The Ages of Exploration

Vasco da gama, age of discovery.

Quick Facts:

Portuguese explorer and navigator who found a direct sea route from Europe to Asia, and was the first European to sail to India by going around Africa.

Name : Vasco da Gama [vas-koh]; [(Portuguese) vahsh-koo] [duh gah-muh]

Birth/Death : ca. 1460 CE - 1524 CE

Nationality : Portuguese

Birthplace : Portugal

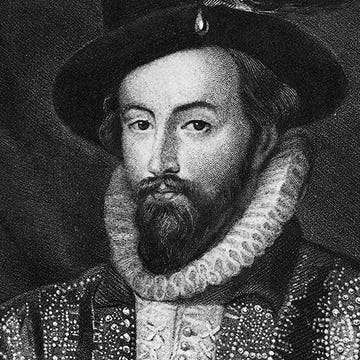

Portrait of Vasco da Gama by artist Antonio Manuel da Fonseca in 1838. Vasco da Gama, (c.1469 – 1524) was a Portuguese explorer, one of the most successful in the European Age of Discovery and the commander of the first ships to sail directly from Europe to India. (Credit: National Maritime Museum)

Introduction Vasco da Gama was a Portuguese explorer who sailed to India from Europe. Gold, spices, and other riches were valuable in Europe. But they had to navigate long ways over sea and land to reach them in Asia. Europeans during this time were looking to find a faster way to reach India by sailing around Africa. Da Gama accomplished the task. By doing so, he helped open a major trade route to Asia. Portugal celebrated his success, and his voyage launched a new era of discovery and world trade.

Biography Early Life Vasco da Gama’s exact birthdate and place is unknown. It is believed he was born between 1460 and 1469 in Sines, Portugal. 1 He was the third son to his parents. His father, Estêvão da Gama, was a knight in the Duke of Viseu’s court; and his mother was a noblewoman named Isabel Sodré. 2 His father’s role in the court would have allowed young Vasco to have a good education. But because he lived close to a seaport town, he probably also learned about ships and navigation. Vasco attended school in a larger village about 70 miles from Sines called Évora. Here, he learned advanced mathematics, and studied principles of navigation. By fifteen he became familiar with trading ships that were docked in port. By the age of twenty, he was the captain of a ship. 3 These skills would all make him an acceptable choice to lead an expedition to India.

Vasco da Gama’s maritime career was during the period when Portugal was searching for a trade route around Africa to India. The Ottoman Empire controlled almost all European trade routes to Asia. This meant they could, and did, charge high prices for ships passing through ports. Prince Henry of Portugal – also called Prince Henry the Navigator – began Portugal’s great age of exploration. From about 1419 until his death in 1460, he sent several sailing expeditions down the coast of Africa. 4 In 1481, King John II of Portugal began sending expeditions to find a sea route around the southern shores of Africa. Many explorers made several attempts. It was Bartolomeu Dias who was the first to round Africa and make it to the Indian Ocean in 1488. But he was forced to head back to Portugal before he could make it to India. When Manuel I became king of Portugal in 1495, he continued efforts to open a trade route to India by going around Africa. Although other people were considered for the job, Manuel I finally chose thirty-seven year old Vasco da Gama for this task.

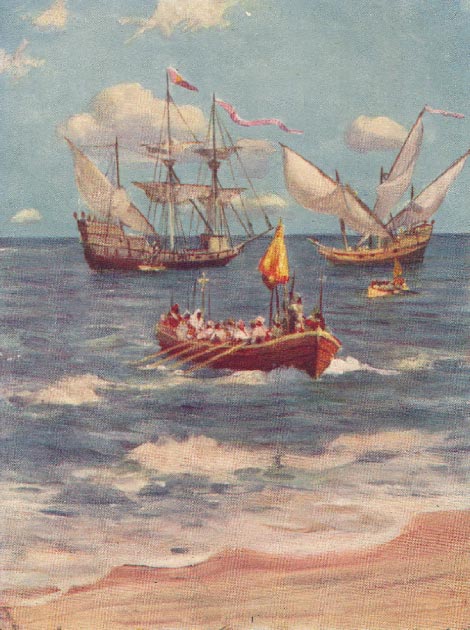

Voyages Principal Voyage On 8 July 1497 Vasco da Gama sailed from Lisbon with a fleet of four ships with a crew of 170 men from Lisbon. Da Gama commanded the Sao Gabriel . Paulo da Gama – brother to Vasco – commanded the São Rafael , a three masted ship. There was also the caravel Berrio , and a storeship São Maria . Bartolomeu Dias also sailed with da Gama, and gave helpful advice for navigating down the African coast. They sailed past the Canary Islands, and reached the Cape Verde islands by July 26. They stayed about a week, then continued sailing on August 3. To help avoid the storms and strong currents near the Gulf of Guinea, da Gama and his fleet sailed out into the South Atlantic and swung down to the Cape of Good Hope. Storms still delayed them for a while. They rounded the cape on November 22 and three days later anchored at Mossel Bay, South Africa. 5 They began sailing again on December 8. They anchored for a bit in January near Mozambique at the Rio do Cobre (Copper River) and continued on until they reached the Rio dos Bons Sinais (River of Good Omens). Here they erected a statue in the name of Portugal.

They stayed here for a month because much of the crew were sick from scurvy – a disease caused by lack of Vitamin C. 6 Da Gama’s fleet eventually began sailing again. On March 2 they reached the Island of Mozambique. After trading with the local Muslim merchants, da Gama sailed on once more stopping briefly in Malindi (in present day Kenya). He hired a pilot to help him navigate through the Indian Ocean. They sailed for 23 days, and on May 20, 1498 they reached India. 7 They headed for Kappad, India near the large city of Calicut. In Calicut, da Gama met with the king. But the king of Calicut was not impressed with da Gama, and the gifts he brought as offering. They spent several months trading in India, and studying their customs. They left India at the end of August. He visited the Anjidiv Island near Goa, and then once more stopped in Malindi in January 1499. Many of his crew were dying of scurvy. He had the São Rafael burned to help contain the illness. Da Gama finally returned to Portugal in September 1499. Manuel I praised da Gama’s success, and gave him money and a new title of admiral.

Subsequent Voyages Vasco da Gama’s later voyages were less friendly with the people he met. He sailed once again beginning in February 1502 with a fleet of 10 ships. They stopped at the Cape Verdes Islands, Mozambique, and then sailed to Kilwa (in modern day Tanzania). Da Gama threatened their leader, and forced him and his people to swear loyalty to the king of Portugal. At Calicut, he bombarded the port, and caused the death of several Muslim traders. Again, later at Cochin, they fought with Arab ships, and sent them into flight. 8 Da Gama was paving the way for an expanded Portuguese empire. This came at the cruel treatment of East African and South Asian people. Finally, on February 20, 1503 da Gama began the return journey home arriving on October 11 1503. King Manuel I died in 1521, and King John III became ruler. He made da Gama a Portuguese viceroy in India. 9 King John III sent da Gama to India to stop the corruption and settle administrative problems of the Portuguese officials. Da Gama’s third journey would be his last.

Later Years and Death After he had returned from his first trip, in 1500 Vasco da Gama had married Caterina de Ataíde. They had six sons, and lived in the town Évora. Da Gama continued advising on Indian affairs until he was sent overseas again in 1524. Vasco da Gama left Portugal for India, and arrived at Goa in September 1524. Da Gama quickly re-established order among the Portuguese leaders. By the end of the year he fell ill. Vasco da Gama died on December 24, 1524 in Cochin, India. He was buried in the local church. In 1539, his remains were brought back to Portugal.

Legacy Vasco De Gama was the first European to find an ocean trading route to India. He accomplished what many explorers before him could not do. His discovery of this sea route helped the Portuguese establish a long-lasting colonial empire in Asia and Africa. The new ocean route around Africa allowed Portuguese sailors to avoid the Arab trading hold in the Mediterranean and Middle East. Better access to the Indian spice routes boosted Portugal’s economy. Vasco da Gama opened a new world of riches by opening up an Indian Ocean route. His voyage and explorations helped change the world for Europeans.

- Emmanuel Akyeampong and Henry Louis Gates, Dictionary of African Biography (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2012), 415.

- Akyeampong and Gates, Dictionary of African Biography , 415.

- Patricia Calvert, Vasco Da Gama: So Strong a Spirit (Tarrytown: Benchmark Books, 2005), 11-12.

- Aileen Gallagher, Prince Henry, the Navigator: Pioneer of Modern Exploration (New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc., 2003), 5.

- Kenneth Pletcher, ed., The Britannica Guide to Explorers and Explorations That Changed the Modern World (New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, 2009), 54.

