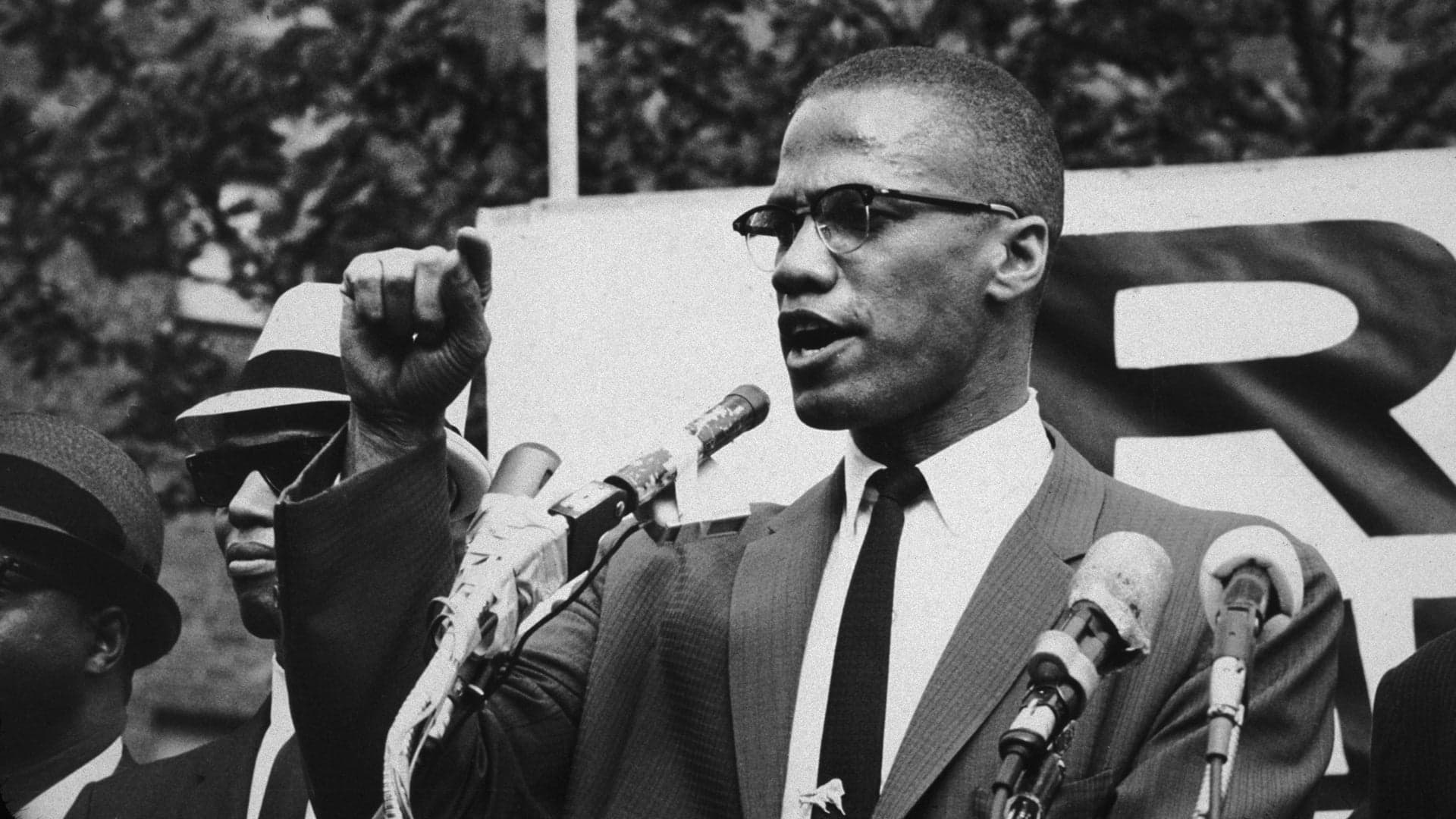

Nixon’s national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, who had secretly helped arrange the visit, was a key figure there.

So was Nixon’s White House chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, who meticulously stage-managed events but would be disgraced along with Nixon in the Watergate scandal , which began to unfold four months later.

The forgotten security guard who discovered the Watergate break-in

To impress the Americans, the Chinese set up fake outdoor scenes of picnickers with transistor radios. But after the VIPs had moved on, officials went around and collected all the radios, MacMillan wrote. And the picnickers were taken away on trucks, ABC’s Ted Koppel said later.

The trip was a blockbuster of a story, especially for television, which beamed back images of a country that had been hidden from the world for almost a quarter-century.

And it constituted a massive thaw in the Cold War.

Chinese premier Zhou Enlai offered first lady Pat Nixon a gift of two giant pandas, which ended up at the National Zoo in Washington. (The United States gave China two musk oxen in return.)

The president asked for the release of a CIA agent, John T. Downey, who had been taken prisoner 20 years before when his plane was shot down during the Korean War. Downey was freed the next year.

The Nixons went to the Great Wall, and the president said that only a great people could have constructed it.

There were toasts and banquets. Nixon had practiced using chopsticks. (One set he used was later filched as a souvenir by a Canadian reporter.)

China had been hostile and closed to the West for 23 years, exporting radical ideology even as it seethed internally.

“People of the world,” Mao had declared in 1964, “unite and defeat the U.S. aggressors and all their running dogs!”

“Monsters of all kinds shall be destroyed,” he said.

No American president had ever been to China. The United States refused to recognize the country’s communist government. There were few diplomatic contacts and scant business ties.

China “was the darkest, most mysterious part of the Communist empire,” Nixon aide Dwight Chapin recalled.

Nixon had accused China of spreading “insurrection, rebellion and subversion in every free country in Asia.”

“What do the Chinese Communists want?” he had asked. “They want the world.”

But now both sides wanted to talk.

Both feared the Soviet Union — the polar bear, as the Chinese called it. Chinese and Soviet troops had fought a nasty border skirmish along the remote Ussuri River in 1969.

The ex-chaplain still haunted by the Vietnam War’s most desperate siege

The United States wanted Chinese help getting out of Vietnam. The Chinese wanted the United States out of Taiwan. And China badly wanted acceptance on the world stage.

Since the end of World War II in 1945, much of the world had been locked in the titanic “Cold War” between Western democracies, led by the United States, and communist dictatorships, led by Soviet Russia and later China.

There had been crisis after crisis, the war in Korea in the 1950s that pitted the United States and South Korea and their allies against North Korea and China and their Soviet allies.

In 1972, the United States remained entangled in Vietnam, where 50,000 U.S. service members already had given their lives.

The Americans killed on a single, bloody day in Vietnam, and the wall that memorializes them

China, for its part, had undergone decades of famine and internal upheaval after Mao seized control in 1949 and imposed his draconian economic and cultural policies.

His disastrous Great Leap Forward economic campaign in the 1950s may have killed 40 million people, MacMillan wrote. Starving peasants should learn to eat less, Mao had decreed.

And the bloody upheaval of his Cultural Revolution of the 1960s may have killed a million more, historians believe.

By the winter of 1972, “Chairman Mao” was an aging cult figure. He had a bad heart, a chronic cough and had just gotten over pneumonia. And he ruled a vast but backward authoritarian state of 800 million people.

A successful early meeting with Nixon would benefit both men.

After getting off Air Force One, Nixon had greeted Zhou, the Chinese premier, with a hearty handshake.

The Americans knew that in 1954, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles had refused to shake Zhou’s hand at a conference in Geneva. And they knew the Chinese had not forgotten.

“Your handshake came over the vastest ocean in the world,” Zhou told Nixon as they rode to the guest quarters that Tuesday. On arrival, the Chinese gave the Americans lunch and then let them relax. There was to be a banquet that night.

But a short time later, Zhou was back. Mao wanted to see Nixon right away.

“I went and got the president,” Nixon aide Chapin said in an interview. Nixon changed out of a blue sport coat and into his suit coat. (Chapin, now 80, also was caught up in Watergate, and served several months in prison for lying to a grand jury.)

Nixon summoned Kissinger. Kissinger summoned his aide, Lord, who had done much of the research and preparation for the visit and had been on Kissinger’s secret trip to China the previous July.

