The 16 major types of accommodation

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

When you are travelling or working in the tourism industry, it is important to understand what the different types of accommodation are. Fortunately, the tourism industry is multifaceted and diverse; meaning that there are lots of types of accommodation to choose from when we travel!

Whether you are planning a trip for a family, a single backpacker or a group of students, there is something to suit everything in the accommodation sector. In this article I will provide an outline of the different types of accommodation, with plenty of examples thrown in too.

The different types of accommodation in the tourism industry

Bed and breakfasts, guest houses and home-stays, youth hostels, aparthotels, static or touring motorhomes, camping- tents, yurts, tepees etc, to conclude: types of accommodation, further reading.

Accommodation is a key component of tourism . When we travel, we need a place to stay!

There are many different types of accommodation to suit different budgets, different types of tourism and different types of customers. The role of an accommodation provider is to provide a safe and secure place for a tourist to stay. Standards differ between different providers and according to different budgets.

Below, I have outlined the most commonly found different types of accommodation and given some examples too. But, before you read on take a look at this handy animation about the types of accommodation that I made….!

Catered accommodation

Types of accommodation can be separated into two categories: catered and not catered.

Catered accommodation provides the tourist with food. The food may or may not be included in the price of the hotel.

Catering comes in different shapes are sizes and in different amounts. Half-board usually means that the tourist will be given breakfast and dinner as part of their hotel package. Full board means that they will be given three meals and all-inclusive means that they have unlimited food and drinks throughout the day. Bed a breakfast provides only breakfast.

Some accommodation is sold as ‘room-only’, but provides the opportunity for the tourist to purchase food at an additional cost. This is still classified as a catered accommodation type.

Catered accommodation is generally associated with a number of facilities including the following facilities:

- restaurant and bar

- housekeeping

- leisure facilities

- gym or health club

- conference and business facilities

- entertainment

Here are some of the most common types of accommodation that can be classified as catered.

Hotels are the most traditional and most common types of accommodation.

Hotels can be large or small. They can be independently owned businesses or they can be part of a hotel chain. Hotels may be part of a holiday resort.

Hotels are ranked using a star rating system. Hotels are awarded a grade between 1-5 stars (1 being the lowest, 5 being the highest). This tells the tourist what level of service to expect at the hotel.

My favourite hotel: We stayed at the Radisson Blu hotel on Yas Island when we travelled to Abu Dhabi for our babymoon . This hotel was part of a beach resort that had excellent facilities. It was the perfect place to get some much needed R&R before the arrival of my baby!

A bed and breakfast is just as it sounds- a type of accommodation that offers a bed and a breakfast!

Bed a breakfast accommodations in the UK are traditional a type of guest house or home-stay. The owners typically live in the accommodation and separate their personal living space away from the guest space. Breakfast served is traditionally an English-style cooked breakfast.

Today, this traditional model of bed and breakfast accommodations does still exist, however the experience described above is not a given. In fact, any type of accommodation that offers breakfast as part of the deal can be described as a bed and breakfast, and the breakfast offered can range from continental to exotic- there doesn’t have to be a sausage or hash brown in sight!

My favourite bed and breakfast: 25 years ago my grandad purchased this beautiful house in a quaint village called Debenham in Suffolk. Sadly he passed away a few years after living here, but since this time his partner and her new husband have transformed this beautiful grade ii listed cottage into a bed and breakfast. They welcome guests from all over the UK and the rest of the world into their home (and cook them a delicious breakfast!).

You can take a look at/book a stay at Cherry Tree Cottage in Debenham, Suffolk on their website.

A guest house is essentially a house that welcomes guests. There is a fine line between a guest house and a bed and breakfast. While there is no hard and fast rule, guest houses tend to be bigger than bed and breakfast accommodations. Guest houses may or may not offer breakfast included in the price of the hotel room.

A homestay is intended to facilitate a deep cultural tourism experience. The intention is that you live and immerse yourself with a family in their home. However, my experience is that whilst many types of accommodation may advertise themselves as a ‘home-stay’, they are in reality just a guest house, with limited interaction between the hosts/owners and the guests.

My favourite guest house: Thailand is one of my favourite countries in the world and I LOVED my stay at Ashi Guesthouse Chiangdao in Chiang Mai. The owners were really friendly and there was such a welcoming atmosphere.

Chalets are typically found in ski resorts and can come on a self-catering or catered basis. Often they are available with your own personal chef!

Chalets are great if you are travelling in a group. Chalets come in different sizes and can fit different amounts of people. You can also opt for a shared chalet if your group size is small.

My favourite chalet: Chaletdorf Auszeit is a gorgeous chalet situated in the Austrian Apls. The chalets come with a private hot pot and sauna, a natural swimming pond and a chef!

A youth hostel is a type of accommodation designed to suit the needs of those on a budget. Whilst anyone can stay in a youth hostel, they are largely aimed at young people.

Youth hostels will often provide dormitory-style accommodation, with shared rooms and bunk beds.

This type of accommodation is perfect for group tours and educational trips.

My favourite youth hostel – In my previous job as Course Team Leader at a UK college we took our students on a residential visit each year to Edinburgh and stayed at the Edinburgh Central Youth Hostel. The hostel was brilliant- it had a restaurant and bar, areas for the students to chill out and relax and a games room!

Self-catered or non-catered accommodation

Self-catered and non-catered accommodation are types of accommodation that do not offer food. Self-catered accommodations offer cooking facilities, such as a small kitchen and cooking equipment. Non-catered accommodation is likely a room-only accommodation with no cooking facilities.

Products and services that are typically offered in self-catered and non-catered accommodation options include the following:

- caravan pitch

- sports facilities

- laundry facilities

Self catering accommodation has become more popular in recent years with the growth of the sharing economy . Properties owners can now easily rent their accommodation to tourists through intermediaries, who connect the tourist with the property owner.

My favourite is Airbnb . We use Airbnb all the time! We have found some fantastic bargains and unique properties over the years. You can read more about why I love Airbnb here .

Here is a little bit more detail about some of the most common self-catered or non-catered types of accommodation.

A cottage is typically a small, cosy house that is classed as being old or traditional. Cottages are quintessential British homes that are often found in semi-rural locations.

Because of their unique character, culture and heritage, cottages make for popular holiday homes.

Cottages provide tourists with the opportunity for a ‘home from home’ experience. Guests can usually cook, do laundry and watch TV as they would in their own home.

My favourite cottage: We stayed in Cheddar , Somerset for two months and we LOVED living in this beautiful country cottage! Strawberry Rose Cottage is a traditional three bedroom cottage with a gorgeous open fire place and a little outside courtyard. The cottage had everything we needed from kids cutlery and a high chair to matches to light the fire and a tumble dryer. I couldn’t have asked for any more, IT WAS JUST PERFECT!

Apartments are a popular self-catering accommodation option. Apartments are found in many areas, but are most common in built up areas such as towns and cities and busy resorts.

Apartments can be large or small and can range from short-term to long-term lets.

My favourite apartment: Shanghai is a city of high-rise buildings and sky-scrapers. It is also a city that doesn’t cater particularly well to those who want to self-cater. This is because people often eat out in China (and much of Asia too). So, we were thrilled to find the Lanson Place Jin Qiao Residence . This apartment was perfect for us. With two bedrooms and a long, it allowed us to enjoy a glass of wine on the sofa after putting the kids to bed!

Some people choose to stay on a boat during their holiday- and what a cool experience!

No, I’m not talking about cruise tourism . I am talking about hiring your own private boat and sleeping on it-cool, huh?

You can stay on a many different types of boats , from yachts, to canal boats, to house boats.

My favourite boat: Staying on a house boat in Kerala was a once in a lifetime experience. Houseboats in this part of India are iconic and you will see them throughout the waterways, known as the ‘Venice of the East.

Log cabins are popular in countries with cooler weather, such as ski destinations.

Log cabins are defined by the material that they are built with- logs. They can be small or large and have varying facilities inside.

My favourite log cabin: We found this beautiful log can near Vancouver, Canada on Airbnb . It was so peaceful and we were surrounded by nature (including bears!). We had the lake all to ourselves and the log cabin came with a canoe too.

As I mentioned before, chalets can be both catered and self-catered. Scroll back up to read more about what a chalet is.

A motel is basically a hotel room with a parking space.

Motels are popular in the USA.

Motels usually offer simple room-only accommodation, but some may have simple cooking facilities.

My favourite motel: The the USA the main method of getting around is by car, so if you car travelling around a lot it makes sense to stay in a motel. We stayed here during our road trip across the USA and this spot in Los Angeles was super convenient.

An aparthotel offers a combination of what you get in a typically hotel with the facilities associated with an apartment. Some claim that this offers ‘the best of both worlds’.

