Giovanni da Verrazzano

Giovanni da Verrazzano was an Italian explorer who charted the Atlantic coast of North America between the Carolinas and Newfoundland, including New York Harbor in 1524. The Verrazano–Narrows Bridge in New York was named after him.

(1485-1528)

Who Was Giovanni da Verrazzano?

Around 1506 or 1507, Giovanni da Verrazzano began pursuing a maritime career, and in the 1520s, he was sent by King Francis I of France to explore the East Coast of North America for a route to the Pacific. He made landfall near what would be Cape Fear, North Carolina, in early March and headed north to explore. Verrazzano eventually discovered New York Harbor, which now has a bridge spanning it named for the explorer. After returning to Europe, Verrazzano made two more voyages to the Americas. On the second, in 1528, he was killed and eaten by the natives of one of the Lower Antilles, probably on Guadeloupe.

Early Years

Giovanni da Verrazzano was born around 1485 near Val di Greve, Italy. Verrazzano was introduced to adventure and exploration at an early age. He first headed to Egypt and Syria, places that were considered mysterious and nearly impossible to reach at the time. Sometime between 1507 and 1508, Verrazzano went to France, where he met with King Francis I. He also came in contact with members of the French navy, and began to get a feel for the navy’s missions and building rapport with the sailors and commanders.

Voyages and Route

Verrazzano and Francis I met between 1522 and 1523, and Verrazzano convinced the king that he would be the right man to undertake exploratory voyages to the West on behalf of France; Francis I signed on. Verrazzano prepared four ships, loaded with ammunition, cannons, lifeboats, and scientific equipment, with provisions to last eight months. The flagship was named Delfina , in honor of the King’s firstborn daughter, and it set sail with the Normanda , Santa Maria and Vittoria . The Santa Maria and Vittoria were lost in a storm at sea, while the Delfina and the Normanda found their way into battle with Spanish ships. In the end, only the Delfina was seaworthy, and it headed to the New World during the night of January 17, 1524. Like many explorers of the day, Verrazzano was ultimately seeking a passage to the Pacific Ocean and Asia, and he thought that by sailing along the northern coastline of the New World he would find a passageway to the West Coast of North America.

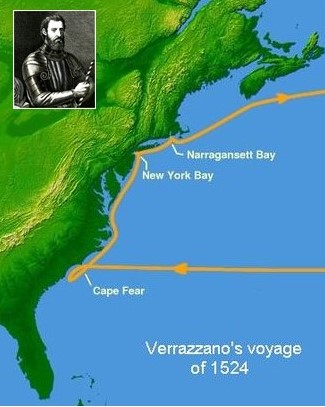

After 50 days at sea, the men aboard the Delfina sighted land — generally thought to be near what would become Cape Fear, North Carolina. Verrazzano first steered his ship south, but upon reaching the northern tip of Florida, he turned and headed north, never losing sight of the coastline. On April 17, 1524, the Delfina entered the Bay of New York. He landed on the southern tip of Manhattan, where he stayed until a storm a pushed him toward Martha’s Vineyard. He finally came to rest at what is known today as Newport, Rhode Island. Verrazzano and his men interacted with the local population there for two weeks, before returning to France in July 1524.

Accomplishments

Verrazzano added greatly to the knowledge base of mapmakers in terms of the geography of the East Coast of North America. In honor of the famed explorer, the bridge spanning the Narrows between Brooklyn and Staten Island now bears his name. The Jamestown Verrazzano Bridge in Rhode Island is also named in honor of the explorer.

In March 1528, Verrazzano left France on his final voyage, yet again seeking the passage to India (after not having found it via a South American voyage the year before). The expedition, which included Verrazzano’s brother, Girolamo, sailed along the coast of Florida before drifting into the Caribbean Sea. This turned out to be the last mistake the explorer would ever make.

While sailing south of Jamaica, the crew spotted a heavily vegetated, seemingly unpopulated island, and Verrazzano dropped anchor to explore it with a handful of crewmen. The group was soon attacked by a large assemblage of cannibalistic natives who killed them and ate them all as Girolamo and the rest of the crew watched from the main ship, unable to help.

QUICK FACTS

- Birth Year: 1485

- Birth City: Val di Greve

- Birth Country: Italy

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Giovanni da Verrazzano was an Italian explorer who charted the Atlantic coast of North America between the Carolinas and Newfoundland, including New York Harbor in 1524. The Verrazano–Narrows Bridge in New York was named after him.

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 1528

- Death City: Lesser Antilles

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

European Explorers

Christopher Columbus

10 Famous Explorers Who Connected the World

Sir Walter Raleigh

Ferdinand Magellan

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Leif Eriksson

Vasco da Gama

Bartolomeu Dias

Jacques Marquette

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

- Hide Sidebar

- First Paragraph

- Bibliography

- Find Out More

- How to cite

- Back to top

DCB/DBC News

New biographies, minor corrections, biography of the day.

b. 30 April 1836 at Montreal, L.C.

Confederation

Responsible government, sir john a. macdonald, from the red river settlement to manitoba (1812–70), sir wilfrid laurier, sir george-étienne cartier, the fenians, women in the dcb/dbc.

Winning the Right to Vote

The Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences of 1864

Introductory essays of the dcb/dbc, the acadians, for educators.

Exploring the Explorers

The War of 1812

Canada’s wartime prime ministers, the first world war.

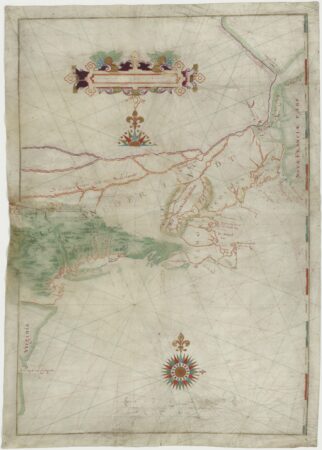

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

VERRAZZANO (“Janus Verrazanus,” the one extant signature on a deed dated 11 May 1526, now in the archives at Rouen, is generally conceded to be a Latinized form of the original Italian spelling ), GIOVANNI DA , explorer, navigator, merchant adventurer, the first European, according to authentic record, to sail the coast of America from Florida to Newfoundland; b. c . 1485 in or near Florence (possibly at Greve) of Piero Andrea da Verrazzano and Fiametta Capelli, both of Florence; d. c . 1528 in the West Indies at the hands of cannibals.

