Brochures | Price Lists and Values | Trek History | Trek Timeline | Serial Numbers Component Dates | Gallery | Contact | Buy/Sell Suggestions Refurbish/Upgrade | Bike Resources | Home

*Trek is a trademark of Trek Bicycle Corporation, Waterloo, WI

All copyrights in the TREK brochures, pricelists, owner's manuals and photographs displayed on this website are the sole property of Trek Bicycle Corporation, Waterloo, Wisconsin.

All materials in this site not copyrighted by others are Copyright © 2001-2015 Skip Echert Web Associates , All rights reserved.

- ALL MOUNTAIN

- ACCESSORIES

- ALL (130 Forums)

- WHEELS & TIRES

Trek 800 Bike Bike 1998 or Older

- USER REVIEWS

The bike is super reliable. The only issue we have ever had is the brakes need adjusting, and maybe the rims, but that is to be expected on a 25 year old bike.

The v brake setup needs to be adjusted because they will slowly move back and forth and sometimes rub on the rim.

Our Trek Antelope 800 was a wedding gift that my parents purchased when they got married, they got it as a Christmas present. Our 1993 Antelope 800 has over 6,000 miles on it, and is still rolling. Trek bicycles are built for quality and reliability, and I will be keeping my Antelope 800 for years to come. I am purchasing an 820 in December, and I am so excited for the matte black color. By the way, the green on the Antelope is awesome!

Dependable, smooth, easy to look at.

non from my point of view

My grandfather bought this bike new in 96' gave it to me in 98' to take to college. I have been riding it ever since. The only thing I have ever replaced are tubes and tires. I changed out the old knobby tires for some smooth road tires. Always shifts smooth and rides straight. I have always kept it in a garage or basment. No rust at all. I just took it into the trek store for its first ever tune up, cleaning and lube in 15 years. It now looks and rides like it is brand new. I thought about upgrading to a new Trek FX 7.1, but this bike just rides so nice I cant do it and after 15 years I have become a little attached. Best Bike i have ever owned. It would have to be destroyed or stolen for me to get a new one. This is a very solid well built bike. Thanks for the 15 years of fun Trek, looking forward to 15 more.

I like my Trek Antelope 800. It was bought in 1991 and now it's 2012. The bike frame is tough and many people who know about bikes have all commented on the excellent welding job and how it's not visible. My bike has endured a house fire and all the rubber and plastic pieces had to be replaced. I live in Montreal Canada and i ride all year round, summer and winter. In 1991, the store was saying the bike usually sells for $800. but we bought two because they were having a sale and were selling each bike for half price at $400. This bike has been to hell and back. I wore out the derailleur and front crank twice. I am on my third chain. I wore out the hand grips twice. Both wheels had to be replaced because the bearings were finished and the wheels got warped after years of hard riding. I bought higher handle bars because i dislike the high-seat low-handle bars idea. I put fenders on the bike and a rack in the back for saddle-bag and i use it for shopping and everything.

The only weakness i can think off were the forks that had to be changed once. What had happened is i saw a cute woman and i was not looking where i was riding and a i hit a car bumper waiting at a red light. I wasn't going fast at all but the result was that my front tire was touching the frame after the hit. Another time, the goose neck cracked inside. But these two incidents happened only after i had the bike for year and years. The gear changer for the crack side of the gears just recently lost it's 1 2 3 dial, but the gears still change alright. The bike is much lighter than most CCM and Supercycle bikes.

Great bike for 1991.I am sure there are better bike nowadays but i see the welding is very noticeable on most bikes i look at these days.

Strong Frame, Good Quality Components, Nimble Handling

No Suspension

I bought this bike in 1997 and got a discount off of the MSRP. I rode the S?$# out of this bike on the forest preserve trails for 5 years, and then stored it for 8 in my unheated garage. When I pulled it out to start getting some exersise again, all it needed was a good cleaning, air in the tires, and some minor adjustments. Wanted a suspension bike since I am getting older (50) and picked up a 1997 Y5 cheap. Gave the 800 Sport to my sister and she is still riding it.

Similar Products Used:

1997 Trek Y5

Great basic entry level mnt bike, i use them for motorbicycle projects

no mounting points for disk breaks, needs a little mod's for wider nuvinci drive axel

WICKED compatible bike for hard core project thiends.

Great solid well built bike. Quality components ie Shimano derailers and gear sets.

A bit heavy. Tire noise on the street (that's a mountain bike)

I bought this bike new in 98". The first thing I did was swapped out the front forks for a ROCKS SHOX and a Schwinn head clamp (to make it work) and narrower bar. If I remember correctly it all came out an inch forward and an inch lower. I had no problems commuting up very steep long hills or playing around on novice single tracks or 20 mile jaunts with the mud tires howling the whole way. Fast forward 8-9 years after a couple kids, and letting the bike set out in a barn for most of a decade, took the bike in for lube and service and installed some slicks (not sure the brand) I am very excited to ride this thing with road tires. All cleaned up this thing still looks in fact brand new! Anyone who wants to buy the JEEP of bikes should seriously look at the TREK800. Only bike I will ever have to buy.

BMX bikes. Wifes Schwinn (really smooth), TREK 8300 (?) friends bike, lighter and more expensive

I had my trek antelope 800 since 1993 and it still rides great! It holds up well in all types of weather.I had the bike for 17 years and the frame is still solid!Make sure you maintain the bike and it will last for ever...

The trek antelope 800 has 21 speeds, wish it had more!!

If you want to get your money worth on a bicycle get the trek antelope 800 P.S. Not sure if Trek still makes this model

Good and strong I have wrecked off a 10 foot cliff I picked it up and rode away with only minor scraches of the paint the weight is a part I like also I like a little weight when I'm riding it makes the bike more stable

None that I have found

It is a great bike sturdy enough to fall 10 feet and nimble enough to go on tight and windy trales I normaly ride dirt bikes and I love doing that but I needed a good way to have fun with friends and famly I love my bike if ur just starting to ride mountain bikes this is the best bike for it's price level. Don't buy it if u don't have a good back because it dosent have front shocks

This is my first nice bike I used wal mart bikes 4 a long time

Do damping forks or daming on seats

luv it, used it for 13 years (since 1997) it is perfect.

Solid - Simple - Sturdy - Stupendous!

Front suspension would be nice. Handlebars should extend higher. Could use a larger main sprocket (3rd).

Had for 14-15 years! I've replaced tubes, tires, and brake pads. That's it! I've given it a lube job 3 times. Performs flawlessly. I will replace the fork/yoke bearings this year though, they have finally worn out. It is faster than the other 3 "good" bikes we have, but high gear is not high enough. It's perfect for flat road with no wind, but if there is a tail wind or a downgrade, I can't pedal fast enough. I do miss the speed of my old schwinn road bike (1982), but for the second bike i've ever owned, I won't complain. I would really like a sprung fork... I'm going to see if I can fit one. If I can, I'll keep it another 15 years. And maybe 15 more after that.

$350-500 mtb's from bike shops. Front only, or full susp.

Get the latest mountain bike reviews, news, race results, and much more by signing up for the MTBR Newsletter

Hot Deals See All Hot Deals >>

- CLASSIFIEDS

- TERMS OF USE

- PRIVACY POLICY

- ADVERTISING

VISIT US AT

© Copyright 2024 VerticalScope Inc. All rights reserved.

Trek 800 (A Detailed Review)

First introduced in 1987 and produced until 2003, the Trek 800 is a classic mountain bike that has stood the test of time. While it may not have all the bells and whistles of modern bikes, the Trek 800 is a great option for entry-level riders or those on a budget.

One of the standout features of the Trek 800 is its 21-speed drivetrain, which allows for smooth and efficient shifting. With a broad gear range, you can easily navigate diverse terrain and find the pedaling speed that suits you best.

The bike’s rigid steel frame with a TIG-welded design also provides a comfortable ride, even on rough roads or steep inclines. Additionally, the Trek 800 came equipped with reliable components such as Shimano parts, making it a great choice for cruising any terrain.

Key Takeaways:

- Classic Mountain Bike Choice: The Trek 800 is a classic mountain bike that has been around for decades, known for its durability and reliability.

- Standout Features: The bike’s standout features include a 21-speed drivetrain, allowing smooth shifting, and a rigid steel frame for a comfortable ride on various terrains.

- Versatile All-Terrain Bike: Designed for entry-level riders and experienced ones alike, the Trek 800 is suitable for different terrains like dirt, gravel, and pavement due to its comfortable riding position and suspension fork.

- Affordable Quality: Priced around $300, the Trek 800 offers good value for money, thanks to its high-quality components and durable steel frame.

- Commute and Mountain Riding: The bike’s design and components make it suitable for both commuting and mountain biking. It offers a comfortable ride, wide tires for traction, and powerful brakes.

- Durability and Quality: The Trek 800 is built to withstand rough terrain with its high-quality steel frame and reliable components. It’s a durable choice for various skill levels.

- Maintenance and Accessories: Regular maintenance tips include pre-ride checks, cleaning, tire pressure checks, lubrication, brake and gear maintenance, and proper storage. The bike also comes with accessories to enhance the riding experience.

