Tourism demand determinants- made simple

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

Understanding tourism demand is vital if we are to create and maintain an efficient, profitable and sustainable tourism industry. But what are the major tourism demand determinants that organisations need to consider? Read on to find out….

What are tourism demand determinants?

Tourism demand- life cycle stage, social structures, population and ageing, tourism demand- the changing economy, tourism demand- education, tourism demand- modern generations and technology, tourism demand- money rich, time poor, tourism demand- fashion, tourism demand- further reading.

The determinants of demand are factors that cause fluctuations in the economic demand for a product or a service. This is important to consider both in the travel and tourism industry as well as in other industries. Ultimately, we need to understand what demand is and do our best to meet that demand. For example, nowadays less people are in search of the traditional package holiday and are instead seeking niche tourism experiences. In response to this, many tour operators have adapted the products that they offer to suit the demands of the tourists- instead of selling predominantly beach and ski holidays, many are now offering the likes of adventure tourism trips and wellness tourism retreats.

Tourism is demand-driven, so to understand current trends in tourism we must understand how patterns of demand are changing. Demographic and social changes are seen as major influences on, in particular, international tourism . Dwyer (2005) argues that several types of demographic variables are changing in ways that will influence future demand for tourism and the specific types of tourism experience that will be preferred.

There are many tourism demand determinants to consider, but the major ones include:

- Life cycle changes

- Ageing population

- Education

- Employment

- Time

- The pleasure industry

The life cycle stage is always an important determinant in tourism demand, because people of different ages tend to have different demands! Here are some typical demands that we may expect from different age groups-

- Children – Will the American version of summer camp become more popular around the world as both parents work longer hours

- Adolescents – Are at the peak of their leisure needs but lack both the freedom and the money to indulge these needs– will this change? If so, how?

- Young people – these represent 20% of the market and the likes of backpacker tourism is assuming ever-greater importance. Young people are taking more gap years and volunteer tourism is growing in popularity. The adventure tourism market is to a large extent driven by ages 17-35.

- Families- Many families are now choosing to travel further afield and for longer than before, educational tourism and slow tourism are growing in popularity.

- Elderly people- As we grow older we tend to have more time and more money to spend on travel. Cruise tourism remains popular with elderly people, but older people are also embracing a range of alternative tourism forms too.

Tourism demand- Social and demographic variables

It is important that tourism industry stakeholders are aware of and up to date with current social and demographic variables associated with their customers.

Many social structures around the world are changing or evolving. This includes aspects such as community aspirations, business structures and family and individual values – all of which are experiencing profound change globally.

- The erosion of Western households is also something to note: households with no children are on the increase as people marry later and have fewer children.

- Family structures are changing too – the nuclear family is being replaced by the vertical family . Three or more generations may choose to holiday together, especially amongst those from developing nations, where families tend to live together across multiple generations.

- One-parent families are common as increasing numbers of families break up.

- There is an increase in the lucrative DINKS (Double Income, No Kids) market – this is an important market for special-interest and long-haul travel.

- There is nowadays a generally more relaxed attitude towards gay couples, and the number of companies targeting gay travellers, has led to growth of the gay market – the ‘pink’ market demonstrates the largest increase of any social group wanting to travel, and has large amounts of disposable income.

The way that we grow old has also changed over time, and this is another important tourism demand factor that tourism industry stakeholders must consider.

- There are an increasing amount of people who divorce nowadays compared to previous years, which naturally changes the way that these people travel.

- Many older people, who are fitter and more active than in previous generations, wish to enjoy the same activities and entertainment that they enjoyed in their youth; they also have more disposable income to spend on these activities.

- ‘Empty nesters’ are high spenders on travel and tourism – active and adventurous they see travel as an integral part of a fulfilling retirement.

- With above-average wealth and relatively few demands on their time the elderly make up an increasingly large part of the tourism market.

- Alongside evidence of a growing propensity to travel and spend (Huang and Tsai 2003; Reece 2004), consumption is often deliberately linked to low seasons balancing out the peaks and valleys for tourism suppliers (Hunter-Jones and Blackburn, 2009).

- New senior citizens, ‘young sengies’ (young senior generation), ‘woopies’ (well off older people), ‘retiring baby boomers’, ‘generation between’, ‘third age’ and the ‘grey market’ (Lohmann and Danielsson, 2001) are all terms used to describe what is collectively known as the ‘senior market’.

- The over-50s form an increasingly complex and diverse group. Many of them are well-off and have a high disposable income, although there is a polarity between the haves and have-nots (Beioley, 2001).

- In the UK, approximately 44% of all adults are 50 plus, that is over 20 million people and the over 60s now account for more than 20% of the population .

- In the US this ‘Third Age’ is set to exhibit the strongest growth of all demographic segments in the next five years, generating a group representing over one-quarter of the total population.

- In OECD countries the over 65s grew from 145.8 million in 2000 to 211.2 million in 2020.

- There is a significant growth in the number of ‘third age’ (49-64) travellers. This is a demanding group for whom self-fulfilment is important, wanting not only adventure but also comfort and putting more emphasis on accommodation quality, sightseeing and social aspects of the holiday and care less about nightlife, beaches and hot weather (Beioley, 2001).

- Because the elderly are often well-travelled they consciously seek new places to visit that are often ‘off the beaten track’.

- They are more environmentally and socially conscious and will reward firms that show high levels of environmental/social responsibility.

- The elderly frequently will demand honesty and integrity from travel companies and will reward such companies with their custom.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, health has and will continue to play an ever-important role in the minds of the consumers. As such, those working in the tourism industry need to understand tourism demand in this area. Major considerations should be paid to:

- Medical facilities at the destination

- Levels of crime and terrorism

Outbound tourism has changed over the years and in response to this the tourism industry needs to meet the demands of the outbound tourists in which they are aiming to attract. Some things to consider include-

- The expanding economies of the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia , India, China) with their growing middle classes.

- Outbound tourists from China have shown the most rapid growth (100 million by 2020) and this is set to continue post-pandemic.

- In India the 45-58 age middle class are already spending most of their disposable income on travel (Future Foundation).

- Recession tourism is a travel trend, which evolved by way of the world economic crisis. Recession tourism is defined by low-cost, high-value experiences taking place of once-popular generic retreats (Landau, 2007).

Education levels also have a significant impact on tourism demand.

- Increased education among the less privileged will necessarily affect travel choices.

- The interest in special-interest tourism has been fuelled by the educated classes.

- Forecasts predict an increase in special interest and educational holidays which provide opportunity to learn from tour guides or other specialists in the field of interest.

- There is arguably greater environmental and social consciousness amongst better-educated tourists – this will fuel the demand for certain types of products.

- Lifelong learning will become the norm as people now entering the workforce can expect to have five separate careers in a lifetime (Cetron, 2002 in Lockwood and Medlik,2002).

- Large chains will increasingly become involved in training to ensure product uniformity and quality (this is important to the supply of tourism).

- Education is also an important element of tourism supply.

As society we have changed and evolved over the years and the tourism industry needs to ensure that it is up to date with the tourism demands of modern generations. Some aspects to consider include:

- Modern generations are increasingly entrepreneurial and favour self-employment.

- They are experimental and willing to try new products, foods and attractions but are often intolerant of products or services that fail to satisfy – repeat purchasing will be out of the question in such cases.

- Customers for tourism are be much more technology-literate than they previously were– this has huge implications for the industry and has seen the introduction of the likes of smart tourism , e-tourism and virtual tourism .

- The modern so-called ‘dot.com’ generation (also known as generation Y) are the ‘connectivity kids’- they are consistently communicating and may join global networks.

- They may tire of well-known brands quickly.

- They are interested in experience and are short-term and opportunity-focused.

- They are also strongly influenced by friends and peers; concerned to achieve a work-life balance; strongly opinionated on social and ethical marketing issues; and supportive of causes such as fair trade and volunteering (Cooper and Hall, 2008).

- Because the proportion of self-employed people has increased, business travel is increasingly self-funded, so the distinction between work time and holiday time will thus become increasingly blurred e.g. the workation .

Ultimately there are two things that we need to be tourists- money and time. However, this balance is not always optimal.

