(916)448-5290

- Mission Vision Values

- Our Origin Story

- PTHV National Network

- Community Schools

- COVID-19 Recovery

- Parent Leadership Development

- Racial Equity

- Restorative Practices – Positive Behavior Supports

- Teaching and Learning

- Social Emotional Learning

- Teacher Preparation and Professional Learning

- National Leadership

- Board of Directors

- The Five Non-Negotiables

- Research & Evaluation

- Information Sessions

- Introduction to Home Visit Training

- Home Visit Hybrid Training

Accredited Partnerships

Implementation support.

- Service Consultation Request

- Educator Resources

- Education Leader Resources

- Resources for Building Support

- PTHV in the News

- 2023 Annual Home Visit Tallies

- Events & Webinars

- PTHV 25th Anniversary

National PTHV Week

Of the many factors that shape student outcomes, authentic family engagement remains a critical piece of the puzzle. But school systems struggle to do it well, and mindsets toward family-school engagement reflect persistent and harmful biases. Our work is to equip educators with the training needed to develop trusting relationships with families in service of student success and school improvement.

- Visits are voluntary.

- Educators are trained and compensated.

- We share hopes and dreams.

- We do not target students.

- Educators go in pairs and reflect.

Through uniquely tailored sessions, teachers emerge with increased understanding of families and respect for their role as children’s first educators. They learn how to build trust with families, and they increase their capacity to better engage students in the classroom. PTHV trainings are interactive, dynamic, and essential to the start of an evidence-based home visit practice.

Growing & Scaling

From eight schools to an international network.

Parent Teacher Home Visits has grown from a local effort at eight schools in Sacramento in 1998 to a national network of hundreds of school sites in 29 states; Washington, D.C.; and Saskatchewan. And we continue to grow.

- 393 Sites in 2023

- 29 States +DC +SK

- 2,746 Educators Trained

Home Visits in 2022-23

Our Training Options

Home Visit Training Options

Training options.

We offer a number of professional learning opportunities to introduce, deepen, and refresh your school's home visit practice.

Put PTHV into Practice

Learn more about our coaching, consultation and professional learning for leaders looking to launch, grow, and sustain a thriving home visit practice.

Training of Trainers

Get in touch to learn more about eligibility requirements and details about how to start a local PTHV training team.

A Video Introduction to Parent Teacher Home Visits

Building Trust & Community

At the center of a first Parent Teacher Home Visit is a conversation about hopes and dreams. That's where deep trust begins.

The core practices that undergird our model are supported by research. And evaluations show that students do better academically and socioemotionally when they attend schools with a Parent Teacher Home Visits practice.

Frequently Asked Questions

About home visits.

What's involved in training?

We offer multiple types of sessions to suit districts’ needs. Each covers the model we use, the research that supports it, a step-by-step guide to implementing an effective home visit practice, and more.

How do you know it works?

We’ve conducted rigorous evaluations of our model with world-class research institutions. Each has demonstrated the effectiveness of the PTHV Model. See our research page for more.

Is it safe?

Remember home visits are always voluntary. Teachers go in pairs, and visits are set up in advance. We delve more deeply into safety and other potential barriers in our introductory training session.

- Bring Home Visits to Your School Community

Testimonials

What parents and teachers say about home visits.

It really is a transcendent experience, both for the teacher and family. We are in a relationship-building profession, and I have never come across a better way in my 30 years of teaching to build those relationships.

- Chris Nixon

In every instance, both the adults and the students have expressed how grateful they were to have this outreach from the school. Many have also shared that they feel much more comfortable with coming to school after meeting with us.

- Karen Platt

After such a difficult year, having the opportunity to connect with families was what was missing for me all year. Talking with parents about what their hopes and dreams are for their child and students sharing what they hope for themselves was incredibly inspiring for me and reminded me why I love doing what I do.

- Ely Corona

PTHVP honors the commitment, love, and support that educators, families, and community members have for the young people in our public schools. There are few organizations that make such a difference in the lives of students, their families, and educators.

- Andrea Prejean

It has been eye-opening to get to know students in a way that I may not ever be able to during the school year. Talking to and learning about students and their families will help me connect with students in a way I may not have been able to without these Bridge Visits.

- Tina Nixon

I did not know how much I truly needed to be more a part of the Bridge Visit program than I was. I just keep preaching to others how much of a difference it has made in my own work life and perspective let alone the kids and families. I have all of my fingers and toes crossed that everyone sees the value of Bridge Visits and continues.

- Jennifer Calton

Virtual Bridge Visits gave us the opportunity to chat with my daughter's teachers and get to know them a little better. Being in a virtual world, you're lost, so I had no connection with her teachers... I feel like having the visit and the follow-up visit are beneficial so that everyone is on the same page to help her learn.

- Cold Springs Elementary Parent

Home visits are something you get to do, not have to do.

- Gretchen Viglione

In every single instance, both the adults and the students have expressed how grateful they were to have this outreach from the school. Many have also shared that both they and their children feel much more comfortable with coming to school after meeting with us.

Meredith Howe

Home visits saved my life as a teacher.

Subscribe for Updates

Subscribe to Our

From the Blog

News & articles.

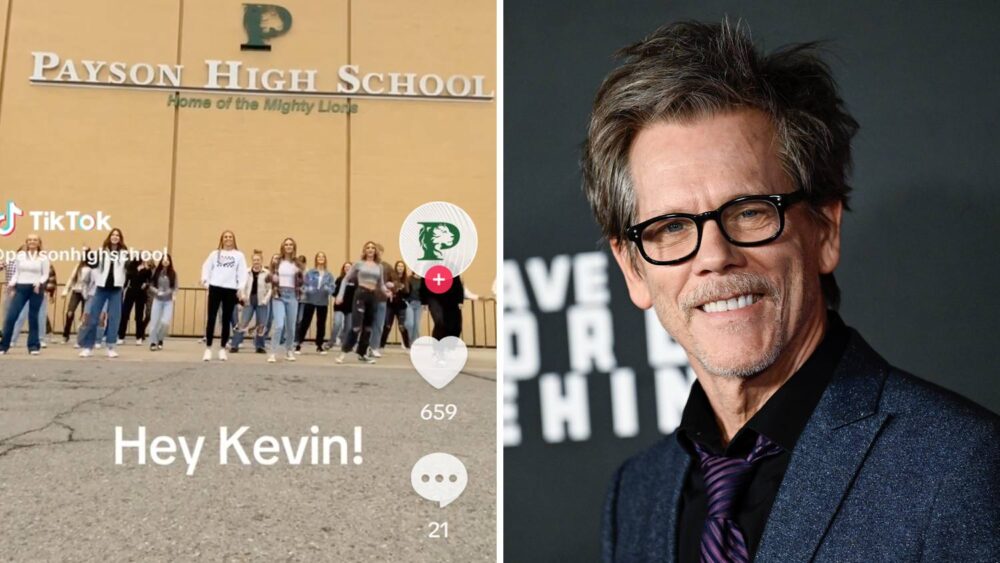

Catch PTHV on Roadtrip Nation

Join Team PTHV at IEL’s CSxFE 2024

Parent Teacher Home Visits Are About Trust, Not Compliance

Learn & network with us.

NCUEA 2023 Summer Meeting

PTHV 25th Anniversary Reception

How Family Engagement Can Improve Student Engagement and Attendance

Our Funders

PTHV advances student success and school improvement by leveraging relationships, research, and a national network of partners to advance evidence-based practices in relational home visits within a comprehensive family engagement strategy.

