Family Life

AAP Schedule of Well-Child Care Visits

Parents know who they should go to when their child is sick. But pediatrician visits are just as important for healthy children.

The Bright Futures /American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) developed a set of comprehensive health guidelines for well-child care, known as the " periodicity schedule ." It is a schedule of screenings and assessments recommended at each well-child visit from infancy through adolescence.

Schedule of well-child visits

- The first week visit (3 to 5 days old)

- 1 month old

- 2 months old

- 4 months old

- 6 months old

- 9 months old

- 12 months old

- 15 months old

- 18 months old

- 2 years old (24 months)

- 2 ½ years old (30 months)

- 3 years old

- 4 years old

- 5 years old

- 6 years old

- 7 years old

- 8 years old

- 9 years old

- 10 years old

- 11 years old

- 12 years old

- 13 years old

- 14 years old

- 15 years old

- 16 years old

- 17 years old

- 18 years old

- 19 years old

- 20 years old

- 21 years old

The benefits of well-child visits

Prevention . Your child gets scheduled immunizations to prevent illness. You also can ask your pediatrician about nutrition and safety in the home and at school.

Tracking growth & development . See how much your child has grown in the time since your last visit, and talk with your doctor about your child's development. You can discuss your child's milestones, social behaviors and learning.

Raising any concerns . Make a list of topics you want to talk about with your child's pediatrician such as development, behavior, sleep, eating or getting along with other family members. Bring your top three to five questions or concerns with you to talk with your pediatrician at the start of the visit.

Team approach . Regular visits create strong, trustworthy relationships among pediatrician, parent and child. The AAP recommends well-child visits as a way for pediatricians and parents to serve the needs of children. This team approach helps develop optimal physical, mental and social health of a child.

More information

Back to School, Back to Doctor

Recommended Immunization Schedules

Milestones Matter: 10 to Watch for by Age 5

Your Child's Checkups

- Bright Futures/AAP Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care (periodicity schedule)

Doctor Visits

Make the Most of Your Baby’s Visit to the Doctor (Ages 0 to 11 Months)

Take Action

Babies need to go to the doctor or nurse for a “well-baby visit” 6 times before their first birthday.

A well-baby visit is when you take your baby to the doctor to make sure they’re healthy and developing normally. This is different from other visits for sickness or injury.

At a well-baby visit, the doctor or nurse can help catch any problems early, when they may be easier to treat. You’ll also have a chance to ask any questions you have about caring for your baby.

Learn what to expect so you can make the most of each well-baby visit.

Well-Baby Visits

How often do i need to take my baby for well-baby visits.

Babies need to see the doctor or nurse 6 times before their first birthday. Your baby is growing and changing quickly, so regular visits are important.

The first well-baby visit is 2 to 3 days after coming home from the hospital, when the baby is about 3 to 5 days old. After that first visit, babies need to see the doctor or nurse when they’re:

- 1 month old

- 2 months old

- 4 months old

- 6 months old

- 9 months old

If you’re worried about your baby’s health, don’t wait until the next scheduled visit — call the doctor or nurse right away.

Child Development

How do i know if my baby is growing and developing on schedule.

Your baby’s doctor or nurse can help you understand how your baby is developing and learning to do new things — like smile or turn their head to hear your voice. These are sometimes called “developmental milestones.”

At each visit, the doctor or nurse will ask you how you’re doing as a parent and what new things your baby is learning to do.

By age 2 months, most babies:

- Lift their head when lying on their stomach

- Look at your face

- Smile when you talk to them

- React to loud sounds

See a complete list of milestones for kids age 2 months .

By age 4 months, most babies:

- Bring their hands to their mouth

- Make cooing sounds

- Hold toys that you put in their hand

- Turn their head to the sound of your voice

- Make sounds when you talk to them

See a complete list of milestones for kids age 4 months .

By age 6 months, most babies:

- Lean on their hands for support when sitting

- Roll over from their stomach to their back

- Show interest in and reach for objects

- Recognize familiar people

- Like to look at themselves in a mirror

See a complete list of milestones for kids age 6 months .

By age 9 months, most babies:

- Make different sounds like “mamamama” and “bababababa”

- Smile or laugh when you play peek-a-boo

- Look at you when you say their name

- Sit without support

See a complete list of milestones for kids age 9 months .

What if I'm worried about my baby's development?

Remember, every baby develops a little differently. But if you’re concerned about your child’s growth and development, talk to your baby’s doctor or nurse.

Learn more about newborn and infant development .

Take these steps to help you and your baby get the most out of well-baby visits.

Gather important information.

Take any medical records you have to the appointment, including a record of vaccines (shots) your baby has received and results from newborn screenings . Read about newborn screenings .

Make a list of any important changes in your baby’s life since the last doctor’s visit, like:

- Falling or getting injured

- Starting daycare or getting a new caregiver

Use this tool to keep track of your baby’s family health history .

What about cost?

Under the Affordable Care Act, insurance plans must cover well-child visits. Depending on your insurance plan, you may be able to get well-child visits at no cost to you. Check with your insurance company to find out more.

Your child may also qualify for free or low-cost health insurance through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Learn about coverage options for your family.

If you don’t have insurance, you may still be able to get free or low-cost well-child visits. Find a health center near you and ask about well-child visits.

To learn more, check out these resources:

- Free preventive care for children covered by the Affordable Care Act

- How the Affordable Care Act protects you and your family

- Understanding your health insurance and how to use it [PDF - 698 KB]

Ask Questions

Make a list of questions to ask the doctor..

Before the well-baby visit, write down 3 to 5 questions you have. Each well-baby visit is a great time to ask the doctor or nurse any questions about:

- How your baby is growing and developing

- How your baby is sleeping

- Breastfeeding your baby

- When and how to start giving your baby solid foods

- What changes and behaviors to expect in the coming months

- How to make sure your home is safe for a growing baby

Here are some questions you may want to ask:

- Is my baby up to date on vaccines?

- How can I make sure my baby is getting enough to eat?

- Is my baby at a healthy weight?

- How can I make sure my baby is sleeping safely — and getting enough sleep?

- How can I help my baby develop speech and language skills?

- Is it okay for my baby to have screen time?

- How do I clean my baby's teeth?

Take a notepad, smartphone, or tablet and write down the answers so you can remember them later.

Ask what to do if your baby gets sick.

Make sure you know how to get in touch with a doctor or nurse when the office is closed. Ask how to reach the doctor on call, or if there's a nurse information service you can call at night or on the weekend.

What to Expect

Know what to expect..

During each well-baby visit, the doctor or nurse will ask you about your baby and do a physical exam. The doctor or nurse will then update your baby’s medical history with all of this information.

The doctor or nurse will ask questions about your baby.

The doctor or nurse may ask about:

- Behavior — Does your baby copy your movements and sounds?

- Health — How many diapers does your baby wet each day? Does your baby spend time around people who are smoking or using e-cigarettes (vaping)?

- Safety — If you live in an older home, has it been inspected for lead? Do you have a safe car seat for your baby?

- Activities — Does your baby try to roll over? How often do you read to your baby?

- Eating habits — How often does your baby eat each day? How are you feeding your baby?

- Family — Do you have any worries about being a parent? Who can you count on to help you take care of your baby?