Lord, now 83, said in an interview that Kissinger also wanted him along because he was a superb note taker — a skill that would allow Kissinger to concentrate on the meeting.

Nixon was pleased that Mao wanted to see him so soon. He, Kissinger, Lord, Secret Service agent Bob Taylor, and Zhou piled into a black Chinese car and headed for the compound where Mao lived.

“They are off to the races, and we have no idea where they are,” Chapin recalled. The staff decided not to say anything publicly, “because we couldn’t answer the questions: Where are they, or who’s with him.”

“We had to wait for him to get back before they could put out the news of what happened,” Chapin said.

Arriving at Mao’s modest home a few miles away, the Americans noticed a ping-pong table in the hallway. (The sport was a Chinese national pastime, and a team of U.S. players had created a sensation when they had visited China the year before.)

In the study, a female aide supported Mao by the arm as he stood up to shake Nixon’s hand. The group sat in a semicircle, in armchairs that had fringed slip covers.

Nixon sat beside Mao. Kissinger sat beside Nixon. Lord, then 34 and sporting conservative sideburns, sat beside Kissinger, taking notes.

“We were used to the elegant presentations, sometimes fairly lengthy, by Zhou Enlai,” Lord said. “So Kissinger and I were somewhat taken aback by Mao’s style. He spoke in brief sentences. He was bantering. He was self-deprecating. He kept deflecting substantive questions.”

His speech was also slurred, and he spoke with a heavy accent from Hunan, his home province in southern China, MacMillan wrote. The Americans thought he’d had a stroke.

The meeting, scheduled for 15 minutes, went on over an hour. Nixon tried to talk about Vietnam, Taiwan and Korea.

Mao called them “troublesome issues” that he would rather not discuss, according to Lord’s notes.

“I discuss the philosophical questions,” he said.

Nixon spoke of Mao’s writings, saying they “moved a nation and have changed the world.”

Mao, whose “Little Red Book” of quotations was waved by fanatics across China, said: “Those writings of mine aren’t anything. There is nothing instructive in what I wrote.”

He said: “I like rightists. People say you are rightists, that the Republican Party is to the right.”

Nixon replied: “In America, at least at this time, those on the right can do what those on the left talk about.”

“Over a period of years my position with regard to the People’s Republic was one that the Chairman ... totally disagreed with,” Nixon said. “What brings us together is a recognition of a new situation in the world.”

The general tone was cordial, if lacking in substance, and Nixon was delighted.

Chinese photographers took pictures of the group.

At the end of what Nixon called “the week that changed the world,” the two sides issued a communique stating their conflicting positions, agreeing to disagree.

But the United States got the Chinese to nudge the Vietnamese communists, MacMillan wrote.

The Soviets, rattled by the visit, became suddenly more agreeable.

And China got its lofty place on the world stage.

Fifty years later, though, Taiwan remains a flash point, as the United States has maintained close ties with the island, to the anger of the Chinese, who insist it is still part of China. And Russia is again a threatening presence in Europe.

After Nixon’s meeting with Mao, a group picture of the event ran on the front page of The Post and in newspapers across the country. But Lord had been cropped out of the shot.

“Lord was never at this meeting,” Lord said Nixon had ordered. “Cut him out of the ... photos. His presence is to be kept secret.”

“That was for a good reason, actually, even though it hurt my ego,” he said.

Secretary of State William Rogers had not been invited to the meeting, and Nixon didn’t want to humiliate him further by showing that a young Kissinger aide had been, Lord said.

On a trip to China a few months later, he said, Zhou gave him a copy of the uncropped photo.

“To prove I was there,” he said.

- How the Watergate scandal broke to the world: A visual timeline June 13, 2022 How the Watergate scandal broke to the world: A visual timeline June 13, 2022

- Microfilm hidden in a pumpkin launched Richard Nixon’s career 75 years ago December 2, 2023 Microfilm hidden in a pumpkin launched Richard Nixon’s career 75 years ago December 2, 2023

- Kissinger held a sobbing Nixon just before the president resigned November 30, 2023 Kissinger held a sobbing Nixon just before the president resigned November 30, 2023

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : February 21

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

President Nixon arrives in China for talks

In an amazing turn of events, President Richard Nixon takes a dramatic first step toward normalizing relations with the communist People’s Republic of China (PRC) by traveling to Beijing for a week of talks. Nixon’s historic visit began the slow process of the re-establishing diplomatic relations between the United States and communist China.

Still mired in the unpopular and frustrating Vietnam War in 1971, Nixon surprised the American people by announcing a planned trip to the PRC in 1972. The United States had never stopped formally recognizing the PRC after Mao Zedong’s successful communist revolution of 1949. In fact, the two nations had been bitter enemies. PRC and U.S. troops fought in Korea during the early-1950s, and Chinese aid and advisors supported North Vietnam in its war against the United States.

Nixon seemed an unlikely candidate to thaw those chilly relations. During the 1940s and 1950s, he had been a vocal cold warrior and had condemned the Democratic administration of Harry S. Truman for “losing” China to the communists in 1949. The situation had changed dramatically since that time, though. In Vietnam, the Soviets, not the Chinese, had become the most significant supporters of the North Vietnamese regime. And the war in Vietnam was not going well. The American people were impatient for an end to the conflict, and it was becoming increasingly apparent that the United States might not be able to save its ally, South Vietnam, from its communist aggressors.

The American fear of a monolithic communist bloc had been modified, as a war of words—and occasional border conflicts—erupted between the Soviet Union and the PRC in the 1960s. Nixon, and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger saw a unique opportunity in these circumstances—diplomatic overtures to the PRC might make the Soviet Union more malleable to U.S. policy requests (such as pressuring the North Vietnamese to sign a peace treaty acceptable to the United States). In fact, Nixon was scheduled to travel to meet Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev shortly after completing his visit to China.

Nixon’s trip to China, therefore, was a move calculated to drive an even deeper wedge between the two most significant communist powers. The United States could use closer diplomatic relations with China as leverage in dealing with the Soviets, particularly on the issue of Vietnam. In addition, the United States might be able to make use of the Chinese as a counterweight to North Vietnam. Despite their claims of socialist solidarity, the PRC and North Vietnam were, at best, strongly suspicious allies. As historian Walter LaFeber said, “Instead of using Vietnam to contain China, Nixon concluded that he had better use China to contain Vietnam.” For its part, the PRC was desirous of another ally in its increasingly tense relationship with the Soviet Union and certainly welcomed the possibility of increased U.S.-China trade.

Also on This Day in History February | 21

This Day in History Video: What Happened on February 21

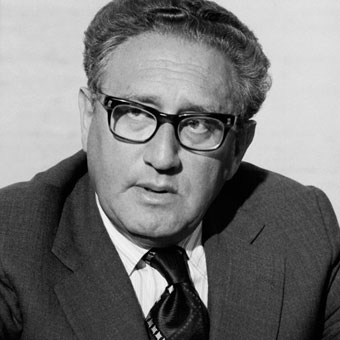

Rockefeller imposter and convicted felon born, dolly parton cements her crossover success as "9 to 5" hits #1, washington monument dedicated, karl marx publishes communist manifesto, malcolm x assassinated.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Henry Kissinger begins secret negotiations with North Vietnamese

Dick button wins second olympic figure skating gold, battle of valverde, nascar founded, japanese prime minister hideki tojo makes himself “military czar”, battle of verdun begins, allied troops capture jericho.

Help inform the discussion

Nixon on China

President Richard Nixon made an unprecedented trip to Beijing in 1972—and changed the trajectory of U.S.-China relations

President Richard Nixon, like his arch-rival President John F. Kennedy, was far more interested in foreign policy than in domestic affairs. It was in this arena that Nixon intended to make his mark. Although his base of support was within the conservative wing of the Republican Party, and although he had made his own career as a militant opponent of Communism, Nixon saw opportunities to improve relations with the Soviet Union and establish relations with the People's Republic of China.

Politically, he hoped to gain credit for easing Cold War tensions; geopolitically, he hoped to use the strengthened relations with Moscow and Beijing as leverage to pressure North Vietnam to end the war—or at least interrupt it—with a settlement. He would play China against the Soviet Union, the Soviet Union against China, and both against North Vietnam.

