- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to this park navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to this park information section

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Alerts in effect, the salmon life cycle.

Last updated: July 22, 2019

Park footer

Contact info, mailing address:.

600 E. Park Avenue Port Angeles, WA 98362

360 565-3130

Stay Connected

This site uses cookies. View our Cookie Policy to learn more about how and why.

Regular hours: 9:30 am – 6 pm Last entry at 5 pm

- Member Login

- Cedar River Salmon Journey

Home » Explore the Aquarium » Public programs » Cedar River Salmon Journey

Thank you for joining us for our 2023 Cedar River Journey season! Please check back again soon for our 2024 program dates.

Join the Seattle Aquarium to learn more about salmon! Trained naturalists will be on-site to help you spot spawning salmon and learn about the things we can all do to help them. Free and family friendly.

FOLLOW THE JOURNEY OF A LIFETIME

Each year, thousands of Pacific salmon return to our local watersheds to produce the next generation of fish. Salmon play a key role in our economy and are the cornerstone of our local ecosystem, which supports us all. These amazing creatures are also critical to the health and well-being of Coast Salish peoples, who stewarded these lands and waters for generations and continue to do so today.

Here in Seattle, we’re fortunate to host one of the few wildlife migrations that runs through the heart of an urban watershed. The Lake Washington/Cedar/Sammamish Watershed supports a threatened run of Chinook—as well as sockeye and coho—salmon. From May to September, adult salmon pass through the Ballard Locks on the final leg of their epic journey from the rivers and streams in which they were born, out to the ocean and back to these same rivers and streams. There, during fall and into winter, these salmon will spawn and die, and the Pacific salmon life cycle will begin again.

Questions? Please email us at [email protected] .

Share your feedback

Thanks for joining us on the Cedar River this season! Let us know what you think by taking our survey below.

Become a naturalist

Interested in becoming a Cedar River Salmon Journey volunteer? Fill out the form below.

Take action on behalf of salmon!

Start by checking out the Aquarium’s Act for the Ocean webpage , review salmon actions below or sign up for the Aquarium’s policy action alerts . Everything you do to help salmon also helps our southern resident orcas—and is good for people too!

Get involved

Volunteer, vote and share your knowledge with others

Conserve water

Sweep driveways, take shorter showers and use drought-tolerant plants in your yard

With your car

Take your car to a commercial car wash and have oil leaks fixed

In your yard

Use fertilizers and pesticides sparingly, or just use compost

Around your dog

Pick up dog waste, bag it and place it in the trash (not in the yard waste bin)

Properly use, store and dispose of hazardous household materials

RESOURCES AND ACTIVITIES

Cedar River informational flyer (English)

Folleto informativo del Cedar River (Español)

Informational Flyer (Chinese)

Cedar River salmon field journal (English)

Diario del ciclo de vida del salmon (Español)

Field Journal (Chinese)

Salmon bingo game (English)

Bingo del viaje del salmón (Español)

Salmon bingo game (Chinese)

Salmon information infographic

Salmon life cycle infographic

Salmon life cycle coloring sheet

“Is it or isn’t it salmon?” cheat sheet

Salmon Conservation and Restoration: We Work to Save Salmon in Your Watershed (King County)

Living with Salmon in King County (a guide to salmon in King County)

Habitat Conservation Plan for the Cedar River Watershed and Fish (Seattle Public Utilities)

Salmon Conservation (WA Department of Fish and Wildlife)

Salmon Identification: Ocean Phase vs Spawning Phase (WA Department of Fish and Wildlife)

Protecting Surface Water in Renton (the City of Renton)

Washington State’s biennial report on salmon, their habitat and recovery efforts (Governor’s Salmon Recovery Office and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service)

Watch our webinar series and hear from an education specialist, a fisheries biologist and a salmon recovery manager about the challenges salmon face, their population trends and local restoration efforts in the Cedar River.

Part 1: The Cedar River, a lifeline for people and salmon (an introduction to the Cedar River watershed)

Part 2: Salmon and the Cedar River (an overview of Cedar River salmon and their population trends)

Part 3: Salmon Recovery in the Cedar River: Restoring a place where salmon and people can live together (salmon recovery actions in the Cedar River watershed)

Thank you to our sponsors

King County Flood Control District

MMS Giving Foundation

Seattle Public Utilities

The WRIA8 Salmon Recovery Council

The City of Renton

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers/Seattle District

- Daily Activities

- Aquarium Map

- Hours, Discounts, Groups

- Lightning Talks

- Directions & Parking

- Sensory Inclusive

- Code of Conduct

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Animal Wellbeing

- Animal Enrichment and Training

- Ocean Pavilion

- Beach Naturalist

- Marine Science Clubs

- Marine Summer Camp

- Toddler Time

- On-Site Classes

- Distance Learning

- Outreach Programs

- Homeschool Programs

- Teacher Resources

- Self-Guided Visits

- Host an Event

- Aquarium Stories

- Help our local orcas

- Pinto Abalone

- Indo-Pacific Leopard Sharks

- Kelp and Coastal Ecosystems

- Plastics and Marine Debris

- Marine Populations

- Sea Turtle Rehabilitation

- Influencing Policy

- Monthly Giving

- Donor Clubs

- Planned Giving

- Corporate Partnerships

- Equity & Inclusion

- Sustainability Commitment

- Community Days

- Empathy for Wildlife

- In the News

- Leadership, Board & Financials

Website maintenance

Please note: Our ticketing and membership systems will be offline for approximately two hours starting at 9pm Pacific on Tuesday, February 20. During the maintenance window, online ticketing and membership will not be available.

Thank you for understanding.

Support the Seattle Aquarium

With your help, the Seattle Aquarium builds connections with our community to inspire conservation and curiosity for marine life. When you make an end-of-year gift by December 31, you'll be joining us in protecting our shared marine environment—now and for generations to come. Thank you!

Giving Tuesday

Make a tax-deductible donation to the non-profit seattle aquarium, your donation will be matched dollar-for-dollar up to $10,000 thanks to a very generous anonymous donor.

Cyber weekend

Get 15% off all memberships.

Understanding the Lifecycle of Salmon

Salmon are one of the most iconic fish species in the world, found in both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

They are known for their distinctive pink flesh and are a popular food source for humans and animals alike.

Understanding the lifecycle of salmon is crucial for conservation efforts and management of fisheries.

There are several species of salmon, including Chinook, Coho, Sockeye, and Pink. Each species has a unique lifecycle, but they all share some commonalities.

Salmon are anadromous, meaning they are born in freshwater streams and rivers, migrate to the ocean to mature and grow, and then return to their birthplace to spawn.

This lifecycle is complex and can take several years to complete. Understanding the different stages of the salmon lifecycle is essential for conservation and management efforts.

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

- Salmon are anadromous fish that migrate from freshwater to the ocean and back to their birthplace to spawn.

- There are several species of salmon, each with a unique lifecycle.

- Understanding the different stages of the salmon lifecycle is crucial for conservation and management efforts.

Salmon Species

Salmon are a diverse group of fish that are famous for their life cycle, which involves traveling from freshwater to the ocean and back again to spawn.

There are two main types of salmon: Pacific salmon and Atlantic salmon .

Pacific Salmon

Pacific salmon are native to the Pacific Ocean and its tributaries. There are five species of Pacific salmon: Chinook, Chum, Coho, Sockeye, and Pink.

Chinook salmon, also known as king salmon, are the largest of the Pacific salmon species and can weigh up to 100 pounds. They are prized for their rich, flavorful meat and are often used in high-end restaurants.

Chum salmon, also known as dog salmon, are the most abundant of the Pacific salmon species. They are known for their mild flavor and firm texture, which makes them a popular choice for smoking.

Coho salmon, also known as silver salmon, are smaller than Chinook and Chum salmon but are still highly valued for their delicate flavor and tender texture.

Sockeye salmon , also known as red salmon, are known for their deep red flesh and rich flavor. They are often used in sushi and other raw preparations.

Pink salmon, also known as humpback salmon, are the smallest of the Pacific salmon species and are known for their delicate flavor and light, flaky texture.

Atlantic Salmon

Atlantic salmon are native to the Atlantic Ocean and its tributaries. They are an anadromous species, which means they migrate from saltwater to freshwater to spawn.

