The Heroine’s Journey: Examples, Archetypes, and Infographic

By Julia Blair

Joseph Campbell popularized the Hero’s Journey that has become a mainstay among writers. But he also said the symbols of ancient myths no longer fit the modern world. This is why we need to add the heroine’s journey to our myths.

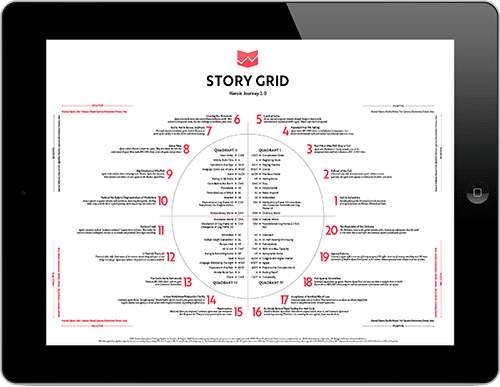

Are you writing a Heroine's Journey?

Download our highly detailed infographic outlining the 20 major scenes you must have in every story.

We Need New Myths

Myths are archetypal stories that reflect our inner selves. They reveal our foibles and laud our innate strengths so that we can better understand our shared humanity.

But society has changed a lot since Theseus slew the minotaur.

“When the world changes, then the religion has to be transformed. The only mythology that is valid today is the mythology of the planet—and we don’t have such a mythology.” – Joseph Campbell

Campbell was right about our changing world. We face challenges our ancestors never even dreamed of.

- Technology revolutionizes our lives. We’ve transferred much of our making and thinking to computers. We socialize online. Memory is digitized.

- Societies struggle to cope with conflict and suffering based on socioeconomic, racial, and gender inequality.

- In business and politics, women are still subject to lower wages and discriminatory policies.

- The Earth itself is in critical danger as climate change impacts land, sea, and air, and alters the habitats of plants and animals.

In a recent tweet, Glasgow International Fantasy Conversations affirmed:

“The great theme of our age is one of loss. In a time of ecological crisis, we need stories. We need to imagine better tomorrows, stories as alibis that get us through the day.”

This failure of old myths to deliver answers is echoed in the very movie franchise that put the Hero’s Journey into popular culture.

In The Force Awakens , Rey exclaims, “Luke Skywalker! I thought he was a myth!”

She speaks for all of us in The Last Jedi when she implores Luke, “I need someone to show me my place in all of this.”

Luke reveals his disillusionment. “I only know one truth: It’s time for the Jedi to end.”

The loss of meaning in one’s life is painful to him—and to us, the audience—a feeling that echoes all too well our era of crisis and loss.

But when a myth becomes part of the collective memory, it’s remarkably persistent. We see that in the repetition of stories and movies based on the Hero’s Journey. The only way to change an outdated myth is to replace it with a better one, whose symbols make more sense and resonate with contemporary society. In this post, I’d like to look at alternative stories of self-discovery based on a pattern called the Heroine’s Journey.

A Female Perspective

Female action heroes like Wonder Woman’s Diana Prince and Divergent’s Tris rake in big bucks for Hollywood, showing that a woman can carry an action film and attract huge audiences. These movies stick to the basic shape of the Hero’s Journey, just replacing the male protagonist with a woman. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but it’s the same old story dressed up in a new outfit.

In movies like Thelma and Louise , where women break the rules, the audience feels empowered. In this David and Goliath trope even when the heroines take freedom to the ultimate extreme, we feel that justice has been done in a fight against an unfair system.

In real life, women who push back against societal norms aren’t always seen in a positive light. “Nevertheless, she persisted,” originally meant to denigrate Senator Elizabeth Warren’s resistance to a male colleague’s effort to stop her from speaking, epitomizes how women who dare to challenge the patriarchy are seen. Intended to demonstrate, the catchphrase was transformed into a feminist call to action.

Psychologists, mythologists, and writers have searched for feminine alternatives to Campbell’s monomyth, one that gives women and disenfranchised protagonists the agency and power to carry stories that follow a different path to self-actualization. From this search, the Heroine’s Journey was born. But unlike the classic Hero’s Journey, there are multiple versions of a Heroine’s Journey. Let’s take a look at two of the best known.

Maureen Murdock’s The Heroine’s Journey

Maureen Murdock wrote The Heroine’s Journey as counterpoint to Joseph Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces .

When she asked Campbell about women and the Hero’s Journey, he famously responded:

“Women don’t need to make the journey. In the whole mythological tradition, the woman is [already] there. All she has to do is to realize that she’s the place that people are trying to get to.”

This reply inspired Murdock, a trained psychologist, to dig deeply into the realms of myth and psychoanalysis to develop an archetypal pattern of a woman’s quest for enlightenment and wholeness: the Heroine’s Journey.

You can trace the path of Heroine’s Journey in two popular stories. In the Pixar movie Brave, the protagonist Merida closely follows Murdock’s model as she struggles to make a place for herself without compromise in a fantasy version of medieval Scotland. And, notably, Zuko from the animated series Avatar the Last Airbender also follows a path that mirrors the Heroine’s Journey, which contributes to a powerful redemption arc of emotional depth and sensitivity.

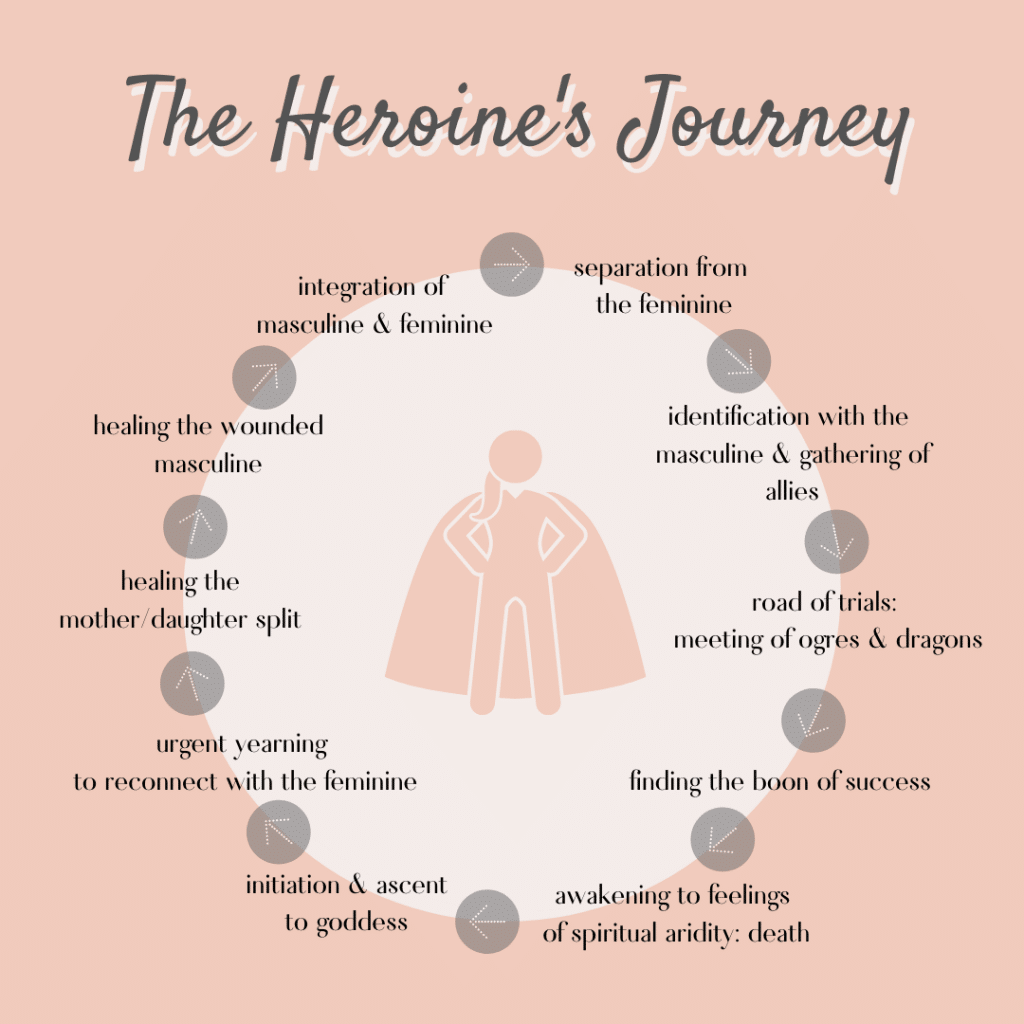

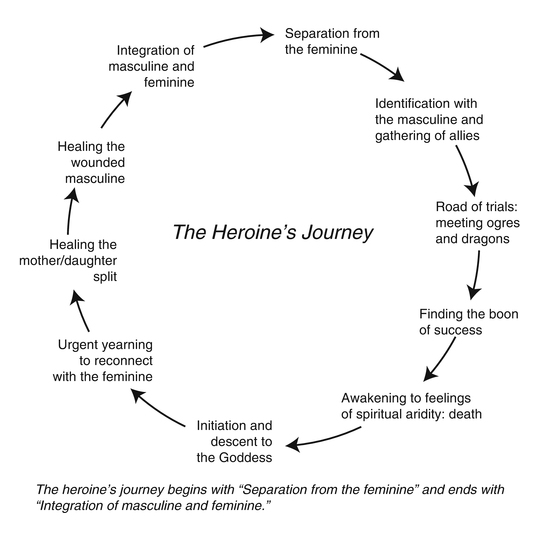

The journey includes ten stages, modeled here:

The Heroine’s Journey

1. separation from the feminine.

Women leave the nurturing shelter of the archetypal Mother behind. Some strike out in search of success and and a sense of self. Others flee from the negative associations of feminine behavior, wanting to be taken seriously and not unrealistically sexualized.

2. Identification with the Masculine

To flourish in a male-oriented world, successful women often emulate male behavior by abandoning the domestic sphere, suppressing emotional displays, and adopting male traits in the boardroom or on the campaign trail. Merida rejects traditional women’s activities such as needlework. She excels in archery, defeating all her potential suitors in a competition. Zuko is separated from the nurturing love of his mother as a child and thrust into his father’s world of domination through conquest.

3. The Road of Trials

The heroine confronts challenges and obstacles to her goals. She survives trials, earns degrees, or learns difficult skills. She must balance her personal and professional lives. She must prove herself to those who think she’s not worthy to succeed by male standards. Zuko chases the Avatar to restore his honor.

4. The Illusory Boon of Success

Having overcome her trials, the heroine attains a measure of success, a powerful title, position, or wealth. She is a superwoman who has it all. Imposter syndrome still sneaks in, and she wonders when she will feel she has truly succeeded.

5. Awakening to Spiritual Emptiness

Despite her successes, the heroine feels empty. She senses that there must be more to life. She may feel betrayed by the system or by her allies. She hears her inner voice after years of ignoring it. Even when he has returned home and regained his honor, Zuko finds the victory hollow. He questions his feelings and realizes that he has chosen the wrong path.

6. Initiation and Descent to the Goddess

The heroine experiences the dark night of her soul. She sometimes withdraws from friends and family. She no longer sees the point in struggling for success by her previous terms. The heroine must face her Shadow, an archetype that, simply put, represents the things within herself that hold her back from what she truly needs. She learns to be , not to do . Merida travels deep into a wild forest to seek help from an old wise woman or witch. The Wise Woman is a strong archetype in her own right, the dark face of the Goddess representing danger and wisdom.

7. Yearning to Reconnect with the Feminine

Having rejected the pursuit of outward success, the heroine may end associations with people or institutions that compromise her newly awakened spiritual growth. She turns to creative work and activities that enable mind-spirit-body connections. She begins to purify herself for the next stage.

8. Healing the Mother/Daughter Split

The heroine reconnects with her roots and finds strength in the past. She emerges from the darkness with a deeper sense of self. She is able to nurture others and be nurtured by them. She reclaims feminine traits she once saw as weak. Merida must draw upon her knowledge of the feminine activities she rejected in order to save her mother from an enchantment.

9. Healing the Wounded Masculine

Having reoriented her concept of femininity, the heroine must shed toxic perceptions of masculinity. If she has rejected her earlier pursuits in the male-oriented world, she searches for what remains meaningful to her. She casts aside unrealistic concepts of men. Having rejected his father’s (and nation’s) violent traditions, Zuko’s loses his firebending skills until he learns how to use them in positive rather than destructive ways.

10. Integration of Masculine and Feminine

Our heroine has come full circle. Male and female aspects of personality are integrated in a union of ego and self. She is whole and capable of genuine love for others. She remembers her true nature. Not until Zuko joins up with Avatar Aang, who represents the antithesis of violence, is Zuko able to integrate his dual nature and achieve wholeness on his own terms before bringing balance to the world. Merida, too, has learned to embrace the different aspects her life. She accepts the value of her mother’s instruction in feminine pursuits while retaining her interest in archery and other stereotypical masculine activities.

Murdock’s model has roots in the women’s movement of the Sixties and Seventies, with a generation who raised their fists against the status quo. She and her contemporaries had heavy cultural shackles to break. Their efforts enabled subsequent generations to build on and benefit from a growing acceptance of the equality of women.

The Heroine’s Journey described by Maureen Murdock is a quest for integration and healing. The circle closes with the union of male and female, representing a journey toward spiritual and societal growth.

Its real strength is found in its understanding of the duality of human nature. The yin-yang symbol incorporates dark in the light, and light in the dark. There is strength in our Shadow selves, but only when we face our personal demons does our Shadow step aside and let us move forward.

Murdock built her model as a path for introspection and self-awareness, not specifically as a tool for writers. Nevertheless, it is one of the most widely known versions of a female counterpart to the Hero’s Journey.

