Advisory Council on Historic Preservation

Each year, millions of travelers visit America’s historic places. The National Trust for Historic Preservation defines heritage tourism as “traveling to experience the places, artifacts, and activities that authentically represent the stories and people of the past and present.” A high percentage of domestic and international travelers participate in cultural and/or heritage activities while traveling, and those that do stay longer, spend more, and travel more often. Heritage tourism creates jobs and business opportunities, helps protect resources, and often improves the quality of life for local residents.

The ACHP has encouraged national travel and tourism policies that promote the international marketing of America’s historic sites as tourism destinations. The ACHP also engages in ongoing efforts to build a more inclusive preservation program, reaching out to diverse communities and groups and engaging them in dialogue about what parts of our national legacy should be more fully recognized, preserved, and shared.

The ACHP developed Preserve America , a national initiative to encourage and support community efforts for the preservation and enjoyment of America’s cultural and natural heritage. In partnership with other federal agencies, the initiative has encouraged the use of historic assets for economic development and community revitalization, as well as enabling people to experience and appreciate local historic resources through heritage tourism and education programs. These goals have been advanced by an Executive Order directing federal agencies to support such efforts, a community designation program, and a recognition program for outstanding stewardship of historic resources by volunteers.

From 2004-2016, over 900 Preserve America Communities were designated in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and two territories, as well as nearly 60 Preserve America Stewards . Many Preserve America Communities are featured in “Discover Our Shared Heritage” National Register on-line travel itineraries . From 2006 through 2010, the National Park Service (in partnership with the ACHP) awarded more than $21 million in Preserve America Grants to support sustainable historic resource management strategies, with a focus on heritage tourism.

These links are being provided as a convenience and for informational purposes only; if they are not ACHP links, they do not constitute an endorsement or an approval by the ACHP of any of the products, services or opinions of the corporation or organization or individual. The ACHP bears no responsibility for the accuracy, legality, or content of the external site or for that of subsequent links. Please contact the external site for answers to questions regarding its content, including its privacy policies.

Related resources.

- eTravel.com

- Car Rentals

- Travel Inspiration

- Write For Us

What is Heritage (Historical) Tourism?

What is Heritage tourism?

Countries famous for historical tourism.

Category: Travel Industry

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Get the best deals and helpful tips from eTravel.com

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

Heritage Tourism

The late Alan Gordon was professor of history at the University of Guelph. He authored three books: Making Public Pasts: The Contested Terrain of Montreal’s Public Memories, 1891–1930, The Hero and the Historians: Historiography and the Uses of Jacques Cartier and Time Travel: Tourism and the Rise of the Living History Museum in Mid-Twentieth Century Canada.

