James Blake House

Top ways to experience nearby attractions

- JFK/UMass • 9 min walk

Most Recent: Reviews ordered by most recent publish date in descending order.

Detailed Reviews: Reviews ordered by recency and descriptiveness of user-identified themes such as wait time, length of visit, general tips, and location information.

Also popular with travelers

James Blake House - All You Need to Know BEFORE You Go (2024)

- (0.44 mi) Courtyard by Marriott Boston-South Boston

- (0.49 mi) Holiday Inn Express Boston, an IHG Hotel

- (0.42 mi) Home2 Suites by Hilton Boston South Bay

- (1.82 mi) Clarendon Square

- (0.29 mi) Boston Homestel

- (0.03 mi) 7-Eleven

- (0.10 mi) Singh's Roti Shop

- (0.06 mi) KFC

- (0.15 mi) 224 Boston Street

- (0.13 mi) Great Wok Restaurants

Dorchester Historical Society

The James Blake House

Architecture, restoration, archaeology.

James Blake House 735 Columbia Road (Richardson Park) Dorchester, MA 02125

Boston's oldest house, the James Blake House, sits on

Dorchester's Columbia Road, about 400 yards from

its original location on what is now Massachusetts

Avenue (where the parking lot of the National Grid

property is located today). The house is one of only a

few examples of West England country framing in the

United States. Most of the early colonial homes in

Dorchester, such as the Pierce House, were built by housewrights from the south and east of England, where brick and plaster building predominated. However, the Blake House was built in the manner of the homes of western England, which had long used heavy timber-framing methods. The James Blake House is a two-story, central chimney, gable-roof dwelling of timber-frame construction. It is on a rectangular plan, three bays wide and one bay deep and measures 38 by 20 feet. Built in 1661, the house is one of a relatively small number of its type - the post-Medieval, timber-frame house - surviving anywhere in New England.

Architecture

The James Blake House is a two-story, central chimney, gable-roof dwelling of timber-frame construction. It is on a rectangular plan, three bays wide and one bay deep, and measures 38 by 20 feet. Built in about 1650, the house is one of a relatively small number of its type--the post-Medieval, timber-frame house--surviving anywhere in New England. The house is thought to be one of only a few examples of West England country framing in the United States. Most of the early colonial homes in Dorchester, such as the Pierce House (1683), were built by housewrights from the south and east of England, where brick and plaster building predominated. However, the Blake House was built in the manner of the homes of western England, which had long used more and heavier timber in their framing methods.

The Blake House was built near a spring and tributary to Mill Creek, west of the Five Corners and therefore west of the first Meeting House at Pond and Cottage Streets, on land adjoining that of the Clap family. Its original occupants were James Blake and his wife Elizabeth. James was born in Pitminster, England, in 1624, and emigrated with his parents to Dorchester in the 1630s. He married Elizabeth Clap, the daughter of Deacon Edward Clap and niece of Roger Clap, in 1651. James became allied through marriage to the large Clap family whose activities of daily life in the New World were based upon practices brought from their English West Country

background. Their agrarian economy included dairy farming with milk and butter production; growing wheat and corn and establishing grist mills; establishing orchards for apples and cider; and maintaining sheep for wool. The tanning business also depended on the rearing of animals. Many of the implements of everyday life were made of leather including harnesses, straps, belts, shoes, clothing, saddlebags and bookbindings.

The Blake House became the primary focal point of a very comfortable and well-to-do 91-acre estate that included a 10-acre home farm with at least two outbuildings and orchard, yards and garden. Deacon James Blake held public office, becoming a constable, town selectman, and deputy to the General Court as well as a pillar of the First Church, serving as Deacon for 14 years and later Ruling Elder for about the same length of time.

In 1700 the house passed to James and Elizabeth's son John, who in turn bequeathed it to his two sons, John and Josiah, in 1718. The estate was settled by subdivision in 1748, and from that time the east and west halves of the house were occupied by separate families for over a century, one half being sold out of the Blake family in 1772 to a neighboring Clap relation. Over the course of time, the house and surrounding land was used for agriculture, for a spinning and weaving shop, and for a tanning business.

In 1825 Caleb and Eunice (Clapp) Williams purchased the west half of the house from Rachel Blake, the sole surviving heir, and in 1829 they acquired the east half by inheritance. The house remained in the Williams family until 1892 when it was acquired by George and Antonia Quinsler who in 1895 sold it to the City of Boston.

The City government acquired the land to complete a large parcel for the building of municipal greenhouses and to widen Massachusetts Avenue as a complement to Olmsted's Emerald Necklace, which included the creation of Columbia Road as a boulevard from Franklin Park to the South Boston waterfront.

The Dorchester Historical Society became interested in saving the James Blake House when it became clear that the house was to be demolished. The 1895-96 move and restoration of the Blake House was an historically significant project in the Richardson Park section of Dorchester, which was just then becoming rapidly urbanized, with new street widenings, new streetcar lines, the creation of new parks, the building of Columbia Road, and new landmarks including new churches. Patriotic feelings associated with the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, combined with growing interest in America's history and the development of new architectural styles that were built upon American motifs, resulted in a frenzied interest in the Colonial Revival. The 1890s preservation and restoration of the colonial Blake House was undertaken with great care and devotion and has become historically and architecturally significant in itself, demonstrating the Colonial Revival interpretation of First Period architecture.

The Society convinced the City to grant the Society the house and the right to move it to Richardson Park at its own expense. By January, 1896, the house had been moved to its new location by a local building mover for $295. This seems to be the first recorded instance of a historic private residence being moved from its original site in order to rescue it from demolition. The Blake House is a museum of early American Home construction and is studied by students of architectural history.

Twenty-first Century Restoration

By the year 2000 the oldest existing house in Boston, the James Blake House required major repairs, and the Massachusetts Historical Commission awarded a grant for exterior renovations. The Dorchester Historical Society employed preservation consultant John Goff of Historic Preservation and Design to prepare a Historic Structures Report on the history, architecture and preservation needs of the Blake House, which was built in 1661, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Report is a wonderful tool, bringing the history of the house and its surroundings into one volume and identifying the extensive and essential restoration work required to bring this ancient house into a historically accurate and weather-tight condition. The report was the cornerstone of the grant application to the Massachusetts Historical Commission.

In consultation with John Goff and the Massachusetts Historical Commission the Dorchester Historical Society found Jerry Eide of Hilltown Restoration, to take on the carpentry and masonry portions of the projects. The repair of the leaded-glass was completed by Glenn Shalan from North Adams. The project was completed in June, 2007. The Society received an award from the Massachusetts Historical Commission and the Boston Preservation Alliance for its work on the Blake House.

In 2007, Ellen Berkland, at that time both the city's archaeologist and the caretaker of the Blake House, performed an archaeological dig and found a huge number of artifacts and a truncated shell midden, providing evidence of a Native American presence at the site. Read about the archaeological excavation at the Blake House here !

Dendrochronology

The Massachusetts Historical Commission also funded the extraction and testing of cores from beams in the building to determine the age of the house. The results of the test showed that the trees from which the timbers were hewn were felled in the winter of 1660-1661, giving a fairly-certain construction date of 1661.

Ground-Penetrating Radar

In 2007 Allen Gontz of the Department of Environmental, Earth and Ocean Sciences at UMass Boston performed a Ground Penetrating Radar survey of the Blake House property. It was known that a pond once filled the area in front of the Blake House where Columbia Road and Pond Street intersect. The survey found an edge of the early pond in the front yard of the Blake House.

- Senior Living

- Wedding Experts

- Private Schools

- Home Design Experts

- Real Estate Agents

- Mortgage Professionals

- Find a Private School

- 50 Best Restaurants

- Be Well Boston

- Find a Dentist

- Find a Doctor

- Guides & Advice

- Best of Boston Weddings

- Find a Wedding Expert

- Real Weddings

- Bubbly Brunch Event

- Properties & News

- Find a Home Design Expert

- Find a Real Estate Agent

- Find a Mortgage Professional

- Real Estate

- Home Design

- Best of Boston Home

- Arts & Entertainment

- Boston magazine Events

- Latest Winners

- Best of Boston Soirée

- NEWSLETTERS

If you're a human and see this, please ignore it. If you're a scraper, please click the link below :-) Note that clicking the link below will block access to this site for 24 hours.

Seven House Museums to Visit Within City Limits

Here's where to admire architecture and antique furniture.

Sign up for our weekly home and property newsletter, featuring homes for sale, neighborhood happenings, and more.

Photo by Ellen Gerst

This grand Federal-style mansion was designed by renowned architect Charles Bulfinch. Built as the first of three homes for former mayor Harrison Gray Otis in 1796, the house is one of the last remaining structures from what used to be Bowdoin Square. Thanks to Boston’s period of urban renewal in the 1960s, the historical home now straddles Beacon Hill and the West End. Inside, its paint colors and carpet designs are historically accurate—and they’re surprisingly vibrant.

