Personalize Your Experience

Log in or create an account for a personalized experience based on your selected interests.

Already have an account? Log In

Free standard shipping is valid on orders of $45 or more (after promotions and discounts are applied, regular shipping rates do not qualify as part of the $45 or more) shipped to US addresses only. Not valid on previous purchases or when combined with any other promotional offers.

Register for an enhanced, personalized experience.

Receive free access to exclusive content, a personalized homepage based on your interests, and a weekly newsletter with topics of your choice.

Home / Parenting, Kids & Teens / Quick guide to your infant’s first pediatrician visits

Quick guide to your infant’s first pediatrician visits

Please login to bookmark.

Frequent checkups with a health care provider are an important part of your baby’s first few years. These checkups — often called well-child visits — are a way for you and your child’s health care provider to keep tabs on your child’s health and development, as well as spot any potential problems. Well-child visits also give you a chance to discuss any questions or concerns you might have and get advice from a trusted source on how to provide the best possible care for your child.

The benefit of seeing your child’s provider regularly is that each visit adds critical information to your child’s health history. Over time, you and the provider will get a good idea of your child’s overall health and development.

In general, the provider will be more attentive to your child’s pattern of growth over time, rather than to specific one-time measurements. Typically what you’ll see is a smooth curve that arcs upward as the years go by. Regularly reviewing your child’s growth chart can also alert you and the provider to unexpected delays in growth or changes in weight that may suggest the need for additional monitoring.

Each health care provider does things a bit differently, but here’s what will generally be on the agenda during your first well-child exams.

Body measurements

Checkups usually begin with measurements. During first-year visits, a nurse or your baby’s health care provider will measure and record your baby’s length, head circumference and weight.

Your child’s measurements will be plotted on his or her growth chart. This will help you and the provider see how your child’s size compares with that of other children the same age. Try not to fixate on the percentages too much, though. All kids grow and develop at different rates. In addition, babies who take breast milk gain weight at a different rate than do babies who are formula-fed.

Keep in mind that a child who’s in the 95th percentile for height and weight isn’t necessarily healthier than a child who’s in the fifth percentile. What’s most important is steady growth from one visit to the next. If you have questions or concerns about your child’s growth rate, discuss them with your child’s provider.

Physical exam

Your child’s health care provider will give your child a thorough physical exam and check his or her reflexes and muscle tone. Be sure to mention any concerns you have or specific areas you want the doctor to check out.

Here are the basics of what providers commonly check for during an exam:

- Head — In the beginning, your child’s health care provider will likely check the soft spots (fontanels) on your baby’s head. These gaps between the skull bones give your baby’s brain plenty of room to grow in the coming months. They’re safe to touch and typically disappear within two years, when the skull bones fuse together. The health care provider may also check baby’s head for flat spots. A baby’s skull is soft and made up of several movable plates. If his or her head is left in the same position for long periods of time, the skull plates might move in a way that creates a flat spot.

- Ears — Using an instrument called an otoscope, the health care provider can see in your child’s ears to check for fluid or infection in the ears. The provider may observe your child’s response to various sounds, including your voice. Be sure to tell the provider if you have any concerns about your son’s or daughter’s ability to hear or if there’s a history of childhood deafness in your family. Unless there’s cause for concern, a formal hearing evaluation isn’t usually needed at a well-child exam.

- Eyes — Your child’s health care provider may use a flashlight to catch your child’s attention and then track his or her eye movements. The provider may also check for blocked tear ducts and eye discharge and look inside your child’s eyes with a lighted instrument called an ophthalmoscope. Be sure to tell the provider if you’ve noticed that your child is having any unusual eye movements, especially if they continue beyond the first few months of life.

- Mouth — A look inside your baby’s mouth may reveal signs of oral thrush, a common, and easily treated, yeast infection. The health care provider might also check your baby’s mouth for signs of tongue-tie (ankyloglossia), a condition that affects the tongue’s range of motion and can interfere with a baby’s oral development as well as his or her ability to breast-feed.

- Skin — Various skin conditions may be identified during the exam, including birthmarks, rashes, and jaundice, a yellowish discoloration of the skin and eyes. Mild jaundice that develops soon after birth often disappears on its own within a week or two. Cases that are more severe may need treatment.

- Heart and lungs — Using a stethoscope, your child’s health care provider can listen to your child’s heart and lungs to check for abnormal heart sounds or rhythms or breathing difficulties.

- Abdomen, hips and legs — By gently pressing a child’s abdomen, a health care provider can detect tenderness, enlarged organs, or an umbilical hernia, which occurs when a bit of intestine or fatty tissue near the navel breaks through the muscular wall of the abdomen. Most umbilical hernias heal by the toddler years without intervention. The provider may also move your child’s legs to check for dislocation or other problems with the hip joints, such as dysplasia of the hip joint.

- Genitalia — Your child’s care provider will likely inspect your son’s or daughter’s genitalia for tenderness, lumps or other signs of infection. The provider may also check for an inguinal hernia, which results from a weakness in the abdominal wall.

For girls, the doctor may ask about vaginal discharge. For boys, the provider will make sure a circumcised penis is healing well during early visits. The provider may also check to see that both testes have descended into the scrotum and that there’s no fluid-filled sac around the testes, a condition called hydrocele.

Your child’s provider will likely ask you about your child’s eating habits. If you’re breastfeeding, the provider may want to know how often you’re feeding your baby during the day and night and whether you’re having any problems. If you’re pumping, the provider may offer suggestions for managing pumping frequency and storing breast milk. If you’re formula-feeding, the provider will likely want to know how often you feed and how many ounces of formula your baby takes at each feeding. In addition, the provider may discuss with you your baby’s need for vitamin D and iron supplements.

Bowel and bladder function

In the first few visits, your child’s health care provider will likely also ask how many wet diapers and bowel movements your baby produces a day. This information offers clues as to whether your baby is getting enough to eat.

Sleeping status

Your child’s health care provider may ask you questions about your child’s sleep habits, such as your regular bedtime routine and how many hours your child is sleeping during the day and night. Don’t hesitate to discuss any concerns you may have about your child’s sleep, such as getting your baby to sleep through the night. Your child’s provider may also help you figure out how to find rest for yourself, especially in the early baby months.

Development

Your child’s development is important, too. The health care provider will monitor your child’s development in the following five main areas.

- Gross motor skills — These skills, such as sitting, walking and climbing, involve the movement of large muscles. Your child’s health care provider may ask you how well your baby can control his or her head. Is your baby attempting to roll over? Is your baby trying to sit on his or her own? Is your child starting to walk or throw a ball? Can your toddler walk up and down steps?

- Fine motor skills — These skills involve the use of small muscles in the hand. Does your baby reach for objects and bring them to his or her mouth? Is your baby using individual fingers to pick up small objects?

- Personal and social skills — These skills enable a child to interact and respond to his or her surroundings. Your child’s health care provider may ask if your baby is smiling. Does your baby relate to you with joy and enthusiasm? Does he or she play peekaboo?

- Language skills — These skills include hearing, understanding and use of language. The health care provider may ask if your baby turns his or her head toward voices or other sounds. Does your baby laugh? Is he or she responding to his or her name?

- Cognitive skills — These skills allow a child to think, reason, solve problems and understand his or her surroundings. Your child’s provider might ask if your baby can bang together two cubes or search for a toy after seeing you hide it.

Vaccinations

Your baby will need a number of scheduled vaccinations during his or her first years. The health care provider or a nurse will explain to you how to hold your baby as he or she is given each shot. Be prepared for possible tears. Keep in mind, however, that the pain caused by a shot is typically short-lived but the benefits are long lasting.

Your child’s provider may talk to you about safety issues, such as the importance of placing your baby to sleep on his or her back and using a rear-facing infant car seat as long as possible.

Questions and concerns

During your son’s or daughter’s checkups, it’s likely that you’ll have questions, too. Ask away! Nothing is too trivial when it comes to caring for your baby. Write down questions as they arise between appointments so that you’ll be less likely to forget them when you’re at your child’s checkup.