Your answers to questions like these will help the doctor or nurse make sure your baby is healthy, safe, and developing normally.

Physical Exam

The doctor or nurse will also check your baby’s body..

To check your baby’s body, the doctor or nurse will:

- Measure height, weight, and the size of your baby’s head

- Take your baby’s temperature

- Check your baby’s eyes and hearing

- Check your baby’s body parts (this is called a physical exam)

- Give your baby shots they need

Learn more about your baby’s health care:

- Read about what to expect at your baby’s first checkups

- Find out how to get your baby’s shots on schedule

Content last updated March 30, 2023

Reviewer Information

This information on well-baby visits was adapted from materials from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health.

Reviewed by: Sara Kinsman, M.D., Ph.D. Director, Division of Child, Adolescent, and Family Health Maternal and Child Health Bureau Health Resources and Services Administration

Bethany Miller, M.S.W. Chief, Adolescent Health Branch Maternal and Child Health Bureau Health Resources and Services Administration

Diane Pilkey, R.N., M.P.H. Nursing Consultant, Division of Child, Adolescent, and Family Health Maternal and Child Health Bureau Health Resources and Services Administration

September 2021

You may also be interested in:

Protect Yourself from Seasonal Flu

Take Care of Your Child's Teeth

Eat Healthy During Pregnancy: Quick Tips

The office of disease prevention and health promotion (odphp) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website..

Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by ODPHP or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

KATHERINE TURNER, MD

Am Fam Physician. 2018;98(6):347-353

Related letter: Well-Child Visits Provide Physicians Opportunity to Deliver Interconception Care to Mothers

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

The well-child visit allows for comprehensive assessment of a child and the opportunity for further evaluation if abnormalities are detected. A complete history during the well-child visit includes information about birth history; prior screenings; diet; sleep; dental care; and medical, surgical, family, and social histories. A head-to-toe examination should be performed, including a review of growth. Immunizations should be reviewed and updated as appropriate. Screening for postpartum depression in mothers of infants up to six months of age is recommended. Based on expert opinion, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends developmental surveillance at each visit, with formal developmental screening at nine, 18, and 30 months and autism-specific screening at 18 and 24 months; the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force found insufficient evidence to make a recommendation. Well-child visits provide the opportunity to answer parents' or caregivers' questions and to provide age-appropriate guidance. Car seats should remain rear facing until two years of age or until the height or weight limit for the seat is reached. Fluoride use, limiting or avoiding juice, and weaning to a cup by 12 months of age may improve dental health. A one-time vision screening between three and five years of age is recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force to detect amblyopia. The American Academy of Pediatrics guideline based on expert opinion recommends that screen time be avoided, with the exception of video chatting, in children younger than 18 months and limited to one hour per day for children two to five years of age. Cessation of breastfeeding before six months and transition to solid foods before six months are associated with childhood obesity. Juice and sugar-sweetened beverages should be avoided before one year of age and provided only in limited quantities for children older than one year.

Well-child visits for infants and young children (up to five years) provide opportunities for physicians to screen for medical problems (including psychosocial concerns), to provide anticipatory guidance, and to promote good health. The visits also allow the family physician to establish a relationship with the parents or caregivers. This article reviews the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines for screenings and recommendations for infants and young children. Family physicians should prioritize interventions with the strongest evidence for patient-oriented outcomes, such as immunizations, postpartum depression screening, and vision screening.

Clinical Examination

The history should include a brief review of birth history; prematurity can be associated with complex medical conditions. 1 Evaluate breastfed infants for any feeding problems, 2 and assess formula-fed infants for type and quantity of iron-fortified formula being given. 3 For children eating solid foods, feeding history should include everything the child eats and drinks. Sleep, urination, defecation, nutrition, dental care, and child safety should be reviewed. Medical, surgical, family, and social histories should be reviewed and updated. For newborns, review the results of all newborn screening tests ( Table 1 4 – 7 ) and schedule follow-up visits as necessary. 2

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A comprehensive head-to-toe examination should be completed at each well-child visit. Interval growth should be reviewed by using appropriate age, sex, and gestational age growth charts for height, weight, head circumference, and body mass index if 24 months or older. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-recommended growth charts can be found at https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/who_charts.htm#The%20WHO%20Growth%20Charts . Percentiles and observations of changes along the chart's curve should be assessed at every visit. Include assessment of parent/caregiver-child interactions and potential signs of abuse such as bruises on uncommonly injured areas, burns, human bite marks, bruises on nonmobile infants, or multiple injuries at different healing stages. 8

The USPSTF and AAP screening recommendations are outlined in Table 2 . 3 , 9 – 27 A summary of AAP recommendations can be found at https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/periodicity_schedule.pdf . The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) generally adheres to USPSTF recommendations. 28

MATERNAL DEPRESSION

Prevalence of postpartum depression is around 12%, 22 and its presence can impair infant development. The USPSTF and AAP recommend using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (available at https://www.aafp.org/afp/2010/1015/p926.html#afp20101015p926-f1 ) or the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (available at https://www.aafp.org/afp/2012/0115/p139.html#afp20120115p139-t3 ) to screen for maternal depression. The USPSTF does not specify a screening schedule; however, based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends screening mothers at the one-, two-, four-, and six-month well-child visits, with further evaluation for positive results. 23 There are no recommendations to screen other caregivers if the mother is not present at the well-child visit.

PSYCHOSOCIAL

With nearly one-half of children in the United States living at or near the poverty level, assessing home safety, food security, and access to safe drinking water can improve awareness of psychosocial problems, with referrals to appropriate agencies for those with positive results. 29 The prevalence of mental health disorders (i.e., primarily anxiety, depression, behavioral disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) in preschool-aged children is around 6%. 30 Risk factors for these disorders include having a lower socioeconomic status, being a member of an ethnic minority, and having a non–English-speaking parent or primary caregiver. 25 The USPSTF found insufficient evidence regarding screening for depression in children up to 11 years of age. 24 Based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends that physicians consider screening, although screening in young children has not been validated or standardized. 25

DEVELOPMENT AND SURVEILLANCE

Based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends early identification of developmental delays 14 and autism 10 ; however, the USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend formal developmental screening 13 or autism-specific screening 9 if the parents/caregivers or physician have no concerns. If physicians choose to screen, developmental surveillance of language, communication, gross and fine movements, social/emotional development, and cognitive/problem-solving skills should occur at each visit by eliciting parental or caregiver concerns, obtaining interval developmental history, and observing the child. Any area of concern should be evaluated with a formal developmental screening tool, such as Ages and Stages Questionnaire, Parents' Evaluation of Developmental Status, Parents' Evaluation of Developmental Status-Developmental Milestones, or Survey of Well-Being of Young Children. These tools can be found at https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Screening/Pages/Screening-Tools.aspx . If results are abnormal, consider intervention or referral to early intervention services. The AAP recommends completing the previously mentioned formal screening tools at nine-, 18-, and 30-month well-child visits. 14

The AAP also recommends autism-specific screening at 18 and 24 months. 10 The USPSTF recommends using the two-step Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) screening tool (available at https://m-chat.org/ ) if a physician chooses to screen a patient for autism. 10 The M-CHAT can be incorporated into the electronic medical record, with the possibility of the parent or caregiver completing the questionnaire through the patient portal before the office visit.

