Our Stories

Coral Reefs and the Unintended Impact of Tourism

The choices we make as tourists can affect the health of Costa Rica’s renowned coral reefs.

By Camila Cossio / International Program

This page was published 8 years ago. Find the latest on Earthjustice’s work.

One day, during my internship in Costa Rica with the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA), I met up with a friend of mine who was visiting from the U.S. She told me about her trips to the gorgeous local beaches. Everything she described sounded beautiful: the clear blue water, hermit crabs that left their shells to eat breakfast in the early morning hours, sweet fruits that fell onto the smooth sand and the lush trees that offered shade from the hot Costa Rican sun.

But her mood changed suddenly from bliss to concern when she told me about how her co-worker swam too close to a coral reef one afternoon and badly cut his thigh. She was concerned by how unprepared their tour guide was to handle the medical situation, and by how irresponsible it seemed that tourists with no diving experience were allowed to swim so close to the reef.

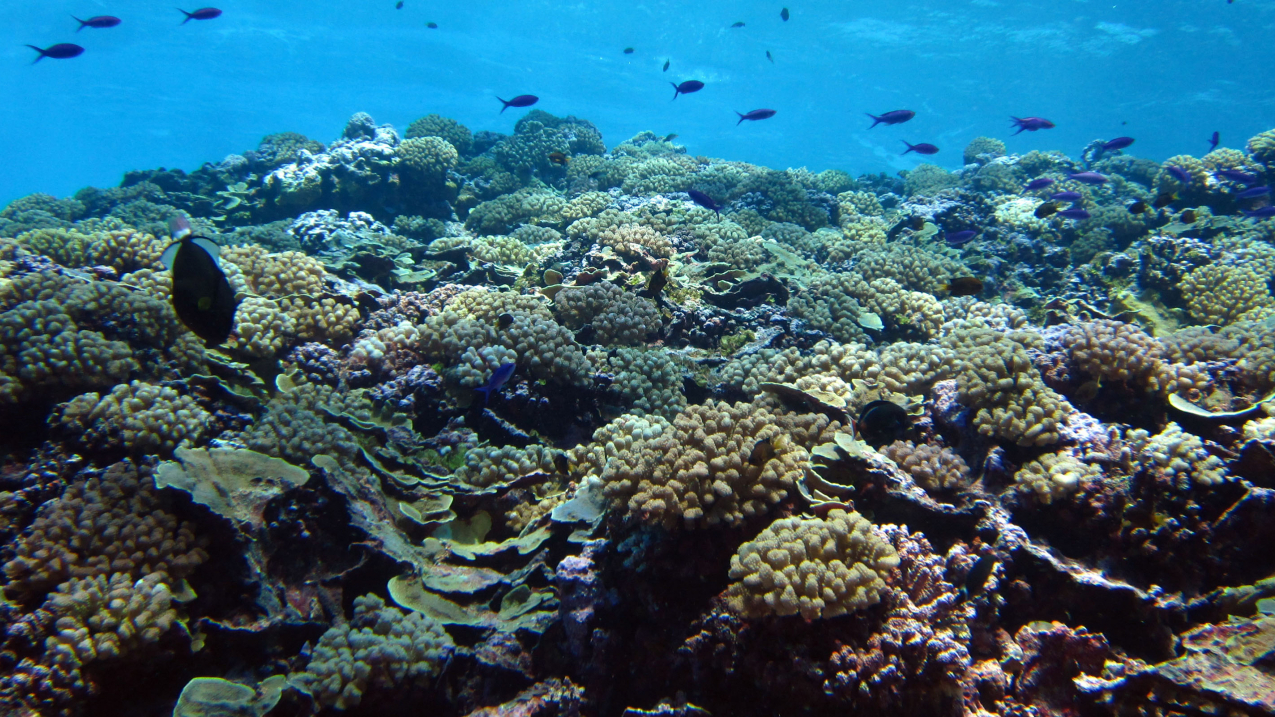

In addition to the physical danger to humans, accidents like these can have a severe impact on sensitive marine ecosystems like coral reefs. Coral reefs are unique and complex systems, vital to the health of the world’s oceans. But 93 percent of the reefs in Costa Rica are in danger , and tourism is a significant factor in their degradation.

How Tourism Threatens Corals

When tourists accidently touch, pollute or break off parts of the reef, corals experience stress. The coral organisms try to fight off the intrusion, but this process often leads to coral bleaching — when corals expel the brightly colored algae that live in them and become completely white. Once corals are bleached, they die and can no longer contribute to the biodiversity of the reef community. And since the disruption of one ocean system impacts all the others, sea grass and mangroves — shallow-water plant species vital to the health of the marine ecosystem — are also threatened by coral stress.

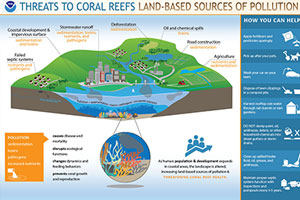

Another significant problem facing coral reefs is sedimentation. When dirt and debris are deposited into the ocean, they pollute marine ecosystems and block the sunlight algae need for photosynthesis. When light is blocked, the immobile coral reefs bleach and die.

In Costa Rica, sources of sedimentation include dredging, logging, agriculture and coastal development driven by the tourism industry. A study by biologist Jorge Cortés documents a decade of negative impacts from tourism on coral reefs in the Cauhita region of Costa Rica. Sedimentation will continue to devastate Pacific reefs if better management principles are not enacted.

Scientists predict that 50 percent of all coral reefs in Latin America are at risk of degradation in the next five to 10 years. Studies show that globally, 30 percent of coral reefs are already seriously damaged. Seventy percent of all reefs are expected to disappear by 2030 if we don’t take corrective action to stop the negative human impacts of climate change on coral reef communities.

Rebuilding a Future for Coral Reefs

Sustainable tourism is a great concept on paper, but hard to enforce in reality. Construction of coastal properties requires dredging. It creates polluted runoff from roads and parking lots and airports. Sewage is dumped into the ocean, and more intensive agriculture to support all the new people increases sedimentation.

Although it’s difficult for an individual to stop massive projects like these, it’s easy to take small but powerful steps in the right direction. Don’t touch living coral and don’t pick up wildlife for souvenirs, including shells, coral rubble and plants. Be conscious of what you bring with you, for example reusable water bottles instead of plastic bottles and a backpack for your trash in case there isn’t an area nearby to dispose of waste properly. Take the bus instead of a car, and if possible, do your research on the hotels or hostels where you stay. Many coastal hotels dump their graywater — wastewater from laundry, cooking and household sinks — into the ocean, contributing to sedimentation and the contamination of coral reefs.

It’s important to be aware of the fact that many land-based activities may directly harm the marine ecosystem. Being an environmentally friendly tourist is not about being perfect, but individual actions, though they may seem small, really can make a big impact.

AIDA provides much-needed recommendations for effective laws and practices to preserve and protect coral reefs in Latin America.

Earthjustice is a founding partner of AIDA , an organization that uses the law to protect the right to a healthy environment in the Americas, with a focus on Latin America. AIDA has documented International Regulatory Best Practices for Coral Reef Protection and is advocating for Costa Rica and Mexico , in particular, to strengthen protections for coral reefs.

Camila Cossio

Camila Cossio is a former intern with the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense.

International Program

The International Program partners with organizations and communities around the world to establish, strengthen, and enforce national and international legal protections for the environment and public health.

“The National Environmental Policy Act is an environmental law, but it is also a tool to fight for worker safety, immigrant rights, and human rights.”

The Stories to read on Biodiversity

- Congress is Trying to Weaken the Endangered Species Act. Again.

- Charting a Path Forward to Recover Salmon in the Columbia River Basin

- Take Action Grizzly bears still need our help

What you need to know this week

- A Fossil Fuel Company Tried to Put a Dirty Gas Plant on a Beautiful Coastline. It Failed.

- How We Stopped a Gas Utility’s Scheme to Propagandize Children

- How We’re Pushing Colorado to Make Buildings Climate-Friendly

- About Us 👨👩👧

How Does Tourism Affect Coral Reefs?

We are drawn to coral reefs. They are colorful, beautiful, and filled with vast amounts of biodiversity that we love to watch and observe. Coral reefs exist in warm tropical regions around the equator that we love to visit when we travel [1] . Unfortunately, our love affair with coral reefs is causing them to be “loved to death”.

While ecotourism has the potential to be a sustainable way to support coastal communities and economies in reef regions without negatively impacting natural resources, in many cases, tourism has caused a great deal of damage to coral reef habitats.