Also, don’t forget your own health. If you’re feeling depressed, stressed-out, run-down or overwhelmed, describe what’s happening. Your child’s provider is there to help you, too.

Before you leave the health care provider’s office, make sure you know when to schedule your child’s next appointment. If possible, set the next appointment before you leave the provider’s office. If you don’t already know, ask how to reach your child’s provider in between appointments. You might also ask if the provider has a 24-hour nurse information service. Knowing that help is available when you need it can offer peace of mind.

Relevant reading

The Human Body

Take a journey inside the body—as an alien! Hop aboard a flying saucer and travel alongside your alien guides who are on a mission to understand the wonders of human body systems. High-impact graphic art explores the circulatory system, the digestive system, the skeletal system, and more. Lively text introduces…

Cricket Helps Out

This inviting chapter book series explores health topics through the friendly lens of therapy dogs. Follow an adorable therapy dog helping a child through appendicitis, with strong messages of empathy, kindness, and courage. Therapy dogs are specially trained to help kids through medical experiences—from lifting spirits, motivating movement, modeling the…

Discover more Parenting, Kids & Teens content from articles, podcasts, to videos.

Want more children’s health and parenting information? Sign up for free to our email list.

Children’s health information and parenting tips to your inbox.

Sign-up to get Mayo Clinic’s trusted health content sent to your email. Receive a bonus guide on ways to manage your child’s health just for subscribing.

You May Also Enjoy

Privacy Policy

We've made some updates to our Privacy Policy. Please take a moment to review.

What To Expect From Baby's First Pediatrician Visit

Pediatricians may be the next best thing to a handbook for newborns., by sharon brandwein.

Whether it’s your first baby or your third, bringing a new life into the world is no easy feat. The parenting journey is long, and having your own little “village” will help you navigate any bumps in the road. But with everything that your support network of friends and family can do, they can’t do it all.

Babies may not come with handbooks, so that’s where your pediatrician comes in. Not only can they, too, offer the support you need, but they’re also there to answer questions about whether or not a poop is normal and crayons in noses (it happens, folks).

Every parent wants to give their baby a healthy start in life, and doing so begins with your baby’s first pediatrician visit, also known as a well baby visit. In what will be the first of many, your baby’s doctor will check in on your little one soon after they’re discharged from the hospital to ensure everything is on track. During this visit, the doctor will not only examine your baby from tip to toe, but they’ll also take the time to answer questions, dispense some sage advice and allay any lingering fears you may have.

When Do Newborns Have Their First Doctor Appointment?

“Your newborn’s appointment should be within 1-2 days after discharge from the hospital,” says Dr. Emily Wisniewski, a pediatrician with Mercy Family Care Physicians . “Some babies can wait a little bit longer, 3-5 days even, provided there were no concerns about feeding, significant weight loss, or jaundice. But otherwise, you [and your baby] should be checked on soon after discharge to make sure your baby is growing and feeding well.”

It’s worth noting that after your baby’s initial visit to the pediatrician, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends well-baby visits at the following intervals for the first two years of your baby’s life.

How Far in Advance Do I Need to Schedule the First Baby Checkup?

Schedules can vary widely from doctor to doctor. If you’re concerned about getting an appointment, consider calling ahead (before your due date) to get a better idea of how busy your preferred pediatrician will be. There’s no harm in being proactive and scheduling your appointment in advance.

What Will Happen During My Newborn’s First Doctor Appointment?

Wisniewski tells Babylist that doctors and nurses cover a lot of ground during the first visit to the pediatrician.

“We get to know the family—especially if they are new to the practice or a first-time parent—and ask questions about feeding, peeing and pooping, safety in the home—regarding safe sleep, smoke detectors/guns in the home and other family members in the home,” she says. “We also will do a postpartum depression screening to check in on parents as well as baby.” In addition to the baby’s physical exam, Wisniewski says doctors will often leave time to “address any questions or concerns the parents have.”

What Will My Baby’s First Physical Exam Look Like?

Once you’ve filled out any required paperwork, the nurse will probably be the next person you see. Ahead of the doctor’s exam, the nurse will weigh and measure your baby. He or she will then chart your baby’s measurements on a growth chart that shows what percentile your baby is measuring. Beyond length and weight, the nurse will also measure the circumference of your baby’s head.

Incidentally, your baby will need to be naked to get the most accurate measurements. So, you’ll want to bring an extra diaper —but more on that later.

After the nurse has all the measurements and numbers plotted, the pediatrician will examine your little one from head to toe. This includes:

Checking Your Baby’s Head: Your doctor will palm your baby’s head to check for a still-soft fontanel, which you may know as the soft spot. Your baby’s head circumference should increase by about 4 inches within their first year, and the soft spots on their skull are designed to accommodate that growth. However, if they close up too quickly, that could be cause for concern.

Checking Their Neck and Collarbone: The doctor will feel your baby’s bones along the neck and collarbone to check for any breaks or fractures that occurred during delivery.

Rolling Your Baby’s Hips: Pediatricians often roll babies’ hips to look for any signs of hip dysplasia. Incidentally, they will do this at every well-baby visit until your little one takes their first steps.

Testing Your Baby’s Reflexes: During this visit and four to follow, your pediatrician will assess your baby’s Moro reflex (also known as the startle reflex). Typically, the Moro reflex test simulates falling. It involves placing the baby face up on a soft padded surface, lifting their head slightly above their body, then gently letting it fall into the doctor’s hand. The doctor is looking for your baby to extend their arms and draw them back quickly (what all of us do when we feel like we’re falling).

In addition to the Moro reflex, your pediatrician will also check your baby’s rooting reflex as well as their sucking reflex. To check the rooting reflex, they will touch or stroke your baby’s cheek to gauge whether or not baby automatically turns their head to that side and opens their mouth. To check the sucking reflex, the doctor will place a gloved finger in your baby’s mouth to see whether they start sucking.

Checking Their Femoral Pulse: Pediatricians typically check the baby’s pulse via the femoral artery. A weak femoral artery pulse could be a sign of a heart condition.

Checking Genitalia: During your baby’s first trip to the pediatrician (and every visit that follows), your pediatrician will check on the development of your baby’s genitalia. In this case, they’re looking for signs of infection from circumcisions, following up on undescended scrotums or labial adhesions.

Examining the Umbilical Stump: Doctors will also check on how the umbilical stump is healing and offer some guidance for care until it falls off on its own—usually within 1-3 weeks after birth.

What Questions Will the Pediatrician Ask?

Throughout the physical exam, your baby’s doctor will ask questions about your child’s feeding patterns, elimination and sleep schedule. Their questions will likely focus on the following topics:

- Feeding Patterns/Schedule: While you don’t necessarily need to keep a food diary, you should be prepared to communicate how often and how well your baby eats. This is also a good opportunity to share any questions or concerns you have about feeding baby.

- Baby’s Digestive System: Peeing and pooping are indicators of overall health so expect your provider to ask questions about baby’s digestive system. They’ll want to know how many wet diapers your baby has each day, how often they’re pooping, as well as the color and consistency of their poop.

- Sleeping Patterns: Your baby’s doctor will also check in on how your baby is sleeping , and they’ll likely go over safe sleeping guidelines.

Will My Baby Be Vaccinated During Their First Visit to the Pediatrician?

Baby’s first official checkup and first immunization will take place at the hospital. Typically, baby won’t get any shots during their first visit to the pediatrician, but Wisniewski notes, “If your baby did not receive the Hepatitis B vaccine in the hospital (usually given prior to discharge), then your infant should receive this at their first pediatrician appointment.”

What Should I Bring With Me to the First Checkup?

The short answer here is simply to bring your diaper bag . Remember that you’ll need to remove baby’s clothing and diaper for the nurse to take their measurements and get an accurate weight. So, it’s a good idea to bring along a blanket and a fresh diaper.

Wisniewski also suggests bringing the discharge summary of your baby’s hospital stay. “It helps the doctor know what happened in the hospital and if any follow-up is needed (like checking for jaundice),” she says.

What Questions Should I Ask the Doctor at My Baby’s First Appointment?

While your baby’s pediatrician will ask plenty of questions about your baby’s general health, this is also the time for you to ask any and all questions you may have about your newborn.