Otis House Museum, 141 Cambridge St., historicnewengland.org .

The Nichols House Museum photo via Wikimedia/ Creative Commons

Nichols House

Beacon Hill’s other Bulfinch-built house museum was once home to suffragist and landscape architect Rose Standish Nichols. Among her many accomplishments, she was a founding member of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom in 1915, which has a mission to unite all women for peace, disarmament, and gender equality.

Nichols inherited the Federal-style home on Mount Vernon Street from her father in 1935, and ruled the roost until her death in 1960. She never married, but often hosted salons at the house, gathering intellectuals to discuss and debate progressive ideas over afternoon tea. Nichols intended for the house to be left as a museum after her death, and since then, it’s shown Bostonians what life was like in Beacon Hill at the turn of the century. Tour highlights include furniture handmade by Rose’s sister, Margaret Nichols Shurcliff.

Nichols House Museum, 55 Mount Vernon St., nicholshousemuseum.org .

Photo by John Woolf for A Glimpse of the Past at the Gibson House

Gibson House

For a snapshot of life in Victorian Boston, step through the double doors of the Gibson House on Beacon Street. Though you wouldn’t know it from the outside, this brownstone conceals a historical interior that hasn’t been altered since 1954. That’s thanks to Charles Gibson Jr., who in the 1930s decided he should preserve the contents and opulence of his family’s 1860 home. A guided hour tour through the house’s four levels features a one-of-a-kind Victorian ventilator shaft (you have to see it to understand its majesty), “Japanese Leather” wallpaper, a 15-piece bedroom set, and more.

Photo by Ed Lyons on Flickr/Creative Commons

James Blake House

Built in 1661, the James Blake House is the oldest house in all of Boston. It’s tucked between Upham’s Corner and Columbia Point on a sliver of green space, though it’s about 400 yards from its original location on what is currently Massachusetts Avenue. The home’s original owner, a minister named James Blake, settled in Dorchester in the 1630s. He built the house in the Western English style, now a rare sight in New England. The Dorchester Historical Society only offers tours of the house on the third Sunday of each month, from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m.

James Blake House, 735 Columbia Rd., Dorchester, dorchesterhistoricalsociety.org .

Photo by Jules Struck

Prescott House

This impressive Federal-style construction dreamed up by architect Asher Benjamin flaunts unique rounded bay fronts and white columns. It was built overlooking the Common in 1808 for a merchant named James Smith Colburn, and on land once owned by portrait painter John Singleton Copley to boot. In 1845, historian William Hickling Prescott moved into the house, and about a century later, it was purchased by the National Society of Colonial Dames. The home, also known as the Headquarters House, is now open as a house museum on select Wednesdays and Saturdays.

William Hickling Prescott House, 55 Beacon St., Boston, nscdama.org .

Photo by Leslee on Flickr/ Creative Commons

Ayer Mansion

Just down the street from the Prescott House, the Ayer Mansion is the only extant home designed by artist Louis Comfort Tiffany. Perhaps best known for his kaleidoscopic stained glass works, Tiffany worked his magic on not just the windows, but on stone and glass mosaics. The famed Gilded Age artist also clad the home in exterior mosaics—only the Ayer Mansion and his private home feature original Tiffany exterior work. Tours of the 1902 mansion are offered at least one Saturday and one Wednesday per month. Though the museum is house is closed to the public for maintenance during August, a tour schedule is regularly available on ayermansion.org .

Frederick Ayer Mansion, 395 Commonwealth Ave., Boston, ayermansion.org .

Photo by Tim Sackton on Flickr/ Creative Commons

Shirley Eustis House

William Shirley, the Royal Governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony until 1756, spent his summers at “Shirley Place,” which he built in 1751. It also served as the summer home of William Eustis, a post-Revolution Massachusetts governor who took office in 1822. Now called the Shirley-Eustis House, the place is one of the last remaining Royal Colonial Governors’ mansions in the country. Tours of the mansion, the carriage house, and the grounds are offered 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. Thursday through Saturday until Labor Day. Offseason tours can arranged by appointment.

Shirley-Eustis House, 33 Shirley St., Roxbury, shirleyeustishouse.org .

- Architecture

You Can Own a Very Special Barnstable Barn for $1.75 Million

Real Estate Showdown: A Condo in the South End vs. a Weston Single-Family

On the Market: A Nature Lover’s Utopia in Topsfield

You Can Own a Very Special Cape Cod Barn for $1.75 Million

On the market: a nature lover’s utopia in topsfield, massachusetts, on the market: a cinematic estate in stowe with a helicopter pad, real estate showdown: a newton colonial vs. a lexington home, so you want to live in lynnfield, massachusetts, in this section.

About James Blake House

Historic Architecture, Architecture, Interesting Places, Other Buildings And Structures

The James Blake House is the oldest house in Boston, Massachusetts, United States. The address is 735 Columbia Road, in Edward Everett Square. This neighborhood of Dorchester is a few blocks from the Dorchester Historical Society which now owns the building. The house is located just a block from Massachusetts Avenue. Tours are given on the third Sunday of the month.

Nearest places in James Blake House

Clapp Houses

Captain Lemuel Clap House

William Clapp House

Dorchester North Burying Ground

Cemeteries, Historical Places, Historic, Burial Places, Interesting Places, Historic Districts

Upham's Corner Market

St. Mary's Episcopal Church (Dorchester, Massachusetts)

Religion, Churches, Interesting Places, Other Churches

Pilgrim Congregational Church (Boston, Massachusetts)

William Monroe Trotter House

Historical Places, Historic, Interesting Places, Historic Districts

Shirley–Eustis House

Benedict Fenwick School

South Boston Boat Clubs Historic District

Historic, Historical Places, Interesting Places, Historic Districts

Governor Shirley Square Historic District

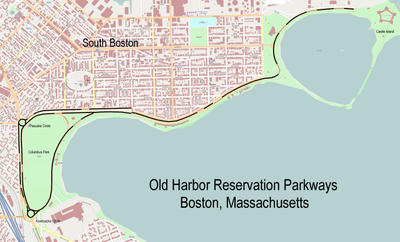

Old Harbor Reservation Parkways

Sarah J. Baker School

Mount Pleasant Historic District (Boston, Massachusetts)

Moreland Street Historic District

Eliot Congregational Church

Roxbury Presbyterian Church

Saint Augustine Chapel and Cemetery

Cemeteries, Religion, Churches, Historic, Burial Places, Interesting Places, Other Churches

Dearborn School

Dorchester Heights

Fields Corner Municipal Building

Congregation Adath Jeshurun

Religion, Churches, Synagogues, Interesting Places, Other Churches

Charles Street African Methodist Episcopal Church

Hibernian Hall (Boston, Massachusetts)

Arlington Street Church

Eliot Burying Ground

Cemeteries, Historic, Burial Places, Interesting Places

Lawrence Model Lodging Houses

Cathedral of St. George Historic District

Religion, Cathedrals, Interesting Places

Copyright © 2024 TourMini. All rights reserved.

- Cookie Policy

Terms and Conditions - Privacy Policy

What's It Like To Live In Boston's Oldest Home?

Set back from Columbia Road in Dorchester, on a small plot of grass in the heart of a bustling neighborhood just outside Edward Everett Square, is one of those old buildings you tend to see around here. It's not unremarkable, but it's not particularly attention-grabbing, either. But this simple, two-story structure, called the James Blake House , is special. It's the single oldest home in the entire city — built in 1661 when Boston was a village of just 3,000 people. But the coolest thing? Somebody lives here.

For three years now, Barbara Kurze has been a live-in caretaker for this historic home. It was purchased by the city in 1891, then saved from demolition by the Dorchester Historical Society, which bought it a few years later and moved it about 400 yards from its original location.

"This is, like, a really cool place — just the history," Kurze told me during a recent visit to Blake House, when I asked her why she decided to become a caretaker here. "I’m not sure I really thought through the move and the living here. That came after the fact."

But live here she does, as caretakers have at the Blake House since the 1910s.

I sat and chatted with Kurze about life in Boston's oldest home in the house’s front room, today called the museum room. Here, there are displays with info about the original owners — England’s James and Elizabeth Blake — and a scale model of the building, one of only a few examples of a post-Medieval timber frame-style house in the country.

"The amount of handcrafting that went into this house, it was all done by hand," said Kurze. "Some of it took a while, and that was OK. People were willing to wait."

Rounding out the room are a variety of items, not original to the house, but meant to evoke the ambiance of its earliest years — including a conspicuously placed musket that caught my eye.

"Yes, it’s a real musket," said Kurze. "I’m pretty sure it does not work."

What is original is the very essence of the building. The walls have recently undergone extensive analysis and — to everyone’s surprise — only needed the most minor of repairs.

"Most of the 1661 plaster is still with us — the original lath and plaster [which was] a mixture of mud, clay, dried plant matter. Apparently, they burned animal bones to strengthen it," Kurze said. "Even better news: The plaster structure is super, super sound."