Overview of Trek 800

The Trek 800 is a popular mountain bike that has been around for over three decades. It is a part of the Trek 800 bike family that includes different variations, such as the Trek 800 Sport, Trek 800 Antelope, and Trek 800 Mountain Track. The bike is designed for entry-level riders who want to get into mountain biking or for more experienced riders who are looking for a secondary bike.

One of the standout features of the Trek 800 is its durable and reliable frame. It is made of high-quality steel that can withstand rough terrain and harsh weather conditions. The bike also features precise gearing that allows for smooth and efficient shifting, making it easier to climb hills and navigate through tricky trails.

The Trek 800 is an all-terrain bike (ATB) that is suitable for a variety of different terrains, including dirt, gravel, and pavement. It has a comfortable and upright riding position that reduces strain on your back and neck, making it ideal for long rides. The bike also comes with a suspension fork that absorbs shocks and vibrations, providing a smoother ride.

If you are looking for an affordable mountain bike that is still high quality, the Trek 800 is a great option. Its retail price is around $300, which is reasonable considering its features and durability. With proper maintenance, the Trek 800 can last for many years, making it a great investment for anyone who loves mountain biking.

Features and Specifications

When it comes to features and specifications, the Trek 800 mountain bike offers a great balance of quality and affordability. In this section, we will take a closer look at the various components that make up this bike.

Frame and Construction

The Trek 800 features a sturdy steel frame, which is known for its durability and strength. The frame is tig-welded, ensuring a solid construction that can withstand the wear and tear of regular use. Additionally, the bike’s design is simple yet stylish, making it a popular choice for both beginners and experienced riders.

Wheels and Tires

The Trek 800 comes with 26-inch wheels, which are a common size for mountain bikes. The tires are designed to provide a comfortable ride on a variety of terrains, from smooth pavement to rocky trails. The bike’s wheels and tires are also available in a range of colors, allowing you to customize your ride to your liking.

Brakes and Gears

The Trek 800 features an aluminum linear-pull brakeset, which provides reliable stopping power in a variety of conditions. The bike also comes with a 7-speed or 21-speed drivetrain, depending on the model you choose. The shift levers and rear derailleur are typically made by Shimano or SRAM, with models like the Shimano C051 and SRAM 5.0 being common choices.

Comfort and Design

The Trek 800 is designed to provide a comfortable ride, with features like a cushioned saddle and ergonomic handlebar. The bike also comes with a suspension fork, which helps absorb shocks and bumps on the trail. The seatpost is adjustable, allowing you to find the perfect riding position for your body type.

Performance and Versatility

The Trek 800 mountain bike is a versatile bike that can handle various terrains, from smooth pavement to rough trails. Its sturdy steel frame and reliable components make it a powerful bike that can handle the rigors of mountain biking and commuting alike.

When it comes to mountain biking, the Trek 800 is a great entry-level bike. Its precise gearing and reliable performance make it easy to handle on rough terrain. The bike’s powerful brakes provide excellent stopping power, which is essential when navigating steep descents. With its sturdy frame and reliable components, the Trek 800 can handle the bumps and jolts of rough trails with ease.

For commuting, the Trek 800 is a reliable and versatile bike. Its sturdy frame and comfortable seating position make it ideal for long rides on rough roads. The bike’s wide tires provide excellent traction on a variety of surfaces, from smooth pavement to gravel paths. With its reliable components and powerful brakes, the Trek 800 is a great choice for commuting in all weather conditions.

The Trek 800’s versatility doesn’t end there. It’s a great multi-terrain bike that can handle a variety of surfaces, from paved roads to light off-road trails. The bike’s wide tires and sturdy frame make it a great choice for exploring new paths and taking on new challenges. Whether you’re cruising through the city or exploring the countryside, the Trek 800 is a reliable and versatile bike that can handle it all.

Durability and Quality

When it comes to durability and quality, the Trek 800 mountain bike is a great choice. The bike is made of high-quality materials, which gives it a long-lasting and durable frame. The frame is made of steel, which is known for its high tensile strength, making it a sturdy and reliable option for riders of all skill levels.

The Trek 800 mountain bike is designed to take on rough and challenging terrain with ease. The bike’s durable frame can withstand the wear and tear of the toughest trails, making it a great option for those who want a bike that can handle anything.

In addition to its sturdy frame, the Trek 800 also features high-quality components that are designed to last. The bike’s gears and brakes are made of durable materials that can withstand heavy use, ensuring that the bike remains reliable and safe to ride for years to come.

Affordability of Trek 800

If you are looking for an affordable mountain bike, the Trek 800 is a great option. With its affordable price, you can get a high-quality bike without breaking the bank. The Trek 800 is perfect for entry-level riders who want to get into mountain biking or for more experienced riders who are looking for a secondary bike.

At a retail price of around $300, the Trek 800 is an excellent value for money. It is one of the most affordable mountain bikes on the market, making it accessible to a wide range of people. The low price does not mean that the bike is of low quality, though. The Trek 800 has many features that make it a great choice for anyone on a budget.

One of the reasons why the Trek 800 is so affordable is that it features a rigid fork, which is less expensive than a suspension fork. While a suspension fork can provide a more comfortable ride on rough terrain, a rigid fork is more than adequate for most riders. It also means that there are fewer moving parts to maintain, which can save you money on repairs in the long run.

Another way that the Trek 800 keeps its price down is by using a steel frame instead of an aluminum one. While aluminum frames are lighter and more expensive, steel frames are more durable and can handle more abuse. The Trek 800’s steel frame ensures that it can withstand the rigors of off-road riding without breaking the bank.

Components and Accessories

When it comes to components and accessories, the Trek 800 mountain bike has a lot to offer. Let’s take a closer look at some of the key features.

The Trek 800 comes with a range of high-quality components designed to enhance your riding experience. The bike features a crankset that is both lightweight and durable, allowing you to power through tough terrain with ease. The headset is also of high quality, providing a smooth and stable ride.

In addition, the Trek 800 comes with a set of pedals that are designed to provide great traction and control. You can choose between plastic pedals or nylon platform pedals, depending on your preferences.

The hubs on the Trek 800 are another standout feature. They are built to last, with stainless steel spokes that provide excellent strength and durability. This means you can ride with confidence, knowing that your bike is up to the task.

Accessories

When it comes to accessories, the Trek 800 has everything you need to hit the trails. The bike comes with a range of accessories designed to make your ride more comfortable and enjoyable.

One of the standout accessories is the bike’s suspension system. This system is designed to absorb shock and provide a smoother ride, even on rough terrain. This means you can ride for longer without feeling fatigued.

The Trek 800 also comes with a range of other accessories, including a water bottle holder, a kickstand, and a rear rack. These accessories are designed to make your ride more convenient and practical.

Maintenance and Care

Maintaining your Trek 800 is essential to ensure that it remains in good condition and lasts for a long time. Here are some tips to help you keep your bike in top shape:

- Pre-ride check: Before every ride, perform a quick check of your bike’s performance. This will give you an idea of what adjustments you need to make before riding and what may require a deeper look.

- Regular cleaning: Clean your bike regularly with a rag or soap and water if it’s too dirty. Inspect the frame and components for signs of wear, such as cracks. Clean and wax the frame to protect the paint/finish (not necessary on bare titanium frames).

- Tire pressure: Check your tire pressure regularly and add air if needed. Proper tire pressure ensures a smooth and safe ride.

- Lubrication: Lubricate your bike’s chain and other moving parts regularly to keep them running smoothly and prevent rust. Use a bike-specific lubricant for best results.

- Brakes: Check your brakes regularly to ensure they are functioning properly. Replace worn brake pads and adjust the brake cable tension as needed.

- Gears: Keep your bike’s gears in good condition by regularly cleaning and lubricating the chain, derailleur, and cassette. Adjust the gears as needed to ensure smooth shifting.

- Storage: Store your bike in a dry, cool place to prevent rust and damage. Use a bike cover to protect it from dust and debris.

FAQ: Trek 800

What is the difference between trek 700 and 800 carbon.

The Trek 700 and 800 carbon bikes are both high-end road bikes, but the Trek 800 is a step up from the 700 in terms of features. The Trek 800 has a lighter frame, better components, and a more advanced carbon fiber construction.

What type of bike is a Trek 800?

The Trek 800 is a mountain bike that is designed for off-road use. It is a versatile bike that can be used for a variety of activities, including trail riding, commuting, and leisurely rides around town.

What year was the Trek 800 made?

The Trek 800 was first introduced in the 1990s and has since become an iconic bike in the mountain biking community. However, the specific year of production may vary depending on the model and edition.

What are the features of the Trek 800 Antelope?

The Trek 800 Antelope is a classic model of the Trek 800 series. It features a lightweight steel frame, 21-speed Shimano gearing, and a suspension fork for a smooth ride. It also has a comfortable saddle and a range of accessories, including a kickstand and water bottle holder.

What is the price of the Trek 800 Sport?

The price of the Trek 800 Sport can vary depending on the location and the condition of the bike. However, it is generally considered to be an affordable option for a high-quality mountain bike, with prices ranging from $100 to $500.

Is the Trek 800 a good mountain bike brand?

The Trek 800 is a reputable and reliable brand of mountain bikes that has been popular among riders for decades. While it may not have all of the latest features and technologies, it is known for its sturdy construction, wide gear range, and affordable price point.

