- Visit Parliament Visit

- Français FR

Research publications

About this publication

Executive Summary

1 introduction, 2 global travel and tourism, 3.1 general, 3.2 key details for 2019, 3.3 travel by canadians, 3.4 indigenous tourism, 3.5 canada–united states tourism, 3.6 international competitiveness, 4.1 destination canada, 4.2 federal tourism strategy, 4.3.1 2008–2013, 4.3.2 2016–2017, 4.3.3 2019, 4.3.4 2021, 4.4 other government players, 5 looking ahead.

Canada’s multi-billion-dollar tourism sector employs hundreds of thousands of Canadians and is supported by all levels of government.

In 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, global tourism and travel sector revenue decreased by 49% from the previous year, to US$4.7 trillion. Global tourism employment fell by 19% to 272 million jobs. Similarly, the Canadian sector earned $49.5 billion in 2020, a decline of 40% from 2019, while domestic employment fell to 1.6 million direct and indirect jobs, a decrease of 24%. About 28% of Canadian tourism revenue is generated from inbound visits.

In 2019, Canadians made 37.8 million foreign trips consisting mainly of 27.1 million visits to the United States. Additionally, Canadians made 10.7 million trips to other countries, most frequently Mexico (1.8 million), Cuba (964,000), the United Kingdom (770,000), China (666,000) and Italy (619,000).

According to the World Economic Forum’s Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019 , which ranks the most competitive countries for travel and tourism, Canada ranked ninth out of 140 countries studied, down from eighth place in 2013. Canada ranked first in several sub-categories, such as safety and security, environmental sustainability and air transport infrastructure. Conversely, Canada was found to be deficient in several areas, including price competitiveness and international openness.

Other studies have found that tourism demand is concentrated in Canada’s largest cities, with Toronto, Vancouver and Montréal accounting for 75% of overall visitors and most of this activity taking place during the summer months. There are also challenges stemming from labour shortages, a lack of investment and promotion, and a lack of coordination of tourism policy between all levels of government.

Destination Canada (formerly the Canadian Tourism Commission) is a federal Crown corporation responsible for national tourism marketing and is governed by the Canadian Tourism Commission Act . In 2019, the federal government announced Creating Middle Class Jobs: A Federal Tourism Growth Strategy , which is based on the following three pillars: building tourism in Canada’s communities; attracting investment to the visitor economy; and renewing the focus on public-private collaboration.

Between 2008 and 2020, the federal government invested approximately $1 billion in the tourism industry. In 2021, it announced another $1 billion in funding, including the Tourism Relief Fund.

If international borders continue to reopen and the industry continues its steady overall growth of the recent years prior to the pandemic, it will again contribute to Canada’s economic well-being. And although the United States continues to be Canada’s biggest tourism trading partner, stakeholders might continue their efforts of focusing on more growth-oriented, lucrative emerging markets to better diversify tourism interests to help Canada fulfil its tourism potential.

Canada’s tourism industry is an important contributor to Canadian economic growth. This industry – which comprises hospitality and travel services to and from Canada – is a multi-billion-dollar business that employs hundreds of thousands of Canadians and is supported by all levels of government. This HillStudy provides information about Canada’s tourism industry, travel patterns of visitors to and from Canada, the importance of the United States (U.S.) to Canada’s tourism economy and the role of the federal government.

The global tourism sector suffered substantial declines in activity due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since this HillStudy incorporates data from 2019 and 2020, special attention should be paid to both explicit tourism figures and relative comparisons to previous years due to the extraordinary effects of the pandemic.

According to the Tourism Industry Association of Canada, “travel and tourism” includes “transportation, accommodations, food and beverage, meetings and events, and attractions,” such as festivals, historical/cultural institutions, theme parks and nature settings. 1

The World Travel & Tourism Council’s latest annual research explains the COVID 19 pandemic’s impact on the global travel and tourism sector:

- The sector suffered a loss of almost US$4.5 trillion in revenues worldwide, standing at US$4.7 trillion in 2020.

- In 2019, the sector contributed 10.4% to the global gross domestic product (GDP); this decreased to 5.5% in 2020 due to ongoing mobility restrictions.

- In 2020, 62 million jobs were lost, representing a drop of 18.5% of global sectoral employment, leaving just 272 million employed compared to 334 million in 2019.

- Globally, domestic visitor spending decreased by 45% and international visitor spending declined by 69.4%. 2

3 The Canadian Tourism Industry: Facts and Figures

Only about 28% of Canadian tourism revenue (about $21.3 billion) is generated from inbound visits. The remainder represents domestic spending – i.e., what Canadians spend on domestic and foreign tourism activities. Table 1 provides further information about the industry’s recent performance.

Note: Domestic spending includes spending while on a trip in Canada, spending on airfares with Canadian carriers on outbound trips and spending on tourism-related goods, e.g., camping equipment. International spending includes spending while on a trip in Canada but excludes any pre-trip purchases. GDP refers to gross domestic product.

There are two ways to categorize jobs in tourism:

- Jobs in tourism-dependent industries – the total number of jobs in industries where a significant portion of the revenue is in tourism; this includes accommodation, passenger transportation, food and beverage, entertainment and recreation, and travel services.

- Jobs directly supported by tourism – the share of jobs in the economy servicing visitors as opposed to local clients. These are jobs that would not exist without visitors; e.g., in food and beverage, a certain portion caters to local clients, and the portion that caters to visitors is captured in this number.

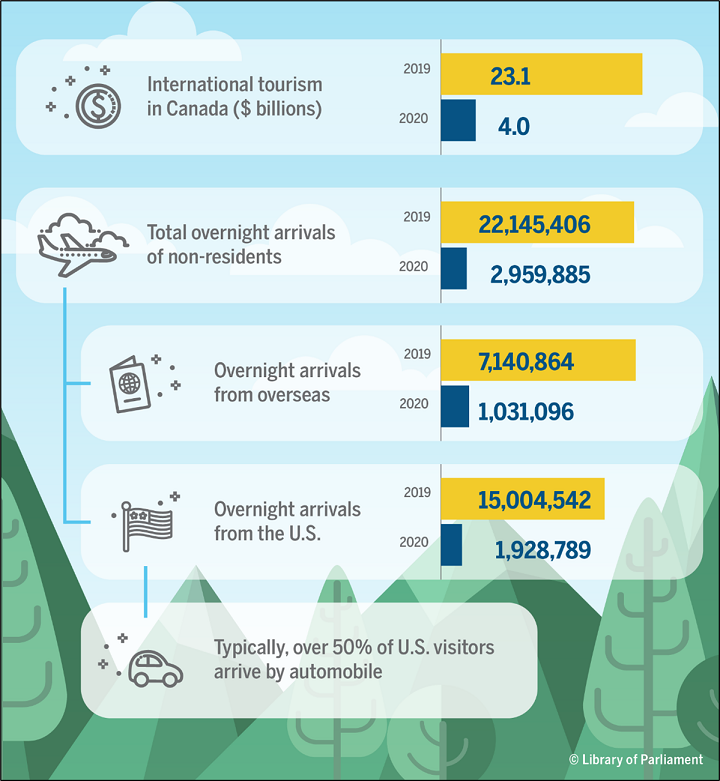

Figure 1 provides further details about international arrivals to Canada.

