Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2019

Using the ‘journey metaphor’ to restructure philosophy of religion

- Timothy Knepper 1

Palgrave Communications volume 5 , Article number: 43 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

4178 Accesses

3 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

This essay forwards a new orientation and point of origin for philosophy of religion—an orientation that does not privilege theism, and a point of origin that does not begin with the attributes and proofs of God (and thereby privilege theism). To do so, it turns to the metaphor theory of George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, specifically their analysis of the metaphor life is a journey . It draws on the internal structure of the journey metaphor to identify its core, constituent parts: journeys have a point of origin and destination, a route that is planned, obstacles and sights that are encountered along the way, and a traveler who is accompanied by and encounters other travelers. It then uses these core, constituent parts to generate five philosophical questions about the “journey” of the self and five philosophical questions about the “journey” of the cosmos: (1) Who am I (as traveler)?; (2) Where do I come from?; (3) Where am I going?; (4) How do I get there?; (5) What obstacles lie in my way?; (6) What is the cosmos?; (7) Where does the cosmos come from?; (8) Where is the cosmos going?; (9) How does the cosmos get there?; (10) What obstacles lie in the cosmos’ way? The majority of the essay then shows how each of these questions generates topics for global philosophy of religion and embraces content from a diversity of religious philosophies. Thus, this essay concludes that the journey metaphor is able to offer a new orientation and point of origin for philosophy of religion that is inclusive of a global diversity of religious traditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

The hedgehog, fox, and quasi-hedgehog approaches in Isaiah Berlin’s, David McLellan’s, and G. Stedman Jones’ Marx research

Reframing the narrative of magic wind in Arthur Waley’s translation of Journey to the West: another look at the abridged translation

The Rosetta Stone and the Nemrud Nomos: the discovery of significant textual and astronomical similarities

Why the journey metaphor.

The premise of this paper is that philosophy of religion is in need of a new orientation and point of origin—an orientation that does not privilege theism, and a point of origin that does not begin with the attributes and proofs of God (and thereby privilege theism). Footnote 1 I won’t spend time offering arguments to support this premise, save to maintain that if philosophy of religion is to be the philosophy of (all) religion, then it needs not only to include all religious traditions and communities (insofar as possible) but also to treat all religious traditions and communities evenhandedly. Insofar as philosophy of religion begins with and remains confined to the philosophical problems of a certain theistic (Christian) God, it can do neither.

My premise is merely the launching point for the rest of my paper, which seeks to offer a different orientation and point of origin for “global-critical” philosophy of religion—philosophy of religion that is globally inclusive of many different religious traditions and critically informed by the academic study of religion. Footnote 2 (Henceforth, I will drop the “global-critical” adjective and just speak of “philosophy of religion” since philosophy of religion really ought to be global and critical.) In my view, there are at least three places where one could look for such an orientation and point of origin: one could turn to a religious tradition that is not theistic, look for the philosophical commonalities in all religious traditions, or seek an orientation and origin that is not proprietary to any religious tradition. For reasons that I’ll now explain, my preference is for the third option.

For me, the first option risks repeating the mistakes of the Enlightenment—i.e., making some particular religious tradition normative in the philosophy of religion. Supposing, for example, that we look to East Asian religious philosophy for a new start for philosophy of religion. Our central topics and issues might then concern moral, political, and mystical philosophy: how to live in harmony with the natural, social, and spiritual worlds; how to organize states that are conducive to flourishing and balance, especially in relationship to “heaven/nature” ( tian ); how to actualize and return to states of non-differentiated unity. Don’t get me wrong; these are all important topics for philosophy of religion. However, if these issues are made the normative ones, then traditional-theistic philosophy of religion ends up looking deficient and strange (rather than the other way around). No doubt, there is something attractive about this. The powerless become powered; the powerful, powerless. Still, if philosophy of religion is going to be global, then it needs to be as inclusive as possible—leveling the playing-field as much as possible, and including as many players on the field as possible. Option one does not achieve these goals.

Realizing the failure of option one, option two looks for commonalities between all forms of philosophy of religion. This is to assume that there is a common philosophical core to all religious traditions such that every philosophical question asked by one religious tradition or community would have answers from all the other religious traditions and communities. However, as we can already see above from East Asian religious philosophy, this assumption is dubious. Maybe, though, there are commonalities to the belief structures of all religious traditions, just not to the forms that their philosophies of religion take, à la perennial philosophy? Maybe, for example, all religious traditions have “higher powers” or “ultimate realities” about which to philosophize? Well, of course many do, but not all. So, if we followed this second route, religio-philosophical traditions like certain Buddhisms and Jainisms and Confucianisms would end up looking deficient or strange. Moreover, the second option just isn’t possible without some sort of starting point or hypothesis. I therefore favor the third approach, adopting a starting point that is not proprietary to some particular religious tradition, while also paying attention to how these categories of inquiry fit all religious traditions and communities.

Instinctively, we might think that option three is the weakest of all. Why look outside the traditions of philosophy of religion for the topics and issues for philosophy of religion? Well, one reason is that the topics and issues of philosophy of religion would not be the “property” of any one form of philosophy of religion. So, we would not have the problem of all the other forms of philosophy of religion trying to fit themselves to it. Another reason, of course, is the failure of the first two options. If there isn’t significant overlap between the forms of philosophy of religion, then we can’t really look to one particular form of philosophy of religion or the commonalities between all philosophies of religion. However, the best reason will simply be the success of option three in providing topics and issues for philosophy of religion that do not privilege any particular form of philosophy of religion and that are inclusive of all philosophies of religion. It will be the burden of the next two sections of this paper to demonstrate, or at least intimate, this success. Of course, though, I first need to provide my starting point that is outside all philosophies of religion. This I will do by turning to metaphor theory in general and journey metaphor in particular.

With regard to metaphor theory in general, I draw on the cognitive metaphor theory of George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, which provides an account of how human thinking is structured by metaphors, especially those drawn from concrete bodily experience. At the heart of this account are two claims: humans draw on concrete bodily experience in understanding and expressing abstract concepts, and humans do so by systematically structuring abstract concepts in accordance with bodily experiences. For Lakoff and Johnson, this systematic structuring is performed by “primary metaphors,” which map sensorimotor experiences to subjective experiences. Take, for example, the sensorimotor experience of warmth and the subjective experience of affection. The primary metaphor affection is warmth maps the sensorimotor experience of warmth to the subjective experience of affection, thereby providing us a way to think about the abstract concept of affection in terms of the concrete experience of warmth.

What’s more, we make this connection both naturally and unconsciously. For Lakoff and Johnson, this is due to a conflation of sensorimotor experiences and subjective judgments in early childhood such that neural activations of a sensorimotor network are immediately “projected” to a subjective network. When we experience of our mother’s warmth along with the subjective experience of her affection, these two experiences get neurologically conflated, with experiences of warmth naturally and unconsciously triggering experiences of affection. Only later, do we begin to differentiate these two experiences, thereby allowing us to deliberately and consciously use sensorimotor concepts to conceptualize and verbalize subjective experiences, even in the absence of their corresponding sensorimotor experiences. We use the concept of warmth to help ourselves understand and express the concept of affection, even when we are not warm.

Given the foundational similarities of early childhood experience, these primary metaphors are, for Lakoff and Johnson, “widespread,” if not universal (Lakoff and Johnson, 1999 : p. 57). Of course, this is not to say that all metaphors are quasi-universal since most metaphors are not primary metaphors. Still, primary metaphors function as the atomic building blocks for the more numerous, molecular, “complex metaphor.” Even the complex metaphor therefore receives an indirect grounding in sensorimotor experience. It is for this reason that Lakoff and Johnson maintain that “[m]any, if not all, of our abstract concepts are defined in significant part by conceptual metaphor” (Ibid.: p. 128).

