- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Patient Perspectives

- Methods Corner

- Science for Patients

- Invited Commentaries

- ESC Content Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Instructions for reviewers

- Submission Site

- Why publish with EJCN?

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Read & Publish

- About European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing

- About ACNAP

- About European Society of Cardiology

- ESC Publications

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- War in Ukraine

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, why patient journey mapping, how is patient journey mapping conducted, use of technology in patient journey mapping, future implications for patient journey mapping, conclusions, patient journey mapping: emerging methods for understanding and improving patient experiences of health systems and services.

Lemma N Bulto and Ellen Davies Shared first authorship.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Lemma N Bulto, Ellen Davies, Janet Kelly, Jeroen M Hendriks, Patient journey mapping: emerging methods for understanding and improving patient experiences of health systems and services, European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing , 2024;, zvae012, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvae012

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Patient journey mapping is an emerging field of research that uses various methods to map and report evidence relating to patient experiences and interactions with healthcare providers, services, and systems. This research often involves the development of visual, narrative, and descriptive maps or tables, which describe patient journeys and transitions into, through, and out of health services. This methods corner paper presents an overview of how patient journey mapping has been conducted within the health sector, providing cardiovascular examples. It introduces six key steps for conducting patient journey mapping and describes the opportunities and benefits of using patient journey mapping and future implications of using this approach.

Acquire an understanding of patient journey mapping and the methods and steps employed.

Examine practical and clinical examples in which patient journey mapping has been adopted in cardiac care to explore the perspectives and experiences of patients, family members, and healthcare professionals.

Quality and safety guidelines in healthcare services are increasingly encouraging and mandating engagement of patients, clients, and consumers in partnerships. 1 The aim of many of these partnerships is to consider how health services can be improved, in relation to accessibility, service delivery, discharge, and referral. 2 , 3 Patient journey mapping is a research approach increasingly being adopted to explore these experiences in healthcare. 3

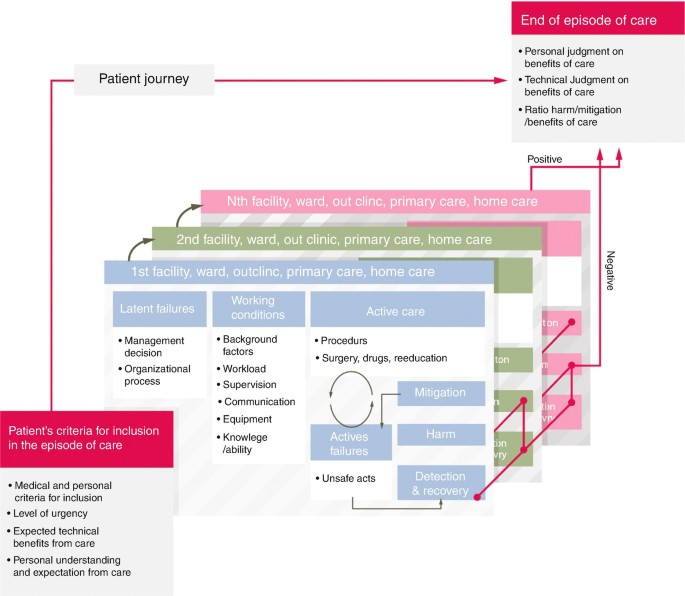

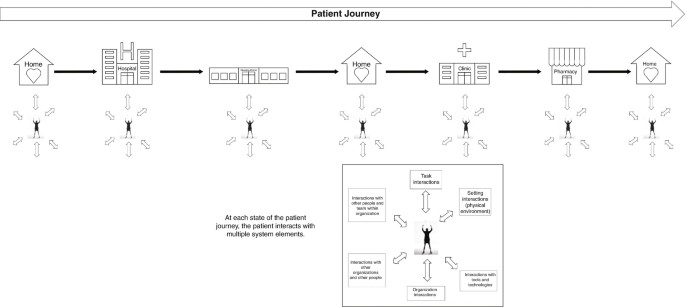

a patient-oriented project that has been undertaken to better understand barriers, facilitators, experiences, interactions with services and/or outcomes for individuals and/or their carers, and family members as they enter, navigate, experience and exit one or more services in a health system by documenting elements of the journey to produce a visual or descriptive map. 3

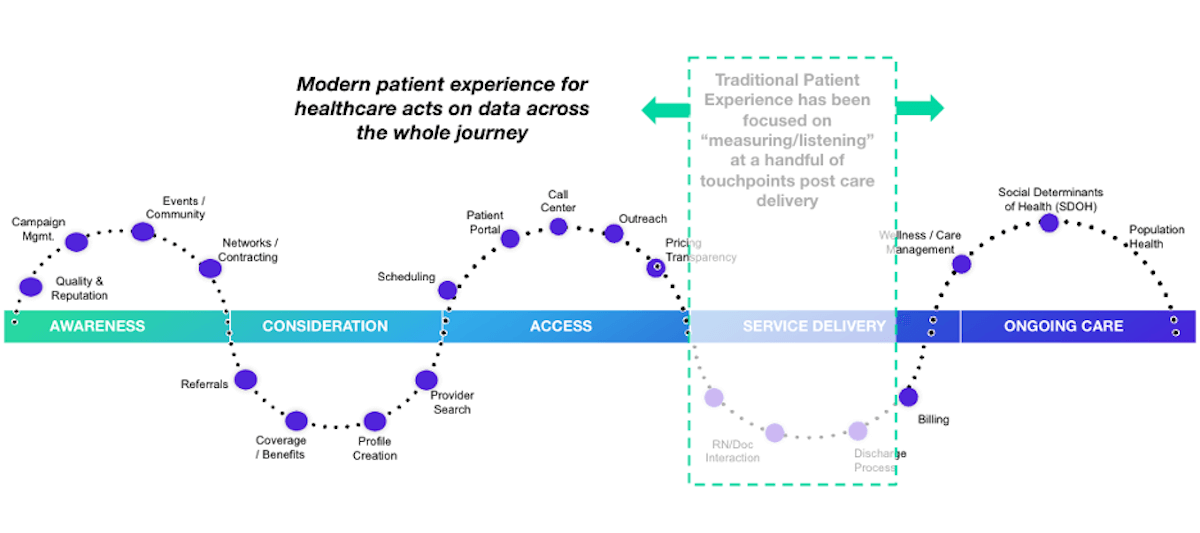

It is an emerging field with a clear patient-centred focus, as opposed to studies that track patient flow, demand, and movement. As a general principle, patient journey mapping projects will provide evidence of patient perspectives and highlight experiences through the patient and consumer lens.

Patient journey mapping can provide significant insights that enable responsive and context-specific strategies for improving patient healthcare experiences and outcomes to be designed and implemented. 3–6 These improvements can occur at the individual patient, model of care, and/or health system level. As with other emerging methodologies, questions have been raised regarding exactly how patient journey mapping projects can best be designed, conducted, and reported. 3

In this methods paper, we provide an overview of patient journey mapping as an emergent field of research, including reasons that mapping patient journeys might be considered, methods that can be adopted, the principles that can guide patient journey mapping data collection and analysis, and considerations for reporting findings and recognizing the implications of findings. We summarize and draw on five cardiovascular patient journey mapping projects, as examples.

One of the most appealing elements of the patient journey mapping field of research is its focus on illuminating the lived experiences of patients and/or their family members, and the health professionals caring for them, methodically and purposefully. Patient journey mapping has an ability to provide detailed information about patient experiences, gaps in health services, and barriers and facilitators for access to health services. This information can be used independently, or alongside information from larger data sets, to adapt and improve models of care relevant to the population that is being investigated. 3

To date, the most frequent reason for adopting this approach is to inform health service redesign and improvement. 3 , 7 , 8 Other reasons have included: (i) to develop a deeper understanding of a person’s entire journey through health systems; 3 (ii) to identify delays in diagnosis or treatment (often described as bottlenecks); 9 (iii) to identify gaps in care and unmet needs; (iv) to evaluate continuity of care across health services and regions; 10 (v) to understand and evaluate the comprehensiveness of care; 11 (vi) to understand how people are navigating health systems and services; and (vii) to compare patient experiences with practice guidelines and standards of care.

