UN Tourism | Bringing the world closer

share this content

- Share this article on facebook

- Share this article on twitter

- Share this article on linkedin

Tourism’s Importance for Growth Highlighted in World Economic Outlook Report

- All Regions

- 10 Nov 2023

Tourism has again been identified as a key driver of economic recovery and growth in a new report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). With UNWTO data pointing to a return to 95% of pre-pandemic tourist numbers by the end of the year in the best case scenario, the IMF report outlines the positive impact the sector’s rapid recovery will have on certain economies worldwide.

According to the World Economic Outlook (WEO) Report , the global economy will grow an estimated 3.0% in 2023 and 2.9% in 2024. While this is higher than previous forecasts, it is nevertheless below the 3.5% rate of growth recorded in 2022, pointing to the continued impacts of the pandemic and Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and from the cost-of-living crisis.

Tourism key sector for growth

The WEO report analyses economic growth in every global region, connecting performance with key sectors, including tourism. Notably, those economies with "large travel and tourism sectors" show strong economic resilience and robust levels of economic activity. More specifically, countries where tourism represents a high percentage of GDP have recorded faster recovery from the impacts of the pandemic in comparison to economies where tourism is not a significant sector.

As the report Foreword notes: "Strong demand for services has supported service-oriented economies—including important tourism destinations such as France and Spain".

Looking Ahead

The latest outlook from the IMF comes on the back of UNWTO's most recent analysis of the prospects for tourism, at the global and regional levels. Pending the release of the November 2023 World Tourism Barometer , international tourism is on track to reach 80% to 95% of pre-pandemic levels in 2023. Prospects for September-December 2023 point to continued recovery, driven by the still pent-up demand and increased air connectivity particularly in Asia and the Pacific where recovery is still subdued.

Related links

- Download the News Release on PDF

- UNWTO World Tourism Barometer

- IMF World Economic Outlook

Category tags

Related content.

International Tourism to Reach Pre-Pandemic Levels in 2024

International Tourism to End 2023 Close to 90% of Pre-P...

International Tourism Swiftly Overcoming Pandemic Downturn

Tourism on Track for Full Recovery as New Data Shows St...

The Geography of Transport Systems

The spatial organization of transportation and mobility

3.1 – Transportation and Economic Development

Authors: dr. jean-paul rodrigue and dr. theo notteboom.

The development of transportation systems is embedded within the scale and context in which they take place, from the local to the global and from environmental, historical, technological, and economic perspectives.

1. The Economic Importance of Transportation

Development can be defined as improving the welfare of a society through appropriate social, political, and economic conditions. The expected outcomes are quantitative and qualitative improvements in human capital (e.g. income and education levels) as well as physical capital such as infrastructures (utilities, transport, telecommunications).

The development of transportation systems takes place in a socioeconomic context. While development policies and strategies focus on physical capital, recent years have seen a better balance by including human capital issues. Irrespective of the relative importance of physical versus human capital, development cannot occur without their respective interactions, as infrastructures cannot remain effective without proper management, operations, and maintenance. At the same time, economic activities cannot take place without an infrastructure base. The highly transactional and service-oriented functions of many transport activities underline the complex relationship between its physical and human capital needs. For instance, effective logistics rely on infrastructures and managerial expertise.

Because of its intensive use of infrastructures , the transport sector is an important component of the economy and a common tool used for development. This is even more so in a global economy where economic opportunities have been increasingly related to the mobility of people and freight, including information and communication technologies. A relation between the quantity and quality of transport infrastructure and the level of economic development is apparent. High-density transport infrastructure and highly connected networks are commonly associated with high levels of development. When transport systems are efficient, they provide economic and social opportunities and benefits that result in positive multiplier effects, such as better accessibility to markets, employment, and additional investments. When transport systems are deficient in terms of capacity or reliability, they can have an economic cost, such as reduced or missed opportunities and lower quality of life .

At the aggregate level, efficient transportation reduces costs in many economic sectors , while inefficient transportation increases these costs. Besides, the impacts of transportation are not always intended and can have unforeseen or unintended consequences . For instance, congestion is often an unintended consequence of providing users with free or low-cost transport infrastructure. However, congestion also indicates a growing economy where capacity and infrastructure have difficulties keeping up with the rising mobility demands. Transport carries an important social and environmental load, which cannot be neglected.

Assessing the economic importance of transportation requires the categorization of the types of impacts it conveys. These involve core (the physical characteristics of transportation), operational and geographical dimensions:

- Core . The most fundamental impacts of transportation-related to the physical capacity to convey passengers and goods and the associated costs to support this mobility. This involves setting routes enabling new or existing interactions between economic entities.

- Operational . Improvement in the time performance, notably in terms of reliability, as well as reduced loss or damage. This implies a better utilization level of existing transportation assets benefiting its users as passengers and freight are conveyed more rapidly and with fewer delays.

- Geographical . Access to a broader market base where economies of scale in production, distribution, and consumption can be improved. Increases in productivity from the access to a larger and more diverse base of inputs (raw materials, parts, energy, or labor) and broader markets for diverse outputs (intermediate and finished goods). Another important geographical impact concerns the influence of transport on the location of activities and its impacts on land values.

The economic importance of the transportation industry can thus be assessed from a macroeconomic and microeconomic perspective:

- At the macroeconomic level (the importance of transportation for a whole economy), transportation and related mobility are linked to a level of output, employment , and income within a national economy. In many developed economies, transportation accounts for between 6% and 12% of the GDP. Further, logistics costs can account for between 6% and 25% of the GDP. The value of all transportation assets, including infrastructures and vehicles, can easily account for half the GDP of an advanced economy.

- At the microeconomic level (the importance of transportation for specific parts of the economy), transportation is linked to producer, consumer, and distribution costs. The importance of specific transport activities and infrastructure can thus be assessed for each sector of the economy. Usually, higher income levels are associated with a greater share of transportation in consumption expenses. Transportation accounts for between 10% and 15% of household expenditures. In comparison, it accounts for around 4% of the costs of each unit of output in manufacturing, but this figure varies greatly according to sub-sectors.

The added value and employment effects of transport services usually extend beyond those generated by that activity; indirect effects are salient. For instance, transportation companies purchase some of their inputs (fuel, supplies, maintenance) from local suppliers. These inputs generate additional value-added and employment in the local economy. In turn, the suppliers purchase goods and services from other local firms. There are further rounds of local re-spending, which generate additional value-added and employment. Similarly, households that receive income from employment in transport activities spend some of their income on local goods and services. These purchases result in additional local jobs and added value, with some of the income from these additional jobs spent on local goods and services, thereby creating further jobs and income for local households. As a result of these successive rounds of re-spending in the framework of local purchases, the overall impact on the economy exceeds the initial round of output, income, and employment generated by passenger and freight transport activities. Thus, from a general standpoint, the economic impacts of transportation can be direct, indirect, and induced :

- Direct impacts. The outcome of improved capacity and efficiency where transport provides employment, added value, larger markets, as well as time and cost improvements. The overall demand of an economy is increasing.

- Indirect impacts. The outcome of improved accessibility and economies of scale. Indirect value-added and jobs result from local purchases by activities directly dependent upon transportation. Transport activities are responsible for a wide range of indirect value-added and employment effects through the linkages of transport with other economic sectors (e.g. office supply firms, equipment, and parts suppliers, maintenance and repair services, insurance companies, consulting, and other business services).