Verrazzano’s distinguished lineage has been traced to the early Middle Ages and the last member of the family died in Florence in 1819. Verrazzano had a younger brother, Gerolamo, to whom he must have been close; another, named Bernardo, was a prominent banker in Rome; and two others found in a genealogical register are given as Nicolo and Piero. It is not known if Giovanni ever married. The position of his family as well-to-do merchants and bankers, and his mastery of the elements of navigation and the literary culture revealed in his famous Letter, are sufficient evidence of a superior education.

Florence was well able to provide it; she was the golden city, a centre of geographical and navigational science. Her prosperous merchants travelled everywhere in prosecution of trade. The twin pursuits of navigation and commerce quickly occupied Verrazzano’s attention for, imbued with the Renaissance spirit, he developed as a man of enlightened thought and imaginative action. As a young man he lived in Cairo for several years as a commercial agent and doubtless he learned his seamanship in the eastern Mediterranean for he was familiar with these waters, where Columbus also had gained experience. One source, Bacchiani, pictures the young Verrazzano as giving ear to a patriot group “nearly all friends of France, because enemies of the Medici and believers in citizen’s rights.” It is not unreasonable to assume that he left Florence, as did so many Florentines in this period, to escape the repressive atmosphere.

There have been suggestions that Verrazzano sailed to America in his early twenties with Thomas Aubert’s famous voyage to Newfoundland in 1508. It is a possibility sufficiently in character, but the evidence is inconclusive. Murphy, Buckingham Smith, and others have identified the navigator with a corsair, named Jean Florin or Florentin (the Florentine), who operated against Spanish and Portuguese treasure ships during these years but Prospero Peragallo has effectively shown this to be a confusion of personalities. Verrazzano was not idle however; indeed one contemporary, writing after the navigator’s return from his 1524 voyage, refers to his travels in Egypt and Syria and “almost through all the known world, and thence by reason of his merit is esteemed another Amerigo Vespucci; another Ferdinand Magellan and even more” (Carli letter). Apart from these speculations, there are no known records to enlighten us further on Verrazzano’s early life.

When Verrazzano entered the maritime service of France is uncertain; the earliest documentary evidence placing him in that country is a report of 1522 from Portuguese merchants in France to their king, where it is said that Verrazzano is quietly soliciting the support of François I for a voyage. It was the eager desire of the age for a sea route westwards to the riches of China and the East Indies, and particularly the French king’s ambition to have a share in the Iberian glories and profits of the New World, that presented Verrazzano with his opportunity. Though a continent south of the latitude of Florida seemed to bar the way to the east, the region northwards to Cape Breton, so far as surviving narrative indicates, was unexplored; here there was still hope for both a passage and new lands. The account of Verrazzano’s voyage to this area is told in versions of a letter or relation he wrote to François I, who commissioned the voyage – the first to America under official French auspices.

The Letter is dated on board his ship, 8 July 1524, immediately upon his return to Dieppe. Although the autographic original has disappeared (it may yet be found), four Italian versions are extant. One is printed in Ramusio, and another is a transcribed codex found in the Strozzi Library, Florence, together with the Carli letter; there is also a manuscript fragment of this text in the Academy at Cimento. It was on the basis of these texts that Smith and Murphy raised the controversy of the latter half of the 19th century, when it was plausibly argued that Verrazzano never reached America and that the Letter was not his work at all. Brevoort, Dexter (in Justin Winsor), and other learned authorities came forward in a strong defence of both the missive and the voyage, restoring confidence in the navigator. After the discovery of the next and most important version, in the Library of Count Giulio de Cèllere, Rome, in 1909 (now in the Pierpont Morgan Library), all suspicions were finally dispelled; this codex bears what are regarded as Verrazzano’s own marginal comments. The last version, a manuscript in the Vatican Library, was reported only in 1925. Still further supporting documents have been discovered in this century, more in fact than during the preceding 350 years.

The Letter says at the outset that the writer was sent by the king “to discover new lands,” and later that “my intention was . . . to reach Cathay”; but there is much evidence indicating that Verrazzano had a keen mercantile as well as exploring interest in his voyages. Two manuscripts dated in March 1523, found in the Rouen archives, record inferentially, in connection with a voyage being planned, an agreement concerning the division of investment and profit among members of a Lyons syndicate which includes Verrazzano; the members are revealingly described as “tous marchans florentins.”

From the Letter we find that its author set out from Dieppe late in 1523 with four ships, but that a storm forced him to find a haven in Brittany with only the Normanda and the Dauphine . After repairs, he skirted the Spanish coast harassing commerce and then, apparently under new orders, resumed his voyage with the Dauphine alone. He set sail from a deserted islet at the westernmost point of the Madeiras (probably Porto Santo) on 17 Jan. 1524 (n.s.), with a Norman crew of 50, his tiny caravel armed and victualled for an eight-month voyage. Sailing west on a course about 150 miles north of that of Columbus, he weathered a violent tempest on 24 February, continued west but bearing “somewhat to the north,” and in 25 more days found “a new land never before seen by anyone.” The position of this landfall, given as in 34°, has been variously placed from Florida (for he reported palm trees) to North Carolina, but was probably close to Cape Fear, North Carolina. After a short exploration southward in vain search for a harbour, he turned about, fearing to meet Spaniards, and coasted north as far as Nova Scotia and “near the land which the Britanni (Britons) found,” Cape Breton – without, apparently, observing the Bay of Fundy. He went ashore at several places along the coast, abducted an Indian boy to take back to France, visited New York harbour, and spent 15 days in Narragansett Bay. His Letter records the earliest geographical and topographical description of a continuous North Atlantic coast of America derived from a known exploration, and his observation on the Indians is the first ethnological account of America north of Mexico.