- The PTHV Model

- Training & Services

PTHV is a nonprofit grassroots network that must raise its operating budget every year. Like the local home visit projects we help, our network is sustained by collaboration.

© Copyright 2023 by Parent Teacher Home Visits

Organizing Engagement

Advancing Knowledge of Education Organizing, Engagement, and Equity

Parent Teacher Home Visit Model

The parent teacher home visit model outlines a process and set of practices that can help educators and families build more trusting and mutually supportive relationships to positively impact a child’s education.

The Parent Teacher Home Visit model was developed by Parent Teacher Home Visits , a nonprofit organization that works with public schools and other partners across the United States to support relationship-building home visits between educators and families. While other home visit models focus on the early childhood years, emphasize academic or behavioral issues, or provide social services, such as advice on childhood health and nutrition, the Parent Teacher Home Visit model can be used during any stage of child and youth development, and the primary goal is to build trusting, mutually supportive relationships between educators and families that will positively impact a child’s education.

“The Parent Teacher Home Visit model developed from an understanding that family engagement is critical to student success, and yet complex barriers often stand in the way of meaningful partnerships between educators and families. In communities where educators and families differ by race, culture, and/or class, educators may have little knowledge of the communities where they teach, including historic racism and poverty. They may also be unaware of their own automatic and unconscious biases that lead to disconnects and missed opportunities in teaching their students…. Decades of research shows that students of color and those from low-income households are often treated differently from White and middle- and upper-class students in ways that have a negative impact on their school experience and learning. Although PTHV did not start as a program explicitly designed to reduce implicit biases in school communities, after close to two decades of practice, leaders of the model believe it does counteract these biases and that bridging divides as a result of race, culture, language, and socioeconomic status is an essential component of the program’s impact.” Mindset Shifts and Parent Teacher Home Visits , RTI International (Study I of a National Evaluation of Parent Teacher Home Visits 2017–2018)

Parent Teacher Home Visits originated in a low-income Sacramento neighborhood in 1998. A group of parents used the principles of community organizing to develop programs intended to build greater trust and accountability between parents and teachers. One of the foundational strategies was a voluntary home visit. In an unprecedented collaboration at the time, the school district, the local teachers union, and Sacramento ACT , a community-organizing group, worked together to pilot the first home visits. Since that time, hundreds of communities and school systems in more than two-dozen states have implemented the model.

The Parent Teacher Home Visit model has been the subject of several research studies and formal evaluations that have connected home visits to a variety of benefits for students, families, and teachers, including:

- Improved educational outcomes for students, such as higher student-attendance rates, increased literacy and reading comprehension, and greater engagement and motivation in the classroom.

- Adoption of more personalized and culturally responsive instructional strategies by educators, and more positive instructional interactions between students and teachers.

- Stronger home-school relationships, including families reporting increased trust in teachers and greater confidence reaching out to educators.

- Positive changes in family perceptions of their child’s school and teachers, and a reduction in negative assumptions or group stereotyping of students and families by educators.

- A more informed understanding of the causes of student behavioral issues, and a reduction in punitive disciplinary practices in the classroom.

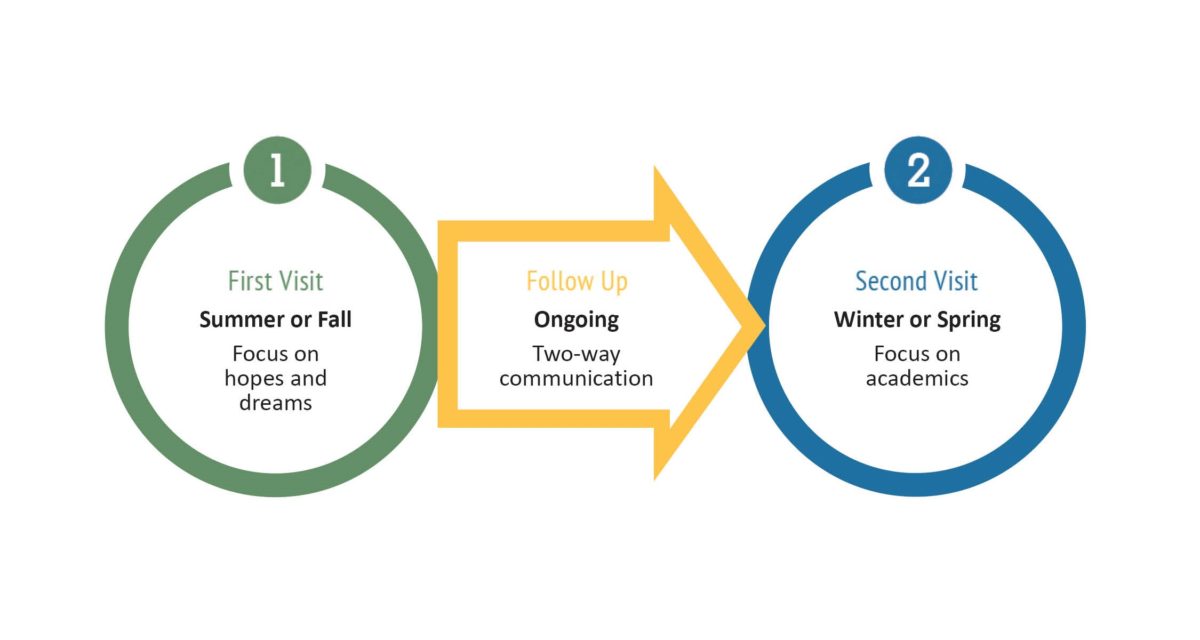

The Parent Teacher Home Visit Model

According to Parent Teacher Home Visits, the home-visit model is designed to “connect the expertise of the family on their child with the classroom expertise of the teachers.” The home visits are not unplanned drop-ins, but scheduled appointments that are coordinated between willing colleagues—teachers and families—in a setting outside of the school. While a student’s home provides unique opportunities for learning about the family and a student’s home life, teachers may also meet with families in a public location—such as a library, park, or coffee shop—if it is more convenient or if the families request an outside-of-the-home location.

Schools typically announce a home-visit program to parents and let them know that their child’s teacher will initiate communication to describe the home-visit process, extend an invitation, and determine a family’s receptivity to a visit. If a family accepts the invitation, the home visits are conducted in teams of two—the child’s teacher and a trusted colleague (in most cases, a fellow teacher). The initial visit can take place at any time during the year, but the first is ideally conducted at the outset of a new school year during either the summer or fall.

Regular communication between the teacher and families continues after the first home visit using a communication method that works for both parties, whether it’s through in-person conversations or emails, texts, or phone calls. Over the course of the school year, teachers apply what they learned about their students to the instructional process, and families usually become more involved in school activities and in their children’s learning progress and coursework. A second visit is then conducted in late winter or spring, which focuses on academic issues, but with reference to the initial home visit conversation and to the mutual understanding that’s been developed since then.

The Five Non-Negotiable Core Practices

The Parent Teacher Home Visit model is routinely adapted and customized across the United States to meet the needs of teachers and families in a given community, but all home visit programs using the model follow these five non-negotiable core practices:

1. Visits are always voluntary for educators and families, and they are arranged in advance.

Home visits are never mandatory: all participants must agree to the visit. Because home visits are a choice, not a contractual or policy requirement, participating teachers and families need to be personally motivated to conduct the visit. In many cases, however, teachers and families who are initially reluctant to participate in a home visit will often change their minds once they hear about the benefits that home visits have had on other teachers and families.

2. Teachers are trained to conduct home visits, and they are compensated for visits that occur outside their normal school day.

