The Straits Times

- International

- Print Edition

- news with benefits

- SPH Rewards

- STClassifieds

- Berita Harian

- Hardwarezone

- Shin Min Daily News

- SRX Property

- Tamil Murasu

- The Business Times

- The New Paper

- Lianhe Zaobao

- Advertise with us

‘Go home’: Too much tourism sparks backlash in Spain

MADRID - Anti-tourism movements are multiplying in Spain, the world’s second most visited country, prompting the authorities to try and reconcile the interests of locals and the lucrative sector.

Rallying under the slogan “The Canaries have a limit”, a collective of groups on the archipelago off north-west Africa are planning a slew of protests on April 20.

The Canaries are known for volcanic landscapes and year-round sunshine, and attract millions of visitors from all over the world.

Groups there want the authorities to halt work on two new hotels on Tenerife, the largest and most developed of the archipelago’s seven islands.

They are also demanding that locals be given a greater say in the face of what they consider uncontrolled development which is harming the environment.

Several members of the collective Canaries Sold Out also began an “indefinite” hunger strike last week to put pressure on the authorities.

“Our islands are a treasure that must be defended,” the collective said.

The Canaries received 16 million visitors in 2023, more than seven times its population of around 2.2 million people.

This is an unsustainable level given the archipelago’s limited resources, Mr Victor Martin, a spokesman for the collective, told a recent press briefing, calling it a “suicidal growth model”.

‘Social revulsion’

Similar anti-tourism movements have sprung up elsewhere in Spain and are active on social media.

In the southern port of Malaga on the Costa del Sol, a centre of Spain’s decades-old “soy y playa” or “sun and beach” tourism model, stickers with unfriendly slogans such as “This used to be my home” and “Go home” have appeared on the walls and doors of tourist accommodations.

In Barcelona and the Balearic Islands, activists have put up fake signs at the entrances to some popular beaches warning in English of the risk of “falling rocks” or “dangerous jellyfish”.

Locals complain a rise in accommodation listings on short-term rental platforms such as Airbnb have worsened a housing shortage and caused rents to soar, especially in town centres.

The influx of tourists also adds to noise and environmental pollution and taxes resources such as water, they add.

In the north-eastern region of Catalonia, which declared a drought emergency in February, anger is growing over the pressure exerted on depleted water reserves by hotels on the Costa Brava.

“Our concern is to continue to grow tourism in Spain so that it is sustainable and does not generate social revulsion,” vice-president Jose Luis Zoreda of tourism association Exceltur told a news conference on April 16 when asked about the protest movements.

The group said it expects Spain’s tourism sector will post record revenues of €202.65 billion (S$290 billion) in 2024.

Loudspeaker ban

Before the Covid-19 pandemic brought the global travel industry to its knees in 2020, protest movements against overtourism had already emerged in Spain, especially in Barcelona.

Now that pandemic travel restrictions have been lifted, tourism is back with a vengeance – Spain welcomed a record 85.1 million foreign visitors in 2023.

In response, several cities have taken measures to try to limit overcrowding.

The northern seaside city of San Sebastian in March 2023 limited the size of tourist groups in the centre to 25 people and banned the use of loudspeakers during guided tours.

The southern city of Seville is mulling over charging non-residents a fee to enter its landmark Plaza de Espana, while Barcelona had removed a bus route popular with tourists from Google Maps to try to make more room for locals.

Housing Minister Isabel Rodriguez said over the weekend that “action needs to be taken to limit the number of tourist flats” but stressed the government is “aware of the importance of the tourist sector”, which accounts for 12.8 per cent of Spain’s economic activity. AFP

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

- Environmental issues

Read 3 articles and stand to win rewards

Spin the wheel now

Next stop for Spanish tourism excellence: Sustainability

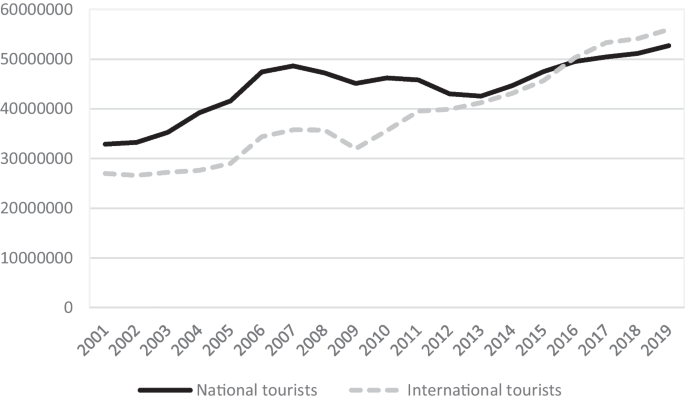

Tourism is vital to Spain. The country’s natural attractions and cultural assets draw crowds from around the world—making many of its communities reliant on tourism. Pre-pandemic, Spain was the second-largest tourism destination in the world, drawing 84 million visitors in 2019 who brought over €92 billion in revenue. 1 “Spain: Economic and infrastructural situation,” Climate ADAPT, Climate ADAPT website, updated March 15, 2021; “Satellite account of tourism in Spain,” INE, January 7, 2022. Travel and tourism accounted for around 14 percent of Spain’s total GDP and provided one in eight jobs. In some communities, tourism contributed to over 20 percent of all economic activity . While these figures plummeted during COVID-19, travel and tourism is recovering and Spain remains dependent on success in tourism.

Spain’s tourism sector now faces new challenges. Fears of a global recession, and geo-political uncertainty, could put pressure on tourism. And as travel resumes in an era of high inflation, Spain will likely face stiff competition from several destinations that also offer sunshine and coastal vacations at similar, or lower, prices—Egypt, Greece, and Turkey, for example.

The sector also faces physical and economic threats due to climate change. The Mediterranean basin is getting warmer: the number of days above 37°C in southern Spain is expected to double by 2050 and rising temperatures increase the risk of drought, water stress, wildfires, and floods. 2 “ A Mediterranean basin without a Mediterranean climate? ” McKinsey Global Institute, May 2020. Extreme weather is already evident as the pre-summer season of 2022 saw temperatures climb above 40°C in Seville. 3 “Spain is hit by the hottest pre-summer heatwave for 20 years as temperatures climb to 43 C,” Euronews, June 14, 2022. An increase in the number of “too hot” days could discourage tourism, particularly in peak season. For instance, a 2022 survey by a travel insurance company found that 65 percent of UK holiday makers thought Spain would be too hot to visit by 2027. 4 Charlotte Elton, “Spain, Greece, Turkey: Most Brits think holiday hotspots will be ‘too hot’ to visit by 2027,” Euronews, September 9, 2022.

Of course, Spain’s tourism sector cannot combat climate change alone. But this backdrop underscores the urgency to act. Globally, tourism is a significant contributor to emissions, and Spain can play a role in emissions reduction. In 2019, tourism was responsible for about 11 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, worldwide. Of this, the largest emissions came from domestic and international tourism in China, India, and the United States. Compared to these top three, Spain ranks at number 16 for emissions from tourism. 5 Sustainability in travel 2021: Quantifying tourism emissions for destinations, Skift Research, June 2021. Considering the size of Spain’s tourism industry, the country compares well against these destinations, but there is room for improvement.

Spain can set itself apart by prioritizing sustainability, including environmental issues such as water usage, plastic waste, carbon emissions, and social issues such as how tourism affects local communities. Globally, travelers are becoming more aware and are seeking out vacations with less impact on the environment and on local communities. Sustainability could become a key differentiator.

Furthermore, sustainable travel could draw discerning premium travelers who will likely be willing to pay for offerings that uphold their values. But efforts to draw these travelers will need to extend beyond marketing and involve real operational changes. Gen Z travelers, in particular, don’t care what tourism businesses say about their sustainability efforts, they want to see it in practice. 6 Dawit Habtemariam, “Tourism’s sustainability pitch needs to be more subtle for Gen Z,” Skift, March 8, 2023. Gen Zs, who typically have a heightened awareness of climate change, are looking for eco-friendly accommodation options. Skift found that 38 percent of Gen Zs across the world would consider staying in green accommodation on their next holiday, compared to the 33 percent response rate of those over 25. 7 Mary Ann Ha, “Meeting the high expectations of the Gen Z traveler: New report,” Skift, June 21, 2022.

This article examines the key aspects of sustainability that are relevant to travel and tourism and suggests ways in which stakeholders across Spain’s tourism sector could prioritize and invest in sustainable offerings. Such actions can ensure that this important sector remains competitive, and help to safeguard its assets for future generations.