My favourite aparthotel: We loved the Aparthotel Stare Miasto in Krakow, Poland. This accommodation option was quirky, stylish and oh so much fun!

Caravans can be transported from place to place, or they can be situated in one location.

In the UK, caravan parks are very popular. Most are located close to the seaside. Some caravan parks are part of well-known holiday parks, such as Butlins , Pontins or Haven.

My favourite caravan: I went to Parkside Caravans many during during my childhood. I have fond childhood memories of converting the dining table into a bed and playing with the kids from the caravan next door until dusk. Happy memories!

A motorhome is just as it sounds- a home that has a motor!

A motorhome is a vehicle that enables you to travel in it by day and sleep in it by night.

Some motorhomes are the size of small vans, with limited facilities and functions. Other motorhomes are large recreational vehicles (RVs) that come with all the mod cons including a kitchen and bathroom.

Motorhomes are very popular in the USA and in Australia , where road trips are common.

My favourite motorhome: I hope to do a road trip through Australia in a camper van like this with my family in the future! It looks like soooo much fun!

Camping is often one of the cheapest types of accommodation, especially if you have your own tent. All you need to do is pay for your spot on a camp site (or find a place where you are allowed to camp for free), and you’re all set.

Many camp sites also offer camping with additional amenities, such as a bed, wardrobe, lamps etc. This is often referred to as glamping .

Yurts (traditional Mongolian tents), teepees and other unusual types of tents are very popular these days too, however, these options do come with a higher price tag.

My favourite camping experience: My friend and I went on a camping trip through France and Spain and we LOVED it. We simply pitched up the tent where ever we found a campsite at the end of the day, cracked open the wine and put the world to rights under the stars. It was just fabulous!

Hostels are pretty much the same as youth hostels, except for they may not provide provisions for catering. Some hostels have a communal area, such as a seating area or kitchen, whereas other may not.

There are many different types of accommodation to choose from when you are travelling, and I have been fortunate enough to try most of them out myself! Types of accommodation can generally be classified as either catered or self-catered/non-catered. Within these two categories there are many different accommodation options available to you.

If you want to learn more about the travel and tourism industry or if you are a travel and tourism student, I strongly suggest you consult the texts listed in the further reading section below. These books are core texts for travel and tourism students, covering all of the fundamental tourism management topics that you will surely be studying.

- 20 Popular Types of Hotels Around The World

- The 10 Major Types of Events

- The 8 Major Types of Cruise

- 150 types of tourism! The ultimate tourism glossary

- 15 Types of Rail Transport To Take You Away

Liked this article? Click to share!

The word hotel is derived from the French hôtel , which refers to a French version of the townhouse. The term hotel was used for the first time by the fifth Duke of Devonshire to name a lodging property in London sometime in AD 1760. Historically, in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and several other countries, a townhouse was the residence of a peer or an aristocrat in the capital of major cities. The word hotel could have also derived from the hostel , which means ‘ a place to stay for travelers ‘.

A hotel is defined by the British Law as a ‘ place where bonafide travelers can receive food or shelter, provided he/she is in a position to pay for it and is in a fit condition to be received ‘. Hence, a hotel must provide food (and beverage) and lodging to a traveler on payment, but the hotel has the right to refuse if the traveler is not presentable (either drunk, or disorderly, or unkempt) or is not in a position to pay for the services.

Alternatively, a hotel may be defined as ‘ an establishment whose primary business is to provide lodging facilities to a genuine traveler along with food, beverage, and sometimes recreational facilities too on the chargeable basis ‘. Though there are other establishments such as hospitals, college hostels, prisons, and sanatoriums, which offer accommodation, they do not qualify as hotels, since they do not cater to the specific needs of the traveler.

A hotel is an establishment that provides paid accommodation, generally for a short duration of stay . Hotels often provide a number of additional guest services, such as restaurants, bars, swimming pools, healthcare, retail shops; business facilities like conference halls, banquet halls, boardrooms; and space for private parties like birthdays, marriages, kitty parties, etc.

Most of the modern hotels nowadays provide the basic facilities in a room- a bed, a cupboard, a small table, weather control (air conditioner or heater), and a bathroom- along with other feature like a telephone with STD/ISD facilities, a television set with cable channel, broadband internet connectivity.

There might also be a mini-bar containing snacks and drinks (the consumption of the same is added to the guest’s bill), and tea and coffee making unit having an electric kettle, cups, spoons, and sachets containing instant coffee, tea bags, sugar, and creamer.

History of Hotels

The invention of currency and wheels sometime in the 5th century BC are regarded as the two main factors that led to the emergence of inn-keeping and hospitality as a commercial activity. While Europe can safely be regarded as the cradle of the organized hotel business, it is in the American continent that one sees the evolution of the modern hotel industry over the past century.

From the rudimentary ancient inns to the present day state-of-art establishment that provides everything under the sun of the modern traveler, the hotel industry has come a long way. The origin and growth of the hotel industry can be broadly studied under the following periods:

Ancient Era

The earliest recorded evidence of the hospitality facilities in Europe dates back to 500 BC. An ancient city, such as Corinth in Greece, had a substantial number of establishments that offered food and drink as well as beds to the traveler. The inns of the biblical era were of the primitive type, offering a cot or bench in the corner of a room and, at times, even a stable. Travelers used to stay in a large hall. Privacy and personal sanitation were non-existent.

In the 3rd century AD, numerous lodging premises mushroomed along with the extensive network of brick-paved roads throughout Europe and minor Asin (part of Asia adjoining Europe). The lodging hotels were known as mansions during that time.

These conditions prevailed for several hundred years, until the Industrial Revolution in England led to the development of railways and steamship, making traveling more efficient, comfortable, and faster. The Industrial Revolution also brought about a shift in the focus of travel that becomes more business-oriented than educational or social.

The lead-in organized hotel-keeping, as we see it today, was taken by the emerging nations of Europe, especially Switzerland. The early establishment was mainly patronized by the aristocracy and took shape in chalets (small cottages) and small hotels that provided a variety of services. Between 1750 and 1825, inns in Britain gained the reputation of being the finest hospitality establishments.

The second half of the eighteenth century, prior to the French Revolution (1780-990, is referred as the ‘ golden era of travel ‘ as the popularity of the ‘ Grand Tour ‘ gave a big push to the hotel industry. In those days, a Grand Tour of the European continent constituted as an indispensable element of the education of scions of wealthy families in Britain.

As this tour often lasted several years, it was a good business opportunity for the people in prominent cities of France, Italy, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Ireland to establish lodging, transportation, and recreation facilities. Far-sighted entrepreneurs, who smelt money in the exercise, developed the skills of the hospitality and pioneered the modern hotel industry.

Prominent among the hotels that emerged during the period were Dolder Grand in Zurich, Imperia in Vienna, the Jahreszeiten in Hamburg, and Des Bergues in Geneva. In 1841 , a simple cabinet marker, Thomas Cook organized a rail tour from Leicester to Loughborough and immortalized himself as the world’s first tour operator .

The improvisation in the mode of transport made journeys safer, easier, and faster, enable economical as well as frequent mass movement. The introduction of Funiculars (the ropeway) made high altitude mountains accessible, leading to the growth of many hotels in Alpine rages. Burgenstock and Giessbach are among the hotels in Switzerland that owe, their existence to the development of the ropeways.

The two world wars, especially the second (1939-45) took their toll on the hospitality industry. The massive destruction caused by the war and the resulting economic depression proved to be a major setback to the travel business. The 1950s witnessed a slow and steady growth of travel on the European continent.

The development of aircraft and commercial passenger flight across the Atlantic stimulated that across the globe, and in the process accelerated the growth of the hotel industry.

But it is the American entrepreneurs who credited with literally changing the face of the hospitality industry with their innovation and aggressive marketing. Prior to the establishment of City Hotel lodging facilities in the American continent was patterned on the European style taverns or inns.

The City Hall, however, triggered a race among American hoteliers, resulting in the construction of the large hotels. The decade of the great depression in the 1930s witnessed the liquidity of most of the hotels in America. The hotel industry streamlined with the slow and steady growth during the 1940s. The increase in automobile travel in the 1950s led to the rise of ‘motor hotels’ or motels , a new category in the hotel industry.

The motel which offered free parking facilities served as rest houses for the people traveling between two cities or tourist destination. The following decades saw the growth of motels on a large scale, and also the introduction of budget hotels that offered basic facilities at half of the rates. Gradually, with the passage of time, they evolved into countrywide and international chains.

