- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.2: Prefixes and Suffixes

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 65807

- Andrea Nelson and Katherine Greene

- University of West Florida

Learning Objectives

- Understand the difference between a prefix and a suffix.

- Differentiate prefixes that deal with body parts, color, and direction.

- Distinguish suffixes that deal with procedures.

Prefixes are located at the beginning of a medical term. The prefix alters the meaning of the medical term. It is important to spell and pronounce prefixes correctly.

Many prefixes that you find in medical terms are common to English language prefixes. A good technique to help with memorization is the following:

- Start by reviewing the most common prefixes.

- Consider common English language words that begin with the same prefixes.

- Compare them to the examples of use in medical terms.

Common Prefixes

Body part prefixes, color prefixes, physical property and shape prefixes, direction and position prefixes, quantity prefixes, concept check.

- Do you know the difference between the prefixes inter- , infra- , and intra- ?

- What color is an erythrocyte? A leukocyte?

- around something else?

- within something else?

- below something else?

Suffixes are word parts that are located at the end of words. Suffixes can alter the meaning of medical terms. It is important to spell and pronounce suffixes correctly.

Suffixes in medical terms are common to English language suffixes. Suffixes are not always explicitly stated in the definition of a word. It is common that suffixes will not be explicitly stated when defining a medical term in the workplace. However, when transcribing or reading medical reports the suffix is always clearly written. In order to properly spell and pronounce medical terms, it is helpful to learn the suffixes.

Common Suffixes

Procedure suffixes.

- Do you know the difference between the suffixes -gram , -graph , and -graphy?

- Which suffixes denote a condition or disease?

Word parts and definitions from “Appendix A: Word Parts and What They Mean” by MedlinePlus and is under public domain.

Definitions of medical term examples from:

- Anatomy and Physiology (on OpenStax ), by Betts et al. and is used under a CC BY 4.0 international license . Download and access this book for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction

- Concepts of Biology (on OpenStax ), by Fowler et al. and is used under a CC BY 4.0 international license . Download and access this book for free at https://openstax.org/books/concepts-biology/pages/1-introduction

- NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms by the National Cancer Institute and is used under public domain.

Medical Dictionary

Search medical terms and abbreviations with the most up-to-date and comprehensive medical dictionary from the reference experts at Merriam-Webster. Master today's medical vocabulary. Become an informed health-care consumer!

Browse the Medical Dictionary

Featured game.

Find the Best Synonym

Test your vocabulary with our 10-question quiz!

Deniz Burnham & 'Astronaut'

Peyton Manning & 'Omaha'

Issa Rae & 'Insecure'

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Games & Quizzes

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Why Patients Are Turning to Medical Tourism

Statistics, Benefits, and Risks

Planning Ahead

Frequently asked questions.

Medical tourism is a term that refers to traveling to another country to get a medical or dental procedure. In some instances, medical tourists travel abroad seeking alternative treatments that are not approved in the United States.

Medical tourism is successful for millions of people each year, and it is on the rise for a variety of reasons, including increasing healthcare costs in the United States, lack of health insurance, specialist-driven procedures, high-quality facilities, and the opportunity to travel before or after a medical procedure.

According to a New York Times article from January 2021, pent-up demand for nonessential surgeries, as well as the fact that many Americans lost their health insurance during the coronavirus pandemic led to a surge in medical tourism once other countries re-opened.

However, there are specific risks that come with traveling overseas for surgery. If you're thinking of pursuing a medical procedure in another country, here's what to know about the benefits and the risks.

Medical Tourism Benefits

The most common procedures Americans go abroad for include dental care, cosmetic procedures , fertility treatments, organ transplants , and cancer treatment.

This is not to be confused with having an unplanned procedure in a foreign country due to an unexpected illness or injury.

Among the reasons a person might choose to go abroad for a medical procedure are:

Lower Costs

Medical tourists can save anywhere from 25% to 90% in medical bills, depending on the procedure they get and the country they travel to. There are several factors that play into this:

- The cost of diagnostic testing and medications is particularly expensive in the United States.

- The cost of pre- and post-procedure labor is often dramatically lower overseas. This includes labor costs for nurses , aides, surgeons , pharmacists, physical therapists , and more.

- High cost of malpractice insurance—the insurance that protects medical professionals against lawsuits—in the United States.

- Hospital stays cost far less in many overseas countries compared to the United States. In other words, quality care, hospital meals, and rehabilitation are far more affordable abroad for many people.

For someone who doesn't have insurance , or someone having a procedure that is not covered by insurance , the difference can be enormous.

Popular Countries for Medical Tourism

Dominican Republic

South Korea

Culture and Language

Many immigrants prefer to have treatments and procedures done in their country of origin—a sensible decision, considering just how much language barriers alone can affect the quality of their care.

Furthermore, at least 25% of immigrants and noncitizen residents in the United States are uninsured, compared to 9% of American citizens. Children with at least one noncitizen parent are also more likely to be uninsured.

Practicalities aside, many people choose to have their procedure done in their country of origin simply because it allows them to be close to family, friends, and caretakers who can assist them through their recovery .

Insurance Incentives

Some insurance companies have started promoting medical tourism. The reason behind this is simple: savings for the insured means savings for the insurance provider and vice versa.

Several insurance providers, including Aetna have programs specifically geared at promoting safe medical tourism. Some insurance providers even offer financial incentives for medical tourism, like discounts on medical bills .

That said, many insurance companies will not pay for surgery performed outside of the country unless it is an emergency.

Luxury and Privacy

Medical tourism is a lucrative business for many countries, and much of the money brought in by medical tourists is reinvested into the local economy and health infrastructure.

The effect of this is apparent in the spa-like luxury that some foreign hospitals offer, providing medical tourists the opportunity to be pampered during their stay for a fraction of the cost they would pay at home.

Some facilities offer hospital rooms that are more like a hotel suite than a traditional hospital room. Other hospitals offer one-on-one private nursing care, which is far more generous and attentive than the staffing ratios that most hospitals allow.

Medical tourists who seek that added layer of privacy can find it abroad. Many can return home from their "vacation" without anyone knowing they had a procedure at all.

Vacation in a Foreign Country

Medical tourists often take advantage of their stay in a foreign country to travel for pleasure by scheduling a vacation before or after their procedure.

This is an especially inexpensive way to travel to a foreign country, especially if their insurance provider is paying for the flight and the cost of staying is low.

While it seems logical to recover on a beach or in a chalet by the mountains, keep in mind that it's important not to jeopardize your recovery.

Swimming isn't recommended until your incisions are completely closed. You may not feel up to doing much more than napping in the days following your procedure, either.

Don't let your vacation disrupt your recovery. Any time you have a procedure done, especially a surgery, it's important to listen to your body, take your medications as directed, and follow your doctor's recommendations closely.

Bypassing Rules and Regulations

Some travelers seek surgery abroad to bypass rules that are set in place by their own government, insurance company , or hospital. These rules are typically in place to protect the patient from harm, so getting around them isn't always the best idea.

For example, a patient may be told that their weight is too low to qualify for weight loss surgery . A surgeon in a foreign country may have a different standard for who qualifies for weight loss surgery, so the patient may qualify overseas for the procedure they want.

Talented Surgeons

Surgeons in certain countries are known for their talent in a specific area of surgery. For example, Brazilian surgeons are often touted for their strong plastic surgery skills .