- Employment patterns necessarily affect tourist demand as money and paid holidays are enablers of travel.

- The workplace is changing: More time is spent at work and we take more work home with us than we did 10 years ago. In Europe 66% of women work outside the home. In the UK the number of non-working hours per year has decreased by 100 hours over the last decade.

- Increasing job insecurity means that people are afraid to be away from work too long, which leads to: More short holidays, more luxury weekend getaways, more intensive holidays, more convenience, relaxation and pampering, more leisure opportunities closer to home, more constant demand for breaks and higher spend.

- When examining the work-leisure continuum it becomes apparent that time pressure will be a determinant of the type of tourism sought.

- Tourist markets are segmented not only by disposable income but also by disposable time, which differs considerably around the world.

- The rhythm of leisure time will change and the work/leisure divide become increasingly blurred as the pace of life speeds up.

Ultimately, tourism is a fashion industry and destinations and types of tourism come in and out of fashion over time.

- The complex relationship between tourism demand and supply is based on the dynamics of people’s perceptions, expectations, attitudes and values.

- The demand for tourism is notoriously fickle as a result of its dependency on status and image.

- The interests and reasons for travel frequently change.

- Holidays that were previously purely recreational have in recent years moved into physical and mental rejuvenation; spiritual rejuvenation will follow.

- Customers are becoming more interested in self-improvement as part of the tourism experience with an emphasis on health, wellbeing, education, skills development and cultural appreciation.

- In an increasingly technological world, rain forests, wilderness areas, oceans and other unpolluted areas will provide a unique and necessary chance to escape from keyboards and mobile phones.

- These changes carry threats and problems but also opportunities.

If you have enjoyed this article, I am sure that you will love these too-

- What is domestic tourism and why is it so important?

- Herzberg theory: Made simple

- What is a tourist board? A SIMPLE explanation

- What is qualitative and quantitative research? An EASY explanation

- What is business tourism and why is it so big?

Liked this article? Click to share!

The USA — a Major Tourism Generator

Cite this chapter.

- Edward Berrol 1

30 Accesses

2 Citations

The importance of the USA as a generating market of international travel cannot be over-estimated. In 1988, the number of Americans travelling abroad reached a peak of over 41m, with spending for foreign travel estimated at nearly $40 billion (including fares to foreign airlines, but not including those paid to American airlines for travel abroad). OECD data for 1986 and 1987 placed Americans as second only to Germans in their expenditure on international travel. About 60 per cent of these foreign visits by Americans are, understandably, concentrated in the neighbouring countries of Canada and Mexico.* However, more than 14m Americans travelled ‘overseas’ in 1988, mainly to Europe (6.4m) and the Caribbean (3.8m).

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Ogilvy & Mather, New York, USA

Edward Berrol ( Vice President )

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Copyright information.

© 1990 Horwath & Horwath

About this chapter

Berrol, E. (1990). The USA — a Major Tourism Generator. In: Quest, M. (eds) Horwath Book of Tourism. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-11687-4_15

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-11687-4_15

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-11689-8

Online ISBN : 978-1-349-11687-4

eBook Packages : Palgrave Business & Management Collection Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

A tourism inflex: Generation Z travel experiences

Journal of Tourism Futures

ISSN : 2055-5911

Article publication date: 16 August 2019

Issue publication date: 18 September 2019

The purpose of this paper is twofold. First, it highlights the emergence of Generation Z and the interface of its members with the tourism system. Second, by way of a theoretical model, the paper provides a more holistic approach to understanding Generation Z travel experiences in which the emphasis is shifted from the destination to the traveller. This is in keeping with the trend which lays more emphasis on people rather than landscape.

Design/methodology/approach

This is qualitative research founded on an interpretive (constructivist) paradigm. Selecting Generation Z as the subject locates this study under generational theory and assumes prima facie a socially constructed reality. The paper is based on research conducted in New Zealand aimed at understanding the travel experiences of inbound Generation Z travellers. Data were collected from 12 semi-structured interviews lasting about 30 min each and from 5 blogs. Nvivo 11 programme was used in analysing data and developing themes. Core categories and related themes were generated forming building blocks of a theoretical model.

Findings revealed interplay of multiple factors in Generation Z’s travel experiences at a destination. The factors are global in nature, destination centric and those which are immediate or proximate to the individual. To fully grasp the notion of experience requires the gestalt of the three as well as pre-trip, during-trip and post-trip factors.

Research limitations/implications

The impact of significant events upon participants is assumed. A specific analysis of the events and the magnitude of their influence on the individual participants may be necessary.

Practical implications

Destination marketers tend to concentrate on psychological aspects to appeal to the traveller. The focus, in this case, is creating an attractive image in the mind of travellers to get them to come to the destination. This research suggests shifting the focus to understanding the evolving traveller.

Social implications

Governments and tourism purveyors may require an ever-increasing budget to map out strategies to meet the continuously morphing needs of the future traveller. The constantly evolving global environment necessitates greater flexibility in institutional framework with less bureaucratic bottlenecks.

Originality/value

Generation Z is a relatively new entrant into the tourism market which makes this research relevant and timely. The paucity of academic literature on a generation which is contemporaneously in its “highly influenceable” period of life and entering adulthood in an increasingly changing world is further credence for this research. A more holistic theoretical model to understanding Generation Z travel experience is proposed.

- Theoretical model

- Generation Z

Realm of experience

- Travel pattern

Robinson, V.M. and Schänzel, H.A. (2019), "A tourism inflex: Generation Z travel experiences", Journal of Tourism Futures , Vol. 5 No. 2, pp. 127-141. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-01-2019-0014

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2019, Victor Mueke Robinson and Heike A. Schänzel

Published in Journal of Tourism Futures . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

Any successful tourism industry player requires not only the ability to recognise change, but also effectively respond to this change. Generational change is one such occurrence, rending both opportunities and challenges for tourism destinations. A new generation is entering adulthood amidst shifting global realities and concerns such as climate change, terrorism and technological advancements. Christened Generation Z, this young generation comprises individuals born in the year 1995 and after, making the oldest members 24 years old ( Eisner, 2005 ; Chhetri et al. , 2014 ). Visitor statistics for the year ending April 2018 show that of the 3,790,505 New Zealand inbound visitors, 428,192 were aged 15–24 years which translates to 11 per cent ( Statistics New Zealand, 2018 ). A key element of a successful tourism industry is the ability to recognise and deal with change across a wide range of key factors and the way they interact ( Dwyer et al. , 2009 ). The key external drivers of global change are economic, political, environmental, technological, social and demographic.

Demographic changes can affect tourism directly or indirectly ( Grimm et al. , 2009 ). Direct impacts relate to demand (volume and structure) and the labour market (number of workers and their qualification) while the indirect impacts relate to jobs within the tourism industry, and tourism services. Demography is, therefore, a key driver for future tourism demand ( Yeoman et al. , 2013 ). Exploring demographic trends allows important change agents, on both the supply side and the demand side of tourism to be highlighted and discussed ( Dwyer et al. , 2009 ). The future growth of tourism will depend to some extent on how well the industry understands the social and demographic trends influencing traveller behaviour ( Moscardo et al. , 2010 ). Destinations and individual operators that make decisions on the supply side without matching them to changing travellers and traveller needs suffer “strategic drift”, a phenomenon which occurs when strategy gradually deviates from addressing the forces in the external environment with a clear direction ( Dwyer et al. , 2009 ).

While numerous market surveys biased towards effective marketing and advertising have been conducted on Generation Z, a dearth of academic literature has been noted. It is only recently that Generation Z literature is beginning to appear in tourism academic journals. The recent special issue on Millennials and Generation Z in Journal of Tourism Futures is one such contribution ( Corbisiero and Ruspini, 2018 ). This may be attributed to the fact that the oldest members of this generation have only recently attained legal age of adulthood and can travel independently. In addition, they no longer require parental consent to participate in research. The USA and Western Europe predominate in generation-based studies, thus creating a gap in other regions. Based on research of New Zealand inbound Generation Z travellers, this paper provides a lens through which the generation’s travel experiences can be understood. It is a contribution to the body of knowledge from which future studies can borrow. In addition it provides, by way of a theoretical model, a more holistic approach and deeper insights into Generation Z travel experiences in which emphasis is shifted from the destination to the traveller.

from an erstwhile “destination-centric” model to a “traveller-centric” model thus focusing more on the “experiencer” ( O’Dell, 2007 );

from market research and surveys orientation to an academic orientation; and

from a unilateral (Managerialist) coverage to a multi-dimensional/cross-disciplinary coverage ( Echtner and Jamal, 1997 ; Hollinshead, 2004 ).