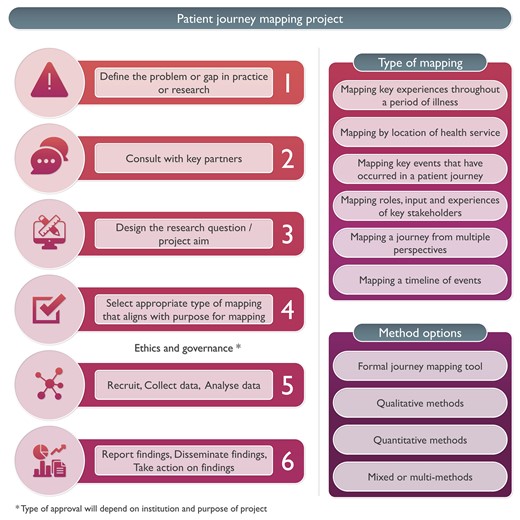

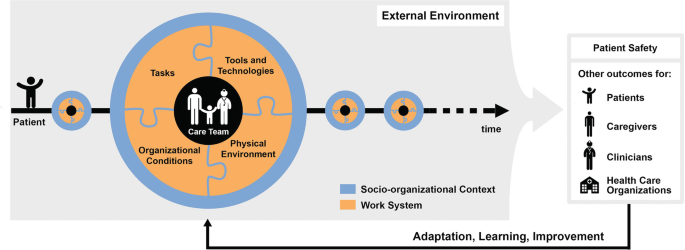

Patient journey mapping approaches frequently use six broad steps that help facilitate the preparation and execution of research projects. These are outlined in the Central illustration . We acknowledge that not all patient journey mapping approaches will follow the order outlined in the Central illustration , but all steps need to be considered at some point throughout each project to ensure that research is undertaken rigorously, appropriately, and in alignment with best practice research principles.

Steps for conducing patient journey mapping.

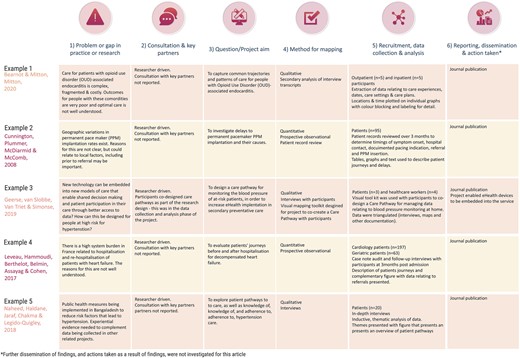

Five cardiovascular patient journey mapping research examples have been included in Figure 1 , 12–16 to provide specific context and illustrate these six steps. For each of these examples, the problem or gap in practice or research, consultation processes, research question or aim, type of mapping, methods, and reporting of findings have been extracted. Each of these steps is then discussed, using these cardiovascular examples.

Examples of patient journey mapping projects.

Define the problem or gap in practice or research

Developing an understanding of a problem or gap in practice is essential for facilitating the design and development of quality research projects. In the examples outlined in Figure 1 , it is evident that clinical variation or system gaps have been explored using patient journey mapping. In the first two examples, populations known to have health vulnerabilities were explored—in Example 1, this related to comorbid substance use and physical illness, 13 and in Example 2, this related to geographical location. 13 Broader systems and societal gaps were explored in Examples 4 and 5, respectively, 15 , 16 and in Example 3, a new technologically driven solution for an existing model of care was tested for its ability to improve patient outcomes relating to hypertension. 14

Consultation, engagement, and partnership

Ideally, consultation with heathcare providers and/or patients would occur when the problem or gap in practice or research is being defined. This is a key principle of co-designed research. 17 Numerous existing frameworks for supporting patient involvement in research have been designed and were recently documented and explored in a systematic review by Greenhalgh et al . 18 While none of the five example studies included this step in the initial phase of the project, it is increasingly being undertaken in patient partnership projects internationally (e.g. in renal care). 17 If not in the project conceptualization phase, consultation may occur during the data collection or analysis phase, as demonstrated in Example 3, where a care pathway was co-created with participants. 14 We refer readers to Greenhalgh’s systematic review as a starting point for considering suitable frameworks for engaging participants in consultation, partnership, and co-design of patient journey mapping projects. 18

Design the research question/project aim

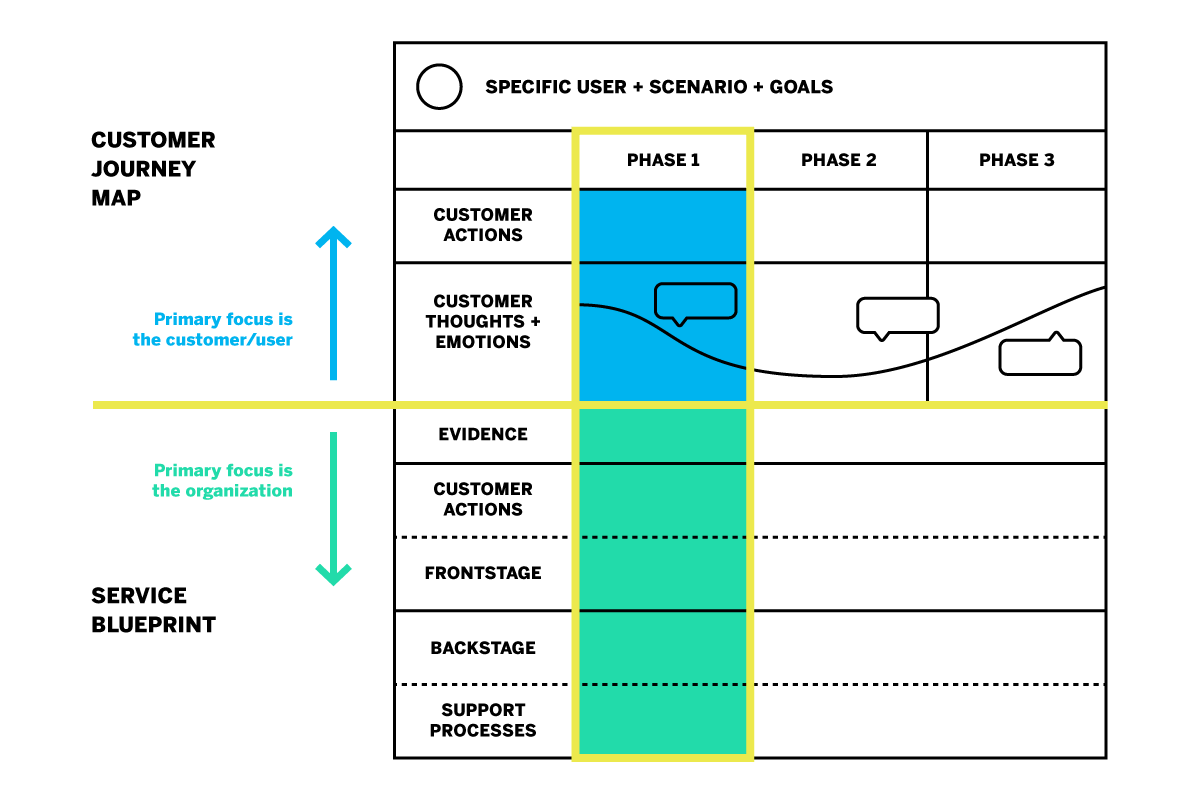

Conducting patient journey mapping research requires a thoughtful and systematic approach to adequately capture the complexity of the healthcare experience. First, the research objectives and questions should be clearly defined. Aspects of the patient journey that will be explored need to be identified. Then, a robust approach must be developed, taking into account whether qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods are more appropriate for the objectives of the study.

For example, in the cardiac examples in Figure 1 , the broad aims included mapping existing pathways through health services where there were known problems 12 , 13 , 15 , 16 and documenting the co-creation of a new care pathway using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods. 14

In traditional studies, questions that might be addressed in the area of patient movement in health systems include data collected through the health systems databases, such as ‘What is the length of stay for x population’, or ‘What is the door to balloon time in this hospital?’ In contrast, patient mapping journey studies will approach asking questions about experiences that require data from patients and their family members, e.g. ‘What is the impact on you of your length of stay?’, ‘What was your experience in being assessed and undergoing treatment for your chest pain?’, ‘What was your experience supporting this patient during their cardiac admission and discharge?’

Select appropriate type of mapping

The methods chosen for mapping need to align with the identified purpose for mapping and the aim or question that was designed in Step 3. A range of research methods have been used in patient journey mapping projects involving various qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods techniques and tools. 4 Some approaches use traditional forms of data collection, such as short-form and long-form patient interviews, focus groups, and direct patient observations. 18 , 19 Other approaches use patient journey mapping tools, designed and used with specific cultural groups, such as First Nations peoples using artwork, paintings, sand trays, and photovoice. 17 , 20 In the cardiovascular examples presented in Figure 1 , both qualitative and quantitative methods have been used, with interviews, patient record reviews, and observational techniques adopted to map patient journeys.

In a recent scoping review investigating patient journey mapping across all health care settings and specialities, six types of patient journey mapping were identified. 3 These included (i) mapping key experiences throughout a period of illness; (ii) mapping by location of health service; (iii) mapping by events that occurred throughout a period of illness; (iv) mapping roles, input, and experiences of key stakeholders throughout patient journeys; (v) mapping a journey from multiple perspectives; and (vi) mapping a timeline of events. 3 Combinations or variations of these may be used in cardiovascular settings in the future, depending on the research question, and the reasons mapping is being undertaken.