Today, it is estimated that 25% of the world’s coral reefs are damaged beyond repair, with another two-thirds being seriously threatened [2] .

Tourist activities that negatively impact coral reefs

Scuba diving and snorkeling.

While most diving and snorkeling activities have little physical impact on coral reefs, physical damages to corals can and do occur when people stand on, walk on, kick, touch, trample, and when their equipment contacts corals.

Coral colonies can be broken and coral tissues can be damaged when such activities occur. Divers and snorkelers can also kick up sediment that is damaging to coral reefs.

Boating and anchors

Boats grounding in coral reef habitat can damage corals, as can anchors. Anchors can cause a great deal of coral breakage and fragmentation, particularly from large boats like freighters and cruise ships. Heavy chains from large ships can break or dislodge corals. These damages to corals can last for many years.

Anchoring can also damage the habitats near reefs such as seagrasses that serve as nurseries and habitats for the juveniles of different coral reef organisms.

Marinas may inappropriately dispose of oils and paint residues, polluting local waters, and additional pollution may occur during fueling [3] .

Fishing and seafood consumption

An abundance of tourist fishing and consumption of local fish stocks may lead to overexploitation and competition with local fishers.

Inappropriate fishing techniques such as bottom trawling can cause physical damage to reefs.

Cruises and tour boats

These vessels can cause physical damage to reefs through anchoring and grounding, as well as through the release of grey water and human waste into coral reef habitat.

Chemicals added to paint used on boats and fishnets that are intended to discourage the growth of marine organisms can also cause pollution in coral reef waters.

Coastal development

Coastline development and artificial beach creation can result in runoff and sedimentation that washes into ocean waters. This sediment load increases the turbidity in coral reef waters, decreasing the amount of sunlight that can penetrate through the water to reach the corals.

This in turn causes the corals to become stressed, and can eventually lead to bleaching, suffocation, and even coral death. Heavy sedimentation can also lead to decreased coral growth rates, decreased productivity and decreased recruitment.

Demand for souvenirs from the sea

Direct harvesting of coral and other products from the sea by tourists is not very common, but there can be local shops that sell such products in tourist areas. The harvesting of such products can lead to the exploitation of vulnerable marine species.

Pollution from sewage, waste, and chemicals

Sewage or other wastes may be released into the local waters surrounding coral reefs from boats, hotels, or resorts.

Such sewage pollution leads to nutrient enrichment in ocean water, which favors algal growth at the expense of coral organisms.

Inappropriate solid waste disposal can lead to the leaching of toxic chemicals into local waters, and litter ( including plastic litter ) and debris can blow and wash into coral reef waters [3] .

Human encounters with marine life

Fish feeding and encounters with charismatic or rare species can alter the natural behavior of coral reef species, such as foraging behavior, changes in home range size, population density, migration patterns, and reproductive activities.

Changes in the distribution of species may occur, as the more aggressive species will tend to dominate in areas where fish feeding is common. Decreases in overall species abundance have also been observed in some high-use areas.

Invasive species

Invasive marine species can be transported and released into new marine habitats through ballast water and through the washing of ship decks, motors and equipment, water lines, and fishing gear.

How can we reduce negative impacts of tourism on coral reef habitats?

Human behavior change is critical to reduce the negative impacts of tourism on coral reefs.

Tourists must be educated about the negative impacts of destructive activities , the ecological importance of coral reef ecosystems and organisms, and how they can help to preserve coral resources when they travel to these regions.

The level of activity at sites should be reduced through restricted access, and effective and practical regulations that prohibit detrimental actions must also be put in place and properly enforced to prevent pollution and conserve the natural resources of these regions.

Ecotourism activities in these regions should be emphasized and promoted by local communities and the tourism industry as a fun and environmentally-friendly way to vacation in these regions and support the preservation of coral reef ecosystems .

References [1] http://www.coral-reef-info.com/where-are-coral-reefs-located.html [2] http://goo.gl/sv0rD6 [3] http://goo.gl/Cf5R52

Was this article helpful?

About greentumble.

Greentumble was founded in the summer of 2015 by us, Sara and Ovi . We are a couple of environmentalists who seek inspiration for life in simple values based on our love for nature. Our goal is to inspire people to change their attitudes and behaviors toward a more sustainable life. Read more about us .

- Agriculture

- Biodiversity

- Deforestation

- Endangered Species

- Green Living

- Solar Energy

Sliding Sidebar

- Latest News

- Conservation Watch

- Our Mission

- Visit ReefCause

The Unintended Impacts of Tourism on Coral Reefs

Coral reefs are some of the world’s most biodiverse habitats, typically found in tropical areas within 30 degrees of the equator. Thousands of people come from all over the world to see their color and beauty. Reef networks provide thousands of jobs and billions of dollars in revenue for diving tours, fishing trips, hotels, restaurants, and other businesses. The tourism industry has recently collapsed as a result of the safety measures placed in place to protect communities from the COVID-19 outbreak. This seemed like an ideal opportunity to consider the effect of tourism on coral reefs.

While sustainable ecotourism can help provide alternative lifestyles for coastal communities, over-exploitation of the industry can endanger the reefs that have already been destroyed. Increased coastal tourism has put more strain on coral reef resources, either directly on the reefs or indirectly through increased coastal construction, sewage discharge, and vessel traffic.

Tourists must make educated decisions and act responsibly, as their activities can have a negative effect on the conservation of these fragile ecosystems. Many people are also unaware of the consequences of their decisions. What are the threats to coral reefs, and how can coral reef etiquette assist you in being a more knowledgeable tourist?

How Tourism Threatens Corals

Corals are stressed when visitors accidentally touch, pollute, or break off sections of the reef. The coral organisms attempt to repel the invaders, but this also results in coral bleaching, which occurs when corals expel the brightly colored algae that live inside them and become fully white. Corals that have been bleached die and will no longer contribute to the reef community’s biodiversity. Seagrass and mangroves—shallow-water plant species important to the survival of the marine ecosystem—are often endangered by coral stress because the destruction of one ocean system affects all others.

Sedimentation is another major issue that coral reefs face. When dirt and debris end up in the water, they pollute aquatic habitats and prevent algae from getting the sunlight they need to photosynthesize. The immobile coral reefs bleach and die when light is blocked.

Dredging, logging, irrigation, and tourism-driven coastal growth are all causes of sedimentation in Costa Rica, for example. In the Cauhita region of Costa Rica, research by biologist Jorge Cortés records a decade of detrimental impacts from tourism on coral reefs. If better management principles are not implemented, sedimentation will continue to devastate Pacific reefs.

In the next five to ten years, scientists expect that half of all coral reefs in Latin America will be degraded. According to studies, 30% of coral reefs around the world are now severely affected. If we don’t take steps to mitigate the negative human impacts of climate change on coral reef ecosystems, 70% of all reefs are projected to vanish by 2030.

Let’s break these threats down further.

Vessels grounding and colliding with shallow coral reefs may cause significant habitat damage. In nearshore environments, propeller scarring, anchoring, and other physical impacts are becoming increasingly problematic. In Florida alone, 136 manatees died last year after being hit by speeding watercraft. Anchors can dislodge, crush, and fragment the benthic ecosystem, displacing resident fish and obliterating critically significant topographic complexity and habitat structure that takes hundreds of years to recover.

What you can do:

- Use mooring buoys to secure your vessel.

- Inquire about diving and snorkeling operations that practice reef-safe boating.

- If you must use an anchor, do so in areas with a sandy bottom to avoid harming the marine life, corals, or other marine ecosystems in the region.

Scuba Diving Swimming And Snorkelling

Corals may be harmed by uninformed and careless divers, snorkelers, and swimmers touching and standing on them. The coral polyps can be suffocated by kicking up sand. Corals, despite their rock-like nature, are extremely vulnerable to injury and disease. Eating, chasing, and touching marine life can change their behavior, the frequency with which they visit the area, and even their home range.

- Avoid standing on, touching, or kicking coral.

- Practice good buoyancy and keep a safe distance from the action. When diving or snorkeling, make sure you’re not dragging any equipment, such as depth gauges or cameras.

- Avoid diving activities that don’t have a crew member on board.

Invasive Species

Invasive species can spread through tourism and recreational activities such as ballast water transportation, cruise ship hull fouling, and recreational boat fouling (e.g., from hulls, outboard motors, live wells, water lines, fishing gear and debris).

Reducing the degree of use at such sites (e.g., by limiting access) and reducing the impacts of use by changes in human behavior are the two primary approaches to controlling recreational activities in coral reef areas (e.g., educating reef users to discourage destructive actions, and imposing regulations prohibiting certain destructive actions).

