Dual Narrative Multi-Day Tour of Israel and Palestine

Global Leader in Socially Conscious Travel.

Embark on an unprecedented mission with MEJDI Tours to confront the complex realities of the current moment in Israel and Palestine.

This initiative aims to transcend the headlines, bringing visitors together with guides, experts, local communities, families and organizations to better grasp the situation on the ground, and to support those who continue to pursue a more just, peaceful future.

For more information, mission dates, and to book – click the link below:

- Trip Includes

- Before you Register

- testimonials

MEJDI’s Dual Narrative Tour™, a patented, socially conscious, award-winning approach to travel.

Explore Israel and Palestine through MEJDI’s industry-first Dual Narrative Tour and see the Holy Land with the help of two local tour guides: one Israeli and one Palestinian.

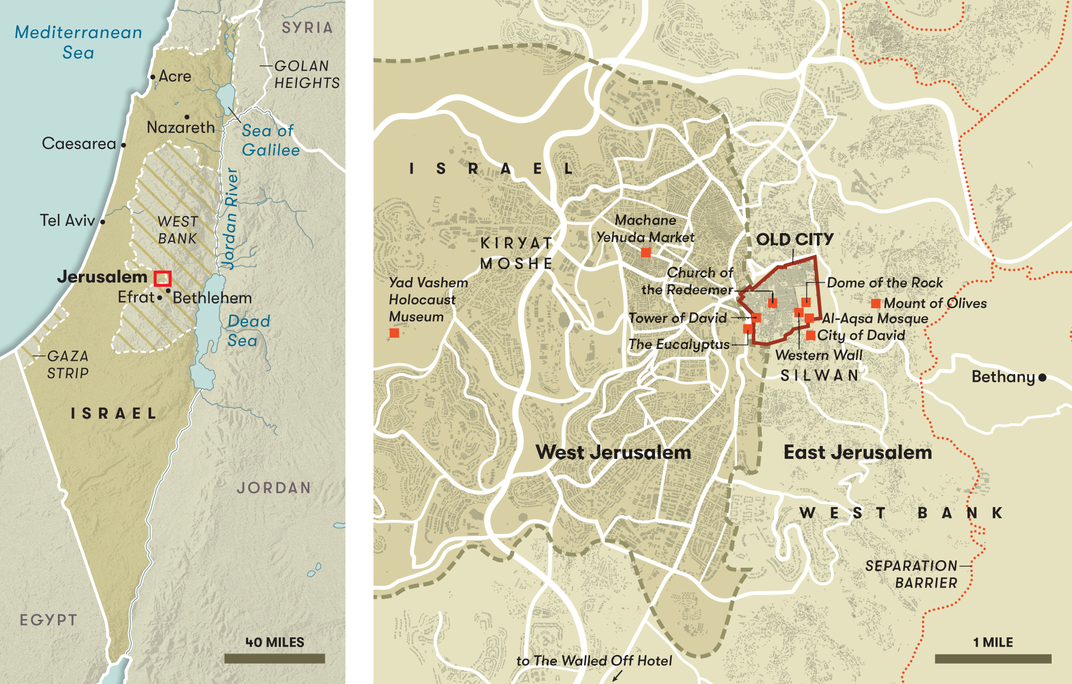

Visit: Tel Aviv and East Jerusalem; optional pre-trip extension in Northern Israel and post-trip extension in Jordan.

We recently redesigned our trip with higher-level accommodations at 4* boutique hotels and with extra inclusions.

For available tour dates click below or download the itinerary:

*Prices are per person and based on double occupancy. Single room supplements are available

As you travel through Tel Aviv, Ramallah, Bethlehem, and Jerusalem—with optional pre-trip and post-trip add-ons in Northern Israel and Jordan—your Israeli and Palestinian guides help you experience the Holy Land’s history, culture, and complex reality from multiple perspectives in a supportive and constructive atmosphere. Through our co-founder’s personal upbringing in Jerusalem and MEJDI’s established relationships, your experience is deepened by intimate discussions with local leaders, peacebuilders, and organizations, and enriched by deeply personal stories from residents, shared meals with a Palestinian family, and private music performances. Join us to see why TED, National Geographic, Smithsonian Magazine , the United Nations, and the New York Times have featured our Israel & Palestine trip.

Enjoy MEJDI’s Dual Narrative Tour™, a patented, socially conscious, award-winning approach to travel.

Guiding in tandem, israeli and palestinian guides debate and highlight different political, religious, and historical opinions at each site in an immersive travel experience that takes you behind the doors of mosques, churches, and synagogues, through the halls of palestinian and israeli government, into active dig sites, and into the homes of arab, jewish, and druze locals., mejdi’s trained guide-facilitators help open a conversation, answer challenging questions, model friendship through respectful dialogue and disagreement, and allow travelers to encounter new voices and perspectives., take a full-day alternative tour of the old city’s jewish, christian, and muslim holy sites and neighborhoods with your two guides, one arab and one jewish., hear stories from members of a grassroots organization of palestinians and israelis who are working towards peace in the conflict., meet a local activist and chef for a food tour in old ramallah and hear about local food, restaurants, and her personal story., hear from a representative of the jewish settlement movement., discuss political and economic challenges in palestine with a palestinian business person., enjoy a traditional home-cooked meal with a local palestinian family and traditional songs from local musicians., 7 nights’ accommodation (double occupancy), 2 mejdi-trained, english-speaking guides for 6 days: 1 israeli and 1 palestinian, 5 days of private bus transportation, meals listed in the itinerary, entrance fees, site visits, and honorariums for speakers, customary tips for drivers, guides, and hotel staff, dedicated pre-trip customer service and on-ground support, interested but not ready to deposit click the “request info” we can keep you updated on the tour status., international airfare, travel insurance-required, single room supplement fee (see itinerary for price), individual/group airport transfers (arrival and departure), meals not mentioned in the itinerary, covid testing, anything not explicitly mentioned in the included section.

All the trips we take are educational and geared towards cultural immersion, and that’s true of MEJDI. But none are so first hand and intentionally personal as the MEJDI tour guides are.

You come away hopeful because the tour guides can have such different backgrounds and experiences and opinions and still respect each other, And, they introduce you to groups that are working to spread that throughout the world.

MEJDI Traveler

Read through the Terms and Conditions

Do not book your flight until you receive the tour confirmation email from us. This tour requires a minimum number of travelers to run and we will send out the tour confirmation (and update this note on the webpage) as soon as we have met that number.

Check out your travel insurance options. Some plans and policies [Cancel For Any Reason (CFAR) or coverage for pre-existing conditions] may only available for a limited time (approximately 2 weeks) following your date of deposit.

At the moment, health insurance is required for medical and COVID related coverage during your time in Israel.

Tour Registration

Click to see all available tour dates. Select your preferred tour date to complete the registration process and pay the deposit.

MEJDI Day Tours

- See all photos

Jerusalem: Dual Narrative Tour

Most Recent: Reviews ordered by most recent publish date in descending order.

Detailed Reviews: Reviews ordered by recency and descriptiveness of user-identified themes such as waiting time, length of visit, general tips, and location information.

MEJDI Day Tours - All You Need to Know BEFORE You Go (2024) - Tripadvisor

Mobile Icons

Header Top Menu

Social icons.

- Email Address

Israeli Scene The Jewish Traveler

Touring the Holy Land With Israeli and Palestinian Guides

When we arrived at the Artist Hotel, an airy boutique property two blocks from Tel Aviv’s Bograshov Beach , the concierge greeted my partner, Paul, and me with a warm “hello” and two breezily delivered dictums: Breakfast was from 6:30 a.m. to 10 a.m. and if air raid sirens blared, head to the bomb shelter or get as close to the ground as possible. Recent Israeli airstrikes in Gaza had “killed three terrorist leaders and some other people,” he told us. Palestinian groups had fired over 600 rockets. Oh, and happy hour was starting. Did we want wine and cheese?

A 65-year-old child of Holocaust survivors , I last visited Israel at age 17, when two friends and I picked apples on a kibbutz. Until my trip in May, I hadn’t been back for nearly 48 years. I’d returned for a seven-day “dual nar rative” expedition created by MEJDI Tours that, according to its promotional literature, would be “led by an Israeli and Palestinian guide who will debate and highlight different political and historical opinions at each site.”

MEJDI Tours was founded in 2013 by Aziz Abu Sarah, a Muslim from East Jerusalem, and Scott Cooper, a Jewish social enterprise entrepreneur and businessman who lives in Chicago. The two shared a background in international conflict mediation and a desire to connect people through travel. In addition to tours in the Middle East, which also include Egypt and Turkey, MEJDI offers trips in other historically strife-ridden lands, such as Ireland and the American South.

As Paul and I sipped Shoresh Blanc from Tzora Vineyards and nibbled chunks of Tzfatit cheese, I confided to him for perhaps the 100th time since booking this trip: “I pray my parents in heaven won’t view my talking to Arabs as betrayal…. But until we see our ‘enemies’ as human beings, how can we find ways to live peacefully side by side?”

I inhaled a second glass of white wine. “I’m still haunted by my mother’s face when we watched Palestinian terrorists attack Israel’s Olympic team at the Munich Games in 1972,” I told Paul. “Israel must exist…but it’s complicated.”

The next morning, we headed to the lobby to meet the 12 other travelers in our group and two guides: Yaniv, a middle-aged peace builder who requested that his real name not be used because of what he described as the heightened political environment in Israel right now, and Alaa, a 2008 graduate of the Conflict Transformation master’s program at Eastern Men nonite University in Virginia. Paul and I instantly felt comfortable with our mostly Medicare-eligible companions, all from the United States and representing diverse heritages, including Native American, Chinese and Black.

Before boarding the bus, Yaniv, who hails from the Negev region, told us that the messages he grew up with “were to be afraid of Palestinians because Jews are always under attack . Until I was 30, I never met ‘the other’ face-to-face unless I was in uniform.”