Reaching Newfoundland (“Bacalaia” in the Cèllere version gloss) and finding his provisions failing, he set course for France, making Dieppe early in July 1524 “having discovered six hundred leagues and more of new land.” His six-month voyage is one of the most important in North American exploration. Though it failed to reveal a passage to China, it enabled Verrazzano to be the first to report that the “New World which above I have described is connected together, not adjoining Asia or Africa (which I know to be a certainty).” Here is reasoning based on experience, freed from the ancient teaching of the schools that the Atlantic bathed both European and Asian shores. Verrazzano had, in fact, joined Canada to the rest of America – to the New World. The Letter concludes with a cosmographical description of the voyage, including detailed nautical and astronomical data which demonstrate Verrazzano’s mastery of the scientific methods of the day.

The voyage was represented cartographically in coastlines from Florida to Cape Breton: Hakluyt (“Discourse on western planting”) mentions a “mightie large olde mappe” (the basis of the 1582 Lok map) and an “Olde excellent globe,” both seemingly made by Verrazzano (now lost); the world map of the Viscount of Maggiolo, 1527 (destroyed during the bombing of Milan in World War II), and, more clearly, Gerolamo da Verrazzano’s world map of 1529 (now in the Vatican); and there are many others which derive this coastline from Verrazzano (Ganong describes them fully). The Robertus de Bailly globe of 1530, and the copper globe of Euphrosynus Ulpius, dated 1542, are notably Verrazzanian in their North American contours. The latter bears the inscription across North America “Verrazana sive Nova Gallia a Verrazano Florentino comperta anno sal. M.D.” (“Verrazana, or New Gaul [i.e., New France], discovered by Verrazano the Florentine, in the year of Salvation M.D.,” date incomplete). Bailly has “Verrazana” written across the North American seaboard. Both globes depict the Sea of Verrazzano, a curiosity beginning with Verrazzano’s own gloss in the Cèllere version of his Letter, where he mentions an isthmus “a mile in width and about 200 long, in which, from the ship, was seen the Mare Orientale between the west and the north. Which is the one, without doubt, which goes about the extremity of India, China and Cathay.” (Hall’s translation in Stokes.) This isthmus, described by Hakluyt from the old map and globe as “a little necke of lande in 40. degrees of latitude,” with the sea on both sides, is the line of islands and sandbars off the coast of North Carolina and the Mare Orientale (Western Sea) extending to Asia is no more than the broad Pamlico and Albemarle sounds. Yet this misconception of a willing mind persisted even into the 17th century. (The cartographical history of the Sea of Verrazzano is traced in Winsor.)

Verrazzano’s voyage also left its impression in the nomenclature of subsequent maps, though regrettably almost every one of his place-names has now disappeared. Maggiolo’s 1527 map is the first to use the appellation “Francesca” (François I) for North America and the chart of the navigator’s brother, Gerolamo, is the earliest to show the names New France (“Nova Gallia”) and Norumbega (if this is his “Oranbega”), a name later applied variously within the area between New York and Cape Breton. Both maps therefore record a French influence in North American exploration, due to Verrazzano, several years before Cartier’s first voyage. “Arcadia,” the name Giovanni gave to Maryland or Virginia “on account of the beauty of the trees,” made its first cartographical appearance in the 1548 Gastaldo map and is the only name to survive in Canadian usage. It has a curious history. In the 17th century Champlain fixed its present orthography, with the “r” omitted, and Ganong has shown its gradual progress northwards, in a succession of maps, to its resting place in the Atlantic provinces.

Verrazzano’s Letter was dispatched from Dieppe to a banker in Rome, but en route at Lyons its contents were evidently available to the merchants with whom the navigator had contracted for the voyage, since a copy of it accompanied a letter from the Florentine merchant Bernardo Carli, resident in Lyons, to his father in Florence, dated 4 Aug. 1524. The Carli letter contains some interesting, though indirect, hints on Verrazzano’s earlier career and offers the hope of his associates that the king will entrust the navigator “again, with half a dozen good vessels and that he will return to the voyage,” that “he may discover some profitable traffic.” Verrazzano shared this hope and late in 1524 he had another French expedition in readiness for the Indies. The military defeats of France that year, however, left her in no mood for transatlantic enterprises; Verrazzano’s ships and crews were commandeered. The evidence for this proposed voyage includes a record that the king, François I, later compensated its promoters for the loss of their investment. Even so, Hakluyt (“Epistle Dedicatorie” to Divers voyages ), in speaking of America, says that Verrazzano “had been thrise on that coast” – though this may have reference to the Aubert voyage of 1508. In the same place Hakluyt refers to a map of Verrazzano “which he gave to King Henrie the eight,” perhaps implying a visit to England, and it has even been argued that Verrazzano sailed in King Henry’s service after his first voyage. This possibility is not countenanced by Bacchiani, but his arguments are unconvincing. It appears probable, nevertheless, that the navigator made only two voyages to America.

The final voyage, also under royal auspices, was planned in 1526; it is attested in a contract of that year by Chabot, the admiral of France, with Verrazzano and other speculators to furnish three vessels (two of them the king’s) to make a trading voyage to the Indies for spices. Our navigator, as chief pilot, was to receive one-sixth of the fruits of the venture after certain expenses had been deducted. Other documents corroborate the voyage; one, a deed dated 11 May 1526, signed “Janus Verrazanus” in the Latin form (an aspect of his Renaissance classicism), is his only known autograph. Preserved in the archives at Rouen, a facsimile appears in Winsor. The deed appoints his brother Gerolamo his heir and attorney during the proposed mission. Another object of the voyage, besides trade, was to search for the elusive passage to Asia south of the region explored in the first journey. All was apparently ready in 1526, yet the start was unaccountably delayed for nearly two years. The arguments for a 1526 expedition, mainly liturgical (the naming of geographical features for the feast days on which they were discovered) are not demonstrable. The cause of the delay is still a matter of conjecture.

With Darien as its likely first destination, the fleet at last set its course in the spring of 1528 for Florida, the Bahamas, and the Lesser Antilles. On an island in the latter group, probably near Guadeloupe, Verrazzano landed with a party and was taken by Caribs, killed, and eaten within sight of his crew. The event is recorded in Ramusio, in Paolo Giovio’s Elogia (Florence, 1548; Basel, 1575, copy in Library of Congress), and in a manuscript poem (in the Museo Civico, Como) by Paolo’s nephew Giulio Giovio. Many have inferred that Gerolamo was an eye-witness to his brother’s shocking death.