He would play China against the Soviet Union, the Soviet Union against China, and both against North Vietnam

Nixon took office intending to secure control over foreign policy from the White House. He kept Secretary of State William Rogers and Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird out of the loop on key matters of foreign policy. The instrument of his control over what he called "the bureaucracy" was his assistant for national security affairs, Henry Kissinger. So closely did the two work that they are sometimes referred to as "Nixinger." Together, they used the National Security Council staff to concentrate power in the White House—that is to say, within themselves.

Ping-pong diplomacy

A year before his election, Nixon had written that "there is no place on this small planet for a billion of its potentially most able people to live in angry isolation." Relations between the two great communist powers, the Soviet Union and China, had been deteriorating since the 1950s and had erupted into open conflict with border clashes during Nixon's first year in office.

The president sensed opportunity and began to send out tentative diplomatic feelers to China. Reversing Cold War precedent, he publicly referred to the Communist nation by its official name, the People's Republic of China.

A breakthrough of sorts occurred in the spring of 1971, when Mao Zedong invited an American table tennis team to China for some exhibition matches. Before long, Nixon dispatched Kissinger to secret meetings with Chinese officials. As America's foremost anti-Communist politician of the Cold War, Nixon was in a unique position to launch a diplomatic opening to China, leading to the birth of a new political maxim: "Only Nixon could go to China."

The announcement that the president would make an unprecedented trip to Beijing caused a sensation among the American people, who had seen little of the world's most populous nation since the Communists had taken power. Nixon's visit to China in February 1972 was widely televised and heavily viewed. It was only a first step, but a decisive one, in the budding rapprochement between the two states.

Detente with the Soviet Union

The announcement of the Beijing summit produced an immediate improvement in American relations with the U.S.S.R.—namely, an invitation for Nixon to meet with Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev in Russia. It was a sign that Nixon's effort at "triangulation" was working. Fear of improved relations between China and America was leading the Soviets to better their own relations with America, just as Nixon hoped. In meeting with the Soviet leader, Nixon became the first president to visit Moscow.

Of more lasting importance were the treaties the two men signed to control the growth of nuclear arms. The agreements—a strategic arms limitation treaty and an anti-ballistic missile treaty—did not end the arms race, but they paved the way for future pacts that sought to reduce and eliminate arms. Nixon also negotiated and signed agreements on science, space, and trade.

Withdrawal from Vietnam

While Nixon tried to use improved relations with the Soviets and Chinese to pressure North Vietnam to reach a settlement, he could only negotiate a flawed agreement that merely interrupted, rather than ended, the war.

In his first year in office, Nixon had tried to settle the war on favorable terms. Through secret negotiations between Kissinger and the North Vietnamese, the president warned that if major progress were not made by November 1, 1969, "we will be compelled—with great reluctance—to take measures of the greatest consequences."

We will be compelled—with great reluctance—to take measures of the greatest consequences

The NSC staff made plans for some of those options, including the resumed bombing of North Vietnam and the mining of Haiphong Harbor. Nixon then took a step designed both to interfere with Communist supplies and as a signal of willingness to act irrationally to achieve his goals: He secretly ordered the bombing of Communist supply lines on the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Cambodia.

Also in keeping with his intention to convey a sense of presidential irrationality—Nixon as "madman"—he launched a worldwide nuclear alert.

None of it worked. The North Vietnamese did not yield; Nixon did not carry out his threats; the war continued. Nixon did not know how to bring the conflict to a successful resolution.

None of it worked. The North Vietnamese did not yield. Nixon did not carry out his threats. The war continued

The president did not reveal any of this to the American people. Publicly, he said his strategy was a combination of negotiating and "Vietnamization," a program to train and arm the South Vietnamese to take over responsibility for their own defense, thus enabling American troops to withdraw. He began the withdrawals even before he issued his secret ultimatum to the Communists, periodically announcing partial troop withdrawals throughout his first term.

After a coup in Cambodia replaced neutralist leader Prince Sihanouk with a pro-American military government of dubious survivability, Nixon ordered a temporary invasion of Cambodia—the administration called it an "incursion"—by American troops.

After a coup in Cambodia, Nixon ordered a temporary invasion of that country—the administration called it an 'incursion'—by American troops

The domestic response included the largest round of antiwar protests in American history. It was during these protests in May 1970 that National Guardsmen fired at rock-throwing protestors at Kent State University in Ohio, killing four. Two weeks later, police fired on students at Jackson State University in Mississippi, leaving two more dead.

By the end of the year, Nixon was planning to finish the American military withdrawal from Vietnam within 18 months. Kissinger talked him out of it.

Nixon's chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, recorded this discussion in his diary on December 21, 1970: "Henry was in for a while and the president discussed a possible trip for next year. He's thinking about going to Vietnam in April [1971] or whenever we decide to make the basic end-of-the-war announcement. His idea would be to tour around the country, build up [South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van] Thieu and so forth, and then make the announcement right afterward. Henry argues against a commitment that early to withdraw all combat troops because he feels that if we pull them out by the end of '71, trouble can start mounting in '72 that we won't be able to deal with, and which we'll have to answer for at the elections. He prefers instead a commitment to have them all out by the end of '72 so that we won't have to deliver finally until after the [U.S. presidential] elections [in November 1972] and therefore can keep our flanks protected. This would certainly seem to make more sense, and the president seemed to agree in general, but he wants Henry to work up plans on it."

Henry argues against a commitment that early to withdraw all combat troops because he feels that if we pull them out by the end of '71, trouble can start mounting in '72 that we won't be able to deal with

In 1971, South Vietnamese ground forces, with American air support, took part in Lamson 719, an offensive against Communist supply lines on the Ho Chi Minh trail in Laos and Cambodia. Since American troops would not take part in ground combat operations in either country, Lamson was considered a test (at least a partial one) of the success of Vietnamization. By all accounts, it went badly, but it disrupted Communist supply lines long enough to aid the war effort.

By all accounts, Lamson went badly, but it disrupted Communist supply lines long enough to aid the war effort

Nixon and Kissinger anticipated that the biggest threat to their plans would be a dry-season Communist offensive in 1972. Their worst fears were realized when the North Vietnamese regular army poured into the South in March 1972. Nixon responded by implementing some of the plans he had made in 1969. He mined Haiphong Harbor and used B-52s to bomb the North. The combined power of the American and South Vietnamese military ultimately stopped the offensive, though not before the Communists had more territory under their control.

The North Vietnamese were eager to reach a settlement before the American presidential election and subsequent removal of U.S. forces from the country. Hanoi made a breakthrough proposal in October 1972 and reached agreement with Kissinger rapidly.

The South Vietnamese government balked, however, chiefly because the agreement preserved North Vietnamese control of all the territory Hanoi currently held. To turn up the political pressure on Nixon, the North Vietnamese began broadcasting provisions of the agreement. Kissinger held a press conference announcing that "peace is at hand" without giving away too many details.

After the election, Nixon told South Vietnamese president Thieu that if he did not agree to the settlement, Congress would cut off aid to his government—and that conservatives who had supported South Vietnam would lead the way.

He promised that the United States would retaliate militarily if the North violated the agreement. To back up this threat, he launched the "Christmas bombings" of 1972.

When negotiations resumed in January, the few outstanding issues were quickly resolved. Thieu backed down. The Paris Peace Accords were signed on January 23, 1973, bringing an end to the participation of U.S. ground forces in the Vietnam War.

Bob Woodward has called Ken Hughes “one of America's foremost experts on secret presidential recordings, especially those of Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon.” Hughes has spent two decades mining the Secret White House Tapes and unearthing their secrets. As a journalist writing in the pages of the New York Times Magazine , Washington Post , and Boston Globe Magazine , and, since 2000, as a researcher with the Miller Center, Hughes’ work has illuminated the uses and abuses of presidential power involved in (among other things) the origins of Watergate, Jimmy Hoffa’s release from federal prison, and the politics of the Vietnam War.

More about U.S.-China relations

Listen to Nixon's own words

After a brief discussion of the possibility of reshuffling ambassadorial appointments in the aftermath of the upcoming announcement of Nixon’s trip to China, the president turned to the size of the entourage he wished to accompany him to the summit in Beijing.

Nixon and Kissinger: July 1, 1971

The Impact of President Nixon's 1972 Visit to China

Nixon's landmark visit to china reshaped global diplomacy and relations..