Alaa grew up in Akko , a mixed city of Jews, Christians and Muslims, where he said he was exposed to the rhetoric of Meir Kahane. The late Orthodox rabbi and founder of the Jewish Defense League referred to Arabs as “dogs” and called for their expulsion from Israel. Alaa ultimately chose to follow the example of coexistence learned from his mother, who helped establish the Sir Charles Clore Jewish Arab Community Center , a local initiative that remains active today.

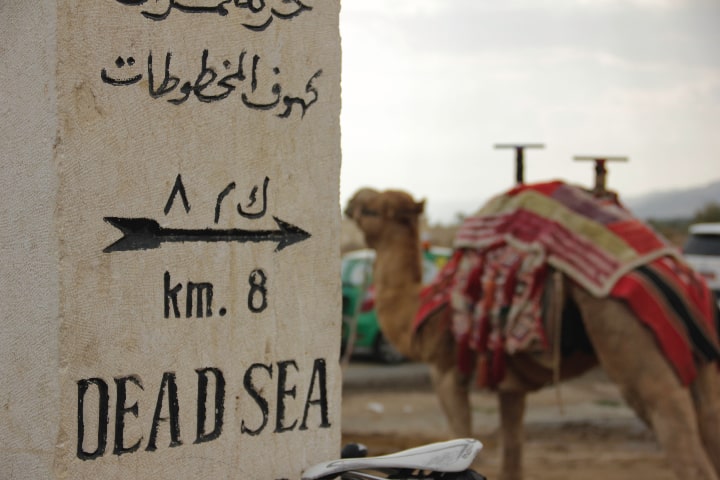

Our first stop was a short drive from the shimmering 24/7 metropolis of Tel Aviv: 4,000-year-old Jaffa. The ancient coastal city has endured many conquerors, including Canaanites, Egyptians, Israelites and the Ottomans—up through May 1948, when Israel took control after, depending on who is narrating, either the War of Independence or the Nakba (Arabic for catastrophe).

Also depending upon the narrator, Jaffa is a symbol of peaceful coexistence or emblematic of the Jewish state’s erasure of Arabs. An erasure initially due to voluntary as well as forced expulsion of Arab residents and, currently, to gentrification, with housing prices almost out of reach for many of the city’s remaining 16,000 Arabs. (The area is home to 30,000 Jews.)

The Wishing Bridge in Jaffa connects Kedumim Square , a beguiling mishmash of archeological remains, chic shops and galleries, to Peak Park . Carved into the wooden structure are bronze statues of the 12 zodiac signs. “Legend says if you stand on this bridge and touch your sign while looking at the sea your wish will come true,” Alaa said. “Not to influence you, but I wish for peace.”

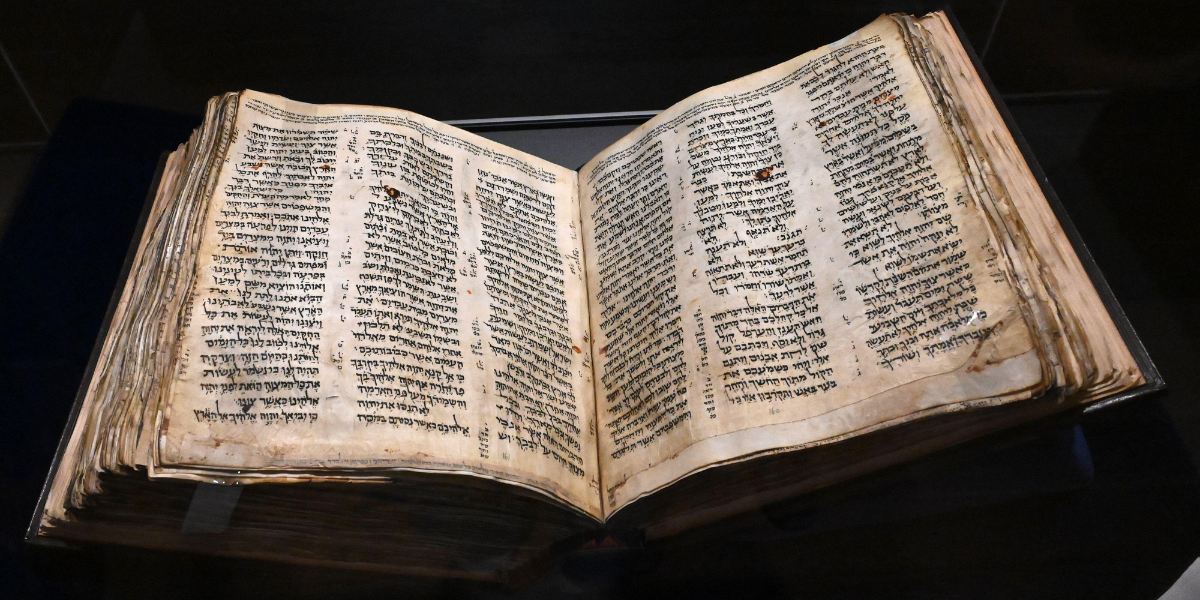

After our next stop at Tel Aviv’s ANU-Museum of the Jewish People , I experienced a swell of pride. The recently renovated and expanded institution utilizes videos, interactive stations and artifacts—ranging from the Codex Sassoon, an 1,100-year-old Hebrew Bible, to a collar worn by late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg—to showcase not just our tragedies but the sweep of Jewish accomplishments.

But my inner “yays” grew quieter during our subsequent excursion into Ramallah and Bethlehem, both located in Area A of the Palestinian Territories.

As outlined by the 1995 Oslo II Accord in what was intended to be an interim agreement, the territories are divided into sections: Area A, which is fully under Palestinian Authority control and where Israel has declared it illegal for its citizens to enter, though an exception is generally made for Israeli Arabs; Area B, in which the Palestinian Authority has administrative control, but security is overseen by Israel; and Area C, covering over 60 percent of the West Bank, where Israel maintains exclusive control.

Temporarily sans Yaniv since he cannot enter Area A, we learned that Ramallah, on the crest of the Judaean Hills , is more liberal than most large Muslim communities. Alcohol is permitted and women freely run businesses. Indeed, female chef Fidaa Abuhamdiya led us on a food tour, which was followed by a visit to a bakery managed by Arab women.

In a meeting room of Farah Locanda , an Ottoman-era house-turned-boutique hotel, our group sipped water as we listened to Samir Othman Hulileh, the chairman of the local stock exchange. Hulileh’s voice cracked as he recalled the morning in 2002 when his approximately 20-mile-drive to the factory that he owns in Bethlehem was interrupted by a call from a close friend who is an Israeli artist and army reservist.

The message: Hulileh should turn back. Israel and Hamas were clashing, and the army needed his factory as an interrogation center. “I’ll watch out for it,” his friend promised. Weeks later, the factory reopened.

“We still visit each other’s homes, but it has never been the same” since his factory was temporarily requisitioned, Hulileh told us. His conclusion? “The conflict is too strong for us to solve without a third party.”

Bethlehem is dominated by a stretch of Israel’s 25-foot-high separation wall topped in this section by watchtowers and barbed wire. Built during the Second Intifada in the early 2000s to prevent suicide bombers from entering Israel, street artist Banksy turned the wall into a tourist destination when he and his team spray-painted it with anti-war imagery—a practice since taken up by other provocateur artists.

Our group toured the multimedia museum that tells (one side of) the story of the barrier inside the nearby Walled Off Hotel , which was founded and financed by Banksy. I pressed “play” on my audio guide to hear a recorded phone message that the Israel Defense Forces typically deploy in the strategy called “roof knocking,” when they warn of an impending demolition of a civilian building. “You have five minutes to leave before we bomb,” I heard on my headset.

Back in Israel the next morning, I asked Yaniv for context about life during the fraught period between 2000 and 2005, when 887 Israeli civilians were killed in terrorist attacks. He recalled being about a dozen feet from a Tel Aviv bus that exploded. “I saw it with my own eyes,” he said. “People on it became soup. It was terrifying, unbearable.”

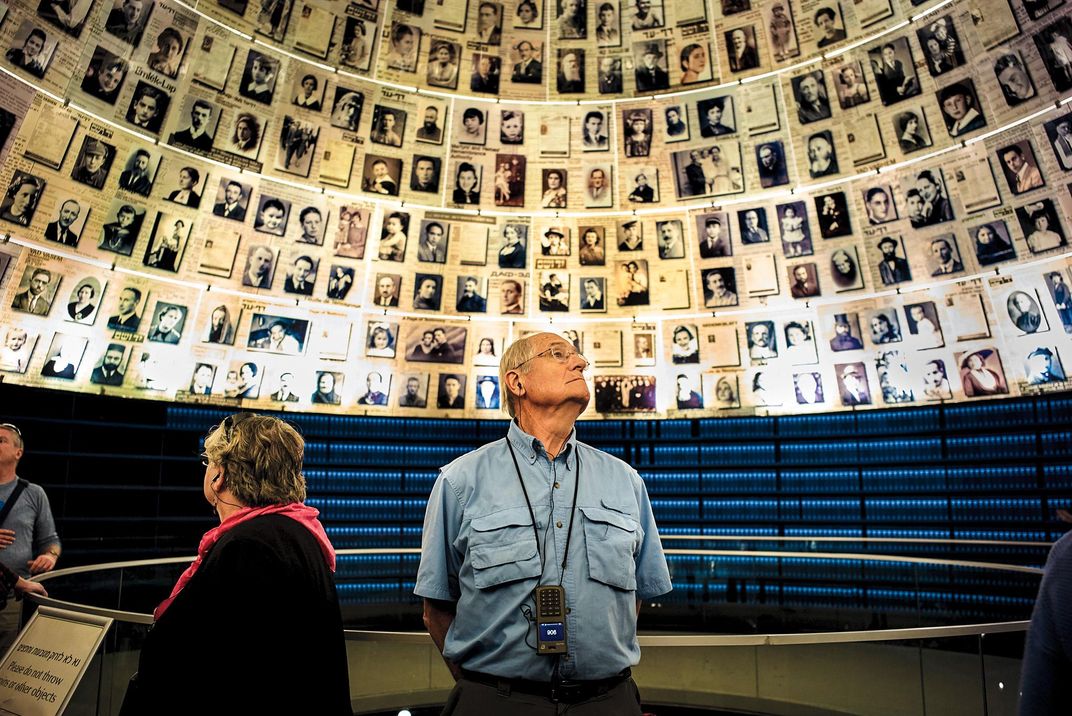

Our Jerusalem stops at the Kotel and Yad Vashem , the World Holocaust Remembrance Center, left me feeling viscerally connected to my par ents. I felt them urging me forward.