Among a group of edicts passed by the Parlement of Normandy in 1532, concerning the financing, fitting out, and lading with trade goods of Verrazzano’s fleet is one which reveals an interesting sequel to his last voyage. It records the unlading from La Flamengue , the navigator’s vessel, at Fécamp in March 1530, of a cargo of brazil-wood. From the context we know, therefore, that Verrazzano’s own ship returned in 1530, and that it definitely visited the Caribbean area – perhaps while Verrazzano was still alive.

William F. E. Morley

The primary sources for the voyages are the Letter in its four versions: Cèllere codex (probably 1524), first printed by A. Bacchiani, with commentary, in Soc. geogr. ital. Bollett ., XLVI (1909), 1274–1323, facsimile in Stokes [ infra ], II, plates 60–81, and tr. by E. H. Hall, in Stokes, IV, 15–19. G. B. Ramusio, Terzo volume delle navigationi et viaggi nel quale si contengono Le Navigationi al Mondo Nuovo . . . (1st ed., Venetia, 1556), III, 420–22; tr. in Hakluyt, Divers voyages (1850), 55–71. Strozzi, or Florentine, codex (late 16th cent.), tr. by J. G. Cogswell in N.Y. Hist. Soc. Coll ., 2nd ser., I (1841), 37–67. Vatican codex (presumably 16th c.), unpublished, but photostatic copy in Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. The Carli letter and Chabot agreement are appended to Murphy [ infra ], with his tr. Reproductions of the Maggiolo, G. da Verrazzano, and Gastaldo maps are in Stevenson [ infra ]. PAC has a Gastaldo 1548 Ptolemy. Pierpont Morgan Library has the Bailly globe, and the N.Y. Hist. Soc. the Ulpius globe.

Some secondary sources are: Bacchiani, commentary [ supra ]; and “I fratelli da Verrazzano,” Soc. geogr. ital. Bollett , LXII (1925), 373–400. J. C. Brevoort, Verrazano the navigator (Albany, 1874). Ganong, “Crucial maps, III.” Hakluyt, “Discourse on western planting.” The iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498–1909 , comp. I. N. P. Stokes (6v., New York, 1915–28), IV, 15–19. H. C. Murphy, The voyage of Verrazzano (New York, 1875). P. Peragallo, “Intorno alla supposta identità di Giovanni Verrazzano,” Soc. geogr. ital. Memorie , VII, Rome, 1897, 165–89. Buckingham Smith, An inquiry into the authenticity of documents . . . (New York, 1864). E. L. Stevenson, Maps illustrating early discovery and exploration in America, 1502–1530 (New Brunswick, N.J., 1903). Justin Winsor, Narrative and critical history of America (8v., Boston, 1884–89), IV. Consulted: L. C. Wroth, study of Verrazzano and his voyages, in preparation.

General Bibliography

© 1966–2024 University of Toronto/Université Laval

Image Gallery

Document History

- Published 1966

- Revised 1979

Occupations and Other Identifiers

Related biographies.

CARTIER, JACQUES (1491-1557)

CHAMPLAIN, SAMUEL DE

GILBERT (Gylberte, Jilbert), Sir HUMPHREY

GOMES, ESTEVÃO

HUDSON, HENRY

LESCARBOT, MARC

GAULTIER DE VARENNES ET DE LA VÉRENDRYE, PIERRE (Boumois)

Cite This Article

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the chicago manual of style (16th edition). information to be used in other citation formats:.

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Marsh, James H. and Erin James-Abra. "Giovanni da Verrazzano". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 22 September 2017, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/giovanni-da-verrazzano. Accessed 30 April 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 22 September 2017, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/giovanni-da-verrazzano. Accessed 30 April 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Marsh, J., & James-Abra, E. (2017). Giovanni da Verrazzano. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/giovanni-da-verrazzano

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/giovanni-da-verrazzano" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Marsh, James H. , and Erin James-Abra. "Giovanni da Verrazzano." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published January 07, 2008; Last Edited September 22, 2017.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published January 07, 2008; Last Edited September 22, 2017." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Giovanni da Verrazzano," by James H. Marsh, and Erin James-Abra, Accessed April 30, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/giovanni-da-verrazzano

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Giovanni da Verrazzano," by James H. Marsh, and Erin James-Abra, Accessed April 30, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/giovanni-da-verrazzano" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Article by James H. Marsh , Erin James-Abra

Published Online January 7, 2008

Last Edited September 22, 2017

Verrazzano was born to a family of merchants and bankers. He was well educated in Florence, then a centre of geographic and navigational science. As a young man he spent time in Cairo and Syria before moving to France between 1506 and 1508 to pursue a maritime career.

First Voyage

As was the case for many colonial powers at the time, France was concerned with finding a westward route to China. Verrazzano convinced France’s king, Francois I, to allow him to attempt to find the route under France’s flag. In 1523, Verrazzano left Dieppe with four ships in what was France’s first official voyage to North America. He was forced to take refuge in Brittany following a storm, and set sail again shortly thereafter with one ship, the Dauphine , and a crew of 50. Verrazzano sailed west and landed at Cape Fear, in what is now North Carolina. From there he sailed south briefly before following the coast north to Cape Breton . Verrazzano occasionally came ashore to explore; during one of these explorations he kidnapped an Indigenous boy to take back to France. By the time he reached Newfoundland he was running low on supplies so returned to France. He arrived back at Dieppe on 8 July 1524.

Final Voyage

In 1528, Verrazzano set sail on what would be his final voyage. The purpose of the trip was to trade for spices in the West Indies, reaching Florida, the Bahamas and the Lesser Antilles. On one of these islands, likely near Guadalope, Verrazzano went ashore and was killed by Caribs, the Indigenous people there.

Recommended

Pierre dugua de mons.

Sir Humphrey Gilbert: Elizabethan Explorer

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The voyages of Giovanni da Verrazzano, 1524-1528

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

Original book is like this.

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

690 Previews

12 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

EPUB and PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by ttscribe6.hongkong on December 10, 2018

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Voyage to the Northeast

710924 composite_full resolution.jpg.