Continue Reading…

- Specialized vs Trek (Brand Comparison)

- Trek Crossrip 2 (A Comprehensive Review)

- Trek X-Caliber 7 (A Detailed Review)

- Trek FX Sport 5 (Analyzed)

Andre Neves

I've been riding bikes for 30 of my 35 years. Nothing gives me more pleasure than grabbing my Enduro bike and take on the mountains. Learn more about me here.

1992 Trek Bikes 800 Base

Trek 800 Antelope

Commuter/touring bike. Cro-moly frame 1992. Nothing special, but it's a pretty bomb-proof bike

Frame: 4130 Cro-Moly, double butted

Fork/Headset: Stock/ Cro moly

Crankset/Bottom Bracket: FSA Comet Triple, 44/34/22, external bearing BB

Pedals: Shimano PD-M545 clipless w/ platform

Drivetrain/Cog/Chainring/Chain: 11-32 SRAM 9 speed Cassette, SRAM PC-971 9 speed chain

Derailleurs/Shifters: Shimano CX60 FD, Shimano XTR 90's RD, Shimano bar end shifters (9 speed)

Handlebars/Stem: anatomic drop bars, Cannondale 90mm stem (unknown rise)

Saddle/Seatpost: WTB Speed V saddle, Titec 26.8mm

Brakes: Tektro CR720 centerpull cantilevers, Tektro A200 levers, Kool Stop Salmon pads

Front Wheel/Hub/Tire: Cheap JoyTech hub laced to a cheap rim, double wall 36h, 4 cross, lacing Schwalbe Marathon Pro 26x1.5

Rear Wheel/Hub/Tire: Avenir Joytec/Weinmann XC-260 36H, 3 cross lacing, JoyTech hub Schwalbe Marathon Pro 26x1.5

Accessories: Planet Bike Blaze 650 XLR (front light), Planet Bike SuperFlash Stealth (rear light) , Bontrager rear rack, occasionally I'll take off the SKS fenders.

More Info: This bike is mine.

Added over 10 years ago by JoWilson . Last updated about 8 years ago.

40degreerake says:

Don't let your antelope.

Posted almost 7 years ago

4130 , 56cm , commuter , cro-moly , steel , tektro , trek

- View JoWilson's Profile

Antelope of the Now: Trek 800

Trek Antelope 800, gold, 42 cm, 15 speed, 26″ wheels, quick release seat & front wheel, new Kenda Kwest tires, center pull brakes, Shimano Alivio derailleur in back, SunTour α 3000 derailleur in front. $300

Trek has a reputation for being both sturdy & nimble; this mountain bike has the additional attraction of an eye-catching shade of gold/yellow very close to National School Bus Glossy Yellow . So you’ll be visible & stylish in traffic or plummeting down the slopes. Some other grace notes distinguish this ride: note the clean drive train & the classy chrome shield protecting the right chain stay.

Our research has revealed that this model has horizontal pupils, even-toed heels & a ruminating gut.

Cycling made Simple.

Made By Cyclists

Trek 800: All in One Review

September 15, 2023

Key Takeaways

- Versatile and durable, the Trek 800 is a reliable all-terrain bike for various riding styles.

- Its comfortable design and adjustable features make it suitable for many riders.

- Its safety innovations enhance performance and the rider’s safety in various terrains.

This article may contain affiliate links where we earn a commission from qualifying purchases.

Here’s the ultimate Trek 800 review! It addresses all your questions and concerns. This is to help you find your perfect ride with our comprehensive analysis!

The Trek 800 is a proper bike that offers a combination of simplicity, sturdy construction, and reliability at an affordable price point. It features a rigid steel frame with a TIG-welded design, 21 speeds, and reliable Shimano components, allowing riders to tackle various terrains confidently.

To provide a comprehensive and authoritative analysis of the Trek 800, I’ve thoroughly researched credible sources, testimonials, and expert opinions in the cycling world. I’ll equip you with the relevant information you need to make an informed decision as you venture into the exciting world of mountain biking. With my personal experience, knowledgeable approach, and unbiased perspective, I’ll guide you toward the best bike for your needs.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Trek 800 History

By 2003, the Trek 800 had already established a reputation for its durability, reliability, and affordability. It was designed as an entry-level mountain bike with a strong and long-lasting frame, making it suitable for various terrains and conditions.

The 2003 Trek 800 showcased major improvements in components and design, catering to the evolving needs of mountain bikers.

Materials and Design

In this all-in-one review of the Trek 800, we’ll cover its materials and design. We’ll focus on its frame types, color variations, and other essential components.

Frame Types

The Trek 800 is designed with a rigid steel frame that provides durability and strength for a comfortable riding experience. For those who prefer a lighter option, there is also a version of this bike with a lightweight aluminum frame.

The steel frame is made from high-quality materials like stainless steel and cro-moly frame, ensuring the bike remains sturdy and resistant to damage despite its low-cost construction.

The rigid steel frame and TIG-welded design of the Trek 800 provide a powerful and comfortable ride, even on rough roads or steep inclines and bumps. On top of that, the reliable components, such as 21 speeds and Shimano parts, make this bike versatile enough to cruise through any terrain.

The Trek 800's well-rounded design is praised for its durability and affordability, making it a great choice for an entry-level mountain bike.

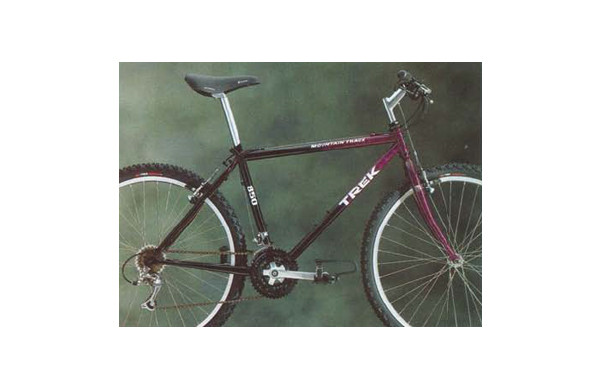

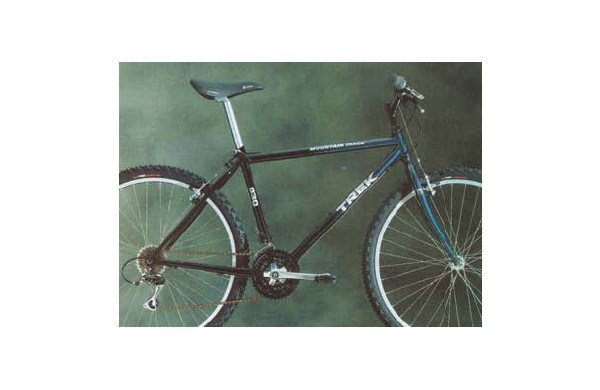

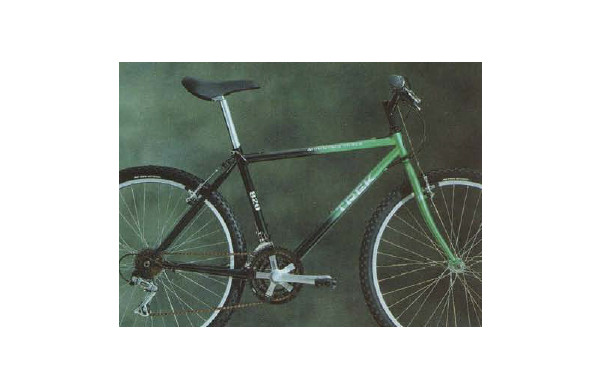

Color Variations

The Trek 800 offers a variety of color options to suit the personal preferences of every rider, with different combinations of frame, fork, and component colors and paint options. Some available colors include classic black, vibrant red, and cool blue shades.

Components and Specifications

In this section, we'll dive into the details of the Trek 800's components and specifications. This all-in-one review will focus on the bike's brake and suspension systems, touching on aspects like Shimano components, gear shifters, tires, and more.

Brake System

The Trek 800 employs an alloy pull cable braking system, which provides adequate stopping power for most riders. These brakes are reliable and relatively easy to maintain, making them a good choice for an entry-level bike.

While they may not be as powerful as disc brakes, the new cables offer a more than sufficient stopping ability for tackling diverse terrains.

Suspension System

One key aspect of the Trek 800 is its rigid fork suspension system, which sets it apart from more advanced bikes like the Trek 4300 . The rigid fork offers a simple design, contributing to the bike's overall durability.

Additionally, the Trek 800 comes with 26-inch wheels, providing an agile and smooth ride. These wheels have spokes that connect to the outer rim and a chain that transfers power from the rider’s pedaling to the rear wheel.

The suspension system may be less sophisticated than bikes with more advanced shocks. Still, it remains a reliable and efficient setup for those just starting in the world of mountain biking.

Performance and Comfort

The Trek 800 MTB offers an impressive blend of performance, riding comfort, and capability suitable for riders of different skill levels. We’ll discuss its performance and comfort, focusing on its riding comfort and the bike's capability.

Riding Comfort

The Trek 800 provides a comfortable ride for its users. Its suspension system is designed to handle various terrains, ensuring the cyclist experiences smoothness even when surfaces get rough.

In addition, this bike offers a padded saddle, ensuring a comfortable ride for beginners and more experienced riders.