Common questions that new parents often have include:

- How do I know if my baby ate enough ?

- What should I do if my baby is not drinking enough breast milk ?

- Should I give supplements to my baby?

- How can I store my breast milk?

- How can I help my baby latch on to my breast?

- What’s the best way to soothe or care for sore nipples?

- How many naps should my baby take?

- How many hours a day should my baby sleep ?

- Is it okay if I wake up my baby to eat?

- How can I help my baby to stay asleep?

- Is it safe for my baby to s leep on their back ?

- How can I try to avoid sudden infant death syndrome?

- Where should my baby sleep?

- When will my baby sleep through the night?

Helpful hint: Keep a digital note or write down all the questions you have for your baby’s doctor. There’s a lot of ground to cover on your baby’s first visit to the doctor, and if your little one is fussing or crying for the duration, you can easily become flustered and forget your questions. Keeping an actual note is the best way to ensure you walk out of the appointment with all your questions answered. But don’t worry! This is a routine visit, and your pediatrician is here to guide you through it all.

Sharon Brandwein

Sharon Brandwein is a Certified Sleep Science Coach and a freelance writer. She specializes in parenting, health, and of course, all things sleep. Sharon’s work has also appeared on ABC News, USAToday, Parents, and Forbes. When she’s not busy writing, you might find her somewhere curating a wardrobe for her puppy.

Family Life

AAP Schedule of Well-Child Care Visits

Parents know who they should go to when their child is sick. But pediatrician visits are just as important for healthy children.

The Bright Futures /American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) developed a set of comprehensive health guidelines for well-child care, known as the " periodicity schedule ." It is a schedule of screenings and assessments recommended at each well-child visit from infancy through adolescence.

Schedule of well-child visits

- The first week visit (3 to 5 days old)

- 1 month old

- 2 months old

- 4 months old

- 6 months old

- 9 months old

- 12 months old

- 15 months old

- 18 months old

- 2 years old (24 months)

- 2 ½ years old (30 months)

- 3 years old

- 4 years old

- 5 years old

- 6 years old

- 7 years old

- 8 years old

- 9 years old

- 10 years old

- 11 years old

- 12 years old

- 13 years old

- 14 years old

- 15 years old

- 16 years old

- 17 years old

- 18 years old

- 19 years old

- 20 years old

- 21 years old

The benefits of well-child visits

Prevention . Your child gets scheduled immunizations to prevent illness. You also can ask your pediatrician about nutrition and safety in the home and at school.

Tracking growth & development . See how much your child has grown in the time since your last visit, and talk with your doctor about your child's development. You can discuss your child's milestones, social behaviors and learning.

Raising any concerns . Make a list of topics you want to talk about with your child's pediatrician such as development, behavior, sleep, eating or getting along with other family members. Bring your top three to five questions or concerns with you to talk with your pediatrician at the start of the visit.

Team approach . Regular visits create strong, trustworthy relationships among pediatrician, parent and child. The AAP recommends well-child visits as a way for pediatricians and parents to serve the needs of children. This team approach helps develop optimal physical, mental and social health of a child.

More information

Back to School, Back to Doctor

Recommended Immunization Schedules

Milestones Matter: 10 to Watch for by Age 5

Your Child's Checkups

- Bright Futures/AAP Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care (periodicity schedule)

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Newborn Care

What to Expect at Your Baby’s First Pediatrician Visit

Nervous about your baby's first pediatrician visit? Here's what to expect, from paperwork to meeting the doctor, plus tips for making the visit easier for you and your baby.

Your baby should have their first well-baby visit at the pediatrician's office three to five days after birth, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). After that, you'll be going in for checkups every few months over the course of the first year.

Since your baby's first pediatrician visit might be the first time your newborn leaves home, it's natural to feel some trepidation. But remember that this visit is often empowering and informative for new parents. Read on to learn what to expect during your baby's first pediatrician visit, from exams to vaccinations, as well as tips for timing and preparation.

There Will Be Paperwork

Be prepared to fill out paperwork when you arrive. Remember to pack the following:

- Your ID and health insurance card

- Information about your newborn's discharge weight

- Any complications during pregnancy or birth

- Your family's medical history

Knowing that your older child has asthma or your parents have diabetes, for example, focuses your pediatrician's attention on likely problems, says Christopher Pohlod, DO , assistant professor of pediatrics at Michigan State University's College of Osteopathic Medicine.

The Nurse Will Do Some Exams

A nurse will probably handle the first part of your baby's exam. They'll do the following:

- Weigh your naked baby on a scale

- Extend their limbs to measure height and width

- Use a tape measure to determine the head circumference

According to the AAP, it's normal for babies to lose weight after birth (up to 10% of their body weight). But they'll generally gain it back within a couple of weeks.

You'll Get to Know the Doctor

The pediatrician will examine your baby, educate you about their health, and answer any questions. One of the biggest components of the first pediatrician visit is developing a relationship with your child's new doctor. They will be a source of information, support, and troubleshooting in the many years to come.

They'll Check Your Baby's Neck and Collarbone

At your baby's first pediatrician visit, a health care provider will feel along your baby's neckline to check for a broken collarbone during the physical exam. That's because some babies fracture their clavicle while squeezing through the birth canal.

If your pediatrician finds a small bump, that could mean a break is starting to heal. It will mend on its own in a few weeks. In the meantime, they may suggest pinning the baby's sleeve across their chest to stabilize the arm so the collarbone doesn't hurt.

They'll Check Your Baby's Head

A pediatrician will also palm your baby's head to check for a still-soft fontanel. They will do this at every well visit for the first one to two years.

Your baby's head should grow about 4 inches in the first year, and the two soft spots on their skull are designed to accommodate that rapid growth. But if the soft spots close up too quickly, it can lead to a condition called craniosynostosis, which is when the tight quarters can curb brain development, and your child may need surgery to fix it.

They'll Check Your Baby's Hips

The doctor will roll your baby's hips to check for signs of developmental hip dysplasia, a congenital malformation of the hip joint that affects 1 in every 1,000 babies. You can expect this exam starting at your baby's first pediatrician visit and every visit until your baby can walk.

"The exam looks completely barbaric," says Vinita Seru, MD , a pediatrician in Seattle. "I tell families what I'm doing so they don't think I'm trying to hurt the baby."

If your pediatrician feels a telltale click from the hips, they'll order an ultrasound. Luckily, when dysplasia is found early, treatment is simple: The baby wears a pelvic harness for a few months.

They'll Check Your Baby's Reflexes

To check for a Moro reflex, a health care provider startles your baby. For the first 3 or 4 months, whenever something startles your infant, they'll fling their arms out as if they're falling. It's an involuntary response that shows your baby is developing normally.

This exam starts at the first pediatrician visit and continues through the first four well-child visits. A health care provider might also check whether your little one grasps a finger or fans their toes after you touch their foot.

They'll Check Your Baby's Pulse

By pressing the skin along the side of the baby's groin, a health care provider checks for your baby's pulse in the femoral artery, which runs up from your baby's thigh. Your pediatrician wants to see if the pulse is weak or hard to detect on one or both sides as that may suggest a heart condition.

You can expect this exam at the first pediatrician visit and all baby well visits. Around 1 in 125 babies are diagnosed with a heart defect every year in the US. This check is a simple way to screen for problems, says Dr. Seru: "When a heart condition is caught early, it can increase the likelihood of a good recovery."

They'll Check Your Baby's Genitalia

Starting at the first pediatrician visit and every well-baby visit after that, a health care provider will check your baby's genitals to ensure everything looks normal.

In about 1 to 3% of babies with testicles, the testicles don't descend into the scrotum before birth. While the problem usually corrects itself by 3 to 4 months of age, your doctor will keep an eye on things to see if your baby needs surgical assistance in the future. They will also check for signs of infection if your baby has been circumcised .

In babies with vulvas, it's not uncommon to find labial adhesions. Although the labia should open up over time, adhesions can shrink the vaginal opening and make your baby more prone to urinary tract infections (UTIs) . "If we know that they're there when your baby has a high fever, we look for a UTI first," says Melissa Kendall, MD , a pediatrician in Orem, Utah.