Italian navigator Giovanni Verrazzano sailed to the New World in 1524, looking for a route to Asia. As the first European to set sights on New York Harbor and Block Island, he helped map the eastern coastline of North America. Map credit: Matthew Trump, CC BY-SA 3.0, Inset credit: F. Allegrini

One of the great quests of the 16th century was to find a northwest passage—a shortcut from Europe to Asia. Such a route would go through or above the lands of the New World. No one ever found it because there isn’t one. But the search gave European mapmakers and scientists a lot of information about the North American coastline.

One example was a search that reached the coast 500 years ago. Italian navigator Giovanni da Verrazzano convinced the king of France to sponsor a search for the northwest passage. The expedition set sail in January of 1524. It reached the coast in March, near Cape Fear, North Carolina.

Verrazzano sailed south for a while, but stopped before he reached Florida, which was claimed by Spain. He then headed north. Over the next few months, he cruised past present-day New York, New England, and toward Canada.

During that time, he and his crew became the first Europeans to see what are now known as New York Harbor, Block Island, and Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island. Verrazzano also bestowed Old World names on many of the features he saw.

His accounts of the journey helped mapmakers begin to craft maps of that part of the American coastline. Verrazzano also became convinced that everything he saw was part of a single vast continent—with no way through it.

Verrazano visited the New World two more times. He was killed during an encounter with the natives of one of the Caribbean islands during the last visit, in 1528.

Looking for something? Search all of our content.

Subscribe to our weekly podcast.

Science and the Sea TM is part of the Texas Podcast Network – the conversations changing the world – brought to you by The University of Texas at Austin. Any opinions that may be expressed in this podcast do not represent the views of The University of Texas at Austin.

The Voyages of Giovanni da Verrazzano, 1524-1528

- Standard View

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Charles E. Nowell; The Voyages of Giovanni da Verrazzano, 1524-1528. Hispanic American Historical Review 1 August 1971; 51 (3): 537–538. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/00182168-51.3.537

Download citation file:

- Reference Manager

Giovanni da Verrazzano was an explorer about whom little is known and much is conjectural. Almost the only certainty is that in 1524, in the caravel Dauphine , he discovered for France the coast from near Cape Fear to Newfoundland. He made other voyages, but from such guidelines as exist it is doubtful that on these he went to places not previously discovered.

Verrazzano called himself a Florentine; Wroth argues convincingly that he was born at Lyons, where numerous Florentines lived who considered themselves citizens of the mother city. His birth year is unknown, though he was evidently in his forties at the time of his death. The author refutes the old assertion that the voyager died on a Spanish gallows as a pirate, showing that from the best evidence he was killed and presumably eaten by Caribbean savages in 1528.

Wroth suggests, without seeking to prove, that Verrazzano visited the Newfoundland area with the Thomas Aubert expedition as early as 1508. If so it would explain his treatment of this vicinity as familiar in his report of the 1524 discoveries.

With so much concerning him uncertain, Verrazzano’s fame depends on the Dauphine expedition of 1524. This went in search of a passage to Cathay, financed by wealthy Florentines in Lyons and a Lombard in Paris, with at least the official blessing of King Francis I. For the resulting discoveries, our evidences are the Cèllere Codex, written or dictated by the commander himself and now in the Pierpont Morgan Library, and a number of maps, one of them the work of the explorer’s brother, Gerolamo. Together, these permit a satisfactory reconstruction of the expedition, whose discoveries included New York harbor.

Is this enough to place Verrazzano among the great explorers? In the Columbus-Vespucci-Magellan sense it is not, as, with the emphasis then being placed upon a waterway through America, it was probably only a question of who would be first to explore this stretch of North American coast. On the other hand, evidence shows Verrazzano to have been an exceptionally able commander who understood the nature of his discoveries. Even before sailing, he realized that, after his trans-Atlantic landfall, Cathay would be far distant.

Wroth’s inclusion of every scrap of evidence regarding Verrazzano makes this appear to be the definitive work on the explorer. Statements of fact to which exception can be taken are peripheral to the main theme. Sixteenth-century maps are abundantly reproduced; I hope it is no carping criticism to say that at least one modern map would have helped.

Data & Figures

- Previous Issue

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Advertisement

Supplements

Citing articles via, email alerts, related articles, related topics, related book chapters, affiliations.

- About Hispanic American Historical Review

- Editorial Board

- For Authors

- Rights and Permissions Inquiry

- Online ISSN 1527-1900

- Print ISSN 0018-2168

- Copyright © 2024

- Duke University Press

- 905 W. Main St. Ste. 18-B

- Durham, NC 27701

- (888) 651-0122

- International

- +1 (919) 688-5134

- Information For

- Advertisers

- Book Authors

- Booksellers/Media

- Journal Authors/Editors

- Journal Subscribers

- Prospective Journals

- Licensing and Subsidiary Rights

- View Open Positions

- email Join our Mailing List

- catalog Current Catalog

- Accessibility

- Get Adobe Reader

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Finding New York: 500th anniversary of Giovanni de Verrazzano historic voyage of discovery

For many people around the globe, New York City is just a flight away.

With three major airports, tunnels, bridges and cruise ship terminals, the Big Apple is easily accessible to millions of visitors each year. People flock here to experience the bustling city life, to snap a selfie with the Statue of Liberty, to see a Broadway show, to enjoy a stroll in Central Park... or simply to devour a slice of the famed New York pizza.

New York City is one of the top-rated tourist attractions in the world, and many have it on their proverbial bucket list.

However, the first outsider to reach New York Bay and to describe it was Giovanni de Verrazzano, an intrepid Italian explorer from Florence.

NICOLAUS COPERNICUS: THE MAN WHO STOPPED THE SUN AND MOVED THE EARTH

He sailed here with a crew of 50 exactly 500 years ago, and he certainly liked what he saw.

READ ON THE FOX NEWS APP

"After a hundred leagues we found a very agreeable place between two small but prominent hills," Verrazzano wrote in his letter to King Francis. "Between them a very wide river, deep at its mouth, flowed out into the sea."

It was the Hudson River , as we now know it, that he was describing.

Verrazzano was born in 1485 in Tuscany, and Castello di Verrazzano is frequently mentioned as his birthplace. Upon finishing his education in Florence, he journeyed to France and began his career as a navigator. Throughout the years, he traveled to the eastern parts of the Mediterranean Sea, known then as the Levant, where Western traders exchanged European commodities for an array of goods including spices and incense.