- Induced impacts. The outcome of the economic multiplier effects when the price of commodities, goods, or services drops and their variety increases. For instance, the steel industry requires the cost-efficient import of iron ore and coal for blast furnaces and export activities for finished products such as steel booms and coils. Manufacturers, retail outlets, and distribution centers handling imported containerized cargo rely on efficient transport and seaport operations.

Transportation links together the factors of production in a complex web of relationships between producers and consumers. The outcome is commonly a more efficient division of production by the exploitation of comparative geographical advantages, as well as the means to develop economies of scale and scope. The productivity of space, capital, and labor is thus enhanced with the efficiency of distribution and personal mobility. Economic growth is increasingly linked with transport developments, namely infrastructures, but also with managerial expertise, which is crucial for logistics. Thus, although transportation is an infrastructure-intensive activity, hard assets must be supported by an array of soft assets, namely labor, management, and information systems. Decisions about using and operating transportation systems must be made to optimize benefits and minimize costs and inconvenience.

2. Transportation and Economic Opportunities

Transportation developments that have taken place since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution have been linked to growing economic opportunities . At each development stage of the global economy , a particular transport technology has been developed or adapted with an array of impacts. Economic cycles are associated with a variety of innovations , including transportation, influencing economic opportunities for production, distribution, and consumption. Historically, six major waves of economic development where a specific transport technology created new economic, market, and social opportunities can be suggested:

- Seaports . The historical importance of seaports in trade has been enduring. This importance was reinforced by the early stages of European expansion from the 16th to the 18th centuries, commonly known as the Age of Exploration. Seaports supported the early development of international trade through colonial empires but were constrained by limited inland access. Later in the industrial revolution, many ports became important industrial platforms. With globalization and containerization, seaports increased their importance in supporting global trade and supply chains. The cargo handled by seaports reflects the economic complexity of their hinterlands. Simple economies are usually associated with bulk cargoes, while complex economies generate more containerized flows. Technological and commercial developments have incited a greater reliance on the oceans as an economic and circulation space.

- Rivers and canals . River trade has prevailed throughout history, and even canals were built where no significant altitude change existed since lock technology was rudimentary. The first stage of the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th and early 19th centuries was linked with the development of canal systems with locks in Western Europe and North America, mainly to transport heavy goods. This permitted the development of rudimentary and constrained inland distribution systems, many of which are still used today.

- Railways . The second stage of the industrial revolution in the 19th century was linked with the development and implementation of rail systems, enabling more flexible and high-capacity inland transportation systems. This opened substantial economic and social opportunities through the extraction of resources, the settlement of regions, and the growing mobility of freight and passengers.

- Roads . The 20th century saw the rapid development of comprehensive road transportation systems, such as national highway systems and automobile manufacturing, as a major economic sector. After the Second World War, individual transportation became widely available to mid-income social classes. This was associated with significant economic opportunities to service industrial and commercial markets with reliable door-to-door deliveries. The automobile also permitted new forms of social opportunities, particularly with suburbanization.

- Airways and information technologies . The second half of the 20th century saw the development of global air and telecommunication networks in conjunction with economic globalization. New organizational and managerial forms became possible, especially in the rapidly developing realm of logistics and supply chain management. Although maritime transportation is the physical linchpin of globalization, air transportation and IT support the accelerated mobility of passengers, specialized cargoes, and their associated information flows.

No single transport mode has been solely responsible for economic growth. Instead, modes have been linked with the economic functions they support and the geography in which growth was taking place. The first trade routes established a rudimentary system of distribution and transactions that would eventually be expanded by long-distance maritime shipping networks and the setting of the first multinational corporations managing these flows. Major flows of international migration that occurred since the 18th century were linked with the expansion of international and continental transport systems that radically shaped emerging economies such as North America and Australia. Transport played a catalytic role in these migrations, transforming the economic and social geography of many nations.

Transportation has been a tool of territorial control , particularly during the colonial era, where resource-based transport systems supported the extraction of commodities in the developing world and forwarded them to the industrializing nations of the time. The goal to capture resource and market opportunities was a strong impetus in the setting and structure of transport networks. More recently, port development, particularly container ports, has been of strategic interest as a tool of integration into the global economy, as the case of China illustrates. There is a direct relationship, or coordination, between foreign trade and container port volumes, so container port development is commonly seen as a tool to capture the opportunities brought by globalization. The growth of container shipping has systematically been 3 to 4 times the GDP growth rate, underlining a significant multiplier effect between economic growth and container trade. However, this multiplying effect has substantially receded since 2009, underlining the maturity of the diffusion of containerization and its dissociation from economic growth.

Due to demographic pressures and urbanization, developing economies are characterized by a mismatch between the limited supply and growing demand for transport infrastructure. While some regions benefit from the development of transport systems, others are often marginalized by conditions in which inadequate transportation plays a role. Transport by itself is not a sufficient condition for development. However, the lack of transport infrastructures can be a constraining factor in development. The lack of transportation infrastructures and regulatory impediments are jointly impacting economic development by conferring higher transport costs, but also delays rendering supply chain management unreliable. A poor transport service level can negatively affect the competitiveness of regions and their economic activities and thus impair the regional added value, economic opportunities, and employment. Tools and measures are being developed to assess and compare the performance of national transportation systems. For instance, in 2007, the World Bank published its first-ever report ranking nations according to their logistics performance based on the Logistics Performance Index . Logistic performance is commonly associated with economic opportunities.

3. Economic Returns of Transport Investments

A common expectation is that transport investments will generate economic returns, which should justify the initial capital commitment in the long run. Like most infrastructure projects, transportation infrastructure can generate a 5 to 20% annual return on the capital invested, with such figures often used to promote and justify investments. However, transport investments tend to have declining marginal returns ( diminishing returns ) . While initial infrastructure investments tend to have a high return since they provide an entirely new range of mobility options, the more the system is developed, the more likely additional investment would lower returns. The marginal returns can sometimes be close to zero or even negative. A common fallacy assumes that additional transport investments will have a similar multiplying effect than the initial investments had, which can lead to capital misallocation. The most common reasons for the declining marginal returns of transport investments are:

- High accumulation of existing infrastructure . Where there is a high level of accessibility and where transportation networks are already extensive, further investments usually result in marginal improvements. This means that the economic impacts of transport investments tend to be significant when infrastructures were previously lacking and tend to be marginal when an extensive network is already present. Additional investments can thus have a limited impact outside convenience.

- Economic changes . As economies develop, their function shifts from the primary (resource extraction) and secondary (manufacturing) sectors towards advanced manufacturing, distribution, and services. These sectors rely on different transport systems and capabilities. While an economy depending on manufacturing will rely on road, rail, and port infrastructures, a service economy is more oriented toward logistics and urban transportation efficiency. Transport infrastructure is important in all cases, but its relative importance in supporting the economy may shift.

- Clustering . Due to clustering and agglomeration, several locations develop advantages that cannot be readily reversed through improvements in accessibility. Transportation can be a factor of concentration and dispersion depending on the context and the level of development. Less accessible regions do not necessarily benefit from transport investments if they are embedded in a system of unequal relations.

Therefore, each transport development project must be considered independently and contextually. Since transport infrastructures are capital-intensive fixed assets, they are particularly vulnerable to misallocations and malinvestments . The standard assumption is that transportation investments tend to be more wealth-producing than wealth-consuming investments such as services. Still, several transportation investments can be wealth consuming if they merely provide conveniences, such as parking and sidewalks , or service a market size well below any possible economic return, with, for instance, projects labeled “bridges to nowhere”. In such a context, transport investment projects can be counterproductive by draining the resources of an economy instead of creating wealth and additional opportunities.