President Richard Nixon made one of the most significant foreign visits in the history of the United States 50 years ago when he traveled to the People's Republic of China in February 1972. This historic trip marked a strategic diplomatic effort to warm relations between the United States and China, which had been estranged for over two decades. The visit not only had immediate implications for international relations but also set the stage for a significant shift in global politics.

An overview of Richard Nixon's February 1972 visit to China and associated Wilson Center publications and Digital Archive resources reveal the meticulous planning and careful negotiation that went into making this diplomatic breakthrough possible. The visit, which took place from February 21-28, 1972, was characterized by high-level meetings, cultural exchanges, and public displays of goodwill between the two nations.

Fifty years ago, US President Richard Nixon traveled to China and established the basis for a normalization of relations between the two countries. The visit was a turning point in the Cold War era, as it demonstrated that even bitter rivals could find common ground and work towards peaceful coexistence. The weeklong trip was hailed as a success, with both sides expressing a desire to move forward in a spirit of mutual respect and cooperation.

When US President Richard Nixon walked down the red-carpeted stairs from Air Force One to shake hands with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai on a cold February day in Beijing, the world watched in awe. The meeting between the leaders of these two powerful nations was a symbolic gesture of reconciliation and a step towards building trust and understanding between the United States and China.

Fifty years ago, a stunned world watched as Nixon met dictator Mao Zedong, whose rule had killed millions of Chinese. The historic handshake between Nixon and Mao signaled a willingness to put aside past grievances and work towards a more stable and peaceful relationship. The visit was seen as a bold move by Nixon, who was willing to take risks in pursuit of a more peaceful world.

Feb. 21 marks the 50th anniversary of President Richard Nixon's historic visit to the People's Republic of China. Heralded as “the week that changed the world,” Nixon's visit laid the groundwork for future cooperation between the United States and China. The trip was a bold diplomatic move that challenged conventional wisdom and paved the way for a new era of engagement between the two nations.

Fifty years ago today, President Nixon landed in Beijing for the historic weeklong trip that effectively ended the United States' long isolation from China. The visit was a watershed moment in international diplomacy, signaling a willingness on the part of both countries to set aside their differences and work towards a more peaceful and prosperous future. Nixon's visit to China was a bold and visionary move that reshaped the global political landscape.

May Interest You

UC Berkeley Library Update

The Week that Changed the World: Nixon Visits China

By Shannon White

February 2022 — This month marks the 50th anniversary of President Richard Nixon’s weeklong visit to China, a trip that resulted in the establishment of a formal diplomatic relationship between the governments of the United States and the People’s Republic of China.

The UC Berkeley Oral History Center’s collection contains several interviews discussing the event, as well as the political and public atmosphere that surrounded Nixon’s 1971 announcement of the impending trip. Included in these are the accounts of both Caroline and John Service, the latter a diplomat and member of the United States Foreign Service. The Services were among the few Americans welcomed back to the country in the early 1970s by Zhou Enlai, then the premier of the PRC.

In Caroline Service’s oral history, she discusses the era of “ping pong diplomacy” in the early 1970s that occurred prior to the president’s visit to China. “We were all electrified one day. . . by seeing on television, reading in the paper, seeing pictures that the American ping pong team was going to Peking,” Service recalls of this turning point in the relations between the two countries.

In this interview, Service also discusses the public perception of Richard Nixon at the time of the trip, echoing the popular opinion that only Nixon, as a staunch anti-communist with the support of his fellow political conservatives, could make such a move without widespread criticism. As Service says:

Now I have hardly a good word to say for Nixon. I have disliked him intensely forever, it seems to me, since ever he appeared on the political scene. Yet, I suppose that only a Republican conservative, reactionary almost, president could have done this. I do not think a Democrat could have done this. I think it had to be done.

In his oral history, Dr. Otto C. C. Lin, whose career is in Chinese technological innovation and entrepreneurship, offers his perspective on Henry Kissinger and Nixon traveling to China. When asked about the effects of the visit on Taiwan, Lin said, “Republicans were always considered friends for KMT [Kuomintang]. Hence, Nixon was considered a turncoat and Kissinger an accomplice of Nixon in betraying his friend, the ROC [Republic of China].” Ultimately, though, Lin says, “I think history would say that Nixon and Kissinger did the right thing to help open up China.”

Cecilia Chiang, a chef and entrepreneur credited with popularizing northern Chinese cuisine in the United States, discusses in her oral history the buzz surrounding the state dinner attended by Nixon and Kissinger during their visit. “The menu was printed in all these newspapers in the United States and also the Chinese Newspaper,” recalls Chiang, “People called in. Called in from New York, from Hawaii, called me. ‘Can you duplicate that dinner? That dinner for us. We would like to just fly in just for that dinner.’”

Chiang remembers her surprise at the simplicity of the meal, stating that when she saw the menu, “I started to laugh. They said, ‘Why do you laugh?’ They put bean sprouts on the menu, because China is so poor at the time. No food, no nothing.”

These interviews contain a wealth of insightful information concerning not just the presidential visit to China, but also the general political climate of US foreign relations in the 1970s. Caroline Service offers the perspective of a family who had by this point been involved in US foreign diplomacy for decades. Otto Lin leverages the Nixon visit in relation to the modern political, cultural, and economic landscape of China. Cecilia Chiang’s oral history provides a glimpse into the culinary landscape of China, a country still struggling with rationing and food shortages in the midst of the Cultural Revolution.

You can find the interviews mentioned here and all our oral histories from the search feature on our home page . Search by name, keyword, and several other criteria.

Shannon White is currently a third-year student at UC Berkeley studying Ancient Greek and Latin. They are an undergraduate research apprentice in the Nemea Center under Professor Kim Shelton and a member of the editing staff for the Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics . Shannon works as a student editor for the Oral History Center.

About the Oral History Center

The Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library has interviews on just about every topic imaginable. We preserve voices of people from all walks of life, with varying political perspectives, national origins, and ethnic backgrounds. We are committed to open access and our oral histories and interpretive materials are available online at no cost to scholars and the public.

Oral Histories Used Here

Caroline Service: State Dept. Duty in China, The McCarthy Era, and After 1933–1977

Otto C.C. Lin: Promoting Education, Innovation, and Chinese Culture in the Era of Globalization Volume I: Oral History

Cecilia Chiang: An Oral History

Related Resources from The Bancroft Library

Cecilia Chiang is included in the Chez Panisse, Inc. pictorial collection . BANC PIC 2001.192.

Caroline Service letters to Lisa Green : TLS and ALS, 1950 Sept.–1995 April. Bancroft BANC MSS 99/81 cz.

Caroline Schulz Service papers, 1919–1997. Bancroft BANC MSS 99/237 cz.

John S. Service papers, 1925–1999. BANC MSS 87/21 cz.

Monthly News & Updates from the Elliott School of International Affairs

50 years later: Richard Nixon’s Historic Visit to China

Two Elliott School faculty members who are leading international experts on U.S./China relations offer commentary on the 1972 foreign affairs breakthrough.

President Richard Nixon made one of the most significant foreign visits in the history of the United States 50 years ago when he traveled to the People’s Republic of China Feb. 21-28, 1972—ending two-plus decades of no communication or diplomatic ties between the two nations.

GW Today sat down with two leading international experts on U.S./China from the Elliott School of International Affairs to discuss the trip to Beijing 50 years later.

David Shambaugh , the Gaston Sigur Professor of Asian Studies, Political Science and International Affairs and director of the China Policy Program, served the State Department and National Security Council during President Jimmy Carter’s administration. He also served on the board of directors of the National Committee on U.S./China Relations and is a life member of the Council on Foreign Relations, U.S. Asia-Pacific Council and other public policy and scholarly organizations. Before GW, he was senior lecturer, lecturer and reader in Chinese politics at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, where he also served as editor of The China Quarterly.

Robert Sutter , Professor of Practice of International Affairs, had a government career that lasted from 1968 until 2001. He served as senior specialist and director of the Foreign Affairs and National Defense Division of the Congressional Research Service, the national intelligence officer for East Asia and the Pacific at the U.S. Government’s National Intelligence Council, the China division director at the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research and professional staff member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Shambaugh and Sutter were asked questions, some the same and some different, separately for this article.