Parent Teacher Home Visits provides training for educators before the launch of a local program, which addresses topics such as the research supporting the model; best practices for coordination and logistics; skill-building and practice sessions for engaging families; overcoming common barriers (e.g., funding, time, fears); cultural sensitivity and cross-cultural connection; and applying insights and lessons from home visits to the instructional process. Once a program is more established, train-the-trainer workshops may be provided to local educators. Compensation for participating educators typically comes from one of three sources: district funds (including Title I funding), foundation grants (from either local and national philanthropies), and union funds (including funding from national, state, or local teachers associations). The Parent Teacher Home Visits provides guidance on how home-visit programs are commonly funded.

3. The first visit focuses on relationship-building: teachers and families discuss hopes, dreams, aspirations, and goals.

While other home visit models focus on academics, student performance, or behavioral issues, Parent Teacher Home Visits has found that such interactions can reinforce potentially problematic power dynamics, such as families experiencing anxiety about being visited by an “authority figure” or feeling intimidated by the use of academic language they may not understand. For this reason, the initial home visit is focused entirely on relationship-building between educators and families, and the discussions address positive and affirming topics such as the family’s hopes and aspirations for their child, the child’s talents and learning strengths, or how the teacher and parents can work together to support the child’s development and educational growth.

4. There is no targeting of specific students, families, or groups: teachers either visit all of the school’s families, or a diverse cross-section of families, to avoid potential stigma.

By not targeting specific students, families, or groups, districts and schools can avoid negative perceptions of home visits. For example, if a school decides that home visits will only be conducted with families who live in a certain neighborhood or with the parents of students who are struggling academically, people are more likely to assume that visits are intended to address “problems,” not build stronger relationships, and other families may, therefore, be less motivated to participate in a visit.

5. Educators always conduct visits in pairs, and after the visit they reflect on the experience with their partner.

Pairing teachers helps to create a safer environment for both teachers and families, and it also gives visiting teachers someone who can help them reflect on the interaction and how it might be applied in the classroom.

Acknowledgments

Organizing Engagement thanks Gina Martinez-Keddy for her contributions to improving this introduction, and Parent Teacher Home Visits for permission to republish images from their website and publications.

Creative Commons

This work by Organizing Engagement is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . When excerpting, adapting, or republishing content from this resource, users should cite the source texts and confirm that all quotations and excerpts are accurately presented.

Previous Post

Michigan State – Rethink Discipline Bills

Parent leadership indicators framework, organize_engage.

@organize_engage

Follow us on Twitter

Stay Connected

Receive News and Announcements

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Email Address *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

The school visit: what to look for, what to ask

by: The GreatSchools Editorial Team | Updated: December 5, 2023

Print article

Be sure to visit all the schools on your list, if you can. A visit is the best way to determine whether a school is right for your child. Even a short visit will help you identify a school’s strengths and challenges. It’s also the only way to get a feel for a school’s climate — intangible but important factors like the dynamism of the teaching, engagement of the students, quality of communication, level of respect between students, teachers, administrators, and parents, and the overall sense that the school offers a safe and inspiring learning environment .

School visit checklists

Use this printable guide to help you plan your elementary, middle, or high school visit.

Before your visit

- Do your homework. Read about the schools you’ll be visiting. Examine their school profiles on GreatSchools.org. Talk to other parents and check your local newspaper for articles about the schools.

- Contact the school. Most schools conduct regular school tours and open houses during the enrollment season — typically in the fall. Call the school or go online to schedule a visit.

- Ask and observe. Jot down your questions before your visit (the sample questions below will help you create your list).

Key questions to ask

- Does this school have a particular educational philosophy or mission?

- What curriculum does the school use for math, reading, science, etc? Ask if the school follows the Common Core State Standards , Next Generation Science Standards , and which program(s) are they using to teach children to read ?

- What is the average class size ?

- What is this school’s approach to student discipline and safety? Do they practice restorative justice ? Are the discipline practices fair for families of color ? Do they practice corporal punishment , and if so, can you opt out of that for your child?

- How much homework do students have? What is the school’s philosophy/approach to homework ?

- What kind of library resources are available to students?

- How is technology used to support teaching and learning at this school?

- How do the arts fit into the curriculum? Is there a school choir, band or orchestra? A drama program? Art classes?

- What extracurricular opportunities (sports, clubs, community service, competitions) are available for students?

- How do students get to school? Is free school busing available?

- Is bullying a problem at the school? Does the school have an anti-bullying policy ?

- Does the school have a program for gifted students ?

- How does this school support students who have academic, social or emotional difficulties?

- What strategies are used to teach students who are not fluent in English?

- What professional development opportunities do teachers have ? In what ways do teachers collaborate?

- Does the school offer Physical Education (PE) classes?

- What are some of the school’s greatest accomplishments? What are some of the biggest challenges this school faces?

Features to look for

- Do classrooms look cheerful? Is student work displayed, and does it seem appropriate for the grade level?

- Do teachers seem enthusiastic and knowledgeable, asking questions that stimulate students and keep them engaged?

- Does the principal seem confident and interested in interacting with students, teachers and parents?

- How do students behave as they move from class to class or play outside?

- Is there an active Parent Teacher Association (PTA) ? What other types of parent involvement take place at this school?

- How well are the facilities maintained? Are bathrooms clean and well supplied, and do the grounds look safe and inviting?

Especially for elementary schools

- What are some highlights of this school’s curriculum in reading , math, science and social studies?

- What criteria are used to determine student placement in classes?

- How does this school keep parents informed of school information and activities? Are they easy to communicate with ?

- Does the school let parents know what their rights are (and aren’t ) in regards to your child’s education?

- Is quality child care available before and after school?

- How much outdoor time do kids get each day?

Especially for middle schools

- How does the school guide and prepare students for major academic decisions that will define their options in high school and beyond? Do they provide advice to parents on how to help this age group ?

- Does the school offer tutoring or other support if students need extra help?

- Are world language classes (French, Spanish, etc.) offered to students?

- If the school is large, does it make an effort to provide activities that create a sense of community ?

Especially for high schools

- Does this school have a particular curriculum focus, such as STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) or the arts?

- What kind of emphasis does the school place on college preparation ?

- Does the school have a good selection of Advanced Placement (AP) and honors classes?

- What percentage of students take the SAT or/and ACT ?

- Where do students go after they graduate? How many attend four-year college? Are graduates prepared for college ?

- Are counselors available to help students make important decisions about classes?

- Is college counseling and support available?

- Does the school offer a variety of career planning options for students who are not college bound?

- Does the school staff set high expectations for all students?

- Does the school have a tutoring program so students can get extra help if they need it?

- How do students get to school? Is there a parking lot, and are buses (public or district-provided) available?

- Does this school have any school-to-work programs or specialized academies ?

- What is the school drop-out rate ?

Especially for charter schools

- When and why was this school created ?

- Does the school have a specific focus?

- Who is the charter holder, or the group that created the school?

- How does the school select teachers? Are the teachers certificated?

- Is this the permanent location or facility for the school? If not, will the school be moving to another location in the near future?

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

Why your neighborhood school closes for good – and what to do when it does

5 things for Black families to consider when choosing a school

6 surprising things insiders look for when assessing a high school

Surprising things about high school

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

- Our Mission

Home Visits: A Powerful Family Engagement Tool

Visiting students and their families at home builds strong bonds of trust and understanding — and impacts academic success.

Five years ago, I was trained by the Parent Teacher Home Visit Project , based in Sacramento, California, whose model is used by educators across the country. Home visits are voluntary and prearranged. School staff are trained; they go out in pairs and are compensated for their time. Students are not targeted for visits because of grades or disciplinary issues. Among family engagement strategies, home visits are recognized for their high impact on student success.