Whereas in the United States, insurance companies might only cover cosmetic procedures if it is medically necessary, cosmetic surgery is often free or low-cost in Brazil's public hospitals—giving cosmetic surgeons there ample practice.

Thailand is reported to be the primary medical tourism destination for individuals seeking gender reassignment . It is often easier to qualify for surgery and the cost is significantly reduced. Surgeons are performing the procedures frequently, and as a result, many have become quite specialized in them.

It is often surprising to many medical tourists that their physician was trained in the United States. Not all physicians are, of course, but a surprisingly high percentage of them working in surgery abroad are trained in English-speaking medical schools and residency programs and then return to their home country. These physicians often speak multiple languages and may be board certified in their home country and a foreign country, such as the United States.

Medical tourism isn’t limited to countries outside of the United States, either. Many people travel to the United States for medical care due to the country's cutting-edge technology, prescription medication supply, and the general safety of healthcare.

Medical Tourism Risks

The financial and practical benefits of medical tourism are well known, and you may even know someone who had a great experience. Nonetheless, the downsides of medical tourism can be just as great if not greater. Sometimes, they can even be deadly.

If you are considering a trip abroad for your procedure, you should know that medical tourism isn't entirely without obstacle and risks. These include:

Poorly Trained Surgeons

In any country—the United States included—there will be good surgeons and bad. And just as there are great surgeons abroad, there are also some surgeons who are less talented, less trained, and less experienced.

Regardless of what procedure you are getting or where, you should always do some preliminary research into the surgeon or physician who will be treating you as well as the hospital you will be treated at.

In the United States, it is fairly easy to obtain information about malpractice lawsuits , sanctions by medical boards, and other disciplinary actions against a physician.

Performing this research from afar can be challenging, especially if you don't speak the local language. Yet countless people take the risk anyway, without knowing whether the physicians who will treat them are reputable.

A physician should be trained in the specific area of medicine that is appropriate for your procedure. For example, you should not be having plastic surgery from a surgeon who was trained to be a heart doctor. It isn’t good enough to be a physician, the physician must be trained in the specialty .

Prior to agreeing to surgery, you should also know your surgeon’s credentials : where they studied, where they trained, and in what specialty(s) they are board-certified. Do not rely on testimonials from previous patients; these are easily made up for a website and even if they are correct, one good surgery doesn’t mean they will all be successful.

Quality of Staff

Nurses are a very important part of healthcare, and the care they provide can mean the difference between a great outcome and a terrible one.

A well-trained nurse can identify a potential problem and fix it before it truly becomes an issue. A poorly trained nurse may not identify a problem until it is too late. The quality of the nursing staff will have a direct impact on your care.

Once again, it's important to research the hospital staff where you will be having your procedure done. Read the reviews but don't trust them blindly. If you can, seek out a recommendation from someone who can vouch for the medical staff where you will be going.

Quality of the Facility

While researching healthcare facilities for your procedure, you want to learn not just about the quality of the facilities themselves, but about the country's healthcare system as a whole.

In some countries, there is a marked distinction between public hospitals and private hospitals. In Turkey, for example, private hospitals are considered on-par with hospitals in the states, while many locals will advise you to steer clear of public hospitals if you can.

You will also want to seek out facilities that are internationally accredited. In the United States, the Joint Commission evaluates hospitals and certifies those that provide safe, quality care. The international division does the same for hospitals outside the United States.

Once you have a few options for potential facilities, you can start to investigate specifics. For one, you should find as many pictures and reviews of the facility as you can. Ask yourself whether the facility is state of the art or whether it seems dirty and outdated.

You will also need to find out if the facility has ICU level care available, in case something goes wrong. If not, there should be a major hospital nearby so that you can be transferred quickly.

To learn more about a healthcare facility, consider joining expat groups on social media for the city or country you will be traveling to. Ask the group for recommendations, or inquire about any positive or negative experiences they may have had at a particular facility.

Flying Home After Surgery

Any surgery comes with risks, including infection and blood clots . Flying home increases the risk of blood clots, especially on long-haul flights that are longer than four hours.

Try to avoid flying home in the days immediately after surgery; waiting a week will decrease the chances of developing a blood clot or another serious complication during the flight.

For longer flights, plan on getting up and walking up and down the aisles each hour to improve blood flow in your legs. You might also benefit from wearing compression socks with your doctor's approval.

If you are taking blood thinners or are at-risk of blood clots , be sure to talk to your doctor about how you can reduce your risk of blood clots after your procedure and while traveling.

Furthermore, you should know the symptoms of blood clots and stay alert.

Unplanned Illness

Any time you travel abroad, you run the risk of catching an illness that you have never been exposed to or that your body is not prepared to fight off. This is especially a concern when spending time in a foreign hospital.

If you have a sensitive stomach, you may also want to think long and hard about having surgery abroad. The food is often very different in foreign hospitals, and in some areas, there is a risk that even the water will be upsetting to your body.

Having diarrhea or postoperative nausea and vomiting makes for a miserable recovery experience, especially if you do not have a friend or family member nearby who can help you through it.

Before you travel abroad, check with your doctor to see if you need any vaccines to travel to your destination or if there are any foreign illnesses you should be aware of. Picking up an illness abroad, particularly after your surgery, can potentially be life-threatening.

Language Barriers

If you are having surgery in a country where English is not the primary language, you will need to make preparations in order to be able to communicate with the staff.

You may be pleasantly surprised to learn that the staff speaks your primary language well. If not, then you will need to consider how you will make your wishes and needs known to the surgeon, the staff, and others you will meet.

Whether you are at home or abroad, remember to speak up and advocate for yourself to make sure your needs are met. If you don't speak the local language, download a language translation app on your smartphone and don't hesitate to use it to communicate your needs. Hiring a translator is another option.

A Word About Transplant Tourism

Transplant tourism is one area of medical tourism that is strongly discouraged by organ and tissue transplant professionals in multiple countries. Most international transplants are considered “black market” surgeries that are not only poor in quality, but ethically and morally wrong.

China, for example, the country that is believed to perform more international kidney transplants than any other country, is widely believed to take organs from political prisoners after their execution.

In India, living donors are often promised large sums of money for their kidney donation, only to find out they have been scammed and never receive payment. Selling an organ in India is illegal, as it is in most areas of the world, so there is little recourse for the donor.

Then there is the final outcome: how well the organ works after the surgery is complete. With black market transplants, less care is often taken with matching the donor and recipient, which leads to high levels of rejection and a greater risk of death. Furthermore, the new organ may not have been screened for diseases such as cytomegalovirus , tuberculosis , hepatitis B , and hepatitis C . It is often the new disease that leads to death, rather than the organ rejection itself.

Finally, transplant surgeons are often reluctant to care for a patient who intentionally circumvented the donor process in the United States and received their transplant from an unknown physician.

It is important to arrange your follow-up care prior to leaving your home country.

Many physicians and surgeons are hesitant to take care of a patient who received care outside the country, as they are often unfamiliar with medical tourism and have concerns about the quality of care overseas.

Arranging for follow-up care before you leave will make it easier to transition to care at home without the stress of trying to find a physician after surgery .

Just be sure to inform your follow-up care physician where you are having your procedure done. After you return, they will also want to know what prescription medications you were given, if any.

What are popular countries for medical tourism?