Q: At the time, what was the significance of Nixon’s visit to China?

Shambaugh : President Nixon’s visit to China in February 1972 was described at the time as “the week that changed the world.” While perhaps hyperbole, there is indeed truth in this characterization—for three principal reasons. First, it ended the 22-year estrangement and total lack of contact between both the governments and the people of China and the United States. It would take another seven years before official diplomatic relations would be consummated under the Carter administration—where I worked on the China staff of the National Security Council staff at the time—which in turn opened a wide variety of direct ties between our two societies, but the Nixon visit catalyzed the process. Second, with the American opening to China, other governments around the world, which had been part of the previous U.S. policy to isolate and contain China, now were free to open their own relations with the People’s Republic of China—thus, in a real sense, the Nixon visit not only opened U.S./China relations, but it also did much to open China’s own doors to the world that had been previously almost completely isolated. Third, the Nixon visit was a strategic stroke of genius and fundamentally altered the balance of power in the so-called strategic triangle (U.S., China, Soviet Union) at the time, aligning America and China against Moscow. That, in turn, led over time to the weakening of the Soviet Union, its collapse and end of the Cold War.

Q: How was the event viewed in the U.S. at the time? What about in China?

Sutter: It was a big news item, and it was widely applauded. Everyone thought this was a great idea. The Chinese were on their best behavior. It was all very cordial. And it was in the interest of both sides to look like they were very close. China was desperate. And China was under the gun from the Soviet Union. It was very much in the Chinese interest because they were very worried about the U.S. and Soviet Union.

Q: Did Nixon’s China policy and visit facilitate the creation of modern China?

Shambaugh: Indirectly, yes. Nixon’s visit facilitated China’s broader opening the world, notably the Western world. This brought China in direct contact with the world’s most developed economies—which have been central to the foreign investment, technology transfer, and professional exchanges that have all contributed much to China’s dynamic economic growth since. But it also took the death of [Chinse President] Mao [Zedong] and the coming to power of Deng Xiaoping in 1978 to relax the repression and xenophobia within China, so the country could take advantage of the door that Nixon and Mao initially opened.

Q: What would be comparable to Nixon’s visit today?

Sutter: I just want to reiterate the fragility of China (in 1972). This was a dangerous mission. They were taking a risk. But they must have had enough evidence that they felt the president could be secured, and they could get him out if they had to. It was like going to North Korea today. China then was a lot like North Korea today. Very secretive. There’s so many things you didn’t know. It was a gamble, in a way.

Q: Why does the Nixon visit still fascinate so many? And why is it important for students today to learn about it?

Shambaugh: The Nixon visit continues to fascinate, in part, because it was such great public theater—because it took place on live television . Here was a society (Communist China) that had been completely closed off from the world since 1949, having recently been convulsed by the cultural revolution (from 1966-76), literally opening itself up for others to peer inside. The drama of Nixon meeting Mao [Zedong], being feted in the Great Hall of the People, touring the Great Wall and signing the Shanghai Communique was all riveting theater. As for students today, I am currently teaching my graduate-level U.S./China relations course this semester, and we watched the film ”History Declassified: Nixon in China” earlier this month, and I also invited to class Winston Lord—who was Nixon’s and [former Secretary of State] Henry Kissinger’s close aide. He participated in Kissinger’s secret 1971 trip to Beijing, the Nixon visit itself, played a key role in negotiating the Shanghai Communiqué, and later became America’s ambassador to China from 1985 until 1989. The students loved it. So, yes, the Nixon visit is still very much alive, at least in my class in the Elliott School. As for what students can still learn from it, I would say that no matter how great a gulf or differences can be between governments or peoples, there is always the possibility of improving ties. This is something we should remember about U.S./China relations when they are as strained as they are today.

Q: Nixon self-described the visit as a “week that changed the world.” Looking back 50 years later and where the two countries are now, is that statement accurate, far off, or somewhere in the middle?

Sutter: It fundamentally changed the world at the time, but the world has also changed since, and China changed. Maybe the United States has changed too, but China has definitely changed. It’s just more powerful. We never knew, we outsiders never knew what China would do if it became very powerful. There was no evidence to back that up. But now we have evidence of it. That changes our perceptions and, and that’s what’s happened over the last few years.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses cookies to offer you a better browsing experience. Visit GW’s Website Privacy Notice to learn more about how GW uses cookies.

Search form

You are here, nixon in china itinerary, feb. 17 -28, 1972.

February 17, 1972

After a departure ceremony on the South Lawn of the White House, the President and Mrs. Nixon went by helicopter to Andrews Air Force Base for the flight to Hawaii, en route to the People's Republic of China.

Arriving at Kaneohe Marine Corps Air Station, Oahu, Hawaii, the President and Mrs. Nixon motored to the residence of the Commanding General, First Marine Brigade, where they remained until Saturday afternoon, February 19, reading and preparing for the China visit.

Saturday, February 19-Sunday, February 20

The President and Mrs. Nixon boarded the Spirit of '76 at Kaneohe Marine Corps Air Station for the 8-hour flight to Guam. Crossing the International Date Line en route, they arrived at Guam International Airport shortly after 5 p.m. on Sunday, February 20, Guam time. They spent the night at Nimitz Hill, the residence of the Commander, Naval Forces, Marianas.

Monday, February 21

At 7 a.m., Guam time, the President and Mrs. Nixon left Guam International Airport for Shanghai, their first stop in the People's Republic of China. They arrived, after a 4-hour flight, at Hung Chiao (Rainbow Bridge) Airport, Shanghai, at 9 a.m., China time, where they were greeted by officials of the People's Republic, headed by Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Ch'iao Kuan-hua. After refreshments and a tour of the terminal, the Presidential party again boarded the Spirit of '76, accompanied by Vice Minister Ch'iao, Chang Wenchin and Wang Hai-jung of the Foreign Ministry, a Chinese navigator, radio operator, and three interpreters, for the final leg of the flight to Peking.

At about 11:30 a.m., China time, the party arrived at Capital Airport near Peking. Premier Chou En-lai greeted the President and members of his party, stood with the President for the playing of the national anthems of the two countries, and accompanied the President in a review of the troops.

The Premier then accompanied the President in a motorcade to Peking, to Taio Yu Tai (Angling Terrace), the guest house where the President and Mrs. Nixon would stay during their visit.

In the afternoon, the President met for an hour with Chairman Mao Tse-tung at the Chairman's residence and for an hour with Premier Chou and other officials in plenary session at the Great Hall of the People.

The President and Mrs. Nixon were guests of Premier Chou at a banquet in the Great Hall of the People in the evening.

Tuesday, February 22

After a morning of staff meetings and attention to other White House business, the President met for 4 hours with Premier Chou in the Great Hall.

The First Lady visited the kitchen of the Peking Hotel, where she toured food preparation and cooking areas, and talked with cooks and helpers. She was accompanied by Mme. Lin Chia-mei, wife of Vice Premier Li Hsiennien, Mme. Chi P'eng-fei, wife of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Sun Hsin-mang, head of the revolutionary committee of the hotel. During the tour, Mrs. Nixon told reporters of plans for the People's Republic to present to the people of America two giant pandas, in appreciation for the two musk oxen which were to be given to the Peking Zoo on behalf of the people of the United States.

In the afternoon, Mrs. Nixon visited the Sununer Palace, an imperial residence and garden during the Ching Dynasty. She toured rooms used by the Empress Tzu Hsi and walked in the gardens, viewing the lake Kun Ming and Longevity Hill. She then went to the Peking Zoo and saw the zoo's pandas.

In the evening, the President and First Lady attended a cultural program with Premier and Madame Chou and Chiang Ch'ing, the wife of Chairman Mao Tse-tung. They saw a performance of the ballet, "The Red Detachment of Women."

Wednesday, February 23

The President and Premier Chou met in the afternoon for four hours of discussions at the guest house where the President was staying.

The First Lady visited the Evergreen People's Commune on the west edge of Peking. In her hour-long tour, she visited the commune's clinic, where she observed acupuncture treatments, second- and third-grade classrooms, a commune home, agricultural areas and greenhouses, and a dri goods store.

In the afternoon, Mrs. Nixon visited the Peking Glassware Factory and talked with workers making glass flowers and animals.