Coastal Development

Coral reefs and the coastal structures that link them provide protection from erosion and storm damage. Coastal growth poses a major threat to marine resources because mangrove forests defend against wave action and serve as a storm surge buffer. Beachfront construction of houses, hotels, restaurants, highways, sea walls, and nourishment are all examples of coastal development.

Coastal construction is putting a lot of pressure on turtles. Turtles mate and lay their eggs on the same beaches where they were born. Sea walls can prevent female nesting turtles from laying eggs and cause unnatural beach erosion. Furthermore, beachfront lighting from resorts, highways, and buildings can harm turtle hatchlings. The juvenile turtles are led to the ocean by light as they emerge from their nests. Artificial lighting can cause hatchling turtles to become disoriented, leading them away from the sea and toward paths, obstacles, and predators.

Sedimentation

Coastal development and construction projects can alter natural drainage patterns, resulting in runoff into nearby reefs, especially where mangroves and plant anchorage have been removed. When soil, dirt, and debris are deposited in the ocean, particularly after heavy rains, sedimentation occurs. Sediment pollutes marine environments by obstructing light and suffocating corals and seagrass. To photosynthesize, seagrass beds require clear shallow water. Corals also rely on zooxanthellae for photosynthesis, which means that light deprivation can cause them to starve, bleach, and die.

Efficient planning and land use policies can help to reduce coastal growth and sedimentation. Visit areas with strict planning and development laws in place to protect the aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems wherever possible. Mangrove conservation, minimum shoreline construction distances, and wastewater collection can all help to reduce local stress on coral reefs and improve tourism’s long-term viability.

The Big Picture

Ocean protection needs education and knowledge. Being mindful of your environment can have a huge impact on the ecosystem’s health. When planning a holiday, prioritize sustainability and do research on the hotels you will stay in and the events you will participate in. Your decisions have the potential to have a significant effect on how the tourism industry grows in the future.

Write a comment

How do invertebrates rely on coral reefs, importance of mapping threats to coral reefs, you might also like.

Freak U.S. Winters Linked To Arctic Warming

How Cities Are Working Together To Protect The Oceans

Plastic Ingestion By Freshwater Turtles: A Review And Call To Action

No comments, leave a reply cancel reply, recent posts, ‘giant penguin-like’ seabird’s fossils discovered in northern hemisphere, 3d printing to save coral reefs: hong kong scientists develop method, 5 coral reef conservation success stories from 2020, 5 reasons to organise a beach clean-up, 90 percent of sharks died mysteriously 19 million years ago: study, a deeper look into marine artificial reefs.

MIT Science Policy Review

Coral reefs are critical for our food supply, tourism, and ocean health. We can protect them from climate change

Hanny E. Rivera * , Andrea N. Chan, and Victoria Luu

Edited by Alexandra Churikova and Anthony Tabet

Full Report | Aug. 20, 2020

* Email: [email protected]

DOI: 10.38105/spr.7vn798jnsk

- Coral reefs provide ecosystem services worth $11 trillion dollars annually by protecting coasts, sustaining fisheries, generating tourism, and creating jobs across the tropics.

- Ocean warming is the most widespread and immediate threat to coral reefs globally, followed by disease, and local stressors.

- Management efforts help address local stressors, however, the root cause of global coral decline – increasing temperatures caused by greenhouse gas emissions – must be addressed to ensure the survival of the ocean’s most diverse habitats through the 21st century.

- International climate agreements that aim to continually reduce emissions are our best hope for the survival of reefs.

Article Summary

As many as 1 billion people across the planet depend on coral reefs for food, coastal protection, cultural practices,and income [1, 2]. Corals, the animals that create these immensely biodiverse habitats, are particularly vulnerable to climate change and inadequately protected. Increasing ocean temperatures leave corals starved as they lose their primary source of food: the photosynthetic algae that live within their tissue. Ocean warming has been impacting coral reefs around the globe for decades, with the latest 2014-2016 heat stress event affecting more than 75% of the world’s corals [3, 4]. Here, we discuss the benefits humans derive from healthy reefs, the threats corals face,and review current policies and management efforts. We also identify management and policy gaps in preserving coral habitats. The gain and urgency of protecting coral reefs is evident from their vast economic and ecological value. Management and restoration efforts are growing across the globe, and many of these have been influential in mitigating local stressors to reefs such as overfishing, nutrient inputs,and water quality. However, the current trajectory of ocean temperatures requires sweeping global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in order to effectively safeguard the future of coral reefs. The U.S. should stand as a world leader in addressing climate change and in preserving one of the planet’s most valuable ecosystems.

Coral reefs are one of our planet’s most biodiverse and economically valuable ecosystems [5], yet they have been declining worldwide due to warming ocean temperatures and other stressors [6]. Many major tropical cities are adjacent to coral reef environments (Figure 1A), with nearly 1 billion people worldwide residing in areas influenced or sustained by coral reefs [1, 2]. Coral reefs provide a myriad of ecosystem services that benefit our economies, our shorelines, as well as our plates and medicine cabinets (Figure 2). Throughout, we discuss the valuable benefits provided by corals, explain the stressors harming coral reef ecosystems across global and local scales, review management and conservation efforts, and identify gaps in current policies.

Why corals matter: A wealth of ecosystem services

Coral reefs are dynamic, vibrant ecosystems, formed by over 800 different species of corals. Corals are animals, closely related to anemones and jellyfish, although considering them rocks or plants would not be entirely off base. Their tripartite nature stems from their ability to create the limestone skeleton in which they live, and from the single-celled algae (marine plants) that live inside their tissues in a mutualistic symbiosis (Figure 3A). These algae provide corals with the vast majority of their energetic needs, by providing sugars they produce via photosynthesis to their coral hosts. In addition, corals also harbor a diverse bacterial flora that contributes to their overall health [7], much like the gut microbiome does in humans [8]. These associations allow corals to thrive and build reefs large enough to be seen from space, such as the Great Barrier Reef or the Florida Reef Tract (Figure 1B, 1C).

Coastal Protection: These massive reefs structures can function as seawalls against storms, hurricanes, and sea level rise by protecting coasts from waves and surge [9]. In fact, coral reefs provide the equivalent of $\$$94 million in coastal protection to the U.S. each year [10]. During severe storms, like category 5 hurricanes, that value increases to $\$$272 billion [10]. Worldwide, the total value of coastal protection provided by reefs is estimated at over $\$$4 billion in averted damages during usual storms [10]. For more extreme events such as one-in-25-year or one-in-a-100-year level storms, corals can prevent $\$$36 billion to $\$$130 billion dollars’ worth of damages, respectively [10]. For comparison, the Port of Miami and Port Everglades (Ft. Lauderdale, FL) collectively represent over 3% of all U.S. seaport trade and are worth over $\$$50 billion dollars each year; while the Miami International Airport comprises over 5% of U.S. airport trade, worth nearly $\$$60 billion per year [11]. Corals can provide equivalent amounts of value during mild storms and much more value during severe storms. Coastal protection by coral reefs not only benefits immediately adjacent cities and residents, but can also prevent downstream economic impacts to trade and commerce. In addition, the presence of coral reefs is often used to define maritime boundaries and jurisdictions (see section on UN Convention on the Law of the Sea), such that deterioration and loss of coral reef habitat can lead to loss of jurisdiction over marine territories.

Biodiversity and Natural Products: The reef structures created by corals provide habitat for thousands of marine species, in a manner that is highly disproportionate to their total area. While comprising only a small fraction of seafloor (0.2%) [12], coral reefs are home to an estimated 830,000 species of organisms [13]. The number of species living per unit area on coral reefs is one of the highest on the planet, with biodiversity that rivals rainforests.

This biodiversity is crucial for the health our oceans, and it can also be harnessed for natural product and drug development. For instance, the antiviral drug Vira-A, which is used to treat herpes simplex infections, as well as AZT, which is used to treat HIV, were derived from a compound (Ara-A) isolated from a Caribbean sponge that lives on coral reefs [14]. Another compound (Ara-C) was isolated from the same sponge and developed into the anti-cancer medication Cytarabine [14]. The drug Ziconotide for the treatment of chronic pain was isolated from cone snails found on coral reefs [15]. In addition, several new antibiotic compounds effective against antibiotic-resistance bacteria have been isolated from soft corals that live in coral reefs [16]. The skeletons of hard corals can even be used as bone regeneration materials for humans [17] Overall, the oceans represent a highly unexplored source of products for human medicine. The drug discovery potential in marine environments, and coral reefs in particular, should be considered an invaluable resource [18, 19].