There is one metaphor in particular that is especially well suited to provide a new framework for philosophy of religion: the journey metaphor. The version of this metaphor that you are probably most familiar with is life is a journey , which uses the conceptual structure of a journey to help us understand and express our lives. By use of this metaphor, we sometimes think of our lives as going somewhere, as following a path, as encountering obstacles on that path, as walking down that path with co-travelers, and so forth. However, the journey metaphor is also used to conceptualize and articulate religious lives , more specifically religious growth, progress, maturation, or cultivation. In fact, the journey metaphor is ubiquitous in the diverse languages, cultures, and religions of the world—a common and ready means by which humans think about and talk about those aspects of our lives that have religious dimensions.

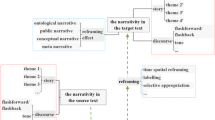

To show how this metaphor can be used to provide a new starting point for philosophy of religion, I must first take a look at its internal structure. According to Lakoff and Johnson, life is a journey is a complex or molecular metaphor composed of the cultural belief that everyone is supposed to have a purpose in life, the primary metaphors purposes are destinations and actions are motions , and the fact that a long trip to a series of destinations is a journey (Ibid.: pp. 52–53, 61–62). This complex metaphor also encompasses four sub-metaphors: a purposeful life is a journey , a person living a life is a traveler , life goals are destinations , and a life plan is an itinerary (Ibid.: pp. 61–62). Finally, the journey metaphor has several entailments or conceptual implications, among which are that one should plan their route, anticipate obstacles, be prepared, and have an itinerary (Ibid.).

I can now draw on Lakoff and Johnson’s analysis of life is a journey to identify the core, constituent parts of the journey metaphor. Journeys have a point of origin and destination, a route that is planned, obstacles and sights that are encountered along the way, and a traveler who is accompanied by and encounters other travelers. Of course, these constituent parts are not themselves philosophical questions or topics, so I need to use them to generate such questions or topics. Here are the five philosophical questions that stand out most to me, each one of which is linked to a constituent part of the journey metaphor:

Who am I (as traveler)?

Where do I come from?

Where am I going?

How do I get there?

What obstacles lie in my way?

The critical reader might by now have several concerns. Let me anticipate and address four of them. First, note that the five questions above are each vague in a way that makes them difficult to answer as stated. The first question, for example, could mean any of the following: Who am I as an individual? Who am I as a member of some group? Who am I as a human being? The five questions above must therefore be asked with respect to the content of philosophies of religion, so as to be able to specify each one in a way that is not only more precise but also explicitly tied to this content. With regard to the first question, for example, the notion of “I” as individual is not present in all religious traditions and communities through time. So, the question “Who am I?” brings into play the question “Am I?” Relatedly, the topics of inquiry with regard to these questions center on the internal parts and external relations of the “self.” Thus, our first question ends up concerning whether humans should be understood as individual entities or as sums of internal parts or sets of external relations. (More on this in the next section below).

Second, one component of the life is a journey metaphor is the cultural belief that everyone is supposed to have a purpose in life. Surely it is not the case that every culture has this belief. True, indeed. Moreover hopefully, my response to the first concern above already anticipates my response to this concern: if it is true that not all cultures or religions think of the self as an individual, then it is true that not all cultures or religions think that every individual has a purpose in life. Still, I want to make it clear that my method for deriving a new set of topics and questions for philosophy of religion does not assume that all philosophies of religion think of individual lives as purposeful, nor even utilize the metaphor life is a journey . As I say above, I do think that the journey metaphor is commonly used in religious traditions to think and speak about religious growth, progress, maturation, or cultivation. More importantly, though, I think that the core components of the journey metaphor (origin, destination, route, obstacles, sights, co-travelers) can be used to generate philosophical questions and topics (traveler, origin, destination, path, obstacles) about which every philosophy of religion has something to say, even if by absence. (More on this immediately below).

Third, it is not the case that a philosophy of religion has to have a positive or explicit answer to the five questions above to have an answer to them at all. Put differently, philosophies of religion can return a “null result” to these questions and do so in a philosophically interesting and important way. As we have already seen, many philosophies of religion “answer” the first question—Who am I?—by, in a sense, not answering it. I am not I but rather I’s or we. Humans are complex internal processes and parts or external relations and obligations. The same holds true for the other four questions. Some philosophies of religion maintain that we do not come from anything and are not going anywhere, or that there is no path intentionally to follow and no obstacles that truly exist. These are among the most interesting and important ways of answering the five questions above, since these answers challenge typical modern-western preconceptions, allow us to see the phenomena of religion more widely, and inspire us to think differently. Footnote 3

Finally, although the five questions above are important and interesting questions for philosophy of religion, as well as questions that are neglected by traditional-theistic philosophy of religion, they are also questions that neglect the topics of traditional-theistic philosophy of religion—for, entirely missing in these five questions are the core problems of traditional-theistic philosophy of religion: the attributes of God, the existence of God, and the problem of evil. My solution to this problem is simple and elegant. It begins with the acknowledgment that in some philosophies of religion it is not only humans in particular but also the cosmos in general that can be thought of as journeying (in the sense of having an origin, destination, path, and obstacles). It then notes that in some philosophies of religion, the crucial relationship is that between humans as microcosm and cosmos as macrocosm. Finally, it shows how reduplicating our five questions with regard to the cosmos yields a second set of rich, inclusive, and fair questions and topics for philosophy of religion:

What is the cosmos?

Where does the cosmos come from?

Where is the cosmos going?

How does the cosmos get there?

What obstacles lie in the cosmos’ way?

Again, I hasten to add that the qualifications above also apply to this set of questions: they will need to be made precise and tied to our philosophies of religion, and null results to them will need to be included. With these qualifications in place, I am confident that these five questions, along with the first set of five questions, offer a radically new point of departure for philosophy of religion, one that can be inclusive of the philosophies of religion of the globe in a manner that does not unduly privilege any one philosophy of religion. Now it is a matter of showing how.

Journeys of the self

In the next two sections I will show how each of these questions generates topics for philosophy of religion and embraces content from a global diversity of religious philosophies. For the sake of space, I consider only 5–6 “traditions” of philosophy of religion around the globe and through time, which for the sake of space I will shorthand as follows: East Asian philosophy of religion, South Asian philosophy of religion, West Asian or Abrahamic philosophy of religion, African and Native American philosophy of religion, and contemporary philosophy of religion. Footnote 4 In doing so, I will engage in a fair amount of generalization, but this is only for the sake of economy in this paper. In reality, I advocate looking at individual thinkers, texts, and debates, rather than generalizing over traditions.

The first question about the self is simply, what is it? It’s important here to note that by “self” I don’t mean a Cartesian self, although that is of course one view of the self. Perhaps to be more accurate, we could ask about the journeyer. Who or what is journeying? As I explained above, this first question leads us into questions about the journeyer’s external relationships and internal processes. Is the “self” an individual being or a set of external relationships with other beings, whether human or not? Is the “self” a substantial being or a set of internal parts or processes? As for content from religious philosophies with which to sharpen these questions, there are of course the rival views of self in South Asian religious philosophy: atman , anatta , jiva , purusha , and so forth. In Southern African religious philosophy, there is the notion of ubuntu , and, if I’m not mistaken, there are similar notions in some Native American traditions. In East Asian religious philosophy, we have the differing understandings of self in early Daoism and Confucianism, even if these are always relational in some sense. Moreover, Abrahamic religious philosophy would make for interesting comparisons with regard to Buber’s and Kierkegaard’s relational selves, as well as the notions of fana and baqa in Sufism. Finally, contemporary philosophy of religion offers the perspectives of cognitive neuroscience and Continental philosophy, each insofar as it undermines the notion of an individual, substantial self. So, in the end, our question about what the self is leads us into interesting territory about whether the self is.