In the evening, with Premier Chou En-lai, the President and Mrs. Nixon attended a public exhibition of gymnastics, badminton, and table tennis at the Capital Gymnasium.

Thursday, February 24

The President and Mrs. Nixon, accompanied by Vice Premier Li Hsien-nien, drove 35 miles north of Peking to visit the Ba Da Ling portion of the Great Wall of China, and then the tombs of the emperors of the Ming Dynasty.

In the afternoon, the President and Premier Chou met again for three hours of discussion. The President and Mrs. Nixon later attended an informal private dinner hosted by Premier Chou in the Great Hall.

Friday, February 25

In the morning, the President and Mrs. Nixon went to the Forbidden City, the site in Peking of the residence of the emperors for some 8oo years prior to the early 20th century. They were accompanied by Marshal Yeh Chien-ying, Vice Chairman of the Military Affairs Commission.

In the afternoon, the President met again with Premier Chou for an hour.

The First Lady toured the Peking Children's Hospital.

Marking the final evening of their Peking, stay, the President and the First Lady hosted a banquet honoring Premier Chou and other Chinese officials in the Great Hall.

Saturday, February 26

At the Peking Airport, the President and Premier Chou and other officials of the United States and the People's Republic met in plenary session for approximately one hour.

The President and the First Lady, with Premier Chou, then boarded the Premier's plane for the flight to Hangchow, People's Republic of China. From Hangchow Airport, they drove to a guest house on West Lake, a park and recreational site. where they were to spend the night.

In the afternoon, thev joined in a walking tour of Flower Fort Park and a boat tour of West Lake, stopping briefly at the Island of Three Towers Reflecting the Moon. Mrs. Nixon also visited the Temple of the Great Buddha.

They were entertained in the evening at a banquet given by the Chekiang Province Revolutionary Committee.

Sunday, February 27

With Premier Chou, the President and the First Lady flew in the Premier's plane from Hangchow Airport to Shanghai. From Shanghai Airport, they motorcaded to the Shanghai Industrial Exhibition, where, with Premier Chou, they toured exhibits of heavy machinery and electronic equipment, handicrafts, surgical techniques, textiles, light industry, musical instruments, toys, and arts and crafts.

Mrs. Nixon also visited the Shanghai Municipal Children's Palace, where she watched demonstrations of dancing, gymnastics, a puppet show, theatrics, swordplay, and art by students at the center. Her guide was Chang Hong, a fifth-grade student.

In the late afternoon, the joint communique agreed upon by the President and Premier Chou was released.

In the evening, the President and First Lady were guests at a banquet in the Shanghai Exhibition Hall hosted by the Shanghai Municipal Revolutionary Committee. Premier Chou and Committee Chairman Chang Ch'un-ch'iao then accompanied the President and Mrs. Nixon to a cultural program of acrobatics in the Exhibition Hall.

Monday, February 28

Premier Chou visited with the President for an hour at the Ching Kiang guest house and then accompanied the Presidential party to the airport for official farewells before the takeoff for the return flight at 10 a.m.

Crossing the International Date Line, the Spirit of '76 arrived at Elmendorf Air Force Base, Anchorage, Alaska, at midnight on Sunday, February 27, Alaska time. The President and the First Lady spent the night at the residence of the Commanding General and left for the final leg of the flight to Washington at 9:40 a.m. on Monday, February 28, Alaska time.

The official party arrived at Andrews Air Force Base near Washington at 9:15p.m, E.S.T.

- Richard Nixon

- Documents - US-China

- Nixon, Richard

Featured Articles

Happy Year of The Dragon! 祝您龙年快乐!

Happy Lunar New Year from the USC US-China Institute!

Passings, 2023

We note the passing of many prominent individuals who played some role in U.S.-China affairs, whether in politics, economics or in helping people in one place understand the other.

From Netflix to iQiyi: As the World Turns, Serial Dramas in Virtual Circulation

Ying Zhu looks at new developments for Chinese and global streaming services.

The War for Chinese Talent in the United States

David Zweig examines China's talent recruitment efforts, particularly towards those scientists and engineers who left China for further study. U.S. universities, labs and companies have long brought in talent from China. Are such people still welcome?

About Search

Richard Nixon

Chronology of visit to the people's republic of china. february 17-28, 1972.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The following chronology of events was prepared from White House announcements and outlines public activities of the President and Mrs. Nixon during their visit to the People's Republic of China.

Thursday, February 17

After a departure ceremony on the South Lawn of the White House, the President and Mrs. Nixon went by helicopter to Andrews Air Force Base for the flight to Hawaii, en route to the People's Republic of China.

Arriving at Kaneohe Marine Corps Air Station, Oahu, Hawaii, the President and Mrs. Nixon motored to the residence of the Commanding General, First Marine Brigade, where they remained until Saturday afternoon, February 19, reading and preparing for the China visit.

Saturday, February 19-Sunday, February 20

The President and Mrs. Nixon boarded the Spirit of '76 at Kaneohe Marine Corps Air Station for the 8-hour flight to Guam. Crossing the International Date Line en route, they arrived at Guam International Airport shortly after 5 p.m. on Sunday, February 20, Guam time. They spent the night at Nimitz Hill, the residence of the Commander, Naval Forces, Marianas.

Monday, February 21

At 7 a.m., Guam time, the President and Mrs. Nixon left Guam International Airport for Shanghai, their first stop in the People's Republic of China. They arrived, after a 4-hour flight, at Hung Chiao (Rainbow Bridge) Airport, Shanghai, at 9 a.m., China time, where they were greeted by officials of the People's Republic, headed by Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Ch'iao Kuan-hua. After refreshments and a tour of the terminal, the Presidential party again boarded the Spirit of '76, accompanied by Vice Minister Ch'iao, Chang Wenchin and Wang Hai-jung of the Foreign Ministry, a Chinese navigator, radio operator, and three interpreters, for the final leg of the flight to Peking.

At about 11:30 a.m., China time, the party arrived at Capital Airport near Peking. Premier Chou En-lai greeted the President and members of his party, stood with the President for the playing of the national anthems of the two countries, and accompanied the President in a review of the troops.

The Premier then accompanied the President in a motorcade to Peking, to Taft Yu Tai (Angling Terrace), the guest house where the President and Mrs. Nixon would stay during their visit.

In the afternoon, the President met for an hour with Chairman Mao Tse-tung at the Chairman's residence and for an hour with Premier Chou and other officials in plenary session at the Great Hall of the People.

The President and Mrs. Nixon were guests of Premier Chou at a banquet in the Great Hall of the People in the evening.

Tuesday, February 22

After a morning of staff meetings and attention to other White House business, the President met for 4 hours with Premier Chou in the Great Hall.

The First Lady visited the e kitchen of the Peking Hotel, where she toured food preparation and cooking areas, and talked with cooks and helpers. She was accompanied by Mme. Lin Chia-mei, wife of Vice Premier Li Hsiennien, Mme. Chi P'eng-fei, wife of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Sun Hsin-mang, head of the revolutionary committee of the hotel. During the tour, Mrs. Nixon told reporters of plans for the People's Republic to present to the people of America two giant pandas, in appreciation for the two musk oxen which were to be given to the Peking Zoo on behalf of the people of the United States.

In the afternoon, Mrs. Nixon visited the Summer Palace, an imperial residence and garden during the Chins Dynasty. She toured rooms used by the Empress Tzu Hsi and walked in the gardens, viewing the lake Kun Ming and Longevity Hill. She then went to the Peking Zoo and saw the zoo's pandas.

In the evening, the President and First Lady attended a cultural program with Premier and Madame Chou and Chiang Ch'ing, the wife of Chairman Mao Tse-tung. They saw a performance of the ballet, "The Red Detachment of Women."

Wednesday, February 23

The President and Premier Chou met in the afternoon for 4 hours of discussions at the guest house where the President was staying.

The First Lady visited the Evergreen People's Commune on the west edge of Peking. In her hour-long tour, she visited the commune's clinic, where she observed acupuncture treatments, second- and third-grade classrooms, a commune home, agricultural areas and greenhouses, and a dry goods store.

In the afternoon, Mrs. Nixon visited the Peking Glassware Factory and talked with workers making glass flowers and animals.