Spain is a leading destination, but faces strong competition and a tough operating environment

The physical and economic consequences of climate change, global economic environment, strong competition, and changing consumer preferences all put pressure on the sector. Worldwide, rising inflation could prompt consumers to cut back on travel, or “downtrade” to cheaper destinations. While “revenge travel” boosted tourism as travel restrictions eased, the threat of a looming recession could dampen appetite for travel.

European travelers want to visit beaches that are conveniently close, warm, and affordable. The largest outbound markets for sun and beach tourism include Germany, the United Kingdom, Scandinavia, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Austria. Spain is a popular destination for sun and sand, accounting for almost one-third of international overnight trips to the EU’s coastal areas in 2021. 8 Eurostat dataset: Nights spent at tourist accommodation establishments by degree of urbanization and coastal/non-coastal area, accessed January 18, 2022. But, Spain competes with other destinations, in the Mediterranean and beyond, that cater to these tourists.

Even if overall demand falls, select locations across the country are at risk of over-tourism. Pre-COVID-19, a World Economic Forum report placed Spain first out of 140 competitive countries in travel and tourism. 9 The Travel & Tourism competitiveness report 2019, World Economic Forum, September 4, 2019. The report warned that one-third of international arrivals are concentrated in the top ten countries, and this concentration can lead to severe pressure, and negative effects, on tourism infrastructure and services as well as local populations.

Several Spanish beach destinations have struggled with unruly visitors, and some cities have experienced an anti-tourism backlash in the wake of overcrowding. 10 “Irish tourist seriously injured in fall from balcony in Spain,” Murcia Today, May 5, 2022; “Why Barcelona locals really hate tourists,” Independent , August 12, 2017. Authorities have stepped in to manage the situation in specific locations. For example, in 2020, Spain introduced new laws to limit alcohol consumption at all-inclusive resorts in the Balearic Islands. 11 “Britons limited to six drinks a day in Ibiza and Majorca on all-inclusive breaks,” Evening Standard, April 29, 2022. And several cities, including Madrid and Barcelona, introduced stricter regulations for private short-term accommodation rental to tourists to protect the long-term housing market. 12 “Barcelona wants to ban renting private rooms to tourists,” Bloomberg, February 5, 2021; “Barcelona takes on Airbnb,” New York Times, September 22, 2021.

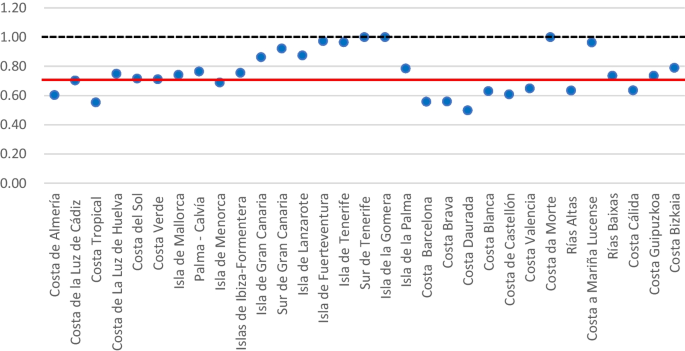

These efforts could make tourism more sustainable for the long term. But the industry itself may be adding to conditions that make tourism unsustainable for the local workforce. Seasonality is a major hurdle in this regard. The country’s core tourism destinations have high seasonality, leading to peaks and troughs in employment. Unemployment reaches around 20 percent in the low season (exhibit).

A focus on all aspects of sustainability can improve the sector’s (and the country’s) perception and reputation—and ultimately affect tourists’ willingness to visit.

Would you like to learn more about our Travel, Logistics & Infrastructure Practice ?

What sustainability means for travel and tourism.

Sustainability is becoming increasingly important to travelers. In 2022, Booking.com found that more than 70 percent of global travelers intend to travel more sustainably over the next year (a 10 percent increase on the company’s 2021 survey) and 35 percent said that the sustainability efforts of accommodation and transport providers play a strong role in their booking decisions. 13 Sustainable travel report 2022 , Booking.com.

But what does sustainable travel mean? According to the World Tourism Organization, sustainable tourism addresses the needs of visitors, the industry, the environment, and host communities based on three interdependent factors: 1) social sustainability (respect for the socio-cultural authenticity of host communities, support for local businesses, and levels of tourism that are acceptable to local communities); 2) environmental sustainability (measures to reduce environmental impact and preserve natural heritage and biodiversity); and 3) economic sustainability (business models that achieve economic growth without negatively impacting social, environmental, or cultural aspects of communities). 14 “Sustainable development,” UNWTO website.

By improving environmental and social sustainability, organizations across the travel and tourism value chain can strengthen their business models and reach economic sustainability. Without considering social and environmental factors, economic viability may be difficult to reach or maintain in the long term.

Several countries are taking an integrated approach to tourism development with the goal of becoming more resilient, sustainable, and inclusive. In some instances, this means adapting a country’s tourism offerings to reduce seasonality and the strain it puts on local infrastructure and resources. Increasing visitors in off-peak periods can lead to year-round jobs and businesses. For example, Slovenia has committed to 20 projects to transform mountain destinations into year-round resorts for active holidays outside of ski season. 15 OECD tourism trends and policies 2022, OECD. And Norway’s “Norway all year round” plan aims to spread tourist traffic across several locations and seasons. The plan intentionally does not market Norway as a cruise destination and aims to attract travelers in source markets who are available to travel all year round, and have the means to do so. 16 “Making Norway an all-year-round destination,” Sustainable Tourism in the North website.

Transforming the tourism workforce

New Zealand’s Tourism Industry Transformation Plan begins with a focus on the workforce as the core element of developing a thriving tourism system. The plan paves the way for better experiences for those within the industry as a way to deliver better outcomes for employees, businesses, and visitors.

The plan puts forward new ways of working, for instance, to improve employment standards and practices relating to decent pay and career progression, and to provide fit-for-purpose education and training.

Another innovation “embrace the flux, enable the flex” aims to reframe the tourism industry’s attitude to seasonality. Rather than the peaks and troughs being a barrier to attracting and retaining employees, the industry can use peaks and troughs to its advantage to upskill people, provide consistent employment, and reduce barriers to people holding multiple jobs across the year and across sectors.

One of the initiatives involves collaboration between tourism and conservation employers to help employees maintain stable employment, remain in regions with limited employment offerings, and support the wider community. It also enables tourism employees to gain local conservation knowledge and skills, and those workers can then share their expertise and insights with visitors and increase the value of the tourism offering in the region.

Source: Tourism Industry Transformation Plan: He Mahere Tiaki Kaimahi, Better Work Action Plan, New Zealand Government, March 2023.

Other country-level social and economic sustainability initiatives focus on the tourism workforce. New Zealand recently launched a transformation plan aimed at improving conditions for those who work in the tourism industry, as a basis for transforming the entire sector (see sidebar “Transforming the tourism workforce”).

Travel businesses have also taken steps to reduce the effects of seasonality on the local workforce, for example, by sharing staff. In Geneva, the Ice Castles attraction that has a four-month winter season shares staff with the Lake Geneva Ziplines & Adventures company. This provides extra work and helps to retain staff at both businesses each season. 17 Nathan Andrew, “How to maximize the value of tourism shoulder season,” Blend, August 2021.

The social, environmental, and economic aspects of sustainability are intertwined in global consumers’ perspectives. Booking.com respondents around the world said they chose sustainable options because they wanted to reduce their impact on the environment, have a more locally relevant experience, or believed that sustainable properties treat communities better. 18 Sustainable travel report 2022 , Booking.com.

Spanish respondents held similar views on sustainability as their global counterparts—they are concerned about waste and energy consumption, and 79 percent intend to walk, cycle, or take public transport during future trips. Respect for local communities is important, too, as 68 percent want authentic experiences that are representative of local culture. In addition, 68 percent will go out of their way to avoid popular destinations and attractions to avoid contributing to overcrowding. 19 Sustainable travel report Spain 2022 (Informe Global Sobre Turismo Sostenible 2022) Booking.com.

Considering that in 2019, 45 percent of tourism spend in Spain was domestic, Spanish traveler sentiment is particularly relevant to Spain’s tourism offerings, for locals and international tourists alike. 20 Global travel service data from Oxford Economics.

Globally, hospitality providers may be at risk of not meeting customer expectations around sustainability as there is a gap between what consumers want and what exists in the market. An earlier Booking.com survey spanning 30 countries—Spain being one of them—found that one-quarter of accommodation providers had not implemented any sustainability measures; and for those that had, only one-third actively informed their customers about the measures they had taken—and this usually happened at check-out. 21 Sustainable travel report 2021, Booking.com.