IRON DEFICIENCY

Multiple reports have associated iron deficiency with impaired neurodevelopment. Therefore, it is essential to ensure adequate iron intake. Based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends supplements for preterm infants beginning at one month of age and exclusively breastfed term infants at six months of age. 3 The USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend screening for iron deficiency in infants. 19 Based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends measuring a child's hemoglobin level at 12 months of age. 3

Lead poisoning and elevated lead blood levels are prevalent in young children. The AAP and CDC recommend a targeted screening approach. The AAP recommends screening for serum lead levels between six months and six years in high-risk children; high-risk children are identified by location-specific risk recommendations, enrollment in Medicaid, being foreign born, or personal screening. 21 The USPSTF does not recommend screening for lead poisoning in children at average risk who are asymptomatic. 20

The USPSTF recommends at least one vision screening to detect amblyopia between three and five years of age. Testing options include visual acuity, ocular alignment test, stereoacuity test, photoscreening, and autorefractors. The USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend screening before three years of age. 26 The AAP, American Academy of Ophthalmology, and the American Academy of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus recommend the use of an instrument-based screening (photoscreening or autorefractors) between 12 months and three years of age and annual visual acuity screening beginning at four years of age. 31

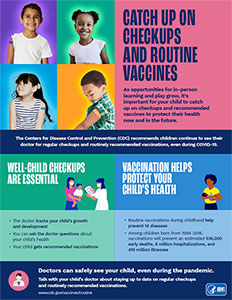

IMMUNIZATIONS

The AAFP recommends that all children be immunized. 32 Recommended vaccination schedules, endorsed by the AAP, the AAFP, and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, are found at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/child-adolescent.html . Immunizations are usually administered at the two-, four-, six-, 12-, and 15- to 18-month well-child visits; the four- to six-year well-child visit; and annually during influenza season. Additional vaccinations may be necessary based on medical history. 33 Immunization history should be reviewed at each wellness visit.

Anticipatory Guidance

Injuries remain the leading cause of death among children, 34 and the AAP has made several recommendations to decrease the risk of injuries. 35 – 42 Appropriate use of child restraints minimizes morbidity and mortality associated with motor vehicle collisions. Infants need a rear-facing car safety seat until two years of age or until they reach the height or weight limit for the specific car seat. Children should then switch to a forward-facing car seat for as long as the seat allows, usually 65 to 80 lb (30 to 36 kg). 35 Children should never be unsupervised around cars, driveways, and streets. Young children should wear bicycle helmets while riding tricycles or bicycles. 37

Having functioning smoke detectors and an escape plan decreases the risk of fire- and smoke-related deaths. 36 Water heaters should be set to a maximum of 120°F (49°C) to prevent scald burns. 37 Infants and young children should be watched closely around any body of water, including water in bathtubs and toilets, to prevent drowning. Swimming pools and spas should be completely fenced with a self-closing, self-latching gate. 38

Infants should not be left alone on any high surface, and stairs should be secured by gates. 43 Infant walkers should be discouraged because they provide no benefit and they increase falls down stairs, even if stair gates are installed. 39 Window locks, screens, or limited-opening windows decrease injury and death from falling. 40 Parents or caregivers should also anchor furniture to a wall to prevent heavy pieces from toppling over. Firearms should be kept unloaded and locked. 41

Young children should be closely supervised at all times. Small objects are a choking hazard, especially for children younger than three years. Latex balloons, round objects, and food can cause life-threatening airway obstruction. 42 Long strings and cords can strangle children. 37

DENTAL CARE

Infants should never have a bottle in bed, and babies should be weaned to a cup by 12 months of age. 44 Juices should be avoided in infants younger than 12 months. 45 Fluoride use inhibits tooth demineralization and bacterial enzymes and also enhances remineralization. 11 The AAP and USPSTF recommend fluoride supplementation and the application of fluoride varnish for teeth if the water supply is insufficient. 11 , 12 Begin brushing teeth at tooth eruption with parents or caregivers supervising brushing until mastery. Children should visit a dentist regularly, and an assessment of dental health should occur at well-child visits. 44

SCREEN TIME

Hands-on exploration of their environment is essential to development in children younger than two years. Video chatting is acceptable for children younger than 18 months; otherwise digital media should be avoided. Parents and caregivers may use educational programs and applications with children 18 to 24 months of age. If screen time is used for children two to five years of age, the AAP recommends a maximum of one hour per day that occurs at least one hour before bedtime. Longer usage can cause sleep problems and increases the risk of obesity and social-emotional delays. 46

To decrease the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), the AAP recommends that infants sleep on their backs on a firm mattress for the first year of life with no blankets or other soft objects in the crib. 45 Breastfeeding, pacifier use, and room sharing without bed sharing protect against SIDS; infant exposure to tobacco, alcohol, drugs, and sleeping in bed with parents or caregivers increases the risk of SIDS. 47

DIET AND ACTIVITY

The USPSTF, AAFP, and AAP all recommend breastfeeding until at least six months of age and ideally for the first 12 months. 48 Vitamin D 400 IU supplementation for the first year of life in exclusively breastfed infants is recommended to prevent vitamin D deficiency and rickets. 49 Based on expert opinion, the AAP recommends the introduction of certain foods at specific ages. Early transition to solid foods before six months is associated with higher consumption of fatty and sugary foods 50 and an increased risk of atopic disease. 51 Delayed transition to cow's milk until 12 months of age decreases the incidence of iron deficiency. 52 Introduction of highly allergenic foods, such as peanut-based foods and eggs, before one year decreases the likelihood that a child will develop food allergies. 53

With approximately 17% of children being obese, many strategies for obesity prevention have been proposed. 54 The USPSTF does not have a recommendation for screening or interventions to prevent obesity in children younger than six years. 54 The AAP has made several recommendations based on expert opinion to prevent obesity. Cessation of breastfeeding before six months and introduction of solid foods before six months are associated with childhood obesity and are not recommended. 55 Drinking juice should be avoided before one year of age, and, if given to older children, only 100% fruit juice should be provided in limited quantities: 4 ounces per day from one to three years of age and 4 to 6 ounces per day from four to six years of age. Intake of other sugar-sweetened beverages should be discouraged to help prevent obesity. 45 The AAFP and AAP recommend that children participate in at least 60 minutes of active free play per day. 55 , 56

Data Sources: Literature search was performed using the USPSTF published recommendations ( https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/BrowseRec/Index/browse-recommendations ) and the AAP Periodicity table ( https://www.aap.org/en-us/Documents/periodicity_schedule.pdf ). PubMed searches were completed using the key terms pediatric, obesity prevention, and allergy prevention with search limits of infant less than 23 months or pediatric less than 18 years. The searches included systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and position statements. Essential Evidence Plus was also reviewed. Search dates: May through October 2017.

Gauer RL, Burket J, Horowitz E. Common questions about outpatient care of premature infants. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(4):244-251.

American Academy of Pediatrics; Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Hospital stay for healthy term newborns. Pediatrics. 2010;125(2):405-409.

Baker RD, Greer FR Committee on Nutrition, American Academy of Pediatrics. Diagnosis and prevention of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in infants and young children (0–3 years of age). Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):1040-1050.

