- Finest Hour

- Publications

Finest Hour 185

Churchill’s greatest triumph: bomber command.

Reading Time: 14 minutes

Lancaster Bomber being escorted by a Hawker Hurricane

- Past Events

- Upcoming Events

- Affiliate and Chapter Events

- Join the Society

- Join Us On Facebook

September 17, 2019

Finest hour 185, third quarter 2019, by roddy mackenzie.

Roddy MacKenzie is a retired Canadian lawyer and son of a Bomber Command pilot. This article is based on his 29 January 2019 address to the Churchill Society of British Columbia.

“The real cause of Germany’s defeat was the failure of the German Air Force.”—Hitler 1

Winston Churchill was involved from the beginning. During the First World War, Prime Minister David Lloyd George appointed Churchill Minister of Munitions in July 1917. Churchill was exceptionally effective. His many responsibilities included overseeing the supply of the new Royal Air Force following its creation on 1 April 1918. By 1919, Churchill was both Secretary of State for War and Air. He concocted with Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Trenchard (the “Father of the RAF”) “methods of using bombers to control large areas of sparsely populated territory” through “force substitution.” 2 This was important, because the two men viewed air power as possessing both offensive and defensive capabilities. This belief was used to overcome pressure from the British Army and Royal Navy to disband the RAF as a separate service. The United States had no Churchill-Trenchard equivalent at the end of the First World War, and so America’s Army and Navy succeeded in preventing the creation of a separate US Air Force until 1947. Churchill’s enthusiasm made the RAF for many years the largest air force in the world. Further, his encouragement of the British air construction industry helped save Britain in the Second World War.

Churchill’s View of Bomber Command

2024 International Churchill Conference

With anyone but Churchill as Prime Minister in May 1940, Britain would most likely have negotiated peace with Hitler. Additionally, without Churchill, Bomber Command would most likely have been sidelined early in the war because of the horrific cost in crewmen killed and aircraft lost. But Churchill, with singular clarity, saw Bomber Command as vital to victory. In September 1940, the first anniversary of the beginning of the Second World War, Churchill said in a memo to the Cabinet: “The Navy can lose us the war but only the Air Force can win it….The Fighters are our salvation… but the Bombers alone provide the means of victory.” 3

A myth has arisen about “The Few,” which needs to be dispelled. Churchill’s immortal words praising “The Few” refer not just to Fighter Command. They refer to all RAF airmen. Here are the three sentences Churchill spoke in Parliament on 20 August 1940:

The gratitude of every home in our Island, in our Empire, and indeed throughout the world, except in the abodes of the guilty, goes out to the British airmen who, undaunted by odds, unwearied in their constant challenge and mortal danger, are turning the tide of world war by their prowess and by their devotion. Never in the field of human has so much been owed by so many to so few. All hearts go out to the fighter pilots whose brilliant actions we see with our own eyes day after day, but we must never forget that all the time, night after night, month after month, our bomber squadrons travel far into Germany, find their targets in the darkness by the highest navigational skill, aim their attacks, often under the heaviest fire, often with serious loss, with deliberate careful discrimination, and inflict shattering blows upon the whole of the technical and war-making structure of the Nazi power. 4

What Was Bomber Command?

Bomber Command was the Commonwealth’s use of airpower to attack Nazi-controlled Europe. The Air Forces of Australia, Britain, Canada, and New Zealand (the Irish Free State was neutral, and South Africa focused on the African air war) came together in a single seamless unit of ever-increasing power and effectiveness. From 22 February 1942 to the end of the war, Bomber Command was led by Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris. The VIII Bomber Command (the “Mighty Eighth”) of the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) joined these forces in the UK on 17 August 1942.

Of Bomber Command’s 125,000 aircrew, 20,000 were Australians, 6,000 were New Zealanders, and 50,000 came from Canada. Bomber Command’s accomplishments came at a horrific cost. One source says Bomber Command sustained 79,281 casualties, and America 79,265. Of Bomber Command’s casualties, 55,573 were killed, 72% of whom were British. More than 9,000 Bomber Command aircraft were destroyed. One out of every four Canadians killed in the war died in Bomber Command, and one out of every five Australians killed died serving in the Royal Air Force.

Take my Dad’s Squadron as an example. The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) seconded my father, Roland W. MacKenzie DFC, to the RAF. There he piloted a Lancaster in Bomber Command’s 166 Squadron for thirty-four combat sorties from April to August 1944. His squadron flew from January 1943 until the end of the war. In those fifty-two months, 944 aircrew in 166 Squadron were killed. Their average age was twenty-three. Of these, 148 were Canadians, forty-five were Australians, and eleven were New Zealanders. Most RAF Squadrons had multiple Commonwealth airmen in their aircrews. The losses were horrific, but the results were vital to victory.

Bomber Command Controversies

While hailed as heroic during most of the war, Bomber Command became a subject of controversy afterwards. The three most divisive subjects are bombing accuracy, the ethics of bombing cities, and Dresden.

GET OUR BULLETIN

Bombing accuracy was brought into question by David Butt’s Cabinet Report of August 1941, which the RAF disputed but Churchill believed. It led to the British Area Bombing Directive of 15 February 1942, which was in turn replaced by the Casablanca Directive of 4 February 1943. These Directives aroused debate about the merits of precision bombing versus area bombing. What many decision makers during the Second World War failed to understand, however, was that this was oftentimes a distinction without a difference. The necessary technology for precision bombing developed only gradually during the war. Bombing accuracy and effectiveness steadily improved as the war progressed, with the introduction of every latest innovation, and especially when Bomber Command created “Pathfinders” to locate and mark targets.

The ethics of bombing cities arose from the reality that most German heavy industry was located in cities—and so ipso facto were the workers. Given the Allies’ demand at Casablanca for unconditional surrender, the only way to defeat the Nazis was to destroy Germany’s ability to wage war. What would have been unethical was losing the war, a very real possibility in the first two years, or suffering the large-scale massacres of Allied soldiers such as happened in 1914–1918. The United Kingdom, for example, lost three times as many soldiers in the first war as it did in the second. The Allied Strategic Bombing Offensive therefore proceeded and, in so doing, achieved its primary objectives of saving the lives of hundreds of thousands of Allied soldiers by shortening the war.

Dresden was bombed on 13–15 February 1945 by 769 British and 527 American heavy bombers. City officials telegraphed Berlin that about 20,000 were killed. Joseph Goebbels’ Propaganda Ministry simply added a zero to make this figure 200,000. The Nazis correctly noted that Dresden was an historic, medieval town but also falsely claimed that it was of no military value. In fact, it was a major industrial, communications, and railway centre with about 50,000 workers in war-related factories. Many people still believe both Nazi lies today. In response to an Associated Press report on 17 February 1945 speculating terror bombing, US Army Chief General George C. Marshall stated that Dresden was bombed at the request of the Russians. 5 That put an end to Dresden as an American controversy, but Churchill’s silence led to the bombing becoming an ongoing Commonwealth controversy.

Roy Jenkins states in his biography of Churchill that the Prime Minister’s decision in late January 1945 to intensify area bombing was founded on Churchill’s belief that this would decisively shorten the war. 6 Britain wanted this war to end, and so did America. Through its “Germany First” policy, America had two-thirds of its fighting force in Europe and only one-third fighting Japan. With Germany seemingly finished, Americans were becoming anxious to transfer their forces to the Pacific. In addition, relations with Stalin were deteriorating. From all this, German leaders had reason to believe that if their armies could dig into fixed positions in Northern Europe as they had already done in Italy, they could conduct a defensive war long enough to force the western Allies into a negotiated peace. The Strategic Bombing Offensive’s escalation, however, destroyed Germany’s means to continue making war and forced the surrender of more than three million soldiers who were no longer equipped to fight.

On 28 March 1945, presumably to distance himself politically from Bomber Command, Churchill signaled General Ismay: “It seems to me that the moment has come when the question of bombing of German cities simply for the sake of increasing the terror, though under other pretexts, should be reviewed…. [and] acts of terror and wanton destruction…” should now cease. 7 This implied terror bombing was taking place.

The Chief of Air Staff, Sir Charles Portal, asked Harris for an immediate rebuttal, persuaded Churchill to withdraw his erroneous signal, and demanded Ismay destroy his copy. Churchill did and Ismay promised to, but did not. The reply Harris sent that day said in part: “We have never gone in for terror bombing and the attacks which we have made in accordance with my Directive have in fact produced the strategic consequences for which they were designed and from which the Armies now profit…. Attacks on cities, like any other act of war, are intolerable unless they are strategically justified. But they are strategically justified in so far as they tend to shorten the war and so preserve the lives of Allied soldiers.” 8

Churchill should have harnessed his extraordinary oratorial skills to articulate the supreme importance of Bomber Command in the spring of 1945. Instead, he sank into silence. In spite of this, Churchill and Harris remained friends and respectful of one another’s considerable talents. At Churchill’s funeral, Harris was accorded the singular honour of serving as an honorary pallbearer.