Taking action on sustainability (and actively communicating what has been done) could bridge this gap, attract new travelers, and help Spain’s tourism sector to flourish while doing good for local communities and the planet. Much of McKinsey’s research on sustainability shows that doing well and doing good are not mutually exclusive —these actions reinforce each other. Industry-wide commitment to sustainability could help to differentiate the sector, and respond to consumer needs, thereby increasing the chances of economic sustainability.

How sustainability-related initiatives provide a unique experience

Destinations around the world have demonstrated that environmental and social sustainability initiatives can protect resources and promote local communities—and become flagship projects that garner international recognition and draw visitors looking for meaningful and authentic travel experiences.

- A Dutch partnership between national NGOs and local communities created a new way to maintain beaches without threatening biodiversity. The initiative involved locals and tourists and led to a new certification method, a first around the world. In 2021, Goeree-Overflakkee was awarded the first “Green Beach” certification, and in 2022 became known as the cleanest beach in the Netherlands. 1 “Green Destinations top 100 stories 2022: Together for a new standard in biodiverse green beaches,” Green Destinations website.

- The Greek region of Attica was named the world’s leading sustainable tourism destination in 2022 by the World Travel Awards based on its cultural wealth, natural beauty, modern infrastructure, and the comprehensive plan implemented by the region in order to turn Attica into the first “green” region. 2 “World's leading sustainable tourism destination 2022,” World Travel Awards website.

- Visitors to Hiiumaa island in Estonia usually rely on private cars to visit key attractions. To provide visitors with a lower-carbon mobility option and a more authentic, nature-based experience of the island, a local entrepreneur created an electric bicycle network (including solar power loading stations) which has become popular with tourists and locals. 3 “Green Destinations top 100 stories 2022: Carbon neutral and local, new opportunities in tourism and public transport in Estonian’s green island Hiiumaa,” Green Destinations website.

- In Istria, Croatia, around half of tourists stay in small, private accommodation. Eco Domus is a certification program that teaches private accommodation providers sustainability practices on topics including water, food, health, and light and noise pollution. The aim is to provide better quality, and more sustainable, local offerings. 4 “Green Destinations top 100 stories 2022: Eco Domus, eco-friendly accommodation,” Green Destinations website.

Of course, taking action requires time, resources, and investment. Individual hotels or tourism businesses may have little incentive to redefine core offerings or invest in infrastructure to demonstrate that sustainability is important to them. But businesses that begin to differentiate themselves could reap the benefits. Many destinations in the region provide examples of how sustainable offerings can become a drawcard for visitors, and earn international acclaim and prestige (see sidebar “How sustainability-related initiatives can offer tourists a unique experience”).

The path toward eco-friendly travel in China

Actions to advance sustainability across spain’s tourism sector are emerging.

Spain developed a Sustainable Tourism Strategy 2030, a national agenda to help the tourism sector address medium- and long-term challenges including socioeconomic and environmental sustainability. 22 “Sustainable tourism strategy of Spain 2030,” Spain’s Ministry of Industry, Trade and Tourism. Even though this national sustainability strategy is in place, there are limited mechanisms to help small businesses partake and contribute. This is particularly challenging as small- and micro-sized businesses make up the vast majority of all businesses in the country’s tourism sector. According to Statista, micro-size businesses account for around 92 percent of Spain’s travel, tourism, and hospitality businesses. Small businesses make up just over 7 percent, and medium and large businesses account for the remaining half a percent. 23 Statista, Distribution of businesses in the tourism sector in Spain in 2020 by size, June 2022.

This fragmentation can halt progress and collective action, for instance in emissions reduction. Spain’s large hospitality providers are making efforts to reduce carbon emissions, and many are pioneers in the field: Melia opened Menorca’s first carbon-neutral luxury hotel in 2022, showcasing carbon-neutral operations, “intelligent” energy-efficient buildings, and circular models for water resources. 24 Tom Otley, “Melia opens Villa Le Blanc By Gran Meliá in Menorca, Spain,” Business Traveller, July 20, 2022. Iberostar has committed to becoming carbon neutral by 2030—a target that is 20 years ahead of many other international hospitality brands. 25 “Iberostar will be carbon neutral by 2030, 20 years ahead of the industry’s global target,” Iberostar press release, November 8, 2022.

In general, smaller and medium-size providers’ goals and targets are less ambitious than those of international peers, presumably because the economic benefits of such actions are unclear, or they may fear first-mover disadvantages like higher costs. Various Spanish hotel chains have committed to reducing emissions by 20 to 35 percent, with timelines ranging from 2030 to 2035. By comparison, many international brands have committed to net zero by 2050 and have strict measures in place to achieve this.

According to the Greenview Hotel Footprinting Tool, which calculates the carbon footprint of a hotel stay anywhere in the world, Spain is among the best-performing countries in terms of low-carbon room footprint and meeting footprint. While this tool points to a strong focus on water-, waste- and emissions-reduction in Spanish hotels, it is difficult to assess what actions many smaller hotels and other tourism businesses are taking on the sustainability front.

Sustainable tourism in Valencia

Valencia claims to be the first city in the world to track the carbon footprint of all tourism activities in the city and has committed to achieving carbon-neutral tourism by 2025. 1 “Valencia becomes the first city in the world to verify and certify the carbon footprint of its tourist activity,” Valencia Tourism official website, July 10, 2020.

Valencia’s official tourism website features sustainable tourism as a key element and makes sustainable offerings visible. For instance, the website encourages visitors to reduce emissions by taking public transport or traveling by bicycle and to support the local economy by shopping at smaller, local stores. It also offers tips on how to be a “responsible tourist who is committed to the environment at all times” such as using energy and water sparingly, recycling, reducing plastic, and respecting local residents.

In this way, the city has positioned itself as “the city taking care of the planet” and made sustainability its differentiating factor.

Even though there may not be concerted and unified action on social and environmental sustainability across the sector, success stories exist of initiatives being put in place that make sustainability a key differentiator (see sidebar “Sustainable tourism in Valencia”). Sector-wide efforts could increase investment into sustainable offerings, make these more visible to tourists, and ultimately position Spain as the destination of choice for sustainable travel.

How Spain could become a sustainable destination of choice

Individual travel and tourism businesses’ environmental and social sustainability efforts need to achieve critical mass if Spain is to become known as a leading destination for sustainability-conscious travelers. These actions are also vital to preserve the sector’s economic sustainability. Collective and concerted action is required to build momentum. All stakeholders have a role to play in addressing the sector’s rationale for action, setting a clear course, and developing the support structure to achieve it.

Identify the value at stake. The sector could take a high-level view to evaluate the status quo, benchmark where Spain could be, and quantify the costs and benefits of prioritizing sustainability throughout the sector, at scale. All stakeholders including policy makers, government, and industry could jointly develop a sustainable travel concept for the sector with a clearly articulated justification for action.

Costa Rica provides an example of a national tourism strategy focused on sustainability. The industry is aligned with national objectives to protect the country’s forests and biodiversity. National parks, nature reserves, and protected areas make up around one-quarter of Costa Rican territory and the sector promotes ecotourism and sustainable offerings that support the conservation of these areas. 26 “Costa Rica, a country committed to the environment,” Aquae Fundacion, July 6, 2021.

Spain’s stakeholders could also agree on industry-wide standards, as having these in place would likely accelerate the transition to sustainable tourism. Standards that align the motivations of different stakeholders and take into account the interests of all parties have a greater chance of adoption. For example, including mandatory sustainability criteria in the hotel star rating system could bring the motivations of hotel owners and operators into alignment. 27 “The path toward eco-friendly travel in China,” McKinsey, March 14, 2023. Setting unified sector sustainability targets could also boost the credibility of sustainability claims or commitments made by individual businesses.

Define a strategy. This includes establishing initiatives to address specific concerns such as decarbonization, water usage, waste management, or overcrowding and setting targets and practical actions to achieve them. For instance, one initiative in Costa Rica—as part of its conservation effort—is a ban on single-use plastic in national parks, biological reserves, and national monuments. 28 “Costa Rica, a country committed to the environment,” Aquae Fundacion, July 6, 2021.

In another example, Iceland set a strategy to reduce seasonality—a long-standing challenge for Icelandic tourism. In 2010, close to half of travelers visited the country during the summer months of June, July, or August. The travel industry, with support from the government and others, launched an international marketing campaign to promote Iceland as a year-round destination. Winter activities such as viewing the Northern lights, snowmobiling, and glacial treks became popular with visitors. Between 2010 and 2019 the share of tourists that visited in summer fell from around 50 to 34 percent, while tourist arrivals continued to grow. 29 Icelandic Tourist Board, Isavia, visitor departure statistics.