- Pletcher, The Britannica Guide, 55.

- Pletcher, The Britannica Guide , 55.

- Pletcher, The Britannica Guide , 57.

- Pletcher, The Britannica Guide , 58.

Bibliography

Akyeampong, Emmanuel, and Henry Louis Gates. Dictionary of African Biography . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Calvert, Patricia. Vasco Da Gama: So Strong a Spirit . Tarrytown: Benchmark Books, 2005.

Gallagher, Aileen. Prince Henry, the Navigator: Pioneer of Modern Exploration . New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc., 2003.

Pletcher, Kenneth ed. The Britannica Guide to Explorers and Explorations That Changed the Modern World. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, 2009.

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

Epic Voyage of Vasco da Gama Connected Europe to the East

- Read Later

Vasco da Gama was a Portuguese sailor and explorer who lived between the 15th and 16th centuries. Not only is da Gama a significant figure in the history of Portugal and Europe, but he is also an important personage in world history. Vasco da Gama was the first European to reach India via an oceanic route.

As a result of Vasco da Gama’s voyages , Portugal cemented its reputation as a formidable seafaring nation and grew rich from the goods that were coming from the East. Moreover, da Gama’s discovery of a maritime route connecting Europe to Asia may be regarded to be the beginning of the age of global imperialism.

Not long after da Gama’s first voyage to the East, the Portuguese established their first colony in Asia, when they conquered Goa, in India, in 1510. Portugal’s last colony, Macau, is also in Asia and was only handed back to China in 1999.

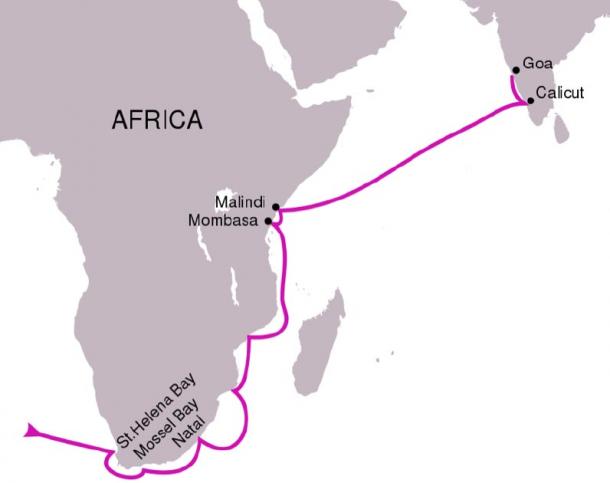

The journey of Vasco da Gama connected Europe and the East. Source: Archivist / Adobe Stock.

The Early Life of Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama was born around 1460 in Sines, a coastal town in the Alentejo region, in the southwestern part of Portugal. da Gama’s father was a minor provincial nobleman by the name of Estêvão da Gama, who served as a commander of the town’s castle. Unfortunately, little else is known about da Gama’s early life.

In fact, the next piece of information about Vasco da Gama’s life prior to his voyage to the East comes from 1492. In that year, the King of Portugal, John II, sent da Gama to Setubal, a port city between Lisbon and Sines, to seize French vessels.

This was carried out in retaliation for attacks by the French on Portuguese shipping interests, despite the fact that the two countries were not at war. da Gama proved his capabilities by performing his mission swiftly and effectively.

Politics and the Portuguese Fleet

In 1497, Vasco da Gama was given the task of seeking an oceanic route from Western Europe to the East and was placed at the head of a Portuguese fleet. Although da Gama is one of Portugal’s greatest maritime explorers, he was certainly not its first. In fact, the kingdom began to explore the uncharted waters to its west and south about 80 years before da Gama’s first voyage.

In 1415, the Portuguese crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and captured Ceuta from the Moors. This is considered to be the starting point of the Portuguese Colonial Empire. In the decades that followed, the Portuguese discovered (and colonized) the island of Madeira, and the Azores, and continued their exploration down the western coast of Africa.

Interestingly, one of the reasons that spurred the Portuguese to seek a sea route to the East was the legend of Prester John, who was rumored to be the monarch of a long-lost Christian kingdom in the East. The rulers of Portugal, as Catholics, saw it as their sacred duty to spread Christianity, and to destroy Islam. Therefore, the Portuguese kings were hoping to find this legendary Christian king in the East, form an alliance with him, and encircle the Muslims .

The envisioned ‘grand alliance’ against the Muslims never materialized, since the Portuguese were not able to locate the legendary Prester John. Nevertheless, the Portuguese grew wealthy as a consequence of the commerce that they conducted during their voyages. The most lucrative of all was the African slave trade and the first consignment of slaves was brought to Lisbon in 1441.

Six years after that, Portuguese seafarers had reached as far south as present-day Sierra Leone. The Portuguese arrived in the Congo in 1482 and 4 years later they were at Cape Cross, in present day Namibia. The Portuguese finally reached the ‘southern end’ of the African continent in 1488, when Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope.

The route followed in Vasco da Gama's first voyage, 1497–1499. (PhiLip / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

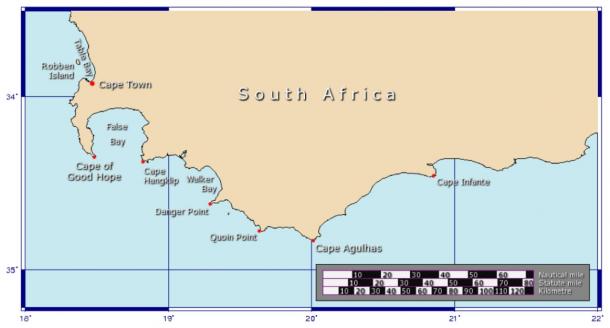

It may be pointed out that the Cape of Good Hope was thought (incorrectly) to be the dividing point between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Today, however, we know that the southern tip of Africa is in fact Cape Agulhas, located to the southeast of the Cape of Good Hope. While some accounts claim that the name of the landmark was given by Dias himself, others claim that Dias had originally named it ‘Cape of Storms’.

- The Age of Discovery: A New World Dawns

- Ferdinand Magellan: Defying all Odds in a Voyage around the World

- The Lost Treasure of Flor de la Mar, Flower of the Sea

Map of the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Agulhas the southernmost point of Africa. (Johantheghost / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

This was a reference to the stormy weather and rough seas that the area is famous for, which was a challenge for the early seafarers who intended to sail round the cape. The story goes on to say that it was John II who changed the name of the cape from ‘Cape of Storms’ to ‘Cape of Good Hope’, as it was supposed to be a good omen indicating that the Europeans could reach India (and presumably the elusive Prester John as well) via the sea.

It seems that there was a hiatus in Portugal’s exploratory voyages after Dias’ rounding of the Cape of Good Hope, as it took the Portuguese another decade before they finally arrived in India. By that time, John was dead, and had been succeeded by Manuel I, the king who gave Vasco da Gama the mission to seek the maritime route to India.

Manuel has a rather unusual, though appropriate epithet, ‘the Fortunate’. He was the ninth child of Dom Fernando, the younger brother of Afonso V, John’s father and predecessor. Considering his position, it was pretty unlikely that Manuel would ever attain the Portuguese throne. In addition, during John’s reign, Manuel’s only surviving brother was murdered by the king on suspicion of conspiracy.

Manuel, however, was spared, and even made Duke of Beja. In 1491, John’s legitimate son, Afonso, died in a horse-riding accident. For the remaining years of his life, John tried to legitimize his bastard son, Jorge de Lencastre, but without success.

The queen, Eleanor of Viseu, herself opposed John on this matter and supported Manuel as the new heir to the throne. The queen, incidentally, was one of Manuel’s sisters. Thus, in 1494, when John’s health was in decline, he named Manuel as his successor, and when the king died in October the following year, Manuel became Portugal’s new king.

Vasco da Gama’s Mission

It was Manuel who placed Vasco da Gama in charge of the fleet that was to sail to India in 1497. da Gama is said to have lacked the relevant experience to lead such an expedition, though some have suggested that he may have studied navigation prior to this. It is more likely that da Gama was chosen for political reasons – Manuel was in favor of the da Gama family and their supporters.

In any case, Vasco da Gama left Lisbon on the 8th of July 1497. The fleet consisted of four vessels – two medium-sized three-masted sailing ships known as carracks, each weighing about 120 tonnes, a smaller caravel, weighing about 50 tonnes, and a supply ship.

Departure of Vasco da Gama to India in 1497. (Dantadd / Public Domain )

The carracks were named São Gabriel and São Rafael , the former commanded by da Gama himself, while the latter by his brother, Paulo da Gama. The caravel was named São Miguel (nicknamed Berrio ) and commanded by Nicolau Coelho, whereas the name of the supply ship is today unknown and was commanded by Gonçalo Nunes.