Bomber Command’s Accomplishments

This brings us to the supreme question: what did Bomber Command accomplish? According to the Canadian government’s website:

The efforts of the approximately 50,000 Canadians who served with the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and the Royal Air Force (RAF) in Bomber Command operations over occupied Europe were one of our country’s most significant contributions during the Second World War….

The men who served in Bomber Command faced some of the most difficult odds of anyone fighting in the war. For much of the conflict, the regular duration for a tour of duty was 30 combat sorties. The risks were so high, however, that almost half of all aircrew never made it to the end of their tour. Despite the heavy losses, Bomber Command was able to maintain a steady stream of aircraft flying over U-boat bases, docks, railways and industrial cities in Germany, as well as enemy targets in occupied Europe. 9

Although the Canadian historical view is clear, only the Germans who experienced the attacks at the time really knew what was being accomplished. And what did the Germans say? Field Marshal Erwin Rommel told his superiors: “If you can’t stop the bombing, we can’t win the war.” Reich Marshal Hermann Goering, Field Marshal of the Luftwaffe Albert Kessselring, General Karl Koller, Field Marshal Erhard Milch, General Sepp Dietrich, and Field Marshal Gerd Von Rundstedt all attributed Germany’s defeat to Allied air superiority and the Strategic Bombing Offensive. 10 Reich Munitions Minister Dr. Albert Speer said Germany’s failure to defeat Bomber Command was Germany’s greatest lost battle of the whole war. He believed the Strategic Bombing Offensive did more damage to the German war effort than losing every battle in Russia, including the surrender of Stalingrad, because bombing continuously damaged with ever increasing ferocity, and then ultimately destroyed, Germany’s ability to produce the means necessary to make war.

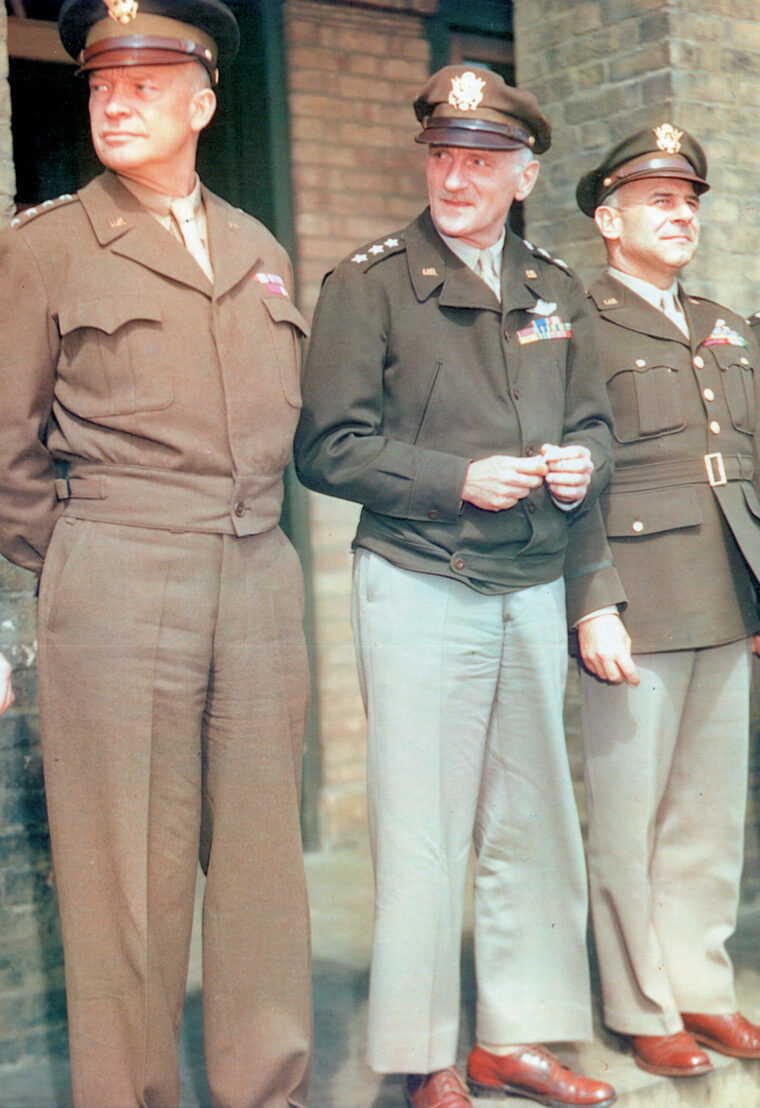

Eisenhower and Churchill—The Last Words

Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower wrote to reassure his superior General Marshall that return of control of Bomber Command to the British in September 1944 would work well. Eisenhower said he had come to regard British Bomber Command as one of the most effective parts of his entire organization, always seeking and finding and using new ways for their particular type of aircraft to be of assistance in forwarding the progress of the Armies on the ground.

Churchill’s famously failed to mention Bomber Command in his victory speech praising the Armed Forces. But a copy of the following telegram from Churchill to Harris, dated 15 May 1945—just one week after the German surrender—is to be found in the Churchill archives:

Now that Nazi Germany is defeated, I wish to express to you on behalf of His Majesty’s Government the deep sense of gratitude which is felt by all the Nation for the glorious part which has been played by Bomber Command in forging the Victory.

For over two years, Bomber Command alone carried the war to the heart of Germany, bringing hope to the peoples of occupied Europe, and to the enemy a foretaste of the mighty power which was rising against him. As the Command expended [sic], in partnership with the Air Forces of our American Ally, the weight of the attacks was increased, dealing destruction on an unparalleled scale to the German Military, Industrial and Economic System. Your Command also gave powerful support to the Allied Armies in Europe and made a vital contribution to the war at sea. You destroyed or damaged many of the enemy’s ships of war and much of his U-Boat organization. By a prolonged series of mining operations you sank or damaged large quantities of his merchant shipping. All your operations were planned with great care and skill; they were executed in the face of desperate opposition and appalling hazards; they made a decisive contribution to Germany’s final defeat.

The conduct of these operations demonstrated the fiery gallant spirit which animated your aircrews and the high sense of duty of all ranks under your Command.

I believe that the massive achievements of Bomber Command will long be remembered as an example of duty nobly done.

WINSTON S. CHURCHILL 11

This telegram is the clearest statement I have seen by any British official regarding what Bomber Command accomplished. In addition, Churchill declared in his war memoirs:

But it would be wrong to end without paying our tribute of respect and admiration to the officers and men who fought and died in this fearful battle of the air, the like of which had never before been known, or even with any precision imagined. The moral tests to which the crew of a bomber were subjected reached the extreme limits of human valour and sacrifice. Here chance was carried to its most extreme and violent degree above all else.

They never flinched or failed. It is to their devotion that in no small measure we owe our victory. Let us give them our salute. 12

Let us indeed! Bomber Command was Churchill’s greatest triumph.

1. Richard Overy, “World War II: How the Allies Won,” BBC. co.uk, 17 February 2011.

2. Patrick Bishop, Air Force Blue: The RAF in World War Two (London: HarperCollins, 2018), p. 35.

3. Ibid., p. 180.

4. David Cannadine, ed., Blood, Toil, Tears, and Sweat: The Speeches of Winston Churchill (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1989), p. 188.

5. Patrick Bishop, Bomber Boys: Fighting Back 1940–1945 (London: Harper, 2008), p. 347.

6. Roy Jenkins, Churchill: A Biography (London: Macmillan 2001), p. 777.

7. Henry Probert, Bomber Harris (London: Greenhill, 2011), p. 321.

8. Alan Cooper, Target Dresden (London: Independent, 1995), p. 196.

9. www.veterans.gc.ca

10. Cooper, pp. 217–32.

11. CHAR 20/229, Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge.

12. Winston S. Churchill, Closing the Ring (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1951), pp. 468–69.

Churchill, Air Power, and Arming for Armageddon

Churchill and Portal: A Strategic Relationship

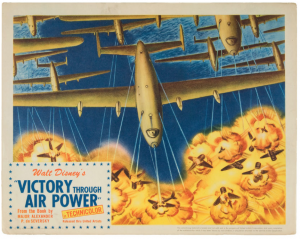

The Artist and the Aviator: The Case for Churchill and Roosevelt Viewing Victory Through Air Power

A tribute, join us, #thinkchurchill, thechurchillsociety.

🔹: ICS OFFICIAL Posts dedicated to the leadership and memory of Sir Winston Churchill. 🇬🇧|🇺🇸

Get the Churchill Bulletin delivered to your inbox once a month.