However, in 1522, when the surviving members of the Magellan expedition returned to Spain with maps and fascinating stories of circumnavigating the entire globe, it became evident to European merchants that the competition in trade had just entered an entirely new phase.

Not to fall behind, French King Francis the 1st gave Verrazzano a green light to sail west and find new trade routes with Asia via the Pacific Ocean. According to historical records, four ships loaded with munitions, scientific equipment and provisions to last eight months left France for the New World. Verrazzano thought the best bet to get there fast was to set sail via the northern route. Unfortunately, not long after the departure, a violent storm swept through the Northern seas, sinking two of the vessels and ruining a third.

In the end, La Dauphine, the first vessel ever built for a transatlantic crossing, remained seaworthy and embarked on a lone journey to the New World from the island of Madeira.

POLISH PRESIDENT ATTENDS PULASKI DAY PARADE, HONORING HERO OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTIONARY WAR

According to Verrazzano's letters, they reached the shores of present-day North Carolina first and were greeted by peaceful Native Americans.

"We anchored off the coast and sent a small boat in to land," Verrazzano wrote to the King. "We had seen many people coming to the seashore, but they fled when they saw us approaching. Several times they stopped and turned around to look at us in great wonderment. We reassured them with various signs, and some of them came up, showing great delight at seeing us and marveling at our clothes, appearance, and our whiteness; they showed us by various signs where we could most easily secure the boat, and offered us some of their food."

The expedition sailed south toward Florida next but did not find a suitable port, so they turned around and headed north to continue their search for a possible passage to the Pacific.

On April 17, 1524, Verrazzano and his crew were the first known Europeans to sail into New York Bay. He recorded seeing the wide entrance to the Hudson River and large numbers of native inhabitants.

"The people were dressed in birds’ feathers of various colors, and they came toward us joyfully, uttering loud cries of wonderment…" Verrazzano wrote about the Lenape tribe.

Assuming that the waterway was merely a lake, he continued his journey along the Long Island Sound toward Rhode Island . He was quite taken by the peoples of this new land. When his ship anchored in Narragansett Bay, some 20 long canoes sailed up to his vessel assessing the big ship and its strangely clad European occupants with great wonder. After the crew handed them some colorful beads and little gifts, some of the native men hopped aboard La Dauphine.

"Among them were two kings, who were as beautiful of stature and build as I can possibly describe," Verrazzano reported. "These people are the most beautiful and have the most civil customs that we have found on this voyage… their manner is sweet and gentle."

He found the Native Americans very generous but curiously uninterested in the items that he considered of most value.

"The things we gave them that they prized the most were little bells, blue crystals, and other trinkets to put in the ear or around the neck. They did not appreciate cloth of silk and gold, nor even of any other kind, nor did they care to have them; the same was true for metals like steel and iron, for many times when we showed them some of our arms, they did not admire them, nor ask for them, but merely examined the workmanship. They did the same with mirrors; they would look at them quickly, and then refuse them, laughing."

Verrazzano and his shipmates stayed with the Narragansett Indians for about two weeks and went on to describe the native village, diet and lifestyle.

However, as he sailed north toward Maine, the native tribes appeared to be more hostile, and he was reportedly driven from shore in an attempt to land.

Verrazano named the newly discovered lands Francesca, in honor of King Francis, then returned home to France without finding a passage to the Pacific.

ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY, SEPTEMBER 3, 1777, 'STARS AND STRIPES' FLIES IN BATTLE FOR FIRST TIME

He ventured to the New World on two more expeditions. During what was his third voyage, he explored the Bahamas and then the Caribbean Islands. However, the islands were different from the lush green North American mainland that abounded with deer, wild turkeys and other wildlife. The inhabitants of the islands mainly depended on the sea when it came to their food supply. Additionally, rumors swirled that some of the somewhat malnourished Caribbean tribes could have even been cannibals.

Verrazzano had the misfortune to find out for himself whether the rumors were correct or not. According to many historians, when he reached the island of Guadeloupe and went ashore, he was captured, killed and eaten by cannibals.

His colorfully described journeys were soon overshadowed by the 1609 voyage of Henry Hudson on behalf of the Dutch Republic. Ultimately, it was the Dutch who purchased the Island of Manhattan from the Native Americans, naming the new settlement New Amsterdam.

In 1664, however, the English took over New Amsterdam and renamed it New York after the Duke of York. However, British rule did not last either.

On Sept. 13, 1788, under the Constitution of the United States, New York City became America's first capital. Seven months later, General George Washington was sworn in as the first president of the United States on the balcony of New York's Federal Hall.

New York City became the beacon of freedom and the port of call for many searching for a better life and perhaps a fortune in the New World.

It was only in the second half of the 20th Century that Verrazzano's name and reputation were re-established as the European discoverer of the New York harbor.

The Verrazzano–Narrows Bridge connecting the New York City boroughs of Staten Island and Brooklyn, was named after the Italian explorer. It is the longest suspension bridge in the United States.

A statue of Verrazzano stands in New York's Battery, overlooking the bay, not far from the National Museum of the American Indian, the native people of this land whom he encountered before any other outsider, and so vividly and colorfully depicted in his letters to the French King.

Original article source: Finding New York: 500th anniversary of Giovanni de Verrazzano historic voyage of discovery

The Ages of Exploration

Giovanni da verrazzano interactive map, age of discovery.

Quick Facts:

Giovannia da Verrazzano’s voyages took him along most of the eastern coast and surrounding waterways of North America

Click on the world map to view an example of the explorer’s voyage.

How to Use the Map

- Click on either the map icons or on the location name in the expanded column to view more information about that place or event

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

- Even more »

Account Options

- Try the new Google Books

- Advanced Book Search

- Barnes&Noble.com

- Books-A-Million

- Find in a library

- All sellers »

Other editions - View all

Bibliographic information.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Monmouth Timeline

The European Explorers of New Jersey

The earliest European explorers of the Americas never caught even a glimpse of any part of the northern Atlantic coast. Christopher Columbus explored and settled various Caribbean nations, while Amerigo Vespucci’ s explorations appear to have been mostly of South America, specifically, from Brazil to Venezuela. Ponce de Leon of Spain discovered Florida and Puerto Rico in the early 16 th century, but went no further north.