Compared to Pacific salmon, Atlantic salmon are generally larger and have a milder flavor.

They are highly valued for their firm, pink flesh and are often used in high-end restaurants.

Atlantic salmon are a popular fish for aquaculture, with Norway being the largest producer of farmed Atlantic salmon in the world.

However, wild Atlantic salmon populations have declined significantly in recent years due to overfishing and habitat destruction.

Salmon Life Cycle

Salmon have a unique and complex life cycle that involves several distinct stages.

Understanding these stages is crucial to understanding the conservation and management of salmon populations. The following sub-sections detail each stage of the salmon life cycle.

The salmon life cycle begins with the female salmon depositing her eggs in a nest, or “redd,” that she has dug in the gravel of a stream or river.

The eggs are fertilized by the male salmon, and the female covers them with gravel to protect them from predators.

The eggs remain in the redd over the winter months, and the embryo develops within the egg.

Alevin Stage

After several months, the eggs hatch into alevins, which are small and have a yolk sac attached to their body.

The alevins remain in the gravel and feed on the yolk sac until it is absorbed into their body.

During this stage, the alevins are vulnerable to predators and require clean, cold water to survive.

Once the yolk sac is absorbed, the alevins become fry and emerge from the gravel to begin feeding on insects and other small aquatic organisms.

Fry are still vulnerable to predators and require clean, cold water with plenty of cover to hide from predators.

Smolt Stage

As the fry grow, they begin to develop the characteristics of adult salmon. At around two years of age, the salmon enter the smolt stage, during which they undergo physiological changes that allow them to transition from freshwater to saltwater environments.

This process is known as smolting, and it prepares the salmon for their migration to the ocean.

Adult Stage

Once they have completed their migration to the ocean, the salmon grow rapidly and mature into adults.

Adult salmon spend several years in the ocean, feeding on small fish and other marine organisms, before returning to their natal stream or river to spawn.

Spawning Stage

When the adult salmon return to their natal stream or river, they are called spawners. Spawners breed and deposit their eggs in the same way that their parents did, and the cycle begins anew.

After spawning, the adult salmon die, and their bodies provide nutrients to the ecosystem.

Habitats and Migration

Salmon are known for their remarkable migration, which takes them from their natal streams to the ocean and back again to spawn.

The salmon lifecycle involves two distinct habitats: freshwater and saltwater .

Freshwater Habitats

Salmon spend the first stage of their lives in freshwater habitats such as rivers, streams, and lakes .

These habitats are crucial for the development of juvenile salmon, providing them with food and shelter.

Salmon eggs are laid in gravel redds, which offer protection from predators and swift currents.

Once hatched, the young salmon, known as fry, emerge from the gravel and begin to feed on insects and other small organisms.

As the fry grow, they move downstream to larger rivers and eventually to the ocean. Some salmon species, such as the sockeye salmon, spend up to three years in freshwater habitats before migrating to the ocean.

Saltwater Habitats

Salmon spend the majority of their adult lives in saltwater habitats such as the ocean and estuaries.

These habitats provide the ideal environment for salmon to grow and mature, with an abundance of food and space to swim.

Salmon are highly migratory fish, and their ability to navigate vast distances is essential for their survival.

The Strait of Juan de Fuca, for example, is a critical migration route for salmon in the Pacific Northwest. Salmon must navigate through rapids, reservoirs, and the Columbia River to reach their natal streams and spawn.

During the spawning season, adult salmon return to their natal streams to lay their eggs. The male salmon, or buck, fertilizes the eggs with milt, and the female salmon, or hen, lays the eggs in the gravel redds. Once the eggs hatch, the salmon lifecycle begins anew.

Reproduction and Breeding

Salmon are anadromous fish, meaning they migrate from the ocean to freshwater streams and rivers to spawn.

The spawning season generally occurs in the spring when the water temperature is between 6-13°C.

During this time, the male salmon develop hooked jaws and humpbacks, while the female salmon develop a swollen belly and reddish coloration.

The female salmon dig redds, which are nests in the stream bed where she will lay her eggs. The male salmon then fertilize the eggs with their sperm, and the eggs are left to develop on their own.

The number of eggs laid by a female salmon can vary greatly depending on the species, but can range from a few hundred to several thousand.

After the eggs are fertilized, they develop into salmon fry and begin their journey downstream to the ocean. The fry will spend several years in the ocean before returning to their spawning grounds to repeat the cycle and ensure the survival of the next generation.

The courtship and spawning behavior of salmon is complex and fascinating. Male salmon compete for the attention of the female salmon, and will often fight each other for the right to mate.

Once a male has successfully courted a female, they will engage in a dance-like behavior where they swim side-by-side and release their eggs and sperm simultaneously.

The success of the salmon breeding cycle is critical to the survival of the species. Factors such as water temperature, habitat destruction, and overfishing can all impact the ability of salmon to reproduce and breed successfully.

Understanding the reproductive biology of salmon and taking steps to protect their spawning grounds is essential to ensuring the continued survival of these remarkable fish.

Challenges and Conservation

The life cycle of salmon is complex and involves various challenges that threaten their survival. Salmon species face numerous threats throughout their life cycle, from incubation to spawning.

These challenges include environmental factors such as pollution , sediment, and dams that obstruct their migration. Predators such as birds , bears, and sea lions also pose a threat to salmon stocks.

Overfishing and habitat destruction have contributed to the decline of salmon populations in the North Atlantic and the West Coast of the United States.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Fisheries and Oceans Canada have implemented conservation measures to protect salmon populations. These measures include habitat restoration, hatchery programs, and fishing regulations.

One of the biggest challenges facing salmon conservation is the impact of dams on their migration. Dams obstruct the natural flow of rivers and prevent salmon from reaching their spawning grounds.

The construction of dams has reduced the number of salmon in Washington and Oregon. Efforts are underway to remove dams and restore natural habitats to protect salmon populations.

Salmon are also affected by pollution and sediment in their habitats. Pollution from agricultural runoff, industrial waste, and urbanization can harm salmon populations.

Sediment from logging and construction can also impact salmon habitats by reducing water quality and covering spawning beds.

Salmon species face different challenges depending on their life cycle. For example, coho salmon and chum salmon are more vulnerable to predators during their ocean phase, while sockeye salmon face challenges during their freshwater phase.

Chinook salmon face challenges throughout their life cycle, including habitat loss, overfishing, and dams.

In addition to natural challenges, salmon also face threats from human activities such as harvest and overfishing.

Harvest regulations have been put in place to protect salmon populations, but illegal fishing still occurs.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the different stages of a salmon’s life cycle.

Salmon have a complex life cycle with several distinct stages. After hatching from eggs laid in freshwater, the young salmon, called fry, remain in the river for several months.

They then undergo a physiological change known as smoltification, which prepares them for life in the ocean.

At this stage, they are called smolts and migrate downstream to the ocean. Once in the ocean, they grow rapidly and become adult salmon. After a few years, they return to their natal rivers to spawn and complete their life cycle.

How long do Pacific salmon live?

The lifespan of Pacific salmon varies depending on the species. Some species, such as pink salmon, have a lifespan of only two years, while others, such as Chinook salmon , can live up to seven years.

After they spawn, all Pacific salmon die, including those that have only spent one year in the ocean.

How old are salmon when they spawn?

The age at which salmon spawn depends on the species. Some species, such as pink salmon, spawn when they are only two years old, while others, such as Chinook salmon, may not spawn until they are six or seven years old.

How many times a year do salmon run?

Salmon typically run only once a year, during their spawning season. The timing of the spawning season varies depending on the species and the location of the river, but it usually occurs in the fall or winter.

Why do salmon change shape when they spawn?

During the spawning process, male salmon undergo physical changes that include developing a hooked jaw, humpback, and a change in coloration.

These changes are believed to help the male salmon compete for females and defend their spawning territory.

What threats are causing declines in salmon populations?

Salmon populations have declined in recent years due to a variety of factors, including habitat loss, overfishing, pollution, and climate change .

These threats can impact the survival of salmon at all stages of their life cycle, from the eggs in the river to the adult salmon in the ocean. Efforts are being made to address these threats and protect salmon populations for future generations.

Add comment

Cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

You may also like

Kokanee Salmon

The Shocking Phenomenon of Zombie Salmon

What’s the Difference Between Sockeye and Steelhead Salmon?