Mexico, India, Costa Rica, Turkey, Singapore, Canada, and Thailand are among the many countries that are popular for medical tourism.

How safe is medical tourism?

Medical tourism is generally considered safe, but it's critical to research the quality of care, physician training, and surgical specialties of each country. There are several medical tourism organizations that specialize in evaluating popular destinations for this purpose.

What countries have free healthcare?

Countries with free healthcare include England, Canada, Thailand, Mexico, India, Sweden, South Korea, Israel, and many others.

A Word From Verywell

If you are considering medical tourism, discuss the risks and benefits with your doctor, and consider working with your insurance provider to arrange a trip that balances financial savings with safety. (Also, before you embark on a trip overseas for your procedure, make sure you are financially prepared for unexpected events and emergencies. Don't go abroad if you don't have enough money to get yourself home in a crisis.)

A medical tourism organization such as Patients Without Borders can help you evaluate the quality and trustworthiness of healthcare in various countries. Making sure a high level of care is readily available will lead to a safer, more relaxing experience.

Centers For Disease Control and Prevention. Medical Tourism: Getting medical care in another country . Updated October 23, 2017.

University of the Incarnate Word. Center for Medical Tourism Research .

Patients Beyond Borders. Facts and figures .

Kaiser Family Foundation. Health coverage of immigrants . Published July 2021.

Paul DP 3rd, Barker T, Watts AL, Messinger A, Coustasse A. Insurance companies adapting to trends by adopting medical tourism . Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2017 Oct/Dec;36(4):326-333. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0000000000000179

Batista BN. State of plastic surgery in Brazil . Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open . 2017 Dec;5(12):1627. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000001627

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health - Global Health Now. Brazilians' risky right to beauty . Published May 2018.

Chokrungvaranont P, Selvaggi G, Jindarak S, et al. The development of sex reassignment surgery in Thailand: a social perspective . Sci World J . 2014 Mar;2014(1):1-5. doi:10.1155/2014/182981

The Joint Commission. For consumers .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Blood clots and travel: what you need to know . Reviewed February 2021.

Hurley R. China harvested organs from political prisoners on substantial scale, says tribunal . BMJ . 2018 Dec;363(1):5250. doi:10.1136/bmj.k5250

Ambagtsheer F, Van Balen L. I'm not Sherlock Holmes: suspicions, secrecy, and silence of transplant professionals in the human organ trade . Euro J Criminol . 2019 Jan;17(6):764-783. doi:10.1177/1477370818825331

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Transplant Surgery. Key facts . Reviewed January 2019.

By Jennifer Whitlock, RN, MSN, FN Jennifer Whitlock, RN, MSN, FNP-C, is a board-certified family nurse practitioner. She has experience in primary care and hospital medicine.

Travel Medicine and International Health

Travel medicine and international health is a specialized branch of medicine that focuses on the prevention, diagnosis, and management of health issues related to international travel and global health. It aims to promote the well-being of travelers by providing pre-travel consultations, vaccinations, prophylactic medications, and post-travel care for various travel-related illnesses and conditions.

Related Fact Sheets

Global health and travel-related maladies, outdoor emergencies and injuries, related news.

Related Departments

Infectious diseases, internal medicine, orthopaedics & rehabilitation.

You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

- Section 6 - Perspectives : Avoiding Poorly Regulated Medicines & Medical Products During Travel

- Section 7 - Pregnant Travelers

Medical Tourism

Cdc yellow book 2024.

Author(s): Matthew Crist, Grace Appiah, Laura Leidel, Rhett Stoney

- Categories Of Medical Tourism

The Pretravel Consultation

Risks & complications, risk mitigation, additional guidance for us health care providers.

Medical tourism is the term commonly used to describe international travel for the purpose of receiving medical care. Medical tourists pursue medical care abroad for a variety of reasons, including decreased cost, recommendations from friends or family, the opportunity to combine medical care with a vacation destination, a preference to receive care from a culturally similar provider, or a desire to receive a procedure or therapy not available in their country of residence.

Medical tourism is a worldwide, multibillion-dollar market that continues to grow with the rising globalization of health care. Surveillance data indicate that millions of US residents travel internationally for medical care each year. Medical tourism destinations for US residents include Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Germany, India, Malaysia, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru, Singapore, and Thailand. Categories of procedures that US medical tourists pursue include cancer treatment, dental care, fertility treatments, organ and tissue transplantation, and various forms of surgery, including bariatric, cosmetic, and non-cosmetic (e.g., orthopedic).

Most medical tourists pay for their care at time of service and often rely on private companies or medical concierge services to identify foreign health care facilities. Some US health insurance companies and large employers have alliances with health care facilities outside the United States to control costs.

Categories of Medical Tourism

Cosmetic tourism.

Cosmetic tourism, or travel abroad for aesthetic surgery, has become increasingly popular. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) reports that most cosmetic surgery patients are women 40–54 years old. The most common procedures sought by cosmetic tourists include abdominoplasty, breast augmentation, eyelid surgery, liposuction, and rhinoplasty. Popular destinations often are marketed to prospective medical tourists as low cost, all-inclusive cosmetic surgery vacations for elective procedures not typically covered by insurance. Complications, including infections and surgical revisions for unsatisfactory results, can compound initial costs.

Non-Cosmetic Medical Tourism

Cancer treatment.

Oncology, or cancer treatment, tourism often is pursued by people looking for alternative treatment options, better access to care, second opinions, or a combination of these. Oncology tourists are a vulnerable patient population because the fear caused by a cancer diagnosis can lead them to try potentially risky treatments or procedures. Often, the treatments or procedures used abroad have no established benefit, placing the oncology tourist at risk for harm due to complications (e.g., bleeding, infection) or by forgoing or delaying approved therapies in the United States.

Dental Care

Dental care is the most common form of medical tourism among US residents, in part due to the rising cost of dental care in the United States; a substantial proportion of people in the United States do not have dental insurance or are underinsured. Dentists in destination countries might not be subject to the same licensure oversight as their US counterparts, however. In addition, practitioners abroad might not adhere to standard infection-control practices used in the United States, placing dental tourists at a potential risk for infection due to bloodborne or waterborne pathogens.

Fertility Treatments

Fertility tourists are people who seek reproductive treatments in another country. Some do so to avoid associated barriers in their home country, including high costs, long waiting lists, and restrictive policies. Others believe they will receive higher quality care abroad. People traveling to other countries for fertility treatments often are in search of assisted reproductive technologies (e.g., artificial insemination by a donor, in vitro fertilization). Fertility tourists should be aware, however, that practices can vary in their level of clinical expertise, hygiene, and technique.

Physician-Assisted Suicide

The practice of a physician facilitating a patient’s desire to end their own life by providing either the information or the means (e.g., medications) for suicide is illegal in most countries. Some people consider physician-assisted suicide (PAS) tourism, also known as suicide travel or suicide tourism, as a possible option. Most PAS tourists have been diagnosed with a terminal illness or suffer from painful or debilitating medical conditions. PAS is legal in Belgium, Canada, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and New Zealand, making these the destinations selected by PAS travelers.

Rehab Tourism for Substance Use Disorders

Rehab tourism involves travel to another country for substance use disorder treatment and rehabilitation care. Travelers exploring this option might be seeking a greater range of treatment options at less expense than what is available domestically (see Sec. 3, Ch. 5, Substance Use & Substance Use Disorders , and Box 3-10 for pros and cons of rehab tourism).