Our second question about the “self” concerns its origins: where does the self come from? Here, I propose tackling questions about how the self understands itself given its origin. So, the question really is this: How does my origin determine or affect what it is that I am as a member of the human species (or some localized people)? Or, to put it succinctly: Why am I the way I am? Here are some elaborations of this question: Am I free or good or intelligent because God created me that way? Or did God create me “broken” in some way? Am I free or good or intelligent because of cosmic or human nature? Or do I have no nature whatsoever? Or am I the way I am because of something I did in a past life? Or because of some fate that has been bestowed on me before or at birth? Or because of the result of thousands of years of random mutation and natural selection? Such questions about the self’s innate freedom, goodness, and intelligence divide fairly neatly between Abrahamic, East Asian, and South Asian religious philosophy. Abrahamic religious philosophy, at least in its Christian and Muslim forms, has wrestled the question of how to reconcile human freedom and divine sovereignty. East Asian religious philosophy, especially Confucianism, has contended about the innate goodness of humans. Moreover, in South Asian religious philosophy one crucial issue concerns in what sense the self is or acquires “enlightenment.” In some African and Native American traditions, there are narratives of a “paradise lost” and what that means for human beings. Finally, contemporary philosophy of religion offers three controversial topics about how humans understand themselves vis-à-vis their “origin”: feminism and patriarchy as a kind of original condition, Darwinianism and biology as a kind of original condition, and Freudianism and psychology as a kind of original condition.

Our third question turns from the self’s origins to its destinations. Here, we are concerned with whether the self survives death and, if so, how. These questions would seem to be among the most pressing for many humans. Moreover, how humans answer these questions sometimes has profound consequences for how they live their lives. Still, in the context of the preceding two questions, one might wonder whether this third question is predicated on false or limited understandings of what the self is. If we are not in fact an individual, substantial, autonomous self, then there isn’t such a “thing” to survive death. Nevertheless, many different religious traditions do maintain the notion of individuated, postmortem, heavenly existence. Interestingly, this view shows up in different cultures across the globe. However, just as interesting is the fact that each of these traditions also contains views of postmortem existence as non-individuated. Still other traditions think of postmortem existence as less “heavenly” and more “familial” (in the sense of reuniting with ancestors/dead). Moreover, in other cases, it just isn’t possible to say what happens after death, or it isn’t important to say what happens after death, or we simply don’t die. Some of the religious-philosophical content to be considered in the context of this question includes, in the case of South Asian philosophy of religion, early Vedic positions, Upanishadic positions, Jain and Buddhist positions, and the positions of some of the “Hindu” philosophical schools. Here, there is no shortage of diverse content. By contrast, there is in East Asian religious philosophy a striking lack of concern with what happens to us after we die, at least in classic Confucian and Daoist sources. However, that lack of concern can and should be contrasted with traditions like Pure Land, in which what happens after death is all consuming. Of course, there is also the importance of ancestors in East Asia, which is also often crucial for many African and Native American traditions. With regard to Abrahamic traditions there is an interesting diversity positions just in the Bible, even if not in the Qur’an. There is also, of course, the mystical traditions of these religions where postmortem unification with God can sometimes be the end of human existence. Finally, naturalistic religious positions in contemporary philosophy of religion bring further enrichment and complexification to the question of postmortem ends.

Our fourth question about the self turns to the paths by which the self reaches its destination. As in the cases of the previous questions, there is an abundance of material to cover—not only different paths for different religious traditions but also different paths within religious traditions. However, there is also, in this case, an abundance of ways to focus this material. One such way would be to look at whether these paths primarily involve the body or the mind or both. Another way would be to look at the difference between “cat” paths and “monkey” paths. Here are yet more ways: Does the path lead to a postmortem, other-worldly destination or to a this-life, this-worldly destination? Does the path require multiple lifetimes or just one? Should the destination be the focus of the path, or does focusing on the destination distract from the path? Does the path need to be found or chosen, or are we already on it and just need to realize that? But the way of focusing this material that I prefer most of all involves the relationship between morality and religion. Whereas many of students whom I have taught assume that the whole point of religion is to teach and reinforce morality, some religious philosophers have argued that to focus on conventional morality and social conformity is to lose the spirit and substance of religion. To put the matter in terms of question four, it is to get distracted from one’s religious path. If I were to focus the material of the fourth question in such a way, I might look first at trickster figures in African and Native American religious philosophies. In South Asia, the content would instead concern amoral and immoral paths as found in some Tantras, Krisnaivisms, and Shaivisms. In East Asia, things are a bit tamer, probably because of the influence of Confucianism. Still, there are certain Daoisms and Buddhisms that offer ostensibly amoral or immoral paths. In the case of Abrahamic religious philosophy, there are certain mystics in the Christian and Muslim traditions who say or do morally questionable things, at least within the context of their societies. Moreover, in contemporary philosophy of religion there is of course the work of Soren Kierkegaard, as well as intriguing material about the relationship between religion and morality in feminism, post-colonialism, and cognitive science of religion.

Our final question about the self looks at the obstacles that prevent it from reaching its destination. When I originally considered the topic of destinations under question three, I focused on the question of whether the self survives death and if so how. Here, I look instead at this-worldly side of our ultimate destinations—salvation, enlightenment, harmony, attunement, obedience, submission, health, flourishing, and so forth. My leading question in this case is: What keeps us from reaching these destinations? Or, to put this question a bit more precisely: What keeps us from living the way we should? In a sense, this is a question of ethics; in another sense, not. One way to think about this question is as the flipside of the fourth question above. There, we looked at the relationship between religion and morality, asking how we should live, focusing on the issue of whether this requires going “beyond morality.” Here, we instead look at what prevents us from living the way we should, which in some cases is immoral behavior but in other cases is just the opposite. Here is another way in which the content of this question goes “beyond ethics”: For many religious traditions, what prevents humans from living the way they should is not a function of the moral decisions that they make but rather an “original condition” that afflicts them simply by virtue of being human. Christians will know this as “original sin.” In other traditions, it is something else: an original imbalance, or evil urge, or selfishness, or ignorance. In still other traditions, this original condition is existence-itself, which keeps us separated from Brahman or Dao or God or ancestors. In yet other traditions, this condition involves our delusion that there is a problem in the first place—what keeps us from living the way we should is thinking that we are not living the way we should. Of course, there is also the problem of evil beings—demons or witches or even human beings that keep us from living the way we should. Moreover, there is also the fact that, for some philosophers of religion, it is certain humans that keep other humans from living the way they should by creating oppressive social realities. Patriarchy certainly fits here. So does slavery. Perhaps also capitalism. Some would even say that what keeps us from living the way we should is religion itself.