During the half-hour visit, we always ask parents about their dreams for their children. Answers vary: “I want my son to have the opportunities my parents couldn’t give me.” “I want my daughter to make something of herself, to be somebody.”

On one occasion, we weren’t prepared for the answer: “I hope she can stay in this country long enough to get an education.” Lindy had an upcoming immigration hearing, and her dad didn’t know whether Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) would deport her or not.

All of my students are immigrant teens. I don’t ask about their documents, thanks to a 1982 Supreme Court decision which guarantees equal access to education regardless of immigration status. But I do read my students’ academic histories. If I see three weeks in Arizona or Texas, I know they spent some time in a detention facility after an arduous journey through Mexico. I know they face a future full of court dates and unknowns.

Lindy had just arrived from Guatemala. She and her dad sat us down in their austere apartment on a rainy afternoon when he didn’t have to work at a distant construction site. He was the first father to tell us that his hope was avoiding deportation. I wondered how this fear affected Lindy’s schoolwork. How could she focus on reviewing vocabulary or organizing her notebook if she worried that ICE would knock on the door at dawn?

Days before her court date, Lindy told me that her dad couldn’t go with her. “Do I need a lawyer?” she asked. I struggled with this: a 17-year-old confronting ICE alone in a language she didn’t speak well. Fortunately, I have a Central American co-worker who had crossed the border herself years ago. Ms. Perez picked up the phone, and soon Lindy was talking with someone at a local nonprofit who agreed to accompany her to the hearing.

Suppose I hadn’t gone to Lindy’s home, met her dad, and learned of their fears. Without the home visit, would Lindy have trusted me enough to mention the hearing? Would she have gone alone? Home visits are designed to build a relationship between families and educators that impacts classroom learning. As we sit in their living rooms, families begin to believe we will treat them respectfully, and educators begin to shed our preconceptions. A relationship develops that can help students confront some very real obstacles to their academic progress.

Be Flexible About Where and Even Who You’ll Meet

Home visits don’t have to happen at home or even with parents. A library may be a good alternative to a crowded apartment, and a sibling may have custody of a student whose parents remain in El Salvador. Mauricio hesitated when we called to set up a visit for his younger brother Vicente, so we met at a nearby McDonald’s. We soon realized that this visit was about Mauricio, not Vicente. Mauricio had just broken up with his girlfriend, so the two brothers were sleeping on couches in a friend’s living room -- Vicente had left the insecurity of El Salvador for the instability of his brother’s life.

Like many other students with limited prior education, Vicente’s initial interest in high school waned. His buddies passed my pre-algebra class, but Vicente couldn’t remember how to solve two-step equations. A year later he was passing many of his math objectives but was often absent.

Every visit reveals another assumption from my own middle-class experience that accompanies me to school. I wondered how Lindy’s dad could leave her alone in front of an immigration judge, while I admired her bravery in going. I shook my head at Mauricio’s chaos but grudgingly respected him for devising a plan B for his brother. The last time I tried to call Mauricio, none of the phone numbers worked. And then Vicente handed me a 3x5 card with a new number: “In case you ever want to call….”

Home visits transform the way we look at ourselves and our students. Building trust with families is a first crucial step in tackling some of the obstacles in our students’ paths toward graduation.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Administration for Children & Families

- Upcoming Events

Home Visitor's Online Handbook

- Open an Email-sharing interface

- Open to Share on Facebook

- Open to Share on Twitter

- Open to Share on Pinterest

- Open to Share on LinkedIn

Prefill your email content below, and then select your email client to send the message.

Recipient e-mail address:

Send your message using:

What Makes Home Visiting So Effective?

By engaging in a warm, accepting relationship with parents, you support a strong and secure relationship between the parent and child. You help parents become more sensitive and responsive to their child. The secure relationship between young children and their families creates the foundation for the development of a healthy brain. The home environment allows you to support the family in creating rich learning opportunities that build on the family's everyday routines. You support the family's efforts to provide a safe and healthy environment. You customize each visit, providing culturally and linguistically responsive services.

The home visiting model allows you to provide services to families with at least one parent at home with the child or children. Families may choose this option because they want both support for their parenting and for their child's learning and development in their home. For example, you are available to families who live in rural communities and who otherwise would not be able to receive needed services. You bring services to families whose life circumstances might prevent them from participating in more structured settings or families challenged by transportation. Some programs are able to be flexible and offer services during non-traditional hours to families who work or go to school.

Every parent and home visitor brings his or her own beliefs, values, and assumptions about child-rearing to their interactions with children. Home visiting can provide opportunities to integrate those beliefs and values into the work the home visitor and family do together.

In addition to your own relationship with the family during weekly home visits, you bring families together twice a month. These socializations reduce isolation and allow for shared experiences, as well as connect them to other staff in the program.

Resource Type: Article

National Centers: Early Childhood Development, Teaching and Learning

Last Updated: December 3, 2019

- Privacy Policy

- Freedom of Information Act

- Accessibility

- Disclaimers

- Vulnerability Disclosure Policy

- Viewers & Players

Home Visits

When is the last time you visited or called a parent or guardian without bad news?

Administrators

How are you equipping teachers to build relationships with families through visits? Learn the benefits of home visits and best practices for how to prepare for and conduct them.

Best Practices

These are some best practices for teachers and administrators concerning home visits:

- Visits should be voluntary for educators and families, but administrators should seek at least 50 percent participation from a school’s staff.

- Home visits should always be arranged in advance. It’s helpful for schools to decide if they want educators to visit families once or twice per year and whether that first visit will take place before the school year begins. Some districts also follow up home visits with family dinners at the school to continue deepening school-family ties.

- If possible, schools should compensate educators for their home-visit work and train them effectively.

- Educators should visit in teams of two. In some cases, teachers partner with other teachers, social workers or the school nurse to help address a student’s well-being in a more comprehensive manner.

- It’s important that educators visit a cross-section of students—ideally all of them—rather than target any particular group.

- The goal of the first home visit is to build relationships. Educators should talk about families’ hopes and aspirations for their students.

Note to teachers: Take extra care when communicating with immigrant families about visiting their homes. Make it clear in advance that you are not from any government immigration agency, such as ICE, and that you will not talk with any such agency. Also, do not ask about immigration status during the visit—or at any other time.

The Benefits

Family engagement contributes to a range of positive student outcomes, including:

- Improved achievement;

- Decreased disciplinary issues;

- Improved parent- or guardian-child and teacher-child relationships.

Different Families, Different Visits

Just as instruction is differentiated, so too are home visits. Depending on the needs of the student and family and the previous history of the teacher-family relationship, a home visit might be:

- A formal conversation on the couch;

- A meal together;

- A guided tour of a home (including favorite toys and hangout spots);

- Walking the family dog in the park or another excursion to an agreed-upon meeting place.

Note: Keep in mind that some families may not be comfortable having guests in their homes and would prefer to meet somewhere else. In this case, you could offer the school or another location as a meeting place.

Story From the Field: Keep Your Eyes On the Speaker

“I once went on a home visit to a trailer home. We sat at the kitchen table, and I was astounded to see a hole around a foot and a half in diameter right in the middle of the kitchen, through which I could see the dirt underneath the trailer. However, as mortified as I was, I thought that it probably was even more mortifying for the mother who so kindly received me. She was probably embarrassed and the least I could do was to keep my eyes on her and focus on our conversation instead of on the material distractions around us. My job is to focus on the human being, not on the dehumanizing conditions many people have to live in.”