The fleet passed the Canary Islands (which was under Spanish control) on the 15th of July and on the 26th arrived at São Tiago in the Cape Verde Islands. The fleet remained on the island until the 3rd of August before continuing their journey. da Gama initially sailed southwards along the west coast of Africa, but then veered far off into the southern Atlantic, in order to avoid the currents in the Gulf of Guinea.

On the 7th of November, the fleet arrived in Santa Helena Bay (in modern South Africa), where unfavorable winds and adverse currents caused da Gama and his men to halt their journey for several weeks. Finally, on the 22nd of November, da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and continued the journey eastwards.

Three days after rounding the Cape of Good Hope, da Gama set foot on Mossel Bay, and erected a padrão (a stone pillar left by the Portuguese explorers to mark significant landfalls and to establish possession of the area) there. It was also here that the supply ship was scuttled. Around Christmas, da Gama sailed passed a coast that was yet to be explored by Europeans and called it Natal (the Portuguese word for Christmas).

Pillar of Vasco da Gama in Malindi, in modern-day Kenya, erected on the return journey. (Mgiganteus / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Vasco da Gama’s Journey Continues

In the months that followed, the fleet sailed northwards along the east coast of Africa. In January 1498, the fleet had arrived in the area that is today Mozambique. On the 25th of that month, da Gama and his men reached the Quelimane River, which they called Rio dos Bons Sinais (meaning ‘River of Good Omens’) and set up another padrão . The fleet rested there for a month, as many of the men were suffering from scurvy and the ships needed to be repaired.

On the 2nd of March, da Gama arrived on the island of Mozambique, which was ruled by a Muslim sultan. The islanders believed that the Portuguese were Muslims like themselves and therefore treated them kindly. da Gama gained much information from them and was even given two navigators by the sultan, one of whom deserted when he learned that the Portuguese were in fact Christians.

In April, the fleet reached the coast of modern day Kenya. On the 14th of April, da Gama was in Malindi, where he obtained the service of a Gujarati navigator who knew the way to Calicut, on the southwestern coast of India. On the 20th of May, the fleet arrived in Calicut after sailing for 23 days directly across the Indian Ocean.

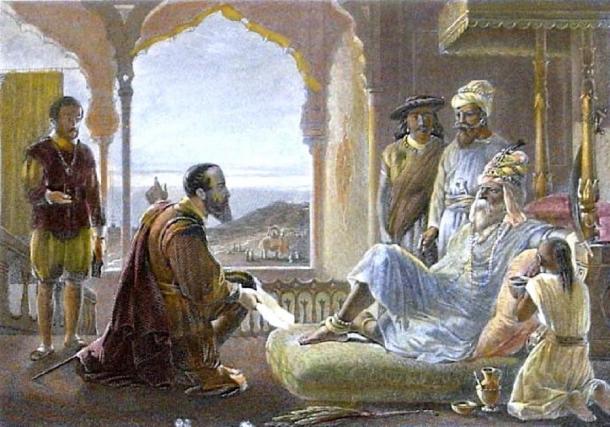

Vasco da Gama landing at Calicut. (Piggy58 / Public Domain )

At Calicut, da Gama’ gifts failed to impress the Zamorin (the Hindu ruler of Calicut). In addition, the Muslims merchants who were already there were hostile towards the Portuguese. As a consequence, the Portuguese failed to conclude a trade treaty with the Indians of Calicut.

- Record Breaking Finds From Portuguese Shipwreck Confirmed by Guinness Book of Records [World’s Oldest Finds]

- Pedro Alvares Cabral: The Lucky Lost Navigator Who Made Brazil Portuguese

- Amerigo Vespucci: The Forgotten Explorer Who Named America

Vasco da Gama meets Zamorin. (Donaldduck100 / Public Domain )

In the meantime, relations between the Portuguese and the Indians grew increasingly tense and Vasco da Gama finally decided to sail back to Portugal at the end of August. The Portuguese, who were still ignorant about the monsoon wind patterns, chose the worst possible time for their return journey. As a result of sailing against the monsoon winds, da Gama took nearly three months to cross the Indian Ocean, during which time many of his crew died of scurvy.

The lack of crew members also forced da Gama to order the destruction of São Rafael when the fleet arrived at Malindi on the 7th of January 1499. The two remaining ships rounded the Cape of Good Hope on the 20th of March but were separated a month later by a storm.

São Miguel arrived in Portugal on the 10th of July, while São Gabriel arrived on the 9th of September. Nine days later, da Gama entered Lisbon, and was welcomed as a hero.

The king bestowed the title Dom on Vasco da Gama, gave him an annual pension of 1000 cruzados, and estates. Nevertheless, da Gama had paid a hefty price for his success – of the original crew of 170 men only 55 returned, and his own brother was among the dead.

The king granted Vasco da Gama the title of Dom. ( laufer / Adobe Stock)

The Success of Vasco da Gama’s Voyage Demands a Repeat

The success of Vasco da Gama’s voyage encouraged the king to send another fleet, this time consisting of 13 ships, to secure a trade treaty with Calicut. Although relations between the Zamorin and the Portuguese began much better this time round, it quickly went south. The Portuguese came into conflict with the Muslim merchants, who wanted to keep their monopoly on the city’s trade.

As a result, a riot broke out, which overran the Portuguese trading post and many Portuguese were slaughtered. The Zamorin was blamed for the incident and his city was bombarded, thus war was declared by the Portuguese on Calicut.

In 1502, another fleet was set out from Lisbon, under the command of da Gama, who was charged with exacting revenge on Calicut, and to force the Zamorin into submission. Raids were also carried out against Arab merchant ships, and, according to one story, da Gama had captured a pilgrim ship with 200-400 passengers, locked them up in the vessel after plundering its goods, and set fire to the ship.

The story, which may have been false, or at least exaggerated, caused Vasco da Gama to be reviled in that part of the world. Incidentally, one of da Gama’s ships from his second voyage has been found off the coast of Oman and excavated between 2013 and 2015.

Vasco da Gama failed to force the Zamorin to submit and seems to have lost the favor of Manuel when he returned. For the next two decades of his life, da Gama retired to the town of Évora and lived a quiet life with his wife and six sons. He was only sent on his third and last voyage in 1524 by John III, Manuel’s successor.

This time, Vasco da Gama was sent to serve as the Portuguese viceroy in India. In September 1524, da Gama arrived in Goa and began combating the corruption that was plaguing the Portuguese administration in India.

Three months later, however, da Gama died in Cochin as a result of illness, either due to overwork or some other reason. His remains were first buried in St. Francis Church in Cochin, and then brought back to Portugal in 1539 and laid to rest Vidigueira before being transferred to the Jerónimos Monastery in Belém, Lisbon during the late 19th century, where they have remained till today.

Tomb of Vasco da Gama in the Jerónimos Monastery in Belém, Lisbon. (Christine und Hagen Graf / CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Top image: Portuguese caravel of the 15th century. Vasco da Gama was a Portuguese sailor and explorer. Credit: Michael Rosskothen / Adobe Stock

By Wu Mingren

Updated on January 21, 2021.

Fernandez-Armesto, F., and Campbell, E. 2019. Vasco da Gama . [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Vasco-da-Gama

History.com Editors. 2018. Vasco da Gama . [Online] Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/exploration/vasco-da-gama

LisbonLisboaPortugal.com. 2020. Vasco Da Gama . [Online] Available at: https://lisbonlisboaportugal.com/Lisbon-information/Vasco_gama.html

Livermore, H. 2019. Manuel I . [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Manuel-I

New World Encyclopedia. 2019. Portuguese Empire . [Online] Available at: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Portuguese_Empire

Romey, K. 2016. Shipwreck Discovered from Explorer Vasco da Gama's Fleet . [Online] Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2016/03/20160314-oman-shipwreck-explorer-vasco-da-gama-age-of-exploration-india-route/

Szalay, J. 2016. Vasco da Gama: Facts & Biography . [Online] Available at: https://www.livescience.com/39078-vasco-da-gama.html

The BBC. 2014. Vasco da Gama (c.1460 - 1524) . [Online] Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/da_gama_vasco.shtml

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2019. Cape of Good Hope . [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/place/Cape-of-Good-Hope

The Mariners' Museum & Park. 2020. Vasco da Gama . [Online] Available at: https://exploration.marinersmuseum.org/subject/vasco-da-gama/

Wu Mingren (‘Dhwty’) has a Bachelor of Arts in Ancient History and Archaeology. Although his primary interest is in the ancient civilizations of the Near East, he is also interested in other geographical regions, as well as other time periods.... Read More

Related Articles on Ancient-Origins

Vasco da Gama

Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama was commissioned by the Portuguese king to find a maritime route to the East. He was the first person to sail directly from Europe to India.