In the late 15 th century, Italian navigator Giovanni Caboto, who became known by his Anglicized name, John Cabot , made several voyages to North America on behalf of English King Henry VII. The first voyage explored the coast of Canada; his final voyage, in 1498, about which there exists some controversy among historians, is believed to have taken him down the Atlantic coast from Canada to the Chesapeake, and possibly even further south to the Caribbean. Thus, if true, Cabot’s final voyage represents the first European exploration of New Jersey.

On January 17, 1524, Giovanni da Verrazzano (1485–1528), an Italian navigator in the service of King Francis I of France, set sail from Brittany to explore the eastern coast of North America. His intent was to find a passage to the Pacific Ocean. On this, one of several voyages he led to the Americas, he explored and mapped the region from Cape Fear, North Carolina, up to Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, Canada. Along the way, he discovered New York harbor, thinking it a large lake; and Cape Cod Bay.

During this period, explorations such as Cabot’s and Verrazzano’s were funded by commissions, typically from either royalty or leading businesses such as the Dutch East India Company. These explorations were the basis for territorial claims by France, Spain, England, The Netherlands and Portugal as they pursued new lands around the world to colonize. Verrazzano’s voyages were a basis for French territorial claims in Canada, while English claims to Canada were based on Cabot’s explorations.

In 1609, English sea captain and explorer Henry Hudson was hired by the Dutch East India Company passage to find a passage to Asia. He ended up exploring the waters off the east coast of America aboard the Half Moon . His first landfall was at Newfoundland and the second at Cape Cod. Hudson believed that the passage to the Pacific Ocean was between the St. Lawrence River and Chesapeake Bay, so he sailed south to the Bay, then turned northward, traveling close along the shore. He discovered Delaware Bay and began to sail upriver looking for the passage. This effort was foiled by sandy shoals, and the Half Moon continued north. After passing Sandy Hook, Hudson and his crew entered Upper New York Bay. Believing he had found the passage to the Pacific, he sailed up the river that now bears his name until the waters became too shallow, at the site of Troy, N.Y.

Upon returning to the Netherlands, Hudson reported that he had found a fertile land and an amicable people willing to engage his crew in small-scale bartering of furs, trinkets, clothes, and small manufactured goods. Thus Hudson’s explorations became the basis for the Dutch territorial claim to the Northeast Atlantic region, which resulted in the settlement of New Netherland in 1610 (see early Dutch map in the photo above). From this point forward, explorations and mapping of the Americas was led by settlers and navigators who made this new land their new home. England and The Netherlands would come to dispute each others’ claim to this new colony, and would go to war several times before the Dutch finally conceded the region to England.

Source: Source: http://www.njfounders.org/history/early-exploration-new-jersey

Reader Interactions

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Monmouth Timeline Inc.

- [email protected]

- 38 Winfield Drive, Little Silver, NJ 07739

Timeline Links

Quick links.

City heralds 500th anniversary of explorer’s arrival

By Theodore W. General • April 29, 2024 @ 8:57 pm

On April 17, the city celebrated the 500th (quincentenary) anniversary of Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano’s 1524 arrival in New York Bay. The explorer’s voyage aboard the La Dauphine was funded by King Francis I of France.

The anniversary was marked by a huge commemorative ceremony at the base of the 27-foot-tall bronze Verrazzano statue in Battery Park. The event was sponsored by the Italian American Leadership Forum, which is an association of major Italian American organizations.

The IALF was founded by Angelo Vivolo , former president and later chairman of the Columbus Citizens Foundation and a current trustee of the City University of New York. Honored guest speakers included Gov. Kathy Hochul ; Fabrizio Di Michele , consul general of Italy in New York; Cedrik Fouriscot , consul general of France in New York; and Susan Donoghue , NYC commissioner of parks. IALF Chairman Michael G. Polo delivered closing remarks. Also in attendance was Edouard Philippe , France’s former prime minister, who currently serves as mayor of LeHavre, the French city where Verrazzano started his long journey.

We were happy to join the festivities as an honorary member of the Italian Historical Society of America. One of the IALF speakers mentioned the key role IHSA founder and President John N. LaCorte had in ensuring the statue was relocated properly and well maintained. Bay Ridge business executive George Prezioso , a trustee with the Bay Ridge Historical Society, was also in attendance. We later attended a reception on the 12th floor of the city landmarked building at One Broadway, which gives a commanding view of New York Harbor.

Over the years we were fortunate enough to attend several events coordinated by John LaCorte and his executive secretary Terry Rosen . John’s imprint is all over Bay Ridge. He is credited with convincing New York State Gov. Averell Harriman to name the new bridge across the Narrows in honor of Giovanni Verrazzano. If you go into John Carty Park on Fort Hamilton Parkway, you see a large bronze raised medallion of Verrazzano embedded into the base of the flagpole. Travel not far up the road to John Paul Jones Park and, once again, is another bronze medallion within a long granite stone wall, which also memorializes John N. LaCorte. If you didn’t know it, LaCorte also convinced the federal government to make the celebration of Christopher Columbus Day a national holiday.

Leave a Reply

Click here to cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Related Articles

Brooklyn Reporter Newsletter

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Giovanni da Verrazzano was born around 1485 near Val di Greve, Italy. ... Verrazzano left France on his final voyage, yet again seeking the passage to India (after not having found it via a South ...

Giovanni da Verrazzano, Italian navigator and explorer for France who was the first European to sight New York and Narragansett bays. He was the first European explorer to name newly discovered North American sites after persons and places in the Old World. ... His final voyage began in the spring of 1528, when he sailed with his brother ...

Giovanni da Verrazzano (/ ˌ v ɛr ə ˈ z ɑː n oʊ,-ə t ˈ s ɑː-/ VERR-ə-ZAH-noh, -ət-SAH-, Italian: [dʒoˈvanni da (v)verratˈtsaːno]; often misspelled Verrazano in English; 1485-1528) was an Italian explorer of North America, in the service of King Francis I of France.. He is renowned as the first European to explore the Atlantic coast of North America between Florida and New ...