Join the International Churchill Society today! Membership starts at just $29/year.

A Tour of Duty

Once on an operational Squadron, a tour of duty was 40 completed operations. An "op" was a successfully completed flight or sortie, where the primary or secondary target had been attacked. Crews turning back early through technical problems did not count as having successfully operated. The loss rate was around the 4 to 5 percent mark, so mathematically it was impossible to survive. Yet about 35 percent of crews survived a first tour, after which they were classed as "tour expired" or "screened", then usually trained as instructors and sent to HCUs (Heavy Conversion Units) and OTUs (Operational Training Units) to train more crews. After a six month rest, they came back for another tour of 20 operations. If they survived this, they could volunteer for more but if they chose not to they remained as instructors unless promoted to higher things.

During the first five operations a new crew was ten times more likely to not return from an operation due to lack of experience. Once a crew survived 20 ops, the odds were thought to be about even.

Aircrew in Squadrons based in England were often able to take leave during a tour of duty. In many squadrons the rule was "no leave until 5 operations are complete", but normally aircrew received one week's leave every six weeks. Most airmen went "home" to wives or parents and it was nothing unusual for a son or husband to turn up at little or no notice with a crewmate or two along, especially if these were Canadians or Australians, sampling British home life.

Crews on Squadrons based outside of England were not so fortunate. The crews were generally granted a one week rest period in the middle of their tour of operations. The week would usually be spent at a local resort or hotel that had been commandeered by RAF specifically for the use of aircrew stationed nearby.

The bomber offensive progressed at such a rate that any period of time away from operations could leave aircrew thoroughly out of date with their knowledge and techniques. A return to operations after a six month break was traumatic, and a great number of crews were lost at the beginning of a second tour. Still, most aircrew found the dull and repetitive life of flying at training units so boring after squadron life that that they usually pulled whatever strings they could to return to operations.

Many of the men, doing a second tour with a different crew than their first, would find that they had finished a tour before the rest of the crew. Such was the comradeship of these crews that most would volunteer to do a few extra so that the crew's unity was preserved. Others thought it would be foolish to push their luck, and would that they be "tour expired" after the proper number of operations. There were many cases of a man doing one extra operation as a favor to their crew, or a tour-expired crew stepping in to make up the numbers, and then failing to return.

Bomber crews had a ten percent chance of baling out after being shot down. The German anti-aircraft system was extremely well organized. The Luftwaffe's night fighter force was also very highly developed, with ground radar stations directing airborne radar-equipped night fighters into the bomber stream. High-flying Luftwaffe aircraft dropped flares to mark the bomber stream's progress.

The .303 inch caliber machine guns of the RAF air-gunners were outgunned by the 20mm and 30mm cannon carried by the Luftwaffe. The RAF air-gunners would not open fire unless attacked by a night-fighter - their guns were defensive. Although the .303's rate of fire was 12 rounds per second, and its effective range reckoned to be 400 yards, at night if within visible range, the night-fighters were also within range of the .303s.

Mid-upper and rear-gunners were isolated from their crewmates except via intercom and had to stay alert for long periods in subzero temperatures. Their fields of fire overlapped somewhat; the mid-upper could rotate through 360 degrees. They could call for a corkscrew (violent evasive action) at a moment's notice. The trick was to take evasive action inside the attacking curve of the fighter, forcing him to steepen his turn in order to be able to shoot into the space where the bomber was expected to be by the time the bullets and shells arrived. Dive port, climb port, roll, dive starboard, climb starboard, roll ... and good air-gunners, knowing what was happening next, could fire into the space where they expected the night fighter to be.

Few night fighter crews persevered with an attack after the bomber had spotted them, and fewer still night fighter pilots had the skill to stay with a corkscrewing bomber and shoot it down as they flew together. A determined and experienced bomber pilot could make the evasive maneuver so violent that rivets popped out of the aircraft.

The Luftwaffe soon developed the "Schrage Musik" upward-firing cannon fitted to some Me110 and Ju88 night fighters. Attacked from directly below, many heavies were lost, and it was not until bombers returned with vertically pierced damage that the new threat was realized. This technique was so effective that night fighter pilots would not shoot directly into a bomber's fuselage for fear the bomb load would explode immediately above, destroying both aircraft. Instead, they tried to aim at the wing in hopes of hitting the fuel tanks and engines.

Gadgets and inventions

Many new electronic devices came into service. "Gee" was a radio navigation system with three transmitters in England sending a synchronized radio pulse at precise intervals. By comparing the slight time difference of arrival time of each pulse, navigators could check a chart and calculate their position very accurately. It did not extend over the radio horizon, and the Germans soon started to jam it, but it was very effective over the UK and the North Sea. Modern day developments of Gee's radio triangulation system are still in use today in the form of the Global Positioning Satellite system. The principle - TDOA or Time Difference of Arrival - is very similar to the wartime Gee.

"H2S" was a downwards pointing radar scanner in the rear belly of the aircraft; a large perspex black-painted blister contained the rotating scanner. It gave a reasonable "picture" of the ground below - water, buildings and roads showed up clearly. It could not be jammed, but specially-equipped Luftwaffe night-fighters could home in on any aircraft using it. Once this was known, H2S was only used by a bomber for very short periods. The popular explanation for the strange name of "H2S" is that a high ranking Air Staff officer was visiting the factory where the units were being built. On being told of the device's expected performance he was openly skeptical. "It stinks", he said bluntly, "call it H2S" [hydrogen sulphide - the smell of rotten-eggs].

These devices and vastly improved training for aircrew - especially navigators - brought about a dramatic increase in bombing accuracy. Still operating by night, RAF Bomber Command could now find their targets, which were by this time very often city centers as well as strategic and tactical military targets.

In the early days, pilots were given a main target, a couple of alternates, and left to plan their own take-off times and routes based on their own experience and preferences, but within a year the defenses were sharpening and it was necessary to co-ordinate tactics, not just for pilots in one squadron, but for the entire Bomber Force.

By mid 1941 it was possible to send many hundreds of medium and the first of the heavy bombers together in large numbers while briefing the crews to attack over a short time period. This swamped the defenses and decreased losses. But RAF Bomber Command's accuracy was still not good enough and the Command was losing prestige. Its new Commander in Chief, Arthur T Harris, mounted the first 1,000 bomber raid on Cologne. By dragging in every possible aircraft and crew from the Squadrons and training units, 1,046 bombers attacked Cologne on the night of 30/31 May of 1942, delivering a devastating blow. This set the scene for the great and terrible bombing offensive which was to follow.

Harris said of the enemy, "They sowed the wind and now they will reap the whirlwind."

Until Path Finder Force (PPF) was formed in August 1942 target marking had been hit-and-miss. After initial problems, PFF soon began to mark targets with great precision and the general accuracy of bombing improved further. Mistakes were made, and wrong targets attacked; but gradually RAF Bomber Command grew to what some called the Mighty Lion.

A second 1,000 bomber raid took place against Bremen on the night of June 25/26 1943 but this was not so successful due to bad weather conditions. On the night of July 30/31 1943 "Operation Gomorrah" took place on Hamburg and over the next four nights, in conjunction with daylight operations by the Americans, the city center was almost completely destroyed by immense fires merging into one firestorm conflagration. This technique was repeated at Dresden on February 14/15 1945, and this city too was almost completely destroyed. Controversies surround this attack even today, as Dresden was not a military objective. Popular opinion is that Stalin wanted a final knock-out blow against the Germans, and the attack was made to appease him.

On the Hamburg raids the radar jamming device "Window" was used. Window was strips of tinfoil cut to such a length and width that clouds of it, dropped at timed intervals by the bombers, corrupted the ground radar signals. All bombers carried dozens of bundles of window and the crews were briefed to throw out a packet of foil strips every minute. Over the nights of the Hamburg raids the German ground radar was rendered completely useless, and for a few months, Bomber Command enjoyed greatly reduced losses. Gradually the German scientists and radar technicians were able to overcome the jamming produced by huge clouds of Window, and losses rose again. Today "Window" is still dropped by aircraft to disrupt enemy radar and missiles - but now it's called "Chaff".

Some historians believe that the introduction of Window was a strategy which although successful in the short term, forced the Germans to greatly strengthen and improve their airborne defenses as well as push forward development of ground radar. This led to very serious losses for Bomber Command in 1944.

Huge controversy still rages today about Bomber Command's contribution to the war. Many argue that by the middle of summer 1944, RAF Bomber Command was an unstoppable machine, directed by Harris. Although able now to attack pinpoint military targets with devastating force, he persisted with area city bombing when it wasn't necessary any more.