Bike's Capability

When it comes to the bike's capability, the Trek 800 is known for its reliable performance. This bike's quality frame and rigid fork ensure durability and stability on the trails.

Another noteworthy feature is the use of resin components that contribute to the bike's overall lightweight design, enhancing maneuverability and speed. With these attributes, it's evident that the Trek 800 can handle the demands of various cycling scenarios while maintaining rider comfort.

Value and Affordability

In this section, we'll discuss the Trek 800, its value and affordability, and how it compares to older bikes in its price range.

Comparison with Other Bikes

To help you compare the Trek 800 with other bikes in its class, here’s a detailed table:

Price Range

The Trek 800 comes at an approximately $300 retail price, making it an affordable and practical choice for many biking enthusiasts. Its simple yet effective design and reliable performance ensure riders get value for their money, particularly beginners or those looking for a secondary bike.

Compared to other bikes in the market, the Trek 800 is a cost-effective option, providing a wide gear range and a sturdy steel frame. The low price of the Trek 800 makes it an attractive choice, proving that high-quality and affordability can indeed go hand in hand.

Advantages of Trek 800

The Trek 800 is known for its simplicity, quality frame, and reliability. The bike is durable, holding up to three times more than your average road bike.

This durability allows you to take longer trips and ride in extreme weather conditions without breaking down. With its smaller wheel sizes, the Trek 800 offers better maneuverability and easier acceleration, making it a great entry-level bike for men and women.

Disadvantages of Trek 800

While the Trek 800 has earned a reputation for its durability and reliability, there are some drawbacks to consider.

Although its tire width provides better agility, it can limit your ability to roll over larger obstacles when riding off-road. Additionally, the Trek 800 mountain bike might not be suited for those seeking a good bike with advanced specifications.

Different Trek 800 Models

When it comes to the Trek 800 series, various models are available to suit different preferences and needs. We’ll focus on two popular models from this brand - the Trek 800 Antelope and the Trek 800 Sport.

These bicycles come with unique features designed to cater to different types of cyclists, so we'll examine each of them in detail.

Trek 800 Antelope

The Trek 800 Antelope has garnered a reputation as a durable and reliable mountain bike among riders. A key reason for its popularity is its high-tensile strength frame, built to withstand harsh outdoor conditions while maintaining optimal comfort levels during rides. This model offers the following features:

- Strong steel frames for enhanced durability

- Rigid front suspension forks for improved stability on rugged terrain

- High-quality Shimano components and a rear derailleur for smooth gear shifting

- Large cargo capacity, making it suitable for backpacking trips

Trek 800 Sport

The Trek 800 Sport model is designed for riders who desire a versatile bike that can handle various cycling activities. It’s equipped with numerous features that provide an enjoyable and comfortable experience on various terrains, including:

- Lightweight aluminum frame for improved maneuverability and speed

- Suspension forks for better handling on bumpy roads

- A gear shifter to cater to different riding styles and conditions

- Disc brakes for consistent stopping power in all weather conditions

Cycling Safety Innovations of Trek 800

The Trek 800 is an all-in-one versatile bike that has gained popularity among cycling enthusiasts for its ruggedness and dependability. In this section, we'll delve into the safety innovations that set the Trek 800 apart from its competitors, making it an excellent choice for riders who value exceptional design and reliable performance.

Starting with its build, the Trek 800 is designed with a TIG-welded Chromoly frame that offers lightweight properties and resistance to rust, ensuring the bike's longevity, especially while riding on an uneven Trek mountain track. This lightweight frame contributes to better handling and maneuverability, enhancing the rider's safety.

Also, the Trek 800's braking system adds to its safety advantage. Power while descending or stopping on slippery surfaces is crucial, and the Trek 800 provides riders with effective and reliable braking that instills confidence and security on unpredictable trails.

Furthermore, the Trek 800 has Bontrager Connection tires, which have excellent traction on various surfaces. This ensures proper grip and stability while cycling, thus reducing the risk of accidents and enhancing the overall safety of the rider.

Why Road Cyclists Are Switching to Gravel Bikes

Why Fitness Enthusiasts Are Switching to Smart Cycling Trainers

Why Competitive Cyclists Are Switching to Aero Road Bikes

Why Eco-Conscious Riders Are Switching to Bamboo Bikes

About THE AUTHOR

Danny Lawson

Mountain biking is more than just a hobby for me - it's a way of life. I love the challenge and excitement that comes with it, and I'm always pushing myself to go faster and ride harder. Some people might think that mountain biking is dangerous, but I see it as the only way to live.

Trending Now

Why City Dwellers Are Switching to Folding Bikes

Why Budget-Conscious Riders Are Switching to Co-op Bike Brands

Why Mountain Bikers Are Switching to Fat Tire Bikes

Why Urban Commuters Are Switching to Electric Bikes

About PedalChef

PedalChef is a blog on all things cycling. We are a group of people who love bikes, and we want to share the joy that comes with the experience. You can read more about us here .

©2024 PedalChef. All rights reserved.

We can be reached at [email protected]

PedalChef.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs, and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies.

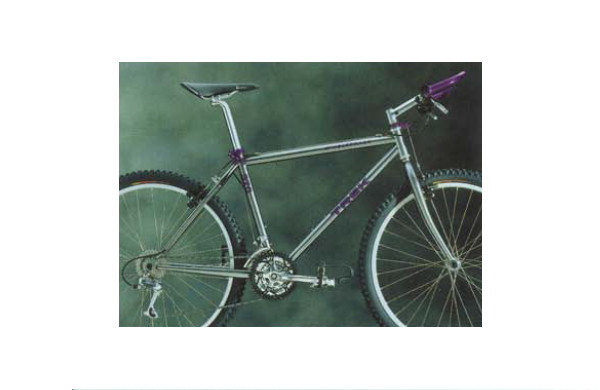

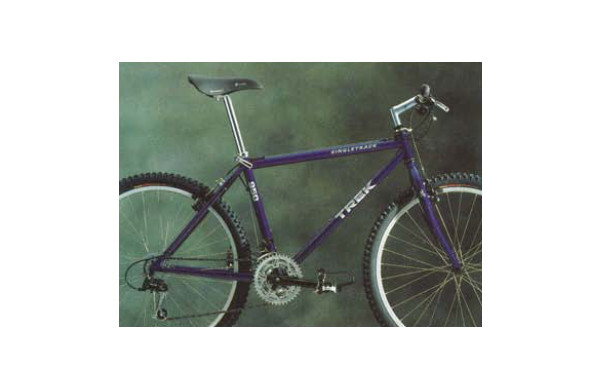

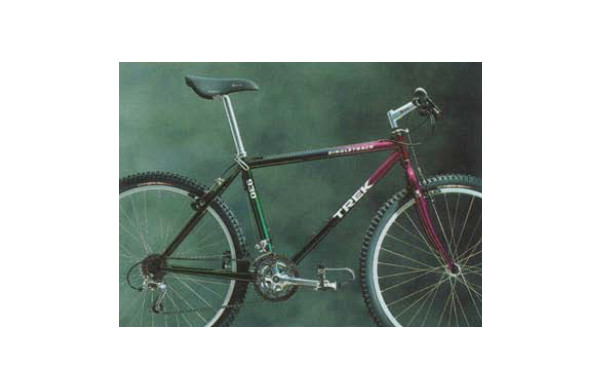

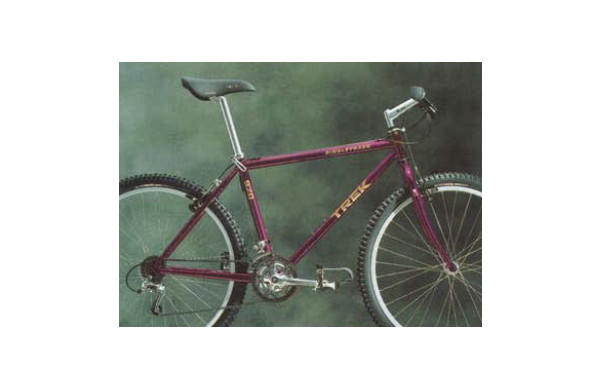

90s Trek MTBs - Steel frames, rigid forks, 26" wheels

Full list of steel, rigid fork mountain bike models Trek made between 1990 and 1999, grouped by year, containing details on frames and main components for easy reference.

Based on riding style, build level and performance, Trek offered these in two series. The 9XX series , called Single Track , consists of a range of race, competition and performance bikes, aimed at pro riders and serious off-road enthusiasts. The 8XX series , called Antelope until 1993 and Mountain Track from 1994, covers a range of multipurpose models, from commuting and recreation to trail and light mountain biking.

1990 View catalog

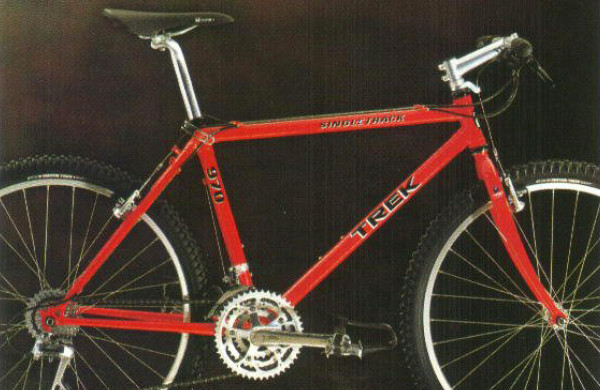

Trek 990 Single Track (1990)

Trek 970 Single Track (1990)

Trek 950 Single Track (1990)

Trek 930 Single Track (1990)

Trek 850 Antelope (1990)

Trek 830 Antelope (1990)

Trek 820 Antelope (1990)

Trek 800 Antelope (1990)

1991 view catalog.