Mahle WT, Martin GR, Beekman RH, Morrow WR Section on Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery Executive Committee. Endorsement of Health and Human Services recommendation for pulse oximetry screening for critical congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):190-192.

American Academy of Pediatrics Newborn Screening Authoring Committee. Newborn screening expands: recommendations for pediatricians and medical homes—implications for the system. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):192-217.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Year 2007 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):898-921.

Maisels MJ, Bhutani VK, Bogen D, Newman TB, Stark AR, Watchko JF. Hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant > or = 35 weeks' gestation: an update with clarifications. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1193-1198.

Christian CW Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect, American Academy of Pediatrics. The evaluation of suspected child physical abuse [published correction appears in Pediatrics . 2015;136(3):583]. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):e1337-e1354.

Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for autism spectrum disorder in young children: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(7):691-696.

Johnson CP, Myers SM American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children with Disabilities. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):1183-1215.

Moyer VA. Prevention of dental caries in children from birth through age 5 years: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):1102-1111.

Clark MB, Slayton RL American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Oral Health. Fluoride use in caries prevention in the primary care setting. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):626-633.

Siu AL. Screening for speech and language delay and disorders in children aged 5 years and younger: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):e474-e481.

Council on Children with Disabilities, Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, Bright Futures Steering Committee, Medical Home Initiatives for Children with Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: an algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening [published correction appears in Pediatrics . 2006;118(4):1808–1809]. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):405-420.

Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for lipid disorders in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316(6):625-633.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents. October 2012. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/media/docs/peds_guidelines_full.pdf . Accessed May 9, 2018.

Moyer VA. Screening for primary hypertension in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(9):613-619.

Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, et al. Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents [published correction appears in Pediatrics . 2017;140(6):e20173035]. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20171904.

Siu AL. Screening for iron deficiency anemia in young children: USPSTF recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2015;136(4):746-752.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for elevated blood lead levels in children and pregnant women. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2514-2518.

Screening Young Children for Lead Poisoning: Guidance for State and Local Public Health Officials . Atlanta, Ga.: U.S. Public Health Service; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Environmental Health; 1997.

O'Connor E, Rossom RC, Henninger M, Groom HC, Burda BU. Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and post-partum women: evidence report and systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315(4):388-406.

Earls MF Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, American Academy of Pediatrics. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):1032-1039.

Siu AL. Screening for depression in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(5):360-366.

Weitzman C, Wegner L American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Council on Early Childhood; Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics; American Academy of Pediatrics. Promoting optimal development: screening for behavioral and emotional problems [published correction appears in Pediatrics . 2015;135(5):946]. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):384-395.

Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Vision screening in children aged 6 months to 5 years: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;318(9):836-844.

Donahue SP, Nixon CN Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, Section on Ophthalmology, American Academy of Pediatrics; American Association of Certified Orthoptists, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Ophthalmology. Visual system assessment in infants, children, and young adults by pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):28-30.

Lin KW. What to do at well-child visits: the AAFP's perspective. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(6):362-364.

American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Community Pediatrics. Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20160339.

Lavigne JV, Lebailly SA, Hopkins J, Gouze KR, Binns HJ. The prevalence of ADHD, ODD, depression, and anxiety in a community sample of 4-year-olds. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2009;38(3):315-328.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, Section on Ophthalmology, American Association of Certified Orthoptists, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Ophthalmology. Visual system assessment of infants, children, and young adults by pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):28-30.

American Academy of Family Physicians. Clinical preventive service recommendation. Immunizations. http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/immunizations.html . Accessed October 5, 2017.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended immunization schedule for children and adolescents aged 18 years or younger, United States, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/child-adolescent.html . Accessed May 9, 2018.

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 10 leading causes of death by age group, United States—2015. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/images/lc-charts/leading_causes_of_death_age_group_2015_1050w740h.gif . Accessed April 24, 2017.

Durbin DR American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Child passenger safety. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):788-793.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. Reducing the number of deaths and injuries from residential fires. Pediatrics. 2000;105(6):1355-1357.

Gardner HG American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Office-based counseling for unintentional injury prevention. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):202-206.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Prevention of drowning in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;112(2):437-439.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. Injuries associated with infant walkers. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):790-792.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. Falls from heights: windows, roofs, and balconies. Pediatrics. 2001;107(5):1188-1191.

Dowd MD, Sege RD Council on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention Executive Committee; American Academy of Pediatrics. Firearm-related injuries affecting the pediatric population. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):e1416-e1423.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Prevention of choking among children. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):601-607.

Kendrick D, Young B, Mason-Jones AJ, et al. Home safety education and provision of safety equipment for injury prevention (review). Evid Based Child Health. 2013;8(3):761-939.

American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Oral Health. Maintaining and improving the oral health of young children. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):1224-1229.

Heyman MB, Abrams SA American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. Fruit juice in infants, children, and adolescents: current recommendations. Pediatrics. 2017;139(6):e20170967.

Council on Communications and Media. Media and young minds. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20162591.

Moon RY Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: evidence base for 2016 updated recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20162940.

American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827-e841.

Wagner CL, Greer FR American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding; Committee on Nutrition. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants, children, and adolescents [published correction appears in Pediatrics . 2009;123(1):197]. Pediatrics. 2008;122(5):1142-1152.

Huh SY, Rifas-Shiman SL, Taveras EM, Oken E, Gillman MW. Timing of solid food introduction and risk of obesity in preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):e544-e551.

Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks AW American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition; Section on Allergy and Immunology. Effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: the role of maternal dietary restriction, breastfeeding, timing of introduction of complementary foods, and hydrolyzed formulas. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):183-191.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. The use of whole cow's milk in infancy. Pediatrics. 1992;89(6 pt 1):1105-1109.

Fleischer DM, Spergel JM, Assa'ad AH, Pongracic JA. Primary prevention of allergic disease through nutritional interventions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(1):29-36.

Grossman DC, Bibbins-Domingo K, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for obesity in children and adolescents: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;317(23):2417-2426.

Daniels SR, Hassink SG Committee on Nutrition. The role of the pediatrician in primary prevention of obesity. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):e275-e292.

American Academy of Family Physicians. Physical activity in children. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/physical-activity.html . Accessed January 1, 2018.

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2018 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

- Second Opinion

Well-Care Visits

What is a well-care visit?

It's important to take your child to the healthcare provider when your child is ill. Or when you child needs an exam to take part in a sport. But routine well-care visits are also recommended.

Well-care, well-baby, or well-child visits are routine visits to your child's healthcare provider for the following:

Physical exam

Immunization updates

Tracking growth and development

Finding any problems before they become serious

Providing information on health and safety issues

Providing information on nutrition and physical fitness

Providing information on how to manage emergencies and illnesses

Your child's healthcare provider can also provide guidance on other issues, such as the following:

Behavioral problems

Learning problems

Emotional problems

Family problems

Socialization problems

Puberty and concerns about teenage years

When should well-care visits be scheduled?