Area bombing did no more to fatally weaken the enemy's capacity to wage war and to destroy morale than the London Blitz in 1940 did. That said, in addition to this Bomber Command carried out strategic and tactical operations on purely military targets. As a result war production and communications suffered massive destruction, forcing the enemy to deploy manpower from the fighting areas to the home front as well as reducing manufacturing capacity.

<< PREVIOUS | NEXT >> Home | Table of Contents

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The Bombing War: Europe 1939‑1945 by Richard Overy – review

B etween the wars, Richard Overy tells us, European city dwellers were terrified at the prospect of being bombed. Alarmists predicted millions of dead in London in a single, devastating attack. The city would be entirely destroyed by explosive and incendiary bombs, and its population annihilated by poison gas dropped from the air. Civilisation would come to an end. In 1908, HG Wells , in his book The War in the Air , had prophesied that New York would be reduced in a matter of hours to "a crimson furnace from which there was no escape". These fears were underlined dramatically by the obliteration of the Basque town of Guernica by German bombers during the Spanish civil war and by the Italian air force's use of poison gas to destroy their opponents' armies on the ground during the invasion of Ethiopia.

Yet the reality, when it came, was very different. In 1939, it was almost universally accepted that air power was best used in conjunction with land invasion, to neutralise enemy air forces and disrupt military communications on the ground. No combatant nation went into the war with a fully developed fleet of heavy bombers. The military men had won out over those who had wanted air forces to act independently. There were hesitations about breaking agreed and, in effect, legally binding international sanctions against the use of air power to attack civilians. Hitler explicitly ruled out "terror bombing" and deployed the Luftwaffe to clear the way for the invasion of the British Isles by destroying the RAF – and then, when the job was done (as the Germans wrongly thought it had been by mid-September), to weaken the British economy in support of the blockade.

If the blitz was the first independent strategic bombing offensive, it was followed soon by a much larger offensive on the part of the British, where, exceptionally, military doctrine favoured the independent use of bombers. The strategy was developed following attempts to suppress colonial uprisings, where long distances and poor communications had made it difficult to deploy ground forces effectively. Bomber Command, above all under Arthur Harris, became, in Overy's words, a "sorceror's apprentice", whose activities eventually far outran the control of its political masters.

Here, too, the targets were supposed to be military and economic; even in the hugely destructive raids on Hamburg in 1943, Harris aimed at the working-class districts of the city because the elimination of workers would damage war production. The raids continued to the end of the war owing to fears in the allied high command that the Germans might regain air superiority with the aid of new devices such as ground-to-air missiles (one of which, the Waterfall, was at an advanced stage of development) and jet fighters (the Me 262 was in action well before the end of the war). Yet Harris went beyond this to attack civil society in Germany itself, hoping that the devastation of its cities would lead to a popular uprising against the regime. He boasted regularly of the total destruction of German towns and cities by Bomber Command and its American allies, and his deputy called the D-day landings "an unnecessary 'boating expedition'" in the light of the imminent collapse of the enemy under the weight of the bombing raids.

It is one of the many achievements of this book to show that almost all expectations were confounded: air force commanders consistently overestimated the damage their aeroplanes caused. Although millions of gas masks were distributed to the populations of Britain and Germany, no gas attacks were ever undertaken; both sides feared the consequences too much, despite elaborate preparations, including the fact that the two countries, particularly the British, had built up massive stocks of gas and chemical weapons by the end of the war. Germans were not driven to rise up against Hitler by the bombing campaign; the raids, especially those of Operation Gomorrah against Hamburg in 1943, caused widespread demoralisation and disillusion with the regime. But just as British society had held together under the blitz, so German society endured to the end, though under an increasingly draconian regime of threats and punishments from the Nazi party.

The economic effects of bombing were hugely exaggerated on all sides: German production was dented but not destroyed. The relocation and dispersal of arms factories to safer areas; the camouflage of manufacturing sites (for example, by painting walls and roofs black to look as if they had been damaged by incendiary attacks); and the rapidity with which key sites, such as the ball-bearing factory at Schweinfurt, were reconstructed after an attack, all helped ensure that Geman arms production peaked quite late on in the war, in 1944, under the impact of arms minister Albert Speer's economic rationalisation programme. As for the blitz, despite the bombing of London's docklands, no more than 5% of production was affected by the raids. The military effects of the campaign on the German war effort were far more important, with significant resources in manpower and equipment being diverted from the eastern front to try and deal with the attacks from the air.

Bombing was surprisingly inefficient. As Overy shows, poor visibility, the sudden deterioration of weather conditions, malfunctioning equipment, outdated and slow-moving aircraft, pilot inexperience or crew exhaustion, and enemy action varying from anti-aircraft batteries to night-fighters or the jamming of navigation beams, all reduced the effectiveness of bomber fleets. Aircraft crashed, ran out of fuel or suffered engine failure with astonishing frequency. In its raids on Britain from January to June 1941, for example, 216 German bombers were lost and 190 damaged; 282 of these were as a result of flying accidents. The death rate among bomber crews was appallingly high (crew members in Bomber Command had a one-in-four chance of surviving their first tour of duty, and a one-in-10 chance of surviving their second) but not all of it was as a result of enemy action. At the end of 1941 Bomber Command reckoned that it was losing six aircraft to accidents for every one shot down by the enemy. The British and especially the Americans could make good these losses, and more besides; in the end, Germany's smaller resources meant that the German air force was increasingly outproduced.

Above all, bombing was staggeringly inaccurate. Bomber fleets had to fly high to avoid anti-aircraft fire from the ground, so even if the weather was clear, they were often unable to locate their targets effectively. On one mission, Robert Kee , a bomber pilot who later became a successful historian, "bombed some incendiaries at what we hoped was Hanover" but mostly dropped his bombs on searchlight concentrations because that was all he could see through the cloud. One report, compiled in September 1941, reported that only 15% of aircraft were bombing within five miles of their target. In the last three months of 1944, it was reckoned that only 5.6% of bombs fell within a mile of the aiming point if there was cloud, despite the use of electronic navigation aids. One raid on a major oil plant saw 87% of the bombs missing their target entirely, and only two actually hitting the buildings.

In 1944, during the controversial bomb attacks on the Italian monastery of Monte Cassino , used by the Germans as a military and communication base, the headquarters of general Oliver Leese, three miles from the abbey, were destroyed, as was the French corps headquarters 12 miles away. It took another three months before the strongpoint was taken. A raid on the V-2 rocket production site in a large park north of The Hague dropped 67 tons of bombs on a residential area on 1 March 1945, largely because the briefing officer had got the map coordinates wrong. Carpet bombing of cities was, in the end, virtually the only way to destroy the economic and military targets they contained.

Under such conditions, the idea of bombing the railway lines to Auschwitz to stop the extermination of the Hungarian Jews shipped there in 1944 was little more than a fantasy; any attack would most likely have inflicted major casualties on the inmates of the camp itself. It was only in the last months of the war that allied air supremacy was so secure, and allied military production so superior to that of the Germans, that really serious damage was inflicted – three-quarters of the entire bomb load dropped on Germany fell during this final period. German industry survived in sufficient strength, however, to eventually provide the basis for the country's "economic miracle" after the war was over.

On this and its other topics, Richard Overy's magnificent survey, based on extensive research into the archives of a large number of countries, must now be regarded as the standard work on the bombing war, not just in Britain and Germany, but in the rest of Europe, too. It is probably the most important book published on the history of the second world war this century, and historians will have to revise many of their long-accepted facts and figures in taking account of it. Unlike other authors writing on this subject, Overy is cautious about making moral judgments; but he has provided the indispensable source of knowledge for those who are not.

- History books

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

About Bomber Command

55,573 young men died flying with Bomber Command during World War Two; that's more than those who serve in the entire Royal Air Force today.

Most who flew were very young, the great majority still in their late teens. Crews came from across the globe – from the UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and all corners of the Commonwealth, as well as from occupied nations including Poland, France and Czechoslovakia.

Strike hard, strike sure

It took astonishing courage to endure the conditions. Flying at night over occupied Europe, running the gauntlet of German night fighters, anti-aircraft fire and mid-air collisions, the nerves of these young men were stretched to breaking point.

The bomber will always get through

RAF Bomber Command was formed in 1936. At the time, it was argued that a strong bomber force provided a deterrent to aggression, as bombing would result in complete and inescapable destruction on both sides. The reality was very different.

Britain on the defensive

War came despite the threat of the bombers. The Nazi Blitzkrieg in 1940 quickly defeated France, leaving Britain to fight on alone. After the RAF's famous victory in the Battle of Britain (during which Bomber Command played a vital and unheralded role, attacking invasion barges in the channel ports), Britain found itself on the defensive everywhere.

To Winston Churchill, and to most of the British people, only the bombers offered a chance to take the fight to the Nazis. Initially the prospects were bleak. Aircraft like the Whitley and Hampden were not capable of launching raids deep into enemy territory, while tactics were primitive and losses were high.