Fisheries and Tourism: The biodiversity of corals reefs also includes fish and seafood species that form part of a 143 billion dollar global fisheries trade industry, such as groupers, lobsters, and snappers [20]. In the U.S., recreational fisheries on coral reefs are worth over $\$$100 million each year. In addition, nearly half of all U.S. fisheries depend on healthy coral reefs ecosystems for sustainable stocks [21]. Excessive fishing on reefs can cause considerable damage and threaten the stability of the ecosystem (see fishing pressure section below). As such, coral reef fisheries benefit from strong management plans that limit the risk of overfishing important species.

Coral reefs also form the foundation of many tourism industries in coastal areas across the globe. In Australia, the Great Barrier Reef received over 26 million visitors in 2016, and tourism to the Queensaland area generates around $\$$6.4 billion (AUD) annually [22]. In the U.S., reef-based tourism in the states of Hawai’i and Florida alone are estimated at over $\$$2 billion dollars annually [23]; and at nearly $\$$240 million in Puerto Rico [21]. ¹

¹Values adjusted for 2020 dollars from the 2007 values reported in [21]

Figure 2: Coral reef ecosystem services (blue) and threats (red). Reefs offer valuable services to humans. Unfortunately, corals are impacted by multiple threats, many of which act to compound each other. Image was created on biorender.com. Icon credits to Lluisa Iborra (skyline), Ifki Rianto (small fishing boat and fisherman), Ruliani (wave), Nikita Kozin (diver), and Luis Prado (large fishing boats), all available from The Noun Project. Reef and associated fish are original artwork by author H.E.R.

What’s killing all the corals: Global and local threats to reefs

Despite their vast ecological, economical, and pharmaceutical importance, coral reefs are one of the planet’s most rapidly degrading ecosystems [6]. On a global scale, corals are most severely impacted by increasing temperatures, coral diseases, and declining pH levels. At regional and local scales, stressors such as overfishing, run-off from land, and coastal development lead to coral mortality and reef degradation [24]. We discuss the causes, effects, and prevalence of different stressors below. While we have organized this section into global and local stressors, reefs are complex ecosystems and are often subjected to multiple stressors simultaneously. It should also be noted that this is not a comprehensive list. For instance, we do not discuss light and noise pollution, ship groundings, invasive species, or tourism pressure. We have focused on the stressors that we consider the most pressing to address given the magnitude of their impact.

Global Stressors

Temperature: Corals can suffer severe stress if water temperatures rise by just 1◦C above their usual summer maximum [25]. While this change in temperature may seem trivial at first, consider the impacts of a fever on human health, where only a 1-2◦C increase can quickly become life threatening. At higher temperatures, corals lose the symbiotic algae that live inside their tissues, and which provide the coral with the majority of their daily food requirements [25, 26] (Figure 3A). This process is called ‘bleaching,’ as the symbionts are also the main source of color in coral tissue (Figure 3B). Bleaching is often fatal to the coral animal, as they can starve to death without their symbionts. If temperatures return to normal within a few days or weeks, the coral can re-establish their community of symbionts and may survive; but this time window is becoming more elusive as heat stress events are becoming both more prolonged and more severe [27].

Since the 1980s, episodes of bleaching have reached reefs around the world, and even iconic and well-protected areas, like the Great Barrier Reef have lost up to 50% of their live coral [6]. Such bleaching events have increased in both frequency and intensity over the last two decades, and it is projected that by 2050 almost all reefs will experience bleaching level temperatures on an annual basis [27, 28]. The most recent global bleaching event (between 2014-2016) caused devastation across the globe [3]. For instance, this event caused 100% bleaching and nearly 95% coral mortality on Jarvis Island, a U.S. territory in the central Pacific [29]. This island had previously been rated as the healthiest and most robust coral ecosystem on the planet [30], and lacks any other sources of coral stress, underscoring the pervasive impact climate change can have on even the most remote and pristine ecosystems. The Great Barrier Reef in particular, has continued to experience bleaching events every year since 2014, and is seeing its most widespread bleaching event this year [31]. On a smaller scale, other stressors can also prompt a bleaching response in corals, including cold temperature, pollution, high UV, and pathogens [16]. However, heat-induced mass bleaching remains the primary cause of coral decline on a global scale [4, 28, 32, 33]. These declines emphasize the desperate need to curtail the carbon emissions that are responsible for increasing ocean temperatures.

Disease: Corals have also been affected by disease outbreaks, especially in the Atlantic/Caribbean, where they have been one of the main sources of decline from the mid 1970’s to today [34]. In the late 1970’s, an outbreak of white band disease decimated the three major Caribbean coral species (Acropora cervicornis, palmata, and prolifera) that were the dominant reef builders in the region [35]. In 2014, a new disease, now called Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD), began in Miami-Dade County, and has since spread throughout the Caribbean [36]. The disease impacts more species than any other known coral diseases, and also kills corals more quickly [36]. In Florida alone, more than 30% of corals have died from the disease over the last few years [36]. Despite much investigation, scientists have yet to isolate the pathogen that causes the disease.

Disease prevalence in corals has also been increasing over time and is sometimes exacerbated by increased temperatures [37]. Combined, disease and bleaching are major causes of coral mortality, and both are predicted to worsen as climate change progresses [33, 37]. Diseases can also be triggered by local stressors such as coastal human inputs. For instance, in Guam, prevalence of white syndrome was linked to increased nitrogen from sewage outfalls [38]. In Florida, the outbreak of SCTLD also coincided with the dredging of Port Miami, which led to substantial sedimentation and coral mortality [39] [40]. An overall increase in nutrients has also been linked to higher disease prevalence in the both field and experimental studies [41]. Given these synergies, outbreaks of coral diseases are expected to increase [42]. Management efforts that aim to limit sources of coral disease should be high priority especially in the Atlantic/Caribbean, where they have already caused substantial decline.

Ocean acidification (declining ocean pH): In addition to warming our planet, carbon dioxide emitted into the atmosphere dissolves into our oceans, triggering chemical reactions that increase the acidity of the water (lower the pH level) [43]. Some studies indicate that pH levels in reef water are declining more rapidly than in the open ocean [44]. At lower pH, the process that corals use to build their skeletons (calcification) and which creates the reef structure requires more energy, meaning coral growth slows and they build less reef [45]. The chemical dissolution of older reef structures, as well as erosion of live corals by live organisms, like encrusting mussels or worms, is also easier at lower pH [46, 47].

Ocean acidification also negatively impacts the many shell-building organisms that reside on reefs, such as mussels, clams, urchins, and other calcifying organisms [48]. Even fish growth and metabolism can be impacted under low pH, especially during larval stages [49] In addition, pH often interacts negatively with warmer temperatures, hindering growth and survival of corals [50]. As with mitigating the effects of warming, addressing the root cause – rising CO2 levels – is the best course of action to prevent further damage.

Local Stressors

Coastal Development and Nutrient Enrichment: Coastal development can generate sedimentation from poor-land use practices and new development, or nutrient run-off from agriculture and wastewater discharge. The construction of new resorts may involve overwater bungalows, built directly on reef structures, or the creation of artificial beaches that change coastline dynamics and increase sedimentation to nearby reefs. The expansion of ports to accommodate cruise liners or large container ships, often requires dredging of the surrounding reef flats in smaller tropical islands [51, 52], or even larger cities like Miami [40]. On a more dramatic scale, territorial conflicts in Spratly Islands in the South China Sea, have led to land reclamation techniques by China in which reefs are filled to create land that can be claimed [53]. Such efforts destroyed an estimated 6 square miles (3,000 football fields) of coral reef habitat in 2015 [54]. Coastal development represents a severe a direct physical risk to coral reef survival. The environmental impacts of development projects should be thoroughly assessed by independent parties prior to permitting to help alleviate such pressures.

Nutrient influx to reefs is primarily driven by human activity. Coastal development, sewage and water treatment effluents, agricultural runoff, and discharges from shipping can all increase nutrient levels on reefs. Macroalgae (different from the microalgae that live inside coral tissues) compete with corals for space on reef environments [55]. Normally, macroalgal growth is limited by nutrient availability, but with an influx of nutrients algae can grow more quickly and begin to grow over the coral [55]. This often results in a shift from a coral-dominated reef to an algal-dominated ecosystem [56] (Figure 3B). These patterns can also be exacerbated if there is overfishing of herbivorous fish, which help keep macroalgal populations in check (see Fishing Pressure).