—Barbie Garayúa-Tudryn, elementary school counselor and TT Advisory Board member

Home Visit Checklist:

- Participate in home-visit training.

- Call each student’s home, and explain the purpose of the visit.

- Schedule the visit.

- Determine if a translator is needed. The student should not serve as a translator.

- Confirm the day before or the day of the home visit.

- Before the visit, reflect on the reason you’re there in the first place: to build a relationship with the family and collaborate with them for the well-being of the child.

- The visit should be 20-30 minutes long.

- Bring a partner.

- Get to know the family. Find out if they have other children in school.

- Talk about the family’s hopes for their students and share yours.

- Avoid taking notes or bringing paperwork, which can make families feel as if they are being evaluated and can cause nervousness and disengagement.

- If you need to share paperwork, wait 20-30 minutes before delivering it or plan to send it at a later date.

- Ask the family what they need from you, and make a plan to connect again in the future.

- Make a phone call or send a text or note thanking the parents or guardians for the meeting.

- Invite the family to an upcoming event.

- Document the visit, and share takeaways with appropriate stakeholders.

- Follow up with any resource needs that came up during the visit.

To learn more, read “ Meet the Family ” and watch our on-demand webinar Equity Matters: Engaging Families Through Home Visits .

Critical Training Elements for Administrators

Training and preparing for a home visit can be as important as the visit itself. Consider these pointers from the experts when designing professional development for your home-visit program.

- Review logistics , such as how to make contact, how and when to schedule visits, whether and how to record discussions with families, and what to do with the documentation and data.

- Remind teachers to leave assumptions behind and keep an open mind regarding each family, their culture and their values.

- Address implicit bias and the impact it can have on what educators or families will perceive during the home visit. To learn more about implicit bias, view our on-demand webinar Equity Matters: Confronting Implicit Bias .

- Some prior knowledge is essential , such as whether a translator will be necessary (it is not appropriate to use the student as a translator), whether the family has access to a working phone or if the child lives between two households.

- Coach teachers to establish the purpose for the visit ahead of time. Goals should focus on getting to know the child as a learner and setting the stage for partnership, not on problematic behavior or performance.

- Model how to talk about both the student and the family. Some families may have significant needs. Connecting them to resources can benefit their child’s learning.

For more information, explore the work of The Parent Teacher Home Visit Project and the Family and Community Engagement Team at Denver Public Schools.

- Student sensitivity.

- The Power of Advertising and Girls' Self-Image

Print this Article

Would you like to print the images in this article?

- Google Classroom

Equity Matters: Engaging Families Through Home Visits

Sign in to save these resources..

Login or create an account to save resources to your bookmark collection.

Learning for Justice in the South

When it comes to investing in racial justice in education, we believe that the South is the best place to start. If you’re an educator, parent or caregiver, or community member living and working in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana or Mississippi, we’ll mail you a free introductory package of our resources when you join our community and subscribe to our magazine.

Get the Learning for Justice Newsletter

Brief Home Visiting: Improving Outcomes for Children

What is Home Visiting?

Home visiting is a prevention strategy used to support pregnant moms and new parents to promote infant and child health, foster educational development and school readiness, and help prevent child abuse and neglect. Across the country, high-quality home visiting programs offer vital support to parents as they deal with the challenges of raising babies and young children. Participation in these programs is voluntary and families may choose to opt out whenever they want. Home visitors may be trained nurses, social workers or child development specialists. Their visits focus on linking pregnant women with prenatal care, promoting strong parent-child attachment, and coaching parents on learning activities that foster their child’s development and supporting parents’ role as their child’s first and most important teacher. Home visitors also conduct regular screenings to help parents identify possible health and developmental issues.

Legislators can play an important role in establishing effective home visiting policy in their states through legislation that can ensure that the state is investing in evidence-based home visiting models that demonstrate effectiveness, ensure accountability and address quality improvement measures. State legislation can also address home visiting as a critical component in states’ comprehensive early childhood systems.

What Does the Research Say?

Decades of research in neurobiology underscores the importance of children’s early experiences in laying the foundation for their growing brains. The quality of these early experiences shape brain development which impacts future social, cognitive and emotional competence. This research points to the value of parenting during a child’s early years. High-quality home visiting programs can improve outcomes for children and families, particularly those that face added challenges such as teen or single parenthood, maternal depression and lack of social and financial supports.

Rigorous evaluation of high-quality home visiting programs has also shown positive impact on reducing incidences of child abuse and neglect, improvement in birth outcomes such as decreased pre-term births and low-birthweight babies, improved school readiness for children and increased high school graduation rates for mothers participating in the program. Cost-benefit analyses show that high quality home visiting programs offer returns on investment ranging from $1.75 to $5.70 for every dollar spent due to reduced costs of child protection, K-12 special education and grade retention, and criminal justice expenses.

Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting Grant Program

The federal home visiting initiative, the Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) program, started in 2010 as a provision within the Affordable Care Act, provides states with substantial resources for home visiting. The law appropriated $1.5 billion in funding over the first five years (from FYs 2010-2014) of the program, with continued funding extensions through 2016. In FY 2016, forty-nine states and the District of Columbia, four territories and five non-profit organizations were awarded $344 million. The MIECHV program was reauthorized under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act through September 30, 2017 with appropriations of $400 million for each of the 2016 and 2017 fiscal years. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 ( P.L. 115-123 ) included new MIECHV funding. MIECH was reauthorized for five years at $400 million and includes a new financing model for states. The new model authorizes states to use up to 25% of their grant funds to enter into public-private partnerships called pay-for-success agreements. This financing model requires states to pay only if the private partner delivers improved outcomes. The bill also requires improved state-federal data exchange standards and statewide needs assessments. MIECHV is up for reauthorization, set to expire on Sept. 30, 2022.

The MIECHV program emphasizes that 75% of the federal funding must go to evidence-based home visiting models, meaning that funding must go to programs that have been verified as having a strong research basis. To date, 19 models have met this standard. Twenty-five percent of funds can be used to implement and rigorously evaluate models considered to be promising or innovative approaches. These evaluations will add to the research base for effective home visiting programs. In addition, the MIECVH program includes a strong accountability component requiring states to achieve identified benchmarks and outcomes. States must show improvement in the following areas: maternal and newborn health, childhood injury or maltreatment and reduced emergency room visits, school readiness and achievement, crime or domestic violence, and coordination with community resources and support. Programs are being measured and evaluated at the state and federal levels to ensure that the program is being implemented and operated effectively and is achieving desired outcomes.

With the passage of the MIECHV program governors designated state agencies to receive and administer the federal home visiting funds. These designated state leads provide a useful entry point for legislators who want to engage their state’s home visiting programs.

Advancing State Policy

Evidence-based home visiting can achieve positive outcomes for children and families while creating long-term savings for states.

With the enactment of the MIECHV grant program, state legislatures have played a key role by financing programs and advancing legislation that helps coordinate the variety of state home visiting programs as well as strengthening the quality and accountability of those programs.

During the 2019 and 2021 sessions, Oregon ( SB 526 ) and New Jersey ( SB 690 ), respectively, enacted legislation to implement and maintain a voluntary statewide program to provide universal newborn nurse home visiting services to all families within the state to support healthy child development. strengthen families and provide parenting skills.

During the 2018 legislative session New Hampshire passed SB 592 that authorized the use of Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) funds to expand home visiting and child care services through family resource centers. Requires the development of evidence-based parental assistance programs aimed at reducing child maltreatment and improving parent-child interactions.