Is Lab Grown Salmon Safe?

What’s the Difference Between Tilapia and Salmon?

What’s the Difference Between Arctic Char and Salmon?

Latest articles.

- What’s the Difference Between Seaweed and Seagrass?

- Hilarious Video Shows How Dolphins Use Pufferfish to Get High!

- The Tallest Bridge Ever Built: A Marvel of Modern Engineering

- Are There Sharks in the North Sea?

- The Largest Lake in the World Isn’t What You Think

- Are There Sharks in Lake Washington?

About American Oceans

The American Oceans Campaign is dedicated primarily to the restoration, protection, and preservation of the health and vitality of coastal waters, estuaries, bays, wetlands, and oceans. Have a question? Contact us today.

Explore Marine Life

- Cephalopods

- Invertebrates

- Marine Mammals

- Sea Turtles & Reptiles

- Sharks & Rays

- Shellfish & Crustaceans

Copyright © 2024. Privacy Policy . Terms & Conditions . American Oceans

- Ocean Facts

Salmon Life Cycle

Salmon are anadromous . This means they start their lives in freshwater, migrate to the ocean where they grow, then return home to their natal, or birth, streams to spawn and die.

There are five species of salmon that live in Washington waters: Chinook, chum, coho, sockeye, and pink. These Pacific salmon species may differ in their life histories, but they all follow a general cycle and have similar habitat requirements to survive.

Click through each section below to learn about the different phases of the salmon life cycle.

Spawning and Death

The salmon carcasses then are distributed by the river’s current along the watershed to provide nutrients to other species and habitat. These dead salmon are particularly special to the surrounding environment because they release nutrients from the ocean.

Banner photograph courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Department of Commerce.

Internet Explorer lacks support for the features of this website. For the best experience, please use a modern browser such as Chrome, Firefox, or Edge.

Life Cycle of the Pacific Salmon

October 24, 2020

A 5-minute animation about the Pacific salmon life cycle and the challenges they face

Salmon are anadromous, meaning they live in the ocean to grow, and come back to their home river to spawn. Throughout their incredible life cycle they travel hundreds, and even thousands, of miles. Along the way, they face many pressures including dams, predators, droughts, poor habitat, water pollution, and more. In this 5-minute animation, you’ll learn about the Pacific salmon life cycle and the challenges they face every day. This animation was created by PNCA Animated Arts in partnership with NOAA Fisheries West Coast Region and the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation.

Last updated by West Coast Regional Office on 02/17/2023

The Life Cycle of Wild Atlantic Salmon

To preserve the dwindling populations of wild Atlantic salmon, we must first understand their life cycle.

Spawning occurs in late winter and early spring when adult salmon return to the streams where they were born. There, they lay eggs in sheltered areas among rocks and gravel. The eggs hatch within a few weeks, and the tiny fry quickly begin to feed on live insects.

As they grow, the fry move into progressively deeper water. In late summer and fall, they migrate back to the streams where they were born, where they spend a year or so before moving out to the lake, again seeking deeper water.

Wild Atlantic Salmon Life Cycle

The Atlantic salmon is an anadromous fish that spends part of its life in freshwater and the other part in the ocean. After hatching and growing in a gravel bed river, the juvenile salmon spend their first year or two in the river before swimming out to sea.

They will typically stay at sea for 2-6 years, feeding on small fish and crustaceans, before returning to their natal rivers to spawn. Salmon spawning occurs in late autumn/early winter, and the eggs hatch in late winter/early spring. When the eggs hatch, the larval fish (alevine) emerge from the gravel and drift downstream until they eventually reach the sea.

The life cycle of wild Atlantic salmon is one filled with wonder and amazement. From their birth in freshwater streams to their migration to the ocean and eventual return as adults, these fish are constantly on the move.

Along the way, they must navigate a complex web of obstacles, all while evading predators. This journey is far from easy, and in many cases only a small percentage of salmon manage to make it back to their homes. Despite the challenges, this life cycle provides a valuable lesson for us all.

The Egg Stage

The Atlantic salmon is an anadromous fish that typically spends 2-3 years in freshwater before migrating to the ocean as a silvery smolt. After an additional 1-3 years at sea it returns to its natal river to spawn. Fertilized eggs hatch in nests called redds in March or April.

The Alevin Stage

The period after hatching from the egg, the salmon is referred to as an alevin and it remains entirely dependent upon the yolk sac for nutrition. Alevin remain buried in the gravel until transitioning to the next phase of development.

The Fry Stage

As the alevins transition to fry, they remain buried in the gravel for approximately six weeks. They emerge from the gravel about mid-May and feed on plankton and small invertebrates. Emergent fry quickly disperse from the nests within the gravel.

The Parr Stage

Next, the fry develop camouflaging stripes along their sides and then enter the parr stage. Parr habitat is typically shallow riffle areas with adequate cover, and moderate-to-fast water flow.

Salmon parr spend 1-3 years in freshwater and then undergo a physiological transformation called smoltification that prepares them for life in a marine habitat.

The Smolt Stage

During the process called smoltification, the camouflage used by fish to blend in with the stream disappears. It is replaced with silvery sides to make the fish more suitable to life at sea. Gills change to make fish ready for saltwater and they begin to swim with the current as opposed to against it.

Ultimately all fish meet the ocean where they begin feeding on plankton. Big fish eat little fish, and in time smolt feed on larger fish such as herring and alewives among others.

The Adult Stage

Atlantic salmon leave Maine rivers in the spring and reach Newfoundland and Labrador by mid-summer. They spend their first winter at sea, west of Greenland.

At sea, salmon feed on a variety of foods which range from squid, sand eels, shrimp and herring. A small percentage of adult salmon return to Maine after one year while the majority spend a second year at sea. One year at sea fish are known as grilse, while two year at sea fish are known as multi-sea winter salmon.

Some Maine salmon are also found in waters along the Labrador coast. Upon return to their native river, females use their tails and the current of the river to create a redd, which is a spawning nest.

The female lays her eggs while the male fertilizes them with milt. Pacific salmon die after spawning while Atlantic salmon head back to sea. They can return to their natal rivers and spawn multiple times.

The ‘Extinction” Life Cycle of Wild Atlantic Salmon in The U.S.?

Maine’s wild Atlantic salmon populations have consistently declined since the mid-1800’s due to a variety of factors, and as a result they have been on the Protected Species List .

The Downeast Salmon Federation (DSF) works on a wide variety of projects all of which are related to wild Atlantic salmon restoration. Dam removals, creation of fish passages, full and partial river restorations, improvements to water quality, conservation education and research are among their many areas of focus. Thanks to their decades of work on the East Machias River, the groundwork has been laid to reintroduce parr into the river.

This website provides information about all types of salmon in the world. Salmon are an important part of the marine ecosystem, and it is critical to understand their role in order to protect them. Bookmark this website to learn more about the life cycle of wild Atlantic salmon, and everything else you need to know about this important species.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Just added to your cart

The salmon life cycle.

Salmon has a unique life cycle in that it does not follow the typical timeline of freshwater fish. Instead, they break their life cycle into six stages, where they undergo significant changes.

How long does salmon live? Learn the answer in our comprehensive guide.

Reproduction and Spawning

During the reproduction and spawning stage, adult salmon return from their oceanic feeding grounds to their natal freshwater habitats, driven by an instinctual homing behavior.

Once in their spawning grounds, the females excavate nests (redds) in clean gravel beds, depositing their eggs, and the males fertilize them with their sperm.

Courtship rituals and aggressive behaviors among males occur to secure mates. Both male and female salmon provide parental care by guarding the redd and eggs from predators. The success of reproduction depends on environmental factors such as water temperature and quality. After incubation, the eggs hatch into fry, continuing the cycle of life for salmon populations and ensuring the overall health of ecosystems.

Egg Development and Hatching

During the egg reproduction and hatching stage, adult female salmon lay their fertilized eggs in carefully excavated nests (redds) in clean gravel beds of freshwater rivers and streams. The eggs are then covered and protected by the female to shield them from potential predators.

The eggs incubate for up to several months, during which the water temperature and environmental conditions play a crucial role in their development. As the incubation period progresses, the eggs absorb nutrients from their yolk sacs, and eventually, the alevins, or newly hatched salmon, emerge.