Figure 1 – Selected Information on International Arrivals to Canada

According to Destination Canada, prior to the pandemic, Canada benefited from the fact that the tourism sector was booming globally. Since 2000, tourism has been growing approximately three to four times faster than the global population and about 1.5 times faster than the overall global GDP . Furthermore, notwithstanding the COVID-19 pandemic, this was expected to continue into the mid-2020s. In fact, 2017’s travel and tourism sector growth of 4.6% exceeded the global GDP growth rate of 3.7%; that is, for the seventh successive year, the sector outpaced global GDP growth, which itself had the strongest growth a decade. 3

However, even with this strong performance, Canada’s tourism industry potential remains significantly underdeveloped. Specifically, even though it has outpaced global population and GDP growth, Canadian tourism growth has lagged behind global tourism growth for several years (see section 3.6 of this Hill Study). 4

Moreover, tourism represents a much smaller fraction of Canada’s exports when compared to peer countries such as the U.S., Japan, the United Kingdom and Australia. Studies suggest there is an opportunity for Canada to more than double its international arrivals and associated revenues by 2030. 5 This could be achieved, in part, by capitalizing on “substantial opportunities to increase the number of tourists to Canada from the United Kingdom, China, France, Germany and Australia.” 6

Beyond its role in helping to create revenue and both direct and indirect jobs in the Canadian tourism industry, the efficient promotion of tourism can be seen as a valuable investment in Canada’s overall economy. A 2013 Deloitte study has shown that “a rise in business or leisure travel between countries can be linked to subsequent increases in export volumes to the visitors’ countries.” 7

In 2019, the Canadian tourism sector had its best year on record, reaching 22.1 million international overnight arrivals, a 4.8% increase over the previous year. Similar to other years, the vast majority (67.7%) came from the U.S.; the top three non-U.S. sources of visitors were the U.K. (875,632), China (715,474) and France (668,490). 8

Destination Canada reported that “air and sea arrivals from the Europe region were mostly on par with 2018 levels, with the exception of France, which led the region (+7.0%).” 9 However, there were mixed results from the Asia-Pacific region as the biggest decline came from the region’s largest market, China (-9.1% in air and sea arrivals), with smaller downward trends from Japan (-1.9%) and Australia (-0.4%). More positively, air and sea arrivals from South Korea were slightly ahead of 2018 levels, while India led the region in year-over-year growth (+9.1%). 10

In North America, the U.S. provided an increase in arrivals on overnight trips entering Canada by air and auto of 6.4%. Mexico was the only one of Destination Canada’s long-haul markets to record double-digit year-over-year growth in overnight arrivals by air and sea (12.3%) in 2019. 11

Canada’s rising popularity among Chinese travellers is particularly noteworthy, as China is now Canada’s second-largest overseas tourism source after the U.K. 12 This is partly attributable to Canada’s having been granted Approved Destination Status by the Chinese government. In 2018, Canada welcomed a record 737,000 Chinese tourists, “surpassing the 700K mark for the first time and doubling the number of annual travellers since 2013, with an average annual growth rate of 16%.” 13 Travelling mainly during July and August, “Chinese tourists spend on average about $2,850 per trip to Canada, staying for around 30 nights.” 14

In 2019, Canadians made 37.8 million foreign trips consisting mainly of 27.1 million visits to the U.S. Although travel to the U.S. declined by 2.3% in 2019 compared to 2018, Canadians “spent $21.1 billion on their trips to the United States in 2019, up 4.8% from a year earlier.” 15

Additionally, Canadians made 10.7 million trips to other countries, the most common of which were Mexico (1.8 million), Cuba (964,000), the U.K. (770,000), China (666,000) and Italy (619,000). 16

Canadians also enjoy travelling within the country, making 275 million domestic trips in 2019, down 1.0% from 2018. Spending on trips within Canada declined 0.3% year over year to $45.9 billion. 17 The top locations were Ontario (116.5 million visits), Quebec (56.9 million visits), British Columbia (34.2 million) and Alberta (32.4 million); this includes both intra and inter-provincial/territorial domestic travel. 18

Canada’s Indigenous tourism sector is diverse and comprises different business models. Although its key drivers of employment and GDP come from air transportation and resort casinos, “it is the cultural workers, such as Elders and knowledge keepers, who define many of the authentic Indigenous cultural experiences available to tourists in Canada.” 19 Moreover, when compared with Indigenous tourism enterprises without a cultural focus, those involved in cultural tourism rely more on visitors from foreign markets as part of their customer base.

Prior to the pandemic, Canada’s Indigenous tourism sector had been rapidly outpacing overall Canadian tourism activity. Specifically, the Indigenous tourism sector’s GDP rose 23.2% between 2014 and 2017, reaching $1.7 billion. 20

Lastly, Indigenous tourism businesses cite access to financing as well as marketing support and training as some of the main barriers to growth. 21

Given its proximity and long shared border, the U.S. is by far the biggest source of Canada’s tourism visitors: in 2018, about two-thirds of all foreign visitors were Americans, 57% of whom arrived by automobile. 22 The U.S. is also the most visited foreign destination by Canadians.

U.S. arrivals to Canada reached 14.44 million in 2018, up 1% over 2017 and the highest level recorded since 2004. American tourists like to take advantage of their long weekends for travel, with Memorial Day (the last Monday in May), Independence Day (4 July) and Labour Day (the first Monday in September) contributing to the largest weekend spikes in road arrivals in 2018. 23

Americans spend around $700 per trip to Canada, staying an average of five nights. In 2018, they preferred mainly nature-based activities, including natural attractions, hiking or walking in nature, and viewing wildlife. 24

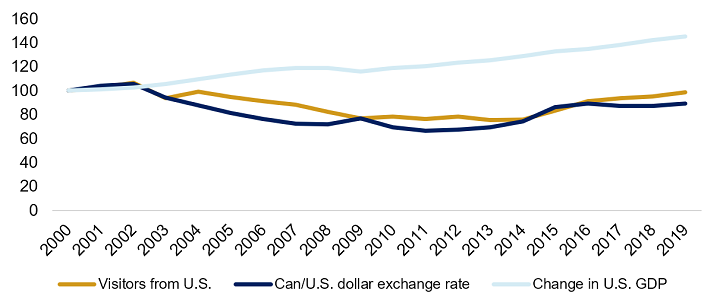

As shown in Figure 2, analysis of various factors over a 20-year period shows that the number of Americans travelling to Canada relates more to the Canadian/U.S. dollar exchange rate than to changes in the U.S. GDP .

Figure 2 – Index Comparing the Number of U.S. Visits to Canada, the Canadian/U.S. Dollar Exchange Rate and the Change in the U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP), 2000–2019 (2000 = 100)

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Statistics Canada, “ Chart 1: Tourists to Canada from abroad, annual ,” The Daily , 20 February 2020; Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “ Canadian Dollars to U.S. Dollar Spot Exchange Rate ,” FRED, Database, accessed 20 August 2021; and World Bank, “ GDP (constant 2010 US$) – United States ,” Database, accessed 20 August 2021.

According to the World Economic Forum’s Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019 , Canada ranked ninth out of 140 countries studied, down from eighth place in 2013. 25 Canada was ranked first in several sub-categories, such as safety and security, environmental sustainability and air transport infrastructure.

In contrast, Canada was found to be deficient in several areas, such as price competitiveness and international openness (e.g., visa requirements, air service agreements).

A 2018 report further indicated the following challenges facing the Canadian tourism sector:

- CONCENTRATED DEMAND – Toronto, Vancouver and Montréal (Canada’s three largest cities) account for 75% of all visitors, and most of this activity takes place during the summer months. Plus, 70% of visitors to Canada come from the U.S., making the sector very vulnerable to the vagaries of the American economy.

- ACCESS – Coming to (and travelling within) Canada can be expensive, difficult and time-consuming; this is true for travel both inter-regionally (e.g., visiting a national park from a large city) and within urban centres.

- LABOUR SHORTAGES – Similar to many sectors that service the public, the tourism industry has been facing labour shortages for some time. In fact, this sector “could face a shortage of 120,000 people by the mid-2020s, and up to 230,000 people by 2030.”

- LACK OF INVESTMENT/PROMOTION – As hotels face up to 95% occupancy during the summer months, there are insufficient room-nights for additional large-attendance events such as conventions, conferences and festivals. Also, compared to peer countries, Canada spends less on marketing and promotion per international tourist arrival (in some cases up to 20% less). One of the contributing factors is that most tourism businesses are small enterprises that face difficulties in securing capital.

- GOVERNANCE – Given that the sector is extremely diverse and made up of many destinations in different regions, successful efforts for one region or operator will not necessarily carry over to other parts of the country or service providers. Also, as tourism policies and programs are spread across numerous organizations within every level of government, making a well-coordinated and integrated Canadian approach is difficult. 26

These assessments suggest that even though Canada is doing well in certain areas, other jurisdictions may be greatly improving their ability to attract international tourism. Changing trends in consumer preferences may also play a role in determining which destinations may be more popular than others at any particular time.