Algal-dominated habitats quickly begin to lose fish species that relied on corals for shelter [56]. Algae can also trap sediments, leading to negative feedback loops that further stress the remaining corals [57]. Algal-dominated reefs lose their value as protective barriers to shorelines, as dead corals can no longer create additional reef structure. In addition, nitrogen and carbon inputs from land can alter the pH of coastal waters, exacerbating ocean acidification in those areas [58]. Policies that limit the environmental impact of coastal development projects and ensure that coastal infrastructure (e.g. sewage pipes and water treatment plants) is well-maintained can significantly limit continued damage to coral reefs locally.

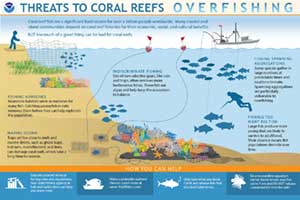

Fishing Pressure: Corals rely on healthy populations of herbivorous fish and invertebrates to keep macroalgal populations from outcompeting them [59]. Overfishing of herbivores like parrotfish and rabbitfish can result in algal population spikes [60, 61]. In 1990, Bermuda banned pot fishing, a practice that mainly impacted herbivorous fish species. As a result, populations of herbivores rebounded [62]. Other fishing practices like dynamite (also called blast fishing) or cyanide fishing can directly destroy reef habitats and kill coral reef organisms. While these methods are not practiced in the U.S., they still represent a significant threat to reefs in the Indo-Pacific, where many U.S. and international non-profits dedicate efforts to reef conservation. Dynamite and cyanide fishing are often practiced by smaller-scale fishermen, harvesting coral reef fish for the aquarium trade (most of which is sent to U.S.) or direct consumption. In Tanzania, for example, dynamite fishing was outlawed in the 1970s, but has continued essentially unchecked [63]. Cyanide fishing allows for the live capture of fish by temporarily anesthetizing them [64]. The concentrations of cyanide used to target the desired fish, however, can be quickly detrimental to coral reef organisms, such as smaller fish and invertebrates [64]. Efficient enforcement against both these practices in the Indo-Pacific would be a substantial relief to local coral reefs; as would limiting overfishing of herbivorous species across coral habitats.

Figure 3: Overview of coral biology. (A) Coral symbiosis. Corals form massive reef structures made of calcium carbonate (limestone) as their skeleton. The live coral tissue is at the surface of this rock, where colonies of polyps (middle inset) cover the skeleton. Inside the polyps, single-celled algal symbionts (left inset) live in specialized tissues. In addition, a diverse microbial community (right inset) lives on and within corals. (B) Coral bleaching and algal overgrowth. A healthy reef (left) undergoes bleaching due to high temperatures (middle). The coral is unable to recover and dark brown macroalgae now grows over the dead coral skeleton (right) causing a shift from a coral-dominated ecosystem to an algae-dominated one. (C) Coral life cycle. Corals can reproduce sexually to create larvae that then float and swim until finding a new home, where they settle down and attach to the seafloor. Corals can also reproduce asexually via fragmentation, whereby a piece of an adult colony breaks but then reattaches elsewhere on the seafloor and continues growing to form another colony. Photo credits: Coral images in A and B are from the Coral Image Bank (Ocean Agency/Caitlin XL Survey: CC license). Symbiont image in panel A was taken by T. LaJeunesse and is reproduced with permission. Polyp image was taken by author H.E.R. Diagram in panel C is original artwork by Nicola G. Kriefall and is reproduced with permission.

What’s protected: U.S. policies addressing coral reefs

Reducing human access to reefs can mitigate the impact of local stressors on corals – buying them time to become more tolerant of global stressors [65]. Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are defined as: “[an] area of the marine environment that has been reserved by federal, state, territorial, tribal, or local laws or regulations to provide lasting protection for part or all of the natural and cultural resources therein” (Executive Order 13158, 2000). MPAs may differ in their level of restrictions depending on the conservation goals surrounding their designation. Two specific classes of MPAs are sanctuaries and monuments. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and Congress may both designate sanctuaries under the National Marine Sanctuaries Act (16 U.S.C. §§ 1431 et seq., 1972), while the President can establish marine national monuments under the Antiquities Act of 1906 (54 U.S.C. §§ 320301-320303, 1906). A number of MPAs include coral reef habitats within U.S. jurisdiction:

• Papahānaumokuākea National Marine Monument in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands was established in 2006 and is the largest contiguous marine conservation area under U.S. jurisdiction (Proclamation 8031, 2006). A proclamation by President Obama expanded the monument to cover the entire U.S. exclusive economic zone west of 163 West Longitude, providing greater protection for the region’s coral reefs (Proclamation 9478, 2016). • Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument includes Wake, Baker, Howland, and Jarvis Islands, Johnston and Palmyra Atolls, and Kingman Reef. Protecting the high coral diversity and endemic coral species in these areas was a major justification for its establishment (Proclamation 8336, 2009). • Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary protects the largest coral barrier reef in the United States (15 C.F.R. part 922, subpart P; Pub. L. 101–605, 1990). • Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary was established to protect the northernmost living coral reefs on the U.S. continental shelf (56 F.R. 63634, 1991). • Marianas Trench Marine National Monument protects one of the most diverse coral ecosystems in the Western Pacific and the deepest part of our world’s ocean (Proclamation 8335, 2009). • National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa (formerly Fagatele Bay National Marine Sanctuary) was designated in response to a proposal from the government of American Samoa, in part to preserve a pristine coral reef terrace ecosystem (51 F.R. 15878, 1986). • Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument protects coral reefs as essential habitat for sustaining the fragile biological communities in this region (Proclamation 7399, 2001). • Red Hind Spawning Aggregation Areas west of Puerto Rico are federally managed. All three areas prohibit fishing during the spawning season by implementing area closures from December to February (50 C.F.R. § 622, 1996). A later amendment to this rule established a marine conservation district east of Puerto Rico, in which fishing activity and anchoring by fishing vessels are banned to protect its coral reef habitat (50 C.F.R. § 622, 1999)

Which groups manage and enforce MPAs?

Through related domestic legislation and international trade law (Table 1), several U.S. federal agencies play important roles in the protection of coral reef environments, among their other duties. In 1998, Presidential Executive Order 13089 (Coral Reef Protection) established the United States Coral Reef Task Force (U.S.CRTF), which includes representatives from the Department of the Interior, the Department of Commerce, NOAA, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Department of Defense, the National Science Foundation, the Department of Transportation, the Department of Agriculture, the Department of State, the Agency for International Development, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Executive Order 13089, 1998). The U.S.CRTF is charged with leading U.S. stewardship of coral reef ecosystems by supporting scientific research, mapping, monitoring, restoration, international cooperation, and the reduction of threats to reefs in coordination with other stakeholder groups.

The groundbreaking Coral Reef Conservation Act of 2000 authorized major contributions to the research, mapping, monitoring, conservation, and management of coral reefs, in large part through the development of a National Action Strategy in consultation with USCRFT and the establishment of NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program (CRCP) (Coral Reef Conservation Act of 2000, 2000). The CRCP is one of few federal programs whose direct mission is to address coral reef conservation efforts and the only one with a legislative mandate. In addition to supporting the USCRTF, the CRCP’s multifaceted work involves funding coral research, delivering sound scientific information and tools for management, establishing core partnerships with various stakeholders, and capacity building to help local staff members implement projects that address threats and restore habitats, among other functions. The monumental work of this program relies on federal funds appropriated by Congress. In addition, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service manages 10 coral reef National Wildlife Refuges in the Pacific and enforces international trade laws, which regulate the import and export of corals for jewelry or the aquarium trade. The Environmental Protection Agency protects coral reefs by implementing Clean Water Act programs that maintain water quality in watersheds and coastal zones of coral reef areas. While these functions are important, their pertinence to coral reefs is not congressionally mandated.

A summary of other key domestic policies and the primary agencies responsible for them is shown in Table 1. There are also several international policies that impact coral reefs, though the U.S. is notably absent from several (see gaps section below). The U.S. is contracting party of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES, 1973), which serves to regulate international trade of animal and plant samples in order to promote conservation and reduce the risk of overexploitation and extinction. All hard coral species (Scleractinia spp.) are listed in the CITES Appendix II, and transport of live specimens or products of these species requires a CITES permit (Resolution Conf. 9.24 Rev. CoP17, 1994).