(1460-1524)

Who Was Vasco Da Gama

In 1497, explorer Vasco da Gama was commissioned by the Portuguese king to find a maritime route to the East. His success in doing so proved to be one of the more instrumental moments in the history of navigation. He subsequently made two other voyages to India and was appointed as Portuguese viceroy in India in 1524.

Early Years

Da Gama was born into a noble family around 1460 in Sines, Portugal. Little is known about his upbringing except that he was the third son of Estêvão da Gama, who was commander of the fortress in Sines in the southwestern pocket of Portugal. When he was old enough, young da Gama joined the navy, where was taught how to navigate.

Known as a tough and fearless navigator, da Gama solidified his reputation as a reputable sailor when, in 1492, King John II of Portugal dispatched him to the south of Lisbon and then to the Algarve region of the country, to seize French ships as an act of vengeance against the French government for disrupting Portuguese shipping.

Following da Gama's completion of King John II's orders, in 1495, King Manuel took the throne, and the country revived its earlier mission to find a direct trade route to India. By this time, Portugal had established itself as one of the most powerful maritime countries in Europe.

Much of that was due to Henry the Navigator, who, at his base in the southern region of the country, had brought together a team of knowledgeable mapmakers, geographers and navigators. He dispatched ships to explore the western coast of Africa to expand Portugal's trade influence. He also believed that he could find and form an alliance with Prester John, who ruled over a Christian empire somewhere in Africa. Henry the Navigator never did locate Prester John, but his impact on Portuguese trade along Africa's east coast during his 40 years of explorative work was undeniable. Still, for all his work, the southern portion of Africa — what lay east — remained shrouded in mystery.

In 1487, an important breakthrough was made when Bartolomeu Dias discovered the southern tip of Africa and rounded the Cape of Good Hope. This journey was significant; it proved, for the first time, that the Atlantic and Indian oceans were connected. The trip, in turn, sparked a renewed interest in seeking out a trade route to India.

By the late 1490s, however, King Manuel wasn't just thinking about commercial opportunities as he set his sights on the East. In fact, his impetus for finding a route was driven less by a desire to secure for more lucrative trading grounds for his country, and more by a quest to conquer Islam and establish himself as the king of Jerusalem.

First Voyage

Historians know little about why exactly da Gama, still an inexperienced explorer, was chosen to lead the expedition to India in 1497. On July 8 of that year, he captained a team of four vessels, including his flagship, the 200-ton St. Gabriel , to find a sailing route to India and the East.

To embark on the journey, da Gama pointed his ships south, taking advantage of the prevailing winds along the coast of Africa. His choice of direction was also a bit of a rebuke to Christopher Columbus, who had believed he'd found a route to India by sailing east.

Following s months of sailing, he rounded the Cape of Good Hope and began making his way up the eastern coast of Africa, toward the uncharted waters of the Indian Ocean. By January, as the fleet neared what is now Mozambique, many of da Gama's crewmembers were sick with scurvy, forcing the expedition to anchor for rest and repairs for nearly one month.

In early March of 1498, da Gama and his crew dropped their anchors in the port of Mozambique, a Muslim city-state that sat on the outskirts of the east coast of Africa and was dominated by Muslim traders. Here, da Gama was turned back by the ruling sultan, who felt offended by the explorer's modest gifts.

By early April, the fleet reached what is now Kenya, before setting sail on a 23-day run that would take them across the Indian Ocean. They reached Calicut, India, on May 20. But da Gama's own ignorance of the region, as well as his presumption that the residents were Christians, led to some confusion. The residents of Calicut were actually Hindu, a fact that was lost on da Gama and his crew, as they had not heard of the religion.

Still, the local Hindu ruler welcomed da Gama and his men, at first, and the crew ended up staying in Calicut for three months. Not everyone embraced their presence, especially Muslim traders who clearly had no intention of giving up their trading grounds to Christian visitors. Eventually, da Gama and his crew were forced to barter on the waterfront in order to secure enough goods for the passage home. In August 1498, da Gama and his men took to the seas again, beginning their journey back to Portugal.

Da Gama's timing could not have been worse; his departure coincided with the start of a monsoon. By early 1499, several crew members had died of scurvy and in an effort to economize his fleet, da Gama ordered one of his ships to be burned. The first ship in the fleet didn't reach Portugal until July 10, nearly a full year after they'd left India.

In all, da Gama's first journey covered nearly 24,000 miles in close to two years, and only 54 of the crew's original 170 members survived.

Second Voyage

When da Gama returned to Lisbon, he was greeted as a hero. In an effort to secure the trade route with India and usurp Muslim traders, Portugal dispatched another team of vessels, headed by Pedro Álvares Cabral. The crew reached India in just six months, and the voyage included a firefight with Muslim merchants, where Cabral's crew killed 600 men on Muslim cargo vessels. More important for his home country, Cabral established the first Portuguese trading post in India.

In 1502, da Gama helmed another journey to India that included 20 ships. Ten of the ships were directly under his command, with his uncle and nephew helming the others. In the wake of Cabral's success and battles, the king charged da Gama to further secure Portugal's dominance in the region.

To do so, da Gama embarked on one of the most gruesome massacres of the exploration age. He and his crew terrorized Muslim ports up and down the African east coast, and at one point, set ablaze a Muslim ship returning from Mecca, killing the several hundreds of people (including women and children) who were on board. Next, the crew moved to Calicut, where they wrecked the city's trade port and killed 38 hostages. From there, they moved to the city of Cochin, a city south of Calicut, where da Gama formed an alliance with the local ruler.

Finally, on February 20, 1503, da Gama and his crew began to make their way home. They reached Portugal on October 11 of that year.

Later Years and Death

Little was recorded about da Gama's return home and the reception that followed, though it has been speculated that the explorer felt miffed at the recognition and compensation for his exploits.

Married at this time, and the father of six sons, da Gama settled into retirement and family life. He maintained contact with King Manuel, advising him on Indian matters, and was named count of Vidigueira in 1519. Late in life, after the death of King Manuel, da Gama was asked to return to India, in an effort to contend with the growing corruption from Portuguese officials in the country. In 1524, King John III named da Gama Portuguese viceroy in India.

That same year, da Gama died in Cochin — the result, it has been speculated, from possibly overworking himself. His body was sailed back to Portugal, and buried there, in 1538.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Vasco da Gama

- Birth Year: 1460

- Birth City: Sines

- Birth Country: Portugal

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama was commissioned by the Portuguese king to find a maritime route to the East. He was the first person to sail directly from Europe to India.

- World Politics

- Nationalities

- Death Year: 1524

- Death date: December 24, 1524

- Death City: Cochin

- Death Country: India

- I am not the man I once was. I do not want to go back in time, to be the second son, the second man.

- I am not afraid of the darkness. Real death is preferable to a life without living.

- We left from Restelo one Saturday, the 8th day of July of the said year, 1479, on out journey. May God our Lord allow us to complete it in His service.

- There was great rejoicing, thanks being rendered to God for having extricated us from the hands of people who had no more sense than beasts.

European Explorers

Christopher Columbus

10 Famous Explorers Who Connected the World

Sir Walter Raleigh

Ferdinand Magellan

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Leif Eriksson

Bartolomeu Dias

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Jacques Marquette

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

Vasco da Gama’s Breakout Voyage

Portuguese explorers reached india in the 15th century, establishing a legacy of misunderstanding, suspicion, hostility—and violence..

While Christopher Columbus has gotten most of the ink for his 1492 transit of the Atlantic Ocean, which proved that a hitherto unknown (by Europeans) but populated hemisphere lay over the western horizon, Portuguese mariner Vasco da Gama’s voyage, just five years later in 1497, was longer and introduced Europeans to the far wealthier cultures of south Asia. He and his crew of 150 veteran mariners first sailed around the African continent, then crossed the Indian Ocean to land on the Malabar coast of the Indian subcontinent.

They did not come in peace. With red crosses on their sails and bronze cannons on their decks, they meant to capture the rich spice trade of Asia and destroy the Islamic cultures they’d first blooded in the Mediterranean. In their armed violence, described by Roger Crowley in the following excerpt from his new book, Conquerors , they set the tone for the next 500 years of Western global expansion.