4 The Role of the Federal Government

Destination Canada is a federal Crown corporation responsible for national tourism marketing and is governed by the Canadian Tourism Commission Act . It targets the following markets “where Canada’s tourism brand leads and yields the highest return on investment”: Australia, Canada, China, France, Germany, Japan, Mexico, the U.K. and the U.S. 27

In 2019, the federal government announced its new tourism strategy entitled Creating Middle Class Jobs: A Federal Tourism Growth Strategy . It is based on the following three pillars:

- BUILDING TOURISM IN CANADA’S COMMUNITIES – expand from the concentration of international visitors to Canada’s three largest cities over a few (mostly summer) months by helping communities “exploit and develop the characteristics that make them special. In so doing, they will be better able to convince tourists to get off the beaten path, explore the lesser-known parts of the country, and to visit during the off-peak seasons.”

- ATTRACTING INVESTMENT TO THE VISITOR ECONOMY – to combat the lack of investment in Canada’s tourism sector, the strategy aims to improve coordination among jurisdictions and help attract private investment by establishing “Tourism Investment Groups in every region of Canada to enable the development of impactful tourism projects, including large-scale destination projects.”

- RENEWING THE FOCUS ON PUBLIC–PRIVATE COLLABORATION – with the establishment of the Economic Strategy Table for Tourism, the federal government aims to stimulate and sustain growth in Canada’s tourism sector by working collaboratively with industry to ensure that tourism is on the front lines of economic policy making. This could include addressing “the high cost of travelling to and within Canada, labour shortages and the lack of investment. It could also look at competitiveness, sustainability, the sharing economy and digital platforms.” 28

Part of the focus on improving tourism has been improving accessibility. To that end, in 2018, the Government of Canada introduced Bill C-81, the Accessible Canada Act , which “aims to achieve a barrier-free Canada through the proactive identification, removal, and prevention of barriers to accessibility in all areas under federal jurisdiction, including transportation services such as air and rail.” 29 The bill received Royal Assent in 2019.

4.3 Federal Funding Initiatives

In 2008–2009, the federal government invested over $500 million in the tourism industry to develop facilities and events, and to promote tourism. This is in addition to investments in other areas that affect tourism, such as improvements for Parks Canada and border services. 30 In 2013, funding of $42 million was allocated to improve visa services, 31 an area where Canada has been found to be deficient.

Since 2016, the regional development agencies have allocated over $196 million to tourism businesses, and the Business Development Bank of Canada has provided more than $1.4 billion in financing. Export Development Canada assists Canadian tourism businesses that aim to expand into global markets. 32 Budget 2017 provided Destination Canada with permanent funding of $95.5 million per year for tourism-related work, up from $58 million. 33

Budget 2019 announced that starting in 2019–2020, $58.5 million over two years would go towards the creation of a Canadian Experiences Fund. The Fund supports “Canadian businesses and organizations seeking to create, improve or expand tourism-related infrastructure—such as accommodations or local attractions—or new tourism products or experiences.” These investments would focus on tourism in rural and remote communities, Indigenous tourism, winter tourism, inclusiveness (especially for the LGBTQ2 communities) and farm-to-table/culinary tourism. 34

Additionally, Budget 2019 included $5 million to Destination Canada for a “tourism marketing campaign that will help Canadians to discover lesser-known areas, hidden national gems and new experiences across the country.” 35

Budget 2019 also included the establishment of the Economic Strategy Table dedicated to tourism, which will bring together “government and industry leaders to identify economic opportunities and help guide the Government in its efforts to provide relevant and effective programs for Canada’s innovators.” 36

Announced in Budget 2021, the Tourism Relief Fund is a $500 million national program that is part of a $1 billion package to support the Canadian tourism sector. 37 Its goal is to position Canada as a destination of choice when domestic and international travel is once again deemed safe (i.e., post-pandemic) by:

- empowering tourism businesses to create new or enhance existing tourism experiences and products to attract more local and domestic visitors; and

- helping the sector reposition itself to welcome international visitors by providing the best Canadian tourism experiences to the world. 38

Initiatives under this fund will help tourism businesses and organizations adapt their operations to meet public health requirements; improve their products and services; and position themselves for post-pandemic economic recovery. 39

Part of this funding includes Destination Canada’s $2-million investment along with $950,000 of in-kind support to the Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada to “support the recovery of Indigenous tourism businesses.” 40

Several federal government institutions also play key roles in shaping the outcome of Canada’s tourism economy. For example, the federal government is responsible for the following:

- establishing ticket taxes and travel tariffs;

- providing customs and border services; and

- addressing matters related to national security.

The National Capital Commission and Parks Canada also help ensure that iconic Canadian places are protected and preserved for current and future visitors to enjoy. As well, provincial and territorial governments help develop and promote tourism in Canada.

The Canadian tourism industry was greatly affected by the global COVID-19 pandemic. However, if international borders continue to reopen and if the industry continues its steady overall growth of the recent years prior to the pandemic, tourism will again contribute to Canada’s economic well-being. And although the U.S. continues to be Canada’s biggest tourism trading partner, stakeholders might continue their efforts of focusing on more growth-oriented, lucrative emerging markets to better diversify tourism interests and help Canada fulfil its tourism potential.

- World Travel & Tourism Council, Economic Impact Reports . [ Return to text ]

- Ibid. [ Return to text ]

- Ibid., p. 7. [ Return to text ]

- Destination Canada, China . [ Return to text ]

- Statistics Canada, “ Canadians made fewer trips within Canada and around the world in 2019 ,” The Daily , 9 December 2020. [ Return to text ]

- Ibid., p. 14. [ Return to text ]

- Ibid., p. 15. [ Return to text ]

- Destination Canada, United States . [ Return to text ]

- Destination Canada, Who we are . See also the Canadian Tourism Commission Act , S.C. 2000, c. 28. [ Return to text ]

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, “ Creating Middle Class Jobs: A Federal Tourism Growth Strategy ,” Creating Middle Class Jobs: A Federal Tourism Growth Strategy . [ Return to text ]

- Ibid.; and Accessible Canada Act , S.C. 2019, C. 10. [ Return to text ]

- Government of Canada, “ Chapter 3.1: Connecting Canadians With Available Jobs –Temporary Resident Program ,” Jobs, Growth and Long-Term Prosperity: Economic Action Plan 2013 , Budget 2013. [ Return to text ]

- Government of Canada, “ Chapter 2: Building a Better Canada – Launching a Federal Strategy on Jobs and Tourism ,” Investing in the Middle Class , Budget 2019. The Government of Canada’s regional development agencies are the Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency (ACOA); Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions (CED); Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency (CanNor); Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario (FedDev Ontario); Federal Economic Development Agency for Northern Ontario (FedNor); Prairies Economic Development Canada (PrairiesCan); and Pacific Economic Development Canada (PacifiCan). [ Return to text ]

- Government of Canada, “ Chapter 2: Building a Better Canada – Launching a Federal Strategy on Jobs and Tourism ,” Investing in the Middle Class , Budget 2019. “LGBTQ2” refers to lesbian, gay, trans, queer and Two-Spirit. [ Return to text ]

- Government of Canada, Tourism Relief Fund . [ Return to text ]

- Destination Canada, Destination Canada providing $2 million in funding to Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada ( ITAC ) . [ Return to text ]

© Library of Parliament

- 44 th Parliament, 1 st Session

- 43 rd Parliament, 2 nd Session

- 43 rd Parliament, 1 st Session

- 42 nd Parliament, 1 st Session

- 41 st Parliament, 2 nd Session

- 41 st Parliament, 1 st Session

- 40 th Parliament, 3 rd Session

- 40 th Parliament, 2 nd Session

- 40 th Parliament, 1 st Session

- 39 th Parliament, 2 nd Session

- 39 th Parliament, 1 st Session

- 38 th Parliament, 1 st Session

- 37 th Parliament, 3 rd Session

- 37 th Parliament, 2 nd Session

- 37 th Parliament, 1 st Session

Related content

- Legislative summaries

- Trade and investment series

- See complete list of research publications

- Publications about Parliament

- Library Catalogue

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

Language selection

- Search and menus

Travel and tourism statistics

- Mobile applications

Sign up to My StatCan to get updates in real-time.