Recruit, collect data, and analyse data

The majority of health-focused patient journey mapping projects published to date have recruited <50 participants. 3 Projects with fewer participants tend to be qualitative in nature. In the cardiovascular examples provided in Figure 1 , participant numbers range from 7 14 to 260. 15 The 3 studies with <20 participants were qualitative, 12 , 14 , 16 and the 2 with 95 and 260 participants, respectively, were quantitative. 13 , 15 As seen in these and wider patient journey mapping examples, 3 participants may include patients, relatives, carers, healthcare professionals, or other stakeholders, as required, to meet the study objectives. These different participant perspectives may be analysed within each participant group and/or across the wider cohort to provide insights into experiences, and the contextual factors that shape these experiences.

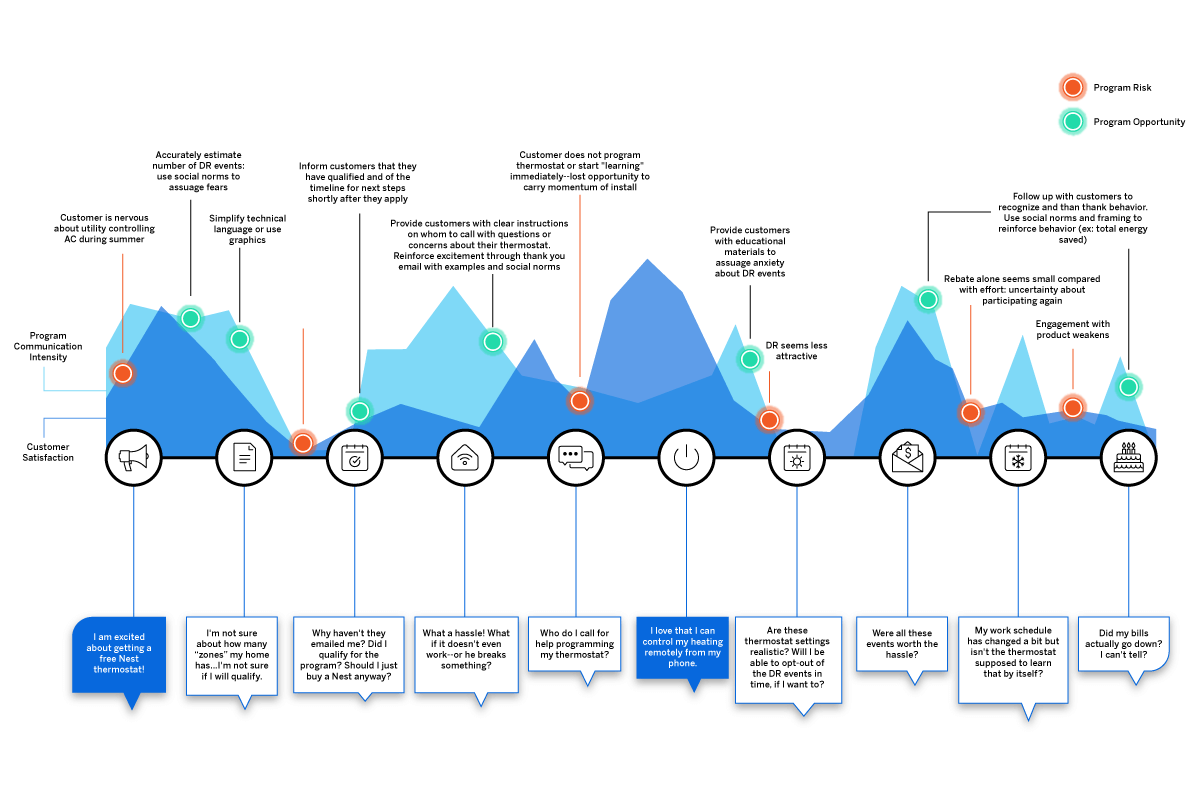

The approach chosen for data collection and analysis will vary and depends on the research question. What differentiates data analysis in patient journey mapping studies from other qualitative or quantitative studies is the focus on describing, defining, or exploring the journey from a patient’s, rather than a health service, perspective. Dimensions that may, therefore, be highlighted in the analysis include timing of service access, duration of delays to service access, physical location of services relative to a patient’s home, comparison of care received vs. benchmarked care, placing focus on the patient perspective.

The mapping of individual patient journeys may take place during data collection with the use of mapping templates (tables, diagrams, and figures) and/or later in the analysis phase with the use of inductive or deductive analysis, mapping tables, or frameworks. These have been characterized and visually represented in a recent scoping review. 3 Representations of patient journeys can also be constructed through a secondary analysis of previously collected data. In these instances, qualitative data (i.e. interviews and focus group transcripts) have been re-analysed to understand whether a patient journey narrative can be extracted and reported. Undertaking these projects triggers a new research cycle involving the six steps outlined in the Central illustration . The difference in these instances is that the data are already collected for Step 5.

Report findings, disseminate findings, and take action on findings

A standardized, formal reporting guideline for patient journey mapping research does not currently exist. As argued in Davies et al ., 3 a dedicated reporting guide for patient journey mapping would be ill-advised, given the diversity of approaches and methods that have been adopted in this field. Our recommendation is for projects to be reported in accordance with formal guidelines that best align with the research methods that have been adopted. For example, COREQ may be used for patient journey mapping where qualitative methods have been used. 20 STROBE may be used for patient journey mapping where quantitative methods have been used. 21 Whichever methods have been adopted, reporting of projects should be transparent, rigorous, and contain enough detail to the extent that the principles of transparency, trustworthiness, and reproducibility are upheld. 3

Dissemination of research findings needs to include the research, healthcare, and broader communities. Dissemination methods may include academic publications, conference presentations, and communication with relevant stakeholders including healthcare professionals, policymakers, and patient advocacy groups. Based on the findings and identified insights, stakeholders can collaboratively design and implement interventions, programmes, or improvements in healthcare delivery that overcome the identified challenges directly and address and improve the overall patient experience. This cyclical process can hopefully produce research that not only informs but also leads to tangible improvements in healthcare practice and policy.

Patient journey mapping is typically a hands-on process, relying on surveys, interviews, and observational research. The technology that supports this research has, to date, included word processing software, and data analysis packages, such as NVivo, SPSS, and Stata. With the advent of more sophisticated technological tools, such as electronic health records, data analytics programmes, and patient tracking systems, healthcare providers and researchers can potentially use this technology to complement and enhance patient journey mapping research. 19 , 20 , 22 There are existing examples where technology has been harnessed in patient journey. Lee et al . used patient journey mapping to verify disease treatment data from the perspective of the patient, and then the authors developed a mobile prototype that organizes and visualizes personal health information according to the patient-centred journey map. They used a visualization approach for analysing medical information in personal health management and examined the medical information representation of seven mobile health apps that were used by patients and individuals. The apps provide easy access to patient health information; they primarily import data from the hospital database, without the need for patients to create their own medical records and information. 23

In another example, Wauben et al. 19 used radio frequency identification technology (a wireless system that is able to track a patient journey), as a component of their patient journey mapping project, to track surgical day care patients to increase patient flow, reduce wait times, and improve patient and staff satisfaction.

Patient journey mapping has emerged as a valuable research methodology in healthcare, providing a comprehensive and patient-centric approach to understanding the entire spectrum of a patient’s experience within the healthcare system. Future implications of this methodology are promising, particularly for transforming and redesigning healthcare delivery and improving patient outcomes. The impact may be most profound in the following key areas:

Personalized, patient-centred care : The methodology allows healthcare providers to gain deep insights into individual patient experiences. This information can be leveraged to deliver personalized, patient-centric care, based on the needs, values, and preferences of each patient, and aligned with guideline recommendations, healthcare professionals can tailor interventions and treatment plans to optimize patient and clinical outcomes.

Enhanced communication, collaboration, and co-design : Mapping patient interactions with health professionals and journeys within and across health services enables specific gaps in communication and collaboration to be highlighted and potentially informs responsive strategies for improvement. Ideally, these strategies would be co-designed with patients and health professionals, leading to improved care co-ordination and healthcare experience and outcomes.

Patient engagement and empowerment : When patients are invited to share their health journey experiences, and see visual or written representations of their journeys, they may come to understand their own health situation more deeply. Potentially, this may lead to increased health literacy, renewed adherence to treatment plans, and/or self-management of chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease. Given these benefits, we recommend that patients be provided with the findings of research and quality improvement projects with which they are involved, to close the loop, and to ensure that the findings are appropriately disseminated.

Patient journey mapping is an emerging field of research. Methods used in patient journey mapping projects have varied quite significantly; however, there are common research processes that can be followed to produce high-quality, insightful, and valuable research outputs. Insights gained from patient journey mapping can facilitate the identification of areas for enhancement within healthcare systems and inform the design of patient-centric solutions that prioritize the quality of care and patient outcomes, and patient satisfaction. Using patient journey mapping research can enable healthcare providers to forge stronger patient–provider relationships and co-design improved health service quality, patient experiences, and outcomes.