Since many transport infrastructures are provided through public funds, they can be pressured by special interest groups, which can result in poor economic returns, even if those projects are often sold to the public as strong catalysts for growth. Further, large transportation projects, such as public transit, can have inadequate cost control mechanisms, implying systematic budget overruns . Infrastructure projects in the United States are particularly prone to these engineered fallacies. Efficient and sustainable transport markets and systems play a key role in regional development, although the causality between transport and wealth generation is not always clear. To better document and monitor the economic returns of transport investments, a series of indicators can be used, such as transportation prices and productivity. Investment in transport infrastructures is thus seen as a regional development tool, particularly in developing countries.

4. Types of Transportation Impacts

The relationship between transportation and economic development is difficult to establish formally and has been debated for many years. In some circumstances, transport investments appear to catalyze economic growth, while in others, economic growth puts pressure on existing transport infrastructures and incites additional investments. Transport markets and related transport infrastructure networks are key drivers in promoting more balanced and sustainable development, particularly by improving accessibility and opportunities for less-developed regions or disadvantaged social groups. Initially, there are different impacts on transport providers (transport companies) and transport users . There are several layers of activity that transportation can valorize , from a suitable location that experiences the development of its accessibility through infrastructure investment to better usage of existing transport assets through more efficient management. This is further nuanced by the nature, scale, and scope of possible impacts:

- Timing of the development . The impacts of transportation can precede (lead), occur during (concomitantly), or take place after (lag) economic development. The lag, concomitant, and lead impacts make it difficult to separate the specific contributions of transport to development. Each case appears specific to a set of timing circumstances that are difficult to replicate elsewhere.

- Types of impacts . They vary considerably as the spectrum ranges from positive to negative. Usually, transportation investments promote economic development, while in rarer cases, they may hinder a region by draining its resources in unproductive transportation projects.

Cycles of economic development provide a revealing conceptual perspective on how transport systems evolve in time and space , including the timing and nature of transport’s impact on economic development. This perspective underlines that after a phase of introduction and growth, a transport system will eventually reach maturity through geographical and market saturation. There is also the risk of overinvestment, particularly when economic growth is credit driven, which can lead to significant misallocations of capital . The outcome is surplus capacity in infrastructures and modes, creating deflationary pressures that undermine profitability. In periods of recession that commonly follow periods of expansion, transportation activities may experiment with a setback in terms of lower demand and a scarcity of capital investment. Because of their characteristics, several transport activities are highly synchronized with the level of economic activity. For instance, if rail freight or maritime rates were to decline rapidly, this could indicate deteriorating economic conditions.

Transport, as a technology, typically follows a path of experimentation, introduction, adoption, diffusion, and, finally, obsolescence, each of which impacts the rate of economic development. The most significant benefits and productivity gains are realized in the early to mid-diffusion phases, while later phases are facing diminishing returns. Containerization is a relevant example of such a diffusion behavior as its productivity benefits were mostly derived in the 1990s and 2000s when economic globalization was accelerating.

If relying upon new technologies, transportation investments can go through what is called a “ hype phase ” with unrealistic expectations about their potential and benefits. Some projects are eventually abandoned as the technology is ineffective at addressing market or operational requirements or is too expensive for its benefits. Since transportation is capital intensive , operators tend to be cautious before committing to new technologies and the significant sunk costs they require. This is particularly the case where transportation is capital-intensive and has a long lifespan. In addition, transport modes and infrastructures are depreciating assets that continuously require maintenance and upgrades. Eventually, their useful lifespan is exceeded, and the vehicle must be retired or the infrastructure rebuilt. Thus, the amortization of transport investments must consider the lifespan of the concerned mode or infrastructure.

5. Transportation as an Economic Factor

Contemporary trends have underlined that economic development has become less dependent on relations with the environment (resources) and more dependent on relations across space . While resources remain the foundation of economic activities, the commodification of the economy has been linked with higher levels of material flows. Concomitantly, resources, capital, and even labor have shown increasing levels of mobility. This is particularly the case for multinational firms that can benefit from transport improvements in two significant markets:

- Commodity market . Improvements in the efficiency with which firms have access to raw materials and parts as well as to their respective customers. Thus, transportation expands opportunities to acquire and sell a variety of commodities necessary for industrial and manufacturing systems.

- Labor market . Improvements in access to labor and a reduction in access costs, mainly by improved commuting (local scale) or the use of lower-cost labor (global scale).

Transportation provides market accessibility by linking producers and consumers so that transactions can occur. A common fallacy in assessing the importance and impact of transportation on the economy is to focus only on transportation costs, which tend to be relatively low; in the range of 5 to 10% of the value of a good. Transportation is an economic factor of production of goods and services, implying that it is fundamental in their generation, even if it accounts for a small share of input costs. This means that irrespective of the cost, an activity cannot take place without the transportation factor and the mobility it provides. Thus, relatively small transport costs, capacity, and performance changes can substantially impact dependent economic activities.

An efficient transport system with modern infrastructures favors many economic changes, most of them positive. The major impacts of transport on economic factors can be categorized as follows:

- Geographic specialization . Improvements in transportation and communication favor a process of geographical specialization that increases productivity and spatial interactions. An economic entity tends to produce goods and services with the most appropriate combination of capital, labor, and raw materials. A region will thus tend to specialize in producing goods and services for which it has the greatest advantages (or the least disadvantages) compared to other regions as long as appropriate transport is available for trade. Through geographic specialization supported by efficient transportation, economic productivity is promoted. This process is known in economic theory as comparative advantages that have enabled the economic specialization of regions.

- Scale and scope of production . An efficient transport system offering cost, time, and reliability advantages enables goods to be transported over longer distances. This facilitates mass production through economies of scale because larger markets can be accessed. The concept of “just-in-time” in supply chain management has further expanded the productivity of production and distribution with benefits such as lower inventory levels and better responses to shifting market conditions. Thus, the more efficient transportation becomes, the larger the markets that can be serviced, and the larger the scale of production. This results in lower unit costs.

- Increased competition . When transport is efficient, the potential market for a given product (or service) increases, and so does competition. A wider array of goods and services becomes available to consumers through competition, reducing costs and promoting quality and innovation. Globalization has been associated with a competitive environment that spans the world and enables consumers to access a wider range of goods and services.

- Increased land value . Land adjacent or serviced by good transport services generally has greater value due to its utility. Consumers can have access to a wider range of services and retail goods. In contrast, residents can have better accessibility to employment, services, and social networks, all of which result in higher land value. Irrespective of if used or not, the accessibility conveyed by transportation impacts the land value. In some cases, due to the externalities they generate, transportation activities can lower land value, particularly for residential activities. Land located near airports and highways, near noise and pollution sources, will thus be impacted by corresponding diminishing land value.

Transport also contributes to economic development through job creation and derived economic activities . Accordingly, many direct (freighters, managers, shippers) and indirect (insurance, finance, packaging, handling, travel agencies, transit operators) employment are associated with transport. Producers and consumers make economic decisions on products, markets, costs, location, and prices, which are based on transport services, availability, costs, capacity, and reliability.