And then there are building's venerable bones: Dozens of handsome, sturdy exposed timber beams that have survived more than 350 years.

"When these trees came down, they did analysis, and so we know they were at least 400 years old," said Kurze.

That's 400 years old in the 1600s. That means the trees used to build this house were growing strong in the area in the 1200s. You know, when Genghis Khan was expanding his Mongol Empire and St. Francis was establishing an Order of Friars near Assisi.

It’s under these august beams that Kurze lives her day-to-day. When at home, her duties are simply to keep an eye on things, watching for signs of damage or emerging issues.

Aside from the museum room, the place is her home: A curious mix of the modern and the post-medieval. There are current-day creature comforts, like electricity and indoor plumbing.

"It does seem kind of odd sometimes, and then we have this modern stuff here," remarked Kurze as she showed me her 21st century refrigerator in her 17th century kitchen.

But there are also plenty of quirks. The ceilings are notably low. Kurze can't hang pictures or shelves on the historic walls, she can’t burn candles, and there are no closets. And while there is oil heat for the winter, in the summer, she cools the place just like the Blakes would have.

"If you are one of the caretakers here ... you will never get to have air conditioning," Kurze told me as she threw open a leaded glass, diamond-shaped pane window for some ventilation. "There is no way you are ever going to get an air conditioning unit in this window.

Kurze says she adjusted to her semi-homestead life here pretty quickly. But one thing she never gets used to? Surprise visitors. Despite the fact that she comes and goes, takes out the trash regularly, and the lights are often on at night, plenty assume the place is empty.

"It’s not infrequently that you’ll be looking out a window and somebody is staring back at you," said Kurze, laughing.

Still, despite the unique challenges of life as a caretaker of a 350-year-old house, or maybe because of them, Kurze is happy here and proud to call Boston’s oldest home her home.

"It does feel sort of special and I do feel good about looking after the house," she said. "It may not look much, but just the fact that it survived this long and you can still visit it, that’s really cool."

The James Blake House is located at 735 Columbia Rd. in Dorchester. Kurze leads a tour every third Sunday of the month, if you want to get a look inside. I’m always looking for story ideas, so tell me what you’ve been curious about lately! Email me at [email protected] .

Explore Topics:

More lifestyle.

Mussels Triestina from Felidia Cookbook

Risotto with Mushrooms

Garides Kerkyraikes – Corfiot Shrimp

Grilled Stone Fruit Cobbler with Cinnamon Vanilla Greek Yogurt

Edited by Matthew J. Kiefer

The James Blake House: A Documentary Study

T HE relatively small number of extant seventeenth-century houses in Massachusetts and the even smaller number which predate 1660 make a thorough investigation of each critical to an understanding of seventeenth-century Massachusetts architecture. The 1650 construction date traditionally assigned to the James Blake House in Dorchester, placing it within the first generation of New England houses built by carpenters born and probably trained in England, makes the house particularly worthy of scholarly attention.

This brief review of surviving documents relating to the Blake House examines published sources, public records, photographs, and other relevant documents for information concerning the house’s construction date, its ownership history, and the sequence of physical changes leading up to and including its restoration by the Dorchester Historical Society beginning in 1895. Though it fails to confirm or refute a 1650 construction date, this study positively links the house to the Blake family in the seventeenth century, establishes an unbroken chain of ownership from the Blake family to the Society, and reveals the origins of the house’s 1650 attribution.

the published tradition

The generally accepted 1650 construction date is the product of a published tradition over one hundred and twenty years old. Its first-known mention is in 1857, by Samuel Blake (a descendant of the builder of the house), who cites “tradition . . . and . . . the most careful examination of old documents” as evidence that the house was built by James Blake, but gives no source for his contention that “the house was doubtless built previous to 1650.” 26 A second source of the same year confuses the house with another, also owned by James Blake; hence the 1680 date of this source may be disregarded. 27

Of these two contemporaneous accounts, most subsequent writers have adhered to the former’s 1650 date. Such books as Ebenezer Clap’s 1859 History of the Town of Dorchester, Massachusetts and William Dana Orcutt’s Good Old Dorchester , published in 1893, repeat the 1650 date without either challenge or corroboration. Thus, by the time of acquisition of the house in 1895 by the Dorchester Historical Society, the date had become generally accepted—in spite of the scant evidence supporting it.

An account written for the Society by James H. Stark in 1907 quotes an excerpt from the Dorchester Town Records of 1669, when at a general meeting the town voted to build a new house for the minister “to be such an house as James Blaks house is. . . .” 28 It then describes the house in dimensions which closely correspond to the present-day house, thus providing the first documented evidence of the building’s age.

A final explanation for the 1650 attribution date is offered in a 1960 pamphlet published by the Society on the subject of its three houses, which states that “it was probably in anticipation of a marriage that James Blake built his house.” 29 Though the date of this event is apparently not recorded, it is known that the first child of James and Elizabeth (Clap) Blake was born in 1652.

ownership history

The James Blake House has been owned and maintained for over eighty years by the Dorchester Historical Society which, following authorization from the Board of Aldermen and mayoral approval, acquired the house in late 1895 from the City of Boston and moved it to its present location in Richardson Park. Interestingly, this is the first recorded instance in New England of a historic building being moved in order to prevent its demolition.

The City had acquired the house on its original site—just west of Massachusetts Avenue about four hundred yards to the northwest of its present location (Fig. 17)—from George J. and Antonia Quinsler in September of 1895, for $8000. The conveyance included nearly 11,000 square feet of land, adjacent to other parcels the City was acquiring for clearance to build municipal greenhouses. 30

Antonia Quinsler had gained title to the land in June of 1892 from Josiah F. Williams, 31 who had inherited it upon his mother’s death the previous year. Jane Williams’ inventory lists her estate as consisting of a “House, barn, and about 11,000 feet of land,” valued at $2000. 32 Jane’s husband, Caleb Williams (1802–1842), a tanner, died intestate; however, an 1843 inventory describes his “House and land situate in Dorchester[,] land ten feet wide around the House and right of passage way to the same,” 33 valued at $450.

This extremely small lot was enlarged by his widow the following year through a purchase from the Trustees of the Hawes Fund of a “doughnut-shaped” lot eighty by one hundred feet in extent which surrounded but did not include the houselot itself. 34 This parcel of land had descended to the Hawes Fund through Benjamin Hawes, who had acquired it from his uncle, John Hawes, in 1828. 35

Jane Williams’ 1843 inheritance of the house and 1844 purchase of the surrounding land ended a period of nearly one hundred and thirty years when the east and west halves of the house and the land surrounding its immediate lot had all been under separate ownership. The process of consolidation had actually begun in 1832, when Caleb Williams purchased from his brother Charles, a laborer, for the sum of $150 “one undivided half part of the land under and ten feet around the dwelling house at present occupied by the said Caleb . . . with all the privileges of passing to and from and around said house and barn, as reserved in a certain deed from Ebenezer Blake to Elisha Clap conveying the other land around said house, and which other land is now owned by the heirs of John Hawes.” 36

17. Detail of Edward Everett Square, Dorchester, Mass., showing original and present locations of the Blake house. G. W. Bromley & Co., Atlas of the City of Boston . . . (Philadelphia, 1918), plates 2 and 4.

John Hawes therefore owned not only the land surrounding the house, ultimately sold to Jane Williams in 1844, but also a part of the house itself. His 1819 will, probated upon his death in 1829, mentions each of these pieces of property separately. Clause number 14 of this will devised to his nephew Benjamin Hawes “the use and improvement of the dwelling house in Dorchester, which I lived in last before I removed from Dorchester to South Boston, with the land adjoining said dwelling house, being about nine or ten acres (excepting such part of the premises, as is herein devised to Eunice Williams). . . .” 37

The following clause of the will states, “I give and devise to Eunice Williams, wife of Caleb Williams, my part of a dwelling house, situate on the land described in the clause last preceding, now occupied partly by the said Caleb Williams, and partly by Elizabeth Fearn and Rachel Blake, together with the land under said house, and a right of passage to the same sufficient for a Cart way as is now used, with the privilege of the well, and a passage ten feet around the house. . . .” 38 Eunice and Caleb Williams were the parents of Caleb Williams, the tanner whose widow, Jane, subsequently bought the first-mentioned parcel from Hawes’ estate.

The portion of the house not bequeathed in the above will, but mentioned as being occupied by Elizabeth Fearn and Rachel Blake in 1819, was purchased by the senior Caleb and his wife, Eunice Williams, in 1825 for the sum of $100 from Rachel Blake. 39 The deed reserves to Rachel Blake the right to occupy the house for the term of her natural life—which, as fate would have it, was approximately one month. Thus at the time of the execution of John Hawes’ will in 1829, the entire house was under the ownership of Caleb and Eunice Williams, who had occupied half of it since at least 1819.

It is at this point that the path of ownership becomes somewhat more labyrinthine. The portion of the house owned by Rachel Blake until 1825 will be traced first, in order to help illuminate the more complicated Hawes side.