Find data on

More related subjects: Travel and tourism

Frontier Counts: Interactive Dashboard

International travel: Advance Information

Crossing the border during the pandemic: 2020 in review

Measuring private short-term accommodation in Canada

Key indicators | All indicators

Changing any selection will automatically update the page content.

Selected geographical area: Canada

- Tourism share of gross domestic product - Canada (Fourth quarter 2023) 1.58%

Latest releases

View the latest Daily releases on the subject of travel and tourism .

Air passenger traffic and aircraft itinerant movements at Canadian airports

The interactive Dashboard for Air Travel is based on estimates from the Airport Activity Survey and the Aircraft Movement Statistics Survey. The Airport Activity Survey collects data on passengers enplaned and deplaned and cargo loaded and unloaded at Canadian airports. The Aircraft Movement Statistics Survey collects data on aircraft movements in Canada. Transportation Statistics: Interactive Dashboard

Canadian Tourism Activity Tracker

The Canadian Tourism Activity Tracker was an experimental product designed in 2021 to assess recovery of tourism activity in Canada. As currently designed, the Tracker has fulfilled this purpose and will no longer be updated after the December 2022 release.

About the Tourism Statistics Program

The Tourism Statistics Program produces detailed statistics on travellers travelling to, from and within Canada, as well as information on travellers' characteristics and spending. The program also provides information to the Canadian System of Macroeconomic Accounts which produces data on travel and tourism expenditures, employment and gross domestic product.

- Destination Canada

- Tourism HR Canada

Provincial and territorial tourism departments

- Government of Canada

- Newfoundland and Labrador

- Prince Edward Island

- Nova Scotia

- New Brunswick

- Saskatchewan

- British Columbia

- Northwest Territories

What do you want to see on this page? Fill out our feedback form to let us know.

Language selection

- Français fr

WxT Search form

Sme profile: tourism industries in canada, 2020.

PDF version

1 MB , 28 pages

This publication is available online at https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/canadian-tourism-sector/en .

To obtain a copy of this publication, or to receive it in an alternate format (Braille, large print, etc.), please fill out the Publication Request Form at www.ic.gc.ca/publication-request or contact:

ISED Citizen Services Centre Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada C.D. Howe Building 235 Queen Street Ottawa, ON K1A 0H5 Canada

Telephone (toll-free in Canada): 1-800-328-6189 Telephone (international): 613-954-5031 TTY (for hearing impaired): 1-866-694-8389 Business hours: 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. (Eastern Time) Email: [email protected]

Permission to Reproduce

Except as otherwise specifically noted, the information in this publication may be reproduced, in part or in whole and by any means, without charge or further permission from the Department of Industry, provided that due diligence is exercised in ensuring the accuracy of the information reproduced; that the Department of Industry is identified as the source institution; and that the reproduction is not represented as an official version of the information reproduced or as having been made in affiliation with, or with the endorsement of, the Department of Industry.

For permission to reproduce the information in this publication for commercial purposes, please fill out the Application for Crown Copyright Clearance or contact the ISED Citizen Services Centre mentioned above.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Industry, 2020.

Aussi offert en français sous le titre Profil des PME : les industries touristique au Canada, 2020 .

Industry Sector, Tourism Branch

Table of contents

Acknowledgements.

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Distribution by industry

- Distribution by geography

- Distribution by employee size

Age of tourism businesses

Method of possessing the business.

- Characteristics of primary decision makers

- COVID-19 Pandemic

- Credit availability and approval

Main provider of debt financing

Amount of financing, terms and conditions, intended use of debt financing.

- Innovation and adoption of advanced technology

- Financial performance

- Conclusions

- Appendix – North American Industry Classification Codes (NAICS) for Tourism industries

Tourism Branch wishes to thank Erin Paton as lead contributor and Krista Apse, Steven Schwendt, Dany Brouillette, Natalie Byers, Patrice Rivard, Connor Johnston, Thepiga Varatharasan, and Madison Olynyk for their helpful contributions, comments and suggestions.

Executive summary

On March 2, 2022, Statistics Canada released the Survey on Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises for the reference year of 2020. The survey is carried out every three years on behalf of Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED) and for this release, data was collected between April and August 2021. ISED's Tourism Branch has contributed funding to this survey every cycle for the past ten years and for this reason, the survey includes a reference sample for Canada's tourism sector.

This report contains a summary of key findings for Canada's tourism sector from the 2020 Survey on Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises, and analysis on employment and financial performance from Statistics Canada's Provincial-Territorial Human Resources Module of the Tourism Satellite Account and ISED's Financial Performance Data, respectively. It provides an overview of business characteristics, innovation activities, and recent financing activities of Canadian small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) in tourism industries in comparison with Canadian SMEs in all industries.

The report reveals:

- Tourism SMEs tend to be younger and larger businesses than all SMEs. More decision makers in tourism industries identify themselves as female, visible minority, or people with disabilities.

- Faced with the unique circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism businesses were more likely to close their doors in 2020 and closed for longer than businesses across all industries.

- Personal financing was the primary source of financing used by tourism SMEs during start-up.

- Debt financing is the most common type of financing sought by tourism SMEs and all SMEs, but both groups experienced more difficulty obtaining this type of financing.

- Tourism SMEs intended to use debt financing primarily on working capital, operating capital and land and buildings.

- Principal challenges faced by tourism SMEs include rising costs of inputs and labour challenges, including shortages and the recruitment and retention of skilled labour.

- Tourism SMEs introduced more overall innovation than all SMEs and were more likely to introduce new product and a new way of selling goods or services than all SMEs.

- Tourism businesses were less likely to be profitable in 2020 than businesses across other sectors but had lower average net losses than other businesses.

The data in this report is appropriately referenced and derived from Government sources reflecting the year 2020 unless otherwise specified, e.g. Employment data from the Provincial-Territorial Human Resources Module, for which the latest available data is for the year 2019.

1. Introduction

Tourism plays a vital role in Canada's economy, accounting for over $45 billion – or over 2% – of Canada's gross domestic product and representing 3.8 of Canada's total exports in 2019. Tourism drives key service industries such as food and beverage services, transportation, accommodations, recreation and entertainment, and travel services. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) constitute the backbone of tourism in Canada, accounting for 99.9% of businesses in tourism industries.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic completely changed the nature of how tourism operators did business. International tourism demand fell nearly to zero with public health measures limiting non-essential travel into the country and many businesses in the tourism sector, like restaurants, recreation businesses like theatres and festivals, and tour companies running sightseeing tours by bus or boat, were required to close or significantly limit customer capacity to meet public health policy on physical distancing of guests and employees.

The pandemic brought about unique conditions for financing of SMEs, including the introduction of new government liquidity programs as well as modifications to eligibility requirements for existing financing programs. In many cases, SMEs experience difficulty obtaining the financing they need to acquire assets, day-to-day expenses or expand into new markets. Obtaining financing can be particularly difficult for SMEs in tourism industries because financial institutions may view them as relatively risky compared with the SMEs in other industries Footnote 1 .

Given the importance of financing to the success and growth of a business, this report investigates the financing activities of tourism SMEs and identifies the financing needs and obstacles they face. This report is an update of SME Profile: Tourism Industries in Canada (Bédard-Maltais, 2015) and provides an overview of business characteristics, ownership characteristics, and recent financing activities of Canadian tourism SMEs in comparison with all SMEs in Canada. It uses data from Statistics Canada's Survey on Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises , 2017–2020. The focus is on results from the 2020 survey and comparisons are made with the 2017 and earlier surveys where relevant.

Data and definitions

The primary data source for this report is Statistics Canada'sSurvey of Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises. The survey defines an SME as a business with a minimum annual revenue of $30,000, with 1 to 499 paid employees. Non-employer businesses and the self-employed are excluded from the survey sample, as are non-profit and government organizations, schools, hospitals, subsidiaries, co-operatives and financing and leasing companies.