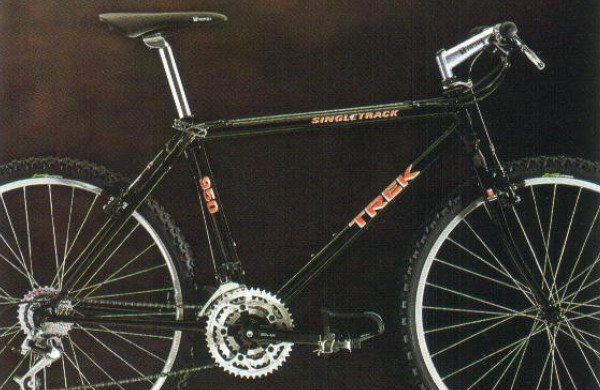

Trek 990 Single Track Competition (1991)

Trek 970 Single Track Competition (1991)

Trek 950 Single Track Performance (1991)

Trek 930 Single Track Performance (1991)

Trek 850 Antelope Performance (1991)

Trek 830 Antelope Mountain Sport (1991)

Trek 820 Antelope Trail Performance (1991)

Trek 800 Antelope Sport Trail (1991)

1992 view catalog.

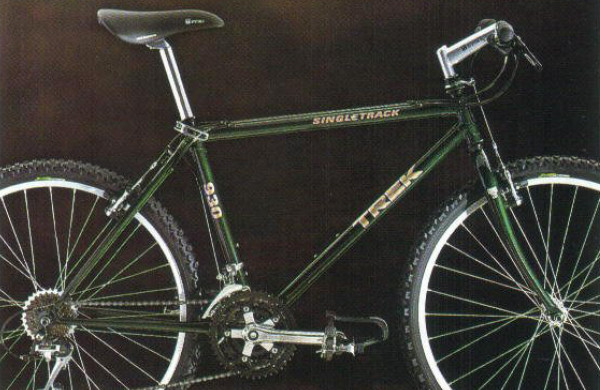

Trek 970 SingleTrack Competition (1992)

Trek 950 SingleTrack Performance (1992)

Trek 930 SingleTrack Performance (1992)

Trek 850 Antelope Performance (1992)

Trek 830 Antelope Trail Performance (1992)

Trek 820 Antelope Sport Trail (1992)

Trek 800 Antelope Sport Trail (1992)

1993 view catalog.

Trek 970 SingleTrack Competition Race (1993)

Trek 950 SingleTrack Performance (1993)

Trek 930 SingleTrack Performance (1993)

Trek 830 Antelope Performance Trail (1993)

Trek 820 Antelope Sport Trail (1993)

Trek 800 Antelope Sport (1993)

1994 view catalog.

Trek 970 SingleTrack Competition (1994)

Trek 950 SingleTrack Performance (1994)

Trek 930 SingleTrack Performance (1994)

Trek 920 SingleTrack Performance (1994)

Trek 850 Mountain Track Performance (1994)

Trek 830 Mountain Track Performance Trail

Trek 820 Mountain Track Sport Trail (1994)

Trek 800 Mountain Track Sport (1994)

1995 view catalog.

Trek 990 SingleTrack ZX Series Competition (1995)

Trek 970 SingleTrack ZX Series Performance

Trek 950 SingleTrack Performance (1995)

Trek 930 SingleTrack Performance (1995)

Trek 850 Mountain Track Sport (1995)

Trek 830 Mountain Track Sport (1995)

Trek 820 Mountain Track Recreation (1995)

Trek 800 Mountain Track Recreation (1995)

1996 view catalog.

Trek 990 SingleTrack ZX Series Competition (1996)

Trek 970 SingleTrack ZX Series High Performance (1996)

Trek 950 SingleTrack High Performance (1996)

Trek 930 SingleTrack Performance (1996)

Trek 850 Mountain Track XC Enthusiast (1996)

Trek 830 Mountain Track XC Enthusiast (1996)

Trek 820 Mountain Track Recreation (1996)

Trek 800 Mountain Track Recreation (1996)

Trek 800 Sport Mountain Track Recreation (1996)

1997 view catalog.

Trek 930 SingleTrack XC Series Performance (1997)

Trek 850 Mountain Track XC Series Enthusiast (1997)

Trek 830 Mountain Track XC Series Enthusiast (1997)

Trek 820 Mountain Track Recreation (1997)

Trek 800 Mountain Track Recreation (1997)

Trek 800 Sport Mountain Track Recreation (1997)

1998 view catalog.

Trek 920 SingleTrack Performance (1998)

Trek 820 Mountain Track Enthusiast (1998)

Trek 800 Mountain Track Recreation (1998)

Trek 800 Sport Mountain Track Recreation (1998)

1999 view catalog.

Trek 820 Mountain Track Recreation (1999)

Trek 800 Mountain Track Recreation (1999)

Trek 800 Sport Mountain Track Recreation (1999)

Acronym for all terrain bike.

Trek's exclusive fork design.

A tube having different wall thicknesses along its length, while its diameter remains constant.

Low alloy steel with a medium carbon content, that gets its name from the primary alloying elements, chromium and molybendium. It has an excellent strength to weight ratio and is considerably stronger, harder more durable than mild carbon steel.

Trek's exclusive fork design using taper gauge tubing and provides a blade with more elasticity for better shock absoption.

The thickness of the tube at both ends is thicker than in the centre.

Shifting system, where part of the handlebar grip rotates back and forth, clicking into each gear.

Low alloy steel that can withstand significant stress before breaking or becoming deformed. The term 'tensile' refers to the amount of stress a material can endure before failing.

Steel tubing connected with socket-like sleeves, called lugs.

Shimano's multi-condition brake system with specialized shoes, levers and cables designed for enhanced stopping power in rain, mud and snow.

A house brand for Trek during the 80s and early 90s.

Optimal Dimension; Trek's large diameter, thin wall tubing design.

Oversize; Trek's large diameter, thin wall tubing design.

Shimano's oversize hub system designed to minimize wheel flex.

Shimano's under handlebar, two-finger shift system, giving riders the ability to downshift more than one gears in one stroke.

Brake lever system that lets riders adjust braking power modulation.

Shimano Integrated Shifting. Shift mechanism indents control cable advance for quick, precise gear changes without over-shifting.

Shimano Linear Response. Friction reducing levers, cables and calipers.

Japanese steel tubing manufacturer for bicycle frames.

A tube having a maller diameter at one end and a larger diameter on the other end.

Tungsten Inert Gas welding is an arc welding process that produces the weld with a non-consumable tungsten electrode.

Trek-designed components. The higher the number ona given component, the higher its performance level.

Three different wall thicknesses along the length.

American tubing manufacturer.

Special all-terrain tubing, developed to withstand demands of off-road cycling.

A lighter weight version of the AT frame set, featuring a triple-butted down tube.

Zero Excess; Trek's guiding principle of making stronger bikes with less material.

Related posts

Subscribe to my YouTube channel for video reviews.

Trek 800 Review: Is It a Good Bike or Waste of Money in 2023?

CyclistsHub is supported by its readers. We may receive a commission if you buy products using our links.

The Trek 800 is a popular mountain bike from the 20th century. It was first introduced in 1987, and production ended in 2003, so it’s an old bike.

The big question is: Is the Trek 800 a good bike?

Compared to modern standards, the Trek 800 is outdated. However, its benefits include simplicity, a quality steel frame, a wide gear range, and a low price. It’s possible to buy a used one for less than $100.

Do you want to learn more about this iconic bike? Let’s dive in!

Is Trek 800 a Good Bike?

Trek 800 was popular worldwide thanks to its simplicity, quality frame, and reliability. Unlike the Trek 4300 , it features a rigid fork.

It wasn’t cheap at a retail price of around $300, considering the average salary at the time.

It came in various sizes (13″, 15.5″, 17.5″, 19.5″, 21.5″…) and different colors, with slightly modified components each year.

Trek 800 was sold with rim brakes and in multiple options:

- Trek 800 Sport

- Trek 800 Antelope

However, details about their differences are not available. The Trek 800 Sport was also available in a step-through frame option, making it suitable for women and people with limited mobility.

The last generation of Trek 800 was released in 2003, and since then, it has been discontinued and replaced by newer models.

Pros and Cons of Trek 800

I summarized the pros and cons of Trek 800 below.

Pros of Trek 800

- Quality and sturdy steel frame

- Available for men and women

- Comfortable geometry, allowing upright riding position

Cons of Trek 800

- 26-inch wheels

- 3X drivetrain (2X and 1X became more popular thanks to their simplicity)

- Rigid front fork

The following section provides a detailed comparison of the features of the Trek 800 with those of modern mountain bikes . It will help you understand the advantages and disadvantages of the Trek 800 better.

Main Features of Trek 800

Let’s now dive deeper into Trek’s 800 components so you better understand its value.

Steel Frame

The frame is one of the most important components of any bike, and the Trek 800 featured a high-tensile steel and Cro-Moly frame.