Journeys of the cosmos

I turn now to the “journey of the cosmos,” repeating each of my five questions, but with respect to the “cosmos” rather than the self. Let me begin, though, with a quick word about the word “cosmos” and its journey. By cosmos, I mean simply everything that exists, taken as an ordered whole. This definition is not far from the one given by Merriam-Webster: “an orderly harmonious systematic universe.” But I want to be careful to point out that by “cosmos” I don’t mean “universe,” at least not if “universe” is taken in the contemporary scientific sense. Certainly, our contemporary scientific understanding of the universe is one type of cosmos. We might even say that it is gradually becoming the most widespread and prominent understanding of the cosmos. However, other understandings of the cosmos remain, some of which articulate themselves in relation to the contemporary scientific paradigm. For some of these cosmoses, there are realities more basic and fundamental than physical entities and processes; for others, there are dimensions or universes beyond the scientific universe.

As for the cosmos’s “journey,” of course this isn’t a literal journey. Still, the structure of the journey metaphor offers productive philosophical questions to ask about the cosmos, just as with the self. Here, again, are our five questions about the cosmos:

What is the cosmos (if anything)?

Where did it come from (if anywhere)?

Where is it going (if anywhere)?

How does it get there (if it all)?

And what obstacles lie in its way (if any)?

In the case of each question, the parenthetical comments are crucial. I don’t presume that the cosmos has an origin, destination, and path (etc.)—for to do so would be to endorse a teleological view of the cosmos, which is often present in Abrahamic religious traditions but lacking in other religious traditions. Put simply: I don’t presume that the cosmos is on a journey. Rather, the structure of the journey metaphor gives me the philosophical questions to ask about the cosmos, and these questions can be answered either positively or negatively. Maybe the cosmos has a beginning and end; maybe it doesn’t.

As for the first (sixth) question—what is the cosmos?—we can begin by recognizing that, just as in the case of the self, appearances can be misleading. We might think that the cosmos exists in a manner that is fully independent and real, just as we did with the self. However, answers to this first question show how many philosophies of religion challenge this commonsense view. Perhaps the cosmos is only illusion (as it is in some South Asian traditions); perhaps it is just God (as it is in some South Asian and Abrahamic mystical traditions); perhaps it is really constituted by underlying cosmic principles and forces (as it is in some East Asian traditions); perhaps it is composed by numerous universes (as it is in some Buddhist traditions); perhaps it involves realms of ancestors (as in some African and Native American traditions); or perhaps it is ultimately a heavenly existence with God (as in some Abrahamic and South Asian traditions). Whatever the case, what is particularly interesting is how these cosmologies serve spiritual practices and rituals. In other words, what we often find is that religious cosmologies are not for the sake of doing “science,” but for the sake of offering worlds in which to live religiously. This raises an interesting question that should be dealt with under this question: as our contemporary scientific cosmology grows in influence and importance, how can religious traditions continue to offer cosmologies for religious practice?

Question two (seven) about the cosmos takes up some of the central questions of contemporary theistic philosophy of religion: Does the cosmos have an origin and, if so, what is its nature? Ever since the Enlightenment, if not earlier, philosophy of religion in Europe and some of its colonies has been predominantly concerned with these questions. So much so, that it is just natural for many of “us” to think that these are the central questions for philosophy of religion in general. However, this is not the case. Many other religious traditions don’t think of God as a creator (e.g., East Asian traditions, for the most part; some South Asian traditions). Moreover, some of those religious traditions that do think of God as a creator tend to think of God as a remote and uninvolved (e.g., some African and Native American religious traditions); in these cases, the existence of God just isn’t very important to actual lived religion. This can be a point of instruction for traditional-theistic philosophy of religion: the origin of the cosmos and nature of its originator isn’t generally all that important for most of the religious traditions of the world. Another point of instruction: these questions just aren’t “live” for most religious traditions because they simply don’t matter to practice.

Question three (eight) turns from the origin of the cosmos to its end. In terms of our journey metaphor, the question is about the “destination” of the cosmos. However, I articulate this philosophically by asking whether the cosmos has an end and, if so, what happens after that. In this case, it is necessary to ask these questions not only about the cosmos writ large but also about “this world” or “this order,” where these terms refer to the way things currently are for humans (as a whole), in their habitable space (as a whole), as interpreted religiously. This is due to the fact that, for many religious traditions, the end is not really the end; rather it is merely the beginning of something new or different—a new or different world here on Earth or a new or different world in some other realm, but not necessarily a new or different cosmos. What is interesting about many of these cases (where worlds or orders are said to come to an end) is that they occur during times of significant trouble. Maybe there is a prolonged drought or flood; maybe there is an invasion and life under oppressive foreign rule; maybe there is a natural disaster that significantly alters the practices and structures of a society; maybe there is a rapid change of customs and values that threaten age-old traditions—it is during such times that we tend to see apocalyptic or eschatological religious ideas and practices. Why? Such ideas and practices provide relief in at least two ways: they predict an imminent end to the trouble and a future state without troubles; they predict a reward for those who have suffered unfairly and a punishment for those who have caused this suffering. Content for this question includes the fascinating case of Wavoka and the “Ghost Dance,” fervor for the Messiah or Mahdi in Abrahamic religion, apocalyptic movements in East Asian religious philosophy, the kalpa theory, as well as future manifestations of avatars and Buddhas in South Asian religious philosophy, and attempts to reconcile “religion” and “science” in contemporary philosophy of religion. Footnote 5

Our fourth (ninth) question concerns the “path” of the cosmos. Of course, I am once again not asking about the literal path of the cosmos. Rather, I am using the metaphor of path to generate interesting and important philosophical questions about how the cosmos operates or functions in-between its origin and end (if it in fact has an origin or end). For many of us “moderns,” questions about how the cosmos operates or functions are answered by science: the cosmos operates or functions according to “natural laws.” But many religious traditions believe in and value the occurrence of things that would appear to violate “natural laws”: miracles, appearances of supernatural beings, and other extraordinary experiences. Some religious traditions also believe that some divine mind or cosmic order predetermines everything that happens in the cosmos, even the so-called laws of nature. Perhaps one issue here concerns what falls under the category laws of nature . Are there current laws or laws yet to be discovered that would encompass so-called miracles? If so, do these laws explain away miracles? Or do they provide scientific mechanisms by which miracles can happen? And what about cultures for which the categories laws of nature and miracles don’t exist or aren’t opposed—cultures for which seemingly miraculous occurrences are understood to be part of the natural, this-worldly order? One should be careful in these cases to contextualize religious philosophies. Still, given the dominance of science in our contemporary world, it would be good to focus on that which would seem to elude scientific explanation or violate natural law. These phenomena include lots of different things: physical events in the natural world (e.g., making the sun stand still), sensory manifestations of divine beings (e.g., angelic appearances), mental appearances of divine beings (e.g., hearing the voice of God in one’s head), journeys of the mind or body to alternate realities (e.g., shamanic phenomena), possession of body or mind by divine beings (e.g., trance in some African traditions), healing of body of mind (e.g., African healers), and other extraordinary religious experiences (e.g., achieving a sense of union with God).

Our final (tenth) question examines the “obstacles” that lie in the way of the “journey” of the cosmos. If, per the last question, the “path” of the cosmos concerns its functioning and order, then the “obstacles” along this path will be things that stand in the way of this functioning and order. The question in this latter case is this: what prevents the cosmos from working the way it should? Note this question is always asked from the perspective of some human questioner. It is we humans who have ideas about how the cosmos should work and want to know why it is not working the way it should when some misfortune befalls us. Sometimes this misfortune can be individual: why am I suffering? More likely, though, it concerns the misfortune of the individual’s clan or community. In some cases, it even concerns the misfortune of an entire nation or people. Whatever the case, it is clear once again that what might seem theoretical is actually practical. We humans want to know why we suffer, as well as how and when that suffering will stop. This is true even in the case of the classical “problem of evil.” Of course, many of “us” think first of the problem of evil when considering content relevant to the question of cosmic obstacles. However, it is important to consider the full range of “evil” and human response to it. This includes the “rational” theodicy of karma-samsara in South Asia, the “mystical” theodicy of balance and harmony in East Asia, concern with tricksters, spirits, and witches in some African and Native American religious philosophies, and an increasing focus on “structural evil” and “proactive theodicies” in contemporary philosophies of religion.