What’s missing: Management and policy gaps in coral reef conservation

The U.S. stance on ocean policy has varied across administrations. Mostly recently it has shifted from an emphasis on conservation and climate to a focus on economic and security concerns (Executive Order No. 13840, 2018). While the stringency of coral reef conservation has fluctuated, it remains indisputable, as described above, that coral reefs provide substantial economic benefits to many U.S. sectors, in addition to their contributions to biological diversity and ecosystem health. Executive Order 13840, Regarding the Ocean Policy to Advance the Economic, Security, and Environmental Interests of the United States, calls to “facilitate the economic growth of coastal communities and promote ocean industries”, among other priorities (Executive Order 13840, 2018). It is clear from the lengthy list of ecosystem services that preservation of coral reefs is necessary for economic growth and security of many coastal communities.

While there are legal mechanisms (e.g., MPAs) to protect coral reefs under U.S. jurisdiction, gaps often remain in implementation and enforcement. For instance, many MPAs are in remote places where enforcement is difficult, even for countries with substantial resources [66, 67]. When properly enforced, protection can help alleviate some, though not all, stressors. An evaluation of the ecological performance of MPAs in the U.S. Virgin Islands revealed that coral reefs outside MPAs showed larger declines in ecosystem performance, such as lower density of fish including adult snappers [68]. Notably, the amount of live coral cover decreased both inside and outside MPAs during the study period due to bleaching events and hurricane damage, pointing to the importance of global stressors in driving community structure [68]. Table 2 details additional policy tools to tackle local stressors and provides some examples of gaps in implementation at the municipal, state, and national level.

Key coral reef legislation also requires immediate attention. The Coral Reef Conservation Act of 2000 expired 15 years ago. Reauthorization attempts thus far have either failed or remained stagnant in Congress. Most recently, the Restoring Resilient Reefs Act of 2019 was introduced in both the House of Representatives (H.R. 4160) and the Senate (S. 2429) is a bipartisan and bicameral bill to reauthorize and modernize the Coral Reef Conservation Act of 2000. This bill, however, has not yet proceed past the introduction stage. This legislation would a provide a strong base for coordinated national efforts as well as provides $\$$160 million of federal funding for the next five years for domestic reef management, conservation, and restoration. Such increases in funding are desperately needed. For instance, the budget for CRCP has held steady around $\$$27 million per year over the past ten years [69]. This stagnant budget supports work that is becoming increasingly demanding and urgent. Given the vast monetary value that coral reefs represent to the U.S., increasing this and other program budgets would expand their capacity and impact.

On a global geopolitical level, the U.S. has the potential to influence coral reef management in other regions, as well. The USCRTF has active working groups that address specific issues and produce incredibly detailed global, regional, and local recommendations based on science that need to be considered in national policy. For example, 60% of the aquarium fish trade is imported into the U.S., with almost 90% originating from Pacific regions [70, 71]. While the U.S.AID’s program in the Philippines and Indonesia are working to improve problems around both overfishing and destructive fishing (e.g. cyanide or dynamite fishing), the program’s limited geographic scope and jurisdiction makes it difficult to coordinate and enforce the larger-scale regional efforts that are needed. To address this, the USCRTF has recommended leveraging work with the Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum and building a strategic partnership with the South Pacific Region Environmental Program [72].

More broadly, however, the U.S. is not party to some major international conventions that would benefit coral reef ecosystems:

• The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982) defines the rights and responsibilities of countries with respect to ocean use in order to maintain peaceful relations between governments (U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, 1982). Currently, the U.S. has signed but not ratified the agreement, a move that may jeopardize future claims to ocean resources [73]. Within the agreement, the extent of coral reefs is used to help define the limits of territorial seas, and thus the continued loss of reefs has strong implications for future designations of maritime boundaries.

• The United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (1992) is a comprehensive agreement between 196 parties dedicated to the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. Although President Clinton signed the agreement in 1993 and had support from the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, a Senate vote to ratify it was never held (U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Activities & Reports). The U.S. is party to smaller scale agreements, like the Inter-American Convention for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles and the Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife Protocol.

Saving corals: Restoration, conservation, and research efforts

Despite legislative protections against local impacts, coral reefs have continued to deteriorate mainly due to increasing global temperatures and disease [6, 74]–[76]. This widespread loss has prompted large-scale restoration efforts, involving government programs (e.g. NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program), non-governmental organizations (e.g. The Nature Conservancy, SECORE International, etc.), academic institutions, and community groups. The Coral Restoration Consortium, which includes international leaders of multiple coral stakeholder groups, provides a collaborative framework that is crucial for successful coral reef restoration on a global scale (crc.reefresilience.org).

Coral restoration aims to increase the number of healthy adult corals on reefs. However, as corals may reproduce asexually (usually via fragmentation) or sexually, restoration also involves promoting asexual and sexual reproductive processes on reefs to increase coral abundance (Figure 3C) [77, 78]. In the U.S., the largest restoration efforts are in Florida, for the fast-growing staghorn and elkhorn Acropora coral species (the same ones that nearly died out across the Caribbean in 1970s). The Coral Restoration Foundation has led this effort since 2007. To date, the foundation has transplanted over 100,000 coral fragments onto the Florida Reef Tract (www.coralrestoration.org). Coral nurseries in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands have also successfully transplanted tens of thousands of coral fragments [79]. Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium (www.mote.org), in addition to managing their own underwater coral nursery, has built upon this effort in recent years by developing a method to micro-fragment and fuse typically slower growing corals, thereby speeding up the cultivation process for other species [80].

While increasing asexual reproduction on reefs can help maintain coral populations, only sexual reproduction can generate new genetic diversity. SECORE International (www.secore.org) is leading global coral restoration efforts by regularly producing millions of coral offspring from naturally released eggs and sperm. Once these newborn corals attach to tiles, they are transplanted onto a natural reef, where in time they can mature and contribute to the next generation [81, 82]. However, restoration success (having transplanted colonies grow and sexually reproduce) is contingent upon the environmental conditions being suitable for corals, since stressors such as poor water quality can significantly reduce fertilization [83, 84] and subsequent bleaching can kill transplanted colonies. Increasing the efficiency of coral restoration, e.g. by transplanting coral colonies that are mostly likely to survive and reproduce, in conjunction with improving local environmental conditions will help managers meet the challenges of continued coral population declines [85].

Despite the benefits restoration can offer at a local scale, the pace of climate change is beyond what most corals can handle. Novel research initiatives exploring the possibilities of assisted evolution in corals and their algal symbionts (Figure 3A), such as selective breeding for heat tolerance, continue to gain traction within science and management communities [2, 95]. Other efforts to save coral diversity include genetic repositories (where live corals are maintained in aquaria or nurseries) and coral sperm banks through cryopreservation [96].

Recent initiatives have shifted focus from individual species to restoring and protecting entire reef ecosystems. NOAA recently launched Mission: Iconic Reefs, which targets seven reefs in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary for multi-phased, active restoration. This will involve removing invasive species and algae, transplanting both fast and slow-growing coral species, and increasing the population of other beneficial species like sea urchins and Caribbean king crabs. Another unprecedented coral conservation project is the 50 Reefs Initiative (led by The Ocean Agency), which identified reefs likely to survive climate change and repopulate nearby reefs once the climate stabilizes [97]. The approach developed by the 50 Reefs Initiative will allow managers to maximize long term conservation benefits while reducing the risks of devoting limited resources to reefs that are unlikely to withstand projected warming and wave damage from increasingly intense cyclones [97].

Saving corals for the long term: Addressing climate change is our largest policy gap

Even with these monumental restoration and conservation efforts, the predictions for climate change-driven coral reef loss are grim. The 2018 IPCC report warned that 1.5◦C increase in global temperatures would correspond to 70-90% coral reef decline, and a 2◦C rise could result in the loss of greater than 99% of reefs [98]. Aggressive international and domestic commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are necessary if coral reefs are to remain functional ecosystems for the benefit of future generations. We, therefore, find it critical to highlight major policies and agreements surrounding greenhouse gas emissions.

The Clean Air Act (42 U.S.C. § 7401, 1963) and the jurisdiction of the Environmental Protection Agency

• 2007 – Massachusetts vs. EPA, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that greenhouse gases are pollutants under The Clean Air Act, and should be regulated as such. • 2010 – Tailoring Rule by EPA establishes emission thresholds and a process for permitting carbon dioxide equivalent emissions for large, stationary emitters like power plants (75 F.R. 31513, 2010). • 2014 – Utility Air Regulatory Group v. EPA, the U.S. Supreme Court confirmed the jurisdiction of the EPA to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. • 2015 – Clean Power Plan by EPA established final emission guidelines for states to use in limiting greenhouse gas emissions from power generators (80 F.R. 64661, 2015). • 2017 – Executive Order 13783 by President Trump prompts the EPA to review the Clean Power Plan as a potential burden to the development of domestic energy resources. The formal process to repeal the plan was initiated that year (Executive Order 13783, 2017). • 2019 – Affordable Clean Energy Rule by the EPA replaces the Clean Power Plan, stating that the Clean Power Plan overstepped the authority attributed to the EPA under the Clean Air Act (84 F.R. 32520, 2019). Instead, the Affordable Clean Energy Rule places the responsibility of developing standards for CO2 emissions from existing coal-fired power plants on the states. The rule also points to heat rate improvement measures as the best strategy for reducing emissions, rather than shifting some power generation to renewable energy sources.