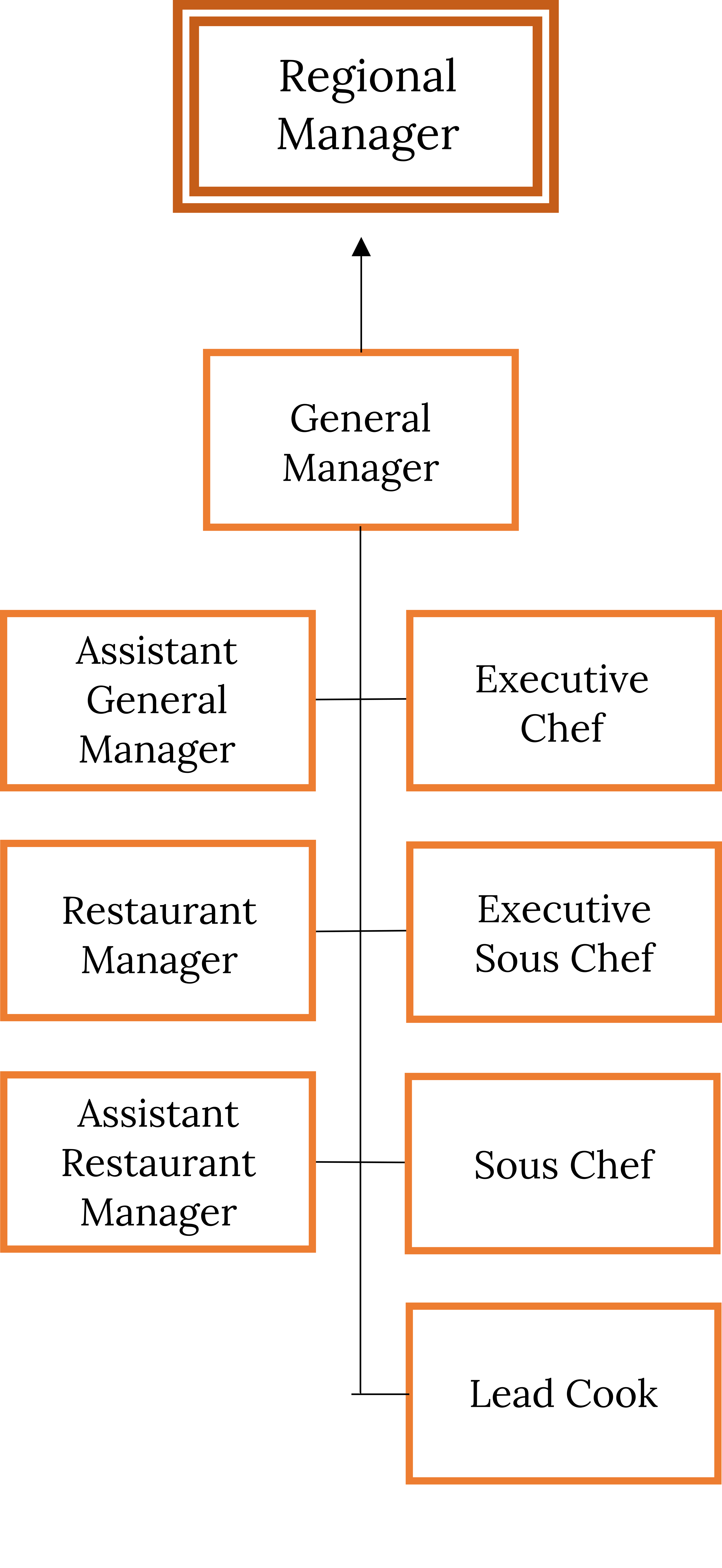

Hotel Organisation Structure

To carry out its vision, mission, objectives, and goals, every hotel requires a formal structure known as the organization structure. The structure defines the company’s distribution of responsibilities and authority among its management staff and employees.

It establishes the manner and extent of roles, power, and responsibilities, and determines how information flows between different level of organization. This structure depends entirely on the organization’s objective and strategies chosen to achieve them.

The most common way to represent the organization structure is through an organization chat. Each hotel is different and has unique features, so the organization charts of hotels vary from each other. The organization structure depends upon the size and function of a hotel.

Some hotel may lease their outlet to another company or may employ another agency to operate restaurant or housekeeping services. In such cases, those portions will not be a part of the organization chart of the hotel. A sample organization chart of a commercial hotel is following as:

Core Areas/Departments of Hotel

The organization of a hotel today is very complex and comprises various departments. The number of departments varies from one establishment to another. All departments may have their own managers, reporting to the general manager and the assistant general manager.

Hotels departments fall under the category of either Revenue earning departments or Support departments .

Revenue earning departments are operational departments that sell services or products to the guest, thus, directly generating revenue for the hotel. These departments include front office, food and beverage, and hotel operated shops.

Support departments are the ones that help to generate revenue indirectly by playing a supporting role in the hotel’s revenue earning departments. These include human resources, maintenance, purchase, housekeeping, and so on.

The various departments in a hotel are discussed below in brief:

Room Division Department

In a large hotel, the housekeeping, front office, and maintenance departments come under room division. These departments together are responsible for maintaining and selling the room in a hotel . In most hotels, these are the departments that directly or indirectly generate more revenue than other departments. This is because the sale of room constitutes a minimum of 50 percent revenue of a hotel.

A hotel’s largest margin of profit comes from the room because a room, once made, can be sold over and over again. The room division is headed by the room division manager to whom the front office manager, executive housekeeper, and very often the chief engineer report.

Housekeeping Department

The housekeeping department is responsible for the cleanliness and upkeep of the front of the house areas as well as the back of the house areas so that they appear as fresh and aesthetically appealing as on the first day when hotel property opened for business. This department is headed by the executive housekeeper or, in chain hotels, the director of housekeeping.

Front Office Department

Headed by the front office manager , the front office department is the operational department that is responsible for welcoming and registering the guests, allotting the rooms and helping the guests check out . Uniformed services like concierge and bell desk and EPBAX operators are the part of the front office department.

Maintenance Department

The maintenance department also called the engineering and maintenance department , is headed by the chief engineer or the chief maintenance officer. The department is responsible for all kinds of maintenance, repair, and engineering work on equipment, machine, fixtures, and fittings .

Food and Beverage Department

The food and beverage (F&B) department include restaurants, bars, coffee shops, banquets, room service, kitchen, and bakery . The department is headed by the F&B director . While the restaurants, bars, coffee shops, banquets, and the room may be grouped specifically under the F&B service department, headed by the F&B manager, the kitchen and bakery fall under the F&B production department, headed by the executive chef.

Human Resource Department

The human resource (HR) department or the personnel department, as it used to be called earlier – is headed by the human resource manager . Recruitments, orientation, training, employee welfare and compensation, labor laws, and safety norms for the hotels come under the purview of the HR department.

The training department is an ancillary department of the HR department. This is headed by the training manager, who takes on the specific task of orientation and training of new employees as well as existing ones.

Sales and Marketing Department

The sales and marketing department is headed by the sales and marketing manager . A large hotel may have three or more employees in this department, whereas a small hotel can do with just one employee.

The function of this department is five-fold – sales, personal relations, advertising, getting MICE (meeting, incentive, conference, and exhibition) business, and market research. All these functions lead to the common goal of selling the product of the hotel – i.e. rooms and the services of the hotel by ‘creating’ customers.

Purchase Department

The purchasing department is led by the purchase manage r, who, in some properties, may report to the financial controller. The procurement of all departmental inventories is the responsibility of the purchasing department. In most hotels, the central stores are the part of purchase department.

Financial Control Department

It is also called the control department , the financial control department is headed by the financial controller , who is responsible for ratifying all the inventory items of the operational departments. Inventory control procedures are the responsibility of the department.

The financial controller, along with the general manager, is responsible for finalizing the budgets prepared by the heads of other departments . The hotel’s accounts are also maintained by the controls department. Accounting activities include making payments against invoices, billing, collecting payments, generating statements, handling bank transactions, processing employee payroll data, and preparing the hotel’s financial statements.

Security Department

It is headed by the chief security officers , the security department is responsible for safeguarding the assets, guests, and employees of the hotel . Their functions include conducting fire drills, monitoring surveillance equipment, and patrolling the property.

Types and Classification of Hotels

Hotels provide accommodation, along with services like food and beverages, and facilities like recreation, conference, and training arrangements, and organization of official or private parties. Each hotel has a unique feature associated with it.

The features may be its location; the number of guests room; special services such as concierge, travel assistance, and valet parking; facilities such as specialty restaurants, bars, business meeting venues, swimming pools, and so on.

The diversity in services and facilities provided by each hotel makes it quite difficult to have any single basis of classification of hotels, and if we classify them in different criteria there will be some hotels that will fall into more than one group. The criteria in which hotels are classified are following as:

Standard Classification of Hotels

The star classification system is among the most widely accepted rating of hotels worldwide. Rating of hotels in different countries is done by the government or quasi-government sources, independent rating agencies, or sometimes the hotel operators themselves.