For the purposes of this report, a tourism SME is defined as a business that meets the above criteria (except where otherwise indicated) and operates within the tourism industries as defined by Statistics Canada's Canadian Tourism Satellite Account (CTSA). Table A in the Appendix provides a list of North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes that define the tourism industries. According to the CTSA, a tourism industry "would cease or continue to exist only at a significantly reduced level of activity as a direct result of an absence of tourism." This implies that a tourism business may serve both tourists and local customers, as is the case with restaurants and hotel facilities. It should be noted that due to difficulty in measuring the share of economic activity attributable to tourism, this report considers all SMEs operating in these tourism industries as tourism SMEs unless otherwise specified.

For the reference year of 2020, the total sample size for the Survey of Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises was 19,283 enterprises across all sampled industries. The final estimates for this survey were generated from the responses of 9,957 SMEs that in 2020 employed between 1 and 499 employees, generating an annual gross revenue of $30,000 or more. The response rate, as a percentage of in-scope businesses, is 55.5%. Survey collection took place from April to August 2021.

The estimates for tourism industries include firms in a number of sectors, such as transportation, recreation and entertainment, accommodations, and food services. It is a special aggregation of Statistics Canada's standard industry categories that is used by Statistics Canada's Tourism Satellite Account, Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, and other organizations. Estimates for the tourism industries were generated from the responses of 1,048 SMEs.

2. Distribution by industry

Tourism businesses are distributed across five main industry groups: food and beverage services, recreation and entertainment, transportation, accommodations, and travel services. In 2020, 8% (or 108,000) of the estimated 1.30 million Footnote 2 SME employers in Canada operated in tourism industries.

According to Statistics Canada's Business Register, the majority of tourism SMEs operated in the food and beverage services industry (63.8%), followed by recreation and entertainment (16.2%), accommodations (9.4%), transportation (7.1%), and travel services (3.6%), as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Share of tourism SMEs by industry, 2020

3. Distribution by geography

Tourism SMEs operate in every province and territory in Canada and their geographical distribution is roughly proportional to the distribution of other SMEs. As seen in Figure 2, tourism SMEs are predominantly concentrated in Ontario (35.9%) and Quebec (22.4%). In Atlantic Canada, Quebec, British Columbia and Canada's North (as an aggregate of Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut), the concentration of SMEs in tourism industries surpasses the concentration of SMEs in all other industries.

Figure 2: Business distribution by province, December 2020

As shown in Table 1, the food and beverage services industry has the highest representation of tourism SMEs in Canada (63.8%), ranging from 55.4% in Atlantic Canada to 68.2% in Ontario. The northern territories of Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut are the only jurisdiction where food and beverage services is not the majority share of tourism businesses, at 29.9% coming second to accommodations industries (at 30.8%). Recreation and entertainment has the second-highest representation of tourism SMEs at 16.2%, ranging from 13.9% in the North to 18.3% in Atlantic Canada. In general, the travel services industry has the lowest share of tourism SMEs in every province and territory.

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Business Counts

4. Distribution by employee size

Small and medium enterprises are defined by the Survey on Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises as those that employ between 1 and 499 employees. On average, tourism SMEs tend to be larger than SMEs in other industries: while 59.6% of non-tourism SMEs have between 1 and 4 employees, only 29.3% of tourism SMEs are this size. Nearly half (44.0%) of tourism SMEs have between 5 and 19 employees, and a further quarter (24.9%) have between 20 and 99 employees, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Distribution of SMEs by size (number of employees), 2020

Although the majority of tourism businesses are those with 5 to 99 employees (in contrast to SMEs across all industries, the majority of which are those with 1-4 employees), this is because nearly two-thirds of tourism SMEs are in the food and beverage sector and these businesses tend to be larger in size: as shown in Table 2, 48.9% of these SMEs have between 5 and 19 employees and a further 28.8% have between 20 and 99 employees. Across the five tourism industries, there is significant variation in business size by industry. For example, more than half (56.6%) of all travel services industries have between 1 and 4 employees but the same is true for only 21.1% of food and beverage businesses. Businesses with more than 100 employees comprised the smallest share of any tourism industry, less than 5.0% of SMEs for all of the five tourism industries.

5. Employment

The Provincial-Territorial Human Resource Module of the Tourism Satellite Accountcaptures data on employment in tourism industries and complements Statistics Canada's Surveys on Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises. It should be noted that data from that module include all jobs in businesses of all sizes within tourism industries, not just those in SMEs that depend upon tourism activities. The most recent release of the Provincial-Territorial Human Resource Module of the Tourism Satellite Account provides an overview on employment for the reference year of 2019 and may not reflect the state of employment in 2020.

Tourism industries employed 1.9 million Canadians in 2019 Footnote 3 , a 9.4% increase since 2015. This includes jobs of all tenures. As seen in Table 3, overall employment growth in tourism industries over this period was stronger than the growth seen in the rest of the Canadian economy, where growth was only 6.4% over this period. The share of tourism in total employment remained stable at roughly 10% of total employment.

Looking at each industry, the accommodations industry experienced the fastest growth in employment (up 25.9%) over the 2015-2019 period, followed by travel services (up 10.2%), recreation and entertainment (up 10.1%), and transportation (9.4%). Jobs in the food and beverage services industry had the slowest growth, up 4.2% over the period.

Sources: Statistics Canada Supplementary tables from the Provincial-Territorial Human Resource Module of the Tourism Satellite Account, 2015–2019; and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada calculations.

6. Business characteristics

Tourism businesses tend to be younger, on average, than other businesses across the Canadian economy. In 2020, the average age of an SME in Canada was 18 years while tourism SMEs averaged an age of 14 years. 38.9% of tourism businesses are between 3 and 10 years old, compared to 31.4% for all businesses (Table 4).

Sources: Statistics Canada, Survey on Financing of Small and Medium Enterprises

Only half (49.4%) of tourism SMEs were started from scratch by the current owner, compared to three-quarters (75.5%) of SMEs in all industries. Tourism businesses were more than twice as likely to have been bought or acquired by the current owner (48.1% of tourism businesses were bought or acquired as the method of possessing the business, compared to 21.1% of businesses in all industries). Inheritance of a business was the least common method of possession, accounting for only 2.4% of tourism businesses and 3.4% of all businesses (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Method of Possessing the Business, 2020

Of those owners that started their business from scratch, more than three-quarters of owners used personal financing for start-up funds regardless of industry (tourism or all); however, owners of businesses in tourism industries were 1.4x more likely to use credit from financial institutions, 2.1x more likely to use financing from friends or family, and 2.5x more likely to use government loans, grants, subsidies, or non-repayable contributions to finance start-up costs. For owners that acquired their business, tourism businesses were more likely to use personal financing or financing from friends or family for acquisition costs, while owners across all industries were more likely to use credit from financial institutions.

7. Characteristics of primary decision makers

The age distribution of primary decision makers in tourism businesses is comparable to that of decision makers across all industries. Although more than half of tourism respondents reported that the primary decision maker of the business is over the age of 50, younger decision makers are more common in tourism businesses than across all industries (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Age of primary decision maker, 2020

As seen in Table 5, tourism SMEs are more likely to have a primary decision maker that is an immigrant to Canada. Across the economy, 71.3% of primary decision makers report their place of birth as Canada, compared to only 51.1% of tourism decision makers. For those tourism decision makers who were not born in Canada, the average period of time they have resided in Canada is 25 years. 1.8% of tourism decision makers who were not born in Canada have resided in Canada for less than 5 years, compared to 1.1% of decision makers in all industries who were not born in Canada. 32.2% of tourism decision makers have a mother tongue other than English or French, compared to only 19.5% in all industries.

Sources: Statistics Canada, Survey on Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises

Table 5 also shows that two-thirds (66%) of tourism decision makers reported having attained some level of post-secondary education, compared to 70% of decision makers across the economy. Tourism decision makers were slightly more likely to report their highest level of education was a Bachelor's degree or a Master's degree or above, at 42.5%, compared to decision makers in all industries, at 40%.