Forward meant traveling to Gush Etzion , a bloc of 20-plus Jewish communities in Area C that is home to around 70,000 Jews. Bob Lang, head of Gush Etzion’s Religious Council, offered cookies and commentary in his home in Efrat, one of the largest Jewish cities in the area. Jews purchased land here in 1927 but were thrice driven out by Arab violence until Israel regained control in 1967 after the Six-Day War. While acknowledging that walls and barriers are not the road to peace, Lang doesn’t foresee change “while Arab leaders teach that killing Jews is a good thing.”

If Hulileh and Lang exuded varying degrees of hopelessness, our next speakers, who met with us at the Holy Land Hotel in Jerusalem, shone a flashlight beam into inky darkness. Osama Eliwat and Elie Avidor represented Combatants for Peace , a movement composed of former fighters on both sides of the conflict.

Raised in East Jerusalem, Eliwat’s first encounter with Jews was watching Israeli soldiers beat his father. At 14, he began throwing stones and hopping on rooftops to spraypaint “Free Palestine.” After twice being arrested and released by Israeli authorities, in 2010, Eliwat accompanied friends to a meeting for peace activists. There he met Israelis who, he recounted, “believed I was human and deserved rights.” It was the first time he heard about the Holocaust. “They said, ‘I hear your pain, and I have stories, too. ’ “

This proved to be his turning point. He attended more meetings and came to believe that “the main source of the conflict is we don’t know each other.” He said that he decided “to dig deep, to fully understand the narrative and fears of Israeli Jews.” At age 35, this quest led to his first plane ride, to visit Auschwitz.

Avidor fought with the IDF in the Golan Heights. “It felt good,” he said of his army service. “I was protecting my family.” After the army, he lived in North America for 20 years. When he returned to his homeland, his perspective had changed. In 2016, he accompanied a friend to the annual Israeli-Palestinian Joint Memorial Day Ceremony, sponsored by Combatants for Peace and The Parents Circle, an organization of over 600 bereaved families on both sides. “For 90 minutes I cried, listening to everyone’s stories,” Avidor recalled.

“People tell me I hate Jews and love Arabs,” he said about his involvement with Combatants for Peace. But, he added, “I do this work because I love my country.”

Our group’s final evening together offered a partial answer to a question Yaniv had posed days earlier: “How do we find a way to communicate without yelling?”

In a modest home in the West Bank town of Al-Eizariya in Area C, our host Mustafa Abu Sarah—brother of MEJDI co-founder Aziz Abu Sarah—served the classic Arab chicken dish of maqluba (upside down). The entrée is so named because the pot of stewed chicken, spiced rice and vegetables is flipped onto a large serving plate.

We worked off calories by dancing to the darbuka and lute-enhanced stylings of two members of Wast El Tarik, an Israeli-Palestinian musical ensemble.

Back on the bus, our group joyously warbled through a medley of friendship-centric songs. As the last notes of “Why Can’t We Be Friends?” faded, our hotel came into view. While our lives would soon physically diverge, 14 souls had been forever transformed by a vision of what is possible.

Sherry Amatenstein is a New York based psychotherapist, author, anthologist and journalist who has written for many publications, including Tablet, New York, Better Homes and Gardens and AARP’s The Ethel .

Jo Ann Friedman says

September 2023 at 12:58 am

Unfortunately I do not see peace in the future until Israel’s right to exist is acknowledged and until being a terrorist is not an exultated status.

And yes, Israel has to acknowledge that Palestinians have a right to live there as well.

sherry amatenstein says

September 2023 at 2:17 pm

I agree on BOTH of your points. Thank you very much for reading my article.

Sharon Weiner says

October 2023 at 1:02 am

I disagree there’s a million Arab countries that didn’t want the Palestinians so they decided that they will going to take land from Israel remember the Dome of the Rock is built on two temples. The Palestinian people have a right to be part of Israel. We do not negotiate with them because they are controlled by Hamas and Hezbollah who in turn is controlled and funded and trained by Iran.

Sheldon Finkelstein says

October 2023 at 4:11 pm

In light of this past weekend’s events, the murder of over 700 Israelis and counting, I’d say the timing of this naive article by a New York based liberal is pretty sad timing.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Footer Menu Column 2

- Israel + Diaspora

- Culture + Travel

- Community + Faith

Footer Menu Column 3

- Terms & Conditions

Footer Menu Column 4

- Make a Gift

©2024 HADASSAH, THE WOMEN’S ZIONIST ORGANIZATION OF AMERICA, INC. HADASSAH, THE H LOGO, AND HADASSAH THE POWER OF WOMEN WHO DO ARE REGISTERED TRADEMARKS OF HADASSAH, THE WOMEN’S ZIONIST ORGANIZATION OF AMERICA, INC.

MEJDI Day Tours

- See all photos

Jerusalem: Dual Narrative Tour

Most Recent: Reviews ordered by most recent publish date in descending order.

Detailed Reviews: Reviews ordered by recency and descriptiveness of user-identified themes such as waiting time, length of visit, general tips, and location information.

MEJDI Day Tours - All You Need to Know BEFORE You Go (2024)

History | July 2019

Two Tour Guides—One Israeli, One Palestinian—Offer a New Way to See the Holy Land

With conflict raging again in Israel, a fearless initiative reveals a complex reality that few visitors ever experience

:focal(2161x919:2162x920)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/ee/21ee120b-041a-4604-8a0c-06b06664d5a6/julaug2019_j01_dualnarratives.jpg)

Geraldine Brooks; Photographs by David Degner

In the fierce morning light of Caesarea, we hike down the beach, following the line of a ruined aqueduct that dates from the era of Herod the Great. The golden sand is littered with tiny russet tiles. Peering up into the dunes, we shade our eyes as our guide points out their source—the crumbling floor of what’s believed to have been a diplomat’s home when this Mediterranean port was an administrative center for the Roman occupation of Judea, some 2,000 years ago. Farther on, we see evidence of the Muslim conquest of the city 600 years later, ushering in Arab rule that lasted until the Crusades. Later, in 1884, Bosnian fishermen settled this shore, and the minaret of their mosque now punctuates a lively tourist precinct beside the leafy and affluent Israeli town where the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, makes his home.