Rachel Blake was born in 1741, one of five children of John Blake, cordwainer, and Abigail (Preston) Blake. Upon her father’s death in 1772, the absence of a will caused his estate, which included the subject house and barn, as well as some thirteen acres of surrounding land, to be divided equally among his children. 40 Each of the individual shares of the surrounding land was sold off separately at different times, and by surviving her four siblings Rachel ultimately gained full possession of the house. Elizabeth Fearn, mentioned in Hawes’ will as a co-occupant of the house, was Rachel’s widowed sister and the last of her siblings to pre-decease her, dying in 1817.

John Hawes, the previously established owner of the remaining half of the house in 1819, purchased it in 1784 from the heirs of his wife’s former husband, Elisha Clap, who had died nine years earlier. 41 In 1772, Clap had purchased from Ebenezer Blake, a weaver, for 200 pounds, “my easterly end of a dwelling house and a shop adjoining thereto [,] . . . and my easterly end or half of the barn standing being upon [a piece] of land which peice containeth seven acres one quarter and twenty two rods . . . allowing and reserving out of this piece of land for my uncle Mr. John Blake his heirs and assigns forever Convenient yard room about his part of the house for laying his wood and other necessities and the use of the way from the house to the highway and barn where it is now used. . . .” 42

It should be noted that these rights reserved by Ebenezer Blake for his uncle remained attached to later conveyances of the property (in slightly modified form) until at least 1825, after which they were specified to be a distance of ten feet around the house. This remained the bounds of the houselot until Jane Williams enlarged it in 1844.

The above-quoted deed is also significant for its reference to John Blake as the owner of the remaining half of the house, which establishes a familial link between the two separate ownership shares in the house.

Ebenezer Blake had inherited his half of the house and barn from his father, Josiah, a weaver, who died intestate in 1747, and whose inventory lists his interest in the house and surrounding land as being valued at 700 pounds. 43 Josiah was the brother of John Blake mentioned in the above deed; hence the house was under the split ownership of two brothers prior to 1747.

John and Josiah were the two youngest of seven children of John Blake (1657–1718), who died intestate with an inventory listing his “Dwelling House” as valued at 50 pounds. The administration of his estate divided the house between his two surviving sons, with sisters Hannah and Elizabeth given occupancy rights until their marriage, when the entire estate would revert to the male heirs. 44

John Blake was one of six children of James and Elizabeth Blake. Thought to be the original builder of the house which now stands in Richardson Park, James’ 1700 will devises to his son John “my Dwelling House and Barns, Orchard, Yard, Garden, and ten acres of land adjoining. . . .” 45 This is the earliest-known reference in the deed or probate records which can confidently be linked to the same house.

James Blake was born in Pitminster, England, in 1624, the son of William and Agnes Blake, who, according to tradition, brought their family of five to America on the Mary and John , which landed in Dorchester in 1630. William Blake, who is mentioned in the Dorchester Town Records for the first time in 1637, died there in 1663, his wife in 1678. William Blake’s will, written in 1661, simply divided his estate in half, assigning one part to his five children, and the other to his “beloved wife.” The 1663 inventory of his estate includes only the simple listing: “his house and lands,” valued at 154 pounds and 15 shillings. 46

18. Division map of John Blake and the heirs of Josiah Blake, April 22, 1748, showing the Blake house and barn. Courtesy Dorchester Historical Society.

No further records have yet been discovered to describe this house more precisely, or document its passage to James Blake, one of four possible heirs. Although the Town Records do make occasional refference to lands granted to or owned by William Blake or, after 1657/8, James Blake, their topographical references are no longer decipherable. It is therefore impossible to say whether the present house was built by James, or inherited from his father’s estate, and the earliest documented mention of the present-day house remains the 1669 reference in the Town Records to building a minister’s house “to be such an house as James Blaks house is.” 47

structural history and restoration

A somewhat sketchy structural history of the Blake House has been pieced together from published records, photographs, prints, and other documents. In particular, the records of the Society yield some interesting information about the restoration of the house and the difficulties resulting therefrom.

The precise measurements which follow the aforementioned reference to the house in the Dorchester Town Records confirm that it was originally a simple, four-square structure basically the same in appearance and plan as it is today. The earliest-known graphic representation of the house is a thumbnail sketch in 1748 on a division map of the lands of John Blake and Josiah Blake’s heirs (Fig. 18). This clearly shows not only a two-story ell at the left-hand end of the house, with a pitched roof and separate entrance, but also the suggestion of dormer windows in the front slope of the main house roof. Structural evidence of facade gables, which apparently had survived until 1748, still remain in the attic of the original structure.

Samuel Blake’s account in 1857 contains the next extant representation of the house, a print which shows no facade gables and, in addition to the ell at the left, a story-and-a-half gable-roofed ell at the right end as well which the author claims “has been added within the last quarter of a century.” 48 The outline of the house on an 1874 real estate atlas clearly shows it to have an ell projecting from each end. A series of photographs in the collections of the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities and the Dorchester Historical Society, several of which were taken shortly before the relocation of the house, confirm that it retained both of the ells until the time of acquisition by the latter Society (Fig. 19).

19. Blake house before removal to new site. Photo, William H. Halliday Collection, before 1896, courtesy Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities.

20. Blake house after removal to new site and restoration. Photo, William H. Halliday Collection, c. 1896, courtesy Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities.

The Dorchester Historical Society, which had been incorporated in 1891 and held its first meeting in 1893, undertook the preservation of the Blake House as the first major project of a fledgling organization. Introduced to the plight of the house in June of 1895 by a letter from Doctor Clarence Blake (presumably a descendant of the builder) who offered $500 toward the cost of moving it to a safe location, the Society had within four months secured an agreement with the City of Boston granting the Society the house and the right to move it to nearby Richardson Park at its own expense. 49

A major subscription drive (destined to be long-lived) was begun to raise funds for the undertaking. By January of 1896 the house had been moved and re-silled—with both ells having been removed in the process—by a local building mover for $295. The move was accomplished, according to Dr. Blake’s recollection twenty years later, by dismantling the chimney and jacking up the house onto a horse winch. 50

Although the name of the moving company and some of the craftsmen involved in the subsequent restoration are identified in the Society’s records, the director of the restoration is unclear. Dr. Blake mentions the assistance of a Mr. Hodgson, “a well known Dorchester architect. . . .” This seems to have been Charles Hodgson, an active member of the Society, who lived near Richardson Park between 1895 and 1907, after which he moved to New Rochelle, New York.

Dr. Blake gives some indication of the actual restoration process in the following passage:

We then tried to have the material in the house duplicated as near as possible to the original material and it was necessary to even send to Holland for the glass in the windows because there was none of its kind in this country. The windows were of the lattice type and on close examination it will even be found that the shingles in the roof are fastened by the original nails which will give you a fine idea of how well built the houses were in those days. The same hinges are even on the doors. 51

Because of continuing difficulties in raising funds to pay off debts incurred during the moving and gradual restoration, the Society voted in September of 1898 to float a $1000 bond issue to cover its $800 debt and advance the restoration. However, the Society’s continued difficulty in paying off its debts suggests that the bond issue was a less than raging success. Not until 1907 do the records indicate the Society’s indebtedness to have been discharged.

The actual physical changes to the house resulting from this restoration effort can be partially deduced from contemporary accounts and photographs. In addition to removing both side ells, then-existing double-hung sash windows were replaced with diamond-leaded casements (which may have been shortened slightly); wood shingles replaced clapboards; and a panelled door was removed in favor of a batten door “in the ancient pattern.” The house was placed on a stone foundation, with the front sill raised about one foot above grade in the front.

Structural evidence indicates that then-existing door openings between the house and ell on the present left end of the house, probably enlargements themselves of original windows, were re-converted to windows after the ell was removed. Finally, it should be noted that the pre-restoration chimney, which was apparently later than the house itself, may have remained partially intact during the moving process. Arrived at the new site, this masonry feature underwent repairs, including a new foundation, at which time also recessed arches were added to the front and back of a newly created chimney top.

Although the exterior restoration had been accomplished fairly quickly, restoration of the interior of the house proceeded gradually, beginning with the two ground-floor rooms. It was not until 1910 that the two upstairs chambers were completed and opened to the public. All that can be said of the details of the interior restoration process, based on documentary evidence, is that it included the stripping, staining, and polishing of exposed oak framing; the replacement of most of the structure’s sills and the bottoms of the posts with new oak which was stained and chamfered to match the original timbers; and the “restoration” of the “antique fireplaces.”