Alevins stay in the gravel temporarily, living off their yolk sacs before their absorption is complete. After the yolk sac depletes, the alevins emerge from the gravel as fry.

Alevin Stage

During the Alevin stage of the salmon life cycle, the recently hatched salmon remain sheltered in their natal habitats. Alevins receive nourishment through their yolk sacs, which provide essential nutrients. Their bodies are translucent, and they lack fully developed fins, making them dependent on the protection provided by the gravel. As the yolk sac is gradually absorbed, the alevins grow stronger and more active.

Mainly, they seek shelter and conserve energy. Once the yolk sac is fully absorbed, the alevins emerge from the gravel and transition into the fry stage, where they begin to actively swim, feed on tiny aquatic organisms, and face the challenges of the outside environment.

During the fry stage, the young salmon emerge from the gravel and become active swimmers, capable of exploring their freshwater environment. At this stage, the fry is still relatively small and vulnerable to predation, so they seek shelter in shallow, slow-moving waters near the riverbanks.

They feed on small aquatic insects, plankton, and other tiny organisms, gradually transitioning from their initial reliance on the yolk sac to external food sources.

Fry demonstrates schooling behavior to enhance their safety and chances of survival. As they grow and gain strength, their bodies develop the distinctive appearance of juvenile salmon, characterized by well-defined fins and scales.

During the Parr stage, the salmon undergoes significant growth and development. At this point, they exhibit the classic appearance of juvenile salmon with dark vertical markings along their sides.

Parr are more robust swimmers, actively navigating freshwater habitats such as rivers and streams, and they can travel past the riverbanks. They seek out deeper and more complex habitats, including areas with submerged rocks and logs, to find shelter from predators and swift currents.

Parr primarily feeds on a diet of small fish, insects, and other aquatic organisms, contributing to their continued growth and energy reserves. As they approach the next life cycle stage, parr undergoes physiological changes in preparation for their downstream migration to the ocean, marking a critical transition in their remarkable journey.

Smolt Stage

During the Smolt stage, the salmon undergo a remarkable physiological transformation to adapt from freshwater to the saltwater environment of the ocean. This stage typically occurs when the salmon are one to three years old, depending on the species and environmental conditions.

Smolts develop a silvery coloration, and their bodies become more streamlined, preparing them for migration and survival challenges in the open sea. As they approach the transition from freshwater to saltwater, smolts gradually adjust their internal salt balance, allowing them to tolerate the higher salinity levels of the ocean.

Smolts instinctively migrate toward the ocean in response to changing environmental cues, such as photoperiod and water temperature. The journey can be perilous as they navigate through rivers, estuaries, and coastal waters, facing predators and human-made obstacles such as dams.

Marine Migration and Adult Feeding

During the migration and adult feeding stage, adult salmon have successfully returned from the ocean to their natal freshwater habitats to spawn.

After spawning, many salmon species, like Pacific salmon, begin the final phase of their life cycle, where they face the challenging journey back to the ocean. This downstream migration takes them through rivers, estuaries, and coastal waters, covering long distances.

Upon reaching the ocean, adult salmon adapt to the marine environment and embark on extensive oceanic migrations, covering vast distances in search of rich feeding grounds.

In the ocean, they feed voraciously on a diet of plankton, small fish, and other marine organisms, building up energy reserves for their eventual return to their natal freshwater habitats in future spawning cycles.

Salmon Life Cycle FAQs

How long does it take for a salmon to complete its life cycle.

The time it takes for a salmon to complete its life cycle varies depending on the species and environmental conditions. In general, the complete life cycle of salmon can range from one to seven years. Here is a rough breakdown of the time frames for some common salmon species:

- Chinook (King) Salmon : 3 to 7 years

- Coho (Silver) Salmon : 2 to 4 years

- Sockeye (Red) Salmon: 2 to 5 years

- Chum (Dog) Salmon: 3 to 5 years

- Pink (Humpy) Salmon: 2 years

Throughout these years, salmon go through various stages, including spawning, egg development, hatching, alevin, fry, parr, smolt, adult migration, and spawning again. The exact duration of each stage may vary based on factors such as species, environmental conditions, and availability of food resources.

Do all salmon species follow the same life cycle?

No, not all salmon species follow the same life cycle. While most salmon species share common stages such as spawning, egg development, hatching, alevin, fry, parr, smolt, adult migration, and spawning again, variations in the timing, duration, and specific behaviors of each stage exist among different species.

What are the major challenges and threats salmon face during their life cycle?

During their upstream migration to spawn, salmon encounter obstacles like dams, culverts, and other barriers that impede their progress. Pollution, habitat degradation, and reduced water quality in freshwater habitats can negatively impact their survival and reproduction. Overfishing , climate change, and competition with non-native species in the ocean further stress salmon populations, affecting their ability to complete their life cycle successfully.

What is the survival rate of salmon from the egg to the adult stage?

Generally, the survival rate is quite low, with only a small percentage of eggs reaching adulthood. In some wild salmon populations, the survival rate from eggs to adults may range from 1% to 5%. Various factors such as predation, habitat degradation, pollution, and human activities like fishing and dam construction can negatively impact these rates.

Compared to freshwater fish, salmon have complex life cycles in six stages. They are anadromous, spending their entire lives in the ocean before migrating to rivers and streams to spawn. Thus, anglers and fishmongers must familiarize themselves with these patterns to get the best, freshest catch.

Get fresh, sushi-grade Alaskan salmon delivered to your door.

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Press the space key then arrow keys to make a selection.

- Environment

Beaver family that moved into Seattle’s Carkeek Park may complicate salmon-spawning journey

Called by the sound of flowing water and ample trees, a family of beavers have moved into Carkeek Park, building a series of dams along the mouth of Pipers Creek.

The largest dam — which incorporates a fixed park bench and two large trees — has widened and grown to the degree that water is spilling on to a walking trail nearby. The dam, reinforced with mud and branches, also may present a challenge for chum salmon, which are set to return and spawn at any moment, said David Koon, the salmon program director at the Carkeek Watershed Community Action Project.

It’s not clear yet how the beaver dam will impact the spawn, he said, and some of that will depend on how much and when it will rain this season. Beavers build dams to create a pond where they can build a “lodge” to provide protection from predators.

Watch: Beavers build dams in Carkeek Park

In a natural environment — where a river flows consistently all the time — a beaver dam would be no problem for spawning salmon, he said. But Pipers Creek, surrounded by a highly urbanized and concrete-laden watershed, is no natural river.

Even without beavers, the survival rates of the salmon’s eggs are low at Carkeek Park, he said. Due to the nonporous nature of the watershed, the stream’s depth often increases and decreases rapidly before and after rain, leading the eggs often to be washed out. Plenty of other things like runoff from fertilizers, tire dust and dog poop also threaten the eggs.

While beaver dams can sometimes help salmon eggs, slowing down water and filtering silt, the ones in Carkeek Park may prevent the salmon from traveling fully upstream. If the downstream waters are high enough — which they aren’t right now — Chinook and coho salmon can jump over the dams and the chum can beat their way through the gaps, Koon said. Otherwise, the salmon will have to wait for when the water levels get high enough during active rain.

“I don’t think there’s going to be anything so dire from this, that we’re like ‘we’ve got to get rid of these beaver right now’ … I think it’s kind of like ‘let’s wait, watch, learn and adapt,’ ” Koon said.

Normally dead salmon at the end of the season are found as far as a half-mile up from the mouth of Pipers Creek in Venema Creek, he said. The beaver dams sit on the first 300 feet of that path.

Seattle Parks and Recreation is working with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife to “explore mitigation strategies” to “manage” the beavers, said Parks spokesperson Rachel Schulkin; though the department will have to wait until after the migration season to make any changes.

Parks and Recreation intends to apply for a permit to install a device within the dam that would drop the water level, and may also implement fencing to protect trees. The beavers, which likely came over from Golden Gardens, may be relocated, she said.

Standing next to a 2-by-6-inch plank built into the largest dam, Koon estimated the dam’s length is more than 50 feet and the depth of the pooled water is at least 5 feet. Koon, who has kept an eye on the salmon at Carkeek Park for years, said he’s seen small dams at Pipers Creek likely built by young inexperienced beavers that get washed out after one big rain in the past.

“These ones are clearly experienced,” he said. “They’ve done some really good, amazing engineering.”