They'll Ask About Your Baby’s Feeding Patterns

The doctor will want information about your baby's feeding patterns. You don't need to keep super-detailed records, but you should have a general idea of the following:

- How often your baby is eating

- How long they feed (if nursing)

- How much they consume (if bottle-feeding)

This is an excellent time to raise concerns or questions about latching, formula brands, and other feeding issues.

They'll Check Your Baby’s Digestive System

You should have a general idea of how often you change your baby's diapers each day. If your doctor knows the consistency, frequency, and color of your baby's poop , they can better assess their digestive system and nutrient absorption.

They'll Ask About Your Baby's Sleeping Patterns

A health care provider will also probably inquire about sleeping patterns at your first pediatrician visit. They'll also make sure you're following safe sleep practices to help reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

They'll Review the Childhood Vaccination Schedule

Hospitals usually give babies their first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine shortly after birth, but if your baby was born at home or at a birth center, they might receive it at their first pediatrician visit.

Most vaccinations start when your baby is 2 months old, and a health care provider might review the vaccine schedule with you so you're prepared for the many vaccines your baby will receive in the months ahead.

There Will Be Time for Questions

You will cover a lot of ground during your baby's first pediatrician visit. Ask the doctor to slow down, repeat, or clarify information if needed. It's also wise to come prepared with any questions you have.

Here are some examples:

- Is this behavior normal?

- Is my baby eating enough?

- Should their stool look like that?

- When should I schedule the next appointment?

- What should I expect in the next few days and weeks?

When you have a written list of talking points, you won't worry about your mind going blank if your baby starts to fuss, says Dr. Pohlod.

You'll Schedule Your Next Appointment

The lineup of well-baby checkups during the first year includes at least a half dozen more pediatrician visits.

Recommended Baby Checkup Schedule

Here is a quick-glance list of what ages the AAP recommends that your child be seen for well-child pediatrician visits through their second year:

- 3 to 5 days old

- 1 month old

- 2 months old

- 4 months old

- 6 months old

- 9 months old

- 12 months old

- 15 months old

- 18 months old

- 24 months old

At first glance, the recommended number of checkups may seem like a lot. But trust the process: This schedule was designed to closely monitor your baby's growth and development to ensure their health and well-being.

The checkups, depending on the age of your baby, will include measurements, sensory screening, and developmental health, which include social, behavioral, and mental health. It will also include vaccinations, oral health, and advice for parents and caregivers.

Frequent appointments with your baby's health care provider are also the best way to get personalized expert answers to your questions about your baby. Ultimately, it's important to be comfortable with your doctor, and seeing them frequently in the first year helps you develop a relationship you may have for years to come.

When you schedule your next appointment, ask about the office's hours of operation, billing policies, and how after-hours communication works. Keep the doctor's phone number handy, and be informed of what to do and who to contact in an emergency or when you have a question.

Tips for Your Baby's First Pediatrician Visit

Leaving the house with a newborn isn't easy, and it can be especially stressful when you're on a timetable (like when you're trying to make it to a scheduled appointment). But your baby's first pediatrician visit doesn't have to be super stressful. Here are some tips for smooth sailing:

- Plan your time. Ask for an appointment during the least busy part of the day. You can also see if a health care provider has specific time slots dedicated to seeing newborns. Expect the visit to take about 25 minutes, but plan for waiting and setbacks as well.

- Bring a support person. Consider bringing your partner or another caregiver to your baby's first doctor appointment. Two people can more effectively care for the baby, remember the doctor's advice, and recall questions you plan to ask.

- Dress your baby with the exam in mind. Since the doctor will examine your baby's entire body, dress them in easy-on, easy-off clothing or even just a diaper and comfortable blanket if weather permits.

- Be prepared, but pack light. Definitely bring a change of clothes, extra diapers, wipes, pacifiers, feeding supplies, and other necessities, but try not to overpack. Ultimately, "warmth, cuddling, loving, and reassuring voices are more helpful than a stuffed animal" at a newborn exam, says Brian MacGillivray, MD, a family medicine specialist in San Antonio.

- Wait in the car, if you can. If you attend the appointment with another person, send them inside to fill out paperwork while you wait in the car with the baby. This limits your newborn's exposure to germs. Some offices even have systems in place that allow you to fill out the paperwork online, wait in your car, and receive a call or text when it's time to go in.

- Keep your distance from others. If you must sit in the waiting room, have your baby face the corner. According to Mary Ellen Renna, MD , a pediatrician from Jericho, New York, the chances of catching sickness are lower if you maintain a 3-foot radius from others.

AAP Schedule of Well-Child Care Visits . American Academy of Pediatrics . 2023.

Weight Loss . The American Academy of Pediatrics . 2020.

Clavicular Fractures in Newborns: What Happens to One of the Commonly Injured Bones at Birth? . Cureus . 2021.

Facts About Craniosynostosis . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2023.

Developmental Dislocation (Dysplasia) Of the Hip (DDH) . American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons . 2022.

Moro Reflex . StatPearls . 2023.

A five (5) chamber heart (Cor Triatriatum) in Infancy: A rare congenital heart defect . Niger Med J . 2013.

Undescended Testicles: What Parents Need To Know . American Academy of Pediatrics . 2022.

Periodicity Schedule . American Academy of Pediatrics . 2023.

Related Articles

The First-Week Well-Baby Visit

Medical review policy, latest update:, the physical checkup, developmental milestones, read this next, 1-week shots, questions to ask your doctor.

You may also want to ask the results of any newborn screening that was done at the hospital and/or find out when all the results will be in. And don’t forget to make the 1-month appointment !

What to Expect the First Year , 3rd edition, Heidi Murkoff. WhatToExpect.com, Your Newborn’s Weight: Normal Gains and Losses and What the Average Baby Weighs , August 2020. WhatToExpect.com, Jaundice in Newborn Babies , October 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Vaccines for Your Children, Vaccine (Shot) for Hepatitis B , August 2019. Stanford Children’s Health, Newborn Reflexes , 2021.

Go to Your Baby's Age

Trending on what to expect, the covid-19 vaccine for infants, toddlers and young children, how to create a night shift system when you have a newborn, ⚠️ you can't see this cool content because you have ad block enabled., when do babies start laughing, baby-led weaning, what happens in the ‘4th trimester’ (and is it a real thing).

Your New Baby's Well-Child Check-Up Schedule (and What to Expect)

Introduction

Well-baby visits are a staple of every new parent’s life. From the day they are born throughout their first year, your baby will have several wellness visits to ensure that they are healthy, happy, and reaching developmental milestones.

Well-baby visits are vital for immunizations, healthcare, and support from your pediatrician. At Juno Pediatrics, we love establishing relationships with parents that last throughout their baby’s childhood. From newborn through adulthood, Juno is there for every step along the way.

In this guide, we will explore new-baby visits in-depth, including what to expect, when to schedule them, and how to give your little one the best care possible.

What Are Well-Baby Visits?

Also known as well-child check-ups, these appointments are pivotal points in their development and healthcare. From the day your baby is born, doctor’s visits will become a regular part of your life. A baby’s first year is filled with trips to the pediatrician where parents can ask questions, get advice and address any concerns they may have.

In addition to spotting any issues or developmental warning signs, parents can seek out advice on common concerns, such as how to soothe teething, when to expect their baby to start walking, weaning, and breastfeeding.

Bear in mind that well-child visits are different from additional doctor’s appointments you may need. For example, if your baby falls ill, is injured or you are concerned about something, you can schedule additional evaluations outside of their well-visit schedule.

Well-Baby Visit Schedule

Each baby receives a well-baby check-up at 2-5 days,1 month, 2 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 12 months from their birth date. You can, of course, also schedule additional appointments to address any concerns with your pediatrician.

Remember that well-visits aren’t just for your baby — they are meant to help you, too! There are many parenting milestones you will reach your baby’s first year. From feeding to sleeping, walking to teething, the team at Juno Pediatrics is here to help you nurture your little one every step of the way.