- Published: 18 August 2022

- Cite Icon Cite

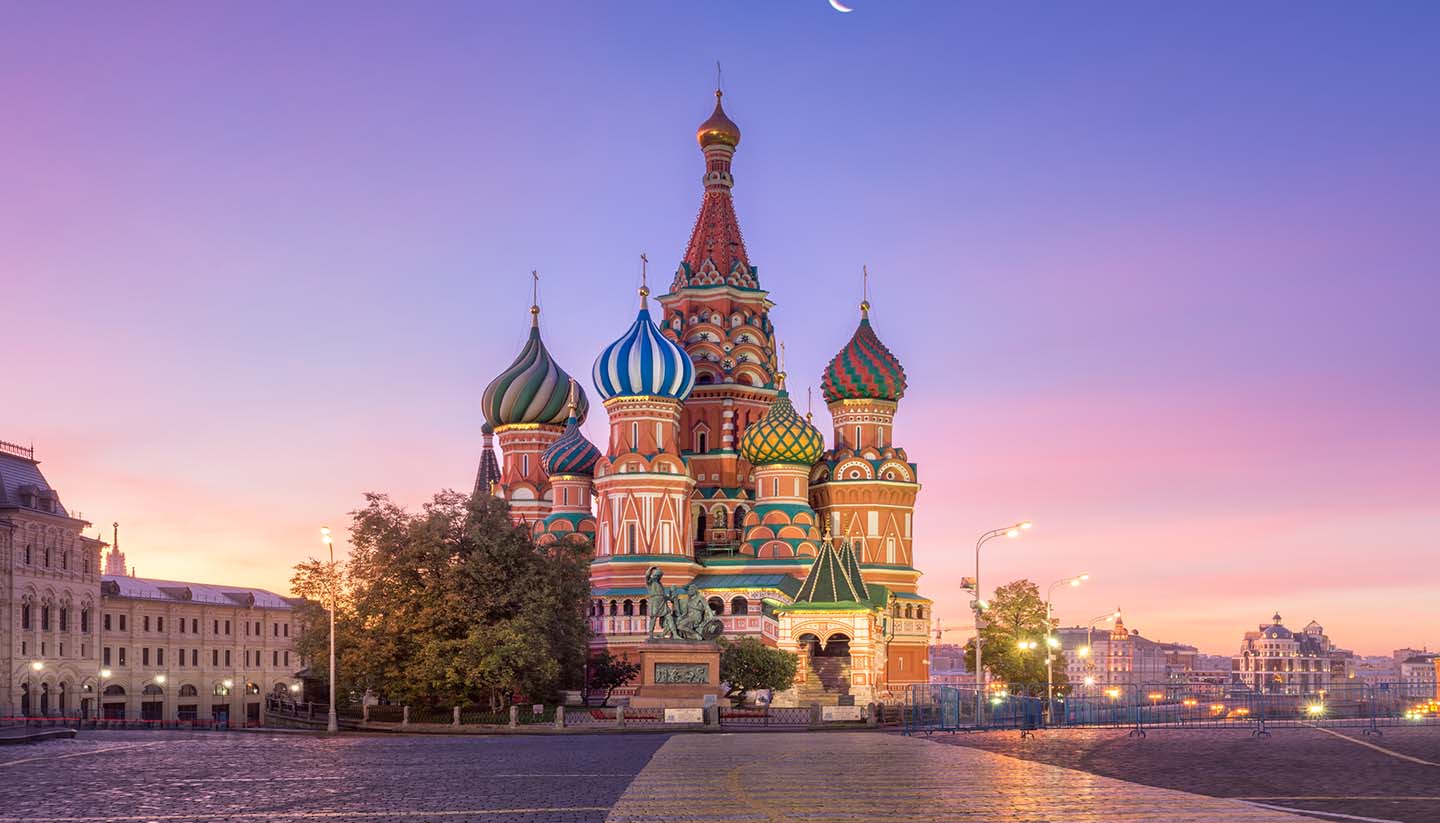

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Heritage tourism is a form of cultural tourism in which people travel to experience places, artifacts, or activities that are believed to be authentic representations of people and stories from the past. It couples heritage, a way of imagining the past in terms that suit the values of the present, with travel to locations associated with enshrined heritage values. Heritage tourism sites are normally divided into two often overlapping categories: natural sites and sites related to human culture and history. By exploring the construction of heritage tourism destinations in historical context, we can better understand how and through what attributes places become designated as sites of heritage and what it means to have an authentic heritage experience. These questions are explored through heritage landscapes, national parks, battlefield tourism, architectural tourism, and the concept of world heritage.

Heritage is one of the most difficult, complex, and expansive words in the English language because there is no simple or unanimously accepted understanding of what heritage encompasses. 1 We can pair heritage with a vast range of adjectives, such as cultural, historical, physical, architectural, or natural. What unites these different uses of the term is their reference to the past, in some way or another, while linking it to present-day needs. Heritage, then, is a reimagining of the past in terms that suit the values of the present. It cannot exist independently of human attempts to make the past usable because it is the product of human interpretation of not only the past, but of who belongs to particular historical narratives. At its base, heritage is about identity, and the inclusion and exclusion of peoples, stories, places, and activities in those identities. The use of the word “heritage” in this context is a postwar phenomenon. Heritage and heritage tourism, although not described in these terms, has a history as long as the history of modern tourism. Indeed, a present-minded use of the past is as old as civilization itself, and naturally embedded itself in the development of modern tourism. 2 The exploration of that history, examining the origins and development of heritage tourism, helps unpack some of the controversies and dissonance it produces.

Heritage in Tourism

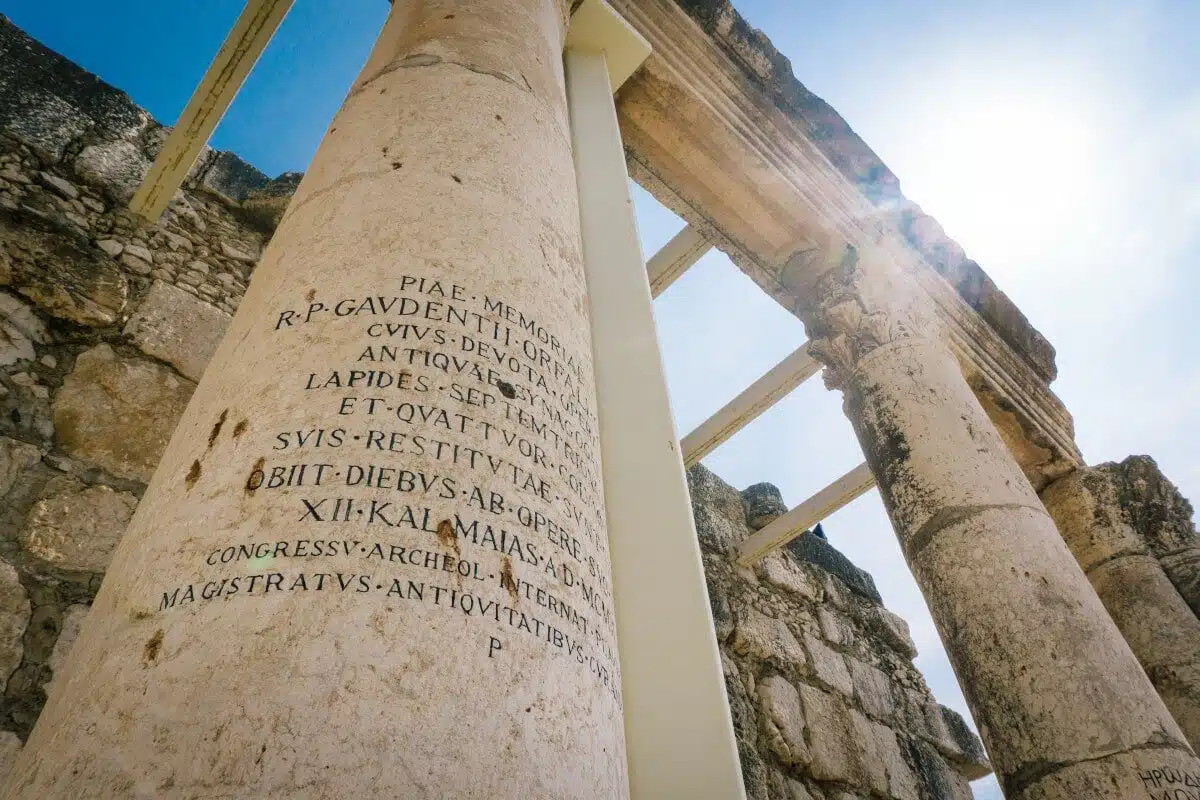

Heritage tourism sites are normally divided into two categories: natural sites and sites of human, historical, or cultural heritage. the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) separates its list of world heritage sites in this manner. Sites of natural heritage are understood to be places where natural phenomena such as wildlife, flora, geological features, or ecosystems, are generally deemed to be of exceptional beauty or significance. Cultural heritage sites, which represent over three quarters of UNESCO-recognized sites, are places where human activity has left a lasting and substantial physical impact that reveals important features of a culture or cultures. Despite the apparent simplicity of this division, it is not always easy to categorize individual sites. UNESCO thus allows for a category of “mixed” heritage sites. But official recognition is not necessary to mark a place as a heritage destination and, moreover, some authors point to versions of heritage tourism that are not tightly place-specific, such as festivals of traditional performances or foodways. 3