ON APRIL 24, WITH THE MONSOON WINDS turning in their favor, the crews headed out to sea “for a city called Calicut.” The turn of phrase suggests that the anonymous diarist on the expedition was hearing this name for the first time—and perhaps the whole expedition, blindly breaking into the Indian Ocean, had only the vaguest sense of their destination. With a continuous following wind, the diagonal crossing of this new sea was astonishingly quick. They were heading northeast. On April 29 they were comforted by the return of the polestar to the night sky, lost to view since the South Atlantic. On Friday, May 18, after only 23 days away from land and 2,300 miles of open water, they spied high mountains. The following day shattering rain thundered on the decks, blotting out visibility; fierce flashes of lightning split the sky. They had hit the early prelude to the monsoon. As the storm cleared, the pilot was able to recognize the coast: “He told us that they were above Calicut, and that this was the country we desired to go to.” Through the breaking rain, they surveyed India for the first time: high peaks looming through the murk. These were the Western Ghats, the long chain of mountains belting southwestern India, on the Malabar Coast; the men could see densely forested slopes, a narrow plain, surf breaking on white sand.

It must have been an emotional sight. They had watched their loved ones wading into the sea at Restelo 309 days ago. They had sailed 12,000 miles and already lost many men. This first blurred view of India stands as a significant moment in world history. Vasco da Gama had ended the isolation of Europe. The Atlantic was no longer a barrier; it had become a highway to link up the hemispheres.…Gama paid off the pilot handsomely, called the crew to prayers, and gave “thanks to God, who had safely conducted them to the long-wished-for place of his destination.”

From the shore there was immediate interest, sparked by both the novelty of the ships themselves, unlike anything sailing the Indian Ocean, and their unlikely timing. Four boats came out to see the strange visitors and pointed out Calicut some way off; the following day, the boats were back. Gama sent one of his convicts ashore with the visitors, a man called João Nunes, a converted Jew, destined to make the most famous landfall in Portuguese history.

The crowd on the beach took him for a Muslim and led him to two Tunisian merchants, who spoke some Castilian and Genoese. The encounter was one of mutual astonishment. Nunes found himself addressed in a language of his own continent: “The Devil take you! What brought you here?”

It was almost anticlimactic, a moment in which the world must have shrunk. The Portuguese had girdled the earth only to be spoken to almost in their own tongue. The commonwealth of Islamic trade, from the gates of Gibraltar to the China Sea, was far more extensive than the Portuguese could yet grasp.

“We came,” replied Nunes, with considerable presence of mind, “in search of Christians and spices.”

The two men took him to their house and fed him delicacies—wheat bread and honey—then enthusiastically accompanied him back to the ships. “Good fortune! Good fortune!” one of them broke out as soon as he had clambered aboard. “Many rubies, many emeralds! You should give many thanks to God for having brought you to a land where there are such riches!” “We were so amazed at this that we heard him speak and we could not believe it,” said the anonymous diarist, “that there could be anyone so far away from Portugal who could understand our speech.”

One of the Tunisians, a man they called Monçaide (perhaps Ibn Tayyib), would help them interpret this new world. He had a nostalgia for the Portuguese, whose ships he had seen trading on the North African coast in the reign of João II. He offered guidance to the labyrinthine manners and customs of Calicut that would prove invaluable. The city, he told them, was ruled by a king, the samudri raja , “the Lord of the Sea,” who would “gladly receive the general as ambassador from a foreign king; more especially if the objects of his voyage were to establish a trade with Calicut, and if the general had brought with him any merchandise proper for that purpose.”

CALICUT, DESPITE THE LACK OF A GOOD NATURAL HARBOR, had established itself as the premier center for the trading of spices along the Malabar Coast because of its rulers’ reputation for good governance and fair dealing with merchants. It had a sizable and deeply settled Muslim trading community. “Formerly,” wrote an earlier Chinese chronicler, “there was a king who made a sworn compact with the Muslim people: You do not eat the ox; I do not eat the pig; we will reciprocally respect the taboo. [This] has been honored right down to the present day.” It was this harmonious arrangement that the Portuguese were destined to disrupt.

The samudri presented the messengers with gifts, expressed his willingness to meet the curious arrivals, and set off with his retinue to the city. He also provided a pilot to lead their ships to a better anchorage some distance away, in a secure harbor at a settlement the Portuguese would call Pandarani. Gama agreed to move his ships, but following his contentious experiences along the African coast, he was cautious and would not proceed right into the berth that the pilot indicated. Suspicion and the tendency to misread motives would dog Portuguese actions in this new world.

On board there followed a heated debate among the captains about how to proceed….Gama, in a speech probably created for him by the chroniclers, insisted that there was now no other way. They had reached India as the king’s ambassador. He must negotiate in person even at the risk of his life. He would take a few men with him and stay for only a short while: “It is not my intention to stay long on shore, so as to give opportunity to the Muslims to plot against me, as I propose only to talk with the king and to return in three days.” The rest must remain at sea under his brother Paulo’s command; an armed boat should be sent close to the shore each day to try to maintain communication; if any harm should befall Gama, they should sail away. On the morning of Monday, May 28, a week after their arrival, Gama set out with 13 men. The party included interpreters and the anonymous writer, well placed to provide an authentic eyewitness account. “We put on our best attire,” he recorded, “placed bombards in our boats, and took with us trumpets and many flags.” Splendor was to be matched by armed defense.

They were greeted in contrasting style by the samudri’s bale—his governor. To the groggy sailors, the sight of the reception committee was alarming: a large number of men, some with big beards and long hair, their ears pierced with glinting gold, many naked to the waist and holding drawn swords. These men were Nayars, members of the Hindu warrior caste, sworn from youth to protect their king until death. The Portuguese took them for Christians, and the reception seemed friendly.

It was nearly sunset when they reached the palace. “We passed through four doors, through which we had to force our way, giving many blows to the people.” Men were wounded at the entrance. At last they came into the king’s audience chamber, “a great hall, surrounded with seats of timber raised in rows above one another like our theaters, the floor being covered by a carpet of green velvet, and the walls hung with silk of various colors.” Before them sat a man they believed to be the Christian king they had come 12,000 miles to find.

THE FIRST SIGHT OF A HINDU MONARCH was, to Portuguese eyes, remarkable:

The king was of a brown complexion, large stature, and well advanced in years. On his head he had a cap or miter adorned with precious stones and pearls, and had jewels of the same kind in his ears. He wore a jacket of fine cotton cloth, having buttons of large pearls and the button-holes wrought with gold thread. About his middle he had a piece of a white calico, which came only down to his knees; and both his fingers and toes were adorned with many gold rings set with fine stones; his arms and legs were covered with many golden bracelets.

The samudri reclined in a posture of Oriental ease on a green velvet couch, chewing betel leaves, the remnants of which he spat into a large gold spittoon.

When Gama was asked to address the assembled company, he asserted his dignity and requested to speak in private. Withdrawing into an inner room with just their interpreters, he talked up his mission: to come to the land of India, which they had been seeking for 60 years on behalf of his king, “the possessor of great wealth of every description,” to find Christian kings. He promised to bring the letters of the Portuguese king, Dom Manuel, to the samudri next day. By this time Gama had evidently assumed the samudri to be a Christian.

As was the custom, the samudri asked if Gama would like to lodge with the Christians (in fact, the Hindus) or the Muslims. Gama warily asked for his men to lodge on their own. It was about 10 o’clock at night. The rain was pouring down in the dark, churning up the street. He was carried on the palanquin under an umbrella…until they reached their lodgings, to which his bed had been delivered by sailors from the boat, along with the presents for the king.

The next morning, Gama collected the items to send to the palace: 12 pieces of striped cloth, 4 scarlet hoods, 6 hats, 4 strings of coral, 6 hand-washing basins, a case of sugar, 2 casks each of honey and oil. These were objects to impress an African chief, not a potentate used to the rich trading culture of the Indian Ocean. The bale just laughed: “The poorest merchant from Mecca, or any other part of India, gave more….If he wanted to make a present it should be in gold.” He refused to forward the paltry items to the Sovereign of the Sea. Furious backpedaling was required. Gama retorted that “he was no merchant but an ambassador….If the king of Portugal ordered him to return he would entrust him with far richer presents.”

The Muslim merchants had sensed a threat from the Christian incomers; they may have received reports of the foreigners’ aggressive tactics and bombardment of the Swahili coast. For all the credited openness of Calicut to trade, there were vested interests to protect; there is evidence that the Muslims had been instrumental in driving Chinese merchants out of the city decades earlier. They probably secured an audience with the samudri to relay the suggestion that Gama was at best a chancer, more likely a pirate. The Portuguese subsequently believed that the Muslims requested Gama’s death.