Related Topics

- 1.5 – Trans p ortation and Commercial Geography

- 3.3 – Transport Costs

- 3.4- The Provision and Demand of Transportation Services

- 1.3 – The Emergence of Mechanized Transportation Systems

- 1.4 – The Setting of Global Transportation Systems

- 2.2 – Transport and Spatial Organization

- B.16 – The Financing of Transportation Infrastructure

Bibliography

- Banister, D. and J. Berechman (2000) Transport Investment and Economic Development, London: Routledge.

- Banister, D. and J. Berechman (2001) “Transport investment and the promotion of economic growth”, Journal of Transport Geography, Vol. 9, pp. 209-218.

- Berry, B.J.L. (1991) Long-wave Rhythms in Economic Development and Political Behavior, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Button K. (2022) Transport Economics, 4th Edition, Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

- Button, K. and A. Reggiani (eds) (2011) Transportation and Economic Development Challenges, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Cidell, J. (2015). “The role of major infrastructure in subregional economic development: an empirical study of airports and cities”, Journal of Economic Geography, 15(6), 1125-1144.

- Docherty, I., and MacKinnon, D. (2013) “Transport and economic development”, in J-P Rodrigue, T. Notteboom, T. and J. Shaw (eds.) The Sage Handbook of Transport Studies. Sage, London, UK.

- European Conference of Ministers of Transport (2001) Transport and Economic Development, Round Table 119, Paris: OECD.

- Hargroves, K., and M. Smith (2005) The Natural Advantage of Nations: Business Opportunities, Innovation and Governance in the 21st Century. The Natural Edge Project. London: Earthscan.

- Henderson, J.V., Z. Shalizi and A.J. Venables (2000) Geography and Development, Journal of Economic Geography, Vol. 1, pp. 81-106.

- Hickman, R., M. Givoni, D. Bonilla & D. Banister (eds.) (2015) Handbook on Transport and Development, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Krugman, P. (1999) “The Role of Geography in Development”, International Regional Science Review, 22(2), pp. 142–161.

- Lakshmanan, T.R. (2011) “The broader economic consequences of transport infrastructure investments”, Journal of Transport Geography, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 1-12.

- MacKinnon, D., G. Pine and M. Gather (2008) “Transport and Economic Development”, in R. Knowles, J. Shaw and I. Docherty (eds.) Transport Geographies: Mobilities, Flows and Spaces, Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 10-28.

- Rodrigue, J-P (2017) “Transport and Development”, in D. Richardson, N. Castree, M.F. Goodchild, A. Kobayashi, W. Liu, and R.A. Marston (eds) The International Encyclopedia of Geography, New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Rodrigue, J-P (2016) “The Role of Transport and Communication Infrastructure in Realising Development Outcomes”, in J. Grugel and D. Hammett (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of International Development. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 595-614.

Share this:

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

The contribution of tourism mobility to tourism economic growth in China

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources

Affiliation School of Tourism, Hubei University, Wuhan, Hubei, China

Roles Software, Writing – original draft

Affiliation School of Urban and Regional Science, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation School of Business, Hubei University, Wuhan, Hubei, China

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology

Affiliation School of Tourism, Hainan University, Haikou, Hainan, China

- Jun Liu,

- Mengting Yue,

- Fan Yu,

- Published: October 27, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275605

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Mobility is the key factor in promoting tourism economic growth (TEG), and the transportation infrastructure has essential functions for maintaining an orderly flow of tourists. Based on the theory of fluid mechanics, we put forward the indicator of tourism mobility (TM). This study is the first to measure the level of TM in China and analyze the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of TM. Applying the Exploratory Spatial Data Analysis method, we analyze the global and local spatial correlation characteristics of TM. Moreover, we further estimate the contribution of TM to TEG by econometric models and the LMDI method. The results show that (1) the TM in China has maintained rapid growth for a long time. However, there are differences in the rate of growth in different regions. The TM in each region only showed a significant positive spatial correlation in 2016–2018. The space-time pattern is constantly changing over time. The local spatial autocorrelation results of TM are stable, and various agglomeration states are stably distributed in some provinces. (2) The regression results of the traditional panel data model and spatial panel data model both show that TM has a significant positive effect on TEG. Moreover, TM has a negative spatial spillover effect on neighboring regions. (3) The result from the decomposition of LMDI shows that the overall contribution of TM to TEG is 15.76%. This shows that improving TM is a crucial way to promote the economic growth of tourism.

Citation: Liu J, Yue M, Yu F, Tong Y (2022) The contribution of tourism mobility to tourism economic growth in China. PLoS ONE 17(10): e0275605. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275605

Editor: Hironori Kato, The University of Tokyo, JAPAN

Received: March 3, 2022; Accepted: September 20, 2022; Published: October 27, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Liu et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data on RAILWAY, HIGHWAY, ROAD1, ROAD2, ROAD, GDP, TERTIARY INDUSTRY, and POPULATION are from the Chinese Nation Bureau of Statistics ( https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01 ). The data on TOURISM REVENUE and VISITORS are from the CEIC database ( https://insights.ceicdata.com ). The data on TRAFFIC, TOURISM MOBILITY, RECPTION, INDUSTRY, and STRUCTURE were calculated by the authors. Please see the paper for details.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from National Social Science Foundation of China [grant number 17CJY051].

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

In recent years, the tourism industry has maintained rapid development. By 2019, the total number of global tourist trips exceeded 12.3 billion, an increase of 4.6% over the previous year. The total global tourism revenue was US$5.8 trillion, equivalent to 6.7% of global GDP (World Tourism Economy Trends Report [ 1 ]). Tourism has made important contributions to economic growth by increasing employment, improving infrastructure, and accumulating foreign exchange earnings for destinations [ 2 ]. Due to the impact of COVID-19, People’s travel is restricted. The total number of international tourists in 2021 decreased by 72% compared with 2019, and international tourism consumption dropped by nearly half compared with 2019 [ 3 ].

The above facts remind us that mobility has become an essential feature of tourism activities [ 4 , 5 ]. Tourists from origins to destinations result in a series of mobility of information, material, and capital. These mobilities have a great influence on tourist destinations [ 6 – 9 ]. If tourism mobility (TM) stagnates, tourist attractions, reception facilities and transportation facilities built for tourists will be idle. Tourism workers will lose their jobs and tourism economic growth (TEG) will also stagnate. Therefore, studying the impact of TM is necessary and important.

As one of the important tourist destinations in the world, China’s domestic tourism and inbound tourism are developing rapidly. In 2019, the total contribution of China’s tourism industry to GDP reached 10.94 trillion yuan, accounting for 11.05% of the total GDP, exceeding the proportion of international tourism in the global GDP. A total of 28.25 million people were directly employed in tourism, and 51.62 million people were indirectly employed in tourism. The total employment in tourism accounts for 10.31% of the total employed population in the country [ 10 ]. However, due to the impact of COVID-19, the development level of China’s tourism industry has not recovered to the level of 2019. In 2021, the total number of domestic tourists in China was 3.246 billion, which is only 54% of that in 2019, and directly leads to a total tourism revenue of 2.92 trillion yuan, which is only 51% of that in 2019. This shows that TM is more important to China’s tourism industry. Therefore, we decide to focus on the TM in this study and take China as the research sample.

