MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

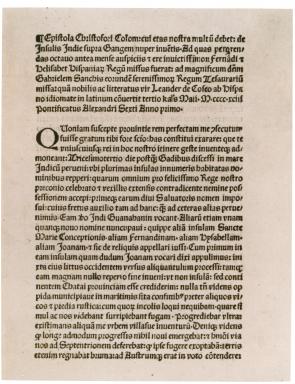

Columbus reports on his first voyage, 1493

A spotlight on a primary source by christopher columbus.

On August 3, 1492, Columbus set sail from Spain to find an all-water route to Asia. On October 12, more than two months later, Columbus landed on an island in the Bahamas that he called San Salvador; the natives called it Guanahani.

For nearly five months, Columbus explored the Caribbean, particularly the islands of Juana (Cuba) and Hispaniola (Santo Domingo), before returning to Spain. He left thirty-nine men to build a settlement called La Navidad in present-day Haiti. He also kidnapped several Native Americans (between ten and twenty-five) to take back to Spain—only eight survived. Columbus brought back small amounts of gold as well as native birds and plants to show the richness of the continent he believed to be Asia.

When Columbus arrived back in Spain on March 15, 1493, he immediately wrote a letter announcing his discoveries to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, who had helped finance his trip. The letter was written in Spanish and sent to Rome, where it was printed in Latin by Stephan Plannck. Plannck mistakenly left Queen Isabella’s name out of the pamphlet’s introduction but quickly realized his error and reprinted the pamphlet a few days later. The copy shown here is the second, corrected edition of the pamphlet.

The Latin printing of this letter announced the existence of the American continent throughout Europe. “I discovered many islands inhabited by numerous people. I took possession of all of them for our most fortunate King by making public proclamation and unfurling his standard, no one making any resistance,” Columbus wrote.

In addition to announcing his momentous discovery, Columbus’s letter also provides observations of the native people’s culture and lack of weapons, noting that “they are destitute of arms, which are entirely unknown to them, and for which they are not adapted; not on account of any bodily deformity, for they are well made, but because they are timid and full of terror.” Writing that the natives are “fearful and timid . . . guileless and honest,” Columbus declares that the land could easily be conquered by Spain, and the natives “might become Christians and inclined to love our King and Queen and Princes and all the people of Spain.”

An English translation of this document is available.

I have determined to write you this letter to inform you of everything that has been done and discovered in this voyage of mine.

On the thirty-third day after leaving Cadiz I came into the Indian Sea, where I discovered many islands inhabited by numerous people. I took possession of all of them for our most fortunate King by making public proclamation and unfurling his standard, no one making any resistance. The island called Juana, as well as the others in its neighborhood, is exceedingly fertile. It has numerous harbors on all sides, very safe and wide, above comparison with any I have ever seen. Through it flow many very broad and health-giving rivers; and there are in it numerous very lofty mountains. All these island are very beautiful, and of quite different shapes; easy to be traversed, and full of the greatest variety of trees reaching to the stars. . . .

In the island, which I have said before was called Hispana , there are very lofty and beautiful mountains, great farms, groves and fields, most fertile both for cultivation and for pasturage, and well adapted for constructing buildings. The convenience of the harbors in this island, and the excellence of the rivers, in volume and salubrity, surpass human belief, unless on should see them. In it the trees, pasture-lands and fruits different much from those of Juana. Besides, this Hispana abounds in various kinds of species, gold and metals. The inhabitants . . . are all, as I said before, unprovided with any sort of iron, and they are destitute of arms, which are entirely unknown to them, and for which they are not adapted; not on account of any bodily deformity, for they are well made, but because they are timid and full of terror. . . . But when they see that they are safe, and all fear is banished, they are very guileless and honest, and very liberal of all they have. No one refuses the asker anything that he possesses; on the contrary they themselves invite us to ask for it. They manifest the greatest affection towards all of us, exchanging valuable things for trifles, content with the very least thing or nothing at all. . . . I gave them many beautiful and pleasing things, which I had brought with me, for no return whatever, in order to win their affection, and that they might become Christians and inclined to love our King and Queen and Princes and all the people of Spain; and that they might be eager to search for and gather and give to us what they abound in and we greatly need.

Questions for Discussion

Read the document introduction and transcript in order to answer these questions.

- Columbus described the Natives he first encountered as “timid and full of fear.” Why did he then capture some Natives and bring them aboard his ships?

- Imagine the thoughts of the Europeans as they first saw land in the “New World.” What do you think would have been their most immediate impression? Explain your answer.

- Which of the items Columbus described would have been of most interest to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella? Why?

- Why did Columbus describe the islands and their inhabitants in great detail?

- It is said that this voyage opened the period of the “Columbian Exchange.” Why do you think that term has been attached to this period of time?

A printer-friendly version is available here .

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter..

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

Christopher Columbus

Italian explorer Christopher Columbus discovered the “New World” of the Americas on an expedition sponsored by King Ferdinand of Spain in 1492.

c. 1451-1506

Quick Facts

Where was columbus born, first voyages, columbus’ 1492 route and ships, where did columbus land in 1492, later voyages across the atlantic, how did columbus die, santa maria discovery claim, columbian exchange: a complex legacy, columbus day: an evolving holiday, who was christopher columbus.

Christopher Columbus was an Italian explorer and navigator. In 1492, he sailed across the Atlantic Ocean from Spain in the Santa Maria , with the Pinta and the Niña ships alongside, hoping to find a new route to Asia. Instead, he and his crew landed on an island in present-day Bahamas—claiming it for Spain and mistakenly “discovering” the Americas. Between 1493 and 1504, he made three more voyages to the Caribbean and South America, believing until his death that he had found a shorter route to Asia. Columbus has been credited—and blamed—for opening up the Americas to European colonization.

FULL NAME: Cristoforo Colombo BORN: c. 1451 DIED: May 20, 1506 BIRTHPLACE: Genoa, Italy SPOUSE: Filipa Perestrelo (c. 1479-1484) CHILDREN: Diego and Fernando

Christopher Columbus, whose real name was Cristoforo Colombo, was born in 1451 in the Republic of Genoa, part of what is now Italy. He is believed to have been the son of Dominico Colombo and Susanna Fontanarossa and had four siblings: brothers Bartholomew, Giovanni, and Giacomo, and a sister named Bianchinetta. He was an apprentice in his father’s wool weaving business and studied sailing and mapmaking.

In his 20s, Columbus moved to Lisbon, Portugal, and later resettled in Spain, which remained his home base for the duration of his life.

Columbus first went to sea as a teenager, participating in several trading voyages in the Mediterranean and Aegean seas. One such voyage, to the island of Khios, in modern-day Greece, brought him the closest he would ever come to Asia.

His first voyage into the Atlantic Ocean in 1476 nearly cost him his life, as the commercial fleet he was sailing with was attacked by French privateers off the coast of Portugal. His ship was burned, and Columbus had to swim to the Portuguese shore.

He made his way to Lisbon, where he eventually settled and married Filipa Perestrelo. The couple had one son, Diego, around 1480. His wife died when Diego was a young boy, and Columbus moved to Spain. He had a second son, Fernando, who was born out of wedlock in 1488 with Beatriz Enriquez de Arana.

After participating in several other expeditions to Africa, Columbus learned about the Atlantic currents that flow east and west from the Canary Islands.

The Asian islands near China and India were fabled for their spices and gold, making them an attractive destination for Europeans—but Muslim domination of the trade routes through the Middle East made travel eastward difficult.

Columbus devised a route to sail west across the Atlantic to reach Asia, believing it would be quicker and safer. He estimated the earth to be a sphere and the distance between the Canary Islands and Japan to be about 2,300 miles.

Many of Columbus’ contemporary nautical experts disagreed. They adhered to the (now known to be accurate) second-century BCE estimate of the Earth’s circumference at 25,000 miles, which made the actual distance between the Canary Islands and Japan about 12,200 statute miles. Despite their disagreement with Columbus on matters of distance, they concurred that a westward voyage from Europe would be an uninterrupted water route.

Columbus proposed a three-ship voyage of discovery across the Atlantic first to the Portuguese king, then to Genoa, and finally to Venice. He was rejected each time. In 1486, he went to the Spanish monarchy of Queen Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon. Their focus was on a war with the Muslims, and their nautical experts were skeptical, so they initially rejected Columbus.

The idea, however, must have intrigued the monarchs, because they kept Columbus on a retainer. Columbus continued to lobby the royal court, and soon, the Spanish army captured the last Muslim stronghold in Granada in January 1492. Shortly thereafter, the monarchs agreed to finance his expedition.

In late August 1492, Columbus left Spain from the port of Palos de la Frontera. He was sailing with three ships: Columbus in the larger Santa Maria (a type of ship known as a carrack), with the Pinta and the Niña (both Portuguese-style caravels) alongside.

On October 12, 1492, after 36 days of sailing westward across the Atlantic, Columbus and several crewmen set foot on an island in present-day Bahamas, claiming it for Spain.

There, his crew encountered a timid but friendly group of natives who were open to trade with the sailors. They exchanged glass beads, cotton balls, parrots, and spears. The Europeans also noticed bits of gold the natives wore for adornment.

Columbus and his men continued their journey, visiting the islands of Cuba (which he thought was mainland China) and Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic, which Columbus thought might be Japan) and meeting with the leaders of the native population.

During this time, the Santa Maria was wrecked on a reef off the coast of Hispaniola. With the help of some islanders, Columbus’ men salvaged what they could and built the settlement Villa de la Navidad (“Christmas Town”) with lumber from the ship.

Thirty-nine men stayed behind to occupy the settlement. Convinced his exploration had reached Asia, he set sail for home with the two remaining ships. Returning to Spain in 1493, Columbus gave a glowing but somewhat exaggerated report and was warmly received by the royal court.

In 1493, Columbus took to the seas on his second expedition and explored more islands in the Caribbean Ocean. Upon arrival at Hispaniola, Columbus and his crew discovered the Navidad settlement had been destroyed with all the sailors massacred.

Spurning the wishes of the local queen, Columbus established a forced labor policy upon the native population to rebuild the settlement and explore for gold, believing it would be profitable. His efforts produced small amounts of gold and great hatred among the native population.

Before returning to Spain, Columbus left his brothers Bartholomew and Giacomo to govern the settlement on Hispaniola and sailed briefly around the larger Caribbean islands, further convincing himself he had discovered the outer islands of China.

It wasn’t until his third voyage that Columbus actually reached the South American mainland, exploring the Orinoco River in present-day Venezuela. By this time, conditions at the Hispaniola settlement had deteriorated to the point of near-mutiny, with settlers claiming they had been misled by Columbus’ claims of riches and complaining about the poor management of his brothers.

The Spanish Crown sent a royal official who arrested Columbus and stripped him of his authority. He returned to Spain in chains to face the royal court. The charges were later dropped, but Columbus lost his titles as governor of the Indies and, for a time, much of the riches made during his voyages.

After convincing King Ferdinand that one more voyage would bring the abundant riches promised, Columbus went on his fourth and final voyage across the Atlantic Ocean in 1502. This time he traveled along the eastern coast of Central America in an unsuccessful search for a route to the Indian Ocean.

A storm wrecked one of his ships, stranding the captain and his sailors on the island of Cuba. During this time, local islanders, tired of the Spaniards’ poor treatment and obsession with gold, refused to give them food.

In a spark of inspiration, Columbus consulted an almanac and devised a plan to “punish” the islanders by taking away the moon. On February 29, 1504, a lunar eclipse alarmed the natives enough to re-establish trade with the Spaniards. A rescue party finally arrived, sent by the royal governor of Hispaniola in July, and Columbus and his men were taken back to Spain in November 1504.

In the two remaining years of his life, Columbus struggled to recover his reputation. Although he did regain some of his riches in May 1505, his titles were never returned.

Columbus probably died of severe arthritis following an infection on May 20, 1506, in Valladolid, Spain. At the time of his death, he still believed he had discovered a shorter route to Asia.

There are questions about the location of his burial site. According to the BBC , Columbus’ remains moved at least three or four times over the course of 400 years—including from Valladolid to Seville, Spain, in 1509; then to Santo Domingo, in what is now the Dominican Republic, in 1537; then to Havana, Cuba, in 1795; and back to Seville in 1898. As a result, Seville and Santo Domingo have both laid claim to being Columbus’ true burial site. It is also possible his bones were mixed up with another person’s amid all of their travels.

In May 2014, Columbus made headlines as news broke that a team of archaeologists might have found the Santa Maria off the north coast of Haiti. Barry Clifford, the leader of this expedition, told the Independent newspaper that “all geographical, underwater topography and archaeological evidence strongly suggests this wreck is Columbus’ famous flagship the Santa Maria.”

After a thorough investigation by the U.N. agency UNESCO, it was determined the wreck dates from a later period and was located too far from shore to be the famed ship.

Columbus has been credited for opening up the Americas to European colonization—as well as blamed for the destruction of the native peoples of the islands he explored. Ultimately, he failed to find that what he set out for: a new route to Asia and the riches it promised.

In what is known as the Columbian Exchange, Columbus’ expeditions set in motion the widespread transfer of people, plants, animals, diseases, and cultures that greatly affected nearly every society on the planet.

The horse from Europe allowed Native American tribes in the Great Plains of North America to shift from a nomadic to a hunting lifestyle. Wheat from the Old World fast became a main food source for people in the Americas. Coffee from Africa and sugar cane from Asia became major cash crops for Latin American countries. And foods from the Americas, such as potatoes, tomatoes and corn, became staples for Europeans and helped increase their populations.

The Columbian Exchange also brought new diseases to both hemispheres, though the effects were greatest in the Americas. Smallpox from the Old World killed millions, decimating the Native American populations to mere fractions of their original numbers. This more than any other factor allowed for European domination of the Americas.

The overwhelming benefits of the Columbian Exchange went to the Europeans initially and eventually to the rest of the world. The Americas were forever altered, and the once vibrant cultures of the Indigenous civilizations were changed and lost, denying the world any complete understanding of their existence.

As more Italians began to immigrate to the United States and settle in major cities during the 19 th century, they were subject to religious and ethnic discrimination. This included a mass lynching of 11 Sicilian immigrants in 1891 in New Orleans.

Just one year after this horrific event, President Benjamin Harrison called for the first national observance of Columbus Day on October 12, 1892, to mark the 400 th anniversary of his arrival in the Americas. Italian-Americans saw this honorary act for Columbus as a way of gaining acceptance.

Colorado became the first state to officially observe Columbus Day in 1906 and, within five years, 14 other states followed. Thanks to a joint resolution of Congress, the day officially became a federal holiday in 1934 during the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt . In 1970, Congress declared the holiday would fall on the second Monday in October each year.

But as Columbus’ legacy—specifically, his exploration’s impacts on Indigenous civilizations—began to draw more criticism, more people chose not to take part. As of 2023, approximately 29 states no longer celebrate Columbus Day , and around 195 cities have renamed it or replaced with the alternative Indigenous Peoples Day. The latter isn’t an official holiday, but the federal government recognized its observance in 2022 and 2023. President Joe Biden called it “a day in honor of our diverse history and the Indigenous peoples who contribute to shaping this nation.”

One of the most notable cities to move away from celebrating Columbus Day in recent years is the state capital of Columbus, Ohio, which is named after the explorer. In 2018, Mayor Andrew Ginther announced the city would remain open on Columbus Day and instead celebrate a holiday on Veterans Day. In July 2020, the city also removed a 20-plus-foot metal statue of Columbus from the front of City Hall.

- I went to sea from the most tender age and have continued in a sea life to this day. Whoever gives himself up to this art wants to know the secrets of Nature here below. It is more than forty years that I have been thus engaged. Wherever any one has sailed, there I have sailed.

- Speaking of myself, little profit had I won from twenty years of service, during which I have served with so great labors and perils, for today I have no roof over my head in Castile; if I wish to sleep or eat, I have no place to which to go, save an inn or tavern, and most often, I lack the wherewithal to pay the score.

- They say that there is in that land an infinite amount of gold; and that the people wear corals on their heads and very large bracelets of coral on their feet and arms; and that with coral they adorn and inlay chairs and chests and tables.

- This island and all the others are very fertile to a limitless degree, and this island is extremely so. In it there are many harbors on the coast of the sea, beyond comparison with others that I know in Christendom, and many rivers, good and large, which is marvelous.

- Our Almighty God has shown me the highest favor, which, since David, he has not shown to anybody.

- Already the road is opened to gold and pearls, and it may surely be hoped that precious stones, spices, and a thousand other things, will also be found.

- I have now seen so much irregularity, that I have come to another conclusion respecting the earth, namely, that it is not round as they describe, but of the form of a pear.

- In all the countries visited by your Highnesses’ ships, I have caused a high cross to be fixed upon every headland and have proclaimed, to every nation that I have discovered, the lofty estate of your Highnesses and of your court in Spain.

- I ought to be judged as a captain sent from Spain to the Indies, to conquer a nation numerous and warlike, with customs and religions altogether different to ours.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Tyler Piccotti first joined the Biography.com staff as an Associate News Editor in February 2023, and before that worked almost eight years as a newspaper reporter and copy editor. He is a graduate of Syracuse University. When he's not writing and researching his next story, you can find him at the nearest amusement park, catching the latest movie, or cheering on his favorite sports teams.

Possible Evidence of Amelia Earhart’s Plane

Charles Lindbergh

Was Christopher Columbus a Hero or Villain?

History & Culture

Alexander McQueen

Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Eleanor Roosevelt

Michelle Obama

Rare Vintage Photos of Celebrities at the Opera

The 12 Greatest Unsolved Disappearances

Henrietta Lacks

Rosalynn Carter

The Ages of Exploration

Christopher columbus, age of discovery.

Quick Facts:

He is credited for discovering the Americas in 1492, although we know today people were there long before him; his real achievement was that he opened the door for more exploration to a New World.

Name : Christopher Columbus [Kri-stə-fər] [Kə-luhm-bəs]

Birth/Death : 1451 - 1506

Nationality : Italian

Birthplace : Genoa, Italy

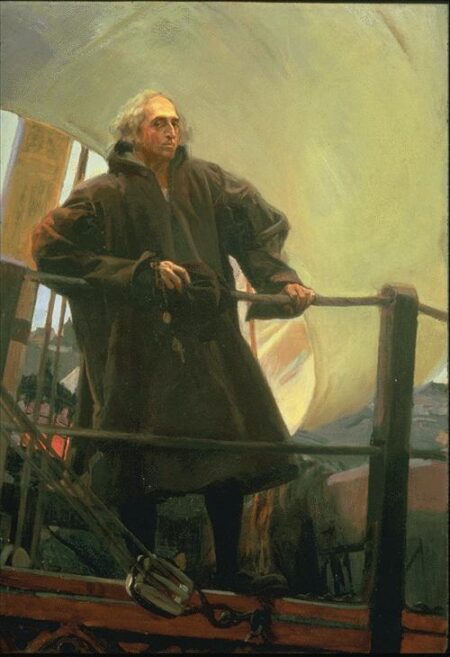

Christopher Columbus leaving Palos, Spain

Christopher Columbus aboard the "Santa Maria" leaving Palos, Spain on his first voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. The Mariners' Museum 1933.0746.000001

Introduction We know that In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue. But what did he actually discover? Christopher Columbus (also known as (Cristoforo Colombo [Italian]; Cristóbal Colón [Spanish]) was an Italian explorer credited with the “discovery” of the America’s. The purpose for his voyages was to find a passage to Asia by sailing west. Never actually accomplishing this mission, his explorations mostly included the Caribbean and parts of Central and South America, all of which were already inhabited by Native groups.

Biography Early Life Christopher Columbus was born in Genoa, part of present-day Italy, in 1451. His parents’ names were Dominico Colombo and Susanna Fontanarossa. He had three brothers: Bartholomew, Giovanni, and Giacomo; and a sister named Bianchinetta. Christopher became an apprentice in his father’s wool weaving business, but he also studied mapmaking and sailing as well. He eventually left his father’s business to join the Genoese fleet and sail on the Mediterranean Sea. 1 After one of his ships wrecked off the coast of Portugal, he decided to remain there with his younger brother Bartholomew where he worked as a cartographer (mapmaker) and bookseller. Here, he married Doña Felipa Perestrello e Moniz and had two sons Diego and Fernando.

Christopher Columbus owned a copy of Marco Polo’s famous book, and it gave him a love for exploration. In the mid 15th century, Portugal was desperately trying to find a faster trade route to Asia. Exotic goods such as spices, ivory, silk, and gems were popular items of trade. However, Europeans often had to travel through the Middle East to reach Asia. At this time, Muslim nations imposed high taxes on European travels crossing through. 2 This made it both difficult and expensive to reach Asia. There were rumors from other sailors that Asia could be reached by sailing west. Hearing this, Christopher Columbus decided to try and make this revolutionary journey himself. First, he needed ships and supplies, which required money that he did not have. He went to King John of Portugal who turned him down. He then went to the rulers of England, and France. Each declined his request for funding. After seven years of trying, he was finally sponsored by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain.

Voyages Principal Voyage Columbus’ voyage departed in August of 1492 with 87 men sailing on three ships: the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María. Columbus commanded the Santa María, while the Niña was led by Vicente Yanez Pinzon and the Pinta by Martin Pinzon. 3 This was the first of his four trips. He headed west from Spain across the Atlantic Ocean. On October 12 land was sighted. He gave the first island he landed on the name San Salvador, although the native population called it Guanahani. 4 Columbus believed that he was in Asia, but was actually in the Caribbean. He even proposed that the island of Cuba was a part of China. Since he thought he was in the Indies, he called the native people “Indians.” In several letters he wrote back to Spain, he described the landscape and his encounters with the natives. He continued sailing throughout the Caribbean and named many islands he encountered after his ship, king, and queen: La Isla de Santa María de Concepción, Fernandina, and Isabella.

It is hard to determine specifically which islands Columbus visited on this voyage. His descriptions of the native peoples, geography, and plant life do give us some clues though. One place we do know he stopped was in present-day Haiti. He named the island Hispaniola. Hispaniola today includes both Haiti and the Dominican Republic. In January of 1493, Columbus sailed back to Europe to report what he found. Due to rough seas, he was forced to land in Portugal, an unfortunate event for Columbus. With relations between Spain and Portugal strained during this time, Ferdinand and Isabella suspected that Columbus was taking valuable information or maybe goods to Portugal, the country he had lived in for several years. Those who stood against Columbus would later use this as an argument against him. Eventually, Columbus was allowed to return to Spain bringing with him tobacco, turkey, and some new spices. He also brought with him several natives of the islands, of whom Queen Isabella grew very fond.

Subsequent Voyages Columbus took three other similar trips to this region. His second voyage in 1493 carried a large fleet with the intention of conquering the native populations and establishing colonies. At one point, the natives attacked and killed the settlers left at Fort Navidad. Over time the colonists enslaved many of the natives, sending some to Europe and using many to mine gold for the Spanish settlers in the Caribbean. The third trip was to explore more of the islands and mainland South America further. Columbus was appointed the governor of Hispaniola, but the colonists, upset with Columbus’ leadership appealed to the rulers of Spain, who sent a new governor: Francisco de Bobadilla. Columbus was taken prisoner on board a ship and sent back to Spain.

On his fourth and final journey west in 1502 Columbus’s goal was to find the “Strait of Malacca,” to try to find India. But a hurricane, then being denied entrance to Hispaniola, and then another storm made this an unfortunate trip. His ship was so badly damaged that he and his crew were stranded on Jamaica for two years until help from Hispaniola finally arrived. In 1504, Columbus and his men were taken back to Spain .

Later Years and Death Columbus reached Spain in November 1504. He was not in good health. He spent much of the last of his life writing letters to obtain the percentage of wealth overdue to be paid to him, and trying to re-attain his governorship status, but was continually denied both. Columbus died at Valladolid on May 20, 1506, due to illness and old age. Even until death, he still firmly believing that he had traveled to the eastern part of Asia.

Legacy Columbus never made it to Asia, nor did he truly discover America. His “re-discovery,” however, inspired a new era of exploration of the American continents by Europeans. Perhaps his greatest contribution was that his voyages opened an exchange of goods between Europe and the Americas both during and long after his journeys. 5 Despite modern criticism of his treatment of the native peoples there is no denying that his expeditions changed both Europe and America. Columbus day was made a federal holiday in 1971. It is recognized on the second Monday of October.

- Fergus Fleming, Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration (New York: Grove Press, 2004), 30.

- Fleming, Off the Map, 30

- William D. Phillips and Carla Rahn Phillips, The Worlds of Christopher Columbus (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 142-143.

- Phillips and Phillips, The Worlds of Christopher Columbus, 155.

- Robin S. Doak, Christopher Columbus: Explorer of the New World (Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2005), 92.

Bibliography

Doak, Robin. Christopher Columbus: Explorer of the New World. Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2005.

Fleming, Fergus. Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration. New York: Grove Press, 2004.

Phillips, William D., and Carla Rahn Phillips. The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Map of Voyages

Click below to view an example of the explorer’s voyages. Use the tabs on the left to view either 1 or multiple journeys at a time, and click on the icons to learn more about the stops, sites, and activities along the way.

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

HISTORIC ARTICLE

Aug 3, 1492 ce: columbus sets sail.

On August 3, 1492, Italian explorer Christopher Columbus started his voyage across the Atlantic Ocean.

Geography, Human Geography, Social Studies, U.S. History, World History

Loading ...

On August 3, 1492, Italian explorer Christopher Columbus started his voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. With a crew of 90 men and three ships—the Niña, Pinta, and Santa Maria—he left from Palos de la Frontera, Spain. Columbus reasoned that since the world is round, he could sail west to reach “the east” (the lucrative lands of India and China). That reasoning was actually sound, but the Earth is much larger than Columbus thought—large enough for him to run into two enormous continents (the “New World” of the Americas) mostly unknown to Europeans. Columbus made it to what is now the Bahamas in 61 days. He initially thought his plan was successful and the ships had reached India. In fact, he called the indigenous people “Indians,” an inaccurate name that unfortunately stuck.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Last Updated

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

A Timeline of North American Exploration: 1492–1585

H. Armstrong Roberts / ClassicStock / Getty Images

- Important Historical Figures

- U.S. Presidents

- Native American History

- American Revolution

- America Moves Westward

- The Gilded Age

- Crimes & Disasters

- The Most Important Inventions of the Industrial Revolution

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- M.A., History, University of Florida

- B.A., History, University of Florida

Traditionally, the age of exploration in America begins in 1492 with the first voyage of Christopher Columbus. Those expeditions began with a desire to find another way to the East, where the Europeans had created a lucrative trade route in spices and other goods. Once the explorers realized they had discovered a new continent , their countries began to explore, conquer, and then create permanent settlements in America.

However, it's best to recognize that Columbus wasn't the first human to put a foot in the Americas. Before about 15,000 years ago, the vast continents of North and South America had no human beings on them whatsoever. The following timeline covers the key events of the exploration of the New World.

Pre-Columbus Explorations

~13,000 BCE: Hunters and fishers from Asia that archaeologists call Pre-Clovis entered the Americas from eastern Asia and spend the next 12,000 years exploring the coastlines and colonizing the interiors of North and South America. By the time the Europeans arrived, the descendants of the first colonists have populated all of both American continents.

870 CE: The Viking explorer Erik the Red (ca. 950–1003) reaches Greenland, begins a colony, and interacts with the local people he calls " Skraelings ."

998: Erik the Red's son Leif Erikson (c. 970–1020) reaches Newfoundland and explores the region from a small settlement called L'Anse aux Meadows (Jellyfish Cove). The colony collapses within a decade.

1200: Polynesian sailors, descendants of the Lapita Culture , permanently settle Easter Island.

1400: Descendants of Easter Islanders land on the Chilean coast of South America and hobnob with the local residents, bringing chickens for dinner.

1473: Portuguese sailor João Vaz Corte-Real (1420–1496) explores (perhaps) the coast of North America, a land he calls Terra Nova do Bacalhau (New Land of the Codfish).

Columbus and Later Explorations (1492–1519)

1492–1493: Italian explorer Christopher Columbus makes three voyages paid for by the Spanish and lands on islands off the coast of the North American continent, not realizing he has found a new land.

1497: Italian navigator and explorer John Cabot (ca. 1450–1500), commissioned by Britain's Henry VII, sights Newfoundland and Labrador , claiming this area for England before sailing south toward Maine and then returning to England.

1498: John Cabot and his son Sebastian Cabot (1477–1557) explore from Labrador to Cape Cod.

Spanish explorer Vicente Yáñez Pinzón (1462–ca. 1514) and the (possibly) Portuguese explorer Juan Díaz de Solís (1470–1516) sail into the Gulf of Mexico and visit the Yucatan peninsula and the coast of Florida.

1500: Portuguese nobleman and military commander Pedro Álvares Cabral (1467–1620) explores Brazil and claims it for Portugal.

Yáñez Pinzón discovers the Amazon River in Brazil.

1501: Italian explorer and cartographer Amerigo Vespucci (1454–1512) explores the Brazilian coast and realizes (unlike Columbus) that he has found a new continent.

1513: Spanish explorer and conquistador Juan Ponce de León (1474–1521) finds and names Florida. As legend has it, he searches for the Fountain of Youth but doesn't find it.

Spanish explorer, governor, and conquistador Vasco Núñez de Balboa (1475–1519) crosses the Isthmus of Panama to the Pacific Ocean to become the first European to reach the Pacific Ocean from North America.

1516: Díaz de Solís becomes the first European to land in Uruguay, but most of his expedition is killed and perhaps eaten by local people.

1519: Spanish conquistador and cartographer Alonso Álvarez de Pineda (1494–1520) sails from Florida to Mexico, mapping the gulf coast along the way and landing in Texas.

Conquering the New World (1519–1565)

1519: Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés (1485–1547) defeats the Aztecs and conquers Mexico.

1521: Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan , funded by Charles V of Spain, sails around South America into the Pacific. Despite Magellan's death in 1521, his expedition becomes the first to circumnavigate the globe.

1523: Spanish conquistador Pánfilo de Narváez (1485–1541) becomes governor of Florida but dies along with most of his colony after dealing with a hurricane, attacks by Indigenous groups, and disease.

1524: In a French-sponsored voyage, Italian explorer Giovanni de Verrazzano (1485–1528) discovers the Hudson River before sailing north to Nova Scotia.

1532: In Peru, Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro (1475–1541) conquers the Inca Empire.

1534–1536: Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (1490–1559), explores from the Sabine River to the Gulf of California. When he arrives in Mexico City, his tales reinforce ideas that the Seven Cities of Cibola (aka Seven Cities of Gold) exist and are located in New Mexico.

1535: French explorer Jacques Cartier (1491–1557) explores and maps the Gulf of Saint Lawrence.

1539: French Franciscan friar Fray Marcos de Niza (1495–1558), sent by the Spanish governor of Mexico (New Spain), explores Arizona and New Mexico searching for the Seven Cities of Gold and foments rumor-mongering in Mexico City that he has seen the cities when he returns.

1539–1542: Spanish explorer and conquistador Hernando de Soto (1500–1542) explores Florida, Georgia, and Alabama, meets the Mississippian chiefdoms there and becomes the first European to cross the Mississippi River, where he is killed by the locals.

1540–1542: Spanish conquistador and explorer Francisco Vásquez de Coronado (1510–1554) leaves Mexico City and explores the Gila River, the Rio Grande, and the Colorado River . He reaches as far north as Kansas before returning to Mexico City. He too searches for the legendary Seven Cities of Gold.

1542: Spanish (or possibly Portuguese) conquistador and explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo (1497–1543) sails up the California Coast and claims it for Spain.

1543: Followers of Hernando De Soto continue his expedition without him, sailing from the Mississippi River to Mexico.

Bartolomé Ferrelo (1499–1550), the Spanish pilot for Cabrillo continues his expedition up the California coast and reaches what is probably present-day Oregon.

Permanent European Settlements

1565: The first permanent European settlement is founded by Spanish admiral and explorer Pedro Menendez de Aviles (1519–1574) at St. Augustine, Florida.

1578–1580: As part of his circumnavigation of the globe, English sea captain, privateer and trader of enslaved people Francis Drake (1540–1596) sails around South America and into San Francisco Bay. He claims the area for Queen Elizabeth .

1584: English writer, poet, soldier, politician, courtier, spy, and explorer Walter Raleigh (1552–1618) lands on Roanoke Island and calls the land Virginia in honor of Queen Elizabeth.

1585: Roanoke in Virginia is settled. However, this is short-lived. When colonist and governor John White (1540–1593) returns two years later, the colony has disappeared. An additional group of settlers is left at Roanoke but when White returns again in 1590, the settlement has yet again disappeared. To this day, mystery surrounds their disappearance.

- 10 Facts About the Spanish Conquistadors

- Amerigo Vespucci, Explorer and Navigator

- The Florida Expeditions of Ponce de Leon

- Facts About the Colony of Georgia

- 10 Notable Spanish Conquistadors Throughout History

- A Brief History of the Age of Exploration

- 10 Facts About Francisco Pizarro

- Amerigo Vespucci, Italian Explorer and Cartographer

- Consequences of the Conquest of the Aztecs

- Biography of Francisco de Orellana, Discoverer of the Amazon River

- Biography of Christopher Columbus, Italian Explorer

- Ten Facts About Pedro de Alvarado

- Biography of Hernán Cortés, Ruthless Conquistador

- Ten Facts About Hernan Cortes

- Who Were the Spanish Conquistadors?

- Biography of Juan Ponce de León, Conquistador

- Navigate to any page of this site.

- In the menu, scroll to Add to Home Screen and tap it.

- In the menu, scroll past any icons and tap Add to Home Screen .

Christopher Columbus: A Latter-day Saint Perspective

Arnold k. garr, first voyage to the americas: columbus guided by the spirit.

Arnold K. Garr, Christopher Columbus A Latter-Day Saint Perspective, (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1992), 39–52.

With a hand that could be felt, the Lord opened my mind to the fact that it would be possible to sail from here to the Indies. . . . This was a fire that burned within me who can doubt that this fire was not merely mine, but also of the Holy Spirit.

—Christopher Columbus

The anticipation and drama associated with Christopher Columbus’ first expedition to the Americas is almost unparalleled in human history. Perhaps the only event of comparable magnitude in our day was man’s first landing on the moon in 1969. Inasmuch as Columbus sailed 33 continuous days into the unknown, with a crew on the verge of mutiny in the final stages, it is apparent that every decision he made was crucial to both the success of his expedition and the survival of his small fleet. It is amazing, said George E. Nunn, a prominent geographer, that Christopher “did not make a single false move in the entire voyage” (Nunn 43). To what can we attribute such incredible seafaring precision, and what were the Admiral’s inner-most thoughts and feelings during the voyage? The answers to these questions lie in the several accounts of the journey that have endured the five centuries since that stunning expedition.

Historians have written about Columbus’ first voyage to America from many points of view. Most secular historians, however, have placed little emphasis on the most important theme of all—the fact that Columbus was guided by the Spirit of God. Beginning with the decision Christopher made concerning his point of departure, and continuing all the way through to his return voyage to Spain, we can find numerous junctures at which the Lord manifested His hand in Columbus’ key decisions.

Before 1492, other navigators had tried unsuccessfully to explore westward from the Azores Islands (800 miles west of the coast of Portugal), assuming that this was the best place from which to set sail (Morison 1:97–98). Although the Azores were the western-most islands known in the Atlantic, Columbus chose to sail from Palos, Spain, to the Canary Islands (off the west coast of Africa) and from there, to launch his voyage into the vast unknown. By doing so, he caught the tradewinds blowing from the northeast to the southwest and avoided the headwinds which blow from the west to the east in the vicinity of the Azores (Nunn 37–38,42).

The route Columbus chose has stood the test of time: five hundred years of sailing have proven it the best possible course for sailing west from southern Europe to North America. Nunn suggested that Columbus’ successful navigation was the result of “an application of reason to . . . knowledge” (Nunn 50). Columbus, however, gave credit to the Lord. Even though he was a successful seaman and an accomplished navigator, he said, “With a hand that could be felt, the Lord opened my mind, to the fact that it would be possible to sail from here to the Indies” (West and Kling 105).

Inspirational Junctures

Columbus experienced relatively easy sailing during the entire outward voyage; had he not done so, he likely would not have reached America before his crew mutinied. There was one occasion, however, on 23 September, when the sea became calm, and the ships were stalled for part of the day. Columbus noted in his journal that the crew, which had not seen land for some days, began to complain that since there were no heavy seas in the region, the wind would never blow hard enough to return to Spain. Soon thereafter, the sea mysteriously rose without wind, astonishing the crew (Dunn and Kelly 41). The Admiral considered this a divine miracle. He said, “the high sea was very necessary to me, [a sign] which had not appeared except in the time of the Jews when they left Egypt [and complained] against Moses, who took them out of captivity” (Ibid).

On the way to America, Columbus changed course only twice during the entire 33 days at sea. The first alteration was on 7 October. Until that time, Christopher had sailed due west for 28 days. Then he noted in his journal that a great multitude of birds passed over, going from north to southwest. Bartolome de Las Casas, the man who transcribed Columbus’ journal, wrote that from this observation, the Admiral “decided to alter course and turn the prow to the WSW [west southwest]” (Fuson 71). Professor Morison claimed that if Columbus had not changed course, “the voyage would have taken a day longer” (Morison 1:283). That extra day would have been critical, since two days before the eventual sighting of land, the crew threatened mutiny. Every extra day at sea heightened their anxiety; the Admiral’s time-saving change of course on 7 October, therefore, just may have saved the expedition.

The story of the threatened mutiny is one of the most dramatic episodes of the first voyage. The incident took place on Wednesday, 10 October 1492, after they had been at sea for over 31 days without seeing land. The sailors, who had been concealing their discontent, now openly threatened insurrection. They had come to believe that Columbus, the foreigner from Genoa, had deceived them; they supposed he was leading them on a journey from which they would never return. According to one account, the sailors even conspired to do away with their leader, whom they “planned to throw into the sea” (d’-Anghera 1:59–60). Yet, “Columbus, by using gentle words, holding out promises and flattering their hopes, sought to gain time, and he succeeded in calming their fears” (Ibid). Others have stated, after the fact, that at this juncture, Columbus promised the men that they would return if they did not sight land within two or three days (Morison 1:286,290–91,292n6). Although Columbus did not record this oft-repeated assertion in his journal, he did report that “I also told the men that it was useless to complain, for I had started out to find the Indies and would continue until I had accomplished that mission, with the help of Our Lord” (Fuson 72; emphasis added). This incident serves as an excellent example of Columbus’ determination and faith in God.

The second instance in which the Admiral altered his route was after sunset on 11 October, just a few hours before land was sighted. For no apparent reason, he gave orders to change direction from west southwest back to the original course of due west (Dunn and Kelly 59). He gave no explanation for the change, but it was, nevertheless, an excellent choice. Had he continued on the west southwest course instead of steering due west, he would have missed the island of San Salvador, and would likely have ended up on the deadly reefs along the coast of Long Island (in the Caribbean), perhaps never returning to Spain (Morison 1:295). Many historians have attributed these changes in course to luck or chance, but Las Casas said, “God gave this man the keys to the awesome seas, he and no other unlocked the darkness” (Las Casas 35), and I agree.

Having made this second course correction, Columbus was then right on target, and Justin time to meet with his destiny—to discover the New Land. That evening as the crew gathered for prayer, the Admiral, “spoke to the men of the favor that [the] Lord had shown them by conducting them so safely and prosperously with fair winds and a clear course, and by comforting them with signs that daily grew more abundant” (Ferdinand 58). His policy since reaching a point 700 leagues beyond the Canaries had been not to sail at night, but the crew’s desire to see land was so great that Columbus decided to sail through the darkness (Morison 1:294). He commanded the night watch to keep an especially sharp lookout because he was confident that land was nearby. In addition to an annuity of 10,000 maravedis guaranteed by the Sovereigns, the Admiral also promised to give a silk jacket to the first sailor who sighted land (Dunn and Kelly 63).

About 10 o’clock that night, Columbus saw a light in the distant dark, but it was so faint that he did not publicly announce it. He did, however, bring it to the attention of Pedro Gutierrez, who also acknowledged seeing the flickering light. Rodrigo Sanchez was also called on to observe the light, but he claimed he could see nothing from where he was (Phillips and Phillips 153). Notwithstanding Columbus’ glimpse of the light, it was some four hours later, at about two in the morning on 12 October, that the fleet sighted land for certain. Rodrigo de Triana, a sailor on the Pinta, shouted, “Tierra! tierra!” while the fleet was still two leagues off shore (Morison 1:298). Martin Pinzon, the captain of the Pinta, quickly verified Triana’s claim and then fired a cannon shot, which was the prearranged signal for sighting land.

One can only imagine the gratitude and relief they all must have felt, after more than a month of anxious days at sea, when their eyes first saw this obscure little island in the middle of the tropical Caribbean Sea. It goes without saying that the crews were ecstatic and their respect and admiration for the Admiral soared, literally, overnight.

For Columbus, this historic sighting was a rendezvous with destiny. He had proven, in spite of mounting opposition and a lack of faith on the part of his crew, that it was possible to sail westward across the great Atlantic. According to his agreement with the monarchs, Columbus officially became Admiral of the Ocean Sea, simultaneously gaining the titles of Viceroy and Governor of this island at the moment he discovered it. Professor Hugh Nibley aptly put this celebrated moment into proper perspective when he said: “Everything else in Columbus’ life is subservient to the carrying out of that one mission. The aim and purpose of all his work and suffering was what happened at 2 a.m. on the morning of October 12, 1492” (Nibley 320).

Impatient and anxious to explore their new discovery, the crew waited through the night, and sailed excitedly to shore at daybreak. Upon reaching dry ground, the landing party knelt, kissed the sand with tears of joy, and offered prayers of thanks to God. Rising from his knees, the Admiral named the island San Salvador (Holy Savior), thus beginning a personal tradition of giving names of religious significance to many newly discovered lands (Ferdinand 59). In deference to the crown, Columbus dedicated San Salvador, which lay off the northern coast of Cuba, to the Spanish monarchs.

Exploring the Wonders of the Caribbean

The arrival of the ships did not go unnoticed by the inhabitants of the island. Many of the natives soon gathered at the crew’s landing site. Columbus observed that, “All of them go around as naked as their mothers bore them; and the women also, although I did not see more than one quite young girl. And all those that I saw were young people, for none did I see of more than 30 years of age. They are very well formed, with handsome bodies and good faces. Their hair [is] coarse—almost like the tail of a horse—and short” (Dunn and Kelly 65–66).

The Admiral’s faithful motive for making the voyage is quickly revealed by his impressions on meeting the island people. He confided, “I recognized that they were people who would be better freed [from error] and converted to our Holy Faith by love than by force” (Ibid 65). Later in his journal, Columbus noted: “I believe that they would become Christians very easily, for it seemed to me that they had no religion” (Ibid 69). He determined to take six of the islanders with him in order to educate them in Spanish and in the ways of European life.

After three days of exploring on San Salvador, the Admiral set sail southward, passing various islands en route to an eventual landing at Cuba on 28 October. An astonishing reception awaited the Spanish explorers at this port. Columbus sent two men inland to survey the island’s interior, and they returned with an inspirational account. Arriving at a village of about 1000 inhabitants 12 leagues from the shore, the men had been greeted with great reverence and adoration: “the Indians touched them and kissed their hands and feet, marveling and believing that the Spaniards came from the heavens” (Dunn and Kelly 137).

Through an Indian interpreter, the village was informed “of the way the Christians lived and that they were good people.” Later, the women of the village came toward the two explorers, “kissing their hands and feet and feeling them, attempting to see if they were, like themselves, of flesh and bone” (Ibid). When it came time for the two Spaniards to leave, hundreds of the natives wanted to go with them. Columbus wrote that, “more than 500 men and women would have come with them, because they thought that the Spaniards would return to the heavens” (Ibid).

This account of native Americans giving reverence to the fair-skinned men whom they believed had come from heaven is intriguing to those who believe in the Book of Mormon. The Indians’ adoration for these men undoubtedly came from their belief in the legend of the bearded white God. Of course many Latter-day Saints believe that this legend is based on the Book of Mormon account in 3 Nephi of Christ’s appearance in ancient America after his resurrection.

Paul Cheesman in The World of the Book of Mormon claimed: “The bearded white God is one of the most universally taught and accepted legends of the Indians of North and South America. Virtually all tribes teach of him. Tribal songs, dances, and sacred rituals are dedicated to his name” (Cheesman 7). Even though the white God’s “name varies from tribe to tribe, his description and teachings are basically the same. In each tribe, in song and story, he was described as white and fair, with long brown hair and a beard” (Ibid). Cheesman further stated that the God’s “message was of love and peace. He announced to the people that he was born of a virgin. And, last of all, He promised to return” (Ibid). Because this legend was part of their culture, it is little wonder that the native Americans of Cuba sincerely believed that Columbus’ fair-skinned sailors literally came from heaven and were, therefore, worthy of reverence and adoration.

Christopher was so impressed with the spiritual potential of the Indians that he made an immediate plea on their behalf in his journal that day: “I truly believe, most Serene Princes . . . that, given devout religious persons knowing thoroughly the language that they use, soon all of them would become Christian.” Continuing his petition to the monarchs, he pleaded, “I hope in Our Lord that Your Highnesses, with much diligence, will decide to send such persons in order to bring to the Church such great nations and to convert them” (Dunn and Kelley 141). These requests, made at a time of such personal accomplishment, further illuminate Christopher’s great devotion to things spiritual; the informed reader cannot doubt that he was truly motivated by his desire to serve God.

Unfortunately, not all of the crew’s discoveries on Cuba were of a spiritual nature: it was there that the Admiral’s men first saw the Indians smoke tobacco, an experience that eventually led to its introduction to Europe and the rest of the world. Written forty years after the fact, Las Casas’ account of the sailors’ experience with tobacco is humorous: he wrote that the Spaniards were then beginning to take up smoking, “although I know not what taste or profit they find in it” (Morison 1:342).

Columbus spent the entire month of November exploring the northeast coast of Cuba; then, on 5 December 1492, he sailed across the windward passage and safely made his way to the island of Hispaniola. The climate and trees of this new land reminded him so much of Spain that he decided to name it Espanola (Dunn and Kelly 215). However, as early as 1494, Peter Martyr, the first New World historian, began referring to the island as Hispaniola, its Latin name, by which it is still known today (Morison 1:370,383n5). Haiti and the Dominican Republic are the two countries currently on the island. This island would soon become the home of the first Spanish colony in the New World. Unfortunately, it would also be the scene of much frustration, tribulation, and humiliation for Columbus.

The Admiral’s first Christmas in America was not destined to be a merry one. Instead, it was the date of a major calamity on this historic voyage. On the days just prior to Christmas, while the fleet was exploring the shores of Hispaniola, the weather had been turbulent making it difficult for the crew to sleep. Then on Christmas Eve the weather finally turned calm. After some Christmas festivities, the tired crew settled in for a restful night’s sleep. Unfortunately, the helmsman was also sleepy and turned the tiller over to a boy, even though Columbus had specifically ordered the crew not to allow a boy to steer the ship (Dunn and Kelley 277).

Disaster struck just before midnight on Christmas Eve as the Santa Maria slid upon a coral reef so gently that the crew was not even aware that they were aground. Nevertheless, the boy knew what had happened as soon as he felt the rudder lodge in the coral (Taviani, The Great Adventure, 130–31). Even though it was not a tumultuous wreck and no lives were lost, the resulting leakage was so severe that the ship was unsalvageable. The accident forced Columbus to abandon the wreckage, and he was obliged to leave 39 of his crew in a make-shift fort built from what was left of the ship. This fort, named La Navidad because of their arrival on Christmas day, became the first Spanish colony in the New World, although it came about quite by chance. The crew members that were left behind to await the Admiral’s return on his next voyage were more than willing to stay, because they would have the first chance at discovering gold, a dream which served to motivate many of the sailors (Morison 1: 393–94).

The Homeward Voyage

After exploring the islands of the Caribbean for three months, Columbus prepared to return to Europe in his substitute flagship, the Nina. The route the Admiral chose for his homeward journey is yet another example of his being inspired of God. On 14 January 1493, he recorded in his log, “I have faith in Our Lord that He who brought me here will lead me back in His pity and mercy . . . no one else was supportive of me except God, because He knew my heart” (Fuson 174). Columbus did not return to Spain by the same southern sea passage that had carried him to America. Instead, he sailed northeast and caught winds coming out of the west that took him back across the Atlantic to the Azores. Once again, Nunn asserted that Columbus’ navigational decisions were remarkable: “So much has been said about his discovery of America that it has been lost to sight and thought that he also discovered both of the great sailing routes in the North Atlantic” (Nunn 50). With no prior trans-Atlantic sailing experience, how did Christopher enjoy such good fortune on both legs of the trip? One noted historian declared, “there can be no doubt that the faith of Columbus was genuine and sincere, and that his frequent communion with forces unseen was a vital element in his achievement” (Morison 1:65).

On 16 January the Admiral began his homeward trek. The unknown winds served him well at first; he experienced relatively smooth sailing for the first four weeks. Then, all of a sudden, it seemed as if the devil himself was attempting to prevent Columbus from achieving his providential destiny. On 12 February, the fleet was overtaken by a violent tempest, perhaps more perilous than any of the other storms the sailors had experienced in their lives. On 14 February, the winds became even more treacherous and Columbus’ ship, the Nina, became separated from the Pinta until their journey’s end. The Admiral said, “The winds increased and the waves were frightful, one contrary to the other, so they crossed and held back the vessel which could neither go forward nor get out from between them, and the waves broke on her” (Dunn and Kelly 363–65). The storm was so terrible that none of the men thought they would live through it

In the midst of this nightmare at sea, Columbus assembled the crew and called on the Lord for help. He ordered all the men on the ship to draw lots to choose one of the crew to take a pilgrimage to Santa Maria de Guadalupe if the Lord would save their lives and allow them to return to Spain. For the drawing, Christopher put a chick-pea into a hat for each member of the crew, with one pea marked with a cross. Columbus drew first and, as fate would have it, he picked the pea with the cross on it. When the storm raged on, Christopher ordered another drawing, this time for a pilgrimage to Santa Maria de Loreto in Italy. The lot fell on a sailor named Pedro de Villa, and Columbus promised to give him money for his journey. The storm intensified so the Admiral ordered a third drawing, this time for a pilgrimage to Santa Clara de Moguer. Surprisingly, the lot fell once again to him, but the storm did not subside. Finally, they all made a solemn covenant that if the Lord would lead them safely to shore, they would immediately “go in their shirtsleeves in a procession to pray in a church” (Dunn and Kelly 365–67). That evening the storm began to subside and the next morning they spotted land—they had reached the Azores, 800 miles off the coast of Portugal.

However, the raging sea had not yet finished with the battered ships. After a week’s stay in the Azores, the Nina set sail for the mainland of Portugal. On 3 March another devastating storm struck, so powerfully that it tore all the ship’s sails. Once again the crew drew lots, this time to send a pilgrim in his shirt-sleeves to Santa Maria de la Cinta in Huelva. Amazingly the lot fell to Columbus again. In addition, all of the men “made a vow to fast on bread and water the first Saturday when they reached land” (Dunn and Kelley 391). The next morning the storm blew them into the mouth of the Lisbon River, and they made their way to a dock. Finally, they arrived at Palos, Spain, on 15 March 1493; and the Pinta sailed into the same port just a few hours later. The next month Christopher Columbus appeared before King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain to give his report. “All the Court and the city came out to meet him; and the Catholic Sovereigns received him in public, seated with all majesty and grandeur on rich thrones under a canopy of cloth of gold. When he came forward to kiss their hands, they rose from their thrones as if he were a great lord, and would not let him kiss their hands but made him sit down beside them” (Ferdinand 101). This reception was a striking contrast from the scene played out the year before, when Columbus left the court in despair after these same monarchs had rejected his proposal.

Thus, with the help of the Lord, Christopher Columbus was able to accomplish one of the greatest feats in human history. After this marvelous achievement, he could have taken all the glory for himself, but throughout his life he consistently gave credit to God. For example, in 1500, he solemnly declared: “Our Lord made me the messenger of the new heaven and the new earth . . . and he showed me the place where to find it” (Brigham, Life, 50, 57n5).

The Admiral’s encounter with America literally opened the floodgate to explorers, colonizers, fortune seekers, and missionaries. Many of these people would accomplish honorable purposes, while others would, unfortunately, be detrimental. Whatever the final outcome, the world would most certainly never be the same.

185 Heber J. Grant Building Brigham Young University Provo, UT 84602 801-422-6975

Helpful Links

Religious Education

BYU Studies

Maxwell Institute

Articulos en español

Artigos em português

Connect with Us

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Columbus’ First Voyage

(by Arnold K. Garr, BYU) – Historians have written about Columbus’ first voyage to America from many points of view. Most secular historians, however, have placed little emphasis on the most important theme of all—the fact that Columbus was guided by [God]. Beginning with the decision he made concerning his point of departure, and continuing all the way through to his return voyage to Spain, we can find numerous junctures at which the Lord manifested His hand in Columbus’ key decisions.

Before 1492, other navigators had tried unsuccessfully to explore westward from the Azores Islands (800 miles west of the coast of Portugal), assuming that this was the best place from which to set sail (Morison 1:97–98). Although the Azores were the western-most islands known in the Atlantic, Columbus chose to sail from Palos, Spain , to the Canary Islands (off the west coast of Africa) and from there, to launch his voyage into the vast unknown. By doing so, he caught the tradewinds blowing from the northeast to the southwest and avoided the headwinds which blow from the west to the east in the vicinity of the Azores (Nunn 37–38,42).

The route Columbus chose has stood the test of time: five hundred years of sailing have proven it the best possible course for sailing west from southern Europe to North America. Geographer George E. Nunn suggested that Columbus’ successful navigation was the result of “an application of reason to . . . knowledge” (Nunn 50). Columbus, however, gave credit to the Lord. Even though he was a successful seaman and an accomplished navigator, he said, “With a hand that could be felt, the Lord opened my mind, to the fact that it would be possible to sail from here to the Indies.” (West and Kling 105).

Columbus experienced relatively easy sailing during the entire outward voyage; had he not done so, he likely would not have reached America before his crew mutinied. There was one occasion, however, on 23 September, when the sea became calm, and the ships were stalled for part of the day. Columbus noted in his journal that the crew, which had not seen land for some days, began to complain that since there were no heavy seas in the region, the wind would never blow hard enough to return to Spain. Soon thereafter, the sea mysteriously rose without wind, astonishing the crew (Dunn and Kelly 41). The Admiral considered this a divine miracle. He said, “the high sea was very necessary to me, [a sign] which had not appeared except in the time of the Jews when they left Egypt [and complained] against Moses, who took them out of captivity” (Ibid).

On the way to America, Columbus changed course only twice during the entire 33 days at sea. The first alteration was on 7 October. Until that time, Columbus had sailed due west for 28 days. Then he noted in his journal that a great multitude of birds passed over, going from north to southwest. Bartolome de Las Casas, the man who transcribed Columbus’ journal , wrote that from this observation, the Admiral “decided to alter course and turn the prow to the WSW [west southwest]” (Fuson 71). Samuel Morison [said] that if Columbus had not changed course, “the voyage would have taken a day longer” (Morison 1:283). That extra day would have been critical, since two days before the eventual sighting of land, the crew threatened mutiny. Every extra day at sea heightened their anxiety; the Admiral’s time-saving change of course on 7 October, therefore, just may have saved the expedition.

The story of the threatened mutiny is one of the most dramatic episodes of the first voyage. The incident took place on Wednesday, 10 October 1492, after they had been at sea for over 31 days without seeing land. The sailors, who had been concealing their discontent, now openly threatened insurrection. They had come to believe that Columbus, the foreigner from Genoa, had deceived them; they supposed he was leading them on a journey from which they would never return. According to one account, the sailors even conspired to do away with their leader, whom they “planned to throw into the sea” (d’-Anghera 1:59–60). Yet, “Columbus, by using gentle words, holding out promises and flattering their hopes, sought to gain time, and he succeeded in calming their fears” (Ibid).

Others have stated, after the fact, that at this juncture, Columbus promised the men that they would return if they did not sight land within two or three days (Morison 1:286,290–91,292n6). Although Columbus did not record this oft-repeated assertion in his journal, he did report that “I also told the men that it was useless to complain, for I had started out to find the Indies and would continue until I had accomplished that mission, with the help of Our Lord” (Fuson 72; emphasis added). This incident serves as an excellent example of Columbus’ determination and faith in God.

The second instance in which the Admiral altered his route was after sunset on 11 October, just a few hours before land was sighted. For no apparent reason, he gave orders to change direction from west southwest back to the original course of due west (Dunn and Kelly 59). He gave no explanation for the change, but it was, nevertheless, an excellent choice. Had he continued on the west southwest course instead of steering due west, he would have missed the island of San Salvador, and would likely have ended up on the deadly reefs along the coast of Long Island (in the Caribbean), perhaps never returning to Spain (Morison 1:295). Many historians have attributed these changes in course to luck or chance, but Las Casas said, “God gave this man the keys to the awesome seas, he and no other unlocked the darkness” (Las Casas 35), and I agree.

Having made this second course correction, Columbus was then right on target, and just in time to meet with his destiny—to discover the New Land. That evening as the crew gathered for prayer, the Admiral, “spoke to the men of the favor that [the] Lord had shown them by conducting them so safely and prosperously with fair winds and a clear course, and by comforting them with signs that daily grew more abundant” (Ferdinand 58). His policy since reaching a point 700 leagues beyond the Canaries had been not to sail at night, but the crew’s desire to see land was so great that Columbus decided to sail through the darkness (Morison 1:294). He commanded the night watch to keep an especially sharp lookout because he was confident that land was nearby. In addition to an annuity of 10,000 maravedis guaranteed by the Sovereigns, the Admiral also promised to give a silk jacket to the first sailor who sighted land (Dunn and Kelly 63).

About 10 o’clock that night, Columbus saw a light in the distant dark, but it was so faint that he did not publicly announce it. He did, however, bring it to the attention of Pedro Gutierrez , who also acknowledged seeing the flickering light. Rodrigo Sanchez was also called on to observe the light, but he claimed he could see nothing from where he was (Phillips and Phillips 153). Notwithstanding Columbus’ glimpse of the light, it was some four hours later, at about two in the morning on 12 October, that the fleet sighted land for certain. Rodrigo de Triana , a sailor on the Pinta, shouted, “Tierra! tierra!” while the fleet was still two leagues off shore (Morison 1:298). Martin Pinzon , the captain of the Pinta, quickly verified Triana’s claim and then fired a cannon shot, which was the prearranged signal for sighting land.

One can only imagine the gratitude and relief they all must have felt, after more than a month of anxious days at sea, when their eyes first saw this obscure little island in the middle of the tropical Caribbean Sea. It goes without saying that the crews were ecstatic and their respect and admiration for the Admiral soared, literally, overnight.

For Columbus, this historic sighting was a rendezvous with destiny. He had proven, in spite of mounting opposition and a lack of faith on the part of his crew, that it was possible to sail westward across the great Atlantic. According to his agreement with the monarchs, Columbus officially became Admiral of the Ocean Sea, simultaneously gaining the titles of Viceroy and Governor of this island at the moment he discovered it. Professor Hugh Nibley aptly put this celebrated moment into proper perspective when he said: “Everything else in Columbus’ life is subservient to the carrying out of that one mission. The aim and purpose of all his work and suffering was what happened at 2 a.m. on the morning of October 12, 1492” (Nibley 320).

Impatient and anxious to explore their new discovery, the crew waited through the night, and sailed excitedly to shore at daybreak. Upon reaching dry ground, the landing party knelt, kissed the sand with tears of joy, and offered prayers of thanks to God. Rising from his knees, the Admiral named the island San Salvador (Holy Savior), thus beginning a personal tradition of giving names of religious significance to many newly discovered lands (Ferdinand 59). In deference to the crown, Columbus dedicated San Salvador, which lay off the northern coast of Cuba, to the Spanish monarchs.

Excerpted from Chapter 5: First Voyage to the Americas of Arnold K. Garr’s book Christopher Columbus p ublished 1992 at Brigham Young University rsc.byu .edu). Reprinted here for educational purposes only. May not be reproduced on other websites without permission from Brigham Young and Arnold Garr.

Bibliography:

- Dunn, Oliver and James E. Kelley, Jr. The Diario of Christopher Columbus’ First Voyage to America, 1492-1493. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1989.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. Admiral of the Ocean Sea. 2 vols. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1942.

- Nibley, Hugh. “Columbus and Revelation.” The Instructor (Oct 1953) 88:319–20.

- Nunn, George E. The geographical Conceptions of Columbus. New York: American Geographical Society, 1924.

- Phillips, William D., Jr., and Carla Rahn Phillips. The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- West, Delno C. “Writings: Marginalia.” The Christopher Columbus Encyclopedia. 2 Vols. Ed. Silvio A. Bedini. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992. 2:746–48. ————. and August Kling. The Libro de las profecías of Christopher Columbus. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1991.

Russia’s Nord Stream vs. U.S. Keystone

May 25, 2021.

World Opinion: U.S. should think twice about Iran nuclear deal

April 13, 2021.

Voter ID Protects Your Vote

March 18, 2021.

A Deep Green Freeze

February 18, 2021.

- Christopher Columbus’ first voyage to America: To the Unknown