Any further determination of exactly how much of the present-day fabric of the house is original and how much the result of this early and well-intentioned restoration effort must be based on careful physical analysis. It is hoped that the claim of a Boston Herald reporter in 1911 that “every piece of old material that could be kept is still in use” will prove true. 52

1. This paper is in large part a distillation of two research reports prepared for the Paul Revere Memorial Association which remain in manuscript form: “History of the Property of Paul Revere Memorial Association,” by William Lebovich, 1973; and “The Early History of the Paul Revere House, North Square, Boston,” by this author, 1974. Both reports are heavily documented; copies of both are available for reference at the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities. Material drawn from these reports will not be specifically footnoted here; footnotes will be limited to the identification of the sources of direct quotations and the documentation of material not included in either of the earlier reports. Readers interested in a structural analysis of the Revere House (as opposed to the documentary study summarized here) are referred to two reports prepared for the Paul Revere Memorial Association by Frederic C. Detwiller, Architectural Historian, Consulting Services Group, SPNEA: “Paul Revere Association Properties, 19–31 North Square, Boston, Massachusetts, Architectural-Historical Analysis,” Feb. 1976; and “Paul Revere House, Structure Report,” 2 vols., July 1976. Copies of both are available for study at SPNEA.

2. Joseph Everett Chandler, the architect who restored the house in 1907–1908, speculated on purely physical evidence that the house was built sometime between 1650 and 1680. See his “Notes on the Paul Revere House,” in the Handbook of the Paul Revere Memorial Association (Boston, 1950), p. 18. Later historians, benefiting from documentary research, have usually placed the date between 1676 and 1681. Among the most authoritative of these: Hugh Morrison, Early American Architecture (New York, 1952), pp. 59–62, says c. 1676; while Esther Forbes, Paul Revere and the World He Lived In (Boston, 1942), p. 169, Harold Comer Read, “A Brief History of the Paul Revere Memorial Association and the Paul Revere House,” in the Handbook of the Paul Revere Memorial Association (Boston, 1950), p. 5, and Walter M. Whitehill, Boston: A Topographical History , 2nd ed. (Cambridge, Mass., 1968), p. 15, all say about 1680. Another recognized authority, Fiske Kimball, does not include the Revere House in his Domestic Architecture of the American Colonies and the Early Republic , reprint ed. (New York, 1966), presumably because it failed to meet his rigorous standards for documentation.

3. Forbes and Morrison both suggest John Jeffs as the original owner; Chandler, Read, and Whitehill hazard no guesses.

4. Chandler, in his “Notes,” suggests that the ell predates the main house; Morrison, in Early American Architecture , assumes the ell to have been a later addition; and the staff of SPNEA, in the two reports for the Paul Revere Memorial Association mentioned in note 1, assumed the main house and ell to have been built in one campaign. This was also the consensus reached by the approximately twenty members of the New England Chapter, Society of Architectural Historians, who examined the Revere House during a special meeting held there on Dec. 3, 1974.

5. What information was turned up on the question of original form supports the single-build theory (see note 21 and the section of text to which it pertains for a discussion of this material). A final answer to this question, however, will probably have to await either the discovery of some conclusive structural evidence in the house itself, or the development of a satisfactory dendrochronological sequence for New England, by which means the timbers in the two sections of the house can be accurately dated.

6. Suffolk County Deeds, xiii , 86, Nov. 2, 1681, Turell and Walker to Howard.

7. Increase Mather Family Records, in the John Cotton Bible, Special Collections (Massachusetts Historical Society).

8. Increase Mather Family Records.

9. Increase Mather, “Diary, 1675–6,” Massachusetts Historical Society, Proceedings , 2nd ser., xiii (1900), 373–374.

10. Increase Mather Family Records.

11. Suffolk County Probate Records, New Series, ii , 352, Dec. 12, 1678, will of Nathaniel Blague.

12. “Records of the Second Church,” ms, iii (Massachusetts Historical Society).

13. “Records of the Second Church,” ms, iv.

14. “Records of the Second Church,” ms, iii .

15. Chandler Robbins, A History of the Second Church, or Old North, in Boston . . . (Boston, 1852), and Increase Mather, “Autobiography,” American Antiquarian Society, Proceedings , lxxi , pt. ii (1962), 300–301, 310.

16. Elna Jean Mayo, Mayo Genealogy . . . (Pueblo[?], Colo., 1963), pp. 2–3.

17. The contract for a house of comparable size built for John Williams in the North End in 1678/79 (published in the “Records of the Suffolk County Court, 1671–1680,” pt. ii , Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Collections , xxx [1933], 1125–1126) was taken at £130 “current mony of New England.” Assuming the construction cost of the Revere House to have been roughly similar, that leaves perhaps £ 150– £ 170 of Howard’s £ 300 purchase price to be accounted for by the value of the land and/or the profit of the church. It does not seem that the land alone could have been worth much more than £ 100– £ 125. Consider that the Revere House lot, as Howard purchased it in 1681, contained roughly 3000 sq. feet, with 30 feet of frontage on North Square. In comparison: in 1683, Howard purchased an adjoining interior lot containing about 4000 sq. feet with no buildings upon it, for £65 (Suffolk County Deeds, xiii , 84, July 19, 1683, Martin heirs to Howard); and, in 1689, Howard purchased the parcel next north of the Revere House, containing some 2000 sq. feet with a 20-foot frontage, and with a dwelling house with leanto standing upon it , for £ 110 “current money of New England” (Suffolk County Deeds, xxviii , 182, May 22, 1689, Paine and Woodbry to Howard). The inference I am drawing is that land values on the west side of North Square were not particularly high in the 1680’s; the Second Church seems to have gotten a pretty good price for its house and lot.

18. There is a very slight possibility that this man was lodging with Increase Mather; more probably, he was renting the house next north to Mather’s. See pages 29–33 of my report to the Paul Revere Memorial Association for a thorough discussion of this point.

19. Boston Record Commissioners, First Report: Boston Tax Lists etc., 1674–1694 , 2nd ed. (Boston, 1881), pp. 91–133, gives the complete 1687 tax schedules for all eight Shawmut precincts and the two outlying precincts at Muddy River and Rumney Marsh (now Brookline and Chelsea, but then parts of Boston).

20. I included the figures from Muddy River and Rumney Marsh in my calculation of the town-wide average tax figure, but I purposely left out the Precinct 6 figures, as there seems to have been some confusion in those records. (The figures in the “Acres” and the “Houseing, Mills and Wharfs” columns appear to have been reversed in some sections of Precinct 6.) The deletion of the Precinct 6 figures lowered the total number of individuals taxed for buildings by perhaps 150–170, and similarly lowered the total of those taxed 20d. or more by about 20. If these dubious Precinct 6 figures had been included, they would have had a negligible effect on the 7d. average tax-assessed figure, and would have raised the percentage of individuals taxed 20d. or more by about one percentage point.

21. As a check against the possibility that Howard might have bought a rather modest house from the Second Church and then radically enlarged or improved it between 1681 and 1687, an attempt was made to determine which of the thirty-two other individuals assessed for exactly 20d. under the “Houseing, Mills and Wharfs” head in 1687 could be satisfactorily demonstrated to have owned just one dwelling house in the late seventeenth century. An attempt was then made to establish the price that each of these individuals had paid for that specific house and lot. I am reasonably confident that this procedure has succeeded in two instances—those of William Coleman in Precinct 1, and Isaac Walker in Precinct 3. Coleman purchased his house and land for £ 260 “current money of New England” in 1679 (Suffolk County Deeds, xii , 24, Sept. 29, 1679, Thacher heirs to Coleman), and Walker paid £ 300 “lawful money of New England” for his in 1675 (Suffolk County Deeds, ix , 187, May 5, 1675, Edwards to Walker). These prices are right in line with the £ 300 “current money of New England” paid by Howard, and suggest that, in 1687, Howard’s house remained largely as constructed by the Second Church.

22. Fiske Kimball, Domestic Architecture of the American Colonies and of the Early Republic (New York, 1922), pp. 283–284.

23. Ibid., p. 39.

24. John H. Hooper, “The Royall House and Farm,” The Medford Historical Register , iii (1900), 143.

25. Middlesex County Probate Records, 1st ser., docket no. 19545.

26. Samuel Blake, The Blake Family: A Genealogical History of William Blake of Dorchester and His Descendants . . . (Boston, 1857), pp. 15–16.

27. Thomas C. Simonds, History of South Boston (Boston, 1857), pp. 31, 264.

28. James H. Stark, The History of the Old Blake House (Boston: Dorchester Historical Society, 1907).

29. Mrs. George A. French, The Dorchester Historical Society and Its Three Houses (Boston: Dorchester Historical Society, 1960), p. 18.

30. Suffolk County Deeds, vol. 2305, p. 30.

31. Ibid., vol. 2066, p. 303.

32. Suffolk County Probate Records, vol. 650, p. 210.

33. Norfolk County Probate Records, docket no. 20436, inventory dated Feb. 4, 1843.

34. Norfolk County Deeds, vol. 151, p. 113.

35. Ibid., lxxxvi , 167, and lxxxvii , 235.

36. Ibid., xciii , 199.

37. Suffolk County Probate Records, vol. 127, p. 339.

39. Norfolk County Deeds, xcvii , 198.

40. Suffolk County Probate Records, lxxii , 33, and lxxiv , 16.

41. Suffolk County Deeds, vol. 143, p. 53.

42. Ibid., vol. 121, p. 143.

43. Suffolk County Probate Records, xli , 451.

44. Ibid., xxi , 555.

45. Ibid., xiv , 192.

46. Samuel Blake, The Blake Family , pp. 12–13.

47. Fourth Report of the Record Commissioners of the City of Boston, 1880, Dorchester Town Records , 2nd ed. (Boston, 1883), p. 162.