The study goes back to more of the roots of generational theory in sociology and psychology. The aim of this research is to understand the travel experiences of New Zealand inbound Generation Z by examining their travel patterns, attitudes and travel motives. The possible factors shaping these experiences are identified.

The next section explores the context of life for Generation Z. This is followed by some projections and economic value of the generation. In the literature review the Generation theory is explored and so is the experience. The research methodology is then presented with findings being discussed thereafter. The main contribution of this research, a theoretical model is then explained along with implications and recommendations.

Generation Z in context

Generation Z is mostly the off-Spring of Generation X and has been raised during changes occasioned by the internet, smartphones, laptops, freely available network and digital media ( Tulgan, 2013 ). Elsewhere they have been called “postmillennial”, “centennials”, “pivotals” or “digital natives” among other tags ( Grail Research, 2011 ; Southgate, 2017 ). Noting that the most common name used for this group is Generation Z, Hertz (2016) tags them Generation K after the fictional character “Katniss Everdeen”, the determined heroine of the Hunger Games. This is attributed to their view of the world as one of perpetual struggle, characterised by inequality and harshness. In her 18 months interviews of 2,000 teenagers in the UK and USA, Hertz (2016) notes that this generation feels profoundly anxious and distrustful. This can be attributed to the fact that the generation developed their personalities and life skills in a socio-economic environment marked by chaos, uncertainty, volatility and complexity ( Sparks and Honey, 2014 ). They have come of age in an era of economic decline, increased inequality, job insecurity and social media presence. As argued by Read and Truelove (2018) , Generation Z has never known a world without war and terrorism and as such they crave safety and financial security.

Although some other generations, such as the First World War and the Second World War generation cohorts lived through war, no generation before has been exposed to war and terrorism 24/7 through the internet and social media. Similarly, Seemiller and Grace (2016) have identified connectivity, information at the fingertips, creative entrepreneurship, diversity and social justice, fear of disaster and tragedies and economic hardships as some of the common events constituting the context for this generation. A further list is offered by Read and Truelove (2018) to include recession, ISIS, Sandy Hook shooting, marriage equality, the first black president of USA and the rise of populism. Instructively, Generation Z members have developed coping mechanisms. They are considered to be highly educated, creative and innovative and able to multi-task in an increasingly changing environment ( Corbisiero and Ruspini, 2018 ).

Generation Z and the economic value

In the USA, Generation Z makes up a quarter of the population. The generation contributes US$44bn to the American economy and influences US$600bn in family spending ( Sparks and Honey, 2014 ; Ketchum, 2015 ; Southan, 2017 ). It is further projected that by 2020 the generation will account for one-third of the USA population and will become the most powerful spenders representing 40 per cent of consumers in the USA, Europe and BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China). In tourism and travel, Generation Z is considered an incredibly important cohort ( Barnes, 2018 ). This, Paul Redmond, a generation cohort expert observes, is due to several factors; first is their powerful influence on family holidays as their parents opt to consult them prior to booking trips. Second, is their preference for experiences rather than possessions thus increasing their propensity to travel in search of “fun experiences”. Furthermore, it is observed that they are open-minded, bucket-list oriented and look for off-the-beaten path locations ( Expedia, 2017 ). Consequently, they can be expected to seek out remote places and engage in numerous travels/activities. Southan (2017) has further noted that Generation Z members are budget conscious travellers and usually start off their travel without a set destination in mind.

Born into a digital age and with increasing international travel, this young generation is likely to transform tourism and destinations. Indeed, it has been argued that “Fordian” (mass) tourism may no longer provide destinations with requisite competitiveness in the face of new tourism ( Stănciulescu et al. , 2011 ). The implication is that destinations relying on mass tourism characterised by an ageing demography will find it increasingly difficult to operate profitably in an environment characterised by an emerging and more contemporary form of tourism comprising youth and youthful travellers. This envisaged demographic change represents an important phenomenon which may pose both opportunities and challenges for the development of tourism and destinations ( Bernini and Cracolici, 2015 ). Generation-based research that identifies different groups of consumers and their specific needs and desires is therefore important ( Chhetri et al. , 2014 ). Recent findings, for instance, indicate that the less technologically enabled tourism destinations can benefit by employing contemporary principles and practices to meet the needs of the new generation of tourists who seek rich digital and gamified tourism experiences ( Skinner et al. , 2018 ).

The importance of this generation and the wider youth market lies in the fact that it represents the market of the future ( Vukic et al. , 2015 ). From an academic perspective, it is to be expected that as the generation matures and takes centre stage as adults more research will be conducted and published.

Generation theory

Generation cohorts have been widely explored. Despite the extensive research, there are differing opinions as to the historical location of any particular generation and what they are to be referred to as. There, however, exists some consensus on what generations are like as explained in Manheim’s concepts of generation actuality and generation unit ( Donnison, 2007 ). Extant generation cohort studies have focussed on mapping consumption patterns so as to develop effective marketing strategies ( Rentz et al. , 1983 ; Holbrook and Schindler, 1989 ; Schuman and Scott, 1989 ; Schewe and Noble, 2000 ; Schewe and Meredith, 2004 ). This, it would seem, deviates from the theory’s “ancestral roots” in sociology and psychology. This research incorporates socio-cognitive thought.

Recent years have seen an increase in generational analysis in the tourism literature ( Beldona et al. , 2009 ; Huh and Park, 2010 ; Li et al. , 2013 ; Pennington-Gray et al. , 2003 ). Studies on lifelong travel patterns have concluded that a greater use of cohort analysis is needed to examine changes in travel behaviour ( Oppermann, 1995 ). Gardiner et al. (2014) indicate that future travel behaviour will differ between the generations. Therefore, there is an implied necessity for continuous studies and research on each generation in order to effectively respond to the needs and demands of each of them. This research on Generation Z is a contribution to this demand.

Experience in tourism

In English, the word experience refers both to lived experiences as well as to the knowledge and expertise gained over time as a result of lived experiences ( Duerden et al. , 2015 ). A distinction is made between experience as a noun and experience as a verb. A further distinction is made between two German words for experience; “Erlebnis” and “Erfahrung” ( Larsen, 2007 ; Cutler and Carmichael, 2010 ). Larsen notes that both these words are applicable to tourism in that tourists participate in events while travelling and also accumulate memories from the trips. Elsewhere, Schmitt (1999) defines experience as the triggered stimulations to the senses, the heart and the mind occurring because of encountering, undergoing or living through situations.

Beyond the definitional lacuna, however, experience is a widely studied phenomenon across disciplines. In tourism, the concept of experience is considered important for a destination’s competitiveness ( Jensen et al. , 2015 ). Tourist experience studies vary in approach and perspectives with concentration being on a social science approach and a management/marketing approach ( MacCannell, 1973 ; Lee and Crompton, 1992 ; Quan and Wang, 2004 ; Volos, 2009 ). Experience has been viewed as an interaction between destinations as the “theatres” and tourists as the “actors” ( Stamboulis and Skayannis, 2003 ). The tourism industry is considered a player in generating, staging and consuming of experiences through manipulation of place and presentation of culture ( O’Dell, 2007 ; Cutler and Carmichael, 2010 ). However, it has also been suggested that places do not attract people, nor do they push people away ( Larsen, 2007 ). Consequently, the author opines, that studies should concentrate on individuals engaged in or about to engage in tourism. The argument shifts the locus of experience and experiencing to the tourist/traveller. Indeed, in his observation, Uriely (2005) notes a shift from tourism’s displayed objects being the determinants of experience to the tourist’s subjective negotiation of meaning being the determinant.

This research regards Larsen and Uriely’s suggestions that the individual is the arena of experience. Experience is realised by the individual and can, therefore, be viewed as subjective. In this regard, experience is a reality bound within the person and not an externality. Similarly, this research holds that travel is more about the person and his/her experiences rather than about places and things ( King, 2002 ; Morgan, 2010 ). Consequently, and as suggested by King (2002) the focus of destination marketing organisations should increasingly shift from promoting physical features of the destination to being more traveller centric. Equally important is that while some literature narrows experience to occurrences at the destination, this research incorporates the gestalt of pre-trip, during trip and after trip in the discourse on experiences. The research underscores the necessity of a multi-dimensional and multidisciplinary analysis of experience in tourism.

Methodology/methods

An interpretivist paradigm underpins this study. This fits with the more sociological and subjective approach taken. Two methods were used to gather data; 12 interviews, and 5 blogs. These methods and approaches were considered reality-aware and context-appropriate ( Hollinshead, 2004 ) in that Generation Z has grown up in a digital environment, thus making use of online platforms to communicate a norm. Increasingly, social media and blogging have become avenues to post and share experiences and life happenings. Therefore, these platforms are a source of potentially rich data. In addition, the methods complement each other. The blogs helped in overcoming limitations of time, space and individuals’ biases; factors which are endemic to face-to-face interviews. Interviews ameliorated the absence of personal cues in blogs.

Recruitment of face-to-face participants was through publicly displayed posters bearing the researcher’s contact details. These were displayed in accommodation facilities where young people frequent as well as by the researcher on the streets. In addition, the referral method – snowballing was applied. For blogs, the process involved the use of search engines such as Google and Explorer. By using key search words such as tourism blogs/bloggers, travel blogs, youth travel blogs and generation Z bloggers/blogs, several blogs were identified from numerous options. Two criteria suggested by Hookway (2008) – diary style blogs and availability of search function according to location were utilised to shortlist the blogs. Eventually, five blogs were selected.

Elimination process followed to ensure that selected blogs entries were by persons within the correct age bracket and who visited New Zealand. Some bloggers were forthright with their age while for some key “give-away” information was used. An example is a participant who posted that she bought a 1997 car and added “it is older than me but runs very good”. Only participants born after 1995 and above 18 years of age were selected. Interviews were digitally recorded and later transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were saved in Microsoft word format and later uploaded to NVivo 11 programme for coding and analysis. For blogs, data were directly copied from the online entries and pasted on a word document. The documents were formatted to an acceptable standard and uploaded to Nvivo 11 programme for coding and analysis. Six steps were used in this process as shown in Figure 1 .

The steps involved data collection, transcribing, back and forth reading of the transcribed and copied data. Codes (referred to as nodes in Nvivo 11) were assigned and later developed into initial themes within which codes were now clustered (referred to as parent and child nodes, respectively, in Nvivo 11). The codes were then assigned more meaningful categories. Step 6 explored the categories to form core categories which are the building blocks of theory ( Goulding, 1998 ). The process yielded nine categories. These were re-assigned to form six core categories. While four of the categories (travel patterns, destination profile, reasons for travel and identity) are common in available literature, two are unique to this research; context and realm of experience. The six core categories and their corresponding themes represent a lens through which travel experiences of Generation Z can be understood.

Findings and discussion

Of all the participants 13 were female, while 4 were male (see Table I ). In total, seven nationalities are represented. Seven participants are from Germany, two from the USA, two from the Netherlands, two from France, two from Luxembourg, one from Iceland and one from England.

Table II presents the six categories and their related themes. Column three provides a more meaningful interpretation associated with each category/themes. It is the synthesis of the interpretations that forms the basis of the theoretical model and thus, an overall of understanding of Generation Z travel experiences.

Travel patterns

The themes related to the core category, travel patterns, are accommodation, activities, places visited, transport and travel profile. These are interpreted as services/destination interfaces and travel career. Destinations are an arena of multiple interactions to a tourist. The tourists/travellers interface with the destination through engaging with the spaces, places, cultures, facilities and systems at the destination ( Wearing and Foley, 2017 ). These contribute to the experiences of the participants. A poor interaction with the above services may lead to an overall negative experience at the destination ( Morgan et al. , 2010 ). Several factors were found to influence the choice of service. These included affordability and budgets, convenience and accessibility to these services, the flexibility of the travel plans but also serendipity. Participant 13 blogged – “After the fair we went to the harbour where someone proposed us a tour on his sailing boat. We couldn’t resist”. Participant 3 said of her travels that – “the plan is to have no plan”. Majority of the participants planned to take up temporary work to supplement their travel budget Participant 12 blogged – “I worked there 2-3 hours a day for accommodation”.

authority constraints which are imposed by law or institutions as noted by Participant 8 – “I think the rules here are too strict because I am not used to strict alcohol rules and also prices for alcohol”;

coupling constraints which relate to family, friends and colleagues; and

capability constraints which are caused by availability of travel options and/or resources such as money.

In this research, participants were drawn from seven different nationalities. The implications of this from a generation cohort perspective are varied. First, it could be argued that each participant would exhibit unique characteristics, values and behaviours because of the unique circumstances within their own country. This, it can be said will differ from a participant from a different nation where he or she experiences a different set of circumstances. Participant 7 notes – “In Germany lots of people go to New Zealand”. Participant 3 said – “New Zealand is a new country, in Europe we are like more old country so we had time to develop”. In these examples it can be said that the participants’ views and behaviours are influenced by their context of life. The context within which travel behaviour of any group occurs is important to understanding the behaviour ( Wilson et al. , 2008 ). These contexts include historical, temporal, institutional, social, global and cultural. Similarly, Jennings (2010) notes that evaluation of tourism experiences requires a consideration of local, glocal, national and global environment.

A study of Millennials by Bernardi (2018) supports this view. In the study, differences relating to country of origin were observed. The Chinese were found to be the largest spenders, while Singaporeans and Indonesians were more budget conscious, seeking budget flights and accommodation. This would put to question the cross-cultural and cross-border generation cohort validity of shared behavioural and attitudinal patterns; each nation would have its own generation cohort. However, observations by Corbisiero and Ruspini (2018) repudiate this. They opine that, due to ubiquitous connectivity, this generation has more in common with their international peers than any previous generation.

Reasons for travel

While it is possible to locate Generation Z’s multiple reasons for travel within different models in literature, an intrinsic-extrinsic classification is preferred for this research. Among the intrinsic factors are, seeking for adventure and novelty. The extrinsic factors included attractions, escapism and engaging in travel because it is the popular culture (norm). While it could be argued that escapism is also intrinsic in nature, it is generated by external circumstances such as undesirable events in country of residence or workplace. Participant 10 from the USA said – “I was kind of running away from the negative changes that are happening and I didn’t really want to be associated with that I guess”. An alternative classification would be on a hedonic-utilitarian continuum. Hedonic reasons have to do with emotional and experiential aspects while utilitarian are benefits driven ( Asraar, 2015 ). Generation Z behaviour and choices were not only consistent with the search of travel experiences, but also with the quest for value for the resources invested in the travel.

Travel for Generation Z is also a time of conviviality, socialisation and empowerment ( Haddouche and Salomone, 2018 ). In travelling, new friendships were forged, interactions with locals and fellow travellers craved and deeper meanings to personal life and self-development sought. Participant 9 – “I’ve met people now in my hostel, now we are going in March for a road trip”. Furthermore, travel was attributed to the popular concept known as fear-of-missing-out. This is a pervasive apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent ( Przybylski et al. , 2013 ). A survey by Smith (2018) corroborates this, reporting that 82 per cent of Generation Z regretted losing out on chances to travel.

Two participants were travelling on internship. However, these participants were intent on using internship as the means to get to New Zealand and do some travelling. While the participants expressed a desire to tour more places in New Zealand, the time limit on their internship prevented them from undertaking longer trips. The diversity of flora and fauna motivated one of the travellers whose interests are botany to visit and immerse in the country’s nature. Research shows that the 15–24 year old age groups are more likely to travel for educational purposes when compared to older age groups ( Collins and Tisdell, 2002 ; Huh and Park, 2010 ). Related to this is partnership and transnational connections between organisations which saw the two afore mentioned participants travel to New Zealand as interns through partnership of an organisation in Germany with a New Zealand-based organisation.