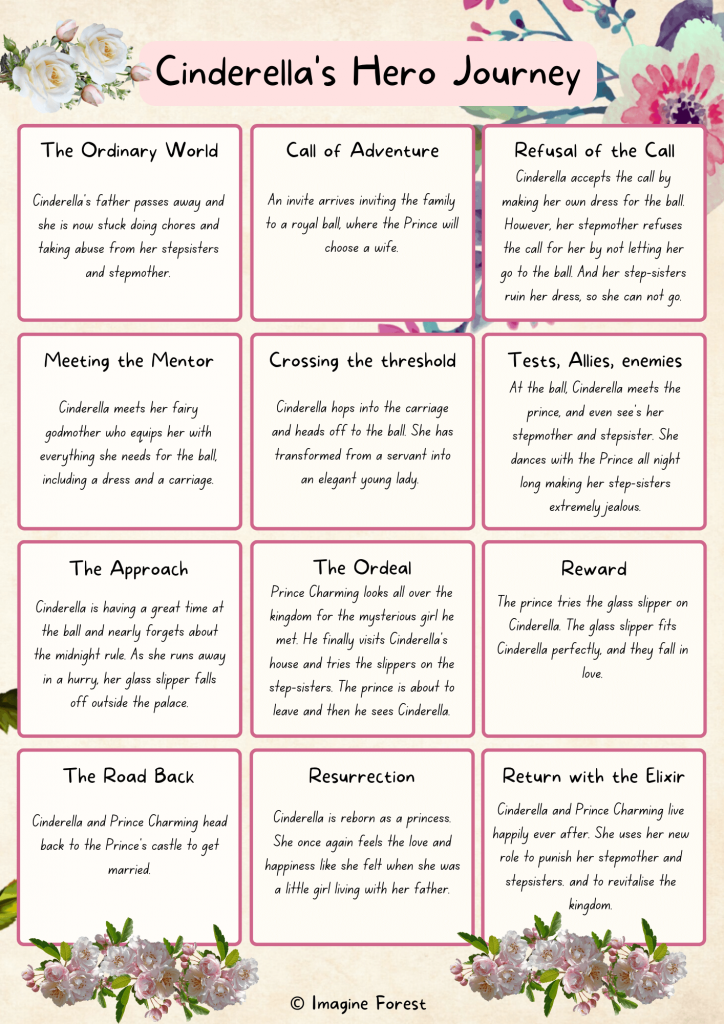

Kim Hudson’s The Virgin’s Promise

Author Kim Hudson describes the Heroine’s and Hero’s Journeys as “two halves of a whole.” Although The Virgin’s Promise portrays a feminine take on the search for one’s authentic self, it avoids limiting the gender of the protagonist. Viola in Shakespeare in Love exemplifies the journey with a female lead and Billy in the movie Billy Elliot , is a male protagonist following a similar path.

Hudson developed her model for writers, specifically screenwriters, so it’s structured in three acts and frames archetypes and imagery in storyteller’s terms.

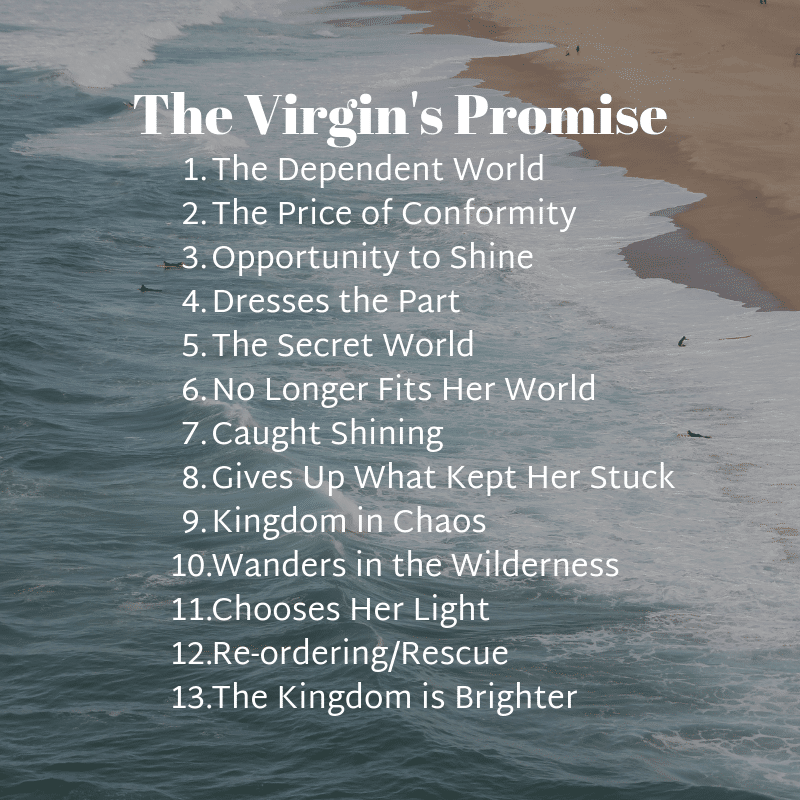

Some of the thirteen stages in this model have no equivalent in the Hero’s Journey. They reflect, instead, an inner emotional approach to life’s challenges. The thirteen stages are:

1. The Dependent World

The protagonist is tied to her normal world in order to survive, either by social convention, physical protection, or as a stipulation of conditional love. She is dependent on others to get by.

2. The Price of Conformity

The Virgin suppresses her inner gift to maintain the status quo. She may not realize she is captive in her Dependent World, or she may be critically aware of the need to hide her true nature. She may believe the low opinions others have of her and feel worthless. She is unable to break her chains or spread her wings.

3. Opportunity to Shine

A chance to express herself comes without risk to her dependent world. She may discover a talent, be pushed to it (fairy godmothers are great at this), or she may act in the interest of another person who requires her help. She recognizes a dormant part of her soul, or uses her talent in a new way.

4. Dresses the Part

The Virgin realizes her dreams may actually be within in reach. “Dressing the part” means she willingly steps into a role. In Shakespeare in Love , for example, Viola dons costume and becomes an actor. Cinderella wears a magical gown and goes to the ball after all. Sometimes, the Virgin receives an object or talisman that symbolizes her secret self. She “becomes beautiful” physically, metaphorically, or both.

5. The Secret World

Now she has a foot in the world of her dreams yet remains unwilling (or unable) to leave her old life behind. People might depend on her. She may be in physical danger, or fears the consequence of letting go of the Dependent World. Change is a hard thing. Who hasn’t hesitated before plunging into the unknown?

6. No Longer Fits Her World

As the Virgin discovers her true nature, she realizes her double life can’t go on. The risk of being caught increases. She may feel that she’s still an outsider in her secret world. Her behavior ranges from risk-taking to rejecting her dreams, thinking she can return to the way she used to be.

7. Caught Shining

The Virgin is revealed, exposed in one world or the other by betrayal or changing circumstance. Her secret is secret no longer. She may reveal her newfound strength by coming to the rescue of another. Ayla, in Clan of the Cave Bear , exposes her skill with a forbidden weapon by saving a child from a hyena.

8. Gives Up What Kept Her Stuck

Many things may hold the Virgin back: fear of losing loved ones, being hurt by a new love, fear of success or loss. Now she faces those fears and breaks the hold that others have on her. Sometimes the Dependent World vanishes and she finds herself on her own for the first time. She is her own boss, the mistress of her fate.

9. Kingdom in Chaos

In the wake of her assertiveness comes disruption. She has rocked the boat and changed the status quo by her rejection of the things that held her back. She has upset the old order and the Dependent World may come after her with all its strength in order to re-establish itself.

10. Wanders in the Wilderness

The Virgin faces her moment of doubt. Despite her newfound confidence, things don’t go as planned. Her belief in herself is tested to the max. Things might look very good back home, tempting her to give up her crazy notions of independence.

11. Chooses Her Light

But the Virgin eventually chooses to shine. She expresses her gifts in an imperfect world, accepting her flaws and her strengths. She gains new insights about the world she left behind. Power has shifted, and she now holds at least some of it. She can take care of herself and has become a self-actualized soul. But her journey doesn’t stop here.

12. Re-ordering/Rescue

The world readjusts itself around her. The Virgin broke ties with the Dependent World in Stage 8. Now she returns to her community. Her transformation makes the old world a better place. She reunites with people she loves who recognize and value her true self. She is no longer controlled by others.

13. The Kingdom is Brighter

Not only has the Virgin grown, but the world has also become a better place as a result of her journey. She integrates her inner self with the outer world. Hudson explains, “She has moved from knowing conditional love to unconditional love.”

Shared Elements of Male and Female Archetypal Journeys

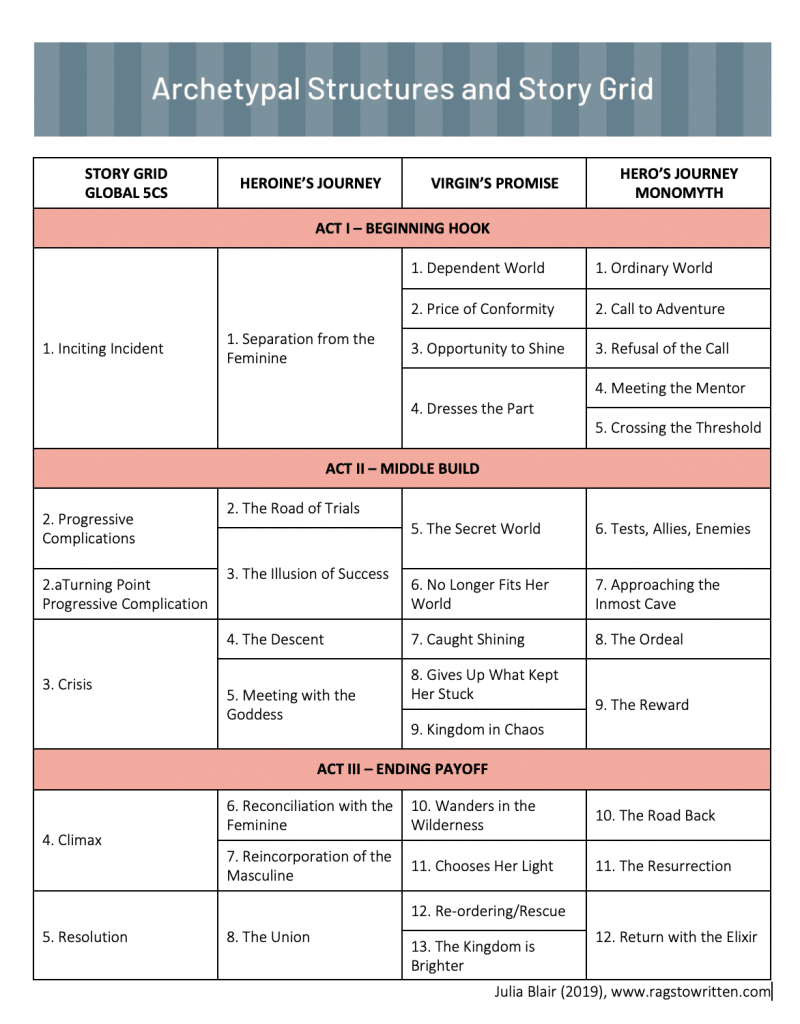

The Heroine’s Journey and The Virgin’s Promise show us what stories are like when women achieve their full potential. The Heroine’s Journey (HJ), The Virgin’s Promise (VP), and the monomyth (MM) share some elements, demonstrating that at least some components of heroic stories are universal:

- The protagonist rejects or suppresses part of themselves to fit in the normal world. HJ: Separation of the Feminine; VP: The Price of Conformity; MM: Call to Adventure, Rejecting the Call.

- The protagonist expresses new talent or knowledge without risking themselves. For a while, things look like they’ll work. HJ: The Illusion of Success; VP: The Secret World; MM: Tests, Allies, Enemies.

- The protagonist experiences a moment of doubt. They wonder if they have chosen the right path and if they can return to the way things used to be. HJ: The Descent; VP: Wanders in the Wilderness; MM: Approaching the Inmost Cave.

- Continuing on the journey, the protagonist does what they must to defeat their demons, conquer the adversary, or complete their quest. HJ: Reconciliation with the Feminine, Reincorporation of the Masculine; VP: Chooses Her Light; Wanders in the Wilderness; HJ: The Road Back, The Final Battle.

- The protagonist integrates their conflicting selves, rejoins the world, brings inner and outer balance. They have transformed themselves and the world. HJ: The Union; VP: Reordering/Rescue; MM: Return with the Elixir.

(The VP crisis occurs in Act III. In HJ and MM, the crisis takes place in Act II.)

You can download a printable version of this chart here .

Contrasts with the Hero’s Journey

The male and female journeys of self-actualization follow different paths but arrive at a similar destination. Both trace a voyage of self-discovery, of confronting and breaking down self-deception and learning to integrate aspects of personality in positive, productive ways.

Heroine’s journeys are about self-worth and identity. The heroine brings balance to herself, then changes the world around her. It’s more about the journey than the destination.

The Hero’s Journey is a quest for an external objective. It is about obligation and rising to the task. The Hero seeks to right a wrong and bring balance to the world. In doing so, he is transformed.

One of the loudest and most legitimate complaints to be made about the Hero’s Journey is that it’s become formulaic. The constant barrage of mediocre action/adventure sequels out of Hollywood attests to that. I’m not saying it’s time to abandon the Hero’s Journey. It’s still capable of surprises. Star Wars’ Darth Vader arc gives us a failed Hero’s Journey and a fascinating character study. The Cohen brothers’ O Brother, Where Art Thou delivers a twist on the classic with escaped convicts as heroes. As writers create new variations on a theme, the archetypal pattern is shifting.

Putting It To Work

If you read my post on archetypes , you know I believe that writers have the ability and responsibility to bring joy, hope and change to the world. Myths and archetypes are powerful tools for accomplishing that.