48. Samuel Blake, The Blake Family , pp. 15–16.

49. Minutes of the Dorchester Historical Society, ms, i , 44–45, 50–51.

50. “Dorchester’s Settlement Appropriately Celebrated,” Dorchester Beacon , undated clipping (June 1916?) in the collections of the Dorchester Historical Society.

52. “Blake House Is Restored,” Boston Herald , Boston, Mass., July 3, 1911.

53. Mr. Peabody’s paper, as presented here, was prepared for publication before his untimely death on March 22, 1977.

54. The Colonial records of Trinity Church are being published at the present time by The Colonial Society of Massachusetts in its regular series of publications. The page proofs of the records are at the printers, and it is, therefore, impossible to give page and volume references to the selections quoted from these records.

55. A summary account in the Church Records entitled “The Cost of the Building of Trinity Church” contains the following entries for 1741:

56. New England Historical and Genealogical Register , xxiv , 55.

57. Charles Shaw, A Topographical and Historical Description of Boston (Boston, 1817), p. 265.

58. “Boston Prints and Printmakers, 1670–1775,” Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Publications , 46 (1973), 43–44.

59. Ibid., pp. 46–49.

60. Samuel G. Drake, The History and Antiquities of the City of Boston (Boston, 1854), opposite p. 654.

61. Phillips Brooks, Trinity Church in The City of Boston 1733–1933 [Historical Sermon] (Boston, 1933), p. 32.

62. Marshall Davidson, American Heritage History of Colonial Antiques (New York, 1967), p. 153. Here the information on the Hancock House is entitled “Lost Landmarks.”

63. Franklin Webster Smith, Designs, Plans and Suggestions for the Aggrandizement of Washington (Washington, 1900, Senate Document No. 209), pp. 37–39. Here Smith, in advocating retention of the White House as the executive mansion, uses the obvious earlier example of the Hancock House demolition.

64. Walter Kendall Watkins, “The Hancock House and Its Builder,” Old-Time New England , xvii (1926–1927), 3–19. Among these are the following: staircase in Greeley Curtis House, Manchester-by-the-Sea; balusters, one from stair and one from roof, two carved capitals in Essex Institute, Salem; larger carved pilaster cap from “Loer Rume” at National Museum, Independence Hall, Philadelphia; modillion from cornice at Massachusetts Historical Society; pendant from staircase, pilaster caps, and additional modillions at SPNEA; front door at the Bostonian Society; balcony at John Hancock Insurance Company, Boston; carved corbel at Martine Cottage, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, home of R. Clipston Sturgis; stone steps at Pinebank, Jamaica Plain, a house designed by John Sturgis in 1869. Many other elements survive as well.

65. For example, architectural measured drawings were the subject of a symposium on November 16, 1973, celebrating the fortieth anniversary of the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), which was established in 1933 using measured drawings as a prime documentary tool.

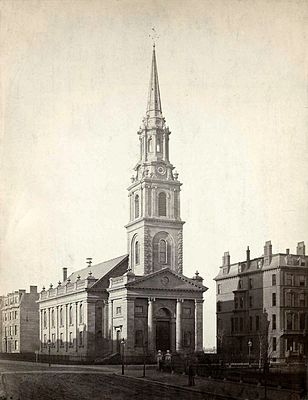

66. Arthur Gilman, “The Hancock House and Its Founder,” Atlantic Monthly , xi (1863), 692–707. One of the most important architects in Boston, Gilman (1821–1882) had designed the Arlington Street Church in Boston (1859) and laid out the plan for the Back Bay. With his partner J. F. Gridley Bryant he had just designed the Boston City Hall (1862). He left Boston for New York and Washington in 1867.

67. Ibid., pp. 692, 694, 706. This sort of poetic approach to old architecture is not without parallel. See, for example, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables (1851), Chapter I.

68. Gilman, “The Hancock House and Its Founder.” Descriptions of the house used in this article are based on Gilman unless otherwise noted.

69. Watkins, “The Hancock House and Its Builder,” p. 19. Here it is specified that the east wing, or ballroom, was removed to Allen Street in Boston’s West End by 1818. Its exact date of construction is not documented but may well have been shortly after John Hancock inherited the house from his uncle (who died in 1764) just prior to the Revolution. Figure 1 showing the house without wings is a lithograph published in 1848 after a drawing of the house by A. J. Davis, the New York architect, who may have executed it as early as 1827–1828 on his well-known sketching trip to Boston.

70. “Surely I Did Not Run Away with the Property of the College,” Harvard Bulletin , x (June 1973), 72.

71. John Sturgis was in partnership with Bryant and Gilman in Boston 1861–1866. He was also designing independently during this period.

72. Charles Brigham to John Hubbard Sturgis, Letters to England, April 5, 1869, and April 18, 1870, Sturgis Papers, The Boston Athenæum. The Hancock staircase was stored in the shop of one Poland, a Boston mason who did considerable other work for Sturgis and his partner Charles Brigham (1841–1925). One of these jobs was “Pinebank” in Jamaica Plain (1869), where the stone steps from the Hancock House are now located. This suggests Sturgis may also have purchased the steps. The Post Office building referred to here (destroyed in the fire of 1872) was designed by Arthur B. Mullett, then architect of government building. Arthur Gilman collaborated with Mullett on the design of the State War and Navy Building in Washington 1871–1875.

73. John Sturgis was visiting with his father Russell Sturgis of Boston, who had settled permanently in London as senior partner of Baring’s Bank. The enterprising Brigham was from Watertown, Massachusetts, where he continued to live all his life. Capital for the architectural partnership, which lasted 1866–1886, was provided by Sturgis.

74. For information on Van Brunt, a pupil of Richard Morris Hunt, see William A. Coles, ed., Architecture and Society, The Selected Essays of Henry Van Brunt (Cambridge, 1969).

75. Bainbridge Bunting, “The Greeley Curtis House,” in Architecture of H. H. Richardson and His Contemporaries in Boston and Vicinity (Philadelphia, 1972), pp. 46–47.

76. See Sturgis Papers. Brigham’s letters make clear that Henry Van Brunt’s academic orientation annoyed him.

77. Adolf Placzek, Librarian, Avery Architectural Library, Paper delivered at HABS Symposium on Architectural Measured Drawings (Washington, D.C., November 1973).

78. Vincent Scully, The Shingle Style (New Haven, 1955), pp. 19–33.

79. James K. Colling Sketchbooks (London, RIBA Drawings Collection). Also see James K. Colling to Russell Sturgis, London, March 6, 1867 (Sturgis Papers). Here Colling discusses making measured drawings of Russell Sturgis’ home Mount Felix in Surrey (1838) by Sir Charles Barry at John Sturgis’ request.

80. See, for example: Edmund Sharpe, The Rise and Progress of Decorated Window Tracery (London, 1849) or The Seven Periods of Gothic Architecture (London, 1851); Samuel Carter Hall, The Baronial Halls and Picturesque Edifices of England, 2 vols. (London, 1848).

81. Asa Briggs, William Morris: Selected Writings and Designs (Baltimore, 1962), pp. 13–26. Concern for architectural preservation in England was well advanced by 1877, and Morris, artist, designer, Pre-Raphaelite, poet, and novelist, first formalized the movement.

82. Margaret Henderson Floyd, “A Terra Cotta Cornerstone for Copley Square: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1870–1876, by Sturgis and Brigham,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians , xxxii (1973), 83–103. Here is further information on Sturgis’ training and on J. K. Colling.

83. Edward W. Hooper was Treasurer of Harvard College and brother-in-law of Henry Adams. Arthur Astor Carey was a grandson of John Jacob Astor and an instructor of English at Harvard. Both men were on the Committee for the Foundation of the Museum of Fine Arts, Copley Square, for which Sturgis was architect. The Cambridge Historical Commission has kindly shared its research with the author on these points.

84. Scully, The Shingle Style , passim. Here the nineteenth-century evolution of the living hall with both staircase and fireplace is extensively documented and the early Colonial Revival discussed.

85. Sturgis used a terra cotta parapet in a similar design on his Charles Joy house, 86 Marlborough Street, Boston (1872), and also on Pinebank, Jamaica Plain (1869).

86. Wheaton A. Holden, “The Peabody Touch: Peabody and Stearns of Boston, 1870–1917,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians , xxxii (1973), 114–131.

87. American Architect and Building News , ii (1877), 133–134. Scully, The Shingle Style , p. 42. Peabody’s comment was made famous within the context of Scully’s landmark volume, where it is reproduced under discussion of the Colonial Revival.