Tourism SMEs are more likely to be majority female-owned than businesses across all industries (Table 6). In 2020, woman held a minimum 51% ownership stake in 18.1% of tourism SMEs, compared to 16.8% in all industries. Equal ownership stakes were held by woman in 22.4% of tourism SMEs, compared to only 14.3% in all industries. Tourism SMEs were also more likely to be majority owned by visible minorities, at 15.5% compared to only 9.3% in all industries, and by people with disabilities, at 1.1% compared to 0.6% in all industries.

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey on Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises

8. COVID-19 pandemic

In the 2020 survey, respondents were asked several questions related to the COVID-19 pandemic and the impact of the pandemic on their business. More than half of tourism businesses (57.8%) reported that they had to close temporarily due to the pandemic, compared to only a third of businesses across all sectors (33.4%). Tourism businesses reported having to close for an average of 14.0 weeks in 2020.

Significant government support, such as the Canada Emergency Business Account (CEBA) and the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS), was made available to businesses throughout 2020. More than 75% of SMEs in Canada applied for at least one type of government financing in 2020 Footnote 4 , such as CEBA or CEWS. The same was true of more than 85% of tourism SMEs, suggesting these industries experienced a more critical need for support during the pandemic. Most tourism SMEs that applied for government financing during this period reported having applied for CEBA (91%) or CEWS (75%) Footnote 5 , and almost half (44%) said they applied for the Canada Emergency Commercial Rent Assistance (CECRA). By comparison, of SMEs in all industries who applied for government financing in 2020, 86% reported having applied for CEBA, 59% for CEWS and only 17% for CECRA (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Share of businesses that applied for government pandemic supports, 2020

Box 2: Government of Canada supports during the COVID-19 pandemic

To help the tourism sector weather the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government of Canada has provided an estimated $23 billion in emergency supports for tourism businesses over the course of the pandemic (Budget 2022). This includes supports provided via economy-wide programs such as CERS and CEWS, as well as supports provided via sector-specific programs such as the Tourism and Hospitality Recovery Program, the Hardest Hit Businesses Program, the Local Lockdown Program, and the Canada Recovery Hiring Program.

In addition to federal government supports, tourism businesses may also have received financial support from provincial, territorial and municipal government programs during this time.

When asked in 2017 about anticipated average sales growth for their business over the coming three years, tourism businesses were optimistic, with more than 60% of SMEs sampled for the survey in that year Footnote 6 anticipating annual sales growth of between 1% and 10%. When asked about their actual average sales growth between 2018 and 2020, only 43.2% of the tourism businesses sampled reported that the growth was in this range. Over this period of time, tourism businesses are more likely to have reported negative sales growth than businesses across the economy, at 30.9% compared to 20.9%, respectively (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Comparison of anticipated average annual sales growth to actual average annual sales growth, 2018 to 2020

As shown in Figure 8, emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic, businesses regardless of industry are optimistic about the next three years, with more than half of businesses anticipating sales growth of between 1% and 10% from 2021 to 2023. However, tourism businesses are more likely to anticipate negative growth in the next three years (2021 to 2023) than businesses across all industries, at 10.3% compared to 7.1%, respectively.

Figure 8: Anticipated sales growth, 2021 to 2023

When asked about the challenges SMEs perceived to be the major obstacles to growth of their business, businesses across the economy and in tourism indicated the same obstacles: the rising cost of inputs, the challenge of recruiting and retaining skilled employees, and a shortage of labour. However, tourism SMEs reported these concerns as major obstacles to growth at much higher rates compared to businesses across all sectors. Fluctuations in consumer demand and government regulation were also seen to be major obstacles to growth. The ability of a business to obtain financing has been considered by some as a challenge for small businesses, especially in the tourism and hospitality sector. Although it does not rank in the top 5 perceived major obstacles, 15.6% of tourism SMEs believed the ability to obtain financing was a major obstacle to their business, compared to only 9.5% of SMEs in all industries (Table 7).

A higher proportion of tourism SMEs have plans to sell, transfer or close their business in the next five years, at 32.2% compared to 24.9% of businesses in all industries. For those businesses that plan to sell, transfer or close their business, most tourism businesses (54.8%) intend to sell to external parties.

10. Financing activities

Credit availability and approval.

In 2017, 47.1% of SMEs required external financing Footnote 7 with goods-producing sectors like manufacturing and resource extraction relying on this financing more frequently than service-producing sectors. More than 61% of manufacturing firms and 56% of resource extraction firms (agriculture, forestry, fishing, hunting, mining, oil and gas extraction) reported a need for external financing in 2017, while for Canada's tourism sector, only 45.9% reported the same need.

In 2020, given the challenging operating conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic, the percentage of firms requiring external financing was significantly higher across the whole of the economy. 82.4% of all SMEs requested some degree of external financing in 2020, compared to an average of 88.9% of tourism SMEs (Table 8). SMEs in accommodations and food services industries reported the highest need, at 90.4%.

Of those firms that reported that they did not request external financing in 2020, the most common reason was that external financing was not required (79.6% for tourism businesses and 86.5% for businesses across all industries). 6.4% of non-applicants in the tourism sector thought their request would be turned down, compared to an average of 3.1% across all industries. The percentage of non-applicants that thought their request would be turned down is higher for businesses in the accommodations and food services industry at 11.3%, suggesting that the impact of COVID-19 on sector financing was uneven across tourism industries.

When looking at the amount of financing authorized, government financing and debt financing were the most important sources of financing used by small businesses. In 2020, more than 85% of tourism SMEs requested government financing (Table 9), accounting for more than half (58%) of all financing received in that year (Figure 9). Just over 16% of tourism SMEs requested debt financing and debt financing accounted for more than one-third (34%) of the total amount of all external financing authorized to tourism SMEs.

Figure 9: Share of total financing authorized to Tourism SMEs in 2020, by financing instruments

Source: Statistics Canada, Survey on Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises , 2020.

In 2020, of those tourism businesses whose debt financing requests were turned down, 24.3% of them indicated that the lender turned down the request because the project was considered too risky, compared to the average of 8.3% for businesses across all industries. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, business needs for debt financing were generally higher in the absence of typical market demand. Federal, provincial and territorial governments implemented new eligibility rules for existing financing programs as well as created new temporary financing programs, which may explain the rise in government institutions as the providers of debt financing between 2017 and 2020.

The majority of debt financing regardless of sector was sought from domestic chartered banks or credit unions. As in 2017, domestic charter banks were the main provider of debt financing in 2020, but a larger share of debt financing was obtained through government institutions in 2020 compared to previous years, indicative of the unique conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Providers of debt financing, 2017 and 2020

In 2014 and 2017, tourism SMEs reported the most common reasons for lenders turning down their financing requests was that the project was too risky, or the business operated in an unstable industry, and reported these reasons at higher rates than SMEs across the economy. Given this perception of risk, tourism SMEs may have relied more on government institutions like the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC) to obtain external financing or to programs such as the Canada Small Business Financing Program to access loan guarantees (see Box 2).

Box 3: Government financing through the business development bank of Canada and the Canada Small Business Financing Program

For the 2020-21 Fiscal Year, which ended in March 2021, the BDC had an outstanding financing commitment of $3.74 billion to tourism-related clients, or approximately 11.6% of BDC's total loans and guarantees portfolio. [Source: Business Development Bank of Canada, BDC 2021 Annual Report]

For Fiscal Year 2020-21, Canadian small businesses received 3,655 loans valued at $864 million through the Canada Small Business Financing Program. Accommodation and food services was the largest industry sector Footnote * , receiving 37.7%, or $326 million, of the total value of loans, a decrease of 41.4% compared to the previous year. These loans were distributed across 1,244 small businesses. For more information, visit Canada Small Business Financing Program [Source: Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, Canada Small Business Financing Act, Overview and Highlights 2020-21.]

On average, the ratio of authorized funding to requested funding was close to or exceeded 90% for tourism SMEs. This means that, on average, a tourism businesses received 89.9% of the amount of debt financing they requested, and 99.2% of the amount of lease financing they requested. These rates are similar to those of businesses across all industries (92.3% for debt financing and 95.2% for lease financing) (Table 10).