None declared.

Farmer J , Bigby C , Davis H , Carlisle K , Kenny A , Huysmans R , et al. The state of health services partnering with consumers: evidence from an online survey of Australian health services . BMC Health Serv Res 2018 ; 18 : 628 .

Google Scholar

Kelly J , Dwyer J , Mackean T , O’Donnell K , Willis E . Coproducing Aboriginal patient journey mapping tools for improved quality and coordination of care . Aust J Prim Health 2017 ; 23 : 536 – 542 .

Davies EL , Bulto LN , Walsh A , Pollock D , Langton VM , Laing RE , et al. Reporting and conducting patient journey mapping research in healthcare: a scoping review . J Adv Nurs 2023 ; 79 : 83 – 100 .

Ly S , Runacres F , Poon P . Journey mapping as a novel approach to healthcare: a qualitative mixed methods study in palliative care . BMC Health Serv Res 2021 ; 21 : 915 .

Arias M , Rojas E , Aguirre S , Cornejo F , Munoz-Gama J , Sepúlveda M , et al. Mapping the patient’s journey in healthcare through process mining . Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020 ; 17 : 6586 .

Natale V , Pruette C , Gerohristodoulos K , Scheimann A , Allen L , Kim JM , et al. Journey mapping to improve patient-family experience and teamwork: applying a systems thinking tool to a pediatric ambulatory clinic . Qual Manag Health Care 2023 ; 32 : 61 – 64 .

Cherif E , Martin-Verdier E , Rochette C . Investigating the healthcare pathway through patients’ experience and profiles: implications for breast cancer healthcare providers . BMC Health Serv Res 2020 ; 20 : 735 .

Gilburt H , Drummond C , Sinclair J . Navigating the alcohol treatment pathway: a qualitative study from the service users’ perspective . Alcohol Alcohol 2015 ; 50 : 444 – 450 .

Gichuhi S , Kabiru J , M’Bongo Zindamoyen A , Rono H , Ollando E , Wachira J , et al. Delay along the care-seeking journey of patients with ocular surface squamous neoplasia in Kenya . BMC Health Serv Res 2017 ; 17 : 485 .

Borycki EM , Kushniruk AW , Wagner E , Kletke R . Patient journey mapping: integrating digital technologies into the journey . Knowl Manag E-Learn 2020 ; 12 : 521 – 535 .

Barton E , Freeman T , Baum F , Javanparast S , Lawless A . The feasibility and potential use of case-tracked client journeys in primary healthcare: a pilot study . BMJ Open 2019 ; 9 : e024419 .

Bearnot B , Mitton JA . “You’re always jumping through hoops”: journey mapping the care experiences of individuals with opioid use disorder-associated endocarditis . J Addict Med 2020 ; 14 : 494 – 501 .

Cunnington MS , Plummer CJ , McDiarmid AK , McComb JM . The patient journey from symptom onset to pacemaker implantation . QJM 2008 ; 101 : 955 – 960 .

Geerse C , van Slobbe C , van Triet E , Simonse L . Design of a care pathway for preventive blood pressure monitoring: qualitative study . JMIR Cardio 2019 ; 3 : e13048 .

Laveau F , Hammoudi N , Berthelot E , Belmin J , Assayag P , Cohen A , et al. Patient journey in decompensated heart failure: an analysis in departments of cardiology and geriatrics in the Greater Paris University Hospitals . Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2017 ; 110 : 42 – 50 .

Naheed A , Haldane V , Jafar TH , Chakma N , Legido-Quigley H . Patient pathways and perceptions of treatment, management, and control Bangladesh: a qualitative study . Patient Prefer Adherence 2018 ; 12 : 1437 – 1449 .

Bateman S , Arnold-Chamney M , Jesudason S , Lester R , McDonald S , O’Donnell K , et al. Real ways of working together: co-creating meaningful Aboriginal community consultations to advance kidney care . Aust N Z J Public Health 2022 ; 46 : 614 – 621 .

Greenhalgh T , Hinton L , Finlay T , Macfarlane A , Fahy N , Clyde B , et al. Frameworks for supporting patient and public involvement in research: systematic review and co-design pilot . Health Expect 2019 ; 22 : 785 – 801 .

Wauben LSGL , Guédon ACP , de Korne DF , van den Dobbelsteen JJ . Tracking surgical day care patients using RFID technology . BMJ Innov 2015 ; 1 : 59 – 66 .

Tong A , Sainsbury P , Craig J . Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups . Int J Qual Health Care 2007 ; 19 : 349 – 357 .

von Elm E , Altman DG , Egger M , Pocock SJ , Gøtzsche PC , Vandenbroucke JP , et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies . Lancet 2007 ; 370 (9596): 1453 – 1457 .

Wilson A , Mackean T , Withall L , Willis EM , Pearson O , Hayes C , et al. Protocols for an Aboriginal-led, multi-methods study of the role of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers, practitioners and Liaison officers in quality acute health care . J Aust Indigenous HealthInfoNet 2022 ; 3 : 1 – 15 .

Lee B , Lee J , Cho Y , Shin Y , Oh C , Park H , et al. Visualisation of information using patient journey maps for a mobile health application . Appl Sci 2023 ; 13 : 6067 .

Author notes

- cardiovascular system

- health personnel

- health services

- health care systems

- narrative discourse

Email alerts

Related articles in pubmed, citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1873-1953

- Print ISSN 1474-5151

- Copyright © 2024 European Society of Cardiology

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 15 April 2021

What does the patient have to say? Valuing the patient experience to improve the patient journey

- Raffaella Gualandi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8602-5249 1 ,

- Cristina Masella 2 ,

- Michela Piredda 3 ,

- Matteo Ercoli 1 &

- Daniela Tartaglini 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 21 , Article number: 347 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

6827 Accesses

19 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Patient-reported data—satisfaction, preferences, outcomes and experience—are increasingly studied to provide excellent patient-centred care. In particular, healthcare professionals need to understand whether and how patient experience data can more pertinently inform the design of service delivery from a patient-centred perspective when compared with other indicators. This study aims to explore whether timely patient-reported data could capture relevant issues to improve the hospital patient journey.

Between January and February 2019, a longitudinal survey was conducted in the orthopaedics department of a 250-bed Italian university hospital with patients admitted for surgery; the aim was to analyse the patient journey from the first outpatient visit to discharge. The same patients completed a paper-and-pencil questionnaire, which was created to collect timely preference, experience and main outcomes data, and the hospital patient satisfaction questionnaire. The first was completed at the time of admission to the hospital and at the end of hospitalisation, and the second questionnaire was completed at the end of hospitalisation.

A total of 254 patients completed the three questionnaires. The results show the specific value of patient-reported data. Greater or less negative satisfaction may not reveal pathology-related needs, but patient experience data can detect important areas of improvement along the hospital journey. As clinical conditions and the context of care change rapidly within a single hospital stay for surgery, collecting data at two different moments of the patient journey enables researchers to capture areas of potential improvement in the patient journey that are linked to the context, clinical conditions and emotions experienced by the patient.

By contributing to the literature on how patient-reported data could be collected and used in hospital quality improvement, this study opens the debate about the use of real-time focused data. Further studies should explore how to use patient-reported data effectively (including what the patient reports are working well) and how to improve hospital processes by profiling patients’ needs and defining the appropriate methodologies to capture the experiences of vulnerable patients. These topics may offer new frontiers of research to achieve a patient-centred healthcare system.

Peer Review reports

Patient-reported data (satisfaction, preferences, outcomes and experience) have been increasingly studied with the aim of providing excellent patient-centred care [ 1 , 2 ]. In particular, the collection of patient experience data is emerging as an increasingly key component in assessing the quality of delivered health services [ 3 , 4 ]. Some authors have emphasised that understanding the patient experience represents an opportunity to design healthcare service delivery [ 5 , 6 ]. However, healthcare professionals need to understand whether and how patient experience data can inform the design of service delivery from a patient-centred perspective more pertinently than other indicators [ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ].

Studies in the service management literature have shown that it is possible to understand the experience starting from the customer journey. The term ‘customer journey’ refers to ‘the processual and experiential aspects of service processes as seen from the customer viewpoint’ [ 11 ]. Kankainen et al. [ 12 ] describe it as ‘the process of experiencing service through different touchpoints from the customer’s point of view’. Customer experience is shaped before, during and after interactions with the service provider. Moving from services to healthcare, the experience of care is not only a matter of interaction but a multifaceted and complex phenomenon in which the health status, the context of care and presence of different health staff play an important role in achieving clinical outcomes [ 9 , 13 ].