Your child's healthcare provider will give you a schedule of ages when a well-care visit is suggested. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends well-care visits at the following ages:

Before a newborn is discharged from the hospital, or at 48 to 72 hours of age

3 to 5 days

2 to 4 weeks

Annually, between ages 6 and 21

- Pediatric Cardiology

- Our Services

- Chiari Malformation Center at Stanford Medicine Children's Health

Related Topics

When to Call Your Child's Healthcare Provider

Home Page - Pediatrics

Pediatrician

Connect with us:

Download our App:

- Leadership Team

- Vision, Mission & Values

- The Stanford Advantage

- Government and Community Relations

- Get Involved

- Volunteer Services

- Auxiliaries & Affiliates

© 123 Stanford Medicine Children’s Health

Internet Explorer Alert

It appears you are using Internet Explorer as your web browser. Please note, Internet Explorer is no longer up-to-date and can cause problems in how this website functions This site functions best using the latest versions of any of the following browsers: Edge, Firefox, Chrome, Opera, or Safari . You can find the latest versions of these browsers at https://browsehappy.com

- Publications

- HealthyChildren.org

Shopping cart

Order Subtotal

Your cart is empty.

Looks like you haven't added anything to your cart.

- Career Resources

- Philanthropy

- About the AAP

- The Role of the Pediatrician in the Promotion of Healthy, Active Living

- How Can You Support Patients in Healthy, Active Living? Check Out Updated Report

- Helping Kids Build Healthy Active Lives: AAP Policy Explained

- Climate Change & Children’s Health: AAP Policy Explained

- News Releases

- Policy Collections

- The State of Children in 2020

- Healthy Children

- Secure Families

- Strong Communities

- A Leading Nation for Youth

- Transition Plan: Advancing Child Health in the Biden-Harris Administration

- Health Care Access & Coverage

- Immigrant Child Health

- Gun Violence Prevention

- Tobacco & E-Cigarettes

- Child Nutrition

- Assault Weapons Bans

- Childhood Immunizations

- E-Cigarette and Tobacco Products

- Children’s Health Care Coverage Fact Sheets

- Opioid Fact Sheets

- Advocacy Training Modules

- Subspecialty Advocacy Report

- AAP Washington Office Internship

- Online Courses

- Live and Virtual Activities

- National Conference and Exhibition

- Prep®- Pediatric Review and Education Programs

- Journals and Publications

- NRP LMS Login

- Patient Care

- Practice Management

- AAP Committees

- AAP Councils

- AAP Sections

- Volunteer Network

- Join a Chapter

- Chapter Websites

- Chapter Executive Directors

- District Map

- Create Account

- Materials & Tools

- Clinical Practice

- States & Communities

- Quality Improvement

- Implementation Stories

Well-Child Visits: Parent and Patient Education

The Bright Futures Parent and Patient Educational Handouts help guide anticipatory guidance and reinforce key messages (organized around the 5 priorities in each visit) for the family. Each educational handout is written in plain language to ensure the information is clear, concise, relevant, and easy to understand. Each educational handout is available in English and Spanish (in HTML and PDF format). Beginning at the 7 year visit , there is both a Parent and Patient education handout (in English and Spanish).

For the Bright Futures Parent Handouts for well-child visits up to 2 years of age , translations of 12 additional languages (PDF format) are made possible thanks to the generous support of members, staff, and businesses who donate to the AAP Friends of Children Fund . The 12 additional languages are Arabic, Bengali, Chinese, French, Haitian Creole, Hmong, Korean, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Somali, and Vietnamese.

Reminder for Health Care Professionals: The Bright Futures Tool and Resource Kit, 2nd Edition is available as an online access product. For more detailed information about the Toolkit, visit shop.aap.org . To license the Toolkit to use the forms in practice and/or incorporate them into an Electronic Medical Record System, please contact AAP Sales .

Parent Educational Handouts

Infancy visits.

3 to 5 Day Visit

1 Month Visit

2 Month Visit

4 Month Visit

6 Month Visit

9 Month Visit

Early childhood visits.

12 Month Visit

15 Month Visit

18 Month Visit

2 Year Visit

2.5 Year Visit

3 Year Visit

4 Year Visit

Parent and patient educational handouts, middle childhood visits.

5-6 Year Visit

7-8 Year Visit

7-8 Year Visit - For Patients

9-10 Year Visit

9-10 Year Visit - For Patients

Adolescent visits.

11-14 Year Visit

11-14 Year Visit - For Patients

15-17 Year Visit

15-17 Year Visit - For Patients

18-21 Year Visit - For Patients

Last updated.

American Academy of Pediatrics

The 12-Month Well-Baby Visit

Medical review policy, latest update:, the physical checkup, developmental milestones, read this next, 12-month vaccines, questions to ask your doctor, recognizing the signs of a delay.

And before you leave, don't forget to get the next appointment scheduled, which will be the 15-month checkup .

What to Expect the First Year , 3rd edition, Heidi Murkoff. WhatToExpect.com, Your Guide to Well-Baby Visits , March 2020. WhatToExpect.com, What Order and When Do Baby Teeth Appear? This Baby Teething Chart Can Help , February 2021. WhatToExpect.com, Your Baby's Vaccine Schedule: What Shots Should Your Child Get When? , January 2021. American Academy of Pediatrics, AAP Schedule of Well-Child Care Visits , September 2021. American Academy of Pediatrics, Assessing Developmental Delays , February 2019. American Academy of Pediatrics, Language Delays in Toddlers: Information for Parents , April 2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Recommended Vaccines by Age , November 2016. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Important Milestones: Your Child by One Year , August 2021. KidsHealth From Nemours, Your Child’s Checkup: 1 Year (12 Months) , April 2021. Mayo Clinic, Language Development: Speech Milestones for Babies , March 2021.

Go to Your Baby's Age

Trending on what to expect, the covid-19 vaccine for infants, toddlers and young children, how to create a night shift system when you have a newborn, ⚠️ you can't see this cool content because you have ad block enabled., when do babies start laughing, baby-led weaning, what happens in the ‘4th trimester’ (and is it a real thing).

Personalize Your Experience

Log in or create an account for a personalized experience based on your selected interests.

Already have an account? Log In

Free standard shipping is valid on orders of $45 or more (after promotions and discounts are applied, regular shipping rates do not qualify as part of the $45 or more) shipped to US addresses only. Not valid on previous purchases or when combined with any other promotional offers.

Register for an enhanced, personalized experience.

Receive free access to exclusive content, a personalized homepage based on your interests, and a weekly newsletter with topics of your choice.

Home / Parenting, Kids & Teens / Quick guide to your infant’s first pediatrician visits

Quick guide to your infant’s first pediatrician visits

Please login to bookmark.

Frequent checkups with a health care provider are an important part of your baby’s first few years. These checkups — often called well-child visits — are a way for you and your child’s health care provider to keep tabs on your child’s health and development, as well as spot any potential problems. Well-child visits also give you a chance to discuss any questions or concerns you might have and get advice from a trusted source on how to provide the best possible care for your child.

The benefit of seeing your child’s provider regularly is that each visit adds critical information to your child’s health history. Over time, you and the provider will get a good idea of your child’s overall health and development.

In general, the provider will be more attentive to your child’s pattern of growth over time, rather than to specific one-time measurements. Typically what you’ll see is a smooth curve that arcs upward as the years go by. Regularly reviewing your child’s growth chart can also alert you and the provider to unexpected delays in growth or changes in weight that may suggest the need for additional monitoring.

Each health care provider does things a bit differently, but here’s what will generally be on the agenda during your first well-child exams.