88. Report of the Massachusetts Board of World’s Fair Managers, World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago 1893 (Boston, 1894), pp. 31–33.

89. Fiske Kimball, Domestic Architecture of the American Colonies and of the Early Republic (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1922), p. 35.

90. Boston Sunday Herald , July 31, 1949, p. 12.

91. George F. Willison, Saints and Strangers (New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1945), p. 425.

92. Kimball, Domestic Architecture , p. 14.

93. Frank A. Demers, “Progress Report No. 1, Chronological Identification of 17th Century New England Oak Timbers through Tree-Ring Analysis” (August 21, 1968), ms , Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities.

94. Historic Houses in Andover, Massachusetts , Compiled for the Tercentenary Celebration, 1946, house no. 23– ii .

95. Essex County Deeds (North District), Lawrence, Mass., vol. 572, p. 242.

96. Ibid., vol. 1244, p. 313.

97. Alice G. Lapham, The Old Planters of Beverly in Massachusetts . . . (Cambridge, Mass.: The Riverside Press, 1930), p. 12.

98. Essex County Registered Land, Doc. no. 4235 (Certif. of Title, no. 2070).

99. Ibid., Doc. no. 26323 (Certif. of Title, no. 9473).

100. Sidney Perley, “Beverly in 1700, No. 1,” Essex Institute Historical Collections , lv (1919), 88.

102. Beverly Town Records, ms , City Clerk, Beverly, Mass., ii (1685–1711), 68.

103. Notes on the Hale House, Beverly, 1903, by Robert Hale Bancroft and Ellen Bancroft, Archives, Hale House Committee, Beverly.

104. Essex County Deeds, vol. 3117, p. 137.

105. Suffolk County Deeds, iv , 313; M. Halsey Thomas, ed., The Diary of Samuel Sewall, 1674–1729 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, c 1973), i , 28.

106. A Report of the Record Commissioners of the City of Boston, Containing the Statistics of the United States’ Direct Tax of 1798, as assessed on Boston . . . (Boston, Mass., 1890), pp. 188 (Gibbs Atkins) and 199 (Eliza Phillis).

107. Samuel Adams Drake, Old Landmarks and Historic Personages of Boston (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1906), opp. p. 158.

108. Boston Building Department Records, City Hall, Boston, Mass., Permit no. 127 (J. G. Carlson).

109. Suffolk County Probate Records, vii , 115.

110. Suffolk County Deeds, vol. 178, p. 220.

111. Caleb H. Snow, A History of Boston . . . (Boston, 1825), p. 244. See also, Nathaniel B. Shurtleff, A Topographical and Historical Description of Boston (Boston, Mass., 1871), pp. 649–662.

112. Suffolk County Deeds, xvii , 341.

113. Ibid., xxi , 270; The Boston Globe , Oct. 28, 1931.

114. Suffolk County Deeds, xx , 544; xxiv , 109.

115. Ibid., xxxii , 46; xxviii , 102.

116. M. Halsey Thomas, ed., The Diary of Samuel Sewall, 1674–1729 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, c 1973), i , 28.

117. Suffolk County Deeds, xiii , 86.

118. Ibid., vol. 116, p. 128.

119. Ibid., vol. 196, p. 291.

120. A Report of the Record Commissioners of the City of Boston, Containing the Statistics of the United States’ Direct Tax of 1798, as assessed on Boston . . . (Boston, Mass., 1890), p. 201.

121. Suffolk County Deeds, vol. 3221, p. 172. See also, Handbook of the Paul Revere Memorial Association (Boston, Mass.: Printed for the Assoc., 1954), pp. 17–25.

122. Thomas Hutchinson, The History of the Colony of Massachusetts-Bay . . . (Boston, Mass., 1764–1828), i , 349n.

123. Boston city directories.

124. Daily Evening Traveller (Boston, Mass.), July 10, 11, 1860. See also Abbott Lowell Cummings, “The Old Feather Store in Boston,” Old-Time New England , ser. no. 172 (Apr.–June 1958), pp. 85–104.

125. Middlesex County Deeds, ii , 152.

126. The Register Book of the Lands and Houses in the “New Towne” . . . (Cambridge Mass., 1896), p. 167.

127. Middlesex County Probate Records, first ser., docket no. 5172.

128. Middlesex County Deeds, vol. 3694, pp. 333, 335 and 338.

129. See “The Repairs on the Cooper-Austin House,” Old-Time New England , ser. no. 8 (Feb. 1913), pp. 12–18.

130. Middlesex County Registered Land (North District), Lowell, Mass., Land Registration Book, lxiv , 215 (Certif. of Title, no. 12308).

131. “Some Reminiscences of Elizabeth (Prince) Peabody,” The Historical Collections of the Danvers Historical Society , xxv (1937), 37–38.

132. Essex County Deeds, vol. 6173, p. 29.

133. Sidney Perley, “Center of Salem Village in 1700,” The Historical Collections of the Danvers Historical Society , vii (1919), 46.

134. Ibid., p. 47.

135. Essex County Deeds, vol. 1915, p. 180.

136. Ibid., vol. 2779, p. 410.

137. Sidney Perley, “The Plains: Part of Salem in 1700,” The Historical Collections of the Danvers Historical Society , vii (1919), 120.

138. Sidney Perley, “The Plains: Part of Salem in 1700,” The Historical Collections of the Danvers Historical Society , vii (1919), 113.

140. Don Gleason Hill, ed., The Early Records of the Town of Dedham, Massachusetts, 1636–1659 . . . (Dedham, Mass., 1892), p. 28; A Plan of Dedham Village, Mass., 1636–1876 , published by the Dedham Historical Society (Dedham, Mass., 1883), pp. 3, 4 and 13.

141. Suffolk County Probate Records, v , 112.

142. Suffolk County Deeds, vol. 103, p. 8, and vol. 104, p. 73.

143. Norfolk County Deeds, vol. 975, pp. 602 ff.

144. Alvin Lincoln Jones, Under Colonial Roofs (Boston, Mass., c 1894), p. 234.

145. Fourth Report of the Record Commissioners of the City of Boston, 1880, Dorchester Town Records , 2nd ed. (Boston, Mass., 1883), p. 162.

146. Plot dated Apr. 22, 1748, ms , Collections, Dorchester Historical Society.

147. Samuel Blake, Blake Family . . . (Boston, Mass., 1857), pp. 15–16.

148. Fourth Report of the Record Commissioners of the City of Boston, 1880, Dorchester Town Records , 2nd ed. (Boston, Mass., 1883), p. 58.

149. Suffolk County Probate Records, xxxvii , 162.

150. Ibid., lxvii , 176 and 174.

151. Suffolk County Deeds, vol. 8205, p. 204.

152. Essex County Deeds, vol. 3577, p. 74.

153. Ibid., vol. 4235, p. 230.

154. Ibid., vol. 5972, p. 412.

155. George Francis Dow, ed., The Probate Records of Essex County, Massachusetts (Salem, Mass.: The Essex Institute, 1916–1920), iii , 63.

156. Essex County Deeds, vol. 5290, p. 327.

157. Ibid., vol. 6128, p. 363.

158. Essex County Deeds, i (Ipswich), 240.

159. Ibid., v (Ipswich), 596.

160. Ipswich Town Records, ms , Town Hall, Ipswich, Mass., iii (1696–1720), 221.

161. Essex County Deeds, xxxiii , 64.

162. Essex County Probate Records, vol. 350, p. 156.

163. John J. Babson, History of the Town of Gloucester . . . (Gloucester, Mass., 1860), p. 230.

164. Essex County Deeds, lxxix , 199.

165. Ibid., vol. 3714, p. 16.

166. Essex County Probate Records, docket no. 3747. (See will of Nathaniel Brown; deed referred to therein not on file.)

167. Essex County Deeds, iii (Ipswich), 68–69.

168. Ibid., iv (Ipswich), 373–374.

169. William Sumner Appleton, “Annual Reports of the Corresponding Secretary . . .,” Old-Time New England , ser. no. 18 (Nov. 1918), p. 29.

170. Notes by William Sumner Appleton on the Brown House, Hamilton, Mass., Sept. 25, 1916, Corr. Files, Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities.

171. Essex County Deeds, iv (Ipswich), 533.

172. Essex County Probate Records, vol. 304, pp. 10 and 14.

173. Essex County Deeds, vol. 2150, p. 327.

174. Suffolk County Probate Records, viii , 24.

175. For correct identification of site with present house see Suffolk County Deeds, xv , 198, and vol. 148, p. 47, and Suffolk County Probate Records, xxv , 450.

176. Plymouth County Deeds, vol. 1429, p. 18.

177. Suffolk County Deeds, x , 83.

178. Suffolk County Probate Records, xiv , 294.

179. Ibid., lxxxiii , 630–632.

180. Ibid., docket no. 21875.

181. C. Edward Egan, Jr., ed., “The Hobart Journal,” New England Historical and Genealogical Register , 121 (1967), 18.

182. Suffolk County Deeds, ii , 161.

183. Ibid., xxi , 341.

184. The title as recorded by Thomas F. Waters, Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony (Ipswich, Mass.: The Ipswich Historical Society, 1905–1917), i , 358 (Philip Call lot), is incomplete.