Transplant Procedures

Transplant tourism refers to travel for receiving an organ, tissue, or stem cell transplant from an unrelated human donor. The practice can be motivated by reduced cost abroad or an effort to reduce the waiting time for organs. Xenotransplantation refers to receiving other biomaterial (e.g., cells, tissues) from nonhuman species, and xenotransplantation regulations vary from country to country. Many procedures involving injection of human or nonhuman cells have no scientific evidence to support a therapeutic benefit, and adverse events have been reported.

Depending on the location, organ or tissue donors might not be screened as thoroughly as they are in the United States; furthermore, organs and other tissues might be obtained using unethical means. In 2009, the World Health Organization released the revised Guiding Principles on Human Cell, Tissue, and Organ Transplantation, emphasizing that cells, tissues, and organs should be donated freely, in the absence of any form of financial incentive.

Studies have shown that transplant tourists can be at risk of receiving care that varies from practice standards in the United States. For instance, patients might receive fewer immunosuppressive drugs, increasing their risk for rejection, or they might not receive antimicrobial prophylaxis, increasing their risk for infection. Traveling after a procedure poses an additional risk for infection in someone who is immunocompromised.

Ideally, medical tourists will consult a travel medicine specialist for travel advice tailored to their specific health needs 4–6 weeks before travel. During the pretravel consultation, make certain travelers are up to date on all routine vaccinations, that they receive additional vaccines based on destination, and especially encourage hepatitis B virus immunization for unvaccinated travelers (see Sec. 2, Ch. 3, Vaccination & Immunoprophylaxis & General Principles , and Sec. 5, Part 2, Ch. 8, Hepatitis B ). Counsel medical tourists that participating in typical vacation activities (e.g., consuming alcohol, participating in strenuous activity or exercise, sunbathing, swimming, taking long tours) during the postoperative period can delay or impede healing.

Advise medical tourists to also meet with their primary care provider to discuss their plan to seek medical care outside the United States, to address any concerns they or their provider might have, to ensure current medical conditions are well controlled, and to ensure they have a sufficient supply of all regular medications to last the duration of their trip. In addition, medical tourists should be aware of instances in which US medical professionals have elected not to treat medical tourists presenting with complications resulting from recent surgery, treatment, or procedures received abroad. Thus, encourage medical tourists to work with their primary care provider to identify physicians in their home communities who are willing and available to provide follow-up or emergency care upon their return.

Remind medical tourists to request copies of their overseas medical records in English and to provide this information to any health care providers they see subsequently for follow-up. Encourage medical tourists to disclose their entire travel history, medical history, and information about all surgeries or medical treatments received during their trip.

All medical and surgical procedures carry some risk, and complications can occur regardless of where treatment is received. Advise medical tourists not to delay seeking medical care if they suspect any complication during travel or after returning home. Obtaining immediate care can lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment and a better outcome.

Among medical tourists, the most common complications are infection related. Inadequate infection-control practices place people at increased risk for bloodborne infections, including hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV; bloodstream infections; donor-derived infections; and wound infections. Moreover, the risk of acquiring antibiotic-resistant infections might be greater in certain countries or regions; some highly resistant bacterial (e.g., carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales [CRE]) and fungal (e.g., Candida auris ) pathogens appear to be more common in some countries where US residents travel for medical tourism (see Sec. 11, Ch. 5, Antimicrobial Resistance ).

Several infectious disease outbreaks have been documented among medical tourists, including CRE infections in patients undergoing invasive medical procedures in Mexico, surgical site infections caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria in patients who underwent cosmetic surgery in the Dominican Republic, and Q fever in patients who received fetal sheep cell injections in Germany.

Noninfectious Complications

Medical tourists have the same risks for noninfectious complications as patients receiving medical care in the United States. Noninfectious complications include blood clots, contour abnormalities after cosmetic surgery, and surgical wound dehiscence.

Travel-Associated Risks

Traveling during the post-operative or post-procedure recovery period or when being treated for a medical condition could pose additional risks for patients. Air travel and surgery independently increase the risk for blood clots, including deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary emboli (see Sec. 8, Ch. 3, Deep Vein Thrombosis & Pulmonary Embolism ). Travel after surgery further increases the risk of developing blood clots because travel can require medical tourists to remain seated for long periods while in a hypercoagulable state.

Commercial aircraft cabin pressures are roughly equivalent to the outside air pressure at 6,000–8,000 feet above sea level. Medical tourists should not fly for 10 days after chest or abdominal surgery to avoid risks associated with changes in atmospheric pressure. ASPS recommends that patients undergoing laser treatments or cosmetic procedures to the face, eyelids, or nose, wait 7–10 days after the procedure before flying. The Aerospace Medical Association published medical guidelines for air travel that provide useful information on the risks for travel with certain medical conditions.

Professional organizations have developed guidance, including template questions, that medical tourists can use when discussing what to expect with the facility providing the care, with the group facilitating the trip, and with their own domestic health care provider. For instance, the American Medical Association developed guiding principles on medical tourism for employers, insurance companies, and other entities that facilitate or incentivize medical care outside the United States ( Box 6-07 ). The American College of Surgeons (ACS) issued a similar statement on medical and surgical tourism, with the additional recommendation that travelers obtain a complete set of medical records before returning home to ensure that details of their care are available to providers in the United States, which can facilitate continuity of care and proper follow-up, if needed.

Box 6-07 American Medical Association’s guiding principles on medical tourism 1

- Employers, insurance companies, and other entities that facilitate or incentivize medical care outside the United States should adhere to the following principles:

- Receiving medical care outside the United States must be voluntary.

- Financial incentives to travel outside the United States for medical care should not inappropriately limit the diagnostic and therapeutic alternatives that are offered to patients or restrict treatment or referral options.

- Patients should only be referred for medical care to institutions that have been accredited by recognized international accrediting bodies (e.g., the Joint Commission International or the International Society for Quality in Health Care).

- Prior to travel, local follow-up care should be coordinated, and financing should be arranged to ensure continuity of care when patients return from medical care outside the United States.

- Coverage for travel outside the United States for medical care should include the costs of necessary follow-up care upon return to the United States.

- Patients should be informed of their rights and legal recourse before agreeing to travel outside the United States for medical care.

- Access to physician licensing and outcome data, as well as facility accreditation and outcomes data, should be arranged for patients seeking medical care outside the United States.

- The transfer of patient medical records to and from facilities outside the United States should be consistent with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Action (HIPAA) guidelines.

- Patients choosing to travel outside the United States for medical care should be provided with information about the potential risks of combining surgical procedures with long flights and vacation activities.

1 American Medical Association (AMA). New AMA Guidelines on Medical Tourism . Chicago: AMA; 2008.

Reviewing the Risks

Multiple resources are available for providers and medical tourists assessing medical tourism–related risks (see Table 6-02 ). When reviewing the risks associated with seeking health care abroad, encourage medical tourists to consider several factors besides the procedure; these include the destination, the facility or facilities where the procedure and recovery will take place, and the treating provider.

Make patients aware that medical tourism websites marketing directly to travelers might not include (or make available) comprehensive details on the accreditations, certifications, or qualifications of advertised facilities or providers. Local standards for facility accreditation and provider certification vary, and might not be the same as those in the United States; some facilities and providers abroad might lack accreditation or certification. In some locations, tracking patient outcome data or maintaining formal medical record privacy or security policies are not standard practices.