The central questions at the heart of heritage tourism ask what it is that designates something as “heritage” and whether tourists have an “authentic” heritage experience there. At its simplest, heritage tourism is a form of cultural tourism in which people travel to experience places, artifacts, or activities that are authentic representations of people and stories from the past. Yet this definition encompasses two, often competing, motivations. Heritage tourism is both a cultural phenomenon through which people attempt to connect with the past, their ancestors, and their identity, and it is an industry designed to profit from it. Another question surrounds the source of the “heritage” in heritage tourism. Many scholars have argued that heritage does not live in the destinations or attractions people seek. Heritage is not innate to the destination, but is rather based on the tourist’s motivations and expectations. Thus, heritage tourism is a form of tourism in which the main motivation for visiting a site is based on the traveler’s perceptions of its heritage characteristics. Following the logic of this view, the authenticity of the heritage experience depends on the traveler rather than the destination or the activity. Heritage features, as well as the sense of authenticity they impart, are democratized in what might be called a consumer-based model of authenticity. 4 This is a model that allows for virtually anything or any place to be a heritage destination. Although such an approach to understanding heritage tourism may well serve present-day studies, measuring motivations is more complicated for historical subjects. Long-departed travelers are not readily surveyed about their expectations; motivations have to be teased out of historical records. In a contrasting view, John Tunbridge and Gregory Ashworth argue that heritage attractions are created through marketing: they are invented to be heritage attractions and sold to a traveling public as such. Yet, heritage attractions, in this understanding, are still deemed authentic when they satisfy consumer expectations about heritage. 5 This insight also implies that heritage tourism destinations might be deceptions, and certainly there are examples of the fabrication of heritage sites. However, if motivations and expectations are arbiters of heritage, then even invented heritage can become authentic through its acceptance by a public. While not ignoring the motivations and expectations of travelers, for historians, any understanding of heritage tourism must include the process by which sites become designated as a places of heritage. It must encompass the economic aspects of tourism development, tourism’s role in constructing narratives of national or group identity, and the cultural phenomenon of seeking authentic representations of those identities, regardless of their origins. Such a practice might include traveling to sites connected to diasporas, places of historical significance, sites of religious pilgrimages, and landscapes of scenic beauty or cultural importance.

Scholarly interest in heritage, at least in the English-speaking world, dates from the 1980s reaction to the emergence of new right-wing political movements that used the past as a tool to legitimize political positions. Authors such as David Lowenthal, Robert Hewison, and Patrick Wright bemoaned the recourse to “heritage” as evidence of a failing society that was backward-looking, fearful, and resentful of modern diversity. 6 Heritage, they proclaimed, was elitist and innately conservative, imposed on the people from above in ways that distanced them from an authentic historical consciousness. Although Raphael Samuel fired back that the critique of heritage was itself elitist and almost snobbish, this line continued in the 1990s. Works by John Gillis, Tony Bennett, and Eric Hobsbawm, among others, concurred that heritage was little more than simplified history used as a weapon of social and political control.

At about the same time, historians also began to take tourism seriously as a subject of inquiry, and they quickly connected leisure travel to perceived evils in the heritage industry. Historians such as John K. Walton in the United Kingdom and John Jakle in the United States began investigating patterns of tourism’s history in their respective countries. Although not explicitly concerned with heritage tourism, works such as Jakle’s The Tourist explored the infrastructure and experience of leisure travel in America, including the different types of attractions people sought. 7 In Sacred Places , John Sears argued that tourism helped define America in the nineteenth century through its landscape and natural wonders. Natural tourist attractions, such as Yosemite and Yellowstone parks became sacred places for a young nation without unifying religious and national shrines. 8 Among North America’s first heritage destinations was Niagara Falls, which drew Americans, Europeans, Britons, and Canadians to marvel at its beauty and power. Tourist services quickly developed there to accommodate travelers and, as Patricia Jasen and others note, Niagara became a North American heritage destination at the birth of the continent’s tourism trade. 9

As the European and North American travel business set about establishing scenic landscapes as sites worthy of the expense and difficulty of travel to them, they rarely used a rhetoric of heritage. Sites were depicted as places to embrace “the sublime,” a feeling arising when the emotional experience overwhelms the power of reason to articulate it. Yet as modern tourism developed, promoters required more varied attractions to induce travelers to visit specific destinations. North America’s first tourist circuits, well established by the 1820s, took travelers up the Hudson River valley from New York to the spas of Saratoga Springs, then utilizing the Erie Canal even before its completion, west to Niagara Falls. Tourist guidebooks were replete with vivid depictions of the natural wonders to be witnessed, and very quickly Niagara became heavily commercialized. As America expanded beyond the Midwest in the second half of the nineteenth century, text and image combined to produce a sense that these beautiful landscapes were a common inheritance of the (white and middle-class) American people. Commissioned expeditions, such as the Powell Expedition of 1869–1872, produced best-selling travel narratives revealing the American landscape to enthralled readers in the eastern cities (see Butler , this volume). John Wesley Powell’s description of his voyage along the Colorado River combined over 450 pages of written description with 80 prints, mostly portraying spectacular natural features. American westward exploration, then, construed the continent’s natural wonders as its heritage.

In America, heritage landscapes often obscured human activity and imagined the continent as nature untouched. But natural heritage also played a role in early heritage tourism in Britain and Europe. Many scholars have investigated the connection between national character and the depiction of topographical features, arguing that people often implant their communities with ideas of landscape and associate geographical features with their identities. In this way, landscape helps embed a connection between places and particular local and ethnic identities. 10 Idealized landscapes become markers of national identity (see Noack , this volume). For instance, in the Romantic era, the English Lake District and the mountains of the Scottish Highlands became iconic national representations of English, Scottish, or British nationalities. David Lowenthal has commented on the nostalgia inherent in “landscape-as-heritage.” The archetypical English landscape, a patchwork of fields divided by hedgerows and sprinkled with villages, was a relatively recent construction when the pre-Raphaelite painters reconfigured it as the romantic allure of a medieval England. It spoke to the stability and order inherent in English character. 11