Bomber Command was compelled to switch to inaccurate night bombing in an effort to reduce casualties.

Bomber Harris

It was not until 1942 that Bomber Command gained a real sense of direction, with the advent of Air Marshal Arthur 'Bomber' Harris .

Harris was appointed as commander in chief of Bomber Command in February 1942, with a mandate to begin attacking German industry, much of which was located in large cities.

His objective was to destroy Germany's industrial might and create a collapse in the morale of the civilian workforce, breaking Germany's will to fight on. To understand these intentions, the mood and desperation of the country has to be considered.

Times were hard. Victory seemed distant, and chivalric notions of war fighting had been burned away in the fire of the Blitz . U-Boats were roaming the Atlantic, sinking merchant shipping in an effort to starve Britain into submission.

Harris' promise to make the German people "reap the whirlwind" resonated with a desire to strike back at the mighty Nazi war machine, no matter what the cost.

Thousand bomber raids

The prospects of success were uncertain. Morale among British workers had largely held firm in the teeth of prolonged attacks by the German Air Force.

Harris, however, firmly believed that through a combination of improved aircraft like the Lancaster and Halifax , better training and navigational aids, and a ruthless will to press the attack, Bomber Command could knock Germany out of the war.

In May 1942, Harris launched his first "thousand bomber raid" against Cologne .

The scale of the attacks shocked Germany, but the country continued to fight. Further massed attacks did have a devastating effect on the Nazi war economy.

Albert Speer, the German armaments minister, believed that a series of raids like that on Hamburg in August 1943, repeated in quick succession, might well have compelled Germany to surrender.

But that did not happen. There were only so many aircraft and so many crews.

Dam Busters

Other more specialised operations also took place. The famous ' Dam Busters ' raid of May 1943 shocked the world with its audacity, as Guy Gibson’s 617 Squadron launched a daring raid on the dams surrounding the Ruhr Valley.

Other attacks, like that on the battleship Tirpitz the following year, eliminated the German navy’s last major surface ship. Raids in 1944 and 1945 against German ' V weapon ' launch sites were also a crucial defensive measure, helping to limit attacks from flying bombs and rockets on British cities.

All these operations demonstrated the adaptability of Bomber Command crews, taking on precision strikes with great effect. Still, the focus remained on bombing industry.

From November 1943 to March 1944, Harris launched a series of huge raids on Berlin, promising to knock Germany out of the war in the process. Over 1000 aircraft and 7000 aircrew were lost during the 'Battle of Berlin', but the city struggled on.

The allies would have to invade to finally defeat Germany.

Bomber Command switched its attentions to tactical objectives in early 1944, helping to pave the way for D-Day , the allied invasion of occupied Europe.

Bomber Command aircraft played a vital and highly effective role attacking infrastructure around the invasion beaches. Attacking railways, roads and other transport links created chaos behind German lines, preventing the defending forces from massing to repel the landings.

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, leading the German defence, said: "Stop the bombers or we can't win!"

In four huge raids by the RAF and United States Army Air Force, a firestorm destroyed the city centre and killed thousands of civilians.

The planners of the raid argued the city was a vital communications hub and needed to be targeted.

The critics said that Germany was well beaten and the bombing was needless.

The truth is that it was a time of total war, and ideas about the boundaries of conflict were very different than those we have today.

Only those who have lived through similar times could understand or pass judgement.

Operation Manna

1945 also saw another, lesser known mission. From 29 April to 7 May Operation Manna saw Bomber Command crews drop food supplies to the starving people of occupied Holland. Flying at 500 feet in broad daylight over hostile territory, the crews brought vital relief to the civilian population.

Contribution to victory

Bomber Command did not win the Second World War independently - but the war could not have been won without their efforts. The RAF’s attacks forced Germany to divert invaluable men, guns, aircraft and equipment to defend its airspace, effectively opening a second front long before D-Day.

The young men of Bomber Command faced dangers that today we can barely imagine, all in defence of our freedom. Their sacrifice and extraordinary courage should never be forgotten.

The debt we owe

The RAF Benevolent Fund was there immediately after the war to repay the debt we owed bomber crews, and is still there today to help all those who served.

It is our great honour to maintain the Bomber Command Memorial for future generations as a lasting symbol of all that they did in defence of our freedom. It is a fitting tribute to an extraordinary generation, who set the standards of duty and sacrifice by which the RAF still serves today.

Support finder

[[ error ]]

[[ title ]]

- [[ answer.text ]] [[ answer.text ]]

Skip to Main Content of WWII

The eighth air force vs. the luftwaffe.

In the grisly battle for European air supremacy, the Luftwaffe proved a deadly foe to Allied bombers.

The United States Eighth Air Force deployed to England with a daunting mission: destroy Germany’s ability to wage war, and gain command of the European skies to pave the way for an Allied land invasion. In order to accomplish it, thousands of American airmen had to face the constant threat of death daily.

German anti-aircraft fire, or flak, was one of those deadly threats. Some targets were more heavily defended by flak batteries than others, but flak was an accepted part of the job at hand, no matter how deadly.

The other more feared threat was the German Luftwaffe. In 1943, the Luftwaffe was at peak strength against American bombers. The pilots flying the ME-109s and FW-190s were professionals—the best in the world. Some of the German pilots had been flying in combat since 1936. Many had dozens of aerial victories; some had over 100. John Keema of the 390th Bomb Group said, “No matter the target they were defending, they were balls to the wall. They were brave. They didn’t hesitate.”

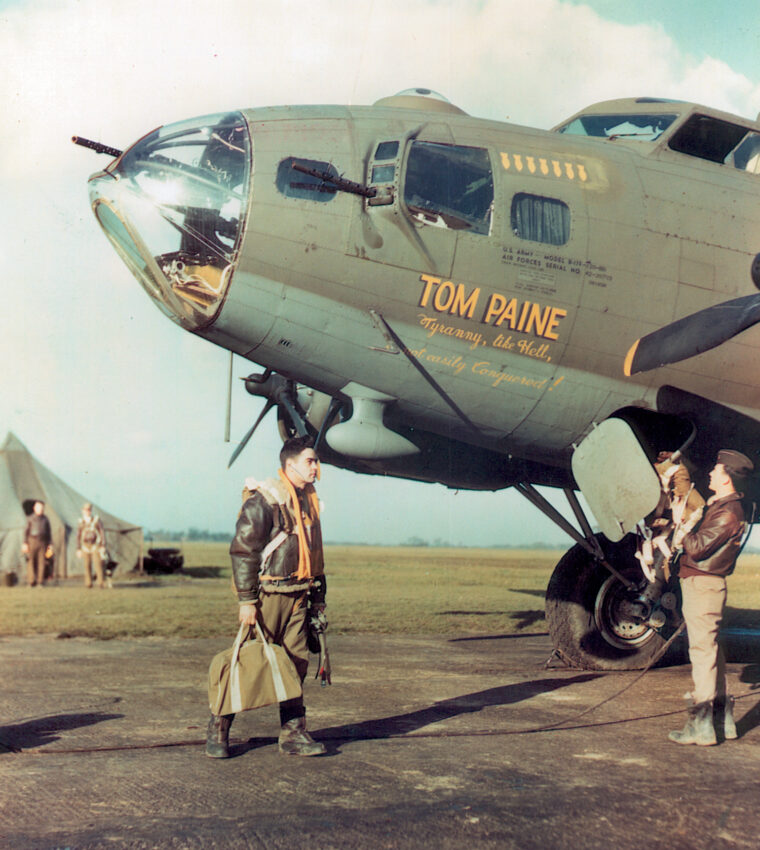

The American theory on daylight bombing lay in the aircraft the crewmen flew: the rugged Boeing B-17 “Flying Fortress,” the main heavy bomber of the Eighth Air Force. The plane carried 10 crewmen, and sported 13 50-caliber guns for self-defense. It was famous for bringing crews home, even when three of its four engines failed. The B-17’s firepower, combined with that of other aircraft in the formation, would be plenty to protect bombers from enemy attacks.

Theory was one thing. Practice was another.

In November 1942, German fighter ace Egon Mayer found the weakest place on a B-17—directly in the front of the aircraft. Defended by only four machine guns, the nose of the B-17—and more importantly the cockpit—was vulnerable to a head-on attack. The attack required great skill and courage, as the German and American aircraft closed at an astonishing speed. The German pilot only had seconds to aim, fire, and peel away before careening into the heavy bombers. Tested by the developer himself, Mayer found the tactic worked exceedingly well. By December, the head-on attack was the preferred method of assailing American heavy bombers by Luftwaffe fighter pilots. Casualties among bomber crews began to mount steadily as B-17s were being blown out of the sky with growing consistency.