Once the strategic direction is set, sector-wide initiatives can be put in place. In New Zealand, a collaborative and concerted effort involving public and private organizations gave rise to the Tiaki Promise, a pledge that encourages visitors to take care of the country’s natural resources: “While traveling in New Zealand, I will care for land, sea, and nature, treading lightly and leaving no trace; travel safely, showing care and consideration for all; and respect culture, traveling with an open heart and mind.” One collaborator in the initiative, Air New Zealand, released an in-flight safety video that introduced the promise to travelers. 30 Kresentia Madina “The Tiaki Promise encourages tourists to care for New Zealand’s nature,” Green Network, August 26, 2022.

It is also important to rank individual measures to address challenges to ensure that competing priorities do not hinder progress. Collective action will have the most impact if all stakeholders are committed to the same issues.

Many travel and tourism businesses across the world have developed and successfully marketed sustainable products and services, such as low-impact tourist offerings that are less harmful to the environment or local communities. In fact, many travel guides publish editions dedicated to sustainable offerings. 31 Examples include Fodor’s Green Travel: The world’s best eco-lodges and earth-friendly hotels and Lonely Planet’s The sustainable travel handbook . Spain’s tourism providers could follow suit. And the sector could make travelers more aware of existing sustainable travel options through communications campaigns to draw sustainability-conscious travelers from across the globe.

Travel and tourism businesses could also extend sustainability efforts across their value chains. Examples include working with suppliers to ensure linen and towels are sustainably produced, procuring energy-efficient equipment, or engaging local communities by sourcing local food suppliers. There are also opportunities for businesses to collaborate and design sustainable offerings that combine products and services, such as sustainability-focused tours featuring carbon-neutral accommodation, electric ground transportation, and trips to local businesses.

Globally, hotel chains have partnered with sustainability-related businesses or action groups to advance their own sustainability initiatives. These actions also help to strengthen the hotel’s brand and reputation for sustainability consciousness. For instance, the luxury hotel, resort, and spa operator Six Senses partnered with the United States Coalition on Sustainability and the action platform SustainChain in an initiative to remove single-use and disposable plastics from its operations. 32 “Six Senses is the first hospitality brand to partner with the United States Coalition on Sustainability and SustainChain,” Six Senses press release, April 26, 2021. And as part of its pathway to net zero, the Radisson Hotel Group partnered with Ecovadis, a sustainability ratings provider, in a collaboration that aims to extend the EcoVadis rating to the group’s global supply chain. 33 “Radisson Hotel Group increases focus on supply chain sustainability; announces partnership with Ecovadis,” Radisson Hotel Group press release, December 16, 2021.

Spanish tourism and hospitality providers might consider similar collaborative partnerships and initiatives to build momentum for industry-wide action and raise global travelers’ awareness that Spain is committed to sustainability.

Provide guidelines and support. Smaller businesses may lack the knowledge or resources necessary to act on sustainability. Actions could be taken to bridge knowledge gaps and secure funding, at government or industry association level. Funding programs, incentive schemes, or financial instruments can accelerate adoption of sustainable solutions, especially for smaller businesses. For example, South Africa’s Green Tourism Incentive Program targets small tourism businesses like lodges and guest houses. The program funds water- and energy-efficiency assessments and recommends the optimum green solution for the business. The bulk of the cost to implement the solution is also funded by the program. 34 “The Green Tourism Incentive Programme,” Industrial Development Corporation, October 4, 2021.

The industry could also draw on available resources and convene stakeholders to share knowledge and expertise. For instance, the World Tourism Organization provides resources and guidelines for building a circular economy, reducing food waste, and tackling plastic pollution. 35 “Sustainable development,” UNWTO website.

Regulation could be put in place to support change. Regions or cities could look to establish regulations that ensure tourism activity is environmentally and socially sustainable. Progress has been made in this regard, as the Law on Circularity and Sustainability in Tourism, approved by Parliament in May 2022, made the Balearic Islands the first sustainable destination by law. 36 “Balearic Islands, sustainable tourism is now a law,” Excellence Magazine, June 21, 2022. This regulation protects seasonal tourism workers, considers local residents’ quality of life (for instance by blocking an increase in the number of beds for the next four years), reduces waste, and protects natural resources. It will also introduce a hotel classification system based on the concrete actions taken to promote sustainable tourism.

Regulatory bodies and industry associations could also support business owners with guidance, encourage implementation through incentives, and enforce regulations through penalties for non-compliance.

Spain’s tourism sector has an opportunity to further develop existing sustainability efforts, thereby protecting the future of the sector. A sector-wide focus on environmental and social sustainability can also act as a key differentiator and draw visitors who are consciously trying to travel more responsibly. Furthermore, all stakeholders could benefit if existing initiatives, and new investments, are made more visible and attractive to tourists.

Javier Caballero is a partner in McKinsey’s Madrid office, Margaux Constantin is a partner in the Dubai office, Steffen Köpke is a capabilities and insights expert in the Düsseldorf office, and Daniel Riefer is a partner in the Munich office.

The authors wish to thank Lisa Kropacek for their contribution to this article.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Has COVID-19 changed tourism in Spain? Experts have identified three types of tourist

Experts predict a continuing trend of mass and sun- and beach-based tourism for summer 2022 (Photo: jlxp / Pixabay)

The COVID-19 pandemic has upset a huge variety of activities and situations worldwide since it first emerged in early 2020. One of the industries most harshly affected by it has been tourism, as a result of restrictions on flights and mobility and people's reluctance to travel for health reasons, all of which have resulted in a significant reduction in tourism in the last two years.

A study conducted by researchers at the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC), and published in the open-access Journal of Tourism Futures, has looked at the impact of people's perceived health risk of travelling immediately after the first wave of COVID-19 and lockdown and identified various tourist profiles and their motivations.

"The experience of the pandemic has led to a variety of reactions affecting people's behaviour as tourists. Some people seem to want to make changes to their consumption habits and the way they do tourism, whereas others have not done this at all or have only done so in a very superficial manner," said Francesc González Reverté , a member of the UOC's Faculty of Economics and Business and New Perspectives on Tourism and Leisure ( NOUTUR ) research group, who led the study together with UOC researchers Joan Miquel Gomis López and Pablo Díaz Luque .

Tourist profiles

According to the authors of the study, there are three profiles of tourists who want to change their future tourism habits and behaviour in terms of the way they organize trips and decide when and how to visit certain places. The first profile is that of the concerned tourist . Members of this category assert that they want to change the way they live, and therefore the way they travel, after the pandemic.

The second profile is that of the pragmatic tourist . People in this category are sensitive to the risk of tourism but are not willing to make serious changes to the way they travel. "Tourists in this category only change their behaviour temporarily, for the duration of the pandemic," said González Reverté.

Finally, sceptical tourists are those who do not want to change either their travel habits or their behaviour. They do not appear to be risk-averse and state that they want to keep travelling to mass tourism destinations.

These profiles were drawn up based on 500 interviews conducted with Spanish tourists in spring 2020, after the first wave of COVID-19 and lockdown, early on in the pandemic, when there were no vaccines. The set of interviewees was composed of 33.7% men and 66.3% women, all of them in the 35-45 and 46-54 age ranges. As to educational background, at the time of the survey 53.5% of respondents had finished secondary school, and 33% had a degree. Furthermore, 79% were working, and 21% were unemployed.

The study also found that people have reacted in very different ways regardless of whether or not they have had the disease themselves. González explained that "We were surprised to find no direct correlation between having been affected by the disease, either personally or through close contacts, and a change in behaviour in tourism or general living habits."

Short-term tourism trends

Although coronavirus diseases, among others, are transmitted faster in this globalized world, particularly in highly populated areas, the authors noted that the behavioural change of some tourists has been very "short-lived". "Although the pandemic has led to an intellectual debate revolving around the new global consciousness of our insignificance as a species, the results of the study suggest that there is no general fear of continuing to travel in the future or any intention of radically changing the way we do so," said González.

In fact, the UOC researchers emphasized that risk perception is a social construct and is therefore not sufficient in itself to make people change unless it is coupled with other measures, such as education or awareness-raising actions. Furthermore, behavioural changes "are more based on factors such as environmental attitudes or individual people's pre-existing worldviews," they noted.

Although there was talk of a change in tourism habits and preferences shortly after the early waves, such as a greater trend towards nature tourism or visiting the countryside, the study has shown that there is a significant number of tourists who will continue to rely on traditional sun- and beach-based mass tourism destinations in the long term . "A significant majority of tourists don't associate going to these very busy places with a higher risk of catching the disease. Furthermore, they often perceive them as safe," said the UOC researcher.