The First Check-Up: 2-5 Days

The first visit is also important to establish a baby’s feeding habits. All babies lose weight after birth, and it is critical to make sure that the baby is within a healthy range of weight loss and maintains adequate hydration while they learn to eat. Sometimes, a newborn needs assistance with latching onto the breast or learning to take a bottle, which the doctor can address and assist with.

Some babies become jaundiced , a condition caused by too much bilirubin in the bloodstream. This is a yellow substance produced by red blood cells as they break down and accumulate in the baby’s skin. This will be closely monitored with physical exams and bloodwork if necessary. If your baby had feeding issues or jaundice at birth, you may have daily visits from birth until their condition improves.

If you have a home birth, then your baby should visit the doctor one to two days after entering the world. This is important because an infant needs vital exams within the first 48 hours of life. Certain tests that were not done at your home birth will be done at this visit, including taking a sample of the baby’s blood for a Newborn Screen. This metabolic screening during this early check-up ensures that your newborn’s body systems are all functioning as they should.

Depending on how your baby is growing and feeding, you will have a weight check between your first and second well-child visits. At this exam, your pediatrician will take your baby’s measurements and start to build their health record. They will address subjects like regular feedings, sleep schedules, and skills like diaper changing and swaddling.

This visit is the perfect time to establish a connection with your baby’s doctor. They are here for you, so don’t hesitate to ask all your questions, share any concerns and be honest about how you’re feeling.

Many new parents struggle in the early days, and if you’re feeling overwhelmed, your pediatrician can help.

The Second Visit: 1 Month

Your baby will grow rapidly throughout its first four weeks of life. You don’t have to schedule this well-visit on the exact 1-month date but aim to make it during the milestone week.

From birth, babies will typically gain 1 ounce every day for the first 30 days. By the time they reach 1-month old , most will have gone through two small but rapid growth periods and gained at least 2 additional pounds.

During their 1-month well-visit, the doctor will begin by checking your baby’s vital signs and taking their measurements. Then, the doctor will check in with you and how you’re feeling. They can offer tips and suggestions on how to nurture your baby’s development through play, tummy time and reading.

Through feeding, playing, cuddling, and rest, your baby will develop according to their own body. If they have a condition that will affect their health and development, the pediatrician will discuss this in detail and give you advice on what to look for.

The Third Check-Up: 2 Months

At the 8-week mark, your baby will be far more alert than when they were born. The average 2-month old is more visually engaged and able to look at an object for several seconds as well as watch you when you move.

At the beginning of this and every visit, your baby’s vital signs measurements will be taken and documented. Your pediatrician will review how they are eating, voiding, stooling, and sleeping. In addition, your pediatrician will review their development and milestone and give you guidance on what to expect for the next two months before their next checkup

This visit is also the time to start immunization. At the 2-month well-visit, your infant will obtain 4 vaccines and be protected against 8 serious bacterial and viral diseases.

The following vaccines are administered at the 2-month visit, and comprises the first set of their primary series:

Hepatitis B

Diphtheria/Tetanus/Pertussis (DTaP)

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib)

Pneumococcal (PCV)

Polio (IPV)

Rotavirus (RV)

Be sure to voice any concerns or questions you have about vaccines and immunization with your pediatrician. Many parents who never second-guessed immunization can become anxious after they have a baby. They will discuss everything you need to know, listen to how you feel and answer your questions.

At Juno Pediatrics , we are committed to providing the highest level of care and protection, and toward that goal, we ensure that all of our patients are vaccinated on schedule and on time. You can find more on our approach to pediatric vaccines on our website . Your pediatrician will be there to answer any and all questions along the way.

The Fourth Check-Up: 4 Months

Four-month-olds are smiling, cooing babies, reaching for toys and your hair, looking around, and holding their heads up with more stability.

The care assistant will take your baby’s vitals and measurements, as usual, review how the child is doing, answer your questions, and let you know what to expect in the coming two months. Additionally, at this visit, we will start discussing introducing solid foods to your baby, a fun new adventure!

Your infant will also receive his second set of vaccines, the exact same one they received at the 2-month visit. This is the second of three of their primary series vaccines.

The Fifth Check-Up: 6 Months

The half-year mark is a major milestone in a baby’s life. Their personality will have emerged and begun to shine through as they engage more with you, their family, and the world around them. By this age , they may begin to sit on their own, enjoy looking at their reflection in mirrors and show emotional responses to others.

Your pediatrician will take your baby’s vitals and measurements as usual, then discuss some of the 6-month-old milestones to expect. If you are worried about your baby’s development, the doctor will listen intently and offer reassurance and guidance.

If your baby is not mobile, does not sit up or hold things, does not laugh or smile, or does not respond to its caretakers, then make sure you bring these issues up with your doctor.

The final 4 vaccines of the primary series will be administered at this visit by the pediatrician. During flu season, your baby is eligible to receive its first influenza vaccine. This is administered to children in 2 doses roughly 1 month apart.

The Sixth Check-Up: 9 Months

A 9-month-old is curious, adventurous, and always interested in the world around them. They will be eating solid foods 2-3x a day in addition to breast milk and formula and are starting to express their independence. At this stage , most babies are very vocal and have some ability to move.

They will have a range of emotional expressions from deep frowns to big, happy smiles. They can also express anger and frustration more clearly, so it will be easier to differentiate their cries and understand their feelings.

Your pediatrician will ensure the baby’s growth is on par with their sex and age. Then, they will begin to discuss their oral hygiene, as your baby may have a tooth erupted. . If you are concerned about any developmental delays, they can be addressed during this time.

Lack of emotional response, limited eye contact, infrequent mobility, and poor motor skills can indicate an issue that the doctor should know about. They can address these concerns and, if need be, refer you and your baby to a specialist.

Bear in mind that every baby is unique, and some children reach milestones later without having any major conditions.

The Seventh Check-Up: 1 Year

As you celebrate your child’s first year of life, your pediatrician will offer advice on how to nurture them through late infancy into early toddlerhood. Over the next year, they will experience many changes to their cognitive, mental, and emotional development.

Your baby’s personality will emerge even more from this point forward, especially as they become more mobile, taking first steps, and communicative, saying first words and phrases.

At the 12-month-old check-up , your baby will undergo a blood test that checks lead level and hemoglobin screening, which checks for anemia .

The 1-year mark is also time for babies to receive the following vaccines:

Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR)

Chickenpox (varicella)

Hepatitis A

Their final boosters of DTaP and Hib vaccines will be given at their 15-month check-up, and their final Hepatitis A vaccine and PCV vaccine will be completed at the 18-month visit.

Your Baby’s Health Journey Starts Here

At Juno, we provide comprehensive healthcare for the entire family. Our medical team includes board-certified pediatricians who take the time to listen to your experiences, hear your concerns, and ensure your baby gets the highest quality care. If you are looking for a long-term practice to nurture your baby, schedule an appointment with Juno Pediatrics today .

The Basics: Overview

Babies need to go to the doctor or nurse for a “well-baby visit” 6 times before their first birthday.

A well-baby visit is when you take your baby to the doctor to make sure they’re healthy and developing normally. This is different from other visits for sickness or injury.

At a well-baby visit, the doctor or nurse can help catch any problems early, when they may be easier to treat. You’ll also have a chance to ask any questions you have about caring for your baby.

Learn what to expect so you can make the most of each well-baby visit.

The Basics: Well-Baby Visits

How often do i need to take my baby for well-baby visits.

Babies need to see the doctor or nurse 6 times before their first birthday. Your baby is growing and changing quickly, so regular visits are important.

The first well-baby visit is 2 to 3 days after coming home from the hospital, when the baby is about 3 to 5 days old. After that first visit, babies need to see the doctor or nurse when they’re:

- 1 month old

- 2 months old

- 4 months old

- 6 months old

- 9 months old

If you’re worried about your baby’s health, don’t wait until the next scheduled visit — call the doctor or nurse right away.

The Basics: Child Development

How do i know if my baby is growing and developing on schedule.

Your baby’s doctor or nurse can help you understand how your baby is developing and learning to do new things — like smile or turn their head to hear your voice. These are sometimes called “developmental milestones.”