In the hospital context, the requirements of responding rapidly to the acute needs of patients through the integration of multiple actors and services increases this complexity. Timely movement of patients from one service to another is a necessary condition both for managing the volume of patients with different pathologies and for obtaining better clinical outcomes. Consequently, the patient experience of care and service delivery is the result of many successive touchpoints across services to receive care from different units, the totality of which constitutes the patient journey. Because on an individual level any experience is subjective, dynamic and context dependent [ 14 ], patient experience data collected at different points of the journey should make it possible to evaluate if there are discontinuities within the hospital units (e.g., inpatient ward) and between the different units (e.g., between hospital wards and operating rooms) crossed by the patient journey. Inter- and cross-organisational gaps such as obstructed data flow, unavailability of relevant information at points of intervention and a lack of services synchronisation may occur when a complete and consequential view of the whole process is missing. However, few studies have analysed how to improve the patient journey by starting from the patient experience of the service provided [ 15 ]. In particular, most of them focus only on a single step of the hospital journey without identifying which are the meaningful touchpoints for the patient [ 16 , 17 , 18 ]. Indeed, if on the one hand, the patient’s stay is itself composed of multiple steps within the hospital, the hospital journey is part of a larger patient journey, which extends further in time before and after hospitalisation. This is particularly the case for patients who have to undergo surgery, for which clinical examinations are required before admission and a follow-up is scheduled after discharge.

Furthermore, it is not yet clear what the best method is for collecting patient experience data throughout the patient journey [ 19 ]. A recent study analysed the hospital stay experience through the use of unstructured diaries completed in a patient’s own words. However, if, on the one hand, the authors confirm that it is possible to collect valuable data for the improvement of the service directly from the patient, then, on the other hand, the education level, age and clinical conditions could be a limit in understanding the experience of fragile patients [ 20 ].

The goal of the current study is twofold: 1) explore which data collected directly from the patient could be useful in improving the patient journey and 2) to analyse whether gathering timely patient experience data at different points of the patient journey within the hospital can capture areas for improvement in the patient journey.

Design and setting

A longitudinal survey was conducted in the orthopaedics department of a 250-bed Italian university hospital between January and February 2019. The unit of analysis was the journey of the orthopaedic patient from the first outpatient visit to hospital discharge. Accordingly, all patients who underwent major or minor orthopaedic surgery during the time period were considered for inclusion. The type of surgery and stage of the patient journey formed the analysis groups. The study was part of a larger hospital project to redesign the orthopaedic patient journey for hip or knee replacement surgery, here starting with the patient experience [ 19 , 21 ]. In particular, the data collected by the hospital management to assess the quality of the service and that are presented in this work were integrated with interviews and the shadowing of patients, whose results are reported in other papers. The entire project received ethical approval from the organisation’s Ethics Committee (Protocol n.: 25/16 OSS ComEt CBM).

The orthopaedics unit has 34 beds for ordinary hospitalisation or day surgery and is divided into two multispecialty wards: one for ordinary admissions and one mainly for day surgery recovery. Some of the healthcare staff working within the various services are specialised, and a large part is composed of staff in training (residents and degree course students of medicine, nursing and physiotherapy). A centralised team that includes administrative staff and bed manager nurses handles the admissions calls and reception procedures.

Reference terminology

To conduct the present research, the authors employed the following terms with corresponding meanings:

Patient-reported data: views and opinions of patients on the care and on the service they have experienced.

Patient satisfaction: ‘the extent to which the patient’s expectations were fulfilled’ [ 22 ].

Patient experience: ‘the sum of all interactions, shaped by an organisation’s culture, that influences patient perceptions, across the continuum of care’ [ 23 ].

Patient preference: ‘statements made by the patients regarding the relative desirability of a range of health experiences, treatment options and health states’ [ 24 ].

Patient outcomes: ‘any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else’ [ 25 ].

Instruments

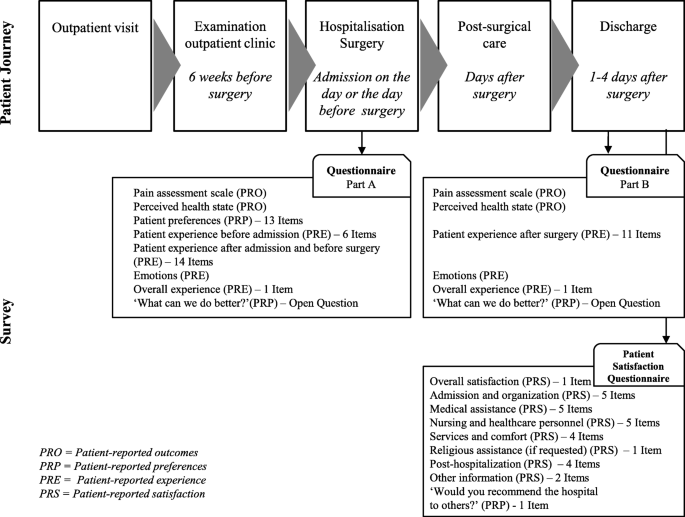

The current study was carried out with two different paper-and-pencil questionnaires delivered to the same patients at two different stages of the hospital patient journey. The first questionnaire was developed on purpose by the authors and completed by the patients at the time of admission to the hospital and at the end of hospitalisation. An English language version of the questionnaire is available as a supplementary file to this paper (see Additional file 1 ). The second questionnaire was the patient satisfaction questionnaire adopted by the hospital and completed by the patients at the end of hospitalisation. In this way, patient-reported outcomes (PRO), patient-reported experience (PRE), patient-reported satisfaction (PRS) and patient-reported preferences (PRP) were collected and analysed.

Figure 1 summarises the points of the patient journey where the data were collected and the focus of each questionnaire.

Patient journey and data collection

Consistent with the need to capture patient-reported data during a relatively rapid surgical pathway, the researchers chose to develop a questionnaire focused on the key themes that emerged from the results of the qualitative study previously conducted [ 19 ]. The questionnaire was developed by the first three authors to capture data on the following patient journey touchpoints: preadmission, admission to hospital, preparation for surgery, the postsurgery period and discharge. The purposes were the following: to create a questionnaire that is easy to read and fill in by the patient and to be administered at two key moments of the journey (at the time of admission before surgery and at discharge); to make the data more easily comparable between the different types of patient-reported data; to minimise the risk of patients not completing the questionnaire because of the high number of questions [ 26 ]; and to avoid less data being recorded in the case of elderly or low-educated patients [ 20 ].

The questionnaire items were identified to cover all the service quality dimensions indicated by Dagger [ 27 ] and Gustavsson [ 28 ]: interpersonal quality, technical quality, environmental quality, administrative quality, family quality and involvement quality. In addition, the international literature was consulted by the first and the second authors to develop a set of items evaluating the patient perspective on the level of importance of the different issues related to the hospital journey.

After a discussion between the authors, the questionnaire resulted in 37 closed items and one open question to be administered when the patient entered the hospital ward (Part A) and 15 closed items and one open question when the patient was discharged (Part B). The answers to the closed questions were possible within a 5- or 10-point Likert scale (depending on the items), on outcomes, preferences, experience and satisfaction.

Part A, which was administered upon arrival in the patient ward, included the following sections:

Pain assessment scale (0 = absent; 10 = the strongest pain) and perceived health state (0 = not satisfied at all; 5 = very satisfied);

Patient preferences: evaluation of the self-perceived impact of the different issues related to the hospital journey on the patient’s life (e.g., instructions on how to get to the hospital or in case of waiting; not feeling pain; trusting professionals, etc.) – 13 items (0 = not at all important; 5 = very important);

Positive or negative emotions experienced at the moment of completing the questionnaire by choosing the main ones from the Plutchik’s wheel: serenity, trust, anticipation, apprehension, fear and anger.

A final open question: ‘What can we do better?’

Part B, administered upon discharge from the hospital ward, included the following sections:

The analysis of the internal consistency of the questionnaire through an analysis of the closed-ended items showed a high level of reliability (Cronbach’s alpha: patient perspective and preference 13 items > 0.7; patient experience before surgery 20 items > 0.8; patient experience after surgery 11 items > 0.8).

The patient satisfaction questionnaire included demographic data (age, gender, education and region of origin) and assessed patient satisfaction. The 28 items included a first question on overall satisfaction; the items were divided into seven macro-areas: admission and organisation; medical assistance; nursing and other healthcare personnel; services and comfort; religious assistance (if requested); posthospitalisation; and other information. A final question was ‘Would you recommend the hospital to others?’ with a 10-point Likert scale (from ‘Absolutely not” to ‘Absolutely yes’).

Data collection

An exploratory sample was used, including all orthopaedic patients admitted for surgery during the study period. The patients were recruited at the time of administrative admission for hospitalisation from among those who could understand and consent, speak Italian fluently and write. The data collected were part of the quality of service survey approved by the hospital management and included in the quality surveys in which the patient agreed to participate by signing the consent form at the time of hospital admission. In addition, a trained research assistant asked them for oral consent to participate by explaining the study’s purpose, discussing how participation was voluntary and about the anonymity of data collection.