This finding challenges the idea that mass tourism destinations "were going to be the big losers" . Although the fall in tourism initially resulted in losses of millions of euros for the industry, we are now moving away from the trend that led to the idea that mass tourism was "going to disappear". For example, the initial visitor forecasts for summer 2022 confirm a continuing trend in this type of mass tourism.

"Although our contributions are clear, we need many more empirical studies to provide new data in order to effectively measure the effect of the pandemic on various aspects of tourist behaviour," concluded González. He also noted that, although many articles about the link between COVID-19 and tourism have been written, their approach is usually theoretical or based on the author's personal opinion or mere speculation, without any field work-based data or information.

This UOC research supports Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 8, Decent Work and Economic Growth; and 12, Responsible Consumption and Production.

González-Reverté, F. , Gomis-López, J. M. and Díaz-Luque, P. (2022 ), "Reset or temporary break? Attitudinal change, risk perception and future travel intention in tourists experiencing the COVID-19 pandemic" , Journal of Tourism Futures , vol. ahead-of-print, no. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-03-2021-0079

UOC R&I

The UOC's research and innovation (R&I) is helping overcome pressing challenges faced by global societies in the 21st century, by studying interactions between technology and human & social sciences with a specific focus on the network society, e-learning and e-health .

Over 500 researchers and 51 research groups work among the University's seven faculties and two research centres : the Internet Interdisciplinary Institute ( IN3 ) and the eHealth Center ( eHC ).

The University also cultivates online learning innovation s at its eLearning Innovation Center ( eLinC ), as well as UOC community entrepreneurship and knowledge transfer via the Hubbik platform.

The United Nations' 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and open knowledge serve as strategic pillars for the UOC's teaching, research and innovation. More information: research.uoc.edu #UOC25years

Experts UOC

Press contact.

- Editorial department [email protected] 93 253 23 00

You may also be interested in…

Most popular, related courses.

Travel, Tourism & Hospitality

Tourism sector in Spain - statistics & facts

Who visits spain the most, how popular is domestic tourism in spain, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Quarterly travel and tourism balance of payments in Spain 2018-2022

Tourism premises in Spain 2015-2021

Tourism employment in Spain 2020-2021

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Current statistics on this topic.

Inbound tourism volume in Spain 2022, by origin

Tourism contribution to Spanish GDP 2006-2023

Destinations

Inbound tourism volume in Spain 2022, by region of destination

Related topics

Tourism in spain.

- Inbound tourism in Spain

- National tourism in Spain

- Tourism in Barcelona

- Travel and tourism in the Canary Islands

Tourism in Europe

- Travel and tourism in Europe

- Backpacking in Europe

- Wine tourism in European countries

- Cruise industry in Europe

- Overtourism in European destinations

Travel trends

- Subscription model in the travel industry

- Mobile travel trends

- Travel and tourism in the metaverse

- Artificial intelligence (AI) use in travel and tourism

Recommended statistics

- Premium Statistic Leading European countries in the Travel & Tourism Development Index 2021

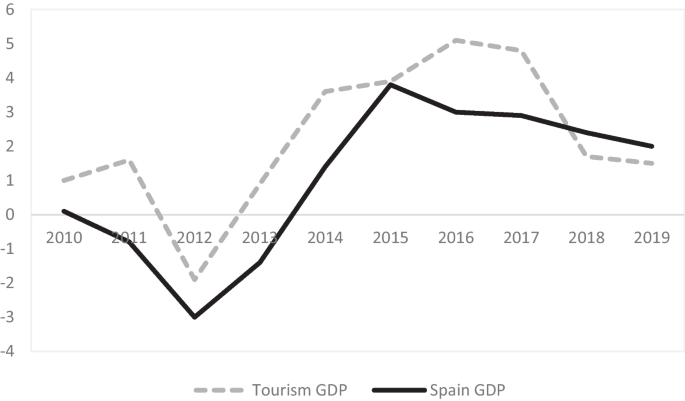

- Premium Statistic Tourism contribution to Spanish GDP 2006-2023

- Premium Statistic Tourism sector as share of GDP in Spain 2010-2021

- Premium Statistic Monthly growth rate of tourism GDP in Spain 2022

- Premium Statistic Tourism employment in Spain 2015-2021

- Premium Statistic Tourism employment in Spain Q4 2022, by industry

Leading European countries in the Travel & Tourism Development Index 2021

Leading European countries in the Travel & Tourism Development Index (TTDI) in 2021

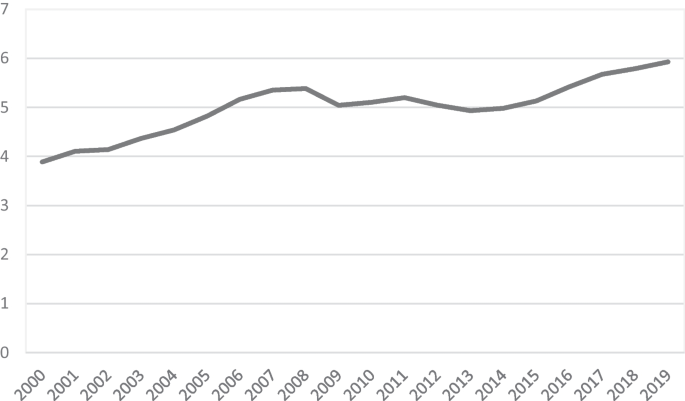

Contribution of the tourism sector to the gross domestic product in Spain from 2006 to 2022, with a forecast for 2023 (in billion euros)

Tourism sector as share of GDP in Spain 2010-2021

Contribution of tourism to gross domestic product in Spain from 2010 to 2021

Monthly growth rate of tourism GDP in Spain 2022

Percentage change in the contribution of travel and tourism to GDP in Spain from January to December 2022

Tourism employment in Spain 2015-2021

Number of employees in the tourism sector in Spain from 2015 to 2021 (in 1,000s)

Tourism employment in Spain Q4 2022, by industry

Number of people working in the tourism sector in Spain in 4th quarter 2022, by industry (in 1,000s)

Tourism volume and expenditures

- Premium Statistic Inbound visitors in Spain 2000-2022

- Premium Statistic Inbound tourism volume in Spain 2022, by origin

- Premium Statistic International tourism spending in Spain 2012-2022

- Premium Statistic Domestic trips in Spain 2015-2022

- Premium Statistic Domestic trips in Spain 2022, by destination

- Premium Statistic Domestic tourism spending in Spain 2015-2022

- Basic Statistic Share of travel and tourism spending in Spain 2022, by traveler origin

Inbound visitors in Spain 2000-2022

Number of international visitors in Spain from 2000 to 2022 (in millions)

Number of international tourists in Spain in 2022, by country of residence (in 1,000s)

International tourism spending in Spain 2012-2022

Expenditure of international tourists in Spain from 2012 to 2022 (in billion euros)

Domestic trips in Spain 2015-2022

Number of domestic trips in Spain in 2015 to 2022 (in millions)

Domestic trips in Spain 2022, by destination

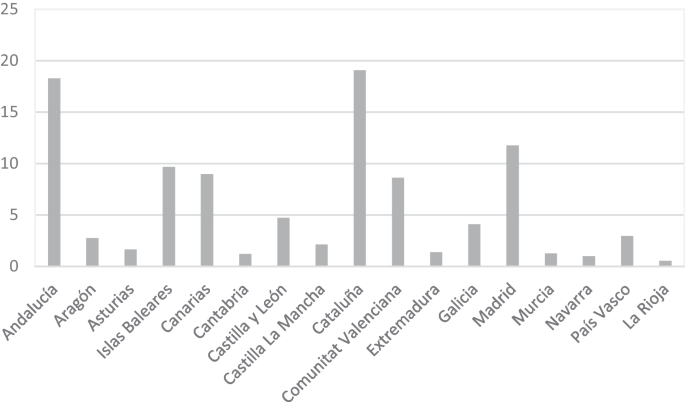

Number of domestic trips in Spain in 2022, by autonomous community of destination (in millions)

Domestic tourism spending in Spain 2015-2022

Expenditure of domestic tourists in Spain from 2015 to 2022 (in billion euros)

Share of travel and tourism spending in Spain 2022, by traveler origin

Distribution of expenditure by tourists in Spain in 2022, by main origin

- Premium Statistic Inbound tourism volume in Spain 2022, by travel reason

- Premium Statistic Domestic trips in Spain 2022, by travel reason

- Basic Statistic Share of travel and tourism spending in Spain 2022, by purpose

- Premium Statistic Inbound trips for cultural purposes to Spain 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of enotourists in Spain 2008-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of skiers and snowboarders in Spain 2010-2022