A B-17 taxis down a runway.

A portrait of Captain John Luckadoo.

Here is B-17 Rose Marie , which served in the 390th Bombing Group.

Throughout the summer of 1943, American bomber crews sustained heavy casualties. Losses of 30 or more aircraft—300 men—were not uncommon throughout the summer. John Luckadoo, a pilot in the 100th Bomb Group recalled that he “calculated a 400 percent turnover in the first 90 days” of combat. In 1943, bomber crews were tasked with a 25-mission tour of duty. Most crews never made it past their fifth. The Luftwaffe owned the skies over Europe and the men of the Eighth Air Force were paying the price.

A fatalistic sense of acceptance became prevalent. A popular saying at the time was that to “fly in the Eighth Air Force then was like holding a ticket to a funeral —your own.” Abnormal behavior became more common. Insomnia, irritability, sudden temper flashes, nausea, weight loss, blurred vision, introverted withdrawal, inability to concentrate, and Parkinson’s-like tremors were a few of the symptoms seen by flight surgeons. Nightmares so vivid that they caused the men to wake up screaming in the night were not uncommon. Men became jumpy and jittery, the “Focke-Wulf Jitters,” or “flak happy,” became commonly used terms in the Eighth Air Force.

As summer turned to autumn in 1943, the Americans felt that, despite the casualties, the air war would ramp up in intensity. Targets that directly affected the German war machine became priorities. Fighter-production facilities, ball-bearing plants, shipyards, and other military targets were in the crosshairs of the Eighth. Conversely, the Eighth was in the crosshairs of the Luftwaffe, determined more than ever to defend their cities and facilities.

Stuttgart, Germany, and the Bosch factory located there were the targets for the Eighth on September 6. Stuttgart was at the very limit of the B-17 in 1943, and fuel was a precious commodity on this particular mission. As usual, as the fortresses approached German territory, German fighters attacked. The assaults were violent, head-on passes that resulted in high casualties among the lead crews. Yet, despite the opposition, the bombers continued toward the Bosch factory. Once over the target, however, the mission began to unravel, as a cloud front had unexpectedly moved in, obscuring its view from the bombardiers perched in the noses of their B-17s 25,000 feet above. General Robert Travis, aerial commander of the mission, made the decision to circle the target and wait for the clouds to move. As the bomber formation circled the target, the tight combat boxes of B-17s became easy targets for enemy fighters. Three passes were made and, the clouds had not broken, all while precious fuel was being burned and B-17s were being shot down by fighters and anti-aircraft artillery. The B-17s had been over the target for nearly thirty minutes when the bombs in the lead aircraft finally dropped.

The bombs missed the target almost completely. Forty-five B-17s failed to return to England that night.

The obvious confusion in the air over Stuttgart and the heavy casualties sustained yet again caused many men to begin to doubt the leadership of the air campaign. A survivor of the Stuttgart mission recalled, “We began to wonder if they were trying to kill all of us. There were fewer and fewer guys returning every day.” One of the many who didn’t return from Stuttgart added, “We felt as if they didn’t know what the hell they were doing up there, especially over Stuttgart. They were just aimlessly flying around.” The fact that the aerial commander made four passes at the target astounded many of the crew. That leadership allowed the men to be exposed to enemy fire for what seemed like an eternity, for little or no results in terms of bombing accuracy, made the crews irate. The pilot continued, “It was a good thing I was shot down honestly. Because if I hadn’t been, I would have turned in my wings I was so fed up.”

The morale among the Eighth Air Force crews was at a low point in September, yet the worst was yet to come. October 1943 yielded the heaviest casualties sustained up to that point in the air campaign.

Beginning on October 8 and continuing until October 14, Eighth Air Force crews attacked targets all over Germany in an attempt to continue the pressure on the Germans. October 8’s target was the shipyard in dreaded Bremen, known as “Flak City” by the aircrews. The flak was so thick, Luckadoo said that “if you put your wheels down you could taxi on it.” Combined with the expected fighter opposition, October 8 was not going to be an easy day for the bomber crews. Luckadoo recalled that the enemy fighters attacked the bombers as soon as they crossed the border into France and continued all the way through to the target. Generally, when bombers approached the target and entered what was called the flak field, enemy fighters peeled away to land, refuel, and rearm.

On October 8, they did not peel away. The enemy fighters, so determined in their mission to deter the B-17s, remained in attack mode over the flak field and flew through their own anti-aircraft fire in order to deliver their assaults. As they approached the initial point, or IP, the fighters pressed even closer. Luckadoo remembered one such attack on the B-17 called Piccadilly Lilly : “Out of the corner of my eye I saw this flight of FW-190s barreling into our squadron. Aiming right for us … they kept coming, kept coming … they may have killed the pilot of the lead ship or else he was so determined that he was going to take down a bomber that he flew into … impacted the ship that I was formed on. When they went down … I had to dump my nose to keep them from taking me with them.” The fighters over Bremen were relentless in their attacks. By the end of the mission, the Eighth Air Force had lost 30 bombers and 300 men. The 100th Bomb Group lost 17 of 19 deployed. The 381st lost seven of 18 deployed. The 300 men shot down were obvious casualties, but when the battered bombers returned to their home bases, they carried another 301 wounded in their fuselages.

For the survivors, there wasn’t much time for contemplation of those lost. The next day proved to be an even longer day, followed by another, and another. The German fighters reaped a devilish harvest in the skies over Bremen, a harvest repeated in the next few missions in what became called “Black Week” by those fortunate enough to live through it.

WWII Air, Land & Sea Festival

Warbirds in flight, tanks on parade, PT-305 in the water. October 27-29 at New Orleans Lakefront Airport.

Seth Paridon

Seth Paridon was a staff historian at The National WWII Museum from 2005 to 2020. He began his career conducting oral histories and research for HBO’s miniseries The Pacific and holds the distinction of being the first historian hired by the Museum’s Research Department. In the 12 years he was Manager of Research Services, Seth and his team increased the oral history collection from 25 to nearly 5,000 oral histories.

Explore Further

Lee Miller in Combat

One of America’s only female war correspondents reported on the aftermath of D-Day, the Battle of Saint-Malo, and the liberation of Paris.

Hitting the Silk: The Caterpillar Club

Named for the silkworm caterpillar, which produced the silk originally used to make parachutes, the club encapsulates the precariousness of its member’s experiences with its motto: “Life depends on a silken thread.”

The Second Great Fire of London: 'A Dreadful Masterpiece'

In this column, journalist Ernie Pyle describes the bombing of London in late December 1940 as “the most hateful, most beautiful single scene” he had ever witnessed as the city was “stabbed with fire” by the German Luftwaffe .

What Happened to Lieutenant Curtis R. Biddick?

V for Victory: A Sign of Resistance

Created by a Belgian politician and broadcaster fleeing Nazi persecution, the V for Victory symbol became one of the most enduring signs of the war.

The 'Bloody 100th' Bomb Group

The Eighth Air Force’s hard luck unit was filled with colorful personalities who made the unit one of the most storied of World War II.

The Air Medal: An Effort to Bolster Morale

Authorized during the one of most difficult periods during the air war, the Air Medal was an effort to rally the US Army Air Forces crews.

Patchwork Plane: Building the P-47 Thunderbolt

Roughly 100 companies, coast to coast, helped Republic Aviation Corporation manufacture each P-47 Thunderbolt.

Explore our digital exhibition content and trails with RAF Museum Tours.

Exhibitions.

- Battle of Britain Exhibitions

- Age of Uncertainty

- The Tirpitz

- Bomber Command Exhibition

- First 100 Years

- First to the Future

- Higher, Faster, Further

- The London Walking Trail

- Royal Trail

- Art Trail: Bomber Command, Triumph and Loss

- The London Family Walking Trail

- Bomber Command Highlights Trail

- Family Sound Trail

- The Battle of Britain Trail

- The Battle of Britain Trail – RAF Hendon

- Falklands 40

- Hangar 1 Quiz

- Scouts and Guides Trail

- Royal Trail London

- Follow my lead: Diversity in the RAF

- RAF Museum Midlands

- Index of all locations

- RAF Museum Shop

Please note our website uses cookies to improve your experience. I understand . For more information see Privacy Notice & Cookies

Please enter at least 3 characters

Photo Credit: In Robert Taylor’s painting Company of Heroes, the 34th Bomb Group B-17 Flying Fortress dubbed “Queenie” sits at its home airfield in Britain following an intense daylight raid against a target in Nazi-occupied Europe. Another B-17 taxis to a stop, while the final bomber makes its approach for landing.

U.S. VIII Bomber Command: From Savannah to Glory

The U.S. VIII Bomber Command grew into a massive, powerful force and became a legend in the skies above Western Europe.