Tourism SMEs received 6.2% of the external financing that was authorized in 2020, a sizeable share considering that the tourism sector (pre-pandemic) accounts for only 2.1% of Canada's GDP. 41% of authorized external financing in 2020 went to production industries such as agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting, mining, oil and gas extraction; construction; and manufacturing.

On average, tourism SMEs were granted similar terms and conditions on their external financing as compared to businesses across all industries. Interest rates did not vary substantially, although tourism businesses were more likely to finance for longer terms (e.g., 138-month term for non-residential mortgages, compared to 111 months for all businesses) and were more likely to provide personal assets as financing collateral than the average SME (49.2% for tourism businesses, compared to 36.9% for all businesses).

Nearly 70% of tourism SMEs who requested debt financing in 2020 intended to use this financing for working or operating capital, such as inventory, paying suppliers, etc. This is common across all industries regardless of sector, although tourism SMEs report this as the intended use of their debt financing more frequently (only 60% of SMEs across all industries reported this as the intended use of their debt financing). Other machinery or equipment (16%) or land/building (15.2%) were the next most common intended uses among tourism businesses.

11. Innovation and adoption of advanced technology

In 2011, the survey introduced a series of questions on the innovation practices of SMEs. Innovation is a key accelerator for business growth and increasing productivity. It constitutes a competitive asset for SMEs and is particularly important for attracting new or repeat customers in the context of very competitive tourism industries. Respondents are asked about their innovation activities in four key areas:

- Product innovation: a new or significantly improved good or service;

- Process innovation: a new or significantly improved production process or method;

- Marketing innovation: a new way of selling goods or services; and

- Organizational innovation: a new organizational method in business practices, workplace organization or external relations.

In the 2020 survey Footnote 9 , more than one-third of tourism businesses (36.4%) reported themselves as an innovator, implementing at least one type of the above innovation activities over the last three years. This is more than the average across all industries, where only 28.4% of businesses reported the same (figure 11)

One in five tourism businesses reported implementing a marketing innovation compared to one in ten businesses across all industries. One in five tourism businesses also reported implementing a product innovation, compared to one in six businesses across all industries.

Figure 11: Innovation developed or introduced between 2018 and 2020

Although half (52.8%) of all tourism SMEs indicated that the adoption or use of advanced technologies were not applicable to the business's activities, almost 20% of tourism SMEs adopted at least one advanced technology between 2018 and 2020. Business intelligence technologies were the most frequent technology adopted by tourism and other businesses, followed by security or advanced authentication systems and Internet of Things (IoT) systems, which include non-traditional computing devices and machines enabled with network connectivity (Table 12).

Tourism businesses were also more likely than other businesses to have an online presence in 2020, with more than three-quarters (77.2%) of tourism businesses reporting being active online, compared to only 58.5% of all businesses. In 2017, only 63.3% of tourism businesses and 53.6% of all businesses reported having a website, but in 2020, more than 80% of businesses in both categories reported having a website (80.6% of tourism SMEs and 82.9% of all SMEs) (table 13).

Tourism businesses also reported being more active on social media in 2020 than businesses across the economy: 77.8% of tourism SMEs reported having social media accounts compared to only 66.2% of all businesses. Tourism businesses were more likely to have adopted digital marketing services and e-commerce platforms, with one in five tourism businesses indicating they had an e-commerce payment system for their customers (compared to one in seven businesses across the whole economy).

12. Financial performance

This section of the profile examines the financial performance of Canadian businesses with annual revenues between $30,000 and $5,000,000 using complete financial data for the 2020 year. The analysis in this section uses data obtained through ISED's Financial Performance Data (link available in references at end of report). This section uses a definition of small business based upon annual gross revenue, as opposed to the definition based upon the number of employees used elsewhere in this profile , because the Financial Performance Data is not available based on the number of people employed by a business. Footnote 10 The definition of tourism industries is consistent with the definition as described in the Appendix.

On average, small businesses in tourism industries had lower total revenues, total expenses, and net profits than the average for small businesses in all industries. In 2020, the average revenue of small businesses in tourism industries was $460,652 compared with $630,959 for small businesses in all industries. Small businesses in tourism industries also had lower than average net profits, at $15,997 compared with $33,763 for small businesses in all industries. A smaller proportion of small businesses in tourism industries (67%) were profitable in 2020 compared with small businesses in all industries (75%). The average net profit of these small businesses in tourism industries was $82,210 compared with $105,479 for small businesses in all industries. A larger share of small businesses in tourism industries were not profitable, but these businesses reported a smaller net loss (−$122,683) on average, compared with non-profitable small businesses in all industries (−$198,802) in 2020.

Source: ISED, Financial Performance Data, 2020

Box 4: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on financial performance

Although the data presented in this section incorporates full year financial data for the 2020 Fiscal Year, it is important to note that in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the financial performance data displayed may not represent a typical year for tourism or other businesses.

In 2017, 80% of tourism businesses with revenues between 30K and 5M were profitable, compared to 78% of businesses in all industries. Although net profit margins for profitable businesses remain relatively unchanged despite the pandemic (tourism businesses had an average net profit of $82,210 in 2020 and $76,307 in 2017), the net loss for non-profitable businesses was much larger in 2020 (−$122,683 compared to −$81,133 in 2017).

Among small businesses in tourism industries, those engaged in transportation and food and beverage service industries had the highest average net profit in 2020 at $19,786 and $10,550 respectively. Despite having the highest average net profit, only three quarters (74%) of small businesses were profitable in the transportation industry and just over half (54%) of the small businesses in the food and beverage services industry were profitable. The travel services industry had the highest average total revenue and highest average total expenses of all tourism industries, and as such it also had the lowest average net profit (an average loss of $7,100) and the lowest percentage of profitable businesses at 51%.

Looking only at profitable small businesses, the transportation industry had the largest average net profit at $90,171 compared to the food and beverage services industry, which had the lowest average net profit of profitable small businesses at $60,400. Looking at only non-profitable small businesses, those in the transportation industry experienced the largest average net loss (−$170,100), whereas businesses in food and beverage services experienced the smallest average net loss (−$49,500).

Source: Industry Canada, Financial Performance Data , 2020.

13. Conclusions

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism industries accounted for 2% of Canada's gross domestic product, 3% of Canada's total exports and 4% of jobs across the country. SMEs are the backbone of tourism industries: more than 99% of tourism businesses are SMEs and approximately 7% of all Canadian SMEs are concentrated in tourism industries. Tourism SMEs were younger and were more likely to be owned by women, visible minorities, immigrants to Canada, and people with disabilities.

Tourism SMEs introduced more overall innovation compared to SMEs in all industries over the 2018-2020 period and were more likely to introduce new products or services (product innovation) and new methods of selling their goods or services (marketing innovation).

Credit providers tend to view tourism SMEs as operators in relatively risky industries compared with SMEs operating in other industries. Compared with all SMEs, tourism SMEs found it slightly harder to obtain debt financing in 2020 under the pandemic conditions. They obtained most of their debt financing from domestic charter banks and were more likely than other businesses to use credit unions and government institutions as their provider of debt financing. Tourism SMEs were more likely to be closed during the first year of the pandemic, and closed for a longer duration, than businesses across the rest of the economy.

Tourism businesses were less likely to be profitable in 2020 than the rest of the economy, with the most acute challenge to profitability seen in the travel services industry, where only half of businesses in 2020 reported being profitable. Though tourism businesses were more likely to be unprofitable in 2020, their average net loss was less than that of unprofitable businesses across the rest of the economy.

Statistics Canada's Survey on Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises is expected to be conducted again in 2024, providing updated insights into tourism industries during the post-pandemic period. In particular, it will be interesting to see if and how business adaptations during the pandemic period influence growth in this unique sector as demand returns to pre-pandemic levels.

Bédard-Maltais, P. 2015. SME Profile: Tourism Industries in Canada .

Business Development Bank of Canada, BDC 2021 Annual Report .

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, Canada Small Business Financing Program Open Data .

Innovation, Science and Economic Development, Financial Performance Data, 2017 and 2020 .