- Premium Statistic Pilgrims on the Way of Saint James 2011-2022

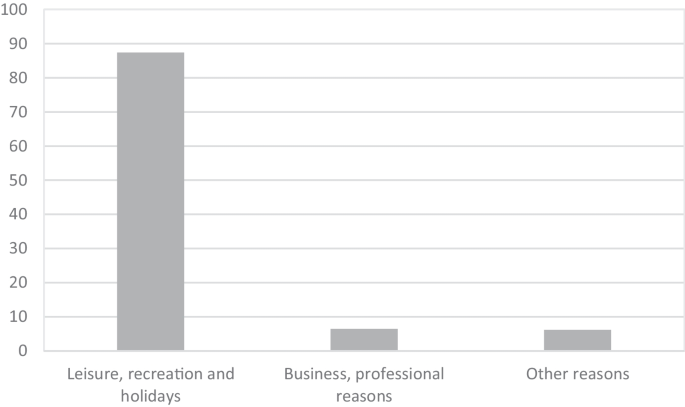

Inbound tourism volume in Spain 2022, by travel reason

Number of international tourists in Spain in 2022, by travel purpose (in 1,000s)

Domestic trips in Spain 2022, by travel reason

Number of domestic trips in Spain in 2022, by travel purpose (in millions)

Share of travel and tourism spending in Spain 2022, by purpose

Distribution of expenditure by tourists in Spain in 2022, by main travel purpose

Inbound trips for cultural purposes to Spain 2010-2022

Number of trips for cultural reasons made by international tourists to Spain from 2010 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Number of enotourists in Spain 2008-2022

Number of visitors to wineries and wine museums in Spain from 2008 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Number of skiers and snowboarders in Spain 2010-2022

Number of visitors to ski resorts in Spain from 2010/2011 to 2021/2022 (in 1,000s)

Pilgrims on the Way of Saint James 2011-2022

Number of pilgrims who traveled to Santiago de Compostela, Spain from 2011 to 2022

- Premium Statistic Tourism premises in Spain 2015-2021

- Premium Statistic Share of tourism companies in Spain 2021, by size

- Premium Statistic Main hotel groups in Spain FY2021, by sales revenue

- Premium Statistic Main passenger airlines in Spain 2022

- Premium Statistic Main travel agencies in Spain FY2021, by sales revenue

- Premium Statistic Main restaurants and food stall companies in Spain FY2021, by sales revenue

- Premium Statistic Ecotourism businesses' average revenue in Spain 2022, by type

Number of establishments in the tourism sector in Spain from 2015 to 2021

Share of tourism companies in Spain 2021, by size

Distribution of businesses in the tourism sector in Spain in 2021, by size

Main hotel groups in Spain FY2021, by sales revenue

Leading hotel companies in Spain in FY2021, based on sales revenue (in million euros)

Main passenger airlines in Spain 2022

Leading airlines in Spain in 2022, based on number of passengers (in millions)

Main travel agencies in Spain FY2021, by sales revenue

Leading travel agencies in Spain in FY2021, based on sales revenue (in million euros)

Main restaurants and food stall companies in Spain FY2021, by sales revenue

Leading restaurant and food stall companies in Spain in FY2021, based on sales revenue (in million euros)

Ecotourism businesses' average revenue in Spain 2022, by type

Average revenue of ecotourism establishments in Spain in 2022, by type (in 1,000 euros)

Main destinations

- Premium Statistic Main coastal destinations in Spain 2022, by number of hotel guests

- Premium Statistic Most visited cities in Spain 2022

- Premium Statistic Attendance to Spanish National Heritage sites 2022

- Premium Statistic Attendance to Spanish national parks 2022

- Premium Statistic Cruise ship calls at Spanish ports 2022, by authority

- Premium Statistic Enotourism destination areas in Spain 2022, by region

Main coastal destinations in Spain 2022, by number of hotel guests

Leading beach destinations in Spain in 2022, based on number of overnight tourists in hotels (in 1,000s)

Most visited cities in Spain 2022

Leading city destinations in Spain in 2022, by number of tourists (in 1,000s)

Attendance to Spanish National Heritage sites 2022

Number of visitors to National Heritage sites in Spain in 2022 (in 1,000s)

Attendance to Spanish national parks 2022

Number of visitors to national parks in Spain in 2022 (in 1,000s)

Cruise ship calls at Spanish ports 2022, by authority

Number of cruise vessels calling at ports in Spain in 2022, by port authority

Enotourism destination areas in Spain 2022, by region

Number of Wine Routes in Spain in 2022, by autonomous community

Online travel market

- Premium Statistic Quarterly online revenue of accommodation businesses in Spain 2014-2022

- Premium Statistic Quarterly online revenue of travel agencies & tours operators in Spain 2014-2022

- Premium Statistic Airbnb revenue in Spain 2015-2020

- Premium Statistic Willingness to purchase tourism services online in Spain 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic Average spend on tourism services booked online in Spain 2018-2022

- Premium Statistic Hotel / private accommodation online bookings by brand in Spain 2023

Quarterly online revenue of accommodation businesses in Spain 2014-2022

E-commerce revenue of hotels and similar establishments in Spain from 1st quarter 2014 to 4th quarter 2022 (in million euros)

Quarterly online revenue of travel agencies & tours operators in Spain 2014-2022

E-commerce revenue of travel agencies and tour operators in Spain from 1st quarter 2014 to 4th quarter 2022 (in million euros)

Airbnb revenue in Spain 2015-2020

Revenue of Airbnb in Spain in 2015, 2019, and 2020 (in million euros)

Willingness to purchase tourism services online in Spain 2019-2022

Share of individuals who intended to buy travel products and services online in Spain from 2019 to 2022

Average spend on tourism services booked online in Spain 2018-2022

Average spend on travel products and services bought online in Spain from 2018 to 2022 (in euros)

Hotel / private accommodation online bookings by brand in Spain 2023

Hotel / private accommodation online bookings by brand in Spain as of December 2023

Further reports Get the best reports to understand your industry

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

Spain Travel Stories

Mar 13, 2024 • 7 min read

Set out for history, natural beauty and delicious flavors on these five road-trip itineraries, which will show you the best of Spain.

Mar 7, 2024 • 10 min read

There are so many incredible experiences awaiting you in Spain. Here are some of the very best.

Feb 13, 2024 • 7 min read

There are so many incredible attractions in Spain it can be hard to know where to begin. Start your shortlist here with the top 8 places to visit in 2024.

Nov 30, 2023 • 3 min read

You’ve booked your trip to Spain. The only thing left to do is pack your bags and we're here to help you decide what to take, and what to leave behind.

Nov 7, 2023 • 7 min read

Everything you need to know from when to go and what to do, to how much to budget for, on a trip to the up-and-coming Murcia region of Spain.

Oct 20, 2023 • 5 min read

Of all the places to travel with children, Spain is up there with the best of them. Here are some of the best things to do with kids in this dynamic country.

Sep 30, 2023 • 4 min read

Planning with a local expert from Elsewhere by Lonely Planet made our family trip to Spain unforgettable.

Sep 25, 2023 • 8 min read

Spain is one of the world’s top gastronomic playgrounds, and this goes double at festival time. Here are the country's top food festivals.

Sep 5, 2023 • 10 min read

Spain is a hikers paradise - and there's a wide variety to explore from day walks through canyons to the Camino Primitivo.

Aug 31, 2023 • 10 min read

There are many stunning hikes to do in Spain's Andalucía from day walks with children to bagging a summit or slowing down on a multi-day hike.

Jul 26, 2023 • 6 min read

Compared to the rest of Europe, Spain is easy on the eyes and even easier on the wallet. Here are the best ways to save money while you're there.

Jul 13, 2023 • 5 min read

We asked four travel writers about the their favorite under-the-radar vacation spots in their native Spain.

Jul 10, 2023 • 7 min read

You’ve probably never been to Spain’s Cíes Islands, but we have a lot of reasons why you should. Here's what you need to know.

Jul 10, 2023 • 4 min read

From the liveliest events to when you'll find the best weather, here's when to visit Spain.

Jul 7, 2023 • 4 min read

Don't let your visa application mess up your trip to Spain. Here's everything you need to know about whether you need one.

Jun 26, 2023 • 5 min read

Traveling around Spain is convenient, efficient and manageable — thanks to its advanced and accessible public transport infrastructure.

Jun 21, 2023 • 6 min read

From speaking Spanish to avoiding common tourist mistakes, this guide full of top tips can get you ready for a trip to Spain.

Jun 6, 2023 • 7 min read

Lonely Planet’s Amy Lynch recently took the new ferry route from southeast Ireland to northern Spain. Here’s her report.