At each visit, the doctor or nurse will ask you how you’re doing as a parent and what new things your baby is learning to do.

The Basics: 2 Months

By age 2 months, most babies:.

- Lift their head when lying on their stomach

- Look at your face

- Smile when you talk to them

- React to loud sounds

See a complete list of milestones for kids age 2 months .

The Basics: 4 Months

By age 4 months, most babies:.

- Bring their hands to their mouth

- Make cooing sounds

- Hold toys that you put in their hand

- Turn their head to the sound of your voice

- Make sounds when you talk to them

See a complete list of milestones for kids age 4 months .

The Basics: 6 Months

By age 6 months, most babies:.

- Lean on their hands for support when sitting

- Roll over from their stomach to their back

- Show interest in and reach for objects

- Recognize familiar people

- Like to look at themselves in a mirror

See a complete list of milestones for kids age 6 months .

The Basics: 9 Months

By age 9 months, most babies:.

- Make different sounds like “mamamama” and “bababababa”

- Smile or laugh when you play peek-a-boo

- Look at you when you say their name

- Sit without support

See a complete list of milestones for kids age 9 months .

What if I’m worried about my baby’s development?

Remember, every baby develops a little differently. But if you’re concerned about your child’s growth and development, talk to your baby’s doctor or nurse.

Learn more about newborn and infant development .

Take Action: Get Ready

Take these steps to help you and your baby get the most out of well-baby visits.

Gather important information.

Take any medical records you have to the appointment, including a record of vaccines (shots) your baby has received and results from newborn screenings . Read about newborn screenings .

Make a list of any important changes in your baby’s life since the last doctor’s visit, like:

- Falling or getting injured

- Starting daycare or getting a new caregiver

Use this tool to keep track of your baby’s family health history .

What about cost?

Under the Affordable Care Act, insurance plans must cover well-child visits. Depending on your insurance plan, you may be able to get well-child visits at no cost to you. Check with your insurance company to find out more.

Your child may also qualify for free or low-cost health insurance through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Learn about coverage options for your family.

If you don’t have insurance, you may still be able to get free or low-cost well-child visits. Find a health center near you and ask about well-child visits.

To learn more, check out these resources:

- Free preventive care for children covered by the Affordable Care Act

- How the Affordable Care Act protects you and your family

- Understanding your health insurance and how to use it [PDF – 698 KB]

Take Action: Ask Questions

Make a list of questions to ask the doctor..

Before the well-baby visit, write down 3 to 5 questions you have. Each well-baby visit is a great time to ask the doctor or nurse any questions about:

- How your baby is growing and developing

- How your baby is sleeping

- Breastfeeding your baby

- When and how to start giving your baby solid foods

- What changes and behaviors to expect in the coming months

- How to make sure your home is safe for a growing baby

Here are some questions you may want to ask:

- Is my baby up to date on vaccines?

- How can I make sure my baby is getting enough to eat?

- Is my baby at a healthy weight?

- How can I make sure my baby is sleeping safely — and getting enough sleep?

- How can I help my baby develop speech and language skills?

- Is it okay for my baby to have screen time?

- How do I clean my baby’s teeth?

Take a notepad, smartphone, or tablet and write down the answers so you can remember them later.

Ask what to do if your baby gets sick.

Make sure you know how to get in touch with a doctor or nurse when the office is closed. Ask how to reach the doctor on call, or if there’s a nurse information service you can call at night or on the weekend.

Take Action: What to Expect

Know what to expect..

During each well-baby visit, the doctor or nurse will ask you about your baby and do a physical exam. The doctor or nurse will then update your baby’s medical history with all of this information.

The doctor or nurse will ask questions about your baby.

The doctor or nurse may ask about:

- Behavior — Does your baby copy your movements and sounds?

- Health — How many diapers does your baby wet each day? Does your baby spend time around people who are smoking or using e-cigarettes (vaping)?

- Safety — If you live in an older home, has it been inspected for lead? Do you have a safe car seat for your baby?

- Activities — Does your baby try to roll over? How often do you read to your baby?

- Eating habits — How often does your baby eat each day? How are you feeding your baby?

- Family — Do you have any worries about being a parent? Who can you count on to help you take care of your baby?

Your answers to questions like these will help the doctor or nurse make sure your baby is healthy, safe, and developing normally.

Take Action: Physical Exam

The doctor or nurse will also check your baby’s body..

To check your baby’s body, the doctor or nurse will:

- Measure height, weight, and the size of your baby’s head

- Take your baby’s temperature

- Check your baby’s eyes and hearing

- Check your baby’s body parts (this is called a physical exam)

- Give your baby shots they need

Learn more about your baby’s health care:

- Read about what to expect at your baby’s first checkups

- Find out how to get your baby’s shots on schedule

Updated At: 03/30/2023 02:03:26 PM

2220 Canterbury Hays, KS 67601

855-429-7633

CONVENIENT CARE

3216 Vine, Suite 20 Hays, KS 67601

785-261-7065

NURSE HOTLINE

M-F 4:30PM – 8AM Weekends & Holidays 24 hrs

1-855-Haysmed

About Us Careers Contact Us Referrals

- Good Faith Estimate

- No Surprise Disclosure

- Nondiscrimination Statement

- Notice of Privacy Practices

- Rights and Responsibilities

- Copyright HaysMed

- Price Transparency

- About Pathways.org

What to Expect At A Well Child Visit

Going to the doctor with your new baby may feel scary—but we’re here to help! Here’s what to expect at a well child visit (plus, a checklist of everything to bring along).

What is an early well child visit?

It’s early check-in with your baby’s pediatrician to make sure they are healthy and seeing all signs of typical development. It is a great place to ask questions, detect and treat any delays, and help parents feel best prepared to care for their child.

When should a well-baby visit take place?

First and foremost, follow the instructions of your doctor. They will let you know when visits should take place for your baby.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that most babies have their first doctor visit when they are 3 to 5 days old. After that, the AAP recommends well-baby visits in the first year at 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, and 12 months. See the list of check-in ages here .

What should you plan to discuss?

The doctor will be checking in on your child’s health, development, and overall well-being. Therefore, doctors will ask questions about their development and functioning.

- They will make sure baby is doing activities such as Tummy Time , remaining calm during diaper changes, etc.

- They will make sure baby is sleeping safely and getting enough sleep .

- They will check in on your child’s motor function .

- They will ask about your child’s feeding

- They may ask you if you’ve noticed any delays or issues in your child’s day-to-day activities. You can always visit our age pages to read about the milestones and abilities your child should reach- -and any signs of delay. If there’s something you want to bring to your child’s healthcare provider sooner than their next well-child visit, you can make an appointment at any time.

- They will be checking in on you as well, to make sure you’re informed on how to best care for your baby, so don’t be afraid to ask them questions about your baby’s care.

Remember that early intervention is key to prevention of further delays and complications—so it is always best to tell the doctor if you’ve seen anything concerning, or if your child is having trouble reaching a certain milestone. If something seems delayed or if you think your child might need extra help, trust your instincts and ask your doctor for their input!

Watch this video to learn more!

Your well-baby visit checklist

Before the visit:.

- Print out and review the Pathways.org Ability and Milestone Checklists . Check your baby to see if they are meeting their developmental milestones.

- If there are any that they are not meeting, just make a note of it! Just be sure to ask your doctor about it at the visit.

- Speak to any caregivers for your baby to see if they have noticed anything in your child that should be brought up to the doctor.

For the visit:

- Your baby needs to be there, as well as at least 1 parent. Your doctor will have questions about how your baby is doing, so it’s recommended that the parent present can accurately answer those questions.

- Bring your checklists with in case any questions come up about their abilities and milestones.

- Bring a pen and notebook, to write down any important information.

- Write down any questions you may have and bring them with the doctor.

Want to learn more about baby’s development and track their milestones?

Download the free pathways.org baby milestones app .

Track your child’s milestones here!