The fourth author delivered the paper-and-pencil questionnaire to the patient to be filled out on the spot upon arrival in the hospital room (10-min duration) and upon discharge (15-min duration, including the patient satisfaction questionnaire). The same author collected the questionnaire after the patient had filled it in, monitored the completeness of the data and reported all the data on an Excel worksheet for subsequent analysis.

Data analysis

A score was created for each quantitative item of the questionnaire by coding the item response from ‘1’ if the experience was considered completely negative to ‘5’ if it was considered completely positive. A higher score indicates a positive experience and satisfaction with the hospital patient journey. Quantitative data were analysed with descriptive statistics, including the mean and standard deviation and by analysis of a significant difference between the following a priori established groups: type of surgery (major surgery or minor surgery) and time of the patient journey (at the entrance to the hospital and at discharge). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Qualitative data were analysed by the first author by reporting and classifying patient responses to the open question ‘What can we do better?’ Specifically, the content of the responses was classified according to the service quality dimensions of Dagger [ 27 ] and Gustavsson [ 28 ].

Sample characteristics

A total of 255 patients were included in the study; of them, only one patient refused to participate because of the limited time available to prepare for surgery upon entering the hospital. Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the participants. The participants had a mean age of 62 years (SD: 14; range: 18–96), and 80% were over the age of 50. The sample was equally distributed between men and women. The most frequent major surgical operations were knee replacement (53% of major surgery) and hip replacement (29%). The most frequent minor surgical procedures were knee arthroscopy (39% of minor surgery) and shoulder arthroscopy (36%). Of the patients admitted for major surgery, 49% had been admitted to the same hospital in the past, while 70% of the patients who had to undergo minor surgery were being admitted to the hospital for the first time.

The evaluation of the patient preferences on the different issues related to the hospital journey that were collected at the beginning of hospitalisation show that the five aspects considered most important for a good hospital journey experience are as follows: ‘Receive the best treatment for the related health conditions’ (Mean: 4.8, SD: 0.4); ‘Have clear instructions on how to prepare for surgery (therapy, fasting, surgery aids)’ (Mean: 4.8, SD: 0.4); ‘Have clear instructions on how to check in at the hospital’ (Mean: 4.7, SD: 0.5); ‘Have clear indications on the treatment pathway I will also have to take’ (Mean: 4.7, SD: 0.5); and ‘Receive explanations from staff in case of waiting’ (Mean: 4.7, SD: 0.5). The least important aspects among those listed are as follows: ‘Have explanations and understand everything that happens to me’ (Mean: 4.0, SD: 0.7); ‘Be involved in all decisions concerning my care’ (Mean: 3.9, SD: 0.8); ‘Feel comfortable in the environments where I have to be’ (Mean: 3.9, SD: 0.9); ‘Wait as little time as possible for a visit or for assistance’ (Mean: 3.9, SD: 0.9); and ‘Have a room where I am not disturbed and with hotel services (TV, landline, etc.)’ (Mean: 3.8, SD: 0.9). When asked if other aspects were important, one participant added ‘Empathic relationship with all the staff’, while another added ‘Admission in a clean facility like this’. No significant differences were found between the major and minor surgery patients.

Evaluating the patient journey at two different points

All patients completed the quantitative items of the experience questionnaire, which was administered on arrival and on discharge, and the satisfaction questionnaire, which was administered on discharge. On admission, 58% of patients answered the open question ‘What can we do better?’ and 68% answered the same question administered on discharge.

Table 2 reports the answers to the overall questions on patient-reported data, referring to the two moments in which the patients were interviewed.

PRO changed between the time of entry and time of discharge, with a different trend between major and minor surgery patients. Upon arrival at the hospital, orthopaedic patients who needed major surgery reported significant pain, here rated on a scale of 0 (absent) to 10 (the strongest pain); this decreased after surgery (Mean: 5.5, SD: 2.7 vs. Mean: 3.8, SD: 2.6). Pain remained constant and not particularly high in minor surgery patients (Mean: 2.8, SD: 2.4 vs. Mean: 2.6, SD: 2.7). The self-reported state of health assessed on a scale of values between 1 (not at all satisfied) to 5 (very satisfied) showed a more evident improvement in patients with major surgery between the time of arrival in the hospital and time of discharge (Mean: 3.7, SD: 0.8 vs., Mean: 4.0, SD: 0.6). Minor surgery patients reported a generally higher level of health than major surgery patients (Mean: 4.0 SD: 0.7 vs. Mean: 4.3, SD: 0.6). In these items, the age group does not seem to be significant.

Regarding the closed-answer items on the overall patient experience, an average of high scores, with a slight difference between the time of entry into the ward and time of discharge, was reported. On discharge, the hospital experience was rated with lower average scores than patient satisfaction. The patient satisfaction relating to hospitalisation showed significant high scores: on a score from 1 to 5, 97% of patients rated 4 (22.8%) or 5 (74.4%). Additionally, 95% of patients would recommend the hospital to other patients.

Table 3 reports how patients’ emotional status changed along the hospital journey. Trust and apprehension were the prevailing emotions at the time of arriving in the ward (respectively 37.8 and 20.5% of patients). Apprehension decreased noticeably among patients after surgery (6.3%), and serenity increased (from 21.7% before surgery to 46.1% at the time of discharge). The change is more evident in major surgery patients: 32.7% of them experienced apprehension or fear before surgery, decreasing to 13.1% at the time of discharge, with an increase in patient serenity from 5.8 to 14.8%.

Detecting areas of improvement by following the patient journey

When analysing the specific items in relation to the time of the journey, the data on experience and satisfaction showed differing information around some key topics. Table 4 shows the experience and satisfaction items that are the most related to the patient’s journey.

At the time of discharge, the patient satisfaction items reported high scores for the quality and cleanliness of the environment (Mean: 4.8, SD: 0.4). However, upon entering the ward, the patients rated the comfort of the room with one of the lowest experience scores (Mean: 4.3, SD: 1.0). The answers to the open questions show the reason for this: the patients wished to have a TV inside the wards and to have larger wards to move more easily with the orthopaedic aids they had to manage (wheelchair, crutches, etc.). One patient suggested the following solution: ‘Small hospital room for physiotherapy: creation of a dedicated space’ (Code: ORTO 63).

In the ‘Satisfaction’ items, patients recognised a high level of professionalism and competence in the healthcare staff (Mean: 4.8, SD: 0.6). However, in the ‘Experience’ questionnaire, the items concerning information received before surgery showed some of the lowest scores. The score on the information received to organise the hospitalisation and prepare for surgery was rated at 4.5 (SD: 0.8). Understandable explanations given before surgery by the doctor of everything the patient needed to know about surgery, length of stay and the postsurgery period was rated 4.3 (SD: 0.9). The same result was recorded for understandable explanations given by the anaesthesiologist on everything the patient needed to know about surgery and pain treatment. The answers to open questions showed that 29 patients would have liked more information concerning the different aspects of hospitalisation, including the necessary aids for surgery and postsurgery path. Two patients emphasised the need for more communication with family members when the patient was in the operating theatre. One patient expressed how this issue can always be improved: ‘In my opinion, improve the information given to patients on the path they have to take inside the hospital. I have been hospitalised five times and I always see an improvement, thanks for everything’ (Code: DS36).

The patient satisfaction questionnaire reported a high score on the availability of doctors and nursing and care staff (Mean: 4.7, SD: 0.7). For the experience items, the patients rated these aspects at 4.4 and 4.6, respectively, at the time of entering the ward. The average score decreased to 4.3 and 4.5, respectively, regarding the postsurgery stay. More specific data emerged from the open questions. The patients reported the need for more of a presence of and contact with doctors (38 quotes) and nurses (21 quotes), and this need was reported in particular regarding the postsurgery stay: ‘More time spent by staff in the postoperative period’ (Code: ORTO2). Twenty-one patients reported a lack of interaction with healthcare staff as a staff shortage problem: ‘Nurses are very professional and well trained, but there should be more of them’ (Code: DS37); ‘too few nurses during the shift to answer the call bells quickly’ (Code: ORTO151). Other patients added that the presence of so many students decreased their confidence in being properly cared for. For example, one patient said, ‘Stay longer with the patient without rushing, too many students unable to solve certain problems and too few nurses and doctors’ (Code: ORTO 116).

The question ‘Were you involved in decisions about your care?’ obtained the lowest score. Specifically, the average rating was 4.0 upon arrival in the ward and increased to 4.3 upon discharge. However, only one participant suggested greater patient involvement.

The satisfaction score on waiting times and admissions procedures was among the lowest (Mean: 4.5, SD: 0.8). The reasons for these scores were expanded by the answers to the open questions captured immediately after entering the ward: 53 patients reported that the waiting times between arrival at the hospital, admission procedures and room assignment were too long. One patient pointed out that hospital discharges and new entries needed to be better coordinated; another suggested that the patient should not come too early in the morning if admission was scheduled during the day; some patients asked for a reduction in the time between entering the hospital and actually entering the operating theatre.