The brief description of the various star categories are following as:

One-star Hotels

These properties are generally small and independently owned, with a family atmosphere. There may be a limited range of facilities the meals may be fairly simple. For example, lunch may not be served or some bedrooms may not have an en-suite bath or shower.

However, maintenance, cleanliness, and comfort would be of an acceptable standard.

Two-star Hotels

In this class, hotels will typically be small to medium-sized and offer more expensive facilities than one-star hotels. Guests can expect comfortable, well equipped overnight accommodation, usually with an en-suite bath and shower.

Reception and other staff will aim for a more professional presentation that at the one-star level and will offer a wider range of straightforward services, including food and beverages.

Three-star Hotels

At this level, hotels are usually of a size to support higher staffing levels as well as significantly higher quality and range of facilities than at the lower star classifications. Reception and other public areas will be more spacious, and the restaurant will normally also cater to non-residents.

All bedrooms will have an en-suite bath and shower and will offer a good standard of comfort and equipment, such as a direct dial telephone and toiletries in the bathrooms. Besides room services, some provision for business travelers can be expected.

Four-star Hotels

Expectations of this level include a degree of luxury as well as quality in the furnishing, décor, and equipment in every area of the hotel. Bedrooms will also usually offer more space than at the lower star levels. They will be well designed with coordinated furnishing and décor.

The en-suite bathrooms will have both a bath an shower. There will be a high staff to guest ratio, with provisions of porter services, twenty-four-hour room service, and laundry and dry cleaning services. The restaurants will demonstrate a serious approach to its cuisine.

Five-star Hotels

Five-star hotels offer spacious and luxurious accommodation throughout the hotel, matching the best international standards. The interior design should impress with its quality and attention to detail, comfort, and elegance. The furnishing should be immaculate.

The services should be formal, well supervised, and flawless in its attention to the guest’s need, without being intrusive. The restaurant will demonstrate a high level of technical skill. The staff will be knowledgeable, helpful, and well versed in all aspects of customer care, combining efficiency with courtesy.

Heritage Hotels

A recent addition to the hotel industry, heritage hotels are properties set in small forts, palaces, or havelis , the mansions of erstwhile royal and aristocratic families. They have added a new dimension to cultural tourism.

In a heritage hotel, a visitor is offered rooms that have their own history, is served traditional cuisine toned down to the requirements of international palates, is entertained by folk artists, can participate in activities that allow a glimpse into the heritage of the region and can bask in an atmosphere that lives and breathes of the past.

Heritage hotels can further be divided into three types:

- Heritage Classis

- Heritage Grand

Classification of Hotels On the Basis of Size

The number of guest rooms in a hotel is a criterion to classify hotels. Hotels can be grouped into the following categories on the basis of the number of rooms or the size of the hotel:

Small Hotel

In India, hotels with twenty-five or less are classified as small hotels. However, in the developed countries of Europe and America, hotels with less than 100 rooms are considered small. These hotels provide clean and comfortable accommodation but may not provide upmarket facilities, such as swimming pool, restaurant, bar etc.

Medium Hotel

Hotels with twenty-six to a hundred rooms are called medium hotels. However, in developed nations, hotels with up to 300 rooms are termed medium-sized.

Large Hotel

In India, hotels with 101 to 300 guest rooms are regarded as large hotels. Whereas, hotels with 400 to 600 rooms are termed as large hotels in the developed world.

Very Large Hotel

Hotels, with more than 300 guest rooms are known as very large hotels in our country. In developed nations, hotels with 600 to 1,000 rooms may be considered very large.

Classification of Hotels on the Basis of Location

The location of the hotel is one of the major criteria for the traveler to select and patronize a hotel. Hotels may be located in the city center, suburban areas, natural locations such as hill stations and sea beaches, near the port of entry into a country, etc. They may be classified into the following categories on the basis of their location:

Downtown Hotel

A downtown hotel is located in the center of the city within a short distance from the business center, shopping areas, theatre, public offices, etc. The center of the city may not necessarily be the geographical center, but it refers to an area that is considered to be the commercial hub of the city.

The room rates in these hotels may be higher than similar hotels in the other areas, so as to cover the huge investment made on land. They are generally preferred by the business clients as they find it convenient to stay close to the place of their business activities.

Sub-Urban Hotel

As the land cost in the city center is higher and space is limited, some entrepreneurs build their hotel near the outskirts of the city. Providing similar facilities to the downtown hotels, these hotels are set in suburban areas and have the advantage of quieter surroundings. Such hotels are ideal for people who prefer to stay away from the hustle and bustle of a city .

The duration of the stay of guests in these hotels may be longer than the at a hotel located in the city. The room rates in such hotels are moderate and may attract the budget travelers.

Resort Hotel

Hotels that are located at a tourist destination such as hill stations, sea beaches, and countryside are referred to as resort hotels . These hotels have a very calm and natural ambiance. They are mostly away from cities and are located in the pollution-free environment. The room rates in these hotels may range from moderate to high, depending on the additional services offered.

These hotels combine stay facilities with leisure activities such as golf, summer and winter support, etc. Some of these hotels are projected as a dream destination to guests who wish to enjoy the beauty of nature and have a memorable holiday. The occupancy in the resorts is normally higher during the vacation time and weekend when guests want to take a break from their weekly routine.

Airport Hotel

Airport hotel is situated in the vicinity and other ports of entry . Offering all the services of the commercial hotel, these hotels are generally patronized by the passengers who need a stopover en-route journey.

The word ‘ motel ‘ is formed by the merging of two words ‘ motor ‘ and ‘ hotel ‘. They are located primarily in the highways and provide modest lodgings to highway travelers. The development of extensive road networks in the early twentieth century led to an increase in the people traveling in their own vehicles.

The phenomenon was quite common in the American European continents. The traveler who was traveling in their own vehicles needed a neat and clean accommodation for the night, so, the motel concept came into existence.

As the name suggests, floatels are types of lodging properties that float on the water . This category consists of all lodging properties that are built on the top of rafts or semi-submersible platforms and includes cruise liners and houseboats .

Some of them provide luxurious accommodation, along with food and beverage facilities to guests.

Classification of Hotels on the Basis of Clients

The hotel caters to the need of its guests. Every individual or a group of people who patronize a hotel has a different set of requirements. While some would prefer luxurious accommodation, others would like to stay in a simple and cheap room. Some would require facilities such as meeting rooms, business centers, and conference halls if their travel is business-oriented.

Being a capital-intensive industry, the diversities in guest requirements discourage hotels from catering to all types of travelers. As a result, hotels choose to carve out a niche for themselves by catering to the needs of specific guest segments. The hotel can be classified into the following categories on the basis of its clients :

Business or Commercial Hotel

Designed to cater to the business traveler , commercial hotels are generally situated in the city center . These hotels provide high standard rooms and amenities, along with high-speed internet connectivity, business centers, and conference halls. They also provide in-house secretarial services, as well as facilities such as letter drafting, typing, fax, and photocopy of documents for the convenience of their guests.

The guest amenities at the commercial hotel may include complimentary newspapers, morning coffee, cable television, and access to channeled music and movies.

The duration of the guest’s stay is generally very short at these hotels. The occupancy level is higher during the weekdays and slightly lower during weekends. These hotels are also known as downtown hotels .

Transient Hotel

Transient hotels cater to the need of people who are on the move and need a stopover en route their journey . Located in the close proximity of ports of entry, such as seaport, airport, and major railway stations, these hotels are normally patronized by the transient traveler.

They have round the clock operational room service and coffee shop and offer all the facilities of a commercial hotel. Transient hotels are usually five-star , and their target market includes business clientele, airline passengers with overnight travel layovers or canceled flights, and airline personnel.

The occupancy rate is usually very high, sometimes more than 100 percent, as rooms can be sold more than once on a given day.

Suite Hotel

Suite Hotels provide the highest level of personalized service s to guests. The guest rooms generally comprise a living area, a compact kitchenette, complete with refrigerator and a microwave, a bedroom attached with bathroom, and sometimes even a dance floor.

The facilities are highly customized and may include in-room safety locker facilities. These hotels are patronized by affluent people and tourists who are fond of luxury.

Residential Hotel

As the name suggests, residential hotels provide accommodation for a longer duration . These hotels are generally patronized by people who are on a temporary official deputation to a city where they do not have their own residential accommodation. Guest stay for a minimum period of one month and up to two years.

The services offered by these hotels are modest. The room’s configuration usually similar to that of suite hotels. Guest rooms generally include a sitting room, bathroom, and small kitchenette. They are akin to the small individual apartment.

These hotels are fully operational restaurants or a dining room for the resident guests and may provide services such as daily housekeeping, telephone, front desk, and uniformed services. The guest may choose to contract some or all the services provided by the apartment hotel. The hotel signs a lease with guest and the rent is paid either monthly or quarterly .

Bed and Breakfast Hotel

A European concept , bed, and breakfast (B&B) hotels are lodging establishments, generally operated in large family residences. These range from houses with few rooms converted into overnight facilities to small commercial building with twenty to thirty guest rooms. The owner usually lives on the premises and is responsible for serving breakfast to guests.

Guests are accommodated in bedrooms and breakfast is served in the room or sometime in the dining room. The bathrooms may be attached to the guest rooms or maybe on a sharing basis. As the tariff is generally lower than a full-service hotel at these properties, they are suitable for budget travelers .

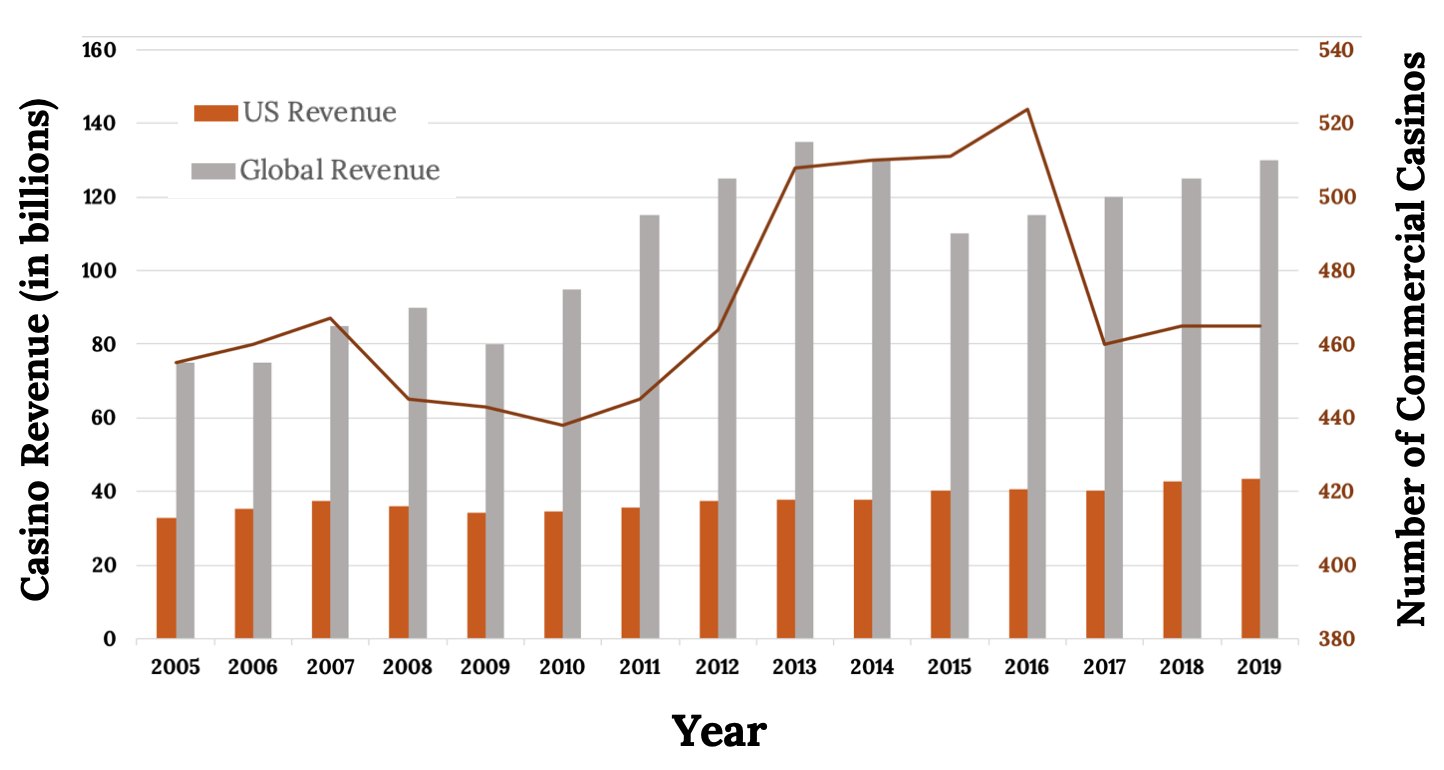

Casino Hotel

Casino hotels provide gambling facilities , such as Luxor Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas. These hotels attract the clients by promoting gambling, arranging extravagant floor shows, and some may provide charter flight services to its clients. They have state-of-the-art gambling facilities, along with the especially restaurant, bars, round the clock room service, well appointed and furnished rooms for its guests.

Nowadays, these hotels are also attracting the MICE (meeting, incentives, conferences, and exhibitions) segment. The casinos of Las Vegas , USA are among the most famous casinos in the world.

Conference Centers

The word conference means ‘ a meeting, sometimes lasting for several days, in which people with a common interest participate in discussions or listen to lectures to obtained information ‘. Thus, a conference center is a hotel which caters to the needs of a conference delegation.

These hotels provide rooms to delegates of conferences; a conference hall with the desired seating configuration for the meetings; food and beverage requirement during and after the conference; and other requirements, such as a flip chart, whiteboard with markers, overhead projector, television, VCR/VCD/DVD player, slide projector, LCD projector with screen, computer, and public address system.

These are large hotels, having more than 400 guest rooms . The services provided are the highest standard. Normally, conferences are charged as packages, which include accommodation and meeting facilities.

Convention Hotels

The convention is defined as ‘ a formal assembly or meeting of members, representatives, or delegates of a group for general agreement on or acceptance of certain practices or attitudes ‘. This type of meeting involves a large number of participants. The hotel catering to the needs of this segment is known as convention hotels .

These hotels may have more than 2,000 rooms to accommodate a large number of delegates. They are equipped with state-of-art convention centers with all the required facilities, such as seating configuration, audiovisual equipment, and public address systems to meet the demands of a convention.

Classification of Hotels on the Basis of Duration of Guest Stay

On the basis of the duration of the guest stay, hotels may be classified into the following categories:

Commercial Hotel

The duration of guest stay in these hotels is short, ranging from a few days to a week.

Mostly occupied by travelers as stopovers en route their journey, the duration of stay at transient hotels are very short, a day or even less.

Semi-residential Hotel

These hotels are generally patronized by people who are staying at a location while in transit to another place. The duration of stay may range from a few weeks to some months. They incorporated the feature of both transient and residential hotels.

Residential/Apartment Hotel

As the name suggests, residential hotels provide accommodation for long duration and are patronized by the people who stay for a long time. The duration of stay may range from a few months to a few years.

Extended Stay Hotel

In today’s age of downsizing, outsourcing and mobility business executive are often away from their hometowns for extended periods of time and require more than a hotel room.

These hotels are for those guests who wish to stay for long period (from few days to weeks), and cater to their long-term needs with special services, amenities, and facilities, such as full-fledged kitchens with dishes and kitchenware, separate area to wash clothes, housekeeping services, grocery services, and recreational facilities. The room rates of these hotels are determined by the length of stay.

Classification of Hotels on the Basis of Level of Services

On the basis of services offered by a hotel, they may be classified into the following categories:

Upmarket/World Class Luxuries Hotels

Targeting the affluent segment of society, hotels in the upmarket category offer world-class products with personalized services to the higher standard. The emphasis is on excellence and class. These hotels provide upscale restaurants and lounges, exquisite décor, concierge service, opulent rooms, and abundant amenities.

The design and interior decoration of the hotel itself reflects the standards maintained by the hotel. The guest rooms are large with exquisite decoration and furnishings.

Mid-Market/Mid-range Services Hotels

These hotels offer modest services without the frills and personalized attention of luxury hotels, and appeal to the largest segment of travelers. They may offer services such as room service, round-the-clock coffee shop, airport and railway station pick-up and drop facilities; multi-cuisine restaurant with bar.

A typical hotel offering mid-range service would be medium-sized, having roughly 150 to 300 rooms. The room rent is much lower than the upmarket hotels. These hotels are patronized by business traveler, individual traveler, and groups.

Budget/Economy Hotels

Budget hotels focus on meeting the most basic needs of guests by providing clean, comfortable, and inexpensive rooms. These are also known as economy or limited services hotels , they appeal primarily to budget-minded traveler groups.

The clientele of budget hotels may also include families with children, bus tour groups, traveling business people, vacationers, retired persons, and groups. These hotels have clean and comfortable guest rooms, a coffee shop, a multi-cuisine restaurant, in-room telephone, and channeled music and movies.

Classification on the Basis of Ownership

On the basis of ownership of a hotel, they may be classified into the following categories:

Proprietary Ownership

Proprietary ownership is the direct ownership of one or more properties by a person or company. Small lodging properties by the person or company. Small lodging properties that are owned and operated by a couple or family are common of proprietary ownership.

Let us understand the following terminologies related to the franchise before we talk about it :

Franchise It is authorization given by a company to another company individual to sell its unique products/services and use its trademark according to the guidelines given by the former, for a specified time, and at a specified place.

Franchisor The franchisor is the company that owns the trademark, product, a business format that is being franchised.

Franchisee The franchisee is the company or the individual to whom franchise confers the right to do business under its name as per the term and condition agreed upon.

Franchising A continuing relationship in which the franchisor provides a licensed privilege to do business, plus assistance in organizing, training, merchandising, and management in return for a consideration from the franchise.

In the hospitality industry, we often come across many big chains that are operating on a franchise basis. In this kind of contract, which is mutually beneficial to both parties, the franchisor allows the franchisee to use the company’s ideal methods, trademarks, as well as the brand logo to do business.

Management Contract

Managing a hotel requires professional expertise. A new entrepreneur with little or no experience in the business may safely choose to become the franchisee of any well-established hotel chain.

There could still be a problem in operating the business because the franchisor provides a well-established image, a tested and successful operating system, training programme, marketing, advertising, and reservation system, but does not provide the cadre of an experienced manager and the employees necessary to run the business on a day to day basis.

To bridge the gap, management contract companies came into existence. These companies have the required expertise to manage hotels. They operate on the basis of management fee and the sometimes on a percentage of gross revenue.

Time-share Hotels

Time-share hotels, also referred to as vacation-interval hotels , are a new concept in the hospitality industry. As the name suggests, it entails purchasing a tourist accommodation at a popular destination for a particular time slot in a year.

The buyer can then occupy the property for the appointed time or rent the unit to other vacationers if they cannot avail the facilities. They have to make a one-time payment for the time slot and a yearly fee to cover the maintenance costs and related expenses and take a share in the profit from the income generated if they are not utilizing their time slot.

Condominium Hotels

Condominium hotels are similar to timeshare hotels, expect that condominium hotels have a single owner instead of multiple owners sharing a hotel. In a condominium hotel, the owner informs the management company when they would occupy the unit.

The management company is free to rent the unit for the remainder of the year, and this revenue goes to the owner. The owner generally pays a monthly or annual maintenance fee to the management company that takes care of the premises, including landscaping, cleaning of common areas, water, and power supply etc.

Alternative of Hotels Accommodation

Alternative accommodation can be simply defined as ‘ all those types of accommodation that are available outside the formal or organized accommodation sector’ . These establishments provide bed and breakfast and some basic services required by the guest at a reasonable price.

An alternative accommodation, thus, providing sleeping space and modest food for its users. There are certain properties that cater to the needs of a large group.

The lodging houses constructed for the welfares of common travelers, such as sarais , dharmshalas , dak bungalows, circuits, houses, inspection bungalows, lodges, youth hostels, yatri niwas , and forest lodges are the example of alternative accommodation.

Sarai/Dharmshala

These lodging properties are mostly found at popular pilgrimage places. They are generally constructed by welfare trusts, social organizations, or even the state, and provide basic security and sleeping facilities for a nominal fee.

Dak Bungalow/Circuit House

These accommodation are situated in remote areas and at scenic locales. All these properties have an ageless charm and an old world style of hospitality as well as special cuisine, which forms a part of the attraction, apart from the low traffic. Often these are the only lodging properties in remote areas.

Lodge/Boarding House

Lodges are modest hotels situated away from the center of the city or located at a remote destination. These are self-sufficient establishments that offer standard facilities, such as clean and comfortable rooms, food and beverage (F&B) services.

Boarding houses are establishments that usually provide accommodation and meal at a specified period of time, such as weekends, or for a specified time of stay.

Youth Hostel

The youth, from rural as well as urban areas, travel for various reasons, such as education, adventure, and recreation. Youth hostels were established to cater to the youth on the move, who couldn’t afford steep hotel rents.

A youth hostel generally provides low-cost dormitory accommodation with common bathing and cafeteria facilities. They may also provide kitchens for self-catering.

Yatri Niwas

A yatri niwas provides low cost, self-service accommodation to domestic tourists in cities. The emphasis is on modest comfort and affordability. These are generally frequented by people during brief stopovers while traveling between places, or by families with modest budgets.

These properties are located at historical, cultural, and natural sites.

Camping Grounds/Tourist Camps

Camping grounds are normally located within cities in open space. They provide parking spaces along with the water, electricity, and toilets. Camps must follow certain regulation regarding the quality of services and cost and are set up by municipalities.

Railway/Airport Retiring Rooms

A retiring room is for the convenience of the transit travelers. These are situated at a major railway station and domestic and international airports. They provide resting rooms are available at reasonable rates and are often air-conditioned. Booking for the same is made through the station superintendent or the airport manager.

They are equipped with clean sanitation facilities and may include F&B facilities at a cost.

Paying Guest Accommodation

A paying guest (PG) accommodation is a non-institutional accommodation offered by individual households at various destinations. Besides tourist haven like Goa, this kind of accommodation is becoming popular in large metropolitan cities among outstation students and the employed youth migrants from other towns.

Guests normally pay for accommodation, while the rules for F&B services may differ from host to host.

Hotel Traffic Plans

The various traffic patterns followed by hotels have come to be identified with the area where such patterns originated. Hotels charge their guest according to European, Continental, American, Bed and Breakfast meal plans, etc. We shall briefly discuss these plans. These are followed as:

European Plan

The tariff consists of room rate only. All other expenses would be paid by the guest as per the actual use of consumption.

Continental Plan

The room tariff includes continental breakfast, along with the room rent. Continental breakfast includes a choice of fresh or canned juices; bread like the croissant, toast, brioche, etc. with butter or preserves like jam, jellies, and marmalade; beverage like tea or coffee, with or without milk.

American Plan

It is also known as en-pension or full board . The tariff includes all meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) along with the room rent. The menu for the food and beverage is fixed.

Modified American Plan

It is also known as demi-pension or half board. The tariff consists of breakfast and one major meal (lunch or dinner) along with the room rent.

Bed & Breakfast (B&B) or Bermuda Plan

The room traffic includes American breakfast along with room rent. American breakfast includes most or all of the following: two eggs (fried or poached), sliced bacon or sausage, sliced bread or toast with jam/jelly/butter, pancakes with syrup, cornflakes or other cereal, coffee/tea, and orange/grapefruit juice.

Types of Hotel Guest Rooms

A hotel sells a combination of accommodation, food, drinks, and other services and facilities to its guests. The main accommodation product is the room, which is among the principal source for the hotel. Other facilities and benefits such as ambiance, décor, in-room amenities, and security, are the add-on that plays a significant role in the pricing of the services.

In order to suit the profile and pocket of various guests, hotels offer different types of rooms that cater to the specific need of guests. The rooms may be categorized on the basis of the room size, layout, view, interior decoration, and services offered. The various types of rooms offered by a hotel are as follows:

Single Room

A single room has one single bed for single occupancy. An additional bed (called extra bed) may be added to this room on the request of a guest and charged accordingly. The size of the bed is normal 3 feet by 6 feet. However, the concept of single rooms is vanishing nowadays. Mostly, hotels have twin or double rooms and charge for the single room, if occupied by one person.

A twin room has two single beds for double occupancy. An extra bed may be added to this room on the request of the guest and charged accordingly. The bed size is normally 3 feet by 6 feet. These rooms are suitable for sharing accommodation among a group or delegates meeting.

Double Room

A double room has one double bed for double occupancy. An extra bed may be added to this room on the request of a guest and charged accordingly. The size of the double bed is generally 4.5 feet by 6 feet.

Triple Room

A triple room has three separate single beds and can be occupied by three guests. This type of room is suitable for groups and delegates of meetings and conferences.

A quad room has four separate single beds and can accommodate four persons together in the same room.

Hollywood Twin Room

A Hollywood twin room has two single beds with a common headboard. This type of room is generally occupied by two guests.

Double-Double Room

A double-double room has two double beds and normally preferred by a family or group as it can accommodate four persons together.

A king room has a king-size bed. The size of the bed is 6 feet by 6 feet. An extra bed may be added to this room on the request of a guest and charged accordingly.

A queen room has a queen-size bed. The size of the bed is 5 feet by 6 feet. An extra bed may be added to this room on the request of a guest and charged accordingly.

Interconnecting Room

Interconnected rooms have a common wall and a door that connects the two rooms. This allows guests to access any of the two rooms without passing through a public area. This type of room is ideal for families and crew members.

Adjoining Room

Adjoining rooms share a wall with another hotel room but are not connected by the doors. For eg. Room no. 201 and 202, 203, and 204, 205 are adjoining as each pair of rooms shares a common wall.

Adjacent Room

An adjacent room is very close to another room but does not share a common wall with it.

Parlor Room

A parlor room has a living room without a bed and may have a sofa and chairs for sitting. It is generally not used as a bedroom.

Studio Room

A studio room has a bed and a sofa-cum-bed and is generally used as a living room.

A cabana is situated away from the main hotel building, in the vicinity of a swimming pool or sea beach. It may not have beds and is generally used as a changing room and not as a bedroom.

A suite comprises more than one room; occasionally, it can also be a single large room with clearly defined sleeping and sitting areas. The décor of such units is of very high standards, aimed to please the affluent guest who can afford the high traffic of the room category.

A duplex suite comprises two rooms situated on different floors, which are connected by an internal staircase. This suite is generally used by business guests who wish to use the lower level as an office and meeting place and the upper-level room as a bedroom. This type of room is quite expensive.

Efficiency Room

An efficiency room has an attached kitchen and bathroom for guests preferring a longer duration of stay. Generally, this type of room is found on holiday and health resorts where the guest stays for a longer time.

Hospitality Room

A hospitality room is designed for hotel guests who would want to entertain their own guests outside their allotted rooms. Such rooms are generally charged on an hourly basis.

A penthouse is generally located on the topmost floor of hotels and has an attached open terrace or open sky space. It has very opulent décor and furnishings and is among the costliest rooms in the hotels, preferred by celebrities and major political personalities.

A lanai has a veranda or roofed patio and is often furnished and used as a living room. It generally has a view of a garden or sea beach.

Top Leaders in Hospitality Industry

They are those persons who contribute in the hospitality industry a lot. Some famous names are following as:

Ellsworth Statler

Ellsworth Statler is a famous name in the field of hospitality as he was one of the pioneers of this industry and contributing and contributed immensely to the development of the hospitality industry through his innovative ideas, which are still applicable in the various fields of the hospitality industry.

In 1908 A.D., he opened as an innovative hotel of its own kind during that time called Buffalo Statler which had the room with some modern facilities such as attached bathrooms, telephone facilities, and restaurant facilities.

Statler also contributed a great deal towards the international marketing efforts in the field of the hospitality industry. Statler was also very popular among his employees, as he believed in the concept of the internal marketing as he used to consider his employees as internal guests.

Conrad Hilton

Conrad Hilton is also a very famous name in the field of hospitality and was one of the pioneers of the modern hotel industry. Hilton becomes a famous and successful hotelier after World War I when he brought the Mobley hotel in Texas and built the Hilton Hotels in Dallas, Texas in 1925. After the World War II, he formed the Hilton Hotels Corporation in 1946 and then he formed Hilton International Company, which had about 125 hotels under its banner.

Hilton was the first major and organized hotel chain of American hotels when Conrad Hilton purchased the Statler chain of hotels in 1954. Today Hilton Hotels are spread in most of the countries of the world and includes Conrad International, Doubletree, Red Lions Hotels, Harrison Conference Centers, Homewood Suites and Embassy Suites.

J. Willard Marriott

J.W Marriot was another pioneering name in the world of the hospitality industry. He started the Marriott Chain of Hotels and thus became a frontline leader in the field of hospitality. He was thoroughly aware of the employees/consumer relationship and tried to make sure that his employees were totally satisfied with their job and working environment.

He had a strong marketing brain and could forecast the importance of airline catering business for various airlines operations and was the first to enter in the field of hospitality. In today scenario, Marriot Corporation is one of the leading companies in the field of hospitality with an annual sale of $7.5 billion and has a variety of food and beverage service operation under his banner.

The lodging chain of Marriott includes Marriott Hotels and Resorts, Marriott Suites, Residence Inns, Courtyard Hotels and Fairfield Inns.

Ralph Hitz was also a very popular personality in the hospitality industry. He was the head of a large hotel organization in U.S.A called the National Hotel Company. His hotel management used to receive a management fee for running day by day administration of hotel owned by real estate investors.

Hitz had excellent marketing brain, as he was the first intellectual to develop a customer database for providing the guests of hotels with personalized service leading to guest satisfaction and overall profitability of the hotels. Hitz also believed in training and motivating the employees of the hotels to give and improved services for guest satisfaction.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 28 November 2022

Architectural characteristics of accommodation buildings within the context of sustainable ecotourism in Cyprus: evaluation and recommendations

- Miray Dizem Üzümoğlu nAff2 &

- Zihni Turkan 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 9 , Article number: 422 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

2268 Accesses

2 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cultural and media studies

- Science, technology and society

Tourism, a socioeconomic activity generally defined as an exchange of culture, is diversified by its different purposes. Ecotourism, which emerged and has been constantly developing in the last quarter century, is based on the principles of protecting the natural environment and recognising the original local culture in an interaction with the environment. As significant components of tourism activities, accommodation structures play a major role in the realisation of ecotourism. Due to its location, cultural heritage and rich history together with its Mediterranean climate, Cyprus is an especially important tourism destination for people from Middle East and European countries. The traditional living culture in this small island country has created a huge demand for ecotourism in Cyprus. The ecotourism industry in Cyprus provides housing structures restored with the traditional architectural characteristics of the island as well as new buildings. The new accommodation structures should be constructed in compliance with the traditional architectural characteristics of Cyprus to contribute to the island’s cultural tourism. Our study was conducted through a literature review regarding the main concepts of tourism and ecotourism and on-site field work on the architectural characteristics of existing ecotourism accommodation structures located in the ecotourism villages of Cyprus. In consideration of the field study findings, this study also proposes recommendations that could be a model for the architectural characteristics of new accommodation structures to be constructed for sustainable ecotourism in Cyprus. Within the framework of our study, the location, construction date, and architectural characteristics of fifteen accommodation structures were selected from Cyprus ecotourism villages; their layout and sketch drawings were completed using measurements and observations, while outdoor-indoor photographs were taken. As a result of these findings and based on the common architectural characteristics of existing ecotourism accommodation structures, the architectural characteristics of future accommodation structures have been identified accordingly.

Similar content being viewed by others

A geographical perspective on the formation of urban nightlife landscape

Yi Liu, Yifan Zhang, … Ying Zhao

Aula Verde (tree room) as a link between art and science to raise public awareness of nature-based solutions

A. Conte, R. Pace, … L. Passatore

Implications of ideology on school buildings and cultural pluralistic context of Gazimağusa, North Cyprus

Ejeng B. Ukabi & Huriye Gurdalli

Introduction

Tourism is generally defined as a consumer’s act of travelling and obtaining temporary accommodation at a place other than their permanent residence for holiday relaxation and recreational purposes (Yörük, 2003 ). Tourism, which is performed by changing locations for various reasons, comprises social, cultural, sports and special interest activities. Specific places and regions are chosen for different purposes and activities, making it possible to diversify. Accommodation buildings, among other tourism facilities, are vital components of tourism activities. Accommodation buildings that first provide a safe shelter for individuals and meet their various needs, such as comfort, relaxation, food and beverages, and entertainment, are categorised as hotels, motels, holiday resorts, bed and breakfasts, mountain resorts and thermal facilities (Kozak et al., 2014 ).

With its significant place among the various types of tourism, ecotourism, which emerged in the 1980s, is an important tourism activity for cultural exchange between countries. Ecotourism, namely, ecological tourism, can be defined as travel to natural and ecologically uninterrupted areas or regions (Özhan, 2007 ). Ecotourism accommodation buildings have characteristics that differ from the others, and they are similar to boutique hotels that are compatible with their natural surroundings while providing quality services. Eco-accommodation structures minimise the environmental impact on natural and cultural assets and involve landscape design and gardens and sustainable design construction, use green technologies, integrate the local community into the development and implementation of eco-accommodation buildings, and ensure environmental and cultural education for its visitors (Hakim and Nakagoshi, 2014 ). Accommodation structures, which are crucial for tourism activities, play an important role in the promotion and maintenance of traditional living culture for their visitors.

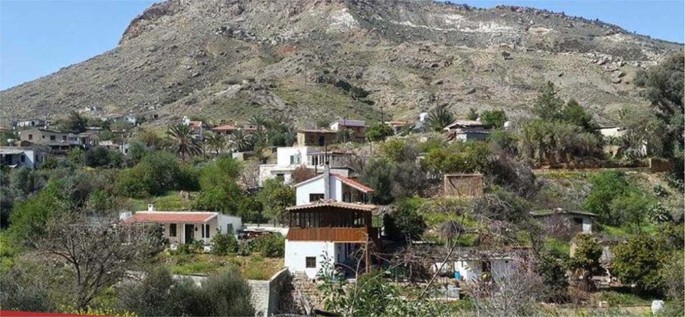

For centuries, Cyprus has been an important tourism centre due to its geographical location, Mediterranean climate, rich history and cultural heritage. As an island in the Mediterranean, Cyprus connected with other countries via the sea and maintained trade relations. The arrival of people from other countries began with British administrative and military officers during the British administration (1878–1960) (Turkan, 2008 ). After the division of the island in 1974 into north and south, Ercan Airport was opened in 1976, connecting the north with the outside world through means other than sea transportation. In the early 1980s, tourism became more active in Cyprus, and small holiday resorts were built and opened (Bıçak and Turkan, 2018 ). Since the 2000s, most accommodation buildings, particularly those along the eastern and northern coastlines, have been multi-storey and luxurious modern buildings that provide services based on the triangle of sea, bed, and sea (Ölçer, 2011 ; Emekli, 2003 ).

The residents of the island managed to continue their rural life and traditional living culture since the distances between the settlements are not too far and transportation is easy. The sustainable traditional lifestyle on the island provided positive conditions for ecotourism. Since 2005, Bağlıköy (Ambelikou), Büyükkonuk (Komi Kebir) and Dipkarpaz (Risokarpaso) were selected for the introduction of ecotourism, and the houses built with local architectural characteristics were restored and transformed into boutique hotel-style buildings. Annual ecotourism days are organised for the exhibition and selling of local food, beverages and handcrafts; and folk dance and various rural life events are held, all of which promotes and preserves the traditional life and cultural assets of Cyprus.

Ecotourism has recently become popular in Cypriot domestic and foreign tourism. The housing buildings at the related villages reflecting the traditional architectural characteristics of the island have been restored for use in ecotourism, and additional spaces and new accommodation buildings have been constructed to eliminate the shortcomings. These ecotourism accommodation buildings were chosen as the subject matter of our study with the aim of contributing to the improvement and sustainability of ecotourism since the traditional cultural assets of the island can only be promoted through accommodation buildings with traditional architectural characteristics. Because of this, future ecotourism accommodation buildings should be designed and built with the traditional architectural nature of the island.

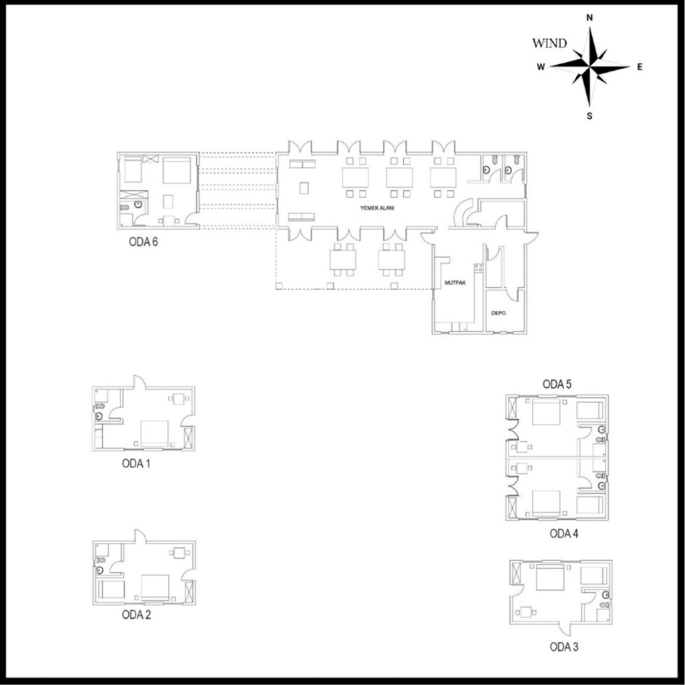

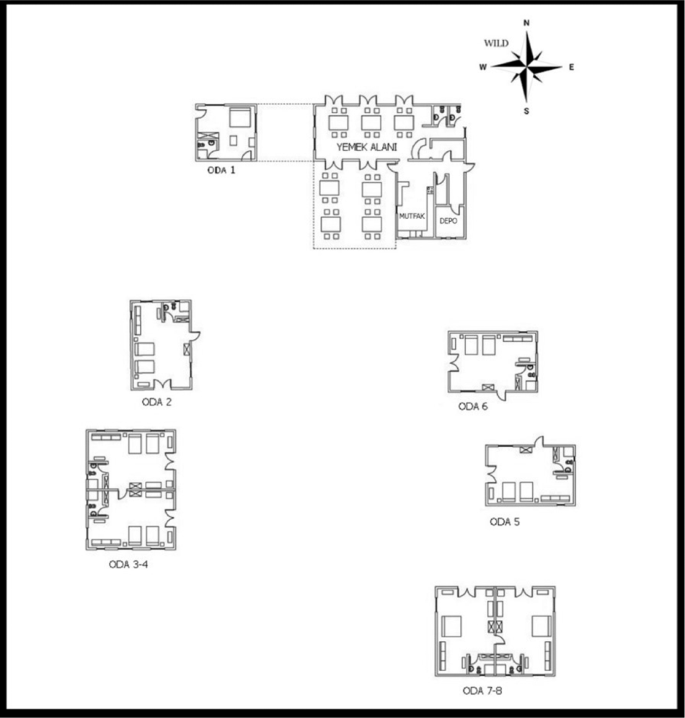

Since the early 2000s, ecotourism has become so important among worldwide tourism activities that Cyprus’s domestic and foreign tourism visitors prefer ecotourism as their first choice. In line with such choices, there is an increasing need for accommodation buildings as a significant component in ecotourism. Considering the findings from our field studies on the architectural characteristics of the existing accommodation buildings in ecotourism villages, which were conducted to support the sustainability of ecotourism activities in Cyprus, the aim of this study is to make recommendations on the architectural characteristics of future ecotourism accommodation buildings that would promote and maintain the traditional living culture and all other local cultural heritage through spaces with traditional architectural characteristics of the island furnished with local authentic fittings.

Cyprus is an important tourism destination due to its location, rich historical and cultural heritage and Mediterranean climate (Bıçak and Turkan, 2018 ). Cyprus is particularly compatible with the notion of ecotourism since rural areas that are very close to urban life opportunities yet merged with nature still operate in a traditional way. The existing accommodation buildings used in tourism activities are not sufficient in terms of reflecting and promoting the historical pattern, traditional architecture and living culture of the island; hence, they cannot be useful for ecotourism. Therefore, there are not enough accommodation buildings in the villages to meet the increasing demand for ecotourism. As a result of our study, we identified the architectural characteristics that have a major role in the island’s ecotourism activities and proposed these for the design of accommodation buildings. While there are various studies on ecotourism in Cyprus, our study is the first detailed and comprehensive study on how ecotourism accommodation buildings contribute to the promotion of ecotourism through future accommodation buildings with the proposed architectural characteristics. Moreover, the study findings make a major contribution to the correct performance and sustainability of ecotourism through the new ecotourism facilities to be built with the proposed architectural characteristics.

Starting from the concept of tourism as the basis of our research, the types of tourism, the accommodations in tourism, the concept of ecotourism and its properties and effects, the ecotourism villages in Cyprus, the architectural characteristics of accommodation buildings in such villages and the architectural characteristic recommendations for the design of new ecotourism accommodation buildings are the focus of our study.

The research process table is shown in Table 1 .

Theoretical framework

Ecotourism is generally defined as nature-conscious travel that aims to protect the environment and consider the welfare of the local community (Ayman, 2013 ). In other words, the concept of ecotourism comprises travels to visit or study the landscape, flora and fauna, and activities unique to such places (Soykan, 2003 ). According to Elizabeth Boo, ecotourism is nature-oriented tourism protecting nature and improving tourism by fundraising for parks, protected areas and surrounding communities and organising environmental training courses for the local community (Erkut, 2005 ). Kutay noted that ecotourism is considered a development model at natural sites and is planned as a part of biological source-based tourism within a socioeconomic structure (Özyaba, 2001 ). The World Tourism Organisation recognises ecotourism as responsible travel to natural areas with the aim of protecting the environment and enhancing the welfare of the local community. Ecotourism, which has grown and continues to grow, involves travelling to a place where the natural environment and unique culture are protected and where tourists can interact with their surroundings to learn about the local community and culture (Özhan, 2007 ). The concept of ecotourism was first used by Hector Ceballos-Lascurain in 1983. According to Hector Ceballos-Lascurain, ecotourism has the least impact on the environment; it covers visits to unspoiled or unpolluted natural areas with the special purpose of analysing, observing and living with the landscape, wildlife and rural concepts. The most important aspect of ecotourism is the inclusion of the local community; hence, socioeconomic benefits are acquired (Boo, 1993 ).

The trend in ecotourism has the fastest growth among the worldwide tourism industries. The most important factors that provide significance to ecotourism are as follows (Hawkins and Lamoureux, 2001 ):

International awareness.

Desire for nature-oriented experience.

Necessity to preserve natural resources for future generations.