Body measurements

Checkups usually begin with measurements. During first-year visits, a nurse or your baby’s health care provider will measure and record your baby’s length, head circumference and weight.

Your child’s measurements will be plotted on his or her growth chart. This will help you and the provider see how your child’s size compares with that of other children the same age. Try not to fixate on the percentages too much, though. All kids grow and develop at different rates. In addition, babies who take breast milk gain weight at a different rate than do babies who are formula-fed.

Keep in mind that a child who’s in the 95th percentile for height and weight isn’t necessarily healthier than a child who’s in the fifth percentile. What’s most important is steady growth from one visit to the next. If you have questions or concerns about your child’s growth rate, discuss them with your child’s provider.

Physical exam

Your child’s health care provider will give your child a thorough physical exam and check his or her reflexes and muscle tone. Be sure to mention any concerns you have or specific areas you want the doctor to check out.

Here are the basics of what providers commonly check for during an exam:

- Head — In the beginning, your child’s health care provider will likely check the soft spots (fontanels) on your baby’s head. These gaps between the skull bones give your baby’s brain plenty of room to grow in the coming months. They’re safe to touch and typically disappear within two years, when the skull bones fuse together. The health care provider may also check baby’s head for flat spots. A baby’s skull is soft and made up of several movable plates. If his or her head is left in the same position for long periods of time, the skull plates might move in a way that creates a flat spot.

- Ears — Using an instrument called an otoscope, the health care provider can see in your child’s ears to check for fluid or infection in the ears. The provider may observe your child’s response to various sounds, including your voice. Be sure to tell the provider if you have any concerns about your son’s or daughter’s ability to hear or if there’s a history of childhood deafness in your family. Unless there’s cause for concern, a formal hearing evaluation isn’t usually needed at a well-child exam.

- Eyes — Your child’s health care provider may use a flashlight to catch your child’s attention and then track his or her eye movements. The provider may also check for blocked tear ducts and eye discharge and look inside your child’s eyes with a lighted instrument called an ophthalmoscope. Be sure to tell the provider if you’ve noticed that your child is having any unusual eye movements, especially if they continue beyond the first few months of life.

- Mouth — A look inside your baby’s mouth may reveal signs of oral thrush, a common, and easily treated, yeast infection. The health care provider might also check your baby’s mouth for signs of tongue-tie (ankyloglossia), a condition that affects the tongue’s range of motion and can interfere with a baby’s oral development as well as his or her ability to breast-feed.

- Skin — Various skin conditions may be identified during the exam, including birthmarks, rashes, and jaundice, a yellowish discoloration of the skin and eyes. Mild jaundice that develops soon after birth often disappears on its own within a week or two. Cases that are more severe may need treatment.

- Heart and lungs — Using a stethoscope, your child’s health care provider can listen to your child’s heart and lungs to check for abnormal heart sounds or rhythms or breathing difficulties.

- Abdomen, hips and legs — By gently pressing a child’s abdomen, a health care provider can detect tenderness, enlarged organs, or an umbilical hernia, which occurs when a bit of intestine or fatty tissue near the navel breaks through the muscular wall of the abdomen. Most umbilical hernias heal by the toddler years without intervention. The provider may also move your child’s legs to check for dislocation or other problems with the hip joints, such as dysplasia of the hip joint.

- Genitalia — Your child’s care provider will likely inspect your son’s or daughter’s genitalia for tenderness, lumps or other signs of infection. The provider may also check for an inguinal hernia, which results from a weakness in the abdominal wall.

For girls, the doctor may ask about vaginal discharge. For boys, the provider will make sure a circumcised penis is healing well during early visits. The provider may also check to see that both testes have descended into the scrotum and that there’s no fluid-filled sac around the testes, a condition called hydrocele.

Your child’s provider will likely ask you about your child’s eating habits. If you’re breastfeeding, the provider may want to know how often you’re feeding your baby during the day and night and whether you’re having any problems. If you’re pumping, the provider may offer suggestions for managing pumping frequency and storing breast milk. If you’re formula-feeding, the provider will likely want to know how often you feed and how many ounces of formula your baby takes at each feeding. In addition, the provider may discuss with you your baby’s need for vitamin D and iron supplements.

Bowel and bladder function

In the first few visits, your child’s health care provider will likely also ask how many wet diapers and bowel movements your baby produces a day. This information offers clues as to whether your baby is getting enough to eat.

Sleeping status

Your child’s health care provider may ask you questions about your child’s sleep habits, such as your regular bedtime routine and how many hours your child is sleeping during the day and night. Don’t hesitate to discuss any concerns you may have about your child’s sleep, such as getting your baby to sleep through the night. Your child’s provider may also help you figure out how to find rest for yourself, especially in the early baby months.

Development

Your child’s development is important, too. The health care provider will monitor your child’s development in the following five main areas.

- Gross motor skills — These skills, such as sitting, walking and climbing, involve the movement of large muscles. Your child’s health care provider may ask you how well your baby can control his or her head. Is your baby attempting to roll over? Is your baby trying to sit on his or her own? Is your child starting to walk or throw a ball? Can your toddler walk up and down steps?

- Fine motor skills — These skills involve the use of small muscles in the hand. Does your baby reach for objects and bring them to his or her mouth? Is your baby using individual fingers to pick up small objects?

- Personal and social skills — These skills enable a child to interact and respond to his or her surroundings. Your child’s health care provider may ask if your baby is smiling. Does your baby relate to you with joy and enthusiasm? Does he or she play peekaboo?

- Language skills — These skills include hearing, understanding and use of language. The health care provider may ask if your baby turns his or her head toward voices or other sounds. Does your baby laugh? Is he or she responding to his or her name?

- Cognitive skills — These skills allow a child to think, reason, solve problems and understand his or her surroundings. Your child’s provider might ask if your baby can bang together two cubes or search for a toy after seeing you hide it.

Vaccinations

Your baby will need a number of scheduled vaccinations during his or her first years. The health care provider or a nurse will explain to you how to hold your baby as he or she is given each shot. Be prepared for possible tears. Keep in mind, however, that the pain caused by a shot is typically short-lived but the benefits are long lasting.

Your child’s provider may talk to you about safety issues, such as the importance of placing your baby to sleep on his or her back and using a rear-facing infant car seat as long as possible.

Questions and concerns

During your son’s or daughter’s checkups, it’s likely that you’ll have questions, too. Ask away! Nothing is too trivial when it comes to caring for your baby. Write down questions as they arise between appointments so that you’ll be less likely to forget them when you’re at your child’s checkup.

Also, don’t forget your own health. If you’re feeling depressed, stressed-out, run-down or overwhelmed, describe what’s happening. Your child’s provider is there to help you, too.

Before you leave the health care provider’s office, make sure you know when to schedule your child’s next appointment. If possible, set the next appointment before you leave the provider’s office. If you don’t already know, ask how to reach your child’s provider in between appointments. You might also ask if the provider has a 24-hour nurse information service. Knowing that help is available when you need it can offer peace of mind.

Relevant reading

Mindfulness and My Emotions

Hands-on mindfulness activities to help young reader manage all their emotions, big and small.

Discover more Parenting, Kids & Teens content from articles, podcasts, to videos.

Want more children’s health and parenting information? Sign up for free to our email list.