- 0-3 month milestones

- 4-6 month milestones

- 7-9 month milestones

- 10-12 month milestones

- 13-18 month milestones

- 19-24 month milestones

- 2-3 year milestones

Related Resources

When To Use Swaddles and Sleep Sacks

Do The “Sleep Switch” Every Night to Help Prevent Plagiocephaly

Doctor Visits

Make the Most of Your Child’s Visit to the Doctor (Ages 1 to 4 Years)

Take Action

Young children need to go to the doctor or nurse for a “well-child visit” 7 times between ages 1 and 4.

A well-child visit is when you take your child to the doctor to make sure they’re healthy and developing normally. This is different from other visits for sickness or injury.

At a well-child visit, the doctor or nurse can help catch any problems early, when they may be easier to treat. You’ll also have a chance to ask questions about things like your child’s behavior, eating habits, and sleeping habits.

Learn what to expect so you can make the most of each visit.

Well-Child Visits

How often do i need to take my child for well-child visits.

Young children grow quickly, so they need to visit the doctor or nurse regularly to make sure they’re healthy and developing normally.

Children ages 1 to 4 need to see the doctor or nurse when they’re:

- 12 months old

- 15 months old (1 year and 3 months)

- 18 months old (1 year and 6 months)

- 24 months old (2 years)

- 30 months old (2 years and 6 months)

- 3 years old

- 4 years old

If you’re worried about your child’s health, don’t wait until the next scheduled visit — call the doctor or nurse right away.

Child Development

How do i know if my child is growing and developing on schedule.

Your child’s doctor or nurse can help you understand how your child is developing and learning to do new things — like walk and talk. These are sometimes called “developmental milestones.”

Every child grows and develops differently. For example, some children will take longer to start talking than others. Learn more about child development .

At each visit, the doctor or nurse will ask you how you’re doing as a parent and what new things your child is learning to do.

Ages 12 to 18 Months

By age 12 months, most kids:.

- Stand by holding on to something

- Walk with help, like by holding on to the furniture

- Call a parent "mama," "dada," or some other special name

- Look for a toy they've seen you hide

Check out this complete list of milestones for kids age 12 months .

By age 15 months, most kids:

- Follow simple directions, like "Pick up the toy"

- Show you a toy they like

- Try to use things they see you use, like a cup or a book

- Take a few steps on their own

Check out this complete list of milestones for kids age 15 months.

By age 18 months, most kids:

- Make scribbles with crayons

- Look at a few pages in a book with you

- Try to say 3 or more words besides “mama” or “dada”

- Point to show someone what they want

- Walk on their own

- Try to use a spoon

Check out this complete list of milestones for kids age 18 months .

Ages 24 to 30 Months

By age 24 months (2 years), most kids:.

- Notice when others are hurt or upset

- Point to at least 2 body parts, like their nose, when asked

- Try to use knobs or buttons on a toy

- Kick a ball

Check out this complete list of milestones for kids age 24 months .

By age 30 months, most kids:

- Name items in a picture book, like a cat or dog

- Play simple games with other kids, like tag

- Jump off the ground with both feet

- Take some clothes off by themselves, like loose pants or an open jacket

Check out this complete list of milestones for kids age 30 months .

Ages 3 to 4 Years

By age 3 years, most kids:.

- Calm down within 10 minutes after you leave them, like at a child care drop-off

- Draw a circle after you show them how

- Ask “who,” “what,” “where,” or “why” questions, like “Where is Daddy?”

Check out this complete list of milestones for kids age 3 years .

By age 4 years, most kids:

- Avoid danger — for example, they don’t jump from tall heights at the playground

- Pretend to be something else during play, like a teacher, superhero, or dog

- Draw a person with 3 or more body parts

- Catch a large ball most of the time

Check out this complete list of milestones for kids age 4 years .

Take these steps to help you and your child get the most out of well-child visits.

Gather important information.

Bring any medical records you have to the appointment, including a record of vaccines (shots) your child has received.

Make a list of any important changes in your child’s life since the last doctor’s visit, like a:

- New brother or sister

- Serious illness or death in the family

- Separation or divorce

- Change in child care

Use this tool to keep track of your child’s family health history .

Ask other caregivers about your child.

Before you visit the doctor, talk with others who care for your child, like a grandparent, daycare provider, or babysitter. They may be able to help you think of questions to ask the doctor or nurse.

What about cost?

Under the Affordable Care Act, insurance plans must cover well-child visits. Depending on your insurance plan, you may be able to get well-child visits at no cost to you. Check with your insurance company to find out more.

Your child may also qualify for free or low-cost health insurance through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Learn about coverage options for your family.

If you don’t have insurance, you may still be able to get free or low-cost well-child visits. Find a health center near you and ask about well-child visits.

To learn more, check out these resources:

- Free preventive care for children covered by the Affordable Care Act

- How the Affordable Care Act protects you and your family

- Understanding your health insurance and how to use it [PDF - 698 KB]

Ask Questions

Make a list of questions you want to ask the doctor..

Before the well-child visit, write down 3 to 5 questions you have. This visit is a great time to ask the doctor or nurse any questions about:

- A health condition your child has (like asthma or an allergy)

- Changes in sleeping or eating habits

- How to help kids in the family get along

Here are some questions you may want to ask:

- Is my child up to date on vaccines?

- How can I make sure my child is getting enough physical activity?

- Is my child at a healthy weight?

- How can I help my child try different foods?

- What are appropriate ways to discipline my child?

- How much screen time is okay for young children?

Take a notepad, smartphone, or tablet and write down the answers so you remember them later.

Ask what to do if your child gets sick.

Make sure you know how to get in touch with a doctor or nurse when the office is closed. Ask how to get hold of the doctor on call — or if there's a nurse information service you can call at night or during the weekend.

What to Expect

Know what to expect..

During each well-child visit, the doctor or nurse will ask you questions about your child, do a physical exam, and update your child's medical history. You'll also be able to ask your questions and discuss any problems you may be having.

The doctor or nurse will ask questions about your child.

The doctor or nurse may ask about:

- Behavior — Does your child have trouble following directions?

- Health — Does your child often complain of stomachaches or other kinds of pain?

- Activities — What types of pretend play does your child like?

- Eating habits — What does your child eat on a normal day?

- Family — Have there been any changes in your family since your last visit?

They may also ask questions about safety, like:

- Does your child always ride in a car seat in the back seat of the car?

- Does anyone in your home have a gun? If so, is it unloaded and locked in a place where your child can’t get it?

- Is there a swimming pool or other water around your home?

- What steps have you taken to childproof your home? Do you have gates on stairs and latches on cabinets?

Your answers to questions like these will help the doctor or nurse make sure your child is healthy, safe, and developing normally.

Physical Exam

The doctor or nurse will also check your child’s body..

To check your child’s body, the doctor or nurse will:

- Measure your child’s height and weight

- Check your child’s blood pressure

- Check your child’s vision

- Check your child’s body parts (this is called a physical exam)

- Give your child shots they need

Learn more about your child’s health care:

- Find out how to get your child’s shots on schedule

- Learn how to take care of your child’s vision

Content last updated February 2, 2024

Reviewer Information

This information on well-child visits was adapted from materials from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health.

Reviewed by: Sara Kinsman, M.D., Ph.D. Director, Division of Child, Adolescent, and Family Health Maternal and Child Health Bureau Health Resources and Services Administration

Bethany Miller, M.S.W. Chief, Adolescent Health Branch Maternal and Child Health Bureau Health Resources and Services Administration

Diane Pilkey, R.N., M.P.H. Nursing Consultant, Division of Child, Adolescent, and Family Health Maternal and Child Health Bureau Health Resources and Services Administration

You may also be interested in:

Take Care of Your Child's Teeth

Get Your Child’s Vision Checked

Healthy Snacks: Quick Tips for Parents

The office of disease prevention and health promotion (odphp) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website..

Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by ODPHP or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

Planning for a baby?

- Preconception Health

- Preparing for Pregnancy

- Assisted Pregnancy

- Second Pregnancy

Already Pregnant?

- Pregnancy Week by Week

- Health & Safety

- Live life better

- Preparing for the baby

- Pregnancy Diet & Fitness

Have a Baby?

- Baby Milestones

- Baby Basics

- Mother Care

- Activity & Fun

Have a Toddler?