This year, as the stream has moved and broken through some of the smaller dams, he’s seen the beavers expand and lengthen the large dam, patching up sections overnight. Koon said the two adult beavers and a “kit” or baby beaver have had additional baby beavers since moving into Carkeek.

Most Read Local Stories

- How King County's $500-a-month guaranteed income program fared

- Update: Seattle teacher responds to suspension after Israel-Hamas comments

- UW football's Tybo Rogers pleads not guilty to rape charges VIEW

- North Cascades Highway is opening a little early this year

- Seattle mayor to push for quicker demolition of 'public nuisance' buildings

The opinions expressed in reader comments are those of the author only and do not reflect the opinions of The Seattle Times.

The Epic Migration of Salmon

Published: January 25, 2024

Every year, the rivers and streams of North America witness a spectacular natural phenomenon – the migration of salmon. This awe-inspiring journey, fraught with challenges and perils, serves as a testament to the resilience and tenacity of these remarkable fish. In this article, we delve into the intricacies of the salmon migration, the constant threat they face from bears, and the underlying reasons for this epic journey.

The Migration Route

Salmon embark on a long and arduous journey, navigating their way from the ocean back to their natal freshwater streams to spawn. This cyclical migration is a critical phase in the life cycle of various salmon species, including the iconic Pacific salmon. The journey takes them hundreds, and in some cases, thousands of miles, through a complex network of rivers and streams.

Bear Threats Along the Way

One of the most formidable challenges that salmon encounter during their migration is the presence of bears, particularly in the riverine habitats. Grizzly bears and black bears, well-aware of the annual salmon run, eagerly await the arrival of these nutrient-rich fish. Salmon serve as a vital food source for bears, offering a high-energy meal crucial for their survival, especially as they prepare for the upcoming winter hibernation.

The salmon-bear interaction is a dramatic display of nature’s balance. As salmon navigate upstream, bears are quick to seize the opportunity. They employ various fishing techniques, from patiently waiting near the water’s edge to skillfully catching leaping salmon mid-air. The sheer volume of salmon during the migration provides a feast for bears, contributing to their overall health and chances of survival in the harsh winter months.

The Circle of Life

While the threat of bears is significant, it is an integral part of the natural cycle that benefits both species and the ecosystem at large. The bears’ predation on salmon not only sustains their populations but also redistributes vital nutrients from the ocean to the forest ecosystem. The remains of salmon carcasses left by bears serve as a crucial fertilizer for the surrounding flora, promoting the growth of plants and supporting a diverse array of wildlife.

Why the Migration?

The primary motivation behind their epic migration lies in their reproductive strategy. Salmon are anadromous, meaning they are born in freshwater, migrate to the ocean to mature, and return to freshwater to spawn. The journey back to their natal streams is an instinctual behavior deeply ingrained in their biology. Once they reach their spawning grounds, female salmon lay their eggs in carefully crafted nests called redds, and males fertilize them. This cyclical migration ensures the continuation of their species, maintaining the delicate balance of aquatic ecosystems.

The migration of salmon is a marvel of nature, showcasing the intricate interconnectedness of species and ecosystems. Despite the challenges posed by bears, the salmon’s journey is a testament to their remarkable adaptability and the finely tuned ecological dance that unfolds annually. As we witness this awe-inspiring migration, we are reminded of the fragility and resilience of the natural world, where each species, no matter how small or large, plays a vital role in the grand tapestry of life.

- Latest Posts

- American Animal Shelters Are Running Out of Space, Here’s What We Know - April 18, 2024

- Viola, a 58-Year-Old Circus Elephant, Spotted Jaywalking Through Montana - April 17, 2024

- Watch 100,000 Live Salmon Escape After Truck Crashes in Oregon - April 16, 2024

You've encountered an obstacle

Manmade Dam

The dam is blocking your path. how will you make it past.

Pick one option to proceed

Oh no! You try to find your way past the dam, but you're not able to make it through safely/

You lose one fish.

Follow your salmon on their journey as they travel from the ocean back upstream to spawn. Find safe refuge as you travel, face helpful or harmful encounters, and make decisions that impact whether your salmon live or die.

How to Play

Salmon challenges, keep your salmon alive.

Guide your salmon upstream to spawn, and help them make important decisions and avoid dangerous obstacles along the way.

Explore and Learn

Encounter (tap or click) animated objects as they float down the river to learn about salmon — maybe even find more fish to join you on your journey to spawn!

Congratulations

You made it.

You survived your long journey upstream with 1 salmon left after encountering 13 obstacles and 16 random objects along the way.

The Return Upstream

Pick your salmon.

Sockeye salmon is the dominant commercial species of Pacific salmon.

The Steelhead is often viewed as prize catch for commercial and sports fishers. Steelhead can return multiple times to spawn.

The Chinook is the largest in size but least abundant Pacific salmon species.

Best Places to See Salmon Migration in Seattle Area

This post may contain affiliate links and I may be compensated for this post. Please read our disclosure policy here .

Sharing is caring!

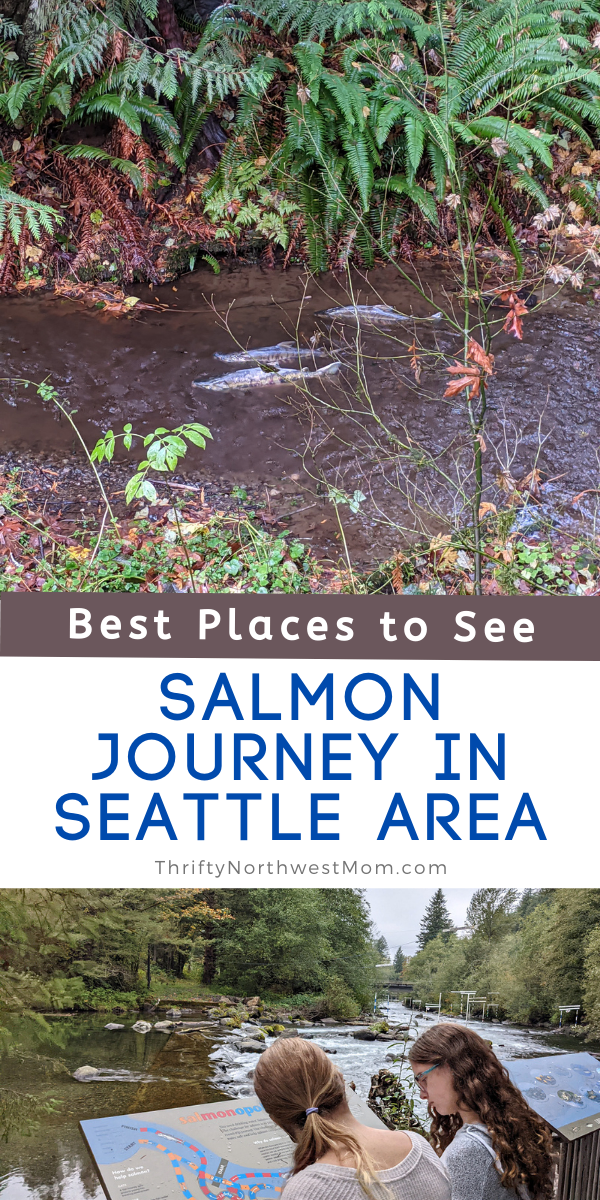

Living in the Pacific Northwest, we have a unique fall opportunity to learn more about the salmon life cycle by watching the salmon return to the rivers of their birth where we can see them much easier as they journey back home. They are returning to spawn (or give birth) in the river where they were born to produce a new generation of fish.

Salmon are such an integral part of our ecosystem here in the northwest, so we found it so educational & interesting to go and see the salmon migration. We learned so much about the salmon life cycle as well as things we can do in our homes to protect the salmon, too.

If you are interested in learning more about the salmon life cycle, there are several great educational opportunities to learn more as you go see the salmon in their native rivers & creeks. We checked out the Kennedy Creek Salmon trail last year, which is on private land, but they open up this educational salmon trail with volunteers several weekends in the fall for visitors. And this year, we visited the Cedar River on a fall weekend when Seattle Aquarium naturalists were out at all the locations to teach more about the salmon journey, which was so helpful to learn more from each of them.