This article appears in: May 2004

By Sam McGowan

When World War II in Europe came to an end, the Eighth Air Force was the most famous unit in the U.S. Army Air Forces and, until the massive Boeing B-29 Superfortress raids against Japan in the spring of 1945, it was the most powerful.

After more than two years of aerial bombardment of targets throughout Germany and Occupied Europe, the Eighth Air Force had come to symbolize heavy bombing. While the Eighth is known as the heavy bombardment outfit, it did not start out that way. When it was first established on January 2, 1942, the unit that became famous as the Eighth Air Force was actually designated as the Fifth Air Force. However, this number had already been reserved for an Air Corps unit in the Southwest Pacific, so the designation was subsequently changed to the Eighth.

Nor was the Eighth conceived to be solely dedicated to aerial bombardment; its original mission was tactical. It came into existence to serve as an air element to support Operation Gymnast, the planned invasion of Northwest Africa that was scheduled to take place later in the year.

On January 28, 1942, Eighth Air Force Headquarters was activated at Savannah Army Airfield, Ga., under the command of Colonel Asa N. Duncan. Over the next several weeks the Eighth underwent several changes. Gymnast was canceled due to the emergency situation in the Pacific, eliminating the need for the new unit as it had originally been conceived and leaving it without a mission. One Army plan called for the establishment of an Army Air Force in Great Britain. On March 31, Maj. Gen. Carl Spaatz, commander of the Army Air Force Combat Command, proposed that the taskless Eighth Air Force be made available for duty in England and that he be chosen to command it. General Ira Eaker had already gone to England with an Army Air Forces advance party, and Spaatz decided that it would pave the way for his new command.

With the change in task, the size and makeup of the Eighth changed as well. Previously, Colonel Duncan had requested the assignment to England of three heavy bomber groups, two groups of medium bombers, and three fighter groups. The reorganization for the new mission increased the planned size to 23 heavy, three medium, and five light bomber groups, along with four groups of dive-bombers and 13 fighter groups. Two troop carrier groups would also be added. The dive-bomber groups would never materialize, and the light bombers would become part of a new organization when they finally arrived in England.

In April Duncan, who had been promoted to brigadier general, was made subordinate to Spaatz, and the headquarters was split into two echelons. Administrative functions remained in Savannah while operations moved to Bolling Field on the outskirts of Washington, DC, near Spaatz’s headquarters. General Spaatz took formal command on May 5, and preparations began to move the Eighth to England.

Shortly after Spaatz assumed command, an advance echelon left for England, where it joined Eaker’s organization, which had been redesignated as the Army Air Forces British Isles. Other Eighth headquarters personnel followed over the next few weeks. In mid-April Eaker took over a girls’ school at High Wycombe for his headquarters.

Eaker’s role was to prepare the way for the arrival of the Eighth Air Force staff, so in the interim his organization was redesignated as Detachment Headquarters, Eighth Air Force. Eaker’s staff worked diligently to develop a plan of action for the combat units when they arrived in England, with particular emphasis on bombardment. They borrowed heavily on the experiences of the British and closely followed the lines of the Royal Air Force Bomber Command in developing the organization. When Spaatz arrived in England, Eaker became commander of VIII Bomber Command and Brigadier General Frank O’D. Hunter was placed in command of VIII Fighter Command.

The movement of the combat units to England was delayed by the Battle of Midway when the 97th Bomb Group and some fighter groups were sent to the West Coast. When the battle concluded, the combat units began their move, with the 97th Bombardment Group and the 14th Fighter Group the first to go. The first Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses arrived in England on July 1, followed by Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters. Several fighter groups that had been equipped with Bell P-39 Airacobras left their airplanes behind and were equipped with Supermarine Spitfires when they arrived overseas. The Eagle Squadrons, three Royal Air Force fighter units made up of American volunteers flying Spitfires, transferred into the U.S. Army and joined VIII Fighter Command as the 4th Fighter Group later in the year.

Interestingly, the first Eighth Air Force unit to fly a combat mission wasn’t a B-17 outfit, nor had it been intended as a bombardment group. In May 1942, the 15th Bombardment Squadron deployed to England as an independent squadron to fly Douglas A-20 Bostons as night fighters. When they got there the squadron’s crews learned that the British weren’t using their DB-7 Bostons in that role, so they began training for light attack missions with RAF 226 Squadron.

By the end of June several crews were considered combat-ready, and Spaatz decided to put them into action. The first mission was set for the Fourth of July; six U.S. Army crews were assigned to fly six RAF Bostons on a low-level mission with six RAF crews against German airfields in Holland. The results were less than spectacular. Four crews failed to find the targets, two airplanes were shot down, and a third was badly damaged. An RAF Boston was also lost.

One of the American pilots, Captain Charles C. Kegelman, was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for attacking a German flak tower with only one operating engine. The 15th Bomb Squadron soon received its own Bostons and for several weeks was the only Eighth Air Force bomber unit flying combat missions.

Spaatz Wired an Exaggerated Account to Washington That the Bombing “Far Exceeded” any Previous Bombing by British or German Planes in Accuracy.

After a weather cancellation on August 10, the 97th Bomb Group flew its first mission on August 17, 1942. Twelve B-17s attacked a railroad marshaling yard at Rouen, France, while six others made a diversionary sweep along the French coast. General Spaatz watched the bombers take off and General Eaker flew as a passenger in the lead airplane. Escorted by RAF Spitfires, the B-17s set out across the English Channel under generally clear skies. All 12 airplanes dropped their bombs, and about half fell in the general vicinity of the target. One of the aiming points was hit, while the second was missed by about half a mile.

Spaatz wired Washington that the bombing “far exceeded” any previous bombing by British or German planes in accuracy. He claimed that the results “justified” American faith in “daylight precision bombing” and optimistically asserted that the mission proved that “the bombers could get through.” His claims were a bit of an exaggeration—only three German fighters had actually attacked the formation, while several others observed from afar. Damage from antiaircraft fire had been “slight.”

The first fighter attacks came on August 21, when the bombers arrived over the coast of Holland without a fighter escort due to a communications foul-up. Even though a recall message was sent out, German fighters intercepted the bombers. Surprisingly, in spite of attacks by more than 40 Luftwaffe fighters, only one of the B-17s suffered serious damage and the co-pilot, 2nd Lt. Donald Walter, who died of wounds, became the Eighth’s first heavy bomber combat casualty. The gunners claimed scores of German fighters, but the final number was determined to have been two shot down, five probables, and six damaged.

The 97th Bomb Group was alone in the daylight heavy bomber role until September 5, when the formation of 37 B-17s including 12 from the newly arrived 301st BG on Mission Number Nine joined in. Another group, the 92nd, made its first contribution to the bombing campaign the following day, when 14 group airplanes joined 27 from the 97th on a mission to Meaulte. Thirteen 301st BG Flying Fortresses attacked the airfield at St. Omer while an even dozen 15th Bomb Squadron Bostons attacked Abbeville. Two B-17s were shot down, the first Eighth Air Force heavy bombers lost in combat.

On October 2, 37 B-17s went back to Meaulte, this time encountering large numbers of German fighters, but all of the bombers made it home. The B-17 gunners put in so many claims that they had to be interrogated twice. The final results were listed as four destroyed, five probables, and one damaged. More than 400 escorting Allied fighters failed to keep enemy fighters away from the bombers.

On October 9, the Eighth Air Force flew its first truly large-scale mission to Lille. The mission consisted of 108 heavy bombers, including two dozen Consolidated B-24 Liberators from the 93rd Bombardment Group on their inaugural mission. The B-17-equipped 306th Bombardment Group was also on its first mission. German opposition was fierce, as it was their first real effort against the bombers. The Luftwaffe ignored the British and American fighters and went straight for the bombers, shooting down three B-17s and one B-24. Four B-17s suffered heavy damage, while another 32 B-17s and 10 B-24s received slight damage.

Initial claims by the gunners were 56 destroyed, 26 probables, and 20 damaged, an impossible score since it would have accounted for 15 percent of the estimated Luftwaffe fighter strength in Western Europe. This number was subject to constant revision over the next several months and finally went in the books as 21 destroyed, 21 probables, and 15 damaged. These numbers were still too high since British intelligence believed that no more than 60 German fighters could have possibly intercepted the formation.

In October the Eighth Air Force lost much of its strength to the Mediterranean Theater. Two B-17 groups and nearly all of the fighters, as well as the two troop carrier groups and the Bostons of the 15th Bombardment Squadron, left to support the invasion of North Africa. The Eighth also lost its commander. When General Spaatz moved to Africa, Eaker took his place. In addition, three squadrons of B-24s from the 93rd also went to Africa for temporary duty. Two new B-17 groups and one of B-24s soon became operational to take up the slack left by the transfers.