Travel literature combined with landscape art to develop heritage landscapes and promote them as tourist attractions. Following the 1707 Act of Union, English tourists became fascinated with Scotland, and in particular the Scottish Highlands. Tourist guidebooks portrayed the Highlands as a harsh, bleak environment spectacular for its beauty as well as the quaintness of its people and their customs (see Schaff , this volume). Over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, tourist texts cemented the image of Highland culture and heritage. Scholars have criticized this process as a “Tartanization” or “Balmoralization” of the country by which its landscape and culture was reduced to a few stereotypes appealing to foreign visitors. Nevertheless, guidebook texts described the bens, lochs, and glens with detail, helping create and reinforce a mental picture of a quintessential Highland landscape. 12 The massacre of members of the Clan MacDonald at Glencoe, killed on a winter night in 1692 for insufficient loyalty to the monarchy, added romance. Forgotten for over a century, the event was recalled in the mid-nineteenth century by the historian Thomas Babington Macaulay, and quickly became a tragic tale associated with the scenic valley. At the same time the Highlands were being re-coded from a dangerous to a sublime landscape, its inhabitants became romanticized as an untainted, simple, premodern culture. The natural beauty of the landscape at Glencoe and its relative ease of access, being close to Loch Lomond and Glasgow, made it an attraction with a ready-made tragic tale. Highlands travel guides began to include Glencoe in their itineraries, combining a site of natural beauty with a haunting human past. Both natural and cultural heritage, then, are not inherent, but represent choices made by people about what and how to value the land and the past. On France’s Celtic fringe, a similar process unfolded. When modern tourism developed in Brittany in the mid-nineteenth century, guidebooks such as Joanne’s defined the terms of an authentic Breton experience. Joanne’s 1867 guide coupled the region’s characteristic rugged coastlines with the supposedly backward people, their costumes, habitudes, beliefs, and superstitions, who inhabited it. 13 Travel guides were thus the first contributors in the construction of heritage destinations. They began to highlight the history, real and imagined, of destinations to promote their distinctions. And, with increasing interest in the sites of national heritage, people organized to catalog, preserve, and promote heritage destinations.

Organizing Heritage Tourism

Among the world’s first bodies dedicated to preserving heritage was the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), organized in England in 1877. Emerging as a result of particular debates about architectural practices, this society opposed a then-popular trend of altering buildings to produce imaginary historical forms. This approach, which was most famously connected to Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc’s French restorations, involved removing or replacing existing architectural features, something renounced by the SPAB. The society’s manifesto declared that old structures should be repaired so that their entire history would be protected as part of cultural heritage. The first heritage preservation legislation, England’s Ancient Monuments Protection Act of 1882, provided for the protection initially of 68 prehistoric sites and appointed an inspector of ancient monuments. 14 By 1895, movements to conserve historic structures and landscapes had combined with the founding of the National Trust, officially known as the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, as a charitable agency. Much of the Trust’s early effort protected landscapes: of twenty-nine properties listed in 1907, seventeen were acreages of land and other open spaces. 15 Over the twentieth century, however, the Trust grew more and more concerned with protecting country houses and gardens, which now constitute the majority of its listed properties.

British efforts were duplicated in Europe. The Dutch Society for the Preservation of Natural Landmarks was established in 1904; France passed legislation to protect natural monuments in 1906. And in Sweden, the Society for the Protection of Nature was established in 1909, to name only a few examples. Nature was often connected to the spirit of “the folk,” an idea that encompassed a notion of an original ethnic core to the nation. Various European nationalisms of the period embraced the idea of an “authentic” national folk, with each folk considered unique due to its connection with a specific geography. Folklore and the celebration of folk culture offered Europeans links to imagined national heritages in a rapidly modernizing world, as modern, middle-class Europeans turned their attention to the romanticized primitive life of so-called simple peasants and linked notions of natural and human heritage. Through the concept of the folk, natural and human heritage combined to buttress emerging expressions of nationalism. 16

Sweden provides an instructive example. As early as the seventeenth century, Swedish antiquarians were intrigued by medieval rune stones, burial mounds, and cairns strewn across the country, but also saw these connected to natural features. Investigations of these relics of past Nordic culture involved a sense of the landscape in which they were found. This interest accelerated as folk studies grew in popularity, in part connected to nationalist political ambitions of Swedes during the growing tensions within the Kingdom of Sweden and Norway, which divided in 1905. Sweden’s preservation law required research into the country’s natural resources to create an inventory of places. Of particular interest were features considered to be “nature in its original state.” The intent was to preserve for future generations at least one example of Sweden’s primordial landscape features: primeval forests, swamps, peat bogs, and boulders. But interest was also drawn to natural landmarks associated with historical or mythical events from Sweden’s past. Stones or trees related to tales from the Nordic sagas, for example, combined natural with cultural heritage. 17

Although early efforts to protect heritage sites were not intended to support tourism, the industry quickly benefited. Alongside expanding tours to the Scottish Highlands and English Lake District, European landscapes became associated with leisure travel. As Tait Kellar argues for one example, the context of the landscape is crucial in understanding the role of tourism in the German Alps. 18 Guidebooks of the nineteenth and early twentieth century did not use the term “heritage,” but they described its tenets to audiences employing a different vocabulary. Baedeker’s travel guides, such as The Eastern Alps , guided bourgeois travelers through the hiking trails and vistas of the mountains and foothills, offering enticing descriptions of the pleasures to be found in the German landscape. Beyond the land, The Eastern Alps directed visitors to excursions that revealed features of natural history, human history, and local German cultures. 19