While reading about alternatives to the Hero’s Journey, I began to see that the Heroine’s Journey and Virgin’s Promise are more than just female versions of the monomyth. They meet the responsibility to spark change because they arose in response to a need for change.

Immutable Story Grid Truth: All good stories are about change.

All of them. Without exception. In every scene, sequence, and act there must be a change, or it’s not a working scene, sequence or act. Characters must change or fail.

The Virgin’s Promise and the Heroine’s Journey are different ways to achieve transformation. They’re alternative narrative structures that can breathe new life into the stories we tell and have the potential to bring some hope and joy as well.

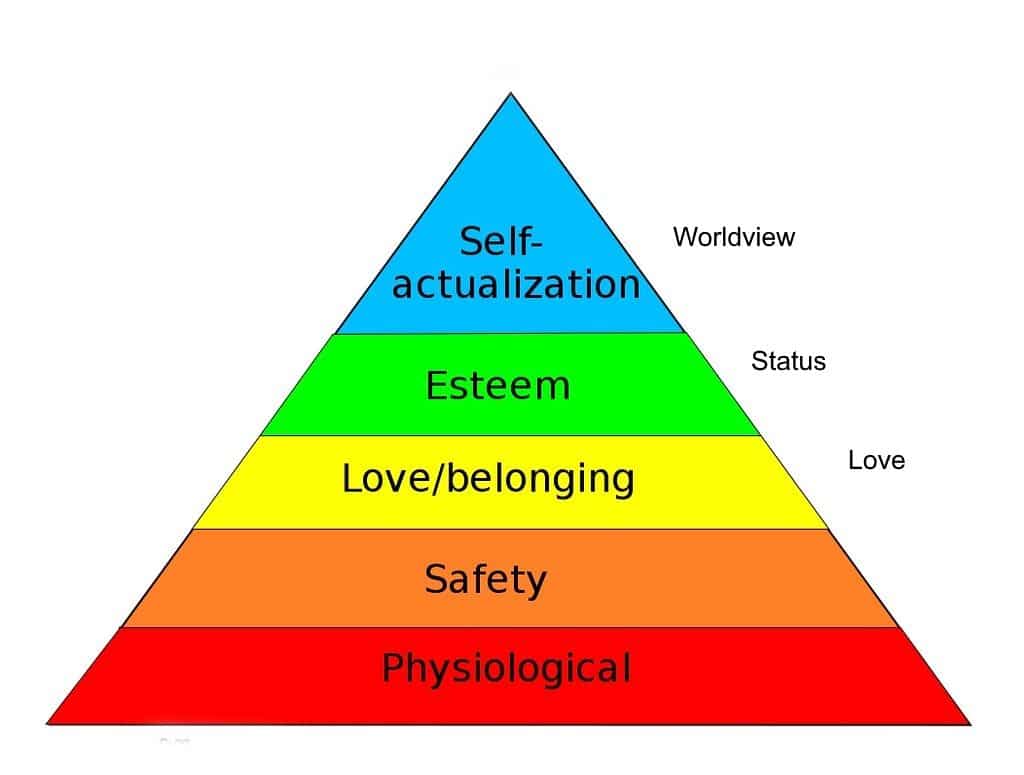

In Story Grid terms, these models relate to the higher ranges of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. You’ll find them especially good fits for the internal genres of Worldview (self-actualization) and Status (self-esteem). You can also find elements of these models in the Love Story, an external genre, when characters seek a mature and unconditional love.

MASLOW’S HIERARCHY OF NEEDS

Balancing internal and external genres within a plot is one of the hallmarks of a compelling story. Both Heroine’s Journey models enable us as writers to delve into the psyche of a character in a different way. They inspire new responses to the challenges of change and growth and the consequences of failing to change.

How might your current work-in-progress benefit by incorporating elements of the Heroine’s Journey?

Consider how your protagonist changes through the course of your story. Are they thrust into a situation that forces them to change whether they want to or not? Very often that’s the monomyth, and you can draw from the stages of the Hero’s Journey for inspiration.

Does your protagonist feel a growing dissatisfaction with the way things are? Are they faced with the realization that the problem is something inside them? Are they held back by external circumstance and lacking opportunity for their inner gift to bloom? You’ve got a great candidate for the Virgin’s Promise or Heroine’s Journey.

A Call To Action

Old myths are no longer as relevant in our complex 21 st century world as they once were, but we’ve not yet replaced them with something as strong and inspiring—and we need to. Campbell says that the most important purpose of myth is to guide humans through the stages of life, from cradle to grave.

Robert McKee, an authority on writing powerful stories, tells writers to write the truth. The truth is, we need desperately need new myths to guide us forward in a compassionate and enlightened way.

So where do new myths come from?

Mythologists don’t create our myths, they study them. They dissect them, examine the pieces, investigate symbols and themes. But myth is far more than just the search for meaning. It is the experience of meaning.

That’s precisely what happens inside a reader’s head when they read a book. Consuming stories gives readers the experience of meaning. Stories are how we deliver the new myths that the world needs now.

You, dear writer, are a mythmaker.

It’s our calling as writers to create new myths, to draw upon our experiences, uncover new symbols, and reinterpret archetypes.

McKee and others tell us that through story, people experiment with change without risking themselves. Readers and movie-goers try on different mindsets and personas, just like trying on clothes before a mirror.

When they find something that fits, a new way of thinking about themselves, the world, and themselves in the world, you the writer have made a change.

J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series taught me that there is no greater power in all the world than love. Masashi Kishimoto’s long-running anime Naruto taught me to never give up on my dreams. The Gate to Women’s Country , a novel by Sheri S. Tepper, taught me that going through a stupid phase doesn’t mark me for life.

The monomyth has roots in humanity’s psycho-emotional past. It connects us with ancient storytellers. And that’s not a bad thing. But there are other ways of knowing.

It’s time we looked to the future. You have a superpower that can change lives. Use it wisely, but use it.

It is time for us to imagine and write better tomorrows.

More Heroic Journey Resources

- Villain Archetype

- Hero Archetype

- Mentor Archetype

- Trickster Archetype

- Shapeshifter Archetype

- Herald Archetype

- Threshold Guardian Archetype

- Allies Archetype

I am grateful to Shelley Sperry for her insightful comments and assistance in making this a better post.

Share this Article:

🟢 Twitter — 🔵 Facebook — 🔴 Pinterest

Sign up below and we'll immediately send you a coupon code to get any Story Grid title - print, ebook or audiobook - for free.

Julia Blair

Julia Blair knows firsthand the challenges of balancing writing, family, and an outside job. Her most creative fiction always seemed to flow when faced with grad school deadlines. While raising a family of daughters, horses, cats, and dogs, Julia worked as an archaeologist and archivist. She brings a deep appreciation of history and culture to the editing table.

As a developmental editor and story coach, her mission is to help novelists apply the Story Grid methodology to their original work and create page-turning stories that readers love. Her specialties are Fantasy, SciFi, and Historical Fiction.

She is the published author of the short story Elixir, a retelling of fairy tale Sleeping Beauty, and has several several articles on the Story Grid website. She the co-author of a forthcoming Story Grid masterguide for the Lord of the Rings.

Level Up Your Craft Newsletter

Author, educator, and photographer

- Meet Maureen

- Selected Work

- Changing Woman Gallery

- Speaking/Contact

Articles: The Heroine’s Journey

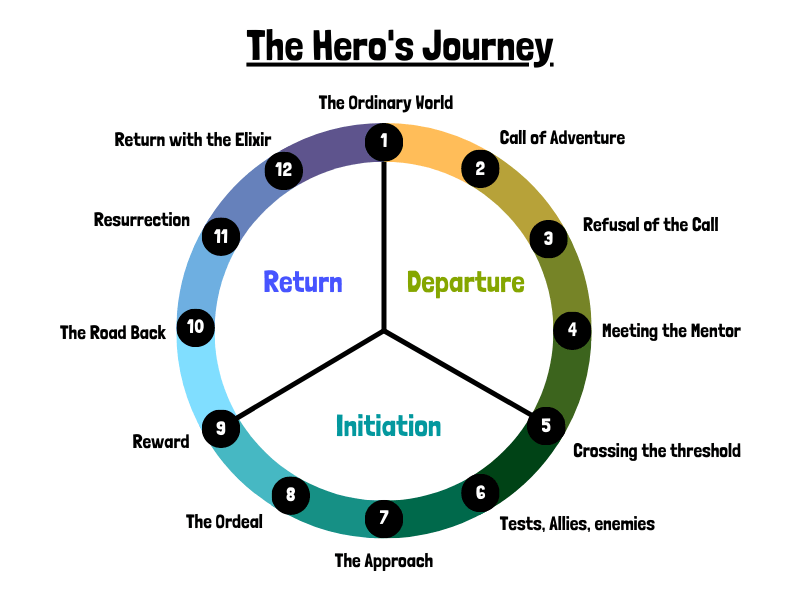

By Maureen Murdock Published in the Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion edited by David A. Leeming, 2016

In 1949 Joseph Campbell presented a model of the mythological journey of the hero in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, which has since been used as a template for the psycho-spiritual development of the individual. This model, rich in myths about the travails and rewards of male heroes like Gilgamesh, Odysseus, and Percival, begins with a Call to Adventure. The hero crosses the threshold into unknown realms, meets supernatural guides who assist him in his journey, and confronts adversaries or threshold guardians who try to block his progress. The hero experiences an initiation in the belly of the whale, goes through a series of trials that test his skills, and resolves before finding the boon he seeks – variously symbolized by the Grail, the Rune of Wisdom, or the Golden Fleece. He meets a mysterious partner in the form of a goddess or gods, enters into a sacred marriage, and returns across the final threshold to bring back the treasure he has found (Campbell 1949, pp. 36–37).

The hero’s journey is a search for one’s soul and is chronicled in mythologies and fairy tales throughout the world. This quest motif does not, however, address the archetypal journey of the heroine. For contemporary women, this involves the healing of the wounding of the feminine that exists deep within her and the culture.

Fig. 1: The Heroine’s Journey

In 1990, Maureen Murdock wrote The Heroine’s Journey: Woman’s Quest for Wholeness as a response to Joseph Campbell’s model. Murdock, a student of Campbell’s work, felt his model failed to address the specific psycho-spiritual journey of contemporary women. She developed a model describing the cyclical nature of the female experience. Campbell’s response to her model was, “Women don’t need to make the journey. In the whole mythological tradition the woman is there. All she has to do is to realize that she’s the place that people are trying to get to” (Campbell, 1981). That may be true mythologically as the hero or heroine seeks illumination but psychologically, the journey of the contemporary heroine involves different stages.

The Heroine’s Journey begins with an Initial Separation from feminine values, seeking recognition and success in a patriarchal culture, experiencing spiritual death, and turning inward to reclaim the power and spirit of the sacred feminine. The final stages involve an acknowledgement of the union and power of one’s dual nature for the benefit of all humankind (Murdock, 1990, pp. 4-11). Drawing upon cultural myths, Murdock illustrates an alternative journey model to that of patriarchal hegemony. It has become a template for novelists and screenwriters, shining a light on twentieth-century feminist literature.

The Heroine’s Journey is based on the experience of fathers’ daughters who have idealized, identified with, and allied themselves closely with their fathers or the dominant masculine culture. This comes at the cost of devaluing their personal mothers and denigrating values of the female culture. This occurs for both men and women if not on a personal level, then certainly on a collective level. If the feminine is seen as negative, powerless or manipulative the child may reject those qualities she associates with the feminine, including positive qualities such as nurturing, intuition, emotional expressiveness, creativity and spirituality. On a cultural level, the Separation from the Feminine results from a reaction to images of the feminine presented by the media that are impossible to identify with or because of a lack of feminine imagery in religion.

Gods and goddesses are often seen as diverse ways of being in the world and the ancient goddess Athena symbolizes the second stage of the Heroine’s Journey. This Greek goddess of civilization sprang full grown from the head of her father, Zeus. Her mother Metis had been swallowed whole by Zeus, thus depriving Athena of a relationship with her mother. This stage involves an Identification with the Masculine, but not one’s inner personal masculinity. Rather, it is the outer patriarchal masculine whose driving force is power. An individual in a patriarchal society is driven to seek control over themselves and others in an inhuman desire for perfection.

The young girl may see men and the male world as adult and becomes identified with her inner masculine voice, whether that is the voice of her father, god the father, the professional establishment, or the church. Unfortunately, masculine consciousness often tries to help the feminine to speak; it jumps in, interrupts, and takes over, not waiting for her body to know its truth.

The next stage, like the hero’s journey, is the Road of Trials where the focus is on the tasks necessary for ego development. In the outer world, the heroine goes through the same hoops as the hero to achieve success. Everything is geared to climbing the academic or corporate ladder, achieving prestige, position and financial equity, and feeling powerful in the world.

However, in the inner world, her task involves overcoming the myths of dependency, female inferiority or deficit thinking, and romantic love. Many females have been encouraged to be dependent, to disregard their needs for another’s love, to protect another from their success and autonomy.

We live in a society dominated by a masculine perspective where the feminine is perceived as less than the masculine. The Mother Tongue, the language of experience and body knowing is not seen as valid as the Father tongue, the language of analysis. In some families, cultures and religions, being born in a female body is second rate; the female child has therefore failed from the beginning and is marked psychologically as inferior solely because of her gender. In this century the foremost moral issue, from third world countries to the leading world powers, is the abuse and oppression of women and girls around the globe.

The myth of romantic love is that the other will complete her life whether the other is a husband, lover, son, ideology, political party or spiritual sect. The attitude here is that the “other” will actualize her destiny. This stage is symbolized by the myth of Eros and Psyche.