The top priority of this study is to obtain the right measurement of TM. Transportation infrastructure is an important carrier for the exchange of factors in tourism. Existing studies have confirmed that transportation is a key factor in promoting TEG [ 11 – 13 ]. The establishment of the transportation system has an obvious effect on improving the accessibility of tourist destinations and promoting the inflow of the tourist population [ 14 ]. However, most existing studies only take tourist arrivals to characterize TM [ 15 – 21 ]. They ignore that the transportation infrastructure is also an important factor affecting the TEG. Therefore, this study redefines TM, which considers both transport infrastructure and tourist arrivals.

Another important purpose of this study is to explore the effect of TM on TEG. Existing literature analyzes the links between TM and international trade [ 22 , 23 ] or focuses on the relationship between economic growth [ 24 , 25 ]. However, less literature has focused on the relationship between TM and TEG. There are two possible reasons for the lack of attention. First, the positive and significant impact of the tourist arrivals and TEG no longer needs to be verified. It is common sense that the more tourists the destination receive, the higher the tourism income. Second, tourist arrivals, as a single indicator to measure TM, are able to affect the TEG. Our measurement of the TM concludes both transport infrastructure and tourist arrivals in this study. Therefore, we decide to explore the contribution of TM to the TEG based on the new measurement for TM.

We first use econometric methods to test whether there is a significant impact of TM on TEG. Considering the positive impact of transport infrastructure on China’s TEG [ 26 ], we hypothesize that TM has a positive impact on TEG. Previous studies have also shown that the spatial spillover effect of tourism may significantly affect the TEG [ 27 – 29 ]. Therefore, we further apply the spatial Durbin model to test the impact of TM on TEG.

Moreover, we also use the LMDI (Logarithmic Mean Divisia Index) method to further analyze the contribution of TM to TEG in more detail. The LMDI method is often used to study environmental issues such as energy consumption and carbon emissions [ 30 , 31 ]. In the field of tourism research, the LMDI method is mostly used to decompose tourism carbon emissions or energy consumption [ 32 , 33 ]. Few studies are using the LMDI to analyze TEG. Therefore, we further use the LMDI method to decompose TEG into five influencing factors including the tourism mobility effects ( TM ), the cumulative traffic effects ( Traffic ), the effects of the tertiary industry ( Industry ), the structural effects of the tourism industry ( Structure ) and the reception effects ( Reception ), and examine the contribution of TM to TEG.

Different from previous studies, this study makes two contributions to the literature. First, we introduce the related concepts of fluid mechanics to construct the indicator TM. We also consider the superposition effect of tourist arrivals and transportation infrastructure. This deepens the understanding of TM and promotes the integration of interdisciplinary knowledge. Second, we are the first to examine the impact of TM on TEG using econometric models and the LMDI method. This deepens the understanding of the mechanisms that influence TEG. The results of this study also provide a reference for tourism-related policy makers. Regions wishing to develop tourism can achieve TEG by expanding the size of the source market and promoting the construction of transportation infrastructure.

The rest of this study is organized as follows. Section 1 summarizes the relevant literature. Section 2 presents the theoretical framework, methods, and data. Section 3 introduces the spatiotemporal pattern and evolutionary trend of TM. Section 4 analyzes the contribution of TM to TEG from two different perspectives. Section 5 discusses and analyzes the research results. The last section concludes this study.

Literature review

As the core of tourism activities, TM refers to the mobility of tourists from the origin to the destination, and the stay of tourists in the region [ 34 ]. It is often associated with tourism demand and is measured by tourist arrivals [ 35 ]. Since the 1970s, many studies have paid attention to the influencing factors and the spatial structure of TM [ 15 , 16 ]. The existence of regional heterogeneity makes TM affected by many factors, such as infrastructure, income, GDP, and cultural distance [ 17 , 18 , 20 ]. Moreover, it also makes the spatial structure of TM different. Therefore, TM prediction has become one of the research hotspots [ 36 ]. A large body of research has focused on TM forecasting [ 21 ], including using a combination and integration of forecasts, using nonlinear methods for forecasting, and extending existing methods to better model the changing nature of tourism data [ 37 ]. The gravity model is an earlier method used to analyze international TM [ 38 ]. Due to its effectiveness in explaining TM [ 22 ], gravity models are often used to analyze international tourism service trade. Although the use of gravity models to predict bilateral TM still lacks a corresponding theoretical explanation mechanism, empirical evidence supports the applicability and robustness of gravity models for TM [ 23 ]. Existing research focuses on examining the movement patterns and spatial structure of international TM in destinations [ 39 ], such as the transfer of inbound TM within regions and the influencing factors of inbound TM within destinations [ 40 ]. There are still few studies on the overall spatial characteristics of TM within destination countries, and the only literature is mainly based on digital footprints or questionnaire data to analyze the spatial structure of TM [ 41 , 42 ].

Unlike the tourist arrivals indicator, which focuses more on the mobility of people, TM examines a wider range of content, including the mobility of people, the mobility of materials, the mobility of ideas (more intangible thoughts and fantasies), and the mobility of technology [ 8 ]. The early tourist movement focused more on tourist travel decisions and the resulting movement patterns. Lue et al. [ 43 ] summarized five travel patterns of tourists between destinations. Li et al. [ 44 ] revealed the spatial patterns of TM and tourism propensity in the Asia-Pacific region over the past 10 years. McKercher and Lau [ 45 ] took Hong Kong as an example and identified 78 movement patterns and 11 movement styles of TM within the destination. In recent years, with the help of technologies such as GPS, GIS, and RFID, the movement of tourists within scenic spots has attracted attention [ 46 ]. Research on visitor movement in national parks, theme parks, protected areas, etc. continues to increase [ 47 – 49 ], and explore the influencing factors of visitor movement [ 50 ], broadening the microscale visitor mobility research content. TM also has economic, social, and cultural impacts on destinations through the movement of tourists. Numerous empirical studies have shown that tourist arrivals have a positive impact on economic growth [ 51 ]. Tourism is an important driver of economic growth [ 52 ]. However, some studies have shown that tourist arrivals do not directly lead to economic growth, but promote TEG through regional economic development [ 53 – 55 ]. The mobility of tourism will also bring about changes in destination transportation facilities. Transportation is not only an important carrier of TM but also an important part of tourists’ travel experience [ 8 ]. It also has a positive impact on destination company value together with TM [ 26 ].

There are many theoretical discussions and empirical studies on the factors influencing TEG. From the perspective of suppliers, resource endowment [ 56 – 58 ] and environmental quality [ 59 – 62 ] are the fundamental factors determining tourism development. Simultaneously, as a typical service industry, human capital and physical capital in the tourism industry [ 63 , 64 ] and service level [ 65 ] will impact tourism economic efficiency. From the perspective of demanders, the rise of per capita income and consumption upgrading continue to drive the transformation in the tourism industry [ 66 ], which in turn leads to an increasing scale of market demand [ 67 ], which provides the possibility of increasing the foreign exchange earnings, local capital accumulation, and consumption spillovers. From the perspective of supporters, scholars have verified the significant effects of factors on TEG, including the transportation facilities and accessibility [ 68 – 71 ], the basis of the economy and marketization [ 72 ], industrial structure [ 73 ], public policy [ 74 – 76 ], and technological progress [ 77 ].

In summary, the research on TM has paid attention to its impact on the regional economy, but they both ignored the role of TM on TEG. Studies of TEG based on static factors have primarily relied on econometric models [ 78 ]. Although the spatial spillover effects of influencing factors have gradually gained attention, its depth is limited and fails to explore the impact of TM and other related factors on the TEG. TM is becoming central to tourism activities and understanding the capital mobility of tourism will have implications for tourism development under the new mobility paradigm [ 79 ]. This study proposes the concept of TM based on the theory of fluid mechanics, explores its impact on TEG, and analyzes the contribution of each influencing factor to TEG.