Children’s health information and parenting tips to your inbox.

Sign-up to get Mayo Clinic’s trusted health content sent to your email. Receive a bonus guide on ways to manage your child’s health just for subscribing.

You May Also Enjoy

Privacy Policy

We've made some updates to our Privacy Policy. Please take a moment to review.

All About Your Child’s Well-Baby Visits

From the first few days of life all the way through to age 21, your child will have regular appointments with her healthcare provider. These are often referred to as well-baby visits or well-child checkups. Initially, they will happen every few months or so, but later on they will happen annually. Learn why well-child checkups are important, what the typical schedule is, and how to get the most out of each visit.

Well-Child Checkup Schedule

Well-child checkups are crucial for keeping your little one healthy and safe as she grows and develops. Below you will find the standard schedule of well-child checkups for the first three years, along with a few examples of what may come up during each checkup. Beginning at age 3, most children will have annual well-child visits. Keep in mind that your child’s healthcare provider may recommend additional visits, and you can always schedule an extra visit between appointments if your little one needs medical care.

The First Week

This visit usually happens within 72 hours of your newborn being home—usually when your baby is about 3 to 5 days old. As part of this checkup your child’s skin color may be checked for signs of jaundice . Your child’s provider may also take a peek inside your newborn’s mouth for signs of tongue-tie . If you are breastfeeding, your little one’s provider can answer any questions you have about latch or sore nipples , for example. The provider may also be able to recommend a lactation consultant for additional help and support.

1 Month Old Checkup

During this visit, your child’s healthcare provider may check things like your baby’s reflexes and muscle tone, as well examining the soft spots on your baby’s head called the fontanelles. If there’s something specific you’d like your child’s provider to check, go ahead and mention it. Your baby’s provider may ask you about how feeding is going. For example, you may be asked how much formula you’re offering, or how often you breastfeed your baby. If you’re planning to return to work soon while continuing to breastfeed, your newborn’s provider may give you advice on pumping and storing breast milk. You might also like to use this opportunity to ask how to go about finding good childcare. Use this appointment to ask any questions you have about adjusting to life as a parent. For example, if you suspect you may have postpartum depression or are not recovering as you had hoped after childbirth , bring this up as well. If you’re the dad, you might like to ask about what you can do to bond with your baby.

2 Months Old Checkup

At this visit your baby may receive some vaccines, including the DTaP, Hib, and IPV vaccines. Vaccinations will be given at a number of different well-child checkups, so it’s worth taking a look at the immunization schedule or asking your child’s provider for guidance on which vaccines to expect when. Your baby’s heart and lung health may be checked. Your child’s provider will use a stethoscope to listen to your baby’s heartbeats for signs of irregularity, and to listen to your baby’s lungs for signs of breathing difficulties. If your baby has diaper rash , your child’s healthcare provider can recommend ointments or barrier creams for treatment and prevention. Your child’s provider can also let you know about other common baby rashes to keep an eye out for.

4 Months Old Checkup

At this visit, your baby’s provider may examine your child's eyes and track her eye movements. Your child’s provider may also move your baby’s legs to check that the joints are developing well, and press gently on your baby’s tummy to check whether the organs are forming well. At this point your doctor will ask you about your baby’s sleep, including nap times. To help you keep track of this, and to help make sure your baby’s sleeping well, we suggest downloading the Smart Sleep Coach by Pampers™. Co-developed with pediatricians and backed by science, this easy-to-use app is like having a personal sleep coach, in your pocket! Get started today by taking their free sleep assessment .

6 Months Old Checkup

This month, your child’s healthcare provider may offer pointers on introducing solids and tell you about signs of an allergic reaction to watch for as you introduce new foods one at a time. Your child’s provider can also give you personalized advice on which foods to start with, how to set up healthy eating habits, and how to actually feed your baby solids.

9 Months Old Checkup

As your baby’s teeth start erupting , your child’s healthcare provider may check on their growth and recommend a good pediatric dentist in your area. Your baby’s provider can also show you how to care for those first tiny teeth. Other topics that may come up at this checkup include how to wean your baby off the bottle when the time comes, when to start giving cow’s milk, and when to introduce utensils and a sippy cup.

1 Year Old Checkup

During this visit your child’s healthcare provider may ask about certain fine and gross motor skills , such whether your child can pull up to a standing position, or walk on his own or with his hand held, or use his finger to point at objects he wants. You might like to ask your child’s healthcare provider about when your little one might start walking , if he isn’t already; what baby proofing measures you should take at home now that your child is getting more mobile; and where to go to get shoes fitted for your child.

15 Months Old Checkup

Your child’s healthcare provider may ask about how your toddler’s interpersonal, language, and cognitive skills are coming along. For example, she might ask whether your child is starting to explore more independently, whether he points to common objects when you say their names, and whether he can follow simple instructions like “give the spoon to Daddy.” If you are planning to have another baby soon, you might like to ask the healthcare provider about how to introduce your toddler to the concept of him getting a little brother or sister.

18 Months Old Checkup

As your child gets more active and independent you may like to ask your child’s provider about strategies for keeping your child safe in your home environment. This is also a good time to discuss ways to manage your child's behavior and set up age-appropriate rules and boundaries. If your toddler has certain risk factors, the relevant screening tests may be offered at this checkup. For example, screening tests may be recommended for things like hearing, vision, development delays, or autism. Your provider may also bring up the topic of potty training, and go over some of the signs of readiness for potty training .

2 Years Old Checkup

Before this visit you may have been wondering about the upcoming “terrible twos” and how you should handle temper tantrums and the inevitable meltdowns at the grocery store. This visit is a great chance to bring up your questions and concerns around how your child’s behavior and personality may be evolving. Your child’s provider will explain what is normal during this stage of development and how to support your child’s growing independence. Preschool could be coming up in the next year or two, and your provider can help you find a preschool that's a good fit for your child.

2 ½ Years Old Checkup

Besides the usual checks, one topic that may come up during this visit is potty training. If potty training has begun and isn't going well, or if you're unsure how to get the process started , your provider can offer suggestions. This checkup may also be a great time to talk to your child’s provider about your little one’s temperament and personality. For example, if you have any concerns about how your toddler is interacting with other children, or if your child seems particularly shy, you might like to bring it up to see what advice or reassurance your toddler’s provider can give you.

3 Years Old Checkup

During this session your toddler’s healthcare provider may ask you about anything that’s disturbing your child’s sleep, like nightmares, for example, and how to handle other sleep issues. Screen time may also come up. You may talk about how much screen time a 3-year-old should be getting, and what type of programming is good for a child of this age.

Baby Growth Chart Calculator

Keep an eye on your baby’s average growth by tracking height, weight, and head circumference with our simple tool.

This is a mandatory field.

*Input details of your baby’s last measurements. **Source: World Health Organization

What Happens at a Well-Child Visit?