Name: Giovanni da Verrazzano [jaw-vahn-nee] [dah] [ver-uh-zah-noh; (Italian) ver-rah-tsah-naw] Birth/Death: 1485 CE - 1528 CE Nationality: Florentine Birthplace ... Verrazzano set off on his final voyage in 1528. His brother Girolamo joined Verrazzano on this journey. The expedition left from Dieppe with either two or three ships once again in ...

Giovanni da Verrazano. The Italian navigator and explorer Giovanni da Verrazano (ca. 1485-ca. 1528) made a voyage to North America in 1524-1525, in the service of France, during which he explored and charted the Atlantic coast of North America.. Following the Spanish discovery of rich Indian civilizations in Mexico and Peru, other European powers also sought footholds in the New World.

Selections from "Giovanni da Verrazzano and his discoveries in North America, 1524...English version, with introduction by Edward Hagaman Hall..1910," published in the Fifteenth annual report of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society ... taken from translations of the text published by H.C. Murphy in his "Voyage of Verrazzano ...

The final voyage, also under royal auspices, was planned in 1526; it is attested in a contract of that year by Chabot, the admiral of France, with Verrazzano and other speculators to furnish three vessels (two of them the king's) to make a trading voyage to the Indies for spices. ... William F. E. Morley, "VERRAZZANO, GIOVANNI DA," in ...

Giovanni da Verrazzano. Giovanni da Verrazzano, explorer (born in or near Florence circa 1485; died in the West Indies circa 1528). Verrazzano explored North America's eastern coastline on behalf of France, while searching for a westward route to China. His explorations demonstrated to Europeans that the coast from Florida to Cape Breton was ...

Selections from "Giovanni da Verrazzano and his discoveries in North America, 1524...English version, with introduction by Edward Hagaman Hall..1910," published in the Fifteenth annual report of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society. An extract from the letter of João da Silveira and the letter of Bernardo Carli, taken from translations of the text published by H.C. Murphy in ...

Letter of Fernando Carli to his Father. [Footnote: The letter of Carli was first published in 1844, with the discourse of Mr. Greene on Verrazzano, in the Saggiatore (I, 257), a Roman journal of history, the fine arts and philology. (M. Arcangeli, Discorso sopra Giovanni da Verrazzano, p. 35, in Archivio Storico Italiano.

"Verrazzano", pp. 387-91; Francesco Surdich, Verso il nuovo mondo: La dimensione e la coscienza delle scoperte (Firenze, 1991), pp. 47-9. 8 Giovanni da Verrazzano and his brother Girolamo also took part in other transatlantic ventures. A second voyage, that might have taken place in 1526-8, our knowledge of which is based on

The voyages of Giovanni da Verrazzano, 1524-1528 ... Maps relating to North America and the world antedating Verrazzano's voyage of 1524 Notes. Original book is like this. Access-restricted-item true ... v1.61-final . Show More. Full catalog record MARCXML. plus-circle Add Review. comment ...

Italian navigator Giovanni da Verrazzano convinced the king of France to sponsor a search for the northwest passage. The expedition set sail in January of 1524. It reached the coast in March, near Cape Fear, North Carolina. Verrazzano sailed south for a while, but stopped before he reached Florida, which was claimed by Spain.

Giovanni da Verrazzano was an explorer about whom little is known and much is conjectural. Almost the only certainty is that in 1524, in the caravel Dauphine, he discovered for France the coast from near Cape Fear to Newfoundland.He made other voyages, but from such guidelines as exist it is doubtful that on these he went to places not previously discovered.

Quick Facts: Verrazzano's Map of Voyage (Credit: NASA) Approximate route of the voyage of Giovanni da Verrazzano in North America in 1524.

On April 17, 500 years ago, Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed into New York Bay, describing the land and his encounters with its native inhabitants. The Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge in ...

Click on the world map to view an example of the explorer's voyage. How to Use the Map. After opening the map, click the icon to expand voyage information. You can view each voyage individually or all at once by clicking on the to check or uncheck the voyage information. Click on either the map icons or on the location name in the expanded ...

The Voyage of Giovanni da Verrazzano A Newly Discovered Manuscript by Dionysios Hatzopoulos and Richard Virr ... While the final report in French, if there ever was one, has never been found, a number Fontanus V 1992 7 . The Voyage of Giwanni da Verrazzano - Figure 1. Title page of the McGill copy of Ramusio with the Verrazzano arms

The Voyage of John De Verazzano, written 1524, was a letter to King Francis the I of France by Giovanni (or John) da Verrazzano upon his exploration of North Carolina and the Pamlico Sound, which he thought was the entrance to the Pacific Ocean. His analysis resulted in one of many errors in the way North America was represented on a map; it was not fully and correctly mapped until the late 1800s.

Selections from "Giovanni da Verrazzano and his discoveries in North America, 1524...English version, with introduction by Edward Hagaman Hall..1910," published in the Fifteenth annual report of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation... Contributor: New York (State). State Historian - Verrazzano, Giovanni Da Date: 1916

Verrazano's Voyage Along the Atlantic Coast of North America, 1524 Giovanni da Verrazzano Full view - 1916. ... Giovanni da Verrazzano, New York (State) State Historian: Edition: illustrated: Publisher: Creative Media Partners, LLC, 2018: ISBN: 1378538072, 9781378538074: Length: 32 pages: Subjects:

Verrazzano went ashore near Cape Fear in mid March 1524. ship. Seeing that the land continued to the south [so as not. to meet with the Spaniards], we decided to turn and skirt it toward the north, where we found the land we had sighted earlier. So we anchored off the coast and sent the small boat in to land.

Thus, if true, Cabot's final voyage represents the first European exploration of New Jersey. On January 17, 1524, Giovanni da Verrazzano (1485-1528), an Italian navigator in the service of King Francis I of France, set sail from Brittany to explore the eastern coast of North America. His intent was to find a passage to the Pacific Ocean.

The Giovanni da Verrazzano statue in Battery Park. Eagle Urban Media/photos by Ted General On April 17, the city celebrated the 500th (quincentenary) anniversary of Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano's 1524 arrival in New York Bay. The explorer's voyage aboard the La Dauphine was funded by ...