So, we wanted to share about these locations so you can put them on your list to visit in the fall if you are wanting a unique fall opportunity with your family here in the Pacific Northwest!

We’d also love to know which areas you have seen the salmon spawning that you think are best for viewing!

Cedar River in Renton / Maple Valley Area:

The Seattle Aquarium provides an awesome resource for seeing the salmon life cycle as they have special programs all along the Cedar River in Renton and Maple Valley with naturalists stationed at 5 different points along the river where it’s easy access to see the salmon up close.

The Cedar River is one of the few areas where wildlife migration runs thru an urban watershed. The adult salmon first make their way from May thru September from the ocean to Lake Union through the Ballard Locks ( it’s so cool to go see the fish ladders there in the summer! ) to Lake Washington & then on to the Cedar & Sammamish rivers to return the same rivers they were born in. You’ll find the threatened Chinook salmon as well as sockeye & coho salmon returning to the Cedar river for their final journey to spawn & then die.

Every weekend in October thru October 29, 2023, the Seattle Aquarium will have naturalists at these 5 locations along the Cedar River who have tents set up with information as well as resources to learn more about the salmon & they will talk with you about the salmon life cycle as well.

Plus, they have polarized glasses they will hand out at each of the locations which you can use to see the salmon better in the water as it helps to take the glare off the water.

The 5 locations along the Cedar River are very clearly marked on weekends with signs showing where to go to “See Salmon”. But you can actually go anytime if you can’t make the times that the naturalists are available as these locations are so easily accessible & kid-friendly. The first 3 locations are within 5-10 minutes of each other – you can walk to each of them along the Cedar River trail if you’d like. {There may be other parks & locations to access the river all along the Cedar River trail – these are just the spots where the naturalists were & are also easy access points to visit anytime}.

Cedar River Locations with Seattle Aquarium Naturalists :

Renton library.

Did you know that the Renton downtown library is built over a bridge on the Cedar River? This is definitely one of the easiest & quickest spots to access the river & see the salmon swimming upstream. You’ll want to look on both sides of the river – we found the salmon on the north side of the river when we were there.

The volunteer naturalists were so helpful in sharing about the salmon life cycle & journey they go on from the ocean to the lakes to their home rivers. My girls enjoyed seeing the models of the salmon eggs & more.

An extra bonus to heading to this site is that there is a newer playground built on the other side of the river from the parking lot on the Liberty park grounds . It was a great kid-friendly park with lots of fun features & a unique swing for two kids to swing together. There is also a skate park here too. There is plenty of parking in the library parking lot & bathrooms inside the library too. It is all wheelchair & stroller accessible.

Cedar River Park

The Cedar River park is where we saw the highest number of salmon in one place as this is the location where they have a trap set up to catch the salmon to remove them & bring them to the hatchery. This is to ensure that the salmon will be able to lay their eggs in a more protected space to give the eggs a better chance of survival.

Don’t worry, though, there are some tough salmon coming thru and there are still a number of salmon that outsmart this area & get past it & continue upstream along the river for you to see them at later points along the river too.

This location is a nice big area for salmon viewing and it also has quite a bit of parking & bathrooms inside the community center, too. It is all wheelchair & stroller accessible.

This park is easily accessed by highway 405 – in fact, you can see it right next to the freeway. We parked at the library & then walked across the street & under the highway to visit this park since it was so close. It was a short 5 minute walk & it goes under a train bridge, so this could be fun for your kids who love trains to see them up close as they go by.

Riverview Park

This is another very quick & easy location to visit & watch the salmon migration as it’s a short walk from the parking lot to the small bridge over the river. The downside is that the parking lot is quite small if it’s a busy weekend, but if you go during the week, then it shouldn’t be a problem.

You will see the salmon closer up from this location (compared to the previous 2 locations) & it’s a great place to look for where the salmon are actually starting to spawn as the river is a bit slower /not as deep here. The naturalists showed us how you can tell where the salmon are spawning – look for areas in the gravel river bed where it is lighter colored – that is where the fish have worked hard to move the rocks away to deposit their eggs so they can then be covered back up. You’ll find circular or oval shaped areas in the gravel where they have been laying their eggs.

When we went a few weeks ago, the trees were just starting to turn colors, but I bet they are about prime color viewing now if you walk past the bridge & into a pretty park-like setting or along the Cedar River trail right there. It was a nice park to let the kids run around in the grass.

Belmondo Reach

My personal favorite location to see the salmon up close was the Belmondo Reach park location. This is a short little walk thru a salmon habitat restoration area and then you come upon the banks of the Cedar River.

You can walk right out to the river & we found a big rock to stand on & it was fascinating to have the salmon come right up by the rock & the banks of the river on their journey upstream.

The downside to this location is once again a very small parking area. It does not have a paved path, but our friend was able to take a stroller down to the river bank, but it’s definitely not wheelchair friendly.

Landsburg Park

This location is the furthest away but it’s definitely worth the visit! If you go on a weekend thru 10/29 between the hours of 11 and 4pm, they will have people on hand who can give you a tour of the dam & fish ladders at this location. Even if you miss the dam tour, you can still view the salmon well from the viewing platform after they have worked their way up a variety of rock platforms – you might even see some jumping thru the air to make their way up. Look for spawning areas once they make it past the rocks as this is a popular place for them to spawn. This location does have a lot of parking on both sides of the road. It is not wheelchair friendly, but I’d say it’s mostly stroller friendly.

Kennedy Creek Salmon Trail – near Olympia / Shelton

Last year, we had the opportunity to head to the popular Kennedy Creek Salmon Trail outside of Olympia & Shelton. This is a 1.5 mile trail that is an interactive learning site where you can view up to 80,000 salmon (typically the number is 20,000 – 40,000) who come to spawn in the lower 2 miles of this creek every fall. This land is now owned by Washington DNR (Dept of Natural Resources) & they work with the South Puget Sound Salmon Enhancement Group to provide volunteer docents who are on hand to give invaluable information about the salmon migration.

The salmon return to this location a bit later, during the month of November & the Kennedy Creek Trail will be open Saturdays – Sundays from November 4th to December 6th . The Trail is open to the public on weekends from 10am to 4pm , for free for visitors to come & walk the trail & see hundreds of salmon cramming the creek!

It is so impressive & hard to describe or photograph the sheer amount of salmon in this creek without going to see it for yourself! This was definitely the best salmon migration experience we had with seeing them so close up & so many of them so active as they’d jump & make their way up the creek.

They do also offer field trips & group hour long guided tours Monday – Thursday with the docents, so make sure to contact them if you’d like to schedule. No dogs are allowed on this trail since you do get so close to the salmon & it’s to protect both the salmon & the dogs. The first 1/2 mile of the trail is ADA accessible.

There will be docents on hand every day to answer questions & provide information about the salmon journey, but they do not lead guided tours except with scheduled group tours during the week. We were so grateful for all of the interesting information that the docents provided to us last year as they answered our questions about the salmon spawning process.

More Resources & Places to See Salmon Migration:

Tumwater Falls – Olympia WA – this is a great location to view the salmon returning to spawn from mid September to mid October. There are fish ladders with new glass walls to help the salmon make their way up past the Upper Falls to spawn. There is also a salmon hatchery at this location too & new interpretive signs explaining the salmon migration process.

This is a beautiful park to visit & walk along the Deschutes River & see these beautiful waterfalls and take in the gorgeous fall colors all around too! Make sure to read our full review of Tumwater Falls here !

Bayshore Preserve – Shelton WA – head to the Johns Creek trail, Johns Creek Estuary trail & the end of the Lookout Trail to see the salmon move upstream thru the creek. Docents will be at the preserve the first 2 weekends of November ( Nov 4, 5, 10, 11 and 12 ) to provide information about the salmon migration from 10am to 12pm.

They also have a cool option at this salmon viewing station where they will have underwater cameras set up in multiple locations to live-stream the salmon action to handheld tablets on the shore. With wifi you can sync your phones to the camera to take real-time photos & videos of the salmon in Johns Creek. This lets you see the underwater activity & look as if you were actually swimming with the salmon. So cool!