The move from the Clean Power Plan (CPP) to the Affordable Clean Energy Rule (ACE) demonstrated a clear shift away from federal regulation of greenhouse gas emissions, and federal promotion of renewable energy use. The CPP was enacted to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from power generation by 32% compared from 2005 levels by 2030 (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 2015). In contrast, the ACE does not set limits on carbon emissions, and instead relies on individual states to take the initiative to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from power plants. The emission reductions projected under the CPP totaled around 870 million tons, compared to 11 million tons under the ACE (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 2015, 2019). Given the sensitivity of corals to bleaching under increasing global temperatures caused by elevated greenhouse gas emissions [98] this change in legislation undermines efforts to protect and restore coral reefs.

The lack U.S. leadership in reducing global greenhouse gas emissions is further demonstrated by its absence from several international agreements:

• 2012 – Kyoto Protocol operationalizes the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change by holding industrialized countries to their committed target reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. The U.S. signed but never ratified the agreement. The Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol includes assigned percentage reductions of greenhouse gas emissions by 2020 for individual countries (not including the U.S.), but has not yet entered into force due to the lack of ratification (United Nations, 2012).

• 2015 – The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Paris Agreement strives to limit average global warming to well below 2◦C relative to preindustrial measurements, with an overall goal to keep the temperature increase to a maximum of 1.5◦C (United Nations, 2015). The U.S. president announced the U.S. withdrawal from this agreement in 2017, due to the negative impact it would have on the U.S. economy (Trump, 2017). However, withdrawing from the Paris Agreement takes four years given the start date of November 4, 2016 (United Nations, 2015), so the earliest possible official withdrawal date is not until November 4, 2020.

Progress towards the global reduction of greenhouse gas emissions continues with the carbon market systems established by other parties to the Paris Agreement. The European Union (EU) Emissions Trading System was the first, and continues to be the largest. The EU system functions by setting a cap on the total amount of specific greenhouse gases emitted, which is lowered over time. Individual companies are then assigned emission allowances for free or purchase allowances via auctions, which they can trade amongst each other [99]. The EU is actively supporting China – the country with the highest annual emissions [100] – in the development of a nationwide carbon emissions trading system [101]. Similar carbon markets already exist in the U.S., but only a small minority of states participate [102, 103], limiting realized emission reductions due to the transfer of electricity generation to unregulated sectors [104].

Despite these federal decisions to abstain from strong action against the root cause of climate change, many states have made their own commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions consistent with the Paris Agreement. The United States Climate Alliance was formed in response to the impending U.S. withdrawal from the agreement, and includes 24 states and Puerto Rico. The U.S. governors in the alliance have promised to enact policies that reduce emissions 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2025, track and report progress to the international community, and promote clean energy within their states.

Coral reefs are one of our planet’s most valuable ecosystems [5]. The coastal protection, tourism revenue, biodiversity services, and drug discovery potential of coral reefs are worth trillions of dollars annually [105]. The continued loss of coral reef habitat will represent a significant economic cost to many countries around the world, including the U.S.. The recent actions taken by the U.S. government in national and international policy arenas fall short of an effective strategy to address the greatest global threat to reefs: climate change resulting from increased greenhouse gas emissions. As a country with the second highest annual emissions and the highest cumulative emissions since 1751 [100], the U.S. should take a leading role in the battle against climate change, thereby helping preserve coral reefs for current and future generations. Local management efforts should prioritize the protection of coral reef habitats and strive to mitigate local stressors as much as possible. However, a national and international effort to limit the main source of coral death – increasing global temperatures – is imperative for the future survival of these vibrant marine ecosystems.

Rivera H. E., Chan A. N. & Luu V. Coral reefs are critical for our food supply, tourism, and ocean health. We can protect them from climate change. MIT Science Policy Review 1 , 18-33 (2020).

Open Access

This MIT Science Policy Review article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ic

Legislation Cited (in order of appearance in text, then tables)

• Executive Order 13158, Marine Protected Areas, 65 F.R. 34909 (May 26, 2000). https://www. federalregister.gov/documents/2000/05/ 31/00-13830/marine-protected-areas

• National Marine Sanctuaries Act, 16 U.S.C. §§ 1431 et seq. (1972).

• Antiquities Act, 54 U.S.C. §§ 320301-320303 (1906).

• Proclamation 8031, Establishment of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument, 71 F.R. 36441 (June 15, 2006). https://www. federalregister.gov/documents/2006/ 06/26/06-5725/establishment-of-thenorthwestern-hawaiian-islands-marinenational-monument

• Proclamation 9478, Papahanaumoku ¯ akea Marine ¯ National Monument Expansion 81 FR 60225 (August 31, 2016). https://www.federalregister. gov/documents/2016/08/31/2016-21138/ papahamacrnaumokuamacrkea-marinenational-monument-expansion

• Proclamation 8336, Establishment of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, 74 F.R. 1565 (January 6, 2009). https://www. federalregister.gov/documents/2009/01/ 12/E9-500/establishment-of-the-pacificremote-islands-marine-national-monument

• Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, 15 C.F.R. part 922, subpart P; Pub. L. 101–605, Nov. 16, 1990, 104 Stat. 3089, as amended by Pub. L. 102–587, title II, §§2206, 2209, Nov. 4, 1992, 106 Stat. 5053 , 5054.

• Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, 56 F.R. 63634, Dec. 5, 1991; 60 F.R. 10312, Feb. 24, 1995; 15 C.F.R. part 922, subpart L; Pub. L. 100–627, title II, §205(a)(2), Nov. 7, 1988, 102 Stat. 3217 ; Pub. L. 102–251, title I, §101, Mar. 9, 1992, 106 Stat. 60 ; Pub. L. 104–283, §8, Oct. 11, 1996, 110 Stat. 3366 .

• Proclamation 8335, Establishment of the Marianas Trench Marine National Monument, 74 F.R. 1555 (January 6, 2009). https://www. federalregister.gov/documents/2009/01/ 12/E9-496/establishment-of-the-marianastrench-marine-national-monument

• National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa (former Fagatele Bay National Marine Sanctuary), 51 F.R. 15878, Apr. 29, 1986; 15 C.F.R. part 922, subpart J; 77 F.R. 43942, July 26, 2012, effective Oct. 15, 2012 (see 77 F.R. 65815).

• Proclamation 7399, Establishment of the Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument, 3 C.F.R. 7399 (January 17, 2001). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/ pkg/WCPD-2001-01-22/pdf/WCPD-2001-01-22- Pg156.pdf

• Fisheries of the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, and South Atlantic; Reef Fish Fishery of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands; Red Hind Spawning Aggregations, 50 C.F.R. § 622 (1996).

• Fisheries of the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, and South Atlantic; Coral Reef Resources of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands; Amendment 1, 50 C.F.R. § 622 (1999).

• Executive Order 13089, Coral Reef Protection, 63 F.R. 32701 (June 11, 1998). https://www.govinfo. gov/content/pkg/FR-1998-06-16/pdf/98- 16161.pdf

• Coral Reef Conservation Act, 16 U.S.C. §§ 6401 et seq. (2000).

• Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, March 3rd, 1973, 993 U.N.T.S. 243 [hereinafter CITES].

• Criteria for Amendment of Appendices I and II, Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP17), Fort Lauderdale (1994). https://cites.org/sites/default/files/ document/E-Res-09-24-R17.pdf

• Executive Order 13840, Ocean Policy To Advance the Economic, Security, and Environmental Interests of the United States, 83 FR 29431 (June 22, 2018). https: //www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/ 06/22/2018-13640/ocean-policy-to-advancethe-economic-security-and-environmentalinterests-of-the-united-states

• Restoring Resilient Reefs Act of 2019. 116 U.S.C. §§ H.R. 4160 et seq. (2019).

• Restoring Resilient Reefs Act of 2019. 116 U.S.C. §§ S.2429 et seq. (2019).