May 16, 2023 • 6 min read

With Santiago de Compostela in sight, the best part of the Camino Portugués may require you to take a detour.

May 12, 2023 • 5 min read

Spain has an unmatched lineup of unique summertime festivals. Here are the best to experience in 2023.

May 5, 2023 • 7 min read

A new train line takes riders through lesser-known regions of northern Portugal and Spain with an intriguing Celtic heritage.

Apr 21, 2023 • 5 min read

It takes a few transfers to get between the two Iberian capitals by train. And they’re worth it.

Spain’s tourism renaissance will drive economic growth this year

The recovery of the tourism sector in Spain is expected to continue, putting the industry at the centre of economic growth this year. However, due to macroeconomic uncertainty, high price pressure in the sector and lagging long-haul travel, it may take until 2024 for the number of international visitors to return to pre-pandemic levels

Spain's tourism revival expected to continue despite macroeconomic challenges

Despite macroeconomic challenges, Spain's tourism sector rebounded strongly in 2022. The country saw a remarkable increase in the number of international visitors, rising by 130% from 31.2 million in 2021 to 71.6 million in 2022, showing a strong appetite to travel again after two years of strict travel restrictions. Although disposable income was under severe pressure in many European countries last year, consumers refused to cut back on their travel spending. That being said, the number of international tourists entering Spain still remained 14% below pre-pandemic levels, proving that there is still a long way to go to full recovery.

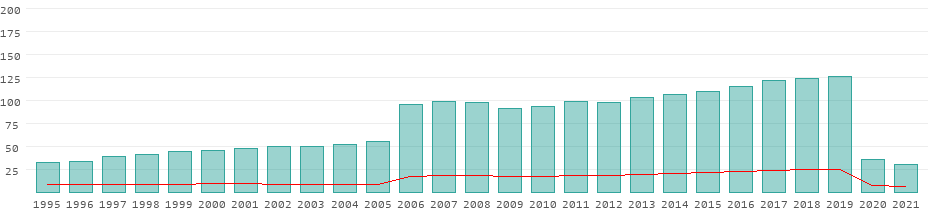

Number of international visitors entering Spain, in absolute values and as % of 2019 levels

Challenges on the horizon: factors hindering the growth of international tourism in spain.

There are several factors that could hamper the growth of international tourism. One is that for Spain's main source countries, the UK and Germany, which accounted for 22% and 13% of international visitors in 2019 respectively, the economic outlook looks bleak. In the UK, the cost-of-living crisis has hit hard and we expect the UK economy to grow by only 0.2% this year. Meanwhile, the German economy has contracted over the past two quarters and is officially in a technical recession. We expect economic growth in Germany to stagnate this year. While the sharp fall in purchasing power is not currently deterring Europeans from travelling, it could cause price-sensitive travellers to swap Spain for cheaper destinations.

Unfavourable exchange rates are also encouraging British travellers to choose Turkey over southern European countries including Spain. A recent report by the European Travel Commission showed that Turkey had 69% more arrivals from the UK in the first quarter of this year than in 2019, while the number of arrivals in Spain was lower than in 2019. This shift in preference can be attributed to the significant price difference. The depreciation of sterling against the euro, combined with the continued devaluation of the Turkish lira against the euro, has made travelling to Turkey much more affordable for British tourists than visiting southern European countries such as Spain.

Another factor hampering recovery is the current travel restrictions on Russian travellers. In 2019, Spain welcomed 1.3 million visitors from Russia, accounting for about 1.6% of total tourist arrivals. This particular group of visitors will be completely absent in 2023. And Spain will not get a boost from Chinese tourism this year either. Although Chinese tourists are eager to travel again, they are favouring domestic trips or visits to neighbouring countries. The number of Chinese tourists visiting Spain was relatively modest even before the pandemic: about one million Chinese tourists travelled to Spain in 2019, which was only 1.3% of the total number of visitors that year.

Business travel to Spain bounces back to pre-pandemic levels

Spain is witnessing a remarkable recovery in business travel after the sharp decline during the pandemic. In the first quarter of 2023, the number of international business travellers increased by 48% compared to the same period last year, returning to pre-pandemic levels. Business travellers represent a significant proportion of the total number of visitors. In 2019, 5.4 million foreign visitors visited Spain for professional reasons, or 6.5% of the total number of foreign visitors in 2019. This means that more than one international arrival in 20 comes to Spain for business reasons.

Last year, business travel recovered more slowly than leisure travel. Due to the shift online during the pandemic, many companies became more selective about the necessity and frequency of business travel, opting more for digital meetings or conferences. In addition, economic uncertainty and the energy crisis also caused a pullback in business travel at the turn of the year. While business travel was already at 96% of its pre-crisis level in October 2022, it fell to 74% in December as many companies adopted cost-saving measures and reduced their travel budgets.

Business travel has been steadily catching up since the beginning of this year. The Spanish economy has recovered strongly from the energy crisis, growing by 0.5% in the first quarter, and business confidence has returned. In March, the number of international business travellers was already back to 94% of the 2019 level. We expect that the recovery will persist throughout this year, resulting in half a million additional business travellers visiting Spain compared to 2022. Towards the end of the year, however, we might see a slight decline again if the pace of recovery slows and the US economy falls into recession.

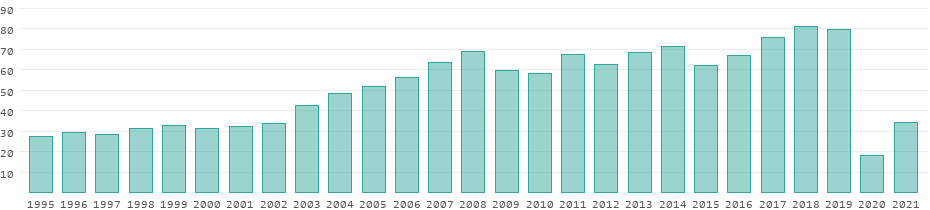

Number of international visitors coming to Spain for professional reasons, in % of their number in 2019

Outlook for international travel in 2023.

Despite the headwinds, the first months of 2023 already showed a promising start for international tourism in Spain this year. In the first quarter, the number of foreign visitors reached 97% of pre-pandemic levels. Falling energy prices and stable labour market conditions may have underpinned the tourism sector. If this trend continues into the summer peak, it is likely that tourism figures in the summer months could match or even exceed 2019 levels for the first time.

The recovery in international travel is expected to continue into 2023, albeit at a slower pace than last year. The tourism sector is benefiting from continued strong travel appetite and a slightly improved economic outlook, thanks to a sharp fall in energy prices. However, persistent macroeconomic concerns will slow the pace of recovery, especially in the second half of this year. All in all, we expect a total of 80.7 million tourists to visit Spain in 2023, up by 13% from the previous year but still 3% below the pre-pandemic level. It will probably take until 2024 for the annual number of international tourists to reach 2019 levels again.

Number of international visitors entering Spain each year, including ING forecast (in millions)

Inflationary challenges in the tourism sector remain elevated.

Inflation in the tourism sector remains stubbornly high, with significant pressure on all tourism activities. The consumer price index (CPI) for tourism and hospitality, a specific category within the broader index measuring price changes for tourism and hospitality-related goods and services, stood at 8.1% in April. This figure is just slightly below the peak level of 8.5% recorded in August 2022. Since the start of the pandemic, prices for tourism products and services have risen by an average of 16%.

Inflationary pressures can be attributed to two main factors. First, there are general inflationary pressures due to the increased cost of labour, raw materials and other inputs, which are passed on to consumers. In addition, sustained high demand and consumers' increased willingness to spend on travel and accommodation have given travel and accommodation providers greater pricing power. This allows them to capitalise on this higher demand by raising prices more easily.

Price pressures in the tourism sector show no signs of cooling yet

Increased price levels also have negative consequences. They may lead to a drop in domestic demand, especially among price-conscious travellers or those with limited disposable income. Moreover, potential international visitors may opt for alternative destinations that offer similar travel experiences at more affordable prices. Those who still visit Spain will adjust their spending patterns to mitigate the impact of high prices.

In March, foreign tourists spent an average of €168 per day, up 7% from March 2022. However, given average inflation of 8.1% in the tourism sector, this equates to a 1% drop in real spending. It seems that, in order to cope with significant price increases, visitors are cutting back on certain expenses, such as choosing cheaper accommodation, budget-friendly restaurants and cost-effective activities. In addition, many travellers shorten their trips as another effective strategy to reduce overall travel costs. While the average duration of a trip was 8.0 days in March last year, it has now dropped to 7.6 days.