In 2016 Rhode Island lawmakers passed the Rhode Island Home Visiting Act ( HB 7034 ) that requires the Department of Health to coordinate the system of early childhood home visiting services; implement a statewide home visiting system that uses evidence-based models proven to improve child and family outcomes; and implement a system to identify and refer families before the child is born or as early after the birth of a child as possible.

In 2013 Texas lawmakers passed the Voluntary Home Visiting Program ( SB 426 ) for pregnant women and families with children under age 6. The bill also established the definitions of and funding for evidence-based and promising programs (75% and 25%, respectively).

Arkansas lawmakers passed SB 491 (2013) that required the state to implement statewide, voluntary home visiting services to promote prenatal care and healthy births; to use at least 90% of funding toward evidence-based and promising practice models; and to develop protocols for sharing and reporting program data and a uniform contract for providers.

View a list of significant enacted home visiting legislation from 2008-2021 . You can also visit NCSL’s early care and education database which contains introduced and enacted home visiting legislation for all fifty states and the District of Columbia. State officials face difficult decisions about how to use limited funding to support vulnerable children and families.

Key Questions to Consider

State officials face difficult decisions about how to use limited funding to support vulnerable children and families and how to ensure programs achieve desired results. Evidence-based home visiting programs have the potential to achieve important short- and long-term outcomes.

Several key policy areas are particularly appropriate for legislative consideration:

- Goal-Setting: What are they key outcomes a state seeks to achieve with its home visiting programs? Examples include improving maternal and child health, increasing school readiness and/or reducing child abuse and neglect.

- Evidence-based Home Visiting: Have funded programs demonstrated that they delivered high-quality services and measureable results? Does the state have the capacity to collect data and measure program outcomes? Is the system capable of linking data systems across public health, human services, and education to measure and track short and long-term outcomes?

- Accountability: Do home visiting programs report data on outcomes for families who participate in their programs? Do state and program officials use data to improve the quality and impact of services?

- Effective Governance and Coordination: Do state officials coordinate all their home visiting programs as well as connect them with other early childhood efforts such as preschool, child care, health and mental health?

- Sustainability: Shifts in federal funding make it likely that states will have to maintain programs with state funding. Does the state have the capacity to maintain the program? Does the state have the information necessary to make difficult funding decisions to make sure limited resources are spent in the most effective way?

DO NOT DELETE - NCSL Search Page Data

Related resources, supreme court hears arguments over oregon city’s crackdown on homelessness.

Arguments before the U.S. Supreme Court in a case out of Oregon could reshape how cities enforce penalties for homeless people camping on public property throughout the western United States.

Family First State Plans and Enacted Legislation

Child support and family law legislation database, contact ncsl.

For more information on this topic, use this form to reach NCSL staff.

- What is your role? Legislator Legislative Staff Other

- Is this a press or media inquiry? No Yes

- Admin Email

News & Blog

- Why HOME WORKS!

- Testimonials

- Impact Reports

- A HOME WORKS! Playbook: Getting Patrick Henry Connected

- Mission & Vision

- About HOME WORKS!

- Our Program

- Participating Schools 2023-2024

- Parent Resources

Learn More About the Need Learn More About What We Do

How We Help

We Support Teachers

HOME WORKS! trains, supports, and helps pay teachers to make home visits and get their families engaged in their kids' education.

We Engage Parents

HOME WORKS! connects teachers to parents with home visits and Parent-Teacher Workshops that involve and empower the entire family.

We Transform Schools

Partnering with families and schools, HOME WORKS! improves students’ classroom performance.

The Teacher Home Visit Program Works!

of parents surveyed felt that home visits improved relationships with their children's teachers.

of teachers surveyed felt that home visits strengthened their understanding of their students' cultures and home lives.

of teachers surveyed believe that home visits improved students motivation and attitudes toward school.

Why It Works

HOME WORKS! The Teacher Home Visit Program from Karen Kalish on Vimeo .

Explore the content categories

- Anxiety and depression

- Assisted reproductive technology

- Breastfeeding

- Child care – Early childhood education and care

- Child nutrition

- Child obesity

- Crying behaviour

- Divorce and separation

- Epigenetics

- Executive functions

- Father – Paternity

- Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD)

- Gender: early socialization

- Head Start policy

- Home visiting

- Hyperactivity and inattention (ADHD)

- Immigration

- Immunization

- Importance of early childhood development

- Injury prevention

- Integrated early childhood development services

- Language development and literacy

- Learning disabilities

- Low income and pregnancy

- Maltreatment (child)

- Maternal depression

- Mental health

- Nutrition – Pregnancy

- Outdoor play

- Parental leave

- Parenting skills

- Peer relations

- Physical activity

- Play-based learning

- Prematurity

- Preschool programs

- Prosocial behaviour

- School readiness

- School success

- Second language

- Sleeping behaviour

- Social cognition

- Social violence

- Stress and pregnancy (prenatal and perinatal)

- Technology in early childhood education

- Temperament

- Tobacco and pregnancy

- Welfare reform

Impacts of Home Visiting Programs on Young Children’s School Readiness

Grace Kelley, PhD, Erika Gaylor, PhD, Donna Spiker, PhD SRI International, Center for Education and Human Services, USA January 2022 , 2nd rev. ed.

Introduction

Home visiting programs are designed and implemented to support families in providing an environment that promotes the healthy growth and development of their children. Programs target their services to families and caregivers in order to improve child development, enhance school readiness, and promote positive parent-child interactions. Although programs differ in their approach, populations served and intended outcomes, high-quality home visiting programs can provide child development and family support services that reduce risk and increase protective factors. Home visiting programs addressing school readiness are most effective when delivered at the community level, through a comprehensive early childhood system that includes the supports and services that ensure a continuum of care for all family members across the early years. School readiness includes the readiness of the individual child, the school’s readiness to support children, and the ability of the family and community to support early child development, health, and well being. In addition to home visiting services, appropriate referrals to community services, including to preschool programs, offer a low-cost universal approach that increases the chances of early school success. This comprehensive approach to home visiting as a part of a broad early childhood system has been identified as an effective strategy to help close the gap in school readiness and child well-being associated with poverty and early childhood adversity. 1,2

Home visitation is a type of service-delivery model that can be used to provide many different kinds of interventions to target participants. 3,4 Home visiting programs can vary widely in their goals, clients, providers, activities, schedules and administrative structure. They share some common elements, however. Home visiting programs provide structured services:

- in a home a ;

- from a trained service provider;

- in order to alter the knowledge, beliefs and/or behaviour of children and caregivers or others in the caregiving environment, and to provide parenting support. 5

Home visits are often structured to provide consistency across participants, providers, and visits and to link program practices with intended outcomes. A visit protocol, a formal curriculum, an individualized service plan, and/or a specific theoretical framework can be the basis for activities that take place during home visits. Services are delivered in the living space of the participating family and within their ongoing daily routines and activities. The providers may be credentialed or certified professionals, paraprofessionals, or volunteers, but typically they have received some form of training in the methods and topical content of the program so that they are able to act as a source of expertise and support for caregivers. 6 Finally, home visiting programs are attempting to achieve some change on the part of participating families—in their understanding (beliefs about child-rearing, knowledge of child development), and/or actions (their manner of interacting with their child or structuring the environment, ability to provide healthy meals, engage in prenatal health care)—or on the part of the child (change in rate of development, health status, etc.). Home visiting also may be used as a way to provide case management, make referrals to existing community services including early intervention for those with delays and disabilities, or bring information to parents or caregivers to support their ability to provide a positive and healthy home environment for their children. 3,4,7