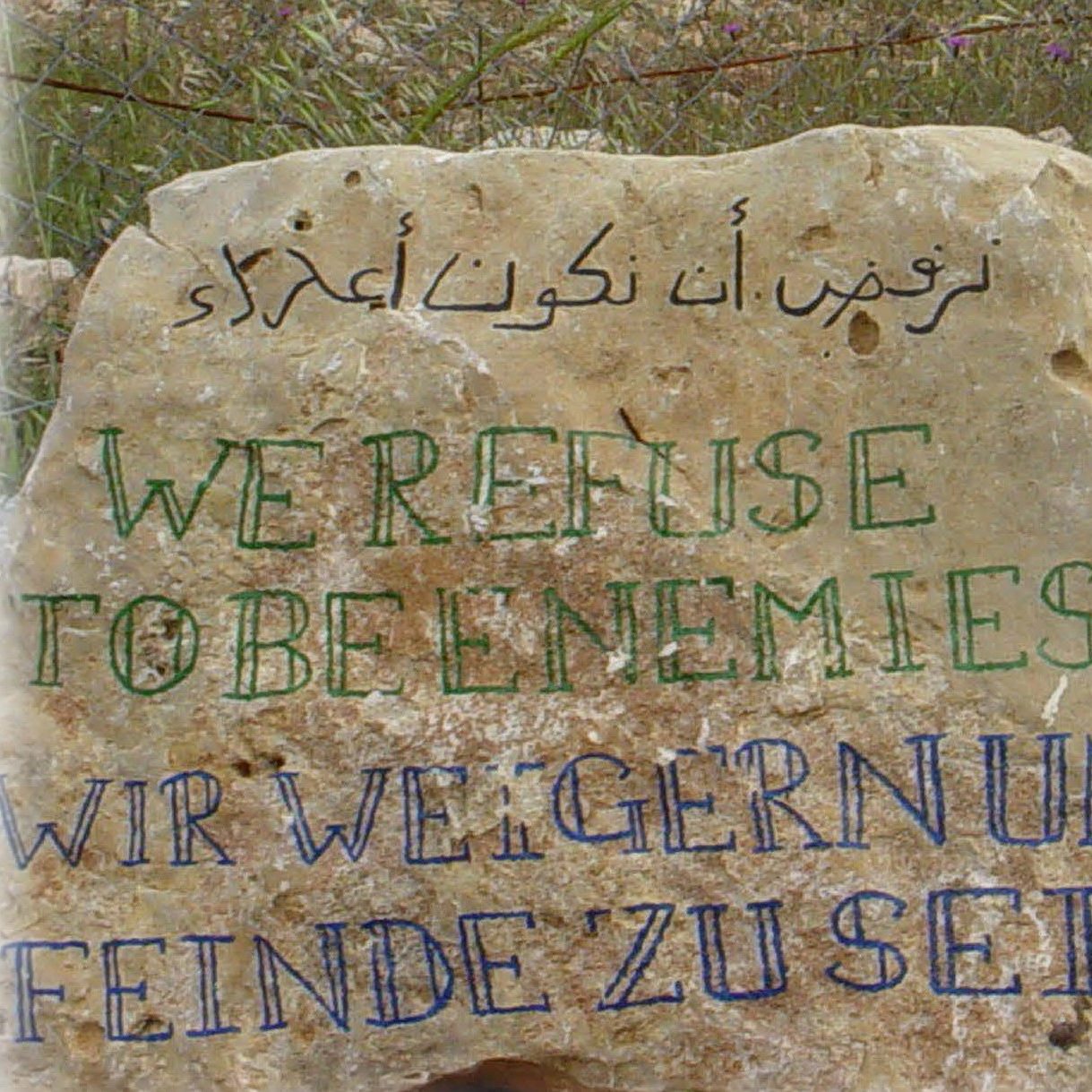

It’s our first morning in Israel, and already we’ve covered thousands of years of overlapping cultures, a perfect introduction to this tiny notch of land, so long inhabited, so often fought over and brimming with stories that have shaped the world. The group I’m with, mostly members of a Lutheran church in Lake Forest, Illinois, outside Chicago, is part of a tourist boom that last year brought four million visitors to this nation of fewer than nine million people. At many stops, we are surrounded by a babel of languages, representing visitors from every corner of the world, all drawn to this land and its stirring history. But our experience differs from that of most visitors. Instead of one guide, we have two—an Israeli and a Palestinian—and each gives a dramatically different perspective on everything we see. During the next week, we will travel from places of worship to archaeological sites and into private homes, crossing and recrossing Israeli military checkpoints and the approximately 285-mile separation barrier that divides much of this society.

Our Israeli guide is Oded Mandel, 38, the son of Romanian Jews, whose father survived the Holocaust as a child. Oded’s parents immigrated to Israel in the 1970s, after the Jewish state reportedly made cash payments to the oppressive regime of Nicolae Ceausescu in exchange for exit visas. Oded serves as a reserve officer in the Israel Defense Forces. Bearded and bespectacled, he describes himself as “proud in my military service, in being Jewish, proud in my parents and what they did to come here.”

Aziz Abu Sarah, also 38, a Palestinian Muslim, lives under occupation in his birthplace, East Jerusalem. He was 9 years old during the first Palestinian Intifada, when Israeli soldiers burst into his bedroom one night to arrest his older brother, Tayseer, who was accused of throwing stones. Tayseer went to prison and, after his release nine months later, died from injuries he sustained there.

I first visited Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories during that uprising, in the winter of 1987. I was a young correspondent for the Wall Street Journal , dodging stones and rubber bullets to interview boys like Tayseer as well as reservists like Oded. I empathized with the Palestinians, many still children, risking their lives to protest poverty and daily indignity. But I also felt the crushing anxiety of Israelis, especially Holocaust survivors and terror victims, and I sympathized with soldiers, many of whom despised their new duties skirmishing with civilians. I also grew frustrated, in the safe comfort of European and American cities, with the smug certainties of friends who could feel sympathy for only one side. Either all Israelis were brutalizing oppressors or all Palestinians were bloodthirsty terrorists. I wished my acquaintances could spend even a week doing what I did, listening to stories from both sides that were often equally harrowing.

Aziz Abu Sarah created Mejdi Tours to offer just such an experience. He was well aware that most visitors receive just one view: Jewish tourists and many Christian groups focus heavily on Jewish history and rarely visit the West Bank or interact with Palestinians. Palestinian tours, by contrast, focus on difficulties of life under occupation and the Christian pilgrimage sites in Palestinian towns such as Bethlehem, while millennia of Jewish history is ignored.

Aziz, like an archaeologist at one of the country’s celebrated tels , or archaeological mounds, had the idea to present visitors with the multiple narratives of the people who share this land, digging down layer by layer and story by story, undaunted by complexity—indeed, reveling in it.

Arriving in Nazareth feels like crossing an invisible border into an Arab country. Minarets stud the skyline, mixing with church spires. Clutching falafel sandwiches, we wander past neon signs in Arabic and women wearing colorfully embroidered Palestinian dresses. In the market, spice sacks gape open, revealing bright saffron and paprika. Cardamom and coffee scent the air.

The Chicagoans I’m with are a well-traveled group, mostly professionals, but only a few have been to Israel before. They lob questions at our guides. Though Aziz’s and Oded’s perspectives are not aligned, they share an easy, bantering relationship. Aziz, wearing a pearl-buttoned Western-style shirt that signals his love of country music, is naturally ebullient, with the affect of a stand-up comic. Oded, affable and measured, says he likes the Mejdi Tours approach “as a way to challenge what I am thinking.” Frequently, each offers the same caveat before answering a question: “It’s complicated.”

Now some in our group are struggling to understand the legal status of the people in Nazareth, which is one of the largest Palestinian communities within Israel. Arab Israelis, or Palestinian citizens of Israel, as most prefer to be called, make up 21 percent of Israel’s population. They carry Israeli passports, can vote in national elections and send Palestinian members to the Knesset, or Parliament. Why, one traveler asks, did some Arabs stay inside the new State of Israel while so many others fled during the Arab-Israeli War of 1948?

Oded gives the Israeli narrative, explaining how European Jews, fleeing pogroms and discrimination, began to return to their ancient homeland in the 19th century, when it was under Ottoman and later British rule. Occasional acts of violence between Arabs and Jews turned to outright conflict when Jewish migration accelerated during and after the Second World War, as displaced refugees and survivors had few other places to go. In 1947, as the British mandate was ending, the United Nations voted to partition the land into separate homelands for Jews and Arabs. “The Jewish side said, ‘Yes, we need a state right now.’ We tried to live here in peace, we acknowledged partition,” Oded says. “But the Arabs said ‘No,’ and in 1948 we had to fight five different Arab armies” during what Israelis call the War of Independence.

When Aziz takes up the narrative, he uses the Palestinian term for the 1948 war: al-Nakba , the Catastrophe. He describes the killing of Palestinian civilians by Jewish paramilitaries. “People were terrified,” he says. Arabic radio broadcasts fanned the panic, warning of massacre and rape. In fear for their lives, huge numbers fled to the West Bank and Gaza Strip as well as to Lebanon, Jordan and Syria. “They thought the fighting would end in a few days, and they would come back to their homes. They were not allowed to, and those who fled—at least 700,000 people—became refugees.”

Oded interjects that more than 800,000 Jews were themselves forced to flee Arab countries such as Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Yemen following violent reactions to Israel’s founding.

“I don’t accept that parallel,” counters Aziz. “What Egypt did is not the Palestinians’ responsibility.”

The discussion is interrupted when our bus rounds a curve on an olive-studded hillside and a shimmering sheet of water comes into view. “ That’s the Sea of Galilee?” exclaims one incredulous Midwesterner. “It looks like a little lake in Wisconsin!” This issue of scale will come up again and again—the trickle of water that is the “mighty” Jordan River, even the size of the disputed land itself, which is slightly smaller than New Jersey. It is vividly on display in the Golan Heights, in Israel’s far north, where barbed wire surrounds an army post that looks into Syria. A sign indicates that Damascus lies just 60 kilometers, or 37 miles, away.

For a long time after the death of his brother, Aziz would not have listened to an Israeli perspective like Oded’s. A self-described radical bent on revenge, Aziz refused to learn Hebrew because it was the “language of the enemy.” But, after graduating from high school, he couldn’t get a decent job, so he joined a class at a language center designed for recent Jewish immigrants. For the first time, he met an Israeli who wasn’t a soldier. His teacher was sensitive and welcoming. “Since I didn’t know enough Hebrew to argue with her, we had to become friends first,” he tells me.

That experience kindled a new curiosity. Aziz went to work for a Jewish ceramics company in the ultra-Orthodox Jerusalem neighborhood of Mea She’arim (“My employers were very good to me”), and attended an Evangelical Christian Bible college in Jerusalem. (“I didn’t want to know what Muslims think Christians believe. I wanted to understand from Christians what they believe.”) Aziz then joined a support group for those who had lost a family member in the conflict; members shared their stories and discussed reconciliation.

In front of often-hostile audiences, he retold the story of Tayseer’s death alongside an Israeli with his or her own tragic tale of violence and bereavement. He saw that such stories had immense power to change people’s thinking, and he expanded on that experience by creating a radio program, in Hebrew and Arabic, in which Israeli and Palestinian guests would each speak about a dramatic change in their life or attitude. Eventually, Aziz’s activism brought him to the attention of Scott Cooper, then a director of George Mason University’s Center for World Religions, Diplomacy and Conflict Resolution in Fairfax, Virginia, where Aziz was recruited to create programs in interfaith outreach, peace-building, negotiation and government reform, which he then led in person in Afghanistan and Syria and in online courses for Iranians.

In 2009, Aziz and Cooper created Mejdi Tours, adhering to strict principles of social and environmental responsibility. The company has spent more than $900,000 in the communities it visits, and its tours and tourists have spent $14 million at local businesses. Groups are almost never booked in chain hotels and are encouraged to shop at small stores or fair-trade co-ops. The company offers similar multinarrative tours in Northern Ireland, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Iraqi Kurdistan and other places that have experienced conflict.

“In a place like Barcelona, people can’t stand tourists, because they don’t connect with the locals,” Aziz says. “We’re all about making connections.” He quotes the 14th-century Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta: “Travel makes you speechless, then it turns you into a storyteller.”

On Friday morning, as we prepare to explore the ancient port city of Acre, a mixed Jewish-Arab city on the northwest coast, Aziz mentions the widespread view that the city has the country’s best hummus. “Personally, I don’t agree with that,” he adds.

“Me neither,” says Oded.

“Finally, we have one narrative here,” Aziz quips.