Across the Atlantic people also cherished escapes to the countryside for leisure and recreation and, as economic and population growth increasingly seemed to threaten the idyllic tranquility of scenic places, many banded together to advocate for their conservation. Yet, ironically, by putting in place systems to mark and preserve America’s natural heritage, conservationists popularized protected sites as tourist destinations. By the second half of the nineteenth century, the conservation movement encouraged the US government to set aside massive areas of American land as parks. For example, Europeans first encountered the scenic beauty of California’s Yosemite Valley at midcentury. With increasing settler populations following the California Gold Rush, tourists began arriving in ever larger numbers and promoters began building accommodations and roads to encourage them. Even during the Civil War, the US government recognized the potential for commercial overdevelopment and the desire of many to preserve America’s most scenic places. 20 In 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant, designating acres of the valley protected wilderness. This set a precedent for the later creation of America’s first national park. In 1871, the Hayden Geological Survey recommended the preservation of nearly 3,500 square miles of land in the Rocky Mountains, in the territories of Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho. Ferdinand V. Hayden was concerned that the pristine mountain region might soon be as overrun with tourists as Niagara Falls had by then become. 21 The following year, Congress established Yellowstone National Park, the world’s first designated “heritage” site. Yet, from the beginning, Yellowstone and subsequent parks were assumed to be tourist attractions. By 1879, tourists to Yellowstone had established over 200 miles of trails that led them to the park’s most famous attractions. Although thought of as nature preserves, parks were often furnished with railway access, and amenities and accommodations appeared, often prior to official designation. National parks were immediately popular tourist attractions. Even before it had established a centralized bureaucracy to care for them, the United States government had established nine national parks and nearly two dozen national monuments. Canada lagged, but established Rocky Mountain National Park (now Banff) in 1885 to balance interests of resource extraction and conservation. (The world’s second national park was Australia’s Royal National Park, established by the colony of New South Wales in 1879.) By the outbreak of the Great War, Canada and the United States had established fifteen national parks, all but one west of the Mississippi River.

Establishing parks was one component of building a heritage tourism infrastructure. Another was the creation of a national bureaucracy to organize it. The Canadian example reveals how heritage and tourism drove the creation of a national parks service. Much of the mythology surrounding Canada’s national parks emphasized the role of nature preservationists, yet the founder of the parks system, J. B. Harkin, was deeply interested in building a parks network for tourists. 22 Indeed, from early in the twentieth century, Canada’s parks system operated on the principle that parks should be “playgrounds, vacation destinations, and roadside attractions that might simultaneously preserve the fading scenic beauty and wildlife populations” of a modernizing nation. 23 Although Canada had established four national parks in the Rocky Mountains in the 1880s, the administration of those parks was haphazard and decentralized. It was not until the approaching third centennial of the founding of Quebec City (now a UNESCO World Heritage Site) that the Canadian government began thinking actively about administering its national heritage. In 1908, Canada hosted an international tourist festival on the Plains of Abraham, the celebrated open land where French and British armies had fought the decisive battle for supremacy in North America in 1759. The event so popularized the fabled battlefield that the government was compelled to create a National Battlefield Commission to safeguard it. This inspired the creation of the Dominion Parks Branch three years later to manage Canada’s natural heritage parks, the world’s first national parks service. By 1919 the system expanded to include human history—or at least European settler history—through the creation of national historic parks. These parks were even more explicitly designed to attract tourists, automobile tourists in particular. In 1916, five years after Canada, the United States established the National Parks Service with similar objectives.

As in Europe, nationalism played a significant role in developing heritage tourism destinations in America. The first national parks were inspired by the series of American surveying expeditions intended to secure knowledge of the landscape for political control. Stephen Pyne connects the American “discovery” of the Grand Canyon, for example, to notions of manifest destiny following the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) that ended the Mexican-American War and ceded over 500,000 square miles of what is today the western United States. Popularized by the report of John Wesley Powell (1875) , the canyon began attracting tourists in the 1880s, although Congress failed to establish it as a national park. 24 Tourism was central to developing the Grand Canyon as a national heritage destination. Originally seen by Spanish explorers as an obstacle, and as a sacred place by the Navajo, Hopi, Hualapai, and Havasupai peoples, the canyon came to mark American exceptionalism. Piece by piece, sections of the canyon were set aside as reserves and finally declared a national park in 1919. By then, the park had been serviced by a railway (since 1901) and offered tourists a luxury hotel on the canyon’s south rim.

Archaeology also entered into the construction of American heritage. Almost as soon as it was annexed to the United States, the American southwest revealed to American surveyors a host of archaeological remains. For residents of the southwest, the discovery of these ancient ruins of unknown age pointed to the nobility of a lost predecessor civilization. By deliberately construing the ruins as being of an unknown age, Anglo-American settlers were able to draw distinctions between the ancients and contemporary Native Americans in ways that validated their own occupation of the territory. The ruins also had commercial potential. In Colorado, President Theodore Roosevelt established Mesa Verde National Park in 1906 to protect and capitalize on the abandoned cliff dwellings located there. These ruins had been rediscovered in the 1880s when ranchers learned of them from the local Ute people. By the turn of the century, the ruins had attracted so many treasure seekers that they needed protection. This was the first national park in America designated to protect a site of archaeological significance and linked natural and human heritage in the national parks system. 25

If, as many argue, heritage is not innate, how is it made? Part of the answer to this question can be found in the business of tourism. Commercial exploitation of heritage tourism emerged alongside heritage tourism, but was particularly active in the postwar years. Given their association with tourism, it is not surprising that railways and associated businesses played a prominent role in promoting heritage destinations. Before World War II, the most active heritage tourism promoter was likely the Fred Harvey Company, which successfully marketed, and to a great degree created, much of the heritage of the American southwest. The Fred Harvey Company originated with the opening of a pair of cafés along the Kansas Pacific Railway in 1876. After a stuttering beginning, Harvey’s chain of railway eateries grew in size. Before dining cars became regular features of passenger trains, meals on long-distance trips were provided by outside business such as Harvey’s at regular stops. With the backing of the Santa Fe Railroad, the company also developed attractions based on the Southwest region’s unique architectural and cultural features. The image capitalized on the artistic traditions of Native Americans and early Spanish traditions to create, in particular, the Adobe architectural style now associated with Santa Fe and New Mexico. 26 These designs were also incorporated into tourist facilities on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, including the El Tovar hotel and the Hopi House souvenir and concession complex, designed to resemble a Hopi pueblo.