Data about the efficacy of home visiting programs have been accumulating over the past several decades. The federal Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) program launched in the U.S. in 2012 and its accompanying national Mother and Infant Home Visiting Program Evaluation (MIHOPE) (which included 4 models - Early Head Start’s Home-based option, Healthy Families America, Nurse-Family Partnership, and Parents as Teachers), and the Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness (HoMVEE) reviews has contributed much new data about program features, implementation, and impacts. 8-12 More of the research has used randomized controlled trial (RCT) or quasi-experimental designs, with multiple data sources and outcome measures, and longitudinal follow-up. These studies, along with older reviews, and recent meta-analyses have generally found that home visiting programs produce a limited range of significant effects and that the effects produced are often small. 4,13,14 Nevertheless, a review of seven evidence-based home visiting models showed all seven to have at least one study with positive impacts on child development and school readiness outcomes. 13 Detailed analyses, however, sometimes reveal important program effects. For example, certain subsets of participants may experience long-term positive outcomes on specific variables. 15,16 These results and others suggest that in assessing the efficacy of home visiting programs, it is important to include measures of multiple child and family outcomes at various points in time and to collect enough information about participants to allow for an analysis of the program effects on various types of subgroups. Averaging effects across multiple studies is currently seen as an inadequate approach to understanding what works for whom. 17

Other difficulties when conducting or evaluating research in this area include ensuring the equivalency of the control and experimental groups in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 18 controlling for participant attrition (which may affect the validity of findings by reducing group equivalence) and missed visits (which may affect validity by reducing program intensity), 19 documenting that the program was fully and accurately implemented, and determining whether the program’s theory of change logically connects program activities with intended outcomes.

Research Context

Because home visiting programs differ in their goals and content, research into their efficacy must be tailored to program-specific goals, practices, and participants. (See also chapter by Korfmacher and coll. ) In general, home visiting programs can be grouped into those seeking medical/physical health outcomes and those seeking parent-child interaction and child development outcomes. The target population may be identified at the level of the caregiver (e.g., teen mothers, low-income families) or the child (e.g., children with disabilities). Some programs may have broad and varied goals, such as improving prenatal and perinatal health, nutrition, safety, and parenting. Other programs may have narrower goals, such as reducing the incidence of child abuse and neglect. Program outcomes may focus on adults or on children; providers frequently cite multiple goals (e.g., improved child development, parent social-emotional support, parent education). 10

In this chapter, we focus on the effectiveness of home visiting programs in promoting developmental, cognitive, and school readiness outcomes in children. The majority of home visiting services and research have focused on the period prenatally through 2 to 3 years and thus have not measured long-term impacts on school readiness and school achievement, but some of the more recent studies have done follow up into elementary school. However, most of the available studies have examined the impact on these outcomes indirectly through changes in parenting practices and precursors to successful school success (i.e., positive behaviour outcomes including self-regulation and attention).

Key Research Questions

Key research questions include the following:

- What are the short-term and long-term benefits experienced by participating families and their children relative to nonparticipating families, particularly for children’s school readiness skills and parenting to support child development?

- What factors influence participation and nonparticipation in the program?

- Do outcomes differ for different subgroups?

Research Results

Recent advances in program design, evaluation and funding have supported the implementation of home visiting as a practical intervention to improve the health, safety and education of children and families, mitigating the impact of poverty and adverse early childhood experiences. 3 Although program approaches and quality may vary, there are common positive effects found on parenting knowledge, beliefs, and/or behaviour and child cognitive, language, and social-emotional development. In order to achieve the intended outcomes, programs need to have clearly defined interventions and outcome measures, with a process to monitor quality. 20 Recent research has begun to focus on how measures to assess quality can be used to monitor programs and program improvement efforts. 21,22

A review of seven home visiting program models across 16 studies conducted over a decade ago that included rigorous evaluation components and measured child development and school readiness outcomes concluded positive impacts on young children’s development and behaviour. Six models showed favourable effects on primary outcome measures (e.g., standardized measures of child development outcomes and reduction in behaviour problems). 23 Only studies with outcomes using direct observation, direct assessment, or administrative records were included. More recent reviews also show relatively small effects on developmental outcomes, but authors noted that “modest effect sizes in studies concerning developmental delay can result in important population-level effects given the high proportion of children in low-income families (nearly 20%) meeting criteria for early intervention services”. 3 A rigorous review conducted more recently in 2018 identified 21 home visiting models that met criteria of being an evidence-based model. 11 That review concluded that 12 of the models had evidence for favorable impacts on child development and school readiness outcomes. Recent and continuing research has been focusing on families with infants and toddlers living in poverty who are at higher risk for adverse early childhood experiences (ACES) that can lead to lifelong negative effects on physical and emotional health, and educational success. 3,24 For example, the Adverse Childhood Experiences study indicates that traumatic experiences in early childhood can have lifelong impacts on physical and mental health. Data from this study indicate that children with 2 or more adverse experiences are more likely to repeat a grade. Home visiting programs can mitigate the effects of toxic stress, enhancing parenting skills and creating more positive early childhood experiences. 24,25 This research points to the importance of targeted home visiting programs to families who are experiencing stress and a recent meta-analysis of home visiting with such families indeed shows decreases in both social-emotional problems and stressful experiences. 26

Problems identified in earlier reviews completed in the 1990s still plague this field, however, including that many models have limited rigorous research studies. In many of the studies described in previous and more recent reviews and meta-analyses, programs struggled to enroll, engage, and retain families. When program benefits are demonstrated, they usually accrued only to a subset of families originally enrolled in the programs, they rarely occurred for all of a program’s goals, and the benefits were often quite modest in magnitude. 27 The generally small effects on outcomes averaged across studies have led researchers to call for precision home visiting research to look at what works for whom. 17,28 (Also see chapter by Korfmacher and coll .).

Research into the implementation of home visiting programs has documented a common set of difficulties across programs in delivering services as intended. (See also Paulsell chapter ) First, target families may not accept initial enrollment into the program. Two studies that collected data on this aspect of implementation found that one-tenth to one-quarter of families declined invitations to participate in the home visiting program. 29,30 In another study, 20 percent of families that agreed to participate did not begin the program by receiving an initial visit. 19 Second, families may not receive the full number of planned visits. Evaluation of the Nurse Family Partnership model found that families received only half of the scheduled number of visits. 31 Evaluations of the Hawaii Healthy Start and the Parents as Teachers programs found that 42 percent and 38 percent to 56 percent of scheduled visits respectively were actually conducted. 29,32 Even when visits are conducted, the planned curriculum and visit activities may not be presented according to the program model, and families may not follow through with the activities outside of the home visit. 33,34 Recent research has begun to examine how technical assistance and training supports delivered to home visiting program supervisors and home visitors can improve model fidelity. 35 (See Paulsell chapter. ) In a review of home visiting research in the 1990s, Gomby, Culross, and Berman 27 found that between 20 percent and 67 percent of enrolled families left home visitation programs before the scheduled termination date. More recent studies continue to show a persistent problem with families leaving the program and not engaging in visits as intended by program developers. For example, in the MIHOPE evaluation, about 28% of families left MIHOPE home visiting programs within six months, while about 55% were still receiving about two visits per month after a year. 9 With only about half of families remaining after one year, many families were only receiving half of the intended number of visits. 8 Studies of Early Head Start also show that families with the greatest number of risk factors are the most likely to drop out which was also observed in the recent MIHOPE study. 36

The assumed link between parent behaviour change and improved outcomes for children has received mixed research support. In other words, even when home visitation programs succeed in their goal of changing parent behaviour, these changes do not always appear to produce significantly better child outcomes in the short term, but in some cases appear to have an impact in the long term. 37,38 Examples include a study of the Home Instruction Program for Preschool Youngsters (HIPPY) model with low-income Latino families showing changes in parenting practices and better third-grade math achievement and positive impacts on both math and reading achievement in fifth grade. 39,40 Earlier evaluations of HIPPY found mixed results regarding program effectiveness. In some cohorts, program participants outperformed nonparticipants on measures of school adaptation and achievement through second grade, but these results were not replicated with other cohorts at other sites.