We visit the green-domed Al-Jazzar Mosque just as worshipers are arriving for Friday midday prayers, the week’s most important communal observance. Most of the travelers have never set foot in a mosque. They gaze at the intricate tilework adorned with calligraphic inscriptions from the Quran. Since Islam regulates every aspect of a believer’s life, Aziz explains, the imam’s sermon may extend beyond the spiritual, touching on some matter of daily existence—diet, say, or finance. Or the sermon might be intensely political, which is one reason demonstrations often erupt on Fridays after prayers.

Later, on the road to Jerusalem, Oded remarks that Friday is special for Jews as well, as sunset marks the beginning of Shabbat , the Sabbath. “You’ll see that the traffic is going to get lighter. Religious people will be walking to synagogue.” Soon we are walking ourselves, having left the bus behind at the entrance to Kiryat Moshe, an Orthodox Jewish neighborhood where driving is discouraged between sundown Friday and sundown Saturday.

At the apartment of Rabbi Joshua Weisberg, we squeeze around a table, humming along as his family sings a traditional song to greet the Sabbath. “And now,” says the rabbi, “I’m going to bless my children. It’s going to take a while.” There are eight children, ranging in age from 3 to 20. The eldest, a daughter, is away, studying at a religious seminary, but one by one the others come to the head of the table, snuggling against their father as he embraces them and whispers the ancient Israelite blessing: “May God shine his face upon you and show you favor....”

Over dumpling soup and platters of chicken, Rabbi Weisberg tells us that the same blessing was found etched onto a 2,800-year-old silver amulet excavated at an archaeological site only a few miles from the apartment. “A parent in Isaiah’s Jerusalem probably put that amulet on his child, expressing the same hopes and concerns, in the same Hebrew I prayed tonight,” he says. “That’s one of the reasons it’s important for me to be here—to feel that continuity of Jewish life in this place.”

When the rabbi’s two eldest daughters finished high school, they chose to do two years of national service, working with disadvantaged and disabled kids, which is an alternative to military service open to religious youth. But the third daughter plans to join the army, a controversial choice among Orthodox girls. “Israel defends me,” she told her father. “I won’t serve?” To the rabbi, that independence of mind is welcome. “I want my children to be Jewish, and to have a connection with God—I’d be devastated if they didn’t have that. But for the rest, they will decide.”

On the way back to our hotel, Aziz, who had not met Rabbi Weisberg before, is enthusiastic about his humor and openness. “I told him I’d like him to be involved with more of our groups. He said, ‘Are you sure you want me? I’m a right-wing guy.’ I told him, ‘That’s why I want you—I know plenty of leftists already.’”

The West Bank settlement of Efrat, about an hour south of Jerusalem, consists of red-roofed residences slung across seven hilltops, and is surrounded by long-settled Palestinian villages. Efrat is populated mainly by traditional religious Zionists, many of whom believe they have a national and spiritual imperative to settle the biblical lands of Judea and Samaria. But lots of residents, says Shmil Atlas, who directs development in the settlement, move there for other reasons, too. He cites the settlement’s proximity to Jerusalem, good schools, a well-educated professional community, as well as cost: a three-bedroom house, for example, can be bought for about the same price as a one-bedroom apartment in Jerusalem.

Efrat is now home to about 12,000 Israelis, and the community plans to grow by 60 percent over the next few years. Part of the settlement is in lockdown this morning, because of suspected infiltrators detected by electronic sensors. When we arrive, security personnel are searching house to house. Palestinians who usually work here have been banned from entering. (No infiltrators were found.)

Despite the heightened tension, Atlas paints a sunny picture for us of the settlement’s relationship to its Palestinian neighbors. Nearby villagers, Atlas says, are glad of the work the settlement offers—around a thousand jobs, mostly in construction, maintenance and agriculture. Since most of the Israeli residents commute to work in Jerusalem, he jokes that by day the mayor of Efrat is “the mayor of a Palestinian city.” One woman in our group is clearly taken with Efrat—the crisp, luminous air of its hilltop setting, the charming villas splashed with bougainvillea.

But the cost to Palestinians of ongoing settlement expansion is on stark display less than ten miles north, where the town of Bethlehem is being slowly choked by military checkpoints and is unable to grow because of the looming separation barrier. “The whole town is essentially walled in,” the Rev. Dr. Mitri Raheb, president of Dar al-Kalima University College of Arts & Culture, tells the group. When Raheb’s mother was hospitalized for cancer treatment in East Jerusalem, he was able to get a permit from Israel to visit her; his mother’s sisters were denied. When his father-in-law was suffering a heart attack, a border guard required him to exit the ambulance and walk through the checkpoint. He died a few days later.

“We have no room to grow,” Raheb laments. “It is destroying the character of the little town, and its economy.” A quarter of Bethlehem’s work force is unemployed, and the need to use every inch of land means little green space. “Our kids don’t know what spring looks or smells like,” he says. But Raheb, a Palestinian Christian, paraphrases a comment attributed to Martin Luther, on the essential need to retain hope: “If the world is ending tomorrow, go out and plant an olive tree.” He fulfills that ideal by leading the sole Palestinian university dedicated to arts and culture. “We are educating the next generation of creative leaders in Palestine,” he says proudly.

Snarled in traffic at a checkpoint, the traveler who had earlier been drawn to Efrat now works through her feelings. “I thought, I’d like to live there: It’s intellectual, it’s a mix of young and old, it’s a really pretty community. But then in Bethlehem you see how suffocated they are. It’s like a ghetto.”

To Aziz, this is how a Mejdi trip is supposed to work. “Most people who come here will hear only one of these two narratives,” he says. “If they come here already very pro-Palestinian, I’ll say, let me push you a bit harder to see the other side. Same thing if they’re very pro-Israel. Being able to see the other side doesn’t mean you have to agree with it.”

One morning, we find ourselves on the Mount of Olives—picking olives. It’s a volunteer effort for the beleaguered Augusta Victoria Hospital, a Lutheran institution that cares for about 700 patients a day from Gaza, the West Bank and East Jerusalem, specializing in oncology and nephrology. The gray-green olive groves cover the hillside, and the Chicagoans climb into tree branches to harvest ripe fruit onto waiting tarps. Oil from these 800 trees will be sold to raise funds for the hospital, which has been under severe financial pressure, especially since the Trump administration halted aid to the Palestinians. Previously, such aid covered almost a quarter of the hospital’s bills, explains Pauliina Parhiala of the Lutheran World Federation. “There are USAID stickers on a lot of the equipment.”

Money isn’t the only challenge. Palestinian hospital staff who live in the West Bank are sometimes delayed at checkpoints. Not quite two-thirds of the Gazans who apply to come to the hospital receive permission to enter Israel, and sometimes the parents of children who need dialysis or chemotherapy are denied entry on security grounds. Still, Parhiala says, medicine is a bright spot of Palestinian and Israeli cooperation. Palestinian doctors receive overwhelming support from Israeli colleagues, training together and working side by side. “Even in the most difficult times, this has continued, and that’s a ray of hope for me,” Parhiala says.

Later, as Oded and Aziz lead the group through the narrow alleyways of Jerusalem’s Old City, Aziz unfolds his story as a Jerusalemite. Although born here, he is merely a permanent resident, not a citizen. After the Six-Day War in 1967, when Israel captured the

West Bank and Gaza Strip, it annexed East Jerusalem and 28 surrounding Palestinian villages, home to some 70,000 Palestinians, including Aziz’s family. Those Palestinians were not granted citizenship, and though they are eligible to apply for it, the process is difficult. Even Aziz’s tenuous residency status can be revoked if the government determines he is not “centering his life” in the city. That’s a risk for someone who runs an international travel company, has lived in the United States, and works on conflict resolution around the globe.

Last September, Aziz announced that he would run for mayor of Jerusalem, intending to take a case to court to test the right of a noncitizen to do so. But he was assailed from both sides before he could even file suit. He learned that his Israeli-issued residency permit was suddenly under review. Activists linked to the Palestinian Authority threw eggs at him and threatened his life for breaking with a long-standing election boycott and “legitimizing” the Israeli occupation. (Only about 2 percent of Palestinians who are eligible to vote in Jerusalem’s municipal elections actually do so.) Aziz eventually withdrew, but he still thinks his strategy was the right one. “Our leaders aren’t pragmatic,” he laments. “Instead of opening a discussion, they resort to violence and threats.”

One evening, our group visits Aziz’s family home, in the village of Bethany, just beyond the area annexed by Israel. Aziz’s father built the large house himself, and planted trees and gardens, only to learn that living in the house would disqualify the family as residents of Jerusalem. The family faced a choice between staying in the home and losing the right to travel freely to and from the city of their birth, or moving into a cramped apartment within the city lines. They chose the apartment, to protect their status. Today they may only visit the home in Bethany, never sleep there.

On the wall of the house’s main salon is a photograph of Aziz’s brother, Tayseer. When 19-year-old Tayseer was released from prison, in 1991, he was vomiting blood. His family rushed him to the hospital, but it was too late. Aziz reflects that it was hard to abandon a desire for revenge, but demonizing and dehumanizing the enemy, he says, only serve to fuel the conflict. He realized he had a choice to defy that impulse.

From the kitchen, Aziz’s mother, aunts and sister-in-law emerge with huge pots of maqluba , “upside down” in Arabic. With great flourish, they invert the pots and present perfectly layered towers of rice, chicken and vegetables. A band whose members are Israeli and Palestinian performs songs reflecting both traditions. Aziz and his nephews teach us some Arabic dance moves while his parents, clad in traditional Palestinian robes, look on in amusement.

On Sunday morning, we make our way through the teeming alleys of the Old City, where merchants pushing handcarts cry out for right of way through processions of Franciscan monks in rope-belted robes and hordes of tourists. Hidden behind a high wall, we find the 19th-century Church of the Redeemer. Its cool, geranium-decked courtyard is an unexpected oasis from the bustle of the ancient city.