Tourism will be the main catalyst for economic growth this year

Tourism is a significant contributor to Spain's GDP. According to data from the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC), for the year 2019, tourism represented 12.4% of Spain's GDP. This includes the direct impact of sectors such as accommodation, catering, transport and tourist attractions. Taking into account indirect effects as well, tourism's total contribution to Spanish GDP reached 15.2%.

Further recovery of the tourism sector will play a central role in the country’s growth this year. After a significant decline during the pandemic, Spanish tourism could further restore its importance to the Spanish economy. With household consumption declining and expected interest rate hikes dampening investment dynamics, tourism will be a key driver of growth this year. Our forecast is for growth of 1.9% for Spain, surpassing the eurozone's expected growth rate of 0.5%.

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- March Madness

- AP Top 25 Poll

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Don’t let it flow: Tourists to Spain’s Catalonia may soon see water restrictions in the dry season

FILE - Joan Torrent, 64, walks toward his house carrying two plastic jugs of water refilled at a natural spring in Gualba, about 50 km, (31 miles) northwest of Barcelona, Spain, Wednesday, Jan 31, 2024. Spain’s drought-stricken northeastern Catalonia is considering imposing water restrictions on tourists in the driest parts of the region if domestic consumption is not curtailed, the Catalan government said Tuesday April 16, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti, File)

- Copy Link copied

BARCELONA, Spain (AP) — Spain’s drought-stricken northeastern Catalonia is considering imposing water restrictions on tourists in the driest parts of the region if domestic consumption is not curtailed, the Catalan government said Tuesday.

The restriction of 100 liters (26 gallons) per tourist per day for hotels would go into effect if a municipality fails to keep domestic water use by residents below established limits for three consecutive months under the current “drought emergency” for Catalonia, officials said.

Barcelona, Spain’s second largest city and the regional capital, uses 160 liters of water per resident per day — well below the current limit of 200 liters, Catalonia’s water agency said. That includes uses by residents for both washing and drinking.

Tourism represents nearly 12% of Spain’s economy. But there has been growing pressure by water conservationist groups to limit the use of water by tourists during the drought.

According to Barcelona’s hotel guild, the average tourist to Barcelona in 2022 used some 163 liters per day, while the figure rose to over 240 liters for luxury hotels.

The limits for tourists would not include the water used to fill swimming pools.

Also Tuesday, the Catalan government loosened restrictions that prohibited the filling of swimming pools with fresh water. Under the new measure, a privately-owned swimming pool can be refilled in a severe drought if authorities declare it a “climate refuge” open to residents seeking relief from the heat.

The regional government also made modifications to its drought restrictions to allow for the private use of desalination installations, a move hotel owners have demanded.

Catalonia has borne the brunt of a drought driven by climate change that has also impacted parts of southern Spain, though a wet spring this year has helped the situation . The reservoirs for Barcelona and surrounding areas that were at 15% of their capacity are now 18% full.

Even so, Catalonia has kept in place its restrictions under a water emergency declared in February to combat a drought regional authorities call historic. Those limitations include reducing average water use by 80% for crop irrigation, 50% for herd animals and 25% for industry.

Read more of AP’s climate coverage at http://www.apnews.com/climate-and-environment

Tourism in Spain

The most popular destinations in spain, development of the tourism sector in spain from 1995 to 2021.

Revenues from tourism

All data for Spain in detail

A cluster analysis of tourist attractions in Spain: Natural and cultural traits and implications for global tourism

European Journal of Management and Business Economics

ISSN : 2444-8494

Article publication date: 13 April 2018

Issue publication date: 17 October 2018

Natural and cultural tourism are important motivators for international tourism. Spain has impressive tourist attractions that are outstanding on the natural and cultural tourism dimensions. The purpose of this paper is to identify traits of the most attractive destinations in Spain and to understand the relative importance of natural, cultural, and dual (natural and cultural) attractions to target consumers.

Design/methodology/approach

The authors compare the level of tourism in the 17 major regions of Spain and identify the key natural, cultural, and dual attractions using a two-step cluster analysis to ascertain the relative importance of the three types of attractions.

The findings of the cluster analysis suggest that natural attractions had the highest importance, followed by dual attractions, with cultural attractions having the lowest importance in affecting the level of tourism in a region. The study identified four categories of regions resulting from “high vs low” total number of attractions by “high vs low” levels of tourism (operationalized via the number of tourist-nights). The regions with high levels of tourism were either located in the bodies of water (a group of islands) or on ocean/sea(s) surrounding Spain. The study suggests placing greater emphasis on promoting cultural attractions in Spain.

Practical implications

The findings suggest that there is a need to put more emphasis on promoting the cultural attractions in Spain. Spain is a diverse country with huge potential for tourism from people all over the world, due to its diverse geography and rich history.

Originality/value

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study that analyzes 17 regions of Spain in relation to their tourism characteristics, identifying attractions that are not sufficiently leveraged, and suggesting strategies for identifying opportunities for the tourism industry in Spain.

- Cultural attractions

- Dual attractions

- Natural attractions

- Tourist attractions

Lascu, D.-N. , Manrai, L.A. , Manrai, A.K. and Gan, A. (2018), "A cluster analysis of tourist attractions in Spain: Natural and cultural traits and implications for global tourism", European Journal of Management and Business Economics , Vol. 27 No. 3, pp. 218-230. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJMBE-08-2017-0008

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2018, Dana-Nicoleta Lascu, Lalita A. Manrai, Ajay K. Manrai and Allison Gan

Published in European Journal of Management and Business Economics . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

In 2016, the travel and tourism industry supported the global economy with 10.2 percent of global gross domestic product; this industry provided $7.6 trillion to the global economy and generated 292 million jobs. In 2016, these tourism-related jobs accounted for 10 percent of the jobs in entire world ( World Travel and Tourism, 2017 ). These figures are projected to grow even more over the next decade, and hold great potential for countries to generate economic growth, job creation, and develop nationally and regionally. International tourist arrivals were at 68.5 million in 2017, and that number is only projected to see more and more growth.

In Spain, tourism accounts for 5 percent of GDP and is a key economic sector; the industry employs one in ten of the workforce ( Euromonitor, 2017 ). Revenue from tourism has increased by 4.6 percent in 2017, and this trend is expected to continue ( Euromonitor, 2017 ). The success of tourism in Spain is attributed to the fact that, as a destination, it provides both cultural resources (ranked 2nd worldwide) and natural resources (ranked 9th), according to the World Economic Forum (2017) . Other important factors for Spain are the fact that it combines successful tourism service infrastructure with air transportation and policy support ( World Economic Forum, 2017 ). The cultural and natural attractions are recognized as the two top considerations and motivations for tourism. The fastest growing segments of the tourism industry today are the cultural – and historical – sites ( Timothy and Nyaupane, 2009 ) along with natural tourism ( Kuenzi and McNeely, 2008 ).

In its 2017 annual Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report, the World Economic Forum ranked Spain as first among the top ten countries on the Tourism Competitiveness Index. The rankings were as follows: (1) Spain, (2) France, (3) Germany, (4) Japan, (5) UK, (6) USA, (7) Australia, (8) Italy, (9) Canada, and (10) Switzerland ( World Economic Forum, 2017 ).

Spain is geographically very diverse. It shares borders with Portugal in the West and France in the Northeast. Spain is surrounded by many bodies of water – Mediterranean Sea in the East, Atlantic Sea, Gulf of Gibraltar and Gulf of Cadiz in the South, Atlantic Ocean in the West, and Bay of Biscay in the North. This waterfront location of Spain creates ample opportunities for water sports and adventure for tourists. Two very popular tourist destinations, namely, Balearic Islands and Canary Islands, are a part of Spain and a big draw for tourists. Inland, Spain has several mountain ranges, such as the Cantabrian Mountains, Iberian Mountains, Sierra Morena Mountains, etc. The country of Spain is thus gifted with abundant natural attractions.

Spain has a very rich history as well. Dating back to the Iberians and Phoenicians, cave paintings from that era still exist. Many historical attractions go back to the times of Romans. Roman rule was followed by the rule of Germanic tribes. A significant event in Spanish history is the Moorish invasion in 711 AD, with the Moorish rule lasting for nearly seven centuries, particularly in cities such as Seville and Granada. In later years, many of the Islamic monuments and buildings were taken over by Christian rulers, who built churches and cathedrals within the walls of the mosques. A classic example of the building of Islamic and Christian architecture is the Palace of Alhambra, which is probably the top cultural/historical attraction in Spain.

The purpose of the study is to identify traits of the most attractive tourism destinations in Spain using a two-step cluster analysis to ascertain the relative importance of natural, cultural, and dual attractions to target consumers. Once identified, promoting attractions that are not sufficiently leveraged will offer important opportunities to the tourism industry in Spain.