Both older and more recent reviews of home visiting programs described above included only studies using rigorous designs and measurement and a number of models show significant impacts on child development and school readiness outcomes. The Early Head Start model used a RCT design to study the impact of a mixed-model service delivery (i.e., center-based and home-visiting) on developmental outcomes at 2- and 3-year follow-up. Overall, there were small, but significant gains on cognitive development at 3 years, but not 2 years. More recent Early Head Start evaluations find positive impacts at ages 2 and 3 on cognition, language, attention, behaviour problems, and health and on maternal parenting, mental health, and employment outcomes, with better attention and approaches toward learning and fewer behavior problems at age 5 than the control group, but no differences on early school achievement. 41 Nonexperimental follow-up showed, however, that those children who went on to attend preschool after EHS did have better early school achievement. Studies of the Nurse Family Partnership model followed children to 6 years and found significant program effects on language and cognitive functioning as well as fewer behaviour problems in a RCT study. 42 In addition, evaluations of Healthy Families America have shown small, but favourable effects on young children’s development. 43,44

Home visiting programs focusing on supporting parents’ abilities to promote children’s development explicitly appear to impact children’s development positively. One meta-analysis found that programs that taught parent responsiveness and parenting practices found better cognitive outcomes for children. 4 A meta-analysis of RCTs found that the most pronounced effect for parent-child interactions and maternal sensitivity can be improved in a shorter period of time, where effects of interventions on child development may take longer to emerge. 45 Several studies find longer-term impacts on parenting and associated positive effects for child outcomes. In a RCT of a New York Healthy Families America program, the program reduced first grade retention rates and doubled the number of first graders demonstrating early academic skills for those participating in the program. 2 And at least one recent longitudinal study of Parents as Teachers found positive school achievement and reduced disciplinary problems in early elementary school along with increased scores on parent measures of interactions, knowledge of child development, and family support. 46

Other studies were unable to document program impacts on parenting and home environment factors that are predictive of children’s early learning and development through control group designs. An evaluation of Hawaii’s Healthy Start program found no differences between experimental and control groups in maternal life course (attainment of educational and life goals), substance abuse, partner violence, depressive symptoms, the home as a learning environment, parent-child interaction, parental stress, and child developmental and health measures. 43 However, program participation was associated with a reduction in the number of child abuse cases.

Other models show mixed impacts. A 1990’s RCT evaluation of the Parents as Teachers (PAT) program also failed to find differences between groups on measures of parenting knowledge and behaviour or child health and development. 32 Small positive differences were found for teen mothers and Latina mothers on some of these measures. However, another RCT study with the Parents as Teachers Born to Learn curriculum did find significant effects on cognitive development and mastery motivation at age 2 for the low socioeconomic families only. 47 Furthermore, a more recent RCT in Switzerland found that children receiving the PAT program had improved adaptive behavior and enhanced language skills at age 3 with the most high-risk children also having reductions in problem behaviours. 48 A randomized controlled trial of Family Check-Up demonstrated favourable impacts on at risk toddlers’ behaviour and positive parenting practices. 49

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have also shown that programs are more likely to have positive effects when targeted to the neediest subgroups in a population. For example, in the Nurse Family Partnership model children born to mothers with low psychological resources had better academic achievement in math and reading in first through sixth grade compared to their control peers (i.e., mothers without the intervention with similar characteristics). 50,51 (See also updated information in the Donelan-McCall & Olds chapter ).

The largest RCT of a comprehensive early intervention program for low-birth-weight, premature infants (birth to age three), the Infant Health and Development Program, included a home visiting component along with an educational centre-based program. 52 At age three, intervention group children had significantly better cognitive and behavioural outcomes and improved parent-child interactions. The positive outcomes were most pronounced in the poorest socioeconomic group of children and families and in those who participated in the intervention most fully. In follow-up studies, improvements in cognitive and behavioural development were also found at age 8 and 18 years for those in the heavier weight group. 53 The Chicago Child-Parent Center Program also combined a structured preschool program with a home visitation component. This program found long-term differences between program participants and matched controls. Participating children had higher rates of high-school completion, lower rates of grade retention and special education placement, and a lower rate of juvenile arrests and impacts lasting into adulthood. 54-56 Another example showing more intensive programming has larger impacts is the Healthy Steps evaluation showing significantly better child language outcomes when the program was initiated prenatally through 24 months. 57 Early Head Start studies cited earlier also show that combining home visiting with later preschool attendance will yield better school readiness impacts than home visiting alone. Finally, there is a need to look at how home visiting could be beneficial for improving school outcomes when combined with a preschool program as in a recent study with families in Head Start programs that found reduced need for educational and mental health services in third grade. 58 These studies suggest that a more intensive intervention involving the child directly may be required for larger effects on school readiness to be seen with home visiting as one part of a more comprehensive approach.

Conclusions

Research on home visitation programs has not been able to show that these programs alone have a strong and consistent effect on participating children and families, but modest effects have been repeatedly reported for children’s early development and behaviour and parenting behaviours and discipline practices. Programs that are designed and implemented with greater rigour seem to provide better results. Home visitation programs also appear to offer greater benefits to certain subgroups of families, such as low-income, single, teen mothers.

These conclusions support recent attention to use of research designs that look at more differentiation of the program models and components to match the needs of the families aimed at improving child development and other outcomes. Precision home visiting uses research to identify what aspects of home visiting work for which families in what circumstance, resulting in programs that target interventions to the needs of particular families. 17

Future research needs to examine the role of evidence-based home visiting within a more comprehensive system of services across the first five years of life. It can be an initial cost -effective strategy to build trusting relationships and support early positive parenting that will improve children’s development over the long run because families will have increased likelihood of enrolling their children in preschool programs and use other needed child and family supports.

Furthermore, efficacy research needs to include longitudinal designs and simultaneously include cost-benefit studies to demonstrate the long-term cost savings that will build public support for both early home visiting programs and a more comprehensive early childhood system.

The recent Covid-19 pandemic brought to light the disparities and inequities of our early childhood service systems (as well as our later education systems). This state of affairs also has reinforced the benefit of more authentic participatory approaches in research and evaluation to identify what works and for whom. Research and evaluation that includes various stakeholders, from those who are affected by an issue to those that fund the programs, promises to provide insights and perspectives that can strengthen the impact of home visiting programs.

Implications

Programs that are successful with families at increased risk for poor child development outcomes tend to be programs that offer a comprehensive focus—targeting families’ multiple needs—and therefore may be more expensive to develop, implement, and maintain. In their current state of development, home visitation programs alone do not appear to represent the low-cost solution to child health and developmental problems that policymakers and the public have hoped for for decades. However, as the field continues to research more precision approaches that match program components to child and family needs, add the needed assistance and professional development supports to ensure model fidelity, and incorporate home visiting programs within a comprehensive early childhood system across the first five years of life, more consistent and positive results for participating target families are to be expected.

For high risk families with multiple challenges and levels of adversity, home visiting programs can serve to encourage families to take advantage of preschool programs available to them and their children and increase their participation in other family support programs during the preschool through 3 rd grade years 59 to further support school readiness outcomes.