Theoretical framework, research methods, and data sources

Theoretical framework.

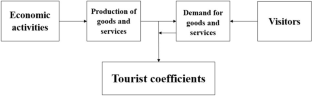

Traditionally, tourism research considers the tourism system as tourist sources, tourist destinations, and tourist corridors (transportation systems) [ 80 , 81 ]. Under the new mobility paradigm, this study regards the spatial transfer of tourists from the source to the destination as a mobility process. Tourist mobility is the fundamental reason for the existence of tourism. If tourists stop flowing, tourism will cease to exist.

It is known that the fluid will be affected by a variety of factors, such as viscosity, density, resistance coefficient, and altitude. As shown in Fig 1 , the total mobility of tourists from a tourist origin to a tourist destination is the number of tourists (Q). The spatial transfer of tourists, on the other hand, requires the use of transportation infrastructure as well as means of delivery. As an essential vehicle to support tourism development, transportation infrastructure directly reflects regional accessibility and relevance and is a crucial factor influencing TM [ 82 – 84 ], and its construction level has different effects on TEG in different regions [ 11 , 85 – 87 ]. According to the equations in fluid mechanics, the average velocity is equal to the flow rate ratio to the cross-sectional area. It can be deduced that TM = Q/TL. TM is determined by the number of tourists (Q) and the length of transportation infrastructure (TL). According to the definition, this indicator considers both tourist arrivals and flow rate, and its significance lies in its ability to characterize the mobility of tourism factors relying on tourists and physical transportation. This paper also connects the factor decomposition method to determine the importance of TM to TEG and presents theoretical implications for identifying essential factors to enhance tourism efficiency and stimulate tourism industry development.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275605.g001

Research methods

Measurement of tourism mobility..

Exploratory spatial data analysis.

It is generally believed that tourism has a spatial spillover effect and spatial correlation [ 28 ]. Therefore, we use Exploratory Spatial Data Analysis (ESDA) to detect spatial correlation among the variables. ESDA is used to analyze spatial characteristics through global and local spatial autocorrelation measurements [ 42 , 89 ].

The global Moran’s I is an indicator of whether factors are spatially correlated and its value ranges from -1 to 1. When 0<I≤1, it indicates a positive spatial correlation; when -1≤I <0, it indicates a negative spatial correlation; when I = 0, there is no spatial relationship. The equation is as in ( 2 ).

With a Z statistical test as in Formula ( 4 ), the cluster and outlier analyses can identify H_H (High_High) clusters, L_L (Low_Low) clusters, L_H (low value surrounded by high values) clusters, and H_L (high value surrounded by low values) clusters at a 95% confidence level.

Econometric model.

The econometric model, including tourism economic growth (TEG), tourism mobility (TM), physical capital in the tourism industry (TP), and human capital in the tourism industry (TH), is constructed according to economic growth theory without considering spatial spillover effects. Besides, since the measurement of TM only considers land transportation infrastructure data, the passenger traffic by the airport (TA) is introduced in the model to characterize the air capacity. Eq ( 5 ) represents the econometric model (TEG it ) in province i and year t, where α is the constant term, β is the parameter to be estimated, μ i denotes the spatial effect, and ε it denotes the random error term.

However, the spatial correlation of TEG will lead to biased parameter estimates of traditional econometric models. If the test results of global Moran’s I indicate that TEG is significantly spatially correlated, a spatial econometric model should be introduced to solve the bias-variance problem. The spatial Durbin model ( Eq 6 ) is developed according to Eq 5 . The spatial weight matrix used in the spatial Durbin model is an adjacency matrix. y it represents the TEG in province i and year t; x it represents the TM, TP, TH, and TA in province i and year t; and W ij y jt and W ij x jt are the TEG and lagged terms of each influencing factor, respectively. ρ and φ are spatial lagging coefficients, and v t denotes the time effect.

LMDI decomposition.

The LMDI decomposition method is widely used because it can effectively solve the residual problem in the decomposition and zero and negative values in the data. LMDI In this study, TEG is decomposed according to Eq ( 7 ). The influencing factors of TEG are decomposed into tourism mobility effects ( TE ), cumulative traffic effects ( Traffic ), effects of the tertiary industry ( Industry ), structural effects of the tourism industry ( Structure ), and reception effects ( Reception ). The equations are shown in ( 8 ) to ( 11 ). Traffic indicates the weighted road length; GDP (service) intimates the value added of the tertiary industry; Population represents the population in each province, and Visitors is the number of tourists. Introducing the log-average function L(x,y) defined in Eq ( 12 ). Eq ( 7 ) is decomposed into Eq ( 13 ) by LMDI, where ΔTEG denotes the amount of change in TEG from initial time 0 to period t, and ΔTM、ΔT、ΔI、ΔS、ΔW represent the contribution of each influencing factor to TEG. The equations are shown in ( 14 ) to ( 18 ).

Data sources

The study area is 31 provinces of China (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan), which is divided into seven regions according to the geographical divisions of China. The provinces included in each region are listed in supporting information. Since data availability varies widely across regions, the research period of TM and LMDI decomposition is from 2000 to 2018. As the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS) started to collect the employment data of private enterprises and individuals by sector in 2004 and the data for 2018 has not been updated yet, the research period of the spatial econometric model only covers the period from 2004 to 2017.

The data sources involved in the paper are as follows: the transportation infrastructure data come from the China Statistical Yearbook; the number of tourists is obtained from the Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development. Air passenger traffic data is collected from Civil Aviation Airport Production Statistics Bulletin. We employ the social fixed asset investment in transportation, storage, and postal services, wholesale and retail trade, accommodation and catering, and culture, sports, and entertainment as proxies for physical capital in the tourism industry (TP). This is because various aspects influence tourism development. Considering that only direct tourism investment does not reflect the total investment in tourism by society, we choose the four industries closely related to tourism development as physical capital in the tourism industry.

In this paper, private and individual employees in the transport, storage, and postal industry, wholesale and retail trade, and accommodation and catering industries are used to represent the human capital in the tourism industry (TH). The main reason for this is that, on the one hand, most studies only consider the number of employees in travel agencies, scenic spots, and star hotels, which differs significantly from the actual number of direct and indirect employees in tourism. On the other hand, since private enterprises and individual employment solve more than 80% of the urban employment problem, the number of private enterprises and individual employment in the three industries related to the tourism industry is chosen to represent the human capital. All the above data are collected from the NBS ( http://data.stats.gov.cn ). In the LMDI decomposition, the value added of the tertiary industry and the population in each province come from the China Statistical Yearbook.

Analysis of tourism mobility measurement results

Spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of tourism mobility.

Limited by space, Table 1 only shows the results of TM over five years. During the study period, TM increased from 56~12745 p visitors /km to 382~18865 p visitors /km, with an average annual growth rate between 2.20% and 13.46%. According to the average value of TM ( Fig 2 ), the study areas are divided into the following three types.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275605.g002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275605.t001

- “Leading Area”, including East China and North China, ranked first and second in all regions. Their TM increased from 2679.39 and 1884.34 p visitors/km in 2000 to 5859.93 and 5209.94 p visitors/km in 2018. However, their annual average growth rates were 5.07% and 6.43%, respectively, ranking first and second from the bottom in all regions. East China is located on the coast, relying on superior natural conditions and an economic foundation, and its regional transportation system is relatively complete. Therefore, it has formed many advantageous tourist resource gathering areas and has become the main tourist destination of inbound tourists in China, and its mobility has long ranked first in the country. As a political and economic center, Beijing has become a tourist attraction for domestic and inbound tourism with a large number of historical and cultural tourism resources. It also drives the joint development of the tourism industry in North China with the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration as the core, making North China the second largest core area of TM after East China.