Carkeek Park – Seattle. Keep an eye on their Facebook page for details on when to expect the salmon in this area

Chuckanut Creek – Bellingham . The bridge in Arroyo Park is a great place to see the returning salmon

Clark’s Creek Park – Puyallup. Keep an eye on the Puyallup Watershed Salmon Info page on Facebook for more info about when the salmon are returning to Clark’s Creek Park in Puyallup

Issaquah Creek – Issaquah – They have a great viewing area of the Issaquah Creek & the Issaquah Hatchery also offers guided tours – make sure to sign up early though – they were booking out 2-3 weeks or more in advance this year. From the hatchery, you can have creekside viewing as well as a chance to look thru the glass windows into the fish ladders.

Longfellow Creek – West Seattle . Check the King County website for best viewing areas

North Creek Trail – Bothell – check the website for directions on best viewing areas along this trail.

Nooksack River – Whatcom County . Not only can you see returning salmon here, but once the salmon have spawned & then died, this area brings in hundreds of eagles from mid November thru January. You can easily see the eagles from the road , especially the bridge at Mosquito Lake Road, just off the Mount Baker Highway near Deming.

Swan Creek Park – Tacoma . They offer naturalist led walks & a salmon celebration most years at Swan Creek. Keep an eye on the Puyallup Watershed Salmon Info page for more info.

Tolt River – Carnation – you can view the salmon returning from the Snoqualmie Valley Trail – make sure to check out the website to see the exact locations

Resources to find more about viewing Salmon in Washington:

Where to See Salmon in Washington State – this is a great listing of places & organizations providing information & tours/visits etc to see the salmon migration.

King County Salmon Viewing Sites – this is a great resource listing all of the different sites around King County to see the salmon migration

Parent Map Salmon Viewing List – this list compiled some great options around the south Puget Sound to see the salmon spawning

Let us know your favorite place to see the salmon journey back to their birth rivers!

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Welcome to Thrifty NW Mom! We are based in the greater Seattle / Tacoma area. We are a one-stop resource for ways to save money all around the Pacific Northwest! You’ll find everything from ways to save at the grocery store , online shopping deals , free or affordable family events in the Northwest, dining discounts , frugal DIY tips and much more!

Recent Posts

Five gifts under $5 that are perfect for gifting, 15 things i love to buy at the dollar tree (or dollar store near you), best day trips from seattle (puget sound area) to enjoy, things to do in bellevue on a staycation.

Copyright © 2015 Thrifty Northwest Mom. All Rights Reserved.

- Latest News

- Press Releases

Salmon Migration: Interactive Map Illustrates Fantastic Journey in Peril

- Jacqueline Koch

- Feb 22, 2021

Endangered Columbia River Basin Salmon Connect Communities Across Northwest, New Proposal Offers Opportunity to Recover Them

SEATTLE — The release of a media-rich, interactive storymap, Salmon Migration: A journey that connects us all , highlights the iconic wildlife event that brings together diverse Northwest communities, from the Pacific Coast to central Idaho. Columbia River Basin salmon and steelhead are essential for Northwest tribes, local economies, and the region’s way of life — yet they’re running out of time. The Salmon Migration storymap is a timely addition to a national conversation ignited by U.S. Representative Mike Simpson’s (R-Idaho) recent proposal for the Columbia Basin Fund, a jobs and infrastructure framework that offers a strong starting point to save the Northwest’s valuable fisheries and river-dependent communities by restoring a free-flowing lower Snake River.

“The endangered salmon of the Columbia and Snake Rivers sustain a fragile ecosystem, diverse communities and the Northwest’s economic prosperity. The Columbia Basin Fund is a bold step in the right direction, it’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to launch the greatest river restoration and salmon recovery effort in history,” said Sarah Bates, acting regional executive director for the National Wildlife Federation’s Northern Rockies, Prairies, and Pacific Region.

Traveling across the region, the Salmon Migration storymap weaves together personal stories and insights from communities and generations connected by the Columbia River, from teenage conservationists in Boise, ID, to seasoned commercial fishermen on the Pacific coast. The storymap takes viewers on a journey of discovery and prompts an important question for us all: Can we transform the interconnected challenges of energy, agriculture and salmon into a stronger, more resilient Northwest?

“If we follow the migration of these magnificent fish, we can fully understand why the Northwest needs a comprehensive solution that restores salmon. Idaho Congressman Mike Simpson answered our calls with a blueprint for the largest river and salmon restoration effort in history that also creates jobs and strengthens the energy and agriculture sectors,” said Chris Hager, executive director of Association of Northwest Steelheaders. "We applaud his dedication and look to our regional delegates to engage with Simpson’s proposal to bring urgent innovative solutions to this issue.”

The Salmon Migration storymap is a guide to understanding the many ways Northwest salmon runs have shaped our lives, communities and the region. The Columbia River Basin framework and recent media reports highlight the interconnected challenges—and opportunities—of a region-wide salmon recovery effort:

- Read Rep. Simpson’s Columbia Basin Fund framework

- What would the Columbia Basin Fund do? Watch the video

- A Seattle Times feature by Lynda Mapes outlines a new vision for the Northwest: GOP congressman pitches $34 billion plan to breach Lower Snake River dams in new vision for Northwest

- A New York Times article highlights the urgent need to address warming water temperatures in the Columbia River Basin: How long before these salmon are gone? Maybe 20 years.

- The Seattle Times outlines our best opportunity to make good on treaty obligations and promises to Northwest tribes: Salmon People: A tribe’s decades-long fight to take down the Lower Snake River dams and restore a way of life

View the interactive Salmon Migration story map here to learn more about the salmon that are the lifeforce of the Columbia and Snake River systems.

Read the National Wildlife Federation’s statement on the release of the Rep. Simpson’s Columbia Basin Fund here .

Get Involved

Donate Today

Sign a Petition

Donate Monthly

Nearby Events

Sign Up for Updates

What's Trending

Take the Pledge

Encourage your mayor to take the Mayors' Monarch Pledge and support monarch conservation before April 30!

UNNATURAL DISASTERS

A new storymap connects the dots between extreme weather and climate change and illustrates the harm these disasters inflict on communities and wildlife.

Come Clean for Earth

Take the Clean Earth Challenge and help make the planet a happier, healthier place.

Creating Safe Spaces

Promoting more-inclusive outdoor experiences for all

Where We Work

More than one-third of U.S. fish and wildlife species are at risk of extinction in the coming decades. We're on the ground in seven regions across the country, collaborating with 52 state and territory affiliates to reverse the crisis and ensure wildlife thrive.

- ACTION FUND

PO Box 1583, Merrifield, VA 22116-1583

800.822.9919

Join Ranger Rick

Inspire a lifelong connection with wildlife and wild places through our children's publications, products, and activities

- Terms & Disclosures

- Privacy Policy

- Community Commitment

National Wildlife Federation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization

You are now leaving nwf.org

In 4 seconds , you'll be redirected to our Action Center at www.nwfactionfund.org.

- Black Caviar

- Seafood Samplers

- Live Seafood

- Tuna & Mahi Mahi

- Fish Market

- Smoked Seafood

- Marine Collagen

- Cooking Tools Set

- - $25 Off -

- Free Shipping

Related Products

Premium Alaskan King Salmon Fillet Portions

Also in news.

Salmon: The Nutritional Powerhouse Backed by Experts

November 17, 2023

Salmon, often hailed as a superfood, has earned its reputation as a nutritional powerhouse. This delectable fish not only delights the taste buds but also offers a myriad of health benefits. Dr. Mehmet Oz, a renowned cardiothoracic surgeon and television personality, emphasizes the importance of omega-3s:

"Omega-3 fatty acids, found abundantly in salmon, are like magic for your heart. They can lower your risk of heart disease, reduce inflammation, and improve cholesterol levels."

But salmon's benefits go beyond heart health. It's also a fantastic source of high-quality protein, vitamins, and minerals. Dr. David Perlmutter, a neurologist and author, highlights salmon's brain-boosting potential:

"The omega-3s in salmon play a crucial role in brain health. They support cognitive function and may even help reduce the risk of neurodegenerative diseases."

Ready to savor the delights of salmon? At GlobalSeafoods.com , we offer a diverse selection of premium salmon varieties that will satisfy your culinary cravings and provide you with the health benefits you seek.

View full article →

Seafood Market with Fresh Fish: A Comprehensive Guide

The Ultimate Guide to Enjoying Live Maine Lobster

- Crab & Shellfish

- Frozen Fish

- Ocean Supplements

- Kitchen Accessories

+ Call to Action $25 Gift

+ categories.