Medical tourists also should be aware that the drugs and medical products and devices used in other countries might not be subject to the same regulatory scrutiny and oversight as in the United States. In addition, some drugs could be counterfeit or otherwise ineffective because the medication expired, is contaminated, or was improperly stored (for more details, see the previous chapter in this section, . . . perspectives: Avoiding Poorly Regulated Medicines & Medical Products During Travel ).

Table 6-02 Online medical tourism resources

Checking credentials.

ACS recommends that medical tourists use internationally accredited facilities and seek care from providers certified in their specialties through a process equivalent to that established by the member boards of the American Board of Medical Specialties. Advise medical tourists to do as much advance research as possible on the facility and health care provider they are considering using. Also, inform medical tourists that accreditation does not guarantee a good outcome.

Accrediting organizations (e.g., The Joint Commission International, Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care) maintain listings of accredited facilities outside of the United States. Encourage prospective medical tourists to review these sources before committing to having a procedure or receiving medical care abroad.

ACS, ASPS, the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, and the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery all accredit physicians abroad. Medical tourists should check the credentials of health care providers with search tools provided by relevant professional organizations.

Travel Health Insurance

Before travel, medical tourists should check their domestic health insurance plan carefully to understand what services, if any, are covered outside the United States. Additionally, travelers might need to purchase supplemental medical insurance coverage, including medical evacuation insurance; this is particularly important for travelers going to remote destinations or places lacking medical facilities that meet the standards found in high-income countries (see Sec. 6, Ch. 1, Travel Insurance, Travel Health Insurance & Medical Evacuation Insurance ). Medical tourists also should be aware that if complications develop, they might not have the same legal recourse as they would if they received their care in the United States.

Planning for Follow-Up Care

Medical tourists and their domestic physicians should plan for follow-up care. Patients and clinicians should establish what care will be provided abroad, and what the patient will need upon return. Medical tourists should make sure they understand what services are included as part of the cost for their procedures; some overseas facilities and providers charge substantial fees for follow-up care in addition to the base cost. Travelers also should know whether follow-up care is scheduled to occur at the same facility as the procedure.

Health care facilities in the United States should have systems in place to assess patients at admission to determine whether they have received medical care in other countries. Clinicians should obtain an explicit travel history from patients, including any medical care received abroad. Patients who have had an overnight stay in a health care facility outside the United States within 6 months of presentation should be screened for CRE. Admission screening is available free of charge through the Antibiotic Resistance Laboratory Network .

Notify state and local public health as soon as medical tourism–associated infections are identified. Returning patients often present to hospitals close to their home, and communication with public health authorities can help facilitate outbreak recognition. Health care facilities should follow all disease reporting requirements for their jurisdiction. Health care facilities also should report suspected or confirmed cases of unusual antibiotic resistance (e.g., carbapenem-resistant organisms, C. auris ) to public health authorities to facilitate testing and infection-control measures to prevent further transmission. In addition to notifying the state or local health department, contact the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention at [email protected] to report complications related to medical tourism.

The following authors contributed to the previous version of this chapter: Isaac Benowitz, Joanna Gaines

Bibliography

Adabi K, Stern C, Weichman K, Garfein ES, Pothula A, Draper L, et al. Population health implications of medical tourism. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(1):66–74.

Al-Shamsi, H, Al-Hajelli, M, Alrawi, S. Chasing the cure around the globe: medical tourism for cancer care from developing countries. J Glob Onc. 2018;4:1–3.

Kracalik I, Ham C, Smith AR, Vowles M, Kauber K, Zambrano M, et al. (2019). Notes from the field: Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase–producing carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in U.S. residents associated with invasive medical procedures in Mexico, 2015–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(20):463–4.

Pavli A, Maltezou HC. Infectious complications related to medical tourism. J Travel Med. 2021;28(1):taaa210.

Pereira RT, Malone CM, Flaherty GT. Aesthetic journeys: a review of cosmetic surgery tourism. J Travel Med. 2018;25(1):tay042.

Robyn MP, Newman AP, Amato M, Walawander M, Kothe C, Nerone JD, et al. Q fever outbreak among travelers to Germany who received live cell therapy & United States and Canada, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(38):1071–3.

Salama M, Isachenko V, Isachenko E, Rahimi G, Mallmann P, Westphal LM, et al. Cross border reproductive care (CBRC): a growing global phenomenon with multidimensional implications (a systematic and critical review). J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35(7):1277–88.

Schnabel D, Esposito DH, Gaines J, Ridpath A, Barry MA, Feldman KA, et al. Multistate US outbreak of rapidly growing mycobacterial infections associated with medical tourism to the Dominican Republic, 2013–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(8):1340–7.

Stoney RJ, Kozarsky PE, Walker AT, Gaines JL. Population-based surveillance of medical tourism among US residents from 11 states and territories: findings from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2022;43(7):870–5.

File Formats Help:

- Adobe PDF file

- Microsoft PowerPoint file

- Microsoft Word file

- Microsoft Excel file

- Audio/Video file

- Apple Quicktime file

- RealPlayer file

- Zip Archive file

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Himmelfarb Library News

Resources, tools & health news from GW Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

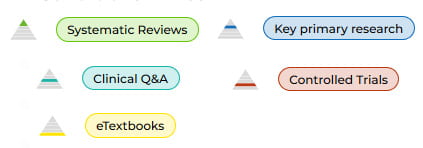

Trip Database: An Overview

The Trip Database is a medical search engine with an emphasis on evidence based practice (EBP), clinical guidelines and queries. Himmelfarb Library provides access to the freely accessible version of Trip. Started in 1997, Trip aims to help users “find evidence fast” with an easy to use search interface that filters results based on the evidence pyramid . A pyramid icon is displayed with the resource that indicates where the resource falls on the evidence pyramid.

Journals covered in Trip include high impact titles such as the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), The Lancet , the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), the British Medical Journal (BMJ), and Annals of Internal Medicine . In addition, content from EvidenceAlerts and PubMed ’s core journal content is included. You can learn more about journal content included in Trip in their recent blog post on the subject.

In addition to the journal articles, Trip results provide a full range of resources including e-textbooks, patient information leaflets, educational courses and news. One thing to keep in mind about Trip is that publishers are classified by their output. Cochrane is known for publishing systematic reviews, and therefore Cochrane published resources will appear in the Systematic Reviews filter. The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) is classified as Primary Research. This means that if a systematic review is published in NEJM, it will appear in the Primary Research filter. However, when a systematic review is reviewed by the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), it will eventually appear in the Systematic Reviews filter, although there is a time delay.

Trip can be used by practicing physicians who would like to broaden their background knowledge on conditions such as diabetes or cancer, or who need to find relevant evidence-based information on testing guidelines or to make sure a “don’t miss” diagnosis is included in their differential diagnosis. Trip is also useful for medical students who may find the PICO search tool an effective way to search for applicable resources. Check out this blog post to learn more about case studies for using Trip.

Trip has responded to the War in Ukraine by creating a combat injuries filter . While this effort is still a work in progress, the filter attempts to gather the best combat evidence available.

Interested in learning more about Trip? Check out the short video below:

Share this post:

- Campus Advisories

- EO/Nondiscrimination Policy (PDF)

- Website Privacy Notice

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

Subscribe By Email

Get every new post delivered right to your inbox.