After a church service, Oded brings us to the Western Wall, the last remnant of the Second Temple, which was destroyed by the Romans in A.D. 70. Known as the Kotel, it is the most sacred space in Judaism. As the midday sun beats down on the ancient stones, Oded holds up a copy of a famous photograph. It shows young Israeli soldiers in the Six-Day War who were the first to fight their way through Jordanian troops and minefields, uniting the city under Jewish control. The soldiers’ faces are battle-weary, but their expression as they gaze up at the wall is filled with awe. “Two thousand years of yearning in this photograph,” says Oded.

Oded outlines the evolution of Israel’s military vision, from the euphoric invincibility born of that swift victory in 1967—when Israel pushed the Syrian Army back from the strategic Golan Heights, drove the Egyptians out of the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza and the Jordanians out of the West Bank and East Jerusalem—to the beginning of the military occupation there that continues more than 50 years later. Then he explains the attempted reversal in 1973, when Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack on Yom Kippur, the holy day when Jews fast and pray. It took hours to contact key reservists and several days to mobilize the unready forces. “We thought we were on the verge of the third temple destruction,” says Oded, meaning that it seemed possible the Jewish state could be wiped out, as it was in ancient times.

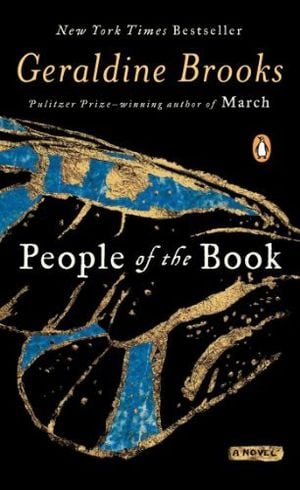

That afternoon is spent at Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial and museum. I wander outside, to the Garden of the Righteous Among the Nations, in search of a plaque honoring Dervis and Servet Korkut, Muslims who sheltered a Jewish girl during the Nazi occupation of Sarajevo. Dervis Korkut, an Islamic scholar and the national museum’s chief librarian, also saved a masterpiece of medieval Judaica, a rare illuminated codex known as the Sarajevo Haggadah.

In 2008, I wrote a novel, People of the Book , based on the journey of that haggadah, imagining the stories of those who carried it to safety over hundreds of years. The haggadah was created in Spain before the Inquisition, at the time of La Convivencia , or The Coexistence, when Muslims, Christians and Jews lived peacefully together until violent Catholic bigotry forced Muslims and Jews into exile. The haggadah was saved from Catholic book burning by a priest in Venice in 1609, and, by the 19th century, had made its way to Sarajevo, where in early 1942 Korkut saved the book from Nazi looters, hiding it among Qurans in a mosque. Fifty years later, Sarajevo’s own celebrated convivencia was ripped apart by ethnic cleansing during the Bosnian War. This time, another Muslim librarian rescued the haggadah as the museum was being shelled. For many, the book has come to symbolize how an ideal of multiplicity—of religion, of ethnicity, of culture—can survive, if only enough people care.

Novelists live by imagining the unlikely, and walking in Yad Vashem’s sun-dappled, pine-fragrant shade, my mind drifts to an alternate narrative in which that Syrian border in the north isn’t filled with skeins of razor wire, and a person of any background or creed could hop in her car and drive those 37 miles for dinner in a peaceful Damascus. It’s the kind of reverie that feels irresistible when visiting this place.

Back in 1991, when I was still a foreign correspondent, I asked people across the region to play this mind game with me on the eve of the Madrid Peace Conference, the first time Israeli and Palestinian officials sat down publicly to speak about an accord. At first, everyone shrugged off my question: Peace was impossible, the hatred ran too deep.

But when I prodded, they began to unspool wondrous visions of a golden age of friendship and prosperity, a convivencia for a new era. A Palestinian shipping magnate exiled in Jordan dreamed of plunging into the surf at Caesarea, as he used to as a child. A Syrian man longed to visit the place his parents had honeymooned on the West Bank. An Israeli cartoonist told me he just wanted to “sit and schmooze over coffee, like normal neighbors.”

It was bittersweet to recall those conversations, yet it seemed apt to reflect on such possibilities at Yad Vashem. Israel and Germany had become staunch allies less than half a century after the Second World War. Who had a right to say peace was unthinkable?

When I rejoin our group, they are meeting with Berthe Badehi, a Holocaust survivor who spent her childhood hiding from Nazis among French farmers. After the war, she immigrated to Israel, and she recalls her astonishment the first time she went to the bustling food market of Jerusalem’s Machane Yehuda. “There were Jews everywhere,” she says. “I had been in hiding all my life. Finally, here was a place to be myself.”

But there was a high price. In 2002, her oldest grandson was killed at 22, when he was part of an army unit attempting to free Israeli soldiers trapped inside Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat’s besieged compound headquarters during the Second Intifada. She shows us a picture of the young man, and Oded gasps. He recognizes him. He embraces Berthe, and tells her that he lives in the same community as another of her grandsons, where every year they commemorate her elder grandson’s death. It is another reminder of the intimacy and interconnectedness of this society.

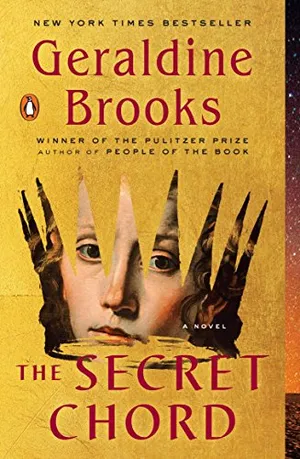

The next morning, we visit the “City of David,” an extensive and glossily presented archaeological dig just outside the southern wall of the Old City. Excavations have uncovered the ruins of a large palace possibly built during the Davidic era (c. 1000 B.C.), as well as the probable source of the ancient city’s water supply. I had been here before, researching The Secret Chord , a novel I wrote about the life of King David. Then, as now, the excavations fueled my imagination, conjuring the city as it is described in the Bible, rising up out of the crumbled stones, peopled with musicians and artisans.

Our guide to the site, a British immigrant to Israel, is a practiced presenter who radiates enthusiasm as he describes a recent discovery: a processional way closely matching details from the story of young Solomon, mounted on his father’s mule, anointed king by Tzadok the priest and Nathan the prophet—a ceremony still enacted at every British royal coronation.

For a person like me, who excavates the past for fiction, it’s easy to get swept up by all of this. But I am shaken from my daydream when we tour Silwan, the predominantly Palestinian village that sits atop the excavations. Our guide here is neither practiced nor fluent in English, just an old man in a dingy robe who fears for his neighborhood. Many of the humble dwellings here are cracking, undermined by the excavations, and others have been occupied by Jewish settlers. There is palpable tension, as Palestinians sidle warily past armed Israeli guards to reach their homes, while Israeli school buses have mesh over the windows to protect against stones, Molotov cocktails, or worse. If this was, indeed, the site of David’s city, I imagine he would despair to find it in such a state.

Our final stop is a close-up look at the separation barrier, which, when it is completed, is designed to carve the landscape for 440 miles. The first sections were built in 2003, at the height of the Second Intifada, when, Israel says, it was necessary to prevent suicide bombings, which have practically ceased since. But for Palestinians, the wall has meant further loss of land; in some places, families have been separated, and many farmers have lost access to their own fields.

In 2017, the British artist Banksy opened the Walled Off Hotel, not far from Bethlehem. Billed as the hotel with “the worst view in the world,” it is hard up against a soaring concrete section of the Palestinian side of the barrier, which has become a canvas for portraits of Palestinian resistance figures and for sarcastic graffiti: “In my previous life I was the Berlin Wall. The beer was better there.” “Make hummus not walls.” The hotel is part political statement, part immersive artwork, with edgy décor like the bullet-strafed water tank that fills the hot tub in the presidential suite. A sardonic multimedia account of the conflict, delivered in a plummy British-colonial accent, concludes with the line: “If you are not completely baffled, then you don’t understand.”

Visitors nod in agreement.

We share a farewell dinner at the Eucalyptus, a kosher restaurant in Jerusalem, where the Israeli chef, Moshe Basson, explains how he uses indigenous ingredients, including many frequently mentioned in the Bible—hyssop, dates, pomegranate, almonds.

Over an array of fragrant dishes, the guests share the lessons of an intense week.

“Before I came, I didn’t know what I didn’t know,” observes Kim Morton.

“I came thinking I was going to hear two sides,” says Roger Bennett. “Now I’ve figured out there are many more than two sides.”

For Craig Linn, the most enlightening moment came in Yad Vashem. “The need for security is so great,” he says. “When Berthe says, ‘I just wanted a place where I could be myself.’” He pauses, recalling the emotion of the moment. “But then, the Palestinians feel that, too....”

Cathy Long, who is a generation older than our guides, takes a personal tone. “I’m leaving all of this feeling you two are my sons,” she says, her voice catching. “I just wish there was an answer, something we could do, so that your kids could be safer.”

Oded, who has two small children, is clearly moved. “I hope that next time you come, there will be something more positive to show you,” he says. “But you help by keeping an open heart, and by being curious about everything.”

Aziz concludes the meal by quoting the poem “Tourists,” by the celebrated Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai. The poem is shot through with bitterness about the way some tourists see his country, connecting more with its edifices than its people. In the last lines, a tour guide fixates on a Roman arch not far from the Tower of David, in the Old City.

Redemption will come

Only if their guide tells them,

“You see that arch from the Roman period?

It’s not important:

But next to it, left and down a bit,

There sits a man who’s bought fruit and vegetables for his family.”

The tower Amichai mentions is one of the most prominent features of the city’s ancient wall. When I was a young reporter covering the conflict, I would often sit in the evenings on a bench in the lovely old neighborhood across the valley, and gaze at the tower as the moon rose behind it, turning the stones pearly against a blushing sky. In those days, it provided a moment of solace after witnessing so much violence.