Steel is a durable, affordable, and stiff material commonly used for low-end bikes .

However, the bike’s weight of around 13 kg (26 lbs) was pretty heavy, especially considering it had a rigid fork.

On the other hand, you didn’t have to worry about its durability because Trek 800 was designed to last and withstand a lot of abuse.

26-Inch Wheels

The Trek 800 was equipped with 26-inch wheels, which are nimble and allow for quick acceleration but are not as fast, stable, or comfortable as 27.5 or 29-inch wheels.

In today’s market, it’s rare to find adult mountain bikes with 26-inch wheels. They are primarily used for kids’ mountain bikes and dirt bikes.

The trend in the market has shifted towards 27.5 and 29-inch wheels, which are more comfortable, stable, and faster. They may not accelerate as quickly, but they have many other advantages.

The following video showcases the sprint of different bike types (and wheel sizes) over various distances. Keep in mind that their gearing may differ. However, the video effectively demonstrates the quick acceleration of smaller wheels (BMX vs. MTB).

The Trek 800 combined Shimano, SRAM, and other 3rd party components.

Interestingly, some components were supplied by other manufacturers, such as SRAM, which supplied cassettes, Suntour forks, and cranks.

The Trek 800 had a narrow handlebar, no front suspension, and a wide saddle compared to today’s standards.

Most Trek 800 models had a 3×7spd drivetrain offering 21 gears, while some had a 3×8spd gearing.

In contrast, modern mountain bikes typically use 2X or 1X drivetrains for simplicity, lower weight, and less chance of cross-chaining.

However, the Trek 800 had similarities to today’s hybrid bikes due to its rigid fork and geometry. Hybrids still use 2X or 3X drivetrains, providing a wide gear range for various terrains.

One of the main downsides of the Trek 800 was the rigid fork. The only “suspension” came from its wide, high-volume tires.

Riding through rougher terrain required more caution. The Trek 820 was a later model that addressed this issue by including a suspension fork.

Overall, the Trek 800 was best suited for paved, dirt, and forest roads without many bumps.

Trek 800 Specifications

Below, I summarize the most important technical specifications. Remember, they differ based on the year:

- Frame material: Steel

- Weight: ±13kg (29lb) depending on frame size, brakes, and year made

- Wheel size: 26-inch

- Brakes: Rim

- Groupset: Shimano Altus, Tourney

- Gears: 3×7spd or 3×8spd

- Colors: Differ based on the year

The Trek 800 is a budget-friendly mountain bike mainly produced in the last century. Despite its age, it still makes a good choice for those looking for an affordable MTB, thanks to its depreciation and low price.

Since it has already been discontinued, you may find good deals on websites like Craigslist or eBay. For a mint condition bike, aim for a price of up to $150; for a decent condition bike, look for a price under $100.

Additionally, you may want to check out Trek’s current mountain bike offerings. The Trek 820 , which also comes in a step-through option , is a mountain bike worth considering.

Trek 800 FAQ

If you’re searching for an affordable mountain bike , the Trek 800 is still a good option today. Look for one in mint condition for under $150 or in decent condition for under $100. Remember that it’s a mountain bike from the previous century, so it may not compare to today’s models, but it’s still useful for activities like commuting. For more information, be sure to read the entire article.

Trek 800 was made between 1987 and 2003.

Trek 800 weighs ±13 kg (29 lbs). Its weight differs based on its size and year made. Also, the Trek 800 with disc brakes is heavier than with rim brakes.

About The Author

Petr Minarik

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Start typing and press enter to search

- Скидки дня

- Справка и помощь

- Адрес доставки Идет загрузка... Ошибка: повторите попытку ОК

- Продажи

- Список отслеживания Развернуть список отслеживаемых товаров Идет загрузка... Войдите в систему , чтобы просмотреть свои сведения о пользователе

- Краткий обзор

- Недавно просмотренные

- Ставки/предложения

- Список отслеживания

- История покупок

- Купить опять

- Объявления о товарах

- Сохраненные запросы поиска

- Сохраненные продавцы

- Сообщения

- Уведомление

- Развернуть корзину Идет загрузка... Произошла ошибка. Чтобы узнать подробнее, посмотрите корзину.

Oops! Looks like we're having trouble connecting to our server.

Refresh your browser window to try again.

1992 Trek 800 Antelope

- Serial: T1LB43144

- Manufacturer: Trek

- Model: 800 Antelope

- Primary colors: Green

- Frame size: 17IN

- Frame Material: Steel

What Life Was Like on Moscow’s Streets After the USSR Collapsed

As we all know, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics is no more. It has ceased to be. It has rung down the curtain and joined the choir invisible. It is a late Union. Bereft of life, it is pushing up the daisies. It is an ex-Union. (It’s not just “resting,” either.) The landmass it formerly occupied is now taken up by new countries with old names, such as Russia, Ukraine (out, damned the!), Kazakhstan, and Byelorussia, which I half expect, once capitalism takes hold, to rename itself Sellhighrussia. Yet even though the corporeal and temporal actuality of the Soviet Union has ended, the Soviet Union is not nowhere. It has simply moved to a different plane of existence. It has fled to the realm of myth and mystery, of fright and fable, where it abides with other empires that must be imagined to he believed (whether or not they were ever real)—empires good and empires evil, empires like Atlantis, Ancient Rome, the Middle Kingdom, Oz, and the Third Reich.

Of course, even when it was alive the Soviet Union was a fabulous kingdom, a place of the blackest black magic. How could it have been otherwise? After all, here was a country founded upon a vast and elaborate fantasy, the fantasy of the Workers’ Suite, a fantasy sustained not only by the cruel and bloodsoaked apparatus of fear but also, and above all during its wickedest decades, by the blind goodwill of millions of believers within and without its borders. The literature of and about the Soviet Union was steeped in weird phantasmagoria. Almost every word of Soviet journalism was fiction disguised as fact; by the same token, any Soviet writer wishing to publish a bit of honest social analysis had to disguise his facts as fiction. Many of the books written in praise of the Soviet Union described an imaginary place. Some of the most eloquent attacks on it did likewise, albeit in a more conscious way—Zamyatin’s We , Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984 . The most spookily on-target visual portrait of the pre-collapse USSR is Terry Gilliam’s great cult film Brazil . The movie has nothing directly to do with the Soviet Union (or with Brazil either), and I doubt that Gilliam had the Soviet Union in mind when he made it. He captured its essence all the same. It you want to know what the texture of this very odd country was like before the fall, see Brazil .

I’ve been here three times now. The first time, Moscow seemed to me less like a foreign city than an alien planet—a planet that had developed along amazingly similar lines to earth. This faraway planet, like our own, is populated by bilaterally symmetrical bipeds who, like us, garb themselves in clothing differentiated by gender, use four-wheel motorized vehicles for transport, live in boxlike structures, and consume grain-based products for both nourishment and recreation. They have equivalents of almost everything we have—shoes, newspapers, traffic lights—yet there is always something about these everyday items that makes them seem utterly strange. It’s hard to say which is more eerie, the resemblances or the differences. They have shops, for example, but the signs on the outside say harsh generic things—PRODUCTS, REPAIRS, MILK, PHOTO—and inside there are only drab, empty display cases and coiled lines of shuffling people. That was three years ago. It’s still basically the same, only now this exotically gray planet has begun to be colonized by earthlings.

Three years ago, there were still a few big signs of the COMRADES! WE ARE BUILDING COMMUNISM variety to be seen. On my second visit, a year and a half ago, I saw only one sign of this type—red background, block letters—but when I asked someone to translate it for me it turned out to say YOUNG PEOPLE! INVEST IN HIGH-YIELD SECURITIES! This time, the signs are advertising Mars candy bars, Hyundai cars, Panasonic electronics. The consistent thread is that all the signs, whether communist, perestroika-ist, or post-communist, advertise things that are either nonexistent or unavailable.

Some other changes. The lines at the state stores are longer than they were eighteen months ago, but elsewhere there is much more evidence of non-state commerce. The Metro corridors and the passageways under the broad Moscow avenues are lined with card tables where people sell books, magazines, scarves, flowers, chewing gum. cans of German beer. There are musicians on the subway, too—another absolutely new development. Homeless people, too—ditto. Three years ago the hot newspaper was Moscow News , which had emerged from decades as a weekly for tourists published by the Novosti Press Agency to become the voice of glasnost. A year and a half ago it was Commersant, a business weekly. Now it’s Moscow’s Nezavisimaya Gazeta ( The Independent ), a sober thrice-weekly broadsheet, and St. Petersburg’s Chas Pik ( Rush Hour ), a spunky afternoon daily. Three years ago, an American in Moscow felt utterly invulnerable. Now every foreigner knows someone who’s been mugged or burgled. But Moscow still feels a lot safer than New York.

If you have dollars and a few Russian-speaking friends to guide you, the Commonwealth of Independent States is, for the moment, a vacationer’s and shopper’s paradise. I traveled here on frequent flyer miles courtesy of Pan Am (another institution that has gone the way of the USSR) and stayed in the apartment of a friend of a friend. A couchette on the night train to St. Petersburg set me back about 26 cents’ worth of rubles; on the return trip I bought a whole four-passenger compartment. Lunch for three at a “cooperative” restaurant (pickled veggies, not-bad pizza, cognac), about 38 cents. Reverse-chic Soviet neckties at TSUM (Central Universal Stores), the Gimbel’s to Moscow’s Macy’s, the more famous GUM (Government Universal Stores), a nickel each. Subway rides, about two-tenths of a cent each. The whole nine-day trip has cost me about $200, mostly for gifts and meals for Russian friends and souvenirs to take home.