Relying on existing and manufactured heritage sites, North American railways popularized attractions as heritage sites. The Northern Pacific Railroad financed a number of hotels in Yellowstone Park, including the Old Faithful Inn in 1904. In 1910, the Great Northern Railroad launched its “See America First” campaign to attract visitors (and new investments) to its routes to the west’s national parks. In Canada, the Dominion Atlantic Railway rebuilt Grand Pré, a Nova Scotia Acadian settlement to evoke the home of the likely fictional character Evangeline from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1848 poem by the same name. In the poem, Evangeline was deported from Acadia in 1755 and separated from her betrothed. By the 1920s, the railway was transporting tourists to Grand Pré, christened “Land of Evangeline,” where reproductions stood in for sites mentioned in the poem. 27 However, following World War I, heritage tourism in North America became increasingly dependent on automobile travel and the Dominion Atlantic eventually sold its interest to the Canadian government.

Conflict as Cultural Heritage

Tourism to sites of military history initially involved side trips from more popular, usually natural, attractions. Thomas Chambers notes that the sites of battles of the Seven Years’ War, Revolutionary War, and War of 1812 became tourist attractions as side trips from more established itineraries, such as the northern or fashionable tours. War of 1812 battlefields, many of them in the Niagara theater of the war, were conveniently close to the natural wonders people already came to see. By visiting the places where so many had sacrificed for their country, tourists began attaching new meaning to the sites. Ease of access was essential. Chambers contrasts sites in southern states with those in the north. In the south, the fields of important American Revolution victories at Cowpens and King’s Mountain were too remote to permit easy tourist access and long remained undeveloped. 28 In a contrary example, the Plains of Abraham, the scene of General Wolfe’s dramatic victory over France that led to the Conquest of Canada, was at first a curiosity. The visit to Quebec, a main destination on the northern tour, was originally based on its role as a major port and the attraction of the scenic beauty of the city on the cliffs, compared favorably to Cintra in Portugal. 29 Ease of access helped promoters convert an empty field near the city into the “hallowed Plains.”

Access to battlefields increased at almost the exact moment that one of the nineteenth century’s most devastating wars, the American Civil War, broke out. Railway travel was essential to both the success of the Union Army in reconquering the rebelling Confederacy, and in developing tourism to the sites of the slaughter. Railway travel made sites accessible for urban travelers and new technologies, such as photography and the telegraph, sped news of victories and defeats quickly around the nation. Gettysburg, the scene of a crucial Union victory in July 1863, became a tourist attraction only a few days later. Few would call the farmland of southeastern Pennsylvania sublime, but dramatic human history had unfolded there. The battle inspired the building of a national memorial on the site only four months later, the Soldiers’ National Cemetery. At the inauguration of the cemetery Abraham Lincoln delivered his “Gettysburg Address,” calling on the nation to long remember and cherish the “hallowed ground” where history had been made.

Gettysburg sparked a frenzy of marking sites of Civil War battles and events. Battle sites became important backdrops for political efforts at reunion and reconciliation after the war and attracted hundreds and later thousands of tourists for commemorative events and celebrations. Ten thousand saw President Rutherford Hayes speak at Gettysburg in 1878 and, for the 50th anniversary of Gettysburg, some 55,000 veterans returned to Pennsylvania in July 1913. What had once been a site of bloody, brutal combat had been transformed into a destination where tourists gathered to embrace their shared heritage, north and south. As the years progressed, more attractions were added as tourists began to see their heritage on the battlefield. 30

The conflict that most clearly created tourist attractions out of places of suffering was the World War I. Soon after the war ended, its sites of slaughter also became tourist attractions. As with the Civil War in America, World War I tourists were local people and relatives of the soldiers who had perished on the field of battle. By one estimate 60,000 tourists visited the battlefields of the Western Front by the summer of 1919, the same year that Michelin began publishing guidebooks to them. Numbers grew in the decades following the war. Over 140,000 tourists took in the sites of the war in 1931, which grew to 160,000 for 1939. Organizations such as the Workers’ Travel Association hoped that tourism to battle sites would promote peace, but the travel business also benefited. Travel agencies jumped at the chance to offer tours and publishers produced travel guides to the battlefields. At least thirty English guidebooks were published by 1921. 31

This interest in a conflict that killed, often in brutal fashion, so many might seem a ghoulish form of heritage tourism. Yet Peter Slade argues that people do not visit battlefields for the love for death and gore. They attend these sites out of a sense of pilgrimage to sites sacred to their national heritage. Organized pilgrimages reveal this sense of belonging most clearly. The American Legion organized a pilgrimage of 15,000 veterans in 1927 to commemorate the decade anniversary of America’s entry to the war. The following year 11,000 Britons, including 3,000 women, made a pilgrimage of their own. Canada’s first official pilgrimage involved 8,000 pilgrims (veterans and their families) to attend the inauguration of the Vimy Ridge Memorial, marking a site held by many as a place sacred to Canadian identity. Australians and New Zealanders marched to Gallipoli in Turkey for similar reasons. 32 As with the sites of the Western Front, Gallipoli and pilgrimages to it generated travel accounts and publishers assembled guidebooks to help travelers navigate its attractions and accommodations. In these episodes, tourism was used to construct national heritage. In the interwar years, tourist activity popularized the notion that sites of national heritage existed on the battlefields of foreign lands, where “our” nation’s history was forged. National heritage tourism, then, became transnational.

Since the end of World War II, battlefield tourism has become an important projection of heritage tourism. Commercial tour operators organize thousands of tours of European World War I and World War II battlefields for Americans and Canadians, as for other nationalities. The phenomenon seems particularly pronounced among North Americans. The motivation behind modern battlefield tourism reveals its connection to heritage tourism. If heritage is an appeal to the past that helps establish a sense of identity and belonging, the feelings of national pride and remorse for sacrifice of the fallen at these sites helps define them as sacred to a particular vision of a national past. The sanctity of the battle site makes the act of consuming it as a tourist attraction an act of communion with heritage.