In the evening, with Premier Chou En-lai, the President and Mrs. Nixon attended a public exhibition of gymnastics, badminton, and table tennis at the Capital Gymnasium.

Thursday, February 24

The President and Mrs. Nixon, accompanied by Vice Premier Li Hsien-nien, drove 35 miles north of Peking to visit the Ba Da Ling portion of the Great Wall of China, and then the tombs of the emperors of the Ming Dynasty.

In the afternoon, the 'President and Premier Chou met again for 3 hours of discussion. The President and Mrs. Nixon later attended an informal private dinner hosted by Premier Chou in the Great Hall.

Friday, February 25

In the morning, the President and Mrs. Nixon went to the Forbidden City, the site in Peking of the residence of the emperors for some 800 years prior to the early 20th century. They were accompanied by Marshal Yeh Chien-ying, Vice Chairman of the Military Affairs Commission.

In the afternoon, the President met again with Premier Chou for an hour.

The First Lady toured the Peking Children's Hospital.

Marking the final evening of their Peking stay, the President and the First Lady hosted a banquet honoring Premier Chou and other Chinese officials in the Great Hall.

Saturday, February 26

At the Peking Airport, the President and Premier Chou and other officials of the United States and the People's Republic met in plenary session for approximately one hour.

The President and the First Lady, with Premier Chou, then boarded the Premier's plane for the flight to Hangchow, People's Republic of China. From Hangchow Airport, they drove to a guest house on West Lake, a park and recreational site, where they were to spend the night.

In the afternoon, they joined in a walking tour of Flower Fort Park and a boat tour of West Lake, stopping briefly at the Island of Three Towers Reflecting the Moon. Mrs. Nixon also visited the Temple of the Great Buddha.

They were entertained in the evening at a banquet given by the Chekiang Province Revolutionary Committee.

Sunday, February 27

With Premier Chou, the President and the First Lady flew in the Premier's plane from Hangchow Airport to Shanghai. From Shanghai Airport, they motorcaded to the Shanghai Industrial Exhibition, where, with 'Premier Chou, they toured exhibits of heavy machinery and electronic equipment, handicrafts, surgical techniques, textiles, light industry, musical instruments, toys, and arts and crafts.

Mrs. Nixon also visited the Shanghai Municipal Children's Palace, where she watched demonstrations of dancing, gymnastics, a puppet show, theatrics, swordplay, and art by students at the center. Her guide was Chang Hong, a fifth-grade student.

In the late afternoon, the joint communiqué ¡greed upon by the President and Premier Chou was released.

In the evening, the President and First Lady were guests at a banquet in the Shanghai Exhibition Hall hosted by the Shanghai Municipal Revolutionary Committee. Premier Chou and Committee Chairman Chang Ch'un-ch'iao then accompanied the President and Mrs. Nixon to a cultural program of acrobatics in the Exhibition Hall.

Monday, February 28

Premier Chou visited with the President for an hour at the Ching Kiang guest house and then accompanied the Presidential party to the airport for official farewells before the takeoff for the return flight at 10 a.m.

Crossing the International Date Line, the Spirit of '76 arrived at Elmendorf Air Force Base, Anchorage, Alaska, at midnight on Sunday, February 27, Alaska time. The President and the First Lady spent the night at the residence of the Commanding General and left for the final leg of the flight to Washington at 9:40 a.m. on Monday, February 28, Alaska time.

The official party arrived at Andrews Air Force Base near Washington at 9:15 p.m., e.s.t.

APP Note 1: This document is undated but the American Presidency Project used the first date of the chronology as the date for inclusion in our database.

APP Note 2: This is Public Papers of the Presidents, Richard Nixon: 1972, document #63A

Richard Nixon, Chronology of Visit to the People's Republic of China. February 17-28, 1972 Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/255085

Filed Under

Simple search of our archives, report a typo.

Faculty Scholarship

When nixon went to china.

On the 50th anniversary of President Nixon’s trip, China experts William Alford and Mark Wu discuss that history-making journey

On February 21, 1972, Richard Nixon became the first sitting United States president to set foot in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Over the course of a week, he met with Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong, negotiated with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, and toured historical and cultural institutions including the Great Wall, the Forbidden City, Shanghai, and Hangzhou. Fifty years after Nixon’s history-making journey, Harvard Law Today turned to two China experts to understand its significance, both then and now. William P. Alford ’77 is the Jerome A. and Joan L. Cohen Professor of Law and director of the East Asian Legal Studies Program. Mark Wu is the Henry L. Stimson Professor of Law. They stress the need to see the trip not only through a U.S.-centric lens and caution that, for all the change it spurred, its full import remains to be seen.

Harvard Law Today: This is the 50th anniversary of Richard Nixon’s trip to China. What was the backdrop?

Nixon repeatedly tried to cast Kennedy as soft in his willingness to defend allies against communism. So, the fact that Nixon, as president, would be willing to embark in outreach to Beijing came as a surprise. Mark Wu, Henry L. Stimson Professor of Law

Mark Wu: On July 15, 1971, President Nixon shocked the world by announcing that he was planning to visit the PRC the next year. In the aftermath of the Chinese civil war, the communists had captured mainland China and declared the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. The Nationalist government, supported by the Americans, fled to Taiwan, where the Republic of China (ROC) continued to be recognized by the United States and most other Western countries as the legitimate government for all of China.

Throughout the 1950s and much of the 1960s, the U.S. and PRC maintained a frosty relationship. The two sides fought each other during the Korean War, and the U.S. had troops based on Taiwan. Nixon himself had served as vice president during the Eisenhower administration, which had been steadfast in its support of the ROC, when the Chinese Communists attempted to retake the islands of Kinmen and Matsu. Those islands featured repeatedly during the famous 1960 presidential debates when Nixon repeatedly tried to cast Kennedy as soft in his willingness to defend allies against communism. So, the fact that Nixon, as president, would be willing to embark in outreach to Beijing came as a surprise.

William P. Alford: Thank you, Mark. To be sure, some American academics, including Jerome Cohen, who was the founding director of Harvard’s East Asian Legal Studies program, had from the late ’60s been urging a re-evaluation of U.S.-China policy. (As you know, the professorship I am now privileged to hold is named in honor of Jerry and Joan Cohen.)

HLT: What was most significant about that trip? What is not well understood about it?

Alford: I think that, as with so much else in the U.S.-China relationship for the past two centuries, treatment of the Nixon trip remarkably has been viewed almost exclusively through a U.S. prism, with almost no attention to the Chinese side. That lack of attention has been very costly for the relationship, inflating our sense of agency and fostering undue expectations among policymakers here and in the American public more generally about our capacity to shape events in China to our liking.

As with so much else in the U.S.-China relationship for the past two centuries, treatment of the Nixon trip remarkably has been viewed almost exclusively through a U.S. prism William P. Alford ’77, Jerome A. and Joan L. Cohen Professor of Law

The outreach by Nixon and [National Security Adviser Henry] Kissinger was of great consequence, of course, but the portrayal of China as entirely passive waiting for the U.S. to come along irks me. Yes, China was still experiencing the turmoil of the latter years of the Cultural Revolution, but let’s not forget that the PRC had its own agenda which it used the visit to help advance. The trip provided the opportunity, which it seized, to alter its own troubled relationship with the Soviet Union, to reduce tensions with the U.S. — which had regarded the PRC as an implacable enemy — and, for some leaders, to foster a potential source of help as China sought to compensate for years lost to that turmoil.

This undue focus on ourselves shows up again in the 1980s and 1990s, when far too many Americans — including policymakers and academics — assumed that the PRC wanted nothing more than to emulate us and converge toward an idealized version of our economy, law and society. While very much a product of the “end of history” hubris here that reached its apogee with the collapse of the Soviet Union, that attitude seemed to me at that time to be woefully inattentive to China’s history and contemporary circumstances and not especially discerning about our own country or the course of world history.

These days we see the same inattention but with the opposite coloration. The conventional wisdom here treats almost every major decision in China as being driven by its antipathy toward the U.S. There certainly is antipathy there, but in trying to understand its policy decisions, we shouldn’t be ignoring either domestic considerations there or China’s need to address certain challenges that all nations face.