Each visit may be a little different based on your child’s age and stage of development, any specific needs your child has, and the way your child’s healthcare provider does things. However, here are some of the things that typically happen at a well-child visit in the early years:

Tracking your child’s growth by measuring her length, weight, and head circumference

A physical exam that could include checking your baby’s ears, eyes, mouth, skin, limbs, tummy, and other body parts

An assessment of your child's physical development, including her movement and motor skills

An evaluation of her emotional and cognitive development; for example, checking that your child is reacting and interacting normally for her age, and is learning appropriately for her age

Immunizations may be given

Screening tests or other tests may be recommended if needed

Your child’s provider may give you advice on feeding and nutrition or recommend extra vitamins or supplements, like vitamin D or iron, if they are needed

Your provider may share insights into the next phase of your child’s development. If your child is not developing as expected, the provider will also be able to offer recommendations on treatment or therapies to help your child get back on track.

Your child’s healthcare provider will answer any questions you have about parenting or about your child’s health and well-being. No question is too big or too small. You can ask anything from how much your child should be sleeping during the day to when to switch your car seat from rear facing to front facing.

Your child’s healthcare provider can give your information about resources in your area, and about how to go about certain things like choosing a good babysitter, finding an affordable pediatric dentist, or selecting the right preschool.

Benefits of the Well-Child Visit

Well-child checkups are invaluable for both you and your child. Here are just some of the benefits of the well-child checks:

Spotting issues early. Your child’s healthcare provider will use these visits to keep an eye out for any possible problems so that steps can be taken to get your child back on the right track. As an example, if your little one is gaining too much weight, your provider can give you advice on nutrition so that your child gets back to a healthy weight.

Preventing problems. As an example, ensuring your child is immunized against certain childhood diseases helps prevent your child from getting sick with a preventable disease.

Getting answers. You might have some questions that aren’t pressing enough to warrant a separate doctor’s visit. Knowing that you have a well-child visit coming up gives you a chance to collect all of your questions and have them answered by a medical professional you trust. Remember, there are no “silly questions” when it comes to your child’s health and well-being.

Learning about what’s to come. Your child’s healthcare provider can give you insights and information about the next stage of your child’s development. That means that certain things might be less of surprise when they happen. As an example, your child’s provider might tell you what kind of behavioral changes to expect with the “terrible twos” and how to manage the tantrums that follow.

Creating a strong relationship with your child’s healthcare provider. Seeing your child’s provider regularly gives you the chance to build up a rapport. You’ll get to know her during these well-child visits, and she’ll get to know you and your little one. Having a relationship built on trust ensures that you can work as a team for the best outcomes for your child.

How to Make the Most of the Well-Child Visit

There are a few things you can do to ensure you get the most out of your child’s well-child checkups:

If it’s workable, schedule the visit for a time when you think your child will be well-rested and well-fed, and try to pick a time when you yourself aren’t rushed. Also, consider how busy your child’s healthcare provider will be. It may be easiest if you can get the first appointment of the day, or one that’s not during “rush hour.”

If it’s possible, both parents should be at the first few visits to ensure that you both get to know your child’s healthcare provider and get the same basic information about newborn baby care

Pack everything you’ll need like your insurance information, your child’s medical history, and your diaper bag (filled with extra diapers, snacks, and toys)

Consider keeping a physical or digital record of what was discussed at each well-child visit. Keep copies of your child’s lab results and evidence of immunizations in the same spot or format as well. Having all this information in one place from the start will make it easier to look back and find the information when you need it. When your child enters preschool or school, you may need to provide documentation of certain medical details.

Dress your child in clothes that are easy to remove and put back on. Your little one may be undressed for part of the visit and your child’s healthcare provider may need easy access to give immunizations.

Write down any questions you have and take the list with you so you don’t forget anything important. Having a list of questions also allows you to focus on the answers instead of thinking ahead about what to ask next.

Using the Smart Sleep Coach by Pampers™ to track your baby’s night sleeps and naps can be a huge help when discussing your baby’s health and development with your doctor. By taking a broad view of your baby’s sleep, you can understand and shape your baby’s sleep and give them the rest they need to keep growing and developing well. In fact, if you're experiencing sleep challenges, you can take this free sleep assessment to get helpful guidance and support on how to get sleep back on track!

The bottom line

Well-child checkups are important for your child. They allow the healthcare provider to to track your child’s growth and development, give vaccinations or screening tests that are needed, and identify any problems nice and early. By working together, you and your child’s provider can give your child the best possible start in life.

Plus, each well-child visit is a great opportunity for you to ask any questions you have about your child’s health and parenting in general.

Try not to miss your scheduled well-baby checkups; they can be a wealth of information and an important way to help ensure your child’s happy and healthy development. By taking advantage of these one-on-one sessions with your child’s provider, you may find he becomes less of a “provider” and more of a partner in your parenting journey.

How We Wrote This Article The information in this article is based on the expert advice found in trusted medical and government sources, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. You can find a full list of sources used for this article below. The content on this page should not replace professional medical advice. Always consult medical professionals for full diagnosis and treatment.

- healthychildren.org. “AAP Schedule of Well-Child Care Visits.”

- Kids Health. “Your Child's Checkup: 3 Years.”

- CDC. “Developmental Monitoring and Screening.”

- Kids Health. “Your Child's Checkup: 1.5 Years (18 Months).”

- Kids Health. “Your Child's Checkups.”

Review this article:

Read more about baby.

- Explore Baby Sleep

- Parenting Life

- Development

Join a World of Support

through Pregnancy and Parenthood.

TRACK WITH TOOLS

LEARN WITH EXPERTS

GET REWARDED

Where You Already Belong

- Pregnancy Weeks

- Nursery Design

- Toddler Sleep

- White Noise

What to Expect at Well-Child Visits

On This Page

Well-child visit schedule.

- Newborn Well-Child Visit

- Baby Well-Child Visits

1-Month Well-Child Visit

2-month well-child visit, 4-month well-child visit, 6-month well-child visit, 9-month well-child visit, 12-month well-child visit, toddler well-child visits, 15-month well-child visit, 18-month well-child visit, 24-month well-child visit, 30-month well-child visit, 3-year well-child visit.

- Vaccines Schedule From 0-2 Years

While it’s a no-brainer that you take your baby or toddler to the doctor when they’re sick, it’s also important to bring your child to the pediatrician for regularly scheduled visits when they are feeling just fine! Enter: The well-child visit. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that each kiddo goes to the doctor within days of birth, then almost monthly, then annually for must-have screenings and assessments. Here’s what to expect at childhood checkups—and when to expect them .

In the first few years of life, you’ll get to know your child’s healthcare provider very well.

Typical child well visit schedule:

- Within 3 to 5 days of birth

- Annually after 3 years

What to Expect at the Newborn Well-Child Visit

Congrats! You just brought your baby home from the hospital…now pack up the diaper bag and head to their very first visit to the pediatrician! (Still haven’t secured your baby’s pediatrician? Use our guide to help you find the perfect doc .) All newborns need a first-week checkup within 3 to 5 days from birth.

What to bring to Newborn Well-Child Visit

Beyond your sweet babe, you may need to bring all your hospital paperwork, which should contain info about your baby’s discharge weight and/or any possible complications that occurred during pregnancy or birth. Some hospitals and practices use online charts that multiple providers can access, but if yours doesn’t, you’ll want to have that information on hand. (If you’re unsure, just ask!)

Newborn Well-Child Visit Vaccines

If your little one did not receive the Hepatitis B (HepB) vaccine while at the hospital, they should receive the first HepB vaccine dose now.

Newborn Well-Child Visit Screenings

Your baby’s pediatrician will likely tackle the following screening measure and exams: