A tour like no other: School Journal Year 7: Part 04 No. 02: 2011 OR

About this item.

A brief history of the 1981 Springbok tour that divided the nation.

What can I do with this item?

Check copyright status and what you can do with this item

Report this item

If you believe this item breaches our terms of use please report this item

DigitalNZ brings together more than 30 million items from institutions so that they are easy to find and use. This information is the best information we could find on this item. This item was added on 05 July 2019 , and updated 05 July 2019 . Learn more about how we work.

What is the copyright status of this item?

See below for specifics about how you may use this item.

You must always check with Services to Schools to confirm the specific terms of use, but this is our understanding:

Non-infringing use

NZ Copyright law does not prevent every use of a copyright work. You should consider what you can and cannot do with a copyright work.

You may not copy and/or share this item with others without further permission. This includes posting it on your blog, using it in a presentation, or any other public use.

No modifying

You are not allowed to adapt or remix this item into any other works.

No commercial use

You may not use this item commercially.

Related items

Springbok tour research: how does history interpret?

This weekend marks 40 years since the notorious flour-bomb incident at Eden Park during the 1981 Springbok tour.

Violence erupted outside the stadium grounds as protesters and police faced off, while others threw flour bombs and flares on the field to stop the game.

Although apartheid was a major factor behind the unrest, protesters were also actually critiquing wider New Zealand society, says sports historian Sebastian Potgieter .

- Download as Ogg

- Download as MP3

- Play Ogg in browser

- Play MP3 in browser

- Check out RNZ's collection of audio about the 1981 Springbok Tour

Dr Sebastian Potgieter is a South African who moved to Dunedin to conduct a PhD on the Springboks tour.

Back in 1981, the general public in South Africa wasn't too familiar with what was going on in New Zealand yet the Springbok tour of that year negatively affected the team's ability to play internationally, Dr Potgieter tells Kathryn Ryan.

"The South African government had a very strict information policy in place, which means that a lot of information, particularly that which was critical of the apartheid government, didn't actually make it through to the general public.

"In the wake of that tour, South African rugby came to be seen as somewhat of a symbolic liability and a lot of countries didn't want to play against South Africa.

"They felt that if the '81 tour is anything to go by, there was a likelihood of very extreme protests taking place in those countries which did host South Africa."

Dr Potgieter found it interesting to hear how vividly New Zealanders remembered the tour as it's not often spoken about in South Africa.

"We sort of know about incidents like the 'flour-bomb' test, but in general, South Africans don't know too much about this tour.

"It's still a matter which polarises opinions, so people have a lot to say about the tour, and have a lot to say about where they were, what they were doing during that tour."

Dr Sebastian Potgieter Photo: Supplied

It wasn't just apartheid that people were upset about in 1981 - protesters were also taking a stand against the deportation of Pacific Islanders and overstayers and the annexed Māori lands, Dr Potgieter says.

"We very selectively remember the past. It's impossible to remember the past in its entirety ... so certain parts of the past become elevated and contemporarily what we see in New Zealand.

"If you go back and look at some of the recollections of protesters who are writing shortly after the tour, we see that they say yes, apartheid was a problem, it was certainly what mobilised protests.

"But in the process of protesting a lot of people ... linked the protests to a lot of the racial discrimination that was happening in New Zealand at that time.

"It's more complex than simply saying this was an anti-apartheid protest and the anti-apartheid side of things is what's elevated at the moment, but it certainly doesn't define what those protests were about."

The demonstrations were also used as a platform to discuss the problematic aspects of rugby culture such as violence, gender stereotyping and alcoholism, he says.

People also need to remember that many New Zealanders supported the tour, Dr Potgieter says.

"Every single stadium during that entire tour was sold out and that there were large numbers of New Zealand television audience who tuned in to watch every game.

"We also see that a lot of New Zealand's far right and extremist groups actually have their biggest sort of phase of public acceptance or public profile when the question of South African tours cropped up in New Zealand.

"When those tours became put into jeopardy, these extremist groups or far right groups - whatever one wants to call them - received tremendous support in New Zealand."

Dr Sebastian Potgieter is a teaching fellow at the University Of Otago's school of physical education, sports and exercise sciences.

- Sebastian Potgieter

- anniversary

To embed this content on your own webpage, cut and paste the following:

<iframe src="https://www.rnz.co.nz/audio/remote-player?id=2018811821" width="100%" frameborder="0" height="62px"></iframe>

See terms of use .

Recent stories from Nine To Noon

- The week that was with Michele A'Court and Irene Pink

- Sports commentator Sam Ackerman

- New music with Jeremy Taylor

- Around the motu: Peter Newport in Queenstown

- Book review: How to Solve Your Own Murder by Kristen Perrin

Get the RNZ app

for easy access to all your favourite programmes

Subscribe to Nine To Noon

Podcast (MP3) Oggcast (Vorbis)

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Rugby, racism and the battle for the soul of Aotearoa New Zealand

The Springboks’ tour and the protests that ensued 40 years ago helped set the fight for Māori rights on a stronger path

The 1981 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand will always have a special place in any narrative about the international fight against apartheid in South Africa.

The protests against the Springboks reverberated around the world – delivering a savage psychological blow to South Africa’s white regime while giving a resounding boost to the oppressed majority.

This weekend marks the 40th anniversary of the first rugby Test of the Springboks’ tour of New Zealand in Christchurch, but well before that game was played, the political significance of the visit had eclipsed any results on the field.

Three weeks before the first Test, the second game of the tour was to be played in Hamilton, and white South Africans in their droves got out of bed in the middle of the night to watch the first ever live telecast of a rugby game in the country.

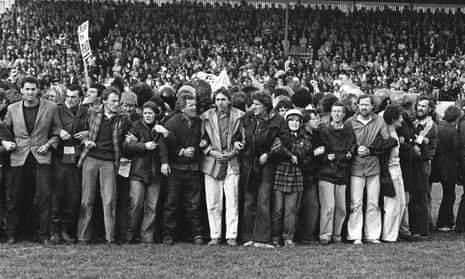

It was to be a special moment in South Africa, but not as expected. Instead of the Springboks vs Waikato game, fans saw 300 protesters linking arms in the middle of Hamilton’s Rugby Park – declaring they would not leave till the tour had been called off.

The anger that swept through white South Africa was nearly as palpable, if not as physical, as the anger expressed on Hamilton’s streets in the ensuing hours.

On South Africa’s Robben Island, Nelson Mandela was spending his 18th year in jail. He said when the prisoners learned that an anti-apartheid protest had stopped the game, they were jubilant. They grabbed the bars of their cell doors and rattled them around the prison; he said it was like the sun came out.

Here in Aotearoa New Zealand, the tour protests also had a profound impact, although this took longer to play out. It was the closest we had come to civil war since the 19th century land wars, but more importantly the tour shone a harsh spotlight on racism in this country. Māori activists asked how could we be concerned about racism 10,000km away and ignore it in our own backyard? Fair question.

In the aftermath of the tour, racism took centre stage with an intense public debate that helped set Aotearoa New Zealand on a new path.

A decade earlier, Māori activist groups like Ngā Tamatoa (the young warriors) had challenged the Pākehā (European) majority about patronising attitudes and lazy racism that meant Māori were in effect second-class citizens.

Politicians are slow followers of public opinion, but four years after the tour and the wide discussion and debate it helped spur, the Waitangi Tribunal was given the responsibility to investigate historic breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi – previously the tribunal had only been mandated to look at possible future breaches. And so began its investigations into our history of racism and oppression and the injustices of colonisation, which continue to resonate for Māori in the present.

Since then numerous positive developments have given a stronger political voice to Māori.

In our most recent budget, the health minister, Andrew Little, announced the formation of a national Māori health authority that will have the power to contract health services for Indigenous New Zealanders where the state system has served them poorly. “By Māori, for Māori” is seen as a way to enhance our democracy with a turn away from the “tyranny of the majority”, under which they have fared poorly.

It’s not all plain sailing though, and recent debate about Māori rights to representation on local councils has met hostile, albeit minority, opposition.

But the direction continues to be forward and work is under way to incorporate the history of colonisation in these South Pacific islands into the school curriculum.

The irony in these positive developments is that the overall situation for most Māori is getting worse, with New Zealand’s Indigenous people disproportionately affected by poverty and inequality, which continues to grow relentlessly with the pandemic.

The civil disruption from the tour and the debate that followed benefited both New Zealand and South Africa in ways that we didn’t see at the time. We are a better country for it.

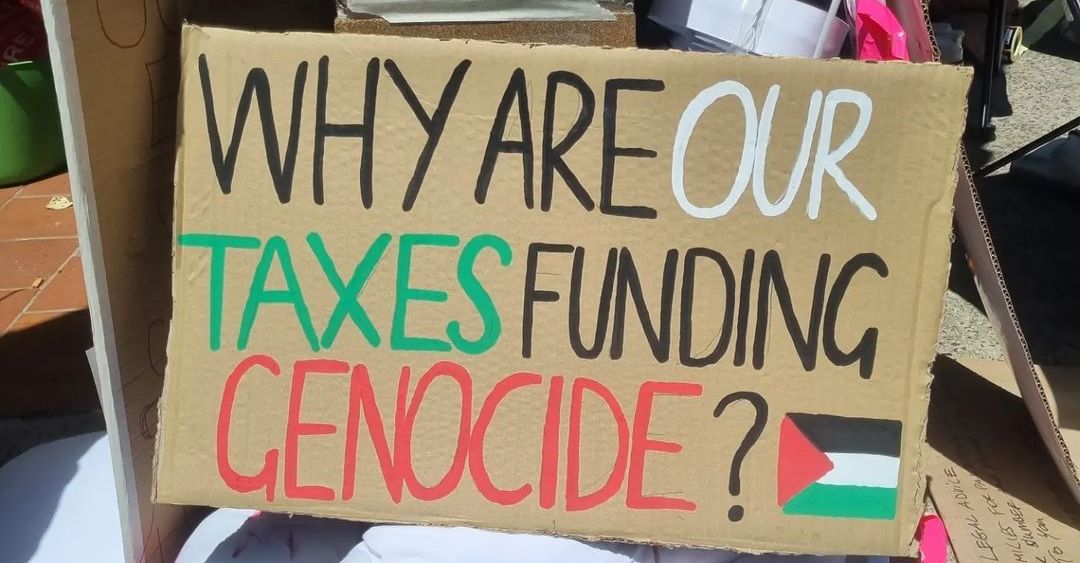

John Minto was national organiser of Halt All Racist Tours (HART) in 1981 and is currently the national chair of Palestine Solidarity Network Aotearoa.

- New Zealand

- Asia Pacific

- Rugby union

Most viewed

Remembering (and forgetting) the 1981 Springbok tour

10 September 2021

The narrative of the 1981 Springbok tour continues to reflect New Zealand's anti-apartheid views, but in fact protestors treated it more as a critique of New Zealand Society, research shows.

This weekend's 40th anniversary of the historic Springbok Eden Park rugby match, also marks the completion of five years of research by Dr Sebastian JS Potgieter, a teaching fellow at the School of Physical Education, Sport and Exercise Sciences , on the enduring narrative of the nation-defining tour.

Dr Potgieter, who was raised in South Africa, says the 1981 Springbok tour is primarily viewed as an anti-apartheid struggle which serves to construct New Zealand society in a favourable way.

“Apartheid was a major factor in catalysing the protests, but protestors treated it more as a critique of New Zealand society in a broader sense,” Dr Potgieter says.

“Continuing to view 1981 as primarily an anti-apartheid struggle serves to forget some of the unpalatable realities that accompanied the tour.”

It was a box of documents about the 1981 tour, stored in a farm shed in South Africa, that was the starting point of five years of postgraduate research for Dr Potgieter.