- Toddler Mile Stones

- Toddler Basics

- Food & Feeding

- Child Safety & Health

- Games & Playtime

- Special Child

Positive Parenting

- Health & Hyginie

- Learning and Development

- Family Basics

Child Safety

- Special child Care

- Planning for Future

- Play, Games, activity & Fun

Life Skills

Premature baby, baby products, have a baby, baby health, how to prepare your baby for doctor’s visits – challenges and tips.

Written by Gayathri Lakshminarayanan

Gayathri Lakshminarayanan

Gayathri’s passion for writing had its foundation at the very early stages of her life when she was on her college editorial board and also won several awards for writing events and book review competitions. She combines her corporate experience with her writing skills and her experience as a homemaker makes her an empathetic contributor in the parenting domain . Her shift from full-time accounting professional to a homemaker gave her career a new direction.

Why Do You Need to Take Your Baby to the Doctor During Their First Year?

Challenges parents face when taking baby for doctor’s visits, top 10 tips to prepare your baby for doctor’s visits, faq’s.

1. Other Crying Babies

2. your baby’s separation anxiety , 3. fear of the injection pain, 4. the doctor, 6. parents’ anxiety, 7. overcrowding, 8. hunger or soiled diapers.

1. Time the Visit Well

2. do not make the baby wait for too long, 3. keep the baby busy during waiting time, 4. carry their favorite toy along, 5. plan to go out after the checkup, 6. do not get stressed about doctor’s visits, 7. explain the purpose of the visit, 8. prepare to breastfeed, 9. always carry the diaper bag, 10. avoid last-minute hurry, 1. at what ages do you take your baby to the doctor, 2. why is it important to take the babies for regular visits to the doctor, 3. what is the duration of a regular baby visit, advantages of saffron during pregnancy.

Saffron is the dried stigma of Crocus Sativus flower, i.e. the thread-like part at the centre which contains pollen.

Gayathri Lakshminarayanan,CA, B.Com

Gayathri’s passion for writing had its foundation at the very early stages of her life when she was on her college editorial board and also won several awards for writing events and book review competitions. She combines her corporate experience with her writing skills and her experience as a homemaker makes her an empathetic contributor in the parenting domain . Her shift from full-time accounting professional to a homemaker gave her career a new direction. Read more.

Responses (0)

Want curated content sharply tailored for your exact stage of parenting, read this next, related articles.

Puzzles For Babies – How it Helps in Baby’s Development

Top 10 Baby Clothes Brands in India

Port Wine Stain Birthmarks in Babies – Causes, Symptoms & Treatment

Baby Growth Charts – Everything You Need To Know

Kissing a Baby – Is it Safe?

Chair Method of Sleep Training Your Baby – Know All About it

Sponsored content

Discover great local businesses around you for your kids..

Get regular updates, great recommendations and other right stuff at the right time.

Premium Access

Join our community of 50K+ Moms and get access to exclusive features & resources in our app.

Pay Rs 25/- and read this article (One time access)

Our site uses cookies to make your experience on this site even better. We hope you think that is sweet.

Create account

Focus your wanderlust. create your account to get curated stories and recommendations., already have an account sign in.

Don't have an account? Sign up forgot password?

Get curated personalized content., articles and resources served personalized as per the stage of your parenting., already have an account login, choose one..

Enter dates

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 04 April 2024

The infant–doctor relationship: an examination of infants’ distress reactions in the presence of a doctor

- Motonobu Watanabe 1 , 2 ,

- Masaharu Kato 1 ,

- Yoshi-Taka Matsuda 1 , 3 ,

- Kosuke Taniguchi 1 , 4 &

- Shoji Itakura 1

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 7968 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

343 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Medical ethics

- Paediatric research

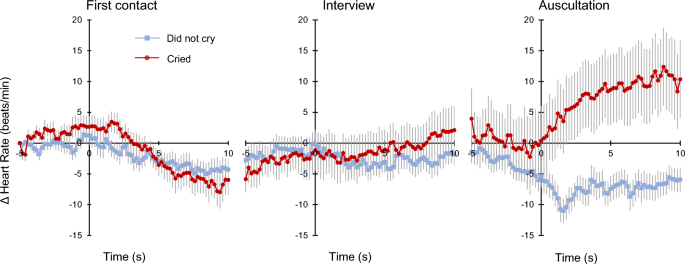

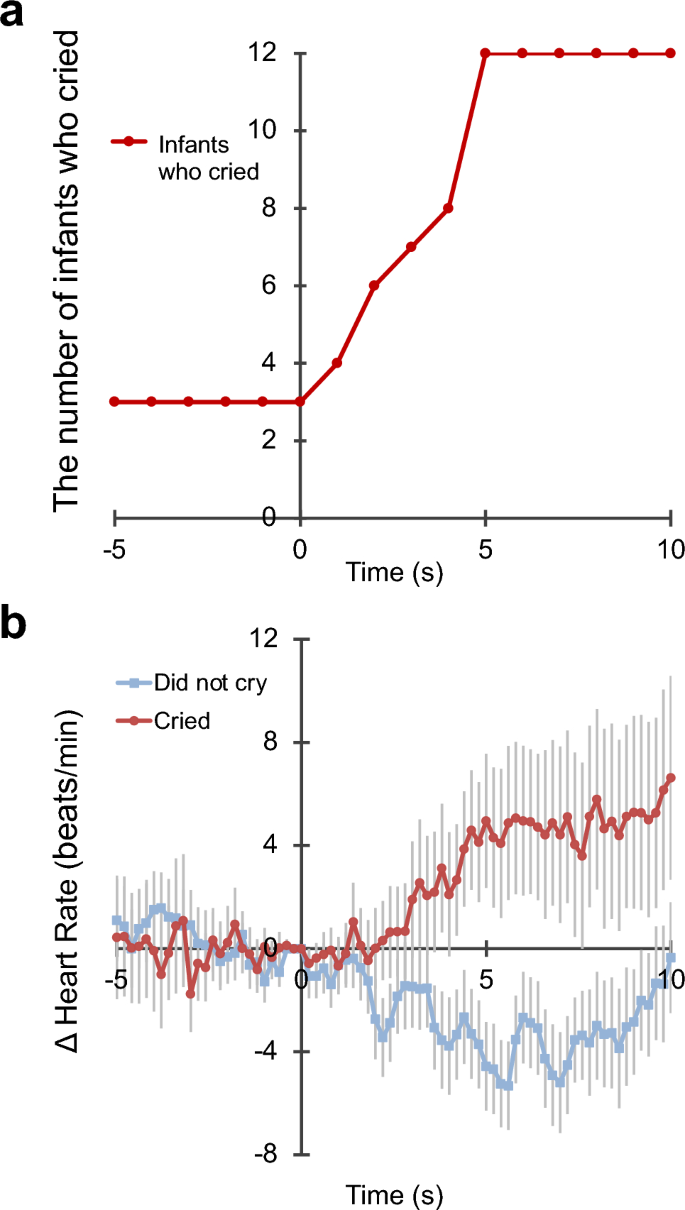

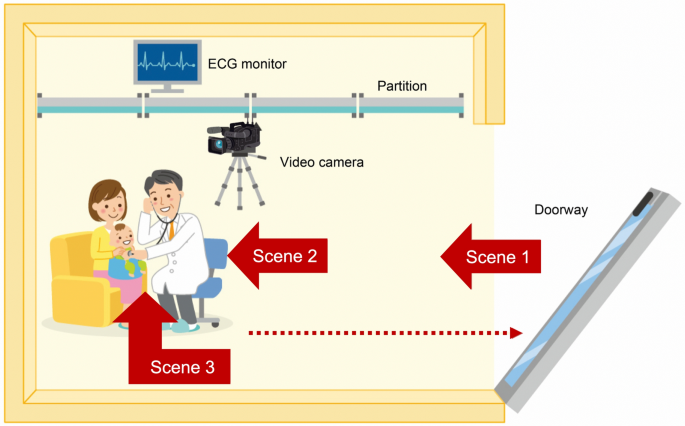

- Paediatrics