Some hidden but not openly stated needs for adaptation by the patient to hospital rules are evident in this quote: ‘I found everything well, no complaints, I understood that having a relative’s personal assistance is impossible but I would have liked it’ (Code: ORTO26). In the presurgery period, the patients reported the desire for family members to be nearby when they wanted (Mean: 4.4, SD: 0.9). The score increased in the postoperative period (Mean: 4.7, SD: 0.6), and only nine patients stated they wanted more time with their families, with more flexible visiting hours and with their presence before surgery.

Although unsolicited, feedback on what works, in addition to what needs to be improved, was given. For example, one patient reported, ‘I did not expect to find such a comfortable environment with such professionalism from all the staff. Nothing is perfect, therefore everything is perfectible, but here, in this hospital, we are at a good point’ (Code: ORTO16). Another said, ‘Nothing to improve, on the contrary I would like to point out the particular care, attention and professionalism of the student F.A.’ (Code: ORTO33).

Table 5 reports the improvements suggested by the patients collected at the two different points of their journey.

Numerous studies have explored how different types of data collected directly from patients can improve the quality of care, while few studies have analysed whether the data reported by patients on a cross-hospital process can be useful to improve the process itself [ 29 , 30 ]. The current study was designed to explore whether patient-reported data, specifically experience data, can identify areas of improvement within the hospital and between the different units crossed by the patient journey.

By timely and simultaneously gathering preferences, satisfaction, outcomes and experience data, it is possible to have a complete picture of the hospital patient journey. In particular, the satisfaction and preference data measure the levels of importance given to different aspects by the patient— what is important for the patient experience—and outcomes data show the patient’s circumstances and present conditions— why it is important for the patient. Satisfaction data may not reveal pathology-related needs, while patient experience data can detect important areas of improvement along the hospital journey. In the current study, for instance, the score of preference for room comfort was one of the lowest items (Mean: 3.8). However, by answering to the open question on what can be improved, when the patient entered the room, he judged it not very comfortable (Mean: 4.3) because of the lack of space for movement with orthopaedic aids. The satisfaction item cannot capture this information (average score of 4.8 on the quality and cleanliness of the environments).

These same results also show how at the beginning of the journey, patients might consider an issue as not critical, but while living the hospital experience, it becomes important. As another example, although on admission, patients declared that waiting as little time as possible for a visit or for assistance was one of the least important aspects (Mean: 3.9), the satisfaction score on waiting times and admissions procedures was among the lowest (Mean: 4.5). Timely experience data show how as soon as the patient enters the room, he or she clearly remembers having waited too long from the moment of admission and suggests a better organisation of the hospitalisation.

Numerous factors can influence the patient experience. In the presurgery stage, trust and apprehension are the prevailing emotions (37.8 and 20.5% of patients, respectively), and the patient seems to lack knowledge of what to do. The experience data show that the scores related to information received to organise the hospitalisation and prepare for surgery and explanations given before surgery are very low. Improving information concerning the different aspects of hospitalisation, including the necessary aids for surgery and the postsurgery path, emerged as a fundamental need.

Even if related to a very specific case, the results of the current study show that patients do not have the technical competence to predict their needs before and after surgery; thus, nursing competence is needed to effectively anticipate patient needs and attend to the organisation of patient journeys to improve experiences of care. These data support the claim of a recent NHS report in which nurses are shown to play an essential role in the way in which data are collected, interpreted and used to improve care [ 10 ].

Because clinical conditions and the context of care change rapidly within a single hospital stay for surgery, capturing data at key moments in the journey, rather than at the end, can better represent the patient’s experience [ 31 ]. In particular, analysing the answers to the open question ‘What can we do better?’ allows for understanding what happened to the patient that may have influenced his or her experience (e.g., apprehension and pain before surgery, pathology and age-related needs, fast-track recovery, waiting without entertainment, etc.). Moreover, one patient may reveal the important needs made impossible by circumstances (e.g., need of having a family member being close to the patient before surgery made impossible by hospital organisation). For example, when redesigning fast-track recovery from major orthopaedic surgery, significant touchpoints for the patient should be treated with respect to his or her need for interaction with professionals, his or her emotional state and social conditions and by considering the changing circumstances he or she will face along the journey [ 19 , 32 , 33 ]. In particular, the emotional state should be better explored to understand how this variable affects patient experience along the journey and to improve ways of interacting with the patient: by giving more information, by offering support or simply by accompanying him or her in critical moments of the presurgery period.

In the present study, to encourage patient participation, the authors decided to ask a few questions at two critical moments of the journey: at the arrival before surgery and at discharge. Moreover, despite the older population involved, the simplicity of the questionnaire, which even used emoticons, made it possible to capture the experience of those patients who were able to read and write. In this way, a high rate of responses was achieved. Nevertheless, further studies should investigate how to collect real-time feedback from those who are unable to describe their own experience [ 34 ]. Moreover, because data were collected in paper format, the process of returning data to the management team and front-line professionals to stimulate quality improvement slowed down because of the necessary data analysis times. The challenges in handling real-time big data collection and storage in health information systems will bring new advancements in the continuous improvement process by immediately returning the patient-reported data at all organisational levels. These data should help redesign hospital care processes at the top and middle management levels in an integrated and patient-centred way. At the front-line level, healthcare professionals can immediately make corrections with micro-interventions, fixing the way of giving attention to the patient by focusing on his or her experiences.

In present study, patient-reported data on satisfaction and experience were significantly positive in almost all the items investigated, with an average score between 4 and 5 on a scale of 1 to 5. This result is in line with the literature showing that little variation occurs in the answers to questions about the quality of care with high patient satisfaction scores [ 35 , 36 ]. Further studies should investigate if the asymmetrical relationship between the health care professional and patient [ 37 ], the vulnerable situation of a patient [ 34 ] and the primary need to solve a clinical problem and fear of surgery that are deemed more important than anything else could result in high and undistributed response rates.

When asking the patient ‘What can we do better?’ the question assumes that the patient only identifies what does not work. However, patients are also able to report what worked well. Managers and health care teams should study which factors, from the patient’s point of view, determine a good experience and must be supported. Further studies should analyse whether positive patient-reported data may explain what factors produce a good patient journey experience and how they may reinforce the quality improvement solutions adopted and, hence, influence health professionals’ behaviour [ 38 ].

The results of the current study emphasise that personalised medicine should no longer only refer to the targeted therapy. This requires management teams to be able to customise the patient journey and identify different patient profiles, which should not be reduced to the clinical pathway.

The limitations of the current study are manifold; in large part, they are connected to the nature of the original project, which aimed to produce local actionable improvements in the setting. First, the results cannot be generalised: the study was conducted in a single hospital and only on how the orthopaedic surgical path; this influences the significance and transferability of the results. However, the study aimed to provide useful insights to hospital management to promote a review of the processes in a real patient-centred way. In particular, the results offer a stimulus for the debate on the use of patient experience data for the design of service delivery. Second, the orthopaedic surgical path is very different, for example, from the oncological one. Specifically, the orthopaedic surgical journey is generally shorter, has a beginning and an end and does not extend over time with a worsening of the initial clinical conditions. This aspect could influence the results and methodology should be tested on different clinical pathways, in particular by considering chronic pathologies. Finally, the authors preferred to use a questionnaire with relatively few questions instead of using the validated ones already present in the literature. The choice was made to favour real-time data collection and the patient’s response rate to the questions. These objectives have been achieved, and future studies will have to validate the single items for patients with different pathologies. However, by considering the very different and complex contexts in which each hospital operates, the literature will increasingly have to consider single longitudinal studies by starting from the analysis of the patient journey that takes place in each hospital.

Several issues would benefit from further exploration, including the impact of the patient-healthcare staff relationship in the hospital journey experience; the opportunity of bringing patients’ and professionals’ experiences together for joint knowledge of improvement solutions; and the study of new methodology to capture the real-time experiences of vulnerable patients.

Providing customers with quality experiences is a key competitive advantage in a range of service sectors, including the healthcare service. Measuring patient experiences is a practice increasingly used, and researchers and managers are seeking to understand how to use these measures to improve service delivery [ 39 , 40 , 41 ].

The current study provides insights for healthcare practitioners caring for patients in hospitals and those responsible for planning and designing the hospital patient journey. By contributing to the literature on how patient-reported data could be collected and used in hospital quality improvement, it also opens the debate about the use of real-time focused data when capturing experiences from vulnerable patients. Furthermore, the present study asks for a more positive perspective on patients’ data that can be used not only to detect what does not work, but also what is working well.