Destination profile

This relates to perceptions about New Zealand as a destination, the attractions and facilities and the resultant expectations. Expectations are further linked to the appraisal of the destination by the traveller, which relates to satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Eventually, this will influence the sort of experience that the traveller has. However, a destination is not just a geographical unit but is also subject to people’s judgement and evaluation ( Chen and Šegota, 2015 ). Implied are not only the evident physical features but, also the abstract and subjective psychological elements as perceived by the tourist. Elsewhere, this dichotomy is observed by Echtner and Ritchie (1993) who opine that destinations have functional (tangible) and psychological (abstract) characteristics.

cognitive which constitutes what Generation Z knew about the destination;

affective which relates to Generation Z’s feelings about the destination;

evaluative which describes how the destination was appraised – Participant 3 – “I think the rules here are too strict because I am not used to strict alcohol rules”; and

behavioural which is tied to decisive actions to undertake an activity or to visit a place.

The regular frequency of terrorist attacks has seen increased measures by governments to curb the menace. This has significantly changed the mind-set of international tourists. Some of the participants believed destinations have become safer because of terror attacks. Reasons presented included the resultant increase in surveillance and security procedures. Still others believed that shrinking back from travelling would mean a triumph of terrorism. It would therefore appear that, Generation Z has become accustomed to and adapted to the volatile global environment in which they have grown up in.

On environmental issues a participant thought it contradictory that New Zealand is portrayed as this pristine green environment but there appeared to be a crisis with plastic bags: Participant 8 – “I always thought New Zealand is so natural, and they take care of their environment but, the biggest problem is the plastic bags at the super market, it’s so crazy”. This participant also considered it paradoxical that there were issues with harsh sun rays, but that protective sunscreen was expensive or at least higher than at her home country.

A further area of focus is the socio-political issues in the destination (New Zealand). Commenting on society, a participant reported what they perceived as discrimination against indigenous people. There was a feeling that the Maori were treated unfairly. Participant 2 – “We spoke to a lot of Maori and local people and I think, I don’t know whether it’s right to say but, there was quite a lot of discrimination which we found shocking”. Separately, some participants who engaged in part time jobs felt exploited by their employers. Another participant felt extorted by mechanics and car dealers. The use of English as an official language contributed to a seamless and fulfilling experience to some as it eliminated possible language barriers: Participant 7 – “Because it is an English country and a lot of people speak English so it’s a good place to come”. However, this might be viewed differently by participants drawn from non-English speaking regions. Immigration policy permitting work is critical to the long period of stay. Participants needed work to supplement their travel budget or subsidise on spending such as accommodation and activities.

Seasonality and weather patterns were factored before and during travel. To some the timing of the trip was to coincide with Summer season in the destination. Participant 9 – “Winter is starting in Germany. This is the reason I came here”. Locally, some participants altered their schedules to fit to the weather patterns of the time. Whereas the majority favoured Summer, there were some who, because of their passion for skiing thought Winter months would be good time to plan a visit to Queenstown. A study in Romania showed that seasonality was a determinant of the type of adventure and sport tourism practiced by the youth ( Demeter and Brătucu, 2014 ). New Zealand statistical data show a preference for the warmer Autumn and Summer months by international travellers. In the year 2017, international arrivals during the Autumn–Summer months were 57.8 per cent while Spring–Winter months were 42.2 per cent ( Smiler, 2018 ). In this regard, global, socio-political and environmental factors appear to alter or modify the travellers’ behaviours and contribute to their overall experience.

Because Generation Z is characterised as being digitally adept, social and mobile, ICT is a critical component and a linkage to services or to the outer world. The widespread use of mobile apps, such as Campmate, and the reliance on social media was a common feature among the participants. Participant 1 – “Instagram is a big feature because I have seen so many beautiful pictures of New Zealand holy crap and I want to visit these places and take these exact photos”. There was reliance on social media to make travel decisions. These technological advancements facilitate ease of access to information, facilities and places. Therefore, Generation Z behavioural patterns in a destination and their experiences may be impacted or influenced by ICT advancements.

It is observed that travel offered the opportunity to plan one’s life. Being far away from the accustomed way of life, New Zealand provided the requisite environment for self-reflection: Participant 3 – “I think in those moments you really get to know yourself”. Photos and experiences shared online by the participants is a way of building personal identity and part of experience ( Bernardi, 2018 ).

physiological realm (sensory experience – relating to body);

psychological realm (cognitive, affective and conative experiences – relating to the soul); and

spiritual realm – spirit (spiritual experiences – relating to spirit).

Seemingly, this agrees with Walls’ (2013) definition of tourist experience as a blend of many individual elements coming together and may involve the tourist emotionally, physically and intellectually. Indeed, everything tourists go through at a destination can be experience, whether behavioural or perceptual, cognitive or emotional, expressed or implied ( Oh et al. , 2007 ). Noteworthy though is that, the reasons and patterns of travel exhibited by Generation Z do not appear to be fundamentally different to previous generations when they were of the same age. In this regard, this research evinces extant literature on youth/backpacker/gap year or even other recent generations such as Generation Y travellers ( Adler, 1985 ; Benckendorff et al. , 2010 ; Luo et al. , 2015 ; Richards, 2015 ). While the reasons and/or patterns may be similar, contemporary factors can impact on a generation’s experiences. The advances in technology (internet, social media and smartphones), for example, have fostered internet-based travel services, thus, altering traveller expectations, and resultant travel experiences.

Conclusions and recommendations

Immediate influences (forces) – including family, friends, events in the home country. Participant 13 offered – “We took a bath in the outdoor bathtubs of the villa. It was like a childhood memory. As children we always used to take a bath together. Still another observed, we grew up buying fish in a supermarket in plastic but here someone comes with fresh fish caught an hour ago”.

Destination influences (forces) – including socio-political, cultural, physical features/attributes. A participant talking about a local couple she met said – we ate together and shared our food. I really enjoyed listening to all their stories. Participant 3 noted – “I also did glow worms which is definitely an experience that I will remember probably for the rest of my life”. On her part Participant 4 said – “We listened to locals’ advice”.

Global influences (forces) – including events with global ramifications, climate change, terrorism, financial volatility, geo-politics and technological advancements as noted by Participant 1 – “For me going to New Zealand it was like stepping out of the craziness happening in Europe”. Participant 5 mentioned – “I’m from Germany, the east, so my parents did not get a chance to travel at all because of the separation […] I think they could only go to Ukraine and maybe Russia […] They didn’t have the chance to travel like we are doing now”.

The individual arrives at the destination with embedded subjective elements as a result of interfacing with immediate influences and global influences. Additional elements are embedded in the individual through interfacing with the tourism system at the destination. The amalgamation of these elements contributes to the traveller’s experience at the destination. The destination can further be described as an “agitator” or “instigator” of the experience. To effectively understand the individual’s experience requires an appreciation of the context of life from which he/she has come. This entails awareness of both historical and contemporary influences in the life of that individual or group of individuals. While it is a logistical and practical impossibility to fully profile each individual travelling to a destination, an understanding of the multiple channels that contribute to the individual’s ethos would lend additional credence to understanding and managing tourist experiences.

Generation Z is progressively taking the centre stage. Members of this generation will soon be the adults occupying leadership positions and become the financiers of tourism and travel. Investment into more research informed by an impending future is recommended. While tourism infrastructure development is important, significant focus needs to be placed on understanding the tourist of the future. Governments and tourism purveyors may require an ever-increasing budget to map out strategies to meet the continuously morphing needs of the future traveller. In addition, strategies are required to address the evolving global consumer trends, especially bearing in mind the global influences (forces). Incorporating current technologies at every level should be at the forefront of government and industry future planning. This may include deployment of internet connectivity in remote areas which lack strong links. Greater flexibility in institutional frameworks, with less bureaucratic bottlenecks is further suggested. Destination marketers tend to concentrate on psychological aspects to appeal to the traveller. The goal, in this case, is creating an attractive image in the mind of travellers to get them to come to the destination. Emphasis is more about the destination. This research suggests shifting the focus to understanding the evolving traveller’s needs and preferences.