Conclusion: which journey, if any, is true?

These are the ten questions that I believe could offer a means of restructuring philosophy of religion to make it globally inclusive. As a “post-scriptum” of sorts, I want to end by observing that one central question of Western philosophy of religion is not among these questions. It is a rather recent addition; nevertheless, it has caused much ink to be spilt. I am referring here to John Hick’s so-called problem of pluralism. Is it the case that only one religious tradition, at most, can be true? Hick, of course, proposed that humans simply can’t know which, if any, religious tradition is true of the “Real in itself.” At best, each human can engage “authentically” with her own religious tradition—the “real as she thinks and experiences it” (Hick, 1999 ).

To put Hick’s problem into the terminology of the journey metaphor is to ask whether it can be the case that all—or at least many—of these religious journeys can be true or useful. Allow me to respond to this issue in two ways. First, this issue should and does find a home within my restructured account of philosophy of religion as a sort of meta-question—an eleventh question, if you will. Where religions offer a coherent system of beliefs and practices, this eleventh question asks whether that system can be true or useful, particularly with regard to the fact that there are other such systems. I suspect that it is this question that will be asked more and more as the inhabitants of our earth find themselves living closer and closer to people of different religious traditions. Nevertheless, I am quick to follow this first response with a second: the philosophy of religion that I practice is not primarily concerned with sorting out either which religious traditions are more or less true and useful or how different religious traditions can all be true or useful. On the one hand, I do not find it as viable and valuable as asking about the forms of religious reasoning with respect to the ten questions above. On the other hand, I tend to think that it is not up to the philosophers of religion to settle this matter (just as it is not up to the philosophers of science to determine which scientific theories are true).

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this paper as no datasets were generated or analyzed.

I contend that philosophy of religion is in need of such a new orientation and point of origin; I do not insist, however, that the framework advanced in this paper must be used in doing so. It is just one of many attempts to reorient philosophy of religion globally. For others, see Wildman ( 2010 ) and Schilbrack ( 2014 ). See also my own earlier attempt (Knepper, 2013 ).

See the forthcoming publications by the American Academy of Religion’s seminar in Global-Critical Philosophy of Religion (GCPR): an undergraduate textbook in GCPR, a teaching supplement in GCPR, and a series of essay volumes in GCPR.

This is one way that my proposal differs from classical “perennial philosophies.” I do not maintain that all philosophies of religion philosophize about the same content or contain the same doctrinal core. I do, however, think that each of my ten questions returns philosophically interesting and important answers, even when those answers reject their questions.

Below, I often treat African and Native American religious philosophies together, not because I think all African and Native American religious traditions are the same, but because there are sometimes interesting resonances between certain African and Native American religious traditions.

Another interesting and important philosophical topic related to this question concerns the ways in which “eastern” philosophies of religion with cyclical views of time have attempted to demonstrate a tighter fit with contemporary scientific cosmology.

Hick J (1999) An Interpretation of Religion: Human responses to the transcendent. Yale University Press, New Haven

Google Scholar

Knepper T (2013) The Ends of Philosophy of Religion: Terminus and Telos. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, NY

Book Google Scholar

Lakoff G, Johnson M (1999) Philosophy in the Flesh: The Embodied Mind and its Challenge to Western Thought. Basic Books, New York, NY

Schilbrack K (2014) Philosophy and the Study of Religions: A Manifesto. Wiley-Blackwell, New York, NY

Wildman W (2010) Religious Philosophy as Multidisciplinary Comparative Inquiry: Envisioning a Future for the Philosophy of Religion. SUNY Press, Albany

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Philosophy and Religion, Drake University, Des Moines, IA, USA

Timothy Knepper

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Timothy Knepper .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Knepper, T. Using the ‘journey metaphor’ to restructure philosophy of religion. Palgrave Commun 5 , 43 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0252-7

Download citation

Received : 18 December 2017

Accepted : 08 April 2019

Published : 30 April 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0252-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

What is the Point of a Pilgrimage?

What is the point of a pilgrimage? Where did this idea come from for Catholics? There is considerable evidence throughout Scripture, which supplies theological significance to the concept. Even today we see many embracing this activity with passion and the commitment of time and resources.

While many would regard a basic definition of pilgrimage as a “journey made on foot or by other means to a site of particular religious significance,” this might be insufficient for two basic reasons that ignore the universal appeal of a pilgrimage or the pilgrim’s motivation.

Humanity inherently has a curiosity and desire to dive into certain questions. The Second Vatican Council’s declaration Nostra Aetate (Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions) acknowledges this natural, basic curiosity of human beings to ask: “What is man? What is the meaning, the aim of our life? What is moral good, what is sin? Whence suffering and what purpose does it serve? Which is the road to true happiness? What are death, judgment and retribution after death?” (No. 1).

Pilgrimage is a part of many of the great religions of the world, for in religion humanity seeks the answers to the questions above. So, pilgrimage is a common human experience in which one seeks to fulfill a ritual obligation, perform an act of devotion to atone their own sins, live an experience of spirituality, or implore a grace, a miracle, a cure, etc. As profound as the reasons for pilgrimages may be, so are the destinations for them: Jerusalem (Jews and Christians), Mecca (Muslims), Sarnath (Buddhist), Banares (Hindu), Amritsar (Sikh), to name a few, plus innumerable lesser sites of historical-spiritual importance to these religions and others.

In Christianity, there are few acts of devotion as rich in history, traditions or spirituality. This is true to such a degree that the image of the pilgrimage has become a metaphorical image of life itself. We are all on a journey heavenward. Chapter VII of Vatican II’s Lumen Gentium (Dogmatic Constitution on the Church) speaks of the pilgrim Church that journeys onward toward the heavenly Jerusalem. The council’s Gaudium et Spes (Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World) says in its preface that the Church is a community of disciples “led by the Holy Spirit in their journey to the kingdom of the Father.”

Pilgrimage in Scripture

The idea of a pilgrimage has an incredibly strong foundation in both the Old and New Testaments. The spiritual importance of pilgrimage is manifested often in physical journeys and trials — from Abraham’s journey of faith all the way to the missionary journeys of St. Paul.

In Genesis, we observe how God specifically summons Abram to trust Him — to leave his country, to come into God’s land, where he will inherit God’s promises that will make his innumerable descendants into a great nation.

Later, in the Letter to the Hebrews, more is said about Abraham’s pilgrimage: “By faith Abraham obeyed when he was called to go out to a place that he was to receive as an inheritance; he went out, not knowing where he was to go. By faith he sojourned in the promised land as in a foreign country, dwelling in tents with Isaac and Jacob, heirs of the same promise; for he was looking forward to the city with foundations, whose architect and maker is God” (11:8-10).

The Bible tells of many physical journeys, especially to Jerusalem, or “Zion.” Fifteen of the Psalms were written specifically for pilgrimage to Jerusalem (see Ps 120-134). They are called the Psalms of Ascent, as the Jews would climb the steep grade up to Jerusalem, the city on the hill. The prophet Micah says, “Many nations shall come, and say, / ‘Come, let us climb the Lord’s mountain, / to the house of the God of Jacob, / That he may instruct us in his ways, / that we may walk in his paths” (Mi 4:2).