Statistics Canada. Table 36-10-0230-01 - Tourism demand in Canada, quarterly (dollars) .

Statistics Canada, Survey on Financing of Small and Medium Enterprises, 2017 .

Statistics Canada, Survey on Financing of Small and Medium Enterprises, 2020 .

Statistics Canada, Provincial-Territorial Human Resource Module of the Tourism Satellite Account, 2019 .

Statistics Canada, Canadian Business Counts, December 2020 .

Statistics Canada, Tourism Satellite Account Handbook

Appendix – North American Industry Classification Codes for Tourism Industries

Tourism Statistics in Canada

- Updated: March 13, 2024

- Canadian Statistics

Many industries were hit hard by the global COVID pandemic, but the hardest hit industry was the tourism industry. The ban on travel directly affected airlines, cruise lines, accommodation services, tourist attractions, and food services.

It also had an indirect impact on other industries such as retail when visiting shoppers didn’t bring in extra revenue. Some areas, such as the South Shore area in Nova Scotia, were hit harder than others because many local businesses rely on the revenue brought in by tourists.

In this article, we have collected data on how the pandemic affected the tourist industry. We have also included statistics from the first quarter of 2022 to see what has been happening with the number of tourists in Canada since travel bans were lifted.

Tourism Statistics for Canadians

Canada recorded 32 million tourists in 2019 with Toronto and Vancouver the two most popular destinations among international tourists.

- The number of jobs in tourism-dependent industries fell from 2.1 million in 2019 to 1.6 million by the end of 2020.

- Post-pandemic, the tourist industry has struggled to find staff and at the end of the first quarter of 2022, there were 170,000 unfilled jobs in tourism.

- The revenues from the aviation industry fell by 89.9% from April to December 2020.

The tourism spending in the first quarter of 2022 was 34.2% below the pre-pandemic levels of 2019.

- The GDP from tourism increased by 11.9% in the final quarter of 2021.

- Spending by Canadians was 85.8% of the total tourism spending in the first quarter of 2022.

There were 315,400 overseas tourists in Canada in May 2022.

- There were almost ten times more trips to Canada made by US residents in May 2022 compared to the year before and almost twelve times the number of overseas visitors.

- There were seven times as many trips to the United States by Canadian residents in May 2022 compared to the previous May.

- 593,200 Canadians flew to the United States in May 2022, which represents 73.6% of the trips by air recorded in May 2019. Overseas flights returned to 67.2% of the pre-pandemic levels in May 2019.

- 44% of Canadians feel confident welcoming tourists from overseas to their area, while 70% are happy to welcome tourists from other parts of Canada.

84% of Canadians believe tourism is important to the Canadian economy.

Before the Pandemic

In 2019, before COVID forced countries around the world to close their borders, Canada recorded a total of 32 million tourists, the ninth-highest number in the world. However, when looking at the number of tourists in relation to the population, Canada is 49th in the world with 0.85 tourists per resident. It ranked number one in North America.

Toronto and Vancouver were the most popular destinations in Canada among international travellers. In 2019, Toronto ranked 53rd and Vancouver 68th among the world’s most popular cities with 4.74 million and 3.4 million tourists respectively.

In 2019, there were 2.1 million jobs in the tourism-dependent industries and there were 232,000 tourism establishments.

During the Pandemic

Initially, in the first quarter of 2020, only 187,000 jobs were lost in the industry, but as the pandemic forced the borders to stay closed for much longer than initially thought, the second quarter of 2020 saw 581,000 jobs lost. By the end of 2020, there were 1.6 million jobs in the tourism-dependent industries.

The number of active tourism businesses fell by 9.9% in December 2020 compared to January 2020. This was over three times the overall contraction of the Canadian economy, which was 3.1% during the same period.

The aviation industry was one of the hardest hit, with the revenues from April to December 2020 declined by 89.9%. In the same period, accommodation revenues from hotel stays fell by 71.2%. Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver recorded the lowest occupancies in Canada and saw the biggest revenue drop at 90.8% representing a loss of $2.3 billion across the three cities.

Post Pandemic

In the first quarter of 2022, tourism’s share of the gross domestic product in Canada was 1.3% of the total. The gross domestic product from tourism was up by 0.9% and it was the fourth consecutive quarterly increase. Tourism spending increased by 50.7% in the last four quarters, but in the first quarter of 2022, it was still 34.2% below the pre-pandemic levels of 2019.

The growth in the first quarter was largely due to an increase in tourism spending by Canadians during domestic trips. This was up 2.9% compared to the final quarter of 2021. In the first quarter of 2022, tourism spending by international tourists was down by 6.9% compared to the final quarter of 2021. However, there had been a large increase in the number of overnight visitors from the United States and overseas in the final quarter of 2021 especially during the Christmas holidays.

The tourism sector has been steadily adding back over half a million jobs and the number of jobs in the tourist industry went up by a further 0.8% in the first quarter of 2022. However, the industry has struggled to fill these jobs and there were still 170,000 jobs unfilled by the end of the quarter.

Closer look at the tourism spending increases

GDP: The GDP from tourism increased by 11.9% in the final quarter of 2021. It was followed by a more modest increase of 0.9% in the first quarter of 2022. The biggest contribution to the tourism GDP came from the transportation services at 2.9%.

Employment: The number of jobs attributed to tourism has been steadily rising since travel restrictions were relaxed. The number of jobs rose by 4.8% in the fourth quarter of 2021 and by a further 0.8% in the first quarter of 2022. Travel services were the largest contributor with a 10.2% increase followed by transportation services (2.6%).

Domestic Tourism Spending: The amount Canadians spend on travel increased by 2.9% in the first quarter of 2022. The main contributors towards the increase were passenger air transport, and pre-trip expenses such as camping equipment, recreational vehicles and crafts and activities equipment. Spending by Canadians was 85.8% of the total tourism spending in the first quarter of 2022.

International Tourism Spending: Spending by international tourists was up by 116.4% in the last quarter of 2021. However, it well by 6.9% in the first quarter of 2022. The biggest contributor to the decline in the first quarter of 2022 was passenger air transport at 11.4% followed by accommodation services at 4.8%.

Tourism Statistics for May 2022

In May 2022, the number of international tourists in Canada continued to rise but was still not at the pre-pandemic levels of 2019. There were almost twelve times as many trips to Canada from overseas countries in May 2022 compared to May 2021. It was still less than half of the trips in May 2019. There were 315,400 overseas tourists in Canada in May 2022.

There were almost ten times more trips to Canada made by residents of the United States in May 2022 compared to the year before. The number of trips represented more than half (52.1%) of the trips taken in May 2019.

The number of visits from US residents in May 2022 was over 1.1 million compared to May 2021 when there were 113,500 trips made by US residents. In May 2019, there were 2.1 million trips to Canada from the United States.

Out of the American arrivals recorded in May 2022, 692,000 were by automobile and 43.7% of the trips were day trips. In May 2021, there were 105,000 trips by automobiles and 1.4 million in May 2019.

Visitor numbers from major markets in Europe and Asia continued to grow. In May 2021, there were 7,100 European visitors to Canada compared to 164,000 in May 2022. Trips to Canada from Asia went up from 8,500 to 72,700 during the same period.

The table below shows the numbers of overnight trips before the pandemic in May 2019 and post-pandemic in May 2021 and May 2022 and the year-on-year differences. We can see from the table that the numbers travelling from France and Mexico have recovered the best while travel from China, Japan and South Korea has been the slowest to recover.

Travelling abroad by Canadians

At the same time as travel to Canada increased again, Canadians started to travel more to the United States and overseas. In May 2022, there were 2.2 million trips to the United States by Canadian residents. In May 2021 there were 311,800 trips to the United States by Canadian residents, so the number of trips a year later was around seven times higher.

The majority of the trips, 1.6 million were by automobile and 58.5% of all trips were one-day trips. The number of Canadians travelling to the United States by air in May 2022 edged closer to the pre-pandemic levels. The 593,200 flights to the United States in May 2022 represented 73.6% of the trips recorded in May 2019. In contrast, only 28,200 Canadians were flying to the United States in May 2021.