The first part of the heroine’s journey is propelled by the mind and the second part is in response to the heart. The heroine has been working on the developmental tasks necessary to be an adult, to individuate from her parents, and to establish her identity in the outer world. However, even though she has achieved her hard-earned goals, she may experience a sense of Spiritual Aridity. Her river of creativity has dried up and she begins to ask, “What have I lost in this heroic quest?” She has achieved everything she set out to do, but it has come at great sacrifice to her soul. Her relationship with her inner world is estranged. She feels oppressed but doesn’t understand the source of her victimization.

At this stage, she is afraid to look into the depths of herself and clings instead to past patterns of behavior, old relationships, and a familiar life style. There’s a fear of saying “no” and holding the tension of not knowing what’s next. In Leaving My Father’s House, Jungian analyst Marion Woodman (1992) writes,

“It takes a strong ego to hold the darkness, wait, hold the tension, waiting for we know not what. But if we can hold long enough, a tiny light is conceived in the dark unconscious, and if we can wait and hold, in its own time it will be born in its full radiance. The ego then has to be loving enough to receive the gift and nourish it with the best food that new life may eventually transform the whole personality” (p. 115).

At this point, the heroine is faced with a Descent or dark night of the soul, a time of major de-structuring and dismemberment. A descent brings sadness, grief, a feeling of being unfocused and undirected. What usually throws a person into a descent is leaving home, separating from one’s parents, the death of a child, lover or spouse, the loss of identity with a particular role, a serious physical or mental illness, an addiction, the midlife transition, divorce, aging, or loss of community. The descent may take weeks, month, years, and cannot be rushed because the heroine is reclaiming not only parts of herself, but also the lost soul of the culture. The task here is to reclaim the discarded parts of the self that were split off in the original separation from the feminine–– parts that have been ignored, devalued, and repressed, words and feelings swallowed in her quest for success.

Dismemberment and renewal is a key feature of the ancient Sumerian myth of Inanna and Ereshkigal. Inanna, the Queen of the Great Above, journeys to the Underworld to be with her sister Ereshkigal, the Queen of the Great Below. Ereshkigal’s consort has died and Inanna traverses seven thresholds and seven gates to be with her sister in her grief. At each gate she divests herself of symbols of her power. When she reaches the Underworld, Ereshkigal fixes her with the eye of death and hangs her on a peg to rot. Inanna sacrifices herself for the earth’s need for life and renewal. Her death and subsequent return to life predates Jesus Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection by three thousand years.

At this stage in the heroine’s journey, a woman seeks to reclaim a connection with the sacred feminine to better understand her own psyche. She may become involved in research about ancient goddess figures such as Inanna, Ereshkigal, Demeter, Persephone, Kali, or the Marian mysteries. There is an Urgent Yearning to reconnect with the Feminine and to heal the mother/daughter split that occurred with the initial rejection of the feminine. This may or may not involve a healing with one’s personal mother or daughter, but it usually involves grieving the separation from the feminine and reclaiming a connection to body wisdom, intuition and creativity.

The next stage involves Healing the Unrelated or Wounded Aspects of her Masculine Nature as the heroine takes back her negative projections on the men in her life. This involves identifying the parts of herself that have ignored her health and feelings, refused to accept her limits, told her to tough it out, and never let her rest. It also involves becoming aware of the positive aspects of her masculine nature that supports her desire to bring her images into fruition, helps her to speak her truth and own her authority.

The final stage of The Heroine’s Journey is the Sacred Marriage of the Masculine and Feminine, the hieros gamos . A woman remembers her true nature and accepts herself as she is, integrating both aspects of her nature. It is a moment of recognition, a kind of remembering of that which somewhere at the bottom she has always known. The current problems are not solved, the conflicts remain, but one’s suffering, as long as she does not evade it, will lead to a new life. In developing a new feminine consciousness, she has to have an equally strong masculine consciousness to get her voice out into the world. The union of masculine and feminine involves recognizing wounds, blessing them, and letting them go.

The heroine must become a spiritual warrior. This demands that she learn the delicate art of balance and have the patience for the slow, subtle integration of the feminine and masculine aspects of her nature. She first hungers to lose her feminine self and merge with the masculine, and once she has done this, she begins to realize this is neither the answer nor the objective. She must not discard nor give up what she has learned throughout her heroic quest, but view her hard-earned skills and successes not so much as the goal but as one part of the entire journey. This focus on integration and the resulting awareness of interdependence is necessary for each of us at this time as we work together to preserve the health and balance of life on earth (Murdock, 1990, p.11).

In the Navaho Creation Story Changing Woman speaks to her consort the Sun:

“Remember, as different as we are, you and I, we are of one spirit. As dissimilar as we are, you and I, we are of equal worth. As unlike as you and I are, there must always be solidarity between the two of us. Unlike each other as you and I are, there can be no harmony in the universe as long as there is no harmony between us” (Zolbrod,1984, p. 275).

See also : The Hero Within, Dark Mother, Inanna, Ereshkigal, Demeter, Persephone, Femininity, Great Mother, Campbell, Joseph, Mother, Myths and Dreams, Feminine Psychology, Feminine Spirituality

Bibliography

Campbell, J. (1949). The hero with a thousand faces. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP. Campbell, J. interview with author, New York, 15 September 1981. Murdock, M. (1998). The heroine’s journey workbook. Boston: Shambhala Pub. Murdock, M. (1990). The heroine’s journey: Woman’s quest for wholeness. Boston: Shambhala Pub. Woodman, M. (1992). Leaving my father’s house: A journey to conscious femininity. Boston: Shambhala Pub. Zolbrod, P. G. (1984). Dine bahane: The Navaho creation story. Albuquerque: U of New Mexico P.

Holiday Savings

cui:common.components.upgradeModal.offerHeader_undefined

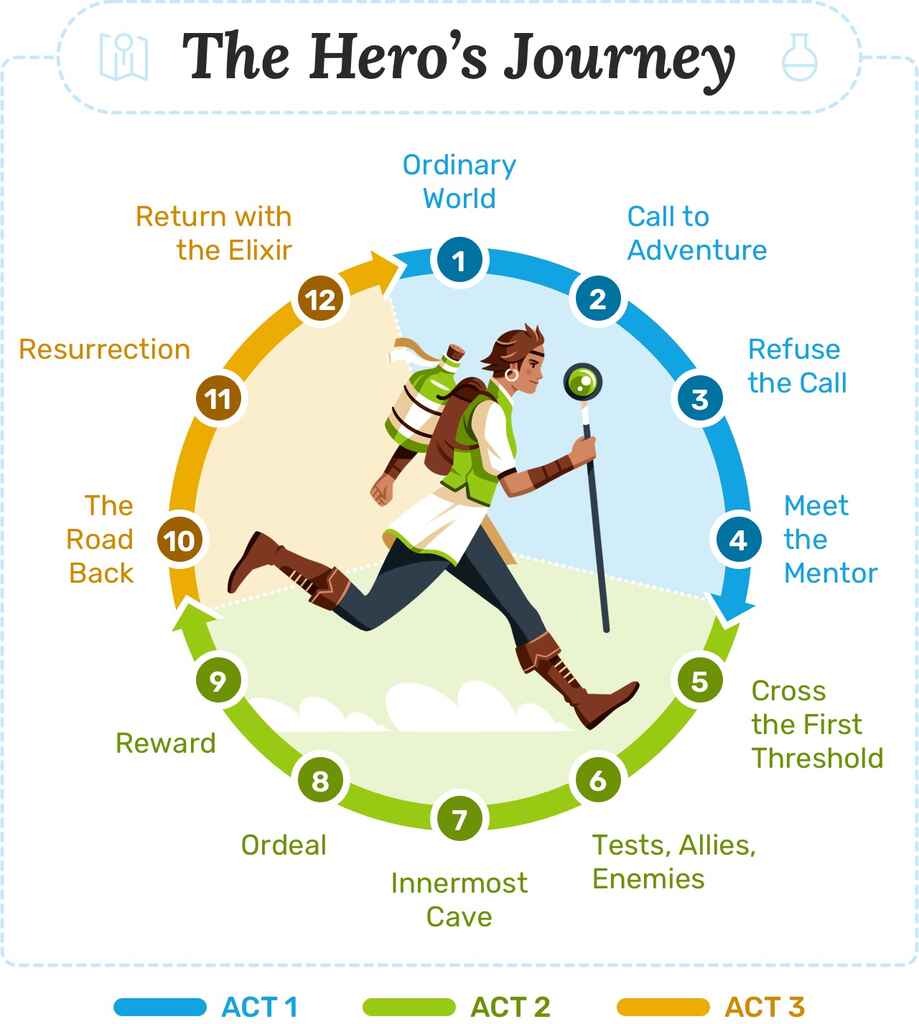

The hero's journey: a story structure as old as time, the hero's journey offers a powerful framework for creating quest-based stories emphasizing self-transformation..

Table of Contents

Holding out for a hero to take your story to the next level?

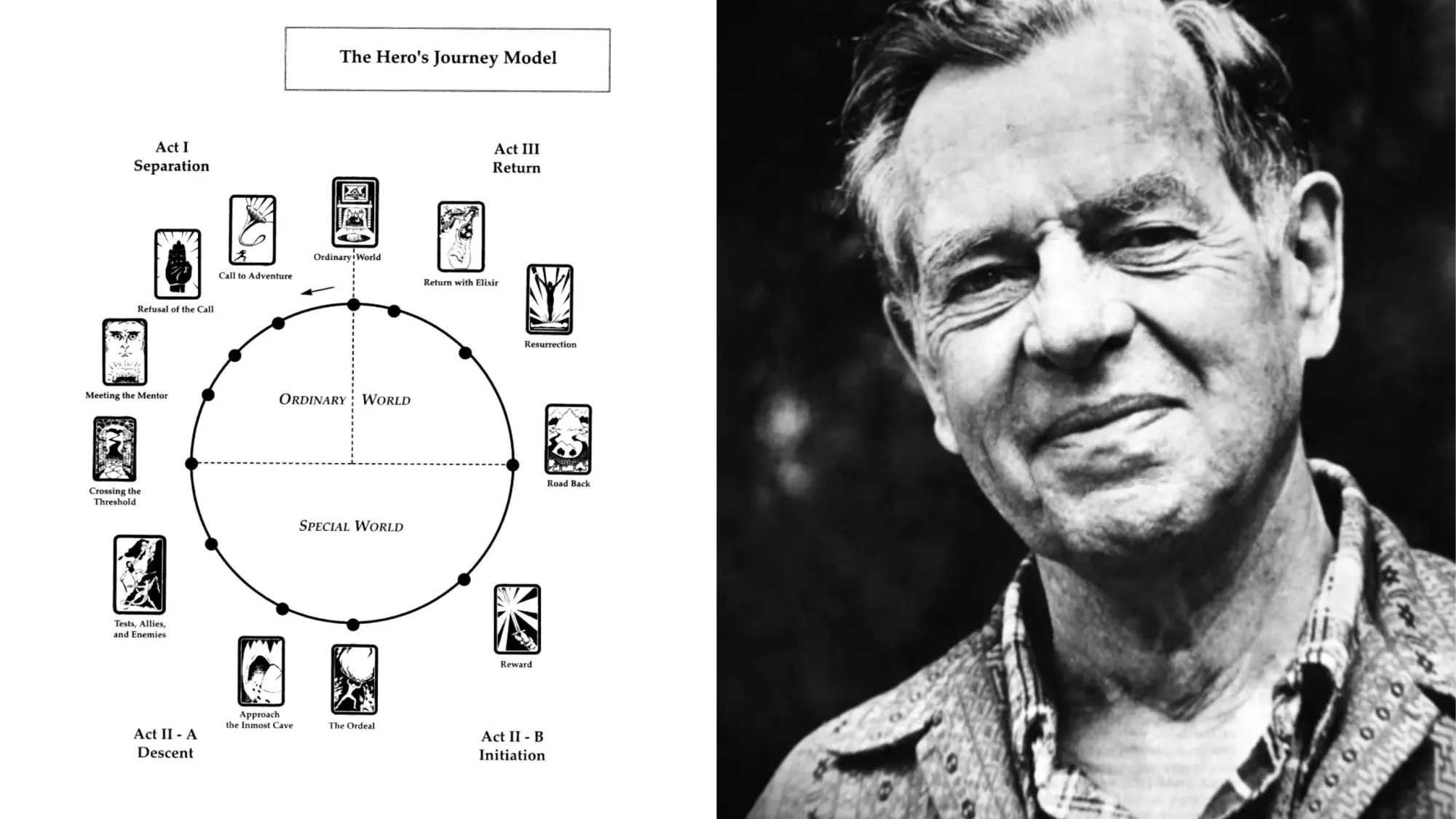

The Hero’s Journey might be just what you’ve been looking for. Created by Joseph Campbell, this narrative framework packs mythic storytelling into a series of steps across three acts, each representing a crucial phase in a character's transformative journey.

Challenge . Growth . Triumph .

Whether you're penning a novel, screenplay, or video game, The Hero’s Journey is a tried-and-tested blueprint for crafting epic stories that transcend time and culture. Let’s explore the steps together and kickstart your next masterpiece.

What is the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey is a famous template for storytelling, mapping a hero's adventurous quest through trials and tribulations to ultimate transformation.

What are the Origins of the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey was invented by Campbell in his seminal 1949 work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces , where he introduces the concept of the "monomyth."

A comparative mythologist by trade, Campbell studied myths from cultures around the world and identified a common pattern in their narratives. He proposed that all mythic narratives are variations of a single, universal story, structured around a hero's adventure, trials, and eventual triumph.

His work unveiled the archetypal hero’s path as a mirror to humanity’s commonly shared experiences and aspirations. It was subsequently named one of the All-Time 100 Nonfiction Books by TIME in 2011.

How are the Hero’s and Heroine’s Journeys Different?