A key limitation of the research is that the impact of significant events upon participants is assumed. A specific analysis of the events and the magnitude of their influence on the individual participants may be necessary. Research is recommended for not only the different ephemeral factors, but also longitudinal studies of generations.

Coding process

A theoretical model of Generation Z travel experiences

Demographic profile of New Zealand inbound Generation Z participants

Core categories, related themes and interpretation of Generation Z travel experiences

Adler , J. ( 1985 ), “ Youth on the road: reflections on the history of tramping ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 12 No. 3 , pp. 335 - 54 .

Asraar , A.K.A. ( 2015 ), “ Utilitarian and hedonic motives of university students in their online shopping – a gender based examination ”, Global Management Review , Vol. 9 No. 4 , pp. 75 - 91 .

Avraham , E. and Ketter , E. ( 2008 ), Media Strategies for Marketing Places in Crisis. Improving the Image of Cities, Countries and Tourist Destinations , Butterworth-Heinemann , Amsterdam .

Barnes , R. ( 2018 ), “ Gen-Z expert panel the ‘little extraordinaires’ to consult for Royal Caribbean ”, Cruise Trade News, May, available at: www.cruisetradenews.com/gen-z-expert-panel-the-little-extraordinaires-to-consult-for-royal-caribbean/ (accessed 16 May 2018 ).

Beldona , S. , Nusair , K. and Demicco , F. ( 2009 ), “ Online travel purchase behavior of generational cohorts: a longitudinal study ”, Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management , Vol. 18 No. 4 , pp. 406 - 20 .

Benckendorff , P. , Moscardo , G. and Pendergast , D. ( 2010 ), Tourism and Generation Y , CAB International , Cambridge, MA .

Bernardi , M. ( 2018 ), “ Millennials, sharing economy and tourism: the case of Seoul ”, Journal of Tourism Futures , Vol. 4 No. 1 , pp. 43 - 56 .

Bernini , C. and Cracolici , M.F. ( 2015 ), “ Demographic change, tourism expenditure and life cycle behaviour ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 47 , pp. 191 - 205 .

Charmaz , K. ( 2006 ), Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis , Sage Publications , Thousand Oaks, CA .

Chen , N. and Šegota , T. ( 2015 ), “ Resident attitudes, place attachment and destination branding: a research framework ”, Tourism and Hospitality Management , Vol. 21 No. 2 , pp. 145 - 58 .

Chhetri , P. , Hossain , M.I. and Broom , A. ( 2014 ), “ Examining the generational differences in consumption patterns in South East Queensland ”, City, Culture and Society , Vol. 5 No. 4 , pp. 1 - 9 .

Collins , D. and Tisdell , C. ( 2002 ), “ Age-related lifecycles: purpose variations ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 29 No. 3 , pp. 801 - 18 .

Corbisiero , F. and Ruspini , E. ( 2018 ), “ Millennials and Generation Z: challenges and future perspectives for international tourism ”, Journal of Tourism Futures , Vol. 4 No. 1 , pp. 253 - 5 .

Cutler , Q.S. and Carmichael , B. ( 2010 ), “ The dimensions of the tourist experience ”, in Morgan , M. , Lugosi , P. and Ritchie , B.J.R. (Eds), The Tourism and Leisure Experience: Consumer and Managerial Perspectives , Channel View Publications , Tonawanda, NY , pp. 3 - 26 .

Dellaert , B.G.C. , Ettema , D.F. and Lindh , C. ( 1998 ), “ Multi-faceted tourist travel decisions: a constraint-based conceptual framework to describe tourists’ sequential choices of travel components ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 19 No. 4 , pp. 313 - 20 .

Demeter , T. and Brătucu , G. ( 2014 ), “ Typologies of youth tourism ”, Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov Series V: Economic Sciences @BULLET , Vol. 7 No. 56 , pp. 115 - 22 .

Donnison , S. ( 2007 ), “ Unpacking the millennials: a cautionary tale for teacher education ”, Australian Journal of Teacher Education , Vol. 32 No. 3 , p. 1 .

Duerden , M.D. , Ward , P.J. and Freeman , P.A. ( 2015 ), “ Conceptualizing structured experiences ”, Journal of Leisure Research Copyright , Vol. 47 No. 5 , pp. 601 - 20 .

Dwyer , L. , Edwards , D. , Mistilis , N. , Roman , C. and Scott , N. ( 2009 ), “ Destination and enterprise management for a tourism future ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 30 No. 1 , pp. 63 - 74 .

Echtner , C.M. and Jamal , T.B. ( 1997 ), “ The disciplinary dilemma of tourism studies ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 24 No. 4 , pp. 868 - 83 .

Echtner , C.M. and Ritchie , J.R.B. ( 1993 ), “ The measurement of destination image: an empirical assessment ”, Journal of Travel Research , Vol. 31 No. 4 , pp. 3 - 13 .

Eisner , S.P. ( 2005 ), “ Managing Generation Y ”, SAM Advanced Management Journal , Vol. 70 No. 4 , pp. 4 - 15 .

Expedia ( 2017 ), “ Connecting the digital dots: the motivations and mindset of European travellers ”, available at: https://info.advertising.expedia.com/hubfs/Content_Docs/Premium_Content/pdf/Research_MultiGen_Travel_Trends_European_Travellers-2017-09.pdf?t=1527792003705 (accessed 5 June 2018 ).

Gardiner , S. , Grace , D. and King , C. ( 2014 ), “ The generation effect: the future of domestic tourism in Australia ”, Journal of Travel Research , Vol. 53 No. 6 , pp. 705 - 20 .

Goulding , C. ( 1998 ), “ Grounded theory: the missing methodology on the interpretivist agenda ”, Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal European Journal of Marketing , Vol. 14 No. 4 , pp. 50 - 7 .

Grail Research ( 2011 ), “ Consumers of tomorrow: insights and observations about Generation Z ”, available at: www.grailresearch.com/pdf/ContenPodsPdf/Consumers_of_Tomorrow_Insights_and_Observations_About_Generation_Z.pdf (accessed 8 March 2018 ).

Grimm , B. , Lohmann , K. , Heinsohn , K. , Richter , C. and Metzler , D. ( 2009 ), “ The impact of demographic change on tourism and conclusions for tourism policy at a glance ”, available at: http://observgo.uquebec.ca/observgo/fichiers/73044_PSEC-15.pdf (accessed 11 May 2018 ).

Haddouche , H. and Salomone , C. ( 2018 ), “ Generation Z and the tourist experience: tourist stories and use of social networks ”, Journal of Tourism Futures , Vol. 4 No. 1 , pp. 69 - 79 .

Hägerstrand , T. ( 1970 ), “ What about people in regional science? ”, Papers of the Regional Science Association , Vol. 24 No. 1 , pp. 7 - 21 .

Hertz , N. ( 2016 ), “ Think Millennials have it tough? For ‘Generation K’, life is even harsher ”, The Guardian , 19 March, available at: www.theguardian.com/world/2016/mar/19/think-millennials-have-it-tough-for-generation-k-life-is-even-harsher (accessed 8 May 2018 ).

Holbrook , M.B. and Schindler , R.M. ( 1989 ), “ Some exploratory findings on the development of musical tastes ”, Journal of Consumer Research , Vol. 16 No. 1 , pp. 119 - 24 .

Hollinshead , K. ( 2004 ), “ A primer in ontological craft: the creative capture of people and places through qualitative research ”, in Phillimore , J. and Goodson , L. (Eds), Qualitative Research in Tourism: Ontologies, Epistemologies and Methodologies , Routledge , London , pp. 63 - 82 .

Hookway , N. ( 2008 ), “ Entering the blogosphere: some strategies for using blogs in social research ”, Qualitative Research , Vol. 8 No. 1 , pp. 91 - 113 .

Huh , C. and Park , S.H. ( 2010 ), “ Changes in patterns of trip planning horizon: a cohort analytical approach ”, Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management , Vol. 19 No. 3 , pp. 260 - 79 .