The 329th Bomb Squadron from the 93rd BG remained in England to experiment with electronically guided bad weather harassment missions that the crews referred to as “moling.” Unfortunately, the first mission into German airspace was canceled when the B-24s broke out of the clouds into clear weather over the Ruhr! The crews had been instructed to attack only through the clouds to prevent the sensitive equipment from falling into German hands. The fact that American heavy bombers had penetrated German air space for the first time was kept secret.

During the fall and winter of 1942, the main effort of the Eighth was aimed at German submarine pens in France and the Occupied countries. On January 27, 1943, the first large-scale mission into Germany saw a mixed force of 91 heavy bombers, including a small formation of B-24s, go against Wilhelmshaven. The mission met with limited success due to clouds over the target, but the weather also hindered fighter opposition. Two B-24s and a B-17 were lost to fighters, but the bomber gunners claimed 22 enemy aircraft (actual German losses were seven).

Although the Eighth Air Force included a fighter command, operations in North Africa severely depleted U.S. fighter strength in England. For several weeks, the only American fighters still in England were P-38s being held in reserve to reinforce North Africa, and the Spitfires of the new 4th Fighter Group. In January 1943, the 56th Fighter Group arrived in England with Republic P-47 Thunderbolts.

Bomber losses had so far been low, causing the Eighth Air Force leadership to erroneously conclude that the heavy firepower on the bombers was sufficient to defend against fighter attack. When General Henry “Hap” Arnold ordered the transfer of the 78th Fighter Group’s P-38s to North Africa to replace losses, the group was left without airplanes. Both the 78th and the 4th Fighter Group were equipped with P-47s, but it was well into the spring of 1943 before VIII Fighter Command became active in the air war in Europe.

While the 93rd Bomb Group was in Africa, the 44th Bomb Group was left as the only Liberator outfit with the Eighth—except for the 329th Bomb Squadron—for several weeks. When it began combat operations, the 44th endured a number of unfortunate incidents that soon gained the group a reputation as a “hard luck” outfit. The group’s losses came in ones and twos and were as often due to accident as to combat. The heaviest losses occurred on a mission when the leading B-17s got lost and left the B-24s low on fuel (they had only enough fuel on board to complete the mission).

Several airplanes had to crash-land in English pastures. The incident led to the replacement of the group commander by Colonel Leon Johnson, but the losses continued. The 44th’s high losses led some people to begin complaining that the B-24 was inferior to the B-17, asserting that perhaps the B-24s should be withdrawn from the theater.

The Mission was a Failure in Spite of the Low-Level Attack, Which Should have Resulted in Accurate Bombing, as not a Single Bomb Hit the Target.

By mid-March the 93rd had returned from Africa, and on the 18th the two Liberator groups flew their first mission together. Because of their faster speed, the B-24s maintained their own formation within the larger bomber stream. With only two groups of Liberators, and with more and more B-17 groups arriving in England every month, General Eaker began assigning the B-24s to tasks other than daylight bombing. Both groups were understrength, and at one point the 44th had more airplanes than crews.

In late April Eaker selected the 93rd to train for night bombing, using the technology with which the 329th Bomb Squadron was experienced, but the experiment was short-lived. Within a couple of weeks, both the 93rd and 44th were pulled off combat operations altogether to train for a classified mission: a low-level attack on the oil fields at Ploesti, Romania. The 389th Bombardment Group joined them when it arrived in England, and all three groups set out for North Africa for a stint of temporary duty with the Ninth Air Force.

In May 1943, just as the VIII Bomber Command Liberators were taken off combat operations, the medium bombers of the 322nd Bombardment Group made their combat debut—with disastrous results. The 322nd was equipped with the twin-engine Martin B-26 Marauder, an airplane surrounded by controversy due to a high accident rate during ferry flights and in training. On May 14, the 322nd launched its first mission, a low-level raid against a power plant at Ijumuiden on the Dutch coast. The mission was a failure in spite of the low-level attack, which should have resulted in accurate bombing, as not a single bomb hit the target. Several airplanes were hit by flak, and one crew was forced to bail out.

Since the target was left undamaged, a second mission was scheduled for May 17. Half of the force of 11 B-26s was to hit the power plant again, while the other half struck another generating plant at Haarlem. Disaster was the order of the day—only one airplane returned from the raid, and its pilot had aborted before reaching the Dutch coast. The attacking formation got lost and blundered into the most heavily defended airspace in Holland.

Several airplanes were shot down, and two were lost in a midair collision. Every airplane engaged was lost, along with 62 airmen. As a consequence, the B-26s were taken off combat operations until new tactics could be developed. Under the new tactics, the medium bombers were restricted to attacks at medium altitudes from 12, 000 to 15,000 feet where they were out of range of the automatic antiaircraft weapons that were so deadly to low-altitude attackers. They were always escorted, usually by RAF Spitfires, and were very rarely intercepted.

General Eaker had hoped that the B-26s would serve as a diversion to draw German fighters away from the heavy bombers, but the concept was never fulfilled as the German fighters left the mediums alone and went after the heavies. The medium bombers left the Eighth and transferred to the Ninth Air Force for tactical operations when it arrived in England in the fall of 1943.

The summer and fall of 1943 is the period sometimes called “The Fall of Fortresses.” With the Liberators off in Africa, the B-17s were left alone in the skies over Germany and Western Europe. As heavy bomber strength increased, VIII Bomber Command began sending the B-17s on deeper and deeper penetration raids into Germany. With the longer missions came increased exposure to German fighters and antiaircraft fire, and aircraft losses began to mount. The April 17 mission to Bremen was an indicator of things to come: out of 115 B-17s from the 1st Bombardment Wing, 16 were shot down and 46 damaged.

During the early bombing campaign, the Luftwaffe had held its fighters back, leading some air officers to underestimate the true strength and effectiveness of the German fighter force. As Allied bombers began appearing in daylight over Germany in greater numbers, Luftwaffe fighter strength in Western Europe began increasing until it had almost doubled by mid-1943. As bomber losses mounted, the AAF leadership recognized the need for long-range escort fighters. In mid-1943 the only fighter with true long-range capabilities was the Lockheed P-38, but all of those had been sent to North Africa. They were replaced by Republic P-47s equipped with external fuel tanks, but even with the tanks the Thunderbolts were only able to provide escort for 175 miles into enemy airspace. While the P-38s had the range to go deep into Germany, there were none in England until late summer. When they did arrive, the twin-engine fighters were plagued with mechanical problems that temporarily limited their effectiveness.

After a two-week rest in early August, VIII Bomber Command scheduled its most ambitious mission yet: an attack on the aircraft factories at Regensburg, Germany, and Wiener-Neustadt, Austria. The original plan called for the B-17s to hit the targets, then go on to Africa, but since only a few airplanes had been equipped with long-range fuel tanks, a new plan was developed.

The three Eighth Air Force B-24 groups were still in Africa, recuperating from the effects of the maximum-effort, low-level attack on the Ploesti oil fields that had taken place on August 1. They would join the two Ninth Air Force Liberator groups in a raid on Wiener-Neustadt, while the B-17s struck Regensburg in a two-pronged attack that would split the German fighter defenses. The date was set for August 7, but bad weather over Europe kept the B-17s from making the trip and their mission was postponed.

On the 13th, the Liberators went against Wiener-Neustadt, one of the most heavily defended targets in Europe, without the benefit of the B-17s to split the German fighter defenses. Fortunately, the Germans were caught by surprise due to the long distance involved and losses were much lighter than expected.

Finally, on August 17, seven B-17 groups from the 4th Bombardment Wing took off from England on the first “shuttle bombing” mission of the war. After striking Regensberg, they were to continue to North Africa to refuel and rest their crews, then come back to England on another mission.

The 1st Bombardment Wing’s B-17s were assigned to attack the ball-bearing factories at Schweinfurt. Unfortunately, things did not work out as planned. The 1st Wing was delayed for several hours due to bad weather, then the P-47s that were supposed to escort the trailing sections of the Regensburg force failed to make the rendezvous, leaving the rearmost B-17s unescorted. When the escorts reached their fuel limit and turned back, Luftwaffe fighters came in for the kill and the crews learned that their Flying Fortresses were ambitiously named. The Fortresses were under constant attack for an hour and a half and 17 were shot down with scores damaged.

By the time they reached Africa, 24 B-17s were MIA, including several that ditched in the Mediterranean. The Schweinfurt force also met with vicious attacks and suffered even heavier losses. They fell under attack as soon as they came over land above the port city of Antwerp, Belgium. No fewer than 36 B-17s were shot down. All told, 60 Flying Fortresses and their crews were lost on August 17, and the heavy losses were not going to stop. The B-17 gunners were credited with 288 German fighters, but true German losses were only 25.