In the morning they were taken back to the palace, where they waited four hours. To Gama, now thoroughly worked up, it was a calculated snub. Finally word came that the king would see only the captain major and two others. The whole party thought “this separation portended no good.” Gama stepped through the doorway, heavily guarded by armed men, with his secretary and interpreter.

The second interview was frosty and perplexing. Unable to understand what motives these strangers could have if not to trade, the samudri’s questions followed in quick succession to the effect that if he were from a rich country, why had he not brought gifts? And where were his letters? Gama was forced to extemporize answers about how he had brought nothing because this was a voyage of discovery. It would be followed up by others, with rich gifts. He did at least have the letters at hand. The king probed the gift mystery again: “What had he come to discover: stones or men?” he demanded ironically. “If he came to discover men, as he said, why had he brought nothing?” Finally there was the issue of the merchandise: Gama might return to the ships, land, and sell it as best he could. He never saw the samudri again.

The following morning, Gama asked for boats. The bale requested the ships to be brought closer inshore to make the transfer easier in the monsoon weather. The Portuguese feared a trap, orchestrated by the Muslim faction in the city; the bale suspected that these strange visitors might try to leave without paying their customs dues.

“The captain said that if he ordered his vessels to approach, his brother would think that he was being held a prisoner, and that he gave this order on compulsion, and would hoist the sails and return to Portugal.” He demanded to return, with his complaints, to the samudri, “who was a Christian like himself.” The bale agreed but then placed a heavily armed guard on the doors, “none of us being allowed to go outside without being accompanied by several of these guards.” The bale requested that if the ships remained offshore, they should give up their rudders and sails so as not to make off. Gama refused. When he declared that they would die of hunger, the reply was that “if we died of hunger we must bear it.” There was a tense standoff.

The journal recorded a day of tightening fear, offset by an ability to live in the moment.

We passed all that day most anxiously. At night more people surrounded us than ever before, and we were no longer allowed to walk in the compound, within which we were, but confined within a small tiled court, with a multitude of people around us. We quite expected that on the following day we should be separated, or that some harm would befall us….

Next morning, the whole problem inexplicably vanished. Their captors came back, with “better faces,” as the journal writer said. They would do as the king had requested: If the Portuguese landed their goods, they might go. They explained what the bristling Gama had failed to understand: that “it was the custom of the country that every ship on its arrival should at once land the merchandise it brought, as also the crews, and that the vendors should not return on board until the whole of it had been sold.” Gama promptly sent a message to his brother to send “certain things”—not all, and the prisoners were released back to their ships. “At this we rejoiced greatly, and rendered thanks to God for having extricated us from the hands of people who had no more sense than beasts.”

The Portuguese had come to the Indian coast with their visors lowered. Hardened by decades of holy war in North Africa, their default strategies were suspicion, aggressive hostage taking, the half-drawn sword, and a simple binary choice between Christian and Muslim, which seemed genuinely not to have factored into calculation the existence of Hinduism. These impatient simplicities were ill suited to the complexities of the Indian Ocean, where Hindus, Muslims, Jews, and even Indian Christians were integrated into a polyethnic trading zone.

IN THE WEEKS THAT FOLLOWED, THE PORTUGUESE started to unravel the different strata of Malabar society. Informal dealing allowed them to glimpse the mechanisms and rhythms of the Indian Ocean trade and an outline of the supply networks, information they would store for future reference. Calicut itself was a major producer of ginger, pepper, and cinnamon, although better quality of the latter could be had from “an island called Ceylon, which is eight days journey to the south.” Cloves came from an “island called Malacca.” “The Mecca vessels” (from the Arabian Peninsula, 50 days’ sailing away) would carry spices to the Red Sea, and then, via a series of transshipments, successively to Cairo and up the Nile to Alexandria, where the galleys of Venice and Genoa would load up. The Portuguese noted all the checks and barriers in this trade: the inefficient transshipments, the robbery on the road to Cairo, the exorbitant taxes paid to the sultan there. It was this complex supply chain that they were keen to disrupt.

Once more relations unraveled. Gama failed to understand that all merchants were obliged to pay port taxes and that the poor goods they had left onshore provided no surety. Instead, the interpretation of this behavior was that “the Christian king” had been influenced by the Muslims for commercial purposes; that they had told the samudri “that we were thieves, and that if once we navigated to his country, no more ships would come from Mecca…nor from any other part…that he would derive no profit from this [trade with the Portuguese] as we had nothing to give, and would rather take away, and that thus his country would be ruined.” The basic strategic assumption would prove accurate, even if Portuguese fears that the Muslims had offered “rich bribes to the king to capture and kill us” might not. During all this period, Gama continued to receive advice and insights from the two Tunisian Muslims they had met on first landing, and who played a significant part in their understanding of this confusing world.

ON AUGUST 19, 25 MEN CAME OUT [to the expedition’s ships], including “six persons of quality” (high-caste Hindus). Gama saw his chance and promptly kidnapped 18 of them and demanded his man back [Diego Dias had been detained by the samudri]. On August 23, he bluffed that he was leaving for Portugal, sailed away, and waited 12 miles offshore. The next day he returned and anchored within sight of the city.

Cagey negotiations ensued. A boat called to offer to exchange Dias for the hostages. Suspicious as ever, Gama chose to believe that his man was dead and that this was just a delaying tactic “until the ships of Mecca able to capture us had arrived.” He was playing tough, threatening to fire his bombards and to decapitate the hostages unless Dias was returned. He bluffed a farther retreat down the coast.

The samudri sent for Dias and tried to untie the knot. He offered to return him for the hostages on board, and via a double interpretation process—Malayalam to Arabic, Arabic to Portuguese—he dictated a letter, addressed to King Manuel and written by Dias with an iron pen upon a palm leaf, “as is the custom of the country.” The gist read: “Vasco Gama, a gentleman of your household, came to my country, whereat I was pleased. My country is rich in cinnamon, cloves, ginger, pepper and precious stones. That which I ask of you in return is gold, silver, corals and scarlet cloth.” The samudri was perhaps hedging his bets against future trade. He also permitted the erection of a stone pillar—the ominous calling card of Portuguese intentions.

Offshore, the bargaining went on. Dias was brought out and the hostages were exchanged in a rowboat.…The stone pillar was winched into the boat, and six of the hostages were released. The other six Gama “promised to surrender if on the morrow the merchandise was restored to him.” Then he summarily decided to abandon the goods and carry the hostages off to Portugal. He left with a parting shot: “Be careful, as he hoped shortly to be back in Calicut, when they would know whether we were thieves.” Gama was not one to forgive or forget. “We therefore set sail and left for Portugal, greatly rejoicing at our good fortune in having made so great a discovery,” the diarist reported with satisfaction.

The samudri was furious at the broken bargain and sent a swarm of boats in pursuit. They caught the Portuguese, becalmed farther up the coast, on August 30. “About 70 boats approached us…crowded with people wearing a kind of cuirass made of red cloth.” As they came within range, the Portuguese fired their bombards. A running fight ensued for an hour and a half, until “there arose a thunderstorm which carried us out to sea; and when they could no longer do us harm they turned back, while we pursued our route.” It was to be the first of many naval engagements in the Indian Ocean.

On September 22, they sustained a second attack from a flotilla from Calicut, but Portuguese gunnery crippled the lead ship and the others fled. The presence of these alien vessels was causing continuous interest and suspicion, and Gama was finding the coast increasingly uncomfortable.

On October 5 the ships put out to sea. They now had no pilot. No one who had knowledge of the monsoon winds would have set out to sail west at this time. They probably had little choice, given the circumstances, but whether Gama was aware that it would prove a terrible mistake is unknown.

On January 2, 1499, the battered ships sighted the African coast. It had taken just 23 days to make the voyage across; the return took 93. The lessons of the seasonal monsoon were hard won.

The voyage had been epic; they had been away a year, traveled 24,000 miles. It was a feat of endurance, courage, and great luck. The toll had been heavy. Two-thirds of the crew had died. Unaware of the rhythms of the monsoon, they had been fortunate to survive; scurvy and adverse weather could have taken all of them in the Indian Ocean, leaving ghost ships floating on an empty sea. MHQ

ROGER CROWLEY is a UK-based writer and historian. His particular interests are the Byzantine, Venetian, and Ottoman empires, and seafaring and eyewitness history. Excerpted from the book Conquerors , by Roger Crowley. Copyright © 2015 by Roger Crowley. Reprinted by arrangement with Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

PHOTO: “Bold in actions, severe in his orders, and very formidable in his anger,” Vasco da Gama, a minor nobleman in his 30s, had been second choice to lead the Portuguese expedition to India. Prisma/UIG/Getty Images

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2016 issue (Vol. 28, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Vasco da Gama’s Breakout Voyage.