The morning after our final meal, as the group disperses to catch flights homeward, I visit the tower again. There is no weary man with his vegetables resting there today. In fact, as I climb the steps to the base of the tower, the area is unexpectedly deserted. For a few minutes, I’m alone.

When I was writing my novel about King David, I wanted to set a scene inside the tower that bears his name. But my research quickly revealed that the striking stone structure had nothing to do with him. King Hezekiah may have built the first tower on the site, long after David’s era. In time, that tower fell, and other structures rose in its place, as Jews, Romans, Byzantine Christians, Arabs, Crusaders and Ottoman Turks bled and died for control of these stones. The graceful edifice that stands today is actually a minaret—the remains of a mosque built in 1637.

And that makes it the perfect symbol of this land’s many-layered narratives, the inspired fictions we cling to and the painful truths we bury.

People of the Book

Inspired by a true story, People of the Book is a novel of sweeping historical grandeur and intimate emotional intensity by an acclaimed and beloved author.

The Secret Chord: A Novel

Peeling away the myth to bring David to life in Second Iron Age Israel, Brooks traces the arc of his journey from obscurity to fame, from shepherd to soldier, from hero to traitor, from beloved king to murderous despot and into his remorseful and diminished dotage.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

A Note to our Readers Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

Geraldine Brooks | READ MORE

Geraldine Brooks is the author of several books, including the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel March .

David Degner | READ MORE

David Degner is an editorial photographer based in Boston, Massachusetts.

MEJDI Day Tours

- See all photos

Jerusalem: Dual Narrative Tour

Most Recent: Reviews ordered by most recent publish date in descending order.

Detailed Reviews: Reviews ordered by recency and descriptiveness of user-identified themes such as waiting time, length of visit, general tips, and location information.

MEJDI Day Tours - All You Need to Know BEFORE You Go (2024)

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Can Travel Be a Force for Peace? This Tour Leader Thinks So.

‘We tend to think of travel in terms of distance, but I think travel is really a lifestyle, a state of mind,’ says Aziz Abu Sarah of Mejdi Tours, which explores both sides of longstanding conflicts in places like Belfast and Jerusalem.

By Paige McClanahan

Aziz Abu Sarah and his business partner, Scott Cooper, had a big ambition when they started their tour company: They wanted to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

Well, sort of. It was kind of a joke between the two of them, Mr. Abu Sarah said recently. But the two friends — one a Palestinian who grew up in Jerusalem, the other an American Jew — had worked together in international conflict mediation and resolution in places like Syria, Afghanistan and Colombia. Feeling limited by the number of people they could reach through that work, Mr. Abu Sarah and Mr. Cooper decided to apply their experience in a completely different realm: tourism. Their goal was nothing less than to transform travel — and travelers — into a force for peace.

A defining feature of the tour company they founded in 2009 is the “dual narrative” tour, in which a group of tourists is led by two guides: one from either side of a longstanding conflict or division that has affected the area that the group is visiting. On the company’s tour of Ireland and Northern Ireland, for example, a Unionist and a Nationalist jointly lead the tour of sites around Belfast, Derry and Dublin. And on their tour of the Holy Land, the groups visit Tel Aviv, Bethlehem and Jerusalem accompanied by both a Palestinian Arab and an Israeli Jew.

“Literally, everyone we knew told us this was the dumbest idea,” Mr. Abu Sarah said recently from his home in South Carolina. “They thought that nobody would ever pay to do something like this. But within a year, we proved them wrong.”

More than a decade after its founding, Mejdi Tours has hosted over 20,000 guests, and the company now runs trips to the Balkans, Colombia, Egypt, Morocco, Chile and Costa Rica, among other places. Meanwhile, Mr. Abu Sarah has been named a TED Fellow and a National Geographic Emerging Explorer . He has also written a book that makes the case for travel as a force for peace.

The company’s tours have been mostly on hold during the pandemic, but Mr. Abu Sarah and Mr. Cooper used the downtime to develop or expand several new trips in the United States, including a history-of-civil-rights tour of the U.S. South, an Indigenous tour of the U.S. Southwest, and “Red/Blue Divide tours” of Washington, D.C., and Detroit.

When I reached him, Mr. Abu Sarah was about to head off to lead a group tour in Egypt. But he took the time to talk about the danger of the single narrative, the power of bringing together opposing perspectives, and what he learned from the hardest trip he’s ever taken.

Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Why is the dual narrative approach so important?

In so many places that Scott and I had traveled to, we always came across a single dominant narrative, and then there were all these other narratives that were never given a voice in the public sphere. So with our tours, we thought: “No more single story. No more single narrative.” We decided to start in Jerusalem, Palestine and Israel, because Scott is Jewish and I’m Palestinian, and that’s the area we knew the best. And what we’ve seen is that the dual narrative is so powerful because it gives you the opportunity to hear different opinions, but also to understand the people you meet, to understand their fear and their anger, and to really fall in love with the place you’re visiting.

The discussions must get heated sometimes. Have you ever had problems with tension in the groups?

It’s extremely rare. If there are conflicts, it’s personality oriented, which you would see on any group tour. We have very conservative people and very liberal people coming on the same trips, but because these two guides with different backgrounds are able to hold a conversation, that somehow helps the group to hold these conversations, as well, without starting to fight. So we almost never have a problem between the guests themselves — or between the guides, which was the other worry people had.

And now you’re applying this approach to tours in the United States?

I used to live in Washington, D.C., which is a very segregated city, especially on a class level, and I realized that my friends and I wouldn’t venture out of the neighborhoods we already knew. So we started to develop a tour of the city, and we got a Republican and a Democrat to colead it. That first trip was incredible. Watching the news, you would think that if you put a Republican and a Democrat together, they would just talk past each other. But that wasn’t the case at all. One of the most interesting conversations we had was on a visit to the Heritage Foundation, which is very conservative. Some of the liberal people in the tour group had never had this kind of open conversation with a conservative that wasn’t just sound bites, but a real, productive conversation. By the end of it, the discussion was about “What’s the solution?” rather than “You’re doing this wrong or that wrong.” It was fascinating. And that’s what happens on our tours in Israel and Palestine. That’s what happens in Bosnia, Croatia and Serbia.

You spent your childhood in a place with a long history of conflict. How has that experience informed this work?

I grew up in Jerusalem, but I never had a real conversation with a Jewish-Israeli person until I was 18 years old. My brother was killed by being beaten up in prison by Israeli soldiers, so I grew up very angry, very much with the idea that the other is evil. And then when I was 18, I decided to study Hebrew because I had to — not because I wanted to. Living in Jerusalem, you can’t survive without Hebrew. I remember walking into the class thinking, “None of these people probably want me to be here.” And I couldn’t have been more wrong. My Hebrew teacher was the most incredible human being. She even tried to speak Arabic to me to make me feel welcome. And that was the first time I felt like I was treated like a human being by the other.

But before that moment, I only knew one narrative of Israel, and many Israelis probably only know one narrative of Palestinians: the one they hear in the news.

Is that what you mean when you say that the most difficult trips can be the ones that are closest to home?

I think it can be much easier to be open to learning about issues or problems that are happening five or six thousand miles away. Often when I talk about my work with Syrian refugees, people will say, “Oh, I would like to go and volunteer with Syrian refugees in Jordan or Turkey.” And I ask them, “Have you volunteered with Syrian refugees in your own community? Because if not, you should start there, and then maybe go to Syria.”

We tend to think of travel in terms of distance, but I think travel is really a lifestyle, a state of mind. And if you learn to travel in your own community, you’ll learn to travel when you go abroad. For me, the hardest trip I ever took was going from my home in East Jerusalem to West Jerusalem. It’s just a 15- or 20-minute walk, but making that trip brought about the biggest change for me, because it challenged me the most.

Many people want to relax when they go on vacation. Why should they choose to go on a challenging, dual-narrative trip?

There’s an assumption that when people travel, they’re not interested in learning. And that’s not true. Even surveys tell us it’s not true. People want to do good as they travel, and they are looking for culture and connection. I have fun in my travels: I go see museums, I swim in the ocean, I enjoy music, all of that. But that’s not all that I do. I like to say that travel is an act of diplomacy: Be a diplomat as you’re traveling and go out and meet someone new and hear their stories. And it’s so much fun! It’s the thing that you will remember, and that you’ll tell people about when you come back.

Paige McClanahan is the host of The Better Travel Podcast .

Follow New York Times Travel on Instagram , Twitter and Facebook . And sign up for our weekly Travel Dispatch newsletter to receive expert tips on traveling smarter and inspiration for your next vacation. Dreaming up a future getaway or just armchair traveling? Check out our 52 Places list for 2022 .

Open Up Your World

Considering a trip, or just some armchair traveling here are some ideas..

52 Places: Why do we travel? For food, culture, adventure, natural beauty? Our 2024 list has all those elements, and more .

Mumbai: Spend 36 hours in this fast-changing Indian city by exploring ancient caves, catching a concert in a former textile mill and feasting on mangoes.

Kyoto: The Japanese city’s dry gardens offer spots for quiet contemplation in an increasingly overtouristed destination.

Iceland: The country markets itself as a destination to see the northern lights. But they can be elusive, as one writer recently found .

Texas: Canoeing the Rio Grande near Big Bend National Park can be magical. But as the river dries, it’s getting harder to find where a boat will actually float .

Trips to the Middle East

Interested in Pilgrimage and Advocacy-Oriented Travel ?

Plan Your Next Trip with CMEP

Churches for Middle East Peace (CMEP) partners with MEJDI tours to offer custom group travel to Israel, Palestine, Egypt, Turkey, and other destinations in the Middle East. Trips to the region offer pilgrimages and advocacy-oriented travel. If you travel to the Holy Land, trips provide the chance to hear multi-narrative perspectives through the use of two local guides, one Israeli and one Palestinian. They offer various perspectives on the history and current realities of the land. Get in touch with us by filling out this form or emailing Adysen Moylan our CMEP Trips Coordinator at [email protected] .