I’ve been asking people if Communism left anything worthwhile behind. Everyone gives the same answer: the Metro, the legendary Moscow subway that served as an argument-clincher for a generation of American communists. True enough: the Moscow subway is the only Soviet institution that is indisputably the best of its kind in the world. Like the pyramids of Egypt, the temples of the Incas, and the Roman colosseum, it has a brutal splendor that transcends the moral squalor of its origins. A Russian friend adds something else to the list: the “Seven Stalinist Sisters.” the mock-gothic, wedding-cake skyscrapers that dot the cityscape. “I hate them, myself,” the friend says, “but my eight-year-old daughter loves them. She says they’re magic castles. She says gremlins and goblins must live there.” A wise little girl.

Hendrik Hertzberg is a former editor of The New Republic.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Moscow, a Newspaper City

By David Remnick

At his dacha in the woods outside Moscow, Mikhail Gorbachev climbed into the back seat of a Zil limousine and headed north, toward the Kremlin. It was the morning after Christmas, and suddenly the Soviet Union was a half-remembered dream and its last general secretary a pensioner. Gorbachev wanted to take care of some final meetings and clean out his desk before starting a few weeks of vacation. The Russian government had promised him a peaceful day or two before it took up residence in the Kremlin. But when he arrived at his office he saw that his nameplate had already been pried off the wall. “Yeltsin, Boris Nikolaevich” was there, gleaming brassily, in its place. Inside the office, Yeltsin was sitting behind the desk. For days, there had been an air of self-pity about Gorbachev, and this petty incident seemed to transform it into fury. Never mind Gorbachev’s own assaults on Yeltsin over the years. “For me, they have poisoned the air,” he complained to a reporter. “They have humiliated me.”

This was a historic moment in Moscow: for the first time, an elected President occupying the Kremlin; the hammer and sickle gone from the flagpole; the regime and the empire dissolved. And yet history felt like nothing more than a miserable winter day; the Western press corps roamed Red Square in search of passion or comment. “You care, we don’t,” an old woman from the provincial city of Tver told a clutch of reporters. With that, she stormed off in search of potatoes and milk for her family.

In the afternoon, Gorbachev’s press secretary, Andrei Grachev, invited a small group of aides, foreign reporters, and Russian editors to a reception at the Oktyabrskaya Hotel. A farewell party, Grachev called it, and he could not have chosen a more appropriate stage. For years, the hotel, across the street from the French Embassy, was a symbol of the Communist Party’s kitschy opulence. The lobby and the dining rooms are heavy on marble and mirrors. Every fixture, it seems, was designed with a certain solicitude for the aging members of the Central Committee—feudal lords of the provinces—who would visit Moscow a few times a year for their plenary sessions and shopping sprees. The Communist Party discovered in its dying days that its financial situation had declined dramatically, and that the only solution was the quick sale of its assets. The Oktyabrskaya Hotel, once known to Muscovites as the Waldorf-Astoria of the Central Committee, is now open for the high-end tourist trade.

At a few minutes before five o’clock, the reporters and the editors stood waiting at the top of the marble stairs for Gorbachev to arrive. By chance, I took my place near two of the city’s best-known newspaper editors: Len Karpinsky, the editor-in-chief and a columnist of the weekly Moscow News ; and Vitaly Tretyakov, a young defector from Moscow News , who had started Nezavisimaya Gazeta ( Independent Newspaper ), the closest thing Russia has ever had to a Western daily. Standing there, I was struck by the fact that Gorbachev’s resignation meant a transition from Karpinsky’s generation of intellectual idealists to a breed of younger men and women like Tretyakov—business neophytes, scholars, hustlers, newspaper editors—who would build a new world not so much out of the jagged ruins of the old experiment as out of fragmentary notions gathered from the West.

Karpinsky is what Muscovites call a shestidesyatnik —someone who came of age in the early nineteen-sixties, during the exhilarating thaw under Nikita Khrushchev, and grew disillusioned when Soviet tanks crushed the Prague Spring, in 1968. That generation harbored the dream of a humane socialism in Russia. Its members did not dare take the risks of full-blown dissidence but found a measure of independence and sanity in their work. There were scholars who fled the oppressive scrutiny of Moscow for institutes in provincial cities from Tartu to Novosibirsk; there were journalists who fled Pravda for Prague and wrote for Problems of Peace and Socialism . Some shestidesyatniki even found it possible to work and think in small, relatively liberal pockets of the Communist Party apparatus in Moscow. Karpinsky first met Gorbachev thirty years ago, when both were prominent in the Komsomol, the Young Communist League. Shared hints of dissatisfaction, of irony, made them comrades of a sort. But Karpinsky was both ambitious and angry, and he had long since veered into the dangerous terrain of what he always called “my life as a half-dissident.” Gorbachev’s appearance as a leader of reform, in 1985, was what Karpinsky had been waiting for all his adult life. Under Gorbachev, Karpinsky went from disgrace to rehabilitation, then on to real stardom in the new world of journalism. When Gorbachev, in the last months of his rule, made serious miscalculations and proved unable to act decisively against the hard-liners who eventually placed him under house arrest for three days in the Crimea, Karpinsky quit the Party and put his hopes in Yeltsin. Yet that conversion, after the assault on Lithuania, in January of 1991—a conversion nearly unanimous among the Moscow intellectuals of Karpinsky’s age and background—was a kind of afterword, a coda to the failed dream of perestroika . Now, as Gorbachev was leaving center stage, so was Karpinsky. Moscow News , which had broken one taboo after another in the first years of perestroika , had become a tired paper: still interesting at times, still honest, but one that spoke to a generation that now seemed, with Gorbachev, exhausted.

“It’s good that Gorbachev’s leaving now, but I am moved to the core,” Karpinsky told me. “How can I deny that I have just finished the most important chapter of my life?”

That day in Moscow, Vitaly Tretyakov was thirty-nine years old—a quarter of a century younger than Karpinsky. In just one year, Tretyakov had developed a paper totally alien to what had been the Soviet Union. From its first issue, in December of 1990, Nezavisimaya Gazeta had never known government interference or censorship, and its language was free of ideology. The first issue appeared just as Eduard Shevardnadze resigned as Foreign Minister and made his uncanny prediction of an incipient dictatorship. The paper’s coverage of the rise of the hard-line counter-revolution and the August coup was unmatched. Nezavisimaya Gazeta ’s combination of news, conflicting commentaries, highbrow essays, and satire made Moscow News seem hopelessly earnest and a little antique. While the pages of Moscow News were filled with the avuncular columns and the hand-wringing of old and worn-out men, reporters in their twenties at Nezavisimaya Gazeta were filching Party documents, printing the confessions of military spies, and conducting irreverent interviews with government leaders. Tretyakov gave free rein to people like Tatyana Malkina, who is twenty-four years old and once worked as a researcher at Moscow News . At a news conference held by the eight conspirators during the August coup, Malkina asked the most penetrating question of the hour. Fixing her eyes on the half-drunk pretender to power, Gennadi Yanayev, she said, “Tell me, please, do you realize that you have carried out a state coup? And which comparison would you find more appropriate—1917 or 1964?” Yanayev’s hand began to quiver uncontrollably as he careered through his reply.

“I’m supposed to be young, but sometimes I feel a hundred years old when I watch what my reporters dare to do,” Tretyakov told me later. “They are the first generation that knows no fear. Journalism is not a mission for them, as it was for us at Moscow News . It’s a terrific game.”

It was now five o’clock, and everyone at the top of the stairs was looking down, to see if Gorbachev would appear. Then the front doors opened and a few of Gorbachev’s closest advisers walked through—owlish little men in mouse-gray overcoats, among them Aleksandr Yakovlev, Georgi Shakhnazarov, and Anatoly Chernyaev. These were the bookish apparatchiks who had warned Gorbachev of the enemies in their midst, and had failed, ultimately, to penetrate their man’s gigantic, and tragic, self-possession. Just behind them was Gorbachev, wearing a coat the color of smoke. He looked up at the crowd and seemed embarrassed; there was something feeble in his smile. For years, he had played the press corps so easily. At first, it was enough that he was ambulatory and reasonably fluent in his own language—that he was not Brezhnev or Chernenko—but with time it was clear as well that he had an apparently effortless ability to connect, to seem to recognize a face in a crowd. And he had the gifts of surprise and agility. Now, at the end, if he was going to remain a force in politics and become Yeltsin’s moderate opposition he would want to give a decent performance at this reception. As Gorbachev shed his coat and began climbing the stairs, the reporters and the photographers began applauding; the applause was hesitant at first, but then it grew louder, and the sound reverberated from the marble and the high windows. Gorbachev clasped his hands together and shook them, more relieved than triumphant.