Built Heritage and Tourism

During the upheaval of the Civil War, some Americans began to recognize historic houses as elements of their heritage worthy of preservation. These houses were initially not seen as tourist attractions, but as markers of national values. Their heritage value preceded their value as tourist attractions. The first major preservation initiative launched in 1853 to save George Washington’s tomb and home from spoliation. Behind overt sectional divisions of north and south was an implied vesting of republican purity among the patrician families that could trace their ancestors to the revolutionary age and who could restore American culture to its proper deferential state. The success of preserving Mount Vernon led to a proliferation of similar house museums. By the 1930s, the American museum association even produced a guide for how to establish new examples and promote them as sites of heritage for tourist interest. Historic houses provided tangible, physical evidence of heritage. Like scenic landscapes attached to the stories of history, buildings connected locations to significant events and people of the past. Architectural heritage came to be closely associated with tourism. Architectural monuments are easily identified, easy to promote, and, as physical structures, easily reproduced in souvenir ephemera. Although the recognition of architectural monuments as tourist draws could be said to have originated with the Grand Tour, or at least with the publication of John Ruskin’s “Seven Lamps of Architecture” (1849), which singled out the monuments of Venice for veneration, twentieth century mobility facilitated a greater desire to travel to see historic structures. Indeed, mobility, especially automobility, prompted the desire to preserve or even reinvent the structural heritage of the past.

A driving factor behind the growth of tourism to sites associated with these structural relics was a feeling that the past—and especially the social values of the past—was being lost. For example, Colonial Williamsburg developed in reaction to the pace of urban and social change brought about by automobile travel in the 1920s. Williamsburg was once a community of colonial era architecture, but had become just another highway town before John D. Rockefeller lent his considerable wealth to its preservation and reconstruction. 33 Rockefeller had already donated a million dollars for the restoration of French chateaux at Versailles, Fontainebleu, and Rheims. 34 At Williamsburg, his approach was to remove structures from the post-Colonial period to create a townscape from the late eighteenth century. By selecting a cut-off year of 1790, Rockefeller and his experts attempted to freeze Williamsburg in a particular vision of the past. The heritage envisioned was not that of ordinary Americans, but that of colonial elites. Conceived to be a tourist attraction, Colonial Williamsburg offered a tourist-friendly lesson in American heritage. Rockefeller, and a host of consultants convinced the (white) people of Williamsburg to reimagine their heritage and their past. America’s heritage values were translated to the concepts of self-government and individual liberty elaborated by the great patriots, Washington, Madison, Henry, and Jefferson. The town commemorated the planter elites that had dominated American society until the Jacksonian era, and presented them as progenitors of timeless ideals and values. They represented the “very cradle of that Americanism of which Rockefeller and the corporate elite were the inheritors and custodians.” 35

Rockefeller’s Williamsburg was not the only American heritage tourist reconstruction. Canada also underwent reconstruction projects for specifically heritage tourism purposes, such as the construction of “Champlain’s Habitation” at Port Royal, Nova Scotia or the attempt to draw tourists to Invermere, British Columbia with a replica fur trade fort. 36 Following World War I and accelerating after World War II, the number and nature of places deemed heritage attractions grew. Across North America, all levels of governments and private corporations built replica heritage sites with varying degrees of “authenticity.” Although these sites often made use of existing buildings and landscapes, they also manufactured an imaginary environment of the past. The motivation behind these sites was almost always diversification of the local economy through increased tourism. Canada’s Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site is perhaps the most obvious example. It is a reconstructed section of the French colonial town, conquered and destroyed in 1758, built on the archaeological remains of the original. Constructed by the government of Canada as a means to diversify the failing resource economy of its Atlantic provinces, the tourist attraction was also designated a component of Canada’s national heritage. The US government also increased its interest in the protection of heritage destinations, greatly expanding the list of national historic landmarks, sites, parks, and monuments. As postwar governments became more concerned with managing their economies, tourism quickly came to be seen as a key economic sector. The language of national heritage helped build public support for state intervention in natural and historic artifacts and sites that could be presented as sacred national places.

In Europe, many historic sites were devastated by bombardment during World War II. Aside from pressing humanitarian issues, heritage concerns also had to be addressed. In France, the war had destroyed nearly half a million buildings, principally in the northern cities, many of which were of clear heritage value. The French government established a commission to undertake the reconstruction of historic buildings and monuments and, in some cases, entire towns. Saint-Malo, in Brittany, had been completely destroyed, but the old walled town was rebuilt to its seventeenth century appearance. Already a seaside resort, the town added a heritage site destination. In the 1920s and 1930s, European fascist states had also employed heritage tourism. In Mussolini’s Italy and Nazi Germany, workers’ leisure time was to be organized to prevent ordinary Italians and Germans from falling into unproductive leisure activities. Given the attachment to racialized views of purity and identity, organized tourism was encouraged to allow people to bond with their national heritage. Hiking in the Black Forest or the alpine Allgau might help connect Germans to the landscape and reconnect them to the traditional costumes and folkways of rural Germany. As Kristin Semmens argues, most studies of the Nazi misappropriation of the past ignore the displays of history aimed toward tourists at Germany’s heritage sites. Many museums and historic sites twisted their interpretations to fit the Nazi present. 37 In ways that foreshadowed the 1980s British left’s critique of heritage, fascist regimes made use of heritage tourism to control society. After the war, a vigorous program of denazification was undertaken to remove public relics of the Nazi regime and in formerly occupied territories, as was a program of reconstruction. In the communist east, blaming the Nazis for the destruction of German heritage was an ideological gift. It allowed the communist regime to establish itself as the true custodian of German identity and heritage. 38 In the capitalist west, tourism revived quickly. By early 1947, thirteen new tourist associations were active in the Allied occupation zone. Tourism rhetoric in the postwar years attempted to distance German heritage from the Nazi regime to reintroduce foreign travelers to the “real Germany.” Despite this objective, Alon Confino notes that traces of the Nazi past can be located in postwar tourist promotions that highlighted Nazi-era infrastructure. 39