Your Email Leave this field blank

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

This site uses cookies to offer you a better browsing experience. Visit GW’s Website Privacy Notice to learn more about how GW uses cookies.

Raj Palraj, M.B.B.S., M.D.

- Infectious Diseases

Recent Posts

- Behavioral Health

- Children's Health (Pediatrics)

- Exercise and Fitness

- Heart Health

- Men's Health

- Neurosurgery

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Orthopedic Health

- Weight Loss and Bariatric Surgery

- Women's Health

Stay healthy abroad: Why you should see a travel medicine specialist before your trip

As you get ready to travel to another country, you probably have many details to coordinate and plan. One essential task, depending on where those travels take you, may be to make an appointment to see a travel medicine specialist.

A travel medicine specialist assesses travel-related risks and provides information to ensure your health and safety while minimizing the potential for health-related situations during on your trip.

Adding a consultation to your travel to-do list

A consultation with a travel medicine specialist includes discussing travel-related illnesses, risk factors for infectious and noninfectious diseases, required immunizations , health regulations and drug-resistant organisms you may encounter.

It's crucial to schedule a pretravel consultation at least two weeks or preferably, four to eight weeks, before your trip to ensure you get complete protection from any needed vaccinations.

When requesting a travel medicine consultation, be prepared to provide information about your trip, including:

- All countries you're visiting

- Any transportation, accommodation or other unusual circumstances

- Dates and duration of travel

A travel medicine specialist will review your itinerary before your consultation to identify country-by-country health risks, such as exotic infectious agents, the potential for altitude sickness or heat exhaustion, as well as appropriate vaccinations and possible need for malaria prevention medications.

Your opportunity to learn about staying healthy abroad

A consultation gives you the opportunity to learn about health risks you may face while you're traveling and once you reach your destinations.

Based on your itinerary, the travel medicine specialist may:

- Explain the risks of infection from mosquito-borne illnesses and the steps for protecting yourself. This includes reviewing medications to prevent malaria , which is a potentially life-threatening illness.

- Ensure you receive protection against vaccine-preventable illnesses, such as hepatitis A or typhoid fever , and verify that other routine vaccinations are current.

- Evaluate your overall health for travel and discuss with you how to manage preexisting conditions.

- Give tips for preventing jet lag, motion sickness, altitude illness and blood clots .

- Review how to prevent and treat traveler's diarrhea , the most common travel-related illness.

- Help you reduce the chance of becoming ill during travel.

- Provide a yellow fever vaccination and an International Certificate of Vaccination , also known as a yellow card, if you travel to a country where the vaccine is recommended or required.

- Review food and water precautions. Contaminated food and water can pose disease risk for travelers, many of which are transmitted via swallowing or coming in contact with impure water, such as fresh or sea water and swimming pools.

Be sure to ask the specialist any questions you may have about your personal health, and raise any safety concerns about your travel itinerary.

What to do if you got sick on your trip

Once you return home, a travel medicine specialist also can conduct a comprehensive post-travel evaluation of any illnesses you may have picked up while away, including parasitic infections and other tropical diseases that are rare in the U.S.

No matter the reason for travel — vacation, business, studying abroad, visiting friends or relatives or medical tourism — always be prepared, and take steps to ensure your health and safety.

Raj Palraj, M.B.B.S., M.D. , is an infectious diseases specialist in La Crosse , Wisconsin.

Related Posts

Our Response to COVID-19 →

10 Essentials You Need to Pack for Your Medical Tourism Trip

Packing is always a chore under the best circumstances, but when you are traveling away from home for a medical procedure, it is especially important that you pack with care. Given the heightened security for travelers and the fact that you might not be feeling your best, you want to be sure you don’t add to your stress by forgetting something important.

Making a list of everything you might possibly need and then checking it before leaving the house will ensure your trip gets off to a good start. Here are some essentials you’ll need during your medical tourism trip.

Documents and Paperwork

Getting your papers in order with plenty of time to spare is always a good idea, just in case you have to send off something. If you wait until the last minute, you are setting yourself up for a possible last-minute glitch. For instance, ordering a passport to replace an expired one may take weeks.

If you’re lucky, you already have everything you need for the trip, but it’s always a good idea to triple check to be sure you don’t leave home without something crucial. The last hassle anyone wants to deal with is to be working out of a hotel, trying to get papers sent out and possibly delaying the procedure.

1. Medical Papers

Medical papers and records are a necessity and should be at the top of your list of things to pack. Just to be safe, it is always a good idea to have extra copies of key documents in different suitcases to be covered in case some of your luggage is lost.

2. Passports and Visas

Keep your passport close at all times and have some foreign currency on hand for incidentals. The first thing that should be done during the planning stage is to check the rules for passports in different countries and read them carefully.

In addition to a passport, some countries require travelers to have a visa too. You should always check with the embassy to see if this is a requirement for visiting that country.

3. Currency

Exchanging currency is easier done ahead of time when you can exchange it at a trusted institution in your hometown, getting the best rates. If you wait until you are out of your element on foreign soil, you may not fare as well financially when you exchange foreign currency. It’s always a good idea to get bills in smaller denominations so there is no problem using them and getting change for low cost items.

Bonus Tip: Credit Card Alerts

Credit card limits should be checked ahead of time so you are sure to bring the ones you need. It is also a good idea to let the credit card companies know where you will be, so there is no risk of having them block a transaction for “security reasons.”

While it is nice to know they are watching out for us, it can be problematic when you find yourself trying to pay and your credit card is declined. Save yourself the headache by giving them a “heads up” before you leave.

After Care Medications

4. medication and pain relievers.

You can’t always know what a hospital or care facility in a different country will have on hand. Aspirin and other painkillers may be abundant in your country, but they may be much harder to find in the country where you are headed. Assumptions about other cultures and hospitals in other countries can leave you without something you need.

5. After Care Products

Plan ahead to save money and guarantee your comfort. Depending on the procedure and the country you’re visiting, some common items you might want to bring are wound dressings, gauze, scissors, band-aids, and over-the-counter medications.

Miscellaneous Care Items

6. comfortable clothing.

You will need to include clothes for traveling and for the hospital. Considering how unpredictable the weather can be, it makes sense to be prepared for whatever is possible. The last thing you will feel like doing is going shopping after your medical procedure. Loose clothing that works in a hospital setting should be packed. Pajamas with buttons in the front and a robe offer comfortable choices.

Overseas, you’ll be eating different foods. It is always a good idea to have medicine on hand to treat an upset stomach or motion sickness. Even people who rarely worry about this type of ailment can have problems in other countries where the food and spices can be quite different.

Being over-prepared is always better than the alternative, particularly in countries where you do not know the language and you might struggle to explain what you need. It is important to remember that tablets travel better than liquids and gels, especially if you’re flying.

8. Insect Repellant

Don’t forget the insect repellant. Some areas popular as medical tourism destinations also have a lot of insects. It would be a terrible calamity to travel to a country to take care of one medical problem, only to contract another. Some of the diseases spread by insects can be serious and even deadly.

9. Comforts from Home

Pillows, slippers and even bed linens are recommended for medical tourism trips. By having the comforts of home, you won’t have to depend on the hotel or country you are visiting to have what you need. Given the difference in customs and what is considered adequate by another country’s standards, you might be in for a big surprise if you don’t take some extra measures to take care of yourself.