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!

Related stories

Portfolio: Images of War as Landscape

Whether they produced battlefield images of the dead or daguerreotype portraits of common soldiers, […]

Jerrie Mock: Record-Breaking American Female Pilot

In 1964 an Ohio woman took up the challenge that had led to Amelia Earhart’s disappearance.

10 Pivotal Events in the Life of Buffalo Bill

William Frederick Cody (1846-1917) led a signal life, from his youthful exploits with the Pony Express and in service as a U.S. Army scout to his globetrotting days as a showman and international icon Buffalo Bill.

The One and Only ‘Booger’ Was Among History’s Best Rodeo Performers

Texan Sam Privett, the colorfully nicknamed proprietor of Booger Red’s Wild West, backed up his boast he could ride anything on four legs.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Native Americans

- Age of Exploration

- Revolutionary War

- Mexican-American War

- War of 1812

- World War 1

- World War 2

- Family Trees

- Explorers and Pirates

Vasco Da Gama Timeline For Kids

Published: Aug 11, 2022 · Modified: Oct 30, 2023 by Russell Yost · This post may contain affiliate links ·

1469 - Vasco da Gama is born in Sines, Portugal, to Estêvão da Gama, who was the commander of the fortress in his hometown of Sines.

1480 - Vasco da Gama joins the Order of Santiago and improves his standing. The master of the order would become King John II of Portugal. King John II would eventually reignite Henry the Navigator 's plans and continue his push south to find a route to India.

1492 - Da Gama begins to gain a reputation as a great sailor and warrior when he defeats the French in the Algarve region.

First Voyage for Vasco Da Gama

Second voyage for vasco da gama, third voyage for vasco da gama.

July 8, 1497 - King Manuel sponsors Vasco to sail around the southern tip of Africa. He leaves with 4 ships.

November 4, 1497 - He rounds Sierre Leone and makes landfall on the west coast of Africa.

December 16, 1497 - He makes it to the Cape of Good Hope, which is where Bartolomeu Dias had anchored previously. Here, he would journey where no other European had been before.

March 29, 1498 - in the vicinity of Mozambique Island. The Arab-controlled territory on the East African coast was an integral part of the network of trade in the Indian Ocean.

Fearing the local population would be hostile to Christians, the famous explorer impersonated a Muslim and gained an audience with the Sultan of Mozambique.

With the paltry trade goods he had to offer, the explorer was unable to provide a suitable gift to the ruler. Soon, the local populace became suspicious of da Gama and his men. Forced by a hostile crowd to flee Mozambique, da Gama departed the harbor, firing his cannons into the city in retaliation.

April 7 - 13, 1498 - Became the first European to visit the dock at Mombasa. His visit was brief due to hostilities in the area.

April 14, 1498 - Vasco da Gama sailed into the friendlier port of Malindi, whose leaders were having a conflict with those of Mombasa.

There, the expedition first noted evidence of Indian traders. Da Gama and his crew contracted the services of a pilot who used his knowledge of the monsoon winds to guide the expedition the rest of the way to Calicut, located on the southwest coast of India.

May 20 - August 29, 1498 - The fleet arrived in Calicut, reaching their final destination. Vasco da Gama visited the King of Calicut but did not impress him. The King did not believe him to be a royal ambassador but a pirate. Da Gama fled but took with him the Calicut military and 16 fishermen by force.

The fleet initially inched north along the Indian coast and then anchored in at Anjediva island for a spell.

October 3, 1498 - The fleet left Anjediva to cross the Indian Ocean. On the outgoing journey, sailing with the summer monsoon wind, da Gama's fleet crossed the Indian Ocean in only 23 days; now, on the return trip, sailing against the wind it took 132 days.

January 2, 1499 - They passed the coastal Somali city of Mogadishu but did not stop. It was the first time they had seen the city, which was under the control of the Ajuran Empire. An anonymous diarist of the expedition noted that it was a large city with houses four or five stories high, big palaces in its center, and many mosques with cylindrical minarets.

January 7, 1499 - Da Gama made it to Malindi, but not without a cost. Half of his crew had died, and many were afflicted with scurvy. He ordered one of his three ships to be sent to sea and dispersed the remaining crew.

March 20, 1499 - Sailing began to go smoother, and they rounded the Cape of Good Hope. They would not see trouble until Vasco da Gama's brother became seriously ill.

April 25, 1499 - August 1499 - The two ships make it to the West African coast, and they continue to Cape Verde, where Nicolau Coelho's Berrio separated from Vasco da Gama's São Gabriel and sailed on by itself.

The Berrio arrived in Lisbon on 10 July 1499, and Nicolau Coelho personally delivered the news to King Manuel I and the royal court, then assembled in Sintra. In the meantime, back in Cape Verde, da Gama's brother, Paulo da Gama, had become deathly sick.

Da Gama elected to stay by his side on Santiago island and handed the São Gabriel over to his clerk, João de Sá, to take home. The São Gabriel under Sá arrived in Lisbon sometime in late July or early August.

Da Gama and his sickly brother eventually hitched a ride with a Guinea caravel returning to Portugal, but Paulo da Gama died en route. Da Gama disembarked at the Azores to bury his brother at the monastery of São Francisco in Angra do Heroismo and lingered there for a little while in mourning.

August 29, 1499 - A still somewhat grieving Vasco da Gama took passage on an Azorean caravel and finally arrived in Lisbon. He was given a hero's welcome and showered with much praise.

February 12, 1502 - In response to Pedro Alvares Cabral 's failure to secure a treaty with Calicut and initiate a conflict, Vasco da Gama launched the 4th India Armada from Lisbon.

October 1502 - September 1503 - Vasco da Gama left Lisbon with victory in mind. Once he reached eastern Africa, he opened contact with the East African gold trading port of Sofala and reduced the sultanate of Kilwa to tribute, extracting a substantial sum of gold.

He encountered a ship of Pilgrims traveling from Calicut to Mecca and lit the ship on fire, forced some to convert to Christianity, and plundered their gold.

He next moved to Calicut, where much violence followed. After the Zamorin did not meet his demands, da Gama used acts of brutality to instill fear. He then began to bombard the city with his ships, causing tremendous damage. The Zamorin, in response, summoned his fleet and sent them to meet the Portuguese. Vasco da Gama was a proven naval commander and defeated the fleet.

He then loaded his fleet with spices and left behind a small fleet to harass Calicut shipping. He returned to Portugal but did not brought the Zamorin to submission, which did not sit well with King Manuel I.

1519 - After sitting dormant and unused for almost two decades due to his failure to bring the Zamorin to submission, Vasco da Gama followed the example of Ferdinand Magellan and threatened to defect to the Crown of Castile.

After years of ignoring his petitions, King Manuel I finally hurried to give Vasco da Gama a feudal title, appointing him the first Count of Vidigueira, a count title created by a royal decree issued in Évora.

After a complicated agreement with Dom Jaime, Duke of Braganza, who ceded him on payment to the towns of Vidigueira and Vila dos Frades.

The decree granted Vasco da Gama and his heirs all the revenues and privileges related, thus establishing da Gama as the first Portuguese count who was not born with royal blood.

April 1524 - December 24, 1524 - After the death of King Manuel I, King John III took the throne and made Vasco da Gama a Viceroy and an advisor. He also sent da Gama on his third voyage to India.

He set out with a fleet of fourteen ships; Vasco da Gama took as his flagship the famous large carrack Santa Catarina do Monte Sinai on her last journey to India, along with two of his sons, Estêvão and Paulo. After a troubled journey (four or five of the ships were lost en route), he arrived in India in September.

Vasco da Gama immediately invoked his high viceregent powers to impose a new order in Portuguese India, replacing all the old officials with his own appointments. But Gama contracted malaria not long after arriving and died in the city of Cochin on Christmas Eve .

<- Return to Age of Exploration Timeline

Have Fun With History

Vasco da Gama Timeline

Vasco da Gama, a prominent Portuguese explorer of the late 15th and early 16th centuries, is renowned for his pioneering voyages that opened new sea routes to distant lands.

Born in the 1460s, da Gama’s remarkable expeditions aimed to establish direct trade connections with India and the East, bypassing traditional overland routes.

His tenacity and navigation skills led to the discovery of a sea route to India in 1498, revolutionizing global trade and reshaping the world’s interconnectedness.

This brief introduction offers a glimpse into the life and significance of Vasco da Gama, an explorer whose journeys left an enduring impact on exploration and trade routes.

Timeline of Vasco da Gama

1460s – vasco da gama is born in sines, portugal.

Vasco da Gama is born in Sines, Portugal, during the 1460s. The exact year of his birth is not well-documented, but it’s believed to be around 1469.