Wu: No doubt the reversal of U.S. foreign policy toward the PRC in the 1970s will be seen as an important historical inflection point. But the story is still playing itself out — we are only fifty years into a historical event that may require several more decades before its eventual outcome is known. And it’s only one of several important “what if” moments, where we can second-guess the counterfactual about what would’ve happened otherwise.

The visit and subsequent normalization of relations with the West provided the ideological cover necessary for the economic reforms of the 1980s that launched China from a pariah state to the economic juggernaut that it is today. Mark Wu

As for the visit itself, I agree with Bill’s prescient observation that we pay too little attention to what was happening within China itself. By the time of Nixon’s visit, Mao was ailing, and his succession plans, as set forth by the 1969 Party Congress, had fallen apart. During the ensuing two decades, various factions in the party would fight over whether economic and political reform was necessary. The visit and subsequent normalization of relations with the West provided the ideological cover necessary for the economic reforms of the 1980s that launched China from a pariah state to the economic juggernaut that it is today.

Another element that is not well understood is how divided U.S. allies were in their China policy in the early 1970s. France had already severed diplomatic ties with Taipei and normalized relations with the People’s Republic in 1964, and Canada and Italy did so in 1970. The U.K., West Germany, Japan, and Australia quickly switched their diplomatic recognition in the months following the Nixon visit, even though the U.S. would not formally do so until 1979. Nixon did not shift the West’s policy toward Communist China; it was already happening. We still suffer from the illusion that the U.S. can successfully lead the West in a strong unified response to China, when in fact, our allies historically have been generally more willing to placate Beijing.

HLT: It is generally portrayed as Nixon changing the world — indeed, leading to the phrase a “Nixon goes to China” moment. What’s your assessment of that?

Alford: It also irks me that Nixon is seen as a global strategic genius. Let’s not forget his central role in the Red Scare rhetoric that essentially prevented other political figures from advocating for engagement with the PRC in a more tempered manner. His attacks on Jerry Voorhis and Helen Gahagan Douglas for being “soft on communism” were instrumental in his early electoral victories and, as Mark noted, he sought to deploy that same strategy against Kennedy in the 1960 presidential race. Had Nixon not helped foster that atmosphere, arguably there would have been no need for a “Nixon goes to China” moment or it would have been much less dramatic. I can’t help but see his behavior on this front as redolent of the duplicity we saw in his approach to the Vietnam War and race relations at home, and that eventually did him in.

Wu: The phrase “Nixon goes to China” is overused to describe all sorts of political events where individuals flip positions and bring their followers along. I also think that in today’s world of fragmented social media, it’s also much harder to pull off than it was in the early 1970s.

The visit certainly laid the groundwork for a much more stable relationship between China and the West for decades to come. This fostered sustained economic growth. But whether the visit truly changed the course of world history, as I said earlier, it’s far too early to tell. I think it’s only one of a series of contingent events that altered the course of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Domestic events in China that followed the visit, such as Deng Xiaoping prevailing in the leadership struggle, will likely prove even more important.

HLT: Why was the trip, and the agreement coming out of it, significant? How has it framed the subsequent development of the U.S.-PRC relationship?

Wu: The visit resulted in the issuance of the Shanghai Communiqué, which provided the pathway for the Carter administration to normalize relations with the People’s Republic. The communiqué also contained an acknowledgment that the U.S. does not challenge the view that there is only “one China” and that “Taiwan is a part of China” — and therefore helped shape the policy of U.S. strategic ambiguity toward Taiwan that remains today.

Alford: The U.S. and PRC were certainly not going to agree on everything and the intentional ambiguity that marked the Shanghai Communiqué proved beneficial for decades. When I accompanied then-Dean Martha Minow to Taiwan in 2013, we had a very stimulating conversation with then-President Ma Ying-jeou S.J.D. ’81, who had been a classmate, about times when ambiguity may be preferable to clarity. One could, however, also argue that some of the massive distrust that marks the U.S.-PRC relationship today stems in part from the fact that the public in China and, to a lesser degree, the U.S. was not apprised of the extent to which Beijing and Washington’s positions regarding Taiwan diverged in 1972 and, then again, when the Carter administration normalized relations in the late 1970s.

HLT: What have been the implications of that trip for Taiwan?

Alford: The Nixon trip certainly caught Taiwan off guard, as did the normalization of U.S.-PRC relations during the Carter administration. And while Taiwan’s democratization is predominantly attributable to domestic factors, I do think a secondary consideration has been to distinguish itself from the PRC internationally.

The Nixon trip certainly caught Taiwan off guard, as did the normalization of U.S.-PRC relations during the Carter administration. William Alford

Wu: Taiwan saw the Nixon and Carter administration’s actions as betrayals. The U.N. expulsion, the Nixon visit, and the severing of diplomatic ties by many countries afterwards catapulted Taiwan into a diplomatic isolation that is still ongoing.

HLT: How would you characterize U.S.-PRC relations these days?

Wu: There are areas of profound disagreement, but also narrower areas where the two sides may choose to cooperate. Overall, I think we’re in a period of strategic competition, with a lingering sense of mistrust on both sides.

Alford: It is no exaggeration to say that this is the most important bilateral relationship in the world. As Mark suggests, there are and will be areas of profound disagreement, given important differences in values. That said, it seems to me that without some measure of principled engagement (meaning an engagement in which we do not abandon our values), no global regime (be it about climate change, trade, rights or anything else) will flourish.

HLT: You each have personal and professional ties with respect to the PRC and Taiwan. What has the Nixon visit meant to you?

Alford: Professionally and personally, I have been a beneficiary of the trip. I remember as a student in Cambridge, England being excited seeing Nixon’s reception in Beijing covered extensively on the BBC and itching to get there. Later that decade, I made my first of what became scores of trips to China that have informed my research and teaching greatly. I have benefited from having superb students and excellent colleagues from China, as well as Taiwan. Most importantly, but for the opening, I would not, while in the mid-1980s creating the first academic program in U.S. law in the PRC, have met my wonderful wife. She, by the way, remembers Nixon’s visit to her hometown of Hangzhou — during which all but selected individuals were ordered to stay inside.

Wu: Gish Jen, a visiting professor in the English department, just released a new book, “Thank You Mr. Nixon.” It’s a wonderful read. Although fictional, it illustrates how the Nixon visit impacted the subsequent lives of numerous Chinese American families. Mine was one of those. At the time of the visit, my grandparents, my father, and my aunt were all in the U.S., but two of my uncles and their families had remained in China after 1949. For two decades, my grandparents had been afraid to get in touch, lest it cause further harm to my uncles. In fact, they weren’t even sure my uncles had survived the Cultural Revolution. Only after the Nixon visit did my father dare to reach out to his brothers, leading to the family being reunited many years later.

Modal Gallery

Gallery block modal gallery.

- Asia-Pacific

- Middle-East and Africa

- Learn Chinese

File: Premier Zhou Enlai (R) and U.S. President Richard Nixon shake hands at an airport in Beijing, China, February 21, 1972. /Xinhua

On the morning of February 21, 1972, when he strode down the stairs of Air Force One after landing in Beijing, U.S. President Richard Nixon was quick to extend his hand toward Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai.

"Your hand has reached across the world's broadest ocean to shake mine," Premier Zhou told the first sitting U.S. president to visit the People's Republic of China. "It's been 25 years of no communication."

"When our hands met, one era ended and another began," Nixon wrote about the encounter later in his memoir.

Fifty years later, China and the United States are now holding a series of commemorative activities to honor the beginning of the era that has seen increasingly interwoven contacts and exchanges in different fields between the world's two largest economies today, and to take stock of the history and look into the future.

Leading up to the visit

On the first day of Nixon's trip, or rather, just hours after his arrival in the Chinese capital, Chairman Mao Zedong met with him at Zhongnanhai, the leadership compound in downtown Beijing. They talked for more than an hour, and had a "serious and frank" exchange of views on China-U.S. relations and world affairs.

The face-to-face meeting between the two leaders came after years of testing and contact between the Chinese and the American sides.

In the late 1960s, when great changes took place in the world situation, both governments readjusted their diplomatic policies. In 1970, China and the United States resumed talks on the ambassador level.

Since his first days in office, Nixon had repeatedly signaled his desire to secure a U.S.-China rapprochement. To that end, he took the initiative through Pakistan and Romania to pass on messages to China.