- Alaskan King Crab Legs

- Alaskan Pollock

- Alaskan Sockeye Salmon

- Albacore Tuna

- Anxiety Relief

- Atlantic Salmon

- Beluga Caviar

- black caviar

- Bluefin Tuna

- Boiling Crab

- Brain Function

- Caviar Recipes

- Chef Knives

- Chilean Sea Bass

- coastal creatures

- cocktail caviar

- Coho Salmon Caviar

- conservation

- Cooking Methods

- Crab Recipes

- culinary tips

- decline-sturgeon

- Diver Scallops

- Dry Aged Fish

- Dungeness Crab

- Dungeness crab clusters

- Dungeness Crab Legs

- Exotic Shellfish Sampler

- Fish and Seafood

- FLOUNDER FISH

- Fresh Seafood Delivery

- Fresh Wild Alaskan Salmon

- Gooseneck Barnacles

- Gourmet Seafood Platter

- Halibut Recipes

- healthy eating

- Japanese restaurants

- Jumbo Sea Scallops

- Kaluga Caviar

- King Crab Legs

- King Salmon

- Live King Crab

- Live Lobsters for Sale

- Live Scallops

- Live seafood

- Lobster Tail

- luxury food

- Ora King Salmon

- Osetra Caviar

- Ossetra Sturgeon Caviar

- Pacific Cod

- Pacific Halibut

- Pacific Ocean

- Pacific Whiting

- Paddlefish Caviar

- Petite Oysters

- Petrale Sole

- Premium Caviar Selection

- Salmon Caviar

- Salmon Poke

- Sashimi-Grade Tuna

- Sea Urchin Sushi

- Seafood Dishes

- Seafood Market

- Seafood Restaurants

- sevruga caviar

- Shrimps & Prawns

- Silver Salmon

- Smoked Salmon

- Smoked Tuna

- Snail Caviar

- Sturgeon Caviar

- Sustainable Seafood Choices

- Tartar Sauce

- Tilapia Fish

- weathervane scallops

- White Sturgeon

- White Sturgeon Caviar

- Whiting Fish

- Wild Caught Shrimp

- Yellowfin Tuna

- Yellowtail snapper

- Terms & Conditions

- Affiliate Marketing Partners

News & Updates

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more…

Email Address

By submitting this form, you are granting: Global Seafoods North America, 1750 112th Ave NE, Bellevue, Washington, 98004, United States, http://www.globalseafoodsstore.com permission to email you. You may unsubscribe via the link found at the bottom of every email. (See our Email Privacy Policy for details.) Emails are serviced by Constant Contact.

© 2024 Global Seafoods North America .

- 0 Shopping Cart $ 0.00 -->

Where to see salmon spawning this fall

Born in freshwater rivers and streams, Pacific salmon migrate to the ocean where they spend several years feeding and growing, then return to their natal stream as spawning salmon to reproduce and die.

On their upstream journey home, adult salmon spawners may travel hundreds of miles and often evade many obstacles — predators, competition, and environmental impediments. Once they return to their spawning grounds, the adults reproduce and die soon after, their bodies nourishing the surrounding ecosystems.

From late summer to early winter, you can see Pacific salmon as they return to B.C.’s rivers and streams.

“The opportunity to observe the journey and life cycle of Pacific salmon is nothing short of spectacular. We invite you to join us and witness the marvel,” says Michael Meneer, PSF President and CEO. “Seeing salmon in our own communities emboldens us to take action and do everything in our power to take care of this iconic species. We can come together as People for Salmon to make a difference.”

Our newly launched interactive Salmon Spotting map has the best public spots in the province to see the fish in action. The map includes more than 70 family-friendly locations with clearly marked trails and public viewing areas across Metro Vancouver, Fraser Valley, Sea-to-Sky, Vancouver Island, Sunshine Coast, Southern Interior, and Northern B.C. You can also read safety tips to prepare for your visit, and share your favourite public-access salmon spotting location with us by submitting a location or using #SalmonSpotting on social media.

Opportunities to see salmon spawning are expected to be especially remarkable this year because 2022 is a dominant year for Fraser River sockeye, which return in greater abundance every four years. To celebrate the return of wild salmon, there are several events taking place around the province:

- 43rd Annual Coho Festical in North Vancouver (Sunday, September 11, 2022)

- Salmon Festival, Horsefly, BC (September 10-11, 2022)

- Salute to the Sockeye Festival, Adams River (September 30 – October 23, 2022)

- Salmon Come Home Event, Coquitlam (Sunday, October 23, 2022)

*if you would like your event to be included in this list, please contact us .

Join our Newsletter

First Name *

Last Name *

- State of Salmon

- Contributors

- Annual Report 2022

- Climate Action

- Community Investments

- Marine Science

- Salmon Health

- Salmon Watersheds

- Blog Stories

- Media Releases

- Species & Lifecycle

- Salmon Facts

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Knowledge Exchange Workshop Series

- Document Library

- Ways to Give

- Donate Online

Journey of the Salmon

- Post author: Infowellsgray

- Post published: August 26, 2013

- Post category: Wildlife

Watching the salmon jump at Bailey’s Chute in Wells Gray Park is a very powerful experience. The journey of salmon is one of the most epic natural journey’s to unfold each fall. Chinook Salmon travel over 600km through lakes, up heavy rapids, strong currents, and against natural predators to their spawning ground, leaving the last bit of effort to spawn, and then to die.

Knowing this and witnessing these incredible creatures battle against all odds is both heartbreaking and overwhelming. Lets take a closer look at the journey of the Clearwater River Chinook Salmon.

Chinook Salmon are one of the largest Pacific Salmon , weighing between 8 – 22kg. The salmon you see this fall were born four to six years ago in a gravely area, a few kilometers downstream of Bailey’s Chute, known as the Horseshoe. They have spent the last few years roaming the Pacific Ocean. Their journey will take them little over a month, and will see them enter the Fraser River near Vancouver, cross Kamloops Lake, up the North Thompson River and then along the Clearwater River. They will feed very little if at all; their only motive is to reach their spawning grounds.

Once they reach the Horseshoe , redds (nests) are dug in the gravel, where their eggs are deposited and fertilized. After all this, all that is left is death. A few salmon, for some unknown reason will overshoot the Horseshoe and battle against the strong currents of Bailey’s Chute. Some believe that it is these salmon that overshoot their spawning ground who are responsible for establishing new spawning grounds, and are actually accredited for returning the salmon back to Clearwater River after the last ice age (Nature Wells Gray, 1995, P 131).

Where to watch Salmon

Bailey’s Chute is located approximately 59.5 km along the Clearwater Valley Road from the Wells Gray Park and Clearwater Information Center. The best time to view these salmon would be early morning and evening in early September. Make sure to call the Information Center as Salmon’s return date vary from year to year, as do their numbers.

Raft River Viewing platform is just outside Clearwater, and here you can view Sockeye Salmon spawning. Each year the return of the sockeye salmon are celebrated through the First Fish Ceremony; a traditional Simpcew First Nation ceremony to give thanks to the creator for the returning salmon.

For more information about the First Fish Ceremony and where to view Salmon contact the Wells Gray Park and Clearwater Information Center at tel: 250 674 3334

Huge database gives insight into salmon patterns at sea

A massive new analysis of high seas salmon surveys is enhancing the understanding of salmon ecology, adding details about where various species congregate in the North Pacific Ocean and their different temperature tolerances.

The project, led by researchers at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, integrates numerous international salmon studies from the North Pacific dating back to the 1950s. Although many individual reports were published by nations and agencies that funded those efforts, they were never fully compiled into an overarching database or analyzed comprehensively at this scale. This new research effort builds upon the extensive and valuable past body of work on the marine component of the salmon life cycle.

Together the data represent a trove of more than 44,000 high seas survey gear hauls across the North Pacific, netting over 14 million salmon. That ocean-based data also provides a contrast from the bulk of salmon research, which tends to focus on river habitat.

"This is a portion of the salmon life cycle that arguably gets overlooked, at least in terms of the grand investment in salmon research," said Curry Cunningham, an assistant professor at UAF's College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences. "As someone who always wondered where all these fish went when they left Bristol Bay, seeing that pattern come to life was so satisfying."