Israel / Palestine

Encounter the Holy Land and the “Living Stones”

- Experience multi-narrative perspectives on the complex Holy Land

- Travel that combines pilgrimage and advocacy-oriented learning

- Visit the sites where Jesus walked, taught, and lived

Visit key Christian sites and faith leaders

- See key sites in from Joseph, Mary, and Jesus’ Flight into Egypt

- Visit Mount Sinai, where Moses recieved the Ten Commandments

- Visit the 6th century St. Catherine’s monestary

- Experience the rich, long Christian tradition in Egypt which lives on today

- Engage with local Copts and other Christian minority groups who keep the faith alive in Egypt

Travel to Turkey, Jordan or Greece

- Walk the footsteps of Paul in Turkey

- Visit the Hagai Sophia and the centuries of Muslim and Christian history represented within its walls

- See the 6th century Basilica of St. John in Ephesus and visit the Christian community which is still active in the region

CMEP Offers:

- Itinerary building and consultation for group tours – let our experts help you plan a tour that includes visits to historical and holy sites, as well as meetings with the people who live and work for peace in the land. All trips offer pre-trip orientation and a post-trip debrief.

- Invite a CMEP staff member to travel with you – based on availability, a CMEP staff member may be available to join and serve as a leader to help your group connect what they are seeing on the ground with tangible action steps to continue working for peace at home.

- CMEP-planned open tours – great for individuals or small groups (less than five) who want to travel. Individuals can purchase a spot on these trips without needing to plan an entire group tour. These opportunities, when available, will be shared below on this page!

- Opportunities for experts to meet with you and your church community for orientation and debrief meetings via video conference or in-person in order to be educated about theological considerations, the spiritual significance of the land, the current geopolitics of the region, and other areas of interest so that you and your community may be best prepared for your journey.

Who Should Travel with CMEP?

Anyone is welcome to travel on CMEP’s open tours. If you’d like to plan a custom group tour , here are some guidelines on the type of groups that best fit a CMEP-designed tour:

Groups that include 15-45 people

Trips that last between 8-20 days

The desire to meet people who live in the land, Middle Eastern Christians, peace activists, and others; and to explore beyond the standard itinerary for a trip to the Holy Land

Plan to travel to the region within the next 10-24 months

Already Planning a Trip?

You can still meet with our staff based in Israel, Palestine, and Egypt. Get in touch with us by filling out this form or emailing [email protected] and we will work to arrange a meeting, or even have them speak to your group! CMEP you can meet with us on the ground to hear about what we do and learn about next steps in engagement through advocating, elevating, and educating your home community.

About MEJDI Tours:

Dedicated to providing customized itineraries for travel groups as diverse as our destinations, MEJDI Tours is a full-service tour company-differentiating itself from the crowd through exclusive access, authentic experiences, extraordinary customer service, and much more – founded on the belief that tourism should be a vehicle for a more positive and interconnected world. MEJDI-which translates to “honor” and “respect” in Arabic – was established to achieve one goal: change the face of tourism through a socially responsible business model that honors both clients and communities.

CMEP’s Executive Director, Rev. Dr. Mae Elise Cannon, serves as MEJDI’s Chief Advisor for Christian engagement. We are grateful for the constructive partnership between MEJDI and CMEP.

After going on a trip with CMEP and Peace Not Walls, Anthony and Mary reflect on what they learned on the “Counter Stories” podcast.

Rev. Charlie Lewis says his life has been deeply impacted by his visit to the Nassar Farm in the West Bank. This is just one of the many spots we visit on CMEP trips to Israel/Palestine.

After their trip to the Middle East, Overlake Church in Washington reflected on their time in this short video.

“As someone from a non-Christian background, it was really meaningful to me to learn about Christ by actually going where he lived and moved around – and then to see how that history shaped the people and the lands. I felt very privileged to have this be my first in depth look at His story.”

— Former CMEP Trip Member

Best part of the trip: “Connecting with a couple young boys in Hebron by playing soccer in the street with them for about an hour.”

One trip participant described his time in Hebron as his favorite part of the trip, as he was able to play soccer in the streets of Hebron with young boys for an hour. Our trips allow you to not only experience the places, but truly encounter the people of the land.

Resources for Trips:

Want more info? Get in touch with us by filling out this form or emailing Ana Moylan our CMEP Trips Coordinator at [email protected] .

© 2024 Churches for Middle East Peace

Share this on:

Palestinian, jew give both sides on joint jerusalem tours.

- Each "dual narrative" tour is jointly led by Israeli and Palestinian guides

- They include a former settler, former Israeli soldiers and former Palestinian militants

- Social guides use personal experience to explain their communities' perspective

(CNN) -- As a soldier in the Israeli Defense Forces, Kobi Skolnick once fired shots at Aziz Abu Sarah's aunt's house in the West Bank town of Hebron.

Ten years later, Skolnick, a former Israeli settler, who grew up in an ultra-orthodox household, and Abu Sarah, once a Palestinian militant, work together explaining both sides of the Middle East conflict to tourists.

They discovered the uncomfortable coincidence during a tour in Hebron for Mejdi , a "dual-narrative" tour company co-owned by Abu Sarah, where every tour is jointly led by Jewish and Palestinian guides.

Abu Sarah, 30, said: "He (Skolnick) was talking about which houses he shot at, and one of the houses was my aunt's."

Skolnick said of the revelation: "I had shot at her house, and there had been shots fired from the house, but we were so glad we could share that with no judgment.

"We have profound moments like that all the time on our tours because I used to fight Palestinians and some of them used to fight Israelis. Now we come together and try to find a solution."

Mejdi guides explain landmarks and historic sites from their personal experiences and those of their communities.

One of the tour groups from an American synagogue even spent several days on home-stays in a Palestinian refugee camp.

"They formed incredibly close relationships," said Abu Sarah. "When they left there was hugging, kissing and crying. It was one of the most emotional things I've ever seen."

Abu Sarah's own journey from extremist to peace activist inspired his work.

He was 10 years old when his brother Tayseer died after being released from an Israeli prison. Tayseer had been arrested for throwing stones during the first Intifada and Abu Sarah says he was tortured in prison.

The experience turned Abu Sarah into an "angry and bitter" teenager and he became a youth leader of Fatah -- a cornerstone Palestinian political party along with Hamas -- at an early age.

He said: "I grew up as an anti-peace activist. I had never met an Israeli or a Jew other than soldiers or settlers. I was as extreme as you can get."

The turning point came at the age of 18 when Abu Sarah realized he would need to learn Hebrew to further his career.

"I had always refused because it was the language of the enemy," he said. After enrolling on a Hebrew course for newcomers to Jerusalem, Abu Sarah came face-to-face with Jewish people for the first time in his life and realized they could be friends.

"Slowly I realized that there's an emotional wall of fear that eventually becomes hatred, and from that moment my work was to bang our heads against that wall to bring it down," he said.

Skolnick, 30, grew up in an ultra-orthodox Hasidic Jewish community and moved to a settlement near Nablus when he was 14.

During his national service in the Israel Defense Forces, Skolnick was sent to protect settlers from Palestinian militants.

He said: "This was 2001 and there was serious violence. I protected Israelis from gunshots and suicide bombers. At the time, I just felt I was protecting people. It was special to feel you are part of history and defending your own people.

"Now I have different feelings. I don't feel regret, but I wish I had known more about the politics and the wider issues."

Abu Sarah said he started Mejdi tours, a social enterprise, 18 months ago to combat the propaganda spread by both sides during traditional tours. So far it has taken around 20 tour groups, mostly students, Synagogues, churches and interfaith groups from the United States, Europe and Australia.

He said: "I realized that friends of mine who had come on Israeli tours hardly wanted to talk to me afterwards because they had heard the Israeli narrative, and others who heard the Palestinian side left almost anti-Semitic.

"We don't want to spread this hate. We have three million tourists come to this country every year. Imagine if we could transform tourism to spread peace instead of hate?"

Shira Nesher, 23, a student at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and one of Mejdi's social guides, used to be a tour guide in the Israel Defense Forces.

She said: "I was the granddaughter of Holocaust survivors on both sides, so I was reminded every day that the Israeli state was the stability the Jewish people needed after the Holocaust. The Jewish story was all I knew.

"In the IDF I gave talks to soldiers and main emphasis was on creating a will to make sacrifice for the state.

"This was an eye-opener because I wanted to be able to hear both sides of the story, but I couldn't do that in the IDF."

Palestinian Mazen Faraj, 36, has lived all his life in Dheisheh Palestinian Refugee Camp near Bethlehem in West Bank, leads tours around the camp for Mejdi.

He was arrested for the first time at the age of 15 during the first Intifada and many times over the following years for being involved in demonstrations against Israeli soldiers. He spent three and a half years in jail in total.

In 2002, Faraj's father was shot dead by an Israeli soldier while traveling from Jerusalem to Bethlehem, he said.

"We just received a call from the hospital in Bethlehem to say they had his body," Faraj said. "We asked the soldiers but weren't allowed to go to the hospital because we were under curfew, so we had to wait until the morning.

"You can't imagine what that was like."

Faraj said he gradually became involved in peace work a few years later.

"After this tragedy I had to find somewhere to put all the anger and suffering in my head, otherwise there's just more violence and revenge," he said.

"It was a long process. I didn't just wake up in the morning and decide to talk to Israelis.

"It doesn't mean I forget or forgive, but it does mean we can create a message of getting to know each other and wanting to change the situation."

Most Popular

Fine art from an iphone the best instagram photos from 2014, after ivf shock, mom gives birth to two sets of identical twins, inside north korea: water park, sacred birth site and some minders, 10 top destinations to visit in 2015, what really scares terrorists.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS