Mechanical doping claims resurface at Tour de France

Three anonymous riders claim to hear 'strange noises' from four team's rear wheels during the race

The spectre of mechanical doping has reared its head once again at the Tour de France following a report citing several unnamed riders claiming to hear "strange noises" in the rear wheels of a number of team's bikes at the race.

An article published by Swiss newspaper Le Temps on Thursday alleged that three separate riders at the Tour had heard noises they had never heard before coming from bikes involving four teams at the race.

According to the report , one rider told the newspaper during the first week of the race that he was hearing odd new noises coming from the rear of several bikes. During the race, the UCI had announced that no forms of mechanical doping had been detected.

"There is a strange noise. I can hear it while riding. It comes from the rear wheels. A strange metallic noise, like a badly adjusted chain. I've never heard that anywhere," the rider said.

Tadej Pogacar says there is nothing illegal about his bike at Tour de France Tour de France leader Pogacar: Maybe one day I will publish my data French inquiry into mechanical doping dropped for lack of evidence

Two days later, the same rider reported back pointing out that the four teams that featured the noises coming from their rear wheel. "Four teams have this little sizzle in the rear wheel," he said.

Another rider said that talk in the peloton isn't about a motor in the crankset or seat-tube – the most popular rumour that has been circulated about possible mechanical doping in the past decade or so. Instead, he talked of an energy recovery system similar to the technology used in Formula 1 cars.

"There is no longer talk of a motor in the crankset or an electromagnet system in the wheel rims, but of a device hidden in the hub," he said. "We are also talking about an energy recuperator via the brakes. The inertia is stored like in Formula 1."

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

A third rider, not quoted in the article, is also reported to have raised concerns about the situation. One of the riders noted the relative strength of the four teams in question, with 13 of the 19 stages so far having been shared among them.

"Who will dare to speak out? We're not doing anything, and the situation is serious," one of the riders said. "Usually, we have a team that dominates. Or a team that is weaker than the others. That's sport... This year, four teams are far above the rest. The smallest rider who signs with them becomes very strong. If he changes team, he becomes average again. How can you explain that?"

Following Friday's stage 18, race leader Tadej Pogačar, who rides for UAE Team Emirates, denied that his bike was in any way illegal.

"I don't know. We don't hear any noise," Pogačar said in the post-stage press conference. "We don't use anything illegal. It's all Campagnolo materials, Bora. I don't know what to say."

On Monday's rest day, the UCI announced technological testing figures for the first 15 stages of the Tour, with nothing suspicious found after 720 tests had been carried out, including testing with magnetic scanning tablets and X-ray technology.

"A total of 720 tests have been conducted before and after every stage. All tests have come back negative," read the UCI statement.

"Of the tests carried out, 606 were conducted on bikes before the start of each stage using magnetic scanning tablets. Meanwhile, X-ray technology was used to test another 114 bikes at the end of each stage.

"The UCI underlines that the post-stage testing pool always includes the bike ridden by the winner of that day's stage as well as the leader of the general classification. The remainder of the post-stage testing pool is decided on a two-pronged approach: bikes selected by the UCI based on its information and intelligence, and bikes ridden by athletes selected for targeted anti-doping controls by the International Testing Agency (ITA), the independent body in charge of the UCI's anti-doping activities."

The statement continued with an announcement that a new form of testing will debut at the upcoming Tokyo Olympic Games, with mobile technology able to scan bikes on the move, rather than just before or after races.

"After the introduction of magnetic tablets in 2016 and mobile X-ray technology in 2018, a new backscatter technology will be used to test bikes at the Tokyo Olympic Games. This relatively compact and light hand-held device provides instant images of the interior of the bike that can be shared in real-time to anywhere in the world via a secure platform. It will be used in Tokyo at the road, mountain bike and track cycling events."

So far, only one rider has ever been caught and banned for mechanical doping. Cyclo-cross rider Femke Van den Driessche was banned for six years in 2016 after a motor was discovered in a bike with her pit crew at the Cyclo-cross World Championships that year.

In 2020, the French National Financial Prosecutor's Office (PNF) ended a multi-year investigation into mechanical doping at the sport's top level earlier this year without finding any further evidence of the practice.

A tech writer's analysis

Cyclingnews tech writer Josh Croxton gives his thoughts on the allegations:

Having not heard the noise that these anonymous riders are claiming to have heard, it's impossible to say what it's likely to be.

With that said, chains interacting with cassettes and derailleurs all make a noise, some are louder than others, and each setup will likely have a different pitch to the noise.

All four of the mentioned teams use groupsets that have been around for years already. Three of the teams use Shimano Dura-Ace R9170, while the fourth team use Campagnolo SuperRecord EPS 12-speed, and they all use stock components – there are no aftermarket pulley wheel systems attached to derailleurs.

They have all likely swapped out the stock bearings for oiled ceramic bearings, but even so, the noise of the chain interacting with the pulleys and the cassette shouldn't be anything that riders haven't heard before.

One thing that has changed in recent times is the use of waxed chains. It's not a new technology by any means – certainly not new to the 2021 Tour de France – and it's impossible to know for sure which teams are using waxed chains instead of a typical oil-based lubricant, but with the promise of a more efficient drivetrain, it's possible that more teams have made the switch.

One of the named teams, for example, are sponsored by CeramicSpeed and are running the brand's pre-treated UFO race chains. However, for any teams treating chains themselves, these chains need time to 'break in', since the wax dries and hardens. During that initial 10 kilometres or so, chains are considerably noisier than average.

That aside, unfortunately, there's no common denominator between the components used by the four mentioned teams. One team have used Vision wheels, another team has used both Vision and Shimano, while one are on Roval and the fourth team use Campagnolo wheels.

Ultimately, while these claims are very intriguing, there's very little to substantiate them at this stage.

Thank you for reading 5 articles in the past 30 days*

Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read any 5 articles for free in each 30-day period, this automatically resets

After your trial you will be billed £4.99 $7.99 €5.99 per month, cancel anytime. Or sign up for one year for just £49 $79 €59

Try your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Dani Ostanek is Senior News Writer at Cyclingnews, having joined in 2017 as a freelance contributor and later being hired full-time. Prior to joining the team, they had written for numerous major publications in the cycling world, including CyclingWeekly, Rouleur, and CyclingTips.

Dani has reported from the world's top races, including the Tour de France and the spring Classics, and has interviewed many of the sport's biggest stars, including Wout van Aert, Remco Evenepoel, Demi Vollering, and Anna van der Breggen.

As well as original reporting, news and feature writing, and production work, Dani also oversees The Leadout newsletter and How to Watch guides throughout the season. Their favourite races are Strade Bianche and the Volta a Portugal.

'You can never count us out' - Matteo Jorgenson warns against underestimating Visma in Tour of Flanders

Former Tour of Flanders winner Asgreen predicts 'new dynamic' on Sunday

Cancellara’s Classics column: Attack might be Mathieu van der Poel’s best form of defence in chaotic Tour of Flanders

Most Popular

By Stephen Farrand March 29, 2024

By Jackie Tyson March 28, 2024

By Dani Ostanek March 28, 2024

By Tom Wieckowski March 28, 2024

By James Moultrie March 28, 2024

By Simone Giuliani March 28, 2024

- off.road.cc

- Dealclincher

- Fantasy Cycling

Support road.cc

Like this site? Help us to make it better.

- Sportive and endurance bikes

- Gravel and adventure bikes

- Urban and hybrid bikes

- Touring bikes

- Cyclocross bikes

- Electric bikes

- Folding bikes

- Fixed & singlespeed bikes

- Children's bikes

- Time trial bikes

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Child seats

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Arm & leg warmers

- Base layers

- Gloves - full finger

- Gloves - mitts

- Jerseys - casual

- Jerseys - long sleeve

- Jerseys - short sleeve

- Shorts & 3/4s

- Tights & longs

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Gear levers & shifters

- Handlebars & extensions

- Inner tubes

- Quick releases & skewers

- Energy & recovery bars

- Energy & recovery drinks

- Energy & recovery gels

- Heart rate monitors

- Hydration products

- Hydration systems

- Indoor trainers

- Power measurement

- Skincare & embrocation

- Training - misc

- Cleaning products

- Lubrication

- Tools - multitools

- Tools - Portable

- Tools - workshop

- Books, Maps & DVDs

- Camping and outdoor equipment

- Gifts & misc

Cheating at the Tour de France — a rich history dating back 120 years

The sight of a couple of dozen riders holding on to team cars as they went up the Stelvio in the Giro Next Gen under-23 race earlier this month shows that when it comes to cheating in cycling, it’s often a case of Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose – go back 120 years to the early years of the Tour de France and you’ll find riders ejected from the race for slipstreaming cars, or even taking a lift in one.

That got us thinking about some of the more egregious and bizarre forms of cheating that cycling’s biggest race has seen down the years, as well as examples of riders who have pushed the rules as far as they will go while keeping to the letter, if not quite the spirit, of the regulations that govern the race.

> A brief history of motor doping in cycling

Our selection is by no means exhaustive, so feel free to add chip in with other examples in the comments. Given the sport’s history, we’ve not addressed anything here that is drug-related – but will do in a separate article coming here shortly on road.cc.

Maurice Garin - letting the train take the strain

The Giro d'Italia may have its own train now... but riders still aren't allowed on it

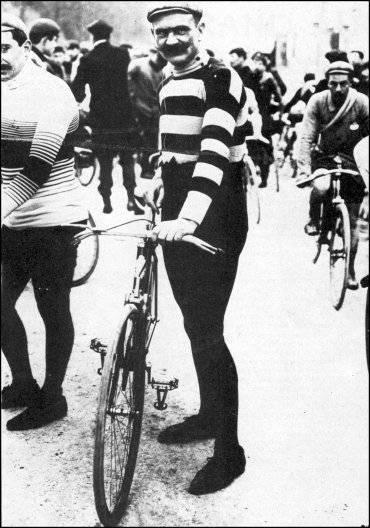

The first edition of the Tour de France in 1903 saw a couple of riders sanctioned for drafting cars, plus a fair bit of skulduggery by overall winner Maurice Garin – but it was the following year that provided some of the most egregious examples of rule-breaking in the Grand Boucle’s infant years, and very nearly led to the race being scrapped altogether.

Garin, winner of the opening stage in 1904, appeared to have successfully defended – only to be disqualified, alongside 11 other riders including the rest of the top on the general classification, and the winners of all six stages, for illegally taking trains, or riding in cars, for part of the route.

His disqualification, accompanied by a two-year ban, followed a four-month investigation by the Union Vélocipédique Française (UVF) and resulted in Henri Cormet, who had finished fifth overall (and had also been warned during the race after getting a lift in a car) being awarded victory, and at 19 he remains the youngest ever winner of the Tour.

Wacky Races

That wasn’t the full extent of the cheating at an edition of the race that comes across as something akin to the 1970s Wacky Races cartoon featuring Dastardly and Muttley. During Stage 2, race officials had to fire shots in the air to disperse a 200-strong crowd that had assembled to cheer on their favourite, Antoine Fauré , with rival riders including Garin attacked and glass and nails spread on the road. Other shenanigans involved itching powder being poured into rival riders’ shorts.

The prize for inventiveness that year though surely goes to Hippolyte Aucouturier (above), who had been forced to abandon the first edition due to food poisoning (possibly due to a drink being spiked) and who returned to the race in 1904, winning four stages, only to be disqualified for taking a tow from a motor car by – and this may put your teeth on edge – chomping down on a cork attached, via string, to the vehicle.

Eugene Christophe - a myth is forged

During the sixth stage of the 1913 Tour de France, disaster struck Eugene Christophe, who had led his rivals over the Col du Tourmalet by 18 minutes on a brutal day in the Pyrenees when he realised there was a problem with his bike and discovered his front forks had broken. With no outside help permitted, all he could do was sling his bike over his shoulder and try and find somewhere to fix it.

It’s part of Tour mythology that Christophe was thrown off the race because, despite fixing the broken forks himself, the blacksmith’s boy in Ste-Marie-de-Campin had operated the bellows for the fire, which was deemed outside assistance and thereby cheating. In fact, the watching officials only docked him 10 minutes for that – but with his rivals by now hours down the road, his chance of victory had long gone. To add insult to injury, the car that had crashed into him, causing his front forks to break belonged to the organisers.

Jean Robic - heavy metal descender

An example of pushing the rules as far as they could go to gain an edge came from Jean Robic, who in 1947 won the Tour de France the first time it was raced following World War 2. Breaking an unwritten rule (and not, therefore, cheating, albeit guilty of unsportsmanslike behaviour), he attacked the yellow jersey on the last stage to Paris, which he began third overall.

Once dispensing with the race leader, Robic then bribed the eventual runner-up to ensure his victory. He’s perhaps best remembered though for a rather innovative approach to descending, which would involve him picking up bottles containing lead from team staff at a summit, adding weight – and thereby greater speed – to his descent. Once organisers got wise to what was happening and banned solid metal, he switched to mercury. Many copied him, but Robic was the pioneer.

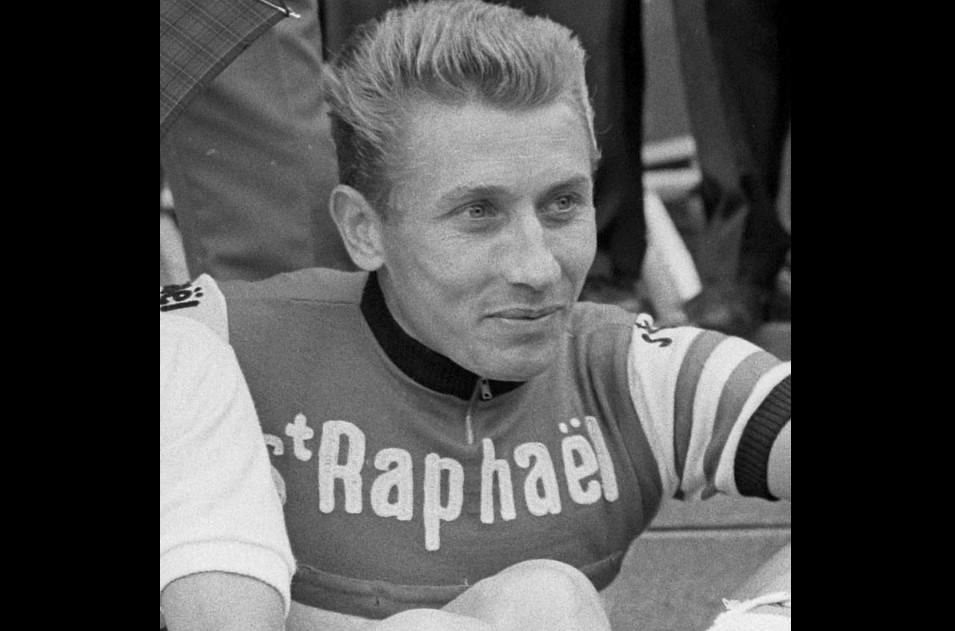

Anquetil’s broken gear cable

Bike changes ahead of a major climb aren’t an uncommon sight these days – but at the Tour it’s only been permitted since 1964, except where the bike being ridden developed a mechanical problem. The previous year, it had been a broken gear cable that allowed Jacques Anquetil to swap bikes to a lighter, lower-geared model ahead of the Stage 17 climb of the Col de la Forclaz in the Swiss Alps.

If that seems like fortuitous timing, with Anquetil going on to clinch his fourth overall win, there was a reason for that – the ‘snapped’ gear cable was a trick devised by Anquetil and his team manager, Raphael Géminiani to get around the rules. Anquetil would win the stage from Federico Bahamontes and take the yellow jersey from the Spaniard ahead of winning the race in Paris four days later.

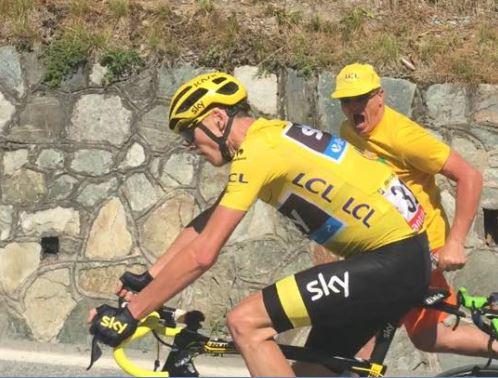

Froome has a hunger bonk

Stage 18 of the 100th Tour de France in 2013 saw eventual winner Chris Froome extend his lead over his rivals on his way to succeeding team-mate Bradley Wiggins as champion – although it could have been a disastrous day for the Team Sky rider had it not been for a deliberate decision to break the rule regarding not being allowed to obtain food or drink in the closing 10km of the stage.

> Chris Froome nearly cracks on Alpe d'Huez

On a stage that included an unprecedented double ascent of the Alpe d’Huez, Froome was flagging badly as the race tackled the famous hairpins for the second time. With 5k left, he sent Richie Porte back to the team car for an illegal gel and water bottle – the calculation no doubt being that the penalty imposed by the race jury would be less than the time he’d have lost without refuelling.

As we said at the top, this article aims to look at aspects of cheating within the Tour beyond those associated with doping, which has always been a feature of the race, and came close to threatening its existence with the Festina affair that broke 25 years ago at a time when drugs cheats dominated the race – an issue we’ll be looking at in more detail soon, but if in the meantime you have your own favourite examples of (non-drugs-related) cheating at the Tour, please let us know in the comments below.

Help us to fund our site

We’ve noticed you’re using an ad blocker. If you like road.cc, but you don’t like ads, please consider subscribing to the site to support us directly. As a subscriber you can read road.cc ad-free, from as little as £1.99.

If you don’t want to subscribe, please turn your ad blocker off. The revenue from adverts helps to fund our site.

Help us to bring you the best cycling content

If you’ve enjoyed this article, then please consider subscribing to road.cc from as little as £1.99. Our mission is to bring you all the news that’s relevant to you as a cyclist, independent reviews, impartial buying advice and more. Your subscription will help us to do more.

Simon joined road.cc as news editor in 2009 and is now the site’s community editor, acting as a link between the team producing the content and our readers. A law and languages graduate, published translator and former retail analyst, he has reported on issues as diverse as cycling-related court cases, anti-doping investigations, the latest developments in the bike industry and the sport’s biggest races. Now back in London full-time after 15 years living in Oxford and Cambridge, he loves cycling along the Thames but misses having his former riding buddy, Elodie the miniature schnauzer, in the basket in front of him.

Add new comment

Quote: During Stage 2, race officials had to fire shots in the air to disperse a 200-strong crowd that had assembled to cheer on their favourite, Antoine Fauré , with rival riders including Garin attacked and glass and nails spread on the road.

Whereas that's now something that only happens on commutes...

- Log in or register to post comments

Isnt it funny how we look down on some forms of cheating but fully accept and even embrace others. The assistance from a moving vehicle (aka sticky bottle) springs to mind. The only time i have ever booed anyone in a sporting event was watching someone being pulled up Caerphilly mountain in the Tour of Britain a few years ago, so blatant and obvious that you have to wonder what other form of cheating these people commit. At least there has been a clamp down on the "magic spanner" con.

Latest Comments

I'm not saying it's easy but I'm pretty sure there are examples of legislating in just such a manner. Question is would this be enforced at all? ...

But LeCol designs are poor, bar the all black jersey,this looks to have had some thought go into it, but £185 for a jersey is daft....

the carpet pedals also facilitate time travel - gettign everywhere earlier than planned

I'll steal the 3000th post with a positive story....

The Radcliffe First thread is on Facebook here:...

https://www.velocitycyclewear.cc/ https://www.swrve.co.uk/collections/trousers# https://www.giro.com/c/mens-bike-apparel/

I have a couple of sets of Jones's plugs from their grips which I keep trying to remember to take into work, Hope grip doctors for the Ultimate...

So every 'occasion' he is convicted is an average of just over 6 months of his adult life, presumably will be able to keep up the average if he...

Ah, welcome to the cognotive dissonance of 'true cycling fans', for whom the purity of the sport is all, the Velominati isn't satire, and doping is...

Everything you need to know about the motorised doping scandal

As the 'technological fraud' scandal heats up, here is everything you need to know about the history of motorised doping

- Sign up to our newsletter Newsletter

Femke Van Den Driessche

The cycling world is in a frenzy about 'technological fraud', with riders, managers and race organisers calling for a full investigation into whether motors are being hidden in bikes used in races.

Motorised doping, as it's colloquially been dubbed, has been rumoured for years , but the discovery of a motor in a spare bike of Femke Van den Driessche at the U23 cyclo-cross World Championships in January gave some foundation for the previously dismissed allegations.

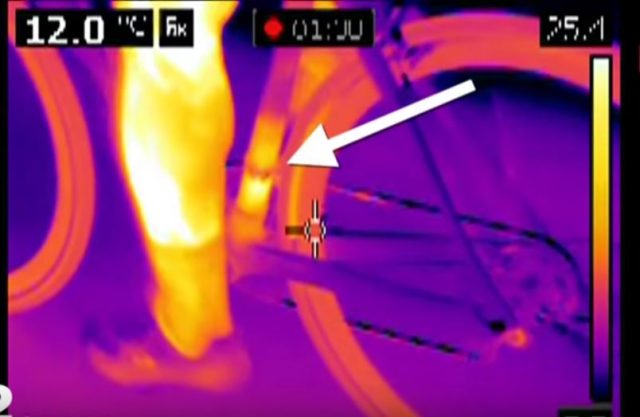

The UCI started scanning bikes for motors at races using a magnetic resonance app, but a report on French television claimed that heat sensors picked up motors in seven bikes at two top Italian races.

How is it done? Why do riders do it? And what can be done to stop it? All questions we hope to answer here.

How is it done?

It sounds easy to do and hard to spot - putting a motor in a bike doesn't seem to be rocket science.

In layman's terms, all you need to do is slip a small motor into your seat tube with a gear that will power your bottom bracket axle and your pedals will essentially go round on their own.

While the motor will require a battery pack, this can also be stored down the seat tube if you're on a bike with at least a 30.9mm tube diameter in order to disguise it from your fellow competitors and prying eyes from the UCI.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

If set up correctly, the motor can be started and stopped with a touch of a button, allowing you a boost when you need it the most.

More advanced methods include using electromagnetic wheels to gain extra power.

Why is it done?

As Greg LeMond famously said, cycling "doesn't get any easier, you just get faster", but with a motor in your bike cycling does get easier and you will get faster.

Winning bike races often comes down to making a move in a decisive moment, one which could only last two or three seconds.

Imagine you're riding the Tour de France and riding up mountains for days on end - having a motor in your bike could give you a few minutes respite, leaving you slightly fresher than your opponents when you need it the most.

>>> Great Britain team manager slams electric motor cheating

In a race like Paris-Roubaix , an attack when your opponents are floundering could be the difference between getting your own cobblestone and being known as the perennial runner-up. Having assistance in your pedals could give you the extra boost you need to distance yourself from your rival.

Many of us have been out on rides, slogging away into the wind and been overtaken by someone on an e-bike who's making it look like a leisurely spin - we're always looking for ways to make cycling easier.

With money, reputation and sponsorship on the line at races, professional riders and teams are always looking for ways to win races, and now it seems that putting motors in bikes is a way to do that.

A brief history of motorised doping allegations

Davide Cassani accuses Fabian Cancellara in 2010

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Nd13ARuvVE

Allegations of motorised doping first really appeared when former professional rider Davide Cassani suggested that suspicious hand movements by Fabian Cancellara in the 2010 Paris-Roubaix and Tour of Flanders indicated a motor in his frame.

In both races, Cassani alleges, the Swiss rider speeds away from other riders after moving his hand over his right brake lever momentarily. At Roubaix, Cancellara is seen effortlessly riding away from a group of riders including Tom Boonen , before again powering away from Bjorn Leukemans to effectively seal the win.

Then, the video shows the Swiss making the same hand movement before riding away from Boonen at the Tour of Flanders.

Cancellara vigorously denied the allegations and the UCI said the Swiss rider had no case to answer.

Ryder Hesjedal's spinning bike at the 2014 Vuelta a España

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ynLMfzLTc8M

When Ryder Hesjedal, then riding for Garmin-Sharp, crashed on a descent on stage seven of the 2014 Vuelta a España something strange happened.

Instead of lying stationary on the road, Hesjedal's bike spun in a circle as if it had a life of its own - the back wheel seemed to move the bike around.

Hesjedal, in a rush to get back on his bike to continue the chase down the hill, had to scramble to catch his bike.

The UCI moved to investigate Garmin-Sharp's Cervélos and found nothing untoward.

Philippe Brunel points finger at Alberto Contador at 2015 Giro d'Italia

The case against Alberto Contador seems to be that he's just 'too good' to not have some kind of motorised bike. L'Equipe's chief cycling writer Philippe Brunel angled such suspicion at the Tinkoff rider as he won the Giro d'Italia in 2015.

The reporter claimed that Contador faked a puncture on a descent on stage 16 in order to ditch his motorised bike for a regular one, so that UCI testers would not find anything dodgy.

Contador dismissed the allegation as 'ridiculous' and then was seen frolicking around on an e-bike made by Specialized after the climax of the final stage where he cemented the pink jersey.

French TV report claims seven riders used motors at Italian races in 2016

French television station Stade 2 claimed in April 2016 that seven riders used motors at Strade Bianche and Coppi e Bartali, picked up by heat sensors disguised as cameras.

The report said that five of these bikes had heat-emitting devices in the seat tube, while the others were located in the hub of the rear wheel.

What the riders say

Riders have long been concerned about the possibility that motors are being used in bikes, so much so that the independent report into doping - the CIRC report - made reference to the practice .

“This particular issue was taken seriously, especially by top riders, and was not dismissed as being isolated,” the report says.

While the report didn't go into any details about which riders were concerned or how they came to the conclusion that motors were in use - but it appears they might have been close to the mark.

>>> Motor found in Belgian cyclo-cross bike ‘a disgrace’ says national cycling coach

At the cyclo-cross World Championships, British riders reacted to the news of a motor being found, mostly with incredulity.

Helen Wyman said: “It’s extraordinary and I can’t understand why you would do it. Women’s cyclo-cross is at such an accessible level I don’t understand why you would have to do it.

“I just think it’s crazy personally because I can win races, Sanne [Cant] can win races and Nikki [Harris] can too because we train hard and race to the best of our ability.

“This year has been the most open year there has ever been and it’s so accessible to get to that top level. Yet she feels that she still wants to cheat – I just don’t understand.”

Cancellara, in 2010, said a similar thing : “It’s a sad and really outrageous story. Believe me, my feats are the result of hard work.”

What the UCI are doing about it

From 2015, the UCI announced a 200,000 CHF fine and minimum six-month ban for any rider caught with a motor in their bike and stepped up their spot searches at races.

It is reported, though, that the UCI are pushing for a lifetime ban for Van den Driessche, with people such as Tour de France director Christian Prudhomme calling for the "most severe measures" to be taken against those who cheat the system

No motors have been found at road races, which has so far made everyone wonder whether mechanical doping actually exists. But rather than simply responding to accusations of cheating, the UCI proactively went on the hunt for motorised bikes, dismantling bikes at Milan-San Remo in March .

Throughout this season and last, random bike checks have been made after races, including one on Contador's bike at the 2015 Giro d'Italia, which was captured on video.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=twzXs6lxSOs

Additionally, the UCI have now developed a scanning machine to test for motors, which was reportedly present at the Cyclocross World Championships, but it is unclear whether the motor was discovered by the machine.

>>> Motorised bikes may have been used in the WorldTour, admits UCI technical chief

What this discovery means for cycling

It's not great news for cycling, admittedly - it's similar to Lance Armstrong denying doping for years and then admitting that he did it, but slightly less high profile.

Rumours have circled for years and riders have strenuously denied accusations, but with the discovery of an actual motor the whole thing seems a lot more real.

This means that motorised doping is, indeed, a 'thing' - even if there has only been one discovery in nearly a year of bike checks. The fact that one bike has been modified means that many more could have been in the past and gone undetected.

>>> Motorised bike? Movistar respond to social media conspiracy theories

Granted, taking performance enhancing drugs would probably give you a bigger boost than a small motor in your seat tube, but dopers get busted all the time, whereas motorised dopers may have walked free for years.

As Prudhomme said in an interview with La Derniere Heure , cycling has taken great steps forward to move on from doping scandals only to be hit by this latest bombshell.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Stuart Clarke is a News Associates trained journalist who has worked for the likes of the British Olympic Associate, British Rowing and the England and Wales Cricket Board, and of course Cycling Weekly. His work at Cycling Weekly has focused upon professional racing, following the World Tour races and its characters.

In-form Italian praises Lidl-Trek team after repeating feat she achieved in 2015

By Tom Davidson Published 31 March 24

World champion becomes seventh man in history to win the race three times

Useful links

- Tour de France

- Giro d'Italia

- Vuelta a España

Buyer's Guides

- Best road bikes

- Best gravel bikes

- Best smart turbo trainers

- Best cycling computers

- Editor's Choice

- Bike Reviews

- Component Reviews

- Clothing Reviews

- Contact Future's experts

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookies policy

- Advertise with us

Cycling Weekly is part of Future plc, an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate site . © Future Publishing Limited Quay House, The Ambury, Bath BA1 1UA. All rights reserved. England and Wales company registration number 2008885.

- The A.V. Club

- The Takeout

- The Inventory

How Pro Cyclists Cheat Using Motorized Bikes

If you thought Lance Armstrong’s doping scandal would be the last controversy to rock the world of professional cycling—you were wrong.

In the latest reports of ongoing corruption in pro cycling, the international governing body Union Cycliste Internationale confirmed that a 19-year-old rider Femke Van den Driessche cheated in the World Championships using a small motor to power the rear wheel. The revelation is part of a growing problem in professional cycling that forced the UCI to add a clause to the rulebook about “ technological doping ” early last year.

The report is somewhat shocking given the nature of cheating scandals in major American sports: Historically, some of the most well-known cheating scandals have been socially engineered like paying referees or using performance-enhancing drugs . The reason that the UCI revelation was so big was that it marks the first time a cheater in a sport competition has been caught using motorized technology to receive an unfair advantage.

Image from Vivax

How Do You Hide a Motor in a Bicycle?

There are two common ways a person can install a motor into a bicycle: one way is to use a throttle, or a little lever on the handlebar that makes the motor run. When you push the button or twist the throttle, the motor speed increases, and the bike accelerates. The downside to this methods is that the throttle is visible, so if you’re trying to use the bike to cheat in a professional cycling competition, this type isn’t an option.

The other way to install a motor on a bicycle is by using a cadence sensor or torque sensor. These methods work a lot like a throttle, but rather than regulating the power by pressing a button, you actually control it with your feet. The sensor is placed by your pedals, and it’s able to detect the speed of your pedal movement typically by monitoring a small magnet that passes by the sensor with every turn of the pedal. The motor runs at a higher speed when the pedals are going faster. These types of kits often referred to as pedal-assist bicycles because the speed of the motor is entirely controlled by the rotation of the bike’s pedals.

Cheaters using electric motors in professional competitions prefer pedal-assist bicycles to ones with throttles because it’s much harder to detect the illegal motor at first glance. There are also a lot of options when ti comes to installing a pedal-assist motor into a racing bicycle.

For instance, the Vivax Assist is a popular torque sensor that costs 2700 Euros (approximately $2940) and can be retrofitted into most racing bike frames. The company even touts the inconspicuous look of the motor on its website, saying, “The special design of the drive unit allows it to be built into any bicycle frame with the requisite seat tube internal diameter of 31.6 mm or 30.9 mm and is therefore invisible on the bicycle.”

There are literally dozens of other popular electric bike motors on the market. Although they’re not specifically being marketed as tools for cheaters, the shrinking size of the motors as well as the ease of installation makes them very tempting for riders who lack moral fortitude. We’re now reaching a boiling point where the technologically is finally cheap enough for people to buy.

Image via AP

How Does UCI Prevent The Use of Illegal Electric Motors?

For several years, the UCI has used large, airport-style x-ray machines at the Tour de France to scan bicycles for illegal use of electric motors in competing bicycles. Last year, rider Chris Froome was accused of using a motor inside his bicycle during competition (in addition to the doping allegations that hung over his head). Accusers cited Froome’s unusual acceleration speeds as reason to believe that he was being propelled by an electronic motor. Froome applauded the bicycle checks that were levied against him and other racers because he felt like it would put an end to speculation about whether or not he cheated.

The UCI reportedly caught Van den Driessche by using a computer that can read radio frequencies emitted by the motor. When the computer detected signs of a motor in Van den Driessche’s bicycle, the governing body reportedly removed the seat post and discovered wires sticking out.

For now, the vetting process for all professional cyclists is still being put together by governing bodies. Just like any other areas technological innovation, the rules have not yet caught up to what’s possible. In the future, there are bound to be more powerful motors that require less battery power and can be hidden in just about any part of a bicycle. On the other hand, new methods of motor detection are likely to emerge. I’d expect to see many scanning technologies that are already being used in military settings and airports to be used in cycling competitions. Possible scanning technologies include thermal scanning, listening for radio frequencies, and millimeter wave scanning. It’s crazy that officials might need to use something like weapons-grade TSA scanners to keep cycling honest.

Lead image via AP

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The Two-Way

International, no motor(ized) bikes: tour de france unveils new plan to catch cheats.

Bill Chappell

Cyclists in this year's Tour de France will face new controls for what organizers call "technological fraud." Here, elite cyclists are seen riding in the Paris-Nice race in March. Kenzo Tribouillard/AFP/Getty Images hide caption

Cyclists in this year's Tour de France will face new controls for what organizers call "technological fraud." Here, elite cyclists are seen riding in the Paris-Nice race in March.

Thermal cameras and other tools that can detect "mechanical doping" — small but powerful motors that boost riders' power levels — will be used in this year's Tour de France, in a change race officials announced just days before the prestigious race's start on July 2.

"This problem is worse than doping," France's Secretary of State for Sports Thierry Braillard tells Le Journal du Dimanche . "This is the future of cycling that's at stake."

The bid to keep professional cycling clean will rely on techniques developed by a large French government agency that also conducts nuclear research. In the Tour de France, the image tests can be done anywhere, officials say — and they add that they won't be publicizing the thermal cameras' locations.

The move is an attack on a method of cheating that had long been suspected but wasn't proven at the sport's highest levels until this year. If cycling still had any trusting and faithful fans in January of 2016, the scales fell from their eyes when Belgian Femke Van den Driessche, a promising 19-year-old cyclocross rider, was found to be using a motor during the U-23 World Championships.

As far back as at least 2010 , accusations have flown that elite cyclists were turning in superhuman performances with the help of motors that are hidden inside their bike's seat tube (the one running from the seat down to the pedals).

Commercial versions of such devices can provide a steady power stream of around 200 watts — the lower range of a pro cyclist's average output in a stage race. They can also be set to assist riders automatically if their pedaling cadence falls below a certain threshold.

Tour de France officials explain how the detection system will work :

"Developed by the CEA (the French Atomic Energy Commission), the method consists of using a thermal imaging camera capable of detecting mechanical anomalies on the riders' bikes. The checks can be made in the race and on the side of the roads."

If that level of sophistication seems unwarranted, consider that the hidden motors are seen as the most obvious of the mechanical doping techniques. A sneakier – and lighter – method involves magnets hidden in the wheels. From the Fittish blog over at Deadspin:

"Unlike cheating with heavy tube motors, moto-doping via electromagnetic wheels is much more subtle. A series of neodymium batteries are hidden inside the rear wheel, and a coil tucked away below the seat generates an induction force, which gets you 60 extra watts of power. The field is controlled via a bluetooth activator."

Such magnet-based systems are seen as being beyond the reach of all but the most well-funded cyclists. If you're wondering how the seat-tube motors work, here's how Vivax Assist , a German company, describes its device:

"Sophisticated motor power is hidden in the bike's seat tube. It only weights 1.8 kg (inkl. battery). Press the button and the motor delivers 200 watts to the crankshaft. Press the button again and the motor stops. "Without motor power the bike functions as normal without any kind of resistance. The Lithium-Ion high-performance battery, which fits into a conventional saddlebag, provides you with motor-assisted cycling lasting for min. 60 minutes (6 Ah) or min. 90 minutes (9 Ah). The special design of the drive unit allows it to be built into any bicycle frame with the requisite seat tube internal diameter of 31.6 mm or 30.9 mm and is therefore invisible on the bicycle – except the on/off switch, which is unobtrusively located on the bar end."

Here's how it went when a couple of cyclists decided to try out a similar system:

- Tour de France

- Spring Classics

UCI conducts 997 tests for hidden motors at Tour de France

All pre and post-stage tests returned negative results

Tom Hallam-Gravells

Online production editor.

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

© Velo Collection (David Ramos) / Getty Images

The UCI conducted 997 tests for hidden motors at the Tour de France.

The UCI has warned that it’s “impossible” to get away with motor doping after revealing its testing figures for the Tour de France .

In total, cycling’s governing body conducted 997 tests for hidden motors at the three-week race, down on the 1008 tested last year, but they all returned negative results.

Bikes were tested ahead of each stage before taking to the start line, with a total of 837 pre-stage tests carried out during the race. A random six riders, who also underwent anti-doping tests, then had their bikes checked after each stage, along with the stage winners and the holder of the yellow jersey. 160 bikes were checked in this way.

"The large number of tests carried out at the 2023 Tour de France as part of our Technological Fraud Detection Programme sends a very clear message to riders and the public: it is impossible to use a propulsion system hidden in a bike without being exposed,” UCI director general Amina Lanaya said in a press release.

“To ensure the fairness of cycling competitions and protect the integrity of the sport and its athletes, we will continue to implement our detection programme and to develop it further.”

As laid out in its Technological Fraud Testing Strategy for the Tour, the UCI used three different systems to check the bikes.

Pre-stage tests were carried out using magnetic tablets which the UCI confirmed were recently upgraded, having first been introduced in 2016.

Checks after the stage were carried out using X-ray technology along with the newest weapons in the UCI’s arsenal, backscatter and transmission technologies, which provide instantaneous images of the interior of a bike.

“The UCI continues to take the possibility of technological fraud extremely seriously,” the UCI’s Head of Road and Innovation Michael Rogers said in a press release ahead of the Tour.

“Our range of tools to fight against any form of such cheating enables us to carry out checks that are rapid and effective. This is essential to be sure that cycling competitions are fair and to protect the integrity of the sport and its athletes.”

Rumours of motor doping have swirled around for a long time and the topic resurfaced at the 2021 Tour de France when Le Temps , a newspaper based in Switzerland, reported that unnamed riders had heard strange noises emanating from the rear wheels of certain teams’ bikes.

Despite the rumours, only one professional rider has ever been officially charged with motor doping. That came at the 2016 Cyclo-cross World Championships, where the UCI found a motor in Femke Van den Driessche’s spare bike, with the Belgian rider receiving a six-year suspension.

MAIN.jpg?w=600&auto=format)

Tour de France

- Dates 1 Jul - 23 Jul

- Race Length 3,401 kms

- Race Category Elite Men

Latest Videos

1 We Found The Best Bike Tech At The 2024 Classics

2 We Rode Cobbles Too Rough For Paris-Roubaix!

3 Arnaud De Lie's Orbea Orca Aero

4 We Tried To Copy A Pro Cyclist's Diet | Did We Puke?

5 How Much Fitter Did I Get In 6 Weeks of Training for Flanders?

Tom is our Online Production Editor who creates tech content for the GCN website

Related Content

Tour de France bikes ranked: cheapest to most expensive

Which team has the most expensive bike in the Tour de France peloton?

Tour de France pro bike: Jonas Vingegaard’s 1x Cervélo S5

Defending Tour de France champion Jonas Vingegaard goes 1x on his aero Cervélo S5

GCN Tech Clinic: How do pros get custom-painted bikes so quickly?

GCN's Alex Paton is joined by GMBN’s Isaac Mundy to answer your latest tech questions

GCN Tech Show: How powerful are Tour de France riders?

Pro power numbers, the hottest Tour de France tech, and the resurgence of 1x

Subscribe to the GCN Newsletter

Get the latest, most entertaining and best informed news, reviews, challenges, insights, analysis, competitions and offers - straight to your inbox

Team Sky, Armstrong deny secret motor cheating: Report

- Share on Twitter

- Share on WhatsApp

- E-mail this article

- 0 Engagements

Team Sky, which have produced four of the past five Tour de France champions, and Lance Armstrong both denied using secret motors in bicycles, a CBS television report said on Sunday.

A segment on the show "60 Minutes" examined the possibility of motorised cheating in pro cycling, with three-time Tour de France winner Greg LeMond, admitted dope cheat ex-rider Tyler Hamilton and Hungarian designer Istvan Varjas, who makes hidden motors for bikes, saying they believe such cheating exists.

"I know the motor is still in the sport," LeMond said. "There's always a few bad apples because it's a lot of money."

Armstrong, an admitted dope cheat who was stripped of seven Tour de France titles from 1999-2005, denied to CBS through his lawyer ever using a motor.

Armstrong's winning streak began just after Varjas claims he sold his first secretly motorised bike to an anonymous buyer, promising not to make more or talk of it for 10 years.

Jean Pierre Verdy, a former French anti-doping agency testing director, told CBS some informants among riders and team managers told him that about 12 riders used motors in the 2015 Tour de France.

Tour de France champ Froome to compete in Singapore

Related stories, tour de france to stage criterium race in singapore on oct 29-30, no guarantee tour will go ahead, says france sports minister, s'pore cycling federation targets tour de france spot, asian games gold by 2030.

Varjas said he sold secretly motorised bicycles to an unknown client just before the 2015 Tour, delivering the bikes to a locked storage room.

The silent motor, which is made of military-grade metal, is powered by a lithium battery. A secret button provides a power boost for 20 minutes.

The motor can also be activated when a rider's heart rate gets too high, by linking it remotely with the rider's heart-rate monitor, said Vargas.

He noted one motor design can be hidden inside the hub of the back wheel but would boost the normal wheel weight by about 800 grams.

In the 2015 Tour de France, peloton bikes were weighed before a time-trial stage, with CBS reporting French authorities said Team Sky were the only squad with heavier bikes, each about 800 grams more.

Britain's Chris Froome, riding for Sky, won the 2013, 2015 and 2016 Tour de France crowns.

In 2015, he was also "King of the Mountains" for his times in the tough climbing stages that often prove decisive.

A Team Sky spokesman told CBS the team never used mechanical assistance, saying time-trial bikes might be heavier to allow for better aerodynamics and all Sky bikes were cleared by the International Cycling Union. - AFP

Get The New Paper on your phone with the free TNP app. Download from the Apple App Store or Google Play Store now

- Share on Facebook

Watch CBS News

Have secret motors been used to cheat in pro cycling?

January 27, 2017 / 9:59 AM EST / CBS News

The Hungarian designer of a secret bike motor tells Bill Whitaker he thinks the motors have been used to cheat in pro cycling as far back as 1998. Istvan Varjas speaks to Whitaker for a 60 Minutes investigation into mechanical cheating in a sport already infamous for its doping scandals. One of the sport’s champions, three-time Tour de France winner Greg LeMond, is convinced the motors are being used. He’s also in the 60 Minutes report, to be broadcast Sunday, Jan. 29 at 7 p.m. ET/PT.

Varjas, a scientist and former cyclist, says he first designed a motor to fit inside a bike’s frame in 1998. He says a friend found an anonymous buyer who offered him nearly $2 million for it. Varjas says he took the money and agreed not to work on such motors, nor sell or speak of them, for 10 years. Asked whether he believes hidden motors like his have been used since then, he answers, “I think. Yes.”

Varjas claims it’s not his fault if pro cyclists ended up with his bike. “If a grandfather came and buy a bike and after it’s go to...his grandson who is racing, it’s not my problem,” he says. Asked whether he would sell a motor to a person who told him he was going to cheat with it, he replies with a little laugh, “If the money is big, why not?”

60 Minutes met Varjas in a Budapest bike shop where he demonstrated his motor designs and completed motorized bicycles that he sells to wealthy clients. He showed 60 Minutes how a secret switch can engage the hidden motors, or, in a more sophisticated model, they can be engaged when a racer’s heart rate peaks. He allowed Whitaker to test ride some of the bikes with hidden motors.

The first time it was publicly suspected a motor was being used in pro cycling was in 2010 when a Swiss rider raced at an unusually high speed. That rider denied using a motor. There have been other suspicious incidents and one rider was caught with a secret motor in 2016. Jean-Pierre Verdy, former testing director of the French Anti-Doping Agency, says the sport has a problem. “It’s been the last three to four years when I was told about the use of the motors,” Verdy tells Whitaker. “There’s a problem. By 2015, everyone was complaining and I said, ‘something’s got to be done.’”

LeMond, an outspoken advocate for drug testing, wants his former sport to do more testing for the motors, too. “This is curable. This is fixable. I don’t trust it until they figure out...how to-- take the motor out. I won’t trust any victories of the Tour de France,” says LeMond.

More from CBS News

How to watch today's Tennessee vs. Purdue Elite 8 men's March Madness game: Livestream options, game time, more

7 minors injured in mass shooting outside Indianapolis mall, police say

AT&T informs users of data breach and resets millions of passcodes

This week on "Sunday Morning" (March 31)

- Mobile Site

- Staff Directory

- Advertise with Ars

Filter by topic

- Biz & IT

- Gaming & Culture

Front page layout

Vicious cycle —

Tour de france to use thermal imaging to fight mechanical doping, want to catch cyclists cheating with hidden motors, neodymium magnets..

Tom Mendelsohn - Jun 28, 2016 1:21 pm UTC

They call it "mechanical doping," but the name simply doesn't do it justice. Cycling is not a sport celebrated for honesty amongst even its top riders, but following several very high-profile doping cases in recent years, it seems as though the cheats have been trying a different route: hiding motors in their seat posts that help push them to superhuman feats of endurance.

The technique has been known since at least 2010; commercial versions of the motors can put out 200 steady watts of power, nearly doubling a typical pro-cyclist's output. An onboard motor can help riders go faster, and can keep their pedalling cadence—the number of revolutions through the crank per minute—up while energy dips in endurance stages.

With the biggest cycling event in the world, the Tour de France, set to begin on July 2, mechanical doping is a serious concern—one that has moved France's sports minister Thierry Braillard to tell the French press : "This problem is worse than doping; this is the future of cycling that's at stake."

Until now, mechanical doping has been very hard to unmask. The Tour de France has developed a detection method in partnership with the CEA, the French atomic energy commission. They will use thermal imaging cameras which can detect mechanical anomalies in bikes, with checks made during the race from the roadside. Other more devious tricks will be used, but they are understandably not releasing more details about those to the public.

The authorities hope this system will be able to detect a subtler, more recent development in mechanical doping : neodymium batteries hidden in the rear wheel, generating induction force with a coil somewhere under the seat, and controlled using Bluetooth. This can net the cyclist a few more watts of power that can be fed into a hidden motor.

Christian Prudhomme, the man in charge of the Tour, said: “Protecting the Tour de France is the most important thing. We now have a real deterrent. The cycling world must form a united front to fight against cheating rather than setting off in a dispersed manner.”

reader comments

Channel ars technica.

clock This article was published more than 8 years ago

Forget doping, Greg LeMond thinks Tour de France riders could be cheating with tiny motors

Retired cyclist Greg LeMond is used to speaking his mind, especially when it comes to cheating in the sport. The three-time Tour de France champion spoke out about Lance Armstrong long before it was popular to do so and now he’s alleging some cyclists could be gaining an unfair edge in major races like the Tour de France by installing tiny motors in their bikes.

“I believe it’s been used in racing, I believe it’s been used sometimes in the Grand Tours,” LeMond told the Associated Press on Wednesday. He did not specify whether he thought any riders in this year’s iteration of the race have been using the technology, but he did accuse the sport’s governing body of “not doing enough” to ensure racers don’t use the technology. He said the International Cycling Union’s (UCI) pre-race equipment checks are “fluff” and “all words.”

UCI President Brian Cookson, however, says his team takes all accusations of cheating seriously, including “mechanical doping” as it’s coming to be known.

“We understand that although this subject sometimes causes amusement and derision we know that the technology is available: we have seen examples of it in laboratory conditions,” Cookson told AFP last week after Cedric Vasseur, a former cyclist-turned-analyst on French television, commented Tour de France leader Chris Froome’s bike looked to be “pedaling itself.”

“We’ve done some testing already for concealed motors,” Cookson said. But the testing has only been done periodically.

“[W]e’ve done testing at Milan-San Remo, the Giro (d’Italia), Paris-Nice and from time to time we’ll do tests during the rest of the season,” he said. “We have no evidence that it has been used in competition yet but sadly we do know that in competitive sport sometimes some people will try to find ways of cheating. This is one way that would be very damaging and dangerous to an individual’s reputation, a team’s reputation and to the sport’s reputation, so we’re taking it very seriously.”

The miniscule motors may sound more like science fiction than reality, but the technology does seem to exist — at least on television.

During the 2010 Giro d’Italia retired cyclist Davide Cassani demonstrated how the motor works on Italy’s Rai television.

Hidden in the bike’s tube, the battery-operated motor is controlled by a switch located near the bike’s brake levers. Once the motor gets the back wheel spinning on its own, the pedals start to go and a rider presumably just needs to go through the motions while the motor propels him at up to 31 mph.

“I tried the bike, and I can tell you that with this bike and its engine, I may win a Giro stage although I’m 50 years old,” Cassani said.

Italian journalist Michele Bufalino later backed up Cassani’s claims in a video of his own, in which he showed one of the motors being installed. He also then accused cyclist Fabian Cancellara of using it during both the Tour of Flanders and Paris-Roubaix.

Cancellara, who now races for Trek Factory Racing, denied the allegations at the time.

“It’s so stupid I’m speechless,” Cancellara, then of the Saxo Bank team, told the Telegraph in 2010. “I’ve never had batteries on my bike.”

The UCI never brought a case against Cancellara, but the organization also had no evidence.

LeMond says if any type of cheating in cycling should be easy to decisively determine, it should be this, though.

“It’s simple to check for, much easier than doping,” he told CyclingNews.com in May. “You need a thermal heat gun, you can use it in the race. It can be seen from meters away if there a difference in the heat in the bottom bracket. I’d recommend that to the UCI.”

LeMond, who claims to have met the inventor of the motorized bikes, also suggests UCI ban cyclists from changing bikes during the race “unless you have a real mechanical problem.”

“I know that motors exist, I’ve ridden a bike with one. … If people think they don’t exist, they’re fooling themselves, so I think it’s a justified suspicion,” he said. “It seems too incredible that someone would do it, but I know it’s real.”

A 19-year-old Belgian cyclist got caught cheating at the world championships after racing a bike that had a motor hidden in the frame

Cycling officials on Saturday detained a bicycle during the cyclocross world championships in Zolder, Belgium, to investigate " technological fraud ," and on Sunday they confirmed the bike had a concealed motor in the frame .

The International Cycling Union said the bike belonged to 19-year-old Belgian Femke Van den Driessche.

It is the first official case of " mechanical doping " or " bike doping " at cycling's highest level. If used at the right time during a race even a small motor can provide a critical burst of power and speed.

Italian manufacturer Wilier Triestina said it will sue Van den Driessche .

For years there has been speculation in cycling that motorized cheating might be happening at the sport's highest professional level, but it has never been revealed until now.

'Technological fraud'

"It's absolutely clear that there was technological fraud — there was a concealed motor," UCI President Brian Cookson told a news conference, AFP reported.

The rider, Van den Driessche, was among the race favorites but was forced to withdraw from the women's under-23 event because of a mechanical problem. Belgian news site Sporza reported that there were " electrical cables " seen coming out of the bike.

—José Been (@TourDeJose) January 30, 2016

'It wasn't my bike'

Van den Driessche denied she had used a bike with a concealed motor on purpose , saying that it was identical to her own but belonged to a friend and that a team mechanic had given it to her by mistake before the race, AFP reported.

"It wasn't my bike — it was that of a friend and was identical to mine," a tearful Van den Driessche told Sporza , AFP reported. "This friend went around the course Saturday before dropping off the bike in the truck. A mechanic, thinking it was my bike, cleaned it and prepared it for my race," she added, insisting that she was "totally unaware" it was fitted with a hidden motor.

"I feel really terrible. I'm aware I have a big problem. (But) I have no fears of an inquiry into this. I have done nothing wrong," she added. AFP also reported that Belgian coach Rudy De Bie said he was "disgusted."

"We thought that we had in Femke a great talent in the making but it seems that she fooled everyone," he told Sporza. Sven Nys, a veteran of cyclocross and one of its best riders, said he was shocked and disappointed .

—kristof ramon (@kristoframon) January 30, 2016

"We've heard some stories for a long time now about the possibility of this. We have been alive to a potential way that people might cheat and we have been testing a number of bikes and a number of events for several months," Cookson said, according to AFP.

"I am committed and the UCI is committed to protecting the riders who do not want to cheat in whatever form and to make sure that the right riders win the race. We have been looking at different methods of testing this kind of technology and we tested a number of bikes yesterday and one was found.

"We will keep testing both at this event and subsequent events. Whether this means that there is widespread use of this form of cheating remains to be seen."

Cookson said that the matter would next go before the UCI's disciplinary commission.

Here come the lawsuits

Bike manufacturer Wilier Triestina 's managing director, Andrea Gastaldello, said he was "stunned" by the news that Van den Driessche competed with a concealed motor in her Wilier Triestina bike, AP reported Monday.

" Our company will take legal action against the athlete and against any (person) responsible for this very serious matter to safeguard the reputation and image of the company," he said.

Here is the full statement :

Related stories

We are literally shocked, as the main technical partner, we want to distance from this act absolutely contrary to the basic values of our company, and with the principles of each sporting competition. Really unacceptable that the photos of our bike is making the rounds of the international media due to this unpleasant fact. We work every day to bring worldwide the quality of our products and when we know that a Wilier Triestina’s bike is meanly tampered we’re very sad. Our Company will take legal action against the athlete and against any responsible for this very serious matter, in order to safeguard the good name and image of the company, marked by professionalism and seriousness in 110 years of history.

A Sporza journalist, Renaat Schotte, posted this photo on Instagram on Sunday. It apparently shows an official checking a different bike for technological fraud with a tablet device:

Newspeak: bikecheck tablet #CXZolder16 #cyclocross A photo posted by Renaat Schotte (@wielerman) on Jan 31, 2016 at 10:16am PST Jan 31, 2016 at 10:16am PST

Call for 'lifetime suspension'

Etixx team manager Patrick Lefevere called for a "lifetime suspension for the cheat."

"I never thought that such schemes were possible. It's a scandal that Femke's entourage have deceived the Belgian federation," he said.

The news is a fresh blow to a sport still recovering from the Lance Armstrong doping scandal after the disgraced American cyclist admitted to cheating throughout his career in 2013 following years of denials and ruthless attacks on his accusers, AFP noted.

The UCI has been taking the possibility of technological fraud more seriously over the past few years. New penalties include disqualification, a suspension of six months, and a fine of up to 200,000 Swiss francs (about $195,000). Teams could be fined 1 million francs (roughly $977,500).

Here are the UCI rules and penalties regarding technological fraud (PDF):

Business Insider reported in September from the UCI Road World Championships in Richmond, Virginia, that the winner of the elite men's individual time trial, Vasil Kiryienka of Belarus, had his bike inspected for a motor after he crossed the finish line.

This photo, provided to Business Insider, showed the device used to inspect the inside of Kiryienka's frame:

When asked by Business Insider about the inspection in Richmond, the UCI replied:

The Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) takes extremely seriously the issue of technological fraud such as concealed electric motors in bikes, and has therefore added far-reaching sanctions in its Regulations. We have been carrying out controls for many years and although those controls have never found any evidence of such fraud, we know we must be vigilant. We have carried out several unannounced checks on this year’s Tour de France and other Grand Tours. The 2015 UCI Road World Championships in Richmond is the latest event where bikes have been controlled this season, including all top 3 riders of each race. These are extensive controls and nothing was found.

No motor was found in Kiryienka's bike.

This video by CyclingTips features Greg LeMond, the only American to win the Tour de France, showing how one version of a bike motor works:

Hidden Motor demonstration with Greg LeMond from cyclingtips on Vimeo .

“I believe it’s been used in racing [and] I believe it’s been used sometimes in the Grand Tours,” LeMond told the Associated Press last summer.

And here's another video showing a bike motor in action:

Motor demo from cyclingtips on Vimeo .

At the 2015 Giro d'Italia, the most important stage race after the Tour , an official was shown on video checking eventual race winner Alberto Contador's bike:

There are videos on YouTube that purport to show images of mechanical doping , and show that the matter goes back some time . This clip, for instance, shows Canadian Ryder Hesjedal's bike after he crashed at the 2014 Tour of Spain. His rear wheel appears to keep spinning after the crash, so much so that it whips the bike around on the ground after he comes to a stop:

The video below — which has over 3.8 million views on YouTube — claims to show "how mechanic doping may be done," with images of Swiss pro Fabian Cancellara that "may be considered as incontrovertible evidences." It's important to note that Cancellara and his team denied all of this long ago, and they were never penalized or fined.

In the elite women's race later on Saturday, another Belgian rider took a dramatic over-the-bars tumble but managed to get up and keep racing:

—daniel mcmahon (@cyclingreporter) January 30, 2016

Watch: Officials discovered a hidden motor inside the frame of a Belgian cyclist’s bike

- Main content

Amateur Rider Caught With Motorized Bike Following Race in Southwest France

Cycling officials say it's the first known case of "mechanical doping" to occur in France

The tampered bicycle was discovered in a joint operation conducted by the French Anti-Doping Agency, the French Cycling Federation (FFC), and the local public prosecutor's office. The rider, whose name and age were not released, admitted to the use of the system. Also known as mechanical doping , it is considered serious technological fraud.

RELATED: Are Tour de France Racers Cheating With Secret Motors?

"We were alerted by an employee of the French Anti-Doping Agency of suspected cheating by the use of an electronic system, seemingly a little motor," said Jean-François Mailhes, who is the public prosecutor for Perigueux in the Dordogne commune.

The rider was interviewed by police in an attempt to discover the amount of prize money he had earned while using the motorized bike.

See how hidden bike motors work:

RELATED: Italian Cyclist Disqualified From Race for Mechanical Doping

The FFC said this is the first such case to occur in France. A similar incident took place at the 2016 UCI Cyclo-cross World Championships in Belgium, when Femke Van den Driessche was charged with mechanical doping . As a result, she received a six-year ban from the sport.

To stay on top of the latest cycling stories, subscribe to our newsletter.

.css-1t6om3g:before{width:1.75rem;height:1.75rem;margin:0 0.625rem -0.125rem 0;content:'';display:inline-block;-webkit-background-size:1.25rem;background-size:1.25rem;background-color:#F8D811;color:#000;background-repeat:no-repeat;-webkit-background-position:center;background-position:center;}.loaded .css-1t6om3g:before{background-image:url(/_assets/design-tokens/bicycling/static/images/chevron-design-element.c42d609.svg);} News

Tour de France 2024 Contender Power Rankings

Demi Vollering Announces Departure from SD Worx

Australia’s $60K Olympic Track Bike

Strava Gives Cyclists More Data to Obsess Over

Laura Kenny Announces Retirement

Reviving the Philly Cycling Classic

Van der Poel Signs Ten-Year Deal with Canyon

UCI Sanctions Lefevere Over Derogatory to Women

Rohan Dennis Headed to Court Next Week

130 Riders Abandon Spanish Amateur Race

Zwift Academy Champs Secure Pro Contracts for 2024

COMMENTS

On the crucial summit finish of Stage 18 of the 2014 Tour de France, ten Dam averaged 370 watts on the 37-minute final ascent to Hautacam, preserving a top-10 overall finish.

The Tour de France peloton during stage 17 of the race in the Pyrenees ... "There is no longer talk of a motor in the crankset or an electromagnet system in the wheel rims, but of a device hidden ...

Three-time Tour de France winner Greg LeMond and his wife Kathy first learned about hidden motors in 2014 when Greg met Stefano Varjas in Paris and took a test ride.

Indeed, at the 2023 Tour de France several staff members of various teams shared unverified anecdotes with me of teams being caught with motors in previous years, or of suspicious activity ...

US television programme 60 Minutes investigated motorised cheating in professional cycling in a show aired last night, claiming that motorised bikes have been used in the Tour de France. 60 ...

The sight of a couple of dozen riders holding on to team cars as they went up the Stelvio in the Giro Next Gen under-23 race earlier this month shows that when it comes to cheating in cycling, it's often a case of Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose - go back 120 years to the early years of the Tour de France and you'll find riders ejected from the race for slipstreaming cars ...

According to Union Cycliste Internationale, the sport's governing body, mechanical doping testing began in January. Race officials took 500 scans at the Tour de Suisse and over 2,000 at the Giro d ...

Imagine you're riding the Tour de France and riding up mountains for days on end ... >>> Great Britain team manager slams electric motor cheating. In a race like Paris-Roubaix, an attack when your ...

For several years, the UCI has used large, airport-style x-ray machines at the Tour de France to scan bicycles for illegal use of electric motors in competing bicycles. Last year, rider Chris ...

It only weights 1.8 kg (inkl. battery). Press the button and the motor delivers 200 watts to the crankshaft. Press the button again and the motor stops. "Without motor power the bike functions as ...

The UCI has warned that it's "impossible" to get away with motor doping after revealing its testing figures for the Tour de France. In total, cycling's governing body conducted 997 tests for hidden motors at the three-week race, down on the 1008 tested last year, but they all returned negative results.

Motor doping, or mechanical doping, in competitive cycling terminology, is a method of cheating by using a hidden motor to help propel a racing bicycle. The term is an analogy to chemical doping in sport, ... For the 2016 Tour de France, thermal cameras were used to detect hidden motors. The UCI ...

Now, the American cyclist is suspected of another type of doping: the mechanical doping. Armstrong is accused of competing on the Tour with a motor in his bikes.. The accusation arises from Jean-Pierre Verdy, former head of the French Anti-Doping Agency between 2006 and 2015, in a book entitled 'Dopage: Ma guerre contre les tricheurs' (Doping: My War Against Cheaters).

Team Sky, which have produced four of the past five Tour de France champions, and Lance Armstrong both denied using secret motors in bicycles, a CBS television report said on Sunday. A segment on the show "60 Minutes" examined the possibility of motorised cheating in pro cycling, with three-time Tour de France winner Greg LeMond, admitted dope ...

One of the sport's champions, three-time Tour de France winner Greg LeMond, is convinced the motors are being used. He's also in the 60 Minutes report, to be broadcast Sunday, Jan. 29 at 7 p.m ...

French authorities will crack down on the use of hidden motors in this year's Tour de France with the cheating tactic described as worse than doping.

Tour de France to use thermal imaging to fight mechanical doping Want to catch cyclists cheating with hidden motors, neodymium magnets. Tom Mendelsohn - Jun 28, 2016 1:21 pm UTC

The Tour de France and cycling's governing body, the UCI, are taking steps to verify that riders are not cheating by using bikes that have hidden motors.…REA...

Retired cyclist Greg LeMond is used to speaking his mind, especially when it comes to cheating in the sport. The three-time Tour de France champion spoke out about Lance Armstrong long before it ...

In 2016, a Belgian rider Femke Van den Driessche was handed a six-year racing ban after a bike with a motor was found inside her pit area during the women's U23 cyclocross worlds. Another case this fall involved a Cat. 3 rider in France, who was using a bicycle with a motor hidden inside the frame.

A 19-year-old Belgian cyclist got caught cheating at the world championships after racing a bike that had a motor hidden in the frame Daniel McMahon 2016-02-01T12:54:00Z

RELATED: Are Tour de France Racers Cheating With Secret Motors? ... seemingly a little motor," said Jean-François Mailhes, who is the public prosecutor for Perigueux in the Dordogne commune. ...