In different clinical settings, further studies should explore how to effectively use patient-reported data to improve hospital processes, profile patients’ needs and identify appropriate methodologies to capture the experiences of vulnerable patients. These topics may offer new frontiers of research to achieve a patient-centred healthcare system.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Patient-reported outcomes

Patient-reported experience

Patient-reported satisfaction

Patient-reported preferences

Number count

Standard deviation

National Health Service (UK)

Murante AM, Seghieri C, Brown A, Nuti S. How do hospitalization experience and institutional characteristics influence inpatient satisfaction? A multilevel approach. Int J Health Plann Mgmt. 2014;29(3):e247–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2201 .

Article Google Scholar

Klose K, Kreimeier S, Tangermann U, Aumann I, Damm K, RHO Group. Patient- and person-reports on healthcare: preferences, outcomes, experiences, and satisfaction - an essay. Heal Econ Rev. 2016;6(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-016-0094-6 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):e001570. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Nuti S, De Rosis S, Bonciani M, Murante AM. Rethinking Healthcare Performance Evaluation Systems towards the People-Centredness Approach: Their Pathways, their Experience, their Evaluation. Healthc Pap. 2017;17(2):56–64. doi: https://doi.org/10.12927/hcpap.2017.25408 . Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/report-of-the-mid-staffordshire-nhs-foundation-trust-public-inquiry . Accessed 15 Jan 2020.

Francis R. Report of the mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation trust public inquiry. 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/report-of-the-mid-staffordshire-nhs-foundation-trust-public-inquiry . Accessed 15 Jan 2020.

Baig A, Dua A, Riefberg, V. How US state governments can improve customer service. 2014. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-sector/our-insights/how-us-state-governments-can-improve-customer-service . Accessed 15 Jan 2020.

Asprey A, Campbell JL, Newbould J, Cohn S, Carter M, Davey A, et al. Challenges to the credibility of patient feedback in primary healthcare settings: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(608):e200–8. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp13X664252 .

Boiko O, Campbell JL, Elmore N, Davey AF, Roland M, Burt J. The role of patient experience surveys in quality assurance and improvement: a focus group study in English general practice. Health Expect. 2015;18(6):1982–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12298 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ponsignon F, Smart A, Philps L. A customer journey perspective on service delivery system design: insights from healthcare. IJQRM. 35(3). https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-03-2018-0073 .

Donetto S, Desai A, Zoccatelli G, Robert G, Allen D, Brearley S, et al. Organisational strategies and practices to improve care using patient experience data in acute NHS hospital trusts: an ethnographic study. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2019;7(34):112. https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr07340 .

Følstad A, Kvale K. Customer journeys: a systematic literature review. JSTP. 2018;28(2):196–227. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-11-2014-0261 .

Kankainen A, Vaajakallio K, Kantola V, Mattelmäki T. Storytelling group – a co-design method for service design. BIT. 2012;31(3):221–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2011.563794 .

Tax SS, McCutcheon D, Wilkinson IF. The service delivery network (SDN): a customer-centric perspective of the customer journey. J Serv Res. 2013;16(4):454–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670513481108 .

Law EL-C, Roto V, Hassenzahal M, POS VA, Kort J. Understanding, scoping and defining user experience: a survey approach. Proceedings from the CHI conference. CHI; User experience April 7th 2009. Boston; 2009.

Gualandi R, Masella C, Tartaglini D. Improving hospital patient flow: a systematic review. BPMJ. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-10-2017-0265 .

Richardson S, Casey M, Hider P. Following the patient journey: older persons' experiences of emergency departments and discharge. Accid Emerg Nurs. 2007;15(3):134–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aaen.2007.05.004 .

Kydd A. The patient experience of being a delayed discharge. J Nurs Manag. 2008;16(2):121–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00848.x .

Browall M, Koinberg I, Falk H, Wijk H. Patients' experience of important factors in the healthcare environment in oncology care. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2013;6(8):20870. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v8i0.20870 .

Gualandi R, Masella C, Viglione D, Tartaglini D. Exploring the hospital patient journey: what does the patient experience? PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0224899. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224899 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Webster CS, Jowsey T, Lu LM, Henning MA, Verstappen A, Wearn A, et al. Capturing the experience of the hospital-stay journey from admission to discharge using diaries completed by patients in their own words: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e027258. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027258 PMID: 30862638; PMCID: PMC6429883.

Gualandi R, Masella C, Viglione D, Tartaglini D. Challenges and potential improvements in hospital patient flow: the contribution of frontline, top and middle management professionals. JHOM. 2020;34(8):829–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-11-2019-0316 .

Crow R, Gage H, Hampson S, Hart J, Kimber A, Storey L, et al. The measurement of satisfaction with healthcare: implications for practice from a systematic review of the literature. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6(32):1–2.

The Beryl Institute, 2018, Available at: https://www.theberylinstitute.org/page/DefiningPatientExp . Accesed November 27, 2018.

Brennan PF, Strombom I. Improving health care by understanding patient preferences: the role of computer technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998;5(3):257–62. https://doi.org/10.1136/jamia.1998.0050257 .

Guidance for Industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labelling claims. Food and Drug Administration; 2009, p. 6; Accessed 10 Jan 2015; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf .

Kost RG, de Rosa JC. Impact of survey length and compensation on validity, reliability, and sample characteristics for Ultrashort-, short-, and long-research participant perception surveys. J Clin Transl Sci. 2018;2(1):31–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2018.18 .

Dagger TS, Sweeney JC, Johnson LW. A Hierarchical Model of Health Service Quality: Scale Development and Investigation of an Integrated Model. J Serv Res. 2007;10(2):123–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670507309594 .

Gustavsson S, Gremyr I, Kenne SE. Designing quality of care--contributions from parents: Parents' experiences of care processes in paediatric care and their contribution to improvements of the care process in collaboration with healthcare professionals. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(5–6):742–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13050 .

Garratt AM, Solheim E, Danielsen K. National and cross-national surveys of patient experiences: a structured review. Report from Kunnskapssenteret (Norwegian knowledge Centre for the Health Services) no 7–2008. Oslo: Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services.

Beattie M, Murphy DJ, Atherton I, Lauder W. Instruments to measure patient experience of healthcare quality in hospitals: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2015;23(4):97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0089-0 .

Kjellsson G, Clarke P, Gerdtham UG. Forgetting to remember or remembering to forget: a study of the recall period length in health care survey questions. J Health Econ. 2014;35:34–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.01.007 .

Altringer B. The emotional experience of patient care: a case for innovation in health care design. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2010;15(3):174–7. https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2009.009064 .

McColl-Kennedy JR, Danaher TS, Gallan AS, Orsingher C, Lervik-Olsen L, Verma R. How do you feel today? Managing patient emotions during health care experiences to enhance well-being. J Bus Res. 2017;79:247–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.03.022 .

Goldberg SE, Harwood RH. Experience of general hospital care in older patients with cognitive impairment: are we measuring the most vulnerable patients' experience? BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(12):977–80. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001961 Epub 2013 Jul 18. PMID: 23868868; PMCID: PMC3888593.

Schoenfelder T, Klewer J, Kugler J. Determinants of patient satisfaction: a study among 39 hospitals in an in-patient setting in Germany. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23(5):503–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzr038 .

Harrison R, Walton M, Kelly P, Manias E, Jorm C, Smith-Merry J, et al. Hospitalization from the patient perspective: a data linkage study of adults in Australia. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(5):358–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzy024 .

Pilnick A, Dingwall R. On the remarkable persistence of asymmetry in doctor/patient interaction: a critical review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(8):1374–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.033 Epub 2011 Mar 29. PMID: 21454003 .

Murante AM, Vainieri M, Rojas D, Nuti S. Health policy. Does feedback influence patient - professional communication? Empirical evidence from Italy. 2014;116(2–3):273–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.02.001 .

Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin R, Glickman SW. The patient experience and health outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(3):201–3. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1211775 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Coulter A, Locock L, Ziebland S, Calabrese J. Collecting data on patient experience is not enough: they must be used to improve care. BMJ. 2014;26:348–g2225. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g2225 .

Chambers M, LeMaster J. Collecting and using patient experience data: caution, commitment and consistency are needed. Health Expect. 2019;22(1):1–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12863 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

No funding was received for this research.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Campus Bio-Medico di Roma University, Rome, Italy

Raffaella Gualandi, Matteo Ercoli & Daniela Tartaglini

Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy

Cristina Masella

Research Unit Nursing Science, Campus Bio-Medico di Roma University, Rome, Italy

Michela Piredda

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

RG, CM and DT contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation was performed by RG. Data collection was performed by ME. Data analysis was performed by RG and MP. The first draft of the manuscript was written by RG and CM contributed to the analysis and drafting of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Raffaella Gualandi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study is part of a large project approved by the organisation’s Ethics Committee of University Campus Bio-Medico of Rome (Protocol n.: 25/16 OSS ComEt CBM), which included acquiring written consent for patient interviews and shadowing. The data reported in the current study and included in the project were part of a hospital assessment of patient satisfaction. The study was approved by the Management Team of the hospital.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

Questionnaire. Questionnaire used for the study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.