While both the Hero's and Heroine's Journeys share the theme of transformation, they diverge in their focus and execution.

The Hero’s Journey, as outlined by Campbell, emphasizes external challenges and a quest for physical or metaphorical treasures. In contrast, Murdock's Heroine’s Journey, explores internal landscapes, focusing on personal reconciliation, emotional growth, and the path to self-actualization.

In short, heroes seek to conquer the world, while heroines seek to transform their own lives; but…

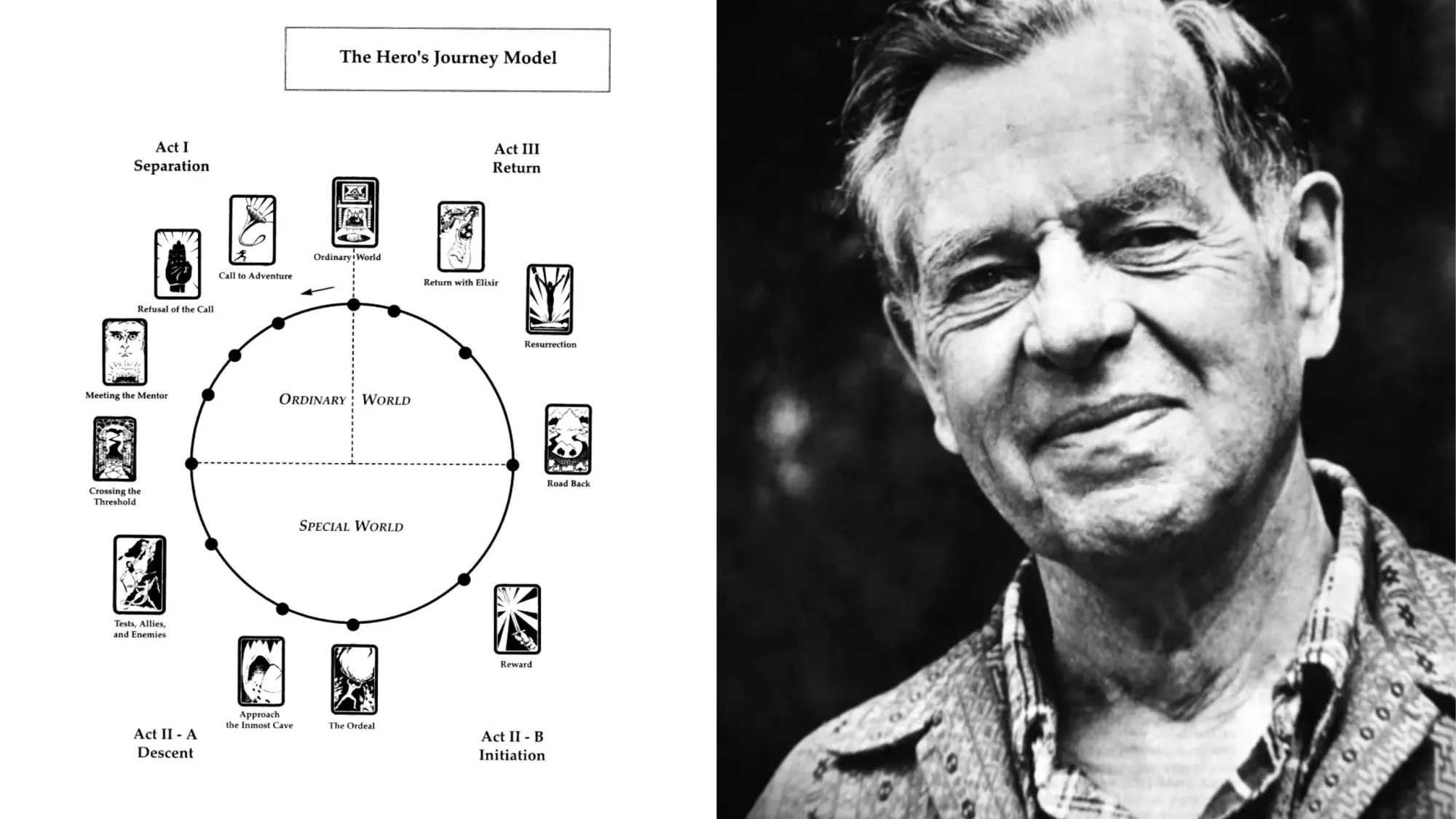

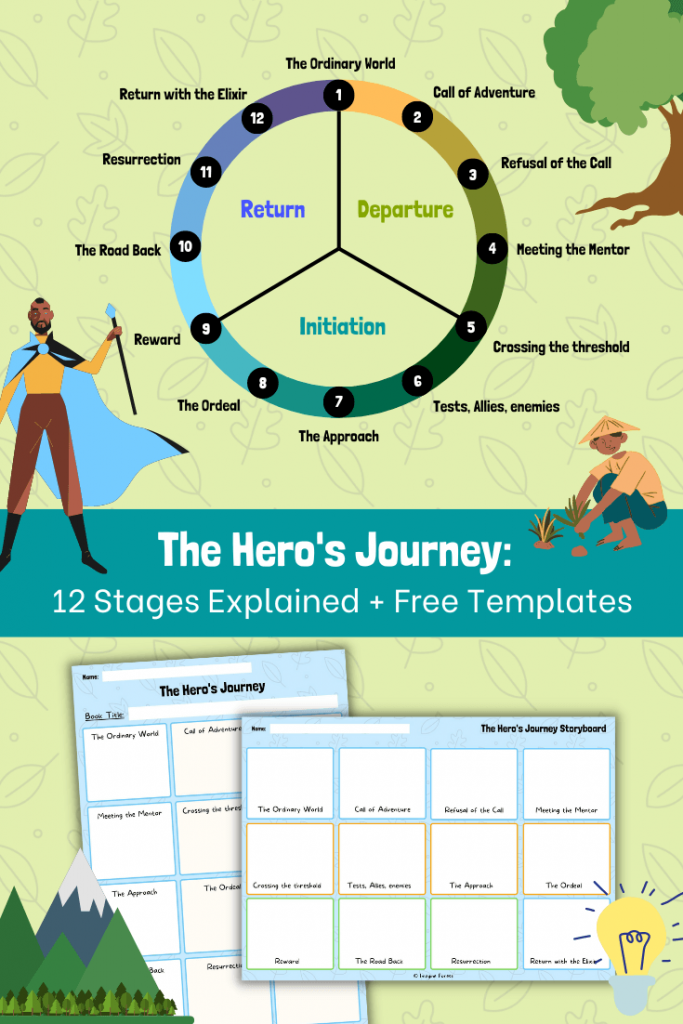

Twelve Steps of the Hero’s Journey

So influential was Campbell’s monomyth theory that it's been used as the basis for some of the largest franchises of our generation: The Lord of the Rings , Harry Potter ...and George Lucas even cited it as a direct influence on Star Wars .

There are, in fact, several variations of the Hero's Journey, which we discuss further below. But for this breakdown, we'll use the twelve-step version outlined by Christopher Vogler in his book, The Writer's Journey (seemingly now out of print, unfortunately).

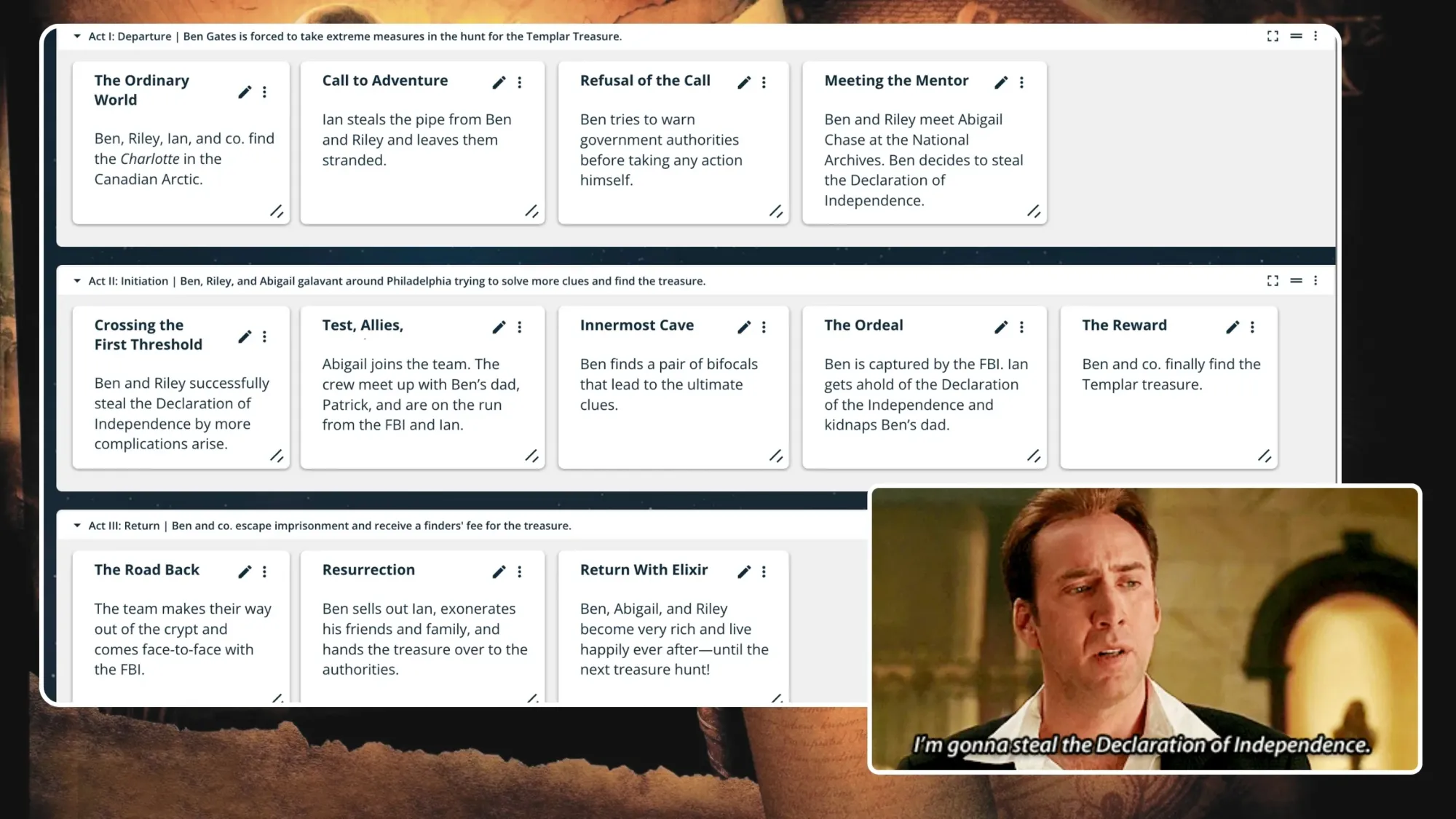

You probably already know the above stories pretty well so we’ll unpack the twelve steps of the Hero's Journey using Ben Gates’ journey in National Treasure as a case study—because what is more heroic than saving the Declaration of Independence from a bunch of goons?

Ye be warned: Spoilers ahead!

Act One: Departure

Step 1. the ordinary world.

The journey begins with the status quo—business as usual. We meet the hero and are introduced to the Known World they live in. In other words, this is your exposition, the starting stuff that establishes the story to come.

National Treasure begins in media res (preceded only by a short prologue), where we are given key information that introduces us to Ben Gates' world, who he is (a historian from a notorious family), what he does (treasure hunts), and why he's doing it (restoring his family's name).

With the help of his main ally, Riley, and a crew of other treasure hunters backed by a wealthy patron, he finds an 18th-century American ship in the Canadian Arctic, the Charlotte . Here, they find a ship-shaped pipe that presents a new riddle and later doubles as a key—for now, it's just another clue in the search for the lost treasure of the Templars, one that leads them to the Declaration of Independence.

Step 2. The Call to Adventure

The inciting incident takes place and the hero is called to act upon it. While they're still firmly in the Known World, the story kicks off and leaves the hero feeling out of balance. In other words, they are placed at a crossroads.

Ian (the wealthy patron of the Charlotte operation) steals the pipe from Ben and Riley and leaves them stranded. This is a key moment: Ian becomes the villain, Ben has now sufficiently lost his funding for this expedition, and if he decides to pursue the chase, he'll be up against extreme odds.

Step 3. Refusal of the Call

The hero hesitates and instead refuses their call to action. Following the call would mean making a conscious decision to break away from the status quo. Ahead lies danger, risk, and the unknown; but here and now, the hero is still in the safety and comfort of what they know.

Ben debates continuing the hunt for the Templar treasure. Before taking any action, he decides to try and warn the authorities: the FBI, Homeland Security, and the staff of the National Archives, where the Declaration of Independence is housed and monitored. Nobody will listen to him, and his family's notoriety doesn't help matters.

Step 4. Meeting the Mentor

The protagonist receives knowledge or motivation from a powerful or influential figure. This is a tactical move on the hero's part—remember that it was only the previous step in which they debated whether or not to jump headfirst into the unknown. By Meeting the Mentor, they can gain new information or insight, and better equip themselves for the journey they might to embark on.

Abigail, an archivist at the National Archives, brushes Ben and Riley off as being crazy, but Ben uses the interaction to his advantage in other ways—to seek out information about how the Declaration of Independence is stored and cared for, as well as what (and more importantly, who) else he might be up against in his own attempt to steal it.

In a key scene, we see him contemplate the entire operation while standing over the glass-encased Declaration of Independence. Finally, he firmly decides to pursue the treasure and stop Ian, uttering the famous line, "I'm gonna steal the Declaration of Independence."

Act Two: Initiation

Step 5. crossing the threshold.

The hero leaves the Known World to face the Unknown World. They are fully committed to the journey, with no way to turn back now. There may be a confrontation of some sort, and the stakes will be raised.