Jennings , G. ( 2010 ), “ Research processes for evaluating quality experiences: reflections from the ‘experience field(s)’ ”, in Morgan , M. , Lugosi , P. and Ritchie , B.J.R. (Eds), The Tourism and Leisure Experience: Consumer and Managerial Perspectives , Channel View Publications , Bristol , pp. 81 - 98 .

Jensen , Ø. , Østergaard , P. and Lindberg , F. ( 2015 ), “ How can consumer research contribute to increased understanding of tourist experiences? A conceptual review ”, Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism , Vol. 15 No. S1 , pp. 9 - 27 .

Ketchum ( 2015 ), “ Engaging Gen Z ”, available at: www.ketchum.com/engaging-gen-z (accessed 8 May 2018 ).

King , J. ( 2002 ), “ Destination marketing organisations – connecting the experience rather than promoting the place ”, Journal of Vacation Marketing , Vol. 8 No. 2 , pp. 105 - 8 .

Larsen , S. ( 2007 ), “ Aspects of a psychology of the tourist experience ”, Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism , Vol. 7 No. 1 , pp. 7 - 18 .

Lee , T. and Crompton , J. ( 1992 ), “ Measuring novelty seeking in tourism ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 19 No. 4 , pp. 732 - 51 .

Li , X. , Li , X. (Robert) and Hudson , S. ( 2013 ), “ The application of generational theory to tourism consumer behavior: an American perspective ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 37 , pp. 147 - 64 .

Luo , X. , Huang , S. (Sam) and Brown , G. ( 2015 ), “ Backpacking in China: a netnographic analysis of donkey friends’ travel behaviour ”, Journal of China Tourism Research , Vol. 11 No. 1 , pp. 67 - 84 .

MacCannell , D. ( 1973 ), “ Staged authenticity: arrangements of social space in tourist settings ”, American Journal of Sociology , Vol. 79 No. 3 , pp. 589 - 603 .

Morgan , M. ( 2010 ), “ The experience economy 10 years on: where next for experience management ”, in Morgan , M. , Lugosi , P. and Ritchie , B.J.R. (Eds), The Tourism and Leisure Experience: Consumer and Managerial Perspectives , Channel View Publications , Bristol , pp. 218 - 30 .

Morgan , M. , Lugosi , P. and Ritchie , B.J.R. ( 2010 ), The Tourism and Leisure Experience , Channel View Publications , Bristol .

Moscardo , G. , Murphy , L. and Benckendorff , P. ( 2010 ), “ Generation Y and travel futures ”, in Yeoman , I. , Hsu , C. , Smith , C. and Watson , S. (Eds), Tourism and Demography , Goodfellow Publishers , Oxford , pp. 87 - 100 .

O’Dell , T. ( 2007 ), “ Tourist experiences and academic junctures ”, Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism , Vol. 7 No. 1 , pp. 34 - 45 .

Oh , H. , Fiore , A.M. and Jeoung , M. ( 2007 ), “ Measuring experience economy concepts: tourism applications ”, Journal of Travel Research , Vol. 46 No. 2 , pp. 119 - 32 .

Oppermann , M. ( 1995 ), “ Family life cycle and cohort effects: a study of travel patterns of German residents ”, Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing , Vol. 4 No. 1 , pp. 23 - 44 .

Pennington-Gray , L. , Kerstetter , D.L. and Warnick , R. ( 2003 ), “ Forecasting travel patterns using Palmore’s cohort analysis ”, in Song , H. and Wong , K.K.F. (Eds), Tourism Forecasting and Marketing , Taylor & Francis , New York, NY , pp. 127 - 45 .

Phillimore , J. and Goodson , L. ( 2004 ), “ Progress in qualitative research in tourism: epistemology, ontology and methodology ”, in Phillimore , J. and Goodson , L. (Eds), Qualitative Research in Tourism: Ontologies, Epistemologies and Methodologies , Routledge , London , pp. 3 - 29 .

Przybylski , A.K. , Murayama , K. , DeHaan , C.R. and Gladwell , V. ( 2013 ), “ Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out ”, Computers in Human Behavior , Vol. 29 No. 4 , pp. 1841 - 8 .

Quan , S. and Wang , N. ( 2004 ), “ Towards a structural model of the tourist experience: an illustration from food experiences in tourism ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 25 No. 3 , pp. 297 - 305 .

Read , A. and Truelove , C. ( 2018 ), “ The incoming tide of Generation Z ”, AMA Quarterly , Vol. 4 No. 10 , pp. 43 - 6 .

Rentz , J.O. , Reynolds , F.D. and Stout , R.G. ( 1983 ), “ Analyzing changing consumption patterns with cohort analysis ”, Journal of Marketing Research , Vol. 20 No. 1 , pp. 12 - 20 .

Richards , G. ( 2015 ), “ The new global nomads: youth travel in a globalizing world ”, Tourism Recreation Research , Vol. 40 No. 3 , pp. 340 - 52 .

Schewe , C.D. and Meredith , G. ( 2004 ), “ Segmenting global markets by generational cohorts: determining motivations by age ”, Journal of Consumer Behaviour , Vol. 4 No. 1 , pp. 51 - 63 .

Schewe , C.D. and Noble , S.M. ( 2000 ), “ Market segmentation by cohorts: the value and validity of cohorts in America and abroad ”, Journal of Marketing Management , Vol. 16 Nos 1-3 , pp. 129 - 42 .

Schmitt , B.H. ( 1999 ), Experiential Marketing : How to Get Customers to Sense, Feel, Think, Act, and Relate to your Company and Brands , Free Press , New York, NY .

Schuman , H. and Scott , J. ( 1989 ), “ Generations and collective memories ”, American Sociology Review , Vol. 54 No. 3 , pp. 359 - 81 .

Seemiller , C. and Grace , M. ( 2016 ), Generation Z goes to College , John Wiley & Sons , San Francisco, CA .

Skinner , H. , Sarpong , D. and White , G.R.T. ( 2018 ), “ Meeting the needs of the Millennials and Generation Z: gamification in tourism through geocaching ”, Journal of Tourism Futures , Vol. 4 No. 1 , pp. 93 - 104 .

Smiler , J. ( 2018 ), “ New Zealand tourism state of the industry 2017 ”, available at: https://tia.org.nz/assets/Uploads/State-of-the-Tourism-Industry-2017-final.pdf (accessed 8 May 2018 ).

Smith , A. ( 2018 ), Generation Z is the most Regretful of all Ages about Missed Travel Opportunities , Lonely Planet , 15 May, available at: www.lonelyplanet.com/news/2018/05/14/generation-z-missed-travel-opportunities/ (accessed 8 June 2018 ).

Southan , J. ( 2017 ), “ From boomers to Gen Z: travel trends across the generations ”, Globetrender Magazine, 19 May, available at: http://globetrendermagazine.com/2017/05/19/travel-trends-across-generations/ (accessed 8 June 2018 ).

Southgate , D. ( 2017 ), “ The emergence of Generation Z and its impact in advertising: long-term implications for media planning and creative development ”, Journal of Advertising Research , Vol. 57 No. 2 , pp. 227 - 35 .

Sparks and Honey ( 2014 ), “ Meet Generation Z: forget everything you learned about Millenials ”, available at: https://emp-help-images.s3.amazonaws.com/summitpresentations/generationZ.pdf (accessed 8 June 2018 ).

Stamboulis , Y. and Skayannis , P. ( 2003 ), “ Innovation strategies and technology for experience-based tourism ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 24 No. 1 , pp. 35 - 43 .

Stănciulescu , G. , Molnar , E. and Bunghez , M. ( 2011 ), “ Tourism’s changing face: new age tourism versus old tourism ”, Annals of the University of Oradea , Economic Science Series , pp. 245 - 9 .

Statistics New Zealand ( 2018 ), “ International visitor arrivals to New Zealand: June 2018 | Stats NZ ”, available at: www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/international-visitor-arrivals-to-new-zealand-june-2018 (accessed 8 June 2018 ).

Tulgan , B. ( 2013 ), “ Meet Generation Z: the second generation within the giant ‘Millennial’ cohort ”, Rainmaker Thinking, available at: http://rainmakerthinking.com/assets/uploads/2013/10/Gen-Z-Whitepaper.pdf (accessed 8 May 2018 ).