Also Read: Vasco da Gama Accomplishments

He was born into a noble family, which gave him access to education and opportunities that would later shape his career as an explorer.

1497 – Sets sail from Lisbon on his first voyage to find a sea route to India

In July 1497, Vasco da Gama embarks on his first significant voyage. He leads a fleet of four ships: the São Gabriel, São Rafael, Berrio, and a storage ship.

Also Read: Vasco da Gama Facts

The expedition is sponsored by King Manuel I of Portugal and has the primary goal of finding a sea route to India, bypassing the overland trade routes that were controlled by various intermediaries and often resulted in high costs for valuable spices and other goods from the East.

1498 – Reaches Calicut, India, completing his first successful voyage

On May 20, 1498, after several months of sailing along the African coast and overcoming various challenges including harsh weather and dwindling supplies, Vasco da Gama’s fleet arrives in Calicut, a major trading port in India.

This marks a historic achievement, as Vasco da Gama becomes the first European explorer to successfully reach India by sea, establishing a direct maritime route between Europe and Asia. This accomplishment opens up new opportunities for trade and cultural exchange.

1499 – Returns to Portugal with valuable goods from India

Having successfully established contact with Indian merchants and acquired valuable spices like pepper and cinnamon, Vasco da Gama’s fleet begins its return journey to Portugal. They face additional challenges, including storms and conflicts with local rulers along the African coast. The journey takes nearly a year, but in September 1499, Vasco da Gama and his crew arrive back in Lisbon. The expedition is considered a major success, as it not only brings back valuable goods but also proves the viability of a sea route to India.

1502 – Leads a second expedition to India, establishing Portuguese influence

Building on the success of his first voyage, Vasco da Gama leads a second expedition to India in 1502. This time, his mission is not only to establish trade relations but also to solidify Portuguese dominance in the Indian Ocean trade network.

The expedition involves a more assertive approach, including the use of military force to secure trading privileges and establish Portuguese forts and trading posts along the East African coast.

1503 – Captures the Arab ship “Mirí” and continues his expedition

During his second expedition, Vasco da Gama captures the Arab trading ship “Mirí.” This victory is significant, as it not only demonstrates Portuguese naval power but also sends a clear message to other traders and rulers in the region about Portuguese strength. This event further bolsters Vasco da Gama’s reputation and the Portuguese presence in the Indian Ocean.

1503-1504 – Returns to Portugal after a successful second voyage

Vasco da Gama’s second expedition takes him to various key locations. He visits the island of Mozambique, where he establishes a Portuguese trading post.

He continues along the east coast of Africa, making stops at several ports to negotiate treaties and secure trading rights. His expedition also takes him back to the Malabar Coast of India, where he engages in further trade negotiations and establishes Portuguese outposts.

1524 – Appointed as the Portuguese Viceroy of India

After a period of time back in Portugal, Vasco da Gama is appointed as the Portuguese Viceroy of India in 1524.

As the Viceroy, his responsibilities include overseeing the Portuguese trading posts, forts, and diplomatic relations in the region. His appointment reflects the importance of maintaining Portuguese control and influence in the Indian Ocean trade network.

1524 – Begins his third and final voyage to India

In 1524, Vasco da Gama embarked on his third and final voyage to India. This expedition marked another chapter in his efforts to establish and consolidate Portuguese influence in the lucrative Indian Ocean trade network.

As the newly appointed Viceroy of India, da Gama undertook this journey with a dual purpose: to reinforce Portuguese control over existing trading posts and to address challenges posed by local rulers and merchants who resisted their dominance.

1524 – Oversees administrative and military activities in India

As Viceroy of India, Vasco da Gama returns to India for his third and final voyage. During this period, he engages in various administrative and military activities to strengthen Portuguese control and suppress any challenges to their dominance.

He faces resistance from local rulers and merchants who seek to resist Portuguese control, leading to conflicts and tensions.

1524 – Dies on December 24 in Cochin, India

Unfortunately, Vasco da Gama’s final voyage is marked by personal hardship. He falls seriously ill during his time in India and, despite receiving medical treatment, his condition worsens. On December 24, 1524, Vasco da Gama passes away in Cochin, India. His death marks the end of an era in Portuguese exploration and trade in the Indian Ocean.

The incredible voyage of Vasco da Gama to India

The Portuguese explorer, Vasco da Gama, is famous for being the first European to sail from Europe to India. Every European naval power was seeking a trade route to the east over the ocean during the 15th century.

Building upon the efforts of previous explorers who had traveled down the west coast of Africa, da Gama was the one that finally made it a reality.

Vasco da Gama was born at the town of Sines in Portugal at some time before 1470.

Both of his parents were from the Portuguese nobility, and his father was involved in the royal court.

da Gama went to school in Evora village, where he developed a love of navigation and sailing.

By the time he had turned 20 years old, he had become a sea captain.

As da Gama was growing up, Portugal was in the middle of an exploration boom. European nations were looking for a sea route to the east.

Traditionally, any trade between Europe and Asia had to travel over land and through the Muslim nations in the Middle East.

These nations would charge high taxes for anyone travelling through their lands.

Therefore, the kings and queens of the various European kingdoms thought that a sea route to the east, travelling around the south of Africa, would be quicker and cheaper.

To that end, Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal, paid for a number of explorers to sail down the west coast of Africa in search of a safe route.

Then, from 1481, King John II of Portugal did the same. One of these explorers, called Bartolomeu Dias , finally made it to the Indian Ocean in 1488, but did not reach India.

In 1495, a new king ruled in Portugal.

He was called Manuel and he decided to send another fleet to try and reach India .

He chose Vasco da Gama for the task.

da Gama's voyages

da Gama sailed from Lisbon on the 8th of July 1497. By November 22, da Gama reached Mossel Bay in South Africa.

In March he reached Mozambique on the east coast of Africa: the furthest any Portuguese sailor had yet reached.

While there, da Gama spoke to local Muslim merchants to gain information about crossing the Indian Ocean.

After paying for the services of an experienced navigator to join his crew, da Gama set sail for India.

After a journey on the open ocean for 23 days, he finally reached India on the 20th of May 1498.

At the Indian city of Calicut, da Gama had a meeting with the king, but was treated with suspicion.

da Gama spent a few months in India, trading goods and studying India culture. In August 1498, da Gama set off home again, and arrived back in Portugal in September 1499.

King Manuel I was thrilled that da Gama had achieved a round-trip from India, and promoted him to the position of admiral.

Deteriorating reputation

Vasco da Gama sailed back to India in February 1502 with a much larger fleet. On the way, he stopped at Tanzania in Africa, where tensions with the locals led to da Gama threatening them to become servants of the Portuguese king.

This event was the first sign of da Gama's willingness to use force to achieve his aims.

When da Gama arrived back at Calicut in India, he fired his ships cannons at the city's port, killing a number of Muslim traders.

Sailing on to Cochin, they successfully fought a naval engagement against Arab ships.

By this stage, da Gama had gained a reputation as a competent, yet ruthless, captain.

After conducting a trade mission, da Gama sailed back to Portugal in February 1503, arriving back in October.

da Gama did not sail to India again until King Manuel I died in 1521. The new king, John III, promoted da Gama to be the Portuguese viceroy of India to deal with mass corruption among officials that had developed since Portuguese traders had flooded into the country.

da Gama arrived in India, at Goa, in September 1524 and immediately enforced laws to control corrupt Portuguese merchants.

However, he soon fell ill and died on December 24, 1524 in Cochin.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : May 20

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Vasco da Gama reaches India

Portuguese explorer Vasco de Gama becomes the first European to reach India via the Atlantic Ocean when he arrives at Calicut on the Malabar Coast.

Da Gama sailed from Lisbon, Portugal, in July 1497, rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and anchored at Malindi on the east coast of Africa. With the aid of an Indian merchant he met there, he then set off across the Indian Ocean. The Portuguese explorer was not greeted warmly by the Muslim merchants of Calicut, and in 1499 he had to fight his way out of the harbor on his return trip home. In 1502, he led a squadron of ships to Calicut to avenge the massacre of Portuguese explorers there and succeeded in subduing the inhabitants. In 1524, he was sent as viceroy to India, but he fell ill and died in Cochin.

Also on This Day in History May | 20

This Day in History Video: What Happened on May 20

Supreme court defends rights of gays and lesbians in romer v. evans, charles lindbergh takes off across the atlantic in the spirit of st. louis, christopher columbus dies, battle for "hamburger hill" ends after 10 grueling days.

Levi Strauss and Jacob Davis receive patent for blue jeans

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Germans break through to English Channel at Abbeville, France