185. Essex County Probate Records, docket no. 4528.

186. Essex County Deeds, xxvi , 176.

187. Ibid., xlii , 79.

188. Ibid., vol. 163, p. 117.

189. Essex County Registered Land, Certif. of Title, no. 36484.

190. Essex County Deeds, ii (Ipswich), 128.

191. Essex County Probate Records, vol. 303, pp. 84–85 and 154.

192. [Thomas F. Waters], “Thomas Dudley and Simon and Ann Bradstreet,” Publications of the Ipswich Historical Society , xii (1903), 15.

193. Essex County Deeds, vol. 4298, p. 52.

194. Essex County Deeds, xv , 115.

195. Ibid., vol. 137, p. 212.

196. Thomas F. Waters, “A History of the Old Argilla Road . . . ,” Publications of the Ipswich Historical Society , ix (1900), 17.

197. Essex County Deeds, xi , 216.

198. The Celebration of the Two Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary . . . of the Town of Ipswich . . . (Boston, 1884), next to frontispiece.

199. Notes by William Sumner Appleton on the Thomas Burnham house, Ipswich, Mass., Sept. 17, 1914, Corr. Files, Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities.

200. Essex County Deeds, vol. 1678, p. 438; see also vol. 1682, p. 515.

201. Ye Olde Burnham House . . . kept by Martha Lucy Murrary (promotional pamphlet, no publisher, no date), unpaged; see also, Thomas F. Waters, “The Old Bay Road . . .,” Publications of the Ipswich Historical Society , xv (1907), 2n.

203. Ralph Ladd to author, Feb. 27, 1954, Corr. Files, American Wing, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

204. Essex County Deeds, vol. 2466, p. 256.

205. Secretary’s Files, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

206. Essex County Deeds, xi , 92.

207. Ibid., xxiii , 76; xli , 265, and lxxix , 185.

208. Essex County Probate Records, vol. 331, p. 136.

209. Essex County Deeds, lxxxv , 229.

210. Thomas F. Waters, Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony (Ipswich, Mass.: The Ipswich Historical Society, 1905–1917), i , 482.

211. Essex County Deeds, vol. 5307, p. 173.

212. Thomas F. Waters, Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony (Ipswich, Mass.: The Ipswich Historical Society, 1905–1917), i , 481.

213. Essex County Deeds, i (Ipswich), 169.

214. Ibid., iv (Ipswich), 501.

215. Essex County Probate Records, docket no. 14024.

216. Essex County Deeds, vol. 1682, pp. 241–242.

217. Ibid., vol. 2857, p. 369.

218. Essex County Deeds, v , 338.

219. Ibid., xliv , 218.

220. Ibid., vol. 4974, p. 196.

221. George A. Schofield, ed., The Ancient Records of the Town of Ipswich . . . (Ipswich, Mass., 1899), unpaged.

223. George Francis Dow, ed., Records and Files of the Quarterly Courts of Essex County, Massachusetts (Salem, Mass.: The Essex Institute, 1911–1975), i , 308.

224. Essex County Deeds, xi , 147.

225. Ibid., xxi , 188.

226. Ibid., vol. 5451, p. 705.

227. The title of this house is confused by Thomas F. Waters, Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony (Ipswich, Mass.: The Ipswich Historical Society, 1905–1917), i , 358 (Cartwright lot).

228. Essex County Probate Records, docket no. 17017.

229. [Thomas F. Waters], “Thomas Dudley and Simon and Ann Bradstreet,” Publications of the Ipswich Historical Society , xii (1903), 5 and 8.

230. Essex County Deeds, xxiv , 236.

231. [Waters], op. cit. , p. 10.

232. Essex County Deeds, vol. 5156, p. 235.

233. Incorrectly identified by Thomas F. Waters as having been built by Job Harris before 1751; Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony (Ipswich, Mass.: The Ipswich Historical Society, 1905–1917), i , 355.

234. Essex County Deeds, iv (Ipswich), 74.

235. Ibid., v (Ipswich), 492.

236. Essex County Probate Records, docket no. 26839.

237. Essex County Deeds, v (Ipswich), 590.

238. Ibid., xvii , 21.

239. Ibid., vol. 2334, p. 585.

240. Essex County Deeds, xvii , 108.

241. Ibid., xxxv , 104–105. See also, Thomas F. Waters, Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony (Ipswich, Mass.: The Ipswich Historical Society, 1905–1917), i , 389–390.

242. Essex County Deeds, vol. 5384, p. 592.

243. Essex County Deeds, vol. 809, p. 196.

244. Thomas F. Waters, “Jeffrey’s Neck and the way leading thereto . . . ,” Publications of the Ipswich Historical Society , xviii (1912), 4–5, 8–11.

245. See Russell H. Kettell, “The Reconstruction of the Captain Matthew Perkins House . . . ,” Scrapbook, Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities.

247. Daniel S. Wendel, in conversation with the author.

248. Essex County Deeds, lxxi , 131.

249. Ibid., lxxii , 269.

250. Thomas F. Waters, Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony (Ipswich, Mass.: The Ipswich Historical Society, 1905–1917), i , 448.

251. Essex County Deeds, vol. 2583, p. 304.

252. Thomas F. Waters, “The John Whipple House in Ipswich, Mass . . . ,” Publications of the Ipswich Historical Society , xx (1915), 1–2.

253. Essex County Deeds, i (Ipswich), 89.

254. Essex County Probate Records, vol. 304, p. 10.

255. Ibid., vol. 313, p. 458.

256. Essex County Deeds, vol. 1549, p. 6, and vol. 1561, p. 534.

257. Essex County Deeds, iii (Ipswich), 285.

258. Ibid., v (Ipswich), 182.

259. Ibid., ix , 287.

260. Ibid., xv , 109.

261. Essex County Probate Records, vol. 315, p. 307.

262. Essex County Deeds, vol. 2793, p. 246.

263. Harriette M. Forbes, “Some Seventeenth-Century Houses of Middlesex County, Massachusetts,” Old-Time New England , ser. no. 95 (Jan. 1939), pp. 97–99.

264. Middlesex County Deeds, vol. 12800, p. 721.

265. Essex County Deeds, ii , 92.

266. Essex County Deeds, ix , 3.

267. Essex County Probate Records, vol. 319, p. 31.

268. Sidney Perley, “Marblehead in the Year 1700, No. 5,” Essex Institute Historical Collections , xlvii (1911), 68.

269. Essex County Deeds, vol. 2461, p. 585.

270. “Re: House 15 Glover Street, Marblehead,” undated notes by William Sumner Appleton, Corr. Files, Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities.

271. Essex County Deeds, xxii , 210.

272. Norfolk County Deeds, vol. 1604, p. 301.

273. John H. Hooper, “Some Old Medford Houses . . . ,” Medford Historical Register , vii (1904), 49.

274. Joshua Coffin, A Sketch of the History of Newbury [Massachusetts] . . . (Boston, Mass., 1845), p. 391.

275. See James W. Spring, “The Coffin House in Newbury, Massachusetts . . . ,” Old-Time New England , ser. no. 57 (July 1929), pp. 16–18.

276. Ms Collections, Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities.

277. Essex County Deeds, vol. 2798, p. 446.

278. Essex County Deeds, vol. 4094, p. 504.

279. Joshua Coffin, A Sketch of the History of Newbury [Massachusetts] . . . (Boston, Mass., 1845), p. 375.

280. Essex County Deeds, iii (Ipswich), 215, and x , 17.

281. See ibid., xviii , 48; xxxi , 61; and xxxviii , 18; and Essex County Probate Records, docket no. 19766 (inventory).

282. Essex County Deeds, xcv , 192.

283. Ibid., vol. 104, p. 10.

284. William Sumner Appleton, “The Ilsley House,” Old-Time New England , ser. no. 4 (Aug. 1911), p. 10.

285. John J. Currier, “OuId Newbury” . . . (Boston, Mass., 1896), pp. 196–197.

286. Essex County Deeds vol. 194, p. 233.

287. Ibid., vol. 2088, pp. 301 and 306.

288. William Sumner Appleton, “Annual Report of the Corresponding Secretary,” Old-Time New England , ser. no. 14 (May 1916), pp. 5–9.

289. John J. Currier, History of Newburyport, Mass., 1764–1909 (Newburyport, Mass.: Printed for the Author, 1909), ii , 54.

290. Essex County Deeds, xiv , 108.

291. Essex County Probate Records, vol. 316, p. 289.

292. Essex County Deeds, xiv , 107. See also, John J. Currier, “Ould Newbury” . . . (Boston, Mass., 1896), pp. 119 and 142.

293. Essex County Deeds, vol. 167, p. 306.