“It was only when I started going through all the documents and correspondence that it became apparent what a huge event it was on so many levels, and that in South Africa we weren't fully aware of what the tour had meant for New Zealand,” Dr Potgieter explains.

“What fascinated me were the 'aspects' of the 1981 tour which were consistently and selectively remembered, and in particular the predominant anti-racist and anti-apartheid aspects that still remain the main narrative by which the tour is remembered.”

Dr Potgieter says this narrative is a very selective understanding of the tour and conflicts with the accounts of those who had participated in the anti-tour campaigns in 1981, and their recollections of what they were battling against at the time.

“Apartheid was a major factor in catalysing the protests, but protestors treated it more as a critique of New Zealand society such as a conservative government which deported Pacific Island 'overstayers', annexed Māori lands, but at the same time encouraged the immigration of white South Africans. Many Māori also linked institutionalised racism to the experiences of black South Africans.”

In addition, rugby culture as the national sport was also seen as promoting toxic patriarchal masculinity, restrictive gender roles, excessive consumption of alcohol, and a culture of violence.

These wider issues are no longer 'remembered' in the retelling of the 1981 tour Dr Potgieter explains, however collectively make the 1981 tour a kaleidoscope of shifting and contested narratives which impose particular meanings.

“Rather than accepting historical accounts at face value, it is important to ask why some narratives rather than others endure and come to represent what we 'know' about the past and the evolution of our society.”

Dr Potgieter's work discussing the legacy of the tour for South African rugby has been published in the Australian journal Sporting Traditions, and his doctorate research will be published in the North American Journal of Sport History later this year, as well as in a co-authored book chapter in Sport in Aotearoa/New Zealand: Contested Terrain in December.

Dr Potgieter says applying a cultural history approach to the 1981 Springbok tour provides a rich understanding of how particular types of ideological and cultural politics shape how we interpret and reinterpret past events.

“The political, social, and cultural implications of the tour were huge, and the changing narrative of the event in the 40 years since is a powerful example of a national sport like rugby being a mechanism through which we are able to view the intricate workings of society.”

For further information, please contact:

Dr Sebastian Potgieter School of Physical Education, Sport and Exercise Sciences University of Otago Email [email protected]

Guy Frederick Communications Adviser Sciences University of Otago Mob +64 21 279 7688 Email [email protected]

Find an Otago Expert

Use our Media Expertise Database to find an Otago researcher for media comment.

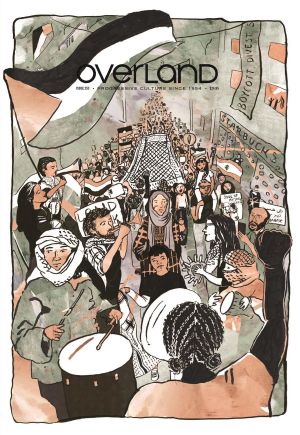

Overland literary journal

- The Journal

253 Summer 2023/4

Dženana Vucic on the subtle and not-so-subtle Marxist symbolism in Sailor Moon, John Docker, a "non-theatre person" by his own admission on The New Theatre, Sarah Schwartz on prison healthcare as punishment and the killing of Veronica Nelson, a poignant short story on memory and displacement from Nasrin Mahoutchi-Hosaini, Jeanine Leane's prize-winning poem, "Water under the bridge", and more.

Browse by format:

- Browse by Theme

- Browse by Author

Do you remember the 1981 Springbok Tour?

If the historical footage is any indication, the protesters who demonstrated in the streets, clashed with police and attempted to disrupt the games during the 1981 Springbok rugby union tour of New Zealand didn’t chant Nelson Mandela’s name. They chanted Steven Biko’s and Amandla Ngawethu .

If the historical footage is any indication, the protesters who demonstrated in the streets, clashed with police and attempted to disrupt the games during the 1981 Springbok rugby union tour of New Zealand didn’t chant Nelson Mandela’s name. They chanted Steven Biko’s and Amandla Ngawethu . The near-exclusive identification of Mandela with the global struggle against Apartheid came later, but has affected those events retroactively, to the point of grafting itself onto some personal recollections. ‘The Specials’ “Free Nelson Mandela” was the soundtrack to that year,’ wrote Michele A’Court in one of our newspapers this week . But no, it can’t be. The song wasn’t recorded until 1984.

Memory can be tricky like that. But one aspect on which people who lived through those years seem especially unanimous is the rift that the issue provoked, both within (and between) families, and within (and between) entire sectors of society. Even if you didn’t protest or directly oppose the protests, you weren’t allowed not to have an opinion or to refuse to pick a side. Political memory can be tricky, too, so we may wish to test this narrative against the documents produced at the time. But even if it were true only in hindsight, the perception that a stand was required of the entire nation would still matter a great deal. For then who would want to be the one who says: ‘not me’? Or: ‘this history of which you speak, it didn’t really concern me’?

That would be John Key, my prime minister. Asked in a radio interview where he stood on the subject of the 1981 Springbok Tour, the normally relaxed, affable Key broke into a nervous laugh followed by some mumbling, and then offered one or two hesitant declaratives that amounted to look, I don’t know, it was a long time ago, I don’t remember , while the subtext was a much sharper why in the world are you asking me this?! It was a rare, unscripted moment, in which Key’s remarkable instinct for the politically safe ground failed him: here was an issue in which he couldn’t articulate a position that didn’t risk alienating someone, and so he produced an answer likely to alienate everyone. You could either believe him, and conclude that he was a man of little conviction, or disbelieve him, and reason that he was trying to soften his image or hide his true beliefs from the public. The outside possibility – that a young man of twenty, in his first year at university, might really not have cared to such an extent that it would make no sense to ask him, three decades later, about his feelings – was both inconsistent with the ‘rift’ narrative and with the retrospectively constructed image of a man who would one day be a prime minister.