But the pivotal pilgrimage in Scripture is the Exodus — the story of Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt — through the desert, trials, temptations and sin, ever journeying toward the Promised Land. This episode has become one of the primary models of the relationship between journeying and the life of conversion and faith.

In the New Testament, we likewise see a pilgrimage’s importance, not so much in the sense of a physical journey, but in the idea of living our current, earthly lives in a way that brings us closer to the eternal.

Even mysterious and enigmatic figures like the Three Kings are pilgrims who appear in the Gospel of Matthew after the birth of Jesus: “Behold, magi from the east arrived in Jerusalem, saying, ‘Where is the newborn king of the Jews? We saw his star at its rising and have come to do him homage’” (2:1-2).

Apart from the legends, little is known about these men of great culture who came from a distant land, but they beautifully embody the idea of pilgrimage. As Pope Benedict XVI wrote in the third volume of his “Jesus of Nazareth” trilogy: “The Wise Men of the East … represent the setting out of humanity towards Christ, they inaugurate a procession through the whole history. They are not only the people who have found the way to Christ. They represent the interior desire of the human spirit, the encountering of religions and human reason with Christ.” With this perspective, one can see that any religious pilgrimage takes on a Christian meaning, as humanity searches for God, knowingly or unknowingly.

The Infancy Narratives include an account of a pilgrimage taken by the Holy Family: “Each year his parents went to Jerusalem for the feast of Passover, and when he was twelve years old, they went up according to festival custom” (Lk 2:41-42). The 12-year-old Jesus stays behind in the Temple, unbeknownst to His parents, and speaks of His Father with the scholars.

After the inauguration of Jesus’ public life — following His baptism in the Jordan — His entire ministry unfolds as a pilgrimage back to Jerusalem, day after day, along the roads of Palestine.

Christ’s death on the cross has a massive effect on the evolving definition of pilgrimage. His sacrifice introduces the idea of redemption, and the temporary nature of what we experience, as we journey toward heaven.

We see this in the Gospels, or in the accounts of the apostles. They recount to us how Jesus’ death has opened the door to heaven. With this understanding we realize that the struggles we face now — trials, sufferings, temporary worries and problems — can be our sacrifices of praise as we journey toward salvation.

After His passover from death to life at the Resurrection, the community of Jesus’ first disciples, animated by the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, travel throughout the world to spread the Gospel. After their martyrdoms, their tombs immediately become places venerated by the ancient Christians — most notably those of Sts. Peter and Paul in Rome. “In fact, if you want to go to the Vatican or along the way to Ostia, you will find the trophies of those who have founded this Church,” the famous Church historian Eusebius writes about A.D. 200.

The official pilgrimages of the Twelve Apostles (who all died as martyrs, save St. John) branches from Spain to India to Ethiopia. Tradition relates stories, however, that associate each apostle (and also other figures of the New Testament) to a place where he died and often to where his relics are preserved.

St. John, in his Book of Revelation, reminds the faithful that our life on the earthly terrain is just a temporary state, until we get closer to that end God has envisioned.

Pilgrimage in History

The scriptural motivations for pilgrimage compel people today to experience this for themselves. But also in the Christian tradition the practice of pilgrimage has always been linked to the saints. They are especially honored in churches and shrines, especially those that preserve their bodies and tombs.

Once Christianity was legalized in A.D. 313, the paths most frequented by pilgrims draw a dense network on the European map. “Egeria’s Travels” was a primitive kind of travel diary by a devout pilgrim, written around the early part of the fifth century, which documents the practice of pilgrimage to the sites associated with Christ’s life. But later, when the Holy Land was conquered by Arabs, other routes were opened in the West.

Rome became an important destination for medieval pilgrims and remains so today. There also is Santiago de Compostela, in northwestern Spain, where pilgrims walk along the famous Camino . It also is still a popular destination, where the relics of St. James the Great are venerated. There are many official routes from all over Europe, with specific hostels along the way for pilgrims to rest and meet one another.

From the 11th century or so, indulgences became intertwined with pilgrimages. There was an indulgence reserved for the Crusaders departing to the Holy Land with arms to protect pilgrims.

With the passing of the centuries, other places of pilgrimage become important. Around the world, especially in countries of ancient Christian tradition, sanctuaries were built in memory of a supernatural apparition, miraculous event or other spiritual or historical relevance to the lives of saints. People have traveled to them for a variety of reasons.

The list of all world destinations of pilgrimage is many thousands in number, but here are some which are visited by more than a million pilgrims every year. In addition to Rome, the Holy Land and Santiago de Compostela, it is important to highlight significant Marian shrines: Loreto in Italy, where the Holy House of Nazareth is kept; Lourdes in France, where the Virgin Mary appeared to St. Bernadette Soubirous and many experience physical healing; Fátima in Portugal, where this year the centenary of the apparitions to three shepherd children will be celebrated.

In the Americas, standing out for fame and number of pilgrims are the sanctuary of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico and the Shrine of Aparecida in Brazil. But every country has its national shrine — in the United States it is the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C.

Fruits of a Pilgrimage

Looked at from a religious perspective, a pilgrimage is a trip different than usual. It is not only for admiring masterpieces of art, although many places of pilgrimage are full of history and beauty. In days gone by pilgrims could be imagined as ragged and emaciated, willing to forgo any comfort along long roads full of dangers. But a conscientious pilgrim still chooses a certain restraint and intentionality as one chooses accommodation, food and drink, and, of course, places an importance on silence and prayer.

To experience something different from other trips, the pilgrim must be different and live differently in the simplicity of faith. Otherwise, the pilgrimage does not contribute to real change. The pilgrim moves within the geography of faith, along the path on which are scattered traces of holiness, in places where God’s grace has been shown with particular splendor and produced abundant fruits of conversion and holiness.

One goes on a pilgrimage to ask God for help needed to live more generously your own Christian vocation once back in your home, explains the Vatican’s Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy. Therefore, the pilgrimage is not, and never should be, just “a journey to a place of religious interest.” Alone or with others, it is a physical component of the path of one’s heart toward God.

Deborah Castellano Lubov writes from Rome where she covers the pope and the Holy See.

You might also like...

Type on the field below and hit Enter/Return to search

What Inspires Spiritual Journeys? Explore the World’s Pilgrimages

Interested in spiritual journeys? We give you the definition of spiritual journeys from academic experts who explain the history and cultural significance of spiritual journeys. We report on the experiences of a cross-section of people who have undertaken spiritual journeys. Even more, we explain how this tradition is one of the cultural universals shared by all of the world's different cultures .

Spiritual journeys have been around since antiquity, and mankind has felt the call to journey afar in search of meaning. From those of the Abrahamic religions to Zoroastrians, as well as many who subscribe to no particular belief set, a time comes to cross their threshold on what they consider a pilgrimage.

Here, we dig deep into the concept of spiritual journeys, to learn more about our yearning for them. Is it the destination that calls to us, or something deeper?

“Evolution of modern transportation systems and the requirement to fit into work schedules have changed pilgrimage,” observed Dr. Justine Digance of Griffith University in Australia. “Few today would entertain a year-round trip from the U.K. to the Holy Land, which was the norm in the Middle Ages—along with all the hardships.”