Ben and Riley infiltrate the National Archives during a gala and successfully steal the Declaration of Independence. But wait—it's not so easy. While stealing the Declaration of Independence, Abigail suspects something is up and Ben faces off against Ian.

Then, when trying to escape the building, Ben exits through the gift shop, where an attendant spots the document peeking out of his jacket. He is forced to pay for it, feigning that it's a replica—and because he doesn't have enough cash, he has to use his credit card, so there goes keeping his identity anonymous.

The game is afoot.

Step 6. Tests, Allies, Enemies

The hero explores the Unknown World. Now that they have firmly crossed the threshold from the Known World, the hero will face new challenges and possibly meet new enemies. They'll have to call upon their allies, new and old, in order to keep moving forward.

Abigail reluctantly joins the team under the agreement that she'll help handle the Declaration of Independence, given her background in document archiving and restoration. Ben and co. seek the aid of Ben's father, Patrick Gates, whom Ben has a strained relationship with thanks to years of failed treasure hunting that has created a rift between grandfather, father, and son. Finally, they travel around Philadelphia deciphering clues while avoiding both Ian and the FBI.

Step 7. Approach the Innermost Cave

The hero nears the goal of their quest, the reason they crossed the threshold in the first place. Here, they could be making plans, having new revelations, or gaining new skills. To put it in other familiar terms, this step would mark the moment just before the story's climax.

Ben uncovers a pivotal clue—or rather, he finds an essential item—a pair of bifocals with interchangeable lenses made by Benjamin Franklin. It is revealed that by switching through the various lenses, different messages will be revealed on the back of the Declaration of Independence. He's forced to split from Abigail and Riley, but Ben has never been closer to the treasure.

Step 8. The Ordeal

The hero faces a dire situation that changes how they view the world. All threads of the story come together at this pinnacle, the central crisis from which the hero will emerge unscathed or otherwise. The stakes will be at their absolute highest here.

Vogler details that in this stage, the hero will experience a "death," though it need not be literal. In your story, this could signify the end of something and the beginning of another, which could itself be figurative or literal. For example, a certain relationship could come to an end, or it could mean someone "stuck in their ways" opens up to a new perspective.

In National Treasure , The FBI captures Ben and Ian makes off with the Declaration of Independence—all hope feels lost. To add to it, Ian reveals that he's kidnapped Ben's father and threatens to take further action if Ben doesn't help solve the final clues and lead Ian to the treasure.

Ben escapes the FBI with Ian's help, reunites with Abigail and Riley, and leads everyone to an underground structure built below Trinity Church in New York City. Here, they manage to split from Ian once more, sending him on a goose chase to Boston with a false clue, and proceed further into the underground structure.

Though they haven't found the treasure just yet, being this far into the hunt proves to Ben's father, Patrick, that it's real enough. The two men share an emotional moment that validates what their family has been trying to do for generations.

Step 9. Reward

This is it, the moment the hero has been waiting for. They've survived "death," weathered the crisis of The Ordeal, and earned the Reward for which they went on this journey.

Now, free of Ian's clutches and with some light clue-solving, Ben, Abigail, Riley, and Patrick keep progressing through the underground structure and eventually find the Templar's treasure—it's real and more massive than they could have imagined. Everyone revels in their discovery while simultaneously looking for a way back out.

Act Three: Return

Step 10. the road back.

It's time for the journey to head towards its conclusion. The hero begins their return to the Known World and may face unexpected challenges. Whatever happens, the "why" remains paramount here (i.e. why the hero ultimately chose to embark on their journey).

This step marks a final turning point where they'll have to take action or make a decision to keep moving forward and be "reborn" back into the Known World.

Act Three of National Treasure is admittedly quite short. After finding the treasure, Ben and co. emerge from underground to face the FBI once more. Not much of a road to travel back here so much as a tunnel to scale in a crypt.

Step 11. Resurrection

The hero faces their ultimate challenge and emerges victorious, but forever changed. This step often requires a sacrifice of some sort, and having stepped into the role of The Hero™, they must answer to this.

Ben is given an ultimatum— somebody has to go to jail (on account of the whole stealing-the-Declaration-of-Independence thing). But, Ben also found a treasure worth millions of dollars and that has great value to several nations around the world, so that counts for something.

Ultimately, Ben sells Ian out, makes a deal to exonerate his friends and family, and willingly hands the treasure over to the authorities. Remember: he wanted to find the treasure, but his "why" was to restore the Gates family name, so he won regardless.

Step 12. Return With the Elixir

Finally, the hero returns home as a new version of themself, the elixir is shared amongst the people, and the journey is completed full circle.

The elixir, like many other elements of the hero's journey, can be literal or figurative. It can be a tangible thing, such as an actual elixir meant for some specific purpose, or it could be represented by an abstract concept such as hope, wisdom, or love.

Vogler notes that if the Hero's Journey results in a tragedy, the elixir can instead have an effect external to the story—meaning that it could be something meant to affect the audience and/or increase their awareness of the world.

In the final scene of National Treasure , we see Ben and Abigail walking the grounds of a massive estate. Riley pulls up in a fancy sports car and comments on how they could have gotten more money. They all chat about attending a museum exhibit in Cairo (Egypt).

In one scene, we're given a lot of closure: Ben and co. received a hefty payout for finding the treasure, Ben and Abigail are a couple now, and the treasure was rightfully spread to those it benefitted most—in this case, countries who were able to reunite with significant pieces of their history. Everyone's happy, none of them went to jail despite the serious crimes committed, and they're all a whole lot wealthier. Oh, Hollywood.

Variations of the Hero's Journey

Plot structure is important, but you don't need to follow it exactly; and, in fact, your story probably won't. Your version of the Hero's Journey might require more or fewer steps, or you might simply go off the beaten path for a few steps—and that's okay!

What follows are three additional versions of the Hero's Journey, which you may be more familiar with than Vogler's version presented above.

Dan Harmon's Story Circle (or, The Eight-Step Hero's Journey)

Screenwriter Dan Harmon has riffed on the Hero's Journey by creating a more compact version, the Story Circle —and it works especially well for shorter-format stories such as television episodes, which happens to be what Harmon writes.

The Story Circle comprises eight simple steps with a heavy emphasis on the hero's character arc:

- The hero is in a zone of comfort...

- But they want something.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation...

- And adapt to it by facing trials.

- They get what they want...

- But they pay a heavy price for it.

- They return to their familiar situation...

- Having changed.

You may have noticed, but there is a sort of rhythm here. The eight steps work well in four pairs, simplifying the core of the Hero's Journey even further:

- The hero is in a zone of comfort, but they want something.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation and have to adapt via new trials.

- They get what they want, but they pay a price for it.

- They return to their zone of comfort, forever changed.

If you're writing shorter fiction, such as a short story or novella, definitely check out the Story Circle. It's the Hero's Journey minus all the extraneous bells & whistles.

Ten-Step Hero's Journey

The ten-step Hero's Journey is similar to the twelve-step version we presented above. It includes most of the same steps except for Refusal of the Call and Meeting the Mentor, arguing that these steps aren't as essential to include; and, it moves Crossing the Threshold to the end of Act One and Reward to the end of Act Two.

- The Ordinary World

- The Call to Adventure

- Crossing the Threshold

- Tests, Allies, Enemies

- Approach the Innermost Cave

- The Road Back

- Resurrection

- Return with Elixir

We've previously written about the ten-step hero's journey in a series of essays separated by act: Act One (with a prologue), Act Two , and Act Three .

Twelve-Step Hero's Journey: Version Two

Again, the second version of the twelve-step hero's journey is very similar to the one above, save for a few changes, including in which story act certain steps appear.

This version skips The Ordinary World exposition and starts right at The Call to Adventure; then, the story ends with two new steps in place of Return With Elixir: The Return and The Freedom to Live.

- The Refusal of the Call

- Meeting the Mentor

- Test, Allies, Enemies

- Approaching the Innermost Cave

- The Resurrection

- The Return*

- The Freedom to Live*

In the final act of this version, there is more of a focus on an internal transformation for the hero. They experience a metamorphosis on their journey back to the Known World, return home changed, and go on to live a new life, uninhibited.

Seventeen-Step Hero's Journey

Finally, the granddaddy of heroic journeys: the seventeen-step Hero's Journey. This version includes a slew of extra steps your hero might face out in the expanse.

- Refusal of the Call

- Supernatural Aid (aka Meeting the Mentor)

- Belly of the Whale*: This added stage marks the hero's immediate descent into danger once they've crossed the threshold.

- Road of Trials (...with Allies, Tests, and Enemies)

- Meeting with the Goddess/God*: In this stage, the hero meets with a new advisor or powerful figure, who equips them with the knowledge or insight needed to keep progressing forward.

- Woman as Temptress (or simply, Temptation)*: Here, the hero is tempted, against their better judgment, to question themselves and their reason for being on the journey. They may feel insecure about something specific or have an exposed weakness that momentarily holds them back.

- Atonement with the Father (or, Catharthis)*: The hero faces their Temptation and moves beyond it, shedding free from all that holds them back.

- Apotheosis (aka The Ordeal)

- The Ultimate Boon (aka the Reward)

- Refusal of the Return*: The hero wonders if they even want to go back to their old life now that they've been forever changed.

- The Magic Flight*: Having decided to return to the Known World, the hero needs to actually find a way back.

- Rescue From Without*: Allies may come to the hero's rescue, helping them escape this bold, new world and return home.

- Crossing of the Return Threshold (aka The Return)

- Master of Two Worlds*: Very closely resembling The Resurrection stage in other variations, this stage signifies that the hero is quite literally a master of two worlds—The Known World and the Unknown World—having conquered each.

- Freedom to Live

Again, we skip the Ordinary World opening here. Additionally, Acts Two and Three look pretty different from what we've seen so far, although, the bones of the Hero's Journey structure remain.

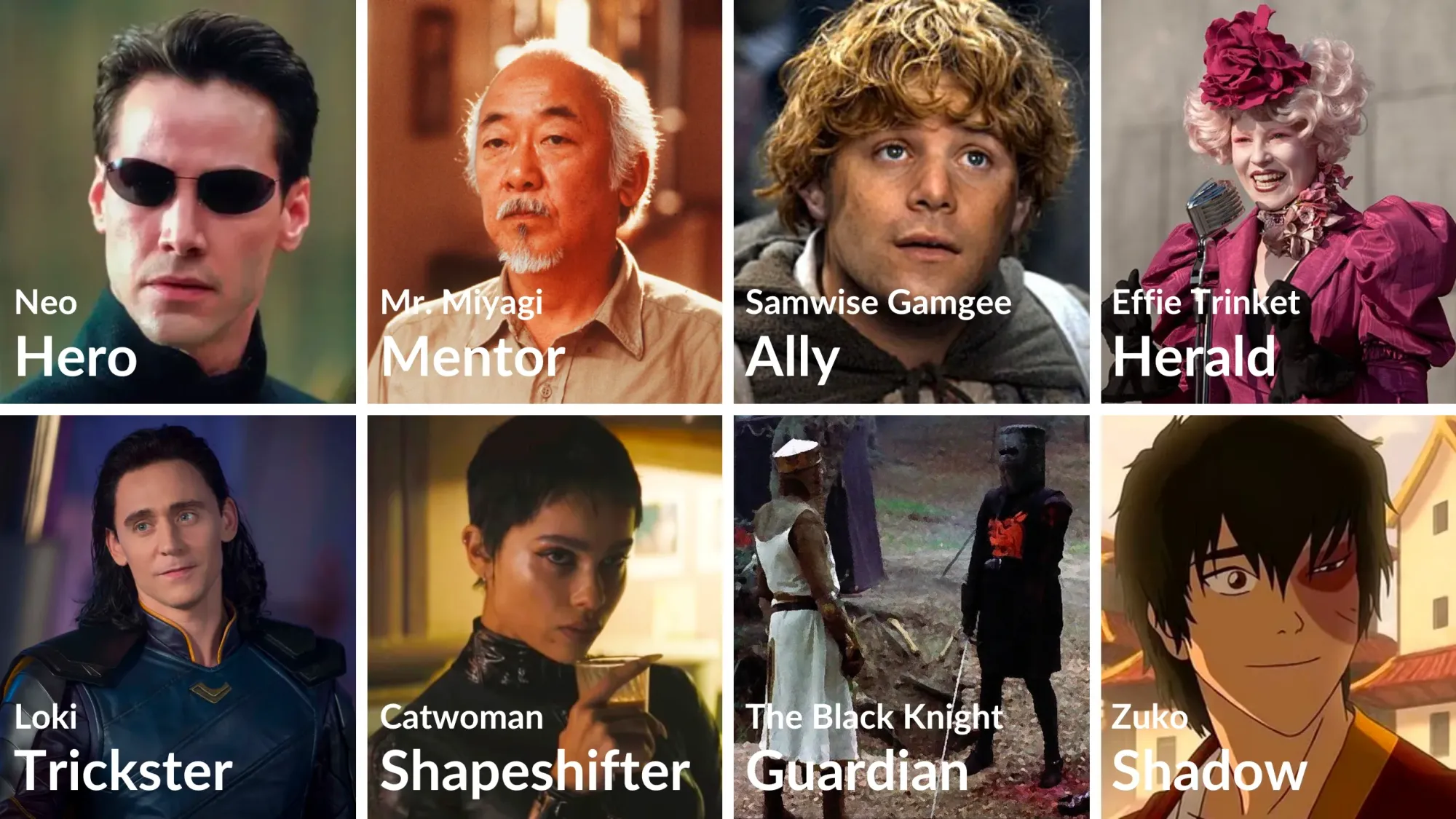

The Eight Hero’s Journey Archetypes

The Hero is, understandably, the cornerstone of the Hero’s Journey, but they’re just one of eight key archetypes that make up this narrative framework.

In The Writer's Journey , Vogler outlined seven of these archetypes, only excluding the Ally, which we've included below. Here’s a breakdown of all eight with examples:

1. The Hero

As outlined, the Hero is the protagonist who embarks on a transformative quest or journey. The challenges they overcome represent universal human struggles and triumphs.

Vogler assigned a "primary function" to each archetype—helpful for establishing their role in a story. The Hero's primary function is "to service and sacrifice."

Example: Neo from The Matrix , who evolves from a regular individual into the prophesied savior of humanity.

2. The Mentor

A wise guide offering knowledge, tools, and advice, Mentors help the Hero navigate the journey and discover their potential. Their primary function is "to guide."

Example: Mr. Miyagi from The Karate Kid imparts not only martial arts skills but invaluable life lessons to Daniel.

3. The Ally

Companions who support the Hero, Allies provide assistance, friendship, and moral support throughout the journey. They may also become a friends-to-lovers romantic partner.

Not included in Vogler's list is the Ally, though we'd argue they are essential nonetheless. Let's say their primary function is "to aid and support."

Example: Samwise Gamgee from Lord of the Rings , a loyal friend and steadfast supporter of Frodo.

4. The Herald

The Herald acts as a catalyst to initiate the Hero's Journey, often presenting a challenge or calling the hero to adventure. Their primary function is "to warn or challenge."

Example: Effie Trinket from The Hunger Games , whose selection at the Reaping sets Katniss’s journey into motion.

5. The Trickster

A character who brings humor and unpredictability, challenges conventions, and offers alternative perspectives or solutions. Their primary function is "to disrupt."

Example: Loki from Norse mythology exemplifies the trickster, with his cunning and chaotic influence.

6. The Shapeshifter

Ambiguous figures whose allegiance and intentions are uncertain. They may be a friend one moment and a foe the next. Their primary function is "to question and deceive."

Example: Catwoman from the Batman universe often blurs the line between ally and adversary, slinking between both roles with glee.

7. The Guardian

Protectors of important thresholds, Guardians challenge or test the Hero, serving as obstacles to overcome or lessons to be learned. Their primary function is "to test."

Example: The Black Knight in Monty Python and the Holy Grail literally bellows “None shall pass!”—a quintessential ( but not very effective ) Guardian.

8. The Shadow

Represents the Hero's inner conflict or an antagonist, often embodying the darker aspects of the hero or their opposition. Their primary function is "to destroy."

Example: Zuko from Avatar: The Last Airbender; initially an adversary, his journey parallels the Hero’s path of transformation.

While your story does not have to use all of the archetypes, they can help you develop your characters and visualize how they interact with one another—especially the Hero.

For example, take your hero and place them in the center of a blank worksheet, then write down your other major characters in a circle around them and determine who best fits into which archetype. Who challenges your hero? Who tricks them? Who guides them? And so on...

Stories that Use the Hero’s Journey

Not a fan of saving the Declaration of Independence? Check out these alternative examples of the Hero’s Journey to get inspired:

- Epic of Gilgamesh : An ancient Mesopotamian epic poem thought to be one of the earliest examples of the Hero’s Journey (and one of the oldest recorded stories).

- The Lion King (1994): Simba's exile and return depict a tale of growth, responsibility, and reclaiming his rightful place as king.

- The Alchemist by Paolo Coehlo: Santiago's quest for treasure transforms into a journey of self-discovery and personal enlightenment.

- Coraline by Neil Gaiman: A young girl's adventure in a parallel world teaches her about courage, family, and appreciating her own reality.

- Kung Fu Panda (2008): Po's transformation from a clumsy panda to a skilled warrior perfectly exemplifies the Hero's Journey. Skadoosh!

The Hero's Journey is so generalized that it's ubiquitous. You can plop the plot of just about any quest-style narrative into its framework and say that the story follows the Hero's Journey. Try it out for yourself as an exercise in getting familiar with the method.

Will the Hero's Journey Work For You?

As renowned as it is, the Hero's Journey works best for the kinds of tales that inspired it: mythic stories.

Writers of speculative fiction may gravitate towards this method over others, especially those writing epic fantasy and science fiction (big, bold fantasy quests and grand space operas come to mind).

The stories we tell today are vast and varied, and they stretch far beyond the dealings of deities, saving kingdoms, or acquiring some fabled "elixir." While that may have worked for Gilgamesh a few thousand years ago, it's not always representative of our lived experiences here and now.

If you decide to give the Hero's Journey a go, we encourage you to make it your own! The pieces of your plot don't have to neatly fit into the structure, but you can certainly make a strong start on mapping out your story.

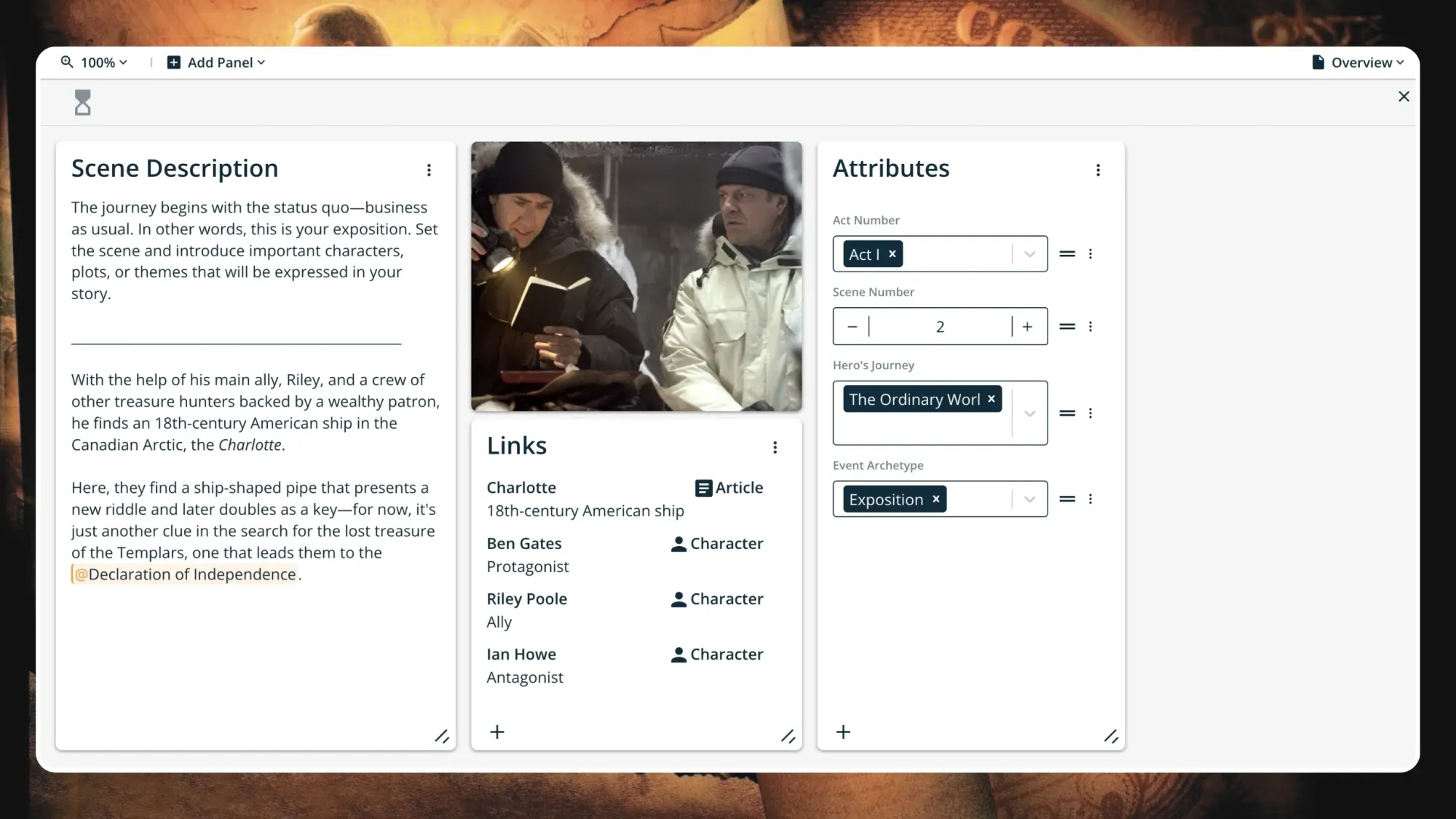

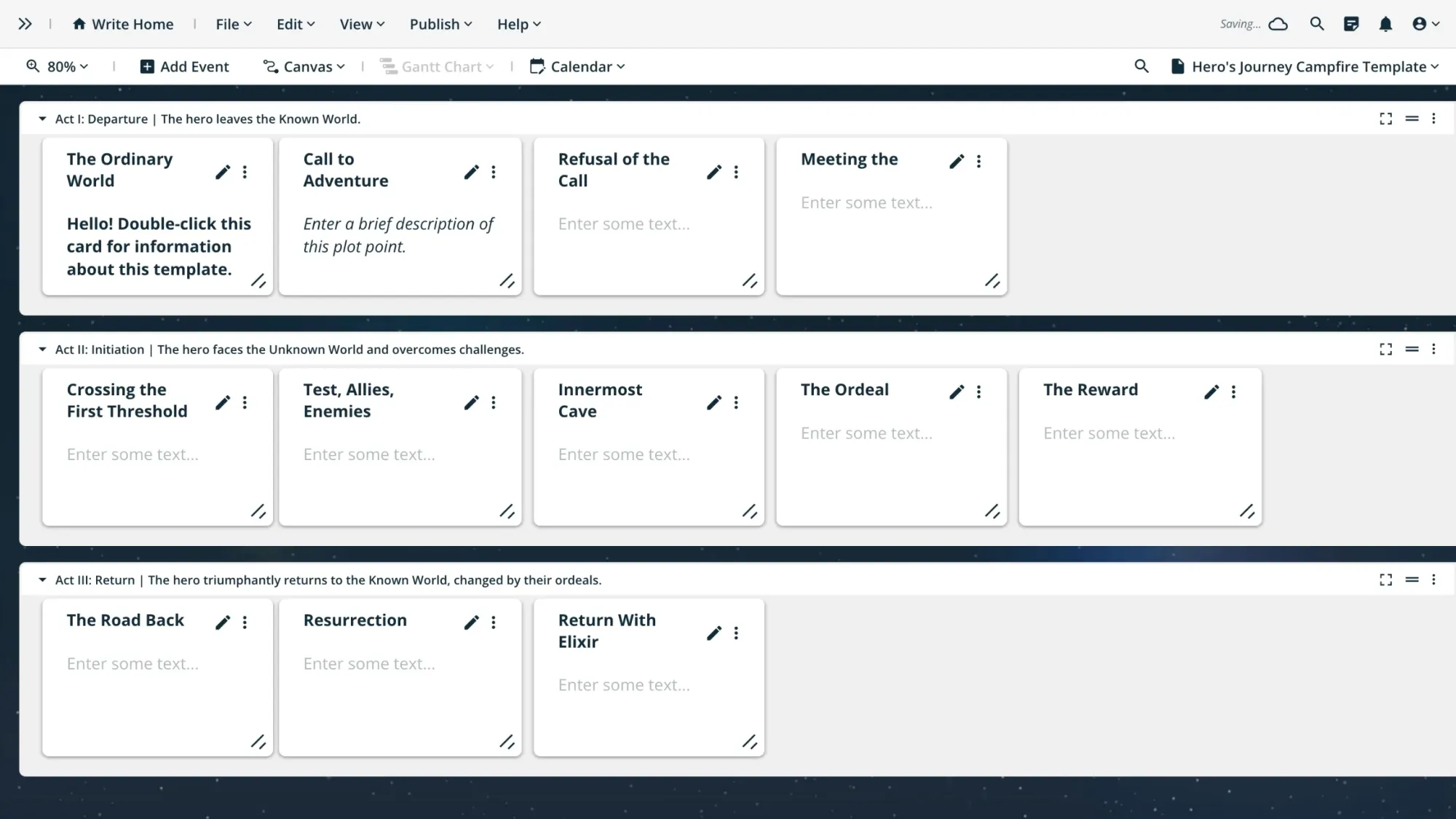

Hero's Journey Campfire Template

The Timeline Module in Campfire offers a versatile canvas to plot out each basic component of your story while featuring nested "notebooks."

Simply double-click on each event card in your timeline to open up a canvas specific to that card. This allows you to look at your plot at the highest level, while also adding as much detail for each plot element as needed!

If you're just hearing about Campfire for the first time, it's free to sign up—forever! Let's plot the most epic of hero's journeys 👇

Lessons From the Hero’s Journey

The Hero's Journey offers a powerful framework for creating stories centered around growth, adventure, and transformation.

If you want to develop compelling characters, spin out engaging plots, and write books that express themes of valor and courage, consider The Hero’s Journey your blueprint. So stop holding out for a hero, and start writing!

Does your story mirror the Hero's Journey? Let us know in the comments below.

TRY OUR FREE APP

Write your book in Reedsy Studio. Try the beloved writing app for free today.

Craft your masterpiece in Reedsy Studio

Plan, write, edit, and format your book in our free app made for authors.

Last updated on Aug 10, 2023

The Hero's Journey: 12 Steps to a Classic Story Structure

The Hero's Journey is a timeless story structure which follows a protagonist on an unforeseen quest, where they face challenges, gain insights, and return home transformed. From Theseus and the Minotaur to The Lion King , so many narratives follow this pattern that it’s become ingrained into our cultural DNA.

In this post, we'll show you how to make this classic plot structure work for you — and if you’re pressed for time, download our cheat sheet below for everything you need to know.