10. Emergency Contact Information

Be sure to have all doctors’ names, relevant phone numbers, and addresses for the hospital, hotel and any other important destination. In countries where you don’t speak the language, you can always show them the address and get some help. Having everything written down in an easily accessible notebook can make life easier.

Travel Companion

Lastly, it is always recommended that you bring a trusted companion with you on your medical tourism trip. Although, you can’t pack them, it is important to bring someone along in case of emergencies. They will also be beneficial to have someone to keep you company during recovery and assist you during the trip back home.

Medical tourism offers many people a viable solution for healthcare as medical procedure costs continue to rise, making it difficult for everyone to afford the care they require. While traveling for a medical procedure solves one problem, it can create others if you aren’t careful when you pack.

Anytime you travel far from home, there is always the chance that something unexpected can happen and you won’t be able to run home quickly and retrieve something you need. Making a checklist ensures that you are prepared for whatever comes your way and that your trip will be less stressful.

About the Author

British Solomon is a contributing writer and media specialist for Bacteriotstatic . She regularly produces content for a variety of health and travel blogs.

Exploring the Surge of Cosmetic Tourism: Trends and Considerations in Aesthetic Procedures Abroad

Holistic healing: exploring integrative medicine and wellness retreats, meeting the surge: the growing demand for knee replacement surgeries and advances in the field, innovations in medical technology: how cutting-edge technology drives medical tourism, stem cells have powerful anti-aging properties, breakthrough stem cell treatment for autism, new shift for thailand’s medical travel landscape as mta launches new moves, continue reading, informed decision-making in medical tourism: the significance of clinical outcome reports, avoiding pitfalls: top 5 mistakes medical tourism startups should steer clear of, reshaping cataract surgery with advanced technology, featured reading, dominican republic’s giant strides to becoming a global leader in medical tourism, exploring niche markets in medical tourism, medical tourism magazine.

The Medical Tourism Magazine (MTM), known as the “voice” of the medical tourism industry, provides members and key industry experts with the opportunity to share important developments, initiatives, themes, topics and trends that make the medical tourism industry the booming market it is today.

- En español – ExME

- Em português – EME

Trip database – a different way to find evidence

Posted on 1st July 2013 by Alice Buchan

The Trip database may at first seem like any other search engine for scientific and medical research – plug your key words into the box, press enter, and watch what comes back. What makes Trip different, is what appears on the results page. Trip originally stood for translating research into practice – which is what it aims to help you do.

Searching Trip

To illustrate this, I’ll start by searching the database, with a topical (at the time of writing [1]) entry: “diclofenac heart” . The most obvious point is that results are colour coded – this is made clear by the toolbar at the side, where secondary evidence, such as systematic reviews, is green, primary evidence red, and so on. The order in which the results appear is what makes Trip unique; their algorithm includes research quality, date (more recent first), and a text score (relevance) [2], which combine to give you relevant, recent, and high quality results first (with a few odd exceptions I’ll come to later).

Colour coded results

Back to my search “diclofenac heart” – the default is to sort with quality as the top priority – but you can also make date or relevance more central to the ordering of results. When sorting by date, this highlights one of the idiosyncrasies of Trip; quality is based on journal or source [2], so a meta-analysis, which is high quality secondary research, (Lancet 2013 in the screen grab) is coded red, for key primary research. This isn’t much of an issue, but worth bearing in mind. Flicking through all 3 sorting options can help you find papers the first one might have missed. Another way of finding more relevant papers is by using the synonyms tab at the top of the search results. You may start your search knowing you want a certain type of evidence, such as a Cochrane review or a set of guidelines, and you can filter using the buttons on the right hand side, which also includes filters for evidence relevant to the developing world.

Filtering the results

As with many other databases, Trip features an advanced search, including the ability to define the proximity of key words within the document, but the PICO search is really unique, and I think it’s a fantastic way of finding what you are interested in quickly. For the uninitiated, PICO is Patients, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome, and the importance of these 4 measures is explained in detail here [3]. Making my search more specific, I searched for heart outcomes in patients with arthritis taking diclofenac.

Searching using PICO

I found Trip really intuitive to use and clearly laid out, but they also have a series of “How-to” videos to help [4] . My favourite features were the wide range of evidence and sources available, including things like guidelines, which aren’t in some other databases, as well as colour-coding.

[1] Trip Database http://www.tripdatabase.com

[2] Trip Database. About Trip http://www.tripdatabase.com/about

[3] CEBM. Asking Focused Questions. http://www.cebm.net/?o=1036

[4] Trip Database. How to use Trip http://www.tripdatabase.com/how-to-use-trip

Alice Buchan

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

No Comments on Trip database – a different way to find evidence

Subscribe to our newsletter.

You will receive our monthly newsletter and free access to Trip Premium.

Related Articles

Epistemonikos: the world’s largest repository of healthcare systematic reviews

Learn more about the Epistemonikos Foundation and its repository of healthcare systematic reviews. The first in a series of three blogs.

How do you use the Epistemonikos database?

Learn how to use the Epistemonikos database, the world’s largest multilingual repository of healthcare evidence. The second in a series of three blogs.

Epistemonikos: All you need is L·OVE

Discover more about the ‘Living OVerview of Evidence’ platform from Epistemonikos, which maps the best evidence relevant for making health decisions. The final blog in a series of three focusing on the Epistemonikos Foundation.

- Call 908-281-0610

- General Inquiries

- Request an Appointment

- Patient Portal

- Search Search for:

- Patient Appointment

- Organization Consultation

What Does a Travel Medicine Specialist Do?

This article was medically reviewed by Dr. Ellen Hirsh.

Travel is on the rise among Americans, and after weathering the COVID-19 pandemic, travelers are especially aware of the health and safety risks that come with vacations or business trips to many popular destinations. But COVID-19 is only one consideration when traveling today, especially abroad. Many travelers may not be aware that they can contract dangerous infectious diseases through contaminated food, water, soil, mosquitoes, and more. Understanding these health risks is only part of the reason to see a travel medicine specialist before traveling internationally, or domestically if you have health conditions that leave you immunocompromised. In this blog, infectious disease physician Dr. Ellen Hirsh of ID Care explains how these doctors help travelers by addressing the question you’ll need to explore as you plan your trip: What does a travel medicine specialist do?

Travel medicine specialists are like medical travel guides who offer advice, preventive measures, and treatments designed to protect your health during every phase of a trip. Infectious disease doctors like those at ID Care can provide more comprehensive guidance than doctors at walk-in travel clinics, who may simply offer a couple of vaccines and send you on your way. Infectious disease doctors are also the best choice when help is needed after a trip, as they have the most experience treating exotic diseases.

Travel medicine specialists are key partners for travelers to consult:

- Before travel, when they evaluate a patient’s health history, immunization records, and travel itinerary and offer detailed recommendations, vaccinations, and medicine to bring along.

- During a trip, when doctors can be available via phone or telemedicine to advise sick travelers or provide guidance if needed.

- After a trip, when these specialists see sick patients returning for care and treatment, although this is less frequent among those who received pre-travel guidance.