“Many state that to be a pilgrim, one must encounter suffering,” she noted. “I don’t see that it has a role in today’s discussion of pilgrimage unless it is offered as part and parcel of the event, such as barefoot climbing of Crough Patrick in August is said to bring merit, as does certain pilgrimages done barefoot in both the Buddhist and Hindu traditions.”

Climbing Crough Patrick

A resident of Kenmare, Ireland, Des Dempsey, 41, said that people come from all over to climb Crough Patrick, or the Reek, as it is known locally.

“From Balintubber Abbey there is a traditional pilgrimage route across the fields and wild lands to the base of the mountain,” Dempsey said. “Reek Sunday is traditionally the last Sunday in August when thousands come and climb it, though generally not the locals. They will usually beat the crowds and climb it the Friday before.”

“The Reek is a difficult climb, involving some suffering, physically and mentally, often with harsh exposure to the elements and some sacrifice — of time, comfort, requiring endurance and strength, challenging a person physically, mentally and spiritually,” he continued. “When I did the climbs, I was considering the rewards, rather than the cost.”

“To walk such well-trodden pilgrimage routes are journeys worthwhile doing in themselves, but they make the arriving all the more rewarding,” he went on. “You become part of a bigger journey, something bigger than the self. As for climbing barefoot, it makes it a very different journey. You have to be so much more conscious of every step, to be in the moment and the attention you get is great.”

“People have been traveling that route on pilgrimage for generations untold, long before Christianity came to Ireland certainly,” he concluded. “Then they climbed it for Lugh of the Long Arm, the Sun God. When St. Patrick arrived, he climbed it too and declared it for the new Christian God and the Irish, ever accommodating, said “Grand,” and continued climbing. It’s a special place, immediately obvious to me the first time I ever saw it, regardless of in whose name it is climbed.”

Varanasi and the Cosmic Dance

Just as mountains have attracted those seeking spiritual heights, the confluences of big rivers are often places of powerful mythology according to Rana P. B. Singh, professor of cultural geography and heritage studies at Banaras Hindu University in Varanasi.

“The notion of Pudyadayi or ‘merit-giving’ refers to the inherent ‘spirit of place’ of a particular site, which since ancient times attracted sensitive and spiritual persons to come and get interconnected with the divine spirit as described in ancient texts,” he stated. “In the process of adding more representation from other religious places, and continuous superimposition of such mythic-mystic-sacrosanct images and rituals, the ‘merit-giving’ capacity of these places increased, expanded and attracted more people.”

According to Professor Singh, “Along the riverfront Ganga Ghats in Varanasi ‘life’ and ‘death’ both go together in the vision of Shiva’s cosmic dance. Shiva is the supreme and ultimate god of ‘life’ and ‘death’ together, and Varanasi is the resort of Shiva, that is how ‘life’ and ‘death’ are considered as two phases of life. The Ganga, being the liquid energy of Shiva, takes care of both the conditions: birth — life started in water, and death — final mergence is in the river.”

Spiritual Journeys to Holy Places

According to Tasoula Manaridis, 42, of Nicosia in Cyprus, it is the vestiges of spiritual leaders that make a locale sacred and beckon those seeking guidance and inspiration.

“In the Greek Orthodox faith a widespread and long-lasting custom is the journey to holy places to kneel in worship,” she said. “From antiquity and until present the conviction has persisted that prayer or the performance of religious duties are more effective in places where saints were born, died, wrought miracles, suffered martyrdom or merely existed; in ones where there were churches, relics of saints or miraculous icons. It is very common in the Orthodox religion that when someone faces a problem such as a serious illness to visit a place of worship, light a candle and pray for the well being of the ill.”

“Kykkos Monastery is one of those places,” she asserted. “The Monastery located in the Troodos Mountains is one of the richest monasteries on the island and it possesses one of the three icons of Virgin Mary ascribed by St Luke. Many pilgrims take day trips to the Monastery to pray and give an offering — it can be a piece of jewelry — to the Icon of Virgin Mary.”

The Hajj, a Tribute

For some pilgrims, the very journey itself is an offering.

According to a 75-year old Muslim and resident of the Republic of Djibouti in Africa who preferred to remain anonymous, “The Hajj is first of all an obligation for the believer. It is a tribute to God. The pilgrim does not go there to be cured or to receive something. As a result of it, one feels purified of all earthly blemishes, having made a sacrifice for his spirituality . Because it is a distant place, it is a financial challenge for many Muslims all over the world, especially as many are poor.”

“Being the most sacred place of Islam, a pilgrimage to Mecca is obviously a sacred journey,” he continued. “It is not, however, a tourist trip — it is forbidden to non-Muslims. According to tradition, the Kaaba was built by Abraham and Ismael. It is a house of prayer in the shape of a perfect cube. Their coming here is considered the first and founding pilgrimage. It is on this site that Abraham was willing to sacrifice his son Ismael, the father of the Arabs. Mecca is also the birthplace of the prophet Mohammed.”

“Mecca is the holiest and most sacred place in the world for Muslims,” said Sari Pitaloka, 46, of Jakarta. “More in particular, Masjid-il-Haram, the mosque where the Kaaba is located is the centre point to which the whole world community of Muslims physically, emotionally and spiritually directs their prayers, every single day, five times per day.”

“One of the qualifications to do Hajj is to be healthy mentally, physically and emotionally,” she continued. “Why would someone want to visit the house of the Creator if not in her/his best condition? The journey itself needs heath to support us to achieve the destination and to enjoy, get the best value of it.”

Buddhist Temples of Shikoku, Japan

Bob Davies, 65, of Durban, South Africa would likely agree. He considers pilgrimage visitation to a sacred place and made the route of 88 Buddhist temples on the island of Shikoku, Japan in 2005, a journey he said required stamina.

“I am generally extremely physically and mentally active, but walking so intensely for such a long period and distance naturally begs proper preparation,” he said. “That I undertook over the preceding three months in the local gym and a few long, backpack-laden hikes over the preceding weekends. As far as the joys and appeals of hiking are concerned, Shikoku per se is certainly not a preferred or recommendable destination.”

When asked if he would undertake the Shikoku pilgrimage again, Davies was uncertain.

“Maybe, if the need arises to experience certain aspects alluded to during the pilgrimage become singularly important to warrant deeper experience. Only spiritual need over the time ahead will tell,” he answered.

Spiritual Journeys Inside or Out?

While for some, pilgrimage is a one-time event, for others it can represent a way of life.

“For me, a pilgrimage is a journey of the soul,” declared Ben Drake, 50, of New Forest, Hampshire in the United Kingdom. “There must be a destination or one never sets out, but that destination might be physical or spiritual. In my case, I attempted to make it both. I think I succeeded, I was certainly happy with what I got. Most Importantly it fitted with the greater pilgrimage of my life and nourished that.”

Drake conducted his pilgrimage on the occasion of his 50th birthday and faced a few fears in the process.

“I was inspired by the writings and example of Satish Kumar, a great pilgrim who undertook a walk around many of the spiritual places of Britain for his 50th,” Drake explained. “I wanted to mark a turning point in my life, a time when my soul and its wellbeing is the most important thing in my life.”

“I walked on my own, across the country just over 100 miles from the place that I am pleased to call home to a place that inspires me,” he said. “I attempted to be open, positive and loving with everyone and everything that I met — often my greatest challenge. I was challenged especially by two days of walking a 500-foot cliff top in thick fog, often disorientated and lost and also often in the grip of a fear of heights and of the unknown. There is a lot of unknown when you can only see 15 yards but you can hear the wind over the cliff top.”