FREE RESOURCE

Hero's Journey Template

Plot your character's journey with our step-by-step template.

What is the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero's Journey, also known as the monomyth, is a story structure where a hero goes on a quest or adventure to achieve a goal, and has to overcome obstacles and fears, before ultimately returning home transformed.

This narrative arc has been present in various forms across cultures for centuries, if not longer, but gained popularity through Joseph Campbell's mythology book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces . While Campbell identified 17 story beats in his monomyth definition, this post will concentrate on a 12-step framework popularized in 2007 by screenwriter Christopher Vogler in his book The Writer’s Journey .

The 12 Steps of the Hero’s Journey

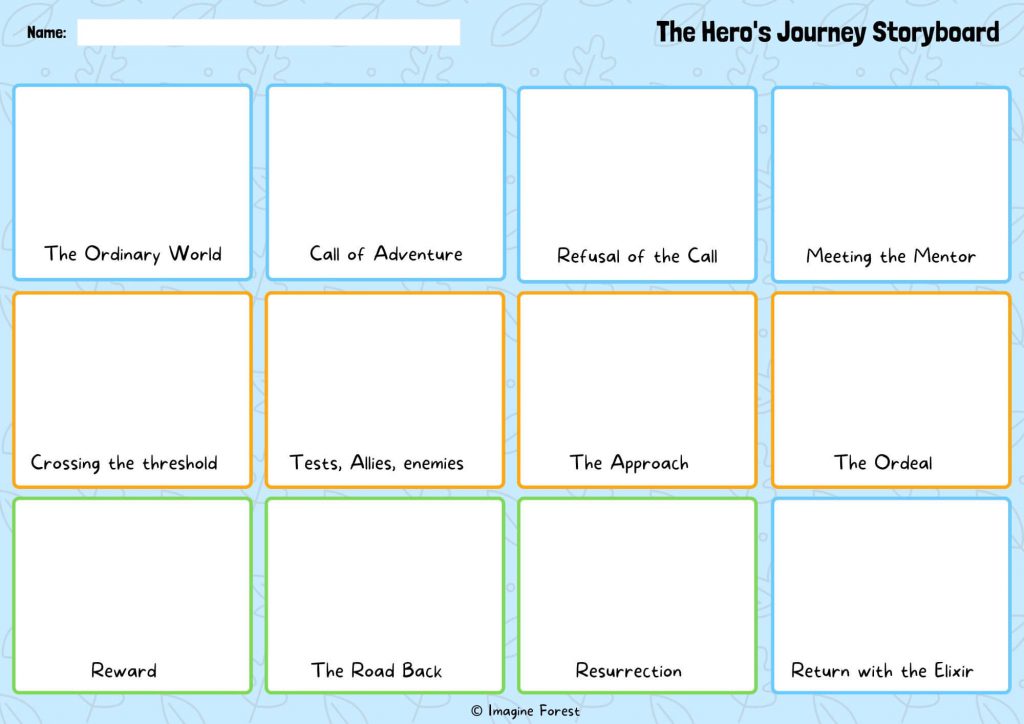

The Hero's Journey is a model for both plot points and character development : as the Hero traverses the world, they'll undergo inner and outer transformation at each stage of the journey. The 12 steps of the hero's journey are:

- The Ordinary World. We meet our hero.

- Call to Adventure. Will they meet the challenge?

- Refusal of the Call. They resist the adventure.

- Meeting the Mentor. A teacher arrives.

- Crossing the First Threshold. The hero leaves their comfort zone.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies. Making friends and facing roadblocks.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave. Getting closer to our goal.

- Ordeal. The hero’s biggest test yet!

- Reward (Seizing the Sword). Light at the end of the tunnel

- The Road Back. We aren’t safe yet.

- Resurrection. The final hurdle is reached.

- Return with the Elixir. The hero heads home, triumphant.

Believe it or not, this story structure also applies across mediums and genres (and also works when your protagonist is an anti-hero! ). Let's dive into it.

1. Ordinary World

In which we meet our Hero.

The journey has yet to start. Before our Hero discovers a strange new world, we must first understand the status quo: their ordinary, mundane reality.

It’s up to this opening leg to set the stage, introducing the Hero to readers. Importantly, it lets readers identify with the Hero as a “normal” person in a “normal” setting, before the journey begins.

2. Call to Adventure

In which an adventure starts.

The call to adventure is all about booting the Hero out of their comfort zone. In this stage, they are generally confronted with a problem or challenge they can't ignore. This catalyst can take many forms, as Campbell points out in Hero with a Thousand Faces . The Hero can, for instance:

- Decide to go forth of their own volition;

- Theseus upon arriving in Athens.

- Be sent abroad by a benign or malignant agent;

- Odysseus setting off on his ship in The Odyssey .

- Stumble upon the adventure as a result of a mere blunder;

- Dorothy when she’s swept up in a tornado in The Wizard of Oz .

- Be casually strolling when some passing phenomenon catches the wandering eye and lures one away from the frequented paths of man.

- Elliot in E.T. upon discovering a lost alien in the tool shed.

The stakes of the adventure and the Hero's goals become clear. The only question: will he rise to the challenge?

3. Refusal of the Call

In which the Hero digs in their feet.

Great, so the Hero’s received their summons. Now they’re all set to be whisked off to defeat evil, right?

Not so fast. The Hero might first refuse the call to action. It’s risky and there are perils — like spiders, trolls, or perhaps a creepy uncle waiting back at Pride Rock . It’s enough to give anyone pause.

In Star Wars , for instance, Luke Skywalker initially refuses to join Obi-Wan on his mission to rescue the princess. It’s only when he discovers that his aunt and uncle have been killed by stormtroopers that he changes his mind.

4. Meeting the Mentor

In which the Hero acquires a personal trainer.

The Hero's decided to go on the adventure — but they’re not ready to spread their wings yet. They're much too inexperienced at this point and we don't want them to do a fabulous belly-flop off the cliff.

Enter the mentor: someone who helps the Hero, so that they don't make a total fool of themselves (or get themselves killed). The mentor provides practical training, profound wisdom, a kick up the posterior, or something abstract like grit and self-confidence.

Wise old wizards seem to like being mentors. But mentors take many forms, from witches to hermits and suburban karate instructors. They might literally give weapons to prepare for the trials ahead, like Q in the James Bond series. Or perhaps the mentor is an object, such as a map. In all cases, they prepare the Hero for the next step.

GET ACCOUNTABILITY

Meet writing coaches on Reedsy

Industry insiders can help you hone your craft, finish your draft, and get published.

5. Crossing the First Threshold

In which the Hero enters the other world in earnest.

Now the Hero is ready — and committed — to the journey. This marks the end of the Departure stage and is when the adventure really kicks into the next gear. As Vogler writes: “This is the moment that the balloon goes up, the ship sails, the romance begins, the wagon gets rolling.”

From this point on, there’s no turning back.

Like our Hero, you should think of this stage as a checkpoint for your story. Pause and re-assess your bearings before you continue into unfamiliar territory. Have you:

- Launched the central conflict? If not, here’s a post on types of conflict to help you out.

- Established the theme of your book? If not, check out this post that’s all about creating theme and motifs .

- Made headway into your character development? If not, this character profile template may be useful:

Reedsy’s Character Profile Template

A story is only as strong as its characters. Fill this out to develop yours.

6. Tests, Allies, Enemies

In which the Hero faces new challenges and gets a squad.

When we step into the Special World, we notice a definite shift. The Hero might be discombobulated by this unfamiliar reality and its new rules. This is generally one of the longest stages in the story , as our protagonist gets to grips with this new world.

This makes a prime hunting ground for the series of tests to pass! Luckily, there are many ways for the Hero to get into trouble:

- In Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle , Spencer, Bethany, “Fridge,” and Martha get off to a bad start when they bump into a herd of bloodthirsty hippos.

- In his first few months at Hogwarts, Harry Potter manages to fight a troll, almost fall from a broomstick and die, and get horribly lost in the Forbidden Forest.

- Marlin and Dory encounter three “reformed” sharks, get shocked by jellyfish, and are swallowed by a blue whale en route to finding Nemo.

This stage often expands the cast of characters. Once the protagonist is in the Special World, he will meet allies and enemies — or foes that turn out to be friends and vice versa. He will learn a new set of rules from them. Saloons and seedy bars are popular places for these transactions, as Vogler points out (so long as the Hero survives them).

7. Approach to the Inmost Cave

In which the Hero gets closer to his goal.

This isn’t a physical cave. Instead, the “inmost cave” refers to the most dangerous spot in the other realm — whether that’s the villain’s chambers, the lair of the fearsome dragon, or the Death Star. Almost always, it is where the ultimate goal of the quest is located.

Note that the protagonist hasn’t entered the Inmost Cave just yet. This stage is all about the approach to it. It covers all the prep work that's needed in order to defeat the villain.

In which the Hero faces his biggest test of all thus far.

Of all the tests the Hero has faced, none have made them hit rock bottom — until now. Vogler describes this phase as a “black moment.” Campbell refers to it as the “belly of the whale.” Both indicate some grim news for the Hero.

The protagonist must now confront their greatest fear. If they survive it, they will emerge transformed. This is a critical moment in the story, as Vogler explains that it will “inform every decision that the Hero makes from this point forward.”

The Ordeal is sometimes not the climax of the story. There’s more to come. But you can think of it as the main event of the second act — the one in which the Hero actually earns the title of “Hero.”

9. Reward (Seizing the Sword)

In which the Hero sees light at the end of the tunnel.

Our Hero’s been through a lot. However, the fruits of their labor are now at hand — if they can just reach out and grab them! The “reward” is the object or knowledge the Hero has fought throughout the entire journey to hold.

Once the protagonist has it in their possession, it generally has greater ramifications for the story. Vogler offers a few examples of it in action:

- Luke rescues Princess Leia and captures the plans of the Death Star — keys to defeating Darth Vader.

- Dorothy escapes from the Wicked Witch’s castle with the broomstick and the ruby slippers — keys to getting back home.

10. The Road Back

In which the light at the end of the tunnel might be a little further than the Hero thought.

The story's not over just yet, as this phase marks the beginning of Act Three. Now that he's seized the reward, the Hero tries to return to the Ordinary World, but more dangers (inconveniently) arise on the road back from the Inmost Cave.

More precisely, the Hero must deal with the consequences and aftermath of the previous act: the dragon, enraged by the Hero who’s just stolen a treasure from under his nose, starts the hunt. Or perhaps the opposing army gathers to pursue the Hero across a crowded battlefield. All further obstacles for the Hero, who must face them down before they can return home.

11. Resurrection

In which the last test is met.

Here is the true climax of the story. Everything that happened prior to this stage culminates in a crowning test for the Hero, as the Dark Side gets one last chance to triumph over the Hero.

Vogler refers to this as a “final exam” for the Hero — they must be “tested once more to see if they have really learned the lessons of the Ordeal.” It’s in this Final Battle that the protagonist goes through one more “resurrection.” As a result, this is where you’ll get most of your miraculous near-death escapes, à la James Bond's dashing deliverances. If the Hero survives, they can start looking forward to a sweet ending.

12. Return with the Elixir

In which our Hero has a triumphant homecoming.

Finally, the Hero gets to return home. However, they go back a different person than when they started out: they’ve grown and matured as a result of the journey they’ve taken.

But we’ve got to see them bring home the bacon, right? That’s why the protagonist must return with the “Elixir,” or the prize won during the journey, whether that’s an object or knowledge and insight gained.

Of course, it’s possible for a story to end on an Elixir-less note — but then the Hero would be doomed to repeat the entire adventure.

Examples of The Hero’s Journey in Action

To better understand this story template beyond the typical sword-and-sorcery genre, let's analyze three examples, from both screenplay and literature, and examine how they implement each of the twelve steps.

The 1976 film Rocky is acclaimed as one of the most iconic sports films because of Stallone’s performance and the heroic journey his character embarks on.

- Ordinary World. Rocky Balboa is a mediocre boxer and loan collector — just doing his best to live day-to-day in a poor part of Philadelphia.

- Call to Adventure. Heavyweight champ Apollo Creed decides to make a big fight interesting by giving a no-name loser a chance to challenge him. That loser: Rocky Balboa.

- Refusal of the Call. Rocky says, “Thanks, but no thanks,” given that he has no trainer and is incredibly out of shape.

- Meeting the Mentor. In steps former boxer Mickey “Mighty Mick” Goldmill, who sees potential in Rocky and starts training him physically and mentally for the fight.

- Crossing the First Threshold. Rocky crosses the threshold of no return when he accepts the fight on live TV, and 一 in parallel 一 when he crosses the threshold into his love interest Adrian’s house and asks her out on a date.

- Tests, Allies, Enemies. Rocky continues to try and win Adrian over and maintains a dubious friendship with her brother, Paulie, who provides him with raw meat to train with.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave. The Inmost Cave in Rocky is Rocky’s own mind. He fears that he’ll never amount to anything — something that he reveals when he butts heads with his trainer, Mickey, in his apartment.

- Ordeal. The start of the training montage marks the beginning of Rocky’s Ordeal. He pushes through it until he glimpses hope ahead while running up the museum steps.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword). Rocky's reward is the restoration of his self-belief, as he recognizes he can try to “go the distance” with Apollo Creed and prove he's more than "just another bum from the neighborhood."

- The Road Back. On New Year's Day, the fight takes place. Rocky capitalizes on Creed's overconfidence to start strong, yet Apollo makes a comeback, resulting in a balanced match.

- Resurrection. The fight inflicts multiple injuries and pushes both men to the brink of exhaustion, with Rocky being knocked down numerous times. But he consistently rises to his feet, enduring through 15 grueling rounds.

- Return with the Elixir. Rocky loses the fight — but it doesn’t matter. He’s won back his confidence and he’s got Adrian, who tells him that she loves him.