- “Stable Area”, including South China, Southwest China, Central China, and Northeast China, ranked third to sixth in all regions. Their TM increased from 903.57p visitors/km, 695.15p visitors/km, 632.06p visitors/km, 493.33 p visitors/km in 2000 to 2626.11p visitors/km, 2754.97p visitors/km, 2857.88p visitors/km, 2244.68 p visitors/km in 2018. The average annual growth rates were 6.58%, 8.81%, 9.06%, and 9.38%, respectively. TM in South China grew rapidly during 2005~2015, while it has gradually slowed down in recent years. This is mainly due to the construction of the early transportation system in South China, which increased tourist mobility. After the basic construction of facilities, the incremental tourist inflows decreased, and the overall growth remained stable. Central China has become one of the core transportation hubs under its location and has driven regional tourism development, becoming a central province in the second echelon of TM. Due to geographical restrictions, Northeast and Southwest China are less connected to the transportation network than coastal areas, resulting in relatively low levels of TM. Northeast China focuses on the development of heavy industry but pays little attention to the tertiary industry, and tourism infrastructure construction and resource development are relatively weak, which leads to low TM. There are many mountains in Southwest China, and its early traffic development level lags. With the opening of the Chengdu-Chongqing high-speed railway and Chengdu-Guizhou high-speed railway, and the development of the air transportation industry, the land and air transportation layout in Southwest China is becoming increasingly mature. Southwest China actively developed its resources, and the tourist inflow increased from 145 million (2000) to 2.994 billion (2018), with an average value of TM catching up with that of southern China during 2016~2018.

- “Potential Area”, including Northwest China, ranks last in terms of average tourist mobility. Its TM increased from 282.01 p visitors/km in 2000 to 1427.58 p visitors/km in 2018, but its average annual growth rate was 10.01%, ranking first among all regions. As less developed region, Northwest China has a poor foundation in economic development and openness to the outside world, and TM has long been at the bottom of the list. Although TM in Northwest China has long been at the bottom of the list, its mobility growth rate leads other regions as tourism infrastructure construction and resource development levels have improved under the active promotion of Western Development policies, the Five-Year Plan, and the Territorial Tourism Strategy.

To more intuitively observe the temporal and spatial change characteristics of TM during the study period, we apply the method of natural breaks to classify the 31 provinces. Natural breaks classes are based on natural groupings inherent in the data. Class breaks are identified that best group similar values and maximize the differences between classes. The features are divided into classes whose boundaries are set where there are relatively big differences in the data values. The natural breaks classification method is a data classification method designed to determine the best arrangement of values into different classes. This is done by seeking to minimize each class’s average deviation from the class mean while maximizing each class’s deviation from the means of the other groups [ 92 ]. We divided the 31 provinces into five categories, highest-value area, higher-value area, medium-value area, lower-value area, and lowest-value area, according to the TM in 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2018. As shown in Fig 3 , (1) Shanghai and Beijing have long been in the highest-value area and higher-value area of TM. Tibet, Qinghai, Ningxia, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, Gansu, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Hubei, and Hainan have long been in the lowest-value and lower-value areas. (2) Over time, the number of provinces in the highest-value area and the higher-value area increased significantly, from 2 provinces in 2000 to 12 provinces in 2018. The number of provinces in the lowest-value area and lower-value area significantly decreased, from 26 provinces in 2000 to 12 provinces in 2018; the number of provinces in the medium-value area fluctuated randomly, with the fewest 3 in 2000 and the most 13 in 2015. (3) Except for Shanxi, Northwest China has been in the lowest-value area and the lower-value area for a long time; The TM values in Southwest China have changed greatly. Chongqing and Guizhou have jumped from the lower-value area to the higher-value area, and Yunnan has jumped from the low-value area to the medium-value area. Tibet is relatively stable and has been in the lowest-value area for a long time; South China is relatively stable, but the average value TM in Guangxi has changed greatly, jumping from the lower-value area to the higher-value area; The average TM in Central China has been in the low-value area for a long time. Central China is also relatively stable, and its average TM has long been located in the lower-value area and the medium-value area. Except for Shanghai, which has always been in the highest-value area, the initial value of TM in other provinces in East China has jumped upward. In the Northeast, Liaoning’s TM has always been in a leading position, and it has gradually transitioned from a lower-value area to a higher-value area. However, Jilin and Heilongjiang have always been in the lowest-value area and the lower-value area, respectively. Changes in TM in North China are diverse. Beijing has long been located in the highest-value area and higher value area. Inner Mongolia has been in the lowest-value area for a long time. Hebei is in the lower-value area most of the time. Tianjin and Shanxi changed greatly and finally jumped to the highest-value area and the higher-value area, respectively.

a. 2000, b. 2005, c. 2010, d. 2015, e. 2018.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275605.g003

We use the standard deviation ellipse to identify the direction of TM in each province. As shown in Fig 3 , the lengths of the minor semiaxis and major semiaxis of the ellipse increased significantly. The growth of the short semiaxis reveals that the degree of dispersion of TM in China’s provinces is gradually increasing. This result is consistent with the previous analysis conclusions that TM in some provinces shows a more obvious transition trend, which makes the overall dispersion of TM increase.

Spatial correlation characteristics of tourism mobility

Global spatial autocorrelation of tourism mobility..

We use ArcGIS 10.8 to calculate the global Moran’s I of TM for 2000–2018, and the results are shown in the table below ( Table 2 ). The global Moran’s I values from 2000 to 2018 were all positive, and the results from 2000 to 2015 were not significant, and the results from 2016 to 2018 were all significant at the 90% level. TM presents a significant positive spatial correlation. This shows that provinces with high TM in China have relatively high TM in their surrounding areas. From the overall trend, the spatial correlation degree of China’s TM has gradually increased, but its value has not exceeded 0.1, indicating that the spatial agglomeration effect of China’s TM is still weak.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275605.t002

Local spatial autocorrelation cluster of tourism mobility.

The global Moran’s I cannot reflect the spatial correlation exhibited by local regions or individual provinces. We further use ArcGIS 10.8 to draw the LISA cluster diagram for 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2018 ( Fig 4 ). The research samples are divided into four types of agglomeration: provinces with high TM are surrounded by provinces with high TM (H-H agglomeration), provinces with high TM are surrounded by provinces with low TM (H-L agglomeration), provinces with low TM are surrounded by provinces with high TM (L-H agglomeration), and provinces with low TM are surrounded by provinces with low TM (L-L agglomeration).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275605.g004

The results show that (1) provinces with H-H aggregation of TM in different periods are relatively stable; L-L and L-H aggregation types are stable but mixed with changes; The H-L aggregation type does not appear, which indicates that there is no "darkness under the light" area for China’s provincial TM. Provinces with high TM can improve the TM of weekly provinces to a certain extent. (2) The H-H agglomeration is mainly concentrated in Jiangsu and Zhejiang. These regions are economically developed and have high per capita discretionary income. Moreover, the tourism infrastructure in these regions is more complete than that in other regions, and the tourist reception scale is also higher, so their TM shows a high local concentration. (3) The L-L agglomeration types are mainly distributed in geographically remote areas such as Qinghai, Tibet, Gansu, and Xinjiang in inland China. Moreover, Xinjiang and Gansu temporarily withdraw from the L-L agglomeration area. The main reason for this pattern is that the transportation infrastructure in the areas above mentioned is relatively underdeveloped. The "space-time compression effect" brought about by the rapid development of China’s transportation is not significant. Furthermore, due to the distance from the main tourist source markets, although the TM shows a high growth rate, it is still in the lowest-value area and the lower-value area for a long time. (4) L-H agglomeration is mainly transferred in Anhui, Shandong and Hebei, and these provinces are located in the “Leading Area”. The average value of TM in the surrounding provinces is generally high, forming a "collapse area" for TM.