“My view, based on many years studying the activity in Japan, is that pilgrimage is not just about one-off journeys out of the ordinary,” Ian Reader, professor of Japanese Studies at the University of Manchester in England observed. “It is a complex phenomenon in which a variety of apparently contradictory themes interact, and can co-exist without there being a real conflict. It is not a singular event; for many pilgrims, it is very much embedded in the structures of their daily lives as well. For some of the pilgrims I met in Japan, they went to Shikoku so regularly and spent so much time doing or preparing for pilgrimages that Shikoku became a sort of home for them and the pilgrimage became a normal part of their lives.

Outer Journey to Inner Destination

Tom Nowakowski, 40, is an avid long-distance hiker originally from Lodz, Poland, now of Palm Springs, California. He has traversed the Appalachian Mountain Trail, the Pyrenees, Swiss Alps, and just returned from hiking KommEmine across Bulgaria. Over four and a half months in 2007, he hiked the Pacific Crest Trail, a 2,650-mile journey stretching from Mexico to Canada.

The trek involved traversing 700 miles of Colorado and Mojave deserts and the snows of the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

“Pilgrimage to me it is a physical, outer journey to a spiritual, inner destination,” Nowakowski said. “Along thru-hike like the PCT is a perfect example of a pilgrimage. A journey where it is all about the going — not about what is at the end of the road. You walk for months at a time but there is nothing waiting for you at the end of the trail. Actually, when you get there it means that the trip is over – a very emotional experience for many. All that is truly important happens while you are journeying.”

“The hike is a chance to get rid of all the things you really don’t need, physically, mentally, emotionally,” he continued. “It is the art of deprivation. You are carrying your pack so you simplify. People often start the trail carrying everything but the kitchen sink and end up shipping a lot of stuff home. Water is very heavy so you walk from water source to water source. On the trail, the longest hike between water sources is 40 miles or two days.”

“You’re moving, your body is healthy and your mind goes quiet,” he recalled. “You’re mindful, aware — if you don’t pay attention, there will be a copperhead or rattlesnake, or you will slip on the trail. In spite of that, your mind doesn’t have over-stimulation of the everyday world, it empties. You start to digest things from far, far in the past, things have a chance to re-surface, it has a cleansing quality, a detoxifying effect.”

Nowakowski is not alone in finding that the open road leads to an open mind.

Spirituality in Everyday Life

Amanda Pressner, 32, is a co-author of “The Lost Girls: Three Friends. Four Continents. One Unconventional Detour Around the World.” The book is an account of a year-long backpacking adventure she and two friends embarked upon after quitting their high-pressure New York media jobs.

“Our journey was a pilgrimage, one that initially seemed to have no specific endpoint,” she said. “Unlike many religious pilgrimages, where a journey is made in order to worship at one specific place of great spiritual significance, we had no specific physical destination that we’d set out to reach.

“I was definitely awed by the devotion, its many forms, that I encountered in Southeast Asia,” she continued. “Religion and spirituality seemed to be infused into everyday life in places like Bali — with its ever-present offerings to the gods — and Myanmar — with its thousands upon thousands of stupas and temples. Faith was all around, rather than concentrated in a few very important sites where pilgrims might gather — you were reminded of that at nearly every turn.”

“We had some idea that the very act of leaving everything familiar behind, taking a leap, getting on the road—and being open-minded during our journey—would help us reach destinations of great emotional significance, and our hunch was correct,” Pressner concluded. “We eventually realized that our sacred endpoint was home and that we just had to go the long way around, and learn a lot about ourselves, in order to get there.”

Sometimes, the pilgrimage road can seem to extend forever, regardless of its length.

Argentina's Pilgrimage of the Young

Fourteen years ago, Estani Puch, 36, made Argentina’s “Pilgrimage of the Young.” Held every October, thousands walk 65 kilometers from the barrio of Liniers in Buenos Aires to Luján, a journey that generally takes about 18 hours.

The Basilica of Luján is one of Argentina’s major places of pilgrimage. According to legend, in 1630, a tiny, terracotta statue being transported on an oxcart to Santiago del Estero, got stuck in the mud in Lujan. Nothing could make the cart budge until the statue was removed. It was taken as a sign that the 18-inch statue of the Virgin wanted to remain there.

Over time, a small shrine grew into one of Argentina’s major places of pilgrimage, now also known as “the Capital of Faith.”

“I was 22, and working in Wal-Mart at the time and trying to get a job in Citibank selling financial products,” Puch recalled. “This is back in 1996 when the unemployment rate was something like 17% in Argentina so it was really hard to get a decent job and hard to change jobs as well. So, while I was in the process of interviews, I promised that if I got the job, I would walk to Lujan.”

“I did the journey with a friend from work and with a Catholic congregation from Buenos Aires — there were around 150, 000 people walking,” he said. “You start walking at 8 a.m. and go all day and all night, till 3 or 4 in the morning. It is very tiring but if you stop it is impossible to start again. There is also support on the way — if you get tired or pass out they help you. Everything was organized — once you arrive at Lujan, there is a bus that brings you back to B.A.”

“Something funny about this walk is that the Basilica is quite tall, so you can see it from really far,” he continued. “That makes you think that you are getting really close, but it is still a long way to get there — you walk and walk and walk. Whoever you talk to will tell you they had the same impression.”

“The view of the church is what gives you faith to continue, but at the end you realize that what was important was the journey there or all the things in life that you have done,” Puch concluded. “I guess life is a pilgrimage and it is all about the journey, not the destination.”

Whether one considers pilgrimage to be a spiritual journey or a sacred destination, mankind has sought answers and enlightenment through movement since time immemorial. Be it a metaphor for life or a one-time occasion, pilgrimage is likely to be a feature of the landscape for some time to come.

Interested in learning about other Spiritual Practices around the world?

- Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 is Best Quirky Attraction in New Orleans

- Documenting Indian Art is Calling for Benoy K. Behl

- The Purpose of An Iconographer Explained by Renowned Icon Painter

- Celtic Priest on Spiritual Heritage and Traditions of Aran Islands

- Good Friday Tradition in Trapani Sicily Honors Faith and Heritage

- Interview with Mayan Shaman on Spiritual Practices and Philosophy

- San Juan Chamula Community Shares But Protects Traditions

- Curacao Synagogue is the Oldest Jewish Congregation Site in North America

- Culture in Malta Features Faith, Family, and Pageantry

- Estonia’s Onion Route and The Old Believers

- Taize in Findhorn Eco Village Scotland

- Easter Baskets in Slovenia At Tustanj Castle

- Eva Michaelsen on Walking Meditation and El Camino de Santiago

- What is Pilgrimage ? Spiritual Seekers Share Experiences

- Icon Painter in Cyprus Honors Byzantine and Family Traditions

- Author Eric Weiner on “Man Seeks God”

Publisher and editor of People Are Culture (PAC). This article was created by original reporting that sourced expert commentary from local cultural standard-bearers. Those quoted provide cultural and historical context that is unique to their role in the community and to this article.

Cultural Legacy of Spain’s Civil War Inspires Museum Director

Clark art institute transforms troubled kids with art, leave a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- CERC español

- Guardians of Truth

- Ways To Give

- Religion & Philosophy

- Spiritual Life

The Journey

- Written by Super User

- FATHER ANTONINUS WALL, O.P.

The most common symbol of the dynamic of Christian salvation is that of a "journey".

Every journey is a process made up of various parts. The journeyman's advancement along the way is determined by the milestones whereby he is able to measure his progress. Father Wall shows us that this pattern applies to the spiritual life as well.