• United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, December 10, 1982, 1833 U.N.T.S. 397.

• United Nations Convention on on Biological Diversity, June 5, 1992, 1760 U.N.T.S. 69.

• The Clean Air Act of 1963, 42 U.S.C. § 7401 (1963).

• Massachusetts et al. v. Environmental Protection Agency et al., 549 U.S. 497 (2007).

• Prevention of Significant Deterioration and Title V Greenhouse Gas Tailoring Rule, 40 C.F.R. §§ 51-52 and 40 C.F.R. §§ 70-71, 75 F.R. 31513 (August 2, 2010). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/ 2010/06/03/2010-11974/prevention-ofsignificant-deterioration-and-title-vgreenhouse-gas-tailoring-rule

• Utility Air Regulatory Group v. Environmental Protection Agency et al., 573 U.S. 302 (2014).

• Carbon Pollution Emission Guidelines for Existing Stationary Sources: Electric Utility Generating Units (Clean Power Plan), 40 C.F.R. § 60, 80 F.R. 64661 (December 22, 2015). https://www. federalregister.gov/documents/2015/10/23/ 2015-22842/carbon-pollution-emissionguidelines-for-existing-stationarysources-electric-utility-generating

• Executive Order 13783, Promoting Energy Independence and Economic Growth, 82 F.R. 16093 (March 28, 2017). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/ 2017/03/31/2017-06576/promoting-energyindependence-and-economic-growth

• Repeal of the Clean Power Plan; Emission Guidelines for Greenhouse Gas Emissions From Existing Electric Utility Generating Units; Revisions to Emission Guidelines Implementing Regulations (Affordable Clean Energy Rule), 40 C.F.R. § 60, 84 F.R. 32520 (September 6, 2019). https://www.federalregister.gov/ documents/2019/07/08/2019-13507/repealof-the-clean-power-plan-emissionguidelines-for-greenhouse-gas-emissionsfrom-existing

• US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) 2015, Regulatory Impact Analysis for the Clean Power Plan Final Rule https://epa.gov/ttnecas1/docs/ ria/utilities_ria_final-clean-power-planexisting-units_2015-08.pdf

• US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) 2019, Regulatory Impact Analysis for the Repeal of the Clean Power Plan, and the Emission Guidelines for Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Existing Electric Utility Generating Units https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2019-06/documents/utilities_ria_ final_cpp_repeal_and_ace_2019-06.pdf

• United Nations, Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol, C.N.718.2012.TREATIES-XXVII.7.c (December 8, 2012).

• United Nations, Paris Agreement, December 12th, 2015, T.I.A.S. No. 16-1104.

• Trump, D.J. (2017). Statement by President Trump on the Paris Climate Accord. https://www.whitehouse. gov/briefings-statements/statementpresident-trump-paris-climate-accord/

• Beaches Environmental Assessment and Coastal Health Act of 2000, 33 U.S.C. §§ 1313 et seq. (2000).

• Federal Water Pollution Control Act (Clean Water Act), 33 U.S.C. §§ 1251 et seq. (1972).

• Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, 16 U.S.C. §§ 1451 et seq. (1972).

• The Endangered Species Act of 1973, 16 U.S.C. §§ 1531 et seq. (1973).

• Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Final Rule to List the Dusky Sea Snake and Three Foreign Corals Under the Endangered Species Act, 50 C.F.R. §§ 223-224, 80 F.R. 60560 (November 6, 2015). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/ 2015/10/07/2015-25484/endangered-andthreatened-wildlife-and-plants-finalrule-to-list-the-dusky-sea-snake-andthree

• Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants: Final Listing Determinations on Proposal to List 66 Reef-Building Coral Species and to Reclassify Elkhorn and Staghorn Corals, 50 C.F.R. § 223, 79 F.R. 53851 (October 10, 2014). https://www. federalregister.gov/documents/2014/09/10/ 2014-20814/endangered-and-threatenedwildlife-and-plants-final-listingdeterminations-on-proposal-to-list-66

• Endangered and Threatened Species: Final Listing Determinations for Elkhorn Coral and Staghorn Coral, 50 C.F.R. § 223, 71 F.R. 26852 (June 8, 2006). https: //www.federalregister.gov/documents/2006/ 05/09/06-4321/endangered-and-threatenedspecies-final-listing-determinations-forelkhorn-coral-and-staghorn-coral

• Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (Fishery Conservation and Management Act of 1976), 16 U.S.C. §§ 1801 et seq. (1976).

• Marine Debris Research, Prevention, and Reduction Act (Marine Debris Act), 33 U.S.C. §§ 1951-1958 (2006).

• The Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act, 16 U.S.C. §§ 1431 et seq. and 33 U.S.C. §§ 1401 et seq. (1988).

• The National Environmental Policy Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 4321 et seq. (1969).

• Notice of Availability of a Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Restoration Blueprint; Announcement of Public Meetings, 84 F.R. 45728 (August 30, 2019). https://www.federalregister.gov/ documents/2019/08/30/2019-18783/noticeof-availability-of-a-draft-environmentalimpact-statement-for-the-florida-keysnational

• Rivers and Harbors Appropriation Act of 1899, 33 U.S.C. §§ 401 et seq. (1899).

• The Shore Protection Act, 100 U.S.C. §§ 2601-2609 (1988).

• RPPL No. 10-02. House Bill No. 10-22-1, HD1, SD2, PD1. Tenth Olbill Era Kelulau First Regular Session. §2706 (January 2017).

• The Virgin Islands Revenue Enhancement and Economic Recovery Act of 2017. 2 Bill No. 32-0005. §1. (2017).

• U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2002). Asset Management for Sewer Collection Systems Fact Sheet. https://www3.epa.gov/npdes/pubs/ assetmanagement.pdf

• White House (2018). Legislative Outline for Rebuilding Infrastructure in America. https: //www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/ 2018/02/INFRASTRUCTURE-211.pdf

• The White House (2020). Historic Investment in America’s Infrastructure: A Budget for America’s Future. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wpcontent/uploads/2020/02/FY21-Fact-SheetInfrastructure.pdf

• Water Infrastructure and Improvement Act. 115 U.S.C. H.R.7279 (2019)

• Chapter 403.077. (Florida Statutes 2019)

• Florida Department of Environmental Protection Consent Order OGC No. 16-1487 (2017).http: //www.trbas.com/media/media/acrobat/2017- 09/69895557084220-05111531.pdf

• Florida Administrative Code Rule 62-302.530 et seq.

[1] Cinner, J. Coral reef livelihoods. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 7, 65–71 (2014). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.11.025.

[2] Anthony, K. et al. New interventions are needed to save coral reefs. Nature Ecology and Evolution 1, 1420–1422 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0313-5.

[3] Normille, D. El Niño’s warmth devastating reefs worldwide. Science 352, 15–16 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1126/ science.352.6281.15.

[4] Hughes, T. P. et al. Global warming transforms coral reef assemblages. Nature 556, 492–496 (2018). https://doi. org/10.1038/s41586-018-0041-2.

[5] de Groot, R. et al. Global estimates of the value of ecosystems and their services in monetary units. Ecosystem Services 1, 50–61 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser. 2012.07.005.

[6] Hughes, T. P. et al. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature 543, 373–377 (2017). https: //doi.org/10.1038/nature21707.

[7] Thompson, J. R., Rivera, H. E., Closek, C. J. & Medina, M. Microbes in the coral holobiont: Partners through evolution, development , and ecological interactions. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 4, 1–20 (2014). https://doi. org/10.3389/fcimb.2014.00176.

[8] Schmidt, T. S., Raes, J. & Bork, P. The Human Gut Microbiome: From Association to Modulation. Cell 172, 1198–1215 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.044.

[9] Woodhead, A. J., Hicks, C. C., Norström, A. V., Williams, G. J. & Graham, N. A. Coral reef ecosystem services in the Anthropocene. Functional Ecology 33, 1023–1034 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13331.

[10] Beck, M. W. et al. The global flood protection savings provided by coral reefs. Nature Communications 9 (2018). https:// doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04568-z.

[11] Inc., W. C. U.S. airports, seaports, & border crossings (2020).

[12] Smith, S. V. Coral-reef area and the contributions of reefs to processes and resources of the world’s oceans. Nature 273, 225–226 (1978).

[13] Fisher, R. et al. Species richness on coral reefs and the pursuit of convergent global estimates. Current Biology 25, 500–505 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub. 2014.12.022.

[14] Bruckner, A. Life-saving products from coral reefs. Issues in Science and Technology 18 (Spring 2002).