Postwar Heritage Tourism

As tourism became a more global industry, thanks in no small part to the advent of affordable air travel in the postwar era, heritage tourism became transnational. Ethnic heritage tourism became more important, and diaspora or roots tourism, which brought second- and third-generation migrants back to the original home of their ancestors, accelerated. Commodifying ethnic heritage has been one of the most distinctive developments in twenty-first century tourism. Ethnic heritage tourism can involve migrants, their children, or grandchildren returning to their “home” countries as visitors. In this form of tourism, the “heritage” component is thus expressed in the motivations and self-identifications of the traveler. It involves a sense of belonging that is rooted in the symbolic meanings of collective memories, shared stories, and the sense of place embodied in the physical locations of the original homeland. Paul Basu has extensively studied the phenomenon of “roots tourism” among the descendants of Scottish Highlanders. He suggests that in their trips to Scotland to conduct genealogical research, explore sites connected to their ancestors, or sites connected to Scottish identity, they construct a sense of their heritage as expatriate Scots. 40 Similar “return” movements can be found in the migrant-descended communities of many settler colonial nations. For second-generation Chinese Americans visiting China, their search for authentic experiences mirrored those of other tourists. Yet, travel to their parents’ homeland strengthened their sense of family history and attachment to Chinese cultures. 41 On the other hand, Shaul Kellner examines the growing trend of cultivating roots tourism through state-sponsored homeland tours. In Tours that Bind , Kellner explores the State of Israel and American Jewish organizations’ efforts to forge a sense of Israeli heritage among young American Jews. However, Kellner cautions, individual experiences and human agency limit the hosts’ abilities to control the experience and thus control the sense of heritage. 42

Leisure tourism also played a role in developing heritage sites, as travelers to sunshine destinations began looking for more interesting side trips. Repeating the battlefield tourism of a century before, by the 1970s access to historic and prehistoric sites made it possible to add side trips to beach vacations. Perhaps the best example of this was the development of tourism to sites of Mayan heritage by the Mexican government in the 1970s. The most famous heritage sites, at least for Westerners, were the Mayan sites of Yucatan. First promoted as destinations by the American travel writer John Lloyd Stephens in the 1840s, their relative inaccessibility (as well as local political instabilities) made them unlikely tourist attractions before the twentieth century. By 1923, the Yucatan government had opened a highway to the site of the Chichén Itzá ruins, and local promoters began promotions in the 1940s. It was not until after the Mexican government nationalized all archaeological ruins in the 1970s that organized tours from Mexican beach resorts began to feature trips to the ruins themselves. 43

Mexico’s interest in the preservation and promotion of its archaeological relics coincided with one of the most important developments in heritage tourism in the postwar years: the emergence of the idea of world heritage. The idea was formalized in 1972 with the creation of UNESCO’s designation of World Heritage Sites. The number of sites has grown from the twelve first designated in 1978 to well over 1,000 in 167 different countries. In truth, the movement toward recognizing world heritage began with the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, which did not limit its activities to preserving only England’s architectural heritage. Out of its advocacy, European architects and preservationists drafted a series of accords, such as the Athens Charter of 1931, and the later Venice Charter of 1964, both of which emerged from a growing sense of cultural internationalism. These agreements set guidelines for the preservation and restoration of buildings and monuments. What UNESCO added was the criterion of Outstanding Universal Value for the designation of a place as world heritage. It took until 1980 to work out the first iteration of Outstanding Universal Value and the notion has never been universally accepted, although UNESCO member countries adhere to it officially. Once a site has been named to the list, member countries are expected to protect it from deterioration, although this does not always happen. As of 2018, 54 World Heritage Sites are considered endangered. This growth mirrored the massive expansion of tourism as a business and cultural phenomenon in the late twentieth century. As tourism became an increasingly important economic sector in de-colonizing states of Asia and Latin America, governments became more concerned with its promotion by seeking out World Heritage designation.

Ironically, World Heritage designation itself has been criticized as an endangerment of heritage sites. Designation increases the tourist appeal of delicate natural environments and historic places, which can lead to problems with maintenance. Designation also affects the lives of people living within the heritage destination. Luang Prabang, in Laos, is an interesting example. Designated in 1995 as one of the best-preserved traditional towns in Southeast Asia, it represents an architectural fusion of Lao temples and French colonial villas. UNESCO guidelines halted further development of the town, except as it served the tourist market. Within the designated heritage zone, buildings cannot be demolished or constructed, but those along the main street have been converted to guest houses, souvenir shops, and restaurants to accommodate the growing tourist economy. Critics claim this reorients the community in non-traditional ways, as locals move out of center in order to rent to foreign tourists. 44 While heritage tourism provided jobs and more stable incomes, it also encouraged urban sprawl and vehicle traffic as local inhabitants yielded their town to the influx of foreign, mostly Western, visitors.

Heritage tourism may hasten the pace of change by making destinations into attractions worth visiting. To accommodate the anticipated influx of global tourists, Luang Prabang airport was renovated and its runway extended to handle larger jets in between 2008 and 2013. The influx of tourists at Machu Picchu in Peru has repeatedly led the Peruvian government to attempt to control access to the site, yet dependent on tourism’s economic contribution, such restrictions are difficult. The temple at Borobudur in Indonesia undergoes near continuous maintenance work to repair the wear and tear caused by thousands of tourists walking its steps every day. Indeed, the preserved ruins are said to be under greater threat than when they were discovered in the early nineteenth century, overgrown by the jungle.

Another colonial aspect of world heritage designation stems from the narratives of the sites themselves. Many critics accuse UNESCO of a Eurocentric conception of Outstanding Universal Value and world heritage. 45 Cultural heritage destinations in non-Western countries are often associated with sites made famous by the projects of European imperialism. The fables of discovering ancient ruins, for instance, prioritize the romance of discovery. Many of the most famous non-Western sites were “discovered” by imperial agents in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Angkor Wat in Cambodia was introduced to the world by the French explorer Henri Muhot in 1860. Machu Picchu, the Mayan sites of Yucatan, and the ancestral Anasazi sites of the American southwest were excavated, in some cases purchased, and their narratives constructed by American and European adventurers. The cultural relics of these ancient places were looted and assembled in Western museums, the stories of adventure and discovery published for Western audiences, and eventually a travel infrastructure was established to bring mostly Western tourists to the destinations. Western tourism thus forms another kind of imperialism, as the heritage of a destination is determined to suit the expectations and motivations of the visitors. This tends to obscure other features of local history, leaving those features of heritage not suitable to the tourist trade less valuable.

Made or Experienced?