The impact of tourism mobility on tourism economic growth

Spatial autocorrelation of tourism economic growth.

In this study, a Monte Carlo simulation was selected to analyze the spatial autocorrelation of TEG ( Table 3 ). Moran’s I was positive from 2000 to 2018. They passed the significance test of different degrees except in 2006, indicating that TEG has a significant positive spatial correlation. Therefore, a spatial econometric model should be selected to analyze the influencing factors of TEG.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275605.t003

Traditional panel data model

The unit root test using LLC and Fisher showed no unit root for TEG, TM, TH, TP, and TA ( Table 4 ). The Kao test, Pedroni test, and Westerlund test were used to determine the cointegration relationship between the variables. The test results showed a cointegration relationship, indicating that the data can be used for modeling.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275605.t004

In terms of the regression model, the BP Lagrangian test results show the rejection of the mixed model. Wooldridge and Wald’s test indicates the presence of heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation in the data. The presence of heteroskedasticity would lead to an increase in the variance of the model parameters and invalidate the Hausman test results. If the regression is still performed using the method without heteroskedasticity, it will undermine the validity of the t-test and F-test, while autocorrelation will exaggerate the significance of the parameters. Therefore, the panel model is selected by the over-identification test (Hausman test result is significant), and the result shows that the Sargan-Hansen statistic is 14.32 and significant, so fixed effect modeling should be selected.

To further address heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation, this study uses Driscoll-Kraay standard errors for regression. The results in Table 5 show a significant positive effect of each variable on TEG, where each 1% increase in TM will promote 0.62% growth in the tourism economy.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275605.t005

Spatial panel data model

In this paper, the specific form of the spatial panel data model was determined by LM-LAG and LM-ERROR tests. If the result of LM-lag is significant and LM-error is not significant, then SLM should be used, and vice versa, SEM should be used. If LM-lag and LM-error statistics are significant, it indicates that the spatial correlation of the lag term and the spatial correlation of the residuals should be considered. In this case, the SDM can be used to set the model. Subsequently, this study determined whether the SDM model would degenerate into SLM or SEM by Wald and LR tests, and the results showed that all passed the significance test. Meanwhile, the test results of LM-lag, LM-error, LM-lag (robust), and LM-error (robust) were significant ( Table 6 ), indicating that the model set using SDM has a certain rationality.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275605.t006

We selected the regression model through the Hausman test, and the result showed that the value was 19.31, and the corresponding probability value was 0.007, which indicated that the null hypothesis of random effect was rejected. Therefore, the fixed-effect model was selected for regression analysis. Table 7 shows the estimation results, where ρ rejects the original hypothesis only in the Spatio-temporal fixed-effects model. Therefore, this paper provides a specific analysis of the Spatio-temporal fixed-effects model. The regression results indicate that TM shows a significant positive effect on regional TEG.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275605.t007

According to the results and spatial effect decomposition ( Table 8 ), ρ is -0.559, indicating that the growth of the tourism economy in neighboring provinces will have a negative impact on the local area. The direct effect of TM is significant, indicating that TM will promote TEG. However, the indirect effect results show that the increase in TM in neighboring provinces will have a negative impact on the local TEG.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275605.t008

Decomposition of the influencing factors by LMDI.

We decompose the influencing factors and analyze their contribution trend. Table 9 shows the specific contribution of each influencing factor to the TEG in the seven regions.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275605.t009

ΔT increases from 15.41% in 2000~2005 to 22.55% (2005~2010), and then decreases to 9.35% in 2010~2015 and 7.01% in 2015~2018. Overall, the ΔT showed a downward trend, but it is still an important factor in promoting TEG. The average contribution rate of the ΔT from 2000 to 2018 reached 14.82%.

ΔI maintained an overall downward trend during 2000 ~2018. It gradually decreased from 31.42% (2000~2005) to 22.94% (2015~2018). In contrast, the added-value of tertiary industry per capita increases from 3653 yuan to 34,969 yuan in the same period, indicating that the contribution of tertiary industry to TEG continues to decline, and tourism is gradually decoupled from the development of the tertiary industry.

ΔS maintained an overall upward trend during 2000~2018, from 7.09% (2000~2005) to 14.67% (2015~2018). The overall contribution rate was 11.50%, indicating that increasing the proportion of the tertiary industry in tourism can promote TEG.

ΔR shows a negative effect on TEG, and the degree of adverse effect increases slowly from 26.22% to 27.67%. The overall contribution rate was 28.67%. Reception is defined as the ratio of the resident population to the number of tourists. This shows that on the premise that the permanent resident population remains basically unchanged, the contribution to TEG can be effectively increased by expanding the scale of tourists.

Regression results of tourism mobility on tourism economic growth

This study briefly analyzes the regression results of the traditional and spatial panel data model. However, the spatial autocorrelation test results of TEG show an overall trend of fluctuating and increasing spatial correlation, especially with 2009 as the abrupt change point and a significant increase in the degree of agglomeration. Therefore, the article discusses the results of the spatial panel data model in detail, and the primary purpose of analyzing the traditional panel data model is to compare it with the spatial econometric results.

The regression results of the spatial econometric model show that both TM and TA have a significant positive impact on TEG, which verifies the hypothesis we proposed above. This result is also consistent with Wu et al. [ 93 ] and Perboli et al. [ 94 ]. In contrast, TP and TH have no significant impact on TEG. However, previous studies have also shown that the spatial spillover effect of tourism can significantly affect the TEG [ 27 – 29 ]. Therefore, the impact of TP and TH on TEG remains to be further confirmed.

According to the decomposition results, TM will promote the growth of the local tourism economy but will have a negative impact on neighboring provinces, which indicates a more obvious competition in tourism development among provinces. The increase in mobility in a particular place under a given number of tourists will lead to a diversion of tourists, which will have a negative impact on neighboring regions. Therefore, the tourism industry should also pay attention to the competitive situation in the surrounding areas. The development of tourism focus not only on improving local tourism mobility but also on neighboring areas. Both TP and TH manifest substantial spatial spillover effects. The increase in TP and TH in neighboring areas will produce positive effects, making local areas attach importance to the development of tourism resources and enhancing tourism attraction. TA has a significant positive contribution to TEG, which is consistent with the conclusion of Yang and Wong [ 27 ]. However, the spatial spillover effects of TA on TEG are not significant, which may be related to the fact that air traffic does not depend on adjacent spaces.

Analysis of influencing factors’ contribution rate to tourism economic growth

Tm and δtm..