Uriely , N. ( 2005 ), “ The tourist experience: conceptual developments ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 32 No. 1 , pp. 199 - 216 .

Volos , S. ( 2009 ), “ Conceptualizing experience: a tourist based approach ”, Journal of Hospitality and Leisure Marketing , Vol. 18 Nos 2-3 , pp. 111 - 26 .

Vukic , M. , Kuzmanovic , M. and Stankovic , M.K. ( 2015 ), “ Understanding the heterogeneity of Generation Y’s preferences for travelling: a conjoint analysis approach ”, International Journal of Tourism Research , Vol. 17 No. 5 , pp. 482 - 91 .

Walls , A.R. ( 2013 ), “ A cross-sectional examination of hotel consumer experience and relative effects on consumer values ”, International Journal of Hospitality Management , Vol. 32 , pp. 179 - 92 .

Walters , T. ( 2016 ), “ Using thematic analysis in tourism research ”, Tourism Analysis , Vol. 21 No. 1 , pp. 107 - 16 .

Wearing , S.L. and Foley , C. ( 2017 ), “ Understanding the tourist experience of cities ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 65 , pp. 97 - 107 .

Wilson , J. , Fisher , D. and Moore , K. ( 2008 ), “ Van tour and ‘doing a Contiki’: grand ‘backpacker’ tours of Europe ”, in Hannam , K. and Ateljevic , I. (Eds), Backpacker Tourism: Concepts and Profiles , Channel View Publications , Clevedon , pp. 113 - 27 .

Yeoman , I. , Schänzel , H. and Smith , K. ( 2013 ), “ A sclerosis of demography ”, Journal of Vacation Marketing , Vol. 19 No. 2 , pp. 91 - 103 .

Corresponding author

About the authors.

Victor Mueke Robinson is based at the School of Hospitality and Tourism, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand.

Heike A. Schänzel is based at the School of Hospitality and Tourism, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand.

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Understanding Poverty

- Competitiveness

Tourism and Competitiveness

- Publications

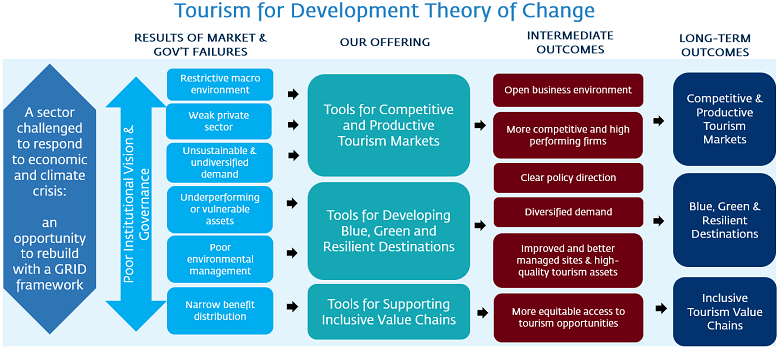

The tourism sector provides opportunities for developing countries to create productive and inclusive jobs, grow innovative firms, finance the conservation of natural and cultural assets, and increase economic empowerment, especially for women, who comprise the majority of the tourism sector’s workforce. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism was the world’s largest service sector—providing one in ten jobs worldwide, almost seven percent of all international trade and 25 percent of the world’s service exports —a critical foreign exchange generator. In 2019 the sector was valued at more than US$9 trillion and accounted for 10.4 percent of global GDP.

Tourism offers opportunities for economic diversification and market-creation. When effectively managed, its deep local value chains can expand demand for existing and new products and services that directly and positively impact the poor and rural/isolated communities. The sector can also be a force for biodiversity conservation, heritage protection, and climate-friendly livelihoods, making up a key pillar of the blue/green economy. This potential is also associated with social and environmental risks, which need to be managed and mitigated to maximize the sector’s net-positive benefits.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been devastating for tourism service providers, with a loss of 20 percent of all tourism jobs (62 million), and US$1.3 trillion in export revenue, leading to a reduction of 50 percent of its contribution to GDP in 2020 alone. The collapse of demand has severely impacted the livelihoods of tourism-dependent communities, small businesses and women-run enterprises. It has also reduced government tax revenues and constrained the availability of resources for destination management and site conservation.

Naturalist local guide with group of tourist in Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve Ecuador. Photo: Ammit Jack/Shutterstock

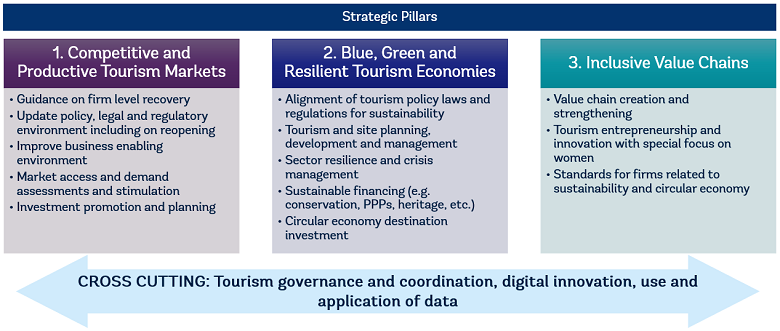

Tourism and Competitiveness Strategic Pillars

Our solutions are integrated across the following areas:

- Competitive and Productive Tourism Markets. We work with government and private sector stakeholders to foster competitive tourism markets that create productive jobs, improve visitor expenditure and impact, and are supportive of high-growth, innovative firms. To do so we offer guidance on firm and destination level recovery, policy and regulatory reforms, demand diversification, investment promotion and market access.

- Blue, Green and Resilient Tourism Economies. We support economic diversification to sustain natural capital and tourism assets, prepare for external and climate-related shocks, and be sustainably managed through strong policy, coordination, and governance improvements. To do so we offer support to align the tourism enabling and policy environment towards sustainability, while improving tourism destination and site planning, development, and management. We work with governments to enhance the sector’s resilience and to foster the development of innovative sustainable financing instruments.

- Inclusive Value Chains. We work with client governments and intermediaries to support Small and Medium sized Enterprises (SMEs), and strengthen value chains that provide equitable livelihoods for communities, women, youth, minorities, and local businesses.

The successful design and implementation of reforms in the tourism space requires the combined effort of diverse line ministries and agencies, and an understanding of the impact of digital technologies in the industry. Accordingly, our teams support cross-cutting issues of tourism governance and coordination, digital innovation and the use and application of data throughout the three focus areas of work.

Tourism and Competitiveness Theory of Change

Examples of our projects:

- In Indonesia , a US$955m loan is supporting the Government’s Integrated Infrastructure Development for National Tourism Strategic Areas Project. This project is designed to improve the quality of, and access to, tourism-relevant basic infrastructure and services, strengthen local economy linkages to tourism, and attract private investment in selected tourism destinations. In its initial phases, the project has supported detailed market and demand analyses needed to justify significant public investment, mobilized integrated tourism destination masterplans for each new destination and established essential coordination mechanisms at the national level and at all seventeen of the Project’s participating districts and cities.

- In Madagascar , a series of projects totaling US$450m in lending and IFC Technical Assistance have contributed to the sustainable growth of the tourism sector by enhancing access to enabling infrastructure and services in target regions. Activities under the project focused on providing support to SMEs, capacity building to institutions, and promoting investment and enabling environment reforms. They resulted in the creation of more than 10,000 jobs and the registration of more than 30,000 businesses. As a result of COVID-19, the project provided emergency support both to government institutions (i.e., Ministry of Tourism) and other organizations such as the National Tourism Promotion Board to plan, strategize and implement initiatives to address effects of the pandemic and support the sector’s gradual relaunch, as well as to directly support tourism companies and workers groups most affected by the crisis.

- In Sierra Leone , an Economic Diversification Project has a strong focus on sustainable tourism development. The project is contributing significantly to the COVID-19 recovery, with its focus on the creation of six new tourism destinations, attracting new private investment, and building the capacity of government ministries to successfully manage and market their tourism assets. This project aims to contribute to the development of more circular economy tourism business models, and support the growth of women- run tourism businesses.