In a reception room, near tables covered with huge platters of smoked fish and roasted meats, Gorbachev gave a wheezy little speech, made all the worse by a horrendous public-address system. His clichés about the great missions of the past few years came out like the muffled, echoing announcements at a bowling alley. His aides looked bored and weary. But then, with that ritual over, Gorbachev threw himself into the event with gusto. He polished off a shot of lemon vodka and a slice of pickled herring, dangling the herring between forefinger and thumb and dropping it onto his tongue. In a voice of tricked-up cheer, he held his glass up to the guests and the cameras and said, “You think I can’t do it, but now I can afford to.” As Gorbachev worked the room, moving from one cluster of questioners to another, he made it clear that he had no intention of fading away. “I have big plans,” he said. “I am not leaving the political scene.” The later it got, the more pointed his gibes about his successors became. “I just could not go on,” he said. “Everything I did in the last few months, Yeltsin was always opposing. There was just no way. No way. It’s easy to be against Gorbachev, always against Gorbachev all the time. They have always been in opposition. So now I’m gone. There’s no one for them to oppose. So now let them do what they can.”

The transition in Russia these past few months has been far more profound than the turn from Gorbachev to Yeltsin. Genuine democracy is only now in the making, and economic reform remains a distant hope. So far, the great change in Russia has been one of mind and attitude.

The regime knew that it could not modernize without entering the age of information. And it was information—the truth about Soviet history and the failure of ideology—that brought an end to the regime. In the first years of perestroika , the intellectual, spiritual, and journalistic leaders of that change of mind were the shestidesyatniki —men and women like Karpinsky, idealists who suddenly provided an open, civil discourse where there had been none. In the past year, these people have given way to the new generation, less encumbered by the past or by self-doubt, more hardheaded, cynical, practical. Its members are businessmen who travel to Europe for weekend meetings; young academics specializing in the works of Hayek, Mill, and Burke; journalists who find their models in American investigative reporters and, not infrequently, the New York Post . The transition in journalism from Moscow News to Nezavisimaya Gazeta was perhaps the quickest and most visible of these shifts. To witness Len Karpinsky’s transformations—in print and in person—over the Party, socialism, and Gorbachev, and then to confront an army of kids, untroubled by the murk of ideology or by the censor’s pen, was to get a sense of the transition of Russian generations which is now in play.

Len Karpinsky’s parents were Old Bolsheviks. He was named in honor of his father’s mentor and friend Lenin. “ ‘Len’ was pretty common then, and so was ‘Ninel’—‘Lenin’ backward—or ‘Vladilen,’ for Vladimir Ilyich Lenin,” Karpinsky told me at his office one afternoon. “I’m just glad I didn’t get a name like ‘Elektrifikatsiya’ or some others my friends were stuck with.”

Karpinsky’s father, Vyacheslav Karpinsky, belonged to a generation of revolutionary romantics, the fin-de-siècle Communists. He joined the Communist Party in 1898, and in 1903, after his activities as a political organizer got him into trouble with the police in the Ukrainian city of Kharkov, he went into foreign exile, according to an interview that was published in “Voices of Glasnost,” by Stephen F. Cohen and Katrina vanden Heuvel. In Switzerland, he became Lenin’s aide and copy editor. In Moscow, after the revolution, he helped Lenin assemble his personal archives and held various posts at Pravda and the Central Committee’s Department of Propaganda. He received three Orders of Lenin, and in 1962 became the first journalist ever named a Hero of Socialist Labor.

For the Karpinsky family, a life in revolution provided an elevated existence. From 1932 to 1952, they lived in the famous House on the Embankment—a huge pile across the river from the Kremlin. Other tenants were the Kremlin élite: generals, Central Committee members, agents of the secret police. There were special dining halls stocked with groceries of a sort unknown to the rest of the socialist paradise. There were billiard halls, swimming pools, and, for the children, Special School No. 19. When Len Karpinsky was a boy, he was friendly with a couple of Stalin’s nephews. At a birthday party once, Stalin appeared in a doorway. “Children!” one of the adults announced. “Joseph Vissarionovich is here!” Stalin waved and smiled. The children all waited in silence until he left, and then resumed their games.

That was in 1935. In the coming years, Karpinsky watched dumbstruck as one after another of his friends in the building lost parents, aunts, uncles, and grandparents to Stalin’s purges. Nearly every night, secret-police vans would arrive and there would be arrests—an admiral, a lecturer on Marxism-Leninism, the sisters of a spy in a foreign embassy. “There was a knock and then they disappeared,” Karpinsky said. It had been the world of Yuri Trifonov’s novella “The House on the Embankment”—a world where “a life went on that was utterly different” from the life of ordinary people. Now it was a world where the most devoted revolutionaries, the most obsequious ministers, suddenly found themselves declared “plotters” and “infiltrators” and “enemies of the people.” Karpinsky’s family was, by the standards of the building, not hard hit. One of his aunts and her two brothers were sent off to the camps. To this day, Karpinsky does not quite understand why his father, the very sort of Lenin loyalist who so threatened Stalin, was not arrested and executed. The only reason he can think of now, he says, is that by 1937 or 1938 his father was semi-retired and out of politics.

From the moment I moved to Moscow, in January of 1988, until leaving, four years later, I read Moscow News , and particularly Karpinsky, avidly. Everyone did. The leadership had installed Karpinsky’s old friend Yegor Yakovlev as editor-in-chief of the newspaper in 1986, and almost from that point it was clear that Moscow News would be the paper of the thaw generation, the one that would subtly break the taboos formed over seventy years. From time to time, I visited Karpinsky at the Moscow News office, on Pushkin Square, and he always seemed to me an honest man, if a limited writer—a representative figure, whose life had been, as he remarked to me, “an inner conflict between the ambition to be a boss in the Communist Party and the almost involuntary development of a conscience.” His appearance today, waxen and drawn, speaks of that struggle. His face is long, lined, and worn. The fingers of his right hand are yellowed up to the first knuckle, from tobacco. More often than not, when I called and asked how he was he would say dryly, “My health is awful. I’m spending the week in a sanatorium. I may die.”

Karpinsky is so unassuming, and so ironic about his own failures and hesitations, that it is hard to believe he was once an ambitious Communist, a dutiful apparatchik who believed deeply in Communism and in himself—in his entitlement to success. After entering Moscow State University, in 1947, he began working as a “propaganda man” at factories and construction sites during the days before the Party’s single-candidate elections. “My assignment was to make the workers get up at 6 a.m. and go to the polls,” he told me one afternoon. “There was a competition among the propaganda men over whose group would be the first to finish voting. The deadline was midday, by which time the whole Soviet people was supposed to have voted. That was a decision of the Party. We eighteen-year-olds were supposed to carry on propaganda among the workers, and our only tool was the promise to improve their housing conditions. They lived in horrible slums, or in railway cars, with no toilets, no heat. I loved the work, thought it was a great service—and, yes, a stepping stone. At the university, Yuri Levada, who is now a well-known sociologist, wrote an article about me called ‘The Careerist.’ And it was true. I did it all with the idea of getting to the top. That was what it was all about—to be one of the bosses.”

After a pause, Karpinsky ground out a cigarette and went on, “But, having said that, I have to say a few words in self-defense. Society during the Stalin era left open no real opportunities for self-realization or self-expression except within this perverted system of the Communist Party. The system destroyed all the other channels—the artist’s canvas, the farmer’s land. All that was left was the gigantic hierarchic system of the Party, wide at the base and growing narrower as one climbed to the top. You had to have a Party membership just for admission. That was your only opportunity. When you are engaged in that work, you forget about the social and political implications and just do it. Gradually, though, this sort of life bifurcates your mind, your intellect. You do eventually begin to understand that life is life and it’s better to do something good for thy neighbor than to climb upward stepping on his bones. It all depends on moral principles. I suppose my first doubts came when I went to Moscow State University. A Jewish friend of mine named Karl Kantor was attacked by the university’s Party committee at the beginning of Stalin’s anti-Jewish campaign. That was just the start of a long transformation.

“After graduation, I was sent to the city of Gorki for Komsomol work. At that point, Stalin had one more year to live. I got to know the working class and the peasants in Gorki. I saw the utter degradation, the ruin. I saw Soviet society as it had really emerged. Some people still think, erroneously, that the life of the apparatchik breeds only conformists and subjects loyal to the regime. Actually, the regime splits people into two opposing factions—those who believe they can make it only through conformism and timeserving, and those who, thanks to a different structure of mind, dare to question the surrounding reality.”

He paused again, and then said, “So when Stalin died I realized perfectly well what he had been all about. Still, I went to the funeral in Moscow, out of curiosity. I felt like one of those prisoners in the camps who threw their hats in the air and cried, ‘The man-eater has finally kicked the bucket!’ My father’s reaction to Stalin’s death was interesting. By then, he was retired, working for the Central Committee only as a consultant. He sat there in his office, typing on an old Underwood, which he had brought from the offices he shared with Lenin in Switzerland. He called me into his study and said, ‘Son, Comrade Stalin has passed away. And, having been an epigone of Lenin, he created all the necessary conditions for our cause to triumph.’ It was so strange. My father had never before in his life talked so formally to me. I think he talked that way because his generation had always carried the burden of promoting the Party line at all times, and he felt that it was his duty to pass that down to his children. But this was a man, eighty years old, who had conceived his idea of the Party before the revolution and while living in exile. He had to convince not me but himself. He was talking to himself.”