Asked later to clarify those comments, and after having had time no doubt to discuss the best course of action with his advisors, Key characterised his position as having been anti-Apartheid, but very mildly pro-Tour, which was the safest course out of those particular shallows. But now that Mandela has died the spectre haunts him again, of a past carelessly remembered, as he selects a delegation that fails pitifully to account for it .

It is a complicated, tortuous past, in which the racial politics of segregation abroad is mixed in with the struggle for Indigenous rights and sovereignty at home, and in which politics intrudes – almost always unwelcome – in the national sport, our layman’s religion. It’s a long history, too. The ban on non-white players touring South Africa had sparked the ‘No Maoris, No Tour’ campaign of 1960. There was an aborted tour, in 1973, when the Labour Government of Norman Kirk kept the Springboks out. There was the boycott by twenty-five nations of the 1976 Olympic Games, after the All Blacks toured South Africa in defiance of the international community.

1981 is when things came to a head. In spite of New Zealand having since signed up to the Gleneagles Agreement, Tory Prime Minister Rob Muldoon gave the Springboks permission to enter the country, after an invitation was extended to them again by the local rugby union. The team had to fly via Los Angeles and Hawaii, as Malcolm Fraser refused to allow the plane to refuel in Australia. When they arrived, they were met by an organisation – Halt All Racist Tours – that had been active, on and off, for over a decade, and had solid ties with the trade unions and with the Maori militants that had fought in struggles such as the occupation of Bastion Point. It’s no coincidence, in fact, that the most vivid document of the two months that followed was produced by the same filmmaker who directed Bastion Point: Day 507 , which chronicles the day in 1978 when the police and the army put an end to the occupation, making over two-hundred arrests.

Merata Mita’s Patu! is a raw, unflinching, extraordinary film. While it speaks for a movement that was clearly conscious of the need to document itself – the footage, recorded by camera-people working in each of the major centres where the protests took place, includes planning meetings and even training sessions on how to occupy the grounds and resist removal – its true force lies in the ability to show the actions of the police up close, often from within their ranks and to profoundly alienating effect. Thus the movement’s moment of glory – when protesters successfully occupied the ground in Hamilton forcing the cancellation of the second game of the Tour – is greeted by Mita without triumphalism, as if she were anxious to get to the repression to follow, after the army became involved and the police attacked peaceful marchers in a reprisal action in Wellington. The protesters would never succeed in disrupting a game again: we stand with them impotent, looking over through the barbed wire or over walls of shipping containers erected around the rugby grounds. We look outward, again, from the chilling viewpoint of the police in riot gear. We advance, our batons thrusting forward in a stabbing motion, while they chant ‘Biko! Biko! Biko!’ in obsessive monotone.

The history of protest and struggle is also always the history of repression, and of that encounter with the might of the state that shocks each generation of militants as they come of age. That is the central subject of Patu! , and with it comes the reminder of what it is that we are actually called upon to remember: a painful struggle locked inside other struggles, with no discernable solution or end.

Giovanni Tiso

Giovanni Tiso is an Italian writer and translator based in Aotearoa/New Zealand and the editor of Overland ’s online magazine. He tweets as @gtiso.

Overland is a not-for-profit magazine with a proud history of supporting writers, and publishing ideas and voices often excluded from other places.

If you like this piece, or support Overland ’s work in general, please subscribe or donate .

Related articles & Essays

Emmanuel Macron and the rearming of French demography

Australia’s Palestinian citizens are second class citizens

Coincidentally, last night I went to a candlight remembrance for Nelson Mandela at Rugby Park (now Waikato Stadium) in Hamilton. This was the scene of the 1981 pitch invasion and it was a very different experience in 2013. Unlike the tearing down of fences, bottle throwing and anger of 1981, Hamilton City Council opened the ground (the turf of many recent Chiefs rugby victories) for those who were involved in the 1981 struggle to gather and remember. I wasn’t there in 1981 (I was doing a my doctorate in the US) but last night was a meaningful time–especially the reconciliation between John Minto (a leader of the anti-tour movement) and Ross Meurant (second in charge of the brutal Red Squad, who policed demonstrations). The place was also very important–Mandela, in his Robben’s Island, is said to have declared that ‘it was like the sun coming out’ when he heard the news of the game being called off.

“There was an aborted tour, in 1973, when the Labour Government of Norman Kirk kept the Springboks out.”

The reality wasn’t quite that rosy. According to an editorial in Socialist Action, April 27, 1973:

‘Behind the smokescreen of “law and order”, Kirk has been able to decree a form of “postponement” which opens the door for the South African authorities to put together a bogus system of “merit selection” for its next Springbok team, which, Kirk said, might tour the country in the near future.

‘Kirk has also been able to avoid coming out against the visit of all-white South African teams in sports other than rugby (unlike his counterpart Gough Whitlam)….

‘Black Africa is far from satisfied with the New Zealand government’s decision to “postpone” this single tour: they demand a total sporting boycott of South Africa. According to the Supreme Council of African Sport, there may still be a boycott of the 1974 Commonwealth Games.’

“The protesters would never succeed in disrupting a game again” is not completely accurate. The protesters never stopped another game from proceeding, but did succeed in eclipsing some of them. I doubt if many of the spectators at the Auckland game would remember much of the rugby action from that day – but who among them would not remember the gauntlet of riot cops and barbed wire barricades they had to go through to get there, the constant chanting coming from outside the park, the protesters’ plane buzzing the field with the police helicopter in pursuit, the white patches on the field and the player felled by flour bombs dropped from the plane, etc. The game itself became a side-show to the real event, and at that point everyone sensed that the pro-apartheid forces had lost the battle. For the protesters themselves, personal memories can be deceptive, as you say, but on the other hand, can also be extraordinarily vivid considering that the events took place more than thirty years ago.

Even as a 10 year old child it had a massive impact on me. I knew abstractly from things my parents had said that Biko had been beaten to death in SA, but it came home a lot clearer to see the smashed up faces of friend’s fathers who had got onto Rugby Park that day, and to wonder what was going to happen when both my parents went off to protest many times. There was no way on earth that people got away with not having a position, certainly not university students. Key is lying.

Thanks for this, Giovanni. You’re an ideal candidate to survey it all.

The thing with Key’s claim of no memory was, indeed, the implausibility of it. I’m a year younger than him, we went to the same school, I packed down against him in scrums (I can’t remember him, but the almanac holds that we were both hookers). I did not believe that he couldn’t remember where he stood, even if he didn’t think much of it either way.

The Tour set off a five-year period in which the consensuses of 60 or 70 years — around the two wars and rugby, our fancied racial harmony and the welfare state — were terminated. Three years later, the Lange-Douglas Labour government came to office. That same year, the odious policing culture of the Tour and the younger New Zealanders’ loss of fear and respect of the police met head-on in the Aotea Square riot. (The police culture lost.) There’s no way anyone doesn’t remember that.

What makes it all the more notable is that there has long been no shame in admitting you were on the wrong side of history over this. Second thoughts from Tour supporters have usually been generously received, as if it’s our modest version of truth and reconciliation.

Why is why I’ve been quite puzzled by the online discourse sparked by Mandela’s death. It’s fraught in a way that memories at the 30th anniversary were not. People have been more inclined to police each other’s speech, or disqualify each other from speaking. Yet Mandela’s name wasn’t on everyone’s lips in 1981. Steve Biko, whose death in custody had been news, was much more likely to be invoked.

I saw one left-wing tweeter warn his younger followers they could not assume they’d have been anti-Tour had they been around in 1981 (to be honest, they could quite confidently do so – the young, urban social demographics of the Tour were quite stark). I had to close the Mandela thread on Public Address because two of our readers simply could not accept that the recollections of a well-known centre right figure, Matthew Hooton, were being accepted in good faith. When I shared a memory on Twitter there was drive-by snark that I was posing (I wasn’t!). I lost track of the number of lectures about how white people weren’t allowed to appropriate the radical Mandela as a maker of peace. On the right, the Kiwiblog commenters were bilious in a way they weren’t in 2011.

It’s been interesting.

It has. For my part, I’ve loved the comments on this post so far and the tweets I received over the weekend when I asked people about their recollections, with which people have been very generous. But remembering and evaluating (or speculating) are very different activities.

I’ve just watched Patu! and heard Nelson Mandela’s name used in a chant in the first minute of clip1: “Remember Soweto…, remember Sharpeville…, and Nelson Mandela”.

In early 1970s I was a young socialist feminist and took part in several anti-tour marches. By the time of the 1981 Springbok Tour, I’d been at home with young children for five years. We took the children on two non-violent anti-tour marches, at the beginning and the end of the campaign. My brother-in-law, a police photographer, didn’t like the shift towards more aggressive policing tactics at that time. He told me I was on a list of “known agitators” that was distributed to police officers in preparation for the Springbok Tour. I was both shocked and amused. Had the SIS been monitoring my library loans? Did they know I was indoctrinating my children with Michael Foreman’s “War and Peas”, Jan Balet’s “The Fence”, or the Aussie classic, “Snugglepot and Cuddlepie”, which includes a full-page picture of a Strike procession?

My strongest memory of that time is of the huge crowd walking through Wellington’s streets before the match on 29 August. I think it was shown live on television. Among the thousands was my former boss, a genteel librarian in her sixties. This brought home to me how widespread the opposition to the tour – and the Muldoon government’s repressive response – had become.

I watched the protests outside Eden Park from a Kingsland hillock. It was violence, State violence on a scale I had only seen in Smith’s Dream. John Key was in my sister’s class at my school, she has the class photo. I was 2 years behind. I don’t remember him, she does…”annoying boy, you know the one’s who annoy you all the time.” Memoria.

Is this the Peter Bradburn I worked with at Commsoft

If yes..pls connect [email protected]

“The near-exclusive identification of Mandela with the global struggle against Apartheid came later”

My memories are that Mandela was never quite the cult figure for the NZ anti-apartheid movement as he was for overseas movements. There was a strong pro-PAC lobby in NZ for one thing, and I think, less tendencies to idealise the SA movement than in some other countries.

It seems now the centre-right, in particular, likes to differentiate between the now deified Mandela and the rest of the South African and international anti-apartheid movement. Its an interesting exercise in hero formation – Mandela is a hero by definition, therefore he cannot have been part of the left-wing rabble and PC liberals who made up the movement.

Its particularly strong in NZ where the ’81 tour has come to not only symbolise the anti-apartheid movement, but define it. This is problematic for the left as the primary lessons for activists to learn from the anti-apartheid movement relate to the long-term organisation, strategy and movement building carried out, not the media-friendly confrontations of ’81.

It would be intriguing to ask how many people remember that the biggest anti-apartheid protests in NZ were in 1985, not 1981.

Sam Buchanan

There was a guy who used to come to all the ChCh demos, and would shout “free Nelson Mandela” very frequently. He was regarded as a tad eccentric, and I don’t remember the chant catching on.

I do remember it being a very hateful time though, and feeling that I needed to consciously harden-up to avoid being physically intimidated by the riot squads. We were always going to lose the public battles (not least because only one side got to carry sticks) which I think partly explains why there was so much nefarious night-time activity going on, most of which was never reported.

The tour turned ordinary mild-mannered people into radicals. My father was with us in a major face-off outside the first test, aged 56. Nothing actually happened (on that occasion) but we were fully expecting all hell to break loose at any time. Afterwards, he said he’d prepared himself to run straight at a cop who looked scared.

I sure do remember the tour. I remember standing at the kitchen bench listening to what was happening in Hamilton and hearing my brand new husband of two weeks saying all the protesters should be put up against a wall and shot…and realizing two weeks too late that I had seriously married the wrong guy. Needless to say we are now divorced…

Love must be blind. You had no prior inkling that you were hooking up with a fascist?

A little unfair there. The Tour polarised Kiwis like nothing else.

I came from a family where the rest were dyed in the wool Rugby supporters but where hardly “Fascists”, far from it. I supported the cancellation of it but my father and brothers were all for the Tour going ahead. It was a situation that split families and some even today, can’t get along. That is so sad. Our family agreed to disagree and carried on with life.

Interesting to read some of the responses for an event from so long ago August 1981 “The SpringBok Tour”. My recollection was that I and my brother were part of orange squad. We dressed up in heavy gear and I had my umbrella. Our church minister and our whole congregation were mobilised. I heard that he was dressed in his robes? We were a whole predominantly Maori Chritian faith bible based congregation in Newtown, Wellington and had discussed the oppressive apatheid regime of the South African Government of that time and took action. It certainly was a time of a split country. The question of debate did sport and politics belong on the same playing field. I was 25 at the time. I was adamnant the sports does affect politics and vice versa. I was confronted with hostility at parties due to my stance. I saw cousins on both sides of the fence at the Wellington rugby game. Our squad did not get into any major physical dust up but a lot of manouvering and posturing and confrontation – eye balling, keeping our lines and rows facing off the police. I heard that the brown squad had a lot of encouters. It was an exciting day. If any Kiwi had no view or stance at that year and about the tour and about apatheid -well! that would be a rarity! I have had the privaledge to meet up a number of South Africans since Mandelas reign as President and have recalled with them the 81 Tour and prophecies attributed to the rainbow nation from the visit by TW RATANA to their lands early last century. Freedom has a price. Amandla Be well people.

I came across this post only recently , hence the late participation. I find it difficult to articulate the memory I have of the 1981 Tour, as it is enmeshed with the killing of a close friend only a few months earlier. I needed to be with my friends at this time; close friends can save your life. We were in the Stands together at Waikato stadium – I wasnt a rugby fan but my mates were; I played soccer – left wing! ( only by virtue of being left footed ) You are right Giovanni- there was no room for neutrality. Christ; imagine Northern Ireland. So I supported the tour, parroting the prevailing sentiments of those around me and joined my mates for the short drive from Te Awamutu to Hamilton. All around 17 years of age ; small town boys from a mostly conservative and pro-tour town. It is hard to express how bleak, ugly, violent and tense that period was. My guts in a knot as we walked towards the stadium barricaded in places by cattle trucks, barbed wire, police. The feeling of wanting to leave. Patu captures the moment the protestors broke through the fence. The supporters ; my mates, were enraged that the police formed a ring around the protestors on the pitch…and faced the crowd!. Occasionally a rugby supporter would run onto the pitch and land as many blows on a protestor as he could before the police intervened. The most vivid memory; the most difficult for me, occurred when the game had been called off. The police pretty much abandoned the protestors and told them to leave the pitch. They were then at the mercy of a vicious, angry mob hurling bottles, cans and whatever else to inflict injury. We were right there – very close to that exit. John Minto – a figure of intense, seething hatred to pro tour people was especially targeted. And do you know what he did?. He took it. I vividly remember him ducking, protecting his head with his arm, as he directed the protestors through the narrow exit to get the hell out of there. That image is locked in my head. Can you imagine the courage, the composure, and the leadership that was displayed on that day by him?. It was extraordinary. My memory is that it was that scene which has affected me the most. I knew then that I shouldn’t have been there. I was stupid, naive, arrogant, ignorant..It made me realise the consequences of following a mob; of mob mentality.

John Key didn’t know where he stood in 1981?. I have the benefit of writing as the Dirty Politics saga plays out. Who cares where the fuck John Key was. History will consign him where it sees fit. We know where John Minto was. Hone Harawira. Annette Sykes. Trevor Richards. Tama Iti .On and on.

I am not ashamed by the way. I can see who I was then; why I was there; why we went that day. I am still close to two in that original group. I went back to Waikato Stadium with my friend and his three children to watch a game a couple of years back. As we walked together I mentioned I hadn’t been back since 1981. It was the first time the tour and our position in it was discussed with the kids. We gave them a short synopsis. I think they thought we were telling tall tales.

Cheers, Bill

Thank you for the great comment, Bill. I don’t have much to add to it, other than my partner – also from Te Awamutu, and 12 years old at the time – was pro-tour, if you can call a child that, for the reasons you so eloquently expressed.

The evening gathering at Waikato Stadium late last year, where people came together to celebrate the life of Nelson Mandela was something special. Many of those there were directly involved in the 1981 events. Even Ross Meurant was there, with a message of reconciliation.

Thanks very much for this, Bill. Although only 11 in Te Awamutu at the time, I was on the side of the tour because that’s what I was told was right. It’s hard to live with. It’s great that you were there, a bit older, and you knew where you stood. In solidarity, Justine

Thanks Justine. It is perhaps an expression of love towards one’s parents that determines whether a child takes their worldview as gospel; amongst other reasons of course. Good children do as their parents do right?!. So I would let that lingering feeling of being on the wrong side of history go. There were other factors more relevant to you at that age, it was difficult for some adults to grasp, let alone an 11 year old. I try to draw on positives where I can. I guess this experience has given me empathy for the adversary, the other side. That’s a gift. I’m thankful for it.

You are correct to pointing up peer pressure and environment as a powerful determinant of political choice. In 1981 I chaired a local group who were evenly divided; pro and anti tour. One of the group returned from an extended overseas tour and was forthright in his opposition to the tour. A day or two after returning and catching up with his pub mates he became pro tour saying the overseas media had not been telling the whole story and he did not “want to talk about it.” Not wanting to talk about it is symptomatic of the PM’s response to the allegations facing him and those who follow him.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Overland ’s free fortnightly newsletter highlights the best of Overland online, new writing from the print journal, and regularly collates writing events and opportunities in the community.

- Preplanned tours

- Daytrips out of Moscow

- Themed tours

- Customized tours

- St. Petersburg

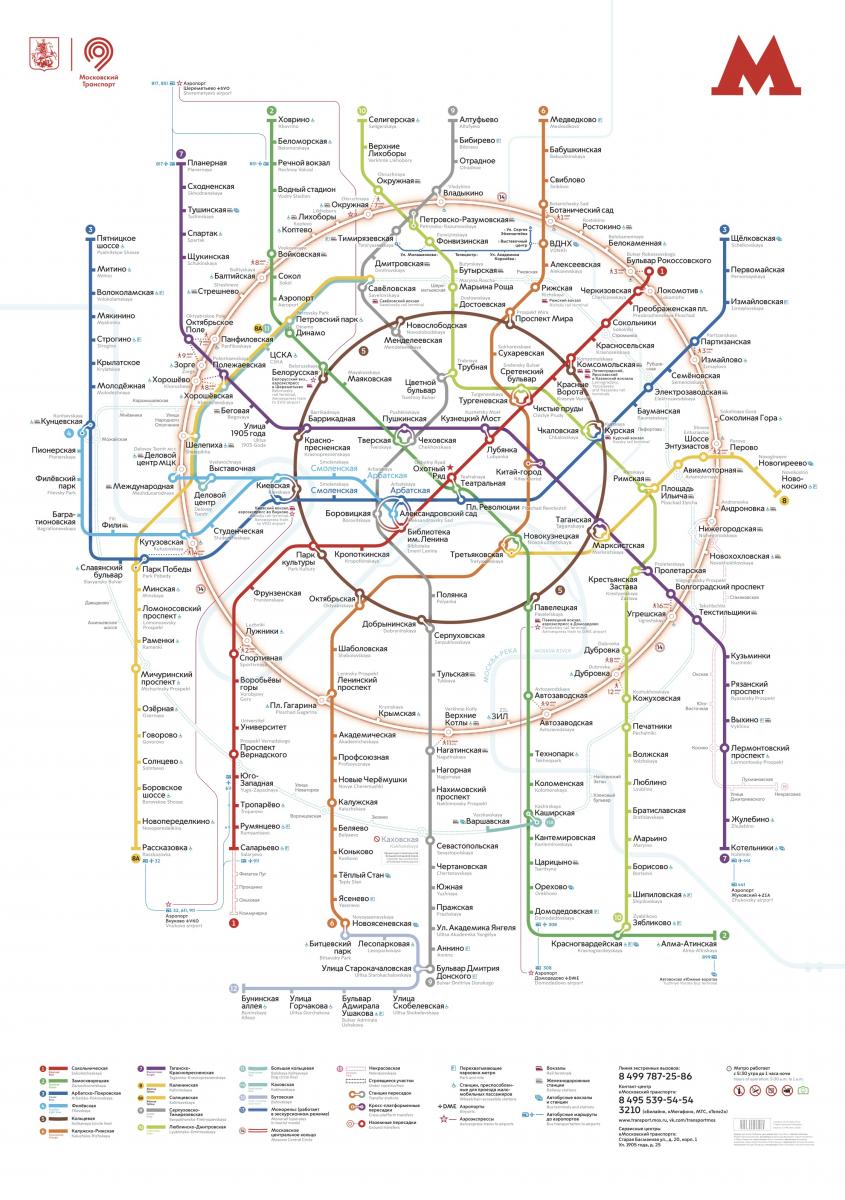

Moscow Metro 2019

Will it be easy to find my way in the Moscow Metro? It is a question many visitors ask themselves before hitting the streets of the Russian capital. As metro is the main means of transport in Moscow – fast, reliable and safe – having some skills in using it will help make your visit more successful and smooth. On top of this, it is the most beautiful metro in the world !

. There are over 220 stations and 15 lines in the Moscow Metro. It is open from 6 am to 1 am. Trains come very frequently: during the rush hour you won't wait for more than 90 seconds! Distances between stations are quite long – 1,5 to 2 or even 3 kilometers. Metro runs inside the city borders only. To get to the airport you will need to take an onground train - Aeroexpress.

RATES AND TICKETS

Paper ticket A fee is fixed and does not depend on how far you go. There are tickets for a number of trips: 1, 2 or 60 trips; or for a number of days: 1, 3 days or a month. Your trips are recorded on a paper ticket. Ifyou buy a ticket for several trips you can share it with your traveling partner passing it from one to the other at the turnstile.

On every station there is cashier and machines (you can switch it to English). Cards and cash are accepted. 1 trip - 55 RUB 2 trips - 110 RUB

Tickets for 60 trips and day passes are available only at the cashier's.

60 rides - 1900 RUB

1 day - 230 RUB 3 days - 438 RUB 30 days - 2170 RUB.

The cheapest way to travel is buying Troyka card . It is a plastic card you can top up for any amount at the machine or at the ticket office. With it every trip costs 38 RUB in the metro and 21 RUB in a bus. You can get the card in any ticket office. Be prepared to leave a deposit of 50 RUB. You can get it back returning the card to the cashier.

SamsungPay, ApplePay and PayPass cards.

One turnstile at every station accept PayPass and payments with phones. It has a sticker with the logos and located next to the security's cabin.

GETTING ORIENTED

At the platfrom you will see one of these signs.

It indicates the line you are at now (line 6), shows the direction train run and the final stations. Numbers below there are of those lines you can change from this line.

In trains, stations are announced in Russian and English. In newer trains there are also visual indication of there you are on the line.

To change lines look for these signs. This one shows the way to line 2.

There are also signs on the platfrom. They will help you to havigate yourself. (To the lines 3 and 5 in this case).

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Springbok Tour 1981. Protests against the South African rugby team touring New Zealand divided the country in 1981. Discover the reasons behind this civil disobedience, as well as the demonstrations, police actions and the politics of playing sports. ... A tour like no other: School Journal Year 7: Part 04 No. 02: 2011 OR

Instructional focus - Reading Social Sciences (Level 4 - Social studies: Understand how people participate individually and collectively in response to community challenges.) English (Level 4 - Ideas: Show an increasing understanding of ideas within, across, and beyond texts.) Reading standard: by the end of year 8 The Literacy Learning Progressions

Being mocked at school for opposing the Springbok tour had put her in a black mood." ... School Journal Level 4 November 2016. Learning area: English, Social Sciences. Curriculum level: 4. Category: Fiction. Topics: 1981 tour, apartheid, change, conflict, courage, Elsie Locke writing prize, historical fiction, New Zealand history, protest ...

By 1981, New Zealand's Halt All Racist Tours was taking the local lead in an international campaign against sporting links with South Africa. Tour supporters were commonly of the view that sport and politics should not mix. As the three-month Springbok tour proceeded, protest against it grew to unprecedented levels.

Springbok Tour 1981. A DigitalNZ Story by National Library of New Zealand Topics. ... A tour like no other: School Journal Year 7: Part 04 No. 02: 2011 OR. Services to Schools. Data. Opinion around New Zealand on the 1981 Springbok tour. Services to Schools. Research paper. Rugby, racism and fear.

By 1981, New Zealand's Halt All Racist Tours was taking the local lead in an international campaign against sporting links with South Africa. Tour supporters were commonly of the view that sport and politics should not mix. As the three-month Springbok tour proceeded, protest against it grew to unprecedented levels.

A tour like no other: School Journal Year 7: Part 04 No. 02: 2011 OR Content partner Services to Schools Collection Topic explorer resources Description. A brief history of the 1981 Springbok tour that divided the nation. Format Article URL https://journalsurf.co.nz/search

Check out RNZ's collection of audio about the 1981 Springbok Tour; Dr Sebastian Potgieter is a South African who moved to Dunedin to conduct a PhD on the Springboks tour. Back in 1981, the general public in South Africa wasn't too familiar with what was going on in New Zealand yet the Springbok tour of that year negatively affected the team's ability to play internationally, Dr Potgieter tells ...

Friday 10 September 2021 10:05am. Dr Sebastian Potgieter's PhD research focused on the 1981 Springbok tour of New Zealand. This weekend marks the 40th anniversary of the history-defining Eden Park Springboks rugby match, a tour that's been the focus of five years of research by Dr Sebastian JS Potgieter, a teaching fellow at Otago's School of Physical Education, Sport and Exercise Sciences.

PDFs of all the texts in this issue of the School Journal are available online as well as teacher support materials (TSM) for the ... Parihaka, passive resistance, petitions, protest, right to vote, riots, rugby, Springbok tour 1981, strikes, Te Whiti-o-Rongomai, Tohu Kākahi, Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPPA), unions, Vietnam ...

But you should find plenty of good sources that are free to access. The good old Minto bar. There's a recent podcast about the Polynesian panthers and the last episode is all about the springbok tour and has a lot of first hand recollections and viewpoints.

PDFs of all the texts in this issue of the School Journal are available online as well as teacher support materials (TSM) for the following: TSM Stories By the River ... Being mocked at school for opposing the Springbok tour had put her in a black mood." Text. Series: School Journal Level 4 November 2016. Learning area: ...

Rugby, racism and the battle for the soul of Aotearoa New Zealand. John Minto. The Springboks' tour and the protests that ensued 40 years ago helped set the fight for Māori rights on a stronger ...

Police officers guarding a barbed wire perimeter around Eden Park near Kingsland railway station.. The 1981 South African rugby tour (known in New Zealand as the Springbok Tour, and in South Africa as the Rebel Tour) polarised opinions and inspired widespread protests across New Zealand.The controversy also extended to the United States, where the South African rugby team continued their tour ...

This thesis uncovers the untold stories of everyday New Zealanders, who participated in, witnessed or have memories of the 1981 Springbok Rugby Tour of New Zealand. It is these stories that are missing from the existing historiography on the Tour which tends to focus on the rugby games, the politics of the time, and the protest movement. This thesis uses an oral history methodology in order to ...

The narrative of the 1981 Springbok tour continues to reflect New Zealand's anti-apartheid views, but in fact protestors treated it more as a critique of New Zealand Society, research shows. Dr Sebastian Potgieter, School of Physical Education, Sport and Exercise Sciences.

This Springbok Fact Sheet is a great catalyst for further activities or to support students in learning about various topics. This resource would be a great writing aid for students practising sequencing information or writing for different purposes and audiences. For example, students could use this resource to write a newspaper report about the Springbok Tour or a journal entry from the ...

Women's groups were prominent in the widespread protests against the 1981 Springbok tour of New Zealand. This poster, produced by Women Against the Tour, announces a march from Christchurch's Merivale Mall to Cathedral Square, to take place on 1 May 1981. That date was the second National ...

Giovanni Tiso. If the historical footage is any indication, the protesters who demonstrated in the streets, clashed with police and attempted to disrupt the games during the 1981 Springbok rugby union tour of New Zealand didn't chant Nelson Mandela's name. They chanted Steven Biko's and Amandla Ngawethu. The near-exclusive identification ...

Overview. Go beneath the streets on this tour of the spectacular, mind-bending Moscow Metro! Be awed by architecture and spot the Propaganda, then hear soviet stories from a local in the know.Finish it all up above ground, looking up to Stalins skyscrapers, and get the inside scoop on whats gone on behind those walls.

Moscow has some of the most well-decorated metro stations in the world but visitors don't always know which are the best to see. This guided tour takes you to the city's most opulent stations, decorated in styles ranging from neoclassicism to art deco and featuring chandeliers and frescoes, and also provides a history of (and guidance on how to use) the Moscow metro system.

Moscow Metro. The Moscow Metro Tour is included in most guided tours' itineraries. Opened in 1935, under Stalin's regime, the metro was not only meant to solve transport problems, but also was hailed as "a people's palace". Every station you will see during your Moscow metro tour looks like a palace room. There are bright paintings ...

Will it be easy to find my way in the Moscow Metro? It is a question many visitors ask themselves before hitting the streets of the Russian capital. As metro is the main means of transport in Moscow - fast, reliable and safe - having some skills in using it will help make your visit more successful and smooth. On top of this, it is the most beautiful metro in the world!