“We hate to see someone get sick abroad with a terrible illness that not only ruins their vacation but sets them back in many ways after they get home,” Dr. Hirsh said. “That’s why anyone who is traveling, whether for business or pleasure, should come see us at ID Care before they leave, as opposed to dropping into a more generalized travel clinic or doing nothing at all. This will not only prepare travelers to protect themselves but will give them somewhere to turn for immediate attention if they do get sick.”

Infectious Disease Doctors: The Best Travel Medicine Specialists

Different parts of the world harbor different types of viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites, and while your body may be used to certain pathogens in your native area, it may be very vulnerable to them in distant locations abroad. This is one reason a pre-travel medical consultation is so important.

Infectious disease doctors are the most qualified travel medicine specialists because:

- They understand global health trends , such as which bacteria have become resistant to specific antibiotics that are sold over the counter in some countries. As a result, they are well prepared to diagnose and treat travelers who pick up these germs.

- They can care for patients with complex medical histories. “These patients may need to avoid drug interactions, or they may have a condition that limits the kinds of treatments they can receive,” Dr. Hirsh said. “For instance, people who are allergic to eggs can’t tolerate the vaccine for yellow fever because it contains egg protein. Patients who are immunocompromised also cannot receive the vaccine as it is a live viral vaccine.”

- They are the only physicians with comprehensive expertise about all types of infections, so they are best equipped to guide travelers about infectious disease prevention, along with health risks and treatment options.

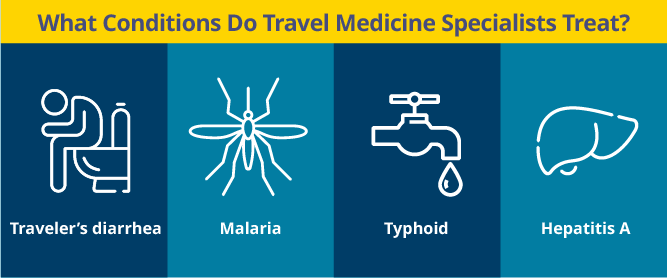

What Conditions Do Travel Medicine Specialists Treat?

An array of diseases pose a threat to people who travel internationally, and travel medicine specialists are comfortable treating all of them. Those most encountered by the travel medicine doctors at ID Care are:

- Traveler’s diarrhea , caused by bacteria, viruses, and/or fungi passed through food or water that are prevalent in parts of Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Mexico, and Central and South America.

- Malaria , caused by a parasite passed via mosquito bites and common in Africa, Asia, and South America.

- Typhoid , caused by the bacteria Salmonella typhi that are transmitted through contaminated food or water and prevalent in parts of Asia, the Middle East, Africa, the Caribbean, and Central and South America.

- Hepatitis A , a virus contracted through food, water, or close contact with an infected person and common throughout the world.

Less common but still a risk are several diseases caused by viruses transmitted by mosquitoes:

- Yellow fever, common in certain parts of Africa and South America.

- Japanese encephalitis , present in some parts of Asia and the Western Pacific.

- Dengue fever, present in many countries in the Americas, Africa, the Middle East, Asia, and the Pacific Islands.

- Chikungunya, present in countries within Africa, Asia, and the Americas, and on islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

Who Should See a Travel Medicine Specialist?

As you prepare for your trip, you might wonder if you really need to reserve time to see a travel medicine specialist. Anyone traveling internationally does, especially if the destination is a developing country, a safari, or any place considered exotic – all popular travel destinations.https://idcare.com/blog/a-safety-guide-for-international-travelers/

“Special notice should also be taken by those who have moved to the U.S. but are paying a visit to family or friends in their native country, because the feel familiar with the area and thus immune, but they are not. It’s easier for these individuals to take one pill a day to prevent malaria than to come back sick,” said Dr. Hirsh.

In addition, people who are immunocompromised should see a travel medicine specialist before taking a trip anywhere, as they face a higher risk of contracting an infection.

“People who are immunocompromised may face concerns when going to different areas of the U.S., as certain infections are endemic to specific areas,” Dr. Hirsh said. “There are some fungal infections that are seen only in the Four Corners area in the Southwest, while others are seen only in the Midwest Ohio area. And of course, Lyme disease is often seen in New Jersey, but may be much less likely in other parts of the country.”

When to Book a Travel Medicine Appointment

It’s not too late to see your travel medicine specialist even if it’s the day before a trip, but “it takes two weeks to make full antibodies in response to many of our vaccines and some vaccines require a series of shots, so we like to see you around two months before your trip,” Dr. Hirsh said.

It is recommended that people bring their health and immunization records as well as a detailed itinerary to the appointment, as this information is crucial in determining what kind of care and travel guidance they will need.

The Goals of a Pre-Travel Appointment

During a pre-travel appointment, your travel medicine doctor will ask the details of your trip and anticipate the diseases that could be of concern. In addition, the doctor will assess your health and immunization history, including drug allergies; offer preventive vaccines and advice; and prescribe medications for diseases you may contract while away.

“We are an internal medicine-based field, so we look at everything you need, from head to toe, and advise accordingly,” Dr. Hirsh said.

Evaluating Your Itinerary

In asking about your itinerary, a travel medicine specialist will want to know:

- Timing of the trip. Whether you are visiting a country during its wet or dry season can shed light on the level of concern related to mosquitoes or ticks.

- Altitude of the destination. This can indicate the likelihood of mosquito-borne diseases or altitude sickness.

- Mode of travel. Travel medicine doctors can prescribe medications in advance for motion sickness on planes or ships.

- Activities planned . Handling animals, visiting bat caves, or traveling through an area by bicycle — which can lead to encounters with dogs — may open the door to diseases such as rabies . Meanwhile, spending time in a rural area, where there may be more mosquitoes, could increase the risk of Japanese encephalitis.

- Typical level of food and water safety in the target area. For people not local to an area, the germs that live in food and water can cause illness, even at a five-star hotel. If that problem is likely, the doctor will recommend measures such as drinking only bottled water and remembering not to use tap water when brushing teeth.

- Prevalence of polio in the destination country. Three countries still have active polio cases and others continue to use an oral polio vaccine that can transmit the disease, so travelers planning visits can benefit from a preventive booster.

Vaccines and Other Medications

Based on a traveler’s trip itinerary and health history, travel medicine doctors can determine whether a patient needs preventive measures and care. These often include vaccines given in advance of a trip and medicines to bring along in case of illness.

Vaccines might be designed to protect against diseases in the destination region, such as typhoid, yellow fever, or cholera, or to ensure compliance with standard U.S. immunizations that the patient never received or is due to repeat, which protect against conditions such as diphtheria, tetanus , shingles , and hepatitis A.

“The preventive vaccine for yellow fever, previously recommended every 10 years for travelers, is now given once as a lifetime dose,” Dr. Hirsh said. “Better yet, while not every practice is licensed to give that vaccine, ID Care offers it. This is crucial, because travelers need to show certification that they’ve had the vaccine in order to travel in and out of certain countries. We are fortunate to carry all the travel-related vaccines that are available in the U.S. at all 10 of our locations, and we can give them onsite the day of a patient’s appointment.”

Travel medicine specialists might also prescribe:

- Preventive medications such as pills to prevent malaria.

- Antibiotics that target a disease the traveler may encounter, such as traveler’s diarrhea, along with instructions for when and how to use them.

- Altitude or motion sickness

- Medication to assist with sleep when adjusting to a new time zone.

Good Advice: The Other Preventive Medicine